Arbues knelt there in a flood of brightness from the lighted altar. Suddenly there was a muffled shout—a cry. He raised his head;—too late,—escape was impossible.

The Project Gutenberg eBook of Gold and glory, by Grace Stebbing

Title: Gold and glory

or, Wild ways of other days, a tale of early American discovery

Author: Grace Stebbing

Release Date: May 31, 2022 [eBook #68211]

Language: English

Produced by: Juliet Sutherland, Mary Meehan and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

A TALE OF EARLY AMERICAN DISCOVERY

Author of "Silverdale Rectory," "Only a Tramp," etc.

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS

New York

THOMAS WHITTAKER

2 AND 3, BIBLE HOUSE.

Only an apology for having written this historical tale.

My private opinion is, that all writers of historical tales should return me thanks if I apologize for them with myself, all in a body, the truer the tale the ampler being the spirit of the apology.

While I have been writing this tale, sometimes in its most important or serious portions, I have been startled by detecting my own mouth widening with an absurd smile, or by hearing a ridiculous chuckle issuing from my own lips, and have suddenly discovered that I was quite unconsciously repeating to myself the famous old Scotch anecdote of the old woman and the Scotch preacher—"That's good, and that's Robertson; and that's good, and that's Chalmers; ... and that's bad, and that's himsel'."

Turning the old woman into the more learned among my possible readers, and the Scotch preacher into myself, I read the anecdote—"That's good, and that's Prescott; that's good, and that's Robertson; that's good, and that's guide-book; that's good, and that's Arthur Helps; and that's bad, and that's hersel'."

I can only wind up my apology by pleading, that at least my badness has not gone the length of distorting a single fact, nor of giving to this wonderful page of history any touch of false colouring.

G. S.

In an apartment, gorgeous with a magnificence that owed something of its style to Moorish influence, were gathered, one evening, a number of stern-browed companions.

A group of men, whose dark eyes and olive complexions proclaimed their Spanish nationality, as their haughty mien and the splendour of their attire bore evidence to their noble rank.

The year was 1485: a sad year for Aragon was that of 1485, and above all terrible for Saragossa. But as yet only the half, indeed not quite the half, of the year had gone by, when those Spanish grandees were gathered together, and when one of them muttered beneath his breath, fiercely:

"It is not the horror of it only, that sets one's brain on fire. It is the shame!"

And those around him echoed—"It is the shame."

During the past year, 1484, his Most Catholic Majesty, King Ferdinand of the lately-united kingdoms of Castile and Aragon, had forced upon his proud, independent-spirited Aragonese a new-modelled form of the Inquisition. The Inquisition had, indeed, been one of the institutions of the noble little kingdom for over two hundred years already, but in the free air of Aragon it had been rather an admonisher to orderliness and good manners than a deadly foe to liberty. Now, all this was changed. The stern and bitter-spirited Torquemada took care of that. The new Inquisition was fierce, relentless, suspicious, grasping, avaricious, deadly. And in their hearts the haughty, freedom-loving Aragonese loathed its imperious domination even more than they dreaded its cruelty.

"It was not the horror of it only," said Montoro de Diego truly, "that made their eyes burn, and sent the tingling blood quivering into their hands. It was the shame."

And those others around him, even to Don James of Navarre, the King Ferdinand's own nephew, echoed the words with clenched hands, and between clenched teeth—

"It is the shame!"

But what cared Torquemada, the Grand Inquisitor, that mortal wounds should be inflicted on the noblest instincts of human nature? or what cared his tools in Aragon? Crushed, broken-spirited men would be all the easier to handle—all the easier to plunder or destroy.

Montoro de Diego had been one of the deputation sent by the Cortes to the fountain-head, as it was then believed, of all truth and mercy and justice, to implore release from the new infliction; for whilst one deputation had gone to the king himself, to implore him to abolish his recent innovation, another, headed by Diego, had gone to the pope. But the embassy was fruitless. The pope wanted money, and burning rich Jews, and wealthy Aragonese suspected of heretical tendencies, put their property into the papal coffers. The pope very decidedly refused to give up this new and easy way of making himself and his friends rich. The king's refusal was equally peremptory, and the deputations returned with dark brows and heavy hearts to those anxiously awaiting them.

The burnings and confiscations had already begun.

Soon after Diego and his companions entered the city of Saragossa they encountered a great procession, evidently one of importance judging from the sumptuousness of the ecclesiastics' dresses, their numbers, and the crowds of attendants surrounding them, crucifix-bearers, candle-bearers, incense-bearers, and others. There was no especial Saint's Day or Festival named in the Calendar for that date, and for a few moments the returning travellers were puzzled. But the procession advanced, and the mystery was solved.

In the centre of the gorgeous train moved a group so dismal, so heart-rending to look upon, that it must have rained tears down the cheeks of the Inquisitors themselves, had they not steeled their hearts with the impenetrable armour of a cold, utter selfishness.

Deadly pale, emaciated, unwashed, uncombed, with wrists and fingers twisted and broken, and limping feet, came the members of this group clad in coarse yellow garments embroidered with scarlet crosses, and a hideous adornment of red flames and devils. Some few of the tortured victims of base or bigoted cruelty were on their way to receive such a pardon as consisted in the fine of their entire fortunes, or life-long imprisonment; the others—they were to afford illuminations for the day's ceremonies with their own burning bodies. For each member of the wretched group there was the added burden of knowing that they were leaving behind them names that were to be loaded with infamy, and families reduced to the lowest depths of beggary.

"And all," muttered a voice beside Diego's elbow, "for the crime, real or suspected, or imputed, of having Jewish blood in their veins."

"Say rather," fiercely muttered back the noble—"say rather, for the crime of having gold and lands, which will so stick to the hands of the Inquisitors, that the king's troops in Granada will keep the Lenten fast the year through, before a sack of grain is bought for them out of those new funds."

"Ay," answered the unknown voice, "the Señor saith truth, unless there shall be hearts stout enough, and hands daring enough, to rid our Aragon of yon fiend Arbues de Epila."

Montoro de Diego turned with an involuntary start to look at the speaker of such daring words. For even though they had been uttered in low cautious tones they betokened an almost mad audacity, during those late spring days when the very breath of the warm air seemed laden with accusations, bringing death and ruin to the worthiest of the land, at the mandate of that very Arbues.

But Diego's eyes encountered nothing more important than the wondering brown orbs of a little beggar child, who was taking the whole imposing spectacle in with artistic delight, unmixed with any idea of horror, and who was evidently astonished at the agitated aspect of his tall companion, and irritated too, that the Señor should thus stand barring the way, instead of passing on with the rest of the rabble-rout trailing after the procession.

Whoever had ventured to express his fury against the new Inquisitor of Saragossa, it was evidently not this curly-headed little urchin, and with a somewhat impatient gesture of disappointment the noble turned away in search of his companions. But they also had disappeared. Carried away by the excitement or curiosity of the moment, they also had joined in the dread procession of the Auto da Fé.

"It is the shame," that was the burden of the low and emphatic consultation that was being held by the group of men, gathered privately in the palace of one of the indignant nobles of Aragon. Little more than twenty-four hours had passed since the disappointed deputation to Rome had returned, in time to witness the full horrors of the cruel tribunal they had so vainly tried to abolish, and the feeling of humiliation was keen.

And shame, indeed, there was for the brave, proud Aragonese, that the despotic tyranny of the Inquisition should hold sway amidst their boasted freedom and high culture.

"We are not alone in our indignation," added Montoro de Diego after a pause, and with a keen, swift glance around at the faces of his companions to satisfy a lurking doubt whether the muffled voice at his elbow, yesterday, had not indeed belonged to one of them.

But every face present was turned to his suddenly, with such vivid, evident curiosity at the changed and significant tone of his voice, that the shadowy supposition quickly faded, and with a second cautious but sharp glance, this time directed at doors and windows instead of at the room's occupants, the young nobleman replied to the questioning looks by a sign which gathered them all closer about him as he repeated:

"No; we are not alone in our just resentment. The spirit of disaffection is rife in Saragossa."

"The Virgin be praised that it is so," muttered one of the grandees moodily, while another asked hastily:

"But how know you this? What secret intelligence have you received?"

