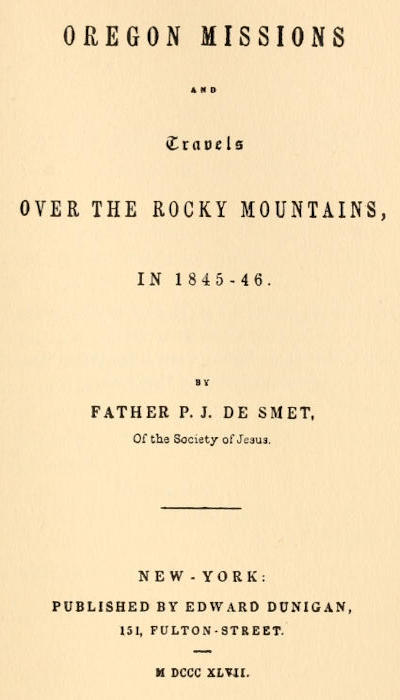

The Lodge Pole (Indian name); Great Chief of the Flat-heads. Victor (in baptism)

Volume XXIX

The Lodge Pole (Indian name); Great Chief of the Flat-heads. Victor (in baptism)

Early Western Travels

1748-1846

A Series of Annotated Reprints of some of the best

and rarest contemporary volumes of travel, descriptive

of the Aborigines and Social and

Economic Conditions in the Middle

and Far West, during the Period

of Early American Settlement

Edited with Notes, Introductions, Index, etc., by

Reuben Gold Thwaites, LL.D.

Editor of “The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents,” “Original

Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition,” “Hennepin’s

New Discovery,” etc.

Volume XXIX

Part II of Farnham’s Travels in the Great Western Prairies,

etc., October 21-December 4, 1839; and De Smet’s

Oregon Missions and Travels over the Rocky

Mountains, 1845-1846

Cleveland, Ohio

The Arthur H. Clark Company

1906

Copyright 1906, by

THE ARTHUR H. CLARK COMPANY

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

The Lakeside Press

R. R. DONNELLEY & SONS COMPANY

CHICAGO

| I | |

| Travels in the Great Western Prairies, the Anahuac and Rocky Mountains, and in the Oregon Country [Part II, being chapter v of Volume II of the London edition, 1843.] Thomas Jefferson Farnham. | |

| Text: [CHAPTER V] Departure from Vancouver—Wappatoo Island—The Willamette River—Its Mouth—The Mountains—Falls—River above the Falls—Arrival at the Lower Settlement—A Kentuckian—Mr. Johnson and his Cabin—Thomas M’Kay and his Mill—Dr. Bailey and Wife and Home—The Neighbouring Farmers—The Methodist Episcopal Mission and Missionaries—Their Modes of Operations—The Wisdom of their Course—Their Improvements, &c.—Return to Vancouver—Mr. Young—Mr. Lee’s Misfortune—Descent of the Willamette—Indians—Arrival at Vancouver—Oregon—Its Mountains, Rivers and Soil, and Climate—Shipment for the Sandwich Islands—Life at Vancouver—Descent of the Columbia—Astoria—On the Pacific Sea—The Last View of Oregon—Account of Oregon, by Lieut. Wilkes, Commander of the late exploring Expedition | 13 |

| II | |

| Oregon Missions and Travels over the Rocky Mountains, in 1845-46. Pierre Jean de Smet, S.J. | |

| Copyright Notice | 108 |

| Author’s Dedication | 109 |

| Preface by the First Editor. C. C. P. | 111 |

| An Outline Sketch of Oregon Territory and its Missions. Anonymous | 115 |

| Text | 145 |

[Note: In the original edition the illustrations not only are not placed with reference to the text, but some of them do not even illustrate the text. The inscriptions printed below several of the plates, referring to certain of the Letters, are also misleading. We have, therefore, rearranged the order of the plates, placing them as nearly as possible in juxtaposition to the appropriate textual matter.—Ed.]

| “The Lodge Pole (Indian name), Great Chief of the Flat-heads. Victor (in Baptism).” From De Smet’s Oregon Missions | Frontispiece |

| Facsimile of illuminated title-page, De Smet’s Oregon Missions | 105 |

| Facsimile of regular title-page, De Smet’s Oregon Missions | 107 |

| “Oregon Territory, 1846”—folding map | 114 |

| “Interior of St. Mary’s Church, Flat-head Mission: Communion at Easter” | 175 |

| “Mission of St. Ignatius at Kalispel Bay, among the Pends d’Oreilles” | 187 |

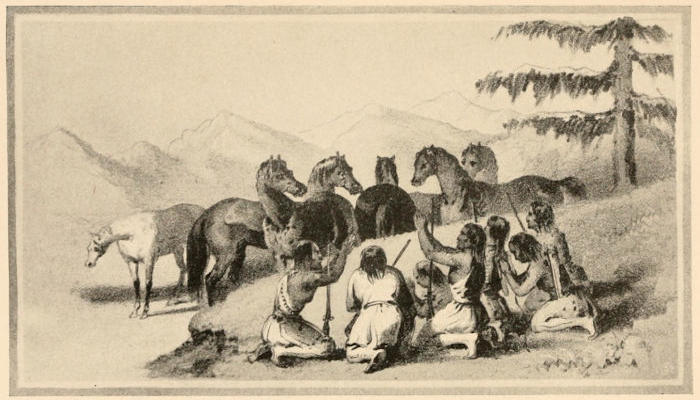

| “The Hunters at the Buffalo Feast” | 227 |

| “View of the new Mission Establishment in 1846, among the Pointed-Hearts” | 315 |

| “St. Mary’s, among the Flat-heads” | 323 |

| “Insula, or Red Feather (Michel), Great Chief and Brave among the Flat-heads” | 333 |

| “Great Buffalo Hunt,—View of the Muscle-Shell Mountains” | 337 |

| “Announcement of the Discovery of Buffalos” | 347 |

| “The Chief reports to his Camp that Buffalos are in sight” | 351 |

| “The Chief at the head of his Hunters” | 355 |

| “Buffalos discovered” | 387 |

| “A Prayer for success in hunting” | 401 |

Reprint of chapter v of Volume II of original London edition, 1843

Departure from Vancouver—Wappatoo Island—The Willamette River—Its Mouth—The Mountains—Falls—River above the Falls—Arrival at the Lower Settlement—A Kentuckian—Mr. Johnson and his Cabin—Thomas M’Kay and his Mill—Dr. Bailey and Wife and Home—The Neighbouring Farmers—The Methodist Episcopal Mission and Missionaries—Their Modes of Operations—The Wisdom of their Course—Their Improvements, &c.—Return to Vancouver—Mr. Young—Mr. Lee’s Misfortune—Descent of the Willamette—Indians—Arrival at Vancouver—Oregon—Its Mountains, Rivers and Soil, and Climate—Shipment for the Sandwich Islands—Life at Vancouver—Descent of the Columbia—Astoria—On the Pacific Sea—The Last View of Oregon—Account of Oregon, by Lieut. Wilkes, Commander of the late exploring Expedition.

On the morning of the 21st, I left the Fort and dropped down the Columbia, five miles, to Wappatoo Island. This large tract of low land is bounded on the south-west, south and south-east, by the mouths of the Willamette, and on the north by the Columbia. The side contiguous to the latter river is about fifteen miles in length; the side bounded by the eastern mouth of {201} the Willamette about seven miles, and that bounded by the western mouth of the same river about twelve miles. It derives its name from an edible root called Wappatoo, which it produces in abundance.[2] It is generally low, and, in the central parts broken with small ponds and marshes, in which[14] the water rises and falls with the river. Nearly the whole surface is overflown by the June freshets. It is covered with a heavy growth of cotton-wood, elm, white-oak, black-ash, alder, and a large species of laurel, and other shrubs. The Hudson Bay Company, some years ago, placed a few hogs upon it, which have subsisted entirely upon roots, acorns, &c. and increased to many hundreds.

I found the Willamette deep enough for ordinary steamboats, for the distance of twenty miles from its western mouth. One mile below the falls are rapids on which the water was too shallow to float our canoe. The tide rises at this place about fourteen inches. The western shore of the river, from the point where its mouths diverge to this place, consists of lofty mountains rising immediately from the water-side, and covered with pines. On the eastern side, beautiful swells and plains extend from the {202} Columbia to within five or six miles of the rapids. They are generally covered with pine, white-oak, black-ash, and other kinds of timber. From the point last named to the rapids, wooded mountains crowd down to the verge of the stream. Just below the rapids a very considerable stream comes in from the east. It is said to rise in a champaign country, which commences two or three miles from the Willamette, and extends eastward twenty or thirty miles to the lower hills of the President’s range. This stream breaks through the mountain tumultuously, and enters the Willamette with so strong a current, as to endanger boats attempting to pass it.[3] Here were a number of Indian huts, the inmates of which were busied in taking and curing salmon. Between the rapids and the falls, the country adjacent to the river is similar to that just described; mountains clothed with impenetrable forests.

