THE HARRAP LIBRARY

![]()

1. EMERSON’S ESSAYS

First Series

2. EMERSON’S ESSAYS

Second Series

3. THE POETRY OF EARTH

A Nature Anthology

4. PARADISE LOST

John Milton

5. THE ESSAYS OF ELIA

Charles Lamb

6. THE THOUGHTS OF MARCUS AURELIUS ANTONINUS

George Long

7. REPRESENTATIVE MEN

R. W. Emerson

8. ENGLISH TRAITS

R. W. Emerson

9. LAST ESSAYS OF ELIA

Charles Lamb

10. PARADISE REGAINED AND MINOR POEMS

John Milton

11. SARTOR RESARTUS

Thomas Carlyle

12. THE BOOK OF EPICTETUS

The Enchiridion, with Chapters from the Discourses, etc. Translated by Elizabeth Carter. Edited by T. W. Rolleston.

13. THE CONDUCT OF LIFE

R. W. Emerson

14. NATURE: ADDRESSES AND LECTURES

R. W. Emerson

15. THE ENGLISH HUMOURISTS OF THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

W. M. Thackeray

16. DAY-DREAMS OF A SCHOOLMASTER

D’Arcy W. Thompson

17. ON HEROES AND HERO-WORSHIP

Thomas Carlyle

18. TALES IN PROSE AND VERSE

Bret Harte

19. LEAVES OF GRASS

Walt Whitman

20. HAZLITT’S ESSAYS

21. KARMA AND OTHER ESSAYS

Lafcadio Hearn

22. THE GOLDEN BOOK OF ENGLISH SONNETS

Edited by William Robertson

Further volumes will be announced later

MICHAEL FIELD

![]()

![]()

![]() BY MARY STURGEON

BY MARY STURGEON

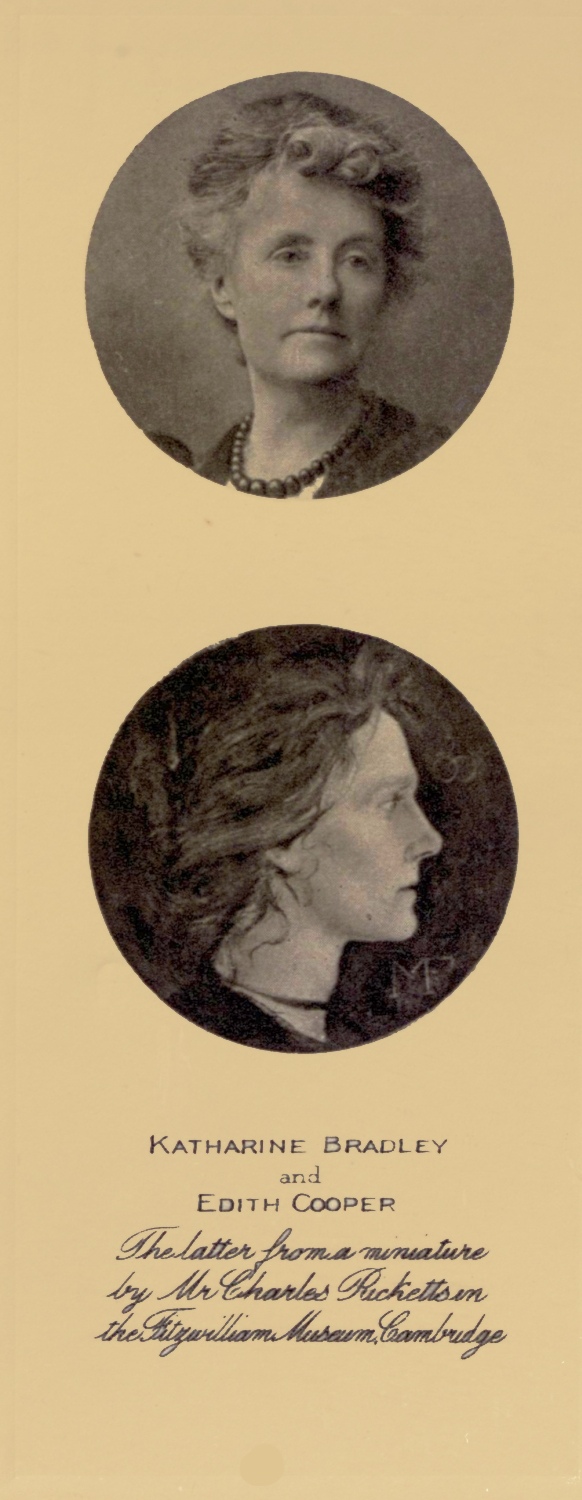

Katharine Bradley

and

Edith Cooper

The latter from a miniature

by Mr Charles Ricketts in

the Fitzwilliam

Museum, Cambridge

BY MARY STURGEON

AUTHOR OF “STUDIES OF CONTEMPORARY

POETS” “WESTMINSTER ABBEY” ETC.

LONDON: GEORGE G.

HARRAP & CO. LTD.

2-3 PORTSMOUTH ST. KINGSWAY

& AT CALCUTTA AND SYDNEY

First published March 1922

Printed in Great Britain at The Ballantyne Press by

Spottiswoode, Ballantyne & Co. Ltd.

Colchester, London & Eton

SOME years ago the writer of this book discovered to herself the work of Michael Field, with fresh delight at every step of her adventure through the lyrics, the tragedies, and later devotional poems. But she was amazed to find that no one seemed to have heard about this large body of fine poetry; and she longed to spread the news, even before the further knowledge was gained that the life of Michael Field had itself been epical in romance and heroism. Then the theme was irresistible.

But although it has been a joy to try to retrieve something of this life and work from the limbo into which it appeared to be slipping, the matter may wear anything but a joyful aspect to all the long-suffering ones who were ruthlessly laid under tribute. The author remembers guiltily the many friends of the poets whom she has harried, and kindly library staffs (in particular at the Bodleian) who gave generous and patient help. To each one she offers sincere gratitude; and though it is impossible to name them all, she desires especially to record her debt to Mr Sturge Moore and Miss Fortey; Father Vincent McNabb, Mrs Berenson, and Mr Charles Ricketts; Dr Grenfell, Sir Herbert Warren, and Mr and Mrs Algernon{8} Warren; Miss S. J. Tanner, Mr Havelock Ellis and Miss Louie Ellis; the Misses Sturge; Professor F. Brooks and the Rev. C. L. Bradley; Professor and Mrs William Rothenstein; Mr Gordon Bottomley and Mr Arthur Symons—;who will all understand her regret that this book is so unworthy a tribute to their friend and that the scheme of it, designed primarily to introduce the poetry of Michael Field, rendered impossible a fuller use of the material for a Life which they supplied.

To the courtesy of Mr Sydney C. Cockerell, the Director of the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, the author owes the copy of Edith Cooper’s portrait. This portrait is a miniature set in a jewelled pendant (both drawing and setting the work of Mr Charles Ricketts) which was bequeathed to the Fitzwilliam Museum on the death of Katharine Bradley.

Warm thanks are also tendered to the publishers who have kindly given permission to use extracts from the poets’ works, including Messrs G. Bell and Sons, the Vale Press, the Poetry Bookshop (for Borgia, Queen Mariamne, Deirdre, and In the Name of Time); to Mr T. Fisher Unwin, Messrs Sands and Company, and Mr Eveleigh Nash; and to{9} Mr Heinemann for Mr Arthur Symons’s poem At Fontainebleau.

A Bibliography is appended of all the Michael Field books which have been published to date; but there still remain some unpublished MSS.

MARY STURGEON

Oxford

November 1921

| I. | BIOGRAPHICAL | 13 |

| II. | THE LYRICS | 65 |

| III. | THE TRAGEDIES—;I | 114 |

| IV. | THE TRAGEDIES—;II | 162 |

| V. | THE TRAGEDIES—;III | 197 |

| BIBLIOGRAPHY | 245 |

ONE evening, probably in the spring of 1885, Browning was at a dinner-party given by Stopford Brooke. He had recently met for the first time two quiet ladies who had come up to the metropolis from Bristol to visit art galleries and talk business with publishers, and he suddenly announced to the company in a lull of conversation, “I have found a new poet.” But others of the party had made a similar discovery: it had jumped to the eye of the intelligent about a year before, when a tragedy called Callirrhoë had been published; and several voices cried simultaneously to the challenge, “Michael Field!”

