The Project Gutenberg eBook of Marlborough and Other Poems, by Charles Hamilton Sorley

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online

at

www.gutenberg.org. If you

are not located in the United States, you will have to check the laws of the

country where you are located before using this eBook.

Title: Marlborough and Other Poems

Author: Charles Hamilton Sorley

Release Date: April 7, 2022 [eBook #67791]

Language: English

Produced by: D A Alexander, Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by University of California libraries)

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MARLBOROUGH AND OTHER POEMS ***

Marlborough

and other poems

CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS C. F. CLAY, Manager

London: FETTER LANE. E.C.

Edinburgh: 100 PRINCES STREET

New York: G. P. PUTNAM’S SONS

Bombay, Calcutta and Madras: MACMILLAN AND Co., Ltd.

Toronto: J. M. DENT AND SONS, Ltd.

Tokyo: THE MARUZEN-KABUSHIKI-KAISHA

All rights reserved

Marlborough

and other poems

by

CHARLES HAMILTON SORLEY

LATE OF MARLBOROUGH COLLEGE

SOMETIME CAPTAIN IN THE SUFFOLK REGIMENT

Third edition

with illustrations in prose

Cambridge:

at the University Press

1916

Published, January 1916

Second edition, slightly enlarged, February 1916

Reprinted, February, April, May 1916

Third edition, with illustrations in prose, October 1916

PREFACE

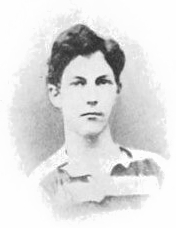

WHAT was said concerning the author in the preface to the first edition

may be repeated here. He was born at Old Aberdeen on 19 May 1895. From

1900 onwards his home was in Cambridge. He was at Marlborough College

from September 1908 till December 1913, when he was elected to a

scholarship at University College, Oxford. After leaving school he spent

a little more than six months in Germany, returning home on the outbreak

of war. He was gazetted Second Lieutenant in the Seventh (Service)

Battalion of the Suffolk Regiment in August 1914, Lieutenant in

November, and Captain in the following August. His battalion was sent to

France on 30 May. He was killed in action near Hulluch on 13 October

1915. “Being made perfect in a little while, he fulfilled long years.”

Many readers have asked for further information about the author or

contributions from his pen. I am not able to give all that is asked for;

but in this edition I have done what I can to meet the wishes of my

correspondents by appending to the poems a certain number of

illustrations in prose. With the exception of a few sentences from an

early essay, these prose passages are all taken from his letters to his

family and friends. They have been selected as illustrating some idea or

subject mentioned in the poems and prominent in his own mind. But the

relevancy is not always very close; the moods of the moment are

sometimes expressed rather than matured judgments; and it has to be

remembered that what was written was not intended for other eyes than

those of the person to whom it was addressed.

With the poems it is different; and, had he lived, he would probably

himself have published a selection of them with such revision as he

deemed advisable. But when a suggestion about printing was made to him,

soon after he had entered upon his life in the trenches of Flanders, he

put the proposal aside as premature, adding “Besides, this is no time

for oliveyards and vineyards, more especially of the small-holdings

type. For three years or the duration of the war, let be.” His warfare

is now accomplished, and his relatives have felt themselves free to

publish.

The original order of the poems is retained in this edition. The first

place is assigned to the title-poem; some early poems are printed at the

end; the other contents are arranged in the order of their composition,

as nearly as that order could be ascertained. When the date given

includes the day of the month, it has been taken from the author’s

manuscript; some of the other dates are approximate. Of the undated

poems, XIII to XVI were received from him in October 1914, XVII to XXIV

in April 1915, XXVII was found in his kit sent back from France, and

XXVIII (which appeared for the first time in the second edition) was

sent to a friend towards the end of July 1915. A single piece of

imaginative prose has been included amongst the poems.

Some further information regarding them has been obtained recently. XVI

was written when he was at the Officers’ Training Camp at Churn early in

September 1914, and XVII a few days later, XV had its origin in his

journey from Churn to join his regiment at Shorncliffe on 18 September.

The first draft of it was sent to a friend soon afterwards with the

words: “enclosed the poem which eventually came out of the first day of

term at Paddington. Not much trace of the origin left; but I think it

should get a prize for being the first poem written since August 4th

that isn’t patriotic.” This draft differs slightly from the final form

of the poem, and instead of the present title (“Whom therefore we

ignorantly worship”), it is preceded by the verse “And these all, having

obtained a good report through faith, received not the promise.” The

poem called “Lost” (XXIV) was sent to the same friend in December 1914.

“I have tried for long,” he wrote, “to express in words the impression

that the land north of Marlborough must leave”; and he added,

“Simplicity, paucity of words, monotony almost, and mystery are

necessary. I think I have got it at last.” The signpost, which figures

here as well as elsewhere in the poems, stands at “the junction of the

grass tracks on the Aldbourne down—to Ogbourne, Marlborough,

Mildenhall, and Aldbourne. It stands up quite alone.”

Three of the poems at least—II, VIII, and XII—were written entirely in

the open air. Concerning one of these he said, “‘Autumn Dawn’ has too

much copy from Meredith in it, but I value it as being (with ‘Return’) a

memento of my walk to Marlborough last September [1913].” Sending his

“occasional budget” in April 1915 he said, “You will notice that most of

what I have written is as hurried and angular as the handwriting:

written out at different times and dirty with my pocket: but I have had

no time for the final touch nor seem likely to have for some time, and

so send them as they are. Nor have I had time to think out (as I usually

do) a rigorous selection as fit for other eyes. So these are my

explanations of the fall in quality. I like ‘Le Revenant’ best, being

very interested in the previous and future experience of the character

concerned: but it sadly needs the file.”

The letter in verse, fragments of which are given on pages 73-78, was

sent anonymously to an older friend whose connexion with Marlborough is

commemorated in the poem entitled “J. B.” J. B. discovered the

authorship of the epistle by sending the envelope to a Marlborough

master, and replied in the words which, by his permission, are printed

on the opposite page.

W. R. S.

From far away there comes a Voice,

Singing its song across the sea—

Song to make man’s heart rejoice—

Of Marlborough and the Odyssey.

A voice that sings of Now and Then,

Of minstrel joys and tiny towns,

Of flowering thyme and fighting men,

Of Sparta’s sands and Marlborough’s Downs.

God grant, dear Voice, one day again

We see those Downs in April weather,

And snuff the breeze, and smell the rain,

And stand in C House Porch together!

CONTENTS

{1}

I

MARLBOROUGH

I

CROUCHED where the open upland billows down

Into the valley where the river flows,

She is as any other country town,

That little lives or marks or hears or knows.

And she can teach but little. She has not

The wonder and the surging and the roar

Of striving cities. Only things forgot

That once were beautiful, but now no more,

Has she to give us. Yet to one or two

She first brought knowledge, and it was for her

To open first our eyes, until we knew

How great, immeasurably great, we were.{2}

I, who have walked along her downs in dreams,

And known her tenderness, and felt her might,

And sometimes by her meadows and her streams

Have drunk deep-storied secrets of delight,

Have had my moments there, when I have been

Unwittingly aware of something more.

Some beautiful aspect, that I had seen

With mute unspeculative eyes before;

Have had my times, when, though the earth did wear

Her self-same trees and grasses, I could see

The revelation that is always there,

But somehow is not always clear to me.

II

So, long ago, one halted on his way

And sent his company and cattle on;

His caravans trooped darkling far away

Into the night, and he was left alone.{3}

And he was left alone. And, lo, a man

There wrestled with him till the break of day.

The brook was silent and the night was wan.

And when the dawn was come, he passed away.

The sinew of the hollow of his thigh

Was shrunken, as he wrestled there alone.

The brook was silent, but the dawn was nigh.

The stranger named him Israel and was gone.

