Transcriber’s Note

The cover image was created by Susan Ehrlich from elements of the original publication and is placed in the public domain.

See end of this document for details of corrections and other changes.

GALLIPOLI DIARY

BY

MAJOR JOHN GRAHAM GILLAM

D.S.O.

LONDON: GEORGE ALLEN & UNWIN LTD.

RUSKIN HOUSE 40 MUSEUM STREET, W.C. 1

First published in 1918

(All rights reserved)

[5]

In the kind and courteous letter which you will read on p. 15 General Sir Aylmer Hunter-Weston says that it is not possible for him to write a Preface to this book. That is my own and the reader’s great loss, for General Hunter-Weston, as is well known, commanded the 29th Division at the landing on the Gallipoli Peninsula on April 25, 1915, and during those early months of desperate fighting, until to the universal regret of all who served under him he became one of the victims of the sickness that began to ravage our ranks; and as one of the chief players of the great game that was there enacted, his comments would have been of supreme interest and would have added immeasurably to such small value as there may be in this Diary of one of the pawns in that same game. But since the player cannot, the pawn may perhaps be allowed to say a few words by way of comment on and explanation of the following pages.

Towards the completion of the mobilization of the 29th Division in the Leamington area in early 1915, I heard secretly that the Division was bound for the Dardanelles at an early date, instead of for France as we had at first expected. By this I knew that in all probability the Division was destined to play a most romantic part in the Great War. I had visions of trekking up the Gallipoli Peninsula with the Navy bombarding a way for us up the Straits and along the coast-line of the Sea of Marmora,[6] until after a brief campaign we entered triumphantly Constantinople, there to meet the Russian Army, which would link up with ourselves to form part of a great chain encircling and throttling the Central Empires. I sailed from England on March 20, 1915, firmly convinced that my vision would actually come true and that some time in 1915 the paper-boys would be singing out in the streets of London: “Fall of Constantinople—British link hands with the Russians”; and I am sure that all who knew the secret of our destination were as firmly convinced as I was that we should meet with complete success. We little appreciated the difficulties of our task.

For these reasons, and perhaps because the very names—Gallipoli, Dardanelles, Constantinople—sounded so romantic and full of adventure, I determined to revive an old, if egotistic, hobby of mine—the keeping of a diary. Throughout the Gallipoli campaign, therefore, almost religiously every day and with very few exceptions I recorded, as I have done in the past, the daily happenings of my life and the impressions such happenings made on me, and the thoughts that they created. The diary was written by me to myself, as most diaries are, to be read possibly by myself and my nearest relations after the war, but with no thought of publication.

But when the Division was in Egypt, after the evacuation, and just prior to its embarking for France, a Supply Officer joined us whom I had met and talked to on the Peninsula, as one meets hundreds of men, without knowing, or caring to know, anything more about them than that they are trying to do their job as one tries to do one’s own. His name is Launcelot Cayley Shadwell, and we became firm friends. We talked often of Gallipoli, and one day, in France, I showed him my diary. He read it, and then told me that I should try to get it published. I laughed[7] at the idea, but he assured me that these first-hand impressions might interest a wider circle than that for which they were primarily intended, but that beforehand the diary should be pruned and edited, for of course there was much in it which was too personal to be of interest to anybody but myself. I asked him if he would edit it for me. He consented, and very kindly undertook the necessary blue pencilling, and in addition to his labour of excision was good enough to insert a few passages describing, so far as words can, the exquisite loveliness of the Peninsula. For these, which far surpass the powers of my own pen, I am deeply indebted to him. They will be found under dates:—May 2nd, Moonlight at Helles; May 13th, The sensations one experiences when a shell is addressed to you; May 26th, Moonlight scenes; May 30th, Colouring of Imbros; July 15th, Alexandria; September 16th and 17th, The bathing cove.

I am also indebted to the kindness of Captain Jocelyn Bray, the A.P.M. of the 29th Division on the Peninsula, for many excellent photographs.

The diary next had to be submitted to the Censor, who naturally refused to pass it until the Dardanelles Commission had finished its sittings, and it was nearly a year before it came back into my hands, passed for publication, but with a few further blue pencillings, this time not personal, but official. And in this form—hastily scribbled by me from day to day, with a stumpy indelible pencil on odd sheets of paper, pruned, edited and improved by Shadwell, and extra-edited, if not notably improved, by the Censor—my diary is now presented for the consideration of an all-indulgent public.

Enough has been said to show, if internal evidence did not shout it aloud, that my diary has no literary pretensions whatsoever. I am no John Masefield, and do not[8] seek to compete with my betters. Those who desire to survey the whole amazing Gallipoli campaign in perspective must look elsewhere than in these pages. Their sole object was to record the personal impressions, feeling, and doings from day to day of one supply officer to a Division whose gallantry in that campaign well earned for it the epithet “Immortal.” If in spite of its many deficiencies my diary should succeed in interesting the reader, and if, in particular, I have been able to place in the proper light the services of that indispensable but underrated arm, the A.S.C., I am more than content.

I have now seen the A.S.C. at work in England, Egypt, France and Flanders, as well as in Gallipoli, and the result is always just the same. Tommy is hungry three times a day without distinction of place, and without distinction of place three times a day, as regularly as the sun rises and sets, food is forthcoming for him, food in abundance with no queues or meat cards. The A.S.C. must never fail, and it never does fail, for its organization is one of the most brilliant the Army knows. But few, other than those in the A.S.C. itself or on the staffs of armies, can appreciate its vastness and its infallibility. To do so one should watch the supply ships dodging the enemy submarines and arriving at the bases, the supply hangars at the base supply depots receiving and disgorging the supplies to the pack trains, the arrival of the trains at the regulating stations on the lines of communication, whence they are dispatched to the railheads just behind the line, the staff of the deputy directors of supplies and transport of armies at work, following carefully the movements of formations and the rise and fall of strengths, to ensure that not only shall sufficient food arrive regularly each day at the railheads, but that there shall be no surpluses to choke the railheads. It is hardly[9] less important that there should not be too much than that there should not be too little.

The slightest miscalculation may easily lead to chaos—to the blocking of trains carrying wounded back and ammunition forward, or the deprivation of a few thousand men of their food at a critical moment. One should watch the arrival of the supply pack trains at the railheads where the supply columns of motor lorries or the divisional trains of horse transport unload the pack trains and load their vehicles, regularly each day at scheduled times, under all conditions, even those caused by a 14-inch enemy shell bursting at intervals of five minutes in the railhead yard, causing all and sundry to get to cover, except the A.S.C., who must never fail to clear the train at the scheduled time. One should watch the divisional train H.Q. at work, following its division and arranging for the daily correct distribution and the delivery of the rations to units. Often horse transport, by careful managing on the part of train H.Q., is released for other duties than those of drawing and delivering supplies to units. Then one may watch the A.S.C. driver delivering R.E. material, etc., to the line, along roads swept by high-explosive shell and shrapnel and machine guns, where all but the A.S.C. driver can get to ground, while he must stand by his horses and get cover for them and himself as best he can. Then, although one has only seen the skeleton framework of this vast service, and has had no opportunity to go into the technicalities of the system or to investigate the many safety valves of base supply depots, field supply depots, reserve parks and emergency ration dumps in the line, all of which are ready to come to the rescue should a pack train be blown up or a convoy scuppered, nor to study the wonderfully efficient organization of transport, covering mechanical transport,[10] horse transport, Foden lorries and tractors which ply from the base to the line, carrying, as well as supplies, ammunition, R.E. material, and every imaginable necessity of war, and moving heavy guns in and out of position, at times under the very noses of the enemy, yet one cannot fail to have gained a great respect for that vast and wonderfully silent organization, the Army Service Corps.

J. G. G.

France,

May 1918.

[11]

| PAGE | |

| PREFACE | 5 |

| INTRODUCTION | 15 |

| THE CLIMATE AT THE DARDANELLES | 17 |

| PROLOGUE—MARCH 1915 | 23 |

| APRIL | 25 |

| MAY | 62 |

| JUNE | 114 |

| JULY | 156 |

| AUGUST | 180 |

| SEPTEMBER | 218 |

| OCTOBER | 237 |

| NOVEMBER | 256 |

| DECEMBER | 282 |

| JANUARY 1916 | 310 |

| EPILOGUE | 325 |

| INDEX | 326 |

[13]

