Illustrated by Williams

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Astounding Science-Fiction, November 1945.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Cal Blair paused at the threshold of the Solarian Medical Association and held the door while four people came out. He entered, and gave his name to the girl at the reception desk, and then though he had the run of the place on a visitor basis, Cal waited until the girl nodded that he should go on into the laboratories.

His nose wrinkled with the smell of neoform, and shuddered at the white plastic walls. He came to the proper door and entered without knocking. He stood in the center of the room as far from the shelves of dangerous-looking bottles on one wall as he could get—without getting too close to the preserved specimens of human viscera on the other wall.

The cabinet with its glint of chrome-iridium surgical tools seemed to be like a monster, loaded to the vanishing point with glittering teeth. In here, the odor of neoform was slightly tainted with a gentle aroma of perfume.

Cal looked around at the empty room and then opened the tiny door at one side. He had to pass between a portable radiology machine and a case of anatomical charts, both of which made his hackles tingle. Then he was inside of the room, and the sight of Tinker Elliott's small, desirable head bent over the binocular microscope made him forget his fears. He stepped forward and kissed her on the ear.

She gasped, startled, and squinted at him through half-closed eyelids.

"Nice going," she said sharply.

"Thought you liked it," he said.

"I do. Want to try it over again?"

"Sure."

"Then don't bother going out and coming in again. Just stay here."

Cal listened to the words, but not the tone.

"Don't mind if I do. Shall we neck in earnest?"

"I'd as soon that as having you pop in and out, getting my nerves all upended by kissing me on the ear."

"I like kissing you on the ear."

Tinker Elliott came forward and shoved him onto a tall laboratory chair. "Good. But you'll do it at my convenience, next time."

"I'd rather surprise you."

"So I gathered. Why did you change your suit?"

"Change my suit?"

"Certainly."

"I haven't changed my suit."

"Well! I suppose that's the one you were wearing before."

"Look, Tinker, I don't usually wear a suit for three months. I think it was about time I changed. In fact, this one is about done for."

"The one you had on before looked all right to me."

"So? How long do you expect a suit to last, anyway?"

"Certainly as long as an hour."

"Hour?"

"Yes ... say, what is this?"

Cal Blair shook his head. "Are you all right?"

"Of course. Are you?"

"I think so. What were you getting at, Tinker? Let's start all over again."

"You were here an hour ago to bid me hello. We enjoyed our reunion immensely and affectionately. Then you said you were going home to change your suit—which you have done. Now you come in, acting as though this were the first time you'd seen me since Tony and I took off for Titan three months ago."

Cal growled in his throat.

"What did you say?" asked Tinker.

"Benj."

"Benj! Oh no!"

"I haven't been here before. He's my ... my—"

"I know," said Tinker softly, putting a hand on his. "But no one would dream of masquerading as anyone else. That's unspeakable!"

"It's ghastly! The idea is beyond revolting. But, Tinker, Benj Blair is revolting—or worse. We hate each other—"

"I know." Tinker shuddered and made a face that might have resulted from tasting something brackish and foul. "Ugh! I'm sorry, Cal."

"I'm raving mad! That dupe!"

"Cal—never say that word again. Not about your twin brother."

"Look, my neuropsychiatristic female, I'm as stable as any twin could be. Dwelling on the subject of duplication is something I won't do. But the foul, rotten trick. What was he after, Tink?"

"Nothing, apparently. Just up to deviltry."

"Deviltry is fun. He was up to something foul. Imagine anyone trying to take another's identity. That's almost as bad as persona duplication."

Tinker went pale, and agreed. "Theft of identity—I imagine that Benj was only trying to be the stinker he is supposed to be. That was a rotten trick"—Tinker wiped her lips, applied neoform on a cello-cotton pad and sterilized them thoroughly—"to play on a girl." She looked at the pad and tossed it into the converter chute. "A lot of good that will do. Like washing your hands after touching a criminal. Symbolic—"

"Tinker, I feel cheated."

"And I feel defiled. Come here, Cal." The result of his approach was enough to wipe almost anything from the minds of both. It went a long way towards righting things, but it was not enough to cover the depths of their mental nausea at the foul trick. That would take years—and perhaps blood—to wash away.

"Hello, Cal," she said, as they parted.

"I'm glad you're back."

"I know," she laughed. "Only Dr. Tinker Elliott could drag Specialist Calvin Blair into anything resembling a hospital, let alone a neurosurgical laboratory."

"Wild horses couldn't," he admitted.

"That's a left-handed compliment, but I'll treasure it—with my left hand," she promised.

"Benj—and I can speak without foaming at the mouth now—couldn't have played that trick on you if you'd seen me during the last three months."

"True. Three months' absence from you made his disguise perfect. I'd forgotten just enough. The rotter must have studied ... no, he's an identical twin, isn't he?"

"Right," gritted Cal. "But look, Tinker. This is no place to propose. But why not have me around all the time?"

"Nice idea," said Tinker dreamily. "You'll come along with us on the next expedition, of course?"

"You'll not go," said Cal.

"Now we're at the same old impasse. We've come up against it for three years, Cal."

"But why?"

"Tony and I promised ourselves that we'd solve this mystery before we quit."

Cal snorted. "You've been following in the footsteps of medical men who haven't solved Makin's Disease in the last hundred years. You might never solve it."

"Then you'll have to play my way, Cal."

"You know my opinion on that."

"You persist in putting me over a barrel, Cal. I think a lot of you. Enough—and forgive me for thinking it—to ignore the fact that you are a twin. But I'll not marry you unless we can be together—somehow. I love surgery and medical research. I like adventuring into strange places and seeking the answer to strange things. Tony is my ideal and he loves this life too, as did our father. It's in our blood, Tony's and mine, and saying so isn't going to remove it."

Cal nodded glumly. "Don't change," he said firmly. "Not willingly. I'm not going to be the guy to send someone to a psychiatrist to have his identity worked over. I've been hoping that you'd get your fill of roistering all over the Solar System, looking for rare bugs and viruses. I've almost been willing to get some conditioning myself so that I could join you—but you know what that would mean."

"Poor Cal," said Tinker softly. "You do love me. But Cal, don't you change either! Understand? If you change your identity, you'll not be the Cal I love. If the change comes normally, good and well, but I'll not have an altered personality for my husband. You love your ciphers and your codes and your cryptograms. You are a romanticist, Cal, and you stick to the rapier and the foil."

"Excepting that I get accused of cowardice every now and then," snorted Blair.

"Cowardice?"

"I've a rather quiet nature, you know. Nothing really roils me except Benj and his tricks. So I don't go around insulting people. I've been able to talk a lot of fights away by sheer reasoning, and when the battle is thrust upon me, I choose the rapier. There's been criticism, Tink, because some have backed out rather than cross rapiers with me, and those that do usually get pinked. I've been accused of fighting my own game."

"That's smart. That's your identity, Cal, and don't let them ridicule you into trying drillers."

"I won't. I can't shoot the side of a wall with a needle beam."

"Stay as you are, Cal."

"But that's no answer. You like space flying. I hate space flying. You love medicine and neurosurgery. I hate the smell of neoform. I hate space and I hate surgery—and you love 'em both. To combine them? To call them Life? No man in his right mind would do that. No, Tinker, I'll have nothing to do with either!"

The ghost of Hellion Murdoch, pirate, adventurer, and neurosurgeon stirred in his long, long sleep. Pirates never die, they merely join their fellows in legend and in myth, and through their minions—the historians and novelists—their heinous crimes are smoothed over, and they become uninhibited souls that fought against the fool restrictions placed upon them by a rotten society.

Hellion Murdoch had joined his fellows, Captain Kidd, Henry Morgan, Dick Turpin, and Robin Hood three hundred and fifty years ago. And like them, he went leaving a fabulous treasure buried somewhere. This came to be known to all as Murdoch's Hoard, and men sought up and down the Solar System for it, but it was never found.

But the words of Cal Blair aroused the ghost of Hellion Murdoch. He listened again as the words echoed and re-echoed through the halls of his pirate's citadel in the hereafter. The same halls rang with his roaring laughter as he heard Calvin Blair's words. He sprang to his feet, and raced with the speed of thought to a mail chute.

