[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Weird Tales August and September 1928.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

As the control-levers flashed down under my hands our ship dived down through space with the swiftness of thought. The next instant there came a jarring shock, and our craft spun over like a whirling top. Everything in the conning-tower, windows and dials and controls, seemed to be revolving about me with lightning speed, while I clung dizzily to the levers in my hands. In a moment I managed to swing them back into position, and at once the ship righted herself and sped smoothly on through the ether. I drew a deep breath.

The trap-door in the little room's floor slid open, then, and the startled face of big Hal Kur appeared, his eyes wide.

"By the Power, Jan Tor!" he exclaimed; "that last meteor just grazed us! An inch nearer and it would have been the end of the ship!"

I turned to him for a moment, laughing. "A miss is as good as a mile," I quoted.

He grinned back at me. "Well, remember that we're not out on the Uranus patrol now," he reminded me. "What's our course?"

"Seventy-two degrees sunward, plane No. 8," I told him, glancing at the dials. "We're less than four hundred thousand miles from Earth, now," I added, nodding toward the broad window before me.

Climbing up into the little conning-tower, Hal Kur stepped over beside me, and together we gazed out ahead.

The sun was at the ship's left, for the moment, and the sky ahead was one of deep black, in which the stars, the flaming stars of interplanetary space, shone like brilliant jewels. Directly ahead of us there glowed a soft little orb of misty light, which was growing steadily larger as we raced on toward it. It was our destination, the cloud-veiled little world of Earth, mother-planet of all our race. To myself, who had passed much of my life on the four outer giants, on Jupiter and Saturn and Uranus and Neptune, the little planet ahead seemed insignificant, almost, with its single tiny moon. And yet from it, I knew, had come that unceasing stream of human life, that dauntless flood of pioneers, which had spread over all the solar system in the last hundred thousand years. They had gone out to planet after planet, had conquered the strange atmospheres and bacteria and gravitations, until now the races of man held sway over all the sun's eight wheeling worlds. And it was from this Earth, a thousand centuries before, that there had ventured out the first discoverers' crude little space-boats, whose faulty gravity-screens and uncertain controls contrasted strangely with the mighty leviathans that flashed between the planets now.

Abruptly I was aroused from my musings by the sharp ringing of a bell at my elbow. "The telestereo," I said to Hal Kur. "Take the controls." As he did so I stepped over to the telestereo's glass disk, inset in the room's floor, and touched a switch beside it. Instantly there appeared standing upon the disk, the image of a man in the blue and white robe of the Supreme Council, a life-size and moving and stereoscopically perfect image, flashed across the void of space to my apparatus by means of etheric vibrations. Through the medium of that projected image the man himself could see and hear me as well as I could see and hear him, and at once he spoke directly to me.

"Jan Tor, Captain of Interplanetary Patrol Cruiser 79388," he said, in the official form of address. "The command of the Supreme Council of the League of Planets, to Jan Tor. You are directed to proceed with all possible speed to Earth, and immediately upon your arrival there to report to the Council, at the Hall of Planets. Is the order heard?"

"The order is heard and will be obeyed," I answered, making the customary response, and the figure on the disk bowed, then abruptly vanished.

I turned at once to a speaking-tube which connected with the cruiser's screen rooms. "Make all speed possible to reach Earth," I ordered the engineer who answered my call. "Throw open all the left and lower screens and use the full attraction of the sun until we are within twenty thousand miles of Earth; then close them and use the attraction of Jupiter and Neptune to brake our progress. Is the order heard?"

When he had acknowledged the command I turned to Hal Kur. "That should bring us to Earth within the hour," I told him, "though the Power alone knows what the Supreme Council wants with a simple patrol-captain."

His laugh rumbled forth. "Why, here's unusual modesty, for you! Many a time I've heard you tell how the Eight Worlds would be run were Jan Tor of the Council, and now you're but 'a simple patrol-captain!'"

With that parting gibe he slid quickly down through the door in the floor, just in time to escape a well-aimed kick. I heard his deep laughter bellow out again as the door clanged shut behind him, and smiled to myself. No one on the cruiser would have permitted himself such familiarity with its captain but Hal Kur, but the big engineer well knew that his thirty-odd years of service in the Patrol made him a privileged character.

As the door slammed shut behind him, though, I forgot all else for the moment and concentrated all my attention on the ship's progress. It was my habit to act as pilot of my own cruiser, whenever possible, and for the time being I was quite alone in the round little pilot-house, or conning-tower, set on top of the cruiser's long, fishlike hull. Only pride, though, kept me from summoning an assistant to the controls, for the sun was pulling the cruiser downward with tremendous velocity, now, and as we sped down past Earth's shining little moon we ran into a belt of meteorites which gave me some ticklish moments. At last, though, we were through the danger zone, and were dropping down toward Earth with decreasing speed, as the screens were thrown open which allowed the pull of Neptune and Jupiter to check our progress.

A touch of a button then brought a pilot to replace me at the controls, and as we fell smoothly down toward the green planet below I leaned out the window, watching the dense masses of interplanetary shipping through which we were now threading our way. It seemed, indeed, that half the vessels in the solar system were assembled around and beneath us, so close-packed was the jam of traffic. There were mighty cargo-ships, their mile-long hulls filled with a thousand products of Earth, which were ponderously getting under way for the long voyages out to Uranus or Neptune. Sleek, long passenger-ships flashed past us, their transparent upper-hulls giving us brief glimpses of the gay groups on their sunlit decks. Private pleasure-boats were numerous, too, mostly affairs of gleaming white, and most of these were apparently bound for the annual Jupiter-Mars space-races. Here and there through the confusion dashed the local police-boats of Earth, and I caught sight of one or two of the long black cruisers of the Interplanetary Patrol, like our own, the swiftest ships in space. At last, though, after a slow, tortuous progress through the crowded upper levels, our craft had won through the jam of traffic and was swooping down upon the surface of Earth in a great curve.

In a panorama of meadow and forest, dotted here and there with gleaming white cities, the planet's parklike surface unrolled before me as we sped across it. We rocketed over one of its oceans, seeming hardly more than a pond to my eyes after the mighty seas of Jupiter and the vast ice-fringed oceans of Neptune; and then, as we flashed over land again, there loomed up far ahead the gigantic white dome of the great Hall of Planets, permanent seat of the Supreme Council and the center of government of the Eight Worlds. A single titanic structure of gleaming white, that reared its towering dome into the air for over two thousand feet, it grew swiftly larger as we raced on toward it. In a moment we were beside it, and the cruiser was slanting down toward the square landing-court behind the great dome.

As we came to rest there without a jar, I snapped open a small door in the conning-tower's side, and in a moment had descended to the ground by means of the ladder inset in the cruiser's side. At once there ran forward to meet me a thin, spectacled young man in the red-slashed robe of the Scientists, an owlish-looking figure at whom I stared for a moment in amazement. Then I had recovered from my astonishment and was grasping his hands.

"Sarto Sen!" I cried. "By the Power, I'm glad to see you! I thought you were working in the Venus Laboratories."

My friend's eyes were shining with welcome, but for the moment he wasted no time in speech, hurrying me across the court toward the inner door of the great building.

"The Council is assembling at this moment," he explained rapidly as we hastened along. "I got the chairman, Mur Dak, to hold up the meeting until you arrived."

"But what's it all about?" I asked, in bewilderment. "Why wait for me?"

"You will understand in a moment," he answered, his face grave. "But here is the Council Hall."

By that time we had hastened down a series of long white corridors and now passed through a high-arched doorway into the great Council Hall itself. I had visited the place before—who in the Eight Worlds has not?—and the tremendous, circular room and colossal, soaring dome above it were not new to me, but now I saw it as few ever did, with the eight hundred members of the Supreme Council gathered in solemn session. Grouped in a great half-circle around the dais of the chairman stretched the curving rows of seats, each occupied by a member, and each hundred members gathered around the symbol of the world they represented, whether that world was tiny Mercury or mighty Jupiter. On the dais at the center stood the solitary figure of Mur Dak, the chairman. It was evident that, as my friend had informed me, the Council had just assembled, since for the moment Mur Dak was not speaking, but just gazing calmly out over the silent rows of members.

