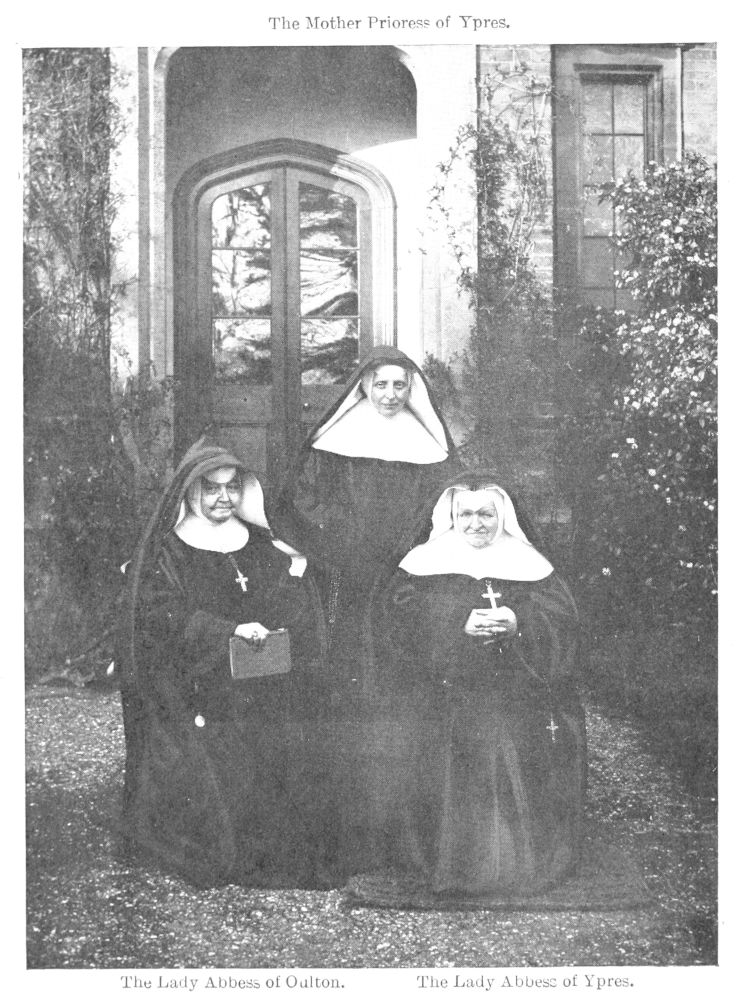

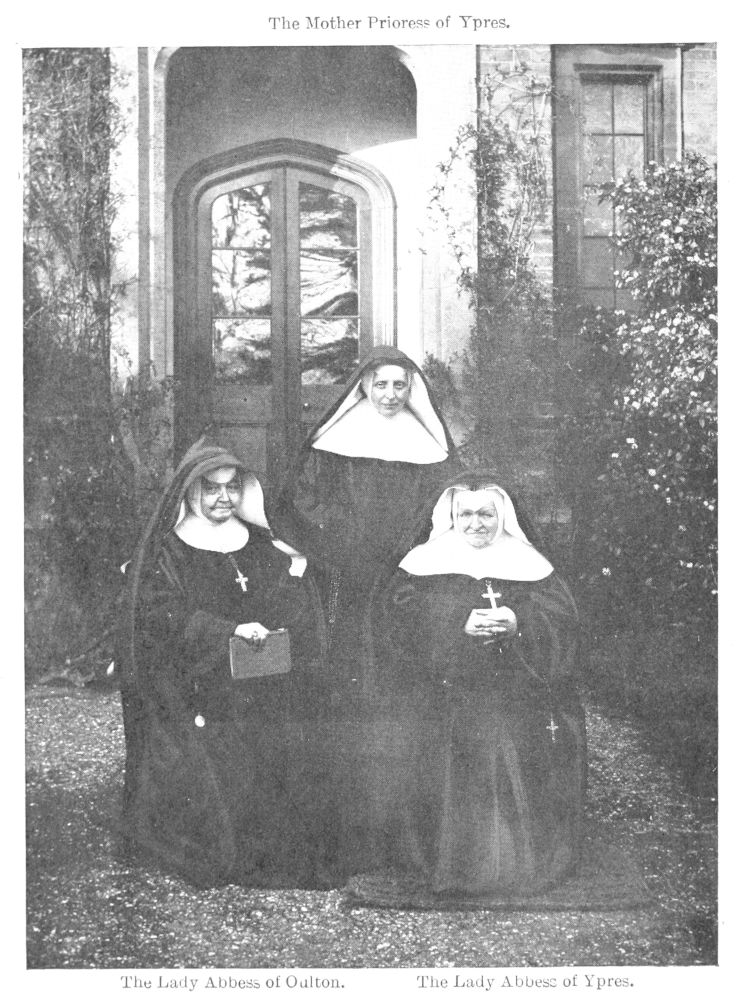

The Mother Prioress of Ypres.

The Lady Abbess of Oulton. The Lady Abbess of Ypres.

Oulton and Ypres.

The Mother Prioress of Ypres.

The Lady Abbess of Oulton. The Lady Abbess of Ypres.

Oulton and Ypres.

THE IRISH NUNS

AT YPRES

AN EPISODE OF THE WAR

BY

D. M. C.

O.S.B. (Member of the Community)

EDITED BY

R. BARRY O’BRIEN, LL.D.

WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY

JOHN REDMOND, M.P.

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS

LONDON

SMITH, ELDER & CO.

15 WATERLOO PLACE

1915

[All rights reserved.]

[Pg v]

The following narrative was originally intended, as a record of the events it relates, for the use of the Community only. But, shortly after the arrival of the Mother Prioress in England, the manuscript was placed in my hands. I soon formed the opinion that it deserved a larger circulation. My friend Reginald Smith shared this view, and so the story has come before the public.

It is in truth a human document of thrilling interest, and will, I believe, make an abiding contribution to the history of this world-wide war. D. M. C., though a novice in literary work, describes with graphic force the transactions in which she and her Sisters played so conspicuous and so courageous a part. The moving pictures, which pass before our eyes in her pages, are full of[Pg vi] touching realism, and throw curious sidelights on the manifold aspects of the titanic struggle which comes home to everyone and everything.

The heroism, the self-devotion, the religious faith, the Christian zeal and charity of those Irish nuns at Ypres, in a terrible crisis in the history of their Order, will, I venture to say, command universal respect and admiration, mingled with pity for their fate, and an earnest desire, among all generous souls, to help them in retrieving their fortunes.

A Note by the Prioress, and an Introduction by Mr. Redmond, who, amid his many onerous occupations, is not unmindful of the duty which Irishmen owe to the historic little Community of Irish Nuns at Ypres, form a foreword to a narrative which belongs to the history of the times.

The illustration on the cover is a reproduction of the remnant (still preserved in the Convent) of one of the flags captured by the Irish Brigade at the battle of Ramillies. On this subject I have added a Note in the text.

[Pg vii]

There are names in Belgium which revive memories that Irishmen cannot forget. Fontenoy and Landen are household words. Ypres, too, brings back recollections associated with deeds which mark the devotion of the Irish people to Faith and Fatherland.

R. BARRY O’BRIEN.

100 Sinclair Road,

Kensington, W.

May 1915.

[Pg ix]

These simple notes, destined at first for the intimacy of our Abbey, we now publish through the intervention of Mr. Barry O’Brien to satisfy the numerous demands of friends, who, owing to the horrors of the fighting round Ypres, have shown great interest in our welfare.

Owing, also, to the numerous articles about us, appearing daily in the newspapers—and which, to say the least, are often very exaggerated—I have charged Dame M. Columban to give a detailed account of all that has befallen the Community, since the coming of the Germans to Ypres till our safe arrival at Oulton Abbey. I can therefore certify that all that is in this little book, taken from the notes which several of the nuns had kept, is perfectly true, and only a simple narrative of our own personal experiences of the War.

[Pg x]

May this account, to which Mr. Redmond has done us the honour of writing an introduction at the request of Dame Teresa, his niece, bring us some little help towards the rebuilding of our beloved and historic monastery, which, this very year, should celebrate its 250th anniversary.

M. MAURA, O.S.B.,

Prioress.

April 1915.

[Pg xi]

I have been asked to write an introduction to this book, but I feel that I can add little to its intense dramatic interest.

Ypres has been one of the chief centres of the terrible struggle which is now proceeding on the Continent, and it is well known that this same old Flemish town has figured again and again in the bloody contests of the past.

It may, perhaps, be well to explain, in a few words, how the tide of war has once more rolled to this old-world city.

On Sunday, June 28, 1914, in Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia, the Archduke Francis Ferdinand of Austria-Hungary and his wife, the Duchess of Hohenberg, were assassinated. Although it was known throughout Europe that there was in existence in Serbia an anti-Austrian conspiracy (not of[Pg xii] a very formidable character), and although suspicion pointed towards the assassinations being due in some way to the influence of this conspiracy, no one dreamt for a moment that the tragedy which had occurred would have serious European consequences; and, as a matter of fact, it was not until July 23 that the Austro-Hungarian Government presented an ultimatum to Serbia. On that day, however, a note of a most extraordinary and menacing character was delivered to the Serbian Government by Austria-Hungary. It contained no less than ten separate demands, including the suppression of newspapers and literature; the disappearance of all nationalist societies; the reorganisation of Government schools; wholesale dismissal of officers from the army; and an extraordinary demand that Austro-Hungarian officials should have a share in all judicial proceedings in Serbia; besides the arrest of certain specified men, and the prevention of all traffic in arms.

