Statue of a Lohan or Buddhist Apostle, T'ang dynasty

(618–906 A.D.)

Height with stand 50 inches. British Museum.

AN ACCOUNT OF THE POTTER'S ART IN CHINA

FROM PRIMITIVE TIMES TO THE PRESENT DAY

BY

R.L. HOBSON, B.A.

Assistant in the Department of British and Mediæval Antiquities and

Ethnography, British Museum. Author of the "Catalogue of the

Collection of English Pottery in the Department of British

and Mediæval Antiquities of the British Museum";

"Porcelain: Oriental, Continental, and British";

"Worcester Porcelain"; etc.; and Joint Author

of "Marks on Pottery"

Forty Plates in Colour and Ninety–six in Black and White

VOL. I

Pottery and Early Wares

CASSELL AND COMPANY, LTD

London, New York, Toronto and Melbourne

1915

| CHAPTER | PAGE |

| INTRODUCTION | xv |

| BIBLIOGRAPHY | xxvii |

| 1. THE PRIMITIVE PERIODS | 1 |

2. THE HAN  DYNASTY, 206 B.C. TO 220 A.D. DYNASTY, 206 B.C. TO 220 A.D. |

5 |

3. THE TANG  DYNASTY, 618–906 A.D. DYNASTY, 618–906 A.D. |

23 |

4. THE SUNG  DYNASTY, 960–1279 A.D. DYNASTY, 960–1279 A.D. |

43 |

| 5. JU, KUAN, AND KO WARES | 52 |

6. LUNG–CH´ÜAN YAO  |

76 |

7. TING YAO  |

89 |

8. TZ´Ŭ CHOU  WARE WARE |

101 |

| 9. CHÜN WARES AND SOME OTHERS | 109 |

| 10. MIRABILIA | 136 |

| 11. PORCELAIN AND ITS BEGINNINGS | 140 |

| 12. CHING–TÊ CHÊN | 152 |

13. THE YÜAN  DYNASTY, 1280–1367 A.D. DYNASTY, 1280–1367 A.D. |

159 |

14. KUANGTUNG  WARES WARES |

166 |

15. YI–HSING  WARE WARE |

174 |

| 16. MISCELLANEOUS POTTERIES | 184 |

| 17. MARKS ON CHINESE POTTERY AND PORCELAIN | 207 |

| STATUE OF LOHAN OR BUDDHIST APOSTLE, T´ANG DYNASTY (618–906 A.D.). | |

| British Museum (Colour) | Frontispiece |

| PLATE | FACING PAGE |

| 1. CHOU POTTERY | 4 |

| Fig. 1.—Tripod Food Vessel. Eumorfopoulos Collection. | |

| Fig. 2.—Jar with deeply cut lozenge pattern. Eumorfopoulos Collection. | |

| 2. HAN POTTERY | 8 |

| Fig. 1.—Vase, green glazed. Boston Museum. | |

| Fig. 2.—Vase with black surface and incised designs. Eumorfopoulos Collection. | |

| Fig. 3.—Vase with designs in red, white and black pigments. British Museum. | |

| Fig. 4.—"Granary Urn," green glazed. Peters Collection. | |

| 3. HAN POTTERY | 12 |

| Fig. 1.—"Hill Jar" with brown glaze. Eumorfopoulos Collection. | |

| Fig. 2.—Box, green glazed. Eumorfopoulos Collection. | |

| Fig. 3.—"Lotus Censer," green glazed. Rothenstein Collection. | |

| 4. MODEL OF A "FOWLING TOWER" | 12 |

| Han pottery with iridescent green glaze. Freer Collection. | |

| 5. T´ANG SEPULCHRAL FIGURES | 26 |

| Fig. 1.—A Lokapala or Guardian of one of the Quarters, unglazed. Benson Collection. | |

| Fig. 2.—A Horse, with coloured glazes. Benson Collection. | |

| Fig. 3.—An Actor, unglazed. Benson Collection. | |

| 6. T´ANG SEPULCHRAL FIGURES, UNGLAZED | 26 |

| Figs. 1, 2 and 4.—Female Musicians. Eumorfopoulos Collection. | |

| Fig. 3.—Attendant with dish of food. Eumorfopoulos Collection. | |

| 7. T´ANG SEPULCHRAL POTTERY | 26 |

| Fig. 1.—Figure of a Lady in elaborate costume, unglazed. Eumorfopoulos Collection. | |

| Fig. 2.—Vase, white pottery with traces of blue mottling. Breuer Collection. | |

| Fig. 3.—Sphinx–like Monster, green and yellow glazes. Eumorfopoulos Collection. | |

| 8. THREE EXAMPLES OF T´ANG WARE WITH COLOURED GLAZES: | |

| IN THE Eumorfopoulos Collection (Colour) | 30[viii] |

| Fig. 1.—Tripod Incense Vase with ribbed sides; white pottery with deep blue glaze, | |

| outside encrusted with iridescence. | |

| Fig. 2.—Amphora of light coloured pottery with splashed glaze. | |

| Fig. 3.—Ewer of hard white porcellanous ware with deep purple glaze. | |

| 9. T´ANG POTTERY | 32 |

| Fig. 1.—Ewer of Sassanian form with splashed glazes; panels of relief ornament. | |

| Alexander Collection. | |

| Fig. 2.—Vase with mottled glaze, green and orange. Eumorfopoulos Collection. | |

| Fig. 3.—Ewer with dragon spout and handle; wave and cloud reliefs; brownish yellow glaze | |

| streaked with green. Eumorfopoulos Collection. | |

| 10. T´ANG POTTERY | 32 |

| Fig. 1.—Dish with mirror pattern incised and coloured blue, green, etc.; inner border of ju–i | |

| cloud scrolls on a mottled yellow ground, outer border of mottled green; pale green glaze | |

| underneath and three tusk–shaped feet. Eumorfopoulos Collection. | |

| Fig. 2.—Ewer with serpent handle and trilobed mouth; applied rosette | |

| ornaments and mottled glaze, green, yellow and white. Eumorfopoulos Collection. | |

| 11. T´ANG WARES | 32 |

| Fig. 1.—Cup with bands of impressed circles, brownish yellow glaze outside, green within. | |

| Seligmann Collection. | |

| Fig. 2.—Cup of hard white ware with greenish white glaze. Eumorfopoulos Collection. | |

| Fig. 3.—Melon–shaped Vase, greyish stoneware with white slip and smooth ivory glaze. | |

| Breuer Collection. | |

| Fig. 4.—Cup of porcellanous stoneware, white slip and crackled creamy white glaze, | |

| spur marks inside. Breuer Collection. | |

| 12. T´ANG POTTERY WITH GREEN GLAZE | 40 |

| Fig. 1.—Bottle with impressed key–fret. Eumorfopoulos Collection. | |

| Fig. 2.—Ewer with incised foliage scrolls. Alexander Collection. | |

| Fig. 3.—Vase with foliage scrolls, painted in black under the glaze, incised border on the shoulder. | |

| Eumorfopoulos Collection. | |

| 13. T´ANG POTTERY | 40 |

| Fig. 1.—Pilgrim Bottle with lily palmette and raised rosettes, green glaze. KOECHLIN COLLECTION. | |

| Fig. 2.—Pilgrim Bottle (neck wanting), Hellenistic figures of piping boy and dancing girl in relief | |

| among floral scrolls, brownish green glaze. Eumorfopoulos Collection. | |

| 14. T´ANG WARES | 40 |

| Fig. 1.—Incense Vase, lotus–shaped, with lion on the cover, hexagonal stand with moulded ornament; | |

| green, yellow and brown glazes. Rothenstein Collection. | |

| Fig. 2.—Sepulchral Amphora, hard white ware with greenish white glaze, | |

| serpent handles. Schneider Collection. | |

| Fig. 3.—Ewer with large foliage and lotus border in carved relief, green glaze. Koechlin Collection. | |

| Fig. 4.—Sepulchral Vase, grey stoneware with opaque greenish grey glaze. Incised scrolls on the body, | |

| applied reliefs of dragons, figures, etc., on neck and shoulder. (?) T´ang. Benson Collection. | |

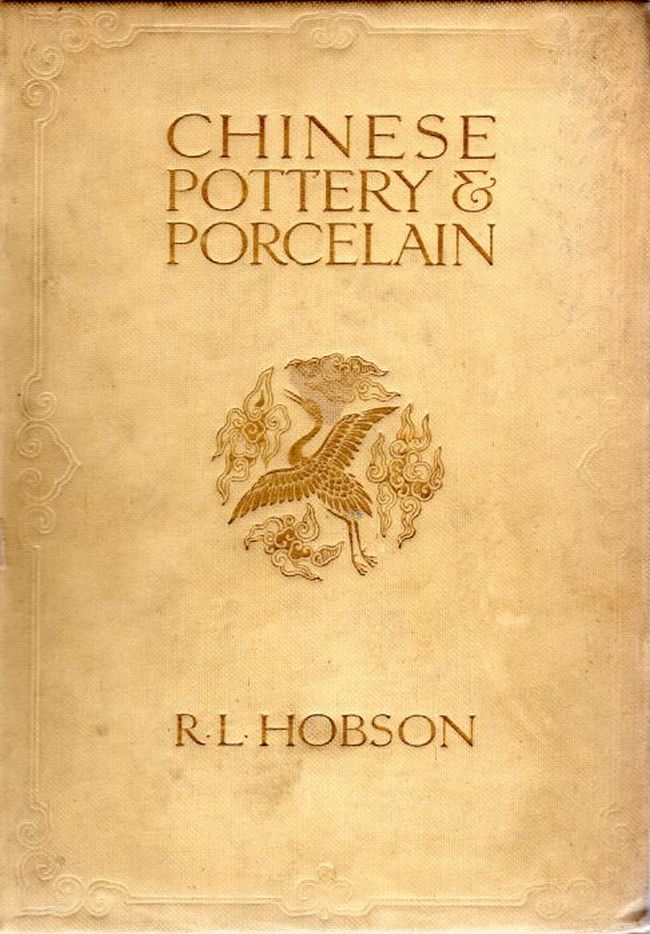

| 15. SUNG WARES | 48[ix] |

| Fig. 1.—Peach–shaped Water Vessel, dark–coloured biscuit, smooth greenish grey glaze. (?) | |

| Ju or Kuan ware. Eumorfopoulos Collection. | |

| Figs. 2 and 3.—Shallow Cup with flanged handle, and covered box, opalescent grey glaze. | |

| Kuan or Chün wares. Rothenstein Collection. | |

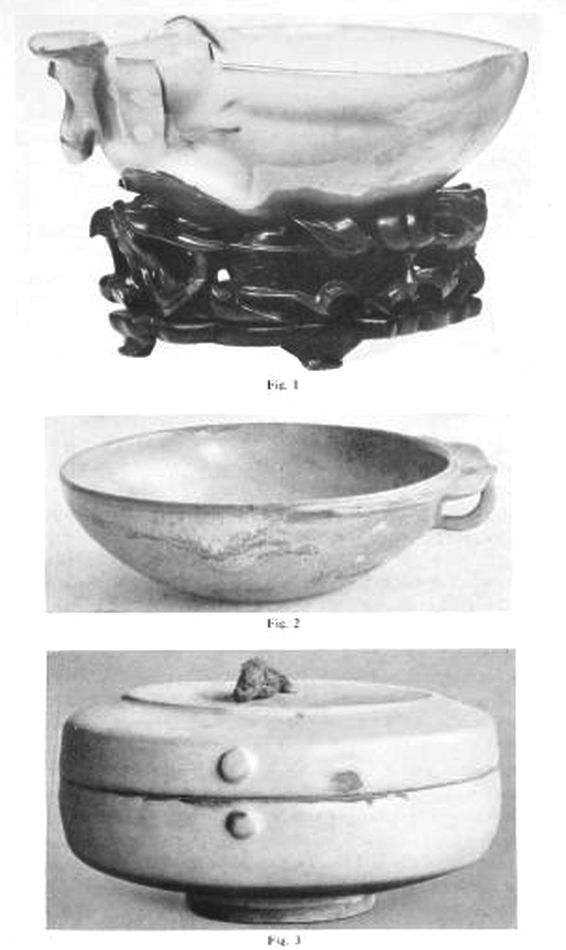

| 16. SUNG WARES (Colour) | 58 |

| Fig. 1.—Bowl with six–lobed sides; thin porcellanous ware, burnt brown at the foot–rim, | |