The river, thus far, appeared to have an average width of four hundred yards, water limpid. As we approached the falls, the eastern shore presented a solid wall of basalt, thirty feet in perpendicular height. On the top of this wall was nearly an acre of level area, on which the Hudson Bay Company {203} have built a log-house.[4] This plain is three or four feet below the level of the water above the falls, and protected from the floods by the intervention of a deep chasm, which separates it from the rocks over which the water pours. This is the best site in the country for extensive flour and lumber-mills. The valley of the Willamette is the only portion of Oregon from which grain can ever, to any extent, become an article of export; and this splendid waterfall can be approached at all seasons, from above and below, by sloops, schooners, &c. The Hudson Bay Company, aware of its importance, have commenced a race-way, and drawn timber on the ground, with the apparent intention of erecting such works. On the opposite side is an acre or two of broken ground, which might be similarly occupied.

The falls are formed by a line of dark rock, which stretches diagonally across the stream. The river was low when I passed it, and all the water was discharged at three jets. Two of these were near the eastern shore; the other was near the western shore, and fell into the chasm which divides the rocky plain before named, from the cliffs of the falls. At the mouth of this chasm {204} my Indians unloaded their canoe, dragged it up the crags,[16] and having borne it on their shoulders eight or ten rods, launched it upon a narrow neck of water by the shore; reloaded, and rowed to the deep water above.

The scene, however, was too interesting to be left so soon, and I tarried awhile to view it. The cataract roared loudly among the caverns, and sent a thousand foaming eddies into the stream below. Countless numbers of salmon were leaping and falling upon the fretted waters; savages almost naked were around me, untrained by the soothing influences of true knowledge, and the hopes of a purer world; as rude as the rocks on which they trod; as bestial as the bear that growled in the thicket. On either hand was the primeval wilderness, with its decaying and perpetually-renewing energies; nothing could be more intensely interesting. I had passed but a moment in these pleasant yet painful reflections, when my Indians, becoming impatient, called me to pursue my voyage.

A mile above the falls a large creek comes in from the west. It is said to rise among the mountains near the Columbia, and to run south and south-east and eastwardly through a series of fine prairies, interspersed {205} with timber.[5] Above the falls, the mountains rise immediately from the water’s edge, clothed with noble forests of pine, &c.; but at the distance of fifteen miles above, their green ridges give place to grassy and wooded swells on the west, and timbered and prairie plains on the eastern side. This section of the river appeared navigable for any craft that could float in the stream below the falls.

It was dark when I arrived at the level country; and[17] emerging suddenly in sight of a fire on the western bank, my Indians cried “Boston! Boston!” and turned the canoe ashore to give me an opportunity of speaking with a fellow countryman. He was sitting in the drizzling rain, by a large log-fire—a stalwart six foot Kentucky trapper. After long service in the American Fur Companies, among the rocky mountains, he had come down to the Willamette, accompanied by an Indian woman and his child, selected a place to build his home, made an “improvement,” sold it, and was now commencing another. He entered my canoe and steered across the river to a Mr. Johnson’s.[6] “I am sorry I can’t keep you,” said he, “but I reckon you’ll sleep better under shingles, than this stormy sky. Johnson {206} will be glad to see you. He’s got a good shantee, and something for you to eat.”

We soon crossed the stream, and entered the cabin of Mr. Johnson. It was a hewn log structure, about twenty feet square, with a mud chimney, hearth and fire-place. The furniture consisted of one chair, a number of wooden benches, a rude bedstead covered with flag mats, and several sheet-iron kettles, earthen plates, knives and forks, tin pint cups, an Indian wife, and a brace of brown boys. I passed the night pleasantly with Mr. Johnson; and in the morning rose early to go to the Methodist Episcopal Mission, twelve miles above. But the old hunter detained me to breakfast; and afterwards insisted[18] that I should view his premises, while his boy should gather the horses to convey me on my way. And a sight of fenced fields, many acres of wheat and oat-stubble, potato-fields, and garden-vegetables of all descriptions, and a barn well stored with the gathered harvest compensated me for the delay. Adjoining Mr. Johnson’s farm were four others, on all of which there were from fifty to a hundred acres under cultivation, and substantial log-houses and barns.

One of these belonged to Thomas M’Kay, {207} son of M’Kay, who figured with Mr. Astor in the doings of the Pacific Fur Company.[7]

After surveying these marks of civilization, I found a Dr. Bailey waiting with his horses to convey me to his home. We accordingly mounted, bade adieu to the old trapper of Hudson Bay and other parts of the frozen north, and went to view M’Kay’s mill. A grist-mill in Oregon! We found him working at his dam. Near by lay French burr stones, and some portions of substantial and well-fashioned iron work. The frame of the mill-house was raised and shingled; and an excellent structure it was. The whole expense of the establishment, when completed, is expected to be £1,400 or £1,600. M’Kay’s mother is a Cree or Chippeway Indian; and M’Kay himself is a compound of the two races. The contour of his frame and features, is Scotch; his manners and intellects strongly tinctured with the Indian. He has been in the service of the Fur Companies all his life, save some six or seven years past; and by his daring enterprise, and courage in battle has rendered himself the terror of the Oregon Indians.

Leaving M’Kay’s mill, we travelled along a circuitous track through a heavy forest of fir and pine, and emerged[19] into a beautiful {208} little prairie, at the side of which stood the doctor’s neat hewn log cabin, sending its cheerful smoke among the lofty pine tops in its rear. We soon sat by a blazing fire, and the storm that had pelted us all the way, lost its unpleasantness in the delightful society of my worthy host and his amiable wife. I passed the night with them. The doctor is a Scotchman, his wife a Yankee. The former had seen many adventures in California and Oregon and had his face very much slashed in a contest with the Shasty Indians near the southern border of Oregon. The latter had come from the States, a member of the Methodist Episcopal Mission, and had consented to share the bliss and ills of life with the adventurous Gael; and a happy little family they were.[8]

The next day Mrs. Bailey kindly undertook to make me a blanket coat by the time I should return, and the worthy doctor and myself started for the Mission. About a mile on our way, we called at a farm occupied by an American, who acted as blacksmith and gunsmith for the settlement. He appeared to have a good set of tools for his mechanical business, and plenty of custom. He had also a considerable tract of land under fence, and a comfortable house and {209} out-buildings. A mile or two farther on, we came upon the cabin of a Yankee tinker:[9] an odd fellow, this; glad to see a countryman, ready to serve him in any way, and to discuss the matter[20] of a canal across the isthmus of Darien, the northern lights, English monopolies, Symmes’s Hole, Tom Paine, and wooden nutmegs. Farther on, we came to the Catholic Chapel, a low wooden building, thirty-five or forty feet in length; and the parsonage, a comfortable log cabin.[10]

Beyond these, scattered over five miles of country, were fifteen or twenty farms, occupied by Americans and retired servants of the Hudson Bay Company. Twelve or thirteen miles from the doctor’s we came in sight of the Mission premises. They consisted of three log cabins, a blacksmith’s shop, and outbuildings, on the east bank of the Willamette, with large and well cultivated farms round about; and a farm, on which were a large frame house, hospital, barn, &c., half a mile to the eastward.[11] We alighted at the last-named establishment, and were kindly received by Dr. White and his lady. This gentleman is the physician of the Mission, and is thoroughly devoted to the amelioration of the physical condition of the natives.[12]

{210} For this object, a large hospital was being erected near his dwelling, for the reception of patients. I passed[21] the night with the doctor and his family, and the following day visited the other Mission families. Every one appeared happy in his benevolent work.—Mr. Daniel Leslie, in preaching and superintending general matters;[13] Mr. Cyrus Shepard, in teaching letters to about thirty half-breed and Indian children; Mr. J. C. Whitecomb, in teaching them to cultivate the earth; and Mr. Alanson Beers, in blacksmithing for the mission and the Indians, and instructing a few young men in his art.[14] I spent four or five days with these people, and had a fine opportunity to learn their characters, the objects they had in view, and the means they took to accomplish them. They belong to that zealous class of Protestants called Methodist Episcopalians. Their religious feelings are warm, and accompanied with a strong faith and great activity. In energy and fervent zeal, they reminded me of the Plymouth pilgrims, so true in heart, and so deeply interested were they with the principles and emotions which they are endeavouring to inculcate upon those around[22] them. Their hospitality and friendship were {211} of the purest and most disinterested character. I shall have reason to remember long and gratefully the kind and generous manner in which they supplied my wants.

