Plate 1. to face Pa. 48.

click here for larger image.

click here for larger image.

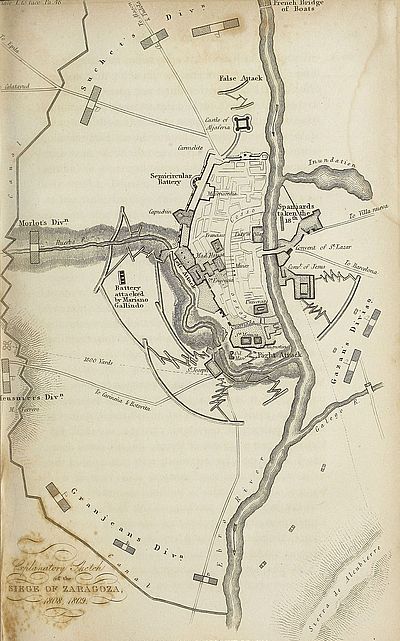

SEIGE OF ZARAGOZA,

1808, 1809.

London. Published by T. & W. BOONE, July 1829.

TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE

Footnote anchors are denoted by [number], and the footnotes have been placed at the end of the book.

With a few exceptions noted at the end of the book, variant spellings of names have not been changed.

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

Some minor changes to the text are noted at the end of the book. These are indicated by a dotted gray underline.

AND IN THE

SOUTH OF FRANCE,

FROM THE YEAR 1807 TO THE YEAR 1814.

BY

W. F. P. NAPIER, C.B.

LT. COLONEL H. P. FORTY-THIRD REGIMENT.

VOL. II.

LONDON:

THOMAS AND WILLIAM BOONE, STRAND.

MDCCCXXIX.

| BOOK V. | |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Slight effect produced in England by the result of the campaign—Debates in parliament—Treaty with Spain—Napoleon receives addresses at Valladolid—Joseph enters Madrid—Appointed the emperor’s lieutenant—Distribution of the French army—The duke of Dantzig forces the bridge of Almaraz—Toledo entered by the first corps—Infantado and Palacios ordered to advance upon Madrid—Cuesta appointed to the command of Galluzzo’s troops—Florida Blanca dies at Seville—Succeeded in the presidency by the marquis of Astorga—Money arrives at Cadiz from Mexico—Bad conduct of the central junta—State of the Spanish army—Constancy of the soldiers—Infantado moves on Tarancon—His advanced guard defeated there—French retire towards Toledo—Disputes in the Spanish army—Battle of Ucles—Retreat of Infantado—Cartoajal supersedes him, and advances to Ciudad Real—Cuesta takes post on the Tagus, and breaks down the bridge of Almaraz | Page 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Operations in Aragon—Confusion in Zaragoza—The third and fifth corps invest that city—Fortification described—Monte Torrero taken—Attack on the suburb repulsed—Mortier takes post at Calatayud—The convent of San Joseph taken—The bridge-head carried—Huerba passed—Device of the Spanish leaders to encourage the besieged—Marquis of Lazan takes post on the Sierra de Alcubierre—Lasnes arrives in the French camp—Recalls Mortier—Lazan defeated—Gallant exploit of Mariano Galindo—The walls of the town taken by assault—General Lacoste and colonel San Genis slain | 18 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| System of terror—The convent of St. Monica taken—Spaniards attempt to retake it, but fail—St. Augustin taken—French change their mode of attack—Spaniards change their mode of defence—Terrible nature of the contest—Convent of Jesus taken on the side of the suburb—Attack on the suburb repulsed—Convent of Francisco taken—Mine exploded under the university fails, and the besieged are repulsed—The Cosso passed—Fresh mines worked under the university, and in six other places—French soldiers dispirited—Lasnes encourages them—The houses leading down to the quay carried by storm—An enormous mine under the university being sprung, that building is carried by assault—The suburb is taken—Baron Versage killed, and two thousand Spaniards surrender—Successful attack on the right bank of the Ebro—Palafox demands terms, which are refused—Fire resumed—Miserable condition of the city—Terrible pestilence, and horrible sufferings of the besieged—Zaragoza surrenders—Observations | 38 |

| CHAPTER IV. [vi] | |

| Operations in Catalonia—St. Cyr commands the seventh corps—Passes the frontier—State of Catalonia—Palacios fixes his head-quarters at Villa Franca—Duhesme forces the line of the Llobregat—Returns to Barcelona—English army from Sicily designed to act in Catalonia—Prevented by Murat—Duhesme forages El Vallés—Action of San Culgat—General Vives supersedes Palacios—Spanish army augments—Blockade of Barcelona—Siege of Rosas—Folly and negligence of the junta—Entrenchments in the town carried by the besiegers—Marquis of Lazan, with six thousand men, reaches Gerona—Lord Cochrane enters the Trinity—Repulses several assaults—Citadel surrenders 5th December—St. Cyr marches on Barcelona—Crosses the Ter—Deceives Lazan—Turns Hostalrich—Defeats Milans at San Celoni—Battle of Cardadeu—Caldagues retires behind the Llobregat—Negligence of Duhesme—Battle of Molino del Rey | 54 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Tumult in Tarragona—Reding proclaimed general—Reinforcements join the Spaniards—Actions at Bruch—Lazan advances, and fights at Castel Ampurias—He quarrels with Reding, and marches towards Zaragoza—Reding’s plans—St. Cyr breaks Reding’s line at Llacuna—Actions at Capelades, Igualada, and St. Magi—French general, unable to take the abbey of Creuz, turns it, and reaches Villaradona—Joined by Souham’s division, takes post at Valls and Pla—Reding rallies his centre and left wing—Endeavours to reach Taragona—Battle of Valls—Weak condition of Tortosa—St. Cyr blockades Taragona—Sickness in that city—St. Cyr resolves to retire—Chabran forces the bridge of Molino del Rey—Conspiracy in Barcelona fails—Colonel Briche arrives with a detachment from Aragon—St. Cyr retires behind the Llobregat—Pino defeats Wimpfen at Tarrasa—Reding dies—His character—Blake is appointed captain-general of the Coronilla—Changes the line of operations to Aragon—Events in that province—Suchet takes the command of the French at Zaragoza—Colonels Pereña and Baget oblige eight French companies to surrender—Blake advances—Battle of Alcanitz—Suchet falls back—Disorder in his army—Blake neglects Catalonia—St. Cyr marches by the valley of Congosto upon Vich—Action at the defile of Garriga—Lecchi conducts the prisoners to the Fluvia—St. Cyr hears of the Austrian war—Barcelona victualled by a French squadron—Observations | 78 |

| BOOK VI. | |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Transactions in Portugal—State of that country—Neglected by the English cabinet—Sir J. Cradock appointed to command the British troops—Touches at Coruña—At Oporto—State of this city—Lusitanian legion—State of Lisbon—Cradock endeavours to reinforce Moore—Mr. Villiers arrives at Lisbon—Pikes given to the populace—Destitute state of the army—Mr. Frere, and others, urge Cradock to move into Spain—The reinforcements for sir J. Moore halted at Castello Branco—General Cameron sent to Almeida—French advanced guard reaches Merida—Cradock relinquishes the design of reinforcing the army in Spain, and concentrates his own troops at Saccavem—Discontents in Lisbon—Defenceless state and danger of Portugal—Relieved by sir J. Moore’s advance to Sahagun | 112 |

| CHAPTER II. [vii] | |

| French retire from Merida—Send a force to Plasencia—The direct intercourse between Portugal and sir J. Moore’s army interrupted—Military description of Portugal—Situation of the troops—Cradock again pressed, by Mr. Frere and others, to move into Spain—The ministers ignorant of the real state of affairs—Cradock hears of Moore’s advance to Sahagun—Embarks two thousand men to reinforce him—Hears of the retreat to Coruña, and re-lands them—Admiral Berkely arrives at Lisbon—Ministers more anxious to get possession of Cadiz than to defend Portugal—Five thousand men, under general Sherbrooke, embarked at Portsmouth—Sir George Smith reaches Cadiz—State of that city—He demands troops from Lisbon—General Mackenzie sails from thence, with troops—Negotiations with the junta—Mr. Frere’s weak proceedings—Tumult in Cadiz—The negotiation fails | 127 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Weakness of the British army in Portugal—General Cameron marches to Lisbon—Sir R. Wilson remains near Ciudad Rodrigo—Sir J. Cradock prepares to take a defensive position at Passo d’Arcos—Double dealing of the regency—The populace murder foreigners, and insult the British troops—Anarchy in Oporto—British government ready to abandon Portugal—Change their intention—Military system of Portugal—the regency demand an English general—Beresford is sent to them—Sherbrooke’s and Mackenzie’s troops arrive at Lisbon—Beresford arrives there, and takes the command of the native force—Change in the aspect of affairs—Sir J. Cradock encamps at Lumiar—Relative positions of the allied and French armies—Marshal Beresford desires sir J. Cradock to march against Soult—Cradock refuses—Various unwise projects broached by different persons | 142 |