With his toe, the ghost of Hellion Murdoch dislodged a small package from where it had lain for years. With his ghostly pencil, he strengthened certain marks, plying the pencil with the skill of a master-counterfeiter. The stamp was almost obliterated by the smudged and unreadable cancellation. The addressee was scrawled and illegible, but the address was still readable. Water had done its job of work on the almost imperishable wrapper and ink of the original, and when the ghostly fingers of Hellion Murdoch were through, the package looked like a well-battered bundle, treated roughly by today's mail.

With his toe, he kicked it, and watched it run through the automatic carrier along the way to an operating post office. It came to light, and the delivery chute in Cal Blair's apartment received the package in the due course of time.

Cal Blair looked at the package curiously. He hadn't ordered anything. He was expecting nothing by mail. The postmark—completely smudged. He paid no attention to the stamp, which might have given him to think. The address? The numbers were fairly plain and they were his, Cal Blair's. The name was scrawled, and the wrapping was scratched across the name. Obviously some sharp corner of another package had scratched it off.

He inspected the package with the interest of a master cryptologist, and then decided that opening the package was the only way to discover the identity of the owner. Perhaps inside would be a packing slip or something that might be traced—

Paper hadn't changed much in the last five hundred years, he thought ruefully. At least, not the kind of paper this was wrapped in. No store, of course. Someone sending something almost worthless, no doubt, and wrapping it in the first piece of paper that was handy. He tore the wrapping carefully, and set it aside for future study.

Inside the package was a tin box, and inside the box was a small cross standing on a toroidal base. The whole trinket stood two inches tall, and the crossarms were proportional—though they were cylindrical in cross-section instead of rectangular.

It would have made a nice ornament for an altar, or a religious person's desk except for the tiny screw-stud that projected out of the center of the bottom. That prevented it from standing. Other taped holes in this flat base aroused his attention.

"This is no ornament," said Cal Blair, aloud. "No mere ornament would require that rugged mounting."

There seemed to be some microscopic engravings around the surface of the toroid. Cal set up the microscope and looked. Characters in the solarian were there, micro-engraved to perfection. But they were in no order. They had a randomness that would have made no sense to any but a master cryptologist—a specialist. To Cal Blair they took on a vague pattern that might be wishful thinking, and yet his reason told him that men do not microengrave things just to ornament them. A cipher it must be by all logic.

He was about to take it into the matter-converter and enlarge it mechanically, when he decided that it might spoil the things for the owner if he did and was not able to return it to the exact size. He decided on photographs.

Fully three hours later, Cal Blair had a complete set of photographic enlargements of the microengravings.

Then with the patience and skill of the specialist cryptologist, Cal Blair started to work on the characters.

The hours passed laboriously. The wastebasket filled with scrawled sheets of paper, and mathematical sequences. Letters and patterns grew beneath his pencil, and were discarded. Night passed, and the dawn grayed in the east. The sun rose, and cast its rays over Cal's desk, and still he worked on, completely lost in his work.

And then he looked startled, snapped his fingers, and headed across the room for an old book. It was a worthless antique, made by the reproducer in quantity. It was a Latin dictionary.

Latin. A dead and forgotten language.

Only his acquaintance with the folks at the Solarian Medical Association could have given him the key to recognition. He saw one word there, and it clicked. And then for four solid hours he cross checked and fought the Latin like a man working a crossword puzzle in an unknown language, matching the characters with those in the dictionary.

But finally the message was there before him in characters that he could read. It was clear and startling.

"The Key to Murdoch's Hoard!" breathed Cal Blair. "The fabulous treasure of the past! This trinket is the Key to Murdoch's Hoard!"

A cavity resonator and antenna system, it was. The toroid base was the cavity resonator, and the cross was the feedline and dipole antenna. Fitted into the proper parabolic reflector and shock excited periodically, it would excite a similar antenna at the site of Murdoch's Hoard. This would continue to oscillate for many milli-seconds after the shock-excitation. If the Key were switched to a receiving system—a detector—the answering oscillation of the sympathetic system would act as a radiator. Directive operation—scanning—of the parabolic reflector would give directive response, leading the user to the site of Murdoch's Hoard.

How men must have fought to find Murdoch's Hoard in the days long past!

Cal Blair considered the Key. It would lead him to nothing but roistering and space travel and the result would be no gain. Yet there was a certain scientific curiosity in seeing whether his deciphering had been correct. Not that he doubted it, but the idea sort of intrigued him.

The project was at least unique.

He looked up the history of the gadget in an ancient issue of the Interplanetary Encyclopedia and came up with the following description:

Murdoch's Hoard: An unknown treasure said to be cached by the pirate Hellion Murdoch. This treasure is supposed to have been collected by Murdoch during his years as an illegal neurosurgeon. For listings of Murdoch's better known contributions to medicine, see.... (A list of items filled half a page at this point, which Cal Blair skipped.)

Murdoch's Hoard is concealed well, and has never been found. The Key to Murdoch's Hoard was a minute cavity resonator and antenna system which would lead the user to the cache. No one has been able to make the Key function properly, and no one was ever able to break the code, which was engraved around the base.

The value of the Key is doubtful. Though thousands of identical Keys were made on the Franks-Channing matter reproducer, no scientist has ever succeeded in getting a response. Engravings on the base are obviously a code of some sort giving instructions as to the use of the Key, but the secret of the code is no less obscure than the use of the Key itself. The original may be identified by a threaded stud protruding from the bottom. This stud was eliminated in the reproduction since it interfered with the upright position of the Key when used as an ornament. The original was turned over to the Interplanetary Museum at the time of Channing's death from which place it has disappeared and has been rediscovered several times. At the present time, the original Key to Murdoch's Hoard is again missing, it having been stolen out of the Museum for the seventeenth time in three hundred years.

Cal smiled at the directions again. He envisioned the years of experimentation that had gone on with no results. The directions told why. Without them, its operation was impossible. And yet it was so simple.

The idea of owning contraband bothered Cal. It belonged to the Interplanetary Museum, by rights. It would be returned. Of that, Cal was definite. But some little spark of curiosity urged him not to return it right away. He would return it, but it had been gone for several years and a few days more would make no difference. He was far from the brilliant scientist—any of the engineers of the long-gone Venus Equilateral Relay Station would have shone like a supernova against his own dim light. But he, Cal Blair, had the answer and they did not.

But it was more to prove the correctness of his own ability as cryptographer that he took on the job of making the little Key work.

The job took him six weeks. An expert electronics engineer would have done it in three days, but Cal had no laboratory filled with equipment. He had neither laboratory technique nor instruments nor a great store of experience. He studied books. He extracted a mite of information here and a smidgin there, and when he completed the job, his equipment was a mad scramble of parts. Precision rubbed elbows with sloppiness, for unlike the trained technician, Cal did not know which circuits to let fly and which circuits needed the precise placing. He found out by sheer out-and-try and by finally placing everything with care. The latter did not work too good, but continuous delving into the apparatus disrupted some of the lesser important lines to the point where their randomness did not cause coupling. The more important lines complained in squeals of oscillation when displaced, and Cal was continually probing into the gear to find out which wire was out of place.

He snapped the main switch one evening six weeks later. With childlike enthusiasm he watched the meters register, compared notes and decided that everything was working properly. His testing equipment indicated that he was operating the thing properly—at least in accordance with the minute engravings on the side.

But with that discovery—that his rig functioned—there came a let-down. It was singularly unexciting. Meters indicated, the filaments of the driver tubes cast a ruddy glow behind the cabinet panel, a few ill-positioned pilot lamps winked, and the meter at the far end of the room registered the fact that he was transmitting and was being detected. It was a healthy signal, too, according to the meter, but it was both invisible and inaudible as well as not affecting the other senses in any way.

Now that he had it, what could he use it for?

Treasure? Of what use could treasure be in this day and age? With the Channing-Franks matter reproducer, gold or any rare element could be synthesized by merely introducing the proper heterodyning signal. Money was not metal any more. Gold was in extensive use in electrical works and platinum came in standard bars at a solarian credit each. Stable elements up to atomic weights of six or seven hundred had been made and investigated. A treasure trove was ridiculous. Of absolutely no value.

The day of the Channing-Franks development was after the demise of Hellion Murdoch. And it was after the forty years known as the Period of Duplication that Identium was synthesized and became the medium of exchange. Since identium came after Murdoch's demise by years, obviously Murdoch's Hoard could only be a matter of worthless coin, worthless jewels, or equally worthless securities.

Money had become a real medium of exchange. Now it was something that did away with going to the store for an egg's worth of mustard.

