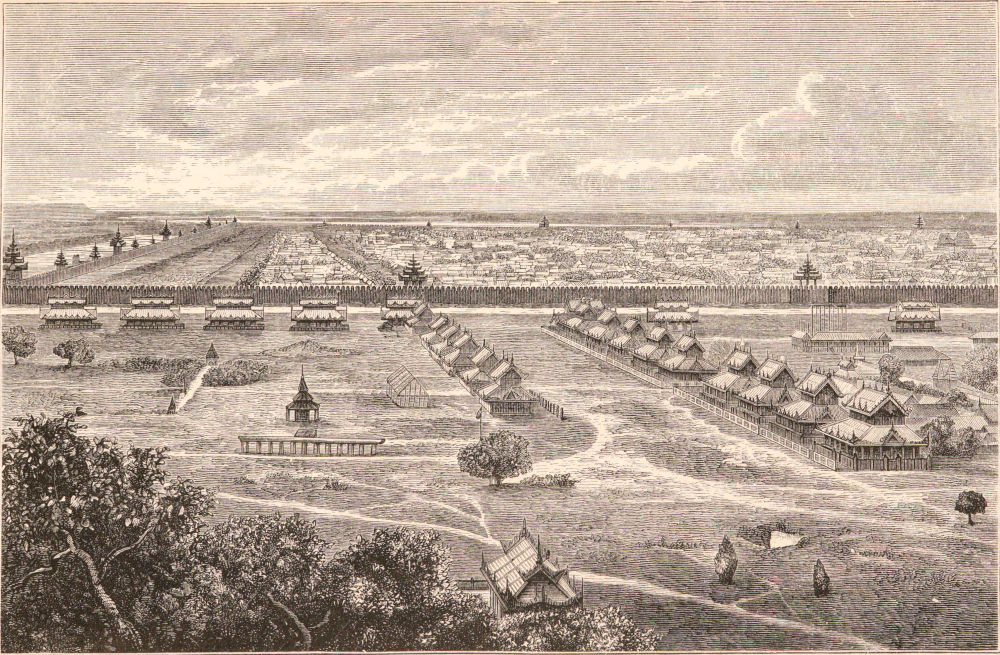

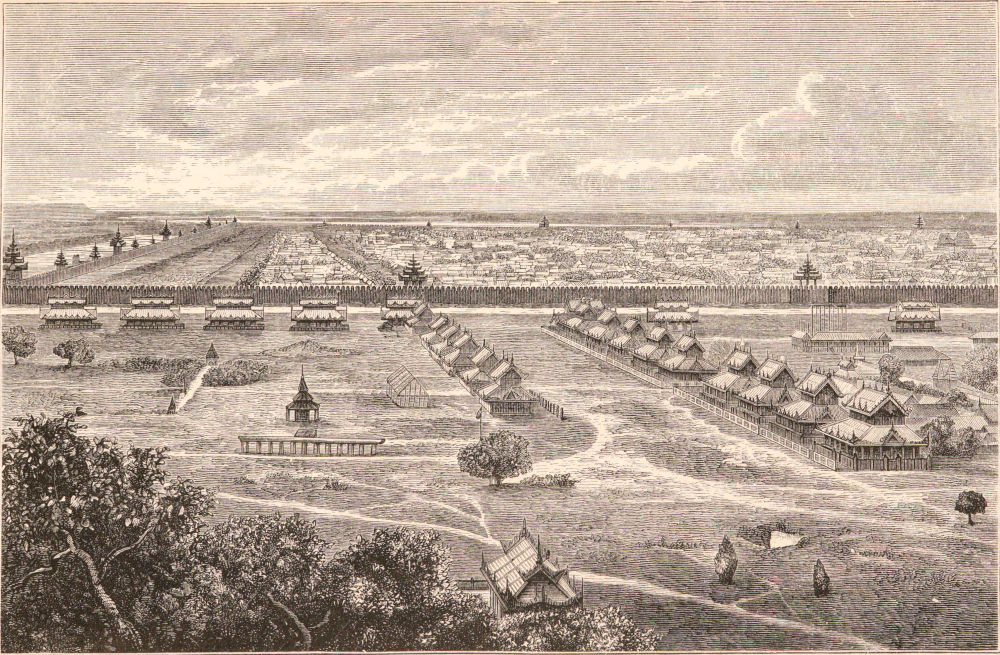

MANDALAY, THE CAPITAL OF INDEPENDENT BURMA; FROM MANDALÉ HILL.

A NARRATIVE

OF THE

TWO EXPEDITIONS TO WESTERN CHINA

OF 1868 AND 1875

UNDER

COLONEL EDWARD B. SLADEN

AND

COLONEL HORACE BROWNE.

BY

JOHN ANDERSON, M.D.Edin., F.R.S.E., F.L.S., F.Z.S.

FELLOW OF CALCUTTA UNIVERSITY;

CURATOR OF IMPERIAL MUSEUM AND PROFESSOR OF COMPARATIVE ANATOMY,

MEDICAL COLLEGE, CALCUTTA;

MEDICAL AND SCIENTIFIC OFFICER TO BOTH EXPEDITIONS.

WITH MAPS AND ILLUSTRATIONS.

London:

MACMILLAN AND CO.

1876.

LONDON:

PRINTED BY WILLIAM CLOWES AND SONS,

STAMFORD STREET AND CHARING CROSS.

[Pg iii]

Seven years have elapsed since the date of the expedition which furnishes the subject of the larger portion of this work. Its results have been recorded, but can hardly be said to have been published, in the official reports of the several members, printed in India, and not accessible to the general reader.

The public interest in the subject of the overland route from Burma to China, called forth by the repulse of the recent mission and the tragedy which attended it, has suggested the present publication. It is hoped that a compendious and popular account of the expedition of 1868 will be acceptable, if only as an introduction to the simple narrative of the mission of this year, commanded by Colonel Horace Browne. The statement of the difficulties which beset our advance in 1868 will prepare the reader to estimate the opposition which, under a changed political condition of the country, compelled the mission under Colonel Browne to return without accomplishing its object.

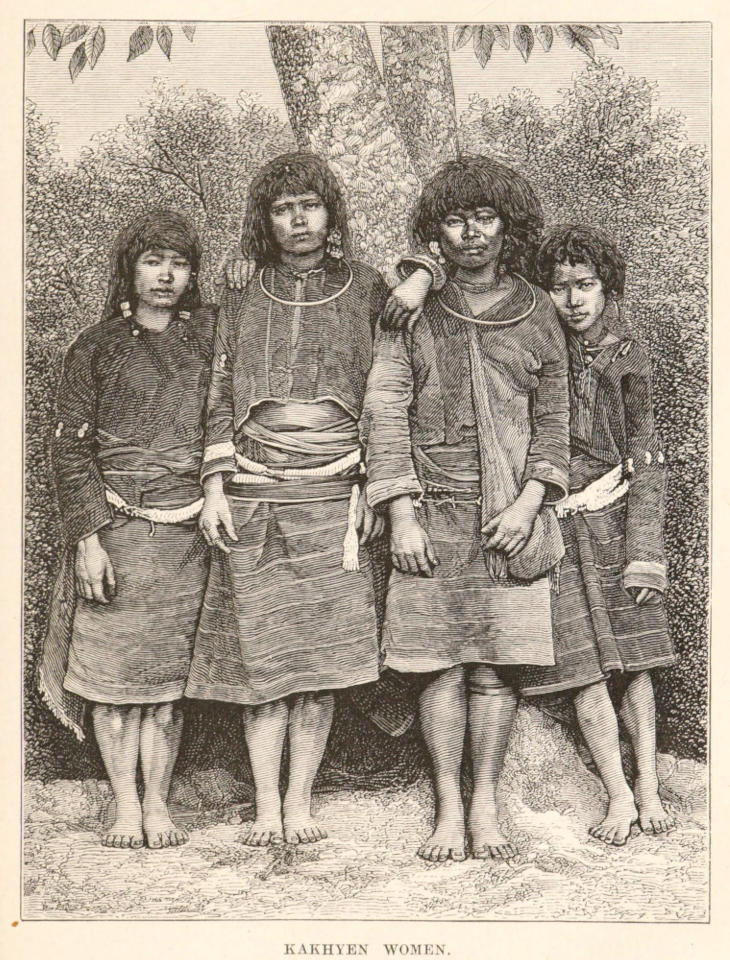

The narrative of our experiences of the border[Pg iv] country between Bhamô and Yunnan, and its motley population, has been supplemented from materials collected by Colonel Sladen, including a catalogue of Kakhyen deities obtained by him, and which will be found in the Appendix, along with a Panthay account of the origin of the Chinese Mahommedans. To him, as well as to my fellow travellers, Captain Bowers and Mr. Gordon, I gladly record my obligations for the information that has been derived from them.

For many details illustrating the condition of Yunnan and the Mahommedan revolt in that province, I am indebted to the volumes, issued by the French government, which contain the results of the French expedition from Saigon to Yunnan, under Lagrée, Garnier, and Carné, whose premature loss their country has to deplore, and to the travels of that enterprising pioneer of commerce, Mr. T. T. Cooper.

No one can treat of the border lands of Cathay without deriving assistance from the stores of knowledge collected and arranged by the erudite editor of ‘Marco Polo,’ Colonel Yule, to whom I tender my tribute of admiration and indebtedness.

My observations on the Kakhyens are confirmed by the learned Monsig. Bigandet, the annotator of the ‘Life of Gaudama,’ who was the first[Pg v] European to visit those hill tribes, and who communicated his experiences to the columns of the leading Rangoon journal. The reader will find among the appendices a valuable note by the same author, on Burmese bells, especially those of Rangoon and Mengoon.

The list of Chinese deities given in the Appendix has been translated from the original by the well-known Chinese scholar, Professor Douglas, of the British Museum, who has kindly added an explanatory note. The appended vocabularies may prove interesting to philologists.

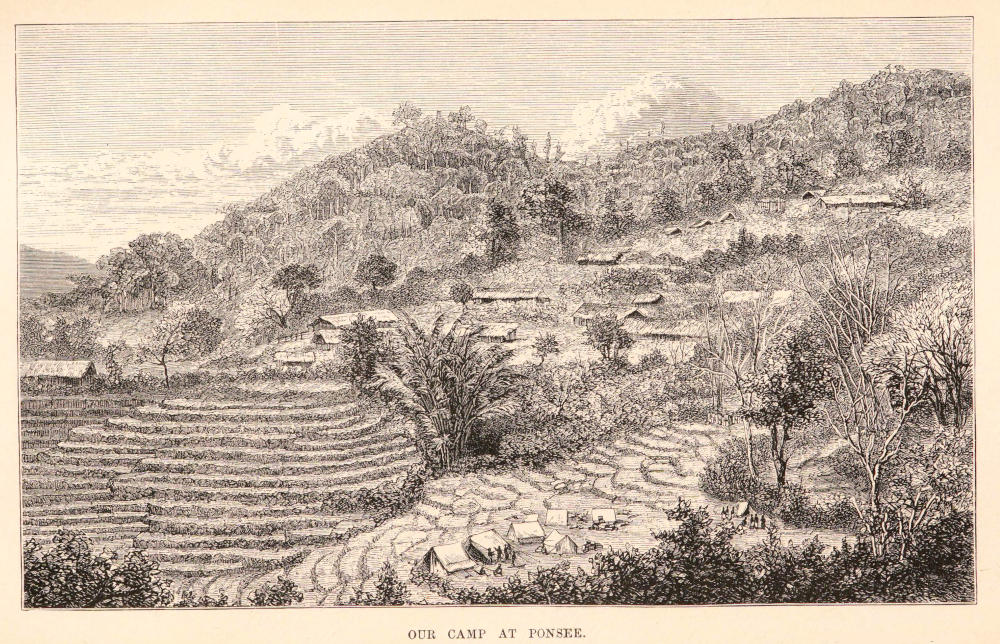

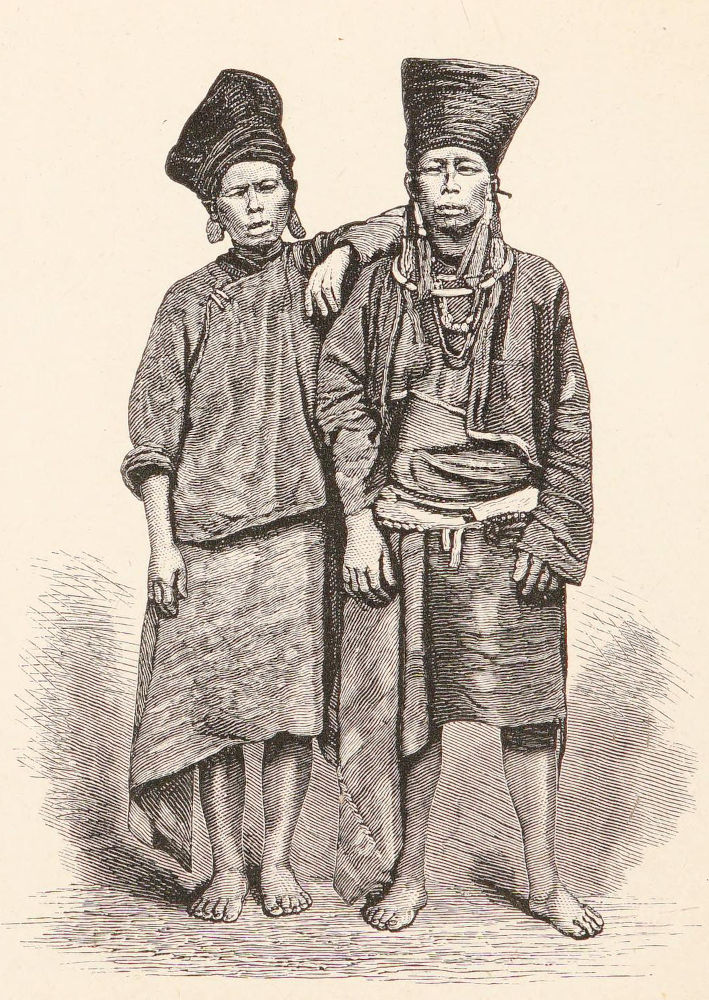

The illustrations of the country and people as far as Ponsee have been executed from photographs taken by Major Williams and myself, while the views of the country to the east are reproductions of sketches which fairly claim the merit of accurate delineation of its features.

