THE TOMB OF TIMOUR

Through Russian

Central Asia

By

STEPHEN GRAHAM

With Photogravure and many

Black-and-White Illustrations

from Original Photographs

Cassell and Company, Ltd

London, New York, Toronto and Melbourne

1916

| PAGE | ||

| Introduction | ix | |

| 1. | Leaving Vladikavkaz | 1 |

| 2. | Where the Desert Blossoms | 15 |

| 3. | Wonderful Bokhara | 24 |

| 4. | Mohammedan Cities and Mohammedanism | 35 |

| 5. | The History of the Tribes | 44 |

| 6. | To Tashkent | 55 |

| 7. | The Russian Conquest | 63 |

| 8. | On the Road | 72 |

| 9. | The Pioneers | 134 |

| 10. | Fellow-Travellers | 156 |

| 11. | On the Chinese Frontier | 173 |

| 12. | “Midsummer Night among the Tent-Dwellers” | 184 |

| 13. | Over the Siberian Border | 203 |

| 14. | On the Irtish | 210 |

| 15. | The Country of the Maral | 218 |

| 16. | The Declaration of War | 228 |

| APPENDICES[vi] | ||

| 1. | Russia and India and the Prospects of Anglo-Russian Friendship | 237 |

| 2. | The Russian Empire and the British Empire | 249 |

| Index | 271 | |

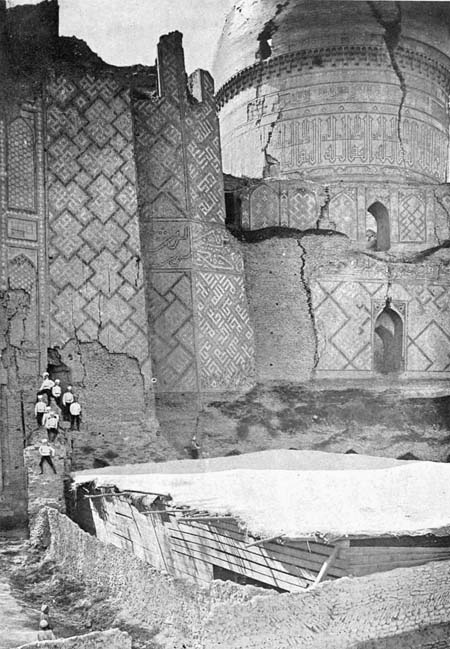

| The Tomb of Timour | Photogravure Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

| The Central Asian Railway: Nearing the Oxus | 18 |

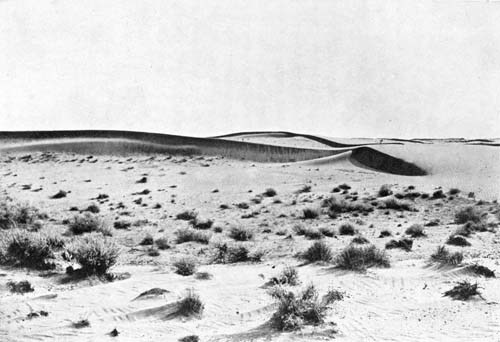

| The Central Asian Desert | 20 |

| Bokhara: The Escort of a Magistrate | 28 |

| Outside One of the Most Famous of the Mosques | 32 |

| A Holiday at Samarkand: Boys of the Military School Playing among the Ruins of the Tomb of Tamerlane | 36 |

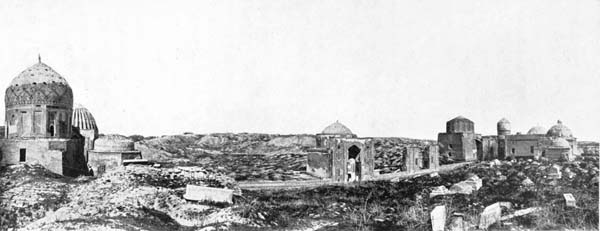

| Mohammedan Tombs and Ruins in the Youngest of the Russian Colonies | 40 |

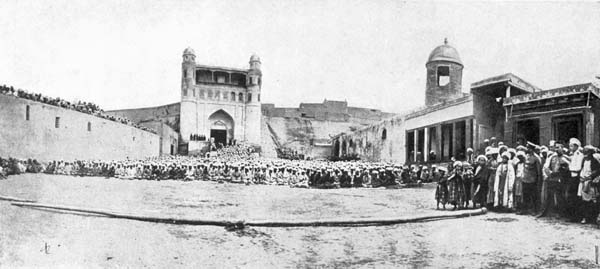

| A Mohammedan Festival at Samarkand—The Hour of Prayer | 48 |

| Central Asian Jewesses | 50 |

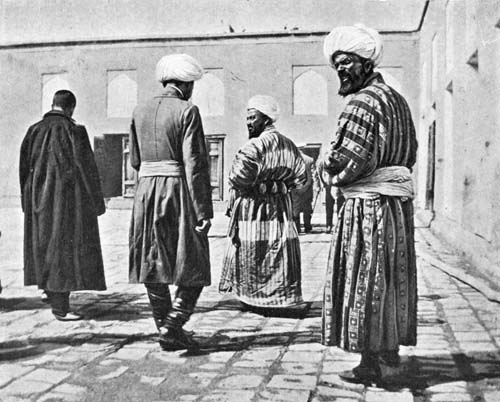

| Fine-looking Sarts in Old Tashkent | 56 |

| Outside a German Shop in Old Tashkent | 58 |

| Tashkent: A Football Match at the College | 60 |

| Pleasant Country Outside Tashkent | 64 |

| Hearty Shepherds: All Kirghiz | 66 |

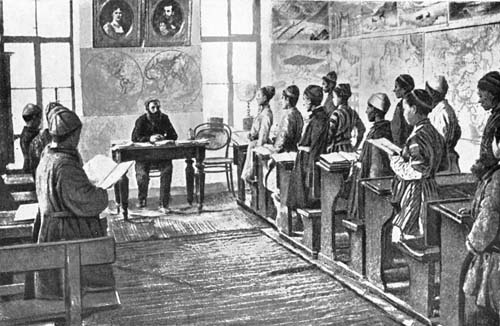

| The Russian Teacher: A Native School in Tashkent | 68 |

| A Kirghiz Grandmother: Vendor of Koumis | 74 |

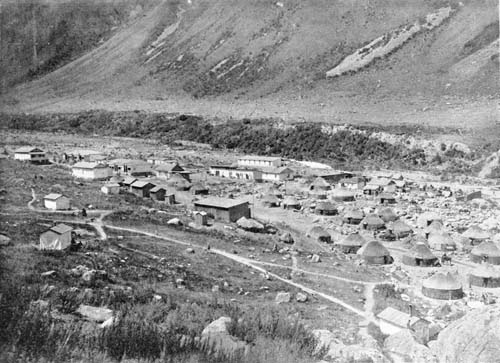

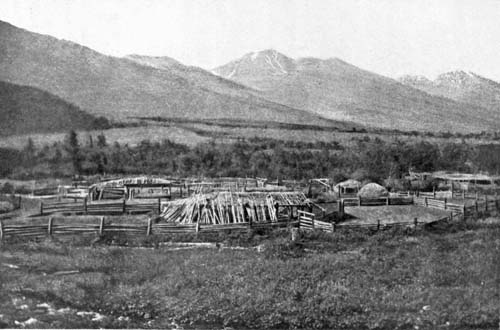

| Russians and Kirghiz Living Side by Side at the Foot of the Mountains | 76 |

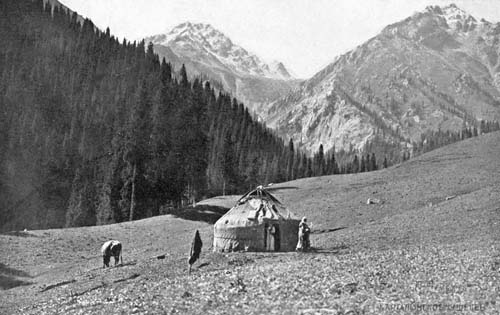

| A Tent of Lonely Nomads on a Summer Pasture in Central Asia | 80 |

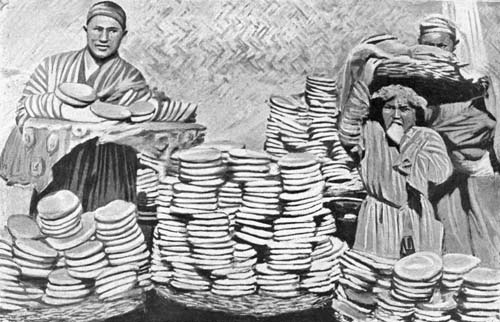

| Sarts Selling Bread: The Lepeshka Stall | 84 |

| [viii]The Native Orchestra: See the Men with the Ten-foot Horns, “Trumpets of Jericho,” as the Russians Call Them | 104 |

