THE purest and most perfect Face Powder that science and skill can produce. Makes the skin soft and beautiful and removes Sun-burn, Tan, Freckles, and all shiny appearance. Invisible on closest inspection. Absolutely harmless. We invite chemical analysis and the closest search for injurious ingredients. It is used and indorsed by the most prominent society and professional ladies in Europe and America. Insist upon having Lablache Powder; or risk the consequences produced by cheap powders. Flesh, White, Pink, and Cream Tints.

| Title | Author | Page |

| The Great Star Ruby. | Barnes MacGreggor. | 1 |

| The Interrupted Banquet. | René Bache. | 11 |

| The Archangel. | James Q. Hyatt. | 19 |

| Asleep at Lone Mountain. | H. D. Umbstaetter. | 24 |

| Kootchie. | Harold Kinsabby. | 37 |

| Frazer's Find. | Roberta Littlehale. | 40 |

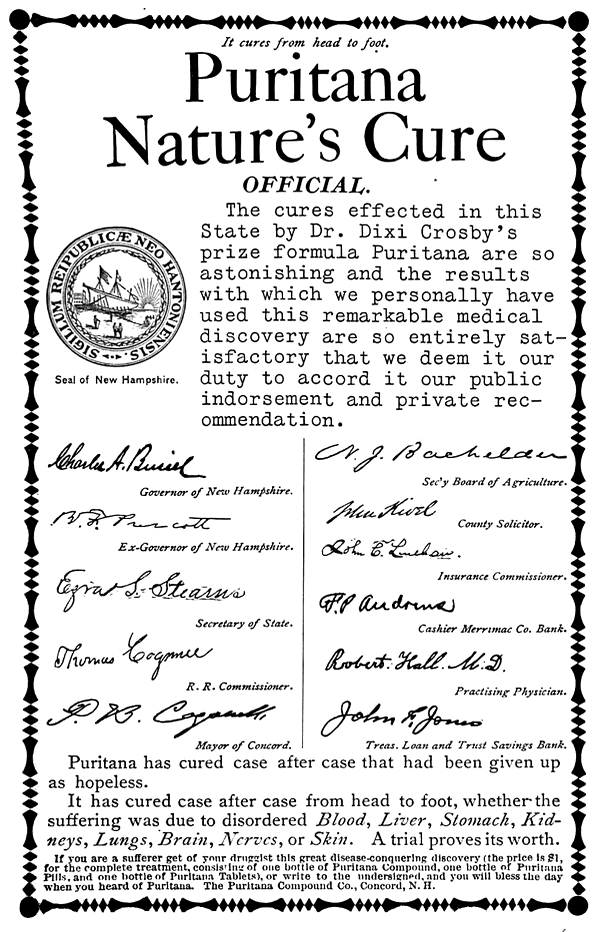

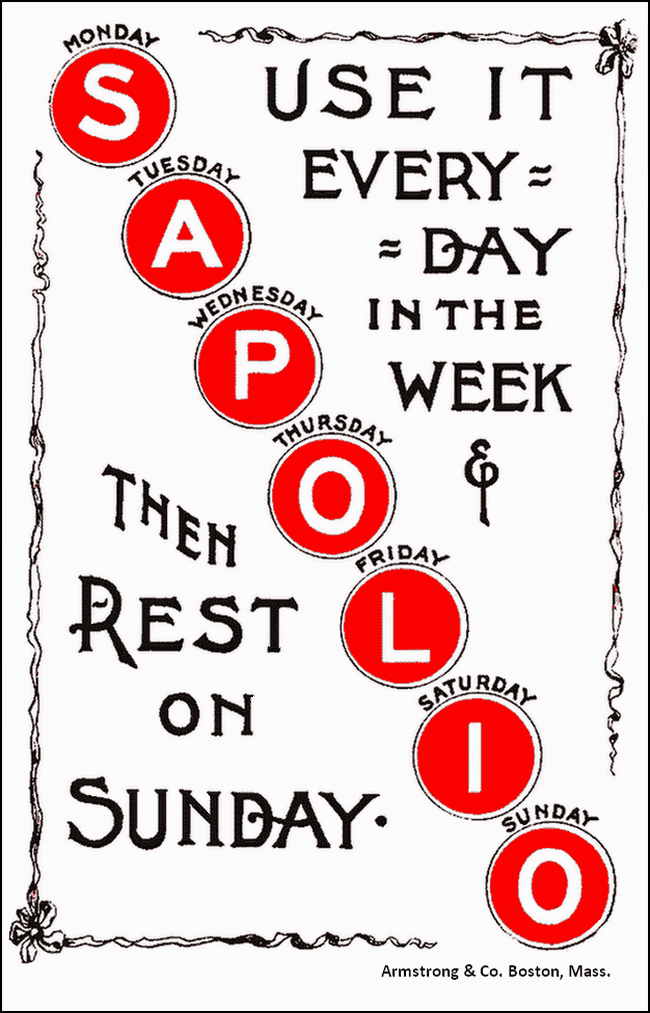

| Advertisements. | 47 |

BY BARNES MACGREGGOR.

IT was late in the evening of Melbourne Cup Day. In one of the dining-rooms of the Victoria Club three men sat smoking and talking earnestly together. Certainly the events of the last sixteen hours furnished ample subject for conversation. Melbourne Cup Day means to the Australian all that Derby Day does to the Englishman. It means, also, many things that even the greatest sporting event of the English year cannot mean to the inhabitants of the compact little island, provided with so many other facilities for amusement and intercourse. In this land of tremendous distances—where four million people occupy an area equal to that of the United States,—in this island continent of opposites—where Christmas comes in midsummer and Fourth of July in midwinter, where swans are black and birds are songless,—this is the one day when all classes and conditions assemble at one place and take their pleasures as a unit.

From Victoria and New South Wales, from North, South, and West Australia, from Queensland, even from Tasmania and the sister colony of New Zealand, separated from the continent by miles of water, visitors of all kind and degree had flocked by the thousands. When the starting flag fell that morning there were [Pg 2] assembled about the track picturesque miners and rugged bushmen, self-made capitalists, book-makers, and millionaire wool growers, charming women and well-groomed men, to the number of almost a quarter of a million. To all of these the occasion was one anticipated and planned for during twelve months past. It was the occasion when their long pent Anglo-Saxon sporting taste—for nine out of every ten Australians are of English ancestry—intensified by the free, out-of-door life, and by the absence of the outlets furnished in a more concentrated state of civilization, found exuberant expression. To each it carried, besides, some special significance, according to his rank and occupation. To the betting man it meant that a single firm of book-makers had on deposit in the banks of Melbourne and Sidney wagers to the amount of over one hundred thousand pounds sterling; for, like the English Derby, this is a "classical" event, upon which bets are often made for the coming year the very day after the preceding race has been run. Among the women it meant triumphs of millinery, gowns that had been ordered from London and Paris many months or even a year in advance, the fashionable display of Goodwood, the Derby, and the Ascot all compressed into a single day.

Among the mine owners and wool growers it meant journeys by rail, boat, or private coach, extending over hundreds, sometimes thousands of miles, and lasting for days and weeks, even months. Australia has well been called "The Land of the Golden Fleece." Its flocks of sheep are the largest, its gold mines and coal mines the richest in the world. Its flocks are counted not merely by hundreds or thousands, but by hundreds of thousands; and a single sheep station often extends over a hundred thousand acres. But with this immensity of interests there is linked the familiar loneliness of grandeur. The greater a country gentleman's possessions, the farther he is removed from society, until the largest proprietors are often separated by forty or fifty miles from their nearest neighbors. For this solitude the one outlet is the journey to Melbourne for the annual cup races.

Upon this particular day the fashionable parade had eclipsed in size and splendor that of any previous year. In addition to [Pg 3] the races, there had been the notable first night of the Grand Opera House, opened now for the first time to the public; and the day had culminated in an evening of such brilliancy and distinction that the three men who sat talking at the Victoria Club found superlatives too weak to express their enthusiasm.

"Rather than miss this day, I would have lost five years of my life," said one of the group. Then, turning to beckon the waiter, in order that he might emphasize his words by some refreshment, he observed a guest of the club—evidently a stranger—sitting alone at an adjoining table. With the exuberant new-world hospitality of a man who had evidently not been a loser in the day's exchange of wealth, he stretched out a welcoming hand, with, "Stranger, won't you join us?"

Without waiting for further formality, the solitary man strode up to the group and seated himself at their table.

