Figure 1

Building a

CHAMPIONSHIP

Football Team

PAUL W. “BEAR” BRYANT

Athletic Director and

Head Football Coach,

University of Alabama

Englewood Cliffs, N.J.

PRENTICE-HALL, INC.

© 1960, BY

PRENTICE-HALL, INC.

Englewood Cliffs, N.J.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. NO PART OF THIS BOOK

MAY BE REPRODUCED IN ANY FORM, BY MIMEOGRAPH

OR ANY OTHER MEANS, WITHOUT PERMISSION

IN WRITING FROM THE PUBLISHER.

Library of Congress

Catalogue Card Number: 60-53173

Eighth Printing February, 1968

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

08605—BC

To a few close associates who were genuinely dedicated to the game of football. These men were not only great assets to the game; they also exemplified the true American way of life. Had it not been for men like these, many of us would have fallen by the wayside. To them, I am forever grateful.

| Robert A. Cowan Fordyce, Arkansas |

Herman Hickman Yale University—Sports Illustrated |

| Frank W. Thomas University of Alabama |

Jim Tatum University of North Carolina |

| W. A. Alexander Georgia Tech |

G. A. Huguelett University of Kentucky |

| H. R. “Red” Sanders U. C. L. A. |

Herman L. Heep Texas A & M |

| Charles Caldwell Princeton University |

Rex Enright University of South Carolina |

This book would not have been possible had it not been for the untiring efforts of Eugene Stallings, co-captain Texas A & M 1956, All Conference SWC End, and assistant football coach, University of Alabama. “Bebes” Stallings exemplifies the true meaning of football, both as a player and as a coach.

If Sir Andrew were coaching football today, he would be accused of teaching “hard-nosed football,” for his battlecry “I’ll rise and fight again” is that of Paul “Bear” Bryant, author of this book and self-acknowledged teacher of hard-nosed or all-out football.

Paul Bryant is one of the ablest, most colorful, most controversial mentors. Fans either love Bear Bryant or despise him—which makes him excellent box office.

Competitive fires flame high in Coach Bryant. Legend has it he once played an entire game with a broken leg, believable when one considers the all-out effort he demands of himself and his players. Deep down, he is a sentimentalist who leaves a heavy imprint on his players. John David Crow, All-American back and Heisman Trophy winner under Bryant at Texas A & M, and now a National Football League star, says, “Coach Paul Bryant is the greatest coach in America. He made a man out of me.”

Paul Bryant is a builder. When he came to Texas A & M in 1954, Aggie fortunes were at a low ebb. In four years, Bryant’s Aggies won 25, lost 14, tied 2, and nine of those losses were in his first year.

As a sports writer and television commentator, this observer has watched Southwest Conference football since 1915, the first[viii] year a grid champion was crowned. The conference’s best job of coaching was Bryant’s, beginning in 1954. His outstanding player walked out of the Junction, Texas training camp, and Bryant would not let him return. In their first game, the Aggies lost to Texas Tech 9 to 41. The Aggies dropped all six conference games, but only Baylor was able to achieve a two-touchdown margin. In 1956, Bryant built an unbeaten team, with “my Junction boys” the nucleus.

There was something almost mystical about Bryant’s story of why he was leaving Texas A & M for his alma mater, the University of Alabama: “As a small boy, I sometimes would play until after dark, and then, from afar off, I’d hear my beloved mother calling, ‘Paul, come home.’ I’d run as fast as my legs would carry me.”

Some cynics sneer at Paul Bryant’s explanation. But the many sportsmen who hold for him lasting respect and affection know this warm-hearted man is telling the truth.

Lloyd Gregory

Houston, Texas

| Chapter | Page | |

| 1. | Why Football? | 1 |

| 2. | The Theory of Winning Football | 8 |

| 3. | Making the Most of the Coaching Staff | 18 |

| 4. | Defense—Our Kind of Football | 24 |

| 5. | Pass Defense—Objectives and Tactics | 62 |

| 6. | Our Kicking Game Techniques | 111 |

| 7. | Our Offensive Running Game | 140 |

| 8. | Our Offensive Passing Game Techniques | 176 |

| 9. | Training the Quarterback | 186 |

| 10. | Planning for a Game | 203 |

| 11. | Our Drills | 215 |

| 12. | Those Who Stay Will Be Champions | 231 |

| Index | 235 |

Have you ever wondered about football? Why it’s only a game which is as fundamental as a ball and a helmet. But the sport is a game of great importance. If you take all of the ingredients that go into making up the game of football and put them into a jar, shake well and pour out, you’ve got a well-proportioned phase of the American way of life.

Football is the All-American and the scrub. It’s the Rose Bowl with 102,000 cheering fans, and it’s the ragged kids in a vacant lot using a dime-store ball. It’s a field in Colorado ankle-deep in snow, and one in Florida sun-baked and shimmering.

Leaping cheerleaders, a brassy band, and the Dixie Darlings are a part of the wonderful game of football. It’s a rich guy being chauffeured to the stadium gate, and a frightened boy shinnying the fence and darting for the end zone seats. It’s a crowd which has gone crazy as it rips down the goal posts. And it’s a nation stunned and wet-eyed at the news of Knute Rockne’s death.

Football is drama, music, dignity, sorrow. It’s exhilaration and shock. It is also humor and, at times, comedy. It’s a referee sternly running the game. It’s an inebriated character staggering onto the field and trying to get into the action.

Football is the memory of Red Grange, the Four Horsemen, and the Seven Blocks of Granite. It’s a team’s traditional battle cry, such as, “War Eagle,” in the middle of the summer. It’s[2] a crisp fall day, traffic jams, portable radios and hip flasks. It’s train trips, plane flights and victory celebrations. It’s the losers moaning, “You were lucky, just wait’ll next year!”

Names are football, such as Bronco, Dixie, Night Train, The Horse, Hopalong, Bad News, The Toe, and Mr. Outside.

For four quarters, football is the Great American Novel, with chapters from Frank Merriwell, the Bible, Horatio Alger, the life of Lincoln and Jack the Giant-Killer.

Newspaper photos, arguments, Mr. Touchdown USA, yellowed clippings, the Hall of Fame, The Star-Spangled Banner—they’re all football.

It’s a game of young men with big shoulders and hard muscles. It’s also a game of old pros, such as, 38-year-old Charlie Conerly quarterbacking the New York Giants to a football championship.

Football is popcorn, cokes, banners and cigaret smoke. It’s people standing for the kick-off, lap blankets, pacing coaches, penalties and melodious alma maters.

Football is a game of surprises. The big guy everybody picks in pre-season as All-American fizzles out. But a kid nobody ever heard of scores the winning touchdown and a star is born. It’s Tennessee going 17 games without being scored on. It’s also tiny Chattanooga upsetting mighty Tennessee, making a coach’s dream come true.

It’s the pro halfback who is a movie star. And the water boy who got into a game at Yale. It’s Bronco Nagurski butting down a sandbag abutment, and dwarfish Davey O’Brien disappearing from sight behind an array of 250 pound linemen. It’s Harry Gilmer jumping high to pass, and Coach Jim Owens proving that nice guys finish first.

Football is Bud Wilkinson, whose Sooners are 40 points ahead, walking up and down the sideline like a caged lion. It’s 35-year-old Paul Dietzel and 90-year-old Amos Alonzo Stagg. It’s 6′8″ Gene “Big Daddy” Lipscomb and 5′6″ Eddie LeBaron.

Women who don’t know a quick kick from a winged-T cheer every move on the field, waving pennants, purses and even mink[3] stoles. That’s football. So is the pressbox with its battery of clattering typewriters. And the oldtimer who claims they played a better game in his day is a part of football, too.

It’s Ray Berry, who wears contact lenses, making unbelievable catches for the Baltimore Colts. And after the game, when he dons his thick glasses, he looks the part of a studious school teacher—which he is after football season terminates.

It’s a scramble for tickets, playing parlays, wide-eyed youngsters getting autographs, a fist fight in the stands, second guessing, banquets, icy rains, color guards, fumbles, goal line stands, homecoming queens, and the typical mutt running onto the field attracting everyone’s attention.

Football is Tommy Lewis jumping off the bench in the Cotton Bowl game and tackling a touchdown-bound Rice runner simply because, “I’ve got too much Alabama in me, I guess.” It’s the quivering voice of a dying George Gipp telling his Notre Dame teammates, “Win one for the Gipper.”

It’s New Year’s, Christmas and the Fourth of July rolled into one. It’s VJ Day, the Declaration of Independence, Haley’s comet and Bunker Hill. It’s tears and laughter, pathos and exuberance.

Football is a game that separates the men from the boys, but also it’s a game that makes kids of us all.

Most of all it’s a capsule of this great country itself.[1]

[1] The author extends sincerest thanks to Clettus Atkinson, Assistant Sports Editor, Birmingham Post-Herald, for contributing his fine depiction to the meaning of football.

Football, in its rightful place, can be one of the most wholesome, exciting and valuable activities in which our youth can possibly participate. It is the only sport I know of that teaches boys to have complete control of themselves, to gain self-respect, give forth a tremendous effort, and at the same time learn to observe the rules of the game, regard the rights of others and stay within bounds dictated by decency and sportsmanship.

Football in reality is very much the American way of life. As in life, the players are faced with challenges and they have an opportunity to match skills, strength, poise and determination against each other. The participants learn to cooperate, associate,[4] depend upon, and work with other people. They have a great opportunity to learn that if they are willing to work, strive harder when tired, look people in the eye, and rise to the occasion when opportunity presents itself, they can leave the game with strong self-assurance, which is so vitally important in all phases of life. At the same time they are developing these priceless characteristics, they get to play and enjoy fellowship with the finest grade and quality of present day American youth.

Not only is football a great and worthwhile sport because it teaches fair play and discipline, but it also teaches the number one way of American life—to win. We are living in an era where all our sympathy and interest goes to the person who is the winner. In order to stay abreast with the best, we must also win. The most advantageous and serviceable lesson that we can derive from football is the intrinsic value of winning. It is not the mere winning of the game, but it is teaching the boys to win the hectic battle over themselves that is important. Sure, winning the game is important, and I would be the last to say that it wasn’t, but helping the boy to develop his poise and confidence, pride in himself and his undertakings, teaching him to give that little extra effort are the real objectives of teaching winning football.

If I had my choice of either winning the game or winning the faith of a boy, I would choose the latter. There is no greater reward for a coach than to see his players achieve their goals in life and to know he had some small part in the success of the boys’ endeavors.

Boys who participate in football, whether in high school or college, are in their formative years. It is every coach’s responsibility to see that each boy receives the necessary guidance and attention he so rightly deserves. I would be deeply hurt and embarrassed if I learned a boy wasn’t just a little better person after having played under my guidance. If we, as coaches, lose the true sense of the value of football and get to a point where we cannot contribute to a boy progressing spiritually, mentally,[5] and physically, we will be doing this wonderful game of football a great injustice by remaining in coaching.

The coaching profession is honorable and dignified and we football coaches are in a position to contribute to the mental development and desirable attitudes which will remain with the boys throughout their lives. We have the opportunities to teach intangible lessons to our players that will be priceless to them in future years. We are in a position to teach these boys intrinsic values that cannot be learned at home, church, school or any place outside of the athletic field. Briefly, these intangible attributes are as follows: (1) Discipline, sacrifice, work, fight, and teamwork; (2) to learn how to take your “licks,” and yet fight back; (3) to be so tired you think you are going to die, but instead of quitting you somehow learn to fight a little harder; (4) when your team is behind, you learn to “suck up your guts” and do whatever it takes to catch up and win the game; and (5) you learn to believe in yourself because you know how to rise to the occasion, and you know you will do it! The last trait is the most important one.

One personal reference will illustrate the intangible attributes that football teaches. We have all seen or heard someone tell about the greatest display of courage a team has ever shown. When a team you coach has had such an experience, it makes you exceedingly happy and proud of your position and the team. While I have never been ashamed of any of my football clubs, I will always have a soft spot in my heart for one of my teams in particular. I think my 1955 Texas A & M team displayed the greatest courage, rose to the occasion better, and did more of what I call “sucking up their guts and doing what was required of them” in a particular game than any other team with which I’ve ever been associated.