So Cal Blair felt a let-down. With his problem solved, there was no more to it, and that was that. He smiled. He'd send the Key to Murdoch's Hoard to the museum.

And, furthermore, let them seek Murdoch's Hoard if they wanted to. Doubtless they would find some uniques there. A pile of ancient coins would be uniques, all right. But the ancient papers and coins and jewels would not be detectable from any of the duplicates of other jewels and coins of that period that glutted the almost-abandoned museum.

Benj Blair snarled at the man in front of him. "You slinking dupe! You can't get away with that!"

The man addressed blanched at the epithet and hurled himself headlong at Benj. Cal's twin brother callously slipped a knife out of his belt and stabbed down on the back of his attacker. It was brutal and bloody, and Benj kicked the dead man back with a lifted knee and addressed the rest of the mob.

"Now look," he snarled, "it is not smart. This loke thought he could counterfeit. He's a dead idiot now. And anybody that tries to make identium in this station or any place that can be traced to any one of us will be treated likewise. Get me?"

There was a growl of absolute assent from the rest.

"Is there anyone who doesn't know why?"

"I'm dumb," grinned a man in the rear. "Make talk, Benj."

"O.K.," answered Benj. "Identium is a synthetic element. It is composed of a strictly unstable atom that is stabilized electronically. It starts off all right, but at the first touch of the scanning beam in the matter-converter, it becomes unstable and blows in a fission-reaction. Limpy, there, tried it once and it took his arm and leg. The trouble with identium explosions is the fact that the torn flesh is sort of seared and limb-grafting isn't perfect. That's why Limpy is Limpy. Then, to make identium, you require a space station in the outer region. The manufacture of the stuff puts a hellish positive charge on the station which is equalized by solar radiation in time. But the station must be far enough out so that the surge inward from Sol isn't so high that the inhabitants are electrocuted by the change in charge.

"Any detector worthy of the name will pick it up when in operation at a half light-year—and the Patrol keeps their detectors running. That plus the almost-impossible job of getting the equipment to perform the operation. I'll have no identium experiments here."

A tiny light winked briefly above his head. It came from a dusty piece of equipment on a shelf. Benj blinked, looked up at the winking light, and swore.

"Tom!" he snorted. "What in the name of the devil are you doing?"

The technician put his head out of the laboratory door. "Nothing."

"You're making this detector blink."

"I'm trying to duplicate an experiment."

"Trying?"

Tom grinned. "I'm performing the actual operation of the distillation of alcohol."

"That shouldn't make the detector blink."

"There's only one thing that will do that!"

"Not after all this time."

"It's not been long. About ten years," objected Tom. "Look, Benj. Someone has found the Key. And not only that, but they've made it work."

"I'd like to argue the point with you," said Benj pointedly. "Why couldn't you make it tick when we had it seven years ago? You were sharp enough to make a detector, later."

"Detecting is a lot different than generating, Benj. Come on, let's get going. I want to see the dupe that's got the Key."

Had Cal Blair been really satisfied to make his gadget work, he might never have been bothered. But he tinkered with it, measured it, and toyed with it. He called Tinker Elliott to boast and found that she had gone off to Northern Landing with her illustrious brother to speak at a medical convention, and so he returned to his toy. Effectively, his toying with the Key gave enough radiation to follow. And it was followed by two parties.

The first one arrived about midnight. The doorbell rang, and Cal opened it to look into the glittering lens of a needle beam. He went white and retreated backwards until he felt a chair behind his knees. He collapsed into the chair.

"P-p-p-put that thing away!"

"This?" grinned the man, waving the needle beam.

"Shut up, Logy," snapped the other. To Cal, he said: "Where is it?"

"W-w-w-where is w-w-w-what?"

"The Key."

"Key?"

"Don't be an idiot!" snarled the first man, slapping Cal across the face with the back of his hand. Cal went white.

"Better kill me," he said coldly, "or I'll see your identity taken!"

"Cut it, Jake. Look, wiseacre, where did you get it?"

"The Key? It came in the mail."

"Mail hell! That was mailed ten years ago!"

"It got here six weeks ago."

"Musta got lost, Logy," offered Jake. "After all, Gadget's been gone about that long."

"That's so. Those things do happen. Poor Gadg. An' we cooled him for playing smart."

"We wuz wrong."

"Yep. So we was. Too bad. But Gadget wasn't too bright—not like this egg. He's made it work."

"Logy, you're a genius."

"So we chilled Gadget because we thought he was playin' smart by tryin' to swipe the pitch. He didn't lam wit' the Key at all."

"How about this one?" asked Logy.

"He ain't going to yodel. Better grab him and that pile of gewgaws. The rest of the lads'll be here too soon."

"Rest?"

"Sure. The whole universe is filled wit' detectors ever since Ellswort' made the first one."

"Git up, dope," snapped Jake, motioning to the door with his beam.

Blair walked to the door with rubber joints in his knees. Logy lifted the equipment from the table and followed Jake. "He ain't made no notebook," complained Jake.

"He had some plans," said Logy, "but the fool set the stuff on 'em and they're all chewed up. He can make 'em over."

"O.K. Git goin', Loke."

Blair could not have protested against the pair unarmed. With two needle beams trained on his back, he was helpless. He went as they directed, and found that his helplessness could be increased. They forced him into a spacecraft that was parked on the roof.

The autopilot was set, and the spacecraft headed across the sky, not into space, but making a high trajectory over Terra itself. Once into the black of the superstratosphere, they turned their attention back to Cal.

"Gonna talk?"

"W-w-w-what do you w-w-want me to s-s-say?" chattered Cal.

"Dumb, isn't he?"

"Look, sweety, tell us what's with this thing."

"It's a c-c-cavity resonator."

"Yeah, so we've been told," growled Logy. "What makes?"

"B-b-b-but look," stammered Cal. "W-w-what good'll it do you?"

"Meaning?" snarled Jake.

"Whatever treasure might be there is useless now."

Jake and Logy split the air with peals of raw laughter. Jake said: "He is dumb, all right."

"Just tell us, bright-eyes. We'll decide," snapped Logy.

"W-w-well, you send out a signal with it and then stop it and switch it to the detecting circuit. You listen, and the signal goes out and starts the other one going like tapping a bell. It resonates for some time after the initial impulse. It returns the signal, and by using the directional qualities, you can follow the shock-excited second resonator right down to it. Follow?"

"Yeah. That we all know," drawled Jake in a bored voice. His tone took on that razor edge again and he snarled: "What we're after is the how, get me? How?"

"Oh, w-w-w-well, the trick is—"

"Creeps!" exploded Logy. He crossed the cabin in almost nothing flat and jerked upward on the power lever.

The little ship surged upward at six gravities, making speech impossible. Blair wondered about this, sitting there helpless and scared green, until a blast of heat came from behind, and the ship lost drive. A tractor beam flashed upward, catching the ship and hurling it backwards. The reaction threw all three up against the ceiling with considerable force, and the reverse acceleration generated by the tractor's pull kept them pasted to the ceiling. Another ship was beside them in a matter of seconds, and four spacesuited men breached the air lock and entered, throwing their helmets back.

"Jake Jackson and Freddy Logan," laughed the foremost of the newcomers. "How nerce of you to meet us here."

"Grab the blinker," said the one behind.

"Naturally. Naturally. Pete and Wally take Blair. Jim and I'll muscle the gripper."

Two of them carried Cal to the larger ship. The other two scooped up the equipment and carried it behind them. Once inside, the tractors were cut and the smaller ship plummeted towards Terra. With no concern over the other ship and its two occupants, they hurled Cal back against the wall while they put his apparatus on the navigator's table.

"Very nice and timely rescue, eh Cal?"

Cal whirled. "Benj," he snarled. "Might have known—" He started forward, but was stopped by the ugly muzzles of three needle beams that waggled disconcertingly at the pit of his stomach. He laughed, but it had a wild tone. "Go ahead and blast! Then run the Key yourselves!" he hurled at them. But he stopped, and the waggling of the three weapons became uncertain.

"Hell's fire," snorted Pete, looking from one to the other. "They're duplicates!"

Cal leaped forward, smashed Pete's beam up, where it furrowed the ceiling. His fist came forward and his knee came up. Beneath Cal's arm flashed a streak of white. It caught Pete in the stomach and passed down to the knee, trailing a bit of smoke and a terrible odor. Cal dropped the lifeless form and whirled. Benj stood there, his needle beam held rock-steady on the form that lay crumpled beneath Cal's feet.