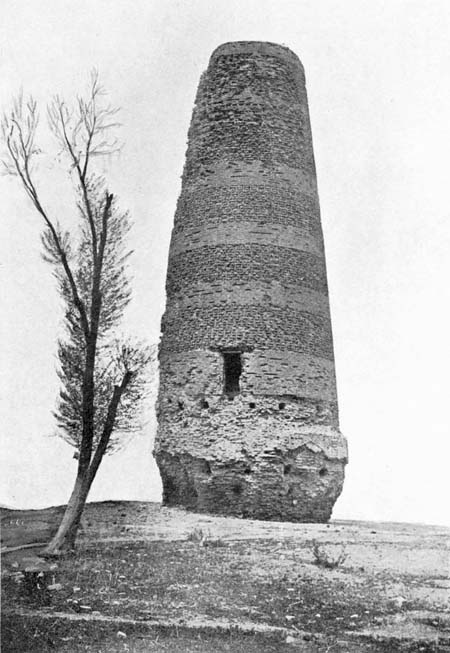

| “Past the Ruins of Ancient Towers” | 120 |

| A Settled Kirghiz: One of the Characters of Pishpek | 130 |

| The Irrigated Desert—an Emblem of Russian Colonisation in Central Asia | 136 |

| The Shady Village Street—One Long Line of Willows and Poplars | 152 |

| The Cathedral of St. Sophia at Verney—After the Earthquake of 1887 | 158 |

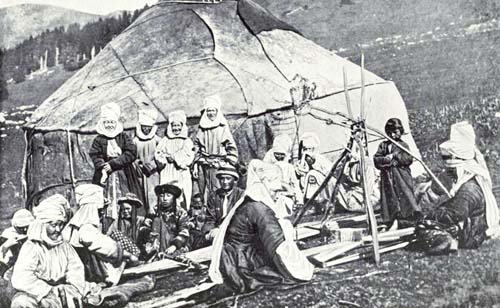

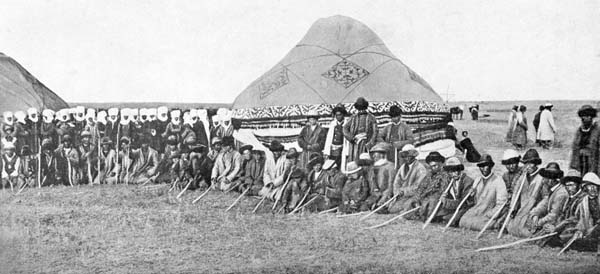

| Visitors at a Kirghiz Wedding | 168 |

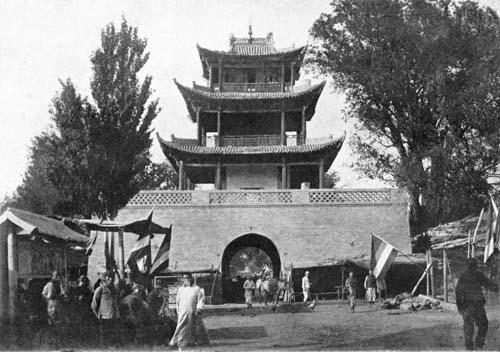

| Chinese Praying-House at Djarkent | 178 |

| Lepers in a Frontier Town | 180 |

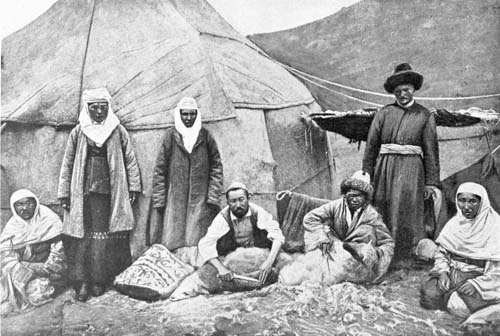

| A Patriarchal Kirghiz Family | 186 |

| Sheep-Shearing Outside the Tent Home | 194 |

| In Summer Pasture: Evening Outside the Kirghiz Tent | 198 |

| Four Wives of a Rich Kirghiz | 205 |

| At a Kirghiz Funeral | 207 |

| Kirghiz Praying | 215 |

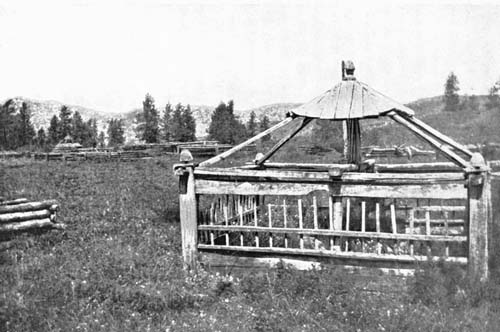

| In the Altai: Kirghiz Tombs near Medvedka | 222 |

| Altaiska Stanitsa: View of Mount Bielukha | 230 |

| Mobilisation Day on the Altai: The Village Emptied of its Folk | 232 |

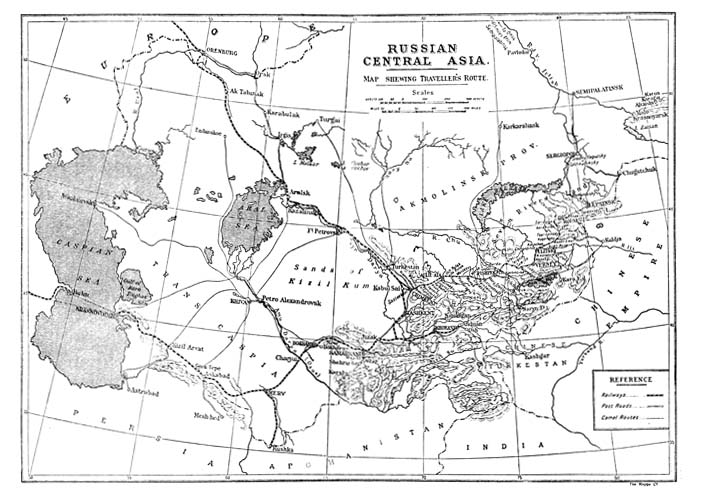

| Map of Route taken by Author | 270 |

THE journey recorded in these pages was made in the summer before the great war, and although the record of my impressions and the story of my adventures were fully written in my road diary and in the articles I sent to The Times, I had thought to postpone issuing my book to some quieter moment beyond the war. But the days go on, and we are getting accustomed to live in a state of war; war has almost become a normal condition of existence. At first we could do nothing but consider the facts of the great quarrel of nations and the exploits of the armies. War for the moment seemed to be our life, our culture, and our religion. But things have changed. War started by concentrating us and making us narrow, but now it is giving us greater breadth. We have become more interested in the home life of our Allies, in the “after-the-war” prospects of Europe, in the future of our own British Empire and of the wide world generally. The war has given us a larger consciousness, and we have become, as some say, “Continental.” In any case,[x] we are much less insular. France and Russia have become real places to the man in the street, and the account he gives of them is more credible. Even our country labourer can say where Gallipoli is, Mesopotamia, Egypt, Salonica, Bulgaria, Serbia, though, indeed, I have frequently heard the latter spoken of as Siberia. “My son’s gone to Siberia,” says the countryman; “it’s a cold place.” Our imagination ranges farther afield, and young men of all classes think of making far travels when the war is over. We are not less interested in other things, but more; only less interested in the old suffocating business and industrial life of the time before the war, of the stuffy rooms, the circumscribed horizons, the dull grind. All eyes are opened wider, all hearts have greater hopes, and that which dares in us dares more. We are reading more, reading better, and, among other matters, are thinking more of foreign countries, empires, far-away climes. The war, bringing so many nations together, has touched imaginations. It has mixed our themes of conversations and enriched our life with new colours, new ideas. So, perhaps, the story of this journey and my impressions of an interesting but remote portion of the Tsar’s Empire will not come amiss just now. Moreover, during the war many problems have become clearer, especially those of the British Empire, clearer, but none the less unsolved, and I feel that a study of a vast stretch[xi] of the Russian Empire, and of its problems and its prospective future, cannot but be helpful.

Among the letters sent me care of The Times there is one written about an article which has become a chapter in this book:

“Since I was a child and steeped myself in the ‘Arabian Nights,’ I have never been so enthralled as I was by an article of yours called ‘Towards Turkestan,’ which appeared in The Times long since, as it seems now (last May?). I am an old, tired recluse. I have been reading for over sixty years. I’m very much extinct, but my desert also blossomed with your roses.

“Charm inexpressible breathed from the roses (I think they must have been the black-red sort). Strange figures—rich garments, all solemnised by, as it were, a twilight glamour made of magical influences. All so real, yet remote. I repeat, I have never been taken away so far since I was a child. There was another article which I cut out and lost ... but I did not prize it as I did the Turkestan article, where figures both bizarre and dignified greeted you and bade you farewell with roses. And sunset steeps them in a golden haze. And they still move there whilst the traveller who has spell-bound them in his writing has gone on his way....”

I have printed this letter because it was sweet to have it, and it touched me. May the roses bloom again!

I am indebted to the Editors of The Times and Country Life for permission to republish portions of this book previously printed in their columns, and to Country Life for permission to republish photographs.[xii] For these photographs, except those relating to the Altai, I am chiefly indebted to the professor of French at Tashkent Military School and to M. Drampof, of Pishpek. Special permission has to be obtained to enter Russian Central Asia, and, as I was going on foot, the possession of a camera might have led to the suspicion of military spying. So I had my camera sent to Semipalatinsk, which is in Siberia, and only used it on the Siberian part of my journey. My thanks are also due to Mr. Wilton, the courteous and able correspondent of The Times at Petrograd, who obtained for me my permit for travel in Russian Central Asia.

Stephen Graham.

Through Russian Central Asia

IN the early spring of 1914 I walked once more to the Kazbek mountain. It was really too early for tramping, too cold, but it was on this journey that I decided what my summer should be. Once you have become the companion of the road, it calls you and calls you again. Even in winter, when you have to walk briskly all day, and there is no sitting on any bank of earth or fallen tree to write a fragment or rest, and when there is no sleeping out, but only the prospect of freezing at some wretched coffee-house or inn, the road still lies outside the door of your house full of charm and mystery. You want to know where the roads lead to, and what may be on them beyond the faint horizon’s line.

So it is March, and I am walking out from Vladikavkaz on the Georgian road, and only on a four days’ journey—to the Kazbek mountain and back. Indeed, the road beyond is probably choked with snow, and there is no further progress. But I shall see how the year stands on the Caucasus.