"Gentlemen," he began, "I couldn't help overhearing what you said. I, too, would have given a good deal to have been a spectator. In fact, I had been looking forward to this event for a whole year, and, as luck would have it, missed it by the delay of an hour. If the steamer from Calcutta had reached Sydney half an hour before sundown yesterday, instead of half an hour after, I should have been in Melbourne early this morning, instead of late to-night. As it is, I arrived only ten minutes ago, and, having a card to your club from the Wanderer's in London, I came here to take the edge off my disappointment. The next best thing to being on the scene of action is to hear about it from an eye-witness. So I depend upon you to give me an account of the affair. At any rate, I only hope the races aren't finished."

"Oh, of course there will be more races," said the spokesman of the party; "but such a sight as the opening of the Opera House Melbourne isn't likely to see again. There were stars, of course, but no one noticed what was going on on the stage, you understand; the real show was in the house, which was simply packed. Such women! Such stunning gowns! And the jewels—why, it looked as though half the kingdoms of Europe had lent their crown jewels for the occasion.

"In all that gorgeousness it was mighty hard to pick out the handsomest face or the finest ornaments. But of course there was [Pg 4] one woman here, just as there is everywhere, who carried off the palm. It wasn't only that she was beautiful, though in her dark, stately fashion she was far and away the handsomest woman present; and it wasn't only that she sat where she did in the front of the stage box, with her solitary escort in the background, when every other box in the theater was crammed; but upon the bodice of her gown—it was a gorgeous gold and white brocaded and lace-trimmed affair, so I heard it whispered among the women—she wore the most striking and gorgeous ornament in the entire audience. This was a jockey-cap made entirely of precious stones; the peak was a solid mass of diamonds, the band a row of sapphires, while the crown consisted of an enormous ruby. 'Twas rather showy, of course, but so appropriate for this particular race night that no woman could have resisted wearing it. Of course it stood out wonderfully—it was as big as a half-crown piece, you understand,—and it wasn't long before every glass in the house was fixed upon that pin and the beautiful woman that wore it.

"I turned my glass on it with the rest," he added, laughing, "and that's how I got such a good photograph of it."

"Speaking of precious stones," said the stranger, who so far had listened without comment, "reminds me of a fifty-thousand-pound ruby that once involved a daring young Englishman in a series of strange adventures."

"Give us the adventures," said the spokesman of the party, scenting at once a stirring tale that would make a fitting wind-up to the day's varied excitements. "A jewel always serves as a magnet for romance, especially if the jewel is a fifty-thousand-pound ruby."

"To begin with," said the strange man, apparently unmoved by his host's last remarks, "you must understand that, while there are millions of rubies mined every year, a really first-class stone is one of the rarest as well as the most valuable gems in the world. In Ceylon, where some of the largest ruby mines in the world are located, the Moormen, who have a monopoly of the gem trade, often bring down from the north country bullock cartloads of uncut rubies, but probably in handling ten million gems not one will be found of the desired fineness and of flawless purity and luster. These Moormen are the shrewdest, with a [Pg 5] few exceptions the most unscrupulous, and always the most wonderful judges of gems in the world, and they are without exception rich. They have parceled out the gem-fields in the Tamil districts, and the natives whom they hire to hunt gems along the river bottoms, where the finest are found, are subjected to the most rigid scrutiny and daily search; for, though the diggers are always naked, they often attempt to conceal gems in their ears, nostrils, armpits, or elsewhere, with the end in view of disposing of them to rival Moormen. For, though these Moormen are openly fair dealers among themselves, they cannot resist buying gems smuggled from their neighbors' fields. Consequently, a complete detective service is attached to each one of these diggings, and woe to the Tamil who is caught attempting to smuggle gems across the lines! He simply disappears, that's all. No one is ever called to account, and the awful secrecy of his captors and the mystery surrounding his end appal his fellows, keeping them in a subjection that is all but slavery, and in some respects infinitely worse.

"But these Tamil diggers are very wise, and they know when they happen upon a grand uncut gem. Perhaps they will bury it again and spend a whole year maneuvering to get the jewel over the lines to the rival buyers, finally giving it up, and turning it over to the owners of the fields. As the really fine ones are rarely larger than a hazelnut, and each is worth from twenty to one hundred times as much as a diamond of the same size, it is worth the digger's while to make a lifelong study of the relative values, and then profit thereby.

"Now, this young Englishman had a curious hobby. For years he had desired to possess one of these almost priceless rubies, and it was partly with the hope of obtaining one that he visited Ceylon, where he had left orders with the Moormen gem dealers to reserve for him the finest and largest stone that could be found.

"Meantime he headed an exploring party, whose way lay through the jungles about a hundred miles north of Kandy, toward the ancient Buddhist city Anarajapoora, the throne of the famous King Tissa, the shrine of the oldest tree in the world,—the sacred Bo. It was a long and tedious march. The travelers usually halted at mid-morning, slept till the shadows cooled the [Pg 6] air a little, then resumed the journey as far into the night as possible, sometimes continuing till the next mid-morning, when the sun's heat again brought them to a standstill. On this particular daybreak they had halted beside a swift stream, doubtful at which point to attempt to ford it. The leader had sent men both up and down the stream to search for a suitable spot, and wandered along its banks, more occupied with the glories of the tropic sunrise, the sparkle of the dew on the giant spider-threads stretched from limb to limb, the stir of rare birds and animals with which the jungle was more than alive, than with the problem of fording the stream. Upon reaching an inviting nook, he sat down to roll a cigarette, first taking care to search for any jungle enemies in ambush which might make him legitimate prey. Suddenly he heard a great crashing of branches in the thicket on the opposite side of the river. Then, like a flash of lightning, a naked Tamil, red with blood, a look of desperation and hopeless despair on his face, plunged out of the avalanche of green beyond, and, leaping headlong into the water, struck out across the stream. The traveler had risen to his feet, and stood watching amazedly the course of the swimmer, which was aimless, like that of a desperate man wandering through a totally unfamiliar country. His head was shaven closely, though the natives usually wear their hair long. He swam with great effort. Indeed, the watcher on the bank saw that it was ten to one against the swimmer's success, and instinctively his heart went out in pity. The unfortunate wretch was now being carried rapidly down stream and toward the man on the bank, who could see the straining of every fiber in the Tamil's body, even the look of despair in his bloodshot eyes. Suddenly, just as success seemed assured, the swimmer threw up his hands, uttered a strange moan, and went down. The man on the bank rushed down the stream, stopped at a point where a huge banyan tree spread its branches far over the swollen waters, and climbed out on a thick limb. A moment later he saw the body of the Tamil rise almost directly beneath him. Clinging with one hand to the tree, he lowered himself over the treacherous torrent, and with a mighty effort seized the drowning man by the ankle and so dragged him to the shore.

"Back into ambush he half carried the poor wreck, and, laying [Pg 7] him on the sod, began the task of reviving him. In less than ten minutes the Tamil opened his eyes, discharged a gallon of water, then gasped, struggled up into a half-sitting posture, and looked about him. When he saw the Englishman bending over him, and comprehended, he uttered the most pitiful wails of gratitude imaginable, groveling in the dust, kissing his preserver's feet. The water had washed the blood from him, but he was a mass of wounds, scars, bruises, lash marks, and bullet cuts. How he ever managed to go as far as he must have gone, leaving a trail of blood behind him, was a mystery. But what specially attracted the Englishman's attention was a blood-stained bandage around the fugitive's leg, midway between the knee and thigh, which was the only rag on the poor fellow's body. He was about to question him, by signs and syllables, for his knowledge of the Tamil patois was very limited, when he heard another great crashing of the thicket across the stream, accompanied by the sound of voices. Instantly, there flashed across the poor creature's face a look of unspeakable terror, as he panted out in hoarse gutturals, 'Sa-ya-ta! Sa-ya-ta!' an appeal for salvation which would have moved a heart of stone. Motioning to him to remain quiet—an unnecessary precaution, since he was scarcely able to lift his head from the marshy ground—his preserver gave him brandy; then, by a circuitous route, ran up stream, coming out directly opposite four mounted Moormen who were ranting up and down the shore.

"Upon his appearance, the horsemen approached, and asked if he had seen any one go by. They were on the track, they explained, of a Tamil gem-digger, who was smuggling a ruby worth fifty thousand pounds over the lines of the Bakook-Khan gem-fields, and with the owner of the fields had chased him sixty miles. The man could be recognized, they said, because his head was shaven, and he was quite naked, except for a bandage tied around one leg, in which he had cut a hole and buried the ruby.

