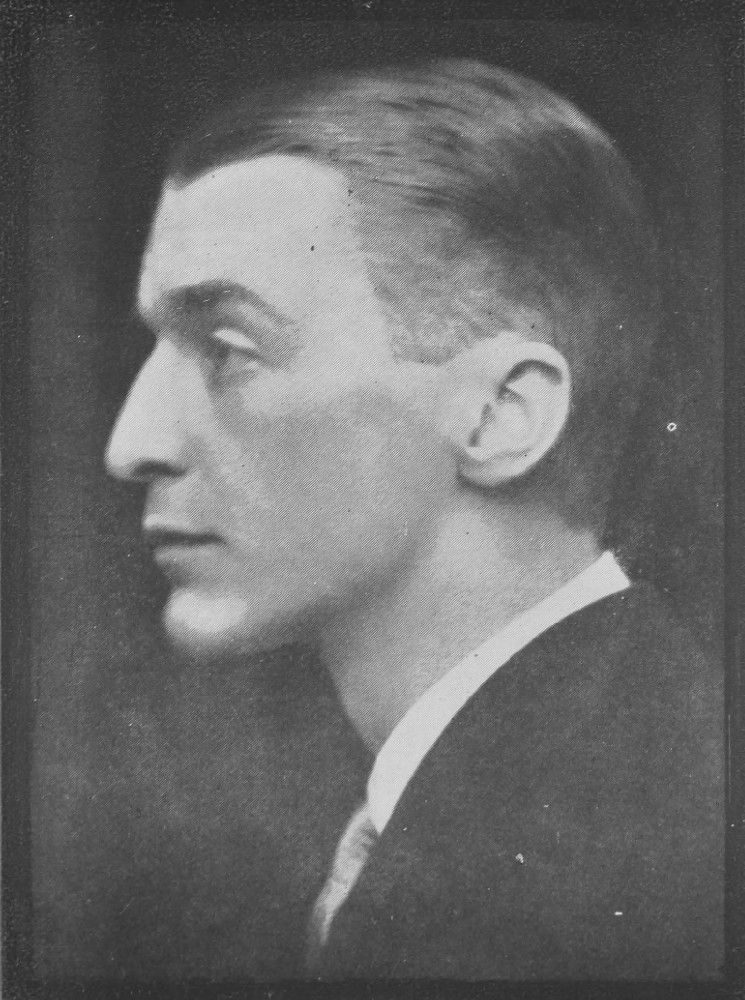

Thomas Hardy

Thomas Hardy

GODS OF

MODERN GRUB STREET

IMPRESSIONS OF CONTEMPORARY AUTHORS

BY

A. ST. JOHN ADCOCK

WITH THIRTY-TWO PORTRAITS

AFTER PHOTOGRAPHS BY

E. O. HOPPÉ

NEW YORK

FREDERICK A. STOKES COMPANY

MCMXXIII

Copyright, 1923, by Frederick A. Stokes Company

All Rights Reserved

Printed in the United States of America

[Pg v]

[Pg vii]

[Pg 3]

Those who dissent from Byron’s dictum that Keats was “snuffed out by an article” usually add that no author was ever killed by criticism; yet there seems little doubt that the critics killed Thomas Hardy the novelist, and our only consolation is that from the ashes of the novelist, phœnix-like rose Thomas Hardy the Poet.

As a novelist, Hardy began and finished his career in the days of Victoria, but though he has only been asserting himself as a poet since then, his earliest verse was written in the sixties; his first collection of poetry, the “Wessex Poems,” appeared in 1898, and his second in the closing year of the Queen’s reign. These facts should give us pause when we are disposed to sneer again at Victorian literature. Even the youngest scribe among us is constrained to grant the greatness of this living Victorian, so if we insist that the Victorians are over-rated we imply some disparagement of their successors, who have admittedly produced no novelists that rank so high as Hardy and few poets, if any, that rank higher.

Born at Upper Bockhampton, a village near Dorchester, on the 2nd June, 1840, Mr. Hardy passed[Pg 4] his childhood and youth amid the scenes and people that were, in due season, to serve as material for his stories and poems. At seventeen a natural bent drew him to choose architecture as a profession, and he studied first under an ecclesiastical architect in Dorchester, then, three years later, in London, under Sir Arthur Blomfield, proving his efficiency by winning the Tite prize for architectural design, and the Institute of British Architects’ prize and medal for an essay on Colored and Terra Cotta Architecture.

But he was already finding himself and realizing that the work he was born to do was not such as could be materialized in brick and stone. He had been writing verse in his leisure and, in his twenties, “practised the writing of poetry” for five years with characteristic thoroughness; but, recognizing perhaps that it was not to be taken seriously as a means of livelihood, he presently abandoned that art; to resume it triumphantly when he was nearing sixty.

His first published prose was a light, humorous sketch of “How I Built Myself a House,” which appeared in Chambers’s Journal for March, 1865. In 1871 came his first novel, “Desperate Remedies,” a story more of plot and sensation than of character, which met with no particular success. Next year, however, Thomas Hardy entered into his kingdom with that “rural painting of the Dutch school,” “Under the Greenwood Tree,” a delightful, realistic prose pastoral that has more of charm and tenderness than any other of his tales, except “The Trumpet Major.” The critics recognized its quality and,[Pg 5] without making a noise, it found favor with the public. What we now know as the distinctive Hardy touch is in its sketches of country life and subtle revelations of rural character, in its deliberate precision of style, its naked realism, its humor and quiet irony; and if the realism was to grow sterner, as he went on, the irony to be edged with bitterness, his large toleration of human error, his pity of human weakness, were to broaden and deepen with the passing of the years.

It is said that Frederick Greenwood, then editing the Cornhill, picked up a copy of “Under the Greenwood Tree” on a railway bookstall and, reading it, was moved to commission the author to write him a serial; and when “Far from the Madding Crowd” appeared anonymously in Cornhill its intimate acquaintance with rural England misled the knowing ones into ascribing it to George Eliot—an amazing deduction, seeing that it has nothing in common with George Eliot, either in manner or design.

“A Pair of Blue Eyes” had preceded “Far From the Madding Crowd,” and “The Hand of Ethelberta” followed it; then, in 1878, came “The Return of the Native,” which, with “The Mayor of Casterbridge” and “The Woodlanders,” stood as Hardy’s highest achievements until, in 1891 and 1896, “Tess of the D’Urbervilles” and “Jude the Obscure” went a flight beyond any that had gone before them and placed him incontestibly with the world’s greatest novelists.

Soon after Hardy had definitely turned from architecture to literature he went back to Wessex,[Pg 6] where he lived successively at Cranbourne, Sturminster, and Wimborne, until in 1885 he removed to Max Gate, Dorchester, which has been his home ever since. And through all those years, instead of going far afield in search of inspiration, he recreated the ancient realm of the West Saxons and found a whole world and all the hopes, ambitions, joys, loves, follies, hatreds—all the best and all the worst of all humanity within its borders. The magic of his genius has enriched the hundred and forty square miles of Wessex, which stretches from the Bristol Channel across Somerset, Devon, Dorset, Wilts and Hampshire to the English Channel, with imaginary associations that are as living and abiding, as inevitably part of it now, as are the facts of its authentic history.

A grim, stoical philosophy of life is implicit alike in Hardy’s poetry and stories, giving a strange consistency to all he has written, so that his books are joined each to each by a religion of nature that is in itself a natural piety. He sees men and women neither as masters of their fate nor as wards of a beneficent deity, but as “Time’s laughing-stocks” victims of heredity and environment, the helpless sport of circumstance, playing out little comedies or stumbling into tragedies shaped for them inexorably by some blind, creative spirit of the Universe that is indifferent to their misery or happiness and as powerless to prolong the one as to avert the other. The earlier pastoral comedies and tragi-comedies have their roots in this belief, which reaches its most terribly beautiful expression in the[Pg 7] epic tragedies of “Tess” and “Jude the Obscure.”

