Illustrated by Williams

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Astounding Science-Fiction, April 1945.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Gerd Lel Rayne stood in the arched doorway of the living room of his home and smiled at the Terran. Andrew Tremaine smiled up at his host with an almost microscopic feeling of annoyance. The Terran was a large man, well proportioned, but the other was somewhat larger and somewhat in better proportion. The annoyance was the usual jealousy of the better man.

Tremaine knew that Gerd was a better man, and he stifled his feeling of annoyance because hating Gerd was unjust. Besides, Tremaine wanted a favor and one does not irritate a favor-giver.

Gerd Lel Rayne was of a breed that could know when a man disliked him no matter how well it was concealed. Therefore—

Andrew smiled. "You've been well?"

"Positively dripping with good health," boomed Gerd in a resonant voice. "And yourself?"

"Fair to middling."

"Good. I'm glad to hear it. Will you have refreshment?"

"A cigarette, perhaps."

Gerd opened an ornate box on the table and offered Andrew a cigarette. Andrew puffed it into illumination and exhaled a cloud of smoke. "Busy?" he asked.

"Yes," drawled Gerd. "I'm always busy, more or less. But being busy or un-busy is my own desire. Being without something to do would drive me crazy, I'm sure." Gerd laughed at the thought. "At the present time I'm busy seeing you. Is this a business visit or a personal visit?"

"Partly pleasure, partly business. There's something been bothering me for some time."

"Glad to help—That's what I'm here for, you know."

"Now that I'm here," admitted Andrew with some abashment, "I have a feeling that the same question has been asked and answered before. But I want to hear, firsthand, why your race denies us the secret of interstellar travel."

"Because you have not developed it yet," said Gerd. "Yes, we could give it to you. You couldn't use it."

"You're looking down at us again."

"I'm honestly sorry that I give you that opinion. I have no desire to look down at anything or anyone. Please believe me."

"But—"

"May I offer an hypothetical case?" asked Gerd, and then went on because he knew the answer to his own question: "A hundred years ago, the Terrans were living without directive power. You used solar phoenix power. It brought you out of the mire of wire and machinery under which Terra writhed. You were, you thought, quite advanced. You were. But, Andy, could you have used directives? Supposing that I had given you the secret of directive power? What would have happened?"

"Um—Trouble, perhaps. But with supervision?"

"I can not give you supervision. I am but one. Consider, Andy. A planet filled with inventive people, a large quantity of which are highly trained technically. What would they say to a program which restricted them to any single phase? We came, and all that we could do to assist was to let your race know that directive power was available. The problem of power is an interesting thing, Andy. The initial steps into any realm of power are such that the discoverers are self-protected by their own lack of knowledge, and their investigations lead them into more and more knowledge; they gain the dangerous after learning how to protect themselves against it. The directive power could destroy not only Terra but the entire Solar System if improperly applied."

"What you're saying is that we could not understand it," objected Andrew.

"I admit it. Could a savage hurt himself if permitted to enter a powerhouse—even one of the primitive electronic places? Obviously he could. Even were he given the tools of the art, his survival might be a matter of guesswork. Only study permits any of us to work with power, Andy. When the Terrans are capable of handling the source of interstellar power, it shall come to them—be discovered by them, if you will. Meanwhile I can but watch and wait, and when I am approached I can and will try to guide Terra. That, Andy, is my job."

"We'll hunt for it!"

"I know," said Gerd Lel Rayne with a smile. "Your fellows are hunting now. I approve. But I may not point the way. Your race must only find it when you are ready to handle it."

Gerd arose from his chair and flexed the muscles across his back. The reason for his arising was not clear to Andrew immediately, but it came less than three seconds later—It was Gaya Lel Rayne, Gerd's mate. Andrew arose and greeted her with genuine pleasure.

Her smile was brilliant and genuine. "Business?" she asked.

"Yes," answered Gerd. "But do not leave, because the discussion is interesting. Andy, the perfect example of the persistent newsman, is holding forth on the interstellar power."

"They've discovered it?" asked Gaya in hopeful pleasure.

"No," answered Tremaine. "We'd like to, though."

"You will," said Gaya. "I know you will."

"We know we will, too," said Andrew. "Our irritation is not that we shall be denied it, but that it takes us so long to find it when there is one on Terra that knows it well."

"Please, Andy. I do most definitely not know it well. I am no technician."

Gaya looked at her husband quickly. "He's excusing himself," she said with a laugh.

"He's hoping that we'll believe that his knowledge is no better than ours and that we'll be content. But, Gerd, I know that you know enough to give us the answer."

"You know? How, may I ask?"

"It is inconceivable that you would not know."