"To all of this the Englishman answered that he had seen such a man leap from the jungle and plunge into the river only a few moments ago, adding that they would better wait until the flood went down before searching the river bottom, as it would be impossible to find even an elephant in that muddy water. At this the Moormen set up a howl of rage, and, after an angry consultation, [Pg 8] passed on down the stream, scanning the river bank. The traveler was about to return to the Tamil, realizing the man's immediate danger, when another crowd burst through the jungle opposite, and at the sight of the Englishman approached him with much the same story as had the first, except that, according to their tale, the gem-digger had been smuggling from the Sabat- Keel fields. To them he made the same reply, adding that another party had just been there from the Bakook-Khan fields, making a similar claim. At this the spokesman set up a terrific wail, denouncing them as rogues, thieves, impostors, and heaven knows what not. But just in the midst of his tirade he was cut short by the approach of still another band of claimants, and immediately the three groups of angry Moormen were in the midst of a wrangle over the ownership of the disputed gem.

"In their absorption the Englishman saw his chance to escape. With an occasional glance backward to make sure that he was not observed, he made his way stealthily to that spot in the ambush where he had left the wounded Tamil.

"The man was gone!

"For a moment his rescuer stood nonplussed. Then, as he looked first one way and then the other, his eye caught the gleam, a few yards away, of the silver top of the brandy flask that he had left with his patient by way of a comforter. As he stooped to recover it, he detected a fresh blood stain on the grass, and farther on still another. Evidently the Tamil, overcome by his fear of capture, had attempted flight,—an undertaking that in his enfeebled state meant certain and early death. Without stopping to consider the danger of following his ill-fated protégé alone into the unknown depths of the jungle, the Englishman started in pursuit. Before he had gone five steps, however, he realized his peril. Beyond him, creeping along on all fours, he saw the blood-stained fugitive, moving, unconscious of his peril, into the very jaws of a huge tiger, crouched ready to spring upon his prey."

"And the Tamil was killed?" cried the party.

"No," said the stranger; "the Tamil was saved from this horrible death, though only after his rescuer had passed through a hand-to-hand struggle with the tiger, in which he was almost killed. As it was, he lost the use of his right arm for the rest of [Pg 9] his life. But, in spite of all that he could do, the fugitive died a few hours later, overcome by fright and fatigue."

"And the ruby?"

"The ruby, of course, fell into the hands of the Englishman, who, convinced that, owing to the multiplicity of claimants, it would be impossible ever to ascertain the stone's rightful owner, concealed it in his tobacco pouch before he was joined by his party. These, he learned when he was brought to his senses, had returned several hours ago from the other side of the river, to which they had retired, frightened by the many outcries of the mounted Moormen, and had found their leader only after a long search, which would have been hopeless except for the blood trail left by the wounded Tamil.

"For a few days after his return to their camp, wounded as he was, and weakened by his encounter with the tiger, he gave little thought to the stone that had fallen into his hands, as if from the sky. But with his earliest convalescence, his jewel mania returned, intensified by the actual possession of a ruby that it afterwards proved was, no doubt, the finest in the world. By the time that he reached Amsterdam, to which he had taken passage at his earliest opportunity, with the idea of having his treasure cut by an expert, this mania had reached such a pitch that it was only with the greatest effort that he could finally make up his mind to leave it in the hands of a jewel cutter; and from the moment that it was out of his possession he began to suspect every person that he met, the jewel cutter included, of a desire to rob him of his treasure. What gave color to his suspicions was the fact that at the shop where he left the ruby delay followed delay, and postponement succeeded postponement, the dealer putting him off each time with vague excuses and never-fulfilled promises. At length, after five weeks of these mysterious delays and excuses, almost crazed by wearing anxiety, he confided his secret to one of a firm of private detectives, a man whom he employed to watch and investigate the movements of the jewel cutter.

"On the very night of the day in which he had taken this step, the jewel was returned to him; it had proved to be a stone not only magnificent in size and color, but curiously ribbed with white rays,—that is, a star ruby, pronounced to be the finest in existence. [Pg 10] But the reaction from his fright and anxiety, joined with the effect of his recent adventure, from which he had not yet fully recovered, cut short his joy. He was seized with brain fever, and for days lay unconscious in the room of his lodging-house, unattended except by his doctor and landlady. When he finally returned to his senses he found that the jewel was gone. At a time when his life was despaired of, the detective employed to protect his interests called at his lodging, and, thinking the man as good as dead, stole the gem, and—"

Suddenly the eyes of the listeners turned to the door behind the speaker. There was a rustle of skirts and the whispered exclamation: "There she is now."

The story teller started, flushing at the interruption, but only for an instant. Then he faced about, leaped to his feet, and, rushing forward like a maniac, tore from the breast of the mysterious beauty of the opera the glittering ornament upon which, an hour before, had been focused the attention of an entire audience.

"Here," he cried, brandishing a handful of lace and satin from which gleamed the jeweled jockey-cap, "is the stolen star ruby!—and there," pointing to a man's figure that appeared in the doorway, "is the cowardly wretch that stole it!"

It was not until then that his companions observed that the stranger's right arm hung useless at his side.

BY RENÉ BACHE.

THOUGH quite familiar with the street, I could not remember having seen that particular house before. My recollection had been that there was a vacant lot just there. But I must have been mistaken, for the dwelling before me was substantial enough, though old-fashioned, with high front steps and large windows. A trifle out of repair it looked, by the way, and I even noticed that two or three panes of glass were gone. On the whole, the mansion presented a somewhat mournful appearance, as if fallen from an old-time respectability into a condition of decay and decrepitude.

I am sure that it would never have occurred to me to enter, had it not been that the young lady who accompanied me turned and deliberately mounted the steps towards the front door. Of course I followed. She did not ring the bell; for, in truth, there seemed to be no bell to pull. But the portal was noiselessly thrown wide from within, and we entered. I looked in vain for the servant who, I supposed, would receive our cards; but, to my surprise, Mabel walked straight ahead through the wide hall, without hesitation, appearing quite familiar with the place. There should have been a light, I thought, though it was only two o'clock in the afternoon; for the interior of this strange mansion was very dark, and I could only make out in an indistinct sort of way the faces that looked down upon me from some old portraits, obviously fine works of art, as I passed.

Mabel had introduced me to most of her friends, for we had been engaged for six months and were to be married very soon; but she had never spoken to me of these people, who, perhaps, were rather out of the fashion and had been forgotten. As these reflections passed through my mind, we ascended a broad staircase to the second floor, and then it was that I heard a sound of revelry [Pg 12] which came from a room which I correctly judged to be the dining-room of the house. The heavy oaken doors of the room were slightly ajar, and through them was cast a strong beam of light that fell full upon an object which startled me for an instant. It was a headless human figure. A second later I smiled at my own alarm, inasmuch as the figure was nothing but a suit of old armor without the helmet.

If I had had a chance, I should have questioned Mabel, in order to make sure that our unannounced entrance was not an intrusion; also, I might have asked why, after starting out for a day's yachting trip, we had returned so early and for so strange an entertainment. But either query would have been out of place just then. Very likely, I thought, she had some surprise in store for me,—a lunch party, maybe, arranged by some friends in our honor; for quite a series of dinners and other entertainments had been given to us in celebration of our engagement. Moreover, all that I have related took place within less than a minute and a half, and in another moment I found myself in the large and brilliantly lighted dining-room. If the rest of the mansion was dark, there was no lack of illumination here. I was fairly dazzled by the numerous lights, clusters of which, arranged in silver candelabra, helped to adorn a long table, at which twenty-five or thirty people were seated. There were flowers in profusion, with a great display of silver and cut glass.

To my astonishment, not one of the people present seemed to take the slightest notice of our entrance. Near one end of the table were two vacant chairs together. Mabel quietly took one of them, and I, deeming the time hardly proper for an explanation, seated myself in the other. Soup was immediately placed before us—evidently we were not very late—and I took two or three spoonsful of it. It struck me as being singularly tasteless.

The courses followed each other in the usual mechanical fashion. What there was to eat I do not remember with any distinctness, for I was so absorbed in wonder and in studying the other guests that I took little notice of the viands. Opposite me was a funny-looking old lady in white silk, cut low at the neck to such a degree, I thought, as would have been more appropriate to a younger and plumper person. I particularly recall the fact that [Pg 13] she wore camellias in her hair—a fashion which I had heard of as belonging to a generation ago. It was palpable, too, that her front hair was false. Withal she was most agreeable and amiably disposed, as I presently discovered from her conversation. She was the first person who addressed any remark to me, abruptly making some inquiry about my grandfather, and stating in the same breath that she was from Philadelphia.

