SATIRE IN THE VICTORIAN NOVEL

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

NEW YORK · BOSTON · CHICAGO · DALLAS

ATLANTA · SAN FRANCISCO

MACMILLAN & CO., Limited

LONDON · BOMBAY · CALCUTTA

MELBOURNE

THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, Ltd.

TORONTO

BY

FRANCES THERESA RUSSELL, Ph.D.

ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH, STANFORD UNIVERSITY

SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE FACULTY OF PHILOSOPHY, COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY

New York

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

1920

All rights reserved

Copyright, 1920,

By THE MACMILLAN COMPANY.

Set up and electrotyped. Published January, 1920.

VIRO DOCTISSIMO

DAVID STARR JORDAN

ET

DIS MANIBUS

GUILELMI JAMES

SACRUM

QUI MIHI TEMPORE MEO GRAVISSIMO, NOVA SUPPEDITANTES

OFFICIA NOVAM VITÆ SEMITAM MONSTRAVERUNT

[vii]

If the following monograph were to be presented from the point of view of a proponent, the author would be put triply on the defensive in relation to the theme. For, from one cause or another, the trio of terms in the title lies under a certain blight of critical opinion.

Satire, being a thistle “pricked from the thorny branches of reproof,” cannot expect to be cherished in the sensitive human bosom with the welcome accorded to the fair daffodil or the sweet violet. It must be content to be admired, if at all, from a safe distance, with the cold eye of intellectual appraisal.

Victorianism has the distinction of being the only period in literature whose very name savors of the byword and the reproach. To be an Elizabethan is to be envied for the gift of youthful exuberance and an exquisite joy in life. To be a Queen Annian (if the phrase may be adapted) is to be respected for the accomplishments of mature manhood,—a dignified mein, ripened judgment, and polished wit. To be a Victorian—that indeed provokes the question whether ’twere better to be or not to be. The chronological analogy cannot, however, be carried out, for the Victorian, whatever the cause of his unfortunate reputation, can hardly be accused of senility. On the contrary, the impression prevails that the startled ingenuousness, for instance, with which he opened his eyes at Darwin, Ibsen, and the iconoclasts in Higher Criticism; the vehemence with which he opposed and refuted and fulminated against everything hitherto undreampt[viii] of in his philosophy; the complacency with which he viewed himself and his achievements, were attributes more appropriate to adolescence than to any later time of life. Withal there was little of the grace and gayety of youth, and not much more of the poise and humor of manhood. That the Victorian was never at ease, in Zion or elsewhere, that he was prone to take himself and his disjointed times very seriously, without achieving a proportionate reformation, is a charge from which he never can be acquitted. To our modern authorities, especially such dictators as Shaw and Wells, contemplating him from the vantage ground of a higher rung in the ladder of civilization, the Victorian looks as Wordsworth did to Lady Blandish, like “a very superior donkey,” protected by the side-blinders of conventionality, saddled and bridled by authority, and ridden around in a circle by sentiment (most tyrannical of drivers), with much cracking of whip and raising of dust, but no real change of intellectual or spiritual locality. Nor can all the cavorting fun of Dickens, all the pungent playfulness of Thackeray, all the sardonic gibes of Carlyle, all the grotesque gesturing of Browning, all the winged irony of George Eliot and Matthew Arnold, not even all the quips and cranks in Punch itself, avail to quash the indictment. The Victorian may be defended, appreciated, exonerated even; he may in time succeed in living it down. But to live it down is not quite the same as to have had nothing that had to be lived down.

The Novel has been called the Cinderella of Literature. And it is true that while she may be useful, indispensable, a secret favorite of the whole family, no magic wand can give her the real enchantment of a caste that survives the stroke of twelve. She may act as the drudge to[ix] fetch and carry our theories, or the playmate to amuse our idle hours, but she must be kept in her place, and her place is with neither the esthetic aristocracy of poetry nor the didactic patricianism of philosophy and criticism. She has, indeed, recently been fitted with a golden slipper, but her Prince hails from the Kingdom of Dollars, and his rank is recorded in Bradstreet instead of the Peerage.

The indifferent or repellent nature of a subject, even though triple distilled, has nothing to do, however, with its value as a topic for investigation. I present this study neither as apologist nor enthusiast. If we expand Browning’s “development of a soul” to include the mental as well as the spiritual stages, as the poet himself did in actual practice, we must agree with him that “little else is worth study.” So persistent and insistent in the mind of man has been, and still is, the satiric mood, so devoted has he been from immemorial ages to the habit of story-telling (and seldom for the mere sake of the story), so voluminous and emphatic did he become in the nineteenth century, that no complete account of him can be rendered up until, amid the infinite variety of his aspects, he has been viewed as a Victorian satirist, using as his medium the English novel.

Whatever the result of this observation may be, the process has been one of continual delight, tempered by despair; for one enters as it were a room of tremendous size not only full of curious and challenging objects (over-furnished perhaps), but supplied also with numerous doors opening into other apartments, and these ask an amount of time and attention which only the span of a Methuselah could place at one’s disposal.

It must be admitted, though, that it is a happier lot to stand before open doors, even in dismay at the illimitable[x] vistas, than to confront closed doors or none at all. And I wish in this connection to offer my tribute of appreciation and admiration to one who has prëeminently the scholar’s talisman of Open Sesame into the many and rich realms of literature. It was my good fortune to prepare this study under the direction of Professor Ashley H. Thorndike, of Columbia University, by whose benignly severe criticism so many students have profited, by whose sure taste and searching wisdom so many have been guided. To him, to his colleagues in the English Department, and to the other officers of the University who helped to make my term of residence the satisfaction it has been, it is a pleasure to express my gratitude. To my Stanford colleague, Miss Elisabeth Lee Buckingham, I am indebted for the drudgery of copy-reading, both in manuscript and in proof, and for many valuable suggestions.

F. T. R.

[xi]

| PART I | |

| PREMISES | |

| Chapter I | |

| THE SATIRIC SPIRIT | |

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

| Various interpretations because of various manifestations. Chief constituents, criticism and humor. Relation of these in the formula. Testimony of satirists as to the presence of humor, criticism being taken for granted. The satiric motive; temperamental cause and ethical intent. Testimony as to both. Symposium on the discrepancy between prospectus and performance. The realizable ideal. Objects: empiric data on vice, folly, and deception. Reason for universal criticism and ridicule of deception. Criteria of good satire. Difficulties, limitations, and real function | 1 |

| Chapter II | |

| THE CONFLUENCE | |

| Relationship between satire and fiction. Ancient but incomplete and uneven alliance. Union in the nineteenth century. The Victorian novelists. Their chronology and background. Classification as satirists. Testimony of the novelists themselves as to satire | 41 |

| PART II | |

| METHODS | |

| Chapter I | |

| THE ROMANTIC | |

| Possible methodic categories. Reason for present choice. Proportion of the romantic or fantastic type. Peacock and Butler. Lytton and Disraeli. Thackeray and Meredith. Characteristics of this form of satire: [xii]wit, invention, exaggeration, and concentration | 59 |

| Chapter II | |

| THE REALISTIC | |

| Character of Victorian realism. Nature of realistic satire. Subdivisions, based on authors’ methods and devices. The direct or didactic satirists: Lytton, Thackeray, Dickens, Meredith. Satire in plot or situation: Martin Chuzzlewit, Vanity Fair, The Egoist. Minor episodes. Satire expressed by witty characters, of various types | 84 |

| Chapter III | |

| THE IRONIC | |

| Verbal and philosophic irony. Banter and sarcasm. The Irony of Fate. Relation of irony to satire. Differing opinions. Distribution of irony among the novelists. Direct or verbal: present in varying degrees in practically all. Crystallized and pervasive forms. Irony in circumstance: Trollope, Eliot, and Meredith. Subdivisions: dramatic irony; the reversed wheel of fortune, the granted desire; the lost opportunity. Meredithian irony directed against the ironic interpretation of life | 121 |