| FACING PAGE | |

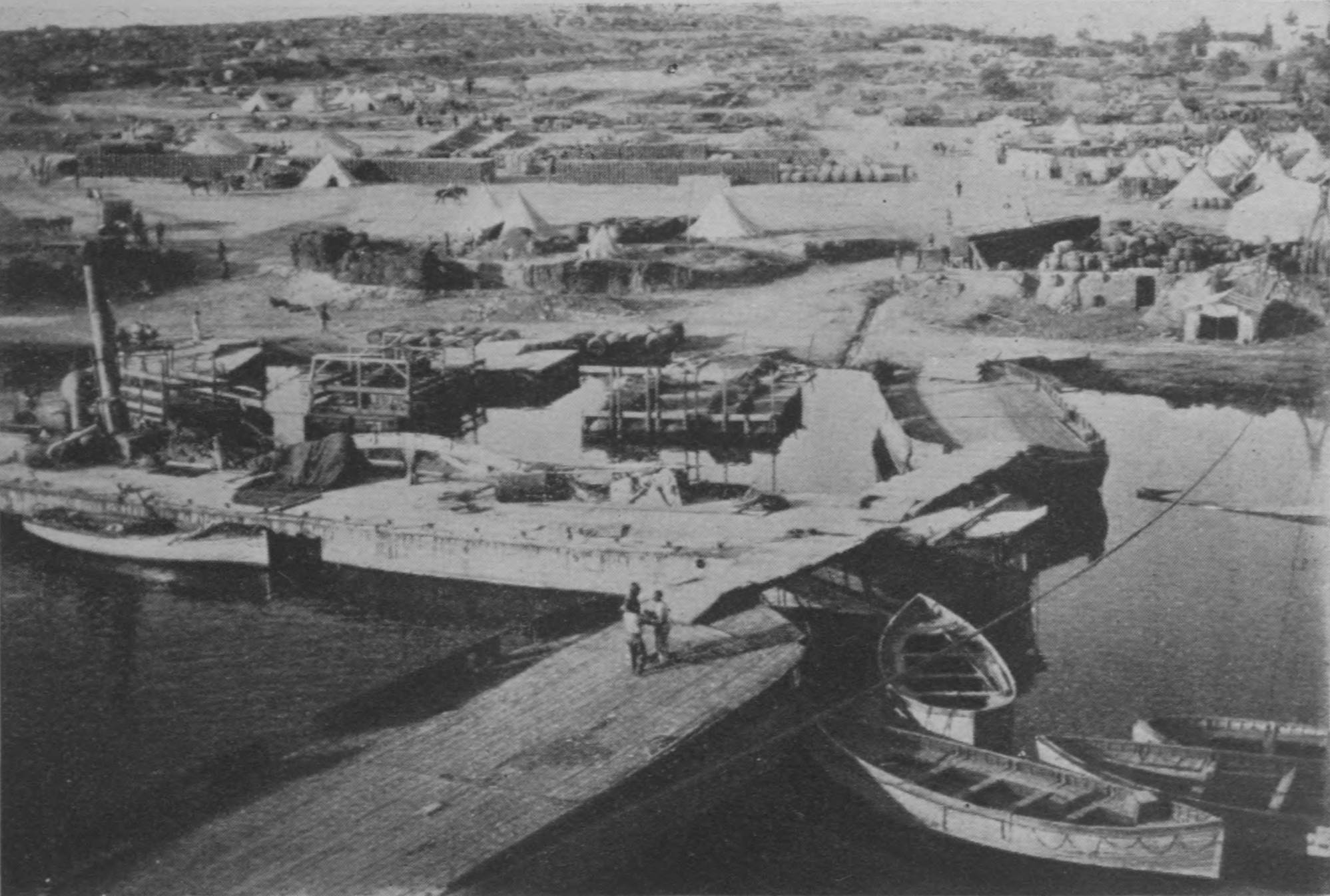

THE GANGWAY OF THE RIVER CLYDE, OUT OF WHICH TROOPS POURED AS SOON AS THE SHIP GROUNDED ON APRIL 25, 1915. CAPE HELLES |

32 |

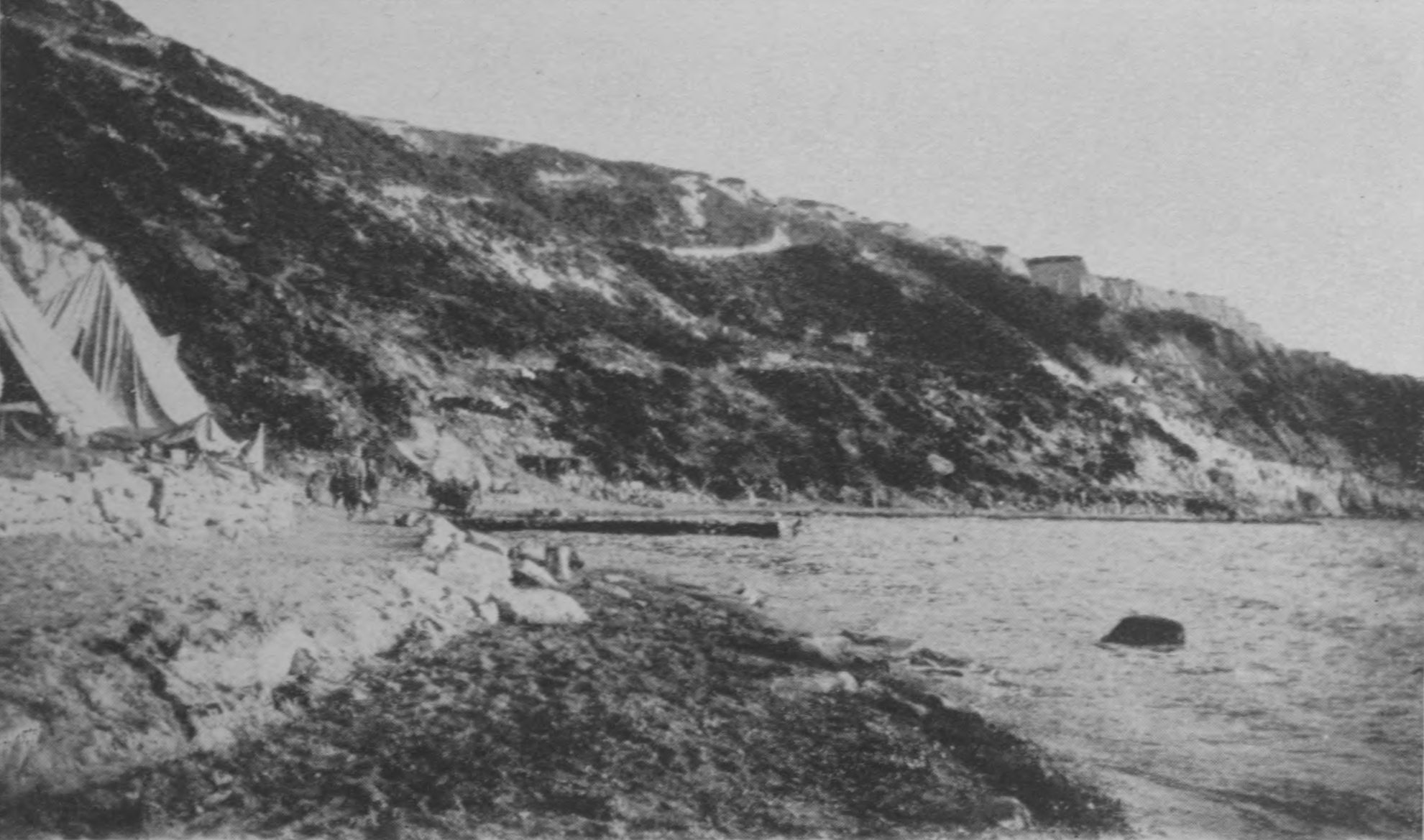

BATHING OFF GULLY BEACH, HELLES |

64 |

“Y” BEACH, CAPE HELLES, WHERE THE K.O.S.B.’S LANDED ON APRIL 25, 1915, HAVING TO EVACUATE THEREFROM ON THE FOLLOWING DAY |

64 |

29TH DIVISIONAL HEADQUARTERS, GULLY BEACH, AT THE FOOT OF THE GULLY, HELLES |

92 |

VIEW OF “V” BEACH, CAPE HELLES, TAKEN FROM THE RIVER CLYDE |

92 |

COAST LINE, CAPE HELLES |

176 |

A VIEW OF THE GULLY, CAPE HELLES, LOOKING TOWARDS THE ENEMY LINES |

176 |

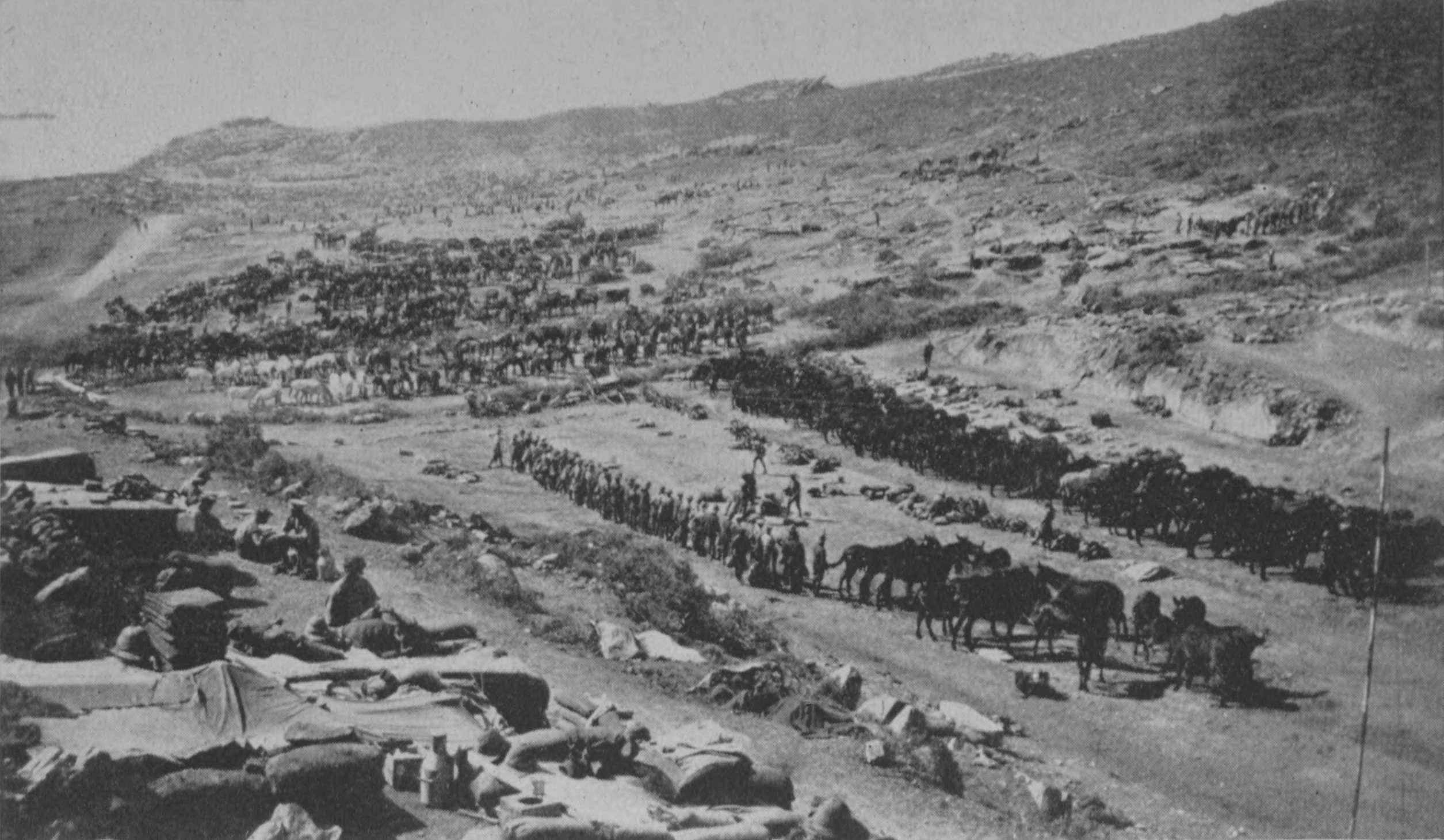

A VIEW OF THE PROMONTORY, SUVLA BAY, TAKEN FROM 29TH DIVISIONAL HEADQUARTERS |

200 |

A CAPTURED TURKISH TRENCH, SUVLA BAY |

216 |

A VIEW OF SUVLA BAY |

216 |

GENERAL DE LISLE’S HEADQUARTERS, SUVLA BAY |

224 |

4·5 HOWITZER IN ACTION, SUVLA BAY |

244 |

29TH DIVISIONAL HEADQUARTERS, SUVLA BAY, HIDDEN FROM THE ENEMY BY THE SLOPE OF THE HILL |

244 |

Left-click any illustration to see a larger version.