| with bluish green celadon glaze irregularly crackled. Alexander Collection. | |

| Fig. 2.—Tripod Incense Burner. White porcelain burnt pale red under the feet. (?) | |

| Lung–ch´üan celadon ware. Eumorfopoulos Collection. | |

| 17. TWO EXAMPLES OF SUNG WARES OF THE CHÜN OR KUAN FACTORIES (Colour) | 64 |

| Fig. 1.—Bowl with lavender glaze, lightly crackled. O. Raphael Collection. | |

| Fig. 2.—Vase with smooth lavender grey glaze suffused with purple. Eumorfopoulos Collection. | |

| 18. SUNG DYNASTY | 66 |

| Fig. 1.—Bowl with engraved peony design under a brownish green celadon glaze. | |

| Northern Chinese. Eumorfopoulos Collection. | |

| Fig. 2.—Vase moulded in form of a lotus flower, dark grey stoneware, burnt reddish brown, | |

| milky grey glaze, closely crackled. Freer Collection. | |

| 19. VASE OF CLOSE–GRAINED, DARK, REDDISH BROWN STONEWARE, WITH THICK, SMOOTH GLAZE, | |

| BOLDLY CRACKLED. Ko ware of the Sung dynasty. Eumorfopoulos Collection (Colour) | 70 |

| 20. DEEP BOWL OF REDDISH BROWN STONEWARE, WITH THICK, BOLDLY CRACKLED GLAZE. | |

| Ko ware of the Sung dynasty. Eumorfopoulos Collection (Colour) | 74 |

| 21. THREE EXAMPLES OF LUNG–CH´ÜAN CELADON PORCELAIN | 80 |

| Fig. 1.—Plate of spotted celadon. (?) Sung dynasty. Eumorfopoulos Collection. | |

| Fig. 2.—Octagonal Vase with crackled glaze and biscuit panels moulded with figures | |

| of the Eight Immortals in clouds. (?) Fourteenth century. Eumorfopoulos Collection. | |

| Fig. 3.—Dish with engraved lotus scrolls and two fishes in biscuit. Sung dynasty. | |

| Gotha Museum. | |

| 22. VASE OF LUNG–CH´ÜAN PORCELAIN | 88 |

| With grey green celadon glaze of faint bluish tone, peony scroll in low relief. | |

| Probably Sung dynasty. Peters Collection. | |

| 23. IVORY–WHITE TING WARE, WITH CARVED ORNAMENT. Sung dynasty | 96 |

| Fig. 1.—Bowl with lotus design. Eumorfopoulos Collection. | |

| Fig. 2.—Dish with ducks and water plants. Alexander Collection. | |

| 24. SUNG AND YÜAN PORCELAIN | 96[x] |

| Fig. 1.—Ewer, translucent porcelain, with smooth ivory white glaze. Sung or Yüan dynasty. | |

| Alexander Collection. | |

| Fig. 2.—Vase of ivory white Ting ware with carved lotus design. Sung dynasty. | |

| Eumorfopoulos Collection. | |

| 25. TING WARE WITH MOULDED DESIGNS. Sung dynasty | 96 |

| Fig. 1.—Plate with boys in peony scrolls, ivory white glaze. Peters Collection. | |

| Fig. 2.—Bowl with flying phœnixes in lily scrolls, crackled creamy glaze; t´u ting ware. | |

| Koechlin Collection. | |

| 26. T´U–TING WARE, SUNG DYNASTY, WITH CREAMY CRACKLED GLAZE | 96 |

| Fig. 1.—Brush washer in form of a boy in a boat. Rothenstein Collection. | |

| Fig. 2.—Figure of an elephant. Eumorfopoulos Collection. | |

| 27. VASE OF BRONZE FORM, WITH ROW OF STUDS AND MOULDED BELT OF | |

| k´uei DRAGON AND KEY–FRET PATTERNS | 96 |

| "Ostrich egg" glaze. (?) Kiangnan ware, of Ting type; Sung dynasty. Peters Collection. | |

| 28. VASE OF BRONZE FORM, WITH BANDS OF RAISED KEY PATTERN | 96 |

| Thick creamy glaze, closely crackled and shading off into brown with faint tinges of purple. (?) | |

| Kiangnan Ting ware. Fourteenth century. Koechlin Collection. | |

| 29. VASE OF PORCELLANOUS STONEWARE | 104 |

| With creamy white glaze and designs painted in black. Tz´ŭ Chou ware, Sung dynasty | |

| (960–1279 A.D.). In the Louvre. | |

| 30. FOUR JARS OF PAINTED TZ´Ŭ CHOU WARE | 104 |

| Fig. 1.—Dated 11th year of Chêng T´ing (1446 A.D.) Eumorfopoulos Collection. | |

| Fig. 2.—Painted in red and green enamels. (?) Sung dynasty. Alexander Collection. | |

| Fig. 3.—Lower half black, the upper painted on white ground. Sung dynasty. Benson Collection. | |

| Fig. 4.—With phœnix design, etched details. Sung dynasty. Rothenstein Collection. | |

| 31. TZ´Ŭ CHOU WARE | 104 |

| Fig. 1.—Tripod Incense Vase in Persian style with lotus design in pale aubergine, in | |

| a turquoise ground. Sixteenth century. Eumorfopoulos Collection. | |

| Fig. 2.—Pillow with creamy white glaze and design of a tethered bear in black. Sung dynasty. | |

| Eumorfopoulos Collection. | |

| 32. TZ´Ŭ CHOU WARE | 104 |

| Fig. 1.—Figure of a Lohan with a deer, creamy white glaze coloured with black slip and | |

| painted withgreen and red enamels. Said to be Sung dynasty. Eumorfopoulos Collection. | |

| Fig. 2.—Vase with graffiato peony scrolls under a green glaze. Sung dynasty. | |

| Eumorfopoulos Collection. | |

| 33. TZ´Ŭ CHOU WARE | 104[xi] |

| Fig. 1.—Vase with panel of figures representing music, painted in black under a blue glaze. | |

| Yüan dynasty. Eumorfopoulos Collection. | |

| Fig. 2.—Vase with incised designs in a dark brown glaze, a sage looking at a skeleton. | |

| Yüan dynasty. Peters Collection. | |

| Fig. 3.—Vase with painting in black and band of marbled slips. Sung dynasty. | |

| Eumorfopoulos Collection. | |

| 34. TZ´Ŭ CHOU WARE | 104 |

| Fig. 1.—Bottle of white porcellanous ware with black glaze and floral design in lustrous brown. | |

| Sung dynasty or earlier. (?) Tz´ŭ Chou ware. Eumorfopoulos Collection. | |

| Fig. 2.—Bottle with bands of key pattern and lily scrolls cut away from a black glaze. | |

| Sung dynasty. Eumorfopoulos Collection. | |

| Fig. 3.—Bottle with graffiato design in white slip on a mouse–coloured ground, | |

| yellowish glaze. Sung dynasty. Eumorfopoulos Collection. | |

| 35. FLOWER POT OF CHÜN CHOU WARE OF THE SUNG DYNASTY (Colour) | 112 |

| Grey porcellanous body: olive brown glaze under the base and the numeral shih (ten) incised. | |

| Eumorfopoulos Collection. | |

| 36. CHÜN WARE (Colour) | 116 |

| Fig. 1.—Flower pot of six–foil form. Chün Chou ware of the Sung dynasty. | |

| The base is glazed with olive brown and incised with the numeral san (three). | |

| Alexander Collection. | |

| Fig. 2.—Bowl of Chün type, with close–grained porcellanous body of yellowish colour. | |

| Sung dynasty. Eumorfopoulos Collection. | |

| 37. CHÜN CHOU WARE WITH PORCELLANOUS BODY (tz´ŭ t´ai). Sung dynasty | 118 |

| Fig. 1.—Flower Pot, with lavender grey glaze. Numeral mark ssŭ (four). | |

| Eumorfopoulos Collection. | |

| Fig. 2.—Bulb Bowl, of quatrefoil form, pale olive glaze clouded with opaque grey. | |

| Numeral mark i (one). Freer Collection. | |

| 38. CHÜN WARE (Colour) | 122 |

| Fig. 1.—Bowl of eight–foil shape, with lobed sides, of Chün type. Sung dynasty. | |

| Alexander Collection. | |

| Fig. 2.—Pomegranate shaped Water Pot of "Soft Chün" ware. Probably Sung dynasty. | |

| Alexander Collection. | |

| 39. TWO EXAMPLES OF "SOFT CHÜN" WARE (Colour) | 126 |

| Fig. 1.—Vase of buff ware, burnt red at the foot rim, with thick, almost crystalline glaze. | |

| Found in a tomb near Nanking and given in 1896 to the FitzWilliam Museum, Cambridge. | |

| Probably Sung dynasty. | |

| Fig. 2.—Vase of yellowish ware with thick opalescent glaze. Yüan dynasty. | |

| Alexander Collection. | |

| 40. CHÜN CHOU WARE | 128 |

| Fig. 1.—Bulb Bowl, porcellanous ware with lavender grey glaze passing into mottled | |

| red outside. Numeral mark i (one). Sung dynasty. Eumorfopoulos Collection. | |

| Fig. 2.—Vase of dense reddish ware, opalescent glaze of pale misty lavender with | |

| passages of olive and three symmetrical splashes of purple with green centres. | |

| Sung or Yüan dynasty. Peters Collection. | |

| 41. CHÜN CHOU WARE | 128[xii] |

| Fig. 1.—Dish with peach spray in relief. Variegated lavender grey glaze with purplish | |

| brown spots and amethyst patches, frosted in places with dull green. Sung dynasty. | |

