HENRY W. NEVINSON

Photograph by Elliott & Fry

BY

HENRY W. NEVINSON

ILLUSTRATED

LONDON AND NEW YORK

HARPER & BROTHERS PUBLISHERS

MCMVI

Copyright, 1906, by Harper & Brothers.

All rights reserved.

Published May, 1906.

DEDICATED TO

MY SISTER

MARIAN NEVINSON

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I. | Introductory | 1 |

| II. | Plantation Slavery on the Mainland | 19 |

| III. | Domestic Slavery on the Mainland | 40 |

| IV. | On Route to the Slave Centre | 59 |

| V. | The Agents of the Slave-Trade | 83 |

| VI. | The Worst Part of the Slave Route | 104 |

| VII. | Savages and Missions | 126 |

| VIII. | The Slave Route to the Coast | 149 |

| IX. | The Exportation of Slaves | 168 |

| X. | Life of Slaves on the Islands | 187 |

| Index | 211 | |

[Pg vii]

The following chapters describe my journey in the Portuguese province of Angola (West Central Africa), and in the Portuguese islands of San Thomé and Principe, during the years 1904, and 1905.

The journey was undertaken at the suggestion of the editor of Harper’s Monthly Magazine, but in choosing this particular part of Africa for investigation I was guided by the advice of the Aborigines Protection Society and the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society in London, and I wish to thank the secretaries of both these societies for their great assistance.

I also wish to thank the British and American residents on the mainland and the islands—and especially the missionaries—for their unfailing hospitality and help. As far as possible, I kept the object of my journey from them, knowing that direct aid to my purpose might bring trouble on them afterwards. Yet even when they knew or suspected the truth, I found no difference in their[Pg x] kindliness, though I was often tiresome with sickness, and their own provisions were often very short.

The illustrations are from photographs taken by myself, but on the mail slave-ship from Benguela to San Thomé I had the advantage of borrowing a better camera than my own.

London, March, 1906.

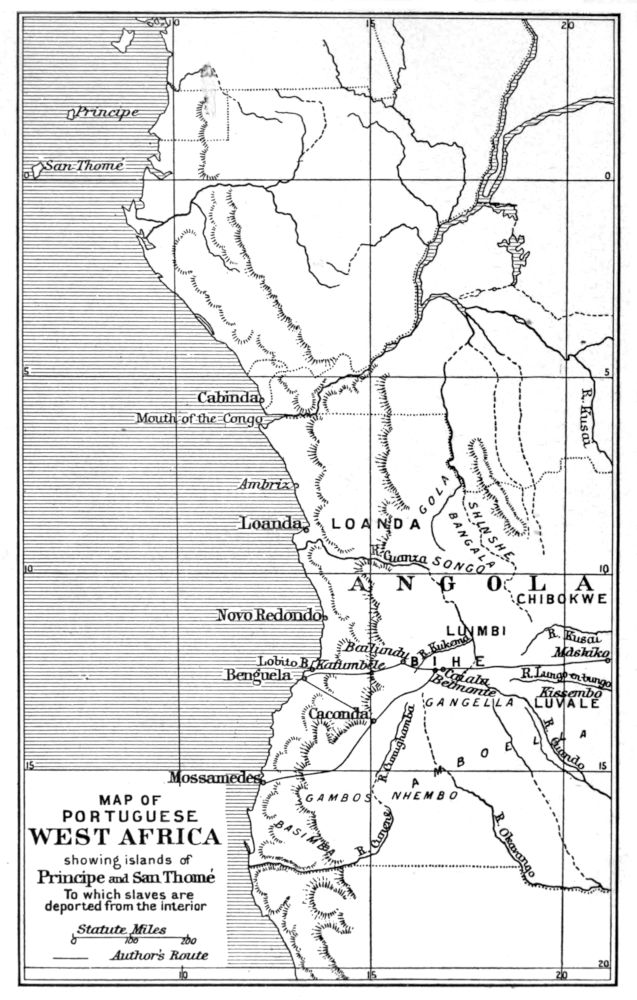

MAP OF PORTUGUESE WEST AFRICA showing islands of Principe and San Thomé To which slaves are deported from the interior

[Pg 1]

For miles on miles there is no break in the monotony of the scene. Even when the air is calmest the surf falls heavily upon the long, thin line of yellow beach, throwing its white foam far up the steep bank of sand. And beyond the yellow beach runs the long, thin line of purple forest—the beginning of that dark forest belt which stretches from Sierra Leone through West and Central Africa to the lakes of the Nile. Surf, beach, and forest—for two thousand miles that is all, except where some great estuary makes a gap, or where the line of beach rises to a low cliff, or where a few distant hills, leading up to Ashanti, can be seen above the forest trees.

It is not a cheerful part of the world—“the Coast.” Every prospect does not please, nor is it only man that is vile. Man, in fact, is no more vile than elsewhere; but if he is white he is very often dead.[Pg 2] We pass in succession the white man’s settlements, with their ancient names so full of tragic and miserable history—Axim, Sekundi, Cape Coast Castle, and Lagos. We see the old forts, built by Dutch and Portuguese to protect their trade in ivory and gold and the souls of men. They still gleam, white and cool as whitewash can make them, among the modern erections of tin and iron that have a meaner birth. And always, as we pass, some “old Coaster” will point to a drain or an unfinished church, and say, “That was poor Anderson’s last bit.” And always when we stop and the officials come off to the ship, drenched by the surf in spite of the skill of native crews, who drive the boats with rapid paddles, hissing sharply at every stroke to keep the time—always the first news is of sickness and death. Its form is brief: “Poor Smythe down—fever.” “Poor Cunliffe gone—black-water.” “Poor Tompkinson scuppered—natives.” Every one says, “Sorry,” and there’s no more to be said.

It is not cheerful. The touch of fate is felt the more keenly because the white people are so few. For the most part, they know one another, at all events by classes. A soldier knows a soldier. Unless he is very military, indeed, he knows the district commissioner, and other officials as well. An official knows an official, and is quite on speaking terms with the soldiers. A trader knows a trader, and ceases to watch him with malignant jealousy[Pg 3] when he dies. It is hard to realize how few the white men are, scattered among the black swarms of the natives. I believe that in the six-mile radius round Lagos (the largest “white” town on the Coast) the whites could not muster one hundred and fifty among the one hundred and forty thousand blacks. And in the great walled city of Abeokuta, to which the bit of railway from Lagos runs, among a black population of two hundred and five thousand, the whites could hardly make up twenty all told. So that when one white man disappears he leaves a more obvious gap than he would in a London street, and any white man may win a three days’ fame by dying.

Among white women, a loss is naturally still more obvious and deplorable. Speaking generally, we may say the only white women on the Coast are nurses and missionaries. A benevolent government forbids soldiers and officials to bring their wives out. The reason given is the deadly climate, though there are other reasons, and an exception seems to be made in the case of a governor’s wife. She enjoys the liberty of dying at her own discretion. But Accra, almost alone of the Coast towns, boasts the presence of two or three English ladies, and I have known men overjoyed at being ordered to appointments there. Not that they were any more devoted to the society of ladies than we all are, but they hoped for a better chance of surviving[Pg 4] in a place where ladies live. Vain hope; in spite of cliffs and clearings, in spite of golf and polo, and ladies, too, Death counts his shadows at Accra much the same as anywhere else.

You never can tell. I once landed on a beach where it seemed that death would be the only chance of comfort in the tedious hell. On either hand the flat shore stretched away till it was lost in distance. Close behind the beach the forest swamp began. Upon the narrow ridge nine hideous houses stood in the sweltering heat, and that was all the town. The sole occupation was an exchange of palm-oil for the deadly spirit which profound knowledge of chemistry and superior technical education have enabled the Germans to produce in a more poisonous form than any other nation. The sole intellectual excitement was the arrival of the steamers with gin, rum, and newspapers. Yet in that desolation three European ladies were dwelling in apparent amity, and a volatile little Frenchman, full of the joy of life, declared he would not change that bit of beach—no, not for all the cafés chantants of his native Marseilles. “There is not one Commandment here!” he cried, unconsciously imitating the poet of Mandalay; and I suppose there is some comfort in having no Commandments, even where there is very little chance of breaking any.

The farther down the Coast you go the more melancholy is the scene. The thin line of yellow[Pg 5] beach disappears. The forest comes down into the sea. The roots of the trees are never dry, and there is no firm distinction of land and water. You have reached “the Rivers,” the delta of the Niger, the Circle of the mangrove swamps, in which Dante would have stuck the Arch-Traitor head downward if only he had visited this part of the world. I gained my experience of the swamps early, but it was thorough. It was about the third time I landed on the Coast. Hearing that only a few miles away there was real solid ground where strange beasts roamed, I determined to cut a path through the forest in that direction. Engaging two powerful savages armed with “matchets,” or short, heavy swords, I took the plunge from a wharf which had been built with piles beside a river. At the first step I was up to my knees in black sludge, the smell of which had been accumulating since the glacial period. Perhaps the swamps are forming the coal-beds of a remote future; but in that case I am glad I did not live at Newcastle in a remote past. As in a coronation ode, there seemed no limit to the depths of sinking. One’s only chance was to strike a submerged trunk not yet quite rotten enough to count as mud. Sometimes it was possible to cling to the stems or branches of standing trees, and swing over the slime without sinking deep. It was possible, but unpleasant; for stems and branches and twigs and fibres are generally[Pg 6] covered with every variety of spine and spike and hook.

In a quarter of an hour we were as much cut off from the world as on the central ocean. The air was dark with shadow, though the tree-tops gleamed in brilliant sunshine far above our heads. Not a whisper of breeze nor a breath of fresh air could reach us. We were stifled with the smell. The sweat poured from us in the intolerable heat. Around us, out of the black mire, rose the vast tree trunks, already rotting as they grew, and between the trunks was woven a thick curtain of spiky plants and of the long suckers by which the trees draw up an extra supply of water—very unnecessarily, one would have thought.

Through this undergrowth the natives, themselves often up to the middle in slime, slowly hacked a way. They are always very patient of a white man’s insanity. Now and then we came to a little clearing where some big tree had fallen, rotten from bark to core. Or we came to a “creek”—one of the innumerable little watercourses which intersect the forest, and are the favorite haunt of the mud-fish, whose eyes are prominent like a frog’s, and whose side fins have almost developed into legs, so that, with the help of their tails, they can run over the slime like lizards on the sand. But for them and the crocodiles and innumerable hosts of ants and slugs, the lower depths of the mangrove swamp[Pg 7] contain few living things. Parrots and monkeys inhabit the upper world where the sunlight reaches, and sometimes the deadly stillness is broken by the cry of a hawk that has the flight of an owl and fishes the creeks in the evening. Otherwise there is nothing but decay and stench and creatures of the ooze.