Their object in settling in Oregon I understood to be twofold; the one and principal, to civilize and christianize the Indians; the other, and not less important, the establishment of religious and literary institutions for the benefit of white emigrants. Their plan of operation on the Indians, is to learn their various languages, for the purposes of itinerant preaching, and of teaching the young the English language. The scholars are also instructed in agriculture, the regulations of a well-managed household, reading, writing, arithmetic and geography.

The principles and duties of the Christian religion form a very considerable part of the system. They have succeeded very satisfactorily in the several parts of their undertaking. The preachers of the Mission have traversed the wilderness, and by their untiring devotion to their work, wrought many changes in the moral condition of these proverbially debased savages; while with their schools they have afforded {212} them ample means for intellectual improvement.

They have many hundred acres of land under the plough, and cultivated chiefly by the native pupils. They have more than a hundred head of horned cattle, thirty or forty horses, and many swine. They have granaries filled with wheat, oats, barley, and peas, and cellars well stored with vegetables.

A site had already been selected on the opposite side of the river for an academical building; a court of justice had been organised by the popular voice; a military corps was about to be formed for the protection of settlers, and other measures were in progress, at once showing that[23] the American, with his characteristic energy and enterprize, and the philanthropist, with his holy aspirations for the improvement of the human condition, had crossed the snowy barrier of the mountain, to mingle with the dashing waves of the Pacific seas the sweet music of a busy and virtuous civilization.

During my stay here, several American citizens, unconnected with the Mission, called on me to talk of their fatherland, and inquire as to the probability that its {213} laws would be extended over them. The constantly repeated inquiries were—

“Why are we left without protection in this part of our country’s domain? Why are foreigners permitted to domineer over American citizens, drive their traders from the country, and make us as dependent on them for the clothes we wear, as are their own apprenticed slaves?”

I could return no answer to these questions, exculpatory of this national delinquency, and therefore advised them to embody their grievances in a petition, and forward it to Congress. They had a meeting for that purpose, and afterwards put into my hand a petition, signed by sixty-seven citizens of the United States, and persons desirous of becoming such, the substance of which was, a description of the country, their unprotected situation, and, in conclusion, a prayer that the Federal Government would extend over them the protection and institutions of the Republic. Five or six of the Willamette settlers, for some reason, had not an opportunity to sign this paper. The Catholic priest refused to do it.[15]

These people have put fifty or sixty fine {214} farms under cultivation in the Willamette valley, amidst the most discouraging circumstances. They have erected for themselves comfortable dwellings and outbuildings, and have herds of excellent cattle, which they have from time to time driven up from California, at great expense of property and even life. The reader will find it difficult to learn any sufficient reasons for their being left by the Government without the institutions of civilised society. Their condition is truly deplorable. They are liable to be arrested for debt or crime, and conveyed to the jails of Canada![16]

For, in that case, the business of British subjects is interfered with, who, by way of retaliation, will withhold the supplies of clothing, household goods, &c., which the settlers have no other means of obtaining. Nor is this all. The civil condition of the territory being such as virtually to prohibit the emigration to any extent of useful and desirable citizens, they have nothing to anticipate from any considerable increase of their numbers,[25] nor any amelioration of their state to look for, from the accession of female society.

{215} In the desperation incident to their lonely lot, they take wives from the Indian tribes around them. What will be the ultimate consequence of this unpardonable negligence on the part of the Government upon the future destinies of Oregon cannot be clearly predicted; but it is manifest that it must be disastrous in the highest degree, both as to its claims to the sovereignty of that territory, and the moral condition of its inhabitants.

Mr. W. H. Wilson, superintendent of a branch mission on Puget’s Sound, chanced to be at the Willamette station, whose polite attentions it affords me pleasure to acknowledge.[17] He accompanied me on many excursions in the valley, and to the heights, for the purpose of showing me the country. I was also indebted to him for much information relative to the Cowelitz and its valley, and the region about the sound, which will be found on a succeeding page.

My original intention had been to pass the winter in exploring Oregon, and to have returned to the States the following summer, with the American Fur traders. But having learned from various credible sources, that {216} little dependence could be placed upon meeting them at their usual place of rendezvous on Green river, and that the prospect of getting back to the States by that route would, consequently, be exceedingly doubtful, I felt constrained to abandon the attempt. My next[26] wish was to have gone by land to California, and thence home through the northern States of Mexico. In order, however, to accomplish this with safety, a force of twenty-five men was indispensable; and as that number could not be raised, I was compelled to give up all hopes of returning by that route.

The last and only practicable means then of seeking home during the next twelve months, was to go to the Sandwich Islands, and ship thence for New York or California, as opportunity might offer. One of the company’s vessels was then lying at Vancouver, receiving a cargo of lumber for the Island market, and I determined to take passage in her. Under these circumstances, it behooved me to hasten my return to the Columbia. Accordingly, on the 20th I left the mission, visited Dr. Bailey and lady, and went to Mr. Johnson’s to take a canoe down the river. On reaching this {217} place, I found Mr. Lee, who had been to the Mission establishment on the Willamette for the fall supplies of wheat, pork, lard, butter, &c., for his station of the “Dalles.”

He had left the Mission two days before my departure, and giving his canoe, laden with these valuables, in charge of his Indians, proceeded to the highlands by land. He had arrived at Mr. Johnson’s, when a message reached him to the effect that his canoe had been upset, and its entire contents discharged into the stream. He immediately repaired to the scene of this disaster, where I found him busied in attempting to save some part of his cargo. All the wheat, and a part of the other supplies, together with his gun and other paraphernalia, were lost. I made arrangements to go down with him when he should be ready, and left him to call upon a Captain Young, an American ex-trader, who was settled near. This gentleman had formerly explored California and Oregon in[27] quest of beaver—had been plundered by the Mexican authorities of £4,000 worth of fur; and, wearied at last with his ill-luck, settled nine or ten years ago on a small tributary of the Willamette coming in from the west.[18]

{218} Here he has erected a saw and grist mill, and opened a farm. He has been many times to California for cattle, and now owns about one hundred head, a fine band of horses, swine, &c. He related to me many incidents of his hardships, among which the most surprising was, that for a number of years, the Hudson Bay Company refused to sell him a shred of clothing; and as there were no other traders in the country, he was compelled during their pleasure to wear skins.[19] A false report that he had been guilty of some dishonourable act in California was the alleged cause for this treatment; but perhaps, a better reason would be, that Mr. Young occasionally purchased beaver skins in the American territory.

I spent the night of the 12th with the excellent old captain, and in the afternoon of the 13th, in company with my friend Mr. Lee, descended the Willamette as far as the Falls. Here we passed the night, more to the apparent satisfaction of vermin than of ourselves. These creature comforts abound in Oregon. But it was not these alone that made our lodging at the {219} Falls a rosy circumstance for memory’s wastes. The mellifluent odour of salmon offal regaling our nasal sensibilities, and the squalling of a copper-coloured baby, uttered in all the sweetest intonations of such an instrument, falling with the liveliest notes upon the ear, made me dream of war to the knife, till the sun called us to our day’s travel.

Five miles below the Falls, Mr. Lee and myself left the canoe, and struck across about fourteen miles to an Indian village on the bank of the Columbia opposite Vancouver. It was a collection of mud and straw huts, surrounded and filled with filth which might be smelt two hundred yards. We hired one of these cits to take us across the river, and at sunset of the 15th, were comfortably seated by the stove in “Bachelor’s Hall” of Fort Vancouver.

The rainy season had now thoroughly set in. Travelling any considerable distance in open boats, or among the tangled underbrush on foot, or on horseback, was quite impracticable. I therefore determined to avail myself of whatever other means of information were in my reach; and as the gentlemen in charge of the various trading-posts {220} in the territory, had arrived at Vancouver to meet the express from London, I could not have had for this object a more favourable opportunity. The information obtained from these gentlemen, and from other residents in the country, I have relied on as correct, and combined it with my own observations in the following general account of Oregon.

Oregon Territory is bounded on the north by the parallel of 54 deg. 40 min. north latitude;[20] on the east by the Rocky Mountains; on the south by the parallel of 42 deg. north latitude; and on the west by the Pacific Ocean.

