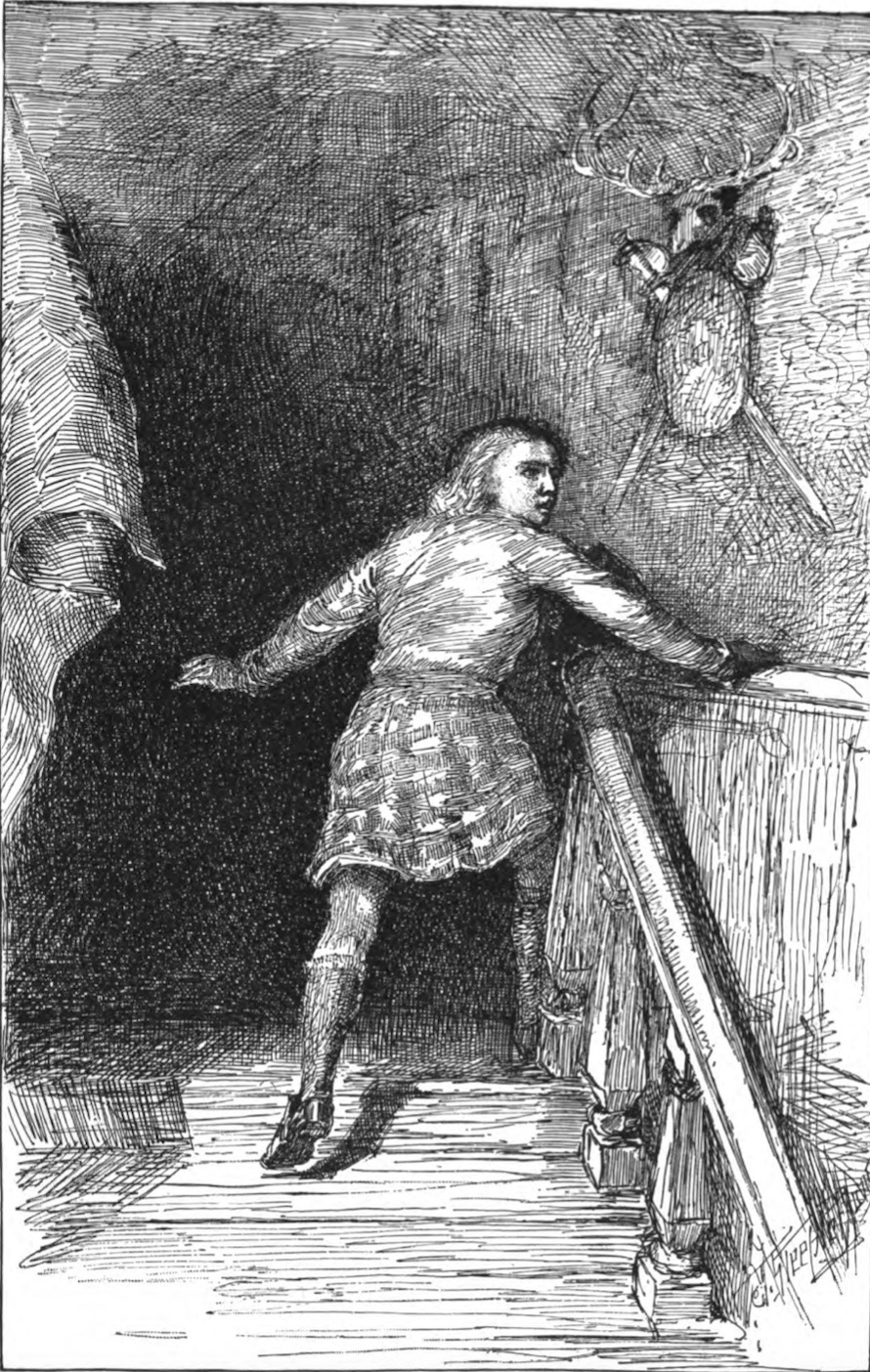

"All was dark as he turned toward the landing."

—(p. 68.)

An Incident of the "Forty-Five"

BY

EDWARD IRENÆUS STEVENSON

AUTHOR OF "THE GOLDEN MOON," ETC.

NEW YORK

CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS

1887

Copyright, 1887, by

CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS

TROW'S

PRINTING AND BOOKBINDING COMPANY,

NEW YORK.

TO

CLINTON BOWEN FISK, JR.

| CHAPTER I. | PAGE |

| In a Highland Glade, | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| A Story and a Shelter, | 17 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| "In the King's Name", | 30 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| "Puss in the Corner", | 52 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| In which Captain Jermain's Memory is Useful, | 66 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| A Desperate Shift, | 85 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Prisoner and Sentry, | 109 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Meeting—Flight, | 140 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Colonel Danforth, | 161 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| All for Him, | 184 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Under the Oak, | 202 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| L'Envoi, | 213 |

WHITE COCKADES

AN INCIDENT OF THE "FORTY-FIVE"

Just as the brilliancy of a singularly clear July afternoon, in the year above named, was diminishing into that clear, white light which, in as high a Scotch latitude as Loch Arkaig, lasts long past actual sunset, Andrew Boyd, a Highland lad of sixteen, was putting the finishing strokes to the notch in the trunk of a good-sized oak he was felling. Its thick foliage waved rather mournfully, as if in expectancy of near doom, over the boy's head. That oak had engaged Andrew's attention pretty much all the afternoon. He was glad to be so well on toward his work's close.

Around the young wood-cutter soughed the dense forest. It clothed the mountain side, straight from the margin of the loch below. Andrew's blows rang quick and true against the trunk. His springy back, his well-developed legs and arms, came handsomely into play. On the moss lay his plaid and bonnet. The sweat dripped from his forehead, not much cooled by the breeze that tossed his yellow hair and the folds of his kilt.

Young Boyd did not cut down oak-trees for a livelihood, though he just now worked as if fortune had mapped a no less arduous career for him. He was the only son of a wealthy landholder of the vicinity, a man of English descent and English thrift. Andrew's grandfather came north into Scotland from Shrewsbury, in a sort of angry freak after a local quarrel. He bought and developed a valuable farm near Loch Arkaig, and then suddenly died upon it, leaving the newly acquired estate to Gilbert Boyd, the father of young Andrew. All of which had happened some forty years before this tale's beginning.

One, two—one, two—rang the axe upon the tough wood which Andrew wished for the boat he was building, down at the loch side. His thoughts ran an accompaniment. We spare the reader their translation from the Scotch dash in which they were couched, the result of Andrew's schooling and intimacies round about him.

"There! Have at you again, old tree! How I wish you were a dragon, and I some Saint George busy at carving you!" One, two—one, two—quoth the axe, approvingly. "No, I don't! Away with any wish that meddles with saint or man that the Lowlanders love!" One, two—one, two—assented the axe. "Better wish that you were the little English King George himself! and I a stout headsman, ready to knock his crown off, head and all!"

The chopper's brows knit. His eyes flashed at a notion that struck a specially sensitive chord. "Ah, you stockish trunk, if you only were George, the Dutchman! Tyrant! Monster! Will you withdraw your troops from our harried counties? Will you end now, at once, your bloodthirsty hunt for the Prince?—God bless him! Will you empty out that horrid Tower, full of our noble gentlemen and lords who fought for the Lost Cause? Will you pardon my father's friend, the Earl of Arkaig, and send him home straightway to us? What, you won't? Take that, then!—and that!"

Here the axe-strokes descended with such vim and amid such a meteoric shower of chips that no clear-headed listener could entertain for a moment doubt as to hot-headed young Boyd's politics. The oak sighed, and rather unexpectedly crackled and snapped, and came crashing down most magnificently.

But halloa! At the instant that its mighty top smashed into the underbrush and saplings, a single sharp, piercing cry of pain and terror rang out above the crackle and splinterings.

Andrew dropped the axe. He rested rigid as stone, open-mouthed, in sudden alarm and consternation. "What!" he exclaimed. "Great Heaven! Can it be that—that a human creature—a man—was hid in the thicket, and that when the oak fell——"

"Help! help! for the love of mercy!" The appeal, fainter than the first cry, rose from the densest crush of the shattered oak branches. There could be no mistake. Some one had been slinking in the bushes near young Boyd; possibly a Hanoverian spy! Through his own unaccountable carelessness the unseen person had allowed himself to be suddenly trapped by the boughs of the falling tree. He was pinned in a torturing, if not a fatal trap.

Andrew's sharp eyes could not penetrate the barricade of dark green. "Hi, there! Halloa!" he shouted. "Are ye under the oak? What has befallen ye, man, or whatever ye be?"

No answer. To catch up his axe and plunge boldly into the tangle was his next impulse. He hewed and trampled a path toward the centre of the felled tree, which had been young but very vigorous and leafy. No trace of any unusual object imprisoned beneath the knitted boughs, no new cry for help guided him.