At her left sat a gentleman of rather more than middle age, as I judged, with a remarkably pink nose and a great expanse of shirt-front, who was devoting himself so assiduously to his plate that not a word escaped his lips. On the other side of the old lady with the camellias was an extremely thin man, with a peaked countenance, who so strongly reminded me of an undertaker that I felt almost tempted to ask him a question or two about the state of the market in respect to coffins and other funeral equipments. His necktie was black and likewise his hair, while his expression was one of extreme solemnity. Mabel was seated at my right, while on my other hand was a buxom matron of forty or so, who manipulated knife and fork with an activity that suggested a most excellent digestion.

Among the guests these were the first whom I noticed particularly. As I looked along the table, I was rather surprised to find that not a face was known to me. There was a cadaverous-looking young man with a prematurely bald head whom I pointed out to Mabel, asking who he was; for I had noticed that a sign of recognition passed between them.

"My brother," she replied quietly and, as I imagined, sadly.

Now this was a surprise, for I did not know that Mabel had a brother. Perhaps, I thought, he was not an especially estimable youth, and so was ignored by her family. If that were so, why should he be present on this occasion? Here was another puzzle, to be solved when a suitable opportunity offered for questioning my fianceé.

On the left of Mabel's brother was a remarkably pretty, though very pale young lady, who wore in her hair, oddly enough, what looked to me like a bridal wreath. But the handsomest woman present was she whom I supposed to be our hostess. She was of regal presence, and, with her velvety eyes and coronet of black [Pg 14] braids, resembled a Spanish señorita. Though I had never seen her before, I took it for granted that she must know who I was, and repeatedly I tried to catch a glance from her; but it was in vain, for her conversation and attention were addressed almost exclusively to an elderly man on her right, apparently a foreign diplomat, as half a dozen orders glittered upon his breast. At the other end of the festive board sat a gentleman with a huge gray moustache, presumably our host. I heard no remarks from him, save now and then a request to "pass the decanter," addressed to one or another of the guests near him. I had no opportunity for speech with him, inasmuch as Mabel and I were divided from him by almost the length of the table.

On the whole, the affair struck me as entirely extraordinary. Here we were, myself completely a stranger, at a banquet in a house which I had never visited before! Indeed, had it not been for Mabel's assurance of welcome and the two seats apparently reserved for us, I should have supposed that we had made some mistake. Mabel herself was singularly silent, though ordinarily quite talkative and even jolly, and offered no explanation of the situation. But perhaps what astonished me more than anything else was my discovery, some time after we were seated at the table, of a young man, some distance away, who bore a striking resemblance to my chum at college. Upon my word, I was on the point of shouting at him across the board. In fact, the words, "Why, Bill, old man, how did you get here?" were on my lips, when I checked myself in time, owing to a remembrance of the fact that Bill had been dead for eight years, having met a most untimely fate in a railway disaster.

While engaged in wondering whether the young man could be a near relation of my former chum's, I was startled at seeing a telegram in the familiar Western Union envelope laid beside my plate. Some people, notably stock brokers and newspaper men, are accustomed to telegrams, and for that reason are not alarmed by them. But habit had not rendered me thus callous, and with some haste I tore open the envelope and glanced over the contents. It read:—

"Mabel died this morning of acute congestion of the lungs.

"Amelia Parker."

[Pg 15]

I declare that I trembled as if I had a chill. If Mabel had not been by my side, I should have been overcome by the shock. Holding the telegram before Mabel's eyes, I exclaimed in a voice that trembled with conflicting emotions of horror and anger: "This is carrying a practical joke too far. Here, some brainless wretch telegraphs me in your mother's name that you are dead."

Careless of the almost frenzied energy with which I spoke, I looked around upon the faces of my fellow-guests as one does who is confident of sympathy. To my amazement, in response to my speech, there arose a cackle of laughter which was presently transformed into a general ripple of mirth. And such mirth! The like of it I had never heard before, and, please heaven, I hope I never may again. It was not like real laughter, but rather the empty and strident cachinnation of beings lost to the feelings of humanity.

Pale with anger, I rose to my feet and, steadying myself with one hand on the back of my chair, exclaimed:

"What does this mean?"

Dead silence was the only response. Conversation had ceased, but I felt that every eye was fixed upon me. Aghast, I looked at Mabel, but she did not return my gaze. At length, the old woman with the camellias in her hair, who sat opposite, addressed me, saying:

"Why do you think that Mabel is not dead?"

"Good God!" I replied. "Here she is. Don't you see her? What do these people mean?"

The old woman grinned and waved her feather fan at me, playfully, saying:

"Ask her if she isn't dead?"

I turned to Mabel in wonderment, but she only shook her head sadly.

"Why, of course she's dead!" said the old woman. "Don't you know that all of us here are dead?"

"Indeed, yes; we are all dead," cried the other guests in general chorus.

"This is getting beyond patience!" I exclaimed. "You, too, are pleased to joke with me, but I tell you frankly that I fail to [Pg 16] see the fun of it. Perhaps, since you possess such a fund of humor, you will be telling me next that I am dead, also."

Then came that laugh again. I never shall forget it. Beginning with a cackling titter, it spread until the whole table was in a roar, making my very flesh creep. Then all at once it ceased, and again there was dead silence.

"Certainly you are dead," said the old lady with the camellias. "She's dead, and all of us are dead. She died this morning of acute congestion of the lungs, but I have been dead for these twenty years, and he, too," indicating with her fan the elderly gentleman with the pink nose. "My own complaint was cerebrospinal meningitis."

My legs gave way under me and I sank into my chair. As I did so my hand touched Mabel's, and I grasped hers tightly. It was cold as ice. Leaning toward me, she whispered in my ear:

"Don't make a scene! It is all quite true. You were run over an hour ago by a trolley car."

Not daring to believe my senses, I replied:

"And this house—?"

"Sh—h!" said Mabel. "It is only the ghost of a house,—the phantasmal reproduction of an old mansion that used to stand on this spot, where there has been an empty lot for fifteen years past."

"I—I think I understand," I gasped. Then, though my brain swam, I made a tremendous effort to summon up my courage and face composedly this dreadful situation. Addressing myself to the old woman opposite, I said:

"Perchance you were acquainted with the former occupants of this dwelling?"

"Oh, yes," she answered pleasantly. "I am somewhat distantly related to our host and hostess of this evening. They were drowned—lost on the ill-fated Ville de Paris. This house belonged to them, and not very long afterwards it was torn down."

"But suppose that the present owner of the lot were to build upon it?" I suggested. "It would be necessary to hold these charming entertainments elsewhere?"

"Not at all," she said, laughing and waving her fan. "The [Pg 17] occupancy of the site by a real house would not interfere. It frequently happens, of course, that a building is put up on ground previously occupied by another dwelling. You must understand, though I might have supposed you knew it, that, while the material parts of a tenement may be removed at any time, its astral shell remains in perpetuity. Thus the ghosts of half a dozen or more dwellings may remain on the site occupied by a new and substantial structure. They are none the less real for being invisible to living eyes. The most remarkable instances of haunted houses that you have heard about are due to conditions of that sort,—several families of phantasms, perhaps, tenanting premises topographically coincident with a mansion which affords physical accommodation to people in the flesh. I trust I make myself clear?"

"Quite so," I replied politely.

This conversation was interrupted by the elderly gentleman with the pink nose, who seemed to be dissatisfied with something. Having poured out a water goblet half full of sherry from a decanter, he called for brandy, and with those strong spirits filled it to the brim. Then he took a caster of red pepper and sprinkled its contents liberally on the surface of the mixture. Raising the goblet to his lips, he drained its contents to the last drop and set it down with a sigh.

"Ah!" he exclaimed, "it has no strength. If only I could get a schooner of real beer."

The old lady regarded this performance attentively, with a lorgnette held to her nose. Said she sympathetically:

"That is the way with all pleasures in the after world. They seem to have no savor. Even the milk is chalk and water."

"I suppose that is why this mince pie tastes so insipid," I responded, toying absently with a bit of pastry on my plate.

"Of course it is," she said. "Don't you see it is only the ghost of a mince pie."