Mountains of Oregon. Different sections of the great chain of highlands which stretch from the straits of Magellan to the Arctic sea, have received different names—as the Andes, the Cordilleras, the Anahuac, the Rocky and the Chippewayan Mountains. The last mentioned appellation has been applied to that portion of it which lies between 58° of north latitude and the Arctic sea. The Hudson Bay Company, in completing the survey of the[29] Arctic coast, have ascertained that these mountains preserve a strongly defined outline entirely to the sea, and hang in towering cliffs over it, {221} and by other surveys have discovered that they gradually increase in height from the sea southward.

The section to which the term Rocky Mountains has been applied, extends from latitude 58° to the Great Gap, or southern pass, in latitude 42° north. Their altitude is greater than that of any other range on the northern part of the continent. Mr. Thompson, the astronomer of the Hudson Bay Company, reports that he found peaks between latitudes 53 and 56 north, more than twenty-six thousand feet above the level of the sea.[21] That portion lying east of Oregon, and dividing it from the Great Prairie Wilderness, will be particularly noticed. Its southern point is in the Wind River cluster, latitude 42° north, and about seven hundred miles from the Pacific Ocean. Its northern point is in latitude 54° 40′, about seventy miles north of Mount Browne,[22] and about four hundred miles from the same sea. Its general direction between these points is from N. N. W. to S. S. E.

This range is generally covered with perpetual snows; and for this and other causes is generally impassable for man or beast. There are, however, several gaps through {222} which the Indians and others cross to the Great Prairie Wilderness. The northernmost is between the peaks Browne and Hooker. This is used by the fur[30] traders in their journeys from the Columbia to Canada.[23] Another lies between the head waters of the Flathead and the Marias rivers. Another runs from Lewis and Clarke’s river to the southern head waters of the Missouri. Another lies up Henry’s fork for the Saptin, in a northeasterly course to the Big-horn branch of the Yellowstone. And still another, and most important of all, is situated between Wind river cluster and Long’s mountains.[24]

There are several spurs or lateral branches protruding from the main chain, which are worthy of notice. The northernmost of these parts off north of Fraser’s river, and embraces the sources of that stream. It is a broad collection of heights, thinly covered with pines. Some of the tops are covered with snow nine months of the year. A spur from these passes far down between Fraser’s and Columbia rivers. This is a line of rather low elevations, thickly clothed with pines, cedar, &c. The highest portions of them lie near the Columbia. Another spur {223} puts out on the south of Mount Hooker, and lies in the bend of the Columbia, above the two lakes.

These are lofty and bare of vegetation. Another lies[31] between the Flatbow and Flathead rivers; another between the Flathead and Spokan rivers; another between the Kooskooskie and Wapicakoos rivers.[25] These spurs, which lie between the head waters of the Columbia and the last mentioned river have usually been considered in connexion with a range running off S. W. from the lower part of the Saptin, and called the Blue Mountains. But there are two sufficient reasons why this is an error. The first is, that these spurs are separate and distinct from each other, and are all manifestly merely spurs of the Rocky Mountains, and closely connected with them.

And the second is, that no one of them is united in any one point with the Blue Mountains. They cannot therefore be considered a part of the Blue Mountain chain, and should not be known by the same name. The mountains which lie between the Wapicakoos river and the upper waters of the Saptin, will be described by saying that they are a vast cluster of dark naked heights, descending from the average elevation of fifteen thousand feet—the altitude of the {224} great western ridge—to about eight thousand feet—the elevation of the eastern wall of the valley of the Saptin. The only qualifying fact that should be attached to this description is, that there are a few small hollows among these mountains, called “holes;” which in general appearance resemble Brown’s hole, mentioned in a previous chapter; but unlike the latter, they are too cold to allow of cultivation.

The last spur that deserves notice in this place is that which is called the “Snowy Mountains.” It has already been described in this work; and it can only be necessary here to repeat that it branches off from the Wind river[32] peak in latitude 41° north, and runs in an irregular broken line to Cape Mendocino, in Upper California.

The Blue Mountains are a range of heights which commence at the Saptin, about twenty miles above its junction with the Columbia, near the 46° of north latitude, and run south-westerly about two hundred miles, and terminate in a barren, rolling plain. They are separated from the Rocky Mountains by the valley of the Saptin, and are unconnected with any other range. Some of their loftiest peaks are more than ten thousand feet above the level of the sea. Many beautiful valleys, many hills covered {225} with bunch grass, and very many extensive swells covered with heavy yellow pine forests, are found among them.

The President’s range is in every respect the most interesting in Oregon. It is a part of a chain of highlands, which commences at Mount St. Elias, and gently diverging from the coast, terminates in the arid hills about the head of the Gulf of California. It is a line of extinct volcanoes, where the fires, the evidences of whose intense power are seen over the whole surface of Oregon, found their principal vents. It has twelve lofty peaks; two of which, Mount St. Elias and Mount Fairweather, lie near latitude 55° north;[26] and ten of which lie south of latitude 49° north. Five of these latter have received names from British navigators and traders.

The other five have received from American travellers,[33] and Mr. Kelly, the names of deceased Presidents of the Republic. Mr. Kelly, I believe, was the first individual who suggested a name for the whole range. For convenience in description I have adopted it.[27] And although it is a matter in which no one can find reasons for being very much interested, yet if there is any propriety in adopting Mr. Kelly’s name for the whole {226} chain, there might seem to be as much in following his suggestion, that all the principal peaks should bear the names of those distinguished men, whom the suffrages of the people that own Oregon[28] have from time to time called to administer their national government. I have adopted this course.

Mount Tyler is situated near latitude forty-nine degrees north, and about twenty miles from the eastern shore of those waters between Vancouver’s Island, and the continent. It is clad with perpetual snow.[29] Mount Harrison is situated a little more than a degree south of Mount Tyler, and about thirty miles east by north of Puget’s Sound. It is covered with perpetual snow.[30] Mount Van Buren stands on the isthmus between Puget’s Sound[34] and the Pacific. It is a lofty, wintry peak, seen in clear weather eighty miles at sea.[31] Mount Adams lies under the parallel of forty-five degrees, about twenty-five miles north of the cascades of the Columbia. This is one of the finest peaks of the chain, clad with eternal snows, five thousand feet down its sides. Mount Washington lies a little north of the forty-fourth degree north, and about twenty miles {227} south of the Cascades.[32] It is a perfect cone, and is said to rise seventeen thousand or eighteen thousand feet above the level of the sea. More than half its height is covered with perpetual snows. Mount Jefferson is an immense peak under latitude forty-one and a half degrees north. It received its name from Lewis and Clark.[33] Mount Madison is the Mount McLaughlin of the British fur-traders. Mount Monroe is in latitude forty-three degrees twenty minutes north, and Mount John Quincy Adams is in forty-two degrees ten minutes; both covered with perpetual snow.[34]

Mount Jackson is in latitude forty-one degrees ten minutes. It is the largest and highest pinnacle of the President’s range.[35] This chain of mountains runs parallel with the Rocky Mountains, between three hundred and four hundred miles from them. Its average distance from the coast of the Pacific, south of latitude forty-nine degrees, is about one hundred miles. The spaces between the peaks are occupied by elevated heights, covered with an enormous growth of the several species of pines, and firs, and the red cedar, many of which rise two hundred feet without a limb; and are five, six, seven, eight, and even nine fathoms in circumference at the ground.

{228} On the south side of the Columbia, at the Cascades, a range of low mountains puts off from the President’s range, and running down parallel to the river, terminates in a point of land on which Astoria was built. Its average height is about one thousand five hundred feet above the river. Near the Cascades the tops are higher; and in some instances are beautifully castellated. They are generally covered with dense pine and fir forests. From the north side of the Cascades, a similar range runs down to the sea, and terminates in Cape Disappointment.[36] This range also is covered with forests. Another[36] range runs on the brink of the coast, from Cape Mendocino in Upper California to the Straits de Fuca. This is generally bare of trees; mere masses of dark stratified rocks, piled many hundred feet in height. It rises immediately from the borders of the sea, and preserves nearly a right line course, during their entire length. The lower portion of the eastern sides is clothed with heavy pine and spruce, fir and cedar forests.

I have described in previous pages the great southern branch of the Columbia, called Saptin by the natives who live on its banks, and the valley of volcanic deserts, through which it runs, as well as the Columbia {229} and its cavernous vale, from its junction with the Saptin to Fort Vancouver, ninety miles from the sea. I shall therefore in the following notice of the rivers of Oregon, speak only of those parts of this and other streams, and their valleys about them, which remain undescribed.

