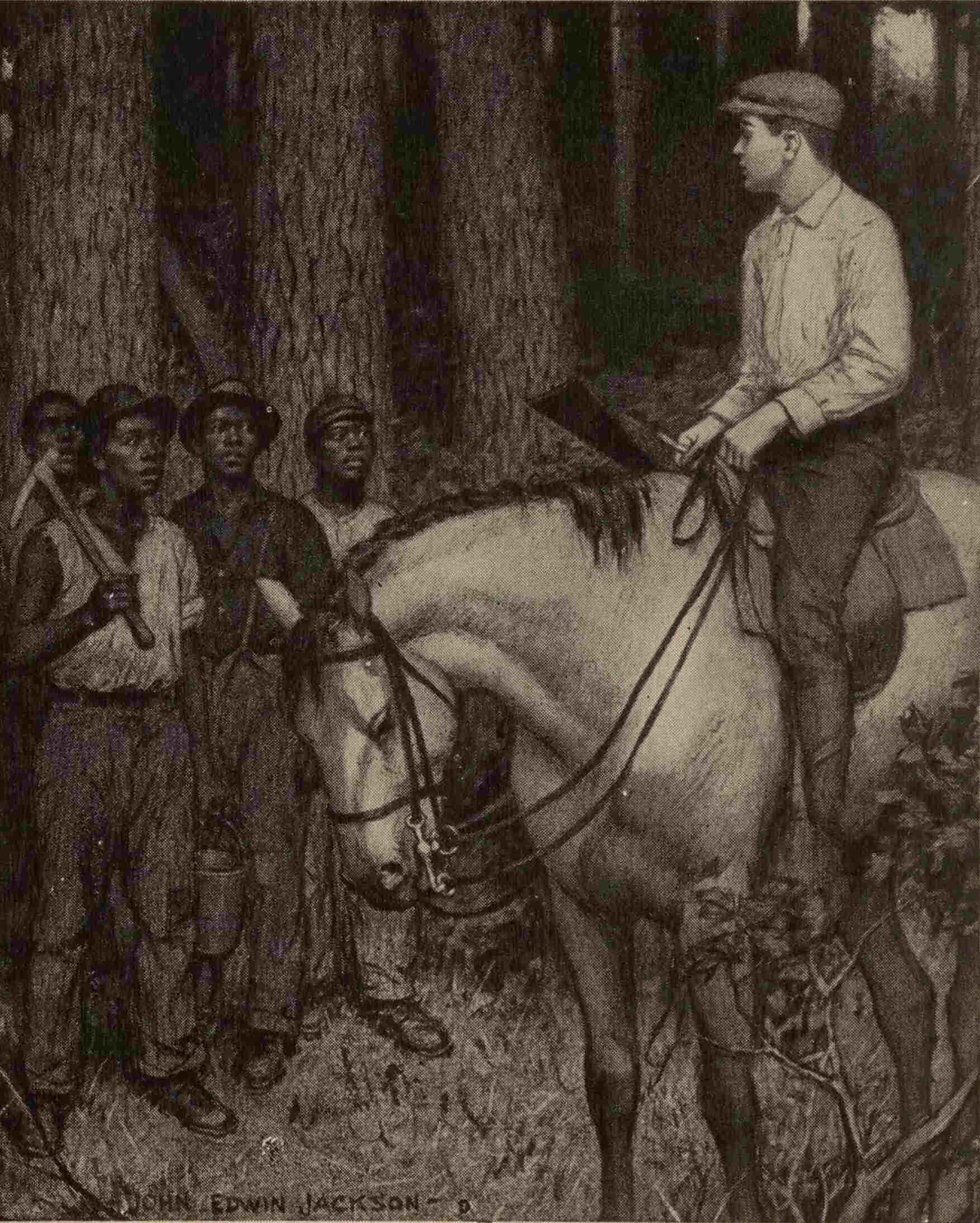

THE WOODS-RIDER

“What’s the matter? Why aren’t you boys at work?”

“What’s the matter? Why aren’t you boys at work?”

Leaning from his saddle, Joe Marshall looked into the cup that hung on the turpentine-tree. One side of the great long-leaf pine had been stripped of its bark to a height of three feet, leaving a tall, livid scar, sticky with resinous exudation. A thick layer of hardened gum crusted over its lower edge, and two tin gutters near the top carried the gummy oozings into the two-quart tin cup suspended from a hook driven into the tree. It was only March, but the weather had been unusually warm, and the gum was running in thin viscous threads imperceptibly slow, but the cup was half full of the sticky whitish mass.

“I declare, we can begin dipping soon!” Joe said to himself, glancing around at the other pines, which were all similarly blazed and tapped.

This was the best corner of the Burnam turpentine “orchard.” The trees that grew here were splendid long-leaf pines, shooting up straight as arrows almost a hundred feet before they broke into palm-like branches; and many of them were so large that the turpentine gatherers had been able to chip them on both sides, and hang two cups on them.

For about two hundred yards this park-like growth lasted, where his horse’s feet trod silently on the thick layer of pine-needles; then a slight descent took him out into the open ground. The sunlight seemed blinding after the shade of the woods. The sky was hazily blue, radiating an intense heat. High overhead two buzzards soared in circles. The ground was a tangle of gallberry-bushes, and Joe rode through them by a trail that he followed daily on his rounds. From the gallberry flat it led down to a creek swamp, dense with titi and bay-trees and tangled with bamboo-vine, and it wound through this jungle across the creek itself.

“Want to drink, Snowball?” said Joe, as the black horse showed an inclination to pause at the clear water; and while Snowball drank Joe dismounted and dashed water over his face and arms. It was unusually hot for March, even in southern Alabama, and from the look of the sky he judged that there might be thunder before night.

Joe was one of Burnam’s three woods-riders, and it was his duty to keep his eye on the run of gum and the work of the negroes on a third of the big tract. As he rode on he encountered several of the “chippers” at work, making the regular enlargement of the blaze on the pine-bark; occasionally he found a tree neglected, and had to find the man in whose “furrow” it lay, reprimand him, and send him back; now and then he had to stop and readjust a cup that had become displaced. Once he found two negroes idling and swapping stories behind a thicket, and he sent them back to work with good-natured bullying, which they took with equal good nature. They understood Joe Marshall, and he understood them.

He swung through the woods in a wide circle that would at last take him back to the camp. It was growing late in the afternoon, and most of the negroes were also straggling out of the woods. Provided they finished their furrow, they could leave when they pleased; but from the top of a ridge Joe caught sight of a chipper still at work, going at a fast trot from tree to tree. His clothes were ragged and there were not many of them; his arms were bare, and his black face streamed with perspiration. He carried a “turpentine-hack,” a tool very like a small pick with a keen, gouging end, and at each tree he ripped away with a skilful stroke another inch of the gummy bark at the top of the slash.

“Seems to me you’re working mighty hard for a hot day, Sam,” Joe remarked as he rode up.

The chipper threw back his head and laughed loudly. Sam was one of the “Marshall negroes.” His father had been a slave, owned by Joe’s grandfather, and Joe and Sam had both been born on the Marshall estate, before the place was broken up. They were about the same age and had played together as white and negro children will. Sam had been Joe’s lieutenant in many a hunting and fishing expedition, and when Joe had taken this place as woods-rider Sam had come as chipper in order to work in the woods with him.

“Yes-suh, Mr. Joe!” he cried, “I shorely is hot, but I reckon de weather goin’ change, an’ I wants to finish my furrow. Jus’ you look down yander in de souf. What you reckon comin’ up dere, Mr. Joe?”

“Thunderstorm, maybe,” said Joe, looking at the haze over the sky, and the coppery clouds low in the south, rising out of the Mexican Gulf. Sam looked too, intent, seeming to sniff the air, and his eyes looked suddenly wise and far-seeing, like a wild animal’s.

“I dunno, suh. Some kind o’ storm, shore. Anyhow, I’s goin’ mek for camp soon’s I finish my few mo’ trees. Mr. Joe, you better ride back home.”

“Oh, a thunderstorm won’t hurt us,” said Joe, laughing, and he rode on, intending to finish his usual round. He was anxious to give especial attention to his tract that day, for the next three days were to be a vacation. The other two wood-riders had agreed to look after his duties, and he was going to ride over to Uncle Louis’s plantation, ten miles south, to meet his cousins from Canada.

He had never seen these cousins—Carl, Bob, and Alice Harman—children of his father’s sister who had married a Canadian, for they had never been south before, and he had never been north of Tennessee. Both their parents had been dead for some years. The three lived together, and, Joe understood, were in bee-keeping. It seemed to Joe an odd and shiftless sort of pursuit, especially in the land of snow and ice which he dimly conceived Canada to be. They had been in Alabama now for several weeks, and had been ten days at Uncle Louis’s place, where they were to remain till spring. Joe understood that they were looking for more bees, and he chuckled at the idea. He knew where there were at least a dozen bee-trees. “Reckon I can show ’em all the bees they want!” he reflected. He had planned great entertainments for them. He would take them fishing for the giant Alabama catfish, take them ’possum hunting, show them the turpentine woods.

