SCUD.

The Project Gutenberg eBook of The life story of a squirrel, by T. C. Bridges

Title: The life story of a squirrel

Author: T. C. Bridges

Release Date: June 5, 2022 [eBook #68252]

Language: English

Produced by: Tim Lindell and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

Animal Autobiographies.

THE LIFE STORY OF A SQUIRREL

IN THE SAME SERIES

PRICE 6s. EACH

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS IN COLOUR

THE BLACK BEAR

By H. PERRY ROBINSON

CONTAINING TWELVE FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS

by J. Van Oort

THE CAT

By VIOLET HUNT

CONTAINING TWELVE FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS

by Adolph Birkenruth

THE DOG

By G. E. MITTON

CONTAINING TWELVE FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS

by John Williamson

THE FOX

By J. C. TREGARTHEN

CONTAINING TWELVE FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS

by Countess Helena Gleichen

THE RAT

By G. M. A. HEWETT

CONTAINING TWELVE FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS

by Stephen Baghot-de-la-Bere

PUBLISHED BY

A. & C. Black, Soho Square, London, W.

AGENTS

| AMERICA | THE MACMILLAN COMPANY 64 & 66 Fifth Avenue, NEW YORK |

| CANADA | THE MACMILLAN COMPANY OF CANADA, LTD. 27 Richmond Street West, TORONTO |

| INDIA | MACMILLAN & COMPANY, LTD. Macmillan Building, BOMBAY 309 Bow Bazaar Street, CALCUTTA |

SCUD.

THE LIFE STORY OF

A SQUIRREL

BY

T. C. BRIDGES

LONDON

ADAM·&·CHARLES·BLACK

1907

| PAGE | |

| CHAPTER I | |

| MY FIRST ADVENTURE | 1 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| THE GREAT DISASTER | 21 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| THE PLEASURES OF IMPRISONMENT | 40 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| A DAY IN RAT LAND | 63 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| BACK TO THE WOODLANDS | 81 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| A NARROW ESCAPE | 95 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| THE GREY TERROR | 119[vi] |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| I FIND A WIFE | 150 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| WAR DECLARED AGAINST OUR RACE | 174 |

| CHAPTER X | |

| POACHERS AND A BATTUE | 192 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| MY LAST ADVENTURE | 210 |

