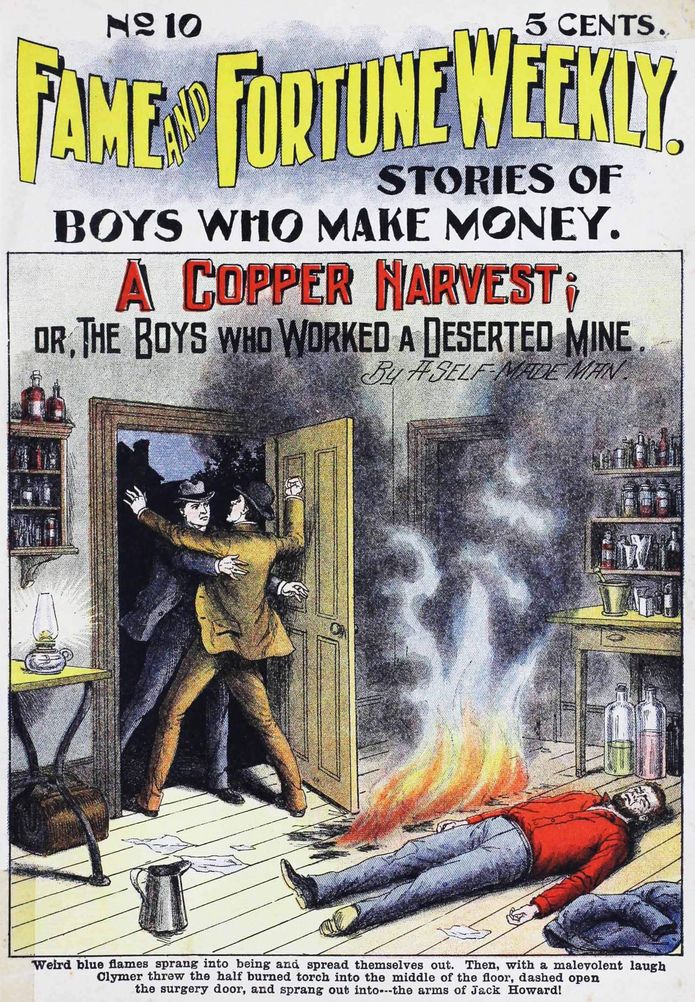

The Project Gutenberg eBook of Fame and Fortune Weekly, No. 10, December 8, 1905, by Self-Made Man

Title: Fame and Fortune Weekly, No. 10, December 8, 1905

A Copper Harvest; or, The Boys who Worked a Deserted Mine

Author: Self-Made Man

Release Date: February 25, 2022 [eBook #67500]

Language: English

Produced by: David Edwards, SF2001, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (Northern Illinois University Digital Library)

Issued Weekly—By Subscription $2.50 per year. Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1905, in the office of the Librarian of Congress, Washington, D. C., by Frank Tousey, Publisher, 24 Union Square, New York.

| No. 10 | NEW YORK, DECEMBER 8, 1905. | Price 5 Cents |

By A SELF-MADE MAN.

BACK TO LIFE.

“He’s the most lifelike corpse I ever saw in my life, and I’ve seen several in my time,” said Jack Howard, a stalwart, bronze-featured boy of seventeen. He looked down at the body stretched out on a slate slab in the center of the little surgery at the rear of Dr. Phineas Fox’s drugstore in the town of Sackville, Neb.

“He certainly does look natural—not at all like the usual run of subjects that find their way in here occasionally,” admitted his friend and chum, Charlie Fox, the doctor’s son, holding the kerosene lamp he carried in his hand well up, so as to bring the dead man into full relief.

“What would you imagine he died of?”

“Want of breath,” snickered Charlie, raising one of the corpse’s arms and then letting it fall back on the slab with a flop.

“Funny boy,” grinned Jack.

“Well, he dropped dead up at Mugging’s farm, where he stopped this morning and asked for something to eat. Of course he was sent here for father to hold a post-mortem on to determine the cause of death.”

Charlie’s father was the leading physician in Sackville.

He also officiated as coroner in all cases of sudden death occurring in the county.

At the present time he was absent on a similar kind of a case at a village some distance away, and was not expected back until late that night.

The doctor and his family lived in a neat little cottage, divided from his drugstore by the garden, and he was generally considered well-to-do.

Sackville was a town of some three or four thousand inhabitants, with outlying farms and farmhouses.

It was the county seat, and, being the largest place in the county, country people for miles around traded at its stores.

A good-sized river skirted its northern boundary, and the traffic in that direction made Sackville quite a lively place, and consequently of some local importance.

Jack Howard was a lad of good family whose people lived in New York.

A close student, too intense application to his studies had undermined his general health, and the family physician recommended that he be sent out West to rough it awhile on the large farm of a distant relative in Nebraska.

This farm was about three miles outside of Sackville.

Jack had already lived and worked like an ordinary farmhand on his relative’s place for the best part of a year, and his new life had made an altogether different looking boy of him—so much so, indeed, that his parents and friends in the East could hardly recognize the photograph of himself which he had lately sent them.

He often came to Sackville; and, being a genial, whole-souled kind of a boy, had made himself popular with all with whom he came in contact.

This was particularly the case with Charlie Fox, who instantly took an uncommon fancy to him, and the consequence was that they became chums.

Charlie had just graduated at the Sackville high school.

He had taken up the study of medicine under his father a year or so before, as the old gentleman intended his son should be his successor, and Charlie rather liked the profession.

His father proposed to send him to a medical school at Omaha soon, where he would get hospital practice.

Jack had come in to visit Charlie that afternoon, and as a matter of course he stayed to supper.

Mrs. Fox and her daughter Flora had received him with their usual hospitality, and after the meal the ladies and the two boys had put in a very pleasant evening.

About the time Howard was thinking of mounting his horse to ride back to the farm a fierce thunder and lightning storm had swooped down on the town, and so Jack was easily persuaded to postpone his departure until morning, to Charlie a great satisfaction, for he never tired of the society of his friend.

As soon as Charlie’s sister and mother went upstairs for the night the budding medicus proposed to his chum that they visit the surgery and inspect the corpse.

This gruesome suggestion meeting Jack’s approbation, they put on their hats and made a dash across the garden through the rain.

Charlie lit the surgery lamp and then turned down the sheet which had hidden the body from view.

It was then that Jack made the remark with which this chapter opens.

“Does your mother and sister know that this body is here?” asked Jack.

“No,” replied Charlie, shaking his head.

“Would it bother them any?”

“Well, they’re rather delicate about having dead ones so close at hand. Pop always keeps these things a secret; they never have the least idea there’s going to be an inquest till the jurors come—and not always then.”

“Put the lamp on that bracket, Charlie.”

“You don’t mind staying in here awhile, then?” said his friend, in a tone of satisfaction, as he placed the lamp on its rest, where the rays diffused a soft light around the little room and upon the various bottles and packages with their strange and peculiarly smelling contents.

“Not in the least,” answered Jack, heartily, pulling out a small briar-root pipe and a package of short cut and preparing to have a smoke.

“Glad to hear it. Some fellows would have the creeps at the idea of staying in this place with a corpse.”

“It doesn’t worry me in the least,” said Jack. “As for you, I suppose you are used to such things.”

“I see ’em occasionally, but not often enough to suit me,” replied Charlie, with professional enthusiasm. “In the last three months, however, I helped Mold, the undertaker, to lay out half a dozen of his cases, just to get used to handling dead bodies. I don’t want to be at all squeamish when I come to cut up parts of subjects on the dissecting table at Omaha. The old-timers there always have the joke on the newcomers, and as my father is a surgeon, I don’t want to disgrace the family, you know.”

“That’s right. Gee, what a crash!”

Jack walked over to the window, drew the curtain aside, and glanced out into the storm, which was now getting in its fine work with a vengeance.

“I’ll bet that bolt struck a house or barn not far away,” nodded the embryo medical student.

“I wouldn’t be surprised,” replied Jack, as he came back to the center of the room and viewed the face of the dead man meditatively, as if he was wondering what sort of a character he had been in life.

The corpse was that of an apparently well-nourished man of about fifty years of age; the bearded features were coarse and rugged, as if he had roughed it upon the plains or in the mountains of the West.

“Looks as if he might have been a miner, eh, Charlie?” suggested Jack.

“Yes, or a prospector, or something of that sort.”

“Or maybe a ranchman.”

“Sure; or a bad man from Piute Flat, or some other tough joint in the wild and woolly.”

“Hardly that,” objected his chum. “It is not a bad face, by any means. I don’t think I should be afraid to trust a fellow with his physiognomy.”

“You have more confidence in his face than I have, then. I prefer the civilized man every day in the year.”