He rode on his wide curve through the pines, looking after the turpentine-cups, thinking of the Canadian visitors, when he suddenly became aware that the sun had disappeared. Glancing up through the feathery pine crests he saw a huge bank of tumbled, coppery-black clouds rolling up fast from the south. The air seemed dead still, but a chill had come into it. Far away he heard a growl of thunder, still faint and distant, and Snowball tossed his head, snorted, and stamped, looking back nervously at his master.

It was not the usual time of the year for tornadoes, but he knew how terrific these Gulf thunderstorms sometimes are, and he did not want to be caught in the pine woods where any tall tree might draw the flash. But he remembered a bare, open flat not half a mile away, and, kicking Snowball in the ribs, he started through the woods at a reckless gallop, over logs and brush without ever swerving.

A wind rushed heavily over the trees, carrying a curtain of black cloud. Twilight seemed to fall in a single instant. Snowball was almost uncontrollable with fright, but he saw the open space ahead. As he tore out of the woods, Joe saw behind them a wall of blackness sweeping up the sky with an appalling roar. He jumped from the horse, scared, uncertain what to do, knowing well now that this was no mere thunderstorm. Snowball reared, jerking the bridle from Joe’s hand, and bolted. The next moment the storm burst.

The sheer force of the wind swept Joe off his feet and rolled him over and over. The air was thick with torn pine-needles, flying branches, and strips of bark; trees were crashing and rending, and there was an uproar as if a giant were treading down the forest like grass. Rain suddenly came down in a blinding torrent. Half dazed, Joe tried to get to his feet, made a staggering run without knowing where he went.

A sheet of bluish lightning seemed to explode just over the tree-tops. In the midst of the deafening thunder a great pine snapped at the butt, not a hundred feet away. Joe heard the roaring swish as it came down through the air, straight towards him. He made a plunge to get away, but stumbled; and the next instant he was struck down in a whirl of snapping branches.

That was the last he knew for several minutes at least. When he came to his senses, rain was still pouring down upon him. The ground was streaming with water; a cold river seemed running under his back. The wind still blew fiercely but the lightning was more distant, and the worst of the storm seemed to have passed. He had no idea how long he had lain there, but the darkness now seemed to be, not of the storm, but of night.

He endeavored to raise himself, and found that something held him down with apparently enormous weight. It hurt, too; there was a pain in his chest, a sharp pain in his head. Dimly Joe imagined that the tree had fallen on him, and that he must be seriously wounded; but by groping with his hands he found that the trunk of the big pine had missed his body by a scant yard. His last jump had just saved his life, but one of the smaller branches had caught him across the body and pinned him down, though the mass of twigs had saved him from being crushed. Something had hit him on the head, too, but as he gradually came to himself he decided that he was not as badly broken to pieces as he had imagined. But for all his efforts, he could not work his way out from under the branch that pinned him fast down.

He wormed himself this way and that; he tried to hollow out the earth under him, until he had exhausted his strength. Then he shouted at the top of his voice, but in that roar of wind and splash of rain he knew that there was scarcely a chance of any one’s hearing him. Nearly all the men had left the woods.

The rain ceased to fall in torrents, slackening to a drizzle. The thunder already sounded far away. The storm was passing over as swiftly as it had come up. It had grown almost completely dark when at last Joe heard the far-away voice of a negro calling, echoing strangely through the woods. He yelled in answer; the voice approached; and presently he heard some one crashing through the bushes.

“Who dat a-callin’?” he heard a well-known voice. “Where is you?”

“Sam!” shouted Joe in delight. “Here—this way! I’m down under a tree.”

Sam appeared, a vague black shape in the blackness.

“Fo’ de land’s sake, Mr. Joe!” he exclaimed. “How you git dere? Is you hurted bad? Wait—I git you out!”

Sam pulled and hauled, aiding Joe’s fresh efforts. He tried to shift the branch in vain, and it was too dark to see what he was about. Presently he stopped, groped about in the dark for some time, and then, squatting in a sheltered spot, began to scratch matches.

By its light he was able to find a strong enough piece of wood for a lever

They were damp, and it was some time before he produced a flame. Then there was a sizzle, a flash, and a brilliant flare sprang up. Sam had found a cup half full of gum, and stuck the match down into the resinous stuff. It flamed up like a huge torch, blown in the wind, casting a lurid light on the chaos of the fallen timber, and Sam elevated it on a stick where it would illuminate his proceedings.

By its light he was able to find a strong enough piece of wood for a lever, which he inserted under the pine branch, and he raised it just enough to let Joe wriggle out. The negro solicitously looked him over; Joe felt himself anxiously, but he could not find any worse damage than a few bruises and a slight cut on the head just above his ear.

“No bones broken, Sam,” he said. “I’ll be all right now in no time. But why weren’t you back at camp?”

“Couldn’t mek it,” said Sam. “De big wind cotched me in de woods, an’ I just crawled under a log an’ laid still, scared most to death. Seemed like all de woods was goin’ down, an’ I reckon de best of ’em is down. Where de turpentine goin’ to come from now? Say, Mr. Joe, don’t you reckon dis de end of Mr. Burnam’s turpentine camp?”

The same question had already occurred to Joe and troubled him. It meant a great deal.

“I don’t know, Sam,” he answered rather irritably. “Let’s try to get back to camp and see how things are there. Do you know where we are? I feel dizzy and turned around.”

“Yessuh, Mr. Joe, I shore knows de way!” cried Sam with a loud burst of laughter. “I’s a piney-woods nigger, I is. Bawn an’ raised right in dese hyar woods. Couldn’t lose my way here no-ways, no suh, capt’n!”

To show his confidence he started at once, conducting his young master with one hand and holding the flaring torch with the other. It was hard traveling. The ground was covered with trees, large and small, blown criss-cross in every direction, and Joe’s heart sank more and more at the sight of the destruction of the turpentine pines.

For he was not merely an employee of Burnam’s camp. He was a shareholder. Everything he possessed in the world was tied up in that turpentine business. At the death of his father he had inherited a little money, placed in the hands of Uncle Louis as trustee and guardian. As he grew out of boyhood Joe had formed the plan of entering the turpentine business, a commerce which had been familiar to him from childhood, and Uncle Louis had invested the capital in the new camp which Burnam was starting. Joe went in as woods-rider, and it was supposed to be a good job and a safe investment. Burnam was well known as a successful operator, and the business promised a good return.

Uncle Louis, however, had carelessly failed to ascertain Burnam’s financial responsibility. He was thought to be solid; but of late Joe had heard rumors that the camp had been started on a little money borrowed here and there like his own, and that it was now being carried mainly by the bank. Instead of a good investment it was a shaky speculation. Burnam was a skilful and experienced turpentine man. With luck he might pull through successfully: but a stroke of misfortune would be likely to put him into bankruptcy. And it looked as if that stroke had come.

Sam burned two or three more cups of gum before they finally came out of the wrecked woods, and sighted the camp, built a hundred yards back from the main road that led in from the river landing. From a distance they could see a swarming and rushing of torches, and hear the voices of men, but the camp did not seem to be demolished as he had feared. It was less a camp than a small village of nearly fifty negro cabins and dwellings for the white officers, built in a hollow square around the turpentine-still, the cooper-shop, the storehouse, and the commissary-store. The road and the square were running with water, but everybody was out, and, to Joe’s relief, he saw that the buildings seemed to be intact.

Just at the edge of the camp he met Tom Morris, one of the other woods-riders.

“Gracious, Joe!” he exclaimed. “You look as if you’d been through a mill. Snowball came in half an hour ago, covered with mud and scared to death. Your saddle and rifle were on him, and we thought you’d sure gone up. We were just getting ready to go out to look for you. How are the woods?”

“Smashed up. How’s the camp?”

“No damage to speak of. The still’s all right, by good luck. The roofs of two or three cabins blew off, but the main track of the storm went a little west of us. But, say! isn’t this going to hit Burnam pretty hard?”

“Afraid so, Tom,” said Joe seriously. He did not want to discuss the matter; he felt too sore and uneasy. He avoided Burnam, who was hurrying about with Wilson, the camp foreman, to ascertain the damage. He went to look at Snowball, whom one of the negroes had unsaddled and brushed down a little, and then he slipped into his room at Wilson’s house, where all the woods-riders boarded. He went to bed, intensely tired and aching, intending to think it all over; but he was scarcely there when he fell soundly asleep.

It was a little late when he awoke, to find brilliant sunshine at the windows. Morris, who shared his room, had already gone. Joe still felt somewhat stiff and sore, but he dressed and quickly went out.

The sky was as clear as if there had never been a storm, and the air was full of sparkle and lightness. The hard sand of the camp square was dry and firm already; the surrounding pines were a fresh-washed, vivid green. There were not many signs of the tempest visible here—only an unroofed cabin or two, a pine that had fallen right into the camp area, and the brook beside the road that flowed muddy and bank-full.

The routine of the camp was disorganized that morning. Negro women and children swarmed about the cabins, calling to one another; the chippers from the wrecked area loafed in the sun, smoking cigarettes, waiting for orders. Joe found Tom Morris near the still, talking with the foreman.

“I was waiting for you, Joe,” said the rider. “Feel all right this morning? Burnam was up at daylight and rode off to look at the woods. He left word for you and me to go over your tract and report. Had your breakfast? Well, go get it quick.”