| PART III | |

| OBJECTS | |

| Chapter I | |

| INDIVIDUALS | |

| Personalities the original and primitive element in satire. Effect of this influence upon the satiric product, and of this in turn upon the attitude toward satire. Citations. In fiction no hard and fast line between real and imaginary characters. Lack of personal satire among the novelists. Its prevalence limited to the earlier writers: Peacock, Lytton, Disraeli, and Thackeray before 1850 | 167 |

| Chapter II | |

| INSTITUTIONS | |

| Victorian attitude toward established institutions. Satire directed against the following: Society, including the home, woman, marriage; the State, including politics, sociology, law, charities and corrections, war; the Church, treated both by partisans on the inside, and pagans on the outside; [xiii]the School, signifying education, from the fireside to the college; Literature and the Press; the English as a nation. Lack of complementary reconstruction | 179 |

| Chapter III | |

| TYPES | |

| Impossibility of maintaining fixed classes. Unity and emphasis secured by artificial devices. Several human traits temptingly vulnerable, though all some form of deceit. Hypocrisy the specialty of Dickens, Folly, of Dickens and Meredith, Snobbishness, of Thackeray, Sentimentality and Egoism, of Meredith. Scattered fire against vulgarity, fanaticism, and other targets. Combination and interplay of traits in one character exemplified by Trollope’s Lady Carbury | 229 |

| PART IV | |

| CONCLUSIONS | |

| Chapter I | |

| RELATIONSHIPS | |

| The various novelists compared as to respective quality, quantity, and range of satirical element. Discussion of the merging of satire into cynicism, tragedy, and idealism on the critical side, and into comedy, wit, and philosophic humor, on the humorous. Relation to intellect and emotion. Relative ranking of satirists influenced by these considerations | 269 |

| Chapter II | |

| THE VICTORIAN CONTRIBUTION | |

| The cumulative inheritance. Recent change in form from heroic couplet to prose fiction. Progressive change in substance from hypocritical to sentimental side of deceit. Seen in institutions as well as in types of character. Science and democracy the most influential factors. Scientific search for causes of failure. Democratic sense of social responsibility. Satire directed against self-deceived inefficiency mistaken for success. Satiric method concentrated on exposure of motives. Satiric manner less assertive and more casual and urbane. Recognition of the paradox in ridicule. Reduction of it to minor rôle, though staged with more finesse and effectiveness. Stress shifted from the critical element to the ironically humorous | 288 |

| Bibliographical note | 317 |

| Index | 329 |

[1]

Satire in the Victorian Novel

“Are ye satirical, sir?” inquired the Ettrick Shepherd, warily suspicious of the cryptic eulogy just pronounced by his companion on the minds and manners of the English shopocracy.

“I should be ashamed of myself if I were, James,” was the grieved reply.

We know very well, however, that Christopher North was not ashamed of himself, at least not with the true contrition that leads to reformation. On the contrary, we fear that he cherished and cultivated quite shamelessly his gift of caustic wit. In any case, whether the disavowal came from ironic whim or from a concession to the popular attitude toward satire, it illustrates the first difficulty confronting the student of this indeterminate subject.

To recognize the satirical at sight, to know whether a man is telling the truth, either when he claims to be a satirist or when he disclaims the charge, is something of an accomplishment. For the complex and Protean nature of satire, varium et mutabile semper, has naturally led to much disagreement not only as to its existence in certain cases, but as to its justification in general. To its eulogist, usually the satirist himself, satire is an instrument of discipline with a divine commission,—a[2] Scourge of God. To its apologist, usually the detached observer, it is a more or less dubious means to a more or less necessary end. To its disparager, usually the satirized, it is a wanton mischief-maker, superfluous and intolerable. The personal resentment of this last may be fortified by the convenient logic which identifies the agent with the cause. “People who really dread the daring, original, impulsive character which is the foundation of the satirical,” says Hannay in one of his lectures on Satire, “ingenuously blame the satirist for the state of things which he attacks.”

These varieties of attitude toward satire arise not only from varieties in temperament and satirical experience, but from the diverse manifestations of satire itself. Take, for instance, those characters in literature which seem to be an incarnation of the satiric spirit. Thersites is the dealer in personalities, scoffing and gibing at the élite with the licensed audacity of the court fool. Reynard is the satirical rogue who not only perceives the weaknesses of his fellow citizens but turns them to his own advantage. Alceste is the misanthrope, “critic,” as Meredith says, “of everybody save himself,” but lifting his strictures out of the merely personal by attaching them to a general interpretation of life. The Hebrew Adversary is the cynic with a scientific zest for experiment. He impugns motives, fleers at fair appearances, prides himself on his superior penetration, and questions the price for which a prosperous Job serves God. His loss of the wager through actual test of his theory has been taken as proof that such suspicions are unwarranted, and that the trust of the Divine Idealist in human nature was justified. This conclusion, however, must be qualified by the admission that the inductive process was conducted[3] on limited data, and that if Eliphaz, Bildad, or Zophar had been chosen for the trial, the result might have been different. As it was, the final silence of the quenched satirist, and his absence from the happy ending may be construed as a sign of defeat in one instance that by no means invalidated his general attitude of doubt and interrogation.

Of all these embodiments, however, the most perfect representation of the satiric spirit is a product of English genius. The melancholy Jaques has abundant slings and arrows of his own wherewith to retaliate for those of outrageous fortune, but he never fails to wing them with laconic wit and imperturbable humor. He expressly denies being guilty of personalities.

He snubs with careless aplomb the too oratorical Orlando, and cannily avoids the too loquacious Duke. “I think of as many matters as he,” he observes, “but I give heaven thanks, and make no boast of them.” He reviews the career of man, and sees him proceeding with pretentious futility through his seven sad ages to an inglorious conclusion. And yet this philosopher admits his very pessimism to be something of a pose, and turns his humor reflexively against himself. All satirists have a fondness for sucking melancholy out of a song as a weasel sucks eggs; all are prone to rail at the first born of Egypt simply because they cannot sleep, but few have the honesty to acknowledge it. Meanwhile, although this courtier claims motley as his only wear, his companions perceive the genuineness of his humanity and the value of his protests.

[4]

And thus have diverse manifestations of the satiric spirit appeared from time to time. Few seem to be visible just at present, but we may be sure that the Spirit of Satire has not deserted our planet. Still is he busy walking up and down in the earth and going to and fro in it. Still does he probe and mock, sometimes with penetrative wisdom, sometimes in prejudice and error, but always as a challenge not to be ignored.

Satire has not only embodied itself in certain characters of literature, but has made and maintained for itself an important place in that realm. This place may be divided into two fairly distinct areas. The narrower one is known as formal satire, and has always been expressed in verse: the Latin hexameter, the Italian terza rima, the French Alexandrine, the English heroic couplet. The larger and less definite section is formed by surcharging with the satiric tone some other literary type. Such a combination is found in the Aristophanic comedy, the dialogues of Lucian, the romances of Rabelais, Cervantes, and Swift. Such also are The Rape of the Lock, Don Juan, The Bigelow Papers, Man and Superman, and countless others. In addition to these there is a third estate, the largest and most heterogeneous, consisting of writings mainly serious, with a more or less pronounced satiric flavor.

Any study, therefore, which tries to deal with satire as a mode rather than a form will profit by using the adjective instead of the noun. Without fully accepting the erasure of the old literary boundaries advocated by Croce, Spingarn, and the modern school, we may say[5] that in this particular field at least, the substitution of the descriptive satiric for the categoric satire shows that discretion which is the better part of valor. Still, since to avoid the responsibility of deciding whether or not a given production is a satire, by the non-committal device of calling it satiric, is only to beg the question so far as a definition is concerned, it is advisable to produce some identifying label. Stated in brief, satire is humorous criticism of human foibles and faults, or of life itself, directed especially against deception, and expressed with sufficient art to be accounted as literature.