Only Browning, however, and a few intimate friends of the poets, knew that Michael Field was not a man, but two women, Katharine Bradley and Edith Cooper. They were an aunt and niece, and came of a Derbyshire family settled at Ashbourne. Joseph Bradley, its representative there in 1749, with his son and grandson after him, were merchants of substance and culture. They were men of intellect as well as business men, and seem to have possessed between them all the elements which ultimately became concentrated in our two poets. There is evidence of a leaning to philosophy, a feeling for the arts, an interest{14} in drama; and, more significant still, there is one Charles Bradley who was “a prolific and meditative writer both of prose and song.”

Katharine Harris Bradley, the elder of the two poets, was born at Birmingham on October 27, 1846. Her grandfather had migrated there from Ashbourne in 1810, and her father, Charles Bradley, was a tobacco-manufacturer of that city. He had married in 1834 a Miss Emma Harris of Birmingham, and, in the simpler fashion of those times, he and his wife were living in a house adjoining their place of business in the old quarter of the town. There, at 10 Digbeth, Katharine was born, The only other child of the union was a daughter who was eleven years old at Katharine’s birth. She was named Emma, and was of first importance in the lives of the Michael Fields. For, being a thoughtful creature, of rare sweetness and strength of character, she largely shaped the life of the little sister who was so much younger than herself; and, still more vital fact, she afterward became the mother of our second poet. She married, about 1860, James Robert Cooper, and went with him to live at Kenilworth. Her daughter, Edith Emma Cooper, was born there, at their house in the High Street, on January 12, 1862.{15}

Both poets, therefore, took their origin in the heart of a Midland city and came of merchant stock. These facts may have larger significance than their bearing on environment and nurture, though that was important. But regarded more widely, they seem to relate Michael Field and her fine contribution to English literature to that movement in our modern civilization which, in the last two or three generations, has drawn commerce into intimate connexion with our art and letters. Such names as Horniman, Fry, Beecham (and there are others of similar import) suggest at once drama, art, music. They are associated in one’s mind with new impulse, energy, initiative, and above all with disinterested service of the arts; and they are connected chiefly with Midland towns. In like manner Michael Field, with her gift of tragic vision sublimated from fierce Derbyshire elements, may be seen spending a strenuous life and a moderate fortune, without reward or encouragement, to enrich English poetry.

Neither poet ever attended school, or swotted to gain certificates; which is probably one reason why they both became highly educated and cultured people. When Katharine was two years old her father died from cancer—;a disease which afterward carried off her mother, and{16} from which both our poets died. Mrs Bradley removed to a suburb of Birmingham, and was careful to provide that the lessons which she gave her little girls should be supplemented, as the need arose, by other and more advanced teaching. But the children were allowed to follow their bent, and authority took the form of a wise and kindly directing influence. We hear in those early days of eager studies in French, painting, and Italian. We hear, too, of friendships with a group of lively cousins. One of them remembers Katharine’s vivid childhood, and speaks of her as a gay and frolicsome creature, highly imaginative and emotional, with whom he used to act and recite. She adored poetry, would write even her letters in rhyme, and had, as a small child, a particular fondness for Scott’s Lady of the Lake. And she joined with the greatest delight in the dramatic ventures which the group from time to time attempted, such as the representation at Christmas of the passage of the Old Year and the coming of the New.

It is probable that such conditions were ideally suited to a child of great natural gifts and buoyant temperament. Katharine evidently thrived under them both in mind and body; and by the time of her sister’s marriage to Mr Cooper she was not only the healthy,{17} happy, and well-developed young animal who was the potential of all she afterward became, but she had already embarked upon the classics and was beginning to interest herself in German language and literature. Thus it happened that when, about 1861, she and her mother made their home with the Coopers at Kenilworth, Katharine became the natural companion of the little Edith, born in the following year, when Katharine was sixteen. But she was, from the first, much more than that. Mrs Cooper remained an invalid for life after the birth of her second daughter, Amy, and Katharine fostered Edith as a mother. She lavished on her an eager and rather imperious affection. She led her, as the child grew old enough, along the paths that she herself had adventurously gone, and although Edith was always shyer and more hesitating than Katharine, poetic genius was dormant in her too, only waiting to be stimulated by Katharine’s exuberance and led by her audacity. Edith, stepping delicately, followed the daring lead of her elder with a steadiness of mental power which was her proper gift; and she reaped from Katharine’s educational harvest (won in all sorts of fields, from literatures ancient and modern, from the Collège de France, Newnham, University College, Bristol, and numerous private{18} tutors) fruits more solid and mature than even Katharine herself.

When the poets removed to Stoke Bishop, Bristol, in 1878 it was with intellectual appetites still unsatisfied, and determined to pursue at University College their beloved classics and philosophy. They were already, in the opinion of a scholar who knew them at that time, fair latinists: they possessed considerable German and French, and some Italian, while Edith’s enthusiasm for philosophy was balanced by Katharine’s for Greek. Edith, docile in so much else, yet “could not be coaxed on” in Greek; not even later, when Browning, who used to speak affectionately of her as “our little Francesca,” one day gently pressed her hand and said “in honied accents, ‘Do learn Greek.’” What could a young poet do, overwhelmed by the courtly old master’s flattery, except promise softly, “I will try”? But it is not recorded that the effort took her very far. Katharine the Dionysian (always a little over-zealous for her divinities, whether Thracian or Hebrew) did not cease from coaxing; and perhaps did not perceive, for she could be obtuse now and then, how radical was Edith’s austere latinity. A poem of this period, addressed by Katharine to Edith, and called An Invitation, throws a gleam on their student days. Through it one sees as{19} in morning sunlight their strenuous happy existence, their eager welcome to the best that life could offer, and their fortunate freedom to grasp it, whether it were in books or art, in sunny aspects or beautiful new Morris designs and textures. For they were, from the first, artists in life.

Three stanzas describe the woodbine and the myrtles outside the window, and the cushioned settee inside. Then:

It is clear from all the testimony that Katharine and Edith were extremely serious persons in those first years at Stoke Bishop, a fact which seems to have borne rather hard on the young men of their acquaintance. Thus, a member of their college, launching a small conversational craft with a light phrase, might have his barque swamped by the inquiry of one who really wanted to know: “Which do you truly think is the greater poem, the Iliad or the Odyssey?” It was an era when Higher Education and Women’s Rights and Anti-Vivisection were being indignantly championed, and when ‘æsthetic dress’ was being very consciously worn—;all by the same kind of people. Katharine and Edith were of that kind. They joined the debating society of the college and plunged into the questions of the moment. They spoke eloquently in favour of the suffrage for women,{21} and were deeply interested in ethical matters. They were devotees of reason, and would subscribe to no creed. Katharine was a prime mover of the Anti-Vivisection Society in Clifton, and was its secretary till 1887. She was, too, in correspondence with Ruskin, was strongly influenced by him in moral and artistic questions, and was a companion of the Guild of St George—;though that was as far as she ever went in Ruskinian economics. Both of the friends adored pictures, worked at water-colour drawing, wore wonderful flowing garments in ‘art’ colours, and dressed their hair in a loose knot at the nape of the neck.

But more than all that, they were already dedicated to poetry, and sworn in fellowship. That was in secret, however. Student friends might guess, thrillingly, but no one had yet been told that Katharine had published in 1875 a volume of lyrics which she signed as Arran Leigh, nor that Edith had timidly produced for her fellow’s inspection, as the experiment of a girl of sixteen, several scenes of a powerful tragedy; nor that the two of them together were at that moment working on their Bellerophôn (with the accent, please), which they published in 1881, signed “Arran and Isla Leigh.” But such portentous facts kept them very grave; and their solemnity naturally provoked the{22} mirth of the irreverent, especially of undergraduate friends down from Oxford, who knew something on their own account about æsthetic crazes and the leaders of them. Thus a certain Herbert Warren came down during one vacation and poked bracing fun at them. The story makes one suppose that he must have disliked the colour blue in women and the colour green in every one—;possibly because he was then in his own salad days. For when somebody mischievously asked him in Katharine’s presence, “Who are this æsthetic crowd?” he promptly replied, “They’re people as green as their dresses.”

But their women friends were more favourably impressed. To them the two eager girls who walked over the downs for lectures every morning were persons of a certain distinction who, despite careless hair and untidy feet, could be “perfectly fascinating.” Their manner of speech had been shaped by old books, and was a little archaic. Later it became a “mighty jargon,” understood only of the initiate. Their style of dress was daringly clinging and graceful in an age of ugly protuberances. And though these things might suggest a pose to the satirical, they were very attractive to the ingenuous, who saw them simply as the naïve signs they were of budding individuality. Their{23} friendship, too, was clearly on the grand scale and in the romantic manner. They were, indeed, absorbed in each other to an extent which exasperated those who would have liked to engage the affections of one or the other in another direction. Yet they were companionable souls in a sympathetic circle, Katharine with abounding vitality and love of fun and keen joy in life, expansive and forthcoming despite an occasional haughtiness of manner; and Edith lighting up more slowly, to a rarer, finer, more delicate exaltation.

