The Project Gutenberg eBook of Stroke of Genius, by Randall Garrett

Title: Stroke of Genius

Author: Randall Garrett

Release Date: March 8, 2022 [eBook #67587]

Language: English

Produced by: Greg Weeks, Mary Meehan and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Illustrated by PHILLIPS

Crayley plotted a murder that was

scientific in both motive and method—and

as perfect as the mask of his face!

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Infinity Science Fiction, August 1956.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

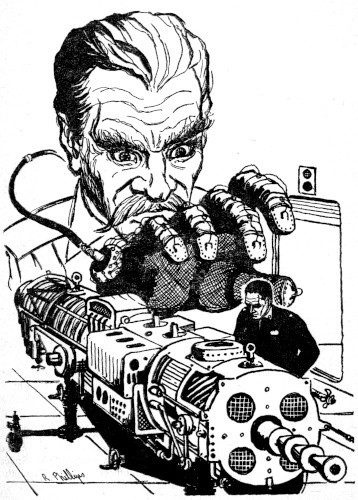

Crayley stood thoughtfully before the huge screen and watched the fingers move.

Metal fingers, five on each hand; each hand attached to an arm, and each pair of arms connected to a silvery sphere that sat atop a four-foot pillar. Within the pillar, micro-relays ticked and chuckled, sending delicately measured surges of power here and there through silver nerves to metal muscles. Responding, the hands built an energy generator. And when they finished, they built another. And another. On and on, monotonously.

Crayley rubbed absently at his mustache and plotted murder.

"—be a great deal cheaper, Mr. Crayley?"

Crayley realized he hadn't been listening to what the man beside him was saying. He turned his head to look at the Space Force officer and said quietly, "I'm sorry, major; I didn't quite get you."

"I said that it seems to me that ordinary production machinery would be a great deal cheaper. Why do they use those waldoes?"

Crayley smiled faintly. "Why do you use waldoes to repair a generator on a ship?"

The major looked at Crayley to see if he was kidding, then said, "A man can't live five seconds near an unshielded generator, and you have to take the shielding off to get at the innards. But I don't see how that applies. Each repair job is different. I'll admit that I'm not a drive engineer—I wouldn't know the first thing about repairing one—but I do know that the engineer has to use remote control hands because the work is so delicate.

"But this—" He waved a hand at the screen. "—is recorded. It's routine. Why spend all the money on those tape-controlled robots when much simpler machines can be made to do the job?"

I wonder, Crayley thought to himself, if this blockhead knows which end of his ship to point up when he's taking off? "Two reasons, Major. In the first place, building a sub-nucleonic converter is also a delicate job—as delicate as repairing it. In the second place, we have something here that will save money in the long run. Do you know what re-tooling would cost in this business if we used ordinary bit-by-bit production line methods?"

The major spread his hands. "I have no idea."

"Millions. Every day, some physicist comes up with a new idea on sub-nucleonics. Within a week or so, enough of these ideas have snowballed to produce a slight modification that will improve a spacedrive—increase its speed, improve its efficiency, and so on. Within six or eight months, enough improvements have built up to make it worthwhile to incorporate them into the drive we're building. If North American used production line robots, we'd have to rip out the whole bunch and rebuild 'em to make the new generator. Why? Because the ordinary robotic device is a specialist; it can, at most, do two or three things—usually only one. And if you eliminate the thing that a particular robot does, or change it a little, you have to rebuild the tools and re-arrange them before reprogramming the whole line.

"The waldo, a working replica of the human arm and hand, isn't specialized like that; it's adaptable; it can do anything. If we have to modify the design, all we have to do is reprogram the tapes, which is a comparatively easy job.

"And besides, if anything goes wrong down there, we can put the hands on manual and go trouble-shooting, something we couldn't do with production line stuff."

"I see," the major said, nodding. "Ingenious." He glanced at his wrist. "Do you suppose Mr. Klythe is through yet?"

The smile that touched Crayley's mind did not reach his face. "I think he's just about through." His voice was completely innocent of any subtle innuendoes.

He glanced again at the screen that pictured the hundreds of hands moving automatically through their intricate motions in the production tunnel deep underground, then touched a switch. As the screen faded to blankness, he turned and led the way down the corridor to Klythe's office.

Crayley paced his steps neatly so that he would stay just a foot in the lead. A foot, no more. Too much would be obvious. A foot was quite enough to show who was leading.

His lean face was, as always, set in a placid mask. A thousand years before, Lewis Crayley might have worn a helmet of steel to hide his thoughts. Two hundred years before, he might have worn eyeglasses. Now, since there was no excuse to wear either, Crayley could only hide behind his own face.

It was a face well constructed for the purpose. The nose was large and prominent—plenty of room to hide behind a nose like that. The brows were craggy and shaggy, overshadowing the half-closed eyes beneath them. The heavy mustache, which he wore in spite of the fact that it was looked upon as an anachronism, effectively concealed any expression the thin, firm mouth might show.

His hands, too, were useful. Their quick, nervous movements distracted attention from the face when they were away from it, and effectively concealed it when they were nervously rubbing his nose or stroking his mustache.

Using only God-given materials, Lewis Crayley had built a magnificently efficient wall between himself and the world. He could see out, but no one could see in.

Not that Crayley thought of it that way. Crayley was just calm, that was all. He had control over his emotions; he didn't let them run away with him. Poise and impartial objectivity were his. He allowed nothing to bother him, and no one to thwart him.