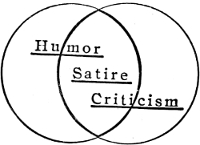

When we say, however, that satire is a union of those two intangible, subjective elements, criticism and humor, we do not assume the equation fully to be expressed by the formula—Antagonism plus Amusement equals Satire. For neither is all criticism humorous nor all humor critical. The relation is that of two circles, not coincident but overlapping.

Confusion has arisen because, while the boundaries of the two separate circles are fairly distinct in our minds, the circumference made by their conjunction is merged in their respective planes. Accordingly, the term satire is sometimes used to denote humorless criticism,—which is really invective, denunciation, any sort of reprehension; and sometimes uncritical humor,—which is mere facetiousness and jocularity. Not every prophet, preacher, or pedagogue is a satirist, nor yet every merry clown, or exuberant youth, or mild worldly-wise man enjoying the blunders of innocent naïveté.

Professor Dewey reminds us that the ideal state of mind is “a nice balance between the playful and the serious.”[6] But in the satiric circle a nice balance would be found only at the center. Wherever there are boundaries, there are always some sections of the enclosure nearer the margin than others. Thus, although satire is a compound, it does not follow that its fractions stand in a constant uniform ratio. On the contrary, the proportion ranges all the way from a minimum of humor in a Juvenal or a Johnson to a minimum of criticism in a Horace, a Gay, or a Lamb. Either quality may reach the vanishing point, but when it passes it, the remaining one cannot alone create satire, any more than oxygen or hydrogen can be transformed into water.

Nor can either quality be defined in other than psychological terms. The critical sense is rooted in the instincts of attraction and repulsion, the reaction of an organism to any new stimulus being pro or con according to the preëstablished harmony or antagonism between them. As each human being grows to maturity by responding to experience, he acquires his individual set of opinions and ideals, largely borrowed from the habits and conventions of his groups, ethnic, social, and what not, with a small residue of his own originality. Equipped with this outfit of criteria he looks upon life and finds it complete or wanting, tests his fellow men and approves or condemns, examines all created things and calls them good or bad. But he is so constituted that his acquiescence is likely to be somewhat passive, and his protests active, his commendation grudging and qualified, his condemmation sweeping and thorough. Says an eighteenth century satirist,—[1]

The humorous sense is likewise an essence and an index of disposition. The inadequacy of most definitions of the ludicrous, from Aristotle’s “innocuous, unexpected incongruity,” to Bergson’s “mechanical inelasticity,” lies in their concentration on the objective side of it,—the stimulus to mirth,—whereas the subjective,—the mirthful person,—deserves the emphasis. Laughter throws a far more illuminating ray on the laugher than the laughed at, for it indicates not only taste and mood but the trend of one’s philosophy. In betraying a man’s idea of the incongruous, it implies his conception of the congruous, and reveals his whole coördination of life. We may, it is true, define humor by saying that intellectually it is a contemplation of life from the angle of amusement, and emotionally, a joyous effervescence over the absurdities in life ever present to the discerning eye; but we can never quite capture it, any more than pleasure or tragedy. We can, however, use these abstractions as refracted definers of character, by noting what sort of a man it is who regards such and such things as amusing, or delightful, or unendurable. For not only as a man thinks, but also as he laughs and exults and censures and suffers, so is he.

That satire is woven from double strands, the blue of rebuke and the red of wit,—becoming thereby in a chromatic sense the purple patch of literature,—is testified to by satiric theory as well as practice. The critical element may of course be taken for granted, but since it has been sometimes over-emphasized at the expense of the humorous, some testimony as to the latter must be given.

It is to Horace that we are indebted not only for the first finished formal satire, but for the first attempt at[8] an analysis of the then newest literary type. He sketches the history of satire as an exposure of crime, but insists that this mission may be performed with courtesy and the light touch, since even weighty matters are sometimes settled more effectively by a jest than by grim asperity.

It is interesting to note that his own consistent practice in this matter is acknowledged by his successor Persius, who says of him,

When Jonson reintroduced the Aristophanic vehicle of comedy to carry his satire, though fashioned in a different style, he also re-voiced the Horatian satiric philosophy, promising realism,—such characters and actions as comedy would choose,

A writer of the Restoration Period carries on the tradition:

[9]

The spokesman of the eighteenth century on this point is Young.

“No man can converse much in the world but, at what he meets with, he must either be insensible, or grieve, or be angry, or smile. Some passion (if we are not impassive) must be moved; for the general conduct of mankind is by no means a thing indifferent to a reasonable and virtuous man. Now, to smile at it, and turn it into ridicule, I think most eligible; as it hurts ourselves least, and gives Vice and Folly the greatest offense.

“Laughing at the misconduct of the world will, in a great measure, ease us of any more disagreeable passion about it. One passion is more effectually driven out by another than by reason.”[6]

And about the same time our first satirical novelist was avowing his own creed and performance:

“If nature hath given me any talents at ridiculing vice and imposture, I shall not be indolent, nor afraid of exerting them.”[7]

Again: “I have employed all the wit and humour of which I am master in the following history; wherein I have endeavoured to laugh mankind out of their favorite follies and vices.”[8]

[10]

The self-conscious nineteenth century is full of comments on this topic, as on all others, but two or three representative ones will suffice as examples.

It is not really the great Greek satirist but his modern interpreter who utters this explanatory sentiment:

Finally, turning to the encyclopedia for a modern official pronouncement, we find humor again cited as a sine qua non.[10]

“Satire in its literary aspect may be defined as the expression in adequate terms of the sense of amusement or disgust excited by the ridiculous or unseemly, provided that humor is a distinctly recognisable element, and that the utterance is invested with literary form. Without humor, satire is invective; without literary form, it is mere clownish jesting. * * * This feeling of disgust or contempt may be diverted from the failings of man individual to the feebleness and imperfection of man universal, and the composition may still be a satire; but if the element of scorn or sarcasm were entirely eliminated it would become a sermon.”

The matter of ingredients is more easily disposed of, however, than that of causation. It is obviously easier to scrutinize a finished product and see what it is made of than to go back to its origin and discover why it was made. For the latter process leads us to the domain of motives, that shadowy realm where the real is often made to hide behind the assumed or at least the instinctive[11] kept down by the acquired. In this mental kingdom many an impulsive little prince has been smothered by a deliberative, ambitious usurper who felt a call to rule.

In the province of satire the real internal stimulus is temperament. If a man has a critical disposition, he is bound to criticise. If he has a keen sense of humor, he will be alive to the absurd. If he possesses both, he is a natural-born satirist and cannot escape his manifest destiny,—so long as he is not inarticulate. But the declared motives are for the most part ethical and altruistic, a lineage much more presentable and worthy of high command.

This human tendency to justify its instinctive behavior by ex post facto morality has produced an impressive symposium on the thesis that satire has a definite purpose and moreover a noble one. Thus while the satirist admits his malice aforethought, he protests that the malicious suffers a sea change into the beneficent, for that he must be cruel only to be kind. The modest and honest confession of Horace[11] that he wrote satire because he had to write something and was not equal to epic, was soon supplanted by the Juvenalian declaration of saeva[12] indignatio, and it is from this perennial spring that a steady flow of eulogy has irrigated the history of satire.

A representative of the Elizabethan group is Marston:[12]

Milton manages here as elsewhere to sound a clarion note over the clash of seventeenth century partisanship:[13]

“A taste for delicate satire cannot be general until refinement of manners is general likewise; till we are enlightened enough to comprehend that the legitimate object of satire is not to humble an individual, but to improve the species. * * * For a satire as it is born out of a tragedy so it ought to resemble its parentage, to strike high, to adventure dangerously at the most eminent vices among the greatest persons.”

