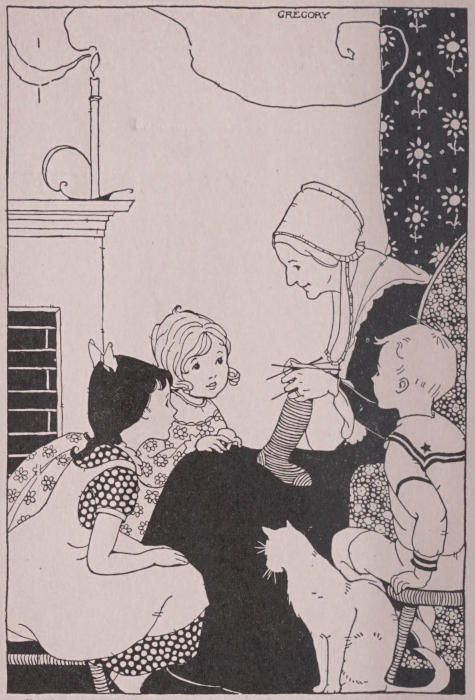

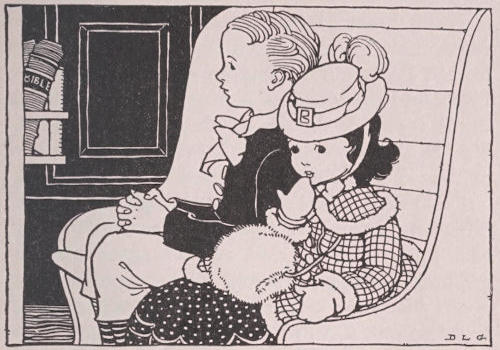

Bobby and Alice and Pink drew their stools closer and waited eagerly for Grandma to begin

Bobby and Alice and Pink drew their stools closer and waited eagerly for Grandma to begin

EARLY CANDLELIGHT

STORIES

By

STELLA C. SHETTER

Illustrated by

DOROTHY LAKE GREGORY

RAND McNALLY & COMPANY

CHICAGO NEW YORK

Copyright, 1922, by

Rand McNally & Company

Copyright, 1924, by

Rand McNally & Company

Made in U.S.A.

| PAGE | |

| Grandma Arrives | 9 |

| A Whistling Girl | 16 |

| Chased by Wolves | 23 |

| The Yellow Gown | 30 |

| A War Story | 37 |

| Easter | 45 |

| At a Sugar Camp | 52 |

| The New Church Organ | 60 |

| School Days | 68 |

| A Birthday Party | 76 |

| The Locusts | 83 |

| The Fourth of July | 92 |

| The Bee Tree | 99 |

| Brain Against Brawn | 106 |

| A Wish That Came True | 114 |

| Joe’s Infare | 122 |

| Pumpkin Seed | 130 |

| A School for Sister Belle | 138 |

| Andy’s Monument | 146 |

| Memory Verses | 155 |

| The Courting of Polly Ann | 163 |

| Earning a Violin | 171 |

| At the Fair | 179[6] |

| Hallowe’en | 187 |

| Measles | 195 |

| Something to be Thankful for | 203 |

| Taking a Dare | 210 |

| Dogs | 218 |

| The Last Indian | 226 |

| A Present for Mother | 234 |

| A Christmas Barring Out | 243 |

| A Vocabulary | 251 |

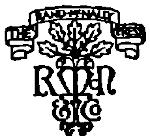

Grandma’s Room ready for the housewarming

Grandma had come to spend the winter, and Bobby and Alice and Pink were watching her fix up her room. It was the guest room, and the children had always thought it a beautiful room, with its soft blue rug, wicker chairs, and pretty cretonne draperies. But Grandma had had all the furniture taken out, and the rug, carefully rolled up and wrapped in thick paper to keep the moths out, had been carried to the attic.

Then Grandma—but Mother called Bobby and Alice and Pink to come and get their wraps and go out to play a while.

Grandma, seeing them edge reluctantly toward the head of the stairs, said cheerfully, as she bustled about unpacking the great box that held her “things,” “Never mind, dears. Run out and play now, and tonight we’ll have a regular housewarming. Come to my[10] room at seven o’clock and we will have a little party.”

Just as the clock in the hall downstairs struck the first stroke of seven, Alice rapped loudly on Grandma’s door.

Grandma opened the door immediately and the children stepped in—then stared in astonishment. They had never seen a room like this before. In place of the blue rug was a gayly colored rag carpet. The bed, to which had been added a feather tick, was twice as high as any they had ever seen. It was covered with a handmade coverlet of blue and white. Patchwork cushions were on the chairs, and crocheted covers on bureau and chiffonier. The windows were filled with blooming geraniums, and in one window hung a canary in a gilt cage. On a round braided rug before the fire lay a gray cat, asleep. By a low rocker stood a little table that held a work basket running over with bright-colored patches, bits of lace, balls of scarlet yarn, knitting needles, pieces of velvet, silk, and wool. On the chiffonier stood a basket filled with big, red apples, polished till they shone, and beside the apples was a plate covered with a napkin.

“Well, well,” said Grandma, “here you are, every one of you! Just on time, too. Come right in and see my house and meet my family. This is Betsy.” She touched the cat gently and Betsy lifted her head and started to purr. “I raised her from a kitten and brought her here in a basket all the way on the train. One conductor wouldn’t let me keep her in the coach with me, so I went out and rode in the baggage car with Betsy.”

“Did you bring the bird, too?” asked Pink, smoothing Betsy’s fur.

“No, I just got the bird a little while ago. He hasn’t even a name yet. I thought maybe I’d call him Dicky. That’s a nice name for a bird, don’t you think so? My baby sent me the bird and the flowers, too. Aren’t they lovely?”

“Have you a baby, Grandma?” asked Alice, looking around the room wonderingly.

“Yes, I have a baby, but he isn’t little any more. Still he is my baby all the same, the youngest of my ten children. Wasn’t it thoughtful of him to send me the bird and the flowers?”

Alice and Bobby and Pink looked at one another. They knew their daddy had sent[12] the flowers, for they had heard Grandma thank him for them. The idea of their big, broad-shouldered daddy being anyone’s baby seemed funny to them, and they giggled.

“Say, Grandma, he’s some baby, all right,” Bobby remarked.

“You can’t rock him to sleep the way I do my baby,” observed Pink.

“Not now, but I used to,” said Grandma. Then she brought three stools from the corner—low, round stools covered with carpet. “You children sit on these stools and I’ll sit in this chair and we’ll spend the evening getting acquainted. You must tell me all about yourselves.”

The children told Grandma about their school and their playmates, their dog and their playhouse, about how they went camping in summer time and what they did on Christmas and Easter, and about the flying machine that flew over the town on the Fourth of July, and about the Sunday school picnic. When they finally stopped, breathless, Grandma looked so impressed that Bobby said pityingly, “You didn’t have so many things to do when you were little, did you, Grandma?”

“Well, now, I don’t know about that,” Grandma answered slowly. “We didn’t have the same things to do, but we had good times, too.”

“Tell us about them,” Alice begged.

“When I was a little girl,” Grandma began, “I lived in the country on a large farm. All around our house were fields and woods. You might think I would have been lonely, but I never was. You see, I had always lived there. Then I had six older brothers and sisters, and one brother, Charlie, was just two years older than I was. And there were so many things to do! The horses to ride to water and the cows to bring from the pasture field. On cool mornings Charlie and I would stand on the spots where the cows had lain all night, to get our feet warm before starting back home. I had a pet lamb that followed me wherever I went, and we had a dog—old Duke. He helped us get the cows and kept the chickens out of the yard and barked when a stranger came in sight. And when the dinner bell by the kitchen door rang, how he did howl!

“And the cats! You never saw such cats, they were so fat and round and sleek. No[14] wonder, for they had milk twice a day out of a hollow rock that stood by the barnyard gate.

“And birds were everywhere. Near the well, high in the air, fastened to a long pole, was a bird house. Truman and Joe had made it, and it was just like a little house, with tiny windows and doors and a wee bit of a porch where the birds would sit to sun themselves.

“Then there were the chickens to look after, often a hundred baby chicks to feed and put in their coops at night. And in the spring what fun we had hunting turkey hens’ nests! In February we tapped the sugar trees and boiled down the sap into maple sugar and sirup. We had Easter egg hunts and school Christmas treats, and in the fall we gathered in the nuts for winter—chestnuts, hickory nuts, walnuts.”

Grandma paused a moment and glanced at the clock on the mantel.

“Dear me,” she exclaimed in surprise, “see what time it is! We must have our refreshments right away. Bobby, will you pass the apples? And, Alice, under the napkin are some ginger cookies that I brought with me. You may pass them, please, and Pink and I will be the company.