Joe hurried over the meal, had Snowball brought round, and they rode off, Wilson going with them. The former wagon-trail into the woods was badly choked with fallen timber; they had to make continual detours, and pick their way among the pines. The big turpentine tract lay in a rough rectangle north and south, and the storm, passing right down the middle, had raked it from end to end. The magnificent pines strewed the ground, were broken off at mid-height, stood leaning against one another, ready to fall at the next wind. Some of the gum-cups still clung to the trees; others lay scattered over the ground, spilling their thick contents. They rode through this scene of wreck for a mile or two, and then Wilson stopped his horse.

“I don’t want to see no more, boys,” he announced. “Looks to me like this camp’s plumb ruined. I reckon we’ll all have to hunt another job right soon.”

“Oh, I don’t know,” said Morris, encouragingly. “It ain’t all as bad as right here. And then, Burnam’s got the river orchard.”

The river orchard was a tract of about five hundred acres lying close to the Alabama River, three miles away. The remainder of the turpentine woods had been merely leased for three years, but this tract belonged to Burnam outright. He had never turpentined it, because the tapping of the trees materially injures them for timber.

“Burnam won’t turpentine the river orchard,” said Wilson. “He’s saving it for timber.”

“Well,” he continued, after a gloomy pause, “I s’pose I’d better go back to camp and get some niggers and gather up these here cups. Better save what we can.”

For two or three hours Joe and Morris rode through the woods, finding it a depressing spectacle. In the direct track of the storm, fortunately not very wide, it looked as if hardly anything was left fit to turpentine. Outside that belt the damage was not so great, but the woods were so choked with fallen trees and debris that it would take weeks of labor, it seemed, to clear them enough to carry on operations.

“I was going off on a holiday to-day,” Joe remarked. “I reckon that’s indefinitely postponed.”

“I don’t see why,” Morris returned. “This is just the time. There won’t be much woods-riding done for a week. The men’ll all be busy clearing up the mess.”

“Well, I’ll see what Burnam thinks. I want to talk to him anyway,” said Joe. “I’ve got to find out if this camp is busted or not.”

Burnam had come in by the time the riders got back, and Joe found him in his little office in the rear of the commissary-store, bending over a heap of papers and looking worried. The turpentine operator was past middle age, tall, spare, and wiry, burned brown by the Alabama sun. He had spent all his life among the pines, working in turpentine and rosin and lumber; he had a reputation for success and luck and for generosity and for a violent and uncontrollable temper. He had been known to draw a gun on one of his men, threaten him with death, discharge him and be ready to forget it all the next day. He was dressed as he had come in from riding, in flannel shirt and khaki leggings; his soft black hat was pushed on the back of his head, and he met Joe’s entrance with a glance of irritation. He was in no smooth temper, but neither was Joe.

“Morris and I have looked over most of the tract, Mr. Burnam,” Joe began. “Nearly half the timber looks to be down, or all tangled up. We can save a lot of gum by gathering up the cups right away, but everything is in bad shape.”

Burnam said nothing, but frowned as if he knew this already.

“Is the camp going to go on, or shut down?” Joe ventured.

“That’s my business!” Burnam snapped.

“Mine, too. You’re forgetting that all my money is tied up in this outfit. It was supposed to be a good investment.”

“Well, ain’t you getting ten per cent. on it?” Burnam demanded.

“Yes—so far. But will I ever get the principal back?”

Burnam gave him a furious glance. For a moment Joe expected one of the turpentine man’s famous explosions of rage; but then Burnam leaned back in his seat, took off his hat and put it on the table, and grinned.

“I don’t blame you much for being worried, Joe,” he said. “You can bet that I’m worried myself. But I’ll pull through. I’m going to turpentine the river orchard.”

“All right,” said Joe, surprised and relieved. “Do you want me to ride it?”

“Sure. I hadn’t intended to turpentine that tract, but now I’ve got to. I was looking over it this morning, and there’s right smart of good pine there.”

“All right,” said Joe. “I’ll do the best I can—I’ll work like any nigger—for myself as well as for you.”

“I reckon you’ll pull us through, then,” returned Burnam, with some dryness. “You were fixing to take a few days off now, I think.”

“I was—but of course I won’t now,” Joe hastened to say. “I wouldn’t leave the camp in this fix.”

“No, that’ll be all right. For the rest of this week the men’ll be doing nothing but clearing up fallen timber. You go and visit with your kin-folks for three days if you like; we can spare you as well as not. I can’t let you have the car to-day, but to-morrow’s boat day, and you can ride down to the landing and take your horse with you on the boat.”

Joe had no hesitation about accepting this offer. He had been looking forward to seeing his Canadian cousins, and now he particularly wanted to talk to Uncle Louis about the financial prospect. He knew that Burnam would not let him go unless he could really be well spared, and he thanked the turpentine operator and went out, feeling as if he had been treated with more generosity than he deserved.

The rest of that day he spent with Morris and Wilson, setting the negroes at clearing up the woods, collecting the scattered gum-cups, opening trails for the wagons again, and planning to get what turpentine could still be obtained from the wrecked “orchard.”

While he was still at breakfast the next morning he heard the deep roar of the river-steamer’s whistle resounding tremendously through the woods. There was no hurry; she was still far away, for her great siren would carry fifteen miles in calm weather; but as soon as he could finish eating he jumped on Snowball and rode at a gallop from the camp and down the road to the landing.

It was three miles to the landing. The road, of yellow sand and clay, had already dried hard since the rain, and it ran between banks of brilliantly-colored clay, vermilion and greenish and white like striped marble. A rivulet of clear water ran on each side of the road, and on each side rose the vivid green of the pines. As he approached the end he passed through a belt of dense swamp, a tangle of creepers and thorns and titi-shrubs and bay-trees, and then he came in sight of the Alabama River.

There was no wharf, merely a freight warehouse and a cotton-shed at the landing, and three or four men were already there looking out for the boat. The river was a quarter of a mile wide here, running full and strong after the heavy rain, wallowing around its great curves, muddy and opalescent. Down to the water’s edge the shores were densely wooded with sycamore and willow and cypress, overrun with yellow jessamine and hung with gray Spanish moss, and, except for the freight-shed, the scene must have been exactly as it had been when the first Spanish explorers came up from the Gulf to look for the fabled Indian treasure-cities.

The steamboat’s whistle roared again, perhaps four or five miles away. As Joe rode up to the landing he saw a black object drifting slowly down the river. It was a houseboat—a flatboat with a rough cabin that covered the whole deck, except for a small deck-space at each end. It was painted or tarred a rusty black; it looked heavy in the water, and it moved sluggishly. A big steering-sweep trailed idly astern, and no one showed his face aboard her.

Joe had seen many such houseboats before. There is a migratory population using them upon all the large rivers of the South; but the somber appearance of this one caught his attention. It looked vaguely sinister to him.

The white bulk of the steamboat came majestically around the bend, puffing pine smoke from her tall double chimneys, and hauled in to the landing. Joe was well known on the boat; Burnam was a heavy shipper of freight, and none of the turpentine men ever paid anything for passage. As he was not going far, there was no difficulty about Snowball’s transportation either, and the horse was led aboard and tied among the piles of wood for the furnaces on the lower deck.

There was an hour’s wait at the landing, and it was another hour down the winding river to Magnolia, which was the landing for Joe’s destination. He went ashore, mounted Snowball again, and rode up the road through swamps and pine woods, till the forests gave place to more and more continuous cultivated fields, and at last he sighted his uncle’s plantation.

The great, white, rambling ante-bellum house stood far back from the road, in a grove of oaks and chinaberry-trees. Beyond it were the scattered barns and stables, and farther still the remains of a dozen cabins that had been the slave quarters fifty years ago. As Joe rode in the gate he heard a shot and a shout of laughter. A pretty, brown-haired, bare-headed girl was standing in front of the house, her extended arm still holding a smoking pistol, while two boys were applauding her shot at a paper target pinned to an oak. They all glanced up at the trample of the hoofs, and Joe took off his hat and waved it. He knew at once that these must be his cousins from the far North.

The three young Harmans had arrived in Alabama in February, on a trip of combined business and pleasure. But for the business they would not have come; for it was a long way from their old home at Harman’s Corners, Ontario, to these Alabama forests, and they had to plan carefully to stand the expenses of the journey.

Three years before they had been left orphans, inheriting little but debts. Alice, however, had for some time been a skilful keeper of bees on a small scale, and they had invested all their worldly capital in a large outfit of bees in the wild country of northern Ontario. It had been a rough experience, sometimes a dangerous one; they had had plenty of adventures, and had come more than once within an ace of losing their apiary in the first season, but the venture had been a success. After the second season they had the apiary fully paid for, and the balance at the bank had been a growing source of satisfaction to them.

They had a big crop of honey, and it might have been well if they had been content, but they were tempted by a high cash offer for their bees, and they sold all but fifty hives in the autumn, trusting to be able to replace them at a lower figure before the next season. But this turned out difficult to do. Honey was beginning to rise greatly in price that autumn, and looked as if it would be higher still next year, and nobody had bees for sale. On the contrary, most apiarists wished to buy more, for they expected to coin gold the next summer.