It at once became evident to the whole world that no nation could possibly agree[Pg xiii] to these demands and maintain a semblance of national independence; and, when it was found that the ultimatum required a reply within forty-eight hours, it became clear that the whole of Europe was on the brink of a volcano.

Great Britain, through Sir Edward Grey, had already urged Serbia to show moderation and conciliation in her attitude towards Austria-Hungary; and, when the ultimatum was submitted to her, Great Britain and Russia both urged upon her the necessity of a moderate and conciliatory answer.

As a matter of fact, Serbia agreed to every one of the demands in the Austro-Hungarian ultimatum, with only two reservations, and on these she proposed to submit the questions in dispute to The Hague. Serbia received no reply from Austria-Hungary; and, immediately on the expiration of the forty-eight hours, the Austro-Hungarian Minister quitted Belgrade. During those forty-eight hours, Great Britain and Russia had urged (1) that the time-limit for the ultimatum should be extended, and[Pg xiv] that Germany should join in this demand; but Germany refused. Sir Edward Grey then proposed (2) that Great Britain, France, Germany, and Italy should act together, both in Austria-Hungary and in Russia, in favour of peace. Italy agreed; France agreed; Russia agreed; but Germany again held back. Sir Edward Grey then proposed (3) that the German, Italian, and French Ambassadors should meet him in London. Italy and France agreed; Russia raised no objection; but Germany refused.

On July 29, the German Imperial Chancellor made to the British Ambassador in Berlin the extraordinary and historic proposal that Great Britain should remain neutral, provided that Germany undertook not to invade Holland, and to content herself with seizing the colonies of France, and further promised that, if Belgium remained passive and allowed German troops to violate her neutrality by marching through Belgium into France, no territory would be taken from her. The only possible[Pg xv] answer was returned by Great Britain in the rejection of what Mr. Asquith called ‘an infamous proposal.’

On July 31, the British Government demanded from the German and French Governments an undertaking, in accordance with treaty obligations, to respect Belgium’s neutrality, and demanded from the Belgian Government an undertaking to uphold it. France at once gave the necessary undertaking, as did Belgium. Germany made no reply whatever, and from that moment war was inevitable.

On Monday, August 3, the solemn treaty, guaranteeing the neutrality of Belgium, signed by Germany as well as by France and Great Britain, was treated as ‘a scrap of paper,’ to be thrown into the waste-paper basket by Germany; Belgian territory was invaded by German troops; and, on the next day, Tuesday, August 4, German troops attacked Liège. From August 4 to August 15, Liège, under its heroic commander, General Leman, barred the advance of the German armies, and, in all human probability,[Pg xvi] saved Paris and France and the liberties of Europe.

On August 17, the Belgian Government withdrew from Brussels to Antwerp. On August 20, Brussels was occupied by the Germans. On August 24, Namur was stormed. On August 25, Louvain was destroyed, and, after weeks of bloody warfare, after the retreat from Mons to the Marne, and the victorious counter-attack which drove the Germans back across the Aisne and to their present line of defence, Antwerp was occupied by the Germans on the 9th of October. On October 11, what may be called the battle of Ypres began in real earnest; but the town, defended by the Allies, held heroically out; and by November 20, the utter failure of the attempt of the Germans to break through towards Calais by the Ypres route was acknowledged by everyone.

During the interval, Ypres was probably the centre of the most terrible fighting in the War. This delightful old Flemish town, with its magnificent cathedral and its unique[Pg xvii] Cloth Hall, probably the finest specimen of Gothic architecture in Europe, was wantonly bombarded day and night. The Germans have failed to capture the old city; but they have laid it in ruins.

The following pages show the sufferings and heroism of the present members of a little community of Irish nuns, which

‘The world forgetting, by the world forgot,’

has existed in Ypres since the days, some two hundred and fifty years ago, when their Royal Abbey was first established. It is true that, during those centuries, Ypres has more than once been subjected to bombardment and attack, and, more than once, Les Dames Irlandaises of the Royal Benedictine Abbey of Ypres have been subjected to suffering and danger. But never before were they driven from their home and shelter.

Why, it may be asked, is there a little community of Irish Benedictine nuns at Ypres? During the reign of Queen Elizabeth, three English ladies—Lady Percy,[Pg xviii] with Lady Montague, Lady Fortescue and others—wishing to become Religious, and being unable to do so in their own country, assembled at Brussels and founded an English House of the ancient Order of St. Benedict. Their numbers increasing, they made affiliations at Ghent, Dunkerque, and Pontoise.

In the year 1665, the Vicar-General of Ghent was made the Bishop of Ypres, and he founded there a Benedictine Abbey, with the Lady Marina Beaumont as its first Lady Abbess. In the year 1682, on the death of the first Lady Abbess, Lady Flavia Cary was chosen as the first Irish Lady Abbess of what was intended to be at that date, and what has remained down to the present day, an Irish community. At that time, the Irish had no other place for Religious in Flanders. A legal donation and concession of the house of Ypres was made in favour of the Irish nation, and was dedicated to the Immaculate Conception under the title of ‘Gratia Dei.’ Irish nuns from other houses were sent to Ypres to form the first Irish community. From that day to this,[Pg xix] there have been only two Lady Abbesses of Ypres who have not been Irish, and the community has always been, so far as the vast majority of its members are concerned, composed of Irish ladies.

Its history,[1] which has recently been published, contains the names of the various Lady Abbesses. They are, practically, all Irish, with the familiar names Butler, O’Bryan, Ryan, Mandeville, Dalton, Lynch, and so on.

In 1687, James II of England desired the Lady Abbess of the day, Lady Joseph Butler, to come over from Ypres to Dublin and to found an Abbey there under the denomination of ‘His Majesty’s Chief Royal Abbey.’ In 1688, the Lady Abbess, accompanied by some others of the community at Ypres, arrived in Dublin, and established the Abbey in Big Ship Street, leaving the House at Ypres in the charge of other members of the community. It is recorded that, when passing through London, she was received[Pg xx] by the Queen, at Whitehall, in the habit of her Order, which had not been seen there since the Reformation. In Dublin, James II received her, and granted her a Royal Patent, giving the community ‘house, rent, postage’ free, and an annuity of £100. This Royal Patent, with the Great Seal of the Kingdom, was in the custody of the nuns at Ypres when this War began. It was dated June 5, 1689.

When William III arrived in Dublin, in 1690, he gave permission to the Lady Abbess, Lady Butler, to remain. But she and her nuns refused, saying ‘they would not live under a usurper.’ William then gave her a pass to Flanders, and this particular letter was also amongst the treasures at Ypres when the War broke out.

Notwithstanding William’s free pass, the Irish Abbey in Dublin was broken into and pillaged by the soldiery, and it was with difficulty that the Sisters and the Lady Abbess made their way, after long and perilous journeys, home to their House at Ypres. They brought with them many relics from Dublin,[Pg xxi] including some old oak furniture, which was used in the Abbey at Ypres up to the recent flight of the community.

And so the Irish Abbey at Ypres has held its ground, with varying fortunes. In January, 1793, forty or fifty armed soldiers broke into the Abbey; but the Lady Abbess of the day went to Tournai to seek aid from the General-in-Chief, who was an Irishman. He withdrew the troops from the Convent. The following year, however, Ypres was besieged by the French; but, although the city was damaged, the Convent, almost miraculously, escaped without injury.

An order for the suppression of Convents was issued in the very height of the Revolution. The heroic Lady Abbess Lynch died. She was succeeded by her sister, Dame Bernard Lynch, and the Community were ordered to leave. They were, however, prevented from so doing by a violent storm which broke over the town, and next day there was a change of government, and the Irish Dames and the Irish Abbey were allowed to remain, and, for several years[Pg xxii] the Irish Abbey was the only Convent of any Order existing in the Low Countries.[2]

So it has remained on to the present day, from the year 1682 down to 1915, when, for the first time during that long period, this little Irish community has been driven from Ypres and its Convent laid in ruins.

Amongst the other relics and antiquities treasured by the Community at Ypres, at the opening of this war, was the famous flag, so often spoken of in song and story, captured by the Irish Brigade in the service of France at the battle of Ramillies; a voluminous correspondence with James II; a large border of lace worked by Mary Stuart; a large painted portrait of James II, presented by him to the Abbey; a church vestment made of gold horse-trappings of James II; another vestment made from the dress of the Duchess Isabella, representing the King of Spain in the Netherlands; and a[Pg xxiii] number of other most valuable relics of the past.

All these particulars can be verified by reference to the Rev. Dom Patrick Nolan’s valuable history.

This little community is now in exile in England. Their Abbey and beautiful church are in ruins. Some of their precious relics are believed to be in places of safety. But most of their property has been destroyed. They escaped, it is true, with their lives. But what is their future to be? Surely Irishmen, to whom the subject especially appeals, and English sympathisers who appreciate courage and fortitude, will sincerely desire to help those devoted and heroic nuns to go back to Ypres—the home of the Community for over two centuries—to rebuild their Abbey and reopen their schools, to continue in their honourable mission of charity and benevolence, and to resume that work of education in which their Order has been so long and so successfully engaged.

JOHN E. REDMOND.

April 1915.

[1] The Irish Dames of Ypres. By the Rev. Dom Patrick Nolan, O.S.B.