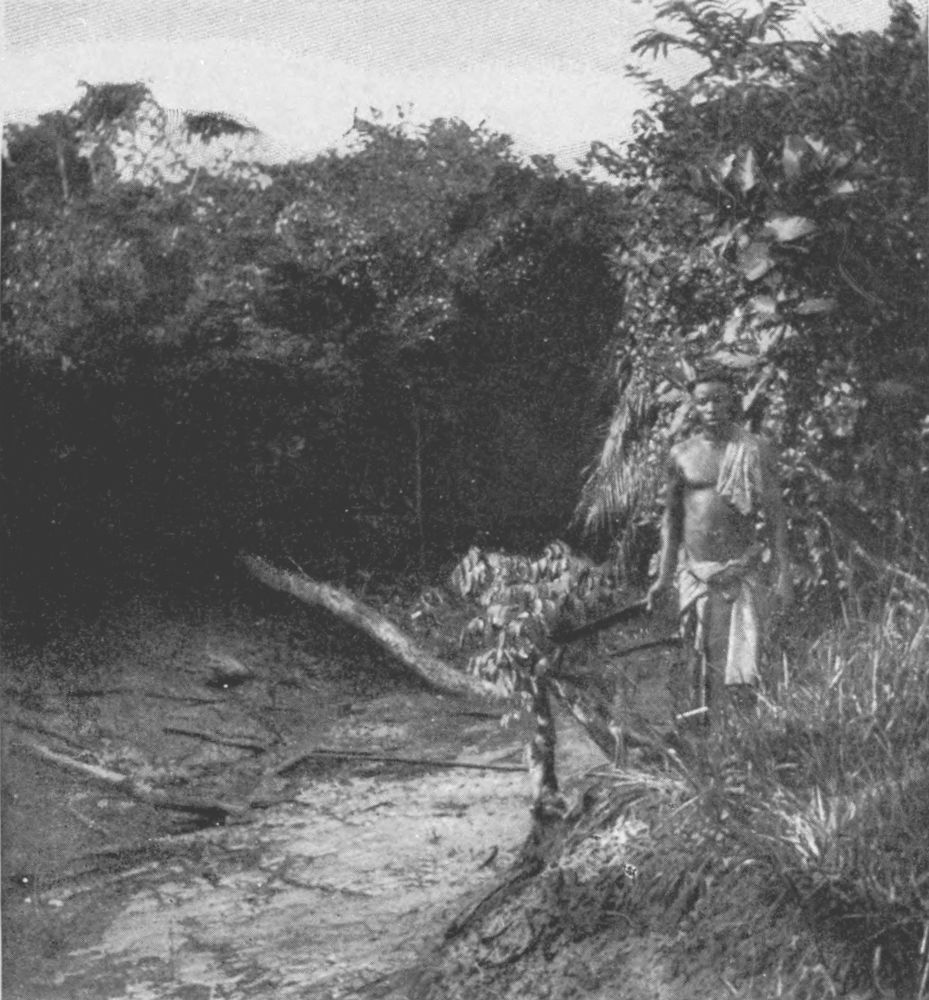

AN AFRICAN SWAMP

After struggling for hours and finding no change in the swamp and no break in the trees, I gave up the hope of that rising ground, and worked back to the main river. When at last I emerged, sopping with sweat, black with slime, torn and bleeding from the thorns, I knew that I had seen the worst that nature can do. I felt as though I had been reforming the British War Office.

It is worth while trying to realize the nature of these wet forests and mangrove swamps, for they are the chief characteristic of “the Coast” and especially of “the Rivers.” Not that the whole even of southern Nigeria is swamp. Wherever the ground rises, the bush is dry. But from a low cliff, like “The Hill” at Calabar, although in two directions you may turn to solid ground where things will grow and man can live, you look south and west over miles and miles of forest-covered swamp that is hopeless for any human use. You realize then how vain is the chatter about making the Coast healthy by draining the mangrove swamps. Until the white man develops a new kind of blood and a new kind of inside, the Coast will kill him. Till[Pg 8] then we shall know the old Coaster by the yellow and streaky pallor of a blood destroyed by fevers, by a confused and uncertain memory, and by a puffiness that comes from enfeebled muscle quite as often as from insatiable thirst.

It is through swamps like these that those unheard-of “punitive expeditions” of ours, with a white officer or two, a white sergeant or two, and a handful of trusty Hausa men, have to fight their way, carrying their Maxim and three-inch guns upon their heads. “I don’t mind as long as the men don’t sink above the fork,” said the commandant of one of them to me. And it is beside these swamps that the traders, for many short-lived generations past, have planted their “factories.”

The word “factory” points back to a time when the traders made the palm-oil themselves. The natives make nearly the whole of it now and bring it down the rivers in casks, but the “factories” keep their name, though they are now little more than depots of exchange and retail trade. Formerly they were made of the hulks of ships, anchored out in the rivers, and fitted up as houses and stores. A few of the hulks still remain, but of late years the traders have chosen the firmest piece of “beach” they could find, or else have created a “beach” by driving piles into the slime, and on these shaky and unwholesome platforms have erected dwelling-houses with big verandas, a series of sheds for the stores,[Pg 9] and a large barn for the shop. Here the “agent” (or sometimes the owner of the business) spends his life, with one or two white assistants, a body of native “boys” as porters and boatmen, and usually a native woman, who in the end returns to her tribe and hands over her earnings in cash or goods to her chief.

The agent’s working-day lasts from sunrise to sunset, except for the two hours at noon consecrated to “chop” and tranquillity. In the evening, sometimes he gambles, sometimes he drinks, but, as a rule, he goes to bed. Most factories are isolated in the river or swamp, and they are pervaded by a loneliness that can be felt. The agent’s work is an exchange of goods, generally on a large scale. In return for casks of oil and bags of “kernels,” he supplies the natives with cotton cloth, spirits, gunpowder, and salt, or from his retail store he sells cheap clothing, looking-glasses, clocks, knives, lamps, tinned food, and all the furniture, ornaments, and pictures which, being too atrocious even for English suburbs and provincial towns, may roughly be described as Colonial.

From the French coasts, in spite of the free-trade agreement of 1898, the British trader is now almost entirely excluded. On the Ivory Coast, Dahomey, French Congo, and the other pieces of territory which connect the enormous African possessions of France with the sea, you will hardly find a British[Pg 10] factory left, though in one or two cases the skill and perseverance of an agent may just keep an old firm going. In the German Cameroons, British houses still do rather more than half the trade, but their existence is continually threatened. In Portuguese Angola one or two British factories cling to their old ground in hopes that times may change. In the towns of the Lower Congo the British firms still keep open their stores and shops; but the well-known policy of the royal rubber merchant, who bears on his shield a severed hand sable, has killed all real trade above Stanley Pool. In spite of all protests and regulations about the “open door,” it is only in British territory that a British trader can count upon holding his own. It may be said that, considering the sort of stuff the British trader now sells, this is a matter of great indifference to the world. That may be so. But it is not a matter of indifference to the British trader, and, in reality, it is ultimately for his sake alone that our possessions in West Africa are held. Ultimately it is all a question of soap and candles.

We need not forget the growing trade in mahogany and the growing trade in cotton. We may take account of gold, ivory, gums, and kola, besides the minor trades in fruits, yams, red peppers, millet, and the beans and grains and leaves which make a native market so enlivening to a botanist. But, after all, palm-oil and kernels are the things that[Pg 11] count, and palm-oil and kernels come to soap and candles in the end. It is because our dark and dirty little island needs such quantities of soap and candles that we have extended the blessings of European civilization to the Gold Coast and the Niger, and beside the lagoons of Lagos and the rivers of Calabar have placed our barracks, hospitals, mad-houses, and prisons. It is for this that district commissioners hold their courts of British justice and officials above suspicion improve the perspiring hour by adding up sums. For this the natives trim the forest into golf-links. For this devoted teachers instruct the Fantee boys and girls in the length of Irish rivers and the order of Napoleon’s campaigns. For this the director of public works dies at his drain and the officer at a palisade gets an iron slug in his stomach. For this the bugles of England blow at Sokoto, and the little plots of white crosses stand conspicuous at every clearing.

That is the ancestral British way of doing things. It is for the sake of the trade that the whole affair is ostensibly undertaken and carried on. Yet the officer and the official up on “The Hill” quietly ignore the trader at the foot, and are dimly conscious of very different aims. The trader’s very existence depends upon the skill and industry of the natives. Yet the trader quietly ignores the native, or speaks of him only as a lazy swine who ought to[Pg 12] be enslaved as much as possible. And all the time the trader’s own government is administering a singularly equal justice, and has, within the last three years, declared slavery of every kind at an end forever.

In the midst of all such contradictions, what is to be the real relation of the white races to the black races? That is the ultimate problem of Africa. We need not think it has been settled by a century’s noble enthusiasm about the Rights of Man and Equality in the sight of God. Outside a very small and diminishing circle in England and America, phrases of that kind have lost their influence, and for the men who control the destinies of Africa they have no meaning whatever. Neither have they any meaning for the native. He knows perfectly well that the white people do not believe them.

The whole problem is still before us, as urgent and as uncertain as it has ever been. It is not solved. What seemed a solution is already obsolete. The problem will have to be worked through again from the start. Some of the factors have changed a little. Laws and regulations have been altered. New and respectable names have been invented. But the real issue has hardly changed at all. It has become a part of the world-wide issue of capital, but the question of African slavery still abides.

[Pg 13]

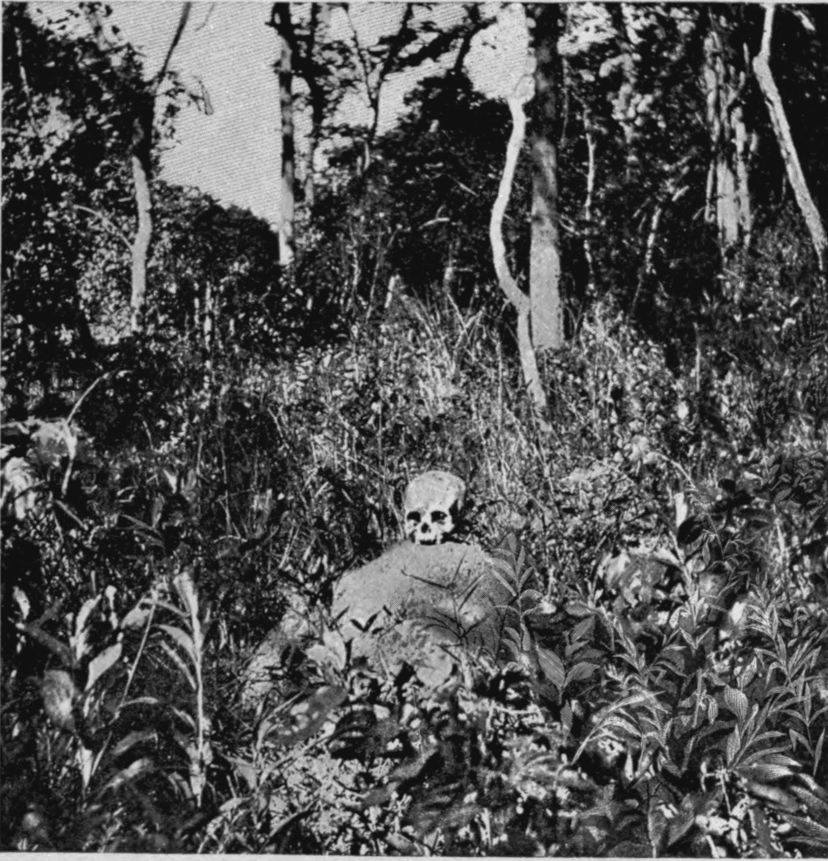

We may, of course, draw distinctions. The old-fashioned export of human beings as a reputable and staple industry, on a level with the export of palm-oil, has disappeared from the Coast. Its old headquarters were at Lagos; and scattered about that district and in Nigeria and up the Congo one can still see the remains of the old barracoons, where the slaves were herded for sale or shipment. In passing up the rivers you may suddenly come upon a large, square clearing. It is overgrown now, but the bush is not so high and thick as the surrounding forest, and palms take the place of the mangrove-trees. Sometimes a little Ju-ju house is built by the water’s edge, with fetiches inside; and perhaps the natives have placed it there with some dim sense of expiation. For the clearing is the site of an old barracoon, and misery has consecrated the soil. Such things leave a perpetual heritage of woe. The English and the Portuguese were the largest slave-traders upon the Coast, and it is their descendants who are still paying the heaviest penalty. But that ancient kind of slave-trade may for the present be set aside. The British gun-boats have made it so difficult and so unlucrative that slavery has been driven to take subtler forms, against which gun-boats have hitherto been powerless.