And the sun rose on Jacob; and he knew

That he was no more Jacob, but had grown

A more immortal vaster spirit, who

Had seen God face to face, and still lived on.

The plain that seemed to stretch away to God,

The brook that saw and heard and knew no fear,

Were now the self-same soul as he who stood

And waited for his brother to draw near.{4}

For God had wrestled with him, and was gone.

He looked around, and only God remained.

The dawn, the desert, he and God were one.

—And Esau came to meet him, travel-stained.

III

So, there, when sunset made the downs look new

And earth gave up her colours to the sky,

And far away the little city grew

Half into sight, new-visioned was my eye.

I, who have lived, and trod her lovely earth,

Raced with her winds and listened to her birds,

Have cared but little for their worldly worth

Nor sought to put my passion into words.

But now it’s different; and I have no rest

Because my hand must search, dissect and spell

The beauty that is better not expressed,

The thing that all can feel, but none can tell.

{5}

II

BARBURY CAMP

WE burrowed night and day with tools of lead,

Heaped the bank up and cast it in a ring

And hurled the earth above. And Caesar said,

“Why, it is excellent. I like the thing.”

We, who are dead,

Made it, and wrought, and Caesar liked the thing.

And here we strove, and here we felt each vein

Ice-bound, each limb fast-frozen, all night long.

And here we held communion with the rain

That lashed us into manhood with its thong,

Cleansing through pain.

And the wind visited us and made us strong.{6}

Up from around us, numbers without name,

Strong men and naked, vast, on either hand

Pressing us in, they came. And the wind came

And bitter rain, turning grey all the land.

That was our game,

To fight with men and storms, and it was grand.

For many days we fought them, and our sweat

Watered the grass, making it spring up green,

Blooming for us. And, if the wind was wet,

Our blood wetted the wind, making it keen

With the hatred

And wrath and courage that our blood had been.

So, fighting men and winds and tempests, hot

With joy and hate and battle-lust, we fell

Where we fought. And God said, “Killed at last then? What?

Ye that are too strong for heaven, too clean for hell,

(God said) stir not.

This be your heaven, or, if ye will, your hell.{7}”

So again we fight and wrestle, and again

Hurl the earth up and cast it in a ring.

But when the wind comes up, driving the rain

(Each rain-drop a fiery steed), and the mists rolling

Up from the plain,

This wild procession, this impetuous thing,

Hold us amazed. We mount the wind-cars, then

Whip up the steeds and drive through all the world.

Searching to find somewhere some brethren.

Sons of the winds and waters of the world.

We, who were men.

Have sought, and found no men in all this world.

Wind, that has blown here always ceaselessly.

Bringing, if any man can understand,

Might to the mighty, freedom to the free;

Wind, that has caught us, cleansed us, made us grand

Wind that is we

(We that were men)—make men in all this land,{8}

That so may live and wrestle and hate that when

They fall at last exultant, as we fell,

And come to God, God may say, “Do you come then

Mildly enquiring, is it heaven or hell?

Why! Ye were men!

Back to your winds and rains. Be these your heaven and hell!”

{9}

III

WHAT YOU WILL

O COME and see, it’s such a sight,

So many boys all doing right:

To see them underneath the yoke,

Blindfolded by the elder folk,

Move at a most impressive rate

Along the way that is called straight.

O, it is comforting to know

They’re in the way they ought to go.

But don’t you think it’s far more gay

To see them slowly leave the way

And limp and loose themselves and fall?

O, that’s the nicest thing of all.{10}

I love to see this sight, for then

I know they are becoming men,

And they are tiring of the shrine

Where things are really not divine.

I do not know if it seems brave

The youthful spirit to enslave,

And hedge about, lest it should grow.

I don’t know if it’s better so

In the long end. I only know

That when I have a son of mine,

He shan’t be made to droop and pine.

Bound down and forced by rule and rod

To serve a God who is no God.

But I’ll put custom on the shelf

And make him find his God himself.{11}

Perhaps he’ll find him in a tree,

Some hollow trunk, where you can see.

Perhaps the daisies in the sod

Will open out and show him God.

Or will he meet him in the roar

Of breakers as they beat the shore?

Or in the spiky stars that shine?

Or in the rain (where I found mine)?

Or in the city’s giant moan?

—A God who will be all his own,

To whom he can address a prayer

And love him, for he is so fair,

And see with eyes that are not dim

And build a temple meet for him.

{12}

IV

ROOKS

THERE, where the rusty iron lies,

The rooks are cawing all the day.

Perhaps no man, until he dies,

Will understand them, what they say.

The evening makes the sky like clay.

The slow wind waits for night to rise.

The world is half-content. But they

Still trouble all the trees with cries,

That know, and cannot put away,

The yearning to the soul that flies

From day to night, from night to day.

{13}

V

ROOKS (II)

THERE is such cry in all these birds,

More than can ever be express’d;

If I should put it into words,

You would agree it were not best

To wake such wonder from its rest.

But since to-night the world is still

And only they and I astir,

We are united, will to will,

By bondage tighter, tenderer

Than any lovers ever were.{14}

And if, of too much labouring.

All that I see around should die

(There is such sleep in each green thing,

Such weariness in all the sky),

We would live on, these birds and I.

Yet how? since everything must pass

At evening with the sinking sun,

And Christ is gone, and Barabbas,

Judas and Jesus, gone, clean gone,

Then how shall I live on?

Yet surely, Judas must have heard

Amidst his torments the long cry

Of some lone Israelitish bird,

And on it, ere he went to die,

Thrown all his spirit’s agony.{15}

And that immortal cry which welled

For Judas, ever afterwards

Passion on passion still has swelled

And sweetened, till to-night these birds

Will take my words, will take my words,

And wrapping them in music meet

Will sing their spirit through the sky,

Strange and unsatisfied and sweet—

That, when stock-dead am I, am I,

O, these will never die!

{16}

VI

STONES

THIS field is almost white with stone

That cumber all its thirsty crust.

And underneath, I know, are bones.

And all around is death and dust.

And if you love a livelier hue—

O, if you love the youth of year,

When all is clean and green and new,

Depart. There is no summer here.

Albeit, to me there lingers yet

In this forbidding stony dress

The impotent and dim regret

For some forgotten restlessness.{17}

Dumb, imperceptibly astir,

These relics of an ancient race,

These men, in whom the dead bones were,

Still fortifying their resting-place.

Their field of life was white with stones;

Good fruit to earth they never brought.

O, in these bleached and buried bones

Was neither love nor faith nor thought.

But like the wind in this bleak place,

Bitter and bleak and sharp they grew.

And bitterly they ran their race,

A brutal, bad, unkindly crew:

Souls like the dry earth, hearts like stone.

Brains like that barren bramble-tree:

Stern, sterile, senseless, mute, unknown—

But bold, O, bolder far than we!

{18}

VII

EAST KENNET CHURCH AT EVENING

I STOOD amongst the corn, and watched

The evening coming down.

The rising vale was like a queen,

And the dim church her crown.

Crown-like it stood against the hills.

Its form was passing fair.

I almost saw the tribes go up

To offer incense there.

And far below the long vale stretched.

As a sleeper she did seem

That after some brief restlessness

Has now begun to dream.{19}

(All day the wakefulness of men,

Their lives and labours brief,

Have broken her long troubled sleep.

Now, evening brings relief.)

There was no motion there, nor sound.

She did not seem to rise.

Yet was she wrapping herself in

Her grey of night-disguise.

For now no church nor tree nor fold

Was visible to me:

Only that fading into one

Which God must sometimes see.

No coloured glory streaked the sky

To mark the sinking sun.

There was no redness in the west

To tell that day was done.{20}

Only, the greyness of the eve

Grew fuller than before.

And, in its fulness, it made one

Of what had once been more.

There was much beauty in that sight

That man must not long see.

God dropped the kindly veil of night

Between its end and me.