We were playing Rice Institute in Houston on a hot, humid afternoon. Our play was very sluggish and before we fully realized it, the game was almost over, and we were behind 12-0. We were leading the Conference race up to this point, but it[6] was beginning to look as if we were going to be humiliated before 68,000 people. Having become disgusted with my starting unit’s ineffective play, I withdrew the regulars from the game early in the fourth quarter. With approximately four minutes left to play, I decided to send the regulars back in. I told them they still had time to win the game if it meant enough to them to do so.

The first unit went on to the field and immediately called time out. I later found out they vowed to each other they were going to do whatever it took to win the game. We eventually got possession of the football on our own 42-yard line, and the clock showed 2:56 remaining to play. Again the boys called time out, giving each man a few seconds to make up his mind just exactly what he was going to do. On the first play from scrimmage, Lloyd Taylor, a little halfback from Roswell, New Mexico ran 58 yards around left end for a touchdown. He kicked the extra point and the score was 12-7, with 2:08 remaining in the game. We tried an on-side (short) kick, and Gene Stallings recovered the ball on Rice’s 49-yard line. Our quarterback, Jimmy Wright, then threw a 49-yard pass to Lloyd Taylor who made a beautiful catch as he crossed the goal line. Taylor scored his fourteenth point as he kicked his second point-after-touchdown placement. With the score 14-12, we lined up and kicked the ball deep to Rice. Forcing Rice to gamble since they were behind, they attempted a deep pass which our great fullback, Jack Pardee, intercepted and returned 40 yards to the 3-yard line. On the next play Don Watson carried the ball across for a touchdown, making the final score 20-12 in our favor.

After the game in our dressing room when everyone was congratulating each other, and everything was in a state of confusion, Lloyd Taylor suggested we thank the Master for giving us the courage to make the great comeback. From that game on we have always said a prayer of gratitude after the game, win, lose, or draw.

The particular incident cited was the greatest display I have ever seen of boys reaching back and getting that little extra, showing their true colors, and rising to the occasion and putting into practice the thing that we preach and believe in.

What do we get out of coaching? There is nothing in the world I would swap for the associations with those boys, and the other fine men I have coached, and the self satisfaction of knowing I’ve helped many boys to find themselves. In my estimation, football is truly a way of life.

Every football team has a slogan, and each coach has his own theory as to what makes a winning team. We are no exception. Our slogan is, “Winning is not everything, but it sure beats anything that comes in second.” Our theory on how to develop a winning team is very simple—WORK! If the coaches and players will work hard, then winning will be the result.

We want to win. We play to win. We are going to encourage, insist and demand that our players give a 100% effort in trying to win. Otherwise we would be doing them a great injustice. It is very important for the boys to have a complete understanding of what they must do in order to win.

When a boy has completed his eligibility or has played four years under our guidance, I like to believe he will graduate knowing how to suck up his guts and rise to the occasion, and do whatever is required of him to get his job done. If our boys are willing to work hard, and we give them the proper leadership and guidance, then they will graduate winners and our athletic program will be a success.

Building a winning football team is something that cannot be accomplished overnight, or even in a year or two, if the program is starting from scratch. I believe, irrespective of the time element involved, a football program has little chance of succeeding unless the following “musts” are adhered to:

1. The coach must have a definite plan in which he believes, and there must be no compromise on his part.

2. The football coach must have the complete cooperation and support of the administrators and the administration, who must believe in the head coach, his staff, and his plan.

3. The coach must have a long term contract.

4. The coach must not only be dedicated to football, but he must be tough mentally.

5. The head coach must have the sole responsibility and authority of selecting his staff of dedicated men, who must believe in the head coach and his plan.

It is vitally important that a coach build a solid foundation for his program. In order to do this he must have complete cooperation from every member of the school’s administration. In many cases the school officials will not have a complete and thorough understanding of your athletic program. It is important that you explain to them just what you are trying to accomplish, how long it will take, and why you are doing it in your particular manner. The administrators and the administration must understand the value the program has for each boy who participates, and the ways the program can benefit the entire school system. Therefore, before a coach accepts a particular position he should give considerable thought to the administration’s philosophy, attitude or point-of-view toward the football program. If the school president or principal is skeptical, consider the position seriously before accepting it. Building a championship team is difficult enough with full cooperation from everyone, but it is an impossible coaching situation without the administration’s full support and confidence.

If a college coach is going to build a team, it is an absolute must that he have a long term contract. There is little use in believing or thinking any other way. It is very possible, and highly probable, it will take at least four or five years to shape a ball[10] club into winning form. Without the security of a long term contract, a coach can be forced to concentrate on winning a certain number of games each year, and it is possible this can completely disrupt or disorganize a rebuilding program. I am not saying that a coach should not try to win every game, because he obviously should strive to win ’em all. I merely want to point out the fact that without the security of a job for a period of years, he might be forced to revert to certain practices which he knows are not sound principles on which to build a winning program. As an illustration, he might have to revert to such a practice as playing individuals of questionable character because of their immediate ability, rather than weeding them out and concentrating on the solid citizens. The latter group will stay with you and will eventually be winners, if you are given job security and adequate time to work with them.

Unless a person is dedicated to his chosen trade or profession, regardless of his field of endeavor, he is never going to be highly successful. Building a winning football team is no exception. The head coach, as well as his assistants, must be dedicated to football. All of them must be tough mentally, too.

Many times a coach’s job is unpopular and unrewarding. From time to time a coach must make decisions that are unpleasant. He cannot compromise, however, if he expects to build a winner. He must be tough mentally in order to survive.

In addition, a coach must be tough mentally in another sense. He must be able to spend numerous hours studying football all ways and always. A coach who hopes to be successful must drive himself and be so dedicated to his job that he puts it ahead of everything else in his life, with the exception of his religion and his family. One can have a tremendous knowledge of the game, but he cannot possibly make the grade unless he can stand up to the long hours and the trying times. It is not an absolute necessity for a coach to be exceptionally smart or a brilliant strategist, but he must be a hard worker, mentally tough, and dedicated to the game of football. One can only be honest with himself in determining whether or not he has these qualifications.

As head football coach, you must give leadership and direction to your program if you expect it to be successful. Therefore, you must have a definite plan in which you and your assistants believe. In order to build winners you cannot deviate from your plan, and there cannot be any compromises.

Many factors go into the plan, such as organizing the program and the type of boys whom you have on your squad, both of which will have a great deal to do with your ultimate success or failure. These and other phases of the plan will be discussed in detail shortly, and in later chapters in this book.

In order to build winners, the head coach must surround himself with a dedicated staff of hard working coaches. While I have touched on this point briefly already, this particular must will be discussed in greater detail in Chapter 3, “Making the Most of Your Coaching Staff.”

The team with the best athletes will usually win the tough ball games, other things being equal. It is a well recognized fact that a coach is no better than his material. Therefore we must have the best material available in order to be a winner. I tell my coaches if they can recruit the best athletes to our school, then I can coach them. If they recruit mediocre athletes, then the assistants will have to coach them.

There are a number of qualifications that we look for in our athletes, and some of these are musts if the boys are to become champions. Football is nothing more than movement and contact. If a player has excellent movement but won’t make contact, he will never be a winner. Conversely, if a boy is mean, loves body contact, and likes to hit people, but is so slow he never gets to the ball carrier, then he will never make a winner either. There are ways to improve an individual’s quickness, but if a boy refuses to make contact, there is nothing that I know of to correct it.

The type of boy you select to play on your football team has a great deal to do with your ultimate success or failure. In order for our program to be successful, we try to select the boy with the following traits:

1. He must be dedicated to the game of football.

2. He must have the desire to excel and to win.

3. He must be tough mentally and physically.

4. He must be willing to make personal sacrifices.

5. He must put team glory first in place of personal glorification.

6. He must be a leader of men both on and off the field.

7. He should be a good student.

A player must be dedicated to the game to the extent he is willing to work, sacrifice, cooperate and do what he possibly can to aid the team in victory. It is our duty as coaches to explain and show our boys the advantages of being winners, and to impress upon them the absolute necessity of it so they will put forth the much needed effort to accomplish the objective. It is important for the players to understand that football is not an easy game; nor is achieving fame an easy task. However, anything worth doing, is worth doing right. Therefore let’s do it right and be winners.

We refer to “the little extras” a boy must give in order to be a winner. These little extras really make the difference between good and great, whether it be on an individual or a team basis. When a boy puts into practice what you have been preaching about giving that extra effort when he is dog tired, going harder, rising to the occasion and doing what is necessary to win, then you are making progress and he is on the way to becoming a winner both individually and for his team.

There is nothing else I would rather see than when our boys are in their goal line defense, and they have supreme confidence they will keep the opposition from scoring. Every boy is taking it upon himself personally to do what is necessary to stop the ball carrier from scoring. When a coach has a team thinking[13] like this, he will have a winner, and the boys will be winners when they get out of school.

We talk about the importance of particular aspects of coaching, such as full cooperation, long contracts, and other phases connected with coaching, but in the final analysis the success or failure of your program depends on the performance of the boys on the playing field. The game is generally won by the boys with the greatest desire. The difference in winning and losing is a very slight margin in a tough ball game. The same applies to two players of equal ability, except that one is great and the other is average. What is this slight margin? It’s the second and third effort, both individually and as a team. The boy who intercepts a pass or blocks a punt, or who gets his block then goes and knocks down another opponent is the individual who wants to excel. He will make the “big play” when it counts the most. He and others will give us “the winning edge.” These are the deciding factors in a tough ball game.

The teams that win consistently are the ones in the best physical condition. As a result they can play better football than their opposition in the fourth quarter. We also believe and teach our boys they must be more aggressive and “out-mean” our opponents if they expect to win consistently.

We may not be as smart and as tricky as our opposition, so we have to out-work ’em. If our boys are in top physical condition, if we “out-mean” and physically whip our opponents by hard blocking and tackling, and we are consistent in doing it, we’ll win a lot of football games. Football is a contact sport, and we must make the initial contact. In order to be a winner a boy must whip his man individually, and the team must beat the opponent physically.

Unity is the sound basis for any successful organization, and[14] a football team is no exception. Without team unity you cannot have winners. We believe and coach team victory. Our goal is to win every game we play. We go into every game believing we will win it. Obviously we don’t win all of them, but we never go into a game believing we cannot come out of it the winner.

In order to have a winner, the team must have a feeling of unity; every player must put the team first ahead of personal glory. The boy who plays for us must be willing to make sacrifices. Victory means team glory for everyone. Individual personal glory means little if the team loses.

In order to have winners your boys must be leaders both on and off the field. They should be good students, too. As was indicated previously, if your contract will give you sufficient time to work with the “solid citizens,” they will stay with you even if the going gets tough, and eventually they will be winners.

Most coaches take pride in their ability to pick out boys with athletic ability. I am no exception. However, you can never be absolutely certain about a boy because you cannot see what is inside of his heart. If we could do this, we would never make a mistake on a football player. We have seen it occur frequently where a player was pitiful in his freshman year, and the coaches almost give up on his ever improving. However, through determination, hard work, pride and desire the boy would finally develop and would play a lot of football before he graduated.

My assistant coaches have a favorite story they like to tell about a player we had at the University of Kentucky. We had started our first practice session in the fall of 1948 when a youngster walked out on the field. His appearance literally stopped practice. He had on a zoot suit with the trouser legs pegged so tightly I am certain he had difficulty squeezing his bare feet through the narrow openings. His suspenders drew up his trousers about six inches above his normal waist line. His long zoot coat extended almost to his knees. His “duck tail”[15] hair style looked quite unusual. He was standing in a semi-slump, and twirling a long chain around his finger when one of my assistants walked over and asked him if he wanted someone. His answer, “Yeah. Where’s the Bear?”

He found me in a hurry. Our first impression was that he would never be a football player, but he was issued a uniform anyway. I figured he wouldn’t have the heart for our type of football and would eliminate himself quickly from the squad. To help him make up his mind in a hurry I instructed one of the coaches assisting me to see that he got plenty of extra work after practice. The boy’s name was difficult to pronounce, so we started calling him “Smitty.”

