BESSY’S REFLECTIONS.

APRIL, 1860.

| PAGE | |

| Lovel the Widower. (With an Illustration.) | 385 |

| Chapter IV.—A Black Sheep. | |

| Colour Blindness | 403 |

| Spring. By Thomas Hood | 411 |

| Inside Canton | 412 |

| William Hogarth: Painter, Engraver, and Philosopher. Essays on the Man, the Work, and the Time | 417 |

| III.—A long Ladder, and Hard to Climb. | |

| Studies in Animal Life | 438 |

| Chapter IV.—An extinct animal recognized by its tooth: how came this to be possible?—The task of classification—Artificial and natural methods—Linnæus, and his baptism of the animal kingdom: his scheme of classification—What is there underlying all true classification?—The chief groups—What is a species?—Re-statement of the question respecting the fixity or variability of species—The two hypotheses—Illustration drawn from the Romance languages—Caution to disputants. | |

| Strangers Yet! By R. Monckton Milnes | 448 |

| Framley Parsonage. (With an Illustration.) | 449 |

| Chapter X.—Lucy Robarts. | |

| ” XI.—Griselda Grantly. | |

| ” XII.—The Little Bill. | |

| Ideal Houses | 475 |

| Dante | 483 |

| The Last Sketch—Emma (a fragment of a Story by the late Charlotte Brontë) | 485 |

| Under Chloroform | 499 |

| The How and Why of Long Shots and Straight Shots | 505 |

LONDON:

SMITH, ELDER AND CO., 65, CORNHILL.

LEIPZIG: D. TAUCHNITZ. NEW YORK: WILLMER AND ROGERS.

MELBOURNE: G. ROBERTSON.

⁂ Communications for the Editor should be addressed to the care of Messrs. Smith, Elder and Co., 65, Cornhill, and not to the Editor’s private residence. The Editor cannot be responsible for the return of rejected contributions.

APRIL, 1860.

The being for whom my friend Dick Bedford seemed to have a special contempt and aversion, was Mr. Bulkeley, the tall footman in attendance upon Lovel’s dear mother-in-law. One of the causes of Bedford’s wrath, the worthy fellow explained to me. In the servants’ hall, Bulkeley was in the habit of speaking in disrespectful and satirical terms of his mistress, enlarging upon her many foibles, and describing her pecuniary difficulties to the many habitués of that second social circle at Shrublands. The hold which Mr. Bulkeley had over his lady lay in a long unsettled account of[386] wages, which her ladyship was quite disinclined to discharge. And, in spite of this insolvency, the footman must have found his profit in the place, for he continued to hold it from year to year, and to fatten on his earnings such as they were. My lady’s dignity did not allow her to travel without this huge personage in her train; and a great comfort it must have been to her, to reflect that in all the country houses which she visited (and she would go wherever she could force an invitation), her attendant freely explained himself regarding her peculiarities, and made his brother servants aware of his mistress’s embarrassed condition. And yet the woman, whom I suppose no soul alive respected (unless, haply, she herself had a hankering delusion that she was a respectable woman), thought that her position in life forbade her to move abroad without a maid, and this hulking incumbrance in plush; and never was seen anywhere in watering-place, country-house, hotel, unless she was so attended.

Between Bedford and Bulkeley, then, there was feud and mutual hatred. Bedford chafed the big man by constant sneers and sarcasms, which penetrated the other’s dull hide, and caused him frequently to assert that he would punch Dick’s ugly head off. The housekeeper had frequently to interpose, and fling her matronly arms between these men of war; and perhaps Bedford was forced to be still at times, for Bulkeley was nine inches taller than himself, and was perpetually bragging of his skill and feats as a bruiser. This sultan may also have wished to fling his pocket-handkerchief to Miss Mary Pinhorn, who, though she loved Bedford’s wit and cleverness, might also be not insensible to the magnificent chest, calves, whiskers, of Mr. Bulkeley. On this delicate subject, however, I can’t speak. The men hated each other. You have, no doubt, remarked in your experience of life, that when men do hate each other, about a woman, or some other cause, the real reason is never assigned. You say, “The conduct of such and such a man to his grandmother—his behaviour in selling that horse to Benson—his manner of brushing his hair down the middle”—or what you will, “makes him so offensive to me that I can’t endure him.” His verses, therefore, are mediocre; his speeches in parliament are utter failures; his practice at the bar is dwindling every year; his powers (always small) are utterly leaving him, and he is repeating his confounded jokes until they quite nauseate. Why, only about myself, and within these three days, I read a nice little article—written in sorrow, you know, not in anger—by our eminent confrère Wiggins,[1] deploring the decay of, &c. &c. And Wiggins’s little article which was not found suitable for a certain Magazine?—Allons donc! The drunkard says the pickled salmon gave him the headache; the man who hates us gives a reason, but not the reason. Bedford was angry with Bulkeley for abusing his mistress at the servants’ table? Yes. But for what else besides? I don’t care—nor possibly does your worship, the exalted reader, for these low vulgar kitchen quarrels.

Out of that ground-floor room, then, I would not move in spite of the utmost efforts of my Lady Baker’s broad shoulder to push me out; and with many grins that evening, Bedford complimented me on my gallantry in routing the enemy at luncheon. I think he may possibly have told his master, for Lovel looked very much alarmed and uneasy when we greeted each other on his return from the city, but became more composed when Lady Baker appeared at the second dinner-bell, without a trace on her fine countenance of that storm which had caused all her waves to heave with such commotion at noon. How finely some people, by the way, can hang up quarrels—or pop them into a drawer, as they do their work, when dinner is announced, and take them out again at a convenient season! Baker was mild, gentle, a thought sad and sentimental—tenderly interested about her dear son and daughter, in Ireland, whom she must go and see—quite easy in hand, in a word, and to the immense relief of all of us. She kissed Lovel on retiring, and prayed blessings on her Frederick. She pointed to the picture: nothing could be more melancholy or more gracious.

“She go!” says Mr. Bedford to me at night—“not she. She knows when she’s well off; was obliged to turn out of Bakerstown before she came here: that brute Bulkeley told me so. She’s always quarrelling with her son and his wife. Angels don’t grow everywhere as they do at Putney, Mr. B.! You gave it her well to-day at lunch, you did though!” During my stay at Shrublands, Mr. Bedford paid me a regular evening visit in my room, set the carte du pays before me, and in his curt way acquainted me with the characters of the inmates of the house, and the incidents occurring therein.

Captain Clarence Baker did not come to Shrublands on the day when his anxious mother wished to clear out my nest (and expel the amiable bird in it) for her son’s benefit. I believe an important fight, which was to come off in the Essex Marshes, and which was postponed in consequence of the interposition of the county magistrates, was the occasion, or at any rate, the pretext of the captain’s delay. “He likes seeing fights better than going to ’em, the captain does,” my major-domo remarked. “His regiment was ordered to India, and he sold out: climate don’t agree with his precious health. The captain ain’t been here ever so long, not since poor Mrs. L.’s time, before Miss P. came here: Captain Clarence and his sister had a tremendous quarrel together. He was up to all sorts of pranks, the captain was. Not a good lot, by any means, I should say, Mr. Batchelor.” And here Bedford begins to laugh. “Did you ever read, sir, a farce called Raising the Wind? There’s plenty of Jeremy Diddlers now, Captain Jeremy Diddlers and Lady Jeremy Diddlers too. Have you such a thing as half-a-crown about you? If you have, don’t invest it in some folks’ pockets—that’s all. Beg your pardon, sir, if I am bothering you with talking!”

