Its rays fell on the craft just in time to see Tom's limp form

being hauled on board.—Page 26.

BY

DEXTER J. FORRESTER

AUTHOR OF "THE BUNGALOW BOYS," "THE BUNGALOW BOYS MAROONED

IN THE TROPICS," "THE BUNGALOW BOYS IN

THE GREAT NORTHWEST," ETC.

WITH FOUR ILLUSTRATIONS

BY J. PAUL BURNHAM

NEW YORK

HURST & COMPANY

PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1912,

BY

HURST & COMPANY

CONTENTS

CHAPTER

II. Lost Overboard

III. Tom Encounters Some Old Foes

VIII. A Tour of Exploration

IX. "Fifty Dollars to the Man that Gets Them!"

XI. Out of the Dark

XII. Mr. Ironsides' Submarine—Huron

XIII. The Strangest Vessel on the Lakes

XIV. Off on a Long Chase

XV. "We've Struck a Submerged Wreck!"

XVII. Captain Rangler Re-appears

XVIII. A Man of Queer Manners

XIX. Within the Tower

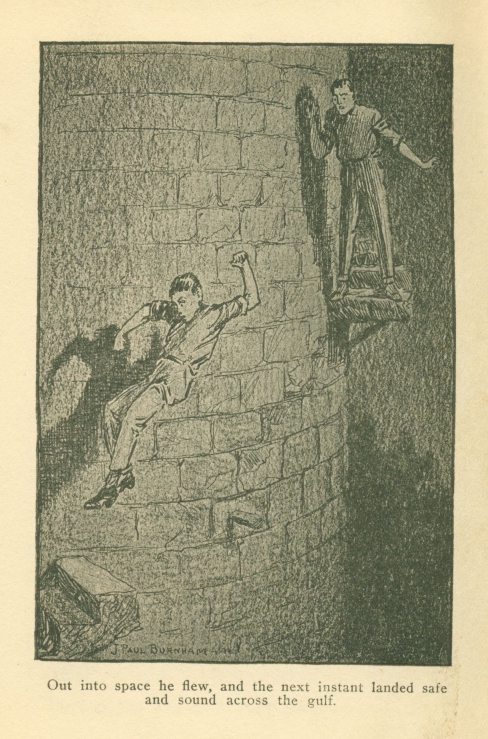

XXI. "There is a Way—I Mean to Try It"

XXII. A Bit of Madcap Daring

XXIII. Brains and Grit—A Combination Hard to Beat

XXIV. "Coward!"

XXV. What Will Happen Next?—Conclusion

The Bungalow Boys on the Great Lakes

"Looks as if it might be blowing up for nasty weather, Tom."

Jack Dacre, the younger of the Bungalow Boys, spoke, as his head emerged from the engine room hatchway of the sixty-foot, motor-driven craft, Sea Ranger.

Tom nodded, and spun the spokes of the steering wheel ever so little. The Sea Ranger responded by heading up a trifle more into the seas, which were already growing threatening.

"I've been thinking the same thing for some time," he said presently. "If Alpena wasn't so far behind us, I'd turn back now."

"We can't be more than three miles off shore. Why not head in toward it?"

The elder Dacre boy shook his head.

"Don't know the coast," he said; "and it's a treacherous one."

The sky, cloudless but a short time before, was now heavily overcast. To the northwest, black, angry-looking clouds were banked in castellated masses. Their ragged edges would have shown a trained eye that, as sailors say, "there was wind behind them."

The waters of Lake Huron, recently sparkling under the bright sun, were now of a dull, leaden hue. The long water rows began to rise sullenly in heaving billows, over the crests of which the Sea Ranger plunged and wallowed.

"What are we going to do?" asked Jack presently, after an interval in which both brothers rather anxiously inspected the signs of "dirty weather."

"How are your engines working?" was Tom's way of answering with another question.

"Splendidly; as they have done ever since we left New York. I'm not anxious about them."

"Then we'll keep right on as we are. It would be risky to turn back to Thunder Bay now. The Sea Ranger is stanch. We saw to that before we chartered her. She will weather it, all right."

"I guess you're right. But I can see here and now that our camping cruise isn't going to be all fun. These Lake Huron storms have a bad reputation. When we were down off Florida, old Captain Pangloss said that they were as bad as anything he had encountered, even in the China seas."

"At any rate, that trip taught us a lot about boat-handling," said Tom, "and other things, too," he added, with a rather grim smile, as he recalled the stirring times they had had on the voyage referred to. Those adventures were all set forth in full in The Bungalow Boys Marooned in the Tropics.

"They sure did," agreed the younger Dacre. "The weather looked like this off Hatteras, before the time we beat out Dampier and Captain Walstein in the search for the sunken treasure-ship."

"And thereby helped to get large enough bank accounts to plan this trip," interpolated Tom. "By the way, I wonder whatever became of those two rascals after their escape from jail?"

"The papers said that they were supposed to have made their way to Canada. But nobody knows for certain."

While he spoke, the sea was growing more and more turbulent.

"I'll go below and rouse up Sandy and Professor Podsnap. We want to have everything secure and snug in the cabin before the storm hits us."

Jack found the professor and Sandy deep in a game of chess. One, at least, of the players, namely Sandy, was not sorry to have the game broken up. The professor had his hand poised above his bishop, and was about to make a move that would speedily have checkmated the Scotch youth, when Jack burst into the cabin.

They had been so interested in the game that they had not noticed the increased motion of the Sea Ranger. But, as Professor Podsnap leaped to his feet, when Jack rapidly made them aware of the situation, the bald-headed professor went sliding off to leeward across the cabin floor. An unusually heavy lurch had propelled him, and his speed was great.

To save his angular form from an ignominious tumble, he clutched at the cloth on the cabin table. As might have been expected, it did not prove a substantial support. Before either of the boys could interfere, the professor was in a heap on the floor, struggling blindly to extricate himself from the folds of the drapery which enveloped him. Struggling to check their laughter, the boys rescued him. But their subdued mirth broke into a loud shout as they beheld the professor's countenance. A bottle of ink had been standing on the table, and its contents were now spilled in black rivulets all over the professor's face. His bony features fairly streamed with the black fluid, while his spectacles hung suspended from one ear, in a most undignified manner.

He gazed about him in a bewildered fashion, as he scrambled to his feet. He made such a comical sight that the boys, in spite of their respect for his learning and age, could no longer check their merriment at the ludicrous figure, and they laughed till the tears ran down their cheeks, only stopping to gasp out apologies and then go off into more paroxysms of mirth.

"The sea—as someone has observed—is no respecter of persons," observed the professor, wiping the ink in long smudges with his pocket handkerchief.

"Of parsons, sir?" inquired Sandy.

"Of persons," said the professor solemnly.

"Which reminds me," said Jack, controlling his laughter and rapidly describing to the professor and Sandy the condition of things outside. They at once set to work securing everything movable. The professor didn't even take time to clean his face.

In the meantime, Jack had returned to the deck, passing through the engine room on his way. The Sea Ranger was driven by a powerful forty-horsepower, six-cylinder, gasolene engine. The boy paused only to ascertain that everything was in good order before he rejoined Tom, who stood on a sort of bridge amidships.

Even in the short time he had been below, the weather had noticeably roughened. It was almost dark.

"What time is it?" inquired Jack, as he gained Tom's side. The other drew out his watch.

"Only a little after five. But it's getting as dark as if it were three hours later."

"It certainly is. We are in for a hummer, all right."

"Don't make any mistake about that."

The rising wind began to scream about the laboring craft. Whitecaps flecked the lead-colored waves. The sky was overshadowed by a dark canopy of clouds.

Across the tempest-lashed waters, Tom, by straining his eyes, could manage to make out a dark point of land.

"That ought to be Dead Fish Point," he observed to Jack. "But I couldn't be sure unless I saw the light."

"What kind of a light is it?" asked Jack.

"White and red, in one-minute flashes, I looked it up on the chart before we left Thunder Bay."

"Well, they ought to light up now. It's dark enough," opined Jack. "By the way," he went on, "wasn't it from that lighthouse that they drove off the gang that has been wrecking vessels by displaying false lights?"

"Yes. The men visited the light just as an increased force of lighthouse keepers had been put on, owing to the number of wrecks that have happened recently from the operations of this gang. They were driven off. But they had a swift tug and escaped. The authorities have been looking for them since."

"If the newspapers are right, it is the same outfit that has been operating on all the Great Lakes."

"Yes. It's a new and up-to-date method of piracy, as the police claim. The gang engaged in it wrecks vessels by means of changing or extinguishing lights, and then raids the cargo. It is dastardly business!"