Despite “Smitty’s” outward appearance, he had the heart of a competitor and the desire to show everyone he was a good football player. He worked hard and proved his point. In his senior year he was selected the outstanding player in the 1951 Sugar Bowl game when we defeated the University of Oklahoma. After graduation he played for several years with the New York Giants as a fine defensive end. I shall always have the greatest respect for him.

Other coaches probably have had similar experiences where a boy with questionable ability has made good. If a boy has a great desire to play football, regardless of his ability, and you work with him, he is likely to make tremendous progress toward fulfilling his objective.

Without good organization our thoughts or plans of any kind would be absolutely useless. Good organization is a must if a team is to operate at maximum efficiency. There are many plans of organization that are good, and I am not saying mine is the best, but I believe my plan is sound and this is what really counts.

It always has been my practice to observe people who are successful in a particular field, and try to determine what makes their operation successful. There is little originality remaining[16] in the field of coaching. Consequently we have gotten many of our ideas from other people. As Frank Howard of Clemson College put it, “If we get something from one team, it’s called stealing; but if we get ideas from several different teams, it’s called research.”

I borrowed my plan of organization from some ants in Africa. I realize this sounds ridiculous and far fetched; nevertheless, it’s the truth. It is interesting how it all came about.

While I was in the Navy in Africa, one hot, humid afternoon I was sitting under a tree feeling sorry for myself. I started to watch some ants building an ant hill. At first I was amused, but as I watched I became very interested. What at first appeared to be confusion was actually a carefully organized plan as the ants all worked toward their objective of building a home. The longer I watched the more obvious it became that all of the ants were working, many in small groups here and there. There was no inactivity, no wasted motion. There was unity and there was a plan. It appeared the ants had planned their work and they worked their plan.

With the ant plan in mind, we try to organize our practice sessions so that we have everyone working and no one standing around idle. We work in small groups and this eliminates inactivity. As a result we feel that we can get more work done in a shorter period of time. Consequently we believe the less time a player spends on the practice field, the higher will be his morale.

I did not have to watch the ants to learn the value of teamwork and cooperation, although this was evident in their activity. The main lesson I learned from them was the value of small group work in order to keep everyone busy.

There are many other factors that must be taken into consideration when organizing the program, and I shall discuss the subject more fully in Chapters 3 and 10. Planning and organization are the backbone of a successful team. Planning a practice so that you get maximum results from the players and the assistant[17] coaches requires a great deal of time. The importance of this cannot be emphasized too greatly.

Winning theories vary from coach to coach, but our philosophy toward building a winner consists of the following factors: (1) a hard working staff that is dedicated to football; (2) players with a genuine desire to excel, to “out-mean” the opponent, and be in top physical condition; (3) a strong organization and a sound plan; (4) mental toughness in both staff and players; and (5) the full confidence of the school administration. In addition, you must teach sound football. Your boys and your staff must have confidence in your type of football. I shall discuss our methods fully in later chapters.

I am a firm believer in the old saying, “A head coach is no stronger than his assistant coaches.” In order for any head coach to have a good program he must surround himself with a staff of good assistant coaches. This does not mean that every coach must have six or eight assistants. In some cases the head coach may not have more than two or three assistants. The principles are the same, however, regardless of the number of assistant coaches. I have been fortunate in having an excellent group of assistants every place I have coached, and I want to give credit to them for any measure of coaching success I may have had in the past.

There are many characteristics I am seeking in an assistant coach. I shall not attempt to list them in the order of importance because I think they all belong at the top of the list. Briefly, the desirable traits and characteristics I am seeking in an assistant are as follows:

1. He should be dedicated to the game of football.

2. He should be willing to work hard and to make personal sacrifices.

3. He should be an honest person.

4. He should have a sound knowledge of football.

5. He should have a great deal of initiative.

6. He should be a sound thinker.

7. He should be tough mentally.

The first trait, “Be dedicated to the game of football,” is a must for all coaches, assistants as well as head coaches. Don’t ever try to fool yourself or anyone else. If you are not truly dedicated to your work, and you dread spending many hours every day working and planning on building a good football team, then you are in the wrong business. I’ll guarantee there is no easy way to develop a winning team. If it were an easy task, all of us would be undefeated and “Coach of the Year.” Unfortunately one team generally wins and the other loses, and if it is the latter it doesn’t make a coach’s job any easier. If you will look at the consistent winners, you will find behind them a group of coaches who are dedicated 100% to their work.

Regardless of whether it’s the college or high school level of competition, there are coaches and teams that win year after year. The real reason for this success, other than good material, is the coaches of these particular teams are dedicated to the extent that they “want” to do what is necessary to win. There is a big difference between “wanting to” and “willing to” do something to be a winner. Frankly, I don’t like the word “willing” in connection with an assistant coach. First, if the coaches are not willing, they should not be coaching. Coaching is not an 8 A.M. to 5 P.M. job. The assistant who is “willing” to work a little extra is not the one I want on my staff. The assistant who “wants” to do what is necessary in order to get the team ready to play, regardless of the time element involved, is the man whom I want to assist me.

A head coach cannot expect his assistants to be dedicated to their work, unless he leads by example. The head coach must work harder, longer, and be more dedicated to his work than any of his assistants, if he expects to have a good, hard-working staff and winners.

Another qualification I consider a must for all assistant coaches is their 100% loyalty to the head coach’s plan. It is[20] very important for a coach and his staff to know they have mutual trust and loyalty to each other. These characteristics are obvious, and an assistant coach who does not possess them commits professional suicide.

An assistant coach should have a great deal of initiative and ambition. I prefer to have my assistants study the game all ways and always. They should constantly try to improve themselves. There is no corner on the brain market and a person advances in his field through hard work and his own initiative.

It is a must that all coaches be good “mixers.” They must be able to get along with each other, the head coach, the players, and the people in the community. On the college level a coach must know how to recruit, and most of the time the successful recruiter is a good mixer. He must sell your product—the school, the team, the coaching staff, etc.—to athletes and their parents, and his job will be easier if he has this type of personality.

It is an absolute must that all coaches be honest with themselves, the people for whom they work, and the others with whom they come in contact. If I cannot trust a person, I do not want him around. Along this same line, we like our coaches to be active in their church work. We emphasize to our players the value of attending church, and we like our coaches to set a good example for everyone.

In order for a coach to be competent, he must be a sound thinker and possess a good knowledge of the game of football. I have mentioned this previously. I expect my assistants to study, plan, discuss and try to come up with ideas that might aid us in winning a football game. We are going to toss around all ideas in our staff meetings before we adopt any of them, but your brand of football can become stale and unprogressive if the coaches do not study the game.

Morale on a squad is very important. The morale of a coaching staff is very important, too. I feel the latter group will influence the former group, consequently I am vitally concerned about my assistants having good morale. With this thought in mind, I try to delegate duties and responsibilities so the assistants enjoy their work. Each man is really a specialist, or he can do some phase a little better than another coach. Therefore it’s just common sense to permit him to work at the specialty in which he is going to excel. He will not only have more enthusiasm for his work, but his enthusiasm will be reflected in the players’ work. There is no substitute for enthusiasm. Under such conditions the players learn more quickly and the coaches are able to do a better job of coaching.

I do not think it advisable for a head coach to do group work with one of his assistants. If an assistant is directing a group and the head man comes over to help out, he takes the lead away from the assistant. As a result the assistant coach is likely to lose his initiative—the very trait you want him to develop. Secondly, the players are likely to give the head coach all of their attention, and this isn’t fair to the assistant working with the same group of boys. Thirdly, I do not think it is desirable to suggest changes, make corrections or reprimand an assistant on the field. I feel the proper time to get the matter straightened out is after practice, and not while the players are around. I always try to avoid situations which are not conducive to good team and staff morale because you’ve got to have good morale in order to build a winner.

I think it is important for my assistants to specialize in either offensive or defensive football. I feel they can do a better job of coaching if they devote most of their time and effort toward one aspect or the other. We still want them to be cognizant of[22] the opposite phase, however, as the defensive coaches must understand offensive football, and vice versa for the offensive coaches. In fact, from time to time I will put an offensive coach with the defense so he can learn more about this particular phase of the game. I believe it would be advisable for a high school coach, with possibly only a staff of two, to follow the same plan—one offensive coach and the other on defense.

Immediately after practice every day during the season I meet with my staff. I have little patience with the assistant who wants to hurry away from practice immediately. I want my staff members to meet in the staff room so we can discuss all phases of the day’s practice schedule while it is still fresh in our minds. Evaluation of personnel goes on all the time. Therefore, I want my assistants to list on the blackboard the work schedule for the next day for their particular group of boys. In addition I want their suggestions and comments as to the type of teamwork needed. Now I am in a better position to do a more intelligent job of setting up the practice schedule for the next day since I have been made aware of our individual and team needs, strengths and weaknesses. We have found this procedure very helpful, and I encourage my assistants to express themselves. I shall explain our procedures more fully in Chapter 10.

The head coach must delegate responsibility to his assistants in order to have a more effective plan of operation. The head coach must let each assistant know what he expects from him. An explanation of duties and responsibilities in the beginning is likely to eliminate misunderstanding later on. Secondly, a person with some responsibility is likely to do a better job than the individual who doesn’t have any. I have found it gives the assistant more confidence in himself and more pride in his work if he has been given a certain amount of responsibility.

As I mentioned previously in Chapter 2, in order to get the most from your staff, they must be completely sold on your plan for building a winner. Of course, the head coach must believe in his own plan 100%, along with the assistants, and he cannot make any compromises if he expects to be successful.

We stress the point frequently that coaching is teaching of the highest degree, and a good coach is a good teacher. It is not what you and your assistants know about football that is going to win the games, but rather what you are able to teach your players. In order to give our coaches an opportunity to improve their coaching techniques, we have them get up at staff meetings and explain and demonstrate various points. The other coaches will pretend they do not understand the coach who has the floor, and he must explain and answer the questions to our satisfaction. We have found this method gives the coaches a lot of confidence and they do a better job of coaching on the field.

In order for the head coach to get the maximum from his assistants, he must set a good example. Since others will follow a leader who actually leads, rather than one who merely tells what to do, I believe a head coach must work longer, harder, and stay a jump ahead of his assistants and the other coaches in the profession. He must be dedicated to the game of football, well organized, sound in his thinking, and have the ability to delegate authority and responsibility to his assistants if he expects to build a successful program.

We believe defense is one of the most important phases of football. As a matter of fact, we work on defense more than we do on offense. We feel if we do not permit the opposition to score, we will not lose the football game. While in reality most teams actually score on us, we still try to sell our players on the idea that if the opposition does not score we will not lose.

If you expect to have a good defensive team, you must sell your players on the importance of defensive football. Our players are enthusiastic about defensive football. I believe we do a good job of teaching defensive football because the staff and players are sold on what we are trying to do. Defense is our kind of football.

The primary objective of defensive football is to keep the opposition from scoring. We want our players to feel their ultimate objective is to keep the opposition from crossing our goal line.

A more functional facet of the primary object is to keep the opposition from scoring the “easy” touchdown, which is the cheap one, the long pass or the long run for six points. While a singular long run or a long completed pass may not actually defeat us, it is very likely if either play breaks for the “easy” touchdown we will be defeated.

Secondly, our kicking game must be sound, which I shall[25] discuss fully in Chapter 6. We must be able to kick the ball safely out of dangerous territory. Providing we do this, and eliminate the “easy” touchdown, we believe our opposition’s own offense will stop itself 65% of the time through a broken signal, a penalty, or some other offensive mistake. Therefore, if my boys are aggressive while on defense, we’ll probably keep our opposition from scoring about 25% of the time they have the ball. The remaining 10% will be a dog fight. Therefore, we must instill in our defensive men a fierce competitive pride that each player is personally responsible for keeping the opposition from scoring.

Our next objective is to sell the players on the idea our defensive unit can and will score for us. There are more ways to score while on defense than on offense; consequently, the odds favor the defense. If statistics are kept on the defensive team’s performance, and the defensive team is given credit for all scores made by running back a punt, recovering a fumble or any other defensive maneuver where they either score or get the ball for their offense inside of the opposition’s 25-yard line, which results in a score, the players can be sold on the idea of the offensive-minded defense.