| BOOK VII. | |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Coruña and Ferrol surrender to Soult—He is ordered, by the emperor, to invade Portugal—The first corps is directed to aid this operation—Soult goes to St. Jago—Distressed state of the second corps—Operations of Romana and state of Gallicia—Soult commences his march—Arrives on the Minho—Occupies Tuy, Vigo, and Guardia—Drags large boats over land from Guardia to Campo Saucos—Attempt to pass the Minho—Is repulsed by the Portuguese peasantry—Importance of this repulse—Soult changes his plan—Marches on Orense—Defeats the insurgents at Franquera, at Ribidavia, and in the valley of the Avia—Leaves his artillery and stores in Tuy—Defeats the Spanish insurgents in several places, and prepares to invade Portugal—Defenceless state of the northern provinces of that kingdom—Bernadim Friere advances to the Cavado river—Sylveira advances to Chaves—Concerts operations with Romana—Disputes between the Portuguese and Spanish troops—Ignorance of the generals | 162 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Soult enters Portugal—Action at Monterey—Franceschi makes great slaughter of the Spaniards—Portuguese retreat upon Chaves—Romana flies to Puebla Senabria—Portuguese mutiny—Three thousand throw themselves into Chaves—Soult takes that town—Marches upon Braga—Forces the defiles of Ruivaens and Venda Nova—Tumults and disorders in the Portuguese camp at Braga—Murder of general Friere and others—Battle of Braga—Soult marches [viii] against Oporto—Disturbed state of that town—Sylveira retakes Chaves—The French force the passage of the Ave—The Portuguese murder general Vallonga—French appear in front of Oporto—Negotiate with the bishop—Violence of the people—General Foy taken—Battle of Oporto—The city stormed with great slaughter | 183 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Operations of the first and fourth corps—General state of the French army—Description of the valley of the Tagus—Inertness of marshal Victor—Albuquerque and Cartoajal dispute—The latter advance in La Mancha—General Sebastiani wins the battle of Ciudad Real—Marshal Victor forces the passage of the Tagus, and drives Cuesta’s army from all its positions—French cavalry checked at Miajadas—Victor crosses the Guadiana at Medellin—Albuquerque joins Cuesta’s army—Battle of Medellin—Spaniards totally defeated—Victor ordered, by the king, to invade Portugal—Opens a secret communication with some persons in Badajos—The peasants of Albuera discover the plot, which fails—Operations of general Lapisse—He drives back sir R. Wilson’s posts, and makes a slight attempt to take Ciudad Rodrigo—Marches suddenly towards the Tagus, and forces the bridge of Alcantara—Joins Victor at Merida—General insurrection along the Portuguese frontier—The central junta remove Cartoajal from the command, and increase Cuesta’s authority, whose army is reinforced—Joseph discontented with Lapisse’s movement—Orders Victor to retake the bridge of Alcantara | 208 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| The bishop of Oporto flies to Lisbon, and joins the regency—Humanity of marshal Soult—The Anti-Braganza party revives in the north of Portugal—The leaders make proposals to Soult—He encourages them—Error arising out of this proceeding—Effects of Soult’s policy—Assassination of colonel Lameth—Execution at Arifana—Distribution of the French troops—Franceschi opposed, on the Vouga, by colonel Trant—Loison falls back behind the Souza—Heudelet marches to the relief of Tuy—The Spaniards, aided by some English frigates, oblige thirteen hundred French to capitulate at Vigo—Heudelet returns to Braga—The insurrection in the Entre Minho e Douro ceases—Sylveira menaces Oporto—Laborde reinforces Loison, and drives Sylveira over the Tamega—Gallant conduct and death of colonel Patrick at Amarante—Combats at Amarante—French repulsed—Ingenious device of captain Brochard—The bridge of Amarante carried by storm—Loison advances to the Douro—Is suddenly checked—Observations | 231 |

| BOOK VIII. | |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Anarchy in Portugal—Sir J. Cradock quits the command—Sir A. Wellesley arrives at Lisbon—Happy effect of his presence—Nominated captain-general—His military position described—Resolves to march against Soult—Reaches Coimbra—Conspiracy in the French army—D’Argenton’s proceedings—Sir A. Wellesley’s situation compared with that of Sir J. Cradock | 262 |

| CHAPTER II. [ix] | |

| Campaign on the Douro—Relative position of the French and English armies—Sir Arthur Wellesley marches to the Vouga—Sends Beresford to the Douro—A division under general Hill passes the lake of Ovar—Attempt to surprise Francheschi fails—Combat of Grijon—The French re-cross the Douro and destroy the bridge at Oporto—Passage of the Douro—Soult retreats upon Amarante—Beresford reaches Amarante—Loison retreats from that town—Sir Arthur marches upon Braga—Desperate situation of Soult—His energy—He crosses the Sierra Catalina—Rejoins Loison—Reaches Carvalho d’Esté—Falls back to Salamonde—Daring action of major Dulong—The French pass the Ponte Nova and the Saltador, and retreat by Montalegre—Soult enters Orense—Observations | 277 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Romana surprises Villa Franca—Ney advances to Lugo—Romana retreats to the Asturias—Reforms the government there—Ney invades the Asturias by the west—Bonnet and Kellerman enter that province by the east and by the south—General Mahi flies to the valley of the Syl—Romana embarks at Gihon—Ballasteros takes St. Andero—Defeated by Bonnet—Kellerman returns to Valladolid—Ney marches for Coruña—Carera defeats Maucune at St. Jago Compostella—Mahi blockades Lugo—It is relieved by Soult—Romana rejoins his army and marches to Orense—Lapisse storms the bridge of Alcantara—Cuesta advances to the Guadiana—Lapisse retires—Victor concentrates his army at Torremocha—Effect of the war in Germany upon that of Spain—Sir A. Wellesley encamps at Abrantes—The bridge of Alcantara destroyed—Victor crosses the Tagus at Almaraz—Beresford returns to the north of Portugal—Ney and Soult combine operations—Soult scours the valleys of the Syl—Romana cut off from Castile and thrown back upon Orense—Ney advances towards Vigo—Combat of San Payo—Misunderstanding between him and Soult—Ney retreats to Coruña—Soult marches to Zamora—Franceschi falls into the hands of the Capuchino—His melancholy fate—Ney abandons Gallicia—View of affairs in Aragon—Battles of Maria and Belchite | 308 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| State of the British army—Embarrassments of sir Arthur Wellesley—State and numbers of the French armies—State and numbers of the Spanish armies—Some account of the partidas, commonly called guerillas—Intrigues of Mr. Frere—Conduct of the central junta—Their inhuman treatment of the French prisoners—Corruption and incapacity—State of the Portuguese army—Impolicy of the British government—Expedition of Walcheren—Expedition against Italy | 334 |

| BOOK IX. | |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Campaign of Talavera—Choice of operations—Sir Arthur Wellesley moves into Spain—Joseph marches against Venegas—Orders Victor to return to Talavera—Cuesta arrives at Almaraz—Sir Arthur reaches Plasencia—Interview with Cuesta—Plan of operation arranged—Sir Arthur, embarrassed by the want of provisions, detaches sir Robert Wilson up the [x] Vera de Plasencia, passes the Tietar, and unites with Cuesta at Oropesa—Skirmish at Talavera—Bad conduct of the Spanish troops—Victor takes post behind the Alberche—Cuesta’s absurdity—Victor retires from the Alberche—Sir Arthur, in want of provisions, refuses to pass that river—Intrigues of Mr. Frere—The junta secretly orders Venegas not to execute his part of the operation | 357 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Cuesta passes the Alberche—Sir Arthur Wellesley sends two English divisions to support him—Soult is appointed to command the second, fifth, and sixth corps—He proposes to besiege Ciudad Rodrigo and threaten Lisbon—He enters Salamanca, and sends general Foy to Madrid to concert the plan of operations—The king quits Madrid—Unites his whole army—Crosses the Guadarama river, and attacks Cuesta—Combat of Alcabon—Spaniards fall back in confusion to the Alberche—Cuesta refuses to pass that river—His dangerous position—The French advance—Cuesta re-crosses the Tietar—Sir Arthur Wellesley draws up the combined forces on the position of Talavera—The king crosses the Tietar—Skirmish at Casa de Salinas—Combat on the evening of the 27th—Panic in the Spanish army—Combat on the morning of the 28th—The king holds a council of war—Jourdan and Victor propose different plans—The king follows that of Victor—Battle of Talavera—The French re-cross the Alberche—General Craufurd arrives in the English camp—His extraordinary march—Observations | 377 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| The king goes to Illescas with the fourth corps and reserve—Sir R. Wilson advances to Escalona—Victor retires to Maqueda—Conduct of the Spaniards at Talavera—Cuesta’s cruelty—The allied generals hear of Soult’s movement upon Baños—Bassecour’s division marches towards that point—The pass of Baños forced—Sir A. Wellesley marches against Soult—Proceedings of that marshal—He crosses the Bejar, and arrives at Plasencia with three corps d’armée—Cuesta abandons the British hospitals, at Talavera, to the enemy, and retreats upon Oropesa—Dangerous position of the allies—Sir Arthur crosses the Tagus at Arzobispo—The French arrive near that bridge—Cuesta passes the Tagus—Combat of Arzobispo—Soult’s plans overruled by the king—Ney defeats sir R. Wilson at Baños, and returns to France | 410 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Venegas advances to Aranjues—Skirmishes there—Sebastiani crosses the Tagus at Toledo—Venegas concentrates his army—Battle of Almonacid—Sir Arthur Wellesley contemplates passing the Tagus at the Puente de Cardinal, is prevented by the ill-conduct of the junta—His troops distressed for provisions—He resolves to retire into Portugal—False charge made by Cuesta against the British army refuted—Beresford’s proceedings—Mr. Frere superseded by lord Wellesley—The English army abandons its position at Jaraceijo and marches towards Portugal—Consternation of the junta—Sir A. Wellesley defends his conduct, and refuses to remain in Spain—Takes a position within the Portuguese frontier—Sickness in the army | 429 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| General observations on the campaign—Comparison between the operations of sir John Moore and sir A. Wellesley | 447 |