{21}

VIII

AUTUMN DAWN

AND this is morning. Would you think

That this was the morning, when the land

Is full of heavy eyes that blink

Half-opened, and the tall trees stand

Too tired to shake away the drops

Of passing night that cling around

Their branches and weigh down their tops:

And the grey sky leans on the ground?

The thrush sings once or twice, but stops

Affrighted by the silent sound.

The sheep, scarce moving, munches, moans.

The slow herd mumbles, thick with phlegm.

The grey road-mender, hacking stones,

Is now become as one of them.{22}

Old mother Earth has rubbed her eyes

And stayed, so senseless, lying down.

Old mother is too tired to rise

And lay aside her grey nightgown,

And come with singing and with strength

In loud exuberance of day,

Swift-darting. She is tired at length,

Done up, past bearing, you would say.

She’ll come no more in lust of strife,

In hedges’ leap, and wild birds’ cries,

In winds that cut you like a knife,

In days of laughter and swift skies,

That palpably pulsate with life,

With life that kills, with life that dies.

But in a morning such as this

Is neither life nor death to see,

Only that state which some call bliss,

Grey hopeless immortality.{23}

Earth is at length bedrid. She is

Supinest of the things that be:

And stilly, heavy with long years,

Brings forth such days in dumb regret,

Immortal days, that rise in tears,

And cannot, though they strive to, set.

* * * * * * *

The mists do move. The wind takes breath.

The sun appeareth over there,

And with red fingers hasteneth

From Earth’s grey bed the clothes to tear,

And strike the heavy mist’s dank tent.

And Earth uprises with a sigh.

She is astir. She is not spent.

And yet she lives and yet can die.

The grey road-mender from the ditch

Looks up. He has not looked before.

The stunted tree sways like the witch

It was: ’tis living witch once more.{24}

The winds are washen. In the deep

Dew of the morn they’ve washed. The skies

Are changing dress. The clumsy sheep

Bound, and earth’s many bosoms rise,

And earth’s green tresses spring and leap

About her brow. The earth has eyes,

The earth has voice, the earth has breath,

As o’er the land and through the air,

With wingéd sandals, Life and Death

Speed hand in hand—that winsome pair!

{25}

IX

RETURN

STILL stand the downs so wise and wide?

Still shake the trees their tresses grey?

I thought their beauty might have died

Since I had been away.

I might have known the things I love,

The winds, the flocking birds’ full cry,

The trees that toss, the downs that move,

Were longer things than I.

Lo, earth that bows before the wind,

With wild green children overgrown,

And all her bosoms, many-whinned,

Receive me as their own.{26}

The birds are hushed and fled: the cows

Have ceased at last to make long moan.

They only think to browse and browse

Until the night is grown.

The wind is stiller than it was,

And dumbness holds the closing day.

The earth says not a word, because

It has no word to say.

The dear soft grasses under foot

Are silent to the listening ear.

Yet beauty never can be mute,

And some will always hear.

{27}

X

RICHARD JEFFERIES

(LIDDINGTON CASTLE)

I SEE the vision of the Vale

Rise teeming to the rampart Down,

The fields and, far below, the pale

Red-roofédness of Swindon town.

But though I see all things remote,

I cannot see them with the eyes

With which ere now the man from Coate

Looked down and wondered and was wise.{28}

He knew the healing balm of night,

The strong and sweeping joy of day,

The sensible and dear delight

Of life, the pity of decay.

And many wondrous words he wrote,

And something good to man he showed,

About the entering in of Coate,

There, on the dusty Swindon road.

{29}

XI

J. B.

THERE’S still a horse on Granham hill,

And still the Kennet moves, and still

Four Miler sways and is not still.

But where is her interpreter?

The downs are blown into dismay,

The stunted trees seem all astray,

Looking for someone clad in grey

And carrying a golf-club thing;

Who, them when he had lived among,

Gave them what they desired, a tongue.

Their words he gave them to be sung

Perhaps were few, but they were true.{30}

The trees, the downs, on either hand,

Still stand, as he said they would stand.

But look, the rain in all the land

Makes all things dim with tears of him.

And recently the Kennet croons,

And winds are playing widowed tunes.

—He has not left our “toun o’ touns,”

But taken it away with him!

{31}

XII

THE OTHER WISE MAN

(Scene: A valley with a wood on one side and a road running up to

a distant hill: as it might be, the valley to the east of West

Woods, that runs up to Oare Hill, only much larger. Time: Autumn.

Four wise men are marching hillward along the road.)

One Wise Man

I wonder where the valley ends?

On, comrades, on.

Another Wise Man

The rain-red road,

Still shining sinuously, bends

Leagues upwards.{32}

A Third Wise Man

To the hill, O friends,

To seek the star that once has glowed

Before us; turning not to right

Nor left, nor backward once looking.

Till we have clomb—and with the night

We see the King.

All the Wise Men

The Third Wise Man

A Fourth Wise Man

Brother, see,

There, to the left, a very aisle

Composed of every sort of tree—

The First Wise Man

The Fourth Wise Man

Oak and beech and birch,

Like a church, but homelier than church,

The black trunks for its walls of tile;

Its roof, old leaves; its floor, beech nuts;

The squirrels its congregation—

The Second Wise Man

Tuts!

For still we journey—

The Fourth Wise Man

But the sun weaves

A water-web across the grass,

Binding their tops. You must not pass

The water cobweb.

The Third Wise Man

Hush! I say.

Onward and upward till the day{34}—

The Fourth Wise Man

Brother, that tree has crimson leaves.

You’ll never see its like again.

Don’t miss it. Look, it’s bright with rain—

The First Wise Man

O prating tongue. On, on.

The Fourth Wise Man

And there

A toad-stool, nay, a goblin stool.

No toad sat on a thing so fair.

Wait, while I pluck—and there’s—and here’s

A whole ring ... what?... berries?

(The Fourth Wise Man drops behind, botanizing.){35}

The Wisest of the remaining Three Wise Men

O fool!

Fool, fallen in this vale of tears

His hand had touched the plough: his eyes

Looked back: no more with us, his peers,

He’ll climb the hill and front the skies

And see the Star, the King, the Prize.

But we, the seekers, we who see

Beyond the mists of transiency—

Our feet down in the valley still

Are set, our eyes are on the hill.

Last night the star of God has shone,

And so we journey, up and on,

With courage clad, with swiftness shod,

All thoughts of earth behind us cast,

Until we see the lights of God,

{36}—And what will be the crown at last?

All Three Wise Men

On, on.

(They pass on: it is already evening when the Other Wise Man limps

along the road, still botanizing.)

The Other Wise Man

A vale of tears, they said!

A valley made of woes and fears,

To be passed by with muffled head

Quickly. I have not seen the tears,

Unless they take the rain for tears,

And certainly the place is wet.

Rain laden leaves are ever licking

Your cheeks and hands ... I can’t get on.

There’s a toad-stool that wants picking.

There, just there, a little up,

What strange things to look upon

With pink hood and orange cup!{37}

And there are acorns, yellow—green ...

They said the King was at the end.

They must have been

Wrong. For here, here, I intend

To search for him, for surely here

Are all the wares of the old year,

And all the beauty and bright prize,

And all God’s colours meetly showed,

Green for the grass, blue for the skies,

Red for the rain upon the road;

And anything you like for trees,

But chiefly yellow brown and gold,

Because the year is growing old

And loves to paint her children these.

I tried to follow ... but, what do you think?

The mushrooms here are pink!

And there’s old clover with black polls

Black-headed clover, black as coals,

And toad-stools, sleek as ink!{38}

And there are such heaps of little turns

Off the road, wet with old rain:

Each little vegetable lane

Of moss and old decaying ferns,

Beautiful in decay,

Snatching a beauty from whatever may

Be their lot, dark-red and luscious: till there pass’d

Over the many-coloured earth a grey

Film. It was evening coming down at last.