Berin Klythe was attempting to do just that. There was, Crayley admitted, nothing malicious about it. Klythe was not trying to suppress Crayley; there was just nothing else he could do. There is nothing malicious about an asteroid, either, but when one lies directly athwart the orbit of a spaceship, either the ship must veer aside or the asteroid blasted out of the way. And Crayley was not the type to change his orbit.

There was no malice or hatred on Crayley's part, either. One does not hate an asteroid.

He pushed open the door to Klythe's outer office and allowed the Space Force major to follow him in. The girl behind the desk was sliding her fingers expertly over the sparkling panel of a photowriter, and her pace didn't change as she looked up.

"Yes, Mr. Crayley?"

"Is Mr. Klythe through yet?"

Her hand touched another panel. "Mr. Crayley is here with the gentleman from the Space Force." She listened for a moment to a sonobeam the men couldn't hear, then she nodded. "Go right in."

Berin Klythe was coming out from behind his desk when they stepped into the inner office. His smile was broad and his hand outstretched. Crayley snapped his voice into action.

"Berin, this is Major Stratford. Major—Mr. Klythe, our Director."

Klythe was pumping the major's hand. "Sorry to have kept you waiting, Major. Just one of those things that has to be cleared up to keep things moving."

"Perfectly all right. I was a little bit early, and Mr. Crayley was good enough to show me around."

Crayley rubbed his mustache and waited for the greetings to get themselves over with. The major was trying to act nonchalant, but it was easy to see that he was somewhat in awe of Klythe. Klythe had taken the Big Gamble and won, and not very many people had done that. In the first place, the government only picked a few of the very best men to go through Rejuvenation. Men who were necessary, brilliant, useful. Men like Berin Klythe, who was important and a genius.

That was a point that Crayley admitted. Klythe was a genius. And, very likely, a more capable one than Crayley. But Crayley, too, was a genius in his own way, and he didn't feel that mere brilliancy should allow Klythe to block his path.

Three years ago, Berin Klythe had been a graying, stocky, aging man of sixty. Now he was lithe, dark of hair, clear of eye, and full of the energy of a twenty-five year old body.

He'd be good for another century. And Lewis Crayley wouldn't.

"Sit down, Major," Berin was saying. "Commander Edder told me you'd be around, but he only hinted at the trouble."

"Is this room sealed, Mr. Klythe?" the major asked calmly.

Klythe reached across his desk and touched a panel. "It is now."

The major nodded. "We don't want any of this to leak out; it might cause panic." He paused for a moment. "You're a Sirian by birth, aren't you, Mr. Klythe?"

Klythe nodded. "My grandparents were among the first colonists on New Brooklyn."

"Then you probably know first hand how tough it is to tame an extra-solar planet, no matter how closely it approaches Earth-type."

Klythe nodded, narrowing his eyes.

"So when a colony disappears, we don't think anything of it—" Stratford stopped, frowning. "No, I don't mean that. What I mean is, we usually attribute it to another loss in our fight against the natural forces of the planet. The colony's gone; you blame disease, the flora, the fauna, the storms, everything else. Then you try to re-establish the colony.

"But lately things have been happening in a certain sector. I'm not at liberty to say where, nor what happened. Whole colonies were gone when the five-year check came. The pattern was only in one area, but we're pretty sure of what's happening. Something out there, something intelligent in its own way, is erasing those colonies. Our analysts suspect that whoever or whatever is doing it doesn't know we're intelligent. What it boils down to is this: we have an interstellar war on our hands."

Klythe nodded slowly after a moment. "I get it. That's why you asked for this funny modification of the drive generator—the new J-233. It isn't supposed to be a drive generator at all."

"That's right," said Major Stratford, "it's a weapon."

"Why tell us now?" Crayley asked softly. "I mean, you've ordered the thing; we've practically got it ready. Why not leave us in the dark?"

"We don't want you to build it now. We've got a better one—much better. But it calls for a gadget that you'd immediately know was not a driver. We decided to tell you rather than have you asking embarrassing questions.

"And we have neither the facilities nor the capacity to build it ourselves."

Crayley said slowly, "You mean the J-233 is obsolete? We scrap it without ever putting it in production?"

"That's right," said the major. He grinned. "You were just telling me how adaptable your production machinery is to—ah—re-tooling, I think you called it. I was glad to hear it."

Damn! Crayley thought. Damdamdamdamdamn!

His mind whirled for a moment, hopping frantically from one point to another. Then he forced it to be calm. Everything wasn't lost—just delayed.

"—in the strictest confidence," the major was saying. "Nothing must leak out. We don't want to throw a scare into the world population just now."

Klythe looked as though he had a good case of goosebumps himself.

Crayley felt nothing. He said, "How soon can you get the original down here?"

The major spread his hands. "I'm not prepared to say. You'll have to take that up with our technicians. Out of my field, you understand.

"I am also to ask you how soon you can get this into production. We'll need five thousand units."

Klythe looked thoughtful. "It'll depend on the breakdown, of course; these things take time. Five thousand units. Hmmmm. Assuming increasing complexity—figure twice the time for a regular model and extra time for analysis—mmmm." He appeared to be figuring deeply.

Five days, thought Crayley contemptuously.

"It'll take all of a week to set up for it," Klythe said. "If we get three tunnels running, you can have your five thousand units in—say twelve weeks."

