WITH A COMPLETE DESCRIPTION OF

AMERICAN COINAGE,

From the earliest period to the present time. The

Process of Melting, Refining, Assaying, and

Coining Gold and Silver fully described:

WITH BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCHES OF

Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, Robert Morris, Benjamin Rush,

John Jay Knox, James P. Kimball, Daniel M. Fox, and the Mint

Officers from its foundation to the present time.

TO WHICH ARE ADDED

A GLOSSARY OF MINT TERMS

AND THE

LATEST OFFICIAL TABLES

OF THE

Annual Products of Gold and Silver in the different

States, and Foreign Countries, with Monetary

Statistics of all Nations.

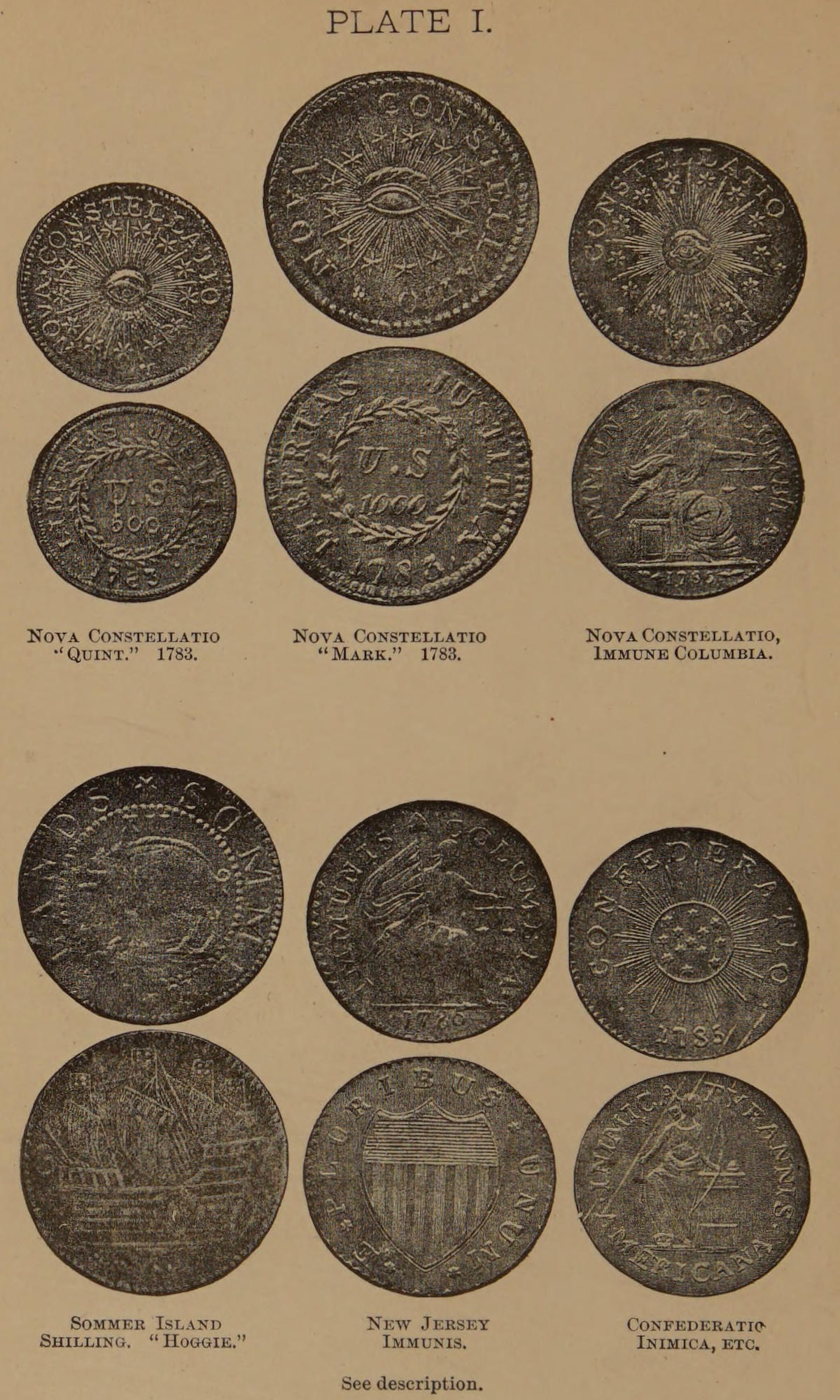

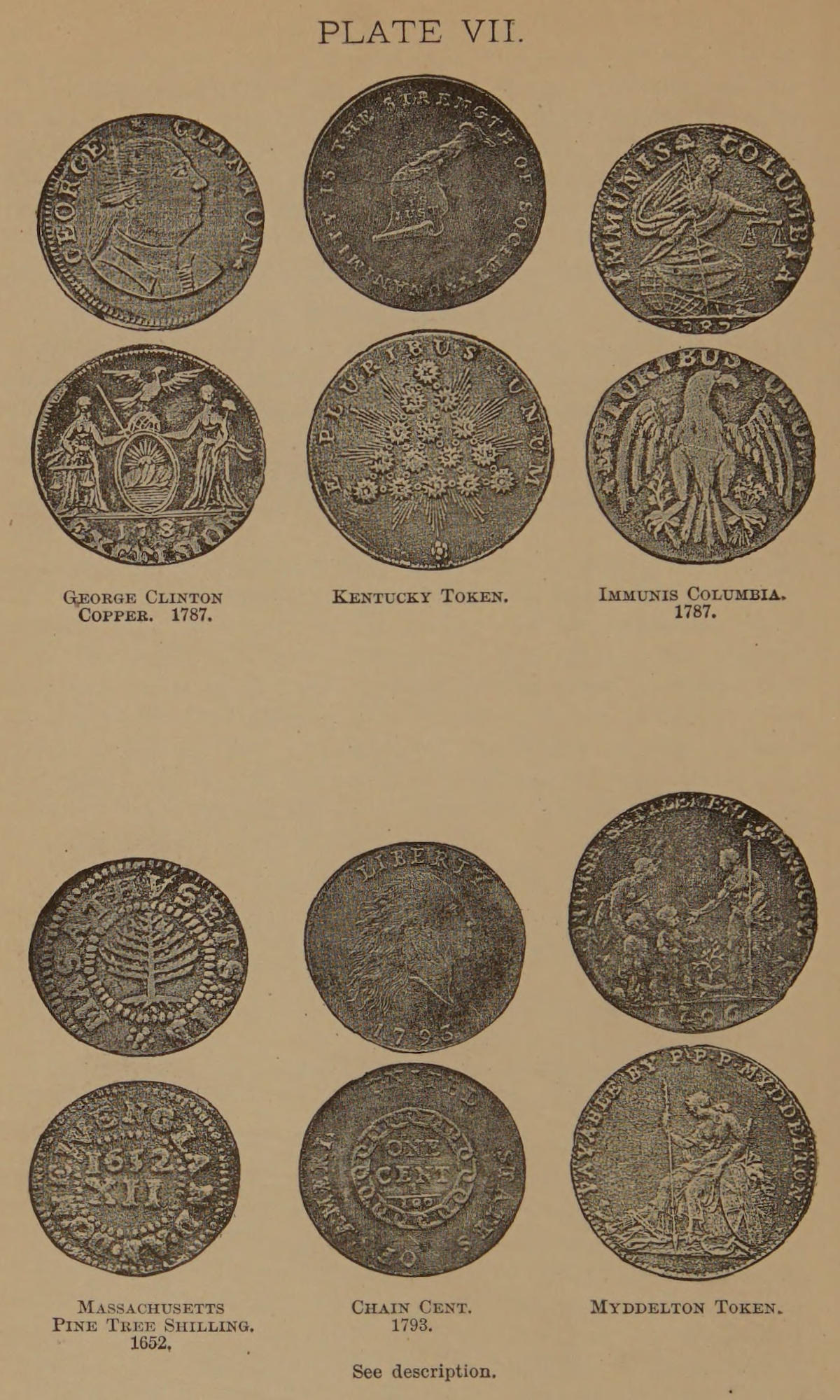

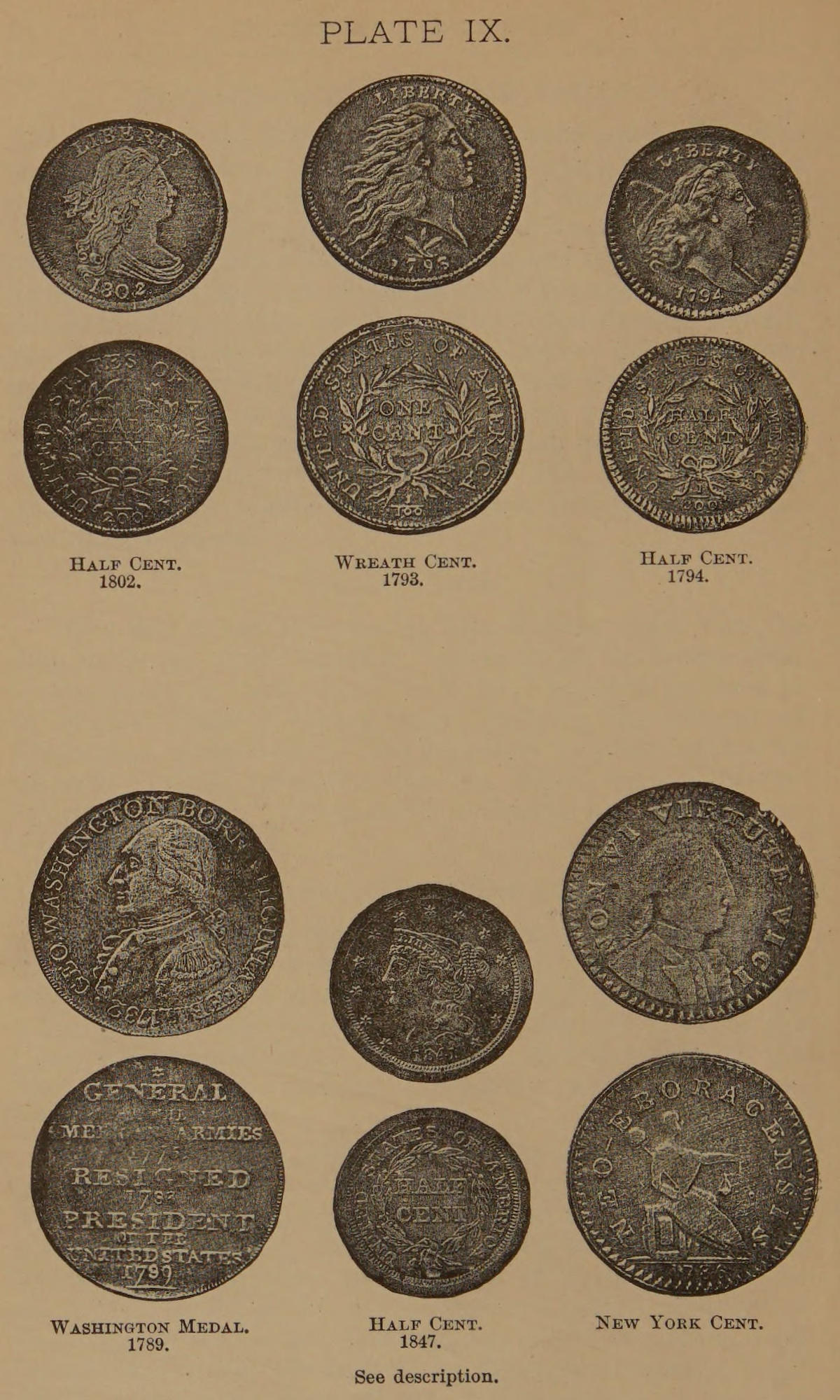

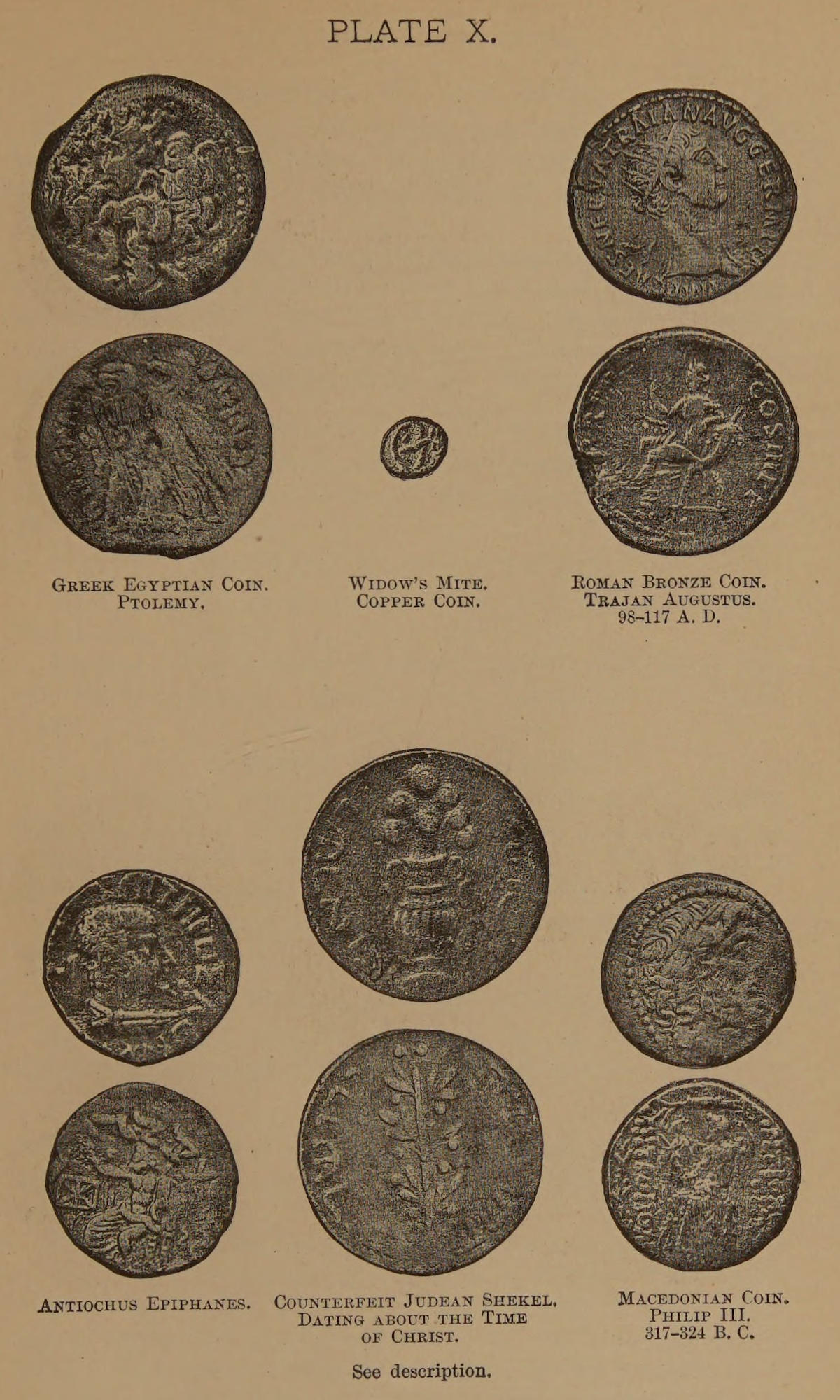

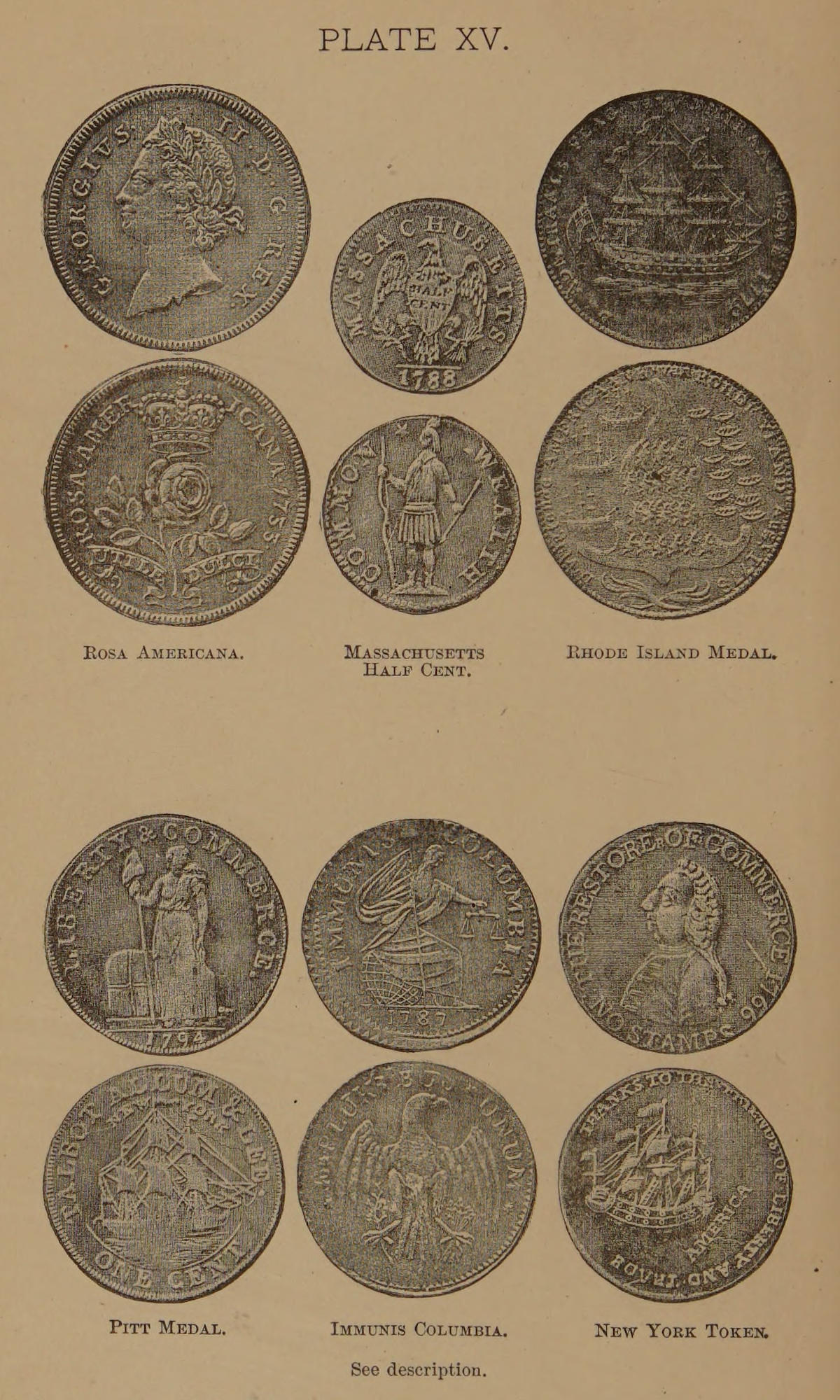

ILLUSTRATED with PHOTOTYPES, STEEL PLATE PORTRAITS and WOOD ENGRAVINGS,

with NUMEROUS PLATES of Photographic Reproductions of RARE AMERICAN

COINS, and Price List of their numismatic value.

New Revised Edition, Edited by the Publisher.

PHILADELPHIA:

GEORGE G. EVANS, Publisher.

1888.

Copyrighted by

George G. Evans.

1885.

Recopyrighted, 1888.

DUNLAP & CLARKE,

Printers and Book Binders.

819-21 Filbert Street,

Philadelphia.