| Page | ||

| No. I. | Six Sections, containing the returns of the French army | 471 |

| II. | Three Sections; justificatory extracts from sir J. Moore’s and sir J. Cradock’s papers, and from Parliamentary documents, illustrating the state of Spain | 475 |

| III. | Seven Sections; justificatory extracts from sir J. Cradock’s papers, illustrating the state of Portugal | 480 |

| IV. | Extracts from sir J. Cradock’s instructions | 491 |

| V. | Ditto from sir J. Cradock’s papers relative to a deficiency in the supply of his troops | 492 |

| VI. | Three Sections; miscellaneous | 495 |

| VII. | Extracts from Mr. Frere’s correspondence | 497 |

| VIII. | Ditto from sir J. Cradock’s papers relating to Cadiz | 499 |

| IX. | General Mackenzie’s narrative of his proceedings at Cadiz | 500 |

| X. | Three Sections; extracts from sir J. Cradock’s papers, shewing that Portugal was neglected by the English cabinet | 506 |

| XI. | State and distribution of the English troops in Portugal and Spain, January 6, April 6, April 22, May 1, June 25, July 25, and September 25, 1809 | 509 |

| XII. | 1º. Marshal Beresford to sir J. Cradock—2º. Sir J. Cradock to marshal Beresford | 511 |

| XIII. | Justificatory extracts relating to the conduct of marshal Soult | 517 |

| XIV. | Sir A. Wellesley to sir J. Cradock | 519 |

| XV. | Ditto to lord Castlereagh | 520 |

| XVI. | Ditto Ditto | 522 |

| XVII. | Ditto to the marquis of Wellesley | 523 |

| XVIII. | 1º. General Hill to sir A. Wellesley—2º. Colonel Stopford to general Sherbrooke | 534 |

| No. 1. | Siege of Zaragoza | to face page | 48 |

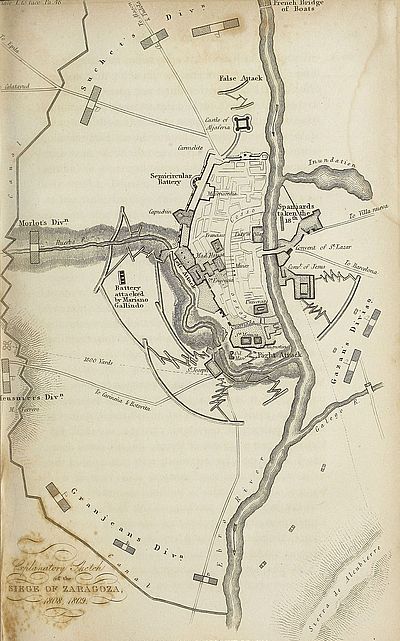

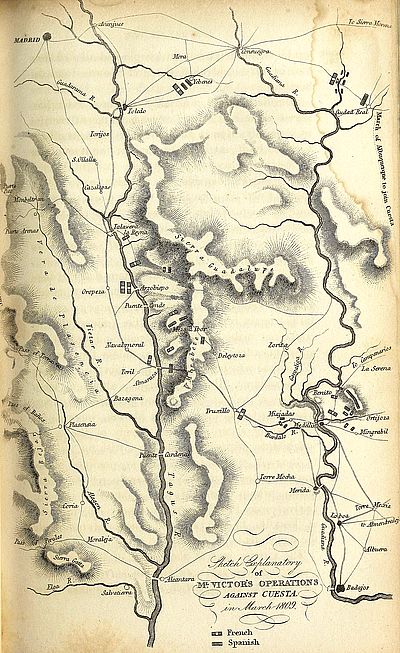

| 2. | Operations in Catalonia | to face page | 102 |

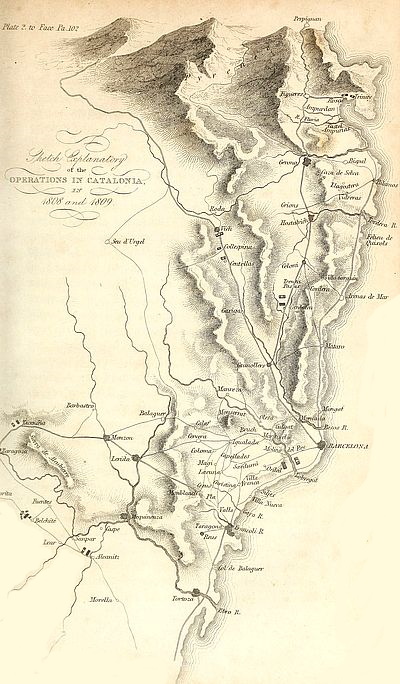

| 3. | Operations of Cuesta and Victor on the Tagus and Guadiana | to face page | 226 |

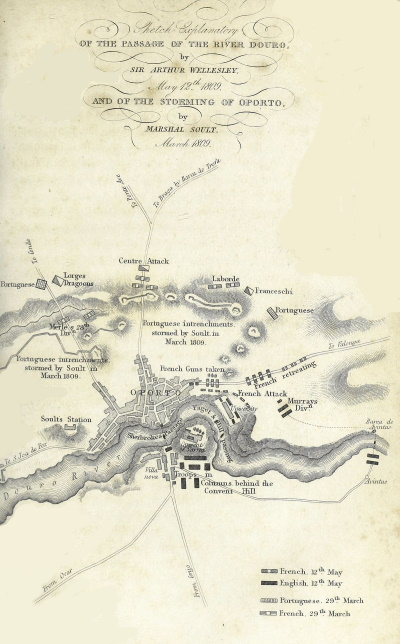

| 4. | Passage of the Douro | to face page | 290 |

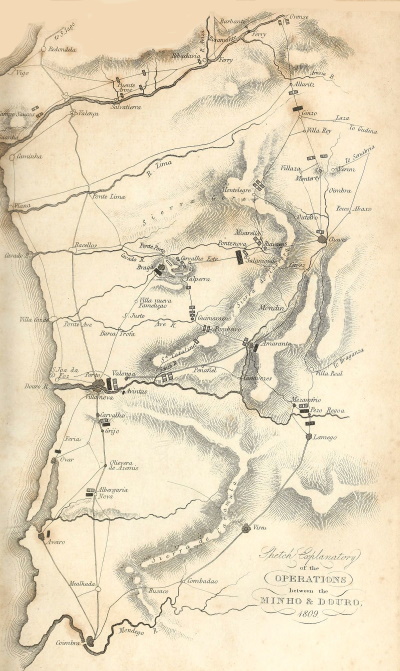

| 5. | Operations between the Mondego and the Mincio | to face page | 300 |

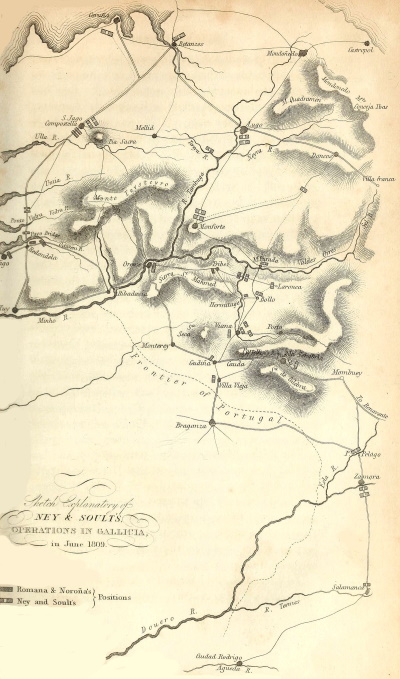

| 6. | Operations of marshals Soult and Ney in Gallicia | to face page | 326 |

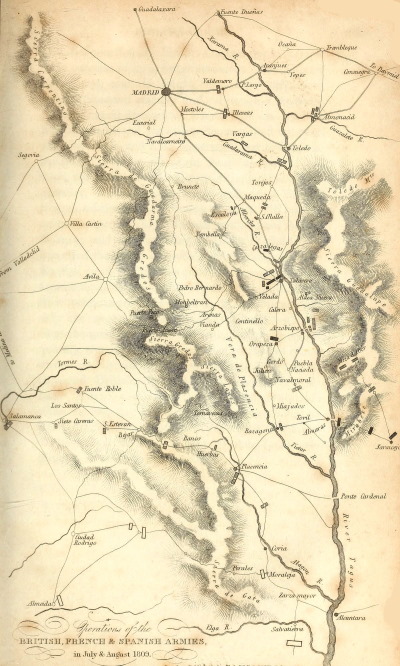

| 7. | Operations of the British, French & Spanish armies | to face page | 409 |

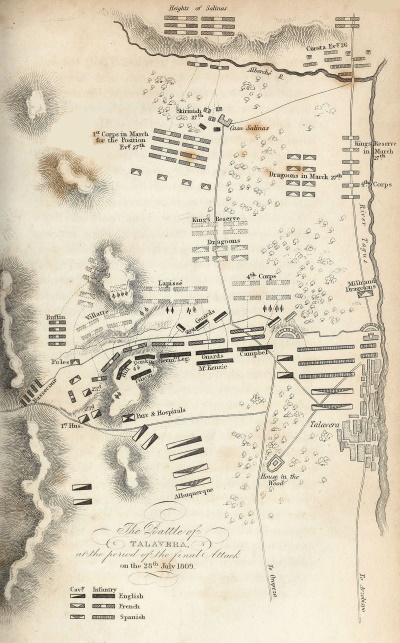

| 8. | Battle of Talavera | to face page | 416 |

General Semelé’s journal, referred to in this volume, is only an unattested copy; the rest of the manuscript authorities quoted or consulted are original papers belonging to, and communications received from, the duke of Wellington, marshal Soult, marshal Jourdan, Mr. Stuart,[1] sir J. Cradock,[2] sir John Moore, and other persons employed either in the British or French armies during the Peninsular War.