Bitterly regretting their lost bees, the young Harmans searched and advertised without result.

“There’s only one thing to do—get bees from the South,” Alice said.

The Southern States, with their mild winters and early springs, have always been a great source of supply for bees for the North. Of late years a great trade has arisen in “pound packages”—a pound or two of bees and a queen, enclosed in a wire-screened box and shipped by express. Such a package of bees, put in a hive and provided with ready-built combs in May, will often build up to a powerful colony and gather as much honey as any wintered-over hive. But on investigation the Harmans found that prices even for Southern pound packages were rising to extravagant figures.

“Why couldn’t we go down, get some bees, and ship them ourselves?” Bob suggested.

It was the most attractive proposition of all. They wrote to Uncle Louis, whom they had never seen, but who had often invited them to come South and visit him. The letter brought a prompt and cordial reply. They were to come and spend the whole winter at his plantation. There were “worlds of bees” thereabouts, he said, and they could be bought in that remote place for little or nothing.

That settled the matter. But it was already well toward midwinter, and they were not able to leave immediately. They visited two or three large commercial bee-breeding ranches, spent some weeks in Mobile and along the Gulf, and then voyaged up the river to the plantation.

It was a wonderful and novel experience to them, a new and fascinating world, from the rambling, old-time house, the mules, and the negroes, to the vast pine forests and the black swamps along the river, full of wild turkeys, ducks, wildcats, and moccasin snakes. But so far they had failed to find the “world of bees.” Uncle Louis had written too optimistically.

But he gave them a welcome of Southern heartiness, and they enjoyed it all greatly. There were horses to ride, boats to row on the bayou, and game to shoot. Bob had brought his rifle and Carl his shotgun, and Alice had purchased in Mobile the long-barreled target revolver with which they were now practising.

They had been expecting Joe any day, and they knew at once who it must be, at sight of the black horse with the Mexican stirrups, the rifle in its sheath at the saddle, and the boyish rider in dark khaki, with a red tie and creased rough-rider hat. Joe had taken some pains to get himself and his horse up for the occasion, and he rode up and dismounted.

“I know this must be Cousin Alice,” he exclaimed, bowing very low over the hand of his cousin, who was a little disconcerted by so much ceremony. It was different from the abrupter manners of the Canadian country-folk.

He shook hands with Bob and Carl, and there was an exchange of greetings, while the cousins all took stock of one another. They were all within two or three years of the same age. Alice had almost exactly the years of Joe. Bob Harman, tall, strongly-built, fair-haired, was the oldest. Carl was the youngest, and his darker complexion recalled his mother, who had come from Alabama twenty years before.

The Harmans liked the looks of their new cousin, and Alice was privately much impressed with his picturesque appearance and his Southern manner. They had already begun to grow accustomed to the soft Alabama drawl and slurred speech; but Joe at first found difficulty in getting used to the sharper Northern accent.

“Having a little pistol practice?” he said. He shouted loudly for a negro, who presently came and led Snowball away to the stable.

“Try a shot?” Bob suggested. “I expect you can beat us all. Alice bought this pistol in Mobile. She had an idea that she’d have to carry a gun up here in the wild country.”

A few rounds of shooting broke the ice, and they were all presently on the greatest of good terms. They made wild practice, and Joe was no better than any of them.

“I haven’t shot much with a pistol for years,” he said. “I never tote one. I keep a rifle handy when I’m riding, for you never know what you might see. I’ll go back and get mine from the saddle, and we’ll try it.”

He hastened back to the stable and returned with the weapon. It was a small repeater, shooting a twenty-five caliber smokeless cartridge, light enough for rabbits or turkey, and powerful enough to kill anything in those woods, up to a bear or a man. They fired a few shots apiece with it at fifty yards. Bob was supposed to be a rifle-shot, but he was far outscored by Joe, who was used to the little rifle, and generally fired off a box of cartridges a week.

Leaving off shooting, they strolled back to the house and sat down on the steps of the wide veranda, overhung with budding honeysuckle. Uncle Louis was somewhere out on the plantation; Aunt Kate, his wife, was busy indoors and the cousins continued to grow better acquainted. Joe gave some account of his work in the turpentine industry.

“But I believe you-all keep bees up in Canada,” he said. “That seems funny to me. I wouldn’t think they’d do any good up there where it’s so cold.”

“It’s a better place than down here—for bees, I mean,” said Alice. “It isn’t as cold as you think. Our summers are shorter than yours, but just as hot. The winters are long, but then the bees are packed up warm and they have a complete rest, while down here they’re flying all the time, and they get worn out quicker.”

“Didn’t know a bee ever could get worn out,” said Joe. “But we’ve got bees here on the plantation. Didn’t Uncle Louis tell you?”

“I believe he did say there were some,” said Bob. “He was going to show them to us, but we have not seen them.”

“I’ll show ’em to you, if I can find them. I haven’t seen them myself for a year, but I reckon they’re still there.”

He led the way down past the side of the house to a peach orchard. Up against the fence there was a growth of blackberry-canes, and there, sure enough, was a hum of bees.

The Canadian experts had seen several of these primitive “bee-gums” since coming South, and they had got over the amusement that the first sight had caused them. The hives were boxes about a foot square and three feet high, standing on end, made of rough lumber, and showing a great many cracks and rotted holes, which the industrious insects had plastered up with wax and propolis. From a hole at the bottom the bees came and went, and they were flying now in scores, coming in heavy with honey or with their legs yellow with pollen.

“I expect they’re working on the titi,” Bob remarked, stooping to watch them. “Or maybe there’s some blackberry coming out in bloom.”

“Goodness!” exclaimed Joe. “I didn’t suppose you’d know what titi was. Surely you don’t have it up North.”

“I wouldn’t know a titi-tree if I saw one,” Bob confessed. “But before we came down here I read up about the Alabama honey-plants, and just when they all bloomed, and I know the titi ought to be on just about now. I wish you’d show me some.”

“I reckon you’re a real beeman, all right!” said the woods-rider, laughing. “I never knew there were any books about such things as honey-plants. Down here we just let the bees alone, except when they swarm, and when we rob them. They make honey all right, though. Why, one year I remember we robbed these six gums of pretty near a wash-tubful of honey.”

“About sixty pounds, I expect,” Bob calculated. “Alice, what did our best hive make last year?”

“Three hundred and eighty pounds,” said Alice promptly. “We weighed it separately, just to see how much there was. Our total crop last year was twenty-one thousand pounds. We sold most of it at eleven cents.”

Joe opened his eyes wide and glanced at all three of his cousins to make sure that they were not making fun of him.

“What, more than two thousand dollars, just out of bees?” he gasped. “I never heard of such a thing before. Down here we think bees are just a kind of foolishness. I don’t wonder that you are in the business.”

“Next year I’ll bet we make four thousand dollars, if we can only get the bees,” said Bob. “You see, we were fools. We sold out most of our outfit just when we should have held on. We were offered a big price and we took the bait. So we came down here after more, but I don’t know where we are going to get them. All I can hear of is just a few gums like these, scattered here and there; and we want to get a couple of hundred anyway.”

“A couple of hundred gums of bees!” mused Joe. “These things take my breath away—they sure do! But I believe you can get them. There’s certainly lots of bees in this country. I’d help you look for ’em, if I had time. Tell you what!” he added, remembering something, “you ought to locate Old Dick’s bees.”

“Old Dick? Who’s that?” Bob inquired.

“Why, Old Dick was a nigger that lived away down in the river swamps somewhere, and he had worlds of bees, they say. A whole yard full of gums. He used to ship his honey down to Mobile on the boat when he robbed them, and they say he once shipped a cake of wax that weighed a hundred pounds.”

“I shouldn’t wonder. I expect he got more beeswax than honey,” Alice put in. “Well, do you think we could buy his bees.”

“The old nigger’s dead. He lived there all alone with his wife and the bees, and at last he died and his wife moved away.”

“Then somebody must have taken the bees, too.”

“No, according to the story, they were left. Nobody valued bees much, and nobody cared much to fool with Old Dick’s bees. They say those were fighting bees. Anyway, the old man died eight or ten years ago, and they say the bees are there yet. Anybody could get ’em that wanted to take ’em away. Dick didn’t have any heirs.”

Alice’s eyes had grown brighter and brighter during this recital.

“Oh, we must get them!” she exclaimed. “Just think! What a piece of luck! Likely there would be as many as we wanted, and wouldn’t cost us a cent.”

“Do you know where they are, Joe?” Bob inquired.

“Haven’t the least idea, and I don’t believe anybody knows. Dick didn’t live on any road nor near anybody else. It was away down in the swamps by the river somewhere—several miles south, I reckon. I never saw anybody that had been to Dick’s place. I expect the whole establishment would be grown over with vines and blackberries by this time. But I reckon we ought to be able to locate it if we looked long enough.”

“Couldn’t you go with us? It would be just the sort of expedition we want,” asked Carl. “I expect there’d be game and fish.”

“Oh, yes. It’s a mighty rough country down there, where hardly anybody ever goes except hunters. Lots of quail and turkeys, but the open season for them is over. Might see a bear; lots of them down there, wildcats, too.”