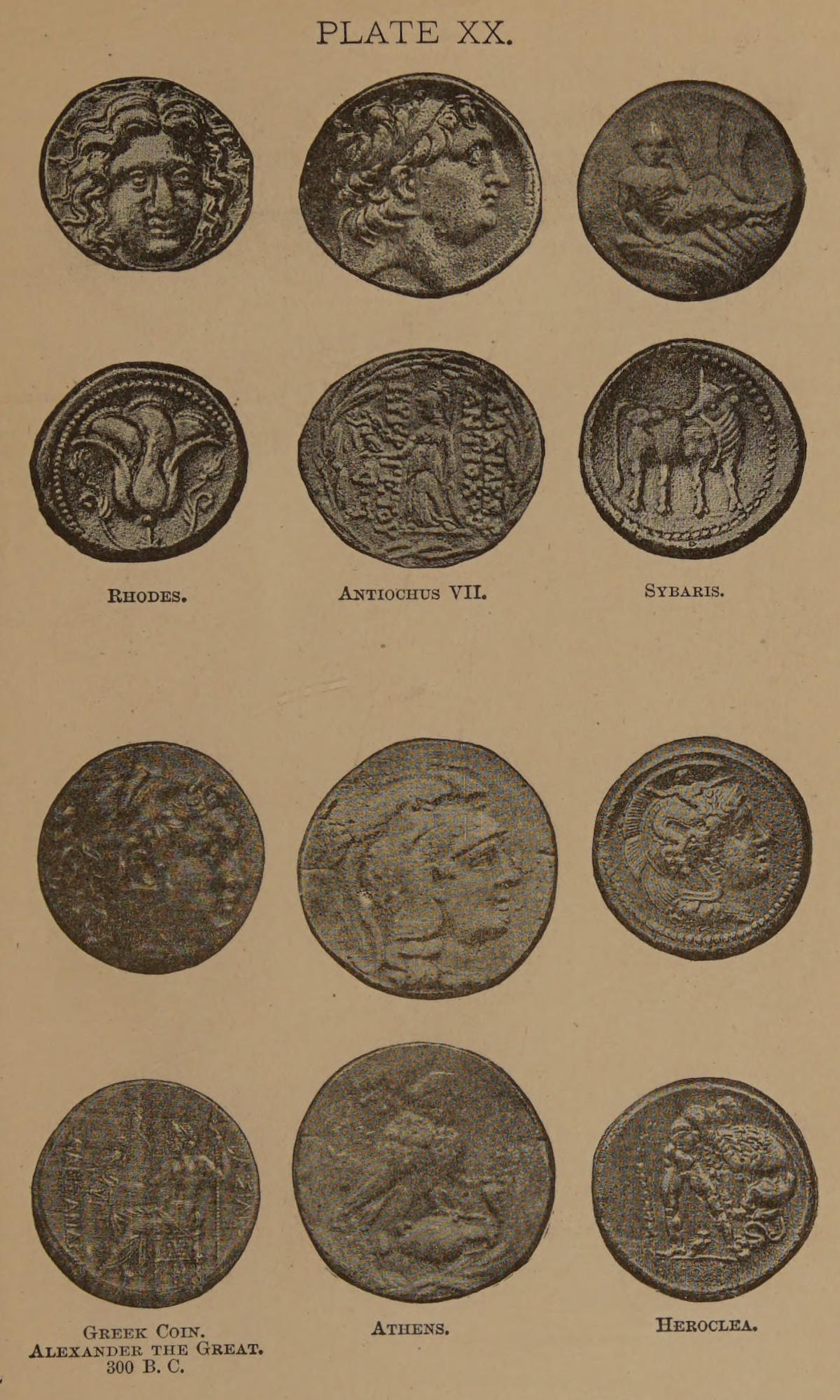

The need of a circulating medium of exchange has been acknowledged since the earliest ages of man. In the primeval days, bartering was the foundation of commercial intercourse between the various races; but this gave way in time, as exchanges increased. In the different ages many commodities have been made to serve as money,—tin was used in ancient Syracuse and Britain; iron, in Sparta; cattle, in Rome and Germany; platinum, in Russia; lead, in Burmah; nails, in Scotland; silk, in China; cubes of pressed tea, in Tartary; salt, in Abyssinia; slaves, amongst the Anglo Saxons; tobacco, in the earliest settlements of Virginia; codfish, in New Foundland; bullets and wampum, in Massachusetts; logwood, in Campeachy; sugar, in the West Indies; and soap, in Mexico. Money of leather and wood was in circulation in the early days of Rome; and the natives of Siam, Bengal, and some parts of Africa used the brilliantly-colored cowry shell to represent value, and some travelers allege that it is still in use in the remote portions of the last-named country. But the moneys of all civilized nations have been, for the greater part, made of gold, silver, copper, and bronze. Shekels of silver are mentioned in the Bible as having existed in the days of Abraham, but the metals are believed to have been in bars, from which proportionate weights were chipped to suit convenience. The necessity for some convenient medium having an intrinsic value of its own led to coinage, but the exact date of its introduction is a question history has not yet determined. It is supposed the Lydians stamped metal to be used as money twelve hundred years before Christ, but the oldest coins extant were made 800 B. C., though it is alleged that the Chinese circulated a square bronze coin as early as 1120 B. C. All of these coins were rude and shapeless, and generally engraved with representations of animals, deities, nymphs, and the like; but the Greeks issued coins, about 300 B. C., which were fine specimens of workmanship, and which are not even surpassed in boldness and beauty of design by the products of the coiners of these modern times. Even while these coins were in circulation spits and skewers were accepted by the Greeks in exchange for products, just as wooden and metal coins were circulated[2] simultaneously in Rome, 700 B. C., and leather and metal coins in France, as late as 1360 A. D. The earliest coins bearing portraits are believed to have been issued about 480 B. C., and these were profiles. In the third century, coins stamped with Gothic front faces were issued, and after that date a profusion of coins were brought into the world, as every self-governing city issued money of its own. The earliest money of America was coined of brass, in 1612, and the earliest colonial coins were stamped in Massachusetts, forty years later.

Ancient and extensive as the use of money has been in all its numerous forms and varied materials, it merely represented a property value which had been created by manual labor and preserved by the organic action of society. In a primitive state, herds of cattle and crops of grain were almost the only forms of wealth; the natural tendency and disposition of men to accumulate riches led them to fix a special value upon the metals, as a durable and always available kind of property. When their value in this way was generally recognized, the taxes and other revenues, created by kings and other potentates, was collected in part or wholly in that form of money. The government, to facilitate public business, stamped the various pieces of metal with their weight and quality, as they were received at the Treasury; and according to these stamps and marks, the same pieces were paid out of the Treasury, and circulated among the people at an authorized and fixed value. The next step was to reduce current prices of metal to a uniform size, shape, and quality, value and denomination, and make them, by special enactment, a legal tender for the payment of all taxes or public dues.

Thus, a legalized currency of coined money was created, and the exchangeable value of the various metals used for that purpose fully established, to the great convenience of the world at large.

The die for the obverse of the piece to be struck having been engraved, so as to properly present the religious or national symbol used for a device and whatever else was to be impressed upon the coin, was fixed immovably in an anvil or pedestal, face upwards. The lumps or balls of metal to be coined, having been made of a fixed and uniform weight and nearly of an oblate sphere in form, were grasped in a peculiarly constructed pair of tongs and laid upon the upturned die. A second operative then placed a punch squarely upon the ball of metal; heavy blows from a large hammer forced the punch down until the metal beneath it had been forced into every part of the die, and a good impress secured. In the meantime the punch[3] would be imbedded in the lump of metal, and on being withdrawn the reverse of the coin would show a rough depression corresponding to the shape given the end of the punch, thereby making an uneven surface and disfiguring the piece; punch marks gradually developed into forms, and these forms combined with figures wrought into artistic design, until, by degrees, the punch itself became a die, making the reverse of each piece upon which it was used equal in every respect to the obverse of which it was the opposite. This perfection of the reverse was, however, secured at the expense of the effectiveness of the punch for its original purpose.

The striking of coin between two dies, which were required to accurately oppose each other, was an operation requiring great dexterity, and the results were not at all certain. The artisans at this stage of the work, hit upon the expedient of using both the obverse and reverse die in a ring of such a size and depth, as to be a guide to each of them. The balls or disks of metal being struck inside the ring, between the dies, were forced to assume an even thickness, and a circular form corresponding with the inside of the ring. After the ring had been used in this way for some time, it was engraved upon the inside, and the coins produced were not only circular in shape, but stamped upon their edges. Thus was produced the perfect coin, and through the introduction of machinery has secured uniformity in the result and saved an immense amount of labor in striking vast sums of money; the artistic beauty of some of the antique specimens has not been surpassed in modern times.

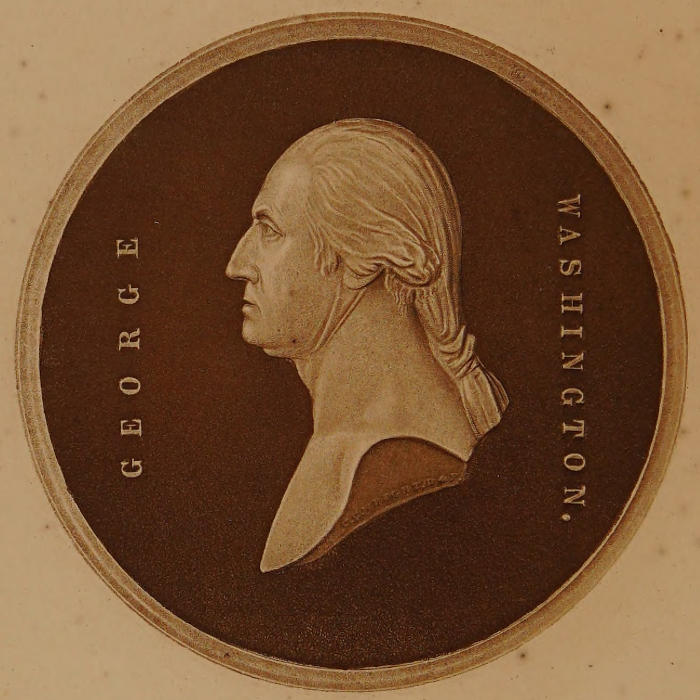

It is said that no human head was ever stamped upon coins until after the death of Alexander the Great; he being regarded as somewhat of a divinity, his effigy was impressed upon money, like that of other gods.

The knowledge of coins and medals, through the inscriptions and devices thereon, is, to an extent, a history of the world from that date in which metals were applied to such uses. Events engraven upon these, remain hidden in tombs or buried in the bosom of the earth, deposited there in ages long past, by careful and miserly hands, only awaiting the research of the patient investigator to tell the story of their origin. Numismatic treasures are scanned as evidence of facts to substantiate statements upon papyrus or stone, and dates are often supplied to define the border line between asserted tradition and positive history. Gibbon remarks: “If there were no other record of Hadrian, his career would be found written upon the coins of his reign.”

The rudeness or perfection of coins and medals furnish testimony of the character and culture of the periods of their production. This is equally true of that rarest specimen of antiquity, the Syracusan silver medal—the oldest known to collectors—and the latest triumph of the graver’s art in gold, the Metis medal.

It is not generally known that the rarest portraits of famous heroes are found upon coins and medals. The historian, especially the historic artist, is indebted to this source alone for the portraits of Alexander, Ptolemy, Cleopatra, Mark Antony, Cæsar, and many other celebrities. Perhaps the valuation of a rare coin or medal may be estimated by reference to one piece in the Philadelphia Mint. It is an Egyptian coin as large as a half-eagle, and has on the obverse the head of the wife of Ptolemy—Arsinoe—the only portrait of her yet discovered.

Are not alone recorded; and as an example of a very different nature may be cited the medals commemorating the destruction of Jerusalem, and the whole series marking that episode, especially those classed “Judæa capta.” They tell sadly of a people’s humiliation: the tied or chained captive; the mocking goddess of victory, all made more real by reason of the introduction, on the reverse of each piece, of a Jewess weeping bitterly, and though she sits under a palm-tree, the national lament of another captivity is forcibly recalled.

An interesting specimen of the series above mentioned was recently found in the south of France called, “Judæa Navillas,” valuable particularly because it strengthens Josephus’s assertion which had provoked some comment, viz.: the fact of the escape of a large number of Jews from the Romans, by means of ships, at Joppa.

Coins and medals mark the introduction of laws; for example, an old Porcian coin gives the date of the “law of appeal,” under which, two centuries and a half later, Paul appealed to Cæsar. Another relic dates the introduction of the ballot-box; and a fact interesting to the agriculturist is established by an old silver coin of Ptolemy, upon which a man is represented cutting millet (a variety of Indian corn) with a scythe. Religions have been promulgated by coins. Islamism says upon a gold coin, “No God but God. Mohammed is the Prophet and God’s chosen apostle.”

Persian coins, in mystic characters, symbolize the dreadful sacrifices of the Fire-Worshippers. Henry VIII, with characteristic egotism, upon a medal announces in Hebrew, Greek, and Latin: “Henry Eighth, King of England, France, and[5] Ireland; Defender of the Faith, and in the land of England and Ireland, under Christ, the Supreme Head of the Church.”

We also find stamped upon coins and medals the costumes of all ages, from the golden net confining the soft tresses of the “sorceress of the Nile,” and the gemmed robe of Queen Irene, to the broidered stomacher of Queen Anne, and the stately ruff of Elizabeth of England.

In this connection may be mentioned the “bonnet piece” of Scotland, a coin of the reign of James VI., which is extremely rare, one of them having been sold for £41. The coin received its name from a representation of the king upon it, with a curiously plaited hat or bonnet which this monarch wore, a fashion that gave occasion for the ballad, “Blue Bonnets over the Border.”

Are faithfully preserved through this medium; in truth, medalic honors may be claimed as the very foundation of heraldic art. We discover medals perpetuating revolutions, sieges, plots, and murders, etc. We prefer directing attention to the fact that coins and medals are not only the land-marks of history, but a favorite medium of the poetry of all nations. Epics are thus preserved by the graver’s art in exceedingly small space. Poets turn with confidence to old coins for symbol as well as fact.

One of the most graceful historical allusions is conveyed in the great seal of Queen Anne, after the union of Scotland with England. A rose and a thistle are growing on one stem, while, from above, the crown of England sheds effulgence upon the tender young plant.

The medal of George I., on the reverse, boastfully presents “the horse of Brunswick” flying over the northwest of Europe, symbolizing the Hanoverian succession. The overthrow of the “Invincible Armada” was the occasion of a Dutch medal, showing the Hollanders richer in faith than in art culture, for the obverse of this medal presents the church upon a rock, in mid-ocean, while the reverse suggests the thought that the luckless Spanish mariner was driving against the walls of the actual building.

Architecture is largely indebted to coins, medals, and seals for accuracy and data. We learn from the medal of Septimus[6] Severus the faultless beauty of the triumphal arch erected to celebrate his victory over Arabs and Parthians. This medal was produced two centuries before the Christian era, and is a marvel of art, for its perspective is wrought in bas-relief—an achievement which was not again attained before the execution of the celebrated Bronze Gates by Ghiberti, for the Baptistery at Florence, A. D. 1425. This exhumed arch was excavated long after its form and structure were familiar to men of letters through the medals.

The effect of coin on language is direct, and many words may be found whose origin was a coin, such as Daric, a pure gold coin; Talent, mental ability; Sterling, genuine, pure; while Guinea represents the aristocratic element, and, though out of circulation long ago, “no one who pretends to gentility in England would think of subscribing to any charity or fashionable object by contributing the vulgar pound. An extra shilling added to the pound makes the guinea, and lifts the subscriber at once into the aristocratic world.”