He began to doubt whether to press to right or left, or to go round about and continue his examination from another point of the oak's circumference, when a low but distinct groan spurred him to more active work in the same direction. Forcing aside the strong branches by his knees, he caught sight of a dark object just beyond. He next discerned a cloth garment, covering a man's back. The yet invisible wearer had been all this time in a faint, and was now able to betray but small sign of interest in his own deliverance.

"This way, this way," Andrew heard him moan, as if articulating with real anguish; "I am hurt badly, I fear. I cannot stir."

The accent, not so Scotch as Andrew's, seemed gentle. The mysterious interloper might then be some well-bred prowler. Andrew thrust away the last intervening twigs. There lay on the turf a man, at full length, and face downward, with one arm and a part of his right shoulder held as if in a vice by the oak's grasp. His well-turned neck and figure implied to Andrew's hasty survey that he was young and comely.

"Whatever you do, man, don't try to move!" exclaimed Andrew; "leave your outgetting to me. I'll set you free in a trice."

He went to work cautiously but swiftly to do it.

"And my ankle is fast too"—came the smothered complaint. "Look—you will see how—my leg—is held!"

Andrew looked. "'Twill be free speedily, sir!" he answered cheerfully, already impressed by the fortitude of the tormented man. "Be but a bit patient, sir. That's it; now you can roll to the left, please." He employed axe and helve adroitly as he spoke. "Now, to the right; up, up—that's it, sir. What a miracle your skull 'scaped the fork."

The victim rolled over, displaying the countenance of an entire stranger, eight or ten years Andrew's senior, and with strikingly handsome features. "Thank you, thank you, my good friend!" he gasped, pulling himself to his feet; "that was the torture of a fiend, I assure you! Your hand, one instant, please."

By dint of leaning on Andrew's arm, and after several battles with successive tough boughs, in which the new-comer showed that he possessed strength and dexterity, the two finally scrambled out of all the labyrinth of foliage and into clear space. Andrew flung down the axe and assisted his new acquaintance to a seat upon the prostrate trunk.

"The next matter is to examine your hurts, sir!" Boyd exclaimed, taking a sharp look at his dignified protégé. The latter returned this scrutiny as keenly, however.

"I begin to suspect that such hurts amount to little or naught," returned the stranger, dropping Andrew's hand which he had held in a grateful pressure. "I have nothing worse than a bruised shin, a scraped shoulder and back, I fancy. Heaven be blessed, nothing is broken in my anatomy!"

Andrew laughed, although he knelt down all the same and began a rigid inspection of the bruises. He remarked how spare and muscular were the stranger's legs and arms, as if from much exertion and little food. His costume was odd: a faded Highland suit, rent and stained, ill-fitting brogans, agape with holes cut by mountain flints; his throat and face were surprisingly sunburnt, though his natural complexion seemed to be fair. But what of his clothing or his tan? As the man leaned against the prostrate trunk, with one leg boldly out before the other for Andrew's care, there was something commanding, fascinating to Boyd in his whole bearing. Andrew had not read Shakespeare, but if he had he might well have recalled the lines in "Coriolanus":

While the hurried surgery progressed the object of it aided therein with no small skill, venting now and then an ejaculation of pain. He stealthily studied Andrew. It was a question which should first act on the opinions shaped by this mutual caution. But in those gray blue eyes sparkled a quizzical light that made Andrew smile, as he suddenly observed it, when rising from his bowed attitude.

"Name for name, it must be, I see; and faction for faction, eh? Well, I don't wonder that you and I have eyed each other askance. These be days when honest men can ill be known as such. It would be strange, too, if loyal subjects of Hanover, like you and your axe, should not remember spies and renegades when you pluck strangers out of tree-tops."

"You—you overheard my thoughts while I hewed!" returned Andrew, first red, then pale. "I—I knew not that I ran them so heedlessly into speech. Evil speech to be overheard, sir."

"Your tongue has a Lowland twang to it, whatever little to please a Lowlander it spoke," said the stranger. "You are right my lad; what you prattled there, by yourself, as you thought, was treason—with a vengeance. Know you not that these mountains are filled with those who would gladly tie your arms behind your back and gallop you off to Neith jail, for half such sentiments. Or"—and here the voice became tinged with a profound sadness, "or, have you been, young as you seem, like myself, a defender of that most unlucky young soldier, my master, Charles Stewart, who, a hunted refugee, with an army cut to pieces and a realm lost, is skulking to-day in some corner of the country with death at his heels and a price upon his head—instead of a crown-royal."

Andrew drew himself back proudly and stared into his questioner's face. "Sir," he exclaimed, "I see you are a soldier! You may be a Southerner as well. I care not. God save the Prince! I love him! God defend him! So will say my father and every man and woman at Windlestrae! I was too young—so they pleased to think—to fight at Culloden Moor, and my father has just tided over a long sickness. But for these things we had both been there—and dead, by now, 'tis very likely."

The stranger fairly leaped from his resting-place. "Your hand, your hand, young sir!" he demanded, his face suffused with color. "Rash as you are loyal, let me press it! I, too, love the Prince, our master; and I, too, hope yet to see him make a footstool of his enemies. My name is Geoffry Armitage—Lord Armitage I am oftenest called. Windlestrae, said you? Then I speak to one of those to whom I am sent on an errand from which yonder villainous tree did its best to let me. Are you Peter—no, Andrew Boyd, the son of Gilbert Boyd, who owns the manor of Windlestrae?"

"I am, sir," replied Andrew, in deepening surprise: "this very nook of the woodland we stand in belongs to my father and is within our farm. The manor house and fields are but half-an-hour from this spot; below the hill-foot yonder."

"Fortune favors me at last!" cried Lord Geoffry, seating himself again on the trunk. "I bring a long message from the minister of Sheilar Kirk, that I have to give to your father. I am a fugitive, as you may have already guessed from the disparity between a title and my dress. A fugitive? Yes, and one who has often thought that his life might better have been left where the cause for which he would have laid it down was lost—on Culloden Moor."

"Culloden!" exclaimed Andrew, "Oh! sir, were you truly in the fight? Tell me more of it, I beseech you."

"Ay—for whatever in my own history is worth telling you or your father begins with it!" the ruined nobleman replied in a melancholy tone. He paused. Andrew heard him murmur, "Can I speak of that day so soon?" But he composed his utterance, and after a quick glance about them looked up at Andrew, to begin his brief account of himself.

"You would hear more of—Culloden?" began the fugitive. "Not from me! I headed a charge of foot under Lord George Murray on that fatal day. My men were cut to pieces before my eyes. I, after what last, desperate stand for liberty one arm could make against a score of the enemy, was taken prisoner in a ditch—in a ditch, like a fox or a badger!——"

"But you escaped?" Andrew interrupted.

"Ay, I escaped, after three days of starvation and brutality. The hand of God seemed to deliver me—I know not what else to call that series of events that saw me free and able to fly for my life. Favored again by a dozen happy occurrences I reached these mountains. They are swarming with gallant fellows as unlucky as myself. Now some brave Highlander sheltered me in his cottage; now I lay, night after night, in holes and caves, when the English troops who scout the hillsides for refugees came too close to my retreat. Some weeks ago I ventured to come westward, and Solomon McMucklestane, the old minister at Sheilar Kirk, received me into his manse. He hid me there, he, at the risk of his all. I have had a brief respite for rest and the regaining of my strength."

"Have you been forced to turn from Sheilar also?" said Andrew, who listened with the deepest interest to the Jacobite's tale.

"Yes. You have heard that Colonel Danforth has lately begun his searches in the neighborhood of Sheilar? It seems that he has lately got wind of the fact that the neighborhood hides one or two lurking Jacobites. My reverend host was warned upon Monday that he and his manse were suspected. I was obliged to be off again. On Tuesday night I quitted him, directed by him to your father, and expecting to reach your farm yesterday. I saw soldiery and abandoned the highway. My path of uncertainty over these wild slopes I quickly lost. With only glimpses of the pallid Loch yonder to guide me, I have wandered in desperation. I slept last night airily—in a stout yew. This evening the sound of your axe all at once caught my ear. I followed it. You can understand that I should think it best to study your face and appearance from the shelter of the thicket before advancing to a stranger. My excitement and fear of your observing me made me careless, I presume, for I did not notice how nearly your wooden King George was done for until too late to escape his clutches. (I hope it is not an omen.) Down came the oak, and I under it.

"Such is my story, friend Andrew. I am glad to have found one from your household at last. You see before you," and Lord Geoffry again smiled bitterly, "no English spy—only a hunted, hiding follower of the Prince, come to beg for your father's and your pity, and to pray for shelter until escape from this dangerous region is possible. It has never seemed less so than now."

Andrew could contain himself no longer.

"What a blessed chance was it which led me to stay here a couple of hours later than I purposed; simply to finish bringing down that oak! Ah, my lord! You do not know my father! I do. You will be welcome a hundred times to our house, and all that we have. It will go hard if you quit Windlestrae, except in safety. Let us lose no more time in getting down to the Manor, and my father's presence. To him must you tell over your story and at once receive the earnest of his help."