And all things hid their faces, covering up

Their peak or hood or bonnet or bright cup

In greyness, and the beauty faded fast,

With all the many-coloured coat of day.

Then I looked up, and lo! the sunset sky

Had taken the beauty from the autumn earth.

Such colour, O such colour, could not die.

The trees stood black against such revelry

Of lemon-gold and purple and crimson dye.

And even as the trees, so I{39}

Stood still and worshipped, though by evening’s birth

I should have capped the hills and seen the King.

The King? The King?

I must be miles away from my journey’s end;

The others must be now nearing

The summit, glad. By now they wend

Their way far, far, ahead, no doubt.

I wonder if they’ve reached the end.

If they have, I have not heard them shout.

{40}

XIII

THE SONG OF THE UNGIRT RUNNERS

WE swing ungirded hips,

And lightened are our eyes,

The rain is on our lips,

We do not run for prize.

We know not whom we trust

Nor whitherward we fare,

But we run because we must

Through the great wide air.

The waters of the seas

Are troubled as by storm.

The tempest strips the trees

And does not leave them warm.

Does the tearing tempest pause?

Do the tree-tops ask it why?

So we run without a cause

’Neath the big bare sky.{41}

The rain is on our lips,

We do not run for prize.

But the storm the water whips

And the wave howls to the skies.

The winds arise and strike it

And scatter it like sand,

And we run because we like it

Through the broad bright land.

{42}

XIV

GERMAN RAIN

THE heat came down and sapped away my powers.

The laden heat came down and drowned my brain,

Till through the weight of overcoming hours

I felt the rain.

Then suddenly I saw what more to see

I never thought: old things renewed, retrieved.

The rain that fell in England fell on me,

And I believed.

{43}

XV

WHOM THEREFORE WE IGNORANTLY WORSHIP

THESE things are silent. Though it may be told

Of luminous deeds that lighten land and sea,

Strong sounding actions with broad minstrelsy

Of praise, strange hazards and adventures bold,

We hold to the old things that grow not old:

Blind, patient, hungry, hopeless (without fee

Of all our hunger and unhope are we),

To the first ultimate instinct, to God we hold.

They flicker, glitter, flicker. But we bide,

We, the blind weavers of an intense fate,

Asking but this—that we may be denied:

Desiring only desire insatiate,

Unheard, unnamed, unnoticed, crucified

To our unutterable faith, we wait.

{44}

XVI

TO POETS

WE are the homeless, even as you,

Who hope and never can begin.

Our hearts are wounded through and through

Like yours, but our hearts bleed within.

We too make music, but our tones

’Scape not the barrier of our bones.

We have no comeliness like you.

We toil, unlovely, and we spin.

We start, return: we wind, undo:

We hope, we err, we strive, we sin,

We love: your love’s not greater, but

The lips of our love’s might stay shut.{45}

We have the evil spirits too

That shake our soul with battle-din.

But we have an eviller spirit than you

We have a dumb spirit within:

The exceeding bitter agony

But not the exceeding bitter cry.

{46}

XVII

A HUNDRED thousand million mites we go

Wheeling and tacking o’er the eternal plain,

Some black with death—and some are white with woe.

Who sent us forth? Who takes us home again?

And there is sound of hymns of praise—to whom?

And curses—on whom curses?—snap the air.

And there is hope goes hand in hand with gloom.

And blood and indignation and despair.

And there is murmuring of the multitude

And blindness and great blindness, until some

Step forth and challenge blind Vicissitude

Who tramples on them: so that fewer come.{47}

And nations, ankle-deep in love or hate,

Throw darts or kisses all the unwitting hour

Beside the ominous unseen tide of fate;

And there is emptiness and drink and power.

And some are mounted on swift steeds of thought

And some drag sluggish feet of stable toil.

Yet all, as though they furiously sought,

Twist turn and tussle, close and cling and coil.

A hundred thousand million mites we sway

Writhing and tossing on the eternal plain,

Some black with death—but most are bright with Day!

Who sent us forth? Who brings us home again?

{48}

XVIII

DEUS LOQUITUR

THAT’s what I am: a thing of no desire,

With no path to discover and no plea

To offer up, so be my altar fire

May burn before the hearth continuously,

To be

For wayward men a steadfast light to see.

They know me in the morning of their days,

But ere noontide forsake me, to discern

New lore and hear new riddles. But moonrays

Bring them back footsore, humble, bent, a-burn

To turn

And warm them by my fire which they did spurn.{49}

They flock together like tired birds. “We sought

Full many stars in many skies to see.

But ever knowledge disappointment brought.

Thy light alone, Lord, burneth steadfastly.”

Ah me!

Then it is I who fain would wayward be.

{50}

XIX

TWO SONGS FROM IBSEN’S DRAMATIC POEMS

I BRAND

THOU trod’st the shifting sand path where man’s race is.

The print of thy soft sandals is still clear.

I too have trodden it those prints a-near,

But the sea washes out my tired foot-traces.

And all that thou hast healed and holpen here

I yearned to heal and help and wipe the tear

Away. But still I trod unpeopled spaces.

I had no twelve to follow my pure paces.

For I had thy misgivings and thy fear,

Thy crown of scorn, thy suffering’s sharp spear,

Thy hopes, thy longings—only not thy dear

Love (for my crying love would no man hear),

Thy will to love, but not thy love’s sweet graces,

That deep firm foothold which no sea erases.

I think that thou wast I in bygone places

In an intense eliminated year.

Now born again in days that are more drear

I wander unfulfilled: and see strange faces.

{51}

II PEER GYNT

WHEN he was young and beautiful and bold

We hated him, for he was very strong.

But when he came back home again, quite old,

And wounded too, we could not hate him long.

For kingliness and conquest pranced he forth

Like some high-stepping charger bright with foam.

And south he strode and east and west and north

With need of crowns and never need of home.

Enraged we heard high tidings of his strength

And cursed his long forgetfulness. We swore

That should he come back home some eve at length.

We would deny him, we would bar the door!{52}

And then he came. The sound of those tired feet!

And all our home and all our hearts are his,

Where bitterness, grown weary, turns to sweet,

And envy, purged by longing, pity is.

And pillows rest beneath the withering cheek,

And hands are laid the battered brows above,

And he whom we had hated, waxen weak,

First in his weakness learns a little love.

{53}

XX

IF I have suffered pain

It is because I would.

I willed it. ’Tis no good

To murmur or complain.

I have not served the law

That keeps the earth so fair

And gives her clothes to wear

Raiment of joy and awe.

For all that bow to bless

That law shall sure abide.

But man shall not abide,

And hence his gloriousness.

Lo, evening earth doth lie

All-beauteous and all peace.

Man only does not cease

From striving and from cry.{54}

Sun sets in peace: and soon

The moon will shower her peace.

O law-abiding moon,

You hold your peace in fee!

Man, leastways, will not be

Down-bounden to these laws.

Man’s spirit sees no cause

To serve such laws as these.

There yet are many seas

For man to wander in.

He yet must find out sin,

If aught of pleasance there

Remain for him to store,

His rovings to increase,

In quest of many a shore

Forbidden still to fare.{55}

Peace sleeps the earth upon,

And sweet peace on the hill.

The waves that whimper still

At their long law-serving

(O flowing sad complaint!)

Come on and are back drawn.

Man only owns no king,

Man only is not faint.

You see, the earth is bound.

You see, the man is free.

For glorious liberty

He suffers and would die.

Grudge not then suffering

Or chastisemental cry.

O let his pain abound,

Earth’s truant and earth’s king!

{56}

XXI

TO GERMANY

YOU are blind like us. Your hurt no man designed,

And no man claimed the conquest of your land.

But gropers both through fields of thought confined

We stumble and we do not understand.

You only saw your future bigly planned,

And we, the tapering paths of our own mind,

And in each other’s dearest ways we stand,

And hiss and hate. And the blind fight the blind.

