BY

CHARLES HOMER HASKINS

AND

ROBERT HOWARD LORD

CAMBRIDGE

HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS

LONDON: HUMPHREY MILFORD

OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

1920

COPYRIGHT, 1920

HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINTED IN THE U.S.A.

TO

ARCHIBALD CARY COOLIDGE

[Pg vii]

The purpose of the lectures here published is to give a rapid survey of the principal elements in that territorial settlement of Europe which has been pronounced “the most reasonable part of the work of the Conference”[1] of Paris. Each problem is placed in its historical setting, while at the same time the effort is made to view it as something demanding practical solution in the treaties of peace. The perspective of proceedings as seen at Paris has been kept in mind throughout, although the authors have not felt at liberty to enter into the details of negotiations which may have become known to them in their official capacity. Limits of time and space restrict the treatment to Europe, and to those parts of Europe which came before the Conference for settlement. Hence Russia is necessarily omitted.

The lectures are printed substantially as delivered at the Lowell Institute last January, with only incidental revision. In the spelling of place names the official local usage has been followed except where there is a well established English form.

The first four chapters were prepared by Mr. Haskins, the last four by Mr. Lord.

Where material has been gathered from such a variety of sources, detailed acknowledgment is[Pg viii] impossible. The bibliographical notes at the end of the several chapters are meant merely to indicate the more obvious references for readers who may wish to follow out particular topics. The authors desire to express their indebtedness to their colleagues on the ‘Inquiry’ and the territorial section of the American Commission to Negotiate Peace, and their appreciation of many courtesies from the experts of the Allied delegations. They are under special obligations to the hospitality of the American Geographical Society and its Director, Dr. Isaiah Bowman. Mr. George W. Robinson has made valuable suggestions in correcting the proof sheets. While grateful for assistance from many sources, each of the authors bears sole responsibility for the opinions he has here expressed.

C. H. H.

R. H. L.

Cambridge, May 1920.

[1] Charles Seignobos, in The New Europe, March 25, 1920.

[Pg ix]

| I | |

| Tasks and Methods of the Conference | 3-35 |

| The Tasks | 3 |

| The Problem of Frontiers | 10 |

| Organization of the Conference | 23 |

| Bibliographical Note | 33 |

| II | |

| Belgium and Denmark | 37-73 |

| Schleswig | 37 |

| The Kiel Canal and Heligoland | 46 |

| Belgium | 48 |

| Position at the Conference | 49 |

| Malmedy, Eupen, and Moresnet | 54 |

| Luxemburg | 57 |

| Limburg and the Scheldt | 60 |

| Bibliographical Note | 72 |

| III | |

| Alsace-Lorraine | 75-116 |

| The Historical Background | 75 |

| The Franco-German Debate | 84 |

| The Armistice and the Treaty | 105 |

| Bibliographical Note | 115[Pg x] |

| IV | |

| The Rhine and the Saar | 117-152 |

| The Rhine | 117 |

| The Left Bank | 123 |

| The Saar Basin | 132 |

| Bibliographical Note | 151 |

| V | |

| Poland | 153-200 |

| The Resurrection of Poland | 153 |

| The Western Frontier and Danzig | 172 |

| Galicia | 188 |

| The Eastern Frontier | 195 |

| Bibliographical Note | 199 |

| VI | |

| Austria | 201-229 |

| The Collapse | 201 |

| Czecho-Slovakia | 213 |

| The Germans in Bohemia | 216 |

| The Austrian Republic | 222 |

| Klagenfurt | 223 |

| The Italian Frontier | 224 |

| Bibliographical Note | 228 |

| VII | |

| Hungary and the Adriatic | 231-262 |

| The End of the Old Hungarian State | 231[Pg xi] |

| Hungary’s Losses | 237 |

| The Slovaks | 237 |

| The Ruthenians | 238 |

| The Roumanians | 239 |

| The Yugo-Slavs | 241 |

| The Adriatic Question | 244 |

| Gorizia, Trieste, and Istria | 249 |

| Dalmatia | 251 |

| Fiume | 256 |

| Bibliographical Note | 261 |

| VIII | |

| The Balkans | 263-290 |

| Bulgaria and her Neighbors | 263 |

| The Macedonian Question | 267 |

| The Dobrudja | 275 |

| Bulgaria’s New Losses | 276 |

| The Aspirations of Greece | 277 |

| Epirus and Albania | 278 |

| Thrace | 281 |

| Constantinople | 285 |

| Bibliographical Note | 288 |

| INDEX | 291-307[Pg xii] |

MAPS

| I. | Belgium and her Neighbors | 74 |

| II. | Alsace-Lorraine and the Saar Valley | 152 |

| III. | Poland | 200 |

| IV. | Territories of the Former Austro-Hungarian Monarchy | 242 |

| V. | The Adriatic | 262 |

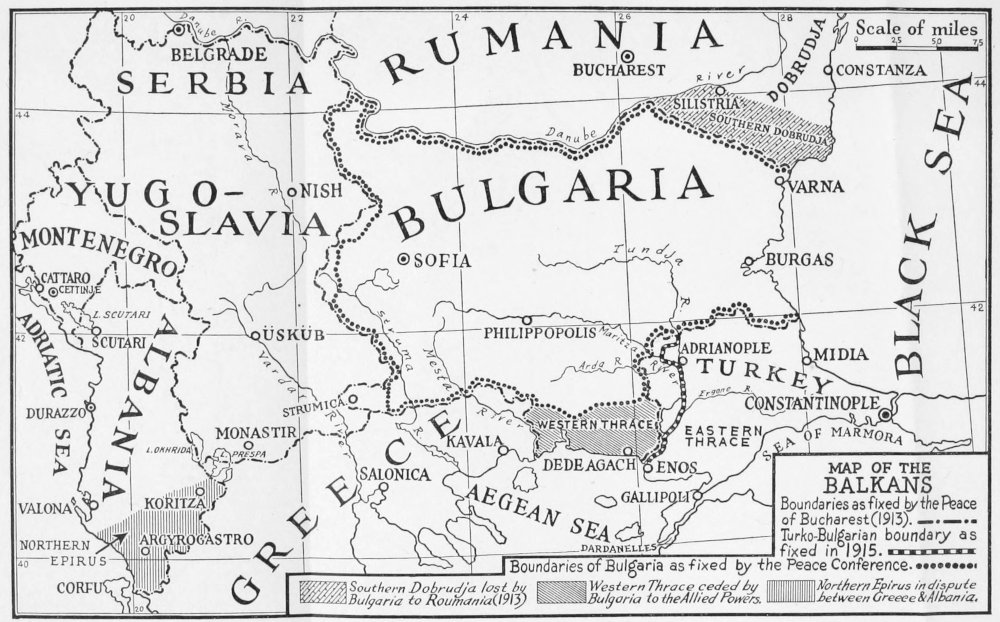

| VI. | The Balkans | 290 |

[Pg 3]

Great peace conferences are proverbially slow bodies. The negotiators of Münster and Osnabrück spent five years in elaborating the treaty of Westphalia; the conferences of Paris and Vienna labored a year and a half at undoing the work of Napoleon. Judged by these standards, the Peace Conference of 1919 was an expeditious body. It began its sessions January 18 and adjourned December 9. It submitted the treaty with Germany, including the covenant of the League of Nations, May 7; the treaty with Austria June 2 and July 20; the treaty with Bulgaria September 19; the treaty with Hungary in November. In the early summer it prepared various treaties with Roumania and the new states of eastern Europe. The heaviest part of its work was done in less than six months, before the departure of President Wilson on June 28.

Judged by its output in a given time, the Conference must also be pronounced a businesslike and efficient body. Whereas the treaty of Vienna covers some seventy pages of print, and the related conventions perhaps a hundred and fifty pages more, the published works of the Paris Conference fill several volumes. The treaties which it drew up were long and detailed, each of the major treaties[Pg 4] running to a couple of hundred pages and comprising some hundreds of articles and annexes—territorial, political, financial, economic, naval, and military—besides the provisions respecting labor and the League of Nations which are common to all.