"Fine," said Stratford. "I am also informed that our own technicians will be on hand for the recording. I have no idea what that may mean, but—"

"I see. Very well, tell them we'll expect them to be here with the original!" Klythe said sharply.

The major raised his eyebrows at Klythe's voice. "Is there something wrong, Mr. Klythe?"

"There is," Klythe said blandly. "But I'm not blaming you, of course. A question of the specialty."

"I see," said the major. One did not question another's work too closely. Get nosy with other people, and they get nosy with you.

"It's rather as though I hired you to take a cargo to Sirius for me and then insisted that you use my crew instead of your own," Klythe explained. "Perhaps the parallel isn't too good—I know nothing of interstellar commerce—but that may get the idea across."

"I sympathize," said Stratford. "If there's anything I can do—?"

"Nothing," said Klythe, smiling. "It isn't fatal. Now—" He rubbed his hands briskly. "Unless there's further business, perhaps you'd like a little something? I know I do; I have a cold kink in my guts."

The major grinned. "Liaison officers are permitted to drink on duty. Pour away."

Klythe poured. As he studiously watched the stream of liquor flow into one of the cups, he said: "Major, may I ask—ah—just how much danger there is to Earth?"

The major appeared to consider this for a moment before answering. "At the moment, none. We know that they can not trace us back here, and they're quite a long distance away. Without violation of confidence, I can say that the distance is several thousand light years."

"Thank you." Klythe passed the cups around.

Crayley eyed the major suspiciously. He had answered the question too readily. Was he lying? No. What, then? The major ran the tip of his tongue over his lips, and Crayley understood. He was going to trade information for information.

Stratford swirled his drink around in his cup and looked at the whirlpool it made. "Mr. Klythe, may I ask you a—a question?" It was properly worded, hesitation and all.

"I shall not be offended by your question," Klythe replied with the standard friendly acceptance of the gambit, "If you will not be offended by my reply."

The major whirled his cup once more, then downed its contents quickly. "I—uh—understand you took the Big Gamble." He paused to see how his opening would be accepted.

Klythe nodded. "I was honored to be chosen; how could I refuse?"

Crayley was enjoying the scene immensely. Both of the men were distinctly uncomfortable.

"I'm afraid I would have been—uh, well—afraid."

"Perhaps I was," Klythe said softly. "But I don't know. That whole year of my life is gone. That's why they call it the Big Gamble, you know; you bet one year of your life against the chance that you'll get an additional century or two. I don't know whether I was frightened or not."

"I'm very happy for you," said the major, closing the subject.

Crayley held out his cup for another drink.

The Big Gamble had paid off for Berin Klythe. The year-long physical reconstruction had not resulted in his death, as it had for so many. But Klythe's gamble hadn't paid off for Lewis Crayley.

Klythe held the Directorship. Crayley was in line for the position. Klythe would never leave of his own accord. It came out as a simple equation in symbolic logic.

Before Klythe had been offered the chance for the Big Gamble, Crayley had been content to wait. At sixty, Klythe had been thirty years older than Crayley. Normally, he would have retired at seventy-five. He would have another forty years of life to go, but they would not be productive years. But if you survived the Big Gamble, you were in better health, both physically and mentally, than you had been at twenty-five. By the time Klythe was ready to retire, Crayley would be dead.

Therefore, Klythe had to go.

The three men finished their drinks; the major shook hands all around, and left quietly.

Klythe's eyes narrowed as he looked at the door through which the Space Force officer had departed. "Running in their own recording technicians on us, eh, Lew? Well, by God, we'll see about that! They'll be working under me; I'll make 'em jump!"

"Jump it is, Berin." Crayley's voice was quiet, but his blood was singing.

The Space Force Research Command team delivered the original two days later. It was obvious that the thing was not a drive generator. The sub-nucleonic converter had been elongated along the acceleration axis and reduced a bit in diameter. Evidently the Space Force wanted a high-velocity beam without much actual volume of energy.

The thing looked like an over-decorated length of sewer pipe instead of having the normal converter's barrel shape.

Crayley himself had accepted delivery of the original. He wanted to have a good look at it before Klythe did. He prowled around it, a handful of schematic prints in his hand, checking the symbols on the schematic against the reality of the converter before him.

For the first time in his life, he wished he knew the theory behind a converter. That wasn't his job, of course, but he had a hunch it would be useful knowledge.

He knew what a standard converter did, but he didn't know how. Therefore, he only knew approximately what this new modification would do.

The Space Force technicians stood off to one side, waiting respectfully for Crayley to finish his examination. Crayley could feel their eyes on him, and he knew full well that the respectful attitude was only superficial; a Space Force man has respect only for the officers above him.

When he was thoroughly satisfied that he could learn nothing more from a superficial examination of the machine, he turned to the technicians. "All right, let's go upstairs. Mr. Klythe wants to talk to you."

It was the incident in the hall of the executive offices that decided Lewis Crayley once and for all that he now had not only a motive but a method for murdering Berin Klythe.

As the recording technicians were filing into the briefing room, Berin stepped out of the lift tube and headed toward the door. Several other engineering executives of North American Sub-nucleonics followed him.

Klythe started to walk in through the door of the conference room, and one of the Space Force techs stepped on his toe. It wasn't painful, and it wasn't done on purpose; the tech was quite polite when he said, "Excuse me, sonny."

Klythe said nothing, but his eyes blazed with sudden anger, and his face grew crimson as he tried successfully to suppress it.