[2] At the time of the Revolution, the nuns of Brussels and Dunkerque (to which Pontoise had been united) and Ghent fled to England, and these three Houses are now represented by Bergholt Abbey (Brussels), Teignmouth (Dunkerque), and Oulton Abbey (Ghent).

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| Preface | v | |

| Note by Prioress | ix | |

| Introduction | xi | |

| I. | The Coming of the Germans | 1 |

| II. | The Allies in Ypres | 14 |

| III. | Incidents of the Struggle | 24 |

| IV. | In the Cellars | 47 |

| V. | The Bombardment | 70 |

| VI. | Flight | 92 |

| VII. | Visiting the Wounded | 107 |

| VIII. | An Attempt to Revisit Ypres | 128 |

| IX. | Preparing to Start for England | 137 |

| X. | A Second Attempt to Revisit Ypres | 143 |

| XI. | The Return Journey to Poperinghe | 157 |

| XII. | On the Way to England | 171 |

| XIII. | Oulton | 192 |

[Pg xxvii]

| Oulton and Ypres | Frontispiece |

| The Lady Abbess of Oulton, The Lady Abbess of Ypres, The Mother Prioress of Ypres. | |

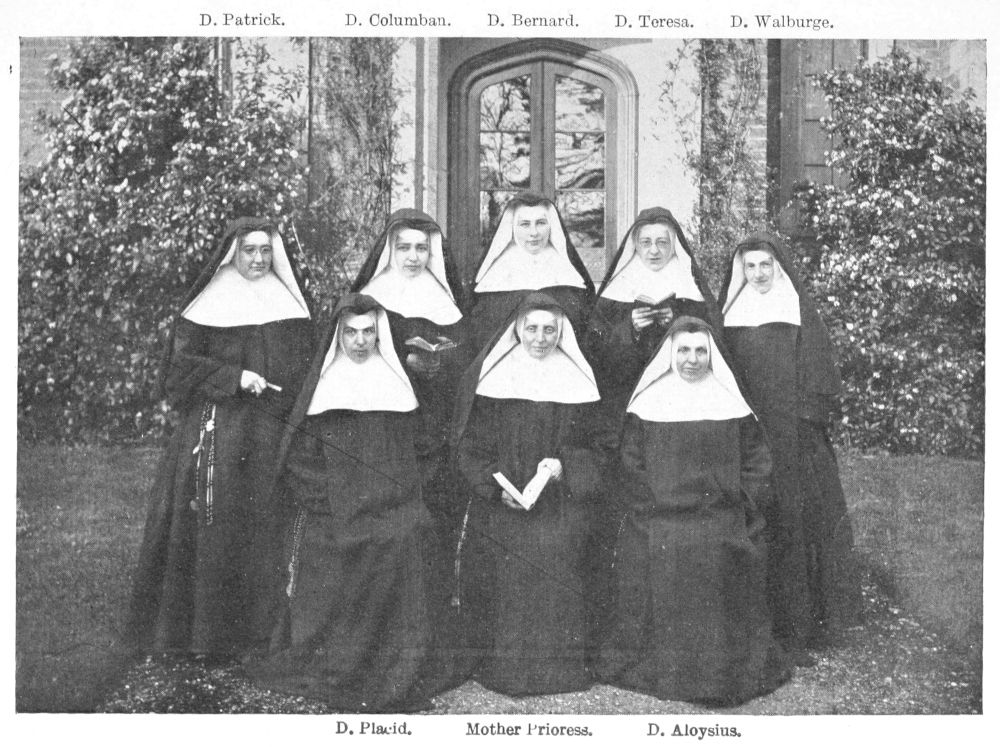

| The Irish Dames of Ypres | To face p. 48 |

| D. Patrick, D. Columban, D. Bernard, D. Teresa, D. Walburge, D. Placid, Mother Prioress, D. Aloysius. | |

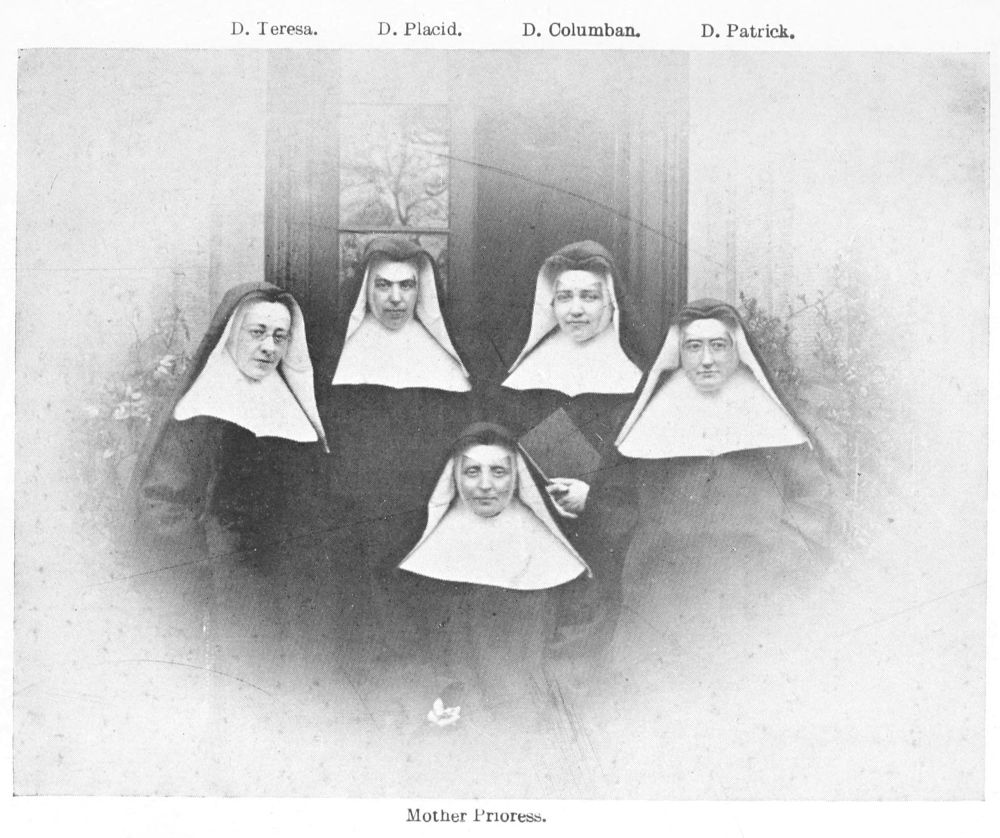

|

The Mother Prioress, Dame Teresa, and the Three Nuns who Revisited Ypres |

144 |

[Pg 1]

The War, with all its horrors, into which the Emperor of Germany plunged the world in August 1914, had been raging nearly six weeks, when, towards the end of September, vague rumours of the enemy’s approach reached us at Ypres. Several villages in the neighbourhood had had visits from the dreaded Uhlans, and, according to report, more than one prisoner had avowed that they were on their way to Ypres. An aeroplane had even been sent from Ghent to survey the town, but had lost its way. In these circumstances, the burgomaster sent round word that from henceforward, until further orders, no strong lights should be seen from the[Pg 2] outside, and no bells should be rung from six in the evening till the following day. Consequently, when night came on, the Monastery remained in darkness, each nun contenting herself with the minimum of light; and a few strokes of a little hand-bell summoned the community to hours of regular observance, instead of the well-known sound of the belfry-bell, which had, for so many years, fearlessly made known each succeeding hour. Another result of the burgomaster’s notice was that we were no longer able to say the office in the choir, as on one side the windows looked on the street, and on the other to the garden, the light being thus clearly visible from the ramparts. We, therefore, said compline and matins, first in the work-room, and afterwards in the chapter-house, placing a double set of curtains on the windows to prevent the least little glimmer of light from being seen from the outside.

An uneasy feeling of uncertainty took possession of the town. This feeling increased as news reached us, in the first days of October, that the enemy had been seen several times in the neighbourhood.[Pg 3] At length, on October 7—a never-to-be-forgotten day for all those then at Ypres—a German aeroplane passed over the town, and shortly afterwards, at about 1.30 P.M., everyone was startled by the sound of firing at no great distance. In the Monastery, it was the spiritual-reading hour, so we were not able to communicate our fears; but, instead of receding, the sound came nearer, till, at 2 o’clock, the shots from the guns literally made the house shake. Unable to surmise the cause of this sudden invasion, we went our way, trying to reassure ourselves as best we could. Shortly after vespers the sound of the little bell called us all together, and Reverend Mother Prioress announced to us, to our great dismay, that what we had feared had now taken place—the Germans were in the town. Some poor persons, who came daily to the Abbey to receive soup, had hastened to bring the dreadful tidings on hearing the bell ring for vespers, because an order had been issued (of which we were totally ignorant) that no bells might be rung, for fear of exciting suspicion. The poor, often more unselfish[Pg 4] and kind-hearted than the rich, showed themselves truly so on this occasion, being more anxious for our safety than their own—one poor woman offering her little house as a shelter for Lady Abbess. She had only one penny for all her fortune, but still she was sure that everything would be well all the same; for, as she wisely remarked, the Germans were less likely to think of pillaging her bare rooms than our splendid monastery.

The cannonading which we had heard at 1.30 was a gallant defence made by 100 Belgian police, who had been obliged to retreat before the 15,000 Germans, who, from 2 till 8 P.M., poured slowly into the affrighted town, chanting a lugubrious war-song. M. Colaert, the burgomaster, and the principal men were obliged to present themselves. It was arranged that the town would be spared on the payment of 75,000 francs, and on condition that no further violence should be offered. M. Colaert and another gentleman were kept as hostages.