The returns of the French army are taken from the emperor Napoleon’s original Muster Rolls.

The letter S. marks those papers received from marshal Soult.

HISTORY

OF THE

PENINSULAR WAR.

The effect produced in England by the unfortunate issue of sir John Moore’s campaign, was not proportionable to the importance of the subject. The people, trained to party politics, and possessing no real power to rebuke the folly of the cabinet, regarded disasters and triumphs with factious rather than with national feelings, and it was alike easy to draw the public attention from affairs of weight, and to fix it upon matters of little moment. In the beginning of 1809, the duke of York’s conduct being impeached, a parliamentary investigation followed; and to drag the private frailties of that prince before the world, was thought essential to the welfare of the country, when the incapacity which had caused England and Spain to mourn in tears of blood, was left unprobed. An insular people only, who are protected by their situation from the worst evils of war, may suffer themselves to be thus deluded; but if an unfortunate campaign were to bring a devastating enemy into the heart of[2] the country, the honour of a general, and the whole military policy of the cabinet, would no longer be considered as mere subjects for the exercise of a vile sophist’s talents for misrepresentation.

It is true that the ill success of the British arms was a topic, upon which many orators in both houses of parliament expatiated with great eloquence, but the discussions were chiefly remarkable, as examples of acute debating without any knowledge of facts. The opposition speakers, eager to criminate the government, exaggerated the loss and distress of the retreat, and comprehending neither the movements nor the motives of sir John Moore, urged several untenable accusations against their adversaries. The ministers, disunited by personal feelings, did not all adopt the same ground of defence. Lord Castlereagh and lord Liverpool, passing over the errors of the cabinet by which the general had been left only a choice of difficulties, asserted, and truly, that the advantages derived from the advance to Sahagun more than compensated for the losses in the subsequent retreat. Both those statesmen paid an honourable tribute to the merits of the commander; but Mr. Canning, unscrupulously resolute to screen Mr. Frere, assented to all the erroneous statements of the opposition, and endeavoured with malignant dexterity to convert them into charges against the fallen general. Sir John Moore was, he said, answerable for the events of the campaign, whether the operations were glorious or distressful, whether to be admired or deplored, they were his own, for he had kept the ministers ignorant of his proceedings. Being pressed closely on that point by Mr. C. Hutchinson, Mr. Canning repeated this assertion. Not long afterwards, sir John Moore’s[3] letters, written almost daily and furnishing exact and copious information of all that was passing in the Peninsula, were laid before the house.

The reverses experienced in Spain had somewhat damped the ardour of the English people; but a cause so rightful in itself, was still popular, and a treaty having been concluded with the junta, by which the contracting powers bound themselves to make common cause against France, and to agree to no peace except by mutual consent, the ministers appeared resolute to support the contest. But while professing unbounded confidence in the result of the struggle, they already looked upon the Peninsula as a secondary object; for the preparations of Austria, and the reputation of the archduke Charles, whose talents were foolishly said to exceed Napoleon’s, had awakened the dormant spirit of coalitions. It was more agreeable to the aristocratic feelings of the English cabinet, that the French should be defeated by a monarch in Germany, than by a plebeian insurrection in Spain. The obscure intrigues carried on through the princess of Tour and Taxis, and the secret societies of Germany emanating as they did from patrician sources, engaged all the attention of the ministers, and exciting their sympathy, nursed those distempered feelings, which led them to see weakness and disaffection in France when, throughout that mighty empire, few desired and none dared openly to oppose the emperor’s wishes, when even secret discontent was confined to some royalist chiefs and splenetic republicans, whose influence was never felt until after Napoleon had suffered the direst reverses.

Unable to conceive the extent of that monarch’s views, and the grandeur of his genius, the ministers[4] attributed the results of his profound calculations to a blind chance, his victories to treason, to corruption, to any thing but that admirable skill, with which he wielded the most powerful military force that ever obeyed the orders of a single chief. And thus self-deluded, and misjudging the difficulties to be encountered, they adopted every idle project, and squandered their resources without any great or decided effort. While negotiating with the Spanish Junta for the occupation of Cadiz, they were also planning an expedition against Sicily; and while loudly asserting their resolution to defend Portugal, reserved their principal force for a blow against Holland; their preparations for the last object being, however, carried on with a pomp and publicity little suitable to war. With what a mortal calamity that pageant closed, shall hereafter be noticed; but at present it is fitting to describe the operations that took place in Spain, coincident with and subsequent to the retreat of sir John Moore.

It has been already stated, that when the capital surrendered to the Emperor, he refused to permit Joseph to return there, unless the public bodies and the heads of families would unite to demand his restoration, and swear, without any mental reservation, to be true to him. Registers had consequently Nellerto. been opened in the different quarters of the city, and twenty-eight thousand six hundred heads of families inscribed their names, and voluntarily swore, in presence of the host, that they were Azanza and O’Farril. sincere in their desire to receive Joseph. After this, deputations from all the councils, from the junta of commerce and money, the hall of the Alcaldes, and from the corporation, waited on the emperor at Valladolid, and being there joined by[5] the municipality of that town, and by deputies from Astorga, Leon, and other places, presented the oath, and prayed that Joseph might be king. Napoleon thus entreated, consented that his brother should return to Madrid, and reassume his kingly functions.

It would be idle to argue from this apparently voluntary submission to the French emperor, that a change favourable to the usurpation had been produced in the feelings of the Spanish people; but it is evident that Napoleon’s victories and policy had been so far effectual, that in the capital, and many other great towns, the multitude as well as the notables were, either from fear or conviction, submissive to his will; and it is but reasonable to suppose, that if his conquests had not been interrupted by extraneous circumstances, this example would have been generally followed, in preference to the more glorious, but ineffectual, resistance made by the inhabitants of those cities, whose fortitude and whose calamities have forced from mankind a sorrowful admiration. The cause of Spain at this moment was in truth lost; if any cause depending upon war, which is but a succession of violent and sudden changes, can be called so; for her armies were dispersed, her government bewildered, and her people dismayed; the cry of resistance had ceased, and in its stead the stern voice of Napoleon, answered by the tread of three hundred thousand French veterans was heard throughout the land. But the hostility of Austria having arrested the emperor’s career in the Peninsula, the energy of the Spaniards revived at the abrupt cessation of his terrific warfare.

Joseph, escorted by his French guards, in number between five and six thousand, entered Madrid[6] in state the 23d of January. He was, however, a king without revenues, and he would have been without even the semblance of authority, if he had not been likewise nominated the emperor’s lieutenant in Spain, by virtue of which title he was empowered to move the French army at his will. This power was one extremely unacceptable to the marshals, and he would have found it difficult to enforce it, even though he had restrained the exercise to the limits prescribed by his brother. But disdaining to separate the general from the monarch, King’s correspondence captured at Vittoria, MSS. he conveyed his orders to the French army, through his Spanish ministers, and the army in its turn disdained and resisted the assumed authority of men, who, despised for their want of military knowledge, were also suspected as favouring interests essentially differing from those of the troops.

The iron grasp that had compressed the pride and the ambitious jealousy of the marshals being thus relaxed, the passions that had ruined the patriots began to work among their enemies, producing indeed less fatal effects, because their scope was more circumscribed, but sufficiently pernicious to stop the course of conquest. The French army, no longer a compact body, terrible alike from its massive strength, and its flexible activity, became a collection of independent bands, each formidable in itself, but, from the disunion of the generals, slow to combine for any great object; and plainly discovering, by irregularities and insubordination, that they knew when a warrior, and when a voluptuous monarch was at their head; but these evils were only felt at a later period; and the distribution of the troops, when Napoleon quitted Valladolid, still bore the impress of his genius.

The first corps was quartered in La Mancha.

The second corps was destined to invade Portugal.

The third and fifth corps carried on the siege of Zaragoza.

The fourth corps remained in the valley of the Tagus.

The sixth corps, wanting its third division, was appointed to hold Gallicia.

The seventh corps continued always in Catalonia.

The imperial guards, directed on Vittoria, contributed to the security of the great communication with France until Zaragoza should fall, and were yet ready to march when wanted for the Austrian war.

General Dessolles, with the third division of the sixth corps, returned to Madrid. General Bonnet, with the fifth division of the second corps, remained in the Montagna St. Andero.

General Lapisse, with the second division of the first corps, was sent to Salamanca, where he was joined by Maupetit’s brigade of cavalry, which had crossed the Sierra de Bejar.