Benj addressed the other two. "My brother and I have one thing in common," he said coolly. "Neither of us cares to be called a duplicate!" He holstered his weapon and addressed Cal. "Where is it?"

"Where is what?" asked Cal quietly.

"Murdoch's Hoard."

"I haven't had time to find out."

"O.K. So tell us how to make this thing run."

"I'll be psyched if I do."

"You'll be dead if you do not," warned Benj.

"Some day, you stinker, I'll take the satisfaction of killing you."

"I'll never give you cause," sneered Benj.

"Stealing my identity is plenty of cause."

"You won't take satisfaction on that," taunted Benj. "Because you'd have to call me and I'll accept battle with beams."

Cal considered. Normally, he would have been glad to demonstrate to anyone the secret of the Key. But he would have died before he told Benj the time of day. But another consideration came. The Key was worthless—and less valuable would be the vast treasures of Murdoch's Hoard. Why not give him the Key and let him go hunting for the useless stuff?

Wally waved an instant-welder in front of Cal's nose. The tip glowed like a white-hot stylus. "Might singe him a bit," offered Wally.

"Put the iron down," snapped Benj. Wally laid the three-foot shaft on its stand, where it cooled slowly. "Cal wouldn't talk. I know. That thing would only make him madder than a hornet."

"So what do we do with the loke?" asked Wally.

"Take him home and work on him there," said Benj. "Trap his hands."

No more was said until they dropped onto Cal's rooftop. He was ushered down the same way that he had gone up—with beams looking at his backbone. They carried his equipment down, and set it carefully on the table.

"Now," said Benj. "Make with the talk."

"O.K.," said Cal. "This is a cavity resonator—"

"This is too easy," objected Wally. "Something's fishy."

Cal looked at the speaker with scorn. "You imbecile. You've been reading about Murdoch's Hoard. Vast treasure. Money, jewels, and securities. Valuable as hell three hundred and fifty years ago, but not worth a mouthful of ashes today. Why shouldn't I tell you about it?"

"That right, boss?" asked Wally.

"He's wishful thinking," snorted Benj.

Cal smiled inwardly. His protestation of what he knew to be the truth was working. The desire to work on Benj was running high, now, and Cal was reconsidering his idea of handing the thing to Benj scot-free.

"Let me loose. I'll show you how it works," he said.

"Not a peep out of it," warned Benj. "Wally, if he touches that switch before he takes the Key out of the reflector, drill him low and safe—but drill him!"

Cal knew the value of that order. The hands were freed, and he stepped forward with tools and removed the Key. "Now?" he asked sarcastically.

"Go ahead," said Benj.

"Thanks," grinned Cal. "That I will!" He took three steps forward and went out of the open window like a running jackrabbit. His strong fencer's wrists caught the trellis at the edge and he swung wide before he dropped to the ground several feet below. He landed running, and though the flashes of the needle beams scored the ground ahead of him, none caught him. He plowed through a hedge, jumped into his car, and drove off with a swaying drive that would disrupt any aim.

He drove to the Solarian Medical Association, where he found Dr. Lange in charge. In spite of the hour of the morning, he went in and spoke to the doctor.

Lange looked up surprised. "What are you doing here at this hour?" he asked with a smile.

"I've got a few skinned knuckles that hurt," said Cal, showing the bruises.

"Who did you hit?" asked Lange. "Fisticuffs isn't exactly your style, Cal."

"I know. But I was angry."

Lange inspected Cal's frame. "Wouldn't like to be the other guy," he laughed. "But look, Cal. Tinker will be more than pleased."

"That I was fighting? Why?"

"You're a sort of placid fellow, normally. If you could only stir up a few pounds of blood-pressure more frequently, you'd be quite a fellow."

"So I'm passive. I like peace and quiet. You don't see me running wild, do you?"

"Nope. Tell me, what happened?"

Cal explained in sketchy form, omitting the details about Benj.

"The Key to Murdoch's Hoard?" asked Lange, opening his eyes.

"Sure."

"What are you going to do with it?"

"Send it back to the museum. They're the ones that own it."

"You'll give them Murdoch's Hoard if you do."

"Granting for the moment that the Hoard is valuable," laughed Cal, "it is still the property of the museum."

"Wrong. The law is a thousand years old and still working. Buried Treasure is his who finds it. That Hoard is yours, Cal."

"Wonderful. About as valuable as a gallon of lake water in Chicago. It's about as plentiful."

"May I have the Key?" asked Lange eagerly.

Cal stopped. This was getting him down. First that pair of ignorant crooks. Then his brother, trying to steal from him something that both knew worthless—just for the plain fun of stealing he'd believed. But now this man. Dr. Lange was advanced in years, a brilliant and stable surgeon. Was he wrong? Did the Key really represent something worth-while? If so, what on earth could it be? A hoard of treasure in a worthless medium of exchange and with duplicates all over the System? What could Murdoch's Hoard be that it made men fight for it even in this day?

"Sorry," said Cal. "This is my baby."

He said no more about it.

Whatever the Hoard might be, it was getting Cal curious. That and the desire to get the best of Benj worked on him night and day during the next week. He was forced to hide out all of that time, for Benj was looking for him. The equipment still required a knowing hand to run it—any number of technicians had concocted the same circuit to drive the Key—it was the technique, not the equipment that made it function properly.

He toyed with the idea for some time. The desire to go and see for himself, however, was not greater than his aversion to space travel. Cal had an honest dislike, he had tried space travel three times when business demanded it. He'd hated it all three times.

But there it was—and there it stayed. The whole affair peaked and then died into a stasis. Murdoch's Hoard was something that Cal Blair would eventually look into—some day.

The one thing that bothered him was his hiding-out. He hated that. But he remained under cover until Tinker Elliott returned and then he sought her advice. She made a date to meet him at a nearby refreshment place later that afternoon.

The major-domo came up with a cheerful smile as Cal sauntered into the chromium-and-crimson establishment. "At your service," greeted the major-domo.

"I'm meeting a friend."

"A table will be reserved. Meanwhile, will you avail yourself of our service in the bar?"

Cal nodded and entered the bar. He climbed up on a tall bar stool and took cigarettes from his pocket. The bartender came over immediately. "Your service?"

"Palan and ginger," said Cal. He was still working on the dregs of his first glass when Tinker came up behind him and seated herself on the stool beside.

"Hi, Tink," he smiled.

"Hello. What are you drinking?"

"Palan and ginger."

"Me too," she said to the bartender. "Cal, you are a queer duck. Your favorite liquors come from Venus and Mars. You seem to thrive on those foul-tasting lichens from Titan as appetizers. You gorge yourself on Callistan loganberry, and your most-ordered dinner is knolla. Yet you hate space travel."

"Sure," he grinned. "I know it. After all, there's nothing that says that I have to go and get it. Four hundred years ago, Tink, there were people who ate all manner of foods that they never saw in the growing stage. And a lot of people lived and died without ever seeing certain of their meat animals."

"I know. Gosh. They used to kill animals for meat back then. Imagine!"

Cal looked sour-faced, and silence ensued for a moment. Then Tinker's face took on a self-horror.

"Hey. That look isn't natural. What's up?"

"Order me a big, powerful, hardy, pick-me-up," said Tinker. "And I'll tell you—if you really want to know."

"I do and I will," said Cal, wonderingly. He ordered straight palan which Tinker took neat, coughed, and then brightened somewhat.

"Now?" asked Cal.

"Better order another one for you," said Tinker. "Anyway, we had one of those jobs last night."

"What jobs?"

"An almost-incurable."

"Oh," said Cal with a shiver. He ordered two more straight drinks, in preparation. "Go ahead and tell, Tink. You won't be free of it until you spill it."

"It was a last resort case and everybody knew it. Even the patient—that's what made it so tough. It's distasteful enough to consider a duplicate when you're well. But to be lying on the brink and then know that they're going to make a duplicate of you for experimental surgery—I can't begin to tell. The patient took it, though.

"And even that wouldn't be too bad. We made our duplicates and went to work on one immediately. We operated, located the trouble and corrected it. The third duplicate lived. Then we operated on the patient successfully. I didn't mind the first two dupes, Cal. It was the disposing of the cured duplicate that got me. It was like ... no, it was disposing of an identity." Tink shuddered, and then drained her second shot of palan simultaneously with Cal.