We looked at one another in consternation. We might then, at any moment, expect a visit, and what a visit! What[Pg 5] if they were to come to ask lodgings for the night? We dared not refuse them. What if they ransacked the house?... Would they touch our beloved Lady Abbess, who, owing to a stroke she had had two years before, remained now partially paralysed?... We instinctively turned our steps to the choir. There, Mother Prioress began the rosary and, with all the fervour of our souls, an ardent cry mounted to the throne of the Mother of Mercy, ‘Pray for us now, and at the hour of our death.’ Was that hour about to strike?... After the rosary, we recommended ourselves to the endless bounty of the Sacred Heart, the Protector of our Monastery, ‘Cœur Sacré de Jésus, j’ai confiance en Vous.’ And putting all our confidence in the double protection of our Divine Spouse and His Immaculate Mother, we awaited the issue of events.

Our old servant-man Edmund—an honest, a fearless, and a reliable retainer, with certainly a comical side to his character—soon came in with news. Prompted by a natural curiosity, he had gone out late in the afternoon to see the troops; for the Germans,[Pg 6] as in so many other towns, made an immense parade on entering Ypres. For six long hours they defiled in perfect order before the gazing multitude, who, although terrified, could not repress their desire to see such an unwonted spectacle. Following the army came huge guns, and cars of ammunition and provisions without end. The troops proceeded to the post office, where they demanded money from the safes. The Belgian officials stated that, owing to the troubled times, no great sum was kept there, and produced 200 francs (the rest having been previously hidden). The railway station had also to suffer, the telegraph and telephone wires being all cut; while four German soldiers, posted at the corners of the public square, and relieved at regular intervals, armed with loaded revolvers, struck terror into the unfortunate inhabitants of Ypres. After some time, however, the most courageous ventured to open conversation with the invaders—amongst the others Edmund, who, coming across a soldier, more affable-looking than the rest, accosted him. The German, only too glad to seize the opportunity, replied civilly enough,[Pg 7] and the two were soon in full conversation. ‘You seem to be in great numbers here.’—‘Oh! this is nothing compared to the rest! Germany is still full—we have millions waiting to come! We are sure to win, the French are only cowards!’ ‘Where are you going to when you leave Ypres?’—‘To Calais!’ ‘And then?’—‘To London!’ ‘Ha-ha-ha! You won’t get there as easy as you think, they’ll never let you in!’—‘We can always get there in our Zeppelins.’... With this the German turned on his heel and tramped off.

It was now time to think of finding lodgings for the night. A great number of horses were put in the waiting-rooms at the station, destroying all the cushions and furniture. The soldiers demanded shelter in whatever house they pleased, and no one dared refuse them anything. Our Abbey, thanks to Divine Providence, of whose favour we were to receive so many evident proofs during the next two months, was spared from these unwelcome visitors—not one approached the house, and we had nothing to complain of but the want of[Pg 8] bread. Our baker, being on the way to the convent with the loaves, was met by some German soldiers, who immediately laid hands on his cart, and emptied its contents. We therefore hastily made some soda-scones for supper, which, though not of the best, were nevertheless palatable. However, all did not escape so easily as we did, and many were the tales told of that dreadful night. The most anxious of all were those who were actually housing wounded Belgian soldiers! If they were discovered, would the brave fellows not be killed there and then? And it happened, in more than one case, that they escaped by the merest chance. Before the convent of exiled French nuns, Rue de Lille, whom we were afterwards to meet at our stay at Poperinghe, and where at that moment numbers of Belgians were hidden, a German stopped a lady, who was luckily a great friend of the nuns, and asked if there were any wounded there. ‘That is not a hospital,’ she replied, ‘but only a school’; and with a tone of assurance she added, ‘If you do not believe me, you can go and see for yourself.’ The soldier answered, ‘I believe[Pg 9] you,’ and passed on. In another case, the Germans entered a house where the Belgians were, and passed the night in the room just underneath them! A jeweller’s shop was broken into, and the property destroyed or stolen; and in a private dwelling, the lady of the house, finding herself alone with four officers—her husband having been taken as hostage—she took to flight, on which the Germans went all through the place, doing considerable damage. In other cases, they behaved pretty civilly. Our washerwoman had thirty to breakfast, of whom several had slept in her establishment, leading their horses into her drawing-room! On seeing her little boys, they had exclaimed, ‘Here are some brave little soldiers for us, later on!’ And, on the mother venturing a mild expostulation, they added, ‘Yes, you are all Germans now—Belgo-Germans’; while, before leaving, they wrote on her board—‘We are Germans; we fear no one; we fear only God and our Emperor!’ What troubled her the most was that her unwelcome guests had laid hold of her clean washing, taking all that they wanted;[Pg 10] amongst other things, our towels had disappeared. We were, as may well be imagined, but too pleased to be rid of the dread Germans at so little cost.

It appears that while the German army was still in Ypres, some 12,000 British soldiers, having followed on its track, stopped at a little distance from the town, sending word to the burgomaster that, if he wished, they were ready to attack the enemy. M. Colaert, however, not desiring to see the town given up to pillage and destruction, was opposed to a British advance.

By this time the whole town was on the qui vive, and no one thought of anything else but how best to secure any valuables that they had; for the stories of what had happened in other parts of Belgium were not at all reassuring. Several tried to leave the town; but the few trains that were running were kept exclusively for the troops, while the Germans sent back all those who left on foot. To increase the panic, no less than five aeroplanes passed during the day; and the knowledge that the enemy had left soldiers with two mitrailleuses at the Porte de Lille, to guard the town, completed the[Pg 11] feeling of insecurity. Moreover—as the soldiers had literally emptied the town of all the eatables they could lay their hands on—sinister rumours of famine were soon spread abroad. Reverend Mother Prioress sent out immediately for some sacks of flour, but none was to be got; and we were obliged to content ourselves with wheatmeal instead. Rice, coffee, and butter we had, together with some tins of fish. The potatoes were to come that very day, and great was our anxiety lest the cart would be met by the Germans and the contents seized. However, the farmer put off coming for some days, and at length arrived safely with the load, a boy going in front to see that no soldiers were about. The milk-woman, whose farm was a little way outside the town, was unable to come in, and no meat could be got for love or money; so we were obliged to make the best of what we had, and each day Mother Prioress went to the kitchen herself to see if she could not possibly make a new dish from the never varying meal—rice, Quaker oats, and maizena.

Ultimately the Allies came to our help,[Pg 12] and a motor-car, armed with a mitrailleuse, flew through the streets and opened fire on the Germans. Taken by surprise, the latter ran to their guns; but, through some mishap, the naphtha took fire in one of them, whereupon the Germans retreated. Three of their men were wounded, and one civilian killed. On the Friday, we began to breathe freely again, when suddenly news came, even to the Abbey, that one hundred Germans were parading round the town. On Sunday, the Allies came once more to chase them; but, for the moment, the Germans had disappeared. Things continued thus for some days, until, to the delight of the inhabitants, the British took entire possession of the town, promising that the Germans would never enter it again. Just one week after the coming of the Germans, the troops of the Allies poured in, until, amid the enthusiastic cheers of the people, 21,000 soldiers filled the streets. Those who came by the monastery passed down the Rue St. Jacques singing lustily:

‘Here we are, here we are, here we are again:

Here we are, here we are, here we are again!’

Then alternately each side repeated: ‘Hallo![Pg 13] Hallo! Hallo! Hallo!’ The crowd, whose knowledge of the English language did not extend far enough to enable them to grasp the meaning of ‘Here we are again’ soon, however, caught up the chorus of ‘Hallo! Hallo!’ and quickly the street resounded with cries, which were certainly discordant, but which, nevertheless, expressed the enthusiastic joy of the people.

[Pg 14]

The contrast between the reception of the two armies was striking. On the arrival of the Germans, people kept in their houses, or looked at the foe with frightened curiosity; now, everyone lined the streets, eager for a glimpse of the brave soldiers who had come to defend Ypres. A week before, the citizens had furnished food to the enemy, because they dared not refuse it—and only then what they were obliged to give. Now, each one vied with the other in giving. Bread, butter, milk, chocolate—everything they had—went to the soldiers, and sounds of rejoicing came from all sides. Perhaps, the most pleased of all were the poor wounded Belgians, who had been so tried the preceding week. All those who were able to drag themselves along crowded to the windows and doors,[Pg 15] to welcome their new comrades; and the latter, unable to make themselves understood by words, made vigorous signs that they were about to chop off the Germans’ heads. What excited the most curiosity were the ‘petticoats,’ as they were styled, of the Highlanders, and everyone gave their opinion on this truly extraordinary uniform, which had not been previously seen in these parts. The soldiers were quartered in the different houses and establishments of the town. Once more the Abbey was left unmolested, though once again also the want of bread was felt—not, that it had been this time stolen, but that, in spite of all their efforts, the bakers could not supply the gigantic demand for bread necessary to feed our newly arrived friends. Seeing that we were likely to be forgotten in the general excitement, Edmund was sent out to see what he could find. After many vain efforts, he at last succeeded in getting three very small-sized loaves, with which he returned in triumph. Scarcely had he got inside the parlour, when there came a vigorous tug at the bell. The new-comer proved to be a man who, having caught sight of the bread,[Pg 16] came to beg some for ‘his soldiers.’ Edmund was highly indignant, and loudly expostulated; but the poor man, with tears in his eyes, turned to Mother Prioress (who had just entered), and offered to pay for the bread, if only she would give him a little. ‘I have my own son at the front,’ he exclaimed, ‘and I should be so grateful to anyone that I knew had shown kindness to him; and now I have been all over the town to get bread for my soldiers, and there is none to be had!’ Mother Prioress’ kind heart was touched, and telling the good man to keep his money, she gave him the loaves as well, with which he soon vanished out of the door, Edmund grumbling all the time because the nuns (and himself) had been deprived of their supper. Mother Prioress, laughing, told him the soldiers needed it more than we. She turned away, thinking over what she could possibly give the community for supper. She went—almost mechanically—to the bread-bin, where, lifting up the lid, she felt round in the dark. What was her delight to find two loaves which still remained, and which had to suffice for supper—as well as breakfast next morning.[Pg 17] We retired to rest, feeling we were, at any rate, well guarded; and the firm tread of the sentries, as they passed under our windows at regular intervals, inspired us with very different feelings from those we had experienced the week before, on hearing the heavy footsteps of the German watch.