Previously I mentioned the importance of good morale in building a winner. In order to sell a boy on defense you must create good morale. Therefore, we sell our boys on the idea that playing defense is the toughest assignment in football. We try to see that our defensive players get most of the recognition and favorable publicity. If our defense makes a goal line stand, and we win the game, we try to give most of the credit to our defensive players.

We want to make our defensive players believe that when the opposing team has the ball inside our 3-yard line they aren’t going to score—they can’t score—they must not score! If a team believes this, it’s almost impossible for the offense to score. In 1950 our defensive unit prevented opposing teams from scoring[26] on 19 occasions from the 3-yard line. The morale of the defensive players was outstanding. They thought it was impossible for another team to score on them even though they had only three yards to defend. I recall in our game with Oklahoma University in the Sugar Bowl, the Sooners got down to our 3-yard line. We were caught with three or four of our best players on the bench, and I was trying to get them back into the game quickly. As Jim McKenzie, who had been replaced, came off the field, he said, “Don’t worry, Coach, they will never score on us.” And they did not score! When I see such evidence as this, I know our players believe what we tell them, and “we are in business!”

I do not believe you can teach defensive football successfully unless you are able to present a clear picture to your players of what you are trying to accomplish. Our objective is to limit the offense to as small an area as possible. By limiting their attack, we can hem them in and catch them. We attempt to build a fence around the ball, and around the offensive operation. I want my players to have a good picture of exactly how we are going to build this fence, and what we hope to accomplish, both of which will be explained later.

Defense is a phase of football I have always considered very interesting because every play is a personal challenge. When a team is on defense, the players are challenging the offensive players in relating to an area of ground or field. Every man on defense should believe, “I am not going to let the offense score.” If you expect to be a winner, either as a player or a coach, you must believe in this philosophy 100%. Your play must be sound, and you must believe in it.

Offensive football is assignment football, while defense is reaction football. One mistake on defense can cost a team a football game. Consequently there cannot be errors on defense. By being sound, and in order to eliminate errors, I mean you must always have the strength of your defense against the strength of the offense. The defensive players must be positioned[27] in such a way that the team as a whole can handle any situation that might arise.

There are numerous defensive alignments, just as there are different points-of-view or theories toward how defense should be played. Regardless of the differences and a coach’s particular plan, the following “musts” are considered basic axioms if a defense is to be sound:

1. The defense must not allow the opponent to complete a long pass for an “easy” touchdown.

2. The defense must not allow the opponent to make a long run for an “easy” touchdown.

3. The defense must not allow the opposition to score by running from within your 5-yard line.

4. The defense must not allow the opposition to return a kick-off for a touchdown.

5. The defense must not allow the opposition to average more than 20 yards per kick-off return.

6. The defense must intercept two passes out of every 13 passes attempted.

7. The defense must average 20 yards per return on each interception.

8. The defense must return three interceptions for touchdowns per season.

9. The defense must force the opposition to fumble the ball on an average of three and one-half times per game.

10. The defense must recover an average of two and one-half fumbles per game.

These 10 basic axioms are extremely important, and must be applied if a team is to be sound defensively.

A good sound defense is one that has every player on defense carrying out his assignment. Then it is impossible for the offense to score. Note that I said every player, which makes defense a[28] team proposition and eliminates the individual defensive play. By this I mean every defense is coordinated and a player just doesn’t do what he wants to do. I do not mean suppressing an individual’s initiative or desire to excel while on defense, as long as the entire defense is a coordinated unit. We try to instill in every boy that he is personally responsible to see that our opposition does not score. When individual players and a team accept this responsibility, I feel we are making progress and beginning to build a winner.

During all phases of our defensive work we elaborate frequently on the importance of gang tackling. We like to see six or seven of our boys in on every tackle. Such tactics are not only demoralizing to ball carriers and wear them down physically, but represent sound football. It is difficult for the ball carrier to break loose and score when half a dozen men are fighting to get a piece of him.

We want the first tackler to get a good shot at the ball carrier, making certain he does not miss him. We want the other defenders to “tackle the ball,” and make the ball carrier fumble it so we can get possession of the football. We are trying to get possession of the football any way we can. Frankly we want the first man to the ball carrier merely to hold him up, and not let him get away, so we can unload on him. You can punish a ball carrier when one man has him “dangling,” and the others gang tackle him hard. I am not implying we want our boys to pile on and play dirty football merely to get a ball carrier out of the game. First, we do not teach this type of football as it is a violation of the rules and spirit of the game. Second, piling on brings a 15-yard penalty. We cannot win when we get penalized in clutch situations.

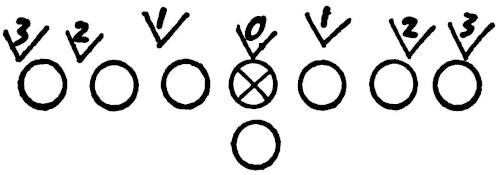

After coaching for a number of years, and always trying to find something that would make football easier to understand[29] for the average player, I came upon a system of defensive numbering that has proven very valuable to me since then. In the past I have used many different defenses. I always employed the technique of giving each defense a name. Most of the time the name had little in common with the defense, and this confused, rather than helped, the players. After discussing the possibility of the numbering system with my own and other college and high school coaches, while at Texas A & M in 1956 I finally come across a feasible plan for numbering defensive alignments. I must give credit to O. A. “Bum” Phillips, a Texas high school coach, for helping work out the solution as he experimented with the numbering system with his high school football team.