Behind his face, Crayley grinned gleefully. He rubbed his nose with a concealing hand.

Inside the room, as they all seated themselves in the chairs, Crayley watched the face of the man who had done the toe-mashing. He was solidly-built, young, good-looking in an ugly sort of way, sensitive and intelligent, as a waldo recorder had to be. When Klythe walked up behind the desk and said: "Good morning, gentlemen: I'm Berin Klythe," the tech's eyes opened a little wider for a fraction of a second, but there was no further reaction. Crayley was satisfied; he turned to watch Klythe.

Klythe was furious, but there was nothing he could do about it. The crimson in his face had died, to be replaced by the faint pallor of anger.

"You may ask me questions later," he said bluntly. "Right now, I'd like to ask you one. Which one of you is co-ordinator here?" One of the men stood. "Your name? Russ? Mr. Russ, may I ask why the Space Force felt that our recording men were not capable of doing this job?"

Russ fumbled uncomfortably. Finally: "Well, sir, this gadget is of—uh—rather radically new design. Since we, as a team, had built the various designs that led up to this one, our superiors felt that we would have a better working knowledge of the piece. They felt it would save time if we made the recording. I'm sure there was no slight intended to your own recording staff."

"I see," Klythe said coldly. "Very well." He turned his head a fraction and looked directly at Crayley. "Lew, what do you think the Space Force will do next time? Send over their own Director?"

The Space Force men looked embarrassed, and Crayley smiled one-sidedly. Nobody but Klythe could have gotten away with that crack. Berin Klythe had been trained by, and had worked under, no less a person than the great Fenwick Greene, acknowledged Grand Old Man of the profession. Crayley recalled that Fenwick Greene, too, had been offered and had survived the Big Gamble.

Klythe began asking questions about the new unit. His tone was sarcastic, and his manner biting. He spent better than an hour singling each man out for some remark about his ability or lack of it.

When he was finally through, he leaned forward on his desk, his knuckles white. "All right, let's get busy and build this thing! But we'll build it my way, understand?"

None of the technicians said a word.

Klythe turned and headed for the door, followed by Crayley and the other engineers. Silently, the technicians followed after.

The original model of the generator lay on a work table in one of the recording rooms. Around it were the recording stations, the seats and controls each of the techs would occupy.

Klythe waved at the seats. "All right, men—to begin with, each of you occupy your regular team position. Let's get this thing disassembled. I want to see how it goes."

The model was just that—a model. It had been built with ordinary metal and plastic; it could never be energized. The wiring was copper, the casing of steel. But it had been built as carefully and with as great precision as if it had actually been constructed of the fiercely radioactive materials that would go into the production models.

The recorders seated themselves around the hulking object, checking and rechecking the intricate controls of the waldoes they were to operate. Finally, they fitted their hands into the glove pickups and waited, watching Klythe.

"Set?" Klythe asked.

"Set!" they said in one voice.

Klythe tapped his finger on the control board at which he had seated himself. The technicians began to disassemble the model, stripping it down to its last essential part, as Klythe watched with a critical eye.

Klythe had tapped the board, but he hadn't actually energized the gloves. This was to be a dry run; there was no need to record a disassembly; it was the assembly that would go down on tape.

It took an hour to complete the job, and all that time Klythe said nothing. He watched the men work, eying each move, each nut removed, each wire unwound.

When it was over, the men folded their hands in their laps, and Klythe tapped the control board once more.

"Let's see if we can't assemble it a little faster than that," he said coldly. He pressed the recording button, and the technicians began rebuilding the model.

Crayley stepped over to the monitor screen set in one wall of the recording room and switched it on. Then he cut in the experimental secondaries, connecting them to the recording primaries. They went through the same motions, their arms waving and gesticulating oddly in the air, since there was nothing for them to work on.

Klythe wasn't silent during the rebuilding. The disassembly had taught him everything he needed to know about the new unit; that was his job and his genius.

"Seven! Move that plate in straight next time! And you, Four, keep your guides straighter!" His voice rang clearly and concisely in the huge room. "Eighty-four! Don't wait so long before you hit that welder! As soon as Nine moves his left away from the shell, hit it!"

Little things, small savings of time, but they added up to greater efficiency in the long run. Klythe watched for every wasted motion, every fumble, every tiny error in timing or spacing, and corrected it with a whiplash voice.

When they had put the model completely back together, they folded their hands and looked at Klythe. Klythe jammed his finger down on the stop button and set the machine to erase the tape they had just made.

He scowled at the men. "I have seen more fumble-fingered recorders," he said acidly, "but they were trainees." He sighed as though his burden was too much. "All right. Rip her down and let's try it again."

The next time through, he was even more vituperative. If a man made an error the second time, Klythe was not above insults—personal ones.

An emergency call came in for Crayley. Something wrong on the second level. He stepped out the door in the middle of one of Klythe's high-tension blasts at a technician.

All the way down to the second level, Crayley was happy.

It took three days of hard work to pound all the kinks out of the recorders' technique. Not all, actually; Klythe still expressed dissatisfaction.

Crayley was in Klythe's office on the morning of the fourth day, sitting on Klythe's desk and smoking one of Klythe's cigarettes.

"The whole damned crew are butterfingers," Klythe was complaining. "I think they've all got arthritis. Why, oh, why couldn't they let me use my own crew?"

"Speed things up, I suppose," Crayley said cautiously.