"And when?" put in a third questioner somewhat jealously.

The new system was already beginning to grow its natural fruit of general suspicion and distrust. But Diego speedily disarmed them as regarded himself on this occasion. His voice had been low before, it sank now to a scarcely audible whisper as he answered:

"One, I know not who—even the voice was a disguised one I believe—spoke to me yesterday in the crowded streets; one who must have marked the anger and mortification of my countenance I judge, and thence dared act the tempter."

"But how?" "In what way?" came the eager, impatient queries.

"In the intimation that the world were well rid of Arbues de Epila."

As those few weighty words were rather breathed than spoken, those self-controlled, impassible grandees of Spain started involuntarily, and stifled exclamations escaped their lips.

Arbues de Epila! The day was hot with brilliant sunshine. Even in that carefully-shaded room the air was heavy with warmth, and yet—as Montoro de Diego muttered the hinted threat against Arbues de Epila, the crafty, cruel, unsparing Inquisitor—those brave, dauntless, self-reliant men felt chill. They were in a close group before, but involuntarily they drew into a still closer circle, and looked over their shoulders. In open fight with the impetuous Italians or with the desperate Moors of Granada, no more fearless warriors could be found than those grandees of Spain, but against this new, secret, lurking, unaccustomed foe their haughty courage provided them no weapons. To be snatched at in the dark, torn secretly from home, fame, and family, buried in oblivion until brought forth to be burnt; and branded, unheard with the blackest infamy—these were agonies to fill even those stout hearts with horror.

Stealthy glances, of which until the present time they would have been altogether disdainful, were cast by each and all of them at one another. Who should say that even in their own midst there might not be standing a creature of the Inquisition, bribed to the hideous work by promises of titles, lands, position, or Paradise without Purgatory?

Quailing beneath these strangely unaccustomed fears all maintained a constrained silence for some time. But meanwhile the suggestion thrown out yesterday, and now repeated, worked in those fevered brains, and at length the fiercest of the number threw back his head, folded his arms across his breast, and spoke. Not loudly indeed, but with a concentrated passion that sent each syllable with the force of an alarum into the hearts of his hearers.

"The stranger was right. We have been cravens—children kissing the rod, with our petitions. Now we will be men once more, judges in our own cause, and Arbues shall die."

As he pronounced that last dread word he held out his hand, and his companions crowded together to clasp it, in tacit acceptance of the declaration. But there was one exception. One member of the group drew back. Montoro de Diego stretched forth no consenting hand, but stood, pale and sorrowful, gazing at his friends. They in turn gazed back at him with mingled astonishment, fear, and fury. But he never blenched. His lip indeed curled for a moment with something of scorn as he detected the expression of terror in some of the gleaming eyes turned on him. But scorn died away again in sadness as he said slowly:

"Is it so then, truly, that we nobles of Aragon have already yielded ourselves voluntarily for slaves, accepting the despicable sins of slaves—cowardice and assassination! Now verily it is time then to weep for the past of Aragon, to mourn over its decay."

But bravely and nobly as Montoro de Diego spoke, he could not undo the harm of his incautious repetition of the stranger's fatal hint. Some of his companions had already their affections lacerated by the loss of friends, torn from their families to undergo the most horrible of deaths, the others were full of dark apprehensions for themselves, or for those whose lives were more precious to them than their own. And the thought of getting quit of the cruel tormentor took all too swift and fast hold of the minds of that assembled group.

"It is very evident," muttered one of the party with a scarcely stifled groan—"it is very evident, my Diego, that you count amongst the number of your friends none of those whose names, or position, or country, place them in jeopardy."

"Ah! indeed," added another, without perceiving the flush that suddenly deepened on the young noble's cheeks, "and it is easy enough to discover, even if one had not known it, that Diego has neither wife nor child for whose sake to feel a due value for his life and lands."

Again that sudden flush on the handsome face, but Montoro stood in shadow, and none marked it. The gathering of men, now turned into a band of conspirators, was more intent on learning from Montoro de Diego whether he meant to betray their purpose, than in taking note of his own private emotion, and once assured of his silence they let him depart, while they remained yet some time longer in secret conclave, to concert their plans for destroying Arbues and the Inquisition both together.

"There cannot be much difficulty one would imagine," muttered one of the conspirators, "in compassing the death of a wretch held in almost universal odium."

But others of the party shook their heads, while one, more fully acquainted with the state of affairs than the rest, replied moodily:

"Nay then, your imagination runs wide of the mark. The difficulty in accomplishing our undertaking will be as great as the danger we incur. The cruel are ever cowards. Arbues wears mail beneath his monastic robes, complete even to bearing the weight of the warrior's helmet beneath the monk's hood. And his person is diligently guarded by an obsequious train of satellites."

"Then we must bribe the watch-dogs over to our side," was the stern remark of the haughty Don Alonso, who had been the first to seize upon the suggestion thrown out by the unknown voice in the crowd.

Immediately after that declaration the noblemen dispersed, for it was not safe just at that time for men to remain too long closeted together.

When Montoro de Diego quitted the palace of Don Alonso his face betokened an anxiety even greater than that warranted by the conversation in which he had just taken part. To say truth his secret belief was, that the deadly decision arrived at by his friends was the frothy result of recent disappointed hopes, and that with the calming influence of time bolder and more honourable counsels would prevail. As he left the palace, therefore, he left also behind him all disquietudes especially associated with the late discussion, and the settled gravity of his face now belonged to matters of more private interest.

Don Alonso had declared, that it was easy enough to see that Don Diego had no friends amongst those looked upon with evil eyes by the authorities of the Inquisition. But Don Alonso was wrong. The two friends whom Don Diego valued more highly than any others upon earth were reputed of the race of Israel. Christians indeed, for two generations past, but still with a true proud gratitude clinging to the remembrance that they had the blood in their veins of the "chosen people of God." They were Don Philip and his daughter Rachel.

Don Miguel had remarked with something of a sneer that it was easy enough to remember, from his present action, that Don Diego was unencumbered with family ties. And Don Miguel was so far right that Montoro de Diego was as yet a bachelor. But he was on the eve of marriage with Don Philip's daughter, and the words of his fellow-nobles had rung in his ears as words of evil omen. As he paced along the streets he tried in vain to shake off his dark forebodings, and it was with a very careworn countenance that he at length presented himself at the home of his promised bride.

To his increased disturbance, upon being ushered into the presence of Don Philip and his daughter, the young nobleman found a stranger with them; at least, one who was a stranger to him, though apparently not so to his friends, with whom he appeared to be on terms of familiar intercourse.

Don Diego at once took a deep aversion to the interloper, for he had entered with the full determination to press upon Rachel and Don Philip the expediency of an immediate marriage, in order that both father and daughter might have the powerful protection of his high position, and undoubted Spanish descent and orthodoxy. But it was, of course, impossible to speak on such topics in the presence of a stranger. So annoyed was he that his greetings to his betrothed bride partook of his constraint, and the girl appeared relieved when her father called to her:

"Rachel, my child, the evening is warm; will you not order in some fruit for the refreshment of our guests?"

As the beautiful young girl left the apartment in gentle obedience to her father's desire the stranger followed her with his eyes, saying with studied softness:

"Your daughter is so lovely it were a pity that she had not been dowered with a fairer name."

The old man sighed before replying: "Perchance, Señor, you are right. And yet, in my ears the name of Rachel has a sweetness that can scarcely be surpassed."

"It might sound sweeter in mine," rejoined the stranger still in tones of studied suavity, "if it were not one of the names favoured by the accursed race of Israel."

A momentary flash shot from the eyes of Don Philip, but hastily he dropped his lids over them as he answered with forced quietude: "Doubtless I should have bestowed another name upon my child had I foreseen these days, when it is counted for a crime to be descended from those to whom the Great I Am, in His infinite wisdom, gave the first Law and the first Covenant."