I am old enough to remember the clash of opinions over the tragic figure of Tess and the author’s presentation of her as “a pure woman”; how there were protests from pulpits; how the critics mitigated their praise of Hardy’s art with reproof of his ethics; but the story gripped the imagination of the public, and time has brought not a few of the moralists round to a recognition that if Hardy’s sense of morality was less conventional, it was also something nobler, more fundamental than their own. He will not accept the dogmas of orthodox respectability, but looks beyond the accidents of circumstance and conduct to the real good or evil that is in the human heart that wrongs or is wronged. The same passion for truth at all costs underlies his stark, uncompromising realism and his gospel of disillusion, his vision of men as puppets working out a destiny they cannot control. If he has, therefore, little faith in humanity, he has infinite compassion for it, and infinite pardon. The irony of his stories is the irony he finds in life itself, and as true to human experience as are the humor and the pathos of them. Other eyes, another temperament, may read a different interpretation of it all; he has honestly and courageously given us his own.

The outcry against “Tess” was mild compared to the babble of prudish censure with which “Jude the Obscure” was received in many quarters, and it is small wonder that these criticisms goaded Hardy to a resolve that he would write no more novels for a world that could so misunderstand his purposes[Pg 8] and misconstrue his teachings. “The Well-Beloved,” though it appeared a year later than “Jude,” had been written and published serially five years before, and it was with “Jude,” when his power was at its zenith, that Thomas Hardy wrote finis to his work as a novelist.

Happily his adherence to this resolve drove him back on the art he had abjured in his youth, and the last quarter of a century has yielded some half dozen books of his poems that we would not willingly have lost. Above all, it has yielded that stupendous chronicle-drama of the Napoleonic wars, “The Dynasts,” which is sometimes acclaimed as the highest and mightiest effort of his genius. This drama, and his ballads and lyrics, often too overweighted with thought to have any beat of wings in them, are at one with his novels in the sincere, sombre philosophy of life that inspires them, the darkling imagination with which it is bodied forth, and the brooding, forceful personality which speaks unmistakably through all.

Hardy, is, and will remain, a great and lonely figure in our literature. It is possible to trace the descent of almost every other writer, to name the artistic influences that went to his making, but Hardy is without literary ancestry; Dickens and Thackeray, Tennyson and Browning, had forerunners, and have left successors. We know, as a matter of fact, what porridge John Keats had, but we do not know that of Hardy. Like every master, he unwittingly founded a school, but none of his imitators could imitate him except superficially, and already the scholars[Pg 9] are going home and the master will presently be alone in his place apart. His style is peculiarly his own; as novelist and poet he has worked always within his own conception of the universe as consistently as he has worked within the scope and bounds of his own kingdom of Wessex, and “within that [Pg 10]circle none durst walk but he.”

[Pg 11]

Hilaire Belloc

[Pg 13]

So long and persistently has Hilaire Belloc been associated in the public mind with G. K. Chesterton—one ingenious jester has even linked and locked them together in an easy combination as the Chesterbelloc—that quite a number of people now have a vague idea that they are inseparables, collaborators, a sort of literary Siamese twins like Beaumont and Fletcher or Erckmann-Chatrian; and the fact that one appears in this volume without the other may occasion some surprise. Let it be confessed at once that Chesterton’s omission from this gallery is significant only of his failure—not in modern letters, but to keep any appointments to sit for his photograph.

I regret his absence the less since it may serve as a mute protest against the practice of always bracketing his name with that of Hilaire Belloc. The magic influence of Belloc which is supposed to have colored so many of G. K. C.’s views and opinions and even to have drawn him at length into the Roman Catholic community, must be little but legendary or evidence of it would be apparent in his writings, and it is no more traceable there than the influence of Chesterton is to be found in Belloc’s books. They share a dislike of Jews, which nearly equals that of William Bailey in “Mr. Clutterbuck’s[Pg 14] Election”; Chesterton has illustrated some of Belloc’s stories, and Belloc being an artist, too, has made charming illustrations for one of his own travel volumes. All the same, there is no more real likeness between them than there was between Dickens and Thackeray, or Tennyson and Browning, who were also, and are to some extent still, carelessly driven in double harness. Belloc’s humor and irony are hard, often bitter; they have none of the geniality, nimbleness, perverse fantasy of Chesterton’s. The one has a profound respect for fact and detail, and learns by carefully examining all the mechanical apparatus of life scientifically through a microscope; while the other has small reverence for facts as such, looks on life with the poet’s rather than with the student’s eye, and sees it by lightning-flashes of intuition. When Chesterton wrote his History of England he put no dates in it; he felt that dates were of no consequence to the story; but Belloc has laid it down that, though the human motive is the prime factor in history, “the external actions of men, the sequence in dates and hours of such actions, and their material conditions and environments must be strictly and accurately acquired.” There is no need to labor the argument. “The Napoleon of Notting Hill” is not more unlike “Emanuel Burden” than their two authors are unlike each other, individually and in what they have written.

Born at St. Cloud in 1870, Belloc was the son of a French barrister; his mother, an Englishwoman, was the grand-daughter of Joseph Priestley, the[Pg 15] famous scientist and Unitarian divine. She brought him over to England after the death of his father, and they made their home in Sussex, the country that has long since taken hold on his affections and inspired the best of his poems. I don’t know when he was “living in the Midlands,” or thereabouts except while he was at Oxford, and earlier when he was a schoolboy at the Birmingham Oratory and came under the spell of Cardinal Newman, and I don’t know when he wrote “The South Country,” but not even Kipling has crowned Sussex more splendidly than he crowns it in that vigorous and poignant lyric—

“When I am living in the Midlands,

That are sodden and unkind,

I light my lamp in the evening;

My work is left behind;

And the great hills of the South Country

Come back into my mind.

The great hills of the South Country

They stand along the sea,

And it’s there, walking in the high woods,

That I could wish to be,

And the men that were boys when I was a boy

Walking along with me....

If ever I become a rich man,

Or if ever I grow to be old,

I will build a house with a deep thatch

To shelter me from the cold,

And there shall the Sussex songs be sung

And the story of Sussex told.

I will hold my house in the high wood,

Within a walk of the sea,

And the men that were boys when I was a boy

Shall sit and drink with me.”

[Pg 16]

Nowadays, he has to some extent realized that desire, for he is settled at Horsham, in Sussex again, if not within a walk of the sea. But we are skipping too much, and will go back and attend to our proper historical “sequence in dates.” His schooldays over, he accepted the duties of his French citizenship and served his due term in the Army of France, as driver in an Artillery regiment. These military obligations discharged, he returned to England, went to Oxford, and matriculated at Balliol. He ran a dazzling career at Oxford, working assiduously as a student, carrying off the Brackenbury Scholarship and a First Class in Honor History Schools, and at the same time reveled joyously with the robust, gloried in riding and swimming and coruscated brilliantly in the Union debates. His vivid, dominating personality seems to have made itself felt among his young contemporaries there as it has since made itself felt in the larger worlds of literature and politics; though in those larger worlds his recognition and his achievements have never, so far, been quite commensurate with his extraordinary abilities or the tradition of power that has gathered about his name. In literature, high as he stands, his fame is less than that of men who have not a tithe of his capacity, and in politics he remains a voice crying in the wilderness, a leader with no effective following. Perhaps in politics his fierce sincerity drives him into tolerance, he burns to do the impossible and change human nature at a stroke, and is too far ahead of his time for those he would lead[Pg 17] to keep pace with him. And perhaps in literature he lacks some gift of concentration, dissipates his energies over too many fields, and is too much addicted to the use of irony, which it has been said, not without reason, is regarded with suspicion in this country and never understood. Swift is admittedly our supreme master in that art, and there is nothing more ironic in his most scathingly ironical work, “Gulliver’s Travels,” than the fact that Gulliver is only popular as an innocently amusing book for children.

Belloc began quietly enough, in 1895, with a little unimportant book of “Verses and Sonnets.” He followed this in the next four years with four delightfully, irresponsibly absurd books of verses and pictures such as “The Bad Child’s Book of Beasts,” “More Beasts for Worse Children,” publishing almost simultaneously in 1899 “The Moral Alphabet” and his notable French Revolution study of “Danton.” In a later year he gave us simultaneously the caustic, frivolous “Lambkin’s Remains” and his book on “Paris,” and followed it with his able monograph on “Robespierre.” It was less unsettling, no doubt, when “Caliban’s Guide to Letters” was closely succeeded by the first and most powerful of his ironic novels, “Emanuel Burden,” but serious people have never known where to have him. He collects his essays under such careless titles as “On Nothing,” “On Anything,” “This and That,” or simply “On”; and the same year that found him collaborating with Cecil Chesterton in a bitter attack on “The Party System,”[Pg 18] found him collaborating with Lord Basil Blackwood in the farcical “More Peers,” and issuing acute technical expositions of the battles of Blenheim and Malplaquet.