“We saw something of wildcats in Canada,” said Carl. “We lived in a deserted shanty at our bee-ranch in the woods. I was there alone the first night, and the place was alive with cats—tame cats gone wild, you know. Savage brutes! I shot one, and got all clawed up.”

“Bears, too,” Bob remarked. “They raided our bee-yards twice. I wonder if they haven’t chewed up all Old Dick’s bees by this time.”

“Well, I don’t know,” said Joe. “I’d like first-rate to go on a bee hunt with you, and I’ll do it if I can get a few days off, a little later. In fact, you make me wish I was in bees along with you, instead of the turpentine business. Our camp is going to pieces, I’m afraid.”

“Well, if it does, you can learn honey production,” said Alice. “We might keep one lot of bees in Canada and another down here, and be able to work all the year around.”

Joe laughed. Bee-keeping still seemed to him a very unsubstantial sort of pursuit; but he had been greatly impressed by what his cousins had said. If he only had his capital out of Burnam’s turpentine business, he said to himself, he would look into the honey business. As it was, he was tied fast and could do nothing, and the mention of the camp recalled his financial perplexities.

That night at supper he asked Uncle Louis what he thought of Burnam’s financial status.

“The storm hit him hard,” he explained. “Half his orchard is wrecked. He says he’s going to turpentine the river orchard—the old Marshall tract. He owns that, doesn’t he?”

“I just thought that storm would hit your camp,” said Uncle Louis. “It missed us here—blowed down a few trees, but nothing to count. Yes, Burnam owns the old Marshall tract—used to belong to the grandfather of all you young folks—but it’s mortgaged, I know for a fact. Pretty heavy, I reckon.” He glanced at Joe anxiously. “Not worrying, are you?” he inquired. “Burnam’ll pull through. But I don’t believe I ought to have got your money into his business.”

“Oh, well, it was my fault too,” returned Joe. “I was wild to get into turpentine then. But now I’m thinking of going into the bee business.”

He laughed as he spoke, and so did his uncle, who made the usual joke about his probably getting stung.

“We’re going to hunt up Old Dick’s bees, Uncle Louis,” Alice cried. “Joe’s going to help us. Do you know anything about them?”

“Why I’ve heard the story,” said the planter, much amused. “I know for a fact that the old nigger did have right smart of bee-gums once. What became of ’em after he died I can’t say. I don’t see why some of ’em shouldn’t be there yet. There’s nothing to kill bees in this country, excepting thieves. Why, I knew an old gum that stood in a fence-corner for ten or twelve years, and nobody ever went near it, and the bees are alive and well now.”

“That’s the way you keep bees, too, isn’t it, Uncle Louis?” said Alice, slyly.

“We’ve got more important things to do with corn and cotton and hogs down here in the South, young lady,” said Mr. Marshall. “We don’t need to fool with insects.”

There was a shout of laughter at this retort, which reduced Alice to silence, but the conversation drifted irresistibly back to the bees. Joe heard talk of great apiaries, of colonies by the hundred, of tons of honey, of car-loads, indeed, mentioned like ordinary matters, and it filled him with greater and greater amazement. Even Uncle Louis was impressed, though he kept up his air of good-natured ridicule of the whole pursuit.

“But we certainly can’t go after Dick’s bees unless you go with us, Joe,” said Bob. “We don’t understand this country; we have to have a guide. Can’t you manage it?”

Joe shook his head doubtfully.

“Wish I could. But I’m afraid Burnam couldn’t spare me for another vacation just now. But what you-all must do,” he added, “is to come up with me, and see the turpentine camp, and the old Marshall place—the old family seat, you know. Nobody’s there now; the old house is rotting down. It won’t last much longer.”

The young Harmans accepted this proposition with enthusiasm. They all spent three active days on the plantation. They rode, practised with firearms, fished in the bayou and the river, hunted quail and rabbits, and once went out before dawn to stalk a wild-turkey roost—not to shoot, for the game was out of season, but to give the Northerners a look at the big birds. The cousins became great friends, and at the end of Joe’s holiday they all took the boat upstream together for Marshall’s Landing, as the place was still called.

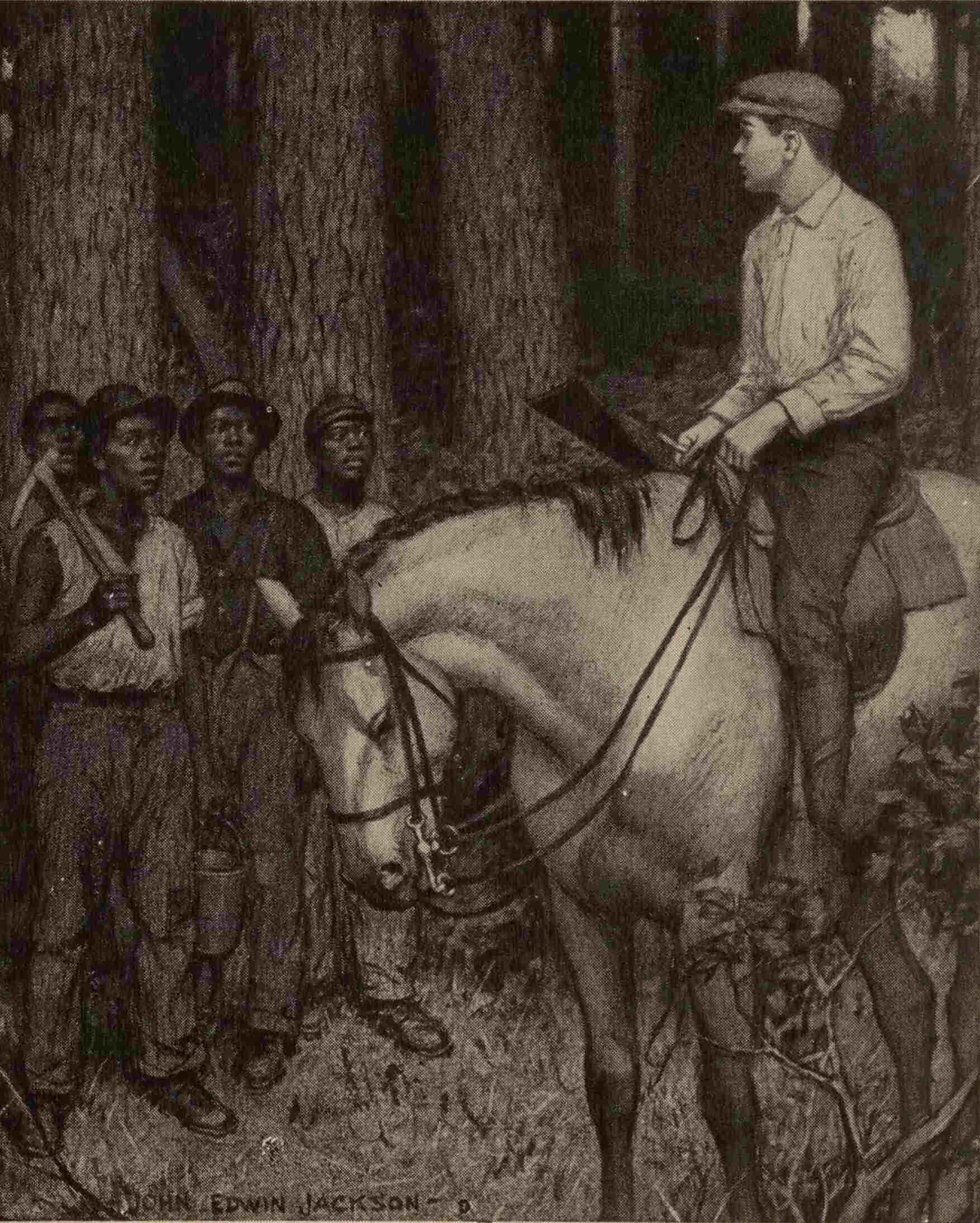

From the landing they walked a mile through the woods to see the old house where their parents had been born, paintless now, crumbling and dilapidated. The glass was gone from the windows; there were birds’ nests in all the rooms, and a drove of half-wild hogs had made a burrow under the building. Like most deserted houses in the South, it was reputed by the negroes to be haunted.

“Over there is the river orchard, that Burnam owns,” said Joe, pointing toward the river. “All this used to belong to our people. They had over a hundred slaves, and used to grow hundreds of bales of cotton in the river-bottoms. I expect they owned ten thousand acres then, but it was mainly timbered, and timber wasn’t worth anything in those days. Only the bottom-lands were considered any account.”

They roamed curiously over the old place with its relics of flower-beds, its fruit orchard, and its chinaberry and walnut-trees, and then walked back to the landing. A rural telephone connected it with the camp, and Joe rang up the commissary-store and begged for Burnam’s car to be sent over, if it was not being used at the moment.

It came in half an hour, and the Harmans drove over to the camp, while Joe rode behind. The turpentine camp was another novel sight to the Northerners, and by good luck the still happened to be working. The men had collected enough gum from the wrecked tract to fill the retort, and they were “running a charge.”