We may draw another distinction still. Quite different from the plantation slavery under European control, for the profit of European capitalists,[Pg 14] is the domestic slavery that has always been practised among the natives themselves. Legally, this form of slavery was abolished in Nigeria by a proclamation of 1901, but it still exists in spite of the law, and is likely to exist for many years, even in British possessions. It is commonly spoken of as domestic slavery, but perhaps tribal slavery would be the better word. Or the slave might be compared to the serf of feudal times. He is nominally the property of the chief, and may be compelled to give rather more than half his days to work for the tribe. Even under the Nigerian enactment, he cannot leave his district without the chief’s consent, and he must continue to contribute something to the support of the family. But in most cases a slave may purchase his freedom if he wishes, and it frequently happens that a slave becomes a chief himself and holds slaves on his own account.

It is one of those instances in which law is ahead of public custom. Most of the existing domestic slaves do not wish for further freedom, for if their bond to the chief were destroyed, they would lose the protection of the tribe. They would be friendless and outcast, with no home, no claim, and no appeal. “Soon be head off,” said a native, in trying to explain the dangers of sudden freedom. At Calabar I came across a peculiar instance. Some Scottish missionaries had carefully trained up a native youth to work with them at a mission. They[Pg 15] had taught him the height of Chimborazo, the cost of papering a room, leaving out the fireplace, and the other things which we call education because we can teach nothing else. They had even taught him the intricacies of Scottish theology. But just as he was ready primed for the ministry, an old native stepped in and said: “No; he is my slave. I beg to thank you for educating him so admirably. But he seems to me better suited for the government service than for the cure of souls. So he shall enter a government office and comfort my declining years with half his income.”

The elderly native had himself been educated by the mission, and that added a certain irony to his claim. When I told the acting governor of the case, he thought such a thing could not happen in these days, because the youth could have appealed to the district commissioner, and the old man’s claim would have been disallowed at law. That may be so; and yet I have not the least doubt that the account I received was true. Law was in advance of custom, that was all, and the people followed custom, as people always do.

Even where there is no question of slave-ownership, the power of the chiefs is often despotic. If a chief covets a particularly nice canoe, he can purchase it by compelling his wives and children to work for the owner during so many days. Or take the familiar instance of the “Krooboys.” The[Pg 16] Kroo coast is nominally part of Liberia, but as the Liberian government is only a fit subject for comic opera, the Kroo people remain about the freest and happiest in Africa. Their industry is to work the cargo of steamers that go down the Coast. They get a shilling a day and “chop,” and the only condition they make is to return to “we country” within a year at furthest. Before the steamer stops off the Coast and sounds her hooter the sea is covered with canoes. The captain sends word to the chief of the nearest village that he wants, say, fifty “boys.” After two or three hours of excited palaver on shore, the chief selects fifty boys, and they are sent on board under a headman. When they return, they give the chief a share of their earnings as a tribute for his care of the tribe and village in their absence. This is a kind of feudalism, but it has nothing to do with slavery, especially as there is a keen competition among the boys to serve. When a woman who has been hired as a white man’s concubine is compelled to surrender her earnings to the chief, we may call it a survival of tribal slavery, or of the patriarchal system, if you will. But when, as happens, for instance, in Mozambique, the agents of capitalists bribe the chiefs to force laborers to the Transvaal mines, whether they wish to go or not, we may disguise the truth as we like under talk about “the dignity of labor” and “the [Pg 17]value of discipline,” but, as a matter of fact, we are on the downward slope to the new slavery. It is easy to see how one system may become merged into the other without any very obvious breach of native custom. But, nevertheless, the distinction is profound. As Mr. Morel has said in his admirable book on The Affairs of West Africa, between the domestic servitude of Nigeria and plantation slavery under European supervision there is all the difference in the world. The object of the present series of sketches is to show, by one particular instance, the method under which this plantation slavery is now being carried on, and the lengths to which it is likely to develop.

THE “KROOBOYS” WORKING A SHIP ALONG THE COAST

“In the region of the Unknown, Africa is the Absolute.” It was one of Victor Hugo’s prophetic sayings a few years before his death, when he was pointing out to France her road of empire. And in a certain sense the saying is still true. In spite of all the explorations, huntings, killings, and gospels, Africa remains the unknown land, and the nations of Europe have hardly touched the edge of its secrets. We still think of “black people” in lumps and blocks. We do not realize that each African has a personality as important to himself as each of us is in his own eyes. We do not even know why the mothers in some tribes paint their babies on certain days with stripes of red and black, or why an African thinks more of his mother than we think of lovers. If we ask for the hidden meaning[Pg 18] of a Ju-ju, or of some slow and hypnotizing dance, the native’s eyes are at once covered with a film like a seal’s, and he gazes at us in silence. We know nothing of the ritual of scars or the significance of initiation. We profess to believe that external nature is symbolic and that the universe is full of spiritual force; but we cannot enter for a moment into the African mind, which really believes in the spiritual side of nature. We talk a good deal about our sense of humor, but more than any other races we despise the Africans, who alone out of all the world possess the same power of laughter as ourselves.

In the higher and spiritual sense, Victor Hugo’s saying remains true—“In the region of the Unknown, Africa is the Absolute.” But now for the first time in history the great continent lies open to Europe. Now for the first time men of science have traversed it from end to end and from side to side. And now for the first time the whole of it, except Abyssinia, is partitioned among the great white nations of the world. Within fifty years the greatest change in all African history has come. The white races possess the Dark Continent for their own, and what they are going to do with it is now one of the greatest problems before mankind. It is a small but very significant section of this problem which I shall hope to illustrate in my investigations.

[Pg 19]

Loanda is much disquieted in mind. The town is really called St. Paul de Loanda, but it has dropped its Christian name, just as kings drop their surnames. Between Moorish Tangiers and Dutch Cape Town, it is the only place that looks like a town at all. It has about it what so few African places have—the feeling of history. We are aware of the centuries that lie behind its present form, and we feel in its ruinous quays the record of early Portuguese explorers and of the Dutch settlers.

In the mouldering little church of Our Lady of Salvation, beside the beach where native women wash, there exists the only work of art which this side of Africa can show. The church bears the date of 1664, but the work of art was perhaps ordered a few years before that, while the Dutch were holding the town, for it consists of a series of pictures in blue-and-white Dutch tiles, evidently representing scenes in Loanda’s history. In some cases the tiles have fallen down, and been stuck on again by natives in the same kind of chaos in which[Pg 20] natives would rearrange the stars. But in one picture a gallant old ship is seen laboring in a tempest; in another a gallant young horseman in pursuit of a stag is leaping over a cliff into the sea; and in the third a thin square of Christian soldiers, in broad-brimmed hats, braided tail-coats, and silk stockings, is being attacked on every side by a black and unclad host of savages with bows and arrows. The Christians are ranged round two little cottages which must signify the fort of Loanda at the time. Two little cannons belch smoke and lay many black figures low. The soldiers are firing their muskets into the air, no doubt in the hope that the height of the trajectory will bring the bullets down in the neighborhood of the foe, though the opposing forces are hardly twenty yards apart. The natives in one place have caught hold of a priest and are about to exalt him to martyrdom, but I think none of the Christian soldiers have fallen. In defiance of the cannibal king, who bears a big sword and is twice the size of his followers, the Christian general grasps his standard in the middle of the square, and, as in the shipwreck and the hunting scene, Our Lady of Salvation watches serenely from the clouds, conscious of her power to save.

Unhappily there is no inscription, and we can only say that the scene represents some hard-won battle of long ago—some crisis in the miserable conflict of black and white. Since the days of those[Pg 21] two cottages and a flag, Loanda has grown into a city that would hardly look out of place upon the Mediterranean shore. It has something now of the Mediterranean air, both in its beauty and its decay. In front of its low red and yellow cliffs a long spit of sand-bank forms a calm lagoon, at the entrance of which the biggest war-ships can lie. The sandy rock projecting into the lagoon is crowned by a Vauban fortress whose bastions and counter-scarps would have filled Uncle Toby’s heart with joy. They now defend the exiled prisoners from Portugal, but from the ancient embrasures a few old guns, some rusty, some polished with blacking, still puff their salutes to foreign men-of-war, or to new governors on their arrival. In blank-cartridge the Portuguese War Department shows no economy. If only ball-cartridge were as cheap, the mind of Loanda would be less disquieted.

There is an upper and a lower town. From the fortress the cliff, though it crumbles down in the centre, swings round in a wide arc to the cemetery, and on the cliff are built the governor’s palace, the bishop’s palace, a few ruined churches that once belonged to monastic orders, and the fine big hospital, an expensive present from a Portuguese queen. Over the flat space between the cliff and the lagoon the lower town has grown up, with a cathedral, custom-house, barracks, stores, and two restaurants. The natives live scattered about in[Pg 22] houses and huts, but they have chiefly spread at random over the flat, high ground behind the cliff. As in a Turkish town, there is much ruin and plenty of space. Over wide intervals of ground you will find nothing but a broken wall and a century of rubbish. Many enterprises may be seen growing cold in death. There are gardens which were meant to be botanical. There is an observatory which may be scientific still, for the wind-gage spins. There is an immense cycle track which has delighted no cyclist, unless, indeed, the contractor cycles. There are bits of pavement that end both ways in sand. There is a ruin that was intended for a hotel. There is a public band which has played the same tunes in the same order three times a week since the childhood of the oldest white inhabitant. There is a technical school where no pupil ever went. There is a vast municipal building which has never received its windows, and whose tower serves as a monument to the last sixpence. There are oil-lamps which were made for gas, and there is one drain, fit to poison the multitudinous sea.

So the city lies, bankrupt and beautiful. She is beautiful because she is old, and because she built her roofs with tiles, before corrugated iron came to curse the world. And she is bankrupt for various reasons, which, as I said, are now disquieting her mind. First there is the war. Only last autumn a Portuguese expedition against a native tribe was[Pg 23] cut to pieces down in the southern Mossamedes district, not far from the German frontier, where also a war is creeping along. No Lady of Salvation now helped the thin Christian square, and some three hundred whites and blacks were left there dead. So things stand. Victorious natives can hardly be allowed to triumph in victory over whites, but how can a bankrupt province carry on war? A new governor has arrived, and, as I write, everything is in doubt, except the lack of money. How are safety, honor, and the value of the milreis note to be equally maintained?