| Freer Collection. | |

| Fig. 2.—Vase and Stand, smooth lavender grey glaze. Sung or Yüan dynasty. | |

| Alexander Collection. | |

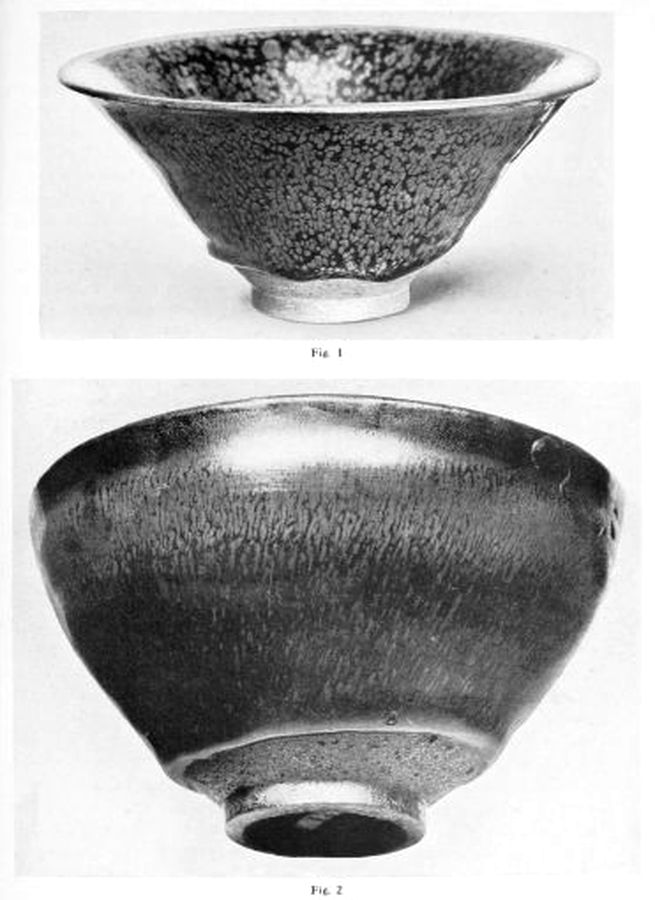

| 42. TWO Temmoku BOWLS, DARK–BODIED CHIEN YAO OF THE SUNG DYNASTY | 130 |

| Fig. 1.—Tea Bowl (p´ieh), purplish black glaze flecked with silvery drops. | |

| Freer Collection. | |

| Fig. 2.—Tea Bowl with purplish black glaze shot with golden brown. British Museum. | |

| 43. THREE EXAMPLES OF "HONAN temmoku," PROBABLY T´ANG DYNASTY | 132 |

| Fig. 1.—Bowl with purplish black glaze, stencilled leaf in golden brown. | |

| Havemeyer Collection. | |

| Fig. 2.—Ewer with black glaze. Alexander Collection. | |

| Fig. 3.—Covered Bowl, black mottled with lustrous brown. Cologne Museum. | |

| 44. EARLY TRANSLUCENT PORCELAIN, PROBABLY T´ANG DYNASTY | 150 |

| Fig. 1.—Cinquefoil Cup with ivory glaze clouded with pinkish buff stains. Breuer Collection. | |

| Fig. 2.—Vase of white, soft–looking ware, very thin and translucent, with pearly white, | |

| crackled glaze powdered with brown specks. Peters Collection. | |

| 45. T´ANG AND SUNG WARES | 150 |

| Fig. 1.—Square Vase with engraved lotus scrolls and formal borders. T´u–ting ware, | |

| Sung dynasty. Peters Collection. | |

| Fig. 2.—Ewer with phœnix head, slightly translucent porcelain with light greenish | |

| grey glaze with tinges of blue in the thicker parts; carved designs. Probably T´ang | |

| dynasty. Eumorfopoulos Collection. | |

| 46. TING WARE AND YÜAN PORCELAIN | 162 |

| Fig. 1.—Bottle with carved reliefs of archaic dragons and ling chin funguses. | |

| Fên ting ware, said to be Sung dynasty. Eumorfopoulos Collection. | |

| Fig. 2.—Bowl with moulded floral designs in low relief, unglazed rim. | |

| Translucent porcelain, probably Yüan dynasty. Eumorfopoulos Collection. | |

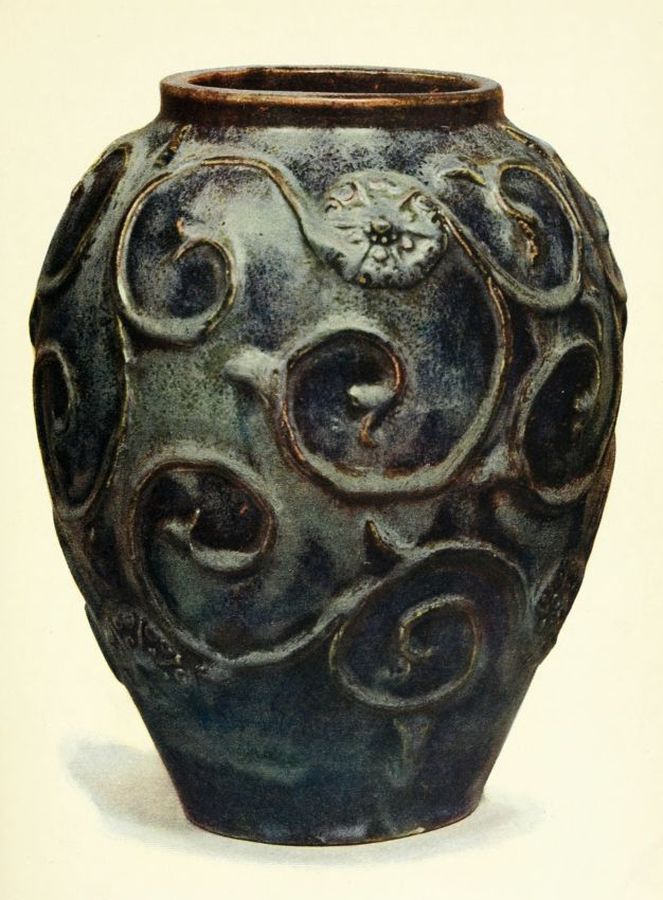

| 47. VASE OF BUFF STONEWARE (Colour) | 170 |

| With scroll of rosette–like flowers in relief: thick flocculent glaze of mottled blue with | |

| passages of dull green and a substratum of brown. Kuantung ware, seventeenth century. | |

| Benson Collection. | |

| 48. KUANGTUNG WARE | 172 |

| Fig. 1.—Dish in form of a lotus leaf, mottled blue and brown glaze. About 1600. | |

| British Museum. | |

| Fig. 2.—Vase with lotus scroll in relief, opaque, closely crackled glaze of pale lavender | |

| grey warmin into purple. (?) Fourteenth century. Peters Collection. | |

| Fig. 3.—Figure of Pu–tai Ho–shang, red biscuit, the draperies glazed celadon green. | |

| Eighteenth century. British Museum. | |

| 49. COVERED JAR OF BUFF STONEWARE | 172[xiii] |

| With cloudy green glaze and touches of dark blue, yellow, brown and white; archaic dragons, | |

| bats and storks in low relief; border of sea waves. Probably Kuangtung ware, | |

| seventeenth century. Eumorfopoulos Collection. | |

| 50. YI–HSING STONEWARE, SOMETIMES CALLED Buccaro | 176 |

| Figs. 1 to 4.—Teapots in the Dresden Collection, late seventeenth century. | |

| (1) Buff with dark patches. | |

| (2) Red ware with pierced outer casing. | |

| (3) Black with gilt vine sprays. | |

| (4) Red ware moulded with lion design. | |

| Fig. 5.—Peach–shaped Water Vessel, red ware. Dresden Collection. | |

| Fig. 6.—Red Teapot, moulded design of trees, etc. Inscription containing the name of | |

| Ch´ien Lung.Hippisley Collection. | |

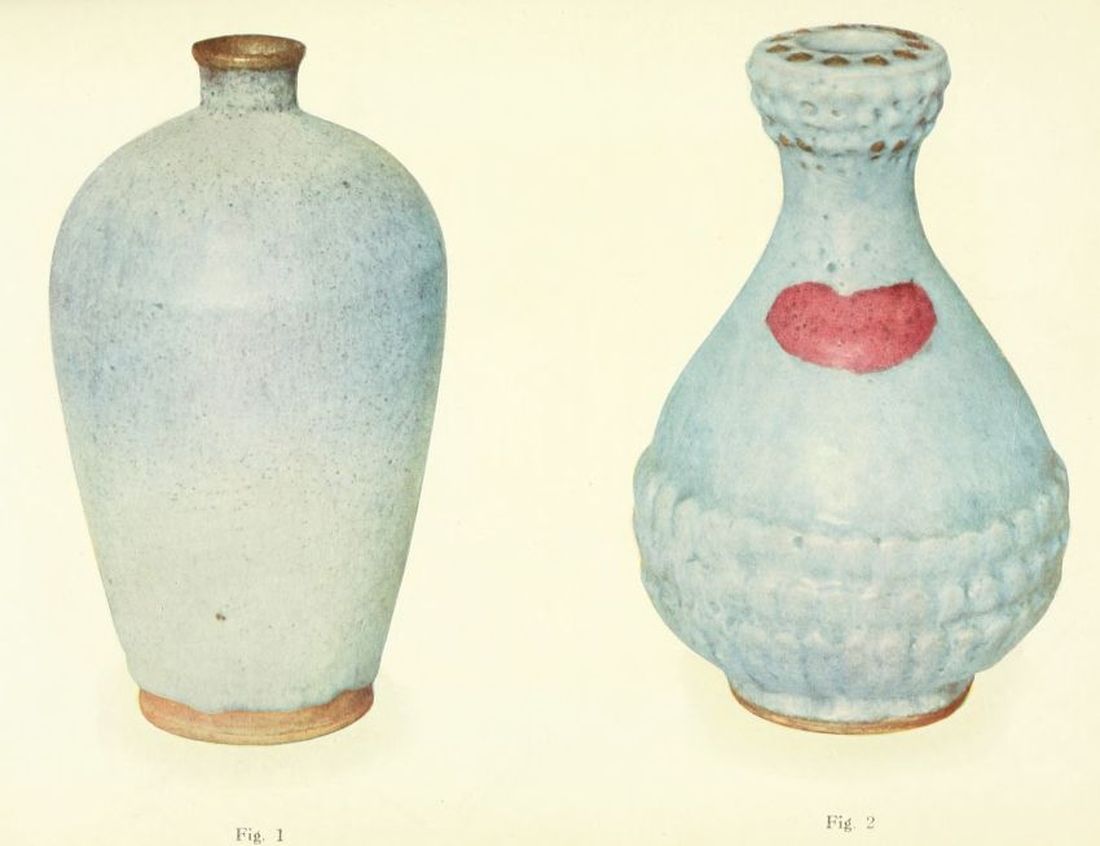

| 51. TWO VASES WITH GLAZE IMITATING THAT OF THE CHÜN CHOU WARE (Colour) | 180 |

| Fig. 1.—Vase of Fat–shan (Kuangtung) Chün ware. Late Ming. Eumorfopoulos Collection. | |

| Fig. 2.—Bottle–shaped Vase, the base suggesting a lotus flower and the mouth a lotus seed–pod, | |

| with a ring of movable seeds on the rim. Thick and almost crystalline glaze of lavender blue | |

| colour with a patch of crimson. Yi–hsing Chün ware of the seventeenth century. | |

| Eumorfopoulos Collection. | |

| 52. WINE JAR WITH COVER AND STAND (Colour) | 186 |

| Fine stoneware with ornament in relief glazed green and yellow in a deep violet blue ground. | |

| Four–clawed dragons ascending and descending among cloud scrolls in pursuit of flaming | |

| pearls; band of sea waves below and formal borders including a ju–i pattern on | |

| the shoulder. Cover with foliate edges and jewel pattern, surmounted by a seated figure of | |