The stillness of the morning—a circumambient silence. A consciousness of the silence in the deep of[2] space. Three miles of level highway stretch straight and brown from the city on the steppes to the dark, blank wall of the mountains. Beyond the black wall and above it are the snow-mantled superior ranges, and above all, almost melting into the deep blue of the Caucasian sky, the glimmering, icy-wet slopes of the dome of the Kazbek. The sun presides over the day, and as a personal token burns the brow, even though the feet tread on patches of crisp snow on the yellow-green banks of the moor. No lizards basking in the sun, no insects on the wing, no flowers—not a speedwell, not a cowslip, not a snowdrop. Only little flocks of siskins rising unexpectedly from sun-bathed hollows like so many fat grasshoppers. Only an occasional crazy brown leaf that scampers over the withered fallen grass. There is vapour over the plumage-like woods on the hills, but no birds are singing. Nature can almost be described in negation, she shows so little of her glory; yet she makes the heart ache the more.

Persian stone-breakers, hammer in hand, sitting on mats by the side of the heaps of rocks; primitive carts lumbering with their loads of faggots or maize-straw or ice; horsemen like centaurs because of their great black capes joining their head and shoulders to little Caucasian horses—that is all the life at this season of the year of the one great highway over the mountains, the great military road from Vladikavkaz to Tiflis—no motor-cars, no trams, no light-rolling carriages with gentry in them, no trains.

Stopping at a sunny mound to have lunch, you[3] hear from a hundred yards away the River Terek like the sound of a wind in the forest, the impetuous stream rushing between white crusts of frozen foam and washing greenly against ice-crowned boulders. For sixty miles the road is that of the valley of the Terek. It passes the Redant and then becomes the visible companion of the river, winding with it among the primeval grandeur of its rocks. The Kazbek begins to disappear, hidden by its barrier cliffs—its Kremlin; but for a mile or so its snowy cap remains in sight over the great lopsided, jagged crags. The blue smokes of Balta and red-roofed nestling Dolinadalin rise into the afternoon sky. The road enters the chilling shadow of the Gorge of Jerakhof, and you look back regretfully on the red sunlit strand behind you. The white-framed Terek moves in a grand curve through a broad wilderness of stones and snow. An icy mountain draught creeps from the cleft in the grey cold rocks. On the deserted road the telegraph poles and wires assume that sinister expression which they have in vast and lonely mountain tracts. The opening by which you entered the gorge becomes a purple triangle, and far above you and behind you glimmers the tobacco-coloured sunlit Table Mountain.

The road becomes narrower: on the one hand the river roars among ice-mantled rocks, on the other the black silt continually trickles and whispers. The faint crimson of sunset lights the wan towers of Fortoug, and then one by one the yellow stars come out like lamps over the mountain walls.

[4]There are three inns between Vladikavkaz and the Kazbek mountain. I stayed at the second, at Larse, and made my supper with some thirty Georgians, Ossetines, and Russians, workmen on the road and chance travellers. Here I heard many rumours of the commercial destiny of the military road, of the thirty-verst tunnel that it is necessary to make, of the Englishman named Stewart, the “Boss of the Terek”—Khosaïn Tereka—who has the contract to supply the whole of the Caucasus with electricity, who will or will not make an electric power station in the shadow of Queen Tamara’s castle, needing an artificial waterfall three hundred sazhens high.

“But the project has grown cold,” said I.

“It will come to nothing,” say the hillmen; “for ten years people have been talking of such things, but nothing has changed except that we have got poorer.”

But the host is an optimist. “It will come. There will be a tramway from the city to the Kazbek. The trams will go past my door. We shall have electric light and electric cooking, and will become rich.”

We remained all thirty in one room all night—square-faced, gentle, sociable Russians in blouses; tall, Roman-looking Georgians and Ossetines in long cloaks, with daggers at their tight waists, with high sheepskin hats on their heads. They ate voraciously bread and cheese and black pigs’-liver, putting the waste ends when they had finished into the bags of their winter hoods—astonishing people to look at,[5] these Caucasians; though half-starved, yet of great stature and iron strength, with fine, broad-topped, intelligent heads, deeply lined, cunning brows, long, beak-like, aquiline noses. They would make splendid soldiers—but not so good “soldiers of industry.” They are a people who often fail when they go to America. They all knew men who had gone there and had returned with stories of unemployment or exploitation. Scarcely one of them had a good word to say of America. They all, however, looked forward to the time when the Caucasus would be developed on American lines and hum with Western prosperity. We slept on the tables of the inn, on the bar, in the embrasures of the windows, on the forms, on sacking on the floor—the kerosene lamp was turned low, and nearly everyone snored.

We were all up before dawn, and I accompanied an Ossetine miller who was in search of flint for his mill, and we entered the Gorge of Dariel whilst the stars were dim in the sky. It was a sharp wintry morning, and as the road led ever upward and became ever narrower, the wind was piercing. The leaking rocks of summer where often I had made my morning tea were now grown old in the winter, and had wisps of grey hair hanging down—yard-long icicles and thick tangles of ice. The precipitously falling streams and waterfalls were ice-marble stepping-stones from the Terek to the mountain-top.

We entered the gorge by the little red bridge which, like a brace, unites the two sides of the river at its narrowest point. The stars disappeared. Somewhere[6] the sun was rising, but his light was only in the sky so far above. We beheld the green, primeval ruin of Nature, the red-brown, grey, and green boulders of Dariel in varied immensity and diversity of shape, the vast shingly, boulder-strewn wastes, the adamantine shoulders of porphyry, the cold, ponderous immensities of rock held over the daring little road, the river eddies springing like tigers over the central ledges between fastnesses of ice.

My Ossetine picked up various stones and struck them with his dagger to see how well they sparked, and, having apparently found what he wanted, accepted a lift in an ox-cart and returned back to the inn at Larse. Perhaps it was too cold for him. I walked up to the square cliff of Tamara and the tooth of the wall of the ancient castle where Queen Tamara treacherously entertained strangers, making love to them and feasting them, and then having them murdered; the castle where the devil once arrived in the guise of such an unlucky wanderer—the scene of the story of Lermontof’s “Demon.”

This was once the frontier of Asia, and the romantic country of a fine fighting people. To this day, despite railway projects and the hope that the river may provide the Caucasus with electricity, Queen Tamara’s castle remains almost the newest thing. It is modern beside the antiquity and majesty of the ruin of Nature. Here the real world seems to jut out through the green turf and flower-carpeted earth into the light of day, striking us awfully, like the apparition of God the Father coming up out of[7] the bowers of Eden. You feel yourself in the presence of something even older than mankind itself, and you wonder what differences you would note if, with the goloshes of Fortune on your feet, you could be transported back a thousand years, a second thousand, a third thousand, and so on. What did the Ancients make of this? They held that it was to the Kazbek mountain that Prometheus was bound as a punishment for stealing fire from heaven. Was that what they said when they first came fearfully through and discovered the plains of the North?

An ancient way! And then at the turn of it, the gate to the “Kremlin” of Dariel, and the towering Kazbek lifting itself to the sky within. Here is truly one of the most wonderful and romantic regions in the world. But it was not to see the Kazbek that I made this journey, but to find again a certain cave where years ago I found my companion on the road, the place where we lived and slept by the side of the river. It was there as I left it, familiar, calm, by the side of the running river, glittering in the noon-day sun, and the granite boulders held threads of ice and ice-pearls—the ear-rings of the rocks. And I would have liked to meet my companion again. But Heaven knew under what part of its canopy the tramp was wandering then. I felt a home-sickness to be tramping again, and I decided that as soon as the snow and ice had gone I would take to the road.

And so, the season having changed, and the cold winds and rains of spring giving way to summer, I take[8] the road once more into new country. The season really changes when it is possible to sleep comfortably out of doors. This year I go into the depths of the Russian East, and, besides taking the adventures of the road, continue my study of Easternism and Westernism in the Tsar’s Empire. I travel by train to Tashkent, the limit of the railway, and then take the road, with my pack on my back, through the deserts of Sirdaria and the Land of the Seven Rivers towards the limits of Chinese Tartary and Pamir, then along the Chinese frontier, north to the Altai mountains and the steppes of Southern Siberia. This is a long, new journey—new for English experience—because, until our entente with Russia, mutual jealousy about the Indian frontier made it extremely difficult for the Russian Government to permit observant and adventurous Englishmen to wander about as I intend to do. Indeed, even now I may be stopped and turned back from some forlorn spot seven or eight hundred miles from a railway station, and then, perhaps, silence may engulf my correspondence for a time. All things may happen; my papers may be confiscated or lost in the post, or my progress may be stopped by various accidents. In any case, I have official permission for my journey, and the weather is fine.

The old grandmother baked me a box of sweet cheesecakes (vatrushki), Vassily Vassilitch brought me fruit and chocolate, another friend brought three dozen cabbage pies—thus one always starts out for the wilderness. We assembled in the grandmother’s sitting-room to say good-bye. I am to beware of earthquakes, of[9] snakes, of having much money on my person, of being bitten by scorpions, of tigers, wolves, bears, of occult experiences.

“It is occult country,” said G——, teacher of mathematics in the “Real School.” “You are likely to have occult adventures; some enormous catacylsm is going to take place this summer. I don’t know what it is, but I should advise you to get across this dangerous country as soon as you can. Siberia is safe, and North Russia, but not Central Asia, and not, as a matter of fact, Germany.”

He had had a strange dream, and, being of occult preoccupation, ventured on vague prophecy, which generally took the form of earthquakes and catacylsms. When I met him in the autumn after my journey, the great war with Germany had broken out, and I was inclined to credit him with a true prophecy; but, with honest wilfulness, he was still figuring out earthquakes and cataclysms to be, and would not have it that the European conflagration was the fulfilment of his dream.