Copper is much preferred to gold for medals. Its firm, unchanging surface accepts and retains finer lines than have yet been produced upon gold and silver, and it offers no temptation to be thrown into the crucible.[1]

In the preparation of this work, I am much indebted to several gentlemen connected with the United States Mint; also, to Messrs. R. Coulton Davis, Ph.G., and E. Locke Mason, who are acknowledged authority on the subject of numismatics.

If it shall be found useful to the public, and especially to visitors of the Mint, it will be a source of satisfaction, and more than repay the labor bestowed in its preparation.

G. G. E.

Philadelphia, March 1, 1888.

The subject of a National Mint for the United States was first introduced by Robert Morris,[2] the patriot and financier of the revolution; as head of the Finance Department, Mr. Morris was instructed by Congress to prepare a report on the foreign coins, then in circulation in the United States. On the 15th of January, 1782, he laid before Congress an exposition of the whole subject. Accompanying this report was a plan for American coinage. But it was mainly through his efforts, in connection with Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton, that a mint was established in the early history of the Union of the States. On the 15th of April, 1790, Congress instructed the Secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton, to prepare and report a proper plan for the establishment of a National Mint, and Mr. Hamilton presented his report at the next session. An act was framed establishing the mint, which finally passed both Houses and received President Washington’s approval April 2, 1792.[3]

1781. July 16th. Wrote to Mr. Dudley at Boston inviting him hither in consequence of the Continental Agent Mr. Bradford’s Letter respecting him referred to me by Congress.

July 17th. Wrote Mr. Bradford respecting Mr. Dudley.

Nov. 10th. Ordered some money on application of Mr. Dudley to pay his expences.

Nov. 12th. Sent for Mr Dudley to consult him respecting the quantity of Alloy Silver will bear without being discoloured, he says he can put 6 drops into an ounce. Desired him to assay some Spanish Dollars and French Crowns, in order to know the quantity of pure Silver in each.

Nov. 16th. Mr. Dudley assayed a number of Crowns and dollars for our information respecting the Mint.

1782. Jan. 2d. Mr. Benjamin Dudley applied for money to pay his Board which I directed to be paid by Mr. Swanwick, this gentleman is detained at the public expence as a person absolutely necessary in the Mint, which I hope soon to see established. My propositions on that subject are to be submitted to Congress so soon as I can get the proper assays made on Silver coins &c.

Jan. 7th. Mr. Dudley applies about getting his wife from England. I promised him every assistance in my power.[4]

Jan. 18th. I went to Mr. Gouvr. Morris’s Lodging to examine the plan we had agreed on, and which we had drawn up respecting the Establishment of a Mint, we made some alterations and amendments to my satisfaction and from a belief that this is a necessary and salutary measure. I have ordered it copied to be sent into Congress.

Jan. 26th. Mr. Dudley applied for money to pay his Lodgings &c. I ordered Mr. Swanwick to supply him with fifty dollars, informed him that the Plan of a Mint is before Congress, and when passed, that he shall be directly employed, if not agreed to by Congress, I shall compensate him for his time &c.

Feb. 26th. Mr. Benjamin Dudley brought me the rough drafts or plan for the rooms of a Mint &c. I desired him to go to Mr. Whitehead Humphreys to consult him about Screws, Smithwork &c. that will be wanted for the Mint, and to bring me a list thereof with an estimate of the Cost.

Feb 28th. Mr. Dudley informs me that a Mr. Wheeler, a Smith in the Country, can make the Screws, Rollers &c. for the Mint. Mr. Dudley proposes the Dutch Church, that which is now unoccupied, as a place suitable for the Mint, I sent him to view it, & he returns satisfied that it will answer, wherefore I must enquire about it.

March 22d. Mr. Dudley and Mr. Wheeler came and brought with them some Models of the Screws and Rollers necessary for the Mint. I found Mr. Wheeler entertained some doubts respecting one of these Machines which Mr. Dudley insists will answer the purposes and says he will be responsible for it. I agreed with Mr. Wheeler that he should perform the work; and, as neither he or I could judge of the value that ought to be paid for it, he is to perform the same agreeable to Mr. Dudley’s directions, and when finished, we are to have it valued by some Honest Man, judges of such work, he mentioned Philip Syng, Edwd. Duffield, William Rush and —— all of whom I believe are good judges and very honest men, therefore I readily agreed to this proposition. And I desired Mr. Dudley to consult Mr. Rittenhouse and Francis Hopkinson Esquire, as to the Machine or Wheel in dispute, and let me have their opinion.

March 23d. Mr. Dudley called to inform me that Mr. Rittenhouse & Mr. Hopkinson agree to his plan of the Machine &c.

April 12th. Mr. Dudley wants a horse to go up to Mr. Wheelers &c.

May 20th. Mr. Dudley wrote me a Letter this day and wanted money. I directed Mr. Swanwick to supply him, and then disired him to view the Mason’s Lodge to see if it would Answer for a Mint, which he thinks it will, I desired him to go up to Mr. Wheelers to see how he goes on with the Rollers &c.

June 17th. Mr. Dudley applied for money to pay his Bill. I directed Mr. Swanwick to supply him.

June 18th. Issued a warrant in favor of B. Dudley £7.11.6.

July 15th. Mr. B. Dudley applied for money, he is very uneasy for want of employment, and the Mint in which he is to be employed and for which I have engaged him, goes on so slowly that I am also uneasy at having this gentleman on pay and no work for him. He offered to go and assist Mr. Byers to establish the Brass Cannon Foundry at Springfield. I advised to make that proposal to Genl. Lincoln and inform me the result to-morrow.[5]

July 16th. Mr. B. Dudley to whom I gave an order on Mr. Swanwick for fifty dollars, and desired him to seek after Mr. Wheeler to know whether the Rollers &c. are ready for him to go to work on rolling the copper for the Mint.

August 22d. Mr. Saml. Wheeler who made the Rollers for the Mint, applies for money. I had a good deal of conversation with this ingenious gentleman.

August 26th. Mr. Dudley called and pressed very much to be set at work.

Sept 3d. Mr. B. Dudley applied for a passage for his Friend Mr. Sprague, pr. the Washington to France & for Mrs. Dudley back. Mr. Wheeler applied for money which I promised in a short time.

Sept. 4th. Mr. Wheeler for money. I desired him to leave his claim with Mr. McCall Secretary in this office, and I will enable the discharge of his notes in the Bank when due.

Novr. 8th. Mr. Dudley applies for the amount of his Bill for Lodgings and Diet &c. and I directed Mr. Swanwick to pay him, but am very uneasy that the Mint is not going on.

Dec. 23d. Mr. Dudley and Mr. Wilcox brought the subsistance paper, and I desired Mr. Dudley to deliver 4000 sheets to Hall and Sellers.[6]

Decr. 26th. Mr. Hall the printer brought 100 Sheets of the subsistence notes this day, and desired that more paper might be sent to his Printing Office, accordingly I sent for Mr. Dudley and desired him to deliver the same from time to time, until the whole shall amount to 4000 Sheets.

1783. April 2d. I sent for Mr. Dudley who delivered me a piece of Silver Coin, being the first that has been struck as an American Coin.

April 16th. Sent for Mr. Dudley and urged him to produce the Coins to lay before Congress to establish a Mint.

April 17th. Sent for Mr. Dudley to urge the preparing of Coins &c. for Establishing a Mint.

April 22d. Mr. Dudley sent in several Pieces of Money as patterns of the intended American Coins.

May 6th. Sent for Mr. Dudley and desired him to go down to Mr. Mark Wilcox’s, to see 15,000 Sheets of paper made fit to print my Notes on.

May 7th. This day delivered Mr. Dudley the paper Mold for making paper, mark’d United States, and dispatched him to Mr. Wilcok’s, but was obliged to advance him 20 dollars.

May 27th. I sent for Mr. Dudley to know if he has compleated the paper at Mr. Wilcock’s paper mill for the Certificates intended for the pay of the Army. He says it is made, but not yet sufficiently dry for the printers use. I desired him to repair down to the Mill and bring it up as soon as possible.

May 28th. Mr. Whitehead Humphreys to offer his lot and buildings for erecting a Mint.

July 5th. Mr. Benjn. Dudley gave notice that he has received back from Messrs. Hall and Sellers the Printers, three thousand sheets of the last paper made by Mr. Wilcocks. I desired him to bring it to this office. He also informs of a Minting Press being in New York for sale, and urges me to purchase it for the use of the American Mint.

July 7th. Mr. Dudley respecting the Minting Press, but I had not time to see him.

August 19th. I sent for Mr. Benjamin Dudley, and informed him of my doubts about the establishment of a Mint, and desired him to think of some employment in private service, in which I am willing to assist him all in my power. I told him to make out an account for the services he had performed for the public, and submit at the Treasury office for inspection and settlement.

August 30th. Mr. Dudley brought the dies for Coining in the American Mint.

Sept. 3d. Mr. Dudley applies for money for his expenses which I agree to supply, but urge his going into private business.

Sept. 4th. Mr. Dudley for money, which is granted. Directed him to make three models for constructing Dry——

Nov. 21st. Mr. Dudley applies for money. He says he was at half a guinea a week and his expenses borne when he left Boston to come about the Mint, and he thinks the public ought to make that good to him. I desired him to write me and I will state his claims to Congress.

Nov. 26th. Mr. Dudley for money, which was granted.

Dec. 17th. Mr. Dudley with his account for final settlement. I referred him to Mr. Milligan.

1784. Jan. 5th. Mr. Dudley applies for a Certificate of the Time which he was detained in the public service. I granted him one accordingly.

Jan. 7th. Mr. Dudley after the settlement of his account, which I compleated by signing a warrant.

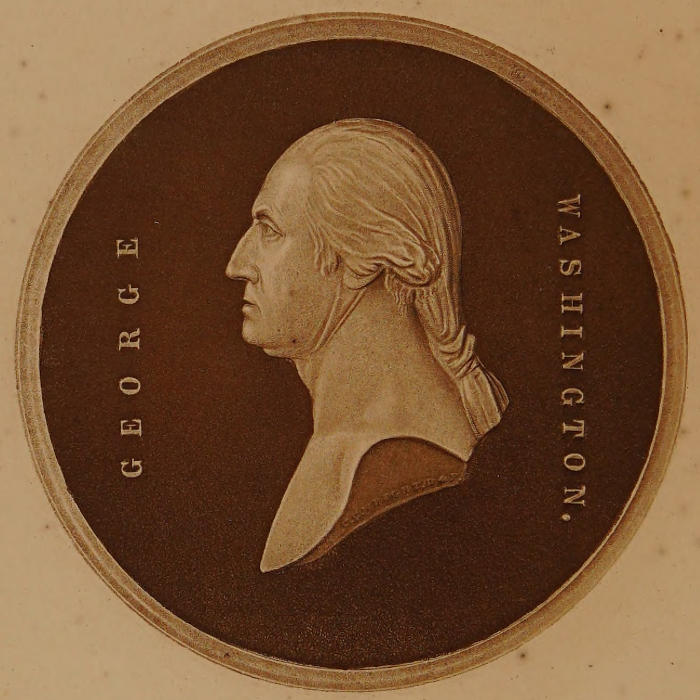

[Fac simile of original, photo-engraved by Levytype Company.]

Congress of the United States:

AT THE THIRD SESSION,

Begun and held at the City of Philadelphia, on

Monday the sixth of December, one thousand

seven hundred and ninety.

Resolved by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That a mint shall be established under such regulations as shall be directed by law.

Resolved, That the President of the United States be, and he is hereby authorized to cause to be engaged, such principal artists as shall be necessary to carry the preceeding resolution into effect, and to stipulate the terms and conditions of their service, and also to cause to be procured such apparatus as shall be requisite for the same purpose.

FREDERICK AUGUSTUS MUHLENBERG, Speaker of the House of Representatives.