Joe had nothing to do with this process, and he explained the operation to his cousins. The heavy barrels of gum were hoisted up to the platform above the furnace and emptied into the great copper retort, together with a certain amount of water. The copper cap was screwed down, and a fire lighted under the retort. Presently a trickle of colorless fluid began to come through the twisted worm of the condenser. It was the turpentine spirit, evaporating more quickly than water, and this was run off into a barrel, until it ceased and pure water began to come through the pipe.

The turpentine being all out, the negroes opened a gate at the bottom of the retort, letting out a great gush of black, boiling rosin, which ran into a trough, passing through three strainers. Still liquid and intensely hot, it was then ladled out into barrels, where it cooled and hardened, ready to be shipped. This rosin was worth six or seven dollars a barrel, and was a most valuable by-product of the turpentine industry.

All this was an old story to Joe, but it was fresh and exciting to the Canadians. Alice in particular was bubbling with enthusiasm. She made friends at once with the camp foreman and with Burnam himself, who, amused at her intense interest in the camp, conducted her about personally and showed her everything. He insisted that they should stay over at the camp till the next day, when he promised to send them home in his car.

So they stayed, having supper that night at the great table with all the white officers of the camp. Alice was placed in the seat of honor next to Burnam, with whom she was carrying on a laughing and chaffing dialogue, when she said suddenly:

“Mr. Burnam, I want you to do something for us. We’re going on an exploring trip into the woods soon, for three or four days, and we must have some one with us who knows the country. We want you to let us have Cousin Joe.”

“Down here in the South we never refuse anything to a lady,” returned the turpentine man. “And when she’s young and pretty like you we give her everything without asking. Sure you can have Joe if you want him.”

Alice blushed hotly at this, and Joe, taken by surprise, started to protest.

“No, I’ll be able to spare him for a while, as soon as we get the cups hung and the gum running in the river orchard,” Burnam went on more seriously. “Fact is, with half our tract ruined, I don’t really need three woods-riders any more. As soon as he gets the new orchard started Morris can look after it for a few days.”

“I knew you could fix it!” exclaimed Alice, beaming.

“But he’ll have to work double hard when he gets back, to make up,” said Burnam, with affected severity.

The next morning, after his cousins had departed in Burnam’s automobile, Joe rode down to look over the river orchard, feeling considerably more optimistic about the future. Burnam had appeared good-natured and confident; all might yet be well with the camp. The notion of the honey business, too, had taken strong hold on Joe’s imagination. He had as yet only the vaguest conception of how it was practised, but as he rode down toward the river he turned over in his mind the astonishing things he had heard from his cousins. Alice had appeared the chief expert. The others always deferred to her opinion when it came to bees; and Joe thought he had never seen a girl so clever, so practical, and so alive with enthusiasm and spirits.

He took the seldom-used road that they had traveled the day before, up past the old Marshall house, and then by a trail down into the woods of the river orchard. That great tract of pine had a very special interest to Joe, for, as he had explained to the Harmans, it had belonged to their family, he had been born on it himself, and with a little good luck it might have been his own that day.

Before the Civil War it had formed part of the great Marshall estate that lay along the river. The property had been huge in area but of little cash value, for most of it was uncleared and uncultivated. Lumber was of no value then; turpentine was not worth much, though Joe’s grandfather had operated a small still somewhere in the woods, shipping turpentine down to Mobile and throwing the rosin away. That had been more than half a century ago, and no one now knew even where the still had been located.

The old-time Marshalls, like many Southern families, had not been thrifty. They sold land recklessly and for a trifle. Joe’s own father had inherited not two thousand acres, of which not one-tenth was under cultivation. Joe could remember the series of bad cotton crops, of too wet summers, of floodings by the river, that had almost ruined his father. At last, weary of hard luck, Mr. Marshall had sold the whole property for six dollars an acre, and moved to Mobile.

No one moved into the old mansion, which fell into decay. The new owner lived forty miles distant. He rented out part of the land, let out part to be farmed for him on shares, and sold to Burnam the tract of pine land toward the river.

When Joe was fifteen his father had died. The boy had neither sisters nor brothers, and his mother had been dead eight years. Almost his only link with humanity was his uncle Louis Marshall, and the negro boy Sam, who had come to Mobile with the family.

Joe had inherited three thousand dollars—all that was left of the once splendid Marshall property. He was graduated shortly afterwards from the Mobile Academy, and became much attracted by the turpentine business. He did not care for the city; he had been brought up in the woods, and they called to him. When Uncle Louis, who was trustee of his money, mentioned that he might put it into Burnam’s new camp, with the additional inducement of a job as woods-rider at seventy-five dollars a month, the boy was enthusiastic. It was as much his fault as Uncle Louis’s that the proposition had been accepted. Sam was also wild with delight. Since Mr. Marshall’s death he had been working in a wholesale warehouse, but he remained at heart, as he said, “a piney-woods nigger,” and he took it for granted that he was to go into turpentining with his young master.

Burnam had leased the tract for the usual three years. It is not considered profitable to work the same pine for a longer term. The first summer all had gone well; the big still had been working twice a week, and almost weekly the river boat had carried a cargo of turpentine and rosin barrels down to Mobile. The second season had also started with great promise, but now the storm had dealt it a staggering blow.

However, to turpentine the river orchard might save the situation. Joe rode observantly through the woods, growing more hopeful as he estimated the number of pines. There must be, he decided, three or four “crops,” of about ten thousand trees each, and the trees were vigorous and well grown. The river acres might, after all, compensate for the damage that the tornado had done to the rest of the tract; for down by the river the wind seemed to have worked little injury. Few trees had fallen except dead ones, which were useless anyway.

For years this tract of woods had not been much visited. It was badly grown up with blackberry-thickets and underbrush, and would need a great deal of clearing out before turpentining could be fairly started. Quail rose occasionally from open glades; rabbits scurried away almost from under Snowball’s hoofs, and once the horse stopped, snorting and scared, afraid to advance. A small rattlesnake was coiled right in the path, refusing to move. It vibrated its two-buttoned tail with an almost imperceptible sound, and Joe had to ride around it. In the moist earth of a creek-bottom he perceived a track much resembling that of a bear, and it made him think of the proposed camping expedition with his cousins. He might be able to make it within a week, and he reminded himself to inquire among the negroes if any of them knew the location of Old Dick’s cabin.

Joe was feeling more cheerful as he rode back to the camp, late for the dinner-hour, but he got a reminder at once of the precarious position. It was Saturday; it was pay-day, but Joe had quite forgotten this fact until he saw the crowd of negroes lounging and waiting outside the commissary-store. They were waiting to get their wages, which they would immediately spend over the counter again for pork and meal and molasses and calico and tobacco. Prices were high at the commissary, too, and it was not the least profitable part of the camp.

But no money was going yet, though it was long past the usual hour. Joe dismounted and went into the store. The cashier’s window was closed; there was a sound of talking in Burnam’s inner office. Joe saw anxiety on the black faces, and overheard a scrap of talk between two “chippers,” who were planning to leave for another camp. There seemed to be a general impression that Burnam’s business was bankrupt.

Joe saw to his horse being put away, and returned to the store. For the first time he noticed a muddy automobile, a strange one, standing on the road. Tom Morris presently came up and joined him.

“They’re fighting it out in the office,” he observed. “A fellow from the bank came over in that car this morning, and he’s been in there ever since, arguing with Burnam, I reckon. I don’t know whether he brought over the cash for the pay-roll or not. We’ll soon see now if the bank’s going to carry us any longer.”

It must have been a hard battle, for the office remained closed for nearly an hour more. Burnam came out, looking worried, and called for Wilson, who entered the conference. Finally the bank man came out, got into his car, and drove away. All the waiting camp was tense with expectation, but Burnam had won this time. Within five minutes the cashier opened his wicket and began to pay the men.

As soon as he could see Burnam, Joe made his detailed report on the river tract and got his instructions. Work was to be started as quickly as it possibly could, with all the negroes that could be spared from the other orchards; and early next morning Joe went down with three wagon-loads of men to clean up the woods.

As he had foreseen, it was a heavy job. The negroes cut down the dense blackberry-thickets, raked away the pine-needles and chips from the trees that were to be tapped, piled up the brushwood, and cut trails for the wagons. Fire is the most terrible of perils in a turpentine forest, and the first duty is always to clear up all inflammable rubbish.

There were occasional bits of excitement as the work went on. Rabbits bobbed out from under the brush-heaps; the negroes killed two or three with clubs. Once they disturbed a nesting wild turkey on an oak ridge. Snakes of all sorts were plentiful; one of the men killed a large kingsnake in a blackberry-thicket. A little later Joe was attracted by a great uproar of whoops and shouting. The negroes had driven an enormous diamond-back rattlesnake out of its lair, and were gathered round it at a respectful distance, laughing and daring one another to approach it. The serpent lay coiled, with the tip of its buzzing tail lifted, and its flat, sinister head turned grimly toward its enemies. It would not run, it was ready to fight, but no one cared to encounter it, till Joe drew the little rifle from its sheath at his saddle. He missed the first shot, but the second bullet went through the snake’s head. The men shouted and cheered, and when the serpent ceased to struggle one of them cut off its rattles and brought them to Joe. There were eight and a button; and he put them in his pocket, thinking of a curiosity for his cousins.