When it is peace, then we may view again

With new-won eyes each other’s truer form

And wonder. Grown more loving-kind and warm

We’ll grasp firm hands and laugh at the old pain,

When it is peace. But until peace, the storm

The darkness and the thunder and the rain.

{57}

XXII

ALL the hills and vales along

Earth is bursting into song,

And the singers are the chaps

Who are going to die perhaps.

O sing, marching men,

Till the valleys ring again.

Give your gladness to earth’s keeping,

So be glad, when you are sleeping.

Cast away regret and rue,

Think what you are marching to.

Little live, great pass.

Jesus Christ and Barabbas

Were found the same day.

This died, that went his way.

So sing with joyful breath.

For why, you are going to death.

Teeming earth will surely store

All the gladness that you pour.{58}

Earth that never doubts nor fears,

Earth that knows of death, not tears,

Earth that bore with joyful ease

Hemlock for Socrates,

Earth that blossomed and was glad

’Neath the cross that Christ had,

Shall rejoice and blossom too

When the bullet reaches you.

Wherefore, men marching

On the road to death, sing!

Pour your gladness on earth’s head,

So be merry, so be dead.{59}

From the hills and valleys earth

Shouts back the sound of mirth,

Tramp of feet and lilt of song

Ringing all the road along.

All the music of their going,

Ringing swinging glad song-throwing,

Earth will echo still, when foot

Lies numb and voice mute.

On, marching men, on

To the gates of death with song,

Sow your gladness for earth’s reaping,

So you may be glad, though sleeping,

Strew your gladness on earth’s bed,

So be merry, so be dead.

{60}

XXIII

LE REVENANT

HE trod the oft-remembered lane

(Now smaller-seeming than before

When first he left his father’s door

For newer things), but still quite plain

(Though half-benighted now) upstood

Old landmarks, ghosts across the lane

That brought the Bygone back again:

Shorn haystacks and the rooky wood;{61}

The guide post, too, which once he clomb

To read the figures: fourteen miles

To Swindon, four to Clinton Stiles,

And only half a mile to home:

And far away the one homestead, where—

Behind the day now not quite set

So that he saw in silhouette

Its chimneys still stand black and bare—

He noticed that the trees were not

So big as when he journeyed last

That way. For greatly now he passed

Striding above the hedges, hot

With hopings, as he passed by where

A lamp before him glanced and stayed

Across his path, so that his shade

Seemed like a giant’s moving there.{62}

The dullness of the sunken sun

He marked not, nor how dark it grew,

Nor that strange flapping bird that flew

Above: he thought but of the One....

He topped the crest and crossed the fence,

Noticed the garden that it grew

As erst, noticed the hen-house too

(The kennel had been altered since).

It seemed so unchanged and so still.

(Could it but be the past arisen

For one short night from out of prison?)

He reached the big-bowed window-sill,

Lifted the window sash with care,

Then, gaily throwing aside the blind,

Shouted. It was a shock to find

That he was not remembered there.{63}

At once he felt not all his pain,

But murmuringly apologised,

Turned, once more sought the undersized

Blown trees, and the long lanky lane,

Wondering and pondering on, past where

A lamp before him glanced and stayed

Across his path, so that his shade

Seemed like a giant’s moving there.

{64}

XXIV

LOST

ACROSS my past imaginings

Has dropped a blindness silent and slow.

My eye is bent on other things

Than those it once did see and know.

I may not think on those dear lands

(O far away and long ago!)

Where the old battered signpost stands

And silently the four roads go

East, west, south and north,

And the cold winter winds do blow.

And what the evening will bring forth

Is not for me nor you to know.

{65}

XXV

EXPECTANS EXPECTAVI

FROM morn to midnight, all day through,

I laugh and play as others do,

I sin and chatter, just the same

As others with a different name.

And all year long upon the stage

I dance and tumble and do rage

So vehemently, I scarcely see

The inner and eternal me.

I have a temple I do not

Visit, a heart I have forgot,

A self that I have never met,

A secret shrine—and yet, and yet{66}

This sanctuary of my soul

Unwitting I keep white and whole

Unlatched and lit, if Thou should’st care

To enter or to tarry there.

With parted lips and outstretched hands

And listening ears Thy servant stands,

Call Thou early, call Thou late,

To Thy great service dedicate.

{67}

XXVI

TWO SONNETS

I

SAINTS have adored the lofty soul of you.

Poets have whitened at your high renown.

We stand among the many millions who

Do hourly wait to pass your pathway down.

You, so familiar, once were strange: we tried

To live as of your presence unaware.

But now in every road on every side

We see your straight and steadfast signpost there.

I think it like that signpost in my land

Hoary and tall, which pointed me to go

Upward, into the hills, on the right hand,

Where the mists swim and the winds shriek and blow,

A homeless land and friendless, but a land

I did not know and that I wished to know.

{68}

II

Such, such is Death: no triumph: no defeat:

Only an empty pail, a slate rubbed clean,

A merciful putting away of what has been.

And this we know: Death is not Life effete,

Life crushed, the broken pail. We who have seen

So marvellous things know well the end not yet.

Victor and vanquished are a-one in death:

Coward and brave: friend, foe. Ghosts do not say

“Come, what was your record when you drew breath?”

But a big blot has hid each yesterday

So poor, so manifestly incomplete.

And your bright Promise, withered long and sped,

Is touched, stirs, rises, opens and grows sweet

And blossoms and is you, when you are dead.

{69}

XXVII

WHEN you see millions of the mouthless dead

Across your dreams in pale battalions go,

Say not soft things as other men have said,

That you’ll remember. For you need not so.

Give them not praise. For, deaf, how should they know

It is not curses heaped on each gashed head?

Nor tears. Their blind eyes see not your tears flow.

Nor honour. It is easy to be dead.

Say only this, “They are dead.” Then add thereto,

“Yet many a better one has died before.”

Then, scanning all the o’ercrowded mass, should you

Perceive one face that you loved heretofore,

It is a spook. None wears the face you knew.

Great death has made all his for evermore.

{70}

XXVIII

THERE is such change in all those fields,

Such motion rhythmic, ordered, free,

Where ever-glancing summer yields

Birth, fragrance, sunlight, immanency,

To make us view our rights of birth.

What shall we do? How shall we die?

We, captives of a roaming earth,

Mid shades that life and light deny.

Blank summer’s surfeit heaves in mist;

Dumb earth basks dewy-washed; while still

We whom Intelligence has kissed

Do make us shackles of our will.

And yet I know in each loud brain,

Round-clamped with laws and learning so,

Is madness more and lust of strain

Than earth’s jerked godlings e’er can know.{71}

The false Delilah of our brain

Has set us round the millstone going.

O lust of roving! lust of pain!

Our hair will not be long in growing.

Like blinded Samson round we go.

We hear the grindstone groan and cry.

Yet we are kings, we know, we know.

What shall we do? How shall we die?

Take but our pauper’s gift of birth,

O let us from the grindstone free!

And tread the maddening gladdening earth

In strength close-braced with purity.

The earth is old; we ever new.

Our eyes should see no other sense

Than this, eternally to DO—

Our joy, our task, our recompense;

Up unexploréd mountains move,

Track tireless through great wastes afar,

Nor slumber in the arms of love,

Nor tremble on the brink of war;{72}

Make Beauty and make Rest give place,

Mock Prudence loud—and she is gone,

Smite Satisfaction on the face

And tread the ghost of Ease upon.

Light-lipped and singing press we hard

Over old earth which now is worn,

Triumphant, buffetted and scarred,

By billows howled at, tempest-torn,

Toward blue horizons far away

(Which do not give the rest we need,

But some long strife, more than this play,

Some task that will be stern indeed)—

We ever new, we ever young,

We happy creatures of a day!

What will the gods say, seeing us strung

As nobly and as taut as they?