| Shou Lao, God of Longevity. About 1500 A.D. Grandidier Collection, Louvre. | |

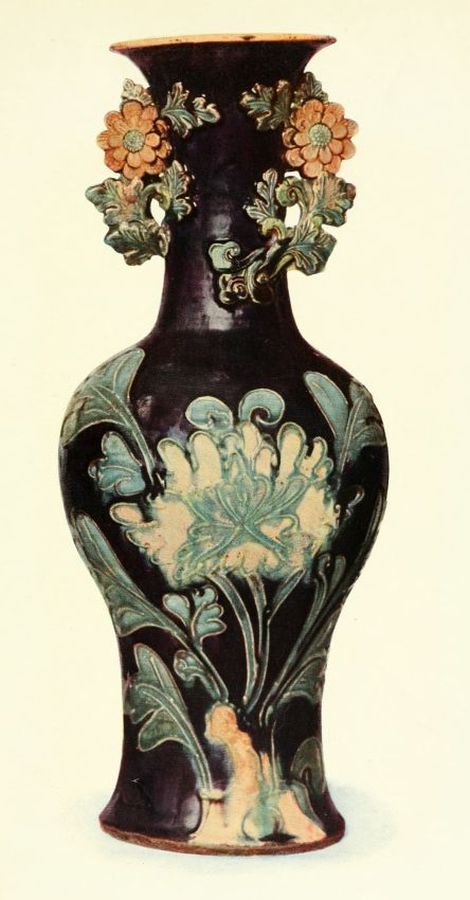

| 53. VASE WITH CHRYSANTHEMUM HANDLES (Colour) | 192 |

| Buff stoneware with chrysanthemum design outlined in low relief and coloured with turquoise, | |

| green and pale yellow glazes in dark purple ground. About 1500 A.D. Eumorfopoulos Collection. | |

| 54. VASE WITH LOTUS HANDLES (Colour) | 196 |

| Buff stoneware with lotus design modelled in low relief and coloured with aubergine, | |

| green and pale yellow glazes in a deep turquoise ground. About 1500 A.D. | |

| Grandidier Collection, Louvre. | |

| 55. MING POTTERY WITH DULL san ts´ai GLAZES | 200 |

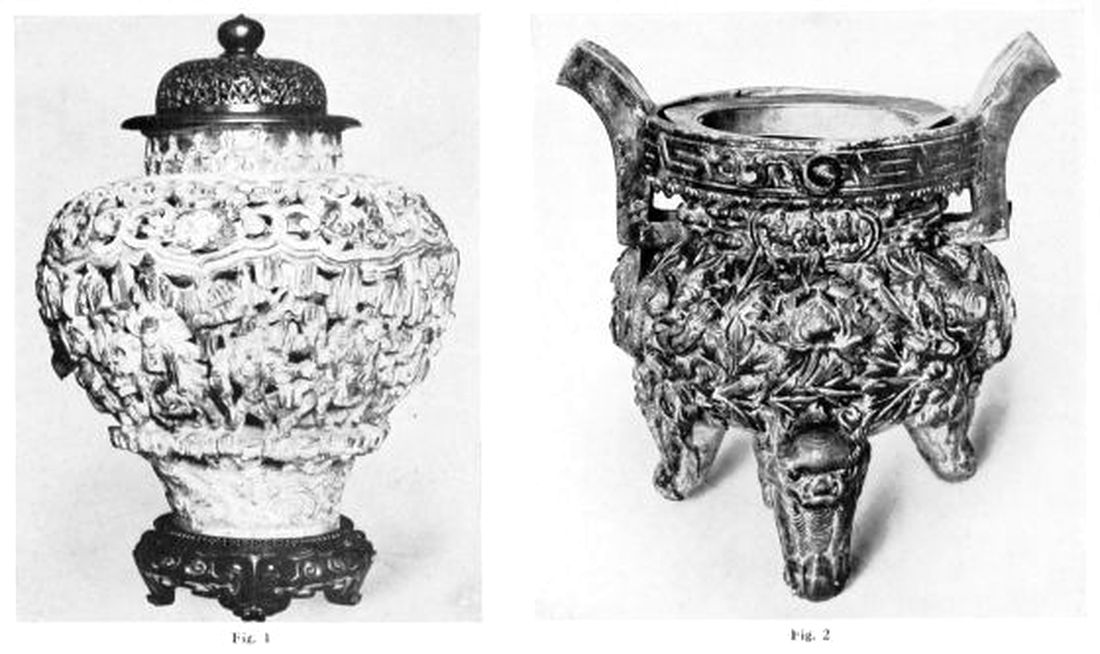

| Fig. 1.—Wine Jar with pierced outer casing, horsemen and attendants, rocky background. | |

| Fifteenth century. Eumorfopoulos Collection. | |

| Fig. 2.—Tripod Incense Vase, dragons and peony designs and a panel of horsemen. | |

| Dated 1529 A.D. Messel Collection. | |

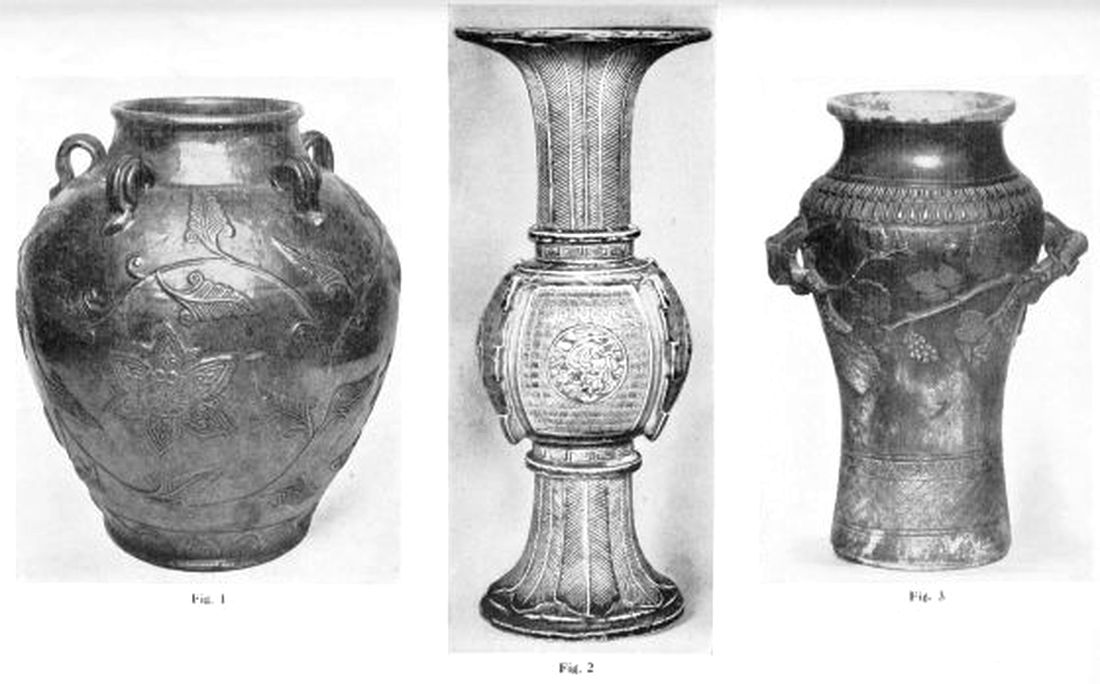

| 56. MISCELLANEOUS POTTERY | 200 |

| Fig. 1.—Jar with dull green glaze and formal lotus scroll in relief touched with yellow | |

| and brown glazes. About 1600. Goff Collection. | |

| Fig. 2.—Beaker of bronze form, soft whitish body and dull green glaze. (?) Seventeenth | |

| century. Eumorfopoulos Collection. | |

| Fig. 3.—Vase of light buff ware with dull black dressing, vine reliefs. Mark, Nan hsiang t´ang. | |

| Eighteenth century. Eumorfopoulos Collection. | |

| 57. SEATED FIGURE OF KUAN YÜ, THE WAR–GOD OF CHINA, A DEIFIED WARRIOR (Colour) | 204[xiv] |

| Reddish buff pottery with blue, yellow and turquoise glazes, and a colourless glaze on the | |

| white parts. Sixteenth century. Eumorfopoulos Collection. | |

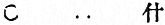

| 58. MISCELLANEOUS POTTERY | 206 |

| Fig. 1.—Jar with lotus design in green, yellow and turquoise glazes in an aubergine ground. | |

| About 1600. Hippisley Collection. | |

| Fig. 2.—Vase of double fish form, buff ware with turquoise, yellow and aubergine glazes. (?) | |

| Seventeenth century. British Museum. | |

| Fig. 3.—Roof–tile with figure of Bodhidharma, deep green and creamy white glazes. | |

| Sixteenth century. Benson Collection. | |

| Fig. 4.—Bottle with archaic dragon (ch´ih lung) on neck, variegated glaze of lavender, | |

| blue and green clouded with purple and brown. (?) Eighteenth century. Yi–hsing ware. | |

| Peters Collection. |

WHEN we consider the great extent of the Chinese Empire and its teeming population—both of them larger than those of Europe—and the fact that a race with a natural gift for the potter's craft and a deep appreciation of its productions has lived and laboured there for twenty centuries (to look no farther back than the Han dynasty), it seems almost presumptuous to attempt a history of so vast and varied an industry within the compass of two volumes. Anything approaching finality in such a subject is out of the question, and, indeed, imagination staggers at the thought of a complete record of every pottery started in China in the past and present.

As far as pottery is concerned, we must be content with the identification of a few prominent types and with very broad classifications, whether they be chronological or topographical. Indeed, the potteries named in the Chinese records are only a few of those which must have existed; and though we may occasionally rejoice to find in our collections a series like the red stonewares of Yi–hsing, which can be definitely located, a very large proportion of our pottery must be labelled uncertain or unknown. How many experts here or on the Continent could identify the pottery made in South Germany or Hungary a hundred years ago? What chance, then, is there of recognising any but the most celebrated wares of China?

In dealing with porcelain as distinct from pottery, we have a simpler proposition. The bulk of what we see in Europe is not older than the Ming dynasty and was made at one of two large centres, viz. Ching–tê Chên in Kiangsi, and Tê–hua in Fukien. Topographical arrangement, then, is an easy matter, and there[xvi] is a considerable amount of information available to guide us in chronological considerations.

The antiquity of Chinese porcelain, its variety and beauty, and the wonderful skill of the Chinese craftsmen, accumulated from the traditions of centuries, have made the study of the potter's art in China peculiarly absorbing and attractive. There is scope for every taste in its inexhaustible variety. Compared with it in age, European porcelain is but a thing of yesterday, a mere two centuries old, and based from the first on Chinese models. Even the so–called European style of decoration which developed at Meissen and Sèvres, though quite Western in general effect, will be found on analysis to be composed of Chinese elements. It would be useless to compare the artistic merits of the Eastern and Western wares.

It is so much a matter of personal taste. For my own part, I consider that the decorative genius of the Chinese and their natural colour sense, added to their long training, have placed them so far above their European followers that comparison is irrelevant. Even the commoner sorts of old Chinese porcelain, made for the export trade, have undeniable decorative qualities, while the specimens in pure Chinese taste, and particularly the Court wares, are unsurpassed in quality and finish.

The merits and beauty of porcelain have always been recognised by the Chinese, who ranked it from the earliest days among their precious materials. Chinese poets make frequent reference to its dainty qualities, its jade–like appearance, its musical ring, its lightness and refinement. The green cups of Yüeh Chou ware in the T´ang dynasty were likened to moulded lotus leaves; and the white Ta–yi bowls surpassed hoar–frost and snow. Many stanzas were inspired by the porcelain bowls used at the tea and wine symposia, where cultivated guests capped each other's verses. In a pavilion at Yün–mên, in the vicinity of Ching–tê Chên, is a tablet inscribed, "The white porcelain is quietly passed all through the night, the fragrant vapour (of the tea) fills the peaceful pavilion," an echo of a symposium held there by some distinguished persons in the year 1101 A. D., and no doubt alluding to wares of local make.[xvii] Elsewhere[1] we read of a drinking–bout in which the wine bowls of white Ting Chou porcelain inspired a verse–capping competition. "Ting Chou porcelain bowls in colour white throughout the Empire," wrote one. Another followed, "Compared with them, glass is a light and fickle mistress, amber a dull and stupid female slave." The third proceeded: "The vessel's body is firm and crisp; the texture of its skin is yet more sleek and pleasing."