“For looks, yes; but as for character—well, there are a good many undesirable individuals walking the streets of our big cities in fine linen and broadcloth to whom, I dare say, this poor fellow could give cards and spades in a lesson in morality. You can’t always judge a book by its cover, old chap.”

“That isn’t any lie, either,” admitted Charlie.

The young medical student had produced a cigarette from a flat, square box he kept hidden away in some mysterious pocket in his jacket, and lighting it, began to fill the surgery with the odor of Turkish tobacco.

“I see you smoke coffin-nails occasionally,” said Jack, beaming upon his friend. “Does the old gentleman stand for that sort of thing?”

“Hardly,” answered Charlie, with a sly wink. “I have to keep ’em out of sight when he’s around. I only tackle one once in awhile.”

Both boys smoked in silence for a moment or two, listening to the steady downpour of the rain on the tin roof, and the intermingled peals of thunder.

The vivid glare of the lightning was apparent in spite of the glow of the lamp.

“You’d have caught it in the neck if you had gone home to-night.”

“I’d have caught it all over, you mean,” grinned Jack. “By the way, you have a galvanic battery handy?”

“Yes. What do you want to do with it?” asked his chum, in some surprise.

“Well, I’ll tell you,” said Howard, confidentially. “This corpse looks so confounded lifelike that I can’t quite get it out of my head that maybe he isn’t as dead as he appears to be. It might be a case of suspended animation, for all you know.”

“I never thought of that,” replied Charlie, in a startled tone. “I’ll test him right away, though I guess he’s dead, all right. Father would do that before he used the knife on him.”

“What are you going to do?”

“I’m going to apply a stethoscope over his heart. Then I’ll try the eye test.”

“Better get the battery and try that. If it doesn’t produce results I’ll believe this man is as dead as a door-nail.”

Charlie stepped to the door leading to the boxlike room at the rear of the place.

“Meyer,” he called.

A short, round-faced German boy answered the hail.

“Vell, Sharlie, vot is der trouble mit you?”

“You know where our galvanic battery is, don’t you?”

“I ped you,” grinned the boy.

“Is it ready for use?”

“Yaw, I dink so.”

“Fetch it into the surgery.”

“So. I bed me your friend Yack is by the surgery, too, ain’d it?”

“Yes, he’s there, all right.”

“Und you vants der battery? You blay some shokes upon dot dead mans, ain’d it?”

“Never mind about that. Just do as I tell you,” and Charlie closed the door.

In a couple of minutes Meyer Dinkelspeil, Dr. Fox’s boy of all work in the shop, came in with the box containing the battery.

“Put it down here, Meyer,” said Jack. “You connect the wire, Charlie, while I turn the battery. Put the handles in the hands of the corpse.”

“They are rigid.”

“Place them between the fingers, then, and hold them tight,” said Jack.

“Chimmnay cribs!” exclaimed Meyer, looking on with wide open eyes. “You dink dot you voke him up mit dot foolishness?”

“Well, if we don’t we’ll try it on you afterwards,” grinned Charlie.

“You vill I don’d t’ink,” replied the German boy.

The apparatus being in place, Jack turned the electric current on.

Every moment the friction became brisker and the power stronger.

All at once the supposed corpse opened its eyes, which rolled in a strange manner.

Then a convulsive movement shook the body, the hands and feet twitched, and the jaw moved slightly.

“B’gee!” exclaimed Jack, “the man isn’t dead at all.”

“Shumping Moses!” ejaculated Meyer, almost frightened out of his skin. “Let me ouid!” and he made a rush for the door and disappeared.

“What a chump I was not to have tried that this morning when they fetched him in here,” said Charlie, as his chum stopped turning the crank of the galvanic battery. “It was a partial failure of the heart’s action, producing a trancelike state. Wait; I’ll get some brandy.”

He rushed into the store, measured out a gill of it, returned, and poured it down the man’s throat.

The effect was instantaneous.

He who but five minutes before had been considered a corpse had actually come back to animation.

THE COPPER SPECIMENS.

The man sat up on the slab, where, like many other unfortunate wretches, he had been placed preparatory to a post mortem.

He stared wildly around him, not comprehending the circumstances in which he was placed.

There was a little of the brandy left in the graduating glass, and Charlie held it to his lips.

He gripped the boy’s hands with his two great, rough fists, almost crushing the glass, and eagerly drained the liquor off.

Then he coughed, blinked his eyes, and sliding off the table, stood up.

He would have fallen, for he was as helpless as a scarecrow. But Charlie caught and supported him.

“Feel better now, do you?” asked the doctor’s son.

“Yes, kinder so; only I feel plaguey weak, and I’m stone cold.”

Charlie assisted him to the only chair in the surgery.

“What’s been the matter with me, and where am I? This is a doctor’s shop, isn’t it?” he added, looking around and observing the bottles and instruments.

“You were brought here this morning,” explained Charlie.

“This morning!” exclaimed the man, looking up at the lamp in its bracket. “And is it night now?”

“That’s what it is.”

“I must have been a long time out of my head, then, youngster,” he said, with a look of perplexity on his features.

“You were more than that.”

“How’s that?”

“You fell down—to all appearance dead—at the Mugging’s farm, three miles outside of town, and you were brought here to await an inquest.”

“Fell down dead!” gasped the stranger, with a look of blank dismay.

“That’s right. If you hadn’t come to under the influence of that battery—which my chum suggested applying to you because you looked so lifelike—my father would have carved you up in the morning to find out what caused your death.”

“By the great hornspoon!” cried the man, who had apparently been snatched from the grave by the experiment of Jack Howard. “I knowed it would come to this some day. I’m subject to epileptic fits. I’ve always been afeard I’d be buried alive in one of them.”

“You’ve had a narrow escape,” chipped in Jack, highly pleased at the success of his galvanic treatment.

“I guess I had,” admitted the man, breathing hard and looking around him with a fearsome expression. “I’m very grateful to you young chaps for what you’ve done for me.”

“Don’t mention it,” replied Jack. “We’re mighty glad we were able to pull you around. If you don’t mind, we should be pleased to know who you are.”

“My name is Gideon Prawle. I’m a prospector and miner by occupation, but just at present I guess I ain’t much better’n a tramp. I’m out of luck, that’s all. But I’ve seen the time when I was worth a cool hundred thousand. But I spent it in drink, at the gaming table, and I was robbed of a good bit of it, and that’s the whole story. I’ve been a blamed fool, but I hope to do better yet afore I die. I know something that ought to be worth another hundred thousand to me, and when I realize on it I shan’t forget you young fellows, not by a jugful.”

“You needn’t worry about us,” said Charlie, cheerfully, winking at Jack, as if it was his opinion the man had wheels in his head. “We don’t expect to be paid for what we did for you.”

The man saw the wink, and was evidently offended.

“Look here, my lads,” he said gruffly; “you think because I look like a tramp that I’m a regular hobo—maybe that I’m talking through my hat. I reckon I kin prove what I say.”

Then he began looking around the room.

“I had a grip with me this morning. Do you know what became of it?”

“I guess that’s it over in the corner,” said Charlie, pointing. “I took hold of it awhile ago, and I must say it’s precious heavy. What have you got in it—gold?” he concluded, with a grin.

“Fetch it here and I’ll show you,” said Prawle.

Charlie brought it forward and laid it at the man’s feet.

The stranger started to bend down to undo the straps, but fell back in the chair with a groan.

“Give me another drink!” he gasped, plaintively, while the perspiration indicative of physical weakness appeared on his forehead.

Charlie rushed into the shop for more brandy and returned in a moment.

Gideon Prawle gulped it down at a draught, and it brought him instant relief.

“That’s good stuff, and it warms me innards nicely,” he said, smacking his lips with a sigh of satisfaction.

“It’s the best in Sackville,” said Charlie. “It’s none of your common saloon firewater. No, sir; that is kept exclusively for the sick.”

“I believe you,” said the Westerner. “Now, if I might ask you another favor, it would be in the shape of something to eat. I’m most famished. Ain’t had a mouthful since yesterday afternoon.”

“Sure thing,” replied Charlie, with alacrity. “I ought to have thought of that myself. Meyer,” he called, stepping to the surgery door.

The German boy poked his head into the room in fear and trepidation.

“Vat haf you done mit der corpse?” he asked, seeing the slab vacant.

Then, as his eyes roved to the chair, his hair almost stood on end with fright.

“Mein Gott! Vot is dot?”

“Don’t be a fool, Meyer,” said Charlie impatiently, grabbing him in time to prevent him making a bolt. “The man was not dead. He was only in a trance, and we brought him out of it with the battery.”