The reserve of heavy cavalry being broken up, was distributed, by divisions, in the following order:—

Latour Maubourg’s joined the first corps. Lorge’s and Lahoussaye’s were attached to the second corps. Lassalle’s was sent to the fourth corps. The sixth corps was reinforced with two brigades. Milhaud’s division remained at Madrid, and Kellerman’s guarded the lines of communication between Tudela, Burgos, and Palencia.

Thus, Madrid being still the centre of operations, the French were so distributed, that by a concentric movement on that capital, they could crush every insurrection within the circle of their[8] positions; and the great masses, being kept upon the principal roads diverging from Madrid to the extremities of the Peninsula, intercepted all communication between the Provinces: while the second corps, thrust out, as it were, beyond the circumference, and destined, as the fourth corps had been, to sweep round from point to point, was sure of finding a supporting army, and a good line of retreat, at every great route leading from Madrid to the yet unsubdued provinces of the Peninsula. The communication with France was, at the same time, secured by the fortresses of Burgos, Pampeluna, and St. Sebastian; and by the divisions posted at St. Ander, Burgos, Bilbao, and Vittoria; and it was supported by a reserve at Bayonne.

The northern provinces were parcelled out into military governments, the chiefs of which corresponded with each other; and, by the means of moveable columns, repressed every petty insurrection. The third and fifth corps, also, having their base at Pampeluna, and their line of operations directed against Zaragoza, served as an additional covering force to the communication with France, and were themselves exposed to no flank attacks, except from the side of Cuença, where the duke of Infantado commanded; but that general was himself watched by the first corps.

All the lines of correspondence, not only from France but between the different corps, were maintained by fortified posts, having greater or lesser garrisons, according to their importance. Between Bayonne and Burgos there were eleven military stations. Between Burgos and Madrid, by the road of Muster-rolls of the French army, MSS. Aranda and Somosierra, there were eight; and eleven others protected the more circuitous route to the capital by Valladolid, Segovia, and the[9] Guadarama. Between Valladolid and Zaragoza the line was secured by fifteen intermediate points. The communication between Valladolid and St. Ander contained eight posts; and nine others connected the former town with Villa Franca del Bierzo, by the route of Benevente and Astorga; finally, two were established between Benevente and Leon.

At this period, the force of the army, exclusive of Joseph’s French guards, was three hundred Appendix, No. 1, section 1. and twenty-four thousand four hundred and eleven men, about thirty-nine thousand being cavalry.

Fifty-eight thousand men were in hospital.

The depôts, governments, garrisons, posts of correspondence, prisoners, and “battalions of march,” composed of stragglers, absorbed about twenty-five thousand men.

The remainder were under arms, with their regiments; and, consequently, more than two hundred and forty thousand men were in the field: while the great line of communication with France was (and the military reader will do well to mark this, the key-stone of Napoleon’s system) protected by above fifty thousand men, whose positions were strengthened by three fortresses and sixty-four posts of correspondence, each more or less fortified.

Having thus shewn to the reader the military state of the French, I shall now proceed with the narrative of their operations; following, as in the first volume, a local rather than a chronological arrangement of events.

The defeat of Galluzzo has been incidentally touched upon before. The duke of Dantzic having[10] observed that the Spanish general, with six thousand raw levies, pretended to defend a line of forty miles, made a feint of crossing the Tagus, at Arzobispo, and then suddenly descending to Almaraz, forced a passage over that bridge, on the 24th of December, killed and wounded many Spaniards, and captured four guns: and so complete was the dispersion, that for a long time after, not a man was to be found in arms throughout Estremadura. Appendix, No. 2, sections 2 and 3. The French cavalry were at first placed on the tracks of the fugitives; but intelligence of sir John Moore’s advance to Sahagun being received, Ibid. the pursuit ceased at Merida, and the fourth corps, which had left eight hundred and thirty men in garrison at Segovia, took post between Talavera and Placentia. The duke of Dantzic was then recalled to France, and general Sebastiani succeeded to the command of the fourth corps. It was at this period that the first corps (of which the division of Lapisse only had followed the emperor to Astorga) moved against Toledo, and that town was occupied without opposition. The French outposts were then pushed towards Cuença on the one side, and towards the Sierra Morena on the other.

Meanwhile, the central junta, changing its first design, retired to Seville, instead of Badajos; and being continually urged, both by Mr. Stuart and Mr. Frere, to make some effort to lighten the pressure on the English army, ordered Palafox and the duke of Infantado to advance; the one from Zaragoza towards Tudela, the other from Cuença towards Madrid. The marquis of Palacios, who had been removed from Catalonia, and was now at the head of five or six thousand levies in the[11] Sierra Morena, was also directed to advance into La Mancha; and Galluzzo, deprived of his command, was constituted a prisoner, along with Cuesta, Castaños, and a number of other culpable or unfortunate officers, who, vainly demanding a judgement on their cases, were dragged from place to place by the government.

Cuesta was, however, so popular in Estremadura, that the central junta, although fearing and detesting him, consented to his being placed at the head of Galluzzo’s fugitives, part of whom had, when the pursuit ceased, rallied behind the Guadiana, and were now, with the aid of fresh levies, again taking the form, rather than the consistence, of an army. This appointment was an act of deplorable weakness and incapacity. The moral effect was to degrade the government by exposing its fears and weakness; and, in a military view, it was destructive, because Cuesta was physically and mentally incapable of command. Obstinate, jealous, and stricken in years, he was heedless of time and circumstances, of disposition and fitness. To punish with a barbarous severity, and to rush headlong into battle, constituted, in his mind, all the functions of a general.

The president, Florida Blanca, being eighty-one years of age, died at Seville, and the marquis of Astorga succeeded him; but the character of the junta was in no manner affected by the change. Some fleeting indications of vigour had been produced by the imminence of the danger during the flight from Aranjuez, but a large remittance of silver, from South America, having arrived at Cadiz, Appendix, No. 13. Vol. I. the attention of the members was so absorbed, by this object, that the public weal was blotted from[12] their remembrance, and even Mr. Frere, ashamed Appendix, No. 2, section 2. of their conduct, appeared to acquiesce in the justness of sir John Moore’s estimate of the value of Spanish co-operation.

The number of men to be enrolled for the defence of the country had been early fixed at five hundred thousand, but scarcely one-third had joined their colours; nevertheless, considerable bodies were assembling at different points, because the people, especially those of the southern provinces, although dismayed, were obedient, and the local authorities, at a distance from the actual scene of war, rigorously enforced the law of enrolment, and sent the recruits to the armies, hoping thereby either to stave the war off from their own districts, or to have the excuse of being without fighting men, to plead for quiet submission.

The fugitive troops also readily collected again at any given point, partly from patriotism, partly because the French were in possession of their native provinces, partly that they attributed their defeats to the treachery of their generals, and partly that, being deceived by the gross falsehoods and boasting of the government, they, with ready vanity, imagined that the enemy had invariably suffered enormous losses. In fine, for the reasons mentioned in the commencement of this history, men were to be had in abundance; but, beyond assembling them and appointing some incapable person to command, nothing was done for defence.

The officers who were not deceived had no confidence either in their own troops or in the government, nor were they themselves confided in or respected by their men. The latter were starved, were misused, ill-handled, and they possessed neither the[13] compact strength of discipline nor the daring of enthusiasm. Under such a system, it was impossible that the peasantry could be rendered energetic soldiers; and they certainly were not active supporters of their country’s cause; but, with a wonderful constancy, they suffered for it, enduring fatigue and sickness, nakedness and famine, with patience, and displaying, in all their actions and in all their sentiments, a distinct and powerful national character. This constancy and the iniquity of the usurpation hallowed their efforts in despite of their ferocity, and merits respect, though the vices and folly of the juntas and the leading men rendered the effect of those efforts nugatory.

Palacios, on the receipt of the orders above mentioned, advanced, with five thousand men, to Vilharta, in La Mancha, and the duke of Infantado, anticipating the instructions of the junta, was already in motion from Cuença. His army, reinforced by the divisions of Cartoajal and Lilli and by fresh levies, was about twenty thousand men, of which two thousand were cavalry. To check the incursions of the French horsemen, he had, a few days after the departure of Napoleon from Madrid, detached general Senra and general Venegas with eight thousand infantry and all the horse to scour the country round Tarancon and Aranjuez; the former halted at Horcajada, and the latter endeavoured to cut off a French detachment, but was himself surprised and beaten by a very inferior force.

Marshal Victor, however, withdrew his advanced posts, and, concentrating Ruffin’s and Villatte’s divisions of infantry and Latour Maubourg’s cavalry, at Villa de Alorna, in the vicinity of Toledo, left[14] Venegas in possession of Tarancon. But, among the Spanish generals, mutual recriminations succeeded this failure: the duke of Infantado possessed neither authority nor talents to repress their disputes, and in this untoward state of affairs receiving the orders of the junta, he immediately projected a movement on Toledo, intending to seize that place and Aranjuez, to break down the bridges, and to maintain the line of the Tagus.

Quitting Cuença on the 10th, he reached Horcajada on the 12th, with ten thousand men, the remainder of the army, commanded by Venegas, being near Tarancon.

The 13th, the duke having moved to Carascosa, a town somewhat in advance of Horcajada, met a crowd of fugitives, and heard, with equal surprise and consternation, that the corps under Venegas was already destroyed, and the pursuers close at hand.