"Perhaps I do," came the slow answer. "Perhaps I do." The tone of the speech was low and self-reflective. "But again, perhaps I, too, am in the dangerous position of not knowing enough. You Terrans have a saying—'A little knowledge is dangerous.' It is true. Again we strike the parallel. I give you stellar power and you, knowing nothing about its intricacies, use it. Can you hope to know down which road lies total destruction?"

"You are possibly right. We could learn."

"But not from me," said Gerd with finality. "That I cannot and will not do. One can not supervise and control the inventiveness of a planet such as yours. Your rugged individualists would be investigating in their small laboratories with inadequate protection, and inevitably one or more of them would strike the danger-spot."

"I'm answered," said Andrew reluctantly. "Answered negatively. I'm forced into accepting your statements. They are quite logical—and Gaya's willingness to be glad for us when she thought that we had discovered it is evidence that you are not withholding it with malice. But logic does not fill an empty spot, Gerd."

Gerd laughed. "If you had everything you want, your race would have died out before it came out of the jungles."

Tremaine laughed. "I know," he admitted. "Also—and I'm talking against my own race—there is the interesting observation that if Heaven is the place where we have everything we want, why are people always trying to live as long as they can?"

"Perhaps they're not certain of the hereafter."

"Whether they are firmly convinced yes or as firmly convinced no, they still view death with disfavor. I'd say their dislike was about even. All right, Gerd. I'll take your statements as you made them and with reluctance I'll return to my work and ponder."

"Stay for dinner," urged Gaya. She gave him the benefit of a brilliant smile, but Andrew shook his head.

"I've got to write an editorial," he said. "I've got to change one already written. I was a bit harsh about you, and I feel it was unfair. Perhaps you'll join us at dinner tomorrow?"

Gaya laughed. "You're speaking for Lenore, too?"

"Yes," nodded Andrew. "She'll be glad to see you."

"Then we'll be glad to come," said Gerd.

As he left, Gerd turned to his wife and said: "He'll bear watching."

"I caught your thought. He will. Shall I?"

"From time to time. Tremaine suspects. He is a brilliant man, Gaya, and for his own peace of mind, he must never know the truth."

"If he suspects," said Gaya thoughtfully, "it may mean that he has too little to do. There are many sciences—would it be possible to hint the way into one. That might occupy his mind enough to exclude the other question."

"In another man it might work. But Andrew Tremaine is not a physical scientist. He is a mental scientist working in an applied line. To give him the key to any science would mean just momentarily postponing the pursuit of the original problem. Were he a physical scientist, his mind would never have come upon the question in the first place. I'm almost tempted to let loose the initial key to stellar power."

Gaya blanched. "They'd destroy everything. No, Gerd, not that. You'd be defying the Ones."

"I know," nodded Gerd. "I have to continue for my own personal satisfaction. Giving in is the easy way—and entirely foreign to our policy. Terra must find their goal alone. You and I, Gaya, must never interfere. We are emissaries only; evidences of good will and friendship. Our position is made most difficult because of the general impression, held by all Terrans, that an ambassador is a man who lies to you, who knows that he is lying, and who further knows that you know he is lying—and still goes ahead and lies, smiling cheerfully at the same time."

"We've given good evidence of our friendship."

"Naturally. That's our main purpose in life. To befriend, to protect, even to aid when possible. One day, Gaya, Terra will be one of us. But guiding Terra and the Solar System into such a channel is most difficult. Yet, who is to do it but you and I?"

"Shall we request advice? Perhaps the Ones will be interested to know that Terrans are overly ambitious?"

"You mean they're too confounded curious? The Ones know that. The Ones put us here because we can cope with Terra—I'll make mention of it in the standard report—but coping with Terra is our problem, presented to us, and given with the expectation that we shall handle it well. To ask for any aid would be an admission of undisputed failure."

"I guess you're right."

Gerd smiled. "Honestly, there is no real danger. If we are capable of protecting them, we should be equally capable of protecting ourselves against them. And," said Gerd with an expansive gesture, "the Ones rate us adequate. We can do no more than to prove their trust. After all, our race has been wrong about a classification only once in three galactic years."

"I might be worried," smiled Gaya. "Isn't it about time for them to make another mistake?"

Gerd put his hands on her shoulders and shook her gently. "Superstitious lady," he said, "that's against the Law of Probabilities."

"No," disagreed Gaya with a smile. "Right in accordance with it. When the tossed coin comes up heads ten million times without a tail, it indicates that there may be two heads on the coin, or that some outside force is at work. I was fooling, Gerd."

"I know," he said with a laugh. "Now enough of our worries. What's on the program this evening?"

"Dinner with Executive General Atkins and wife. Theater afterwards."

"I'd better dress, then," said Gerd. "Complete with all the trimmings. Toni Atkins would be horrified at the idea of dining without the males all girded and braced in full formal dress."

"Once dinner is over, you'll enjoy them."