“So,” replied the German boy, gazing at the stranger in fearful wonderment, “he been in dose transes under dot sheets der whole lifelong day, ain’t it? Vot a great dings dose battery vos, I ped you.”

“Go into the house, Meyer, and see what you can pick up in the pantry in the way of a cold bite. Fetch a jug of milk from the cellar.”

Meyer opened the door leading to the garden and looked out.

The storm had passed over the town by this time and was receding in a northwesterly direction.

“You’ll find the entry door unlocked, Meyer,” added Charlie. “See that you don’t make any unnecessary noise.”

“I vill look oud, I ped you,” replied Dinkelspeil. “Off I voke der cook ub I vouldn’t heard der last off it purty soon I dink.”

Then he vanished into the night.

Gideon Prawle, feeling better after the reaction, began undoing the straps of his grip.

Then he fumbled in his pocket for the key.

After taking out a somewhat rumpled shirt, a suit of underclothes and a couple of pair of socks, Prawle said:

“Now, young gents, I’m going to show you some of the finest specimens of real virgin copper ever dug out of mother earth.”

“Oh!” exclaimed Charlie, a slight shade of disappointment in his voice, “I thought it was gold or silver quartz you had there. But copper——”

“Young man,” said Prawle, diving one hairy paw into his grip and fishing out a magnificent specimen of raw copper, “look at that and hold your breath. There is ninety per cent of copper in that hunk. Think of that! It has only to be separated from its rocky matrix, when it is ready for market. That chunk, just as I took it from the mine, where there are thousands and thousands of tons of it waiting to be dug out, is almost chemically pure copper. That mine, young gentlemen, is a marvel. There’s millions in it. Nothing in this country to match it outside of the great Calumet and Hecla mine of Michigan, which has an annual production of 50,000,000 pounds.”

Jack Howard examined the specimen with great interest.

“Where is this mine you speak of?”

Gideon Prawle winked one eye expressively and moistened his lips with his tongue.

“It’s in Montana,” he said, with a significant grin.

“That’s a pretty big State,” said Jack. “Whereabouts in Montana?”

“That’s my secret,” said Prawle, “and I’m going to Chicago to sell it.”

“Then you have really located a valuable copper deposit?” asked Jack with kindling eyes, for he had a strong enthusiasm for anything connected with mines and minerals.

“That’s the size of it, young gent. It’s an old, deserted surface copper mine that was originally worked after a rude fashion by the Injuns, or some other folks who didn’t know its value. There’s millions of pounds there waiting for modern methods to bring it up to the light of day.”

Jack and Charlie looked at the several rich specimens Prawle laid out for their inspection, and then at one another.

Evidently this tramplike man, whom they had so strangely brought back to life, had stumbled on to a good thing.

Both of the boys had read stories of similar good things having been discovered by the merest accident, and the tales had excited their imagination at the time.

But this was different.

Here was evidence of a thrilling fact, and this prospect of sudden wealth, as it were, could not fail to have its effect on the two lads.

At this point Meyer made his appearance with an abundant cold repast, which, being placed before the stranger, he attacked like a famished wolf.

THE FACE AT THE WINDOW.

“Then you actually own the mine you have been speaking of?” said Jack Howard, regarding Gideon Prawle with a fresh interest.

Had the boy at that moment looked toward the window of the surgery, which had been raised a couple of inches a few moments before by Charlie Fox, he might have noticed that there was an uninvited listener outside.

This eavesdropper was Otis Clymer, late dispensing clerk for Dr. Fox, who had been discharged for his irregular habits and pilfering propensities.

The man had made himself unpopular in Sackville, and, but for the softness of the doctor’s heart, would have long since been sent away.

He had an evil heart, and instead of leaving town, where he could not hope to get suitable employment, he had hung about the lowest drinking resorts in the place and meditated upon revenge.

At this moment he was somewhat under the influence of liquor, and had made his way to the rear of the drugstore for the purpose of setting it on fire if he could find the chance to put his dastardly project into effect.

He was somewhat surprised to find that the little surgery was occupied, and he hung about and listened, hoping the coast would soon be clear.

What he heard through the opening at the bottom of the window, however, completely changed his purpose.

“Yes, siree, bob! I own the ground that there mine is located on,” said Prawle, with his mouth full of food, in answer to Jack Howard’s question. “At least I’ve a sixty-day option on it, which amounts to the same thing.”

“Then you didn’t have the money to buy it out and out?” asked Jack.

“No, I didn’t. Didn’t I tell you I’ve been in hard luck? I had just $100 in my clothes when I discovered that there ground was worth the buying, so I gave it up on account to the feller that owned the diggings. He wanted to sell so bad that he chucked in his shanty with it; not that it’s worth a sight more’n so much kindling wood.”

“How much ground did you buy?”

“I should think he had about four acres staked out.”

“And what did the whole thing cost you, Mr. Prawle?” asked Jack, full of curiosity.

“Well, it cost me $100 down, with $200 to come when I get back with the dust.”

“Pretty cheap for a real copper mine,” spoke up Charlie.

“You don’t s’pose he’d have sold it for that if he’d known as much about it as I did? Not by a jugful.”

“Was he a prospector, too?” inquired Jack.

“Jim Sanders wasn’t much of anything that I know. An old pard of his owned the ground and turned it over to Jim when he died. Sanders thought more of his booze than anything else; that’s why he wanted to realize. He had no use for the ground, and as it hadn’t cost him anything it was like finding money to sell it for anything at all.”

“And you’re going to Chicago to raise money to work the mine—is that your plan?”

“That’s the idea exactly. And I shan’t forget you two chaps in the deal, neither. You saved my life. If I had petered out here on that there table I shouldn’t have got any good out of the Pandora.”

“The Pandora!” exclaimed Charlie.

“Exactly. That’s the name I’ve given to the mine. It’ll look good on the engraved certificates when the company is formed: ‘The Pandora Copper Mining Company,’ Gideon Prawle, president. Maybe you’d like to be secretary, young man?” and he looked keenly at Jack Howard.

“I should rather enjoy the sensation of being secretary to a successful enterprise of that kind.”

“Would you? Well, perhaps you shall, for I’ve taken a liking to you. That reminds me you haven’t either of you told me your names.”

“Mine is Jack Howard, and this is my friend and chum, Charlie Fox. His father owns this store, and is the doctor who was going to hold the inquest on you when he got back to town.”

“I’m afraid he’ll be disapp’inted,” chuckled Gideon Prawle, taking a long drink at the milk jug.

“He’ll be rather pleased than otherwise,” ventured Charlie.

“Is that a fact?” said the stranger from the West. “I always thought doctors enj’yed cutting folks up so as to get at their innards.”

“There are exceptions,” replied Charlie, grinning at Jack.

“What’s the name of this town?”

“Sackville.”

“S’pose you get me a piece of paper, so’s I can put that down along with your names. I want to do what’s right by you young gents.”

Charlie got him a sheet of note-paper and a pencil.

Prawle set to work to jot down what he wanted to preserve for future reference; but it was easy to see that he was more used to handling a shovel or a pick, or something of that sort, than a pen or pencil, though he seemed to be a fairly well educated man, for his language was uncommonly good for a man of his appearance.

“If you were only going west now instead of east I should be tempted to go along with you,” said Jack, with a new-born enthusiasm for the great Northwest.

“Would you now?” replied Prawle, laying down his pencil and regarding Jack attentively.

“Yes. I came out West for my health, and have made myself a new man in a year. My people, who live in New York, look for me to return soon, but I’d rather rough it awhile longer, though not at farming, which is the way I’ve been putting in my time since I came out here. I always had a liking for mining. And I should fancy nothing better than getting an interest in a mine and putting in some big licks, if they would pan me out a fortune. Such things come to some people; why not to me?”

“That’s right, young man. I calculate you’re the man for my money. I’m going to give you an interest in my mine.”

“I’m willing to work for my share,” said Jack, earnestly.

“Oh, there’ll be plenty of work for you, I dare say, by and by when the company’s formed.”

“And how about my chum here?”

“He shall have an interest, too.”

“By shinger!” interrupted Meyer Dinkelspeil from the background, where he had been an interested listener and observer of the proceedings, “vhere don’t I come in in dose deals? Off Yack und Sharley pulled you togedder wit der battery, I put someding better as dot in your stomyack.”

“Haw, haw, haw!” roared the man from the West as he looked at the full-moon countenance of the German boy.

“Haw, haw, haw, yourseluf!” snorted Meyer indignantly. “I don’t see nottings funny in dot. Vot’s der madder mit you, any vay?”

“Would you like to rough it out in the mines, Meyer?” asked Jack, with a wink at his chum.

“Off dere vos plenty off moneys in dot I rough it yust as well as der next fellow, I ped you.”