Defoe[14] echoes Dryden,[15] both speaking with reasonable consistency; and even Pope[16] tries to make out a case for himself. But the completest paean is from the pen of John Brown.[17] His poetic analysis begins at the beginning:

The climax of this human error is perverted ambition and a snobbish idea of excellence:

The author’s optimism mounts even to the disparagement of Force, Policy, Religion, Mercy, and Justice, in comparison with this puissant and impeccable goddess, in whose presence the wicked never cease from trembling,—especially stricken when she draws

[14]

Feeling perhaps that after all his client’s status is a trifle dubious, her advocate continues with a caution and a climax:

The sober eighteenth century brings us back to reality with a characteristic comment by the best satirist of the period, who admires his favorite predecessors, “not indeed for that wit and humour alone which they all so eminently possessed, but because they all endeavoured, with the utmost force of their wit and humour, to expose and extirpate those follies and vices which chiefly prevailed in their several countries.”[18]

But Gifford, akin in spirit to the satirist he translated, goes to the extreme in taking the satiric office seriously:

“To raise a laugh at vice * * * is not the legitimate office of Satire, which is to hold up the vicious as objects of reprobation and scorn, for the example of others, who may be deterred by their sufferings.”[19]

De Quincey carries the tradition over into the nineteenth century by reminding us that “the satirist has a reformative as well as a punitive duty to discharge.” Meredith[20] agrees that “the satirist is a moral agent, often a social[15] scavenger, working on a storage of bile.” Symonds[21] affirms that “Without an appeal to conscience the satirist has no locus standi.” Browning has Balaustion say to Aristophanes:

And Dawson[22] brings satiric utilitarianism into the present century:

“It is quite beside the mark to say that we do not like satire. It is equally beside the mark to say that we have never known such a world as this. The thing to be remembered is that in all ages the satirist of manners has been of the utmost service to society in exposing its follies and lashing its vices. It is the work of a great satirist to apply the caustic to the ulcers of society; and if we are to let our dislike of satire overrule our judgment, we shall not only record our votes against a Juvenal and a Swift, but equally against the whole line of Hebrew prophets.”

All these citations refer more or less directly to the cause—the reason or motive for satirical utterance—but have some bearing on the effect—the tangible result of it,—since the two are to a certain extent inseparable.[16] They are, however, also distinct, and particularly so in this case; as cause is a psychological and hidden thing, and effect is more external and visible. In turning from the first to the second we pass from deductive argument to inductive. The logic of the former is an Idol of the Tribe, particularly of the British tribe, unable to rest until everything has been drafted under the ethic flag and brought into the moral fold. We pass also from spacious promise to rather cramped and meager performance. Satiric intent looms as large as the imposing first appearance of the giant of Destiny, in Maeterlinck’s Betrothal; satiric accomplishment shrinks to the size of his exit as the babe in arms. And while the assertion of inexorability and omnipotence is continued bravely to the end, albeit in a voice of quavering diminuendo, a counter voice is also heard, repudiating extravagant claims.

Both attitudes are expressed in turn by an eighteenth century satirist. In his Epistle to William Hogarth Churchill exclaims,

But in The Candidate, he announces reform of his former practices, in a series of rhetorical “Enoughs,” coming to a climax in—

In his own degenerate days, however,—

[17]

In The Author he asks, “Lives there a man whom Satire cannot reach?” And the author of English Bards and Scotch Reviewers declares that vice and folly will—

But Marston and Defoe, already quoted on the other side, have their dubious moments. Says the former,[23]

And the latter[24] would be sanguine if he could:

“If my countrymen would take the hint and grow better-natured from my ill-natured poem, as some call it, I would say this of it, that though it is far from the best satire that ever was written, it would do the most good that ever satire did.”

Gifford[25] also, though a believer in the mission of satire, admits that “to laugh at fools is superfluous, and at the vicious unwise.”

Cowper[26] allows minor accomplishments:

[18]

Young[27] grants it a fighting chance:

“But it is possible that satire may not do much good; men may rise in their affections to their follies, as they do to their friends, when they are abused by others. It is much to be feared that misconduct will never be chased out of the world by satire; all, therefore, that is to be said for it is, that misconduct will certainly never be chased out of the world by satire, if no satires are written. Nor is that term unapplicable to graver compositions. Ethics, Heathen and Christian, and the scriptures themselves, are, in a great measure, a satire on the weakness and iniquity of men; and some part of that satire is in verse, too. * * * Nay, historians themselves may be considered as satirists and satirists most severe; since such are most human actions, that to relate is to expose them.”

The distrust of the moderns is adequately voiced by Sidgwick:[28]

“Satire is the weapon of the man at odds with the world and at ease with himself. The dissatisfied man—a Juvenal, a Swift, a youthful Thackeray—belabors the world with vociferous[19] indignation, like the wind on the traveller’s back, the beating makes it hug its cloaking sins the tighter. Wrong runs no danger from such chastisement. * * * Satire is harmless as a moral weapon. It is an old-fashioned fowling piece, fit for a man of wit, intelligence, and a certain limited imagination. It runs no risk of having no quarry; the world to it is one vast covert of lawful game. It goes a-travelling with wit, because both are in search of the unworthy.”

Two comments on Aristophanes illustrate the pro and con of satiric accomplishment. Cope, in the Preface to his translation, remarks:

“He felt it his duty to do all he could to counteract the increasing influence of Euripides upon the rising generation, and knowing the power of ridicule, he employs this weapon constantly and mercilessly; but he is careful not to injure his own cause by exaggerated caricature, which might have created sympathy for the object of his censure.”

But White, while warning us against regarding the dramatist as either “a mere moralist or a mere jester,” judges by record:[29]

“If Aristophanes was working for reform, as a long line of learned interpreters of the poet have maintained, the result was lamentably disappointing; he succeeded in effecting not a single change. He wings the shafts of his incomparable wit at all the popular leaders of the day—Cleon, Hyperbolus, Peisander, Cleophon, Agyrrhius, in succession, and is reluctant to unstring his bow even when they are dead. But he drove no one of them from power.”

Yet after due deduction has been made, Satire has left to it an asset of considerable net value; an influence that may be subjective if not objective, general if not specific,[20] and artistic if not rampantly ethical. As an instrument of self criticism, whereby a man may be saved from making a solemn pompous fool of himself, as an antitoxin to vanity, a solvent of sentimentality, a betrayer of hypocrisy, satire may find all the mission it needs to be respectable; and if it can also acquire a degree of grace and comeliness, it may be listed among the muses.

Now this spirit of humorous criticism, sprung from innate prejudice, nurtured by penetrating observation, enlisted at least nominally under the banner of righteousness, and out for conquest, obviously must have something to conquer;—whether he is a soldier fighting an enemy alien, or a roving knight, bound to offer combat on chivalric grounds, though aware in his candid heart that the surpassing loveliness of his lady is a claim gallantly to be maintained rather than an incontrovertible fact. In either case, whether he uses archery or artillery, he must have a target; and a student of his tactics must understand what it is, even better perhaps than he does himself.

Taken individually, the objects of satiric attack are legion, being no fewer than all such victims of human displeasure as may suitably come in for jesting rebuke. Our only chance for any sort of synthesis is to see first if these individuals may be grouped into classes, and next, if these classes may be generalized under some principle, discovered to be under some supreme command.

The grouping is indeed easily discernible. Political parties stand out, social strata, various professions and institutions and movements. But to look upon these as ridiculed for themselves is to be satisfied with a superficial view. The fault is not in themselves but in their stars that they are underlings. What are these evil stars that seem in their courses to fight against them?

[21]

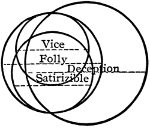

The terms oftenest on the lips of satirists and historians of satire are Vice and Folly. But these fine large entities are taken at their face value and given a conventional interpretation. We are not enlightened as to what vice and folly are, and can define them only as those things which seem vicious and foolish to their several opponents. They also are among the baffling subjectivities.

Juvenal’s conclusion that it is hard not to write satire, from the premise that the number of fools is infinite, is said by Herford to be “the fundamental axiom of all satire.” But as a matter of fact, it was Horace who took the fool for his province, while his sterner successor rather specialized on the knave. From then on there has been as little endeavor to disentangle the two strands as to define them.

One of the earliest English satirists[30] emphasised the knavery; and another[31] includes that and folly in the same indictment. Dryden,[32] inclined to the serious Juvenalian type, discriminates between positive and negative attitudes, but not between the two stock objects.