Another friend is charmed with the idea that I am going to Bokhara, and won’t I bring her home a silk scarf from the great bazaars? Another is touched by the dream that I am realising. To him Central Asia is a fairyland, and the Thian Shan mountains are not real mountains so much as mountains in a book of legends.

At last the old grandmother says:

“All sit down!”

And we sit, and are silent together for a few[10] moments, then rise and turn to the Ikon and cross ourselves. The grandmother marks me in the sign of the Cross and blesses me, praying that I may achieve my journey and come safely back, that no harm may overtake me, and that I may have success. Then I pass to each of the others present and say “Good-bye.” Vera, however, looks at me in such a way that I am sure she means that she feels I shall never return. So I am bound to ask myself: Is not this farewell a final farewell? Does not this Russian see something that is going to happen to me? But she has been very kind to me, and just at parting puts a beautiful Ikon-print into my hand, and I fix it in the inside of the cover of my stiff map.

The train from Vladikavkaz wanders along the northern side of the Caucasus, unable to find a pass over the mountains. The meadows as far as eye can see are yellowed with cowslips. Now and then a derrick tells that you are in the oil region, and in an hour or so the train steams into the pavement-shed station that marks the weariness and mud of Grozdny, capital of the North Caucasian oilfields. There is a breath of salt air at Petrovsk, a few hours later, and you realise that you have reached the Caspian shore. All night long the train runs along to Baku, glad, as it were, to turn south at last and get round the Caucasus it cannot cross. At Baku I change and take steamer across the Caspian Sea to Krasnovodsk, on the salt steppes, but I have a whole day to wait in the city.

Ordinarily, you come to Baku to make money.[11] There is nothing to tempt you there otherwise. In windy weather you are blinded with clouds of flying sand; in the heat of summer you are stifled with kerosene odours. It is a commercial city without glamour. Though it boasts several millionaires and is an important name in every financial newspaper in the world, it has no public works, nothing by virtue of which it can take its stand as a Western city. The working men are very badly paid—that is, according to our Western standards—and they do not obtain the few advantages of industrial civilisation that ought to come to make up for dreary life and health lost. There is a constant ferment amongst the labouring classes in the city, and repeated strikes, even in war time. Baku, again, is one of the last refuges of the horse tram and the kerosene street-lamp. It is only in the eastern quarter that the town has charm. There you may see strings of camels loping up the steep streets, panniers on their worn, furry backs, Persians squatting between the panniers, contentedly bobbing up and down with the movement of the beast. Or you may watch the camels kneeling to be loaded, crying appealingly as the heavy burdens are put on them, cumbrously lifting themselves again, hind-legs first, and joining the waiting knot of camels already loaded.

The great shopping place—the bazaar—is wholly Eastern, and even more characteristic than in Russia proper. I feel how the bazaar and the ways of the bazaar came to Russia from the East. As you go from stall to stall you are besieged by porters holding empty[12] baskets—they want to be hired to walk behind you and carry your purchases as you make them. Characters of the Arabian Nights, these; and yet in the streets of Warsaw and Kief, and many other cities, those men in red hats and brass badges, who sit on the kerb or on doorsteps waiting for passers-by to hire them, are really the lineal Westernised descendants of the tailor’s fifth brother—I think it was the fifth brother who was a porter.

In the harbour, at the pier where my boat is waiting, I watch the Persian dockers working. Real slaves they are, working twelve hours a day for 1s. 4d. (60 copecks). They have straw-stuffed pack carriers on their backs, like the saddling of camels, and the rhythm of their movement as they proceed with their burdens from the warehouse to the ship is that of slavery. The name of slavery has gone, but the fact remains. Still, the European is not awakened to pity. The Persians are the human camels, work hardest of all the people of the East, and are the least discontented. They are singing and crying and calling all the time they work. The East slaves for the West, but still is not much influenced by the West. It is not they who cause the strikes.

Just before the time for my boat to leave another boat arrives from Lenkoran, and out of it come a party of Persian men with carpet bags slung across their shoulders, their wives in black veils, many-coloured cloaks, and baggy cotton trousers, their children all carrying earthenware pots. More labour available on the docks, more homes occupied in the little houses[13] that dot the eight-mile crescent of the mountainous city of Baku.

The boat leaves at nightfall. It is the Skobelef, a handsome steamer, built in Antwerp in 1902. It must have been brought to the Caspian along the waterways of Europe; an officer on board ventures the opinion that it was brought to Baku in parts and fitted up there. A pleasant ship, however it was brought—considerably superior to the ordinary American lake-steamer, for instance. There were very few passengers, and these lay down to sleep at once, fearing the storm that was blowing, so I remained alone on deck and watched the retreating shore. Leaving Europe for America, you sit up in the prow and look ahead, over the ocean; at least, you do not sit and watch the Irish coast disappear. But leaving Europe for Asia, you sit aft and watch her to the last. And the retreating lights of Baku are the lights of Europe.

The night is very dark and starless, and so the eight-mile semicircle of lights is wonderful to behold; the handsome lanterns of the pier, the lights of the esplanade, of the three variety theatres, of the cinemas and shops, the thousands of sparks of homes on the mountain-side. This is the real beginning of my journey, and it is very thrilling; good to sit in the wind and feel the movement of the sea; good to watch the many lighthouses turning red, then green, in the night, and to pass within ten yards of a little lamp, just over the surface of the sea, alternately going out and bursting into brightness every thirty seconds. The lamp seems[14] to say: “There is danger ... there is danger,” and it whispers joyful intelligence to the heart.

There is trouble on the water as we reach the open sea, and the boat begins to roll, but it is still pleasant on the upper deck, and the high wind is warm.

The lights of Baku and Europe have been gradually erased. First to go were the sparks of the homes on the mountain-side, then the lights of the esplanade; the eight great lamps of the pier remain, and one by one they disappear till there is only the great yellow-green flasher that tells ships coming into the harbour just where Baku is. That also disappears at last, and it begins to rain heavily. So I go down to my berth to sleep.

Next morning the wide green sea was sunlit and flecked with white crests of turning waves. Looking out of a port-hole, I saw the bright light of morning shining on the grey and accidental-looking mountains of Asia. The boat was coming into Krasnovodsk.

KRASNOVODSK is one of the hottest, most desert, and miserable places in the world. The mountains are dead; there is no water in them. Rain scarcely ever falls, and the earth is only sand and salt. Strange that even there there is a season of spring, and little shrubs peep forth in green and live three weeks or a month before they are finally scorched up. I spent the day with a kind Georgian to whom I had a letter; a shipping agent at the harbour. He was to have helped me, supposing the local gendarmerie should stop my landing. But by an amusing chance I escaped the inspecting officer’s attention, and got into Transcaspia without questions or passport-showing. One can never be quite sure of passing, even when one’s papers are in order. The Russian Government does not give a written passport for Central Asia, but transmits your name to all the local authorities, and you have to trust, first, to their having received your name and, second, to their agreeing that the name received in its Russian spelling is the same as yours written in English on your British passport. In the case of a name such as mine, which is spelt one way and pronounced another, there is likely to be difficulties. During my stay in Central[16] Asia, moreover, I saw my name spelt in the following cheerful ways—Grkhazkn, Groyansk, and, of course, the inevitable Graggam, and on some occasions I had the difficult task of persuading Russian officials that the names were one and the same. Still, they were inclined to be lenient.

The Georgian was very hospitable; he took me from the pier to his house, behind six or seven wilted and tired acacia trees, gave me a bedroom, bade the samovar and coffee for me; and I made my breakfast and then slept the three hot hours of the day. In the evening he brought up his other Caucasian compatriots from the settlement, a little band of exiles, and we talked many hours to the tune of the humming samovar. We talked of Vladikavkaz and the Kazbek beloved of Georgians, and of my tramps and of mutual acquaintances in Caucasian towns and villages, talked of ethics and politics, and the working man, and of Russia, especially of modern Russia, with its bourgeois and the evil town life. Mine host had almost Victorian-English sentiments, did not like the slit skirt and Tango stocking—so evident in Baku, did not know what women were coming to—despised the Russians for their flirting and dancing and gay living, believed in quiet family life as the foundation of personal happiness, and in Socialism as the foundation of political blessedness. The lights of Europe had not quite disappeared.

As the train did not leave till twelve, we had a long and pleasant evening, and when the time came to go mine host brought me a big bottle of Kakhetian[17] wine, and we all went together to the railway station. I got my ticket, found my carriage. No commotion, no excitement, the empty midnight train crept out of the station, over the salt steppes, and I felt as if in the whole long train there was only myself. It was very vexatious, leaving in the shadow of dark night when no landscape was visible, but there was consolation in the fact that the train accomplished no more than seventy-five miles before sunrise. Next morning, directly I awakened, I looked out of the train, and there before my gaze was the desert; yellow-brown sand as far as eye could see, and on the horizon the enigmatical silhouette of a string of camels, looking like a scrap of Eastern handwriting between earth and heaven. A new sight in front of me, for I had never seen the desert before, except, of course, in Palestine, where it is hardly characteristic. The cliffs of Krasnovodsk had disappeared; the desert was on either hand. I looked in vain for a house or a tree anywhere, but I saw again, as at Krasnovodsk, Nature’s pathetic little effort to make a home—an occasional yellow thistle in bloom, a wan pink in blossom here and there on the sand. The train was going so slowly that it seemed possible to step down on to the plain, pick a flower, and return.