"And you wonder why I dislike medicine," he said flatly.

"I know—or try to. But look, Cal. Aside from the distaste, look at what medicine has been able to accomplish."

"Sure," he said without enthusiasm.

"Well, it has."

"But at what a cost."

"Cost? Very little cost," snapped Tinker. "After all, once one has the stomach to dispose of a duplicate, what is the cost? Doctors bury their mistakes just as always, but the mistake is a duplicate. The sentience remains."

"How can you tell the real article from the duplicate?"

"We keep track."

"I know that. What I mean is this: A man is born, lives thirty years as an identity. He is duplicated for surgical purposes at age thirty. All duplicates and the original are he—complete with thought and habit patterns of thirty years. They are identical in every way right down to the dirt on their hands and the subconscious thoughts that pass inside of their brains. Their egos are all identical. When you kill the duplicate, you might as well kill the identity. The duplicate is as much an identity as the original."

"True," said Tinker. "However, once a duplicate is made, the identities begin to differ. One will have different experiences and different ideas and thoughts. Eventually the two duplicates are separate characters. But in deference to the identity, it is he that we must cure and preserve. For the instant that the duplication takes place, the character starts to differ. We can not destroy the original. The duplicate is not real. It ... how can I say it? ... hasn't enjoyed ... yes it has, too. It was once the original. Cal, you're getting me all balled up."

"Why not let them both live?"

Tinker looked at Cal with wonder. "Inspect your life," she said sharply. "You and Benj. How do I know right now that you are not Benj?"

Cal recoiled as though he had been struck.

"You're Cal, I know. That distaste was not acting. It was too quick and too good, Cal. But can you see what would happen? What is a dupe's lot?"

Cal nodded slowly. "He's scorned, taunted, and hated. He cannot masquerade too well—that in itself is a loss in identity. Yes—it is a matter of mercy to dispose of the duplicate. The whole thing is wrong. Can't something be done about it?"

"Not until you change human nature," smiled Tinker.

"It's been done before."

"I know. But not a thing as ingrained as this."

"Ingrained? Look, Tinker Elliott, up to the period of duplication, three hundred years ago, twins and multiple-births used to dress and act as near alike as possible."

"Hm-m-m. That was before a duplicate could be made. Double birth was something exceptional, and unique. The distaste against duplicates bred the hatred between twins, I know."

"We might be able to change human nature then."

"Not in our lifetime."

"I guess not. What was the big kicker, Cal?"

"About duplication? Well, there was a war in Europe and both warring countries put armies of duplicates into the field. The weapons, of course, were manufactured right along with the troops. There were armies of about nineteen million men on each side, composed of about a thousand different originals. They took the best airmen, the best gunners, the best rangers, the best officers, the best navigators, and the best of every branch of fighting and ran them into vast armies. It was stalemate until the rest of the world stepped in and put a stop to it. Then there were thirty-eight million men, all duplicates, running around. The mess that ensued when several thousand men tried to live in one old familiar haunt ... it was seventy years before things ran down."

"That would send public opinion reeling back," smiled Tinker. "But do you mind if we change the subject? I think that I've gotten last night's experience out of my system. What was all this wild story you were telling me?"

"Let's stroll towards food," he said. "I'll tell you then." Cal dropped some coins on the bar to take care of the check and they went into the dining room. The waiter led them to their table and handed them menus.

"This isn't needed," he told the waiter. "I want roast knolla."

"Please accept the apology of the management," said the waiter sorrowfully. "Today we have no knolla."

"None?" asked Cal in surprise. "That's strange. Every restaurant has knolla."

"Not this one," smiled the waiter. "An accident, sir. The alloy disk containing the recording of the roast knolla dinner slipped from the chef's hands less than an hour ago and fell to the floor. It was thought to be undamaged, close inspection showed it all right. But it was tried, and the knolla came out with the most peculiar flavor. The master files haven't replaced it yet. It will be four hours before they get to our request for transmission of the disk. The engineer there laughed and said something about molecule-displacement when I mentioned the peculiar flavor. It was most peculiar. Not distressing, mind, but most alien. We're keeping the damaged disk. It may be a real unique."

"Good eating?"

"I'll reserve opinion on that until we find out how we like it ourselves," smiled the waiter. "I'd recommend something else, sir."

Cal ordered for both Tinker and himself. Then he leaned forward on his elbows and gave Tinker the highlights of his life for the past few weeks. He finished with the statement: "It's worthless, but somehow I can't see letting Benj get it."

"Worthless? Murdoch's Hoard?"

"Shall I go into that again? Look, Tinker. Murdoch's era was prior to the discovery of the matter-duplicator, which followed the Channing-Franks matter transmitter by only a few weeks. Now, anything that Murdoch could cache away would be in currency of that time. The period of duplication hadn't come yet, and the eventual invention or discovery of identium as a medium of exchange had not come. So what good is Murdoch's Hoard? It must be of some value. But what? I could discount everything as ignorance or hatred except Dr. Lange's quick desire for it. Lange is no fool, Tink. He knew what he was getting. Darn it all, I feel like going out and running the Hoard down myself!"

Tinker's laugh was genuine and spontaneous.

Cal bridled. "Funny? Then tell me why."

"You, who hates roistering, adventure, space, and hell-raising. Going after Murdoch's Hoard! That, I want to see."

"So that you can laugh at my fumbling attempts?"

Tinker sobered. "I've been unkind, Cal. But you are not equipped to make a search like that."

"No?"

"You, with your quiet disposition and easy-going ways. Yes, Cal, I can be honest with you. Forgive me, but the idea of watching you conduct a wild expedition like that intrigues me," Tinker became serious for a moment. "Besides, I'd like to be there when you open Murdoch's Hoard."

"Hm-m-m. Well, it's just an idea."

"You'll get right back into your rut, Cal. You don't really intend to do anything about it, do you?"

"Well—"

"Cal—would you give me the Key?"

"What!"

"I mean it."

"Tinker—what is Murdoch's Hoard?"

"Not unless you give me the Key," teased Tinker.

"Not a Chinaman's chance," said Cal with finality.

"What are you going to do with it?"

"I'm going after it myself!"

Tinker looked into Cal's face and saw determination there. "I want to go along," she said. "Please?"

Cal shook his head. "Nope. I'm not going to have anyone laughing at me. Tell me what it is."

"Take me along."

Cal thought that one over. The idea of having Tinker Elliott along appealed to him. He'd wanted her for years, and this plea of hers was an admission of surrender. But Cal felt that conditional surrender was not good enough. He didn't like the idea of Tinker's willingness to be bought for a treasure unknown. What was really in the depths of her mind he could not guess—unless she were trying to goad him into making the expedition.

"No," he said.

"Then you'll never go," she taunted him.

"I'll go," he snapped. "And I'll prove that I can take care of myself. I hate space-roving, but I'm big enough to do it despite my distaste. Now will you tell me what Murdoch's Hoard is that it is so valuable?"

"Not unless you take me along."

Pride is always cropping up in the wrong place. If Cal or Tinker had not taken such a firm stand in the first place, it would have been easier for either one of them to back down. The argument had started in fun, and was now in deadly earnest. How and where the change came Cal did not know. He reviewed the whole thing again. The first pair were ignorant. Benj was vindictive enough to deprive his brother of a useless thing that interested Cal. Dr. Lange was enigmatic. He had neither personal view or ignorance to draw his desire for Murdoch's worthless Hoard. Tinker Elliott might be goading Cal into making an adventuresome trip for the purpose of bringing him closer to her way of living. He wouldn't put it past her.

But the more he thought about it, the deeper and deeper he was falling into his own bullheadedness. He was going to get Murdoch's Hoard himself if it turned up to be a bale of one hundred dollar bills of the twenty-first century—worth exactly three cents per hundred-weight for scrap paper.

Tinker Elliott returned to the Association after the dinner with Cal. She worked diligently for an hour, and loafed luxuriously for another hour. It was just after this that Cal came into her laboratory and grinned sheepishly at her.

"Now what?" she asked. "Changed your mind?"

"Uh-huh," he said.

"Still squeamish about space?"

He nodded.

"Poor Cal," she said, coming over to him. She curled up on his lap and put her head on his shoulder. "What are we going to do about it?"

"I'm going to give you the Key," he said.