"Well, I should say so!"

At this point the professor and Sandy came on deck.

"Hoot mon!" exclaimed the Scotch youth, "it's as dark as an unco' dark tunnel."

"It resembles midnight," put in the professor, who had, by this time, removed the traces of his encounter with the ink bottle.

The four, who were the only ones on board the Sea Ranger, stood side by side on the bridge, holding tightly to the hand-rail to avoid being thrown off their feet.

"D'ye ken if it'ull get wurss?" asked Sandy presently.

"It will get worse before it gets better," was Tom's pithy rejoinder.

The Sea Ranger had set out from New York three weeks before. Her destination was a small island situated in the Mackinac Straits, called Castle Rock Island. The trip was in the nature of a holiday outing following the Bungalow Boys' trying experiences with the Chinese smugglers, as related in The Bungalow Boys in the Great Northwest.

Mr. Chisholm Dacre, the Bungalow Boys' uncle, with the mystery of whose life the first volume of this series—The Bungalow Boys—was concerned, had decided, after some persuasion, to allow the lads to go. It had been a trip which they had often longed to take. Mr. Dacre and the parents of Sandy MacTavish, whose father was a wealthy importer, agreed that a vacation cruise would do the lads no harm after their really trying experiences in the hands of Simon Lake.

The Sea Ranger had, therefore, been chartered, being a suitable craft for the expedition. Mr. MacTavish, who had a partial claim to Castle Rock Island, had permitted the boys to make it their rendezvous. They meant to use it as a sort of headquarters during their stay on the Great Lakes.

Well provisioned, and manned by as happy a crew as ever left New York harbor, the Sea Ranger had set out on her long trip through the Hudson River and through the canals, to Buffalo. From Buffalo, they voyaged by easy stages to Detroit, and thence to Port Huron. Till that afternoon when they had started on the last "leg" of their cruise, from Alpena, on Thunder Bay, they had not encountered any but ordinary incidents of travel. Now, however, it looked as if they were going to have an unpleasant change. But all the lads were adventurous and daring, and the prospect of a lively blow did not scare them.

A word of explanation is necessary in regard to Professor Podsnap's presence on the Sea Ranger. Two days before she had sailed from New York, the professor, whom the boys and Mr. Dacre had rescued from a drifting raft in Florida waters, appeared at the lads' home. He was about to start out on an expedition in search of Indian relics. By a strange chance, Lake Huron was to form part of his hunting ground. Mr. Dacre, deeming it a good thing to have an elder person along with the boys, had responded to the professor's somewhat broad hints by inviting him to join his nephews. As for the boys, they respected the professor's learning, and had a genuine liking for him, even if his eccentric ways did, at times, amuse them.

And now, what had promised to be a tame voyage, suddenly became fraught with excitement.

"Hold hard, everybody!" cried Tom suddenly.

He had seen a white wall of water sweeping down toward the Sea Ranger. The full fury of the storm was about to burst upon them.

"Here she comes!" yelled Jack, as the howling wind rushed down on them as if it would rend them apart.

This was the beginning of a storm which endured through the night, and which was to have a curious influence on the strange events which lay in the Bungalow Boys' future.

"This is the worst yet!"

Tom fairly shouted the words at Jack, who stood by him on the bridge of the storm-tossed Sea Ranger. The younger lad had just come from below, where he had deluged the engines with oil. He had also gone over them carefully, although the way the little craft was pitching made the job a difficult one. But Jack knew that the safety of the boat might depend on the way the engines kept at work.

"I never saw anything like it," yelled Jack, forming his hands into a funnel to make his voice carry. "Is it letting up at all?"

"Not a bit. It is worse, if anything."

Tom peered into the gloom ahead. But he could see nothing but angry breakers, their white tops whipped off by the furious wind and sent scattering as they formed. Both boys wore oilskins and sou'westers. The spray had drenched them till their garments shone in the gleam of the binnacle lamp.

"Better switch on the side and head lights," observed Tom presently.

He turned a button, and the red port light and its green companion on the starboard side were presently gleaming out. Above them, on the short mast with which the Sea Ranger was equipped, there beamed a white light, and another lantern of the same variety now shone out astern. All were lighted by electricity, furnished from a dynamo in the engine room, so that no matter how hard the wind blew, or how high the spray flew, there was no danger of their being extinguished.

"I feel a little better now," said Tom, after a while. "There's less danger of anything running into us in this smother. What are the professor and Sandy doing?"

"Trying to get a cup of hot coffee, but not succeeding very well. There's too much motion below, to stand still without gripping on to something."

"Are we keeping a straight course?"

It was Jack who spoke, after another interval in which the wind howled and the waves arose still more menacingly.

"As straight as I can steer her in this. I tell you, it's hard work to hold the wheel at all."

Indeed, every time a wave buffeted the Sea Ranger's rudder, it appeared as if the steering wheel was about to be jerked out of Tom's hand. But the elder Dacre boy possessed muscles well-hardened by all kinds of athletic games, and he stubbornly held the laboring craft to her course, despite the storm.

"I'll go below and oil up again," announced Jack presently.

He clawed his way across the bridge and vanished into the engine room. It was a wonderful contrast down there, in the warm, dry motor room, with the brightly polished machinery, working and moving in as rhythmic and unconcerned a fashion as if it was a summer's afternoon without. Incandescent globes made the place as bright as day, and the brass and steel flashed as it rose and fell with hardly any noise.

Oil-can in hand, Jack went his rounds. He poked the long spout in here and there, and then paused to wipe his hands on a bit of waste.

"I wish we were out of this," he was saying. "I wish we——"

There came a sudden, inexplicable jar throughout the whole structure of the Sea Ranger. Jack was flung flat on his back. The engines began to roar and race furiously. Every beam and rivet in her frame seemed to vibrate.

"Something terrible has happened," was the thought that flashed through the lad's mind, as he picked himself up.

He rushed out on deck as soon as he could collect his scattered senses. The wind was still screaming angrily, and the riotous sea was leaping all about the Sea Ranger.

But above the turmoil of the storm, Jack caught a startling cry that came through the darkness.

"Help!"

"Tom's voice!" exclaimed the lad.

He stumbled across the heaving deck and rushed up the two steps that led to the bridge where he had left his brother at the wheel. His pulses were throbbing wildly. The next moment, he, too, uttered a cry.

The bridge was vacant! Tom had vanished!

"Help! Help!"

The shout came once more. But it was fainter this time. Jack gazed about him despairingly. Tom was overboard, that much was certain. But how had it happened? How——?

"Put your helm over there!" roared a voice out of the blackness—a harsh, hoarse voice, that cut the storm like a vessel's siren.

Jack, only half-conscious of what he was doing, spun the spokes over. He was just in time. Dead ahead of their craft a larger vessel loomed up for an instant. She carried no lights, and a glimpse was all Jack had of her. But it gave him a clue as to what had occurred. In the darkness they must have collided with the lightless craft, and only his quickness in getting the helm over had averted a second collision, which might have proved disastrous.

"What is it? What has happened?" came a voice behind him.

It was the professor. The binnacle light shone on his gaunt, alarmed features. Close behind him pressed Sandy.

"Hoots, toots!" exclaimed the Scotch lad. "What was the gr-r-r-r-and bo-o-omp?"

"We collided with a vessel without lights," gasped Jack, "and—and——" his voice choked up, "Tom's gone."

"Gone!" exclaimed the professor. "Overboard, you mean?"

Jack mournfully replied in the affirmative. But he launched into action, too.

The switch that controlled the Sea Ranger's powerful searchlight was handy to the wheel. A quick twist of his wrist, and a white shaft of light from the powerful reflector cut through the night like a scimitar of flame.

With his hand on the controlling lever, Jack swept the beams hither and thither through the blackness. In the meantime, Sandy had cut loose one of the two patent buoys that were lashed to the little craft's bridge. He cast it out from the Sea Ranger's side with a powerful impetus.

As it struck the water, the dampness reached the bottle of chemicals attached to the life-saving contrivance. Instantaneously a dull, ghostly glare lit up the surrounding waves. The light was blue and uncanny, and rendered the scene still more disheartening. As the light struck the tossing waves, it turned them to a steely, unearthly bluish hue.

But if Tom were swimming anywhere near at hand he would be able to see the buoy and strike out for it.

"Look! Look there!" cried the professor, suddenly pointing off into the blue glare of the chemical buoy.

The others hastily glanced in the direction indicated, and, for a second, they could see a head bobbing about on the wave crests.