The Conference of Paris was likewise a laborious body. The gaiety of the Congress of Vienna has become proverbial. “The Congress does not march,” said the Prince de Ligne, “it dances.” “Everybody dances save Talleyrand, who has a club foot. He plays whist.” It is probable, as recent historians of the Vienna assemblage have pointed out, that “the unending series of balls, dinners, reviews, and fêtes did not greatly hinder the work of those whose industry was important.”[2] Nevertheless the presence of a crowd of kings and princes and great ladies—the Prince de Ligne wore out his hat taking it off at every turn—gave the Congress of Vienna an air of splendor and gaiety which was conspicuously lacking at Paris. There were no kings at the Paris Conference, indeed there were few kings left anywhere in Europe by January 1919. There were no balls, no great festivities. If the Conference did not always advance, at least it did not dance. The Marne was too near for that, in space as well as in time. Armageddon was just past. The Germans had barely missed marching up the Champs-Elysées and under the Arc de Triomphe. The American delegates were within[Pg 5] an hour’s ride of Château-Thierry and Belleau Wood, where their countrymen had, only a few months before, done “the things that can’t be done.” Two hours would take them to the heart of the devastated region, refugees from which still filled Paris. The regiments of poilus that marched by with steady stride had looked into the mouth of hell, and their eyes showed it. The Paris which Castlereagh had found “a bad place for business” in 1814 was a better place for business in 1919. The world wanted peace, and it wanted it soon.

It was also a hungry world. Pliny tells of a fabled people of the East so narrow-mouthed that they lived by the smell of roast meat. Even that gladsome and satisfying odor had long since disappeared from the nostrils of a great part of Europe, and the mouths had not shrunk. “If they have no bread, let them eat cake,” a great lady had said at the time of the French Revolution. The cake had gone with the bread. “The wolf,” said Mr. Hoover, “is at the door of the world.” More than once the Peace Conference had to turn from other matters to feed the peoples whose frontiers it was drawing, to deal earnestly and under pressure with problems of blockade and rationing, of transportation by land and sea.

Back of hunger lay anarchy. Great states were on the verge of dissolution, and it was doubtful who, if anyone, could sign the treaty on their behalf. There were times when the Conference had also to interrupt its labors to consider the chaos[Pg 6] into which the world seemed to be drifting. The day after the Bolshevist revolution in Hungary one of the sanest of American journalists remarked, “In the race between peace and anarchy, anarchy seems today to be ahead.”

No peace congress had ever confronted so colossal a task. The assembly at Paris met to end a world war, then in its fifth year, which had destroyed 9,000,000 lives and untold billions of property, and left the world staggering under a crushing burden of debt and destruction. It had in the first instance to liquidate the affairs of three bankrupt empires, the German, the Austro-Hungarian, and the Turkish. The peoples which they had held in unwilling subjection were to be set free, and either attached to the neighboring peoples from which they had once been torn, or established firmly as independent and self-governing states. “As Lord Bryce had predicted, the most knotty disputes which faced the Conference were ‘nearly all problems that involve the claims of peoples dissatisfied with their present rulers and seeking either independence or union with some kindred race.’” Several thousand miles of new boundaries had to be drawn, marking new frontiers, and if possible these frontiers must be just and lasting. Provision must be made for restoring the lands laid waste by war and reëstablishing the normal commercial and industrial life of the warring countries. Those responsible for the war must pay, and they must be punished. Finally, if possible,[Pg 7] effective measures must be taken to prevent the recurrence of a similar war, whether brought about by Germany’s lust of conquest or by any other state. If war could not be prevented, it must at least be rendered more difficult and more abhorrent to the common moral sense of mankind.

Far beyond the more immediate and necessary tasks of the Conference rose the dreams of those who looked for the dawning of a new age of peace and justice, a new social and economic era. The downtrodden and the oppressed looked toward Paris. Visions of peace were confused with visions of the millennium. “We were told,” said a Scotch mill-worker, later in the winter, “that the peace would bring in the New Jerusalem. We want some of that New Jerusalem.” The day President Wilson sailed for Brest, a worker at the Twenty-third Street Ferry, speaking for the early crowd hurrying to their long hours in New York sweatshops, pointed to Hoboken and said, “There goes the man who is going to change all this for us.” Beautiful, extravagant, heart-breaking hopes were centred on the Conference at Paris, most of all on the leader of the American delegation and his programme. And such hopes were in large measure inevitably doomed to disappointment. The congress could not create a new heaven and a new earth; it could at best only make some short advance on the road thither and show the way along which further advance lay. Renan tells of a devout soul, who, seeing so much evil about him,[Pg 8] was periodically afflicted with doubts concerning the goodness of an all-powerful God. “Perhaps,” his parish priest would answer, “you have too high an idea of God and what he can do.” “It was an old world,” writes Mommsen of the age which just preceded the Christian era, “and even Caesar could not make it young again.”

A just peace, a durable peace, if possible a quick peace, could these ends be secured? The task was one which called for compromise and adjustment, it called also for organization. There is said to have been a plan for quick preliminaries which should end the state of war, followed by the leisurely and expert working out of details. If such a course had been possible, it would probably have been the best. Germany would have accepted terms in January at which she howled in June, while the Allied peoples might thus have avoided the long agony of doubt and postponement which delayed the resumption of normal activities and the rehabilitation of the devastated regions. The world that was malleable after the armistice soon grew cold and hard. It is, however, a matter for serious question whether an agreement upon such preliminaries was possible. The problems were too varied and intricate, the conflict of interests too acute, the new ideas too new, to admit of even provisional adjustment in a few weeks. The Conference seemed long, too long, to the outside world which waited. If it did not dance, like the Congress of Vienna, neither did it always seem to[Pg 9] march, like the Congress of Berlin, which had a cut-and-dried programme. At times it was undoubtedly too slow; at times certain special problems, like Fiume, consumed energy altogether out of proportion to their importance; yet the Conference made steady and on the whole rapid progress. It was a hard-working body, and its scanty time was well spent.

It will be many years before the history of the Peace Conference can be written. Its work was too vast and too varied; its records are too scattered and too inaccessible, many of them still unwritten. We are still too near for a true perspective. For some time we must be content with fragmentary, partial, provisional, journalistic accounts, and we do well to keep to the main lines of unmistakable fact. The most obvious results of the work of the Conference, though not necessarily the most permanent results, are its territorial decisions, the readjustment of boundaries and sovereignties, the calling of new states into being. These, so far as they go, are clear and definite. They can be expressed on a map, their origin and occasion can be traced, their nature explained. It is these, the territorial results of the Conference, with their consequences and implications, which form the subject of this volume. The treatment is further limited to Europe, omitting the problems of Asia, Africa, and the isles of the Pacific.

There are those who maintain that the territorial results are unstable and hence relatively[Pg 10] unimportant, liable to speedy readjustment in a fluid state of international relations, subordinated in ever increasing degree to economic and social influences which transcend national boundaries. All this the future must determine. For the present the decisive fact for many millions of Europeans is that they are on one side or another of a political frontier, members or not of the state to which their natural allegiance gravitates; and this is a matter of specific boundary. One may deplore the rivalries over small bits of territory, which acquire a factitious significance in the course of the dispute, but they cannot be ignored. The possession of land is still a passion of peoples, and even of what our census calls ‘minor civil divisions,’ and the history of individual ownership shows that such passions do not grow less with the growth of other interests. So long as states continue to exercise authority within definitely recognized frontiers, the establishing of their territorial limits must remain a fundamental problem of international relations. If an illustration of the meaning of frontiers is desired nearer home, one has only to look at the two sides of the Rio Grande.

Reduced to their lowest terms, the elements which enter into a national boundary are two, the land and the people; and an ideally perfect frontier would be at the same time geographic and ethnographic. Such coincidences are, however, relatively rare, and the problem varies from age to[Pg 11] age as different geographical considerations change in relative importance and as the human elements of race, language, and nationality develop, shift, and grow more complex.