As long as I was at Shrublands, and ready to partake of breakfast with my kind host and his children and their governess, Lady Baker had her[388] own breakfast taken to her room. But when there were no visitors in the house, she would come groaning out of her bedroom to be present at the morning meal; and not uncommonly would give the little company anecdotes of the departed saint, under whose invocation, as it were, we were assembled, and whose simpering effigy looked down upon us, over her harp, and from the wall. The eyes of the portrait followed you about, as portraits’ eyes so painted will; and those glances, as it seemed to me, still domineered over Lovel, and made him quail as they had done in life. Yonder, in the corner, was Cecilia’s harp, with its leathern cover. I likened the skin to that drum which the dying Zisca ordered should be made out of his hide, to be beaten before the hosts of his people and inspire terror. Vous conçevez, I did not say to Lovel at breakfast, as I sat before the ghostly musical instrument, “My dear fellow, that skin of Cordovan leather belonging to your defunct Cecilia’s harp, is like the hide which,” &c.; but I confess, at first, I used to have a sort of crawly sensation, as of a sickly genteel ghost flitting about the place, in an exceedingly peevish humour, trying to scold and command, and finding her defunct voice couldn’t be heard—trying to re-illume her extinguished leers and faded smiles and ogles, and finding no one admired or took note. In the gray of the gloaming, in the twilight corner where stands the shrouded companion of song—what is that white figure flickering round the silent harp? Once, as we were assembled in the room at afternoon tea, a bird, entering at the open window, perched on the instrument. Popham dashed at it. Lovel was deep in conversation upon the wine duties with a member of parliament he had brought down to dinner. Lady Baker, who was, if I may use the expression, “jawing,” as usual, and telling one of her tremendous stories about the Lord Lieutenant to Mr. Bonnington, took no note of the incident. Elizabeth did not seem to remark it: what was a bird on a harp to her, but a sparrow perched on a bit of leather-casing! All the ghosts in Putney churchyard might rattle all their bones, and would not frighten that stout spirit!

I was amused at a precaution which Bedford took, and somewhat alarmed at the distrust towards Lady Baker which he exhibited, when, one day on my return from town—whither I had made an excursion of four or five hours—I found my bedroom door locked, and Dick arrived with the key. “He’s wrote to say he’s coming this evening, and if he had come when you was away, Lady B. was capable of turning your things out, and putting his in, and taking her oath she believed you was going to leave. The long-bows Lady B. do pull are perfectly awful, Mr. B.! So it was long-bow to long-bow, Mr. Batchelor; and I said you had took the key in your pocket, not wishing to have your papers disturbed. She tried the lawn window, but I had bolted that, and the captain will have the pink room, after all, and must smoke up the chimney. I should have liked to see him, or you, or any one do it in poor Mrs. L.’s time—I just should!”

During my visit to London, I had chanced to meet my friend Captain[389] Fitzb—dle, who belongs to a dozen clubs, and knows something of every man in London. “Know anything of Clarence Baker?” “Of course, I do,” says Fitz; “and if you want any renseignement, my dear fellow, I have the honour to inform you that a blacker little sheep does not trot the London pavé. Wherever that ingenious officer’s name is spoken—at Tattersall’s, at his clubs, in his late regiments, in men’s society, in ladies’ society, in that expanding and most agreeable circle which you may call no society at all—a chorus of maledictions rises up at the mention of Baker. Know anything of Clarence Baker! My dear fellow, enough to make your hair turn white, unless (as I sometimes fondly imagine) nature has already performed that process, when of course I can’t pretend to act upon more hair-dye.” (The whiskers of the individual who addressed me, innocent, stared me in the face as he spoke, and were dyed of the most unblushing purple.) “Clarence Baker, sir, is a young man who would have been invaluable in Sparta as a warning against drunkenness and an exemplar of it. He has helped the regimental surgeon to some most interesting experiments in delirium tremens. He is known, and not in the least trusted, in every billiard-room in Brighton, Canterbury, York, Sheffield,—on every pavement which has rung with the clink of dragoon boot-heels. By a wise system of revoking at whist he has lost games which have caused not only his partners, but his opponents and the whole club to admire him and to distrust him: long before and since he was of age, he has written his eminent name to bills which have been dishonoured, and has nobly pleaded his minority as a reason for declining to pay. From the garrison towns where he has been quartered, he has carried away not only the hearts of the milliners, but their gloves, haberdashery, and perfumery. He has had controversies with Cornet Green, regarding horse transactions; disputed turf-accounts with Lieutenant Brown; and betting and backgammon differences with Captain Black. From all I have heard he is the worthy son of his admirable mother. And I bet you even on the four events, if you stay three days in a country house with him, which appears to be your present happy idea,—that he will quarrel with you, insult you, and apologize; that he will intoxicate himself more than once; that he will offer to play cards with you, and not pay on losing (if he wins, I perhaps need not state what his conduct will be); and that he will try to borrow money from you, and most likely from your servant, before he goes away.” So saying, the sententious Fitz strutted up the steps of one of his many club-haunts in Pall Mall, and left me forewarned, and I trust forearmed against Captain Clarence and all his works.

The adversary, when at length I came in sight of him, did not seem very formidable. I beheld a weakly little man with Chinese eyes, and pretty little feet and hands, whose pallid countenance told of Finishes and Casinos. His little chest and fingers were decorated with many jewels. A perfume of tobacco hung round him. His little moustache was twisted with an elaborate gummy curl. I perceived that the little hand which[390] twirled the moustache shook woefully: and from the little chest there came a cough surprisingly loud and dismal.

He was lying on a sofa as I entered, and the children of the house were playing round him. “If you are our uncle, why didn’t you come to see us oftener?” asks Popham.

“How should I know that you were such uncommonly nice children?” asks the captain.

“We’re not nice to you,” says Popham. “Why do you cough so? Mamma used to cough. And why does your hand shake so?”

“My hand shakes because I am ill: and I cough because I’m ill. Your mother died of it, and I daresay I shall too.”

“I hope you’ll be good, and repent before you die, uncle, and I will lend you some nice books,” says Cecilia.

“Oh, bother books!” cries Pop.

“And I hope you’ll be good, Popham,” and “You hold your tongue, Miss,” and “I shall,” and “I shan’t,” and “You’re another,” and “I’ll tell Miss Prior,”—“Go and tell, telltale,”—“Boo”—“Boo”—“Boo”—“Boo”—and I don’t know what more exclamations came tumultuously and rapidly from these dear children, as their uncle lay before them, a handkerchief to his mouth, his little feet high raised on the sofa cushions.

Captain Baker turned a little eye towards me, as I entered the room, but did not change his easy and elegant posture. When I came near to the sofa where he reposed, he was good enough to call out:

“Glass of sherry!”

“It’s Mr. Batchelor; it isn’t Bedford, uncle,” says Cissy.

“Mr. Batchelor ain’t got any sherry in his pocket:—have you, Mr. Batchelor? You ain’t like old Mrs. Prior, always pocketing things, are you?” cries Pop, and falls a-laughing at the ludicrous idea of my being mistaken for Bedford.

“Beg your pardon. How should I know, you know?” drawls the invalid on the sofa. “Everybody’s the same now, you see.”

“Sir!” says I, and “sir” was all I could say. The fact is, I could have replied with something remarkably neat and cutting, which would have transfixed the languid little jackanapes who dared to mistake me for a footman; but, you see, I only thought of my repartee some eight hours afterwards when I was lying in bed, and I am sorry to own that a great number of my best bon mots have been made in that way. So, as I had not the pungent remark ready when wanted, I can’t say I said it to Captain Baker, but I daresay I turned very red, and said “Sir!” and—and in fact that was all.

“You were goin’ to say somethin’?” asked the captain, affably.

“You know my friend, Mr. Fitzboodle, I believe?” said I; the fact is, I really did not know what to say.

“Some mistake—think not.”

“He is a member of the Flag Club,” I remarked, looking my young fellow hard in the face.

“I ain’t. There’s a set of cads in that club that will say anything.”

“You may not know him, sir, but he seemed to know you very well. Are we to have any tea, children?” I say, flinging myself down on an easy chair, taking up a magazine and adopting an easy attitude, though I daresay my face was as red as a turkey-cock’s, and I was boiling over with rage.

As we had a very good breakfast and a profuse luncheon at Shrublands, of course we could not support nature till dinner-time without a five-o’clock tea; and this was the meal for which I pretended to ask. Bedford, with his silver kettle, and his buttony satellite, presently brought in this refection, and of course the children bawled out to him—

“Bedford—Bedford! uncle mistook Mr. Batchelor for you.”

“I could not be mistaken for a more honest man, Pop,” said I. And the bearer of the tea-urn gave me a look of gratitude and kindness which, I own, went far to restore my ruffled equanimity.

“Since you are the butler, will you get me a glass of sherry and a biscuit?” says the captain. And Bedford retiring, returned presently with the wine.

The young gentleman’s hand shook so, that, in order to drink his wine, he had to surprise it, as it were, and seize it with his mouth, when a shake brought the glass near his lips. He drained the wine, and held out his hand for another glass. The hand was steadier now.

“You the man who was here before?” asks the captain.

“Six years ago, when you were here, sir,” says the butler.

“What! I ain’t changed, I suppose?”

“Yes, you are, sir.”

“Then, how the dooce do you remember me?”

“You forgot to pay me some money you borrowed of me, one pound five, sir,” says Bedford, whose eyes slyly turned in my direction.