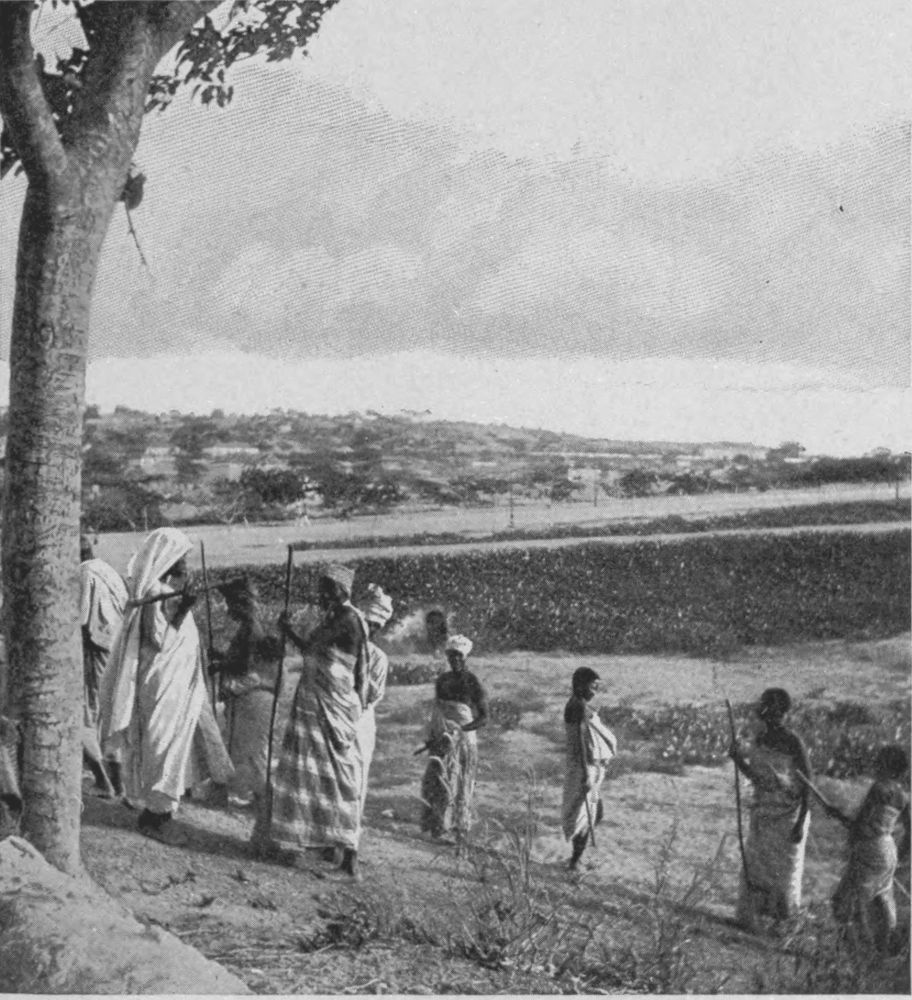

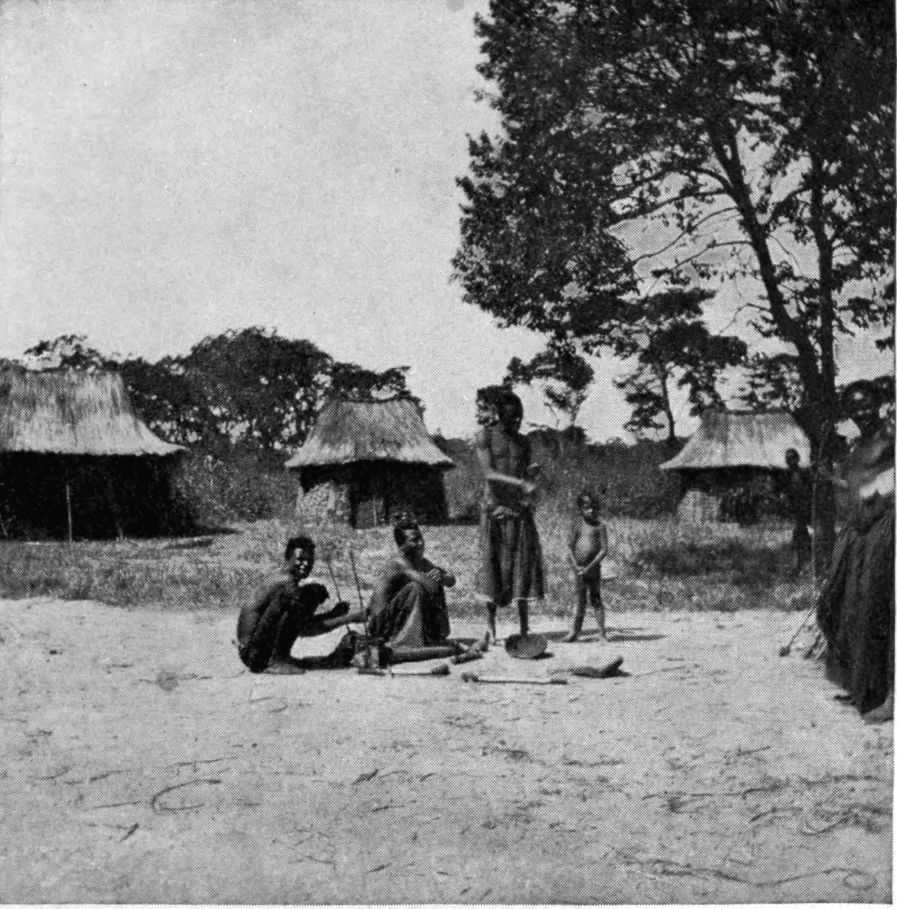

NATIVES IN CHARACTERISTIC DRESS

But there is an uneasy consciousness that the lack of money, the war itself, and other distresses are all connected with a much deeper question that keeps on reappearing in different forms. It is the question of “contract labor.” Cheap labor of some sort is essential, if the old colony is to be preserved. There was a time when there was plenty of labor and to spare—so much to spare that it was exported in profitable ship-loads to Havana and Brazil, while the bishop sat on the wharf and christened the slaves in batches. But, as I have said, that source of income was cut off by British gun-boats some fifty years ago, and is lost, perhaps forever. And in the mean time the home supply of labor has been lamentably diminished; for the native population, the natural cultivators of the country, have actually decreased in number, and other[Pg 24] causes have contributed to raise their price above the limit of “economic value.”

Their numbers have decreased, because the whole country, always exposed to small-pox, has been suffering more and more from the diseases which alcoholism brings or leaves, and, like most of tropical Africa, it has been devastated within the last twenty or thirty years by this new plague to humanity, called “the sleeping-sickness.” Men of science are undecided still as to the cause. They are now inclined to connect it with the tsetse-fly, long known in parts of Africa as the destroyer of all domesticated animals, but hitherto supposed to be harmless to man, whether domesticated or wild. No one yet knows, and we can only describe its course from the observed cases. It begins with an unwillingness to work, an intense desire to sit down and do nothing, so that the lowest and most laborious native becomes quite aristocratic in his habits. The head then keeps nodding forward, and intervals of profound sleep supervene. Control over the expression of emotion is lost, so that the patient laughs or cries without cause. This has been a very marked symptom among the children I have seen. In some the great tears kept pouring down; others could not stop laughing. The muscles twitch of themselves, and the glands at the back of the neck swell up. Then the appetite fails, and in the cases I have seen there is extreme wasting,[Pg 25] as from famine. Sometimes, however, the body swells all over, and the natives call this kind “the Baobab,” from the name of the enormous and disproportioned tree which abounds here, and always looks as if it suffered from elephantiasis, like so many of the natives themselves. Often there is an intense desire to smoke, but when the pipe is lit the patient drops it with indifference. Then come fits of bitter cold, and during these fits patients have been known to fall into the fire and allow themselves to be burned to death. Towards the end, violent trembling comes on, followed by delirium and an unconsciousness which may continue for about the final fortnight. The disease lasts from six to eight months; sometimes a patient lives a year. But hitherto there has been no authenticated instance of recovery. Of all diseases, it is perhaps the only one which up to now counts its dead by cent per cent. It attacks all ages between five years and forty, and even those limits are not quite fixed. It so happens that most of the cases I have yet seen in the country have been children, but that may be accidental. For a long time it was thought that white people were exempt. But that is not so. They are apparently as liable to the sickness as the natives, and there are white patients suffering from it now in the Loanda hospital.

My reason for now dwelling upon the disease which has added a new terror to Africa is its effect[Pg 26] upon the labor-supply. It is very capricious in its visitation. Sometimes it will cling to one side of a river and leave the other untouched. But when it appears it often sweeps the population off the face of the earth, and there are places in Angola which lately were large native towns, but are now going back to desert. So people are more than ever wanted to continue the cultivation of such land as has been cultivated, and, unhappily, it is now more than ever essential that the people should be cheap. The great days when fortunes were made in coffee, or when it was thought that cocoa would save the country, are over. Prices have sunk. Brazil has driven out Angola coffee. San Thomé has driven out the cocoa. The Congo is driving out the rubber, and the sugar-cane is grown only for the rum that natives drink—not a profitable industry from the point of view of national economics. Many of the old plantations have come to grief. Some have been amalgamated into companies with borrowed capital. Some have been sold for a song. None is prosperous; but people still think that if only “contract labor” were cheaper and more plentiful, prosperity would return. As it is, they see all the best labor draughted off to the rich island of San Thomé, never to return, and that is another reason why the mind of Loanda is much disquieted.

I do not mean that the anxiety about the “contract labor” is entirely a question of cash. The[Pg 27] Portuguese are quite as sensitive and kindly as other people. Many do not like to think that the “serviçaes” or “contrahidos,” as they are called, are, in fact, hardly to be distinguished from the slaves of the cruel old times. Still more do not like to hear the most favored province of the Portuguese Empire described by foreigners as a slave state. There is a strong feeling about it in Portugal also, I believe, and here in Angola it is the chief subject of conversation and politics. The new governor is thought to be an “antislavery” man. A little newspaper appears occasionally in Loanda (A Defeza de Angola) in which the shame of the whole system is exposed, at all events with courage. The paper is not popular with the official or governing classes. No courageous newspaper ever can be; for the official person is born with a hatred of reform, because reform means trouble. But the paper is read none the less. There is a feeling about the question which I can only describe again as disquiet. It is partly conscience, partly national reputation; partly also it is the knowledge that under the present system San Thomé gets all the advantage, and the mainland is being drained of laborers in order that the island’s cocoa may abound.

Legally the system is quite simple and looks innocent enough. Legally it is laid down that a native and a would-be employer come before a magistrate or other representative of the Curator-General[Pg 28] of Angola, and enter into a free and voluntary contract for so much work in return for so much pay. By the wording of the contract the native declares that “he has come of his own free will to contract for his services under the terms and according to the forms required by the law of April 29, 1875, the general regulation of November 21, 1878, and the special clauses relating to this province.”

The form of contract continues:

1. The laborer contracts and undertakes to render all such [domestic, agricultural, etc.] services as his employer may require.

2. He binds himself to work nine hours on all days that are not sanctified by religion, with an interval of two hours for rest, and not to leave the service of the employer without permission, except in order to complain to the authorities.

3. This contract to remain in force for five complete years.

4. The employer binds himself to pay the monthly wages of ——, with food and clothing.

Then follow the magistrate’s approval of the contract, and the customary conclusion about “signed, sealed, and delivered in the presence of the following witnesses.” The law further lays it down that the contract may be renewed by the wish of both parties at the end of five years, that the magistrates should visit the various districts and see that the contracts are properly observed and renewed, and that all children born to the laborers,[Pg 29] whether man or woman, during the time of his or her contract shall be absolutely free.

Legally, could any agreement look fairer and more innocent? Or could any government have better protected a subject population in the transition from recognized slavery to free labor? Even apart from the splendor of legal language, laws often seem divine. But let us see how the whole thing works out in human life.

An agent, whom for the sake of politeness we may call a labor merchant, goes wandering about among the natives in the interior—say seven or eight hundred miles from the coast. He comes to the chief of a tribe, or, I believe, more often, to a little group of chiefs, and, in return for so many grown men and women, he offers the chiefs so many smuggled rifles, guns, and cartridges, so many bales of calico, so many barrels of rum. The chiefs select suitable men and women, very often one of the tribe gives in his child to pay off an old debt, the bargain is concluded, and off the party goes. The labor merchant leads it away for some hundreds of miles, and then offers its members to employers as contracted laborers. As commission for his own services in the transaction, he may receive about fifteen or twenty pounds for a man or a woman, and about five pounds for a child. According to law, the laborer is then brought before a magistrate and duly signs the above contract[Pg 30] with his or her new master. He signs, and the benevolent law is satisfied. But what does the native know or care about “freedom of contract” or “the general regulation of November 21, 1878”? What does he know about nine hours a day and two hours rest and the days sanctified by religion? Or what does it mean to him to be told that the contract terminates at the end of five years? He only knows that he has fallen into the hands of his enemies, that he is being given over into slavery to the white man, that if he runs away he will be beaten, and even if he could escape to his home, all those hundreds of miles across the mountains, he would probably be killed, and almost certainly be sold again. In what sense does such a man enter into a free contract for his labor? In what sense, except according to law, does his position differ from a slave’s? And the law does not count; it is only life that counts.

