CHAPTER |

|

|---|---|

XII. |

THE STUARTS—JAMES I. |

XIII. |

CHARLES I. AND THE COMMONWEALTH |

XIV. |

CHARLES II. |

XV. |

JAMES II. |

XVI. |

WILLIAM AND MARY |

XVII. |

QUEEN ANNE |

XVIII. |

GEORGE I. |

XIX. |

GEORGE II. |

XX. |

GEORGE III. |

XXI. |

THE LATE REIGNS |

| The Fire of 1841 | |

| The Fenian Attempt to Blow up the White Tower, Jan. 24th, 1885 | |

APPENDIX |

|

| DISPUTES BETWEEN THE CITY OF LONDON AND THE OFFICIALS OF THE TOWER AS TO THE RIGHTS AND PRIVILEGES OF THE TOWER | |

| THE BEHAVIOUR AND CHARACTER OF THE THREE HIGHLANDERS WHO WERE SHOT ON JULY 18TH, 1743 | |

| DATES OF RESTORATIONS CARRIED ON BY H.M. OFFICE OF WORKS AT THE TOWER OF LONDON TO THE PRESENT TIME | |

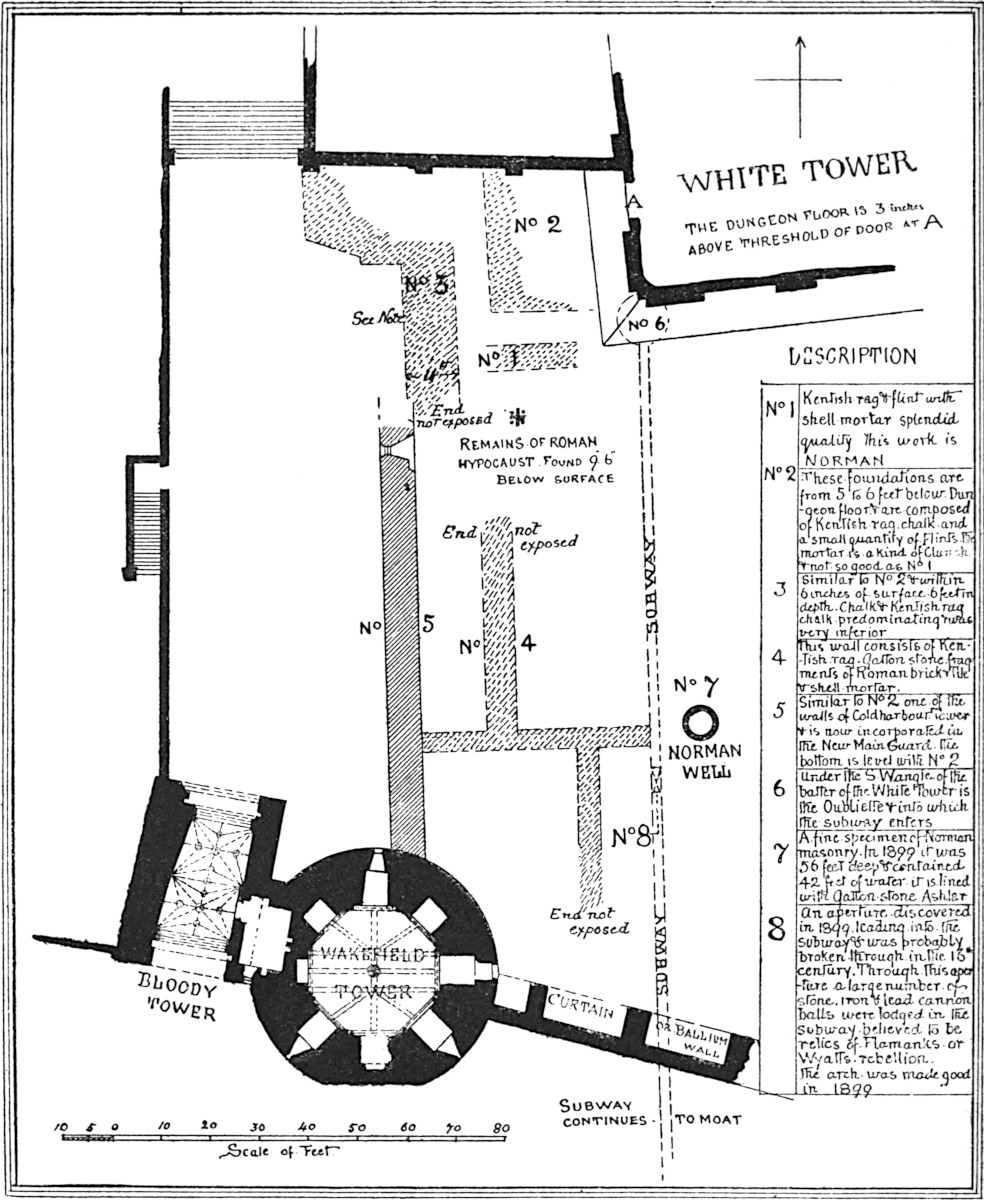

| RECENT DISCOVERIES AT THE TOWER (WITH A PLAN) | |

| THE BLOODY TOWER | |

| STAINED GLASS IN THE TOWER | |

| LIST OF THE CONSTABLES OF THE TOWER | |

ix

In Nichols’s “Progresses,” that mine of information regarding James I., his court and times, it is related that James paid his first visit to the Tower on 3rd May 1603, “when His Majesty set forward from the Charter House and went quietly on horseback to Whitehall where he took barge. Having shot the bridge, his present landing was expected at the Tower stayres, but it pleased His Highness to passe the Towre stairs toward St Katherines, and there stayed on the water to see the ordinance on the White Tower (commonly called Julius Cæsar’s Tower) being in number twenty pieces, with the great ordinance on the Towre wharfe, being in number 100, and chalmers to the number of 130, discharged and shot off. Of which, all services were sufficiently performed by the gunners, that a peale of so good order was never heard before; which was most commendable to all sorts, and very acceptable to the King.”[1]

2

Owing to the plague then raging in London, the customary procession at the coronation was omitted, although the King rode in state from the Tower to Westminster, preparatory to the opening of his first Parliament on 15th of March 1605, as the Londoners had made their welcome for him ready. In Mr Sidney Lee’s “Life of Shakespeare,” he states that Shakespeare, with eight other players of the King’s company of actors, “walked from the Tower of London to Westminster in the procession which accompanied the King in his formal entry into London. Each actor received four and a half yards of scarlet cloth to wear as a cloak on the occasion, and in the document authorising the grant, Shakespeare’s name stands first on the list.” This is the only time that we can positively know that Shakespeare was ever at the Tower; but his frequent introduction of the fortress into his historical dramas makes it certain that he must often have visited a place so full of dramatic episodes and historical memories.[2]

Four months earlier, while staying at Wilton, news had reached James of a plot to place the crown upon the head of Lady Arabella Stuart, and a large batch of alleged conspirators were taken to the Tower in consequence. Among them was Sir Walter Raleigh, Lord Cobham, and his brother, George Brooke, Thomas Lord Grey 3de Wilton, Sir Griffin Maskham, Sir Edward Parham, Bartholomew Brookesby, Anthony Copley, and two priests named Weston and Clarke. This conspiracy, if it deserves the name, and for which Raleigh was for the second time sent to the Tower, owed its existence to the unlucky Arabella, daughter of Charles Stuart, Earl of Lennox, younger brother of Darnley, and consequently James’s first cousin on the mother’s side.

Arabella Stuart was also related to the Tudors, and this double relationship to the reigning sovereign and to the late Queen was her greatest misfortune, and the cause of her untimely death. She appears to have been amiable, refined, virtuous, and good-looking, but of a somewhat frail physique and countenance, to judge by the excellent miniature which Oliver painted of her. That her mind was not a strong one is very evident, and one cannot be surprised that she became insane under the burden of her misfortunes.

Lady Arabella was made use of as a tool by James’s enemies, and at Lord Cobham’s trial it was conclusively proved that she had no share in any of the schemes which had the placing of herself on the throne for their object. Had it not been for her unfortunate marriage she would probably have ended her life in peaceful obscurity. This unhappy lady disliked the life of a court, and had lived principally with her grandmother, old Lady Shrewsbury, “Bess of Hardwicke,” as that much-married and firm-minded dame was nicknamed, in her beautiful homes of Chatsworth and Hardwicke Hall, in Derbyshire. In the last year of Elizabeth’s reign, Arabella, whose hand had been asked in marriage by many suitors, and amongst them by Henry IV. of France, and the Archduke Mathias, met, and fell in love with William Seymour, grandson of the Earl of Hertford, and had been kept in close confinement by the Queen in consequence.

The plot to place Lady Arabella on the throne was regarded as dangerous by the court, owing to James’s4 unpopularity, which was not surprising, for at that time everything Scottish was cordially detested by the English. The Scotch had been as inimical to us as either the French or the Spaniards, and for a far longer period, whilst the Scottish alliance with France had added still more to the national dislike. Neither was the new King’s appearance one to win the admiration of his new subjects, for a more ungainly individual had surely never appeared out of a booth at a fair. The English were as susceptible then, as they are now, to the outward appearance of their rulers, and even Henry VIII., for all his tyranny and cruelty, was popular among the people on account of his fine presence; and when Elizabeth appeared in public, all aglow with splendour, her lieges shouted themselves hoarse with delight, and worshipped that “bright occidental effulgence.” What a contrast to these was James Stuart. With his huge head, and padded shanks, his great tongue lolling from out his mouth, his goggle eyes, and rolling gait, and the incomprehensible, to English ears, jargon of Lowland Scotch which he spoke, his was not a very kingly figure, and he made anything but a favourable impression upon his new subjects. It appears that Raleigh, at the time of James’s arrival, let fall some remarks which were repeated to the King, to the effect that it would be well not to allow the Scottish locusts to eat too much of the Southern pastures. It has been supposed that Raleigh, at a meeting at Whitehall, proposed to found a republic, and Aubrey, a contemporary writer, even gives his words, “Let us keep the staff in our own hands, and set up a commonwealth, and not remain subject to a needy beggarly nation.” Raleigh met the King for the first time at Burleigh, when James, who prided himself on his wit, said to Sir Walter, that he thought but “rawly” of him; it is a vile pun, but is interesting as showing the way in which his contemporaries pronounced Raleigh’s name.

Cecil, who had brought Essex to the scaffold, now lost no time in bringing Raleigh, Essex’s rival, to the5 Tower, and on the 20th of July 1603, the prison gates of that fortress once again closed upon the founder of Virginia, on a charge of treason, based on the Arabella Stuart conspiracy, nor did they open for him until twelve years had passed. On the following day Raleigh attempted to stab himself with a table-knife, for he seems to have been maddened by his treatment by James and Cecil. In November the plague was so violent in London, that the Law Courts were transferred to Winchester, and it was to that city that Sir Walter and his fellow-prisoners were taken and tried on a charge of “attempting to deprive the King of his crown and dignity; to molest the Government, and alter the true religion established in England, and to levy war against the King.”

George Brooke, a brother of Lord Cobham’s, and two priests were found guilty and executed, Lords Grey de Wilton, Cobham, and Raleigh were respited, and were taken back to their prison in the Tower. Cobham never regained his liberty, he was a ruined man, and died probably in the Tower. The place of his burial is unknown.