The author of the P´ing hua p´u, a late Ming work on flower vases, exhorts us: "Prize the porcelain and disdain gold and silver. Esteem pure elegance."

In their admiration of antiques the Chinese yield to none, and nowhere have private collections been more jealously guarded and more difficult of access. Even in the sixteenth century relatively large sums were paid for Sung porcelains, and £30 was not too much for a "chicken wine cup" barely a hundred years old. The ownership of a choice antique—say, of the Sung dynasty—made the possessor a man of mark; perhaps even a marked man if the local ruler chanced to be of a grasping nature.

A story is told on p. 75 of this volume of a Ko ware incense burner (afterwards sold for 200 ounces of gold), which brought a man to imprisonment and torture in the early Ming period; and, if the newspaper account was correct, there was an incident in the recent revolution which should touch the collector's heart. A prominent general, who, like so many Chinese grandees, was an ardent collector, was expecting a choice piece of porcelain from Shanghai. In due course the box arrived and was taken to the general's sanctum. He proceeded to open it, no doubt with all the eagerness and suppressed excitement which collectors feel in such tense moments, only to be blown to pieces by a bomb! His enemies had known too well the weak point in his defence.

Collecting is a less dangerous sport in England; but if it were not so, the ardent collector would be in no way deterred. Warnings are wasted on him, and he would follow his quarry, even though the path were strewn with fragments of his indiscreet fellows. Still less is he discouraged by difficulties of another kind, as illustrated[xviii] 'by the story[2] of T´ang's white Sung tripod, which was so closely imitated that its owner, one of the most celebrated collectors of the sixteenth century, could not distinguish the copy from the original. An eighteenth century Chinese writer points the moral of the story: "When connoisseurs point with admiration to a vessel, calling it Ting ware, or, again, Kuan ware, how can we know that it is not a 'false tripod' which deceives them?" The force of this question will be appreciated by collectors of Sung wares, especially of the white Ting porcelains and the green celadons; for there is nothing more difficult to classify correctly than these long–lived types. There are, however, authentic Sung examples within reach, and we can train our eyes with these, so that nothing but the very best imitations will deceive us; and, after all, if we succeed in obtaining a really first–rate Ming copy of a Sung type we shall be fortunate, for if we ever discover the truth—which is an unlikely contingency—we may console ourselves with thoughts of the enthusiast who eventually bought T´ang's false tripod for £300 and "went home perfectly happy."

In spite of all that has been written in the past on Oriental ceramics, the study is still young, and it will be long before the last word is said on the subject. Still our knowledge is constantly increasing, and remarkable strides have been made in recent years. The first serious work on Chinese porcelain was Julien's translation of the Ching–tê Chên t´ao lu, published in 1856. The work of a scholar who was not an expert, it was inevitably marred by misunderstanding of the material, and subsequent writers who followed blindly were led into innumerable confusions. The Franks Catalogue, issued in 1876, was one of the first attempts to classify Oriental wares on some intelligible system; but it was felt that not enough was known at that time to justify a chronological classification of the collection, and the somewhat unscientific method of grouping by colours and processes of decoration was adopted as a convenient expedient. At the end of last century Dr. S.W. Bushell revolutionised the study of Chinese porcelain by his Oriental Ceramic Art, a book, unfortunately, difficult to obtain, and by editing Cosmo Monkhouse's[xix] excellent History and Description of Chinese Porcelain. These were followed by the South Kensington Museum Handbook and by the translation and reproduction of the sixteenth century Album of Hsiang Yüan–p´ien, and later by the more important translation of the T´ao shuo.

It would be impossible to over–estimate the importance of Bushell's pioneer work; and I hasten to make the fullest acknowledgment of the free use I have made of his writings, the more so because I have not hesitated to criticise freely his translations where necessary. The Chinese language is notoriously obscure and ambiguous, and differences of opinion on difficult passages are inevitable. In fact, I would say that it is unwise to build up theories on any translation whatsoever without verifying the critical passages in the original. For this reason I found it necessary to work laboriously through the available Chinese ceramic literature, a task which would have been quite impossible with my brief acquaintance with the language had it not been for the invaluable aid of Dr. Lionel Giles, who helped me over the difficult ground. I have, moreover, taken the precaution of giving the Chinese text in all critical passages, so that the reader may satisfy himself as to their true meaning.

While Dr. Bushell's contributions have greatly simplified the study of the later Chinese porcelains, little or no account was taken in the older books of the pottery and early wares. The materials necessary for the study of these were wanting in Europe. Stray examples of the coarser types and export wares had found their way into our collections, but not in sufficient numbers or importance to arouse any general interest, and the condition of the Western market for the early types was not such as to tempt the native collector to part with his rare and valued specimens. In the last few years the position has completely changed. The opening up of China and the increased opportunities which Europeans enjoy, not only for studying the monuments of ancient Chinese art, but for acquiring examples of the early masterpieces in painting, sculpture, bronze, jade, and ceramic wares, have given the Western student a truer insight into the greatness of the earlier phases of Chinese art, and have awakened a new and widespread enthusiasm for them.[xx] An immense quantity of objects, interesting both artistically and archæologically, has been discovered in the tombs which railway construction has incidentally opened; and although this rich material has been gathered haphazard and under the least favourable conditions for accurate classification, a great deal has been learnt, and it is not too much to say that the study of early Chinese art has been completely revolutionised. Numerous collections have been formed, and the resulting competition has created a market into which even the treasured specimens of the Chinese collectors are being lured. Political circumstances have been another factor of the situation, and the Western collector has profited by the unhappy conditions which have prevailed in China since the revolution in 1912.

The result of all this, ceramically speaking, is that we are now familiar with the pottery of the Han dynasty; the ceramic art of the T´ang period has been unfolded in wholly unexpected splendour; the Sung problems no longer consist in reconciling ambiguous Chinese phrases, but in the classification of actual specimens; the Ming porcelain is seen in clearer perspective, and our already considerable information on the wares of the last dynasty has been revised and supplemented by further studies. So much progress, in fact, has been made, that it was high time to take stock of the present position, and to set out the material which has been collected, not, of course, with any thoughts of finality, but to serve as a basis for a further forward move. That is the purpose of the present volumes, in which I have attempted merely to lay before the reader the existing material for studying Chinese ceramics as I have found it, adding my own conclusions and comments, which he may or may not accept.

The most striking additions to our knowledge in recent years, have without doubt been those which concern the T´ang pottery. What was previously a blank is now filled with a rich series covering the whole gamut of ceramic wares, from a soft plaster–like material through faïence and stoneware up to true porcelain. The T´ang potters had little to learn in technical matters. They used the soft lead glazes, coloured green, blue, amber, and purplish brown[xxi] by the same metallic oxides as formed the basis of the cognate glazes on Ming pottery. They used high–fired feldspathic glazes, white, brownish green, chocolate brown, purplish black, and tea–dust green, sometimes with frothy splashes of grey or bluish grey, as on the Sung wares. Sometimes these glazes were superposed as on the Japanese tea jars, which avowedly owed their technique to Chinese models. It is evident that streaked and mottled effects appealed specially to the taste of the time, and marbling both of the glaze and of the body was practised. Carving designs in low relief, or incising them with a pointed instrument and filling in the spaces with coloured glazes, stamping small patterns on the body, and applying reliefs which had been previously pressed out in moulds, were methods employed for surface decoration. Painted designs in unfired pigments appear on some of the tomb wares, and it is now practically certain that painting in black under a green glaze was used by the T´ang potters. Moreover, the existence of porcelain proper in the T´ang period is definitely established.

One of the most remarkable features of T´ang pottery is the strong Hellenistic flavour apparent in the shapes of the vessels and in certain details of the ornament, particularly in the former. Other foreign influences observable in T´ang art are Persian, Sassanian, Scytho–Siberian, and Indian, and one would say that Chinese art at this period was in a peculiarly receptive state. As compared with the conventional style of later ages which we have come to regard as characteristically Chinese, the T´ang art is quite distinctive, and almost foreign in many of its aspects.

The revelation of T´ang ceramics has provided many surprises, and doubtless there are more in store for us. There are certainly many gaps to fill and many apparent anomalies to explain. We are still in the dark with regard to the potter's art of the four hundred years which separate the Han and T´ang dynasties. The Buddhist sculptures of this time reveal a high level of artistic development, and we may assume that the minor arts, and pottery among them, were not neglected. When some light is shed from excavation or otherwise upon this obscure interval, no doubt we[xxii] shall see that we have fixed our boundaries too rigidly, and that the Han types must be carried forward and the T´ang types carried back to bridge the gap. Meanwhile, we can only make the best of the facts which have been revealed at present, keeping our classification as elastic as possible. Probably the soft lead glazes belong to the earlier part of the T´ang period and extend back to the Sui and Wei, linking up with the green glaze of the Han pottery, while the high–fired glazes tended to supersede these in the latter part of the dynasty.

The high–fired feldspathic glazes seem to have held the field entirely in the Sung dynasty, and the lead glazes, as far as our observation goes, do not reappear until the Ming dynasty.

The Sung is the age of high–fired glazes, splendid in their lavish richness and in the subtle and often unforeseen tints which emerge from their opalescent depths. It is also an age of bold, free potting, robust and virile forms, an age of pottery in its purest manifestation. Painted ornament was used at certain factories in black and coloured clays, and, it would seem, even in red and green enamels; but painted ornament was less esteemed than the true ceramic decoration obtained by carving, incising, and moulding—processes which the potters worked with the clay alone.

If we could rest content with a comprehensive classification of the Sung wares, as we have had perforce to do in the case of the T´ang, one of the chief difficulties in this part of our task would be avoided. But the Chinese have given us a number of important headings, under which it has become obligatory to try and group our specimens. Some of these types have been clearly identified, but there are others which still remain vague and ill–defined; and there are many specimens, especially among the coarser kinds of ware, which cannot be referred to any of the main groups. But the true collector will not find the difficulties connected with the Sung wares in any way discouraging. He will revel in them, taking pleasure in the fact that he has new ground to break, many riddles to solve, and a subject to master which is worthy of his steel.

Apparently a coarse form of painting in blue was employed[xxiii] at one factory at least in the Sung period,[3] and we may now consider it practically certain that the first essays in painting both under and over the glaze go back several centuries earlier than was previously supposed. Blue and white and polychrome porcelain chiefly occupied the energies of the Imperial potters at Ching–tê Chên in the Ming dynasty, and the classic periods for these types fall in the fifteenth century. The vogue of the Sung glazes scarcely survived the brief intermediate dynasty of the Yüan, and we are told by a Chinese writer[4] that "on the advent of the Ming dynasty the pi sê[5] began to disappear." Pictorial ornament and painted brocade patterns were in favour on the Ming wares; and it will be observed that as compared with those of the later porcelains the Ming designs are painted with more freedom and individuality. In the Ch´ing dynasty the appetite of the Ching–tê Chên potters was omnivorous and their skill was supreme. They are not only noted for certain specialities, such as the K´ang Hsi blue and white and famille verte, the sang de bœuf and peach–bloom reds, and for the development of the famille rose palette, but for the revival of all the celebrated types of the classic periods of the Sung and Ming; and when they had exhausted the possibilities of these they turned to other materials and copied with magical exactitude the ornaments in metal, carved stone, lacquer, wood, shell, glass—in a word, every artistic substance, whether natural or artificial.