I do not wish at present to dwell further upon this original stage in the process of the new slave-trade, for I have not myself yet seen it at work. I only take my account from men who have lived long in the interior and whose word I can trust. I may be able to describe it more fully when I have been farther into the interior myself. But now I will pass to a stage in the system which I have seen with my own eyes—the plantation stage, in which the contract system is found in full working order.

[Pg 31]

For about a hundred miles inland from Loanda, the country is flattish and bare and dry, though there are occasional rivers and a sprinkling of trees. A coarse grass feeds a few cattle, but the chief product is the cassava, from which the natives knead a white food, something between rice and flour. As you go farther, the land grows like the “low veldt” in the Transvaal, and it has the same peculiar and unwholesome smell. By degrees it becomes more mountainous and the forest grows thick, so that the little railway seems to struggle with the undergrowth almost as much as with the inclines. That little railway is perhaps the only evidence of “progress” in the province after three or four centuries. It is paid for by Lisbon, but a train really does make the journey of about two hundred and fifty miles regularly in two days, resting the engine for the night. To reach a plantation you must get out on the route and make your way through the forest by one of those hardly perceptible “bush paths” which are the only roads. Along these paths, through flag-grasses ten feet high, through jungle that closes on both sides like two walls, up mountains covered with forest, and down valleys where the water is deep at this wet season, every bit of merchandise, stores, or luggage must be carried on the heads of natives, and every yard of the journey has to be covered on foot.

After struggling through the depths of the woods[Pg 32] in this way for three or four hours, we climbed a higher ridge of mountain and emerged from the dense growth to open summits of rock and grass. Far away to the southeast a still higher mountain range was visible, and I remembered, with what writers call a momentary thrill, that from this quarter of the compass Livingstone himself had made his way through to Loanda on one of his greatest journeys. Below the mountain edge on which I stood lay the broad valley of the plantation, surrounded by other hills and depths of forest. The low white casa, with its great barns and outhouses, stood in the middle. Close by its side were the thatched mud huts of the work-people, the doors barred, the little streets all empty and silent, because the people were all at work, and the children that were too small to work and too big to be carried were herded together in another part of the yards. From the house, in almost every direction, the valleys of cultivated ground stretched out like fingers, their length depending on the shape of the ground and on the amount of water which could be turned over them by ditch-canals.

It was a plantation on which everything that will grow in this part of Africa was being tried at once. There were rows of coffee, rows of cocoa-plant, woods of bananas, fields of maize, groves of sugar-cane for rum. On each side of the paths mango-trees stood in avenues, or the tree which the parlors[Pg 33] of Camden Town know as the India-rubber plant, though in fact it is no longer the chief source of African rubber. A few other plants and fruits were cultivated as well, but these were the main produce.

The cultivation was admirable. Any one who knows the fertile parts of Africa will agree that the great difficulty is not to make things grow, but to prevent other things from growing. The abundant growth chokes everything down. An African forest is one gigantic struggle for existence, and an African field becomes forest as soon as you take your eyes off it. But on the plantation the ground was kept clear and clean. The first glance told of the continuous and persistent labor that must be used. And as I was thinking of this and admiring the result, suddenly I came upon this continuous and persistent labor in the flesh.

It was a long line of men and women, extended at intervals of about a yard, like a company of infantry going into action. They were clearing a coffee-plantation. Bent double over the work, they advanced slowly across the ground, hoeing it up as they went. To the back of nearly every woman clung an infant, bound on by a breadth of cotton cloth, after the African fashion, while its legs straddled round the mother’s loins. Its head lay between her shoulders, and bumped helplessly against her back as she struck the hoe into the ground.[Pg 34] Most of the infants were howling with discomfort and exhaustion, but there was no pause in the work. The line advanced persistently and in silence. The only interruption was when a loin-cloth had to be tightened up, or when one of the little girls who spend the day in fetching water passed along the line with her pitcher. When the people had drunk, they turned to the work again, and the only sound to be heard was the deep grunt or sigh as the hoe was brought heavily down into the mass of tangled grass and undergrowth between the rows of the coffee-plants.

Five or six yards behind the slowly advancing line, like the officers of a company under fire, stood the overseers, or gangers, or drivers of the party. They were white men, or three parts white, and were dressed in the traditional planter style of big hat, white shirt, and loose trousers. Each carried an eight-foot stick of hard wood, whitewood, pointed at the ends, and the look of those sticks quite explained the thoroughness and persistency of the work, as well as the silence, so unusual among the natives whether at work or play.

At six o’clock a big bell rang from the casa, and all stopped working instantly. They gathered up their hoes and matchets (large, heavy knives), put them into their baskets, balanced the baskets on their heads, and walked silently back to their little gathering of mud huts. The women unbarred the[Pg 35] doors, put the tools away, kindled the bits of firewood they had gathered on the path from work, and made the family meal. Most of them had to go first to a large room in the casa where provisions are issued. Here two of the gangers preside over the two kinds of food which the plantation provides—flour and dried fish (a great speciality of Angola, known to British sailors as “stinkfish”). Each woman goes up in turn and presents a zinc disk to a ganger. The disk has a hole through it so that it may be carried on a string, and it is stamped with the words “Fazenda de Paciencia 30 Reis,” let us say, or “Paciencia Plantation 1½d.” The number of reis varies a little. It is sometimes forty-five, sometimes higher. In return for her disks, the woman receives so much flour by weight, or a slab of stinkfish, as the case may be. She puts them in her basket and goes back to cook. The man, meantime, has very likely gone to the shop next door and has exchanged his disk for a small glass of the white sugar-cane rum, which, besides women and occasional tobacco, is his only pleasure. But the shop, which is owned by the plantation and worked by one of the overseers, can supply cotton cloth, a few tinned meats, and other things if desired, also in exchange for the disks.