[15]

Letter from LIEUT.-GENERAL SIR AYLMER HUNTER-WESTON, K.C.B., C.B., D.S.O., M.P., D.L., who commanded the Division at the landing, April 25, 1915.

Dear Gillam,

The Diary of a man who, like yourself, took part in the historic landing at Gallipoli, and was present on the Peninsula during the subsequent fighting, will, I know, be of interest to many besides myself. There are but few of us who, in those strenuous days, were able to keep diaries, and even fewer were those who had the gift of making of their daily entries a narrative that would be of interest to others.

I should like to have time to write a Preface for this book of yours, giving the salient points of our great adventure and the effect it had both on us and on the enemy. I should also have liked to have shown the influence that you and the Army Service Corps generally had on our operations by the successful manner in which you were able to keep the troops fed and supplied under circumstances of apparently insuperable difficulty.

[16]

But being, as I am, in command of a big Army Corps on one of the most difficult parts of the Front, it is impossible for me to find any time for writing such a Preface.

I can but wish your book the greatest success, and hope that it will be widely read.

Yours sincerely,

AYLMER HUNTER-WESTON.

Headquarters, VIII Corps, B.E.F.,

February 18, 1918.

[17]

By HENRY E. PEARS

[After the evacuation of the Peninsula, the following article, which appeared in the Westminster Gazette early in September 1915, was shown to me. After reading it through, I compared the weather forecasts that the author sets forth, and was interested to find that they agreed very closely with the notes on the weather that I had made in my Diary. The article is therefore republished here, as it may be of interest to the reader.—J. G. G.]

The dispatch of August 31st of Reuter’s Special Correspondent with the Mediterranean Forces, of which a summary was published in the Westminster Gazette of the 18th inst., speaks of the weather at the Dardanelles and as to there being two months of fine autumn weather in which to pile up stores, etc. It would be more correct to say three months rather than two.

It may be interesting to some of your readers to have a few remarks on the weather in the Marmora. Such remarks are based on the results of observations made by a close observer of nature during a period of over thirty years. The fact that particular interest was taken in weather conditions at such a place arose from a cause other than a meteorological interest in the weather, the object being an endeavour to throw light on the migration of birds. Bird naturalists in general, and especially Frenchmen, have fully recognized that the two stretches of land, namely the shores of the Bosphorus and that of the Dardanelles, being the closest points of junction between Europe and Asia, as also the European coast between these points, are the concentrated passage way[18] or route for the huge migratory flocks of birds proceeding from the western half of Europe into Asia. Three results stand out in respect to this migration. First, the absolute regularity of the autumn migration or passage; secondly, certain conditions of weather at almost fixed dates; thirdly, the result of the weather conditions as affecting the density of the flights, the resting and stopping of various birds at certain places. The subject is a very wide one, and is somewhat foreign to the real purpose of my remarks.

Taking the month of September to begin with, the weather is very fine, a continuation of summer; cloudless skies day after day, with perhaps a rain and thunder storm or two, only—one generally in the first week, and another about September 17th, but always brought on by a north to north-west wind. As a rule the constant summer land breezes (north-east about) are of less intensity in September than in August, which allows for a keeping up of an average day temperature, as the Marmora, Bosphorus, and Dardanelles owe their moderate day temperature to these daily breezes (called “Meltem”) from the north to north-east during the summer. The wind generally dies away at sunset, which fact, however, rather tends to make the night temperature higher during the summer; the result being that, as between day and night temperature, when the north wind blows during the day, there is but little drop in the temperature and the nights are hot.

About September 21st to 24th there is, however, a marked period in the weather. It is either a calm as regards winds, and consequently very hot, or such period is marked by southerly winds, but not of any great intensity or strength—very dry, hot winds. These are the first southerly winds of autumn, but as a general rule such period is in nautical terms “calm and fine, with southerly airs.”

From such time up to the end of September the north or north-easterly winds set in again, but later on, generally about the first week of October, the winds get more to the north and north-west, and there is a heavy thunderstorm or so, and as a result a drop in temperature.

[19]

From October 10th to 14th there is a period of uncertainty; sometimes a south-westerly wind, which veers round to the north-west, and a good rain-storm. The first distinct drop in temperature now takes place (about the 10th to the 14th), one feels autumn in the air, the nights continue fairly warm; and this period continues fine and generally calm up to about the 20th—sometimes the 18th or 19th—when a well defined and almost absolutely regular period is entered upon.

This spell begins with three or four days of very heavy northerly or north-westerly wind, sometimes a gale, generally accompanied by rain for several days, and it is this period—from October 20th to 25th—which is intensely interesting to naturalists owing to the big passage of all kinds of birds, the arrival of the first woodcock, the clockwork precision of the passage of the stock-doves (pigeons); in fact, it is the moment of the big migration, when the air night and day is full of birds on the move. Towards the end of October, and in the way of a counter-coup or reaction to the northerly gales, there is generally experienced a fierce three or four days of southerly winds, sometimes gales.

It is to be noted that these gales or changes in the weather are usually of three or seven days’ duration, the first day generally being the strongest, and for some of these regular winds the natives have special names.

November almost always comes in fine, with a lovely first ten days or so. It, however, becomes rather sharp at night, and a very marked period now of cold weather is to be expected—a cold snap, in fact.

This snap is generally in the second or third week of the month, and only lasts a few days, the weather going back to fine, warm, and calm till the end of the month. Barring such cold snap the month is marked by fine weather and absence of wind, and many people consider it the most glorious month of the year, the sunsets being especially fine. The cold snap is rather a peculiar one. Snow has been seen on November 4th, and, if I remember rightly, the battle of Lule Bourgas three years ago was fought on November 5th, 6th, and 7th, and during such[20] time there raged a storm of rain and sleet, succeeded by two or three nights of hard frost, which caused the death of many a poor fellow who had been wounded and was lying out.

Another year there was a very heavy snow-storm on November 16th and 17th. Although the weather may be of this nature for several days, it recovers and drops back into calm, warm weather.

In the last days of November or the first days of December another period is entered upon. There is generally a heavy south wind lasting from three to seven days, which is succeeded by a lovely spell of fine weather, generally perfectly calm and warm, which brings one well through December. From a little before Christmas or just after, the weather varies greatly. The marked periods are passed—the weather may be anything, sometimes calm and mild, sometimes varied by rains, with strong north winds, but no seriously bad weather; in one word, no real winter weather need be looked for until, as the natives put it, the old New Year—otherwise the New Year, old style, which is January 14th, our style—comes in.

After January 14th, or a few days later, the weather is almost invariably bad; there is always a snow blizzard or two, generally between January 20th and 25th. These are real bad blizzards, which sometimes last from three to seven days; and anything in the way of weather may happen for the next six weeks or two months. The snow has been known to lie for six weeks. Strong southerly gales succeed, as a rule, the northerly gales, but one thing is to be noted: that the south and west winds no longer bring rain; it is the north and north-east which bring snow and rain.

This winter period is difficult to speak of with anything like precision; nothing appears to be regular. Some years the weather is severe, other years snow is only seen once or twice. Winter is said to have finished on April 15th. The only point about a severe winter is that a period of cold is generally followed by a period of calm warm weather of ten days or so. It has often been noted that a very cold winter in England and France, etc.,[21] generally gives the south-east corner of Europe about which we are speaking a mild winter with a prevalence of southerly airs, whereas a mild winter in England and France marks the south-east corner of Europe for a severe winter, with a prevalence of northerly winds. No doubt experts will be able to explain this. Of late years no great cold has visited the Marmora. In 1893 the Golden Horn from the Inner Bridge at Constantinople was frozen over sufficiently for people to walk over the ice, and the inner harbour had floes knocking about for some weeks. That winter, however, was an exceptional one, but even then the winter only began about January 18th, lasting into March. The great point about the climate is that, however hot or cold a spell may be, it is always succeeded by calm weather, a blue sky, and a warm sun, quite a different state of things from winter weather under English conditions. To those who have relations or friends at the Dardanelles (and I quote from a letter from a friend), let them send good strong warm stockings for the men, besides the usual waistcoats and mufflers; and as for creature comforts, sweets, chocolate, and tobacco, especially cigarettes. It is the Turks who will suffer from the cold; they cannot stand it long, and being fed generally mainly on bread, they have no stamina to meet cold weather. Most of their troops come from warm climes.