Thus a glance at the map of Europe shows that certain frontiers apparently have been drawn by nature, while others are clearly the work of man. The Spanish peninsula, Italy, the British Isles, and the Scandinavian lands are set apart from the mass of the Continent by broad boundaries of sea or mountain which have come to form permanent political frontiers. On the other hand no such obvious natural obstacles separate France from Germany, Germany from Russia, Belgium from Holland, Austria from its neighbors, Serbia from Bulgaria. So far as the boundaries have been drawn by geographic forces, the forces are less obvious; if they have been drawn by the course of history, this requires explanation and elucidation. It so happened that the Paris congress had to do, not with the outlying regions where the physical and the political maps generally coincide, but with those lands of central and eastern Europe where the adjustment is most complicated. We shall understand its work more clearly if we pause to analyze briefly this problem of frontiers.

Of the geographical elements which go to form frontiers, the most obvious, after the sea, is constituted by mountains. The Pyrenees are a perfect example of a natural frontier which is also an actual frontier, and so in a lesser degree are the Alps and[Pg 12] the Carpathians. Mountains inevitably divide, turning peoples different ways, in spite of modern means of communication, and they have always been valued as military barriers. Rivers, on the contrary, although they have military value, unite rather than divide, so that we need not be surprised if we find no important instances of a river frontier in present-day Europe, save along the Danube and where the Rhine separates Alsace and Baden. Most frontiers are neither mountain ranges nor rivers, yet they are often adjusted to lesser features of topography, with reference either to defence or to means of communication. Communication notably, with the growth of modern systems of transportation, bears an intimate relation to boundary problems. Access to the sea, either directly or by neutralized or internationalized rivers, has become a prime necessity for most states, and occupied the Conference especially in the cases of Poland and Czecho-Slovakia. Even railroad lines, especially where they monopolize natural routes, have their place in frontier adjustments, as in Carinthia or between East and West Prussia.

Another geographical element, essentially modern in its significance, is found in natural resources. This has never been wholly absent from boundary problems, at least in its early form of fertile or less fertile land, but it has taken on a preponderant importance with the growth of modern industrialism. Each state has been anxious to bring within[Pg 13] its limits supplies of mineral resources, and especially of that foundation of modern industry, coal. Now it so happens that some of the most important deposits of coal and mineral wealth lie on or near disputed frontiers. The coal of Upper Silesia, Teschen, Limburg, and the Saar, the iron of Briey and annexed Lorraine, the potash of Upper Alsace, the mercury mines of Carniola, are all cases in point. Prussia was affected by such considerations in drawing the frontiers of 1815 and 1871; other countries had learned the lesson by 1919.

The human elements in frontier-making are still more complex than the geographical. Obviously we have to do not with individuals but with groups, and with those larger groups which have acquired a full measure of what the sociologists call ‘consciousness of kind,’ to the point of constituting some kind of national unity or national organization. We speak of the self-determination of peoples, but what is a people? Is it created by race or language or political allegiance, or only by that more subtle compound which we call nationality? How large must a people be to have a right to stand alone? Can it stand alone without certain economic and even military prerequisites? How far can we go in breaking up states in order to give effect to self-determination?

Such general principles might have a very wide application. Formulated with special reference to the Central Powers, self-determination was seized upon by men who had a case to urge in[Pg 14] any part of the world—in Ireland, in Egypt, in the Philippines. A German map of last spring even represented Hawaii, St. Thomas, Florida, and Texas as trying to escape from their unwilling subjection to the United States[3]—a curious evidence that German mentality had not changed since the notorious Zimmermann note of 1917. More than once it was necessary to point out that the function of the Paris Conference was not to do abstract justice in every corner of the earth, but to make peace with Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, and Turkey. Many causes perhaps excellent in themselves were not the business of the Conference.

Even within the self-imposed limits of the Conference, there were difficulties. “Self-determination,” President Wilson had said, “is not a mere phrase, it is an imperative principle of action.” But President Wilson had also said that self-government cannot be given but must be earned; that “liberty is the privilege of maturity, of self-control,” that “some peoples may have it, therefore, and others may not.”[4] However just and admirable self-determination might be, it could be fully applied only to peoples who had some experience in self-government and thus some means of political self-expression. For this reason it was not applicable to the downtrodden natives of the German colonies. And even among self-governing peoples there are practical limitations. Self-determination[Pg 15] may be only another name for secession, and we fought the Civil War to prevent that; we have been none too successful in securing the subsequent self-determination of the negroes in the southern states. Sometimes a people may be too small to stand alone, and sometimes, as in parts of the Balkans and Asia Minor, the mixture of peoples may defy separation. In western Asia, notably, national aspirations have outrun the social organization.

Wherever you apply it, self-determination runs against minorities. Ireland has its Ulster, Bohemia its Germans, Poland its Germans and Lithuanians. There are minorities along every frontier. Some one remarked that there was need of a fifteenth point, the rights of minorities. The Conference found this out, and upon the newly established states of eastern Europe were imposed special treaties safeguarding the rights of minority peoples—Jews, Germans, Russians, etc.—whom past experience had shown to need such guarantees.

Of these human elements in frontier-making we may begin by eliminating race, for in Europe race is a matter of no importance in drawing national lines. This point is emphasized, here and later, because there has been a great deal of loose talk about race, notably on the part of German writers. So far as it is an exact term at all, race is a physical fact, dependent upon certain elements of stature, color, and shape of the skull which occur and are transmitted in certain fixed combinations[Pg 16] or racial types. There are three such types in Europe, the Teutonic, the Alpine, and the Mediterranean, most prevalent respectively in northern, central, and southern Europe. But in no country do they appear in pure or unmixed form. Migration and conquest have intermingled them to such an extent as to leave no sharp racial frontiers and to make the people of every country a mixture of two or three races. Thus the central or Alpine type is widely prevalent in the south and west of Germany, and the Teutonic type in the north and east of France. Furthermore these physical types are quite without political significance—no one cares whether his neighbors are tall or short, blonde or brunette, round-headed or long-headed. So far as Europe is concerned, all talk of race has to be eliminated from serious international discussion.

Language, on the other hand, is a matter of prime importance. Speech is a fundamental element in creating consciousness of kind: the man in the street knows whether he can understand the speech of his neighbor, and has always had opprobrious epithets for those who speak an alien tongue, from the ‘barbarians’ of the Greeks and the ‘Welsh’ of the Teutonic Middle Ages to the ‘dagoes’ and ‘gringoes’ and ‘wops’ of current parlance. Even differences of dialect engender similar terms, as when the people of the Right Bank are called Schwob in Alsace and the Alsatians are stigmatized as Wacke by those beyond the Rhine.

[Pg 17]

Still, language has its pitfalls as a guide to national lines of cleavage. To begin with, while in the country districts it is singularly persistent, it can also be learned and unlearned by a new generation, especially when the resources of universal education are wielded by the compulsive power of the modern state. The German schoolmaster has labored to reduce the area of Danish in Schleswig and of French in Alsace-Lorraine. The Russians have checked German in the Baltic provinces. In the British Isles Celtic speech is far less widespread than Celtic blood. Moreover, if the government cannot always drive out minority languages, it can at least make its own language statistics. It is easy for the census-taker to impose on the weak or ignorant, to interpret all doubtful cases in one direction, to adopt definitions which fall on one side. The statistics of Polish-speaking districts in Prussia and of Italian-speaking elements in Austria-Hungary are well known examples.

Again, language statistics, even when trustworthy, do not necessarily yield a sharp dividing line. There may be more than two significant elements in the population, or, as in parts of the Balkans and Asia Minor, villages of different speech may be interspersed in a checkerboard fashion.

Finally, language, even when accurately ascertained, is not a certain test of political affiliation. There has been a strong pro-French tradition[Pg 18] among the German-speaking Alsatians. The small German-speaking districts of Belgium are not pro-German.