"I always do," said Gerd. "They're both interesting people. Save for her ideas of propriety."

Gaya pushed him in the direction of the dressing room. "I do, too," she called after him with malicious pleasure. "And remember, that I'm just as they are—and not above them at all."

"I might be able to get the legislature to pass laws against women," returned Gerd thoughtfully.

"The result might be quite devastating," said Gaya.

The answer came back through the closing door. It was a cheerful laugh, and: "Yes, wouldn't it?"

Andrew Tremaine jerked the paper from the electrotyper and pressed two buzzers simultaneously. The answer to one came immediately: "Yes?"

"Tell Jackson that the editorial page is complete and that he should get the revised copy set up."

"Yes, Mr. Tremaine. It's on the way."

"Should be coming out of his typer now."

"I'll call him."

The door opened, and the answer to buzzer number two entered.

He was a tall, thin, pale-looking man with stooped shoulders and thick glasses. He came in and seated himself before Andrew's desk and waited in silence until the editor spoke.

"Gene, how many fields in psychology have you covered?"

The other shook his head. "Since I came to work for you, only one. Applied psychology, or the art of finding out what people want to be told and then telling them."

"That's soft-soapism."

"You name it," grinned the thin man. "You asked for it. Oh, we've carried the burning torch often enough—that's the other psychology. Finding out what people think is good for them and crying against it."

"Or both."

"Or both," smiled Gene.

"This is a crazy business, sometimes. I'm on another branch again, Gene. How much of the human brain is used?"

"Less than ten percent."

"Right. What would happen if the whole brain were used?

"Andy, what kind of a card file would you need to do the following: One: locate from a mention the complete account of a complex experience; two: do it almost instantly, and three: compile the data in five dimensions?"

"Five dim—? Are you kidding?"

"Not at all. Each of the five senses are essentially different and will require separate cards to make the picture complete. A rose smell, for instance, would be meaningless alone—you must classify it. The same card would not fit for all rose-smelling memories since some are strong, some are weak, some are mixed with other minor odors, and so forth. Do you follow?"

"Yes, but aren't we getting off the track?"

"Not at all. If your mind can run through ten to the fiftieth power experiences in five mediums and come up with the proper, correlated accounts, all in a matter of seconds—think what the same mind might be able to do if presented with a lesser problem."

"Why can't it do just that?"

"Because when you start to figure out a problem, something restricts your brain power to less than ten percent of its capability."

"That means that ninety percent of the brain is nonfunctional."

"Right. It is. You can carve better than half of a man's brain out and not impair a single memory, or action, or ability."

"And nature does not continue with a nonfunctional organ."

"Nature would most certainly weed out anything that was completely useless. Evolution of a nonfunctional part does not happen."

"Appendix?"

"It had a use once. It is atrophying now. But the brain should be increasing since we're using it more every year. Instead of being forced into increase by demand, the brain is already too big for the work. How did it get that way?"

"You'll never explain it by the law of supply and demand," said Gene. "We might go over a few brains with analyzers."

"And if you get a nonconforming curve, then what?"

"Fifty years of eliminating the sand to get the single grain of gold."

"You mean process of elimination?"

"Didn't I say it?"

"You'd never recognize it," said Andrew. They both laughed.

"But what brought you to this conference?" asked Gene. "Knowing you as I do, you aren't just spending the time of day."

"No, I'm not. Look, Gene, what do you know about Gerd Lel Rayne?"

"Just common knowledge."

"I know. But catalogue it for me. I am trying to think of something and you may urge the thought into solidification."

"Sounds silly," said Gene. "But here it is—and quite incoherent." He laughed. "What was I saying about the excellence of memory files? Well, anyway, Gerd Lel Rayne is a member of a race that has and employs interstellar travel. Terra has nothing, produces nothing, manufactures nothing that this race requires. Neither, according to Gerd, has this race anything that would interest Terrans. Save power and the stellar drive."

"Stellar power," muttered Andrew.

"What was that? Stellar Power? Call it that if you wish. It may well be called that for lack of a better name. At any rate, it is more than obvious that Gerd Lel Rayne and his wife enjoy us. They are emissaries—ambassadors of good will, if you want to call them that—whose sole purpose is to give advice upon things that Terra does not quite understand."

"Except stellar power."

"Reason enough for that," said Gene. "Terra is a sort of vicious race. We were forced to fight for our very existence. We fought animals, nature, plants, insects, reptiles, the earth itself. We've fought and won against weather and wind and sun and rain. And when we ran out of things to fight, we fought among ourselves because there were too many differences of opinion as to how men should live. We, Andrew Tremaine, are civilized—and yet the one thing we all enjoy is a bare-handed fight to the finish between two members of our own race."

"That's not true."