[23]

On March 20th, 1915, I embarked on the S.S. Arcadian for the seat of war. My destination, I learned, was to be the Dardanelles, and the campaign, I surmised, was likely to be more romantic than any other military undertaking of modern times. Our ship carried, besides various small units, part of the General Staff of the Expedition. The voyage was not to be as monotonous as I first thought, for I found many old friends on board. After the usual orderly panic consequent on the loading of a troopship we glided from the quay, our only send-off being supplied by a musical Tommy on shore, who performed with great delicacy and feeling “The Girl I left Behind Me” on a tin whistle. The night was calm and beautiful, and the new crescent moon swung above in the velvet sky—a symbol, as I thought, of the land we were bound for. As we passed the last point a voice sang out, “Are we downhearted?” and the usual “No!” bawled by enthusiastic soldiers on board, vibrated through the ship, and so with our escort of six destroyers we left the coast of Old England behind us. Nothing of interest happened during the passage across the Bay. On arrival at Gibraltar searchlights at once picked us up, and a small boat from a gunboat near by came alongside—we dropped two bags of mails into her and in return received our orders. As we sailed through the Mediterranean, hugging the African coast, the view of the purple mountains cut sharp against the emerald sky was very beautiful.

Our next stop was Malta, which struck me as very picturesque. The island showed up buff colour against the blue sky, and the creamy colour of the flat-roofed houses made a curious colour scheme. As we went slowly[24] up the fair way of Valetta Harbour, we passed several French warships, on one of which the band played “God Save the King,” followed by “Tipperary,” our men cheering by way of answering the compliment. The grand harbour was very interesting, swarming with shipping of all kinds, the small native boats darting over the blue water interesting me greatly. The buff background of the hills, dotted with the creamy-coloured buildings and a few forts, the pale-blue sky and deeper tint of the water, the wheeling gulls, all went to make up a charming picture. We went ashore for a short time and found the town full of interest. We visited the Club, a fine old building, once one of the auberges of the Knights of Malta, where we were made guests for the day. Afterwards we strolled round the town; the flat-roofed houses made the view quite Eastern, and the curious mixture of fashionable and native clothing at once struck me. The women wore a head-dress not unlike that of a nun—black, and kept away from the face by a stiffening of wire. We passed many fine buildings, for Malta is full of them, and one particularly we noticed, namely the Governor’s Palace, with its charming gardens. As to the country itself, what I saw of it was all arranged in stone terraces, no hedges, except a few clumps of cactus being visible. In the evening we returned to the ship, and before very long set sail once more. I found that two foreign officers had joined us; one was a Russian and the other French, but both belonged to the French Army and both spoke English perfectly.

On April 1st, after an uneventful trip from Malta, we arrived at Alexandria, our Base, and from this date the Diary proper begins.

[25]

GALLIPOLI DIARY

We arrived at Alexandria on April 1st. The harbour is very fine, about three miles wide, and protected from the open sea by a boom. The docks are very extensive, and, just now, are of course seething with industry. All the transports have arrived safely. The harbour itself is full of shipping, and anchored in a long row I am delighted to see a number of German liners which have been either captured on the high seas or captured in port at the beginning of hostilities and interned. All the Division disembarks and goes to four camps on the outskirts of the town. My destination was bare desert, and reminded me irresistibly of the wilderness as mentioned in the Bible. There was a salt-water lake near by, with a big salt-works quite near it.

In the centre of Alexandria is a fine square flanked by splendid up-to-date hotels and picturesque boulevards; but the native quarter is most depressing, consisting of mud hovels sheltering grimy women and still grimier children. The huts themselves are without windows and only partially roofed. Flies abound upon the filthy interstices; a noxious smell of cooking, tainted with the scent of onions, greets the nose of the passer-by at all hours. I find my work at the docks rather arduous, as, after the troops have disembarked, we have to take stock of what supplies remain on board, and then make up all shortages. I sleep and have my meals on a different ship almost every day—which is interesting. About the fifth of the month the troops return to re-embark—I have to[26] work very hard on the ships with gangs of Arabs. These folk are just like children, and have to be treated as such—watched and urged on every moment; if one leaves them to themselves for an instant they start jabbering like a lot of monkeys. I finally find myself on a fine Red Star boat, the S.S. Southland.

There are a lot of our Staff on board—also French Staff, including General D’Amade, the French G.O.C., who did such good work in France in the retreat. He is a distinguished-looking old man with white hair, moustache, and imperial. I hear that Way and myself are to be the first Supply Officers ashore at the landing. Half the A.S.C. have been left behind in Alexandria, and there are only five of my people with me.

We are now steaming through crowds of little islands, some as small as a cottage garden, others as large as Hyde Park. Sea beautifully calm, and troops just had their Church Parade. We have the King’s Own Scottish Borderers on board, and it is very nice having their pipers instead of the bugle.

On account of drifting mines we are keeping off the usual route.

Arrive at our rendez-vous, Lemnos, a big island, with a fine harbour. Seven battleships in, and all our transport fleet as well as some of the French and Australian. We remain in the outer harbour awhile opposite a battleship that had been in the wars, one funnel being nearly blown away. All battleships painted a curious mottled colour, and look weird. One of our cargo-boats has been converted into a dummy battleship to act as a decoy, very cleverly done too. Later, we go into the inner harbour and moor alongside another transport, the Aragon, on which is my Brigade Staff and the Hampshires, who were at Stratford with me. The Staff Captain hands over to me a box, which I find is my long-lost torch and batteries from Gamage.

[27]

French Headquarter Staff and General D’Amade leave and go on board Arcadian. The transport Manitou, one of the boats on which I ate and slept, and which left Alexandria two in front of our transport, was stopped by a Turkish destroyer off Rhodes and three torpedoes were discharged at her. The first two torpedoes missed and the troops rushed to the boats. Owing to some muddle, two boats fell into the sea and a ship’s officer and fifty soldiers were drowned. The third torpedo struck, but did not explode, as the percussion pin had not been pulled out. Two cruisers arrived on the scene and chased the destroyer off, which ran ashore, the crew being captured.

After dinner go on board Aragon with Hampshire officers and see Panton. Also talk to Brigade-Major and Captain Reid, of Hampshires.

Lovely morning. Fleet left. Troops, with full kit on, marching round deck to the tune of piano. Most thrilling. Piano plays “Who’s your Lady Friend?” soldiers singing. What men! Splendid! What luck to be with the 29th!

This is a fine harbour, very broad, and there are quite a hundred ships here, including the Fleet and transports, amongst which are some of our best liners. I had to go to a horse-boat lying in the mouth of the harbour two mornings ago and took two non-commissioned officers and a crew of twelve men. We got there all right, a row of two and a half miles, but the sea was so heavy that it was impossible to row back. I had to return, and fortunately managed to get taken back in a pinnace that happened to call; but the rest had to remain on board till the next day, and then took three hours to row back. This gives us an idea of the difficult task our landing will be at Gallipoli. For a time we were moored alongside the boat on which was the Headquarters of the 88th Brigade, and it was cheering to be able to walk to and fro between the two ships and to see all my pals of the Hampshires.

[28]

The Hampshires and the Worcesters spend the day marching, with full kit on, round the deck to the cheery strains of popular airs played by a talented Tommy. The effect, with the regular tramp, is very exhilarating.

Later, I am ordered to join another ship, the Dongola, in which are the Essex and the Royal Scots, the other regiments of my Brigade. Two Essex officers were staying in the “Warwick Arms” with me, and it was good seeing them again. The harbour at night is a fine sight. A moon is shining and not a cloud in the sky, and the temperature about 50°.

The last few days, however, have been wet and drizzling, just like a typical day in June in England when one has been invited to a garden party.

One can see the outline of the low irregular hills on shore, and the ships are constantly signalling to one another, silently sending orders, planning and arranging for the great adventure.

Have to go up to the signalling deck above the bridge to take a message flashed from a tiny little “Tinker Bell” light away on our starboard. The sight is wonderful. Busy little dot-dash flashes all around the harbour. How the signallers find out which is which beats me.

The view of the hills in the background contrasts strangely with the scenes of modern science and ingenuity afloat.

I saw the Queen Elizabeth at close quarters two days ago, and I hope to go over her to-morrow. Also the Askold, a Russian cruiser, with five funnels. Tommies call her “The packet of Woodbines.” It is interesting to note the confidence the Army and Navy have in each other. While being rowed over here by some bluejackets, “stroke” told me that he was in the Irresistible when she was sunk. He looked sullen, and then said, “However, they’ll catch it now the khaki boys have arrived.” The prevailing opinion amongst the Tommies is that the landing will be a soft job, with Queen Bess and her sisters pounding the land defences with shells. Then the confidence French, British, and Russians have in one another is encouraging. The feeling prevails that when once the landing is effected[29] Turkey will cave in, and that will have a great influence on the duration of the war. But a Scotsman said to me to-day, “Remember, Kitchener said ‘A three years’ war.’”

Sir Ian Hamilton this evening sent round a brief exhortation beginning, “Soldiers of France and of the King,” which bucked up everybody.

A bright day. Took estimate of stores on board to see if troops had enough rations. Found shortage; signalled Headquarters, who send stores to make up. Received orders where to land on Sunday. Have to go ashore at “V” Beach with the first load of supplies and start depot on beach. Naval officer on board with a party. Breezy, good-looking young man, very keen on his job.