The de Cobhams were an early family of importance in the twelfth century, and from the thirteenth to the sixteenth one of the most powerful in the south of England. Henry de Cobham was summoned to Parliament in 1313. The direct line ended in Joan de Cobham, who married five times; her third husband was Sir John Oldcastle, commonly called Lord Cobham, jure uxoris, but inaccurately, for he was summoned to Parliament under his own name, Oldcastle.

In descent from Joan was Henry Brooke, Lord Cobham, attainted first of James the First. He was born 1564, and succeeded to the title 1596–7, and shortly after installed Knight of the Garter. He married Francis Howard, daughter of the Earl of Nottingham, and widow of the Earl of Kildare. He was committed to the Tower December 16th, 1603, tried, and condemned to death, and actually brought out to be executed, but had been6 privately reprieved beforehand by James the First, who played with Cobham and Gray, and their companions, as a cat would with mice. After fifteen years’ rigorous confinement in the Tower, his health failed, and he was allowed out, attended by his gaolers, to visit Bath. This was in 1617, and was taken so ill on his way back he had to stay at Odiham, Hants, at the house of his brother-in-law, Sir Edward Moore. He died, with very little doubt, in the Tower, January 24th, 1619, but the place of his burial has been undiscovered. He had been well supplied with books, for the Lieutenant of the Tower seized a thousand volumes at the time of his death of “all learning and languages.” In a letter from Sir Thomas Wynne to Sir Dudley Carlton (State Papers, Dom Jac, 1st vol., 105), 28th of January 1619, occurs this passage: “My Lord Cobham is dead, and lyeth unburied as yet for want of money; he died a papist.” This probably was only gossip. While in the Tower he was allowed eight pounds a week for maintenance, but very little of this ever reached him, it probably was absorbed by his keepers and the Lieutenant. During his long imprisonment Lady Kildare never troubled herself further about him. She lived comfortably, first at Cobham, and afterwards at Copthall, Essex.

By the will of George, Lord Cobham, 1552, the Cobham estates, by an elaborate settlement, were strictly entailed, so that Henry, Lord Cobham, only had a life interest, and the King could not seize them; and probably it was to that fact he owed his life, for the King could possess them during his life, but not alienate them.

Unfortunately, the next heir was the son of George Brooke, executed for treason at Winchester, Lord Cobham’s brother, who, at the time of his uncle’s death, was an infant of tender age, and without friends, so negotiations were carried on with the next in succession, Duke Brooke, a cousin of Lord Cobham’s, and this man parted with his prospective rights to the King for about £10,000, which 7enabled this “specimen of King craft” to enter into possession. Duke Brooke, dying soon after, Charles Brooke, his brother, parted with several other manors to Cecil, Earl of Salisbury. None of these transactions were legal; Henry, Lord Cobham, was not dead, nor the children of George Brooke, William, and his two sisters, Frances and Elizabeth. For some reason they were “restored in blood,” but with the express proviso they should not inherit any of the property of their fathers or their uncles; nor was William to take the title of Lord Cobham. And this was all done with the connivance of Cecil, Lord Burleigh, brother-in-law to Henry, Lord Cobham. No wonder William Brooke became a devoted Parliamentarian in the next reign, and died fighting against the King at Newbury, 1643. Many letters of Henry Brooke have been preserved while in the Tower: “To my very good Lord and Brother-in-law, Lord Burleigh.” He must both have been clever and learned, for during his captivity he translated Seneca’s treatises, De Providentia, De Ira, De Tranquilitate, De Vita Beata, and De Paupertate: the original manuscript of one, De Providentia, is in the library at Ufford Place, Suffolk, the seat of his representative, Edward Brooke, Esq., written in a beautifully fine hand. Raleigh and Cobham’s “treason” was that known as the Main or Spanish Treason, one of the supposed objects of which was to place the Lady Arabella Stuart on the throne.

Lord Grey de Wilton, a young man of great promise, died in St Thomas’s Tower in 1617, after passing nine years in the Brick Tower. Lord Grey had made an eloquent defence during his trial, which lasted from eight in the morning until eight at night, during which, according to the Hardwicke State Papers, many “subtle traverses and escapes,” took place. When Grey was asked why judgment of death should not be passed against him, he replied, “I have nothing to say.” Then he paused a little, and added, “And yet a word of Tacitus comes into my mind,8 ‘non eadem omnibus decora,’ the house of the Wiltons have spent many lives in their Princes’ service and Grey cannot beg his.”

For the next twelve years the Tower was Raleigh’s home, and not till he had succeeded in bribing King James’s favourite, George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham, by the payment of a large sum of money, did he again obtain his liberty. Before settling down in the Tower, and while the plague was still raging, Raleigh, with his wife and son, were taken to the Fleet Prison on several occasions. At length they were placed in the not uncomfortable rooms in the Bloody Tower, which he, with his family and servants, must have quite filled, for besides Lady Raleigh and her son Carew, there were two servants named Dean and Talbot, and a boy, who was probably a son of Talbot’s. Their imprisonment was not absolutely rigid, for they were allowed the visits of a clergyman named Hawthorne, a doctor, Turner, and a surgeon, Dr John, as well as those of Sir Walter’s agent, who came up from Raleigh’s place, Sherborn, so that he was kept in touch with his affairs; one or two other friends were also admitted. In addition to these privileges Sir Walter was allowed the run—the liberty as it would be called then—of the Lieutenant of the Tower’s garden, which lay at the foot of the Bloody Tower, as has already been mentioned in the description of that place.

In 1604 the penal laws against the Roman Catholics were re-enacted by Parliament, and in the following year the famous Gunpowder Plot was discovered, with the consequence that in the month of November of that year the Tower received many of the principal conspirators, and still more of those individuals who were in some way or other concerned in it. Foremost amongst the latter were the aged Earl of Northumberland, Henry Percy, and with him were Henry, Lord Mordaunt, Lord Stourton, and three Jesuit priests, Fathers Garnet, Oldcorn, and Gerrard. Northumberland, besides having to pay an enormous fine, 9was kept a prisoner in the Tower for sixteen years; Mordaunt and Stourton were also heavily fined and remanded to the fortress during the King’s pleasure; Fathers Garnet and Oldcorn were hanged—the former at St Paul’s, in the usual manner, after being cruelly tortured, the latter at Worcester. As for the third priest, Gerrard, I have in another part of this work described the treatment he endured and his escape from the Tower.

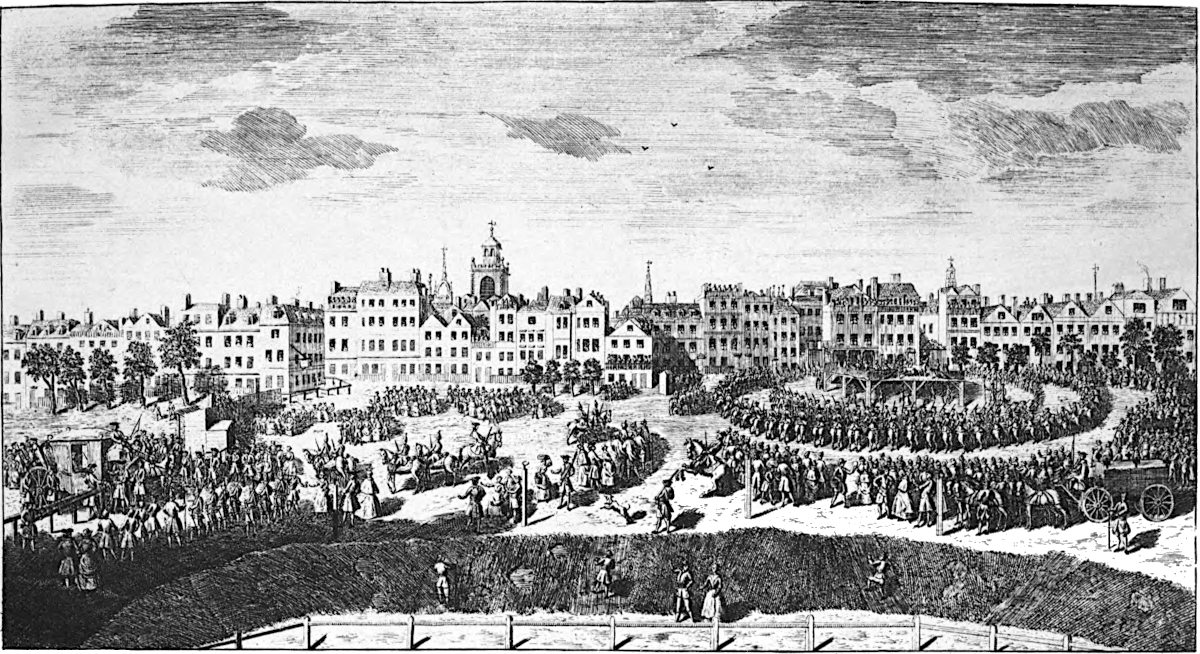

Of the active conspirators, besides Guy Fawkes—who was executed with Thomas Winter, Rookwood, and Keyes in Old Palace Yard—Sir Everard Digby, the father of the accomplished Sir Kenelm, Robert Winter, Grant, and Bates, were drawn on hurdles to the west end of St Paul’s Churchyard, where they were done to death in the approved fashion of execution for high treason.

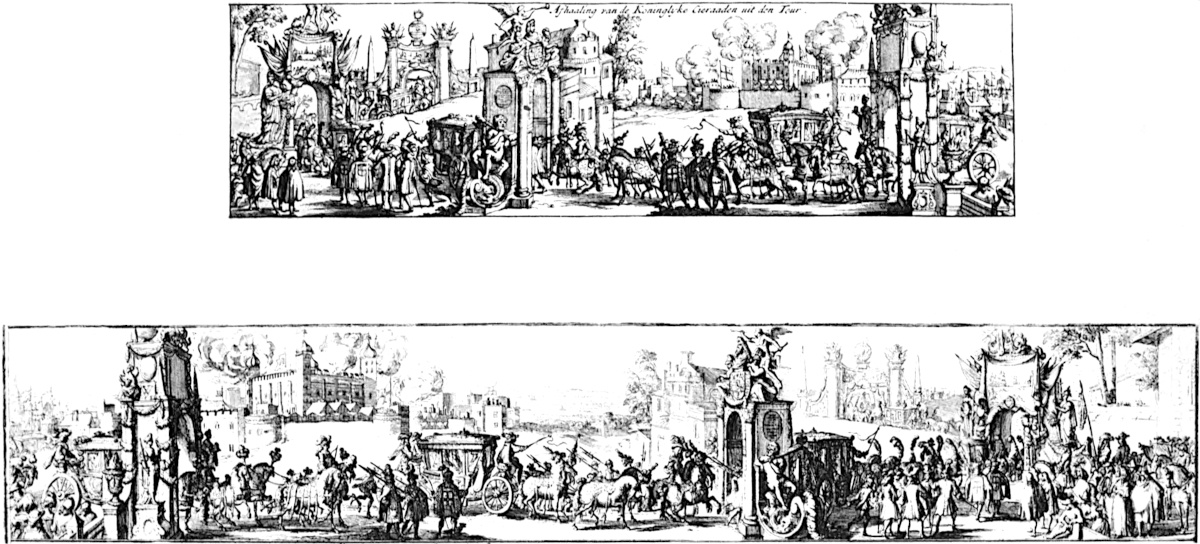

Guy Fawkes and most of his fellow-prisoners while in the Tower had been placed in the subterranean dungeons beneath the White Tower. Fawkes, besides being tortured by the rack, was placed in “Little Ease,” in which horrible hole he is supposed to have been kept for fifty days. Father Oldcorn was imprisoned in the lower room of the Bloody Tower, whilst Father Fisher was in the White Tower; Northumberland, the “Wizard Earl,” as he was called on account of his leaning towards chemical experiments, was lodged in the Martin Tower.