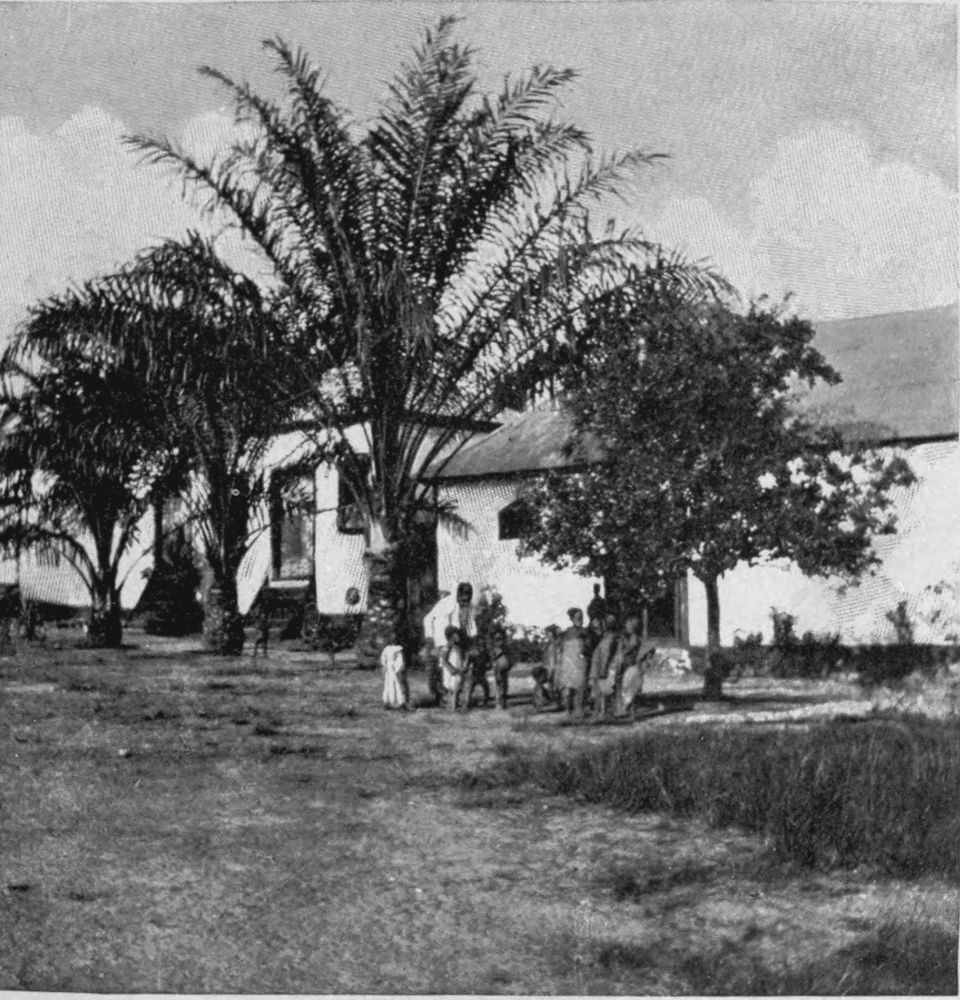

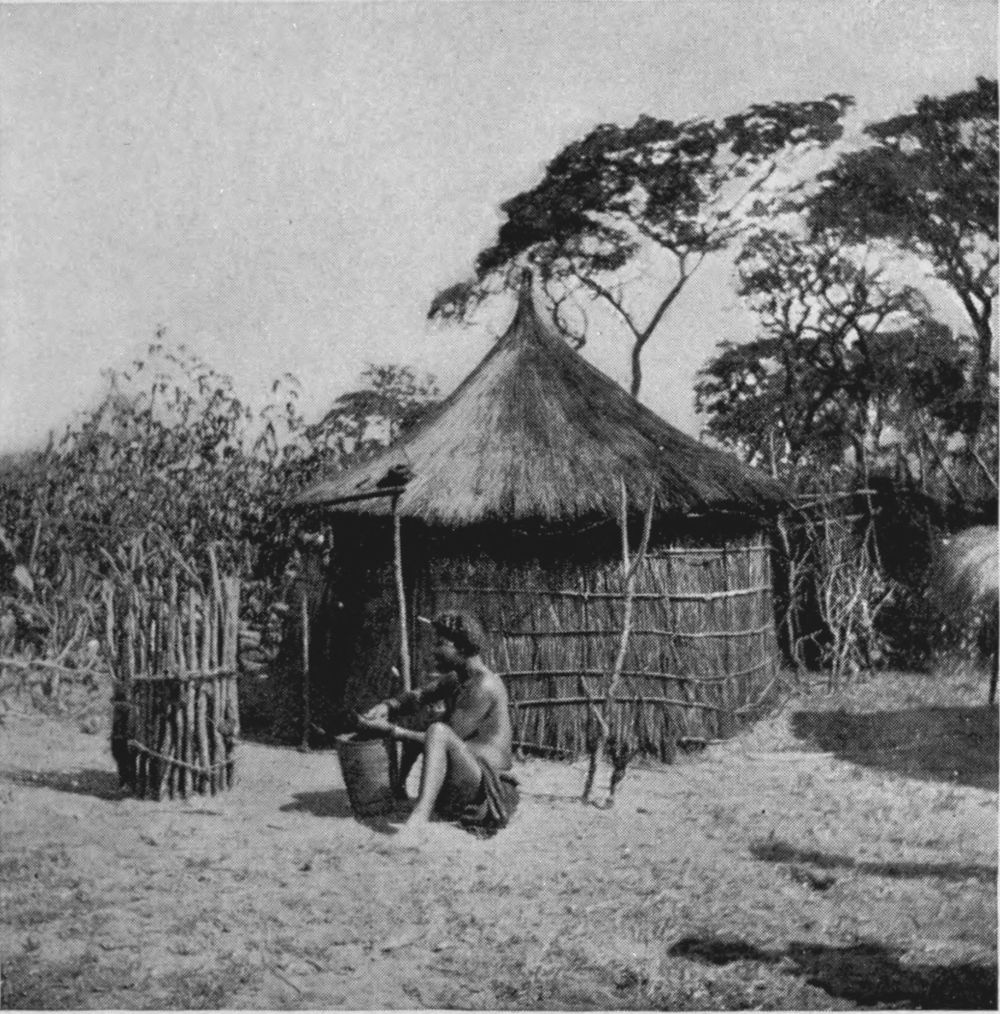

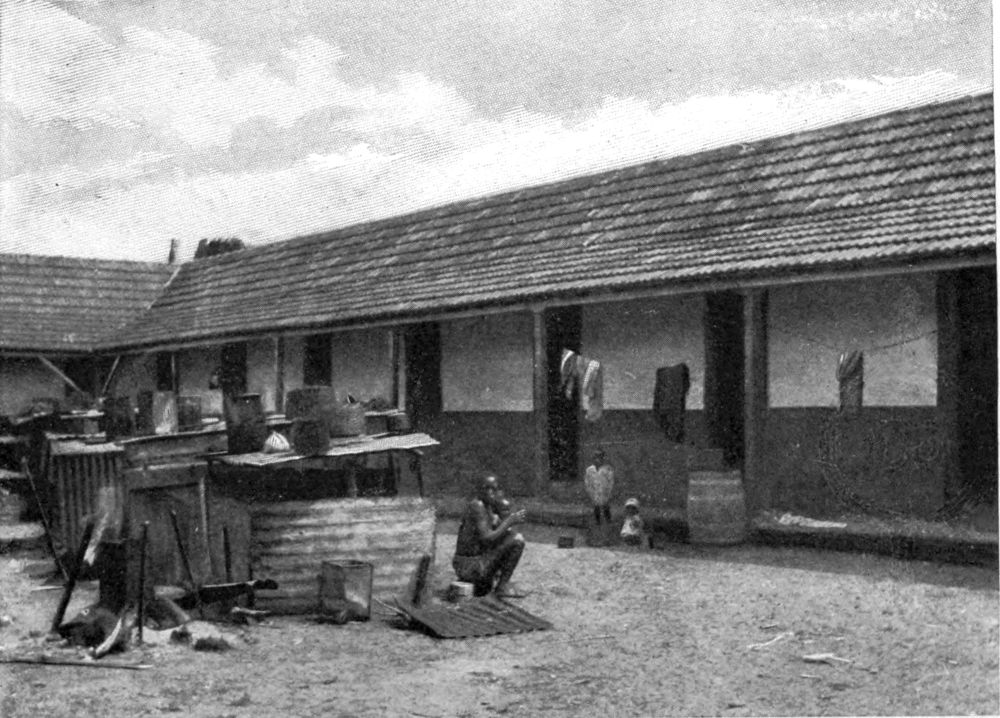

PLANTER’S HOUSE ON AN ANGOLA ESTATE

The casa and the mud huts are soon asleep. At half-past four the big bell clangs again. At five it clangs again. Men and women hurry out and[Pg 36] range themselves in line before the casa, coughing horribly and shivering in the morning air. The head overseer calls the roll. They answer their queer names. The women tie their babies on to their backs again. They balance the hoe and matchet in the basket on their heads, and pad away in silence to the spot where the work was left off yesterday. At eleven the bell clangs again, and they come back to feed. At twelve it clangs again, and they go back to work. So day follows day without a break, except that on Sundays (“days sanctified by religion”) the people are allowed, in some plantations, to work little plots of ground which are nominally their own.

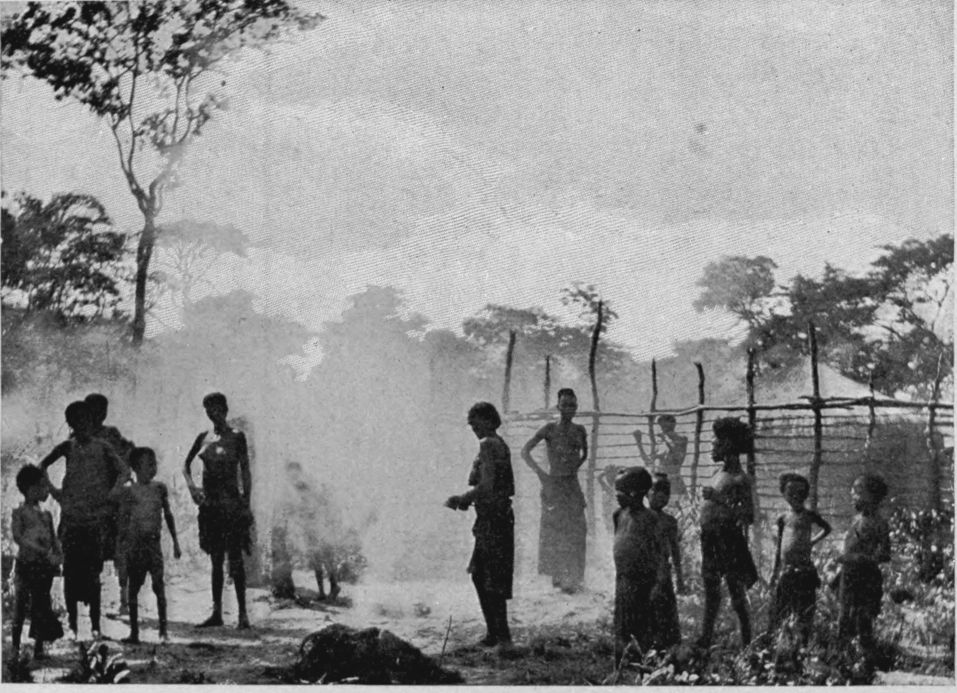

“No change, no pause, no hope.” That is the sum of plantation life. So the man or woman known as a “contract laborer” toils, till gradually or suddenly death comes, and the poor, worn-out body is put to rot. Out in the forest you come upon the little heap of red earth under which it lies. On the top of the heap is set the conical basket of woven grasses which was the symbol of its toil in life, and now forms its only monument. For a fortnight after death the comrades of the dead think that the spirit hovers uneasily about the familiar huts. They dance and drink rum to cheer themselves and it. When the fortnight is over, the spirit is dissolved into air, and all is just as though the slave had never been.

[Pg 37]

There is no need to be hypocritical or sentimental about it. The fate of the slave differs little from the fate of common humanity. Few men or women have opportunity for more than working, feeding, getting children, and death. If any one were to maintain that the plantation life is not in reality worse than the working-people’s life in most of our manufacturing towns, or in such districts as the Potteries, the Black Country, and the Isle of Dogs, he would have much to say. The same argument was the only one that counted in defence of the old slavery in the West Indies and the Southern States, and it will have to be seriously met again now that slavery is reappearing under other names. A man who has been bought for money is at least of value to his master. In return for work he gets his mud hut, his flour, his stinkfish, and his rum. The driver with his eight-foot stick is not so hideous a figure as the British overseer with his system of blackmail; and as for cultivation of the intellect and care of the soul, the less we talk about such things the better.

In this account I only mean to show that the difference between the “contract labor” of Angola, and the old-fashioned slavery of our grandfathers’ time is only a difference of legal terms. In life there is no difference at all. The men and women whom I have described as I saw them have all been bought from their enemies, their chiefs, or their[Pg 38] parents; they have either been bought themselves or were the children of people who had been bought. The legal contract, if it had been made at all, had not been observed, either in its terms or its renewal. The so-called pay by the plantation tokens is not pay at all, but a form of the “truck” system at its very worst. So far from the children being free, they now form the chief labor supply of the plantation, for the demand for “serviçaes” in San Thomé has raised the price so high that the Angola plantations could not carry on at all without the little swarms of children that are continually growing up on the estates. Sometimes, as I have heard, two or three of the men escape, and hide in the crowd at Loanda or set up a little village far away in the forest. But the risk is great; they have no money and no friends. I have not heard of a runaway laborer being prosecuted for breach of contract. As a matter of fact, the fiction of the contract is hardly even considered. But when a large plantation was sold the other day, do you suppose the contract of each laborer was carefully examined, and the length of his future service taken into consideration? Not a bit of it. The laborers went in block with the estate. Men, women, and children, they were handed over to the new owners, and became their property just like the houses and trees.

Portuguese planters are not a bit worse than other men, but their position is perilous. The[Pg 39] owner or agent lives in the big house with three or four white or whitey-brown overseers. They are remote from all equal society, and they live entirely free from any control or public opinion that they care about. Under their absolute and unquestioned power are men and women, boys and girls—let us say two hundred in all. We may even grant, if we will, that the Portuguese planters are far above the average of men. Still I say that if they were all Archbishops of Canterbury, it would not be safe for them to be intrusted with such powers as these over the bodies and souls of men and women.

[Pg 40]

Some two hundred miles south of St. Paul de Loanda, you come to a deep and quiet inlet, called Lobito Bay. Hitherto it has been desert and unknown—a spit of waterless sand shutting in a basin of the sea at the foot of barren and waterless hills. But in twenty years’ time Lobito Bay may have become famous as the central port of the whole west coast of Africa, and the starting-place for traffic with the interior. For it is the base of the railway scheme known as the “Robert Williams Concession,” which is intended to reach the ancient copper-mines of the Katanga district in the extreme south of the Congo State, and so to unite with the “Tanganyika Concession.” It would thus connect the west coast traffic with the great lakes and the east. A branch line might also turn off at some point along the high and flat watershed between the Congo and Zambesi basins, and join the Cape Town railway near Victoria Falls. Possibly before the Johannesburg gold is exhausted, passengers from London to[Pg 41] the Transvaal will address their luggage “viâ Lobito Bay.”

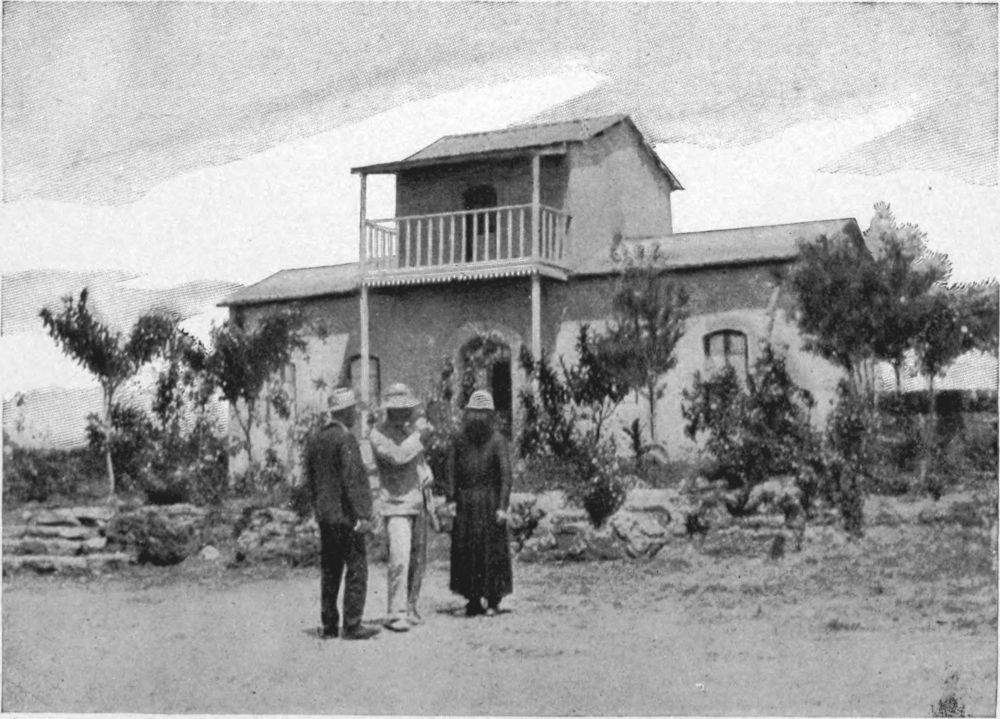

FIRST MAIL-STEAMER AT LOBITO BAY

But this is only prophecy. What is certain is that on January 5, 1905, a mail-steamer was for the first time warped alongside a little landing-stage of lighters, in thirty-five feet of water, and I may go down to fame as the first man to land at the future port. What I found were a few laborers’ huts, a tent, a pile of sleepers, a tiny engine puffing over a mile or two of sand, and a large Portuguese custom-house with an eye to possibilities. I also found an indomitable English engineer, engaged in doing all the work with his own hands, to the entire satisfaction of the native laborers, who encouraged him with smiles.