"Turn the ship ar-oond!" bellowed Sandy.

"I daren't. If we got into the trough of those seas, we'd be swamped in an instant."

Jack spoke the truth. To have attempted to turn the Sea Ranger in the sea that was running might have meant disaster, swift and certain.

"There comes the other craft!" cried Jack suddenly.

As he spoke, he saw a large tug, pitching and heaving fearfully in the heavy sea, come wallowing into the circle of light cast by the chemical buoy. Several men were on her decks. Jack could see that one of them held a line, which he threw out toward the bobbing head on the wave crests.

With the idea of aiding the men on the tug in their work, Jack switched the searchlight over toward them. Its rays fell on the craft just in time for those on board the Sea Ranger to see Tom's limp form being hauled on board.

The brilliant rays of the searchlight lit up the faces of Tom's rescuers as plain as day. As it fell on the wild, dripping countenances of the tug-boat men, Jack gave a sudden start.

"Great Scott!" he burst out. "Can it be possible?"

"Hoots! Can what be possible, mon?" queried Sandy.

"Why, look! Look there!"

"At what, pray? I see that they've rescued poor Tom."

"No—I mean look at that man—the one there by the pilot-house. And the other beside him!"

"What in the name of the haunted kirk of Alloway are ye speekin' aboot, noo'?" inquired the Scotch boy.

"Why, those men. It's Dampier and Captain Walstein, just as sure as we are on this bridge—and—and Tom is in their power!"

"Let us thank Providence he is saved."

It was the professor who spoke. His words made a deep impression upon Jack. After all, it might only have been his fancy. It seemed like a wild dream to imagine that Dampier and Walstein could have——

A sudden deluge of brilliant light encompassed those on the bridge of the tossing Sea Ranger. It was the searchlight from the hitherto lightless tug. For an instant the brilliant effulgence bathed them, and then it vanished as suddenly as it had appeared.

While they were still wondering what could have been the reason of the sudden illumination, there was a crash right above Jack's head, and a shower of glass fell about him. At the same instant, above the screaming of the storm, could be heard the sharp report of a firearm of some kind.

The men on the tug, for some inscrutable reason, had seen fit to shiver the Sea Ranger's searchlight with a bullet.

"It wasn't any mistake of mine," flashed out Jack; "nobody but Dampier or Walstein would have been guilty of such a trick."

Evidently those on the tug were not anxious to be observed. The mere fact that they risked being abroad without lights on such a night showed that. The shivering of the Sea Ranger's searchlight only added emphasis to the mysterious character of the craft.

"Let us pursue them," urged the professor.

"Yes, let's get after them," echoed Sandy. "Puir Tom is in bad hands, I'm thinking."

"How on earth are we going to pursue them?" gasped out Jack, whose pulses were throbbing with indignation, "even if we could sight them in the darkness, they are faster than we."

"That is so," agreed the professor glumly, "and what is worse, they must have recognized us."

The professor, as we have hinted before, had been with the boys on that memorable cruise to tropic waters, when Dampier and Walstein very nearly succeeded in marooning the Dacre party and stealing their treasure recovered from a sunken galleon. He, as well as the boys, knew the desperate character of the two men.

"All we can do is to keep as nearly as possible in this spot all night," advised Jack; "then, as soon as daylight comes, the storm may abate, and we can take some action."

And so it was arranged. Leaving the wheel to Sandy, who was a muscular youth, Jack dived below to attend to the engines, which he had neglected for some time. Luckily, however, the machinery was working smoothly. The professor remained with Sandy on the bridge, doing what he could to help in controlling the vessel through the fury of the night.

Somehow the long hours of darkness passed away, and daylight came. The sunrise was yellow and sickly, breaking through ragged clouds. A chilly wind swept across the lake, but the backbone of the storm was broken.

But, as Jack had feared deep down in his heart, on all the expanse of leaden, rolling water, there was no sign of another craft. The Sea Ranger was alone in the desolate scene. A hasty examination had shown that she had suffered no material damage in the collision. Some paint was scraped off, but that was all.

Sandy got breakfast, which they ate with faint hearts. Jack, for his part, could hardly swallow more than a few mouthfuls of bacon and bread and gulp down a cup of coffee. His mind was actively busied with plans to rescue his brother from the hands of men he knew to be unscrupulous, clever and revengeful.

"It's hardly likely that they'll neglect such a chance to get even on us for sending them to jail and recovering the treasure," thought Jack, with a sigh that was almost a groan.

After a hasty meal, he announced his plans. A consultation of the chart had shown them to be about opposite—so far as Jack could judge—a place called Rockport. The others heartily agreed with his determination, which was to head in to that place, and, by the use of the telegraph and the assistance of the police of the town, to get on the track of the mysterious tug which had vanished with Tom.

While the Sea Ranger is cutting through the seas toward her hastily determined destination, let us see what had become of Tom on board the tug that carried no lights.

"Wonder where under the sun I can be?" was Tom's first thought, as he opened his eyes.

He had swooned from shock and immersion immediately after he had been dragged from the water by the crew of the tug, and had no clear recollection of anything that followed his being knocked overboard when the tug and the Sea Ranger collided.

But it was plain enough to him, on awakening, that he was in a place entirely strange, and of which he had no previous recollection.

He lay in a rough bunk on a pile of none too clean blankets. The walls of the small room were bare, but a round port light and the motion of the tug told him that he was out on the water.

The boy was striving to marshal his thoughts, when the sudden sound of voices struck on his ears. They seemed to come from an adjoining cabin. Tom listened, idly at first, but before long he was shocked into the keenest attention. It was evident that the conversation related to him and his companions of the Sea Ranger. With his senses vibrantly on the alert, he drank in every word that he could catch.

No doubt, the men who were talking so freely thought that the boy was still in a state of coma, for they took no trouble to lower their tones. As Tom listened, a vague sense of having heard at least two of the voices somewhere before stole over him. He could not recall where, at first, but suddenly he caught the name "Dampier," and a moment later "Walstein." The identity of the familiar voices was thus instantly revealed to him as by a flash of lightning.

"I tell you," were among the first words that struck Tom's attention, "that we've run into the biggest stroke of luck yet."

"Then you don't intend to throw the brat overboard, as he deserves?"

In the light of what he heard later, Tom identified this amiable proposal as coming from Walstein.

"Throw him overboard! Why, my dear fellow, I have nothing so crude in mind," came Dampier's sharp, rather fastidious tones. "If we use him rightly, we can make a pile of money with this lad."

"How do you propose to go about it?"

The question came from a third speaker. For the sake of clearness, it may be said here that he was Captain Jeb Rangler, the skipper of the tug, and a man whose character was of the worst.

"Simple enough," rejoined Dampier easily. "His uncle is rich. He was so before they stole the treasure of the sunken galleon away from us."

"That's pretty cool cheek," thought Tom to himself, as he lay listening; "as if the rascals didn't try all sorts of roguery to obtain it from the rightful discoverers."

"Ah; I see what you mean," came in Walstein's rumbling, hoarse tones, "you think we can get a ransom for him?"

"You've caught the idea. I should say that old Chisholm Dacre would give a good bit of money to have his nephew back safe and sound. Especially if he knew into whose hands he had fallen."

There was a laugh, in which all three joined, at this. Tom felt a shudder run through him.

"This is a nice nest of ruffians," he thought to himself. But the voices went on, and he eagerly resumed his listening.

"You've got the head after all, Dampier," rumbled Captain Walstein's heavy bass voice. "I wish we could have got the others, too."

"We might have, only it was too risky to take a chance on attacking their craft."

Tom hailed this as a bit of good news. It showed him that what he had half-feared, namely, the loss of the Sea Ranger in the collision, was no longer to be dreaded.

"Yes; we can't afford to take any more chances," muttered Captain Rangler gloomily. "That last one almost finished us. I don't like the idea of having the authorities so close on our heels."

"We've got to put in for more coal, too," came Walstein's voice.

"Oh, well, there's no danger of the tug being identified," laughed Dampier defiantly. "At Alpena and at Dead Fish Point lighthouse, she was a black and green craft named the War Eagle. Now she is changed to a slate-colored tug named the Flyaway. Jove! that's a good name, too," he chuckled.

A great light broke upon Tom. So this was the mysterious tug for which the authorities had been searching? But, from what he had heard, the gang in control of her had disguised her beyond recognition, and intended to keep on with their evil trade of ship-wrecking.

"Well, I'm going to head in toward the coast," he heard Captain Rangler say presently. "We've only got enough coal for a few hours."