Until the month of August in that year (1605), Sir Walter Raleigh’s imprisonment in the Bloody Tower had not been very stringent. Sir George Harvey had filled the position of Lieutenant of the Tower, and Sir George and Sir Walter were on friendly terms. His lodging, for a prison, was comfortable enough; his wife and son were still with him, Lady Raleigh having been confined of a second son about this time. In addition to the attendance of his servants and the visits of his friends, as I have mentioned before, he was allowed to have all the books he required for the great literary labour that now began to occupy much of his time. When not working in his10 little garden by the Tower, or experimenting with his chemicals and decoctions in a small outbuilding which he had built in the garden, or taking exercise on the wall terrace which overlooked the wharf and the river beyond, he would be writing at his “History of the World,” that wonderful fragment which is one of the marvels of our literature.

Unfortunately for Sir Walter, his friend Sir George Harvey, with whom he often dined and passed the evening, ceased being Lieutenant at this time, being succeeded by Sir William Waad. Raleigh’s feelings towards the new Lieutenant appear to have resembled those of Napoleon to Sir Hudson Lowe. Waad, who had been Clerk of the Council, on his side seems to have had a personal dislike to the great captive over whom he was placed in charge, and to have done all he could—and he had the power of doing a great deal—to render Raleigh’s life as unpleasant and galling as possible. For instance, Waad ordered a brick wall to be built in front of the terrace where Raleigh walked, so that the captive could no longer watch the passing life beneath him on the wharf or river. Then Waad complained to Cecil of Raleigh making himself too conspicuous to the people who passed beneath the Bloody Tower, and, not content with annoying Sir Walter, pestered Lady Raleigh, and deprived her of the poor satisfaction of driving her coach into the courtyard of the fortress, a privilege that had hitherto been allowed her. In these and many other petty ways the new Lieutenant contrived to make himself as unpleasant as he possibly could to Raleigh and his wife.

During the alarm consequent upon the Gunpowder Plot, Raleigh was examined by the Council, probably in the Lieutenant’s, now the King’s House, but naturally nothing could be found to implicate him with the conspiracy, and the King had to bide his time before he could bring his great subject to the block. In 1610, for some unknown reason, Sir Walter was kept a close11 prisoner in his tower for three months, and Lady Raleigh was taken from him.

In Disraeli’s “Amenities of Literature” is the following interesting description of those friends of Sir Walter who shared his pursuits and studies in the Tower:—

“A circumstance as remarkable as the work itself” (“History of the World”) “occurred in the author’s long imprisonment. By one of the strange coincidences in human affairs, it happened that in the Tower Raleigh was surrounded by the highest literary and scientific circle in the nation. Henry, the ninth Earl of Northumberland, on the suspicion of having favoured his relation Piercy, the Gunpowder Plot conspirator, was cast into this State prison, and confined during many years. This Earl delighted in what Anthony Wood describes as ‘the obscure parts of learning.’ He was a magnificent Mecaenas, and not only pensioned scientific men, but daily assembled them at his table, and in these intellectual communions, participating in their pursuits, he passed his life. His learned society was designated as ‘the Atlantis of the Northumberland world’! But that world had other inhabitants, antiquaries and astrologers, chemists and naturalists. There was seen Thomas Allen, another Roger Bacon, ‘terrible and tho’ vulgar,’ famed for his ‘Bibliotheca Alleniana,’ a rich collection of manuscripts, most of which have been preserved in the Bodleian; the name of Allen survives in the ardent commemorations of Camden, of Spelman, and of Selden. He was accompanied by his friend Doctor Dee, but whether Dee ever tried their patience or their wonder by his ‘Diary of Conferences with Spirits’ we find no record, and by the astronomical Torporley, a disciple of Lucretius, for his philosophy consisted of stones; several of his manuscripts remain in Sion College. The muster-roll is too long to run over. In this galaxy of the learned the brightest star was Thomas Hariot, who merited the distinction of being ‘the Universal Philosopher’; his inventions in algebra Descarte, when in England, silently adopted, but which Dr Wallis afterwards indignantly reclaimed; his skill in interpreting the text of Homer excited the grateful admiration of Chalman when occupied by his version. Bishop Corbet has described

‘Deep Hariot’s mineIn which there is no dross.’“Two other men, Walter Warner, who is said to have suggested to Harvey the great discovery of the circulation of the blood, and Robert Huer, famed for his ‘Treatise on the Globes’—these, with Hariot, were the Earl’s constant companions; and at a period when science seemed connected with necromancy, the world distinguished the Earl and his three friends as ‘Henry the Wizard and his three Magi.’... Such were the men of science, daily guests in the Tower during the imprisonment of 12Raleigh; and when he had constructed his laboratory to pursue his chemical experiments, he must have multiplied their wonders. With one he had been intimately connected early in life, Hariot had been his mathematical tutor, was domesticated in his house, and became his confidential agent in the expedition to Virginia. Raleigh had warmly recommended his friend to the Earl of Northumberland, and Sion House became Hariot’s home and observatory.”

The elder Disraeli has argued that Raleigh could not possibly have written the whole of that large tome, “The History of the World,” himself, for want of books of reference whilst in the Tower. But as his friends supplied him with books, and he himself had probably taken copious notes for the work while living in the old home of the Desmonds at Youghal, in Ireland, where a remnant of the old Desmond library is still existing, the argument can scarcely be considered proved. The late Sir John Pope Hennessy has pointed out in his work on “Raleigh in Ireland,” that, by an odd coincidence, the son of the sixteenth Earl of Desmond, whose lands Raleigh held in Ireland, was a fellow-prisoner of Sir Walter’s in the Tower during his first imprisonment in the fortress during Elizabeth’s reign. Desmond died in prison in 1608, and was buried in St Peter’s Chapel. Raleigh had this youth’s sad fate in his mind, it seems, when he wrote from the Tower, “Wee shall be judged as we judge—and be dealt withal as wee deal with others in this life, if wee believe God Himself.”

An almost contemporary historian, Sir Richard Baker, refers to Raleigh’s imprisonment in the following quaint manner:—“He was kept in the Tower, where he had great honour; he spent his time in writing, and had been a happy man if he had never been released.” A strange description, surely, of what is generally understood by the term, “happy man.”

Henry, Prince of Wales, seems to have been the only member of his family who appreciated Sir Walter, frequently visiting him at the Tower. On one of the occasions when he had left him, the young prince remarked to 13one of his following that no king except his father could keep such a bird in such a cage. The Prince’s mother, Queen Anne, seems also to have shown some interest in Raleigh’s fate, and to have tried to induce her miserable husband to set him free.

In 1611 Arabella Stuart was brought a prisoner into the Tower, and with her, Lady Shrewsbury. When the news of Arabella’s marriage with young William Seymour reached the King, her fate was sealed, for by this marriage the half-captivity in which she had lived was changed into captivity for life; and few of James the First’s evil actions, and they were not a few, were more mean or cowardly than his treatment of his poor kinswoman, Arabella Hertford.

She had never been known to mix in politics, and if she had any ambition, it was the noble ambition of wishing to lead a pure life away from an infamous court. Poor Arabella used to declare that although she was often asked to marry some foreign prince, nothing on earth would induce her to marry any man whom she did not know, or for whom she had no liking.

At Christmastide of 1609, James, hearing a rumour that seemed to point to Arabella being married to some foreign prince, had sent her to the Tower, releasing her when he discovered that his fears were groundless, and giving his consent to her marrying one of his subjects should she wish to do so. Unfortunately, Arabella took advantage of the King’s consent, trusting to his word, but she found to her bitter cost how hollow and false that promise was. In the following February (1610) she plighted her troth to William Seymour, both probably relying upon the Royal word. Whether James had forgotten that Seymour was a probable suitor for Arabella’s hand when he gave his promise cannot be known, but Arabella could not have made a more unlucky choice, as far as she herself was concerned, for the Suffolk claims had been recognised by Act of Parliament; and the same Parliament which14 had acknowledged James the First could not alter the order of succession, and, consequently, William Seymour being the grandson of Lord Hertford, by his wife, Catharine Grey, was in what was called the “Suffolk Succession.” His marriage to Arabella brought her still nearer to the Crown, and any children born of the marriage would have had a good chance of succeeding to the throne.

The young couple were summoned to appear before the Council, and were charged to give up all thoughts of marriage. But, in spite of King and Council, they were secretly married in the month of May 1611—a month said to be unlucky for marriages. Two months afterwards the news reached the King, and the storm burst over the unlucky lovers. Arabella was sent a prisoner to Lambeth Palace, and her husband to the Tower. From Lambeth Arabella was first removed to the house of Mr Conyers at Highgate, and thence she was to be sent to Durham Castle in charge of the Bishop. At Highgate, however, she fell ill, or pretended to fall ill, and the famous attempt made to escape by herself and her husband took place.

By some means she procured a disguise in the shape of a wig and male attire, with long, yellow riding-boots and a rapier, and thus accoutred, on the 4th of June she rode to Blackwall, where she had hoped to find her husband, but, failing in this, she rowed with a female attendant and a Mr Markham, who had accompanied her from Highgate, to a French vessel lying near Leigh, which took them on board. Seymour, also disguised, escaped from the Tower by following a cart laden with wooden billets. He got away unperceived, and managed to reach a boat waiting for him by the wharf at the Iron Gate, but, on arriving at Leigh, they found the French ship, with Arabella on board, had put out to sea. The weather was against the ship in which Seymour was sailing making Calais, and he had to go on to Ostend, where he disembarked.

15

Meanwhile, a hue and cry rang out from London. King’s messengers galloped in hot haste from Whitehall to Deptford, and orders arrived at all the southern ports to search all ships and barks that might contain the runaways; a proclamation was issued to arrest the principals and the abettors of their flight. A ship of war was sent over to Calais, and others were despatched along the French coast as far as Flanders to intercept the fugitives. When half-way across the Channel, one of these vessels, named the Adventurer, came in sight of a ship crowding on all sail in order to reach Calais; the wind, meanwhile, had dropped, and further flight was impossible. A boat was lowered from the Adventurer, the crew who manned it being armed to the teeth. A few shots were exchanged, and the flying vessel, which proved to be French, was boarded, and the poor runaway was taken back to the English man-of-war; on board of her Arabella was made a prisoner, and as a prisoner was landed at the Tower, never to leave it again until her luckless body was taken from it for burial at Westminster.