[22]

Speaking of the narrowed use of the word satire in French and English, he adds,

“For amongst the Romans it was not only used for those discourses which decried vice, or exposed folly, but for others also where virtue was recommended. But in our modern languages we apply it only to invective poems, * * * for in English, to say Satire, is to mean reflection, as we use that word in its worst sense; or as the French call it, more properly, medisance.”

Defoe[33] adds to the two a third, but in a somewhat casual enumeration:

Swift[34] echoes the old duality:

And Fielding,[35] though he actually finds good game in folly, evidently considers vice the prime object:

[23]

“But while I hold the pen, it will be a maxim with me, that vice can never be too great to be lashed, nor virtue too obscure to be commended; in other words, that satire can never rise too high, nor panegyric stoop too low.”

He also makes the same point in a historical review:[36]

Although vice is now too powerful for such censure, he dares the lion in his den, and comforts the virtuous with reassurances:

The nineteenth century is full of straws still blowing in the direction of Vice and Folly: such as Taine’s[37] “Satire is the sister of elegy; if the second pleads for the oppressed, the first combats the oppressors.” And Lionel Johnson[38] comments that Erasmus “had something in common with Matthew Arnold: a like satiric yet profoundly felt impatience with intellectual pedantry and social folly.”

We may, however, see satire as opposition, and moreover opposition to vice and folly, and still be taking for granted that which demands more probing. For even if it were so simple a crusade as that, no crusade is as simple as it looks, and this one is particularly open to suspicion.

[24]

It is therefore not wholly superfluous to ask why vice and folly are the favorite satiric goals. Psychologically it would be sufficient to say that it is because anything a man disapproves of naturally seems to him foolish if not actually vicious. But socialized man cannot admit that his reaction to anything is based on mere temperamental prejudice. Condemnation of vice and folly is of course its own justification, and humor is its own reward. Unfortunately, however, humorous condemnation is not always applicable to these offenders against taste and morality. Folly is sometimes too artless to be censured, and vice is often too serious to be ridiculed. Evidently then, yet another solution is needed, a least common denominator that will go into both, even if it does leave a remainder.

Now it happens that a body of explicit testimony, substantiated by a review of satiric practice, does indicate the existence of this unifying bond, this thing which, when present, makes both vice and folly criticizably absurd; and its generic name is deception.

This fraudulent family has two main branches: the intentional type, including hypocrisy and humbug; and the unconscious, represented by sentimentality and other forms of self-befoolment; besides a half-conscious variety, whence come vanity, snobbishness, superstition, vulgarity, and other children of perverted ambition and false reasoning. All these give plenty of scope to the satirist, even when we subtract some possibilities by the important qualification that not all that deceives is ludicrous; deception being sometimes too innocent and even altruistic and sometimes too tragic and cruel.[39]

According to this test, anything which assumes a virtue[25] when it has it not may draw satiric fire. It is the assumption itself, the pose, that furnishes the shining mark loved by the satirist.

On this point we again have Horatian testimony:[40]

Gascoigne[41] symbolised by his steel glass that which reflected the beholders as they were, not flattered as by the plated mirror; and said his effort was to “sing a verse to make them see themselves.” He also identified the root of all evil with hypocrisy;—“So that they seem, and covet not to be.”

Cervantes[42] spoke of his “Herculean labor” as being “nothing more nor less than to banish mediocrity from the realm of Spanish poetry, and to sweep from its sacred precincts, which had become as foul as an Augean stable, all shams, lies, hypocrisies, and vulgar baseness whatsoever.”

But the first to stress this idea with discriminating analysis was, quite appropriately, the first in his own satirical field:[43]

[26]

“The only source of the true Ridiculous (as it appears to me) is affectation. * * * Now affectation proceeds from one of these two causes, vanity or hypocrisy; for as vanity puts us on affecting false characters, in order to purchase applause; so hypocrisy sets us on an endeavour to avoid censure, by concealing our vices under an appearance of their opposite virtues. * * *

“From the discovery of this affectation arises the Ridiculous; * * * I might observe, that our Ben Jonson, who of all men understood the Ridiculous the best, hath chiefly used the hypocritical affectation.”

He remarks that this is more amusing than vanity, from the sharper contrast with reality, and adds:

“Now, from affectation only, the misfortunes and calamities of life, or the imperfections of nature, may become the objects of ridicule. * * *

“The poet carries this very far:

He concludes:

“Great vices are the proper objects of our detestation, smaller faults of our pity; but affectation appears to me the only true source of the Ridiculous.”

Fielding’s comment on Jonson is in turn applied to him by a modern critic:[44]

“All Fielding’s evil characters, it may be remarked, are accomplished hypocrites; on pure vanity or silliness he spends very few of his shafts.”

[27]

Taine[45] would find both easy to account for, on racial grounds:

“The first-fruits of English society is hypocrisy. It ripens here under the double breath of religion and morality; we know their popularity and sway across the channel. * * * This vice is therefore English. Mr. Pecksniff is not found in France. * * * Since Voltaire, Tartuffe is impossible.”

Landor[46] has Lucian say:

“I have ridiculed the puppets of all features, all colours, all sizes, by which an impudent and audacious set of impostors have been gaining an easy livelihood these two thousand years. * * *

“The falsehood that the tongue commits is slight in comparison with what is conceived by the heart, and executed by the whole man, throughout life.”

Meredith’s portrait of The Comic Spirit is applicable to satire, for throughout the essay he gives to the term comic the connotation generally allowed to the term satiric:

“Men’s future upon earth does not attract it; their honesty and shapeliness in the present does; and whenever they wax out of proportion, overblown, affected, pretentious, bombastical,[28] hypocritical, pedantic, fantastically delicate; whenever it sees them self-deceived or hoodwinked, given to run riot in idolatries, drifting into vanities, congregating in absurdities, planning short-sightedly, plotting dementedly; whenever they are at variance with their professions, * * * whenever they offend sound reason, fair justice; are false in humility or mined with conceit, * * * they are detected and ridiculed.”

Meredith[47] also reiterates the distinction made by Swift and Fielding in regard to misfortune:

“Poverty, says the satirist, has nothing harder in itself than that it makes men ridiculous. But poverty is never ridiculous to Comic perception until it attempts to make its rags conceal its bareness in a forlorn attempt at decency, or foolishly to rival ostentation.”

And he remarks of Molière:

“He strips Folly to the skin, displays the imposture of the creature, and is content to offer her better clothing.”

Of the two forms of affectation, Fielding chooses hypocrisy as better satirical game, but Bergson[48] votes for the other:

“In this respect it might be said that the specific remedy for vanity is laughter, and that the one failing that is essentially laughable is vanity.”

Fuess[49] makes for the last great poetic satirist the familiar conventional claim:

“Byron is attacking not virtue, but false sentiment, false idealism, and false faith. His satiric spirit is engaged in * * * tearing down what is sham and pretence and fraud.”

[29]

Previté-Orton[50] applies the test to politics:

“Finally, there is another service political satires render, which is peculiarly necessary to a government based on discussion. One of the greatest evils in such a state is the presence of mere words and phrases, and of the vague Pecksniffian virtues. Now to satire cant and humbug are proper game. It brings fine professions down to fact, points the contrast between the commonplace reality and its tinsel dress, and by the dread of ridicule raises the standard of plain-dealing. Other means of criticism as well act as a check on more opprobrious faults in public life. But satire is the best agent to keep us free from taking words for substance.”

Apparently, then, we may conclude that deception in some form is, so far as any one thing can be, the basic object of satire, or at least is so considered by those who reflect upon it. But we must admit here as elsewhere that to recognise a phenomenon is easier than to account for it.