“These apples,” went on Grandma, helping herself to one, “are out of my orchard. I sent two barrels of them to your daddy, and every night before we go to bed we will each eat one. ‘An apple a day,’ you know, ‘keeps the doctor away.’”

When they had finished and were saying good night, Bobby said, “Lots of things did happen when you were a little girl, Grandma. I wish you’d tell us more.”

“Not tonight,” said Grandma, “It’s bedtime now, but come back some other night. If you still want me to tell you more about when I was a little girl, tap on my door three times, like this, but if you only come to call, tap once, like this.”

Next time we’ll see how often they tapped on Grandma’s door. Can you guess?

The next evening as Grandma sat before the fire knitting on a red mitten, she was startled by three sharp knocks on her door.

“Why, good evening,” she said, when she had opened the door to admit Bobby and Alice and Pink. “Here you are wanting a story, and I haven’t thought of a thing to tell you. Now you tell me what happened at school today, and by that time I shall have thought of something to tell you.”

So Alice told Grandma about chapel that morning. She told her about the recitations and songs by the children and of a lady who had whistled “The Star-Spangled Banner” and “America.”

“Well, well, wasn’t that nice!” Grandma said. “I should have liked to hear that. I always admired to hear any one whistle. I believe I’ll tell you tonight about the time I whistled in meeting.”

The children drew their stools a little closer, and Grandma began:

“When I was a little girl, I wanted more than anything else to be able to whistle. I[17] kept this ambition to myself because it wasn’t considered ladylike for girls to whistle. My mother often said,

“So I never told anyone, not even my brother Charlie, that I wanted to whistle. But when I hunted turkey hens’ nests, or went after the cows, or picked berries, I had my lips pursed all the time trying to whistle as my brothers did. But, though I tried and tried, I never succeeded in making a sound.

“One Sunday in meeting I got awfully tired. To a little girl the sermons were very long and tiresome in those days. For a while I sat still and quiet, watching Preacher Hill’s beard jerk up and down as he talked and looking at the queer shadows his long coat tails made on the wall. But it was warm and close in the church, and after a while I grew drowsy.

“‘Oh, dear!’ I thought to myself, ‘I mustn’t go to sleep. I must keep awake somehow.’ Then I thought about whistling. I would practice whistling to myself—under my breath.

“The seats were high-backed and we sat far to the front. I could not see any one[18] except the preacher and John Strang, who kept company with sister Belle. John sat in a chair at the end of the choir facing the congregation, and several times I noticed him looking curiously at me as if he wondered what I was doing. I would draw in my breath very slowly and then let it out again. Of course I never dreamed of making a sound, and no one could have been more surprised than I was when there came from my lips a loud clear whistle as sweet as a bird note.

“The preacher stopped talking. Mother looked embarrassed. Father’s face turned red with mortification. Sister Belle put her handkerchief up to her face, and Charlie sat up as straight and stiff as if he had swallowed a ramrod.

“As for me, I wished I could sink through the floor and disappear. I thought everybody was looking right at me. I was sorry and I was frightened, too. What would Father and Mother say to me?

“When preaching was over, all of us except Mother went right out to the sled and wrapped up in comforts and robes for the cold ride home. Mother stayed behind to visit and invite people home to dinner just as she[19] always did. I was glad when we started. It was a dreary ride. Father drove, and he sat so stern and silent that no one dared to speak.

“I drew in my breath very slowly and then let it out again”

“I hurried right upstairs to change my dress as I always did. Then, because I was so miserable, I threw myself across my bed and cried. I had disgraced Father and Mother. Nothing that they could do would be bad enough for me. I was aroused by sister Belle’s voice. She was complaining to sister Aggie, who had stayed at home to get dinner.

“‘I don’t see why Charlie can’t behave himself once in a while. Now our whole day[20] is spoiled, and I had asked John and Isabel for dinner, too. You know how sad it always makes Father if he has to punish one of the boys, and the worst of it is that Charlie denies doing it. I could shake Charlie good myself. You can’t believe, Aggie, how everyone looked at us. I was that ashamed!’

“Charlie being accused in place of me! This was something that I had never dreamed of. I jumped up and rushed past the two girls downstairs, through the empty sitting room into the kitchen, where Mother stood looking out a window, still in her gray silk dress. I caught her hand.

“‘Charlie didn’t do it, Mother,’ I said. ‘I did it.’

“‘Oh, Sarah, you cannot whistle, dear,’ said Mother reproachfully. She drew me to her and smoothed my hair and tried to comfort me, but I broke away from her and ran into the kitchen chamber where Father sat talking to Charlie. Father looked stern and Charlie sulky and cross, and no wonder, poor boy, for he was guilty of enough things without being accused of something he did not do.

“‘Father!’ I cried wildly. ‘Charlie did not whistle in meeting. I did it.’

“Mother and the girls had followed me, and they all, even Charlie, stared at me in amazement. It was plain they did not believe me. They thought I was trying to shield Charlie.

“‘I did whistle,’ I said, crying. ‘I can whistle. I tell you I can whistle.’

“‘Then whistle,’ said Father sternly.

“And how I did try to whistle! I puffed my cheeks and twisted and turned my mouth and blew and blew, but I couldn’t make a sound, not a single sound.

“Father looked so hurt and sorry that I longed to throw myself into his arms and make him believe me. You see, it looked to Father as if Charlie and I were both telling stories. Father said we were only making things worse and ordered us all out of the room.

“In the sitting room we found Truman and Joe, who had been tending the horses, and John and Isabel Strang, who had come around past their house to let their family out of the sled before coming on to our house for dinner.

“The minute I saw John I drew Mother’s head down and whispered to her, ‘Ask John. He knows, he saw me do it;’ and Mother in a[22] hesitating way said, ‘John, do you know who whistled in meeting this morning?’

“John turned as red as our old turkey gobbler and looked at me.

“‘Why, I feel pretty sure,’ he said, ‘but I’d hate to say.’

“‘Oh, never mind that!’ I burst out. ‘I’ve told, and they won’t believe I can whistle. They think it was Charlie.’

“Then, of course, John told all he knew. He had been watching me all the time, as I had thought, and was looking right at me when I whistled. Father was called in, and you may be sure he was glad to find that both his children had been telling the truth.

“‘It’s all right, Sarah,’ he said, ‘if you didn’t mean to.’ But Mother made me promise not to try to whistle any more.

“Well, I declare! I finished just on time. Mother’s calling you to bed. Here, don’t forget your ‘apple a day.’ Now run along like good children, and some other time I’ll tell you another story.”

“Seems to me you kiddies go to bed earlier than you used to,” their father remarked one evening when Bobby and Alice and Pink interrupted his reading to kiss him good night.

“We don’t go to bed,” Pink explained. “We go to Grandma’s room. She tells us a story every night.”

“Why, of course, I remember now. Isn’t that fine, though? A story every night! Did she ever tell you a wolf story? Grandma knows a pippin of a wolf story. She used to tell it to me when I was a little boy. Ask her to tell you about the time she was chased by wolves.”

And a few minutes later Grandma began the story.

“It was in the spring. Father was making garden, and he broke the hoe handle. All the boys were away from home helping a neighbor, so Father wanted Aggie or Belle to take the hoe to have a handle put in at the blacksmith shop at Nebo Cross Roads a mile away. But the girls were getting ready to[24] go to a quilting, and I begged to be allowed to take the hoe to the blacksmith shop.

“Mother was afraid at first, but Father said there was nothing to hurt me, and Mother finally gave in. So right after dinner, carrying the hoe and a poke of cookies to eat if I got hungry, I started out.

“I was to leave the hoe at the shop and go on down the road to Strangs’ to wait till the hoe was mended. I can remember yet how important I felt going off alone like that. I picked wild flowers and munched cookies and sang all the songs I knew.

“Mr. Carson, the blacksmith, said it would be a couple of hours before the hoe would be ready, and I went down to Strangs’ to wait. But when I got there I found the house all locked up and no one at home. I sat down on the steps to wait for some one to come, but the heat and the quiet made me sleepy so I got up and moved around the yard. I was lonely there by myself. I walked around looking at the flowers and the garden and the chickens and played a while with a kitten I found sleeping in the sun. I thought that afternoon would never end. Surely I had been there two hours. I started for the blacksmith shop. Maybe it[25] would be closed. I ran all the way. Mr. Carson looked surprised when I asked for the hoe.

I played a while with a kitten

“‘Why, it’s only been a half-hour since you went away,’ he said.

“I went back to Strangs’, and this time I was determined to wait a long time. After a while Isabel Strang came home. She had been at the quilting, but all the rest of the family had gone away to stay several days. Isabel was going to our house to spend the night if she got through the evening’s work in time. She had come past our house, and Mother had told her to keep me all night[26] with her for company if she could not get back before dark and to send me home early in the morning.

