Hyphenation has been standardised.

For the CONTENTS on Page v, Chapter IX—Peewits 51 was missed from print in the original, and has been added.

The layout of the Contents continuation page on Page vi, has been changed to replicate the layout of the previous Contents page.

Page 41—changed cemetries to cemeteries.

Page 55—changed artifical to artificial.

BIRDS AND THEIR NESTS,

BY

MARY HOWITT.

With Twenty-three Full-page Illustrations by Harrison Weir.

NEW YORK:

GEORGE ROUTLEDGE AND SONS, 416, BROOME STREET.

London: S. W. Partridge & Co., 9, Paternoster Row.

All rights reserved.

WATSON AND HAZELL,

Printers,

London and Aylesbury.

| PAGE | |||

| Introductory Chapter | 1 | ||

| CHAPTER | I. | —THE WREN | 8 |

| ” | II. | —THE GOLDFINCH | 15 |

| ” | III. | —THE SONG THRUSH | 20 |

| ” | IV. | —THE BLACKBIRD | 26 |

| ” | V. | —THE DIPPER, OR WATER-OUSEL | 33 |

| ” | VI. | —THE NIGHTINGALE | 37 |

| ” | VII. | —THE SKYLARK | 42 |

| ” | VIII. | —THE LINNET | 47[vi] |

| ” | IX. | —THE PEEWIT | 51 |

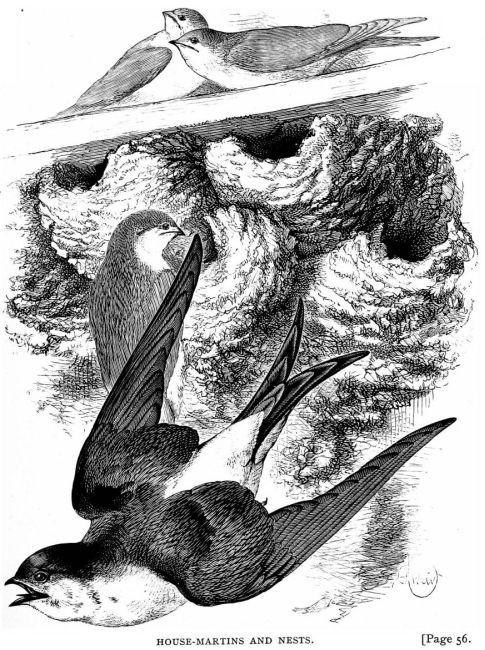

| ” | X. | —HOUSE-MARTINS, OR WINDOW-SWALLOWS, AND NESTS | 56 |

| ” | XI. | —CHIFF-CHAFFS, OR OVEN-BUILDERS, AND NEST | 66 |

| ” | XII. | —GOLDEN-CRESTED WRENS AND NEST | 70 |

| ” | XIII. | —WAGTAIL AND NEST | 76 |

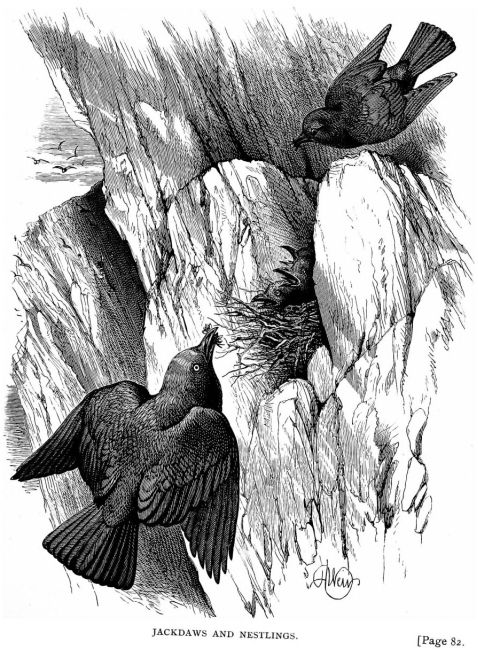

| ” | XIV. | —JACKDAW AND NESTLINGS | 82 |

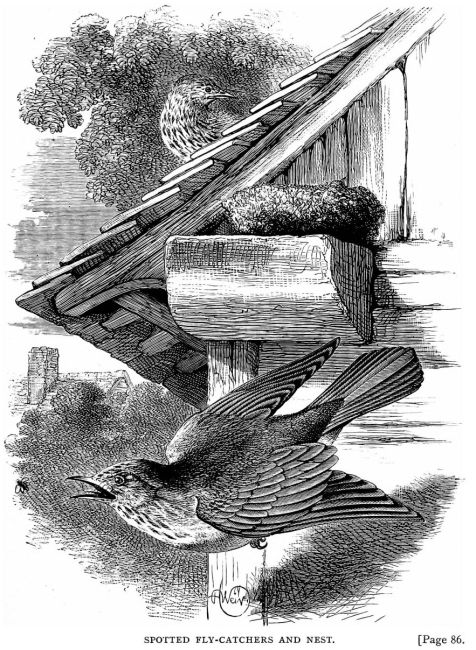

| ” | XV. | —SPOTTED FLY-CATCHERS AND NEST | 86 |

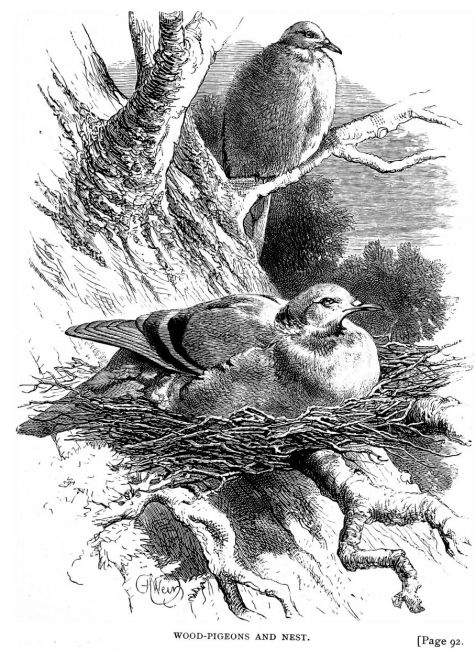

| ” | XVI. | —WOOD-PIGEONS AND NEST | 92 |

| ” | XVII. | —WHITE-THROAT AND NEST | 98 |

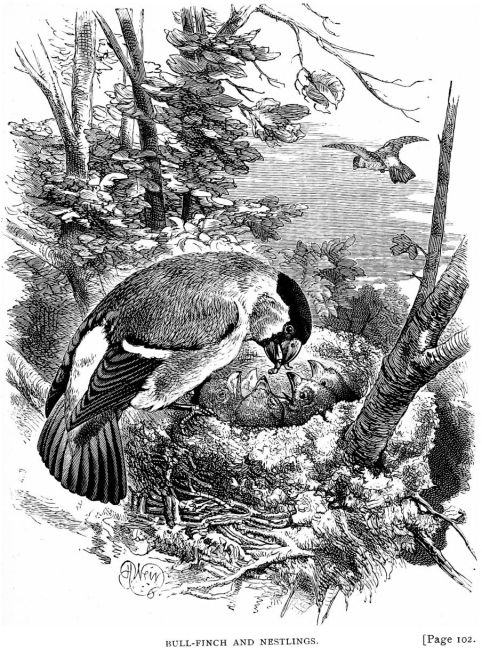

| ” | XVIII. | —BULL-FINCH AND NESTLINGS | 102 |

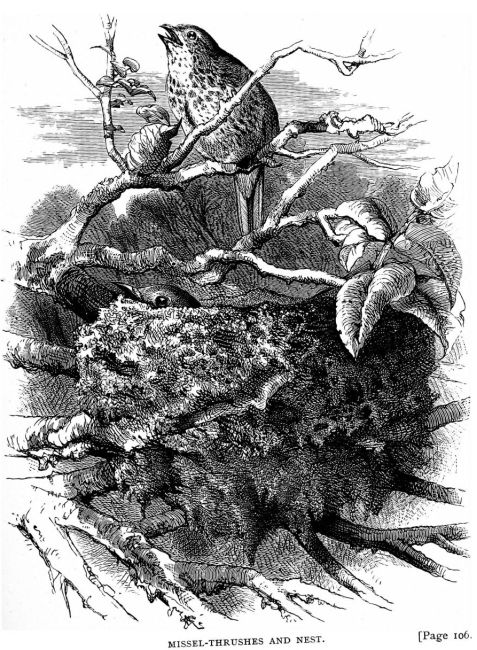

| ” | XIX. | —MISSEL-THRUSHES AND NEST | 106 |

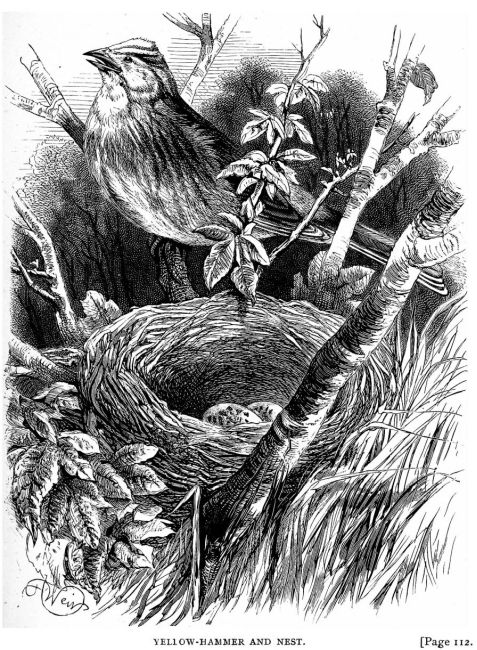

| ” | XX. | —YELLOW-HAMMER, OR YELLOW-HEAD, AND NEST | 112 |

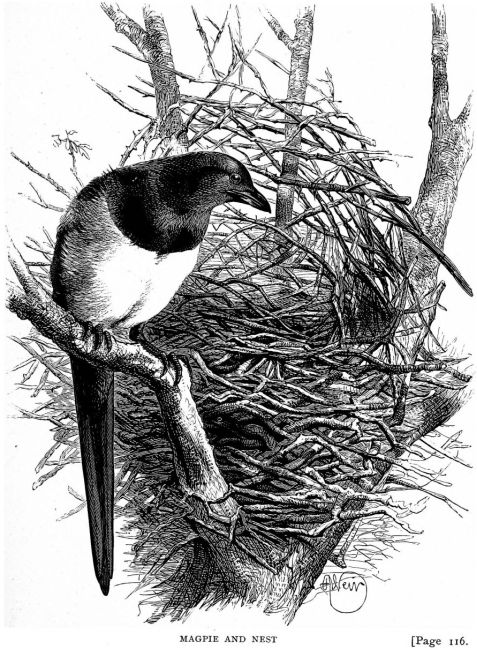

| ” | XXI. | —MAGPIE AND NEST | 116 |

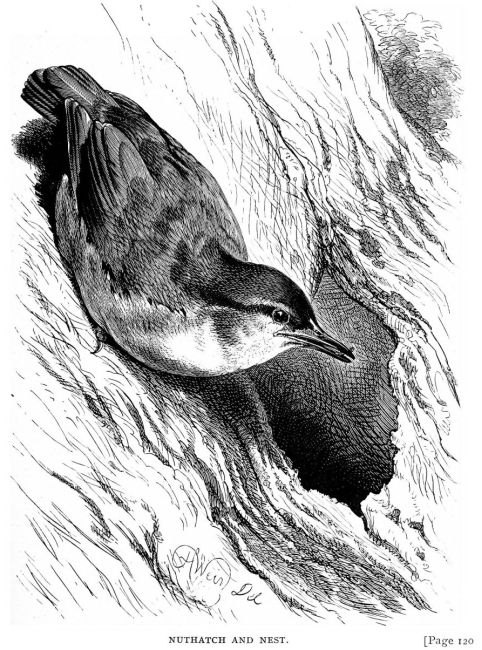

| ” | XXII. | —NUTHATCH AND NEST | 120 |

The birds in these pictures of ours have all nests, which is as it should be; for how could the bird rear its young without its little home and soft little bed, any more than children could be comfortably brought up without either a bed to lie upon, or a home in which to be happy.

Birds-nests, though you may find them in every bush, are[2] wonderful things. Let us talk about them. They are all alike in the purpose for which they are intended, but no two families of birds build exactly alike; all the wrens, for instance, have their kind of nest; the thrushes have theirs; so has the swallow tribe; so has the sparrow, or the rook. They do not imitate one another, but each adheres to its own plan, as God, the great builder and artist, as well as Creator, taught them from the very beginning. The first nightingale, that sang its hymn of joyful thanksgiving in the Garden of Paradise, built its nest just the same as the bird you listened to last year in the coppice. The materials were there, and the bird knew how to make use of them; and that is perhaps the most wonderful part of it, for she has no implements to work with: no needle and thread, no scissors, no hammer and nails; nothing but her own little feet and bill, and her round little breast, upon which to mould it; for it is generally the mother-bird which is the chief builder.

No sooner is the nest wanted for the eggs which she is about to lay, than the hitherto slumbering faculty of constructiveness is awakened, and she selects the angle of the branch, or the hollow in the bank or in the wall, or the tangle of reeds, or the platform of twigs on the tree-top, exactly the right place for her, the selection being always the same according to her tribe, and true to the instinct which was implanted in her at the first.

So the building begins: dry grass or leaves, little twigs and root-fibres, hair or down, whether of feather or winged seed, spangled outside with silvery lichen, or embroidered with green mosses, less for beauty, perhaps—though it is so beautiful—than for the birds’ safety, because it so exactly imitates the bank or the tree-trunk in which it is built. Or it may be that her tenement[3] is clay-built, like that of the swallow; or lath and plaster, so to speak, like an old country house, as is the fashion of the magpie; or a platform of rude sticks, like the first rudiment of a basket up in the tree-branches, as that of the wood-pigeon: she may be a carpenter like the woodpecker, a tunneller like the sand-martin; or she may knead and glue together the materials of her nest, till they resemble thick felt; but in all this she is exactly what the great Creator made her at first, equally perfect in skill, and equally undeviating year after year. This is very wonderful, so that we may be quite sure that the sparrow’s nest, which David remarked in the house of God, was exactly the same as the sparrow built in the days of the blessed Saviour, when He, pointing to that bird, made it a proof to man that God’s Providence ever watches over him.