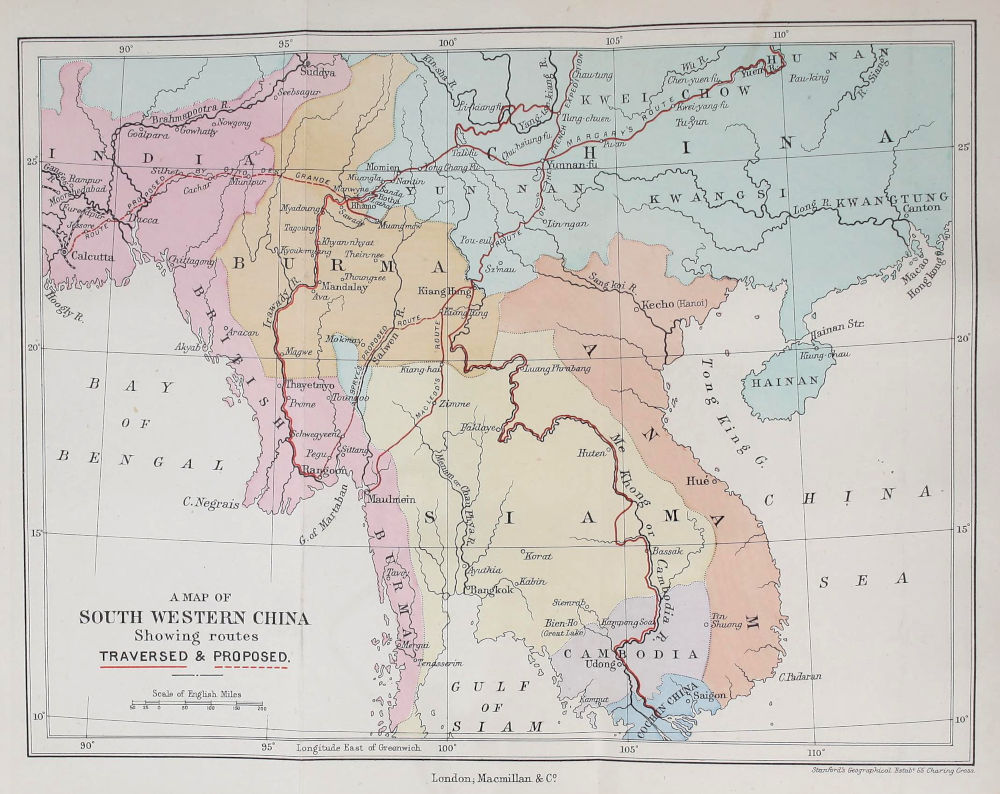

The map illustrating the topography of the district travelled has been based upon surveys made during the expedition by Mr. Gordon and a Burmese surveyor, and a second has been added to show the general relations of our Indian empire to Western China, with the various routes which have been explored or projected, including those followed by the French expedition, and by Margary from the terminus of the boat journey to Bhamô.

[Pg vi]

The journal of our ill-fated companion, recently published in China, and received in this country when this work was completed, unfortunately does not carry him on to Tali-fu, but his impressions of the country beyond this point have been briefly summarised in these pages.

The scientific reader will perhaps be inclined to complain that the following pages do not contain more of the results of the proper work of a naturalist. Of these, a full and illustrated report, unavoidably delayed by absence from this country, is in active preparation. This will be published by the aid of the Indian government, given at the instance of the Chief Commissioner of British Burma, the Hon. Ashley Eden, by whom the opening up of the overland route to China, as a measure beneficial to the province administered by him, has ever been strongly advocated.

J. A.

6 Royal Terrace, Edinburgh,

December 31, 1875.

[Pg vii]

FIRST EXPEDITION:—CHAPTERS I. to XI.

SECOND EXPEDITION:—CHAPTERS XII. to XVI.

|

PAGES

|

||

|

MANDALAY TO BHAMÔ.

|

||

| Overland trade of Burma and China—Early notices—English travellers—Burmese treaty of 1862—Dr. Williams—Objects of the expedition—Its constitution—Arrival at Mandalay—Second coronation of the king—The suburbs—The bazaars—Mengoon—Burmese navigation—Shienpagah—Coal mines—The third defile—Sacred fish—Tagoung and Old Pagan—Ngapé—Katha—Magnetic battery—The first Kakhyens—The Shuaybaw pagodas—The second defile—View of Bhamô | ||

|

BHAMÔ.

|

||

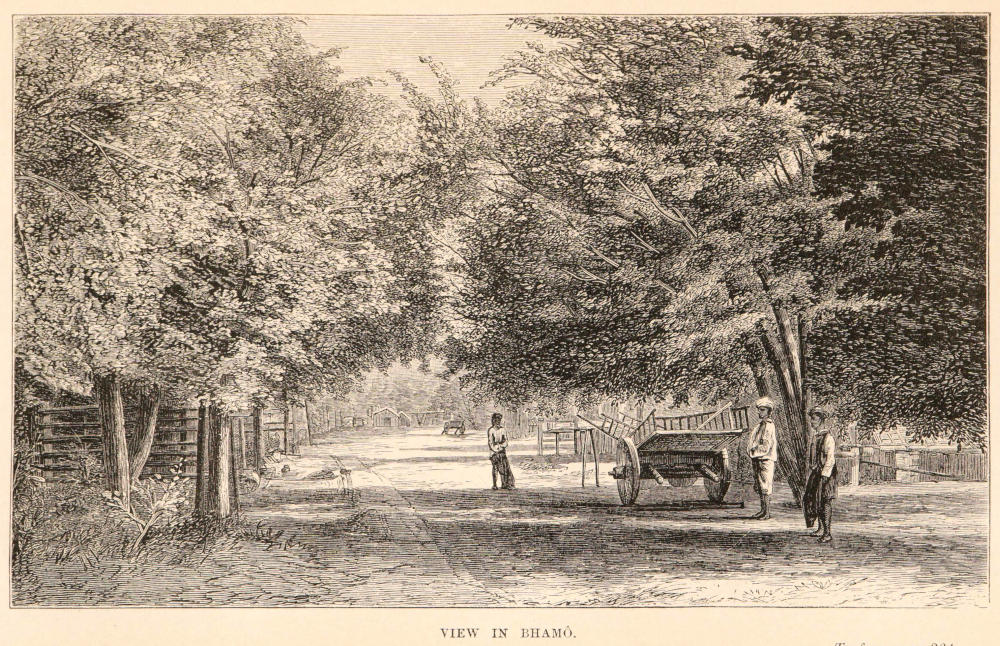

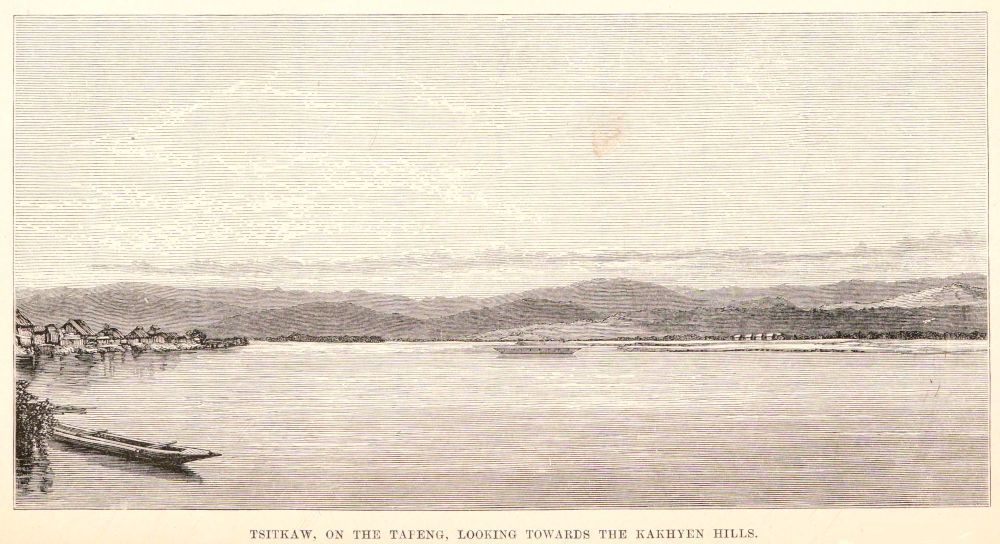

| Arrival at Bhamô—Our quarters—The town—The Woon’s house—The Shan-Burmese—Kakhyen man-stealing—The environs—Old Tsampenago—Legendary history—The Shuaykeenah pagodas—The Molay river—The first defile—Delays and intrigues—Sala—The new Woon—Our departure—Tsitkaw—Mountain muleteers—The Manloung lake—The phoongyee’s farewell | [Pg viii] | |

|

KAKHYEN HILLS.

|

||

| Departure from Tsitkaw—Our cavalcade—The hills—A false alarm—Talone—First night in the hills—The tsawbwa-gadaw—Ponline village—A death dance—The divination—A meetway—Nampoung gorge—A dangerous road—Lakong bivouac—Arrival at Ponsee—A Kakhyen coquette | ||

|

PONSEE CAMP.

|

||

| Desertion of the muleteers—Our encampment—Visit of hill chiefs—Sala’s demands—A mountain excursion—Messengers from Momien—Shans refuse presents—Stoppage of supplies—Ill-feeling—Tsawbwa of Seray—St. Patrick’s Day—Retreat of Sala—The pawmines of Ponsee—A burial-ground—Visit to the Tapeng—The silver mines—Approach of the rains—Hostility of Ponsee—Threatened attack—Reconciliation—A false start—Letters from Momien—A hailstorm—Circular to the members of the mission—Beads and belles—Friendly relations with Kakhyens—Their importance | ||

|

THE KAKHYENS.

|

||

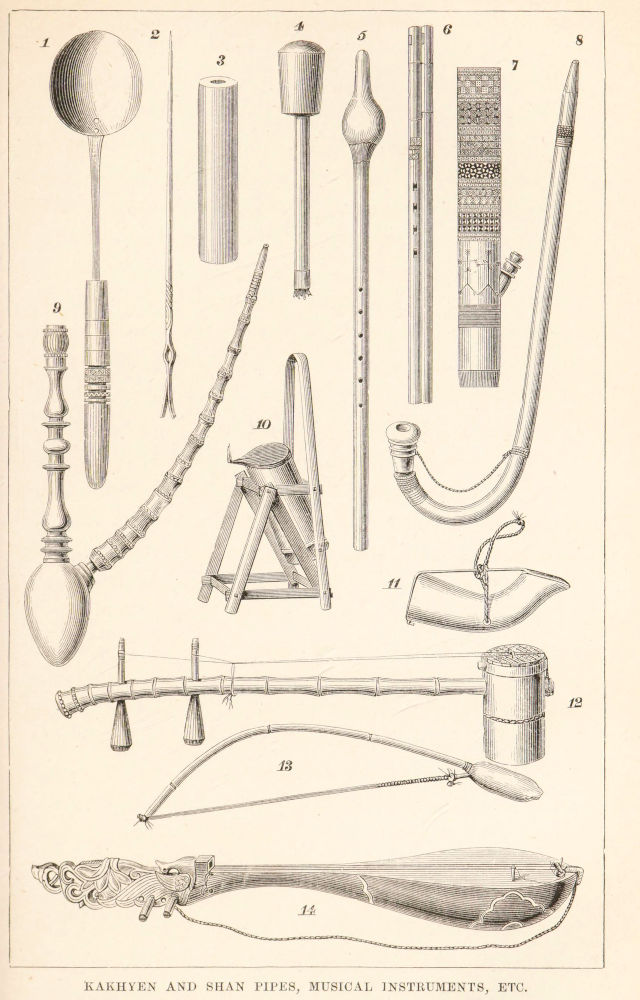

| The Kakhyens or Kakoos—The clans—Their chiefs—Mountain villages—Cultivation and crops—Personal appearance—Costume—Arms and implements—Female dress and ornaments—Women’s work—Sheroo—Morals—Marriage—Music—Births—Funerals—Religion—Language—Character—How to deal with them—Our party | [Pg ix] | |

|

MANWYNE TO MOMIEN.