That portion of the Columbia, which lies above its junction with the Saptin, latitude forty-six degrees eight minutes north, is navigable for bateaux to the boat encampment at the base of the Rocky Mountains, about the fifty-third degree of north latitude, a distance, by the course of the stream, of about five hundred miles.[37] The current is strong, and interrupted by five considerable and several lesser rapids, at which there are short portages. The country on both sides of the river, from its junction with the Saptin to the mouth of the Spokan, is a dreary waste. The soil is a light yellowish composition of sand and clay, generally destitute of vegetation. In a few nooks, irrigated by mountain streams, are found small patches of the short grass of the plains interspersed with another species which grows in tufts or bunches four or five feet[37] in height. A few shrubs (as the small willow, the sumac, and furze), appear in distant and solitary {230} groups. There are no trees; generally nothing green; a mere brown drifting desert; as far as the Oakanagan River, two hundred and eight miles, a plain, the monotonous desolation of which is relieved only by the noble river running through it, and an occasional cliff of volcanic rocks bursting through its arid surface.

The river Oakanagan is a large, fine stream, originating in a large lake of the same name situate in the mountains, about one hundred miles north of its mouth. The soil in the neighbourhood of this stream is generally worthless. Near its union, however, with the Columbia, there are a number of small plains tolerably well clothed with the wild grasses; and near its lake are found hills covered with small timber. On the point of land between this stream and the Columbia, the Pacific Fur Company in 1811 established a trading post. This in 1814 passed by purchase into the hands of the North-West Fur Company of Canada, and in 1819 by the union of that body with the Hudson Bay Company, passed into the possession of the united company under the name of Hudson Bay Company. It is still occupied by them under its old name of Fort Oakanagan.[38]

{231} From this post, latitude forty-eight degrees six minutes, and longitude one hundred and seventeen degrees west, along the Columbia to the Spokan, the country is as devoid of wood as that below. The banks of the river are bold and rocky, the stream is contracted with narrow[38] limits, and the current strong and vexed with dangerous eddies.

The Spokan river rises among the spurs of the Rocky Mountains east south-east of the mouth of the Oakanagan, and, after a course of about fifty miles, forms the Pointed Heart Lake, twenty-five miles in length, and ten or twelve in width; and running thence in a north-westerly direction about one hundred and twenty miles, empties itself into the Columbia. About sixty miles from its mouth, the Pacific Fur Company erected a trading-post, which they called the “Spokan House.” Their successors are understood to have abandoned it.[39] Above the Pointed Heart Lake, the banks of this river are usually high and bold mountains, sparsely covered with pines and cedars of a fine size. Around the lake are some grass lands, many edible roots, and wild fruits. On all the remaining course of the stream, are found at intervals {232} productive spots capable of yielding moderate crops of the grains and vegetables. There is considerable pine and cedar timber on the neighbouring hills; and near the Columbia are large forests growing on sandy plains. In a word, the Spokan valley can be extensively used as a grazing district; but its agricultural capabilities are limited.

Mr. Spaulding, an American missionary, made a journey across this valley to Fort Colville,[40] in March 1837, in relation to which, he thus writes to Mr. Levi Chamberlain of the Sandwich Islands: “The third day from home we came to snow, and on the fourth, came to what I call quicksands,[39] plains mixed with pine trees and rocks. The body of snow upon the plains was interspersed with bare spots under the standing pines. For these, our poor animals would plunge whenever they came near, after wallowing in the snow and mud until the last nerve seemed almost exhausted, naturally expecting a resting-place for their struggling limbs; but they were no less disappointed and discouraged, doubtless, than I was astonished, to see the noble animals go down by the side of a rock or pine tree, till their bodies struck the surface.”

{233} The same gentleman, in speaking of this valley, and the country generally, lying north of the Columbia, and claimed by the United States and Great Britain, says, “It is probably not worth half the money and time that will be spent in talking about it.”

The country, from the Spokan to Kettle Falls, is broken into hills and mountains thinly covered with wood, and picturesque in appearance, among which there is supposed to be no arable land. A little below Kettle Falls,[41] in latitude 48°, 37′ is a trading post of the Hudson’s Bay Company, called Fort Colville. Mr. Spaulding thus describes it:—“Fort Colville is two hundred miles west of north from this, (his station on the Clear Water), three days below Flatland River, one day above Spokan, one hundred miles above Oakanagan, and three hundred miles above Fort Wallawalla. It stands on a small plain of two thousand or three thousand acres, said to be the only arable land on the Columbia, above Vancouver. There are one or two barns, a blacksmith shop, a good flour mill, several houses for labourers, and good buildings for the gentlemen in charge.”

Mr. McDonald[42] raises this year (1837) {234} about[40] three thousand five hundred bushels of different grains, such as wheat, peas, barley, oats, corn, buckwheat, &c., and as many potatoes; has eighty head of cattle, and one hundred hogs. This post furnishes supplies of provisions for a great many forts north, south and west. The country on both sides of the stream, from Kettle Falls to within four miles of the lower Lake, is covered with dense forests of pine, spruce, and small birch. The northwestern shore is rather low, but the southern high and rocky. In this distance are several tracts of rich bottom land, covered with a kind of creeping red clover, and the white species common to the States. The lower lake of the Columbia is about thirty-five miles in length, and four or five in breadth. Its shores are bold, and clad with a heavy growth of pine, spruce, &c.[43] From these waters the voyager obtains the first view of the snowy heights in the main chain of the Rocky Mountains.

The Flathead River enters into the Columbia a short distance above Fort Colville. It is as long, and discharges nearly as much water as that part of Columbia above their junction. It rises near the {235} sources of the Missouri and Sascatchawine.[44] The ridges which separate them are said to be easy to pass. It falls into the Columbia over a confused heap of immense rocks, just above the place where the latter stream forms the Kettle Falls, in its passage through a spur of the Rocky Mountains. About one hundred miles from its mouth, the Flathead River forms a lake thirty-six miles long and seven or eight wide. It is called Lake Kullerspelm. A rich and beautiful country spreads off from it in all directions, to the[41] bases of lofty mountains covered with perpetual snows. Forty or fifty miles above this lake, is the “Flathead House,” a trading post of the Hudson Bay Company.[45]

McGillivray’s, or Flat Bow River, rises in the Rocky Mountains, and running a tortuous westerly course about three hundred miles, among the snowy heights, and some extensive and somewhat productive valleys, enters the Columbia four miles below the Lower Lake. Its banks are generally mountainous, and in some places covered with pine forests. On this stream also, the indefatigable British fur traders have a post, “Fort Kootania,” situated {236} about one hundred and thirty miles from its mouth.[46] Between the lower and upper lakes of the Columbia, are “the Straits,” a narrow, compressed passage of the river among jutting rocks. It is four or five miles in length, and has a current, swift, whirling, and difficult to stem. The upper lake is of less dimensions than the lower; but, if possible, surrounded by more broken and romantic scenery, forests overhung by lofty tiers of wintry mountains, from which rush a thousand torrents, fed by the melting snows.[47]

Two miles above this lake, the Columbia runs through a narrow, rocky channel. This place is called the Lower Dalles. The shores are strewn with immense quantities of fallen timber, among which still stand heavy and impenetrable forests. Thirty-five miles above is the Upper Dalles; the waters are crowded into a compressed channel, among hanging and slippery rocks, foaming and whirling fearfully.[48] A few miles above this place, is the head of navigation, “The Boat encampment,” where the traders leave their bateaux, in their overland journeys to Canada.[49] The country from the upper lake to this place, is a collection {237} of mountains, thickly covered with pine, and spruce, and fir trees of very large size.

Here commences the “Rocky Mountain portage,” to the navigable waters on the other side. Its track runs up a wide and cheerless valley, on the north of which, tiers of mountains rise to a great height, thickly studded with immense pines and cedars, while on the south are seen towering cliffs, partially covered with mosses and stinted pines, over which tumble, from the ices above, numerous and noisy cascades. Two days’ travel up the desolate valley, brings the traveller to “La Grande Cote,” the principal ridge. This you climb in two hours. Around the base of this ridge, the trees, pines, &c., are of enormous size; but in ascending,[50] they decrease in size,[43] till on the summit they become little else than shrubs.