He ceased with another low, quiet sigh, and a short silence ensued, during which Don Diego felt rather than saw the sharp, searching glances being bestowed upon himself by the stranger, who at length rose, and said coolly:

"Ay, truly, Don Philip, a crime it is in the eyes of Holy Mother Church to have aught to do, even to the extent of a name, with the accursed race, and so, to repeat my offer to you for the hand of your fair daughter. I support my offer now with the promise—not a light one, permit me to impress upon you—to gain the sanction of the Church that her old name of Rachel shall be cancelled, and a new and Christian one bestowed upon her?"

As he finished speaking he turned from Don Philip with a look of insolent assurance to Don Diego, who in his turn had started from his seat, and stood with nervous fingers grasping the hilt of his rapier. As the nobleman met the sinister eyes, full of an impertinent challenge, he made a hasty step forward with the haughty exclamation:

"And who are you pray, sir, who dare ask for the hand of one who is promised to Don Montoro de Diego? Know you, sir, that the daughter of Don Philip is my affianced bride?"

"I have heard something of the sort," was the reply, in a tone of indescribable cool insolence. "Yes; I have already learnt that you have had eyesight good enough to discover the fairest beauty in Saragossa. But you had better leave her to me, noble Señor. She will be—" and the speaker paused a moment to give greater emphasis to his next slowly-uttered words—"she will be safer with me than with you—and her father also." And with a parting look and nod, so full of latent knowledge and cruel determination that Don Diego's blood seemed to freeze in his veins as he encountered them, the new aspirant for the beautiful young heiress took his leave.

As the great iron-bound outer door clanged to, behind him, the head of the old man sank forward on his breast with a groan. His daughter re-entered the apartment at the moment, and the smile which had begun to dawn on her countenance at the departure of the unwelcome guest gave way to a cry of dismay. Flying across the floor she threw herself on the ground beside her father with a pitiful little cry.

"Oh! my father, are you ill?—What ails you, my father?"

For some seconds the old man's trembling hand tenderly caressing the soft hair was the only answer. At last he asked with a choked voice:

"My daughter—couldst thou be content to wed yon Italian?"

The words had scarcely passed his lips when the girl sprang to her feet, gazing with wild eyes at her questioner.

"Kill me, my father, but give me not to yon awful, hateful man. Besides—" and with a look of agonized entreaty she turned towards Don Diego—"besides, am I not already given by you to another?"

"And to another who has both the will and the power to claim the fulfilment of the promise," exclaimed Montoro de Diego, coming forward, and clasping the girl's hand in his with an air of iron resolution.

Once again there was a heavy silence in the darkening chamber, and when it was broken the hearers felt scarcely less oppressed by the sound, although the words themselves seemed to speak of happiness.

"My son," said the old man in low and urgent tones, "it is true, I have given you my child—my only one. Fetch the good old priest Bartolo now, at once, and secretly, and let him within this hour make my gift to you secure."

A faint protest against this sudden, unexpected haste was made by the young bride, but Don Diego needed no second bidding to the adoption of a course he considered to be dictated as much by prudence as affection. Two hours later Montoro de Diego wended his way to his own palace with his young wife, Rachel Diego, by his side.

"Do not weep so, my Rachel," entreated the young nobleman as he led his bride into her new home.

But the tears of the agitated girl flowed as bitterly as ever as she moaned, "My father—oh! my father! If but my father had come with us!"

"He has promised to take up his abode with us, if possible, within the next few weeks, my Rachel," returned Montoro de Diego, in the vain endeavour to give her comfort. But she dwelt upon the words, "if possible," rather than upon the promise. She guessed but too well the fears which had dismissed her thus summarily from her father's home. She had heard but too much of the hideous tragedies of the past two months, and her husband himself was too oppressed with forebodings to give her consolation in such a tone of confidence as should secure her belief.

Don Philip had offered his life for his daughter's happiness, and his daughter well-nigh divined the fact.

Had the Christianized Jew consented to give his daughter, and his daughters princely fortune, to the vile informer of the Inquisition, he would have escaped harm or persecution, at any rate for that season. But he counted the cost, and taking his life into his hand, for the sake of his child's happiness, he committed her henceforth to the loving charge of the noble-hearted Don Diego. The fulfilment of the sacrifice was not long delayed.

The days went by, and the weeks—one—two—three. The second day of the fourth week was drawing to its close, since the group of Spanish noblemen had muttered their passionate resolves to rid their Aragon of Arbues de Epila. They had not been idle since then. Time had not quenched their burning indignation, but rather fanned it fiercer as they gathered fresh adherents, and gold, that ever needful aid in all enterprises. But the one adherent Don Alonso and Don Miguel most longed for still held aloof.

The lengthening shadows of that day belonged also, as the reader knows, to the second day of the fourth week since Don Diego's marriage, and his new ties made him but increasingly anxious to keep in the most careful path of rectitude, for the sake of expediency now as much as honour.

The name of Montoro de Diego was hitherto so unblemished, his rank was so important, that he might well believe himself a safe protector for his young bride, and for his new father-in-law, even though it was not wholly unmixed, pure Spanish blood that flowed in their veins. And he was firm in his refusal to have any part in schemes of danger. His wife was safe, hidden up in the recesses of his palace; and his father-in-law, he trusted, had secured safety in flight.

On the day succeeding that on which Don Philip had refused to purchase peace at the price of his daughter's welfare, Rachel Diego had received a few hurried lines of farewell from him, saying that he was going into exile until safer times for Saragossa, and bidding her be of good cheer, as all immediately concerning themselves now promised to go well.

Under these circumstances Don Diego might be pardoned, perhaps, if for a time he forgot the miseries surrounding him—forgot his hopes to infuse a bolder, nobler spirit of upright resistance to evil, into his comrades, and rested content with his own happiness.

But there came a dark awakening.

The day had been one of dazzling heat; and as the sun's rays grew more and more slanting, and the shadows longer, Don Diego bid his gentle young wife a short adieu, and sauntered forth to draw, if possible, a freer breath out-of-doors than was possible within.

He had been more impatient in seeking the evening breeze than most of his fellow-citizens, for the streets were still almost deserted. There was but one pedestrian besides himself in sight, and Montoro de Diego was well content to note that that one was a stranger, for he was in no mood just then for parrying fresh solicitations from his friends by signs, and half-uttered words, to join their secret counsels. He was sufficiently annoyed when he perceived at the lapse of a few seconds that even the stranger was evidently bent on accosting him. Determined not to have his meditations interrupted he turned short round, and began to retrace his way towards his own abode.

But not so was he to secure isolation. The rapid pitpat of steps behind him quickly proved that the stranger was as desirous of a meeting as he was wishful to avoid it; and scarcely had the Spanish nobleman had time to entertain thoughts of mingled wonder and annoyance, when he shrank angrily from a tap on his arm, and faced round to see what manner of individual it might be who had dared such a familiarity with one of the grandees of Aragon. The explanation was sudden and complete.

A low, mocking laugh greeted the involuntary widening of his eyes. Don Diego stood face to face with the man he had seen but once before; but that was on an occasion never to be forgotten, for it was the evening of his marriage, and the man before him was the one who had dared try to deprive him of his bride. For that he bore him no love, nor for the hinted threats then uttered; but now his blood curdled with instinctive horror as he gazed at the sinister, cruel face mocking his with an expression on it of such cool insolence.

Don Diego's most eager impulse was to dash his companion to the ground and leave him; but for the first time in his life fear had gained possession of him. Fear, not for himself, but for those whom he held more precious.

"Why do you stay me? What would you with me?" he questioned at last, in tones that vainly strove for their customary accent of haughtiness. The cynical triumph of the Italian grew more visible.

"Meseems, my Señor," he replied with a sneer; "meseems from your countenance, and your new-found humility of voice, that your heart must have prophesied to you that matter anent which I have stayed you, that counsel that I would, for our mutual advantage, hold with you. It is of Don Philip and his daughter Rachel that I wish to speak with you."

Montoro de Diego inclined his head in silent token of attention, and the foreigner continued in slow, smooth speech:

"Doubtless, my Señor, you remember that in your presence, some few weeks ago, I made proposals of marriage for the fair, rich daughter of Don Philip. The night of the day on which I made these proposals the birds flew from me, and from my little hints in case of contumacy, out of Saragossa. That was a foolish step to take, my Señor, was it not?"