"Oh, hell yes! Speed things up! Sure, I'll admit that it would have taken my boys a little time in disassembly to get the hang of this new generator, but we'd have made it up in recording time. That's the way the goddam military mind works! Nuts!"

Crayley rubbed the tip of his nose with a finger. "Is the team ready for recording today?"

Klythe grinned. "As close as they'll ever be. It takes time to get a team accustomed to my way of doing things. They hate my guts for the way I've yelled at them. But it's as much my fault as theirs. If their own engineer were to take over one of my crews, he wouldn't have any better results. The military just has to do things differently, that's all."

They recorded that afternoon. This time, when Klythe pressed the starter, he said nothing. Only his hands and eyes directed the men through their tasks. And every motion of the men's fingers and arms sent their special impulses to the recording tape that hummed through the machinery.

Crayley looked out from behind his face and smiled secretly.

When the recording was finished, Klythe nodded with satisfaction. "I think we could have shaved a few more seconds off that," he said, "but it'll do. Now disassemble it and we'll run her through on the tape."

They took the model down below to the radiation-proofed assembly tables for the test. The thing was pulled to pieces and each piece positioned. Then Klythe threw the switch that started the waldoes.

The tape purred through the pickup head, transmitting the little bits of information it had received, squirting little pulses of energy to the steel-and-plastic arms that jutted out of the domes atop the pillars. In exact duplication of the men's motions, the waldoes picked up the pieces and put them in their proper places.

It was like a great four-dimensional jigsaw puzzle. Each piece not only had to be located properly in space, but placed there at just exactly the right time. If there were any bugs in the recording, now was the time to find out. When the real thing was assembled, mistakes could be costly.

But there were no flaws in the recording. The model was rebuilt exactly as the men themselves had rebuilt it. That was Klythe's genius; he worked for perfection and got it.

Klythe looked at the model after the last pair of hands had fallen inert, and nodded slowly. Then he climbed all over the model, checking for errors. The interior circuits were tested electrically, one by one and in co-ordination with each other. The test machines showed it clear.

Finally, Klythe said: "I think it'll do. But now we'll disassemble it again by hand—slowly, this time—and see if we've screwed up anywhere."

That night, Crayley went out and got drunk. He sat by himself, grinning and thinking secret thoughts in a booth at the Peg & Wassail, dropping coins in the slot and dialing one beer after another. He managed to maneuver himself home at three o'clock in the morning, singing softly to himself.

He woke up with a horrible headache, but he felt wonderful inside.

Sure enough, Berin was in his usual state of "first-run jitters." Crayley had been a little afraid that Klythe's enthusiasm wouldn't be up to par on this project, but it evidently was.

He was rubbing his hands together, a nervous smile playing around his mouth, coming and going unpredictably.

"Well, we'll see today. Major Stratford will be here with the Space Force Research Staff at fourteen hundred to watch the first one off. I hope the bugs aren't too rough on us."

"Nothing will go wrong," Crayley assured him.

"That's easy to say," Klythe grumbled, "but you know how things can go at the last minute. I'm worried about those tensile differences."

Crayley stroked his mustache and nodded. The material used in the interior of the model was supposed to approximate the highly radioactive material in the real thing as closely as possible, but there might be just enough difference in critical spots to require some small adjustments in the tape. If a man's hand applied just enough pressure and torque to twist a piece of copper wire just so, it might be too much or too little for a radioactive alloy wire that would be used in the same place in the production piece.

After the suppressor field had been switched on in the hull of the finished generator, the energy generated by the workings of the intensely radioactive interior would be compressed to the sub-nucleonic level, where it could be controlled. Unfortunately, the machine couldn't be built inside a suppressor field; that would be like trying to build a ship in a bottle when the bottle's neck was sealed shut.

Crayley said, "I've got a lot of stuff to do on Line Number Two this morning, but I'd like to see the run-off."

"Sure," said Klythe abstractedly, "come ahead."

Crayley didn't go to Number Two. He headed directly for the recording room. All he needed was ten minutes alone in there. Provided, of course, that it was empty.

It was. Crayley took a quick look up and down the corridor and stepped inside. He locked the door behind him. If anyone tried to come in, he'd be able to cover. It was better to have someone wonder why the door was locked than to be caught messing with the tapes when he shouldn't be. Of course, if someone did try the door, it would mean that his chance of getting Klythe this time would be gone. But there would always be another time.

First, the tape. He flipped open the cover to the receiving reel. Sure enough, it was still there from yesterday's trial run, a huge reel of foot-wide blue plastic ribbon. Good enough.

He punched the "fast" button and ran it through to the last few minutes of the recording. He glanced at the monitor screen. The model was still on the assembly table in the tunnel deep underground.

He cut off the current to the secondaries and switched on the manual controls. Then he put his hands into one set of gloves and wiggled his fingers. The secondaries in the room below remained motionless.

Number Nineteen Experimental ought to be empty. He withdrew his hand and turned the selector knob on the monitor screen to Nineteen. No one there. He switched on the power, letting the last few minutes of the taped recording feed into the secondaries in Nineteen.

The waldoes in the screen went through the motions of finishing the assembly—meaningless gestures in the empty air—then fell into the "ready" position. Crayley hit the stop button, then switched back to the tunnel where the model lay.

He took a deep breath. Now came the touchy part. He hadn't handled a pair of primary waldoes for years, and this thing had to be done just right.