Nevertheless, with this unaltered and unalterable working after one pattern, in every species of bird, there is a choice or an adaptation of material allowed: thus the bird will, within certain limits, select that which is fittest for its purpose, producing, however, in the end, precisely the same effect. I will tell you what Jules Michelet, a French writer, who loves birds as we do, writes on this subject:—“The bird in building its nest,” he says, “makes it of that beautiful cup-like or cradle form by pressing it down, kneading it and shaping it upon her own breast.” He says, as I have just told you, that the mother-bird builds, and that the he-bird is her purveyor. He fetches in the materials: grasses, mosses, roots, or twigs, singing many a song between whiles; and she arranges all with loving reference; first, to the delicate egg which must be bedded in soft material; then to the little one which, coming from the egg naked, must[4] not only be cradled in soft comfort, but kept alive by her warmth. So the he-bird, supposing it to be a linnet, brings her some horse-hair: it is stiff and hard; nevertheless, it is proper for the purpose, and serves as a lower stratum of the nest—a sort of elastic mattress: he brings her hemp; it is cold, but it serves for the same purpose. Then comes the covering and the lining; and for this nothing but the soft silky fibre of certain plants, wool or cotton, or, better still, the down from her own breast, will satisfy her. It is interesting, he says, to watch the he-bird’s skilful and furtive search for materials; he is afraid if he see you watching, that you may discover the track to his nest; and, in order to mislead you, he takes a different road back to it. You may see him following the sheep to get a little lock of wool, or alighting in the poultry yard on the search for dropped feathers. If the farmer’s wife chance to leave her wheel, whilst spinning in the porch, he steals in for a morsel of flax from the distaff. He knows what is the right kind of thing; and let him be in whatever country he may, he selects that which answers the purpose; and the nest which is built is that of the linnet all the world over.

Again he tells us, that there are other birds which, instead of building, bring up their young underground, in little earth cradles which they have prepared for them. Of building-birds, he thinks the queerest must be the flamingo, which lays her eggs on a pile of mud which she has raised above the flooded earth, and, standing erect all the time, hatches them under her long legs. It does seem a queer, uncomfortable way; but if it answer its end, we need not object to it. Of carpenter-birds, he thinks the thrush is the most remarkable; other writers say the woodpecker. The shore-birds plait their nests, not very skilfully it is true, but[5] sufficiently well for their purpose. They are clothed by nature with such an oily, impermeable coat of plumage, that they have little need to care about climate; they have enough to do to look after their fishing, and to feed themselves and their young; for all these sea-side families have immense appetites.

Herons and storks build in a sort of basket-making fashion; so do the jays and the mocking birds, only in a much better way; but as they have all large families they are obliged to do so. They lay down, in the first place, a sort of rude platform, upon which they erect a basket-like nest of more or less elegant design, a web of roots and dry twigs strongly woven together. The little golden-crested wren hangs her purse-like nest to a bough, and, as in the nursery song, “When the wind blows the cradle rocks.” An Australian bird, a kind of fly-catcher, called there the razor-grinder, from its note resembling the sound of a razor-grinder at work, builds her nest on the slightest twig hanging over the water, in order to protect it from snakes which climb after them. She chooses for her purpose a twig so slender that it would not bear the weight of the snake, and thus she is perfectly safe from her enemy. The same, probably, is the cause why in tropical countries, where snakes and monkeys, and such bird-enemies abound, nests are so frequently suspended by threads or little cords from slender boughs.

The canary, the goldfinch, and chaffinch, are skilful cloth-weavers or felt makers; the latter, restless and suspicious, speckles the outside of her nest with a quantity of white lichen, so that it exactly imitates the tree branch on which it is placed, and can hardly be detected by the most accustomed eye. Glueing and felting play an important part in the work of the bird-weavers.[6] The humming-bird, for instance, consolidates her little house with the gum of trees. The American starling sews the leaves together with her bill; other birds use not only their bills, but their feet. Having woven a cord, they fix it as a web with their feet, and insert the weft, as the weaver would throw his shuttle, with their bill. These are genuine weavers. In fine, their skill never fails them. The truth is, that the great Creator never gives any creature work to do without giving him at the same time an inclination to do it—which, in the animal, is instinct—and tools sufficient for the work, though they may be only the delicate feet and bill of the bird.

And now, in conclusion, let me describe to you the nest of the little English long-tailed titmouse as I saw it many years ago, and which I give from “Sketches of Natural History”:—

[7]

[8]

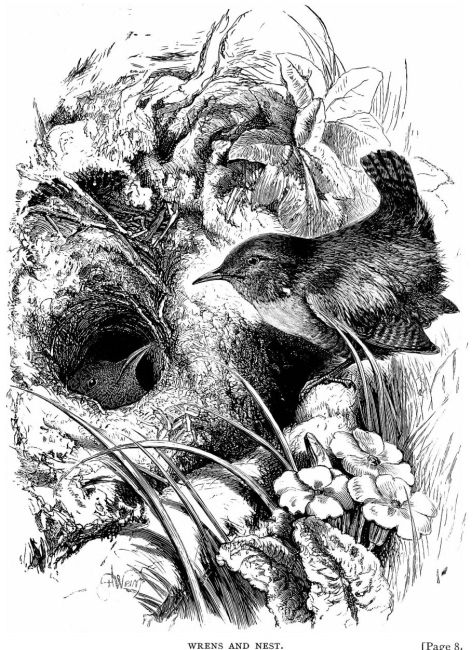

THE WREN.

Truly the little Wren, so beautifully depicted by Mr. Harrison Weir, with her tiny body, her pretty, lively, and conceited ways, her short, little turned-up tail, and delicate plumage, is worthy of our tender regard and love.

The colouring of the wren is soft and subdued—a reddish-brown colour; the breast of a light greyish-brown; and all the hinder parts, both above and below, marked with wavy lines of dusky-brown, with two bands of white dots across the wings.

Its habits are remarkably lively and attractive. “I know no pleasanter object,” says the agreeable author of “British Birds,” “than the wren; it is always so smart and cheerful. In gloomy weather other birds often seem melancholy, and in rain the sparrows and finches stand silent on the twigs, with drooping wings and disarranged plumage; but to the merry little wren all weathers are alike. The big drops of the thunder-shower no more wet it than the drizzle of a Scotch mist; and as it peeps from beneath the bramble, or glances from a hole in the wall, it seems as snug as a kitten frisking on the parlour rug.”

WRENS AND NEST. [Page 8.

“It is amusing,” he continues, “to watch the motions of a young family of wrens just come abroad. Walking among furze, broom, or juniper, you are attracted to some bush by [9]hearing issue from it the frequent repetition of a sound resembling the syllable chit. On going up you perceive an old wren flitting about the twigs, and presently a young one flies off, uttering a stifled chirr, to conceal itself among the bushes. Several follow, whilst the parents continue to flutter about in great alarm, uttering their chit, chit, with various degrees of excitement.”

The nest of the wren is a wonderful structure, of which I shall have a good deal to say. It begins building in April, and is not by any means particular in situation. Sometimes it builds in the hole of a wall or tree; sometimes, as in this lovely little picture of ours, in the mossy hollow of a primrose-covered bank; and because it was formerly supposed to live only in holes or little caves, it received the name of Troglodytes, or cave-dweller. But it builds equally willingly in the thatch of out-buildings, in barn-lofts, or tree-branches, either when growing apart or nailed against a wall, amongst ivy or other climbing plants; in fact, it seems to be of such a happy disposition as to adapt itself to a great variety of situations. It is a singular fact that it will often build several nests in one season—not that it needs so many separate dwellings, or that it finishes them when built; but it builds as if for the very pleasure of the work. Our naturalist says, speaking of this odd propensity, “that, whilst the hen is sitting, the he-bird, as if from a desire to be doing something, will construct as many as half-a-dozen nests near the first, none of which, however, are lined with feathers; and that whilst the true nest, on which the mother-bird is sitting, will be carefully concealed, these sham nests are open to view. Some say that as the wrens, during the cold weather, sleep in[10] some snug, warm hole, they frequently occupy these extra nests as winter-bedchambers, four or five, or even more, huddling together, to keep one another warm.”

Mr. Weir, a friend of the author I have just quoted, says this was the case in his own garden; and that, during the winter, when the ground was covered with snow, two of the extra nests were occupied at night by a little family of seven, which had hatched in the garden. He was very observant of their ways, and says it was amusing to see one of the old wrens, coming a little before sunset and standing a few inches from the nest, utter his little cry till the whole number of them had arrived. Nor were they long about it; they very soon answered the call, flying from all quarters—the seven young ones and the other parent-bird—and then at once nestled into their snug little dormitory. It was also remarkable that when the wind blew from the east they occupied a nest which had its opening to the west, and when it blew from the west, then one that opened to the east, so that it was evident they knew how to make themselves comfortable.

And now as regards the building of these little homes. I will, as far as I am able, give you the details of the whole business from the diary of the same gentleman, which is as accurate as if the little wren had kept it himself, and which will just as well refer to the little nest in the primrose bank as to the nest in the Spanish juniper-tree, where, in fact, it was built.

“On the 30th of May, therefore, you must imagine a little pair of wrens, having, after a great deal of consultation, made up their minds to build themselves a home in the branches of a Spanish juniper. The female, at about seven o’clock in the[11] morning, laid the foundation with the decayed leaf of a lime-tree. Some men were at work cutting a drain not far off, but she took no notice of them, and worked away industriously, carrying to her work bundles of dead leaves as big as herself, her mate, seeming the while to be delighted with her industry, seated not far off in a Portugal laurel, where he watched her, singing to her, and so doing, making her labour, no doubt, light and pleasant. From eight o’clock to nine she worked like a little slave, carrying in leaves, and then selecting from them such as suited her purpose and putting aside the rest. This was the foundation of the nest, which she rendered compact by pressing it down with her breast, and turning herself round in it: then she began to rear the sides. And now the delicate and difficult part of the work began, and she was often away for eight or ten minutes together. From the inside she built the underpart of the aperture with the stalks of leaves, which she fitted together very ingeniously with moss. The upper part of it was constructed solely with the last-mentioned material. To round it and give it the requisite solidity, she pressed it with her breast and wings, turning the body round in various directions. Most wonderful to tell, about seven o’clock in the evening the whole outside workmanship of this snug little erection was almost complete.

“Being very anxious to examine the interior of it, I went out for that purpose at half-past two the next morning. I introduced my finger, the birds not being there, and found its structure so close, that though it had rained in the night, yet that it was quite dry. The birds at this early hour were singing as if in ecstasy, and at about three o’clock the little he-wren came[12] and surveyed his domicile with evident satisfaction; then, flying to the top of a tree, began singing most merrily. In half-an-hour’s time the hen-bird made her appearance, and, going into the nest, remained there about five minutes, rounding the entrance by pressing it with her breast and the shoulders of her wings. For the next hour she went out and came back five times with fine moss in her bill, with which she adjusted a small depression in the fore-part of it; then, after twenty minutes’ absence, returned with a bundle of leaves to fill up a vacancy which she had discovered in the back of the structure. Although it was a cold morning, with wind and rain, the male bird sang delightfully; but between seven and eight o’clock, either having received a reproof from his wife for his indolence, or being himself seized with an impulse to work, he began to help her, and for the next ten minutes brought in moss, and worked at the inside of the nest. At eleven o’clock both of them flew off, either for a little recreation, or for their dinners, and were away till a little after one. From this time till four o’clock both worked industriously, bringing in fine moss; then, during another hour, the hen-bird brought in a feather three times. So that day came to an end.

“The next morning, June 1st, they did not begin their work early, as was evident to Mr. Weir, because having placed a slender leaf-stalk at the entrance, there it remained till half-past eight o’clock, when the two began to work as the day before with fine moss, the he-bird leaving off, however, every now and then to express his satisfaction on a near tree-top. Again, this day, they went off either for dinner or amusement; then came back and worked for another hour, bringing in fine moss and feathers.

[13]

“The next morning the little he-wren seemed in a regular ecstasy, and sang incessantly till half-past nine, when they both brought in moss and feathers, working on for about two hours, and again they went off, remaining away an hour later than usual. Their work was now nearly over, and they seemed to be taking their leisure, when all at once the hen-bird, who was sitting in her nest and looking out at her door, espied a man half-hidden by an arbor vitæ. It was no other than her good friend, but that she did not know; all men were terrible, as enemies to her race, and at once she set up her cry of alarm. The he-bird, on hearing this, appeared in a great state of agitation, and though the frightful monster immediately ran off, the little creatures pursued him, scolding vehemently.

“The next day they worked again with feathers and fine moss, and again went off after having brought in a few more feathers. So they did for the next five days; working leisurely, and latterly only with feathers. On the tenth day the nest was finished, and the little mother-bird laid her first egg in it.”

Where is the boy, let him be as ruthless a bird-nester as he may, who could have the heart to take a wren’s nest, only to tear it to pieces, after reading the history of this patient labour of love?

The wren, like various other small birds, cannot bear that their nests or eggs should be touched; they are always disturbed and distressed by it, and sometimes even will desert their nest and eggs in consequence. On one occasion, therefore, this good, kind-hearted friend of every bird that builds, carefully put his finger into a wren’s nest, during the mother’s absence, to ascertain whether the young were hatched; on her return,[14] perceiving that the entrance had been touched, she set up a doleful lamentation, carefully rounded it again with her breast and wings, so as to bring everything into proper order, after which she and her mate attended to their young. These particular young ones, only six in number, were fed by their parents 278 times in the course of a day. This was a small wren-family; and if there had been twelve, or even sixteen, as is often the case, what an amount of labour and care the birds must have had! But they would have been equal to it, and merry all the time.

[15]

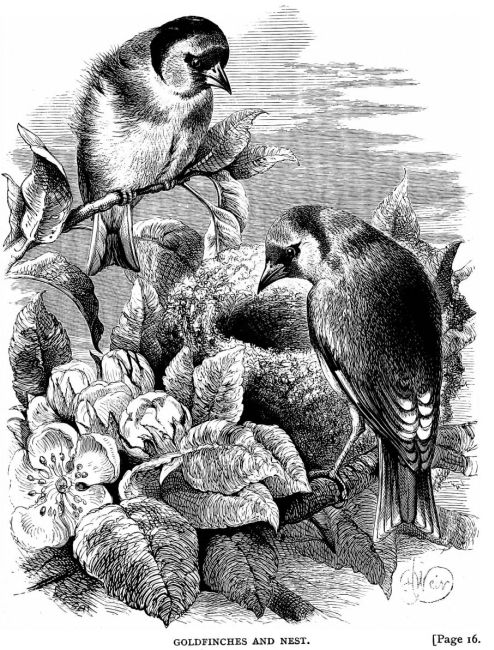

THE GOLDFINCH.

The Goldfinch, which is cousin to the Linnet, is wonderfully clever and docile, as I shall show you presently. In the first place, however, let me say a word or two about bird cleverness in general, which I copy from Jules Michelet’s interesting work, “The Bird.” Speaking of the great, cruel, and rapacious family of the Raptores, or Birds of Prey, he expresses satisfaction in the idea that this race of destroyers is decreasing, and that there may come a time when they no longer exist on the earth. He has no admiration for them, though they may be the swiftest of the swift, and the strongest of the strong, because they put forth none of the higher qualities of courage, address, or patient endurance in taking their prey, which are all weak and powerless in comparison with themselves; their poor unoffending victims. “All these cruel tyrants of the air,” he says, “like the serpents, have flattened skulls, which show the want of intellect and intelligence. These birds of prey, with their small brains, offer a striking contrast to the amiable and intelligent species which we find amongst the smaller birds. The head of the former is only a beak, that of the latter is a face.” Afterwards, to prove this more strongly, he gives a table to show the proportion of brain to the size of the body in these different species of birds. Thus the chaffinch, the sparrow,[16] and the goldfinch, have more than six times as much brain as the eagle in proportion to the size of the body. We may look, therefore, for no less than six times his intelligence and docile ability. Whilst in the case of the little tomtit it is thirteen times as much.

But now for the goldfinch, of which our cut—which is both faithful and beautiful—shows us a pair, evidently contemplating with much satisfaction the nest which they have just finished on one of the topmost boughs of a blossomy apple-tree. This nest is a wonderful little fabric, built of moss, dry grass, and slender roots, lined with hair, wool, and thistle-down; but the true wonder of the nest is the exact manner in which the outside is made to imitate the bough upon which it is placed. All its little ruggednesses and lichen growths are represented, whilst the colouring is so exactly that of the old apple-tree that it is almost impossible to know it from the branch itself. Wonderful ingenuity of instinct, which human skill would find it almost impossible to imitate!

The bird lays mostly five eggs, which are of a bluish-grey, spotted with greyish-purple or brown, and sometimes with a dark streak or two.

The goldfinch is one of the most beautiful of our English birds, with its scarlet forehead, and quaint little black velvet-like cap brought down over its white cheeks; its back is cinnamon brown, and its breast white; its wings are beautifully varied in black and white, as are also its tail feathers. In the midland counties it is known as “The Proud Tailor,” probably because its attire looks so bright and fresh, and it has a lively air as if conscious of being well dressed.

GOLDFINCHES AND NEST. [Page 16.

[17]

Like its relation, the linnet, it congregates in flocks as soon as its young can take wing, when they may be seen wheeling round in the pleasant late summer and autumn fields, full of life, and in the enjoyment of the plenty that surrounds them, in the ripened thistle-down, and all such winged seeds as are then floating in the air.

How often have I said it is worth while to go out into the woods and fields, and, bringing yourself into a state of quietness, watch the little birds in their life’s employment, building their nests, feeding their young, or pursuing their innocent diversions! So now, on this pleasant, still autumn afternoon, if you will go into the old pasture fields where the thistles have not been stubbed up for generations, or on the margin of the old lane where ragwort, and groundsel, and burdock flourish abundantly, “let us,” as the author of “British Birds” says, “stand still to observe a flock of goldfinches. They flutter over the plants, cling to the stalks, bend in various attitudes, disperse the down, already dry and winged, like themselves, for flight, pick them out one by one and swallow them. Then comes a stray cow followed by a herd boy. At once the birds cease their labour, pause for a moment, and fly off in succession. You observe how lightly and buoyantly they cleave the air, each fluttering its little wings, descending in a curved line, mounting again, and speeding along. Anon they alight in a little thicket of dried weeds, and, in settling, display to the delighted eye the beautiful tints of their plumage, as with fluttering wings and expanded tail, they hover for a moment to select a landing place amid the prickly points of the stout thistles whose heads are now bursting with downy-winged seeds.”

[18]

The song of the goldfinch, which begins about the end of March, is very sweet, unassuming, and low—similar to that of the linnet, but singularly varied and pleasant.

Now, however, we must give a few instances of this bird’s teachable sagacity, which, indeed, are so numerous that it is difficult to make a selection.

Mr. Syme, in his “British Song Birds,” says, “The goldfinch is easily tamed and taught, and its capacity for learning the notes of other birds is well known. A few years ago the Sieur Roman exhibited a number of trained birds: they were goldfinches, linnets, and canaries. One appeared dead, and was held up by the tail or claw without exhibiting any signs of life; a second stood on its head with its claws in the air; a third imitated a Dutch milkmaid going to market with pails on its shoulders; a fourth mimicked a Venetian girl looking out at a window; a fifth appeared as a soldier, and mounted guard as a sentinel; whilst a sixth acted as a cannonier, with a cap on its head, a firelock on its shoulder, and a match in its claw, and discharged a small cannon. The same bird also acted as if it had been wounded. It was wheeled in a barrow as if to convey it to the hospital, after which it flew away before the whole company. The seventh turned a kind of windmill; and the last bird stood in the midst of some fireworks which were discharged all round it, and this without showing the least sign of fear.”

Others, as I have said, may be taught to draw up their food and water, as from a well, in little buckets. All this is very wonderful, and shows great docility in the bird; but I cannot greatly admire it, from the secret fear that cruelty or harshness[19] may have been used to teach them these arts so contrary to their nature. At all events it proves what teachable and clever little creatures they are, how readily they may be made to understand the will of their master, and how obediently and faithfully they act according to it.

Man, however, should always stand as a human Providence to the animal world. In him the creatures should ever find their friend and protector; and were it so we should then see many an astonishing faculty displayed; and birds would then, instead of being the most timid of animals, gladden and beautify our daily life by their sweet songs, their affectionate regard, and their amusing and imitative little arts.

The early Italian and German painters introduce a goldfinch into their beautiful sacred pictures—generally on the ground—hopping at the feet of some martyred saint or love-commissioned angel, perhaps from an old legend of the bird’s sympathy with the suffering Saviour, or from an intuitive sense that the divine spirit of Christianity extends to bird and beast as well as to man.

[20]

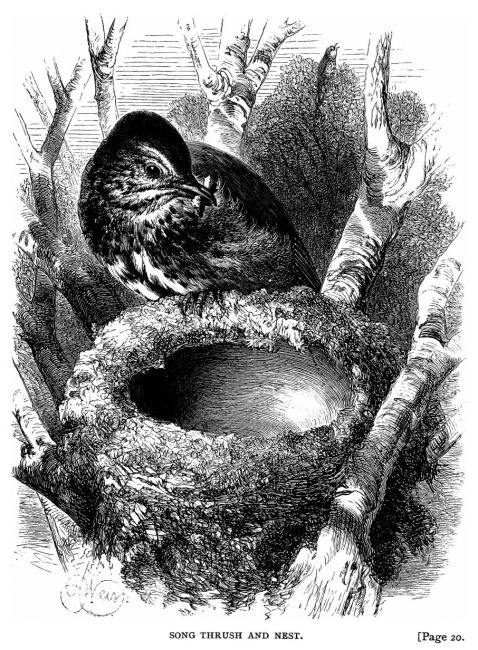

THE SONG THRUSH.

We have here a charming picture of one of the finest and noblest of our song-birds—the thrush, throstle, or mavis. The trees are yet leafless, but the bird is in the act of building, whilst her mate, on the tree-top, pours forth his exquisite melody. The almost completed nest, like a richly ornamented bowl, is before us.

This bird belongs to a grandly musical family, being own cousin to the missel-thrush and the blackbird, each one having a kindred song, but all, at the same time, distinctly characteristic.

The colouring of the thrush is soft and very pleasing; the upper parts of a yellowish-brown; the chin, white; the under part of the body, grayish white; the throat, breast, and sides of the neck, yellowish, thickly spotted with dark brown.

SONG THRUSH AND NEST. [Page 20.

The thrush remains with us the whole year, and may occasionally be heard singing even in the winter, though April, May, and June are the months when he is in fullest song. They pair in March, and by the end of that month, or early in April, begin to build. They have several broods in the year. The nest, which, as we see, is commodious, is placed at no great height from the ground, in a thick bush or hedge, and sometimes, also, in a rough bank, amongst bushes and undergrowth. They are particularly fond of spruce-fir plantations, building on one of [21]the low, spreading branches, close to the stem. Though the structure is so solid and substantial, yet it is built very rapidly; indeed, the thrush seems to be wide awake in all its movements; he is no loiterer, and does his work well. As a proof of his expedition I will mention that a pair of these birds began to build a second, perhaps, indeed, it might be a third nest, on a Thursday, June 15; on Friday afternoon the nest was finished, and on Saturday morning the first egg was laid, though the interior plastering was not then dry. On the 21st the hen began to sit, and on the 17th of July the young birds were hatched.

The frame-work, so to speak, of the nest is composed of twigs, roots, grasses, and moss, the two latter being brought to the outside. Inside it is lined with a thin plastering of mud, cow-dung, and rotten wood, which is laid on quite smoothly, almost like the glaze on earthenware; nor is there an internal covering between this and the eggs. The circular form of the nest is as perfect as a bowl shaped upon a lathe, and often contracts inwards at the top. The eggs, which are generally five in number, are of a bright blue-green, spotted over with brownish-black, these spots being more numerous at the larger end.

The food of the thrush is mostly of an animal character, as worms, slugs, and snails; and, by seasides, small molluscs, as whelks and periwinkles. On all such as are enclosed in shells he exercises his ingenuity in a remarkable way. We ourselves lived at one time in an old house standing in an old garden where were many ancient trees and out-buildings, in the old ivied roots and walls of which congregated great quantities of shell-snails. One portion of this garden, which enclosed an old,[22] disused dairy, was a great resort of thrushes, where they had, so to speak, their stones of sacrifice, around which lay heaps of the broken shells of snails, their victims. I have repeatedly watched them at work: hither they brought their snails, and, taking their stand by the stone with the snail in their beak, struck it repeatedly against the stone, till, the shell being smashed, they picked it out as easily as the oyster is taken from its opened shell. This may seem easy work with the slender-shelled snail, but the labour is considerably greater with hard shell-fish. On this subject the intelligent author of “British Birds” says, that many years ago, when in the Isle of Harris, he frequently heard a sharp sound as of one small stone being struck upon another, the cause of which he, for a considerable time, sought for in vain. At length, one day, being in search of birds when the tide was out, he heard the well-known click, and saw a bird standing between two flat stones, moving its head and body alternately up and down, each downward motion being accompanied by the sound which had hitherto been so mysterious. Running up to the spot, he found a thrush, which, flying off, left a whelk, newly-broken, lying amongst fragments of shells lying around the stone.

Thrushes are remarkably clean and neat with regard to their nests, suffering no litter or impurity to lie about, and in this way are a great example to many untidy people. Their domestic character, too, is excellent, the he-bird now and then taking the place of the hen on the eggs, and, when not doing so, feeding her as she sits. When the young are hatched, the parents may be seen, by those who will watch them silently and patiently, frequently stretching out the wings of the young as if to[23] exercise them, and pruning and trimming their feathers. To put their love of cleanliness to the proof, a gentleman, a great friend of all birds, had some sticky mud rubbed upon the backs of two of the young ones whilst the parents were absent. On their return, either by their own keen sense of propriety, or, perhaps, the complaint of the young ones, they saw what had happened, and were not only greatly disconcerted, but very angry, and instantly set to work to clean the little unfortunates, which, strange to say, they managed to do by making use of dry earth, which they brought to the nest for that purpose. Human intellect could not have suggested a better mode.

This same gentleman determined to spend a whole day in discovering how the thrushes spent it. Hiding himself, therefore, in a little hut of fir boughs, he began his observations in the early morning of the 8th of June. At half-past two o’clock, the birds began to feed their brood, and in two hours had fed them thirty-six times. It was now half-past five, the little birds were all wide awake, and one of them, whilst pruning its feathers, lost its balance and fell out of the nest to the ground. On this the old ones set up the most doleful lamentations, and the gentleman, coming out of his retreat, put the little one back into the nest. This kind action, however, wholly disconcerted the parents, nor did they again venture to feed their young till an artifice of the gentleman led them to suppose that he was gone from their neighbourhood. No other event happened to them through the day, and by half-past nine o’clock at night, when all went to rest, the young ones had been fed two hundred and six times.

Thrushes, however, become occasionally so extremely tame that the female will remain upon her eggs and feed her young,[24] without any symptom of alarm, in the close neighbourhood of man. Of this I will give an instance from Bishop Stanley’s “History of Birds”—

“A short time ago, in Scotland, some carpenters working in a shed adjacent to the house observed a thrush flying in and out, which induced them to direct their attention to the cause, when, to their surprise, they found a nest commenced amongst the teeth of a harrow, which, with other farming tools and implements, was placed upon the joists of the shed, just over their heads. The carpenters had arrived soon after six o’clock, and at seven, when they found the nest, it was in a great state of forwardness, and had evidently been the morning’s work of a pair of these indefatigable birds. Their activity throughout the day was incessant; and, when the workmen came the next morning, they found the female seated in her half-finished mansion, and, when she flew off for a short time, it was found that she had laid an egg. When all was finished, the he-bird took his share of the labour, and, in thirteen days, the young birds were out of their shells, the refuse of which the old ones carried away from the spot. All this seems to have been carefully observed by the workmen; and it is much to their credit that they were so quiet and friendly as to win the confidence of the birds.”

The song of the thrush is remarkable for its rich, mellow intonation, and for the great variety of its notes.

Unfortunately for the thrush, its exquisite power as a songster makes it by no means an unusual prisoner. You are often startled by hearing, from the doleful upper window of some dreary court or alley of London, or some other large town, an outpouring of joyous, full-souled melody from an imprisoned[25] thrush, which, perfect as it is, saddens you, as being so wholly out of place. Yet who can say how the song of that bird may speak to the soul of many a town-imprisoned passer-by? Wordsworth thus touchingly describes an incident of this kind:—

[26]

THE BLACKBIRD.

The Blackbird is familiar to us all. It is a thoroughly English bird, and, with its cousin the thrush, is not only one of the pleasantest features in our English spring and summer landscape, but both figure in our old poetry and ballads, as the “merle and the mavis,” “the blackbird and the throstle-cock;” for those old poets loved the country, and could not speak of the greenwood without the bird.

BLACKBIRD AND NEST. [Page 26.

The blackbird takes its name from a very intelligible cause—its perfectly black plumage, which, however, is agreeably relieved by the bright orange of its bill, the orange circles round its eyes, and its yellow feet; though this is peculiar only to the male, nor does he assume this distinguishing colour till his second year. The female is of a dusky-brown colour.

Sometimes the singular variety of a white blackbird occurs, [27]which seems to astonish even its fellow birds; the same phenomenon also occurs amongst sparrows; a fatal distinction to the poor birds, who are in consequence very soon shot.

This bird is one of our finest singers. His notes are solemn and flowing, unlike those of the thrush, which are short, quick, and extremely varied. The one bird is more lyrical, the other sings in a grand epic strain. A friend of ours, deeply versed in bird-lore, maintains that the blackbird is oratorical, and sings as if delivering an eloquent rhythmical oration.

This bird begins to sing early in the year, and continues his song during the whole time that the hen is sitting. Like his relatives, the thrush and the missel-thrush, he takes his post on the highest branch of a tree, near his nest, so that his song is heard far and wide; and in fact, through the whole pleasant spring you hear the voices of these three feathered kings of English song constantly filling the woods and fields with their melody. The blackbird sings deliciously in rain, even during a thunderstorm, with the lightning flashing round him. Indeed, both he and the thrush seem to take great delight in summer showers.

The blackbird has a peculiar call, to give notice to his brood of the approach of danger; probably, however, it belongs both to male and female. Again, there is a third note, very peculiar also, heard only in the dusk of evening, and which seems pleasingly in harmony with the approaching shadows of night. By this note they call each other to roost, in the same way as partridges call each other to assemble at night, however far they may be asunder.

The nest of the blackbird is situated variously; most frequently[28] in the thicker parts of hedges; sometimes in the hollow of a stump or amongst the curled and twisted roots of old trees, which, projecting from the banks of woods or woodland lanes, wreathed with their trails of ivy, afford the most picturesque little hollows for the purpose. Again, it may be found under the roof of out-houses or cart-sheds, laid on the wall-plate; and very frequently in copses, in the stumps of pollard trees, partly concealed by their branches; and is often begun before the leaves are on the trees. The nest is composed of dry bents, and lined with fine dry grass. The hen generally lays five eggs, which are of a dusky bluish-green, thickly covered with black spots; altogether very much resembling those of crows, rooks, magpies, and that class of birds.

Universal favourite as the blackbird deservedly is, yet, in common with the thrush, all gardeners are their enemies from the great liking they have for his fruit, especially currants, raspberries, and cherries. There is, however, something very amusing, though, at the same time, annoying, in the sly way by which they approach these fruits, quite aware that they are on a mischievous errand. They steal along, flying low and silently, and, if observed, will hide themselves in the nearest growth of garden plants, scarlet runners, or Jerusalem artichokes, where they remain as still as mice, till they think the human enemy has moved off. If, however, instead of letting them skulk quietly in their hiding-place, he drives them away, they fly off with a curious note, very like a little chuckling laugh of defiance, as if they would say, “Ha! ha! we shall soon be back again!” which they very soon are.

But we must not begrudge them their share, though they[29] neither have dug the ground nor sowed the seed, for very dull and joyless indeed would be the garden and the gardener’s toil, and the whole country in short, if there were no birds—no blackbirds and thrushes—to gladden our hearts, and make the gardens, as well as the woods and fields, joyous with their melody. Like all good singers, these birds expect, and deserve, good payment.

The blackbird, though naturally unsocial and keeping much to itself, is very bold in defence of its young, should they be in danger, or attacked by any of the numerous bird-enemies, which abound everywhere, especially to those which are in immediate association with man. The Rev. J. G. Wood tells us, for instance, that on one occasion a prowling cat was forced to make an ignominious retreat before the united onset of a pair of blackbirds, on whose young she was about to make an attack.

Let me now, in conclusion, give a day with a family of blackbirds, which I somewhat curtail from Macgillivray.

“On Saturday morning, June 10th, I went into a little hut made of green branches, at half-past two in the morning, to see how the blackbirds spend the day at home. They lived close by, in a hole in an old wall, which one or other of them had occupied for a number of years.

“At a quarter-past three they began to feed their young, which were four in number. She was the most industrious in doing so; and when he was not feeding, he was singing most deliciously. Towards seven o’clock the father-bird induced one of the young ones to fly out after him. But this was a little mistake, and, the bird falling, I was obliged to help it into its nest again, which made a little family commotion. They were[30] exceedingly tidy about their nest, and when a little rubbish fell out they instantly carried it away. At ten o’clock the feeding began again vigorously, and continued till two, both parent-birds supplying their young almost equally.

“The hut in which I sat was very closely covered; but a little wren having alighted on the ground in pursuit of a fly, and seeing one of my legs moving, set up a cry of alarm, on which, in the course of a few seconds, all the birds in the neighbourhood collected to know what was the matter. The blackbird hopped round the hut again and again, making every effort to peep in, even alighting on the top within a few inches of my head, but not being able to make any discovery, the tumult subsided. It was probably considered a false alarm, and the blackbirds went on feeding their young till almost four o’clock: and now came the great event of the day.

“At about half-past three the mother brought a large worm, four inches in length probably, which she gave to one of the young ones, and flew away. Shortly afterwards returning, she had the horror of perceiving that the worm, instead of being swallowed was sticking in its throat; on this she uttered a perfect moan of distress, which immediately brought the he-bird, who also saw at a glance what a terrible catastrophe was to be feared. Both parents made several efforts to push the worm down the throat, but to no purpose, when, strange to say, the father discovered the cause of the accident. The outer end of the worm had got entangled in the feathers of the breast, and, being held fast, could not be swallowed. He carefully disengaged it, and, holding it up with his beak, the poor little thing, with a great effort, managed to get it down, but was by[31] this time so exhausted that it lay with its eyes shut and without moving for the next three hours. The male bird in the meantime took his stand upon a tree, a few yards from the nest, and poured forth some of his most enchanting notes—a song of rejoicing no doubt for the narrow escape from death of one of his family.

“From four till seven o’clock both birds again fed their young, after which the male bird left these family duties to his mate, and gave himself up to incessant singing. At twenty minutes to nine their labours ceased, they having then fed their young one hundred and thirteen times during the day.

“I observed that before feeding their young they always alighted upon a tree and looked round them for a few seconds. Sometimes they brought in a quantity of worms and fed their brood alternately; at other times they brought one which they gave to only one of them.

“The young birds often trimmed their feathers, and stretched out their wings; they also appeared to sleep now and then.

“With the note of alarm which the feathered tribes set up on the discovery of their enemies all the different species of the little birds seem to be intimately acquainted; for no sooner did a beast or bird of prey make its appearance, than they seemed to be anxiously concerned about the safety of their families. They would hop from tree to tree uttering their doleful lamentations. At one time the blackbirds were in an unusual state of excitement and terror, and were attended by crowds of their woodland friends. A man and boy, who were working in my garden, having heard the noise, ran to see what was the cause of it, and on looking into some branches which were lying on[32] the ground, observed a large weasel stealing slyly along in pursuit of its prey. It was, however, driven effectually from the place without doing any harm. It is astonishing how soon the young know this intimation of danger; for I observed that no sooner did the old ones utter the alarm-cry, than they cowered in their nest, and appeared to be in a state of great uneasiness.”

[33]

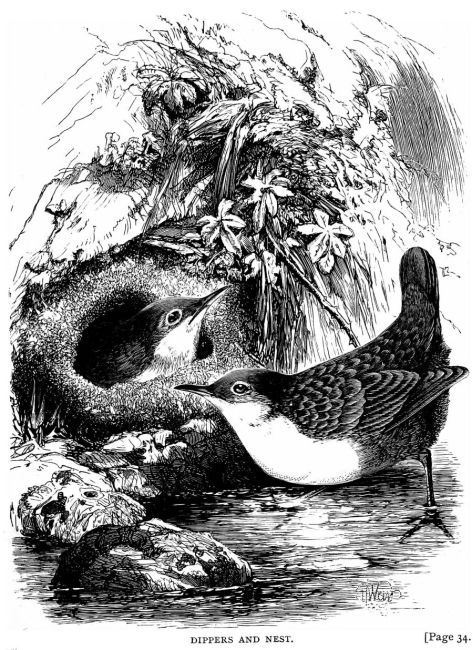

THE DIPPER, OR WATER-OUSEL.

The Dipper, or Water-ousel, of which Mr. Weir has given us a charming and faithful portrait, is very like a wren in form and action, with its round body and lively little tail. Its mode of flight, however, so nearly resembles the kingfisher that, in some places, the country people mistake it for the female of that bird. But it is neither wren nor kingfisher, nor yet related to either of them. It is the nice little water-ousel, with ways of its own, and a cheerful life of its own, and the power of giving pleasure to all lovers of the free country which is enriched with an infinite variety of happy, innocent creatures.

The upper part of the head and neck, and the whole back and wings of this bird, are of a rusty-brown; but, as each individual feather is edged with gray, there is no deadness of colouring. The throat and breast are snowy white, which, contrasting so strongly with the rest of the body, makes it seem to flash about like a point of light through the dark shadows of the scenes it loves to haunt.

I said above that this bird gave pleasure to all lovers of nature. So it does, for it is only met with in scenes which are especially beloved by poets and painters. Like them, it delights in mountain regions, where rocky streams rush along with an unceasing murmur, leaping over huge stones, slumbering in[34] deep, shadowy pools, or lying low between rocky walls, in the moist crevices and on the edges of which the wild rose flings out its pale green branches, gemmed with flowers, or the hardy polypody nods, like a feathery plume. On these streams, with their foamy waters and graceful vegetation, you may look for the cheerful little water-ousel. He is perfectly in character with the scenes.

DIPPERS AND NEST. [Page 34.

And now, supposing that you are happily located for a few weeks in summer, either in Scotland or Wales, let me repeat my constant advice as regards the study and truest enjoyment of country life and things. Go out for several hours; do not be in a hurry; take your book, or your sketching, or whatever your favourite occupation may be, if it be only a quiet one, and seat yourself by some rocky stream amongst the mountains; choose the pleasantest place you know, where the sun can reach you, if you need his warmth, and if you do not, where you can yet witness the beautiful effects of light and shade. There seat yourself quite at your ease, silent and still as though you were a piece of rock itself, half screened by that lovely wild rose bush, or tangle of bramble, and before long you will most likely see this merry, lively little dipper come with his quick, jerking flight, now alighting on this stone, now on that, peeping here, and peeping there, as quick as light, and snapping up, now a water-beetle, now a tiny fish, and now diving down into the stream for a worm that he espies below, or walking into the shallows, and there flapping his wings, more for the sheer delight of doing so than for anything else. Now he is off and away, and, in a moment or two, he is on yonder gray mass of stone, which rises up in that dark chasm of waters like a rock in [35]a stormy sea, with the rush and roar of the water full above him. Yet there he is quite at home, flirting his little tail like a jenny wren, and hopping about on his rocky point, as if he could not for the life of him be still for a moment. Now listen! That is his song, and a merry little song it is, just such a one as you would fancy coming out of his jocund little heart; and, see now, he begins his antics. He must be a queer little soul! If we could be little dippers like him, and understand what his song and all his grimaces are about, we should not so often find the time tedious for want of something to do.

We may be sure he is happy, and that he has, in the round of his small experience, all that his heart desires. He has this lonely mountain stream to hunt in, these leaping, chattering, laughing waters to bear him company, all these fantastically heaped-up stones, brought hither by furious winter torrents of long ago—that dashing, ever roaring, ever foaming waterfall, in the spray of which the summer sunshine weaves rainbows. All these wild roses and honeysuckles, all this maiden hair, and this broad polypody, which grows golden in autumn, make up his little kingdom, in the very heart of which, under a ledge of rock, and within sound, almost within the spray of the waterfall, is built the curious little nest, very like that of a wren, in which sits the hen-bird, the little wife of the dipper, brooding with most unwearied love on four or five white eggs, lightly touched with red.

This nest is extremely soft and elastic, sometimes of large size, the reason for which one cannot understand. It is generally near to the water, and, being kept damp by its situation, is always so fresh, looking so like the mass of its immediate surroundings[36] as scarcely to be discoverable by the quickest eye. When the young are hatched they soon go abroad with the parents, and then, instead of the one solitary bird, you may see them in little parties of from five to seven going on in the same sort of way, only all the merrier because there are more of them.

[37]

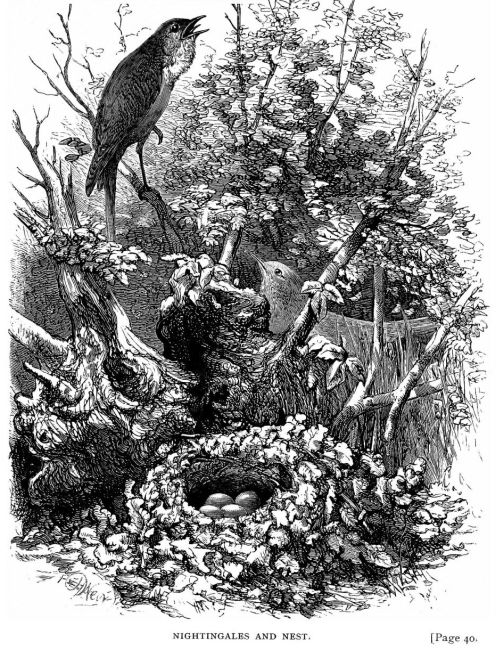

THE NIGHTINGALE.

Philomela, or the Nightingale, is the head of the somewhat large bird-family of Warblers, and is the most renowned of all feathered songsters, though some judges think the garden-ousel exceeds it in mellowness, and the thrush in compass of voice, but that, in every other respect, it excels them all. For my part, however, I think no singing-bird is equal to it; and listening to it when in full song, in the stillness of a summer’s night, am ready to say with good old Izaak Walton:—

“The nightingale, another of my airy creatures, breathes such sweet music out of her little instrumental throat, that it might make mankind to think that miracles had not ceased. He that at midnight, when the weary labourer sleeps securely, should hear, as I have very often heard, the clear airs, the sweet descants, the natural rising and falling, the doubling and redoubling of her voice, might well be lifted above earth and say, ‘Lord, what music hast Thou provided for the saints in heaven, when Thou affordest bad men such music on earth!’”

In colour, the upper parts of the nightingale are of a rich brown; the tail of a reddish tint; the throat and underparts of the body, greyish-white; the neck and breast, grey; the bill and legs, light brown. Its size is about that of the garden warblers,[38] which it resembles in form—being, in fact, one of that family. Thus, the most admired of all singers—the subject of poets’ songs and eulogies, the bird that people walk far and wide to listen to, of which they talk for weeks before it comes, noting down the day of its arrival as if it were the Queen or the Queen’s son—is yet nothing but a little insignificant brown bird, not to be named with the parrot for plumage, nor with our little goldfinch, who always looks as if he had his Sunday suit on. But this is a good lesson for us. The little brown nightingale, with his little brown wife in the thickety copse, with their simple unpretending nest, not built up aloft on the tree branch, but humbly at the tree’s root, or even on the very ground itself, may teach us that the world’s external show or costliness is not true greatness. The world’s best bird-singer might have been as big as an eagle, attired in colours of blue and scarlet and orange like the grandest macaw. But the great Creator willed that it should not be so—his strength, and his furiousness, and his cruel capacity were sufficient for the eagle, and his shining vestments for the macaw; whilst the bird to which was given the divinest gift of song must be humble and unobtrusive, small of size, with no surpassing beauty of plumage, and loving best to hide itself in the thick seclusion of the copse in which broods the little mother-bird, the very counterpart of himself, upon her olive-coloured eggs.

Mr. Harrison Weir has given us a sweet little picture of the nightingale at home. Somewhere, not far off, runs the highroad, or it may be a pleasant woodland lane leading from one village to another, and probably known as “Nightingale-lane,” and traversed night after night by rich and poor, learned and[39] unlearned, to listen to the bird. In our own neighbourhood we have a “Nightingale-lane,” with its thickety copses on either hand, its young oaks and Spanish chestnuts shooting upwards, and tangles of wild roses and thick masses of brambles throwing their long sprays over old, mossy, and ivied stumps of trees, cut or blown down in the last generation—little pools and water courses here and there, with their many-coloured mosses and springing rushes—a very paradise for birds. This is in Surrey, and Surrey nightingales, it is said, are the finest that sing. With this comes the saddest part of the story. Bird-catchers follow the nightingale, and, once in his hands, farewell to the pleasant copse with the young oaks and Spanish chestnuts, the wild rose tangles, the little bosky hollow at the old tree root, in one of which the little nest is built and the little wife broods on her eggs!

Generally, however, the unhappy bird, if he be caught, is taken soon after his arrival in this country; for nightingales are migratory, and arrive with us about the middle of April. The male bird comes about a fortnight before the female, and begins to sing in his loneliness a song of salutation—a sweet song, which expresses, with a tender yearning, his desire for her companionship. Birds taken at this time, before the mate has arrived, and whilst he is only singing to call and welcome her, are said still to sing on through the summer in the hope, long-deferred, that she may yet come. He will not give her up though he is no longer in the freedom of the wood, so he sings and sings, and if he live over the winter, he will sing the same song the following spring, for the want is again in his heart. He cannot believe but that she will still come. The cruel bird-catchers,[40] therefore, try all their arts to take him in this early stage of his visit to us. Should he be taken later, when he is mated, and, as we see him in our picture, with all the wealth of his little life around him, he cannot sing long. How should he—in a narrow cage and dingy street of London or some other great town—perhaps with his eyes put out—for his cruel captor fancies he sings best if blind? He may sing, perhaps, for a while, thinking that he can wake himself out of this dreadful dream of captivity, darkness, and solitude. But it is no dream; the terrible reality at length comes upon him, and before the summer is over he dies of a broken heart.

It is a curious fact that the nightingale confines itself, without apparent reason, to certain countries and to certain parts of England. For instance, though it visits Sweden, and even the temperate parts of Russia, it is not met with in Scotland, North Wales, nor Ireland, neither is it found in any of our northern counties excepting Yorkshire, and there only in the neighbourhood of Doncaster. Neither is it known in the south-western counties, as Cornwall and Devonshire. It is supposed to migrate during the winter into Egypt and Syria. It has been seen amongst the willows of Jordan and the olive trees of Judea, but we have not, to our knowledge, any direct mention of it in the Scriptures, though Solomon no doubt had it in his thoughts, in his sweet description of the spring—“Lo, the winter is past, the rain is over and gone; the flowers appear on the earth; the time of the singing of birds is come, and the voice of the turtle is heard in our land.” A recent traveller in Syria tells me that she heard nightingales singing at four o’clock one morning in April of last year in the lofty regions of the Lebanon.

NIGHTINGALES AND NEST. [Page 40.

[41]

There have been various attempts to introduce the nightingale into such parts of this country as it has not yet frequented; for instance, a gentleman of Gower, a sea-side district of Glamorganshire, the climate of which is remarkably mild, procured a number of young birds from Norfolk and Surrey, hoping that they would find themselves so much at home in the beautiful woods there as to return the following year. But none came. Again, as regards Scotland, Sir John Sinclair purchased a large number of nightingales’ eggs, at a shilling each, and employed several men to place them carefully in robins’ nests to be hatched. So far all succeeded well. The foster-mothers reared the nightingales, which, when full-fledged, flew about as if quite at home. But when September came, the usual month for the migration of the nightingale, the mysterious impulse awoke in the hearts of the young strangers, and, obeying it, they suddenly disappeared and never after returned.

Mr. Harrison Weir has given us a very accurate drawing of the nightingale’s nest, which is slight and somewhat fragile in construction, made of withered leaves—mostly of oak—and lined with dry grass. The author of “British Birds” describes one in his possession as composed of slips of the inner bark of willow, mixed with the leaves of the lime and the elm, lined with fibrous roots, grass, and a few hairs; but whatever the materials used may be, the effect produced is exactly the same.

In concluding our little chapter on this bird, I would mention that in the Turkish cemeteries, which, from the old custom of planting a cypress at the head and foot of every grave, have now become cypress woods, nightingales abound, it having been also an old custom of love to keep these birds on every grave.

[42]

THE SKYLARK.

The Skylark, that beautiful singer, which carries its joy up to the very gates of heaven, as it were, has inspired more poets to sing about it than any other bird living.

Wordsworth says, as in an ecstasy of delight:—

Shelley, in an ode which expresses the bird’s ecstasy of song, also thus addresses it, in a strain of sadness peculiar to himself:—

[43]

James Hogg, the Ettrick shepherd, who had listened to the bird with delight on the Scottish hills, thus sings of it:—

[44]

But we must not forget the earthly life of the bird in all these sweet songs about him.

The plumage of the skylark is brown, in various shades; the fore-part of the neck, reddish-white, spotted with brown; the breast and under part of the body, yellowish-white. Its feet are peculiar, being furnished with an extraordinarily long hind claw, the purpose of which has puzzled many naturalists. But whatever nature intended it for, the bird has been known to make use of it for a purpose which cannot fail to interest us and call forth our admiration. This shall be presently explained. The nest is built on the ground, either between two clods of earth, in the deep foot-print of cattle, or some other small hollow suitable for the purpose, and is composed of dry grass, hair, and leaves; the hair is mostly used for the lining. Here the mother-bird lays four or five eggs of pale sepia colour, with spots and markings of darker hue. She has generally two broods in the year, and commences sitting in May. The he-lark begins to sing early in the spring. Bewick says, “He rises from the neighbourhood of the nest almost perpendicularly in the air, by successive springs, and hovers at a vast height. His descent, on the contrary, is in an oblique direction, unless he is threatened by birds of prey, or attracted by his mate, and on these occasions he drops like a stone.”

SKYLARKS AND NEST. [Page 44.

With regard to his ascent, I must, however, add that it is in a spiral direction, and that what Bewick represents as springs are his sudden spiral flights after pausing to sing. Another peculiarity must be mentioned: all his bones are hollow, and he can inflate them with air from his lungs, so that he becomes, as it were, a little balloon, which accounts for the buoyancy [45]with which he ascends, and the length of time he can support himself in the air: often for an hour at a time. Still more extraordinary is the wonderful power and reach of his voice, for while, probably, the seven hundred or a thousand voices of the grand chorus of an oratorio would fail to fill the vast spaces of the atmosphere, it can be done by this glorious little songster, which, mounting upwards, makes itself heard, without effort, when it can be seen no longer.

The attachment of the parents to their young is very great, and has been seen to exhibit itself in a remarkable manner.

The nest being placed on the open-ground—often pasture, or in a field of mowing grass—it is very liable to be disturbed; many, therefore, are the instances of the bird’s tender solicitude either for the young or for its eggs, one of which I will give from Mr. Jesse. “In case of alarm,” he says, “either by cattle grazing near the nest, or by the approach of the mower, the parent-birds remove their eggs, by means of their long claws, to a place of greater security, and this I have observed to be affected in a very short space of time.” He says that when one of his mowers first told him of this fact he could scarcely believe it, but that he afterwards saw it himself, and that he regarded it only as another proof of the affection which these birds show their offspring. Instances are also on record of larks removing their young by carrying them on their backs: in one case the young were thus removed from a place of danger into a field of standing corn. But however successful the poor birds may be in removing their eggs, they are not always so with regard to their young, as Mr. Yarrell relates. An instance came under his notice, in which the little fledgeling proved too[46] heavy for the parent to carry, and, being dropped from an height of about thirty feet, was killed in the fall.

Of all captive birds, none grieves me more than the skylark. Its impulse is to soar, which is impossible in the narrow spaces of a cage; and in this unhappy condition, when seized by the impulse of song, he flings himself upwards, and is dashed down again by its cruel barriers. For this reason the top of the lark’s cage is always bedded with green baize to prevent his injuring himself. In the freedom of nature he is the joyous minstrel of liberty and love, carrying upwards, and sending down from above, his buoyant song, which seems to fall down through the golden sunshine like a flood of sparkling melody.

I am not aware of the height to which the lark soars, but it must be very great, as he becomes diminished to a mere speck, almost invisible in the blaze of light. Yet, high as he may soar, he never loses the consciousness of the little mate and the nestlings below: but their first cry of danger or anxiety, though the cry may be scarce audible to the human ear, thrills up aloft to the singer, and he comes down with a direct arrow-like flight, whilst otherwise his descent is more leisurely, and said by some to be in the direct spiral line of his ascent.

Larks, unfortunately for themselves, are considered very fine eating. Immense numbers of them are killed for the table, not only on the continent, but in England. People cry shame on the Roman epicure, Lucullus, dining on a stew of nightingales’ tongue, nearly two thousand years ago, and no more can I reconcile to myself the daily feasting on these lovely little songsters, which may be delicate eating, but are no less God’s gifts to gladden and beautify the earth.

[47]

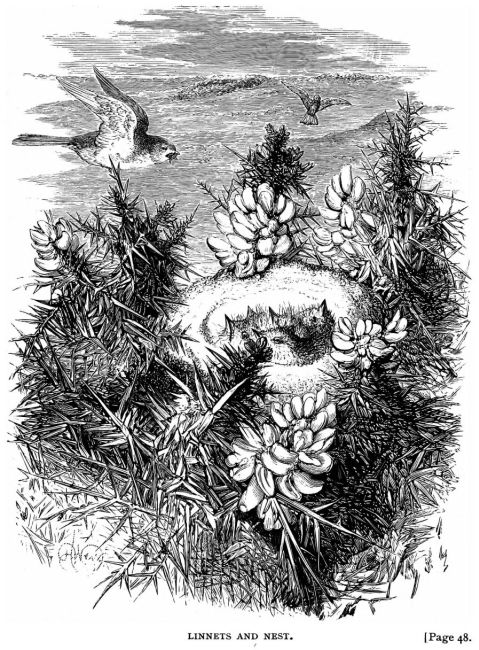

THE LINNET.