His novels, “Emanuel Burden,” “Mr. Clutterbuck’s Election,” “A Change in the Cabinet,” “The Mercy of Allah,” and the rest, satirize the chicanery and humbug rampant in modern commerce, finance, politics, and general society, and are too much in earnest to attempt to tickle the ears of the groundlings.

For four years, in the first decade of the century, Belloc sat in Parliament as Member for Salford, but the tricks, hypocrisies, insincerities of the politicians disgusted and exasperated him; he was hampered and suppressed in the House by its archaic forms, and instead of staying there stubbornly to leaven the unholy lump he came wrathfully out, washing his hands of it, to attack the Party system in the Press, and inaugurate The Witness in which he proceeded to express himself on the iniquities of public life forcefully and with devastating candor.

No journalist wielded a more potent pen than he through the dark years of the war. His articles in Land and Water recording the various phases of the conflict, criticizing the conduct of campaigns, explaining their course and forecasting developments drew thousands of readers to sit every week at his feet, and were recognized as the cleverest, most searching, most informing of all the many periodical reviews of the war that were then current. That his prophecies were not always fulfilled meant[Pg 19] only that, like all prophets, he was not infallible. His vision, his intimate knowledge of strategy, his mastery of the technique of war were amazing—yet not so amazing when you remember his service in the French Army and that he comes of a race of soldiers. One of his mother’s forbears was an officer in the Irish Brigade that fought for France at Fontenoy, and four of his father’s uncles were among Napoleon’s generals, one of them falling at the head of his charging troops at Waterloo. It were but natural he should derive from such stock not merely a love of things military but that ebullient, overpowering personality which many who come in contact with him find irresistible.

As poet, he has written three or four things that will remain immortal in anthologies; as novelist, he has a select niche to himself; “The Girondin” indicates what he might have become as a sheer romantist, but he did not pursue that vein; his books of travel, particularly “The Path to Rome” and “Esto Perpetua,” are unsurpassed in their kind by any living traveler; as historian, essayist, journalist, he ranks with the highest of his contemporaries; nevertheless, you are left with a feeling that the man himself is greater than anything he has done. You feel that he has been deftly modeling a motley miscellany of statuettes when he might have been carving a statue; and the only consolation is that some of the statuettes are infinitely finer than are many statues, and that, anyhow, he has given, and obviously taken delight in the making of them.

[Pg 21]

Arnold Bennett

[Pg 23]

If his critics are inclined to write Arnold Bennett down as a man of great talent instead of as a man of genius, he is himself to blame for that. He has not grown long hair, nor worn eccentric hats and ties, not cultivated anything of the unusual appearance and manner that are vulgarly supposed to denote genius. In his robust, commonsense conception of the literary character, as well as in certain aspects of his work, he has affinities with Anthony Trollope.

Trollope used to laugh at the very idea of inspiration; he took to letters as sedulously and systematically as other men take to farming or shopkeeping, wrote regularly for three or four hours a day, whether he was well or ill, at home or abroad, doing in those hours always the same number of words, and keeping his watch on the table beside him to regulate his rate of production. He was intolerant of the suggestion that genius is a mysterious power which controls a man, instead of being controlled by him, that

“the spirit bloweth, and is still,”

and the author is dependent on such vagrant moods, and he justified his opinions and his practices by becoming[Pg 24] one of the half dozen greater Victorian novelists.

I do not say that Arnold Bennett holds exactly the same beliefs and works in the same mechanical fashion, but that his literary outlook is as practical and business-like is apparent from “The Truth about an Author,” from “The Author’s Craft,” “Literary Taste,” and other of those pocket philosophies that he wrote in the days when he was pot-boiling, and also from the success with which, in the course of his career, he has put his own precepts into practice.

The author who is reared in an artistic atmosphere, free from monetary embarrassments, with social influence enough to smooth his road and open doors to him, seldom acquires any profound knowledge of life or develops any remarkable quality. But Bennett had none of these disadvantages. Nor was he an infant phenomenon, rushing into print before he was out of his teens; he took his time, and lived awhile before he began to write about life, and did not adopt literature as a means of livelihood until he had sensibly made up his mind what he wanted to do and that he could do it. He was employed in a lawyer’s office till he was twenty-six, and had turned thirty when he published his first novel, “A Man from the North.” Meanwhile, he had been writing stories and articles experimentally, and, having proved his capacity by selling a sufficient proportion of these to various periodicals, he threw up the law to go as assistant editor, and afterwards became editor, of a magazine[Pg 25] for women—which may, in a measure, account for his somewhat cynical views on love and marriage and the rather pontifical cocksureness with which he often delivers himself on those subjects.

In 1900 he emancipated himself from the editorial chair and withdrew into the country to live quietly and economically and devote himself to ambitions that he knew he could realize. He had tried his strength in “A Man from the North,” and settled down now, deliberately and confidently, to become a novelist and a dramatist; he was out for success in both callings, and did not mean to be long about getting it, if not with the highest type of work, then with the most popular. For he was too eminently practical to have artistic scruples against giving the public what it wanted if by so doing he might get into a position for giving it what he wanted it to have. He expresses the sanest, healthfulest scorn for the superior but unsaleable author who cries sour grapes and pretends to a preference for an audience fit though few.

“I can divide all the imaginative authors I have ever met,” he has written, “into two classes—those who admitted and sometimes proclaimed loudly that they desired popularity; and those who expressed a noble scorn or a gentle contempt for popularity. The latter, however, always failed to conceal their envy of popular authors, and this envy was a phenomenon whose truculent bitterness could not be surpassed even in political or religious life. And indeed, since the object of the artist is to share[Pg 26] his emotions with others, it would be strange if the normal artist spurned popularity in order to keep his emotions as much as possible to himself. An enormous amount of dishonest nonsense has been and will be written by uncreative critics, of course in the higher interests of creative authors, about popularity and the proper attitude of the artist thereto. But possibly the attitude of a first-class artist himself may prove a more valuable guide.” And he proceeds to show from his letters how keenly Meredith desired to be popular, and praises him for compromising with circumstance and turning from the writing of poetry that did not pay to the writing of prose in the hope that it would. I doubt whether he would sympathize with any man who starved for art’s sake when he might have earned good bread and meat in another calling. The author should write for success, for popularity; that is his creed: “he owes the practice of elementary commonsense to himself, to his work, and to his profession at large.”

Bennett was born in 1887, and not for nothing was he born at Hanley, one of the Five Towns of Staffordshire that he has made famous in his best stories—a somber, busy, smoky place bristling with factory chimneys and noted for its potteries. How susceptible he was to the spell of it, how it made him its own, and how vividly he remembers traits and idiosyncrasies of local character and all the trivial detail in the furnishing of its houses and the manners and customs of its Victorian home-life are[Pg 27] evident from his books. He came to London with the acute commonsense, the mother wit, the shrewd business instinct and energy of the Hanley manufacturer as inevitably in his blood as if he had breathed them in with his native air, and he adapted himself to the manufacture of literature as industriously and straightforwardly as any of his equally but differently competent fellow-townsmen could give themselves to the manufacture of pottery. He worked with his imagination as they worked with their clay; and it was essential with him, as with them, that the goods he produced should be marketable.

There is always a public for a good story of mystery and sensation so, in those days when he was feeling his way, he wrote “The Grand Babylon Hotel,” and did it so thoroughly, so efficiently that it was one of the cleverest and most original, no less than one of the most successful things of its kind. In the same year he published “Anna of the Five Towns,” which was less popular but remains among the best six of his finer realistic tales of his own people. He followed this with three or four able enough novels of lesser note; with a wholly admirable collection of short stories, “The Grim Smile of the Five Towns”; was busy with those astute, provocative pot-boiling pocket-philosophies, “Journalism for Women,” “How to Become an Author,” “How to Live on Twenty-Four Hours a Day,” and the rest; writing dramatic criticisms; plays, such as “Cupid and Commonsense,” “What[Pg 28] the Public Wants”; and, over the signature of “Jacob Tonson,” one of the most brilliant and entertaining of weekly literary causeries.