The voices died away, as the three rose and left the adjoining cabin. But their conversation, brief as it had been, had shown Tom several things. Not the least among these was the fact that he was in one of the most serious predicaments of his life. The reflection that, not his own fault, but a series of extraordinary coincidences had thrown him into his perilous position, failed to console him.

"I might just as well have been hurled into a den of hungry tigers," thought Tom to himself, with a rueful attempt at humor.

The door-latch rattled and the portal was flung open at this juncture. Without waiting to see who his visitor might be, Tom flung himself from his sitting posture down among the blankets. It did not suit his plans that the men in whose power he was should realize that he knew at least a part of their rascally plans concerning him.

Tom, lying quiet amid the blankets, heard some one cross the cabin and come to a pause so close to him that he could hear the man's heavy breathing.

"Wake up, there, Tom Dacre," the man said.

The lad did not move, and the command was repeated in a louder tone. This time Tom, cleverly imitating the gapings and vacant expression of one just aroused from sleep, opened his eyes.

He had no difficulty in recognizing the features of Captain Walstein, even though a long growth of reddish beard now flourished on the lower part of his face. The man's cap was shoved back, and his leonine head of bristling, light-colored hair showed as prominently as ever. His features were heavier and more floridly colored than when Tom had seen him last, but that was the only difference, except that his costume was a rough one,—the ordinary garb of a Great Lake tug-boatman, in fact.

Close behind him, as he entered the cabin had been Dampier. He had paused at the door, to watch events, in the furtive manner that habit had made second nature to him. As Tom appeared to awaken from a sound sleep, however, he, too, came forward. His snake-like eyes, set like two glittering, coal-black specks in his sallow face, gleamed as they met Tom's frank gaze.

"Well," said Walstein, after a pause which Tom did not break, "ain't you surprised to see us?"

"Ye-es," struck in Dampier, in his soft voice, "it must be quite a shock to you to encounter old friends."

"So far as friends are concerned, we'll leave that out," spoke up Tom boldly, "and the surprise part of it is an unwelcome one, I'm sure."

"As you'll see a good deal of us for the succeeding few weeks, you'd better make up your mind to keep a civil tongue in your head," snorted Walstein.

"I keep a civil tongue, as you call it, for those I consider my equals and superiors," said Tom; "neither of you come in that class."

"So-o, my young fighting cock," whistled Dampier softly, "I reckon we'll have to clip your wings a bit. Aren't you grateful to us for pulling you out of the water when all your friends drowned?"

From what he had overheard of the men's conversation, Tom knew that this latter statement was an untrue one. However, he did not contradict it.

"You mean that the Sea Ranger is sunk!" he exclaimed, in a voice into which he managed to put a good deal of shocked amazement.

"That's right," said Walstein, rubbing his hands. "We ran into her and sank her last night, and saved you."

"I'm surprised at that," declared Tom. "I recollect your saying before you were sent to prison for your actions in the tropics, that you'd like to wring all our necks."

"Well, it suited us to save you, anyhow," retorted Walstein. "Where were you going in that craft?"

"That can't matter much to you since she is sunk," parried Tom. "The question is, what are you going to do with me?"

Dampier grinned unwholesomely.

"Oh, it's really too early to tell you that yet," he said, "but before you get free again, we mean to have back a good part of that treasure you and your uncle robbed us of."

"That you tried to rob us of, you mean," said Tom, flushing angrily.

"Well, have it anyway you like it," said Walstein, in his rumbly, throaty tones. "I just want to tell you this, though, that you are in our power, and it will do you no good to try to get away till we want you to."

"That will depend," rejoined Tom.

"Depend on what, pray?"

The question came from Dampier.

"On whether I see a chance to get away or not," replied Tom.

Walstein muttered something about "taking the impudence out of the brat," but Dampier laid a hand on his arm. Then he spoke with extraordinary vehemence.

"See here, Tom Dacre," he hissed, coming quite close, and shaking one long, yellow finger almost in Tom's face, "I hate you. Captain Walstein hates you, too. We've got good reason to, as you know. We're going to get even with you, and get good and even, too."

Before Tom could reply they both left the cabin, leaving the lad in a very unenviable frame of mind. His case looked hopeless, and whatever might have been the intentions of Walstein and Dampier when they entered, they had left again without giving Tom any clue as to what his fate was to be.

Before long, he grew tired of lying still, and got out of the bunk. He was in his shirt and trousers, which were still damp, but his coat was flung down on a nearby chair. Slipping it on, he made for the door of the cabin.

But he had hardly got it open before a gruff voice warned him to "Get back in there, if you know what's good for you." A hulking big tug-boat man stood outside the door. He was evidently stationed there to prevent any attempt to escape on the part of the prisoner. Poor Tom felt that the blockade was quite effectual.

There followed a dreary hour, in which it began to be borne in on the lad that he was exceedingly hungry and thirsty as well. He opened the door once more. The same sailor was on guard.

"Say, don't I get something to eat?" queried Tom pleasantly, in response to the man's growl to "Get back."

"Dunno, an' dun't care," grunted the sailor sullenly.

But Tom's appeal bore fruit, for half an hour later another sailor entered with a tray, on which was coffee, fruit, and a big dish of ham and eggs.

"Well, they don't intend to starve me, anyhow," said Tom, as his eyes fell on this unusual fare for tugboatmen to serve. He fell to heartily, and ate everything before him. So hungry had he been that it was not till the conclusion of his meal that he found leisure to examine the elaborate knife and fork that had been handed him to eat with. He gazed at the richly chased tableware with some interest now, however. It bore a name stamped on both knife and fork.

"S. S. DETROIT CITY."

That was what Tom read. The words caused his pulses to bound. He was actually then, as the overheard conversation had led him to expect, on board the mysterious wreckers' tug that the police of every big lake city were searching for. He recalled reading of the wreck of the Detroit City—a lake passenger steamer,—on a bitter February night. The craft had been lured to her fate—it afterward proved—by lights that had been tampered with.

"And these are the rascals into whose power I have fallen," gasped Tom, his eyes fixed on the bits of tableware which bore the name of the ill-fated craft.

Soon after, Walstein and two sailors entered the cabin. Under the leonine-headed seaman's direction, the sailors ordered Tom to thrust his hands into a pair of rusty and antique-looking handcuffs. His legs, also, were pinioned. This done, he was borne through the door and along the deck, to another doorway. Then his conductors—or rather jailers—conveyed him down a steep flight of metal steps and through the boiler room of the tug, into a dark, ill-smelling hole, suffocatingly hot.

Into one corner of this place they flung him.

"I guess you can howl yourself sick in there, and no one will hear you while we're at the dock," chuckled Walstein brutally, as he went out, slamming the bulkhead door behind him.

Soon after the vibratory motion of the engines ceased, and Tom could hear shouts and tramplings on deck. He guessed they were making fast to some dock, but where their stopping place was, he had, of course, no means of knowing.

In spite of Walstein's words, Tom did shout. He yelled and cried out for help till his throat was sore and cracked, and his voice a mere whisper. But no help came to the dark, stuffy place in which he had been flung.

Tom had no way of gauging how long it was he lay in the pitchy darkness, before there was a scraping and a sliding sound, and a sort of trap-door in the deck above him was opened.

He was still wondering what this might portend, when the lip of a metal chute was suddenly projected into the opening, and without warning a shower of coal started to pour into the place, which, Tom now saw, was an empty coal bunker.

The boy shouted and halloed at the top of his voice, but it was some time before anybody appeared. By the time they did, the avalanche of coal threatened to overwhelm poor Tom, and his position was anything but enviable.

At length, however, a face was poked over the edge of the hole, and Tom, to his great relief, heard a voice shout:

"Stop that coal a minute. There's a boy down in here."

The man, or rather youth, who had shouted this, swung himself down into the bunker the next instant, and despite the grime on his face, Tom recognized an old acquaintance.

"Jeff Trulliber!" he gasped.

The son of the chief of the Sawmill Valley gang of counterfeiters was equally astonished.

"Why, it's Master Dacre!" he exclaimed, starting back in astonishment.

"That's who it is," rejoined Tom, with a rueful grin. "I want you to help me, Jeff. But first tell me if any of the crew of this craft are about."

"Not one of them. The skipper and two other chaps, who seemed to be his cronies, went ashore some time ago, and, as soon as they were gone, the crew left, too. I guess they are all carousing. But what under the sun——"

"Never mind questions now, Jeff. I want you to set me loose. See if there is a cold chisel and hammer in the engine room, and you can soon get this unornamental jewelry off me."