Yet, in spite of many friends and a genuine interest in affairs, one perceives that they constantly gave a sense of seclusion from life, of natures set a little way apart. It was an impression conveyed unwittingly, and in spite of themselves; and one is reminded by it of their sonnet called The Poet, written, I believe, about this time, but not published until 1907, in Wild Honey:

Consciously or not, the poem is a portrait. More than one touch is recognizable, and there can be no doubt that the opening lines give a glimpse of Edith. They suggest for this reason that the sonnet was written by Katharine; and if that is so, her use of the word dullard sweetly turns the edge of the complaint of critical friends that Katharine could be thoroughly stupid. Of course she could!—;why not? though, to be sure, it was very provoking of her. Returning, however, to the resemblance to Edith. She had never the good health of Katharine, and her beauty, which was of the large, regular, blonde type, suffered in consequence. One of her friends says: “She was as if touched by a cloud—;crystalline and fragile as flowers that love the shade.” All who knew her speak of the extraordinary look of vision in her eyes: time after time one hears of the ‘inspiration’ in her face, which is visible in no matter how poor a photograph or hasty a sketch. Katharine had intensity of another{25} kind: warm, rich, glowing, a lyric and almost bacchic expression. But in Edith there was “a Tuscan quality of refinement, the outward expression of an inward beauty of thought.”

One cannot but associate those “lamps of the sanctuary” with the psychic power which Edith undoubtedly possessed. An incident attested by their cousin, Professor F. Brooks, may be given to illustrate this. It was occasioned by the death of Edith’s father in the Alps. He and his younger daughter Amy were there on holiday in 1897, and had planned to climb the Riffelalp. They wrote of their plan to Katharine and Edith, who received the letter at home in England on the day that the ascent was being made. Edith read the letter and passed it to Katharine with the remark: “If they go to the Riffelalp they will go to their doom.” And, probably about the time she was speaking, Mr Cooper met his death, for he was lost in the ascent, and his body was not recovered for many months.

That is only one of several psychic experiences which incontestably occurred to Edith Cooper, the most impressive being the vision which appeared to her as her mother was dying. Edith, who was helping to nurse her mother, had gone into another room to rest, as it was not believed that the end was near. She afterward{26} told her friend Miss Helen Sturge that in the moment of death her mother’s spirit passed through the room and lingered for an instant beside the bed on which Edith was lying. The event is recorded explicitly in a poem published in Underneath the Bough (first edition):

* * *

‘Michael Field’ did not come into existence until the publication of Callirrhoë in 1884. The poets put behind them, as experimental work, the two volumes which they had already published, and began afresh, changing their pen-names the better to close the past. The{27} pseudonym under which they now hid themselves was chosen somewhat arbitrarily, ‘Michael’ because they liked the name and its associations, ‘Field’ because it went well with ‘Michael.’ But it is true also that they had a great admiration for the work of William Michael Rossetti, whom, Katharine says in one of her letters, they regarded as “a kind of god-father”; and it is true, too, that ‘Field’ had been an old nickname of Edith. Their family indulged freely in pet names, and Edith was teased by a nurse, from her boyish appearance during a fever in Dresden, as the “little Heinrich.” Thenceforth she became Henry for Katharine, and Katharine was Michael to her and to their intimates.

Callirrhoë was well received, and went to a second edition in November of the same year. It is amusing now to read the praises that were lavished upon ‘Mr Field’ upon his first appearance. Thus the Saturday Review talked of “the immutable attributes of poetry ... beauty of conception ... strength and purity of language ... brilliant distinction and consistent development of the characters ... a poet of distinguished powers”—;all of which is very true. The Spectator announced “the ring of a new voice which is likely to be heard far and wide among the English-speaking peoples”—;and that may yet become true, if the English-speaking peoples{28} are allowed to hear the voice. The Athenæum saw “something almost of Shakespearean penetration”; the Academy rejoiced in “a gospel of ecstasy ... a fresh poetic ring ... a fresh gift of song ... a picturesque and vivid style.” The Pall Mall Gazette quoted a lyric which “Drayton would not have refused to sign”; and, not to multiply these perfectly just remarks, the Liverpool Mercury crowned them all in a flash of real perception, by noting that which I believe to be Michael Field’s first virtue as a dramatist in these terms: “A really imaginative creator ... will often make his dialogue proceed by abrupt starts, which seem at first like breaches of continuity, but are in reality true to a higher though more occult logic of evolution. This last characteristic we have remarked in Mr Field, and it is one he shares with Shakespeare.”

But alas for irony! These pæans of welcome died out and were replaced as time went on by an indifference which, at its nadir in the Cambridge History of English Literature, could dismiss Michael Field in six lines, and commit the ineptitude of describing the collaboration as a “curious fancy.” Yet the poets continued to reveal the “immutable attributes of poetry”; their “ecstasy” grew and deepened; their “Shakespearean penetration” became a thing almost uncanny in its swift rightness; their “creative{29} imagination” called up creatures of fierce energy; their “fresh gift of song” played gracefully about their drama, and lived on, amazingly young, into their latest years—;which is simply to say that, having the root of the matter in them, and fostering it by sheer toil, they developed as the intelligent reviewers had predicted, and became highly accomplished dramatic poets. But in the meantime the critics learned that Michael Field was not a man, and work much finer than Callirrhoë passed unnoticed or was reviled; while on the other hand Borgia, published anonymously, was noticed and appreciated. One might guess at reasons for this, if it were worth while. Perhaps the poets neglected to attach themselves to a useful little log-rolling coterie, and to pay the proper attentions to the Press. Or it may be that something in the fact of a collaboration was obscurely repellent; or even that their true sex was not revealed with tact to sensitive susceptibilities. But whatever the reason, the effect of the boycott was not, mercifully, to silence the poets: their economic independence saved them from that; and a steady output of work—;a play to mark every year and a great deal of other verse—;mounted to its splendid sum of twenty-seven tragedies, eight volumes of lyrics, and a masque without public recognition. The poets did not greatly care about the neglect.{30} They had assurance that a few of the best minds appreciated what they were trying to do. Browning was their staunch friend and admirer; and Meredith, chivalrous gentleman, wrote to acclaim their noble stand for pure poetry and to beg them not to heed hostility. Swinburne had shown interest in their work, and Oscar Wilde had praised it. Therefore only rarely did they allow themselves a regret for their unpopularity. But they were human, after all, Michael particularly so; and once she wrote whimsically to Mr Havelock Ellis, “Want of due recognition is beginning its embittering, disintegrating work, and we will have in the end a cynic such as only a disillusioned Bacchante can become.”

Their reading at this period, and indeed throughout their career, was as comprehensive as one would expect of minds so free, curious, and hungry. To mention only a few names at random, evidence is clear that they appreciated genius so widely diverse as Flaubert and Walt Whitman, Hegel and Bourget, Ibsen and Heine, Dante, Tolstoi, and St Augustine. Yet so independent were they, that when it comes to a question of influence, proof of it is by no means certain after the period of their earliest plays, where their beloved Elizabethans have obviously wrought them both good and evil. Traces of Browning we should take for granted, he{31} being so greatly admired by them; yet such traces are rare. And still more convincing proof of their independence surely is that in the Age of Tennyson they found his laureate suavity too smooth, and his condescension an insult; while at a time when the Sage of Chelsea thundered from a sort of Sinai those irreverent young women could talk about “Carlyle’s inflated sincerity.”

Again, one may think to spy an influence from Nietzsche’s Birth of Tragedy in their Callirrhoë; but it is necessary to walk warily even here. For the genius of Michael Field, uniting as it does the two principal elements of art, Dionysian and Apolline, is therefore of its nature an illustration of Nietzsche’s theory. They needed no tutoring from him to reveal that nature, for they knew themselves. Nor did they need prompting to the primary spiritual act of the tragic poet. From the beginning the philosophic mind lay behind their artistic temper. Very early they had confronted reality, had discovered certain grim truth, and had resolutely accepted it. Not until they became Roman Catholics did they become optimists, and then they ceased, or all but ceased, to be tragic poets.

* * *

When the Michael Fields left Bristol for Reigate in 1888 they withdrew almost entirely{32} from contact with the world of affairs, and devoted themselves to their art. Old friendships and interests were left behind with the old environment. Their circle became restricted, as did their activities of whatever kind, to those which should subserve their vocation. Family ties, which had always been loosely held, were now (with the exception of Mrs Ryan, Edith’s sister Amy) almost completely dropped. Their life became more and more strictly a life of the mind, and more and more closely directed to its purpose. It was a purpose (that “curious fancy” so called by the learned critic) which had been formulated very early—;long before Katharine found it expressed for her to the echo in Rossetti’s Hand and Soul: “What God hath set in thine heart to do, that do thou; and even though thou do it without thought of Him, it shall be well done. It is this sacrifice that He asketh of thee, and His flame is upon it for a sign. Think not of Him, but of His love and thy love.” To that, as to a religion, they deliberately vowed themselves, guarding their work from trivial interruption, plunging into research, and yielding themselves up to the persons of their drama, in whom they vividly lived. But although their imaginative adventures were stormy and exhausting (the death of one of their characters would leave them stricken), external{33} events were very few. Never had dramatist so undramatic a career; and there is an amazing contrast between the tremendous passions of their Tragic Muse and the smoothness, temperance, and quietude of their existence. One has no right to be surprised at the contrast, of course, for that untroubled, purposeful living was the condition which made possible their achievement. And that a virile genius can consist with feminine power, even feminine power of a rather low vitality, hardly needs to be remarked, since Emily Brontë wrote. Moreover, the contrast is determined by the physical and mental basis proper to genius of this type, one that is peculiarly English, perhaps, with sanity, common sense, and moral soundness at the root of its creative faculty. No doubt the type has sometimes the defects of its virtues, and Michael Field, who was inclined to boast that there was no Celtic strain in her blood, was not immune from faults which the critical imp that dances in the brain of the Celt might have saved her from. For he would have laughed at a simplicity sometimes verging on the absurd, at grandeur when it tended to be grandiose, at emotion occasionally getting a little out of hand; just as he would have mocked a singleness and directness so embarrassing to the more subtle, and have declared that no mature human{34} creature in this bad world has any right to be so innocent as all that!

Happily we are not concerned with the impishness of the satirical spirit: we have simply to note that it was a physical and mental (and possibly a racial) quality which enabled Michael Field thus to dedicate herself to poetry and steadily to fulfil her vow. Even the poets’ journeys now were less disinterested than their early jaunts in France and Germany for the pure pleasure of seeing masterpieces. Thus, in these later days, if they went to Edinburgh, it was for the Marian legend; to the New Forest, it was for some faint sound of Rufus’s hunting-horn; to Italy, it was for innumerable haunting echoes of Imperial Rome, of the Borgia, of the Church; to bits of old France, for memories of Frankish kings; to Ireland, for a vanishing white glimpse of Deirdre; to Cornwall, in the belief that they might be favoured to give “in the English the great love-story of the world, Tristan and Iseult.” All of which does not mean, however, that those journeys were not very joyous affairs. Several of them were sweetened by friendships, as the visits to the Brownings at Asolo, the Italian tours with Mr and Mrs Bernard Berenson, and jolly times in Paris, with peeps at lions artistic and literary. It was on one of these occasions that their British eyes were assailed (not{35} shocked, for they were incapable of that kind of respectability) by a vision of Verlaine “coming out of a shop on the other side of the road with a huge roll of French bread under one arm.” It was Mr Arthur Symons who pointed out to them this apparition; and it was he who delightedly watched their joy in the woods of Fontainebleau, and afterward wrote a poem to recapture the memory of Edith Cooper on that day:

One is not surprised to see how brightly our poets struck the imagination of the few who{36} knew them, particularly of their poet and artist friends. Mr Charles Ricketts, Mr and Mrs Berenson, Father John Gray, Mr and Mrs William Rothenstein, and, later, Mr Gordon Bottomley were of those whose genius set them in tune with the fastidious, discriminating, and yet eclectic adoration of beauty which was the inspiration of Michael Field. They have all confessed the unique charm of the poets (a charm which consisted with “business ability and thoroughly good housekeeping”); and Mr Bottomley has contrived, by reflecting it in a poet’s mirror, to rescue it from Lethe:

The marvellous thing to me is the way in which their lives and their work were one thing: life was one of their arts—;they gave it a consistency and texture that made its quality a sheer delight. I have never seen anywhere else their supreme faculty of identifying being with doing.

I do not mean simply that this beauty of life was to be seen in their devotion to each other; though there was a bloom and a light on that which made it incomparable. Nor do I mean only their characters and personalities, and the flawless rhythm, balance, precision that each got into her own life—;though these, too, contributed to the sensation they always gave me of living as a piece of concerted chamber-music lives while it is being played.

But, beyond all this, I mean that this identity of life and art was to be seen in the slight, ordinary things{37} of existence. They did not speak as if their speech was considered; but in the most rapid, penetrating interchange of speech, their words were always made their own, and seemed more beautiful than other people’s. This always struck me anew when either of them would refer to the other in her absence as “My dear fellow”: the slight change in the incidence and significance of the phrase turned the most stale of ordinary exclamations into something which suddenly seemed valuable and full of delicate, new, moving music. It seemed said for the first time....

With Miss Cooper in particular one had the feeling that her mind moved as her body moved: that if her spirit were visible it would be identical with her presence. The compelling grace and sweet authority of her movement made me feel that her own Lucrezia would have looked so when she played Pope. It is of the great ladies of the world that one always thinks when one thinks of her.

Mr Ricketts first met the poets in 1892, when he and Mr Shannon were editing The Dial. Michael Field became a contributor to that magazine, and the acquaintance thus begun ripened into close friendship and lasted for twenty years. In memory of it Mr Ricketts has presented to the nation a picture by Dante Gabriel Rossetti which now hangs in the National Gallery of British Art. Its subject, Lucrezia Borgia, was treated by Michael Field in her Borgia tragedy, and is one of her most masterly studies. I am{38} indebted to Mr Ricketts for many facts concerning the poets’ lives in their Reigate and later Richmond periods, and for some vivid impressions of them. Thus, at their first meeting:

Michael was then immensely vivacious, full of vitality and curiosity. When young she had doubtless been very pretty, and for years kept traces of colour in her white hair. But if Michael was small, ruddy, gay, buoyant and quick in word and temper, Henry was tall, pallid, singularly beautiful in a way not appreciated by common people, that is, white with gray eyes, thin in face, shoulders and hands, as if touched throughout with gray long before the graying of her temples. Sudden shadows would flit over the face at some inner perception or memory. Always of fragile health, she was very quiet and restrained in voice and manner, a singularly alive and avid spectator and questioner, occasionally speaking with force and vivacity, but instinctively retiring, and absorbed by an intensely reflective inner life.

Yet it is clear that she, as well as Michael, loved the give-and-take of social intercourse within their circle. She too liked to catch up and pass on an amusing story about a contemporary, and thoroughly enjoyed a joke. After the austere Bristol days, when their gravity might have been at least a thousand years old, they grew steadily younger through the next fifteen years. “Michael had,” says Father John Gray, “the look, the laugh, and{39} many of the thoughts of a child.” Both were witty, but Michael, the richer and more spontaneous nature, had a warm gift of humour almost Rabelaisian. She loved fun, and jesting, and mimicry. With her frequent smile, her sparkling eyes, and her emphatic tones and gestures, she was an extremely animated storyteller. Henry’s wit had a more intellectual quality: it was quicker and sharper in edge than Michael’s, and it grew keener as she grew older, till it acquired almost a touch of grimness, as when she said to a friend during her last illness: “The doctor says I may live till Christmas, but after that I must go away at once.”

Henry was not a sedulous correspondent: indulged by Michael, she only wrote letters when a rare mood prompted her to do so. But the fortunate friend who heard from her at those times received a missive that was like an emanation from her soul, tender, wise, penetrative, gravely witty and delicately sweet. One would like to give in full some of those letters, but must be content to quote characteristic fragments of them. Thus, in March of 1888, she wrote to Miss Alice Trusted:

I feel you will never let yourself believe how much you are loved by me.... Your letter is one of the most precious I have ever received. Ah! so a friend thinks of one; would that God could think with her!{40} But it is a deep joy to me to be something to the souls that live along with me on the earth....

In May she wrote to the same friend an account of a visit to their “dear old friend, Mr Browning”:

He came in to us quite by himself, with one of his impetuous exclamations, followed by “Well, my two dear Greek women!” We found him well, lovingly kind, grave as ever. His new home is well-nigh a palace, and his famed old tapestries (one attributed to Giulio Romano) have now a princely setting.... He fell into a deep, mourning reverie after speaking of the death of Matthew Arnold, whom he called with familiar affection—;Mat. Then his face was like the surface of a grey pool in autumn, full of calm, blank intimité.