JOHN ADAMS, Vice-President of the United States, and President of the Senate.

Approved, March the third, 1791.

GEORGE WASHINGTON, President of the United States.

Deposited among the Rolls in the Office of the Secretary of State.

Th. Jefferson Secretary of State.

The following is a copy of an old pay roll, framed and hanging upon the wall of the Cabinet.

Names and Salaries of the Officers, Clerks, and Workmen Employed at the Mint the 10th October, 1795.

| Henry Wm. DeSaussure, Director | @ 2,000 | Drs. | per Ann. |

| Nicholas Way, Treasurer | 1,200 | ” | ” |

| Henry Voigt, Chief Coiner | 1,500 | ” | ” |

| Albion Cox, Assayer | 1,500 | ” | ” |

| Robert Scott, Engraver | 1,200 | ” | ” |

| David Ott, Melter and Refiner pro tem. | 1,200 | ” | ” |

| Nathaniel Thomas, Clerk to the Treasurer | 700 | ” | ” |

| Isaac Hough, ditto to Director and Assayer | 500 | ” | ” |

| Lodewyk Sharp, ditto to Chief Coiner | 500 | ” | ” |

| John S. Gardiner, Assistant Engraver | 936 | ” | ” |

| Adam Eckfeldt, Die Forger and Turner | 500 | ” | ” |

| Workmen Employed in Chief Coiner’s Department. | ||

|---|---|---|

| Wages per day. | Doll. | Cts. |

| John Schreiner, Chief Pressman | 1 | 80 |

| John Cope, Chief Adjuster | 1 | 60 |

| William Hayley, Roller | 1 | 40 |

| Nicholas Sinderling, Annealer | 1 | 40 |

| John Ward, Miller | 1 | 20 |

| Joseph Germon, Drawer | 1 | 20 |

| Lewis Laurenger, Brusher | 1 | 20 |

| Henry Voigt, Junr, Adjuster | 88 | |

| Sarah Waldrake, ditto | 50 | |

| Rachael Summers, ditto | 50 | |

| Lewis Bitting, ditto | 1 | 20 |

| Lawrence Ford, ditto | 1 | 20 |

| Christopher Baum, Pressman | 1 | |

| John Keyser, ditto | 1 | |

| Frederick Bauck, ditto | 1 | |

| Barney Miers, Cleaner | 1 | |

| Martin Summers, Doorkeeper | 1 | |

| Adam Seyfert, Hostler | 1 | |

| John Bay, Boy. | 66 | |

| Workmen Employed at the Furnace of the Mint. | ||

| Peter LaChase, Melter | 1 | 60 |

| George Myers, ditto | 1 | 50 |

| Eberhart Klumback, ditto | 1 | 40 |

| Patrick Ryan, Filer | 1 | 25 |

| Valentine Flegler, Labourer | 1 | 25 |

| Andrew Brunet, ditto | 1 | |

| William Ryan, ditto | 1 | |

Endorsed in two places, “Names and Salaries of the Officers, Clerks and Workmen employed in the Mint the 10th Oct. 1795.”

THE FIRST MINT IN THE UNITED STATES, ERECTED IN 1792.

The popular estimation in which the Mint is held in the United States, is, for obvious reasons, more distinctively marked than that entertained for other public institutions. Its position, in a financial point of view, is so important, its use so apparent, and its integrity of management so generally conceded, that it enjoys a pre-eminence and dignity beyond that accorded to general governmental departments. Party mutations usually effect changes in its directorship, with but slight interference, however, with the other officials, as those of attainments, skill, and long experience in the professional branches, required to intelligently perform the various duties assigned, are few in all countries. Those occupying positions are chosen for their proficiency in the various departments, their characters being always above question. The confidence reposed in the officials of the United States Mint has never been violated, as, for nearly a century of its operations, no[14] shadow of suspicion has marred the fair name of any identified with its history.

The need of a mint in the Colonies was keenly felt to be a serious grievance against England for years before the Revolution, and as soon as practicable after the establishment of Independence, the United States Mint was authorized by an Act of Congress—April 2, 1792.

A lot of ground was purchased on Seventh Street near Arch, and appropriations were made for erecting the requisite buildings. An old still-house, which stood on the lot, had first to be removed. In an account book of that time we find an entry on the 31st of July, 1792, of the sale of some old materials of the still-house for seven shillings and sixpence, which “Mr. Rittenhouse directed should be laid out for punch in laying the foundation stone.”[7]

The first building erected in the United States for public use, under the authority of the Federal Government, was a structure for the United States Mint. This was a plain brick edifice, on the east side of Seventh street, near Arch, the corner-stone of which was laid by David Rittenhouse, Director of the Mint, on July 31, 1792. In the following October operations of coining commenced. It was occupied for about forty years. On the 19th of May, 1829, an Act was passed by Congress locating the United States Mint on its present site.

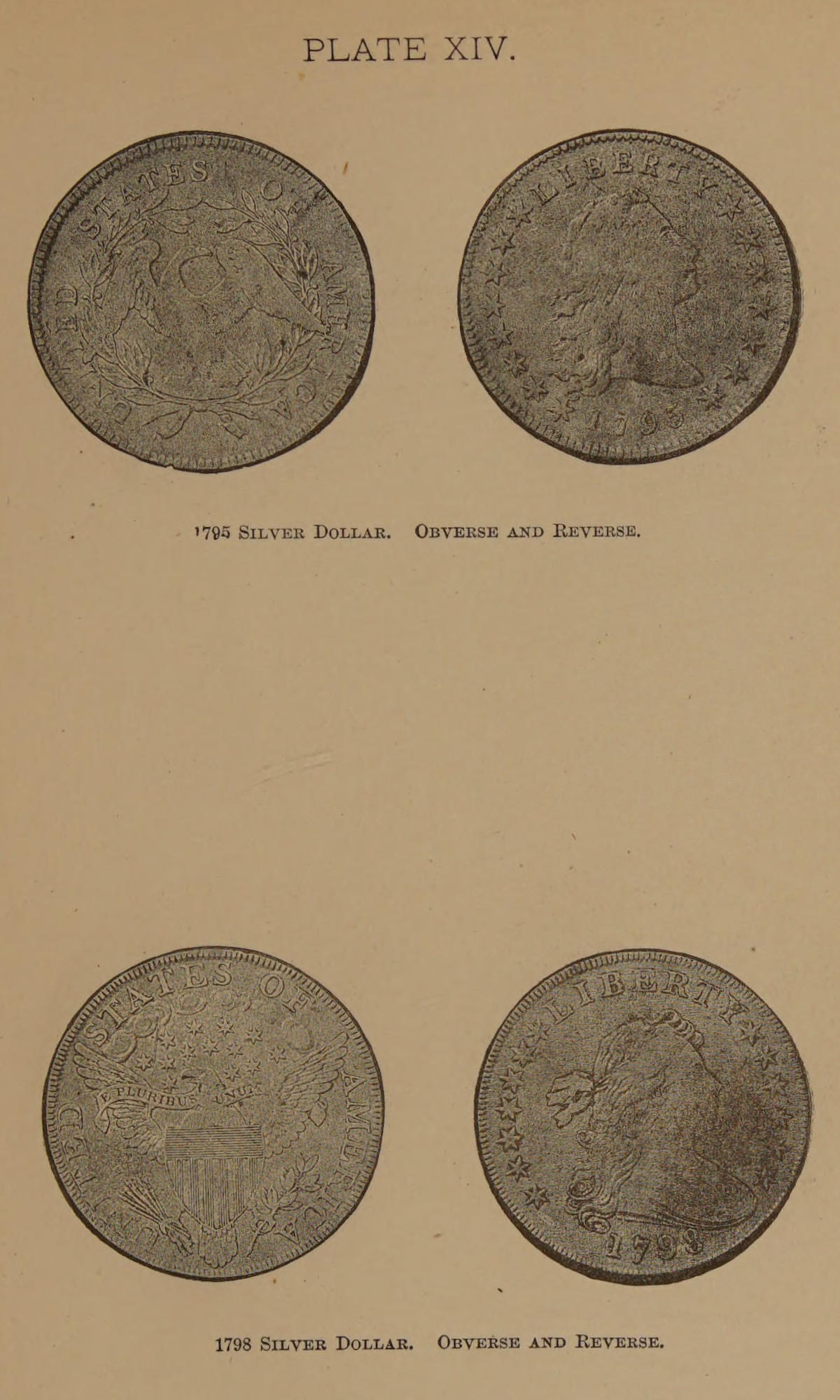

The first coinage of the United States, was silver half-dimes in October, 1792, of which Washington makes mention in his address to Congress, on November 6, 1792, as follows; “There has been a small beginning in the coinage of half-dimes; the want of small coins in circulation, calling the first attention to them.” The first metal purchased for coinage was six pounds of old copper at one shilling and three pence per pound, which was coined and delivered to the Treasurer, in 1793. The first deposit of silver bullion was made on July 18, 1794, by the Bank of Maryland. It consisted of “coins of France,” amounting to $80,715.73½. The first returns of silver coins to the Treasurer, was made on October 15, 1794. The first deposit of gold bullion for coinage, was made by Moses Brown, merchant, of Boston, on February 12, 1795; it was of gold ingots, worth $2,276.72, which was paid for in silver coins.

The first return of gold coinage, was on July 31, 1795, and consisted of 744 half eagles. The first delivery of eagles was in September 22, same year, and consisted of four hundred pieces.

Previous to the coinage of silver dollars, at the Philadelphia Mint, in 1794, the following amusing incidents occurred in Congress, while the emblems and devices proposed for the reverse field of that coin were being discussed.

A member of the House from the South bitterly opposed the choice of the eagle, on the ground of its being the “king of birds,” and hence neither proper nor suitable to represent a nation whose institutions and interests were wholly inimical to monarchical forms of government. Judge Thatcher playfully, in reply, suggested that perhaps a goose might suit the gentleman, as it was a rather humble and republican bird, and would also be serviceable in other respects, as the goslings would answer to place upon the dimes. This answer created considerable merriment, and the irate Southerner, conceiving the humorous rejoinder as an insult, sent a challenge to the Judge, who promptly declined it. The bearer, rather astonished, asked, “Will you be branded as a coward?” “Certainly, if he pleases,” replied Thatcher; “I always was one and he knew it, or he would never have risked a challenge.” The affair occasioned much mirth, and, in due time, former existing cordial relations were restored between the parties; the irritable Southerner concluding there was nothing to be gained in fighting with one who fired nothing but jokes.

The operations of the Mint throughout the year, are to commence at 5 o’clock in the morning, under the superintendence of an officer, and continue until 4 o’clock in the afternoon, except on Saturdays, when the business of the day will close at 2 o’clock, unless on special occasions it may be otherwise directed by an officer. Extra work will be paid for in proportion, on a statement being made of it through the proper officer, at the end of each month. A strict account is to be kept by one of the officers, as they may agree of the absentees from duty, if the absence be voluntary, the full wages for the time will be deducted, if it arise from sickness a deduction will be made at the discretion of the proper officer. A statement of these deductions will be rendered at the end of the month, and the several accounts made out accordingly.

The allowance under the name of drink money is hereafter to be discontinued, and in place of it three dollars extra wages per month will be allowed for the three summer months to those workmen who continue in the Mint through that season. No workman can be permitted to bring spirituous liquors into the Mint. Any workman who shall be found intoxicated within the Mint must be reported to the Director, in order that he may be discharged. No profane or indecent language can be tolerated in the Mint. Smoking within the Mint is inadmissible. The practice is of dangerous tendency; experience proves that this indulgence in public institutions, ends at last in disaster. Visitors may be admitted by permission of an officer, to see the various operations of the Mint on all working days except Saturdays and rainy days; they are to be attended by an officer, or some person designated by him. The new coins must not be given in[16] exchange for others to accommodate visitors, without the consent of the Chief Coiner. Christmas day and the Fourth of July, and no other days, are established holidays at the Mint. The pressmen will carefully lock the several coining presses when the work for the day is finished, and leave the keys in such places as the Chief Coiner shall designate. When light is necessary to be carried from one part of the Mint to the other, the watchman will use a dark lanthorn but not an open candle. He will keep in a proper arm chest securely locked, a musket and bayonet, two pistols and a sword. The arms are to be kept in perfect order and to be inspected by an officer once a month, when the arms are to be discharged and charged anew.