{73}

XXIX

I HAVE not brought my Odyssey

With me here across the sea;

But you’ll remember, when I say

How, when they went down Sparta way,

To sandy Sparta, long ere dawn

Horses were harnessed, rations drawn,

Equipment polished sparkling bright,

And breakfasts swallowed (as the white

Of Eastern heavens turned to gold)—

The dogs barked, swift farewells were told.

The sun springs up, the horses neigh,

Crackles the whip thrice—then away!

From sun-go-up to sun-go-down

All day across the sandy down

The gallant horses galloped, till

The wind across the downs more chill{74}

Blew, the sun sank and all the road

Was darkened, that it only showed

Right at the end the town’s red light

And twilight glimmering into night.

The horses never slackened till

They reached the doorway and stood still.

Then came the knock, the unlading; then

The honey-sweet converse of men,

The splendid bath, the change of dress,

Then—O the grandeur of their Mess,

The henchmen, the prim stewardess!

And O the breaking of old ground,

The tales, after the port went round!

(The wondrous wiles of old Odysseus,

Old Agamemnon and his misuse

Of his command, and that young chit

Paris—who didn’t care a bit

For Helen—only to annoy her

He did it really, κ.τ.λ.){75}

But soon they led amidst the din

The honey-sweet ἀοιδὸς in,

Whose eyes were blind, whose soul had sight,

Who knew the fame of men in fight—

Bard of white hair and trembling foot,

Who sang whatever God might put

Into his heart.

And there he sung,

Those war-worn veterans among,

Tales of great war and strong hearts wrung,

Of clash of arms, of council’s brawl,

Of beauty that must early fall,

Of battle hate and battle joy

By the old windy walls of Troy.

They felt that they were unreal then,

Visions and shadow-forms, not men.

But those the Bard did sing and say

(Some were their comrades, some were they)

Took shape and loomed and strengthened more

Greatly than they had guessed of yore.{76}

And now the fight begins again,

The old war-joy, the old war-pain.

Sons of one school across the sea

We have no fear to fight—

* * * * * *

And soon, O soon, I do not doubt it,

With the body or without it,

We shall all come tumbling down

To our old wrinkled red-capped town.

Perhaps the road up Ilsley way,

The old ridge-track, will be my way.

High up among the sheep and sky,

Look down on Wantage, passing by,

And see the smoke from Swindon town;

And then full left at Liddington,

Where the four winds of heaven meet

The earth-blest traveller to greet.

And then my face is toward the south,

There is a singing on my mouth:{77}

Away to rightward I descry

My Barbury ensconced in sky,

Far underneath the Ogbourne twins,

And at my feet the thyme and whins,

The grasses with their little crowns

Of gold, the lovely Aldbourne downs,

And that old signpost (well I knew

That crazy signpost, arms askew,

Old mother of the four grass ways).

And then my mouth is dumb with praise,

For, past the wood and chalkpit tiny,

A glimpse of Marlborough ἐρατεινή!

So I descend beneath the rail

To warmth and welcome and wassail.

* * * * * *

This from the battered trenches—rough,

Jingling and tedious enough.

And so I sign myself to you:

One, who some crooked pathways knew{78}

Round Bedwyn: who could scarcely leave

The Downs on a December eve:

Was at his happiest in shorts,

And got—not many good reports!

Small skill of rhyming in his hand—

But you’ll forgive—you’ll understand.

{79}

XXX

IN MEMORIAM

S.C.W., V.C.

THERE is no fitter end than this.

No need is now to yearn nor sigh.

We know the glory that is his,

A glory that can never die.

Surely we knew it long before,

Knew all along that he was made

For a swift radiant morning, for

A sacrificing swift night-shade.

{80}

XXXI

BEHIND THE LINES

WE are now at the end of a few days’ rest, a kilometre behind the lines.

Except for the farmyard noises (new style) it might almost be the little

village that first took us to its arms six weeks ago. It has been a fine

day, following on a day’s rain, so that the earth smells like spring. I

have just managed to break off a long conversation with the farmer in

charge, a tall thin stooping man with sad eyes, in trouble about his

land: les Anglais stole his peas, trod down his corn and robbed his

young potatoes: he told it as a father telling of infanticide. There may

have been fifteen francs’ worth of damage done; he will never get

compensation out of those shifty Belgian burgomasters; but it was not

exactly the fifteen francs but the invasion of the soil that had been

his for forty years, in which the weather was his only{81} enemy, that gave

him a kind of Niobe’s dignity to his complaint.

Meanwhile there is the usual evening sluggishness. Close by, a

quickfirer is pounding away its allowance of a dozen shells a day. It is

like a cow coughing. Eastward there begins a sound (all sounds begin at

sundown and continue intermittently till midnight, reaching their zenith

at about 9 p.m. and then dying away as sleepiness claims their

masters)—a sound like a motor-cycle race—thousands of motor-cycles

tearing round and round a track, with cut-outs out: it is really a pair

of machine guns firing. And now one sound awakens another. The old cow

coughing has started the motor-bykes: and now at intervals of a few

minutes come express trains in our direction: you can hear them rushing

toward us; they pass going straight for the town behind us: and you hear

them begin to slow down as they reach the town: they will soon stop: but

no, every time, just before they reach it, is a tremendous railway

accident. At least, it must be a railway accident, there is so much

noise, and you can see the dust that the wreckage scatters. Sometimes

the train behind comes very close, but{82} it too smashes on the wreckage

of its forerunners. A tremendous cloud of dust, and then the groans. So

many trains and accidents start the cow coughing again: only another cow

this time, somewhere behind us, a tremendous-sized cow, θαυμἀσιον ὄσιον,

with awful whooping-cough. It must be a buffalo: this cough must burst

its sides. And now someone starts sliding down the stairs on a tin tray,

to soften the heart of the cow, make it laugh and cure its cough. The

din he makes is appalling. He is beating the tray with a broom now,

every two minutes a stroke: he has certainly stopped the cow by this

time, probably killed it. He will leave off soon (thanks to the “shell

tragedy”): we know he can’t last.

It is now almost dark: come out and see the fireworks. While waiting for

them to begin you can notice how pale and white the corn is in the

summer twilight: no wonder with all this whooping-cough about. And the

motor-cycles: notice how all these races have at least a hundred

entries: there is never a single cycle going. And why are there no birds

coming back to roost? Where is the lark? I haven’t heard him all to-day.

He must have got whooping-cough as{83} well, or be staying at home through

fear of the cow. I think it will rain to-morrow, but there have been no

swallows circling low, stroking their breasts on the full ears of corn.

Anyhow, it is night now, but the circus does not close till twelve.

Look! there is the first of them! The fireworks are beginning. Red

flares shooting up high into the night, or skimming low over the ground,

like the swallows that are not: and rockets bursting into stars. See how

they illumine that patch of ground a mile in front. See it, it is deadly

pale in their searching light: ghastly, I think, and featureless except

for two big lines of eyebrows ashy white, parallel along it, raised a

little from its surface. Eyebrows. Where are the eyes? Hush, there are

no eyes. What those shooting flares illumine is a mole. A long thin

mole. Burrowing by day, and shoving a timorous enquiring snout above the

ground by night. Look, did you see it? No, you cannot see it from here.

But were you a good deal nearer, you would see behind that snout a long

and endless row of sharp shining teeth. The rockets catch the light from

these teeth and the teeth glitter: they are silently removed from the

poison-spitting gums of the mole. For the mole’s gums spit fire and,

they say, send{84} something more concrete than fire darting into the

night. Even when its teeth are off. But you cannot see all this from

here: you can only see the rockets and then for a moment the pale ground

beneath. But it is quite dark now.