"Yes it is. What sport has undergone little change for a thousand years? It is no sport using equipment. The equipment-sports are constantly changing with the development of new materials with which to make the equipment. Take the ancient game of golf, for instance. They used to make four strikes to cover a stinking four hundred yard green. That's because control of materials was insufficiently perfect to maintain precision. No two golf balls were identical, and no two clubs were alike.

"But—and stop me if my rambling annoys you, although it is seldom that I am permitted to ramble—the sport of ring-fighting is still similar to its inception. Men stand in a ring and fight with their hands until one is hors de combat for a period of ten seconds. They used gloves at one time, I believe, but men are harder and stronger now—and surgery repairs scars, mars, and abrasions. Also, my fine and literary friend, the audience, gentle people, like to see the vanquished battered, torn, and slightly damaged. Civilization! One step removed from Ancient Roma, where they tossed malcontents into an arena to see if he could avoid being eaten by a hungry carnivore!

"Well, the one thing that Terra would most probably do is to make use of this drive and go out and fight with the Ones."

"Are they afraid?"

"I don't know. I'd hardly think so."

"Gene, you're wrong. They wouldn't even bother brushing us off."

"No?"

"No. We'd be polished off before we got to see them. There's something else there and I don't know what it is."

"You don't follow the hatred angle?"

"You, my friend, have a warped personality. You have the usual viewpoint of a man of minor stature. That lanky body of yours has driven you into believing that your race is tough, vicious, and most deadly to everything. Not because you really believe it, but you yourself are not tough, deadly, or invincible but you want to belong to a group that is."

"You think them benign?"

"I wonder—but am forced to believe the overwhelming pile of evidence. In every way, Gerd and his wife have been willing to co-operate. They've willingly submitted themselves to our mental testing—and that is complete, believe me—and in every case they have proven intelligent, enthusiastic, and capable. Oh, we make mistakes, but not such complete blunders. I'll tell you one thing, Gene. I went over there today to ask one question. I wanted to know just why they refuse to give us the stellar power. Their answer was that we were not ready for it—and in the face of it, I was forced to agree."

"Whitewash."

"Think so? Then tell me how you can tell."

"Gerd Lel Rayne is a supergenius, according to the card files. Intelligence Quotient 260! That, my friend, is high enough to fool the machine!"

"Nonsense."

"A machine, Andy, is a mechanical projection of a man's mind. It is built to do that which can not be done by man himself. It is capable—sometimes—of exceeding man's desire by a small amount, but is seldom capable of coping with a situation for which it is not engineered. Since no man on Terra has an I.Q. of higher than about 160, for a guess, the machine can not be engineered to analyze mentalities of I.Q. 260 without fail."

"You do not believe the I.Q. 260 then?"

"Yes, I believe that machine. But the one that gives the curves of intent can be fooled by such a man."

"Then what is his purpose?"

"Supposing this race intends to take over?"

"Then why don't they just move in and take?"

"Time. Say this race is overrunning the Galaxy. No matter how they start, plans must be made, even if they originated on Centauri. Since—and let's try to put ourselves in their place and consider. They have not moved in. That means a waiting period of some kind. It also means considerable distance from home base, because if we were close to them, the program would have started already. Now, since there is this waiting program, we can assume that they are not ready yet. And not being ready means one of two things. They are finding opposition on other planets of other systems. In this case it is not Divide and Conquer, but keep divided in order to conquer!"

"I'm beginning to follow you."

"If we had the drive, and the power for it, their job might well be impossible. I doubt that anything alive could make conquest of an armed planet unless that planet was quite inferior in weapons. Given the same weapons and power, and at best stalemate. For the very energy-mass of a planet is unbelievably great, and the weapons that may be permanently anchored in the granite of Terra would be able to withstand anything up to and including another, equally armed planet to stalemate or draw. And granting that Terrans are hard-boiled people because we were brought up that way from infancy, we'd give any race a mighty tough fight."

"Then what do you want me to do?"

"I want knowledge. I want something that will permit me to use that ninety percent of my brain."

"How in the devil do you expect me to come up with something like that?"

Andrew Tremaine smiled solemnly and said, flatly: "Gene, I'm almost convinced that Gerd Lel Rayne and company are generating some force-field that prevents it!"

Gene sat silent after that. He thought about it for some time before answering. "The answer to that," he said very slowly and very carefully, "is this: If some force is being generated to prevent full use of the human brain, a counter-force may be set up to nullify the field. That will be simple enough once we isolate the field that prevents thought. But on the other hand, if no such field exists and it is just one of those paradoxes, we'll have considerable working to do to generate a force-field that will permit one hundred percent brain-usage."

"Right. And remembering that this may be the answer to Terra's existence, we'll have to keep it silent."

"You're handing me the job?"