He paused for an answer, and the dry lips of Don Diego replied stiffly: "Don Philip asked me not for counsel in his actions, neither did I give it."

"Ah!" resumed the Italian with a second sneer, "that may perchance be a true statement, Don Diego; but I shall be better inclined to accept it worthily, when you shall now reverse your professed behaviour, and accept the post of adviser to the obstinate heretic."

"I cannot," was the hasty exclamation. "Don Philip is no heretic, but a faithful son of the Church, and I have no clue to his retreat."

"Then I can give you one," was the low-spoken answer. "Don Philip has been tracked, and brought back. But his daughter is not with him. He refuses to confess her hiding-place, although he is now in the dungeons of the Holy Inquisition, and can purchase freedom by the information."

"Cruel, black-hearted villain!" exclaimed Don Diego, shocked and infuriated at length beyond all prudence; "know this, that Rachel, daughter of Don Philip, is now my bride. And know this yet further, that the nobles of Aragon are not yet so ground beneath the feet of a new dominion that they cannot protect their wives, and those belonging to them, from the perjured baseness of dastards who would destroy them."

Once more the young nobleman turned to quit his abhorred companion, but once more that hated touch fell upon his arm, and the Italian again confronted him with a face literally livid with malice as he hissed out:

"The nobles of Aragon are doubtless all-powerful, my Señor, and yet for your news of your bride I will give you news of her father. Ere this hour to-morrow the burnt ashes of his body will have been scattered to the four winds of heaven. Take that news back to your bride to win her welcome with."

Don Diego was alone. Whether he had been leaning against the walls of that heavy portico five seconds, five minutes, or five hours, he could scarcely tell when he became conscious of his own painful reiteration of the words, "Ere this hour to-morrow—ere this hour to-morrow."

"What is the matter, Montoro? rouse yourself. What about this hour to-morrow?" asked the voice of Don Alonso at his elbow. And Montoro shudderingly raised himself from the wall, looked with dazed eyes at his friend, and repeated:

"Ere this hour to-morrow. Will she know?"

"Will who know?" again questioned Don Alonso, as he passed his arm through his friend's and drew him on, for the street was no longer empty. Doors were opening on all sides, and the people pouring forth to the various entertainments of the evening. Some curious glances had already been cast at Don Diego, as he leant there stupefied with horror and anguish for his wife's threatened misery.

In the early part of the evening the Italian tool of the Inquisition had sought Don Diego. When evening had given way to night, Don Diego sought the Italian, and as a suppliant.

"It ill suits an Aragonese to sue to the villain of a foreigner," said the wretch, with malicious sarcasm. "It makes me marvel, my Señor, that you should deign thus to condescend."

"I marvel also," murmured the Spaniard, rather to himself than to his unworthy companion. "When the sword of the Moor was at my throat I disdained to sue for mercy; when I lay spurned by the pirate's foot I felt no fear; but now—ay now, if you will—I will give you the power to boast that one of the greatest of the nobles of Aragon has knelt at your feet to sue for a favour at your hands."

"And you will not deny the humiliating fact if I should publish it?" demanded the Italian, with a half air of yielding, and Montoro Diego, with a light of hope springing into his face, exclaimed:

"No, no. I will myself declare the deed, if for its performance you will obtain me the life and freedom of Don Philip."

Like a drowning man stretching forth to a straw, Montoro had snatched at a false hope. With that low, mocking laugh that issued freely enough from his thin, cruel lips, the Italian said slowly:

"Ah! your wish is very great, my Señor, I see that—truly very great to save a heart-ache to your bride. But—see you—you have hindered Jerome Tivoli of his desire, and now it is his turn, the turn of the 'base, black-hearted villain,' Jerome. And he takes your desire into his ears, he tastes it on his palate, it is sweet to him, sweetened with the thought of revenge, and then—he spurns it—spits it forth from him—thus!"

The Aragonese tore his rapier from its sheath, and darted forward, his fierce southern blood aflame with fury at the insult. But his companion stood there coolly with folded arms, content to hiss between his teeth:

"We are not unwatched, my Señor. I have plenty to avenge me if you think Doña Rachel will be gratified to lose husband now as well as father."

The mention of his wife was opportune. It restored Don Diego to his self-control. With a mighty effort mastering his pride, he collected his thoughts for one final attempt on behalf of the good old man doomed so tyrannically to an awful death.

Before seeking this second interview with the foreigner Montoro de Diego had schooled himself to bear everything for the sake of his one great object, and although for a moment he had allowed self to rise uppermost, he now once more crushed it down, and returned to the attitude of the humble suppliant.

He did not indeed repeat the offer, so insultingly rejected, to kneel to the informer, but he appealed earnestly to more sordid instincts. The man had alluded to Don Philip's daughter as rich as well as beautiful, and he now offered him the heiress's wealth as compensation for the loss of the heiress herself.

As he spoke a sudden gleam of satisfaction shot into the Italian's eyes, and a second time a hope, far greater than the first, rose in the petitioner's heart; but yet again it was dashed to the ground. Just as he was prepared to hear that his terms were agreed upon, his companion's countenance underwent a sudden change. A shadow had just fallen across the floor, and with a heavy scowl replacing the expression of greed he bent forward with the hasty mutter:

"Fool of a Spaniard, has that idiot tongue of thine but one tone, that thou must needs screech thy offers, like a parrot from the Indies, into all ears that choose to listen?" Then aloud, as though in continuation of a widely-different theme: "And so, as I tell thee, thy offers go for nought, for the wealth will of right flow into the coffers of the Sacred Office when the accursed Jew shall have suffered in the flesh to save his soul. And now," insolently, "I have no more time to listen to thy prating, and so go."

Whether he went of his free will, or was turned out, Montoro de Diego never clearly remembered, but on finding himself beneath the starry sky, he dashed off to the palace of the dread Arbues himself. Well-nigh frantic with despair, as he thought of the torments that the aged prisoner was even then all too probably undergoing, he forced admittance, late though the hour was, to the presence of the stern ecclesiastic, who was prudently surrounded by guards even in the privacy of his own supper-room. Nothing short of the great influence of Don Diego's high rank would have enabled him to penetrate so far, but even that did not protect him from the Inquisitor's rebuke, nor gain him a favourable hearing for his cause.

"It is our blessed office," said the bigoted supporter of Rome's worst errors, "to purge the Church, to—"

"If Don Philip die, others will die with him," sharply interrupted the young Spaniard, with fierce significance, and he left the Inquisitor's palace as abruptly as he had entered it, half determined, in that bitter hour, to throw in his lot with the conspirators. If there were none to listen to reason, none to obey the dictates of justice or mercy, why should he maintain alone his integrity?

So passion and despair tried to argue against his conscience, as he retraced his steps to his own home and the waiting Rachel. But the events of that night were not yet over.

As Montoro de Diego entered the deep portico of his palace entrance, he stumbled against some obstruction in the way. He stooped, and found there was a man dead, or in a deep swoon, lying at his feet.

Before he could ascertain more, or summon his servants, a third person stepped out of the obscurity and muttered rapidly:

"Remember, the gold is to be mine. It is not my fault that he has thus suffered before release."

Then the whisperer of those significant words was gone, and the young man was alone with the prostrate form of his father-in-law. Relinquishing his intention to call for aid, he lifted the inanimate body in his own strong arms, and bore his burden into a small inner apartment, reserved for his own devotion to such learned studies as were then flourishing in Aragon under the fostering care of royal encouragement. Something of medicine and surgery he had also acquired, but he soon discovered with bitter sorrow that in the present case his skill was useless. The old man was dying. Every limb had been dislocated on the rack.

"They tortured me to try to extort the secret of my child's hiding-place," murmured the old man quietly. "But thanks be to the Lord, He gave me strength. This day I shall be with Him. They have but hastened my coming home, my children."

And so, with forgiveness and love in his heart, and the light of coming glory on his face, this rescued victim of the Inquisition died in his daughter's arms, just as the sun's first golden rays were brightening the streets of Saragossa. Those rays that were glowing on the walls of the dungeons, within which slept, for the last time on earth, those innocent ones who were that day to be burnt in one of the awful Autos da Fé; those rays that were glowing on the walls and windows of the palace where Arbues the Inquisitor still slumbered.