Another visit is described in July of the same year:

We have again been to see Mr Browning, and spent with him and his sister almost the only perfect hours of this season. Alice, he has promised me to play, the next time we meet, some of Galuppi’s toccatas!... He read to us some of the loveliest poems of Alfred de Musset, very quietly, with a low voice full of recueillement, and now and then a brief smile at some touch of exquisite playfulness. He is always the poet with us, and it seems impossible to realise that he goes behind a shell of worldly behaviour and commonplace talk when he faces society. Yet so it is: we once saw it was so.{41} In his own home, in his study, he is “Rabbi ben Ezra,” with his inspired, calm, triumphant old age. His eyes rest on one with their strange, passive vision, traversed sometimes by an autumnal geniality, mellow and apart, which is beautiful to meet. Yet his motions are full of impetuosity and warmth, and contrast with his steady outlook and his ‘grave-kindly’ aspect.

One finds acute artistic and literary estimates in these letters. Thus, after an appreciation of Whistler’s nocturnes, she remarks of his Carlyle portrait, “It is a masterpiece; the face has caught the fervid chaos of his ideality.”

Of Onslow Ford’s memorial of Shelley she says: “The drowned nude ... is an excellent portrait of the model, and therefore unworthy of Shelley, to my mind. The conventional lions and the naturalistic apple-boughs don’t coalesce. The Muse is but a music-girl. I like the bold treatment of the sea-washed body.”

She sketches an illuminating comparison between the art of Pierre Loti’s Pêcheur d’lslande and that of Millet; and declares that Huysmans’ work “is the last word of decadence—;the foam on the most recent decay—;and yet there is something of meagre tragedy about it.”

After a visit to the opera she writes:

We went to see Gluck’s Orfeo. Julia Ravogli attaches one to her with that love which is almost{42} chivalry, that one gives to a great and simple artist. Her hands are as expressive as a countenance, and her face is true, is pliant to ideal passion. Her voice is lovely, and she sits down by her dead Euridice and sings Che farò as a woodland nightingale sings her pain.

She exclaims at the “elegant Latin” used by Gerbert in his letters, “written in the dark tenth century”; agrees with Matthew Arnold that Flaubert has “neither compassion nor insight: his art cannot give us the verity of a temperament or soul”; but adds of his (Flaubert’s) correspondence, “To me each letter in which he writes of art is full of incitement, help, and subtle justness.”

She gives her impressions of Pater when delivering a lecture in December 1890:

He came forward without looking anywhere and immediately began to read, with no preface. He never gave his pleasant blue eyes to his audience.... There is great determination, a little brutality (in the French sense) about the lower part of his face; yet it is under complete, urbane control. His voice is low, and has a singular sensitive resonance in it—;an audible capacity for suffering, as it were. His courteous exterior hides a strong nature; there is something, one feels, of Denys l’Auxerrois in him—;a Bacchant, a Zagreus.

A criticism of the comedy of the nineties,{43} and its manner of production, is thrown off lightly in a letter to Miss Louie Ellis:

We went to Pinero. He was taken at snail’s pace, and so much that was disgraceful to humanity had to be endured at that rate that we groaned. Satire should always be taken with rapier speed—;to pause on it is to make it unendurable. The malice and anger must sparkle, or the mind contracts and is bored.

On an Easter visit to the country, in 1894, she wrote to Miss Trusted:

Yesterday we saw our first daffodils: they were growing in awful peace. The sun was setting: it had reached the tranquil, not the coloured stage; the air held more of its effect than the sky yet showed. We did not pluck a daffodil: they grew inviolable. After sunset, as we came thro’ the firs, we saw a round glow behind them—;it was the Paschal moon rising. A chafer passed, like the twang of one string of an Æolian harp. The sound of the wind in the firs is cosmic, the gathering of many waters etherealized; and the sharp notes of individual birds cross it with their smallness, and with a pertinacity that can throw continuance itself into the background.

Writing to another friend at a much later date, she says:

We have seen Tagore for a quarter of an hour—;seen the patient and quiet beauty of a lustrous-eyed animal. He is full of rumination, affability; and his smile is a jewel, the particular jewel of his soul.

And in 1913, the last year of her life, when Mr Rothenstein had been making a sketch of her head for a portrait, she wrote him thanks which were both critical and appreciative, concluding:

It is a lovely and noble drawing: it is such a revelation of a mood of the soul—;so intense, I said, seeing it at first—;that is how I shall look at the Last Judgment, “When to Thee I have appealed, Sweet Spirit, comfort me.”

It is significant that, wherever they went, the servants fell in love with Henry. Her manner, always gracious, was to them of the most beautiful courtesy and consideration. Michael was more imperious, more exigent. Warm and generous in her friendships, she yet was capable of sudden fierce anger for some trivial cause—;when, however, she would rage so amusingly that the offender forgot to be offended in his turn. She might banish a friend for months, for no discoverable reason, or might in some other rash way inconsiderately hurt him; but, though she would be too proud to confess it, she would be the unhappiest party of them all to the quarrel. “Of the wounds she inflicts, Michael very frequently dies,” she once wrote in a letter.

But of her devotion to Henry, its passion, its{45} depth, its tenacity and tenderness, it is quite impossible to speak adequately. From Henry’s infancy to her death—;literally from her first day to her last—;Michael shielded, tended, and nurtured her in body and in spirit. Probably there never was another such case of one mind being formed by another. There surely cannot be elsewhere in literature a set of love-songs such as those she addressed to Henry; nor such jealousy for a comrade’s fame as that she showed to the reviewers after Henry’s death; nor such absolute generosity as that with which she lavished praise on her fellow’s work, and forgot her own share in it. But there is not room, even if one could find words, to speak of these things. One can only snatch, as it were in passing, a few fragments from her letters. And this I do, partly to bring home the other proof of Michael’s devotion, namely, that she always did the very considerable business involved in the collaboration, and wrote nearly all the social letters: but chiefly so that some direct glimpses may be caught of her warm human soul.

Thus we may find, in her correspondence with Mr Elkin Mathews about Sight and Song in 1892, one proof out of many which the poets’ career affords of their concern for the physical beauty of their books. They{46} desired their children to be lovely in body as well as in spirit; and great was their care for format, decoration, binding, paper, and type: for colour, texture, quality, arrangement of letterpress, appearance of title-page, design of cover. In every detail there was rigorous discrimination: precise directions were given, often in an imperious tone; experiments were recommended; journeys of inspection were undertaken; certain things were chosen and certain others emphatically banned. But in the midst of exacting demands on some point or other one lights on a gracious phrase such as “We know you will share our anxiety that the book should be as perfect as art can make it”; or, this time to the printers, “I am greatly obliged to you for your patience.”

Again, Michael is discovered, in 1901, when a beautiful view from the old bridge at Richmond was threatened by the factory-builder, rushing an urgent whip to their friends. That which went to Mr Sydney Cockerell ran:

If you think our rulers incompetent, prove yourself a competent subject. The competent subject does not plead evening engagements when a buttercup piece of his England, with elms for shade and a stretch of winding stream for freshness, is about to be wrenched away. He toddles over to the Lebanon estate, notes the marked trees, learns what trees are already felled,{47} makes himself unhappy ... and then goes home and writes to the papers.

In a letter to Mr Havelock Ellis, in May 1886, there is a picturesque but concise statement of the manner of the poets’ collaboration:

As to our work, let no man think he can put asunder what God has joined. The Father’s Tragedy, save Emmeline’s song and here and there a stray line, is indeed Edith’s work: for the others, the work is perfect mosaic: we cross and interlace like a company of dancing summer flies; if one begins a character, his companion seizes and possesses it; if one conceives a scene or situation, the other corrects, completes, or murderously cuts away.

To the same correspondent she wrote in 1889, on the subject of religion:

If I may say so, I am glad of what you feel about the Son of Man, the divineness of His love and purposes towards the world. There is an atrocious superstition about me that I am orthodox ... whereas I am Christian, pagan, pantheist, and other things the name of which I do not know; and the only people with whom I cannot be in sympathy are those who fail to recognize the beauty of Christ’s life, and do not care to make their own lives in temper like His.

And in 1891, because Henry was recovering from her Dresden illness, Michael wrote in jocular mood:{48}

As you are a follower of Dionysos, I charge you get me Greek wine. The Herr Geheimrath has ordered it for several weeks for Edith, and in England they make as though they know it not.