"Yes. You're a practising psychologist. You're also an amateur technician. If you need anything, no matter what, requisition it and I'll see that it is O.K.'d. Send the thing to me marked personal so that some clerk won't toss it out for not belonging to the publishing business."

"You know how much this will cost?"

"Sure. You'll start off with a copy of the I.Q. Register and recorder and work your way up through the intent-register. From there on in, Gene, you're on your own. And—alone! I do not want to know what you're doing. I might let it out before Rayne or his wife. Come to me as soon as you find something."

"Right. But look, Andy. Why not give me a batch of signed requisitions so that you won't know what I'm working on next?"

"Good. I'll sign me one block, and mail it to your home. You are fired as of now for ... for—"

"Differing with the management in a matter of policy."

"Excellent. And when the requisition numbering the last of the block comes in, I'll sign up and mail another block to your home. Leave a forwarding address. The bank will honor your signature on company checks to the tune of one thousand dollars per month."

"Applied psychology is wonderful," smiled the tall, thin man. "You wouldn't have trusted me a thousand years ago."

"There are a lot of people I wouldn't trust now, today."

"But the difference is, Andy, that nowadays you know whom you can trust."

Gaya Lel Rayne's entry into the grand ballroom had the same effect, just as it always had. In another woman it might have produced triangle-trouble, but Gaya's attraction for men was not her only charm; the woman who hated her for her ability to draw men was one who did not know her. Once introduced, and permitted to talk with Gaya, the jealous dislike died, for Gaya was not far below her husband in wit and intelligence. Like all intelligent people, Gaya was capable of making herself liked by all, even in the face of dislike. Those who still felt the twinge of jealousy often pitied her; feeling that her beauty was compensation for the necessity that she be of high intelligence, and quite certain of their husbands, whom they knew would not care to live their lives with a woman who outshone them in every field. They knew also that there was but one man on the whole planet that Gaya loved—Gerd. He was the only man she could possibly love and the only man who could possibly love her. Gerd was the only man who could even keep up with her thought-processes.

Gerd had his amusement, too. Partly in payment for the slight put upon them by their husbands, Gerd was surrounded by women as he entered. And they knew that he was more than capable of running far ahead of their own devious thought-processes, a condition which they hoped was untrue in their husbands. Yet he was interesting and attractive, and equally as versatile as his wife.

The party took on a faster air, and all were dazzled save one. Andrew Tremaine stood on the side lines and watched.

He saw Gaya whirl from man to man across the dance floor and with equal amusement he saw Gerd moving through a closely-knit crowd. He wished fervently for someone to discuss it with, but even his wife was in the press of people about Gerd Lel Rayne.

Emissaries, he thought. Ambassadors who cut their mentality because they did not care to appear so far beyond their friends would certainly develop a contempt. It must be so, if for no other reason than it could not be otherwise. Andrew wondered what made them tick.

He'd heard from Gene Leglen briefly. It was not good. A negative result—which was inconclusive. Yet, according to the letter, the thought-process frequencies had been inspected carefully by the most delicate detector that Gene could make, and he had found nothing out of line. Strays from the I.Q. Register machine that ran continually in the shielded vault below the psychology building in government square were recorded; a few pip-markers leaked out of the intent-register on strong impulses and caused Gene's machine to chatter wildly at long and indefinite times; even a few infra-faint recordings came from the intent-register machine as a matrix was sent through to record changes from a previous marking were caught on Gene's detector.

But nothing with overall intensity. Nothing that could be expected to block the operation of nine tenths of a man's brain.

Andy saw Rayne approaching with Lenore, and smiled.

"Why so thoughtful?" asked his wife.

"Thinking deeply again?" asked Rayne. "More power?"

"Don't laugh at me, Gerd," pleaded Andrew.

"Laugh at you?" asked Gerd in genuine dismay. "Never. You are a good friend, Andrew. I will never laugh at you." He shook his head. "Tell me, what makes you think I'm laughing?"

"I can not but think, sometimes, that you are playing with all of us."

"Please ... please. Is there nothing I can do to dispel this idea, this fixation of yours?" he turned to Lenore. "Do you, too, think I'm toying?"

"No," she said quickly. "You're too fine a person to toy with another. I know."

Gerd flustered at that. "The trouble with this job of mine," he said, "is that no one ever tells me that I'm a meddling fool or to mind my own business."

"That's your fault," said Andrew. "Honestly, I doubt that there is a man on this confounded planet that wouldn't hasten to carry your banner. You are a well-liked man, Gerd, and as such no one wants to tell you off. Furthermore, you always seem to know when to let a man alone—and that in itself precludes any possibility of telling you to stay away. How do you know that sort of thing?"

"Accident of birth," said Gerd wryly.

"Spacewash."

"You think I studied to learn it?"

Andrew laughed. "If I thought that, I'd apply for entrance to the same school," he said. "I'd like to have that trait myself."