And here, according to her wont at this meal, the dark-robed Miss Prior entered the room. She was coming forward with her ordinarily erect attitude and firm step, but paused in her walk an instant, and when she came to us, I thought, looked remarkably pale. She made a slight curtsey, and it must be confessed that Captain Baker rose up from his sofa for a moment when she appeared. She then sate down, with her back towards him, turning towards herself the table and its tea apparatus.

At this board my Lady Baker found us assembled when she returned from her afternoon drive. She flew to her darling reprobate of a son. She took his hand, she smoothed back his hair from his damp forehead. “My darling child,” cries this fond mother, “what a pulse you have got!”

“I suppose, because I’ve been drinking,” says the prodigal.

“Why didn’t you come out driving with me? The afternoon was lovely!”

“To pay visits at Richmond? Not as I knows on, ma’am,” says the invalid. “Conversation with elderly ladies about poodles, bible-societies, that kind of thing? It must be a doocid lovely afternoon that would make[392] me like that sort of game.” And here comes a fit of coughing, over which mamma ejaculates her sympathy.

“Kick—kick—killin’ myself!” gasps out the captain, “know I am. No man can lead my life, and stand it. Dyin’ by inches! Dyin’ by whole yards, by Jo—ho—hove, I am!” Indeed, he was as bad in health as in morals, this graceless captain.

“That man of Lovel’s seems a d—— insolent beggar,” he presently and ingenuously remarks.

“O uncle, you mustn’t say those words!” cries niece Cissy.

“He’s a man, and may say what he likes, and so will I, when I’m a man. Yes, and I’ll say it now, too, if I like,” cries Master Popham.

“Not to give me pain, Popham? Will you?” asks the governess.

On which the boy says,—“Well, who wants to hurt you, Miss Prior?”

And our colloquy ends by the arrival of the man of the house from the city.

What I have admired in some dear women is their capacity for quarrelling and for reconciliation. As I saw Lady Baker hanging round her son’s neck, and fondling his scanty ringlets, I remembered the awful stories with which in former days she used to entertain us regarding this reprobate. Her heart was pincushioned with his filial crimes. Under her chesnut front her ladyship’s real head of hair was grey, in consequence of his iniquities. His precocious appetite had devoured the greater part of her jointure. He had treated her many dangerous illnesses with indifference: had been the worst son, the worst brother, the most ill-conducted school-boy, the most immoral young man—the terror of households, the Lovelace of garrison towns, the perverter of young officers; in fact, Lady Baker did not know how she supported existence at all under the agony occasioned by his crimes, and it was only from the possession of a more than ordinarily strong sense of religion that she was enabled to bear her burden.

The captain himself explained these alternating maternal caresses and quarrels in his easy way.

“Saw how the old lady kissed and fondled me?” says he to his brother-in-law. “Quite refreshin’, ain’t it? Hang me, I thought she was goin’ to send me a bit of sweetbread off her own plate. Came up to my room last night, wanted to tuck me up in bed, and abused my brother to me for an hour. You see, when I’m in favour, she always abuses Baker; when he’s in favour she abuses me to him. And my sister-in-law, didn’t she give it my sister-in-law! Oh! I’ll trouble you! And poor Cecilia—why hang me, Mr. Batchelor, she used to go on—this bottle’s corked, I’m hanged if it isn’t—to go on about Cecilia, and call her.... Hullo!”

Here he was interrupted by our host, who said sternly—

“Will you please to forget those quarrels, or not mention them here? Will you have more wine, Batchelor?”

And Lovel rises, and haughtily stalks out of the room. To do Lovel justice, he had a great contempt and dislike for his young brother-in-law, which, with his best magnanimity, he could not at all times conceal.

So our host stalks towards the drawing-room, leaving Captain Clarence sipping wine.

“Don’t go, too,” says the captain. “He’s a confounded rum fellow, my brother-in-law is. He’s a confounded ill-conditioned fellow, too. They always are, you know, these tradesmen fellows, these half-bred ’uns. I used to tell my sister so; but she would have him, because he had such lots of money, you know. And she threw over a fellar she was very fond of; and I told her she’d regret it. I told Lady B. she’d regret it. It was all Lady B.’s doing. She made Cissy throw the fellar over. He was a bad match, certainly, Tom Mountain was; and not a clever fellow, you know, or that sort of thing; but at any rate, he was a gentleman, and better than a confounded sugar-baking beggar out Ratcliff Highway.”

“You seem to find that claret very good!” I remark, speaking, I may say, Socratically, to my young friend, who had been swallowing bumper after bumper.

“Claret good! Yes, doosid good!”

“Well, you see our confounded sugar-baker gives you his best.”

“And why shouldn’t he, hang him? Why, the fellow chokes with money. What does it matter to him how much he spends? You’re a poor man, I dare say. You don’t look as if you were over-flush of money. Well, if you stood a good dinner, it would be all right—I mean it would show—you understand me, you know. But a sugar-baker with ten thousand a year, what does it matter to him, bottle of claret more—less?”

“Let us go into the ladies,” I say.

“Go into mother! I don’t want to go into my mother,” cried out the artless youth. “And I don’t want to go into the sugar-baker, hang him! and I don’t want to go into the children; and I’d rather have a glass of brandy-and-water with you, old boy. Here, you! What’s your name? Bedford! I owe you five-and-twenty shillings, do I, old Bedford? Give us a good glass of Schnaps, and I’ll pay you! Look here, Batchelor. I hate that sugar-baker. Two years ago I drew a bill on him, and he wouldn’t pay it—perhaps he would have paid it, but my sister wouldn’t let him. And, I say, shall we go and have a cigar in your room? My mother’s been abusing you to me like fun this morning. She abuses everybody. She used to abuse Cissy. Cissy used to abuse her—used to fight like two cats....”

And if I narrate this conversation, dear Spartan youth! if I show thee this Helot maundering in his cups, it is that from his odious example thou mayest learn to be moderate in the use of thine own. Has the enemy who has entered thy mouth ever stolen away thy brains? Has wine ever caused thee to blab secrets; to utter egotisms and follies? Beware of it. Has it ever been thy friend at the end of the hard day’s work, the cheery companion of thy companions, the promoter of harmony, kindness, harmless social pleasure? be thankful for it. Two years since, when the comet was blazing in the autumnal sky, I stood on the château-steps of a great claret proprietor. “Boirai-je de ton vin, O comète?” I said, addressing the[394] luminary with the flaming tail. Shall those generous bunches which you ripen yield their juices for me morituro? It was a solemn thought. Ah! my dear brethren! who knows the Order of the Fates? When shall we pass the Gloomy Gates? Which of us goes, which of us waits to drink those famous Fifty-eights? A sermon, upon my word! And pray why not a little homily on an autumn eve over a purple cluster?... If that rickety boy had only drunk claret, I warrant you his tongue would not have blabbed, his hand would not have shaken, his wretched little brain and body would not have reeled with fever.

“’Gad,” said he next day to me, “cut again last night. Have an idea that I abused Lovel. When I have a little wine on board, always speak my mind, don’t you know. Last time I was here in my poor sister’s time, said somethin’ to her, don’t quite know what it was, somethin’ confoundedly true and unpleasant I daresay. I think it was about a fellow she used to go on with before she married the sugar-baker. And I got orders to quit, by Jove, sir—neck and crop, sir, and no mistake! And we gave it one another over the stairs. O my! we did pitch in!—And that was the last time I ever saw Cecilia—give you my word. A doosid unforgiving woman, my poor sister was, and between you and me, Batchelor, as great a flirt as ever threw a fellar over. You should have heard her and my Lady B. go on, that’s all!—Well, mamma, are you going out for a drive in the coachy-poachy?—Not as I knows on, thank you, as I before had the honour to observe. Mr. Batchelor and me are going to play a little game at billiards.” We did, and I won; and, from that day to this, have never been paid my little winnings.

On the day after the doughty captain’s arrival, Miss Prior, in whose face I had remarked a great expression of gloom and care, neither made her appearance at breakfast nor at the children’s dinner. “Miss Prior was a little unwell,” Lady Baker said, with an air of most perfect satisfaction. “Mr. Drencher will come to see her this afternoon, and prescribe for her, I daresay,” adds her ladyship, nodding and winking a roguish eye at me. I was at a loss to understand what was the point of humour which amused Lady B., until she herself explained it.

“My good sir,” she said, “I think Miss Prior is not at all averse to being ill.” And the nods recommenced.

“As how?” I ask.