“Isabel hurried, and while she milked the cows and fed the pigs and chickens and got supper I went after the hoe.

“It was growing late when we were ready to start home, but Isabel said we could make it before dark.

“We followed the road half a mile and then took a short cut through the woods up Sugar Creek. We had come out of the woods and were halfway across a big pasture field when from behind us we heard a sound that made us stop in terror. We listened. It came again. It was the cry of a wolf! I had often heard a wolf howl, but I had always been safe at home, and even then it had scared me.

“Again and again came the long drawn-out howl from the woods we had just left.

“Isabel took my hand and we ran as fast as we could toward the little creek that ran through the field. It had been years and years since a pack of wolves had been seen in our neighborhood, but before we reached the foot-log another howl and another and another had been added to the first.

“Looking back over my shoulder as I ran, I saw a skulking form come out of the woods and start across the field. Isabel saw it, too.

“‘We’ll have to stop, Sarah,’ she said. ‘We’ll have to climb a tree.’

“There was a slender young hickory a little this side of the run. Isabel lifted me as high as she could and I caught a branch and pulled myself up into the tree. I turned to help Isabel when, to my horror, I saw that she could never make it. A whole pack of wolves loping across the field were almost upon her.

“Catching up the hoe, Isabel ran for the foot-log. She had barely reached the middle of it when the wolves halted at the creek bank. A few of them had stopped at my tree and were howling up at me. If all had stopped, it would have given Isabel a chance to get into one of the trees on the other side of the creek.

“But she couldn’t do it now. She walked back and forth on the log, brandishing the hoe in the cruel eyes of the wolves. The wolves that had stopped under my tree soon joined their friends on the bank, and Isabel called out to me, ‘Do not make any noise, Sarah, and they will forget you are there.’ I remembered hearing my father tell about some[28] wolves that had gnawed a young tree in two, and I clung there in fear and trembling.

“Isabel held her own all right until one of the bolder wolves swam across the creek and was soon followed by others. Then Isabel had to fight them at both ends of the foot-log. It was dark now, and Isabel, striking at the wolves from first one side and then the other, tried to cheer me up all the time.

“‘Help will soon come, don’t be afraid,’ she said over and over again. She even tried to make me laugh by saying, ‘Now watch me hit this saucy old fellow on the nose. There, that surprised you, didn’t it, Mr. Wolf?’ as she hit him a sharp blow and he fell back.

“What if the wolves should leap on Isabel? Or she might get dizzy and fall in the water. When would help come to us in this lonely, out-of-the-way place? My folks would think I had stayed the night with Isabel, and there was no one at home at Isabel’s.

“Dared I get down and go for help? I peered through the darkness and shook all over when I thought that more wolves might be hidden there. Hardly knowing what I did, I let myself down to the lower limb and then dropped with a soft thud to the ground.

“Without waiting a second I started back the way we had come. How I ran and ran! I was nearly through the woods when I heard something running behind me. I went faster and it went faster, too. Suddenly I tripped and fell and I heard a friendly little whinny at my side. It was our pet colt that had been running behind me. I put my arm around his neck for a second until I got my breath. Then I climbed the fence and was on the road.

“I wasn’t quite so afraid here as I had been in the woods, but I never stopped running till I got home. I was so worn out that I fell panting on the kitchen floor, but I made them understand Isabel’s danger. Father and the boys caught up their guns and went hurrying across the hill to her aid.

“They drove the wolves away and brought Isabel home in safety, and that was the last pack of wolves ever seen around there.

“Well, well, see what time it is! Now run along to bed and go right to sleep without talking the least little bit, or I’m afraid Mother won’t let you come to see me tomorrow evening. That would be a pity, for I’ve got the best story for tomorrow evening about—well, you just wait and see.”

The next evening when the children came to Grandma’s room Bobby brought his new sweater—black with broad yellow stripes—to show her.

“Yellow,” said Grandma admiringly. “I always did like yellow, it’s such a cheerful color. The first really pretty dress I ever had was yellow.

“It was just about this shade, maybe a mite deeper—more of an orange color. It was worsted—a very fine piece of all-wool cashmere. Until then I had never had anything but dark wool dresses—browns or blues made from the older girls’ dresses—and I did love bright colors.

“Sister Belle was to be married in the spring and all winter Mother and Belle and Aggie had sewed on her new clothes. Nearly everything was ready but the wedding gown, and it was to be a present from Father’s younger sister, Aunt Louisa, who lived in Clayville.

“Belle was delighted, because she said Aunt Louisa would be sure to pick something new and stylish.

“My big brother, Stanley, went to Clayville one cold, snowy day in February, and Aunt Louisa sent the dress goods out by him. I remember we were at supper when he came. I had the toothache and was holding a bag of hot salt to my face and trying to eat at the same time.

“Mother ran to take Stanley’s bundles and help him off with his great-coat, and Aggie set a place at the table for him. But before he sat down he tossed a package to Belle. ‘From Aunt Louisa,’ he said.

“Belle gave a cry of delight and tore the package open. Then suddenly the happy look faded from her face. She pushed the package aside and, laying her head right down on the table among the dishes, she burst into tears.

“Aunt Louisa had sent Belle a yellow wedding dress!

“When Mother held it up for us to see, I thought it was the most beautiful color I had ever seen and wondered why Belle cried. I soon learned.

“Belle had light brown hair and freckles, and yellow was not becoming to her. To prove it, she held the goods up to her face.

“‘It does make your hair look dead and sort of colorless,’ Aggie agreed.

“‘And your freckles stand out as if they were starting to meet a fellow,’ Charlie put in.

“At this Belle began to cry again, and Father said that she did not have to wear a yellow dress to be married in if she didn’t want to. She should have a white dress. But this didn’t seem to comfort Belle a bit, for she declared that she wouldn’t hurt Aunt Louisa’s feelings by not wearing the yellow.

“My tooth got worse, and for the next few days I could think of nothing else. Mother poulticed my jaw and put medicine in my tooth, but nothing helped it. I cried and cried and couldn’t sleep at night, and Mother couldn’t sleep. At last she told Father that he would have to take me to Clayville to have the tooth pulled. There was fine sledding, and early the next morning Father and I set out. The last thing Mother said to Father, as she put a hot brick to my feet and wrapped me, head and all, in a thick comfort, was, ‘As soon as the tooth is out, John, take her over to Louisa’s till you get ready to start home.’

“The roads were smooth as glass, Father was a fast driver, and it didn’t seem long till we got to town. My tooth was soon out—it hardly hurt at all—and then Father took me to Aunt Louisa’s. We all liked Aunt Louisa. She was very fond of children and had none of her own.

The roads were smooth as glass, Father was a fast driver

“After dinner we sat by the sitting-room fire and Aunt Louisa cut paper dolls out of stiff writing paper for me and made pink tissue paper dresses for them. The dresses were pasted on. I could not take them off and put them on as Alice and Pink do theirs.

“As she worked, Aunt Louisa asked me about everything at home and about Belle’s clothes and the wedding.

“‘Has she got her wedding dress made yet?’ she asked.

“‘No, ma’am’, I replied, ‘she says she can’t bear to cut into it. She hates the very sight of it.’

“‘Well, I declare!’ exclaimed Aunt Louisa in surprise.

“‘It doesn’t become her,’ I explained carefully. ‘She says it makes her look a sickly green.’ And then I went on to tell Aunt Louisa everything they had all said, and ended up with, ‘Belle says she won’t hold John to his promise to marry her until he has seen her in that yellow dress.’

“‘What does she wear it for if she doesn’t like it?’ asked Aunt Louisa tartly.

“‘Father said she didn’t have to wear it if she didn’t want to, that if she wanted to be married in white, he’d get her a white dress. But Belle said she wouldn’t hurt your feelings by not wearing it for anything in the world.’

“Suddenly Aunt Louisa began to laugh. She threw her head back and laughed and[35] laughed and laughed. I didn’t know what to make of her.

“‘I think it’s a beautiful color,’ I said consolingly.

“‘And you could wear it, too, with your dark hair and eyes and fair skin. What was I thinking about to send a color like that to poor Belle? I’ll tell you!’ she cried, jumping up and letting my paper dolls fall to the floor. ‘I’ll buy another dress for Belle, and you shall have the yellow one, Sarah.’

“She left me in the kitchen with Mettie, the hired girl, while she went over town. Mettie was baking cookies, and she let me dust the sugar on and put the raisins in the middle and I had a real nice time.

“The second dress was white cashmere with bands of pearl trimming and wide silk lace for the neck and wrists.