|

||

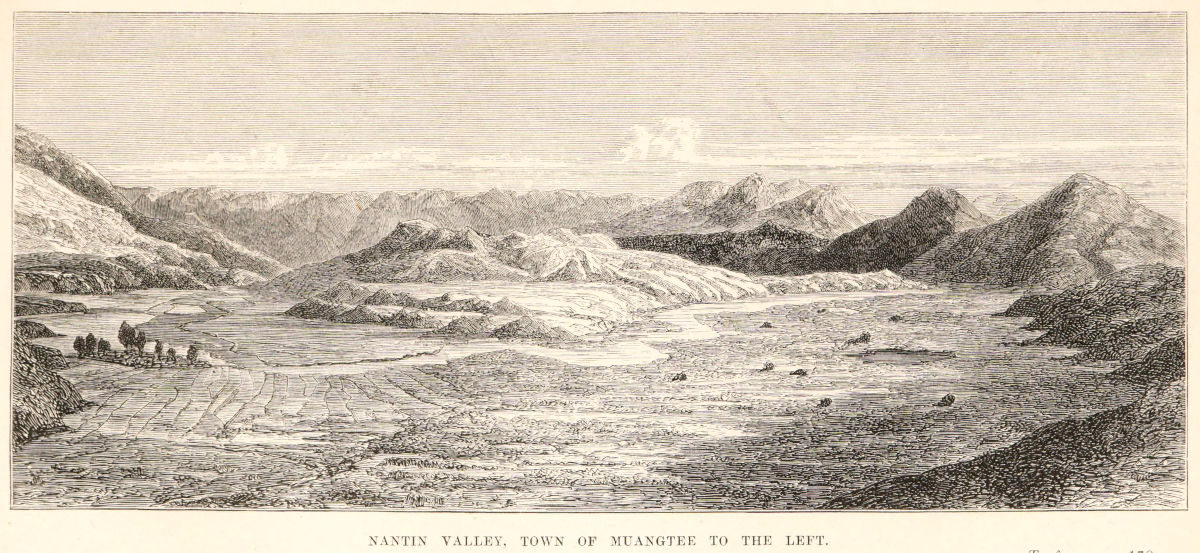

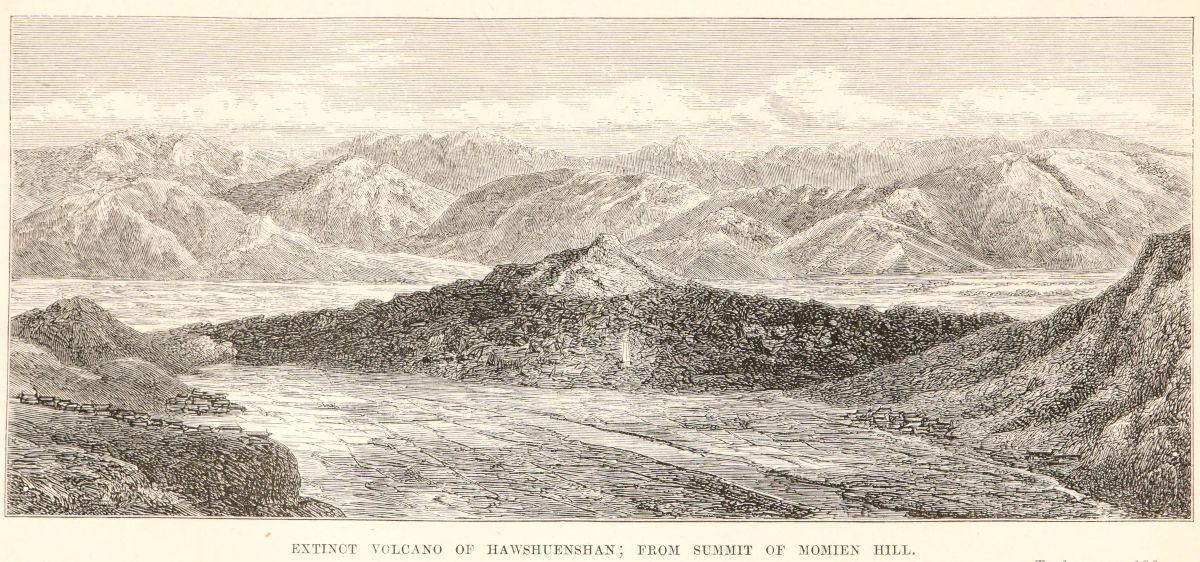

| Departure from Ponsee—Valley of the Tapeng—A curious crowd—Our khyoung—Matins—The town of Manwyne—Visit to the haw—The tsawbwa-gadaw—An armed demonstration—Karahokah—Sanda—The chief and his grandson—Muangla—Shan burial-grounds—The Tahô—A murdered traveller—Mawphoo valley—Muangtee—Nantin—Valley of Nantin—The hot springs—Attacked by Chinese—Hawshuenshan volcano—Valley of Momien—Arrival at the city | ||

|

MOMIEN.

|

||

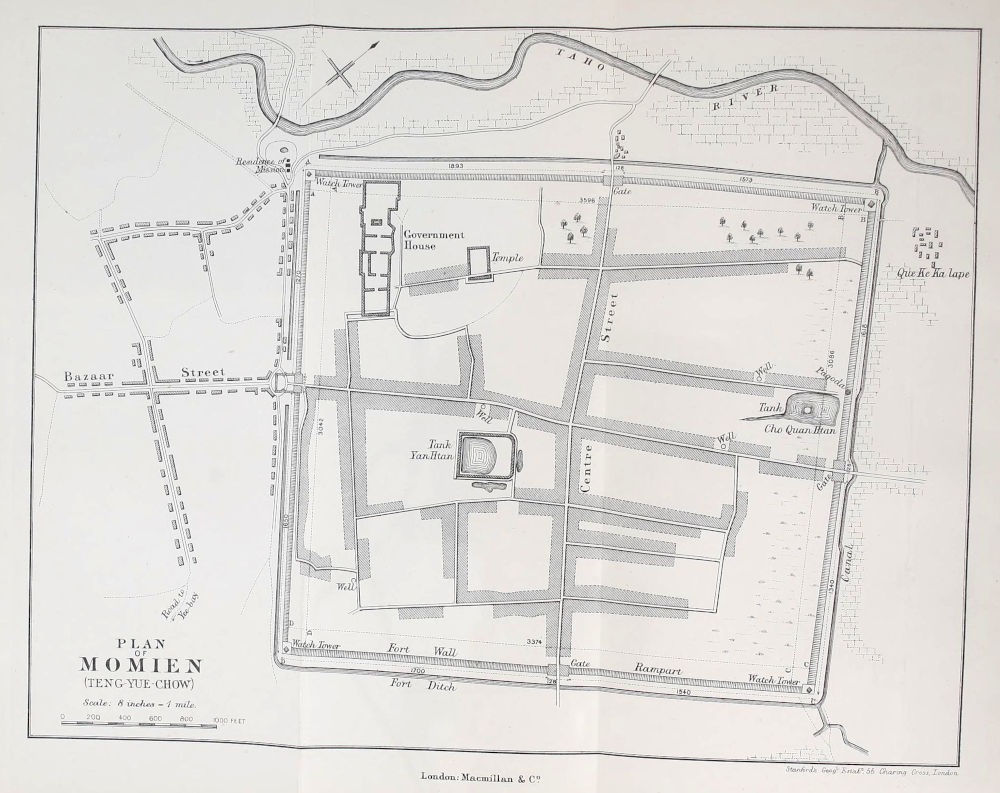

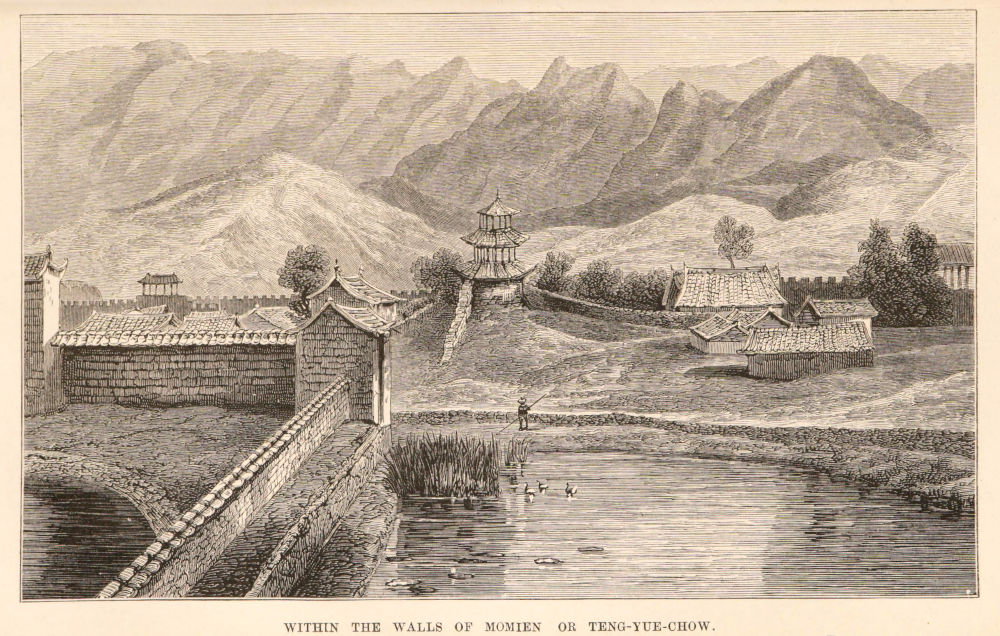

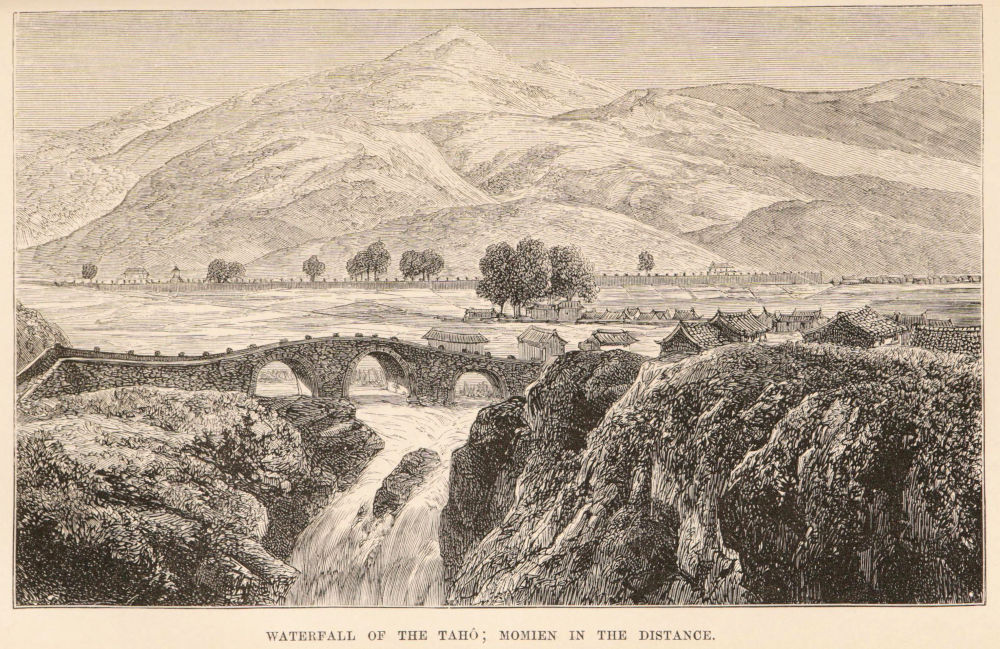

| Momien—The town of Teng-yue-chow—Aspect and condition—An official reception—Return visit—Government house—A Chinese tragedy—The market—Jade manufacture—Minerals—Mines of Yunnan—Stone celts—Cattle—Climate—Environs—The waterfall—Pagoda hill—Shuayduay—Rock temples—Ruined suburbs—City temples—Four-armed deities—Boys’ school—A grand feast—The loving-cup—The tsawbwa-gadaw of Muangtee—Keenzas—The Chinese poor | ||

|

THE MAHOMMEDANS OF YUNNAN.

|

||

| Their origin—Derivation of the term “Panthay”—Early history—Increase in numbers—Adoption of children—The Toonganees—Physical characteristics—Outbreak of the revolt—Tali-fu—Progress of revolt—The French expedition—Overtures from Low-quang-fang—Resources of the Panthays—Capture of Yunnan-fu—Prospects of their success—Our position—The governor’s presents—Preparations for return | [Pg x] | |

|

THE SANDA VALLEY.

|

||

| Departure from Momien—Robbers surprised—At Nantin—Our ponies stolen—We slide to Muangla—A pleasant meeting—The Tapeng ferrymen—A valley landscape—Negotiations at Sanda—The Leesaws—A Shan cottage—Buddhist khyoungs—For fear of the nats—The limestone hill—Hot springs of Sanda—The footprint of Buddha—A priestly thief—The excommunication—The chief’s farewell—Floods and landslips—Manwyne priests—A Shan dinner party—The nunnery—Departure from Manwyne—The Slough of Despond | ||

|

THE HOTHA VALLEY.