“To being ill, or at least to calling in the medical man.”

“Attachment between governess and Sawbones I make bold for to presume?” says the captain.

“Precisely, Clarence—a very fitting match. I saw the affair, even before Miss Prior owned it—that is to say, she has not denied it. She says she can’t afford to marry, that she has children enough at home in her brothers and sisters. She is a well-principled young woman, and does credit, Mr. Batchelor, to your recommendation, and the education she has received from her uncle, the Master of St. Boniface.”

“Cissy to school; Pop to Eton; and Miss Whatdyoucall to grind the[395] pestle in Sawbones’ back-shop: I see!” says Captain Clarence. “He seems a low, vulgar blackguard, that Sawbones.”

“Of course, my love; what can you expect from that sort of person?” asks mamma, whose own father was a small attorney, in a small Irish town.

“I wish I had his confounded good health,” cries Clarence, coughing.

“My poor darling!” says mamma.

I said nothing. And so Elizabeth was engaged to that great, broad-shouldered, red-whiskered, young surgeon with the huge appetite and the dubious h’s! Well, why not? What was it to me? Why shouldn’t she marry him? Was he not an honest man, and a fitting match for her? Yes. Very good. Only if I do love a bird or flower to glad me with its dark blue eye, it is the first to fade away. If I have a partiality for a young gazelle it is the first to——paha! What have I to do with this namby-pamby? Can the heart that has truly loved ever forget, and doesn’t it as truly love on to the—stuff! I am past the age of such follies. I might have made a woman happy: I think I should. But the fugacious years have lapsed, my Posthumus! My waist is now a good bit wider than my chest, and it is decreed that I shall be alone!

My tone, then, when next I saw Elizabeth, was sorrowful—not angry. Drencher, the young doctor, came punctually enough, you may be sure, to look after his patient. Little Pinhorn, the children’s maid, led the young practitioner smiling towards the schoolroom regions. His creaking highlows sprang swiftly up the stairs. I happened to be in the hall, and surveyed him with a grim pleasure. “Now he is in the schoolroom,” I thought. “Now he is taking her hand—it is very white—and feeling her pulse. And so on, and so on. Surely, surely Pinhorn remains in the room?” I am sitting on a hall-table as I muse plaintively on these things, and gaze up the stairs by which the Hakeem (great, carroty-whiskered cad!) has passed into the sacred precincts of the harem. As I gaze up the stair, another door opens into the hall; a scowling face peeps through that door, and looks up the stair, too. ’Tis Bedford, who has slid out of his pantry, and watches the doctor. And thou, too, my poor Bedford! Oh! the whole world throbs with vain heart-pangs, and tosses and heaves with longing, unfulfilled desires! All night, and all over the world, bitter tears are dropping as regular as the dew, and cruel memories are haunting the pillow. Close my hot eyes, kind Sleep! Do not visit it, dear delusive images out of the Past! Often your figure shimmers through my dreams, Glorvina. Not as you are now, the stout mother of many children—you always had an alarming likeness to your own mother, Glorvina—but as you were—slim, black-haired, blue-eyed—when your carnation lips warbled the Vale of Avoca, or the Angels’ Whisper. “What!” I say then, looking up the stair, “am I absolutely growing jealous of yon apothecary?—O fool!” And at this juncture, out peers Bedford’s face from the pantry, and I see he is jealous too. I tie my shoe as I sit on the table; I don’t affect to notice Bedford in the least (who, in fact, pops his own head back again as soon as he sees mine). I take my[396] wide-awake from the peg, set it on one side my head, and strut whistling out of the hall door. I stretch over Putney Heath, and my spirit resumes its tranquillity.

I sometimes keep a little journal of my proceedings, and on referring to its pages, the scene rises before me pretty clearly to which the brief notes allude. On this day I find noted: “Friday, July, 14.—B. came down to-day. Seems to require a great deal of attendance from Dr.—Row between dowagers after dinner.” “B.,” I need not remark, is Bessy. “Dr.,” of course, you know. “Row between dowagers,” means a battle royal between Mrs. Bonnington and Lady Baker, such as not unfrequently raged under the kindly Lovel’s roof.

Lady Baker’s gigantic menial Bulkeley condescended to wait at the family dinner at Shrublands, when perforce he had to put himself under Mr. Bedford’s orders. Bedford would gladly have dispensed with the London footman, over whose calves, he said, he and his boy were always tumbling; but Lady Baker’s dignity would not allow her to part from her own man; and her good-natured son-in-law allowed her, and indeed almost all other persons, to have their own way. I have reason to fear Mr. Bulkeley’s morals were loose. Mrs. Bonnington had a special horror of him; his behaviour in the village public-houses where his powder and plush were for ever visible—his freedom of behaviour and conversation before the good lady’s nurse and parlour-maids—provoked her anger and suspicion. More than once, she whispered to me her loathing of this flour-besprinkled monster; and, as much as such a gentle creature could, she showed her dislike to him by her behaviour. The flunkey’s solemn equanimity was not to be disturbed by any such feeble indications of displeasure. From his powdered height, he looked down upon Mrs. Bonnington, and her esteem or her dislike was beneath him.

Now on this Friday night the 14th, Captain Clarence had gone to pass the day in town, and our Bessy made her appearance again, the doctor’s prescriptions having, I suppose, agreed with her. Mr. Bulkeley, who was handing coffee to the ladies, chose to offer none to Miss Prior, and I was amused when I saw Bedford’s heel scrunch down on the flunkey’s right foot, as he pointed towards the governess. The oaths which Bulkeley had to devour in silence must have been frightful. To do the gallant fellow justice, I think he would have died rather than speak before company in a drawing-room. He limped up and offered the refreshment to the young lady, who bowed and declined it.

“Frederick,” Mrs. Bonnington begins, when the coffee-ceremony is over, “now the servants are gone, I must scold you about the waste at your table, my dear. What was the need of opening that great bottle of champagne? Lady Baker only takes two glasses. Mr. Batchelor doesn’t touch it.” (No, thank you, my dear Mrs. Bonnington: too old a stager.) “Why not have a little bottle instead of that great, large, immense one? Bedford is a teetotaler. I suppose it is that London footman who likes it.”

“My dear mother, I haven’t really ascertained his tastes,” says Lovel.

“Then why not tell Bedford to open a pint, dear?” pursues mamma.

“Oh, Bedford—Bedford, we must not mention him, Mrs. Bonnington!” cries Lady Baker. “Bedford is faultless. Bedford has the keys of everything. Bedford is not to be controlled in anything. Bedford is to be at liberty to be rude to my servant.”

“Bedford was admirably kind in his attendance on your daughter, Lady Baker,” says Lovel, his brow darkening: “and as for your man, I should think he was big enough to protect himself from any rudeness of poor Dick!” The good fellow had been angry for one moment, at the next he was all for peace and conciliation.

Lady Baker puts on her superfine air. With that air she had often awe-stricken good, simple Mrs. Bonnington; and she loved to use it whenever city folks or humble people were present. You see she thought herself your superior and mine: as de par le monde there are many artless Lady Bakers who do. “My dear Frederick!” says Lady B. then, putting on her best Mayfair manner, “excuse me for saying, but you don’t know the—the class of servant to which Bulkeley belongs. I had him as a great favour from Lord Toddleby’s. That—that class of servant is not generally accustomed to go out single.”

“Unless they are two behind a carriage-perch they pine away, I suppose,” remarks Mr. Lovel, “as one love-bird does without his mate.”

“No doubt—no doubt,” says Lady B., who does not in the least understand him; “I only say you are not accustomed here—in this kind of establishment, you understand—to that class of——”

But here Mrs. Bonnington could contain her wrath no more. “Lady Baker!” cries that injured mother, “is my son’s establishment not good enough for any powdered wretch in England? Is the house of a British merchant——”

“My dear creature—my dear creature!” interposes her ladyship, “it is the house of a British merchant, and a most comfortable house too.”

“Yes, as you find it,” remarks mamma.

“Yes, as I find it, when I come to take care of that departed angel’s children, Mrs. Bonnington!” (Lady B. here indicates the Cecilian effigy)—“of that dear seraph’s orphans, Mrs. Bonnington! You cannot. You have other duties—other children—a husband, whom you have left at home in delicate health, and who——”

“Lady Baker!” exclaims Mrs. Bonnington, “no one shall say I don’t take care of my dear husband!”

“My dear Lady Baker!—my dear—dear mother!” cries Lovel, éploré, and whimpers aside to me, “They spar in this way every night, when we’re alone. It’s too bad, ain’t it, Batch?”

“I say you do take care of Mr. Bonnington,” Baker blandly resumes (she has hit Mrs. Bonnington on the raw place, and smilingly proceeds to thong again): “I say you do take care of your husband, my dear creature, and that is why you can’t attend to Frederick! And as he is of a very easy temper,—except sometimes with his poor Cecilia’s mother,—he allows[398] all his tradesmen to cheat him; all his servants to cheat him; Bedford to be rude to everybody; and if to me, why not to my servant Bulkeley, with whom Lord Toddleby’s groom of the chambers gave me the very highest character?”

Mrs. Bonnington in a great flurry broke in by saying she was surprised to hear that noblemen had grooms in their chambers: and she thought they were much better in the stables: and when they dined with Captain Huff, you know, Frederick, his man always brought such a dreadful smell of the stable in with him, that——Here she paused. Baker’s eye was on her; and that dowager was grinning a cruel triumph.

“He!—he! You mistake, my good Mrs. Bonnington!” says her ladyship. “Your poor mother mistakes, my dear Frederick. You have lived in a quiet and most respectable sphere, but not, you understand, not——”

“Not what, pray, Lady Baker? We have lived in this neighbourhood twenty years: in my late husband’s time, when we saw a great deal of company, and this dear Frederick was a boy at Westminster School. And we have paid for everything we have had for twenty years; and we have not owed a penny to any tradesman. And we may not have had powdered footmen, six feet high, impertinent beasts, who were rude to all the maids in the place. Don’t—I will speak, Frederick! But servants who loved us, and who were paid their wages, and who—o—ho—ho—ho!”

Wipe your eyes, dear friends! out with all your pocket-handkerchiefs. I protest I cannot bear to see a woman in distress. Of course Fred Lovel runs to console his dear old mother, and vows Lady Baker meant no harm.

“Meant harm! My dear Frederick, what harm can I mean? I only said your poor mother did not seem to know what a groom of the chambers was! How should she?”

“Come—come,” says Frederick, “enough of this! Miss Prior, will you be so kind as to give us a little music?”

Miss Prior was playing Beethoven at the piano, very solemnly and finely, when our Black Sheep returned to this quiet fold, and, I am sorry to say, in a very riotous condition. The brilliancy of his eye, the purple flush on his nose, the unsteady gait, and uncertain tone of voice, told tales of Captain Clarence, who stumbled over more than one chair before he found a seat near me.

“Quite right, old boy,” says he, winking at me. “Cut again—dooshid good fellosh. Better than being along with you shtoopid-old-fogish.” And he began to warble wild “Fol-de-rol-lolls” in an insane accompaniment to the music.

“By heavens, this is too bad!” growls Lovel. “Lady Baker, let your big man carry your son to bed. Thank you, Miss Prior!”

At a final yell, which the unlucky young scapegrace gave, Elizabeth stopped, and rose from the piano, looking very pale. She made her curtsey, and was departing when the wretched young captain sprang up, looked at her, and sank back on the sofa with another wild laugh. Bessy fled away scared, and white as a sheet.

“Take the brute to bed!” roars the master of the house, in great wrath. And scapegrace was conducted to his apartment, whither he went laughing wildly, and calling out, “Come on, old sh-sh-shugarbaker!”

The morning after this fine exhibition, Captain Clarence Baker’s mamma announced to us that her poor dear suffering boy was too ill to come to breakfast, and I believe he prescribed for himself devilled drum-stick and soda-water, of which he partook in his bedroom. Lovel, seldom angry, was violently wrath with his brother-in-law; and, almost always polite, was at breakfast scarcely civil to Lady Baker. I am bound to say that female abused her position. She appealed to Cecilia’s picture a great deal too much during the course of breakfast. She hinted, she sighed, she waggled her head at me, and spoke about “that angel” in the most tragic manner. Angel is all very well: but your angel brought in à tout propos; your departed blessing called out of her grave ever so many times a day; when grandmamma wants to carry a point of her own; when the children are naughty, or noisy; when papa betrays a flickering inclination to dine at his club, or to bring home a bachelor friend or two to Shrublands;—I say your angel always dragged in by the wings into the conversation loses her effect. No man’s heart put on wider crape than Lovel’s at Cecilia’s loss. Considering the circumstances, his grief was most creditable to him: but at breakfast, at lunch, about Bulkeley the footman, about the barouche or the phaeton, or any trumpery domestic perplexity, to have a Deus intersit was too much. And I observed, with some inward satisfaction, that when Baker uttered her pompous funereal phrases, rolled her eyes up to the ceiling, and appealed to that quarter, the children ate their jam and quarrelled and kicked their little shins under the table, Lovel read his paper and looked at his watch to see if it was omnibus time; and Bessy made the tea, quite undisturbed by the old lady’s tragical prattle.

When Baker described her son’s fearful cough and dreadfully feverish state, I said, “Surely, Lady Baker, Mr. Drencher had better be sent for;” and I suppose I uttered the disgusting dissyllable Drencher with a fine sarcastic accent; for once, just once, Bessy’s grey eyes rose through the spectacles and met mine with a glance of unutterable sadness, then calmly settled down on to the slop-basin again, or the urn in which her pale features, of course, were odiously distorted.

“You will not bring anybody home to dinner, Frederick, in my poor boy’s state?” asks Lady B.

“He may stay in his bedroom, I suppose?” replies Lovel.

“He is Cecilia’s brother, Frederick!” cries the lady.

“Conf——” Lovel was beginning. What was he about to say?

“If you are going to confound your angel in heaven, I have nothing to say, sir!” cries the mother of Clarence.

“Parbleu, madame!” cried Lovel, in French; “if he were not my wife’s brother, do you think I would let him stay here?”

“Parly Français? Oui, oui, oui!” cries Pop. “I know what Pa means!”

“And so do I know. And I shall lend uncle Clarence some books which Mr. Bonnington gave me, and——”

“Hold your tongue all!” shouts Lovel, with a stamp of his foot.

“You will, perhaps, have the great kindness to allow me the use of your carriage—or, at least, to wait here until my poor suffering boy can be moved, Mr. Lovel?” says Lady B., with the airs of a martyr.

Lovel rang the bell. “The carriage for Lady Baker—at her ladyship’s hour, Bedford: and the cart for her luggage. Her ladyship and Captain Baker are going away.”

“I have lost one child, Mr. Lovel, whom some people seem to forget. I am not going to murder another! I will not leave this house, sir, unless you drive me from it by force, until the medical man has seen my boy!” And here she and sorrow sat down again. She was always giving warning. She was always fitting the halter and traversing the cart, was Lady B., but she for ever declined to drop the handkerchief and have the business over. I saw by a little shrug in Bessy’s shoulders, what the governess’s views were of the matter: and, in a word, Lady B. no more went away on this day, than she had done on forty previous days when she announced her intention of going. She would accept benefits, you see, but then she insulted her benefactors, and so squared accounts.

That great healthy, florid, scarlet-whiskered, medical wretch came at about twelve, saw Mr. Baker and prescribed for him: and of course he must have a few words with Miss Prior, and inquire into the state of her health. Just as on the previous occasion, I happened to be in the hall when Drencher went upstairs; Bedford happened to be looking out of his pantry-door: I burst into a yell of laughter when I saw Dick’s livid face—the sight somehow suited my savage soul.

No sooner was Medicus gone, when Bessy, grave and pale, in bonnet and spectacles, came sliding downstairs. I do not mean down the banister, which was Pop’s favourite method of descent, but slim, tall, noiseless, in a nunlike calm, she swept down the steps. Of course, I followed her. And there was Master Bedford’s nose peeping through the pantry-door at us, as we went out with the children. Pray, what business of his was it to be always watching anybody who walked with Miss Prior?

“So, Bessy,” I said, “what report does Mr.—hem!—Mr. Drencher—give of the interesting invalid?”

“Oh, the most horrid! He says that Captain Baker has several times had a dreadful disease brought on by drinking, and that he is mad when he has it. He has delusions, sees demons, when he is in this state—wants to be watched.”

“Drencher tells you everything.”

She says meekly: “He attends us when we are ill.”

I remark, with fine irony: “He attends the whole family: he is always coming to Shrublands!”

“He comes very often,” Miss Prior says, gravely.

“And do you mean to say, Bessy,” I cry, madly cutting off two or[401] three heads of yellow broom with my stick—“do you mean to say a fellow like that, who drops his h’s about the room, is a welcome visitor?”

“I should be very ungrateful if he were not welcome, Mr. Batchelor,” says Miss Prior. “And call me by my surname, please—and he has taken care of all my family—and——”

“And of course, of course, of course, Miss Prior!” say I, brutally; “and this is the way the world wags; and this is the way we are ill, and are cured; and we are grateful to the doctor that cures us!”

She nods her grave head. “You used to be kinder to me once, Mr. Batchelor, in old days—in your—in my time of trouble! Yes, my dear, that is a beautiful bit of broom! Oh, what a fine butterfly!” (Cecilia scours the plain after the butterfly.) “You used to be kinder to me once—when we were both unhappy.”

“I was unhappy,” I say, “but I survived. I was ill, but I am now pretty well, thank you. I was jilted by a false, heartless woman. Do you suppose there are no other heartless women in the world?” And I am confident, if Bessy’s breast had not been steel, the daggers which darted out from my eyes would have bored frightful stabs in it.

But she shook her head, and looked at me so sadly that my eye-daggers tumbled down to the ground at once; for you see, though I am a jealous Turk, I am a very easily appeased jealous Turk; and if I had been Bluebeard, and my wife, just as I was going to decapitate her, had lifted up her head from the block and cried a little, I should have dropped my scimitar, and said, “Come, come, Fatima, never mind for the present about that key and closet business, and I’ll chop your head off some other morning.” I say, Bessy disarmed me. Pooh! I say. Women will make a fool of me to the end. Ah! ye gracious Fates! Cut my thread of life ere it grow too long. Suppose I were to live till seventy, and some little wretch of a woman were to set her cap at me? She would catch me—I know she would. All the males of our family have been spoony and soft, to a degree perfectly ludicrous and despicable to contemplate——Well, Bessy Prior, putting a hand out, looked at me, and said,—

“You are the oldest and best friend I have ever had, Mr. Batchelor—the only friend.”

“Am I, Elizabeth?” I gasp, with a beating heart.

“Cissy is running back with a butterfly.” (Our hands unlock.) “Don’t you see the difficulties of my position? Don’t you know that ladies are often jealous of governesses; and that unless—unless they imagined I was—I was favourable to Mr. Drencher, who is very good and kind—the ladies at Shrublands might not like my remaining alone in the house with—with—you understand?” A moment the eyes look over the spectacles: at the next, the meek bonnet bows down towards the ground.

I wonder did she hear the bump—bumping of my heart? O heart!—O wounded heart! did I ever think thou wouldst bump—bump again? “Egl—Egl—izabeth,” I say, choking with emotion, “do, do, do you—te—tell me—you don’t—don’t—don’t—lo—love that apothecary?”

She shrugs her shoulder—her charming shoulder.

“And if,” I hotly continue, “if a gentleman—if a man of mature age certainly, but who has a kind heart and four hundred a-year of his own—were to say to you, ‘Elizabeth! will you bid the flowers of a blighted life to bloom again?—Elizabeth! will you soothe a wounded heart?’”——

“Oh, Mr. Batchelor!” she sighed, and then added quickly, “Please, don’t take my hand. Here’s Pop.”

And that dear child (bless him!) came up at the moment, saying, “Oh, Miss Prior! look here! I’ve got such a jolly big toadstool!” And next came Cissy, with a confounded butterfly. O Richard the Third! Haven’t you been maligned because you smothered two little nuisances in a Tower? What is to prove to me that you did not serve the little brutes right, and that you weren’t a most humane man? Darling Cissy coming up, then, in her dear, charming way, says, “You shan’t take Mr. Batchelor’s hand, you shall take my hand!” And she tosses up her little head, and walks with the instructress of her youth.

“Ces enfans ne comprennent guère le Français,” says Miss Prior, speaking very rapidly.

“Après lonche?” I whisper. The fact is, I was so agitated, I hardly knew what the French for lunch was. And then our conversation dropped: and the beating of my own heart was all the sound I heard.

Lunch came. I couldn’t eat a bit: I should have choked. Bessy ate plenty, and drank a glass of beer. It was her dinner, to be sure. Young Blacksheep did not appear. We did not miss him. When Lady Baker began to tell her story of George IV. at Slane Castle, I went into my own room. I took a book. Books? Paha! I went into the garden. I took out a cigar. But no, I would not smoke it. Perhaps she——many people don’t like smoking.

I went into the garden. “Come into the garden, Maud.” I sate by a large lilac bush. I waited. Perhaps, she would come. The morning-room windows were wide open on to the lawn. Will she never come? Ah! what is that tall form advancing? gliding—gliding into the chamber like a beauteous ghost? Who most does like an angel show, you may be sure ’tis she. She comes up to the glass. She lays her spectacles down on the mantel-piece. She puts a slim white hand over her auburn hair and looks into the mirror. Elizabeth, Elizabeth! I come!

As I came up, I saw a horrid little grinning, debauched face surge over the back of a great arm-chair and look towards Elizabeth. It was Captain Blacksheep, of course. He laid his elbows over the chair. He looked keenly and with a diabolical smile at the unconscious girl; and just as I reached the window, he cried out, “Betsy Bellenden, by Jove!”

Elizabeth turned round, gave a little cry, and——but what happened I shall tell in the ensuing chapter.

[1] To another celebrated critic. Dear Sir—You think I mean you, but upon my honour I don’t.

If there is one infirmity or defect of those five senses with which we are most of us blest, which more than any other attracts sympathy and claims compassionate consideration, it is blindness—an inability to know what is beautiful in form or in colour, to appreciate light, or to recognize and comprehend the varying features of our fellow-men—a perpetual darkness in the midst of a world of light—a total exclusion from the readiest, pleasantest, and most available means of acquiring ideas.

And yet who would suppose that there exists, and is tolerably common, a partial blindness, which has hardly been described as a defect for more than half a century, and of which it may be said even now that most of those who suffer from it are not only themselves ignorant of the fact, but that those about them can hardly be induced to believe it. The unhappy victims of this partial blindness (which is real and physical, not moral) are at great pains in learning what to them are minute distinctions of tint, although to the rest of the world they are differences of colour of the most marked kind, and, after all, they only obtain the credit of unusual stupidity or careless inattention in reward for their exertions and in sympathy for their visual defect. We allude to a peculiarity of vision which first attracted notice in the case of the celebrated propounder of the atomic theory in chemistry, the late Dr. Dalton, of Manchester, who on endeavouring to find some object to compare in colour with his scarlet robe of doctor of laws, when at Cambridge, could hit on nothing which better agreed with it than the foliage of the adjacent trees, and who to match his drab coat—for our learned doctor was of the Society of Friends—might possibly have selected crimson continuations as the quietest and nearest match the pattern-book of his tailor exhibited.

An explanation of this curious defect will be worth listening to, the more so as one of our most eminent philosophers, Sir John Herschel, has recently made a few remarks on the subject, directing attention at the same time to other little known but not unimportant phenomena of colour, which bear upon and help to explain it.

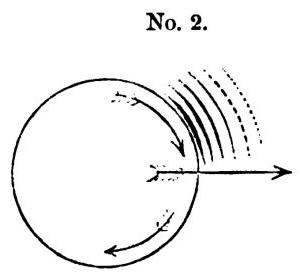

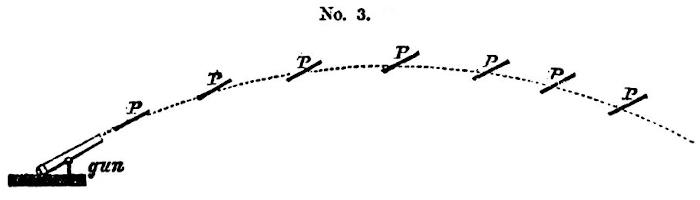

It is known that white light consists of the admixture of coloured rays in certain proportions, and that the beautiful prismatic colours seen in the rainbow are produced by the different degree in which the various rays of colour are bent when passing from one transparent substance into another of different density. Thus, when a small group of colour-rays, forming a single pencil or beam of white sunlight, passes into and through the atmosphere during a partial shower, and falls on a drop of rain, it is first bent aside on entering the drop, then reflected from the inside surface at the back of the drop, and ultimately emerges in an opposite direction to its original one. During these changes, however, although all the colour-rays forming the white pencil have been bent, each has been bent at a different angle—the red most, and the blue least. When therefore they[404] come out of the drop, the red rays are quite separated from the blue, and when the beam reaches its destination, the various colours enter the eye separately, forming a line of variously coloured light, the upper part red and the lower part blue, instead of a mere point of white light, as the ray would have appeared if seen before it entered the drop. The eye naturally refers each part of the ray to the place from whence it appears to come, and thus, with a number of drops falling and the sun not obscured, a rainbow is seen, which represents part of a number of concentric circular lines of colour, the outermost of which is red, the innermost violet, and the intermediate ones we respectively name orange, yellow, green, blue, and indigo.