And now for the fun of the fair! You will hear soon the riding-master

crack his whip—why, there it is. Listen, a thousand whips are cracking,

whipping the horses round the ring. At last! The fun of the circus is

begun. For the motor-cycle team race has started off again: and the

whips are cracking all: and the waresman starts again, beating his loud

tin tray to attract the customers: and the cows in the cattle-show start

coughing, coughing: and the firework display is at its best: and the

circus specials come one after another bearing the merry makers back to

town, all to the inevitable crash, the inevitable accident. It can’t

last long: these accidents are so frequent, they’ll all get soon killed

off, I hope. Yes, it is diminishing. The train service is cancelled (and

time too): the cows have stopped coughing: and the cycle race is done.

Only the kids who have bought new whips at the fair continue to crack

them: and unused rockets that lie about the ground are still sent up

occasionally. But{85} now the children are being driven off to bed: only an

occasional whip-crack now (perhaps the child is now the sufferer): and

the tired showmen going over the ground pick up the rocket-sticks and

dead flares. At least I suppose this is what must be happening: for

occasionally they still find one that has not gone off and send it up

out of mere perversity. Else what silence!

It must be midnight now. Yes, it is midnight. But before you go to bed,

bend down, put your ear against the ground. What do you hear? “I hear an

endless tapping and a tramping to and fro: both are muffled: but they

come from everywhere. Tap, tap, tap: pick, pick, pick: tra-mp, tra-mp,

tra-mp.” So you see the circus-goers are not all gone to sleep. There is

noise coming from the womb of earth, noise of men who tap and mine and

dig and pass to and fro on their watch. What you have seen is the foam

and froth of war: but underground is labour and throbbing and long

watch. Which will one day bear their fruit. They will set the circus on

fire. Then what pandemonium! Let us hope it will not be to-morrow!

{86}

{87}

EARLIER POEMS

XXXII

A CALL TO ACTION

I

A THOUSAND years have passed away,

Cast back your glances on the scene,

Compare this England of to-day

With England as she once has been.

Fast beat the pulse of living then:

The hum of movement, throb of war,

The rushing mighty sound of men

Reverberated loud and far.

They girt their loins up and they trod

The path of danger, rough and high;

For Action, Action was their god,

“Be up and doing” was their cry.{88}

A thousand years have passed away;

The sands of life are running low;

The world is sleeping out her day;

The day is dying—be it so.

A thousand years have passed amain;

The sands of life are running thin;

Thought is our leader—Thought is vain;

Speech is our goddess—Speech is sin.

II

It needs no thought to understand,

No speech to tell, nor sight to see

That there has come upon our land

The curse of Inactivity.

We do not see the vital point

That ’tis the eighth, most deadly, sin

To wail, “The world is out of joint”—

And not attempt to put it in.{89}

We see the swollen stream of crime

Flow hourly past us, thick and wide;

We gaze with interest for a time,

And pass by on the other side.

We see the tide of human sin

Rush roaring past our very door,

And scarcely one man plunges in

To drag the drowning to the shore.

We, dull and dreamy, stand and blink,

Forgetting glory, strength and pride,

Half—listless watchers on the brink,

Half—ruined victims of the tide.

III

We question, answer, make defence,

We sneer, we scoff, we criticize,

We wail and moan our decadence,

Enquire, investigate, surmise;{90}

We preach and prattle, peer and pry

And fit together two and two:

We ponder, argue, shout, swear, lie—

We will not, for we cannot, DO.

Pale puny soldiers of the pen,

Absorbed in this your inky strife,

Act as of old, when men were men

England herself and life yet life.

{91}

XXXIII

RAIN

WHEN the rain is coming down,

And all Court is still and bare,

And the leaves fall wrinkled, brown,

Through the kindly winter air,

And in tattered flannels I

‘Sweat’ beneath a tearful sky,

And the sky is dim and grey,

And the rain is coming down,

And I wander far away

From the little red-capped town:

There is something in the rain

That would bid me to remain:

There is something in the wind

That would whisper, “Leave behind

All this land of time and rules,

Land of bells and early schools.{92}

Latin, Greek and College food

Do you precious little good.

Leave them: if you would be free

Follow, follow, after me!”

When I reach ‘Four Miler’s’ height,

And I look abroad again

On the skies of dirty white

And the drifting veil of rain,

And the bunch of scattered hedge

Dimly swaying on the edge,

And the endless stretch of downs

Clad in green and silver gowns;

There is something in their dress

Of bleak barren ugliness,

That would whisper, “You have read

Of a land of light and glory:

But believe not what is said.

’Tis a kingdom bleak and hoary,

Where the winds and tempests call

And the rain sweeps over all.{93}

Heed not what the preachers say

Of a good land far away.

Here’s a better land and kind

And it is not far to find.”

Therefore, when we rise and sing

Of a distant land, so fine,

Where the bells for ever ring,

And the suns for ever shine:

Singing loud and singing grand,

Of a happy far-off land,

O! I smile to hear the song,

For I know that they are wrong,

That the happy land and gay

Is not very far away,

And that I can get there soon

Any rainy afternoon.

And when summer comes again,

And the downs are dimpling green,

And the air is free from rain,

And the clouds no longer seen:{94}

Then I know that they have gone

To find a new camp further on,

Where there is no shining sun

To throw light on what is done,

Where the summer can’t intrude

On the fort where winter stood:

—Only blown and drenching grasses,

Only rain that never passes,

Moving mists and sweeping wind,

And I follow them behind!

{95}

XXXIV

A TALE OF TWO CAREERS

I SUCCESS

HE does not dress as other men,

His ‘kish’ is loud and gay,

His ‘side’ is as the ‘side’ of ten

Because his ‘barnes’ are grey.

His head has swollen to a size

Beyond the proper size for heads,

He metaphorically buys

The ground on which he treads.

Before his face of haughty grace

The ordinary mortal cowers:

A ‘forty-cap’ has put the chap

Into another world from ours.{96}

The funny little world that lies

’Twixt High Street and the Mound

Is just a swarm of buzzing flies

That aimlessly go round:

If one is stronger in the limb

Or better able to work hard,

It’s quite amusing to watch him

Ascending heavenward.

But if one cannot work or play

(Who loves the better part too well),

It’s really sad to see the lad

Retained compulsorily in hell.

II FAILURE

We are the wasters, who have no

Hope in this world here, neither fame,

Because we cannot collar low

Nor write a strange dead tongue the same

As strange dead men did long ago.{97}

We are the weary, who begin

The race with joy, but early fail,

Because we do not care to win

A race that goes not to the frail

And humble: only the proud come in.

We are the shadow-forms, who pass

Unheeded hence from work and play.

We are to-day, but like the grass

That to-day is, we pass away;

And no one stops to say ‘Alas!’

Though we have little, all we have

We give our School. And no return

We can expect for what we gave;

No joys; only a summons stern,

“Depart, for others entrance crave!{98}”

As soon as she can clearly prove

That from us is no hope of gain,

Because we only bring her love

And cannot bring her strength or brain.

She tells us, “Go: it is enough.”

She turns us out at seventeen,

We may not know her any more,

And all our life with her has been

A life of seeing others score,

While we sink lower and are mean.

We have seen others reap success

Full-measure. None has come to us.

Our life has been one failure. Yes,

But does not God prefer it thus?

God does not also praise success.{99}

And for each failure that we meet,

And for each place we drop behind,

Each toil that holds our aching feet,

Each star we seek and never find,

God, knowing, gives us comfort meet.

The School we care for has not cared

To cherish nor keep our names to be

Memorials. God hath prepared

Some better thing for us, for we

His hopes have known, His failures shared.

{100}

XXXV

PEACE

THERE is silence in the evening when the long days cease,

And a million men are praying for an ultimate release

From strife and sweat and sorrow—they are praying for peace.

But God is marching on.

Peace for a people that is striving to be free!

Peace for the children of the wild wet sea!

Peace for the seekers of the promised land—do we

Want peace when God has none?