She straightened up. "You don't mind if we use it—Tony and I?"

"Not at all."

"I'm going to punish you," she said. "I'm not going to tell what Murdoch's Hoard is until we bring it back."

Cal locked surprised. "All right," he said. "It's worthless anyway. I'll wait."

"You don't want to go along?"

"If I wanted to go at all, I'd go myself," said Cal.

"O.K. Then wonder about Murdoch's Hoard until we get back. That'll be your punishment."

"Punishment? For what?"

"For not having the kind of personality that would go out and get it."

"All right. Do you want the Key?"

"Sure. Where is it?"

"At home."

"Thought you weren't living at home," said Tinker.

"I haven't been. The Key is there, though. You see, Tink, it takes the technique to make it work rather than the equipment. I'll give you both the equipment and the technique as soon as we get there. I'll demonstrate and write out the procedure. Now?"

"The sooner the better," she said.

Tinker graced her hair with a wisp of a hat and said: "I'm ready."

Putting her hand in his arm, she followed him to the street and they drove to his cottage. He led her inside, seated her, and offered her a cigarette.

"Now, Tinker," he said seriously, "where is it?"

"Where is what?"

"The Key."

"You have it as far as I'm concerned."

"You know better than that."

"You had it."

"No, you're wrong. Cal had it."

"I'm wrong—who had it?" exploded Tinker as the words took.

"Cal," smiled he.

"You're Benj."

"Brilliant deduction, Tinker. Now, do you get the pitch?"

"No. You're trying to get Murdoch's Hoard too."

"I haven't your persuasive charm, Tink. The illustrious cryptologist known as my twin brother wouldn't go into space for anything. You want the Key. Ergo, unless I miss my guess, you've been talking and using those charms on him. Don't tell me that he didn't give it to you."

"You stinking dupe."

Benj grew white around the mouth. "Your femininity won't keep you alive too long," he gritted.

"I won't steal anyone's identity," she retorted.

"I'll wreck yours," he rasped. "I'll duplicate you!"

"Then I'll be no better than you are," she spat. "Go ahead. You'll get a dead dupe—two or a million of 'em. I can kill myself in the machine—I know how. I'd do it."

"That wouldn't do me any good," snapped Benj. "Otherwise I'd do it now. I may do it later."

"Keep it up—and I'll see that one half of this duplication is removed. Now, may I leave?"

"No. If you don't know where the Key is—or Cal, you may come in handy later. I think that I might be able to force the Key away from him. He'd die before he permitted me to work on you."

"You rotten personality stealer. You deserve to lose your identity."

"I've still got Cal's."

"Make a million of you," she taunted, "and they'll still be rotten."

"Well, be that as it may. You and I are going to go to Venus. Murdoch's Hoard is still hidden in the Vilanortis Country. We have detectors. We'll just go and sit on the edge of the fog country and wait until we hear Cal's signal."

"How do you know he's going?"

"Assuming that Tinker Elliott could get more out of him than any other person, it means that he said 'no' and is now preparing to make the jaunt himself. That'll be a laugh. The home-and-fireside-loving Cal Blair taking a wild ride through the fog country of Vilanortis, I'd like to be in his crate, just to watch."

"Cal is no imbecile," said Tink stoutly. "He'll get along."

"Sure, he'll get along. But he won't have fun!"

Tinker considered the future. It was not too bright. The thing to do, of course, would be to go along more or less willingly and look for an escape as soon as Benj's suspicions were lulled by her inaction.

Cal boarded the Lady Unique at Mohave Spaceport not knowing of Tinker's capture at the hands of Benj. Benj was careful not to let Cal know of this development, since it would have stopped Cal short and would have possibly have gotten him into a merry-go-round of officialdom and perhaps fighting, in which the Key would most certainly be publicized and lost to all. Courts were still inclined to view the certified ownership rather than the possessor of an object like the Key in spite of the nine points often quoted. This was a case of the unquoted tenth point of the law. Finders of buried treasure were still keepers, but the use of a stolen museum piece to find it might be questioned. So Cal took off in a commercial liner from Mohave at the same time that Tinker was hustled aboard Benj's sleek black personal craft at Chicago.

Cal, during the trip, underwent only a bit of his previous distaste. His feelings were too mixed up to permit anything as simple as mal de space to bother him. He was part curiosity, part hatred, part eagerness and part amazement. He found that he'd had no time to worry about space by the time the Lady Unique put down at Northern Landing Venus.

With his rebuilt equipment in a neater arrangement, and the Key inserted, all packed into a small case, Cal went to the largest dealer in driver-wing fliers and purchased the fastest one he could buy. He then went to the most famous of all the tinker shops in Northern Landing and spoke with the head mechanic.

"Can you soup this up?" he asked.

"About fifty percent," said the mechanic.

"How long will it take?"

"Couple of hours. We've got to beef up the driver cathodes and install a couple of heavier power supplies as well as tinker with the controls. This thing will be hotter than a welding iron when we get through. Can you handle her?"

"I can handle one like this with ease. I have fast reflexes and quick nerve response."

"It'll take some time before you get all that there is in it out of it," grinned the mechanic. "Mind signing an affidavit to the effect that we are not to be held responsible for anything that happens with the souping-up?"

"Not at all."

The mechanic went at the job with interest. His estimate was good, and within two hours the flier was standing on the runway, all ready to go. Cal returned from a shopping trip about this time and packed his bundles into the baggage compartment. He paid off, and then took off at high speed and headed south.

Eight hours later the fog bank that marked the Vilanortis Country came before the nose of Cal's flier. He plunged into the fog at half speed and continued on for a full five hundred miles.

He was about halfway through the vast fog bank when he landed and started to install the Key-equipment for operation. The job took him a full day, and he slept on the divan in the cabin of the flier that night. He could have used the flier at night, for there was no choice between night-operation and the thickness of the eternal fog of the Vilanortis Country. In neither case could he see more than a few yards ahead.

And while Cal slept, Benj dropped his flier on the edge of the fog country and waited. The detectors were installed and operating, and the black flier was all ready to surge forward on the trail as soon as Cal's initial signal went forth. Having had more experience in this sort of thing, Benj knew how to go about it. He'd not follow the trail of Cal's signal, but would turn and follow the answering, sympathetic oscillation from the resonant cavity at Murdoch's Hoard. And with that same experience, Benj knew that he could beat Cal to the spot, and possibly be gone with Murdoch's Hoard before Cal got there. He composed a sarcastic sign to leave on the spot for Cal to find. That, he liked. Not only would he have Murdoch's Hoard, but he would be needling his hated brother too.

Tinker had curbed her tongue. What was going to happen she did not know. Benj was quite intent on the mechanics of the chase and hadn't paid too much attention to her except to see that she was completely held. The idea of her, a sentient identity, being restrained with heavy handcuffs made her rage inwardly. Yet she kept her peace. She was not going to attract Benj's attention to her.

So she dozed on the divan in Benj's flier while Benj cat-napped at the wheel of the flier. He would be up and going at the first wink of the pilot light and the first thrumming whistle that came from the detector. He wanted to waste no time. Running down a source of transmitted signal was a matter of a few hours at most, even though it were halfway around the planet. He chuckled from time to time. He'd had Wally tailing Cal, and had a complete report on the flier and its souping-up. His own flier was capable of quite a few more miles per hour than Cal's, and Benj was well used to his.

And so Tinker dozed and Benj cat-napped until the first glimmer of dawn. Benj shook himself wide-awake, and took a caffeine pill to make certain. Reaching back from the pilot's chair, he shook Tinker. "Pay for your board," he growled. "Breakfast is due."

"I'll poison you," she promised.

"There isn't anything poisonous aboard," he said, roaring with laughter.

It was more self-preservation than his threat that made Tinker prepare coffee and toast. Working with manacles on made it difficult, and she hated him for them again. She was carrying the hot coffee to the forecabin when his roar came ringing through the ship.

"Grab on! Here we go!"

The rush of the ship threw her from her feet, and the hot coffee spilled from the pot and scalded her. She screamed.

"Now what?"

"I'm burned."

"Coffee spill? Why didn't you put it down?"

"I wish I'd spilled it on your face," she snapped. "Mind taking these irons off so I can get some isopicrine for the burn?"

He tossed her the key. "If you run now, you'll starve before you get anywhere," he told her. "But stay out of my way. We're on the trail of Murdoch's Hoard."