"Then it seems that—"

But at this point the banquet was suddenly interrupted by a convulsive swaying and creaking of timbers. The table rocked, the lights in the silver candelabra flickered, and all was darkness. Then, through a ray of brilliant sunlight, I saw the strange dining-hall, [Pg 18] the gleaming table, the ghostly banqueters all fade into the distance. Another moment of utter darkness, of creaking and swaying, during which I made a desperate effort to grasp and steady Mabel's chair. To my bewilderment, my hand touched a coil of rope. I heard familiar voices. There was a burst of sunlight. I sat propped up by cushions on the deck of the pleasure yacht Undine, surrounded by solicitous friends. Mabel, with her warm hand reassuringly clasped in mine, told me of my half hour's unconsciousness. I had fallen overboard in my attempt to recover her hat, and had been rescued only after sinking for the third time. Not until I had heard all this, could I banish from my mind my horrible experience in the house of the dead.

BY JAMES Q. HYATT.

CRAWFORD and I had gone up into the foot-hills of the Sierras to shoot. It was autumn; yet the sun unscrewed us so immediately when we walked abroad that we were forced to seek the shelter of pines and dusty scrub oaks, as often as they fell across our path.

We were lying, one afternoon, under a row of young firs on the crest of a ridge, when the gaunt figure of an old man labored up the slope toward us.

"If all the world'd lay about in the shade like you 'uns and me—not interferin' with Nature—she'd get her hand in again on her own hook," he said, throwing himself down beside us.

What he may have looked like when his features were normal we never knew. At this advanced period he wore so inflated a nose of such eccentric modeling that his eyes couldn't count for much, and his mouth was only suggested under a flippant gray beard.

"I'm the Archangel," he said sweetly, and smiled at us.

Crawford shrugged himself a trifle nearer his gun and smiled back again.

"There's no crack," he assured us immediately. "That's been my title for three years. I got it because I held my hand from gorin' a man under false provocation."

"Tell us about it," we said.

He found a stone to rest his back against, and threw open his shirt at the throat.

"These hot summer days sizzle just as they did then—crisp your throat like coals curl bacon. I'd mined all this country in the gold days, and held my own with the dizziest dog of 'em all in findin' the color and epicuring the liquids. I run a drinking fountain in opposition to the Dead Falls, up Mokelumne way, and [Pg 20] counted on Joaquin and his band for makin' a pot for me regular once a week—but t'aint what I started out to say."

The old man fell into a reverie. He seemed to see only the ends of his toes.

"About the Archangel," Crawford prodded.

"Yes—the Archangel. That's a matter of three short years aback."

This gentle old man stood up, and hitched savagely at his trouser band before he sat down again.

"Adolphe—his name'd tell you, wouldn't it? Chin beard—juicy voice—and hands a-curvin' through the air. Well, Adolphe and me set up backin' and minin' together five years aback. I stayed on and on with him because his bread'd make you hungry in your sleep.

"'Twas flour for that very bread that I went a-ridin' into town for, one summer day. There was a real estate dude'd come up. 'Socks' we called him. Actual—he went round in wormy-lookin' things held up by garters! Well, Socks, he tucked a folded newspaper under my saddle-flap, just as I was tightening up to go home.

"'Read that,' says he. 'It's time all you fellers settled down to raisin' families, so's we could have a population, and school districts, and churches, and sich. Never no hope of doin' anything with a lot of bachelors.'

"Well, d'you know, it struck me like wisdom from the mouth of babes? I rode along a-tryin' of my best to read that paper. Not bein' over profuse in acquaintance with learnin', and the sun strikin' the white clay like a lookin'-glass, I tucked it away and whistled till the barkin' of the dog realized me I was home.

"Later, when the smoke went out of the chimney, curlin' through the trees, Adolphe and me sat out on the saw-bucks a-readin' of that paper,—the Matrimonial Messenger.

"By your names, sirs, there was three pages of 'um saying how enchantin' they was!

"Tall women and short women, and young women and old women, women with children and women without, women that could work, and sew, and cook, and women that could sing, and dance, and talk. Every blamed one of 'em willin' to send their [Pg 21] photograph, swearin' their faces was their fortunes all their life!

"'Twasn't long before we'd settled between two of 'em, but Adolphe, he was for one, and me for the other.

"'What's it to you?' sez I. 'You aint marryin' of her, are you?'

"He couldn't but admit the fact.

"'Still—there's my livin' round her,' he says.

"'Twas a widder, I remember, Adolphe was set on. She'd raven locks, and what she'd most pride in was her cookin', and her sewin', and her lovin' heart. I argued long. I needed him favorable, if it was to be peaceful-like. I remember tellin' of him that we didn't need cookin' and sewin', being used all our lives to managin' these. What we wanted was somethin' amusin' and up in learnin', so's we could feel spiritual proud, you know. I asked him if we'd ever strike it rich, what'd we do with a wife that couldn't go dance and talk with the best of 'em.

"Anyway, seein' it was my business, and I was set like a jumper on a claim, Adolphe, he give in. The woman what made my heart feel empty said she was eighteen. She was decorated with yellow hair and eyes like copper-ore. She could talk French, and understood German, and could play the pianner. She'd marry a man that wanted a companion and not a cook.

"Sez I to myself continual: 'That's you, Daniel.'

"Well, Adolphe and me, we talked this thing, wakin' and sleepin'. I'd more plans than a cow has capers.

"We got up a letter'd melt snow, and then we waited.

"First, nuthin' was said to the boys, but when they caught on to my hangin' round the post-office they began to josh. I always stepped up gallant to the post-mistress, sirs—I've turned the cheeks of most women pink in my day—and I said, said I:

"'Letter, please?' with a doffin' of my hat, and a risin' inflection very polite but understandin'. It got to be so that when there never was anythin' handed out the boys'd take to coughin' down a laugh.

"After awhile it grew so's none of 'em turned up or paid any attention. Even Adolphe—he took to goin' to sleep when I talked her.

[Pg 22]

"Then a whole year ran out to summer again, and I couldn't unthrone her that reigned in my heart.

"One day I said to Adolphe, a-workin' away:

"'Blamed if I can forget her, the ornamint,' I said.

"Adolphe he went in for grub that day and came out late, a-holdin' of a envelope.

"'Here's your letter,' he called.

"Sure enough! I went out on the saw-buck and read it alone. Then he sat down by me and we read it over again.

"'Twas only that she'd arrive on the afternoon train on the fifth, and to have a Methodist minister.

"Well, sirs, it meant a good deal for me to supply the necessaries for a sparklin' jewel—let alone the settlin' down for her to sparkle on! but luck come my way. There'd been a milliner up from San Francisco and fitted her a elegant place. She'd failed, and quick's a winkin' I bought her lookin'-glass and red plush easy-chair. You'd ought to seen that cabin! There hung the thing opposite the stove, all shinin' an' smilin' and gildin'. Right in front of it my red plush chair, so's you could set down and put your feet up on another an' see how you'd look in heaven.

"On the fourth, Adolphe revealed he'd business in a little town a mile up the railway. He suffered a crampy kind of desperation not to be on hand to support me, he said, but he'd come in with the girl. Then he baked up bread and a cake and rode away.

"Sun come up on the fifth like a bull's-eye lantern. I'd set up all the night before, not to disturb anythin', and there was the mornin' for me to shave and git into my riggin'. A calf-skin vest, with the hair on, aint a thing to slight, sirs, ceremonies or no ceremonies.

"When I rode my mule up to the depot the boys was out, to the puniest scrub of 'em all. They give me cheers that'd blast rock.

"And there was an arch, sirs—all flowered! My legs wanted to sit down more than me!

"The train whistled in the distance. There was no slaknin' off round the corner, for the boys braced me everywhere.

"Out she stepped, sirs, and whether she was the sorriest or the [Pg 23] likeliest lookin' critter, I couldn't 'a' told for the flunk I was in!

"After the blackness I see her long yellow hair and red cheeks. All the conquerin' of my youth rose up within me, and I up and held her to me for a kiss.

"By the great snake mine, but women don't shave beards off and drink whisky!

"I dropped her like a nettle, but she went forward with the crowd, smilin' an' smirkin' through the cheerin' an' the uproar.

"'To the parson's,' the boys yelled.

"I was forced off my feet, but out came my gun.

"'Halt!' I cried, in a voice that brought 'em all on their haunches and still as colts raised on the spur.