Lenore interrupted. "Andy," she said, "you must remember that Gerd is a sensitive man. You might have been a sensitive man at one time, but being a publisher has taken all of the reticence out of you. Wresting hidden secrets from people who have things to hide is life and blood for a newsman—and it does not make a man sensitive for other people's feelings."

"Well," grumbled Andrew, "I'd like to be able to recognize when someone does not want to be bothered, anyway."

"And those are just the people you'd bother, I know."

"But what was bothering you?" asked Gerd with honest concern.

"I was just thinking about brains. One of the women said that your wife's brains excluded her from the 'dangerous female' classification because she wouldn't be really bothered with any one of the husbands present. It led to other trains of thought and I came to the universal question: Why does a man use but nine tenths of his brain?"

"Oh that? That's obvious! You have a flier. What is its peak power?"

"About seven dirats."

"And it develops that total power only at high speed. Suppose you drove the machine at that power all the time?"

"Wouldn't last—besides, you couldn't. It takes time to get to that speed."

"Right. It is a matter of capacity. The brain is built to exceed the present demand, Andy. When it is needed, it will be available. Nature expects that the brain will be called on, one hundred percent, and she intends to keep increasing that availability as it is needed. But it takes millions of years to develop and evolve something as intricate as brain-material, and nature does not intend that you and I catch up with her and find her adaptive ultimate inadequate to proceed because of her lack of foresight. The necessities of brain material have far exceeded her ability to evolve it, up to the present time. You're using infinitely greater proportions of your brain than your ancestors. Suppose that they had been running at full capability? You'd be limited; at the top of your capability to progress.

"So, Andrew, you're running on one tenth of your brain all because no real thinking can come out of a full brain. The fill will increase, with evolution and science, to high percentages, but will never reach saturation. Saturation, I believe, might be dangerous."

"Sounds plausible," admitted Andrew.

"It is true," said Gerd. "And now before you drive yourself mad by thinking in circles, come and have a good time."

"No, I've just thought of something important. Your explanation gave me the impetus to think it out. Lenore, do you mind if I leave for an hour?"

"I'd better go along—"

"Please do not," objected Gerd. "Andy, I'll see that Lenore is properly entertained in your absence. May I?"

Andrew nodded, and Lenore smiled brightly. "I'll be in excellent company," she said.

"The best," agreed Andrew. "Don't forget that Gaya is here, too."

"This is an evening of pleasure," said Gerd. "One, I should not deny Gaya her admiration nor her friends the opportunity of being with her. Two, Gaya and I understand one another perfectly."

"Look, Gerd, I was fooling with Lenore. No one has any illusions about either you or Gaya, or fears, or doubts, or worries. If you'll keep Lenore from being lonely while I'm gone, I'll be more than grateful. See you in an hour."

"Fair enough."

Andrew drove his flier at almost peak power all the way to Gene's home and dropped in on the roof with a sharp landing. He raced inside and found Gene working over a bread-board layout of an amplifier for the thought frequencies.

He told Gene about Rayne's speech and waited for an answer.

"What did you expect?" asked Gene. "The answer?"

"No, but I hoped to catch him."

"In catching anything, Andy, you should first know more than your rabbit."

"You do not believe it?"

"Nope." Gene handed the editor a sheet of paper. "Follow that?"

Andrew started down the listed equations and stopped after the fourth. "Way ahead of me. How did you derive this term here?"

"By deduction."

"Guesswork?"

"Deduction. It can be nothing else."

"But knowing that is like establishing the validity of a negative result."

"Yes, but I tried everything else and nothing else worked."

"You tried everything? Look, Gene, everything covers—"

"I know," grinned Gene. "Space is bigger than anything. I'm going to make another try at seeking the possible conflicting term. That is, as soon as I get this field-generator adjusted higher."

"You did it with that?"

"So far, yes. But it still leaves a lot to be desired. Now, I've got it running properly. Give me that paper and stand back out of the way!"

Gene set the temple-clamp over his head and snapped the switch. The equipment warmed for a minute, and then Gene started to put characters down on the page as fast as he could write. He filled a half page in finger-cramping fury, and then stopped writing to stare at the page for a full ten seconds. Another equation appeared after this, and another which Gene combined. There was no more writing for a full minute then, and Andrew lost all track or semblance of order to Gene's writing. A scant term here, a single character there, a summation line—it became a sort of mathematical shorthand; a mere reminder of the salient points in the argument. The manipulation of the terms went on mentally.

The tenseness increased. The shorthand scrawls became fewer and fewer and disappeared entirely. The paper was forgotten, and the pencil dropped from Gene's fingers.

Andrew watched, held by the intensity of Gene's thinking. The other man was motionless, his muscles tensed slightly. An hour passed, and Gene had not moved, before Andrew became worried. He remembered—

"Gene had not blinked his eye for forty minutes!"