"God bless you both! and after a night's rest I shall be better able to hear and discuss new plans for my welfare," said Lord Geoffry. "A little food might not be amiss either," he added carelessly. There was a peculiar sweetness in his smile and an air of dignity which had already made its fascination felt upon young Andrew Boyd.

"Ay, this is a soldier indeed," the lad thought, "able to endure peril, and hunger, and thirst, and fatigue, and laugh over them!"

The boy caught up his bonnet and plaid and thrust the axe under the oak's trunk. "Take my arm, my lord," he urged courteously. The wearied man accepted it, and they set out.

"There are some questions I ought to ask, friend Andrew, while we go," said the young nobleman, as they entered a narrow, stony path leading upward from the glade. The sunless sky was still bright overhead. "First of all, have the soldiery been prowling around your Manor or its neighborhood?"

"Until lately they have scarcely shown themselves near us. Colonel Danforth and his dragoons are stationed at Neith—as you too well know—with orders from the Duke of Cumberland to arrest any suspected Jacobites. But we have seen nothing of Danforth or his band."

"And what of the Duke himself and the garrison to the northeast, at Fort Augustus?"

"They have been equally quiet. The Manor lies midway between both garrisons; the troopers have harried the settlements closer to their hand. But—but—there is a better reason, my lord, for Windlestrae's being let alone."

"And what is that? Your father's friend, at Sheilar, I think hinted at some special one. I did not pay the heed which I should to his words."

"Why, my lord, my grandfather was an Englishman like yourself; and my father lived thirty years upon English ground, and spoke the English tongue before he came hither to live. Our Scottish neighbors have always counted us Whigs! They have never ceased to suspect my father of favoring the cause of King George—though he has said many a bold word for the Lost Cause. Worse still, my father was too ill to enlist under the Prince, as he would gladly have done; and this has set our neighbors yet more bitterly against him. We have no character as patriots, sir."

"You think that the English troops in the town and at the Fort hold your father a good partisan of their own king?"

"Exactly, my lord; and hence is it, I am sure, that our Manor has been so let alone by the enemy during these past weeks of spying and searching. The ill-color of my father's name shall stand you in good stead. There is no house in Scotland where a Jacobite would less be thought a-lurking or protected. But my father has felt the unkind opinions of his Scotch neighbors very deeply."

"Strange!" said Lord Geoffry, as if to himself, "the hand of heaven seems to lead me still. To find, in the heart of Scotland, Englishmen who are loyal to the Stewarts!"

While they spoke the lad guided Lord Geoffry rapidly along the flinty, steep path, which did not admit of their now walking side by side. It so continually twisted and turned and the trees shut it in so closely that Lord Armitage presently confessed that he could not imagine which point of the compass lay before him.

"We cross directly over the top of this mountain, my lord," explained Andrew. "Windlestrae Manor lies in the valley. We shall presently go down by a steep mountain-road which our wood-cutters use, after we reach a clearing on the summit of the hill, whence you might be able to trace all your late wanderings from Balloch and get a glimpse of the chimneys of the Manor also."

Sure enough, our two quick walkers presently attained exactly this spot—the crown of the ridge. A remarkable prospect was to be viewed from it. The loch lay behind them; on the left, a wooded, rugged extent of country, stretching toward Neith; and descending from their feet, the mountain waving with foliage. In the valley below Sir Geoffry could distinctly see some substantial buildings and tall chimney-pots.

"The Manor," said Andrew, pointing at these last. To the north continued the plain, with wild hills on the west closing the scene—altogether a savage Inverness landscape, not less romantic in the evening light.

But neither wished now to tarry for gazing. They left the cleared space behind. At once began the descent of the hill. Their course was almost a series of plunges. They darted between bowlders, they overleaped trees fallen across the scarcely traceable path; they sprang over tiny cascades pouring down the slope. The excitement of such a rapid journey made Armitage forget well-nigh everything except keeping breath and footing. Andrew noticed that he was not much the better mountaineer of the two.

They landed in a glen at the foot of the mountain. "We cross this," explained Andrew. They did so, and as well two tracts of boggy land. Grain-fields and hay-ricks succeeded, and then the barns and Manor House of Windlestrae were suddenly looming before them. Lord Geoffry perceived that Andrew's father must be a man of wealth. Just as he was about to ask the boy whether it would be well for them to enter the house together, Andrew exclaimed, "Huzzah! There is my father this minute!"

"Where?" asked Lord Armitage, eagerly.

"He comes yonder, through the gate, talking with two of the farm-hands. He usually walks here after his supper."

From the southwest corner of the field approached Gilbert Boyd. He was a tall, gray-haired man, decidedly English in style and feature, but dressed in the usual attire of a Highland landholder of the best rank. He appeared engaged in an excited discussion with two stalwart servants accompanying him. Andrew and his companion could catch the sound of the uplifted voices. Andrew put his fingers to his lips and whistled shrill. The elder Boyd, startled by the sound, stopped short in a sentence and looked up. He perceived Andrew and the stranger advancing.

"Stay you where you are," Lord Geoffry heard him say quickly to the tall servants. Gilbert then came on alone. The fugitive began to wonder what sort of a reception awaited him.

He need not have had any misgivings. The rugged face of the Master of Windlestrae underwent rapid changes as he listened to his young son's breathless story. Then he came striding across to the fugitive nobleman with outstretched palm. Andrew looked delighted enough at this quick show of cordiality to a man by whom he already was not a little fascinated.

As the elder Boyd halted in front of Lord Geoffry the latter instantly decided that he had seldom seen a more naturally commanding figure and a face fuller of resolution than this transplanted Englishman's—his tall, sturdy form, iron-grizzled hair, and keen gray eyes.

"Welcome, welcome, my lord!" he exclaimed; "welcome to the board and hearth of Windlestrae! My son has bidden you be so, and I echo his greeting. Surely all Scotland is at the service of those who have drawn blade for—its rightful sovereign."

The two men shook hands, and Boyd's mighty grip thrilled Lord Armitage's heart. He tried to falter out something about being "an ill-omened bird to flutter to so peaceful a roost."

"Peaceful? Tut, tut, my lord, no roost is peaceful when there be so many hawks in the air. Andrew, lad, run—hasten to the Manor before us. Bid Girzie and Mistress Annan prepare supper and all things suitable for our guest. I must trouble Lord Geoffry with questionings and doubtless make him many answers, while we shall come after you."

Andrew sped away toward the house, which ended the lane. The two older men came on more slowly.

"First, my lord," began Gilbert Boyd, "as my son has surely told you, you have come to the house in this neighborhood where you will be safest from pursuit. My good friends hereabouts have never forgot that my father was Southern-born and that I speak Scotch only when I must. Hence it follows that I am worthy to be hanged as a traitor. For once, though, I am glad that I stand in such sorely false light. The soldiers have troubled themselves little about Windlestrae, and have ransacked many of the loud-mouthed patriots instead."

"And you have had no raidings from Colonel Danforth's troop?" asked Lord Geoffry.

Boyd laughed disdainfully. "His soldiery have occasionally moved toward the Manor, my lord, but even that seldom. I confess, I have been surprised at my good fortune. One afternoon Danforth and his company galloped past the crossroads, a couple of miles down yonder, and asked one of my neighbors, 'Who lives up yonder?' 'Boyd of Windlestrae,' says the lad. 'Well, then, we'll go no further up that way to-day!' cries Danforth; 'that man Boyd is as sound a Whig as ourselves and his wine is most properly bad.' So away they rode, good riddance to them."

"Safe for long or not, I can at least be sure of a supper and a bedchamber less airy than a tree," Lord Armitage responded cheerily; "and both I will enjoy, although Danforth suddenly alter his mind and come to open every closet in your Manor House."

"Hm!" grunted Boyd, with a peculiar expression. "He will hardly do that."

They passed thatched barns and low stables. It was now growing murky and dark. The Manor House was next reached, a rambling but dignified structure, built of gray stone and apparently remarkably roomy and comfortable. Gilbert pushed open the thick oaken door and motioned his guest to enter. One or two servants were hurrying along the wainscoted hall, running in and out of a dining-parlor. Andrew appeared from this, and with him an elderly woman, Mistress Janet Annan, the housekeeper, who courtesied to the master and the unexpected guest. Andrew's mother had died in giving birth to her only child.

The hall and aforesaid dining-parlor were brightly lighted. The excellent supper—to which Lord Armitage did ravenous justice, seconded by Andrew—was hurried through in silence; Boyd absorbed in ministering to the wants of his guest. In the Manor it was already rumored that the master had suddenly met an old friend; and this explanation satisfied the present curiosity of the servants' hall.