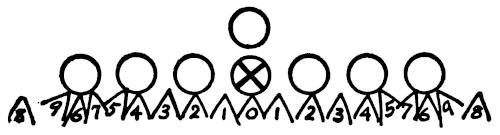

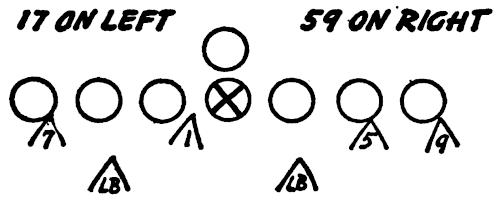

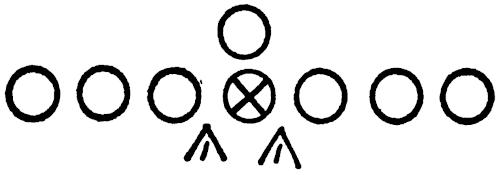

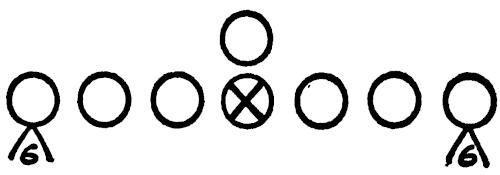

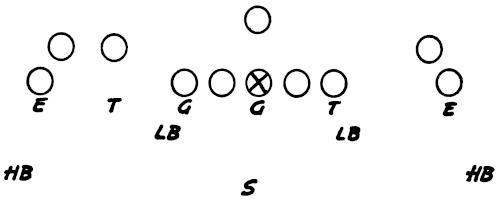

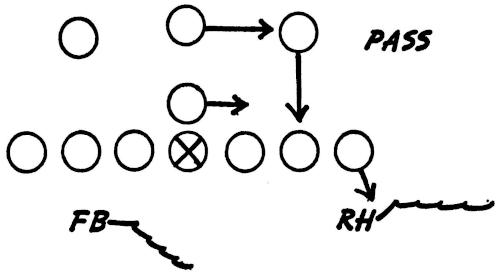

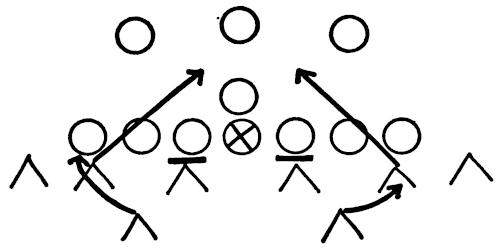

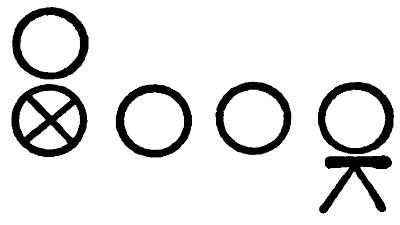

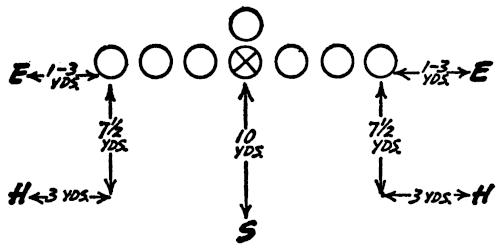

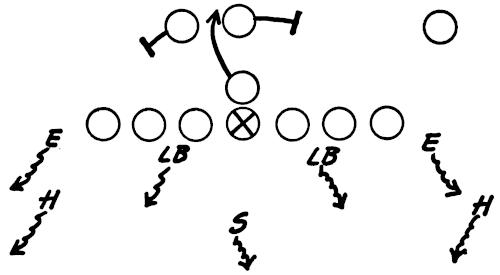

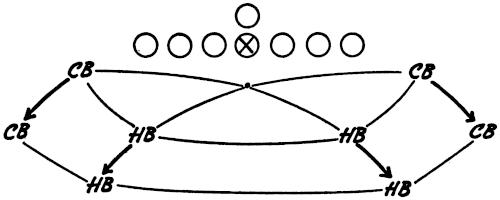

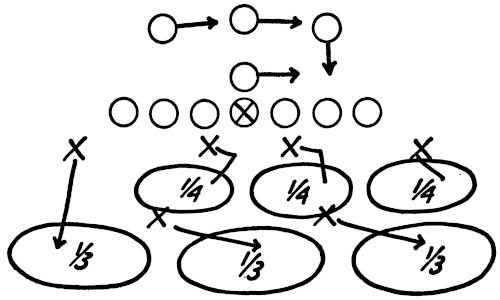

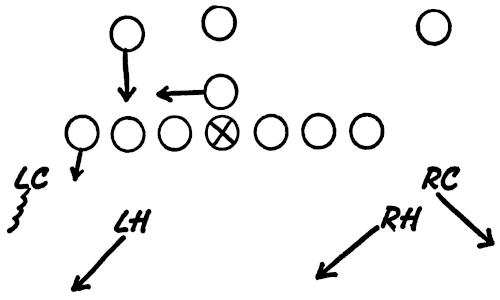

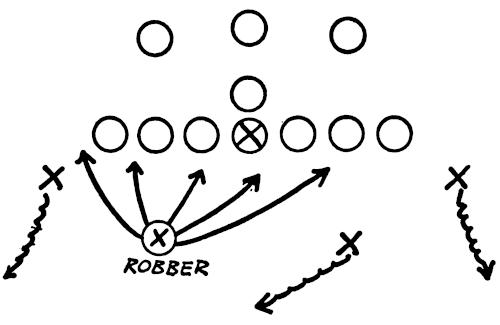

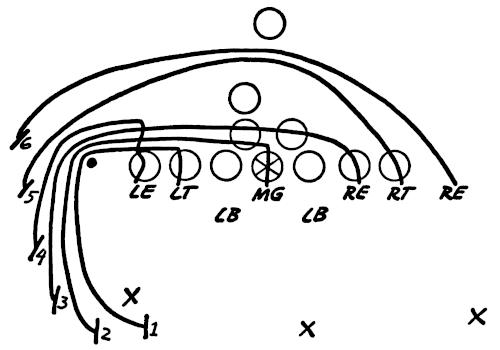

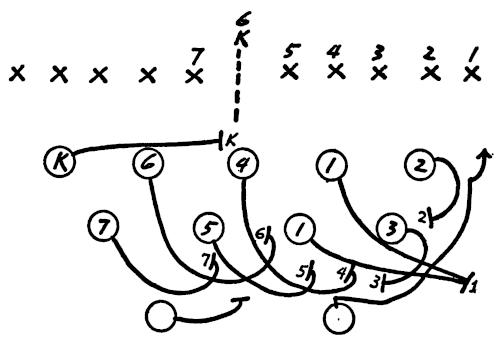

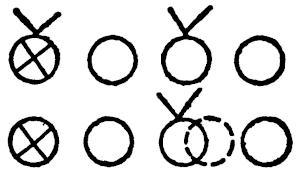

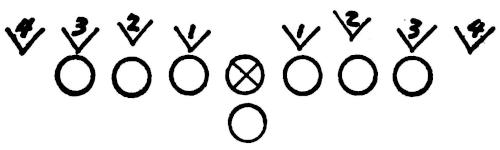

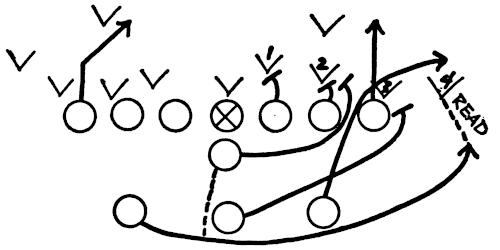

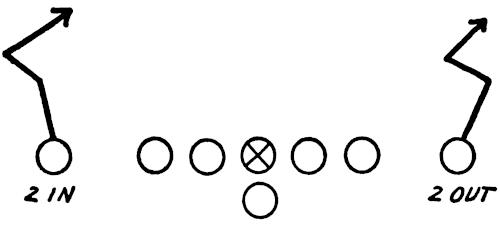

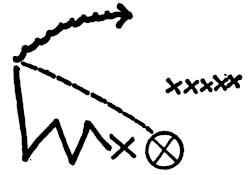

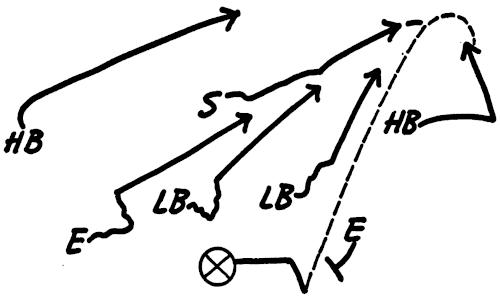

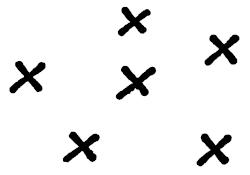

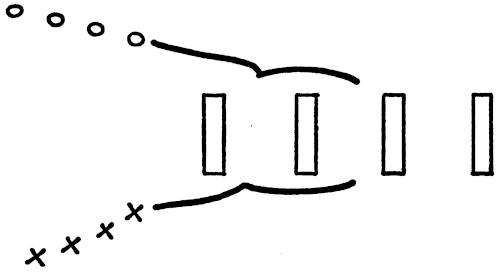

In the numbering of our defense now, we give each offensive man a number, as well as the gaps between the offensive linemen. Figure 1 is an example of our defensive numbering system.

Figure 1

Accompanying each number is a particular “technique,” which will be explained shortly. If a defensive player lines up in a 2 position, he will play what we call a “2 technique”; a 3 position plays a “3 technique,” etc. Therefore, from end to end of the offensive line we can line-up our defensive men and each position has a particular technique.

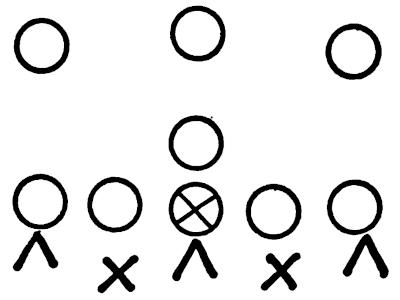

Who calls the defense? How is it called and what does it mean? Who is included in the call? Each linebacker calls the defense for his particular side of the line. He controls his guard, tackle and himself, but he does not control the end on his side of the line. The latter is controlled by the defensive signal caller in the secondary who gives a call for the 4- or 5-spoke defensive alignment.

Each linebacker calls two numbers. The first number tells his guard where to line up and his accompanying defensive[30] technique. The second number gives the same information to the defensive tackle.

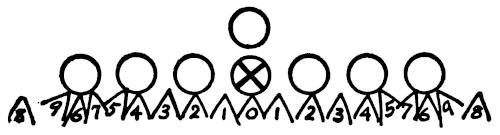

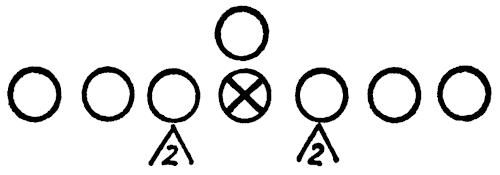

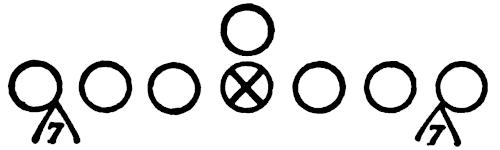

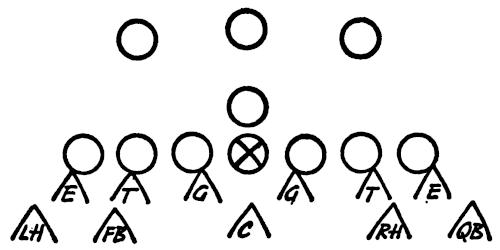

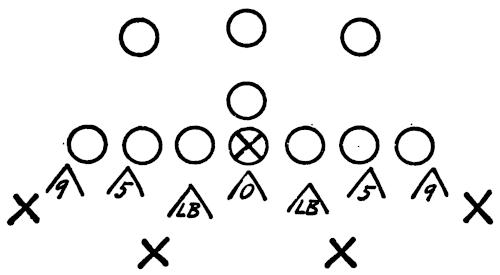

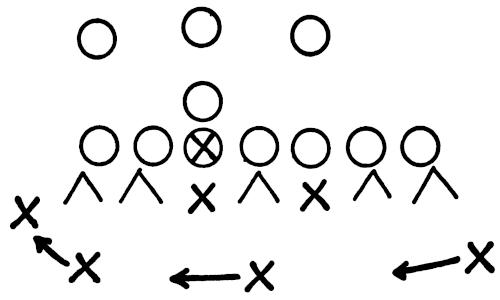

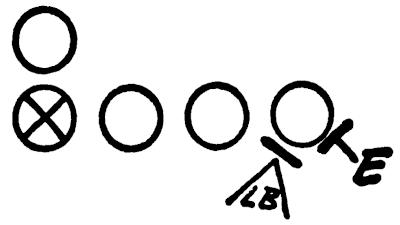

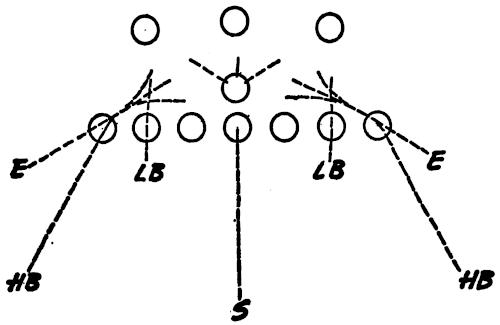

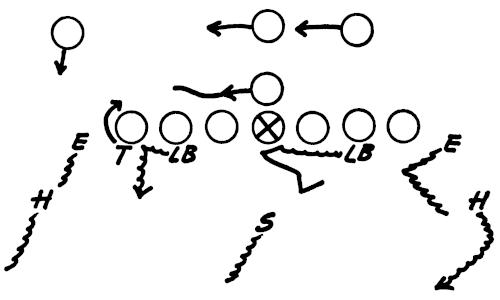

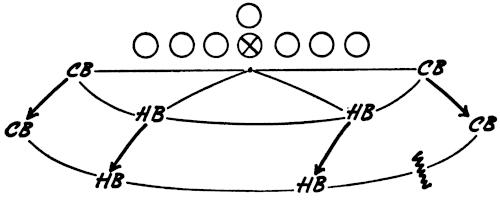

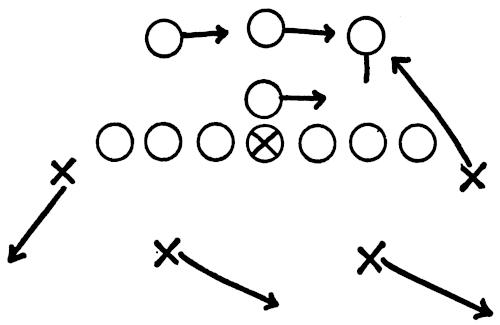

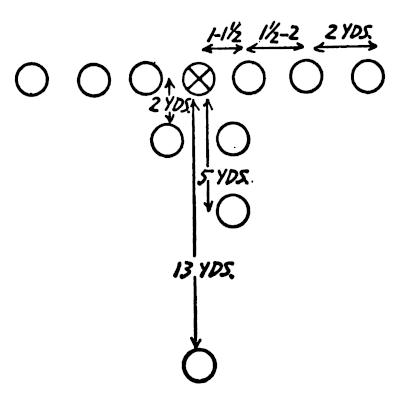

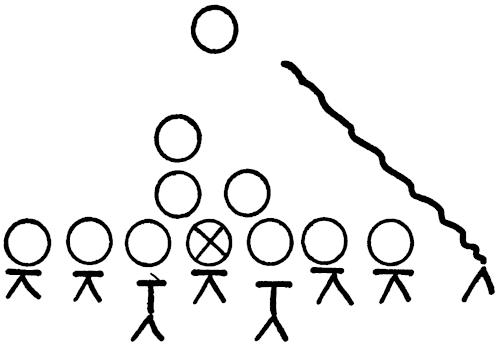

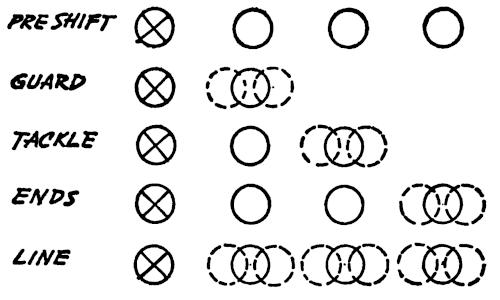

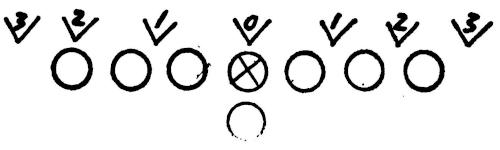

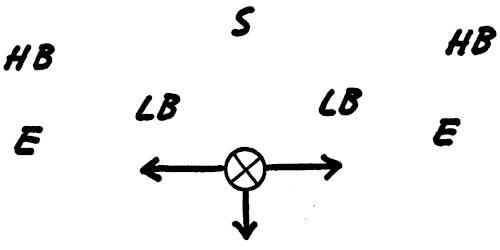

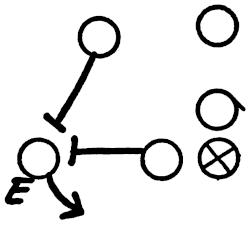

As an example, if the linebacker calls, “26,” the guard will play a 2 technique and the tackle a 6 technique. If the caller said, “59,” the guard would play a 5 technique and the tackle a 9 technique. When the linebacker tells the guard and tackle which techniques to play through his oral call, then he lines up in a position to cover the remaining gaps. As an example, Figure 2 illustrates a 26 call, and the linebacker must take a position between his guard and tackle so he can fill the gap(s) not covered by the other front defenders. You can see by this example the linebacker is in a position to help out over the offensive tackle position, and also on a wide play to his side of the line.