It appeared that Victor, uneasy at the movements of the Spanish generals, but ignorant of their situation and intentions, had quitted Toledo also on the 10th, and marched to Ocaña, whereupon Venegas, falling back from Tarancon, took a position at Ucles. The 12th, the French continued to advance in two columns, of which the one, composed of Ruffin’s division and a brigade of cavalry, lost its way, and arrived at Alcazar; but the other, commanded by Victor himself, and composed of Villatte’s division, the remainder of the cavalry, and the parc of artillery, took the road of Ucles, and came upon the position of Venegas early in the morning of the 13th.

This meeting was unexpected by either party, but the French attacked without hesitation, and the Spaniards, flying towards Alcazar, fell in with Ruffin’s division, and were totally discomfitted. Several thousands laid down their arms, and many, dispersing, fled across the fields; some, however, keeping their ranks, made towards Ocaña, where, coming suddenly upon the French parc of artillery, they received a heavy discharge of grape-shot, and dispersed. Of the whole force, a small party only, under general Giron, succeeded in forcing its way by the road of Carascosa, and so reached the duke of Infantado, who immediately retreated to Cuença, and without further loss, as the French cavalry were too fatigued to pursue briskly.

From Cuença the duke sent his artillery towards Valencia, by the road of Tortola; but himself, with the infantry and cavalry, marched by Chinchilla, and from thence to Tobarra, on the frontiers of Murcia.

At Tobarra he turned to his right, and made for Santa Cruz de Mudela, a town situated near the entrance to the defiles of the Sierra Morena. There he halted in the beginning of February, after a painful and circuitous retreat of more than two hundred miles, in a bad season. But all his artillery had been captured at Tortola, and his forces were, by desertion and straggling, reduced to a handful of discontented officers and a few thousand dispirited men, worn out with fatigue and misery.

Meanwhile, Victor, after scouring a part of the province of Cuença and disposing of his prisoners, made a sudden march upon Vilharta, intending to surprise Palacios, but that officer apprized of the retreat of Infantado had already effected his junction[16] with the latter at Santa Cruz de Mudela. Whereupon the French marshal recalling his troops, again occupied his former position at Toledo. The prisoners taken at Ucles were marched to Madrid, those who were weak and unable to walk were Rocca’s Memoirs. (according to Mr. Rocca) shot by the orders of Victor, because the Spaniards had hanged some French prisoners. If so, it was a barbarous and a shameful retaliation, unworthy of a soldier; for what justice or honour is there in revenging the death of one innocent person by the murder of another.

When Victor withdrew his posts the duke of Infantado and Palacios proceeded to re-organize their forces under the name of the Carolina Army. The levies from Grenada and other parts were ordered up, and the cavalry, commanded by the duke of Alburquerque, endeavoured to surprise a French regiment of dragoons at Mora, but the latter getting together quickly, made a bold resistance and effected their retreat with scarcely any loss. Alburquerque having failed in this attempt retired to Consuegra and was attacked the next day by superior numbers, but retired fighting and got safely off. The duke of Infantado was now displaced, and the junta conferred the command on general Urbina Conde de Cartaojal, who applied himself to restore discipline, and after a time finding no enemy in front advanced to Ciudad Real, and taking post on the left bank of the Upper Guadiana opened a communication with Cuesta. At this period the latter’s force amounted to sixteen thousand men, of which three thousand were cavalry; for, as the Spaniards generally suffered more in their flights than in their battles, the horsemen[17] escaped with little damage and were easily rallied again in greater relative numbers than the infantry.

The fourth corps having withdrawn, as I have already related, to the right bank of the Tagus, Cuesta advanced from the Guadiana and occupied the left bank of that river, on a line extending from the mountains in front of Arzobispo to the Puerto de Mirabete. The French, by fortifying an old tower, held the command of the bridge of Arzobispo, but Cuesta immediately broke down that of Almaraz, a magnificent structure, the centre arch of which was more than a hundred and fifty feet in height.

In these positions the troops on either side remained tranquil both in La Mancha and Estremadura, and so ended the exertions made to lighten the pressure upon the English army. Two French divisions of infantry and as many brigades of cavalry had more than sufficed to baffle them, and hence the imminent danger that menaced the south of Spain, when sir John Moore’s vigorous operations drew the emperor’s forces to the north, may be justly estimated.

From the field of battle at Tudela, all the fugitives of O’Neil’s, and a great part of those from Castaños’s army, fled to Zaragoza and with such speed as to bring the first news of their own disaster. With the troops, also, came an immense number of carriages and the military chests, for the roads were wide and excellent and the pursuit was slack.

The citizens and the neighbouring peasantry were astounded at this quick and unexpected calamity. They had, with a natural credulity, relied on the vain and boasting promises of their chiefs, and being necessarily ignorant of the true state of affairs never doubted that their vengeance would be sated by a speedy and complete destruction of the French. When their hopes were thus suddenly blasted; when they beheld troops, from whom they expected nothing but victory, come pouring into the town with all the tumult of panic; when the peasants of all the villages through which the fugitives passed, came rushing into the city along with the scared multitude of flying soldiers and camp followers; every heart was filled with consternation, and the date of Zaragoza’s glory would have ended with the first siege, if the success at Tudela had been followed up by the French with that celerity and vigour which the occasion required.

Napoleon, foreseeing that this moment of confusion and terror would arrive, had with his usual prudence provided the means and given directions for such an instantaneous and powerful attack as would inevitably have overthrown the bulwark of the eastern provinces. But the sickness of marshal Lasnes, the difficulty of communication, the consequent false movements of Moncey and Ney, in fine, the intervention of fortune, omnipotent as she is in war, baffled the emperor’s long-sighted calculations, and permitted the leaders in the city to introduce order among the multitude, to complete the defensive works, to provide stores, and finally by a ferocious exercise of power to insure implicit obedience to their minutest orders. The danger of resisting the enemy appeared light, when a suspicious word or even a discontented gesture was instantaneously punished by a cruel death.

The third corps having thus missed the favourable moment for a sudden assault, and being reduced by sickness, by losses in battle, and by Muster roll of the French Army, MSS. detachments to seventeen thousand four hundred men, including the engineers and artillery, was too weak to invest the city in form, and, therefore, remained in observation on the Xalon river. Meanwhile, a battering train of sixty guns, with well furnished parcs, which had been by Napoleon’s orders previously collected in Pampeluna, were dragged by cattle to Tudela and embarked upon the canal leading to Zaragoza.

Marshal Mortier, with the fifth corps, was also

directed to assist in the siege, and he was in

march to join Moncey, when his progress also was

arrested by sir John Moore’s advance towards[20]

Burgos. But the utmost scope of that general’s

operation being soon determined by Napoleon’s

counter-movement, Mortier resumed his march to

reinforce Moncey, and, on the 20th of December,

their united corps, forming an army of thirty-five

thousand men of all arms, advanced against Zaragoza.

Cavalhero.

Doyle’s Correspondence, MSS.

At this time, however, confidence had been

restored in that town, and all the preparations

necessary for a vigorous defence were completed.

The nature of the plain in which Zaragoza is situated, the course of the rivers, the peculiar construction of the houses, and the multitude of convents have been already described, but the difficulties to be encountered by the French troops were no longer the same as in the first siege. At that time but little assistance had been derived from science, but now, instructed by experience and inspired as it were by the greatness of their resolution, neither the rules of art nor the resources of genius were neglected by the defenders.

Zaragoza offered four irregular fronts, of which the first, reckoning from the right of the town, extended from the Ebro to a convent of barefooted Carmelites, and was about three hundred yards wide.

The second, twelve hundred yards in extent, reached from the Carmelites to a bridge over the Huerba.

The third, likewise of twelve hundred yards, stretched from this bridge to an oil manufactory built beyond the walls.

The fourth, being on an opening of four hundred yards, reached from the oil manufactory to the Ebro.

The first front, fortified by an ancient wall and

flanked by the guns on the Carmelite, was strengthened

Rogniat’s Seige of Zaragoza.

Cavalhero’s Siege of Zaragoza.

by some new batteries and ramparts, and by

the Castle of Aljaferia, commonly called the Castle

of the Inquisition, which stood a little in advance.

This was a fort of a square form having a bastion

and tower at each corner, and a good stone ditch, and

it was connected with the body of the place by

certain walls loop-holed for musketry.

The second front was defended by a double wall, the exterior one being of recent erection, faced with sun-dried bricks, and covered by a ditch with perpendicular sides fifteen feet deep and twenty feet asunder. The flanks of this front were derived from the convent of the Carmelites, from a large circular battery standing in the centre of the line, from a fortified convent of the Capuchins, called the Trinity, and from some earthen works protecting the head of the bridge over the Huerba.

The third front was covered by the river Huerba, the deep bed of which was close to the foot of the ramparts. Behind this stream a double entrenchment was carried from the bridge-head to the large projecting convent of Santa Engracia, a distance of two hundred yards. Santa Engracia itself was very strongly fortified and armed; and, from thence to the oil manufactory, the line of defence was prolonged by an ancient Moorish wall, on which several terraced batteries were raised, to sweep all the space between the rampart and the Huerba. These batteries, and the guns in the convent of Santa Engracia, likewise overlooked some works raised to protect a second bridge that crossed the river, about cannot-shot below the first.