Not that it is difficult to account for the deception itself. No instinct is more fundamental and irresistible than that of concealment. The primary fear of molestation or harm in which it originates becomes, in a social state of sophistication and artifice, fear of exposure. With increased development, such complex and opposing factors as pride and shame, avarice and generosity, ostentation and modesty, lead us to hide things. We hide all sorts of things, good and bad; faults, virtues, deficiencies, accomplishments, hoardings, and charities. We hide from ourselves as well as from others. The left hand is as a rule not on terms of confiding intimacy with the right, whether[30] it is scattering seeds of kindness or getting into mischief. In the mental realm the same trick of camouflage prevails. Out of spiritual cowardice we conceal from ourselves the disturbing facts of life, and purchase optimism at the easy price of sentimentalism.

But just why this ubiquitous habit should be the peculiar province of the satirist, is another psychological problem; and as such, is best reached through a psychological solution. Why is there about deception something inherently repugnant and at the same time automatically amusing? Why is our incorrigible human predilection for belonging to the Great Order of Shams equalled only by our incorrigible human predilection for joyous exposure of others? The game seems to be mutual and perpetual, and the honors about even.

The repugnance undoubtedly comes less from a noble devotion to truth than from the dislike we all have of being deceived. Nothing do we discover with more exasperation, and admit with more reluctance than the fact that we have been fooled or hoodwinked. It is an experience that fosters present irritation and future distrust; but one which, from its very nature, demands the retort ironic rather than the lofty indignation accorded to an open injury. Most emphatically “We all hate fustian and affectation,” and any knavish trickery, especially in others.

The amusement arises from the triumph of frustrating this attempt at deceptive concealment, intensified by the pleasure in perceiving an incongruity—in this case, between the assumed and the actual—which is the essence of humor.[51] The zest lies in the endless sport of hide and[31] seek, veiling and unveiling, blowing bubbles and pricking them, which is exhilarating through the play of wits and the fun of outwitting.[52]

This would perhaps be a sufficient account were it not for a certain left-handed yet inseparable connection of the psychology of the question with its ethics. Whether or not an intruder, the latter has entered in and firmly entrenched herself. When therefore she maintains that her satiric discontent is divine, she must be given a respectful hearing; though after it we seem unable to concede more than the possibility.

A lively enthusiasm for showing up the ingenuous sentimentalist or the crafty hypocrite may or may not argue a freedom on the exposer’s part from these or other modes of hiding or distorting the truth; or a disinterested love for truth itself. It does go without saying that real respect and admiration for honesty and sincerity is a fundamental human trait, as witness the glowing encomiums bestowed on those guileless virtues, and it might follow that our unmoral impulses are half consciously focussed through a moral function. We must have a sin offering; and deceit is in the most eligible. Thus the satirist may, deliberately or unthinkingly, read deception into his disapproved, in order to have an excuse for laughter, just as he may read vice and folly into his disliked, in order to condemn. Nevertheless it is possible to enjoy the process of unmasking without making it a corollary that masking is wrong and therefore deserving of exposure.

Some observers are more impressed with the resemblances[32] among the members of the great human family, and some more sensitive to the differences. When a consciousness of this variance is dissolved in a humorous solution, it precipitates a satire. The satirist is not always a victorious Saint George, and the satirized a downed and disgraced Dragon. Still, if the Saint could be secularized to the extent of a mocking light in his eye, and a taunting finger pointing at a removed disguise under which the Dragon had been masquerading, we might take the picture as a symbol of an ideal relationship between them, both ethically and artistically.

For there is an ideal in this as in all things that have variation and flexibility; and, as in them all, the question of quality is the most important one. Without some sort of criterion we can form no judgments as to value. The points we have been considering,—what satire is made of, why and how made, against what directed, and in what effective, all lead to the final one,—what is the highest type?

The trend of testimony seems to converge on three requirements for that satire which would disarm criticism while indulging in it: purity of purpose, kindliness of temper, and discrimination as to objects of ridicule.

The first is not to be confused with the reformatory motive. It means simply freedom from the very affectation censured in others. What it rules out is not so much the railing to gratify one’s spleen, as the pose of altruism while doing it; the grieved this-hurts-me-more-than-it-does-you attitude so particularly annoying to the castigated. It also discounts the selfish vanity which courts applause for wit, regardless of the means by which it is won.

On this point Horace[53] again heads the list. He denies[33] the accusation that the satirist is spiteful, and continues:

From the nature of English satire up to the eighteenth century, we do not expect, nor do we find, much interest in this phase of it. Then comes Young,[54] reviving the Horatian caution:

And Cowper[55] completes the portrait:

De Quincey[56] uses Pope as a horrible example of this failing, contrasting him with the indignant Juvenal:

“Pope, having no such internal principle of wrath boiling in his breast, * * * was unavoidably a hypocrite of the first magnitude when he affected (or sometimes really conceited himself) to be in a dreadful passion with offenders as a body. It provokes fits of laughter * * * to watch him in the process of brewing the storm that spontaneously will not come; whistling, like a mariner, for a wind to fill his satiric[34] sails; and pumping up into his face hideous grimaces in order to appear convulsed with histrionic rage. * * * As it is, the short puffs of anger, the uneasy snorts of fury in Pope’s satires, give one painfully the feeling of a locomotive-engine with unsound lungs.”

Whether these strictures are just or not, the principle back of them is sound; and more pithily summed up by Landor’s[57] “Nobody but an honest man has a right to scoff at anything.”

Browning[58] carries the idea a step farther, and sounds a warning to dwellers in glass houses:

The demand for kindliness of temper may seem paradoxical, but for that very reason it is the more insistent. Being under suspicion of unkindness, vindictive spite, retaliation, satire must either admit the charge or prove the contrary, for the real paradox lies in the highest moral claim being made for the literary genre of the greatest immoral possibilities.

However, until the modern humanitarian cult came in, it seemed content to admit the charge. After Horace, with a few isolated exceptions, as Swift[59] and Cowper,[60][35] satire seemed rather to cherish malice and glory in rudeness, often mistaking peevish scolding for noble scorn. Its keynote was “A flash of that satiric rage,” or, according to Hall,

Byron was the last example of both the professional, concentrated form and the truculent mood. Tennyson[61] voices the new spirit of his century:

Birrell,[62] less caustic than De Quincey about Pope, still uses him as an instance of how not to do it:

“Dr. Johnson is more to my mind as a sheer satirist than Pope, for in satire character tells more than in any other form of verse. We want a personality behind—a strong, gloomy, brooding personality; soured and savage, if you will * * * but spiteful never.”

Even the traits of gloom and savagery might be dispensed with, and room made for an infusion of sweetness and light. This is implied in the condition laid down by Lionel Johnson:[63]

“To tilt at superstition, to shoot at folly, is seldom a grateful or a gratifying pursuit, if there be no depth of purpose in it, nothing but pleasure in the consciousness of destructive power, no feeling of sympathetic pity, no tenderness somewhere in the heart, no cordiality sweetening the work of overthrow.”

[36]

And Garnett[64] concludes:

“Satirists have met with much ignorant and invidious depreciation, as though a talent for ridicule was necessarily the index of an unkindly nature. The truth is just the reverse.”

Discrimination as to objects of satire has reference not to their nature, as foolish, vicious, deceitful, but to their legitimacy as objects. It is a matter of taste and justice on the part of the satirist.

The first definite reproof of heedlessness on this score is given in the memorial tribute to Pope:[65]

Another critic[66] of that time utters a similar caution:

[37]

“A satire should expose nothing but what is corrigible, and make a due discrimination between those who are, and those who are not the proper objects of it.”

The best modern expression[67] of this idea happens to be an interpretation of a pioneer satirist. And it is distinctly modern in its recognition that while the real object of satire must be an abstraction,—the sin not the sinner—it must, to be artistic, have a concrete embodiment,—the sinner rather than the sin. The Greek dramatist explains:

But while the good satirist must have these assets, it does not follow that the possession of them will guarantee good satire. It can only be said that without them he cannot be ranked high, though, having them, he may not be ranked at all. It may be difficult for a Juvenal not to write satire, but it is difficult for anyone to produce a fine example of this, as of any other form of art. No more than any art is it exempt from a recognition of truth[68] and [38]even beauty, though its connection with them is the paradoxical one of drawing attention to their opposites. It is a truism that many things are best understood and appreciated by a portrayal of contrasts. In this case it is a perception of the congruous that is particularly concerned, and it is implied in the satirist’s keen sense of the incongruous.