Figure 2

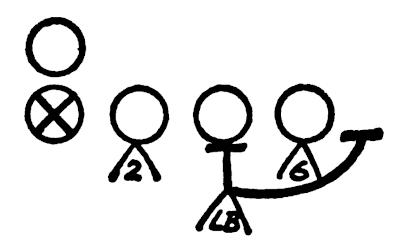

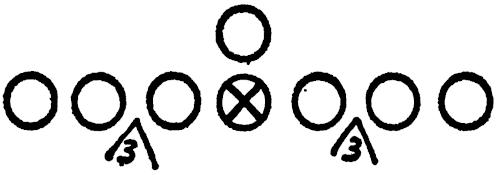

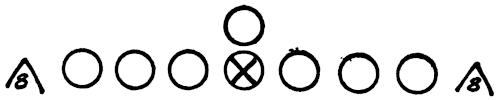

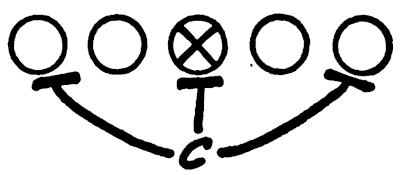

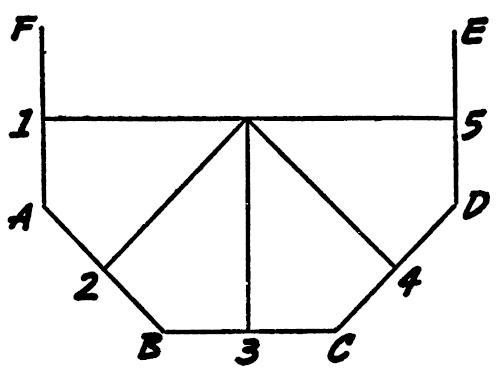

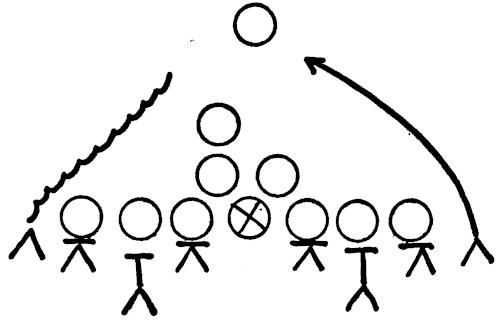

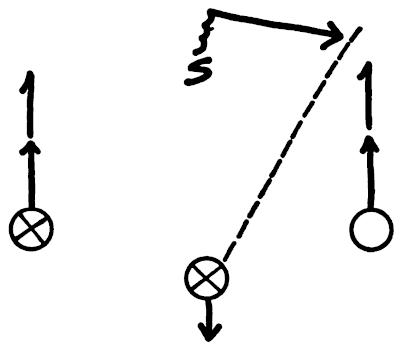

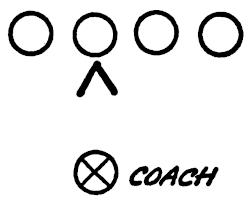

Figure 3 illustrates the position of the defensive right guard, tackle and linebacker when the call is 59. The linebacker is now in a position to help out on a play that is in the middle of the line.

Figure 3

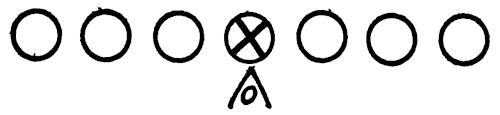

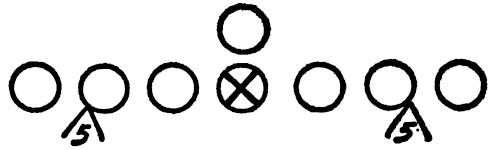

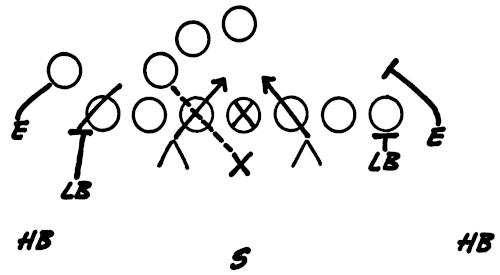

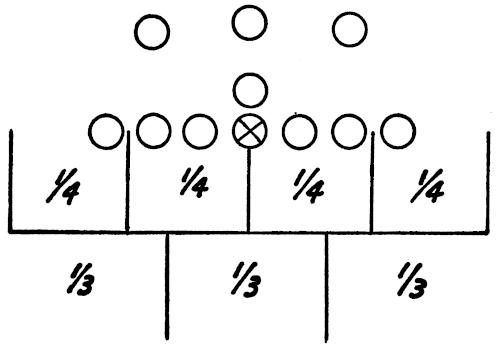

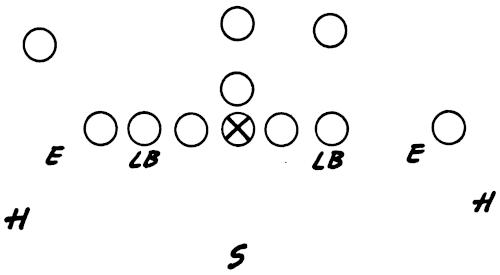

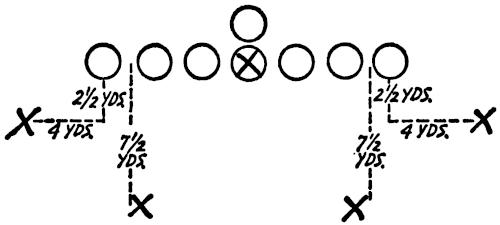

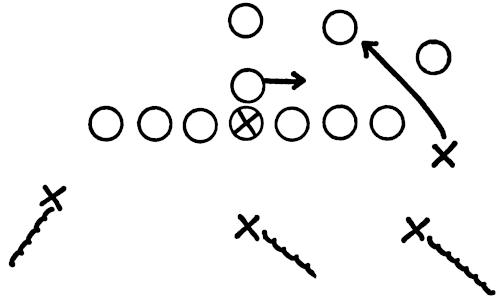

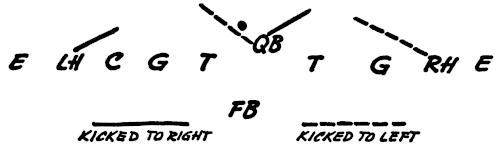

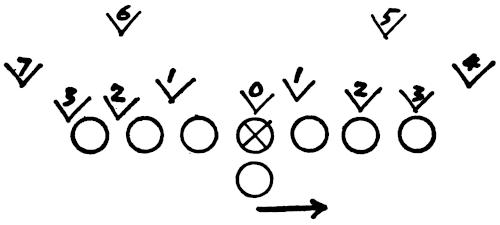

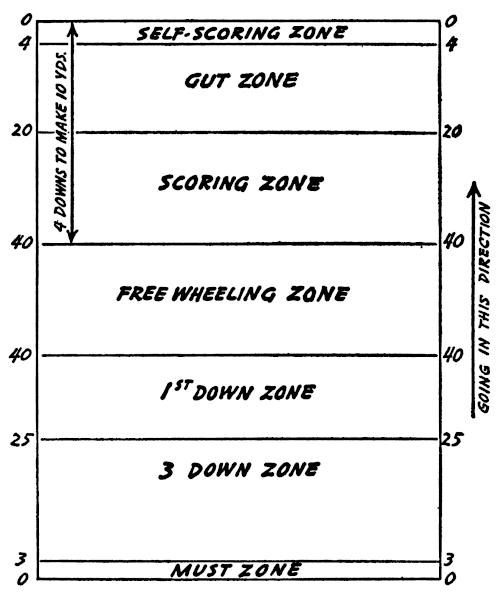

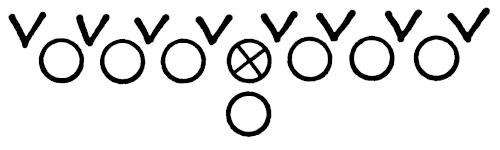

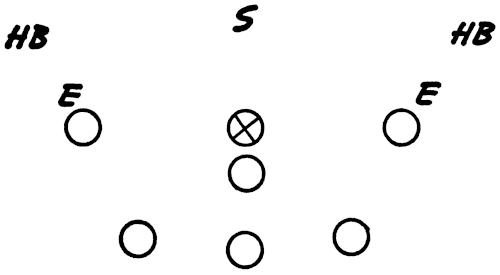

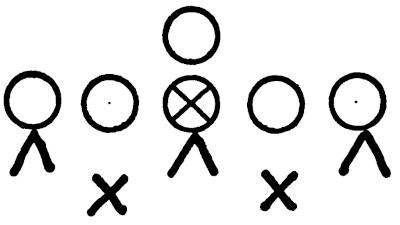

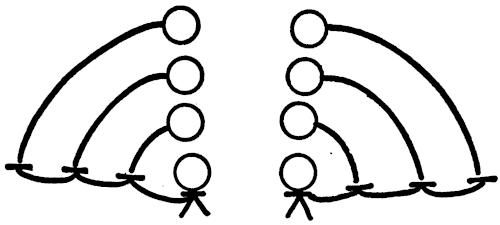

One point I failed to mention, if we are playing a 4-spoke defense, which will be explained and illustrated shortly, we[31] assign one defender to play “head on” the offensive center, and he does not figure in any of the calls. He lines up the same every time, as is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4

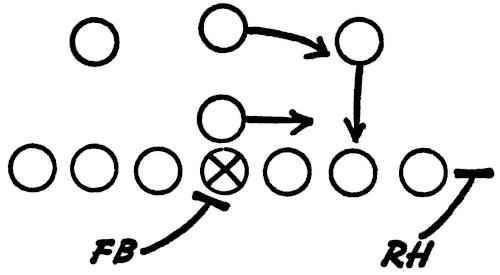

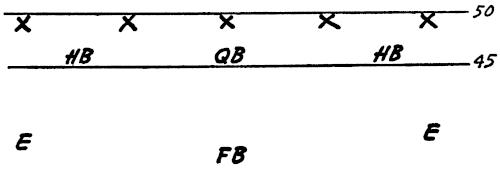

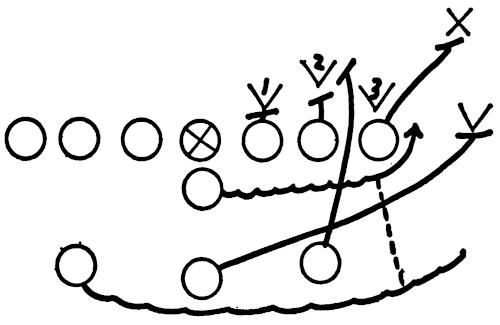

When we play a 5-spoke defense, which will also be explained shortly, the two linebackers assign one player to the area inside the offensive guards. As an example, if we are playing a 5-spoke defense and the call on the right side is 59, the call on the left side must be a one as the first digit, such as, 17, 16, 15. Figure 5 illustrates a 59 call on the right, and a 17 call on the left, with one man playing a 1 technique in order to keep from having a large gap between the two guards.

Figure 5

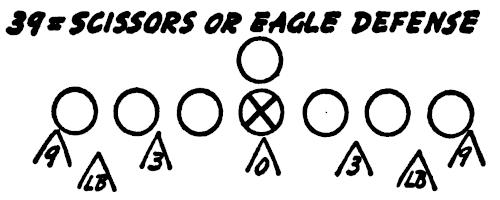

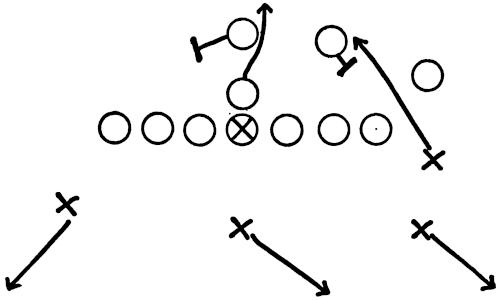

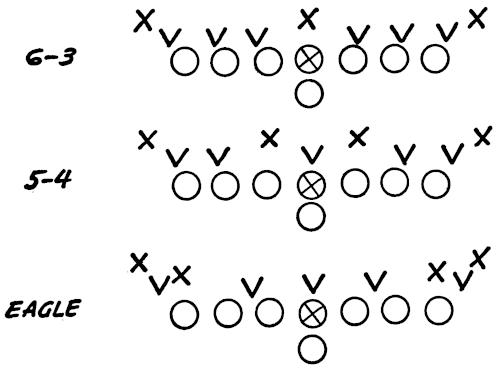

You can quickly observe that by having our players learn only a few numbers and their accompanying techniques, we can line up in numerous defensive alignments merely by calling two numbers. Figures 6 and 7 are examples of 59 and 39 defensive calls, which are 4-spoke defenses with a man in a 0 technique, and are commonly referred to as the Oklahoma and Eagle defenses, respectively.