“When Aunt Louisa kissed me good-by, she whispered in my ear, ‘Tell Belle the trimming is because she was so thoughtful about hurting my feelings and I want her to look her best on her wedding day. And, Sarah, tell your mother to make up the yellow for you with a high shirred waist and low round neck. That is the newest style for[36] children. And be sure to tell her I said not to dare put it in the dye pot.’

“As soon as we got home I gave the new dress to Belle. Mother was astonished, and Belle looked ready to cry again, till Father told them Aunt Louisa wasn’t offended at all. Then Mother was pleased, and Belle was simply wild about the new dress.

“‘Take the yellow and welcome to it, Sarah,’ she said to me when I had told her Aunt Louisa wanted me to have it.

“‘I’ll have to color it,’ Mother said, ‘She couldn’t wear that ridiculous shade.’

“‘No, no, Mother, please don’t!’ I cried. ‘Aunt Louisa said not to dye it. She said it would become me the way it is.’

“‘Tush, tush!’ said Mother severely, ‘You are too little to talk of things becoming you.’ But she didn’t dye it, and a few weeks later at sister Belle’s wedding I wore the yellow dress made just the way Aunt Louisa said to make it.

“And now, ‘To bed, to bed, says sleepy head,’ and we’ll have another story some other night.”

“Well, well,” said Grandma one evening when Bobby and Alice and Pink came to her room for their usual bedtime story, “I don’t know what to tell you about tonight.”

“Tell us a war story,” suggested Bobby eagerly.

“Maybe I might tell you a war story,” agreed Grandma, “a war story of a time long ago.” And she picked up her knitting and began slowly:

“When the Civil War broke out I was a very little girl. Of course there had been lots of talk of war, but the first thing I remember about it was when we heard that Fort Sumter had been fired on. It was a bright, sunshiny morning in the spring. I was helping Father rake the dead leaves off the garden when I saw a man coming up the road on horseback. I told Father, and he dropped his rake and went over to the fence. In those days it wasn’t as it is now. News traveled slowly—no telephones, no trains, no buggies. And this young man, who had been to Clayville to get his marriage license,[38] brought us the news that Fort Sumter had been fired on.

“Father went straight into the house to tell Mother, and after a while he and my big brother, Joe, saddled their horses and rode away. I thought they were going right off to war and started to cry, and then I laughed instead when our big Dominique rooster flew up on the hen-house roof, flapped his wings, and crowed and crowed. A great many men and boys rode by our house that day on their way to Clayville, and when Father and Joe came back next day Joe had volunteered and been accepted and he stayed at home only long enough to pack his clothes and say good-by to us.

“There wasn’t much sleep in our house that night, and I lay in my trundle-bed, beside Father’s and Mother’s bed, and listened to them talking, talking, until I thought it must surely be morning. I went to sleep and wakened again and they were still talking. Finally I could hear Father’s regular breathing and knew that he had gone to sleep at last. In a little bit Mother slipped out of bed and went into the hall. I thought she was going for a drink and followed her,[39] but she went into Stanley’s room, which had been Joe’s room, too, until that night.

“Mother bent over Stanley and spoke his name softly and he wakened and started up in bed.

“‘What is it, Mother?’ he whispered, frightened.

“‘Stanley,’ Mother said slowly, ‘I want you to promise me that you won’t go to war without my consent.’

“Stanley laughed out loud in relief.

“‘Gee, Mother, you gave me a scare!’ he said. ‘I thought some one was sick or something. The war’ll be over long before I’m old enough to go.’ He was going on sixteen then.

“‘It won’t do any harm to promise then,’ Mother persisted, and Stanley promised.

“I crept back to bed and pulled the covers up over my head.

“But Stanley was mistaken about the war being over soon. The war didn’t stop. It went on and on. Two years and more passed, and Stanley was eighteen. Boys of that age were being accepted for service, but Stanley never said a word about volunteering.

“Shortly after his eighteenth birthday there came a change in him. He was not[40] like himself at all. He had always been a lively boy, full of fun and mischief, but now he was very quiet. He never mentioned the war any more, and often dashed out of the room when every one was talking excitedly about the latest news from the battlefield. He avoided the soldiers home on furlough, didn’t seem to care to read Joe’s letters, and as more and more of his friends enlisted he became gloomy and downhearted.

“We could all see as time went on that Father was disappointed in Stanley. He was always saying how much better it was for a young man to enlist than to wait for the draft. The very word ‘draft’ had for Father a disgraceful sound.

“I think Mother must have thought it was Stanley’s promise to her that was worrying him, for one day she came out to the barn where Stanley was shelling corn and I was picking out the biggest grains to play ‘Fox and Geese’ with. Mother told Stanley she released him from his promise, but he didn’t seem glad at all. He only said, ‘Don’t you worry, Mother, I’m not going to war.’

“‘I was troubled about Joe that night,’ Mother said. ‘I thought I couldn’t bear[41] for you to go, too. But you are older now and you must do what you think best.’

One day two recruiting officers came out to Nebo Cross Roads

“As Mother went out of the barn there were tears in her eyes and I knew in that moment that she would rather have Stanley go to war than have him afraid to go.

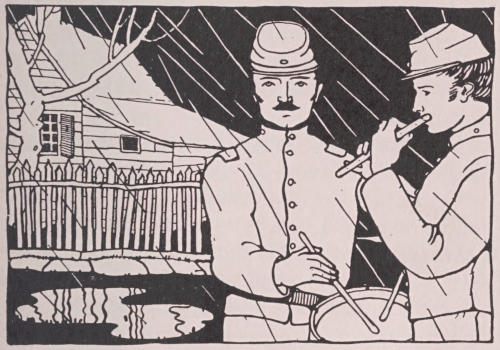

“They were forming a new company in Clayville, and one day two recruiting officers came out to Nebo Cross Roads. Father let Truman take Charlie and me over to see them. It was raining, and I can see those two men yet standing there in the rain. One had a flute and the other had a drum. They[42] played reveille and taps and guard mount and ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ and a new song we had never heard before, ‘Tenting on the Old Camp Ground.’ And how that music stirred the folks! They had to use two wagons to haul the recruits into Clayville that night.

“That evening when I was hunting eggs in the barn I found Stanley lying face down in the hay. He was crying! I could hardly believe my eyes. I went a little nearer and I saw for sure that his shoulders were shaking with sobs. But even while I watched him he got to his feet and began rubbing his right arm. I often saw Stanley working with his arm. He would rub it and swing it backward and forward and strike out with his fist as if he were going to hit some one a blow. He didn’t mind me watching him, and I never told anyone about it. He had broken that arm the winter before, and I had often seen him working with it after he had stopped wearing it in a sling.

“I wondered to myself why, if Father and Mother thought Stanley was afraid to fight, they did not ask him and find out. He knew why he didn’t enlist—he could tell[43] them. At last I decided if they wouldn’t do it themselves I’d do it for them. So the next time I was alone with Stanley, I said, ‘Stanley, are you afraid to go to war?’

“‘Afraid!’ he cried angrily, ‘Who said I was afraid?’ Then his tone changed. ‘They don’t want me. They won’t have me. It’s this arm,’ and he held his right arm out and looked at it in a disgusted sort of way. ‘They claim it’s stiff, but I could shoot if they would only give me a chance. I’ve tried three times to get in, but there’s no use worrying Mother about it since I can’t go. But my arm is getting better. It’s not nearly as stiff as it was. I’ll get in yet.’ Then he looked at me scornfully and said, ‘Afraid! Afraid nothing!’

“I ran as fast as ever I could to find Father and Mother and tell them. Mother hugged me and laughed and cried at the same time and said she always knew it, and Father made me tell over to him three times, word for word, every single thing Stanley had said.

“‘He must never know,’ Mother said. ‘He must never suspect for a minute that we thought he didn’t want to go, the poor dear boy, keeping his trouble to himself for[44] fear of worrying us.’ And she told me to get Charlie and catch a couple of chickens to fry for supper. Then I knew she was happy again, for whenever Mother was happy or specially pleased with one of us she always had something extra good to eat.

“Pass the apples, Alice, please, and tomorrow night if you’re real good and don’t get kept in at school I’ll tell you—well, you just be real good and you’ll see what I’ll tell you about.”

It was the night before Easter. Grandma had told Bobby and Alice and Pink of the first Easter, and had explained about the egg being the symbol of life because it contains everything necessary for the awakening of new life.

“When I was a little girl,” she said, “we had lots of chickens and of course we had lots of eggs. We got so many eggs that we could not use them all—not even if Mother made custards and omelets and angel cake every day.

“Father or the boys would take the eggs we did not need to the store and trade them for sugar or coffee or pepper or rice. But for quite a while before Easter they did not take any eggs to the store.