Then, in 1908, he turned out another romance of mystery and sensation, “Buried Alive,” and in the same year published “The Old Wives’ Tale,” perhaps the greatest of his books, and one that ranked him unquestionably with the leading novelists of his time. A year later came “Clayhanger,” the first volume in the trilogy which was continued, in 1911, with “Hilda Lessways,” and completed, after a delay of five years, with “They Twain.” This trilogy, with “The Old Wives’ Tale,” and the much more recent “Mr. Prohack,” are Arnold Bennett’s highest achievements in fiction. The first four are stories of disillusion; the romance of them is the drab, poignant romance of unideal love and disappointed marriage, and the humor of them is sharply edged with irony and satire. In “Mr. Prohack” Bennett returns to the more genial mood of “The Card” (1911). Prohack is a delightful, almost a lovable creation, and the Card, with his dry, dour humor, for all his practical hardheadedness, is scarcely less so.

Unlike most men, who set out to do one thing and end by doing another, Bennett laid down the plan of his career and has carried it out triumphantly. He is a popular novelist, but, though he cheerfully stooped to conquer and did a lot of miscellaneous writing by the way, while he was building his reputation, the novels that have made him popular are among the masterpieces of latter-day realistic art.[Pg 29] And with “Milestones” (in collaboration with Edward Knoblauch) and “The Great Adventure,” to say nothing of his seven or eight other plays, he is a successful dramatist. His versatility is as amazing as his industry. It may be all a matter of talent and commonsense perseverance but he seems to do whatever he chooses with an ease and a brilliance that is very like genius. His list of nearly sixty volumes includes essays, dramas, short stories, several kinds of novel, books of criticism and of travel; he paints deftly and charmingly in water-colors; and if he has written no poetry it is probably because he is too practical to trifle with what is so notoriously unprofitable, for if he decided to write some you may depend upon it he could. He has analyzed “Mental Efficiency” and “The Human Machine” in two of his little books of essays, and illustrated both in his life.

[Pg 31]

John Davys Beresford

[Pg 33]

There seems to be something in the atmosphere of the manse and the vicarage that has a notable effect of developing in many who breathe it a capacity for writing fiction. Not a few authors have been cradled into literature by the Law, Medicine and the Army, but as a literary incubator no profession can vie with the Church. If it has produced no poet of the highest rank, it gave us Donne, Herrick, Herbert, Crashaw, Young, Crabbe, and a multitude of lesser note, and if it has yielded no greater novelists than Sterne and Kingsley, it has fostered a vast number that have, in their day, made up in popularity for what they lacked in genius.

Moreover, when the parsons themselves have proved immune to that peculiarity of the clerical environment, it has wrought magically upon their children, and an even longer list could be made, including such great names as Goldsmith, Jane Austen and the Brontes, of the sons and daughters of parsons who have done good or indifferent work as poets or as novelists.

Most of the novelists moulded by such early influences have leaned rather to ideal or to glamorously or grimly romantic than to plainly realistic interpretations of life and character, and J. D. Beresford is so seldom romantic, or idealistic, so[Pg 34] often realistically true to secular and unregenerate aspects of human nature, that, if he did not draw his clerical characters with such evident inside knowledge, you would not suspect that in his beginnings he had been subject to the limitations and repressions that necessarily obtain in an ecclesiastical household.

He was born in Castor rectory, and his father was a minor canon and precentor of Peterborough Cathedral, and, if it pleases you, you can play with a theory that the stark realism with which he handles the facts, even the uglier facts, of modern life is either a reaction from the narrow horizon that cramped his youthful days, or that the outlook of the paternal rectory was broader than the outlook of rectories usually is.

After an education at Oundel, and at King’s School, Peterborough, he was apprenticed, first to an architect in the country, then to one in London; but before long he abandoned architecture to go into an insurance office, and left that to take up a post with W. H. Smith & Son, in the Strand where he became a sort of advertising expert and was placed at the head of a bookselling department with a group of country travellers under his control.

Before he was half-way through his teens, he had been writing stories which were not published and can never now be brought against him, for he is shrewdly self-critical and all that juvenilia has been ruthlessly destroyed. He was contributing to Punch in 1908, and a little later had become a reviewer on the staff of that late and much lamented[Pg 35] evening paper the Westminster Gazette. Among the destroyed juvenilia was more than one novel. In what leisure he could get from his advertising and reviewing, he was busy on another which was not destined to that inglorious end. For though “Jacob Stahl” was rejected by the first prominent publisher to whom it was offered, because, strangely enough, he considered it old-fashioned, it was promptly accepted by the second, and its publication in 1911 was the real beginning of Beresford’s literary career. Had it been really old-fashioned, it would have delighted the orthodox reading public, which is always the majority, but its appeal was rather to the new and more advanced race of readers, and though its sales were not astonishing, its mature narrative skill and sound literary qualities were unhesitatingly recognized by the discriminating; it gave him a reputation, and has held its ground and gone on selling steadily ever since. One felt the restrained power of the book, alike in the narrative and in the intimate realization of character; its careful artistry did not bid for popularity, but it ranked its author, at once, as a novelist who was considerably more than the mere teller of a readable tale.

“Jacob Stahl” was the first volume in a trilogy (the other two being “A Candidate for Truth” and “The Invisible Event”)—a trilogy which unfolds a story of common life that might easily have been throbbing with sentiment and noisy with melodramatic sensation; in Mr. Beresford’s reticent hands, however, it is never overcharged with either,[Pg 36] but is touched only with the natural emotions, subdued excitements, unexaggerated poignancies of feeling that are experienced by such men and women as we know in the world as we know it.

Meredith, in “The Invisible Event,” rather grudgingly praises Jacob Stahl’s first novel, “John Tristram,” as good realistic fiction of the school of Madame Bovary. “It’s a recognized school,” Meredith continued. “I don’t quite know any one in England who’s doing it, but it’s recognized in France, of course. I don’t quite know how to define it, but perhaps the main distinction is in the choice of the typical incidents and emotions. The realists don’t concentrate on the larger emotions, you see—quite the reverse; they find the common feelings and happenings of everyday life more representative. You may have a big scene, but the essential thing is the accurate presentation of the commonplace.” “Yes, I think that is pretty much what I have tried to do,” commented Jacob. “I think that’s what interests me. It’s what I know of life. I’ve never murdered any one, for instance, or talked to a murderer, and I don’t know how it feels, or what one would do in a position of that sort.”

That is perhaps a pretty fair statement of Beresford’s own aim as a novelist; he prefers to exercise his imagination on what he has observed of life, or on what he has personally experienced of it. And no doubt the “Jacob Stahl” trilogy draws much of its convincing air of truthfulness from the fact that it is largely autobiographical. In the first volume,[Pg 37] the baby Jacob, owing to the carelessness of a nursemaid, meets with an accident that cripples him for the first fifteen years of his existence; and just such an accident in childhood befell Mr. Beresford himself. In due course, after toying with the thought of taking holy orders, Jacob becomes an architect’s pupil. “A Candidate for Truth” shows him writing short stories the magazines will not accept, and working on a novel, but before anything can be done with this, the erratic Cecil Barker gets tired of patronizing him and, driven to earn a livelihood, he takes a situation in an advertising agency and develops into an expert at writing advertisements. Then, having revised and rewritten his novel, he is dissatisfied with it and burns it. He does not begin to conquer his irresolutions and win some confidence in himself until after his disastrous marriage and separation from his wife, when he comes under the influence of the admirable Betty Gale, who loves him and defies the conventions to help him make the best of himself. Then he gets on to the reviewing staff of a daily newspaper, and writes another novel, “John Tristram,” and after one publisher has rejected it as old-fashioned, another accepts and publishes it, and though it brings him little money or glory, it starts him on the road to success, and he makes it the first volume of a trilogy.