At present the railway, which is to transform the conditions of Central Africa, runs as a little tram-line for about eight miles along the sand to Katumbella. There it has something to show in the shape of a great iron bridge, which crosses the river with a single span. The day I was there the engineers were terrifying the crocodiles by knocking away the wooden piles used in the construction, and both natives and Portuguese were awaiting the collapse of the bridge with the pleasurable excitement of people who await a catastrophe that does not concern themselves. But; to the general disappointment, the last prop was knocked away and the bridge still stood. It was amazing. It was contrary[Pg 42] to the traditions of Africa and of Portugal.

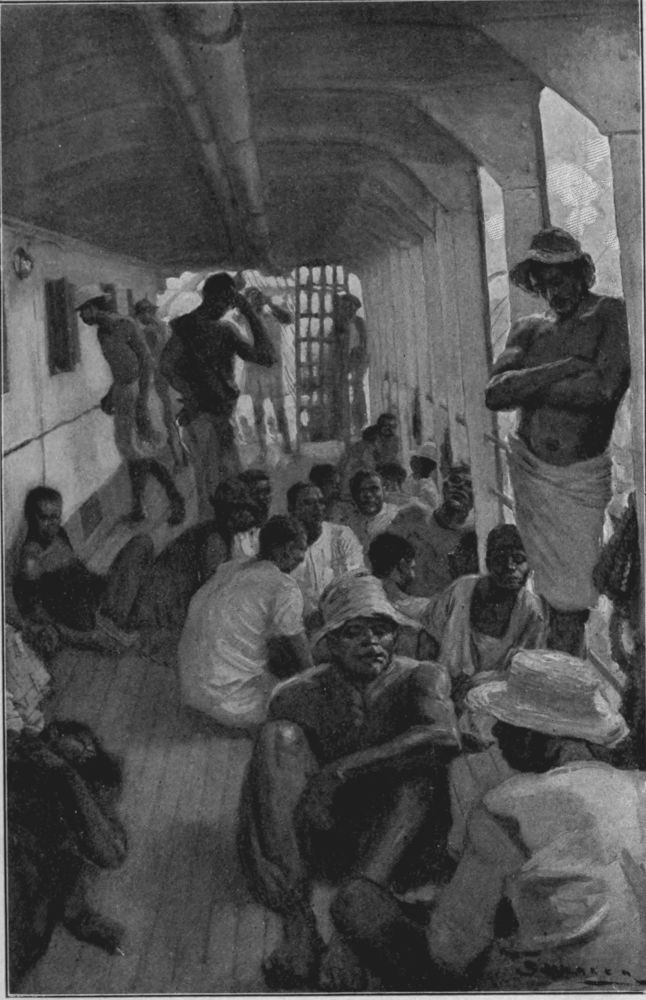

Katumbella itself is an old town, with two old forts, a dozen trading-houses, and a river of singular beauty, winding down between mountains. It is important because it stands on the coast at the end of the carriers’ foot-path, which has been for centuries the principal trade route between the west and the interior. One sees that path running in white lines far over the hills behind the town, and up and down it black figures are continually passing with loads upon their heads. They bring rubber, beeswax, and a few other products of lands far away. They take back enamelled ware, rum, salt, and the bales of cotton cloth from Portugal and Manchester which, together with rum, form the real coinage and standard of value in Central Africa, salt being used as the small change. The path ends, vulgarly enough, at an oil-lamp in the chief street of Katumbella. Yet it is touched by the tragedy of human suffering. For this is the end of that great slave route which Livingstone had to cross on his first great journey, but otherwise so carefully avoided. This is the path down which the caravans of slaves from the basin of the Upper Congo have been brought for generations, and down this path within the last three or four years the slaves were openly driven to the coast, shackled, tied together, and beaten along with whips, the trader considering[Pg 43] himself fairly fortunate if out of his drove of human beings he brought half alive to the market. There is a notorious case in which a Portuguese trader, who still follows his calling unchecked, lost six hundred out of nine hundred on the way down. At Katumbella the slaves were rested, sorted out, dressed, and then taken on over the fifteen miles to Benguela, usually disguised as ordinary carriers. The traffic still goes on, almost unchecked. But of that ancient route from Bihé to the coast I shall write later on, for by this path I hope to come when I emerge from the interior and catch sight of the sea again between the hills.

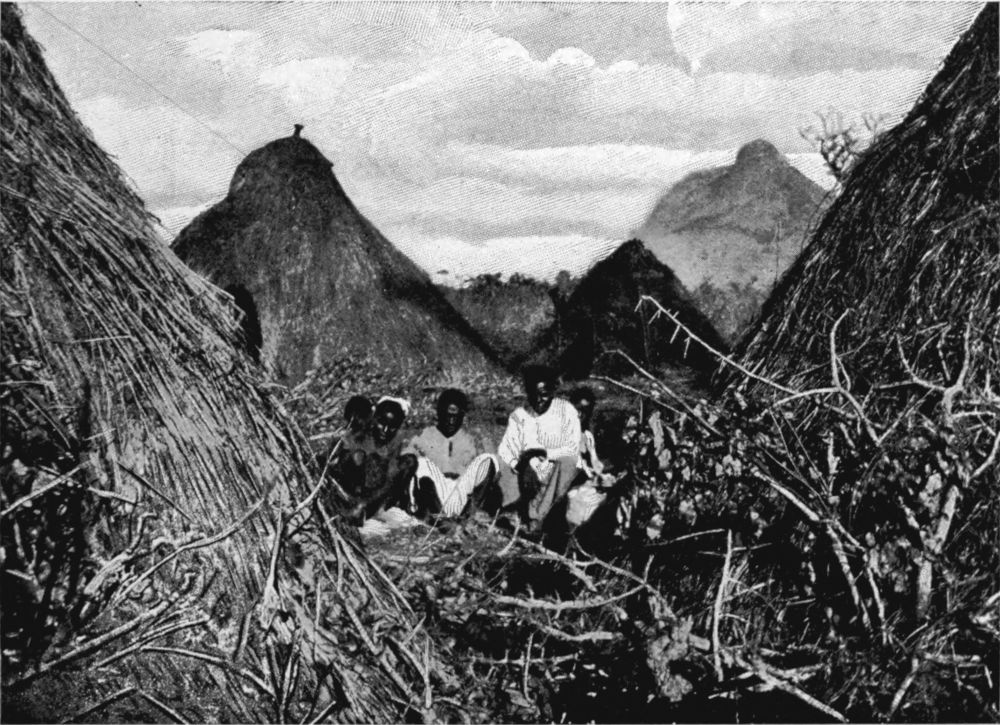

END OF THE GREAT SLAVE ROUTE AT KATUMBELLA

As to the town of Benguela, there is something South African about it. Perhaps it comes from the eucalyptus-trees, the broad and sandy roads ending in scrubby waste, and the presence of Boer transport-riders with their ox-wagons from southern Angola. But the place is, in fact, peculiarly Portuguese. Next to Loanda, it is the most important town in the colony, and for years it was celebrated as the very centre of the slave-trade with Brazil. In the old days when Great Britain was the enthusiastic opponent of slavery in every form, some of her men-of-war were generally hanging about off Benguela on the watch. They succeeded in making the trade difficult and unlucrative; but we have all become tamer now and more ready to show consideration for human failings, provided they pay. Call slaves[Pg 44] by another name, legalize their position by a few printed papers, and the traffic becomes a commercial enterprise deserving of every encouragement. A few years ago, while gangs were still being whipped down to the coast in chains, one of the most famous of living African explorers informed the captain of a British gun-boat what was the true state of things upon a Portuguese steamer bound for San Thomé. The captain, full of old-fashioned indignation, proposed to seize the ship. Whereupon the British authorities, flustered at the notion of such impoliteness, reminded him that we were now living in a civilized age. These men and women, who had been driven like cattle over some eight hundred miles of road to Benguela were not to be called slaves. They were “serviçaes,” and had signed a contract for so many years, saying they went to San Thomé of their own free will. It was the free will of sheep going to the butcher’s. Every one knew that. But the decencies of law and order must be observed.

Within the last two or three years the decencies of law and order have been observed in Benguela with increasing care. There are many reasons for the change. Possibly the polite representations of the British Foreign Office may have had some effect; for England, besides being Portugal’s “old ally,” is one of the best customers for San Thomé cocoa, and it might upset commercial relations if the cocoa-drinkers[Pg 45] of England realized that they were enjoying their luxury, or exercising their virtue, at the price of slave labor. Something may also be due to the presence of the English engineers and mining prospectors connected with the Robert Williams Concession. But I attribute the change chiefly to the helpless little rising of the natives, known as the “Bailundu war” of 1902. Bailundu is a district on the route between Benguela and Bihé, and the rising, though attributed to many absurd causes by the Portuguese—especially to the political intrigues of the half-dozen American missionaries in the district—was undoubtedly due to the injustice, violence, and lust of certain traders and administrators. The rising itself was an absolute failure. Terrified as the Portuguese were, the natives, were more terrified still. I have seen a place where over four hundred native men, women, and children were massacred in the rocks and holes where their bones still lie, while the Portuguese lost only three men. But the disturbance may have served to draw the attention of Portugal to the native grievances. At any rate, it was about the same time that two of the officers at an important fort were condemned to long terms of imprisonment and exile for open slave-dealing, and Captain Amorim, a Portuguese gunner, was sent out as a kind of special commissioner to make inquiries. He showed real zeal in putting down the slave-trade, and set a large[Pg 46] number of slaves at liberty with special “letters of freedom,” signed by himself—most of which have since been torn up by the owners. His stay was, unhappily, short, but he returned home, honored by the hatred of the Portuguese traders and officials in the country, who did their best to poison him, as their custom is. His action and reports were, I think, the chief cause of Portugal’s “uneasiness.”

So the horror of the thing has been driven under the surface; and what is worse, it has been legalized. Whether it is diminished by secrecy and the forms of law, I shall be able to judge better in a few months’ time. I found no open slave-market existing in Benguela, such as reports in Europe would lead one to expect. The spacious court-yards or compounds round the trading-houses are no longer crowded with gangs of slaves in shackles, and though they are still used for housing the slaves before their final export, the whole thing is done quietly, and without open brutality, which is, after all, unprofitable as well as inhuman.