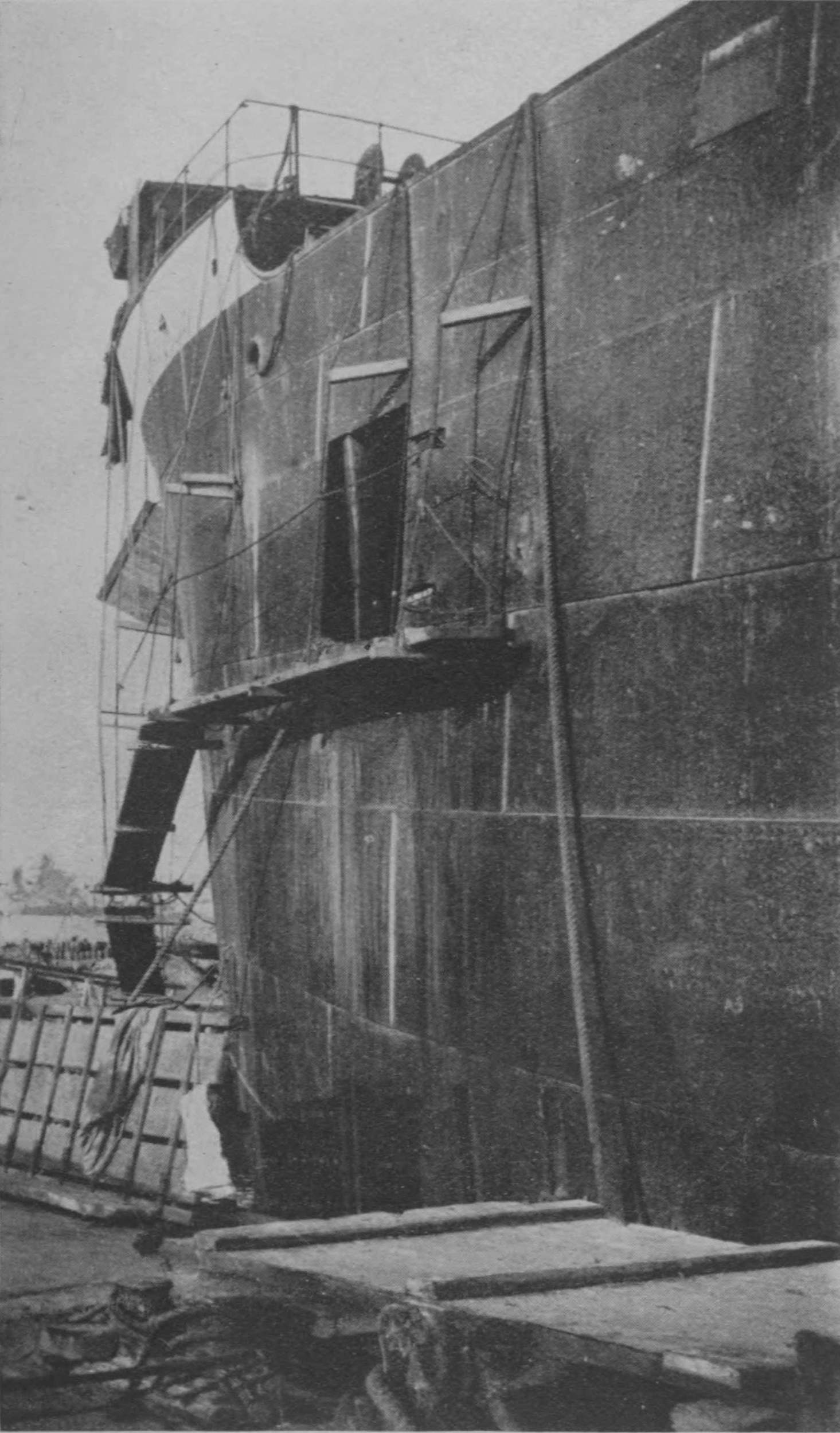

The first boat of the fleet leaves, named the River Clyde, an old tramp steamer, painted khaki. She contains the Dublin and Munster Fusiliers. Fore and aft on starboard and port the sides are cut away, but fastened like doors. She will be beached at “V” Beach, and immediately that is over, her sides will be opened and the troops aboard will swarm out on to the shore. Good luck to those on board! She slowly passes the battleships, and turning round the boom, is soon out of sight.

The strains of the Russian National Anthem float over the harbour from the Askold and the first large transport leaves the harbour, a big Cunarder, the Aucania, with some of the 86th Brigade on board. Great cheering. What a drama, and how impressive the Russian National Anthem is. Evening again. Little “Tinker Bell” flashes begin to get busy.

On lower deck the Tommies give a concert, with an orchestra composed of a tin can, a few mouth-organs, and combs and paper—“Tipperary,” “Who’s your Lady Friend?” etc.

Feel just a bit lonely and homesick. Longing for the time when I can see my sisters again and punt up the river at dear old Guildford. But what about the Tommies on board?—they have just the same feeling, and yet keep[30] playing their mouth-organs. Hear that Ian Hamilton feels a bit anxious over this job, but that Hunter-Weston, our Divisional General, is full of pluck and confidence. He says that he will not “down” the man who makes mistakes yet tries to remedy them, but that the man that he will “down” will be the one who slacks and avoids work.

Another bright day. Some transports and battleships leaving harbour. Issue extra days’ rations to troops on board, which makes four days’ that they will have to carry. Their packs and equipment now equal sixty pounds. How they will fight to-morrow beats me. I tried a pack on and was astonished at its weight. We have left harbour and are steaming for the scene of the great adventure. Hope we shall not meet a submarine or drifting mines. Have spent the evening with some young officers of the Essex. They all seem a trifle nervous, yet brave and cheery. They play a Naval game called “Priest of the Parish,” but it falls flat. I felt nervous myself, but after cheering them up, felt better. Told them it was going to be a soft job.

We arrive at five in the morning, and troops are to land at six. London will be ringing with the news on Monday or Tuesday.

If successful, the war out here will soon be over, we think.

Was awakened up at four by the noise of the distant rumbling of guns, and coming to my senses, I realized that the great effort had started. I dressed hastily and went on deck, and there found the Essex and Royal Scots falling in on parade, with full packs on, two bags of iron rations, and the unexpended portion of the day’s rations (for they had breakfasted), entrenching tools, two hundred rounds of ammunition, rifle and bayonet. I stood and watched—watched their faces, listened to what they said to each other, and could trace no sign of fear in their faces and[31] no words of apprehension at forthcoming events in their conversation.

It was a simple “fall in,” just as of old in the days of peace parades, with the familiar faces of their N.C.O.’s and officers before them, like one big family party.

They seemed to be rather weighed down with their packs, and I pity them for the work that this parade is called for. The booming of the guns grows louder. It is very misty, but on going forward I can just see land, and the first officer points out to me the entrance through the Dardanelles. How narrow it seems; like the Thames at Gravesend almost. I can see the Askold distinctly. A Tommy said, “There’s the old packet of Woodbines giving them what-ho!” She is firing broadsides, and columns of dust and smoke arise from shore. The din is getting louder. I can’t quite make out which is the Asiatic side and which Gallipoli. It is getting clearer and a lovely day is developing. Seagulls are swooping over the calm sea above the din, and a thunderous roar bursts out now and again from Queen Bess. Her 15-inch guns are at work, and she is firing enormous shrapnel shells—terrible shells, which seem to burst 30 feet from the ground.

The Essex are disembarking now, going down the rope ladders slowly and with difficulty. One slips on stepping into a boat and twists his ankle. An onlooking Tommy is heard to remark, “Somebody will get hurt over this job soon.” Young Milward, the Naval Landing Officer, is controlling the disembarkation. He has a typical sailor’s face—keen blue eyes, straight nose and firm mouth, with a good chin. They are landing in small open boats. A tug takes a string of them in tow, and slowly they steam away for “W” Beach. We hear the Lancashires have landed at “W” Beach, and are a hundred yards inshore fighting for dear life. Tug after tug takes these strings of white open boats away from our ship towards land, with their overladen khaki freight. Slowly they wend their way towards the green shore in front of us, winding in and out among transports, roaring battleships, and angry[32] destroyers, towards the land of the Great Adventure. Never, surely, was Navy and Army so closely allied.

I go below to get breakfast, but hardly eat any. The breakfast-tables are almost empty, except for a few Quartermasters and people like myself who do not fight. I feel ashamed to be there, and a friend says the same. The steward calmly hands the menu round, just as he might on a peaceful voyage. What a contrast! Two boiled eggs, coffee, toast, and marmalade.

Here we are sitting down to a good meal and men are fighting up the cliffs a few hundred yards away. I get it over and go up on deck again.

It is quite clear now, and I can just see through my glasses the little khaki figures on shore at “W” Beach and on the top of the cliff, while at “V” Beach, where the River Clyde is lying beached, all seems hell and confusion. Some fool near me says, “Look, they are bathing at ‘V’ Beach.” I get my glasses on to it and see about a hundred khaki figures crouching behind a sand dune close to the water’s edge. On a hopper which somehow or other has been moored in between the River Clyde and the shore I see khaki figures lying, many apparently dead. I also see the horrible sight of some little white boats drifting, with motionless khaki freight, helplessly out to sea on the strong current that is coming down the Straits. The battleships incessantly belch spurts of flame, followed by clouds of buff-coloured smoke, and above it all a deafening roar. It is ear-splitting. I shall get used to it in time, I suppose. Some pinnace comes alongside our ship with orders, and the midshipman in command says the Australians have landed, but with many casualties, and have got John Turk on the run across the Peninsula. I turn my glasses up the coast to see if I can see them, but they are too far away. I can only see brown hills and bursting shells, a sea dead calm, and a perfect day. The work of the Creator and the destroying hand of man in close intimacy. A seaplane swoops from the pale blue of the sky and settles like a beautiful bird on the dark [33] blue of the sea alongside a great battleship, while hellish destructive shells deal out death and injury to God’s creatures on shore. This is war! and I am watching as from a box at the theatre.

THE GANGWAY OF THE RIVER CLYDE, OUT OF WHICH TROOPS POURED AS SOON AS THE SHIP GROUNDED ON APRIL 25, 1915. CAPE HELLES.

Imbros is peaceful and beautiful, Gallipoli beautiful and awful. We have moved closer in to the beach and they are trying to hit us from the shore. Two shells have just dropped near us, twenty yards away; the din is ear-splitting, especially from Queen Bess. I can hear the crack-crack of the rifles on shore, which reminds me of Bulford. I shall be glad when we land. This boat is getting on my nerves. We are just off the “Horse of Troy,” as we call the River Clyde. Are we going to land at “V” Beach? I can see no sign of life there. Nothing but columns of earth thrown into the air and bits of the houses of Sed-el-Bahr flying around, and always those crouching figures behind the sand dunes. Only the Royal Scots left on board. Perhaps they are going to land and make good. I get near Milward to see if he has any orders. He goes up to the bridge to take a signal.