"Gene! Gene!"

No answer.

"Shut that thing off!"

No answer.

Andrew stood up, looked around, and then stepped forward. Nothing happened, so he took another step forward. What had happened to Gene? He didn't know, but he was going to find out. He stepped forward again, and then walked into the field of the machine. A wave of excitement filled him as the leakage-impact caught him; it heightened his perceptive sense and increased his emotional powers proportionately to the square of the distance between himself and the machine. He touched the corner of the desk with the tip of his hand and though he was not looking at the wood he knew that it was Terran oak, had been varnished with synthanic twice, and that it should be refinished again in a few months if it was to be preserved adequately. The air in the room came to his notice, and a portion of his brain found time to wonder at the phenomena for the breath of life is seldom questioned. Yet the air seemed tangy, pleasant, as though some subtle perfumes had been blended in it. He forgot the air in a quick inspection of the inert man. Yes, he knew without close examination that the psychologist was dead. From what cause? Andrew guessed that it was overload; if his senses and brain power were heightened with this mere field-leakage of Gene's machine, the effect of being in absolute contact with the machine's output would be similar to running a small motor without protective circuits from a high-power source. Gene had succeeded too well.

His perception of his surroundings continued to lift into the higher levels. Knotty little problems did not bother him, and his mind leaped from problem to answer without stopping to investigate and inspect the in-between steps.

Andrew wondered whether leaving the machine would cause his increased perception to drop. Forgetting Gene because the dead psychologist was no longer a sentient being, Andrew turned and walked away from the desk. The field must be terrific, he thought, and to further check the field effect, Andrew left the building and made his way down the street.

He finally dismissed the dead man from his mind. The things he saw and felt and knew were of greater consequence—and whether or not the effect failed, there was one great question that he, Andrew Tremaine, was going to solve.

He returned to the party.

He stood upon the rim of the dance floor and considered the crowd of circling dancers. He listened to the light chatter and the foolish laughter and he pitied them. His ears, he found, had taken on a sort of selectivity and were infinitely higher in sensitivity—and yet he could control that sound-pickup to a comfortable degree. Talk from the far side of the floor came to him, filtered from the rest of the general noise-level by his own, newly-found ability. He shamelessly listened to the conversations, and found them dull and uninteresting.

Through the broad doorway at the far side of the floor he looked in upon the bar. The odor of liquor came then, powerful and overwhelming until Andrew decided that it was too strong and caused his smell-sense to drop.

Foolishness.

There were so many important things to be done and these people were frittering their time away in utter foolishness. He wondered whether Gerd Lel Rayne would agree with him, and with the thought he knew where to find the emissary. He turned and went through the moving crowd impatiently until he found Rayne and Lenore.

"You're back?" asked Lenore.

"Obviously," he said shortly. "Rayne, I have a question to ask."

"Come now, Andrew," came the booming, resonant answer, "you're not going to mix business with pleasure?"

"I must—for I may lose the trend of my thought if I wait."

"Then by all means ... Lenore, you'll forgive us?"

"Yes," smiled she, "but not for too long."

Andrew contemplated his wife's exquisite shoulders as she left, and then he turned back to Gerd and bluntly asked: "Gerd, doesn't all this waste of time, effort, and brain-power disgust you?"

"Not at all. I find that relaxation is good."

"But the time—and life is so short."

"Continuous running of any machine will cause its life to be shorter. The same is true of the brain."

"Thought is thought, and we use the same portion of the brain while thinking foolishness as while thinking in deep, profound terms."

"Perhaps so."

"Don't you know?"

"Who does?"

"You and I know. Gerd, what is behind all of this? Who are you?"

"You know who I am."

Yes, Andrew knew. His higher perception told him without argument that Gerd Lel Rayne was exactly what the emissary claimed.

"But why?"

"Pure and sheer altruism."

"What do you want?"

"Nothing. We are but waiting until you evolve to the proper degree to join us. At that time you are welcome."

"Then," stormed Andrew, "why not help us evolve?"

"Impossible."

"Nonsense. You are not too far above me."

"At the present time you and I are fairly equal in intelligence. You've been working with the mental amplifier, haven't you? A more hellish instrument has never been invented, Andy."

"I find myself enjoying the sensation. If there is one thing that will raise our general level sufficiently, it is this machine. Can it be, Gerd, that your race does not want us to evolve? Do you want us to remain ignorant? Do you fear our competition?"

"My race," said Gerd with pride, "has absolutely nothing that your race can use. Your race has absolutely nothing that can possibly be of interest to us—save eventual evolution into our civilization-level. That we desire."

"Since the level of my intelligence has been raised to equal yours, why couldn't the same process work on my race as a whole. The problem then will be solved immediately."