|

||

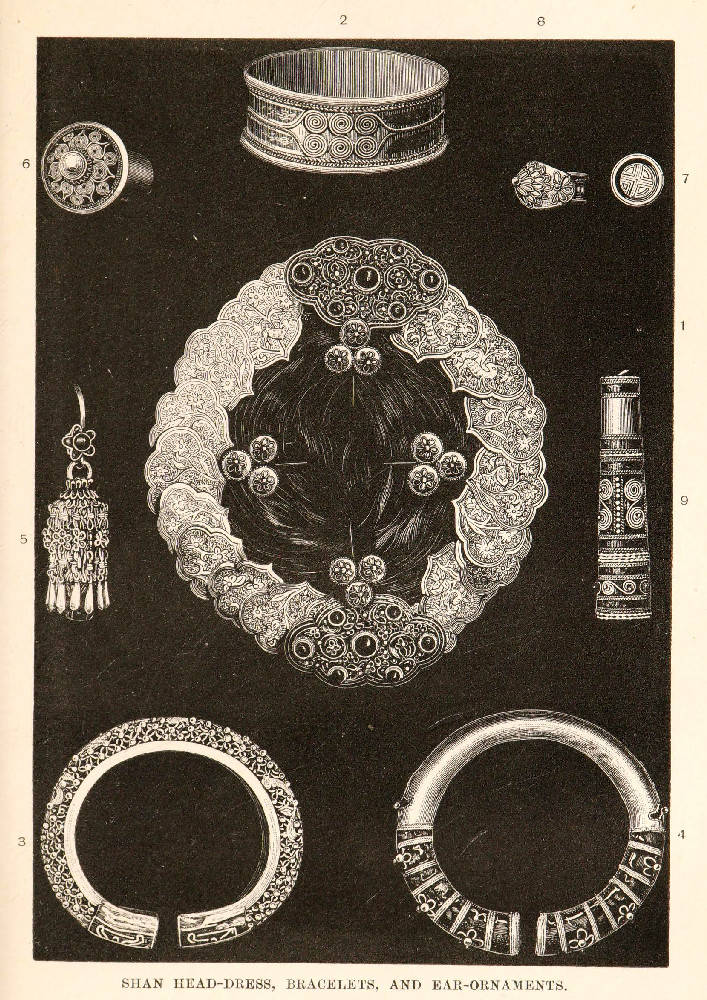

| The mountain summit—A giant glen—Leesaw village—The wrong road—Priestly inhospitality—Town of Hotha—A friendly chief—The Namboke Kakhyens—The Hotha market—The Shan people—The Koshanpyi—The Tai of Yunnan—Their personal appearance—Costume—Equipment—The Chinese Shans—Silver hair ornaments—Ear-rings—Torques, bracelets, and rings—Textile fabrics—Agriculture—Social customs—Tenure of land—Old Hotha—A Shan-Chinese temple—Shan Buddhism—The fire festival—Eclipse of the sun—Horse worship—Ancient pagodas—Roads from Hotha | ||

|

FROM HOTHA TO BHAMÔ.

|

||

| Adieu!—Latha—Namboke—The southern hills—Muangwye—Loaylone—The Chinese frontier—Mattin—Hoetone—View of the Irawady plain—A slippery descent—The Namthabet—The Sawady route—A solemn sacrifice—A retrospective survey | [Pg xi] | |

|

INTERMEDIATE EVENTS.

|

||

| Appointment of a British Resident at Bhamô—Increase of native trade—Action of the king of Burma—Burmese quarrel with the Seray chief—British relations with the Panthays—Struggle in Yunnan—Li-sieh-tai—Imperialist successes—European gunners—Siege of Momien—Fall of Yung-chang—Prince Hassan visits England—Fall of Tali-fu—Sultan Suleiman’s death—Massacre of Panthays—Capture of Momien—Escape of Tah-sa-kon—Capture of Woosaw—Suppression of rebellion—Imperial proclamation—Li-sieh-tai, commissioner of Shan states—Re-opening of trade routes—Second British mission—Action of Sir T. Wade—Appointment of Mr. Margary—Members of mission—Acquiescence of China and Burma | ||

|

SECOND EXPEDITION.

|

||

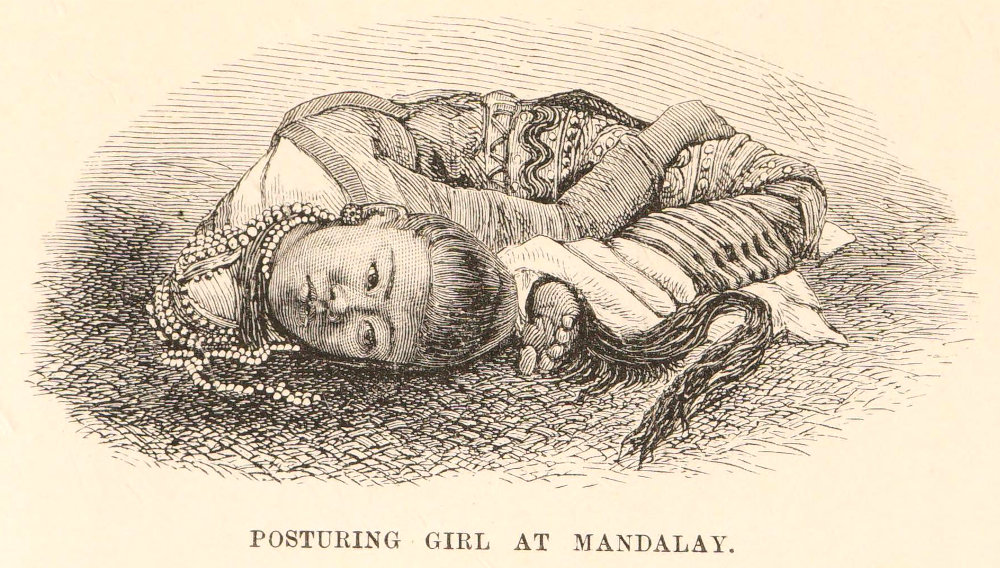

| Start of mission—Arrival at Mandalay—The Burmese pooay—Posturing girl—Reception by the meng-gyees—Audience by the king—Departure of mission—Progress up the river—Reception at Bhamô—British Residency—Mr. Margary—Account of his journey—The Woon of Bhamô—Entertains Margary—Chinese puppets—Selection of route—Sawady route—Bullock carriage—Woon of Shuaygoo—Chinese surmises—Letters to Chinese officials—Burmese worship-day | ||

| SAWADY. | ||

| The hun pooay—Mission proceeds to Sawady—Visit from Woon—Rumoured opposition—The Woon as a musician—Sawady village—Royal orders—Baggage difficulties—Arrival of Mr. Clement Allan—Paloungto chief—Kakhyen[Pg xii] pilfering—Abandon route—Adopt Ponline route—Reasons for change—Tsaleng Woon—Departure of mission to Tsitkaw—Elias and Cooke proceed to Muangmow—Dolphins—Up the Tapeng—Tahmeylon—Arrive at Tsitkaw | ||

|

THE ADVANCE.

|

||

| Residence at Tsitkaw—View from our house—The Namthabet—Junction of the rivers—Arrival of the Woon—Conference of tsawbwas—Hostages—Kakhyen women—Rifle practice—A night alarm—A curious talisman—We leave Tsitkaw—Camp at Tsihet—Burmese guard-house—Lankon, Ponline—Camp on the Moonam—Hostile rumours—Camp on the Nampoung—Departure of Margary for Manwyne—Escape of hostages—Letter from Margary—We enter China—Camp on Shitee Meru—Burmese vigilance—Visit to Seray—Conference with Seray tsawbwa—Suspicious reception—Return to camp—Burmese barricades | ||

|

REPULSE OF MISSION.

|

||

| Appearance of enemy—Murder of Margary—Friendly tsawbwas—Mission attacked—Woonkah tsawbwa bought over—The jungle fired—Repulse of attack—Incidents of the day—Our retreat—Shitee—Burmese reinforcements—Halt at guard-house—Retreat on Tsitkaw via Woonkah—Elias and Cooke’s visit to Muangmow—Li-sieh-tai—Return of Captain Cooke—Elias at Muangmow—Father Lecomte and the Mattin chief—A forged letter—The Saya of Kauntoung—Reports regarding Margary—The commission of inquiry—Return of Elias—Visit to the second defile—Mission’s return to Rangoon | [Pg xiii] | |

| A Note by Bishop Bigandet, on Burmese Bells | ||

| Origin of Mahommedanism in China; from Chinese Document | ||

| Deities worshipped by Kakhyens | ||

| Deities in a Hotha Shan Temple | ||

| Vocabularies:—Kakhyen, Shan, Leesaw, and Poloung | ||

| Index | ||

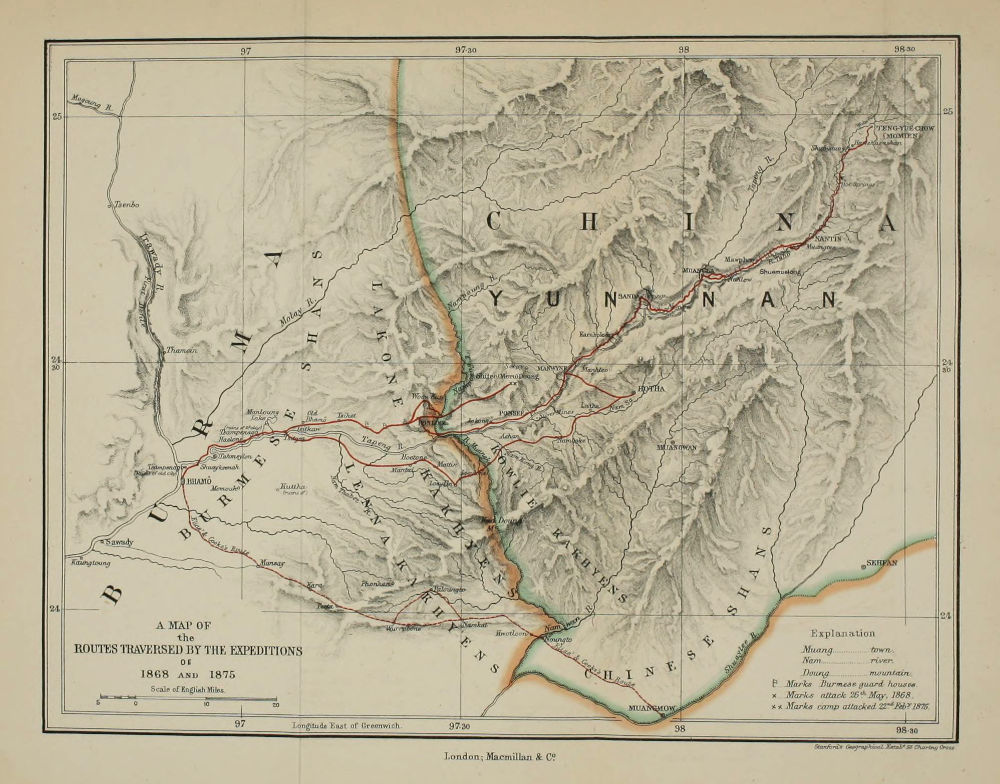

A MAP OF

the

ROUTES TRAVERSED BY THE EXPEDITIONS OF

1868 AND 1875

Stanford’s Geographical Estabᵗ 55 Charing Cross.

London; Macmillan & Cᵒ.

A MAP OF

SOUTH-WESTERN CHINA

Showing routes

TRAVERSED & PROPOSED.

Stanford’s Geographical Estabᵗ. 55 Charing Cross.

London; Macmillan & Cᵒ.

PLAN OF MOMIEN

(TENG-YUE-CHOW)

Stanford’s Geogˡ. Estabᵗ. 55 Charing Cross, London.

London; Macmillan & Cᵒ.

[Pg 1]

For some years previous to the date of the expedition of which the progress is narrated in these pages, the attention of British merchants at home and in India had been directed to the prospect of an overland trade with Western China. Most especially did this interest the commercial community of Rangoon, the capital of British Burma, and the port of the great water highway of the Irawady, boasting a trade the annual value of which had increased in fifteen years to £2,500,000. The avoidance of the long and dangerous voyage by the Straits and Indian[Pg 2] Archipelago and a direct interchange of our manufactures for the products of the rich provinces of Yunnan and Sz-chuen might well seem to be advantages which would richly repay almost any efforts to accomplish this purpose.

One plan, then as now, zealously insisted upon by its promoter, Captain Sprye, was the construction of a railway connecting British Burma and China via Kiang-Hung, on the Cambodia river, and the frontier position or reputed town of Esmok.

But as it was, and still is, necessary to send a surveying expedition over an unknown and alien country, as a preliminary, this project, whether chimerical or not, could not compete with the immediate possibility of opening a trade by way of the river Irawady and the royal city of Mandalay.

Although before 1867 but four English steamers with freight had ascended the river to the capital, harbingers of the numerous flotilla now plying on the Irawady, it was known that a regular traffic existed between Mandalay and China, especially in the supply of cotton to the interior, which was reserved as a royal monopoly.

This trade was reported to be mainly carried on by caravans traversing the overland route via Theinnee to Yunnan. According to the itineraries of the Burmese embassy in 1787, the distance is six hundred and twenty miles, and forty-six hills and mountains, five large rivers and twenty-four smaller ones, had to be traversed in the tedious journey of[Pg 3] two months. But an unbroken chain of tradition and history indicated the natural entrepot of the commerce between Burma and China to be at or near Bhamô,[1] on the left bank of the upper Irawady, and close to the frontier of Yunnan.

The Burmese annals testified that during several centuries this had been the passage from China to Burma either for invading armies or for peaceful caravans. The most recent Burmo-Chinese war had arisen out of the grievances of Bhamô Chinese merchants, and the treaty of peace that was signed at Bhamô in 1769 stipulated that the “gold and silver road” between the two countries should be reopened. Mutual embassies had consequently journeyed between Pekin and Ava, and almost all had proceeded by way of the Irawady and Bhamô.

European travellers and traders had early discerned the importance of this channel of intercourse, which seems to have been alluded to by the great Venetian, Marco Polo, under the name of Zardandan.

The old documents of Fort St. George record that the English and Dutch had factories in the beginning of the seventeenth century at Syriam, Prome, and Ava, and at a place on the borders of China, which Dalrymple supposes to have been Bhamô. According to this authority, some dispute arose between the Dutch and Burmese, and on the former threatening to call in the aid of the Chinese, both the English and Dutch were expelled from Burma. In[Pg 4] 1680 the reputation of this field for mercantile enterprise seems to have again attracted the attention of the authorities at Fort St. George, and four years afterwards one Dod, trading to Ava, was instructed to inquire into the commerce of the country, and to request that a settlement might be sanctioned at Prammoo, on the borders of China. This mission was unsuccessful, and Prammoo cannot with certainty be identified, but the strong similarity of the name seems to point to Pan-mho or Bhamô.