"'I mean to shoot the wig off your head and the paint off your face, Adolphe Lefevre, and leave you for the slimiest viper that crawls without legs.'

"The sight of my gun lay between his eyes an' the crowd was as still as the barrel.

"Of a sudden came a voice in my ear. To this day God only knows from where.

"'Be like unto the archangels.'

"My arm fell to my side. They lifted me onto their shoulders.

"'The Archangel,' they sent out a-echoin' in the hills.

"And it stuck, sirs, from that day to this, though I've lived alone, sirs, ever since."

BY H. D. UMBSTAETTER.

IT occurred nearly fourteen years ago, yet I never enter a sleeping-car without being confronted by that innocent face. It clings to me all the more because I have always looked upon partings and leave-takings as mile-posts of sorrow in the journeys of life. I dislike good-bys. I hate farewells.

I had just returned from Australia and was about to start on my journey across the continent. In company with two old friends who had crossed the ferry from San Francisco to Oakland to see me off, I sat chatting in my sleeper, when two Sisters of Mercy hurriedly entered the car.

Just what it was in the appearance of the newcomers that arrested the attention of the earlier arrivals—whether it was their humble yet characteristic attire, so suggestive of charity the whole world over, the apparent anxiety betrayed by their manner, or the fact that a sleeping child, clasped tenderly in the arms of one, was their sole companion—whether it was any or all of these things that caused a sudden reign of respectful silence in the car, I am unable to say. Certain it is, however, that their coming was not unnoticed; neither was the circumstance that the only visible baggage of the trio consisted of a small square bundle neatly done up in a gray shawl.

Upon being shown to seats in the section directly opposite the one occupied by myself and friends, they at once entered into earnest conversation with the sleeping-car conductor. At the first few whispered words the man's manner showed unmistakable surprise. He appeared either unable or unwilling to comply with some request they had made. Although the nature of the request was not apparent, the occupants of neighboring seats could not fail to note from the conversation, which now and then became [Pg 25] quite audible, that it bore some important relation to the sleeping member of the party. The evident fact that the sisters felt much concerned respecting the safety and welfare of their youthful companion served only to increase the mystery of the situation.

After patiently listening for some minutes to appeals first from one and then the other, and after glancing over a railroad ticket and letter they had handed him, the conductor consented to meet their wishes, declining, however, to accept a sum of money they repeatedly tendered him. Before leaving them the man spoke a few words of reassurance and encouragement, which were cut short by the shrill whistle of the locomotive announcing the train's departure. The sisters arose instantly, hastily expressed their earnest thanks to the conductor, and then, sinking upon their knees before the child, which had been aroused from its slumbers and sat innocently gazing about, first one and then the other clasped the infant in fond embrace, and, amid sobs and kisses, showered upon the little being the most fervent blessings and tender farewells. Then, covering their tearful faces with their hands, they arose, still weeping as though their hearts would break, and hurriedly left the car, which was already moving slowly out of the station.

No sooner had they gone than all eyes were directed towards the diminutive stranger who had caused the scene just witnessed. Too young to realize what was going on, he sat motionless, as though spellbound by fear or astonishment at his strange surroundings. In an instant the child became an object of intense curiosity. More than that, its extreme youth and utter helplessness aroused, on the part of its fellow-travelers, feelings of genuine sympathy and pity—feelings which the heroic silence maintained by the little innocent, in spite of the now swiftly moving train, only served to intensify.

Neither memory nor imagination can suggest to me a more touching picture than the one presented by that plainly clad handful of human loneliness, as it sat there in meek silence, its tiny hand timidly resting on the little bundle by its side, while its eyes remained intently fixed on the door which, a few moments before, had closed upon its late companions. Whose child was this? Who was to care for it? What was to become of it? [Pg 26] Was one of the nuns a relative? Was the younger, perhaps, its sister? Or was either neither? These and similar questions could be easily read on the countenances of the wondering passengers.

Some minutes elapsed before the conductor again made his appearance, when he was at once besieged with questions concerning the mysterious stranger. And, as if determined that not a word should escape their ears, each of the twelve or fifteen occupants of the car crowded about him as he seated himself beside the lonely child.

The story they heard was brief and pathetic. The little boy was as much of a stranger to the conductor as he was to the passengers. His mother was dead. His home was in one of the smaller manufacturing towns of New England, where his father, who was to meet him on the arrival of our train at Omaha, lived in humble circumstances. The conductor had promised the sisters to protect and care for the child during the five days' journey. It was, however, not the little fellow's first trip across the plains, as nearly a year and a half ago, when but a few weeks old he had come to California with his invalid mother. The latter had survived the long journey but a very short time, and died among strangers in one of the foot-hill towns near San Francisco. The Sisters of Mercy of that city had by correspondence arranged with the father to adopt, or, rather, to provide a temporary home for the little waif, until he should be old enough to make the long return journey. And now, although the boy had reached but the tender age of eighteen months, the distant parent, craving for his presence, had begged the sister to enlist in his behalf the sympathies and care of some kind-hearted East-bound passenger or railway employee. Their repeated efforts in the former direction having failed, they had at last applied to the conductor.

In relating the child's sad history, the sisters had, the conductor continued, so feelingly solicited his kindly offices and paid such glowing tribute to the almost angelic disposition and exceptional bravery of the infant that, however disinclined he had been to assume the responsibility, a persistent refusal of their unusual request seemed almost inhuman. He had therefore undertaken the strange charge, and trusted, he said, that the passengers would [Pg 27] in no wise be inconvenienced thereby. From that moment on, every one who had less than half an hour before witnessed the scene of sorrowful parting, which had so touchingly told how completely the little fellow had walked into the hearts of his benefactors,—from that time on, every one felt a personal responsibility for the comfort and safety of the boy. Introduced under circumstances that rendered him a hero at the outset, at the end of the first day he had already become the pet of the passengers and the object of their kindliest attentions.

While the claim that this child was remarkable for beauty and cleverness might lend sentiment and romance to my simple narrative, the fact is that he was neither handsome nor bright. In appearance he was simply a plain, plump, red-cheeked, flaxen-haired baby boy, with apparently little to be proud of, save his evident good health and a pair of large blue eyes that seemed frankness itself. His accomplishments were few, indeed. He was still, as the sisters had said, learning to walk. His vocabulary included but three or four imperfectly spoken words, and he was conspicuously deficient in that parrot-like precociousness so common and frequently so highly prized in little children. But what our youthful companion lacked in attractive outwardness was more than made up by the true inwardness of one accomplishment he did possess. That was silence. This virtue he practised to a degree that soon won for him the admiration and affection of all. Though exhibiting no sign of embarrassment at the friendly advances of the passengers, and while not unmoved by their tender attentions, he maintained through that long journey a humble air of mute contentment that lost its balance on but three occasions.

His quiet ways were a theme of constant comment, while his presence proved not only a source of increasing pleasure to our small band of tourists, but did much to relieve the monotony of the tedious journey.

One important detail in the boy's eventful history was missing. Cared for by strangers from earliest infancy, deprived of his mother's love and father's care, he had thus far not even received that all-important parental gift,—a Christian name. To the sisters he had been known simply as "Baby." By that infantile [Pg 28] appellation he had passed from their gentle mercies to the conductor's care. And only as "Baby homeward bound" was he spoken of in their letter addressed to his father.

Before he had spent a day among us it was suggested that his exemplary conduct entitled him to a more dignified name—at least during the period of our companionship. And this suggestion led to one of many amusing incidents. By what name should the boy be known? After the question had been eagerly answered a dozen times in as many different ways, with apparently little hope of a unanimous choice—for every one felt that his or her preference was peculiarly appropriate—a quiet old man, whose appearance was strongly suggestive of the pioneer days, offered a happy solution of the difficulty. He proposed that, in view of the humble circumstances of the child, the privilege of naming him for the trip be sold at auction among the passengers of our car, adding, by way of explanation, that the sum thus realized might "give the little fellow a start in life."