Where autobiography ends and fiction begins in these three stories is of no importance; what is not literally true in them is so imaginatively realized that it seems as truthful. Philip of “God’s Counterpoint,”[Pg 38] who was injured by an accident in boyhood is a pathological case; there are surrenderings to the morbid and abnormal in “Housemates,” one of the somberest of Beresford’s novels, and in that searching and poignant study in degeneracy, “The House in Demetrius Road”; but if these are more powerful in theme and more brilliant in workmanship they have not the simple, everyday actuality of the trilogy; they get their effects by violence, or by the subtle analysis of bizarre, unusual or unpleasant attributes of humanity, and the strength and charm of the Stahl stories, are that, without subscribing to the conventions, they keep to the common highway on which average men and women live and move and have their being. This is the higher and more masterly achievement, as it is more difficult to paint a portrait when the sitter is a person of ordinary looks than when he has marked peculiarities of features that easily distinguish him from the general run of mankind.

Although, in his time, Mr. Beresford was an advertising expert he has never acquired the gift of self-advertisement; but he found himself and was found by critics and the public while he still counted as one of our younger novelists and had been writing for less than a decade.

He has a subdued humor that is edged with irony, and can write with a lighter touch, as he shows in “The Jervase Comedy” and some of his short stories; and though one deprecates his excursions into eccentricities of psychology, for the bent of his genius is so evidently toward portraying what[Pg 39] Meredith described to Stahl as the representative “feelings and happenings of everyday life,” one feels that he is more handicapped by his reticences than by his daring. He is so conscious an artist that he tones down all crudities of coloring, yet the color of life is often startlingly crude. An occasional streak of melodrama, a freer play of sentiment and motion would add to the vitality of his scenes and characters and intensify their realism instead of taking anything from it; but his native reticence would seem to forbid this and he cannot let himself go. And because he cannot let himself go he has not yet gone beyond the Jacob Stahl series, which, clever and cunninger art though some of his other work may be, remains the truest and most significant thing he has done.

[Pg 41]

John Buchan

[Pg 43]

I have heard people express surprise that such a born romantist as John Buchan has turned his mind successfully to practical business, and been for so long an active partner in the great publishing house of Thomas Nelson & Sons. But there is really nothing at all surprising about that. One of the essays in his “Some Eighteenth Century Byways” speaks of “the incarnation of youth and the eternal Quixotic which, happily for Scotland, lie at the back of all her thrift and prudence”; and in another, on “Mr. Balfour as a Man of Letters”, he says, “the average Scot, let it never be forgotten, is incorrigibly sentimental; at heart he would rather be ‘kindly’ and ‘innerly’ than ‘canny,’ and his admiration is rather for Burns, who had none of the reputed national characteristics, than for Adam Smith, who had them all.” He adds that though Scotsmen perfectly understand the legendary Caledonian, though “in theory they are all for dry light ‘a hard, gem-like flame,’ in practice they like the glow from more turbid altars.”

Having that dual personality himself, it is not incongruous that John Buchan should be at once a poet, a romantic and a shrewd man of affairs. But he is wrong in thinking the nature he sketches is peculiar to his countrymen, the Scots; it is as[Pg 44] characteristically English. Indeed, I should not count him among practical men if he had not proved himself one by doing more practical things than publishing; for publishing is essentially a romantic calling as you may suspect if you consider the number of authors who have taken to it, and the number of publishers who have become authors. Scott felt the lure of the trade, in the past, and in the present you have J. D. Beresford working at it with Collins & Sons; Frank Swinnerton first with Dent, now with Chatto & Windus; Frederick Watson, a brilliant writer of romances and of modern social comedy, with Nisbet; Michael Sadleir with Constable; C. E. Lawrence, most fantastic and idealistic of novelists, with John Murray; Roger Ingram, writing with authority on Shelley and making fine anthologies, but disguised as one of the partners in Selwyn and Blount; Alec Waugh, joining that admirable essayist his father, Arthur Waugh, with Chapman & Hall; C. S. Evans, whose “Nash and Others” may stand on the shelf by Kenneth Grahame’s “Golden Age,” with Heinemanns; B. W. Matz, the Dickens enthusiast and author of many books about him, running in harness with Cecil Palmer; you have Grant Richards writing novels that are clever enough to make some of his authors wonder why he publishes theirs; Sir Ernest Hodder-Williams, an author, with at least half-a-dozen successful books to his name; Herbert Jenkins, a popular humorist and doing sensational detective stories; Sir Algernon Methuen developing a passion[Pg 45] for compiling excellent anthologies of poetry—and there are others.

But here is enough to show that Buchan need not think he is demonstrating his Scottish practicality by going in for publishing. As a fact, I have always felt that publishing should be properly classed as a sport. It is more speculative than racing and I do not see how any man on the Turf can get so much excitement and uncertainty by backing a horse as he could get by backing a new book. You can form a pretty reliable idea of what a horse is capable of before you put your money on it, but for the publisher, more often than not, it is all a game of chance, since whether he wins or loses depends less on the quality of the book than on the taste of the public, which is uncalculable. So when Buchan went publishing he was merely starting to live romance as well as to write it.

A son of the manse, he was born in 1875, and going from Edinburgh University to Brasenose, Oxford, he took the Newdigate Prize there, with other more scholarly distinctions, and became President of the Union. Even in those early days he developed a love of sport, and found recreation in mountaineering, deer-stalking and fishing. His enthusiasm for the latter expressed itself in the delightful verses of “Musa Piscatrix,” which appeared in 1896, while he was still at Oxford, his first novel, “Sir Quixote,” a vigorous romance somewhat in the manner of Stevenson, who was then at the height of his career, having given him prominence[Pg 46] among new authors a year earlier. I recollect the glowing things that were said of one of his finest, most brilliantly imaginative romances, “John Burnet of Barns,” in 1898, and with the fame of that going before him he came to London. There he studied law in the Middle Temple, and was called to the Bar, but seems to have been busier with literary and journalistic than with legal affairs, for two more books, “Grey Weather” and “A Lost Lady of Old Years” came in 1889; “The Half-Hearted” in 1900, and meanwhile he was occupied with journalism and contributing stories to the magazines.

Then for two years he sojourned in South Africa as private secretary to Lord Milner, the High Commissioner. Two books about the present and future of the Colony were the outcome of that excursion into diplomacy; and better still, his South African experiences prompted him a little later to write that remarkable romance of “Prester John,” the cunning, clever Zulu who, turned Christian evangelist, professes to be the old legendary Prester John reincarnate, and while he is ostensibly bent on converting the natives, is fanning a flame of patriotism in their chiefs and stirring them to rise against the English and create again a great African empire. Here, and in “John Burnet of Barns,” and in some of the short stories of “The Watcher by the Threshold” and “The Moon Endureth,” John Buchan reaches, I think, his high-water mark as a weaver of romance.

After his return from South Africa he joined the[Pg 47] staff of the Spectator, reviewing and writing essays for it and doing a certain amount of editorial work. At least, I deduce the latter fact from the statement of one who had the best means of knowing. If you look up “The Brain of the Nation,” by Charles L. Graves, who was then assistant editor of the Spectator, you will find among the witty and humorous poems in that volume a complete biography of John Buchan in neat and lively verse, telling how he came up to town from Oxford, settled down to the law, went to Africa, returned and became a familiar figure in the Spectator’s old offices in Wellington Street:

“Ev’ry Tuesday morn careering

Up the stairs with flying feet,

You’d burst in upon us, cheering

Wellington’s funereal street....

Pundit, publicist and jurist;

Statistician and divine;

Mystic, mountaineer, and purist

In the high financial line;

Prince of journalistic sprinters—

Swiftest that I ever knew—

Never did you keep the printers

Longer than an hour or two.

Then, too, when the final stages

Of our weekly task drew nigh,

You would come and pass the pages

With a magisterial eye,

Seldom pausing, save to smoke a

Cigarette at half past one,

When you quaffed a cup of Mocha

And devoured a penny bun.”

[Pg 48]

The War turned those activities into other channels, and after being rejected by the army as beyond the age limit, he worked strenuously in Kitchener’s recruiting campaign, then served as Lieutenant-Colonel on the British Headquarters Staff in France, and subsequently as Director of Information. The novels he wrote in those years, “The Power House,” “The Thirty-nine Steps,” “Greenmantle,” and “Mr. Standfast,” were written as a relief from heavier duties. They are stories of mystery and intrigue as able and exciting as any of their kind. “Greenmantle,” he says in a preface, was “scribbled in every kind of odd place and moment—in England and abroad, during long journeys, in half hours between graver tasks.” He was present throughout the heroic fighting on the Somme, and his official positions at the front and at home gave him exceptional opportunities of seeing things for himself and obtaining first-hand information for his masterly “History of the War,” which will give him rank as a historian beside Kinglake and Napier.