On a table land of this height, are found two lakes a few hundred yards apart; the waters of one of which flow down the valley just described, to the Columbia, and thence to the North Pacific; while those of the other, forming the Rocky Mountain River, run thence into the Athabasca, and thence through Peace River, the Great Slave Lake, {238} and McKenzie’s River, into the Northern Arctic Ocean. The scenery around these lakes is highly interesting.[51] In the north, rises Mount Browne, sixteen thousand feet, and in the south, Mount Hooker, fifteen thousand seven hundred feet above the level of the sea. In the west, descends a vast tract of secondary mountains, bare and rocky, and noisy with tumbling avalanches. In the vales are groves of the winter-loving pine. In the east roll away undulations of barren heights beyond the range of sight. It seems to be the very citadel of desolation; where the god of the north wind elaborates his icy streams, and frosts, and blasts, in every season of the year.

Frazer’s River rises between latitudes 55° and 56° north, and after a course of about one hundred and fifty miles, nearly due south, falls into the Straits de Fuca, under latitude 49° north. It is so much obstructed by rapids and falls, as to be of little value for purposes of navigation.[52] The face of the country about its mouth, and[44] for fifty miles above, is mountainous and covered with dense forests of white pine, cedar, and other evergreen trees. The soil is an indifferent vegetable deposit six or seven inches in depth, resting on a stratum of sand or {239} coarse gravel. The whole remaining portion of the valley is said to be cut with low mountains running north-westwardly and south-eastwardly; among which are immense tracts of marshes and lakes, formed by cold torrents from the heights that encircle them. The soil not thus occupied, is too poor for successful cultivation. Mr. Macgillivray, the person in charge at Fort Alexandria, in 1827, says:[53] “All the vegetables we planted, notwithstanding the utmost care and precaution, nearly failed; and the last crop of potatoes did not yield one-fourth of the seed planted.” The timber of this region consists of all the varieties of the fir, the spruce, pine, poplar, willow, cedar, cyprus, birch and alder.

The climate is very peculiar. The spring opens about the middle of April. From this time the weather is delightful till the end of May. In June the south wind blows, and brings incessant rains. In July and August the heat is almost insupportable. In September the whole valley is enveloped in fogs so dense, that objects one hundred yards distant cannot be seen till ten o’clock in the day. In October the leaves change their colour and begin to fall. In November, the lakes, and portions of the rivers are {240} frozen. The winter months bring snow. It[45] is seldom severely cold. The mercury in Fahrenheit’s scale sinks a few days only, as low as ten or twelve degrees below zero.

That part of Oregon bounded on the north by Shmillamen River,[54] and on the east by Oakanagan and Columbia Rivers, south by the Columbia, and west by the President’s Range, is a broken plain, partially covered with the short and bunch grasses; but so destitute of water, that a small portion only of it, can ever be depastured. The eastern and middle portions of it are destitute of timber—a mere sunburnt waste. The northern part has a few wooded hills and streams, and prairie valleys. Among the lower hills of the President’s Range, too, there are considerable pine and fir forests; and rather extensive prairies, watered by small mountain streams; but nearly all of the whole surface of this part of Oregon, is a worthless desert.

The tract bounded north by the Columbia, east by the Blue Mountains, south by the forty-second parallel of north latitude, and west by the President’s Range, is a plain of vast rolls or swells, of a light, yellowish, sandy clay, partially covered with the short and bunch grasses, mixed with the prickly {241} pear and wild wormwood. But water is so very scarce, that it can never be generally fed; unless, indeed, as some travellers, in their praises of this region, seem to suppose, the animals that usually live by eating and drinking, should be able to dispense with the latter, in a climate where nine months in the year, not a particle of rain or dew falls, to moisten a soil as dry and loose as a heap of ashes. On the banks of the Luhon, John Days, Umatalla, and Wallawalla Rivers[55]—which[46] have an average length of thirty miles—without doubt, extensive tracts of grass may be found in the neighbourhood of water; but it is also true that not more than a fifth part of the surface within twenty-five miles of these streams, bears grass or any other vegetation.

The portion also which borders the Columbia, produces some grass. But of a strip six miles in width, and extending from the Dalles to the mouth of the Saptin, not an hundredth part bears the grasses; and the sides of the chasm of the river are so precipitous, that not a fiftieth part of this can be fed by animals which drink at that stream. In proceeding southward on the head waters of the small streams, John Days and Umatalla, the face of the plain rises gradually {242} into vast irregular swells, destitute of timber and water. On the Blue Mountains are a few pine and spruce trees of an inferior growth. On the right tower the white peaks and thickly wooded hills of the President’s Range.

The space south-east of the Blue Mountains is a barren, thirsty waste, of light, sandy, and clayey soil—strongly impregnated with nitre. A few small streams run among the sand hills; but they are so strongly impregnated with various kinds of salts, as to be unfit for use. These brooks empty themselves into the lakes, the waters of which are salter than the ocean. Near latitude 43° north, the Klamet River rises and runs westerly, through the President’s Range.[56] On these waters are a few productive valleys;[47] westwardly from them to the Saptin the country is dry and worthless.

The part of Oregon lying between the Straits de Fuca on the north, the President’s Range on the east, the Columbia on the south, and the ocean on the west, is thickly covered with pines, cedars, and firs of extraordinary size; and beneath these, a growth of brush and brambles which defies the most vigorous foot to penetrate. Along the banks of the Columbia, indeed, strips {243} of prairie may be met with, varying from a few rods to three miles in width, and often several miles in length; and even amidst the forests are found a few open spaces.

The banks of the Cowelitz, too, are denuded of timber for forty miles; and around the Straits de Fuca and Puget’s Sound, are large tracts of open country.[57] But the whole tract lying within the boundaries just defined, is of little value except for its timber. The forests are so heavy and so matted with brambles, as to require the arm of a Hercules to clear a farm of one hundred acres in an ordinary life-time; and the mass of timber is so great that an attempt to subdue it by girdling would result in the production of another forest before the ground could be disencumbered of what was thus killed. The small prairies among the woods are covered with wild grasses, and are useful as pastures.

The soil of these, like that of the timbered portions, is a vegetable mould, eight or ten inches in thickness, resting on a stratum of hard blue clay and gravel. The valley of the Cowelitz is poor—the soil, thin, loose, and much washed, can be used as pasture grounds for thirty miles up the stream. At about that distance some tracts {244} of fine land occur. The prairies on the banks of[48] the Columbia would be valuable land for agricultural purposes, if they were not generally overflown by the freshets in June—the month of all the year when crops are most injured by such an occurrence. It is impossible to dyke out the water; for the soil rests upon an immense bed of gravel and quicksand, through which it will leach in spite of such obstructions.

The tract of the territory lying between the Columbia on the north, the President’s range on the east, the parallel of forty-two degrees of north latitude on the south, and the ocean on the west, is the most beautiful and valuable portion of the Oregon Territory. A good idea of the form of its surface may be derived from a view of its mountains and rivers as laid down on the map. On the south tower the heights of the snowy mountains; on the west the naked peaks of the coast range; on the north the green peaks of the river range; and on the east the lofty shining cones of the President’s range—around whose frozen bases cluster a vast collection of minor mountains, clad with the mightiest pine and cedar forests on the face of the earth! The principal rivers are the Klamet and the Umpqua in the south-west, and the Willamette in the north.

{245} The Umpqua enters these in a latitude forty-three degrees, thirty minutes north.[58] It is three-fourths of a mile in width at its mouth; water two-and-a-half fathoms on its bar; the tide sets up thirty miles from the sea; its banks are steep and covered with pines and cedars, &c. Above tide water the stream is broken by rapids and falls. It has a westwardly course of about one hundred miles. The face of the country about it is somewhat broken; in some parts covered with heavy pine and cedar timber, in others with grass only; said to be a fine valley for cultivation and pasturage. The pines on this[49] river grow to an enormous size: two hundred and fifty feet in height—and from fifteen to more than fifty feet in circumference;[59] the cones or seed vessels are in the form of an egg, and oftentimes more than a foot in length; the seeds are as large as the castor bean. Farther south is another stream, which joins the ocean twenty-three miles from the outlet of the Umpqua. At its mouth are many bays; and the surrounding country is less broken than the valley of the Umpqua.[60]

{246} Farther south still, is another stream called the Klamet. It rises, as is said, in the plain east of Mount Madison, and running a westerly course of one hundred and fifty miles, enters the ocean forty or fifty miles south of the Umpqua. The pine and cedar disappear upon this stream; and instead of them are found a myrtaceous tree of small size, which, when shaken by the least breeze, diffuses a delicious fragrance through the groves. The face of the valley is gently undulating, and in every respect desirable for cultivation and grazing.