The satirist has not only these normal obligations, but some peculiar dangers. He is in as perilous a position as Sir Guyon in his voyage to the realm of Acrasia: threatened by the didacticism that besets the critic, the vulgarity and rudeness that prey upon the jester, the prejudice and injustice that warp the opponent, the smugness that undermines the reformer. Moreover, he has his hampering limitations. He is forever confined to the middle plane of life, shut out alike from its sublime heights and tragic depths.

Added to this restriction in range is another in quantity. The nature of satire makes it better adapted for the trimming than the whole cloth. Its rôle in the dramatis personæ of literature is restricted to the minor parts, but this subordination in place does not mean a negligible rank. The untrimmed garment, the all-star cast, these are not desirable even when possible. For the accessory there is also an ideal whose attainment is quite as important as though it pertained to the main substance.[39] In the case of satire such a standard would call for censure that is candid and just, wit that is spontaneous and refined, both actuated by sincere motives, and directed against certain failings of humanity rather than against the human individuals themselves, though these must body forth the abstractions otherwise intangible,—the combination producing an effect essentially truthful and artistic. That all this can come only from one who is more than a mere satirist is axiomatic, and indeed so fundamentally true that it might be said that the more of a satirist a man is in quantity, the less is his chance for fine quality.

The modern author has conquered these requirements and obstacles, not by taking arms against his sea of troubles, but by the less intrepid and more diplomatic method of disowning his title. The satirist is obsolete, but the satiric writer, or even better, the writer with a satiric touch, is more in evidence than ever. It is perhaps too much of a challenge to say that Shakespeare is a greater satirist than Aristophanes, Jonson, or Molière; but no one would deny the superior quality of his smaller amount. The aroma of his delicate spice and lemon extract has not only lasted longer than their pepper and vinegar, but is better relished by the modern palate. The nineteenth century had no Shakespeare to “stoop from the height of a serene intelligence to sport with satire,” but its best satire came from those who took it least seriously and insinuated it with least pomp and circumstance. And so far from being the most conspicuous in the satiric field, these who are greatest in this matter are also greatest and best known for other than satiric gifts and accomplishments.

While these humorous critics would be more content[40] than their forerunners with the early dictum that satire was “invented for the purging of our minds,”[69] rather than for the practical consequences sometimes claimed for it, yet they would not adopt the succeeding phrase of the definition,—“in which human vices, ignorance and errors, * * * are severely reprehended;” for they would qualify more carefully the objects, and abstain from severity in their reprehension.

This dividing line among objects would make, however, a scientific rather than an ethical bisection. The “stolidly conscientious performance” of confining the practice of satire to a moral issue, does indeed, as Dr. Alden points out,[70] argue a “deficiency in wit” that marks the Anglo-Saxon mind. But as the Englishman became more cosmopolitan, he learned to disguise such of his innate solemnity as he could not shed. That he has absorbed more completely the more easily assimilated Hebrew and Roman traits, has not prevented him from acquiring some also from the Greek and the French. The Victorian is naturally a multiplex compound, and in him we see all these elements in various stages of conflict and combination.

[41]

Our present study is concerned with the union of two ancient streams of literature as they come together on the fertile plain of the nineteenth century. This marriage of a satiric Medway and a fictional Thames is a happy English event, though by no means the first alliance between these historic families. In their long careers they are found sometimes entirely separate, but very often united. The latter course works for a decided mutual advantage, with a preponderance of gain accruing to satire, as fiction can live without satire far better than satire without fiction.

A narrative of entire gravity may be a gracious and splendid thing; indeed, pure tragedy is perhaps the highest form of art. But when satire is divorced from fiction it must dispense with fiction’s great contribution, the garment of warm imagination and colorful concreteness; and be content with the severe raiment of bald didacticism and chill abstraction. In truth, satire has always been not only the greater beneficiary but the more dependent partner, though what it has in turn supplied is of unquestionable value. It is like an entertaining but unequipaged traveler, always asking for a ride. Even when it apparently had an establishment of its own and was recognized as a literary genre, it was not independent with the independence of the lyric, the drama, or the treatise, but was constantly borrowing furniture from them all.

[42]

Hence when satire invaded Victorian fiction,—or was adopted by it,—the conjunction brought its benefits to both. The former profited qualitatively from the antidote furnished by creative construction to destructive censure, and quantitatively by the improvement resulting from diminution,—that subordination which is the secret of success with all seasoning, trimming, and such accessories. The latter gained, not so much by the mere infusion of pleasantry, for that refreshing element has a deplorable tendency to degenerate into ill bred pertness, as by the toning up of the criticism inseparable from the realistic novel, and by the pungent and dramatic turn given to its didacticism. “Som mirthe or som doctryne” has ever been the demand of the Englishman, and he has relished them best in that happy unison supplied by satire.

Hence also the combination was but a new and more consequential celebration of an old, traditional connection. From the Greek Menippean mixture and the Milesian tale the line extends, with innumerable ramifications into fabliaux, burlesques, allegories, letters, and characters, in prose and verse, to the perfected eighteenth-century product, whence the increasingly perfected product of the nineteenth century immediately is derived.

Like all such associations, this one is neither accidental on the one hand nor consciously intentional on the other, but is the result of many forces and influences set in operation by circumstances, and available for great effectiveness if rightly comprehended and wisely used. In this Victorian situation we are confronted with the dual factors: a literary form raised to tremendous prestige by a rich inheritance and an especial rapprochement with its own times; and a prevailing temper of humorous criticism[43] which could not fail to thrive under the double stimulus of a fermenting environment about which there were endless things to be said, and a general liberation from external control which allowed these seething utterances free and full play of expression.

Thus have all things worked together for the good of the Victorian novel. It was fortunate alike in its endowment, its alliances, and its surroundings. A period of such upheaval, such introspection, such anxious responsibility, and withal such zest of life, all diffused through a democratic atmosphere, could best be interpreted by a form of literature which, besides being in itself thoroughly democratic, gives large scope for the author’s comments and conclusions.

The drama is an excellent reflector, but necessarily impersonal; a dilemma that is dodged rather than solved by the Shavian device of Prefaces. The lyric, on the contrary, is too personal to be representative. And concentrated exposition is admittedly strong meat for the intellectual babes who constitute the vast majority, or even, as a steady diet, for children of a larger growth. This does not mean, of course, that the novel is a childish product or plaything; but that its union of the dramatic and didactic, the emotional and rational, the picturesque and significant, the merry and sad, together with its absolutely unrestricted range in material, makes it ideal as a popular type in the best sense of the word.

A critic of the time half ironically remarks,—[71]

“The future historians of literature * * * will no doubt analyze the spirit of the age and explain how the novelists, more or less unconsciously, reflected the dominant ideas which were[44] agitating the social organism. * * * The novelists were occupied in constructing a most elaborate panorama of the manners and customs of their own times with a minuteness and psychological analysis not known to their predecessors. Their work is, of course, an implicit criticism of life.”

With all the encouragement bestowed upon them the Victorian novelists could indeed do no less than live up to their opportunities. Not ad astra per aspera lay their destiny. Nothing more was asked of them than to refrain from burying their talents, and to this admonition they were zealously obedient.

The writers themselves supply striking inductive data as to the general diffusion both of fiction and satire. A list of the dozen most prominent Victorian novelists shows that no one of them was wholly devoid of interest in public affairs, and none was entirely lacking in the satiric touch. On the other hand, every one of them saw more on his horizon than current events, and all were something more than mere critics or humorists or even both.