It has also been found by careful experiment, that these are not all pure colours, most of them being mixtures of some few that are really primitive and pure, and necessarily belong to solar light. It is these mixed in due proportion which make up ordinary white light, which is the only kind seen when the sun’s rays have not undergone this sort of decomposition or separation into elements. The actual primitive colours are generally supposed to be red, yellow, and blue, and much theoretical as well as practical discussion has arisen as to how these require to be mixed, what proportion they bear to each other in their power of impressing the human eye, and many other matters for which we must refer to Mr. Field, Mr. Owen Jones, and others, who have studied the subject and applied it.

In a general way it is found convenient to remember, or rather to assume, that three parts of red, five parts of yellow, and eight parts of blue form together white, and, therefore, that the pencil of white light contains three rays of red, five of yellow, and eight of blue. To produce the other prismatic colours, we must mix red with a little yellow to form orange; yellow with some blue to form green; much blue with a little red to form indigo, and a little blue with some red to form violet. In performing experiments on colour it is convenient, instead of a drop of water, to substitute a prism of glass in decomposing the rays of light. We may thus produce at will a convenient image, called a prismatic spectrum, which, when thrown on a wall, is a broad band of coloured lights, having all the tints of the rainbow in the same order. Looking at this image, the red is at the top and the violet at the bottom, and it may be asked, How does the red get amongst the blue to form violet, if the red rays are bent up to the top of the spectrum? The answer is, that a quantity of white light not decomposed, and a part of all the colour rays, reach all parts of the spectrum, however carefully it is sheltered, but that so many more red rays get to the top, so many more of the yellow to the middle, and so many more blue to where that colour appears most brilliant, that these are seen nearly pure, whilst where the red and yellow or yellow and blue mix they produce distinct kinds of colour, and where the blue at the bottom is faint, and some of those red rays fall that do not reach the red part of the spectrum, the violet is produced. In point of fact, therefore, all the colours of the spectrum, as seen, are mixtures of pure colour with white light, while all but red are mixtures of other pure colours with some red and some yellow[405] as well as white. Primitive and pure colours, therefore, are not obtained in the spectrum, and a question has arisen as to which really deserve to be called pure, Dr. Young upholding green against yellow, and even regarding violet as primitive, and blue a mixed colour. A consideration of the results of this theory would lead us farther than is necessary for the purpose we have now in view.

We also find philosophers now-a-days calmly discussing a question which most people considered settled very long ago, namely, whether blue and yellow together really make green.

It is of no use for the artist to lift up his eyes with astonishment at any one being so insane as to question so generally admitted a statement. In vain does he point to his pictures, in which his greens have been actually so produced. The strict photologist at once puts him down, by informing him that he knows little or nothing of the real state of the case: his (the artist’s) colours are negative, or hues of more or less complete darkness; whereas in nature, the colour question is to be decided by positive colours, or hues in which all the light used is of one kind. The meaning of this will be best understood by an example: When a ray of white light falls on a green leaf, part of the ray is absorbed and part reflected, and the object is therefore only seen with the part that is reflected. That which is absorbed consists of some of each of the colour rays, and the resulting reflected light is nothing more than a mixture of what remains after this partial absorption. The green we see consists of the original white light deprived of a portion of its rays. It is not a pure and absolute green, but only a residual group of coloured rays, and thus in so far the green colour is negative, or consists of rays not absorbed. It is therefore partial darkness, and not absolute light. If, however, on the other hand, a ray of white light is passed through a transparent medium (e. g. some chemical salt) which has the property of entirely absorbing all but one or more of the colour rays, and no part of the remainder, then all the light that passes through this medium is of the one colour, or a mixture of the several colours that pass: and if such light is thrown on a white ground, the reflected colour will be positive, and not negative, and is far purer as well as brighter than the colour obtained in the other way. It has been found by actual experiment, that when positive blue, thus obtained, is thrown on positive yellow, the resulting reflected colour bears no resemblance to green. Sir John Herschel considers, that whether green is a primitive colour—in other words, whether we really have three or four primitive colours—remains yet an open question.

It was necessary to explain these matters about colour before directly referring to the subject of this paper, namely, blindness to certain colour rays. It should also be clearly understood that the persons subject to this peculiar condition of vision have not necessarily any mechanical or optical defect in the eye as an optical instrument, which may be strong or weak, long-sighted or short-sighted, quite independently of it. Colour blindness does not in any way interfere with the ordinary requirements of vision,[406] nor is there the smallest reason to imagine that it can get worse by neglect, or admit of any improvement by education or treatment.

Assuming that persons of ordinary vision see three simple colours, red, yellow, and blue, and that all the rest of the colours are mixtures of these with each other and with white light, let us try to picture to ourselves what must be the visual condition of a person who is unable to recognize certain rays; and as it appears that there is but one kind of colour-blindness known, we will assume that the person is unable to recognize those rays of white light which consist of pure red and nothing else. In other words, let us investigate the sensations of a person blind so far only as pure red is concerned.

All visible objects either reflect the same kind of light as that which falls on them, absorbing part and reflecting the rest, or else they absorb more of some colour rays than others, and reflect only a negative tint, made up of a mixture of all the colour-rays not absorbed. To a colour-blind person, the mixed light, as it proceeds from the sun, is probably white, as seen by those having perfect vision; for, as we have explained already, positive blue and yellow (the colour rays when red is excluded) do not make green, and the absence of the red ray is likely to produce only a slight darkening effect. So far, then, there is no difference. But how must it be with regard to colour.

Bearing in mind what has been said above, it is evident that in withdrawing the red rays from the spectrum, we affect all the colours. The orange is no longer red and yellow, but darkened yellow; the yellow is purer, the green is quite distinct, the blue purer, and the indigo and violet no longer red and blue, but blue mingled with more or less of darkness, the violet being the darkest, as containing least blue in proportion to red, while the red part itself, though not seen as a colour, is not absolutely black, inasmuch as its part of the spectrum is faintly coloured with the few mixed rays of blue and yellow and white that escape from their proper place. The red then ought to be seen as a gray neutral tint, the orange a dingy yellow, the indigo a dirty indigo, and the violet a sickly, disagreeable tint of pale blue, darkened considerably with black and gray.

Next let us take the case of an intelligent person affected with colour blindness, but who is not yet aware of the fact. He has been taught from childhood that certain shades, some darker and some brighter, but all of neutral tint, and not really presenting to him colour at all, are to be called by various names—scarlet, crimson, pale red, dark red, bright red, dark green, dark purple, brown, and others. With all these he can only associate an idea of gray; nor can he possibly know that any one else sees more than he does. Having been taught the names they are called by, he remembers the names, with more or less accuracy, and thus passes muster. There is a real difference of tint, because each of these colours consists of more or less blue, yellow, and white, mixed with the red; and our friend is enabled to recognize and name them, more or less correctly, according to his acuteness of perception and accuracy of memory.

If we desire to experiment on such a person, we must ask no names whatever, but simply place before him a number of similar objects differently coloured. Taking, for example, skeins of coloured wools, let us select a complete series of shades of tint, from red, through yellow, green, and blue, to violet, and request him to arrange them as well as he is able, placing the darkest shades first, and putting those tints together that are most like each other. It is curious then to watch the progress of the arrangement. In a case lately tried by the writer of this article, the colour-blind person first threw aside at once a particular shade of pale green as undoubted white, and then several dark blues, dark reds, dark greens, and browns, were put together as black. The yellows and pure blues were placed correctly, as far as name was concerned, by arranging several shades in order of brightness—but the order was very different from that which another person would have selected. The greens were grouped, some with yellows, and some with blues.

The colours in this experiment were all negative and impure, but we may also obtain something like the same result with positive colour, transmitted by the aid of polarized light through plates of mica. In a case of this kind described by Sir J. Herschel, the only colours seen were blue and yellow, while pale pinks and greens were regarded as cloudy white, fine pink as very pale blue, and crimson as blue; white red, ruddy pink, and brick red were all yellows, and fine pink blue, with much yellow. Dark shades of red, blue, or brown, were considered as merely dark, no colour being recognized.

