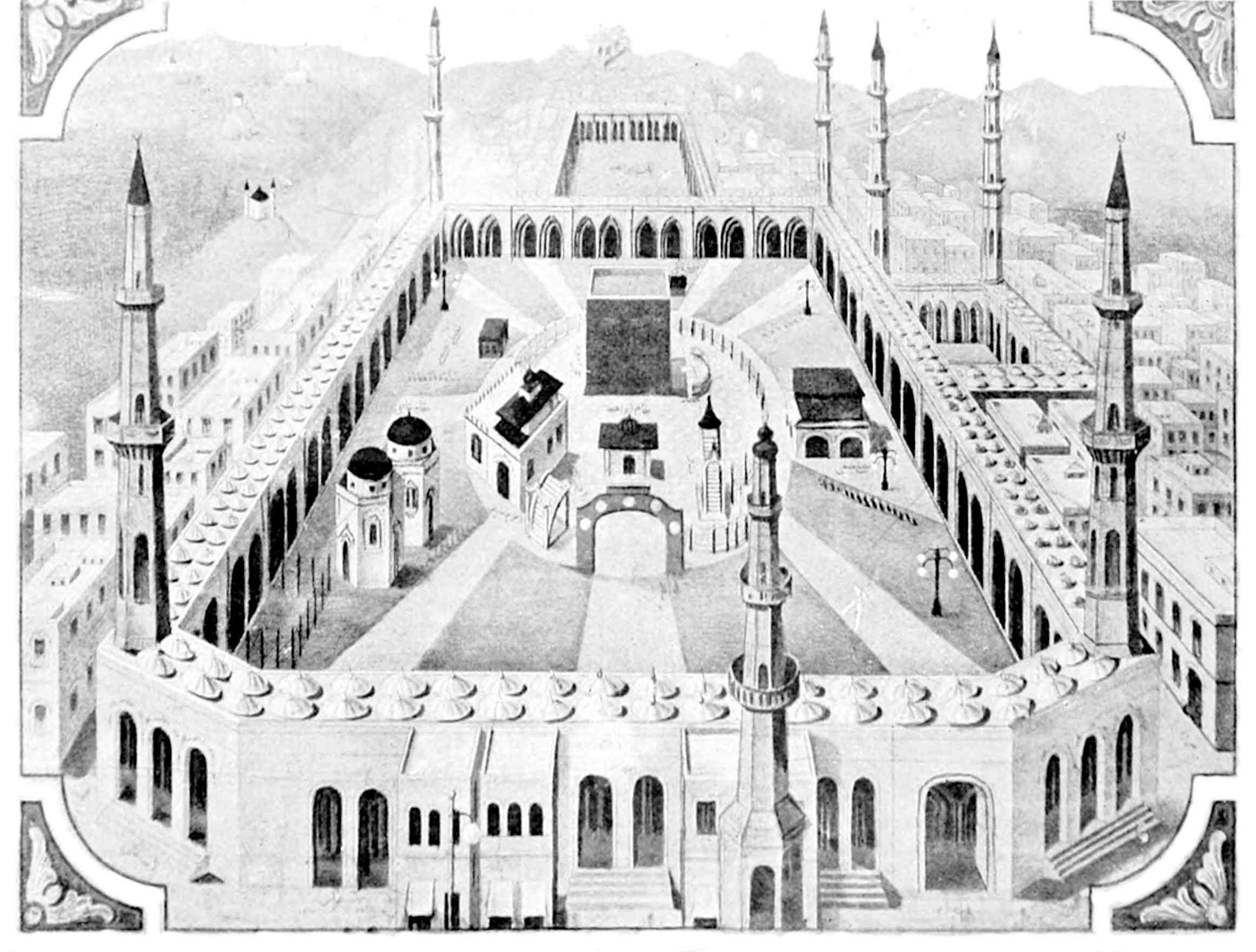

THE HAREM, SHOWING THE KA’BAH, AND THE OTHER SANCTUARIES WITHIN THE HAREM.

(From an old Indian Illustration.)

[Pg 4]

THE HAREM, SHOWING THE KA’BAH, AND THE OTHER SANCTUARIES WITHIN THE HAREM.

(From an old Indian Illustration.)

[Pg 5]

THE GREAT PILGRIMAGE

OF A.H. 1319; A.D. 1902

BY HADJI KHAN, M.R.A.S.

(Special Correspondent of the “Morning Post”)

AND WILFRID SPARROY

(Author of “Persian Children of the Royal Family”)

WITH AN INTRODUCTION

BY PROFESSOR A. VAMBÉRY

LONDON AND NEW YORK

JOHN LANE, MDCCCCV

[Pg 6]

PRINTED BY W. H. WHITE AND SON

THE ABBEY PRESS, EDINBURGH

[Pg 7]

TO

THE HONOURABLE OLIVER A. BORTHWICK

[Pg 9]

The Authors take this opportunity of renewing their acknowledgments of all they owe to the Editor of The Morning Post, to whose friendly interest and encouragement the success of the serial publication, under the title of the “Great Pilgrimage,” was in a considerable measure due. In tendering to him their hearty thanks, they feel it would be scarcely fair to themselves were they to allow the reader to take this, the present fruit of their respective labours, to be a mere republication. It is something far more than that, one-fifth of the book, and that the most interesting part of all, being absolutely new; while the whole of the remainder has been not only carefully revised, but also recast, and, to some extent, rewritten. But the reader owes the new material to Mr. Dunn’s kindness in relinquishing his right to it in order that it might appear for the first time in the pages of “With the Pilgrims to Mecca.”

28th April 1904.

[Pg 10]

Robert Browning.

[Pg 11]

Amongst the varied and manifold impressions of my long and intimate connection with the Mohammedan world none is more lively and more interesting than my experiences with the Hajees, the dear, pious and good-natured companions on many of my wanderings in Moslem Asia. We in Europe can hardly have an idea of the zeal and delight which animate the pilgrim to the holy places of Arabia, not only during his sojourn in Mekka and Medina, not only whilst making the Tawaf (procession round the Kaaba), not only during the excursion to the valley of Mina, where the exclamation of “Lebeitk yá Allah” rends the air round the Arafat—but long before he has started on his arduous and formerly very dangerous journey to the birthplace of Islam. The Hadj, being one of the four fundamental commands of Islam, is looked upon by every true believer as a religious duty the fulfilment of which is always before his eyes, and if prevented by want of means or by infirmity he will strive to find a Wekil (representative), whom he provides with necessary funds to undertake the journey and to pray in his name at the Kaaba, and when the Wekil has returned he hands over the Ihram (a shirt-like dress in which the pilgrimage is performed) to his sender who will use it as his shroud, and appear before the Almighty in the garb used on the Hadj. The further the Moslem lives from Arabia the greater becomes[Pg 12] the passion to visit the holy places of his religion, and if there was a country in which the desire to fulfil this holy command was most fervently cultivated and executed, it was decidedly Central Asia and Eastern Turkestan, where nearly two-thirds of the pilgrims formerly perished, partly in consequence of epidemics and inclemency of weather, partly also at the hands of robbers or through thirst in the desert. And yet these Turk or Tartar Hadjees often disregard all dangers and perils of a long journey, and begin to economise the money necessary for travelling expenses many years before they have set out, for a man destitute of means is not allowed to undertake the Hadj, the same prohibition exists also for a man who is not bodily strong enough, or who has to provide for a family left back at home. It is true, in accordance with the saying “Hem ziaret hem tidjaret” (Pilgrimage and Business together), there are people, who connect trade with religion, but their devotion is often criticised, whereas the pure religious intention meets everywhere with the greatest praise and veneration, and a successfully accomplished visit to the holy places of Arabia makes a Mohammedan respected not only in his community but also in the outlying districts of his country. On his return journey from Mekka and Medina the Hajee gets an official reception all along his route. He is met by young and old, by rich and poor, everybody tries to rub his eyes or his cheeks to the dress of the man, in order to catch an atom of the dust coming from the Kaaba or from the grave of the Prophet, and if the Hajee is the bearer of some Khaki-Mubarak (i.e., blessed earth from the grave of Mohammed), or if he is in possession of a small bottle of “Zemzem” (the holy fountain in the precinct of the Kaaba), there is no end and limit to the pressing throng around him. I have seen people kissing the footsteps of such a pilgrim, embracing and petting him,[Pg 13] and what struck me most was the scene where Kirghis or Turkoman nomads cried like children on seeing one of these Hajees, and when they began to quarrel, nay, to fight, for the opportunity to bestow hospitality on a returning Hajee, be he even an Uzbeg or a Tajik, whom they otherwise dislike.

Yes, the Haj is a most wonderful institution in the interest of the strength, unity and spiritual power of Islam; it is a kind of religious Parliament and a gathering place for the followers of the prophet, where the sacred Hermandad is fostered despite all differences of race and colour, and whereas the temple in Jerusalem does often become the cockpit of different Christian sects, and the arena of bloody fights, which would fatally end without the intercession of the Moslem soldiers of the Padishah, we meet with perfect peace and concord in the court of the Kaaba, where the four sects have got their separate places without interfering with each other, and where Hanefites, Shafaites, Malekites and Hanbalites pay simultaneously their veneration to the founder of their religion. Even the Shiite Persian is not molested as long as he does not offend the believers by an ostentatious exhibition of his schismatic views, what he rarely does, for dissimulation is not prohibited according to the tenets of the Shiites.

The foregoing remarks about the Haj have been quoted here with the intention to realise the importance of this religious custom of Islam, and particularly to show how necessary it is to know and to appreciate duly the political, social and ethical qualities of this precept ordained by the prophet.

Well, in order to gain full information on this subject, we have been in need of an account of the Haj written by a Mohammedan who is not attracted by curiosity, but by religious piety, who had free access to every place, who is[Pg 14] not hampered by fear of being discovered as a Christian, and who is besides a shrewd observer. These essential qualities I find in Mr. Haji Khan, M.R.A.S., the pilgrim, who calls himself also “Haji Raz” (the mystery Haji). It may be well said that Christian travellers like Burkhard, Burton, Maltzan, and others, have exhausted the subject relating to the holy places of Islam, but a Mohammedan sees more and better than any foreigner, and I do not go too far when I say that Mr. Haji Khan, with his thorough English education, would have been more fitted to describe, unaided, the life and the manners of the Haj, than was his Turkish fellow-believer, Emin Effemdi, author of a Turkish account of the same topic.

I daresay it will be the case with many other subjects relating to the actual and past features of the Eastern life, if natives will be only educated to describe the peculiarities of their own nations and creeds, and for this reason it is desirable that the number of scholars like Mr. Haji Khan should increase, and that this present book, written in collaboration with Mr. Wilfrid Sparroy, should meet with a well-deserved reception.

Great credit is due to Mr. Wilfrid Sparroy, to whose high qualities as a writer, this joint production owes so much. Both Mr. Haji Khan and Mr. Wilfrid Sparroy are to be congratulated on the results of their labours: they have succeeded in bringing the East nearer to the West.

A. VAMBÉRY.

[Pg 15]

PART I

A PERSIAN PILGRIM IN THE MAKING—

| PAGE | ||

| 1. | The Message of the Prophet | 21 |

| 2. | Conditions of Pilgrimage | 31 |

| 3. | Forbidden Viands | 32 |

| 4. | The Work of Purification | 33 |

| 5. | Prayers | 35 |

| 6. | Aspects of Social Islám | 37 |

| 7. | Stories of the Muslim Moons | 47 |

| 8. | Persian Súfíism—Persian Shiahism in its Relation to the Persian Passion-Drama | 62 |

PART II

THE STORY OF THE PILGRIMAGE—

| Chap. I. | London to Jiddah | 81 |

| Chap. II. | From Jiddah to Mecca | 102 |

| Chap. III. | Within the Harem—Some Remarks on the Orthodox Sects of Islám | 111 |

| Chap. IV. | Compassing of the Ka’bah | 126 |

| Chap. V. | The Course of Perseverance | 140 |

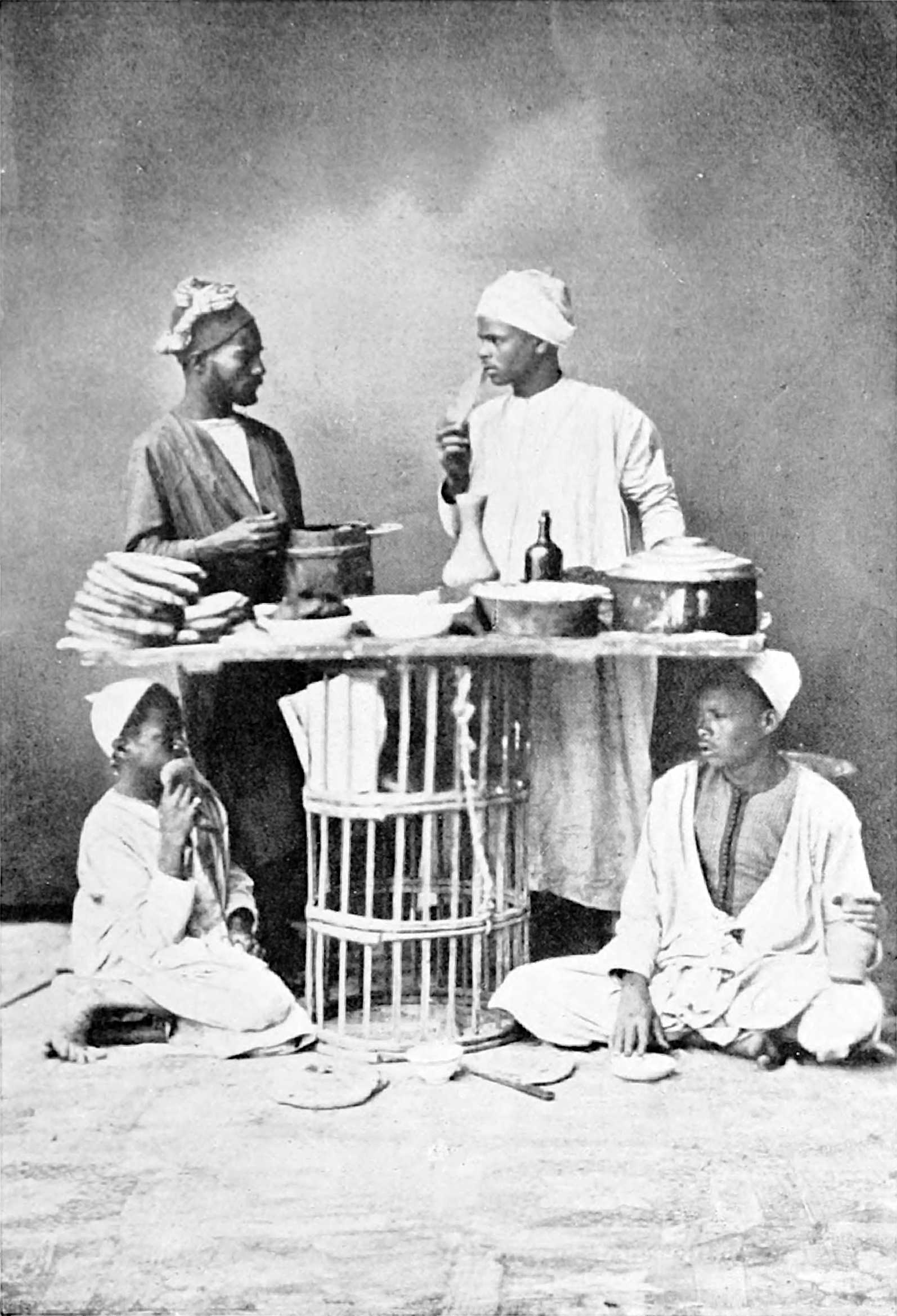

| Chap. VI. | Scene in an Eating-House—Visit to the Ka’bah | 153 |

| Chap. VII. | On the Road to Arafat | 173 |

| Chap. VIII. | On the Road to Arafat (concluded) | 193 |

| Chap. IX. | Arafat Day: Night | 212 |

| Chap. X. | Arafat Day: Daybreak | 223 |

| Chap. XI. | Arafat Day: Forenoon and Afternoon | 234 |

| Chap. XII. | The Day of Victims: From Sundown to Sunset. The Days of Drying Flesh | 245 |

[Pg 16]

PART III

MECCAN SCENES AND SKETCHES—

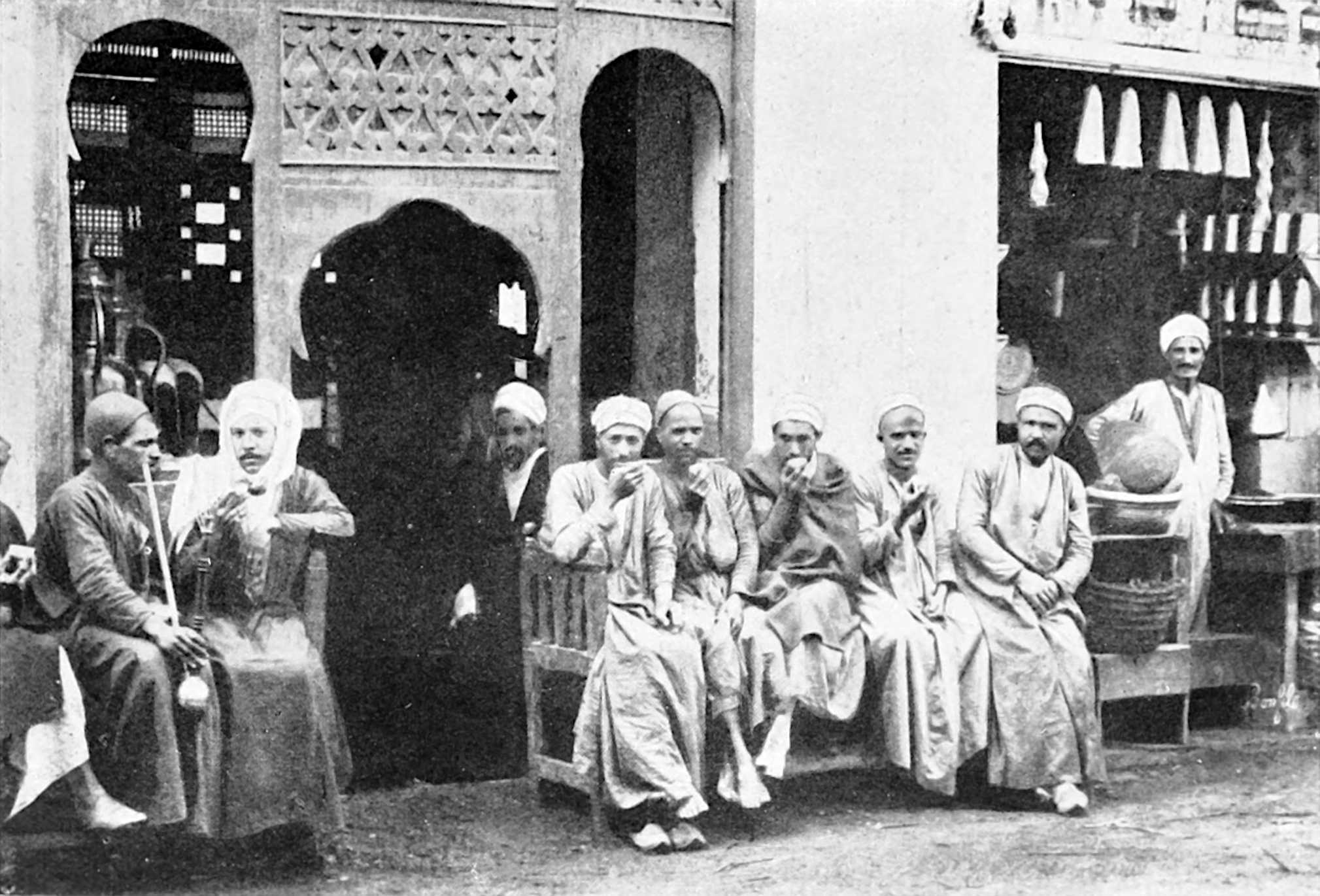

| Chap. I. | The Meccan Bazaars | 255 |

| Chap. II. | The Talisman-Monger | 266 |

| Chap. III. | Seyyid ’Alí’s Story of his Redemption | 280 |

| Chap. IV. | Healing by Faith | 289 |

| Appendix. | Some Reflections on the Existence of a Slave Market in Mecca | 299 |

| Index. | 309 |

[Pg 17]

| PAGE | |

| The Harem, showing the Ka’bah, and the other Sanctuaries within the Harem | Frontispiece |

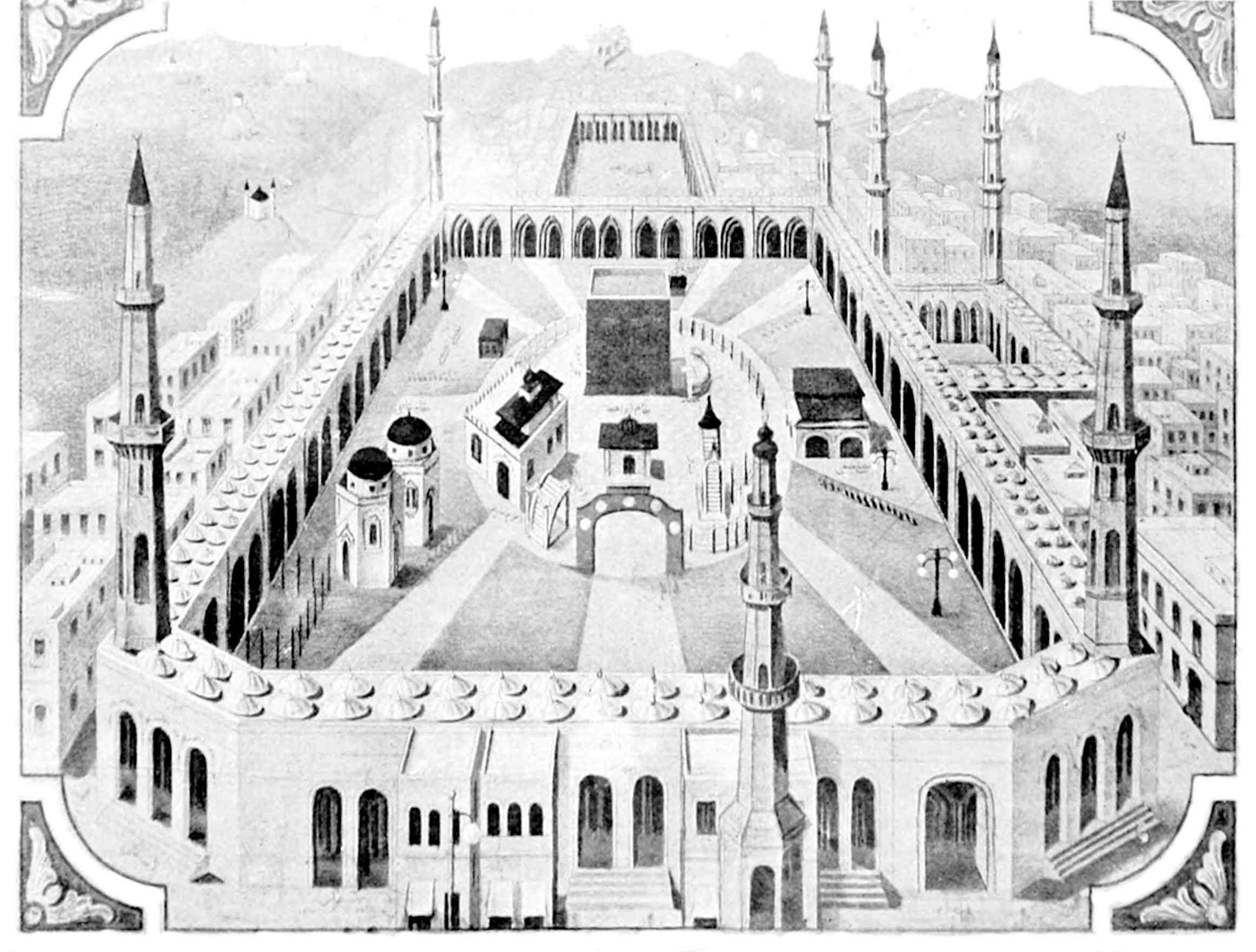

| Copies of the Kurán worn en bandoulière by Muslims when Travelling or on Pilgrimage | 39 |

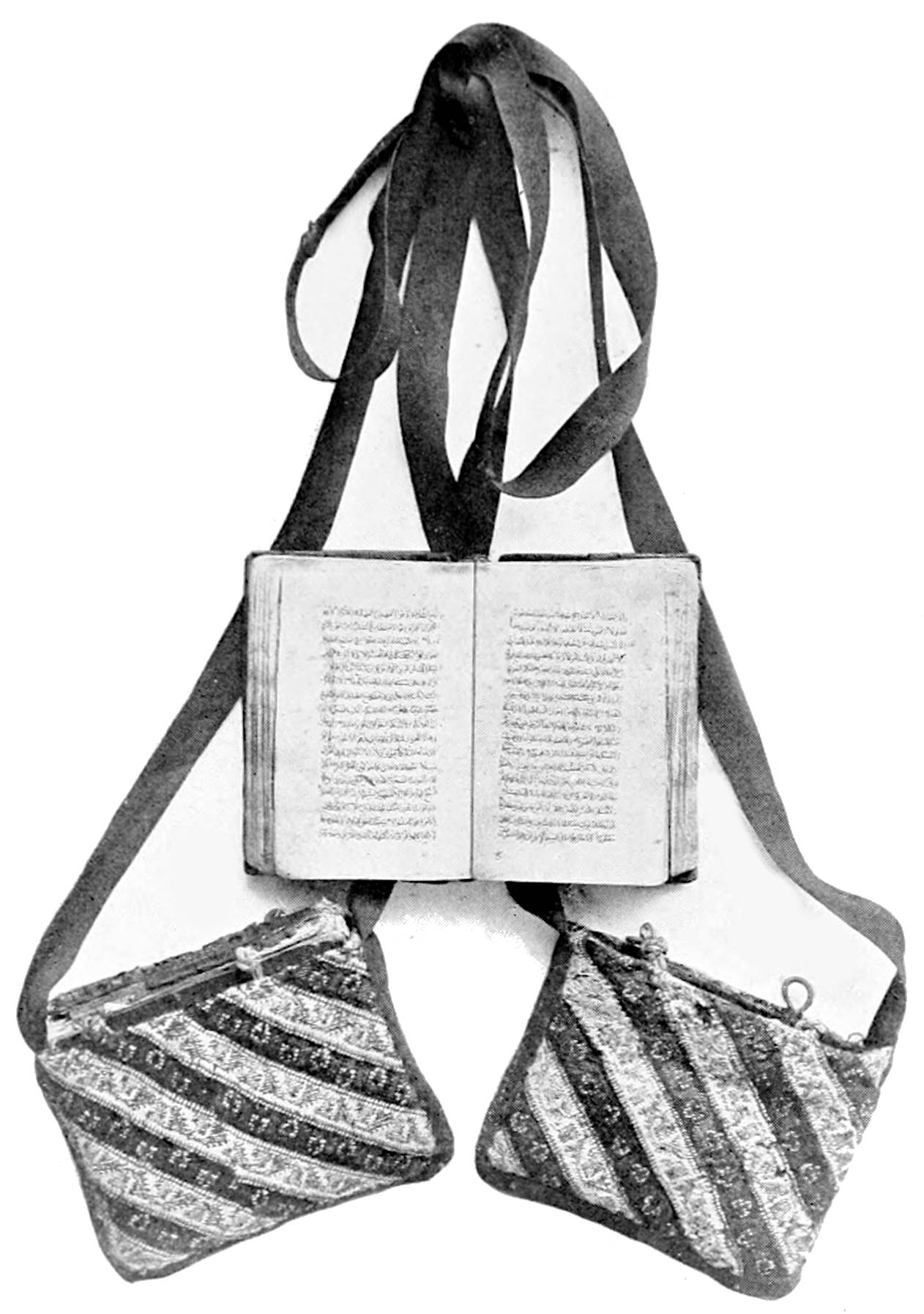

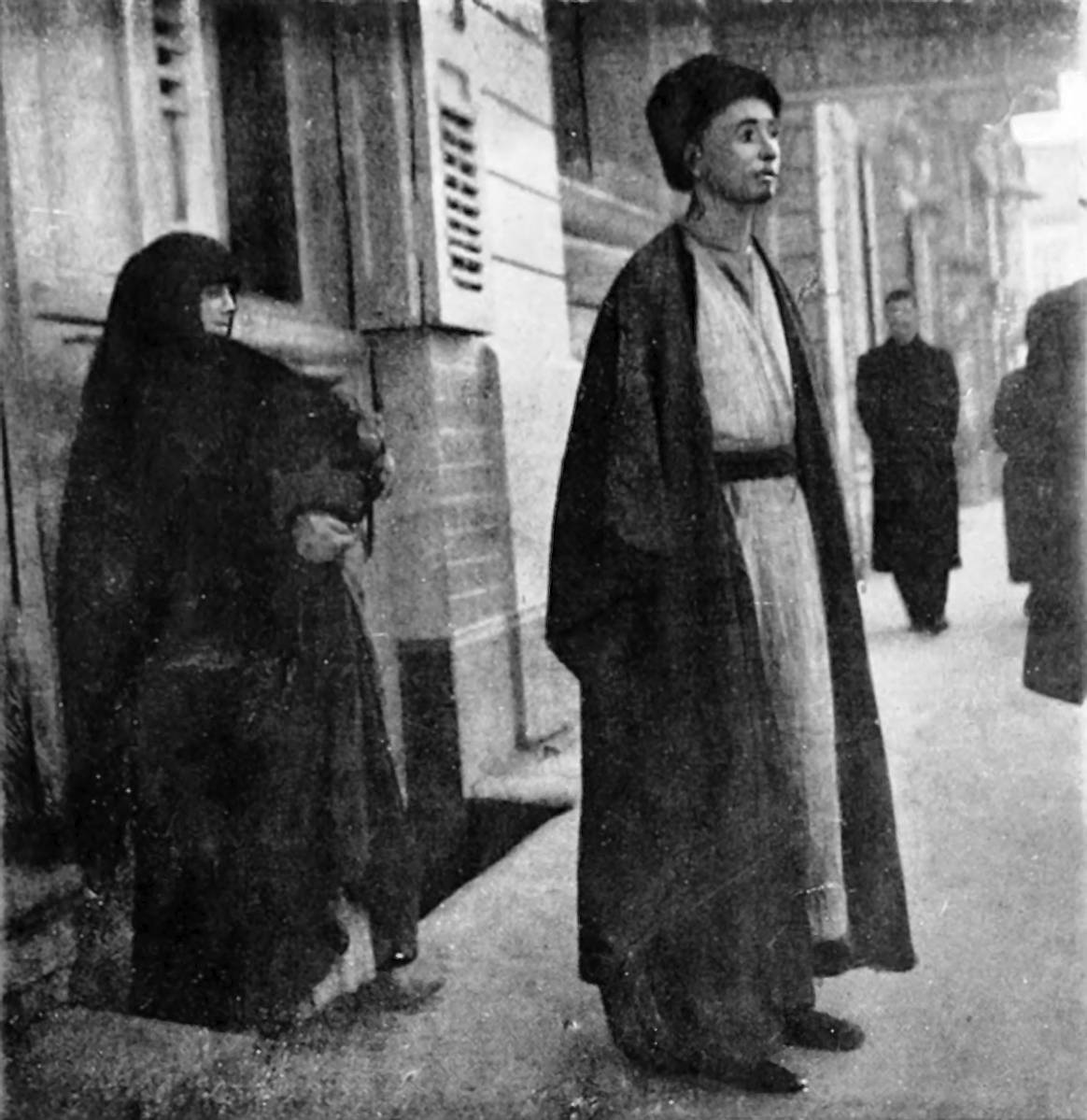

| A Persian Sufí of the Order of the late Sephi ’Alí Sháh | 65 |

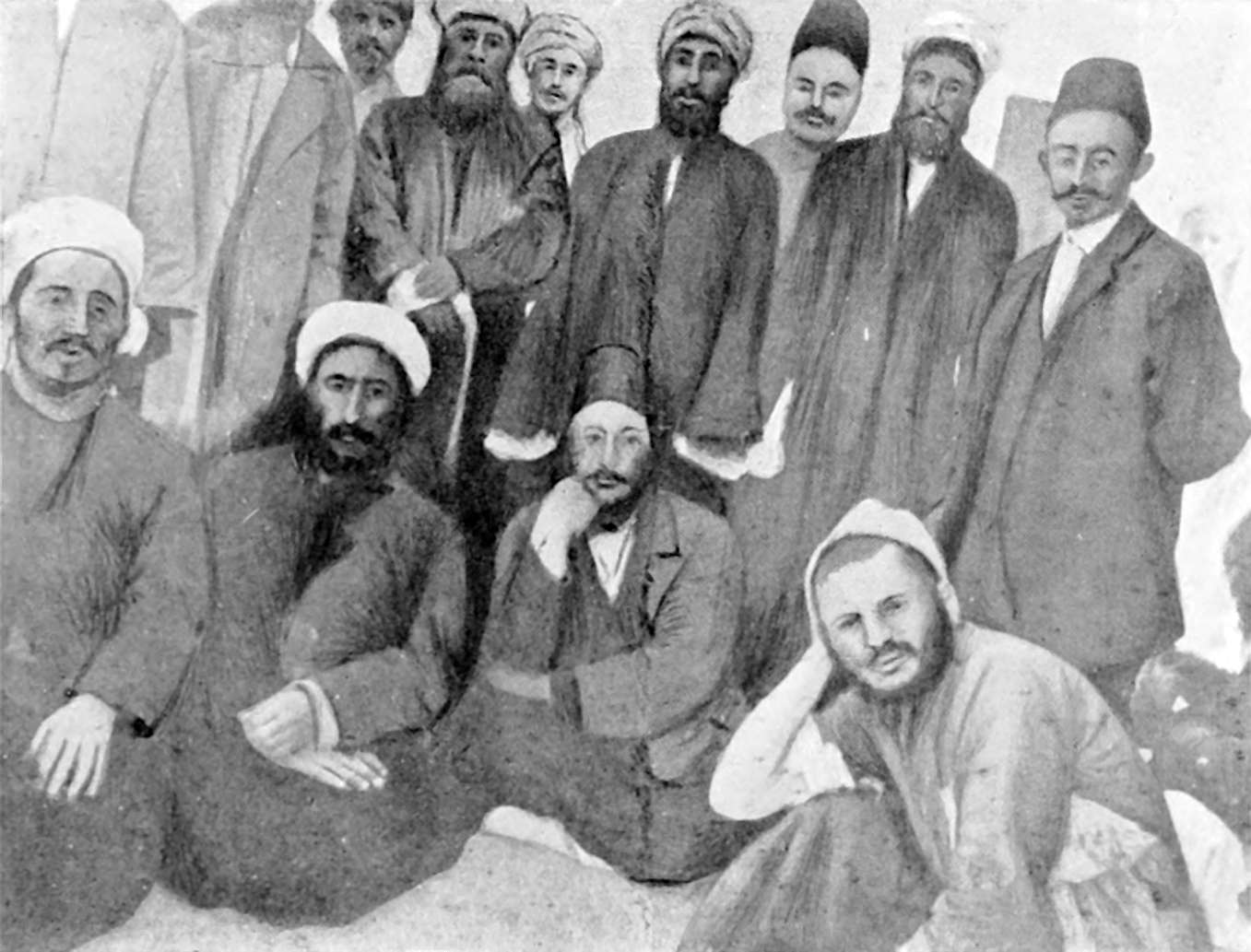

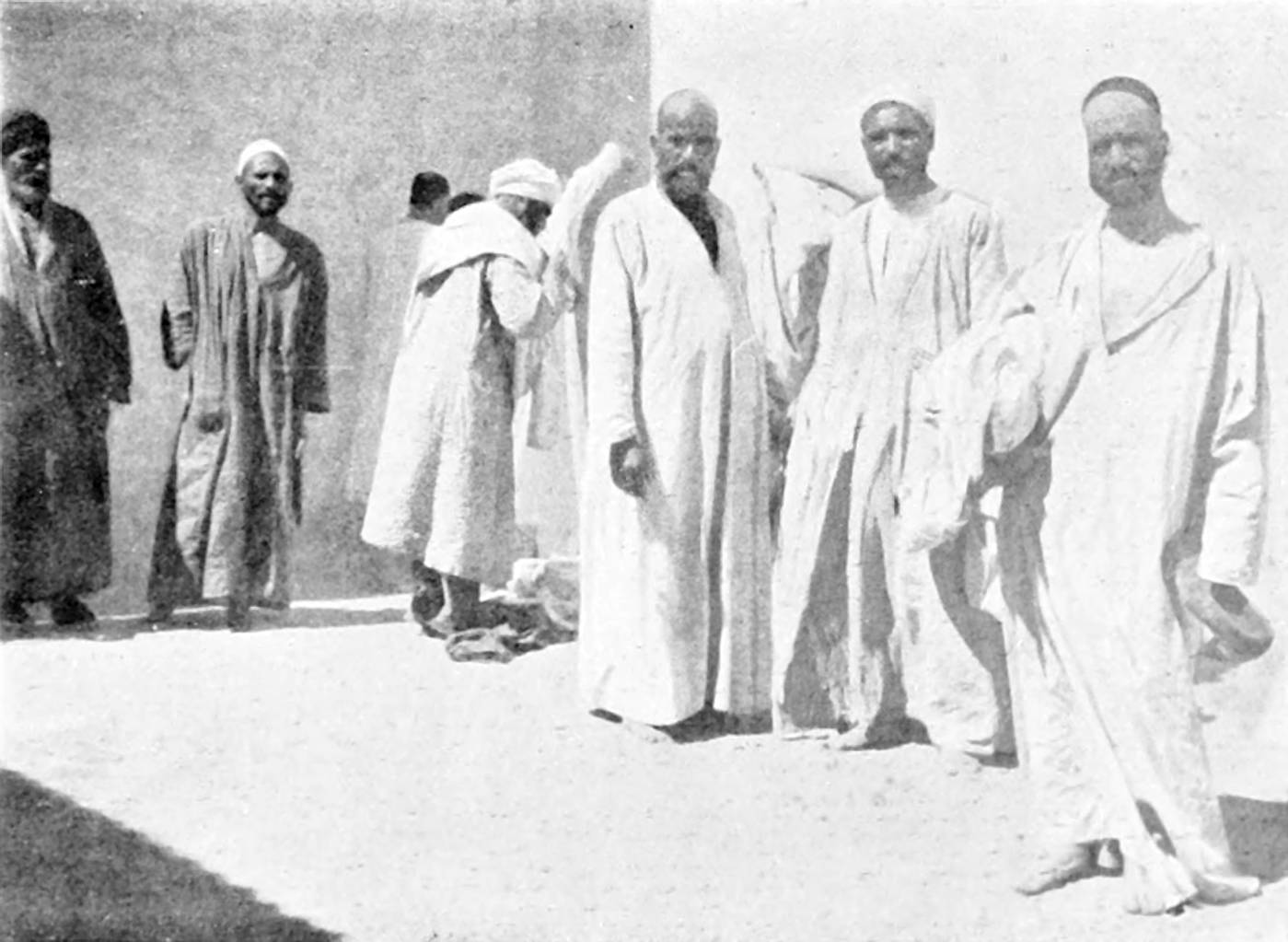

| A Group of Mixed Pilgrims | 85 |

| A Pilgrim “at Sea”—Suez Railway Station | 85 |

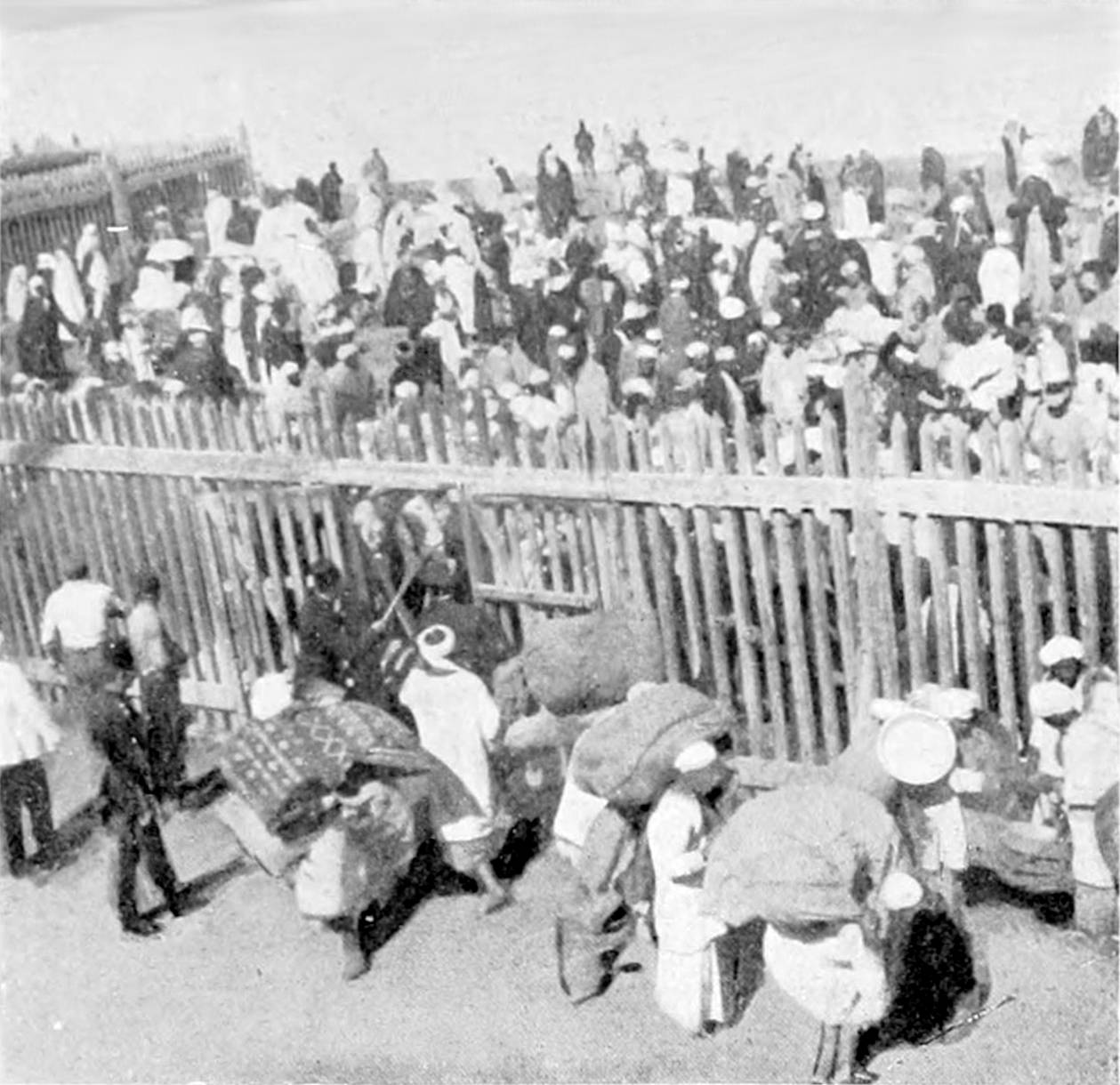

| Preparing to Embark at Suez | 91 |

| Pilgrims Embarking at Suez | 99 |

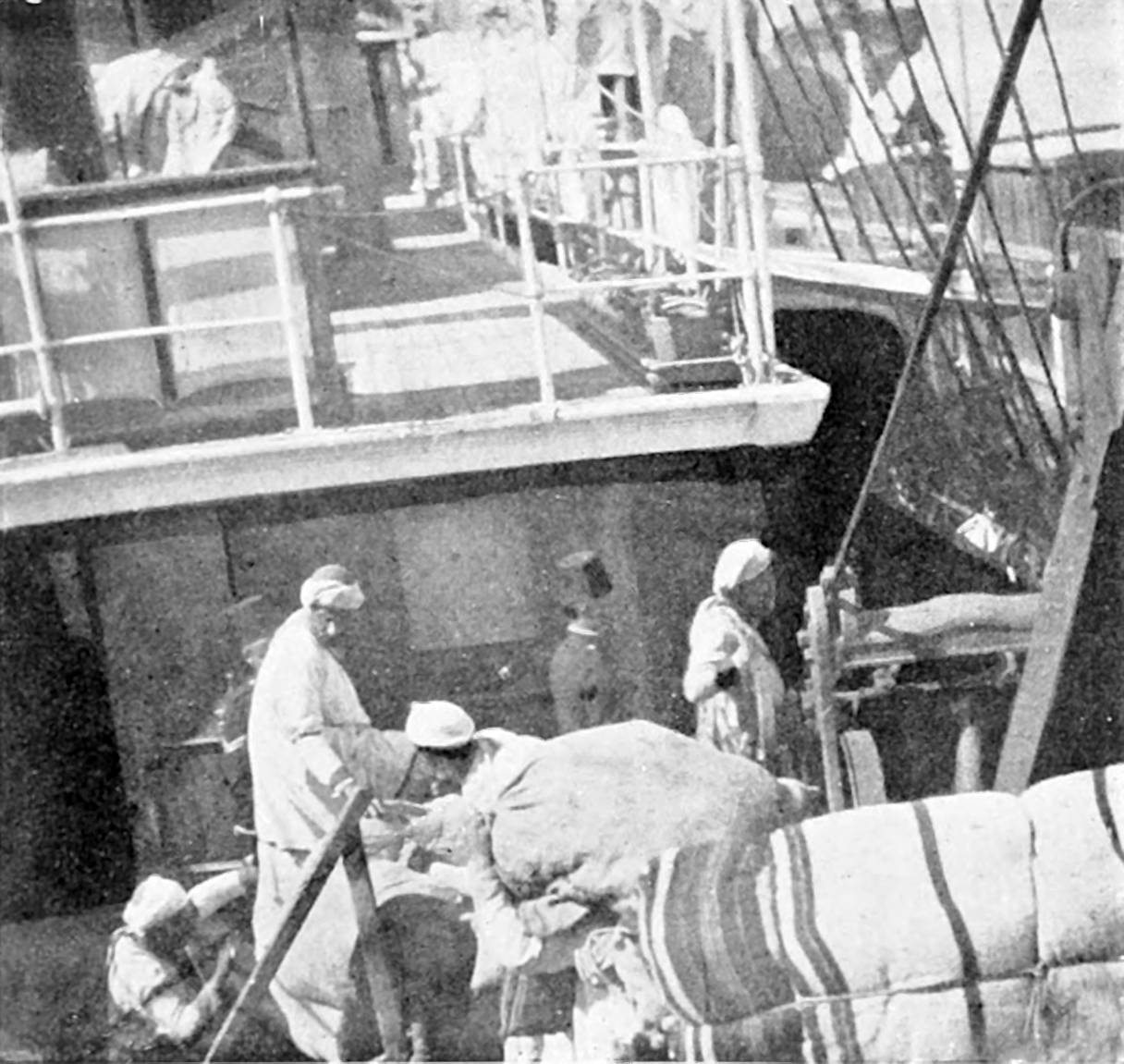

| Before Weighing Anchor at Suez | 99 |

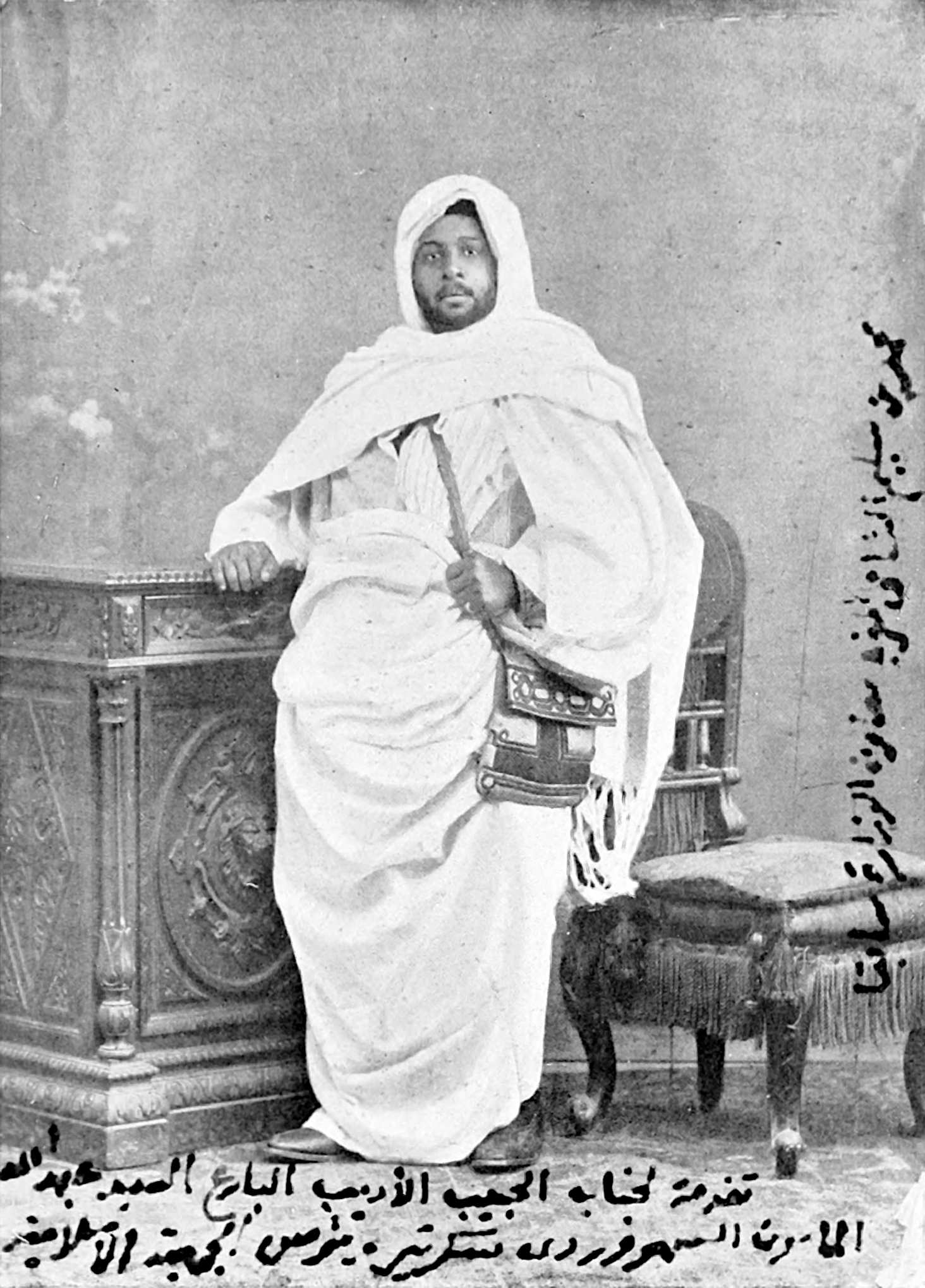

| A Moorish Gentleman in Moorish Dress | 121 |

| The Poorer Side of Egyptian Muslims | 143 |

| Putting on Ihrám at Jiddah | 155 |

| Mussah Street at Mecca | 155 |

| An Egyptian Coffee-house Frequented by the Poor | 161 |

| An Egyptian Donkey and its Driver | 183 |

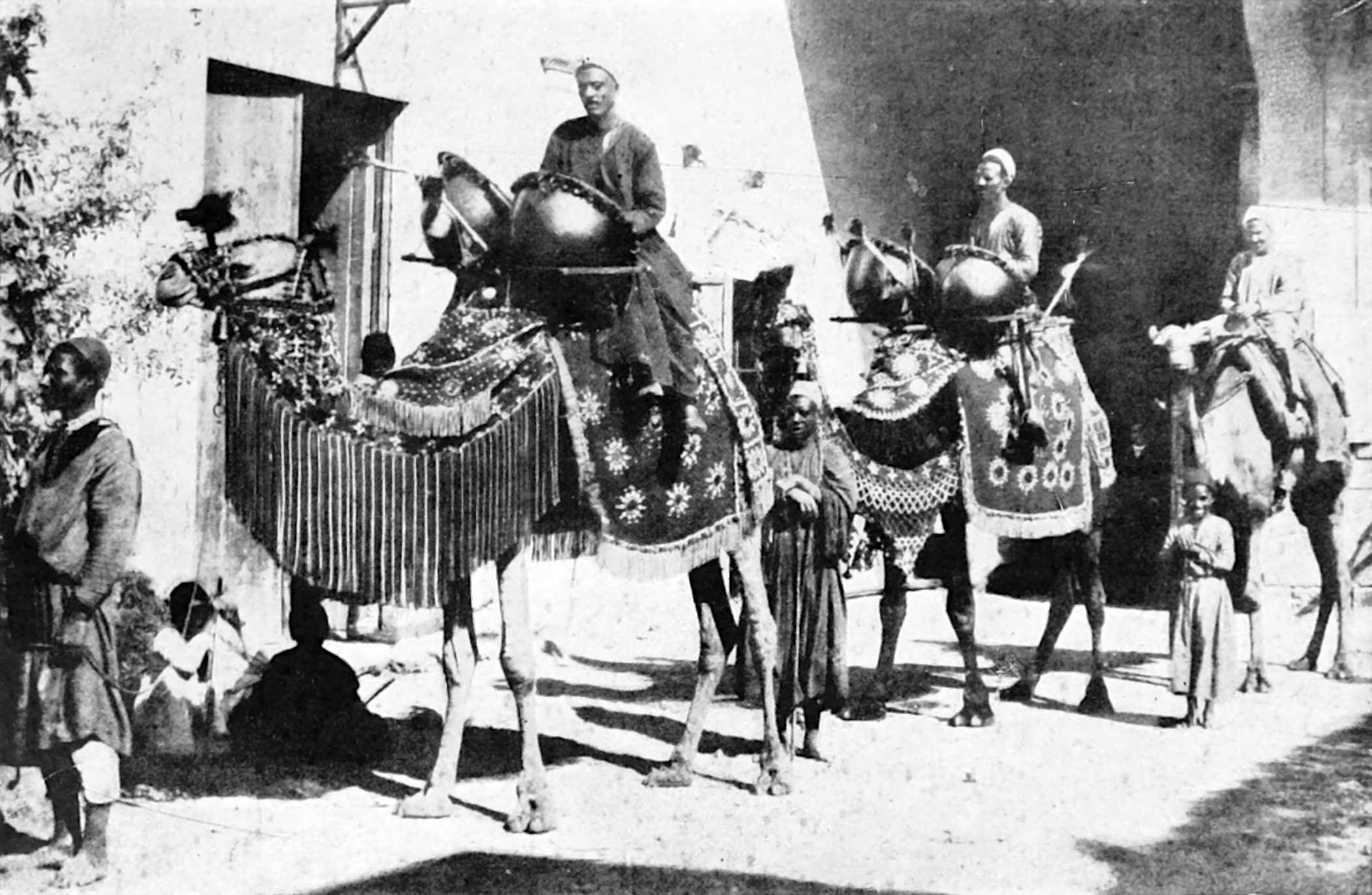

| The Musician Camel Cavalcade | 201 |

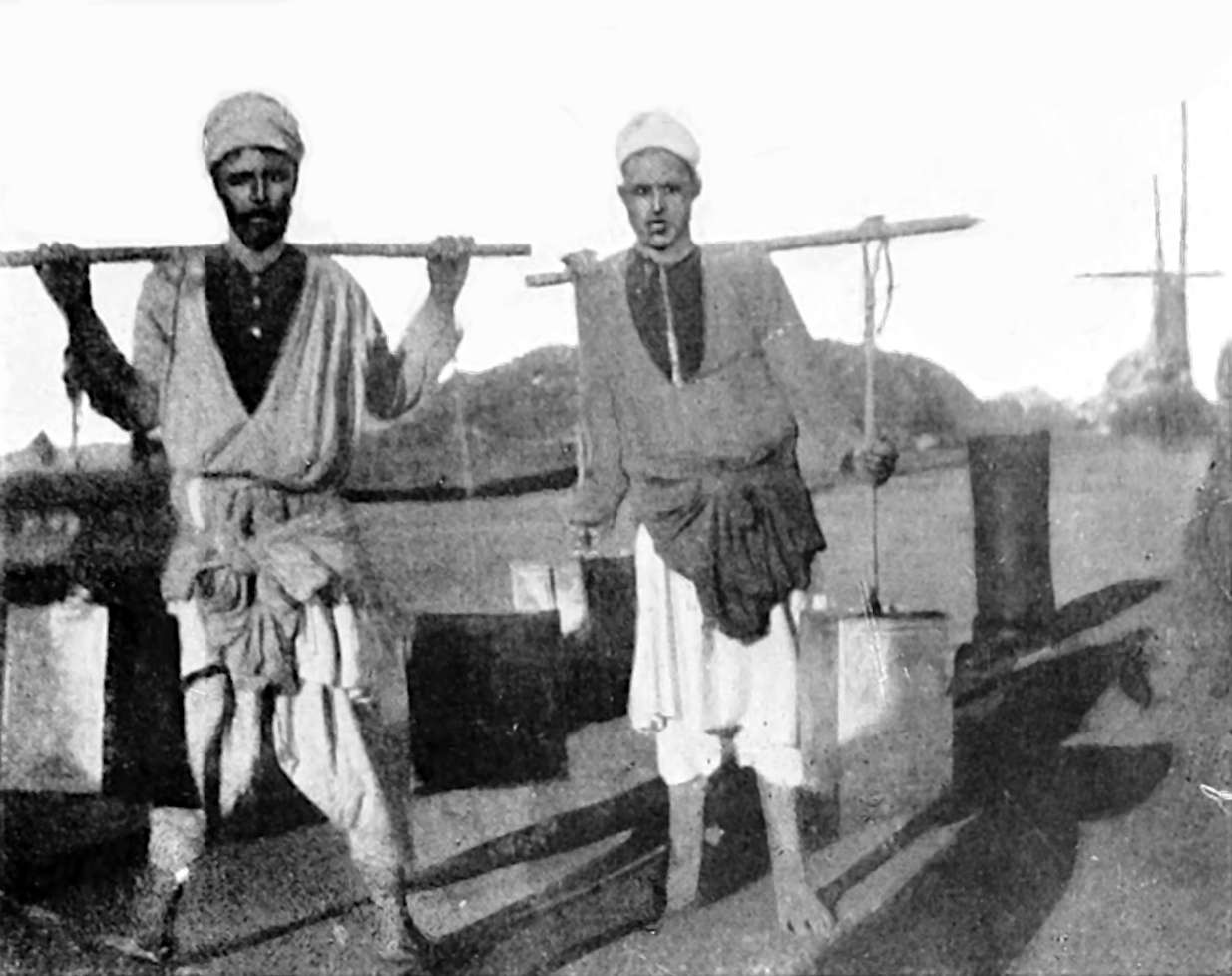

| Water-carriers of Mecca | 207 |

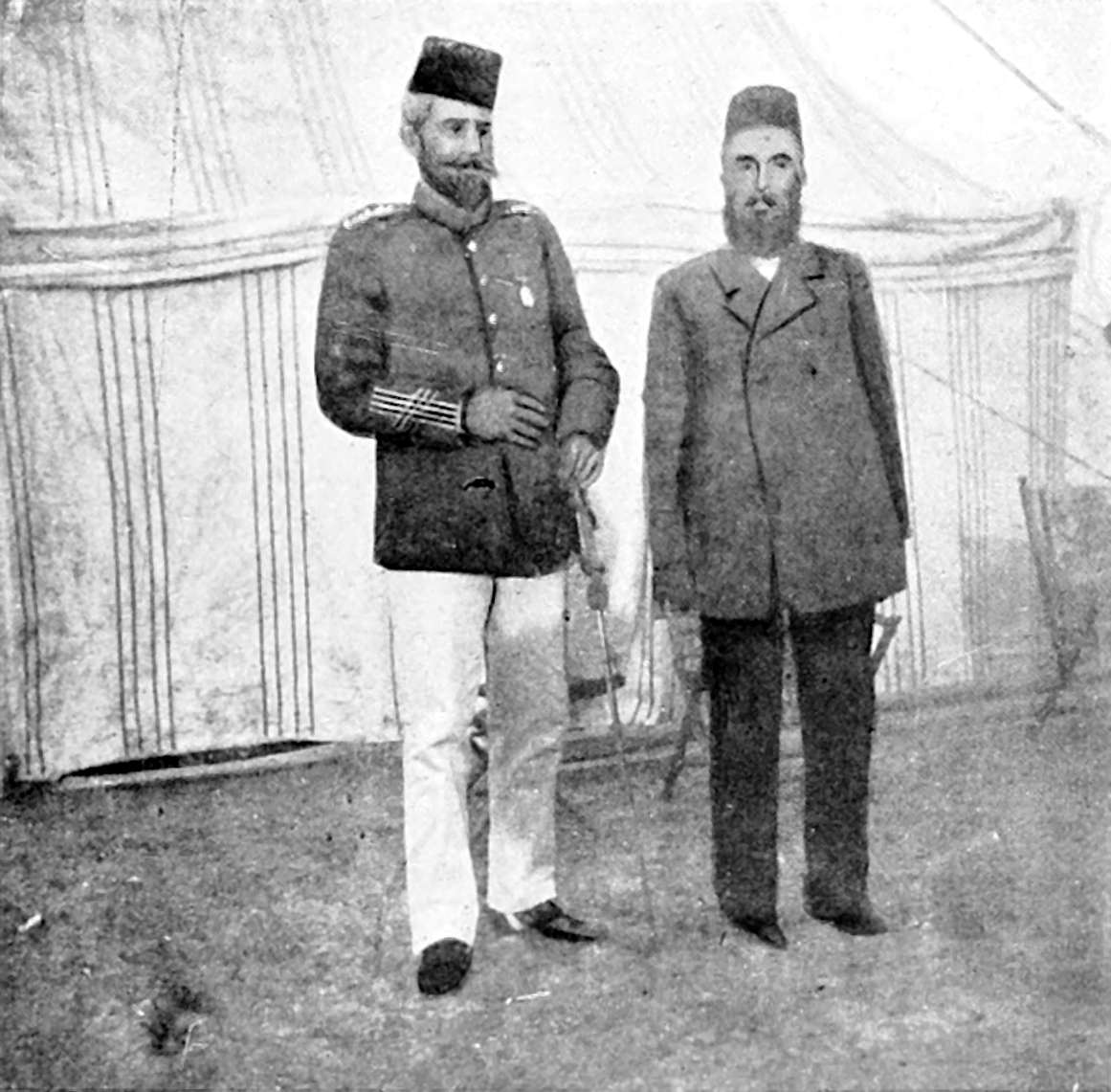

| (a) The Pasha of Hejaz; (b) The Aminus-Surreh | 207 |

| The Sheríf of Mecca in his Uniform | 215 |

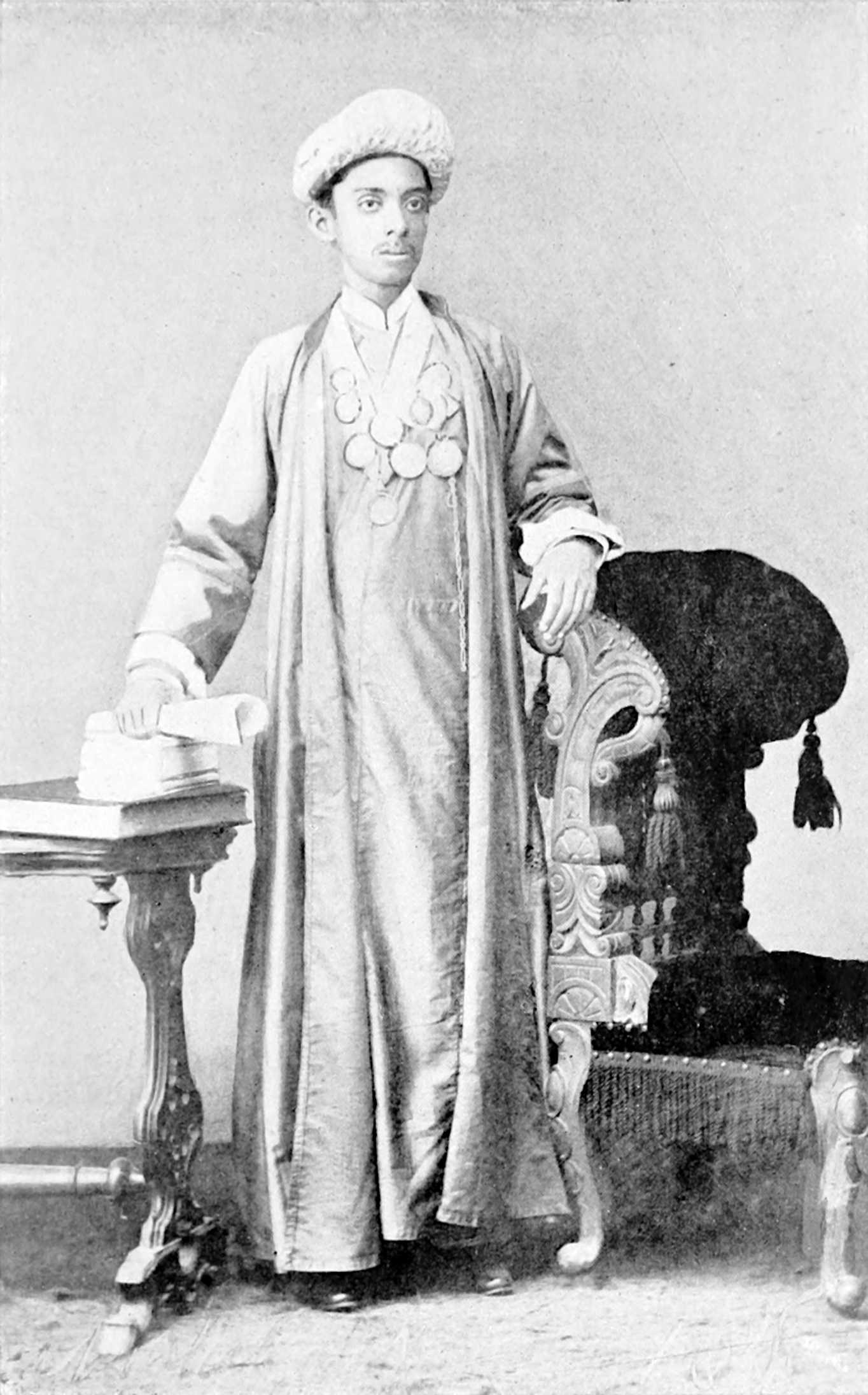

| A Learned Mussulman of India[Pg 18] | 229 |

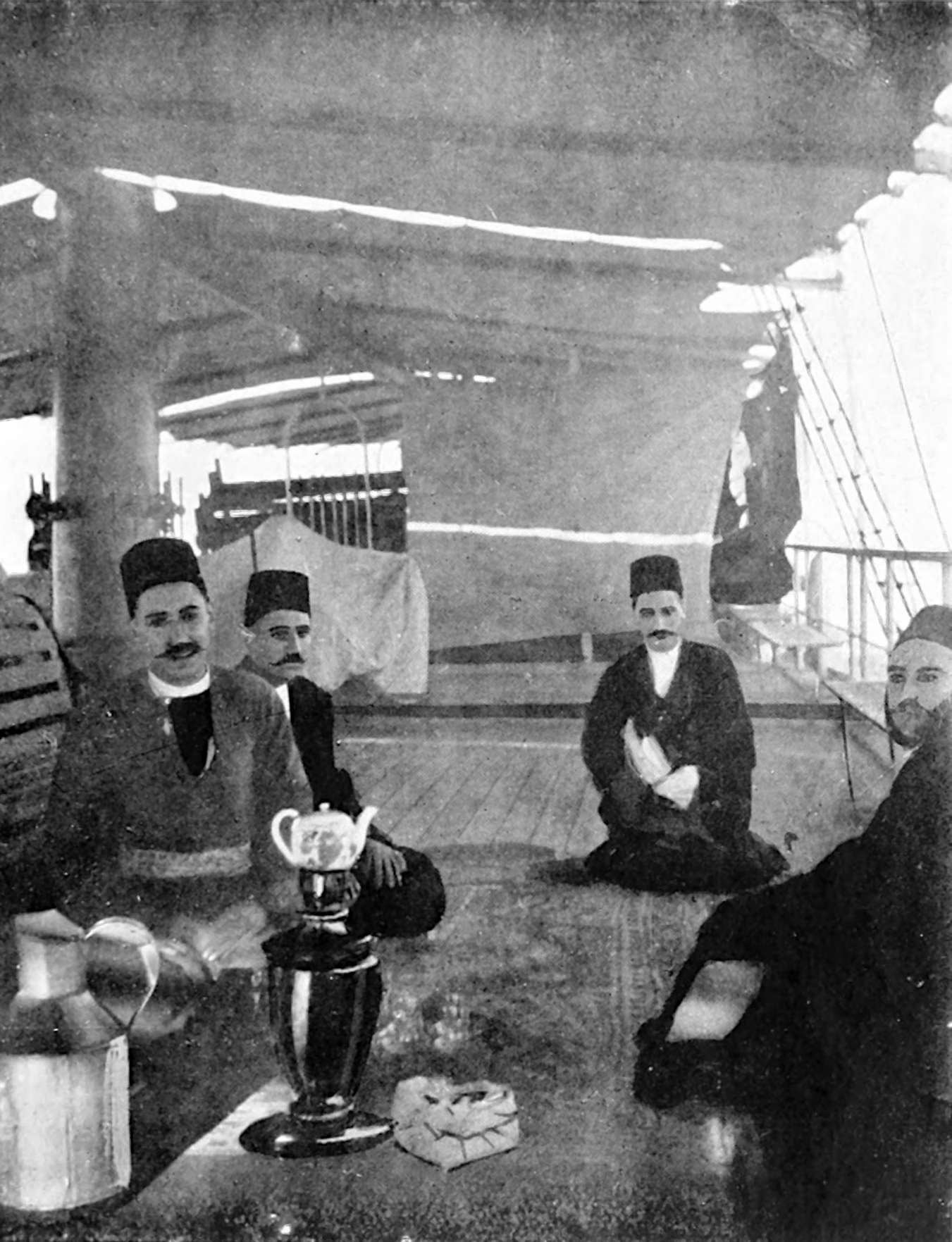

| Persian Pilgrims from Tabriz, having Tea on Board the Steamer | 239 |

| Disembarking at Jiddah | 249 |

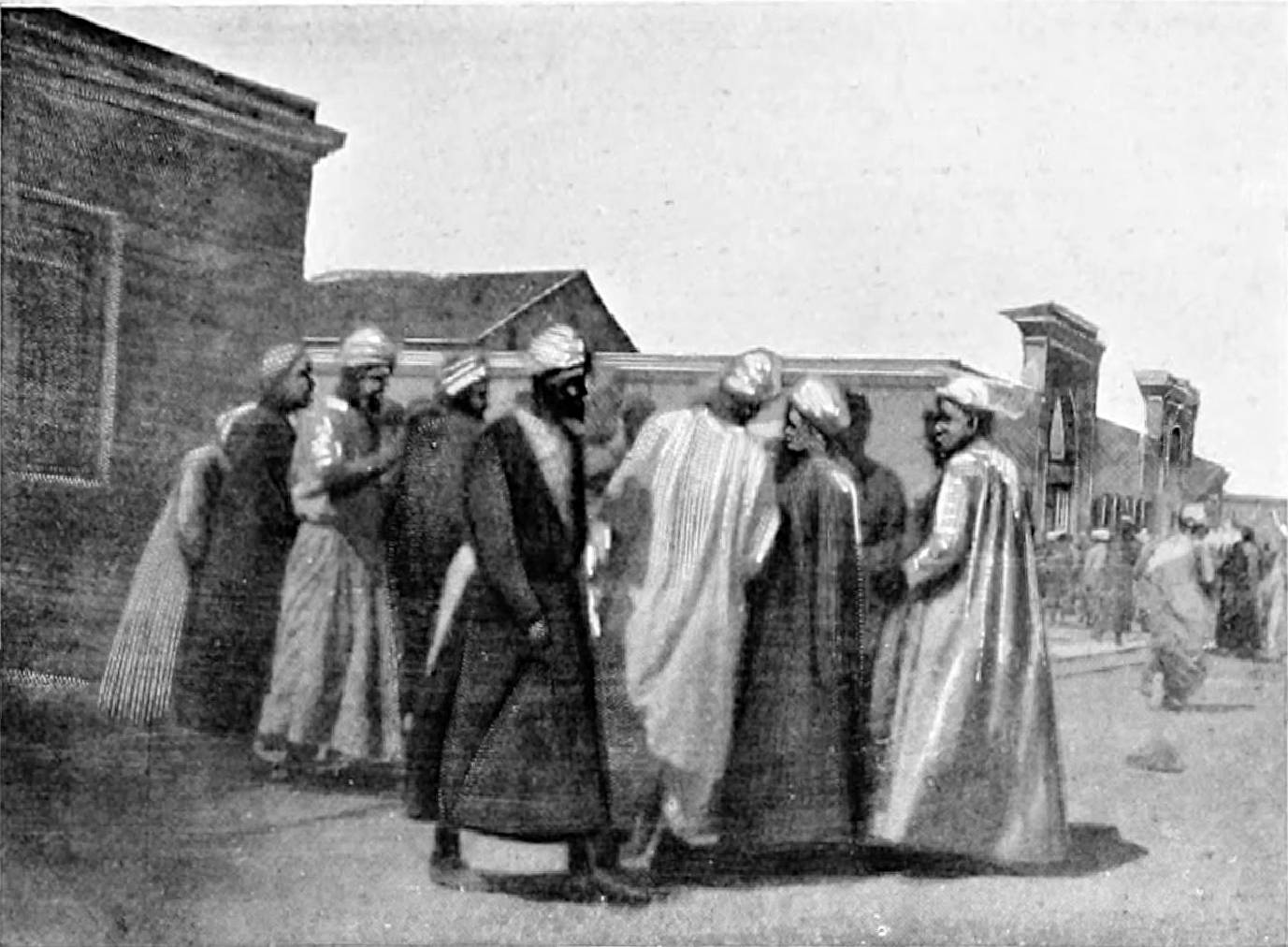

| Pilgrims at Jiddah | 249 |

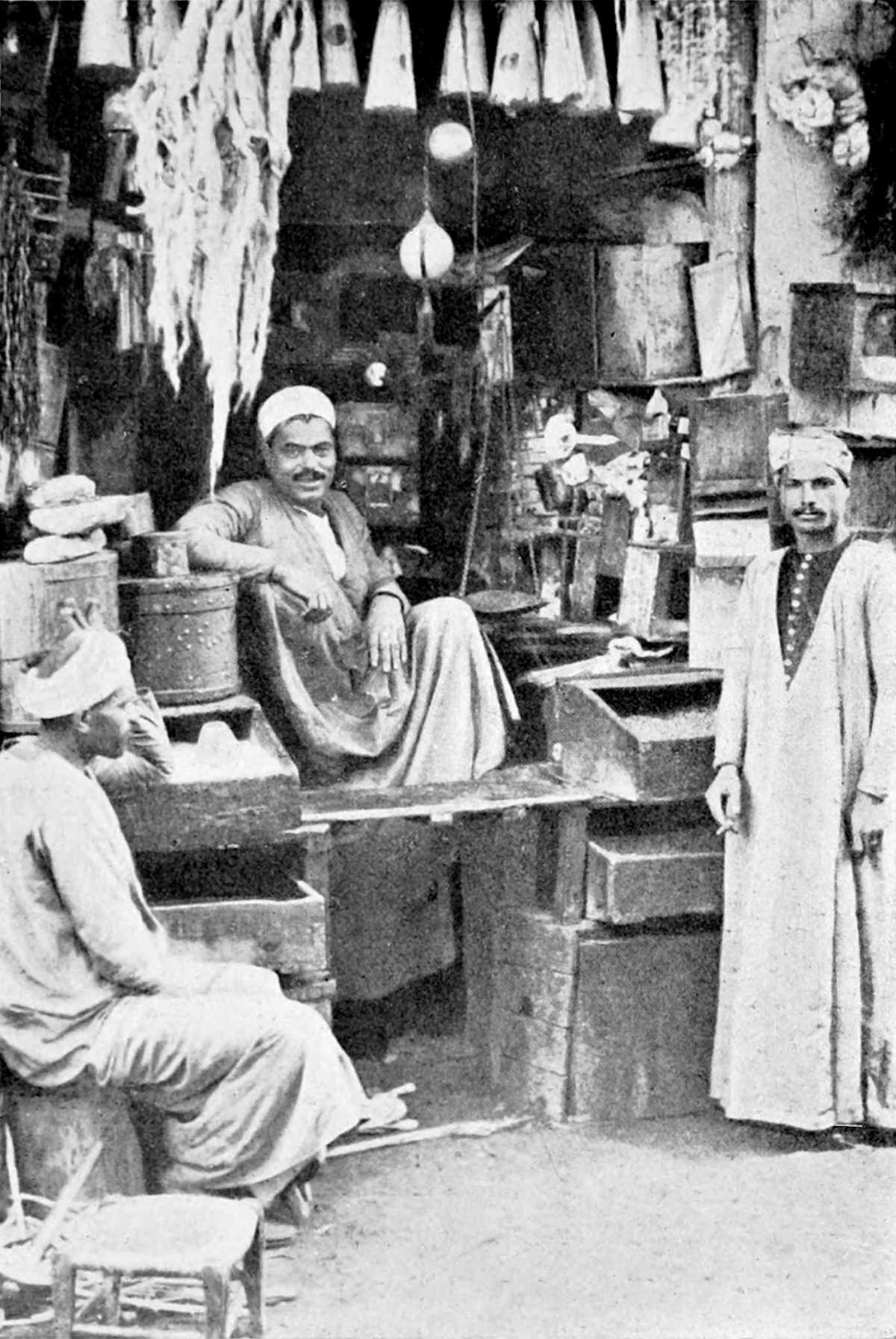

| An Egyptian Grocer | 267 |

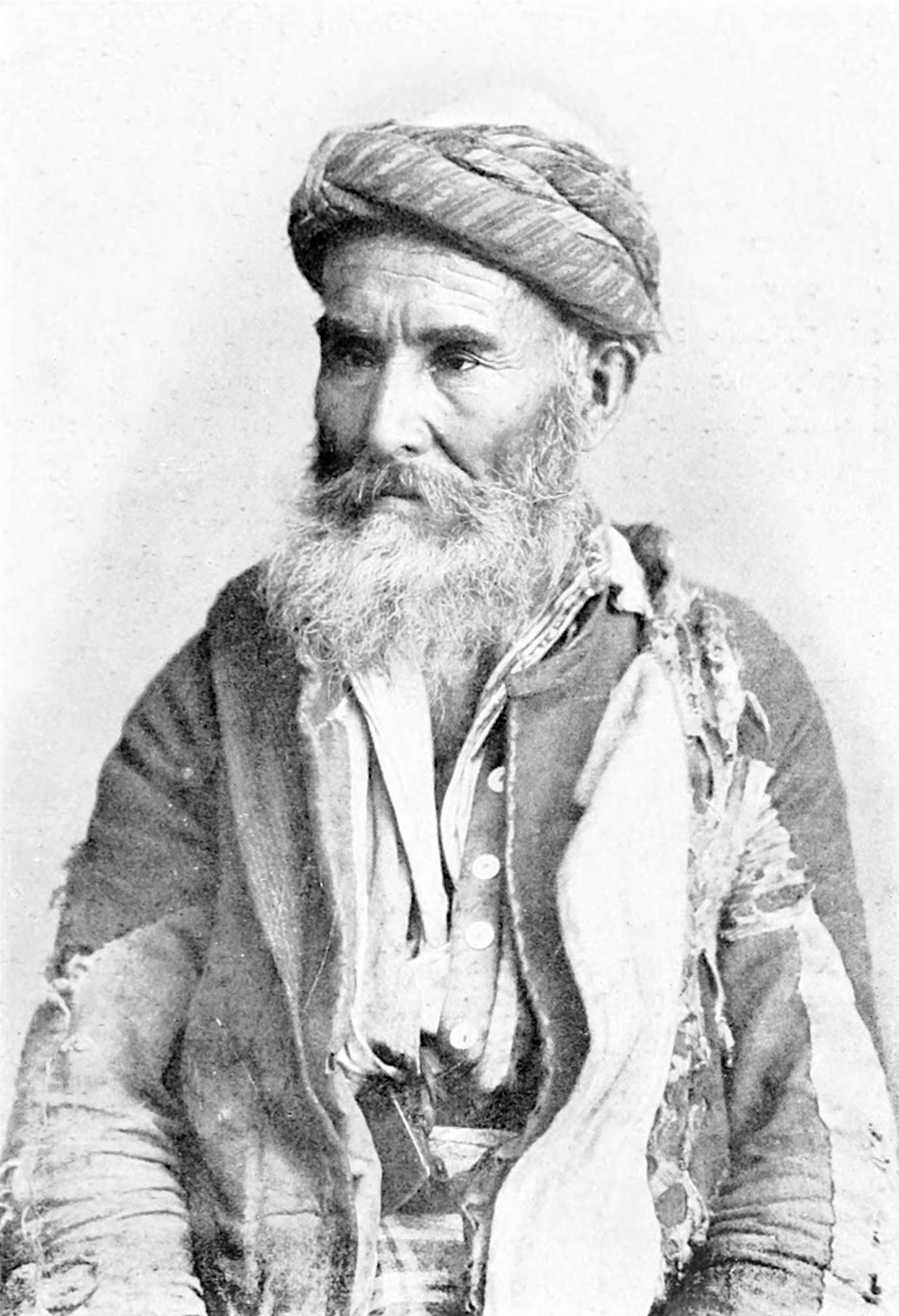

| A Persian Professor of Theology | 291 |

| An Arab Sheykh of the Town | 297 |

[Pg 20]

| Page 22, line 34, | For Jellalu’d-dín’s “Al Beidáwí,” read Al-Beidáwí’s commentary. |

| Page 31, line 10, | For “Hájí Ráz,” read Hadji Khan. |

| Page 31, line 11, | For Chapter V., Part III., read Appendix. |

| Page 32, line 12, | For formerly, read formally. |

| { Page 57, line 1, | For 1320, read 1319. |

| { Page 245, line 19, | |

| Page 69, line 7, | For uncle, read father-in-law. |

| Page 69, lines 29-30, | For too rash and too indiscreet, read too forbearing and too magnanimous. |

| { Page 72, line 12, | For daughter Fatima, read sister Zainab. |

| { Page 76, line 13, | |

| Page 93, line 21, | For Yásuf, read Yûsuf. |

| Page 93, lines 22-23, | For Al Beyyid, read Al Beidáwí. |

| { Page 115, line 1, | For Tomb of Abraham, read Station of Abraham. |

| { Page 130, line 28, | |

| Page 117, line 9, | For Merú, read Merve. |

| Page 134, line 8, | For ordnance, read ordinance. |

| Page 166, line 32, | For mosque, read temple. |

| Page 199, line 19, | For Tabbál, read Tabl. |

| Page 237, line 12, | For Kharnum, read Khanum. |

| Page 237, line 12, | For Mrs. Zobeideh, read Lady Zobeideh. |

| Page 251, line 4, | Omit the Merciful and Compassionate. |

| Page 266, line 20, | For God is just, read God is Great. |

[Pg 21]

WITH THE PILGRIMS TO MECCA

The day before I left England for Persia some seven years ago, I went to see my uncle, the author of the “Siege of Metz.” On saying good-bye he made me a present of the Kurán. “Here,” said he, “is the thing to be read. It will be the best introduction to the new life awaiting you in the East. If you can lay hold of the spirit of this book you will not be alone out there, but among men and brothers, for the Kurán is a sincere revelation of much that is eternally true.” I never saw George Robinson again: in less than a week—before I had left Paris—his spirit had passed to the bourne whence all revelations come, and where truth, in its completeness, will be revealed.

Now, it should be the critic’s aim, in dealing with all true books, to place himself on the same plane as the author, and to look in the same direction, fixing the same end. This is more especially true of what his attitude[Pg 22] should be towards a message that has been held sacred by countless millions for more than thirteen hundred years. The merits of the Kurán and the far-reaching reforms of the Prophet of Islám can be appreciated worthily only by such men as have taken the trouble to acquaint themselves with the idolatrous superstitions of the Arabians in the time of Ignorance, and with the empty logical jangling of the rival Syrian Christian sects at the close of the Sixth Century. And the critic having grasped the lifelessness of religious practice before the coming of Muhammad, would be wise to reveal, first of all, what there is of truth, and to spread what light there is in the written word of the great reformer, abandoning to the bigot and the purblind the less fruitful occupation of stirring in the cauldron of religious controversy. To that end, indeed, it were not amiss that he should cultivate his imagination, for the imaginative have turned the corner of their narrower selves, and theirs is an ever-widening vision. To those who, living by the word of Christ, diffuse darkness, Muhammad will ever be either a charlatan or an unscrupulous man of the sword. Well, the Prophet’s followers must take heart of grace. History itself as well as the Kurán has proclaimed the charges to be false.

The keynote to Muhammad’s character is sincerity. Sincerity rings out clear enough in every word of his book. He was a man in whom the fire-thought of the desert burned so fiercely that he could not help being sincere. He was so truly sincere, indeed, as to be wholly unconscious of his sincerity. Now, of all the stories related of him none affords a more convincing proof of his thorough honesty than the one which shows him to have been, at least once in practice, a backslider from the high ideal of conduct that he preached. This story, from Al-Beidáwí’s commentary, is thus related by Sale:

[Pg 23]

“A certain blind man named Abdallah Ebn Omm Mactúm came and interrupted Muhammad while he was engaged in earnest discourse with some of the principal Kuraish, of whose conversion he had hopes; but, the Prophet taking no notice of him, the blind man, not knowing that Muhammad was otherwise busied, raised his voice, and said, ‘O apostle of God, teach me some part of what God hath taught thee’; but Muhammad, vexed at this interruption, frowned, and turned away from him,” for which he was reprehended afterwards by his conscience. This episode was the source of the revelation entitled “He Frowned.” “The Prophet frowned, and turned aside,” so runs Chapter lxxx. of the Kurán, “because the blind man came unto him; and how dost thou know whether he shall peradventure be cleansed from his sins; or whether he shall be admonished, and the admonition shall profit him? The man who is wealthy thou receivest with respect; but him who cometh unto thee earnestly seeking his salvation, and who fearest God, dost thou neglect. By no means shouldst thou act thus.” We are also told that the Prophet, whenever he saw Ebn Omm Mactúm after this, showed him marked respect, saying, “The man is welcome on whose account my Lord hath reprimanded me,” and that he made him twice Governor of Medina. And yet many still persist in calling Muhammad a charlatan. Surely a prophet who, in reproving others, spared not himself, has won the right to be respected as an honest man. For my part I believe him to have been one whose word was his bond, and whose hand it had been good to grasp.

As for his having been a mere victorious soldier, he was in the beginning “precisely in a minority of one.” Your Napoleon finds in patriotism his most successful recruiting sergeant. But the call of patriotism had[Pg 24] summoned to Muhammad’s standard not a single recruit, because he was despised by the patriotic (if the Kuraish, the predominant tribe in Arabia, and the keepers of the Ka’bah, deserved to be so called) and was rejected by them. Assuredly Muhammad drew the sword; he was driven to draw it in the end. But how did he get the sword, and to what purpose did he put it when he had it? Muhammad’s sword was forged in the furnace of that passionate, human soul of his, was tempered in the flame of divine compassion, and gave to every Arab an Empire and a creed. Islám was the sword! The blade of steel achieved no miracle, it merely drew blood—sufficiently corrupt. It was the sword of Muhammad’s word which freed the Arab heart from its vices and fired it with a wider patriotism and a purer faith. His battle-cry was the declaration of God’s unity; his sword was the faith; his battlefield the human heart and soul; and his enemy idolatry and corruption. “Yá Alláh!” and “Yá Muhammad!” carried the Arabian conquest from Mecca to Granada, and from Arabia to Delhi. The conquering hosts fought rather with their hearts and with their souls than with their swords and their strong right hands; inculcating in the conquered no earthly vanities, as do modern Muhammadan rulers, but the principles of liberty, solidarity, unity, equality, and compassion.

Forty thousand Arabs, under their famous leader, Sád Vaghás, having defeated five hundred thousand Persians and overthrown the mighty Persian Empire, in the battle of Khadasieh, on the plain of Nahavend, deeply rooted their faith in the heart of the alien race, and then left her to be ruled by her own people, in accordance with the precepts of the new revelation. Omar, perhaps the greatest Caliph, is said to have lived throughout his life on a loaf of barley bread and a cup of sour milk a day. And Alí’[Pg 25] the Prophet’s son-in-law, whom the Persians revere as his true successor, lived for no other purpose than to help the poor and to succour the weak. He was, as Carlyle assures us, a man worthy of Christian knighthood. So also was his son, Huseyn, whose glorious martyrdom has endeared him to the hearts of the Persian people.

In the East men are ruled and guided by religious laws and not by positive ones, so Muhammad’s aim was to make the Arabians free and united by lessening the sufferings of the poor and by establishing equality among the people. That these aims and aspirations cannot be consummated through positive laws alone must be abundantly clear to every man in the civilised West who has watched the gradual rise among us of Socialism and the deadly growth of Anarchy. We Western peoples merely pray that God’s will may be done on earth as it is in Heaven. Whereas Muhammad, being, as he was, a practical reformer, made it incumbent on his followers to contribute to the consummation of the Divine Law by bestowing on the poor a fair share of the things that they loved.

The very core of the Muhammadan faith lies, as I conceive, in three broad principles. First, in the declaration of God’s unity. “Say, God is one God; the eternal God: He begetteth not, neither is He begotten: and there is not one like unto Him.” This short chapter, as is well known, is held in particular veneration by the Muhammadans, and declared, by a tradition of the Prophet, to be equal in value to a third part of the whole Kurán. It is said to have been revealed in answer to the Kuraish, who had asked Muhammad concerning the distinguishing attributes of the God he invited them to worship. For Muhammad held that all the prophets from the creation of the world have been Unitarians; that as Moses was a Unitarian so also was Christ; that Christianity, as[Pg 26] practised in Syria, was a break in God’s revelation of Himself as One, and that he, Muhammad, had been specially chosen by God to re-admonish mankind of this fundamental truth.

As this ground idea satisfies the Oriental’s reason, so the second, Islám, that is, resignation from man to God, responds to the inner voice of his soul, and seems to lead his heart warmly to embrace the third principle of the Muhammadan faith, which, in the golden age of the Muhammadan Era, was the means of establishing equality among the people—I mean the principle of charity, of alms-giving, of compassion from man to man. Unswerving obedience to the spirit and the letter of these three laws carried with it the obligation of unswerving loyalty to the Prophet. When we pray, we Christians, we say “Give us this day our daily bread.” The Muhammadans, under penalty of everlasting torment, are obliged to sacrifice, to the poor and needy, a due proportion of the things that they love—not merely of their superfluity—with the result that each man among them, by that fact alone, constitutes himself, as it were, a willing instrument of God’s will that His Kingdom of Heaven shall reign on earth. Another fact that proves Muhammad to have been something far more than a man of the sword is that to this day Muhammadans hail one another on meeting with the word “Salám” (have peace). Indeed, peace being an essential condition of undertaking the sacramental Pilgrimage to Mecca, it is unlawful to wage war during the three months’ journeying of the Muslim lunar year, namely, in Shavvál, Zú-’l-ka’dah, and Zú-’l-hijjah.

“Contribute out of your subsistence towards the defence of the religion of God,” says Muhammad, “and throw not yourself with your own hands into perdition [that is, be not accessory to your own destruction by[Pg 27] neglecting your contributions towards the wars against infidels, and thereby suffering them to gather strength], and do good, for God loveth those who do good. Perform the Pilgrimage of Mecca, and the visitation of God; and if ye be besieged send that offering which shall be the easiest, and shave not your heads until your offering reacheth the place of sacrifice. But whoever among you is sick, or is troubled with any distemper of the head, must redeem the shaving of the head by fasting, by alms, or by some offering [either by fasting three days, by feeding six poor people, or by sacrificing a sheep]. But he who findeth not anything to offer shall fast three days in the Pilgrimage, and seven when he be returned: these shall be ten days complete. This is incumbent on him whose family shall not be present at the Holy Temple.”

“The Pilgrimage must be performed in the known months (i.e., Shavvál, Zú-’l-ka’dah, and Zú-’l-hijjah); whosoever therefore purposeth to go on Pilgrimage therein, let him not know a woman, nor transgress, nor quarrel in the Pilgrimage. The good which ye do, God knoweth it. Make provision for your journey, but the best provision is piety, and fear me, O ye of understanding. It shall be no crime in you if ye seek an increase from your Lord by trading during the Pilgrimage. And when ye go in procession from Arafat [a mountain near Mecca] remember God near the holy monument, and remember Him for that He hath directed you, though ye were before this of the number of those who go astray. Therefore go in procession from whence the people go in procession, and ask pardon of God, for God is gracious and merciful. And when ye have finished your holy ceremonies, remember God, according as ye remember your fathers, or with a more reverend commemoration. Yea, remember God the appointed number of days [three days after slaying the[Pg 28] sacrifices], but if any haste to depart from the Valley of Mina in two days it shall be no crime in him. And if any tarry longer it shall be no crime in him—in him who feareth God. Therefore, fear God and know that unto Him ye shall be gathered.... They who shall disbelieve and obstruct the way of God, and hinder men from visiting the Holy Temple of Mecca, which we have appointed for a place of worship unto all men: the inhabitant thereof and the stranger have an equal right to visit it: and whosoever shall seek impiously to profane it, we will cause him to taste a grievous torment. And proclaim unto the people a solemn Pilgrimage; let them come unto thee on foot, and on every lean camel, arriving from every distant road, that they may be witnesses of the advantages which accrue to them from visiting this holy place, and may commemorate the name of God on the appointed days [namely, the first ten days of Zú-’l-hijjah, or the tenth day of the same month, on which they slay the sacrifices, and the three following days] in gratitude for the brute cattle which he hath bestowed on them. Wherefore eat thereof, and feed the needy and the poor. Afterwards let them put an end to the neglect of their persons [by shaving their heads, and the body from below the neck, and cutting their beards and nails in the valley of Mina, which the pilgrims are not allowed to do from the time they become Muhrims, and have solemnly dedicated themselves to the performance of the Pilgrimage, till they have finished the ceremonies, and slain their victims]; and let them pay their vows [by doing the good works which they have vowed to do in their Pilgrimage], and compass the ancient house [i.e., the Ka’bah, which the Muhammadans pretend was the first edifice built and appointed for the worship of God]. This let them do. And whoever shall regard the sacred ordinances of God: this will be better for him[Pg 29] in the sight of his Lord. All sorts of cattle are allowed you to eat, except what hath been read unto you, in former passages of the Kurán, to be forbidden. But depart from the abomination of idols, and avoid speaking that which is false: being orthodox in respect to God, associating no other god with him; for whosoever associateth any other with God is like that which falleth from heaven, and which the birds snatch away, or the wind bloweth to a far distant place. This is so....”

One of the benefits of this Pilgrimage, and, perhaps, the greatest of all, if we regard the sacrament either from the political and social or from the religious standpoint, was, and is, the gathering together in Mecca of Muhammadans of every race and of every sect. There, and in the city of Medina, they first saw the dawn of their religious faith and their political power; there their hearts were drawn together in unity and strength; and there, in the early days of the Caliphs, they discussed their latest achievements, the glory of their future conquests, and studied the wants and needs of their co-religionists. Within the walls of the Holy of Holies they wept and prayed that God might renew within them a cleaner spirit through faith; and there, too, they strove with all earnestness to raise themselves to the full height of the Prophet’s conception of manhood, which encouraged such virtues as hospitality, generosity, compassion, heroism, courage, parental love, filial respect, and passive obedience to the will of God. Thus Mecca, in the days of Pilgrimage, might be looked upon as an immense club or a university where Muhammadans, from every quarter of the globe, meet and discuss their political and social problems, and prostrate themselves in prayer to the one and only Divinity.

Another effect of this Pilgrimage—an effect which has[Pg 30] grown less marked with the increased facility and comfort of travelling—is that it kindled energy and courage in such people as would never have left the safe seclusion of their harems had it not been for the rewards which the undertaking is said to gain for them hereafter. For the Oriental nations, be it remembered, are not as a rule of a roving spirit; they are far more inclined by nature to a life of ease and security than to one of danger and privation. “Travel,” says an Arab proverb, “is a portion of hell-fire,” and so, perhaps, nothing save the hope of paradise or the dread of perdition would ever have induced the meditative Oriental to brave the trials and the hardships of the long road to Mecca.

In our hearts we believe the proof of the Divine Spirit using any religion is that it does not deteriorate. The chief objection to Welsh Calvinism, which, like Muhammadanism, is based on the theory of Predestination, is that it grows worse. It was once simply and sincerely religious: it is now mainly political spite. Has Muhammadanism deteriorated beyond recognition—say, in the eyes of the student of the Kurán, or does it still hold tight by “the cord of God”? Do the Sunnís hold themselves aloof from the Shi’ahs, or do they dwell together, within the Holy Temple, in brotherly love and concord? Their daily salutation of “Salám,” is it sunk to a mere empty form, or is it still the expression, as it once undoubtedly was, of a hearty wish to bring about the Prophet’s single aim? And of all the nationalities congregated yearly in the city of concourse—the Arabians, the Persians, the Afghans, the Egyptians, the Muhammadans of India and China—which among them all is the most worthy to be commended for its enlightenment and progress? All these questions, and many more on the social and religious life of the East, will be answered in[Pg 31] the course of the second and third parts of this volume. And in the meanwhile, I cannot do better than gather into focus the preliminary notes of my literary partner, beginning with the customs incidental to the pilgrimage; for the main thing now is to leave nothing unsaid which would enable the reader to enter into the spirit and the form of the sacred journey. And henceforward, though I shall always express myself in my own words, the personal pronoun, whenever used, will apply, throughout this work, to my collaborator, Hadji Khan, with the exception of the contents of the Appendix.

That being understood, the conditions must be mentioned which, in theory, though not necessarily in practice, limit the number of Muhammadans that go on the pilgrimage. First, the Muhammadan must be of age—that is, he must have completed his fifteenth year when, according to the Muhammadan Law, a boy becomes a man. Secondly, he must be of a sound constitution in order to endure the fatigue of the journey. Thirdly, he should have no debts whatever, but should be sufficiently well-to-do to defray his own travelling expenses, after having distributed one-fifth of his property among the Seyyids, given one-tenth of the remainder in alms, and made provision during his absence for the support of the family and the servants he leaves behind him. Fourthly, he should support both the mosque in which he prays and the fund of the saint he adores the most by making his religious adviser a present in proportion to his means. Fifthly, he must be either a virtuous or a sincerely penitent man, for he cannot legally[Pg 32] undertake the pilgrimage unless his wealth has been gained in a lawful manner. Strictly speaking, a thief, for example, cannot be a pilgrim, nor can the money earned by accepting bribes be used to cover the expenses of the journey. The best money to use for the purpose is that which has been gained from the produce of the soil, or else that which has been bequeathed by a virtuous father. Sixthly, the Muhammadan who would be a Hájí must start with an absolutely clean conscience: he must look to it that the friends he leaves behind him shall have no just cause to be offended with him. Though he need not heed the slander of the malignant, he must formally repent of his sins, bidding his friends and acquaintances good-bye with the words, “Halálám kuníd.” Seventhly, a woman should be accompanied by one of her Meharem, that is by one of the men who are privileged to see her unveiled—namely, by her father, her husband, her brother, her uncle, her born slave, or her eunuch. In short, the pilgrims should be really good Muslims, adhering firmly to all the laws laid down in the Kurán, and following religiously the special teaching of their chosen directors, whose prescriptive right to regulate the minor details of the rites and observances of the Faith, has resulted in their wielding a tremendous power over their flocks even in political matters.

From the little that has been said of the influence of the Persian clergy you will understand that the priests require their pilgrims to adhere strictly to the letter of the laws appertaining to the prohibition and recommendation of certain articles of food. They must reckon as prohibited[Pg 33] and, therefore, impure, twelve things, among which may be counted pork, underdone meat, the blood of animals, and wines. Though a digression, it will not be out of place to mention here that the wine, of which Omar Khayyám and the Súfís in general sing, is more likely to be the juice of the grape than the interpretation put on it by such commentators as see in it a symbol of God’s love. For the effect produced on the brain by the forbidden drink is in itself something of a mystery, as it were, a divine afflatus, more particularly is it so considered by a people of such a temperate habit as the Persians. Some of the higher classes, no doubt, drink hard, and even drink to get drunk, but upon the whole the Muhammadans, and especially the Persians, are, in comparison with the majority of European peoples, extremely sober, bearing their griefs without seeking the consolation of the bottle.

Now, purifications must be made either in flowing water, or in about half a ton of stagnant pure water. When the nose bleeds it must be dipped three times, after being well washed. Strange to say, the sweat of the camel—the animal that bears the pilgrim to Mecca—is said to be unclean to the touch and its pollution must, like the handling of dogs, pigs, and rats, be cleansed away by the customary purifications. Ablutions, called wuzú’h should precede every prayer that is farz or incumbent, and wuzú’h consists first in washing the hands three times by pouring water from the right hand over the left hand and rubbing them together, next in washing the face three times with the right hand, then in pouring the water with[Pg 34] the right hand over the left elbow and rubbing down the forearm, and last of all in repeating the process with the left hand over the right forearm. After this maseh must be performed by dipping the right hand in water and rubbing it over the front portion of the head, and also by rubbing over the right foot with the wet right hand, and the left foot with the wet left hand. If the hands or the feet be sore or wounded then clay takes the place of water, and this particular kind of purification is called tyammom. The devout before reading the Kurán, or before entering the shrine of a saint or the court of a mosque, should perform wuzú’h or tyammom, and in doing so they should resolve within themselves to recite such and such a prayer. This is called Niyyat, or Declaration of Intention.

According to a Shi’ah traditionalist, Imám Huseyn has laid down twelve rules to be observed at meal times. The first four are essential to the salvation of all true Muslims. They should remember to say “Bismillah” before tasting each dish, and refrain from eating of the forbidden viands; they should also assure themselves that the food laid before them has been bought with money obtained from a legal source, and should end by returning thanks to God. The second four, though not universally obeyed, are admitted by all to be “good form,” and consist in washing the hands before meat, in sitting down inclined to the left, in eating with the thumb and the first two fingers of the right hand, which hand must be kept especially clean for the purpose. The last four rules deal with matters of social etiquette. They are kept by most Muhammadans in polite society, and are as follows: One should not stretch across the tablecloth, but should partake only of such dishes as are within one’s reach; one should not stuff the mouth too full, nor forget to masticate the food thoroughly; and[Pg 35] one should keep the eyes downcast and the tongue as silent as possible.

It is a tradition that the washing of hands before meals will materially help the true Muslim to grow rich, and be the means of delivering him from all diseases. If he rub his eyes immediately after the ablution they will never be sore. The left hand must not be used in eating unless the right be disabled.

All true Muslims when eating are advised to begin with salt and finish with vinegar. If they begin with salt they will escape the contagion of seventy diseases. If they finish with vinegar their worldly prosperity will continue to increase. The host is in etiquette bound to be the first to start eating and the last to leave off. Tooth-picking is considered an act of grace, for Gabriel is reported to have brought a tooth-pick from heaven for the use of the Prophet after every meal. The priests recite certain passages of the Kurán before and after lunch and dinner, and also before drinking water at any hour of the day.

All Muslims must say five prayers every day, and the following six things should be observed before the prayers are acceptable to God: (1) wuzú’h or tyammom, (2) putting off dirty clothes, (3) covering one’s body and head and doffing the shoes, (4) keeping the appointed time, (5) determining the exact position of Mecca, and (6) assuring one’s self as to the purity of the place in which the prayers are said. Before beginning one must say within one’s self what prayers one is about to recite, and for what purpose one is going to recite them, and at the end[Pg 36] one must raise the hands to Heaven, saying, “May peace be with Muhammad and with his disciples.” For prayer was by Muhammad deemed so urgent an act of reverence that he used to call it the pillar of religion and the key of paradise, declaring “that there could be no good in that religion wherein was no prayer.” It behoves every pilgrim, therefore, in his sacred habit, to pray at least five times every twenty-four hours; (1) in the morning before sunrise, (2) when noon is past and the sun begins to decline from the meridian, (3) in the afternoon before sunset, (4) in the evening after sunset and before day be shut in, and (5) after the day is shut in and before the first watch of the night. Besides these, there are certain other prayers which, though not expressly enjoined, are commended as a special act of grace, more particularly perhaps to the pilgrims in ihrám. Among these may be mentioned the separate prayers generally said at night (i.e., the namáz-i-tahajjud and the vitr), and the extra prayers not prescribed by law, the naváfil and the namáz-i-mustahabb. The positions of the body are as follows: (1) kiyám, that is, standing erect, with the hands down by the sides; (2) takbírguftán, declaring God’s greatness, on raising the hands on either side of the face, with the thumbs under the lobes of the ears, and the fingers extended; (3) rukú, inclining the body from the waist and placing the hands on the knees; (4) kunút, standing with the head inclined forward and the hands on either side of the face; (5) dú zánúnishastán, kneeling, the hands lying flat on the thighs; and (6) sijdah, prostration, in which the forehead must touch the ground, or the lump of unbaked clay that is known by the name of “mohre.” A full prayer is made up of five “rakats” or prostrations, during which not a word save the prayer as prescribed should be uttered. Part of the prayer is said aloud and[Pg 37] part in a whispering tone. The greatest care should be taken to pronounce each word with the correct Arabic accent, since ill-pronounced words, unless the result of a natural defect, are said to be unacceptable to the Creator. The pilgrim should say special prayers on Friday, and every time he has recourse to the Kurán before deciding on any course of action whatsoever. A special prayer is said by the devout about one hour after midnight. This is called the midnight prayer, and is, of course, a tedious task. Hence it is sometimes said sarcastically of a man with a loose belief in the Faith: “He says midnight prayers!” The prayers most readily answered are the prayers said in Mecca. Thus when a pilgrim sets out on his journey he is requested by his friends to pray for them at the House of God. The name of the person for whom one prays should be uttered, otherwise the prayer will have no effect. Every pilgrim must take with him a rosary, the square piece of unbaked clay called “mohre,” and a copy of the Kurán, for a passage of the Kurán must be read after every prayer.

It is now time to give the reader, in as terse and as condensed a form as possible, a general idea of the part played by religion in the workaday lives of the children of the Faith, beginning with their toilet, that is, with their dressing and bathing, with the combing of their hair and the cutting of their nails.

A pious Persian Muslim, before wearing any new article of clothing, performs his ablutions and prostrates himself[Pg 38] twice in prayer. A man of a less devout, but a more superstitious, trend of mind contents himself with consulting the taghvím or the estakhhareh[1] muttering to himself, ere he dons the garment, “In the name of God the Merciful and Clement!” His friends on seeing the new apparel cry out, “May it be auspicious!” The rewards of a man who says his prayers before putting on a new suit of clothes will be in proportion to the number of threads in the cloth. Hence it has come to be a practice to preserve the material from the blight of the Evil Eye by besprinkling it with pure water over which a prescribed passage of the Kurán has been read.

It is unlucky for a Muslim to sit down before taking off his shoes. When drawing them on it is equally unlucky for him to stand up. The custom, in the first instance, is to rise, doffing first the left shoe and then the right one. The procedure must be reversed in every particular when putting them on. The universal belief in omens is traditional, and extends, among other things, to precious stones. By far the luckiest of these is the flesh-coloured cornelian, which is a great favourite with the men. It owes its popularity to the fact that the Prophet himself is said to have worn a cornelian ring set in silver on the little finger of his right hand. It grew still more in favour at a later period, because Jafar, the famous Imám, declared that the desires of every man who wore it would be gratified. And thenceforward its property to bless has been regarded as axiomatic by the superstitious to whom I am referring.

COPIES OF THE KURÁN WORN EN BANDOULIÈRE BY MUSLIMS WHEN TRAVELLING OR ON PILGRIMAGE.

The Shiahs have the name of one of the twelve Imáms engraved on the stone; others make use of it as a seal bearing their own names. Hardly less lucky are the turquoise and the ruby, which are believed to have the[Pg 41] effect of warding off poverty from those who are fortunate enough to possess them. This is why they are treasured by the fair sex, the ruby being, perhaps, the more dearly loved of the two.

Every bath has generally three courts. On entering each one of these the devout say the prayers prescribed for the occasion, but the generality of Muslims, unless they intend to perform the religious purifications, consider it sufficient to greet the people who are present with the word “Salám!” It is considered inauspicious to brush the teeth in the baths, but certain portions of hair must be removed by a composition of quicklime and arsenic, called nureh, and the nureh, though efficacious enough, no matter when it may be used, is said to add immeasurably to a man’s chance of salvation by being laid on either on a Wednesday or on a Friday.

The application of the juice of the marsh-mallow as an emollient for the hair is strongly recommended by the saints. Their object in bequeathing this advice to the consideration of their flock was not to inculcate vanity. They had a higher aim than that. Their desire was to stave off starvation from the fold, for that, in their opinion, would be the result of using the lotion on an ordinary day of the week; while rubbing the head vigorously with the precious juice on the Muslim Sabbath would be certain to preserve the skin from leprosy and the mind from madness. To the use of a decoction of the leaves of the lote-tree a divine relief is attributed, for the mere smell of it on the hair of the most unregenerate has on Satan an effect so disheartening that he will cease from leading them into temptation for no less than seventy days.

The pressure of the grave will be mitigated by a skilful and untiring application of the comb in this life.[Pg 42] The blessing of the comb is said to have been revealed to Imám Jafar. Women are not excluded from the spiritual benefits derived from the comb. But, remember, the hair must not be done in a frivolous, much less in a perfunctory fashion. Far from it. On no account whatever must the hair be neglected, for Satan is attracted by dishevelled locks. They are, as it were, a net in which he catches the human soul. Therefore, since the priests and the merchants of Islám shave their heads in most parts of the Muslim world, special attention should be paid by them to their beards and eyebrows. A pocket-comb made of sandal-wood is often carried by the true Believers, who, it may be hoped, turn it to good account in moments of spiritual unwillingness on the part of the natural man.

A Mullá’s beard is an object of veneration to his flock. He may trim it lest it should grow as wild as a Jew’s, but he is forbidden by tradition to shave it. Even the scissors must be plied sparingly and to the accompaniment of prayer. Perhaps the orthodox length of this almost divine appendage of the true Muslim is the length of the wearer’s hand from the point of the chin downwards. This is known as a ghabzeh or handful. A priest may be allowed to add the length of the first joint of his little finger, otherwise his power to awe might grow lax. The soul is in danger every time he forgets to cut his sharib, that is, the tip of his moustache, which should be reduced to bristles once a week. Once on a time a faithful follower of the Prophet asked one of the Imáms what he should do to increase his livelihood. The Imám answered unhesitatingly: “Cut your nails and your sharib on a Friday as long as you live!”

Again, according to a Shi’ah traditionist, if a Muslim gaze into a looking-glass, before saying his prayers, he will be guilty of worshipping his own likeness, however[Pg 43] unsightly it may appear in his eyes. The hand must be drawn across the forehead, ere the hair or the beard be adjusted, or else the mirror will reflect a mind given over to vanity, which is a grievous, if universal sin. The new moon must be seen “on the face” of a friend, on a copy of the Kurán, or on a turquoise stone. Unless one of these conditions be observed, there is no telling what evil might not happen.

The devout who are most anxious to vindicate tradition perform two prostrations on beholding the new moon, and sacrifice a sheep for the poor as an additional safeguard against her baneful rays. The Evil Eye more often than not has its seat in the socket of an unbeliever. Therefore, the Muslim who, on being brought face to face with a heretic, should not say the prayer by law ordained must look to his charms or suffer the inevitable blight. A cat may look at a king; a king may shoot a ferocious animal; and a thief may run away with the spoil. But a true Believer must guard his faith against aggression every time he sees a thief, a ferocious animal, or a king. For very different reasons, he must recite a prescribed formula of prayer on the passing of a funeral procession, and also on his seeing the first-fruits of the season and its flowers. The dead, it is said, will hear his voice if, on crossing a cemetery, he cry aloud: “O ye people of the grave, may peace be with you, of both sexes of the Faithful!”

As the sense of sight gives rise to devotional exercises, so also does the sense of hearing. The holy Muslim should lend a prayerful ear to the cries of the muezzin during the first two sentences of the summons, and when the call to prayer is over he should rub his eyes with his fingers, in order to produce the signs of weeping—a mark of contrition and of emotional recrudescence in the matter[Pg 44] of piety. The true Believer, whenever he hears the Sureh Sújdeh read in the Kurán, should prostrate himself and repeat the words after the reader. If he hear a Muslim sneeze he should say, “May peace be with thee!” and if the sneeze be repeated, “Mayest thou be cured!” But, if a Kafir sneeze, the response must be expressed in the wish to see him tread “the straight path.”

Every child of Islám, before going to bed, should perform his ablutions and say his prayers. If he wish to be delivered from nightmare and all its terrors let him say to Allah: “I take refuge in Thee from the evil of Satan,” and if he is afraid of being bitten by a scorpion let him appeal to Noah, saying, “May peace be with thee, O Noah!” One day Eshagh-ben-Ammar asked Imám Jafar how he could protect himself against the attack of that malignant arachnidan. The Imám replied: “Look at the constellation of the Bear; therein you will find a small star, the lowest of all, which the Arabs call Sohail. Fix your eyes in the direction of that star, and say three times, ‘May peace be with Muhammad and with his people: O Sohail, protect me from scorpions,’ and you will be protected from them.” Eshagh-ben-Ammar goes on to relate that he read the formula every evening before going to bed, and that it proved successful; but one evening he forgot to repeat it, and, as a consequence, was bitten by a black scorpion.

Prayers are also said against mosquitoes and other insects. This cleanses the conscience of the irate Muslim, if it fail in preserving his skin. The Eastern peoples in general and the Muhammadans in particular are early risers. Sleep after morning prayers, which are said before sunrise, is sure to cause folly; sleep in the middle of the day is believed to be necessary and suitable to work; while sleep before evening prayers has precisely the same effect[Pg 45] as after the devotions of the early morning. A traditionist says that the prophets slept on their backs, so as to be able to converse with the angels at any hour of the night; that the faithful must sleep on their right sides, and the Kafirs on their left; and that the deves take their rest on their stomachs.

Usury, though interest on money was strictly prohibited by the Prophet, is among the Muslims of the present day a common practice. They evade the letter of the law by putting what the Persians call “a legal cap over the head” of the usurious transaction. The money-lender picks up a handful of barley and says to the borrower, “Give me the rate of interest as the cost of this grain, which I now offer to sell to you at that price;” and the borrower replies that he accepts the bargain. Also, a merchant must know all the laws appertaining to buying and selling. Imám ’Ali is said to have made a daily round of the bazaars of Kufa crying out the while, “O ye merchants and traders, deal honestly and in accordance with the laws of your Prophet. Swear not, neither tell lies, and cheat not your customers. Beware of using false weights, and walk ye in the paths of righteousness.”

A high priest in Mecca assured me that to enjoy a derham of interest is as bad as taking the blood of seventy virgins. The admonitions of ’Alí the Just, though sometimes read, are less often followed. On leaving his house a merchant must say “Bismillah,” and then blow to his left and his right and also in front of him, so as to clear the way to good business.

The pious recite, on entering the bazaar, a prayer ordained for the occasion. When the bargain is clinched the seller should cry out, “God is great! God is great!” But there should be no dishonest bargaining over the purchasing of these four things: the winding sheets for[Pg 46] the dead, the commodities to be distributed in charity, the expenses on the journey to Mecca, and the price of a slave’s ransom. In all these transactions the buyer and seller must act according to the dictates of fair play. The man who buys a slave should lay hold of him by a hair of his head and say the prescribed prayer; after which, if guided by Imám Jafar, he must change the name of his purchase. Slaves are treated with every consideration, so much so indeed that in the household of Eastern potentates, whose treatment of their dependents is extremely arbitrary, the slaves lord it over the servants.

It is said, in the traditions, that a true Muslim should marry neither for money nor for beauty, but should be guided by the woman’s moral worth and spiritual endowments. His choice is referred to the arbitrament of the estakhhareh. “A chaste maiden will make a good wife; for she will be sweet-tempered to her husband, and mild but firm in the treatment of her children.” This saying is attributed to the Prophet. “A bad wife, a wicked animal, and a narrow house with unsociable neighbours, those are the possessions which try a man’s temper,” cried one of the Imáms, himself a saintly man. “The best woman is she who bears children frequently, who is beloved by her relatives, who shows herself obedient to her husband, who pleases him by wearing her best clothes, and who avoids the eyes of men who cannot lawfully see her.” These words were uttered by Muhammad, if we are to believe tradition.

The wedding must not take place when the moon is under an eclipse, nor when she is in the sign of Scorpio. The best time is between the 26th and the end of the lunar month. Muhammad recommended festivals to be celebrated on five occasions: on wedding and nuptial days, on the birth of a child, on the circumcision of a child, on[Pg 47] taking up one’s abode in a newly-purchased house, and on returning from Mecca. Only persons of unblemished reputation should be invited to the marriage or the nuptial feasts.

To the man who brings him news of the birth of a male child the father should give a present. The nurse should lose no time in singing the first chapter of the prescribed prayer in the baby’s right ear, and what is called the standing prayer in its left one, and if the water of the Euphrates be procurable it should be sprinkled on the baby’s forehead.

On the seventh day after the child’s birth the ceremony of the Aghigheh is performed in Persia. This consists in killing a fatted sheep, in cooking it, and in distributing the flesh among the neighbours or among the poor who come to the door. In memory of the occasion a cornelian engraved with a Kurán text, and sometimes surrounded with precious stones, as in the cover-design to the present volume, is fastened to the baby’s arm by means of a silk band, and is worn perhaps to the end of its life. Not a single bone of the Aghigheh sheep should be broken; certain prayers should be read before the sheep is killed; and the parents should not take part in the feast.

The baby is not often weaned until it is two years old, Muhammad believing that the mother’s milk is the best and acts beneficially on the child’s future character and temperament.

The twelve Muhammadan months are lunar, and number twenty-nine and thirty days alternately. Thus the whole year contains only three hundred and fifty-four days; but[Pg 48] eleven times in the course of thirty years an intercalary day is added. Accordingly, thirty-two of our years are, roughly speaking, equal to thirty-three Muhammadan years. The Muhammadan Era dates from the morning after the Hegira, or the flight of the Prophet from Mecca to Medina, that is, on the 16th of July, A.D. 622. Every year begins earlier than the preceding one, so that a month beginning in summer in the present year will, sixteen years hence, fall in winter. The following are the names of the months, which do not correspond in any way with ours: 1, Muharram; 2, Safar; 3, Rabíu-’l-avval; 4, Rabíu-’s-sání or Rabíu-’l-ákhir; 5, Jumádáu-’l-úlá; 6, Jumádáu-’s-sání or Jumádáu-’l-ákhir; 7, Rajab; 8, Sha’bán; 9, Ramazán; 10, Shavvál; 11, Zú-’l-ka’dah, or Zí-ka’d; 12, Zú-’l-hijjah, or Zí-hajj. Many stories of these months were told to me by the priests and the pilgrims whom I met at Mecca, and it is therefore my intention to tell over again the stories of the most cherished months of the Muslim year. These are Rajab, Sha’bán, Ramazán, Shavvál, Zú-’l-ka’dah, Zú-’l-hijjah, and Muharram.