The thrumming whistle came in clear and strong as Benj headed into the thick fog. And as they drove forward at a wild speed, Benj tinkered with the detector.

He picked up Cal's emitted signal easily and clearly, but was unable to get a response from the other source. He considered, and came to the conclusion that the other resonator might be outside of Cal's range of transmission and therefore inoperative as yet. Knowing Hellion Murdoch's personality by comparison to his own devious way of thinking, he knew that a world-wide broadcast of the response-signal would have been unnecessary. A general location within a hundred miles would have been good enough.

So having no goal but Cal's signal, Benj turned the nose of his flier upon Cal's sharp, vibrating tone and drove deeper and deeper into the fog-blanket of Vilanortis.

As for Cal, he'd awakened by the clock and had tuned up his resonator before taking off. Immediately after making the initial adjustments, and tuning the Key a bit, the response came in strong and clear. Cal lifted the flier and began to trace the source. At almost full throttle he went on a dead straight line for Murdoch's Hoard. He wondered whether his signal were being followed, and suspected that it was. He knew, however, that no one was in possession of the technique of receiving the response, and therefore he drove at high speed. If he could arrive before the others, he would be able to establish his claim on Murdoch's Hoard, whatever it might be, or perhaps remove it if it were not too bulky.

Once he established the direction of the response, Cal wisely turned his equipment off. That would forestall followers, and he could snap the gear on and off at intervals until he came close to the site of the famous Hoard.

Benj swore as the signal ceased. But prior to its cessation, there had been a strong indication as to the relative motion of Cal's ship. He continued by extrapolation and went across the chord of the curve to intercept the other ship at some position farther along.

Tinker smiled openly. "Cal isn't ignorant," she said.

"Turning that thing off isn't going to help at all," responded Benj. "I've got Cal's original junk in the ship. I don't know the technique of finding the real Hoard, but I've been thinking that following the Key in Cal's ship might be possible. After all that's a cavity resonator too, you know."

"Sure it is. But if you can't follow the Hoard resonator, how can you follow Cal's?"

"Murdoch did something to his that makes it different," explained Benj. "What, no one has ever known until that brilliant brother of mine unraveled the code. But if the Hoard had been a standard resonator, people would have uncovered it long years ago. There's nothing tricky about getting a response from a resonant cavity."

Benj set the flier on the autopilot and went forward into the nose of the craft with tools. He emerged a moment later with a crooked smile. "All I had to do was to hitch up Cal's original junk. The detector is running as it always was, but now I can shoot forth a signal from Cal's equipment, stop it, and receive on my own detector. We had a fistful of duplicate Keys around the lab. We can't follow Murdoch's Hoard, but we can follow Cal—who is on the trail of Murdoch's Hoard."

He snapped a switch, and a thrumming whine came immediately. "That will be Cal's response," said Benj cheerfully. "No matter how he tries, he'll lead us to the spot."

Cal sped along in the thick white blanket of fog, not knowing that his own Key was furnishing a lead-spot for another. Had he known, it is possible that he would have stopped and had his argument when the other arrived, or perhaps he could have damped the resonator enough so that its decrement was short enough to prevent any practical detection of the response.

But Cal was admittedly no technician. He did not realize that his own resonator would become a marker. So he sped along through the white at a killing pace. He snapped the switch after some time and listened to the response from Murdoch's Hoard—as well as another signal that blended with his. The latter did not bother him as it might have bothered an engineer. Cal had no way of knowing what the results would be, and so he accepted the dual response as a matter of fact.

It was in the third hour of travel that the inevitable came. By rights, it should have come easily and quietly, but it came with all of the suddenness of two fliers running together at better than five hundred miles per hour.

Out of the whiteness that had blocked his vision all day, Cal saw his brother's black flier. It came through the sky silently, skirling the fog behind it into a spiral whirl. It came at a narrow angle from slightly behind him, and both pilots slammed their wheels over by sheer instinct.

The fliers heeled and cut sweeping arcs in the fog. Inches separated their wingtips and they were gone on divergent courses.

Cal mopped his brow. In the other ship, Benj swore roundly at Cal, and mopped his brow, too. And Tinker sat on the divan, letting her breath out slowly.

But Benj whipped the wheel around, describing a full, sharp loop in the sky. He crammed a bit of power on, and the tail of Cal's ship came into sight through the fog. Cal saw him coming and whipped his plane aside. Benj anticipated the maneuver and followed Cal around, crowding him close.

"What are you trying to do?" screamed Tinker, white-faced.

"Run him down," gritted Benj.

"Kill him?"

"No. He'll glide out of power if I can ram his tail."

He followed Cal up and over in a tight loop, dropping into an ear-drumming dive instead of completing the loop. Cal pulled out and whipped to the left, and Benj, again trying to anticipate the action, missed and turned right. Cal was lost again in the fog.

Cal waited for several minutes to see if he had really lost Benj, hoping and yet knowing that he had not. Yet there was quite a difference between knowing where he was and being within ten feet of his tail. In ten minutes, and one hundred miles later on the straightaway, Cal opened the throttle to the last notch and by compass streaked directly onto his former course.

Benj streaked after him, the resonator in operation, as soon as enough distance had been put between them for the gadget to function. Then Benj started to overhaul Cal's swift flier.

Meanwhile, Cal tried the Key. The answering signal indicated that he was approaching the site of Murdoch's Hoard, and not more than fifteen minutes later the direction indicator whipped to the rear. Cal had passed directly over it.

He circled in a tight hairpin turn and went back.

He forgot about Benj.

The black ship came hurtling out of the fog just a few feet to his right.

Before, they had been approaching on an angle, which had given both men time to turn. But now they were approaching dead on at better than six hundred miles per hour each. They zoomed out of the fog brushed wingtips and were gone into the fog again, but not without damage. At their velocity, the contact smashed the wingtips and whirled them slightly around.

Like falling leaves they came down, and before they could strike the ground with killing crashes, they both regained consciousness.

Benj's ship was beyond repair. It fell suddenly, even though Benj struggled with the controls. It hit ground and skidded madly along the murky swamp, throwing gouts of warm water high and shedding its own parts as it slid. It whooshed to a stop, settled a bit into the muddy ground and was silent.

Cal had more luck. By straining the wiring in his ship to the burnout point he fought the even keel back and came down to a slow, side-slippage that propelled him crabwise. He dropped lower and lower, and because there was nothing against which to measure his course, he did not know that he was describing a huge circle. His ship came to ground not more than a half-mile from Benj's demolished ship.

He set the master oscillator running in his ship and then put the field-locator in his pocket. No matter where he went, he could return to his own craft, at least. Then he stepped out of his flier to inspect the damage.

A roaring went up that attracted Cal's attention. He turned, and started to beat through the swamp towards the noise.

Light caught his eyes, and he came upon the burning wreckage of Benj's flier. Benj was paying no attention to the burning mass behind him, nor was he interested in Tinker Elliott. He was working over Cal's original equipment furiously, plying tools deftly and making swift tests as he worked.

Tinker was struggling across the ground of the swamp, pulling herself along with her hands. Her hips and legs were following limply as though they had not a bit of life. Her face was strained with the effort, though she seemed to be in no pain.

She saw him, and inadvertently cried: "Cal!"

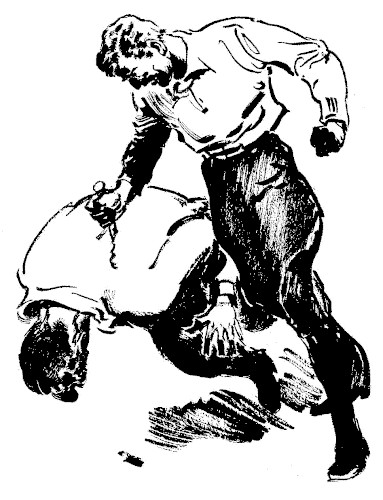

Benj leaped to his feet, his hand swinging one of the three-foot welding irons. He saw Cal, and with his other hand he whipped out the needle beam and fired. The beam seared the air beside Cal's thigh. Cursing Benj tried again, but nothing came from the beam. He hurled the useless weapon into the swamp and came forward in a crouch, waving the welding iron before him.

Cal ducked the first swing and caught Benj in the face with a fist. It hurtled Benj back, but he came forward again, waving the white-hot, needle-sharp iron before him.