We are going out to sea again. A tug comes alongside with wounded, and they are carefully hoisted on board by slings. They are the first wounded that I have ever seen in my life, and I look over the side with curiosity and study their faces. They are mostly Lancashire Fusiliers from “W” Beach. Some look pale and stern, some are groaning now and again, while others are smoking and joking with the crew of the tug.

I talk to one of the more slightly wounded, and he tells me that it was “fun” when once they got ashore, but they “copped it” from machine guns in getting out of the boats into shallow water, where they found venomous barbed wire was thickly laid. He laid out four John Turks and then “copped it” through the thigh, and three hours afterwards was picked up by sailors.

[34]

And then, “Any chance of Blighty, sir?” and I said, “I’m afraid not; it will be Malta or Alex, and back here again,” to which he replied, “Yes; I want to get back to the regiment.”

We are going closer in again, and the Royal Scots are leaving. The Quartermaster, Lieutenant Steel, remains behind with ration parties. He is very impatient and wants to get off; a curious man: tells me he doesn’t think he will come off Gallipoli alive.

I have a dismal lunch, just like the breakfast. I can see French troops pouring out of small boats now on to the Asiatic side and forming up in platoons and marching in open order inland, while shrapnel bursts overhead. During lunch I find that we went out to sea, but are nearing the land now. Oh! when shall I get off this ship? I wonder. Milward tells me that the delay occurred because at first we were to land at “V” Beach, but that it has become so hot there that landing to-day is impossible. He says that I shall land at 4 p.m. I hear a cheer, a real British one. Is that a charge? My imagination had conjured up a mass of yelling and maddened men rushing forward helter-skelter. What I see is crouching figures, some almost bent double, others jog-trotting over the grass with bright sun-rays flashing on their bayonets. Now and again a figure falls and lies still—very still in a crumpled heap; while all the time the crack-crack of musketry and the pop-popping of machine guns never ceases. That is what a charge looks like. I chat to Milward, and he tells me that the Navy are doing their job well, and he will be surprised if a single Turk is alive for three miles inshore by nightfall, but he expresses surprise that we have only the 29th and Australians; as he figures it we want six Divisions and the job over in a month. This depresses me.

I have orders to leave, and I must get ready.

[35]

I give orders to my servant and to the corporal and private of the advanced Supply Section, who are to accompany me, to get kit ready. I am to land at once on “W” Beach with seven days’ rations and water, and a quantity of S.A. ammunition for my Brigade. I superintend the loading of the supplies from the forward hold to the lighter which has moored alongside, my corporal on the lighter checking it, and doing his job just as methodically as he used to at Bulford. While at work, a few shells drop into the sea quite near, throwing up waterspouts as high as the funnel of the ship. Two small boats are made fast to the lighter, and my servant and I get into the lighter down the rope ladder. Beastly things, rope ladders. We sit down on the boxes and wait. We wait a devil of a time while others join us, among whom are the 88th Field Ambulance and the Padre. Suddenly Padre gets a message that he is not to go, and we find that he was trying to smuggle himself ashore. At last up comes a small pinnace with a very baby of a midshipman at the wheel, and a lot of orders are sung out in a shrill voice to men old enough to be his father. We slowly steam for shore.

Passing across the bows of the Implacable, we nearly have our heads blown off by the blast of her forward guns, and the funny thing is, I can hardly see a man on board. Pinnaces, tugs, destroyers are rushing in and out of the fleet of transports and warships. A tug passes close to us on its way to the Dongola, the ship I have just left, loaded with wounded, all slight cases, and they give us a cheer and shout “Best of luck, boys!” We wave back. We approach close into “W” Beach, where lighters are moored to more lighters beached high on the sand, and then the “snotty,” making a sweep with his pinnace, swings us round. He gives the order to cast adrift, and then shouts in a baby voice: “I can’t do any more for you; you must get ashore the best you can.”

We fortunately manage with difficulty to grab a rope from one of the moored lighters and make fast while the two boats are rowed ashore. There we stick. I dare not leave those seven days’ rations and water for[36] four thousand men, and I shout to seamen on shore to try to push us in and so beach us. The bombardment begins to ease off somewhat. The sun begins to sink behind Imbros, and gradually it turns bitterly cold. I sit and shiver, munching the unexpired portion of my day’s ration. I want a coat badly, but by this time my kit is on shore with my servant. We appear to have been forgotten altogether. On the cliffs in front of us Tommies are limping back wounded. One comes perilously near the edge of the cliff, stumbling and swaying like a drunken man. We shout loudly to him as time after time he all but falls over the edge. Two R.A.M.C. grabbed him eventually and led him safely down. I have a smoke, and view the scenes on shore. Gradually the beach is becoming filled with medical stores and supplies. It is gruesome seeing dozens of dead lying about in all attitudes. It becomes eerie as it gets darker. At this beach at dawn this morning there landed the Lancashire Fusiliers. They were waited for until their boats were beached, when, as the troops stepped out of the boats, they were fired on by the Turks, who subjected them to heavy machine gun fire from two cliffs on either side of the beach. The slaughter was terrible. On the right-hand side of the beach the troops had a check, and terrible fighting took place. Finally, one by one the machine guns were pulled from their positions in the cliff, and the sections working them killed in hand-to-hand struggles. On the left side of the beach the troops found no barbed wire, and so were able to get on shore, and to the cry of “Lads, follow me!” from an officer they swarmed up a 50-feet steep cliff, clearing the upper ridge of Turks, but losing heavily. They fought their way inland, and after a while were able to enfilade the Turks holding up our men on the right of the beach, until at last, by 6 a.m., the whole beach was won and John Turk was driven five hundred yards or more inshore.

Midshipmen and Naval Lieutenants were in charge of the pinnaces towing strings of boats, and as they approached the shore, fired for all they were worth with machine guns mounted forward, protected by shields.[37] Then, swinging round, they cast the boats adrift. Each boat had a few sailors, who rowed for shore like mad, and many in so doing lost their lives, shot in the back. To row an open boat, unprotected, into murderous machine gun and rifle fire requires pluck backed by a discipline which only the British Navy can supply. Some of the sailors grabbed rifles from dead and wounded soldiers and fought as infantrymen. I can see many such dead Naval heroes before my eyes now, lying still on the bloody sand. I am sitting on the boxes now, and “ping” goes something past my head, and then “ping-ping,” with a long ringing sound, follows one after the other. The crackle of musketry begins again, and faster and faster the bullets come. At last I know what bullets are like.

The feeling at first is weird. We get behind the pile of boxes, and bullets hit bully beef and biscuit boxes or pass harmlessly overhead. At last, boats come alongside and we unload the boxes into them, and I go ashore with the first batch, and there I meet 86th and 87th Supply Officers, who landed two hours earlier. My servant meets me and asks where shall I sleep. What a question! What does he expect me to answer—“Room 44, first floor”? I say, “Oh, shove my kit down there,” pointing to some lying figures on the sand. Five minutes after he comes up, and with a scared voice says, “Them is all stiff corpses, sir; you can’t sleep there.” I reply, “Oh, damn it; go and sit down on my kit till I come back.” I start to work to get the stores higher up the cliff. Oh! the sand. It is devilish heavy going, walking up and down with my feet sinking in almost ankle-deep. It is quite dark now, and I stumble at frequent intervals over the dead. Parties are removing them, not for burial, but higher up the beach out of the way of the working parties. I run into the Brigade quartermaster-sergeant and ask him, “How’s the Brigadier?” He replies, “Killed, sir.” I can’t speak for a moment. “And the Brigade Major?” “Killed also, sir.” That finishes me. It is my first experience of the real horrors of war—losing those who had become friends, whom one respected. And I had worked in their headquarters in England every day for two months,[38] knew them almost intimately, and looked forward with pleasure to going through the campaign on their Staff. “How did it happen, Leslie?” I ask. The General was shot in the stomach while in the pinnace, before he could step on to the hopper alongside the River Clyde, and died shortly after. The Brigade Major got it walking along the hopper. The River Clyde was to have been Brigade H.Q., and the Brigade was to have taken “V” Beach that day. So far, “V” Beach was still Turkish. Their machine guns kept our men at bay. I wonder what it is like on the River Clyde at present, and whether those few men are still crouching behind that sand dune.

Way comes up and says it is going to be a devil of a job getting those stores ashore, and that he can’t get enough men. I have a few seamen, Cooper, Whitbourn, and my servant, so put them on to it, and I myself help. Thus we struggle on over the sand and up to the grass on the slope of the cliff. Phew! it is work, and I am getting dead tired. We work till eleven o’clock and then Foley and I have a rest behind a pile of boxes on the sand. Bullets steadily “ping” overhead, and now and again a man gives a little sigh of pain and falls helplessly to the sand. The strange part is that I do not feel sick at the sight of the dead and wounded. I think it is because of the excitement, and because I am dead tired. I get a bit cold sitting still, and can’t find my coat, so I huddle against Foley behind the boxes. A philosophical Naval officer sits alongside, smoking a huge pipe. Crack-crack-crack goes the desultory fire of the rifles. The ships cease firing. It is awfully quiet and uncanny. Suddenly the musketry and rifle fire breaks out with a burst which develops into a steady roar. The beach becomes alive with people once more. All seems confusion. The Naval officer goes on steadily smoking, and we sit still, wondering how things are going to develop. The Fleet is silent. But I can just see the outline of the warships, with a few lights showing.