Upon the right bank of the Huerba, and a little[22] below the second bridge, stood the convent of San Joseph, the walls of which had been strengthened and protected by a deep ditch with a covered way and pallisade. It was well placed to impede the enemy’s approaches, and to facilitate sorties on the right bank of the river; and it was, as I have said, open, in the rear, to the fire of the works at the second bridge, and both were again overlooked by the terraced batteries, and by the guns of Santa Engracia.

The fourth front was protected by the Huerba, by the continuation of the old city wall, by new batteries and entrenchments, and by several armed convents and large houses.

Beyond the walls the Monte Torrero, which commanded all the plain of Zaragoza, was crowned by a large, ill-constructed fort, raised at the distance of eighteen hundred yards from the convent of San Joseph. This work was covered by the royal canal, the sluices of which were defended by some field-works, open to the fire of the fort itself.

On the left bank of the Ebro the suburb, built in a low marshy plain, was protected by a chain of redoubts and fortified houses. Finally, some gun-boats, manned by seamen from the naval arsenal of Carthagena, completed the circuit of defence. The artillery of the place was, however, of too small a Cavalhero. calibre. There were only sixty guns carrying more than twelve-pound balls; and there were but eight large mortars. There was, however, no want of small arms, many of which were English that had been supplied by colonel Doyle.

These were the regular external defences of Zaragoza, most of which were constructed at the time, according to the skill and means of the engineers;[23] but the experience of the former siege had taught the people not to trust to the ordinary resources of art, and, with equal genius and resolution, they had prepared an internal system of defence infinitely more efficacious.

It has been already observed that the houses of Zaragoza were fire-proof, and, generally, of only two stories, and that, in all the quarters of the city, the numerous massive convents and churches rose like castles above the low buildings, and that the greater streets, running into the broad-way called the Cosso, divided the town into a variety of districts, unequal in size, but each containing one or more large structures. Now, the citizens, sacrificing all personal convenience, and resigning all idea of private property, gave up their goods, their bodies, and their houses to the war, and, being promiscuously mingled with the peasantry and the regular soldiers, the whole formed one mighty garrison, well suited to the vast fortress into which Zaragoza was transformed: for, the doors and windows of the houses were built up, and their fronts loop-holed; internal communications were broken through the party-walls, and the streets were trenched and crossed by earthen ramparts, mounted with cannon, and every strong building was turned into a separate fortification. There was no weak point, because there could be none in a town which was all fortress, and where the space covered by the city was the measurement for the thickness of the ramparts: nor in this emergency were the leaders unmindful of moral force.

The people were cheered by a constant reference to the former successful resistance; their confidence was raised by the contemplation of the vast works[24] that had been executed; and it was recalled to their recollection that the wet, usual at that season of the year, would spread disease among the enemy’s ranks, and would impair, if not entirely frustrate, his efforts. Neither was the aid of superstition neglected: processions imposed upon the sight, false miracles bewildered the imagination, and terrible denunciations of the divine wrath shook the minds of men, whose former habits and present situation rendered them peculiarly susceptible of such impressions. Finally, the leaders were themselves so prompt and terrible in their punishments that the greatest cowards were likely to show the boldest bearing in their wish to escape suspicion.

To avoid the danger of any great explosion, the powder was made as occasion required; and this was the more easily effected because Zaragoza contained a royal depôt and refinery for salt-petre, and there were powder-mills in the neighbourhood, which furnished workmen familiar with the process of manufacturing that article. The houses and trees beyond the walls were all demolished and cut down, and the materials carried into the town. The public magazines contained six months’ provisions; the convents were well stocked, and the inhabitants had, likewise, laid up their own stores for several months. General Doyle also sent a convoy into the town from the side of Catalonia, and there was abundance of money, because, in addition to the resources of the town, the military chest of Castaños’s army, which had been supplied only the night before the battle of Tudela, was, in the flight, carried to Zaragoza.

Companies of women, enrolled to attend the

hospitals and to carry provisions and ammunition[25]

to the combatants, were commanded by the countess

Doyle’s Correspondence, M.S.

Cavalhero, Siege of Zaragoza.

of Burita, a lady of an heroic disposition, who

is said to have displayed the greatest intelligence

and the noblest character during both sieges.

There were thirteen engineer officers, and eight

hundred sappers and miners, composed of excavators

formerly employed on the canal, and there were

from fifteen hundred to two thousand cannoneers.

The regular troops that fled from Tudela, being joined by two small divisions, which retreated, at the same time, from Sanguessa and Caparosa, formed a garrison of thirty thousand men, and, together with the inhabitants and peasantry, presented a mass of fifty thousand combatants, who, with passions excited almost to phrensy, awaited an assault amidst those mighty entrenchments, where each man’s home was a fortress and his family a garrison. To besiege, with only thirty-five thousand men, a city so prepared was truly a gigantic undertaking!

The 20th of December, the two marshals, Moncey and Mortier, having established their hospitals and Rogniat. magazines at Alagon on the Xalon, advanced in three columns against Zaragoza.

The first, composed of the infantry of the third corps, marched by the right bank of the canal.

The second, composed of general Suchet’s division of the fifth corps, marched between the canal and the Ebro.

The third, composed of general Gazan’s division of infantry, crossed the Ebro opposite to Tauste, and from thence made an oblique march to the Gallego river.

The right and centre columns arrived in front of the town that evening. The latter, after driving back the Spanish advanced guards, halted at a distance of a league from the Capuchin convent of the Trinity; the former took post on both sides of the Huerba, and, having seized the aqueduct by which the canal is carried over that river, proceeded, in pursuance of Napoleon’s orders, to raise batteries, and to make dispositions for an immediate assault on Monte Torrero. Meanwhile general Gazan, with the left column, marching by Cartejon and Zuera reached Villa Nueva, on the Gallego river, without encountering an enemy.

The Monte Torrero was defended by five thousand Spaniards, under the command of general St. Marc; but, at day-break on the 21st, the French opened their fire against the fort, and one column of infantry having attracted the attention of the Spaniards, a second, unseen, crossed the canal under the aqueduct, and, penetrating between the fort and the city, entered the former by the rear, and, at the same time, a third column stormed the works protecting the great sluices. These sudden attacks, and the loss of the fort, threw the Cavalhero. Spaniards into confusion, and they hastily retired to the town, which so enraged the plebeian leaders that the life of St. Marc was with difficulty saved by Palafox.

It had been concerted among the French that general Gazan should assault the suburb, simultaneously with the attack on the Torrero; and that officer, having encountered a body of Spanish and Swiss troops placed somewhat in advance, drove the former back so quickly that the Swiss, unable to make good their retreat, were, to the number of[27] three or four hundred, killed or taken. But, notwithstanding Rogniat. this fortunate commencement, Gazan did not attack the suburb itself until after the affair at Monte Torrero was over, and then only upon a single point, and without any previous examination of the works. The Spaniards, recovering from their first alarm, soon reinforced this point, and Gazan was forced to desist, with the loss of four hundred men. This important failure more than balanced the success against the Monte Torrero. It restored the shaken confidence of the Spaniards at a most critical moment, and checking in the French, at the outset, that impetuous spirit, that impulse of victory, which great generals so carefully watch and improve, threw them back upon the tedious and chilling process of the engineer.

The 24th of December the investment of Zaragoza was completed on both sides of the Ebro. General Gazan occupied the bridge over the Gallego with his left, and covered his front from sorties by inundations and cuts that the low, marshy plain where he was posted enabled him to make without difficulty.

General Suchet occupied the space between the Upper Ebro and the Huerba.

Morlot’s division of the 3d corps encamped in the broken hollow that formed the bed of that stream.

General Meusnier’s division crowned the Monte Torrero, and general Grandjean continuing the circuit to the Lower Ebro, communicated with Gazan’s posts on the other side. Several Spanish detachments that had been sent out to forage were thus cut off, and could never re-enter the town; and a bridge of boats being constructed on the[28] Upper Ebro completed the circle of investment, and ensured a free intercourse between the different quarters of the army.

General Lacoste, an engineer of reputation, and aide-de-camp to the Emperor, directed the siege. His plan was, that one false and two real attacks should be conducted by regular approaches on the right bank of the Ebro, and he still hoped to take the suburb by a sudden assault. The trenches being opened on the night of the 29th of December, the 30th the place was summoned, and the terms dictated by Napoleon when he was at Aranda de Duero, were offered. The example of Madrid was also cited to induce a surrender. Palafox replied, that—If Madrid had surrendered, Madrid had been sold: Zaragoza would neither be sold nor surrender! On the receipt of this haughty answer the attacks were commenced; the right being directed against the convent of San Joseph; the centre against the upper bridge over the Huerba; the left, which was the false one, against the castle of Aljaferia.

The 31st Palafox made sorties against all the three attacks. From the right and centre he was beaten back with loss, and he was likewise repulsed on the left at the trenches: but some of his cavalry gliding between the French parallel and the Ebro surprised and cut down a post of infantry stationed behind some ditches that intersected the low ground on the bank of that river. This trifling success exalted the enthusiasm of the besieged, and Palafox gratified his personal vanity by boasting proclamations and orders of the day, some of which bore the marks of genius, but the greater part were ridiculous.

The 1st of January the second parallels of the true attacks were commenced. The next day Palafox[29] caused the attention of the besiegers to be occupied on the right bank of the Ebro, by slight skirmishes, while he made a serious attack from the side of the suburb on general Gazan’s lines of contrevallation. This sally was repulsed with loss, but, on the right bank, the Spaniards obtained some success.