"I'll do that," responded Jeff eagerly.

Tom indicated the door leading from the bunker into the engine room, and Jeff, after rummaging about in there a while, located the required implements. In a very few minutes, for the irons that confined his limbs were old and rusty, Tom was free.

While they were hastening from the boat, Tom told Jeff rapidly as much as he chose of his story, and then it was his turn to ask questions.

It will be recalled that the last time we saw Jeff was when the canoe, in which he was trying to escape with Dan Dark, was upset in the lake opposite the Maine bungalow. Tom's heroic rescue of the lad, just as he was about to be sucked into the old lumber flume, will also be recalled by readers of The Bungalow Boys, the first volume of this series.

His rescue from a tragic death had proved the turning point in Jeff Trulliber's life. He had recalled the fact that he had an uncle in Michigan who had long disowned himself and his disreputable father. Jeff had sought and found this relative and obtained his forgiveness, and had been placed at work in the coal yard which was one of his uncle's properties. From workman he had rapidly risen to foreman, such was his application and ability. He was genuinely glad to be able to do a service for the lad who had risked so much for him.

"What place is this?" inquired Tom, as Jeff concluded his story, amidst Tom's congratulations.

"Rockport, Michigan. It is quite a town."

"Is there a police force here?" inquired Tom.

"A finely organized one. I see what is in your mind. You want to report the character of this craft and her crew to the authorities. I don't blame you. Tell you what we do—I'll go uptown with you. We can get there and back before the rascals that own the tug can return. I'll tell my men to delay in coaling her, so that even if that outfit does come back, they cannot get away."

"That's a good idea, Jeff. Let's go at once."

Rockport, in Jeff's phrase, proved to be "quite a town." The wharves, at one of which the tug lay, were numerous, and lumber yards and factories extended all along the water front. Quite a lot of lake steamers and smaller craft lay at them, giving the place a busy, bustling appearance.

But, not stopping to waste time on surveying the lake front of the town, Tom and his new ally set out at a good pace for the police station.

In the meantime, Captain Rangler, Dampier and Walstein were making their way back to the tug from the main part of the city where they had been negotiating some purchases of supplies.

As they emerged from a cross street near the water front, their conversation was concerning Tom. Captain Rangler was just remarking, with a grin, that as soon as the letter to Chisholm Dacre was written, they could make for a certain rendezvous of theirs on an island, and wait "for the coin," when Walstein suddenly gave an exclamation, and pulled his companions into a convenient doorway.

"What the dickens—" began Dampier, startled at this move. But Captain Walstein checked him.

"Hist!" he exclaimed. "Look down there, at the bottom of this street. By all that's cussed, there goes the boy now."

"Impossible," burst forth Dampier, but Walstein threw in a swift interjection.

"By the great horn spoon, it is Tom Dacre!" he exclaimed. "How in the name of time did he escape?"

"We'll find that out later," snarled Dampier vindictively. "The thing to do now is to follow him and see what he and that chap with him are up to. Rangler, you go back to the tug. Walstein and I will follow him up. It wouldn't astonish me if he's off to put the police on our track."

"Nor me, either," agreed Walstein, as, after a few words more, Rangler hastened to the lake front, while Dampier and his companion stealthily crept off in pursuit of Tom and Jeff, who were, of course, utterly unconscious of being followed.

Reaching the police station, the two lads found, to their chagrin, only a sleepy sergeant in charge. The captain had been out all night on a case, they were informed, and, with his detectives, was now at a court-house some miles off, with his prisoners.

Tom and Jeff exchanged disgusted looks, as the official yawned and returned to reading the newspaper, in the perusal of which their entrance had interrupted him.

"Can't you do anything for us?" asked Tom eagerly, unwilling to give up all at once. "It may be the last chance the authorities will have to catch those rascals."

The sergeant looked up from his paper.

"See here, young fellow," he said in a belligerent tone, "are you setting to teach me my business?"

Tom hastily assured him that such was not the case.

"But it is urgent that if anything is to be done it should be done at once," pursued the boy. "Those fellows on that tug——"

"Now, stop right there," warned the officer of the law, who had such a high idea of his importance, "what is right to be done will be done. What ain't, won't. Anyhow," he demanded, turning suddenly on the two lads, "how do I know you're speaking the truth, eh?

"Come to think of it," he added, suddenly rising from his seat and coming out from behind the desk, "you two fellows remind me a good deal of the description of two runaway bank messengers we've been asked to look for. They were supposed to be making for Canada. Yes," he said sharply, "I guess you're the lads, all right; anyway, I'll lock you up till you can prove otherwise. Dan!" he raised his voice, "Mike, Pete!"

At the words, three men appeared from a rear room. Tom saw in a flash that if this arrest was submitted to, it might result in the rascals who had abducted him getting clear away. He determined, in a flash, not to allow this if he could help it. As the first of the men ran at him, he thrust out a foot, and the fellow came down with a crash. Before any of the rest could recover from their surprise, the lad was off like a dart.

Behind him came shouts, but Tom was fleet of foot, and dodged and turned, like a rabbit with a pack of dogs hot on its tracks.

Suddenly, as he turned a corner, a voice sounded right at his shoulder: "In here, quick!"

Without thinking what he was doing, Tom darted into the doorway whence the voice had come. Hardly had he entered it, before he was seized, and received a brutal blow on the side of the head, hard enough to stun him.

"What a bit of luck!" exclaimed one of the men who had lured the lad into the doorway.

"It sure is that," was the rejoinder from his companion, who, if the reader has not already guessed it, was none other than Walstein, with his partner, Dampier. Tom, unfamiliar with Rockport, had actually doubled on his own tracks, and thus, the two men on their way up a narrow alley, had spied him just dashing into it. In a flash their minds were made up, and they slid hastily into the doorway in which they had trapped poor Tom.

They had tracked the two lads to the station, but as they neared it, the nerve of the two rascals had failed them.

"We don't want to run our heads into a halter," Dampier had said. "We'll have to let the lad go for the present."

Walstein was quite willing to agree with him in this, having no better liking for the vicinity of the law than his companion.

Naturally, they were considerably mystified as to the cause of Tom's sudden appearance; but Dampier, who had a shrewd mind, partially unraveled the solution, when he said:

"I reckon the police were not quite as willing to listen to his story as he thought they'd be. Maybe he got mad and gave 'em impudence!"

"In that case they'll be right after him," said Walstein. "We'd better be getting out of here on the jump."

"I think so, too. Here, help me with the boy. See, this alley-way runs right through to another street. We'll hurry down it and then get back to the tug as fast as we can. Come on. There's no time to lose."

The alley-way, on which the door opened through which Tom had dashed, proved to lead into a quiet, retired thoroughfare, at the foot of which the masts of shipping could be seen.

The two men, half-dragging, half-supporting poor Tom, hastened down it.

As they neared the water front, however, a strange thing occurred. Their grasp on the supposedly semi-conscious Tom had been light. They had not deemed it necessary to be over-vigilant. Now they realized their mistake, for Tom, with a swift movement, dived out of their grip, and the next instant was darting off—free once more. The blow had been a hard one, but it had not made him half so stupefied as the lad's cleverness had led his captors to believe.

Like the other Tom of the immortal rhyme, our lad went "dashing down the street" as though on the wings of the wind. Behind him came shouts and yells, but he paid no attention to them. He did not know that, at the very moment that he had succeeded in eluding the grip of Walstein and Dampier, the pursuing police had, in turn, picked up the trail of those two worthies. Seeing Tom in the grip of the rascals, the skeptical sergeant, who was one of the party, immediately began to put more stock in Tom's story than he had hitherto.

"The lad was telling the truth after all, I believe," he said.

"Of course he was," said Jeff indignantly, for the boy, who had established his identity and vouched for Tom, had come along, too.

The approach to Walstein and Dampier was made with all due caution, but just as the officers of the law were about to dart forward upon the two rascals, Tom made his surprising escape. At the same instant Walstein and Dampier, likewise, dashed off after Tom, so that there was a sort of triple pursuit on—Tom in chase of liberty, Walstein and Dampier in hot pursuit of Tom, and the police and Jeff in quest of both Tom and his recent captors.

Hearing the shouts of the police behind them, Dampier and Walstein turned to see what this new development might portend. It didn't take them the wink of an eyelid to comprehend what was occurring.

"Stop, or I'll shoot!" cried the leader of the authorities.

Tom heard the shout, and, not having spared time to look behind him, attributed the cry, naturally enough, to Walstein or Dampier. Naturally, also, it caused him to dash on faster than ever.