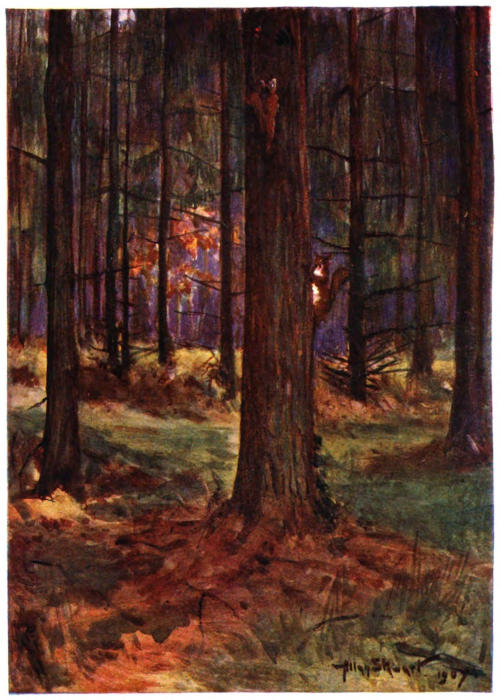

| SCUD | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

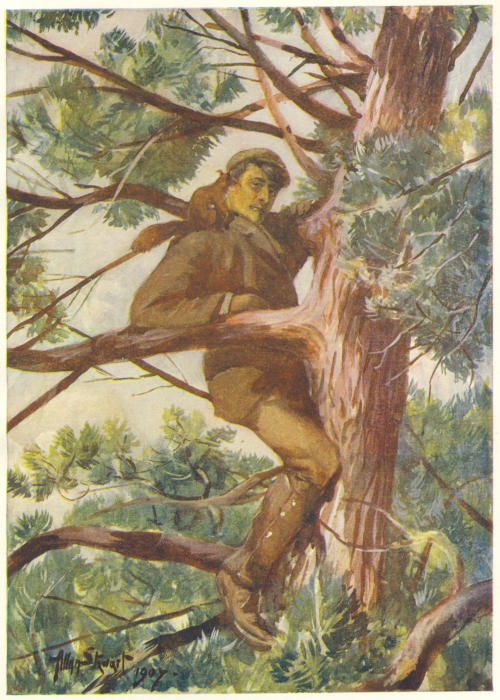

| FATHER LEAPED STRAIGHT TOWARDS THE BOY, LANDING ACTUALLY ON HIS SHOULDER | 32 |

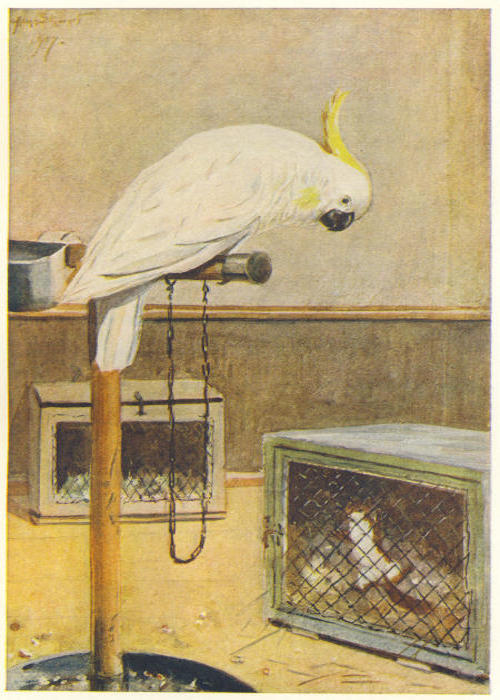

| HE IMITATED ME TO MY FACE | 48 |

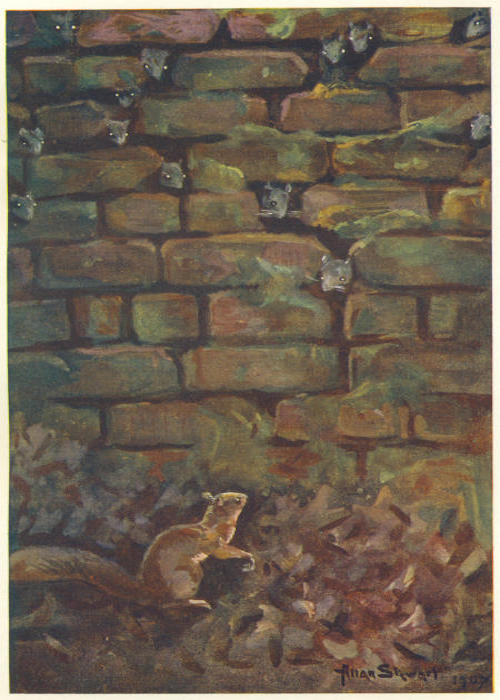

| THE WHOLE OF THE SLIMY OLD WALL SEEMED ALIVE WITH THEM | 74 |

| THE BOYS NEVER MOVED OR SPOKE | 88 |

| CLIMBING INTO ONE OF THE LARGEST TREES, WE LAY PANTING AND TIRED OUT | 112 |

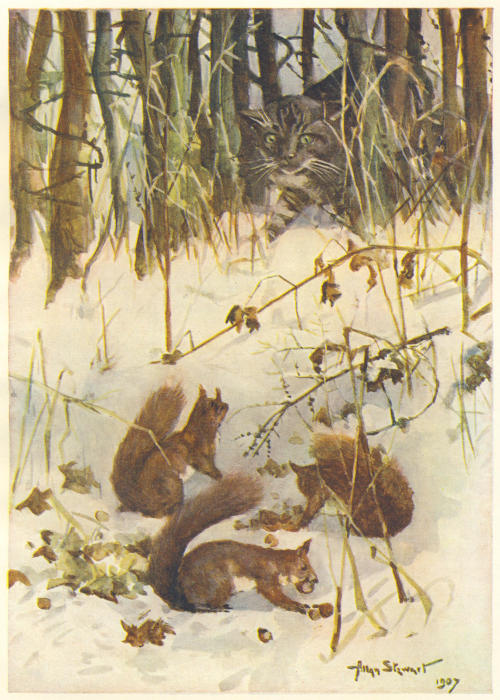

| TWO CRUEL GREEN ORBS SET IN A WIDE GREY FACE | 142 |

| DOWN THE NEAR SIDE OF THE TRUNK WAS A DEEP AND WIDE NEW SCAR | 172 |

| ‘AND TO THINK IT WAS THIS HERE LITTLE RED RASCAL’ | 184 |

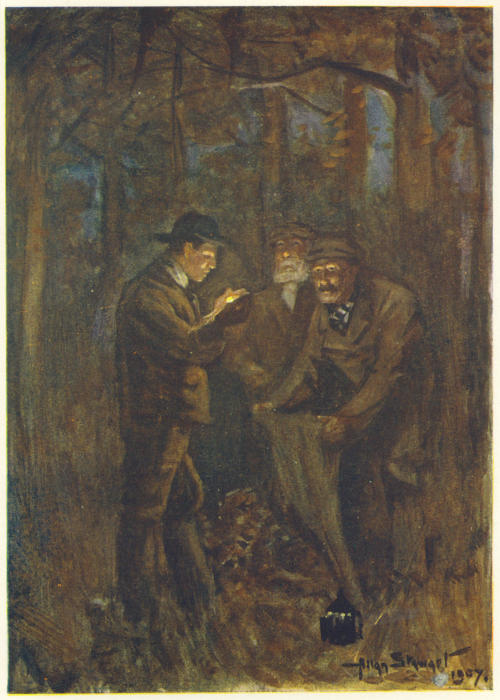

| A SMALL BLUE FLAME ILLUMINATED THREE EAGER FACES | 194 |

| ANOTHER MOMENT FOUND ME COMFORTABLY PERCHED IN THE BRANCHES OF THE HAZEL-BUSHES | 208 |

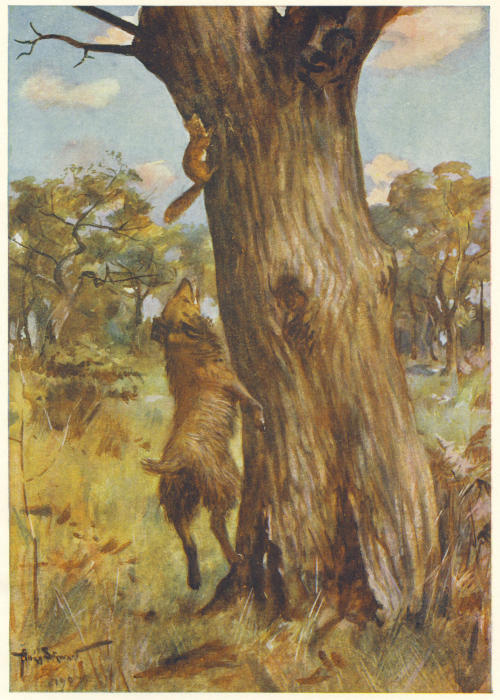

| THE DOG BOUNDED HIGH, BUT I WAS SAFELY OUT OF HIS REACH | 224 |

It was a perfect June morning, not a breath stirring, and the sun fairly baking down till the whole air was full of the hot resinous scent of pine-needles; but, warm as it was, I was shivering as I lay out on the tip of a larch-bough and looked down. I was not giddy—a squirrel never is. But that next bough below me, where my mother was sitting, seemed very far away, and I could not help thinking what a tremendous fall it would be to the ground, supposing I happened to miss my landing-place. I am too old now to blush at the recollection of it, and I don’t mind confessing that at the time I was in what I have since heard called a blue funk.

The fact is, it was my first jumping and climbing lesson. Even squirrels have to learn to climb, just as birds have to be taught by their parents to fly.

My mother called me by my name, Scud, sitting up straight, and looking at me encouragingly with her pretty black eyes. But I still hesitated, crouching low on my branch and clinging tight to it with all four sets of small sharp claws.

Mother grew a trifle impatient, and called to my brother Rusty to take my place.

This was too much for me. I took my courage in both fore-paws, set my teeth, and launched myself desperately into the air. I came down flat on my little white stomach, but as at that time I weighed rather less than four ounces, and the bough below was soft and springy, I did not knock the wind out of myself, as one of you humans would have done if you had fallen in the same way.

Mother gave a little snort. She did not approve of my methods, and told me I should spread my legs wider and make more use of my tail. Then she turned and gave a low call to Rusty to follow.

Even at that early age—we were barely a month old—Rusty was a heavier and rather slower-going[3] squirrel than I. But he already showed that bull-dog courage which was so strong a trait all through his after-life. He crawled deliberately to the very end of the branch, then simply let go and tumbled all in a heap right on the top of us. It was extremely lucky for him that mother was so quick as she was. She made a rapid bound forward, and caught her blundering son by the loose skin at the back of his neck just in time to save him from going headlong to the ground, quite fifty feet below.

She panted with fright as she lifted him to a place of safety with a little shake.

Rusty looked a trifle sulky, and mother gave him an affectionate pat to soothe him down.

Then she told us to follow her back along the branch, and she would show us how to climb up the trunk home again. She sent me first.

I had hardly reached the trunk end of the bough when I heard mother utter a cry which I had never heard her give before. It was a low sharp call. Oddly enough, I seemed to know exactly what it meant. At once I lay flat upon the bough, here quite thick enough to hide my small body, and crouched down, making myself as small as possible. At the same instant mother seized Rusty[4] by the scruff of his neck, and with one splendid leap sprang right up on to the wide, thick bough on the flat surface of which our home was built. In a few seconds she came back for me, and before I knew what was the matter I, too, was safe in the nest, alongside Rusty and my sister, little Hazel.

Mother gave a low note of warning that none of us should move or make any noise; and you may be sure we all obeyed, for something in her manner frightened us greatly. Presently we heard heavy footfalls down below rustling in the dry pine-needles. We sat closer than ever, hardly daring to breathe. The footsteps stopped just below our tree, and a loud rough voice, that made every nerve in my body quiver, shouted out something. From the sound of it we could tell that the speaker was peering right up between the boughs into our tree, and we knew without the slightest doubt he had discovered our drey. He must have spoken loud, even for a human, for his companion gave a sharp ‘S-s-sh!’ as if he were afraid that some one else might overhear and come down upon them. It could not have been of us he was afraid, for we, poor trembling, palpitating little things, lay huddled together, hardly daring to breathe.

The two tormentors turned away a few paces after a few lower-toned remarks, and I began to think they had gone, when——

Crash, a great jagged lump of stone came hurtling up within a yard of our home, frightening us all abominably.

Mother crouched with us closer than ever into our frail little house of sticks, which was not made to stand the force of stones.

Almost immediately there fell another mass of whizzing stone, even nearer than the first. It shore away a large tassel from the bough just overhead, and this fell right on the top of us, frightening Hazel so much that she jumped completely out of the nest, and, if mother had not been after her as quick as lightning, she must have fallen over the edge and probably tumbled right down to the ground and been killed at once. Even a squirrel, particularly a young one, cannot fall fifty feet in safety.

Mother saved her from this fate, but the mischief was done. The quick eyes of our enemies below had caught a glimpse of red fur among the pale green foliage, and they roared out in triumph, the louder and noisier making such a row, I thought that anyone within hearing must come rushing[6] to see what was the matter. Then they began disputing together, perhaps as to which of them should carry us away.

We lay there nestling under mother’s thick fur, shaking with fright.

The two fellows down below argued like angry magpies for several minutes, and at last it was decided that the quieter one should do the climbing. I peeped over timidly and saw him throw off his coat, and drew back to make myself as small as possible. Presently I heard a bough creak, and then there followed a scraping and grinding as his heavy hobnailed boots clawed the trunk in an effort to reach the first branch. Once on that, he came up with dreadful rapidity. The boughs of the larch were so close together that even such a great clumsy animal, with his hind-paws all covered up with leather and iron, could climb it as easily as a ladder. We heard him coughing and making queer noises as the thick green dust, which always covers an old larch, got into his throat, and the little sharp dry twigs switched his face. But he kept on steadily, and soon he was only three or four branches below us, and making the whole top of the tree quiver and shake with his clumsy struggles. But as he got higher the branches were[7] thinner, and he stopped, evidently not daring to trust his weight to them, and called out something to his companion. All the answer he got was a jeering laugh, and this probably decided him, for, with a growl, he came on again. The tree really was thin up near our bough, at least for a great giant like this. The trunk itself bent, and the shaking was so tremendous that I began to think that our whole home would be jerked loose from its platform and go tumbling down in ruins with us inside it.

Suddenly the fellow’s great rough head was pushed up through the branches just below. His fat cheeks were crimson, and his hair all plastered down on his forehead with perspiration. I stared at him in a sort of horrible fascination. I could not have moved for the life of me, and, as Rusty and Hazel told me afterwards, they felt just the same. But mother kept her head. She was sitting up straight, with her bright black eyes fairly snapping with rage and excitement.

The man made a desperate scramble, and up came a large dirty paw and grasped the very branch on which we lived. This was too much for mother. Her fur fairly bristled as she made a sudden dash out of the nest by the entrance[8] nearest to the trunk, and went straight for that grasping fist. Next instant her sharp teeth met deep in his first finger. He gave one yell and let go. All his weight came on his other hand, there was a loud snap, and his large red face disappeared with startling suddenness.

For a moment our tree felt just as it does when a strong gust of wind catches and sways it. Our enemy, luckily for himself, had fallen upon a wide-spreading bough not far below, had caught hold of it, and so saved himself from a tumble right down to the bottom.

I heard his companion cry out in a frightened voice. For a moment there was no reply, and then a torrent of language so angry that I am sure no respectable squirrel would have used anything so bad even when talking to a weasel.