James made as much ado about this attempted escape of the Hertfords as if he had discovered a second Gunpowder Plot. And not only did he have all those who had been concerned in Arabella’s flight seized and imprisoned in the Tower, but kept the Countess of Shrewsbury and the Earl strict prisoners in their house, and ordered the old Earl of Hertford to appear before him.

From all appearances William Seymour showed a lack of courage at this time, not unlike the husband of Lady Catherine Seymour in the last reign, for he remained abroad while the storm with all its fury fell and crushed his young wife. Poor Arabella lingered on in her prison till death released her from her troubles on the 25th of September 1615. She had been kept both in the Belfry Tower and in the Lieutenant’s House, but had lost her reason some time previous to her final release both from durance and the world. Her body was taken in the dead of night to Westminster Abbey, and placed below the coffin of Mary16 Queen of Scots. Mickle, the author of “Cumnor Hall,” and “There’s nae luck about the house,” is credited with having written the touching ballad on Arabella Stuart, which is included in Evans’s “Old Ballads.”

William Seymour survived Arabella for nearly half-a-century; he married again, his second wife being a sister of the Parliamentary general, the Earl of Essex, the son of Elizabeth’s favourite and victim. In 1660 Seymour became Duke of Somerset, and lived just long enough to welcome Charles II. He had shown far more loyalty to Charles I. than he had done to poor Arabella Stuart.

In 1613, Sir William Waad, to the great delight of Raleigh, as well as of the other prisoners in the Tower, vacated his post as Lieutenant. He had been charged with the theft of the unfortunate Arabella’s jewels, but his dismissal was also connected with a still more tragic story—the murder of Sir Thomas Overbury—a murder which throws a very lurid light upon the doings of James the First’s court and courtiers. Two years before Arabella’s death, the Tower had been the scene of a most foul murder. Scandalous as was the court of James, murder had not yet been associated with it, but in the year 1613 the fate of Sir Thomas Overbury added that dark crime to its other villainies.

17

Macaulay has compared the court of James the First to that of Nero; it would have been more correct to have likened it to that of the Valois, Henry III. Although it was never proved, there were strong suspicions that the somewhat sudden death of Henry, Prince of Wales, was brought about by poison, and there is no doubt that poison was made use of by James’s courtiers, as the death of Overbury proves. Sir Thomas Overbury was the confidant of the King’s worthless favourite, Robert Carr, a handsome youth who had been brought by James from Scotland in his train, and whom he had knighted in 1607. James had also given Raleigh’s confiscated estates to his favourite two years after making him a knight, and in 1614 created him Lord Rochester and Earl of Somerset, as well as Lord Chamberlain. Overbury belonged to a Gloucestershire family, and had travelled on the Continent, whence he returned what was then called “a finished gentleman.” Overbury and Carr were firm friends, and it was probably on the recommendation of the latter that James knighted Overbury in 1608. When, however, Somerset determined to marry the notoriously improper Lady Frances Howard, the daughter of the Earl of Suffolk, and the girl-wife of Lord Essex, from whom she was separated, Overbury most strongly persuaded his friend from committing such a rash action. His attitude coming to the knowledge of Lady Frances, she vowed to avenge herself upon Sir Thomas, and carried her threat to its bitter execution. On some frivolous pretext Overbury was sent to the Tower; Lady Somerset, as Lady Frances had become, notwithstanding Overbury’s advice, now determined to rid herself of the man she mostly feared. With the help of a notorious quack, and of a procuress, Mrs Turner, with whom she had been brought up, she set about the task of consummating her revenge. Poison was supplied by Mrs Turner, with which the unfortunate Overbury was slowly killed; but as the drug—it is believed to have been corrosive sublimate—did not act sufficiently quickly, two hired assassins, named Franklin and Lobell, were called in, and stifled the victim with a pillow. Sir William Waad at this time had ceased to be the Lieutenant, through Lady Essex’s influence, and had been succeeded by Sir Gervase Elwes, a creature of Somerset’s, who was not only cognisant of Overbury’s18 death in the Bloody Tower, where he was confined, but even aided Lady Somerset in her crime. Mrs Turner was the inventor of a peculiar yellow starch which was used for stiffening the ruffs worn at that time; she wore one of these ruffs when she was sentenced to die for her participation in this murder by the Chief-Justice, Sir Edward Coke, and was also hanged in it at Tyburn in March 1615, with the natural consequence that yellow starched ruffs suddenly ceased to be the fashion. Lady Somerset was also tried, and although found guilty of Overbury’s murder, received a pardon from the King, but she and her husband, Somerset, spent six years as prisoners in the Tower, where they occupied the same rooms in the Bloody Tower which shortly before had been tenanted by the wife’s victim. Sir Thomas Overbury was buried in St Peter’s Chapel, his grave lying next to that of Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex.

Prince Henry’s death in 1612 was a terrible loss to Raleigh. The Queen had already tasted Sir Walter’s famous cordial or elixir, and when her son was given up by the physicians, Anne implored them to try Raleigh’s specific medicine, which, according to its inventor, was safe to cure all diseases save those produced by poison. Henry was already speechless when the elixir was administered to him, but after he had swallowed one or two drops he was able to utter a few words before he expired. What was the nature of this wonderful mixture of Raleigh’s cannot now be ascertained, although Charles II.’s French physician, Le Febre, prepared what was believed to be the actual concoction and wrote a treatise upon it. Some of its ingredients were indeed awful, the flesh of vipers forming one of them, and it speaks much for the strength of James’s Queen that she survived the taking of this terrible physic.

Raleigh had intended dedicating his history to Prince Henry, but after that young Prince’s death he seems to have lost his former zest in the work. There is a story 19told that he threw part of the manuscript into the fire on hearing that Walter Burr, the publisher of the first edition in 1614, had been a loser by bringing it out. Of that first part Mr Hume, in his “Life of Raleigh,” writes, “The history, as it exists, is probably the greatest work ever produced in captivity, except Don Quixote. The learning contained in it is perfectly encyclopædic. Raleigh had always been a lover and a collector of books, and had doubtless laid out the plan of the work in his mind before his fall. He had near him in the Tower his learned Hariot, who was indefatigable in helping his master. Ben Jonson boasted that he had contributed to the work, and such books or knowledge as could not be obtained or consulted by a prisoner, were made available by scholars like Robert Burhill, by Hughes, Warner, or Hariot. Sir John Hoskyns, a great stylist in his day, would advise with regard to construction, and from many other quarters aid of various sorts was obtained. But, withal, the work is purely Raleigh’s. No student of his fine, flowing, majestic style will admit that any other pen but his can have produced it. The vast learning employed in it is now, for the most part, obsolete, but the human asides where Raleigh’s personality reveals itself, the little bits of incidental autobiography, the witty, apt illustrations, will prevent the work itself from dying. To judge from a remark in the preface, the author intended at a later stage to concentrate his history with that mainly of his own country, and it would seem that the portion of the book published was to a great extent introductory. Great as were his powers and self-confidence, it must have been obvious to him that it would have been impossible for a man of his age (he was in his sixtieth year when he began the work) to complete a history of the whole world on the same scale, the first six books published reaching from the beginning of the world to the end of the second Macedonian war. In any case,” adds Mr Hume, “the book will ever remain a noble fragment of a design, which could only have20 been conceived by a master-mind.” And who, recalling those mighty lines on death with which Raleigh bids farewell to his great work, but will agree with the above admirable criticism of the work?

“O Eloquent, just and mighty Death! whom none could advise thou hast persuaded: what now none hath dared thou hast done; and whom the world hath flattered, thou only hast cast out of the world and despised: thou hast drawn together all the far-stretched greatness, all the pride, cruelty, ambition of man, and covered it over with these two narrow words: ‘Hic Jacet.’” How noble, too, are the introductory lines to Ben Jonson, wherein he commends the serious study of history:

No wonder that James disapproved of such sentiments and said of the “History,” “it is too saucy in censuring the acts of princes.”

To Raleigh, more than to any other of the great Elizabethan heroes, does England owe her mighty earth-embracing dominion. Sir Walter never ceased to urge the expansion of the empire, nor wearied in his efforts to make the English fleet the foremost in all the seas, not only as a check to Spain, but in order that the colonial possessions of the kingdom might be increased; and he, more than any of our great soldier-statesmen deserved those noble lines of Milton: “Those who of thy free Grace didst build up this Brittanick Empire to a glorious and enviable height, with all her daughter islands about her, stay us in this felicitie.”