They were themselves of the Victorian Age. Each one might say Pars fui, if not magna. None therefore had a detached point of view, nor a long perspective. But though their vision was microscopic rather than telescopic, it was searching and enthusiastic, and the report it made was honest if not always dispassionate. It could hardly be otherwise for those who were alive and awake at a time when new information was creating new ideas, and these in turn were becoming dynamic in new movements, political, religious, educational, social. All these things were too tremendous and important to be taken otherwise than seriously. The dominant feeling was grave and earnest, as one of its interpreters has said:[72]

[45]

“In the Victorian era, which we have found so neglectful of literary standards, Literature has been of greater social and ethical stimulus than ever before. * * * It throbs with a new sympathy for those who toil unceasingly in poverty, and a new bewilderment upon the realization that the world which is changing so rapidly is still so full of misery and hopelessness. * * * But, as the world went, the main impulse and the main characteristic of Victorian Literature became this great sense of pity for things as they are and of an imperious duty to make them better.”

But the sense of pity was sometimes voiced with wit, and one of the sharpest weapons at the service of duty was the shaft of ridicule. With nothing to satirize, society would be a paradise. With no satirists, it would be rather a dull inferno. But it is our human world that is purgatorial.

Since the purpose of our present study is to discover the proportion and nature of the satiric element in Victorian fiction, to note its relation to the rest of the work, and to reach some conclusion as to the total effect of its presence and use, it might aid in clearness to subjoin a table of names and dates of the novelists with whom we are concerned.

| Name | Birth | Period of Publication[73] | Death |

| Peacock | 1785 | 1816–1861 | 1866 |

| Lytton | 1803 | 1827–1873 | 1873 |

| Disraeli | 1804 | 1826–1880 | 1881 |

| Gaskell | 1810 | 1848–1865 | 1865[46] |

| Thackeray | 1811 | 1844–1862 | 1863 |

| Dickens | 1812 | 1837–1870 | 1870 |

| Reade | 1814 | 1853–1884 | 1884 |

| Trollope | 1815 | 1855–1880 | 1882 |

| Brontë | 1816 | 1847–1853 | 1855 |

| Kingsley | 1819 | 1848–1871 | 1875 |

| Eliot | 1819 | 1859–1876 | 1880 |

| Meredith | 1828 | 1859–1895 | 1909 |

| Butler | 1835 | 1872–1901 | 1902 |

This list, reaching from Scott to Hardy, not inclusive, has been reckoned as a round dozen, but it actually numbers a baker’s dozen.[74] The noteworthy thing about it is that it would probably be agreed upon as the preëminent list on any count; so that those who are excluded on the score of being too consistently serious or romantic, as Yonge, Collins, Blackmore, Henry Kingsley, MacDonald, would hardly be included on the score of quality, although some of them might rival some of the least among those chosen as members of the satirico-realistic group.

A glance at the preceding table reveals an obvious chronological division into five parts; although the first and the two last consist of one man each. The second contains only two names; and their separation from the main group occurs at the beginning rather than at the end, for Lytton’s race ran beyond five of those who started[47] later, and Disraeli’s beyond seven. Of those, only Reade published novels after 1880.

This main group is one of those remarkable concentrations in which destiny seems to delight. When the second decade of the century gave to the world eight great names in this field alone, and some equally distinguished ones in others, it surely filled its quota toward the advance of civilization.

Meredith comes enough later than this outpouring of God’s plenty to be classed by himself chronologically, especially as he must be by the character of his work also, in spite of the fact that his first novel belongs to the same prolific year as the first of George Eliot’s.

The middle of the century is thus also the center of a circle of activity whose radius extends for about two decades on either side, passing thence into thinner aired intermediate zones,—transition periods from the eighteenth and to the twentieth centuries, seasons whose energies are potential, or spent, rather than vigorously kinetic.

But this central period, something more than a generation, and less than a half century, is dynamic enough. It has frequently been described, and its activities—Chartism, the Oxford Movement, Utilitarianism, Positivism, the Industrial Revolution, Christian Socialism, Darwinism, Pre-Raphaeliteism—are an oft-told tale. It is only to be remembered that this was the atmosphere breathed by the majority of our novelists, and these the vital interests which would concern them in so far as they were concerned with the public affairs of their time.

A review of the satiric strain in literature gives an interesting clew both to the fact and the significance of the relation of satire to the total literary product.

[48]

Nor can one be estimated independently of the other. There is, of course, no such thing as a pure, or mere, satirist. Even a saturated solution involves two elements. The dissolved substance must have a medium to be dissolved in. Starting from this point, we may classify the most conspicuous names according to this relationship.

There are first the completely surcharged. But the important matter is whether the container is itself large,—Aristophanes, Juvenal, Swift, Voltaire,—or of smaller mold and less capacity,—Dunbar, Skelton, Smollett, Churchill, Gifford. To this class come no recruits from the nineteenth century. Sæva indignatio, no longer makes verses, even when witticized, having been put out of fashion by the autonomic humor which informs the sophisticated critic that of all incongruous things the most incongruous and absurd is the satirist who takes himself seriously.

Next come those whose absolute amount of satire may be equal to that of the preceding, but whose versatile interests make it relatively smaller. It is neither of their life a thing apart, nor yet their whole existence. Such are Horace, Cervantes, Jonson, Dryden, Boileau, Pope, Fielding, Burns, Byron. This class on a smaller scale is represented by Gascoigne, Wyatt, Hall, Donne, Lodge, Addison, Goldsmith, Hood, Moore, Mark Twain. Among these we find about half of our novelists,—Peacock and Butler, Dickens and Trollope, Thackeray and Meredith.

In the third division satire is measured still more by the law of diminishing returns. It is composed of those who are never thought of as satirists, not even as satirical, and yet are very far from being innocent. Such are the Hebrew Prophets and the author of Job, Euripides, Spenser,[49] Shakespeare, Milton (in his prose), Johnson, Scott, Shelley, Browning. Similar but of lesser magnitude are Erasmus, More, Defoe, Young, Cowper, Blake, De Quincey. Here are found the other half of the novelists,—Lytton, Disraeli, Gaskell, Reade, Brontë, Kingsley. The impression given by these is not so much a solution at all as of separate and distinguishable particles: of elements native and yet not integral,—like fish in water. They might be taken away, and though the total effect would be very much changed, the real character of the liquid would not.

Quite the opposite of this is the condition of the fourth estate. Here the process of amalgamation is carried to an extreme, one might say, paradoxically, to the vanishing point. It resembles the first class in that the satire is pervasive, and the third in that it is of relatively small quantity; so small that it hardly seems worth taking into account, yet it could not be abstracted. If it could, it would leave a scarcely diminished but almost unrecognizable remainder. It is not revealed so much as betrayed. It seldom indulges in anything so bald as overt satire, or so conscious even as covert innuendo. It is the tone of a personality. It is not Aristotle nor Virgil nor Wyclif nor Wordsworth nor Tennyson. It is Homer, Plato, Lucretius, Dante, Langland, Burton, Gibbon, Sterne, Austen, Arnold, Carlyle, Hardy, Anatole France. Among the Victorian novelists it is George Eliot.

To this matter of quantity there is a fairly definite relation of quality. The fact that the largest quantity is now a discarded type indicates that relation to be one of inverse proportion. The second and third divisions evince hilarity, sarcasm, shoddy flippancy, or profound wit, according to the temperaments of the writers.[50] Therein lies the greatest variety. The fourth occupies the great field of irony. It is the siccum lumen, occasionally flashing, usually lambent, smouldering, gravely glowing.

Amid these differences in kind and degree, the Victorian novelists had a sort of unity in possessing a certain sense of satire, more or less consciously realized, and of themselves as satirists. This is not only discernible in the general air they have of intending to do it, but is made visible by remarks in the nature of Confessions of a Satirist voiced by about half their number.

“Let those who cannot nicely and with certainty discern,” says Charlotte Brontë in Shirley, “the difference between the tones of hypocrisy and those of sincerity, never presume to laugh at all, lest they have the miserable misfortune to laugh in the wrong place, and commit impiety when they think they are achieving wit.”

Thackeray,[75] the “cynic”, is the one to reiterate most strongly the Pauline creed that love of mankind is the root of all good. He remarks that humor means more than laughter, and adds: