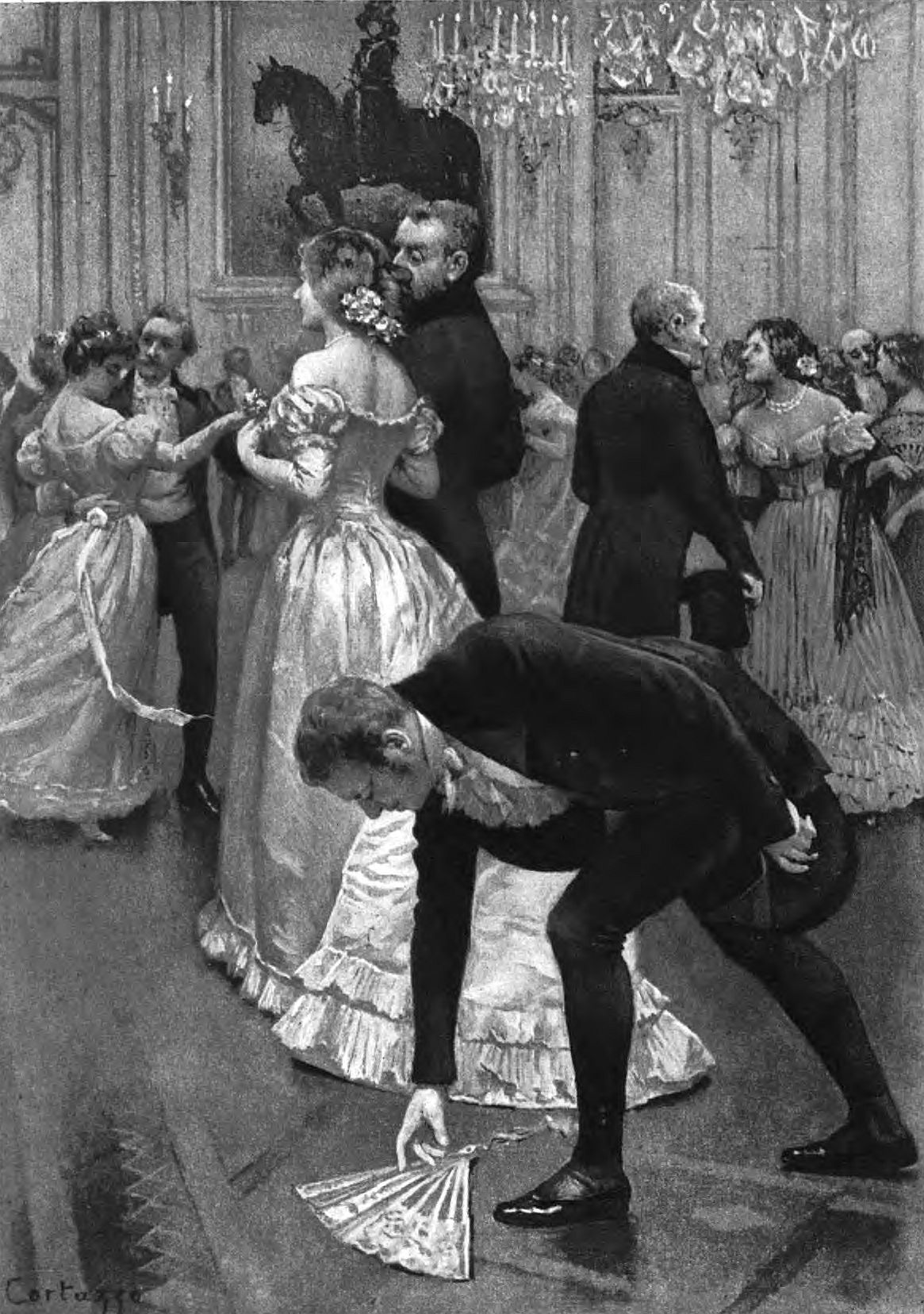

A CORNER AT THE OPERA BALL.

Thérèse was about to retire, when she heard her name mentioned in a corner. She turned and saw the man she had loved so well, seated between two masked damsels.

MEMOIR

SHE AND HE

TO MADEMOISELLE JACQUES

CHAPTER I

CHAPTER II

CHAPTER III

CHAPTER IV

CHAPTER V

CHAPTER VI

CHAPTER VII

CHAPTER VIII

CHAPTER IX

CHAPTER X

CHAPTER XI

CHAPTER XII

CHAPTER XIII

CHAPTER XIV

LAVINIA

A CORNER AT THE OPERA BALL.

PORTRAIT OF GEORGE SAND.

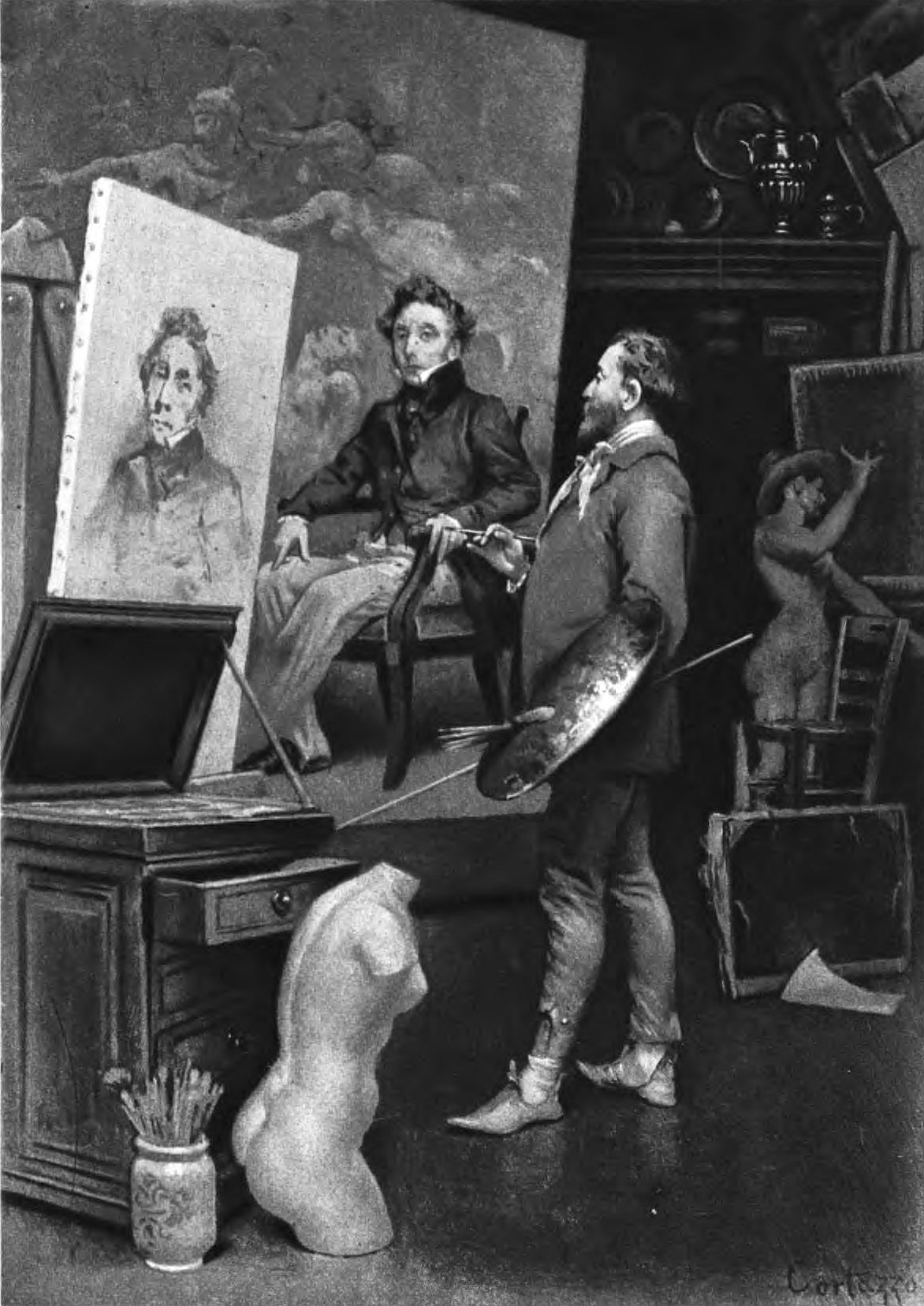

LAURENT PAINTS PALMER'S PORTRAIT.

THEIR FIRST SUPPER.

A FANTASTIC VISION.

THE SEPARATION.

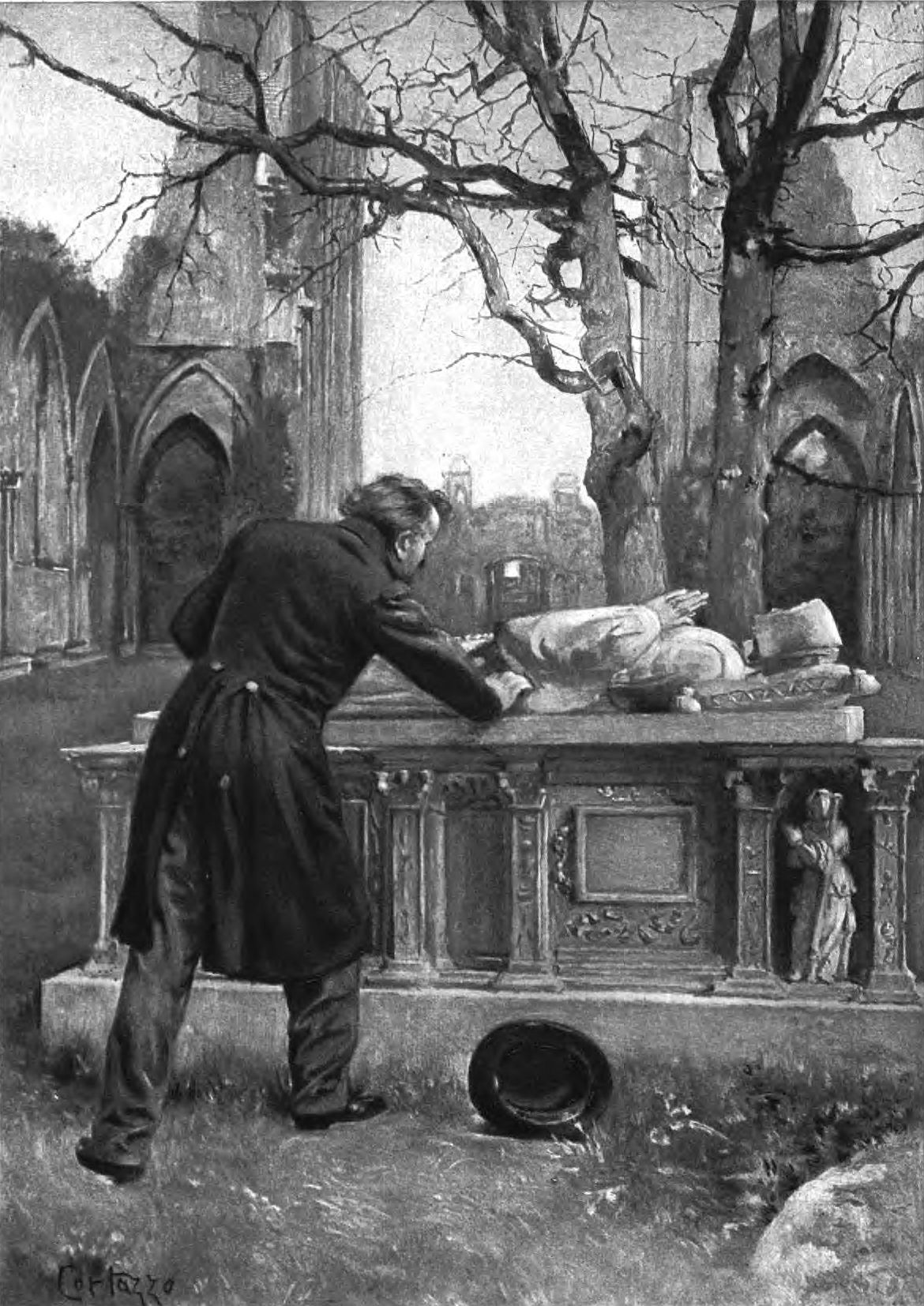

LIONEL SURPRISES LAVINIA.

There is a natural desire to know something of the parentage and birth of renowned authors, and to learn something that may throw light on the formative influences which have operated in producing the works that have rendered them famous. In the case of George Sand, whose nature offers contrasts as striking as were the social conditions of her parents, this desire is particularly strong; therefore, although the limits prescribed to this sketch prevent either an exhaustive review of her life being undertaken, or a psychological study being entered upon, such details may be given as will prove useful and not without interest to readers of this famous writer.

Amandine Lucille Aurore Dupin, who adopted the literary name of George Sand, was born in Paris on July 5, 1804. Her father, Maurice Dupin de Francueil, was of aristocratic birth, being the son of Monsieur Dupin de Francueil and Marie Aurore de Saxe, daughter of Marshal Saxe, a natural son of Augustus II, Elector of Saxony, who was allied to the Bourbons by the marriage of his sister to the Dauphin, the father of Louis XVI. Marie Aurore de Saxe, previous to her marriage with Monsieur Dupin de Francueil, had been the wife of Comte de Horn, a natural son of Louis XV. The author's mother, Antoinette Victoire Sophie Delaborde, was the daughter of a bird-fancier in Paris.

These facts concerning her parentage show the association of the aristocratic with the plebeian in the blood of the author.

Her grandfather was a provincial gentleman of moderate fortune, who died within a few years of his marriage to Comtesse de Horn, who had imbibed all the aristocratic prejudices of her family. Her father, Maurice Dupin (his father had abandoned the suffix De Francueil), was the object of Madame Dupin's tenderest affection and warmest hopes; but, although of a most amiable disposition, he was somewhat reckless and, as his marriage proved, independent in his views. The disturbed condition of France under the Directory left him little choice as to a profession, so he entered the army. He became a lieutenant as the reward of his services at the battle of Marengo in 1800. It was during his sojourn in Italy that he made the acquaintance of Antoinette Delaborde, whose devoted care and nursing during a severe illness resulted in his becoming deeply attached to her. The lieutenant was only twenty-six years old, and his mistress was four years his senior. The liaison was suspected by Madame Dupin, and evoked great opposition on her part; but, in spite of her wounded sentiments, and notwithstanding the fact that Mademoiselle Delaborde was already the mother of two children, the lovers were married in June, 1804. On July 5, 1804, as has been stated, Amandine Lucille Aurore Dupin was born.

Time lightened the weight of the blow to Madame Dupin, who at last consented to recognize her son's wife; but the two women rarely met for some years. The elder Madame Dupin resided at Nohant (a spot which George Sand's writings have made famous), a secluded estate in the centre of France, near La Châtre, in the Department of the Indre. Maurice, who had now become a captain, made his home in Paris, and, when not on duty, spent his time there with his wife and their little daughter in quiet happiness. The good judgment of the younger Madame Dupin, and her kindly disposition and sincere and faithful affection for her husband and child, seem to have found a counterpart in Captain Dupin, and thus, within their own household, they enjoyed all that was essential to their mutual inclinations.

The infant life of George Sand was passed in the unpretentious home in Rue Grange-Batelière, her mother's good sense materially aiding the development of the child's intelligence. This peaceful life, however, was not long to be undisturbed; for the prolonged absence of Captain Dupin, who was serving in Madrid as aide-de-camp to Murat, induced Madame Dupin to journey thither with her child to join him. After a stay of several weeks, the captain escorted his wife and little daughter to France, where they went to the home of the elder Madame Dupin. They had not long enjoyed the restful recreation of this quiet spot, when Captain Dupin was killed by being thrown from his horse one night on returning from La Châtre.

Aurore was only four years old at the time of this tragic event, which was to be of such momentous consequence to her. Although the feelings of the elder Madame Dupin lost some of their bitterness after the death of her son, there was still too wide a gap between the grandmother, with her class prejudices, and the simple-natured, plebeian daughter-in-law to admit of concord between them, or of a mutual understanding as to the education of the young girl, upon whom, after Captain Dupin's death, the grandmother seemed to centre all her affection. The child became the source of constant conflict, and, although she was permitted all freedom in physical exercise and enjoyment, and even in the matter of education, she suffered bitter sorrow because of the disputes and quarrels of which she was the unwitting cause. Notwithstanding the heart-sorrow the little one endured, she was already cultivating her vivid imagination and developing her contemplative disposition, which were, even thus early, marked characteristics. We learn that on the occasion of her father's death, when she was but four years old, she fell into a long reverie, during which she seemed to realize the meaning of death as she mused in silent and seemingly apathetic abstraction. These dreamy periods were so frequent that she soon acquired a stupid look, speaking of which she says: "It has been always applied to me, and, consequently, it must be true."

Her Histoire de ma Vie throws some very interesting light on these earlier years. Aurore was able to read well at four years of age. She studied grammar under old Deschartres, a very pedantic personage, who had formerly acted as secretary to her grandfather, and later as tutor to her father, and who formed part of the household at Nohant. Her grandmother instructed her in music, and sought to impress her with the aristocratic principles which should govern her conduct. Her religious training was formed—if it can be said that she possessed any very clear idea on this subject—on the principles of Voltaire and Rousseau, expounded by the elder Madame Dupin, offset by the simple but devout Christian teaching of Aurore's mother, whose sincere faith better suited the mind of her daughter than did the cold and analytical reasoning of her grandmother.

From the irksome routine of lessons, however, the child turned to the freedom and wild enjoyment of outdoor life. She had as companions in her games a boy and girl who were inmates of the home, the former her half-brother, and the latter Ursule, who in later years was her faithful servant. With these and the peasant children of the neighborhood, she was able to pass numberless hours face to face with Nature, in whose manifold forms she took unbounded delight. Gathered about the fires they kindled in the meadows, they would romp and dance, or vary the pleasure by story-telling. When the hemp-dressers assembled at the farm of an evening, Aurore took the lead in the stories that were told; but she tells us that she could never succeed in evoking one of the visions with which the peasants were familiar. The great beast had appeared to them all, at least once; but she experienced only the excitement of disturbed nerves.

When eight years old, the child had acquired a fair knowledge of her native language, and composition and the cultivation of style were now being taught her, added to which were such subjects as Greek, prosody, and botany; the natural result of which was a brain taxed with details, but lacking in a clear perception of the ideas and principles sought to be established. Yet the imaginative mind was alert; it was storing up a fund of fancy that the future could draw upon almost limitlessly. The conflict between her mother and her grandmother was also exerting a formative influence on the child's mind in cooperation with her tenderness of heart. She could ill bear the grandmother's calm but dignified reproaches, though she entertained for her no little affection.

Constantly reminded of her aristocratic claims, and conscious of the hardly veiled contempt in which her mother was held by the elder Madame Dupin, she grew to despise the pretensions of caste, and her leanings became thoroughly democratic, as if the spontaneous germination of her sorrows. Her mother's angry outbreaks caused her not a tithe of the sorrow that she endured at the cold reproofs of her grandmother; hence, it was apparent to the latter that Aurore's love for her mother was greater than that for herself. She was, however, bent on securing the full love of her granddaughter and on obtaining sole guardianship. To her she looked as her heir, on whom it was incumbent to espouse the prejudices of the aristocracy.

The frequent disputes that arose resulted at length in a separation. The mother was, after much persuasion, brought to the belief that her daughter's future would be best assured by her child's remaining at Nohant in the care of her grandmother; while she retired to Paris, supported by the slender income from her late husband's estate. It was arranged that Aurore should accompany her grandmother to Paris, where she had a house for the winter, when the child could spend whole days in the company of her beloved mother, while, during the summer, the latter would come to Nohant. The grandmother, finding that the child's affection for her mother showed no diminution, but rather the reverse, and that her own share in her granddaughter's affection was rather that inspired by respect and veneration, became more jealous than ever, and sought to make the separation a real one. Hence, after a few years, the visits to Paris ceased.

During all this time, Aurore had been reading promiscuously, but there had been no definite method in her education, and her religious tendencies were left almost free to her own impulses. She had conversed with Nature; she despised conventionality; she had given free rein to her fancy; she had defined little. Her heart was not satisfied, and her mind was reaching out to an ideal.

Aurore still continued, for a long time, to hope that her mother and grandmother would be brought together again and her happiness consummated; but this hope was cruelly shattered. One day, she was startled by some disclosures her grandmother made respecting the past life of Aurore's mother, and which, in the narrator's opinion, rendered it of the first importance that the mother and the daughter should live apart. The moment was badly chosen, in a fit of anger and jealousy, and the loving girl resented her guardian's imprudence most bitterly, while suffering intensely. Her affection for her grandmother was thereby lessened, while her despised mother became dearer to her. She resolved to abandon all those material advantages that were promised by remaining with her grandmother, to neglect instruction, and to renounce accomplishments. She rebelled against the lessons of Deschartres, and, indeed, became a thorough mutineer. This was the situation when Aurore approached her fourteenth year; her grandmother, in view of the circumstances, decided to send her to a convent to complete an education befitting her social position. The Couvent des Anglaises was selected, as being the best institution for girls of aristocratic families.

The young girl entered the convent, weary at heart, wounded in her dearest affections: she found it a place of rest. She tells, in the story of her life, of the sisters and pupils, the routine of instruction, the petty quarrels, the pastimes, and the discipline; of the quest of imaginary captives whose release was undertaken; of the wanderings in vaults and passages. Though Aurore was of a dreamy nature, yet her disposition manifested extremes; for at times she abandoned herself to boisterous enjoyment. So in the convent she became resigned to her lot, yet, yielding to her spirit of independence, she joined in the pranks of the mischievous scholars. Of the two classes into which the girls were divided,—sages and diables,—Aurore made choice of the latter. This life continued for nearly two years, the girl rarely leaving the convent even for a single day, being deprived of her summer vacations by her grandmother, who wished to bring her to a realization of the pleasure and freedom of the Nohant home, which she would be the better capable of by reason of her prolonged absence.

The routine of somewhat indifferent and desultory study and the enjoyment of the diables' pranks were soon to give way to a new impulse. Hitherto, Aurore had felt no attachment to the religious exercises of the convent; but one day she was seated in an obscure corner of the convent chapel, when a spiritual enthusiasm awoke in her mind. She writes of this circumstance: "In an instant, it broke forth, like some passion quickened in a soul that knows not its own force.... All her needs were of the heart, and that was exhausted." The fervent religious emotion which she experienced at once transformed her. With her whole-natured devotion, she yields to the impulse; faith finds her soul unresisting, and she bends to the divine grace that appeals to her. Yet the transformation swayed her soul with its consequences; she shed the scalding tears of the pious, she experienced the exhaustion of feverish exaltation and protracted meditation, but she found a personal faith; and, through all the emotions and changes of the turbulent years that followed, the pure faith that she imbibed in the silent convent cloisters was never wholly obscured. This change wrought wonders in the young girl's conduct; she was no longer a hoyden, but kept herself strictly within the rules of the convent, and devoted herself with regularity to its prescribed studies, yet with no more real interest than before.

In the early part of 1820, Madame Dupin the elder fell seriously ill, and, believing that her life would soon close, she desired her granddaughter's return to Nohant. The lapse of time and the more serious disposition of the latter were calculated to help Aurore in the cares of the household that now devolved upon her, and in the nursing of her grandmother, to whom she devoted herself assiduously during the ten months that remained of her life. Her religious enthusiasm underwent some abatement after her return, and the temporary absences from Madame Dupin's bedside were spent in melancholy reverie, interrupted by active exercise. At the convent, she had been counselled by her spiritual adviser not to entertain the idea of a nun's life, for which she had expressed a desire, but to yield to temporal and physical diversions. At home, she adopted a middle course, neglecting neither her religious nor her temporal duties, while still bent on taking the veil at a later period. It was at this time that she was taught horseback riding by her half-brother Hippolyte, who had become a cavalryman. This exercise became her favorite pastime, and by it she was able to break the monotony of her life and enjoy the beauties of the surrounding country, which, in its peaceful charm and its succession of gentle scenes, was in harmony with her contemplative mind, and evoked the spirit of poetry within her.

The consciousness of the insufficiency of the education she had hitherto received now became apparent to Aurore, and she determined to effect her own instruction. She therefore read eagerly, her convent teaching and experience inclining her first to study works of Christian doctrine and practice, though she pursued her reading with great indefiniteness of plan. The perusal and comparison of the Imitation of Christ with that of Chateaubriand's Génie du Christianisme involved her in serious doubts and apprehensions; her faith in Catholicism was at least sincere, but the reasonings and discrepancies she found in these works were such as to appeal to her intelligence while puzzling her faith in the doctrines. In the orderly obedience to the teachings of the Romish church rendered in the quiet convent, there was nothing to weaken the faith in the system; but face to face with the practice of its tenets, and in view of its inconsequence, apparently, in the lives of the country people by whom she was surrounded, formidable difficulties arose in her conscience. The same wholeness of character and independence of judgment that had hitherto marked her conduct forbade her to give adhesion to principles which were at variance with her reason and conscience. To her, the practice of the confession and the doctrine that salvation could be obtained only by those within the pale of the orthodox Catholic communion were absolutely unacceptable. In her eager search for the truth, she studied the works of the philosophers—Aristotle, Montaigne, Bacon, Pascal, Bossuet, Locke, Leibnitz, Montesquieu, Mably, Condillac. Of these, she preferred Leibnitz, and, speaking of her study of this author, she says: "In reading Leibnitz, I unconsciously became a Protestant." She could not conceive of that being right which denied the liberty of conscience. So far, the result, however, was, as might have been expected, much knowledge of opinions, yet no very definite conviction, or clear establishment of principles; but the desire to arrive at a true ideal faith was intensified.

After the philosophers, came the moralists and poets: La Bruyère, Virgil, Dante, Shakespeare, Milton, Byron, Pope. These writers were read by the young girl with insatiable delight; but, as in the case of the philosophers, without system. Thought piled on thought, principle jostled against principle; all rapidly mastered and sympathetically appreciated. The master was yet to be found, but he was at hand. Jean-Jacques Rousseau's charm of eloquence and powerful logic gave her a halting-point for her reason, and pointed the way to her. Her already relaxed hold on Catholicism was now released.

The mental strain and emotional conflict of such studies resulted, naturally enough, in a complete nervous exhaustion, and her will was incompetent to enable her to formulate the truth, to comprehend the doctrines, or even to fix her choice. Her intellect did not fail her, or her memory betray her; but, in the confusion of her ideas, she lapsed into a deep melancholy, which resulted in a disgust of life. She mused on death, and, she says, often contemplated it, rarely seeing the river without mentally expressing: "How easy it would be! Only one step to take!" To the oft-recurring question yes, or no? as to the plunge into the limpid stream whose waters would forever still the tumult of her mind, she one day answered yes; but, happily, the mare she rode into the deep water to carry out her purpose, by a magnificent bound frustrated its rider's intent and saved the life of the woman who was to thrill so many readers with her passionate prose-poems.

During this period, Aurore Dupin manifested, in her intrepidity in horsemanship and in her independence of conventionality in respect of her exercises and costume, the same spirit that so often brought her under the ban of heedless criticism. It was her custom to don boys' clothes on her expeditions, that she might with perfect freedom enjoy the riding and shooting which were now her favorite pastimes. But this course brought upon her the condemnation of her strict neighbors at La Châtre, who regarded such departures from the prevailing customs as evidences of eccentricity and ill-manners.

The death of her grandmother, in December, 1821, opened a new phase in Aurore's life. The efforts which Madame Dupin the elder had made during life to withdraw the girl from the influence of her mother were perpetuated in her will, by which she appointed her nephew, Comte René de Villeneuve, the guardian of her granddaughter, to whom she had left her property. On the reading of the will, the relations between Aurore's paternal and maternal families were completely severed. Madame Dupin was not ignorant of the clause of the will which sought to deprive her of the guardianship of her daughter, and which was not valid in law, and she resisted its application. As the result of discussion, it was agreed that Deschartres, the trusted adviser of the late Madame Dupin, should be appointed as co-guardian with Aurore's mother. Deschartres was left in charge of Nohant, and Madame Dupin took her daughter with her to Paris. Here her life was by no means happy; the mother she idolized seems to have suffered in temper from the troubles and checks she had undergone, and her capricious outbursts of anger were only exasperated by her daughter's gracious and yielding way. In her mother, Aurore failed to find the guide that her nature required, and to a certain extent she was neglected by her. It is not surprising to find, therefore, that the young girl was ready to welcome any change that would relieve the irritation she endured.

The opportunity presented itself in a visit to the country home of some friends whose acquaintance Madame Dupin had recently made. In the lovely home of the Duplessis family, Aurore was cheered by the companionship of young people and the bright society found at the house. Madame Dupin left her daughter with her friends, promising that she would come for her "next week," but she was persuaded to permit the stay to continue for five months. Here Aurore met the man whom she deliberately chose for her husband. He was a friend of her hosts, Lieutenant Casimir Dudevant, twenty-seven years old, and the natural son of Colonel Dudevant, a Gascon landowner, who had been created a Baron of the Empire for his services under Napoleon. The marriage of the colonel having proved childless, he had acknowledged Casimir, and provided for his succession to his property.

On seeing Mademoiselle Dupin, the lieutenant at once took a liking to her, and this feeling was soon reciprocated by the young girl. The officer does not appear to have been a very romantic suitor, but at least he seems to have been sincere; and the fortunes of the parties being equal, a reasonable prospect of happiness presented itself in a marriage between them. The lieutenant ere long proposed marriage to Aurore, adding: "It is not customary, I know, to propose marriage to the intended affianced; but, mademoiselle, I love you. I am unable to resist telling you of my sentiments, and if you find my appearance not too displeasing—in a word, if you are willing to accept me as your husband, I will make my intentions known to Madame Dupin; if, however, you reject me, I should deem it useless to trouble your mother."

This frank but blunt proposal rather pleased Aurore; it was entirely unconventional. Madame Dupin added her persuasion, as she considered the offer a suitable one, and, the consent of Colonel Dudevant having been obtained, the marriage was solemnized in September, 1822. An incident involved in the preliminaries to the marriage is worthy of notice, as evidence of the generous feelings and tender regard of Aurore for her old and pedantic tutor, Deschartres. Being called upon to render the accounts of his management of his ward's estate, he could not explain a deficit of eighteen thousand francs, for the expenditure of which he could not produce receipts. He was dumfounded; Madame Dupin threatened to cause his arrest; but her daughter, moved to pity at the old man's distress, insisted on taking the blame on herself, explaining that the sum represented money paid to her by Deschartres, for which she had neglected to give him receipts. This generous course saved the old man from disgrace, and perhaps ruin, for he was proposing to sell his own pitiful estate to make good the deficit due to his mismanagement.

Soon after the marriage, Monsieur and Madame Dudevant took up their residence on the bride's estate at Nohant. The life there for some time was tranquil, if not entirely happy. The young wife seems to have abandoned the life of the intellect, and soon her whole dream was of maternity. Matrimony had already failed as the ideal life she may have contemplated. The companionship of her husband was not that living force she had pictured. Probably she had trusted too much to reason and common-sense, and certainly she had married in ignorance of her husband's character and tastes, and, it may be, in ignorance of her own. At any rate, she was not yet unhappy.

In July, 1823, Maurice was born, her beloved son, he who was to be the comfort and joy of her life in all its troubles, and in whom the mother was to find a compensation for the sorrows of the wife. From the time his son was born, Monsieur Dudevant seems to have neglected his wife; he was of a rather interfering disposition, and, moreover, given to the pleasures of hunting, in pursuit of which he frequently left his wife as early as two or three o'clock in the morning. The young wife, whose health was not robust, and whose disposition led her to desire the society of her husband, at first mildly reproached him for his absence, but the effect was only momentary; happily, the joys of motherhood consoled her, at least for a time, and matters progressed placidly.

The seclusion of the life at Nohant was first interrupted in 1824, when a visit was made to Paris and to the home of the Duplessises. Later, in 1825, a journey was taken to some of the watering-places in the Pyrenees, where it was hoped Madame Dudevant's health would be reëstablished, and by means of which the young wife also hoped to bring about a change in her husband's habits. To this trip, which was to be made more entertaining by the company of two friends of her convent life, Madame Dudevant looked with eager interest; for, in a letter to Madame Dupin, written in June, 1825, she says: "I shall be most happy at once more seeing the Pyrenees, which I scarcely remember, but which everybody describes as offering incomparably lovely scenery."

The stay of a few months among the mountains proved of great physical benefit to Madame Dudevant. In her letters to her mother, she describes with almost childish glee the excursions she made, the daring feats she undertook, and the beauty of the scenery. But the hope of changed manners on the part of her husband was not realized; his treatment on their return continued as before; when not engaged in his favorite pastime of hunting, he indulged in the pleasures of the table.

The duties of a mother and a housewife now seemed to absorb Madame Dudevant's thoughts; yet, while outwardly calm and dignified, the experience she was gaining of conjugal life, which had destroyed all her illusions, was establishing her views on the relations of husband and wife and formulating her ideal of satisfied love. It cannot be doubted that her earlier works, especially Indiana, are the pathetic and passionate voice of her soul, long silenced by her obligations as wife and mother; for in a letter to Madame Dupin, written in May, 1831, Madame Dudevant writes: "I cannot bear even the shadow of coercion; that is my principal defect. All that is imposed on me as a duty grows detestable to me; what I can do without any interference, I do whole-heartedly."

For a long time, the bitterness of her disappointment found no confidant; and Monsieur Dudevant's interfering methods, and his indifference to his wife's society, must have hourly wounded her sensitive nature. In the letter last quoted, we read: "I hold liberty of thought and freedom of action as the chief blessings in this world. If to these are joined the cares of a family, then how immeasurably sweeter life is; but where is one to find such a felicitous combination?" But during the years in which her sorrows were accumulating, her letters to those outside bear no sign of bitterness or anger. She endured her grief and disappointment silently, so far as her friends were concerned. The breach between the husband and the wife was, however, opening wider day by day. In 1826, a letter to Madame Dupin tells of the life at Nohant during the Carnival, and of the rustic wedding of two of her domestics, in a cheerful and merry strain. Matters proceeded in this superficial tranquillity, with no remarkable change, until the fall of 1828, when the birth of her daughter, Solange, afforded a new interest and added duties.

We glean from her letters that Madame Dudevant's health had given her serious cause for anxiety; but plenty of outdoor life, and the duties of the home, combined with her constitutional soundness, enabled her to overcome this drawback; she writes to her mother, about this period, in the same strain as before, describing her occupations and condition, and, speaking of her husband, says: "Dear papa is very busy with his harvest.... Dressed in a blouse, he is up at dawn, rake in hand.... As for us women, all day long we sit on corn-sheaves, that fill the yard. We read and work much, hardly ever thinking of going out. We enjoy a plenty of music." According to her own account, Madame Dudevant had become a settled countrywoman.

In 1829, Monsieur and Madame Dudevant passed two months in Bordeaux and at the home of her husband's mother; and on her return to Nohant in July she resumed her quiet home life, restricting the circle of her friends in conformity with her retired tastes. Here they enjoyed the society of her half-brother and his wife. But the period of outward calm and resignation to her condition was fast nearing its term. The relations between the husband and the wife were rapidly growing worse. Among the wife's occupations and diversions of this period were painting and composition. Of the former, Madame Dudevant speaks with enthusiasm later; already, in 1827, she had tried her hand at portrait-painting, for in a letter to her mother she writes: "I send you a profile drawing done from imagination; it is a regular daub. It is well that I should tell you that it is intended as a representation of Caroline. I am the only one who sees a likeness in it.... I also drew my own portrait.... Yet I did not succeed better than with Caroline's.... I laugh in its face on recognizing how pitiable it makes me look, so I dare not send it." And again, early in February, 1830, she sends a portrait of her son to her mother. It is well, as we shall soon see, that Madame Dudevant was so little encouraged by her efforts. Yet of her literary proclivities, which she also indulged by attempts at novel-writing, she was certainly not convinced, and of her ability in this direction still less so.

The education of her son Maurice had now become a matter of extreme importance to Madame Dudevant. The boy was six years old, and she was fortunate enough to secure as his tutor Monsieur Jules Boucoiran, of Paris, who later became her trusted friend and the wise counsellor of her son. How carefully Madame Dudevant still concealed her marital wretchedness from even her mother is evidenced in a letter written in December, 1829, in which she says: "What are you doing with my husband? Does he take you to the theatre? Is he cheerful? Is he good-tempered?... Make use of his arm while you can; make him laugh, for he is always as gloomy as an owl while he is in Paris." The crisis which finally separated the husband and wife was brought about by a discovery that wounded the already stricken heart beyond endurance. Monsieur Dudevant had become even brutal in his conduct; he had gone so far as actually to strike his wife.

One day, Madame Dudevant, while looking for something in her husband's desk, chanced upon a package addressed to herself, and bearing the direction: To be opened only on my death. Deeming that her health did not promise her survival of her husband, and seeing that the package was addressed to her, Madame Dudevant, anxious to know the estimation in which her husband held her, opened the package. Her letter to Monsieur Boucoiran, dated December 3, 1830, best tells the revelation. She writes: "Good God! what a will! For me nothing but maledictions. He had heaped up therein all his violence of temper and ill-will against me, all his reflections concerning my perversity, all his contempt for my character. And that was what he had bequeathed me as his token of affection! I believed that I was dreaming, I, who hitherto had been obstinately shutting my eyes and refusing to see that I was scorned. The reading of that will at last aroused me from my slumber.... My decision was taken, and, I dare declare, irrevocably."

Madame Dudevant at once informed her husband of her decision to leave him, and of the motives thereof. The explanations that followed led to an arrangement whereby Madame Dudevant was to receive from her husband an income of about three thousand francs, and to spend one-half of the year at Nohant and the other half in Paris. The care she took to keep the secret of her troubles from the world, for the sake of her children, may be understood from her letters. She desired that it should be supposed that she was leading a "separate life," hoping that, by her alternate residence in Paris and at Nohant, her husband would "learn circumspection." She writes to Monsieur Boucoiran, on December 8, 1830: "I must confess I am distressed at the thought that the secret of my domestic affairs may become known to others besides you.... The good understanding which, notwithstanding my separation from my husband, I desire to maintain in all that concerns my son, will compel me to act with as much caution when absent as when with him." The momentous step which was to result in Madame Dudevant's entire liberty of action, and, above all, in her giving to the world the masterpieces which soon rendered her famous, was taken in the early days of January, 1831, when, leaving her children, and her home at Nohant, with its cherished associations, she set out for Paris, armed with letters of introduction to one or two literary men, given her by friends at La Châtre.

But there was yet a wide chasm to be gulfed. Her equipment for the life of independence she contemplated was, in a material sense, very limited. Her income was insufficient to secure her the luxuries she had enjoyed at Nohant, and to which her tastes inclined. Her stout heart and indomitable will were, however, not to be shaken. She had cast the die. She would not face the humiliation of failure and a retreat from the position she had created. But live she must, and in her endeavors to secure a livelihood she sought to employ the accomplishments she had acquired. At first, she attempted translating, believing that her knowledge of English, obtained at the convent, would provide her the necessary income; but in this she was doomed to disappointment. Then, too, millinery and dressmaking proved profitless, in spite of long hours of daily toil. Somewhat better results attended her efforts to gain a sufficient subsistence by art. The pastime at Nohant now stood her in stead to some degree. She made a limited success in miniature paintings for fancy articles, such as cigar-cases, snuff-boxes, and tea-caddies. But she still failed in her purpose. So nearly, however, had she adopted art as a profession, that it appears that, had she not been discouraged by the price secured on one occasion, her energies would have been directed away from the field in which she attained her glory!

It is curious to find Madame Dudevant hesitating in her choice between literature and art. The decision was not long before being reached, happily for the world of literature, though it cannot be claimed that the choice was quite voluntary, if we may judge by her letters. Writing to Monsieur Boucoiran on January 13, 1831, she says: "I am embarking on the stormy sea of literature. For one must live," and, later, to Monsieur Duvernet she says that only the "profits of writing tempt my material and positive mind." That a dominant inclination for letters possessed her, however, is surely indicated in her early attempts at composition; even during the previous autumn, while at Nohant, she had wrought out a kind of romance in her grandmother's boudoir, with her children at her side, of which she says: "Having penned it, I was convinced that it was of no value, but that I might do less badly."

The decisive first step in her literary career was due probably more to the advice of Jules Sandeau than to any other cause; for, spite of the rare qualities she possessed, Madame Dudevant was diffident as to her powers. Jules Sandeau was, like herself, a native of Berry; they had formed each other's acquaintance at Nohant some time before the separation between Monsieur and Madame Dudevant. On receiving her confidences as to her straitened circumstances, Sandeau advised Madame Dudevant to adopt the literary career. It was soon arranged that the two should collaborate in writing an article for the Figaro, which was accepted with so much encouragement that others soon followed. Writing of this arrangement to Monsieur Duvernet, Madame Dudevant says: "I have resolved to associate him with my labors, or myself with his, as you may please to put it. Be it as it may, he lends me his name, as I do not wish mine to appear."

But the way to fame, though rapid, was not without discouragement. A novelette had been accepted by the Revue de Paris, but its publication was delayed in favor of known authors, and, meantime, the future favorite was scribbling articles for the Figaro, at the price of seven francs a column, which, she remarks, "enables me to eat and drink, and even attend the play." The drawbacks and discouragements she suffered were many; she writes to Monsieur Duvernet, in February, 1831: "Had I foreseen half the difficulties I encounter, I should never have entered on the career. But, the more the obstacles I meet with, the greater is my determination to go forward.... We must have a passion in life."

But, spite of this "passion," our author began her lifework under circumstances that might well have intimidated a less ardent and determined person. Her imperfect and fragmentary education; her crude and ill-digested ideas of social life; the bitter memories and smarts of domestic life; the disillusionment she had suffered in her hopes of marriage,—all these were sore obstacles; but she still had unbounded faith, a sympathetic mind and heart; and her poetic nature cast a lustre over all her thoughts. If she had no precise ideal, no well-matured method, if she lacked experience of the under-currents that swayed social and political circles, she was endowed with keen perceptive faculties and a rapid insight into character. She loved Nature passionately, and to the cry of human sorrow her heart was quickly responsive.

During these first struggles in the literary path, Madame Dudevant's letters to her son and his tutor manifest her constant anxiety as to the welfare of those she had left behind, and of her longing for the time when, in accordance with her arrangements with Monsieur Dudevant, she could be with her children again. There is no touch of pride or vainglory in her naïve confessions, nor does she claim for herself any but an amateur's position in the world of letters. She writes to Monsieur Duvernet: "I nevertheless long to go back to Berry; for my children are dearer than all else. But for the hope of some day being more useful to them with the pen of the scribe than with the needle of the housewife, I should not be away from them so long. In spite, however, of the innumerable difficulties I encounter, I am resolved to take the first steps in this thorny career."

Soon after the appearance of the articles in the Figaro, the two fellow-provincials produced a novel entitled Rose et Blanche, ou la Comédienne et la Religieuse (Rose and Blanche, or the Actress and the Nun), which, through the good offices of Monsieur de Latouche, the director of the Figaro, also a native of Berry, to whom Madame Dudevant had been recommended by the Duvernets of La Châtre, realized four hundred francs. A difficulty arose touching the name of the author, which must be published with the work. Sandeau was in a quandary, for he risked incurring the reprobation of his relatives, who were averse to his entering upon literature to the prejudice of his law studies, should his name appear; while Madame Dudevant dreaded a scandal, if she were named as the author. As a result, a compromise was effected, and the book appeared as the work of Jules Sand.

The freedom required by Madame Dudevant in her new profession she soon found was greatly hampered by her sex; it was almost indispensable to visit many places from which women were generally barred; consequently, she adopted male attire, apparently at the suggestion of Madame Dupin, to whom such disguise was not infrequent in the course of her travels with her husband. For this shocking procedure she has been unnecessarily condemned; but her own explanation of the causes, and its advantages, seem to justify the singular course. Madame Dudevant was a singular woman; moreover, she found herself shackled in the execution of her new-found aims. The obstacles had to be overcome, and without fuss or parade she brushed the difficulty aside by the most direct means available. Under her disguise, she was free to enter cafés, theatres, lounge about the boulevard, visit picture-galleries, come and go at all hours, attended or otherwise—in a word, mix with all sorts and conditions, to gather the raw material which her rare skill enabled her to spin into such charming and provoking articles as she was at the time writing. But hardly had Madame Dudevant made her début as a journalist, when she found herself within measurable distance of La Force (a prison to which political offenders were consigned), in consequence of an article in the Figaro; for on March 9, 1831, she says in a letter to Monsieur Boucoiran: "You must know that I began with a scandal, a tilt at the National Guards. The issue of the Figaro of the day before yesterday was pounced upon by the police. I was making my preparations to spend six months at La Force, for I had decided that I would shoulder the responsibility for my article. Monsieur Vivien, however, foresaw how ridiculous such a prosecution would be, and caused the proceedings to be abandoned. All the worse for me! My reputation and fortune might have been made by a political conviction."

While the choice of literature as a career seems not to have aroused any opposition on the part of her own kin, the case was different as to her husband's. Baroness Dudevant dreaded the possibility of the name she bore appearing in printed books; but such a circumstance was not contemplated, and the baroness's dignity was saved.

The success of Rose et Blanche, in spite of its defects, was such as to pave the way for further novels. It was arranged between its joint authors that a new novel, entitled Indiana, should be prepared by them. On Madame Dudevant's return to Nohant for three months, she set about her part, and on reaching Paris in July, 1831, she called upon Sandeau, to submit her contribution; her collaborator had not even written a line of his share. Reading her work, he deemed it a masterpiece, and, notwithstanding the objections of Madame Dudevant, insisted on its publication as her sole production. A new difficulty here presented itself, but at the suggestion of Monsieur de Latouche it was solved by the use of their common literary name Sand, with the prefix George. This incident gave to the world the name which was soon to acquire such fame. Henceforward we shall speak of Madame Dudevant as George Sand.

During her early struggles in Paris, the mother and friend is never lost in the enthusiastic and impulsive writer; her letters to her son, to his tutor, and to other friends, present a very intelligible reflex of her mind. She is not to be turned back because she does not meet with success at once. A close observer of all that is going on about her, she is a lively critic, and an equally enthusiastic supporter; she finds enjoyment anywhere "where hatred, suspicion, injustice, and bitterness do not poison the atmosphere." Her children's welfare is the burden of her mind. Her letters are full of tenderness and a complete entering into their joys and pleasures, and are charged with wise and interesting counsel.

With the publication of Indiana, George Sand's renown was established. In a letter to Monsieur Duvernet, written July 6, 1832, she says: "The success of Indiana makes me feel nervous. I never looked for anything like it; but hoped that I might labor without attracting notice, or deserving attention. But the Fates have willed otherwise. It is my part to justify the unmerited favor shown to me." While the authorship of this book was an enigma to many critics, the public seized on the work with avidity. Its success was beyond all cavil. People recognized in it a master hand tracing a new path in romance-writing. We are forbidden by George Sand to consider the book as a romance history of herself, for she always protested against her works being interpreted as autobiographical; still, we might almost say that Indiana came into the world ready-made. Its conception at least was, as it were, the burden of her musings in the quiet hours at Nohant. Her ideal was formed of a loving, tender woman, a woman with a heart that beat only for chaste and profound love, love controlling all, pure in itself, and believing all else to be pure. Unquestionably, the work was the spontaneous outburst of the long-indulged dreams of the disappointed woman. All the accessories to her central idea were not far to seek, and her marvellous imaginative power and poetic fancy sufficed to clothe her ideas with an artistic mantle that would obscure the individuality. Of course, Colonel Delmare is not Maurice Dudevant. Nor is Ralph found in the life about her: he is the creature of her idea.

With the success of Indiana, George Sand found publishers seeking her work, both the Revue de Paris and the Revue des Deux Mondes engaging her services. The irritation of compulsion to work was now largely removed; even in the early part of February, 1832, she writes to her mother: "I can now take it quietly, without worrying myself. If I sometimes work by night, it is simply because I cannot leave a thing half finished." On her return to Paris in April of the same year, she was accompanied by her little daughter, Solange, who was then between three and four years old, and the mother's letters to her son tell of the doings of his little sister, and show how good is the distraction thus afforded to the mother. The visits to the Luxembourg, the Jardin des Plantes, the circus, all the little talk that could please and comfort her boy, the fond mother pours out in child-like, easy prattle that bespeaks her entire sympathy with her children.

Again at Nohant for the summer, George Sand applied herself strenuously to the composition of Valentine; so closely, indeed, that, if she is to be taken seriously as to a letter written in August, 1832, she was rather weary of her work. At any rate, its early issue was marked by so brilliant a success, that the labor and weariness of her task may well have been forgotten. This book, like its predecessor, was severely criticised by those who saw in it an outspoken challenge to recognized social decrees. With what wealth of poetry, what beauty of imagery, and what force, is told the story of a girl sacrificed by a marriage of expediency! The crime is not the author's; she strikes at the system which destroys a pure heart and substitutes misery and shame for happiness and dignity. The author would trace the fault, to have it remedied.

Though the subject of Valentine is, like that of Indiana, unhappy marriage, the former, in arrangement, plan, and style, gave further convincing evidence of the author's artistic skill and promise of rich literary treasures of diverse and widely varying style and conception. Valentine, the heroine, has been brought up according to the prejudices and decrees of the aristocratic class. She marries in accordance with the dictates of her family. Her heart is not involved; she is passive in the matter. Later, the abandonment she suffers, and the passion of her own soul, lead her into a false position, of which the man who is entitled to call her his wife takes advantage. The climax is dishonor, death.

The winter of 1832 finds George Sand again in Paris, where she is comfortably settled; she finds herself bothered with visitors, but out of the clutches of poverty. In her apartments, she seeks her pleasure in her work and the society of her little Solange, of whom she writes at this time: "She brings me more happiness than all the rest." In a letter to her son's tutor, written December 20, 1832, she says: "I am making lots of money; I am receiving propositions from all quarters. The Revue de Paris and the Revue des Deux Mondes are fighting for my work. I finally bound myself to the latter." La Marquise had just been published, the novel having been received with great favor. Thus, within two years from the time she came to Paris to seek liberty of action and thought, wounded in her faith and affection, and her hopes entirely shattered of realizing any joy in her husband's society, George Sand had overthrown all obstacles in the path before her, and had become a distinguished personality in the world of letters.

In her next work, Lélia, written in 1833, the author's riotous imagination produced a poem—for such it is—which was regarded as another manifestation of the wide range of her faculties. The book, however, is now regarded as important chiefly from the fact that George Sand confessedly pictures herself more closely therein than in any other of her works. She writes to Monsieur François Rollinat: "This book will enable you to know the depth of my soul, and also that of your own." Again she says later, in 1836, in a letter to Mademoiselle de Chantepie: "Lélia ... contains more of my inmost self than any other book." Again, writing in 1842, she says: "Lélia is not offered as an example to be followed, but as a martyr who may arouse thoughts in his judges and executioners, those who pronounce the law, and those who execute it.... I have never preached a doctrine; I do not feel that I am intelligent enough to do so."

It was after the publication of Lélia that George Sand first became personally acquainted with Alfred de Musset, then a young man of twenty-three, but already of established fame as a dramatist and poet. That this acquaintance should have rapidly matured into a close friendship is not surprising. On her part, George Sand felt that she had encountered a soul that understood her own, while De Musset was equally enchanted with her. Before the year 1833 had closed, the two attached friends had started for Italy, full of the hope of continued mutual happiness. It is unnecessary here to trace the history of their friendship in detail; it is certain that the mental sufferings and the unsatisfied heart-cravings of George Sand had rendered her morbid. Her letters to friends, written before her journey to Italy, show that she realized too well the hollowness of society to lean upon it for guidance, or even distraction. She says, writing in July: "Of the things I hate or contemn, society is the least." To her, therefore, the companionship of De Musset must have seemed as refreshing as rain to a parched land. In speaking of the separation that followed in April, 1834, when De Musset, still very weak from a sickness, left Venice for Paris, accompanied by a Venetian physician, she writes: "We have parted, perhaps only for a few months; perhaps for ever. Only God knows what will become of my poor head and heart. I feel that I possess strength enough to live, toil, and endure." The story of this painful effort of genius to lead and ennoble genius is told with much interest in Elle et Lui (She and He), which appeared more than twenty-five years later.

The Italian journey was of immense influence on the future literary labors of the novelist. While in Venice, she worked hard in order to pay off the debt due to her publishers for the money advanced for the journey. Here she wrote André, Jacques, Mattea, and the first Lettres d'un Voyageur. Here she toiled while suffering from disappointment and consumed with longing to be with her children again. Of these works, Jacques presents her ideal of a true, loving man; whose passion is deep and exalted, whose soul faints at the prospect of faithlessness; whose self-devotion leads to abandonment of every right, even to self-destruction by suicide in order to shield the beloved woman from the disgrace of an unlawful joy and the consequences of a dishonored happiness. Of the other tales mentioned, it may be said that André offers a style quite distinct from all the author's previous works. The burden of the tale still is love, but love in a weak and docile nature, which yields to its elevating influence, only to be crushed. The early Lettres d'un Voyageur have a charm that none of the later ones possess; they tell of the journeys in the Alps and in the vicinity of the Tyrol; of the author's lonely musings in Venice; of the sorrow that weighed on her heart.

In August, George Sand was once more back in Paris, making her arrangements to visit Nohant again, which she reached before the close of the month. In describing her journey through Switzerland, she relates that she had walked three hundred and fifty leagues; yet, with all the change of scene and novelty of surroundings, a deep melancholy settled in her heart. She writes to Monsieur Boucoiran on August 31, 1834, from Nohant: "I felt that I had come to bid adieu to my birthplace, to all the memories of my youth and childhood; for you must have perceived and divined that life is hereafter hateful, even impossible, for me, and that I have seriously made up my mind to end it before long." Again, in the same letter: "I am very desirous of having a long chat with you, and of confiding to you the fulfilment of my last and sacred wishes." But the presence of friends of sympathetic natures and the care of her children served to dissipate the cloud that had settled on her mind; as she says shortly after, she was "cured, ... because, having become accustomed and resigned to my sorrows, my judgment is no longer led astray by my grief."

Affairs at Nohant for some time after her return from Italy must have added greatly to her unusual mental disturbance; she continued to reside alternately at Paris and Nohant, in accordance with the agreement made in 1830, but the arrangement was becoming irksome. Monsieur Dudevant's management of the estate that his wife had relinquished to him was anything but satisfactory, and, moreover, with the growth of her children, George Sand became increasingly anxious as to their control and care. The complete rupture between herself and De Musset, which was attended with very painful and stormy incidents, augmented her anxiety and grief during the winter of 1834-1835.

By this time, George Sand's fame had surrounded her with a large circle of friends, which included the most eminent men of the day; among them were the leaders of the various schools that contended for the mastery in matters of social progress. To them the eloquent author appeared as a much-to-be-desired ally; their theories would enjoy greater popularity if they could be presented in the entertaining and passionate language and clothed with the poetic imagery of the highly talented author of Indiana and Valentine. In the spring of the year 1835, she became acquainted with Monsieur de Lamennais whose freedom of thought and humanitarian Christianity were well suited to George Sand's predilections, and secured the approval of her intelligence, which had rebelled against the bigoted teachings of the Roman Catholic Church. Hence, for a time, her genius was directed by the philosophy of this eminent teacher, and she wrote for his journal, Le Monde, an unfinished series styled Lettres à Marcie. It is not surprising that George Sand's enthusiasm should have been aroused by the liberal doctrines set forth by this liberal-minded advocate of religious and social progress. Her natural generosity, the whole experience of her life, led her to espouse his views with the fervor of a devotee; and it seems certain from her letters that her troubled mind was soothed by the righteous and humane principles which she conceived the new movement to embody. She says in her letter to Monsieur Adolphe Guéroult, dated May 6, 1835: "You are in error if you consider me more fretful now than in the past. Just the reverse, I am less so. Great men and great thoughts are constantly before me." The same correspondent appears to have taken George Sand mildly to task for her custom of appearing in men's clothes; and it may not be uninteresting to quote from her reply, as the best indication of her position as to this question. She writes: "It is better that you should not trouble yourself concerning my garments. It is a very small matter what kind of costume I wear in my study, and my friends will, I trust, respect me equally whether I wear a vest or a shift. I never appear out of doors in men's clothes without taking a stick with me; so do not feel alarmed. My fancy for wearing a frock-coat occasionally, and under certain circumstances, will not accomplish a revolution in my life."

About the same time, she made the acquaintance of the advocate Michel, of Bourges, whose advanced views on politics, enunciated so eloquently, had acquired for him great renown. A third person also subjected her generous instincts to his philosophical teachings—Pierre Leroux, whose acquaintance she made at this period. George Sand's emotional nature was easily captivated by the eloquent pleadings and close reasonings of these men. She spoke from her heart; she says of herself: "I easily relapse into a wholly sentimental and poetical existence without doctrines and systems." The influence of these leaders is found stamped on the novels of this period, as well as in the Lettres d'un Voyageur.

It is clear that at this time the relations of the husband and the wife were undergoing a strain that threatened an early further change. In May, 1835, Monsieur Dudevant prepared and signed an agreement which was forwarded to his wife for her signature, but which she returned torn up. Explaining this incident, she writes to Monsieur Duteil, of La Châtre: "I also perceive that grief and bad feeling on his part would attend the division of our home and means.... I therefore return to you the agreements that he signed; moreover, I return them torn up, so that he may have only the trouble of burning them, in case he should in the least degree regret the arrangement prepared and set out by himself." This matter dragged on until the fall, and it is not difficult to realize how much the situation in which George Sand was placed grieved and chafed her. Some evidence is found in her own words, written in June, 1835: "Our society is still completely hostile to those who run counter to its institutions and prejudices, and women who realize the need of freedom, but are not yet ripe for it, are wanting both in strength and power to maintain the combat against an entire society which has, to say the least, decreed for them abandonment and misery."

Her chief anxiety in this domestic misfortune was as to her children's welfare and control. She was jealous of their affection for her. Her letters to her son at this period are full of the tender solicitude she feels; she puts before him a high standard for his life's guidance, and strives to inculcate unselfish love as a consoling virtue. She betrays her anxiety lest her children should be separated from her. Finally, in the autumn of 1835, she applied to the courts for a legal decision that should give her the definite and valid settlement which Monsieur Dudevant had previously voluntarily agreed to, but had since avoided. George Sand proposed to pay her husband a yearly income of three thousand eight hundred francs, which, in addition to the small remnant of the income from his own fortune, would make a total revenue of five thousand francs. She was to undertake the charge of her children's education, and to have possession of Nohant. Even in this crisis, the wife's respect for the father of her children is in clear evidence. She writes to her mother in October: "If my husband will be amenable to propriety and duty, neither of my children will love one of their parents at the expense of the other." This suit was delayed, and a final issue was not obtained till the middle of 1836, a decision rendered in February in her favor, by default, having been appealed against. During this period of unrest, George Sand actually contemplated, in case she failed, running away to America with her children.

The months that had passed, however, were not without literary fruit. The works of the first period or style, besides those already mentioned, include Leone Leoni, 1835; Simon, Lavinia, and Metella, 1836. She also rewrote Lélia (of which she says: "Lélia is not myself ... but she is my ideal."), modifying her first production of anger so that it should "harmonize with that of gentleness." Leone Leoni is a tale of a woman's incurable love. The heroine is a bourgeoise, who has been ensnared by the wiles of a Venetian nobleman. She endures manifold sufferings and base indignities, yet her heart triumphs over her mind. While she rebels against the thrall in which she is held, she cannot break from it; and even when rescue is offered her by marriage with a man of heart, and all has been arranged to this end, she forsakes him in favor of the rascal who has wronged her. This morbid love, while alluring enough, does not offer us the type of woman whom we find attractive in the characters drawn by our author. In Simon, a new tone is dominant; there is light in the mind, hope in the heart. Herein she shows social prejudice overcome by deep and patient love.

The term of uncertainty due to the protracted legal proceedings had not been an idle one, nor does it seem to have deadened George Sand's appreciation of the external beauties of nature, or her enjoyment of physical exercise; for she writes cheerfully of her horseback rides at night, of the pleasure she takes in her surroundings at La Châtre, where she is entertained by friends near her own home during the pendency of the trial. She tells of the delight she experienced in watching the transition from night to day, which she speaks of as a "revolution apparently so uniform, but possessing a different character every day." Those evening rides, how much inspiration they furnished for the poet-novelist as she wandered along alone! how much of influence on her marvellous creative mind! In that breaking dawn, indistinct and fanciful, did she not see the image of society in its obscurity, and dream of the dawn of its hoped-for emancipation from the gloom of inequality and prejudice? She was once more face to face with nature, her back was turned upon the vanities of the proud and the machinations of the perverse. She was musing over the new teachings that had been given her. She sought "to believe in no other God than he who preaches justice and equality to men." How calming to her mind her communion with nature was at this time, and how refreshing to her fancy, may be inferred from her own words: "There is not a meadow, not a clump of trees, which, bathed in a lovely and brilliant sun, does not seem entirely Arcadian in my eyes. I teach you all the secrets of my happiness." In the woods, the streams, the sky, and the stars, George Sand found so many religious teachers. All her former spiritual tendencies reawakened, she tells us that through her prayers, few and poor though they were, she experienced a "foretaste of infinite ecstasies and exaltations like those of my youth, when I used to believe that I saw the Virgin, like a white spot on a sun which moved about me. Now my visions are all about stars; but I begin to have strange dreams."

In September, 1836, after reëntering into possession of Nohant, George Sand took her two children with her on a visit to her friend, the Comtesse d'Agoult, at Geneva. In November, she was in Paris again, but not in her old poet's attic, for she occupied a suite of apartments in the Hôtel de France. Her son's health now occasioned her profound trouble. Symptoms of consumption were apparent. In her distress, she begs Monsieur Dudevant to aid her in her anxiety, and entreats him to share her care in effecting their son's recovery. We are able to understand her feelings and the rule of her conduct toward her children in respect of their father by her letter to Monsieur Dudevant. She pleads that their child's health stands before everything else; that, as she encourages the boy's affection for his father, the latter should abstain from thwarting his affection for his mother. She invites him to come to her house as often as he pleases, and volunteers to keep out of his way if her presence should be distasteful to Monsieur Dudevant. She concludes: "What interest could there now be for us to attack each other through the affection of a poor child who is all meekness and love?" A short time later, the boy had recovered his health in the Berry home.