In a moment we had passed down the aisle to his dais and stood beneath him. To my salute he returned a word of greeting only, then motioned us to two empty seats which had apparently been reserved for us. As I slipped into mine I wondered, fleetingly, what big Hal Kur would have thought to see his captain thus taking a seat with the Supreme Council itself. Then that thought slipped from my mind as Mur Dak began to speak.

"Men of the Eight Worlds," he said slowly, "I have called this session of the Council for the gravest of reasons. I have called it because discovery has just been made of a peril which menaces the civilization, the very existence, of all our race—a deadly peril which is rushing upon us with unthinkable speed, and which threatens the annihilation of our entire universe!"

He paused for a moment, and a slow, deep hum of surprize ran over the assembled members. For the first time, now, I saw that Mur Dak's keen, intellectual face was white and drawn, and I bent forward, breathless, tensely listening. In a moment the chairman was speaking on.

"It is necessary for me to go back a little," he said, "in order that you may understand the situation which confronts us. As you know, our sun and its eight spinning planets are not motionless in space. Our sun, with its family of worlds, has for eons been moving through space at the approximate rate of twelve miles a second, across the Milky Way. You know, too, that all other suns, all other stars, are moving through space likewise, some at a lesser speed than ours and some at a speed inconceivably greater. Flaming new suns, dying red suns, cold dark suns, each is flashing through the infinities of space on its own course, each toward its appointed doom.

"And among that infinity of thronging stars is that one which we know as Alto, that great red star, that dying sun, which has been steadily drawing nearer to us as the centuries have passed, and which is now nearest to us of all the stars. It is but little larger than our own sun, and as you all know, it and our own sun are moving toward each other, rushing nearer each other by thousands of miles each second, since Alto is moving at an unthinkable speed. Our scientists have calculated that the two suns would pass each other over a year from now, and thereafter would be speeding away from each other. There has been no thought of danger to us from the passing of this dying sun, for it has been known that its path through space would cause it to pass us at a distance of billions of miles. And had the star Alto but continued in that path all would have been well. But now a thing unprecedented has happened.

"Some eight weeks ago the South Observatory on Mars reported that the approaching star Alto seemed to have changed its course a little, bearing inward toward the solar system. The shift was a small one, but any change of course on the part of a star is quite unprecedented, so for the last eight weeks the approaching star has been closely watched. And during those weeks the effect of its shift in course has become more and more apparent. More and more the star has veered from the path it formerly followed, until it is now many millions of miles out of its course, with its deflection growing greater every minute. And this morning came the climax. For this morning I received a telestereo message from the director of the Bureau of Astronomical Science, on Venus, in which he informed me that the star's change of course is disastrous, for us. For instead of passing us by billions of miles, as it would have done, the star is now heading straight toward our own sun. And our sun is racing to meet it!

"I need not explain to you what the result of this situation will be. It is calculated by our astronomers that in less than a year our sun and this dying star will meet head on, will crash together in one gigantic flaming collision. And the result of that collision will be the annihilation of our universe. For the planets of our system will perish like flowers in a furnace, in that titanic holocaust of crashing suns!"

Mur Dak's voice ceased, and over the great hall there reigned a deathlike silence. I think that in that moment all of us were striving to comprehend with our dazed minds the thing that Mur Dak had told us, to realize the existence of the deadly peril that was rushing to wipe out our universe. Then, before that silence could give way to the inevitable roar of surprize and fear, a single member rose from the Mercury section of the Council, a splendid figure who spoke directly to Mur Dak.

"For a hundred thousand years," he said, "we races of man have met danger after danger, and have conquered them, one after another. We have spread from world to world, have conquered and grasped and held until we are masters of a universe. And now that that universe faces destruction, are we to sit idly by? Is there nothing whatever to be done by us, no chance, however slight, to avert this doom?"

A storm of cheers burst out when he finished, a wild tempest of applause that raged over the hall with cyclonic fury for minutes. I was on my feet with the rest, by that time, shouting like a madman. It was the inevitable reaction from that moment of heart-deadening panic, was the uprush of the old will to conquer that has steeled the hearts of men in a thousand deadly perils. When it had died down a little, Mur Dak spoke again.

"It is not my purpose to allow death to rush upon us without an effort to turn it aside," he told us, "and fortune has placed in our hands, at this moment, the chance to strike out in our own defense. For the last three years Sarto Sen, one of our most brilliant young scientists, has been working on a great problem, the problem of using etheric vibrations as a propulsion force to speed matter through space. A chip floating in water can be propelled across the surface of the water by waves in it; then why should not matter likewise be propelled through space, through the ether, by means of waves or vibrations in that ether? Experimenting on this problem, Sarto Sen has been able to make small models which can be flashed through space, through the ether, by means of artificially created vibrations in that ether, vibrations which can be produced with as high a frequency as the light-vibrations, and which thus propel the models through space at a speed equal to the speed of light itself.

"Using this principle, Sarto Sen has constructed a small ten-man cruiser, which can attain the velocity of light and which he has intended to use in a voyage of exploration to the nearer stars. Until now, as you know, we have been unable to venture outside the solar system, since even the swiftest of our gravity-screen space-ships can not make much more than a few hundred thousand miles an hour, and at that rate it would take centuries to reach the nearest star. But in this new vibration-propelled cruiser, a voyage to the stars would be a matter of weeks, instead of centuries.

"Several hours ago I ordered Sarto Sen to bring his new cruiser here to the Hall of Planets, fully equipped, and at this moment it is resting in one of the landing-courts here, manned by a crew of six men experienced in its operation and ready for a trip of any length. And it is my proposal that we send this new cruiser, in this emergency, out to the approaching star Alto, to discover what forces or circumstances have caused the nearing sun to veer from its former path. We know that those forces or those circumstances must be extraordinary in character, thus to change the course of a star; and if we can discover what phenomena are the causes of the star's deflection, there is a chance that we might be able to repeat or reverse those phenomena, to swerve the star again from the path it now follows, and so save our solar system, our universe."

Mur Dak paused for a moment, and there was an instant of sheer, stunned silence in the great hall. For the audacity of his proposal was overwhelming, even to us who roamed the limits of the solar system at will. It was well enough to rove the ways of our own universe, as men had done for ages, but to venture out into the vast gulf beyond, to flash out toward the stars themselves and calmly investigate the erratic behavior of a titanic, thundering sun, that was a proposal that left us breathless for the moment. But only for the moment, for when our brains had caught the magnitude of the idea another wild burst of applause thundered from the massed members, applause that rose still higher when the chairman called Sarto Sen himself to the dais and presented him to the assembly. Then, when the tumult had quieted a little, Mur Dak went on.

"The cruiser will start at once, then," he said, "and there remains but to choose a captain for it. Sarto Sen and his men will have charge of the craft's operation, of course, but there must be a leader for the whole expedition, some quick-thinking man of action. And I have already chosen such a man, subject to your approval, one whose name most of you have heard. A man young in years who has served most of his life in the Interplanetary Patrol, and who distinguished himself highly two years ago in the great space-fight with the interplanetary pirates off Japetus: Jan Tor!"

I swear that up to the last second I had no shadow of an idea that Mur Dak was speaking of me, and when he turned to gaze straight at me, and spoke my name, I could only stare in bewilderment. Those around me, though, pushed me to my feet, and the next moment another roar of applause from the hundreds of members around me struck me in the face like a physical blow. I walked clumsily to the dais, under that storm of approval, and stood there beside Mur Dak, still half-dazed by the unexpectedness of the thing. The chairman smiled out at the shouting members.

"No need to ask if you approve my choice," he said, and then turned to me, his face grave. "Jan Tor," he addressed me, his solemn voice sounding clearly over the suddenly hushed hall, "to you is given the command of this expedition, the most momentous in our history. For on this expedition and on you, its leader, depends the fate of our solar system. It is the order of the Supreme Council, then, that you take command of the new cruiser and proceed with all speed to the approaching star, Alto, to discover the reason for that star's change of course and to ascertain whether any means exist of again swerving it from its path. Is the order heard?"

Five minutes later I strode with Sarto Sen and Hal Kur into the landing-court where lay the new cruiser, its long, fishlike hull glittering brilliantly in the sunlight. A door in its side snapped open as we drew near, and through it there stepped out to meet us one of the six blue-clad engineers who formed the craft's crew. "All is ready for the start," he said to Sarto Sen in reply to the latter's question, standing aside for us to enter.

We passed through the door into the cruiser's hull. To the left an open door gave me a glimpse of the ship's narrow living-quarters, while to the right extended a long room in which other blue-clad figures were standing ready beside the ship's shining, conelike vibration-generators. Directly before us rose a small winding stairway, up which Sarto Sen led the way. In a moment, following, we had reached the cruiser's conning-tower, and immediately Sarto Sen stepped over to take his place at the controls.

He touched a stud, and a warning bell gave sharp alarm throughout the cruiser's interior. There were hurrying feet, somewhere beneath us, and then a loud clang as the heavy triple-doors slammed shut. At once began the familiar throb-throb-throb of the oxygen pumps, already at work replenishing and purifying the air in our hermetically sealed vessel.

Sarto Sen paused for a moment, glancing through the broad window before him, then reached forth and pressed a series of three buttons. A low, deep humming filled the cruiser's whole interior, and there was an instant of breathless hesitation. Then came a sharp click as Sarto Sen pressed another switch; there was a quick sigh of wind, and instantly the sunlit landing-court outside vanished, replaced in a fraction of a second by the deep, star-shot night of interplanetary space. I glanced quickly down through a side window and had a momentary glimpse of a spinning gray ball beneath us, a ball that dwindled to a point and vanished even in the moment that I glimpsed it. It was Earth, vanishing behind us as we fled with frightful velocity out into the gulf of space.

We were hurtling through the belt of asteroids beyond Mars, now, and then ahead, and to the left, there loomed the mighty world of Jupiter, expanding quickly into a large white-belted globe as we rocketed on toward it, then dropping behind and diminishing in its turn as we sped past it. The sun behind us had dwindled by that time to a tiny disk of fire. An hour later and another giant world flashed past on our right, the icy planet Neptune, outermost of the Eight Worlds. We had passed outside the last frontier of the solar system and were now racing out into the mighty deeps of space with the speed of light on our mad journey to save a universe.

2

An hour after we had left the solar system Hal Kur and I still stood with Sarto Sen in the cruiser's conning-tower, staring out with him at the stupendous panorama of gathered stars that lay before us. The sun of our own system had dwindled to a far point of light behind us, by that time, one star among the millions that spangled the deep black heavens around us. For here, even more than between the planets, the stars lay before us in their true glory, undimmed by proximity to any one of them. A host of glittering points of fire, blue and green and white and red and yellow, they dotted the rayless skies thickly in all directions, and thronged like a great drift of swarming bees toward our upper left, where stretched the stupendous belt of the Milky Way. And dead ahead, now, shone a single orb that blazed in smoky, crimson glory, a single great point of red fire. It was Alto, I knew, the sullen-burning star that was our goal.

It was with something of unbelief that I gazed at the red star, for though the dials before me assured me that we were speeding on toward it at close to two hundred thousand miles a second, yet except for the deep humming of the craft's vibratory apparatus one would have thought that the ship was standing still. There was no sound of wind from outside, no friendly, near-by planets, nothing by which the eye could measure the tremendous velocity at which we moved. We were racing through a void whose very immensity and vacancy staggered the mind, an emptiness of space in which the stars themselves floated like dust-particles in air, a gulf traversed only by hurtling meteors or flaring comets, and now by our own frail little craft.

Though I was peculiarly affected by the strangeness of our position, big Hal Kur was even more so. He had traveled the space-lanes of the solar system for the greater part of his life, and now all of his time-honored rules of interplanetary navigation had been upset by this new cruiser, a craft entirely without gravity-screens, which was flashing from sun to sun propelled by invisible vibrations only. I saw his head wagging in doubt as he stared out into that splendid vista of thronging stars, and in a moment more he left us, descending into the cruiser's hull for an inspection of its strange propulsion apparatus.

When he had gone I plunged at once into the task of learning the control and operation of our craft. The next two hours I spent under the tutelage of Sarto Sen, and at the end of that time I had already learned the essential features of the ship's control. There was a throttle which regulated the frequency of the vibrations generated in the engine-room below, thus increasing or decreasing our speed at will, and a lever and dial which were used to project the propelling vibrations out at any angle behind us, thus controlling the direction in which we moved. The main requisite in handling the craft, I found, was a precise and steady hand on the two controls, since a mere touch on one would change our speed with lightning swiftness, while a slight movement of the other would send us millions of miles out of our course almost instantly.

At the end of two hours, however, I had attained sufficient skill to be able to hold the cruiser to her course without any large deviations or changes of speed, and Sarto Sen had confidence enough in my ability to leave me alone at the controls. He departed down the little stair behind me, to give a few minutes' inspection to the generators below, and I was left alone in the conning-tower.

Standing there in the dark little room, its only sound the deep humming of the generators below and its only lights the hooded glows which illuminated the dials and switches before me, I gazed intently through the broad fore-window, into that crowding confusion of swarming suns that lay around us, that medley of jeweled fires in which the great star Alto burned like a living flame. For a long time I gazed toward the star that was our goal, and then my thoughts were broken into by the sound of Sarto Sen reascending the stair behind me. I half turned to greet him, then turned swiftly back to the window, stiffening into sudden attention.

My eyes had caught sight of a small patch of deep blackness far ahead, an area of utter darkness which was swiftly expanding, growing, until in less than a second, it seemed, it had blotted out half the thronging stars ahead. For a moment the sudden appearance of it dumfounded me so that I stood motionless, and then my hands leaped out to the controls. I heard Sarto Sen cry out, behind me, and had a glimpse of the darkness ahead, obscuring almost all the heavens. The next moment, before my hands had more than closed upon the levers, all light in the conning-tower vanished in an instant, and we were plunged into the most utter darkness which I have ever experienced. At the same moment the familiar hum of the vibration-generators broke off suddenly.

I think that the moment that followed was the one in which I came first to know the meaning of terror. Every spark of light had vanished, and the silencing of the vibration-generators could only mean that our ship was drifting blindly through this smothering blackness. From the cruiser's hull, below, came shouts of fear and horror, and I heard Sarto Sen feeling his way to my side and fumbling with the controls. Then, with startling abruptness, the lights flashed on again in the conning-tower and through the windows there burst again the brilliance of the starry heavens. At the same moment the vibration-generators began again to give off their deep humming drone.

Sarto Sen turned to me, his face white as my own. Instinctively we turned toward the conning-tower's rear-window, and there, behind us, lay that stupendous area of blackness from which we had just emerged. A vast, irregular area of utter darkness, it was decreasing rapidly in size as we sped on away from it. In a moment it had shrunk to the spot it had been when first I glimpsed it, and then it had vanished entirely. And again we were racing on through the familiar, star-shot skies.

I found my voice at last. "In the name of the Power," I exclaimed, "what was that?"

Sarto Sen shook his head, musingly. "An area without light," he said, half to himself; "and our generators—they, too, could not function there. It must have been a hole, an empty space, in the ether itself."

I could only stare at him in amazement. "A hole in the ether?" I repeated.

He nodded quickly. "You saw what happened? Light is a vibration of the ether, and light was non-existent in that area. Even our generators ceased to give off etheric vibrations, there being no ether for them to function in. It's always been thought that the ether pervaded all space, but apparently even it has its holes, its cavities, which accounts for those dark, lightless areas in the heavens which have always puzzled astronomers. If our tremendous speed and momentum hadn't brought us through this one, the pull of the different stars would have slowed us down and stopped us, prisoning us in that dark area until the end of time."

I shook my head, only half-listening, for the strangeness of the thing had unnerved me. "Take the controls," I told Sarto Sen. "Meteors are all in the day's work, but holes in the ether are too much for me."

Leaving him to his watch over the ship's flight, I descended to the cruiser's interior, where the engineers were still discussing with Hal Kur the experience through which we had just passed. In a few words I explained to them Sarto Sen's theory, and they went back to their posts with awed faces. Passing into the ship's living-quarters myself, I threw myself on a bunk there and strove to sleep. Sleep came quickly enough, induced by the generators' soothing drone, but with it came torturing nightmares in which I seemed to move blindly onward through endless realms of darkness, searching in vain for an outlet into the light of day.

When I awoke some six hours later, the position of the ship seemed quite unchanged. The steady humming of its generators, the smooth, onward flight, the legions of dazzling stars around us, all seemed as before. But when I ascended again to the conning-tower, to relieve Sarto Sen at the controls, I saw that already the star Alto had increased a little its brilliance, dimming the stars around and behind it. And through the succeeding hours of my watch in the conning-tower, it seemed to me almost that the red orb was expanding before my sight, as we hurtled on toward it. That, though, I knew to be only an illusion of my straining eyes.

But as day followed day—sunless, dawnless days which we could measure only by our time-dials—the crimson star ahead waxed steadily to greater glory. By the time we marked off the twentieth day of our flight Alto had expanded into a moon of crimson flame, whose sullen splendor outrivaled the brilliance of all the starry hosts around us; for by that time we had covered half the distance between our own sun and the dying one ahead, and were now flashing on over the last half of our journey.

Days they were without change, almost without incident. Twice we had sighted vast areas of blackness, great ether-cavities like the one we had first plunged through, but these we were fortunate enough to avoid, swerving far out of our course to pass them by. Once, too, I had glimpsed for a single moment a colossal black globe which flashed beside our path for an instant and then was left behind by our tremendous speed. Only a glimpse did I get of this dark wanderer, which might have been either a runaway planet or burned-out star. And once our ship blundered directly into a vast maelstrom of meteoric material, a mighty whirlpool of interstellar wreckage spinning there between the stars, and from which we won clear only by grace of Sarto Sen's skilful hands at the controls.

Except for these few incidents, though, our days were monotonous and changeless, days in which the care of the generators and the alternate watches in the conning-tower were our only occupations. And a strange stillness had seized us as we fled onward, a brooding silence that fastened itself upon my friends even as upon myself. Something from the vast, eternal silence through which we moved, some quality out of those trackless infinities of space, seemed to have entered into our inmost souls. We went about our duties like men in a dream. And dreamlike our life had become to us, I think, and still more remote and unreal and dreamlike had become the life of the eight worlds that lay so far behind us.

I had forgotten, almost, the mission upon which we sped, and through the long watches in the conning-tower my eyes followed the steady largening of the red sun ahead with curiosity only. Day by day its fiery disk was creeping farther across the heavens, until at last everything in the cruiser was drenched by the crimson, blood-like light that streamed in through our sunward windows. Then, at last, my mind came back to consideration of the work that lay before us, for over thirty days of our journey had passed and there remained less than a hundred billion miles between Alto and ourselves.

I gave orders to slow our progress, then, and at a somewhat slackened speed our cruiser began to slant up above the plane of the great sun, for it was my plan to gain a position millions of miles directly above the star and then hover there, accompanying it on its race through space and using the powerful little telescopic windows in the conning-tower for our first observations. So through the next two days the giant sun, a single great sea of crimson fire to our eyes, crept steadily downward across the skies as we slanted over it. Our outside instruments showed us that its heat was many times less than that of our own sun, for this was a dying star. Even so it was necessary to slide special light-repelling shields over all our windows, so blinding was the star's glare.

On the fortieth day of our journey we had reached our goal. Gathered in the conning-tower, Sarto Sen, Hal Kur and I gazed down through its circular, periscopic under-window at the mighty star beneath. We had reached a spot approximately twenty million miles above the sun and had turned our course, so that we now raced above it at a speed that matched its own, like a fly hovering over a world. Below us there lay only a single vast ocean of crimson flame, that reached almost from horizon to horizon, all but filling the heavens beneath us. It was in an awed silence that we gazed down into this tremendous sea of fire, knowing as we did that only the power of the ship's generators kept it from plunging downward.

"And we are expected to investigate—that!" said Hal Kur, gazing down into the hell of flame below. "They talk of turning that aside!"

I looked at him, hopelessly. Then, before I could speak, there came a sudden exclamation from Sarto Sen, and he beckoned me to his side. He had been staring out through one of the powerful little telescopic windows set in the conning-tower's wall, and as I reached him he pointed eagerly through it, out beyond the rim of the fiery sun beneath. I gazed in that direction, straining my eyes against the glare, and then glimpsed the thing that had attracted his attention. It was a little spot of dun-colored light lying beyond the crimson sun, a buff-colored little ball that hung steady behind the great sun at a distance of perhaps a hundred million miles and that accompanied it on its flight through space.

"A planet!" I whispered, and he nodded. Then Hal Kur, who had joined us, extended his hand too, with a muttered exclamation, and there, thrice the distance of the first from Alto, there hung another and smaller ball. In a few minutes, using the powerful inset glasses, we had discovered no less than thirteen worlds that spun about the sun beneath us and that accompanied it on its tremendous journey through space. Most seemed to revolve in orbits that were billions of miles from their parent sun, and none of the others was as large as that inmost planet which we had first discovered. It was toward this largest world that we finally decided to head first; so with Sarto Sen at the controls we slanted down again from our position over the great sun, arrowing down at reduced speed toward the inmost world.

Its color was changing from buff to pale red as we neared it, and its apparent size was increasing with tremendous speed as our craft shot down toward it. Gradually, though, Sarto Sen decreased our velocity until by the time we reached an altitude of a few hundred miles above this world our ship was moving very slowly. And now, from outside, came a thin shrieking of wind, a mounting roar that told us plainly that we were speeding through air again, and that this world had at least an atmosphere. None of us remarked on that, though, all our attention being held by the scene below.

Drenched in the crimson light of the sun behind us, it was a crimson world that lay beneath us, a lurid world whose mountains, plains and valleys were all of the same blood-like hue as the light that fell upon them, whose very lakes and rivers gave back to the sky the scarlet tinge that pervaded all things here. And as our cruiser swept lower we saw, too, that the redness of the planet beneath was no mere illusion of the crimson sunlight but inherent in itself, since all of the vegetation below, grassy plains and tangled shrubs and stunted, unfamiliar trees, were of that same red tinge that was the color-keynote of this world.

Strange and weird as it appeared, though, there seemed no sign of life on the broad plains and barren hills beneath us, and abruptly Sarto Sen headed the ship across the planet's face, speeding low over its surface while we scanned intently the panorama that unrolled beneath us. For minutes our straining scrutiny was unrewarded; and then, far ahead, a colossal shape loomed vaguely through the dusky crimson light, taking form, as we sped on toward it, as a tremendous, soaring tower. And involuntarily we gasped as our eyes took in the hugeness of its dimensions. It consisted of four slender black columns, each less than fifty feet in thickness, which rose from the ground at points a half-mile separated, four mighty pillars which slanted up into the crimson sunlight for fully ten thousand feet, meeting and merging at that distance above the ground and combining to support a circular platform two hundred feet in diameter. Our ship was hovering a few thousand feet above this platform, and on it we could see the shapes of what appeared to be machines, and other shapes that moved about them, though whether these last were human or not could not be distinguished from our height. And then, as my gaze fell toward the mighty tower's base, my cry brought the eyes of the others to follow my pointing finger. For gathered beneath and around the tower and extending away into the surrounding country were the massed buildings of a city. Low and flat-roofed and utterly strange in appearance were those buildings, and the narrow streets that pierced their huddled masses were all of the same smooth blackness as the tower itself—black, deep black, the roofs and streets and walls, laced with crimson parks and gardens that lay against their blackness like splashes of blood. And looming over all, its four tremendous columns rearing themselves above the streets and roofs and gardens like the limbs of a bestriding giant, the mighty tower soared into the crimson sunlight.

Sarto Sen flung an arm down toward the tower's platform, beneath us, and toward the shapes that moved on that platform. "Inhabited!" he cried. "You see? And that means that Alto's change in course was—"

He broke off; uttered a smothered cry. A spark of intense white light had suddenly broken into being on the platform beneath us, a beam of blinding light that stabbed straight up toward us, bathing the cruiser in its unearthly glow. And suddenly our ship was falling!

Sarto Sen sprang to the controls, wrenched around the power-lever. "That ray!" he cried. "It's attractive!—it's pulling us down!"

Our ship was vibrating now to the full force of its generators, but still we were falling, plunging headlong down toward the round platform beneath. I glimpsed Sarto Sen working frantically with the controls, and heard a hoarse cry from Hal Kur. There was a blinding glare of light all around us, now, and through the window I saw the platform below rushing up toward us with appalling speed. It was nearer, now ... nearer ... nearer ... crash!

3

I think that in the minute after the crash no one in the conning-tower made a movement. The blinding ray outside had vanished at the moment of our crash, and we were now lying sprawled on the little room's floor, where the shock of the collision had thrown us. In a moment, though, I reached for a support and scrambled to my feet. As I did so there came shouts from the hull beneath us, and then a loud clang as one of the cruiser's lower doors swung open. I sprang to the window, just in time to see our six engineers pour out of the hull beneath me, emerging onto the platform on which our ship rested, and gazing about them with startled eyes.

I ripped open the little door in the conning-tower's side, to shout to them to come back, and even as I did so saw one of the men run back into the cruiser as though in fear. The others were staring fixedly across the broad platform, and in that moment, before I could voice the warning on my lips, their doom struck. There was a quick sigh of wind, and from across the platform there sprang toward them a tiny ball of rose-colored fire, a ball that touched one of the men and instantly expanded into a whirlwind of raging flame. A single moment it blazed there, then vanished. And where the five men had stood was—nothing.

Stunned, stupefied, my eyes traveled slowly across the surface of the great platform. Strange, huge machines stood close-grouped upon it, great shining structures utterly unfamiliar in appearance. At the center of this group of mechanisms stood the largest of them, a great tube of metal fully a hundred feet in length, which was mounted on a strong pedestal and which pointed up into the sky like a great telescope. It was none of these things, though, that held my attention in that first horror-stricken moment of inspection. It was the dozen or more grotesque and terrible shapes which stood grouped at the platform's farther edge, returning my gaze.

They were globes, globes of pink, unhealthy-looking flesh more than a yard in diameter, each upheld by six slender, insectlike legs, not more than twelve inches long, and each possessing two similar short, thin limbs which served them as arms and which projected at opposite points from their pink, globular bodies. And between those arms, set directly in the side of the round body itself, were the only features—two round black eyes of large size, browless and pupil-less, and a circle of pale skin which beat quickly in and out with their breathing.

Motionless they stood, regarding me with their unhuman eyes, and now I saw that one, a little in advance of the others, was holding extended toward me a thin disk of metal, from which, I divined instantly, the destroying fire had sprung. Yet still I made no movement, staring across the platform with sick horror in my soul.

I heard a thick exclamation from Hal Kur, behind me, as he and Sarto Sen came to my side and gazed out with me. And now the grouped creatures opposite were giving utterance to sounds—speech-sounds with which they seemed to converse—low, deep, thrumming tones which came apparently from their breathing-membranes. They moved toward us, the fire-disk still trained upon us, and then one stopped and motioned from us to the platform on which he stood. He repeated the gesture, and its meaning was unmistakable. Slowly we stepped out of the conning-tower and descended by the ladder in the cruiser's side to the platform itself.

Our captors seemed to pause for a moment, now, and I had opportunity for a quick inspection of our ship. Sucked down as it had been by the attractive ray of those strange creatures, it had yet fallen on a clear space on the platform and seemed to have suffered no serious injury, for it was stoutly built and our fall had been short. The lower door in its side was still open, I saw, and now a half-dozen of the globe-creatures entered this, scurrying forward like quick insects on their six short legs. They disappeared from view inside the cruiser's hull, returning in a moment with their fire-disks trained upon the single engineer who had run back into the ship and escaped the doom of his fellows. This man, Nar Lon by name, had been the chief of the six engineers, and as his guards herded him to our side his face was white with terror. Finding us still alive, though, he seemed to take courage a little.

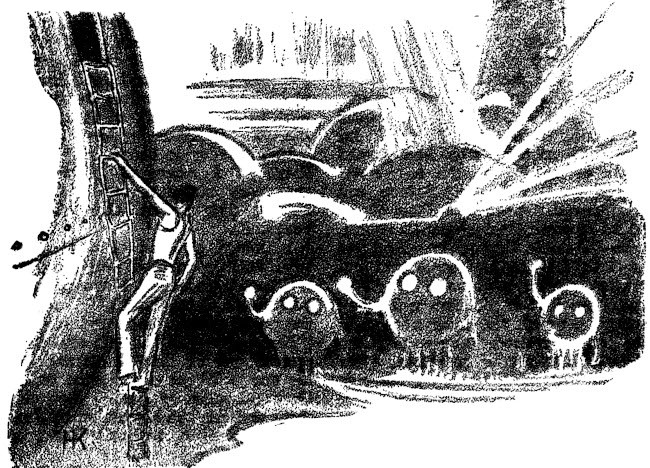

"They had their fire-disks trained upon the engineer."

Now the thrumming conversation of the creatures about us broke off, and one turned to the edge of the platform, touching a stud in the floor there. At once a circular section of the metal floor, some ten feet across, slid aside, revealing a round dark well of the same diameter, which apparently extended down into one of the great tower's four supporting columns. At the top of this shaft hung a small, square metal cage, or elevator, and into this we were shepherded at once, two of our captors entering the cage with us and keeping their fire-disks trained still upon us. There was the click of a switch, then a sudden roar of wind, and instantly the cage was shooting downward with tremendous speed. Only a moment we flashed down through the roaring darkness, and then the cage came to rest and a section of wall beside it slid aside, admitting a flood of dusky, crimson light. At once we stepped out, followed by our two guards.

We were standing at the foot of a mighty column down which we had come, standing on the floor of a great, circular, flat-roofed room, in and out of which were moving scores of the globe-creatures. From the very center of the room, behind us, rose the fifty-foot thickness of the huge pillar, soaring up obliquely and disappearing through the building's roof, two hundred feet above. Except for the pillar and the hurrying figures around us the great room was quite bare and empty, lit only by high, narrow slits in its walls which admitted long, shafting bars of the crimson sunlight. I heard Hal Kur muttering his astonishment at the titanic scale on which all things in this strange world seemed planned, and then there came a thrumming order from our guards, who gestured pointedly toward a high doorway set in the room's wall opposite us. Obediently we started across the floor toward it.

Passing through it, we found ourselves in a long, narrow corridor, apparently a connecting passage between another building and the one we had just left. There were windows on its sides, circular openings in the walls, and as we passed down the hall I glimpsed through these the city that lay around us, a vista of black streets and crimson gardens through which thronged other masses of the globe-creatures. Then, before I could see more, the corridor ended and we passed into a large anteroom occupied by a half-dozen of the globe-men, all armed with fire-disks which they trained instantly upon us.

There ensued a brief conversation between our guards and these, and then they stood aside, allowing us to pass through a narrow doorway into a smaller room beyond. Its sides were lined with shelves holding what seemed to be models of machines, all quite unfamiliar in appearance. At the far end of the room stood a low, desklike structure whose surface was covered with other models and with white sheets of stiff cloth or paper covered with drawings and designs, and behind this sat another of the globe-men, a little larger than any we had yet seen. As we halted before him he inspected us for a moment with his large, unwinking eyes, then spoke in deep, thrumming inflections to our two guards. The latter answered him at length, and again he considered us.

During the moments that we stood there I had noted that Sarto Sen, beside me, seemed intensely interested in the models and design-covered sheets which lay on the desk before us. Now, as the creature behind the desk seemed to pause, my friend moved forward and picked up one of the sheets, and a metal pencil which lay beside it. In a moment he was drawing on the sheet some design which I could not see, and this done he handed it to the monster behind the desk. The latter reached for it, inspected it closely, and then raised his eyes to Sarto Sen with something of surprize apparent even on his unhuman features. He uttered a short command, then, and instantly one of the two guards motioned Sarto Sen aside, while the other herded Hal Kur, Nar Lon and me again toward the door. As we passed out of the room I glanced back and saw Sarto Sen, still under the watchful eyes of his guard, bending over the desk, intensely interested, sketching another design.

Again we were in the anteroom, in which there lounged still the guard of armed globe-men. Instead of returning to the corridor through which we had come, though, we were conducted through a door on the room's opposite side, and passed down a similar long hall, halted at last by our guard before a low door in its side. This he flung open, motioning us to enter, and as the death-dealing disk in his grasp was trained full upon us we had no choice but to obey, and passed into a square, solid-walled little room which was but half-lit by a few loopholes in one of its sides. Behind us the door slammed shut, its strong bolts closing with a loud grating of metal. We were prisoners—prisoners on the planet of a distant star.

And now, looking back, it seems to me that the days of imprisonment which followed were the most terrible I have ever known. Action, no matter of what sort, gives surcease at least from mental agony, and it was agony which we suffered there in our little cell. For with the passing of every day, every hour, the crimson sun above was drawing nearer toward our own by millions of miles. And we, who alone had power to find the cause of the red sun's deflection—we lay imprisoned there in the city of the globe-men, watching doom creep upon our universe.

Hour followed hour and day followed day, remorselessly, while we lay there, hours and days which we could measure only by the steady circling of the sunlight that slanted through our tiny windows. With each night came cold, a bitter cold that penetrated to our bones, and for all the red splendor of the dying sun above, the days were far from warm. Twice each day the door opened and a guard cautiously thrust in our food, which consisted of a mushy mixture of cooked vegetables and a bottle of red-tinged, mineral-tasting water.

We spoke but little among ourselves, except to wonder as to the whereabouts of Sarto Sen. We had heard nothing of him since we had left him and could not know even whether our friend was alive or dead. What our own fate was to be we could not guess, nor, in fact, was even that of much interest to us. A few months longer and we would meet death with all on this planet, when Alto and our own sun crashed together. Whether or not we lived until then was hardly a great matter.

Then, ten days after our capture, there came the first break in the monotony of our imprisonment. There was a rattle of bolts at our door; it swung open, and Sarto Sen stepped inside. As the guards outside closed the door my friend sprang toward me, his face eager.

"You're all right, Jan Tor?" he exclaimed quickly. "They told me you were unharmed, but I worried—"

A phrase in his speech struck me. "They told you?" I repeated. "They?"

He nodded, his eyes holding mine. "The globe-men," he said, simply.

We stared at him, and he stepped swiftly to the door, tried it and found it fast, then came back and sat down beside us.

"The globe-men," he repeated solemnly, "those children of Alto, those creatures of hell, who have turned their parent sun from its course to send it crashing into our own, to wipe out our universe."

At our exclamations of stunned surprize he was silent, musing, his eyes seeming to gaze out through somber vistas of horror invisible to us. When he spoke again it was slowly, broodingly, as though he had forgotten our presence.

"I have found what we came here to learn," he was saying; "have discovered the reason for the deflection of this star. Yet even before, I guessed.... If a star have planets and those planets inhabitants—inhabitants of supreme science, supreme power—would they not use that science and that power to save themselves from death, even though it means death for another universe? And that is what they have done, and what I suspected before.

"It was that suspicion that stood me in good stead when we were examined there by the chief of the globe-men. I had glimpsed on his desk sheets with astronomical designs on them, and so I took a sheet myself and drew on it a simple design which he understood immediately, a design which represented two suns colliding. It convinced him of my knowledge, my intelligence, so that when he sent the rest of you to this cell he retained me for questioning. And for hours afterward I drew other sketches, other designs, while with gestures he interrogated me concerning them. It was slow, fumbling communication, but it was communication, and gradually we perfected a system of signs and drawings by which we were able to exchange ideas. And through the succeeding days our sign-communication continued.

"I informed him, in this way, that we were visitors from another star, but I was too cautious to let him know that we were children of the sun into which Alto was soon to crash. Instead I named Sirius as our native star, explaining that we had come from there in our vibration-cruiser for purposes of exploration. It was the cruiser which interested him most, evidently. The scientists of the globe-people had been examining it, he told me, and he now asked me innumerable questions concerning its design and operation. For though the globe-men have gravity-screen ships, like our own old-fashioned ones, in which they can travel from planet to planet, they have no such star-cruisers as this one of ours. Hence his questions, which I evaded as well as I could, turning the subject to the coming collision of the two suns, which I stated had been foreseen by the astronomers of my own universe. And as I had expected, my news of the coming collision was no surprize to him. For, as he casually explained, that collision was being engineered in fact by his own people, the globe-men, for their own purposes.

"For ages, it seems, these globe-men have dwelt on the planets of Alto. First they had inhabited the outermost planet, billions of miles from Alto itself, but which was yet warm enough for existence because of their sun's titanic size and immense heat. There they had risen to greatness, had built up their science and civilization to undreamed-of heights. But as the ages passed, that outermost world of theirs was growing colder and colder, since Alto, like all other suns, was slowly but steadily cooling, shrinking and dying, radiating less and less heat. At last there came a time when the planet of the globe-men was fast becoming too cold for existence there, and then their scientists stirred themselves to find a way out. Spurred on by necessity, they hit upon the invention of the gravity screen and with it constructed their first interplanetary space-ships. These they made in vast numbers, and in them the globe-people moved en masse to the next innermost planet, which still received enough heat from Alto to support life. There they settled, and there their civilization endured for further ages.

"But slowly, surely, their sun continued to cool and die, and with the terrible, machinelike inevitability of natural laws there came a day when again their world had grown too cold for their existence. This time, though, they had the remedy for their situation at hand, and again there took place a great migration from their cold planet to a warmer inner one. And so, as the ages passed, they escaped extinction by migrating from planet to planet, moving ever sunward as their sun waned in size and splendor, creeping closer and closer toward its dying fires.

"At last, though, after long ages, there drew down toward them the doom which they had averted for so long. Alto was still shrinking, cooling, and now they were settled upon its warmest, inmost planet, and had no warmer world to which to flee. But a short time longer, as they measured time, and their planet would become a frozen, lifeless world, for their sun would inevitably cool still further until it was one of the countless dark stars, dead and burned-out suns, which throng the heavens. It seemed, indeed, that this time there was to be no escape.