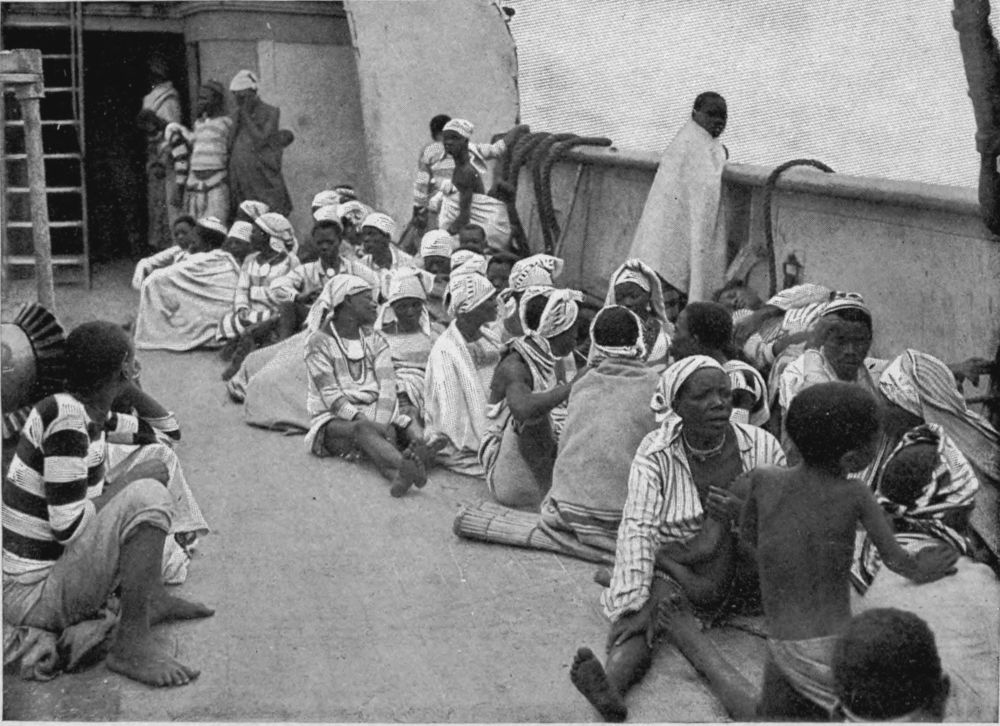

In the main street there is a government office where the official representative of the “Central Committee of Labor and Emigration for the Islands” (having its headquarters in Lisbon) sits in state, and under due forms of law receives the natives, who enter one door as slaves and go out of another as “serviçaes.” Everything is correct. The native,[Pg 47] who has usually been torn from his home far in the interior, perhaps as much as eight hundred miles away, and already sold twice, is asked by an interpreter if it is his wish to go to San Thomé, or to undertake some other form of service to a new master. Of course he answers, “Yes.” It is quite unnecessary to suppose, as most people suppose, that the interpreter always asks such questions as, “Do you like fish?” or, “Will you have a drink?” though one of the best scholars in the languages of the interior has himself heard those questions asked at an official inspection of “serviçaes” on board ship. It would be unnecessary for the interpreter to invent such questions. If he asked, “Is it your wish to go to hell?” the “serviçal” would say “yes” just the same. In fact, throughout this part of Africa, the name of San Thomé is becoming identical with hell, and when a man has been brought hundreds of miles from his home by an unknown road, and through long tracts of “hungry country”—when also he knows that if he did get back he would probably be sold again or killed—what else can he answer but “yes”? Under similar circumstances the Archbishop of Canterbury would answer the same.

The “serviçal” says “yes,” and so sanctions the contract for his labor. The decencies of law and order are respected. The government of the colony receives its export duty—one of the queerest methods[Pg 48] of “protecting home industries” ever invented. All is regular and legalized. A series of new rules for the serviçal’s comfort and happiness during his stay in the islands was issued in 1903, though its stipulations have not been carried out. And off goes the man to his death in San Thomé or Il Principe as surely as if he had signed his own death-warrant. To be sure, there are regulations for his return. By law, three-fifths of his so-called monthly wages are to be set aside for a “Repatriation Fund,” and in consideration of this he is granted a “free passage” back to the coast. A more ingenious trick for reducing the price of labor has never been invented, but, for very shame, the Repatriation Fund has ceased to exist, if it ever existed. Ask any honest man who knows the country well. Ask any Scottish engineer upon the Portuguese steamers that convey the “serviçaes” to the islands, and he will tell you they never return. The islands are their grave.

These are things that every one knows, but I will not dwell upon them yet or even count them as proved, for I have still far to go and much to see. Leaving the export trade in “contracted labor,” I will now speak of what I have actually seen and known of slavery on the mainland under the white people themselves. I have heard the slaves in Angola estimated at five-sixths of the population by an Englishman who has held various influential[Pg 49] positions in the country for nearly twenty years. The estimate is only guesswork, for the Portuguese are not strong in statistics, especially in statistics of slavery. But including the very large number of natives who, by purchase or birth, are the family slaves of the village chiefs and other fairly prosperous natives, we might probably reckon at least half the population as living under some form of slavery—either in family slavery to natives, or general slavery to white men, or in plantation slavery (under which head I include the export trade). I have referred to the family slavery among the natives. Till lately it has been universal in Africa, and it still exists in nearly all parts. But though it is constantly pleaded as their excuse by white slave-owners, it is not so shameful a thing as the slavery organized by the whites, if only because whites do at least boast themselves to be a higher race than natives, with higher standards of life and manners. From what I have seen of African life, both in the south and west, I am not sure that the boast is justified, but at all events it is made, and for that reason white men are precluded from sheltering themselves behind the excuse of native customs.

On the same steamer by which I reached Benguela there were five little native boys, conspicuous in striped jerseys, and running about the ship like rats. I suppose they were about ten to twelve years old,[Pg 50] perhaps less. I do not know where they came from, but it must have been from some fairly distant part of the interior, for, like all natives who see stairs for the first time, they went up and down them on their hands and knees. They were travelling with a Portuguese, and within a week of landing at Benguela he had sold them all to other white owners. Their price was fifty milreis apiece (nearly £10). Their owner did rather well, for the boys were small and thin—hardly bigger than another native slave boy who was at the same time given away by one Portuguese friend to another as a New-Year’s present. But all through this part of the country I have found the price of human beings ranging rather higher than I expected, and the man who told me the price of the boys had himself been offered one of them at that figure, and was simply passing on the offer to myself.

Perhaps I was led to underestimate prices a little by the statement of a friend in England that at Benguela one could buy a woman for £8 and a girl for £12. He had not been to that part of the coast himself, though for five years he had lived in the Katanga district of the Congo State, from which large numbers of the slaves are drawn. Perhaps he had forgotten to take into account the heavy cost of transport from the interior and the risk of loss by death upon the road. Or perhaps he reckoned by the exceptionally low prices prevailing[Pg 51] after the dry season of 1903, when, owing to a prolonged drought, the famine was severe in a district near the Kunene in southeast Angola, and some Portuguese and Boer traders took advantage of the people’s hunger to purchase oxen and children cheap in exchange for mealies. Similarly, in 1904, women were being sold unusually cheap in a district by the Cuanza, owing to a local famine. Livingstone, in his First Expedition to Africa, said he had never known cases of parents selling children into slavery, but Mr. F. S. Arnot, in his edition of the book, has shown that such things occur (though as a rule a child is sold by his maternal uncle), and I have myself heard of several instances in the last few weeks, both for debt and hunger. Necessity is the slave-trader’s opportunity, and under such conditions the market quotations for human beings fall, in accordance with the universal economics.

The value of a slave, man or woman, when landed at San Thomé, is about £30, but, as nearly as I could estimate, the average price of a grown man in Benguela is £20 (one hundred dollars). At that price the traders there would be willing to supply a large number. An Englishman whom I met there had been offered a gang of slaves, consisting of forty men and women, at the rate of £18 a head. But the slaves were up in Bihé, and the cost of transport down to the coast goes for something;[Pg 52] and perhaps there was “a reduction on taking a quantity.” However, when he was in Bihé, he had bought two of them from the Portuguese trader at that rate. They were both men. He had also bought two boys farther in the interior, but I do not know at what price. One of them had been with the Batatele cannibals, who form the chief part of the “Révoltés,” or rebels, against the atrocious government of the Belgians on the Upper Congo. Perhaps the boy himself really belonged to the race which had sold him to the Bihéan traders. At all events, the racial mark was cut in his ears, and the other “boys” in the Englishman’s service were never tired of chaffing him upon his past habits. Every night they would ask him how many men he had eaten that day. But a point was added to the laugh because the ex-cannibal was now acting as cook to the party. Under their new service all these slaves received their freedom.

The price of women on the mainland is more variable, for, as in civilized countries, it depends almost entirely on their beauty and reputation. Even on the Benguela coast I think plenty of women could be procured for agricultural, domestic, and other work at £15 a head or even less. But for the purposes for which women are often bought the price naturally rises, and it depends upon the ordinary causes which regulate such traffic. A full-grown[Pg 53] and fairly nice-looking woman may be bought from a trader for £18, but for a mature girl a man must pay more. At least a stranger who is not connected with the trade has to pay more. While I was in the town a girl was sold to a prospector, who wanted her as his concubine during a journey into the interior. Her owner was an elderly Portuguese official of some standing. I do not know how he had obtained her, but she was not born in his household of slaves, for he had only recently come to the country. Most likely he had bought her as a speculation, or to serve as his concubine if he felt inclined to take her. The price finally arranged between him and the prospector for the possession of the girl was one hundred and twenty-five milreis, which was then nearly equal to £25. For the visit of the King of Portugal to England and the revival of the “old alliance” had just raised the value of the Portuguese coinage.

When the bargain was concluded, the girl was led to her new master’s room and became his possession. During his journey into the interior she rode upon his wagon. I saw them often on the way, and was told the story of the purchase by the prospector himself. He did not complain of the price, though men who were better acquainted with the uses of the woman-market considered it unnecessarily high. But it is really impossible to fix an average standard of value where such things as beauty[Pg 54] and desire are concerned. The purchaser was satisfied, the seller was satisfied. So who was to complain? The girl was not consulted, nor did the question of her price concern her in the least.

I was glad to find that the Portuguese official who had parted with her on these satisfactory terms was no merely selfish speculator in the human market, as so many traders are, but had considered the question philosophically, and had come to the conclusion that slavery was much to a slave’s advantage. The slave, he said, had opportunities of coming into contact with a higher civilization than his own. He was much better off than in his native village. His food was regular, his work was not excessive, and, if he chose, he might become a Christian. Being an article of value, it was likely that he would be well treated. “Indeed,” he continued, in an outburst of philanthropic emotion, “both in our own service and at San Thomé, the slave enjoys a comfort and well-being which would have been forever beyond his reach if he had not become a slave!” In many cases, he asserted, the slave owed his very life to slavery, for some of the slaves brought from the interior were prisoners of war, and would have been executed but for the profitable market ready to receive them. As he spoke, the old gentleman’s face glowed with noble enthusiasm, and I could not but envy him his connection with an institution that was at the same[Pg 55] time so salutary to mankind and so lucrative to himself.

As to the slave’s happiness on the islands, I cannot yet describe it, but according to the reports of residents, ships’ officers, and the natives themselves, it is brief, however great. What sort of happiness is enjoyed on the Portuguese plantations of Angola itself I have already described. As to the comfort and joy of ordinary slavery under white men, with all its advantages of civilization and religion, the beneficence of the institution is somewhat dimmed by a few such things as I have seen, or have heard from men whom I could trust as fully as my own eyes. At five o’clock one afternoon I saw two slaves carrying fish through an open square at Benguela, and enjoying their contact with civilization in the form of another native, who was driving them along like oxen with a sjambok. The same man who was offered the forty slaves at £18 a head had in sheer pity bought a little girl from a Portuguese lady last autumn, and he found her back scored all over with the cut of the chicote, just like the back of a trek-ox under training. An Englishman coming down from the interior last African winter, was roused at night by loud cries in a Portuguese trading-house at Mashiko. In the morning he found that a slave had been flogged, and tied to a tree in the cold all night. He was a man who had only lately lost his liberty, and was undergoing the[Pg 56] process which the Portuguese call “taming,” as applied to new slaves who are sullen and show no pleasure in the advantages of their position. In another case, only a few weeks ago, an American saw a woman with a full load on her head and a baby on her back passing the house where he happened to be staying. A big native, the slave of a Portuguese trader in the neighborhood, was dragging her along with a rope, and beating her with a whip as she went. The American brought the woman into the house and kept her there. Next day the Portuguese owners came in fury with forty of his slaves, breathing out slaughters, but, as is usual with the Portuguese, he shrank up when he was faced with courage. The American refused to give the woman back, and ultimately she was restored to her own distant village, where she still is.