Then I hear an officer shouting angrily, “Now then, fall in, you men! Who are you? Well, fall in. Get a rifle. Find one then, and damn quick!” Then another[39] officer shouts, “All but R.A.M.C. fall in. Who are you? Fall in. Into file, right turn, quick march.” About a dozen or two march off into the night up the cliff—officers’ servants, A.S.C., seamen, R.N.D.—every man who was not either R.A.M.C. or working on the dozen or so lighters that had been beached. I pause a bit. I feel a worm skulking behind these boxes while these events are happening. I express my feelings to Foley, and he says he feels the same. I say, “We must do something,” and he replies, “Let’s get rifles,” and off we go searching for rifles, but can find none in the dark. I lose my temper—why, Heaven only knows. I see some men falling in, and I go up to them and say, “Fall in, you men; why aren’t you falling in?”—although I know they are, and I find an officer in charge and feel an ass. They move up to man the third-line trench just running along the edge of the cliff. All the beach parties have moved up to this trench. I have lost Foley, and so I follow up with no rifle and no revolver, and shivering with cold. But I feel much better, although I am still in a temper. Extraordinary this! I am annoyed with everybody I see. Nerves, I suppose. Then a petty officer comes along and shouts, “Now then, you men, where the —— is the —— ammunition?” and in the darkness I discern some seamen carrying boxes of S.A.A. I go to the first pair, carrying a box between them, and take one side of the box from one of the seamen, and immediately feel delighted with myself, the sailor, and everybody. I have got a definite job. Up we pant; half-way up the cliff, I find Foley on the same job. A voice shouts, “Have you got the ammunition, Foley?” It is O’Hara’s voice, our D.A.Q.M.G., and he comes running down to us.

Suddenly the Fleet open fire, and the infernal din begins all over again, the flashes lighting up the beach, silhouetting men on shore and ships lying off, and all the time the song of bullets. Red Hell and a Sunday night! And this is war at last! I never thought I should ever get as near it as this, when I was a civilian. O’Hara says, “Who’s that?” to me, and I answer my name, and he says, “Righto! give us a hand with this little lot, lad.” He[40] bends down, and he and a sailor lift a box. Foley and I lift another, and six seamen (I find they are off the Implacable) lift the others, and off we pant up the cliff over that third-line trench, lined with men of the beach parties with fixed bayonets. It’s a devil of a walk to the second line, and it reminds me of hurrying to the railway station with a heavy portmanteau to catch a train. Foley and I constantly change hands.

The seamen too find it heavy going. We arrive at the second line and run into the Adjutant of the Lancashire Fusiliers, calmly walking up and down his trench with a stick. We halt, open the boxes, and hang the strings of ammunition around our necks and over our shoulders. I am almost weighed down with the load. We have a rest, taking cover in the trench now and again as bullets come rather thicker than usual. The firing is frightful—now a roar of musketry, and now desultory firing—while the ships’ guns boom away in the same spasmodic way. O’Hara then says, “Come along; follow me,” and we go, headed by the Adjutant of the Lancashire Fusiliers to show us the way, and on over the grass and gorse into the blackness beyond. We are lucky, for it is a quiet moment and we have only to go three or four hundred yards, but just as we approach the first line, out bursts a spell of machine gun and rifle fire—rapid—and I fall headlong into what I think is space, but which proves to be our front-line trench. I fall clean on top of a Tommy, who is the opposite of polite, for my ammunition slings had tapped his nose painfully. I apologize, and feeling a bit done, lie down in the mud like a frog, the coolness of the mud soon reviving me. We pass the ammunition along, each man keeping two or three slings. O’Hara wanders along the trench, having to keep his head low, for it is none too deep and bullets are pretty free overhead, while I remain and chat to the Tommy, another Lancashire Fusilier, who is shivering, with teeth chattering and wet through, for it is raining. A Tommy on the other side of me is fast asleep and snoring loudly. The one awake describes to me the landing of the previous early morning, the machine gun fire and the venomous barbed wire, with the sea[41] just lapping over it, and the exciting bayonet work that followed.

I am enjoying myself now, for I am in the front-line trench with a regiment which has just added a few more laurels to its glorious collection. It is curious, but no shells are coming from the Turks, and bullets are such gentlemanly little things that they do not worry me. It is funny, but everybody up here appears very cool and confident, while on the beach they all are inclined to be jumpy. O’Hara comes back with the two sailors. Foley has disappeared, and the other four sailors also have gone. We push along to the end of the trench, and the firing having died down somewhat, we climb out into the open and wend our way back. We seem to miss our bearing and go wandering off a devil of a way, when another burst of firing from a few machine guns forces us to dive promptly into a hole which by Providence we find in our path. The two sailors have disappeared somewhere. We find two men crouching in the hole, and on asking who they are, find that they are Lancashire Fusiliers, separated from their regiment. I can hear the swish of the machine gun bullets sweeping nearer and nearer, farther and farther from me, and then nearer as the guns are traversed. We are evidently lying in a hole which was dug to begin a trench, but which was abandoned. It is practically only a ditch the shape of a small right angle. O’Hara and I fall one side, and the two Lancashire Fusiliers the other, and we crouch for three-quarters of an hour. If we kneel, our heads are above the parapet. After a while O’Hara says to me, “I am awfully sorry for getting you in this fix, Gillam,” and I reply automatically, just as one might in ordinary life, “Not at all; a pleasure, sir.” Really though, I don’t like it much, but I am much happier here than I would be on the beach. The firing dies down again. The ships’ guns are still banging away steadily. O’Hara disappears somewhere. I follow where I think he has gone, but I hear his voice after a minute talking to an officer, and I therefore lie down. But for a while I can’t make out the situation. Firing starts again and I can almost feel the flight of some bullets, and I lie[42] flat. It dawns on me that I am lying in front of a trench. I wriggle like a snake over the heap of earth in front of me, into the trench behind, and find it not nearly so deep as the one I have just left, nor so roomy. The firing gets so hot that I try to wriggle in beside a form of a man which is perfectly still. An extra burst of firing sends me struggling for room into the trench, and the man whom I thought was dead moves, which sends a shiver down my spine. I apologize, and he makes room for me. A little later, the firing dies down again; two figures run past our trench shouting “All correct, sir,” and an officer shouts “All correct.” They are runners sent up from the beach. I can hear O’Hara talking to some officer the other side of a traverse; then he calls me, and joining him, I follow him down towards the masts of the ships that we can just see silhouetted against the brightening sky. Suddenly an advanced sentry cries, “’Alt, who are you?” “Friend.” “Who are you?” “Friend—friend—friend!” shouts O’Hara. “Hands up; advance one,” and for some stupid reason I think he means advance one pace, which I solemnly do. O’Hara catches me a blow in the “tummy” and nearly winds me, saying, “Stand still, you —— fool,” and I stand stock-still, gasping for breath, with my hands above my head, while he walks slowly forward with hands up, and I can just see the sentry covering him with his rifle the while. I can hear them talking, and after a few sentences O’Hara calls me and I follow, still with my hands up, until I reach the sentry.

I think this frightened me more than all the events of this night. We continue our way. It is not so dark as it was, and it has ceased raining. Then a horrid thing happens. I fall headlong over a dead Turk, with face staring up into the sky and glazed eyes wide open. He wears a blue uniform, and I think he must have been a sailor from Sed-el-Bahr fort. Ugh! I almost touched his face with mine. Shortly after this mishap we arrive at the third-line trench, crowded with troops of all kinds, made up from the parties on the beaches, and get challenged again by some Engineers. Safely passing these, we stumble down the slope to the beach. O’Hara sends me off to look for[43] the stores, and I last see him going back once more with a rifle and bayonet.

I run into Foley, who I find has had an adventurous time. Having had the ammunition taken off him, he tried to find us, but turned the wrong way up the trench. He got out into the open after a bit and wandered apparently just behind our front line towards “V” Beach, well the other side of “W.” The rifle fire was so hot there that he crawled like a caterpillar back to the second line, and from there doubled back to the beach, steering himself by the mast-lights of the ships.

We see that the stores are O.K., and then run into Carver, who has just landed. Afterwards I find my friend Major Gibbon, of the howitzer battery, busy getting his guns ashore. Foley and I then go back to the boxes, and we lie down like dogs, falling to sleep at once on the soft, comfortable sand. Dawn breaks over the hills of Asia.

I awake about seven and find myself nestling up close against Foley, who is still asleep. I wake him, and he promptly falls asleep again, murmuring something about “that —— machine gun.”

The beach quickly becomes alive with men all working for dear life, and we get to our feet, go down to the water’s edge and bathe our faces, and start to finish the work of making a small Supply depot which we left last night. My servant comes to tell me that breakfast is ready, and we go up the cliff and join Way and Carver at a repast of biscuits, jam, bacon, and tea. But the tea tastes strong of sea water. All water had been carried with us in tins, and we had struck a bad batch, for most of them leaked. And then our day’s work begins in all seriousness.

By night O’Hara wishes us to have a proper Supply depot working, the Quartermasters coming with fatigue parties, presenting their B55’s, and rations to the full are promptly issued and accounted for in our books. At frequent intervals the Fleet bombard, but we are quite used to the roar of the guns now. I am covered and coated with clayey mud and have no time to clean myself properly.[44] We have to take cover continually from snipers—unknown enemies who fire at us from Lord knows where. One open part of the beach is especially dangerous, and I cross that part about six times during a day—not a very wide space, but I feel each time I go across that I am taking a long journey. The dead are still lying about, and as there is no time to bury them, we pass to and fro by their bodies unheedingly. In addition to these snipers who pick off one of our number now and again, we have spent bullets flying in all directions, for our firing-line is but a few hundred yards away. The Turk, however, does not appear to have a proper firing-line; he only seems to have advanced posts strongly held, and must have retreated well inshore.

It is a blessing for us that no shells come along, only these spent bullets and the deadly shots from the unseen snipers. Heavy firing sounds, however, from “V” Beach, a rattle of musketry and a roar of the battleships and torpedo-boat destroyers lying at the mouth. Colonel Beadon and Major Streidinger are getting a proper system of supply and transport working.

We become venturesome in the late afternoon, and many of us, quite two to three hundred, go up on the high land on the right and left of the beach and make a tour of the lately captured trenches. Turkish dead are lying about in grotesque attitudes; the trenches are full of equipment, and I notice particularly bundles of remarkably clean linen, and many loaves of bread, one loaf sticking out of a dead Turk’s pocket. Several of the dead are dressed in a navy-blue uniform with brass buttons, but most are in khaki with grey overcoats and cloth hats. Suddenly a whistle blows, and several cry “Get off the skyline!” and we all run helter-skelter for the safety of the beach. When darkness arrives we have a proper Supply depot working, and strings of pack-mules are hard at work carrying stores. Guns, ammunition, and men are everywhere. The Engineers have run out a pier already. Every one is in the best of spirits, for we have tasted a brilliant victory, and organizing brains are still at work in preparation for further ventures. I go to sleep behind boxes with the sound of a heavy rifle fire disturbing the night.