Figure 6

Figure 7

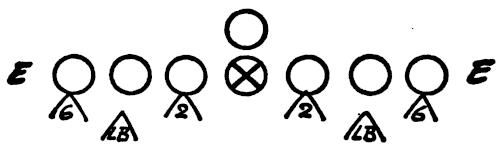

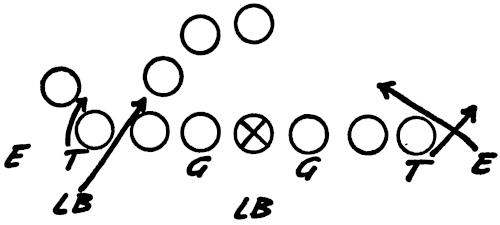

Figure 8 illustrates a 25 call, with a 0 technique, and is a 9-man front defensive alignment.

Figure 8

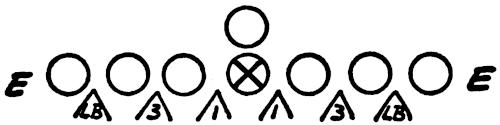

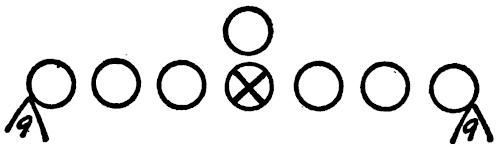

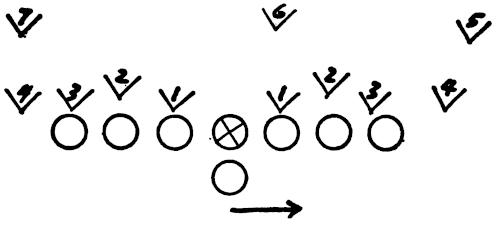

Figures 9-11 are 5-spoke defenses representing 26, 37, and 13 calls, which are commonly referred to as a wide tackle 6, a split 6, and a gap 8 alignment, respectively.

Figure 9

Figure 10

Figure 11

These defenses, Figures 6-11, have the same call to each side. Each side is actually independent of the other as far as the calls are concerned. To eliminate any confusion, merely designate which side (left) is to call first, and the other linebacker (right) can adjust on his call accordingly so there is not a large gap in the middle of the defensive line. The linebackers must be especially aware of this if we are employing a 5-spoke defensive alignment.

The signal caller should never call a defense involving two successive numbers, such as 2-3, 7-6, as this will leave too much territory for him to try to cover (see Figure 1). The caller is always responsible for having a man in, or capable of covering, every gap.

It is very simple for the defensive signal caller to change the guard and tackle assignments even after he has given them a position to line up in and its accompanying technique. The caller merely adds a zero (0) or a one (1) to the end of the number he has called. As an example, if he gives the call 37 and he wants the players in the 3 technique to charge one-half a man toward the inside, he will say, “30.” If he wants this defender to charge one-half a man to the outside, he would say, “31.” This second call is given to only one player at a time, but[34] he can change both of their techniques by saying, “31—71,” or “30—70,” etc.

Our present method is the simplest one I know of for getting players into various defenses quickly with a minimum amount of talking. We feel it eliminates much confusion. We have found the players take a great deal of pride in learning only a few techniques, which they are able to execute well. We know it makes our job easier as coaches, and we can do a better job of coaching the boys. As a coaching point, when a coach talks to a tackle, as an example, he talks in terms of a particular technique (6, 7, etc.), and the player understands him immediately. When the coaches are discussing plays, or in a staff meeting, we identify the particular technique immediately, and everyone understands each other. We have also found the method useful when making out the practice schedule as I merely specify, “Tackle coach work on 6 technique,” etc.

Employing a defensive numbering system requires the defensive signal callers to be alert. They do not merely call several numbers. They must be aware of the tactical situation at all times, and call a sound defense according to a tactical and strategical planning. As an illustration, a good short yardage call would be 13, and sound passing situation calls would be 36, 37, 39, 59 (see Figures 1, 3, 6, 7, 10, 11). I spend at least several minutes every day with my defensive signal callers. It is the linebackers’ responsibility to see that we line up in a sound alignment every time.

As illustrated in Figure 1, and mentioned earlier, our techniques and defensive positions are numbered from 0-9 on both sides of the defensive line, numbering from inside-out (with certain exceptions noted, Figure 1). I now wish to explain in detail each particular technique, although there is only a slight difference between several of them. As an example, when playing the 2 technique, a defender lines up head on the offensive guard,[35] and when playing a 4 technique he is head up on the offensive tackle. Consequently these techniques are similar.

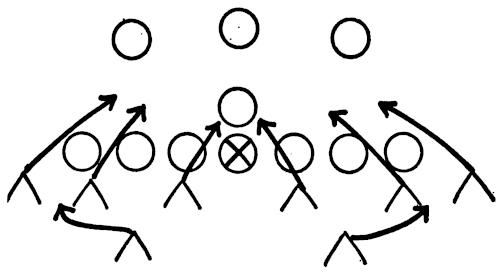

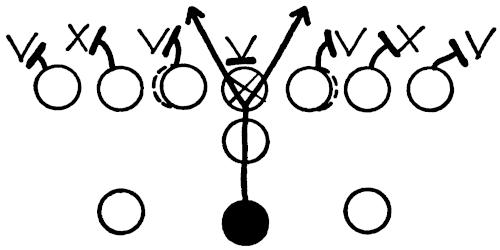

As illustrated in Figure 12, the defender lines up head on the offensive center. Depending upon the situation, the distance he lines up off the football will vary. On a short yardage situation, he will line up close to the center’s head. On a long yardage situation, normally he will be about one yard off the ball. He will use either a three- or a four-point stance, with one foot staggered. His technique is to play the center’s head with a quick hand shiver on the snap of the ball. When he makes contact with the center, he brings his back foot up so his feet are even with each other. If the quarterback goes straight back to pass, the 0 technique man is responsible for the draw play, and then he rushes the passer. If it is a run instead of a pass play, he will keep the center away from his blocking surface, not permitting himself to be tied up in the middle of the line, and he will pursue the ball taking his proper angle depending on the type of running play.

Figure 12

The main job of the player(s) employing the 1 technique is to control the offensive splits, forcing the guards to keep their splits to a minimum, as illustrated in Figure 13. He is also responsible for keeping the center off of the defensive linebacker. If both guards are playing in this technique, as illustrated in Figure 13, only one will “slam” the center, and the other will take a long step toward his guard, playing him from inside-out.[36] He must always be aware of the trap coming from the inside, however. If the play is a back-up pass, he is responsible for the draw first, and rushing the passer second. If it is a running play, he will slam the center or guard and then pursue the football.

Figure 13

The 2 technique is similar to the 0 technique, and is illustrated in Figure 14. One difference is the guard is head on the offensive guard, instead of on the offensive center. The distance he lines up off the ball in a staggered stance will be determined by the tactical situation. On the snap of the ball he plays the guard with a hand shiver, and immediately locates the football. If it is a back-up pass and there is no man in a 0 or 1 technique, he will look for the draw play first, and then rush the passer. If it is a running play, he will look first toward the inside for a trap, and then pursue the football.

Figure 14

The 3 technique is similar to the 1 technique, and is illustrated in Figure 15. The 3 man is responsible for keeping the offensive tackle’s split cut down, and on occasion to keep the offensive guard or tackle from blocking the defensive linebacker.[37] He, too, lines up with the feet slightly staggered, and about one foot off the ball. Depending upon the defense, when the ball is snapped, he will play either the guard or tackle with a quick flipper or shiver, preferably with the hands. He is to watch for the trap at all times. If the play is a straight drop back pass, he will rush the passer from the inside. If it is a running play, he will pursue the football.

Figure 15

The 4 technique man lines up head on the offensive tackle and about one to one and one-half feet off the ball, and is illustrated in Figure 16. He will have his feet slightly staggered, and on the snap of the ball he is to play the offensive tackle with a quick hand or forearm flipper. If it is a running play toward him, he must whip the offensive tackle, be ready to stop the hand-off, and help out on the off-tackle play. If it is a straight back pass, he will rush the passer from the inside. If the play goes away or to the far-side, he will control the offensive tackle and pursue the football. On his angle of pursuit he should never go around the offensive tackle, but pursue the football going through the tackle’s head.

Figure 16

The 5 technique man lines up on the outside eye of the offensive tackle, as illustrated in Figure 17, with the feet staggered (outside foot back in most cases). On the snap of the ball he employs a forearm flip charge into the tackle. As he makes contact, his back foot is brought up even with his front foot. He has 75% off-tackle responsibility, and he should never be blocked in by only one man. If it is a straight back pass, he should rush the passer from inside-out. If the play comes toward him, he should whip the tackle and make the play. He must be certain to keep the offensive blocker in front of him at all times as the 5 man will be eliminated from the play very easily if he tries to go around his blocker. If the play goes away from him, he must pursue the football. He is instructed not to cross the offensive line of scrimmage when employing a 5 technique.

Figure 17

The 6 technique player lines up head on the offensive end, as illustrated in Figure 18. If the end splits too far, the 6 man is to “shoot the gap.” He is primarily responsible for keeping the offensive end from releasing quickly on passes, and he must keep the end from blocking the linebacker. He is responsible for the off-tackle play. Consequently he must not be blocked in or out. The game situation will determine how far he lines up off the ball, but it will usually vary from one to three yards. If the play is a straight back pass, he is responsible for rushing the passer from the outside-in. If the passer runs out of the pocket, the 6 man must not permit him to get to the outside. He must either[39] tackle the passer or force him to throw the football. If the play comes toward the 6 man, he whips the end with a flip or shiver charge, and helps out both inside and outside. He never crosses the line of scrimmage unless it is a back-up pass. If it is an option play toward him, he must make the quarterback pitch the ball or he must tackle the quarterback. If the flow goes away from him, he trails the play. He should be as deep as the deepest man in the offensive backfield so he can contain the reverse play back to his side, not permitting the ball carrier to get outside of him.

Figure 18

The 7 technique player lines up splitting the inside foot of the offensive end, as illustrated in Figure 19. He is responsible for forcing the end to reduce his offensive split. We want him to line up with his outside foot staggered, and he must never be blocked out by the offensive end. He has 75% inside responsibility and 25% outside responsibility. When the ball is snapped, he uses a hand or forearm flipper charge on the offensive end and brings his back foot up even with his front foot. His main responsibility is to whip the offensive end, and to close the off-tackle play. If the play is a straight drop back pass, he is the outside rusher and he must not permit the quarterback to get outside of him. If the play goes away from him, he is to trail the ball carrier. He plays just like the trail or chase man on the 6 technique. He should be as deep as the deepest offensive backfield man so he can contain any reverse play coming back to his side of the line. He should not let such a play get outside of his position.

Figure 19

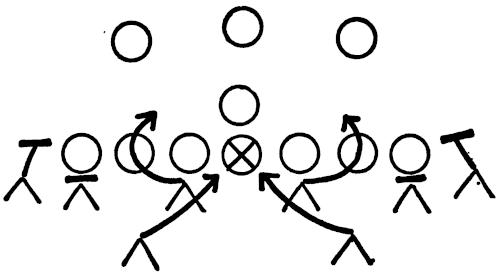

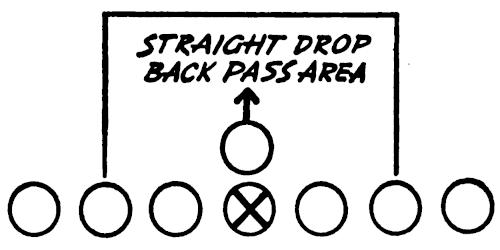

When we speak of a man playing an 8 technique, as illustrated in Figure 20, we are speaking of a “true end,” or a defensive end who lines up outside of the offensive end. The 8 man will be from one and one-half to three yards outside of the offensive end’s normal position, with his inside foot forward, and his shoulders parallel with the line of scrimmage. If it is a straight back pass, the defensive end, without taking his eyes off the passer, will turn to his outside, and using a cross-over step will sprint to his outside trying to get width and depth to play the ball to his side. His depth should be 8-10 yards deep, similar to a linebacker’s position covering the flat. He stops running when the quarterback stops to set up. When the ball is thrown, he sprints for the ball.

If the play comes toward the 8 man, we want him to cross the line of scrimmage about two yards, getting set with his inside foot forward, shoulders parallel with the line of scrimmage, and playing the outside blocker. He is the outside contain man, and he must not permit the ball to get outside of him. He never makes the quarterback pitch on option plays. If it is a running pass toward him, he is the outside contain and rush man. If the flow goes away from him, he must make sure it is not a reverse play back to his side before he takes his proper angle of pursuit, which is through the area where the defensive safety man lined up originally.