Coming down to more recent and certain data, we find that Colonel Symes, H.E.I.C.’s envoy to Ava in 1795 (and who was accompanied by that able geographer, Dr. Buchanan), states that an extensive trade, chiefly in cotton, existed between Ava and Yunnan. “This commodity was transported up the Irawady to Bhamô, where it was sold to the Chinese merchants, and conveyed partly by land and partly by water into the Chinese dominions. Amber, ivory, precious stones, betel-nut, and the edible birds’ nests from the Eastern Archipelago, were also articles of commerce. In return, the Burmans procured raw and wrought silks, velvets, gold-leaf, preserves, paper, and utensils of hardware.” Both the researches of Wilcox and the journal of Crawford’s embassy to Ava in 1826 referred to the trade and routes by Bhamô, and the Bengal government in 1827 published a map containing the best procurable information about the Burmo-Chinese frontier.

[Pg 5]

Colonel Burney, who was Resident at the court of Ava in 1830, published a large number of valuable contributions to the history, geography, and resources of Upper Burma, and accurate itineraries of the Theinnee and Bhamô routes to China. Our experience demonstrated the accuracy of the latter as far as Momien, and it may be inferred that the remainder will be found equally exact. Pemberton[2] seems to have been the first to fully realise that—to use his own words—“the province of Yunnan, to which the north-eastern borders of our Indian empire have now so closely approximated, has become from this circumstance and our existing amicable relations with the court of Ava an object of peculiar interest to us.” In the same year Captain Hannay accompanied a Burmese mission to Mogoung, and for the first time Bhamô was accurately described by an eye-witness, and much valuable information gained respecting the trade then carried on between Ava and China. His description of the importance of the town, however, differed widely from that of Drs. Griffiths and Bayfield, who visited it two years later.[3]

Hannay gives the reported number of houses as one thousand five hundred, while the latter travellers estimated town and suburbs as containing five hundred and ninety-eight houses, “neither good nor[Pg 6] large,” which latter description is more in keeping with the present condition of the town.

In 1848 Baron Otto des Granges published a short survey of the countries between Bengal and China, showing the great commercial and political importance of Bhamô, and the practicability of a direct trade overland between Calcutta and China.

In this paper the far-seeing author advocated the equipment of a small expedition to ascertain the mercantile relations of the country about Bhamô, to examine the mineral wealth of Yunnan, and to enter into negotiations with the Chinese merchants.

In 1862 the government of India, in the prospect of a treaty being negotiated with the king of Burma, directed their Chief Commissioner, Sir A. Phayre, to include in it, if possible, the reopening of the caravan route from Western China by the town of Bhamô, and the concession of facilities to British merchants to reside at that place, or to travel to Yunnan, and for Chinese from Yunnan to have free access to British territory, including Assam. The first of these objects was to be effected by obtaining the king’s sanction to a joint Burmese and British mission to China. A treaty was concluded whereby the British and Burmese governments were declared friends, and trade in and through Upper Burma was freely thrown open to British enterprise. It was further stipulated that a direct trade with China might be carried on through Upper Burma, subject to a transit duty of one per cent. ad valorem on[Pg 7] Chinese exports, and nil on imports. The proposal, however, as to the joint mission was unsuccessful.

In the following year, Dr. Williams, formerly resident at the court of Mandalay, obtained the royal permission to proceed as far as Bhamô, where he arrived in February, after a journey of twenty-two days. His object was to test the practicability of a route through Burma to Western China, and the results of his experience led him to strongly advocate the Bhamô routes as politically, physically, and commercially the most advantageous.

His energetic advocacy led the mercantile community of Rangoon to appreciate the importance of their own position, commanding, as it does, the most ancient highway to Western China. His claim, however, to have been the first to suggest this trade route must yield to that of Otto des Granges; and the assertion that he was the first Englishman who visited Bhamô could only have been made in ignorance or forgetfulness of the labours of Hannay, Bayfield, and Griffiths.

When the commercial acuteness of the merchants was thus directed to the possibilities of the overland trade, it might seem at first sight that the stream could be tapped at Mandalay without following it up to the borders of Yunnan.

But our growing intercourse with the capital of Burma made it known that for twelve years the Burmo-Chinese trade via Bhamô, which in 1855 represented £500,000 per annum, had almost entirely[Pg 8] ceased. Whether this were owing to the effects of the Mahommedan rebellion in Yunnan, or, as some alleged, to Burmese policy, was uncertain. It was an additional problem, and the then Chief Commissioner, General Fytche, anxiously pressed upon the government of India the importance of solving it, and under the treaty of 1862 of thoroughly examining the possibility and probable results of reopening the Bhamô trade route.

This enterprise might be deemed one of hereditary interest to the descendant of that enterprising merchant-traveller, Mr. Fitch, who has left an account of his visit to Pegu in 1586. The proposed expedition was sanctioned by the government of India in September 1867, and the consent of the king of Burma having been duly obtained, arrangements were forwarded for the departure of the mission from Mandalay in January 1868. The chief objects of the expedition were, to use the words of General Fytche, “to discover the cause of the cessation of the trade formerly existing by these routes, the exact position held by the Kakhyens, Shans, and Panthays, with reference to that traffic, and their disposition, or otherwise, to resuscitate it, also to examine the physical conditions of these routes.”

Thus the duties to be discharged were multifarious, pertaining to diplomacy, engineering, natural science, and commerce. These accordingly were all represented among the members of the mission, which consisted of Captain Williams, as engineer; Dr.[Pg 9] Anderson, as medical officer and naturalist; with Captain Bowers and Messrs. Stewart and Burn as delegates from the commercial community of Rangoon.[4] A guard of fifty armed police, with their inspector and native doctor, formed an escort, while the command of the whole was entrusted to Major Sladen, Political Resident at Mandalay. It is saying scarcely enough to add that to the foresight, tact, and resolute patience displayed by him as leader was due whatever measure of success was obtained. He had already secured not only the consent but the co-operation of the king. Written orders had been despatched to the woon, or governor, of Bhamô, and to other places, to render all assistance. Besides these verbal aids, the king placed at his disposal a royal steamer, named the Yaynan-Sekia, better known as “The Honesty,” to convey the party to Bhamô. On no former occasion had it been deemed prudent for steamers to ascend save for a few miles above Mandalay; and great difference of opinion existed as to the navigability of the upper Irawady in the dry season by a steamer, though only drawing three feet of water.

In the morning of January 6, 1868, the steamer Nerbudda, which had conveyed the party from Rangoon, made fast alongside the landing-place of[Pg 10] the present capital of Burma, three miles from the city, of which only the golden spires could be seen above the trees. As our stay was not to exceed three or four days, all the party remained on board until it should be time to embark on the Yaynan-Sekia. Beyond a jetty used by the Burmese in the floods, lay the royal steamer undergoing thorough painting and cleaning for our reception. She was moored in a creek, the royal naval depot, where numerous war-boats of the past and the present fleet of royal steamers are laid up in ordinary. For nearly three miles the river banks presented a busy scene. Native boats were loading or discharging cargo; houses extended the whole distance, those nearer the river being tenanted by fishermen. A large suburb stretched inland from the shore; each house was surrounded by a vegetable garden enclosed in a bamboo fence eight to ten feet high, while all were embosomed in magnificent tamarind, plantain, and palm trees. The women were busily engaged weaving silk putzos and tameins in various patterns.[5] Beyond this suburb lay a large flat of alluvial land, devoted to rice fields, some in stubble, from which the grain had just been reaped; in others men and women were irrigating the young[Pg 11] crop, now about six inches high, three crops yearly being raised from these lands, which formed, as it were, an island of cultivation, surrounded by houses.

The leader of the expedition, Major Sladen, came down to welcome us, and we rode with him to the Residency, situated on the banks of a canal, which runs parallel with the river, and halfway between it and the city. The bank of the canal is lined with houses, and broad streets lead to the city, over numerous strongly built timber bridges, the only defect in which is that the alluvial banks of the canal frequently give way, to the destruction of the bridges and interruption of the traffic. Our road lay through a populous suburb of houses built of teak and supported on piles. To the right lay a quarter occupied by the demi-monde; to the left numerous khyoungs, or monasteries, reared their graceful triple concave roofs. Phoongyees, or Buddhist monks, abounded; so did pigs and dogs, both of which are fed daily by a dole from the king, who, as a pious Buddhist, lays up a store of good works by thus preserving animal life. These ubiquitous pigs have given rise to a well-known saying, which tersely expresses the first impression made on the European visitor by the precincts of the capital. Our stay was too short to admit of more than a flying visit to Mandalay, its palace and countless pagodas.

The city properly so-called lies about three miles from the Irawady, on a rising ground below[Pg 12] the hill Mandalé. It was founded, on his accession in 1853, by the present king; and one of his motives for quitting Ava, and selecting the new site, was to remove his palace from the sight and sound of British steamers. The city is built on the same plan as the old capital, described by Yule, and consists of two concentric fortified squares. The outer is defended by lofty massive brick walls, with earthworks thrown up on the inside. There are four gates, over each of which rises a tower with seven gilded roofs. Similar smaller towers adorn the wall at intervals. A deep moat fifty yards broad has been completed since the date of our visit, and now surrounds the walls. During the night, guard-boats, with gongs beating, patrol its waters. When the king, in compliance with a prophecy, was crowned a second time in 1874, he made the circuit of the city in a magnificent war-boat, the splendour of which eclipses the traditionary glory of the Lord Mayor’s barge. The actual ceremony of the re-coronation took place on the 4th of June, at 8 P.M., the hour pronounced propitious by the court of Brahmins.[6] Captain Strover describes the ceremony as being to a great extent private, only the various ministers of state and about eighty Brahmins being present. Incantations and sprinkling of holy water brought from the Ganges formed the chief[Pg 13] part of the ceremony, after which his majesty was supposed to have become a new king, barring the difficulty of years. Seven days afterwards, the king went through the ceremony of taking charge of the royal city. At nine in the morning a gun announced that he had left the palace, and at half past another was fired, intimating that he had entered the royal barge. The procession round the city moat commenced from the east gate, and was led by the two principal magistrates of Mandalay in gilded war-boats; then followed all the princes in line, a short way in front of the state barge, and behind the king came the ministers and officials. Troops lined the walls all round the city, and cannon were placed every here and there at the corners of the streets. Bands of music played as the procession passed, and, altogether; the sight was most effective and unique. Having gone right round the city, he left the royal barge at the east gate, and a salute announced that he had re-entered the palace, and the ceremony was finished. According to his majesty’s own statement, the ceremony was a purely religious act.

The first square is inhabited by the officials, civil and military, and the soldiers of the royal army. All the houses are in separate enclosures, bordering broad, well kept streets; along the fronts is carried the king’s fence, a latticed palisade, behind which the subjects hide themselves when his majesty passes. During the day, stalls are set up in the streets, and the various Burmese necessaries, even to cloth, are[Pg 14] sold, but at night all are cleared away and the gates closed. The central or royal square is surrounded by an outer stockade of teak timber twelve feet in height, and an inner wall. Entrance is given by two gates opposite each other, opening into a wide place, containing the government offices and the royal mint, on one side; on the other, a wall runs across, and a large gateway, opened only for the king, and a small postern give access to the palace enclosure. All Burmese entering this take off their shoes. Within is a wide open area, as large as a London square. On the opposite side rises a building crowned by nine roofs richly gilded, and surmounted by a golden htee, or umbrella, with its tinkling coronal of bells. This marks the audience hall. All entering this are required to take off their shoes, for the royal abode is sacred. The same rule applies to all temples, and this unbooting is really a mark of religious respect, due as much to the meanest khyoung as to the residence of the king. This fact perhaps, if borne in mind, might soothe the ruffled feelings of those who see in this unbooting a mark of degrading homage. To the left is the abode of the white elephant, which, it may be said, is scarcely distinguishable from any other elephant save by the paler hue of the skin of the head. To the right is the royal arsenal, outside of which the visitor would be now surprised by the sight of a completely armed and equipped deck of a vessel, which serves as a school for naval gunnery.

[Pg 15]

We were not admitted to an audience, nor did we see the royal gardens, which, with the other palace buildings, lie to the rear of the central hall. Dr. Dawson, as quoted in Mason’s ‘Burmah,’ describes the gardens in glowing language, as “truly beautiful, and as picturesque as they are grand.” Outside the walls of the city the suburbs, or unwalled town, stretch away southward in broad streets, which converge towards the Arracan pagoda; and in the distance the spires of pagodas mark the site of Amarapura.

It is impossible to estimate the population, but it must exceed one hundred thousand, to judge by the extent of ground covered by houses. Between the city and Mandalay hill numerous khyoungs have been erected by the queens and other members of the royal family, the teak pillars and roof timbers of which are magnificently carved and richly gilt.

In passing through the enclosures of these monasteries, it is necessary for equestrians to dismount and walk slowly through the sacred precincts. On this side also there is a large stockaded enclosure, to which the Shan caravans always resort. Here their wares, principally hlepét, a sort of salted tea—not, however, made from the true tea plant[7]—are disposed of by means of brokers. At the foot of Mandalay hill is a temple with a large seated statue of Buddha, carved from the white marble of the Tsagain hills. The[Pg 16] hill itself is crowned by a gilded pagoda, and a statue of Buddha. The Golden King stands with outstretched finger pointing down to the golden htee that marks the royal abode, the centre of the city and of the Burman kingdom.