“It was a custom for the children to hide all the eggs that were laid for a couple of weeks before Easter. Father and Mother had done it when they were little, and all the boys and girls who went to our school did it, too. We would bring them in Easter morning and count them. Each of us might[46] keep the eggs we found to sell, and Father always gave a fifty-cent piece to the one who had the most eggs. Even the big boys and Aggie and Belle hid eggs, for money was scarce and sometimes the egg money amounted to a good deal. We were allowed to keep all the eggs we found, no matter to whom they belonged and how we hunted.

“We searched in the hen house, the barn, the haymow, in old barrels and boxes, in fence corners, and even in the wood-box behind the kitchen stove. One spring a brown leghorn hen slipped into the kitchen every other day and laid in the wood-box. You never could tell where a hen might lay, so we looked every place we could think of.

“It was an early spring. The trees were bursting into leaf, the grass was green, the beautiful yellow Easter flowers in the front yard were in bloom. Best of all, the hens had never been known to lay so many eggs before.

“It seemed that every one of us wanted something that the egg money would buy. Truman was going away to school, and he wanted books. Belle was going to be[47] married, and she wanted all the money she could get for pretty clothes. Stanley wanted a new saddle for his courting colt. When the boys turned eighteen, Father gave each one of them a colt to tame and break and have for his own, and they were called the courting colts. I wanted the egg money for a lovely wax doll like one I had seen in a store in Clayville, and if Charlie got it he meant to spend it for a gun. Aggie wanted to buy a pair of long lace mitts to wear to Belle’s wedding. So we all hunted and hunted, each one thinking of what he would buy with the money.

“Once for three days I didn’t have an egg. Then I found a great basketful that was so heavy I could hardly carry it to a new hiding place, and the next day it was gone. So it went on till Easter.

“Charlie and I were up bright and early on Easter morning—not as early as on Christmas, of course. As we all brought in our eggs Father counted them. The kitchen floor was covered with baskets and buckets and boxes of eggs. You never saw so many eggs. Charlie had the most, and he was as happy as happy could be.

“While Mother and the girls finished getting breakfast, Charlie and I hunted for the colored eggs. Under beds, behind doors, in the cupboards, all over the house we hunted.

“‘Here they are!’ shouted Charlie from the spare chamber. And there they were behind the bureau—red eggs, blue eggs, green eggs, big sugar eggs, and eggs with pretty pictures pasted on them and tied with gay ribbons. And there were white eggs that looked just like common hen’s eggs, but when you broke a tiny bit of the shell and put your tongue to it, my, oh my! but that maple sugar was delicious!

“After breakfast there was a rush to get the work done and get ready for meeting. Dear knows how many people would come home to dinner with us. Mother always asked everyone home to dinner.

“We were nearly ready. Mother had picked the lovely, yellow Easter flowers and was wrapping the stems in wet paper to keep them from wilting till we got to the church—she meant to put them in a vase on the pulpit stand—when Father came in and said that the widow Spear’s new house had[49] burned down in the night. There was something the matter with the chimney, no one knew just what.

“Mr. Abraham Harvey had told Father. The Spear family had taken refuge in a little old house that they had lived in before they built the new house. But of course they had nothing to keep house with, and Mr. Harvey was going around in a big wagon collecting things. There were some pieces of old furniture in the wagon, and several bundles of bedclothes and a box of dishes.

“Father gave flour and meat and potatoes and a ham. Mother emptied the shelves of our Easter pies and took the chicken in the pot right off the stove, besides giving bread and a crock of apple butter.

“Then she wrapped up a pair of blankets she had woven herself and sent Charlie and Truman to carry out some chairs and a bedstead that were up in the meathouse loft. Belle and Aggie were sorting out some old clothes to send, and I wanted to do something, too.

“As I was going through the kitchen on an errand for Mother, I noticed the eggs. Such a lot of them—nearly fifty dozen, and[50] they brought ten cents a dozen. Just then Charlie passed the door carrying a chair, and I called to him.

“‘Charlie,’ I said, ‘would you give your egg money if I gave mine?’

“‘No,’ he said at once, ‘I won’t give my egg money. Not on your life, I won’t! Father and Mother’ll give enough,’ and he went out.

“I didn’t say any more about the egg money. I didn’t think it would be fair to Charlie, since he was the one who had the most eggs. I went upstairs to Mother’s room and took my gold breastpin out of the fat pincushion on her bureau.

“‘Here is my breastpin, Mother,’ I said. ‘Send it to Millie. Everything she’ll get will be so plain and ugly.’

“Aggie and Belle laughed.

“‘A breastpin,’ said Aggie, ‘when very likely she has no dress!’

“‘It’s all right, Sarah,’ said Mother, and she went to her bureau drawer and took out a fine linen handkerchief and laid it on the bed beside the breastpin. When she came to get them, Aggie had given a carved back comb and Belle a pretty lace collar.

“Mr. Harvey was starting his horses and Father had come inside the gate when Charlie ran around the house.

“‘Give them my egg money, Father!’ he called and ran out of sight again. Then all the rest of us said we would give our egg money, too, and it made a lot—over five dollars.

“‘I’m proud of you,’ Mother said when she had hunted Charlie up and was tying his necktie. ‘I’m proud of every one of my children.’

“We were a little late to meeting, and when we got home Belle had dinner ready—ham meat and cream gravy and mashed potatoes and hot biscuits. Mother brought out a plate of fruit cake that she kept in a big stone jar for special occasions—the longer she kept it the better it got—and a dish of pickled peaches for dessert.”

“Mm! mm! Wish I’d been there,” sighed Bobby.

“And next time,” Grandma went on, “I think—yes, I’m pretty sure—that I’ll tell you how the maple sugar got in the Easter eggs.”

“Grandma,” said Alice the next evening, “you said you’d tell us how the sugar got in the Easter egg.”

“And so I will,” answered Grandma. “I’ll tell you about that this very evening. Where’s my knitting? I can talk so much better when I knit. There now, are you all ready?”

Bobby and Alice and Pink drew their stools closer and Grandma began:

“On my father’s farm, about half a mile from our house, was a grove of maple trees. We always called them sugar trees. In the spring, you know, the sweet juice or sap comes up from the roots into the trees, and it is from this sap that maple sirup and sugar are made. In the spring Father and the boys would tap our sugar trees. They would take elder branches and make spouts by removing the pithy centers. Then they would bore holes in the trees and put the spouts in the holes and place buckets underneath to catch the sap. These buckets would have to be emptied several times a day[53] into the big brass kettle, where it was boiled down into sirup and sugar.

“Truman tended to the sap buckets and kept a supply of firewood on hand, and Stanley watched the boiling of the sap. He knew just when it was thick enough and sweet enough to take off for sirup and how much longer to cook it for sugar. One of the girls was always there to help, and Father or Mother would oversee it all.

“There was a one-roomed log cabin with a great fireplace in the maple grove. It had been built years and years before by some early settler and was never occupied except during sugar-making time. The girls would go up the week before and clean it out, and Mother would send dishes and bedclothes for the two rough beds built against the wall. The ones making and tending the sirup would camp up there.

“Mother would send butter and bread and pies, and the girls would boil meat or beans in a black iron pot that hung over the fire. In the evenings they would have lots of fun sitting in front of the fire, telling stories and popping corn. Sister Aggie could make the best popcorn balls that were put[54] together with maple sirup. They would often have visitors, too, neighboring boys and girls who would come in to stay until bedtime. And there would be songs and games.

“And they would make the sugar eggs for Easter. Before sugar time came we would blow the contents out of eggs by making little holes in each end. Then we would dry the shells and put them away. When they were taking off the maple sugar, Mother or Belle or Aggie would fill the egg shells and set them aside for the sugar to cool and harden. They would fill goose-egg shells with the maple sugar, too, and when the sugar hardened they would pick the shell off, and by and by the girls would paste pretty pictures of birds or flowers on them and tie them with gay-colored ribbons for Easter.

“Neither Charlie nor I had ever been allowed to stay all night at the sugar camp, and when Mother said we could stay one night with Stanley and Truman and Belle we were wild with joy.

“Truman had shot and cleaned three squirrels that morning, and Belle cooked[55] them in the big black pot with a piece of fat pork until the water boiled off and they sizzled and browned in the bottom of the pot. We had little flat corn cakes baked on the hearth and maple sirup, and, my, but that supper tasted good to me!

“I dried the dishes for Belle, and we had just settled down for the evening when one of the Strang boys came in. He didn’t know we children were there, and he had come up to see if Stanley and Truman and Belle would go home with him to a little frolic. His sister Esther had been married a few days before and had come home that afternoon, and they were going to have a serenade for them. Belle and the boys wanted Charlie and me to go down to the house so they could go, but we wouldn’t do it. We declared we were not afraid to stay by ourselves and told them to go on. Finally they did.