The average overland tourist is never slow to adopt any expedient to relieve the tedium of the journey; and here was, as one chap expressed it, "A chance for an auction on wheels, and one for charity's sake, at that." So the proposition was no sooner stated than acted upon. The auctioneer found himself unanimously elected, and, placing himself in the center of the car, heard the bidding, prompted by every generous impulse that enthusiasm and sympathy can give, rise rapidly in sums of one, two, and three dollars until thirty-five was called. There it halted, but only for a moment. The situation had become exciting. The auctioneer himself now took a hand in the competition; and a round of applause greeted his bid, made in the name of his native State, "Ohio bids fifty dollars." It was regarded as a matter of course that this sum would secure the coveted privilege. But no! Some one remarks that yet another county remains to be heard from. The voice of the weather-worn pioneer,—the suggester of the scheme,—has not yet been heard in the bidding. He has been a silent looker-on, biding his time. Now it has come. As he rises slowly in his seat he is intently watched by every eye, for somehow the impression prevails that he hails from "the coast," and that consequently there can be nothing small in [Pg 29] anything he does; In this no one is disappointed. The heart and purse of the gray-haired veteran are in the cause. Besides, his "pride is up" for the State he worships, almost idolizes. As his clear voice rings out with: "California sees Ohio's fifty, and goes fifty better," he is greeted by a storm of cheers that he will remember as long as he lives. And when the auctioneer announces: "California pays one hundred dollars and secures the privilege of naming the boy; what name shall it be?" the answer comes back quick as a flash:

"Grit! That sounds well and seems to fit well."

The passengers thought so, too, and very plainly showed their approval by overwhelming the man with congratulations and good wishes.

Reports of our proceedings were not slow in reaching the passengers in other parts of the train, whose curiosity or compassion led to numerous daily visits, while thoughtful sympathy found expression in liberal gifts of fruit, photographs, and a variety of Indian toys, as curious as they were welcome. To the old Californian, whose great liberality had secured for him a place in the respect and good-will of the entire party which was second only to that held by Grit himself, these continued attentions proved a source of special delight. Though he bore his honors with becoming modesty, he found early opportunity of proposing the health of the boy, who, as he aptly expressed it, "had been rocked in the cradle of misfortune, but had at last struck the color." Equally happy was his reply to a party of jolly cowboys, whom curiosity had led to solicit "a peep at the silent kid," while the train was delayed at one of the eating stations along the road. Their request having been granted, one of their number felt so highly elated upon receiving a handshake from Grit that he insisted upon presenting him with his huge cowboy spurs as a keepsake, proclaiming as he did so—with a trifle more enthusiasm than reverence—that in "paying a hundred to nominate the cute little kid, 'old California' carved his own name upon the Rock of Ages."

"Bless his little heart," replied the grizzled miner; "I'd give ten thousand more to own him, now that he has won his spurs."

Among the recollections of my personal experiences with Grit, [Pg 30] the second night of the journey stands out with especial clearness. At that time we were passing through the famous snowshed section on the eastern slope of the Sierra Nevada, our train running at a high rate of speed in order to make up lost time. It was here that the bravery of our little hero was put to a cruel test. Some time after midnight I was awakened by a child's frantic screams, that rose loud above the train's thundering noise. And, though up to this time there had not been a single tearful outbreak on the part of the young Trojan, there could be no mistaking the source of the piercing shrieks that now met my ears. I lost no time in hastening to his assistance, for I knew that, by way of experiment, he had been quartered in a "section" entirely by himself, the previous night having been a sleepless one to both the conductor and his charge. Furthermore, it was evident from his agonizing cries that I was the first to hear him. Finding the car in total darkness, the lights on both ends having gone out, I met with some delay in feeling my way to the terrified child, calling to him as I went; and at the first touch of my hand the trembling, feverish little form drew close to me, its chubby arms closed wildly about my neck, while loud, hysterical sobs told more plainly than words can express the agony that the child had endured. Only one who is familiar with sleeping-car travel over mountainous country, who has found himself suddenly aroused by the terrific roaring and swaying of a swiftly running train, and who, unconscious for the instant of his surroundings, has felt his flesh creep and his heart stand still, as he imagined himself engulfed by a mighty torrent or hurled over some awful precipice, only such an one can realize the position of this terror-stricken child.

Arousing the porter, who had gone to sleep while blacking the passengers' boots, I carried Grit to my own berth, where my endeavors to soothe his disturbed feelings proved so highly successful that the re-lighting of the car was greeted by him with loud laughter, through the still lingering tears. But go to sleep again he would not. No matter how often I tucked him beneath the blankets and settled myself to pretended slumbers, he would as often extricate himself, and, in a sitting posture, silently contemplate his surroundings. Fearing to doze off under the circumstances, [Pg 31] I finally concluded to sit up with the little fellow until sleep should overcome him. Making his way to my side as I sat on the edge of the berth, and placing his face close to mine, he imparted the cause of his persistent wakefulness by a gently uttered "dwink!"—repeating the word with more emphasis after a moment's pause. Happily, ample provisions had been made to meet his wants in this direction, and, procuring from the porter's "baby's bakery," as the well-provided lunch basket we had presented him at Sacramento had come to be known, I helped him to a glass of milk, after drinking which he fell quickly to sleep.

After that night's experience, Grit singled me out as his particular friend; and, as a consequence, he was nightly permitted to share my section with me. In these closer relations I found him the gentlest, most loving, and best-behaved child I ever met. It seemed as though he knew and felt that he stood sadly alone in the world, and that the less trouble he gave to others the better he would get on. His spirit of contentment and faculty of self-entertainment were phenomenal. While cards, books, conversation, and sleep served as a means of passing away time among the other passengers, he would for hours at a time remain in sole possession of a favorite corner seat, silently musing over some simple Indian toy. Again, an illustrated time-table or railway map would absorb his entire attention, until he had apparently mastered every detail of the intricate document. To watch the little toddling figure, after these prolonged periods of self-amusement, as, clad in a long, loose, gray gown, it quietly made its way along the car on a tour of inspection, proved an appealing study. Finding his arrival at my seat unnoticed at times—by reason of my absorption in a book or game of cards—he would announce his presence by a series of steady pulls at my coat, and make known his wants by a sweetly mumbled "Mum-mum." Repeated falls, incurred during these excursions, never caused him to falter in his purpose, nor did these, at any time, result in any other than good-natured demonstrations.

On but one occasion, aside from that already alluded to, was he moved to tears—an unlucky incident that happened while our party was taking breakfast at Cheyenne, sadly upsetting the [Pg 32] remarkable tranquillity of his mind. We had scarcely seated ourselves at the table, with the boy, as usual, perched in a baby chair in the midst of the party, when, espying an orange that a little girl next to him had placed beside her plate, Grit, innocently unmindful of its ownership, proceeded to help himself to the inviting fruit. No sooner had he grasped it than a sharp slap from his fair neighbor's hand sent it rolling along the floor. The child started, trembled; keenly hurt in more ways than one by what was, no doubt, the first punishment he had ever received, he burst into heart-rending tears.

Turning to me with outstretched arms, his piteously spoken "Mum-mum" cast a shadow over the festive occasion, and to some of us, at least, placed the further discussion of the meal beyond desire. Taking him back to the car, we were quickly joined by the conductor and our friend from the coast, who, after denouncing the "outrage" with frontier fluency, insisted that he should demand an apology from the offender, who was "plenty old enough to know better," and whose indignity to Grit, "right before a lot of strangers, was nothing short of an insult to our entire party." He "would rather," he continued, "fast a whole month" than sit by and again witness such conduct from one whose "sex and insignificance prevented a man from even drawing his gun in defense of the most helpless and innocent little creature on earth."

Something in the old man's manner, as he uttered these words, left little doubt in the minds of the passengers, now returning from the hurriedly finished meal, that, had Grit's tormentor been unfortunate enough to belong to the sterner sex, the novel experience of serving on a coroner's jury in the cowboy country would doubtless have been afforded us. This tension of feeling was happily relieved, however, by the appearance of the offender in person, who, accompanied by her mother, tearfully presented, not only her humble apology, but that bone of contention, the tropical product itself, which she insisted should be accepted as a peace offering.

As the journey progressed, each day brought to our party frequent reminders of their constantly increasing attachment, not only for the little hero, but for each other. And it became more and more apparent, now that the Rockies had already been left [Pg 33] behind, and our thoughts turned to the inevitable breaking up of the happy band, that Grit's presence had been the unconscious means of forming among his companions a strong bond of friendship and good-fellowship—one that could not be severed without sincere mutual regrets.

The morning of the last day found us still speeding over the seemingly endless cattle plains, where the frequent spectacle of immense grazing herds, guarded by picturesque bands of frolicking cowboys, added novelty and interest to the monotony of the scene.

It was in the early part of the afternoon of that day, while Grit was enjoying his customary mid-day nap, and the final games of whist and euchre so completely enlisted our interest as to render unnoticed the locomotive's shrill notes of warning to trespassing cattle, that a sudden terrific crash, followed by violent jolting and swaying of the car, breaking of windows, and pitching about of passengers and baggage, caused a scene of consternation and suffering.