Marshal Moncey being called to Madrid, Junot assumed the command of the third corps, and, about the same time, marshal Mortier was directed to take post at Calatayud, with Suchet’s division of the fifth corps, for the purpose of securing the communication with Madrid. The gap in the circle of investment left by this draft of eight thousand men, being but scantily stopped by extending general Morlot’s division, a line of contrevallation was constructed at that part to supply the place of numbers.

The besieged, hoping and expecting each day that the usual falls of rain taking place would render the besiegers’ situation intolerable, continued their fire briskly, and worked counter approaches on to the right of the French attacks: but the season was unusually dry, and a thick fog rising each morning covered the besiegers’ advances and protected their workmen, both from the fire and from the sorties of the Spaniards.

The 10th of January, thirty-two pieces of French artillery being mounted and provisioned, the convent of San Joseph and the head of the bridge over the Huerba, were battered in breach, and, at the same time, the town was bombarded. San Joseph was so much injured by this fire that the Spaniards, resolving to evacuate it, withdrew their guns. Nevertheless, two hundred of their men made a[30] vigorous sortie at midnight, and were upon the point of entering one of the French batteries, when they were taken in flank by two guns loaded with grape, and were, finally, driven back, with loss of half their number.

The 11th, the besiegers’ batteries continued to play on San Joseph with such success that the breach became practicable, and, at four o’clock in the evening, some companies of infantry, with two field-pieces, attacked by the right, and a column was kept in readiness to assail the front, when this attack should have shaken the defence. Two other companies of chosen men were directed to search for an entrance by the rear, between the fort and the river.

The defences of the convent were reduced to a ditch eighteen feet deep, and a covered way which, falling back by both flanks to the Huerba, was then extended along the banks of that river for some distance. A considerable number of men still occupied this covered way: but, when the French field-pieces on the right raked it with a fire of grape, the Spaniards were thrown into confusion, and crossing the bed of the river took shelter in the town. At that moment the front of the convent was assaulted; but, while the depth of the ditch and the Spanish fire checked the impetuosity of the assailants at that point; the chosen companies passed round the works, and finding a small bridge over the ditch crossed it, and entered the convent by the rear. The front was carried by escalade, almost at the same moment, and the few hundred Spaniards that remained were killed or made prisoners.

The French, who had suffered but little in this[31] assault, immediately lodged themselves in the convent, raised a rampart along the edge of the Huerba, and commenced batteries against the body of the place and against the works at the head of the upper bridge, from whence, as well as from the town, they were incommoded by the fire that played into the convent.

The 15th, the bridge-head, in front of Santa Engracia, was carried with the loss of only three men; but the Spaniards cut the bridge itself, and sprung a mine under the works; the explosion, however, occasioned no mischief, and the third parallels being soon completed, and the trenches of the two attacks united, the defences of the besieged were thus confined to the town itself. They could no longer make sallies on the right bank of the Huerba without overcoming the greatest difficulties. The passage of the Huerba was then effected by the French, and breaching and counter-batteries, mounting fifty pieces of artillery, were constructed against the body of the place. The fire of these guns played also upon the bridge over the Ebro, and interrupted the communication between the suburb and the town.

Unshaken by this aspect of affairs, the Spanish leaders, with great readiness of mind, immediately forged intelligence of the defeat of the emperor, and, with the sound of music, and amidst the shouts of the populace, proclaimed the names of the marshals who had been killed; asserting, also, that Palafox’s brother, the marquis of Lazan, was already wasting France. This intelligence, extravagant as it was, met with implicit credence, for such was the disposition of the Spaniards throughout this war, that the imaginations of the chiefs were taxed to[32] produce absurdities proportionable to the credulity of their followers; hence the boasting of the leaders and the confidence of the besieged augmented as the danger increased, and their anticipations of victory seemed realized when the night-fires of a succouring force were discerned blazing on the hills behind Gazan’s troops.

The difficulties of the French were indeed fast increasing, for while enclosing Zaragoza they were themselves encircled by insurrections, and their supplies so straightened that famine was felt in their camp. Disputes amongst the generals also diminished the vigour of the operations, and the bonds of discipline being relaxed, the military ardour of the troops naturally became depressed. The soldiers reasoned openly upon the chances of success, which, in times of danger, is only one degree removed from mutiny.

The nature of the country about Zaragoza was exceedingly favourable to the Spaniards. The town, although situated in a plain, was surrounded, at the distance of some miles, by strong and high mountains, and, to the south, the fortresses of Mequinenza and Lerida afforded a double base of operations for any forces that might come from Catalonia and Valencia. The besiegers drew all their supplies from Pampeluna, and consequently their long line of operations, running through Alagon, Tudela, and Caparosa, was difficult to defend from the insurgents, who, being gathered in considerable numbers in the Sierra de Muela and on the side of Epila, threatened Alagon, while others, descending from the mountain of Soria, menaced the important point of Tudela.

The marquis of Lazan, anxious to assist his brother,[33] had drafted five thousand men from the Catalonian army, and taking post in the Sierra de Liciñena, or Alcubierre, on the left of the Ebro, drew together all the armed peasantry of the valleys as high as Sanguessa, and extending his line from Villa Franca on the Ebro to Zuera on the Gallego, hemmed in the division of Gazan, and even sent detachments as far as Caparosa to harass the French convoys coming from Pampeluna.

To maintain their communications and to procure provisions the besiegers had placed between two or three thousand men in Tudela, Caparosa, and Tafalla, and some hundreds in Alagon and at Montalbarra. Between the latter town and the investing army six hundred and fifty cavalry were stationed: a like number were posted at Santa Fé, to watch the openings of the Sierra de Muela, and sixteen hundred cavalry with twelve hundred infantry, under the command of general Wathier, were pushed towards the south as far as Fuentes, Wathier, falling suddenly upon an assemblage of four or five thousand insurgents that had taken post at Belchite, broke and dispersed them, and then pursuing his victory took the town of Alcanitz, and established himself there in observation for the rest of the siege. But Lazan still maintained himself in the Alcubierre.

In this state of affairs marshal Lasnes, having recovered from his long sickness, arrived before Zaragoza, and took the supreme command of both corps on the 22d of January. The influence of his firm and vigorous character was immediately perceptible; he recalled Suchets division from Calatayud, where it had been lingering without necessity, Rogniat. and, sending it across the Ebro, ordered[34] Mortier to attack Lazan. At the same time a smaller detachment was directed against the insurgents in Zuera, and, meanwhile, Lasnes repressing all disputes, restored discipline in the army, and pressed the siege with infinite resolution.

The detachment sent to Zuera defeated the insurgents and took possession of that place and of the bridge over the Gallego. Mortier encountered the Spanish advanced guard at Perdeguera, and pushed it back to Nuestra Señora de Vagallar, where the main body, several thousand strong, was posted. After a short resistance, the whole fled, and the French cavalry took four guns; Mortier then spreading his troops in a half circle, extending from Huesca to Pina on the Ebro, awed all the country lying between those places and Zaragoza, and prevented any further insurrections.

A few days before the arrival of marshal Lasnes, the besieged being exceedingly galled by the fire from a mortar-battery, situated at some distance behind the second parallel of the central attack, eighty volunteers, under the command of Don Mariano Galindo, endeavoured to silence it. They surprised and bayonetted the guard in the nearest trenches, and passing on briskly to the battery, entered it, and were proceeding to spike the artillery, when unfortunately the reserve of the French arrived, and, the alarm being given, the guards of the first trenches also assembled in the rear of this gallant band, intercepting all retreat. Thus surrounded, Galindo, fighting bravely, was wounded and taken, and the greatest part of his comrades perished with as much honour as simple soldiers can attain.

The armed vessels in the river now made an[35] attempt to flank the works raised against the castle of Aljaferia, but the French batteries forced them to drop down the stream again; and between the nights of the 21st and the 26th of January the besiegers’ works being carried across the Huerba, the third parallels of the real attacks were completed. The oil manufactory and some other advantageous posts, on the left bank of the above-named river, were also taken possession of and included in the works, and at the false attack a second parallel was commenced at the distance of a hundred and fifty yards from the castle of Aljaferia; but these advantages were not obtained without loss. The Spaniards made sallies, in one of which they spiked two guns and burnt a French post on the right.

The besiegers’ batteries had, however, broken the wall of the town in several places. Two practicable breaches were made nearly fronting the convent of San Joseph; a third was commenced in the convent of Saint Augustin, facing the oil manufactory. The convent of San Engracia was laid completely open to an assault; and, on the 29th, at twelve o’clock, the whole army being under arms, four chosen columns rushed out of the trenches, and burst upon the ruined works of Zaragoza.

On the right, the assailants twice stormed an isolated stone house that defended the breach of Saint Augustin, and twice they were repulsed, and finally driven back with loss.

In the centre, the attacking column, regardless of two small mines that exploded at the foot of the walls, carried the breach fronting the oil manufactory, and then endeavoured to break into the[36] town; but the Spaniards retrenched within the place, opened such a fire of grape and musquetry that the French were content to establish themselves on the summit of the breach, and to connect their lodgement with the trenches by new works.

The third column was more successful; the breach was carried, and the neighbouring houses also, as far as the first large cross street; beyond that, the assailants could not penetrate, but they were enabled to establish themselves within the walls of the town, and immediately brought forward their trenches, so as to comprehend this lodgement within their works.