"For so He maketh His sun to shine on the evil and the good."

The morning was still young when Don Diego received two visitors. The first, Jerome Tivoli, was quickly dismissed with the curt but satisfying speech:

"A noble of Aragon ever keeps his word. The miserable treasure you crave is yours."

His interview with Don Alonso was far longer.

"Surely now you must join us," urged that fiery spirit with impatient indignation. "You cannot refuse to aid in avenging the wrongs of your father-in-law."

"His mode," murmured the other, "of avenging his own wrongs, was to pray for light for his murderers."

But Don Alonso was marching with hasty strides up and down the apartment, and did not hear the words. His own conscience was ill at ease, as the head of conspirators having assassination for their object, and he had an unacknowledged feeling that he would be more comfortable in his mind if the upright Montoro would throw in his lot with them. But Don Diego was firm in his refusal. That recent death-bed scene had given him back his faith in the wisdom and love of God, in spite of the darkness now around him, and he ended the discussion at last, by saying:

"No, Alonso, I will keep my honour whatever else I may be forced to lose. But, although I will not join you, I will tell you whom I would join, were my Rachel a man, or, being a woman, had she but been inured to hardships as a mountain peasant. I would suffer exile thankfully, so embittered to me has my native land become."

"Embittered indeed to us all," almost groaned the other, adding, "But whom then is it you would join in your exile? Any of our friends, or one I know not?"

"One you know not, nor I either, personally," was the reply; "but one whom we both know well by reputation. That Christopher Colon, the Genoese, who, for the past six months almost, has been wearying our Queen Isabella of Castile to provide him means to find some strange new world; some vision of wonder that has risen in his imagination, brilliant with lands of gold and pearl, and perfumed with sweeter spices than the Indies."

Don Alonso uttered a short laugh of contempt.

"Ah, ha! And you mean to tell me that you would be willing to throw in your lot with that beggarly, visionary adventurer! Our King Ferdinand knows better than to waste his maravedis on such moon-struck projects, or to let his consort do so either."

"And yet," said Montoro, somewhat doubtfully, "and yet, although of course new worlds are foolishness to dream of, some islands might perchance fall to our share, if we adventured somewhat to find them, as such good and profitable prizes have been falling, during the past fifty years, pretty plentifully, to our clever neighbours, the Portuguese."

"Ay, and even they won't listen to this Genoese, you may recollect. Besides, the Pope has given everything in the seas and on it, I have heard, to those lucky neighbours of ours, so of what use for Spaniards to jeopardize lives and treasure to benefit the Portuguese?"

"Nay," answered Don Diego, "the Pope's grant to them is only for the countries from Cape Horn to India. Why should not we obtain a grant for lands in the other hemisphere?"

And so the poor young nobleman tried to stifle grief and apprehension in dreams of other lands, of whose discovery he would not live to hear, although his son would one day help others to found new homes on their far-off soil.

The days went by; the days of that year, 1485: and still the hideous spectacles of the Auto da Fé continued to be witnessed with shame and anguish by the inhabitants of Saragossa. Still the cry of the tortured victims ascended up to heaven, and still Arbues de Epila lived in his case of mail.

Those were busy, agitating days for Spain. The war with Granada was still in progress. King Ferdinand was much exercised in mind with various jealousies connected with French affairs, and, more than all important for future ages, the Queen's confessor, Ferdinand di Talavera, together with a council of self-sufficient pedants and philosophers, was taking into consideration that request of the Genoese, Christopher Colon, or, as we call him, Columbus, to be provided with such an equipment of ships, men, and necessary stores, as should enable him to find and found countries hitherto unheard of, and only thought of, most people declared, by crack-brained dreamers.

"Besides," finally decided Talavera and his sage council, with pompous absurdity; "besides, if there were nothing else against this scheme, such as the convex figure of the globe, for instance, which, of course, would prevent vessels ever getting back again, up the side of the world, once they got down, there was the impudence of the suggestion. It was presumptuous in any person to pretend that he alone possessed knowledge superior to all the rest of the world united."

And such impertinent presumption was certainly not to be encouraged in an "obscure Genoese pilot." And so, for that while, after weary waiting, and the weary hope deferred that maketh the heart sick, Columbus and his splendid plans were dismissed. But this result was not arrived at until four years after the months with which we are, for the minute, more immediately concerned; and so to return to the thread of our narrative, and to add yet further—and still the men of Saragossa gathered into secret bands, discussing rather by tokens, than by words, the unspeakable cruelties that were being committed in their midst, and the proposed destruction of their arch-instigator, Arbues de Epila.

All was ripe at length for the fulfilment of the fatal plot; fatal, alas, not only to the Inquisitor, but to his murderers also, and to many and many another wholly innocent of the crime.

All day long Don Alonso, Don Miguel, Don James of Navarre, with the rest of the conspirators, many of them with the noblest blood of Aragon flowing in their veins, watched with a fierce, hungry eagerness for the moment in which to strike the blow. The hours wore on, the evening came. In low-breathed murmurs one and another rekindled their own fury, or revived the flagging courage of a companion, by recalling the generosity of character, the blameless life, of some friend or relative snatched out of life by this barbarous persecution.

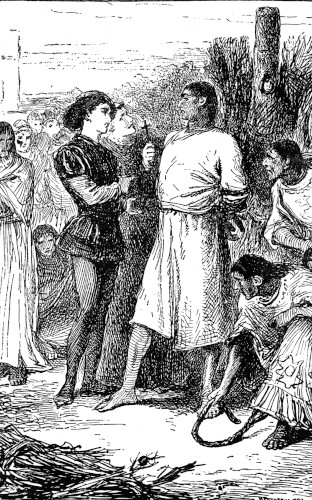

Night fell over the city of Saragossa, and gradually the conspirators stealthily, silently drew round about the walls of the cathedral. It was approaching midnight. The fierce persecutor of his fellow-men was on his knees before the great altar of the cathedral, on his knees before Him who has said, "I will have mercy, and not sacrifice."

Arbues knelt there in the flood of brightness from the lighted altar, and his enemies gathered up around him in the gloomy shadows of the surrounding darkness. Suddenly there was a muffled shout—a cry. He raised his head;—too late,—escape was impossible. Already the arm and hand were streaming with blood that had signed so many warrants for the torture and death of others. Then came the fatal blow.

Arbues knelt there in a flood of brightness from the lighted altar. Suddenly there was a muffled shout—a cry. He raised his head;—too late,—escape was impossible.

A dagger shone, gleaming red with life-blood, in the light, from the back of the victim's neck, in the flesh of which its point was firmly embedded.

Who gave that final thrust none knew but the giver. Only Don Miguel, who stood by in the fierce crush and melée, heard the words hissed out as the deadly weapon was darted forth:

"So dies the fiend, Arbues de Epila!"

And he, too, cast a hasty glance beside him, as Montoro de Diego had done when those words were uttered behind his ear in the Auto da Fé crowd some weeks ago.

But Montoro de Diego had found no one at his elbow but an innocent, wide-eyed child; and Don Miguel only found a crowd of terrified, cringing priests, who with pallid faces and trembling limbs bore off the dying superior to his own apartments, where he lingered two days, blindly giving thanks to God that he had been accepted as a martyr in His cause!

"The enemy of our liberty, our honour, our security is dead," muttered Don Alonso in fierce triumph to Montoro de Diego, as he sought temporary shelter from the dangers of pursuit in his friend's palace. But Don Diego shook his head with prophetic sadness as he answered:

"May the Holy Virgin grant that you have not called down worse evils upon our unhappy city!"

All too soon his fears were realized. The Church was offended, and the sovereigns, at the assassination of the great Inquisitor, and terrible was the vengeance wreaked far and wide upon all who had been, or were supposed to have been, implicated in the impious deed. Hundreds upon hundreds of people died, by torture, in the dungeons, at the stake, by persecutions innumerable, and starvation; and the whole province of Aragon was still further cruelly humiliated in the persons of its nobles, who were condemned in crowds to do penance in the Autos da Fé.