In the following year, George Sand wrote Mauprat. In this book is traced the power of love over an impulsive heart that no culture of the mind has influenced. A gentle woman, pure and gracious, bred in accordance with the dictates of an aristocratic class, gives her love to a boor, and, ignoring all conventional decrees, deliberately chooses to drive the savage out of the nature of her lover, and by his very love raise him to a level at which he stands her fellow and almost an exemplar for even the best of men. George Sand's faith in the transforming power of love is eloquently expressed in this work, in which also she shows the influence of Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

In her letters of this period, we find her imbued with strong Republican theories, insisting on the liberty and dignity of the individual, and inveighing against monarchical principles. In the same year, Les Maîtres Mosaïstes appeared in the Revue. It was a short story, written for her son, telling of the adventures of the Venetian mosaic-workers. The character of Valerio, she says, was penned while she had in mind her friend Calamatta, the artist, who painted one of George Sand's portraits. Here we may give a word-picture of our author by Heine, who was a frequent visitor with her in the Comtesse d'Agoult's salon, and who saw much of George Sand at this period. "Her face might perhaps be described as more beautiful than interesting, yet the cast of her features is not severely antique, for it is softened by modern sentiment, which enwraps them with a veil of sadness. Her forehead is not lofty, and a wealth of most beautiful auburn hair falls on each side of her head to her shoulders. Her nose is not aquiline and decided, nor is it an intelligent little snub-nose. It is merely a straight and ordinary one. A most good-humored, though not very attractive, smile generally plays around her mouth; her lower lip, which is slightly inclined to droop, seems to suggest fatigue. Her chin is plump, but very beautifully formed, as are her shoulders, which are magnificent." So much for her physical traits. From the same source we learn that her voice was dull and muffled, with no sonorous tones, but sweet and pleasant. Her conversation he describes as not being brilliant; that she possessed absolutely none of the sparkling wit that distinguishes her countrywomen; nor had she their inexhaustible power of chattering.

In the summer of 1837, the illness of Madame Dupin disturbed the peaceful and pleasurable life that George Sand was enjoying at Nohant. Hurrying to Paris, she remained with her mother during her last days, but was not present at the moment of her death; for having received a false alarm that her son had been abducted from Nohant, she had sent a messenger there, and had herself gone to Fontainebleau to receive her son, and during the night of her absence her mother had died. At Fontainebleau, George Sand remained with her son for some weeks, riding in the forest, gathering flowers, and chasing butterflies during the daytime, and writing closely at night. It was here that she wrote La Dernière Aldini, a novel reminiscent of Italy, and remarkable for its brilliant style and exquisite descriptions. The patrician lady, her daughter, and Lelio,—how distinct are the characters, how subtle the scenes, and with what ease the current of the romance flows amid the charming pictures that dazzle with their beauty!

Le Secrétaire Intime, Lavinia, and some others, also belong to this period, which was one of constant labor; for the obligation now resting on George Sand of maintaining her old home and providing for the education and future of her children was a heavy burden. By the legal decision of 1836, certain details of the arrangements between Monsieur Dudevant and his wife had been left to private settlement, a circumstance which brought about renewed conflict. The mother was in constant dread lest her son should be kidnapped; indeed, in the case of her daughter Solange, this actually appears to have been undertaken during the mother's stay at Fontainebleau. Another arrangement was effected, by which all future friction was avoided, and the charge and education of Maurice, over whom his father had previously held joint control, was henceforward to rest solely with Madame Sand.

In the winter following, in consequence of the unsatisfactory condition of Maurice's health, a trip to Majorca was determined on, where it was hoped that the climate and a few months' change would reinvigorate him. The family was accompanied by the eminent composer, Chopin, who was suffering from phthisis. The stay in the island, however, was attended by the greatest inconveniences. Here George Sand devoted herself to the education of her children, to the household cooking and cleaning, to the care of her friend, and, lastly, to her literary labors. But the discomfort and extortion were such as to render the visit unendurable, and she left Spain with feelings of thankfulness for her departure, and with her son's health reëstablished. The literary result of this stay is Un Hiver à Majorque, of whose scenery she says: "It is the promised land;" but of whose people she writes in the severest terms: "They are devout, that is to say, fanatical and bigoted, as in the days of the Inquisition. Friendship, loyalty, honor, exist here only in name. The wretches! oh, how I detest and despise them!"

In the cells of Valdemosa, an old and deserted Carthusian monastery, situated in a wild and noble landscape, George Sand found poetic surroundings and associations that were so congenial that she says: "Had I written there that part of Lélia which has a monastery for its scene, I should have produced a finer and more real picture." The occupation of rooms in this lonely old retreat was perhaps the only pleasurable feature of the stay in Majorca. It was here that Spiridion was finished: a tale of a young monk who is filled with the fervor of divine love, but who later strays from his simple faith as the result of the agitations and doubts which philosophic teachings impart. This book probably reflects the experience of the author, more particularly that of her exaltation at the convent, and it also portrays her own spiritual conflicts and the calm of a sincere, broad faith that rises above dogma and rests secure in the divine love. After a short stay at Marseilles and a trip to Italy, George Sand returned to her home at Nohant.

We have now approached a period when Madame Sand's literary work was to show a change from the subjective lyricism of her previous works, which are the voice of her long-repressed early emotions, to a series of works in which she drew her inspiration largely from the religious, philosophic, and socialistic doctrines that her impressionable mind had espoused as expounding the true principles by which society and the individual should govern themselves. But, in yielding her art to the services of the reformers, George Sand had little thought for aught but the goodness of the principles, as they appeared to her, or, at any rate, had not taken measure of the practical difficulties within the circle of the reformers and those which passive resistance on the part of the great masses offered.

Before, however, the first of her books of the quasi-philosophical style appeared, our author made an essay as a playwright, and Cosima, a drama in five acts, was produced at the Théâtre Français. It was received with hisses and hooting.—George Sand writes of it, on May 1, 1840: "The whole audience condemned the play as being immoral, and I am not sure that the Government will not prohibit it.... It was played through, being much attacked by some, and equally defended by others, ... and I will not alter a single word for the subsequent representations." The scene was laid in Florence, and the period was the Middle Ages, both time and place being unsuited to the wholly French sentiment of the play.

Madame Sand had for some time been a regular contributor to the Revue des Deux Mondes, but the novel Horace, written for its pages, was rejected by the editor as being of subversive tendencies; it was, therefore, published in the Revue Indépendante, a very advanced journal founded in 1840 by Pierre Leroux and Louis Viardot, to which George Sand gave her coöperation. This work portrays in its study of the titular character a sort of moral mountebank; the analysis is very clever and interesting of the weak, selfish man who for a time imposes with his claims for distinction, but who appears in his true light at last. Next came the Compagnon du Tour de France, in which socialist doctrines are the animating spirit. Though the freedom of the author's fancy clothes the subject and the characters with great interest and portrays many charming situations, yet there is a strained and not seldom unwelcome contrast presented by the necessity of keeping the individuals in line with the political purpose of the novel. Speaking of her writing, about this time, George Sand says: "Happily, I do not need to seek ideas; they are clearly fixed in my brain. I have no longer to struggle with doubts; these vanished like clouds in the light of conviction. I no longer have to examine my sentiments; their voice sounds aloud from the depths of my heart, and puts to silence all hesitation, literary pride, and fear of ridicule. So much has philosophy done for me."

In 1842, the beginning of Consuelo appeared in the Revue Indépendante, and its opening was so auspicious that the scope originally planned was considerably enlarged. The author tells us that she felt she had before her a grand subject and powerful types of character, with time, place, and historic incidents of deep interest, in great profusion awaiting the explorer. The heroine of the work is a lovely portraiture: lofty in mind, noble in heart, and chaste in thought. Consuelo must ever remain one of George Sand's finest creations. The work abounds in interesting situations; the exuberant fancy and poetic spirit of the author find full play in a series of marvellous and fascinating adventures; and the characters are portrayed with subtle skill and vigor. Nor can the prolixity and gloomy meditations of Comte Albert check the reader's interest. The meeting of Consuelo and Haydn and the wonderful musical performances of these wayfarers present lovely and by no means impossible pictures. The influence of George Sand's friendship with Liszt, who stayed at Nohant during the summer of 1837, and with Chopin, with whom she was on equally close terms, is seen in this work. The Comtesse de Rudolstadt is perhaps less likely to arouse enthusiasm and sustained interest; Consuelo has become the Comtesse de Rudolstadt, and with the change not a little of the charm disappears in the mystifying allegory and humanitarian theories which obscure the artist's poetic fancy and brilliant description. This work likewise appeared in the Revue Indépendante, in 1843.

In 1845, George Sand wrote the Meunier d'Angibault, a work also written under the influence of Leroux's teachings. The socialist idea is presented in the person of an artisan, Lémor, who refuses to marry a rich widow because she is rich, and, consequently, such a union would do violence to his principles. Finally, a fire destroys the widow's château, and she rejoices at her deprivation, inasmuch as she is now no longer separated by the possession of her property from the man who adores her. While this and similar works created for their author much enmity, their characters presented nothing but virtuous, if unrealizable, ideas. Following this, in 1846, appeared La Mare au Diable, an exquisite idyl, a gem of rural poetry. We can well imagine with what delight George Sand penned this touching and beautiful poem. The construction is of the simplest form. A ploughman, a widower, is about to seek a wife, as a prudential step; he undertakes the charge of a young peasant girl who is going to fill a place as shepherdess a few miles from her home. The way is lost, and they camp for the night under great oaks. Here, Marie chats till overcome by sleep, but Germain indulges in dreams which result in cooling his interest in his proposed marriage venture. The rest is easily understood; Germain and Marie become husband and wife. The incidents are all natural and the dénouement quite expected. The reader cannot forget the charming story.