Strange that the Russian Government should take railways over the desert before it has developed its home trade routes! The Western mind would find this railway almost inexplicable. You might almost take it to be an elaborate game of make-believe. The train is scheduled in the time-table among the[18] fast trains, and yet at successive empty desert stations stops 21, 31, 14, 6, 12, 12 minutes respectively, and takes 23 hours to traverse the 390 miles from Krasnovodsk to Askhabad, an average rate of 17 miles an hour. The reason for this slowness lies, perhaps, in the fact that the sleepers are not very well laid, and would be dislodged if greater speed were attempted; and the stops at the stations are impressive, indulge a Russian taste for getting out of trains and having a look round, and also, incidentally, let the wild natives know that the steam caravan is waiting for them if they want to go. We stop longer at one of these blank desert stations than the Nord express at Berlin or a Chicago express at Niagara. Russia is not excited about loss of time. Time may be money in America; it is only copper money in Russia, and it is more interesting to have a political railway across the deserts of Asia than to help the fruit-growers of Abkhasia or to functionise industrially the vast railwayless North.

It is dull travelling, but hills at length appear—the lesser Balkans, the greater Balkans; salt marshes give way to sandbanks—drifts of sand heaped up and shaped by the wind like grey snowdrifts. The beautiful curving lines of the sandbanks are wind runes. All this district was once the bed of the Caspian Sea, or, rather, of an ocean which, it is surmised, stretched on the one hand to beyond the Aral Sea, and on the other to the Azof and the Black Sea. The mountains were islands or shores or dangerous rocks in the sea.

THE CENTRAL ASIAN RAILWAY: NEARING THE OXUS

When we had passed the Balkans the country[19] improved by bits. Suddenly, far away, a patch of green appeared, and one’s eye hailed it as one at sea hails land. When the train drew nearer there came into view a wonderful emerald square thick with young wheat, set in the absolute grey and brown of the wilderness. This was the first irrigated field. Soon a second and a third field appeared in blessed contrast and refreshment. Out of the yellowish, cloudy sky the sun burst free, and I remembered that it was the first of May. So May Day commenced for me.

People began to appear at the stations, which up till then had been desolate; stately Turkomans, wearing from shoulders to ankles red and white khalati, bath-robes rather than dresses; Tekintsi, in hats of white, brown or black sheepskin, hats as big and bigger than the bearskins of our Grenadiers; fat, broad-lipped Kirghiz, with Mongolian brows and rat-tail moustachios drooping to their close-cropped beards; poor Bactrian labourers, in many colours; rich Persian merchants, in sombre black. Many women stood at the stations with hot, just-boiled eggs, with roast chickens, milk or koumis in bottles, even with pats of butter, with samovars. And there were native boys with baskets heaped full of lepeshki (cakes of bread). Each station was provided with a long barrier, and the women, in lines of twenty or thirty, stood behind their wares and cried to the passengers. The many steaming samovars were a welcome sight, and at the charge of a halfpenny I made myself tea at one of them.

The country steadily improved, and the train passed by fields along whose every furrow little artificial[20] streams were trickling, past many more emerald wheatfields surrounded by big dykes. The yellow dust of this desert needs only water to make it abundantly fertile; it is not merely frayed rock and stone, as the sand of the seashore, but an organic substance which has been settling from the atmosphere for ages—the lessovaya zemlya. When we realise that there is of this strange dust a coat deep enough to be a soil, we understand something of the antiquity of the desert and the fact that, when we consider geological history, our mind must range over millions of years, whereas in thinking of the history of man we are almost aghast to think of thousands of years. So the leoss dust settles out of the clear air. Incidentally, what else may not be settling out of the air into the every-day of our world? The spring flowers show the richness of this dust of the wilderness, for now behold the desert under the influence of irrigation blooming as the rose. It does, indeed, actually blossom with the rose, for I notice even on the fringe of the hopeless desert the sweet-briar, and it is unusually lovely. At the new stations little children appear, having in their hands little clusters of deep crimson blossoms. Poppies now appear on the waste, irises, saxifrages, mulleins, toadflax—the voice of a rich country crying in the midst of the sand. Here it is literally true:

THE CENTRAL ASIAN DESERT

By evening the train is running along the frontier of the north of Persia, and every house has a garden of[21] roses. A Persian silk merchant, all in black, with a talisman of green jade hanging from a gold chain round his neck, comes into my carriage, and prepares to occupy the upper shelf. He is travelling all night to Merv, and has brought a great bouquet of sweet-smelling, double roses into the carriage. A knobbly-nosed, grey-faced, animal-eared, antediluvian old sort, this Persian would not stay in my carriage because there was a woman in it, but asked me to keep his place while he went and locked himself in the empty women’s compartment next door. He left his black, horn-handled, slender, leather-wrapped walking-stick behind—its ferrule was of brass, and seven inches long.

We reached Geok-Tepe, a great fortress of the Tekintsi, reduced by Skobelef in 1881. At the railway station there is a room in which are preserved specimens of all the weapons used in the fight. There are also waxwork representations of a Russian soldier with his gun, and a native soldier cutting the air with his semicircle of a sword. Many passengers turned out to have a look at these things. It was sunset time, and the west was glowing red behind the train, the evening air was full of health and fragrance, the stars were like magnesium lights in the lambent heaven, the young moon had the most wonderful place in the sky, poised and throned not right overhead, but some degrees from the zenith, as it were on the right shoulder of the night.

It was an evening that touched the heart. At every station to Askhabad the passengers descended from the train, and walked up and down the platforms and talked. The morning of May Day had been blank and[22] dismal; the evening was full of gaiety and life. We reached Askhabad, the first great city of Turkestan, about eleven o’clock at night, and its platform presented an extraordinary scene. The whole forty-five minutes of our stay it was crowded with all the peoples of Central Asia—Persians, Russians, Afghans, Tekintsi, Bokharese, Khivites, Turkomans—and everyone had in his hand, or on his dress, or in his turban roses. The whole long pavement was fragrant with rose odours. Gay Russian girls, all in white and in summer hats, were chattering to young officers, with whom they paraded up and down, and they had roses in their hands. Persian hawkers, with capacious baskets of pink and white roses, moved hither and thither; immense and magnificent Turkomans lounged against pillars or walked about, their bare feet stuck into the mere toe-places they call slippers—they, too, held roses in their fingers. In the third-class waiting-room was a line of picturesque giants waiting for their tickets, and kept in order meanwhile by a cross little Russian gendarme. Behind the long barrier, facing the waiting train, stood the familiar band of women with chickens and eggs, with steaming samovars and bottles of hot milk. They had now candle lanterns and kerosene lamps, and the light glimmered on them and on the steam escaping from the boiling water they were selling. I walked out into the umbrageous streets, where triple lines of densely foliaged trees cast shadow between you and the beautiful night sky; in depths of dark greenery lay the houses of the city, with grass growing on their far-projecting roofs, with verandas on which the people[23] sleep, even in May. But they were not asleep in Askhabad. I stopped under a poplar and listened to the sad music of the Persian pipes. In these warm, throbbing, yet melancholy strains the night of North Persia was vocal—the night of my May Day.

I returned to the station and bought a large bunch of pink and white roses, and, as the second bell had rung, got back to my carriage, laid my plaid and my pillow, and as the train went out I slipped away from the wonderful city—to a happy dream.

THE promise of Persia was not fulfilled on the morrow after my train left Askhabad. We turned north-east, and passed over the lifeless, waterless waste of Kara-Kum, 100 miles of tumbled desert and loose sand. At eleven in the morning the temperature was 80 in the shade—each carriage in the train was provided with a thermometer—and the air was charged with fine dust, which found its way into the train despite all the closed windows and closed doors. Through the window the gaze ranged over the utmost disorder—yellow shores, all ribbed as if left by the sea, sand-smoking hillocks, hollows specked with faint grasses where the marmot occasionally popped out of sight. At one point on the passage across we came to mud huts, with Tekintsi standing by them, and to a reach of the desert where a herd of ragged-looking dromedaries were finding food where no other animal would put its nose. Then we passed away into uninterrupted flowerless sandhills, all yellow and ribbed by the wind. So, all the way to the red Oxus River. It is called the Amu-Darya now, but it is the ancient Oxus, a fair, broad stream at Chardzhui, but, from its colour, more like a river of red size than of water. All the canals and dykes of the irrigation[25] system of the district flow with the red water of the river, and wherever the water is conducted the desert blossoms like virgin soil. The river is the sun’s wife, and the green fields are their children.

Chardzhui, the port on the Oxus, is the point for embarkation for Khiva. There is a small fleet of Government steamers plying between the two cities, though it is comparatively difficult for travellers on private business to obtain a passage on one of them. When first this fleet was started there was some idea that Russia would use them in her imperial warfare as she pushed south, but probably the vessels have little military significance nowadays. For the rest, Chardzhui is famous for its melons, which grow to the size of pumpkins and are very sweet. Frequently in Petrograd shops or in fashionable restaurants one may see enormous melons hanging from straps of bast—these are the fruits of Chardzhui. At this season of the year Chardzhui has a great deal of mud and does not invite travellers, especially as its inns are bad.

The train entered the Russian Protectorate of Bokhara, and the population changed. From Askhabad the natives had special cattle-trucks afforded them, and they sat on planks stretched over trestles; they were Sarts, Bokharese, Jews, Afghans. Into my carriage came two Mohammedan scholars going to Bokhara city. They washed their hands, spread carpets on one side of the carriage, knelt on the other, said their prayers, prostrated themselves. Then they took out a copy of the Koran, and one read to the other in a sonorous and poetical voice all the way to the city—they[26] were Sarts, a very ancient tribe of Aryan extraction, some of the finest-looking people of Central Asia, tall, dignified, wrinkled, wearing gorgeous cloaks and snowy turbans. The two in my carriage had, apparently, several wives in another compartment, as they each carried a sheaf of tickets. The women hereabout were very strictly in their charchafs. There was no peeping out or peering round the corner, such as one sees in Turkey, but an absolute black, blotting out of face and form. When you looked at five or six sitting patiently side by side, each and all in voluminous green cloaks, and where the faces should appear a black mask the colour and appearance of an oven-shelf, you felt a horror as if the gaze had rested on corpses or on the plague-stricken.