Bang!

The noise of a shot came behind him. The policeman's bullet grazed Dampier's ear, but it didn't stop him.

Right ahead was a lumber yard. Big stacks of timber were piled all about. Tom felt that if he could once gain it, he could find comparative safety from pursuit among its intricacies.

Dampier and Walstein, behind him, had the same feeling. Moreover, they knew the water front of Rockport well, and realized that it was a step from the lumber yard to where their swift tug lay, freshly coaled, and, if their orders had been followed, with steam up.

Tom gained the lumber yard, and darted like an arrow in among the piles of resinous smelling timber. In and out, he dodged, while the cries behind him grew fainter.

"Thank goodness, I seem to have them thrown off my track," he exclaimed, as he stopped to breathe.

After he had recovered a bit, he began to walk forward through the lumber yard. A few turns brought him to a wharf. As he saw the craft that lay moored there, Tom gave a gasp of astonishment, and then a cry of joy.

It was the dear old Sea Ranger!

There she lay, as trim and tight as if the exciting events that had followed the storm had never occurred.

But, as the lad was stepping forward with joyous anticipation of being reunited to his chums, he was brought to a sudden halt by a queer sound behind him.

Tom stood stock-still and listened intently.

The noise came again. It seemed to proceed from behind one of the nearby stacks of lumber.

"Funny sound," mused Tom; "wonder what it is? It——"

"Oo-oo-oo-h!"

"It's a man's groan," the lad exclaimed.

"Oh, don't strike me again! Please don't," came the gurgling moan once more.

"That fellow's badly hurt," decided Tom.

"Guess I'd better see what's the trouble," he resolved the next instant.

Stepping round one of the lumber piles, he came upon the injured man. He lay in a huddle on the planked floor of the wharf. One arm was upraised, as if to ward off a blow, as he heard Tom's footsteps.

"Don't hit me again! Don't!" he begged.

"I'm not going to hurt you. I'm—— Gracious heavens!" he half-shouted the next instant. "It's—it's Professor Podsnap!"

There was a red stain on the professor's face, as if he had been struck by some blunt weapon. His face was white and pitiful, as he looked up at Tom. He recognized him with a groan of dismay.

"You—you've come too late, my boy," he exclaimed weakly, and fell back.

It was some seconds before Tom, kneeling beside him, was able to catch any more. Then the professor spoke again. But his voice was so feeble that Tom had to bend down to catch the words.

"Jack—" gasped the man of science, "Jack and Sandy—they——"

"Yes," spoke Tom eagerly, "yes, where are they?"

"Gone!"

"Gone?"

"Yes, abducted. We entered this port a short time ago. We were setting out for the town to communicate with the authorities concerning your loss, when all of a sudden we ran into a gang of men."

"Yes—yes," said Tom eagerly.

"Well, we didn't pay any attention to them, for they were a rough-looking crowd, but suddenly one of them exclaimed: 'There's two of those boys, now!' With that they all rushed at us, and—and something struck me, and that's all I can recall."

A fear that made him feel sick and faint clutched at Tom's heart.

"These men, what did they look like?" he asked, dreading to hear the answer.

"Like sea-faring men. I should have said they were on their way to some ship. Stay! I heard a name mentioned. It—it was—let me see—Spangler, I think."

"Rangler," struck in Tom, with vibrating heart.

"Yes, that was it—Rangler."

"Good gracious! He is the captain of that tug that Walstein and Dampier were on board of."

"In that case, don't wait here to bother about me. Let us get help at once."

The professor staggered weakly to his feet, while Tom supported him as best he was able.

"Oh, those ruffians will pay dearly for this, if ever I can make them," breathed Tom. "Poor Jack and Sandy, they're in their power now."

Suddenly came voices, several of them. It was the party of police, accompanied by Jeff, and enlarged by several dock loungers and workmen.

"Here's Tom Dacre, now," exclaimed Jeff joyfully, hastening forward as he spied the lad. "Thank goodness, those scoundrels didn't get you. But—but what's happened?" he asked, gazing from the professor to Tom and from Tom to the professor.

Tom explained quickly. Then he said: "Somebody get a doctor, quick, for Professor Podsnap."

"There's one has an office right close," volunteered one of the crowd, "accidents often happen on the docks."

"Officer Dugan, be off and get him," ordered the sergeant of police, who looked very crestfallen. "Young man," he said to Tom, "I owe you an apology for doubting your story."

"You owe me more than that," said Tom, with a bitterness he could not help. "Here, Jeff, help me get the professor on board the Sea Ranger. Be as quick as you can, we must set off in pursuit of Walstein and Dampier."

At these words the police exchanged glances and looked foolish, while Jeff burst out angrily:

"They've slipped through our fingers, Master Tom."

"How—how is that?" bewilderedly asked Tom. "Isn't their tug still there?"

"It slipped out of the port while we were searching for those two rascals," said one of the policemen.

Tom looked thunderstruck. He could not speak. The stupidity of the police of Rockport seemed more than incredible.

"Then they're gone?" he asked dully. There was a ringing pain in his head. His heart felt like a lump of lead.

"Yes, Master Tom," said Jeff wonderfully gently, and slipping to Tom's side, "thanks to those chumps of police they have gotten away without waiting for all the coal to be put in. But we can telegraph every place and soon have them stopped and their craft searched for your brother and your chum. I——"

"Why don't the police get after them?" demanded Tom, anger replacing stupefaction, "why isn't there another tug after them, a——"

"They got too long a start, and there isn't a craft in this harbor that is fast enough to be of any use in chasing them," put in one of the men who had aided in the time-wasting search among the lumber.

Tom flushed angrily.

"Yes, there is—one!" he exclaimed.

"Where?" The question came from the dull-witted sergeant.

"Right there," said Tom, waving his hand toward the Sea Ranger; "do you think I'm going to let those rascals steal my brother and my chum without doing something?"

"By ginger, Tom, when can you start?"

It was Jeff who spoke, warmly, admiringly. His eyes shone with the contagion of Tom's enthusiasm.

"Just as soon as a doctor has attended to the professor. Hello, here he comes now. How do you feel now, professor?"

"Like taking after that cargo of villains as soon as we can get away," was the warlike and unexpected reply of the usually mild-mannered professor.

"But your injury?" asked Tom, self-reproachful at having in his indignation almost forgotten the professor's condition.

"I feel almost sound again—I really do," stoutly declared the professor.

The doctor, who had been so hastily summoned, coming up at this instant, the party adjourned to the stateroom of the Sea Ranger. The medico pronounced that the wound that had laid the professor low, while it had been painful, was not dangerous. He also prescribed some lotion for a large, knobby protuberance that was making itself manifest on Tom's cranium, where Dampier had struck him.

In the midst of this conference, the door was hastily thrown open, and Jeff entered. He carried a big carpet-bag, and behind him stood a bulging-eyed negro.

"Hello, Jeff," exclaimed Tom warmly, looking up. "Come to say good-by?"

"No, I'm going with you," was the decisive answer.

"An' ah hev bin hired as general factotum," announced the negro, with a grin.

"Why, Jeff, what does all this mean?" asked Tom. "I was going to engage some trustworthy men to go along."

"You don't need any," said Jeff shortly. "You did me a good turn once, Tom Dacre, that I'll never forget. You saved me from death, and likewise from a criminal life."

"But your work here, Jeff; you can't leave that to go on this cruise. Really, I——"

"It's all been arranged," calmly announced Jeff. "My uncle agrees that it's my duty to stand by you in your trouble. So another man is already on my job. And now that's all accounted for, let's get under way at once," he went on calmly.

Tom looked interrogatively at the negro, who stood modestly in the doorway, grinning widely and twisting and untwisting a pair of agile legs.

"Oh!" exclaimed Jeff with a laugh, seeing Tom's look, and interpreting it correctly as a question as to the negro's identity, "that's Rosewater. He——"

"Yas, sah! Yas, sah! Yas, sah!" said Rosewater, bowing three times with wonderful swiftness.

"He's been a sort of handy man to me round the dock, and when he heard I was going on this cruise, he insisted on coming, too. We'll find him useful. He can——'

"Kin cook! kin wash! kin sing! kin dance! an'——"

"Can't keep quiet," said Jeff in a jocular undertone to Tom, "he's a West Indian, and faithful as a spaniel dog."

And in this way, Rosewater—they never heard of any other name for him, even the negro did not know of one himself—became a member of the Sea Ranger's crew on one of the most adventurous cruises any of the party had ever embarked upon.