The officials of the British Headquarters entered the town with the army, and for several weeks Ypres was their chief station, from which issued all the commands for the troops in the surrounding districts. We were not long, however, in knowing the consequences of such an honour. The next day, at about 10.30 A.M., the whirr of an aeroplane was heard. We were becoming accustomed to such novelties, and so did not pay too much attention, till, to our horror, we heard a volley of shots from the Grand’ Place saluting the new-comer. We knew from this what nationality the visitor was. The firing continued for some time, and then ceased. What had happened? Our enclosure prevented us from following the exciting events of those troubled times, but friends usually kept us supplied with the most important[Pg 18] news. It was thus that, soon afterwards, we heard the fate of the air monster which had tried to spy into what was happening within our walls. The first shots had been unsuccessful; but at last two struck the machine, which began rapidly to descend. The inmates, unhurt, flew for their lives as soon as they touched ground; but, seizing the first motor-car to hand, the soldiers chased them, and at last took them prisoners. What was their horror to find in the aeroplane a plan of the town of Ypres, with places marked, on which to throw the three bombs, one of these places being the Grand’ Place, then occupied by thousands of British soldiers.

Endless were the thanksgivings which mounted up to heaven for such a preservation, and prayers and supplications for Divine protection were redoubled. Since the beginning of the War, everyone, even the most indifferent, had turned to God, from Whom alone they felt that succour could come; and those who before never put their foot in church were now amongst the most fervent. Pilgrimages and processions were organised to turn aside the[Pg 19] impending calamity; and, heedless of human respect, rich and poor, the fervent and the indifferent, raised their voices to the Mother of God, who has never yet been called upon in vain. Even the procession of Our Lady of Thuyn—so well known to all those who yearly flock to Ypres for the first Sunday in August—with its groups, its decorations, its music, had been turned into a penitential procession; and the ‘Kermess’ and other festivities, which took place during the following eight days, were prohibited. Needless to say, the Monastery was not behindhand. Every day the community assembled together at 1 o’clock for the recitation of the rosary, and, when possible, prayed aloud during the different employments of the day. Numberless were the aspirations to the Sacred Heart, Our Lady of Angels, Our Holy Father St. Benedict, each one’s favourite patron, the Holy Angels, or the Souls in Purgatory. Each suggested what they thought the most likely to inspire devotion. Perhaps the best of all was that which Dame Josephine—Requiescat in Pace—announced to us one day at recreation. It ran as[Pg 20] follows: ‘Dear St. Patrick, as you once chased the serpents and venomous reptiles out of Ireland, please now chase the Germans out of Belgium!’ The Office of the Dead was not forgotten for those who had fallen on the battle-field, and we offered all our privations and sacrifices for the good success of the Allies, or the repose of the souls of the poor soldiers already killed. We also undertook to make badges of the Sacred Heart for the soldiers, though at the moment we saw no possible means of distributing them. At length, to our great joy, the arrival of the British troops, among whom were many Irish Catholics, opened an apostolate for us, which went on ever increasing. The idea had first come to us when, weeks before, a number of Belgian soldiers were announced, of whom 250 were to have been quartered at the college. Reverend Mother Prioress had then suggested that we should make badges, so as at least to help in some little way, when everyone else seemed to be doing so much. We set to work with good will—some cutting the flannel—others embroidering—others writing—till at last we had[Pg 21] finished. What was our disappointment to hear that not a single soldier had come to the college. We then tried, in every way possible, to find a means of distributing our handiwork; but all in vain, till one day, a poor girl, called Hélène, who washed the steps and outer porch leading to the principal entrance of the convent, came to beg prayers for her brother who was at the front. Mother Prioress promised her we should all pray for her brother, at the same time giving her a badge of the Sacred Heart for him, together with a dozen others for anyone else she might know to be in the same position. Hélène soon returned for more, and the devotion spreading through the town, everyone came flocking to the parlour to get badges for a father, a brother, a cousin, a nephew at the front, many even also asking them for themselves, so that they might be preserved from all danger. Even the little children in the streets came, to ask for ‘a little heart!’ until the poor Sister at the door was unable to get through her other work, owing to the constant ringing of the bell. In despair, she laid her complaints before[Pg 22] her Superior, saying that a troop of children were there again, of whom one had come the first thing in the morning for a badge. On receiving it she had gone outside, where, changing hats with another child, she promptly returned, pretending to be some one else. The Sister, who had seen the whole performance through the guichet, had smiled at her innocent trick, and given her another. But now here she was again, this time with some one else’s apron on, and bringing half a dozen other children with her. Mother Prioress then saw the little girl herself, who, nothing abashed, put out her hand saying, ‘Des petits cœurs, s’il vous plaît, ma Sœur!’ This was too much for Mother Prioress’ tender heart, and, instead of scolding, she told them there was nothing ready then; but for the future, if they came back on Mondays, they might have as many ‘petits cœurs’ as they wished. The little troop marched quite contentedly out of the door, headed by the girl—who could not have been more than seven years old—and diminishing in size and age down to a little mite of two, who toddled out, hanging on to[Pg 23] his brother’s coat. The devout procession was brought up by a tiny black dog, which seemed highly delighted with the whole proceeding. This little digression has brought us away from our subject, but was perhaps necessary to show how we were able to send badges to the soldiers, by means of this somewhat strange manner of apostolate; for a young girl, hearing of the devotion, brought them by dozens to St. Peter’s parish (where an Irish regiment was stationed), impressing on each man, as she pinned the badge to his uniform, that it was made by ‘the Irish Dames!’

[Pg 24]

Meanwhile, in the distance, we could hear the sound of cannonading, which told us of the approach of the enemy; and when we met at recreation, the one and only topic of conversation was the War. Each day brought its item of news—such or such a town had fallen, another was being bombarded, a village had been razed to the ground, another was burning, so many prisoners had been taken, such a number wounded, many alas! killed. As often as not, what we heard one day was contradicted the next, and what was confirmed in the morning as a fact, was flatly denied in the afternoon; so that one really did not know what to believe. We could at least believe our own ears, and those told us, by the ever-approaching sound of firing, that the danger was steadily increasing for the brave little town of Ypres. It was[Pg 25] therefore decided that, in case of emergency, each nun should prepare a parcel of what was most necessary, lest the worst should come, and we should be obliged to fly.

Soon, crowds of refugees, from the towns and villages in the firing line, thronged the streets. The city was already crowded with soldiers. Where, then, could the refugees find lodging and nourishment? How were they to be assisted? All helped as far as they were able, and dinner and supper were daily distributed to some thirty or forty at the Abbey doors. This meant an increase of work, which already weighed heavily enough on our reduced numbers; for we had, since September 8, lost four subjects—one choir dame and three lay-sisters—owing to the law then issued, commanding the expulsion of all Germans resident in Belgium. This had been the first shock. Nothing as yet foretold the future, nor gave us the least subject for serious alarm, when, on the afternoon of September 7, an official came to the parlour to acquaint us with the newly published law, and to say that our four German nuns would have to leave within thirty-six hours. We were literally stunned.[Pg 26] Benedictines! Enclosed nuns! All over twenty-five years in the convent! What harm could they do? Surely no one could suspect them of being spies. Telegrams flew to Bruges, even to Antwerp, to obtain grace—all was useless, and at 3.30 P.M., September 8, we assisted at the first departure from the Abbey, which we innocently thought would be at the worst for about three weeks, little dreaming what we should still live to see. These first poor victims were conducted by our chaplain to his lordship the Bishop of Bruges, who placed them in a convent just over the frontier in Holland, where we continued corresponding with them, until all communication was cut off by the arrival of the Germans, as has already been stated. In the result, we found our labours increased by the loss of our three lay-sisters; but we divided the work between us, and even rather enjoyed the novelty. Poor old Sister Magdalen (our oldest lay-sister), however, failed to see any joke in the business; and when she found herself once again cook, as she had been when she was young and active, her lamentations were unceasing. We tried to assist her, but she found us more in[Pg 27] the way than anything else. She discovered at last a consoler in the person of Edmund, who offered to peel apples, pears, and potatoes; and when the two could get together, Sister Magdalen poured forth the tale of her endless woes into Edmund’s sympathetic ear, whilst he in return gave her the ‘latest news’; and it was a curious spectacle to see the two together in the little court anxiously examining a passing aeroplane, to know of what nationality it was, though which of the pair was to decide the matter was rather questionable, Edmund being exceedingly short-sighted, and Sister Magdalen not too well versed in such learned matters. To return to the refugees: Mother Prioress took some of us to help her in the children’s refectory, and with her own hands prepared the food for them. For dinner they had a good soup, with plenty of boiled potatoes, bread, and beer: for supper, a plateful of porridge in which we mixed thin slices of apple, which made a delicious dish, and then potatoes in their jackets, bread, and beer. We had to work hard, for it was no small task to get such a meal ready for about forty starving persons. We left Sister[Pg 28] Magdalen to grumble alone in the kitchen over the mysterious disappearance of her best pots and pans; especially one evening, when, forgetting to turn the appetising mixture which was preparing for supper, we not only spoilt the porridge, but burnt a hole in a beautiful copper saucepan.