From the Oxus valley the people swarmed in a populous land, and it was a sight to see so many Easterns drinking green tea from yellow basins. Already we were nearer China than Russia, and the sight took me back in memory to Chinatown, New York, and the chop suey restaurants. I fell into conversation with a Tartar merchant in carpets, and I tried to obtain an idea of what Bokhara was like in the year of grace 1914.

“Is there an electric tramway in Bokhara, or a horse tramway?”

“No, nothing of the sort. The streets are so narrow, two carts can’t pass one another without collision.”

“Are there any hotels?”

“There are caravanserai.”

[27]“No European buildings?”

“Only outside the town. There is a Russian police-station, and a hotel built for officials. The Emir won’t allow any hotels to be built within the walls.”

At length we reached New Bokhara, the Russian town, with its white houses, avenues of trees, its broad streets, and shops, and we changed to a by-line for Ancient Bokhara. The train drew through pleasant meadows and cornfields, bright and fertile as the South of England, and after twelve sunny versts we came into view of the cement-coloured mud walls of the most wonderful city of Mohammedan Asia, a place that might have been produced for you by enchantment—that reminds you of Aladdin’s palace as it must have appeared in the desert to which the magician transported it. Within toothed walls—a grey Kremlin eight miles round—live 150,000 Mohammedans, entirely after their own hearts, without any appreciable interference from without, in narrow streets, in covered alleys, with endless shops, behind screening walls. The roads are narrow and cobbled, and wind in all directions, with manifold alleys and lanes, with squares where stand handsome mosques, with portals and stairways leading down to the cool and tree-shaded, but stagnant, little reservoirs that hold the city’s water. Along the roadway various equipages come prancing—muddy proletkas, unhandy-looking, egg-shaped carts, with clumsy wooden wheels eight feet high, and projecting axles, gilt and crimson-covered carts made of cane and straw, the shape of a huge egg that has had both ends sliced off. The Bek, or[28] Bokharese magistrate, comes bounding along in his carriage, with outriders, and all others give him salute as he passes. It is noticeable that the drivers of vehicles prefer to squat on the horses rather than sit in drivers’ seats. Strings of laden camels blunder on the cobbles, innumerable Mohammedans come, mounted on asses—it is clear that man is master when you see an immense Bokharese squatting on a meek ass and holding a huge cudgel over its head. Charchaffed women are even seen on asses, and some of them carry a child in front of them. There are continually deadlocks in the narrow lanes, and all the time the drivers shout “Hagh, hagh!” (“Get out of the way, get out of the way!”)

BOKHARA: THE ESCORT OF A MAGISTRATE

The houses are made of the ruins of bygone houses, of ancient tiles and mud. They have fine old doors of carven wood, but no windows looking on the streets. A sort of inlaid cupboard, with a glass window, half open, a spread of wares, and a Moslem sitting in the midst, is a shop. Thus sits the vendor of goods, but also the maker—the tinsmith at work, the coppersmith, the maker of hats. The bazaars are rich and rare, and in the shadow of the covered streets—there are fifty of them—the lustrous silks and carpets, and pots and slippers, in the shops each side of the way, have an extraordinary magnificence; the gorgeous vendors, sitting patiently, not asking you to buy, staring at the heaps of metallics, silver-bits and notes resting on the little tabourets in front of them, belong to an age which I thought was only to be found in books. What a wealthy city it is! It offers more silks and carpets for[29] sale than London or Paris; it is an endless warehouse of covetable goods.

What strikes you at Jerusalem or Constantinople is the abundance of English goods for sale, but here at Bokhara there is a strange absence of Western commodities. Formerly the English sent all sorts of manufactures by the caravan road from India, but since the Russians ringed round their Customs system the commercial influence of England has waned. Western goods come via Russia. What European articles there are come from Germany or Scandinavia. For the rest, as in other Eastern cities, the street arabs hawk churek-cakes and lepeshki; men in white sit at corners selling, in this case, Bokharese delight, brown twists of toffee, old-fashioned sugar-candy which in piles looks like so much rock crystal. Beggars in rags sit outside the mosques and hold up to you Russian basins—they do not, however, cry and clamour and follow you, as in the tourist-visited cities of Asia Minor and North Africa. Outside every other shop is a bird-cage and a large pet bird; in some cases falcons, much prized in these lands. I admired the falcons, and their owners seemed childishly pleased at the attention I gave them. I gave a piece of Bokharese silver to a beggar outside a mosque (the Bokharese have their own silver coinage, which, however, looks like ancient coin rather than any which is now in use). In one of the big shadowy bazaars I bought a delicious silk scarf of old-rose colour full of light and loveliness, falling into a voluminous grandeur as the melancholy Eastern showed it me. I did not[30] bargain about its price, that seemed almost impossible, only five roubles (ten shillings), and the lady who has it now says it is enough to make a whole robe. Somehow I liked it better as a scarf than I could if it were “made up.”

I passed out of the city and walked round the walls. A road encompasses them, and on the road are camels with blue beads on their necks and many Easterns riding them. There is a strange feeling of contrast in being outside the city. The arc of the grey walls goes gradually round and away from you, surrounding and enclosing the life of the city; the city is like a magical box full of strange magicians and singers and toy shop-men and customers; it is like a strange human beehive full of life. And outside the walls there is the sudden contrast of fresh air and space and life and greenery and broad sky. Inside the city the streets are so narrow that you feel the “box” has got the lid on. Someone said to me when I went to New York: “We’ll give you the freedom of the city with the lid off.” Well, Bokhara has the lid on. And you feel that certainly when you get outside and look at the silent, significant enclosing wall. But the fields are deep in verdure, and it is like a lovely June day in England—the willow leaning lovingly over you, overwhelmed with leaves. The walls are battlemented, rent, patched up, buttressed; there are eleven gates, and at each gate the traffic going in and out has a processional aspect. Along the walls, between gate and gate, there is a deep and gentle peace. No sound comes through the walls; they are broad and[31] high and solid. The swallows nesting there twitter. You cannot obtain a glimpse, even of the high mosques within.

I entered the city once more, lost myself in its mazes, and was obliged to take a native cab in order to get out again. I was living outside the town in an inn specially built for men on Government service. I got the last empty room. Pleasant it was to lie back in the sun and be carried along twenty wonderful streets and lanes, seeing once more all I had seen before of colour and Orientalism.

The Bokharese are a gentle people. They wear no weapons. They sit in the grass market and chatter and smile over their basins of tea. The little pink doves of the streets search between their bare feet for crumbs. The wild birds of the desert build in the walls of their houses and bazaars. On the top of the tower of every other mosque is an immense storks’ nest, overlapping the turret on all sides. Some of these nests must be eight to ten feet high; they are round, and so look like part of the design of the architecture. Storks are encouraged to build there by the Mohammedans, by whom they are held sacred. It is pleasant to watch the bird itself, standing on one leg, a black but living and moving silhouette against the sky; to listen to the clatter of bills when the father stork suddenly flies down to a nest with food.

Bokhara is a sort of Mussulman perfection—there is no progress to be obtained there except after the destruction of old forms. The Bokharese keep to the forms of their religion and its ethical laws; they wear[32] their clothes correctly; they know their crafts. They are a great contrast to the Russians, who are careless and inexact, and in their worship often nonchalant to their God; to the Russians, who wear nothing correctly and come out in almost any sort of attire; to the Russians, so ignorant and clumsy in their crafts. Yet Russia has all before her, and Bokhara has all behind her.

The Bokharese have no ambition; civilisation and mechanical progress do not tempt them. They have a happy smile for everything that comes along, but nothing moves them. A Russian motor-car comes bounding over the cobbles, whooping and coughing its alarm signals; a score of dogs try to set on it and bite it as it passes, and the natives sit in their cupboard shops and laugh. If the car stops, they do not collect round it, as would a village of Caucasian tribesmen, for instance. There was one Bokharian—a Sart, in full cloak and turban—who rode a bicycle, an astonishing exception.

OUTSIDE ONE OF THE MOST FAMOUS OF THE MOSQUES

The Russians at present hold Bokhara very lightly, but will no doubt tighten their hands on it later, as they are taking the solidification of their Central Asian Empire very seriously. At present there are no passports, and there is mixed money; but passports are coming in, and the banks are taking up all the ancient Sartish bits they can get and giving Russian silver in exchange. There are several Russian banks within the city walls, and they have a great influence. The Emir is friendly towards Russia, and is a pompous figure at the Russian Court, though it is rumoured that in his[33] native palaces he whiles the long empty day away by playing such elementary card games as durak, snap, and happy family. The Russians have permission to build schools in the city, and the Russian bricklayer is to be seen at work with trowel and line, whilst the native navvy carries the hod to and fro. The foreign goods in the bazaar are mostly cotton, and if you examine the splendidly gay prints that go to form the clothing of the natives you find it is all marked Moscow manufacture. The Bokharese merchants go to Nizhni Fair not only to sell, but to buy. There are no English in the streets, no tourists, no Americans. Indeed, I asked myself once in wonder: Where are the Americans? The only people in Western attire are commercial travellers (commerçants), and they are mostly Russians or Armenians, though Germans are occasionally to be seen. I noticed knots of these men discussing prices of horsehair, wool, oil-cake, carpets, silks. It should be remembered that that district is more justly famous for its carpets than for its silks. The best carpets in the world are made by the Tekintsi. Armenians, Turkomans and Persians work in whole villages and settlements in Transcaspia making carpets with needle and loom. They have the original tradition of carpet-making, a sense for the particular art of weaving those wonderful patterns of Persia, and for them a carpet is not a covering on which it could be possible to imagine a man walking with muddy boots; it is for dainty naked feet in the harem, or it is a whole picture to be hung on a wall, not thrown on the floor. Singer’s sewing machines are, of course,[34] installed at Bokhara; they are in every town in the wide world. The cinema also has come, and a green poster announces that the Tango will be shown after the presentation of a striking comedy called “The Suffragette.”