He had already decided which of the positions he would have to use and what he would have to do. Now, if only his timing was good. It didn't have to be perfect; that was the beauty of the plan. But it did have to be pretty close.

He turned on the waldoes without turning on the recorder and slipped his hands into the gloves. Then, using the foot switch, he kicked on the close-up screen for the position he was occupying. The screen showed the secondaries of the hands he was using. He wiggled his fingers. The secondaries wiggled theirs.

Then he reached out and gingerly touched the model. The secondaries touched the steel plate, and the feedbacks sent back a signal. Crayley's gloves felt the resistance just as though the model were right there in the room.

Several times, he reached out his right hand to one particular spot on the model, practicing to make sure he could hit it every time. Fine, fine.

Then he took his left hand out of the glove, eyed the wall clock, and turned on the recorder. The tape began to move through the recording heads. For five minutes he waited.

Then, suddenly, he reached out with his right hand and grabbed the regulator coil housing on the side of the model. As soon as his fingers touched it, he hit the cut-off for the secondaries, knowing the primaries would continue to record. He didn't want to ruin the model. Simultaneously, he punched the high-power switch.

His right hand, in the primary, grasped at mid-air and jerked down violently.

The thing was done. Had he forgotten anything? He thought for a moment. No. All was well.

He cut off the recorder and started to shut off the primaries when his eyes went to the screen. The secondary arm was still frozen where he had left it, grasping the regulator coil housing!

He shuddered. If he'd missed that....

Quickly, he lowered the secondary to the "ready" position.

Had he forgotten anything? Anything at all?

He thought not, but he went over the whole thing in his mind again, step by step, to make sure.

Nothing wrong, nothing missing. Fine. He wiped out the inside of the primary gloves and walked to the door. No need to worry about any other prints; he had been in that room often, and it might look funny if the whole place was wiped clean. As a matter of fact, he really didn't need to worry about the primaries; the grid inside them probably wouldn't take a print anyway. Still, there was nothing like being cautious.

He opened the door and stepped out as if he had every right to be there. No use peeking around corners; that would only rouse suspicion.

He strolled on down the corridor to the tube lift. He felt wonderful. He actually grinned with his face. There was no one around to see it.

The job he had to do in Number Two kept him busy until well after fourteen hundred, as he intended it should. He didn't want to get there early, but he wanted to have a good excuse for being late.

He actually walked into the monitor room for Number Nine Production Tunnel at fifteen-twenty. The Space Force officers were gathered around the screen watching the unit take shape under the deft, mindless fingers of the waldoes. The weird blue glow of radioactivity obscured the finer details a little, but the operation was worth watching.

Major Stratford turned as he came in. "Hello, Mr. Crayley. I thought you were down below with Mr. Klythe."

Crayley stroked his mustache and smiled a little. "I had some work to do," he said apologetically. "I didn't get through until a few minutes ago. I figured this would be as good a place to watch from as down below."

Stratford grinned. "I suppose so. One screen is as good as another."

They watched. Stratford introduced him around to the other Space Force officers, including a short little man with nervous eyes named Colonel Green who was evidently Stratford's superior. Then everything became silent as they watched the generator being built.

Crayley smiled inwardly as he saw that the hulking generator had already blocked off the view of the one waldo he'd gimmicked. No one would be able to see what happened on the screen, and those who saw it directly wouldn't tell anyone.

Exultant, Crayley watched the screen through the mask of his face. Very shortly, he would again be Director. When Klythe had gone to Denver to take the Big Gamble, he'd left Crayley as Acting Director, with the stipulation that he was to become Permanent Director if Klythe failed to live through the grueling torture of the Rejuvenation chambers. Naturally, Crayley had had every right to feel that the position was already his. He had never considered that Klythe might be one of those few who would live through the Big Gamble.

Even when Klythe had come back, Crayley hadn't immediately considered him as a block in his path; there was always the chance of the Breakdown.

Sometimes something went wrong with Rejuvenation, even when the patient lived through the year. Instead of being better than normal, the body went out of kilter. Some little thing, probably—they hadn't pinpointed it yet. A gland that malfunctioned, a nerve blockage, something. Whatever it was, the rejuvenee suddenly began to age rapidly after a few months, dying of acute senility within the year.

But when a year had passed and Berin Klythe was as healthy as ever, Lewis Crayley had begun to plot murder. And now the plans had matured; soon they would bear fruit. Soon he would be Director—Permanent Director. As Director, it would be easy to erase the end of that tape before anyone else got their hands on it. He, himself, would be the one to head the investigation of the accident.

Crayley watched the assembly impatiently from behind his face.

The hands and arms and fingers of the waldoes in the screen worked together with precision as they put the last finishing touches to the generator unit. Finally they were finished; the arms assumed the "ready" position.

Crayley almost held his breath. Everything depended on Klythe now. Klythe, with his impatience, his pride in a piece of work well done, his eagerness to be sure of perfection; Klythe himself was the only weak link in the chain that led to his own death.

The tunnel was still flooded with radioactivity. In production, that wouldn't matter; the next set would slide into place and the hands would begin again. But this was a test run; the record would be allowed to run to the end instead of recycling, while the huge pumps replaced the argon atmosphere with air suitable for breathing. The radioactive stuff was pumped to a cooling chamber, where its silent violence would be allowed to expend itself below the danger point.