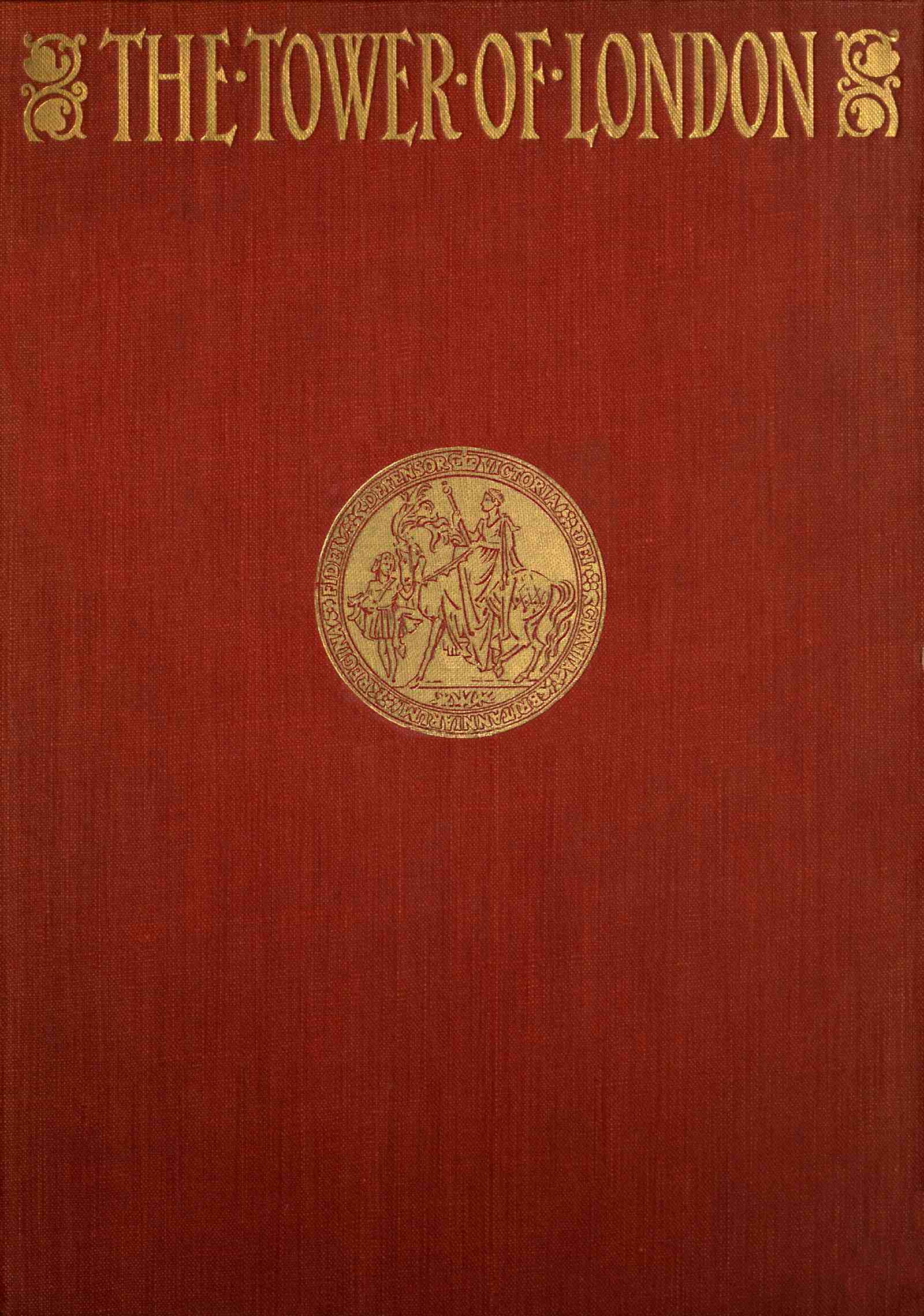

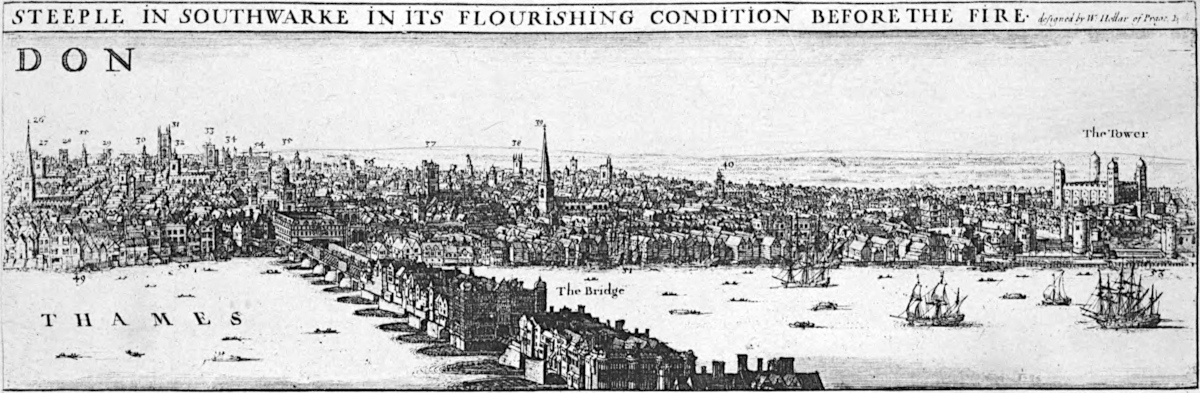

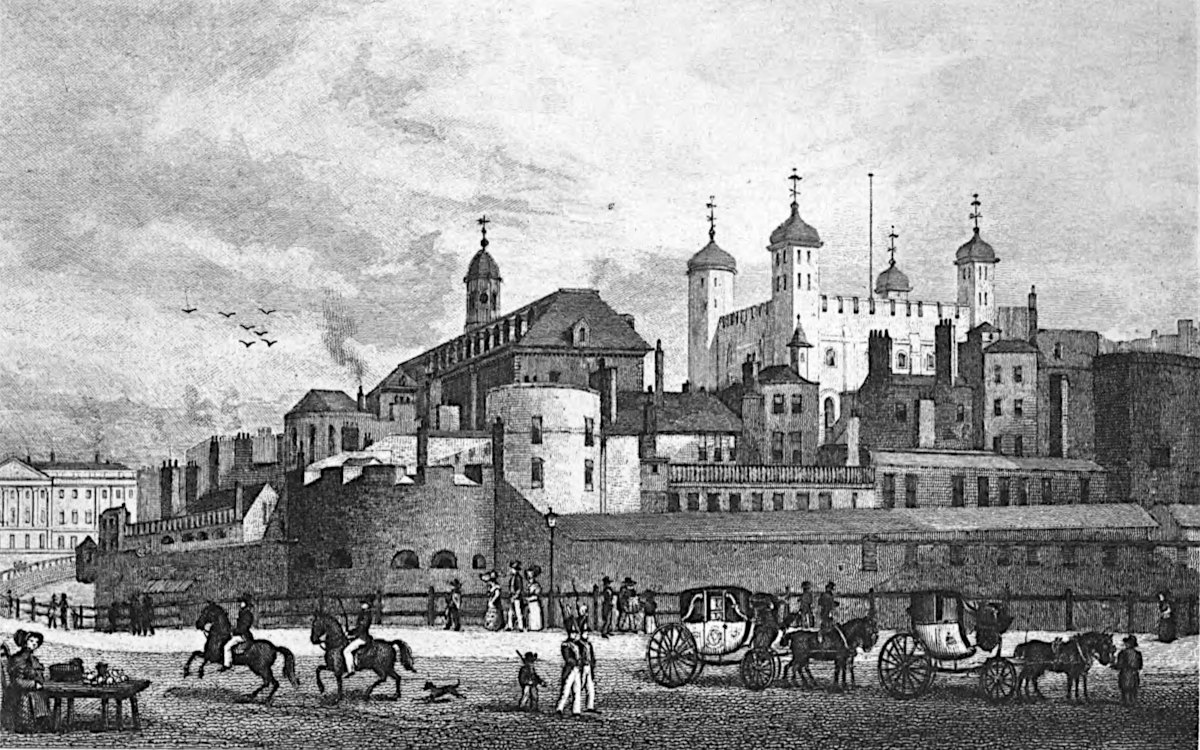

In 1616 Raleigh was allowed to leave the fortress, but, as I have said before, in order to obtain his liberty he had been obliged to bribe George Villiers and his brother, who had roused James’s cupidity by persuading him that if Raleigh were allowed to lead a fresh expedition21 to the West Indies, he might return with a great treasure of which James would take the lion’s share. A warrant, dated the 19th of March of this year, was drawn up, giving Raleigh permission to go abroad in order that he might make the necessary arrangements for his voyage. The twelve years of imprisonment had sadly marred and aged the gallant knight, but his spirit was as bold and courageous as ever, and he employed the first days of his liberty in revisiting his old London haunts; many changes must have struck him in the city. In Visscher’s panoramic view of London, taken from Southwark nearly opposite to St Paul’s, a very clear general impression may be gained of the appearance of the English capital in that year of sixteen hundred and sixteen, the year when Shakespeare was dying at Stratford-on-Avon, when Raleigh was on his way to his last journey across the Atlantic, and when Francis Bacon was writing his famous essays in Gray’s Inn. Those quaint, circular, Martello-like buildings in the foreground are the Globe and Swan theatres, with the Bear Garden close by; but the former theatre, in Visscher’s view, is not the one so intimately connected with Shakespeare, for that was burned down in 1613, and the building represented here is the new one erected upon its site. Opposite to the Swan Theatre, on the Surrey side of the river, are Paris Garden Stairs, where was a much frequented ferry, Blackfriars Bridge now spanning the river where this ferry once used to ply. There was also a theatre at Blackfriars, and Shakespeare and his players must often have used the ferry on their way from the Globe Theatre across the river from Blackfriars, where the poet lived. In front is old St Paul’s, towering over all the surrounding buildings and dwarfing the highest; scores of spires and towers break the skyline as the eye follows the panorama towards the west, where stands the former old London Bridge, covered along its sides with picturesque houses. So large and22 massive are the great blocks of gabled buildings that span the bridge, that it presents the appearance of a little town crossing the river, such as is the Ponte Vecchio at Florence in little. The gates at its ends are covered with men’s heads, stuck all over their roofs like pins upon a pincushion. More steeples and towers crown the opposite bank, and as the eye travels farther eastward it is arrested by the Tower, with its encircling wall, and its river wharf all covered with cannon. The river is alive with vessels of every shape and size, State barges and little pinnaces, great galleons and small craft, appear in all directions, some with, some without sails. Beyond, the distant hills of Middlesex and Essex are dotted with villages and hamlets, whilst on the heights of Highgate cluster a group of windmills. It is a wonderful panorama that the old Dutch artist has handed down to us. Looking at it we see the same scene, the same picture of time-honoured churches and palaces, the noblest river in the world flowing beneath them, and bearing on its shining surface all the pleasure, commerce, industry, and travail of old London, that Shakespeare did, when, standing near his theatre at Bankside, he gazed upon that shifting scene. All is changed now, except the Tower. The great Gothic cathedral of St Paul’s and most of its surrounding churches, whose towers and spires helped to make old London an object of beauty, perished in the great fire which swept over the city fifty years after Visscher drew his panorama. Old London Bridge escaped the fire, and indeed remained until 1834, although the houses clustering over it had been removed at the close of the reign of George II., and the only prominent building in the panorama which Shakespeare or Raleigh would now be able to recognise, could they look across the rivers Styx and Thames, would be the great White Tower with its surrounding lesser towers and battlements. All the rest, like “the baseless fabric of a vision,” has passed away for ever.

23

But to return to Sir Walter Raleigh. He invested all that remained of his own and his wife’s fortunes in furnishing the expedition to Guiana, which proved so disastrous, on which he now embarked. On his return, a ruined man and a prisoner, he expressed his amazement at having thus in one desperate bid placed his life and all that he possessed in that unlucky venture. But before Raleigh had left England, Gondomar, the Spanish Ambassador, had told his master, the King of Spain, that Raleigh was a pre-doomed man. For James had not only revealed every detail relating to the Guiana expedition to Gondomar, but on condition that if any subject or property belonging to Spain were touched he had promised to hand over Raleigh to the Spanish Government in order that he might be hanged at Seville. To assure Gondomar of his good faith, James actually showed the ambassador a private letter written him by Raleigh, in which the exact number of his ships, men, and the place where the great silver mine was said to be located on the Orinoco, were all set forth. As the Spaniards claimed the whole of Guiana, it was evident that if Raleigh landed there he must infringe upon the Spanish possessions, and thus place himself, according to James’s promise to Gondomar, in the power of his enemies.

The expedition sailed from England at the end of March 1617, from Plymouth, and consisted of fourteen ships and nine hundred men. But its story was one of continued disaster, and on the 21st of June 1618, writing to his friend Lord Carew, Raleigh gives a detailed account of all his misfortunes. In the postscript he adds: “I beg you will excuse me to my Lords for not writing to them, because want of sleep for fear of being surprised in my cabin at night” (even on his own ship he was a prisoner, the crew having mutinied) “has almost deprived me of sight, and some return of the pleurisy which I had in the Tower has so weakened my hand that I cannot24 hold the pen.” Sir Walter’s eldest son was killed gallantly fighting in Guiana.

Then followed a miserable time, and on his road to London the hope of life at times impelled him to attempt escape, but he was doomed to drink the bitter cup of his King’s ingratitude to the dregs. On the 10th of August he again entered the Tower where so much of his life had been spent, and which was now to be his last abode on earth.

The next day the Council of State met to decide upon Sir Walter’s fate, and incredible as it seems, it was actually debated whether Raleigh should be handed over to the tender mercies of the Spaniards or executed in London. Surely if what passed on this earth could have been known to Elizabeth, she would have burst her tomb at Westminster to protest against this abomination, this unspeakable shame and disgrace to the name of England.