“Charlie and I didn’t mind being left alone at all. We thought it was great fun. For a while we played we were pioneers. Then Charlie got tired of that and wanted to play Indian, so we played Indian for a long time. But we had been out all day in[56] the cold, and after a while we got sleepy and decided to go to bed. I went to the window to see if Belle and the boys were coming. There was a moon, and I could see the trees with their spouts and the buckets under them. I looked closely. At one of the buckets was a black shadow. I looked and looked at it and just then it moved a little.

“‘Charlie,’ I cried excitedly, ‘Brierly’s old black dog is out there drinking up our sap!’

“Charlie gave one hurried glance out the window, then he picked up a stick of firewood and opened the door.

“‘I bet I give that dog a good scare,’ he said, and rushed out the door and made straight for the black shadow. He raised the stick and brought it down ker-plunk on the back of what we thought was Brierly’s dog. But it wasn’t Brierly’s dog at all, nor anybody’s dog. It was a bear! I don’t know which was the most surprised, Charlie or the bear. Charlie darted back to the cabin, and when he reached the door he threw his stick with all his might and hit the bear on the nose. The nose is the bear’s[57] tenderest point, you know. Charlie must have hurt him, for he gave a growl, backed away from the sap bucket, and scampered up the nearest tree. Maybe he meant to wait a while and come back for more sap, I don’t know. Anyway, up the tree he stayed while Charlie and I watched him through the window.

Up the tree the bear stayed while Charlie and I watched him

“‘If we could only keep him up the tree till the boys come home from Strangs’ one of them could get a gun and kill him,’ said Charlie, ‘and we’d get the money for his pelt.’

“‘Father says wolves won’t come near a fire,’ I remarked, and that gave Charlie an idea. He would build a fire and keep the bear treed until the boys came.

“At first I wouldn’t agree to help him. I was too afraid. But Charlie coaxed and threatened and was getting ready to do it himself. So I helped him carry out the first burning log from the fireplace in the cabin. After that my part was to watch the bear and warn Charlie if he moved while Charlie built up the fire. Once as the fire grew warmer and the smoke got thicker and thicker the bear snorted and moved to a limb higher up.

“Charlie kept a roaring fire going, and it wasn’t long until Belle and the boys came rushing up all out of breath from running. They were nearly scared to death because they had seen the smoke and thought the cabin was on fire.

“At first they wouldn’t believe we had a bear treed. Truman said, ‘Whoever heard of a bear climbing a tree like that?’ But Stanley said nobody knew what a bear might do, and Charlie said that there was the bear all right, they could see for themselves.

“Truman went home and got his gun and shot the bear. It turned out to be a young bear. Father sold the pelt and divided the money between Charlie and me.

“Now, let me see, what shall I tell you about tomorrow night? Oh, I know! I’ve thought of something, but I won’t tell. No, indeed, not a word till tomorrow night.”

Grandma had been to church Sunday morning and heard for the first time the wonderful new pipe organ, and in the evening she was talking about it—how beautiful the music was, how solemn, how sacred.

“And when I think,” she said, “of the opposition there was to the first little organ we had in our church and of the trouble we had getting it—well, well, times certainly have changed.

“It was like this. Some of our people were bitterly opposed to organ music in church and right up till the last minute did everything they could to keep us from getting an organ. This made it very hard to raise money for the organ, but after a long time we got enough—all but about forty dollars. It was decided to have a box social to raise this.

“At a box social each girl or woman took a box containing enough supper for two people. Then the boxes were auctioned[61] off, and the men and boys bought them and ate supper with the girl whose box they got.

“Aggie and Belle trimmed their boxes with colored tissue paper and flowers and ribbon, but Mother just wrapped hers in plain white tissue paper and fastened a bunch of pinks out of the garden on top so Father would know it when it was put up to be sold. Father was going to buy Mother’s box, and I was going to eat with them. Charlie had money to buy a box for himself, and he said he meant to buy Aunt Livvy Orbison’s box because she always had so much to eat.

“Every one in the family was going, and there was a great rush and bustle to get ready. Mother cut Charlie’s hair and oiled it and curled mine. She scrubbed us till we shone, and at last, dressed in our best clothes, we started.

“Father and Mother and Belle and Aggie and I went in the surrey. All the boys walked over the hill, except Joe, who had gone to Clayville on business for Father that morning and was to stop at the church on his way home.

“It was a lovely warm evening, and there was a large crowd at the church when we got there, though it was early. The girls took their boxes in and then came right out again. Every one was having a splendid time, talking and laughing and visiting around.

“I was with Father. After a while I got tired hearing the men talk about the crops and the price of wool and the election, and I went to hunt Mother. I looked all around and I couldn’t find her. I thought maybe she had gone into the church, so I went in there to look for her, but there was no one in the church at all. The boxes had been piled on the pulpit and covered with a sheet so that no one could see them. Just as I was going out the door I noticed that the sheet was lying on the floor and the boxes were nowhere to be seen. I went on out and presently I found sister Belle. She was talking to John and Isabel Strang and Will Orbison.

“I tugged at Belle’s dress and pulled her to one side.

“‘What did they do with the boxes?’ I asked her.

“‘Why, they put them in the church, and after a while they will sell them,’ she said. ‘You run and find Mother now, like a good girl.’

“‘But the boxes aren’t on the pulpit,’ I whispered. ‘I was in the church hunting Mother, and the boxes are all gone and the sheet is lying on the floor.’

“Belle told the others, and they all went hurrying into the church, I following after. The boxes were gone, sure enough. The pulpit windows, which faced a strip of woods, were open. The boys said the boxes could have been taken out that way as the crowd was in front of the church. There was no place in the church to hide them. There was a loft, but it was entered through a hole in the ceiling and there was no ladder. Belle placed two chairs with their seats touching and covered them with the sheet so that no one could tell the boxes were not there.

“‘It looks as if some of the people who don’t want the organ have spoiled this box supper,’ said John Strang, ‘and they will keep us from having our organ for a while, too.’

“‘But that isn’t the worst of it,’ put in Isabel. ‘It’ll cause no end of trouble and hard feelings.’

“‘It may have been some of the boys who did it for a joke,’ said Belle. ‘Let us raise the money anyway and get ahead of them.’

“‘But how,’ Isabel asked anxiously, ‘with no boxes?’

“Then they thought out their plan. It was that John and Will were to go out and explain quietly to the boys in favor of the organ what had happened and get them to give the money they meant to spend on their boxes to John. Brother Joe had bought a new pair of shoes in town. They would put his shoe box up for sale just as if all the rest of the boxes were still under the sheet. Will was to bid against John and run the box up to the amount they had collected.

“Isabel stayed in the church to see that no one disturbed the sheet, and John and Will and Belle went outside to carry out their plan. I found Mother, and pretty soon we went into the church. The lamps had been lit, and I thought how nice it looked. The girls had come up the day before and[65] swept the floor and dusted the benches and shined the tin reflectors on the lamps, and put great bunches of flowers and ferns over the doors and windows and covered the two big round stoves with boughs of evergreen. There was a short program first, and then Stanley, who was to auction off the boxes, stepped to the front of the pulpit and held up a plain white box tied with stout string.

“‘How much am I offered for this box?’ he said.

“The bidding started at twenty-five cents. At first there were lots of bids, but finally every one dropped out but John and Will. There wasn’t a sound in the church as the bidding went higher and higher—thirty dollars for that plain, white box, thirty-five dollars, forty dollars, forty-one dollars. Will stopped bidding and the box went to John for forty-one dollars.

“Some one called out, ‘Open the box!’ and that started things. ‘Open the box!’ they shouted. ‘Open it!’ ‘Let’s see what’s in it!’ ‘Open, open, open!’

“When they quieted down a little, Stanley explained about the boxes disappearing and[66] everything. Then he untied the string, took the lid off the box, and held up a pair of men’s shoes number ten. Then that crowd went wild. They clapped and shouted and yelled. Stanley said he thought the boxes had been taken for a joke and suggested that they be returned.

Stanley held up a pair of men’s shoes

“‘We have enough money for the organ,’ he said. ‘Now let us have our suppers and some fun.’

“One of the boys on the side opposing the organ got up and said that the boxes had been taken for a joke and would immediately[67] be returned. And you couldn’t guess where those boxes were hidden! Right in the big round stoves there in the church! Of course everybody laughed again and laughed and laughed. Such a good-humored crowd you never saw.

“They handed out the boxes first to the people who had paid in their money, and sold the others. There weren’t enough boxes to go around, but each had plenty in it for three or four people. Every one divided, and there was not a person in the church who did not get something to eat. People who had been in favor of the organ ate out of the same boxes with those who had been against it and forgot that they had ever disagreed. And when the organ came and sister Aggie played it that first Sunday, why, it sounded sweeter to me than that beautiful big organ in your church did this morning.