Five minutes. Crayley could see in his mind's eye that tape running through the pickup head, running through five minutes of nothing. Then a light flashed above the door to the tunnel as the detectors signalled the all-clear. It was safe to enter the tunnel now.

Crayley found himself clenching his teeth for a fraction of a second before Klythe opened the door and stepped through. There was a long, almost timeless instant as Crayley watched Klythe's face on the screen. Then there was a sudden sound, a brilliant light, and the screen went dead.

Crayley smiled inside himself as he yelled and sprinted out to the tube lift. The hidden hand of the secondary had reached up and ripped off the regulator coil—housing, innards, and all. The resulting explosion had been felt, even up here, as a dull rumble.

The lower level was a mess. The emergency door had slammed down to prevent the spread of contaminated air, and the huge pumps were going full blast to clear the area. At the first door, Lesker, one of the safety engineers, stopped him.

"You can't go in there, Lew. One whiff of that stuff, and you'd be gone."

"What happened?" Crayley asked briskly.

Lesker shrugged. "Who knows? That new generator blew, somehow. Not much harm done, really; as far as we can tell, the only real damage was in the tunnel itself. The temperature must have averaged better than a thousand Centigrade for a few seconds, though it was a lot hotter than that at the center of the blaze. It's cooled down a little now, but that generator must still be burning." He stopped for a second, then: "Nobody got out of it alive. We're sending in the mobiles now. The secondaries in there won't work. It's going to be a rough job because we'll have to use cables; we couldn't possibly get a UHF beam through that static."

The safety men were setting up a monitor screen bank for the mobile waldoes. Two of them, four-foot wheeled robots with TV cameras mounted where human heads would be, rolled up to the closed door.

"It's safe in that first section," Lesker said. "Roll 'em in." He turned back to Crayley. "You'd better get on a radiation suit if you want to watch this. We've got to seal off this section from the rest and open up the corridor all the way down to let the cables through. There's still a lot of hot air in there in spite of the pumps."

Crayley climbed into a suit and adjusted the air flow. Then he walked over to where the safety technicians were putting on the primary gloves for the mobile waldoes. From each control board, a long snake of cable ran to the mobile it controlled. The safety men switched on the power and the mobiles rolled down the corridor out of sight.

Crayley watched their progress over the shoulder of one of the safety techs. The screen showed the walls of the corridor sliding by. Then there was a shifting as the camera panned to the left. After several more turns, the robot came to the door of Tunnel Nine. The door itself lay crumpled against the far wall. Two bodies lay near it. The robot glided into the tunnel itself.

The inside of the tunnel was still fiercely hot; the new generator glowed a yellow orange, and the waldo secondaries had been warped and ruined by the heat.

And on the floor, human in shape only, lay what had once been Berin Klythe.

The mobiles went to work to take care of the glowing hulk of the ruined generator.

Crayley looked at the safety engineer. "There's not much I can do down here," he said. "You take care of the bodies, will you?"

Lesker nodded. He seemed suddenly to realize that he was speaking to the new Director. "You can shuck your suit in the next section. I'll let you know how things are going."

Crayley felt quite light-hearted by the time he reached the upper levels again. In fact, he was almost ready to sing. It had been so easy, so simple! They had called Berin Klythe a genius and given him a chance at the Big Gamble; well, let them see who was the genius now! The plan itself had been a stroke of genius.

There was only one thing left to do; slip into the control room and erase the tail end of that tape. The explosion would go down as "unexplained." Berin Klythe had died in an industrial accident—and Lewis Crayley would replace him.

When he opened the control room door, only his mask of a face saved him. The room was full of men.

"What's going on here?" he asked softly.

One of the younger engineers turned toward him. "These men say they're going to confiscate the tape, Mr. Crayley." He waved in the direction of the uniformed Space Force men.

Crayley looked mildly at Major Stratford. "I'm Acting Director here, Major. I'm afraid I can't let you take our property."

The major turned to the smaller man standing nearby. "Colonel, perhaps you'd better—"

"I'll take care of it," the smaller man said choppily. "We're not confiscating it, exactly, Mr. Crayley. The tape will remain where it is. Immediately after the accident, I phoned the Executive Secretary at the capital. He is sending down an investigating board by special jet."

"May I ask why this rather high-handed action, Colonel Green?"

The colonel patted the air with a nervous hand. "Calm yourself, Mr. Crayley. I am Fenwick Greene; the 'colonel' is merely a military title I have to put up with."

"Fenwick Greene!" It was one of the few times in his life that Crayley's screen, his wall, his defense, collapsed. "My—my apologies, sir! I didn't realize—I mean, I had no idea it was you—in the Space Force!"

He had never seen Fenwick Greene's picture, of course. No newspaper would dare commit such a flagrant violation of privacy.

Greene accepted Crayley's hand for a few seconds, then withdrew his own hand. "I was—ah—drafted," he explained.

Major Stratford smiled. "When the Space Force needs men, they pick the best."

Crayley nodded dumbly. Fenwick Greene was undoubtedly the greatest co-ordination engineer who had ever lived. The late Berin Klythe couldn't hold a candle to him. His waldo recordings were like symphonies of precision and speed. Someone had once said that, given enough recording technicians and enough time to train them his way, Fenwick Greene could build a spaceship faster than parts could be made for it. It was an exaggeration, of course, but it showed what the trade thought of Fenwick Greene.

Greene tapped his teeth with his thumbnail. "We aren't confiscating the tape; we simply want it run. We're guarding it."