On the hill is a vast colony of fowls, numbers of which are purchased by the royal piety every morning, and maintained at the king’s expense. The eastern side of the city is skirted by a long swamp, which forms a lagoon in the rains. The Myit-ngé river, six miles to the south, may be said to complete the insulation of the environs of the capital. Not far from the Residency, but on the other side of the canal, there is a large bazaar, enclosed with brick walls, which presents a most busy scene. This may be said to be the principal enclosed market-place; but there are other smaller cloth bazaars; and several quarters or streets are occupied by special trades, a very noisy quarter being that of the gold-beaters. The fondness for gilding which characterises the Burmese causes an immense demand for gold-leaf, the gold used being principally brought by the caravans from Yunnan. Another quarter is tenanted by Chinese. By a curious coincidence, on the day of our arrival, a Chinese caravan of two hundred mules arrived from Tali-fu. They had come by the long overland Theinnee route, bringing hams, walnuts, pistachio-nuts, honey, opium, iron pots, yellow orpiment, &c. We noticed many Suratees among the inhabitants[Pg 17] of the city. These acute and enterprising traders come to Burma in great numbers, and are found everywhere busily engaged in money-making. European adventurers of various nationalities form an element in the population, small, but mischievous; it is hardly to be wondered at if an ill impression of kalas[8] is formed by the Burmese nobility and gentry, judging from the conduct of some of these foreigners; while again they spread monstrous reports about the king, his social and political habits and ideas, which find their way into the Indian and English press.

The transshipment of ourselves and followers and baggage was duly effected, and in the afternoon of the 18th of January the Yaynan-Sekia left her moorings. We only proceeded as far as Mengoon, on the right bank, a few miles from the capital. Thus far we had the company of Mr. Manouk, an Armenian gentleman, who held the office of kala woon, or foreign minister. We duly visited the huge ruin of solid brickwork, which, as Colonel Yule says, represents the extraordinary folly of King Mentaragyi, the founder of Amarapura in 1787.

Intended for a gigantic pagoda, it was left unfinished, in consequence of a prediction that its completion would be fatal to the royal founder; the earthquake of 1839 split the huge cube of solid brickwork, and it is now a fantastic ruin.

Yule gives the dimensions of the lowest of the five[Pg 18] encircling terraces as four hundred feet square; if completed, the whole edifice would have been five hundred feet high. Near this is the great bell, twelve feet high, and sixteen across at the lips, and weighing ninety tons.[9]

The most interesting object is the Seebyo pagoda, built by the grandson and successor of Mentaragyi in 1816, and named after his wife. The substructure from which the pagoda rises is circular, and consists of six successive concentric terraces. Each terrace is five feet above the one below, and six feet in breadth, and is surrounded by a stone parapet of a wavy design. In the niches of each terrace are images, fabulous dragons, birds, and beloos, or monsters. By a rough measurement the walled enclosure is four hundred yards in circumference, but an open space of thirty-five yards deep intervenes between the wall and the first terrace. The design of the pagoda is intended to represent the mythical Myen Mhoo Doung, or Meru Mountain, the central pillar of the universe, and the seven encircling ranges of mountains, or the six continents, each of which is guarded by a monster, the first by the dragon, the second by the bird Kalon. It might be also suggested that those terraces may represent the six happy abodes of nats which form successive Elysiums below the seat of Brahma.

From the rising ground above Mengoon a magnificent panorama unfolds itself: the valley from the[Pg 19] dry and treeless Tsagain hills, a few miles to the rear, spreads out for fifteen miles in width to the eastern line of mountains, which, emerging from the north bank of the Myit-ngé, stretch away as far as the eye can reach to the north-east. The long flowing sweep of these summits singularly contrasts with the irregularly peaked outline of the Myait-loung hills, south of the Myit-ngé. Immediately beneath the spectator, the Irawady, curving under the western hills, broadens, till opposite to the capital its main banks are nearly three miles and a half apart.

The river is broken up into channels by large islands, on one of which the royal gardens are situated, and numerous sandbanks, exposed in the dry season, and cultivated with tobacco and other crops. In the foreground the various channels of the splendid river present an animated spectacle of numerous canoes, timber rafts, and boats of every form and size. In the middle distance, the golden roofs of the city gates and of the many monasteries which cluster outside the red city walls flash back the sunbeams. The fantastic forms of the many roofed spires of the zayats and rest-houses, and the sparkling htees of pagodas, everywhere perplex and please the eye, which looks from the picturesque hill to the north, crowned by the gilded temple, to the irregular outlines of the bazaar, stretching far down to the successive line of the abandoned capitals. A glorious picture, especially when the[Pg 20] glowing orange tints of sunset are relieved by the rich purple of the cloudlike distant hills!

From Mengoon the steamer made its unaccustomed way under the right bank, passing sandbanks covered with numerous flocks of whimbrel, golden plover, and snake-birds. Although at the present time both royal and private steamers ply regularly between Mandalay and Bhamô, at the dry season frequent delays, caused by grounding on sandbanks, make the upward voyage of very uncertain duration. We as the pioneers had to feel our way most cautiously, the water being very low. Our crew, from captain to firemen, were to a man Burmese, and great was our admiration of the coolness and skill shown by the skipper in navigating the narrow channels; he seemed to have an almost instinctive intuition of the depth of the water. It was no work of love on his part, as he took no pains to disguise his dislike of the kalas, or foreigners, and was devoid of the jovial openheartedness generally characteristic of Burmese. A rich illustration of the character of the Burmese crew was afforded us by the leadsman, who quitted his post, unobserved by the captain. He provided, however, for the navigation, by telling one of his fellows to sing out for him in his absence, and imaginary depths, varying several feet, were accordingly shouted at intervals to the unconscious captain, who steered accordingly—fortunately without mishap. A court official accompanied us to see that the orders for provision of[Pg 21] firewood were duly obeyed, and to purvey boats in case of the river proving unnavigable; but as no difficulties arose, he had nothing to do save that he once showed his zeal by inflicting an unmerciful beating on a village headman who failed to supply milk.

The banks of the river presented a succession of picturesque headlands, fifty to sixty feet high, separated by luxuriant dells, each containing a village. Between two such heights, covered with pagodas accessible only by flights of steps, lay Shienpagah, a thriving town of some four hundred houses. A brisk trade is here carried on in fish and firewood for the capital, and salt procured from the swamps behind the sterile Tsagain hills.[10] Above Shienpagah we changed our course to the other side. The villages on the eastern bank seemed small and few, each embowered among tall trees and groves of palmyra, mixed with a few cocoa-nut palms, relieved by the bright, pale, tropical green of the plantain. A broad alluvial[Pg 22] flat extended to the low broken ranges of the Sagyen and Thubyo-budo hills, from the former of which comes nearly all the marble used in Mandalay. The distant Shan mountains rose beyond another plain sparsely covered with lofty trees and richly cultivated.

Our course lay up a channel, skirting the long island and town of Alékyoung, till the rounded hill of Kethung, dotted with white pagodas, rose over the dense greenery in which nestled the village so called. On the opposite bank lay Hteezeh, the village of oil merchants. A belt of bright yellow sand, and then a fine green sward, led up from the river to the village, shaded by noble palmyras and gigantic bamboos, which formed a background to a river scene of exquisite colouring and beauty. A mile or two above Alékyoung, the river narrowed, flowing in a stream unbroken by islands or sandbanks. Soon the short well wooded Nâttoung hills abutted on the right bank, in a pagoda-crowned headland, with Makouk village at its base. On the opposite side, the small town of Tsingu, once fortified, and still showing fragments of the old walls, occupied another headland, marking the entrance of the third defile of the Irawady.

From this point, for thirty miles, as far as Malé and Tsampenago, the country on either bank is hilly, and covered to the water’s edge with luxuriant forest. Winding in a succession of long reaches, the river presents a series of lovely lake landscapes. The[Pg 23] stream, one thousand to fifteen hundred yards wide, flows placid and unbroken, save by the gambols of round-headed dolphins. As, preceded by long lines of these creatures, we steamed slowly along, each successive reach seemed barred by wooded cliffs. Reminiscences of the lake scenery of the old country were vividly awakened as we passed from one apparently land-locked scene of beauty to another. The high irregular hills were clothed with forest trees almost hidden by brilliant orchids and gigantic pendant creepers. Palms of various kinds feathered the water’s edge. Here and there fishing-villages peeped out, and everywhere graceful pagodas and priests’ houses gleamed amid the foliage. Parroquets darted and hornbills winged their heavy flight across the stream, while chattering troops of long-tailed black monkeys escorted the unusual visitors along the banks.

The chief object of interest is the little rocky island of Theehadaw, which boasts the only stone pagoda in Burma, and is resorted to by numbers of pilgrims at the great Buddhist festival in March. The pagoda is of no great size, but is substantially built of greyish sandstone admirably cut and laid in mortar. The building rises from a quadrangular base, with a chamber facing the east and closed with massive doors. The three other faces have false doors, and the sides of all, as well as the angles, are adorned with quasi-Doric pilasters. Our attention, like that of most pilgrims, was chiefly given to the famous tame[Pg 24] fish. Having supplied ourselves with rice and plantains, the boatmen, called “Tit-tit-tit.” Soon the fish appeared, about fifty yards off, and after repeated cries, they were alongside, greedily devouring the offering of food. In their eagerness they showed their uncouth heads and great part of their backs, to which patches of gold leaf, laid on by recent devotees, still adhered. So tame were they that they suffered themselves to be stroked, and seemed to relish having their long feelers pulled. One fellow to whom a plantain skin was thrown indignantly rejected it, and dived in disgust.

For three miles above and three below the island fishing is prohibited by royal order, and the priests, who feed them daily, assured us that the fish never stray beyond the boundaries of their sanctuary. An offer of fifty rupees failed to secure a single specimen, but it may be here told that on another occasion, under cover of night, and without Burmese observation, one was hooked, and, though not easily, landed, photographed, and duly preserved. Two miles above the island we stopped at Thingadaw to coal. This is a depot for the produce of the coal mines, which having been accidentally discovered by some hunters were being worked by the king.

We set out to visit a newly opened mine, said to be two miles distant, but failed to find it after a walk of two hours over a broken undulating country covered with dense tree and bamboo jungle. The soil is poor and sandy, save in hollows, which[Pg 25] afford good grazing to ponies and cattle. Fossilised wood abounds all over the surface, and soft white and reddish sandstones crop out, so soft that the cart wheels cut them into deep ruts. In these places the surface presented a remarkable appearance, being covered with symmetrical pillars of soft reddish sand, two inches high, and capped by a hard ashen-grey top of the consistence of stone, and as large as a penny piece. The little pillars in many places had crumbled away, and the soil was strewed with the little caps, giving it the appearance of an ash heap. In a later visit to the coal district, made from Kabyuet, a little south of Theehadaw, we had the assistance of the headman of the mines, who was most anxious to show us everything and secure a good report to the king.

At the first mine, called Lek-ope-bin, five miles from the river, the coal-bed, six feet thick, crops out in a hollow, and dips south-west at an angle of thirty-five degrees. A little to the north-east is the Ket-zu-bin mine, said to yield the best coal. During our visit a few men were quarrying the coal with common wood axes and wooden-handled chisels, so that they could only win a small quantity of broken coal. Under proper management these mines could give an abundant supply of useful fuel. We learned that the sand of an adjacent stream is washed for gold, and a single worker can make 303 yuey = 3s. per diem.

The black sand of the Pon-nah, a stream falling[Pg 26] into the Irawady, is also washed for gold, which it is said to yield in large quantities at a place two days’ journey up the stream.

On the 17th of January, we reached the northern entrance of the defile, marked by two prominent headlands—the western one crowned by the pagoda of Malé, or Man-lé, formerly Muang-lé, and the eastern by those of the old Shan town of Tsampenago, above which none but Chinese could formerly trade.[11]

Malé contains about three hundred houses, and is the customs port for clearing boats bound from Bhamô to Mandalay, and the centre of a considerable trade in bamboo mats, sesamum oil, and jaggery. From it we beheld rising to the eastward the fine peaked mountains of Shuay-toung, about six thousand feet high, on which snow is said to lie in the winter.

Above Malé the river widens to a great breadth, with numerous islands, as far as Khyan-Nhyat. Thence it contracts to an unbroken stream about one hundred yards wide, flowing for twenty-two miles between high, well wooded banks.

Having halted at Tsinuhat, a little village to the south of a long promontory, on which are the ruins of Tagoung and Old Pagan, we made a short excursion to the sites of these ancient capitals. According to the Burmese chronicles, Tagoung was founded by Abhi-rája—of the Shakya kings of Kappilawot—who fled before the invasion of his[Pg 27] country by the king of Kauthala or Oudh. After the death of Abhi-rája the succession was disputed by his two sons. They agreed that each should endeavour to construct a large building in one night, and that the crown should belong to him whose building should be found completed by the morning. As usual in legends, the younger son outwitted the elder. He artfully set up a framework of bamboos and planks, covered with cloth and whitewashed over, so as to present the semblance of a finished building. The elder brother, believing himself to have been vanquished by the aid of nats or demons, migrated to Pegu, and finally settled in the city of Arracan (Diniawadee).