We pray for rest and beauty that we know we cannot earn,

And ever are we asking for a honey-sweet return;

But God will make it bitter, make it bitter, till we learn

That with tears the race is run.{101}

And did not Jesus perish to bring to men, not peace,

But a sword, a sword for battle and a sword that should not cease?

Two thousand years have passed us. Do we still want peace

Where the sword of Christ has shone?

Yes, Christ perished to present us with a sword,

That strife should be our portion and more strife our reward,

For toil and tribulation and the glory of the Lord

And the sword of Christ are one.

If you want to know the beauty of the thing called rest,

Go, get it from the poets, who will tell you it is best

(And their words are sweet as honey) to lie flat upon your chest

And sleep till life is gone.

I know that there is beauty where the low streams run,

And the weeping of the willows and the big sunk sun,

But I know my work is doing and it never shall be done,

Though I march for ages on.{102}

Wild is the tumult of the long grey street,

O, is it never silent from the tramping of their feet?

Here, Jesus, is Thy triumph, and here the world’s defeat

For from here all peace has gone.

There’s a stranger thing than beauty in the ceaseless city’s breast,

In the throbbing of its fever—and the wind is in the west,

And the rain is driving forward where there is no rest,

For the Lord is marching on.

{103}

XXXVI

THE RIVER

HE watched the river running black

Beneath the blacker sky;

It did not pause upon its track

Of silent instancy.

It did not hasten, nor was slack,

But still went gliding by.

It was so black. There was no wind

Its patience to defy.

It was not that the man had sinned,

Or that he wished to die.

Only the wide and silent tide

Went slowly sweeping by.{104}

The mass of blackness moving down

Filled full of dreams the eye;

The lights of all the lighted town

Upon its breast did lie.

The tall black trees were upside down

In the river’s phantasy.

He had an envy for its black

Inscrutability;

He felt impatiently the lack

Of that great law whereby

The river never travels back

But still goes gliding by;

But still goes gliding by, nor clings

To passing things that die,

Nor shows the secrets that it brings

From its strange source on high.

And he felt “We are two living things

And the weaker one is I.{105}”

He saw the town, that living stack

Piled up against the sky.

He saw the river running black

On, on and on: O, why

Could he not move along his track

With such consistency?

He had a yearning for the strength

That comes of unity:

The union of one soul at length

With its twin-soul to lie;

To be a part of one great strength

That moves and cannot die.

* * * * * *

He watched the river running black

Beneath the blacker sky.

He pulled his coat about his back,

He did not strive nor cry.

He put his foot upon the track

That still went gliding by{106}

The thing that never travels back

Received him silently.

And there was left no shred, no wrack

To show the reason why:

Only the river running black

Beneath the blacker sky.

{107}

XXXVII

THE SEEKERS

THE gates are open on the road

That leads to beauty and to God.

Perhaps the gates are not so fair,

Nor quite so bright as once they were,

When God Himself on earth did stand

And gave to Abraham His hand

And led him to a better land.

For lo! the unclean walk therein,

And those that have been soiled with sin.

The publican and harlot pass

Along: they do not stain its grass.

In it the needy has his share,

In it the foolish do not err.

Yes, spurned and fool and sinner stray

Along the highway and the way.{108}

And what if all its ways are trod

By those whom sin brings near to God?

This journey soon will make them clean:

Their faith is greater than their sin.

For still they travel slowly by

Beneath the promise of the sky,

Scorned and rejected utterly;

Unhonoured; things of little worth

Upon the highroads of this earth;

Afflicted, destitute and weak:

Nor find the beauty that they seek,

The God they set their trust upon:

—Yet still they march rejoicing on.

{109}

{110}

{111}

ILLUSTRATIONS IN PROSE

I

RICHARD JEFFERIES (p. 27)

I am sweatily struggling to the end of Faust II, where Goethe’s just

showing off his knowledge. I am also reading a very interesting book on

Goethe and Schiller; very adoring it is, but it lets out quite

unconsciously the terrible dryness of their entirely intellectual

friendship and (Goethe’s at least) entirely intellectual life. If Goethe

really died saying “more light,” it was very silly of him: what he

wanted was more warmth. G. and S. apparently made friends, on their own

confession, merely because their ideas and artistic ideals were the

same, which fact ought to be the very first to make them bore one

another.

All this is leading to the following conclusion. The Germans can act

Shakespeare, have good beer and poetry, but their prose is cobwebby

stuff. Hence I want to read some good prose again. Also it is summer.

And for a year or two I had always laid up “The Pageant of Summer” as a

treat for a hot July. In spite of all former vows of celibacy{112} in the

way of English, now’s the time. So, unless the cost of book-postage here

is ruinous, could you send me a small volume of Essays by Richard

Jefferies called The Life of the Fields, the first essay in the series

being the Pageant of Summer? No particular hurry, but I should be

amazingly grateful if you’ll send it (it’s quite a little book),

especially as I presume the pageant of summer takes place in that part

of the country where I should be now had——had a stronger will than

you. In the midst of my setting up and smashing of deities—Masefield,

Hardy, Goethe—I always fall back on Richard Jefferies wandering about

in the background. I have at least the tie of locality with him. (July

1914.)

I’ve given up German prose altogether. It’s like a stale cake compounded

of foreign elements. So I have laid in a huge store of Richard Jefferies

for the rest of July, and read him none the less voraciously because we

are countrymen. (I know it’s wrong of me, but I count myself as

Wiltshire....) When I die (in sixty years) I am going to leave all my

presumably enormous fortune to Marlborough on condition that a thorough

knowledge of Richard Jefferies is ensured by the teaching there. I think

it is only right considering we are bred upon the self-same hill. It

would also encourage Naturalists and discourage cricketers....{113}

But, in any case. I’m not reading so much German as I did ought to. I

dabble in their modern poetry, which is mostly of the morbidly religious

kind. The language is massively beautiful, the thought is rich and

sleek, the air that of the inside of a church. Magnificent artists they

are, with no inspiration, who take religion up as a very responsive

subject for art, and mould it in their hands like sticky putty. There

are magnificent parts in it, but you can imagine what a relief it was to

get back to Jefferies and Liddington Castle. (July 1914.)

II

IBSEN (pp. 50-52)

Ibsen’s last, John Gabriel Borkman, is a wonderfully fine play, far

better than any others by Ibsen that I have read or seen, but I can

imagine it would lose a good deal in an English translation. The acting

of the two middle-aged sisters who are the protagonists was marvellous.

The men were a good deal more difficult to hear, but also very striking.

Next to the fineness of the play (which has far more poetry in it than

any others of his I’ve read, though of course there’s a bank in the

background, as there always seems to be in Ibsen)—the apathy of the

very crowded house struck me most. There was very little clapping at the

end{114} at the acts: at the end of the play none, which was just as well

because one of them was dead and would have had to jump up again. So

altogether I am very much struck by my first German theatre, though the

fineness of the play may have much to do with it. It was just a little

spoilt by the last Act being in a pine forest on a hill with sugar that

was meant to look like snow. This rather took away from the effect of

the scene, which in the German is one of the finest things I have ever

heard, possessing throughout a wonderful rhythm which may or may not

exist in the original. What a beautiful language it can be! (13

February 1914.)

I have been reading many criticisms of John Gabriel Borkman, and it

strikes me more and more that it is the most remarkable play I have ever

read. It is head and shoulders above the others of Ibsen’s I know: a

much broader affair. John Gabriel Borkman is a tremendous character. His

great desire, which led him to overstep the law for one moment, and of

course he was caught and got eight years, was “Menschenglück zu

schaffen.” One moment Ibsen lets you see one side of his character (the

side he himself saw) and you see the Perfect Altruist: the next moment

the other side is turned, and you see the Complete Egoist. The play all

takes place in the last three hours of J. G. B.’s life, and in these

three hours his real love, whom he had rejected{115} for business reasons

and married her twin-sister, shows him for the first time the Egoist

that masqueraded all its life as Altruist. The technique is perfect and