The Project Gutenberg eBook of Angola and the River Congo, vol. 2, by Joachim John Monteiro

Title: Angola and the River Congo, vol. 2

Author: Joachim John Monteiro

Release Date: May 26, 2022 [eBook #68176]

Language: English

Produced by: Peter Becker and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

[Pg i]

BY

JOACHIM JOHN MONTEIRO,

ASSOCIATE OF THE ROYAL SCHOOL OF MINES, AND CORRESPONDING MEMBER OF THE ZOOLOGICAL SOCIETY.

IN TWO VOLUMES.

Vol. II.

WITH MAP AND ILLUSTRATIONS.

London:

MACMILLAN AND CO.

1875.

All Rights Reserved.

[Pg ii]

LONDON:

PRINTED BY WILLIAM CLOWES AND SONS,

STAMFORD STREET AND CHARING CROSS.

[Pg iii]

[Pg v]

[Pg 1]

ANGOLA AND THE RIVER CONGO.

The distance from Ambriz to Loanda is about sixty miles, and the greater part of the country is called Mossulo, from being inhabited by a tribe of that name. These natives have not yet been reduced to obedience by the Portuguese, not from any warlike or valorous opposition on their part, but entirely from the miserable want of energy of the latter in not taking the few wretched towns on the road. Incredible as it may appear, it is nevertheless a fact that to the present day the Mossulos will not allow a white man to pass overland from[Pg 2] Libongo (about half-way from Loanda) to Ambriz, although this last place was occupied in 1855, and several expeditions have since been sent to and from Ambriz to Bembe and San Salvador. Nothing could have been easier than for one of these to have passed through the Mossulo country and to have occupied it, at once doing away with the reproach of allowing a mean tribe to bar a few miles of road almost at the gates of Loanda, the capital of Angola.

One of these expeditions, on its return from chastising the natives of a town on the road to Bembe for robbery, was actually sent to Loanda by road. The Governor-General (Amaral) was then at Ambriz, and being unacquainted with the negro character, and having mistaken humanitarian ideas, gave strict orders that the natives of Mossulo, who had committed several acts of violence, should not be punished, but that speeches should be made to them warning them of future retribution if they continued to misconduct themselves. Their towns and property were not touched, nor were hostages or other security exacted for their future good conduct.

[Pg 3]

The natural consequence was that this clemency was ascribed by the natives to weakness, and that the Portuguese were afraid of their power, as not a hut had been burnt, a root touched, or a fowl killed, and they consequently, in order to give the white men an idea of their power and invincibility, attacked some American and English factories at Mossulo Bay, the white men there having the greatest difficulty to save their lives and property; a Portuguese man-of-war landed some men, and so enabled the traders to get their goods shipped, but the factories were burnt to the ground. This was in September 1859.

I was at Ambriz when the expedition started, so I determined to join it, and examine the country to Loanda.

The expedition consisted of 150 Portuguese and black soldiers, and as many armed “Libertos,” or slaves, who are freemen after having served the Government for seven years; these “Libertos” dragged a light six-pounder gun. The commander was Major (now General) Gamboa, an officer who had seen upwards of twenty years’ service in Moçambique and Angola, and to whom I was indebted[Pg 4] for great friendship during the whole time I was in the country. The major and two officers rode horses; two others and myself were carried in hammocks. We started one afternoon and halted at a small village consisting of only a few huts, at about six miles south of Ambriz. There we supped and slept, and started next morning at daybreak. The start did not occupy much time, as the Portuguese troops and officers in Angola do not make use of tents when on the march, and their not doing so is undoubtedly the cause of a good deal of the sickness and discomfort they suffer. In the evening we arrived at the Bay of Mossulo, where we were hospitably entertained by the English and American traders there established.

The country we passed through on our march was of that strange character that I have described as occurring in the littoral region of Ambriz. In the thickets dotted over the country a jasmine (Corissa sp.) is a principal plant. It grows as a large bush covered with long rigid spines, and bears bunches of rather small white flowers having the scent of the usual jasmine. Also growing in[Pg 5] these thickets, and very often over this species, are two creeping jasmines—the “Jasminum auriculatum” (J. tettensis? Kl.) and “Jasminum multipartitum?”

Various kinds of birds abounded, principally doves and the beautiful purple starlings, and on the ground small flocks (from two to four or five) of the bustards Otis ruficrista and Otis picturata were not uncommon, appearing in the distance like snakes, their heads alone being visible over the tops of the short rough grass as they ran along. A small hare is found in abundance, and also several species of ducks in some small marshes near Great Mossulo. Of larger game only some small kinds of antelope are found.

I had gone on some distance ahead of the troops, and on approaching one large town, about a dozen natives armed with muskets stopped my hammock, and told me I must return to Ambriz, as no white man could be allowed to pass. I told them that the soldiers were close behind, and that resistance would be useless, as their town would be taken and burnt if they attempted any; they, however, still persisted in not letting me go forward,[Pg 6] so I had to wait for a few minutes till they saw Major Gamboa and the two officers approaching on horseback, when they scampered off into the bush without even saying good-bye, and on our entering the town we found it deserted save by the king and a few other old men, who were all humility, and protested that they would never more insult or ill treat white men.

Major Gamboa was perfectly convinced of the uselessness of only talking to blacks, his intimate knowledge of them telling him that the only safe plan would have been to have burnt the towns on the road and taken the king and old men to Loanda as hostages, but he had to obey his instructions, and the result was that they attacked the factories and killed a number of natives. The Portuguese, however, instead of punishing this outrage, tamely pocketed the affront, and left the Mossulos in undisputed possession of the road.

In these towns were the largest “fetish” houses I have seen in Angola. One was a large hut built of mud, the walls plastered with white, and painted all over inside and out with grotesque drawings, in black and red, of men and animals.[Pg 7] Inside were three life-size figures very roughly modelled in clay, and of the most indecent description. Behind this hut was a long court the width of the length of the hut, enclosed with walls about six feet high. A number of figures similar in character to those in the hut were standing in this court, which was kept quite clean and bare of grass. What, if any, were the uses to which these “fetish” houses were applied I could not exactly ascertain. I do not believe that they are used for any ceremonials, but that the “fetishes” or spirits are supposed to live in them in the same manner as in the “fetish” houses in the towns in the Ambriz and Bembe country. At one of the towns we saw a number of the natives running away into the bush in the distance, carrying on their backs several of the dead dry bodies of their relatives. I hunted in all the huts to find a dry corpse to take away as a specimen, but without success; they had all been removed.

Next day we continued our journey, and bivouacked on the sea-shore, not very far from Libongo, and near the large town of Quiembe.

On the beach we found the dead trunk of a[Pg 8] large tree that had evidently been cast ashore by the waves, and had been considered a “fetish;” for what reason, in this case, I know not, as trees stranded in this way are common. It was hung all over with strips of cloth and rags of all kinds, shells, &c. As it was dry, it was quickly chopped up for firewood by the soldiers and blacks.

The following morning our road lay along the beach till we reached the dry mouth of the River Lifune, a small stream that only runs during the rainy season. We then struck due inland for about three miles to reach the Portuguese post of Libongo, consisting of a small force commanded by a lieutenant. This officer (Loforte) I had known at Bembe, and he gave us a cordial welcome.

The “Residencia,” or residence of the “Chefe,” as the commandants are called, was a large, rambling old house of only one floor, and it contained the greatest number of rats that I have ever seen in any one place.

One large room was assigned to the use of Major Gamboa, two officers, and myself, a bed being made in each corner of the room. We had taken[Pg 9] the precaution of leaving the candle burning on the floor in the middle of the room, but we had scarcely lain down when we began to hear lively squeaks and rustlings that seemed to come from walls, roof, and floor. In a few minutes the rats issued boldly from all parts, running down the walls and dropping in numbers from the roof on to the beds, and attacking the candle. We shouted, and threw our boots, sticks, and everything else that was available at them, but it was of no use, and we could hardly save the candle. It was useless to think of sleep under these circumstances, for we considered that if the rats were so bold with a light in the room, they would no doubt eat us up alive in the dark, so we dressed ourselves, and pitched our hammocks in the open air, under some magnificent tamarind-trees, and there slept in comfort.

Libongo is celebrated for its mineral pitch, which was formerly much used at Loanda for tarring ships and boats. The inhabitants of the district used to pay their dues or taxes to government in this pitch. It is not collected at the present time, but I do not know the reason why.

[Pg 10]

I was curious to see the locality in which it was found, as it had not been visited before by a white man, so Lieutenant Loforte supplied me with an old man as guide, and Major Gamboa and myself started one morning at daybreak.

We had been told that we might reach the place and return in good time for dinner in the evening, and consequently only provided a small basket of provisions for breakfast and lunch; we travelled about six miles, and reached a place where we found half-a-dozen huts of blacks belonging to Libongo, engaged in their mandioca plantations. These tried hard to dissuade us from proceeding farther, saying that we should only reach the pitch springs next morning. I, of course, decided to proceed, but Major Gamboa, who did not take the interest in the exploration that I did, determined to return to breakfast at Libongo at once, leaving me the provisions for my supposed two days’ journey.