Don Alonso and Don Miguel were hanged instead of burned, not in mercy, but in sign of greater infamy, and that they might feel themselves ground to the very dust by the intense degradation of their punishment. And Don Diego did not escape the general ruin of his friends.

The heat of the search for victims had somewhat abated, when the covetous desires of one of the members of the Inquisition turned upon the possessions of the wealthy nobleman.

A path to the coveted riches was soon found. Montoro de Diego's words were suddenly remembered that he uttered on the night of Don Philip's death—"If Don Philip die others will die with him." On these words he was condemned, first to lingering months in a loathsome dungeon, then to death; and his young wife was driven forth from the gates of Saragossa in widowed penury and despair. The second Montoro de Diego was born a beggar and fatherless, but he had the brave, upright spirit of his father in him for his portion; and with his fortunes our tale is, for the future, concerned.

Poverty and pride do not go well in company, and so a Spanish lad of some fourteen or fifteen years of age had begun to learn. But the lesson was hard, and one badly learnt, when one evening some broken victuals were flung to him as they might have been to a famished dog, and accompanied by the exclamation:

"There, starveling, be not squeamish, but feed those lean cheeks of thine, and give me thanks for thy supper."

"I'll give thee that for thy base-born impudence," was the passionate retort, as the youth seized the package of broken meats and was about to use it as a missile to hurl at the donor's head.

But as the muscular young arm was raised it was suddenly grasped from behind, and a sweet, soft voice said hurriedly:

"My son, bethink you. For those of noble blood to be street-brawlers brings as great disgrace as beggary. You have never yet so far shamed me, or forgotten the due restraints of your rank."

As the slight, pale woman spoke the lad's clutched fingers loosened their hold of the parcel; it dropped back into the dusty gutter; and with burning cheeks he suffered himself to be led away from the neighbourhood of the half-angry, half-contemptuous man whose well-intentioned gift had been so spurned. When the mother and son had disappeared the man turned, with a short laugh, from watching them, and addressed himself to a neighbour.

"Easy to see who they are. Holy Mother Church has had something to say to their belongings in the past, I wager. But noble though they may be still, and rich though they may have been once, they are clearly starving now, and had better accept good food when they can get it."

And in this declaration the worthy Sancho was certainly most right, although the bread of charity, even when most delicately bestowed, tasted bitter in those hungry mouths; for the man was further right in his belief that mother and son were of high birth, and the mother had also been reared in luxury.

However, the little incident over, with the alms-giver's comment upon it, the worthy burgess of the small town of El Cuevo, upon the very borders of Aragon, turned his thoughts to matters of greater interest and importance.

"What thinkest thou, friend Pedro, of the new expedition preparing to set out for yon troublesome new-found island of Hispaniola—has it thy approval?"

The friend Pedro thus addressed was busily engaged in inspecting various samples of foreign spices. He now raised a solemn pair of eyes from his aromatic treasures as he replied:

"Troublesome it may be to those who govern it; but so long as my son doth continue to send me home a sufficiency of these marketable commodities, it is not he nor I that shall grumble at its finding."

The burly Sancho laughed.

"Ay, ay, neighbour, I know thee of old. A well-lined pocket thou ever holdest good recompense for a few thwacks. Would that the grand old Admiral Columbus could find comfort for ingratitude and sorrows with such ease!"

"But so he might do if he would but try," was the shrewd answer. "You see our brave Genoese hath ever been more needful for empty-handed honour and glory, than for gathering together good store of worldly spoil, to fall back upon when men should begrudge him the shadow-prizes he desired. Now it seemeth that he may chance to have neither."

"Well, well, I know not," continued Sancho. "The queen hath ever a good will to the great man. And although he is not to be commissioned to go himself to the punishment of that Jack-in-office Bobadilla, men say that the Commendador of Lares, Don Nicolas de Ovando, who is now preparing to set out thither, hath all the virtues under the sun. Wise and prudent and abstemious, and of a winning manner."

"Umph!" grunted the spice-dealer. "Don Ovando had needs be a second St. Paul if he is to win justice and mercy for the poor natives out yonder, at the hands of the off-scouring of our streets; and that is what our gentle-hearted queen hath most at heart."

Master Sancho nodded his head gravely.

"Ah, friend Pedro, I say not but you are right. And that minds me: if my head were not so thick, I might have bethought me to advise yon lad, with the great eyes and the short temper, to seek fortune, like many another of his peers, in those far-off lands across the ocean. I daresay he would have accepted that advice with a better grace than he did my scraps."

His neighbour looked up this time more fully than he had yet done, and let his hands rest for a few moments idle on the samples with which he had been so occupied, as he exclaimed with genuine astonishment:

"Why, friend Sancho, verily it seems to me that you have taken some queer true interest in yon ragged piece of impudence. I have noted you more than once, ay, than twice, watch him of an evening as he went by till out of sight. And now, when he would have flung your kindness back at you, still talking of him, forsooth. Nay then, had he so treated me he would have been roundly cuffed, I tell thee; and so an end."

Broad-shouldered, easy-going Sancho laughed and gave a shrug.

"I am not fond of being ready with my fists, friend Pedro; my hands are large, and might hap to be over heavy; besides, I have a broken thumb. But you judge rightly; I have taken a fancy to that set-up, handsome-faced young beggar. And I have watched him, not only of an evening past these doors, but at other hours in the town; and although he rejects help for himself, many a time have I seen him give it to those weaker or more helpless than himself."

Meantime, while he was being thus discussed, that same "set-up, handsome-faced young beggar" was remonstrating with his mother against her oft-reiterated lectures to him on humility, and on a studied avoidance of everything that should draw observation upon them.

"I will not slink into corners like a thief, nor hide myself in holes like a rat," he exclaimed at last, with haughty indignation. "Hast thou not told me thyself, my mother, that I am an Aragonese?"

But Rachel Diego replied with a lip that trembled while it curled:

"In truth art thou, my son, a child of a barren land. The heir of territories so stricken from the Maker's hand with poverty, that perchance we waste life's breath in lamenting that treasures so miserable should be wrested from us."

But the mother's new line of argument, to soothe her son's dangerous agitation, was fruitless as the other. His eyes flashed still more brilliantly with his burning indignation, as he retorted again:

"You say right, my mother. The land of Aragon is so poor and barren, that perchance her sons and daughters might all long since have forsaken their churlish, niggard-handed mother, and finally renounced her, but that she gives them liberty. Even in our oath of allegiance we tender no slaves' submission to oppression."

The widowed mother turned her sad eyes upon her proud-spirited boy.

"My son, no oath of allegiance has as yet been called for from thy lips."

The flush deepened on the young Spaniard's face. He pressed his teeth into the crimson lower lip for some seconds to strangle back a groan that sought escape from his own over-burdened heart. He had heard of the tragedies of those months before his birth.

"No," he muttered at length bitterly. "No. It is true. I am esteemed too contemptible to have even vows wrung from me that are counted worthless. But the oath that my father spoke is registered in my heart; the oath due from us, whose proud heritage it is to call ourselves the nobles of Aragon. And such is the oath that I, in my turn, tender to my sovereign, Ferdinand of Aragon and Castile."

The lad paused a moment, and then, with folded arms, and in low, firm tones, repeated the proud words of the Aragonese oath of allegiance.

"We, who are each of us as good, and who are altogether more powerful than you, promise obedience to your government if you maintain our rights and liberties, but if not, not."

As he spoke Rachel Diego dropped her face into her hands, and as he ended she murmured in stifled tones:

"Your father pronounced that haughty vow, and what availed the boast?"

What indeed! The young Montoro gazed for a moment at his wan mother, at the bare room, and then, with all his haughtiness lost in a flood of sudden despair, he darted from the miserable apartment to wrestle with his agitation in the wild darkness of a stormy night.

That his heart should be torn with bitterness and grief was little wonder, for all too well he knew how it came to pass that his mother was fatherless and a widow, and how he himself had been robbed of his parent and his patrimony. Something of the dismal tale of Don Philip's tortured death, and of the base villain who had grasped at his daughter's fortune, had been told the boy from time to time by his mother. Something, also, of the avarice and barbarity that had wrested a few despairing words to the destruction of his own father, the noble Don Montoro de Diego.