"To-morrow morning they shall be told the truth," Boyd said reflectively. "They must not be permitted to gossip. They are all loyal-hearted men and women. And now, my lord," he continued, as Lord Geoffry pushed back his chair from the table and exclaimed, "I am quite another man already!" in his refreshment—"now you must to your rest without a moment's loss. To-morrow we can discuss together the means of forwarding you to the sea-coast. Candles, son Andrew! To the Purple Chamber."

Andrew led the way up a staircase of very respectable breadth and ease. The room designated as "the Purple Chamber"—from sundry faded hangings—proved a fair-sized apartment with three casements and a low-studded ceiling. A formidable four-posted bed and accompanying furniture graced it, and a trifle of fire flickered on the hearth. Gilbert locked the door, as Andrew set down the candlesticks on a tall chest of drawers. "Nay, wait my lad," he said, as he turned toward the door, "I have something to impart to both our guests and you."

In some surprise, Andrew returned and leaned against one of the heavy chairs in silence.

"My lord," began Boyd, turning to Armitage, "you spoke a while ago of Danforth searching the very closets—was it?—of Windlestrae Manor, if once his suspicions that it sheltered such refugees as yourself should be stirred. I care not if he do—provided no earthquake and no traitor disclose to him one of them, built in this old rookery long before my father bought it and added to it. Until this day have I preserved one secret of it from you, son, with the rest. There opens from the wall yonder as snug a hiding-hole as any in Scotland."

"A secret chamber!" ejaculated both Boyd's auditors, following the pointing of his hand.

"Ay," replied he, approaching Andrew, with a smile upon his grim features. "The Mouse's Nest—so my father heard it called. I doubt not that it hid many a Jacobite in the first uprising. Andrew, is yonder door locked? Good. Now mark!"

Boyd pushed back the hangings and pressed his hand steadily on the joining of the wainscot at some spot which he identified after an instant's quick scrutiny. To Andrew's intense astonishment, part of the jamb of the chimney-piece slid back into the thickness of the wall. A narrow door-way was revealed leading into darkness.

Andrew was more surprised at the existence of this unsuspected mystery than Lord Armitage. The latter had been shown many similar hiding-places in old French and English mansions, he declared.

"Let us within," Gilbert Boyd said; and they passed into a long and narrow sort of closet, not more than five feet wide, but of six or seven times that length. Gray stone, above, below—everywhere; rough-hewn and clammy; no plastering. The place would have been scarcely at all lighted, and that only at its upper end, without the candles carried by Boyd. An opening a few inches square, that Andrew discovered, some ten feet above their heads, seemed constructed only to admit air, although a faint light also found entrance thereby.

On the floor lay two or three stag-skins, and a couple of small stools, a taper, and flint and steel; and a pallet in the farther corner completed the furnishings.

Lord Armitage and Andrew surveyed the place curiously, and Gilbert explained the means of opening it and securing the panel from within.

"It has not been used in my recollection, my lord," he said, laughing, as the jamb reclosed. "I trust it may not be; yet if Danforth come too close, your retreat is secure; and I warrant you one he will not fathom! Knowing that I have such a guest-room for such a guest is a rare satisfaction to me to-night."

Father and son then bade the young refugee good-night and left him to get to bed; he declining all valeting from Andrew. Lord Geoffry was indeed so exhausted, and the homespun sheets of Mistress Annan's purveyance seemed so cool, that he fell back into them, asleep, almost as he touched them.

That sound repose lasted far into the afternoon of the next day. The Manor House was kept quiet by the master's order, lest word or foot-fall should waken the young knight out of season. He left his chamber, on Andrew's arm, as the tall clock on the landing of the staircase struck four.

"Ha! you look like a new man!" exclaimed Gilbert; "your color has come back; your eye sparkles like a live coal!"

Seated at the table in the dining-room, the master showed that, while his guest had slept, he had not been careless for his welfare. In the first place, the trustworthy servants of the Manor had been solemnly informed of the situation at morning prayers, and each one pledged to secrecy and assistance.

"And when do you think that I can proceed eastward to the sea-coast?" asked Lord Geoffry, anxiously.

"Within three weeks, I trust," replied the master—"not before. Inside of that time I shall have marked out your route for you, and started you in loyal hands upon it from one shelter to the other. In the meantime, you must abide here with us plain folk of Windlestrae. I am glad to say that we have heard no more of Danforth to-day."

Nor came there any such unwelcome tidings. The day passed quietly, each hour benefiting Lord Armitage in body and spirit. The second night that he slept under the Manor's roof was spent as tranquilly as the first. His strength and vivacity were doubled by it. The next few days he did nothing but eat and sleep, or, shut up for the most part within the comfortable Purple Chamber, talk with Andrew and Boyd or Mistress Annan of his travels and hardships. The rest and a sense of security did him worlds of good, and he grew more entertaining and full of merriment each hour of it.

"I never saw such a fellow!" Gilbert remarked once to Mistress Annan. "One would think that he were at ease and freedom in some court, instead of in daily danger of a hanging! What a careless, happy temper! Hearken to him, laughing this minute with my lad, as though he had never a trouble in the world!"

"And I am na sorry for it, sir," Mistress Annan stoutly responded; "'tis o' God's favor that his heart is sae licht! Wad ye hae the puir man gae roun' wi' the shadow o' the gibbet in front o' his twa bonny eyes?" Mistress Annan, in truth, was quite bewitched with Lord Geoffry's engaging glances and his gay tongue.

Both Andrew and his father observed one thing--how little the young exile spoke of England; of his home there, or of the Lowland life and cities. But he explained this one morning by confessing that he had lived most of his life in Paris, his only brother, Guy, looking after the family estate.

"I am more a Frenchman than an Englishman, I fear," he admitted, smiling; and often, as if unconsciously, he would begin a sentence in the French, that seemed to come upon his lips spontaneously; and the light songs he hummed were echoes of the gay days of Fontainebleau and the court of Louis XV. But, French or English, all the little household agreed that a more gallant, a jollier spirit had never sat at their table, or whiled away long evenings with reminiscences of famous men, fair women, and strange adventures.

It was not until the third day, by the way, that they discovered him to be a Roman Catholic; but then so great a proportion of the Stewart adherents were of the older faith that Gilbert was not displeased. Besides, the refugee was quite as devout at the morning and evening prayers and accompanying Bible-reading of the Manor family as Mistress Annan herself. That good woman was so edified by Lord Geoffry's respect to religion and solemn recognition of Providence in his escapes that she confessed to Girzie Inglis, her head hand-maiden: "Aiblins thae Papists are nae all sic children o' the Deil, as I hae been tauld! Yon's a gude young man—a gude young man! The Lord bring him to mair pairfect licht!"

So passed four days. At noon of the fourth the sky was overcast. In less than an hour thick mist and rain shut out almost all the light, and it grew so dark that the Manor had to be illumined by candles. At supper everybody was in the best of moods; Gilbert at the head of the table, the red firelight showing his grim face relaxed as he listened to Lord Geoffry's keen speeches; Andrew next the knight; and Mistress Annan forgetting to put her cup to her lips or adjust her cap more trimly, in her reluctant enjoyment of such unaccustomed fun. "I fear me 'tis no Christian behavior in me to be sae frivolous!" her Presbyterian conscience whispered; but she laughed all the more in spite of the Presbyterian conscience. Neil Auchcross, Boyd's main manager of the farm, was the only other person for whom a cover was laid. The table was bountifully spread, and Mistress Annan had set it with their store of silver, in honor of Lord Geoffry. In the kitchen the more menial servants were also supping.

Suddenly, in a brief silence throughout the dining-parlor, there came a sound to the ears of each one present. It struck them all alike with alarm. Lusty voices, not far off, were singing together.

"Hark!" exclaimed Boyd, "what do you think that sound can be?"

Auchcross leaped up and threw open the heavy window.

Through the mist and darkness rang into the cheerful old room the notes of a familiar drinking-song:

The trampling of hoofs, the dull clank of steel, accompanied this chorus, borne on the murky breeze of the night.

"Danforth's cavalry!" cried Boyd and Auchcross.

"What! coming up toward Windlestrae?" exclaimed Lord Geoffry, springing from his seat.

"I fear it—I fear it!" muttered Boyd, leaning out of the casement into the driving mist. The rest hearkened at his back, breathless.

The roystering voices, the thud of hoofs and a single whinny, sounded nearer than before.

Gilbert drew himself quickly inside the room again and pulled Neil and the shutters with him.

"It is! It is Danforth!" he cried. "This misty night, of all others! We have not a moment to waste! They may have set out directly for the Manor to see what discoveries can be made here. Very good! Andrew, ask no questions, but assemble all the household in the hall! Neil, go you to find Hugh and Malcolm. My lord, with me to the Purple Chamber—and the Mouse's Nest!"

The singers in their saddles were not fifty yards off by the time Andrew, Neil, and Mistress Annan had executed Boyd's orders, in ignorance of what was to be gained by them; and seen the four or five women and as many men-servants, constituting the Windlestrae household, seated on the benches and stools in the hall. Each one knew what was the imminent danger which had stolen a march on them and their guest. Each was prepared to do all possible to avert it. Mistress Annan and the maids were so white and trembling that Andrew feared discovery through their very looks. But Armitage was his next thought. Turning his back on the confused and whispering group in the hall, he dashed up-stairs.