After a short rest I started off again, and about mid-day arrived at the place I was in search of. It was the head of a small valley or gully, worn by the waters from the plain on their way[Pg 11] to the sea, which was not far off, as although it could not be seen from where I stood, the roll of the surf on the beach could just be heard. It must have been close inland to the place where we had bivouacked a few nights before, and had burnt the “fetish” tree for firewood.

The rock was a friable fine sandstone, so impregnated with the bitumen or pitch, that it oozed out from the sides of the horizontal beds and formed little cakes on the steps or ledges, from an ounce or two in weight to masses of a couple of pounds or more.

Although it was very interesting to see a rock so impregnated with pitch as to melt out with the heat of the sun, I was disappointed, as from the reports of the natives I had been led to believe that it was a regular spring or lake. My guide was most anxious that I should return, and as I was preparing to shoot a bird, begged me not to fire my gun and attract the attention of the natives of the town of Quiengue, close by, whom we could hear beating drums and firing off muskets. Next day we knew at Libongo that these demonstrations had been for the purpose of calling together[Pg 12] the natives, to attack the factories at Mossulo Bay.

There was great talk at Loanda about sending an expedition to punish these natives, but, as usual, it ended in smoke, and no white man has since been allowed to pass through the Mossulo country.

Several years after, the King of Mossulo sent an embassy to me at Ambriz, begging me to open a factory at Mossulo. On condition that I, or any white man in my employ, should be free to pass backwards and forwards from Loanda to Ambriz, I promised to do so, and was taken to the king’s town at Mossulo, where it was all arranged. I did not believe them, of course, but I gave a few fathoms of cloth and other goods that they might build me a hut on the cliff at Mossulo Bay, which they did, and I then declared myself ready to send a clerk with goods to commence trading, as soon as they should send me hammock-boys to carry me to Loanda. As I expected, they never sent them, and for several years, whilst the hut on the cliff lasted, it served as a capital landmark to the steamers and ships on the coast. The Governor-General[Pg 13] at Loanda, to prevent traders from establishing factories at Mossulo Grande, warned us at Ambriz that if we did so we must take all risks, that he would not only not protect us, but that all goods for trading at Mossulo would have to be entered and cleared at the Loanda custom-house. Far from such disgraceful pusillanimity being censured at Loanda, it was, with few exceptions, considered by the Portuguese there as a very praiseworthy measure.

The rock of the country at Libongo is a black shale; also strongly impregnated with bitumen. A Portuguese at Loanda, believing that this circumstance indicated coal in depth, sunk a shaft some few fathoms in this shale, and I visited the spot to see if any organic remains were to be found in the rock extracted, but could not discover any. About half way from Libongo to the place where I saw the bituminous sandstone formation, I observed a well-defined rocky ridge of quartz running about east and west, which appeared to have been irrupted through the shale.

The ground about Libongo is evidently very fertile, the mandioca and other plantations being[Pg 14] most luxuriant, and I particularly noticed some very fine sugar-cane. Some of the tamarind-trees were extremely fine, and on the stem of a very large one a couple of the “engonguis,” or double bells, were nailed, which had belonged to the former native town there, and as they are considered “fetish,” no black would steal or touch them.

A few hours’ journey (or about fifteen miles) to the south of Libongo is the River Dande, navigable only by large barges, and draining a fertile country.

It is only within the last two years that the value of this river, for trading or produce, has attracted attention at Loanda, and I am glad to say that it was owing to two foreign houses that trading was commenced there on anything like a respectable scale. The interior is rich in coffee, gum-copal, ground-nuts, and india-rubber, and this country promises an important future; cattle thrive here, and Loanda is now supplied with a small quantity of excellent butter and cream cheese from some herds in the vicinity of this river near the bar.

Limestone is also burnt into lime, which is sold at a good price at Loanda; and were the Portuguese[Pg 15] and natives more enterprising and industrious, the banks of the river would be covered with valuable gardens and plantations; but apathy reigns supreme, and the authorities at Loanda prevent any attempt to get out of this state by the obstructions of all kinds of petty and harassing imposts, rules, and regulations, having no possible aim but the collection of a despicable amount of fees to keep alive and in idleness a few miserable officials.

The country is comparatively level, and calls for no particular description, till about eighteen miles southward the high and bold cliff of Point Lagostas (Point Lobsters) marks the bay into which runs the beautiful little river Bengo, or Zenza, as it is called farther inland.

This is even a smaller river than the Dande, though more important from its near proximity to Loanda, and the remarks as to the wonderful indifference and hindrance to the development of the River Dande, apply with still greater force to the Bengo, a very mine of wealth at the doors of Loanda! It is hardly possible to restrain within reasonable limits the expression of surprise at the fact that Loanda, with its thousands of inhabitants,[Pg 16] should be still destitute of a good supply of drinking water, when there is a river of splendid water only nine miles off, whence it receives an insignificant and totally inadequate supply brought in casks only, carried by a few rotten barges and canoes that are often prevented from leaving or entering the river for days together, on account of the surf at the bar. A small cask of Bengo water, holding about six gallons, costs from twopence to fourpence! All kinds of fruit and vegetables grow luxuriantly on the banks of the Bengo, and yet Loanda, where nothing can grow from its sandy and arid soil, is almost unprovided with either—a few heads of salad or cabbage, or a few turnips and carrots being there considered a fine present.

At Point Lagostas a good deal of gypsum is found, and also specimens of native sulphur.

Both the River Bengo and the River Dande are greatly infested by alligators, and a curious idea prevails amongst all the natives of Angola, that the liver of the alligator is a deadly poison, and that it is employed as such by the “feiticeiros” or “fetish”-men.

The Manatee is also not uncommon in these[Pg 17] rivers;—this curious mammal is called by the Portuguese “Peixe mulher” or woman fish, from its breasts being said to resemble those of a woman. Near the mouth of the Dande this animal is sometimes captured by enclosing a space, during the high tides, with a strong rope-net made of baobab fibre, so that when the tide falls it is stranded and easily killed. I was never so fortunate as to see one of these animals, and am therefore unable to describe it from personal observation, but it is said to be most like a gigantic seal. I once saw a quantity of the flesh in a canoe on the River Quanza, and was told that the greater part had been already sold, and I had given me a couple of strips of the hide of one that had been shot in the River Loge at Ambriz. These strips are about seven feet long and half an inch thick, of a yellowish colour, and semi-transparent. They are used as whips, being smooth and exceedingly tough. The flesh is good eating, though of no particular flavour, and is greatly liked by the natives. The marshes and lagoons about the River Bengo are full of wild duck and other water-fowl, and are favourite[Pg 18] sporting places of the officers of the English men-of-war when at Loanda. The Portuguese, not having the love of sport greatly developed, seldom make excursions to them.

The country from the Bengo to Loanda rises suddenly, and the coast line is high and bold, but the soil is very arid and sandy, the rocks being arenaceous, evidently of recent formation, and full of casts of shells.

There is much admixture of oxide of iron, and some of the sandy cliffs and dunes close to Loanda are of a beautiful red from it. The vegetation is, as might be expected, of a sterile character, being principally coarse grass, the Sanseviera Angolensis, a few shrubs, euphorbias, and a great number of giant baobabs. Though the vegetation is comparatively scarce, birds of several species are common; different kinds of doves are especially abundant, as are several of the splendidly coloured starlings; kingfishers are very common, and remarkable for their habit of choosing a high and bare branch of a tree to settle on, from whence, in the hottest part of the day, they incessantly utter their loud and plaintive whistle, and, after darting down on[Pg 19] the grasshoppers and other insect prey, return again to the same branch.

The exquisitely coloured roller (Coracias caudata) is also very common in the arid country surrounding Loanda.

The pretty runners (Cursorius Senegalensis, and C. bisignatus, n. sp.) are also seen in little flocks on the sandy plains, and are most elegant in their carriage as they swiftly run along the ground. Two or three species of bustards are also common.

The great road from the interior skirts the River Bengo for some miles to the bar, where it turns south to Loanda; and the last resting or sleeping place for the natives carrying produce is at a place called Quifandongo, consisting of a row of grog-shops and huts on either side of the road.

It is a curious sight to see hundreds of carriers from the interior lying down on the ground in the open air, each asleep with his load by his side. A march of two hours brings them to a slope leading down to the bay, at the end of which Loanda is built.