The Willamette rises in the President’s range, near the sources of the Klamet. Its general course is north northwest. Its length is something more than two hundred miles. It falls into the Columbia by two mouths; the one eighty-five, and the other seventy miles from the sea. The arable portion of the valley of this river is about one hundred and fifty miles long, by sixty in width. It is bounded on the west by low wooded hills of the coast range; on the south by the highlands around the upper waters of the Umpqua; on the east by the President’s[50] range; and on the north by the mountains that run along the southern bank of the Columbia. Its general appearance as seen from the heights, is that of a {247} rolling, open plain, intersected in every direction by ridges of low mountains, and long lines of evergreen timber; and dotted here and there with a grove of white oaks. The soil is a rich vegetable mould, two or three feet deep, resting on a stratum of coarse gravel or clay. The prairie portions of it are capable of producing, with good cultivation, from twenty to thirty bushels of wheat to the acre, and other small grains in proportion. Corn cannot be raised without irrigation. The vegetables common to such latitudes yield abundantly, and of the best quality. The uplands have an inferior soil, and are covered with such an enormous growth of pines, cedars and firs, that the expense of clearing would be greatly beyond their value. Those tracts of the second bottom lands, which are covered with timber might be worth subduing, but for a species of fern growing on them, which is so difficult to kill, as to render them nearly worthless for agricultural purposes.

The climate of the country between the President’s range and the sea, is very temperate. From the middle of April to the middle of October, the westerly winds prevail, and the weather is warm and dry. Scarcely a drop of rain falls. During the remainder of the year, the southerly winds {248} blow continually, and bring rains; sometimes in showers, and at others terrible storms, which continue to pour down incessantly for many weeks.

There is scarcely any freezing weather in this section of Oregon. Twice within the last forty years the Columbia has been frozen over; but this was chiefly caused by the accumulation of ice from the upper country. The grasses grow during the winter months, and wither to hay in the summer time.

The mineral resources of Oregon have not been investigated. Great quantities of bituminous coal have however been discovered on Puget’s Sound,[61] and on the Willamette. Salt springs also abound; and other fountains highly impregnated with sulphur, soda, iron, &c., are numerous.

Many wild fruits are to be met with in the territory, that would be very desirable for cultivation in the gardens of the States. Among these are a very large and delicious strawberry, the service berry, a kind of whortleberry, and a cranberry growing on bushes four or five feet in height. The crab apple, choke cherry, and thornberry are common. Of the wild animals, there are the white tailed, black tailed, jumping and moose deer; the elk; red and black and grey wolf; the black, brown, and grisly bear; {249} the mountain sheep; black, white, red and mixed foxes; beaver, lynxes, martin, otters, minks, muskrats, wolverines, marmot, ermines, wood-rats, and the small curly-tailed short eared dog, common among the Chippeways.

Of the feathered tribe, there are the goose, the brant, several kinds of cranes, the swan, many varieties of the duck, hawks of several kinds, plovers, white eagles, ravens, crows, vultures, thrush, gulls, woodpeckers, pheasants, pelicans, partridges, grouse, snowbirds, &c.

In the rivers and lakes are a very superior quality of salmon, brook and salmon trout, sardines, sturgeon, rock cod, the hair seal, &c.; and in the bays and inlets along the coast, are the sea otter and an inferior kind of oyster.

The trade of Oregon is limited entirely to the operations of the British Hudson Bay Company. A concise[52] account of this association is therefore deemed apposite in this place.

A charter was granted by Charles II, in 1670, to certain British subjects associated under the name of “The Hudson’s Bay Company,” in virtue of which they were allowed the exclusive privilege of establishing {250} trading factories on the Hudson’s Bay and its tributary rivers. Soon after the grant, the Company took possession of the territory, and enjoyed its trade without opposition till 1787; when was organized a powerful rival under the title of the “North American Fur Company of Canada.” This company was chiefly composed of Canadian-born subjects—men whose native energy and thorough acquaintance with the Indian character, peculiarly qualified them for the dangers and hardships of a fur trader’s life in the frozen regions of British America. Accordingly we soon find the North-westers outreaching in enterprise and commercial importance their less active neighbours of Hudson’s Bay; and the jealousies naturally arising between parties so situated, led to the most barbarous battles, and the sacking and burning each others posts. This state of things in 1821, arrested the attention of Parliament, and an act was passed consolidating the two companies into one, under the title of “The Hudson’s Bay Company.”[62]

This association is now, under the operation of their charter, in sole possession of all that tract of country bounded north by {251} the northern Arctic Ocean; east by the Davis’ Straits and the Atlantic Ocean; south and south-westwardly by the northern boundary of the Canadas,[53] and a line drawn through the centre of Lake Superior; thence north-westwardly to the Lake of the Wood; thence west on the 49th parallel of north latitude to the Rocky Mountains, and along those mountains to the 54th parallel; thence westwardly on that line to a point nine marine leagues from the Pacific Ocean; and on the west by a line commencing at the last mentioned point, and running northwardly parallel to the Pacific coast till it intersects the 141st parallel of longitude west from Greenwich, England, and thence due north to the Arctic Sea.

They have also leased for twenty years, commencing in March, 1840, all of Russian America, except the post of Sitka; the lease renewable at the pleasure of the Hudson’s Bay Company.[63] They are also in possession of Oregon under treaty stipulation between Britain and the United States. Thus this powerful company occupy and control more than one-ninth of the soil of the globe. Its stockholders are British capitalists, resident in Great Britain. From these are elected a board of managers, who {252} hold their meetings and transact their business at “The Hudson’s Bay House” in London. This board buy goods and ship them to their territory, sell the furs for which they are exchanged, and do all other business connected with the Company’s transactions, except the execution of their own orders, the actual business of collecting furs in their territory. This duty is entrusted to a class of men who are called partners, but who in fact receive certain portions of the annual[54] net profits of the Company’s business, as a compensation for their services.

These gentlemen are divided by their employers into different grades. The first of these is the Governor-General of all the Company’s posts in North America. He resides at York Factory, on the west shore of Hudson’s Bay.[64] The second class are chief factors; the third, chief traders; the fourth, traders. Below these is another class, called clerks. These are usually younger members of respectable Scottish families. They are not directly interested in the Company’s profits, but receive an annual salary of £100, food, suitable clothing, and a body servant, during an apprenticeship of seven years. At the expiration {253} of this term they are eligible to the traderships, factorships, &c. that may be vacated by death or retirement from the service. While waiting for advancement they are allowed from £80 to £120 per annum. The servants employed about their posts and in their journeyings are half-breed Iroquois and Canadian Frenchmen. These they enlist for five years, at wages varying from £68 to £80 per annum.[65]

An annual Council composed of the Governor-General, chief factors and chief traders, is held at York Factory. Before this body are brought the reports of the trade of each district; propositions for new enterprises, and modifications of old ones; and all these and other matters deemed important, being acted upon, the proceedings had thereon and the reports from the several districts are forwarded to the Board of Directors in London, and subjected to its final order.

This shrewd Company never allow their territory to be overtrapped. If the annual return from any well trapped district be less in any year than formerly, they order a less number still to be taken, until the beaver and other fur-bearing animals have time to increase. The income of the company {254} is thus rendered uniform, and their business perpetual.

The nature and annual value of the Hudson Bay Company’s business in the territory which they occupy, may be learned from the following table, extracted from Bliss’s work on the trade and industry of British America, in 1831:[66]

| Skins. | No. | each | £. | s. | d. | £. | s. | d. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beaver | 126,944 | ” | 1 | 5 | 0 | 158,680 | 0 | 0 |

| Muskrat | 375,731 | ” | 0 | 0 | 6 | 9,393 | 5 | 6 |

| Lynx | 58,010 | ” | 0 | 8 | 0 | 23,204 | 0 | 0 |

| Wolf | 5,947 | ” | 0 | 8 | 0 | 2,378 | 16 | 0 |

| Bear | 3,850 | ” | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3,850 | 0 | 0 |

| Fox | 8,765 | ” | 0 | 10 | 0 | 4,382 | 10 | 0 |

| Mink | 9,298 | ” | 0 | 2 | 3 | 929 | 16 | 0 |

| Raccoon | 325 | ” | 0 | 1 | 6 | 24 | 7 | 6 |

| Tails | 2,290 | ” | 0 | 1 | 0 | 114 | 10 | 0 |

| Wolverine | 1,744 | ” | 0 | 3 | 0 | 261 | 12 | 0 |

| Deer | 645 | ” | 0 | 3 | 0 | 96 | 15 | 0 |

| Weasel | 34 | ” | 0 | 0 | 6 | 00 | 16 | 0 |

| £203,316 | 9 | 0 |

Some idea may be formed of the net profit of this business, from the facts that the shares of the company’s stock, which originally cost £100, are at 100 per cent premium, and that the dividends range from ten per cent upward, and this too while they are creating out of the net proceeds[56] an immense reserve fund, to be {255} expended in keeping other persons out of the trade.