One finds in letters to Miss Louie Ellis amusing evidence of both our poets’ love of beautiful clothes, as well as of Michael’s gift of humorous expression. Thus, in 1895, just before a visit to Italy, she wrote:

I dream an evening frock to wear at Asolo. It is of a soft black, frail and billowy, and its sleeves are in part of this, with silvery white satin ribbon tied about. If you have a better dream, send word; if not, tell me how much (I mean how little) the gown would be. I want this to be not expensive—;not the evening gown, but an evening gown.

And later, after the frock was received, she wrote:

How often, from “Afric’s coral strand,” will a voice of praise go up to Louie for that perfect silk gown; I shall want to be in little black frills for ever.... Do you know where in the city I can get a big shady hat to wear with it in Italy? Not a monster, but of a kind Theocritus would admire.

The following too brief passages are from some of Michael’s letters to the Rothensteins: the occasion of the first being to commiserate them on the discomforts of a removal:{49}

February 1907.—;Unhappy ones! Take care of your everlasting souls! I have got my soul bruised black and blue, beside some still ridging scars, in removals.

Yet there was once a transportation that was a triumph. It was suggested we should be drawn by pards to Richmond in a golden chariot. The pards was a detail not carried out; but of Thee, O Bacchus, and of Thy ritual, the open landau piled high with Chow and Field and Michael, doves and manuscripts and sacred plants!—;all that is US was there; and we drove consciously to Paradise.

There are delightful letters about the Rothenstein children, in particular of an unfortunate catastrophe to a parcel of birds’ eggs sent to a certain small John in January 1907:

Leaving home on Monday in great haste, I besought Cook to pack the tiny gift to John, and to blow the eggs. This may have been ill done, I fear. Poets are the right folk for packing....

My heart goes out to your son. It is so odd—;in a play we are writing there is half a page of Herod Agrippa (the highly revered slaughterer of the innocents, though that’s ‘another story’). He talks exactly like John—;and the FUTURE will say I copied him!...

Two days later.—;Furious am I over the smashed eggs. But what can we hope? It is the office of a cook to smash eggs. More eggs will be born, and John shall have some whole.

January 20th, 1907.—;Say to John—;if Nelson had{50} promised a postcard to a lady, he would not have kept her waiting. He would have gone forth, in the snow, with guns being fired at him all round, and a lion growling in front, to choose that postcard. Say, I am quite sure of this.

In the spring of 1908 the poets went on one of their frequent country visits, which were often rather in the nature of a retreat, and this time they put up at an inn called the Tumble-Down-Dick. Thence they wrote:

You must some day visit us here, in our bar-parlour. The masons have been having a grand dinner next door—;smoke and excellent knife-and-fork laughter, discussion, the pleasure of all speaking at once—;how these things enchant the poets from their muttered breviaries!

And a few days later:

If Noli wants a jest, tell her Edith has heard from a Richmond priest—;our reputation is completely gone in Richmond.... A lady had said to him she did not understand how anyone with self-respect could put up at the Tumble-Down-Dick Inn! The priest, who is Irish and sent us here under counsel of a Benedictine friar, is in great bliss!!

And in March 1910, having both been ill, they conclude thus an invitation:

Try to come on Wednesday. We are gradually gathering together the teeth, glasses, wigs, and com{51}plexions that may enable us again to greet our friends. Henry is among the flowers. Henry sees the flowers: I see Henry, I have little to say. Speech, I suppose, will go next!! “Yet once,” as Villon says....

From the time of the Dial contributions Mr Ricketts became their adviser in matters of book-production. It was on his suggestion, too, that they removed from Reigate to the small Georgian house at 1 The Paragon, Richmond, which overlooks the Thames from its balconies and sloping garden, and remained their home until their death. That was in 1899, after the death of Henry’s father had left them free to choose another home. It was in this year that they published their masque, Noontide Branches, from the Daniel Press at Oxford. They had been in Oxford two years earlier, in October 1897, while they were still under the shadow of Mr Cooper’s uncertain fate. He had been lost on the Riffelalp in June, and his body had not yet been recovered. But the beauty of Oxford brought them peace, and the kindliness which met them there, in particular from Mr and Mrs Daniel, lightened the cloud that lay on their spirits. Michael wrote afterward from Richmond to Miss Trusted to record gratefully how Mr Daniel, though she had been quite unknown to him,{52} had consented to print the masque and warmly befriended them.

They would joke about the minute size of the house at Richmond, which nowadays has dwindled to a mere annexe. “Do not squirm at the lowly entrance,” they wrote in an invitation to a friend; “within the snail-shell are two poets most gay and happy”; and added, referring to their dog, “Do come! Chow says you will, or he will know the reason why.” Probably there never was so modest a shell with so exquisite an interior; but of this it is Mr Gordon Bottomley who can best speak:

Their rooms were not less flawless than their poems. Their interiors showed a rarer, wider, more certain choice than those of the Dutch painters. The silvery, clear lithographs of their friend Mr C. H. Shannon were hung all together in a cool northern room, which they seemed to permeate with a faint light; and in another room the gold grain of the walls, alike with the Persian plates that glowed on the table as if they were rich, large petals, seemed to find their reason for being there in the two deeply and subtly coloured pictures by Mr Charles Ricketts on the walls.

But always there was the same feeling of inevitable choice and unity everywhere: in a jewelled pendant that lay on a satin-wood table, in the opal bowl of pot-pourri near by on which an opal shell lay lightly—;a shell chosen for its supreme beauty of form, and taken from its rose-leaf bed by Miss Cooper to be shown to a{53} visitor in the same way as she took a flower from a vase, saying, “This is Iris Susiana,” as if she were saying “This is one of the greatest treasures in the world,” and held it in her hand as if it were a part of her hand.

It is true that at Paragon they were gaily and happily busy: the years there were fruitful of mellow achievement. Nevertheless, it was there that the spiritual crisis of their life came, when in 1907 both poets entered the Roman Catholic Church. Henry was received into the Church at St Elizabeth’s, Richmond, on April 19th of that year; and Michael went to Edinburgh on May 8th to be received by their old friend the poet Father John Gray.

The crisis had been prepared for partly by Henry’s ill-health, which encouraged her contemplative habit of mind—;that in turn operating upon the religious sense which had always underlain their rationality. It was Henry who first made the great decision when, after reading the Missal in Latin, she suddenly exclaimed: “This is sacrifice: from this moment I am a Catholic.” But their curious small volume called Whym Chow suggests (and the suggestion is confirmed by the facts) that the course of that event was strongly influenced by the death of their Chow dog. It was a mental process of great interest for the student of the psychology of religious conversion, but too{54} intimate and subtle to be discussed here; and Whym Chow, printed privately in an exquisite small edition in the Eragny Press, was intended only for the eyes of friends. The chief value of the book is therefore bibliographical. Yet, in order to comprehend how the rationalists of the year 1887 and the declared pagans of 1897 became the Catholics of the year 1907, one thing may at least be said—;that in the manner of the death of the little creature they loved both the poets came to realize sacrifice as the supreme good. It was not by any means a new idea to them; on the contrary, it will be seen that it was their earliest ideal. And the reason for its triumphant force at this stage lay precisely in the fact that what had been an instinct then, an intuitive, hardly conscious, but integral element of character, became now a passionate conviction.

In February 1911 Henry was attacked by cancer; and in one of the few letters that she wrote she says (to the Rothensteins):

Of course the shock was great and the struggle very hard at first. I write this that you may both understand our silence.... We had to go into Arabian deserts to repossess our souls.

At the same time her fellow was writing to their friend Miss Tanner:{55}

Think of us as living in retreat, as indeed we are.... Henry has very sharp pains, with moments of agony every day to bear. The Beloved is showing her how great things she must suffer for His Name’s sake.... For the rest, I am all dirty from the battle, and smoked and bleeding—;often three parts dragon myself to one of Michael—;and sometimes I have only clenched teeth to offer to God.