[Pg 20]

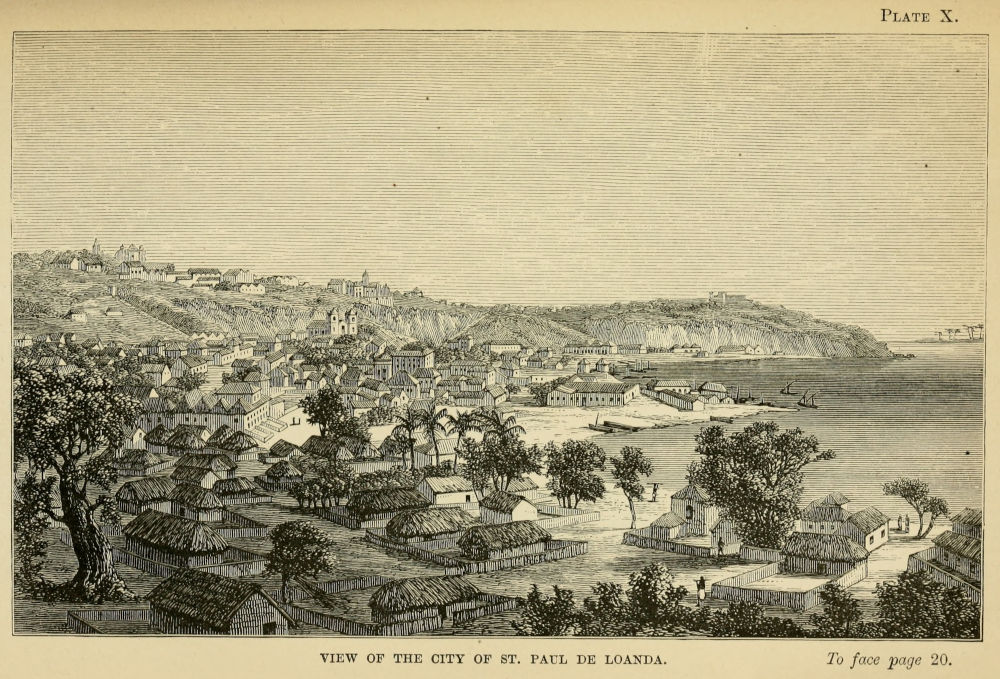

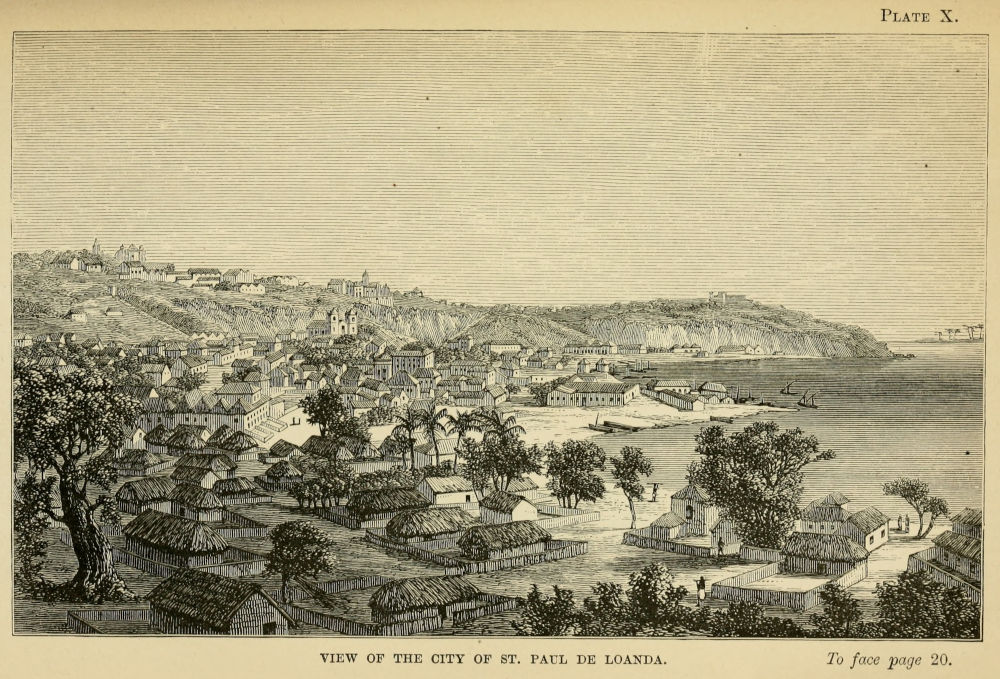

The city of St. Paul de Loanda is situated in a beautiful bay, backed by a line of low, sandy cliff that at its southern end sweeps outward with a sharp curve, and terminates at the water’s edge in a bold point, on which is perched the Fort of San Miguel (Plate X.).

The “Cidade Baixa,” or lower town, is built on the shore of the bay, on the flat sandy ground thus enclosed on the land side.

The “Cidade Alta,” or high town, is built on the high ground, at the end of which stands the fort above named.

In front of the bay a long, low, and very narrow spit of pure sand stretches like a natural break-water, and protects the harbour of Loanda perfectly from the waves and surf of the ocean.

Plate X.

VIEW OF THE CITY OF ST. PAUL DE LOANDA.

To face page 20.

[Pg 21]

A small opening called the Barra (or bar) da Corimba, about a mile south of Loanda, breaks the end of this long spit into an island; the rest joins the mainland about twelve miles to the south.

The whole length of the spit is very low and narrow, so that in high tides the waves break over it in places, but, singular to say, it has never been washed away at any place.

The bay was formerly much deeper;—vessels could anchor quite near the town, and could pass out of the Barra da Corimba, but now they have to anchor about a couple of miles to the north of the town, and boats only can pass over this bar.

A number of huts inhabited by native fishermen are built on the island, also a few houses belonging to the Portuguese, who are fond of going over to it for the purpose of bathing in the open sea beyond. The cocoanut-palm tree thrives very well on this sandy spit, but only a comparatively small number are growing on it.

Some years ago the Government sent to Goa for a Portuguese planter to plant this valuable[Pg 22] palm, and to teach the natives its cultivation. On his arrival he was only afforded means to sow a very small number, and was then appointed postmaster of Loanda, an office he held for many years, till his death, and I do not believe that a single cocoa-palm has been planted since, either by Government or private individuals; and thus a valuable and easy branch of cultivation and source of wealth is entirely neglected.

Loanda contains about 10,000 or 12,000 inhabitants, of whom about one-third are whites. The houses are generally large and commodious, built of stone, and roofed with red tiles; blue is a favourite colour for painting window-sills, door-posts, &c., and gives a very pretty appearance to the city. The greater part of the houses consist only of a ground floor,—the better class have a first, but rarely a second floor. Verandahs more or less open are the rule, in which it is customary to take meals.

Not many houses have been built within the last few years; they mostly date from the time when Loanda was a wealthy city, and the chief shipping port for slaves to the Brazils, when as[Pg 23] many as twelve or fifteen vessels were to be seen at a time taking in their cargoes of blacks. The slavers on their way out to Loanda used to bring timber from Rio de Janeiro for the rafters and flooring of the houses, and so hard and durable was it that it can be seen at the present day in the old buildings, as perfect and sound as when first put down, resisting perfectly the white ant, beetle larvæ, dry rot, and mildew that soon attack and destroy native woods.

Loanda has improved immensely since I first landed there in February 1858. It was then in a very dilapidated and abandoned condition. No line of steamers communicating with Europe then existed; four and six months elapsed without a vessel arriving, except perhaps one from Rio de Janeiro with sugar and rum; the slave-trade had ceased there for some years, and hardly any trade in produce had been started, a little wax, ivory, and orchilla-weed, being almost the only exports.

There was no trade or navigation whatever on the River Quanza, and hardly any shops in the town, so that provisions and other necessaries were constantly exhausted and at famine prices. A[Pg 24] large subsidy was granted to the colony by Portugal, to defray its expenses, always far in excess of its receipts. Now there is a monthly line of large steamers from Lisbon, another from Liverpool, and a considerable number of sailing-vessels constantly loading and discharging, to attest to the wonderful increase in the trade of the place. The colony now pays its own expenses, and shows a yearly surplus; and a couple of steamers running constantly from the River Quanza to Loanda can hardly empty the river of its produce.

All the public buildings are in an efficient state, a large extent of flat, stinking shore has been filled up and embanked, ruins of churches and monasteries cleared away, walks and squares laid out and planted, a large new market is being built, and good shops and stores are now abundantly supplied with every description of European goods; and if a good supply of water were brought to the city from the River Bengo, there would certainly not be a finer place to live in on the whole Western Coast of Africa.

From most of the houses having large yards, in which are the kitchens, stores, well, and habitations[Pg 25] for the slaves and servants, the city is luckily very open, and there is as yet no overcrowding; the roads and streets are also wide and spacious. The principal street, running through the whole length of the town, is remarkably wide, and for some distance has a row of banyan trees in the centre, under the shade of which a daily market or fair is held of cloth and dry goods.

This is called a “quitanda,” the native name for a market, and the sellers are almost all women, and are either free blacks, who trade on their own account, or are the slaves of other blacks, mulattoes, or whites.

Many of the natives and carriers from the interior prefer buying their cloth, crockery, &c., of these open-air retailers, to going into a shop.

Four sticks stuck in the ground, and a few “loandos,” or papyrus mats, form a little hut or booth in which presides the (generally) fat and lazy negress vendor.