The younger son assumed the throne at Tagoung, and was succeeded by thirty-three kings. An inroad of Tartars and Chinese, said to have come from Kandahar,[12] destroyed the city and expelled the last of the dynasty, who had married Nagazein, whose name indicates one of the mythical serpent race. This event may be referred to the century preceding the Christian era, and, according to the late Dr. Mason, must have occurred after the Tartar conquest of Bactria.[13]

[Pg 28]

After the death of the Tagoung king, one portion of his people migrated eastwards and founded the Shan states. Another, under the widowed queen Nagazein, settled on the river Malé. After the advent of Gaudama and the second overthrow of the cities of the Shakya kings, one of their race, named Daza-Yázá, migrated to Malé, and, having there found and married Nagazein, founded Upper or Old Pagan. A dense forest of magnificent timber and thousands of seedling eng trees surrounds and covers the sites and ruins of the ancient cities, of which nothing now remains but low lines and shapeless masses of brickwork. Near them stand pagodas of later date, still in tolerable preservation. Of the most ancient within the bounds of Old Pagan, only a single wall remained, behind a seated Buddha eight feet high. From the former we obtained small metal images of Buddha, and from the pagoda in Old Pagan bricks bearing in relief an image of Gaudama as the preceding Buddha. One of these was exactly the same as that described by Captain Hannay. Each bears an inscription in the old Devanagari character, beginning, “Ye Dhammá.”

The ancient name of Tagoung is now borne by a little fishing-village of forty houses. At the time of our passage the villagers were located in temporary huts on a long sandbank, and busily engaged in preparing ngapé or mashed salt-fish. The fishing stakes were fixed athwart a deep narrow channel separating the sandbank from the village. Such[Pg 29] fishing-stations are numerous all along the river. Every morning large quantities of fish are taken, and sold by weight to the makers of ngapé. The fish, when cleaned, are packed between layers of salt and trodden down by the feet in long baskets lined with the leaves of the eng tree. While this narrative was being prepared for the press, a suggestion was made in the columns of a most able weekly paper that in the event of difficulties with Burma the Viceroy of India should prohibit the exportation from British Burma of ngapé, “which must be imported from the seaboard.” Undoubtedly there is a large exportation from our territories, but the fish composing that curious Burmese condiment, which, as Yule says, resembles “decayed shrimp paste,” are caught in the Irawady. The upper river teems with fish; fourteen species[14] were purchased by us at Tagoung, and the numerous fishing-villages could probably render the capital independent of the supply from British Burma.

The Shuay-mein-toung hills, on the right or western bank, opposite Tagoung, are very high, and wooded to their summits, with white pagodas peeping out amidst the dense foliage. A few miles to the north they recede from the river, where, on the[Pg 30] eastern bank, the isolated range of the Tagoung-toung-daw, about twenty miles long and one thousand feet high, runs almost parallel to the river, in its intervening valley six miles wide. The Irawady is here studded with large islands, covered with long grass and forest trees; during the rains they are submerged, and become very dangerous to descending boats. A serpentine course, following a broad deep channel to the east of the large island of Chowkyoung, brought us to the town of Thigyain on the right bank, opposite to the village of Myadoung on the left. This latter gives its name to the district south of Bhamô. Here we were startled by the news that the Woon of Bhamô, to whom we were accredited, had been killed during a riot at Momeit, about thirty-six miles south-east of Myadoung. The Woon had proceeded thither with a force of three hundred men to collect taxes, when the Shans and Kkahyens broke out into revolt and surrounded the royal troops, many of whom, with their leader, had been killed. It was impossible not to feel a presentiment that this untoward event would prove a source of delay, by compelling us to deal with subordinates who would be timid, even if well disposed to assist. We passed, hidden by an island, the mouth of the Shuaylee, three miles above Myadoung, and halted at Katha, on the right bank, the largest place met with since Shienpagah. It is a long town, containing at least two hundred well-built timber houses, disposed in two parallel streets,[Pg 31] and surrounded by bamboo palisades with three gates. It is the head-quarters of the woon of a considerable district, inhabited by Shan-Burmese. Long hollows of rich alluvium cultivated for rice, and closed in by undulating land covered with valuable forest trees, including teak, separate the town from the western hills. Some cotton is grown and tobacco largely raised on the islands and sandbanks. At the time of our visit, a number of Shan merchants had arrived with salted tea-leaves and other commodities. A few Yunnan Chinese, who had probably come down the Shuaylee, were also in the town. The people seemed well-clad and well-to-do, and the women were busily employed in weaving and preparing coloured cotton yarns for the manufacture of putzos and tameins.

A dense morning fog delayed our departure from Katha, and the whole population of the town swarmed on board the steamer. After satisfying their curiosity with the novelties of machinery, &c., we bethought ourselves of amusing them with a magnetic battery. At first all held back, but a few more venturous spirits leading the way, the operators were speedily besieged by eager candidates for a shock. The grimaces of each patient produced shouts of laughter. The good-humoured Shans discovered or fancied that the shock was good for would-be parents; some coaxed their timid wives to the front, while the matrons brought up their pretty young daughters to obtain a share of the[Pg 32] benefits going. Above Katha the river is broken up by large islands into tortuous, deep, and narrow channels. Large flocks of geese kept passing us for nearly an hour, and the sandbanks and shores of the islands were covered with varieties of wild ducks. As evening closed in, at Shuaygoo-myo, immense flocks of Herodias garzetta, or the little egret, were seen roosting in the tall grass and on the high trees, which seemed illuminated by their white forms.

In this neighbourhood we saw several villages deserted for fear of the Kakhyens, who had occupied some of the abandoned houses.

Two of our party set out to visit and make their first acquaintance with those wild highlanders, who reminded them of the East Karens; they were civil, but declined an invitation to the steamer, pleading that they must rejoin their chief, but really fearing reprisals from the Burmese. Of their kidnapping habits, several proofs were given, one being in the person of a boy of Chinese extraction, who had been sold by them to the village headman for twenty-five rupees. At our departure in the morning, young women and boys raced along the river-side, keeping up with us, to secure protection from the hillmen on the way to their villages. We were also informed that the priests’ pupils who collected food from village to village were obliged to creep along under the high banks to escape the kidnappers. Subsequent experience has shown that the villagers on the eastern shore, as far as Bhamô, are in the[Pg 33] habit of sleeping in boats moored in the river; only thus can they be secure from the nocturnal raids of their dangerous neighbours.

Leaving Shuaygoo-myo, we passed the large island of Shuaybaw, with its thousand pagodas, their bright golden htees strikingly contrasting with the rich green massive foliage, above which they rose. The great pagoda is about sixty feet high, enclosed on two sides by a richly carved zayat of teak with an elaborately decorated roof, and a cornice of small niches, containing seated marble Buddhas. Two broad paved ways, one known as the Shuaygoo-myo and the other as the Bhamô entrance, approach the pagoda, which is three quarters of a mile distant from the river. Numerous zayats cluster round the central shrine, piled to the ceiling with Buddhistic figures in metal, wood, and white marble, offered by the worshippers who yearly throng this holy place sanctified by the footprint of Gaudama.

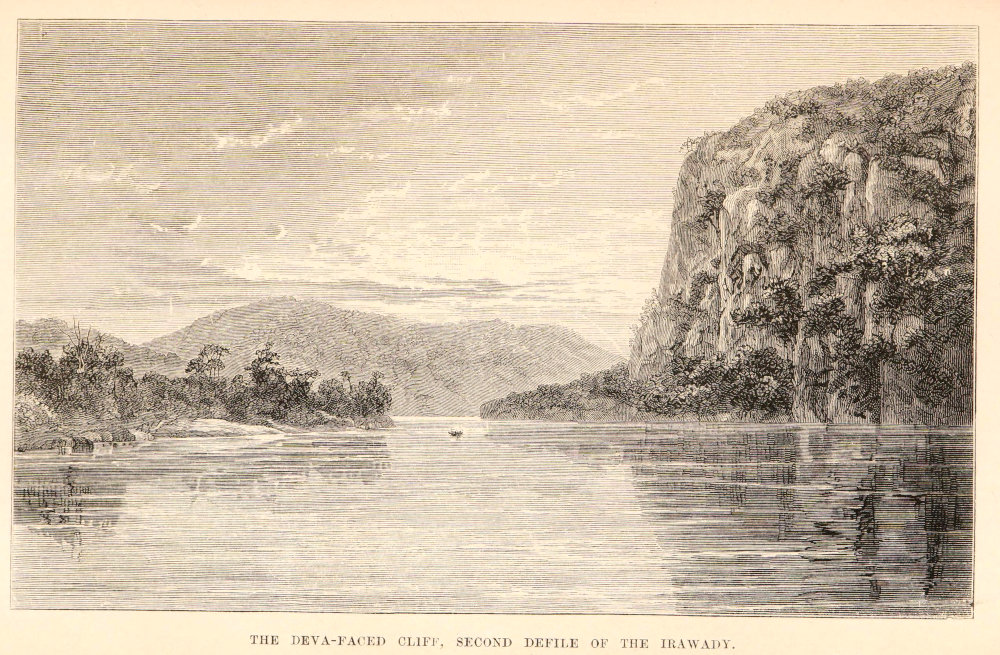

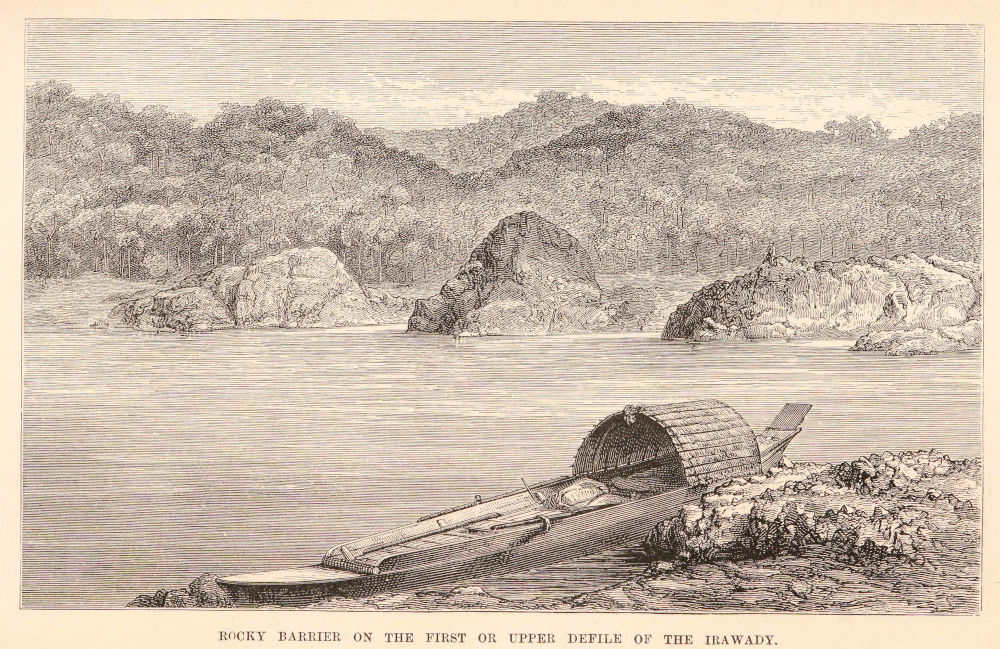

Three miles above the island is the entrance to the second defile, where the Irawady flows through a magnificent gorge piercing a range of hills at right angles. For five miles the deep dark green current, narrowed to three hundred yards, but deepening to one hundred and eighty feet and more, is overhung by gigantic precipices. Their summits are mostly covered with scanty stunted trees, but some rise bare, with splintery peaks, and red, rocky escarpments; lower down their bold sides are mantled in dark green forest, picked out here and there with the[Pg 34] fresher green of festooned clumps of bamboos, palms, and luxuriant musæ. Little fishing-villages enclosed in bamboo palisades lie snugly in the hollows. Entering the defile, we rounded a many-peaked hill on the left bank, which rose precipitously four hundred feet, its outline broken by huge black rocks standing out against the blue sky. The little white pagoda of Yethaycoo, in front of a cave, and dominating a grey limestone precipice one hundred and fifty feet in height, looked across the gorge to a phoongyee’s house perched on high, and accessible only by bamboo ladders. The most striking feature was the great limestone precipice which rose like a gigantic wall eight hundred feet from the water’s edge. This is the Deva-faced cliff celebrated in the mythical history of Tsampenago. At its base the little pagoda of Sessoungan was perched on a detached pyramid of limestone embowered in fine trees. During the March festival many devotees scale the long bamboo ladders which form the only access to the shrine. The Buddhist love for preserving animal life is here manifested towards the large monkeys (Macacus assamensis, M’Lelland), which, like the tame fish, come when called, and devour the offerings of the devotees. Projecting and depending from the precipice were huge masses of stalagmite formation, seemingly liable to fall at any moment. Water was dripping over them, and the natives say that during the rains the water pours over the face of the precipice in a tremendous[Pg 35] cascade, the roar of which is deafening. It may well be so, for the echoes in the defile are most wonderful, echoing and re-echoing in almost harmonious reverberations. In the earliest morning the loud shouting of the hoolock monkeys in the forest made the whole air resonant, as it was taken up by another troop on the opposite bank, and echoed along the hills and from cliff to cliff in a constant wave of sound, curiously blended with which rang the shrill crowing of jungle cocks. As the sun rose higher, a deep bass was supplied by the hum of innumerable bees, whose pendant nests thickly studded the rocky projections of the precipice. At the next turn of the river another pagoda, with a handsome many-roofed zayat by its side, high on the western hills, marked the northern entrance of the defile, and we soon passed the ancient mart of Kaungtoung, celebrated for the repulse of the Chinese invading army in 1769, and the treaty which thenceforward secured peace and commerce between Burma and China. Subsequently it became a rival of Bhamô as an emporium of Chinese trade by the valley of the Shuaylee and the Muangmow route. The river now spread itself into a broad stream, broken up by islands and sandbanks, but in some places not less than a mile and half wide between the main banks. In front of the village of Sawady a long stretch of sand was occupied by a large encampment of Shan, Chinese, and other traders, a large fleet of boats lying ready to convey the goods down the river.