“Why, they wouldn’t do a thing to you out there,” grinned Charlie.

“Is dot so?” retorted Meyer, incredulously. “Don’d you dink dot I took care off mineseluf yust so well as you or Yack?”

“S’pose you ran up against a bad man with a gun, what would you do?” asked Jack, with a wink at Prawle.

“Vot vould I done? I toldt you petter after I found me one off dose kind of snoozers.”

“I’m thinking if you acted as sassy as you do to us he’d fill you full of lead.”

“Is dot so-o-. He vould I don’d dink.”

“Well,” laughed Prawle, “I guess I’ll take you in with us—that is, if you’ll agree to go out to the mine and make yourself useful.”

“I done dot purty quick, I ped you,” said Meyer, eagerly. “I’m dot sick of dese places dot I shump der ranch so soon as now off you spoke der vord.”

“Why, I thought you wanted to become a doctor, Meyer?” grinned Jack.

“Vell, you know vot thought done, ain’d it?”

“My father wouldn’t want to lose so valuable an assistant as you, Meyer,” said Charlie.

“Off I vos you I vould forget id,” retorted the German boy, a bit crustily, for he could see that the doctor’s son was chaffing him.

“I tell you what,” said Jack, enthusiastically, “why couldn’t we go out to this place in Montana and take a look at the mine? This is your vacation, Charlie. You have more than four weeks yet ahead of you before you have to be in Omaha. We can let Mr. Prawle have the money to complete the purchase of the ground, so there won’t be any hitch about that. Then we could pay his way on to Chicago after that, and I would go with him to see that the mining promoter he picks out doesn’t do him up.”

“B’gee!” exclaimed Charlie, alive at once to the proposal, “it will be just the thing. If I represent the matter right to my father, he won’t object.”

“What do you say to that, Mr. Prawle? Will you go back with Charlie, myself——”

“Und dis shicken, don’d forget dot, off you blease,” piped Meyer.

“And Meyer Dinkelspeil,” continued Jack. “We’ll put up the $200 and all expenses; and afterward I’ll see you through to Chicago.”

“Do you mean it, young gentlemen?” said Gideon Prawle, interested in the proposal.

“Certainly we mean it,” replied Jack.

“Then it’s a bargain. I look on you now as my partners in the enterprise. Now, I’ll show you the paper by which I hold claim to the mine.”

Whereupon Prawle took out an old red pocketbook, extracted a not overclean bit of paper, which he unfolded and spread out on the slab which had lately been his bed.

“There’s my option on the ground,” he said, complacently. “The mine is situated at the head of Beaver Creek, three miles southeast of Rocky Gulch mining camp, and a mile eastward of the trail. The creek runs into the north branch of the Cheyenne River, which flows past Trinity, a railroad town, so that the copper can be easily shipped by rail East. Here’s a map, with all the points named, which I drew up to show its location in the State. Young gentlemen, it was a lucky day for you that you came to know Gideon Prawle.”

“And it was a lucky thing for you, Mr. Prawle, that I thought of applying the galvanic battery to your body,” replied Jack Howard, with a significant smile.

“Well, you shan’t never regret it,” answered the prospector heartily.

At that moment the clock in the surgery struck midnight.

Hardly had the last stroke died away when Meyer Dinkelspeil suddenly started to his feet and, pointing toward the window, exclaimed excitedly:

“By shinger! Look, vunce by der vinder—quick! Somepody vos looking in.”

A FIENDISH ACT.

Meyer’s sudden exclamation rather startled the group, and every eye was turned to the window.

If any one had been looking in, he had taken immediate alarm and vanished, for there wasn’t the sign of an eavesdropper to be seen.

Jack, however, rushed to the window and threw it up.

He looked up and down the street.

No one was in sight at that hour.

It was possible though for an active person to have sneaked around in front of the closed drugstore and made his escape by way of the cross street.

“I guess you imagined you saw somebody, Meyer,” said Jack, as he closed the window.

“I don’d dink,” asserted the German boy, stoutly. “Off I didn’t see der faces off dot Otis Clymer, I’m a liar.”

“Otis Clymer!” exclaimed Charlie Fox, blankly.

“Dot’s vot I said, I bed you.”

“What could he want around here at this hour of the night?”

“Nottings goot, off you took mine vord for id,” said Meyer, wagging his head sagely. “Dot rooster vos a bad egg.”

“That’s no lie, Meyer,” nodded Charlie, as if that fact had been patent to him for some time.

Just then a buggy drove up and turned into the yard of the Fox home.

Dr. Fox had returned, and, noting the unusual feature of a light in the surgery, he lost no time in making an investigation.

He opened the back door and walked into the room.

“What is the meaning of this gathering?” he asked a bit severely of his son. “Why aren’t you in bed, Charlie?”

Then he noticed Jack Howard, and nodded to him.

“Meyer, go to the stable and put the rig up,” he said to the German boy, who was the only one he had expected to find up waiting his return.

It was up to Charley to explain matters, and he hastened to do so.

Dr. Fox was amazed to find that the subject whom he had expected to hold an inquest on had come back to life in so astonishing a way.

He looked the man over with not a little curiosity, felt of his pulse, and then intimated that he guessed he didn’t stand in need of any treatment.

“I don’t wish to unnecessarily alarm you, sir,” he said to Gideon Prawle, “but it is probable you will die in one of those fits some day.”

“Then I hope that day may not be soon,” replied the man from the West.

“You may not have another one in years, and then again you may have one in a month. It is impossible to say,” was all the consolation Dr. Fox could offer him.

“If you wouldn’t mind, I’ll turn in here on the floor for the night,” said the Western man. “I’m used to roughing it. If you had a blanket, it’s all I ask.”

“I’d offer you a bed, if I had a spare one,” said the doctor; “but since you’re contented to stay here I’ll send you a blanket.”

This arrangement being quite satisfactory to Prawle, a blanket was presently brought to him by Meyer Dinkelspeil, and fifteen minutes later all was dark and silent in the surgery.

For a full hour there was no movement in the vicinity of the drugstore or the Fox cottage, yet all this time a form was hidden in the shadow of a big bush in the garden.

The intruder was Otis Clymer.

The night air had somewhat cleared his brain of the effects of the liquor he had imbibed early in the evening, and now his thoughts were busy with what he had seen and overheard in the surgery.

“If I could get hold of that paper—the option that fellow has on the ground where he discovered that valuable copper deposit—as well as the map and directions for locating the place, I should be a made man for life. I must manage it somehow. The man is doubtless asleep in the surgery long before this, and I have a duplicate key to the door which will readily admit me. Perhaps the fellow is a light sleeper and might hear me come in. That would be awkward for me, for he looks like a strong customer. Well, nothing venture, nothing win. It’s the chance of a lifetime. Then I shall want more money than I’ve got to get out there, not speaking of the $200 due on the ground. I must get a partner in with me, and who better than Dave Plunkett, who runs the joint where I’m stopping? He’ll back me in a good thing for half of the pickings. So, those boys propose going to the mine, do they? Ho, ho, ho! Not if I get my finger in the pie first. It must be one o’clock by this time. I’ll wait a while longer, and then I’ll make the attempt.”

Otis Clymer waited till half-past one o’clock, and then he left his damp berth under the big bush and approached the surgery door.

The moonshine projected his shadow across the turf, but for all the noise he made he might have passed for a ghost.

He cautiously inserted the key he had stolen into the lock and softly turned it.

Then he passed into the building like a shadow, and the door closed behind him.

The sound of deep breathing in one corner of the surgery located the sleeping man from the West, although Clymer could not distinguish his form very well in the darkness.

But the discharged drug clerk had planned what he would do, and, now that he was inside, he started to put his scheme in practice.

“I may as well kill two birds with one stone while I’m about it,” he muttered, moving softly toward the door leading into the shop.

The place was so familiar to him that he had no difficulty in finding his way about in the gloom.

He lit a small night lamp on the prescription counter; then he took down the bottle containing chloroform, and, not finding a rag suitable for his purpose, pulled out his handkerchief and soaked it with the stuff.

Then, taking the lamp with him, he re-entered the surgery.

Gideon Prawle lay curled up like a tired man close to the window overlooking the street.

Otis Clymer looked down at him with some curiosity.

The man had made a pillow of his coat, in one of the pockets of which were the papers the ex-drug clerk coveted.

His gray woolen shirt, open at the throat, exposed his broad shaggy breast where it came into view beneath his heavy, unkempt brown beard.

He certainly looked like a tough customer.

Clymer had resolved to drug the man into insensibility in order to avert the possibility of a personal encounter with him.

He knelt down by his side, and gently laid the saturated handkerchief over his face.