On the ground are laid out temptingly pieces of cotton, gaily coloured handkerchiefs, cheap prints, indigo stripes, and other kinds of cloths; “quindas,” or baskets with balls and reels of cotton,[Pg 26] seed-beads, needles, &c.; knives, plates, cups and saucers, mugs and jugs, looking-glasses, empty bottles, and a variety of other objects. At other stalls may be seen balls of white clay called “pemba,” and of “tacula,” a red wood of the same name rubbed to a fine paste with water on a rough stone, and dried in the sun. Resting against the trunks of the trees are long rolls of native tobacco, plaited like fine rope and wound round a stick, which a black is selling at the rate of a few inches for a copper coin, the measure being a bit of stick attached by a cord to the roll of tobacco, or round the neck of the black. Others sell clay tobacco-pipes and pipe-stems, and as all men and women smoke as much tobacco as they can afford, a thriving trade is driven in the fragrant weed. All the tobacco used by the natives is grown in the country; but little is imported from abroad, and this is mostly purchased by the Portuguese for the weekly allowance which it is customary in Angola to make to the slaves.

“Diamba,” or wild hemp for smoking, is also largely sold.

The women vendors at these booths are amongst[Pg 27] the best-looking and cleanest to be seen in Loanda, and with often quite small and well-formed hands and feet; they are very sharp traders, and all squat or lie down at full length on the hot sand, enjoying the loud gossip and chatter so dear to the African women with their friends and customers.

A square at the back of the custom-house is the general market of Loanda, and presents a curious scene, from the great variety of articles sold, and the great excitement of buyers and sellers crying out their wares and making their purchases at the top of their voices. The vendors, here again, are mostly women, and, as no booths are allowed to be put up, they wear straw hats with wide brims, almost as large as an ordinary umbrella, to shade themselves. Every kind of delicacy to captivate the negro palate and fancy is to be had here:—wooden dishes full of small pieces of lean, measly-looking pork; earthen pots full of cooked beans and palm-oil, retailed out in small platters, at so much a large wooden spoonful, and eaten on the spot; horrible-looking messes of fish, cakes, and pastry, &c., everything thickly[Pg 28] covered with black flies and large bluebottles; large earthen jars, called “sangas,” and gourds full of “garapa,” or indian-corn beer; live fowls and ducks, eggs, milk, Chili peppers, small white tomatoes, bananas, and, in the season, oranges, mangoes sour-sop, and other fruits, “quiavos,” a few cabbage-leaves and vegetables, firewood, tobacco, pipes and stems, wild hemp, mats, pumpkins, sweet potatoes, palm and ground-nut oil, and dried and salt fish. The women squat on their heels, with their wares in front, all round and over the square, while hundreds of natives are jabbering and haggling over their bargains, as if their existence depended on their noisy exertions.

To the markets, especially, the black women take their dirty babies (they all seem to have babies, and the babies seem always dirty), and they let them roll about in the sand and rubbish, along with a swarm of children, mongrel dogs, and most miserable, lean, long-snouted pigs that turn over the garbage and quarrel for the choice morsels.

There are two other marketing places, one principally for fruit and firewood, the other where fried fish is the chief article, and where a number of[Pg 29] negresses are always busy frying fish in oil in the open air. The natives swarm round to buy and eat the hot morsels which the greasy cooks are taking out of the hissing pans placed on stones on the ground over a wood fire,—these they put into wooden platters by their side, and then suck their oily fingers with their thick lips or rub them over their warm and perspiring faces and heads.

Loanda is most abundantly supplied with fish of many kinds, and fortunate it is for many of its inhabitants that the sea is so prodigal of its riches to them. The fish-market is an open space at the southern end of the town, under the cliff on which stands the Fort of San Miguel. Here, in the early morning and in the afternoon, come the fishermen with laden canoes and toss their cargoes on the sandy beach, loud with a perfect Babel of buyers and vendors. The smallest copper coin enables a native to buy enough fish for one day;—the crowd that collects daily at the fish-market, and the strange scene that it presents of noisy bustle, can therefore be imagined.

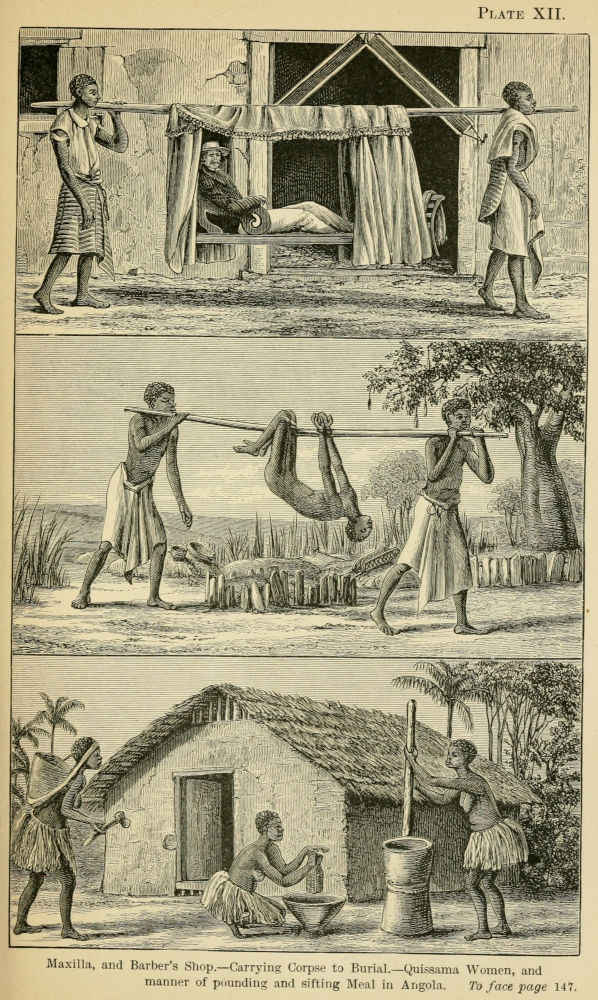

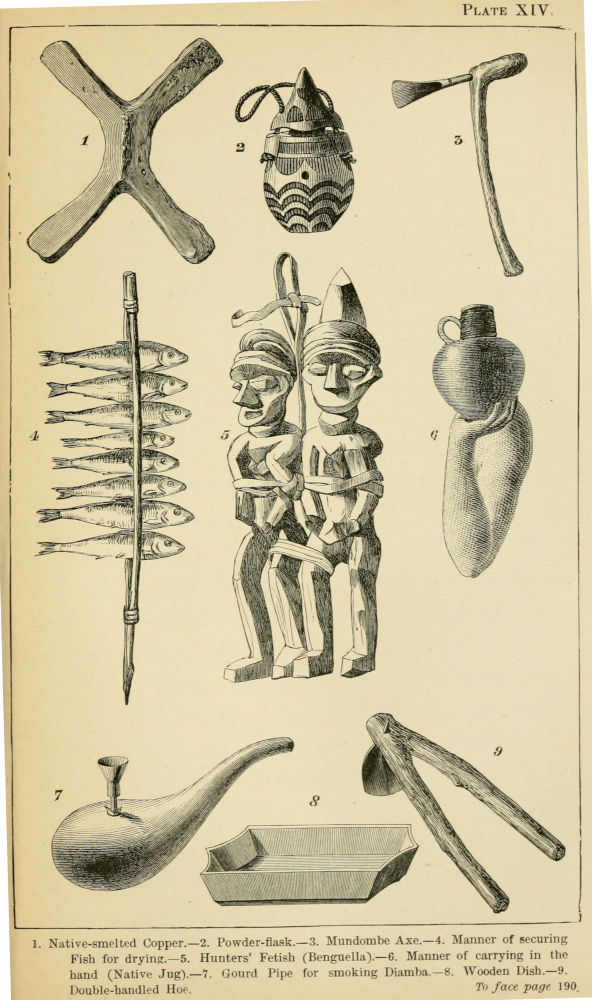

A number of women and children are always busy scaling and gutting fish, or cutting the large[Pg 30] “pungos” and sharks into small pieces in large wooden tubs, where they lie slopping in their reddish, watery blood; others are frying fish, and roasting a fish like a herring, held in cleft sticks (Plate XIV.), six or seven in each, stuck upright in the sand all round a fire, or opening fish flat to dry in the sun for sale to the natives from the interior. The fish are caught, both in the bay and out at sea, with hook and line and with nets made of native-spun cotton.

The quantity of fish on the coast is incredible. I have often watched the bay at night to listen to the wonderful swishing noise made by the fish on the surface of the water, as they were scared by every flash of lightning. Steaming once into Ambriz Bay, its whole surface was alive and boiling, as it were, with fish. The captain of the steamer, who had in his lifetime been to all parts of the world, declared that he had never witnessed such a sight.