With “The Path of the King,” and more so with “Huntingtower,” he is back in his native air of romance, and one hopes he will leave the story of plot and sensation to other artists and stay there.

Like all romancists, he is no unqualified lover of the democracy; it is too lacking in picturesqueness, in grace and glamor to be in harmony with his temperament. He belongs in spirit to the days when heroism walked in splendor and war was glorious. He has laid it down that the “denunciation of war rests at bottom upon a gross materialism.[Pg 49] The horrors of war are obvious enough; but it may reasonably be argued that they are not greater than the horrors of peace ... the true way in which to ennoble war is not to declare it in all its forms the work of the devil, but to emphasize the spiritual and idealist element which it contains. It is a kind of national sacrament, a grave matter into which no one can enter lightly and for which all are responsible, more especially in these days when wars are not the creation of princes and statesmen but of peoples. War, on such a view, can only be banished from the world by debasing human nature.”

That is the purely romantic vision. Since 1914, Buchan’s experiences of War and the horrors of peace that result from it may have modified his earlier opinions.

Anyhow, it is a wonderful theme for romance when it is far enough away. It shows at its best in such chivalrous tales of adventure and self-sacrifice as have gathered round the gallant figure of the Young Pretender. You know from his books that John Buchan is steeped in the lore of the Jacobites and sensitive to the spell of “old songs and lost romances.” Dedicating “The Watcher by the Threshold” to Stair Agnew Gillon, he says, “It is of the back-world of Scotland that I write, the land behind the mist and over the seven bens, a place hard of access for the foot-passengers but easy for the maker of stories.” One owns to a wish that the author of “John Barnet of Barns” would now set his genius free from the squabble and squalor[Pg 50] of present-day politics (by the way, he once put up for Parliament but fortunately did not get in) and write that great story of the ’45 which he hints elsewhere has never yet been written.

[Pg 51]

Donn Byrne

[Pg 53]

There are more gods than any man is aware of, and there is really more virtue in discovering a new one, and catching him young, than in deferring your tribute until he is old and so old-established that all the world has recognized him for what he is. You may say that Donn Byrne is not a god of modern Grub Street, but you can take it from me that he is going to be. He has all the necessary attributes and is climbing to his due place in the hierarchy so rapidly that he will have arrived there soon after you are reading what I have to say about him.

There is a general idea that he is an American; unless an author stops at home mistakes of that kind are sure to happen. People take it for granted that he belongs where he happens to be living when they find him. Henry James had lived among us so long that he was quite commonly taken for an Englishman even before he became naturalized during the War. The same fate is overtaking Ezra Pound; he is the chief writer of a sort of poetry that is being largely written in his country and in ours, and because he has made his home with us for many years he is generally regarded here as a native. On the other hand, Richard Le Gallienne left us and has passed so large a part of his[Pg 54] life in the United States that most of us are beginning to think of him as an American.

The mistake is perhaps more excusable in the case of Donn Byrne, for he was born at New York in 1889, but before he was three months old he was brought over to Ireland which ought to have been his birthplace, since his father was an architect there. He was educated at Trinity College, Dublin, and when he was not improving his mind was developing his muscles; he went in enthusiastically for athletics, and in his time held the light-weight boxing championships for Dublin University and for Ulster. He knows all about horses, too, and can ride with the best, and has manifested a more than academic interest in racing. In fact, he has taken a keen interest in whatever was going on in the life around him wherever he has been, and he has been about the world a good deal, and turned his hand to many things. There is something Gallic as well as Gaelic in his wit, his vivacity, his swiftly varying moods. He is no novelist who has done all his traveling in books and dug up his facts about strange countries in a reference library. When he deals with ships his characters are not such as keep all the while in the saloon cabin; they are the ship’s master and the sailors, and you feel there is a knowledge of the sea behind them when he gets them working; and if he had not been an athlete himself he could not have described with such vigor and realistic gusto that great fight between Shane Campbell and the wrestler from Aleppo in “The Wind Bloweth.”

[Pg 55]

How much of personal experience has gone into his novels is probably more than he could say himself. But when he is picturing any place that his imaginary people visit, you know from a score of casual, intimate touches that he, too, has been there, and is remembering it while he writes. Take this vivid sketch of Marseilles, for example:

“Obvious and drowsy it might seem, but once he went ashore, the swarming, teeming life of it struck Shane like a current of air. Along the quays, along the Cannebière, was a riot of color and nationality unbelievable from aboard ship. Here were Turks, dignified and shy. Here were Greeks, wary, furtive. Here were Italians, Genoese, Neapolitans, Livornians, droll, vivacious, vindictive. Here were Moors, here were Algerians, black African folk, sneering, inimical. Here were Spaniards, with their walk like a horse’s lope. Here were French business men, very important. Here were Provencals, cheery, short, tubby, excitable, olive-colored, black-bearded, calling to one another in the langue d’oc of the troubadors, ’Te, mon bon! Commoun as? Quezaco?”

There is that same sense of seeing things in the glamorous description of the Syrian city where Shane lived with the Arab girl he had married; and in the hasty outline of Buenos Aires:

“Here now was a city growing rich, ungracefully—a city of arrogant Spanish colonists, of poverty-stricken immigrants, of down-trodden lower classes ... a city of riches ... a city of blood.... Here mud, here money.... Into a city half mud[Pg 56] hovels, half marble-fronted houses, gauchos drove herd upon herd of cattle, baffled, afraid. Here Irish drove streams of gray bleating sheep. Here ungreased bullock carts screamed. From the bluegrass pampas they drove them, where the birds sang and waters rippled, where was the gentleness of summer rain, where was the majesty of great storms.... And by their thousands and their tens of thousands they drove them into Buenos Aires, and slew them for their hides....”

That was the Buenos Aires of Shane’s day, in the Victorian era; but in essentials it was probably as Donn Byrne saw it. For when he was about twenty-two he quitted Ireland and went back to America, and presently made his way to Buenos Aires to get married. His wife is the well-known dramatist Dolly Byrne who wrote with the actress Gilda Varesi, the delightful comedy “Enter Madam,” which has had long runs in London and in New York.

It was during this second sojourn in the States that Donn Byrne settled down seriously to literary work. He says he began by contributing to American magazines some of the world’s worst poetry, which he has never collected into a volume; but he is given to talking lightly of his own doings and you cannot take him at his own valuation. One of the poems, at least, on the San Francisco earthquake, appropriately enough, made something of a noise and was reprinted in the United Irishman, but Ireland had not then become such a furious storm-center[Pg 57] and an earthquake was still enough to excite it. Before long he was making a considerable reputation with his short stories, and a collection of these, “Stories Without Heroes,” was his first book.

But he will tell you he does not like that book and will not have it reprinted. He says the same about his first novel, “The Stranger’s Banquet,” though it met with a very good reception and had a sale that many successful authors would envy. Then followed in succession three novels that are original enough in style and idea and fine enough in quality to establish the reputation of any man—“The Wind Bloweth,” “Messer Marco Polo,” and “The Foolish Matrons.” These were all written and published in America, and America knew how to appreciate them. The third enjoyed such a vogue that we became aware of him in England and the second, then the first, in quick succession, were published in this country, and “The Foolish Matron” is, at this writing, about to make its appearance here also. And with his new-won fame Donn Byrne came home and is settled among his own people—unless a wandering fit has taken him again before this can be printed.

The beauty and charm of that old-time romance of the great Venetian adventurer, “Messer Marco Polo,” are not easily defined; different critics tried to shape a definition of it by calling it fascinating, fantastic, clever, witty, strangely beautiful, a thing for laughter and tears, and I think they were all[Pg 58] right; and that the book owes its success as much to the racy humor, the vision and emotional power with which it is written as to the stir and excitement of the story itself. Half the books you read, even when they greatly interest you, have a certain coldness in them as if they had been built up from the outside and drew no warmth from the hearts of their writers; but “Messer Marco Polo” glows and is alive with personality, it is not written after the manner of any school, but it is as full of eager, vital, human feeling as if the author had magically distilled himself into it and were speaking from its pages.