"But now there came forward a party among them which advanced a proposal of colossal proportions. They pointed out that Alto was moving steadily toward another sun, one much the same size as their own but flaming with heat and life, which it would pass closely within a short time. But if, instead of passing each other, the two suns should meet, should crash into each other, what then would be the result? It would be, of course, that the collision would form one new sun instead of the former two—one titanic, flaming sun whose heat would be sufficient to support life on any planet for countless ages. The inmost planets of Alto's system, and virtually all the planets of the other sun's system, would be annihilated by the collision, of course, would perish in that flaming shock of suns. But the outermost planets of Alto, which lay in orbits billions of miles from it, would be safe enough and would take up their orbits around this great new sun in place of Alto. And on these planets the globe-people could exist for eons, supported by the heat of the great new sun. It was a perfect plan, and required only that their own sun, Alto, be swerved from its path just enough to make it crash into the other sun instead of passing it.

"To accomplish this, to swerve their star from its course, the globe-men made use of a simple physical principle. You know that a round, spinning body, moving across or through any medium, changes its direction if the rate of its spinning is changed. A ball that rolls across a smooth table without spinning at all will move in a straight line. But if the ball spins as it rolls it will move in a curved line, the amount and direction of curve depending upon the amount and direction of spin. Now their sun, which had rotated at the same rate for ages, had rolled through the ether for ages on the same great course, never swerving. And so, they reasoned, if their sun's rate of spin or rotation could be increased a little it would curve aside a little from its accustomed course.

"The problem, then, was to increase their sun's rate of spin, and to accomplish this they gathered all their science. A mighty tower was erected over their city, on whose great top-platform were placed machines which could generate an etheric ray or vibration of inconceivable power, a ray which could be directed at will through the great telescopelike projector which they had provided for it.

"This done, they waited until the moment calculated by their astronomers, then aimed the great projector-tube at the edge of their sun that was rotating away from them, and turned on the ray. This was the crucial point of their scheme, for now they were risking their very universe. It was necessary for them to increase their sun's rate of spin just enough to make it swerve aside, but if the rate of spin were increased just a little too much it would mean disaster, since when a sun spins too fast it breaks up like a great flywheel, splits into a double star. It is that process, the process of fission, which has formed the countless double stars and bursted suns in the heavens around us, since each was only a single star or sun which broke up because of its too-great speed of rotation, or spin. And the globe-men knew that it would require but very little increase in their own sun's rate of spin to make it, too, split asunder. So they watched with infinite care while their brilliant ray stabbed up toward the sun's edge, and when, under the terrific power of that pushing ray, the star began to spin faster, they at once turned off the ray, which was used for a short time only. But it had been effective; for now, as their sun spun faster, it began to swerve a little from its usual course, and they knew that now it would crash into the other approaching sun instead of passing it. So their end was achieved, and so they began their preparations for their great migration out to Alto's outermost planets, a migration which would take place just before the collision. And then—we came.

"We came, and now we have discovered that for which we came, the reason for Alto's change in course. For it was the science and will of the globe-men that turned their sun aside, that threatens now the annihilation of the Eight Worlds. Doom presses upon them, and to escape that doom they are destroying our sun, our planets, our very universe!"

4

I do not remember that any of us spoke when Sarto Sen's voice had ceased. And yet, stunned as we were by the thing he had told us, our knowledge was in some ways a relief. We had discovered, at least, what had swerved Alto from its course, and if science and intelligence alone could cause the sun to veer from its path, science and intelligence might steer it back into that path.

When I said as much to Sarto Sen his face lit up. "You are right, Jan Tor!" he exclaimed. "There's a chance! And even as Mur Dak predicted, that chance depends on us. For if we can escape from here and get back to the Eight Worlds, we can come back with a greater force and crush these globe-men, and use their own force-projector to swerve their sun out of its present path."

"But why go back to the Eight Worlds?" objected Hal Kur. "Why not get up to that platform, if we escape, and use the projector ourselves?"

Sarto Sen shook his head. "It's impossible," he told the big engineer. "If we escape from here at all it will be by night, for by day the rooms and corridors outside are thronged with globe-men. And by night we could do nothing, for Alto, the sun itself, would not then be in the sky. Nor could we wait for its rising, there on the platform, since our escape would soon be discovered, and we should be attacked there. Our only chance is to get out of here by night, make our way up to the platform, and make a dash for our ship. If we can do that we can flash back to our own universe and get the help we need to crush these globe-people."

"But when shall we make the attempt?" I asked, and my heart leaped at Sarto Sen's answer. "To-night! The sooner we get out the better. A few hours after dark we'll try it."

He went on, then, to unfold his plan for escape, and we listened intently, while big Hal Kur's eyes gleamed at the prospect of action. Our plan was simple enough, and likely enough to fail, we knew, but it was our only chance. What course we would follow after getting free of our cell we did not even discuss. There was nothing for it but to make our break and trust to luck to bring us through the thousand obstacles that lay between us and the tower-platform which held our ship.

The remaining hours of that day were the longest I have ever experienced. The slanting shafts of light from the loopholes seemed to move across the room with infinite slowness, while we awaited impatiently the coming of night. At last the light-bars darkened, disappeared, as the dying crimson sun sank beyond the rim of the world outside. Darkness had descended on that world, now, and here and there among the buildings and streets of the weird city outside flared points of red light. Still we waited, until the vague, half-heard sounds of soft movement and thrumming speech outside had lessened, ceased, until at last the only sound to be heard was an occasional shuffling movement of the guard outside the door.

Sarto Sen rose, making to us a signal of readiness, and then threw himself flat on the floor of the room's center. At the farther side of the cell lay Hal Kur and Nar Lon, as though sleeping, with a thick roll of garments between them which resembled another sleeping figure. These preparations made, I stepped to the door and stationed myself directly inside it, to one side, my heart pounding now as the moment for action approached.

All was ready, and seeing this, Sarto Sen began his part. Lying there on the floor he gave utterance to a low, deep groan. There was silence for a moment, and then another low moan arose from him, and now I heard a shuffling movement outside the door as the guard there approached to listen. Again Sarto Sen groaned, terribly, and after a moment's pause there came a rattling of bolts as the guard slid them aside. I flattened myself back against the wall, and in a second the door opened.

Even in the darkness, glancing sidewise, I could make out the round, globular form of the guard, his eyes peering into our cell and his fire-disk held out in cautious readiness. A moment he paused, peering at the three dim figures lying across the room; then, as if satisfied, turned his eyes back upon Sarto Sen, at the same moment taking a step inside the door. And with a single bound I was upon him.

Of all the fights in my career I place that struggle there in the darkness with our globe-man guard as the most horrible. I had leaped with the object of wresting the deadly fire-disk from him before he could make use of it, and fortunately the force of my spring had knocked it from his grasp. His short, thin arms clutched at me with surprizing power, though, while the insectlike lower limbs grasped my own and pulled me instantly to the floor. A moment I rolled there in mad combat, striving to gain a hold on my opponent's smooth, round body, and then a thing happened the memory of which sickens me even now. For as my hands clutched for a hold on the sleek, cold, globular body, that body suddenly collapsed beneath my weight, breaking like a skinful of water and spurting out a mass of semi-liquid, jellylike substance which flowed across the floor in a shining, malodorous mass. Flesh-like as they were in appearance, these creatures were but globular shells of ooze.

Sick to my very soul I rose to my feet, looking wildly at the others, who had rushed to aid me. There had been no cry from our guard during that moment of combat and the silence around us was unchanged. Sarto Sen was already at the door, peering down the corridor, and in a moment we were out of the cell and making our way stealthily down the long hall. As we left the cell, though, my foot struck against something, and reaching down I picked up the little fire-disk of our guard. As we crept down the long corridor I clutched it tightly in my hand.

The long hall, dimly lit by a few red flares set in its walls, seemed quite deserted. Ahead, though, shone a square of brighter light, and we knew this to be the spot where the corridor crossed the anteroom of the guards. Nearer we crept toward it, ever more stealthily, until at last we crouched at the edge of the open doorway, staring into the bright-lit anteroom.

There were but four of the globe-men guards in it now, and three of these were apparently sleeping, resting with closed eyes on a long, low seat against the wall. The other, though, was moving restlessly about the room, the deadly fire-disk in his grasp ready for action. We must cross this room, I knew, to reach the hall of the great pillar, yet it would mean instant death to attempt it beneath the eyes of this creature.