[45]

I am ordered to make a small advanced depot just behind the firing line, using pack-mules under Colonel Patterson, of the Zion Mule Corps. The drivers are Syrian refugees from Syria, and curiously enough speak Russian as their common language. While up there, but a very short walk from the beach, I sit down on the layer’s seat of one of the 18-pounders of one of the batteries in position just behind our line. The battery is not dug in at all. I look through a telescopic sight, but can only see a lovely view of grass, barley, gorse and flowers, hillocks, nullahs, and the great hill of Achi Baba in the background, looking like Polyphemus in Dido and Æneas, with an ugly head and arms outstretched from the Straits to the Ægean.

I ask where the Turks are, and they point to a line some two thousand yards away, marked by newly turned earth, which is just distinguishable through strong glasses. I can see no sign of life, but away up on the ridges of Achi Baba columns of earth and smoke suddenly burst from the ground, caused by the shells of our Fleet.

Rifle fire has died down; hardly a shot on our front comes over, and no shells at all.

On our right, shell fire continues. I hear that “V” Beach is taken. It was taken midday yesterday, but with heavy casualties. The Dublins, Munsters, and Hants had the job, and the Hants did magnificently. Colonel Williams, the G.S.O.1, behaved most gallantly. Snipers were worrying after the village was taken, and in crossing a certain part of the village he exposed himself by mounting a wall, and, standing there for a time, looked down, saying to men round him, “You see, there are no snipers left, men.” They leapt after him like cats, and were through the village in no time. Man after man had been hit on that wall that morning.

I make a little depot of boxes just behind the battery, and go back to the beach and load for another journey. On arrival there, Colonel Beadon orders me to proceed to “V” Beach to collect all stores there and make an inventory. For at first this was to have been our beach, had we been[46] able to land on the first day. The French are to take it over now, as they are coming back from the Asiatic side, evacuating it entirely. I go down to “W” Beach for a fatigue party of the R.N.D., and am told to apply to the Naval Landing Officer, and an officer standing talking on the sands is pointed out to me as he. I go up to him and wait for an opportunity to catch his eye; for he is an Admiral. He is talking to a Captain, and two midshipmen are standing near. I wait fifteen minutes, manœuvring for position so that he may ask me what I want. I think I must have shown signs of impatience, for the Admiral turned full round toward me, and after looking at me in mild surprise for a few seconds, during which I felt a desire to turn round and run up the cliff, quietly turned round to the Captain and continued his conversation. A minute or two passed and he walked away with the midshipmen, and the Captain asked me what I wanted. I told him a fatigue party, and he pointed out an R.N.D. officer a hundred yards away, to whom I went, at once obtained satisfaction, and to whom I should have gone at the start. I find I have made an ass of myself, and therefore administer mental kicks. With my fatigue party, my corporal, private, and servant, I march up the cliff toward “V” Beach. We pass the lighthouse, which has been badly knocked about, following the line of the Turkish trench, which is along the edge of the cliff, to the fort, which had withstood the bombardment well. At the fort we see two huge guns of very old pattern, knocked about a good deal. Then we dip down to “V” Beach, a much deeper and wider beach than “W,” and walk towards the sea. Then I see a sight which I shall never forget all my life. About two hundred bodies are laid out for burial, consisting of soldiers and sailors. I repeat, never have the Army and Navy been so dovetailed together. They lie in all postures, their faces blackened, swollen, and distorted by the sun. The bodies of seven officers lie in a row in front by themselves. I cannot but think what a fine company they would make if by a miracle an Unseen Hand could restore them to life by a touch. The rank of major and the red tabs on one of the bodies arrests[47] my eye, and the form of the officer seems familiar. Colonel Gostling, of the 88th Field Ambulance, is standing near me, and he goes over to the form, bends down, and gently removes a khaki handkerchief covering the face. I then see that it is Major Costaker, our late Brigade Major. In his breast-pocket is a cigarette-case and a few letters; one is in his wife’s handwriting. I had worked in his office for two months in England, and was looking forward to working with him in Gallipoli.

It was cruel luck that he even was not permitted to land, for I learn that he was hit in the heart on the hopper shortly after General Napier was laid low. His last words were, “Oh, Lord! I am done for now.” I notice also that a bullet has torn the toes of his left foot away; probably this happened after he was dead. I hear that General Napier was hit whilst in the pinnace, on his way to the River Clyde, by a machine gun bullet in the stomach. Just before he died he said to Sinclair-Thomson, our Staff Captain, “Get on the Clyde and tell Carrington-Smith to take over.” A little while later he apologized for groaning. Good heavens! I can’t realize it, for it was such a short while ago that we were all such a merry party at the “Warwick Arms,” Warwick. I report to Captain Stoney, of the K.O.S.B.’s, who is the M.L.O., and he hands over supplies to me. I clear the beach, make a small Supply depot and take stock, and start to issue to all and sundry as on “W” Beach the previous day. All day the French are arriving from the Asiatic side. No shelling. Evidently the Turks have no artillery. Davidson, an R.N.D. officer, tells me that he is quite used to handling the dead now. He has been told off to identify them on this beach and to take charge. I have a good look at the River Clyde. She managed to get within two hundred yards of shore, and now she is linked to the beach by hoppers. Two gangways are down at either side at a gentle slope from holes half-way up her sides, and very flimsy arrangements they are. It is difficult for the troops to pass each other on them. Men poured out from these holes in the ship at a given signal early on Sunday morning, and were quickly caught by machine gun fire, dropping like flies into the sea, a[48] drop of 20 feet. Some of those who fell wounded from the hopper in the shallow water close inshore drowned through being borne down by the weight of their packs. Colonel Carrington-Smith, who took over command of the Brigade when General Napier was killed, was looking round the corner of the shelter of the bridge through glasses at the Turkish position on shore when he was caught by a bullet clean in the forehead and died instantly. Sunday night on the Clyde was hell. One or two shells, luckily small ones from Asia, burst right through the side of the ship. Doctors did splendid work for the wounded all night on board. A sigh of relief came from all on board when the signal was given next day to land and take the beach, which was taken after much hand-to-hand fighting, the enemy putting up a gallant resistance, encouraged as they were by their success in preventing us from landing on this beach on Sunday.

Addison, of the Hants, is gone; he met his end in the village of Sed-el-Bahr. He was leading his men, firing right and left with his revolver. He met a Turk coming round the corner of a street; he pulled the trigger of his revolver: nothing happened. He opened it, found it empty, threw it to the ground with a curse, went for the Turk with his fist, but was met by a well-aimed bomb, which exploded in his face, killing him instantly.

It sounds horrible, but it is war these days. Perhaps I am over-sensitive, but a lump comes to my throat as I write this, for just over a month ago Addison and I used to talk about books at the “Warwick Arms,” Warwick, and the sight of him reading with glasses, smoking his pipe before the fire of an evening, is still fresh in my memory. It would have been hard to believe then that such a quiet, reserved soul would meet his end fighting like a raging lion in the bloody streets of Sed-el-Bahr a few weeks later. But that has now actually happened, and similar ends will meet like brave men again and again before this war is over.

A little amusing diversion is caused in the afternoon of to-day by a hare running across the beach, chased by French “poilus,” and being very nearly rounded up.

[49]

At 5 p.m. while making up my accounts for the day, I hear from the Asiatic side the boom of a gun, followed by a sound not unlike the tearing of linen, ending in a scream and explosion. Not very big shells, and the first, so far, that I have experienced on shore. I look towards Asia and see a flash in the blue haze of the landscape there, and over comes another, dropping in the sea near the Clyde. They follow quickly in succession, and each time I see the flash, I duck with my three stalwart henchmen behind our little redoubt of supplies, proof only against splinters. The nearest falls but twenty yards away, and does not explode. I see through my glasses two destroyers creep up towards the enemy’s shores and fire rapid broadsides. After a few of these we are left in peace.

I am once or twice called up on the telephone—a telephone worked by a signaller lying on the ground, the instrument being in a portable case. It is strange saying “Are you there?” under these conditions and with these surroundings. The signal arrangements are excellent. Calls come in constant succession from “W,” “X,” and “S” Beaches. A wireless instrument is hard at work, run by a Douglas engine in a tent, controlled by a detachment of Australians. One of the Australians, a corporal, offers me a shakedown in his tent for the night, and lends my men some blankets for their bivouac, which they have constructed out of my little Supply depot. Owen, O.C. Signals, says that I shall not get much sleep in the wireless tent, and that I had better share his tent, which is in a little orchard behind a ruined house close handy. I have my evening meal of bully, biscuit, and jam, and lighting my pipe, go for a stroll in the village, but am stopped by sentries, for snipers are still at large there, and several casualties have occurred to-day there through their industry. I cannot help admiring the pluck of these snipers, for their end is certain and not far off. Two mutilated bodies of our men are lying in a garden of a ruined house, but this case so far is isolated. We have seen the Turks dressing the wounds of some of our men captured by them. The Turks appear to be a strange mixture.

[50]

I awake feeling very fit and refreshed, and find a beautiful morning awaiting me. Opposite our tent is a little “bivvy,” made of oil-sheets and supported by rope to one of the walls of the house and a lilac-tree. A head pokes out from under this “bivvy” with a not very tidy beard growing on its chin, and the owner loudly calls for his servant. While making his toilet he joins in a merry banter with Owen, who is indulging in a cold douche obtained from a bucket of water. Some of the French having invaded the sanctuary of our walled-in camp, picking several of the iris growing in the wild grass, the officer with the beard asks me to tell them to get off his lawn, which I do. I find later that he is Josiah Wedgwood, M.P., and being interested, get into conversation with him. He is a most entertaining man, and tells me that he is O.C. Armoured Cars, but that as it is not possible for his cars to come on shore, he had been instructed to use his intelligence and make himself useful, which he was trying to do with a painful effort.