One day’s work cleared up a good many acres. While the cleaning gang moved on to a fresh area the next day, a second gang came down from the camp to chip and “stick tin” on the prepared ground. The new men worked in pairs, one carrying the hack and the other the cups and the tin gutters. While the first ripped a broad, V-shaped gash in the pine-bark with his keen tool, the second fixed the two gutters in place, and hung the cup under them on a nail. These men were expert “turpentine niggers”; they worked fast, and by night several thousand trees were beginning to drip gum.

Meanwhile more of the woods had been cleared up and was ready to be tapped. Joe drove the men to their utmost efforts; and they worked valiantly. In three days the whole orchard was cleaned up and cut with trails, and most of the chipping was done. Burnam came over and rode rapidly through, going away without saying anything, but Joe knew that he was pleased. The river tract gang had made the biggest week’s wages of their lives, and Joe thought with some apprehension of the Saturday pay bill; but the cashier opened his wicket punctually this time, and the commissary did a roaring trade for the rest of the day. Evidently the bank had not yet shut down on Burnam.

By the first of the next week all the tin was stuck and the cups hung in the new tract. The weather had been unusually hot and there had been a wonderful run of gum for so early in the season, but now a sudden cold wave came over. The nights were chilly; fires blazed in all the negro cabins, and the gum ceased to trickle.

It was another piece of hard luck. There would be no more flow until the weather turned hot again, and the cold wave was overspreading the whole country, with no prospect of immediate change. There was not much to do in the woods. Joe rode mechanically, thinking that it was a great opportunity for his promised holiday, but he disliked reminding Burnam of his promise.

The pine woods lay well back from the river, and Joe seldom went down to the water, but to-day Snowball broke loose during the noon-hour and wandered toward the bottom lands, probably in search of better grazing than he could find among the pines. Joe did not discover it for half an hour, and it took him some time to find and catch the horse. He was riding along the shore when he was startled to notice the marks on the bank where a large boat had been tied up. There were the ashes of a camp-fire ashore, too, scattered pork bones, a broken bottle, and several scraps of cloth. Evidently some of the river nomads had camped there, and Joe at once remembered the black houseboat that he had seen floating down past the landing. It could not have been that one, however, for it was gone never to return. Such houseboats have no means of propulsion, and cannot return against the stream without being towed.

The camp looked several days old, and it was a matter of no particular importance. Joe went back to the orchard, glancing into the turpentine-cups that still hung unfilled, and was astonished to meet Burnam at the upper end of the range.

“Getting any gum, Marshall?” he inquired.

“Not a drop since the cold spell,” returned Joe drearily.

“Well, never mind!” said Burnam. “It’s bound to turn warm again. But everything’s dead just now, and I reckon this is just the time to send you down to that pretty cousin of yours. Want to go?”

“Well—as you say, there isn’t much to do,” said Joe. “If I’m going to take a holiday, this is the time for it.”

“All right,” said the operator. “You’ve done a big week’s work here, and you deserve it. Wilson’ll drive you down in my car in the morning. Tell your cousin that I’ve kept my promise, and that you’ve got to bring her up to visit us again.”

Joe had already made many inquiries among the turpentine negroes about Old Dick’s bees, but had not obtained any definite information. Everybody had heard the story; Dick’s bees had become legendary in that district, but nobody seemed to have any idea where they had been situated. They were certainly somewhere down the river, and, most agreed, on the other side, but estimates of the distance ranged from five to fifty miles. One man declared Old Dick had dwelt in the River Island, a tangled and almost unknown swamp thirty miles down the stream; but this was highly improbable. He hoped that his cousins had been able to learn something more accurate; but in reality he had very little idea that they would ever be able to find the old negro’s apiary, or that they could do anything with it if they did.

Joe’s arrival was unexpected, but he got a great welcome. The Harmans had been active during his absence. They had walked and driven about the country with characteristic energy, and had discovered about thirty “gums” of bees which the owners were willing to sell at prices of seventy-five cents or a dollar apiece. It was not many, but these bees would be better than nothing. They had also made assiduous inquiries about Old Dick, but had been little more successful than Joe.

“They all say he lived quite close to the river,” said Alice. “He used to send away his wax and honey on the steamboat. And it seems he lived near a big bayou opening off the river. Some say it was ten miles down, and some say twenty.”

“There must be only a limited number of big bayous between ten and twenty miles from here,” said Bob. “Seems to me we might look into them all, if necessary.”

Joe laughed. He knew the wild and impenetrable nature of that bayou country, which his cousins had little idea of. He was ready for the trip all the same. The Harmans had already made a rough scheme for it, and their plans took shape as they talked.

Of course they would have to go by water, and fortunately Uncle Louis owned a good boat at the landing, which he put at their service. He also had a small shelter-tent, and he told them to help themselves to all the grub and cooking-utensils they could find about the place.

“But supposing we do find the bees, Uncle Louis,” Alice asked, “who do they belong to? Would we be allowed to have them?”

“Who’s to stop you?” returned the planter. “The law is that bees become wild animals when nobody’s keeping them. Anybody can take them, same’s a bee-tree. Besides, I know all the land-owners from here to Mobile, and I could fix it. No, you-all find your bees, and raft ’em off, and you can have ’em all right. You’ll sure deserve them.”

“There might be a hundred gums there,” said Alice optimistically. “We could extract the honey and melt up the wax, and drive all the bees into wire-cloth cages, and express them home. Just think what a crop they’d make for us on the Ontario clover!”

“And think of all the wax we’d get from the old gums!” said Carl, with equal enthusiasm. “Two or three pounds to the gum and it’s worth fifty cents now.”

“But of course you’re not thinking of going on this hunt with us, Allie,” said Bob. “You couldn’t go. It would be much too rough a trip for you, through the swamps. Wouldn’t it, Joe?”

“Too rough!” cried his sister indignantly. “I guess it won’t be any rougher than our first season in the north woods, with bears and thieves and forest fires. As if I couldn’t go anywhere you could! What do you think I came South for? I should rather think I am going!”

“Surely she can go,” Joe put in. “There won’t be any danger.”

Bob only laughed. He knew well that Alice could not be kept out of any such adventure, and in fact she was as capable of traveling through the wilderness as either of her brothers. Probably he would have objected strongly to leaving her behind, indeed, for she was a great expert in camp cookery.

As they expected to be out only three or four days they did not need a heavy outfit. Joe had brought his rifle, his cousins their own fire-arms, including Alice’s pistol, which she wore strapped around her waist in a belt of cartridges. They had fishing-tackle, and they carried several loaves of fresh-baked “light-bread,” with pork, corn-meal, and a large number of hard-boiled eggs. One of the plantation mule wagons carried them and their equipment down to Magnolia Landing early the next morning, and they embarked aboard the boat and started down the big river.

For two hours they went on, rowing and floating with the current, round bend after bend of the twisting stream, banked on each side with the incessant swamps and forests. Occasionally there was a bottom-land patch of corn; occasionally a glimpse of low pasture where scrawny and half-wild cattle were grazing.

“What a different country from Canada!” Alice remarked.

All the Harmans had been secretly impressed with the desolation of the scene, the pitiful farming, the dwarfed cattle, so different from the great Holsteins and Herefords of the Ontario clover-pastures; but they had been too polite to voice their impressions to Joe.

“Yes, this is no country for farming,” Joe admitted. “Land too poor, I reckon. It’s a turpentine and timber country. What they’ll do when the pine is all cut off I can’t imagine. But this sand strip along the river is the very worst bit of the State. North and east of here you’ll see as fine plantations as anywhere in the world.”

“But this is a great country for cheap bees,” said Bob, “and that’s the main thing just now. When do you suppose we’re coming to that big bayou?”

Joe thought they must have come six or eight miles, and within another mile a wide opening did appear on the other shore of the river. They pushed the boat into it with great hopes. On either side it was tangled with dense cypress and sycamore and cotton wood, heavy-laden with gray Spanish moss, but within fifty yards it shoaled off into a morass of liquid mud.

“This certainly isn’t it,” said Carl, contemplating the depressing spectacle.

“No, Old Dick never lived here,” Joe admitted. “Well, there are plenty more bayous to look at.”

As they returned to the river the steamboat passed, coming up from Mobile, and blew a deafening blast from her whistle as they waved at her from the rowboat. It was the first human life they had seen since leaving the landing.

As Joe had said, there were plenty more bayous and creeks. For a while it seemed that there was a fresh one every hundred yards. Some of them proved choked and impassable with fallen timber; some were too shallow to navigate far; once they got far in and became involved in a maze of backwater channels, shut in by thickets of titi and bay-trees, tangled with rattan and bamboo-vine. Moccasin snakes popped into the sluggish waters; birds strange to the Canadians shrieked discordantly overhead; lizards darted up and down the tree-trunks; but there was no spot where a cabin had ever stood, nor anything resembling a beeyard.

Growing very tired of being cramped in the boat, they went ashore after another quarter of a mile down-stream, where the land seemed unusually high and dry. It was “hammock land,” only occasionally overflowed by high water, wooded with black-gum and bay-trees, and the moist earth bore dense clumps of palmetto. Through this they walked inland till they came to still higher pine woods, then circled around to the left till they came back to the river again, without having seen anything encouraging.