Cal couldn't face that unarmed. He dropped below the thrust, and his hand fastened on the matching iron to the pair that went in every flier repair-kit. He flung himself back, and came up in a crouch as his thumb found the switch that heated his own point.

Silently, their feet making soggy sounds in the swamp, Cal and Benj crossed points in a guard of hatred.

Benj lunged in a feint, first. That started it. Cal blocked the feint swiftly and then crossed his iron down to block the real lunge that came low. While Benj recovered, Cal thrust and missed by inches. Benj brought the hot tip up and passed at Cal's face. Cal wiped the iron aside with a circular motion and caught Benj on the crook of the elbow. Smoke curled from the burn and Benj howled. It infuriated him and he pressed forward, engaging Cal's point. Cal blocked another thrust, parried a low swing, and drove Benj's point high. He dropped under the point and lunged in a thrust that almost went home. Benj dropped his white-hot iron and deflected the thrust. He jabbed forward as Cal regained his balance, and pressed forward again before Cal could get set.

The mugginess caught Benj's feet and slowed him. Cal was slowed too, but his backward scramble to regain balance was swifter than Benj's advance. The white-hot points made little circles in the foggy murk as they swung and darted.

Benj wound Cal's point in a circular motion and then disengaged to lunge forward. His point caught Cal in the thigh and the sear burned like live flame, laming Cal slightly. Cal parried, and then pressed forward with a bit of the fastest handwork Benj had ever seen. By sheer luck, Benj blocked and parried this encounter. The final lunge found Benj retreating fast enough to evade the thrust that might have caught him fair had he been slow in retreat.

He regained and forced Cal back. His dancing point kept Cal too busy blocking to counterthrust, and Cal fought a stubborn retreat. The ground behind him grew harder as he went back, and so he took a full backward step to get the benefit of hard, dry ground. He made his stand on the bit of dry knoll, and fought Benj to a standstill.

He fought defensively, waiting for Benj to come close enough to hit. Their irons danced in and out, and Benj circled Cal slowly. Part way around, Benj forced Cal's point up and rushed him. Cal backed away three steps—and tripped over Tinker's hips. He went rolling in a heap, curling his feet and legs up into his stomach.

Benj leaped over Tinker and rushed down on Cal, who kicked out with both feet and caught Benj hard enough to send him flying back.

Both men jumped to their feet, circled each other warily, waiting for an opening. Benj rushed forward and Cal went to meet the charge. The ring of the irons came again and the white-hot points fenced in and out.

Benj thrust forward, high, and Cal blocked him with the shaft of the iron. Their arms went up, shaft across shaft, and shoulder to shoulder they strived in a body-block.

"Steal my identity, will you?" snarled Cal.

"Destroy it," rasped Benj. "You've been asking for this."

Cal's mind flashed, irrelevantly, to books and pictures he had seen. In such, the villain always spit in the hero's face in such a body-block. Cal snarled, pursed his lips and spat in Benj's face. Then with a mighty effort, Cal shouldered Benj back a full three feet and crossed points with him again.

Benj wiped his face on his shirt sleeve and raving mad, he drove forward, his point making wicked arcs. Cal parried the dancing point, engaged Benj in a thrust and counterthrust, and then with Benj's point blocked high, he drilled forward.

The white-hot point quenched itself in Benj's throat with a nauseating hiss.

Cal stood there, shaking his head at the sight, and retching slightly. His face, which had been set like granite, softened. He dropped his iron and turned away.

"Tink!" he cried.

"Nice job, Cal," she said with a strained smile.

"But you?"

"I'm in no pain."

"But what's wrong?"

"Fractured vertebra, I think. I'm paralyzed from the waistline down. That crash—"

"Bad. Now what?"

"Where's your ship?"

"Back there a half-mile or so," said Cal.

"Don't carry me," she warned as he tried to lift her. "Go back there and either bring it here or get something to strap me on."

"It'll take hours. The ship won't fly. I'll have to radio back to Northern Landing for help."

"I ... won't last."

"You—" the meaning hit him then. "You won't last?"

"Not unless that vertebra is repaired."

"Then what can we do?"

"Cal ... where's Murdoch's Hoard?"

"Nearby, but you're more important than anything that might be in Murdoch's Hoard."

"No, Cal. No."

"Look, Tink, you mean more to me than—"

"I know that, Cal. But don't you see?"

"See what?"

"What could possibly be of value?"

"No. Nothing that I have any knowledge of."

"That's it! Knowledge! All of the advanced work in neurosurgery is there. All in colored, detailed three-dimensional pictures with a running comment by Murdoch himself. Things that we cannot do today. Get it, Cal. It'll tell you how to fix this crushed spinal cord."

Cal knew she was right. Murdoch, in his illegal surgery had advanced a thousand years beyond his fellow surgeons who could legally work on nothing but cadavers or live primates while Murdoch had worked on the delicate nervous system of mankind itself. Murdoch's Hoard was a board of information—invaluable to the finder and completely unique and non-duplicative. At least until it was found.

"I can't leave you."

"You must ... if you want me! I'm good for six or seven hours. Go and get that information, Cal."

"But I'm no physician. Much less a surgeon. Even less a neurosurgeon."

"Murdoch's records are such that a deft and responsible child could follow them. According to history, his hoard is filled with instruments and equipment. Cal—"

"Yes?"

"Cal. This is the place where Murdoch worked on living nerves!"

Tinker Elliott closed her eyes and tried to rest. She did not sleep, nor did she feel faint. But her closed eyes were a definite argument against objection on Cal's part. Worrying, he left her and went back to his flier. He called for help and then he went to work on the Key.

Cal does not remember the next four hours. It was a whirling montage of dismal swamp and winking pilot lights and thrumming whistles. It was a lonely boulder with a handle on it that Cal lifted out of the ground with ease. It was an immaculate hospital driven deep into the murky ground of Venus. Three hundred and fifty years ago, Dr. Allison Murdoch worked here and today his refrigerating plants started to function as soon as Cal snapped the main switch.

On a stretcher that must have held many a torn and mangled set of nerves before, Cal trundled Tinker through the muggy swamp of Venus and lowered her into Murdoch's hospital.

In contrast, the next few hours will live forever in Cal's mind. He came to complete awareness when he realized that he did not know his next move.

"Tinker?" he asked softly.

"Here ... and still going," she said. "Ready?"

Cal swallowed deep. "Yes," he said hoarsely.

"In that case over there ... see it? Take an ampule of local—it's labeled Neo-croalaminol-opium, ten percent. Get a needle and put three cubic centimeters of it into space between the sixth and seventh cervical vertebra. Go in between four and five millimeters below the surface of the bone. Can do?"

"I ... I can't."

"You must! How I wish we had a duplicator."

Cal shuddered. "Never."

"Well, I could show you how it's done on the duplicate, and then the duplicate could fix me up."

Cal gritted his teeth, "And which one would I dispose of? No, Tinker. It's bad enough this way!"

"Well, do it my way then!"

Cal fumbled for the needle and then with a steady hand he broke the glass ampule and filled the needle. "Is this still good?"

"It never deteriorates in a vacuum. We must chance everything."

Cal inserted the needle and discharged the contents. His face was gray.

"Now," said Tinker. "I'm immobilized completely from the shoulder blades down and can't harm myself. Cal, find the library and locate the reel that will deal on vertebra and spinal operations."

"How do you know it is here?" demanded Cal.

"It's listed, in Murdoch's diary. Now quit arguing and go!"

"How come this diary isn't common knowledge?"

"Because too many prominent people did not want their names mentioned as fostering Murdoch's surgery. Their offspring have never known about it and the medical profession has been keeping it under their hats so long that it has become a habit like the Px mark."

Cal located the library and consulted the card file. He returned with a reel of film. He inserted the reel into the operating room projector and focused it on the screen.

As the film progressed, Cal took the proper tools from the boiling water, and placed them on a sterilized carrier.

Then as Tinker instructed him through a system of mirrors, Cal lifted the scalpel and made his first incision.

With increasing skill, Cal applied retractors and hemostats and tweezers. Tinker kept up a running fire of comment, and the motion picture on the screen progressed as he did, with appropriate close-ups to show the condition of the wound during each step. Cal came upon the fractured bone as it said he should, and then though the fracture was not just as that in the picture, Cal plied his instruments carefully and lifted the crushed bone away from the spinal cord. With a wide-field microscope, Cal inspected the cord.