Michael’s sufferings, through the long ordeal of Henry’s illness, were not, however, confined to spiritual anguish. She herself was attacked by cancer six months before Henry’s death on December 13th, 1913. But she did not reveal the fact; no one knew of it save her doctor and her confessor, and they were under a bond of secrecy. She nursed her fellow tenderly, hiding her own pain and refusing an operation which might have been remedial, encouraging Henry in the composition that she still laboured at, attending to the details of its publication, and snatching moments herself to write poems which are among the most poignant in our language. Neither poet would consent to the use of morphia, for they desired to keep their minds clear; and to the last, in quiet intervals between attacks of pain, they pursued their art. In a cottage in the village of Armitage, near Hawkesyard Priory, where they stayed for a few weeks in the summer of 1911, I stood in{56} the small sitting-room they occupied, and there, so the good housewife told me, Miss Cooper, though very weak, sat day after day—;writing, writing. All through 1912, with occasional weeks of respite and certain visits to Leicester and Dublin, the work went on: Poems of Adoration, Henry’s last work, was published in that year. In the summer of 1913, from the Masefields’ house at 13 Well Walk, Hampstead (taken for the poets by the generosity of Mrs Berenson), Michael wrote to Miss Fortey:

Henry has now fearful pain to bear, and the fighting is severe. Pray for me, dear Emily. Mystic Trees is faring horribly.

Yet Mystic Trees, Michael’s last written book, was published in that year.

When December brought release at last to Henry’s gentle spirit, Michael’s endurance broke down. A hæmorrhage revealed her secret on the day of Henry’s funeral; a belated operation was performed, and for some weeks Michael was too ill to do more than rail angrily against the Press notices of her fellow:

Nothing in the least adequate has yet been done—;nothing of her work given. I am hovering as a hawk over the reviewers.

By March 1914, however, she was at work again, collecting early poems of Henry’s to{57} publish in a volume called Dedicated, and about this time she wrote to Miss Fortey:

You will rejoice to know I have written a poem or two—;one pagan. I am reverting to the pagan, to the humanity of Virgil, to the moods that make life so human and so sweet.

The poems she mentions appeared in the Dedicated volume shortly afterward.

As the summer grew her malady gained the mastery; and, knowing that death was approaching, she removed to a house in the grounds of Hawkesyard Priory, in order to be near the ministration of her friend and confessor, Father Vincent McNabb, a Dominican priest who was at that time Prior at Hawkesyard. One of the few recorded incidents of her last days (it was on August 24th, 1914, just a month before she died) is touchingly characteristic. Father Vincent had taken tea with her, and Michael, propped by her pillows, yet contrived to add dignity and grace to the little ceremony with which she presented to him a copy of Henry’s Dedicated. One can imagine the scene—;the long, low room on the ground floor in which her bed had been placed for greater convenience in nursing her; the windows giving on to an unkempt lawn and a tangle of shrubs; summer dying outside, and{58} inside the dying poet reading to the white Dominican poem after poem by her fellow, in a voice that must have shaken even as the feeble hand shook in writing the record down. Finally the priest, taking the book in his turn, read to her her own poem Fellowship, and, hearing her soft prayer for absolution on account of it, turned away his face and could find no answer.

I

II

III

IV

The weeks of Michael’s passing witnessed the passing of the age to which she belonged, for they were those in which the Great War began. It is clear that Michael Field, in the noble unity of her life and work, represented something that was finest in the dying era; and yet she was, in certain respects, aloof from that Victorian Age, and in advance of it. It is profoundly moving to see how, even in extremity, her genius remained true to itself. It was so true, indeed, that in her pitiful, scanty record of those days one may catch a glimpse, through her winging spirit, of the moments of greatness to which the spirit of England rose in that crisis.

She was desolated at the thought of the killing, the suffering, the destruction of beauty. But she too felt the stimulus which the vastness of the danger gave to the national spirit,{60} and she longed to serve. “I want to live now the times are great,” she wrote to Mrs Berenson. “There are untended wounds to think of—;that makes me ashamed”—;ashamed, she meant, of the tendance that her own wound was receiving. Again, on August 13th:

But Michael cannot join with Jenny the cook. “What news of the war, Jenny?” ... “Good news; fifty thousand Germans killed!”

She followed with desperate anxiety the calamitous events in Belgium, writing on August 28th:

I am suffering from the folly of our English troops being wasted, and making fine, orderly retreats.... Namur gave me a shock from which I cannot recover.

And finally, on September 19th:

Father Prior mourns Louvain even worse than Bernard—;the destruction of the precious beauty. Tell me, is Senlis safe?

After that day little or nothing more was written. Every morning she rose at seven o’clock, and, assisted by her nurse, dressed and was wheeled in a chair through the Priory park to hear Mass at the chapel. On September 23rd the nurse wrote at Michael’s bidding to Miss Fortey:{61}

Miss Bradley is anxious about you: she fears you may be ill. She is frightfully weak to-day, but had a splendid night and is very happy.

On September 26th Michael for the first time did not appear in the chapel at her usual early hour. Father Vincent, seeing her vacant place, had a sudden certainty of the end. “Consummatum est” rushed to his lips as he ran down the grassy slopes to the house. He found Michael stretched on the floor of her room, dead, with her head on the bosom of the kneeling nurse. She had sighed her last breath one moment before. She had succeeded in dressing ready to go to Mass, but the effort to step into the carriage had been too much. She sank down and died quietly in the nurse’s arms.

* * *

There are questions of intense interest involved in the life of the Michael Fields—;personal, psychological, literary—;which one must put aside, angry at the compulsion of restricted space. But their life was in itself a poem, and the beauty of it is unmistakable. These were heroic and impassioned souls, who, in honouring their vow to poetry, gave life, it is true, “a poor second place”; and yet they fulfilled life itself, with a completeness few are capable of, in love and sacrifice. Michael would{62} quote from her copy of St Augustine: “Aime, donc, et fais ce que tu voudras ensuite”; and love was her gift to the fellowship, as Henry’s was intellect. But the collaboration was so loyal, the union so complete, that one may search diligently, and search in vain, for any sign in the work both wrought that this is the creation of two minds and not of one. It is possible to sift the elements, of course, seeing in this work vividly contrasting qualities; that it is at one and the same time passionate and intellectual, exuberant and dignified, swift and stately, of high romantic manner and yet psychologically true; that it is fierce, sombre, vehement, and at the same time gentle, delicate, of the last refinement of perception and feeling. One can even identify the various elements (when one knows) as more characteristic of one poet or the other; perceiving that Michael was the initiator, the pioneer, the passionate one from whom the creative impulse flowed; and that to Henry belonged especially the gift of form, that hers was the thoughtful, constructive, shaping, finishing genius of the fellowship. But it is not possible, in the plays on which the two worked, to point to this line or that speech, and say “It is the work of Michael” or “It is the work of Henry.” You cannot do it, because the poets themselves could not have{63} done it. The collaboration was so close, so completely were the poets at one in the imaginative effort, that frequently they could not themselves decide (except by reference to the handwriting on the original sheet of manuscript) who had composed a given passage.

In like manner it is possible to follow the poets through the facts of their existence, and to see that existence shape itself, despite mental vicissitude and apparent change, triumphantly of one piece throughout—;generous in colour, rich in texture, graceful in design. It might seem that gulfs were fixed between their grave, austere, studious girlhood, the joyous blossoming of their maturity with its pagan joy in beauty, and the mysticism of their last years. They appeared to go through many phases, and even to pass, under the eyes of astonished and indignant friends, out of all mental resemblance to what they were believed to be. A friend of Bristol days, Miss Carta Sturge, writing in a strain of regret for this apparent inconsistency, adds generously:

Perhaps the fine flavour of their genius, its subtle sensitiveness to impressions, its unspoilt bloom, might have suffered had they had more ... consistency and stability. It is enough that their genius was great, their spirit beautiful, and their companionship of unexampled delight. And that is how we gratefully remember them.

That is finely true; and yet it may be that the tone of regret is unnecessary; for on a complete survey it will be found that Michael Field was deeply consistent from first to last. Through perhaps a hundred changes—;of opinion, of taste, and of deeper things—;she remained the same; and those changes were but steps toward the fulfilment of what she had been from the beginning. Thus one sees the ending of the poets’ life as the inevitable outcome of that which they always were—;of a magnificence touched with grace. The Dionysian wine of those early days was poured at last to the Man of Sorrows; the Bacchic revel was turned to tragedy. But it was the same wine; the same energy of enthusiasm; and the latest-written lyrics, devotional pieces composed in suffering and very near to death, have often the audacity and abandon of the worshipper of the vine-god. The poet is Mænad still.{65}

THE lyrical poetry of Michael Field is much smaller in bulk than her dramatic work; yet there are eight volumes of it. On the other hand, it is more perfect in its kind than her tragedies, and yet its chiselled, small perfection cannot approach their grandeur.