The watchman of the Mint must attend from 6 o’clock in the evening to 5 o’clock in the morning, and until relieved by the permission of an officer, or until the arrival of the door-keeper. He will ring the yard bell precisely every hour by the Mint clock, from 10 o’clock until relieved by the door-keeper, or an officer, or the workmen on working days, and will send the watch dog through the yard immediately after ringing the bell. He will particularly examine the departments of the engine and all the rooms where fire has been on the preceding day, conformably to his secret instructions. For this purpose he will have keys of access to such rooms as he cannot examine without entering them.

If an attempt be made on the Mint he will act conformably to his secret instructions on that subject. In case of fire occurring in or near the Mint, he will ring the Alarm Bell if one has been provided, or sound the alarm with his rattle, and thus as soon as possible bring some one to him who can be dispatched to call an officer, and in other particulars will follow his secret instructions. The secret instructions given him from time to time he must be careful not to disclose. The delicate trust reposed in all persons employed in the Mint, presupposes that their character is free from all suspicion, but the director feels it his duty nevertheless, in order that none may plead ignorance on the subject, to warn them of the danger of violating so high a trust. Such a crime as the embezzlement of any of the coins struck at the Mint, or of any of the metals brought to the Mint for coinage, would be punished under the laws of Pennsylvania, by a fine and penitentiary imprisonment at hard labor. The punishment annexed to this crime by the laws of the United States, enacted for the special protection of deposits made at the Mint, is DEATH. The 19th Section of the Act of Congress, establishing the Mint, passed April 12, 1792, is in the following words: Section 19, and be it further enacted, That if any of the gold or silver coins, which shall be struck or coined at the said Mint, shall be debased or made worse as to the proportion of fine gold or fine silver, therein contained, or shall be of less weight or value than the same ought to be, pursuant to the directions of this act, through the default or with the connivance of any of the officers or persons who shall be employed at said Mint, for the purpose of profit or gain, or otherwise, with a fraudulent intent, and if any of the said officers or persons shall embezzle any of the metal which shall at any time be committed to their charge, for the purpose of being coined, or any of the coins which shall be struck or coined at the said Mint, every such officer or person who shall commit any or either of the said offences, shall be deemed guilty of Felony, and shall suffer death. Printed copies of the Rules here recited are to be kept in convenient places for the inspection of the workmen, but as all may not be capable of reading them, it shall be the duty of the proper officer of the several departments, or such person as he may appoint, to read them in the hearing of the workmen, at least once a year, and especially to read them to every person newly employed in the Mint.

SAMUEL MOORE, Director.

Up to 1836 the work at the Mint was done entirely by hand or horse power. In that year steam was introduced. At different periods during the years 1797, 1798, 1799, 1802, and 1803, the operations of the Mint were suspended on account of the prevalence of yellow fever.

“Bond of Indemnity or Agreement of Operatives to return to the service of the Mint.” Dated August, 1799.

“We, the subscribers, do hereby promise and engage to return to the service of the Mint as soon as the same shall be again opened, after the prevailing fever is over, on the penalty of twenty pounds.”

“As witness our hands this 31st day of August, 1799.

The above are the signatures of the parties agreeing, written on old hand-made unruled foolscap paper.

This is part of the Mint records, which has been framed for convenience and protection. It hangs in the Cabinet.

The Mint was established by Act of Congress the second of April, 1792, and a few half-dimes were issued towards the close of that year. The general operations of the institution commenced in 1793. The coinage effected from the commencement of the establishment to the end of the year 1800 may be stated in round numbers at $2,534,000; the coinage of the decade ending 1810 amounted to $6,971,000, and within the ten years ending with 1820—$9,328,000. The amount within the ten years ending with 1830 is stated at $18,000,000, and the whole coinage from the commencement of the institution at $37,000,000. On the second of March, 1829, provisions were made by Congress for extending the Mint establishment, the supply of bullion for coinage having increased beyond the capacity of the existing accommodations. The Mint edifice, erected under this provision, stands on a lot purchased for the object at the northwest corner of Chestnut and Juniper streets, fronting 150 feet on Chestnut street and extending 204 feet to Penn Square, (the central and formerly the largest public square in the city). The corner-stone of the new edifice was laid on the fourth of July, 1829; the building is of marble and of the Grecian style of architecture, the roof being covered with copper. It presents on Chestnut street and Penn Square a front of 123 feet, each front being ornamented with a portico[18] of 60 feet, containing six Ionic columns. In the centre of the structure there was formerly a court-yard (now built up) extending 85 by 84 feet, surrounded by a piazza to each story, affording an easy access to all parts of the edifice. Present officers of the Mint: Hon. Daniel M. Fox, Superintendent; William S. Steel, Coiner; Jacob B. Eckfeldt, Assayer; Patterson Du Bois, Assistant Assayer, James C. Booth, Melter and Refiner; N. B. Boyd, Assistant Melter and Refiner; Charles E. Barber, Engraver; George T. Morgan and William H. Key, Assistant Engravers; M. H. Cobb, Cashier; George W. Brown, Doorkeeper.

On July 4, 1829, Samuel Moore, then Director, laid the corner stone of the present building, located at the northwest corner of Chestnut and Juniper streets. It is of white marble, and of the Grecian style of architecture, and was finished, and commenced operations, in 1833. Subsequent to that date necessary changes in the interior arrangements, to accommodate the increase in business, have been introduced at various times, and it was made more secure as a depository for the great amount of bullion contained within its vaults, by having been rendered fire-proof in 1856.

This corner stone of the Mint of the United States of America, laid on the 4th day of July, 1829, being the fifty-third anniversary of our independence, in the presence of the Officers thereof, Members of Congress of the adjacent districts, architect, and artificers employed in the building, and a number of citizens of Philadelphia, in the which with this instrument are deposited specimens of the Coins of our Country struck in the present year. The Mint of the United States commenced operations in the year A. D., 1793, increasing constantly in utility, until its locality and convenience required extension and enlargement, which was ordered by the passage of a bill appropriating $120,000 for the erection of new and convenient buildings, to accommodate its operations, vesting the disbursement in the judgment and taste of the Director and President of the United States. In pursuance of the above bill, passed during the Presidency of John Quincy Adams, arrangements were made and designs adopted; William Strickland appointed architect; John Struthers, marble mason; Daniel Groves, bricklayer; Robert O’Neil, master carpenter, and in the first year of the Presidency of Andrew Jackson, this corner stone was placed in southeast corner of the edifice.

The names of the officers of the Mint of the United States at this time, are as follows:

Mint of the United States,

Philadelphia, March 20, 1838.

To Hon. Levi Woodbury, Secretary of the Treasury.

Sir:—I had the honor to receive your letter asking my attention to a resolution of the House of Representatives of the United States, passed March 5, 1838, as follows:

Extract from Resolution of Congress relating to Mint.

“Resolved, That the Secretary of the Treasury report to this House the cost of erecting the principal Mint and its branches, including buildings, fixtures, and apparatus; the salaries and expenses of the different officers; the amount expended in the purchase of bullion; the loss arising from wastage, and all other expenses; and the average length of time it requires to coin at the principal Mint all the bullion with which it can be furnished; and further, what amount of coin has been struck at the several branch mints, since their organization.”

Mint of the United States, Philadelphia.

| The cost of the edifice, machinery, and fixtures, was | $173,390 |

| Ground, enclosure, paving, etc. | 35,840 |

| Total cost of buildings, etc. | $209,230 |

This amount does not include expenditures made under special appropriations for the years 1836 and 1837, for milling and coining by steam power; and for extensive improvements in the assaying, melting, and parting rooms, and machine shops, amounting to $28,270.

It may be proper to mention that the Mint building is on the best street in the city, is of large dimensions, with the whole exterior of marble, and two Ionic porticos; and that the machinery and apparatus are of the best construction. The cost must therefore be considered as very moderate. The new Mint lately erected by the British India Government at Calcutta, cost 24 lacs of rupees, or about $1,138,000.

| The | Director receives per annum | $3,500 |

| Treasurer | 2,000 | |

| Chief Coiner | 2,000 | |

| Assayer | 2,000 | |

| Melter and Refiner | 2,000 | |

| Engraver | 2,000 | |

| Second Engraver | 1,500 | |

| Assistant Assayer | 1,300 | |

| Treasurer’s Clerk | 1,200 | |

| Bookkeeper | 1,000 | |

| Clerk of the weighing room | 1,200 | |

| Director’s Clerk | 700 | |

| Total for salaries | $20,400 |

No expenses are allowed, beyond the above sums, to any officer, assistant, or clerk, for the performance of his duties.

As all the gold and silver brought to the Mint is purchased at the nett Mint price, there is no expense, properly so called, incurred on this account.

R. M. PATTERSON, Director of the Mint.

Previous to the passage of the law by the Federal government for regulating the coins of the United States, much perplexity arose from the use of no less than four different currencies or rates, at which one species of coin was recoined, in the different parts of the Union. Thus, in New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Maine, Rhode Island, Connecticut, Vermont, Virginia and Kentucky, the dollar was recoined at six shillings; in New York and North Carolina at eight shillings; in New Jersey, Pennsylvania and Maryland at seven shillings and six pence; in Georgia and South Carolina at four shillings and eight pence. The subject had engaged the attention of the Congress of the old confederation, and the present system of the coins is formed upon the principles laid down in their resolution of 1786, by which the denominations of money of account were required to be dollars (the dollar being the unit), dismes or tenths, cents or hundredths, and mills or thousandths of a dollar. Nothing can be more simple or convenient than this decimal subdivision. The terms are proper because they express the proportions which they are intended to designate. The dollar was wisely chosen, as it corresponded with the Spanish coin, with which we had been long familiar.

The Mint, on Chestnut street near Broad, is open to the public daily, excepting Sundays and holidays, from 9 to 12 A. M. Visitors are met by the courteous ushers, who attend them through[21] the various departments. It is estimated that over forty thousand persons have visited the institution in the course of a single year. Owing to the immense amount of the precious metals which is always in course of transition, and the watchful care necessary to a correct transaction of business, the public are necessarily excluded from some of the departments. These, however, are of but little interest to the many and are described under their proper heads. The system adopted in the Mint is so precise and the weighing so accurate, that the abstraction of the smallest particle of metal would lead to almost immediate detection.

On entering the rotunda, the offices of the Treasurer and Cashier are to the right and left. Farther in, in the hall, to the rear, on the right, is the room of the Treasurer’s clerks; a part of this was formerly used by the Adams Express Company, who transport to and from the Mint millions of dollars worth of metal, coin, etc.

SCALES.

On the left is the Deposit or Weighing-room, where all the gold and silver for coining is received and first weighed. The largest weight used in this room is five hundred ounces, the smallest, is the thousandth part of an ounce. The scales are wonderfully delicate, and are examined and adjusted on alternate days. On the right of this room is one of the twelve[22] vaults in the building. Of solid masonry, several of them are iron-lined, with double doors of the same metal and most complicated and burglar-proof locks.

AUTOMATIC WEIGHING SCALES.

It is estimated that about fifteen hundred million dollars worth of gold has been received and weighed in this room; probably nine-tenths of this amount was from California, since its discovery there in the year 1848. Previous to that time the supplies of gold came principally from Virginia, North Carolina, and Georgia. During the past ten years considerable quantities have been received from Nova Scotia, but most of the gold that reaches the Mint, at the present time, comes from California, Montana, Colorado, Idaho, Nevada, Arizona, Oregon, Dakota, Virginia, South Carolina, and New Mexico.