James was now all impatience to get rid of Raleigh as quickly as possible; he trembled at the threats of Gondomar, and had the sapient monarch not given his word that Raleigh should die? The great difficulty before the Council, however, was to find a pretext for condemning Raleigh to death. Bacon and his colleagues racked their wise brains to invent a cause by which he could be found guilty of high treason. At length the Lord Chief-Justice, Montagu, with a committee of the Council decided that the King should issue a warrant for the re-affirmation of the death sentence given at Winchester in 1603, by which it might be made valid and carried out. Sir Walter pleaded that the King’s commission appointing him head of the Guiana expedition with powers of life and death, invalidated the former sentence and its punishment, both in the eyes of justice and of reason. But Sir Walter was overruled. On the 24th of October the warrant for the execution was signed and sealed by the King, and four days later Sir Walter was taken from the Tower to the King’s Bench. He 25was then suffering from ague, and having been roused from his sleep very early had not had time to have his now snow-white hair dressed with his usual care. One of his servants noticed this as he was being taken away, and telling him of it, Raleigh answered, smiling, “Let them kem (comb) it that have it,” then he added, “Peter, dost thou know of any plaister to set a man’s head on again when it is cut off?”

The end being now so certain and so near, the bright courage of the man returned; there was no shrinking with the closing scene so close at hand. He was not brought back to the Tower after his condemnation, and he passed his last night upon earth in the Gate House at Westminster, close to which the scaffold stood in Old Palace Yard. He had a last parting that evening with his devoted wife, his “dear Bess,” but neither dared to speak of their only remaining son—that would have been too bitter a pang for them to bear. Sir Walter’s last words to his wife were full of hope and courage: “It is well, dear Bess,” he said, referring to Lady Raleigh having been promised his body next day, the only mercy allowed her by the Council, “that thou mayest dispose of that dead which thou hadst not always the disposing of when alive.” Then she left him. During the long hours of that last night, he composed those beautiful lines which will last as long as the language in which they are written:

Raleigh wrote these lines in a Bible which he had brought with him from the Tower.

26

Carlyle has summed up Raleigh’s life and death in the following pregnant lines, in his “Historical Sketches”:—

“On the morning of the 29th of October 1618 in Palace Yard, a cold morning, equivalent to our 8th of November, behold Sir Walter Raleigh, a tall gray-headed man of sixty-five gone. He has been in far countries, seen the El Dorado, penetrated into the fabulous dragon-realms of the West, hanged Spaniards in Ireland, rifled Spaniards in Orinoco—for forty years in quest a most busy man; has appeared in many characters; this is his last appearance on any stage. Probably as brave a soul as lives in England;—he has come here to die by the headman’s axe. What crime? Alas, he has been unfortunate: become an eyesore to the Spanish, and did not discover El Dorado mine. Since Winchester, when John Gibb came galloping (with a reprieve), he has been lain thirteen years in the Tower; the travails of that strong heart have been many. Poor Raleigh, toiling, travelling always: in Court drawing-rooms, on the hot shore of Guiana, with gold and promotions in his fancy, with suicide, death, and despair in clear sight of him; toiling till his brain is broken (his own expression) and his heart is broken: here stands he at last; after many travails it has come to this with him.”

Sir Walter Raleigh died a martyr to the cause of a Greater Britain; his life thrown as a sop to the Spanish Cerberus by the most debased and ignoble of our kings. Raleigh’s faults were undoubtedly many, but his great qualities, his superb courage, his devotion to his country, his faith in the future greatness of England, were infinitely greater, and outweighed a thousand times all his failings. The onus of the guilt of his death—a judicial murder if ever there was one—must be borne by the base councillors who truckled to the King, and by the King himself who, Judas-like, sold Raleigh to Spain.

Some less interesting State prisoners occupied the Tower towards the close of the inglorious reign of James Stuart. Among these were Gervase, Lord Clifford, imprisoned for threatening the Lord Keeper in 1617. Clifford committed suicide in the Tower in the following year. About the same time, Sir Thomas Luke, one of the Secretaries of State, and his daughter, were imprisoned in the Tower on the charge of insulting Lady Exeter, whom they accused of incest and witchcraft, but, whether the charges were true27 or false, they were soon liberated. James’s court seems to have combined all the vices, for Lord and Lady Suffolk were also prisoners in the fortress about the same time, accused of bribery and corruption.

To the Tower also were sent the two great lawyers—Lord Chancellor Bacon, and Sir Edward Coke—the former for having received bribes, the latter for the part he had taken in supporting the privileges of the House of Commons. Here, also, two noble lords, the Earl of Arundel and Lord Spencer, were in durance, owing to a quarrel between them in the House of Lords, when Arundel had insulted Spencer by telling him that at no distant time back his ancestors had been engaged in tending sheep, to which Lord Spencer responded: “When my ancestors were keeping sheep, yours were plotting treason.” The dispute seems scarcely of sufficient importance to have sent both disputants to the Tower.

In 1622 the Earl of Oxford and Robert Philip, together with some members of Parliament, were sent to the fortress for objecting too publicly to the suggested marriage of the Prince of Wales, afterwards Charles I., with a Spanish princess; and the Earl of Bristol was also in the Tower for matters connected with the same projected alliance. It was not always safe to have an opinion of one’s own under James the First.

The last State prisoner of mark to be sent to the Tower in James’s reign was Lionel Cranfield, Earl of Middlesex, who had been found guilty of receiving bribes in his official capacity as Lord High Treasurer.

With the close of the reign of James I. the Tower ceased to be a royal residence—the Stuart kings, in fact, never passing more than a night or two in the old fortress prior to their coronation, after which they only visited it on very rare occasions. James himself only occupied the Tower-Palace on the eve of opening his first Parliament; and as the plague had broken out in the city at the time of Charles the First’s coronation, that king did not even stay the previous night in the building, nor does he appear ever to have visited the fortress during the whole of his stormy reign of four and twenty years.

A very remarkable man occupied a prison in the Tower early in Charles’s reign. This was Sir John Eliot, “fiery Eliot” Carlyle calls him. He was first of that noble band of patriots who defied Charles’s tyranny, and had been sent to the Tower in the winter of 1624–25 for censuring Buckingham during Charles’s second Parliament, but he remained there only a short time. In the March of 1628, however, Eliot, with a batch of independent members of the House of Commons—amongst whom were Denzil Holles, Selden, Valentine, Coryton, and Heyman—was again imprisoned in the Tower. Eliot had boldly declared that the “King’s judges, Privy Council, Judges and learned Council had conspired to trample under their feet the liberties of the subjects of the realm, and the liberties of the House.” Denzil Holles and Valentine were the two members who had kept the Speaker in his chair by 29main force; the others were committed to prison for using language reflecting on the King and his Ministers. For the following three months these members of Parliament were kept in close confinement in the fortress, books and all writing materials being strictly kept from them. In May, Sir John Eliot was taken to Westminster, where an inquiry was held but no judgment given. After his return to the Tower, however, Eliot was allowed to write letters, and was also given “the liberty of the Tower,” and permitted to see a few friends. In the month of October Eliot and the others were taken to the chambers of the Lord Chief-Justice, and thence to the Marshalsea Prison, a change which he jokingly described as having “left their Palace in London for country quarters at Southwark.” Then they were tried, and Eliot, being judged the most culpable, was fined two thousand pounds, and ordered to be imprisoned in the Tower during the King’s pleasure. As for the fine, Eliot remarked that he “possessed two cloaks, two suits of clothes, two pairs of boots, and a few books, and if they could pick two thousand pounds out of that, much good might it do them.” The fearless member never quitted the Tower again, for a galloping consumption carried him off two years after he had written the above lines. There can be no doubt that this consumption was not a little owing to the harsh treatment he endured. In 1630 he wrote to his friend Knightley, alluding to rumours of his being released. “Have no confidence in such reports; sand was the best material on which they rested, and the many fancies of the multitude; unless they pointed at that kind of libertie, ‘libertie of mynde.’ But other libertie I know not, having so little interest in her masters that I expect no service from her.” His prison was frequently changed, and many restraints were put upon him, for, on the 26th of December, he writes to his old friend, the famous John Hampden, that his lodgings have been moved. “I am now,” he says, “where candle-light may be suffered, but scarce fire. None30 but my servants, hardly my sonne, may have admittance to me; my friends I must desire for their own sake to forbear coming to the Tower.” Poor Eliot was dying fast in the year 1632, but his last letter to Hampden, dated the 22nd of March, is full of his old brave spirit, and the gentle humour that distinguished this great and good man. The letter concludes thus: “Great is the authority of princes, but greater much is theirs who both command our persons and our will. What the success of their Government will be must be referred to Him that is master of their power.” The doctor had informed the authorities that any fresh air and exercise would help Eliot to live, but all the air they gave him was a “smoky room,” and all the exercise, a few steps on the platform of a wall. On the 27th of November Eliot died, “not without a suspicion of foul play,” wrote Ludlow some years afterwards.

Eliot’s staunch friends, Pym and Hampden, moved in the House for a committee “to examine after what manner Sir John Eliot came to his death, his usage in the Tower, and to view the rooms and place where he was imprisoned and where he died, and to report the same to the House,” a motion which shows how matters had changed for the better since the days of Elizabeth, none of whose Parliaments would have dared thus to question the treatment of State prisoners.

The blame of his untimely death—for he was but forty-two—rests upon those who let him die by inches in his prison as much as if they had beheaded him on Tower Hill. John Eliot died a martyr in the cause of constitutional liberty as opposed to monarchical autocracy. Eliot’s son petitioned the King to be allowed to remove his father’s body to their old Cornish home at St Germains, but the vindictive and narrow-minded monarch, who would not even forgive Eliot after death had intervened, refused the prayer, writing at the foot of the petition, “Lett Sir John Eliot’s body be buried in the church of the parish where he died.” No stone marks the spot where he is31 buried, and his dust mingles with that of the illustrious dead in St Peter’s Chapel in the Tower, but his name will be remembered as long as liberty is loved in his native land.

We now come to a period of quite another sort.

In Carlyle’s “Historical Sketches,” John Felton, the assassin of Buckingham, is thus described:—“Short, swart figure, of military taciturnity, of Rhadamanthian energy and gravity.... Passing along Tower Hill one of these August days (in 1628) Lieutenant Felton sees a sheath-knife on a stall there, value thirteen pence, of short, broad blade, sharp trowel point.” We know the use Felton made of that Tower Hill knife on his visit to Portsmouth, where Buckingham was then about to set sail for his second expedition to La Rochelle; how he stabbed the gay Duke to the heart, exclaiming, as he struck him: “God have mercy on thy soul!” how he was promptly arrested, brought to London and imprisoned in the Tower.

The reason, or reasons, for Felton killing Buckingham have never been made clear. He appears to have been a soured religious fanatic, but the crime was doubtless owing to some fancied injustice regarding his promotion in the army; and it has been thought that it was merely an act of private vengeance, rather than one of political significance. But after his arrest a paper was found fastened in Felton’s hat, with the following writing upon it:—“That man is cowardly, base, and deserveth not the name of a gentleman or soldier, that is not willing to sacrifice his life for the sake of his God, King, and his countrie. Lett no man commend me for doing of it, but rather discommend themselves as the cause of it, for if God hath not taken away our hearts for our sins, he would not have gone so long unpunished.—Jno. Felton.” A sentiment which goes to show that Felton assassinated Buckingham with the fanatical idea of benefiting his country.