But much fuller details of those dismal days of 1485 had been given to the disinherited son of a blameless father by the old priest Bartolo, who had secretly aided the outcast young widow and her infant when they were first driven from their home, and who had continued to give them all the assistance in his power until his death, some months ago; in that very month of December, in fact, of 1500, when the hearts of so many in Spain, and elsewhere, throbbed with indignation at the news that a vessel had arrived in the port of Cadiz with the great discoverer on board, in chains like a common malefactor.

While the young Montoro was mourning over the dying priest, however, he little heeded the gossip going on around him about one who, during the remaining five years of a well-worn life, was to have a far greater influence on the orphan lad's career than ever the good old priest would have had the power to exercise.

But the days of December passed on. The old priest was buried. Columbus was delivered from his chains by hasty order of the king and queen, and was further invited in flattering terms of kindness to join the royal Court at Granada; a thousand ducats to defray expenses, and a handsome retinue as escort on the journey, being sent in testimony that the friendliness of the invitation was sincere. And so the saddened heart of the glorious old Admiral was once more warmed with half-fallacious hope. Not so with poor Rachel Diego and her son.

Life had been hard enough while Father Bartolo lived, but after his death the struggle for existence became well-nigh desperate; and by the time the months had come round to this following December of 1501, more people, in the obscure little town of El Cuevo, than the worthy burgess Sancho, had come to the conclusion that the unknown young widow and her handsome son were dying of starvation.

But death was evidently preferable, in the minds of the helpless couple, to degradation. Work they could not obtain, and charity they would not accept.

"And small blame to them after all," muttered Master Sancho to himself, a few days after his vain effort to bestow a supper on the objects of his interest. "I don't believe that I, either, should relish the taste of other men's leavings. Thanks be to the virgin that I have never had to eat them. But yet—to starve? Umph! I know not whether I should like the flavour of starvation any better."

And he folded his arms across his portly person with a slightly mocking laugh of self-consciousness.

This short soliloquy had been occasioned by the sight of young Montoro Diego passing the end of the street. His reappearance now, in the street itself, with a large loaf of bread in his arms, brought the soliloquy to a sudden stop; and Sancho left his post of observation in his own doorway, and hurried as fast as his weighty figure would allow to the pedestrian, finding no very great difficulty in barring the lad's further progress along the narrow roadway with his broad form. Montoro threw back his head impatiently.

"What now?" he demanded, with flushed cheeks. "Have you some more dog's meat that you wish to be rid of?"

The burgess laughed.

"Verily, my son, there is a bold spirit hidden under those rags of thine. But a truce to laughter; for verily I feel angered with you now, and I have a right?"

"Because I would none of your mean gifts?" asked Montoro hotly.

"Nay, indeed; that was your affair. But I am angry, and have a right to be, that you should accept aid from others which you will not have from me."

"Accept aid!" repeated the lad wonderingly. "Of what are you speaking? What aid have we received since the only friend died of whom we would accept it?"

But even as he spoke he caught the eyes of his companion fixed upon the loaf by way of significant answer, and he added shortly:

"This I have earned. It is no gift."

Then slipping under his questioner's arm he thought to have escaped; but Master Sancho caught him by the shoulder and held him fast.

"Look here, my son, by your air and looks I judge you to have been born to a rank far above my own and so if it be your pleasure I will speak to you with uncovered head by way of deference. But speak to you I will, for I have taken a fancy to you; and if you are not as set against work as against alms I may help you."

There was a spasmodic twitch of the shoulder at those last words; and the boy's face was so turned away that his captor could not read it. But after a moment's silence the worthy-hearted man continued, with a different accent of somewhat impatient anger:

"Hark ye, lad, ye may be as indifferent about thyself as it may please thee; but I cry shame on thee to refuse aught that may provide needful nourishment for that sweet and gentle mother of thine. To nourish thy false pride—ay, I will even call it by a juster name, thy base pride—thy mother is offering herself a sacrifice."

There was a gulping sound in the boy's throat, and then with a choking gasp he muttered:

"She could not, she would not, live on charity."

"No," instantly agreed the burgess of El Cuevo; "that I begin to believe. But she could and would live on the honest earnings of your hands. And be you noble or no, you'll find ne'er a priest in Spain to dare tell you that it is more honourable to let a mother starve than to work for her."

For the first time Montoro Diego let his eyes fairly rest on his mentor's face. There was something so genuinely true in the ring of the voice that the boy's anger and indignation dwindled away he scarce knew how, and gave place to a growing trust. With an effort he crushed down his emotion as he replied in low tones:

"I have no coward scruples against work, believe me. But I am noble, as you say. The son of one who died wrongfully for the death of Arbues de Epila. It was at the peril of their lives that any helped my mother, even with work, at the time that my father was thus barbarously mur—"

Burgess Sancho sharply clapped his hand over the boy's mouth, muttering with half-angry solicitude:

"Knowest thou not, my son, that a still tongue is wisdom? Keep thy information of the past for those who ask for it, and to those who do so give it not. You, a starving boy in the streets of El Cuevo, I can help. You may have dropped from the clouds for aught I know. Dost thou not comprehend me?"

Montoro's dark eyes gleamed with a flitting smile. The Aragonese of those days were not wanting in intelligence. But at the same time his native pride, and even his nobility of character, forbade him to accept aught at the expense of his identity, and so he quickly let his new friend understand.

"I have no inheritance but my father's name and my father's unsullied memory," he declared firmly; "and I will bear that openly. I have earned this loaf to-day, and more, by grinding colours for the great painter staying yonder; but first I told him who I was."

"More foolish you," remarked Master Sancho, with a shrug. "But what said he to thy news?"

"Even as thou—that I had more truth than wit. But he gave me work all the same, for he said that he need have no fear. The king could replace heretic nobles with other nobles, but he could not replace a painter, and so he would be wise enough to keep the one he had."

"Ay, then," agreed Master Sancho, "the Señor is right; and if I were you I would turn painter also, for the royal ordinance of last September did not name that amongst the many things you may not be."

"No," returned Montoro with a bitter laugh; "that last ordinance of persecution only excludes me from such employments as would be possible, not from those needing gifts vouchsafed only to the few. But I must say adios, for my mother will already have feared some mischance has come to me."

"To our next meeting, then," said the worthy burgess. "And meantime I will cudgel my brains till I find some means to help you, for all you are so self-willed and impracticable, my son."

The friendly look and the confident nod that accompanied these gruffly good-humoured words were full of such pleasant encouragement that Montoro Diego flew home with a heart suddenly grown as light as though he had already regained the power to use the title of 'Don' before his name, and had already won back the heritage of his ancestors.

We say "already," for of course Montoro, like all brave-spirited, properly-constituted individuals, was perfectly convinced, even in the lowest stage of rags and hunger, that the day would most positively come when he should re-enter his fathers home as the publicly-acknowledged Don Montoro de Diego. Meantime there was good bread for his supper that night, and for his mother, together with a handful of roasted chestnuts and a bottle of thin wine, grateful in that warm climate from its very sourness.

"And to-morrow," he said cheerfully, "the great painter says, my mother, that I may work in his studio again. And, if only you would go with me, he would not again sigh that there were none beautiful and tender-faced enough in the land to sit to him for the Holy Mother."

Rachel Diego said hastily, "Hush, my son," and shook her head at him; but at the same time she smiled, and a delicate flush tinted the pale cheeks, for her boy's loving praises were so sweet in her ears that they turned the humble supper into a feast.

The mother and son were very happy together that night; but had those two who so greatly loved each other known that even then schemes were being revolved in a shrewd and busy brain that would result, within a few short months, in placing a wide and storm-tossed ocean between them, one at least of the couple would have found the bread given to her turned to ashes in her mouth, and would have changed her smiles to weeping.

Happily for them, however, no prevision marred the rare joyousness of those few hours, nor disturbed the sleep that followed, gladdened with bright dreams.

"Friend Pedro!"

"Ay, what now?"

And the spice-dealer looked up from a small pile of curiosities, lying on a tray on his knees, with a more than half-betrayed idea that nothing his neighbour had to say could be so important, as calculating how much he might hope to make by the sale of those uncommon wares.