A small shark is often caught which is much esteemed by the natives, and is dried in the sun; also the “pungo,” which attains to as much as a hundred pounds in weight. It is no unusual sight[Pg 31] to see one slung on a stick passed through the gills and carried on the shoulders of two blacks, with the tail dragging on the ground. It has very large, flat scales, and the flesh is not at all coarse in flavour. Latterly, the Portuguese have salted this fish in barrels, and when I was last at Loanda I was told of one man who had already salted 2000, and the season was not then over. It is this fish that is said by the natives to make the very loud and extraordinary noise that one hears so plainly at night or early morning, when in a boat or ship; it is said to press its snout against the vessel and then make the curious sound. I have heard it so strongly and plainly when lying in a bunk on board steamers that I have no doubt whatever the fish must have been touching the side of the vessel, and I have seen the blacks at other times splashing the water with an oar, because the loud drumming of the pungo kept them awake when lying in the bottom of a barge. The sound is like a deep tremolo note on a harmonium, and is quite as loud, but as if played under water. This low, sustained note has a very strange effect when first heard so unexpectedly in the still water. It is[Pg 32] a migratory fish, and comes in shoals on the coast only from about June to August.

Another fish like a small cod, called “corvina,” is also migratory, visiting the coast from July to September, and appears to come from a northerly direction, as it is a month later in arriving at Mossamedes than it is at Benguella, a distance of about 160 miles.

Till quite lately the roads and streets of Loanda were of fine, loose, red sand, rendering walking difficult and uncomfortable, particularly in the daytime, when the sand becomes burning hot from the sun’s rays; hence very few people ever walked even short distances, and the consequence was the constant recourse to the “maxilla” for locomotion. This is a flat frame of wood and cane-work, with one, or sometimes two arms at the side, and a low back provided with a cushion. This frame is hung by cords to hooks on a “bordão,” or palm-pole, about fifteen or eighteen feet long, and is carried by two blacks (Plate XII.). It is a very comfortable and lazy contrivance, and the carriers take it easily at the rate of about three to four miles an hour. The maxilla is provided with a light painted[Pg 33] waterproof cover, and with curtains to draw all round and effectually hide the inmate, if necessary. The Portuguese ladies were never seen walking out at any time, and when going to church, or paying visits, always went in a maxilla closely curtained that no one might see them. It is difficult to explain the reason for this, but I believe that a fear of Mrs. Grundy was at the bottom of it.

There is a very fair military band at Loanda, which plays twice a week in the high town, and once in a square near the bay. When I was last at Loanda with my wife, two other English ladies were also there with their husbands, and as we all listened to the band regularly, enjoying the cool evening promenade, we, no doubt, at first shocked the Portuguese greatly by so doing. It had at last, however, the good effect of bringing many of the Portuguese ladies out also, and they did not draw the curtains of their maxillas quite so closely as they used. An officer from Lisbon explained to my wife that the reason his countrywomen did not like to go about and be seen was that they were so ugly! But I can emphatically testify that this[Pg 34] was an ill-natured libel on the white ladies of Loanda.

There is a commodious custom-house in the centre of the town. On the quay are some benches on which the merchants sit in the afternoon to discuss current events, and to retail the choice bits of scandal of the day. There are several large and roomy Roman Catholic churches in the lower town, at which the attendance, however, is not very great, except at some of the principal festivals. I once saw, in a procession from one of the churches, in carnival time, a number of little black girls dressed to represent angels, with white wings affixed to their backs, and intensely funny they looked. On these occasions, and also at weddings, christenings, &c., quantities of rockets are sent up in the daytime, no feast being considered complete without an abundant discharge of these fire-works, to the immense delight of the black juvenile population, who yell and scream like demons and throw and roll themselves about in the sand.

At several places may be seen open barbers’ shops for the natives, distinguished by a curious sign, namely, two strips of blue cloth edged with[Pg 35] red, about three or four feet long and six inches wide, stretched diagonally over the entrance (Plate XII.). Inside, a chair covered with a clean white cotton cloth—with the threads at the ends pulled out for about four inches, to leave a lace-like design, called “crivo”—invites customers to enter and sit down, and have their heads shaved quite bare, the usual custom at Loanda, particularly of the negro women.

The dress of the blacks at Loanda is the same as elsewhere in Angola;—a cloth round the waist reaching to the knees or ankles and another thrown over the shoulders, or a cotton shirt, is the most common. Those who can afford it are fond of dressing in white man’s costume of coat and trousers, but the grand ambition of all is to possess an ordinary chimney-pot hat, which is worn on special occasions, no matter whether the wearer be dressed in cloths or coat.

The costume of the black women of Loanda is hideous. An indigo black cotton cloth is folded round the body and envelopes it tightly from the armpits to the feet; another long piece of the same black cloth covers the head and is crossed[Pg 36] over the bosom, or hangs down loosely over the shoulders, showing only the face and arms.

The correct costume is to have a striped, or other cotton cloth or print under the black cloths, but as only these latter are seen, the women have a dreadfully funereal appearance. The poorer class and slaves wear bright cotton prints, &c., and always a white or red handkerchief folded narrow and wound round the head very cleverly, suiting their dark skins remarkably well. A very common ornament round the forehead is a narrow strip of seed bead-work of different colours and patterns, and the women are fond of copying the large capital letters of the advertisements in the Portuguese newspapers, quite unconscious, of course, of the meaning of their pattern:—I once saw “Piannos para alugar” (Pianos for hire) worked in beads round the head of a black woman.

The Loanda women have a singular habit of talking aloud to themselves as they walk along, which at first strikes a stranger very forcibly; the men do the same, but to nothing like the extent that the women do. All loads are carried by the women on their heads, in all parts of Angola, and[Pg 37] the ease with which they balance anything on their shaven heads is wonderful. It is not difficult to understand that baskets or heavy loads can be easily balanced, but it is no uncommon thing to see women and girls walking along with a tea-cup, bottle, tumbler, or wine glass on their heads, and turning round and talking without the least fear of its dropping off. The manner in which they balance the “sangas,” or earthen pots in which they carry water, is the most curious of all; these are large, and have round, rather pointed bottoms; a handkerchief is rolled round into a small cushion and put on the side of the head, and the “sanga” is placed on it, not quite on its bottom, but a little on one side.

All the natives of Angola, but particularly the women of Loanda, are very fond of “cola,” the beautiful rose-coloured fleshy fruit of the Sterculia cola. The tree bearing it is very handsome, with small pretty flowers having a powerful and most disgusting odour. The first time I became acquainted with the tree was at Bembe. I was out walking, and suddenly noticed a very bad smell, and on asking a black with me where it could[Pg 38] possibly come from, thinking it was from some dead animal in a high state of decomposition, he laughed, and pointing to a tree said it came from the flowers on it;—I plucked a small bouquet of them, and when I reached home put them in a wine-glass of water to keep them fresh, and left them on the table of the padre (with whom I was then staying). When he went into his room he began to call out for his servants, and asked them why they had allowed cats to get into his room, and it was some time before he was pacified, or convinced that the few innocent-looking flowers had made the room stink to that degree. The flowers are succeeded by large pods, in which are contained five or more large seeds like peeled chestnuts, closely wedged together, soft and fleshy, and with a very peculiar, disagreeable, acrid, bitter flavour. The natives eat a small piece of “cola” with a bit of green ginger the first thing in the morning, and wash it down with a dram of gin or other spirit.

Amongst the mulattoes and black women it is usual to send a fresh “cola” as a present, and there is a symbolical language expressed by the[Pg 39] number of nicks made on it by the nail, of greeting, good wishes, &c.

A considerable quantity of “cola” was formerly exported to Rio de Janeiro from Loanda, packed in moist clay or earth to keep it fresh.

Servants in Loanda are almost all slaves. It is very difficult to hire free men or women. Those seeking service as carriers, porters &c., are nearly all slaves to other natives. Slaves as a rule are very well treated in Angola by the Portuguese, and cases of neglect or ill-usage are rare. Public opinion is strongly opposed to ill-treatment of slaves, and there is a certain amount of rivalry in presenting household slaves, especially well-dressed, and with a healthy appearance, and even on the plantations inland, or removed from such influence, I never knew or heard of slaves being worked or treated in the hard and cruel manner in which they are said to have been in the Southern States of America, or at the present day in Cuba. It is easy for slaves in Angola to run away, and it is hardly worth while to take any steps to recapture them; and if they have any vice or bad habits, it is so well known that harsh[Pg 40] measures will never cure them of it, that they are sold at once. An ordinary slave is not worth much, 3l. to 5l. being the utmost value. If proficient in any trade, or good cooks, then they fetch as much as 20l. or more. Many of the old-established houses make it a point of never selling a slave they have once bought; and when a slave requires correction or punishment, he is delivered over to the police for that purpose, and as desired, he is either placed in the slave-gang, chained by the neck to others, and made to work at scavengering, carrying stone, &c., or receives a thrashing with a cat-o’-nine-tails, or a number of strokes on the palms of the hands with a flat, circular piece of wood pierced with five holes and with a short handle.