So hated was Buckingham by the people, that Felton passed into the Tower amid blessings and prayers. He32 was placed in the prison lately occupied by Sir John Eliot in the Bloody Tower, and before his death made two requests—one, that he might be permitted to take the Holy Communion, and the other that he might be executed with a halter round his neck, ashes on his head, and sackcloth round his loins. On being threatened with the rack in order to induce him to give the names of his accomplices, Felton said to Lord Dorset that, in the first place, he would not believe that it was the King’s wish that he should be tortured, it being illegal; and, secondly, that if he were racked, he would name Dorset, and none but him—a capital answer. When he was asked why sentence of death should not be passed upon him, he answered: “I am sorry both that I have shed the blood of a man who is the image of God, and taken away the life of so near a subject of the King.” As a last favour, he begged that his right hand might be struck off before he was hanged. He suffered at Tyburn, and his body was gibbeted in chains at Portsmouth. “His dead body,” writes Evelyn, “is carried down to Portsmouth, hangs high there. I hear it creak in the wind.” An eye-witness describes Felton as showing much courage and calm during his trial and at his death, and Philip, Earl of Exeter, who attended the execution, declared that he had never seen such valour and piety, “more temperately mixed,” as in Felton’s demeanour. This is surely one of the strangest mysteries in our history.

Prisoners still continued to come to the Tower, and in 1631, Mervin, Lord Audley, was executed on Tower Hill for a crime not of a political nature. Six years later a very distinguished ecclesiastic, John Williams, Bishop of Lincoln, was imprisoned for four years within the Tower walls. Williams, who was a Privy Councillor, had repeated some remarks made by the King, in which His Majesty had advocated greater leniency in the treatment of the Puritans, and was accused of revealing Charles’s private conversation, and being an enemy of Laud’s was33 very hardly dealt with in consequence. He was deposed from his bishopric, fined £10,000, and imprisoned in the Tower, where he caused some surprise, if not scandal, by not attending the church services in the fortress. However, after his release, Williams was reconciled to the King, and in 1641 became Archbishop of York. He had been successively Dean of Salisbury and Dean of Westminster, and had succeeded Bacon as Lord Chancellor in 1621, just before he had been appointed to the See of Lincoln. Williams certainly belonged to the Church Militant, and during the Civil War defended Conway Castle most gallantly for the royal cause. At the end of December 1641, he was back again in the Tower, with ten other Bishops who had protested that, owing to their being kept out of the House of Lords by the violence of the mob, all Acts passed during their absence were illegal. The Peers arrested the protesting Bishops on a charge of high treason; and on a very cold and snowy December night they were all sent to the Tower, where they remained until the May of 1642.

Lord Loudon, who had been sent by the Scottish Covenanters to Charles, had a narrow escape of leaving his head on Tower Hill in 1639. According to Clarendon, a letter was discovered of a treasonable nature, signed by Loudon, addressed to Louis XIII. of France, and Charles ordered Sir William Balfour, by virtue of a warrant signed by the royal hand, to have the Scottish lord executed the following morning. In this terrible dilemma Loudon bethought him of his friend, the Marquis of Hamilton, and gave the Lieutenant a message for that nobleman. Now it was one of the privileges of the Lieutenant of the Tower that he could at any time, or in any place, claim an audience with the sovereign. Hamilton persuaded Balfour to go with him to Charles, but on arriving at Whitehall, they found that the King had already retired for the night. Balfour, however, taking advantage of his privilege, entered the room with Hamilton, and together they besought34 Charles to re-consider his decision, pointing out to him that Loudon was protected by his quality as Ambassador from the Scotch. The King, as was his wont, was obdurate. “No,” he said; “the warrant must be obeyed.” At length the Marquis, having begged in vain, left the chamber, saying, “Well, then, if your Majesty be so determined, I’ll go and get ready to ride post for Scotland to-morrow morning, for I am sure before night the whole city will be in an uproar, and they’ll come and pull your Majesty out of your palace. I’ll get as far as I can, and declare to my countrymen that I had no hand in it.” On hearing this, Charles called for the warrant and destroyed it. Loudon was soon afterwards released (Oldnixon’s “History of the Stuarts”).

Now comes the story of the last days of one of Charles’s most noted counsellors—last days that, as in the case of many before him, were passed within the grim precincts of the Tower, and were the prelude to execution. On the 11th of November 1640, the Earl of Strafford was at Whitehall laying before Charles a scheme for accusing the heads of the parliamentary party of holding a treasonable correspondence with the Scotch army, then encamped in the North of England. Whilst he was with the King the news reached him that Pym at that very moment was impeaching him in the House of Commons on the charge of high treason. Strafford at once made his way to the House, but was not allowed to speak, and shortly afterwards heard his committal made out for the Tower. At the same time Archbishop Laud was arrested at Lambeth Palace, and carried off to the great State prison. “As I went to my barge,” Laud writes in his diary, “hundreds of my poor neighbours stood there and prayed for my safety and return to my home.” But neither he nor Strafford were ever to return to their homes. Perhaps Strafford’s life might have been saved had it not been for the King’s action, for when it became known that Charles had plotted with the hope of inducing the Scottish army35 to march on London, seize the Tower and liberate Strafford, the great Earl was practically doomed. The city rose as one man, a huge mob surging round the Houses of Parliament and the Palace of Whitehall, shouting “Justice.”

For fifteen days Strafford faced his accusers and judges at Westminster Hall, his defence being a splendid piece of oratory. He proved that on the ground of high treason his judgment would not count, and his judges were compelled to introduce an Act of Attainder in order to convict him; but for the next six months he was kept in the Tower, uncertain as to his ultimate fate until the 12th of May 1641, when the Bill of Attainder was passed by the Lords.[3]

Charles had sworn to Strafford that not a single hair of his head should be injured; but on the Earl writing to him and offering his life as the only means of healing the troubles of the country, the King yielded, and deserting his minister, gave his assent to the execution, and signed the warrant.

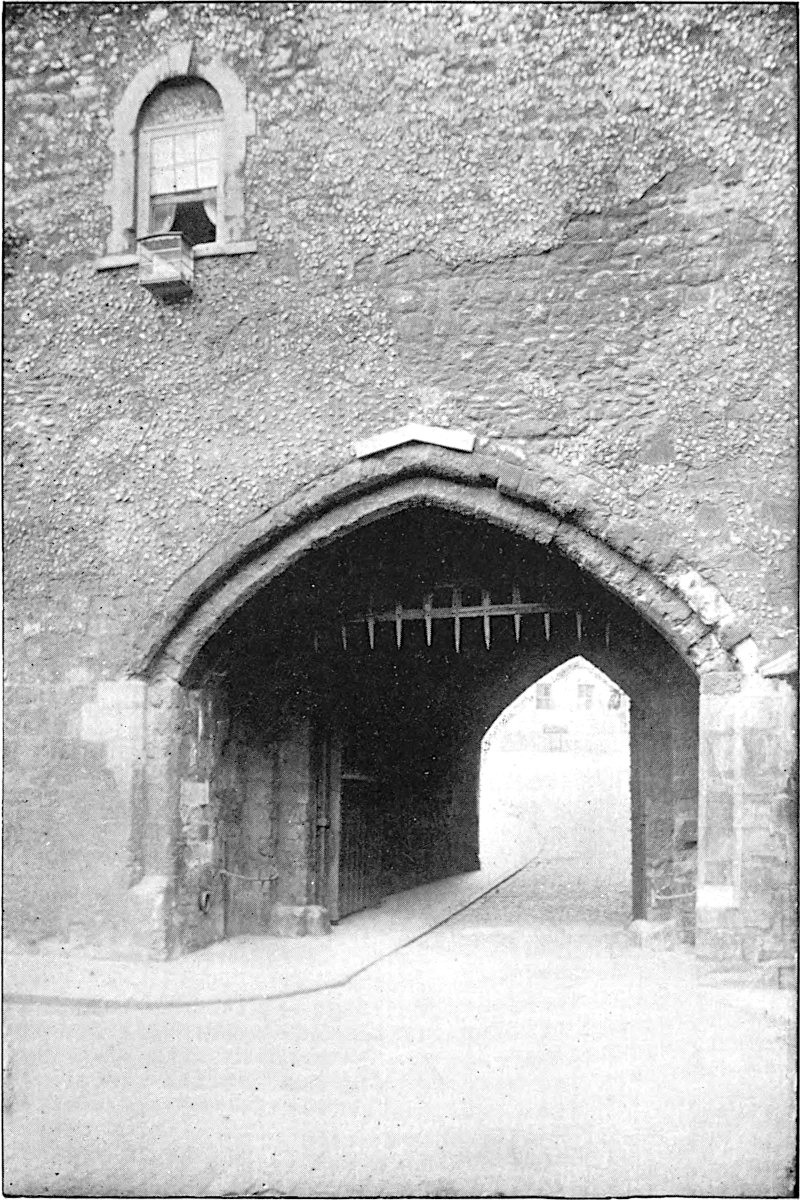

On the following morning Strafford was led out to die. There is no more dramatic episode in the great struggle between Charles and his people than that when Strafford, amidst his guards, passed beneath the gateway of the Bloody Tower, where, from an upper window, his old friend, Archbishop Laud, gave him his blessing. The Archbishop, overcome, sank back fainting into the arms of his attendants. “I hope,” he is reported to have said, “by God’s assistance and through mine own innocency that when I come to my own execution, I shall shew the 36world how much more sensible I am to my Lord Strafford’s loss than I am to my own.”

Knowing how bitterly Strafford was hated by the people, the Lieutenant of the Tower invited him to drive to Tower Hill in his coach, fearing he might be torn to pieces if he went on foot. Strafford, however, declined the offer, saying, “No, Mr Lieutenant, I dare look death in the face, and I trust the people too.” With the Earl were the Archbishop of Armagh (Ussher), Lord Cleveland, and his brother, Sir George Wentworth. On reaching the scaffold Strafford made a short speech, followed by a long prayer, and giving his final messages for his wife and children to his brother, said: “One stroke more will make my wife husbandless, my dear children fatherless, my poor servants masterless, and will separate me from my dear brother and all my friends; but let God be to you and to them all in all.” He then removed his doublet, and said, “I thank God that I am no more afraid of death, but as cheerfully put off my doublet at this time as ever I did when I went to bed.” Then placing a white cap upon his head, and thrusting his long hair beneath it, he knelt down at the block, the Archbishop also kneeling on one side and a clergyman upon the other, the Archbishop clasping Strafford’s hands in both his own. After they had left him Strafford gave the sign for the executioner to strike by thrusting out both his hands, and at one blow, “the wisest head in England,” as John Evelyn, who was present, says, “was severed from his body.” On that night London blazed with bonfires, and the people rejoiced as if in celebration of some great victory.