In 1805 the Missouri Fur Company established a trading-post on the headwaters of the Saptin.[67] In 1806 the North-West Fur Company of Canada established one on Frazer’s Lake, near the northern line of Oregon.[68] In March, 1811, the American Pacific Fur Company built Fort Astoria, near the mouth of the Columbia.[69] In July of the same year, a partner of the North-West Fur Company of Canada descended the great northern branch of the Columbia to Astoria. This was the first appearance of the British fur traders in the valleys drained by this river.[70]

On the 16th of October, 1813, (while war was raging between England and the States) the Pacific Fur Company sold all its establishments in Oregon to the North-West Fur Company of Canada. On the 1st of December following, the British sloop of war Raccoon, Captain Black commanding, entered the Columbia, took formal possession of Astoria, and changed its name to Fort George.[71] On the 1st of October, 1818, Fort George was surrendered[57] by the British Government to the Government of the States, according to a stipulation in the Treaty of Ghent.[72]

{256} By the same treaty, British subjects were granted the same rights of trade and settlement in Oregon as belonged to the citizens of the Republic, for the term of ten years; under the condition, that as both nations claimed Oregon the occupancy thus authorized should in no form affect the question as to the title to the country. This stipulation was by treaty of London, August 6, 1827, indefinitely extended; under the condition that it should cease to be in force twelve months from the date of a notice of either of the contracting powers to the other, to annul and abrogate it; provided such notice should not be given till after the 20th of October, 1828.[73] And this is the manner in which the British Hudson’s Bay Company, after its union with the North-West Fur Company of Canada, came into Oregon.

They have now in the territory the following trading posts: Fort Vancouver, on the north bank of the Columbia, ninety miles from the Ocean, in latitude 45½°, longitude 122° 30′; Fort George, (formerly Astoria), near the mouth of the same river;[74] Fort Nasqually, on Puget’s Sound, latitude 47°; Fort Langly, at the outlet of Fraser’s[58] River, latitude 49° 25′; Fort McLaughlin, on the Millbank Sound, latitude 52°;[75] Fort {257} Simpson, on Dundas Island, latitude 54½°.[76] Frazer’s Fort, Fort James, McLeod’s Fort, Fort Chilcotin, and Fort Alexandria, on Frazer’s river and its branches between the 51st and 54½ parallels of latitude;[77] Thompson’s Fort,[59] on Thompson’s River, a tributary of Frazer’s River, putting into it in latitude 50° and odd minutes; Kootania Fort, on Flatbow River; Flathead Fort, on Flathead River; Forts Hall and Boisais, on the Saptin; Forts Colville and Oakanagan, on the Columbia, above its junction with the Saptin; Fort Nez Percés or Wallawalla, a few miles below the junction;[78] Fort McKay, at the mouth of the Umpqua river, latitude 43° 30′, and longitude 124° west.[79]

They also have two migratory trading and trapping establishments of fifty or sixty men each. The one traps and trades in Upper California; the other in the country lying west, south, and east of Fort Hall. They also have a steam-vessel, heavily armed, which runs along the coast, and among its bays and inlets, for the twofold purpose of trading with the natives in places where they have no post, and of outbidding and outselling any American vessel that attempts to trade in those seas. They likewise have five sailing vessels, measuring from one hundred[60] to five hundred tons {258} burthen, and armed with cannon, muskets, cutlasses, &c. These are employed a part of the year in various kinds of trade about the coast and the islands of the North Pacific, and the remainder of the time in bringing goods from London, and bearing back the furs for which they are exchanged.

One of these ships arrives at Fort Vancouver in the spring of each year, laden with coarse woollens, cloths, baizes, and blankets; hardware and cutlery; cotton cloths, calicoes, and cotton handkerchiefs; tea, sugar, coffee and cocoa; rice, tobacco, soap, beads, guns, powder, lead, rum, wine, brandy, gin, and playing cards; boots, shoes, and ready-made clothing, &c.; also, every description of sea stores, canvas, cordage, paints, oils, chains and chain cables, anchors, &c. Having discharged these “supplies,” it takes a cargo of lumber to the Sandwich Islands, or of flour and goods to the Russians at Sitka or Kamskatka; returns in August; receives the furs collected at Fort Vancouver, and sails again for England.

The value of peltries annually collected in Oregon, by the Hudson Bay Comp., is about £140,000 in the London or New York market. The prime cost of the goods exchanged {259} for them is about £20,000. To this must be added the per centage of the officers as governors, factors, &c. the wages and food of about four hundred men, the expense of shipping to bring supplies of goods and take back the returns of furs, and two years’ interest on the investments. The Company made arrangements in 1839 with the Russians at Sitka and at other ports, about the sea of Kamskatka, to supply them with flour and goods at fixed prices. As they are now opening large farms on the Cowelitz, the Umpqua, and in other parts of the Territory, for the production of wheat for that market; and as they can afford to sell goods purchased[61] in England under a contract of fifty years’ standing, 20 or 30 per cent cheaper than American merchants can, there seems a certainty that the Hudson’s Bay Company will engross the entire trade of the North Pacific, as it has that of Oregon.

Soon after the union of the North-West and Hudson’s Bay Companies, the British Parliament passed an act extending the jurisdiction of the Canadian courts over the territories occupied by these fur traders, whether it were “owned” or “claimed by Great Britain.” Under this act, certain {260} gentlemen of the fur company were appointed justices of the peace, and empowered to entertain prosecutions for minor offences, arrest and send to Canada criminals of a higher order, and try, render judgment, and grant execution in civil suits where the amount in issue should not exceed £200; and in case of non-payment, to imprison the debtor at their own forts, or in the jails of Canada.

It is thus shown that the trade, and the civil and criminal jurisdiction in Oregon are held by British subjects; that American citizens are deprived of their own commercial rights; that they are liable to be arrested on their own territory by officers of British courts, tried in the American domain by British judges, and imprisoned or hung according to the laws of the British empire, for acts done within the territorial limits of the Republic.

It has frequently been asked if Oregon will hereafter assume great importance as a thoroughfare between the States and China? The answer is as follows:

The Straits de Fuca, and arms of the sea to the eastward of it, furnish the only good harbours on the Oregon coast. Those in Puget’s Sound offer every requisite facility {261} for the most extensive commerce. Ships beat out and into the straits with any winds of the coast,[62] and find in summer and winter fine anchorage at short intervals on both shores; and among the islands of the Sound, a safe harbour from the prevailing storms. From Puget’s Sound eastward, there is a possible route for a railroad to the navigable waters of the Missouri; flanked with an abundance of fuel and other necessary materials. Its length would be about six hundred miles. Whether it would answer the desired end, would depend very much upon the navigation of the Missouri.[80]

As, however, the principal weight and bulk of cargoes in the Chinese trade would belong to the homeward voyage, and as the lumber used in constructing proper boats on the upper Missouri would sell in Saint Louis for something like the cost of construction, it may perhaps be presumed that the trade between China and the States could be conducted through such an overland communication.

The first day of the winter months came with bright skies over the beautiful valleys of Oregon. Mounts Washington and Jefferson reared their vast pyramids of ice and {262} snow among the fresh green forests of the lower hills, and overlooked the Willamette, the lower Columbia, and the distant sea. The herds of California cattle were lowing on the meadows, and the flocks of sheep from the downs of England were scampering and bleating around their shepherds on the plain; and the plane of the carpenter, the adze of the cooper, the hammer of the tinman, and the anvil of the blacksmith within the pickets, were all awake when I arose to breakfast for the last time at Fort Vancouver.

The beauty of the day, and the busy hum of life around me, accorded well with the feelings of joy with which[63] I made preparations to return to my family and home. And yet when I met at the table Dr. McLaughlin, Mr. Douglas, and others with whom I had passed many pleasant hours, and from whom I had received many kindnesses, a sense of sorrow mingled strongly with the delight which the occasion naturally inspired. I was to leave Vancouver for the Sandwich Islands, and see them no more. I confess that it has seldom been my lot to feel so deeply pained at parting with those whom I had known so little time. But it became me to hasten {263} my departure; for the ship had dropped down to the mouth of the river, and awaited the arrival of Mr. Simpson, one of the company’s clerks,[81] Mr. Johnson, an American from St. Louis, and myself. While we are making the lower mouth of the Willamette, the reader will perhaps be amused with the sketch of life at Fort Vancouver.