The mastery of such a large and complex subject as Oriental ceramics requires not a little study of history and technique, in books and in collections. The theory and practice should be taken simultaneously, for neither can be of much use without the other. The possession of a few specimens which can be freely handled and closely studied is an immense advantage. They need not be costly pieces. In fact, broken fragments will give as much of the all–important information on paste and glaze as complete specimens.[xxiv] Those who have not the good fortune to possess the latter, will find ample opportunity for study in the public museums with which most of the large cities of the world are provided. The traveller will be directed to these by his "Baedeker," and I shall only mention a few of the most important museums with which I have personal acquaintance, and to which I gratefully express my thanks for invaluable assistance.

London.—The Victoria and Albert Museum possesses the famous Salting Collection, in which the Ch´ing dynasty porcelains are seen at their best: besides the collection formed by the Museum itself and many smaller bequests, gifts, and loans, in which all periods are represented. The Franks Collection in the British Museum is one of the best collections for the student because of its catholic and representative nature.

Birmingham and Edinburgh have important collections in their art galleries, and most of the large towns have some Chinese wares in their museums.

Paris.—The Grandidier Collection in the Louvre is one of the largest in the world. The Cernuschi Museum contains many interesting examples, especially of the early celadons, and the Musée Guimet and the Sèvres Museum have important collections.

Berlin.—The Kunstgewerbe Museum has a small collection containing some important specimens. The Hohenzollern Museum and the Palace of Charlottenburg have historic collections formed chiefly at the end of the seventeenth century.

Dresden.—The famous and historic collection, formed principally by Augustus the Strong, is exhibited in the Johanneum, and is especially important for the study of the K´ang Hsi porcelains. The Stübel Collection in the Kunstgewerbe Museum, too, is of interest.

Gotha.—The Herzögliches Museum contains an important series of the Sung and Yüan wares formed by Professor Hirth.

Cologne.—An important and peculiarly well–arranged museum of Far–Eastern art, formed by the late Dr. Adolf Fischer and his wife, is attached to the Kunstgewerbe Museum.

New York.—The Metropolitan Museum is particularly rich in[xxv] Ming and Ch´ing porcelains. It is fortunate in having the splendid Pierpont Morgan Collection and the Avery Collection, and when the Altmann Collection is duly installed in its galleries it will be unrivalled in the wares of the last dynasty. The Natural History Museum has a good series of Han pottery.

Chicago.—The Field Museum of Natural History has probably the largest collection of Han pottery and T´ang figurines in the world. It has also an interesting series of later Chinese pottery, including specimens from certain modern factories which are important for comparative study. These collections were formed by Dr. Laufer in China. There is also a small collection of the later porcelains in the Art Institute.

Boston.—The Museum of Fine Arts has a considerable collection of Chinese porcelain, in which the earlier periods are specially well represented. The American collections, both public and private, are especially strong in monochrome porcelains, and in this department they are much in advance of the European.

To acknowledge individually all the kind attentions I have received from those in charge of the various museums would make a long story. They will perhaps forgive me if I thank them collectively. The private collectors to whom I must express my gratitude are scarcely less numerous. They have given me every facility for the study of their collections, and in many cases, as will be seen in tile list of plates, they have freely assisted with the illustrations. I am specially indebted to Mr. Eumorfopoulos, Mr. Alexander, Mr. R. H. Benson, Mr. S. T. Peters, and Mr. C. L. Freer, who have done so much for the study of the early wares in England and America. Without the unstinted help of these enthusiastic collectors it would have been impossible to produce the first volume of this book. What I owe to Mr. Eumorfopoulos can be partly guessed from the list of plates. His collection is an education in itself, and he has allowed me to draw freely on it and on his own wide experience. Of the many other collectors who have similarly assisted in various parts of the work, I have to thank Sir Hercules Read, Mr. S. E. Kennedy, Dr. A. E. Cumberbatch, Mr. C. L. Rothenstein, Dr. Breuer, Dr. C. Seligmann, M. R.[xxvi] Koechlin, Mr. O. Raphael, Mr. A. E. Hippisley, Hon. Evan Charteris, Lady Wantage, Mr. Burdett–Coutts, the late Dr. A. Fischer, Mr. L. C. Messel, Mr. W. Burton, Col. Goff, Mrs. Halsey, Mrs. Havemeyer, Rev. G. A. Schneider, and Mrs. Coltart. A portion of the proofs has been read by Mr. W. Burton. Mr. L. C. Hopkins has given me frequent help with Chinese texts, and especially in the reading of seal characters; and my colleague, Dr. Lionel Giles, in addition to invaluable assistance with the translations, has consented to look through the proofs of these volumes with a special view to errors in the Chinese characters. Finally, I have to thank my chief, Sir Hercules Read, not only for all possible facilities in the British Museum, but for his sympathetic guidance in the study of a subject of which he has long been a master.

R. L. HOBSON.

ANDERSON, W., Catalogue of the Japanese and Chinese Paintings in the British Museum. 1886.

BINYON, L., "Painting in the Far East."

BRETSCHNEIDER, E., "Mediæval Researches from Eastern Asiatic Sources," Truebner's Oriental Series. 1878.

BRINKLEY, CAPT. F., "China, its History, Arts and Literature," vol. ix. London, 1904.

BURTON, W., "Porcelain: A Sketch of its Nature, Art and Manufacture." London, 1906.

BURTON, W., AND HOBSON, "Marks on Pottery and Porcelain." London, 1912.

BUSHELL, S. W., "Chinese Porcelain, Sixteenth–Century coloured illustrations with Chinese MS. text," by Hsiang Yüan–p´ien, translated by S.W. Bushell. Oxford, 1908. Sub–title "Porcelain of Different Dynasties."

BUSHELL, S. W., "Chinese Porcelain before the Present Dynasty," being a translation of the last, with notes. Peking, 1886.

BUSHELL, S. W., "Description of Chinese Pottery and Porcelain," being a translation of the T´ao shuo. Oxford, 1910.

BUSHELL, S. W., "Oriental Ceramic Art, Collection of W.T. Walters." New York, 1899.

BUSHELL, S. W., Catalogue of the Pierpont Morgan Collection. New York.

BUSHELL, S. W., "Chinese Art," 2 vols., "Victoria and Albert Museum Handbook." 1906.

CHAVANNES, EDOUARD, "La Sculpture sur pierre en Chine au temps des deux dynasties Han." Paris, 1893.

CHAVANNES, EDOUARD, "Mission Archéologique dans la Chine Septentrionale." Paris, 1909.

The Chiang hsi t´ung chih

. The topographical history of the province of Kiangsi, revised edition in 180 books, published in 1882.

The Ch´in ting ku chin t´u shu chi ch´êng

. The encyclopædia of the K´ang Hsi period, Section XXXII. Handicrafts (k´ao kung). Part 8 entitled T´ao kung pu hui k´ao, and Part 248 entitled Tz´ŭ ch´i pu hui k´ao.

Chin shih so

"Researches in Metal and Stone," by the Brothers Fêng. 1821.

The Ch´ing pi ts´ang

"A Storehouse of Artistic Rarities," by Chang Ying–wên, published by his son in 1595.

The Ching–tê Chên t´ao lu

, "The Ceramic Records of Ching–tê Chên," in ten parts, by Lan P´u, published in 1815. Books VIII. and IX. are a corpus of references to pottery and porcelain from Chinese literature.

The Ching tê yao

, "Porcelain of Ching–tê Chên," a volume of MS. written about 1850.

The Cho kêng lu

, "Notes jotted down in the intervals of ploughing," a miscellany on works of art in thirty books, by T´ao Tsung–i, published in 1368. The section on pottery is practically a transcript of a note in the Yüan chai pi hêng, by Yeh Chih, a thirteenth–century writer.

D'ENTRECOLLES, PÈRE, "Two Letters written from Ching–tê Chên in 1712 and 1722," published in Lettres édifiantes et curieuses, and subsequently reprinted in Bushell's "Translation of the T´ao shuo" (q.v.), and translated in Burton's "Porcelain" (q.v.).

DE GROOT, J. J. M., "Les Fêtes Annuellement Célébrées à Émoi," "Annales du Musée Guimet," Vols. XI. and XII. Paris, 1886.

DE GROOT, J. J. M., "The Religious System of China." Leyden, 1894.

DILLON, E., "Porcelain" (The Connoisseur's Library).

DUKES, E. J., "Everyday Life in China, or Scenes in Fuhkien." London, 1885.

FOUCHER, A., "Étude sur l'iconographie bouddhique de l'Inde." Paris, 1900.

FRANKS, A. W., Catalogue of a Collection of Oriental Porcelain and Pottery. London, 1879.

GILES, H. A., A Glossary of Reference on Subjects connected with the Far East. Shanghai, 1900.

GRANDIDIER, E., "La Céramique Chinoise." Paris, 1894.

GRÜNWEDEL, A., "Mythologie des Buddhismus in Tibet und der Mongolei." Leipzig, 1900.

GULLAND, W. G., "Chinese Porcelain." London, 1902.

HIRTH, F., "China and the Roman Orient." Leipzig, 1885.

HIRTH, F., "Ancient Porcelain," a Study in Chinese Mediæval Industry and Trade. Leipzig, 1888.

HIRTH, F., AND W. W. ROCKHILL, "Chau Ju–kua, his Work on the Chinese and Arab Trade in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, entitled Chu–fan–chi." St. Petersburg, 1912.

HOBSON, R. L., "Porcelain, Oriental, Continental and British," second edition. London, 1912.

HOBSON, R. L., "The New Chaffers." London, 1913.

HOBSON, R. L., AND BURTON, "Marks on Pottery and Porcelain," second edition. London, 1912.

HSIANG YÜAN–P´IEN. See BUSHELL.

JACQUEMART, A., AND E. LE BLANT, "Histoire de la Porcelaine." Paris, 1862.

JULIEN, STANISLAS, "Histoire et Fabrication de la Porcelaine Chinoise." Paris, 1856. Being a translation of the greater part of the Ching–tê Chên t´ao lu, with various notes and additions.

The Ko ku yao lun

, "Essential Discussion of the Criteria of Antiquities," by Tsao Ch´ao, published in 1387 in thirteen books; revised and enlarged edition in 1459.

LAUFER, BERTHOLD, "Chinese Pottery of the Han Dynasty," Leyden, 1909.

LAUFER, BERTHOLD, "Jade, a Study in Chinese Archæology and Religion," Field Museum of Natural History, Anthropological Series, Vol. X. Chicago, 1912.

The Li t´a k´an k´ao ku ou pien

, by Chang Chin–chien. 1877.

MAYERS, W. F., "The Chinese Reader's Manual." Shanghai, 1874.

MEYER, A. B., "Alterthümer aus dem Ostindischen Archipel."

MONKHOUSE, COSMO, "A History and Description of Chinese Porcelain, with notes by S.W. Bushell." London, 1901.

PLAYFAIR, G. M. H., "The Cities and Towns of China." Hong–Kong, 1910.

The Po wu yao lan

, "A General Survey of Art Objects," by Ku Ying–t´ai, published in the T´ien Ch´i period (1621–27).

RICHARD, L., "Comprehensive Geography of the Chinese Empire." Shanghai, 1908.

SARRE, F., AND B. SHULZ, "Denkmäler Persischer Baukunst." Berlin, 1901–10.