The man who had fallen was dancing about, holding his hand in his mouth, and taking it out to show his comrade. I watched him excitedly, hoping that now he had been hurt he would go away; but no, picking himself up he began again clumsily climbing up towards us. He came more slowly than before, trying each branch carefully before he put his weight on it. Presently I saw his furious face rising up again through the branches,[9] and now he had something shining and sharp, like a long tooth, clutched between his lips. I did not know then what a knife was, but I thought it looked particularly unpleasant. There was a nasty shine, too, in his pale blue eyes. I could feel my heart throbbing as if it would burst. Again his great ugly paw came clutching up at our bough. Fortunately he could not quite reach it. Having broken off the branch just below us, he had nothing to hold on to. However, he was so angry that there was no stopping him. He got his arms and legs round the trunk and began to swarm up.

It looked as if nothing could save us now. Mother herself was too frightened of that long gleaming tooth to try to bite our enemy again. She jumped out of the nest by the entrance on the far side, and did her best to persuade us to follow her out to the end of the branch where we had been having our jumping lessons. But we were much too frightened to move. We lay shivering in the moss at the bottom of the nest, and made ourselves as small as we knew how.

The man’s head was level with the bough; he was stretching out for a good hand-hold, when suddenly I heard the sharp clatter of a blackbird from the hedge at the border of the spinny, and[10] immediately afterwards the crash of dry twigs under a heavy boot.

A sharp hiss came from below in warning. Bill’s hand stopped in mid-air, just as I once saw a rabbit stop at the moment the shot struck it. His cheeks, which had been almost as red as my tail, went the colour of a sheep’s fleece. He listened for a moment, then suddenly dropped to the bough below, and began clambering down a good deal more quickly than he had come up.

We guessed it was the keeper, who had always left us alone, though we had often seen him about.

The steady tramp of his boots suddenly changed to a quick thud, thud; and when he saw the fellows at the tree, he gave a deep roar, just like the bull that lives in the meadow by the river when he gets angry. He came running along at a tremendous pace, making such a tramping among the leaves and pine-needles that the blackbird, though she had flown far away, started up again with a louder scream than ever.

The man on the ground did not wait. Deserting his companion, he made off at top speed. But old Crump, the keeper, knew better than to waste his time in catching him. He had seen the boughs shaking and he came straight for our tree, and[11] shouted triumphantly as he caught sight of the other one, who was by this time only a few boughs from the ground.

In his hurry and fright the fellow missed his hold. Next moment there was a tremendous thump, and a worse row even than when he had taken his first tumble.

I peeped out of the nest again more confidently, and I thought they were fighting. But what had happened was that the poacher had fallen right on the top of Crump’s head, flooring him completely, and, I should think, knocking all the breath out of him. Then, before the keeper, who was as fat as a dormouse, could gain his feet, the other had picked himself up and gone off full tilt after his friend.

The keeper growled and muttered to himself as he rose slowly. He picked up his gun and walked round the tree, looking up, evidently puzzled as to what the men had been after. Then he caught sight of us, and shook his head, as if he would have much liked to capture us himself He certainly could not have had any friendly feeling for us, as we bit the tips off his young larches. But he must have had orders to let us alone, for he did not attempt to molest us, and presently, to our[12] great relief, he too stumped off and left us undisturbed.

We lay very still for a long time, slowly getting over our fright. Suddenly mother gave a pleased little squeak and jumped out of the nest. I crawled out too, as boldly as you please, and looked down. Here came father running along over the thick brown carpet of pine-needles which covered the ground. I know some of you humans laugh at a squirrel on the ground. But it is not our fault that we do not look so well there as in our proper place—a tree. Why, even the swan, supposed to be the most graceful thing in the world, waddles in the clumsiest fashion imaginable when it is on dry land! At any rate, even over flat ground a squirrel can move at a good pace.

Father was lopping along with his fore-paws very wide apart, and stopping now and then to sniff or burrow a little among the pine and larch needles. In one place he evidently found something good—possibly a nice fat grub—for he stopped, sat up on his hind-legs, and, holding whatever it was in his fore-paws, began to nibble at it daintily. How handsome he looked sitting there, with his beautiful sharp ears cocked, his splendid brush hoisted straight up, and the rich, ruddy fur of his back[13] just touched by a stray gleam of sunshine, contrasting beautifully with the snowy whiteness of his waistcoat! It has always been my opinion that he was the handsomest squirrel I ever saw, and I was never more pleased in my life than when mother once told me that she thought I was more like him than any of her other children.

Mother called again. Father looked up, caught sight of her, gave a quick flick of his tail and an answering call. Next instant we heard the rattle of his claws on the rough bark, and almost before I could look round here he was with us.

He was full of good-humour, for he had been over to the beech copse, and the mast, he told us, was the finest crop he had seen for years. We must collect a good store as soon as it got ripe.

But he suddenly noticed that mother was quivering all over, and he had not time to ask what had upset her before she burst into an account of all the dreadful things that had happened that morning.

Then he looked very grave.

‘We must go,’ he said. ‘It means building a new house. And this tree has suited us so admirably. I do not think that I have ever seen a weasel near it; then, too, we are so capitally[14] sheltered from bad weather by all these thick evergreens. In any case I shall not leave the plantation, but I suppose we must look out for another tree. We cannot do anything to-day; it is too late. Now I will mount guard over the youngsters while you go and get some dinner.’

And rather uneasily she went off.

The heat of the day was over, but the sun was still warm. A little breeze was talking gently up in the murmurous tops of the trees, causing the shadows to sway and dance in dappled lights on the lower branches. You humans, who never go anywhere without stamping, and running, and talking loudly, and lighting pipes with crackly matches, have no idea what the real life of the woods is like, especially on a fine June afternoon such as this one was. Though our larch was one of a thick clump, yet from the great height of our nest we could see right across into the belt of oaks, beeches, and old thorn-trees which lay along the slope below, and could even catch a glimpse of the tall hedge and bank, and of the sandy turf beyond where the rabbit-warren lay.

One by one the rabbits lopped silently out of their burrows and began to feed till the close turf was almost as brown as green. Stupid fellows,[15] rabbits, I always think, but I like to watch them, especially when the young ones play, jumping over and over one another, or when some old buck, with a sudden idea that a fox or weasel is on the prowl, whacks the ground with one hind-leg, and then all scuttle helter-skelter back into their holes.

A pompous old cock pheasant came strutting down a ride in the young bracken, the sun shining full on his glossy plumage and black-barred tail. Presently his wife followed him, and behind her came a dozen chicks flitting noiselessly over the ground like so many small brown shadows. A pair of wood-pigeons were raising their second brood in a fir-tree, not far away from where we lived, and every now and then, with a rapid clatter of wings, one of the old birds came flapping through the aisles of the plantation with food for their two ugly, half-fledged young ones. I wonder, by the by, why a wood-pigeon is so amazingly careless about its nest building. I never can understand how it is that the young ones do not fall off the rough platform of sticks which is their apology for a nest. And it must be shockingly cold and draughty, too. Birds are supposed to be ahead of all other nest-builders, but I can tell you there are a good many besides the wood-pigeon who might[16] take a few pointers in architecture from us squirrels, to say nothing of our distant cousin the door-mouse.

A sharp rat-a-tat just behind startled me, and there was a big green woodpecker hanging on tight against the trunk of our own larch with his strong claws, and pounding the bark with his hammer-like beak. Father looked at him with interest.

‘Ah,’ he observed, ‘it’s about time we did move. The old tree must be getting rotten, or we shouldn’t have a visit from him.’

It was all most pleasant and peaceful as we sat there—Rusty, Hazel, and I—enjoying the gentle swinging in the soft west wind, and waiting for mother to come home.

It was a very fine summer, that one. I have never seen one like it since. We had very little rain and no storms for weeks on end, and the crops of mast and nuts were splendid.

But I am running ahead too fast. The very next day after our narrow escape from the two loafers, father set to work to make a new house in the fir-tree he had spoken of. Luckily for him, there was an old carrion crow’s nest handy in the top branches, and he got plenty of sticks out of this for the framework. Mother helped him to[17] gather some moss—nice dry stuff from the roots of a beech, and he made a tidy job of it within three days. Of course, he did not build so elaborately as if he had been constructing a winter nest—we squirrels never do. But all the same, he put a good water-tight roof over it.

Meantime mother had been keeping us youngsters hard at work with our climbing and jumping lessons. We all got on very well, and the day before we were to move she actually let me come down to the ground. It was the funniest feeling coming down so low, and at first I cannot say that I liked it. There was no spring in the earth, and one did not seem able to get a good hold for one’s claws. The pine-needles slipped away when one tried to jump. However, after the first novelty wore off, I enjoyed the new sensation hugely, and my joy was complete when mother showed me a little fat brown beetle which she said I might eat. I tried it, and really it might have been a nut, it was so crisp and plump.

Rusty and Hazel were sitting on a bough overhead, and as full of envy as ever they could be, for mother had said that she really could not have more than one of us at a time down among the dangers of the ground, and that I was the only[18] one quick enough to look after myself if anything happened.