The sound of hostilities came ever nearer and nearer. Dreadful rumours were current of an important battle about to be fought in the proximity of Ypres. What made things worse was the great number of spies that infested the neighbourhood. Daily they were arrested, but yet others managed to replace them. Four soldiers and one civilian kept a vigilant watch on the town, examining every one who seemed the least suspicious, as much as the prisoners themselves.

Roulers, Warneton, Dixmude, and countless other towns and villages had succumbed; and at last, to our great grief, news reached us that the Germans were in Bruges, and had taken possession of the episcopal palace—and our much-loved Bishop, where was he? Alas! we were doomed not to hear, for all communication was cut off, and for the future we only knew what was happening[Pg 29] in and around Ypres. And was it not enough? The windows already shook with the heavy firing. The roar of the guns in the distance scarcely stopped a moment. From the garret windows, we could already see the smoke of the battle on the horizon; and to think that, at every moment, hundreds of souls were appearing before the judgment-seat of God! Were they prepared? Terrifying problem!

As everywhere else, the German numbers far exceeded those of the Allies. It consequently came to pass that the latter were forced to retreat. It was thus that on Wednesday, October 21, we received the alarming news that the town would probably be bombarded in the evening. We had already prepared our parcels in case we should be obliged to fly and now we were advised to live in our cellars, which were pronounced quite safe against any danger of shells or bombs. But our dear Lady Abbess, how should we get her down to the cellar, when it was only with great difficulty that she could move from one room to another? If we were suddenly forced to leave, what then would she do?[Pg 30] We could only leave the matter in God’s hands. We carried down a carpet, bed, arm-chair, and other things, to try to make matters as comfortable as possible for her—then our own bedding and provisions. The precious treasures and antiquities had already been placed in security, and we now hastened to collect the remaining books and statues, which we hoped to save from the invaders. We had also been advised to pile up sand and earth against the cellar windows to deaden the force of the shells should they come in our direction. But if this were the case, they would first encounter the provision of pétrole in the garden—and then we should all be burnt alive. To prepare for this alarming contingency, Dame Teresa and Dame Bernard, armed with spades, proceeded to the far end of the garden, where they dug an immense hole, at the same time carrying the earth to block the entrances to the different cellars. After a whole day’s hard labour, they succeeded in finishing their excavation and in tilting the huge barrel, which they could neither roll nor drag—it being both too full and too heavy—to the[Pg 31] place prepared. Their labour, however, proved all in vain; for Edmund, displeased at the barrel’s disappearance, then highly amused at the brilliant enterprise, declared he could not draw the pétrole unless put back in its old position.

The reported fortunate arrival of a large number of Indian troops (they said 400,000, though 40,000 would be nearer the mark) had a reassuring effect: but we still remained in suspense, for if the Allies came by thousands, the Germans had a million men in the neighbourhood. The Allies and Germans also sustained frightful losses. The ambulance cars continually brought in the unfortunate victims from the battle-field, till at last the town was full to overflowing. One Sunday morning, a French officer and military doctor came to visit the convent to see if it would not be possible to place their wounded with us. We willingly offered our services, and Mother Prioress showing them the class-rooms, it was decided that the whole wing facing the ramparts, including the class-rooms, children’s dormitory and refectory, the library, noviceship and work-room, should[Pg 32] be emptied and placed at their disposal. The great drawback was the lack of bedding; for already, before the arrival of the Germans in the town, we had given all we could possibly spare for the Belgian wounded, who had at that time been transported to Ypres. The two gentlemen took their leave, very pleased with their visit, the officer—who seemed to all appearances a fervent Catholic—promising to send round word in the afternoon, when all should be decided. Despite the fact that it was Sunday, we listened (after having obtained permission) to the proverb, ‘Many hands make light work,’ and soon the rooms in question were emptied of all that would not serve for the soldiers, and were ready for their use. What was our disappointment, in the afternoon, to hear that the French officer, thanking us profusely for our offer, had found another place, which was more suitable, as being nearer the site of the engagement. We had always shown our goodwill, and were only too pleased to help in any little way the brave soldiers, who daily, nay hourly, watered with their blood Belgium’s unfortunate soil. This was not the last we heard of[Pg 33] the officer; for we soon had a visit from a French deacon, who was serving as infirmarian at the ambulance, begging for bandages for the wounded soldiers. All our recreations and free moments were spent in ‘rolling’ bandages, for which were sacrificed sheets and veils, and in fact anything that could serve for the purpose—to all of which we of course added dozens of badges of the Sacred Heart. The deacon was overjoyed and returned several times ‘to beg,’ giving us news of the fighting. One day he brought a little souvenir, by way of thanks for our help. It consisted of a prayer-book found on a German wounded prisoner, who had died. The prayers were really beautiful, being taken mostly from passages of the Psalms, adapted for the time of war; while the soiled leaves showed that the book had been well read.

One afternoon, about this time, the Sister who acted as portress announced the visit of an ‘English Catholic priest,’ serving as army chaplain. Mother Prioress went immediately round to the parlour to receive the reverend visitor, who stated that he had been charged by a well-known English lord,[Pg 34] should he ever pass by Ypres, to come to our convent, to see the ‘English flag’ which one of his ancestors had sent to the Abbey. Mother Prioress assured him that the only flag in the convent was the famous one captured by the Irish Brigade in the service of France at the battle of Ramillies.[3] She added that she would be happy to give him a photograph of the flag. He said he would be enchanted, promising to call the next day to fetch it. Accordingly, the following day he returned, accompanied by two officers. Dame Josephine, together with Dame Teresa and Dame Patrick, were sent to entertain them. On entering the parlour, Dame Josephine immediately knelt to receive the ‘priest’s’ blessing, who looked rather put out at this unwonted respect. After an interesting conversation on various topics, she asked how long he had been attached to the army. He said he had volunteered as chaplain, being in reality a monk, having also charge of a community of nuns. More and more interested at not only finding a ‘priest’ but a ‘monk,’ Dame Josephine expressed her[Pg 35] admiration of the sacrifice he must have made in thus leaving his monastery, and asked to what Order he belonged. The reverend gentleman said that he was of the Order of St. John the Evangelist, and that he was indeed longing to be able to put on once more his holy habit. Then, making a sign to the officers, he abruptly finished the conversation, stating that he had an appointment, which he could by no means miss, and quickly vanished out of the parlour. Dame Teresa and Dame Patrick, who had hardly been able to keep in their laughter, now told Dame Josephine of her mistake; for they had truthfully divined that the supposed ‘priest’ was a Protestant clergyman. In fact he had stated on his introduction that he was ‘a priest of the Church of England,’ from which Dame Josephine had inferred that he was an ‘English Catholic priest’; and so her special attention to him. Dame Teresa and Dame Patrick had rightly interpreted the visitor’s description of himself as a Protestant clergyman, and enjoyed Dame Josephine’s mistake.

Outside, the noise grew ever louder.[Pg 36] The roar of the cannon, the rolling of the carriages, Paris omnibuses, provision and ambulance cars, the continual passage of cavalry and foot soldiers, and the motor-cars passing with lightning-like speed, made the quiet, sleepy little town of Ypres as animated as London’s busiest streets. At night even the Allied regiments poured in, profiting by the obscurity to hide their movements from the Germans; while, contrasting with the darkness, the fire from the battle-field showed up clearly against the midnight sky. One evening, as we made our usual silent visit to the garrets before going to bed, a signal of alarm announced that something more than ordinary had occurred. In the distance thick clouds of smoke rose higher and higher, which, from time to time rolling back their dense masses, showed sheets of fire and flame. Were the Germans trying to set fire to the town? No one was near to enlighten us; so, anxious and uneasy, we retired to our cells, begging earnest help from Heaven. Since the first warning of bombardment one or other of us stopped up at night, being relieved after some hours, in case anything should happen while the community took their rest.

[Pg 37]

The most alarming news continued to pour in. The soldiers, by means of their telescopes, had descried two German aeroplanes throwing down pétrole to set the country and villages on fire. Were we to expect the same fate? Stories of German atrocities reached us from all quarters; but what moved us most was the account of the outrageous barbarities used upon women, even upon nuns.

We were far from an end of our troubles. Despite the danger and anxiety, we strove to keep up religious life, and the regular Observances went on at the usual hours. Instead of distracting us, the roar of the battle only made us lift up our hearts with more fervour to God; and it was with all the ardour of our souls that we repeated, at each succeeding hour of the Divine Office: ‘Deus, in adjutorium meum intende! Domine, ad adjuvandum me festina!’ The liturgy of Holy Mass, also—one would have said it had been composed especially for the moment.