The abolition of slavery in the Portuguese possessions was decreed some years ago. The names of all the existing slaves had to be inscribed in the Government office as “Libertos,” and the owners were obliged to supply them with proper food, clothing, and medicine, and were not allowed to punish them; while they, on their part, were required to work for seven years as compensation to[Pg 41] their owners, at the expiration of which time they were to be free. This has been allowed to remain virtually a dead-letter, the slaves never having had the law explained to them, and the authorities not troubling themselves to enforce their liberation at the end of the seven years.

The complete abolition of slavery in Angola has, however, been decreed to take place in the year 1878; and should the measure be strictly enforced, the total annihilation and ruin of the thriving and rising cotton and sugar-cane plantations, &c., will be the result, with a vast amount of misery to the thousands of liberated blacks.

It is a pity that philanthropy should blindly put so sudden a stop to a custom that has existed from time immemorial, and of which the evils are, in a country like Angola, exceedingly slight. The effect of this measure will be to destroy its nascent industry, the only means for its progress and development, and will plunge a great part of its population into helpless misery for years to come. Let slavery be abolished by all means, but only in the most gradual manner, and in proportion to the industrial and moral advancement of the race.

[Pg 42]

The natives of Angola are specially fitted for the introduction of habits of industry and usages of civilization, as they are naturally of a peaceable, quiet, and orderly disposition. The difference between them and the natives of Sierra Leone and the rest of the West Coast is very striking and pleasing. They have none of the disgusting swagger, conceit, or cant of the former, but are invariably civil and kindly, and under a firm and enlightened policy they would become more really civilized and industrious than any other natives of the West Coast.

That such would be the case is abundantly proved by what has already been done under the Portuguese in Angola, notwithstanding the intolerable system of rapine and oppression which the natives have borne for so many years from their government, a system in which only quite recently has any improvement been noticed. Were the natives otherwise than inoffensive and incapable of enmity, they would long ago have swept away the rotten power of the Portuguese in that large extent of territory.

Two good paved roads lead from the lower to the[Pg 43] upper town of Loanda; in this are the Governor’s palace, the prison, the treasury and other public offices, the barracks, and the military and general hospital. This is the healthiest part of the town, being fully exposed to the strong sea breeze, and splendid views are obtained from it of the bay, shipping, and town to the north, and of the coast and the “Ilha” or island to the south.

The country inland, immediately beyond the town, is dotted with “mosseques” or country-houses and plantations, and in one depression or valley are situated the huts comprising the dwelling-places of the native population, which have lately been removed from the back of the lower town, where they were a nuisance. In the “Cidade Alta” there existed till lately the ruins of the former cathedral: these were cleared away and a tower built on the spot, in which are a few meteorological instruments, and observations of temperature, height of barometer, &c., are taken daily. The extensive ruins of a monastery have also been levelled, and a public garden laid out on their site. These ruins gave some idea of the importance of Loanda in former and richer times.

[Pg 44]

A tame pelican has lived in the “Cidade Alta” for some years. He is fed daily with a ration of fresh fish from the Governor’s palace, and flies over every morning to the island to have his bath and plume himself at the water’s edge, returning regularly after completing his ablutions. He is very playful, and is fond of giving the nigger children sly pokes and snaps, or trying to pick the buttons off people’s coats. On the evenings when the band plays he may be seen promenading about with becoming gravity as if he enjoyed the music. He is very fond of being taken notice of, and having his head, and the soft pouch under his long bill, stroked.

About a mile from the high town, on the road south to Calumbo on the River Quanza, is an old and deep well called the “mayanga,” where hundreds of blacks flock daily to draw a limited supply of clear though slightly brackish water, but the best to be had in Loanda, the usual wells affording water quite unfit for drinking purposes.

The vegetation about Loanda is scanty, but a milky-juiced, thin-stemmed euphorbia, called “Cazoneira,” and the cashew-tree, grow very abundantly[Pg 45] on the cliffs, and inland about the “mosseques;”—mandioca, beans, &c., grow sparingly in the sandy, arid soil.

Oxen thrive, but very little attention is given to rearing them, Loanda being supplied with cattle from the interior for the beef consumed by the population.

Angola is one of the penal settlements of Portugal, where capital punishment was abolished some years ago, and whence the choicest specimens of ruffians and wholesale assassins are sent to Loanda to be treated with the greatest consideration by the authorities. On arriving on the coast, some are enlisted as soldiers, but the more important murderers generally come provided with money and letters of recommendation that ensure them their instant liberty, and they start grog-shops, &c., where they rob and cheat, and in a few years become rich and independent and even influential personages.

Although most of the convicts are sentenced to hard labour, very few are made to work at all; but I must do these gentlemen the justice of saying that their behaviour in Angola is generally very good, and murders or violence committed by them[Pg 46] are extremely rare, though they may have been guilty of many in Portugal,—the reason of this furnishes an argument against the abolition of capital punishment; it is because they have the certainty of being killed if they commit a murder in Angola, whereas in their mother country they may perpetrate any number of crimes with the knowledge that if punished at all, it is at most by simple transportation to a fine country like Angola, where many have made their fortunes, and where no hardships await them.

In Angola they are thrashed for every crime, and none survive the punishment if such crime has been of any magnitude. One of the few cases that I remember at Loanda was that of two convicts who agreed to kill and rob another who kept a low grog-shop, and who was supposed to be possessed of a small sum of money. They accomplished their purpose one night, and returned to the hut where one of them lived, to wash away the traces of their crime, and hide the money they had stolen. A little girl, the child of one of the murderers, was in bed in a small room in the hut at the time, and heard the whole of the proceedings. Before leaving,[Pg 47] the other assassin, suddenly remembering the presence of the child in the adjoining room, declared that she might have heard their doings and that it was necessary to kill her also, lest she might divulge their crime. The monsters approached her little bed for that purpose, but she feigned sleep so successfully that they spared her life, thinking she had been fast asleep.

The next day the child informed a woman of what she had heard the night before, and the inhuman father and his companion were arrested, tried, and condemned to receive a thousand stripes each. They were thrashed until it was considered that they had had enough for that day, but luckily both died on their way to the hospital. At the investigation or inquest held on their bodies, the doctor certified that their deaths had been caused by catching cold when in a heated condition on their way to the hospital from the place of punishment!

In Angola convicts cannot run away, nor would they meet with protection anywhere, and they would most certainly be killed off quietly for any crime they might commit, and no one would care to inquire how they came by their death.

[Pg 48]

The police of Loanda are all blacks, but officered by Portuguese. They manage to preserve public order pretty well, and are provided with a whistle to call assistance, as in Portugal. No slave is allowed to be about at night after nine o’clock unless provided with a pass or note from his master.

The lighting of the city is by oil-lamps suspended at the corners of the streets by an iron framework, so hinged as to allow the lamp to be lowered when required for cleaning and lighting, and it is secured by a huge flat padlock.

The military band plays twice a week. There are no places of public amusement except the theatre, which is a fine one for so small a place as Loanda, but only amateur representations are given. It was once closed for a considerable length of time on account of a difference of opinion amongst the inhabitants as to whether only the few married and single ladies should be admitted, or whether the many ladies living under a diversity of arrangements should be on equal terms with the rest. This very pretty quarrel was highly amusing, and gave rise to most lively scandal and[Pg 49] recrimination between the two contending parties, but the latter and more numerous and influential section carried the day, and ever since the doors have been open to all classes of the fair sex, and the boxes on a gala night may be seen filled with the swells of the place, accompanied by the many black, mulatto, and white lady examples of the very elastic state of morals in fashion in Angola.

There is a well attended billiard-room and café, and lately an hotel was opened. There is not much society in Loanda, as but few of the Portuguese bring their wives and families with them, and there are but few white women.

An official Gazette is published weekly, but it seldom gives any news beyond appointments, orders, and decrees, movements of shipping, &c.; a newspaper was attempted, but owing to its violent language it was suppressed for a time and its editors imprisoned. There are at present two newspapers, but they indulge abundantly in scurrilous language and personalities. There is no doubt that a well-conducted newspaper, exposing temperately the many abuses, and ventilating the questions of interest in the country, would be of great benefit.

[Pg 50]

The province of Angola is divided by the Portuguese into four governments, viz., Ambriz (or Dom Pedro V.), Loanda, Benguella, and Mossamedes. These are again subdivided into districts, each ruled by a military “chefe” or chief subordinate to the governors of each division, and these in their turn to the Governor-General of the province at Loanda. In this great extent of country under Portuguese rule, from the difficulty and delay in the communications with the central head of military and civil government at Loanda, and from the fact that the “chefes” combine both military[Pg 51] and civil functions, the tyrannical injustice and spoliation the natives have so long suffered at their hands can be easily imagined.