That is part of the secret, too, of the charm of his more realistically romantic “The Wind Bloweth.” You are convinced, as you read, that those early chapters telling how the boy Shane gets a holiday on his thirteenth birthday and goes alone up into the mountains to see the Dancing Town in the haze over the sea, are a memory of his own boyhood in Ireland. From the peace and fantasy of that beginning in the Ulster hills, from an unsympathetic mother and his two quaint, lovable uncles, Shane, at his own ardent desire, goes to knock about the world as a seafarer, and, always with the simplicity and idealism of his boyhood to lead and mislead him, is by-and-by tricked into marrying the cold southern Irish girl who dies after a year or so, and, his love for her having died before, he can feel no grief but only a strange dumb wonder. Then, while his trading ship is at Marseilles,[Pg 59] he meets the beautiful, piteous Claire-Anne, and their lawless, perfect love ends in tragedy. After another interval, comes the episode of his charming little Moslem wife, and he loses her because he never understands that she loves him not for his strength but for his weakness. Thrice he meets with disillusion, but retains his simplicity, his idealism throughout, and is never really disillusioned; and it is when he is in Buenos Aires again that the kind, placid, large-hearted “easy” Swedish woman, Hedda Hages, gives him the truth, and makes clear to him what she means when she says, “No, Shane, I don’t think you know much about women.”

And it is not till his hair is graying that he arrives at the true romance and the ideal happiness at last. The story is neither planned nor written on conventional lines; you sense the tang of a brogue in its nervous English, which is continually flowering into exquisite felicities of phrase, and it lays bare the heart and mind of a man with a most sensitive understanding. It is a sort of Pilgrim’s Progress, and Shane Campbell is a desperately human pilgrim, who drifts into danger and disasters, and stumbles often, before he drops his burden and finds his way, or is led by strange influences, into the City Beautiful.

I daresay Donn Byrne will laugh to discover that I have put him among the gods; he is that sort of man. But it is possible for others to know him better than he knows himself. Abou Ben Adhem[Pg 60] was surprised you recollect, when he noticed that Gabriel had recorded his name so high in the list of those that were worthy; and though I am no Gabriel I know a hawk from a handsaw when the wind is in the right quarter.

[Pg 61]

William Henry Davies

[Pg 63]

The lives of most modern poets would make rather tame writing, which is possibly why so much modern poetry makes rather tame reading. It is a pleasant enough thing to go from a Public School to a University, then come to London, unlock at once a few otherwise difficult doors with the open sesame of effective introductions, and settle down to a literary career; but it leaves one with a narrow outlook, a limited range of ideas, little of personal experience to write about. Fortunately W. H. Davies never enjoyed these comfortable disadvantages. He did not come into his kingdom by any nicely paved highroads, but over rough ground by thorny ways that, however romantic they may seem to look back upon, must have seemed hard and bitter and sufficiently hopeless at times while he was struggling through them.

There is nothing to say of his schooling, except that it amounted to little and was not good; but later he learned more by meeting the hard facts of life and by desultory reading than any master could have taught him. Born at Newport, Monmouthshire, in 1870, he was put to the picture-frame making trade, and went from that to miscellaneous farm work. But work, he once confessed to me, is among the things for which he has never had a[Pg 64] passion, and a legacy from a grandfather gave him an interval of liberty. This grandfather, with a sensible foresight, left him only a small sum in ready cash, but, in addition, the interest on an investment that produced a steady eight shillings a week. With the cash Davies went to America, and saw as much of that country as he could as long as the money lasted. Then he subdued his dislike of manual labor and did odd jobs on fruit farms; wearied of this and went on tramp, and picked up much out-of-the-way knowledge of the world and of men from the tramps he fell in with during his roamings. Presently, he got engaged as a hand on a cattle-boat, and as such made several voyages to England and back.

At length, getting back to America just when the gold rush for Klondike was at its height, he was seized with a yearning to go North and try his luck as a digger. The price of that long journey being beyond his means, he followed a common example and tried to “jump” a train, fell under the wheels in the attempt and was so badly injured that he lost a foot in that enterprise and had to make a slow recovery in hospital. When he was well enough, his family sent out and carried him home into Wales.

But he could not be contented there. Although he says himself that he became a poet at thirty-four (when his first book was published), the fact is, of course, he has been a poet all his life and through all his wanderings was storing up memories and impressions of nature and human nature that live[Pg 65] again now in vivid lines and phrases of his verse and prose. He had already written poems, and sent them to various periodicals in vain, and had a feeling that if he could be at the center of things, in London, fortune and fame as a poet might be within his reach.

So to London he came, early in the century, and took up residence in a common lodging-house at Southwark, his eight shillings a week sufficing to pay his rent and keep him in food. The magazines remaining obdurate, he collected his poems into a book, and started to look for a publisher. But the publishers were equally unencouraging, till he found one who was prepared to publish provided Davies contributed twenty pounds toward the cost of the adventure. Satisfied that, once out, the book would quickly yield him profits, he asked the trustees who paid him his small dividends to advance the amount and retain his income until they had recouped themselves. They, however, being worldly-wise, compromised by saying that if he would do without his dividends for some six months, when ten pounds would be due, they would pay him that sum and advance a further ten, paying him no more till the second ten was duly refunded.

This offer he accepted; and he tramped the country as a pedlar, selling laces, needles and pins, and occasionally singing in the streets for a temporary livelihood. When the six months were past he returned to London, took up his old quarters at the lodging-house, drew the twenty pounds, and before[Pg 66] long “The Soul’s Destroyer and Other Poems” made its appearance. But so far from putting money in his purse, it was received with complete indifference. Fifty copies went out for review, but not a single review was given to it anywhere. No publisher’s name was on the title page, but an announcement that the book was to be had, for half-a-crown, “of the Author, Farmhouse, Marshalsea Road, S.E.,” and possibly this conveyed an impression of unimportance that resulted in its remaining unread. After a week or so, seeing himself with no money coming in for the next few months, the author became desperate. He compiled from “Who’s Who,” at a public library, a list of people who might be expected to take an interest in poetry, and posted a copy of his book to each with a request that, if it seemed worth the money, he would remit the half-crown.

One of the earliest went to a journalist who was, in those days, connected with the Daily Mail. He read it at once and recognized that though there were crudities and even doggerel in it, there was also in it some of the freshest and most magical poetry to be found in modern books. Mingled with grimly realistic pictures of life and character in the doss-house were songs of the field and the wayside written with all Clare’s minute knowledge of nature and with something of the imagination and music of Blake. Being a journalist, he did not miss the significance of this book issuing from a common lodging-house (and one, by the way, that is described in a sketch of Dickens’), could easily[Pg 67] read a good deal of the poet’s story between the lines of his poems, promptly forwarded his remittance and asked Davies to meet him. Not sure that he would be welcome at the doss-house, he suggested a rendezvous on the north of London Bridge, and a few evenings later the meeting came about at Finch’s a tavern in Bishopsgate Street Within. “To help you to identify me,” Davies had written, “I will have a copy of my book sticking out of my pocket”; and there he was—a short, sturdy young man, uncommunicative at first, as shy as a squirrel, bright-eyed, soft of speech, and with a general air about him of some woodland creature lost and uneasy in a place of crowds. By degrees his shyness diminished, and in the course of a two hours’ session in that bar he unfolded the whole of his story without reserve. Then said the journalist, “If I merely review your book it will not sell a dozen copies, but if you will let me combine with a review an absolutely frank narrative of your career I have an idea we can rouse public interest to some purpose.”

This permission being given, such an article duly appeared in the news columns of the Daily Mail, and the results were more astonishing than any one could have foreseen. Not only did the gentle reader begin to send in money for copies, but ladies called at the doss-house and left At Home cards which their recipient was much too reticent to act upon. Editors who had ignored and probably lost their review copies sent postal orders for the book and lauded it in print; illustrated papers sent photographers[Pg 68] and interviewers; a party of critics, having now bought and read the poems, made a pilgrimage to the Farmhouse, and departed to write of the man and his poetry. After a second article in the Mail had recounted these and other astonishing happenings, a literary agent wrote urging Davies to entrust him with all his remaining copies and he could sell them for him at half-a-guinea and a guinea apiece.