“And now, ‘’night, ’night,’ everybody, and next time I think—yes. I’m pretty sure—next time we’ll have something about my school.”

“All my brothers and sisters had liked to go to school,” Grandma began the next evening, “and in the sitting room, after supper, Father would hear their lessons while Mother knitted or sewed or darned. Father had read books and papers aloud to us as long as I could remember, and he always told us how important education was. So as soon as I got to be six years old I was anxious to start to school.

“I was small for my age, and as we lived two miles from the schoolhouse and the snow in winter was often two or three feet deep, Mother did not want me to go until I was seven or eight years old. She said she and Father could teach me at home for a couple of years yet, but I coaxed and coaxed to go. At last Mother said I could go as long as the weather was good.

“So on the very first day—it was along toward the last of October—I started down the road with a brand new primer under my arm and a lunch basket of my very own and shiny new shoes. Mother stood at the[69] front gate to watch me out of sight and wave when I came to the turn in the road.

“Our schoolhouse wasn’t like yours. It was just a little frame building painted red. There were no globes or books or maps or pictures to make learning interesting. Just rough, scarred benches, a water bucket and a dipper on a shelf in one corner, and a big round stove in the center of the room, and of course the teacher’s desk and chair on the platform up in front.

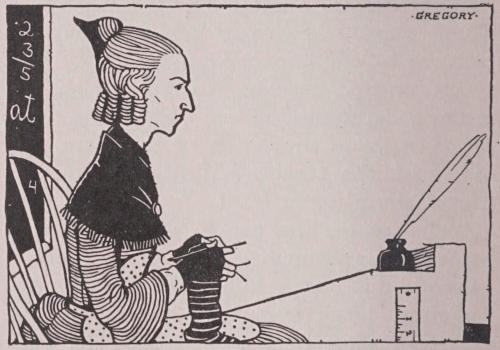

“The teacher was usually a man, but that winter it was a woman—Miss Amma Morton. Miss Amma was a tall, bony woman with snapping, black eyes that saw everything, and thin gray hair combed straight back from her face. She wore a brown alpaca dress with a very full gathered skirt and black and white calico aprons and a little black shoulder shawl fastened with a gold brooch.

“She lived with a married sister who had a very large family. In those days all the stockings and socks were knitted at home, and Miss Amma did the knitting for her sister’s family. She did it in school. She would sit at the stove or at her desk and[70] knit and knit on long gray stockings or on red mittens. She would knit all day while she heard our lessons. The only time she couldn’t knit was when she set our copies. We had no copy books, and the teacher had to write the copies out for us.

Miss Amma would knit all day while she heard our lessons

“I liked to go to school. It was fun to peep into my lunch basket at recess to see what Mother had put in and maybe slip out a piece of pie or cake to eat. I liked to make playhouses on the big flat rocks with Annie Brierly and the other little girls, and hunt soft, green moss to furnish them with,[71] and smooth pebbles down at the run. I loved to learn my A B C’s and listen to the older children recite, and at noon and recess to play ‘Prisoners’ Base’ and ‘Copenhagen.’ But school wasn’t always so pleasant.

“One day not long after I started there was a heavy wind and rain storm. We couldn’t recite our lessons, the rain made so much noise on the roof. Through the windows we could see the trees swaying this way and that in the wind.

“At afternoon recess Annie and I ran out to see if our playhouses had been spoiled by the rain. When we came back the girls were standing around in little excited groups. They told us that the roof had blown off Bowser’s house—they lived about half a mile down the road—and that most of the boys had gone to see it.

“‘Did Charlie go?’ I asked eagerly.

“‘I reckon he did,’ one of the girls answered. ‘He was with the other boys and they went that way. I wouldn’t be in their boots for anything. They won’t be back before books, and Teacher’ll whip them if they’re late.’

“I drew Annie away. ‘I’m going after Charlie,’ I told her. ‘I’m going to take the[72] short cut across the hill and catch up to him and bring him back.’

“Annie said she would go with me, and we started. The ground was wet and it was hard walking. We slipped at every step. After I thought about it a little, I was not at all sure that Charlie would thank me for coming. Maybe he’d sooner take a whipping than miss seeing a house without a roof. Boys are so different from girls that way.

“We got clear to Bowser’s without seeing a sign of a single boy, and the roof wasn’t off at all—just a little corner of it. Mr. Bowser was nailing it up as fast as ever he could. He said none of the boys had been there, so we started back.

“That was the longest walk I ever took. I thought we’d never get to the schoolhouse. My feet were wet and my legs ached and I was so tired I could hardly move. When we got to the top of the hill and looked down at the schoolhouse, there was no one in sight. Recess was over! We reached the door at last and stood trembling outside, afraid to open it and go in and afraid not to. Annie had been[73] to school the winter before and was not so scared as I was. She took my hand reassuringly.

“‘Don’t let on you’re frightened,’ she whispered. ‘Maybe Miss Amma hasn’t missed us and we can slip into our seats without being seen.’

“Annie opened the door just as easy, and we slid in without a sound. But alas! alas! Miss Amma was hearing the advanced arithmetic class and she stood facing the door, so the second we stepped in she saw us.

“She stopped explaining a problem long enough to order Annie and me to stand in opposite corners up on the platform where everybody could see us.

“No one had had to stand in the corner since I had started to school, so instead of facing the corner as I should have done I stood with my face toward the school. I looked to see if Charlie was in his place. When he saw me looking at him, he began making motions. I thought he meant for me to stand tight in the corner, so I pushed as close as I could to the wall. All over the room pupils were smiling at me and pointing and shaking their heads. I wondered what[74] they meant. I looked across at Annie. She was laughing and she made a motion, too. Then I thought of what she had said—not to let on I was frightened. Maybe I looked scared. I looked at Annie again. She stuck her head into the corner, looked at me, frowned, put her head in the corner again. What did she mean? It was too funny the way they were all acting. Then I laughed, too, right out loud, before I knew it. I laughed and laughed. I couldn’t stop.

“Teacher gave me a long, severe look.

“‘Turn around and face the corner, Sarah,’ she said, ‘and you may remain after school.’

“Then I knew what Charlie and Annie and the others had been trying to tell me. I stood there in the corner until the scholars had all gone home and Miss Amma had swept the floor and cleaned the blackboard and emptied the water bucket.

“Finally she called me, and I went over to her desk. When she asked me why I had run off at recess and then disturbed the whole school by laughing, I told her all about it, and she said she would forgive me that time and helped me on with my cape and hood.

“Charlie was waiting for me down the road a piece. He hadn’t even thought of going to see Bowser’s house, but had been down in the meadow watching the big boys dig out a woodchuck.

“And, now, an apple all around and good night.”

“Mm! Isn’t it beautiful?” exclaimed Grandma as she stood with Bobby and Alice and Pink admiring the table decorated for Pink’s birthday party. Everything was pink and white. The lovely white-frosted cake had pink candles in pink rose-holders—seven, one for each year and one to grow on. There were pink candies and pink flowers and pink caps for the little girls and boys to wear.

“‘And the ice cream is to be pink,’ Alice explained, ‘pink ice cream shaped like animals—dogs and bunnies and kittens.’

“My, but isn’t that fine!” said Grandma. “Now my first party wasn’t a bit like this. Maybe tonight if you are not too tired I’ll tell you about my party.”

And that night after they had told Grandma about Pink’s party she told them about hers.

“We didn’t have many parties when I was little,” Grandma began, “and we never had regular little girls’ parties. Everyone, big and little, came, and they were generally surprise parties and the guests would bring the refreshments with them. One evening[77] going home from school, the girls were wishing that some one would get up a surprise party, when suddenly Annie Brierly said, ‘Why don’t we get up a party for Sarah, girls? Friday is her birthday. Do you think your Mother would care, Sarah?’

“‘We’d both help her,’ Callie Orbison put in before I could answer. ‘You don’t need to do much getting ready for a surprise party. We could have it Friday night, and Saturday we’d both come over and help clean up the house.’

“‘Not a soul but Callie and me would know you knew anything about it,’ urged Annie, ‘and we could have just loads of fun.’

“I promised to think about it, and the more I thought about it the better I liked the idea of having a party of my very own. It didn’t take much persuasion the next day to make me consent. Annie and Callie were delighted and immediately fell to making plans, but they agreed that nothing should be said to Mother until Thursday evening, the date set for the party being Friday night.

“The days that followed were full of mingled pleasure and pain for me. I was happy at the idea of having a real party, but it didn’t[78] seem fair to deceive Mother. Once I thought of telling her all about it just as I told her about everything else. But I was afraid she would say I was too young to have a party, and I had never been to a party in my life. Sister Aggie was visiting Aunt Louisa in Clayville, and Mother had no one to help her except for what I could do mornings and evenings. But I would be at home all day Saturday, and Annie and Callie had said that they would help.