After all, it is the opinion of the people concerned which we wish to ascertain with respect to a given frontier, and language is important chiefly as a guide to that. Unequivocal expressions of popular opinion are, however, hard to reach, especially in times of stress and in regions that are under dispute. At best a plebiscite may be but a poor indication of real opinion, and the opinion it registers well may be only transitory. Moreover, caution may be required in giving effect to a vote or an otherwise well ascertained expression of opinion. Thus it is open to debate whether the vote of a small district should necessarily carry with it the disposal of a great key deposit of mineral wealth which concerns a much wider constituency. It is also possible that in the long run commercial intercourse and economic interest may create ties more lasting than language or national sentiment, and that a given boundary may do more ultimate harm by violating the fundamental economic interests of a region than by violating its momentary political sentiments.

Again, the political sentiment of the moment may run counter to strong historic forces, as in Bohemia, where the considerable German element has been settled for centuries, so that its incorporation with adjacent German-speaking countries would tear apart the historic unity of the Czech[Pg 19] state. Indeed, it is a nice question how far it was the task of the Peace Conference to right ancient territorial wrongs. “The wrong done to France by Prussia in 1871 in the matter of Alsace-Lorraine” was a clear case for rectification, if only because, in President Wilson’s phrase, it had “unsettled the peace of the world for nearly fifty years.” Much the same could be said for the restoration of North Schleswig, seized by Prussia in 1864, and even for Poland, though its destruction dates back to the eighteenth century. On the other hand, more recent acts of injustice, such as the Prussian annexations of 1814, the Conference left untouched, except on the Belgian frontier, evidently considering them as internal German questions which time had adjusted. Some notion of prescription had evidently to be admitted, else in seeking to right ancient wrongs the Conference would have done a greater wrong by introducing confusion into every part of the world. The only noteworthy attempt to reach far back into history would be the restoration of the Jews to Palestine, now inhabited by a preponderantly Mohammedan and Christian population. Here, as in many parts of eastern Europe, religion becomes an important element in national cleavage.

In general, the Paris Conference was disposed to give more weight to the principle of nationality, in its broader historic sense, than to economic or strategic considerations. This idea of nationality runs through the programme of President Wilson,[Pg 20] which the members of the Conference had accepted in advance. It is, of course, easier to set peoples free from their rulers than from economic necessity, and the creation of new political frontiers undoubtedly complicates questions of trade and commercial policy. Nevertheless, it is a curious inconsistency that some who are most eager to find discrepancies between the programme of the Conference and its achievements should at the same time propose to destroy the economic and political independence of the newly liberated peoples of central Europe and the Balkans by imposing on them a compulsory customs union after the manner of Germany’s Mitteleuropa.[5]

Finally, the nature of the frontiers to be drawn at Paris depended on the kind of world for which they were to be made. If Europe was to continue to be an armed camp, divided between two competing systems of alliances, then the strongest possible military frontiers would be required—along the Rhine and the Danube, in the Alps and in the Balkans—, and the strategic element must preponderate in every boundary. If, on the other hand, some better form of international organization could be found through a League of Nations, however rudimentary, strategic considerations could drop into the background in favor of the economic convenience and the political desires of the people concerned. If colonial rivalries were to be reduced in the interest of world peace, the[Pg 21] German colonies ought to be subjected to some international control, and they could not be internationalized without creating some international authority. An international control of ports and rivers might affect the whole problem of access to the sea, while areas of special tension or perplexity, like Danzig or the Saar valley, might be placed under some form of international administration such as commissions of the League of Nations. This explains why the problem of the League could not be postponed until after the conclusion of peace, but formed an integral part of the negotiations and of the treaty itself. At every turn the problem of the League of Nations obtruded itself, and the elaboration of the plan for a League facilitated, instead of hindering, the work of the Conference.

In addition to the fundamental principle of self-determination expressed in President Wilson’s speeches, Germany and the Allies had accepted his specific Fourteen Points as the basis of the negotiations. This immensely simplified the task of the Conference in certain directions, and gave a firm ground for discussion wherever these applied; but much was required in the way of interpretation, extension, supplementing, and application before the two pages of the Fourteen Points could grow into the two hundred pages of the treaty with Germany and the correspondingly long texts of the other treaties. The Fourteen Points did not[Pg 22] cover the whole field, and even where they were clearly and directly applicable, much knowledge and much negotiation were required to put them into effect.

The Congress of Vienna had its Statistical Commission, one of the most successful parts of the Congress, which collected the statistical data for parcelling out peoples among the various princes. It was limited, however, to statistics of population, the counting of heads being the only basis there admitted in the balancing of territorial adjustments. The Paris Conference needed a far larger and more varied body of knowledge, not only because it covered every part of the world, but because its declared principles necessitated information of every sort respecting the history, traditions, aspirations, ethnology, government, resources, and economic conditions of the peoples with which it was to deal.

Information the Conference had in huge quantities, literally by the ton. It came in every day in scores of foreign newspapers, in masses of pamphlets, in piles of diplomatic reports and despatches. Every special interest was on hand, eager to present its case orally to the Conference or its commissions, to enlighten personally the commissioners or their subordinates, to hand in endless volumes of more or less trustworthy ethnographical maps and statistics, of pictures and description, of propagandist matter of every conceivable sort. A steady head, a critical judgment,[Pg 23] and a considerable background of fact were required to keep one’s vision clear amidst this mass of confusing and conflicting material.

The collecting and sifting of such information for the Conference had begun years before. The French, systematic as always, had appointed governmental commissions, economic, military, geographic, and had also a special university committee with Professor Lavisse as chairman, the Comité d’Etudes, which prepared two admirable volumes, with detailed maps, on the European problems of the conference. The British had printed two considerable series of Handbooks, one got out by the Naval Intelligence Division under the guidance of Professor W. McNeil Dixon of Glasgow, the other prepared in the Historical Section of the Foreign Office under the editorship of Sir George Prothero. The United States had put little into print, but more than a year before the armistice, by direction of the President, Colonel Edward M. House had organized a comprehensive investigation, known as the ‘Inquiry,’ with its headquarters at the building of the American Geographical Society in New York City, whose secretary, Dr. Isaiah Bowman, served as executive officer. It enlisted throughout the country the services of a large number of geographers, historians, economists, statisticians, ethnologists, and students of government and international law; and carloads of maps, statistics, manuscript reports, and fundamental books of[Pg 24] reference accompanied the American Commission to Paris. The specialists who went along or were later brought together were organized into a group of economic advisers—Messrs. Baruch, Davis, Lamont, McCormick, Taussig, Young, and their staffs—; two technical advisers in international law—Messrs. David Hunter Miller and James Brown Scott—with their assistants; and a section of territorial and political intelligence.

Peace conferences are always represented as sitting around green tables, and this pleasant fiction is perpetuated with reference to Paris in the widely circulated advertisement of a well known fountain pen. Now the Paris Conference never sat around a table. It is true that for certain formal sessions of the whole Conference there was arranged a long table lining three sides of the principal room in the French Foreign Office on the Quai d’Orsay, and that the delegates could be packed in here twice as close as nature meant them to sit. But there were very few formal meetings of this sort, and they could not by any stretch of the imagination be thought of as round-table conferences, if indeed as conferences at all. Certain leaders delivered prepared speeches, and rarely did lesser lights venture to break the prearranged course of the proceedings.

It was early apparent that the Conference could not profitably meet and do business as a whole. Twenty-seven different states were represented,[Pg 25] besides the five British dominions. There were seventy authorized delegates. Such a body would have become a debating society; it would still be in session, its labors scarcely begun. Some guiding or steering executive committee was obviously required, and it was early found in the delegates of the five chief Powers: America, England, France, Italy, and Japan.

The five Great Powers themselves had thirty-four delegates, and it was plain that this also was too large a body for doing ordinary business. So there was early organized a Committee or Council of Ten, each state having two members, ordinarily the chief delegate and the foreign secretary; and this became the active agency of the Conference. It had a secretariat; and expert advisers, civil or military, attended as they were needed. If a military matter came up, Marshal Foch would be on hand, member of the Conference in his capacity of Commander-in-Chief, with his curving shoulders, fine face, and clear eye. A naval question brought in the British sea lords, Admiral Benson, and a keen-looking lot of Japanese. When economic questions were to the fore, the American delegation bulked large, with the square jaw of Mr. Herbert Hoover well in evidence.