“That’ll quiet him effectually,” said the clerk, grimly.

Then he straightened up and waited.

After sufficient time had elapsed for the drug to operate, Clymer removed the handkerchief and looked at his victim.

Once more Gideon Prawle was the picture of death.

“He’s safe. Now for the papers.”

With no fear that he would be interrupted in his nefarious project Clymer went deliberately about his work.

He pulled the coat from under Prawle’s head and began to rummage the inside pockets for the faded red pocketbook he had seen the man produce before the boys.

Of course he found it.

“One wouldn’t think such a disreputable looking affair as this contained the germ of a big fortune,” he whispered to himself, while his little gray eyes twinkled greedily as he nervously fumbled with the rubber strap which held it together.

The option given by Jim Sanders was soon in his fingers, and he perused it eagerly.

After that he examined the directions which located the position of the mine.

There were also some newspaper clippings touching the recent market price of copper, as well as other odds and ends, which didn’t interest Clymer at that moment.

Returning all the documents to the pocketbook he restrapped it and put it into his pocket.

“That ought to satisfy Plunkett that I’ve a good thing in sight. I’ll offer him a third interest as an inducement for him to put up the money necessary to win out. If the mine is as valuable as this fellow, who seems to be an expert in such matters, asserts it to be, Plunkett and I will surely make a fortune.”

Clymer looked around the room with a wicked expression in his eyes.

“What’s one life more or less?” he muttered. “Nothing. They’ll think he got up in the night and accidentally set fire to the place. Thus, I’ll have my revenge on Fox for discharging me from the shop, and no one will be any the wiser. Ha! matters couldn’t have worked out more my way if I had arranged everything beforehand. With this man out of the way, the papers gone, the boys will have to give up their fascinating scheme of going out to the Northwest, and the way will be clear and easy for Plunkett and myself. I knew I was not born to have to drudge for a beggarly living. No; it takes money to see life, and money is now almost within my grasp.”

Clymer then took the night lamp and re-entering the back of the drugstore lifted a trap leading to the cellar.

Descending the stairs he went directly to a particular corner, where he knew a certain inflammable acid was kept in a large globular bottle of green glass, enclosed in a wooden framework for protection.

He took a quart measure, which lay on top of another carboy, and filled it with the fluid.

Then he returned to the surgery and began to sprinkle the stuff about on the floor and upon the surfaces of the walls.

This atrocious piece of work completed, he went to the door and looked out.

All was as silent as before.

Not a sound save the gentle sighing of the early morning breeze through the branches and leaves of the trees that lined the street.

The moon, shining over the roof of the Fox cottage, threw his figure into bold relief as he stood there in the doorway.

It lighted up the malignant grin which spread over his features as he glanced over at the doctor’s house.

“It’s a nice awakening you’ll have in a few minutes, doc,” he chuckled sardonically. “It isn’t much you have gained by giving me the sack. No man does me dirt but I get back at him for it.”

Then he shut the door again, leaving it slightly ajar, so that nothing might hinder the rapidity of his escape as soon as he had put the finishing touch to his contemplated crime.

This he hastened to do.

He made a torch of an old newspaper, ignited one end at the night lamp, and then touched the acid-sprinkled floor here and there, and wherever the fire of the torch touched the wood weird blue flames sprang into being and spread themselves out.

Then, with a malevolent laugh, Clymer threw the half-burned torch into the middle of the floor, dashed open the surgery door and sprang out into—the arms of Jack Howard.

WITHIN AN INCH OF HIS LIFE.

“Otis Clymer, what are you doing here at this hour in the morning?” exclaimed Jack, holding a strong grip on the struggling clerk.

“None of your business—let me go!” gritted the villain, using every effort to free himself.

Then Jack caught a glimpse of the spreading fire through the half-open surgery door, and the sight clearly startled him.

“You rascal,” he shouted. “You’ve set fire to the store.”

Clymer, fairly frantic at the idea that he had been caught in the act of not only destroying the doctor’s establishment, but also a human life, struck the boy a heavy blow in the face.

Half stunned, Jack partially released his hold on Clymer, and the villain, taking advantage of that fact, wrenched himself free, tripped the lad up and rushed out of the garden into the street and disappeared.

Jack, however, pulled himself together in a moment, and seeing that Clymer was beyond his reach he banged open the surgery door and rushed inside that he might ascertain the extent of the danger.

The glare of the fire showed him the ghastly countenance of Gideon Prawle turned toward the ceiling.

“Wake up! Wake up, Prawle! The place is on fire!” cried Jack, seizing the man from the West and shaking him roughly.

But Prawle never made a move of his own accord, but lay like a log in the boy’s grasp.

“What’s the matter with you? Wake up!”

Jack grabbed him with both hands and pulled him up into a sitting posture.

Prawle’s head rolled over on his shoulder like that of a dead man.

“In Heaven’s name, what can be the matter with the man? He looks like death. Has he had another fit?”

It may be easy to ask questions, even in a moment of intense excitement, but it certainly is not so easy to find an answer to them when the object to whom they are addressed turns a deaf ear to our importunities.

“This is terrible!” exclaimed the boy, the perspiration oozing out on his forehead. “I must drag him out of here.”

Gideon Prawle hung a dead-weight in his arms, but Jack was strong enough to handle him easily enough.

He laid him down in the damp grass a short distance from the surgery, and then started in to put out the fast increasing flames.

There was a water-butt at one corner of the building, and somebody, probably Meyer, had left a horse bucket beside it that afternoon.

Jack seized the bucket, pushed the cover off the barrel, and filling the implement with rain water rushed into the blazing surgery and dashed the water upon the flames.

This he repeated as fast as he could traverse the short space between the barrel and the room.

Fearing he might not be able single-handed to subdue the flames he yelled “Fire!” lustily each time he came out.

Both Dr. Fox and his son, who were sleeping soundly, heard his shouts at the same moment, and both sprang out of their beds and rushed to a window to look out.

Charlie missed his chum at once, for the pair had occupied the same bed, and for an instant he wondered where he had gone.

“Fire!” came up Jack’s voice again.

“Good gracious!” exclaimed Charlie, “That surely is his voice,” and he threw up his window, which faced almost directly on the surgery.

At the same moment he heard the window of the front room go up with a bang, and his father’s voice exclaim:

“Hello! What’s wrong?”

For the moment there was no answer as Jack had just taken another bucket of water inside.

But he presently reappeared with the empty bucket swinging in his hand.

He presented a strange sight to Charlie, for his hair was disheveled, he was attired only in his trousers, undershirt and boots, and his face was flushed from the exertion and excitement.

“Hello, Jack!” exclaimed the doctor’s son. “What the mischief is wrong?”

“The surgery is on fire,” replied Jack, hurriedly.

“On fire!” ejaculated Charlie, aghast. “Great Scott!”

“Come down and lend me a hand. I think I have got it under control.”

Thus speaking, he vanished into the building again with another pail of water.

Dr. Fox had caught enough of this brief colloquy to understand that something was out of joint at the store, and naturally he hastened to get into a portion of his clothes and rush to the scene of action, where he arrived almost as soon as his son.

The flames had obtained some headway before Jack Howard had got busy in an effort to subdue them; but his exertions had been well directed, and he had managed to keep them from spreading to the shop.

“Get another bucket or something, Charlie,” he shouted, as soon as he perceived his chum dashing out from the side door.

There should have been a bucket beside the well in the yard near the barn, but as it was not there now it is probable it was the one in Jack’s hands, misplaced by the German boy.

To get another, Charlie had to get into the stable or barn, as the building was called, and as it was always kept locked at night, the key being in charge of Meyer, who slept in the loft or attic, the doctor’s son had to wake up the Dutch boy, who was a heavy sleeper, by pounding like mad on the side door which opened on to the stairs.

He had to make noise enough to awaken the Seven Sleepers before one of the small windows in the loft was opened and Meyer’s big head appeared.

“Vot you vants down dere, any vays? Vot you dook me for?—der doctor? Well, go by your pus’ness aboud und voke ub der right barty.”

“Wake up, you thick-headed fool!” cried Charlie, quite out of patience.

“Vhy, it don’d peen you, Sharlie?” exclaimed Meyer in an astonished voice.

“Will you throw down the key of the barn?”

“Vot you vants mit der key off der barns?”

“Do you want me to come up and fire you out of the window? Throw down the key, do you hear?”

“I hear, I ped you. Vell, vait a moments und I vill drow it down.”

Charlie waited for it in a fever of impatience.

“Now, get into your clothes and come down yourself as quick as you can,” he cried to the boy, when the key flopped at his feet.

“Shimmany Christmas!” grumbled the German lad, as he watched Charlie rush to the barn with the key. “Dis vos a nice hour to voke a feller ub, I don’d dink. Off I stood it much longer I am a yackass.”