But what does this really matter? Let us ask the deliberate stork, standing on one leg on the height of the mosque of Lava-Khedei. The mosque tower has a clock, and the stork seems to be trying to read the time. But he will give no answer, nor will the Mussulmans below; they also are scanning the wall to see if it is nearer the hour to pray. And the clock, be it observed, is not set by Petrograd time.

THE consideration of the wonderful Moslem cities, Constantinople, Cairo, Jerusalem and Bokhara, with their marvellous blending of colours, their characteristic covered ways and bazaars, their great spreads of lace and silk and carpets, slippers, fezes, turbans, copper ware, their gloomy stone ways and close courts, their blind houses, made windowless that their women be not seen, their great mosques and splendid tombs, inevitably suggests a great question of the East. What is Mohammedanism, what does it mean? At Cairo and Jerusalem, and even at Constantinople, it is possible to doubt the real nature of the Moslem world; it seems a makeshift world giving way readily to Western influence, or, in any case, reproved by the more splendid and vital institutions of the West standing side by side with many shabby and wretched phenomena of the East.

But Bokhara is a perfect place. It is much more remote even than Delhi, and is almost untouched, unaffected by Western life. It is a city of a dream, and if a magician wished to transport some modern Aladdin to a fairy city, where there would be nothing recognisable and yet everything would be beautiful and[36] bewildering, he need only bring him to the walls of Bokhara. Through Bokhara and its undisturbed peace and beauty, one obtains a new vision of Mohammedanism, and it becomes absurd to think that the real Moslem world is of the same pattern as the Westernised and yet strangely picturesque cities with which we are familiar. We remember the fact that there are so many millions more Mohammedans than there are Christians, that they live off the railways, in deserts, in far away and remote cities, that they journey on camels and in caravans, and that to them their religion and way of life are sufficient, that they do not seek new words or inspiration, nor do they want time to do other things, nor change of any kind. We remember their mystery, their faith and loyalty, their superb detachment, their state of being enough unto themselves, their playfulness, audacity, hospitality, how they shine compared with Christians in the keeping of the conventions of their religion, their punctual piety, their pilgrimages, and, with all that, their fixed and definite inferiority of caste.

A HOLIDAY AT SAMARKAND: BOYS OF THE MILITARY SCHOOL

PLAYING AMONG THE RUINS OF THE TOMB OF TAMERLANE

Their pilgrimage to Mecca, which we are apt to regard merely as something picturesque, is in reality one of the most mysterious of human processions. From Northern Africa, from Syria, from Turkey and Armenia, from Turkestan, from the Chinese marches (there are even Chinese Mohammedans, the Duncani), from India, from the depths of Arabia and Persia—to Mecca. Through Russia alone there travel annually considerably more Moslems to Mecca than there do Christian pilgrims to Jerusalem; and some of these[37] Mohammedan pilgrims are the most outlandish pilgrims. They are illiterate, simple, unremarked. They do not possess minds which could understand our modern Christian missionaries, and Russia, at least, has no desire to proselytise among them. If the peoples of the world could be seen as part of a great design of embroidery on the garment of God, it would probably be seen that Mohammedanism at the present moment is part of the beauty of the pattern and the amazing labyrinthine scheme. It is not a rent, not a disfigurement.

Mahomet and the Mohammedans is not a subject to dismiss, and when we look at those wondrous cities of the East it is worth while remembering that we are looking at a new image and superscription, and are in the presence of people who own a different but none the less true allegiance. As upon one of the planets we might come across a different race that had not had, and could not have, our revelation.

Our prejudice as militant Christians, however, ought necessarily to be against Mohammedans. They have ever been our religious enemies in arms, the Saracens, the Paynim, the Tartar hordes; we are not very amicably disposed to those of our argumentative brothers who, to show their independence of thought, say they prefer Mohammedanism or Buddhism or Confucianism or what not.

In reading Carlyle’s “Heroes and Hero-worship” there is a haunting feeling that it was a pity that for the “Hero as Prophet” he chose Mahomet and not Jesus, or that, choosing Mahomet, he had not[38] travelled in Mohammedan countries, investigating his subject more thoroughly and giving a truer picture of the significance of Mohammedanism and of the man who founded it. The Mahomet section of “Heroes” is like a note that does not sound. Heading the lecture over again, one is struck with a new fact about Carlyle—his insularity of intelligence. Despite the fact that he is preoccupied with French and German history, you notice his narrowness of vision, or perhaps it is that the general vision of the world which men have now was not so accessible in his day, and the differences in national psychology now manifest were hidden in obscurity then. Carlyle saw mankind as Scotsmen, and all true religion whatsoever as a sort of Southern Scottish Puritanism. He saw all national destinies in one and the same type, without any conception of fundamental differences of soul. He admired the Germans, and the Germans adopted him and his works. And he disliked the French because so few of them had that “fixity of purpose” and “manliness,” “thoroughness,” “grim earnestness” of his compatriots. Russia was a very vague country, but Carlyle approved of the Tsar, dimly discerning in him one who must have something in common with Cromwell or Frederick the Great, “keeping by the aid of Cossack and cannon such a vast empire together.” And the further his imagination ranges the more do his notions of foreign peoples and races fail to correspond with his patterns of humanity. Among the many other destinies which Carlyle might have had and lived through, one can imagine one wherein he travelled,[39] and found in real life what he sought in museums and libraries. He would have been a wonderful traveller, and would have known and shown more of the verities and mysteries of the world than he was able to do through the medium of history.

Carlyle’s Mahomet is an example of old-fashioned visions. It is clear now that this “deep-hearted Son of the Wilderness, with his beaming black eyes and open social deep soul,” was not that determined, conscientious British sort of character that he is made out to be, nor has Mohammedanism that Cromwellian earnestness which Carlyle imputed to it.

It is impossible to find in the Moslem soul “the infinite nature of duty,” but we would not explain the “gross sensual paradise” and the “horrible flaming hell” of the Mohammedans by saying that to them “Right is to Wrong as life is to death, as heaven to hell. The one must nowise be done, the other in nowise be left undone.” Mahomet and Mohammedanism are not explainable in these terms.

Probably the most common assumption in the West is that Mohammedanism does not count. In its adherents it greatly outnumbers Christianity, but not even those who believe that the will of majorities should prevail would recognise the Mohammedan majority. For though more warlike than we, they have not our weapons, and though they are finer physically, they have not our helps to Nature, nor our civilisation, nor our passion. They are apart, they are scarcely human beings in our Western sense of the term, and are negligible. Still, Mohammedanism is an extraordinary[40] portent in the world. The Mohammedans, those many millions, are not merely potential Christians, a set of people remaining in error because our missionary enterprise is not sufficient to bring them to the Light. It is not an accident, or a makeshift religion, but evidently a happy form suitable to the millions who embody it. It is a poetically fitting religion, part of the very fibre of the people who have it, and it cannot easily be got rid of or supplanted.

As enthusiastic Christians we consider the Moslem world with some vexation; some of us even with malice and a readiness to take arms against it. But as pleasure-seeking tourists and worldly men and women, we rather love the Turk and the Arab for his “picturesqueness,” for the picturesqueness of his religion. As sportsmen, we love him because he has the reputation of fighting well.

MOHAMMEDAN TOMBS AND RUINS IN THE YOUNGEST OF THE RUSSIAN COLONIES

It was with a certain amount of dissatisfaction that I fell into the hands of an Arab guide when I was in Cairo, and was shown, first of all, the picturesque mosques so beloved of tourists—the Mosque of Sultan Hassan, the Alabaster Mosque, and so on. Not the ancient Egyptian remains, which are the most significant thing in Egypt; not the Early Christian ruins, which are most dear to us (the old Christian monasteries which the Copts possess seemed to be known by none), but the mosques made of the stolen stones of the Pyramids and of the tombs, and inlaid with the jewels taken from ikon frames and rood-screens of the first churches of Christianity. And as I listened to the details of the blinding of the architects, the destruction[41] of the Mamelukes, the fighting and the robbing, the disparaging thought arose: “They are all a pack of robbers, these Mohammedans.”

They are robbers by instinct, and non-progressive not only in life, but in ideas. But they are picturesque, and have given to a considerable portion of the earth’s face a characteristic quaintness and beauty. They cannot be dismissed.

Carlyle tries to see some light in the Koran, and fails. Probably the Koran is translated in a wrong spirit or to suit a British taste. But obviously it is meant to be chanted, and it is full of rhythms with which we are unfamiliar, as unfamiliar as we are with the sobbing, plaintive, screaming music that is melody in the Moslem’s ears. The soul of the Koran is not like the soul of the Bible, just as the soul of a mediæval Christian city such as Florence or Rome is unlike Khiva or Bokhara or Samarkand, just as the souls of our eager mystical populations are different from the souls of those simple, satisfied and fatalistic people. It is not easy to communicate the difference by words; it is not merely a difference in clothes. It is a difference in the spirit, a difference in the spirit that causes the expression to be different, whether that expression be clothes, or houses, or cities, or way of life, or music, or literature, or prayer. And while our expression changes, theirs remains the same. Our spirit remains the same, theirs remains the same, but only with us does the expression change.