Even the Council of Ten was not seated about a table, although it is so imagined in an ‘inside history’ of the Conference by one who was never inside.[6] Nor did the American delegation meet[Pg 26] around a table, notwithstanding the preparation of an official picture which represents the members in a room where they never met, seated at one end of a table and backed by an imposing array of secretaries and assistants. The Council of Ten sat along three sides of the pleasant office of M. Pichon, the French Foreign Secretary, its walls covered with bright tapestries after the style of Rubens, its windows looking out over a beautiful French garden which tempted the roving eye while a long speech was being translated. M. Clémenceau presided, a tiger at rest, his eyes mostly on the ceiling, sometimes bored but always alert and never napping. Others sometimes appeared to sleep or to distract themselves as best they could; but no one lost touch with the proceedings. Certainly the President of the United States, long trained by golf, kept his eye steadily on the ball.

The Council of Ten met almost daily at three. Each special interest, each minor nationality, had a chance to come forward and state its case, usually at considerable length. Whatever was said in French was translated into English, and vice versa. The sessions grew long and tiresome, and progress was slow. More and more people were called in. One of them remarked that he would not have missed his first meeting for a thousand dollars, but would not give ten cents to see a second! For its last two sessions the Council moved into the large room reserved for the plenary sessions of the Conference. One of these meetings was reported at[Pg 27] length in the Paris papers, and it was alleged that undue publicity, as well as undue prolixity, was responsible for the sudden change on March 24. After that date the Council of Ten ceased to meet. Cartoonists represented it as seeking a bomb-proof shelter. At times thereafter the foreign ministers met as a Council of Five. But the real power rested with a new body, the Council of the four principal delegates of England, France, Italy, and the United States—Messrs. Lloyd George, Clémenceau, Orlando, and Wilson.

The Council of Four left the spacious quarters of the Quai d’Orsay. Sometimes it met in M. Clémenceau’s office at the Ministry of War, sometimes at Mr. Lloyd George’s apartment, most frequently at President Wilson’s residence, either in his study, or, when several outsiders were present, in the large drawing-room. The meetings in the study were not always “private and unattended,” nor were the occasional conferences upstairs the confused gatherings which an infrequent spectator has pictured.[7] Outsiders were called in as needed, but ordinarily the Four met by themselves, with a confidential interpreter, Captain Mantoux, very able and very trustworthy. There was no stenographer, not even a secretary, though secretaries were usually outside the door to execute orders. The meetings were quite conversational, and the[Pg 28] records necessarily fragmentary. But the Council at least worked rapidly, sometimes perforce too rapidly. Steadily the main lines of the treaty emerged.

By March the expert work of the Conference had been largely organized into commissions, not systematically and at the outset, as the French had proposed in January, but haltingly and irregularly, as necessity compelled. Foresight and organizing ability were not the strong points of the congress. One by one there were created commissions on Poland, on Greece, on Morocco, on Roumania, etc., on reparation, finance, waterways, and the principal economic problems of the conference. Ordinarily a commission consisted of two members from each of the five great powers, with a secretary from each and special advisers as required. Their proceedings were regularly noted, and formal minutes of each session were approved in print. Each country expressed its opinion, but efforts were made to reach and report a unanimous conclusion. On one occasion a Japanese delegate, perplexed by a detailed problem of local topography, gave as his vote, “I agree with the majority.” As the commission had just divided, two to two, he scarcely clarified the situation.

Some of the best work of the Conference was done in these commissions, and it is to be regretted that the system was not organized earlier and used more widely. Some matters were never referred to commissions, delicate questions like Fiume and[Pg 29] Dalmatia and the Rhine frontier being reserved for the exclusive consideration of the Four. Problems of an intermediate sort were sent to special committees, extemporized and set to work at double speed. Such were the Saar valley and Alsace-Lorraine, referred to a committee of three, Messrs. Tardieu, Headlam-Morley, and Haskins. Not being an organized commission, this body had no secretariat. Economic and legal advisers might be present, but often there were only the three. This committee met for a certain period very steadily, sometimes twice a day. It reported unanimously the chapters of the treaty on the Saar and Alsace-Lorraine, and was present at the meetings of the Council of Four each time these questions came up.

One naturally asks how far the recommendations of these commissions and special committees were followed in framing the final draft of the treaty. To this it is hard to give a general answer, for in the nature of the case there was no uniform policy. The printed minutes of the commissions will some day be public and can then be compared with the several clauses of the treaty. In general, the territorial commissions were thought of in the first instance as gatherers and sifters of evidence, rather than as framers of treaty articles, questions of policy being reserved for the ultimate consideration of the Council of Ten. As time went on, the commissions tended to acquire more responsibility and to throw their reports into the form of specific[Pg 30] articles or sections of a treaty. These naturally required coördination with the work of other bodies, such as the commissions on finance, reparation, or waterways, and a general correlation of the territorial reports was attempted by a Central Territorial Commission of five. Some final suggestions were also made by the Drafting Commission. The reports of the commissions were, however, first made directly to the Ten or the Four or the Five, as the case might be. Each report had its place on the docket, and the members of the commission were then present, each at the elbow of his principal, to furnish any necessary explanations in his ear, but not to speak out. Later in the summer members of the commissions were allowed to take part in the discussions of the Council of Five.

Sometimes the report, presented in print, would be accepted without debate. Sometimes a particular question would be considered at length, perhaps with the result of recommitting the report. Unanimous reports were likely to go through rapidly. A session of the Council of Four might take an important report clause by clause, with explanations from the committee and suggestions from members of the Council, but without fundamental modifications. On the other hand important changes in one chapter of the treaty were made at the last moment by the Four without any consultation of the commission concerned.

In general, the American delegation was disposed[Pg 31] to trust its experts, both on matters of fact and on matters of judgment, and trusted them in greater measure as the Conference wore on. It did not dictate or even suggest their decisions, but left them free to form their opinions on the basis of the evidence. They could have been used to better advantage if they had been set to work earlier, and there were unfortunate instances where they were consulted too late; but in general this is to be explained by the haste and confusion inevitable in the rapid movement of events rather than by any desire to ignore the facts or the judgment based upon them. Certainly none of the chief delegates was more eager for the facts of the case than was the President of the United States, and none was able to assimilate them more quickly or use them more effectively in the discussion of territorial problems.

The treaty of Versailles, like the other treaties drawn up at Paris, is by no means a perfect instrument. Those who took part in framing it would be the last to believe it verbally inspired. It is necessarily a peace of compromise and adjustment, and that means that it does not embody completely the desires of any one person or any one country. It was also framed rapidly, not always with sufficient preliminary study, and in some places it bears the marks of haste. But it represents an honest effort to secure a just and durable settlement, and neither the Conference in general nor the United States in[Pg 32] particular need be ashamed of it. It is easy to criticise in detail, easy to magnify the defects and forget the substantial results achieved, just as it was easy to criticise the Constitution of the United States when it issued from the Convention of 1787, and to discover therein dangers which history has shown to be imaginary. For one result of the Paris treaties, however, their framers are not responsible, namely the delays in ratification and enforcement. The treaties were drawn for the world of 1919 by men of 1919, on the assumption that what was needed was an early peace as well as a just settlement. The governing commissions and mandates were to begin at once, the plebiscites were to be held as soon as possible, the disarmament of Germany was to be prompt and real, the difficult work of reparation was to be taken up immediately. None of these expectations has been realized, and the responsibility lies less with the Peace Conference than with the failure of America to ratify the treaties and to take part in carrying out their provisions.