My quickness was fated to be tested. While mother was scratching about the tree-roots, having a hunt for any stray nuts of last autumn’s store that might hitherto have been overlooked, I moved off to see if I could not discover another of those tasty beetles. At a little distance lay a great log, the slowly-rotting remains of a tall tree that had been torn up by the roots in some winter gale many years before, and was now half buried in the ground. On its far side was a perfect thicket of bracken, and a great bramble grew in the hollow where the roots of the tree had once been, and hid the fast decaying trunk. There was a curious earthy smell about the place which somehow attracted me. I know now that it was from a sort of fungus which grows in the rotten wood, and is quite good to eat, but at that time I was still too young to understand this. However, I went gaily grubbing about, and at last ventured on the very top of the log and pattered down it towards the trunk end. Near the butt was a hollow in the worm-eaten wood. The bramble was thick on all sides, but there was an opening above through which a patch of bright sunlight leaked down. In the[19] middle of this dry, warm cavity was a small coil of something of almost the same colour as the wood on which it lay. At first I took it for a twisted stick, but it attracted me strangely, and I gradually moved nearer. It was not until I came to the very edge of the hollow and sat up on my hind-legs that I suddenly became aware that the odd coil had a little diamond-shaped head, in which were set two beady eyes. There was a horrible cold, cruel look in those unwinking eyes which had a strange effect upon me. I turned cold and stiff, and felt as if, for the very life of me, I could not move. Suddenly a forked tongue flickered out, the dead coil took life, I saw the muscles ripple below the ashen skin. It was that movement which saved me. As the horrid head flashed forward, I leaped high into the air. The narrow head and two thin, keen fangs gleaming white passed less than my own length below me, and I fell into the thick of the bramble, the worst scared squirrel in the wood. How I scrambled out I have no idea, but in another instant I was scuttling back to my mother, full of my direful tale.

When I told her what had happened she looked very grave.

‘It was an adder,’ she said, shivering. ‘If it[20] had bitten you, you would have been dead before sunset. Keep close to me, Scud.’

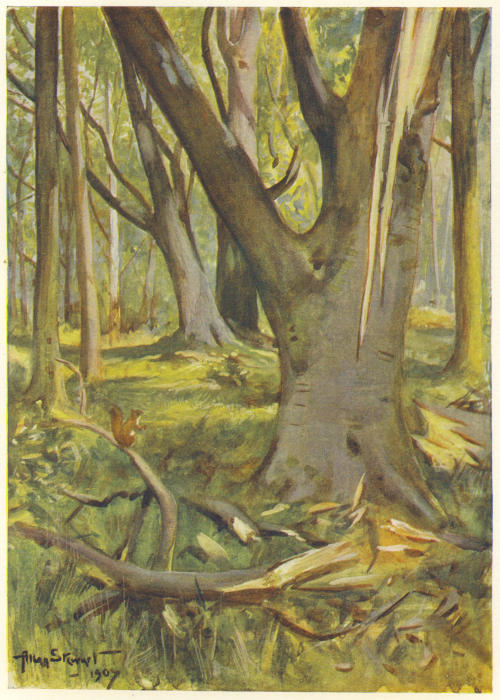

The next day we moved into our new quarters in the fir-tree. Personally, I never liked a fir so well as most other trees. It is so dark and gloomy, and you get so little sun. My own preference has always been for a beech. An old beech has such delightful nooks and crannies, and often deep holes, sometimes deep and large enough to build a winter home in—always capital for the storage of nuts. There was no doubt, however, that the fir which father had chosen had many points to recommend it. It was an immensely tall tree, and thick as a hedge, yet there were no branches close to the ground to tempt evil-minded young humans like our recent invaders to climb up. What was still better, so cunningly had father chosen his site that it was quite impossible for any evil-minded, two-legged creatures to see us from below. Our nest was founded on a large, flat-topped branch close in to the thick red trunk, and only about two-thirds of the way up to the top. Another branch almost equally thick formed a roof over our heads, so that we were very snug and comfortable.

The day on which the great disaster befell us was wet in the early morning, and when the sun rose a thick, soft mist, white like cotton-wool, hung over the country-side. Not a breath of air was stirring, and it was so intensely still that it seemed as though one could hear everything that moved from one end of the wood to the other. The plop of a water-rat diving into a pool in the stream on the far side of the coppice came as clearly to my ears as though the water had been at the bottom of our own tree instead of several hundred yards away, and when the wood-pigeons began to move unseen in the smother, the clatter of their wings was positively startling.

We squirrel folk are not fond of wet, so we lay still and snug in our cosy retreat until the sun began to eat up the mist. Soon the grey smother thinned and sank, leaving the tree-tops bathed in brilliant light, every twig dripping with moisture,[22] and every drop sparkling with intense brilliance. Then we crept out one by one, and, sitting up straight upon our haunches, began our morning toilet. No other woodland creature is so careful and tidy in its habits as a squirrel, and mother had already thoroughly instructed us in the proper methods of using our paws as brushes and our tongues as sponges, and in making ourselves neat and smart as self-respecting, healthy squirrels should be.

Suddenly a peal of distant bells came clanging through the moist, calm air with such a vibrating note that they made us all start. Father sat up sharply, and mother asked him what was the matter.

He explained to us that he had learnt by experience that when those bells rang out it was a dangerous time for us, for all the mischievous boys and rough fellows in the neighbourhood seemed to appear in the woods, and the keeper was never seen. He did not know why this should be, but from long custom he had grown to be uneasy at the sound.

Mother shuddered sympathetically, and rubbed against him caressingly, with a movement that told him not to worry, and she reminded him consolingly[23] that even if our tormentors did take it into their heads to come into the wood they would not be likely to find us, since we had moved.

But father, instead of responding, suddenly pricked up his ears, and, signalling to us to be quiet, listened eagerly to some sound which the rest of us had not yet caught. For a moment he sat up straight, as still as though stuffed; then he turned and spoke sharply, with a warning sound that told us to lie as still as mice, for some danger was approaching.

Sure enough, a minute later we all heard the warning cry of a frightened blackbird, and immediately afterwards the brushing and trampling of a number of heavy boots through the wet grass and fern in the distance. At once we all stretched ourselves out tight as bark along the flat bough which formed the foundation of our nest, and lay there still as so many sleeping dormice.

The steps came rapidly nearer, and soon voices sounded plainly through the hush of the quiet wood. Imagine how I shuddered when I recognized the coarse tones of our former enemies mixed with others equally harsh and unpleasant! They were making straight for our part of the wood.

Shaking though I was in every limb, curiosity drove me to peep cautiously over the edge of the bough. The mist was all gone now, and there, below the tall larch-tree which had been our old home and the scene of our recent narrow escape, stood four young louts, our old enemies and two others about the same size and age, all craning their necks and staring upwards through the thick, pale-green branches. Each was carrying in his right hand a short, flexible stick with a heavy head. These were not long enough for walking-sticks, such as Crump, the keeper, and other humans who sometimes came through the wood carried; and, in spite of my fright, I wondered greatly what they were for. Alas! it was not long before I learnt the terrible powers of the cruel ‘squailer.’

After a good deal of argument and dispute one of the new-comers swung himself up on to the lowest bough. He climbed far better and faster than the one who had tried before, and in a very short time had reached a bough close below our old drey.

By this time I was getting over my fright a little. I turned to Rusty, who was next me.

‘What a sell for them when they find no one at home!’ I whispered in his ear.

But Rusty only grunted, and a sharp signal for silence came from father.

The bough which had been broken before stopped the climber for a few moments, but presently he managed to swarm up the trunk and seat himself astride of the very branch upon which our former home was founded.

They shouted to him from below to be careful. The fellow in the tree paid no heed, but, clutching the trunk with one hand to steady himself, boldly thrust the other into the nest. There was a sharp exclamation of disgust; and he cried out furiously that there was nothing there.

They were all in great excitement, and kept urging him to look further and to make sure we weren’t hiding. He felt in every crevice of the nest, and peered about in the boughs, and then, having evidently made up his mind we had really gone, prepared to descend.

But the others called to him to look again, so, steadying himself once more upon the bough, he peered upward. Then he solemnly declared, shaking his head, that there was nothing in the tree. To prove it, with a sweep of his great red paw, he carelessly ripped our old home from its perch and sent it tumbling to the ground. I heard[26] mother give a little gasp as she saw destroyed in an instant the results of so many hours of careful and loving toil; but my own thoughts and eyes were so concentrated upon the invader of our rightful domain that I am afraid I hardly considered her injured feelings. Still they would not allow him to come down; and now came in a very real danger. From the ground it would have been quite impossible for them to spy us out in our new quarters, but up the tree this fellow was on a level with us, and had only to get a clear look between the boughs to spy our little red bodies, which, however much we crouched together, made a considerable ball of fur.

Climbing to his feet, he stood upright on the bough, clinging with one arm to the trunk. It was this movement which proved our undoing. Standing thus, his head was clear of the dwindling foliage near the spire-like summit of the larch, and from his lofty perch his eye commanded the tree-tops in the neighbourhood. A moment later his gaze fell upon us, five small scared balls of red fur, and his roar of triumph struck terror to our quaking hearts.

Without paying the slightest attention to the shouted questions of his friends below, he swung[27] himself down hand over hand, and in a very short time had dropped to the ground, and was running across towards our fir-tree, with the others yelping at his heels like a pack of harriers after a hare.

Mother and father exchanged a few hurried words, but what they said I in my excitement had not the faintest idea. Next moment father had me by the scruff of the neck, and darted away up into the thick and almost impenetrable top of the giant fir. Mother, with Hazel between her teeth, came after him like a flash.