Dr. Fox, when he appeared on the scene, was amazed to find the unconscious form of Gideon Prawle lying stretched out like a dead man upon the grass.

He passed him, however, to take a flying look into the surgery, and see how serious matters were in that quarter.

“You can’t do any good here,” said Jack. “Better look after Prawle. I’m sure something serious has happened to him. Charlie will be with me in a moment with another bucket, and the pair of us ought to be able to put this blaze out.”

Jack spoke encouragingly, for he saw that he already had the fire under control.

So Dr. Fox returned to the stranger from the West, and his experienced nostrils immediately detected the fresh odor of chloroform.

“Has the man committed suicide?” was his first thought. “No, he is not dead,” he said to himself, after he had put his ear down to the man’s chest and listened with professional accuracy for indications of heart-beats.

Dr. Fox being a small man, it was a physical impossibility for him to drag the big prospector up on his stoop out of the dampness.

The best he could do was to drag him over to the gravel walk, and this required much effort on his part.

Then he went into the cottage to get certain remedies to bring the man back to his senses.

With Charlie’s assistance Jack finally subdued the flames inside of another ten minutes, but a considerable amount of damage had been done to the surgery.

“B’gee! This is fierce!” cried Charlie, as the two boys, having thrown their buckets aside, stood contemplating the ruin wrought by the fire. “Have you any idea how this occurred?” he added, turning to his chum.

“Well, I think I have,” replied Jack, with a frown upon his handsome face. “The surgery was set on fire by Otis Clymer.”

“You don’t mean that!” exclaimed young Fox, starting back in astonishment.

“Well, I don’t mean anything else,” replied Jack stoutly.

“Tell me what ground you have for thinking so. This is a serious charge to bring against that fellow. It will lead to his immediate arrest and prosecution. If sustained he will surely be sent to the State prison for a good many years, for arson is a crime severely dealt with.”

“He’s not merely guilty of attempted arson, Charlie,” said Jack, with a serious face, “but the scoundrel actually left Gideon Prawle to perish in the flames.”

OTIS CLYMER AND DAVE PLUNKETT AGREE TO PULL TOGETHER.

“Is it possible!” gasped Charlie Fox, his eyes sticking out.

“It is an awful truth,” answered Jack, solemnly. “I don’t know exactly what made me wake up, unless it was the dream I had. At any rate, I woke up with a feeling upon me that something was wrong. I tried to get asleep again, but I couldn’t, which is an unusual circumstance with me. Finally I got up and went to the window of your room to look out. It was bright moonlight, and everything was quiet all about. The surgery, you know, was almost in front of me, and my eyes took it in with the rest of the scene. I was astonished to see the door open and some one standing on the doorstep. At first I fancied it was Prawle, but I soon perceived it was the figure of a much smaller man. He was standing in the full glow of the moonshine. Then I recognized Otis Clymer. I knew he had no right to be there after what had occurred, and I watched him attentively. In a moment he turned around and disappeared into the building, closing the door after him. I was sure he had some bad purpose in view, so without waking you, I hurriedly slipped on my shoes and trousers; ran down stairs, let myself into the garden by the side door and started for the surgery. Hardly had I reached there before the door was suddenly jerked open and Clymer rushed out into my arms, nearly upsetting me. But my suspicions being aroused, I held on to him and demanded to know what had brought him there at that hour. He told me it was none of my business, and struggled to get away. Then I caught sight of the fire inside. I accused him of the crime, when he managed to strike me a stunning blow in the face, wrenched himself free and dug out of the garden. Then I entered the surgery, and found Prawle stretched out, the picture of death, and I had all I could do to get him out of reach of the flames.”

“This is terrible!” ejaculated Charlie. “I never liked Clymer, and it is only lately we found out he was actually crooked in many little ways; but for all that I should never have dreamed him capable of committing such a dastardly act as setting fire to the store, not to speak of abandoning a fellow creature to such a fearful death as must have been the case if his plan had succeeded. Jack,” continued his chum, grasping him by the hand and shaking it warmly, “Mr. Prawle not only owes his life to you a second time, but father and all of us owe you a debt of gratitude for saving our property.”

“Don’t mention it, Charlie; rather thank an all-wise Providence, whose humble instrument I was, that an awful crime has been averted.”

“Boys,” interrupted the voice of Dr. Fox at that moment, “I want you to help me carry our strange visitor into my office.”

“Sure we will,” answered the boys in a breath.

“How is he?” asked Jack, as they drew up alongside the still unconscious Prawle. “Not dead, I hope.”

“No,” replied the doctor, in a serious voice, “but he is in a bad way. He has been drugged by chloroform. Must have tried to take his own life.”

“Not at all,” answered Jack, much to the doctor’s surprise. “If he is drugged, it is the work of Otis Clymer.”

“Impossible!” cried Dr. Fox, incredulously.

“Well, after I tell you what I know of this night’s, or rather morning’s, affair, I think you will agree that a deliberate murder, as well as arson, has been attempted.”

And Jack retailed the whole story to the doctor as soon as he and Charlie had laid Prawle upon the office lounge.

Dr. Fox was thunderstruck.

He could not doubt but Jack had stated the facts exactly as he had found them.

“What a villain that fellow is! And to think he has been in my employ for nearly a year. Why, the man might have poisoned one of my patients, and have got me into endless trouble.”

The doctor wiped the perspiration from his face.

“He shall be arrested at once, and prosecuted to the full extent of the law. Indeed,” with a glance at Prawle, “it may yet end in a hanging matter. What could have been his object?”

“I suppose it was to revenge himself on you for his discharge,” suggested Jack. “But why he should have included this poor fellow in his scheme is more than I can guess. It is possible Prawle may have woke up and caught him in the place, and that Clymer then struck him down and managed to give him a dose of the drug, which, from his knowledge of the store, he could readily put his hands on.”

“We shall probably get at the truth after this man comes to his senses, or it will come out when that young scoundrel is tried.”

“Well, he will have to be caught first. I’ll bet he is out of town long before this.”

“I’m afraid so,” admitted Dr. Fox, reflectively. “You had better dress yourself, Charlie, and run around to the home of the head constable, Martin Willett, and have him come here at once.”

“All right,” acquiesced his son. “Jack had better come with me.”

So the two boys ran up to their room to put themselves into shape to go out.

In the meantime, Otis Clymer, thinking of the ill-luck which had led to his recognition and the probable failure of his scheme to get square with Dr. Fox, made the best time he could in the direction of the small hotel kept by Dave Plunkett down near the river which ran by the town.

The Plunkett House was the one eyesore of Sackville.

All self-respecting people considered it a disgrace to the town.

But as Plunkett was shrewd enough to keep within the pale of the law he could not be disturbed.

Report represented him as an ex-prize fighter, and report was probably correct.

He looked it at any rate.

Some people even hinted that they believed his picture adorned the Rogue’s Gallery of more than one big city.

At any rate, when he sported his summer crop of hair his smoothly shaven face would have stood as a good model for a convict’s.

It is quite possible all the evil things whispered about Plunkett were more or less exaggerated, but, just the same, the good citizens of Sackville would have been well pleased to have parted company with him.

And this was the man Otis Clymer had cultivated as a friend.

The acquaintance began when Otis went into the billiard-room to play pool.

Then he made himself solid by treating the crowd frequently.

Finally Plunkett suggested that he come there to board.

Clymer fell in with the idea, and that settled whatever little reputation Otis had not already lost.

Dr. Fox put up with a great deal from his clerk, but he couldn’t stand for that, and so he discharged the foolish young man.

It is probable Plunkett was playing Otis Clymer for a good thing, and would give him the bounce as soon as his funds ran out.

It was close on to three o’clock when Clymer reached the Plunkett House, all out of breath from his run.

As far as appearances went, Plunkett’s was closed for the night.

But it wasn’t really so.

There was a big game of pool on in the billiard and bar-room, the participants in which were mostly bargemen who plied on the river.

They were a rough lot, but you could not class them as really bad men, at least not the large majority.

They frequented Plunkett’s because it was a free-and-easy resort, and was handy for them to congregate at.

Dave Plunkett was behind the bar, helping his assistant out.

Clymer rushed into the place through a side door abutting on the river.

This was the only entrance open to customers after one o’clock in the morning.

Otis called for whisky, and poured out such a stiff dose that Plunkett looked at him in some surprise.

He swallowed it at a single gulp, and then asked Dave if he could see him in private.

“Cert,” answered Plunkett, regarding his customer with a suspicious stare. “But what’s up? You looked excited. You ain’t been doin’ nothin’ that’ll get you into limbo, have you?”