In one fundamental respect the treaties drawn up at Paris differ from all such instruments in the past: they do not pretend to be final. The treaty of Vienna lasted, in many respects, for a hundred years, and parts of it are still in force, unchanged by the war or the Conference. For all this the Congress of Vienna deserves its full measure of credit, but it must be remembered that it provided no method of change or adjustment. Only a new[Pg 33] war could undo its provisions, and more than one such war proved necessary. At Paris it was recognized from the start that much of the treaty must be temporary and provisional. No one could determine in advance how peoples would vote, or just how much of an indemnity Germany could pay, or whether she would endeavor to execute or to avoid the obligations she there assumed, or what would happen in Austria or in Turkey. Some means of amendment, adjustment, correction, and supplementing was required, and this was found primarily in the League of Nations. In the League the treaties possess the possibility of their own betterment, the starting-point of a new development. Hence, unlike all previous treaties, those of 1919 are dynamic and not static: they are constructive and not merely restorative; they look to the future more than to the past.

The published records of the Paris Conference are limited to the official reports of the plenary sessions and the official text of the treaties, in French and English, with authoritative maps, subject to correction after the frontiers have been fixed on the spot. The proceedings of the Council of Ten and the Council of Five were kept by a regular secretariat, those of the Council of Four less officially and systematically; these minutes were manifolded but not printed. The minutes of the various commissions, while printed, have not been made public.

The German and Austrian treaties and related documents are printed as supplements to the American Journal of International Law since July 1919. The German treaty is also printed as a Senate Document and as a publication of the American Association for International Conciliation. The entire series of[Pg 34] treaties is best available in the British Parliamentary Papers, Treaty Series, 1919 and 1920. A bibliographical list of all these treaties by Denys P. Myers is to be published by the World Peace Foundation, League of Nations Series, iii, no. 1. Documents and Statements relating to Peace Proposals and War Aims, December 1916 to November 1918, have been edited by G. Lowes Dickinson (London and New York, 1919).

There is as yet no memoir literature by members of the Conference. Some confidential papers are printed in the Hearings before the Committee on Foreign Relations of the United States Senate (Washington, 1919), but these do not concern territorial problems. Some things touching France will be found in the report of the Barthou committee to the Chamber of Deputies, supplemented by the articles of A. Tardieu in L’Illustration since February 1920. The official German criticisms of the Treaty of Versailles were published in various languages and have been freely reproduced by pro-German writers in other countries. A Kommentar in six volumes has been prepared by one of the German delegates, Walter Schücking.

So far the printed accounts of the Conference are the work of journalists, who from the nature of the proceedings cannot be fully informed. The most direct information was perhaps possessed by Ray Stannard Baker, chief of the American service of publicity, but his volume, What Wilson did at Paris (New York, 1919), is ex parte and very brief. E. J. Dillon, The Inside History of the Peace Conference (New York, 1920), is a diffuse composite of hearsay and newspaper clippings; it is anti-French but in general friendly to small nations. H. Wilson Harris, The Peace in the Making (New York, 1920), is an intelligent account by a fair-minded British Liberal. Sisley Huddleston, Peace-Making at Paris (London, 1919), is more impressionistic. J. M. Keynes, The Economic Consequences of the Peace (London and New York, 1919), is the brilliant but untrustworthy work of a British financial expert who finally repented of the treaty. Influenced by German propaganda, it is in general anti-French, anti-Belgian, and anti-Polish, and disparages political self-determination in favor of economic frontiers. Of the various critiques which the book has called out, the most searching is that of David Hunter Miller, in the New York Evening Post, February 6 and 10, 1920, and in separate pamphlets.

A volume on the Conference, with an elaborate atlas, is announced by an American territorial expert, Isaiah Bowman; a fuller work is in preparation by British and American experts under the editorship of Harold W. V. Temperley, of Peterhouse, Cambridge.

[Pg 35]

Of the material collected in France for the Conference, the only systematic publication is the Travaux du Comité d’Etudes, in two volumes with an atlas (Paris, 1919). Most of the British material was printed but not published, a useful exception being C. K. Webster, The Congress of Vienna (Oxford, 1918). The Foreign Office series of Handbooks has now been made public (London, 1920). The most important American publication of the sort is the Atlas of Mineral Resources to be issued by the United States Geological Survey (Washington, 1920).

There is no entirely satisfactory discussion of the general problem of frontiers. T. L. Holdich, Political Frontiers and Boundary Making (London, 1916), is concerned chiefly with ‘natural’ frontiers outside of Europe. For the facts of race, see W. Z. Ripley, The Races of Europe (New York, 1899). Leon Dominian, Frontiers of Language and Nationality in Europe (New York, 1917), is convenient. A more authoritative work on the linguistic side is A. Meillet, Les langues dans l’Europe nouvelle (Paris, 1918). Experience with plebiscites is brought together in Miss Sarah Wambaugh’s elaborate Monograph on Plebiscites (New York, 1920). A. Toynbee, Nationality and the War (London, 1915), is an attempt to state the territorial problems in the early months of the war; L. Stoddard and G. Frank, Stakes of the War (New York, 1918), seeks to sum them up at its close. The relation of certain of these problems to a league of nations is discussed in The League of Nations, edited by Stephen P. Duggan, with references (Boston, 1919); and by Lord Eustace Percy, The Responsibilities of Peace (London and New York, 1920).

[Pg 36]

[2] Webster, The Congress of Vienna, p. 93.

[3] Was von der Entente übrig bliebe wenn sie Ernst machte mit dem “Selbstbestimmungsrecht” (Berlin, D. Reimer).

[4] Atlantic Monthly, xc, pp. 728, 731 (1902).

[5] Keynes, Economic Consequences of the Peace, p. 265.

[6] Dillon, The Inside History of the Peace Conference, p. 151.

[Pg 37]

[7] Keynes, The Economic Consequences of the Peace, pp. 30-32. M. Mantoux asserts that Mr. Keynes never attended a regular session of the Council of Four. London Times, February 14, 1920.

Our examination of the specific territorial problems of the Conference may most conveniently begin with the simplest, the frontier between Germany and Denmark. This had been established by force of arms when Schleswig was taken from Denmark in 1864, while a promise made in 1866 to consult the population had never been fulfilled. Only at the close of the World War did an opportunity come to fix the boundary in accordance with the will of the inhabitants. The duty of the Conference was to provide the means of giving effect to their desires.

The territory of the former duchy of Schleswig comprises the portion of the peninsula of Jutland lying between the Danish frontier on the north and the River Eider and the Kiel Canal on the south. Called by the Danes South Jutland (Sönderjylland), it is similar in most respects to Denmark, being chiefly agricultural, with a fishing population on the Frisian islands to the west and a considerable shipping industry in its principal town, Flensburg, a town of 63,000 at the head of the Flensburg fiord. The region has an area of 3385 square miles, and 474,355 inhabitants, not far from twice the extent and population of the state of Delaware. About one-third of the people speak Danish; these are chiefly in the northern[Pg 38] portion of the province. The rest, save for an isolated group of Frisians on the west coast, speak German.

The earlier history of Schleswig would take us into the tangled history of the Schleswig-Holstein question, which is for present purposes unnecessary. Suffice it to say that, whatever the previous rights of the king of Denmark may have been, the attempt to unite the duchy of Schleswig fully to the kingdom of Denmark by the constitution of 1863 led in the following year to war with Austria and Prussia and to the defeat of Denmark, whose king, by the treaty of Vienna, renounced all rights over Schleswig, Holstein, and Lauenburg. In 1866, at the conclusion of the war between Austria and Prussia, the treaty of Prague transferred the rights of Austria to the king of Prussia, with the reservation that the “inhabitants of North Schleswig shall be again reunited with Denmark if they should express such a desire in a vote freely given.” Nothing could be clearer, and nothing more ineffective, for the article was contained in a treaty between two powers neither of which had the slightest interest in the performance of the obligation. As a matter of fact, the provision had been suggested by Napoleon III, but the interested parties, Denmark and the inhabitants of the district, were not put in a position to secure its execution. Bismarck, who seems at first to have expected a referendum, maintained in 1867 that the people as Prussian subjects had no right to[Pg 39] demand it, the only right to such a demand resting with the emperor of Austria. Prussia made no effort to put the article into effect, and in 1878 it was abrogated by agreement with Austria.