"Back, son!" Gilbert Boyd exclaimed, sternly, catching the lad in his arms on the landing-place. "Back, I say! He is safe!"

"Safe? Lord Geoffry? Is he in the Mouse's Nest? Oh, father, tell me!"

The sound of the singing, mingled with calls and something like argument, as if the intruders were discussing the direction of the Manor House in the fog, now were clearly audible. Boyd sprang down-stairs into the hall, drawing Andrew with him.

"Girzie!" cried he—"Mistress Annan! They have turned up from the gate! Bring candles—candles—from the table."

They were back with them at once, the grease dripping to the floor through the trembling of their hands. Gilbert motioned them all not to move from the settles along the wainscot. "Sit ye still there," he whispered, hoarsely. He dropped into an arm-chair beside the candles, flapped open some book which he carried, and exclaimed, in a firm voice, "Let us sing the praise—of God—in the Thirtieth Psalm."—and thereupon led off the verse!

Andrew caught the idea that lay behind this extraordinary conduct. But could Windlestrae seem to Colonel Danforth a quiet Scotch household, engaged in the usual family prayers, untroubled by trembling hearts or the care of a Jacobite refugee?

Somehow or other he and the rest found voice to unite in the psalm with the master. Those approaching outside heard the melody. Then came a louder trampling, the thud of dismounting riders, loud, coarse accents, and spurs jingling on the very porch.

A thundering knock broke off the Thirtieth Psalm in its second verse. Mistress Annan gasped audibly in terror.

"Halloo there! Open, in the King's name!" rang out a stern voice.

"Andrew, open the door!" commanded Gilbert.

Andrew obeyed.

In the fog outside flared a torch or two. The candle-lit hall sent forth a pale stream. Five horsemen in their saddles could be discerned—but not Danforth. Nor was Danforth the trooper who had alighted to knock—a short, young fellow with a swarthy skin, a magnificent mustache, and eyes as black as the long, damp cloak tossed back over his shoulder. It swayed as he bowed with unexpected ceremony.

"Is this the Manor House of Windlestrae?—and do I address its master?" he asked, in a commanding but civil tone, peering past Andrew into the hall.

Gilbert Boyd laid aside the psalm-book with studied calmness, coming forward to the doorway.

"It is. I am Gilbert Boyd, the Master of Windlestrae, sir," he responded, courteously. "What is your pleasure?"

Both his own and Andrew's minds were fully prepared for the answer: "I am in the service of the King and have reason to believe that there is now hidden in this dwelling a Jacobite rebel and refugee, Lord Geoffry Armitage."

But, oh, unexpected occurrence! not such was the response. In an accent yet more courteous, the unknown cavalier returned. "Pardon the rudeness of our summons, Mr. Boyd. I fear—I see, that we disturb your evening devotions. The house was so dark as we rode hither that we could scarce tell whether it was really tenanted or not. My name is Jermain—Captain Jermain. I was ordered this morning to convey a message to Colonel Danforth at Neith, and I set out from Fort Augustus with a few of our troop. Unluckily this fog came up apace. Our escort speedily became dispersed. They are now somewhere in the hills, behind. We lost our own road; and, encumbered by a rebel prisoner that we were fortunate enough to capture on the way, we found ourselves almost at your doors before we knew our bearings."

Andrew's heart gave a leap, as he realized that these were not the expected and dreaded guests; but others who came by accident! Evidently they knew nothing of the man hidden within his father's walls. It was an unspeakable relief!

Gilbert Boyd was not a whit behind him in apprehension and gratefulness: "You have, indeed, fared poorly, sir," he said, motioning the young officer to step within his threshold. "What with by-paths and cross-roads the track is difficult in fair weather. I presume that my sending one of my household with you, until you need his guidance no longer, will be a welcome offer."

"For which I thank you," laughed the young trooper; "but, begging your pardon, I don't intend to ask that favor until to-morrow. It is no evening for travelling, Mr. Boyd—and my faith! nothing but a bayonet's point, I fear, will turn me out of your hospitable doors to-night. You must find quarters, no matter how poor, for us few weary men, until daylight. I have learned too much of Highland kindness to fear that you will not—eh? House, barn or shed—it is all one to me and my little troop."

In spite of the ingratiating tone, a command of a sort common enough to all the region at the time, lurked unmistakably in the dragoon-captain's smooth words. Gilbert recognized this. At the precise hour when he was sheltering a proscribed and hunted Jacobite, he must entertain, as best he could, a handful of the very men who, did they suspect the other's nearness, would delight to drag him forth to his death, as, very possibly, they were preparing to do with their prisoner out yonder!

But it was no moment to allow more than a bewildered thought of the untoward complication and how it must be met.

"Gude sauf us!" ejaculated poor Mistress Annan in her heart, "what an awfu' kind o' game o' puss in the corner we're a' like to be playin' this night!"

For she heard Gilbert, with well-simulated cordiality say, "Neil—Morgan—Mistress Annan! Girzie Inglis! You hear? Pray request your companions to dismount, sir. We will offer you and them any such poor entertainment as my house affords. Step within, gentlemen!"

One grateful thought of the infinitely less trying situation that now seemed ahead of him and his family, and another of gratitude at what appeared an uncommon refinement on the part of this young soldier crossed him, as Captain Jermain bowed and prepared to follow. The other dragoons threw themselves from their saddles with exclamations of satisfaction.

"Captain, Captain? How about this Highland wild-cat that we've got on our hands," called one of the party to Jermain, who stood on the porch giving some directions.

"Oh, bring him along with you," returned he. "We can keep him in the kitchen for the present, and find a hole to stow him safely in over-night. Meanwhile, see that no one speaks with him."

Captain Jermain preceded his escort into the hall. They who tramped along at his back were of quite inferior social stamp and address. Two of the party led between them the captured Highlander.

Andrew started back and stared half in pity, half curiosity. The troopers had tied their prize's hands at his back, and he limped, as if in the contest he had hurt his foot. There were stains of blood and soil on his rough garments, and a ragged bandage was tied across his forehead. A thick shock of black hair effectually disguised his sunburnt and unshaven face from close recognition. A more wretched figure it would have been hard to draw. He gave a piercing look at the group in the hall as he passed, as if seeking compassion; but there was too much else to engross the attention of the Master and Andrew for them now to proffer it. Even the women shrunk back as he was forced along. Gilbert directed Angus to show two of the four guards to a small outer room adjoining the rear passage, where Captain Jermain suggested that supper be served them speedily, and thus their charge remain directly under their eyes and ears.

"Sit down, Captain," Gilbert said, as Andrew once more closed the door. "We shall have some refreshment at your service in a few moments. We finished our own evening meal just before you arrived. Be seated, gentlemen."

"I must again regret that we disturbed your family-prayers, Mr. Boyd," apologized the young soldier, dropping into a seat: "I have too much respect for your kindness and for religion, soldier that I am, to willingly disarrange you. Ah, this is a fine old house! It is like a bit of home for a Southerner to slip into such a spot for a night."

"You have not been long in the army?" Gilbert inquired.

"Oh, dear, no," returned the young captain, stretching out his long legs luxuriously—"only a couple of months, and all of those loitering about the Fort. I haven't gained much military experience, I dare swear, by all this famous Rebellion! Have I, Mr. Dawkin? Have I, Roxley?"

Two of the other men laughed; and confirmed Boyd in his idea that this was a very simple-hearted young soldier, a good theorist likely, but not much experienced in anything except fox-hunting, or slaying soft hearts at Lowland balls. Very boyish and frank did he look, sitting there, in spite of his dignity and manliness; and also very much like a boy was his evident enjoyment in finding himself so comfortably situated. In spite of his apprehensions, Gilbert could not help fancying this Achilles the pride of some Surrey household, the darling of some mother whose breeding of him all the rough life of a barracks had not effaced. How much worse the peril would have been if such a guest, forcing himself on the household, were a rude, wary old officer full of strange oaths, exactions and suspicions of everybody and everything about him! "Praise be to God!" Gilbert exclaimed, in his soul, "for we may tide over the danger yet!"

He led the conversation with increased self-control into such topics as could be discussed in common. Each sentence went further in convincing Captain Jermain, as well as his two companions, that they were meeting quite the most frank and friendly of hosts.

Girzie appeared and announced the supper, hastily got together by Mistress Annan's trembling but energetic hands.

"Walk into the next room, captain. This way, gentlemen," said Boyd, rising. Then, turning to Andrew, he added, with a meaning look, but no accent in his voice that might awaken any interest in his remark among the enemy. "My son, step upstairs and see if you can be of use. The East Room will be wanted—tell Mistress Annan so."

The three troopers, headed by Gilbert, passed into the dining-parlor.