But this belief was somewhat lessened when his eyes rested on his friend's countenance. "Hey, then!" he ejaculated; "our painter yonder saith that thou art never a true Spaniard, for thy face is too round, but were he to see thee now he would surely tell a different tale."

"It is but lengthened by the height of my considering-cap," was the answer, with a laugh that speedily restored his visage to its usual good-humoured breadth.

Master Pedro appeared greatly relieved by the change. To say truth, in that land of solemn faces and staid deportments, a cheerful neighbour was as refreshing as a sunlit breeze in the early days of spring; and the spice-dealer, although the solemnest of the solemn himself, duly appreciated the fact, not to mention that he had a true though hidden affection for this especial neighbour, and would have grieved greatly if sorrow had befallen him. But long faces only due to considering-caps—well, that was another thing, and really not worth wasting the minutes of a working-day upon. He bent his head once more over his tray of West Indian treasures, as he asked with diminished interest:

"And pray then what has led thee to the wearing of a cap so weighty? Have the good fathers of St. Jacomb refused the purchase of thy Venice lustres, or will not they give thee a fair price for them?"

Burgess Sancho laughed again. "Nay, neighbour, trouble not thyself to guess, for thy guess is wide of the mark. The good fathers closed eagerly with my offer of the lustres, and the maravedis I demanded in exchange are already in my pouch. But hark ye, friend Pedro!—with the lustres came to me also two Venice glasses of the most changeful pearly hue, tall and thin, and of a good capacity. And I have a mind to keep them to myself, and, moreover, to try to-night how the flavour of a good wine from Madeira goes with them. Come thou in, when the sun hath gone down, and help me with my judgment."

"And also with my judgment on a matter of far more moment," muttered the worthy trader to himself, with a shrewd twinkle in his eye at having thus cleverly angled for his neighbour's company.

For the spice-dealer was one difficult to entice farther than his own doorway; and nothing short of those promises of choice wine from the Portuguese island of Madeira, to be drunk out of yet choicer goblets, would have tempted him on the present occasion to break his rule. As it was, the last glimmer of daylight had disappeared more than an hour when a cloaked figure stepped from one door to the next, and gave a tap upon the nail-studded panels.

"Better late than never, friend; come thy ways in," said Master Sancho heartily, as he acted the part of his own door-porter, and ushered his neighbour into a room brightly lighted with fire and lamp; for even in that sunny land of Spain the cold, damp winds of December made the blaze of crackling logs pleasant after sundown. What would not have been so pleasant to English ideas, was the overpoweringly pervading odour of burning lavender, a bundle of which was slowly smouldering on the hearth, by way of giving the atmosphere of the apartment that special tone and perfume considered desirable by its occupants.

On a small table in front of the cheerful hearth stood the beautiful Venice glasses, tall and slender, shimmering with opal tints in the ruddy glow, which also shone through a flask of golden-tinted Madeira, and danced hither and thither over various dishes daintily set forth with sweet-meats. For, ascetic-looking as Master Pedro was in appearance, he had as sweet a tooth as any Roman, and Master Sancho was too anxious to gain his aid or counsel to neglect anything that might tend to put him in good humour.

But although Pedro's eyes gleamed with a certain satisfaction at sight of the festive preparations, he was shrewd enough to read between the lines; and as he stretched his feet comfortably towards the fire, and put back his delicate glass after a contented sip, he asked with grim humour:

"And now, friend Sancho, that you have baited your net and caught your fly, tell me, what wouldest thou seek from out it?"

The merchant's face flushed at the unexpected question, and he began hastily: "Now, by the Holy Virgin, I protest that good fellowship—"

"And some perplexity besides," interrupted Pedro with a knowing smile, "made you anxious for my company. But tell me without hesitation what you would have of me, for I would stretch many a point to serve so good a neighbour."

"Thou sayest so!" exclaimed worthy Sancho, as he rose hastily to his feet, and with hand resting on the table bent over his companion, eagerly scanning his countenance. "Thou sayest so, and would hold to that thou hast said?"

"Ay verily," was the calm answer. "Almost, maybe, to the extent of putting my limbs in danger of the rack, if they might save thine from the like peril thereby."

However, in spite of his declaration, Master Pedro was somewhat taken aback when his companion dropped again into his chair, muttering thoughtfully:

"Nay then, not quite so bad as that, I hope; not quite so bad as that; although—" and he raised his voice slightly once more, and raised his eyes to his friend again as he added—"although I certainly did think it were prudent to seek your advice in the privacy of my own home, rather than to proclaim my desires to the ears of the whole town. It is now three weeks since you accused me of taking an interest in a certain large-eyed vagrant boy—"

"Ay indeed," with fading interest, "of watching the bundle of rags as a dog might watch a rat."

"Even so. And when you have watched anything in that way for the space of months, you end by either loving it, or holding it in abhorrence. I have ended by loving it. And unfortunately I love where the law hates. Father and grandfather of that bundle of rags have perished at the mandate of the Holy Tribunal."

Master Sancho ceased, and bestowed a long, silent stare upon the glowing logs, while his companion took a long, slow sip of the rich wine. At last the spice-dealer put down his glass, placed his hands slowly, outspread, on his knees, and said in slow, muffled tones:

"Friend Sancho, I have some rules for life which I have found good. One of them is, 'Never give advice.' But this once I will depart from that rule, and advise thee to rid thy heart of this unlucky love, and for the future ever to wear thine eyes within thy cloak when yon lean-cheeks is within sight."

"Umph!" calmly ejaculated the host, still staring into the fire. "I knew that would be thy first well-meant advice; and, to tell thee the truth, I reckon that it may be as well for me not to be gazing at the lad quite so much as I have done of late. It is with that belief that I have turned to you to help me to get quit of the poor starveling."

At these last unexpected words the guest started, and cast a keen, swift glance of almost angry wonder upon his entertainer, as he said hastily:

"Nay, neighbour, what is that thou sayest? I advise thee to have nought to do with the lad, that is true; but canst thou think, even for thy safety, that I would aid thee to get rid of the poor fatherless one?"

A smile began to steal over the merchant's broad countenance, as he replied coolly:

"Ay, verily, and that is what I can and do expect. But not, as you seem to fear, to the lad's hurt. Here, in our Spain, it is not easy just now to set him on his feet. But if you will give him some commission to your son—nay, be calm and hear me out—if you will do that for the comfort of his mother, I will furnish him clothes and a fair purse, and trust me, I will also find means some way to smuggle him on board one of the ships, now fitting out in the southern port of Cadiz to carry the Commendador to Hispaniola. That is my scheme; many a good hour that I might have enjoyed in sleep have I bestowed upon it, and now you are going to aid me to carry it through."

"Never!" exclaimed Master Pedro, excitedly; "never, never! Not for all the maravedis that ever fell into the coffers of the Holy Office will I help thee to help one who inherits its suspicions. Dost hear me, neighbour Sancho?—I say, never!"

"Ay, ay, I hear thee," calmly replied the individual addressed. "I heard thee say that same 'never' in my dreams two days ago, and answered thee with 'ever.' Now I hear thee say it actually with thy lips, and still I answer it with 'ever.' But take another taste of the wine, friend Pedro; fill thy glass again, if but to see the mingling of the colours, and draw in thy chair closer to the warmth. No need to neglect the comforts of the body because thy mind is perturbed."

"Ah!" growled the other. "Thou hast well put into words the doctrine of thy life, I warrant me."

Master Sancho laughed.

"And if so, neither words nor doctrine, can any say, have served me shabbily. If it should so fall out in the future that even in this world I must suffer for my sins, or for other folks' caprices, nevertheless in the past my face hath had its share of rejoicing in the sunshine of its own smiles."

"It is in the sunshine of the smiles of others," retorted the spice-dealer, "that most men would fain be able to rejoice."

"Ay, even so, and that is where most men fall into error," was the calm reply. "Comfort from the smiles of others is like the fleeting comfort a sick beggar gets from the glow of another man's fire. A healthy man has the abiding glow in his own veins, and he carries it about with him where he goes. Thus is it when the spring of smiles is within thine own heart, man, and thou art led to accept gratefully blessings as they fall to thy hand."