Figure 20

Figure 21 illustrates where the defensive men line up when playing a 9 technique, splitting the outside foot of the offensive end. He should line up 14 inches off the line of scrimmage, with most of the weight on his outside foot which is back. When the ball is snapped, the 9 technique man will take a short step with his inside foot toward the offensive end, and at the same time he will deliver a hand or forearm shiver to the head of the offensive end. If the offensive end blocks in and the play comes toward him, the 9 man immediately looks for the near halfback or the trapper expecting to be blocked by either offensive man.

If a running play comes toward him and the quarterback is going to option the football, he must make the quarterback pitch the ball. If the quarterback is faking the ball to the fullback, the 9 man must “search” the fullback for the ball first. The 9 technique man never crosses the line of scrimmage. If the offensive play is a straight back pass, the 9 man delivers a blow to the end, and drops back two or three yards looking for the screen or short pass. He is in a position to come up and make the tackle if the quarterback gets outside of your outside rusher and the quarterback decides to run with the football. If the flow goes away, he is the trail man and has the same responsibilities as the 6 and 7 technique men, which I explained previously. The most important coaching point is that the man playing the 9 technique must deliver a good blow to the offensive end on every play.

Figure 21

We are not too particular about the stance our defensive players employ, but on the other hand we are not so indifferent that we ignore how they line up defensively. We want them to[42] be comfortable, but at the same time the linemen must be in a position so they can uncoil, make good contact, and be in a good position so they can move quickly. We never permit a man to take a stance in which he gets too extended and loses most of his hitting power. There are a few basic techniques we insist our defensive players use. These techniques vary to some extent from position to position. The defensive stance for linemen, linebackers, and the secondary is as follows:

Guards—The defensive stance our guards take is very similar to the stance we use offensively. We like them to be in a four-point stance with their feet even and spread about three inches wider than their shoulders. The weight must be slightly forward, and their tail slightly higher than their shoulders. Their back is straight, and their shoulders are square. Their hands are slightly outside of their feet, elbows relaxed, with thumbs turned in and forward of the shoulders slightly.

Tackles—The defensive stance our tackles take is very similar to the stance we use offensively. We want our tackles to use a four-point stance, having their inside foot staggered back slightly. Their feet should be a little wider than their shoulders. The weight must be forward slightly, and the tail should be slightly higher than the head. Just like the guards’ stance, we want their back straight and their shoulders square. Their neck must be relaxed, but their eyes must be focused on the man opposite or on the ball. The hands are slightly outside of the feet, elbows relaxed, and the thumbs turned in and forward of the shoulders slightly.

Ends—The defensive ends line up with their inside foot forward and perpendicular to the line of scrimmage. We want our ends standing up in a good football position. The knees are slightly bent, as is their body bent forward slightly at the waist. They must have their eyes on the quarterback, but still be able to see the offensive halfback and end closest to them on their side. When the action starts toward an end, we want him to come across the line and make contact with the outside blocker. The shoulders should remain parallel with the line of scrimmage upon contact with an offensive back.

Linebackers—We want our linebackers to be standing with[43] their feet even and parallel with each other. They should be in a good football position—tail down, back straight, slight bend at the waist, weight on the balls of the feet, knees bent, and coiled to the extent that when a guard or tackle fires out on the linebacker the defensive man can whip him. Our linebacker takes a step forward with the inside foot toward the blocker who is firing out at him. We want him to drop his tail and hit on the rise when making contact. He then brings his back foot up even with his forward foot so that he will be in a position to move laterally.

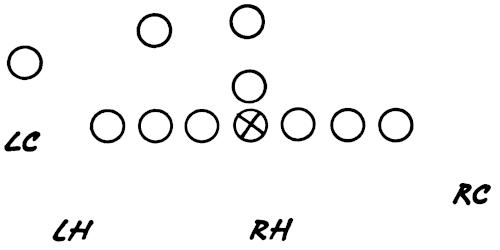

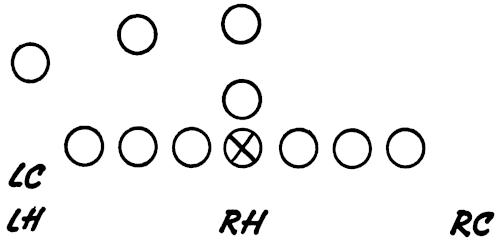

Halfbacks—Our defensive halfbacks line up in their regular position which is three yards outside of the offensive end in a 3-deep defense, and on the inside shoulder of the offensive end in a 4-spoke defense. We want our halfbacks to have their outside foot back with the inside foot pointing perpendicular to the line of scrimmage. The outside foot is about 14″ behind the front foot, and pointing out at a 45 degree angle. The halfback’s knees should be flexed slightly, and he must be in a good football position. His arms should be in a cocked position. He must face the quarterback. His first step is backward and outward.

Corner man—The corner man lines up in his regular position about four yards wide and two and one-half yards deep, with his feet parallel and even about 18″ apart pointing directly toward the offensive quarterback. He should be in a good football position, weight on the balls of the feet, arms cocked, etc. He should not rest his hands on his knees. From a good football position he can rotate quickly and properly, or he can come forward and meet the play if it comes toward him.

Safety—The safety man lines up a little deeper than the other backs. He should face slightly the wide side of the field or the strong side of the offensive backfield. He has his outside foot back, and he is permitted to stand a little straighter than the other deep backs. He, too, is in a good football position watching the quarterback. His first step is backward and outward, and he must be able to cover a pass from sideline to sideline.

We never send our boys into a football game without trying to prepare them for every conceivable situation that might arise[44] during the contest. We must try to anticipate every situation, and counteract with a sound defense. A situation might be very unusual, and we cannot actually defense it properly until the coach in the press box tells us exactly what the opposition is doing. Then we can work out the proper defense on the sideline and send it in. In the meantime the boys must have something they can counteract with immediately or the opposition is likely to score with its surprise offense. Consequently our signal caller will yell, “Surprise Defense,” when he sees an unusual offensive formation, and the boys will react accordingly. Our rules for covering a spread or unusual offensive alignment are as follows:

1. If one man flanks, our halfback will cover him.

2. If two men go out, our halfback and end will move out and cover them.

3. If three men go out, our halfback, tackle and end move out and cover them.

4. If four offensive men go out, we put out the halfback, end and tackle, and our linebacker goes out half-way. The alignment for the linebacker would be a yard deeper and a yard wider than he usually lines up.

5. If five men go out on the offensive team, we put out our halfback, end, tackle, linebacker half-way, and the defensive guard. If they put more than five men out, we do not change our alignment.

6. If there is any doubt about how to meet strength with strength, we start with the outside man and put a defender on every other offensive man.

7. The safety man will always play in the middle of the field or in the middle of the eligible receivers.

8. A defensive end must never be flanked by one offensive man unless he can beat the flanker through the gap and into the offensive backfield.

9. A tackle should never be flanked by two offensive men unless he can beat the nearest opponent.

10. The initial charge of the players who are left on defense is to the outside, unless there is a concentration of offensive backs. Should the latter be the case, then the defensive charge will be normal.

11. The greater the offensive team splits its line, the farther off the line of scrimmage the defenders must play.

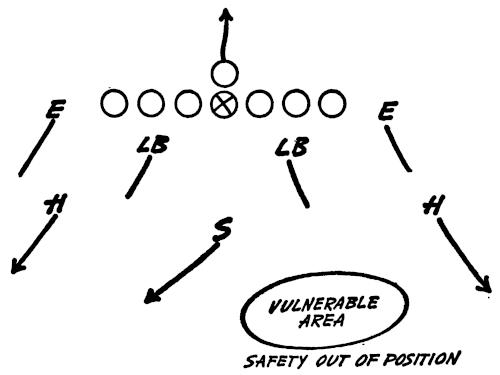

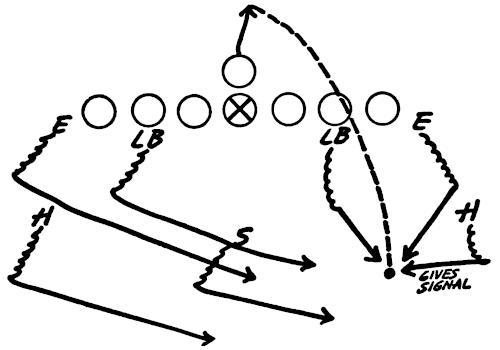

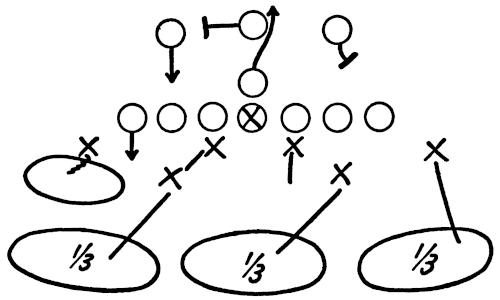

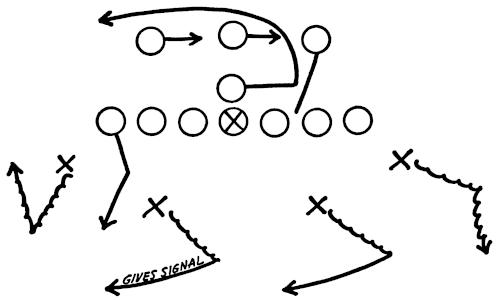

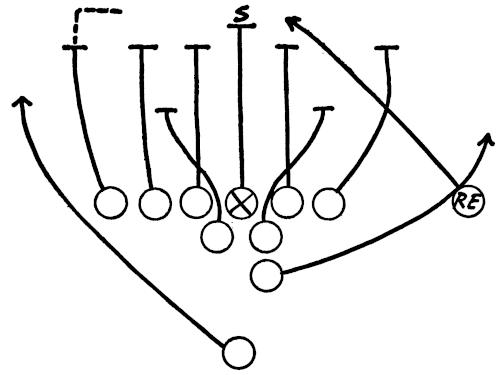

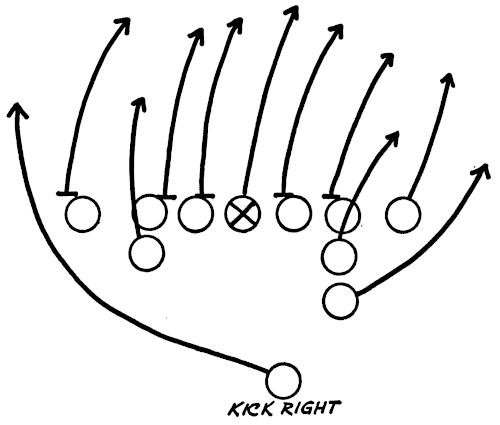

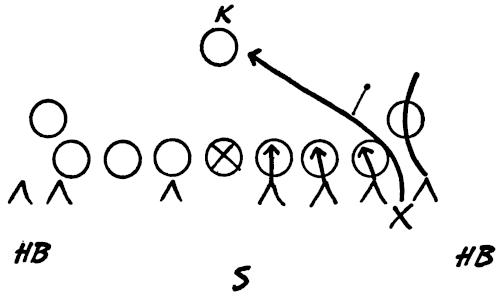

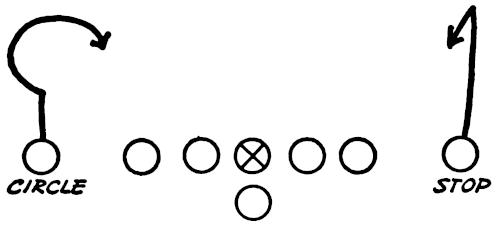

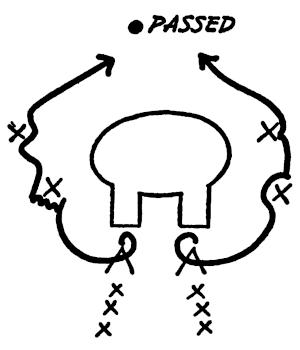

Figures 22-23 illustrate two examples of spread formations, and the application of our surprise defense coverage rules.

Figure 22