On Wednesday, October 28, between 1.30 and 2 P.M.—the hour for our pious meditation—we were suddenly interrupted[Pg 38] by a noise to which we were not as yet accustomed. It seemed at first to be only a cannon-ball, flying off on its deadly errand; but instead of growing feebler, as the shell sped away towards the German ranks, the sound and whirr of this new messenger of death grew ever louder and more rapid, till it seemed, in its frightful rush, to be coming straight on our doomed heads! Instinctively some flew to the little chapel of Our Blessed Lady at one end of the garden; others remained still where they were, not daring to move, till after a few seconds, which seemed interminable, a deafening explosion told us that something dreadful (alas! we knew not what) must have occurred. We learned, afterwards, that it was the first of the bombs with which the enemy, infuriated at the resistance of what they disdainfully styled ‘a handful of British soldiers,’ determined to destroy the town which they already feared they would never retake. The first bombs, however, did no damage—the one which had so frightened us falling into the moat which surrounds Ypres, behind the Church of St. James, and two others just outside the town. At about[Pg 39] 9.30 P.M., when we were retiring to our cells after matins, another sound, far from musical, fell on our ears. As usual, some sped silently to the garrets, where, though hearing strange noises, they could see nothing; so everyone went to rest, concluding it was the sound of bombs again. In fact the Germans were bombarding the town. We heard, the next day, that several houses in the Rue Notre-Dame had been struck, and all the windows in the street broken. The owners innocently sent for the glazier to have the panes of glass repaired, little thinking that, in a few weeks, scarce one window would remain in the whole of Ypres.

Not content with fighting on the ground, it seemed as though the sky also would soon form a second battle-field. Aeroplanes passed at regular hours from the town to the place of encounter, to bring back news to the Headquarters how the battle was waging. Besides this, German Taubes made their appearance, waiting to seize their opportunity to renew, with more success than their first attempt, the disastrous ruin caused by the bombs. It was high time to think of our dear Abbess’ safety. It was therefore decided[Pg 40] that she should take refuge at Poperinghe, and Mother Prioress sent out for a carriage to convey her there; but in the general panic which reigned, every possible means of conveyance had been seized. After several enquiries, a cab was at last secured, and soon drove up to the convent. Our dear Lady was so moved, when the news was broken to her, that four of us were obliged to carry her downstairs. After a little rest, we helped her to the carriage, which had driven round into the garden, to avoid the inconveniences which would necessarily have arisen had the departure taken place in the street. It proved almost impossible to get her into the carriage, owing to her inability to help herself. At length, thanks to the assistance of one of the Sisters of Providence, who had been more than devoted to her ever since her stroke, we succeeded; and accompanied by Dame Josephine, a Jubilarian, Dame Placid, and Sister Magdalen, our beloved Abbess drove out of the enclosure,[4] the great door soon hiding her from our sight. Sad, troubled, and anxious, we turned[Pg 41] back, wondering what would become of our dear absent ones. Would they arrive safely at their destination? Would they find kind faces and warm hearts to welcome them? Only the boom of the guns mockingly answered our silent enquiries.

[3] See Note at end of Chapter.

[4] By the Constitution of the Order, the enclosure may be broken in times of war, and in other cases provided for.

The ‘Flag’ at Ypres

BY R. BARRY O’BRIEN

There is a ‘legend’ of a ‘blue flag’ said to have been carried or captured by the Irish Brigade at the battle of Ramillies, and which was subsequently deposited in the Irish convent at Ypres. This is a sceptical age. People do not believe unless they see; and I wished to submit this ‘blue flag’ to the test of ocular demonstration. Accordingly, in the autumn of 1907, I paid a visit to the old Flemish town, now so familiar to us all in its misfortunes. I was hospitably received by the kind and cheerful nuns who answered all my questions about the flag and the convent with alacrity. ‘Can I see the flag?’—‘Certainly.’[Pg 42] And the ‘flag’ was sent for. It turned out not to be a blue flag at all. Blue was only part of a flag which, it would seem, had been originally blue, red, and yellow. An aged Irish nun described the flag as she had first seen it.

‘It was attached to a stick, and I remember reading on a slip of paper which was on the flag “Remerciements Refuged at Ypres, 170....” The flag consisted of three parts—blue with a harp, red with three lions, and yellow. The red and yellow parts were accidentally destroyed, and all that remains is the blue, as you see it, with a harp; and we have also preserved one of the lions. The story that has come down to us is that it was left here after the battle of Ramillies I think, but whether it was the flag of the Irish Brigade, or an English flag captured by them at the battle, I do not know.’

The flag, of course—blue with a harp, red with three lions, and yellow—suggests the royal standard of England, with a difference. At the time of the battle of Ramillies, the royal standard, or ‘King’s Colour,’ consisted of four quarterings: the first and fourth quarters were subdivided, the three[Pg 43] lions of England being in one half, the lion of Scotland in the other. The fleurs-de-lis were in the second quarter; the Irish harp was in the third.[5] But this (the Ypres) flag had, when the nun saw it, only three quarters—blue with harp, red with three lions, and yellow; the rest had then been apparently destroyed.

At the famous battle of 1706, the Irish Brigade was posted in the village of Ramillies. They fought with characteristic valour, giving way only when the French were beaten in another part of the field. The Brigade was commanded by Lord Clare, who was mortally wounded in the fight. Charles Forman writes, in a letter published in 1735:—

‘At Ramillies we see Clare’s regiment shining with trophies and covered with laurels even in the midst of a discomfited routed army. They had to do with a regiment which, I assure you, was neither Dutch nor German, and their courage precipitated them so far in pursuit of their enemy that they found themselves engaged at last in the throng of our army, where[Pg 44] they braved their fate with incredible resolution. If you are desirous to know what regiment it was they engaged that day, the colours in the cloister of the Irish nuns at Ypres, which I thought had been taken by another Irish regiment, will satisfy your curiosity.’[6]

Mr. Matthew O’Conor, in his ‘Military Memoirs of the Irish Nation,’ says:—

‘Lord Clare ... cut his way through the enemy’s battalions, bearing down their infantry with matchless intrepidity. In the heroic effort to save his corps he was mortally wounded, and many of his best officers were killed. His Lieutenant, Colonel Murrough O’Brien, on this occasion evinced heroism worthy of the name of O’Brien. Assuming the command, and leading on his men with fixed bayonets, he bore down and broke through the enemy’s ranks, took two pair of colours from the enemy, and joined the rere of the French retreat on the heights of St. Andre.’

Forman does not state to what regiment the colours belonged. O’Callaghan, in his ‘History of the Irish Brigade,’ quotes him as[Pg 45] saying: ‘I could be much more particular in relating this action, but some reasons oblige me, in prudence, to say no more of it.’

O’Conor says that the colours belonged to a celebrated English regiment. O’Callaghan is more precise. He says:—

‘According to Captain Peter Drake, of Drakerath, County of Meath (who was at the battle with Villeroy’s army, in De Couriere’s regiment), Lord Clare engaged with a Scotch regiment in the Dutch service, between whom there was a great slaughter; that nobleman having lost 289 private centinels, 22 commissioned officers, and 14 sergeants; yet they not only saved their colours, but gained a pair from the enemy. This Scotch regiment in the Dutch service was, by my French account, “almost entirely destroyed”; and, by the same account, Clare’s engaged with equal honour the “English Regiment of Churchill,” or that of the Duke of Marlborough’s brother, Lieutenant-General Charles Churchill, and then commanded by its Colonel’s son, Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Churchill. This fine corps, at present the 3rd Regiment of Foot, or the Buffs, signalized itself very much in the[Pg 46] action with another, or Lord Mordaunt’s, “by driving three French regiments into a morass, where most of them were either destroyed or taken prisoners.” But the “Régiment Anglois de Churchill,” according to the French narrative, fared very differently in encountering the Regiment of Clare, by which its colours were captured, as well as those of the “Régiment Hollandois,” or “Scotch regiment in the Dutch service.”’

The question may, or may not, be problematical, but it seems to me that what I saw in the convent at Ypres was a remnant of one of the flags captured, according to the authorities I have quoted, by the Irish Brigade at the battle of Ramillies; and that flag was, apparently, the ‘King’s Colour’ which reproduces the royal standard.

[Pg 47]

[5] Enc. Brit. 11th ed.

[6] Courage of the Irish Nation.

We were soon recalled from our reflections; for Mother Prioress, emerging from the parlour, announced to us that we were to have visitors that night. Two priests and five ladies had begged to be allowed to come to sleep in our cellars, as news had been brought that the Germans might penetrate into the town that very evening. One could not refuse at such a moment, though the idea was a novel one—enclosed nuns taking in strangers for the night. But in the face of such imminent peril, and in a case of life or death, there was no room for hesitation. So to work we set, preparing one cellar for the priests, and another for the ladies. In the midst of dragging down carpets, arm-chairs, mattresses, the news soon spread that there was word from Poperinghe. We all crowded round Mother[Pg 48] Prioress in the cellar, where, by the light of a little lamp, she endeavoured in vain to decipher a letter which Dame Placid had hurriedly scribbled in pencil, before the driver left to return to Ypres. The picture was worth painting! Potatoes on one side, mattresses and bolsters on the other—a carpet half unrolled—each of us trying to peep over the other’s shoulder, and to come as near as possible to catch every word. But alas! these latter were few in number and not reassuring. ‘We can only get one room for Lady Abbess.... Everywhere full up.... We are standing shivering in the rain.... Please send ——’ Then followed a list of things which were wanting. Poor Lady Abbess! Poor Dame Josephine! What was to be done? Mother Prioress consoled us by telling us she would send the carriage back the first thing next morning to see how everyone was, and to take all that was required. We then finished off our work as quickly as possible, and retired to our own cellar to say compline and matins; for it was already 10 o’clock. After this we lay down on our ‘straw-sacks’—no one undressed. [Pg 49]Even our ‘refugees’ had brought their packages with them, in case we should have to fly during the night. Contrary to all expectations, everything remained quiet—even the guns seemed to sleep. Was it a good or evil omen? Time would show.