Linnets are a branch of a larger family of finches, all very familiar to us. They are cousins, also, to the dear, impudent sparrows, and the pretty siskin or aberdevines.

The linnets are all compactly and stoutly built, with short necks and good sized heads, with short, strong, pointed bills, made for the ready picking up of seed and grain, on which they live. Most of them have two broods in the season, and they build a bulky, deep, and compact nest, just in accordance with their character and figure; but, though all linnet-nests have a general resemblance of form, they vary more or less in the material used.

Linnets change their plumage once a year, and have a much more spruce and brilliant appearance when they have their new summer suits on. They are numerous in all parts of the country, and, excepting in the season when they have young, congregate in flocks, and in winter are attracted to the neighbourhood of man, finding much of their food in farm-yards, and amongst stacks.

The linnet of our picture is the greater red-pole—one of four brothers of the linnet family—and is the largest of the four; the others are the twit or mountain-linnet, the mealy-linnet, and the lesser red-pole—the smallest of the four—all[48] very much alike, and easily mistaken for each other. The name red-pole is given from the bright crimson spot on their heads—pole or poll being the old Saxon word for head. The back of our linnet’s head and the sides of his neck are of dingy ash-colour, his back of a warm brown tint, his wings black, his throat of a dull white, spotted with brown, his breast a brilliant red, and the under part of his body a dingy white.

The linnet, amongst singing birds, is what a song writer is amongst poets. He is not a grand singer, like the blackbird or the thrush, the missel-thrush or the wood-lark, all of which seem to have an epic story in their songs, nor, of course, like the skylark, singing up to the gates of heaven, or the nightingale, that chief psalmist of all bird singers. But, though much humbler than any of these, he is a sweet and pleasant melodist; a singer of charming little songs, full of the delight of summer, the freshness of open heaths, with their fragrant gorse, or of the Scottish brae, with its “bonnie broom,” also in golden blossom. His are unpretending little songs of intense enjoyment, simple thanksgivings for the pleasures of life, for the little brown hen-bird, who has not a bit of scarlet in her plumage, and who sits in her snug nest on her fine little white eggs, with their circle of freckles and brown spots at the thicker end, always alike, a sweet, patient mother, waiting for the time when the young ones will come into life from that delicate shell-covering, blind at first, though slightly clothed in greyish-brown—five little linnets gaping for food.

LINNETS AND NEST. [Page 48.

The linnet mostly builds its nest in low bushes, the furze being its favourite resort; it is constructed outside of dry grass, roots, and moss, and lined with hair and wool. We have it [49]here in our picture; for our friend, Mr. Harrison Weir, always faithful in his transcripts of nature, has an eye, also, for beauty.

Round the nest, as you see, blossoms the yellow furze, and round it too rises a chevaux de frise of furze spines, green and tender to look at, but sharp as needles. Yes, here on this furzy common, and on hundreds of others all over this happy land, and on hill sides, with the snowy hawthorn and the pink-blossomed crab-tree above them, and, below, the mossy banks gemmed with pale-yellow primroses, are thousands of linnet nests and father-linnets, singing for very joy of life and spring, and for the summer which is before them. And as they sing, the man ploughing in the fields hard-by, and the little lad leading the horses, hear the song, and though he may say nothing about it, the man thinks, and wonders that the birds sing just as sweetly now as when he was young; and the lad thinks how pleasant it is, forgetting the while that he is tired, and, whistling something like a linnet-tune, impresses it on his memory, to be recalled with a tender sentiment years hence when he is a man, toiling perhaps in Australia or Canada; or, it may be, to speak to him like a guardian angel in some time of trial or temptation, and bring him back to the innocence of boyhood and to his God.

Our picture shows us the fledgeling brood of the linnet, and the parent-bird feeding them. The attachment of this bird to its young is very great. Bishop Huntley, in his “History of Birds,” gives us the following anecdote in proof of it:—

“A linnet’s nest, containing four young ones, was found by some children, and carried home with the intention of rearing and taming them. The old ones, attracted by their chirping,[50] fluttered round the children till they reached home, when the nest was carried up stairs and placed in the nursery-window. The old birds soon approached the nest and fed the young. This being observed, the nest was afterwards placed on a table in the middle of the room, the window being left open, when the parents came in and fed their young as before. Still farther to try their attachment, the nest was then placed in a cage, but still the old birds returned with food, and towards evening actually perched on the cage, regardless of the noise made by several children. So it went on for several days, when, unfortunately, the cage, having been set outside the window, was exposed to a violent shower of rain, and the little brood was drowned in the nest. The poor parent-birds continued hovering round the house, and looking wistfully in at the window for several days, and then disappeared altogether.”

[51]

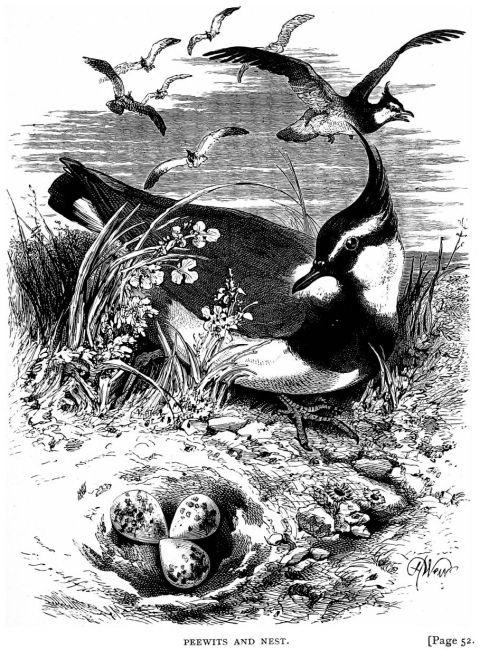

THE PEEWIT.

The Peewit, lapwing, or plover, belongs to the naturalist family of Gallatores or Waders, all of which are furnished with strong legs and feet for walking, whilst all which inhabit watery places, or feed their young amongst the waves, have legs sufficiently long to enable them to wade; whence comes the family name.

The peewit, or lapwing, is a very interesting bird, from its peculiar character and habits. Its plumage is handsome; the upper part of the body of a rich green, with metallic reflections; the sides of the neck and base of the tail of a pure white; the tail is black; so is the top of the head, which is furnished with a long, painted crest, lying backwards, but which can be raised at pleasure. In length the bird is about a foot.

The peewit lives in all parts of this country, and furnishes one of the pleasantly peculiar features of open sea-shores and wide moorland wastes, in the solitudes of which, its incessant, plaintive cry has an especially befitting sound, like the very spirit of the scene, moaning in unison with the waves, and wailing over the wide melancholy of the waste. Nevertheless, the peewit is not in itself mournful, for it is a particularly lively and active bird, sporting and frolicking in the air with its fellows, now whirling round and round, and now ascending to a great[52] height on untiring wing; then down again, running along the ground, and leaping about from spot to spot as if for very amusement.

It is, however, with all its agility, a very untidy nest-maker; in fact it makes no better nest than a few dry bents scraped together in a shallow hole, like a rude saucer or dish, in which she can lay her eggs—always four in number. But though taking so little trouble about her nest, she is always careful to lay the narrow ends of her eggs in the centre, as is shown in the picture, though as yet there are but three. A fourth, however, will soon come to complete the cross-like figure, after which she will begin to sit.

These eggs, under the name of plovers’ eggs, are in great request as luxuries for the breakfast-table, and it may be thought that laid thus openly on the bare earth they are very easily found. It is not so, however, for they look so much like the ground itself, so like little bits of moorland earth or old sea-side stone, that it is difficult to distinguish them. But in proportion as the bird makes so insufficient and unguarded a nest, so all the greater is the anxiety, both of herself and her mate, about the eggs. Hence, whilst she is sitting, he exercises all kinds of little arts to entice away every intruder from the nest, wheeling round and round in the air near him, so as to fix his attention, screaming mournfully his incessant peewit till he has drawn him ever further and further from the point of his anxiety and love.

PEEWITS AND NEST. [Page 52.

The little quartette brood, which are covered with down when hatched, begin to run almost as soon as they leave the shell, and then the poor mother-bird has to exercise all her little [53]arts also—and indeed the care and solicitude of both parents is wonderful. Suppose, now, the little helpless group is out running here and there as merry as life can make them, and a man, a boy, or a dog, or perhaps all three, are seen approaching. At once the little birds squat close to the earth, so that they become almost invisible, and the parent-birds are on the alert, whirling round and round the disturber, angry and troubled, wailing and crying their doleful peewit cry, drawing them ever further and further away from the brood. Should, however, the artifice not succeed, and the terrible intruder still obstinately advance in the direction of the young, they try a new artifice; drop to the ground, and, running along in the opposite course, pretend lameness, tumbling feebly along in the most artful manner, thus apparently offering the easiest and most tempting prey, till, having safely lured away the enemy, they rise at once into the air, screaming again their peewit, but now as if laughing over their accomplished scheme.

The young, which are hatched in April, are in full plumage by the end of July, when the birds assemble in flocks, and, leaving the sea-shore, or the marshy moorland, betake themselves to downs and sheep-walks, where they soon become fat, and are said to be excellent eating. Happily, however, for them, they are not in as much request for the table as they were in former times. Thus we find in an ancient book of housekeeping expenses, called “The Northumberland Household-book,” that they are entered under the name of Wypes, and charged one penny each; and that they were then considered a first-rate dish is proved by their being entered as forming a part of “his lordship’s own mess,” or portion of food; mess[54] being so used in those days—about the time, probably, when the Bible was translated into English. Thus we find in the beautiful history of Joseph and his brethren, “He sent messes to them, but Benjamin’s mess was five times as much as any of theirs.”

Here I would remark, on the old name of Wypes for this bird, that country-people in the midland counties still call them pie-wypes.

But now again to our birds. The peewit, like the gull, may easily be tamed to live in gardens, where it is not only useful by ridding them of worms, slugs, and other troublesome creatures, but is very amusing, from its quaint, odd ways. Bewick tells us of one so kept by the Rev. J. Carlisle, Vicar of Newcastle, which I am sure will interest my readers.