Mingled with shouts of "Collision!" from men, and the screams of panic-stricken women, came the engineer's piercing signal for "Down brakes!" and before the car had fairly regained its balance upon the rails and the occupants had time to extricate themselves or realize what had happened, the train had come to a standstill.

More frightened than hurt, people instantly began bolting frantically for the doors, questioning and shouting to one another as they went. In the midst of the wild confusion arose cries of "Save Grit! Look out for the baby!" The words sent a shock to the heart of every hearer. Fear vanished. Personal peril was forgotten for the moment. Not a soul left the car! Though women had fainted and men lay motionless as if paralyzed, but one thought filled the minds of those who had heard the appeal: Was Grit safe?

In a moment the answer to this unasked question fell from the lips of one whose intense affection for the boy he had so appropriately named needed no appeal to carry him to his side in time of peril. "The child is hurt! Somebody go and see if there is a doctor on the train!" In willing response, several men rushed out among the excited throng that poured from the other cars.

Before us, on a pillowed seat, to which he had just borne him ,[Pg 34] lay Grit, half unconscious, pale, limp, and breathing with painful difficulty. The sudden shock which had almost overturned the car had rudely thrown him from his bed to the floor. There, between two unoccupied seats on the opposite side of the car, we had found him, convulsively gasping for breath, one little hand still grasping tightly the Indian doll-baby that for days had been his cherished companion. Though an examination of his body revealed no marks of violence, he was evidently in great pain. Applying such restoratives as were at hand, we gradually revived consciousness. Every attempt, however, to lift him or change his reclining position visibly increased his suffering.

Word soon came back that no physician could be found, that the accident was caused by the train coming into collision with a band of stray cattle. So far as could be hastily ascertained, one man had been fatally injured, while many persons had sustained serious bruises and strains. From the train conductor it was further learned that neither the locomotive nor any of the cars had been sufficiently damaged to prevent our proceeding to Omaha—still some five or six hours distant.

After a brief stop for the purpose of a careful examination of all parts of the train, we were again under way; the engineer having orders, in view of the injured passengers, to make the run in the fastest time possible.

The remainder of the journey was, even to the most fortunate, associated with sadness. But whatever the suffering on that ill-fated train, memory carries me back to but one sorrowful scene,—the bedside about which lingered the friends of the little stranger whom we had learned to love so well. In the presence of his suffering our own lesser injuries were forgotten, and all efforts were bent upon securing for the little sufferer every comfort possible under the adverse circumstances. With a view to lessening the painful effect of the constant jarring and shaking motion, a swinging bed was speedily improvised in the middle of the car, and here, surrounded by his sorrowing companions, lay Grit, enduring in silence the pains that his pale, sadly troubled face so keenly expressed.

Late in the evening the train reached its destination, without further mishap.

[Pg 35]

It had not yet come to a standstill in the station when, accompanied by the sleeping-car conductor, the father of Grit entered the car. Early in the day it had been resolved by the passengers that three of their number should meet the father upon his arrival, for the purpose of exonerating the conductor from any carelessness, and also for offering their assistance in caring for the child during the night. Now, however, reminded of their former happy anticipation of the meeting between parent and child, a shudder of sadness caused them irresistibly to shrink from a scene of welcome more deeply sad, even, than that sorrowful parting which they had witnessed on entering upon their journey a few days before.

As the stranger, deeply agitated, anxiously made his way to the central group, however, earnest sympathy found ready expression; and ere his eye had met the object of its search a friendly voice checked and bade him be calm and hopeful. "Your child, sir," continued the speaker reassuringly, "has not entirely recovered from the rough shaking-up we got a little while ago. He had a lucky escape, but now needs rest and quiet, and—you and I had perhaps better go for a doctor, while our friends here convey the boy to the hotel, where we shall join them shortly." And as the uneasy parent bends over the little bed and with inquiring look seeks from the calm blue eyes some token of recognition or sign of hope, the voice, more urgent—as though suddenly stirred by memories of an eventful past—again breaks in: "Let us lose no time in making the child more comfortable."

A few moments later Grit's friends stood around his bed at the neighboring hotel, listening to the verdict of the physician hastily summoned by the big-hearted pioneer. Internal injury of an extent unknown, but whose nature would probably develop before morning, was the verdict given after a careful examination. Alleviating measures, however, were suggested, which the distracted father hastened to put into effect. It was during one of his absences from the room that the big-hearted pioneer, drawing the doctor to one side, appealed to him in faltering tones to save the child "at any sacrifice or any cost."

But the appeal, though touching, was unnecessary. Higher considerations than those of personal gain prompted the kind [Pg 36] doctor to exercise his utmost skill. After his first visit not an hour passed but what his footsteps brought to the watchers reassuring proof of his deep interest in the case. And finally, yielding apparently to the soothing remedies, Grit fell into slumber that brought encouragement to his friends, none of whom could be induced, however, to forsake his bedside.

During the vigils of the night the father was repeatedly moved to speak of the sorrows of his life; of the sudden, fatal illness of his loving young wife; and of her ardent assurance that her last thoughts were solely of himself "and baby," coupled with the fervent wish that the two might "some day find a home in California, where in their final rest all three might once again be side by side."

Towards morning the boy grew suddenly restive, and violent coughing spells brought back the condition of semi-unconsciousness of the previous day. The doctor, evidently expecting a crisis, now remained constantly at his side.

The change came at last.

Just after dawn a beam of light broke softly over the little face, and new hope came to the anxious watchers. But, mistaking the silent messenger's approach for the herald of returning health, they had hoped in vain. The peaceful smile lingered but a moment, then returned once again, as though the beckoning spirit

"Was loth to quit its hold,"

and Grit had fallen asleep.

As a token of affection for her child, and in compliance with the dying mother's wish, the friends of Grit secured for the husband and father—chiefly through the generosity of one whose deeds shall outlive the recollection of his name—a permanent home in California; while the boy sleeps by her side, where the peaceful silence be so sweetly symbolized is never broken save by the weird lullaby of the waves that gently rise and fall over the distant shadows of Lone Mountain.

BY HAROLD KINSABBY.

THE east wind had failed to put in an appearance that evening, and the thermometer registered ninety-five under the stately elms of the Boston Common.

The family had gone away for the summer, and Buttons and the butler were out for an airing. Both were so well fed and so little exercised that they needed something to stir their blood.

Buttons was a sleek, fat pug, with a knowing eye and oily manner. They called him Buttons because the harness he wore about his forequarters was studded with shining ornaments.

His companion was likewise sleek and fat, and the amount of lofty dignity he stored under his bobtailed jacket and broadcloth trousers told everybody that he was the butler. He carried a wicked little cane with a loaded head, and seemed to own the greater part of the earth.

As the two strolled proudly through the Beacon Street Mall, fate favored Buttons and the butler. There was a cat on the Common,—a pet cat without an escort. This cat belonged to one of the wealthy families who at the tail end of winter board up their city residences and go to the country to spend the summer and save their taxes. The owners of this particular cat had speeded missionaries to the four corners of the globe to evangelize the heathen, but their pet puss they had turned into the streets of the modern Athens to seek its own salvation. With no home or visible means of support, but with true Christian fortitude, the dumb creature now haunted the doorstep of the deserted mansion and grew thin. Hunger had at last driven her to the Common in the hope that she might surprise an erring sparrow, or, perchance, purloin a forgetful frog from the pond.

The instant Buttons spied her he gave chase and drove her for [Pg 38] refuge into a small tree. Then he stood below and barked furiously, until the sympathizing butler shook the tree and gave him another chance. This time the cat barely succeeded in reaching a low perch on the iron fence, from which with terrified gaze she watched her tormentor.

"Why do you torture that cat?" angrily asked a quiet gentleman who sat on one of the shady benches holding a yellow-haired little girl on his knee.

"Oh, me and Buttons is having a little fun," answered the butler. "Buttons is death on cats."

The quiet man said nothing, but got up, helped the frightened cat to escape to a safe hiding-place, and then resumed his seat.

That night puss went to bed without a supper, while her owner presided at the one hundred and eleventh seaside anniversary of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, and punctuated the courses of a fish dinner with rare vintages of missionary port.

The next evening the same heat hung heavily over the Beacon Street Mall, and Buttons and the butler were again taking an airing and looking for fun.