Formerly the silver used by the Mint came principally from Mexico and South America, but since the discovery of the immense veins of that metal in the territories of the United States the supply is furnished from the great West.

The copper used comes principally from the mines of Lake Superior, the finest from Minnesota. The nickel is chiefly from Lancaster County, Pa.

After the metal has been carefully weighed in the presence of the depositor and the proper officials, it is locked in iron boxes and taken to the melting room, where it is opened by two men, each provided with a key to one of the separate locks. There are four furnaces in this room, and the first process of melting takes place here. The gold and silver, being mixed with borax and other fluxing material, is placed in pots, melted and placed in iron moulds, and when cooled is again taken to the deposit room in bars, where it is reweighed, and a small piece cut from each lot by the Assayer. From this the fineness of the whole is ascertained, the value calculated, and the depositor paid. The metal in its rough state is then transferred to the Melter and Refiner.

Adjoining the Deposit Melting Room are the Melter and Refiner and assistants. This is the general business office of the head of this department, and is also used for weighing the necessary quantities of the metals used in alloying coin.

The two essential things regarding every piece of metal offered in payment of any dues were, first, the weight or quantity, next, the fineness or purity of the same. The process of weighing even the baser metals used in coining must be conducted by the careful use of accurate scales, with precise notes of the results. In precious metals, gold, silver, and their high grade alloys, a very small variation in the fineness makes a great difference in the value. Nothing is more essential than the accurate determination of the weight of the sample and of the metal obtained from it. It requires keen sight and most delicate adjustment in the hand which manipulates the Lilliputian scales of an Assayer’s table. The smallest weight used in the Mint is found in the Assay Room; it is the thirteen-hundredth part of a grain, and can scarcely be seen with the naked eye, unless on a white ground. The Assay Department is strictly a technical and scientific branch of the service. It has been practically under one regime, for the last fifty years. There have been but three Chief Assayers in that time, the only removals being by death, the only appointments by promotion. Its workmen are all picked men, selected from other parts of the Mint for special fitness and good character.

These are on the second floor, in the southwest corner of the building. In one of these are fires, stills, and other appliances used in the delicate and complicated process of assay, by which the specific standard of the fineness and purity of the various metals are established and declared.

The gold is melted down and stirred, by which a complete mixture is effected, so that an assay piece may be taken from any part of the bar after it is cast. The piece taken for this purpose is rolled out for the convenience of cutting. It is then taken to an assay balance (sensible to the ten-thousandth of a half gramme or less), and from it is weighed a half gramme, which is the normal assay weight for gold, being about 7.7 grains troy. This weight is stamped 1000; and all the lesser weights (afterwards brought into requisition) are decimal divisions of this weight, down to one ten-thousandth part.

Silver is next weighed out for the quartation (alloying), and as the assay piece, if standard, should contain 900-thousandths of gold, there must be three times this weight, or 2700-thousandths of silver; and this is the quantity used. The lead used for the cupellation is kept prepared in thin sheets, cut in square pieces, which should each weigh about ten times as much as the gold under assay. The lead is now rolled into the form of a hollow cone; and into this are introduced the assay gold and the quartation silver, when the lead is closed around them and pressed into a ball. The furnace having been properly heated, and the cupels placed in it and brought to the same temperature, the leaden ball, with its contents, is put into a cupel (a small cup made of burned bones, capable of absorbing base metals), the furnace closed, and the operation allowed to proceed, until all agitation is ceased to be observed in the melted metal, and its surface has become bright. This is an indication that the whole of the base metals have been converted into oxides, and absorbed by the cupel.

The cupellation being thus finished, the metal is allowed to cool slowly, and the disc or button which it forms is taken from the cupel. The button is then flattened by a hammer; is annealed by bringing it to a red heat; is laminated by passing it between the rollers; is again annealed; and is rolled loosely into a spiral or coil called a cornet. It is now ready for the process of quartation. This was formerly effected in[25] a glass matrass, and that mode is still used occasionally, when there are few assays. But a great improvement, first introduced into this country by the Assayer in 1867, was the—“platinum apparatus,” invented in England. It consists of a platinum vessel in which to boil the nitric acid, which is to dissolve out the silver, and a small tray containing a set of platinum thimbles with fine slits in the bottom. In these the silver is taken out, by successive supplies of nitric acid, without any decanting as in the case of glass vessels. The cornets are also annealed in the thimbles; in fact there is no shifting from the coiling to the final weighing, which determines the fineness of the original sample by proportionate weights in thousandths. In this process extra care has to be taken in adding the proportions of silver, as the “shaking” of any one cornet, might damage the others.

The process of assaying silver differs from that of gold. To obtain the assay sample, a little of the metals is dipped from the pot and poured quickly into water, producing a granulation, from portions of which that needed for assay is taken. In the case of silver alloyed with copper there is separation, to a greater or less degree, between the two metals in the act of solidification. Thus an ingot or bar, cooled in a mould, or any single piece cut from either, though really 900-thousandths fine on the average, will show such variations, according to the place of cutting, as might exceed the limits allowed by law. But the sudden chill produced by throwing the liquid metal into water, yields a granulation of entirely homogeneous mixture that the same fineness results, whether by assaying a single granule, or part of one, or a number.

From this sample the weight of 1115 thousandths is taken; this is dissolved in a glass bottle with nitric acid. The standard solution of salt is introduced and chloride of silver is the result, which contains of the metallic silver 1000 parts; this is repeated until the addition of the salt water shows but a faint trace of chloride below the upper surface of the liquid. For instance: if three measures of the decimal solution have been used with effect, the result will show that the 1115 parts of the piece contained 1003 of pure silver; and thus the proportion of pure silver in the whole alloyed metal is ascertained. Extensive knowledge and experience are required in such matters as making the bone-ash cupels, fine proof gold and silver, testing acids, and other special examinations and operations. The Assayer must, himself, be familiar with all the operations of minting, as critical questions are naturally carried to him.[26] The rendering of decisions upon counterfeit or suspicious coins has long been a specialty in this department. Once a year the President appoints a scientific commission to examine the coins of the preceding year. There has never yet been a Philadelphia coin found outside of the tolerance of fineness.

This department occupies the largest part of the west side of the building, on the second floor. Here the gold and silver used by the Mint in the manufacture of coin and fine bars are separated from each other, or whatever other metals may be mixed with them, and purified. It goes to this room after having been once melted and assayed. In separating and purifying gold, it is always necessary to add to it a certain quantity of pure silver. The whole is then immersed in nitric acid, which dissolves the silver into a liquid which looks like pure water. The acid does not dissolve the gold, but leaves it pure. The silver solution is then drawn off, leaving the gold at the bottom of the tub. It is then gathered up into pans and washed.

The silver in the condition in which it is received from the hands of the depositor, and generally filled with foreign impurities, is melted and then granulated, after which the whole mass is dissolved with nitric acid. The acid dissolves the base metals as well as the silver. The liquid metals are then run into tubs prepared for it, and precipitated, or rendered into a partially hard state, by being mixed with common salt water. After being precipitated it is called “chloride,” and resembles very closely new slacked lime. By putting spelter or zinc on the precipitated chloride, it becomes metallic silver, and only needs washing and melting to make the purest virgin metal. The base metals remain in a liquid state, and being of little value are generally thrown away. The process of refining silver is of two kinds; that of melting it with saltpetre, etc., which was known some thousands of years since, and the modern process of dissolving it in nitric acid, like the method of extracting it from gold in the above described operation.

After the separating process has been completed, the gold or silver is conveyed to the Drying Cellar, where it is put under pressure of some eighty tons, and all the water pressed out. It is then dried with heat, and afterwards conveyed in large cakes to the furnaces.

are on the first floor, in the west side of the building. Here all the metal used in coining is alloyed, melted and poured into[27] narrow moulds. These castings are called ingots; they are about twelve inches long, a half-inch thick, and vary from one to two a half-inches in breadth, according to the coin for which they are used, one end being wedge-shaped to allow its being passed through the rollers. The value of gold ingots is from $600 to $1,400; those of silver, about $60. The fine gold and silver bars used in the arts and for commercial purposes, are also cast in this department.

CASTING INGOTS.

INGOTS.

These are stamped with their weight and value in the deposit room. The floors that cover the melting rooms are made of iron in honey-comb pattern, divided into small sections, so[28] that they can be readily taken up to save the dust; their roughness acting as a scraper, preventing any metallic particles from clinging to the soles of the shoes of those who pass through the department, the sweepings of which, and including the entire building, averages $23,000 per annum, for the last five years.

The copper and nickel melting rooms, wherein all the base metals used are melted and mixed, is on the same side and adjoining to the gold and silver department. Up to the year 1856, the base coin of the United States was exclusively copper. In this year the coinage of what was called the nickel cents was commenced. These pieces, although called nickel, were composed of one-eighth nickel; the balance was copper.

The composition of the five and three cent pieces is one-fourth nickel; the balance copper. The bronze pieces were changed in 1859, and are a mixture of copper, zinc and tin, about equal parts of each of the two last; the former contributing about 95 per cent. There are seven furnaces in this room, each capable of melting five hundred pounds of metal per day. When the metal is heated and sufficiently mixed, it is poured into iron moulds, and when cool, and the rough ends clipped off, is ready to be conveyed to the rolling room.

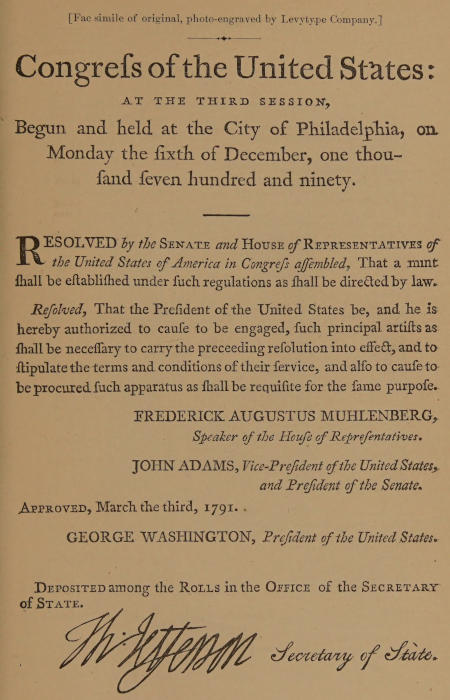

From the melting rooms through the corridor we reach the rolling room. The upright engine, on the right, of one hundred and sixty horse power, supplies the motive force to the rolling machines, four in number. Those on the left, are massive and substantial in their frame-work, with rollers of steel, polished by service in reducing the ingots to planchets for coining. The first process or rolling is termed breaking down; after that it requires to be passed through the machine until it is reduced to the required thinness—ten times if gold, eight if silver, being annealed in the intervals to prevent breaking. The rollers are adjustable and the space between them can be increased or diminished at pleasure, by the operator. About two hundred ingots are run through per hour on each pair of rollers.

The pressure applied is so intense that half a day’s rolling heats, not only the strips and rollers, but even the huge iron stanchions, weighing several tons, so hot that you can hardly hold your hand on them.

When the rolling is completed the strip is about six feet long, or six times as long as the ingot.

It is impossible to roll perfectly true. At times there will be a lump of hard gold, which will not be quite so much compressed as the rest. If the planchets were cut from this place, it would be heavier and more valuable than one cut from a thinner portion of the strip. It is, therefore, necessary to “draw” the strips, after being softened by annealing.

Rolling Machine.

These are in the same room, to the right facing the rollers. The gold and strips are placed in copper canisters, and then placed in the furnaces and heated to a red heat; silver strips being laid loosely in the furnace. When they become soft and pliable, they are taken out and allowed to cool slowly.