D. Patrick. D. Columban. D. Bernard. D. Teresa. D. Walburge.

D. Placid. Mother Prioress. D. Aloysius.

The Irish Dames of Ypres.

At 5 o’clock next morning the alarm-clock aroused the community, instead of the well-known sound of the bell. There was no need, either, of the accustomed ‘Domine, labia mea aperies’ at each cell door. At 5.30, we repaired to the choir as usual for meditation, and at 6 recited lauds—prime and tierce. At 7, the conventual Mass began; when, as though they had heard the long-silent bell, the guns growled out, like some caged lion, angry at being disturbed from its night’s rest. The signal given, the battle waged fiercer than before, and the rattling windows, together with the noise resounding through the church and choir, told that the silence of the night had been the result of some tactics of the Germans, who had repulsed the Allies. Day of desolation, greater than we had before experienced! Not because the enemy was nearer, not because we were[Pg 50] in more danger, but because, at the end of Holy Mass, we found ourselves deprived of what, up till then, had been our sole consolation in our anguish and woe. The sacred species had been consumed—the tabernacle was empty. The sanctuary lamp was extinguished. The fear of desecration had prompted this measure of prudence, and henceforth our daily Communion would be the only source of consolation, from which we should have to derive the courage and strength we so much needed.

The Germans nearer meant greater danger; so, with still more ardour, we set to work, especially as we were now still more reduced in numbers. The question suddenly arose, ‘Who was to prepare the dinner?’ Our cook, as has already been said, had been one of the three German Sisters who had left us on September 8; subsequently, Sister Magdalen had replaced her, and she, too, now was gone. After mature deliberation, Dame Columban was named to fulfil that important function. But another puzzle presented itself—What were we to eat? For weeks, no one had seen an egg! Now, no milk could be got.[Pg 51] Fish was out of the question—there was no one left to fish. To complete the misery, no bread arrived, for our baker had left the town. Nothing remained but to make some small loaves of meal, and whatever else we could manage—with potatoes, oatmeal, rice, and butter (of which the supply was still ample), adding apples and pears in abundance. Edmund was sent out to see if he could find anything in the town. He returned with four packets of Quaker oats, saying that that was all he could find, but that we could still have a hundred salted herrings if we wished to send for them.

We had just begun the cooking, when the tinkling of the little bell called everyone together, only to hear that a German Taube was sailing just over the Abbey; so we were all ordered down to the cellars, but before we reached them there was crack! crack! bang! bang! and the rifle-shots flew up, from the street outside the convent, to salute the unwelcome visitor. But to no purpose, and soon the sinister whistling whirr of a descending projectile grated on our ears, while, with a loud crash, the[Pg 52] bomb fell on some unfortunate building. We had at first been rather amused at this strange descent to our modern catacombs; but we soon changed our mirth to prayer, and aspiration followed aspiration, till the ceasing of the firing told us that the enemy was gone. We then emerged from the darkness, for we had hidden in the excavation under the steps leading up to the entrance of the Monastery, as the surest place of refuge, there being no windows. This was repeated five or six times a day; so we brought some work to the cellars to occupy us. The firing having begun next morning before breakfast was well finished, one sister arrived down with tea and bread and butter. Later on, while we were preparing some biscuits, the firing started again; so we brought down the mixing-bowl, ingredients and all. We continued our work and prayers and paid no more attention to the bombs or the rifle-shots.

Our dear Lady Abbess was not forgotten. The next day Mother Prioress sent for the carriage, while we all breathed a fervent ‘Deo gratias’ that our aged Abbess was[Pg 53] out of danger; for what would she have done in the midst of all the bombs? Owing to the panic, which was now at its height, all the inhabitants who were able were leaving the town, abandoning their houses, property—all, all—anxious only to save their lives. There was no means of finding a carriage.

Our life, by this time, had become still more like that of the Christians of the first era of the Church, our cellars taking the place of the catacombs, to which they bore some resemblance. We recited the Divine Office in the provision cellar under the kitchen, which we had first intended for Lady Abbess. A crucifix and statue of Our Lady replaced the altar. On the left were huge wooden cases filled with potatoes, and one small one of turnips—on the right, a cistern of water, with a big block for cutting meat (we had carefully hidden the hatchet, in case the Germans, seeing the two together, should be inspired to chop off our heads). Behind us, other cases were filled with boxes and sundry things, whilst on top of them were the bread-bins. We were, however, too much taken up with the danger we[Pg 54] were in to be distracted by our surroundings. We realised then, to the full, the weakness of man’s feeble efforts, and how true it is that God alone is able to protect those who put their trust in Him. The cellar adjoining, leading up to the kitchen, was designed for the refectory. In it were the butter-tubs, the big meat-safe, the now empty jars for the milk. A long narrow table was placed down the centre, with our serviettes, knives, spoons, and forks; while everyone tried to take as little space as possible, so as to leave room for her neighbour. The procession to dinner and supper was rather longer than usual, leading from the ante-choir through the kitchen, scullery, down the cellar stairs, and it was no light work carrying down all the ‘portions,’ continually running up and down the steps, with the evident danger of arriving at the bottom quicker than one wanted to, sending plates and dishes in advance.

Time was passing away, we now had to strip the altar—to put away the throne and tabernacle. Some one suggested placing the tabernacle in the ground, using a very large iron boiler to keep out the damp, and thus prevent it from being spoilt. This plan,[Pg 55] however, did not succeed, as will be seen. Dame Teresa and Dame Bernard flew off to enlarge the pit they had already begun, watching all the time for any Taube which might by chance drop a bomb on their heads, and, indeed, more than once, they were obliged to take refuge in the Abbey. Strange to say, these things took place on Sunday, the Feast of All Saints. It was rather hard work for a holiday of obligation, but we obtained the necessary authorisation. Towards evening the hole was finished and the boiler placed in readiness. But how lift the throne, which took four men to carry as far as the inner sacristy? First we thought of getting some workmen, but were any still in the town? No, we must do it ourselves. So, climbing up, we gradually managed to slip the throne off the tabernacle, having taken out the altar-stone. We then got down; and whether the angels, spreading their wings underneath, took part of the weight away or not, we carried it quite easily to the choir, where, resting it on the floor, we enveloped the whole in a blanket which we covered again with a sheet. The tabernacle was next taken in the same manner, and, reciting the ‘Adoremus,’[Pg 56] ‘Laudate,’ ‘Adoro Te,’ we passed with our precious load through the cloisters into the garden. It was a lovely moonlight night, and our little procession, winding its way through the garden paths, reminded us of the Levites carrying away the tabernacle, when attacked by the Philistines. We soon came to the place, where the two ‘Royal Engineers’—for so they had styled themselves (Dame Teresa and Dame Bernard)—were putting all their strength into breaking an iron bar in two, a task which they were forced to abandon. We reverently placed our burden on the edge of the cauldron, but found it was too small. Almost pleased at the failure, we once more shouldered the tabernacle, raising our eyes instinctively to the dark blue sky, where the pale autumn moon shone so brightly, and the cry of ‘Pulchra ut luna’ escaped from our lips, as our hearts invoked the aid of Her, who was truly the tabernacle of the Most High. As we gazed upwards, where the first bright stars glittered among the small fleecy clouds, wondering at the contrast of the quiet beauty of the heavens and the bloodshed and carnage on earth, a strange cloud, unlike its smaller[Pg 57] brethren, passed slowly on. It attracted our attention. In all probability it was formed by some German shell which had burst in the air and produced the vapour and smoke which, as we looked, passed gradually away. We then re-formed our procession and deposited the tabernacle in the chapter-house for the night. Needless to say, it takes less time to relate all this than it did to do it, and numberless were the cuts, blows, scrapes, and scratches, which we received during those hours of true ‘hard labour’; but we were in time of war, and war meant suffering, so we paid no attention to our bruises.

Our fruitless enquiries for a means to get news of Lady Abbess were at last crowned with success. Hélène, the poor girl of whom mention has been already made, and who now received food and help from the monastery, came, on Sunday afternoon, to say that two of her brothers had offered to walk to Poperinghe next day, and would take whatever we wished to send. After matins, Mother Prioress made up two big parcels, putting in all that she could possibly think of which might give[Pg 58] pleasure to the absent ones. The next day was spent in expectation of the news we should hear when the young men returned.

Breakfast was not yet finished, when the portress came in with a tale of woe. One of our workmen was in the parlour, begging for help. During the night a bomb had been thrown on the house next to his; and he was so terrified that, not daring to remain in his own house any more, he had come with his wife and four little children to ask a lodging in our cellars. For a moment Reverend Mother hesitated; but her kind heart was too moved to refuse, and so the whole family went down into the cellar underneath the class-room, which was separated from the rest, and there remained as happy as could be. We were soon to feel the truth of the saying of the gospel, ‘What you give to the least of My little ones, you give it unto Me.’