So, since 1864, Schleswig has been under Prussian rule, and since 1867 an integral part of the kingdom of Prussia. Once probably wholly Danish, it had been subject for centuries to penetration from the south, and by this time possessed a large German element which henceforth had the active support of the Prussian government. The history of the attempt to Germanize Schleswig is, on a smaller scale, much the same as the history of the Germanization of Prussian Poland. Efforts at replacement of the population by Germans had little success, but the spread of German culture and the suppression of Danish culture were everywhere steadily pushed. German was made compulsory in the schools, the courts, and the churches; Danish was put under the ban in public meetings and theatres; and the Danish press and Danish societies were subjected to various forms of persecution. Intercourse with Denmark was in various ways restricted or made difficult. Constant war was waged against the Danish flag, and even against dresses which displayed the red and white colors of Denmark. It was even said that the owner of a white dog was obliged to repaint his red kennel! The regular agents of Prussian policy were omnipresent: the police, the pastor, and the schoolmaster. The officers’ duty was[Pg 40] chiefly negative, the suppression of Danish tendencies; the schoolmaster’s was more positive, to instil Germanism into the rising generation, partly by teaching only in the German language save for a small amount of religious instruction, partly by the well known propagandist methods of German history and patriotic songs. Thus all were compelled to sing, “Ich bin ein Preusse, will ein Preusse sein”; and if a little girl should say, “Ich bin kein Preusse, will kein Preusse sein,” she was whipped and sent home.

Inevitably the zone of German speech crept gradually northward. In some villages of central Schleswig which spoke only Danish half a century ago, it is said that the language has disappeared save among the very old. Still the process of Germanization was slow, and as time went on active resistance was organized in the three great societies of the Language Union, the School Union, and the Voters’ Union. Leaders found in Denmark the Danish education which was forbidden them at home, and kept alive a strong tradition of Danish speech and Danish sympathies. A local political party was maintained, and the Danish vote increased after 1886, although under the German gerrymander of 1867 it was still allowed to return only one member of the Reichstag, and that in the extreme north. Treasonable acts were in general avoided, but the hope of reunion with Denmark was never entirely lost.

The fortunes of the World War gave at first but[Pg 41] little hope to the pro-Danish Schleswigers. They served in the German army up to their full capacity; probably, as is stated, their losses were proportionately greater than those among purely German troops. If they were not fighting their own kin and friends, like the soldiers of Alsace-Lorraine, they were at least fighting in another’s cause. Denmark, too, walked warily during the war, with the fate of other small nations ever before her eyes and the profits of German friendship dangled in front of her. It was no time for Schleswig to look for help in this quarter. With the armistice, matters took on a new aspect. Foreseeing that the Schleswig question would be raised at the peace table, Germany proposed a separate arrangement with Denmark, and it was some time before Denmark readjusted her policy to correspond to a world in which the victorious Allies were able to impose terms on a defeated Germany. Even then the readjustment was incomplete. Germany might become powerful again, and Denmark must beware, so many thought, of laying up vengeance for the future by acquiring territory which Germany might demand back. In many quarters there seemed to be genuine terror lest the Allies might impose territory and obligations upon an unwilling Denmark. A natural hesitation over absorbing alien elements was accompanied by a fear lest many new voters might upset the party balance in a small country. In determining the future of Schleswig, it appeared that the timidity[Pg 42] of Denmark was to have its weight, as well as the hopes of the population. The Radical party, then in power, wished only limited accessions of population in the region of North Schleswig; while the Conservatives favored a more decided policy extending into southern Schleswig, though few went so far as to demand outright the ancient frontier of the Eider or even the old rampart of the Dannevirke.

No mention had been made of Schleswig in President Wilson’s Fourteen Points, but a just determination of the question was promised by him in a letter to certain Danish-Americans just after the armistice (November 21). Diplomatic conversations had indeed already begun, and February 21 the Danish government formally placed the matter before the Peace Conference in an exposé made to the Council of Ten by its minister in Paris, Chamberlain Bernhoft. It asked for a plebiscite as soon as possible in the region of unquestioned Danish speech north of a line stretching west from the head of the Flensburg fiord to the north of the island of Sylt in the North Sea, a line which had been demanded, November 17, 1918, by the North Schleswig Voters’ Union at Aabenraa. By February sentiment was ready to ask for a plebiscite also in a zone to the south, which included Flensburg and certain adjacent territory. In order that all possibilities of pressure might be removed, the evacuation of German troops and German higher officials was requested in a considerable strip of territory farther south.

[Pg 43]

The commission to which the Conference referred the Schleswig problem heard delegates from the different parts of the territory, as well as reports of the various points of view in Denmark. The commission saw no reason why the right of voting should be refused to any part of the region to be evacuated, though it was plain that some judgment would need to be used in drawing a frontier upon the basis of the voting, so as to avoid enclaves and inconvenient meanderings. Definite evidence was before it of a desire to vote on the part of many persons in south Schleswig. Accordingly its report, incorporated in the draft treaty submitted to the Germans in May, provided for a plebiscite by three zones, so that the frontier between Germany and Denmark might be fixed in conformity with the wishes of the population. In the first or northernmost zone, where the voting was supposed to be largely a matter of form, the plebiscite was to take place for the whole district within three weeks of the German evacuation. In the second zone of mixed speech in middle Schleswig, where opinion was likely to vary in different districts and to be affected somewhat by the result in the first zone, the voting was to occur not more than five weeks later and to be taken commune by commune. The same method was to be applied two weeks thereafter in the third zone, which comprised the remainder of the evacuated territory extending to the Eider and the Schlei, a region of predominantly German speech, where the Danish tradition had[Pg 44] been greatly weakened in course of time and where the people would likewise want to know the result in the neighboring zone to the northward. Within ten days of the coming into force of the treaty German troops and higher officials were to evacuate the whole territory north of the Eider and the Schlei, and the administration was to be carried on by an International Commission of five, one appointed by Norway, one by Sweden, and three by the Allied and Associated Powers. This commission was to hold the plebiscites in accordance with provisions which had been suggested by the Danish government; and upon the result of the voting, with due regard to geographic and economic conditions, recommend a permanent boundary to the Allied and Associated Powers. The whole plan was carefully drawn to secure as full and free an expression as possible of the desires of the population.

Opposition came from two sources. The German criticisms, as handed in to the Conference in May, had little weight. They proposed to limit the voting, and hence any possible loss of German territory, to a portion of the first zone, on the ground that only there did more than half of the population speak Danish. Apart from the fact that this affirmation was based on the official language statistics of the Prussian census, which was notoriously unfavorable to non-German elements, the proposal started from two inadmissible assumptions: one that language is the sole test of political sympathy; the other that no region where[Pg 45] Germans were in a majority should be allowed self-determination, for, it was implicitly believed, no German could possibly want to leave the Fatherland. Germany thus sought to prevent free expression of opinion where it might turn to Germany’s disadvantage, at the very moment she clamored for it in Upper Silesia, where it might possibly turn out in her favor. How Germany hoped to control the plebiscite appeared from another proposal, namely that, all German officials still remaining in the country, the administration and the voting should be in charge of a commission of Germans and Danes, with a Swedish chairman!

The Danish objection, as voiced by the majority Radicals, was against the inclusion of the third zone in the voting. The reason most generally given was that districts in this zone might vote for Denmark from purely economic motives, especially the desire to escape German war taxes and war indemnities, and thus form an irredentist minority in a country with which they were not really in sympathy. Probably also there was still the lurking fear of the powerful neighbor of the past and the future, as well as some measure of friendliness for the new regime in Germany.