The fir-trunk forked near the summit; it was to this point that father carried me, and dropped me in the niche between the two boughs. Instantly he was off again to fetch Rusty. Before our enemies had noticed what was happening, and while they were still arguing as to which of them should do the climbing, all we three youngsters had been deposited together in our lofty refuge.

A scuffling noise and the sound of heavy breathing came from below. One of the gang had begun the ascent of the tree. Mother looked at father in a sort of dumb agony. She was palpitating with fright, and her dark eyes were large and brilliant with terror.

‘Can we reach another tree, Redskin?’ she asked tremblingly.

But father knew better, and signified, ‘No.’ They two might have done it themselves, but carrying us the jump would be too long to risk.

From far below the bumping, scuffling noise slowly grew louder and nearer. It was a long way up to the first bough of the fir-tree, and the climber—it was the same one again—was obliged to swarm the scaly red trunk. We could not, of course, see anything of him, for the matted tangle of crooked branches below, with their foliage of thick, dark green needles, formed an impenetrable screen.

I cannot even now remember that long wait in the sunny tree-top, while ever from below the unseen danger crept upon us, without an unpleasant thrill, and I know that both my brother and my sister shared my feelings. The worst part of it all was the sight of the terror of our father, who had always been to us a pattern of bravery. The fact was that he realized the position, which we younger ones did not do fully. He was only too well aware that we were trapped. He and mother might have easily escaped by descending to the longer branches below, and thence jumping into a spruce which[29] grew close by; but they would not desert us, and both remained clinging tightly to the main trunk just beside us.

The hollow in which my brother and sister and I were placed gave us complete shelter from below, but there was only just room for the three of us. Father and mother were forced to expose themselves. The fir was, as I have said before, a very large tree—quite seventy feet high—old, thick, and gnarled, and the boughs were of considerable thickness near to its very summit. Father no doubt understood that our bulky enemy would, if he had the pluck, be able to pursue us right up to our lofty perch, and was aware of our almost hopeless position.

Slowly, very slowly, our persecutor came upwards. The branches, once he was among them, were so close and thick that he evidently found it difficult to force his way between them. Every now and then he would stop and puff and blow; then the creaking of large boughs and the cracking of small twigs announced a fresh effort on his part.

At last he was only separated from our second nest by a very small interval. Yet he had not discovered it was empty. The others kept yelling out questions to him, but he made no reply, only[30] forced his way through the tree, which, I am bound to say, was very thick indeed.

More scrambling. Then he caught sight of the nest and redoubled his efforts. But when he was nearly up to it he reached up his arm, and without the slightest fear that he might be bitten as his companion had been, thrust his huge hand into it. The result was a savage exclamation. Angrily he seized the empty nest, tore it out, and sent it flying down as he had done the other.

By this time the others were a little tired of waiting, and began to scatter out from the tree to try to spy us themselves. Common sense must have told them that we had only left the nest when we heard them, and could not be far, and that we could probably be seen somewhere in the surrounding boughs. A few moments’ suspense, and then the awful warning shout again told us we were discovered. The man was still in the tree, though some way below, and by pointing and gesticulations they directed him where to go to find us. So he came panting up again, the thinner branches swaying and rustling beneath his weight. After a very few moments his head appeared in the greenery below. He was of a different type from the others, taller, black-haired,[31] and sallow-faced. It did not take him many seconds to see us, and he quickly pulled himself up towards us.

With his eyes fixed on mother, he came rapidly upwards. Mother crouched where she was on a small branch, very close to the extreme summit of the tree, watching our enemy’s every movement. By a lucky chance the main stem hid us three youngsters from his sight. I think that father and mother must have purposely placed themselves on the other side from us with the express object of drawing the boy’s attention away from their helpless babies.

When he drew near he paused, and pulling a red cotton handkerchief from his pocket, deliberately wrapped it round one hand. Then, getting a good grip with the other, he edged outwards and made a sudden rapid grasp at mother. My heart almost stopped as I saw the great hand extended. But quick as he was, no human can hope to rival the lightning action of a squirrel’s muscles, and before the grasping hand touched her the little lithe red body flew into the air as though driven by a spring, and, flashing downwards, landed fully twenty feet below, and disappeared into the thickest part of the tree.

With a violent exclamation the tormentor turned his attention to father, who was only a foot or two further away, and crouching on the extreme outer end of a bough. Evidently he intended to make sure of him, for he worked himself round so as to get between father and the tree, and managed it so well that he seemed to me to have cut off all chance of escape. I think he must have actually touched father’s tail, when the most unexpected thing happened. Instead of jumping outwards, which, as the bough tip projected a good way, would in all probability have ended in a fall to the ground, into the very hands of the three watchers below, father leaped straight towards the boy, landing actually on his shoulder. This startled him so much that he very nearly let go altogether, and if I had not been in such a panic I could have laughed at his fright. Then, before the boy could recover himself, another quick bound, and father was out on another branch, ten feet away, quite out of reach of his would-be captor.

FATHER LEAPED STRAIGHT TOWARDS THE BOY LANDING ACTUALLY ON HIS SHOULDER

A torrent of language worse than any magpie’s burst from the fellow’s lips, as he turned and scrambled after father again. He might as well have tried to catch a will-o’-the-wisp. Every[33] time he got near enough to make a snatch, father would make another nimble jump, all the time artfully luring his pursuer lower down the tree and away from our hiding-place.

The game went on for a good ten minutes, and by the end of that time the enemy was dripping with perspiration and speechless with fury. His rage was increased by the jeers of his friends below. At last he gave it up, having made up his mind it was not much of a game to be made a fool of by a squirrel and mocked by the onlookers.

He dropped quickly from bough to bough, and presently I heard his heavy boots thud on the ground. But before he had reached the foot of the tree, both our parents were back with us. Then the sound of loud wrangling came up to us. Surely now they would go; but no! we were not safe yet.

There was further talk, and then the whole four spread out in a circle round the fir-tree. Presently, with a loud whizzing sound, some heavy object came hurtling up past us. It struck a twig near the summit of the tree and clipped it like a bullet. Thud! Another struck the main stem just below us with a force that sent the bark[34] flying in a shower. Then we saw what those lead-weighted canes were for.

A third squailer passed only a few inches above father’s head. He called to mother:

‘They’ll kill us if we stop here. Come along; take Hazel and follow me.’

In an instant he had snatched me up and was scuttling down the trunk. It was wonderful how exactly he knew which branch-end stretched furthest towards the spruce which was our next neighbour. Out along it he ran, and using the natural spring of the bough to help him, made a gallant leap outwards and downwards, legs and tail wide spread to assist him in his flight.

The air hissed past my ears, and then with a little thud we landed safely in the spruce. But his gallant jump had been seen by those greedy eyes, and excited shouts came from below.

Then—ah, even now I can hardly bear to speak of it! As father was in the very act of running up the branch towards the thick centre of the tree and comparative safety, there came a cruel thud, and he and I together were whirling through the air.

Crash! we came to the ground with a shock that knocked my small senses out of me, and before[35] I could pick myself up a hard hand had closed over me. I turned and, with the instinct of despair, fixed my teeth deep in a horny finger. There was a yell, and I was again flung to the ground with a force that almost killed me. I knew no more for many minutes, and when I woke again to stunned and aching misery, I was lying helpless in a sort of bag, which smelt horribly of something which I now know to have been tobacco. The bag was being shaken up and down with a steady swing; but I, almost beside myself with pain and flight, did not attempt to move or free myself.

Suddenly the motion stopped abruptly, and the hand was poked cautiously into the bag. It was carefully protected this time by a handkerchief, but I had no longer spirit left to bite. Out I was pulled and held up before the gaze of all the four robbers, who were seated at ease on a mossy bank on the outer side of the hedge close by the gate of our coppice. The very first thing that my eyes fell upon was the body of my poor father lying limp upon the bank, his white waistcoat dabbled with crimson stains and his brilliant black eyes closed in death. I felt a cold shiver run through me, and the stupor of despair clutched my beating heart. I hardly even had strength left to wonder what[36] had become of my dear mother and my brother and sister.

They passed me from one coarse hot hand to another, and their voices grew louder and louder as they disputed who should have possession of me.

They then went on to blows, when suddenly the quarrel was brought to an abrupt end in a most startling fashion.

Leaping over the hedge out of the coppice behind came two tall, smart-looking boys, a startling contrast to the four loutish hobbledehoys around poor little me.

One of them, pointing at me, demanded in a ringing voice where they had got me from.

Three of the four cads stood sheepishly regarding the new-comers, and said never a word; but the one who had climbed the tree faced them boldly enough, answering impudently.

The new-comer strode up to him. He was evidently master here, and the others were trespassing, and they knew it, for they slunk back. Yet, in reply to his reiterated commands, the lout who was boldest snatched me up and refused to part with me. He was so big and strong that he seemed a giant, and I felt I should die there and then. I closed my eyes and gave myself up,[37] but in a minute I was down on the bank once more, and the two—the new-comer and the great rough fellow—were fighting hard, with coats off and red faces.