Andrew stood bewildered. His father had surely intended some special reference to Lord Geoffry Armitage! Was Lord Geoffry waiting all this time within ear-shot? Andrew could hardly force himself into walking toward the stair with assumed indifference—to mount step after step leisurely, as if reluctant to quit the sudden stir going on below and the company of the soldiers.

All was dark as he turned toward the landing. The boy's nerves were by this time strained intensely. He nearly uttered a cry as he ran into a figure kneeling at the top of the staircase. Lord Geoffry's strong clasp about him and exclamation of caution saved him.

"Oh, my lord, my lord! Have you heard? Do you know it all? It is not Danforth!" Andrew whispered, still clasped in the imperiled young nobleman's arms.

"Yes, yes, dear lad! I have been listening. I stole out from the Mouse's Nest and the Purple Chamber—I can retreat to it again at an instant's warning, you see! Be calm, dear Andrew. Do not tremble so. I am yet safe."

"But, my lord, they may discover that you are here!"

"I do not know how," whispered the fugitive. "We have no traitors, and walls have not tongues." He pressed the Highland boy yet more warmly to his breast, as if in that hour of ill-fortune, standing there within ear-shot of his foes, he was glad to feel a human heart so near him, however young, that he knew already loved him too well to betray him, even at the point of the bayonet.

The boy murmured passionately in his ear: "If you—are taken—I shall die!" all of a tremor, that came from dread and love.

"Pshaw! Keep up heart!" hoarsely replied the young nobleman, with something like tears in his voice at the gallant lad's devotion; "you must not die, nor must I, either. We shall all come out right and safe, I am sure. Quick—back to that handful of knaves below! I can see already that they have a bigger child than you for their leader. Find out for me, if possible, who is their prisoner. Contrive to let your father know that I am in spirits—that is why he sent you. Go, play your part well. My life is in your hands too, remember."

"I shall, I shall! But oh, my lord—go back to the Mouse's Nest. Promise me that you will."

"So be it!" And Andrew thought he heard the intrepid young man laugh shame-facedly at yielding to his terrified importunity, "I promise!" Then they pressed hands and parted in the gloom.

Andrew entered the dining-parlor timorously. He made his way thither by the little passage into which opened the outer kitchen containing the Highland prisoner and his guards. It was shut. The servants, who questioned him eagerly as to Lord Armitage's security, told him that to knock at the door was only to have one of the guards come to it and slam it in his face. They would allow nobody within but themselves.

His father sat at the head of the long table, only half of which was laid. The three cavaliers had begun hungrily on meats, bread, and potables.

"Come and sit down here, my lad," called out Captain Jermain kindly, well-disposed to pay some attention to his host's attractive son; "you are a fine, tall fellow. I dare say you will be carrying the king's colors yourself one of these days—eh?"

Andrew seated himself between the captain and Gilbert. A glance passed between father and boy as he did so. Boyd read in it a quick reassurance upon the state of mind of Lord Armitage above-stairs.

A man who better liked plain-dealing than Gilbert Boyd of Windlestrae it would be hard to light upon. To seem to be what he was not stifled him. Nevertheless, his feeling of sacred duty to the fugitive, to whom he had sworn protection by every lawful means, induced him to waive scruples and to preside at this supper with a remarkable simulation of calmness and of desire to make the three soldiers at ease in the Manor. As far as possible, he diverted the talk from politics, where he must and would betray himself rather than lie! "I have been rumored a Whig so long to no good," he thought, resignedly, "that I may as well let the error keep alive on such a night as this, when it can save a life. Humph."

Presently he said aloud: "Help yourselves freely, gentlemen. I am sorry, by the way, that the Manor can offer you no better liquors than our own ales and usquebaugh."

"Oh, no apologies, no apologies," replied Captain Jermain. "This is the very lap of luxury for us. I trust that when these troubled times end—and his ragged Princeship with his bare-legged support are hanged—many a hospitable Whig like yourself will call upon us in London, or anywhere else, and be repaid for your trouble in kind. To your health, Mr. Boyd!"

"Be entirely at ease, sir, as to trouble," Gilbert answered, raising his ale-glass; "there is always room and to spare in this old nook."

Andrew nerved himself in the instant of silence ensuing: "Was the prisoner that you captured—was he—a person of consequence, sir?" he faltered.

Roxley, the elder of the two other troopers (and who, Gilbert soon decided, was a special favorite with the young captain and a man of some petty rank), exclaimed, with a sneering oath: "Consequence? I should scarce think so!" Jermain, however, bent his eyes pleasantly on the embarrassed boy, and replied: "Faith, no, my young warrior! A tattered and villainous hind, lurking about, whom we sighted slipping into a copse two or three miles above the crossroads."

Our hero longed to put the captive upstairs in possession of even this slight portion of what he desired to know. But Boyd took up the cue intuitively.

"Did you run him down?"

"Ay. By some awkwardness the villain tripped; and though he wrestled with Roxley like a tiger, and won sundry thumps and cuts for his pains, we managed to master him. He is all bone and muscle, I verily believe."

"Simply a wandering spy, Captain, depend upon it!" affirmed Dawkin. "Whatever he was busy about," he continued, to Andrew's father, "he refused to speak a syllable of, in spite of all our little measures—ha, ha, Captain! But we will see what the guard-room at Neith can do for him to-morrow. Here's to his obstinacy after Danforth gets hold of him!"

"His straps must be looked to sharply before we go to bed," suggested Roxley.

"Yes," added the captain, drinking; "'tis a pity that Tracey and Saville must lose their sleep to-night on his account."

Boyd shuddered at the mention of those "little measures," and the persuasions of the Neith guard-room. The Spanish boots, the whip-corded eyeballs, the thumb-screw, and brimstone-sliver were meant. God help the poor wretch who became Danforth's victim! Clearly nothing more was to be discovered as to the prisoner from his captors. Andrew determined to slip back to the outer kitchen, and thence up to Lord Armitage with just so much intelligence as he had come by. But he would do well to wait until the exactly right excuse should offer for his leaving the room. The troopers pushed back their chairs and refilled their glasses of whiskey-and-water. Good cheer began to tell on their tongues. Jermain rose, stretched himself, and stared about the room in great good-humor. He noticed a small hanging-shelf with half a dozen books on it, and thereupon turned amiably to Andrew.

"So you go to school up in this forsaken region of the kingdom, do you, Andrew? You remind me not a little of a fair young cousin of mine, Eustace Jermain, down in Warwickshire. He is now a scholar, too, prosing away at some Oxford college."

"I have always been at school when there was any school to go to, sir. But my father has taught me for the most part, and once or twice I had a tutor, by good luck."

"And I, too, by ill-luck!" The young man laughed, sauntering up to the shelf and glancing over the titles. "What a life I led them! Ah! 'The Pilgrim's Progress,' 'The Call to Truth,' 'Common Prayer,' 'An History of Rome,' 'Virgil's Æneid—' So you know Latin here, friend Boyd? I used to know it myself. How begins old Virgil?—

it goes, don't it?" He opened the volume idly. In so doing his eye fell upon the title-page.

He read the name written there with an exclamation of surprise. Then holding the Virgil he came back to his chair, puzzling over the fly-leaf. Next he smote his hand upon the board with an impetuous, "By the sword of Claver'se! 'Jonas Lockett, His Book.' Can it be the man? What Jonas, except our long-legged Jonas, wrote that cramped fist? Tell me, friend Boyd, was Jonas Lockett, an Edinboro' pedagogue, ever in your house, here, a certain winter?"

"One of my son's instructors, years ago, was so named," replied Boyd, cautiously. He did not like to give these interlopers the least significant bit of information upon his family or its history.

"Was he from Edinboro'? Tell me of him. Well, well, well—Jonas Lockett! Ha!"

"There is little to tell, sir. I understood that he was from Edinboro'. His health suffered there and he travelled into Perthshire and Inverness to recruit it. He was poor and somehow came to me for help. Andrew's ignorance enabled me to give it him. But he only stayed with us a season. I have scarce thought of him since. Did you know him also?"

"Know him! Truly I did. I recollect that he came from Scotland directly before he entered my father's employ. A tall, lean, quick-spoken fellow, with a sly eye and many odd stories at his tongue's end."

"The same, I dare say," Boyd assented, indifferently; "an odd coincidence. But the world is a narrow place, Captain."

Andrew glanced uneasily from one face to the other. Was even this trivial discovery likely to breed the seed of any fresh danger? Danger lurked in every turn of thought or speech.

Jermain continued turning over the leaves of the Virgil absently.

"Upon my honor!" he suddenly cried, throwing down the book; "of what have I been thinking? This, too, must be the very old Scotch house that Lockett told me all about one evening at the Parsonage! I declare—I have heard of you and it before this night, friend Boyd. I remembered it not until now."

"Ah!" came Gilbert's dry monosyllable. Boyd's whole being was at once wholly on the alert. Andrew thought it best not to make for that outer door quite yet.