Half an hour after the doctor had patched up the professor, and had left the craft, the engines, under Tom's management, began to revolve.

With Jeff—a skilful steersman—at the wheel, the professor "standing by," and Rosewater in the galley, they glided out of the harbor of Rockport, heading at top speed for a distant smudge of smoke on the Huron horizon.

That smudge of smoke marked the tug of the desperadoes of whom they were in pursuit, but it seemed terribly faint and far off and almost as impossible of attainment as the pot of gold at the rainbow's foot.

"Are you there, Sandy?"

Through the darkness in the hold of the tug, in which they were confined (and which had recently been the place of Tom's captivity), Jack's voice reached the Scotch lad.

"I dinna ken. But I think so," he responded cautiously. "Some of me's here, anyhow. Whist, Jack, we're in a tight place."

"And a dark one, too," said Jack gloomily.

"What d'ye think they'll do wi' us?"

"I have no notion. But what they have done already gives a sufficient idea of what they are capable of. There may be bigger rascals on earth than this outfit, but I don't know where you'd look for them."

"By the peak of Ben Nevis, that was a dire crack on the head that Captain Mangler gave me when they attacked us in that lumber yard."

"His name's Rangler—though 'Mangler' would about fit him," rejoined Jack. "They didn't strike me, but just picked me up and stifled my cries—just as I was going to the rescue of the poor professor, too, I fear they may have killed him."

"I dinna think so. But I hope he is not on board this tug."

"Why?"

"Because, if he is, there'll be no one left behind to give a clue as to our whereabouts."

"Even if they could, I don't see what good it would do," was the gloomy rejoinder. "Poor Tom's still missing, and——"

"Whist, lad! Dinna be downcast. Tom will turn oop—like a bad penny—not that he is one, but in a manner of speaking. I'm sure he's all right. He will look out for himself and rescue us, too, I'll bet ye a siller bit."

"I hope you are right, Sandy, but this is surely a disastrous ending to what promised to be a pleasure trip."

"There's a linin' of bonnie gold to every cloud," comforted the philosophical Sandy. "But," he added with Scotch candor, "I'm blessed if I can see aught but the cloud the noo'."

There was silence for a time.

"Let's explore this place a bit," suggested Jack presently.

"Too dark," responded Sandy, "we might fall into some trap-door or hole."

"We can feel our way with our hands—oh!" and Jack almost laughed at his mistake—"mine are handcuffed."

"Mine, too, but I hadna' forgotten the fact," said Sandy dryly.

"I suppose, then, we must wait here till somebody comes."

"I guess that's aboot it. It's no' vera cheerful, but it can't be helped, as the man said when they were gangin' to hang him."

The vibration of the propeller of the tug could be plainly felt. The whole craft shook with it. It was clear that all the speed possible was being crowded on.

The heat, too, grew almost stifling. The hold was back of the boiler room, in which forced draught was being kept up, while the steam-gauges showed a pressure almost up to bursting point. Walstein and Dampier, after safely gaining the tug, following the chase through the lumber yard, had decided to lose no time in putting all the distance possible between themselves and Rockport. Their joyful reception of the news that, although they had lost Tom Dacre, his place had been taken by his brother Jack, may be imagined. Sandy they did not care so much about. They did not know that his father was quite as rich—or richer—than Chisholm Dacre. But both had been warm in their congratulations to Captain Rangler on what they deemed his clever capture.

"Phew-w-w-w! This place is like a furnace," observed Jack, after another silence of some duration. "How about you, Sandy?"

"It's hot, all right. I'd give a whole lot for a drink of water. I feel as dry as a stale loaf of bread."

"Talking of bread, I wonder if they mean to starve us or let us die of thirst?"

"Impossible to tell. I dinna ken what they mean to do. I suppose they are capable of anything."

"Yes, the inhuman ruffians! But what is worrying me is, that, supposing they don't mean to starve us, or let us die of thirst, what do they mean to do with us?"

The question was a puzzling one.

"If they don't kill us, they'll have to keep us with them all the time," said Sandy gloomily, after a while.

"Maybe they'll maroon us, like they did down in the tropics. There are plenty of islands in this part of Lake Huron."

"Yes, but this isn't an untraveled region, like it was down there. In course of time we should be picked up."

"Hum! Yes, that's so. Tell you what, Sandy, if we get a chance to escape, we'll make for some island and hide there till an opportunity comes to get off."

"Jack, do you recall that island where the ghost was snoopin' around? Ye ken the one I mean?"

"Do I? I should say so. Well, that was as tight a scrape as this, but we got out of it, all right."

"So we did," agreed Sandy, cheering up, and with almost a lively ring in his tones, "and that fix was our own fault, too. If we hadn't tried tricks on the professor and got tied to that turtle, we wouldn't have been marooned."

"Well, in this case we haven't even the satisfaction of blaming ourselves," whimsically remarked Jack.

The hours wore slowly away. At first the long wait in the darkness was merely tedious. Then it began to grow painful, and at length, such were the boys' thirst and hunger and suffering from the intense heat, that they went almost crazy.

Work as they would at their bonds, they could not loosen them. The steel bracelets resisted all efforts to unfasten them. To make matters worse, when the lads flung themselves wearily down to try and pass the interminable hours in the forgetfulness of sleep, they found that they were not the sole tenants of the hold.

Huge rats presently began scampering about. The creatures at first rushed off when the boys cried "Scat!" But, after a time, they grew bolder, and came in legions. The lads could hear their squeakings and bickerings as they nosed about them. It was truly a horrible sensation. Little red eyes, like needlepoints of fire, burned through the darkness, and Jack recalled tales he had read of prisoners whose bones had been picked of flesh by the loathsome rodents.

"They'd find us tough picking," laughed Sandy, when Jack communicated his fears, but in his easy manner the Scotch lad concealed a world of real, almost desperate, anxiety.

Their position was plainly growing more and more untenable. Already their heads felt as if they would burst from the intense heat and stuffiness of the hold. Then, too, their long fast had made them weak. Queer buzzings sounded in their ears. Shapes, that they knew were unreal, flitted through the darkness, like forms compounded of greenish, luminous smoke.

And still the tug raced along. The roar of her laboring engines filled the little craft, making her quiver from stem to stern.

"Wonder where on earth she can be?" thought Jack, in a dull sort of semi-stupid voice.

"I dinna ken, an' before long it willna' matter to us, anyhow," was Sandy's miserable response. All his fund of hopefulness had vanished.

As if in mockery at his words, the rats squeaked louder than ever as he uttered them. Their little bright eyes darted here and there in the darkness before the boys' swimming vision, like thousands of crazy fireflies. Clearly, if help did not come soon, there would be two less among the company the tug was carrying across Lake Huron, at racing speed.

"Hullo, the motion of the tug seems to have stopped."

The thought filtered dully through Sandy's benumbed mind. For some minutes, indeed, the speed had been sensibly slackening, but in the lads' deplorable circumstances, they were neither of them in a condition to be speedily aware of the fact.

"Jack! Jack!" hailed Sandy, eager to announce his news. But no answer came out of the darkness. Poor Jack lay unconscious on the floor of the hold. He had given way under the strain and stifling heat.

Sandy guessed as much, when he got no reply. The realization of Jack's condition acted as a tonic to him. Summoning up every one of his dormant faculties, the lad resolved on a last effort.

Reckless of the consequences, if there were any trap-doors or holes in the floors of the hold, he plunged forward into the velvety darkness. He could hear the patter-patter of myriads of tiny rat feet as he did so, but the Scotch lad was long past caring for that. The fighting instinct of a race of fighting ancestors was fully aroused in him. He felt that it would have taken half a dozen men to stop him.

Bump! Without warning, Sandy had suddenly blundered up against what seemed to be a solid wall.

"Well, here's something, at any rate," he mused to himself. "Now, if I can only find a door in it, I'll fling myself against it and make such a racket that they'll be bound to come down, unless they are made of steel and iron instead of flesh and blood."

Then began what seemed an eternity of groping. Raising his handcuffed wrists, Sandy felt for a chink in the smooth bulkhead. Quite as suddenly as he had collided with the wall, his fingers encountered a crack.

"Eureka!" exclaimed the boy. "I guess this is what I want."

As well as he could judge, after a brief examination, the crack extended clear to the floor of the hold.

"It must be a door," thought Sandy. And then:

"Now for it," he murmured.

With a blood-curdling yell, he flung his form against the bulkhead.

The next instant he was lying flat on his face.

The door against which he had flung himself had opened smoothly and noiselessly, and the strenuous force of Sandy's shove had carried him, with a crash, into what seemed to be a cabin.