“Never mind what I’ve been doing,” retorted Clymer, shortly. “I’ve got something to tell you that you’ll be glad to learn.”

“Will I?” said Plunkett coolly. “Well, go into my little room, at the back of the office. I’ll be with you in a moment.”

“When I left here to-night,” said Clymer to Plunkett, when the proprietor of the establishment joined him in his private room, “I was half-shot; but I was resolved to get square somehow with old Fox for discharging me from his shop.”

Plunkett nodded as if he had suspected some such intention ran in his customer’s brain.

“I may as well tell you I meant to set the old ranch on fire if I could get the chance, and I thought I could, as I had a key to the surgery in my pocket.”

His companion said nothing, but regarded him with attention.

“When I reached there about half-past eleven I expected to find the coast clear, for I knew a dead man had been fetched to the surgery in the morning for a post-mortem, and such being the case the room is usually not visited.”

Plunkett, perhaps scenting a longish story, got out his pipe, filled it and began to smoke.

“I was surprised to find the surgery lit up, and, wondering what was going on inside, I crept up to the window overlooking the street and peered in. Fortunately, it was open several inches, and I heard something which set me on a new track.”

“Umph!” muttered Plunkett.

Then Clymer proceeded to detail how the corpse had been brought back to life, much to his listener’s amazement.

When he came to disclose what had transpired in relation to the copper mine out in Montana, Plunkett got interested.

“I determined to get possession of that mine myself,” went on Clymer.

“You!” exclaimed Plunkett, in some astonishment.

“Yes, me. If I could get hold of the papers, especially the option on the property, I believed I could depend on you to see me through in change for an interest in the mine that would be as good as a fortune to you.”

“Well,” said the hotel keeper, more interested than ever.

“Well, I’ve got them,” replied Clymer, triumphantly.

“You have?” in surprise.

“I have; but——” and Otis looked at his friend the landlord with a shaky expression.

“Well, what’s the trouble?”

“The trouble is, I was detected in the act of setting the surgery on fire by a friend of the doctor’s son, named Jack Howard, and had to run for it.”

Plunkett whistled softly.

“You can’t get out of town any too quick for your personal safety, Clymer. Arson is a serious charge to have brought against you, and if convicted would mean anywhere from ten to fifteen years in the State prison.”

“Yes, I realize that. But there is no use now in crying over spilled milk. I’m going out to Montana to try and get possession of that copper mine, and what I want to know is, Are you with me? This is my plan.”

Otis Clymer produced the faded red pocketbook which belonged to Gideon Prawle, discoursed glowingly as to the exceptionally rich quality of the copper specimens brought from the mine by the prospector, and explained how he believed that a small amount of money judiciously invested in the person of Jim Sanders would secure them the ownership of the mine, as the option held by Prawle being in his (Clymer’s) possession it could not be produced to complete the original bargain.

“Five hundred dollars ought to do the business for us,” concluded Otis, eagerly. “Prawle, if he survives the drug I gave him, will be left out in the cold, and you and I will come into a mint of money when we sell our right and title to the mine to capitalists who know a good thing when they see it.”

Plunkett was a cautious man as a rule—a virtue which kept him out of difficulties many a time; but the arguments advanced by Clymer seemed convincing, and at the same time excited his cupidity.

The two men talked over the scheme until daylight, and finally came to an agreement satisfactory to both.

Arrangements being completed, Clymer packed a grip with such articles as he considered indispensable and left the Plunkett House to catch a freight train which passed through Sackville at five o’clock.

Two days afterward, Plunkett himself vanished from town, leaving his establishment in charge of his wife.

ROCKY GULCH AND NEIGHBORHOOD.

It was a bright day one week from the stirring events just narrated.

The scene has changed from the bustling little Western town of Sackville to the wilds of the State of Montana.

The exact spot was a point three miles southeast of a rough-and-ready mining settlement known as Rocky Gulch, and seven miles, as the crow flies, from the town of Trinity on the North Branch of the Cheyenne River.

On one side was a rocky hill, pierced at this particular locality by a rude opening, which might correctly be termed a cave, though it looked more like a hole in the wall of rock than anything else.

On the other side was the head of a wide creek, to which the name of Beaver had been applied, and a narrow, circuitous stream ran into it from its source somewhere in the hills beyond.

Two men—one of whom bore a strong likeness to Otis Clymer, the other to Dave Plunkett—were standing midway between the cave and the creek.

“This must be the place,” said the former, referring to a slip of paper he held in his hand.

“Where’s the mine?” asked Plunkett, in a tone which showed he was not wholly pleased with the outlook.

“That hole yonder must be the entrance to it,” suggested Clymer.

“If you think so, then the sooner we look into it and find out whether it is or not, the better I’ll be pleased. Before I plank up the dust I want to know what I’m investing in.”

“That’s all right,” returned Clymer. “But you didn’t expect to pick up a full-grown mine all in working order, with machinery on the ground, for a paltry two or three hundred dollars, did you?”

“I don’t say that I did,” asserted Plunkett; “but I ain’t goin’ to buy a hole in the ground without I’ve some idea of what’s behind it. If you can show me real copper in there, that’ll be proof the man’s story wasn’t all moonshine. Then we’ll go and hunt up this fellow Sanders and make it an object for him to forget he ever gave an option to somebody else, and buy him out.”

“Come along, then. We’ve got torches which, when lighted, will show us the way through the darkness.”

The two schemers walked over to the opening in the rock and entered the crevice.

They were out of sight for perhaps an hour, and when they emerged into the light of day once more it was apparent their quest had been satisfactory, for their eyes burned with an eager glow.

“I hope you’re satisfied,” said Otis Clymer, triumphantly.

“Satisfied!” exclaimed Plunkett. “Well, I guess I am—more’n satisfied. That there mine is a mint for us two. I’m with you hand and glove from this minute, but it must be halves—share and share alike, do you understand?”

“But you agreed to take a third in the first place,” protested Clymer, half angrily. “The risk of getting those papers has all been mine. I ought to have the larger share.”

“Can’t help that,” replied Plunkett, doggedly. “You can’t do nothing without money, and I’ve got the dust. I’ve made up my mind to be an equal partner, and so halves it’s got to be.”

“But I hold the option on the ground,” insisted Otis.

“Pooh! What good is it to you? It ain’t in your name, and if it was you haven’t the money to complete the deal. What you want to do with that option is to destroy it; then it won’t turn up to put us in a hole, may be. I’m goin’ to look up Jim Sanders right away. If he’s the soak you say he is, I shan’t have much trouble in gettin’ a bill of sale for that hill out of him. Now let us settle the thing right here. Are we even partners, or are we not?”

“You’ve got me where the shoe pinches, so I have to agree,” said Clymer, reluctantly.

“Now you’re talkin’ sensibly. I never like to go into a deal where the other man has the bulge on me. I’m treatin’ you perfectly fair, for money counts every time, and it’ll take money to put this thing through. You don’t know what trouble we may be up against if that fellow Prawle turns up out here and makes a squeal. Without me at your back you would be lost. Now that we’re equal partners in the enterprise I’ll see you out of it same as myself, no matter what the consequences happen to be. So shake hands on it.”

Otis Clymer saw that Plunkett was really master of the situation, and he had sense enough to understand that he couldn’t do a thing without his companion’s backing, so he held out his hand in an apparently cordial way, and the compact between the two was sealed then and there.

Plunkett produced a big flat bottle from one of his hip pockets, and they both drank success to the scheme in which they were embarked.

Then they took the back track, which brought them to the trail a mile distant, and the trail landed them in Rocky Gulch in the course of an hour.

The Gulch was a settlement of perhaps three hundred inhabitants.

It was not greatly different from some hundreds of other mining camps which have from time to time sprung up in the western wilderness in a night, flourished for a brief time, and then disappeared as the occasion for their existence passed away.

It had its stores, saloons, assay offices, so-called hotels, and all the business establishments that characterize such places.

It was picturesque and novel in its way, though life here was perhaps a sterner reality than in more civilized communities.

Many of the buildings were constructed of wood brought from Trinity, but by far the majority were of canvas, being both cheaper and more readily moved.

The stores, saloons and hotels were ranged side by side along what might be considered the main thoroughfare, while the canvas dwellings were pitched here and there irregularly.

The majority of the men at Rocky Gulch were industrious miners; but, as might be expected, there were not a few disreputable characters also—gamblers, whisky sellers and loafers, who lived on the sweat of other men’s brows.

Though Trinity, the river town, was not far away, Rocky Gulch had found it necessary to elect a vigilance committee to preserve a semblance of order, and this committee had a repressing effect on the lawless element.