“Thursday morning Annie told me that she had baked a cake and put my initials on top in little red candies, and Callie said her mother was going to bake an election cake with spices and raisins in it. All day Thursday I kept thinking about the party. It wasn’t off my mind a minute. I couldn’t study for thinking about it, and I missed a word in spelling—the first word I’d missed that term—and had to go to the foot of the class.

“But by the time we had started home I had made up my mind to one thing, that if I could not have a party with everything open and above board I did not want one at all. And so I told the girls that I had changed my[79] mind and did not want them to have a surprise party for me. They coaxed and argued and teased, but I was firm. I was sorry that Annie had baked a cake and I hated to disappoint them, but I did not want a party. The girls were cross with me, and I felt miserable when Annie turned in her gate without saying good-by.

“Aggie had come home from Clayville that afternoon, and she was so busy telling Mother the news and describing the latest fashions, and showing the things she had bought, that no one noticed me much. Not a word was said all evening about my birthday being so near. Even Charlie didn’t tease me about what he would do, such as ducking me in the rain barrel, as he always did, and I thought everyone had forgotten all about my birthday.

“But Friday morning just before I started to school Aggie gave me a plain little handkerchief that she had hemstitched before she went away, and then I knew for sure that she had not brought me anything from Clayville. And when Mother gave me a pair of common home-knit stockings, I thought I should cry right out before everybody instead of waiting until I got started to school.

“Annie and Callie were in a good humor again and as pleasant as could be, but I felt so unhappy that day that I didn’t notice that the girls at school seemed unusually happy and excited. When I finally did notice it, I was afraid that Annie and Callie had gone ahead with plans for the party. I accused them of this, but they denied it.

“‘No, no, we didn’t do another thing about the party,’ they declared. But they looked at each other and laughed when they said it, and I didn’t believe them.

“‘You did,’ I said, ‘you know you did.’

“‘Cross my heart and hope to die if we did,’ Callie insisted.

“‘Here’s some of the cake that I baked for your party that we didn’t have,’ said Annie. ‘Now will you believe us? I brought you girls each a piece, but it was a sin to cut that cake—it was such a beautiful cake.’ And she handed us each a slice of delicious, yellow sponge cake decorated with red candies.

“Mother had given me an errand to do at the store on my way home, so it was later than usual when, hungry and tired, I opened the kitchen door. Mother met me and took my bundles and books.

Out from the hall rushed Annie and Callie and seven other little girls

“‘Take your wraps off here, Sarah,’ she said. ‘Aggie has company in the sitting room.’ I didn’t hear anyone talking, but I took off my coat. Then Aggie called me and I went into the sitting room, but I stopped in amazement just inside the door.

“In the center of the room was a table set with Mother’s best linen and china and silver, and while I gazed at it, out from the hall rushed Annie and Callie and seven other little girls all near my own age dressed up in their Sunday frocks and each one thrusting some sort of package toward me.

“I couldn’t say a word—I just burst into tears. I went upstairs with Mother to wash my face and put on my best dress. She told me Aggie had written invitations on cards she had bought in Clayville, and Charlie had carried them to the girls that morning. Then I told Mother all about the party we had planned to have, and she said not to think any more about it but that she was glad I had told her.

“We played games—‘Pussy wants a corner’ and ‘Button, button, who’s got the button’ and ‘Hide the thimble’—and asked riddles and had a good time.

“Then we had supper. There were cold roast chicken, tiny hot biscuits and peach preserves, three kinds of cake, and hot chocolate that Aggie had learned to make in Clayville and none of us had ever tasted before.

“Mother and Aggie had given me those presents in the morning just to fool me. Aggie had brought me a lovely story book, and Mother had a string of pretty pink beads for me. Charlie gave me a little basket he had whittled out of a peach seed, and from Father I got a silver dollar.

“And now good night, pleasant dreams.”

“Grandma,” said Bobby one evening, “did you ever see a locust—a seventeen-year locust? And why are they called seventeen-year locusts?”

“Oh, yes, I’ve seen locusts and heard them, too,” answered Grandma, taking up her knitting. “They are called seventeen-year locusts because they come every seventeen years. They lay their eggs in a tree. These eggs hatch tiny worms, called larvae, which fall to the ground and stay there for seventeen years changing slowly until they have turned into locusts. They live only about thirty days, but they often do a great deal of damage in this time. One year when I was a little girl all our fruit was eaten by the locusts and many of the trees were killed. They ate the garden stuff, the potato tops, and even the flowers, so it must have been somewhat as it was in Pharaoh’s time.

“You remember Pharaoh was the king of Egypt who refused to let the children of Israel go. For this God sent the plagues on Pharaoh and the people of Egypt. One of these[84] plagues was the locusts. God caused a strong east wind to blow all day and all night, and this wind brought the locusts. They were every place—all over the ground, in Pharaoh’s house, and in the houses of his people. They ate all the vegetables and fruits, even the leaves on the trees, so there was nothing green left in all the land. The noise they made must have been awful. When Pharaoh repented, the Lord sent a strong west wind which blew the locusts away, and they were drowned in the Red Sea. Ever since that time people have thought the locusts say ‘Pharaoh.’

“I believe I’ll tell you tonight about the first time I ever heard a locust. Mother wondered one day at dinner whether there were any blackberries ripe yet. She said she wished she had enough for a few pies. So that afternoon I took a pail and started for the blackberry field. I didn’t tell anyone where I was going, for I wanted to surprise Mother. I was afraid that if she knew she mightn’t let me go alone, for she was timid about snakes. Sure enough, I saw a snake nearly the first thing, but it was a harmless little garter snake and scuttled away into the bushes as soon as it heard me.

“There were lots and lots of red berries, but only a few ripe ones here and there. I wandered on and on, thinking every minute I should come to a patch of ripe berries where I could fill my pail in a few minutes. It wasn’t much fun blackberrying all by myself. I scratched my hands and face and tore my dress on the briars and wished many times that I was back home, but I kept on picking until my pail was full.

“I did not realize how far I had gone nor how long I had been out until I noticed that the sun was going down. Then I started to hurry home as fast as I could. But I was tired and my bucket grew heavier with every step, so I often sat down to rest. I rested a long time under a chestnut tree, and then after I had walked miles, it seemed to me, I found myself back under this same tree. I knew it was the same tree because Charlie had cut my initials on it the summer before. I had been going around in a circle! I started out again. I looked to the right and to the left and straight ahead, but I couldn’t find the path.

“I was lost—lost in that great blackberry patch over a mile from home. Night was[86] coming on, and no one knew where I had gone. I wondered where I should sleep if no one found me before it got dark, and what I should eat. Of course I could climb a tree, but I might go to sleep and fall out of it. I shouldn’t starve, for I could eat blackberries, but the very thought of eating any more blackberries made me feel sick.

“I hurried this way and that, trying to find my way out and growing more frightened every minute.

“Then suddenly I heard some one calling to me.

“‘Sa—rah! Sa—rah!’ I heard as plain as plain could be, and I answered them. I screamed at the top of my voice, ‘Here I am! Here I am!’ But the voices—there seemed to be a great many of them—only kept on saying over and over again, ‘Sa—rah! Sa—rah!’

“I ran, stumbling and falling through the bushes, still holding to my precious pail of berries, but I didn’t seem to get any nearer to the folks who were calling me. All the neighbors must be out helping hunt for me, I thought to myself. That was queer, too, for it wasn’t really dark and Mother was[87] used to having me play for hours at a time down by the run or on the hill under the oak trees.

“Presently I came to an open space. There was a group of trees at the far edge, and there under those trees, to my great surprise, stood Mother’s little Jersey cow. I ran toward her, and when she saw me she gave a weak ‘moo.’ But when she tried to move I saw that she was caught fast by the horns in a wild grapevine that grew around the tree. I tried to free her, but I couldn’t. The wild grapevine is very tough and strong, and Jersey was securely fastened by it. I petted her and talked to her and forgot to be afraid any more. Then I happened to think that if she had been there very long she must be thirsty. She was not giving any milk and had been turned out to graze in the pasture field that joined the berry patch and had probably come through a bad place in the fence. I remembered having passed a spring a little way back, and I emptied my berries carefully in a pile on the ground and ran back and filled my bucket with water. But I couldn’t reach Jersey’s mouth, and though she tried frantically to get at the water she couldn’t get her head[88] down to it. I dragged two pieces of old log over and built up a platform. Then I climbed up on it with my bucket of water, and my, how glad Jersey was to get that cool drink!

“Then I sat down on a log to wait for some one to come. To keep from getting lonely I began to say over my memory verses for the next Sunday. I was committing the Twenty-third Psalm and I had just reached the line beginning, ‘He restoreth my soul,’ when I heard them calling again.