To such arguments the Conference yielded, cutting out of the final treaty the plebiscite in the third zone and its evacuation as well. The change was made at the last moment, without readjustment of the other provisions, so that this[Pg 46] section of the treaty shows certain signs of haste. The effect was to take away all opportunity for self-determination in the third zone and to leave the German troops and administration here in a position to exert pressure on the region to the northward.[8]

The vote in the first zone, held February 10, 1920, resulted in a decisive Danish majority of three to one, and led to occupation by Denmark, as the treaty had provided. Feeling ran high in the second zone, where the German government sought to influence the decision by threats in the Reichstag; the struggle centred around Flensburg, certain in either event to be a frontier town now that the third zone had been eliminated. The plebiscite, held March 14, resulted decisively for Germany, the vote in Flensburg being overwhelming and only a few scattered villages on the islands voting for Denmark. The result failed to satisfy either party entirely, a large Danish group still wanting Flensburg, while in the first zone the Germans wished to recover Tönder, where the voting had favored Germany. Indeed it remains to be seen whether German hopes of recovery will be limited to Tönder.

One question of which Denmark and the Schleswigers showed great desire to keep clear was the Kiel Canal. Even the widest limit of evacuation proposed carefully left a belt of Schleswig territory between its southern border and the canal,[Pg 47] lest what was fundamentally a question of popular rights might become complicated with a wholly distinct international problem. Only in case of the internationalization of the canal would its fate have reacted on the Schleswig problem by leaving an isolated strip of German territory to the north which might then have been separated from Germany and attached to the adjacent Danish territory. Whatever might have been said for the internationalization of this great waterway, the question was not seriously considered at the Conference. The parallel to Suez and Panama was too close! The treaty leaves the canal under German control, but provides that it shall be open on terms of entire equality to the vessels of commerce and of war of all nations at peace with Germany.[9]

The island of Heligoland, which England had seized from Denmark in 1807 and ceded to Germany in exchange for Zanzibar in 1890, is not restored to either of its former owners. Instead it is stipulated that all fortifications and harbor works there shall be destroyed by German labor and at Germany’s expense, and that no similar works shall be constructed in the future.[10] Immunity for the future might do something to offset the great price which England had paid for Zanzibar throughout the World War.

[Pg 48]

The case of Belgium at the Peace Conference was widely different from that of Denmark. Denmark had remained neutral; her neutrality had been respected by others, and had even been a source of commercial profit; and at the end of the war, without the slightest effort on her part, she saw all her desires gratified in Schleswig. Indeed, her only fear was lest she should receive more territory than she wanted. The neutrality of Belgium, specially guaranteed by an international treaty, and thus far more binding on her neighbors than that of Denmark, had been violated by Germany at the very outbreak of the war. Belgium had suffered more than four years of German occupation, including the systematic spoliation of her farms, her factories, and her railroads, and the deliberate attempt to divide her people into two separate Walloon and Flemish states; she had barely escaped permanent incorporation with Germany. Yet all this time she had fought as best she could beside the Allies; she had made heavy sacrifices; she had stood for international right. Belgium expected much from the peace, and Belgium was in large measure disappointed.

Belgium was disappointed on the economic side, for she was flooded with depreciated German currency which the Allies did not take over, and her hopes for full priority on the account of restoration and reparation were not entirely fulfilled. Indeed, it soon became apparent that the general bill for reparation would far exceed the ability of[Pg 49] Germany to pay, and that there were not resources enough in all Germany to meet that restoration of invaded territory upon which President Wilson had declared “the whole world was agreed.” Belgium had suffered less than France by the destruction of war itself, for her territory, save in the case of the Meuse fortresses and the battle zone in Flanders, had not been fought over; but the German occupation which she had borne in equal measure was relatively far more serious, for it affected the whole country and not merely a part, and it produced stagnation of industry and cessation of commerce on a scale that destroyed enterprise and left idleness as well as poverty in its stead.

In territorial matters Belgium’s desires, save for a small correction of the German frontier, concerned neutral powers, Holland and Luxemburg, which were not members of the Peace Conference and not subject to its jurisdiction. The most that the Conference could do was to help in the adjustment of Belgium’s claims, and Belgium feels strongly that the Conference did not help enough.

Finally, Belgium was dissatisfied with her whole position at the Conference. During the war she had acted as one of the Allies and had her representation in the Allied councils. At Paris she was only a small power, limited to three delegates—at first even to two—and excluded from the guiding and deciding group of the Five Great Powers.[Pg 50] Even the decisions which directly concerned her were taken by the Council of Ten or the Council of Four. She was outside, while Italy and Japan were inside. Individually her delegates sat on important committees, but there were times when Belgium must have felt far removed from the central tasks of the Conference, in the outer limbo occupied by Liberia, Panama, and Siam. A Belgian told the story of an officer who had lost both legs. “You will always be a hero,” said a consoling friend. “No,” replied the officer, “I shall be a hero for a year and a cripple for the rest of my life.” Belgium felt that the days of her position as a hero were over. You will recall Mr. Dooley on Lieutenant Hobson: “I’m a hero,” said the Lieutenant. “Are ye, faith?” said Admiral Dewey, “Well, I can’t do anything f’r ye in that line. All th’ hero jobs on this boat is compitintly filled be mesilf.”

Let us call to mind so much of Belgium’s history as is necessary to approach her modern problems. Belgium as a separate and independent state has existed only since 1830, but her national history goes back into the Middle Ages. Easy of access from both the Rhine and the north of France, the territory of modern Belgium has always been a highroad of peoples, for migration, commerce, and war, and the natural meeting-point of races and civilizations from north and south. It formed a part of the great middle kingdom created between France and Germany by the partition of[Pg 51] the Frankish empire in the ninth century, and with the break-up of the middle kingdom it became a natural object of ambition from both sides. The various feudal principalities which shared this territory in the Middle Ages divided their allegiance between the king of France and the German emperor; and it was not till the fifteenth century that the rise of a new middle kingdom under the dukes of Burgundy brought the region of the Netherlands, northern as well as southern, under a single hand and made them for practical purposes independent of France and Germany. Enlarged toward the east by the Emperor Charles V in the sixteenth century, the territories of the Netherlands comprised seventeen provinces and included substantially what is now Holland and Belgium.

By the marriage of Mary, heiress of Burgundy, to Maximilian of Austria in 1477 the seventeen provinces of the Netherlands passed to the house of Hapsburg, and thus to their grandson, the Emperor Charles V. Upon the division of his possessions in 1556 they went with Spain to the so-called Spanish branch of the family, represented by Philip II. Religious and political reasons led to the great revolt against Philip II in 1568, a movement in which the whole seventeen provinces joined. The skilful policy of Philip’s general, Alexander Farnese, succeeded in detaching the southern provinces, which had remained for the most part Catholic, from the Protestant, or United, Netherlands of the north, and from 1579 on the southern provinces led[Pg 52] a separate existence under Spanish rule, being generally known as the Spanish Netherlands. In this period they lost considerable territory on the north to the Dutch and on the south to the French.

Upon the division of the Spanish dominions by the treaty of Utrecht in 1713, the Spanish Netherlands were in the following year transferred to Austria, and were known as the Austrian Netherlands until their conquest by the armies of the French Revolution in 1794. They were then incorporated with France (1795) and organized into nine departments, a state of affairs which lasted until 1814.

By the Congress of Vienna in 1815 the northern and the southern Netherlands were reunited, under the rule of a king of the house of Nassau. After a separation of one hundred and thirty-five years the union proved unsatisfactory to the southern population. Marked differences of religion, economic interest, and language produced friction from the start, which was aggravated by the exclusive policy of the Dutch, who, though a minority, monopolized the higher offices and enforced the use of the Dutch language. The revolutionary movement of 1830 kindled a revolt in the southern provinces, and a separate government was organized under a constitutional monarch, Leopold of Saxe-Coburg. The separation was declared “final and irrevocable” by a convention of representatives of the five Great Powers meeting in London in 1831, and the treaty was accepted by Holland in 1839. The[Pg 53] boundaries of the new kingdom were, as we shall see, drawn in a manner quite unsatisfactory to the Belgians.

The treaty of 1839 guaranteed the independence and the neutrality of Belgium, while at the same time it placed restrictions on the new state. By Article VII it was provided that

Belgium ... shall form an independent and perpetually neutral state. It shall be bound to observe the same neutrality toward all other states.