A story is told about one of the books of lyrics which is amusingly characteristic of the poets. Underneath the Bough made its appearance first in the spring of 1893, and was well received. The Athenæum reviewer even went so far in admiration as to suggest, of obvious defects, that Michael Field probably preferred to write in that way! Soon after the book came out, however, the poets went on an Italian journey with some friends who took a different view of the function of criticism, and who dealt with them faithfully about the weakness of some of the pieces. Thereupon, with a gesture that is entirely their own in its grace and emphasis, the poets confessed their repentance for the defective work by immediately cutting the book to the extent of one-half, and reissued it in the autumn of 1893 with the careful legend “Revised and Decreased Edition.” The story, however, does not close on that access of humility which, on a comparison of the two editions, would certainly appear{66} somewhat excessive. But humility was not, at any rate with Michael, a pet virtue. Repenting at leisure of their hasty repentance, they brought out yet another edition, and reinstated many of the poems which they had rejected from number two—;this with a word of defiance to the critics of number one, and a recommendation to them to look for a precedent to Asolando.

The third edition is rare, but a copy of it may be seen at the British Museum. It was published in Portland, Maine, in 1898. It still omits about thirty of the pieces from the first edition, but it introduces a number of new ones and restores, among others, the In Memoriam verses for Robert Browning which appeared first in the Academy for December 21st, 1889, on the occasion of Browning’s death:

It would appear from the preface, however, that there was an additional motive for publishing a third edition in an invitation from the{67} United States to contribute a volume to the “Old World” series, and the poet adds a note of gratitude to her American readers who, as she says, “have given me that joy of listening denied to me in my own island.”

Considering the lyrical work as a whole, it is seen to cover Michael Field’s poetical career from beginning to end. Not that the lyric impulse was constant (for there were times when the poets’ dramatic work absorbed them almost completely); but it never entirely failed. It was, as one would expect, strongest in their early years: it recurred intermittently through the period of the later tragedies, and returned in force when, toward the end of their life, tragic inspiration gave place to religious ardour. Thus, although this poetry is subjective in a less degree than lyrical verse often is, most of the crucial events of the poets’ lives are reflected there. The lover of a story will not be disappointed, and the student of character will find enough for his purpose in personal revelation both conscious and unconscious. Moreover, a spiritual autobiography might, with a little patience, be outlined from these eight volumes; and it would be a significant document, illuminating much more than the lives of two maiden ladies in the second half of the nineteenth century.{68}

Such a spiritual history would be complete, in extent at least, for it would begin with Michael’s earliest work in The New Minnesinger (that title at once suggesting the German influence in English life and letters at the moment, 1875), with its strenuous ethic of Unitarian tendency based on a creed so wide as to have no perceptible boundary; and it would end only with the devotional poetry of her last written volumes where, with no concern for ethics as such, the poet stands at the gate of the well-fenced garden of the Roman Church with a flaming sword in her hand and a face of impassioned tenderness. But in the interval it would pass through her pagan phase, when she revelled in joyful living—;and in the classics, turning their myths into pleasant narrative verse; when in Long Ago (1889) she daringly rehandled the Sapphic themes; and when in Sight and Song (1892) she tried to convey her intense delight in colour and form by translating into poetry some of the old master-pictures that she loved. More important, however, than those books are in such an autobiography is the human record of joys and loves and sorrows contained in the volume called Underneath the Bough (1893); while Wild Honey (1908), a collection covering about ten years of her life, brings us down to the epoch{69} of religious crisis and reconciliation with the Church of Rome. Then, with tragic inspiration quelled by Christian hope and submission, all her creative energy flowed into the Catholic lyrics contained in Poems of Adoration (1912) and Mystic Trees (1913).

One does not pause long on The New Minnesinger in this survey of the lyrics, because it was published by Katharine Bradley as Arran Leigh, and is not, therefore, strictly a work of Michael Field. Nor shall we deal with the lyrics in Bellerophôn, a volume published by the two poets as Arran and Isla Leigh in 1881. Not that either book is unworthy of study; on the contrary, there are some fine pieces in both. But the poets having elected to leave them in limbo, where one has had to grope for this mere reference to them, there, for my part, they shall remain. Except to note in passing that, following Swift’s Advice to a Young Poet to “make use of a quaint motto,” the poet has inscribed on the front of The New Minnesinger the phrase “Think of Womanhood, and thou to be a woman.” That has a significance which is elaborated in the name-piece, whose theme is of love and of the woman-poet’s special aptitude to sing about it; and where it is insisted that the singer shall be faithful to her own feminine nature and experience. All through{70} the work of the two poets it will be seen that the principle stated thus early and definitely by the elder one ruled their artistic practice; so that we are justified in extracting this, at least, from Michael’s earliest book, and noting it as a conscious motive from the beginning.

I think, too, we are entitled to recover from the shades one small song. For, after all, a great literary interest of the work of the Michael Fields is the amazing oneness of the two voices. The collaboration, indeed, deserves much more space than it is possible to give it here. But it is something to the good if we can glance, in passing, at undoubted examples of each poet’s work, hoping to see hints of the individual qualities which each contributed to the fellowship. We have already told how, after Henry’s death and when Michael knew that she too must soon die, she hastened to gather together certain early pieces by her fellow, and published them, with a poignant closing piece of her own, in the book called Dedicated (1914). That closing poem, Fellowship, closed her artistic life: it is Michael’s last word as a poet. But the point for the moment is that she has given us in Dedicated the means of recognizing Henry, and distinguishing between the two poets in their youthful work. One may take from The New Minnesinger, therefore, as characteristic of{71} the younger Michael, such a piece as The Quiet Light:

That is a slight thing which does not, of course, represent Michael at anything like her full power; but it does already suggest the emotional basis of her gift, and her lyrical facility. The piece which follows, Jason, is a luckier choice for Henry, not only in that it gives her greater scope, but in that it is probably a maturer work than the other. The comparison would, therefore, be unfair to Michael if one were judging of relative merits; but we are thinking for the moment only of a difference in kind of poetic equipment. And the poem is given for this further fact—;it was chosen by Michael herself to read to Father Vincent{72} McNabb a few days before she died, in exultation at her fellow’s genius:

Clearly there are elements here different from those of The Quiet Light. One feels in{73} this poem a dramatic movement and a sense of tragedy which are not simply given in the data of the noble old story; one sees structural skill in the shaping of the narrative, and recognizes in a memorable line or two—;“A golden aim I followed to its truth” and “Ashes of flame she was, ashes of flame”—;the final concentration of thought and feeling where great poetry begins.

Perhaps we are not mistaken, therefore, in distinguishing, even so early as these two poems, the contrasting qualities of the two poets which, met in happy union, made so clear a single voice that Meredith was amazed when he discovered that Michael Field was two people. One may define these qualities as emotional on the one side and intellectual on the other. It is, of course, the old distinction between rhetoric and imagination, matter and form; and clearly shows itself again in the two volumes of devotional poetry at the end of their life, where Henry is seen as kin to Herbert and Michael as kin to Vaughan. And though the whole story of the collaboration cannot be contained within any statement so simple as that, its fundamentals are rooted in this complementary relation between the two minds.

Returning to the lyrics, I choose frankly the{74} pieces which throw some light on the poets’ lives. And although I do this from an unashamed interest in their story, and without immediate reference to the merits of the verse as poetry, there should be a chance that the poetical values of pieces wrought under the stress of intimate feeling will be not lower but higher than those of others. So, indeed, the event proves; for of the lyrics which may be safely attributed to Michael those are the best which can be called her love-poems. Of love-interest, in the attractive common meaning of the term, there is not a great deal in the work of either poet; and in that of Michael it is mainly comprised in half a dozen songs in Underneath the Bough. Sapphic affinities notwithstanding (and imaginary adventures in that region), the two ladies had their measure of Victorian reticence; though that did not decline upon Victorian prudishness. But Michael wrote love-poetry of another kind than the romantic, in a series about her fellow which is probably unique in literature. It will be found in the third book of Underneath the Bough, and is supplemented by pieces scattered through later books, notably a small group at the end of Mystic Trees. Those poems are a record of her devotion to Edith Cooper, and it is doubtful whether Laura or Beatrice or the Dark{75} Lady had a tenderer wooing. They explain, of course, the slightness of a more usual (or, as some would put it, a more normal) love-interest in Michael’s work. But it need not be supposed that there was anything abnormal in this devotion. On the contrary, it was the expression of her mother-instinct, the outflow of the natural feminine impulse to cherish and protect. And this she herself realized perfectly; for there is a passage in one of her letters to Miss Louie Ellis which runs:

I speak as a mother; mothers of some sort we must all become. I have just been watching Henry stripping the garden of all its roses and then piling them in a bowl for me....