[Pg 36]

THE DEVA-FACED CLIFF, SECOND DEFILE OF THE IRAWADY.

Here we sighted Bhamô in the distance, situated on an elevated bank overlooking the river, the htees of its few pagodas glistening brightly in the setting sun. To the right the high range of the Kakhyen hills was seen stretching away in an unbroken line to the east-north-east, and on the left a low range of undulating tree-clad hills bent round to join the western heights of the defile.

The almost level sweep of country, about twenty-five miles broad between these limits, was closed in, about ten miles to the north, by another low range, marking the upper khyoukdwen, or first defile, of the Irawady.

[1] Pronounced “Bhamaw.”

[2] ‘Report on Eastern Frontier of British India,’ 1835.

[3] Vide ‘Selection of Papers on the Hill Tracts between Assam and Burmah,’ Calcutta, 1873.

[4] The Chamber of Commerce, under the able president, Mr. M’Call, had been most active in urging the despatch of the mission, and had subscribed £3000 for all expenses of their representatives, and for the purchase of specimens of manufactures.

[5] The putzo is a long narrow silken cloth of a chequered pattern, which a Burman winds round him to form a suit of clothes. The tamein is the feminine equivalent, partly of cloth, partly of silk, with a zigzag pattern, the silken portions forming the skirt, which, according to ancient custom, exposes one leg almost completely in walking.

[6] These Brahmins act as royal astrologers, who are consulted on all great occasions. The Buddhist priests took no part in the ceremonial.

[7] It appears to be made from the leaves of Elæodendron persicum, Persoön.

[8] Kalas, Burmese word for “foreigners.”

[9] See Appendix I.

[10] At this time about one million viss of salt were annually exported up the river from Shienpagah, finding its way chiefly to Bhamô and to Tsitkaw, for the supply of the Kakhyens and Shans. Lately, however, English salt is beginning to take its place, and on my last voyage up the Irawady, one flat from Mandalay carried nothing but salt. In order to proceed to Tsitkaw, it is transshipped at Bhamô into small boats, which carry only five thousand viss each, as the Tapeng is a rapid river, and rather shallow during the dry weather. On salt from Shienpagah, a duty is levied at Malé, Yuathét, and Bhamô, in addition to a boat tax, and when it proceeds up the Tapeng, an additional impost has to be paid at Tsitkaw, and a boat tax at Haylone and Tsitgna. (A viss = about 3 lbs.)

[11] Hannay, ‘Selection of Papers,’ Calcutta, 1873.

[12] In the ecclesiastical translation of the classical localities of Indian Buddhism to Indo-China, which is current in Burma, Yunnan is represented by Gandhara or Kandahár. Yule’s ‘Marco Polo,’ ii. p. 59, edition of 1874.

[13] Colonel Yule remarks that “Tartars on the Indian frontier in those centuries are surely to be classed with the Frenchmen whom Brennus led to Rome” (‘Marco Polo,’ i. p. 12).

[14] Wallago attu, Bloch and Schn.; Callichrous bimaculatus, M’Lelland; Macrones cavasius, H. B.; Macrones corsula, H. B.; Labeo calbasu, H. B.; Labeo churchius, H. B.; Cirrhina mrigala, H. B.; Barbus sarana, H. B.; Barbus apogon, C. and V.; Carassius auratus, Linn.; Catla buchanani, C. and V.; Rhotee cotio, H. B.; Rhotee microlepis, Blyth; Notopterus kapirat, Bonn.

[Pg 37]

We found some difficulty in steering the long steamer through the channels, but anchored about 5 P.M. on the 22nd of January off the river front of Bhamô, in a very deep and broad channel. Our arrival attracted crowds, but the whistle and rush of steam drove many into a precipitate retreat. We had now reached our true point of departure. Whatever had been the uncertainties of the untried navigation of the river, the real dangers and difficulties of the attempt to penetrate Western China were now to begin. We bore the proclamation of the king commanding all Burmese subjects to aid us. But there was no governor of Bhamô to execute the royal orders, and the secret intentions or inclinations of the Burmese were yet to be tested. The difficulties of the unknown road over the Kakhyen mountains,[Pg 38] the hostility or friendship of the mountaineers, and of the Shan population between them and Yunnan, were equally untried. Moreover, though it had scarcely been realised in all its bearings by our own British officials, Yunnan was no longer a well ordered province of the Chinese empire; it was disorganised by the successful rebellion of the Mahommedan Chinese, called Panthays by the Burmese, who had established a partial sovereignty, extending from Momien to Tali-fu. The frontier trade had been materially interrupted, partly by the desolation caused by the internecine warfare, and partly by the depredations of imperial Chinese partisans. Of these, the most dreaded leader was a Burman Chinese, known as Li-sieh-tai, a faithful officer of the old régime, who had established himself on the borders of Yunnan, and waged a guerilla war against the Panthays and their friends. His name is Li, and his so-called small name is Chun-kwo, while from his mother having been a Burmese, he is also known as Li-haon-mien, or Li the Burman. As having been raised to the rank of a Sieh-tai in the Chinese army, he was called Li-sieh-tai or Brigadier Li.[15]

In Bhamô itself there were a number of Chinese merchants, who were unlikely to favour any project which threatened to admit the hated barbarians to a[Pg 39] share of their monopoly and profits. This may give some idea of the state of things which we found on our arrival. Our illusions as to a speedy or easy progress were soon dissipated, and after a formal visit from the two tsitkays, or magistrates, ruling the northern and southern divisions of the town, it became evident that we must prepare for a long stay at Bhamô. The royal order to provide transport had only been received by the Woon on the eve of his departure on his fatal expedition to Momeit. Nothing, therefore, had been done; nor could they venture to act until the new governor arrived. The next best thing was to insist on their carrying into effect the royal order to build a house for us, which had not been done. This they reluctantly performed, and in a few days a bamboo edifice was run up close to the Woon’s house, consisting of a central hall, with three bedrooms on either side, and a verandah at each end of the house. A small outhouse accommodated the servants and baggage, and the guard was quartered in an adjacent zayat; a tent pitched in front of the house served as a refectory. Till these quarters were prepared, we remained on board the steamer, receiving crowds of visitors. In the press a heavy log of timber fell on a little girl and fractured her thigh; she was at once carried on board, and the broken limb duly set. This incident speedily established the reputation of the foreign doctor, and for the rest of our stay patients flocked in every day, some coming from long[Pg 40] distances, and blind and lame eagerly expecting to be made young and whole. A great deal of blindness had resulted from small-pox. Ophthalmia was also prevalent. A common affection was a form of ulcerous inflammation, chiefly on the legs, amongst those whose occupation led them into the jungles. This was so intractable as to incline one to attribute it to poisonous thorns; but subsequent personal experience proved that slight bruises and abrasions are most apt in this country to become painful and tedious. During the whole time no case of fever was treated, nor did any occur among our party of one hundred men. This speaks volumes for the salubrity of the place during the dry season. The highest temperature experienced was 80° Fahrenheit, the average maximum being not more than 66° Fahrenheit, while the nights were very pleasant, cooling down, if we may put it so, to fifty or forty-five degrees. Fever is rather more prevalent during the rains, when the Irawady rolls down a huge volume of water, a mile and half broad, and the low lands are submerged twelve to fifteen feet.[16]

But this is a digression somewhat professional, and it is needful to revert to the narrative and try to give the reader some notion of our surroundings and proceedings until we got away fairly on the march.

Bhamô, known by the Chinese as Tsing-gai, and in Pali called Tsin-ting, is a narrow town about one[Pg 41] mile long, occupying a high prominence on the left bank of the Irawady. Instead of walls, there is a stockade about nine feet high, consisting of split trees driven side by side into the ground and strengthened with crossbeams above and below. This paling is further defended on the outside by a forest of bamboo stakes fixed in the ground and projecting at an acute angle. However formidable to barefooted natives, the stockade does not always exclude tigers, which pay occasional visits, and during our stay killed a woman as she sat with her companions. There are four gates, one at either end and two on the eastern side, which are closed immediately after sunset; a guard is stationed at the northern and southern gates, while several look-out huts perched at intervals on the stockade are manned when an attack of the Kakhyens is expected. The population numbers about two thousand five hundred souls, occupying about five hundred houses, which form three principal streets. There are many thickly wooded by-paths, and bridges over a swamp in the centre of the town, leading to scattered houses, dilapidated pagodas, zayats, and monasteries.

The street following the course of the bank, with high flights of steps ascending from the river, has a row of houses on either side, with a row of teak planks laid in the middle to afford dry footing during the rains. The houses of the central portion are all small one-storied cottages, built of sun-dried bricks,[Pg 42] with tiled concave roofs with deep projecting eaves. Through an open window the proprietor can be seen calmly smoking behind a little counter, for this is the Chinese quarter, and the colony of perhaps two hundred Celestials here offer for sale Manchester goods, Chinese yarns, ball tea, opium, Yunnan potatoes, lead, and vermilion, &c. They also regulate the cotton market, and the traffic in this product, which is brought both from the south and the north, is carried on even during the rains. The head Chinaman, who is responsible for order amongst his compatriots, is a man of great influence. He and his fellow merchants, professing great friendship, invited us to a grand feast and theatrical entertainment given in the Chinese temple, or rather in the theatre which formed a portion thereof. We entered through what was to us a novelty in this country, a circular doorway, into a paved court. The theatrical portion of the building was over the entrance to a second court, facing the sanctuary, which is on a higher level. A covered terrace surrounded the holy place on three sides, with recesses containing seated figures nearly life size, with rubicund faces and formidable black beards and moustaches. Each of these was carefully protected from dust by being enshrined in a square box closed in front with gauze netting. Besides the theatrical entertainment, which was interminable, we were regaled with preserved fruits and confectionery, with tea and samshu, or rice spirit, followed by numerous courses of pork, fowls,[Pg 43] &c. The staple of conversation was the dangers and impossibilities of getting through to Yunnan; every argument they could think of to induce us to abandon the idea of progress was then and afterwards employed. It can readily be imagined that the Bhamô Chinese traders viewed with utter dismay the prospect of Europeans sharing their trade; to their schemes of hindrance we shall again recur.

The rest of the townspeople are exclusively Shan-Burmese, living in small houses built of teak and bamboo, all detached and raised on piles. The Woon’s house, on a low promontory running out into the swamp behind the Chinese quarter, was a large tumbledown timber and bamboo structure; but its double roof and high palisade covered with bamboo mats marked the dignity of its occupier. A small garden overrun with weeds contained the remains of a rockery and fish-pond, and a neglected brass cannon, under a low thatched shed, guarded either side of the gate; in a large adjacent space stood the court-house. All the public buildings were then in a state of dilapidation and decay; this the inhabitants attributed to Kakhyen raids, destructive fires, decay of trade since the Panthay wars, and misrule. Evidence was not wanting in the numerous neglected pagodas and timber bridges, and in the ruinous and charred remains of what must have been handsome zayats, that Bhamô, in palmier days, deserved the eulogiums passed on it by Hannay and other travellers.

[Pg 44]

The Shan-Burmese seemed a peaceful, industrious class. In each house a loom is found in the verandah, and the girls are taught to weave from an early age. The women are always busy weaving silk or cotton putzos and tameins, preparing yarns, husking rice, or feeding and tending the buffaloes, besides doing their household duties. The men till the fields, but are not so industrious as the softer sex. A few are employed in smelting lead, and others work in gold, or smelt the silver used as currency. To six tickals[17] of pure silver purchased from the Kakhyens, one tickal eight annas of copper wire are added, and melted with alloy of as much lead as brings the whole to ten tickals’ weight. The operation is conducted in saucers of sun-dried clay bedded in paddy husk, and covered over with charcoal. The bellows are vigorously plied, and as soon as the mass is at a red heat, the charcoal is removed, and a round flat brick button previously covered with a layer of moist clay is placed on the amalgam, which forms a thick ring round the edge, to which lead is freely added to make up the weight. As it cools, there results a white disc of silver encircled by a brownish ring. The silver is cleaned and dotted with cutch, and is then weighed and ready to be cut up. Another industry is confined to the women, who make capital chatties from a tenacious yellow clay, which overlies this portion of the river valley, in some places forty feet thick; the earthenware is[Pg 45] coloured red with a ferruginous substance found in nodules embedded in the clay.

From the same clay, a number of Shan-Chinese from Hotha and Latha make sun-dried bricks outside the town, and a colony of the same people sojourn every winter at Bhamô, making dahs, or long knives, which are in great demand. A number of Kakhyens are often to be seen near the town, bringing rice, opium, silver, and pigs for sale. Their chief object is to procure salt, for which necessary they are dependent on Burma. They are not allowed to encamp within the town, but are compelled to shelter themselves outside the gates, in miserable wigwams. The Burmese assigned as a reason for their exclusion their dread of the Kakhyen propensity for kidnapping children and even men, and also because a small party might be the precursors of a raid.[18] A few days after our arrival, four children who had been stolen were recovered. One of them was brought by her mother, to show the large round holes bored in the back of the ears as a sign of servitude. The other three were little fat Chinese children, and adopted by the head tsitkay. A curious illustration of their habits of man-stealing was also afforded us.