STEIN, M. A., "Ruins of Desert Cathay." London, 1912.

STEIN, M. A., "Sand–buried Ruins of Khotan." London, 1903.

Shin sho sei, etc., "Japan, Antiquarian Gallery." 1891.

T´ao lu. See Ching–tê Chên t´ao lu.

T´ao shuo

, "A Discussion of Pottery," by Chu Yen, in six parts, published in 1774. See BUSHELL.

Toyei Shuko, An Illustrated Catalogue of the Ancient Imperial Treasury called Shoso–in, compiled by the Imperial Household. Tokyo, 1909.

T´u Shu. See Chin ting ku chin t´u shu chi ch´êng.

WARNER, LANGDON, AND SHIBA–JUNROKURO, "Japanese Temples and their Treasures." Tokyo, 1910.

WILLIAMS, S. WELLS, The Chinese Commercial Guide. Hongkong, 1863.

YULE, SIR H., "The Book of Ser Marco Polo." London, 1903.

ZIMMERMANN, E., "Chinesisches Porzellan." Leipzig, 1913.

BAHR, A. W., "Old Chinese Porcelain and Works of Art in China." London, 1911.

BELL, HAMILTON, "'Imperial' Sung Pottery," Art in America, July, 1913.

BÖRSCHMANN, E., "On a Vase found at Chi–ning Chou," Zeitschrift für Ethnologie, Jahrg. 43, 1911.

BRETSCHNEIDER, E., Botanicon Sinicum, Journal of the North–China Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. New Series, Vol. XVI., Part 1, 1881.

BRINKLEY, F., Catalogue of the Exhibitions at the Boston Museum of Arts, 1884.

Burlington Magazine, The, passim.

BUSHELL, S. W., "Chinese Porcelain before the Present Dynasty," Journal of the Peking Oriental Society, 1886.

Catalogue of a Collection of Early Chinese Pottery and Porcelain, Burlington Fine Arts Club, 1910.

CLENNELL, W. J., "Journey in the Interior of Kiangsi," Consular Report. H.M. Stationery Office.

COLE, FAY–COOPER, "Chinese Pottery in the Philippines, with postscript by Berthold Laufer," Field Museum of Natural History, Publication 162. Chicago, 1912.

EITEL, E. J., "China Review," Vol. X., p. 308, "Notes on Chinese Porcelain."

GROENEVELDT, W. P., Notes on the Malay Archipelago, Verhandelingen van het Bataviaasch Genootschap van Kunsten en Wetenschappen, Deel. xxxix.

HIPPISLEY, A. E., Catalogue of the Hippisley Collection of Chinese Porcelains, Smithsonian Institute. Second Edition. Washington, 1900.

HOBSON, R. L., Catalogue of a Collection of Early Chinese Pottery and Porcelain, Burlington Fine Arts Club. 1910.

HOBSON, R. L., Catalogue of Chinese, Corean and Japanese Potteries. New York Japan Society, 1914.

HOBSON, R. L., Burlington Magazine, Wares of the Sung and Yüan Dynasties, in six articles, April, May, June, August, and November, 1909, and January, 1910.

HOBSON, R. L., "On Some Old Chinese Pottery," Burlington Magazine. August, 1911.

HOBSON, R. L., AND O. BRACKETT, Catalogue of the Porcelain and Works of Art in the Collection of the Lady Wantage.

KERSHAW, F. S., Note in Inscribed Han Pottery, Burlington Magazine, December, 1913.

LAFFAN, W., Catalogue of the Pierpont Morgan Collection in the Metropolitan Museum, New York.

MARTIN, DR., Note on a Sassanian Ewer, Burlington Magazine, September, 1912.

MEYER, A. B., "On the Celadon Question," Oesterreichische Monatsschrift, January, 1885, etc.

MORGAN, J. P., Catalogue of the Morgan Collection of Chinese Porcelains, by S.W. Bushell and W.M. Laffan. New York, 1907.

PARIS, Exposition universelle de 1878, Catalogue spécial de la Collection Chinoise.

PERZYNSKI, F., "Towards a Grouping of Chinese Porcelain," Burlington Magazine, October and December, 1910, etc.

PERZYNSKI, F., "Jagd auf Götter," in the Neue Rundschau, October, 1913.

PERZYNSKI, F., on T´ang Forgeries, Ostasiatischer Zeitschrift, January, 1914.

READ, C. H., in Man, 1901, No. 15, "On a T´ang Vase and Two Mirrors from a Tomb in Shensi."

REINAUD, M., "Relation des Voyages faits par les Arabes et les Persans dans l'Inde et à la Chine dans la IX⚭ siècle de l'ére chrétienne." Paris, 1845.

SOLON, L., "The Noble Buccaros," North Staffordshire Literary and Philosophic Society, October 23rd, 1896.

TORRANCE, REV. TH., "Burial Customs in Szechuan," Journal of the N. China Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, Vol. XLI., 1910, p. 58.

VORETZSCH, E. A., Hamburgisches Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe, Führer durch eine Ausstellung Chinesischer Kunst, 1913.

WILLIAMS, MRS. R. S., Introductory Note to the Catalogue of a Loan Exhibition of Chinese, Corean, and Japanese Potteries held by the Japan Society of New York, 1914.

ZIMMERMANN, E., "Wann ist das Chinesische Porzellan erfunden und wer war sein Erfinder?" Orientalisches Archiv. Sonderabdruck.

THE PRIMITIVE PERIODS

POTTERY, as one of the first necessities of mankind, is among the earliest of human inventions. In a rude form it is found with the implements of the late Stone Age, before there is any evidence of the use of metals, and all attempts to reconstruct the first stages of its discovery are based on conjecture alone.

We have no knowledge of a Stone Age in China, but it may be safely assumed that pottery there, as elsewhere, goes back far into prehistoric times. Its invention is ascribed to the mythical Shên–nung, the Triptolemus of China, who is supposed to have initiated the people in the cultivation of the soil and other necessary arts of life. Huang Ti, the semi–legendary yellow emperor, in whose reign the cyclical system of chronology began (2697 B. C.), is said to have appointed "a superintendent of pottery, K´un–wu, who made pottery," and it was a commonplace in the oldest Chinese literature[6] that the great and good emperor Yü Ti Shun (2317–2208 B. C.) "highly esteemed pottery." Indeed, the Han historian Ssŭ–ma Ch´ien (163–85 B. C.) assures us that Shun himself, before ascending the throne, "fashioned pottery at Ho–pin," and, needless to say, the vessels made at Ho–pin were "without flaw."

According to the description given in the T´ao shuo, the evolution of the potter's art in China took the usual course. The first articles made were cooking vessels; then, "coming to the time of Yü (i.e. Yü Ti Shun), the different kinds of wine vessels are distinguished by name, and the sacrificial vessels are gradually becoming complete."[7]

I should add that the author of the T´ao shuo, after accepting the earlier references to the art, inconsistently concludes: "I humbly suggest that the origin of pottery should strictly be placed in the reign of Yü Ti Shun, and its completion in the Chou dynasty" (1122–256 B. C.).

Unfortunately, none of the writers can throw any light on the first use of the potter's wheel in China. It is true that, like several other nations, the Chinese claim for themselves the invention of that essential implement, but there is no real evidence to illuminate the question, and even if the wheel was independently discovered in China, the priority of invention undoubtedly rests with the Near Eastern nations. Palpable evidence of its use can be seen on Minoan pottery found in Crete and dating about 3000 B. C., and on Egyptian pottery of the twelfth dynasty (about 2200 B. C.); while it is practically certain that it was used in the making of the Egyptian pottery of the fourth dynasty (about 3200 B. C.).

So far, the Chinese have nothing tangible to oppose to these facts earlier than the Chou writings, in which workers with the wheel (t´ao jên) are distinguished from workers with moulds (fang jên), the former making cauldrons, basins, colanders, boilers, and vessels (yü), and the latter moulding the sacrificial vessels named kuei and tou. We learn that at this time the Chinese potters also used the compasses and the polishing wheel or lathe. With this outfit they were able, according to the T´ao shuo, to effect the "completion" of pottery.

Whatever the truth of this pious statement may be, reflecting as it does the true Chinese veneration of antiquity, it is certain, at any rate, that the potter was not without honour at this time: for we read in the Tso Chuan[8] that "O–fu of Yü was the best potter at the beginning of the Chou dynasty. Wu Wang relied on his skill for the vessels which he used. He wedded him to a descendant of his imperial ancestors, and appointed him feudal prince of Ch´ên."

Examples of these early potteries have been unearthed from ancient burials from time to time, and the T´ao shuo describes numerous types from literary sources. But neither the originals, as far as we know them, nor the verbal descriptions of them, have anything but an antiquarian interest.

The art of the Chou dynasty, as expressed in bronze and jade, is fairly well known from illustrated Chinese and Western works. It reflects a priestly culture in its hieratic forms and symbolical ornament. It is majestic and stern, severely disdainful of sentiment and sensuous appeal. Of the pottery we know little, but that little shows us a purely utilitarian ware of simple form, unglazed and almost devoid of ornament.

On Plate 1 are two types which may perhaps be regarded as favourable examples of Chou pottery. A tripod vessel, almost exactly similar to Fig. 1, was published by Berthold Laufer,[9] who shows by analogy with bronzes of the period good reasons for its Chou attribution, which he states is confirmed by Chinese antiquarians. His example was of hard "gray clay, which on the surface has assumed a black colour," and it had the surface ornamented with a hatched pattern similar to that of our illustration. It has been assumed that this hatched pattern is a sure sign of Chou origin, and I have no doubt that it was a common decoration at the time. But its use continued after the Chou period, and it is found on pottery from a Han tomb in Szechuan, which is now in the British Museum. It is, in fact, practically the same as the "mat marking" on the Japanese and Corean pottery taken from the dolmens which were built over a long period extending from the second century B. C. to the eighth century A. D.

The taste of the time is reflected in a sentence which occurs in

the Kuan–tzŭ, a work of the fifth century B. C.: "Ornamentation

detracts from the merit of pottery."[10] The words used for ornamentation

are wên ts´ai  (lit. pattern, bright colours), and they

seem to imply a knowledge of some means of colouring the ware. As

there is no evidence of the use of glaze before the Han period,

and enamelling in the ordinary ceramic sense is out of the question,

we may perhaps assume that some of the pottery of the Chou

period was painted with unfired pigments, a method certainly in

use in the Han dynasty. There is a vase in the British Museum

of unglazed ware with painted designs in black, red and white

pigments, which has been regarded as of Han period, but may

possibly be earlier (Plate 2, Fig. 3).

(lit. pattern, bright colours), and they

seem to imply a knowledge of some means of colouring the ware. As

there is no evidence of the use of glaze before the Han period,

and enamelling in the ordinary ceramic sense is out of the question,

we may perhaps assume that some of the pottery of the Chou

period was painted with unfired pigments, a method certainly in

use in the Han dynasty. There is a vase in the British Museum

of unglazed ware with painted designs in black, red and white

pigments, which has been regarded as of Han period, but may

possibly be earlier (Plate 2, Fig. 3).

In addition to the Chou tripod, Laufer[11] illustrates five specimens[4] of pre–Han pottery, excavated by Mr. Frank H. Chalfant "on the soil of the ancient city of Lin–tzŭ in Ch´ing–chou Fu, Shantung," a district which was noted for its pottery as late as the Ming period.[12] This find included two pitchers, a deep, round bowl, a tazza or round dish on a high stem, and a brick stamped with the character Ch´i, all unglazed and of grey earthenware. From this last piece, and from the fact that Lin–tzŭ, until it was destroyed in 221 B. C., was the capital of the feudal kingdom of Ch´i, Laufer concluded that these wares belonged to a period before the Han dynasty (206 B. C. to 220 A. D.).