These machines resemble long tables, with a bench on either side, at one end of which is an iron box secured to the table. In this are fastened two perpendicular steel cylinders, firmly supported in a bed, to prevent their bending or turning around, and presenting but a small portion of their circumference to the strip. These are exactly at the same distance apart that the thickness of the strip is required to be. One end of the[30] strip is somewhat thinner than the rest, to allow it to pass easily between the cylinders. When through, this end is put between the jaws of a powerful pair of tongs, or pincers, fastened to a little carriage running on the table. The carriage to the further bench is up close to the cylinders, ready to receive a strip, which is inserted edgewise. When the end is between the pincers, the operator touches a foot pedal which closes the pincers firmly on the strip, and pressing another pedal, forces down a strong hook at the left end of the carriage, which catches in a link of the moving chain. This draws the carriage away from the cylinders, and the strip being connected with it has to follow. It is drawn between the cylinders, which operating on the thick part of the strip with greater power than upon the thin, reduces the whole to an equal thickness. When the strip is through, the strain on the tongs instantly ceases, which allows a spring to open them and drop the strip. At the same time another spring raises the hook and disengages the carriage from the chain. A cord fastened to the carriage runs back over the wheel near the head of the table, and then up to a couple of combination weights on the wall beyond, which draw the carriage back to the starting place, ready for another strip.

DRAWING BENCH.

After being thoroughly washed, the strips are consigned to the cutting machines. These are in the rear of the rolling mills,[31] and are several in number, each when in active operation cutting two hundred and twenty-five planchets per minute. The press now used, consists of a vertical steel punch, which works in a round hole or matrix, cut in a solid steel plate. The action of the punch is obtained by an eccentric wheel. For instance, in an ordinary carriage wheel, the axis is in the centre, and the wheel revolves evenly around it. But if the axis is placed, say four inches from the centre, then it would revolve with a kind of hobble. From this peculiar motion its name is derived. Suppose the tire of the wheel is arranged, not to revolve with, but to slip easily around the wheel, and a rod is fastened to one side of the tire which prevents its turning. Now as the wheel revolves and brings the long side nearest the rod, it will push forward the rod, and when the long side of the wheel is away from the rod, it draws the rod with it.

CUTTING MACHINE.

STRIP FROM WHICH PLANCHETS ARE CUT.

The upper shaft, on which are seen the three large wheels, has also fastened to it, over each press, an eccentric wheel. In[32] the first illustration will be seen three upright rods running from near the table to the top. The middle one is connected with a tire around the eccentric wheel, and rises and falls with each revolution. The eccentric power gives great rapidity of motion with but little jerking.

The operator places one end of a strip of metal in the immense jaws of the press, and cuts out a couple of planchets, which are a fraction larger than the coin to be struck. As the strips are of uniform thickness, if these two are of the right weight, all cut from that strip will be the same. They are therefore weighed accurately. If right, or a little heavy, they are allowed to pass, as the extra weight can be filed off. If too light, the whole strip has to be re-melted. As fast as cut the planchets fall into a box below, and the perforated strips are folded into convenient lengths to be re-melted. From a strip worth say eleven hundred dollars, eight hundred dollars of planchets will be cut.

DELICATE SCALES.

The planchets are then removed to the adjusting room, where they are adjusted. This work is performed by ladies. After inspection they are weighed on very accurate scales. If a planchet is too heavy, but near the weight, it is filed off at the edges; if too heavy for filing, it is thrown aside with the light[33] ones, to be re-melted. To adjust coin so accurately requires great delicacy and skill, as a too free use of the file would make it too light. Yet by long practice, so accustomed do the operators become, that they work with apparent unconcern, scarce glancing at either planchets or scales, and guided as it were by unerring touch.

The exceedingly delicate scales were made under the direction of Mr. Peale, who greatly improved on the old ones in use. So precise and sensitive are they that the slightest breath of air affects their accuracy, rendering it necessary to exclude every draft from the room.

The methods of coining money have varied with the progress in mechanic arts, and are but indefinitely traced from the beginning; the primitive mode, being by the casting of the piece in sand, the impression being made with a hammer and punch. In the middle ages the metal was hammered into sheets of the required thickness, cut with shears into shape, and then stamped by hand with the design. The mill and screw, by which greater increase in power, with finer finish was gained, dates back to the Sixteenth Century. This process, with various modifications and improvements, continued in use in the Philadelphia Mint until 1836.

ANCIENT COINING PRESS.

The first steam coining press was invented by M. Thonnelier, of France, in 1833, and was first used in the United States Mint in 1836. It was remodeled and rebuilt in 1858, but in 1874 was superseded by the one now in operation, the very perfection of mechanism, in which the vibration and unsteady bearing of the former press were entirely obviated, and precision attained by the solid stroke with a saving of over seventy-five per cent. in the wearing and breaking of the dies.

STEAM COINING PRESS.

DIES.

The dies for coining are prepared by engravers, especially employed at the Mint for that purpose. The process of engraving them consists in cutting the devices and legends in soft steel, those parts being depressed which, in the coin, appear in relief. This, having been finished and hardened, constitutes an “original die,” which, being the result of a tedious and difficult task, is deemed too precious to be directly employed in striking coins; but it is used for multiplying dies. It is first used to impress another piece of soft steel, which then presents the appearance of a coin, and is called a hub. This hub, being hardened, is used to impress other[35] pieces of steel in like manner which, being like the original die, are hardened and used for striking the coins. A pair of these will, on an average, perform two weeks’ work.

The transfer lathe, a very complicated piece of machinery, is used in making dies, for coins and medals. By it, from a large cast, the design can be transferred and engraved in smaller size, in perfect proportion to the original.

This department, the most interesting to the general visitor, occupies the larger portion of the first floor on the east side of the building. The rooms are divided by an iron railing, which separates the visitors, on either side, from the machinery, etc., but allows everything to be seen.

MILLING MACHINE.

The planchets, after being adjusted, are received here, and, in order to protect the surface of the coin, are passed through the milling-machine. The planchets are fed to this machine through an upright tube, and, as they descend from the lower aperture, they are caught upon the edge of a revolving wheel[37] and carried about a quarter of a revolution, during which the edge is compressed and forced up—the space between the wheel and the rim being a little less than the diameter of the planchet. This apparatus moves so nimbly that five hundred and sixty half-dimes can be milled in a minute; but, for large pieces, the average is about one hundred and twenty. In this room are the milling machines, and the massive, but delicate, coining presses, ten in number. Each of these is capable of coining from eighty to one hundred pieces a minute. Only the largest are used in making coins of large denominations.

PERFECTED COINING PRESS.

COINING PRESS.

The arch is a solid piece of cast iron, weighing several tons, and unites with its beauty great strength. The table is also[38] of iron, brightly polished and very heavy. In the interior of the arch is a nearly round plate of brass, called a triangle. It is fastened to a lever above by two steel bands, termed stirrups, one of which can be seen to the right of the arch. The stout arm above it, looking so dark in the picture, is also connected with the triangle by a ball-and-socket joint, and it is this arm which forces down the triangle. The arm is connected with the end of the lever above by a joint somewhat like that of the knee. One end of the lever can be seen reaching behind the arch to a crank near the large fly-wheel. When the triangle[39] is raised, the arm and near end of the lever extends outward. When the crank lifts the further end of the lever it draws in the knee and forces down the arm until it is perfectly straight. By that time the crank has revolved and is lowering the lever, which forces out the knee again and raises the arm. As the triangle is fastened to the arm it has to follow all its movements.

Under the triangle, buried in the lower part of the arch, is a steel cup, or, technically, a “die stake.” Into this is fastened the reverse die. The die stake is arranged to rise one-eighth of an inch; when down it rests firmly on the solid foundation of the arch. Over the die stake is a steel collar or plate, in which is a hole large enough to allow a planchet to drop upon the die. In the triangle above, the obverse die is fastened, which moves with the triangle; when the knee is straightened the die fits into the collar and presses down upon the reverse die.

Just in front of the triangle will be seen an upright tube made of brass, and of the size to hold the planchets to be coined. These are placed in this tube. As they reach the bottom they are seized singly by a pair of steel feeders, in motion as similar to that of the finger and thumb as is possible in machinery, and carried over the collar and deposited between the dies, and, while the fingers are expanding and returning for another planchet, the dies close on the one within the collar, and by a rotary motion are made to impress it silently but powerfully. The fingers, as they again close upon a planchet at the mouth of the tube, also seize the coin, and, while conveying a second planchet on to the die, carry the coin off, dropping it into a box provided for that purpose, and the operation is continued ad infinitum. These presses are attended by ladies, and do their work in a perfect manner. The engine that drives the machinery is of one hundred and sixty horse-power.

After being stamped the coins are taken to the Coiner’s room, and placed on a long table—the double eagles in piles of ten each. It will be remembered that, in the Adjusting Room, a difference of one-half a grain was made in the weight of some of the double eagles. The light and heavy ones are kept separate in coining, and when delivered to the treasurer, they are mixed together in such proportions as to give him full weight in every delivery. By law the deviation from the standard weight, in delivering to him, must not exceed three pennyweights in one thousand double eagles. The gold coins—as small as quarter eagles being counted and weighed to verify the count—are put up in bags of $5,000 each. The three-dollar pieces are put up in bags of $3,000, and one-dollar pieces in $1,000 bags. The silver pieces, and sometimes small gold, are counted on a very ingenious contrivance called a “counting-board.”

COUNTING BOARD.

By this process twenty-five dollars in five-cent pieces can be counted in less than a minute. The “boards” are a simple flat surface of wood, with copper partitions, the height and size of the coin to be counted, rising from the surface at regular intervals, and running parallel with each other from top to bottom. They somewhat resemble a common household “washing board,” with the grooves running parallel with the sides but much larger. The boards are worked by hand, over a box, and as the pieces are counted they slide into a drawer prepared to receive them. They are then put into bags and are ready for shipment.[8]

The room in the Mint used for the Cabinet is on the second floor. It was formerly a suite of three apartments connected by folding-doors, but the doors have been removed, and it is now a pleasant saloon fifty-four feet long by sixteen wide. The eastern and western sections are of the same proportions, each with a broad window. The central section is lighted from the dome, which is supported by four columns. There is an open space immediately under the dome, to give light to the hall below, which is the main entrance to the Mint. Around this space is a railing and a circular case for coins. The Cabinet of Coins was established in 1838, by Dr. R. M. Patterson, then Director of the Mint. Anticipating such a demand, reserves had been made for many years by Adam Eckfeldt,[9] the Coiner, of the “master coins” of the Mint; a term used to signify first pieces from new dies, bearing a high polish and struck with extra care. These are now more commonly called “proof pieces.” With this nucleus, and a few other valuable pieces from Mr. Eckfeldt, the business was committed to the Assay Department, and especially to Mr. Du Bois, Assistant Assayer. The collection grew, year by year, by making exchanges to supply deficiencies, by purchases, by adding our own coin, and by saving foreign coins from the melting-pot—a large part in this way, at a cost of not more than their bullion value, though demanding great care, appreciation, and study. Valuable donations were also made by travelers, consuls, and missionaries. In 1839, Congress appropriated the sum of $1,000 for the purchase of “specimens of ores and coins to be preserved at the Mint.” Annually, since, the sum of $300 has been appropriated by the Government for this object. More has not been asked or desired, for the officers of the Mint have not sought to vie with the long established collections of the national cabinets of the old world, or even to equal the extravagance of some private numismatists; but they have admirably succeeded in their purpose to secure such coins as would interest all, from the schoolboy to the most enthusiastic archæologist. The economic principle upon which the collection has been gathered is a lesson to all governmental departments in frugality, as well as a restraint upon the natural tendency to extravagance which has heretofore distinguished those who have a passion for old coins. There are thousands of coin collectors in the United[42] States, and fortunes have been accumulated in this strange way. More than one authenticated instance has been known in this country where a man has lived in penury, and died from want, yet possessed of affluence in time-defaced coins.