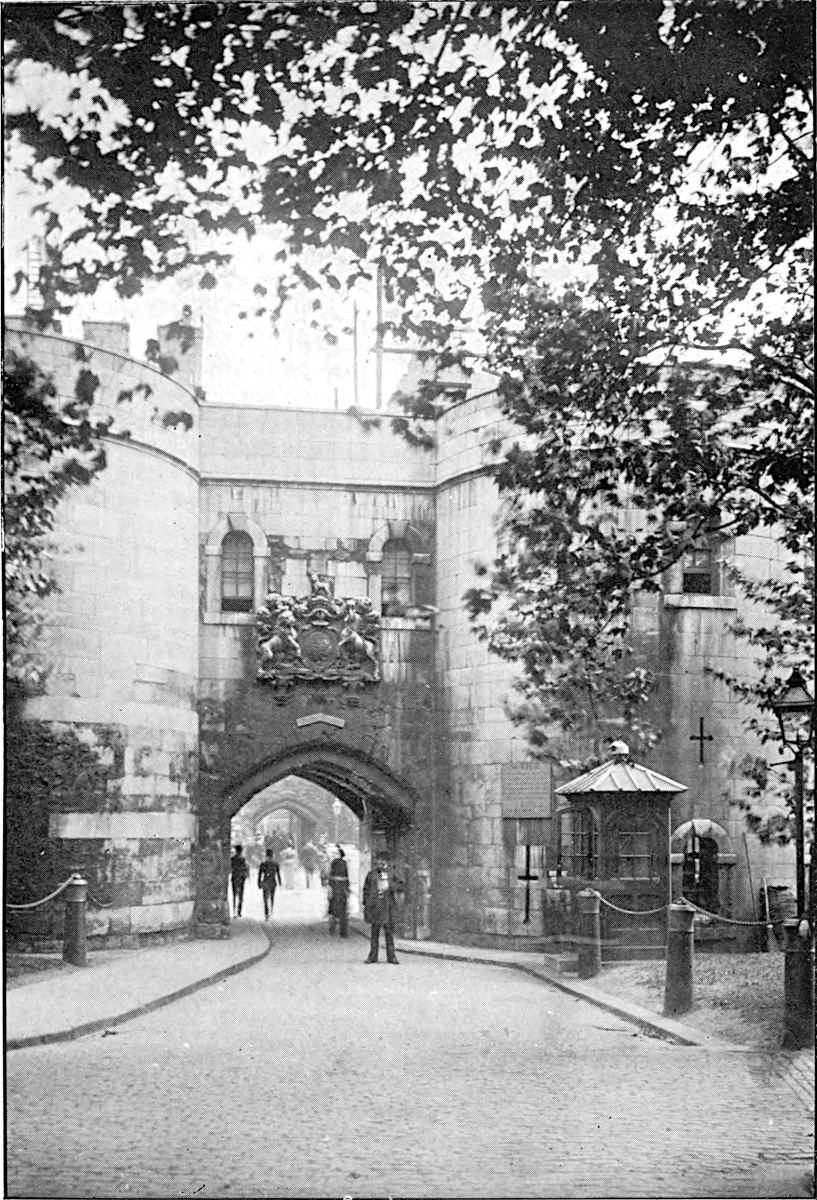

The great Earl’s mistake was in serving and trusting such a king as Charles. Later on it transpired that Charles had a plan of removing Strafford from the Tower by throwing a hundred men into the fortress, thus relieving the Earl, and keeping possession of the Tower as a check upon the city. In pursuance of this plan, on the 2nd May 1641, Captain Billingsby with a force of one hundred 37men presented himself at the gates of the Tower, but Sir William Balfour refused to admit them, and the King’s scheme for taking the fortress fell to the ground.

The first beginnings of a Tower regiment, according to Mr J. H. Round, was the appointment of two hundred men as Tower Guards in 1640. In November of the same year Charles promised to remove this garrison, but he did not do so until the city offered to lend him £25,000, on the condition that these troops should be taken away, as well as the ordnance from the White Tower, which was a perpetual menace to the safety of the city. Aersen, the Dutch Ambassador, writing to his Government about this time, says, “le dessein semble aller sur le tour.” Still the King would not withdraw the soldiers or the cannon, and then the House of Lords expostulated with him, but Charles excused his breach of faith by saying that his object was merely to insure the safety of the stores and ammunition in the fortress.

After his plot to seize the Tower had been made public, the train bands belonging to the Tower Hamlets occupied and garrisoned the fortress. These train bands, as well as those of Southwark and Westminster, were distinct from the city train bands. On the 3rd of January 1642, the King made another attempt to garrison the Tower with his own troops, which also proved a failure. On this occasion Sir John Byron entered the fortress with a detachment of gunners and disarmed the men of the Tower Hamlets, but the city train bands came to the rescue, and Byron, with his gunners, had to beat a retreat. When, in 1642, the Lieutenant of the Tower, Sir John Conyers, resigned his charge, the Parliament conferred the Lieutenancy upon the Lord Mayor of London. Later, in 1647, when the city had taken the side of the Parliament against the King, Fairfax was appointed Constable; the Constables had succeeded each other according to the chances which brought the King or the Parliament to the top, thus Lord Cottrington had been replaced by Sir38 William Balfour, and he in his turn had given room to Sir Thomas Lumsford, a “soldier of fortune,” writes Ludlow of him in his “Memoirs,” “fit for any wicked design.” Lumsford, so uncomplimentarily referred to by Ludlow, was supposed to be willing to act according to the King’s good pleasure, and succeeded in making himself so unpopular with the Londoners, that they petitioned the House of Lords to beg the King to place the custody of the Tower in other hands, the Lord Mayor saying he could not undertake to prevent the apprentices from rising were Lumsford allowed to remain in office; so Charles unwillingly gave the keys of the fortress to the care of Sir John Byron. Byron, in his turn, was succeeded by Sir John Conyers, who had distinguished himself in the Scottish wars and had been Governor of Berwick; and after Conyers followed Lord Mayor Pennington,[4] “in order,” as Clarendon writes, “that the citizens might see that they were trusted to hold their own reins and had a jurisdiction committed to them which had always checked their own.” From 1643 to 1647 the Tower remained in the hands of the Parliament. In the latter year the army obtained the mastery, and Sir Thomas Fairfax, the Commander-in-Chief, became its Constable, under him being Colonel Tichbourne as Lieutenant of the fortress. Shortly after the King’s execution, however, Fairfax resigned his post of Constable, none other than Cromwell, himself, stepping into the vacant place.

But we must return to Archbishop Laud, who for four years was a prisoner in the Bloody Tower in the prison chamber over the gateway of that gloomy building.

In his diary, the Archbishop has left a minute account of a domiciliary visit paid him by William Prynne in 1643. The Archbishop’s trial being determined on by the House 39of Lords, Prynne was commissioned by the Peers to obtain Laud’s private papers. “Mr Prynne,” writes the Archbishop, “came into the Tower with other searchers as soon as the gates were open. Other men went to other prisoners; he made haste to my lodging, commanded the warder to open my doors, left two musketeer centinels below, that no man might go in or out, and one at the stairhead. With three others, which had their muskets already cocked, he came into my chamber, and found me in bed, as my servants were in theirs. I presently thought on my blessed Saviour when Judas led in the swords and staves about him.”—This surely is rather a bold comparison for an Archbishop to make?—“Mr Prynne, seeing me safe in bed, falls first to my pockets to rifle them; and by that time my two servants came running in half ready. I demanded the sight of his warrant; he shewed it to me, and therein was expressed that he should search my pockets. The warrant came from the close committee, and the hands that were to it were these: E. Manchester, W. Saye and Seale, Wharton, H. Vane, Gilbert Gerard, and John Pym. Did they remember when they gave their warrant how odious it was to Parliament, and some of themselves, to have the pockets of men searched? When my pockets had been sufficiently ransacked, I rose and got my clothes about me, and so, half ready, with my gown about my shoulders, he held me in the search till half-past nine of the clock in the morning. He took from me twenty and one bundles of papers which I had prepared for my defence; two Letters which came to me from his gracious Majesty, about Chartham and my other benefices; the Scottish service books or diary, containing all the occurrences of my life, and my book of private devotions, both which last were written through with my own hand. Nor could I get him to leave this last, but he must needs see what passed between God and me, a thing, I think, scarce offered to any Christian. The last place that he rifled was my trunk, which stood by my bedside. In that he40 found nothing, but about forty pounds in money, for my necessary expenses, which he meddled not with, and a bundle of some gloves. This bundle he was so careful to open, so that he caused each glove to be looked into. Upon this I tendered him one pair of gloves, which he refusing, I told him he might take them, and fear no bribe, for he had already done me all the mischief he could, and I asked no favour of him, so he thanked me, took the gloves, bound up my papers, left two centinels at my door, and went his way.”—(From “Troubles and Trials of Archbishop Laud.”)

Prynne, whose ears Laud had been the means of cutting off some half-dozen years before, must have enjoyed this visit to his old foe. On the 10th of March 1643, the Archbishop was brought to his trial in Westminster Hall, but amongst all the charges brought against him none could be considered as proving him guilty of high treason. Serjeant Wild was obliged to admit this, but said that when all the Archbishop’s transgressions of the law were put together they made “many grand treasons.” To this Laud’s counsel made answer, “I crave you mercy, good Mr Serjeant, I never understood before this that two hundred couple of black rabbits made a black horse.”—(In Archbishop Tennison’s MSS. in Lambeth Library. Quoted by Bayley.)

Laud’s trial lasted for twenty days, the chief accusation brought against him being that he had “attempted to subvert religion and the fundamental laws of the realm.” The outcome of the trial was that Laud was beheaded on Tower Hill on 10th of January 1644. Laud was a strange compound of bigotry and intolerance, of courage and of devotion to what he considered to be the true Church, and of which he seemed to regard himself as a kind of Anglican Pope. His life and character are enigmas to those who study them, and his death became him far better than his life had done.

41

Carlyle, in a delightful passage in his posthumously published “Historical Studies,” writes: “Future ages, if they do not, as is likelier, totally forget ‘W. Cant,’ will range him under the category of Incredibilities. Not again in the dead strata which lie under men’s feet, will such a fossil be dug up. This wonderful wonder of wonders, were it not even this, a zealous Chief Priest, at once persecutor and martyr, who has no discernible religion of his own?” “No one,” said Laud, when told of the day on which he was to die, “no one can be more ready to send me out of life than I am to go.” Indeed, no one could have left life in a calmer or more tranquil manner than did the Archbishop. It must be a great support to have a sublime opinion of oneself, and if ever man had a sublime opinion of himself it was Laud. The comparison he made in his diary, and which I have already quoted, between his Saviour and himself—between Prynne-Judas and Laud-Christ—proves the ineffable self-conceit of the prelate.

The fact that he himself was notoriously indifferent, if not callous, to the sufferings of others, has destroyed all the sympathy that might have been felt for this strange character in his fall and tribulations. For a mere difference of opinion Laud would order ears to be lopped off, noses slit, and brows and cheeks to be branded with red-hot iron. His best and most enduring monument is the addition he made to St John’s College at Oxford, of which he was at one time the president, and in whose chapel his remains were re-interred, after resting for a time in the Church of All Hallows, Barking, and in the library of which his spectre is said to be seen occasionally gliding on moonlight nights, between the old bookshelves.