Other causes also concurred to produce this disgraceful state of things in Angola. The wretched pay of the Portuguese officers almost obliged them to prey upon the utterly defenceless population. The great bribery and corruption by means of which places that bled well or yielded “emoluments,” as they were called, were filled; the ignorant and ordinary class of officers, as a rule, who could be forced to serve in Angola; and the knowledge that scarcely any other future was open to them than the certainty of loss of health after years of banishment in Africa—must be mentioned as causes of the despotic oppression that crushed the whole country under its heel, depopulating it, and stifling any attempt at industrial development on the part of the natives. That this is a truth, admitting of no denial or defence, is at once shown by the fact that the sources of the great exports of native produce are all places removed from the direct misrule of the Portuguese.

The pay of the Governor-General of Angola is[Pg 52] 1333l. per annum. That of the Colonial Secretary is 444l. A major’s pay is now 10l. per month; that of a captain, 6l. 13s. 4d.; a lieutenant’s, 5l. 12s. 1d.; a sub-lieutenant’s, 4l. 8s. 11d. Some few years ago the pay was actually, incredible as it may appear, thirty-seven and a half per cent. below the above amounts: the present pay is only the same as in Portugal. When in command, a major and captain have thirty per cent., and a lieutenant and sub-lieutenant twenty-five per cent. in addition.

For the above mean and miserable pay Portugal sent, and still continues to send, men to govern her extensive semi-civilized colonies. Can any one in his senses be astonished at the result? Not a penny more did a poor officer get when perhaps sent miles away into the interior, where the carriage of a single load of provisions, &c., from Loanda would cost half a sovereign or more, and where even necessaries were often at enormous prices.

In the fifteen years that I have principally lived in, and travelled over a great part of Angola, and passed in intimate intercourse with the natives and Portuguese, I have had abundant opportunities of[Pg 53] witnessing the miserable state to which that fine country has been reduced by the wretched and corrupt system of government. This state is not unknown to Portugal, and she has several times sent good and honest men as governors to Loanda to try to put a stop to the excesses committed by their subordinates, but they have been obliged to return in despair, as without good and well-paid officials it was no use either to change, or to make an example of one or two where all were equally bad or guilty. There is, of course, but little chance of any change until Portugal sees that it is to her own advantage that this immensely rich possession should be governed by enlightened and well-paid officials. Let her send to Angola independent and intelligent men, and let them report faithfully on the causes that have depopulated vast districts, that have destroyed all industry, and that continually provoke the wars and wide dissatisfaction among tribes naturally so peaceable and submissive, and amenable to a great extent to instruction and advancement.

A few instances will give an idea of the persecution that the natives were subject to in Angola[Pg 54] from the rapacity of their rulers, and from which no redress was possible.

To assist the traders established at Pungo Andongo, Cassange, and other parts of the interior to transport their ivory, wax, and other produce to the coast, the government directed that a certain number of carriers should be supplied by the “Soba” or native king of each district, and that a stipulated payment should be made to these carriers for their services by the traders. This was immediately turned by the Portuguese “chefes” to their own advantage. The carriers were forced to work without any pay, which was retained by the “chefe;” and as fines and imprisonments helped to depopulate whole districts, and carriers became more difficult to obtain, the “chefes” in their rapacity exacted a larger and larger sum from the traders for each, over and above the stipulated pay. This frightful abuse existed in full force till 1872, when the forced liability of the natives to serve as carriers was abolished by law.

So easy and successful a robbery was this, that large sums were spent, and much interest employed,[Pg 55] for the sake of getting the post of “chefe” to the more important districts, such as Golungo Alto, Pungo Andongo, &c., even for a short time. The “chefe” being military commandant and civil judge, the population were perfectly incapable of resistance or complaint, and if such reached Loanda, it was of course quashed by the friends of the despot in power, who had themselves received a heavy sum to obtain him the post.

While I was exploring the district of Cambambe, an order arrived from Loanda for the “chefe” to draw up and forward a list of the number of men capable of bearing arms and being called out as a native militia. Such an apparently simple order supplied the “chefe” with a means of committing a dastardly robbery on the defenceless natives; and he in his turn was cheated of more than half of it by his subordinates, two mulatto militia officers, who were sent by him with half-a-dozen black soldiers to scour the country and obtain the desired information.

I was staying at the house of a Portuguese trader, at a place called Nhangui-a-pepi, on the road to Pungo Andongo, and about half way[Pg 56] between that place and Dondo, when these two scoundrels arrived, and arranged the following plan with the trader, whose name was Diaz. They had agreed with the “chefe” of Cambambe at Dondo, to receive a small share of the plunder they were to collect for him, but as they considered this share was not sufficiently liberal, they proposed to Diaz to send him part of the horned cattle they should obtain, for which he was to pay them in cash,—a certain amount below the value of course. This was agreed to, and they departed in high spirits.

A month after, on calling again on Diaz, I found that the two villains had already sent him seventy oxen, and that their journey was not yet completed! How many they had sent to the “chefe” at Cambambe of course I could not ascertain.

The manner of proceeding was simple and ingenious. They pretended that the Governor-General at Loanda had sent an order that all men in the district should be enlisted as soldiers and sent to the coast to serve in some war, that the names of all were down from the registers at[Pg 57] Cambambe, and they had come to revise the list, and that all would be liable to serve and be taken from their homes unless they were bribed to have the names erased.

In this way they robbed the poor inhabitants wholesale of oxen, sheep, goats, fowls, money, &c., with what success will be seen from the number of cattle only that they sent Diaz in one month, and from a part only of an extensive district.

On my arrival at Loanda some months later, I informed the governor personally of what I had witnessed, but he declared himself unable to prevent it or punish the culprits, from the impossibility of obtaining legal proofs, and from the influential position held by the principal robber.

Shortly after the commencement of steam navigation on the River Quanza, the Governor-General was asked to order the “chefes” of Cambambe and Muxima to cause stumps and snags that were dangerous to the steamers to be removed from the river. By a similar ingenious interpretation this inoffensive order of the government was converted into a means of levying black-mail on the natives of the river. The subordinates intrusted[Pg 58] with the execution of the measure declared that they had orders to cut down all palm-trees on or near the banks of the river, and would do so unless bribed to spare them. In this way a considerable sum of money was netted by the rogues in power.

The natives of the interior of Loanda are very fond of litigation, and this again is a source of considerable profit to the “chefes,” as they will not receive any petition, issue a summons, &c., without being bribed, and the crooked course of justice may in consequence be imagined.

A friend told me, that being once with the “chefe” of a district in the interior, they saw two bullocks approaching the “chefe’s” house, and on his asking a black standing near whose cattle they were, he answered very coolly that “they were two oxen that were bringing a petition!”

I need not say that I have known some honest “chefes” who discharged the duties of their ill-paid and thankless office honourably and with intelligence, but these exceptions are too rare to influence in the least the sad state into which the country has been sunk by long years of rapacity[Pg 59] on the part of its irresponsible rulers. Only a total change in the system of government can again people the vast deserted tracts with industrious inhabitants to cultivate its rich land; but, I am sorry to say, a termination to the long reign of corruption that has existed in Angola is not to be expected for years to come.

Whilst in Portugal itself patriotism and public morality are debased by an unchecked system of bribery and greed of money and power, it is too much to expect that her rich colonies will be purged of their long-existing abuses.

As might be expected, the great peninsular obstruction and impediment of high custom-house duties, so fatal to all commercial and industrial development, is in full and vexatious force in Angola, with the exception of Ambriz, where the total annihilation of trade from this cause, after its occupation by the Portuguese, was so striking, that I at last prevailed upon the Governor, Francisco Antonio Gonçalves Cardozo, to reduce the duties to a moderate figure, with what wonderful results I have already explained in a former chapter.

With the great want of roads and carriers, or[Pg 60] other means of conveyance, either for goods into or produce from the interior, transport is very expensive, and it is evident that the levying of high import duties besides on all goods for trade so enhances their value, that it becomes impossible to offer an adequate return or advantage to the native for the result of his labour or industry, or to leave much margin for profit to the merchant; consequently, the development of the country becomes completely paralysed and the revenue of the state remains small in proportion. Such a simple fact, apparent to the meanest understanding, is perfectly incomprehensible to the Portuguese! To mention one instance only: the last time I was at Golungo Alto the price of gunpowder was nearly six shillings a pound, and that of other goods in proportion! That the natives of Angola will cultivate large quantities of produce, if they can get moderately well paid for their trouble, is evidenced by the considerable exports from the country from Ambriz to the River Congo, where there are no custom-houses, and also on the River Quanza, where steam navigation enables goods to be sent up the country cheaply, and so to bear[Pg 61] the almost prohibitive duties levied on them at Loanda.

It is not only the excessively high duties paid to the custom-house that are complained of by the merchants at Loanda, but the absurd, petty, and vexatious manner in which the whole system is worked; the mean prohibitions and regulations attending the loading, discharging, and clearing of goods, vessels, and boats; the great delay and trouble about the simplest operations; the intense obtuseness of the officials, and the utter want of reason or object for such irritating proceedings. They do not prevent smuggling, as that can be most easily effected by any one desiring to do so, the lower officers and police being all common blacks or mulattoes in the receipt of miserable pay; and I remember one of the first merchants of Loanda once opening a drawer in his office, and showing me significantly, when speaking on this subject, a number of vouchers for small sums of money he had advanced on loan to the petty officers employed by the custom-house, and paid liberally at the rate of a few pence a day to prevent smuggling!