Many dangerous and worthless characters had been run out of the camp time and again, but for all that the inhabitants with one accord always went about armed, for no one could say when he might be up against trouble.

When Otis Clymer and Dave Plunkett came over from Trinity that morning to look up the copper mine they first put up at the Rocky Gulch Hotel.

This establishment, the most pretentious by the way in the place, consisted of three good-sized rooms, constructed of timber.

The front room, facing on the street, was occupied by a small office and a big bar; the middle apartment as a kitchen and dining-room, while the rear room was lined with rough bunks, without bedding of any kind, for the guests to spread their own blankets and sleep as best they could.

It was dinner time when the two schemers got back to Rocky Gulch, and after that meal they lost no time striking up acquaintance with many of the habitues with the view of finding out the present whereabouts of Jim Sanders.

But not one whom they accosted could say where Sanders might be found, though the general opinion seemed to be that Jim was blind drunk somewhere in Trinity.

He had disappeared from Rocky Gulch on the day he had received the hundred dollars from Gideon Prawle, and given that individual the option on his property.

That was all Clymer and Plunkett could learn, and they were grievously disappointed.

They were extremely anxious to settle up the business right away, lest Prawle appear on the scene and cause trouble.

“I don’t see but that we must go back to Trinity,” said Clymer. “The man doesn’t seem to be here.”

And so to Trinity they returned and began a search for Sanders there.

JIM SANDERS.

On the afternoon of the following day a party of four stood facing the opening into the deserted copper mine.

The most prominent of the group was the bronzed and bearded Gideon Prawle, who had fully recovered from the effects of the drug administered to him by Otis Clymer.

The other three, it is almost needless to say, were Jack Howard, Charlie Fox and Meyer Dinkelspeil.

No difficulty had been experienced by Charlie in obtaining his father’s permission to accompany Jack Howard and Mr. Prawle to Montana after Gideon had explained the situation to the doctor and shown him the magnificent specimens of pure copper he carried in his grip.

As soon as Prawle missed his pocketbook a new light broke in on those in the secret.

They agreed that the thief was Otis Clymer; that Meyer had been right when he said he had seen Clymer’s face at the partly open window that night, and that the villain set fire to the surgery not only for the purpose of revenging himself on Dr. Fox, but to effectually get rid of Gideon Prawle as a bar to his newly-hatched plan of getting possession of the copper mine for himself.

Dr. Fox had strongly objected to losing the services of his German boy, who was a handy factor in his establishment.

But Meyer had made up his mind to go to Montana with the others, and it was useless to oppose him, for he declared he would surely run away of his own accord.

As Prawle and the two boys took his part, and interceded in his favor, the doctor was prevailed upon to give a reluctant consent to his going with the party.

“Well, boys, here we are on the ground at last,” said Prawle, enthusiastically. “Here’s the creek I spoke to you about which runs into the North Branch of the Cheyenne River, five miles or so away, and yonder you see the hole in the rock which affords entrance to one of the richest copper deposits in the great Northwest. Unfortunately, it isn’t really ours as yet till we find Jim Sanders, who sold me the option on the property.”

“And it may never be ours as the case stands,” said Jack, gloomily. “Otis Clymer, who robbed you of your pocketbook, and thereby came into possession of the option, has probably destroyed that document, and it’s pretty certain he lost no time coming here to get the inner track of you. His object, of course, if he has been able to raise the money necessary for his purpose, is to meet Sanders and persuade that very unreliable person to sell him the ground, knowing that this course will be perfectly safe, since you will never be able to present the option yourself. If, after he has accomplished this, you interfere with your claim he will demand that you produce the option, which, of course, you cannot do. Our only hope in this matter is to run across Jim Sanders before Clymer can get his work in. All you will then have to do is to pay down the balance of the purchase money, and get a bill of sale of the ground.”

“That’s all right,” spoke up Charlie Fox; “but even if he does succeed in getting the bulge on us, what is to prevent us having him arrested on a telegraphic order from Sackville, for the double crime of attempted murder and arson?”

“We could try that, of course, but I fear we should meet with many difficulties out here, especially if he is smart enough to make friends with an eye to that particular contingency, and the fellow is not such a fool but to understand and provide against the risk of arrest and subsequent extradition to Nebraska.”

“Vell, off ve lets dot rooster got der best off us, den I votes ve go py der wilderness oud und kick ourselufs for a bardy of shackasses,” interjected Meyer Dinkelspeil, with solemn earnestness.

“Good for you, Dutchman,” said Prawle, slapping the round-faced youth on the shoulder. “And now, boys, follow me into the mine and I will show you a sight which will make your mouth water. You will see more copper in five minutes than you ever looked at in all your lives before.”

A couple of hours later Gideon Prawle and the boys returned to Rocky Gulch.

They ate supper at the hotel, and having arranged to bunk there for the night, Prawle set about making inquiries relative to Jim Sanders.

“I never know’d Jim Sanders to be of sich importance as he seems to be jest now, stranger,” said the landlord of the Rocky Gulch Hotel, when Prawle button-holed him in search of the information he wanted. “You air ther second one in two days wot wants to know ther wharabouts of Lazy Jim, as we call him, for we’ve never known him to work a day sence he came to ther Gulch nigh on to a year ago. ’Pears to me your face is kinder familiar, pard. Warn’t you ’round these diggin’s a fortnight or three weeks ago?”

“I was,” said Prawle. “I bunked here a couple of nights and had my meals in your dining-room.”

“Wal, now, I thought I warn’t mistook in your phiz. We hev strangers comin’ and goin’ all ther time, but I generally remembers a face, once I takes notice of it. What might be your object in wantin’ to see Jim?”

“I want to see him about a bit of ground down by Beaver Creek I bought of him when I was here last. I paid him $100 down, and owe him a small balance which I am now ready to settle.”

“Wal, now thet accounts for ther wad Jim had at the time. Folks ’round here thought he mought hev robbed somebody, but as thar warn’t no proof agin him, of course he warn’t troubled. But he didn’t stay ’round here more’n a day before he lighted out, and he hain’t been heard from sence.”

“You say there was somebody else looking for him yesterday?”

“Sure. A big cityfied-lookin’ chap named Plunkett.”

That name conveyed no information to Prawle, who had not heard of the landlord of Sackville’s eyesore, and the prospector wondered if he was an emissary of Otis Clymer.

“Mought I ask what you wanted with thet there land down by ther krik?” inquired the proprietor of the Rocky Gulch Hotel, curiously. “It don’t seem a likely sort of place thet I hev heard of. You hain’t diskivered payin’ dirt, hev you?”

This was asked with undisguised eagerness.

“No,” replied Prawle, with assumed carelessness. “No such luck.”

“Wal, now, I wuz in hopes you had,” said the man, in a tone of disappointment. “’Cause why, these here diggin’s aren’t just what they wuz a year ago. Things look like as if they wuz goin’ ter peter out. Wal, you hain’t sed what you bought Jim’s claim for. You aren’t expectin’ ter build a palis an’ live thar jest for ther fun of ther thing, are you?”

“Well, hardly,” replied Prawle, falling in with the man’s rude humor. “I’ve discovered there’s a peculiar kind of stone near the creek that might be used to advantage in railroad building, and——”

“Oh, I see,” said the landlord of the hotel, thrown off the scent as Prawle intended. “Wal, I wish you luck with it.”

Prawle asked several other inhabitants of Rocky Gulch about Sanders, but each one had the same answer—Jim had not been seen in the Gulch for over two weeks, and they did not know where he was.

“Kind of hard luck, isn’t it?” said Prawle, when he rejoined his companions, after more than an hour’s ineffectual search for a clew to Sanders’ present whereabouts.

“I should say it is,” replied Jack Howard. “What are we going to do?”

“We’ll have to go back to Trinity in the morning and see what we can learn in that place. By the way, I heard there was another person trying to locate Sanders.”

“Otis Clymer!” exclaimed Jack and Charlie in a breath.

“No,” replied Prawle, shaking his head. “It was a big man, named Plunkett.”

“Plunkett!” shouted Charlie Fox, in a tone of astonishment. “Not Dave Plunkett?”

“I didn’t hear what his first name was. Do you know somebody by that name?”

“The cheap hotel where Otis Clymer lodged of late in Sackville is kept by a man named Dave Plunkett. I’ll bet Clymer has taken him into his confidence as a moneyed partner in this enterprise, and so that he himself can keep under cover as much as possible. He’s a cute rascal.”

“If that’s the case,” said Gideon Prawle, reflectively, “we’ve got our work cut out for us to beat the pair of them. Tell me what you know about this Plunkett.”

Charlie gave the prospector the history of Dave Plunkett’s operations in Sackville, so far as he knew, as well as his opinion of the man’s character.