His advice was taken, and the last of the edition of five hundred copies went off quickly at these prices. So enriched, the poet quitted his lodging-house and went home into Wales for a holiday, and while there began the first of his prose books, “The Autobiography of a Super-Tramp,” which was published in 1908 with an introduction by George Bernard Shaw. Meanwhile, Davies had written two other volumes of verse, and his recognition as one of the truest, most individual of living lyrists was no longer in doubt. Mr. Shaw notes of his prose that it has not the academic correctness dear to the Perfect Commercial Letter Writer, but is “worth reading by literary experts for its style alone”; and much the same may be said of his poetry. It is not flawless, but its faults are curiously in harmony with its unstudied simplicity and often strangely heighten the beauty of thought and language to which verses flower as carelessly as if he thought and said his finest things by accident. He has the countryman’s intimacy with Nature—not for nothing did he work on farms, tramp the open roads, sleep under the naked sky—knows all[Pg 69] her varying moods, has observed trivial significances in her that the deliberate student overlooks; and he writes of her with an Elizabethan candor and fantasy and a natural, simple diction that is an art in Wordsworth. He has made a selection from his several volumes in a Collected Edition, but has published other verse since. For some years after his success he lived in London, but never seemed at home; he has no liking for streets and shrinks from crowds; and now has withdrawn again into the country, where our ultra modern Georgian poets who, despite the fact that he is in the tradition of the great lyrists of the past, were constrained to embrace him as one of themselves, are less likely to infect him with their artifices.

[Pg 71]

Walter De La Mare

[Pg 73]

Except in the personal sense—and the charm of his gracious personality would surely surround him with friends, whether he wanted them or not—Walter de la Mare is, like Hardy, a lonely figure in modern English poetry—no other poet of our time has a place more notably apart from his contemporaries. You might almost read an allegory of this aloofness into his “Myself”:

“There is a garden grey

With mists of autumntide;

Under the giant boughs,

Stretched green on every side,

“Along the lonely paths,

A little child like me,

With face, with hands like mine,

Plays ever silently....

“And I am there alone:

Forlornly, silently,

Plays in the evening garden

Myself with me.”

only that one knows he is happy enough and not forlorn in his aloneness. You may trace, perhaps, here and there in his verse elusive influences of Coleridge, Herrick, Poe, the songs of Shakespeare, or, now and then, in a certain brave and good use[Pg 74] of colloquial language, of T. E. Brown, but such influences are so slight and so naturalized into his own distinctive manner that it is impossible to link him up with the past and say he is descended from any predecessor, as Tennyson was from Keats. More than with any earlier poetry, his verse has affinities with the prose of Charles Lamb—of the Lamb who wrote the tender, wistful “Dream-Children” and the elvishly grotesque, serious-humorous “New Year’s Eve”—who was sensitively wise about witches and night-fears, and could tell daintily or playfully of the little people, fairy or mortal. But the association is intangible; he is more unlike Lamb than he is like him. And when you compare him with poets of his day there is none that resembles him; he is alone in his garden. He has had imitators, but they have failed to imitate him, and left him to his solitude.

It is true, as Spencer has it, that

“sheep herd together, eagles fly alone,”

and he has this in common with the lord of the air, that he has never allied himself with any groups or literary cliques; yet his work is so authentic and so modern, so free of the idiosyncracies of any period, that our self-centered, self-conscious school of “new” poets, habitually intolerant of all who move outside their circle, are constrained to keep a door wide open for him and are glad to have him sitting down with them in their anthologies.

But he did not enter into his own promptly, or[Pg 75] without fighting for it. He was born in 1873; and had known nearly twenty years of

“that dry drudgery at the desk’s dead wood”

in a city office, before he shook the dust of such business from his feet and began to win a livelihood as a free-lance journalist. One is apt to speak of journalism as if it were an exact calling, like that of the watchmaker; but “journalism” is a portmanteau word which embraces impartially the uninspired records of the junior reporter and the delightful social essays and sketches of Robert Lynd; the witty gossip of a “Beachcomber,” and the dull but very superior oracles of a J. A. Spender. Not any of these, but reviewing was the branch of this trade to which de la Mare devoted himself, and his reviews in the Saturday Westminster, Bookman, Times Literary Supplement, and elsewhere, clothed so fine a critical faculty in the distinction of style which betrays his hand in all he has written that, his reputation growing accordingly, the reviewer for a time overshadowed the poet; for though he did much of it anonymously his work could be identified by the discerning as easily as can the characteristic, unsigned paintings of a master.

Too often, in such a case, the journalist ends by destroying the author; dulls his imagination, dissipates his moods, replaces his careless raptures with a mechanical efficiency; makes him a capable craftsman, and unmakes him as an artist. But de la Mare seems to have learned how to put his heart[Pg 76] into journalism without letting journalism get into his heart; I have seen no review of his that has the mark of the hack upon it; his mind was not “like the dyers hand” subdued to what it worked in. Fleet Street might echo his tread, but his spirit was away on other roads in a world that was beyond the jurisdiction of editors. He was not seeking to set up a home in that wilderness, but was all the while quietly paving a way out of it; and in due season he has left it behind him.

A good deal of what he wrote then bore the pseudonym of “Walter Ramal,” a transparent anagram; and throughout those days he went on contributing poems, stories, prose fantasies to Cornhill, the English Review, and other periodicals. In 1902 he had published “Songs of Childhood,” a first revelation of his exquisite genius for writing quaint nursery rhymes, dainty, homely, faery lyrics and ballads that can fascinate the mind of a child, or of any who has not forgotten his childhood—a genius that flowered to perfection eleven years later in “Peacock Pie.”

“Henry Brocken” (1904) showed another side of his gift. It is a story—you cannot call it a novel—that takes you traveling into a land unknown to the map-makers, that is inhabited by people who have never lived and will never die. You go with Brocken over a wild moor and meet with Wordsworth’s Lucy Gray; you go further to hold converse with Poe’s Annabel Lee, with Keat’s Belle Dame, with Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre, with Swift’s Gulliver, with Lady Macbeth, Bottom,[Pg 77] Titania, with folk from the “Pilgrim’s Progress,” and many another. It is all a riot of fancy and poetry in prose, with an undercurrent of shrewd commentary that adds a critical value to its appeal as a story.

This fresh, individual note is as prevailing in all his prose as in his verse. It is in the prose and verse of his blithe, whimsical tale for children, “The Two Mulla-Mulgars,” and in that eerie, bizarre novel, “The Return”—where, falling asleep by the grave of old Sabathier, Arthur Lawford goes home to find his family do not know him, for, as he slept, the dead man’s spirit had subtly taken possession of him and transformed his whole appearance. And the spiritual adventures through which Lawford has to pass before he can break that grim dominance and be restored to himself are unfolded with a delicate art that never over-stresses the beauty or significance of them.

By common consent, however, de la Mare’s prose masterpiece is “The Midget.” One can think of no other present-day author who might have handled successfully so outre a theme; yet the whole conception is as natural to de la Mare’s peculiar genius as it would be alien to that of any of his contemporaries, and he fashions his story of the little lady, mature and sane in mind and perfect in body, but so small that she could stand in the palm of an average hand, into a novel, a fable, a romance—call it what you will—of rare charm and interest. The midget’s dwarfish, deformed lover, and the more normal characters—Waggett, Percy Maudlin,[Pg 78] Mrs. Bowater, Pollie—are drawn realistically and with fleeting touches of humor, and while you can read the book for its story alone, the quiet laughter and pathos of it, as you can read Bunyan’s allegory, it is veined with inner meanings and a profound, sympathetic philosophy of life is implicit in the narrative.

It was two years after his 1906 “Poems” appeared I remember, that Edward Thomas first asked me if I knew much of Walter de la Mare, and, in that soft voice and reticent, hesitating manner of his, went on to speak with an unwonted enthusiasm of the work he was doing. Until then, I had read casually only casual things of de la Mare’s in the magazines, but I knew Thomas’s fine, fastidious taste in such matters, and that he was not given to getting enthusiastic over what was merely good in an ordinary degree, and it was not long before I was qualified to understand and respond to the warmth of his admiration. The “Poems” were, with a few exceptions, more remarkable for what they promised than for what they achieved, but they had not a little of the unique magic that is in his “Songs of Childhood”; and “The Listeners and Other Poems” (1912), and “Motley and Other Poems” (1918) more than fulfilled this promise and brought him, at last such general recognition that in 1920, after a lapse of eighteen years, his poems were gathered into a Collected Edition.