"Nor is that all," continued the young officer, draining his glass. "I dare wager that through Lockett's describing his life here that winter, besides his being a famous hand to poke and pry about and meddle with other people's concerns, I know a rare little secret of you and your Manor House, friend Boyd."

"Captain Jermain! How—what?—I do not understand you, sir!" exclaimed Gilbert, growing pale and turning sharply upon the young soldier. Andrew grasped the arm of his chair so tightly that his knuckles were white. Peril, relentless peril—could it be possible?—and from so remote a chance! Dawkin and Roxley looked around from their discussion, surprised at the excited turn the talk behind them had taken.

"What's all this in the wind now?" asked Dawkin.

"Nothing, except that I am in possession of a family mystery of friend Boyd's here," returned Jermain gayly, "or I think I am. Forgive me, Boyd, but the jest is too good! Let me explain. You must know that Lockett slept sometimes in a room in your old house called—what the mischief was it called?—the Green—the Red—no, the Purple Chamber! That's it, the Purple Chamber; and opening out of this Purple Chamber is a secret room, to be got at by a spring-panel in the wall; a most curious old place altogether—and, by the by, perhaps just the sort of strong room that Tracey and Saville have been wishing for to shut that slippery rascal into to-night. Ha! ha! ha! Boyd, I'm sorry for you, for you see that I did know this little family secret after all, did I not? Oh, man, don't look so tragic over it. See his face, Roxley! By all that is hospitable to mad wags like ourselves here, you shall make amends for your soberness by taking us all upstairs and helping us to find out this wonderful hole. Up, Roxley! Up, Dawkin!" continued the domineering young trooper, already excited by the usquebaugh and full of a boyish delight at having someone to tease who was quite in his power; "you, too, my blue-eyed Andrew! Your father must pilot us upstairs at once, or he is no honest host. Huzzah!"

"Huzzah! huzzah!" chimed in Roxley and Dawkin. Jermain seized the candles, and, laughing boisterously, forced one of them into the terrified Boyd's hand. Roxley caught hold of the master's arm. Boyd stood between them, the color of the wall, rigid, his eyes conveying to Andrew a despairing signal. Through the crack of the door were peering Mistress Annan and some women-servants, with blanched cheeks.

Ruin had stalked in a few seconds into their midst.

Terrible was the temptation to Gilbert Boyd as he was held there in the half-sportive, half-brutal grasp of the dragoons. Yet might one bold falsehood save everything! How easy to cry out, "That wing of my house was burnt to the ground years ago!" or to declare that the Mouse's Nest itself had been opened up and its secrecy destroyed—one of a half-dozen other excuses, proffered with the dignity of a man in his own house might avert the calamity precipitating. Hospitality—the saving of a guest's life—did not these cry out for a lie?

But he did not utter it. Not he, Gilbert Boyd, of Windlestrae. It was not because with the thought of falsehood he remembered that those beside him would probably exact proof. It was because too keenly upon his conscience pressed the acted-out departures from strict truth of which this bitter evening had already made him guilty. These must be none worse henceforth. He would obey his God; and God would sustain him and his. Nevertheless he was mortal man enough to protest, as he wrested his wrist from the familiar grasp of the leering Dawkin and stood commandingly before the trio: "Gentlemen—Captain Jermain—you have forgotten yourselves! It—it is impossible! The room—the room is all in unreadiness. Mistress Annan hath charge of it—I cannot take you into it to-night. Let me go, I beg, Captain! You carry your wild humors too far."

"Oh, no, Boyd, not a step too far," retorted Roxley, "provided you carry us upstairs with you."

"But—but—I assure you, gentlemen, the—the Nest is wholly unfit for the purposes of a prison. Listen to me, Captain Jermain, I pray. Only be reasonable, Mr. Roxley! It is not in repair; and we have under our roof another, a much securer place of the sort, if you insist on one——"

"Hardly, Mr. Boyd, I dare wager," interrupted Captain Jermain, laughing afresh at what he counted Gilbert's absurd annoyance over the "family secret."

"A strong, well-barred room in the East Wing, overhead, that was fitted up for a gaol, and hath been so employed before now. I will send and have it made ready to show you, gentlemen. Release my arm, Captain, I insist! I will not consent."

Jermain, Dawkin, and Roxley seemed the more amused at his annoyance. It was plain that only forcible resistance would check their folly, and forcible resistance was not to be, for an instant, considered.

Had Lord Armitage been listening? Ought not he to be within the Mouse's Nest—out of earshot? He must be warned and extricated. Andrew responded to that intense look from his father's eyes by a quick step toward the hall-door, frantic to dash headlong up the dark stairs and transmit an alarm through the panel in the Purple Chamber. Ah, by his own pledge he had made more certain the doom of his friend! By his own pledge!

But the captain interrupted him by a single stride. "Hold there, friend Andrew, my bonny Highland chiel! No dodging upward to warn any pretty faces that have shut themselves into this same old room. They shall be gallantly surprised by a serenade before their portal. Here!" continued Jermain, snatching a candle from the elder Boyd, and bestowing it in Andrew's unwilling grasp; "you shall head the exploring party! Huzzah!"

With one arm about Boyd's neck, and holding Andrew between Roxley and himself, Jermain set the unsteady procession on the march from the dining-parlor and out into the hall, the three shouting boisterously: "Above-stairs, all of us! Huzzah!" and singing, like the caricature of a death-hymn, as they approached the first step, that roystering refrain:

In the meantime Lord Armitage had been sitting on one of the two stools in the Mouse's Nest. That retreat was quite too dark for him to see his hand before his face, except precisely in the corner where he was resting. Into this the high opening in the wall, alluded to, seemed to filter a gray gleam.

The young refugee realized that his present insecurity was great; but he had been in deeper danger before it, and that self-control which had rather disconcerted Andrew during that moment they had been standing at the stair-top was not much assumed.

"Bless the boy!" he muttered; "it is something to have won such a stout young heart! Ah, if ever I get away from this accursed land, where death dogs my footsteps to trip me up, Andrew, you shall not be forgotten, depend upon it. But, gadzooks! it looks now very little like my conferring care or honor upon any man, young or old!"

He rose and peered curiously up at the aperture in the blank, black wall, with his hands clasped behind his back.

"A strong draught from that, I note. I wonder with what it communicates? Some sort of an air shaft probably. Faugh, what a den is this! A day or so within it would go far to bring a gay fellow like me to suicide—provided he could lay hand on aught here to take himself away with. When can Andrew get back here to bring me word of the prisoner below? Would to God I knew! My mind misgives me. If it be from them, after all—! Still, still, there are so many of our gallant fellows hiding in thickets and caves. If it were Cameron or Lochiel it would break my heart. That peasant-woman last week told me that she had given shelter to a gentleman of the Prince's army only the day before! Oh, Andrew, Andrew, my lad! make haste, for I am in worse dread for others than for myself until you ease me."

He went softly—though there was no need, for the floor was stone and only the under-arching thickness of the partition was below—down the length of the Nest in the darkness, feeling his way along the wall until he perceived that he stood alongside the sliding panel. A narrow, almost undistinguishable crevice marked it out. He put his ear to this, as he had done a score of times since his entrance; but he could not catch the slightest sound, so impervious and exactly adjusted was the barrier.

"I cannot stand it!" he ejaculated, feeling for the iron lever, a simple turn of which, followed by a prolonged and equable pressure, would slide back the panel. "It is a risk. Andrew is right. Any one of those miscreants may take it into his head to go prowling about the halls or chambers while the rest are at supper. But I must get some inkling of what is going on in that dining-parlor! Andrew may be on his way to me, too."

He moved the lever. A slight tremor—a widening of the crevice—in an instant he perceived that the massive jamb had retreated.

All was dark. He thrust forth his arm and touched the under-side of the thick hangings along the wall of the Purple Chamber. Then he slipped out beneath their folds, like a cat, and stood again in the great room itself—alone. Apparently no one, friendly or hostile, was on that second story as yet. Tiptoe he ventured toward the closed door, the outline of which he could trace.

But he caught his breath as he came to it and set it ajar with trembling caution. He had stolen forth from the Nest exactly as the bustle below, the voices, laughter, and singing culminated in the audacious demand by Captain Jermain that the mysterious secret-chamber be laid open for the diversion of himself and his companions. Boyd's protests he could not hear—nor see the scene at the table—nor guess how it had come about. He heard only the pushing aside of the chairs, the drunken march into the broad hall, the hoarse—

the reiterated cry: "Above-stairs, all of us! huzzah!"

The tone in which that drinking song was sung, those words uttered, assured him that it was not betrayal, but some new train of concurrent circumstances, that was bringing about a startling move. He dared not lock the door. He leaped back, stumbled headlong toward the chimney-piece, tossed aside the arras and threw himself within the Mouse's Nest, with the pant of a hunted stag. To seize the lever was the gesture of a half-second. He could bolt the panel to all outsiders as soon as it shut. Excitement guided his hand truly in the dark. He pushed and pressed. The panel slid obediently back toward its deceptive resting-place. In doing so it creaked slightly—an ominous occurrence that had not accompanied its previous passage. He tugged harder at the lever as, with the creak, something seemed to resist his hand.