On the Day of Judgment, the Holy Muezzin, sitting on the Throne, will cry out, ere he pass judgment on the Faithful, saying: “O moons of Rajab, Sha’bán, and Ramazán, how stands it with the deeds of this humble slave of ours?” The three moons will then prostrate themselves before the Throne, and answer: “O Lord, we bear witness to the good deeds of this humble slave. When he was with us he kept on loading his caravans with provisions for the next world, beseeching Thee to grant him Thy divine favour, and expressing his perfect contentment with the fate that Thou hadst sent unto him.” After them their guardian-angels, meekly kneeling on their knees, will raise their voices in praise of the pious Muslim, crying: “O Lord God Almighty, we also bear witness to[Pg 49] the good deeds of this humble slave of Thine. On earth his eyes, his ears, his nose, his mouth, and his stomach were all obedient both to whatsoever Thou hast forbidden and also to whatsoever Thou hast made lawful. The days he passed in fasting, and the nights in sleepless supplication. Verily he is a good doer!” Then Allah will command his slave to be borne into Paradise on a steed of light, accompanied by angels, and by all the rewards of his piety on camels of light, and there he will be conducted to a palace whose foundation is laid in everlasting felicity, and whose inmates never grow old. The moon of Rajab is the month of Allah. It is said that there is a stream of that name in Paradise, whose water is white, and more wholesome than milk and sweeter than honey. The first to welcome the new arrival will be this stream, which will straightway wend its course round his palace. To Salim, one of his disciples, Muhammad is reported to have said: “If you keep fast for one day during the month of Rajab you will be free from the terror of death, and the agony of death, from the percussion of the grave, and the loneliness thereof. If you keep fast for two days the eight doors of Paradise will be opened unto you.”

The authoritative tradition goes that a crier will make himself heard from between the earth and the sky, summoning the pious who observed the prayers and the privations of the moon of Rajab: “Oh, ye Rajabians, come forth and present yourselves before your Creator.” Then the Rajabians, whose heads will be crowned with pearls and rubies, and whose faces will be bathed in the universal light, will arise and stand before the Throne. And each one among them will have a thousand angels on his right hand and a thousand on his left, and they will shout with one accord, saying: “O, ye Rajabians, may ye be deserving of all the holy favours ye are about to receive!” And last of all,[Pg 50] Allah, in his mercy, will say to them: “O my male and female slaves, I swear by my own magnanimity, that I will give you lodgings in the most delightful nooks of my Paradise, namely, in the palaces around which flow the most refreshing streams of purest water.”

A baby is to the Muslim a symbol of purity: and so a man who worships God in the month of Rajab will become like unto a new-born child, always provided that he repent of the sins which he has committed, and follow the law of the Prophet. Not until then will the pious Rajabian be in a fit state, in his character of new-born babe, to start life afresh. The Muhammadans, in so far as duty and obedience are concerned, put on pretty much the same footing the relation of the slave to his master, of the wife to her husband, of the child to its parent, and of the guest to his host. The parallel between the last-mentioned and the preceding is complete because the guest must acquiesce in his host’s will, which is supreme. In the matter of repentance, that of Nessouh is exemplary among the Muhammadans.

Now, this man Nessouh was in his face and his voice so like a woman that his wicked nature persuaded him to wear skirts that he might add to his experience of the opposite sex by mixing freely among its members. Soon, his curiosity growing in ratio with his acquired knowledge, we hear of him as an attendant in the hammam of the royal seraglio, where he might have pursued his studies in peace and in rapture had not one of the Royal Princesses, who had lost a ring, cast suspicion on every servant in turn. The seed of Nessouh’s repentance was sown when the decree went out that all the attendants of the baths were to be searched. The fear lest his sex should be discovered yielded so swiftly to repentance for having veiled it, that Almighty Allah despatched an angel from Paradise to discover the missing treasure before the decree took effect; and thenceforward[Pg 51] Nessouh, out of the gratitude of his heart, renounced his studies of human nature in petticoats, and vied with the most rigid disciplinarians in prayer and in fasting. His virtues grew so conspicuous in male attire that his repentance has come to be accepted as worthy of imitation by every true Believer.

According to tradition it was on the first day of God’s moon that Noah, having taken his seat in the Ark, commanded all the men and jinns and beasts that were with him to keep fast from sunrise to sunset. On the evening of the same day, when the sun was going down, the Ark, riding over the flood, would have heeled over had not Allah sent seventy thousand of his angels to the rescue. It is interesting to note that the number of all the traditional rewards of virtue, as well as that of such of the heavenly hosts as lend their assistance in cases of distress, is always a multiple of seven. A Meccan priest added the following to my collection of “rewards”: God will build seventy thousand cities in Paradise, each city containing seventy thousand mansions, each mansion seventy thousand houris, each houri surrounded by seventy thousand beautiful serving women, for the pilgrim—mark this—who shall say his prayers with the best accent on the Hájj Day. The Mullá in question was himself a perfect Arabic scholar; his enunciation in reciting the forthcoming bliss was faultlessly correct; each syllable seemed to pay his lips the tribute of a kiss for the pleasure it had derived from listening to the mellifluous sound of its predecessors. This learned priest will be in his element on all scores should the Paradise of his invention be materialised.

As Rajab belongs to Allah so Sha’bán is held sacred to the Prophet. For we read in the history of Islám that Muhammad, who entered Medina on the first day of the gracious moon, commanded the muezzins to make it known[Pg 52] to his people that the good actions which they might perform during the month would help both himself and them to gain salvation; whereas their evil actions would be committed against his apostleship, and would on that account be the more severely punished hereafter.

Once a year, on the approach of Ramazán, the precincts of Paradise, and all its gardens and palaces, are illuminated, festooned, and decorated, and a most tuneful wind, known in Arabic by the name of Meshireh, makes music in the trees. Now, no sooner do the houris hear this sound than they rush out from their seclusion, and cry aloud: “Is there any one to marry us through the desire to perform a good deed towards the creatures of God?” Then, turning to Rezvan, the guardian of Paradise, “What night is this?” they ask; and Rezvan answers, “O ye fair-faced houris, this is the eve of the holy moon of Ramazán. The gates of Paradise have I ordered to be opened unto the fast-keepers of the Faith of the Faithful.” Then Allah, addressing the angel who has the charge of Hell, says to him: “O Málik, I bid thee to close thy gates against the fast-keepers of the faith of my Apostle.” And next, summoning the Archangel of Revelations, He gives command, saying: “O Gabriel, go forth in the earth and put Satan in chains, and all his followers, that the path of my chosen people may be safe.” So, on the first day of Ramazán, Gabriel swoops down on the earth accompanied by hosts of angels. He has six hundred wings, and opens all of them except two. In his hands he bears four green banners, emblems of the Muslim creed. These he plants on the summit of Mount Sinai, and on the Prophet’s tomb at Medina, and in the Harem of Mecca. His army of angels bivouacs on the plains round about the Holy City and on the surrounding mountains. On the eve of the day of reward, which is called Ghadre, the angels are[Pg 53] ordered to disperse throughout the Muslim world, and every true Believer seen praying during that night is embraced by one of them, and his prayer meets with an angelic Amen. At the dawn of Ghadre day a heavenly bugle recalls the angels to Mecca. When Gabriel returns to Heaven it is to say to Allah, “My Lord, all the true Believers have I forgiven in Thy name save those who have been constant wine-bibbers, or incurred the displeasure of their parents, or indulged in abusing their fellow Muslims.”

The various sects of the Muhammadans disagree a good deal as to the date of Ghadre day. Some say it is on the 19th, some on the 21st, and others on the 23rd of the Muslim Lent; but all agree in believing it to be the day on which the books of deeds, good and evil, are balanced, and on which the angels make known to Muhammad the predestination of his followers for whom he intercedes. All Shi’ahs who would win a reputation for piety must keep Ahia, that is, pass the three nights above-mentioned in fasting and holy devotions—a penance of untold severity in that every day of the month must be similarly spent from sunrise to sundown. Through most ardent prayers on the 21st of Ramazán the devout Mussulman may win the privilege of becoming a Hájí in the following year. The 7th is the anniversary of Muhammad’s victory over the Kuraish in the battle of Badre, and is a great day with all Islamites. For the rest, the Arabs follow the example of their Prophet in breaking their fast on dates and water; special angels are appointed to plant heavenly trees, and to build divine palaces in readiness for such of the Muslims as should neither neglect their religious purifications nor forget to behave themselves as “Allah’s guests.” Many Muslims, unquestionably, adhere strictly to all the rites and observances of the occasion; not a few, on the other hand, though they[Pg 54] may fast during the day, devote the night to feasting. Indeed, in every capital of Islám, in Teheran, in Constantinople, and in Cairo, the darkling hours are given up by certain people to amusements and sometimes to vicious pursuits.

The heavenly hosts under the Archangel Gabriel, with his five hundred and ninety-eight wings wide open, and his green banner flying over the gate of the Ka’bah,—the heavenly hosts, I say, dispersing through the Muslim world on the eve of Ghadre will prevail on the ghosts of the one hundred and twenty-four thousand prophets to kiss the Muslims that are piously engaged at night, delivering them from the danger of drowning, of being buried under ruins, of choking at meal times, and of being killed by wild beasts. For them the grave will have no terror, and on leaving it a substantial cheque on the keeper of Paradise, crossed and made payable to bearer, will be placed in the hands of each one of them.

On the first day of the moon of Shavvál, the fast of Ramazán being over, all true Muslims are supposed to give away in charity a measure of wheat, barley, dates, raisins, or other provisions in common use. The guests who stay over the preceding night are entitled to receive a portion of the alms distributed by the master of the house next morning; and hence only the poor and needy are invited to accept hospitality on the occasion of the Zikat-é-Fetre—that is, the festival of alms-giving. The fulfilment of the law is believed not only to produce an increase of wealth in the forthcoming year, but also to cleanse the body of all impurities. So much for the rewards as a stimulus to honesty. Now for the penalty as a deterrent from greed. In the third Súra of the Kurán it is written: “But let not those who are covetous of what God of His bounty hath granted them imagine that[Pg 55] their avarice is better for them; nay, rather it is worse for them. For that which they have covetously reserved shall be bound as a collar about their necks on the day of the resurrection: and God is well acquainted with what ye do.” Shiahs are reluctant to get married in the interval between the first of Shavvál and the tenth of Zú-’l-hijjah, because the Prophet is said to have married Aishah, the enemy of ’Alí, about that time. On the other hand the Sunnis, who reverence that brilliant woman, commemorate her wedding day by solemnising their own during this season, unless they are performing the pilgrimage of Mecca.

The most sacred day of the following month—the moon of Zú-’l-ka’dah—is the twenty-fifth. On that day Adam was created; Abraham, Ishmael, and Jesus were born, and the Shiah Messiah, the concealed Imám, will come again to judge the world. A Muslim, if he keep fast on the twenty-fifth of Zú-’l-ka’dah, will earn the rewards of a man to whom Allah in his mercy should grant the privilege and the power of praying for nine hundred years. On the first of Zú-’l-hijjah, which is the month of pilgrimage, Abraham received from God the title of Al-Khalíl, or the Friend of Allah. It is accounted a good deed to fast from the first to the tenth day of this the last journeying month; it is also wise to do so, for it is not every month in the year that the Mussulman can win, by nine days of fasting, the fruits of a whole lifetime of self-denial. Another tradition deserving of mention in connection with this month is that Jesus, in the company of Gabriel, was sent to earth by God with five prayers, which he was commanded to repeat on the first five days of the pilgrims’ moon; but the two holiest days of the moon of Zú-’l-hijjah are the ninth and the tenth. On the ninth, after morning prayer, the pilgrims, in olden times, departed from the Valley of Mina, whither[Pg 56] they had come on the previous day, and rushed in a headlong manner to Mount Arafat, where a sermon is preached, and where they performed the devotions entitling them to be called Hájís. But nowadays they pass through Mina to Mount Arafat without stopping on the outward journey; and at sunset, after the sermon is over, they betake themselves to Muzdalifah, an oratory between Arafat and Mina, and there the hours of the night are spent in prayer and in reading the Kurán.

On the tenth, by daybreak, the holy monument, or al Masher al harám, is visited, after which the pilgrims hasten back, on the rising of the sun, to the Valley of Mina, where, on the 10th and the two following days, the stoning of the Devil takes place, every pilgrim casting a certain number of stones at three pillars. This rite is as old as Abraham, who, being interrupted by Satan when he was about to sacrifice his son Ishmael, was commanded by God to put the tempter to flight by throwing stones at him. Next, still on the same day, the tenth of Zú-’l-hijjah, and in the same place, the Valley of Mina, the pilgrims slay their victims, and when the sacrifice is over they shave their heads and trim their nails, and then return to Mecca in order to take their leave of the Ka’bah. All these ceremonies will be described in detail in the forthcoming narrative. Meanwhile, by way of further introduction, a few words must be said as to the animals sacrificed. The victims should be camels, kine, sheep, or goats. The camels and kine should be females and the sheep and goats males. In age the camels should be five years and not less; the cows and goats in their second year; and the sheep not younger than six months. All should be without blemish, neither blind nor lame: their ears should not have been cut, nor their horns have been broken. The males should be complete, and all be well fed.[Pg 57] They were woefully lean, however, in the year 1319 of the Flight. The camels are sacrificed while standing, the fore and hind legs being tied together. A single blow is delivered where the head joins the neck, the name of God being uttered the while. The victim must face the Kiblah, and the butcher or the pilgrim, as the case may be, stands on the right of the animal he is going to slay. If the pilgrim be too tender-hearted to deal the blow, he should catch hold of the butcher’s wrist, so as to take part in the act of sacrifice. All the other victims—namely, the kine, the sheep, and the goats—are made to lie on their sides facing Mecca, all four legs being securely fastened, then their throats are cut with a sharp knife, without, however, severing the head from the body.

The custom of sacrificing a camel on the tenth day of Zú-’l-hijjah prevails among the Shiahs in most of the towns of Persia and of Central Asia. The ceremony varies with the locality; but the one we witnessed was so picturesque that we cannot refrain from describing it. For the first nine days the camel, richly caparisoned, is led through the streets of the city; half a dozen Dervishes, intoning passages of the Kurán, swing along at the head of the procession; at every house the camel is made to halt, and subscriptions are raised towards its purchase-money and its maintenance. The victim, goaded on from street to street and from square to square, ends at last by collecting alms for its tormentors. On the eve of the Day of Sacrifice the camel is stripped of its gaudy trappings, and its body is, as it were, mapped out into portions with red ink, one portion being allotted to every quarter of the city. The place of sacrifice is usually outside the city walls, and early in the morning each district arms its strongest men to go and claim its share of the carcase. Each group may contain as many as twenty men, bristling from head to foot with[Pg 58] uncouth weapons, and a band of drummers adds to the barbaric display the sounds of discordant music. One man in each group rides on horseback and wears a cashmere shawl; it is he who receives into his hands the sacrificial share of the parish he represents. Prayers are said, and then, at a given signal, the butcher prepares his knife, and the cutters appointed by the respective quarters make ready to hack the victim in pieces. The camel, bare of covering, and marked all over with the red lines, turns its supercilious eyes on the eager cutters, and they, in their turn, watch the butcher. The wretched victim may or may not be conscious of its fate. I believe it to be conscious; but, whether it is or not, there is no sign of terror in its eyes, only the customary look of sly disdain. No sooner does the butcher plunge the knife into the camel’s windpipe than the cutters vie with one another as to who shall be the first to finish carving the still animate body, each allotted part of which is handed warm and well-nigh throbbing with life, to the horseman of the quarter to which it belongs. He takes it in procession to the house of the magistrate, who distributes it among the poor.

The prayer most acceptable to God is that of Nodbeh, which must be said by the pilgrims on Mount Arafat, with tears pouring from their eyes. The Prophet rose to a noble conception of the next life. He not only believed that the pure-hearted will see God, he also proclaimed that blessing to be the height of heavenly bliss. The Muslim Paradise, therefore, in its material aspect unalloyed, is the invention of the tradition-mongers. According to the orthodox among them, it is situated above the seven heavens, immediately under the Throne of God. Some say that the soil of it consists of the finest wheat flour, others will have it to be of the purest musk, and others again of saffron. Its palaces have[Pg 59] walls of solid gold, its stones are pearls and jacinths, and of its trees, all of which have golden trunks, the most remarkable is the Tree of Happiness, Túba, as they call it. This tree, which stands in the Palace of Muhammad, is laden with fruits of every kind, with grapes and pomegranates, with oranges and dates, and peaches and nectarines, which are of a growth and a flavour unknown to mortals. In response to the desire of the blessed, it will yield, in addition to the luscious fruit, not only birds ready dressed for the table, but also flowing garments of silk and of velvet, and gaily caparisoned steeds to ride on, all of which will burst out from its leaves. There will be no need to reach out the hand to the branches, for the branches will bend down of their own accord to the hand of the person who would gather of their products. So large is the Túba tree that a man “mounted on the fleetest horse would not be able to gallop from one end of its shade to the other in a hundred years.” All the rivers of Paradise take their rise from the root of the Tree of Happiness; some of them flow with water, some with milk, some with wine, and others with honey. Their beds are of musk, their sides of saffron, their earth of camphire, and their pebbles are rubies and emeralds. The most noteworthy among them, after the River of Life, is Al-Káwthar. This word, Al-Káwthar, which signifies abundance, has come to mean the gift of prophecy, and the water of the river of that name is derived into Muhammad’s pond. According to a tradition of the Prophet, this river, wherein his Lord promised him abundance of wisdom, is whiter than milk, cooler than snow, sweeter than honey, and smoother than cream; and those who drink of it shall never be thirsty.