[Pg 62]

It would be amusing to see so much imposing bombast in the custom-house of a little place like Loanda, depending on a lot of poor, ragged, and starving blacks for its preventive service, were it not so annoying to see the effect of the high duties in hindering the development of the riches of the country, whose commercial prosperity is at present the only remedy for the evils of its misgovernment.

From olden times the report has been handed down of the occurrence of silver in the district of Cambambe, and the object of the Portuguese in some of their first wars in the interior was to obtain possession of the mines. There is, however, no record to show that they were successful in their endeavours; and beyond the statement that the natives of Cambambe paid tribute to the Portuguese in silver, part of which was made into a service for a church in Lisbon, nothing more was definitely known about it.

When I left the Bembe mines I was engaged by Senhor Flores of Loanda to explore the supposed locality of the silver mines, as well as various sites in Cambambe, believed in former days[Pg 63] to have been copper workings. I made a preliminary trip into the interior in September 1859, and then left Africa, returning a few months later with miners and the necessary tools and apparatus for a more complete exploration, which the indications I had noticed warranted me in undertaking.

I luckily had with me six capital Ambriz carriers, who had brought me from Ambriz to Loanda, in my journey through the country of Mossulo, which I have described in a preceding chapter, and I readily induced them to take me to Cambambe. I say luckily, as we found the greatest difficulty in obtaining carriers on the road, and we should have had to walk much greater distances than we did, if I had not had the Ambriz blacks. I was accompanied by a Senhor Lobato, of Massangano, the first man who had started trade on the River Quanza by means of barges to and from Loanda. Our route lay from Loanda to the River Bengo, and from thence inland, in an easterly direction, on the high road to Cassange—the farthest point occupied by the Portuguese in Angola.

[Pg 64]

The road, for a couple of days’ journey or more, is on and near the south bank of the River Bengo, and passes through some of the most fertile land imaginable, but, with the exception of small mandioca and other food-plantations, producing but little beyond the requirements of the few inhabitants of the country owing to the absence of cultivation.

We passed many places where towns had formerly existed, but the inhabitants had been obliged to remove farther into the interior, or to the country about the River Dande, to escape the wholesale robbery and exactions of the Portuguese “chefes.”

The second night after leaving Loanda we dined and slept at the house of the “chefe” of the district of Icollo e Bengo, a very intelligent young man, newly appointed to that place, and he gave us a painful description of the wretched condition in which he had found his district.

We were unable to obtain carriers here at any price, those that had brought us from Loanda having been hired for that distance only, as they would not trust themselves farther inland, fearing they might be forced to carry back heavy loads,[Pg 65] for which they would be paid only a miserable pittance, or perhaps nothing at all.

We had, consequently, to rely only on the six Ambriz men we had with us, but subsequently we were fortunate enough to pick up a few more on the road. In six days we arrived at Porto Domingos, on the River Lucala, a tributary of the Quanza. In these six days we passed through very varied scenery, due not only to the gradual elevation of the country from the coast, as noticed on the road from Ambriz to Bembe, but also to the variety of geological formations. On leaving Loanda horizontal beds of limestone, and then fine sandstones, occur. Near the junction, at a place called Tantanbondo, there are curious lines of nodules embedded in the limestone, and numbers loose on the surface from the weathering of the latter. These nodules are generally fractured, and re-cemented with crystalline calcspar; those not fractured are mostly of a singular, rounded shape, like an ordinary cottage-loaf. At Icollo e Bengo, finely micaceous iron ore is found; and at Calunguembe trap-rock occurs, which gives a most picturesque peaky appearance to the country.

[Pg 66]

Porto Domingos is one of the most lovely places I have seen in Africa; the vegetation of palm-trees, baobabs, cottonwood-trees, and creepers of many kinds on the banks of the river is wonderfully luxuriant. We found traces everywhere of a former very much larger population, and the same true tale of the inhabitants having been driven farther inland by the rapine of their Portuguese rulers.

After leaving Porto Domingos we arrived next day at the dry bed of the River Mucozo, a small stream running only in the rainy season and joining the River Quanza at Dondo. We passed through a thick wood, the road being the dry bed of a small stream running through it, and the ground a sandy dust of a bright red colour from oxide of iron. We and our carriers presented a comical appearance after walking an hour and a half through the wood.

The rock of the country is a kind of conglomerate, with a matrix containing much oxide of iron. At the River Mucozo this formation is succeeded by a very hard white quartzose rock, containing but little mica or feldspar, and the scenery[Pg 67] is very beautiful, the country being very hilly and broken.

Three days’ journey over a wild and rocky country brought us to the “Soba” Dumbo, formerly a very powerful king, and from whom the Portuguese have always derived great assistance in their wars, but only a handful of natives remain at the present day in the country, to mark the place of the once populous kingdom of the “Soba” Dumbo.

In the next two or three succeeding days I visited the places where, from the heaps of stones lying close to holes and excavations, it was likely that the natives had formerly worked for minerals; and that copper was what they had extracted or searched for was evident from the indications of blue and green carbonate of copper in these heaps. I saw enough to convince me that an exploration of the country was desirable, and likely to result in meeting with important deposits of copper. Of silver or other metals I saw no indications whatever.

We crossed in a southerly direction to Nhangui-a-pepi, and from thence to Dondo, and down the[Pg 68] River Quanza in a canoe to Calumbo. A night’s journey in a hammock brought us back to Loanda, having been absent exactly a fortnight on this very interesting journey, and though we suffered several times from hunger and thirst, and walked a great part of the distance from want of carriers, it was performed without any accident whatever or ill effects to health.

On my return to Africa in November 1860, I was accompanied from Lisbon by two Portuguese miners, to assist me in the exploration of these localities and in my search for the ancient silver mines. One of these men died on arrival at Loanda of an epidemic of malignant fever then raging there, and the other died shortly after reaching Cambambe, whither I had immediately proceeded.

From November to June I was actively occupied in exploring this district, and I cleared out several of the old workings, but failed to discover metallic deposits or indications of any value, though malachite and blue carbonate of copper were to be noticed abundantly distributed everywhere.

I made many excursions, sometimes of several[Pg 69] days’ duration, in that time—one in the direction of the district of Duque de Bragança, to a place called Ngombi Ndua, on the fine range of granite mountains ending south at Pungo Andongo; but beyond the universal indications of carbonates of copper, my explorations yielded no result.

A very interesting excursion was one I made about thirty miles in a northerly direction, where I passed through most beautiful mountain scenery, the formation of the country being trachyte or volcanic rock.

This evidence of ancient volcanic action is extremely interesting, as it may have caused the ridge or elevation running the whole length of Angola, which elevation has prevented the drainage of the plateau of the interior of that part of Africa from flowing to the Atlantic. This too strengthens my idea of the great River Congo being found to bend to the south, and be the outlet for the waters of the hundreds of miles of country lying behind Angola, and perhaps far beyond to the south, where, as I have already stated, there is no river of any consequence to be found.

[Pg 70]

The only other example of volcanic rock I have met with in Angola is the narrow belt or strip of basalt found at Mossamedes, and on the sea shore to the north of it for about thirty or forty miles.

This trachyte of part of Cambambe is no doubt connected with the trap-rocks noticed in my journey overland from Loanda to that district. The greater part of Cambambe is rocky, and destitute of forest or large trees; large tracts are covered with grass and shrubs, and of these the “Nborotuto” (Cochlospermum Angolense, Welw.), a small shrubby tree with large, bright yellow flowers about four inches across, and like gigantic butter-cups in shape and colour, is extremely common, and very conspicuous. In the cacimbo, or dry season, some very beautiful bulbs and orchids spring up after the ground has been cleared of grass by burning.

Birds of many species and of beautiful colouring are abundant, and in a small collection I made (see ‘The Ibis’ for October 1862), Dr. Hartlaub found several new species, and I have no doubt this district would well repay a collector. The most extraordinary bird in appearance and habits is[Pg 71] certainly a large black hornbill (Bucorax Abyssinicus), called by the natives Engungoashito. It is about the size of a large turkey, but longer in the body and tail. The following is from my notes on this bird in the above publication:—

“They are found sparingly nearly everywhere in Angola, becoming abundant, however, only towards the interior. In the mountain-range in which Pungo Andongo is situated, and running nearly N. and S., they are common, and it was near the base of these mountains that I shot these two specimens. They are seen in flocks of six or eight (the natives say, always in equal number of males and females). Farther in the interior, I was credibly informed that they are found in flocks of from one to two hundred individuals.

“The males raise up and open and close their tails exactly in the manner of a turkey, and filling out the bright cockscomb-red, bladder-like wattle on their necks, and with wings dropping on the ground, make quite a grand appearance.