The sound of the blows that followed, the tramping of feet, the hard breathing of the combatants, nearly deprived me of the few senses that remained to me, and I noticed little of the details of the fight—only it seemed to last a long time, and once I saw the schoolboy flat on his back. But he was up almost as soon as down, and they were at it again hammer and tongs.

The giant made a rush head down, like a bull, but the other jumped back, and there followed a rattle of blows as my champion’s fists got home on the lout’s hard head. But the squire’s son did not wholly escape. The huge fist that had grasped me so roughly caught him on the right cheek and drove him back.

One of my champion’s eyes was closing, his right cheek was turning livid, and there was blood on his broad white collar when they faced one another again. But the ruffian for his part, though not so badly marked, was breathing like a fat pug dog and seemed unsteady on his legs. To do the fellow justice, he had pluck, for he wasted no time[38] in making a last attempt to rush his opponent. For a few moments it was all that the other could do to guard his head against the swinging fists. Then—it was all so quick that one could hardly see what happened—there was a crack like the sound two rams make when they charge one another, and the giant tottered for a moment, his arms waving wildly, then fell like a log and lay quite still.

The other new-comer counted loud and slowly ‘One—two—three—four’—up to ten. But the fellow on the ground did not move.

‘That’s the finish,’ he said.

He turned to where I lay, with hardly a breath in me, a little limp body, and picking me up, handled me tenderly.

Terrified as I was, the change was grateful to my miserable, aching little body. He offered me to the victor in the fight, who had by this time got into his coat again, but he declined.

‘Put him in your pocket, Harry,’ he said to his brother. ‘My hands are too hot to hold him.’

He was quite right. Let me here give a word of advice to all those humans who keep any of my race as pets. Don’t hold us in your hands. In the first place, it frightens us desperately, and in the[39] second, it is bad for us. A squirrel rarely lives long in captivity if he is constantly handled. I speak from experience, and I can assure you that, much as I grew to love my dear master and my other human friends, I was never happy in their hands, though I never minded being kept in their pockets.

Harry put me carefully in the inside pocket of his jacket. It was dark and warm, and, utterly exhausted, I curled up and lay quiet, and so I was carried away and left the home of my babyhood. It was long before I saw it again.

I was aroused from a sort of stupor between sleep and exhaustion by being picked out of my snug retreat and held up for inspection before a third person, a sweet-faced lady, whom I afterwards came to know well and love as the mother of my dear master, Jack Fortescue, and his brother Harry.

She looked at me pitifully when her son had quickly explained the events of the morning. Her fingers were long and slim and cool, and, poor limp little rag that I was, I never offered the slightest resistance to her gentle grasp. She took me straight through a side door into a long, low, shady building with wood-lined walls, and in a minute or two I was placed in a nest of soft hay in a good-sized box covered in front with close wire-netting. Too worn out to trouble my head about the amazing and perplexing change in my circumstances, I simply curled up with my tail over my nose and went sound asleep.

It was Jack who woke me. I must have been asleep for a long time, for now the sun was pouring in through the western windows. The first thing I realized was that I was desperately hungry, and that the little saucer which the boy had pushed gently into the cage had a most appetizing odour. But my sleep had given me fresh life and strength, and quiet as his movements were, I remember that I was desperately frightened, and cowered down, shivering, burrowing close in the hay.

Jack seemed to understand perfectly, for he closed the door again very softly and moved away. Presently the silence restored my confidence a little, and I ventured to peep out. The saucer was quite close to my nose, and, hunger overpowering my fright, I crawled up and tasted the mixture. It was bread and milk, soft and well cooked. I finished it very rapidly, and then, feeling much refreshed, went to sleep for a second time.

Once again before dark Jack came and fed me, and this time brought me a couple of ready cracked nuts, as well as the bread and milk.

Well fed and cared for as I was, I shall never forget the misery of that first night. I don’t suppose that at that very early age I actually remembered much of what had happened during[42] the past eventful day. What I did feel was a sort of horror of loneliness. Instead of the whole five of us snuggling warmly together in our well-lined drey, I was here in this box, which was many times larger than our nest, absolutely alone. Every time I went to sleep I would wake up again with a start, vaguely feeling round for my mother and the rest, and shivering miserably in my unaccustomed solitude.

At last morning came, and it was hardly broad daylight before Jack arrived in his nightshirt and carried me off, cage and all, to his bedroom, where he put me on the window-ledge in the sun and offered me nuts. At first I was much alarmed; but he was so gentle that I gradually got over my terror, and sat up and nibbled the nuts fairly happily.

I will pass over the next few days. My new master fed me assiduously, and very soon I lost all fear of him, and the minute I saw him would make for the door of my comfortable little prison, and wait eagerly for the dainties which were sure to be forthcoming. Every morning he changed my bed and gave me fresh hay, which makes far the best bedding for any of our tribe. During the day my cage was brought down into the bowling-alley,[43] where several other pets were kept, and at night Jack took me up to his room, so that I might not be frightened by servants dusting in the morning.

At last there came a morning when Jack’s hand, instead of offering me the usual nut, gently grasped me. Frightened, I turned at once and bit him sharply. I don’t suppose my small teeth did much damage, for he only laughed, and, lifting me right out of the cage, placed me on his bed. The white counterpane was so very different from anything which I had ever felt under my claws before, that at first I was too much surprised to move, and remained perfectly still. Presently, however, Jack popped a nut down in front of me. That, at any rate, I understood, so I sat up on my hind-quarters, cracked it, and, first carefully removing the brown skin from the kernel, made short work of the dainty.

Hoping for more, I gained confidence and proceeded to explore. First I caught my claws in the little projecting tufts of the counterpane, and heard Jack laughing gently as I shook myself impatiently free, giving a little squeak of disgust. Presently I discovered a cavity that looked dark and inviting. You know a squirrel’s besetting sin is curiosity. He always wants to know the ins and outs of[44] everything. Any object which he has not seen before fascinates him, and I am afraid to say how many of my friends have paid for their inquisitiveness by getting into serious trouble. So I crawled down, and finding it delightfully warm and dark, made my way under the clothes to the very foot of the bed, where, as I was very comfortable, I went sound asleep.

On the next morning my master turned me loose again, this time on the floor, and after a fresh access of timidity I again found nuts. There were more than I wanted, so, obeying a natural instinct, I ate what I could, and hid the rest in various convenient receptacles.

Soon I began to look forward to my daily outing, and took great delight in exploring every corner of the room. I well recollect what a shock I got the first time I reached the window-sill. Outside was a great elm-tree, whose branches reached within a few yards of the window, and the sight of the green leaves waving gently in the early morning breeze roused in me strange longings. I made one jump, and striking full against the glass, fell back half stunned and terrified almost out of my wits at the strange transparent barrier. Jack picked me up at once, and placed me safe in the[45] darkness and warmth under the bedclothes, where I had time to recover from my fright.

Soon he took to letting me out at bedtime, and I had a grand scamper before the light was put out. The window-curtains were my favourite resort. They were so easy to climb, and had such splendid folds and crannies for hiding nuts in. I would race across the curtain-pole, rattling the rings as I went, down the other curtain, round the room full tilt, and finish up with a good hunt in all the corners for nuts which I had concealed the day before and forgotten all about. I rarely went back to my cage to sleep, though it was always open and ready for me. A fold in the window-curtain was my usual place of repose, and another pet perch was an old band-box on the top of the wardrobe. It was half full of tissue paper, which possessed a strange fascination for my young mind. I tore it all up fine with my sharp teeth, and made a most delicious nest with the bits.

When the night was chilly I generally snuggled under Jack’s bedclothes, and always, first thing in the morning, so soon as daylight came, I would make for the bed, and working my way gently down between the sheets, curl up close against Jack’s toes. Sometimes he was so sleepy that he[46] would not wake up and play when I wanted him to; then I would emerge on to the pillow and gently nibble the tip of his nose.

This never failed. ‘Confound you, Nipper!’ (he always called me Nipper), he would mutter drowsily, and then make a lazy grab, which I always eluded with the greatest ease, and with two bounds would land on the end of the bedstead, and, perched there, scold him until he sat up and threw a sock at me.

He was never rough, and never lost his temper with me, although I am sure that I was aggravating enough at times. It must have been trying when he pulled on his boots in a hurry and found a couple of nuts wedged tight in each toe. I do not think that a boy and a squirrel ever became better chums. We were simply devoted to one another. The only dull times for me were when Jack and Harry were busy with their tutor, during which hours I was usually in my box in the bowling-alley.

There, as I think I mentioned before, the Fortescue boys kept several other pets. There was a large white cockatoo with a lemon crest, named Joey, which frightened and puzzled me horribly until I came to understand its odd faculty[47] of imitating every person and animal about the place. It would ‘miaouw’ like a cat, a most disturbing sound, for every squirrel hates cats next to hawks and weasels; would bark so realistically that Mrs. Fortescue’s white Pomeranian was always stirred up to reply, and the two would go on and on, the wily old bird always starting up afresh whenever the dog stopped, until poor Pom nearly had a fit and grew quite hoarse. I shall never forget the first time he imitated me to my face. It gave me a most severe shock, for he did it so well that for a moment I believed that one of my relations was actually in the room. One thing I liked him for: he was devoted to Jack, and invariably bade him a grave ‘good morning’ when he brought my cage down before breakfast. He lived on a perch, to which he was chained by one leg, and up and down this he would sidle by the hour, with one eye cocked for mischief. Sometimes, when all was quiet, he would talk to himself in a language quite unlike that which my master and his family used. The boys said it was some African lingo which Joey had learnt ages ago in his native land. Altogether a most uncanny bird!

Harry had a number of pet mice in wire cages.[48] They were not the least atom like any of the mice I had ever seen in the wood. These were of the queerest colours—piebald—and some of them had marks on their backs just the shape of a saddle. Uninteresting I called them, but Harry was very fond of them, and used to take them out and let them run all over him.

In the darkest corner of the long, low room was the one creature that, from the first moment I saw it, interested me more than all the others put together. All day long it lay hidden in its hay bed and never moved, but slept quietly as a dormouse in its winter nest. In fact, I never set eyes on it at all until one night in August, when the evenings had begun to draw in and I happened to be left a little later than usual in the bowling-alley. No sooner had the room become dusk than I heard from the tiny cage a little twittering, more like a young bird’s voice than anything else, and presently caught sight of a dainty little head poked out of the hay, with two of the largest, most liquid black eyes I ever saw. I gazed in wonder, for the animal was so like myself that I felt sure it was a squirrel, though I had never dreamed that any squirrel existed so tiny as this.

Just then in came the two boys together.

HE IMITATED ME TO MY FACE

‘Hulloa!’ cried Harry, ‘Lops is awake. Bring Nipper to have a look at him, Jack.’

Jack took me out of my cage, and I jumped as usual on to his shoulder and nibbled his ear by way of a kiss. He walked across to the other cage and set me down in front of it.

‘Mr. Lops,’ he said with mock gravity, ‘allow me to introduce Mr. Nipper. This is a small cousin of yours, Nipper, and he comes from Mexico. As you see yourself, he’s a sad character—sleeps all day and only wakes up at night.’

I was so lost in surprise that I sat quite still, gazing through the fine wire mesh at my new acquaintance. I have always had a fairly good opinion of my own looks, as every well-bred squirrel should have, but, upon my word, he put me out of all conceit with myself. He was the tiniest, daintiest, quaintest creature I ever set eyes on. No bright red about him, but though his coat was darker and greyer than mine, it was as soft as fine velvet, and beautifully groomed. His head was perfectly shaped, his ears pricked like my own, and his eyes very large and amazingly bright. But the oddest thing about him were the folds of loose skin which extended in a thin membrane from all his four legs back to his body. When he jumped from[50] the upper, story of his cage to the lower, they spread out almost like the wings of a bat; but when he was sitting still, they folded up so that they did not in the least spoil his beautiful shape. I must say that I felt quite envious, for I thoroughly understood that a squirrel built like that could jump ever so much further than I or any of my family could. We English squirrels can, at a pinch, clear as much as three yards in a straight line. We always spread our legs wide when we jump as well as keeping our tails stretched straight out, and that is why we can leap from great heights and reach the ground unhurt, for we drop parachute fashion. But as for these American cousins of ours, the flying squirrels, they can jump from the top of one tree, and sliding through the air like a soaring hawk, reach another tree fifty feet or more away at a height from the ground only slightly less than that of their starting-point.

Lops—which Jack said was short for Nyctalops, or ‘seer by night’—and I had many a chat afterwards. He told me of his old home in sunny Mexico, not a nest such as I was born in, but a cavity in the trunk of a vast live oak or ilex, from whose boughs long weepers of grey Spanish moss trailed towards the brown palmetto-stained water[51] below; of the hot sun and of the furious tropical storms which lashed the deep river into white foam; of the paroquets, with their brilliant plumage of green and red and blue, which screamed harshly among the upper branches at dawn; of the rusty-hued water-vipers which coiled sluggishly on the steaming mud in summer. He told, too, of the perils from great hawks three times as large as any we know in England, from long, thin tree-snakes wrapped unseen round the branches; and I shuddered when he talked of fierce wild-cats as much at home among the tree-tops as on the ground. It must have been a wonderful country and a wonderful life, so different from our northern island as to be almost beyond my imagination to picture it. All day the land slept breathless beneath the blazing sun, with nothing moving except the birds, the fox-squirrels, and the lizards; and during those hours Lops and his family slept in the dark recesses of their wood-walled fortress; but when the sun set the forest woke to life. Deer came down to the river to drink; peccaries rooted in droves among the bases of the mighty trees; sometimes a great bear came prowling along, uttering now and then a deep ‘woof’ when any unaccustomed sound disturbed him. Up above opossums and[52] racoons moved silently to and fro among the tree-tops; great owls whirled on soft wings, hooting dismally; while all night long—especially in the hot season—the endless chirr of crickets, the pipe of tree-frogs and the deep booming of bull-frogs filled the air with a never-ending concert. Other sounds there were, rarer, but far more terrifying. Enormous bull-alligators, floating like logs with only their gnarled heads and the ridges of their rugged backs above the water, would bellow with a roar that shook the forest; or, again, from some hidden recess of the deepest woods the blood-curdling shriek of the tawny puma would ring hideously through the night.

Poor Lops! Though cared for as few pets are—fed with dainty pecan-nuts and other delicacies from his far-off home across the ocean, and though he loved his mistress Mabel, Jack’s sister, devotedly—yet he was never happy as I was. The damp and cold of our climate oppressed him, and most of his time he spent curled up tightly among the soft bedding of his cage. Then, too, he was a creature of the night, and it was only after dark that he would wake and want to play—and at that time, except for an hour or two, there was no one to play with. I felt very sorry for him, and so, too, were[53] Mabel and the boys. I am sure that if they could they would have set him free again among the great tropical forests that he loved so well, and always mourned for, though only I knew how deeply.

As for me, life ran most pleasantly. I grew plump on the good food I was supplied with. My coat became long and sleek, and my tail, which had been a mere furry appendage like that of a little colt, grew into a glorious brush of richest red-brown, long enough and thick enough to cover me completely when I curled up to sleep. Jack was very proud of my looks, and used to groom me all over with a little brush—a process which I soon grew very fond of. We two came to understand one another most marvellously. I could always tell him what I wanted, whether it was food, or a game, or to be allowed to creep into his coat-pocket and go to sleep there.

One day he opened my cage, slipped me into his pocket, and walked off, and when he took me out again I was out of doors once more!

I cannot tell you how it affected me. You know, we wild creatures—born wild, I mean—never quite forget our rightful heritage of freedom, and here, for the first time for many weeks, I found myself out in the open.

Jack was seated on a wooden bench under a clump of evergreen shrubs in the midst of a great expanse of smooth-shaven lawn. It was August now, and the sun poured down hotter than ever it had been in those June days in the wood. Big bumble-bees droned lazily by; a robin was perched on the bare ground at the foot of an arbor vitæ, cocking a soft round eye at us; all the subtle, fascinating odours of summer were in my nostrils. I gave one spring from his knee on to the back of the bench, and sat there, head high, snuffing the sweet air, and quivering all over with excitement. Jack never moved, and for the moment he passed completely out of my remembrance. My brain was crammed to bursting with half-forgotten instincts and remembrances which crowded in upon me.

So I sat for perhaps half a minute; then a little breath of summer breeze swayed a bough above me, and on the impulse I sprang. Oh, the delight of feeling it yield and swing beneath me! I darted inwards to the trunk, and with one clattering dash was up at its slender summit twenty feet above the turf gazing round in wild delight. When the first ecstasy had worn off, I set myself to explore, and, clambering down a little, jumped into the next[55] tree. So for many minutes I exercised my new-found powers, taking longer and longer leaps, and enjoying myself to the top of my bent.

But the clump of shrubs was small, and soon I had exhausted its resources in the way of jumps. I looked around, and a little way off was a giant elm. Ah! that would give more scope; and with my head full of its possibilities, I turned and came down head foremost. Then, and not till then, did my eyes fall upon my master, who sat where I had left him, still as ever. He looked at me, but I would not heed, and dashed off across the lawn.

‘Hulloa, Jack! what price Nipper?’ came Harry’s voice from a distance. ‘You’ll never see him again.’

But the other only said, ‘You wait!’ and still sat stubbornly in his place.

With a rattle of claws on rough bark I was up the elm like a flash, and, half crazy with joy, went leaping and corkscrewing round and round, sending a couple of tree-creepers off in a terrible fright. I think they must have taken me for a cat. I played for a long time, and still Jack sat on the bench. He seemed to be deep in a book, and after a time I got quite cross at his apparent lack of interest in my proceedings. It was getting late,[56] and the trees threw long, dark shadows across the lawn. The breeze had died down, and, except for the chirping of sparrows in the ivy and the low whistle of some starlings in the distance, all was very still. A sense of loneliness began to oppress me, and at last I came creeping down, and, reaching the lower branch, once more looked across towards my master.

‘Nipper!’ he called softly; and in a trice I was on the ground and lopping across towards him.

Suddenly, and without the slightest warning, there was a sharp ‘yap-yap,’ and a dirty white-and-tan beast rushed out of the shrubbery behind me. On the instant I was running for dear life.