Up the stairway was coming the tramp of the soldiers and the two Boyds. He could overhear more merriment. He pushed with all his might. It was useless labor. Within some three inches of closure, for its bolting, the mechanism operating from the within-side of the panel suddenly had refused to act. Everything stood still—perfectly, terribly still. A wide black crack must inevitably be visible to any person who should draw aside the arras of the chamber wall!

"I am lost if the villains have lighted on the secret of the Nest!" the endangered nobleman exclaimed, in sudden realization and despair. "Oh why, why did I not bethink me that I might not be able to close it—through some weakness of the old apparatus? The chase is up!"

The next moment the shine of candles below the folds of the arras—the loud banter and laughter of Jermain—broken sentences from Boyd—came all within a few yards' length, as the quintet stood within the Purple Chamber.

The young man crouched down. His teeth were set to meet the extreme of his peril. The perspiration oozed from his forehead.

"Once for all, gentlemen," came the angry tones of Gilbert Boyd, amid the scuffling of feet, "I swear to you that no hand but mine shall ever, with my consent, disclose this secret place, however near it may lie to us—and, as I live, it shall not be so disclosed this night!"

"Oh, but it must be, and shall be!" retorted Jermain, more delighted than ever at prolonging and enjoying the old Master's concern; "away with your silly family pride, Boyd! You have too much sense for it."

"We'll never tell, Boyd," said Dawkin; "will we, Roxley? Oh, 'tis rare sport!"

"Never," assented Roxley; "hold up the candles, Andrew, that we may all guess at the very spot."

"Beware, gentlemen, how you tempt my patience further! Surely, you see that I am past the humor for such folly! Leave the room with me, Captain Jermain! I command it—I adjure you all, by the laws of hospitality and courtesy——"

"Ha! ha! ha!" laughed the three tormentors. Had they been less influenced by the excellent cheer at the table just quitted, one or all of them must have by this suspected a deeper motive for Boyd's recusancy. But, as it was, it all was taken with the other details of the scene—an obstinate and proud Scotch householder, unwilling to share a petty secret with some gay guests.

"And I—I adjure you," mimicked Jermain, "by the laws of hospitality and courtesy, not to cross my pleasure so peevishly. Ay, there is the chimney! Lockett particularized the chimney. Behind the corner of the arras, just about where that figure of the Prodigal Son is worked, must lie the plate set in the angle of the stone——"

Lord Armitage stiffened his muscles. "If I had only caught up one of those stools yonder, the battle should begin from my side!" he grimly reflected. "Stay—I must not give them one extra inch of vantage. I will creep into yonder farthest corner—lay hand on a stool, crouch—and wait for them!"

"Oh, merciful God!" thought, or rather prayed Andrew, on the other side, clutching the candles and white as one who swoons. "Does he hear? What can he do? Save him, save him, O Lord—for only thou canst preserve him or us now."

Dawkin made for the chimney-jamb, exclaiming: "Come, I'll draw back the Prodigal from his husks!"

Before he could reach it, Gilbert, desperate, careless of any further pacific measures, seeing in mind nothing but imminent bloodshed, leaped between him and the chimney. Indignation had altered the very fashion of his countenance.

"Hear me, sirs, for the last time!" he cried; "by the God of my fathers, who hath preserved me and mine within this house until these hairs are white, not one step further into its secrets or secret chambers shall you take, nor dare any longer to indulge this unsoldierly curiosity and insolence! I mean what I say. No, I will give no reasons except what I have given, what common decency might prompt to you. This impudent business stops at once. Take away your hand, sir! Put down your arm, fellow! Call it over-respect to my family and its trusts, or call it what you may, I swear that I will strike down the man who sets a finger upon this arras! Must I call up my servants to protect us from you?" [Four or five of these last were already waiting wherever a man could lurk in the hall or adjoining rooms, trembling for their master's safety, and only restrained by Neil from running into the Purple Chamber to chastise the insolent troopers.]

Half-intoxicated though he was, this vehement speech and the gestures accompanying it were enough to change the mood of Captain Jermain to irritation. He turned red, gave a short, hard laugh of contempt, and uttered an oath—with which he darted forward to seize the arras. He slipped, laughing triumphantly, beneath Boyd's extended arm. He clutched the tapestry with a violent pull. The rusty nails above yielded. Down fell the Prodigal and his Swine, partly overturning both disputants. A cloud of dust rose; and, as it cleared away, a cry of surprise broke from the lips of all the group. There, exposed to full sight, rose the broad crack! The panel was unmistakable, because partially open! "O Almighty Protector!" thought Gilbert, a thrill of hope entering his heart, "he overheard—he had time to escape from it."

"Yes, he has escaped—he has escaped!" ejaculated Andrew to himself; "not yet in their power, not yet!"

"Open?" cried Jermain. "Yes, by the sword of Claverhouse, it is open! The easier for us to take our look at it, but a bad sign for its safety as a prison to-night. Let's see—will the doorway widen if we push at the old panel."

There was no sound from the cell. Captain Jermain approached the opening. Boyd could make no further resistance—he wondered whether he might not have undone the success of some defence on his guest's part, as it was; for as Roxley and Dawkin stepped toward the wall Gilbert gave a sigh of exhaustion, and then sank back upon an arm-chair in a half-faint.

Mistress Annan darted into the room unobtrusively, but looking like an elderly Scotch ghost in cap and spectacles, and began chafing her master's cold hands. Andrew would see it out to the end. "If he be there, and if they seize him, I will strike one of them down for him," thought the lad. The end, the end was at hand—life or death in it!

"Works like a charm!" cried Jermain, now quite forgetting his fit of passion in the indulgence of curiosity. "There, we can pass! Ugh! What a stinking hole!" The lever, to outside persuasion, offered no reluctance to move. The door, truly, was wide open. Blackness of darkness—a rush of chill, malodorous wind. But no outrushing or defiant figure!

"Give me one candle, boy," said Jermain—"hold the other before us. So. Watch well your feet, lads. These odd nooks often have holes and traps in their floors." With these words he stepped inside the Nest.

Face the worst, within that pit of gloom, Andrew must. But he contrived, in obeying the command to accompany the three, audaciously to stumble against the captain on the very sill. The latter's taper was thereby cleverly dashed from the candlestick. It rolled to some dusty nook quite beyond their feet.

"Awkward lout!" exclaimed Jermain; "but never mind; one candle shall serve."

Making even it waver as much as he could (a process very easy in the state of his nerves) they advanced well within the Nest, Jermain and the others more awed each step by the dismalness of the retreat, but all talking loudly. No Lord Armitage at bay, desperate, yet faced them. And they moved on—on—now to the very end of the narrow apartment, where were placed the mothy stag-skins and the two stools. Everything seemed undisturbed, as if during the lapse of decades.

"Well, 'tis a dull discovery after all, so far, I admit," said Jermain, peering now to the right, now to the left, or glancing toward the cornice, all a black void some twenty-five feet overhead, in such wretched illumination. "Not worth while to have so hot a question with—ha, ha—friend Boyd, over it! Yes, here we are at its end, I declare. Nothing beyond this dead wall, of course. Look, Roxley, how rough the courses are—how strong."

"There seems to be a glim of light somewhere there," Dawkin remarked, pointing up to the square aperture previously mentioned. "But 'tis a vile den for any poor wretch to be shut into. Plenty snug enough for that Highland dog, though."

"Ay," replied Jermain, frowning, "provided it be secure. Let's back to look. Steady—beware of this uncertain floor. Dawkin, thou wilt need all Andrew's candle-light for thine own share, thanks to the last two glasses I filled thee."

Could it be possible? Andrew was dumb with gratitude. For he realized that, tired of their own rudeness and curiosity, Jermain, Roxley, and Dawkin were retracing their steps to the open panel, and that for all the harm that had been done him by Jermain's acquaintance with the place of his concealment and this visit to it, Lord Geoffry Armitage might as well have been a thousand miles away!

But far more inexplicable was the mystery than he divined; until, on the heels of Dawkin and the other two, he was crossing the threshold. He saw his father standing a few paces outside, himself unable to solve the riddle, but full of thankfulness for that which he felt was the veritable overruling of God's power. He saw Captain Jermain offer his hand with a stammered apology. He heard Roxley call to him, "Come forth, youngster, we must shut up this panel and try what kind of a lock it hath upon it, and then back to the merry board, my friends. Halloa, look, look you at this, Captain. Here, Boyd, don't bear malice, man, but give us your counsel a moment."

And then—and then—just as Andrew hastened to obey Roxley, a voice spoke his name: "Andrew—Andrew." That was all; uttered in a startling, almost magical, whisper. It came from somewhere over his head, like speech evoked from the dense shadow itself.