“I suppose we might as well have dinner,” Joe suggested. “This treasure-hunting is hungry work.”

They lunched plentifully, though simply, on bread and butter and cold boiled eggs, without lighting a fire. There was plenty of drinking water in the river; it looked muddy indeed, but Joe assured them that it was perfectly wholesome. There was not much inducement to linger after they had finished eating. The air of the hammock woods was damp and chilly, deeply shaded from the sun, and they got into the boat and floated down the river again.

All that afternoon they spent in the same fruitless exploration of swamp and creek-mouth and bayou. Wherever the shores looked reasonably dry they landed and searched up and down and half a mile inland, but found nothing that even suggested a deserted cabin. They found the plain tracks of a drove of wild turkeys in the damp soil; they could have shot plenty of quail, but these birds were out of season, and they had provisions enough not to be in need of game. Carl took to fishing from the boat, and landed three or four “yellow cats,” differing greatly from the Northern catfish, which they reserved for supper. Persevering in his angling, Carl presently hooked something that took out all his line, something living that nevertheless hung like a dead weight of hundreds of pounds on the hook. Carl had the end of the line injudiciously tied around his wrist; the skin under the loop turned purple, and he was nearly pulled overboard with the strain.

Joe snatched out his knife and cut the line. Carl sunk back, not yet over his surprise.

“What on earth was it?” he gasped. “An alligator?”

“Likely a big catfish,” said Joe laughing. “They get mighty big in the Alabama—sometimes over a hundred pounds. You can’t land one of those fellows on a line, but it isn’t often they take a bait. He’d have pulled you over if you’d held on.”

Recovering from his shock, Carl presently resumed fishing, but he hooked no more dangerous monsters. The smaller catfish, of a pound or two, were plentiful enough, but Alice looked upon them with some aversion.

“I can cook trout better than anybody in the world,” she declared modestly. “But I don’t know whether I can do anything with these creatures.”

They turned out excellent that night, however, fried with slices of bacon, and Alice also produced a pan of fresh hoe-cake—an accomplishment which she had acquired during her stay at the plantation. They had coffee, too, and more eggs, and a jar of fig-preserves which Aunt Kate had slipped among the more substantial provisions.

A damp fog had fallen on the river and the swamps, and felt intensely cold. They were on a strip of high land a hundred yards back from the water, but the air seemed impregnated with vapor. They built up the fire to a great blaze with dry pine and cypress, like a Canadian camp, Bob said, and they sat beside it until Alice, declaring that she was tired, went to her tent in the background.

The three boys piled fresh wood on the fire and rolled up in their blankets in the warmth. They were all rather depressed and disinclined to talk much. The exploring trip was turning out disappointingly. Joe had a sense of guilt. It was he who had first suggested finding the lost beeyard, and his cousins were neither finding any bees nor having any sport. He was losing what faith he had ever had in Old Dick, and he made up his mind that if they had no success on the morrow they had better go home. He would help them to find gums among the farmers. Meanwhile he would organize some amusements—a grand ’possum and coon hunt. In the midst of these schemes he fell asleep.

But in the morning they all felt more cheerful, after plenty of fried ham, hot coffee, and cornbread. It was clear and sunny; a mocking-bird sang gloriously from a bay-tree overhead, and it had turned warmer. The cold wave seemed to be broken.

“The gum’ll be running again in a day or two if it turns warm, and they’ll be wanting me back at the camp,” Joe remarked.

“Perhaps we’d better go back to-morrow,” said Alice. “But I have a feeling that something is going to happen to-day.”

Something did happen, which came within a hair’s-breadth of turning into a tragedy. They floated down the river after breakfast, explored one creek-mouth after another, landed several times, always with the same discouraging failure to find any deserted cabin. About noon they rowed into a broad, shallow bayou and landed to explore in different directions, Joe following the bayou upwards, Bob up the river shore, and Carl in a midway direction. Alice elected to stay with the boat. She did not care to walk, and she had a belief that if she sat quietly by the bayou she might see an alligator, for which purpose she borrowed Joe’s rifle.

Joe wandered up the swampy shore of the bayou for nearly a mile, when it dwindled away into a small creek. He diverged into a tract of hammock land, circled through this for some time, crossed the head of the bayou, and came down on the other side.

Approaching the river eventually, he saw the boat drawn up on the shore opposite him, but Alice was nowhere in sight. He shouted several times; he wanted to be ferried across; but there was no answer. He became slightly uneasy, though he could not think of any real danger. Probably, he thought, she was ambushed by the river out of hearing, on the watch for an alligator; but when he could get no response to his shouting he determined to wade the bayou.

He did not think there was more than two or three feet of water in it, and he splashed in without hesitation. The bottom was soft sand and mud, and he had to step quickly to keep from sinking in it. It gave him a slight sense of uneasiness, but in his anxiety to get across he waded ahead till he was near the center of the bayou.

Then one foot suddenly went down in the mud far over the ankle. He stumbled and tried to pull it out, and the other foot went even deeper. Instantly realizing his danger, he threw himself forward in the water and tried to swim, but he failed to pull himself free; he went under, gasping; he endeavored to get back to his balance, and found that his legs were down almost to the knees in the loose, apparently bottomless sandy mud.

Joe knew the peril of these treacherous sloughs, where hogs and cattle are frequently engulfed, and, rarely, a human being. He struggled to free himself; he tried to trample his way up. But the stuff was thick enough to hold him, not thick enough to afford any purchase, and his efforts seemed only to sink him deeper.

He stood still and shouted again at the top of his voice. He could hear the echo far over the swamp, but there was no answer. The surface of the water was rising well over his waist; it was creeping up with frightful speed.

The boat lay there, not a hundred feet away. He could see the tin bucket in it, and the rolled-up tent and blankets. It seemed incredible that he could not reach it. He tried again to wallow forward.

His efforts carried him down. Throwing his weight well on one foot sank it deeper. He was down almost hip-deep in the mud; the water was rising over his chest.

Afraid now to stir, he stood still and shouted again and again. A deadly chill seemed to be creeping up from his legs. His feet felt numb and paralyzed. He felt the slow, terrible sinking, as if some malignant force had him by the feet.

From somewhere very far away he thought he heard one of the boys answer his yell—or was it only the echo? The water was muddy all around him, torn up by his struggles. The turbid ripples lapped his throat, rising to his chin. In wild terror, he realized that drowning now was only a matter of moments, and at that instant Alice ran out of the woods, still carrying his rifle.

He saw her laugh at her first glimpse of his head and waving arms above the surface, then the laugh suddenly froze on her face. She dropped the gun, leaped into the boat, and sent it shooting toward him.

The side rasped his shoulder, and he clutched it, as she gripped his arm and tried to raise him, supposing he was merely out of his depth and unable to swim. He threw his head back, just able to clear his mouth.

“Mud! Quicksand!” he ejaculated.

He caught a mouthful of water and seemed to go suddenly down half a foot at once. Alice’s pull was unable to lift him. The muddy water went over his mouth, over his nose. It closed over his nose. It closed over his eyes, and he held his breath, still clutching uselessly on the boat above him.

He held that breath till his lungs felt about to burst. Alice let go her grip on his shoulder. He could feel the water going over his head, roaring and dashing, he thought. Then something struck his head. The water seemed strangely to disappear from his face. Involuntarily he let go the air in his lungs; he drew another breath with a gasp, and opened his eyes.

A tin surface was around his face, enclosing air and not water. He vaguely recognized the big bucket they had carried in the canoe. It had been pushed down over his head, the contained air driving the water down before it.

The fresh air cleared his head as he caught another gasp. It seemed a miracle to him, incomprehensible, but he realized that he was safe—at any rate for some minutes. He could feel himself still sinking; it could be for only some minutes that he was respited.

He tried to pull himself up by the boat, but it only tilted and gave, without producing any effect. Alice seemed to be holding the bucket over his head with one hand, while she was patting his arm encouragingly with the other.

She tapped on the tin as if for warning, and he felt it slowly withdrawn. He held his breath, and in a moment it was replaced, with changed air. It was time; he was choking again, for there were not many lungfuls of air in that bucket.

Through the water he thought he heard a sound of voices. Alice took both his hands and put them on the bucket. He would have to hold it himself. He grasped it, and felt the swirl of the water as the boat started away.

He felt deserted. An endless time seemed to pass. The air in the bucket was growing foul and suffocating again, when the water heaved and the boat’s keel scraped over his shoulder. His arms were gripped; there was a tug and strain that seemed likely to tear him in two; and then he came up, trailing behind the boat. Alice and Carl had him by the arms, while Bob was putting all his strength into the oars.

Without stopping to take him into the boat, they towed him straight across the bayou and pulled him out on the bank. The woods-rider crumbled down in a collapsed heap. He rubbed the water out of his eyes and looked at his rescuers.

“Alice,” he said rather thickly, “you surely saved my life. I—I’ll never forget this.”

“Oh, Joe!” said Alice, and burst into weeping.

“Hold on, Allie! It’s all right now!” exclaimed Bob.

“That bucket trick was the cleverest thing I ever saw,” said Carl.

“How did you come to think of it?” asked Joe.