"Why?" Crayley asked bluntly.

Greene pulled a folded sheet of paper from his pocket. "This is a communication from Berin Klythe to the Construction Command of the Space Force. In it, he notified us that the test would be run today. He also says—" Greene held up the paper. "Quote: 'due to the fact that the Space Force has insisted that I use their technicians for the recording of this unit, I hardly feel I can claim that the recording is up to my usual standards. Had I been permitted to use my own men, I am sure better construction would have been obtained.'" Greene replaced the paper in his pocket.

"Naturally," he continued, "we don't think there is anything really wrong with the recording. Klythe, like myself, was a perfectionist. However, we would like to have the tape played before an examining board in order to clear ourselves and possibly clear Berin's own name. I watched the construction from beginning to end, and I could find no fault with it. However, we want a qualified board to check it. You see—" He coughed apologetically. "—I trained those technicians myself."

Crayley nodded. "I see."

There was nothing he could do. If he objected, they'd know who gimmicked the tape. Well, no matter. They'd know how Berin Klythe had died, but they wouldn't know who had done it.

He was in hot water, and he knew it, but he wasn't licked yet.

If only he hadn't tried to play his part so well! If only he'd gone straight to the control room instead of down below! Nothing to do about it now, he told himself. He couldn't waste time wishing he'd done something else; he had to see what could be done next.

Two hours later, the big jet job carrying the special Executive inquiry board landed on the roof of North American Sub-nucleonics. Crayley himself had to do all the honors. As Acting Director, he had to play host to the men who were—although they did not know it yet—investigating the murder of Berin Klythe.

That was the way Crayley thought of it. The fact that four other men had died with Klythe was immaterial; it meant nothing in the final analysis.

Crayley decided that his best bet was to mislead them. When they saw the extra operation at the end of the tape, he'd do his best to make them think it was a case of sabotage. Someone—probably South Asian Generators, Unltd.—had sent a man in to wreck the unit. Or perhaps bribed one of the technicians. South Asian was perennially trying to get the Space Force contract.

They used the model for the investigation run. The technicians tore it down and placed it on the table. Crayley tried to get to the control panel to run the tape through, hoping he could jab the erase button as soon as the tape was through and the model built, but Fenwick Greene was there ahead of him.

They switched the secondary control over to the experimental room. Half of the inquiry board went there to watch the process first-hand, while the other half watched it from the screens in the control room. They had cameras watching it from every angle this time; they didn't miss a thing.

Greene started the tape and watched closely, his eyes darting from screen to screen as the generator dummy took shape.

Greene's eyes missed nothing. There was actually no necessity for the dummy to be there, as far as he was concerned; he could read the motions of a set of secondaries as accurately as an average man could read a page of print. What appeared to be meaningless wavings in empty air were deft, purposeful action to Fenwick Greene. Mentally, he could see every component as the fingers grasped it. But the inquiry board could work better with a model actually on the board.

Finally it was over. The secondaries fell to the ready position. Crayley had five minutes to get to that erase button.

Fenwick Greene didn't move from the control panel.

"Gentlemen," he said, "that was a beautiful job. I don't think that even I could improve on it much. In my opinion, there is no reason why that unit should have blown." He paused, looking at one of the designers. "Unless, of course, there is something amiss in the theory or design. That, naturally, is out of my province."

There was discussion back and forth among the men.

Crayley's nerves tightened as the minutes slipped away. Would that fool Greene never step away from the control board, even for a minute? Why didn't he shut the damned thing off?

He finally gave up and forced himself to relax. It was too late now. He'd have to talk fast.

"Look!" one of the men snapped. He was pointing at one of the screens. Right on schedule, the waldo's arm reached up, grabbed the regulator coil housing, and ripped it off.

There was an excited babble of voices, and Crayley forced himself to look as flabbergasted as the rest.

The hand dropped down again to the ready position.

Crayley turned to Greene and started to say something that would keep the board's mind on the sabotage track, but he noticed that everyone was looking at the screen again. He swiveled his head around.

The secondary hand had lifted into the air. It extended its forefinger and made meaningless motions.

Crayley's jaw muscles tightened. What the devil did it mean? How had that got on the tape?

The hand dropped. There came a faint chime which signaled the end of the tape.

"Let's run through that again," said Fenwick Greene, an odd note in his voice.

Crayley didn't understand. Had the shrewd, calculating eyes of Fenwick Greene read meaning into that meaningless movement?

Again the hand lifted into the air, extended a finger, and moved it. Then it dropped.

Crayley started to move his own hand, and stopped it in mid-air. He knew in that instant what the gesture was.

The rest were talking, buzzing among themselves; no one was looking at him yet. Only Fenwick Greene gave him a short, sharp glance.

Greene ran the tape back through for a third replay, and watched the hand lift again.

Crayley stared at it as if hypnotized. His mind was a mass of self-hatred. Fool! Fool! Clumsy fool! This was it; this was the end of everything. It wouldn't take them long now—they'd at least have enough evidence to use a lie probe on him. Someone would see it. Someone would see how Lewis Crayley's subconscious mind had betrayed him when he'd made the recording.

Fenwick Greene saw it. His eyes moved from the screen to Crayley's face.

"You," he said very softly. "You're the only one who has one."

And Crayley knew he was right. If there had been a head on the waldo, they'd have understood instantly.

The finger was stroking an invisible mustache.

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this eBook.