Plate 1.—Chou Pottery.

Fig. 1.—Tripod Food Vessel. Height 6 1/8 inches.

Fig. 2.—Jar with deeply cut lozenge pattern. Height 6 3/4 inches.

Eumorfopoulos Collection.

THE HAN  DYNASTY, 206 B. C. TO 220 A. D.

DYNASTY, 206 B. C. TO 220 A. D.

TWO centuries of internecine strife between the great feudal princes culminated in the destruction of the Chou dynasty and the consolidation of the Chinese states under the powerful Ch´in emperor Chêng. If this ambitious tyrant is famous in history for beating back the Hiung–nu Turks, the wild nomads of the north who had threatened to overrun the Chou states, and for building the Great Wall of China as a rampart against these dreaded invaders, he is far more infamous for the disastrous attempt to burn all existing books and records, by which, in his overweening pride, he hoped to wipe out past history and make good to posterity his arrogant title of Shih Huang Ti or First Emperor. His reign, however, was short, and his dynasty ended in 206 B. C. when his grandson gave himself up to Liu Pang, of the house of Han, and was assassinated within a few days of his surrender.

The Han dynasty, which began in 206 B. C. and continued till 220 A. D., united the states of China in a great and prosperous empire with widely extended boundaries. During this period the Chinese, who had already come into commercial contact with the kingdoms of Western Asia, sent expeditions, some peaceful and others warlike, to Turkestan, Fergana, Bactria, Sogdiana, and Parthia. They even contemplated an embassy to Rome, but the envoys who reached the Persian Gulf turned back in fear of the long sea journey round Arabia, the length and danger of which seem to have been vividly impressed upon them by persons interested, it is thought, in preventing their farther progress.[13] A considerable trade, chiefly in silks, had been opened up between China and the Roman provinces, and the Parthians who acted as middlemen had no desire to bring the two principals into direct communication.

Needless to say, China was not uninfluenced by this contact[6] with the West. The merchants brought back Syrian glass, the celebrated envoy Chang Ch´ien in the second century B. C. introduced the culture of the vine from Fergana and the pomegranate from Parthia, and some years later an armed expedition to Fergana returned with horses of the famous Nisæan breed. But from the artistic standpoint the most important event was the official introduction of Buddhism in 67 A. D. at the desire of the Emperor Ming Ti and the arrival of two Indian monks with the sacred books and images of Buddha at Lo–yang. The Buddhist art of India, which had met and mingled with the Greek on the north–west frontiers since Alexander's conquests, now obtained a foothold in China and began to exert an influence which spread like a wave over the empire and rolled on to Japan. But this influence had hardly time to develop before the end of the Han period, and in the meanwhile we must return to the conditions which existed in China at the beginning of the dynasty.

The hieratic culture of the Chou, and the traditions of Chou art with its rigid symbolism and formalised designs, had been broken in the long struggles which terminated the dynasty and banned by the iconoclastic aspirations of the tyrant Chêng, and though partially revived by Han enthusiasts, they were essentially modified by the new spirit of the age. Berthold Laufer,[14] in discussing the jade ornaments of the Chou and Han periods, speaks of the "impersonal and ethnical character of the art of that age"—viz. the Chou. "It was," he continues, "general and communistic; it applied to everybody in the community in the same form; it did not spring up from an individual thought, but presented an ethnical element, a national type. Sentiments move on manifold lines, and pendulate between numerous degrees of variations. When sentiment demanded its right and conquered its place in the art of the Han, the natural consequence was that at the same time when the individual keynote was sounded in the art motives, also variations of motives sprang into existence in proportion to the variations of sentiments. This implies the two new great factors which characterise the spirit of the Han time—individualism and variability—in poetry, in art, in culture, and life in general. The personal spirit in taste gradually awakens; it was now possible for everyone to choose a girdle ornament according to his liking. For the[7] first time we hear of names of artists under the Han—six painters under the Western Han, and nine under the Eastern Han; also of workers in bronze and other craftsmen.[15] The typical, traditional objects of antiquity now received a tinge of personality, or even gave way to new forms; these dissolved into numerous variations, to express correspondingly numerous shades of sentiment and to answer the demands of customers of various minds."

Religion has always exerted a powerful influence on art, especially among primitive peoples, and the religions of China at the beginning of the Han dynasty were headed by two great schools of thought—Confucianism and Taoism. These had absorbed and, to a great extent, already superseded the elements of primitive nature worship, which never entirely disappear. Confucianism, however, being rather a philosophy than a religion, and discouraging belief in the mystic and supernatural, had comparatively little influence on art. Taoism, on the other hand, with its worship of Longevity and its constant questing for the secrets of Immortality, supplied a host of legends and myths, spirits and demons, sages and fairies which provided endless motives for poetry, painting and the decorative arts. The Han emperor Wu Ti was a Taoist adept, and the story of the visit which he received from Hsi Wang Mu, the Queen Mother of the West, and of the expeditions which he sent to find Mount P´êng Lai, one of the sea–girt hills of the Immortals, have furnished numerous themes for artists and craftsmen.

It is not yet easy for people in this country to study the monuments of Han art, but facilities are increasing, and a good impression of one phase at least may be obtained from reproductions of the stone carvings in Shantung, executed about the middle of the Han dynasty, which have been published from rubbings by Professor E. Chavannes.[16] On these monuments historical and mythological subjects are portrayed in a curious mixture of imagination and realism.

But these general considerations are leading us rather far afield, and it remains to see how much or how little of them is reflected in the pottery of the time.

As far as our present knowledge of the subject permits us to[8] see, there is nothing in the pre–Han pottery to attract the collector. It will only interest him remotely and for antiquarian reasons, and he will prefer to look at it in museum cases rather than allow it to cumber his own cabinets. With the Han pottery it is otherwise. The antiquarian interest, which is by no means to be underestimated, is now supplemented by æsthetic attractions caught from the general artistic impetus which stirred the arts of this period of national greatness. Not that we must expect to find all the refinements of Han art mirrored in the pottery of the time. Chinese ceramic art was not yet capable of adequately expressing the refinements of the painter, jade carver, and bronze worker. But even with the somewhat coarse material at his disposal the Han potter was able to show his appreciation of majestic forms and appropriate ornament, and to translate, when called upon, even the commonplace objects of daily use into shapes pleasant to the eye. In a word, the ornamental possibilities of pottery were now realised, and the elements of an exquisite art may be said to have made their appearance. From a technical point of view, the most significant advance was made in the use of glaze. Though supported by negative evidence only, the theory that the Chinese first made use of glaze in the Han period is exceedingly plausible.[17] In the scanty references to earlier wares in ancient texts no mention of glaze appears, and, indeed, the severe simplicity of the older pottery is so emphatically urged that such an embellishment as glaze would seem to have been almost undesirable. The idea of glazing earthenware, if not evolved before, would now be naturally suggested to the Chinese by the pottery of the Western peoples with whom they first made contact about the beginning of the Han dynasty. Glazes had been used from high antiquity in Egypt, they are found in the Persian bricks at Susa and on the Parthian coffins, and they must have been commonplace on the pottery of Western Asia two hundred years before our era.

Plate 2.—Han Pottery.

Fig. 1.—Vase, green glazed. Height 14 inches. Boston Museum.

Fig. 2.—Vase with black surface and incised designs. Height 16 inches. Eumorfopoulos Collection.

Fig. 3.—Vase with designs in red, white and black pigments. Height 11 1/2 inches. British Museum.

Fig. 4.—"Granary urn," green glazed. Height 12 inches. Peters Collection.

It is possible, of course, that evidence may yet be forthcoming to carry back the use of glaze in China beyond the limits at present prescribed, but all we can state with certainty to–day is that the oldest known objects on which it appears are those which for full and sufficient reasons can be assigned to the Han period. To explain all these reasons would necessitate a long excursion into archæology which would be out of place here. Many of them can be found in Berthold Laufer's[18] excellent work on the subject, and others will in due course be set out in the catalogue of the British Museum collections. But it would be unfair to ask the reader to take these conclusions entirely on trust, and some idea of the evidence is certainly his due.

There are a few specimens of Han pottery inscribed with dates, such as the vase (Plate 2, Fig. 1) from the Dana Collection, which is now in the Boston Museum; but in almost every case the inscriptions have proved to be posthumous and must be regarded at best as recording the pious opinion of a subsequent owner. It will be safer, then, to leave inscriptions out of consideration and to rely on the close analogies which exist between the pottery and the bronze vessels of the Han period and between the decorative designs on the pottery and the Han stone sculptures, and, where possible, on the circumstances in which the vessels have been found. Unfortunately, the bulk of the Han pottery which has reached Europe in recent years has passed through traders' hands, and no records have been kept of its discovery. But there are exceptional cases in which we have first–hand evidence of Han tombs explored by Europeans, and in two instances their contents have been brought direct to the British Museum. Both these hauls are from the rock–tombs in[10] Szechuan, the one made by the ill–fated Lieutenant Brooke, who was murdered by the Lolos, the other by the Rev. Thomas Torrance, to whom I shall refer again. The evidence of both finds is mutually corroborative; it is supported by Han coins found in the tombs, by inscriptions carved on their doorways, and by the rare passages of decoration on the objects themselves, which correspond closely to designs on stone carvings published by Chavannes. In this way a whole chain of unassailable evidence has been welded together until, in spite of the remoteness of the period, we are able to speak with greater confidence about the Han pottery than about the productions of far more recent times.

The Han pottery is usually of red or slaty grey colour, varying in hardness from a soft earthenware to something approaching stoneware, and in texture from that of a brick to the fineness of delft. These variations are due to the nature of the clay in different localities and to the degree of heat in which the ware was fired. No chronological significance can be attached to the variations of colour, and to place the grey ware earlier than the red is both, unscientific and patently incorrect. Most of the Szechuan ware is grey and comparatively soft, while of the specimens sent from Northern China the majority seem to be of the red clay. Some of the ware from both parts is unglazed, and in certain cases it has been washed over with a white clay and even painted with unfired pigment, chiefly red and black. The bulk of it, however, is glazed, the typical Han glaze being a translucent greenish yellow, which, over the red body, produces a colour varying from leaf green to olive brown, according to the thickness of the glaze and the extent to which the colour of the underlying body appears through it. Age and burial have wonderfully affected this green glaze, and in many cases the surface is encrusted in the process of decay with iridescent layers of beautiful gold and silver lustre. In other cases the decay has gone too far, and the glaze has scaled and flaked off. Another feature which it shares with many of the later glazes is a minute and almost imperceptible crackle. This feature is almost universal on the softer Chinese pottery glazes, and has nothing to do[19] with the deliberate and pronounced crackle of later Chinese porcelain, being purely accidental in its formation.

The colour of the glaze shows considerable variations, being sometimes brownish yellow, sometimes deep brown, and occasionally mottled like that of our mediæval pottery. A passage in the T´ao shuo[20] seems to imply the existence of a black glaze as well, but it is a solitary literary reference, and it is not perfectly clear whether a black earthenware or a black glaze is meant. It was thought at one time that the fine white ware with pale straw–coloured or greenish glaze, of which much of the T´ang mortuary pottery is made, was in use as early as the Han period, but I am now convinced that this is a later development, and cannot be included in the ware of the Han dynasty.