A moment we crouched there, undecided whether or not to chance all in a rush for the one wakeful guard, when the entire matter was suddenly taken out of our hands. The globe-man, in his pacing about the room, had come within a few feet of the doorway outside which we crouched, and at that very moment the silence around us was shattered by a sound which came to my ears like the thunder of an explosion. Hal Kur had sneezed!

With the sound the pacing guard wheeled instantly and confronted us, uttering a thrumming cry which brought the other three instantly to their feet. We were evenly matched, four to four, and before they had time to use their deadly disks we were upon them. The next moment was one of wild confusion, a whirling of men and globular bodies about the little room, a babel of hoarse shouts and thrumming cries. Clinging desperately to one of the slippery creatures I had a momentary glimpse of Hal Kur raising one of the guards bodily into the air and crashing him down on the hard floor like a smashed egg. Then a powerful twist of my opponent flung me sidewise out of the combat.

I staggered to my feet and saw that one guard lay broken and dead on the floor while the other three had slipped from our clutches and were retreating through the doorway by which we had come. Abruptly they paused, and the arm of one came up with a fire-disk trained full upon us.

In that moment I became aware of something in my hand to which I had clung through all the mêlée, something round and thin and hard, with a raised button on its side. Instinctively, entirely without thought, I raised the thing toward the three guards opposite, pressing the button on its side. A little ball of rosy fire seemed to leap out from my hand with the action, flicking sighingly through the air and striking the group of globe-men squarely. There was a roar of flame, a moment's flaring up of raging pink fire, and then flame and guards alike had vanished.

I turned, staggered with my friends toward the door. From far behind, now, we heard deep, thrumming cries, and the shuffle of quick feet. Our escape was discovered, we knew, and our only chance lay in reaching the great pillar and its cage-lift before we were cut off, so we raced on down the corridor with our utmost speed, sparing no breath for speech. The cries behind were growing swiftly louder and nearer, and somewhere near by there was a sudden clamor of gongs. But now we were bursting recklessly into the great hall, finding it quite empty, its deep shadows dispelled only by a few feeble points of light. Into the upper darkness loomed the vast bulk of the great, slanting column, and with the last of our strength we reeled across the floor toward it.

The door in the pillar's side was open, and through it we tumbled hastily into the little cage-elevator inside. The clamor of pursuit was growing rapidly in volume, now. Frantically I fumbled with the studs in the cage's side, with which I had seen our captors operate it. There was a moment of heart-breaking delay, and then, just as the uproar of pursuit seemed about to burst into the great hall, a switch clicked beneath my fingers and instantly our cage was shooting up the shaft with tremendous speed, toward the platform above.

A moment of this thundering progress and then the car slowed, stopped. We were in absolute darkness, but before sliding aside the section of platform over us I whispered tensely to the others. "There will be guards on the platform," I told them, "but we must make away with them at once and get to the ship. It's our only chance, for there must be cage-lifts in the other pillars too, and they'll come up those after us."

With the words I touched the lever which swung aside the section of floor above us, and instantly it slid back with a metallic jarring sound that made my heart stand still. There was no sound of alarm, though, from above, so after a moment of tense waiting we rose silently from the cage and stepped out upon the platform itself.

We were standing near the edge of the platform, which was partly illuminated by splashes of ruddy light from a few flares suspended over it. Far below in the darkness lay the city of the globe-men, outlined only by a sparse peppering of twinkling crimson lights. Above stretched the splendid, star-jeweled skies, in which I could discern the brilliant yellow orb that was the sun of the Eight Worlds. And now I turned my attention back to the platform, and glancing beyond the dark, enigmatic mechanisms which loomed around us, I saw the long, gleaming bulk of our cruiser, lying still in the clear space where it had fallen. Beside it a suspended flare poured down its red light, and under that light were gathered three of the globe-men, examining intently some small mechanism on the floor.

I wondered, momentarily, whether these creatures had yet discovered the secret of our cruiser's design and operation, and then forgot my wonder as we began to creep stealthily toward them. As we crawled past a little heap of short, thick metal bars, each of us grasped one, and then crept on again. In a moment we were within a dozen paces of the unsuspecting globe-men, and at once we sprang to our feet and charged down upon them with up-lifted maces.

So unexpected and so swift was our attack that the three had time only to turn toward us, half-raising their fire-disks, and then our heavy clubs had crashed down through their round, soft bodies, sending them to the floor in a sprawling, oozing mass. We dropped our weapons and sprang toward the cruiser.

Its lower door was open, and instantly we were inside it. At once Sarto Sen sprang up the stair toward the conning-tower, while Hal Kur and Nar Lon raced into the generator-room. I paused to slam shut the heavy door, its closing automatically starting the throbbing oxygen pumps, and then hastened up the stair also. Even as I did so there began the familiar humming of the vibration-generators, droning out with swiftly gathering power. And now I had reached the conning-tower, where Sarto Sen was working swiftly with the controls.

At the moment that I burst into the little room there came a sudden harsh grating of metal from outside, and then a score of high-pitched, thrumming cries. I sprang to the window, and there, across the red-lit platform, a mass of dark, globular figures had suddenly poured up onto the platform's surface, from another of its pillar-lifts. They ran toward us, heard the humming of the cruiser's generators, and then stopped short. Their fire-disks swept up and a dozen balls of the destroying flame leapt toward us. But at the moment that they did so there was a swift clicking of switches beneath the hands of Sarto Sen, a sudden roar of wind, and then the red-lit platform and all on it had vanished from sight as our ship flashed out again into the void of space.

5

Always, now, I remember the weeks of our homeward flight as a seemingly endless time during which we flashed on and on through space, struggling against our own desire to sleep. For now there were but four of us to operate the cruiser, and the generators alone required the constant care of two of our number, while another must stand watch in the conning-tower. That meant that each of us could grasp but a few hours of sleep at irregular intervals, while our ship fled on. Even so I do not think that we could have managed with any other engineer than Nar Lon, for he, who had been chief of the engineers, was equal to three men in his knowledge and vigilance.

So we sped on, while Alto dwindled in size behind us, and the bright star that was our own sun burned out in waxing glory ahead. And through the long hours of my watches in the conning-tower I watched red star and yellow with an unceasing, growing fearfulness, for well I knew that with each second they were leaping closer and closer toward each other, and toward the doom of the Eight Worlds.

On and on our cruiser hummed, at its highest speed, fleeing through the void toward our own sun with the velocity of light. And surely never was voyage so strange as ours, since time began. A voyage from star to star, in a ship flung forward by unseen vibrations, its crew four haggard and burning-eyed men who were racing against time to carry the news on which depended the fate of our universe. Dreamlike had been our outward voyage, but this homeward flight resembled an endless torturing nightmare.

At last, though, its end drew in sight, and gradually we slackened speed as we flashed nearer toward our own universe. By the time we received our first telestereo challenge from an Interplanetary Patrol cruiser outside Neptune we were moving at a scant million miles an hour. When we announced our identity, though, a peremptory order was flashed across the solar system for all interplanetary traffic to clear the space-lanes between ourselves and Earth, so that we were able to hurtle on toward the green planet at full speed without danger of collisions. And so, at last, our ship was slanting down again over the great Hall of Planets, into the very landing-court from which we had made the start of our momentous voyage.

Fighting against the fatigue which threatened to overwhelm me, I staggered out of the cruiser into the waiting hands of those in the landing-court, and five minutes later I was stumbling onto the dais where Mur Dak faced the hastily assembled Council. Standing there, swaying a little from sheer exhaustion, I spoke to Mur Dak and to the Council, relating in concise phrases the events of our voyage and the discovery we had made. When I had finished, saluting and slumping into a chair, there was an utter, deathlike silence over the great hall, and then a sigh went up as Mur Dak stepped forward to speak.