“God is great; we must submit to God,” is Mohammedan wisdom. It is in a way a common[42] ground—we must submit. But with the Mohammedan there is a waiting for God’s will to be shown, whereas with us rather a divination of it in advance. We are alive to find out what God wills for us. After “Thy will be done!” we put an exclamation mark and rejoice. Mohammedanism is fatalism, but Christianity is not fatalism.

And if fatalism gives a tinge of melancholy to life, especially to an unfortunate life, it still makes life easier. It relieves the soul of care and takes a world of responsibility off the shoulders. The Mohammedan is a care-free being. He has, more than we have, the life of a child.

Consequently, one of the greatest characteristics of Mohammedan people is playfulness. All is play to them. They are playful in their attire, in their business, in their fighting, in their talking. They buy and sell, and make a great game of their buying and selling. They lack “seriousness.” They are in no hurry to strike a bargain and get ahead in trade. Their instinct is for the game rather than for the business. Hence the comparative poverty of the Tartars—the most commercial people of the East. They are not serious enough to get rich in our Western way. If they would get really rich as a Western merchant is rich, they must not waste time playing and haggling. They fight well because they see the game in fighting. Death is not so great a calamity to them as to us, for life is not such a serious thing. They look on playfully at suffering, and laugh to see men’s limbs blown away by bombs. They like the gamble of modern warfare.[43] And, of course, they were warriors and robbers before they were Mohammedans. Fighting is one of their deepest instincts, and as they do not change with time as we do, they have an almost anachronistic love of battle. They are fond of weapons as of toys, fingering blades and laughing, guffawing at the sight of cannon. They love steamboats and battleships as children love toy steamboats, and they sail them on the waters of the Levant as children would their toys. Their hospitality is mirthful, as are also their murders and their massacres. Their heaven and hell are playful conceptions.

The condition of their remaining children is obedience to the simple laws of their religion. These obeyed, they are free of all troubles. And they obey. Hence, from Delhi to Cairo and from Kashgar to Constantinople, a playful and sometimes mischievous and difficult world. Looking at the great cities, with their quaint figures and their chaffering, their elfish spires and minarets, their covered ways and gloomy and mysterious passages; looking at this city of Bokhara, with its covered ways crowded with these children-merchants and children-purchasers, their beggars, tombs, shrines, we must remember it is all a children’s contrivance, something put together by a people who do not grow up and do not grow serious as we do—mysterious yet simple, fierce yet childlike, valorous and yet amused by suffering, Islam, the enemy of the Church in arms, to this day.

FROM Bokhara I proceeded to Samarkand, the grave of Timour. Turkestan has four great cities remaining in splendour from the most remote times—Bokhara, Khiva, Samarkand, and Tashkent. Alexander the Great conquered most of this territory and established himself at Samarkand for winter quarters, but there are few traces of Alexander to-day. In his day the land was inhabited by tribes who had come out of the Pamir—Persians, Indians, Tadzhiks. There were also primeval nomads, with their tents and their herds, a people something like the Jews when they were simply the Children of Israel, when they were a family. There were possibly hordes of Jews, as there were hordes of Tartars and Mongols. At the time of the shepherd dynasty of Egypt the peoples of the East were living in patriarchal families, resembling in a way the families of the Kirghiz in Central Asia to-day.

For the ethnologist Central Asia is necessarily one of the most interesting districts of the world, and its inhabitants are like living specimens in a great ethnological museum. The races there tell us more about the past of the world in which we are interested than any pages in the history book. Here we may feel what the Children of Israel were, the Egyptians, the Syrians,[45] the Persians, the Turks, the Russians. We see the destiny of Rome, the destiny of the Church of Christ, of Christianity, of barbarism.

Not that there are many pure or clear types of historical races in Central Asia to-day. The land has been a running ground for fierce tribes coming out of China and Manchuria, coming from the mysterious and vague regions of the Pamir and Thibet. The Kirghiz to-day exhibit every shade of difference between the Mongol and the Turk.

After the Greeks of Alexander came the first ferocious Huns. To the Greeks what is now Russia and Siberia, Seven Rivers Land and Russian Central Asia was vaguely Scythia. They fumbled northward and eastward as in a great darkness, and they were rather afraid to go on. Yet we know that even before the records of Greek history there was an Eastern trade on the Volga and from the Caspian to the Baltic. The merchants of Persia and India traded with the Russia of those days. The Persians ruled from the Oxus to the Danube, and in the wilderness stretching from the Oxus to the Great Wall of China dwelt the primeval nomads.

South of the Altai Mountains was the fount of the mysterious Huns who, some centuries before the birth of Christ, ravaged China to the Pacific and extended their dominion northward, down the Irtish River to the tundra of the Arctic Circle. These were not a Mongol people, but Turkish, though eventually they were beaten by the Tartars, and the Mongolian and Turkish tended to blend. The reason for their turning[46] westward was an eventual failure against China. The Chinese built their fifteen-hundred-mile wall against the Huns, but the wall did not avail them; they were beaten, and were forced to pay an enormous tribute of silk, gold, and women. Then the Chinese reorganised their armies, turned upon their enemies, and crushed them. Their monarch became a vassal of the Emperor. Fifty-eight hordes entered the service of China—a horde was about four thousand men. The remainder of the Huns, coming to the conclusion that China was too strong for them, resolved to fight somewhere else, and set off westward towards the Oxus and the Volga. They expended themselves on the eastern shores of the Volga, where they remain to this day as the Kalmeeks. Visitors to the Southern Ural and the district of Astrakhan will have pointed out to them the Kalmeeks, a low-browed, broad-nosed type of men, sun-browned, wizened, and squat, the ugliest in Russia; these are the original Huns, ferocious in their day, very peaceful and stupid now, and below even the level of the Kirghiz in intelligence.

The chief Turkish tribes to-day are the Yakuts, on the Lena, the Kirghiz, the Uzbeks, of whom there are a considerable number in Bokhara and Khiva, the Turkomans, and Osmanli, the Turks themselves, and they have all something of the Hun about them. Their history is Hunnish history. A deformed and brutal people were the hordes of the Huns; there were many cripples among them and people of distorted features, many dwarfs. They were the cruellest people that have ever been, and probably that is why they have[47] such a name for ugliness. Cruelty and ugliness of feature go together. Even the most refined torturers of the Spanish Inquisition must have been ugly. There is something terrifying in the aspect of cruelty. It is an aspect of mania, and when it comes out in the race must be called racial mania or aberration.

Successive hordes of pagans rolled forward, and the story of each forward movement of this kind is the same. Each wave, however, seemed to roll farther than the one before and gather in power and volume to the point where it multitudinously broke. The Asiatic heathen were soon over the Volga and across Russia; it was they who set the North German tribes moving and gave an impetus to the plundering and ransacking of the Western world. They astonished even the Goths by their ferocity and ugliness, and in A.D. 376 the Goths had to appeal to the Romans for protection. The Emperor Valens delayed to answer, and a million Goths crossed the Danube and began the conquest of Roman territory. The Huns joined with the Alani, a wild Finnish tribe supposed by some to be the present Ossetini of the Northern Caucasus, and together they obtained glimpses of the splendour of the South and came into touch with the people who would ultimately give them their religion—the Saracens.

Away in the background of Central Asia, however, Mongol tribes were falling on those Huns who had remained behind and ever setting new hordes going westward, and the impact from China was felt all the way to Germany, and hordes of barbarians[48] began to appear before the gates of Rome itself. Soon the Goths burned the capital of the world (A.D. 410). A quarter of a century later the Huns found a new leader in Attila (A.D. 438-453), and became once more the scourge and terror of all existent civilisation. The Huns of Attila were not just the old Huns who came out of Mongolia and fought with the Chinese, but a mixture of all the Turkish tribes of the East. They worshipped the sword, stuck in the ground, and prayed before it as others prayed before the Cross. Attila claimed to have discovered the actual sword of the God Mars, and through the possession claimed dominion over the whole world. He conquered Russia and Germany, Denmark, Scandinavia, the islands of the Baltic. He crushed the Chinese and Tartars who were afflicting the rearguard of his nation in the depths of Asia, negotiating on equal terms with the Emperor of China. He traversed Persia and Armenia and what is now Turkey in Asia, broke through to Syria, and, in alliance with the Vandals, took possession of “Africa.” His followers crossed the Mediterranean, devastating the cities of Greece, Italy, and Gaul. Rome abandoned her Eastern Empire to the Huns in A.D. 446; and, after Attila’s death, the Vandals, a people of Slavonic origin, sacked Rome once more. Western civilisation seemed to be extinguished, and a barbarian became King of Italy.

A MOHAMMEDAN FESTIVAL AT SAMARKAND—THE HOUR OF PRAYER

What was happening in Central Asia is but vaguely known. The people who lived on the horse at the time of Herodotus still lived on the horse as they do at this day, on mare’s milk, koumis, and[49] horseflesh, camping amidst great herds of horses, the same breed as the Siberian ponies which the Cossacks ride now. There were feuds of the hordes, raids, massacres; the Chinese are said to have attempted to introduce Buddhism, though without much success. There was much intermarriage of Turks and Mongols. On the other hand, the conquering Huns returned with wives of the races of the West, and with a smattering of Western ideas, bringing even with them the name of Christianity, and some Christian ideas. Christians began to appear in the ranks of the pagans.