For a few seconds he was past caring what the place was. He just lay there in the light, pumping his lungs full of blessed fresh air.

"Phew! If my lungs aren't saying 'thank you, kind master,' this very instant, they're an ungrateful pair of organs," said the whimsical Scotch lad, half aloud.

The cabin was empty and sparsely furnished. But on deck could be heard the trampling of feet. Sunshine streamed through the skylight above, and Sandy judged it must be very early morning. They had lain in the stifling heat of that black hole for an afternoon and a night then.

After a few minutes, Sandy struggled to his feet and looked about him. The fresh air had hugely strengthened and revived him. He felt a new courage coursing through his veins.

In the center of the cabin was a swinging table, bearing the remains of a rough meal. But never had food looked so good to the boy as did those remnants of corned beef and cabbage, and some sort of soggy pudding, and—a most welcome sight of all—a big glass pitcher full of sparkling, clear water.

Sandy determined to free Jack somehow, and then, together, they would enjoy a long drink and something of a meal, come what might. But how to accomplish this? That was the problem.

All at once, from the hold behind him, came a cry.

"It's Jack! The fresh air must have revived him. Thank goodness for that," breathed Sandy fervently. Then uttering a loud "Hush," he made his way back into the hold.

Even in the short time the door had been open, the air had noticeably freshened. The place was filled with a dull, half light too. The semi-twilight revealed a big pile of boxes and bales in one corner of the place, but Sandy had no eyes for that. All he could see just then was the gaunt, hollow-eyed figure of Jack Dacre, staggering toward him.

"Courage, old chap," he exclaimed. "We've gained one step already."

"How on earth did that door get open?" gasped Jack, breathing the fresher air in great gulping sobs.

"Aweell now," grinned Sandy, "I guess that, unbeknownst to mysel', I must have whispered 'Open Sesame,' for the thing just swung open when I bumped against it."

The two lads were soon in the cabin, their minds busily at work as to how to free their hands. Suddenly Jack spied a bunch of keys hanging on the wall.

"Maybe some of those would fit," he suggested hopefully.

"Perhaps. We can try, anyhow. But how can we get them?"

"Easy enough. Like this."

Jack stood on tiptoe and seized the bunch in his teeth like a terrier seizing a rat. He dropped them on the table. Then came the problem of selecting one that would fit.

"This looks as if it might do," said Jack, literally "nosing" at a small, rusty key among the bunch.

"We can try it, anyhow," said Sandy; "take it in your teeth, and see if it does belong to these bits of iron jewelry."

It was a difficult and tedious task, but Jack at last accomplished it, and had the key inserted in the lock of Sandy's handcuffs. It fitted perfectly. Sandy laid his hands out flat on the table, so as to hold the handcuffs rigid, and then Jack gave a twist.

There was a sharp click, and Sandy was free.

"Now for you," he exclaimed, and, taking the key from Jack, with his now-free hands, he soon had that lad disburdened of his incumbrances. The lads really had some difficulty in keeping from cheering when this was accomplished. But, of course, they didn't. In fact, although they were now a little better off than they had been before, they were by no means "out of the woods" as yet. Like the young bears in the fable, they had still most of their troubles before them. But, nevertheless, it was a great relief to have air and the freedom of their hands.

"I guess the tug must have anchored," observed Sandy. "Wonder if we are lying at any city? If so, we could make a dash for it, and chance to there being somebody around who would help us out of our difficulties."

"I wish we had some sort of weapons," said Jack. "At any rate, we could make a fight for it. I feel as if I'd do anything rather than go back to that hold again."

"So do I. But let's get that water and then tackle some grub. I never felt so hungry in my life."

No more time was wasted on mere words. The boys fell to on the table scraps, as if they were starved—as indeed they were.

And how good that water tasted! Never had the most delicious soda either of them had ever sampled one-quarter of the cool delight of that pitcher full of "aqua pura."

"Ah-h-h-h!" breathed Jack, with a sigh of repletion, "that was something like."

"It was all of that," agreed Sandy, "and then some. But speaking of weapons, what do you know about those?"

He indicated a brace of pistols, which had been hitherto unnoticed by the lads. The weapons lay on a locker, and appeared to have been hastily deposited there by some one who had been engaged in cleaning them, for a small can of oil and some rags lay by them. The lads lost no time in pouncing on their finds.

Both proved to be loaded, and were of heavy caliber and of business-like looking blued steel.

"Look wicked enough for anything," grinned Sandy, examining his. "I don't know about the law-and-order aspect of this, but—'necessity knows no law.'"

"We would really be justified in doing anything to those ruffians," spoke Jack indignantly, "for all they cared, we might have died of hunger and thirst and suffocation in that miserable hole yonder, without a soul coming near us. I feel like facing the whole crew of the ruffianly wretches."

"Yes, let 'em come on," quoth Sandy defiantly, brandishing his pistol.

As if in answer to his words, a door at the head of a short flight of stairs was suddenly flung open, and the figure of a man appeared framed in the portal.

"Now for it," whispered Sandy. He was glad to note that in the hand which Jack impulsively thrust out to meet his, there was no sign of tremor.

Both lads flung themselves into attitudes of defense. Come what might, they felt prepared to face it, nerved by a sense of their wrongs, and of what a return to that pestilential hold would mean.

The newcomer was Captain Rangler.

He was descending into the hold to get the pistols he had barely finished cleaning and loading, when the preparations for anchoring brought a hurry call for him to go on deck.

His amazement at seeing both the lads free of their handcuffs, and defiantly pointing the pistols at his head, may be imagined.

"Well, I'll be hanged!" he exclaimed, pausing on the third step. "What under the North Star does this mean?"

"It means that you must set us free at once," spoke up Jack. "We are at anchor now. Send us ashore in a boat."

"And what if I don't?" demanded the captain. His voice seemed to hold more of curiosity than the ferocity the boys had been prepared for.

The question was rather a puzzling one, and caught the lads at a disadvantage. They had calculated on meeting with resistance. Instead, the captain of the tug, while appearing to be much astonished at their cleverness in escaping from their captivity, didn't seem to be in any way inclined to offer them violence.

Instead, he sat down deliberately on one of the steps, while both boys, rather perturbed in mind, kept their pistols steadily leveled. But their hands were shaky. They had been prepared for anything but this, and it took them aback.

"Well?" said Captain Rangler.

He drew a pipe from his mouth, and leisurely filled and lighted it before Jack found words to reply.

"Are you going to set us ashore?" he questioned in as determined a voice as he could summon.

"Certainly we are," was the astonishing reply. "What's the matter with you kids, anyhow?"

"What did you lock us in that hold for, and almost starve us and nearly let us die of thirst in that foul hole?" choked out Sandy.

Captain Rangler assumed a cleverly imitated look of astonishment.

"Were you locked up in there?" he demanded.

"Of course we were; as if you didn't know it," blurted out Jack.

"Now, now, just hold your horses," counseled the captain. "If you were locked in there, I knew nothing of it. Dampier and Walstein promised me no violence would be offered you if I kidnapped you for them."

"Oh, so you do admit capturing us on that lumber dock at Rockport?" sarcastically inquired Sandy.

"Of course I do; I can't deny that," said the captain with cool effrontery, "but Dampier and Walstein spun me a yarn about you being two runaway sons of some relatives of theirs and that you had stolen quite a sum of money."

"In that case then, you ought to be our friend," struck in Jack. "We are not runaways at all, but lads out on a pleasure trip, and besides, Dampier and Walstein are old enemies of my uncle. They think he wronged them, and are taking this means of avenging themselves."

"Humph," said the captain thoughtfully, emitting a cloud of blue smoke from his lips, "so them two fellers wasn't telling me the truth either, eh?"

"Of course not. They are two of the biggest rascals at large. They——"

Jack got no further. A strong arm was thrown about him from behind. At the same instant Sandy was tripped and thrown flat. The captain burst into a roar of laughter, and sprang down the stairs toward them. His smoking of the pipe had been a signal to those above that all was not well below, and Dampier and Walstein had silently descended by another way, and, sneaking through the hold, had accomplished this disastrous rear attack. Captain Rangler, as the lads might have guessed, had been merely talking against time, to allow his accomplices to descend into the cabin from another direction. The column of smoke from his pipe, curling out of the companion-way, had done its duty well—too well.

But both Jack and Sandy were strong, wiry lads. Though their activity had been much impaired by the hardships they had gone through during the night, there was still a lot of fight left in them, as their attackers soon discovered.