The account of Dr. Dalton’s own peculiarity of vision by himself, offers considerable interest. He says, speaking of flowers: “With respect to colours that were white, yellow, or green, I readily assented to the appropriate term; blue, purple, pink, and crimson appeared rather less distinguishable, being, according to my idea, all referable to blue. I have often seriously asked a person whether a flower was blue or pink, but was generally considered to be in jest.” He goes on further to say, as the result of his experience: “1st. In the solar spectrum three colours appear, yellow, blue, and purple. The two former make a contrast; the two latter seem to differ more in degree than in kind. 2nd. Pink appears by daylight to be sky-blue a little faded; by candlelight it assumes an orange or yellowish appearance, which forms a strong contrast to blue. 3rd. Crimson appears muddy blue by day, and crimson woollen yarn is much the same as dark blue. 4th. Red and scarlet have a more vivid and flaming appearance by candlelight than by daylight” (owing probably to the quantity of yellow light thrown upon them).

As anecdotes concerning this curious defect of colour vision, we may quote also the following: “All crimsons appeared to me (Dr. Dalton) to be chiefly of dark blue, but many of them have a strong tinge of dark brown. I have seen specimens of crimson claret and mud which were very nearly alike. Crimson has a grave appearance, being the reverse of every showy or splendid colour.” Again: “The colour of a florid complexion[408] appears to me that of a dull, opaque, blackish blue upon a white ground. Dilute black ink upon white paper gives a colour much resembling that of a florid complexion. It has no resemblance to the colour of blood.” We have a detailed account of the case of a young Swiss, who did not perceive any great difference between the colour of the leaf and that of the ripe fruit of the cherry, and who confounded the colour of a sea-green paper with the scarlet of a riband placed close to it. The flower of the rose seemed to him greenish blue, and the ash gray colour of quick-lime light green. On a very careful comparison of polarized light by the same individual, the blue, white, and yellow were seen correctly, but the purple, lilac, and brown were confounded with red and blue. There was in this case a remarkable difference noticed according to the nature and quantity of light employed; and as the lad seemed a remarkably favourable example of the defect, the following curious experiment was tried. A human head was painted, and shown to the colour-blind person, the hair and eyebrows being white, the flesh brownish, the lips and cheeks green. When asked what he thought of this head? the reply was, that it appeared natural, but that the hair was covered with a nearly white cap, and the carnation of the cheeks was that of a person heated by a long walk.

There is an interesting account in the Philosophical Transactions for 1859 (p. 325), which well illustrates the ideas entertained by persons in this condition with regard to their own state. The author, Mr. W. Pole, a well-known civil engineer, thus describes his case:—“I was about eight years old when the mistaking of a piece of red cloth for a green leaf betrayed the existence of some peculiarity in my ideas of colour; and as I grew older, continued errors of a similar kind led my friends to suspect that my eyesight was defective; but I myself could not comprehend this, insisting that I saw colours clearly enough, and only mistook their names.

“I was articled to a civil engineer, and had to go through many years’ practice in making drawings of the kind connected with this profession. These are frequently coloured, and I recollect often being obliged to ask in copying a drawing what colours I ought to use; but these difficulties left no permanent impression, and up to a mature age I had no suspicion that my vision was different from that of other people. I frequently made mistakes, and noticed many circumstances in regard to colours, which temporarily perplexed me. I recollect, in particular, having wondered why the beautiful rose light of sunset on the Alps, which threw my friends into raptures, seemed all a delusion to me. I still, however, adhered to my first opinion, that I was only at fault in regard to the names of colours, and not as to the ideas of them; and this opinion was strengthened by observing that the persons who were attempting to point out my mistakes, often disputed among themselves as to what certain hues of colour ought to be called.” Mr. Pole adds that he was nearly thirty years of age when a glaring blunder obliged him to investigate his case closely, and led to the conclusion that he was really colour-blind.

All colour-blind persons do not seem to make exactly the same mistakes,[409] or see colours in the same way; and there are, no doubt, many minor defects in appreciating, remembering, or comparing colours which are sufficiently common, and which may be superadded to the true defect—that of the optic nerve being insensible to the stimulus of pure red light. It has been asserted by Dr. Wilson, the author of an elaborate work on the subject, that as large a proportion as one person in every eighteen is colour-blind in some marked degree, and that one in every fifty-five confounds red with green. Certainly the number is large, for every inquiry brings out several cases; but, as Sir John Herschel remarks, were the average anything like this, it seems inconceivable that the existence of the defect should not be one of vulgar notoriety, or that it should strike almost all uneducated persons, when told of it, as something approaching to absurdity. He also remarks, that if one soldier out of every fifty-five was unable to distinguish a scarlet coat from green grass, the result would involve grave inconveniences that must have attracted notice. Perhaps the fact that a difference of tint is recognized, although the eye of the colour-blind person does not appreciate any difference of colour, when red, green, and other colours are compared together, and that every one is educated to call certain things by certain names, whether he understands the true meaning of the name or not, may help to explain both the slowness of the defective sight to discover its own peculiarity, and the unwillingness of the person of ordinary vision to admit that his neighbour really does not see as red what he agrees to call red.

There is, however, another consideration that this curious subject leads to. It is known that out of every 10,000 rays issuing from the sun, and penetrating space at the calculated rate of 200,000 miles in each second of time, about one-fifth part is altogether lost and absorbed in passing through the atmosphere, and never reaches the outer envelope of the human eye. It is also known that of the rays that proceed from the sun, some produce light, some heat, and some a peculiar kind of chemical action to which the marvels of photography are due. Of these only the light rays are appreciated specially by the eye, although the others are certainly quite as important in preserving life and carrying on the business of the world. Who can tell whether, in addition to the rays of coloured light that together form a beam of white light, four-fifths of which only pass through the atmosphere, there may not have emanated from the sun other rays altogether absorbed and lost? or whether in entering the human eye, or being received on the retina at the back of the eye, or made sensitive by the optic nerve, there may not have been losses and absorptions sufficient to shut out from us, who enjoy what we call perfect vision, some other sources of information. How, in a word, do we who see clearly only three or four colours, and their various combinations, together with their combined white light—how do we know that to beings otherwise organized, the heat, or chemical rays, or others we are not aware of, may not give distinct optical impressions? We may meet one person whose sense of hearing is sufficiently acute to enable him to hear plainly the shrill night-cry of the bat, often totally inaudible, while his friend and daily companion cannot perhaps distinguish the noise[410] of the grasshopper, or the croaking of frogs, and yet neither of these differs sufficiently from the generality of mankind to attract attention, and both may pass through life without finding out their differences in organization, or knowing that the sense of hearing of either is peculiar. So undoubtedly it is with light. There may be some endowed with visual powers extraordinarily acute, seeing clearly what is generally altogether invisible; and this may have reference to light generally, or to any of the various parts of which a complete sunbeam is composed. Such persons may habitually see what few others ever see, and yet be altogether unaware of their powers, as the rest of the world would be of their own deficiency.

The case of the colour-blind person is the converse. He sees, it is true, no green in the fields, or on the trees, no shade of pink mantling in the countenance, no brilliant scarlet in the geranium flower, but still he talks of these things as if he saw them, and he believes he does see them, until by a long process of investigation he finds out that the idea he receives from them is very different from that received by his fellows. He often, however, lives on for years, and many have certainly lived out their lives without guessing at their deficiency.

These results of physical defects of certain kinds remaining totally unknown, either to the subject of them or his friends, even when all are educated and intelligent, are certainly very curious; but it will readily be seen that they are inevitable in the present development of our faculties. In almost everything, whether moral or intellectual, we measure our fellows by our own standard. He whose faculties are powerful, and whose intellect is clear, looks over the cloud that hovers over lower natures, and wonders why they, too, will not see truth and right as he sees them. Those, on the other hand, who dwell below among the mists of error and the trammels of prejudice, will not believe that their neighbour, intellectually loftier, sees clearly over the fog and malaria of their daily atmosphere.

In taking leave of the question of colour blindness, it should be mentioned that hitherto no case has been recorded in which this defect extends to any other ray than the red.

There seems no reason for this, and possibly, if they were looked for, cases might be found in which the insensibility of the optic nerve had reference to the blue instead of the red ray—the least instead of the most refrangible part of the beam of light. It would also be well worth the trial if those who have any reason to suppose that they enjoy a superiority of vision would determine by actual experiment the extent of their unusual powers, and learn whether they refer to an optical appreciation of the chemical or heat rays, or show any modification of the solar spectrum by enlargement or otherwise.