"I see that your answer does not lie with me. Also, since you are equal to me, you must be capable of understanding the whole truth. Will you come to my home immediately?"

"To solve this problem? Certainly."

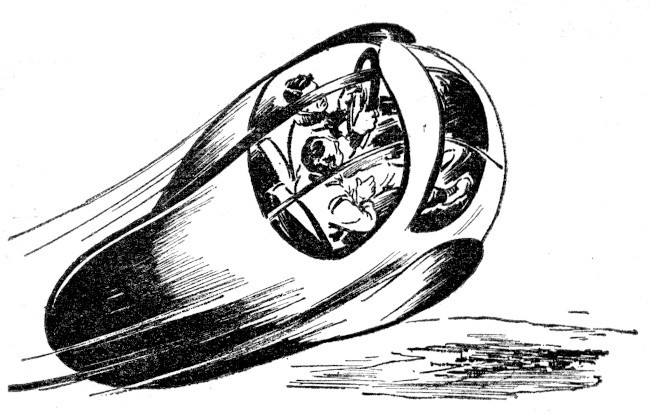

"Then come quickly. A member of the Ones is there now, reading my periodic report. I will prevail upon him to see you. But it must be swift, for he is due to leave in about one hour."

They went from the building side by side and entered Rayne's flier. Andrew wondered whether the emissary was willing to discuss the problem before his visit, and decided to try. "Who is your visitor?"

"He is Yord Tan Verde."

"A sort of high overseer?"

"Sort of. He is not connected with the Grand Council of Galactic Civilization in any managerial position, though. Yord is merely one of the group-leaders—a field representative."

"Do you mind discussing yourself?"

"I'd prefer not—though if you ask me a question that I think is not too personal, I'll be glad to answer."

"Your I.Q. is 260, according to the register. If he is your immediate superior, what must his be?"

Rayne shook his head. "I don't really know," he answered. "Your Terran method of rating intelligence is based upon age. Since your age is based upon a purely Terran concept, we could not possibly rate our intelligence on your basis, until we encounter your machines. Frankly, I'd say his was higher—but you shall see."

Gerd stopped Andrew at the door to his library. "Wait," he said. "I'll see if Yord is willing to see you."

"If he isn't?"

"I'll be as persuasive as I can. I think he may be interested when I inform him that you have artificially increased your I.Q. to my level."

"You think so?"

"I know so. However, Andrew, it will not be a productive interest. Your means is still artificial and not to be assumed adequate."

"Why not?"

"Because without the machine to step up your brain, you'd revert to your original state in a single generation. It is worse than the fabled death of power—for power is also the power to destroy. To lose the power of understanding and to leave the machines of intelligence lying around for all to play with would be disastrous. No, you wait and I'll go in and prepare Yord Tan Verde."

Rayne left the door partly open. There was a greeting in an alien tongue, and then as the other voice continued, Gerd interrupted. "Please—I was trained in Terran. I think best in Terran. May we use it?"

Verde's reply came in Terran. "I'd forgotten."

"Thank you." Gerd Lel Rayne explained the situation to his overseer, and it was quite obvious to Andrew that Gerd accelerated the story continuously, and the emissary ended with an air that gave Andrew to understand that the overseer was quite impatient and that he was ahead of Gerd.

The answer was a single word. It was unintelligible to Andrew at first, and then it soaked in that Verde had uttered the word: "Inconsistent."

Gerd objected at length and began to explain the workings of Andrew's mind.

"Granted!" came the answer half-way through the account. "Have him enter—he may be able to understand."

Gerd came out and nodded at Andrew. "Go in," he said with an encouraging smile. "And—good luck."

"Thanks, Gerd," said Andrew. He straightened up his shoulders and entered the inner library.

He fell under the full, interested glance of Yord Tan Verde as he entered, and Andrew's eyes were held immobile. His springy step faltered, and his swift and purposeful walk slowed to a slogging trudge. Andrew came up to the desk, looked full in the face of the One, shook his head in understanding, finally; and then by sheer force dropped his eyes. He turned and left the room.

Gerd was waiting for him, a sympathetic smile upon his benign face. Andrew looked at him for a long, quiet moment. Then: "You—are his emissary?"

"I am—a moron," Gerd said evenly.

"You have a job."

"I am his in-between."

"Because only a moron can understand us," said Andrew slowly.

"No—because your people can understand me, but not the Ones."

"And my efforts with the mental amplifier can do no more than bring me to your level."

"Worse, Andrew. Nature causes many sports to be sterile because they interfere with her proper plan. Your machine will introduce sterility."

"I have one protecting job to do myself," said Andrew thoughtfully. "Or—perhaps it should be maintained—secretly, of course, for some emergency?"

"Your race is adequately protected."

Andrew shrugged. "I see. Terra will need neither the machine nor its product."

THE END.