I saw Jack bound to his feet and come tearing across towards me. But instead of running straight to him, I made for the nearest tree—a small ornamental evergreen. The dog—it was the gardener’s terrier—wheeled, and was after me like a shot. He was travelling nearly twice as fast as I, and his feet were drumming so close behind me that it seemed nothing could save me. Each instant I expected to feel those snapping teeth close upon me.

There was a sudden crash, and the sharp ‘yap-yap,’ changed to a terrified howl. Jack had hurled his[57] book with all his might and with such good aim that the dog, hit full in the side, had been bowled completely over, giving me time to gain the shrub and safety.

‘Poor old Nipper!’ said Jack softly, as he picked me shivering out of the little tree and stowed me safely inside the breast of his coat. ‘We won’t run any more risks of that sort, will we, old chap?’

Indeed, the fright was so severe that I did not get over it for some time. It gave me a good lesson, and the next time my master let me out I did not venture far from him.

Soon after this I had another adventure which came very near to closing my career abruptly. One dull rainy morning I was loose as usual in Jack’s bedroom. Just as he had almost finished dressing, his brother, whose room was on the same floor, opened the door and called to my master to come and help him to find one of his mice which had got loose and disappeared. Jack ran out, carefully closing the door behind him, and leaving me to play by myself. A few minutes afterwards one of the maids, thinking no doubt that Jack had finished dressing and had gone down to his early morning lesson with his tutor, came in to turn the bed down and tidy up. She never saw me, and I[58] paid no attention to her, for I was busy under the dressing-table with some nuts.

It was some minutes after she had gone away that I became conscious of an animal moving softly about the room, and a spasm of terror seized me, for though I could not see it owing to the hangings of the dressing-table, instinct—that sixth sense which informs us of danger—gave me warning of desperate peril.

Crouching back as near to the wall as possible, I lay there absolutely still, listening with beating heart to the almost noiseless footsteps which came gradually nearer and nearer. I could tell by the soft snuffing that the animal scented me, and terror almost paralysed me. Closer and even closer came the creature, and presently the hangings of the table rustled, and as they were pushed aside a whiskered head appeared, and two eyes that glowed luminous green in the dim light glared upon me. Stiffened in my corner I watched the cat crouch for a spring, her gleaming eyes fixed greedily upon me, while her tail waving quickly from side to side, made a soft tattoo on the carpet. Those cruel green eyes absolutely fascinated me, and for the moment I could not have moved even to save my life.

Suddenly came a loud crash. The door left open by the maid had blown to in the strong draught from the open window. The noise startled the cat almost as much as it did me, and for the moment she took her eyes off me. The spell was broken and I ran for dear life. As I passed under the hangings and out into the open I heard her heavier, larger body strike the very spot where I been crouching, and with another spring she came out from under the table and landed barely her own length behind me. One wild bound to the right and I was inside the fender; another, and my enemy’s outstretched paw actually grazed my tail as I bolted clean up the chimney, and a snarl of disappointed rage gave me the glad tidings that I was for the moment safe.

It was lucky, indeed, for me that the chimneys of the Hall were of the wide, old-fashioned brick type unprovided with dampers. Had it not been so, and had my refuge been the modern, narrow, perpendicular form of grate, it is certain that I should never have been alive now. As it was, the worn, old brickwork gave me footing of a kind, and I never stopped until I had reached the chimney-pot, which barred further progress. The soot nearly choked me, and made me cough and[60] sneeze violently. My foothold was most precarious and I was in deadly terror that I might slip and go tumbling right back into the jaws of my enemy. Indeed, I have rarely spent a worse quarter of an hour than I did then.

Suddenly I heard the door below open. Sounds came to me almost as clearly as if I had been in the room.

‘Nipper! Nipper!’ I heard Jack call, but I was too frightened to come down.

‘Why, where on earth has he got to?’ my master continued in a surprised tone, and then I heard him moving about the room looking for me.

The cat, no doubt, had taken refuge under the dressing-table again when she heard the door open, for she knew as well as possible that she had no right in the bedrooms, her proper place being the kitchen. There was a rustle as Jack raised the hangings, and then he saw her.

For the moment there is no doubt but that he thought she had killed and eaten me, and grief and fury possessed him. I heard a smothered squawk of terror, and even in my plight rejoiced that my enemy was feeling a little of the fright she had given me. Then there was a crash. Jack had flung the beast clean out of the window into the[61] elm opposite. I heard him go to the door again, and there was something in his voice as he shouted to his brother to come that made me shiver all over, but not with fright.

Harry came rushing into the room, and I am bound to say his voice was almost as queer as that of my master.

I was recovering slowly from my terror, and the sound of Jack’s voice was giving me confidence. Also my present refuge was horribly uncomfortable, and the black soot making me feel perfectly miserable, so I turned with the intention of making my way downwards again. You know we squirrels always descend head foremost, holding on with our hind-claws. But I had hardly begun my descent when a bit of hardened soot or plaster gave way beneath me. I made a desperate but quite useless effort to recover myself, and next thing I was sliding helplessly down the steep slope at a pace which increased with every foot I fell.

Thud! And I landed in the grate amid a perfect avalanche of soot. Jack, who was sitting on the bed looking more miserable than I had ever seen him before, sprang to his feet as if electrified, and cleared the intervening space with a bound.

‘Nipper, Nipper, is it you?’ he shouted, and[62] regardless of his smart, clean flannel suit picked me up and positively hugged me in a transport of delight. Then he examined me all over to make sure that I was not hurt, and after that I was only too glad to be allowed to crawl into his pocket and feel that there, at any rate, I was safe.

The worst of it came after breakfast, for I was too filthy to be able to clean myself. Such a miserable, draggled little object I was, black as any sweep! My master got a basin of warm water and washed me all over—a process which I remember I strongly objected to, and resented by nipping his fingers sharply. But he was firm, and presently I was back again in my cage, which was placed before the kitchen fire, and Jack himself kept watch over me until, once more dry and clean, I was fit to return to the bowling-alley.

It was about this time that an unaccustomed quiet seemed to be settling upon the Hall and the demesne. There were less people about, no visitors, and some familiar faces among the servants were missed. I had never seen much of the Squire himself, but in these days he seldom came into the bowling-alley at all, as he had been used to do in the earlier days of my captivity. Even the boys seemed to have grown quieter. They laughed less often, and frequently I saw them talking to one another with grave faces.

At times I had an uneasy conviction of something wrong, but it was only a passing impression, for I, at least, never suffered in any way. Every fine day Jack took me out of doors, and I had a scamper in the clump of shrubs to which, ever since my narrow escape from the terrier, I was careful to confine myself. And as for food, no squirrel could have fared better. My master[64] was always bringing me fresh delicacies. One day it would be a cob of Indian corn, which grew to perfection under the south wall of the kitchen garden, and which I enjoyed vastly, ripping off the thick green husks and pulling the kernels out one by one. Another morning he would pick me a fine summer apple, its sunny side delicately tinged with streaky red, while he was always discovering new nuts for my delectation. Once, I remember, I made myself quite ill with the rich greasy kernel of a huge Brazil-nut. A very pet delicacy of mine in which I was often indulged was a piece of hard ship’s biscuit. There were few other eatables which I enjoyed so much. Now and then I was given a morsel of banana, and perhaps my greatest treat of all was a few of the black, oily seeds of the sunflower.

So things went on until the time that the blackberries began to ripen. Then, one warm sunny morning Jack got up very early and dressed quickly. I wanted to play as usual, but he seemed to have no time, and I was quite hurt at his apparent neglect. As he took me in my cage to the bowling-alley the Squire was in the hall. I had never seen him there so early. He looked old, and worn, and there were new lines in his[65] face, while his hair and beard seemed greyer than I had thought them.

‘Be quick and have your breakfast, Jack,’ I heard him say. ‘Your train goes at nine, remember.’

‘All right, dad,’ returned the boy. ‘Take care of Nipper while I’m gone.’

Then, when he had put me in my place in the bowling-alley just opposite old Joey’s perch, he did a very unusual thing—took me out again and stroked me. Then he put me back very gently and hurried away.

The morning passed; but when afternoon came and I looked for my master, as usual, there was no sign of him. I scratched vehemently at my cage-door, but no one came. Only old Joey made rude remarks and began to mimic me, so at last I retired in a very bad temper, and curling up in my hay began to wonder whether Jack had forgotten me. You see we had never been separated for a single day, and I could not in the least understand his absence.

At last some one came in, and I jumped out eagerly. But, to my great disappointment, it was Harry, not Jack, who came up and opened the door of my cage. ‘Poor old Nipper!’ he said,[66] and held out his hand, inviting me to come with him.

I came eagerly enough, for I had the idea that he would take me to my master. The two brothers were so nearly inseparable that I could not imagine one being long away from the other. He did not, however, carry me out of doors, but up to his own room, where he turned me loose and offered me biscuit. But I am afraid he found me a dull companion, for I was listening the whole time for Jack’s familiar footstep, and did not pay much attention to his friendly overtures. At last he took me back to the bowling-alley and shut me up again, and there I moped sulkily for the rest of the day.