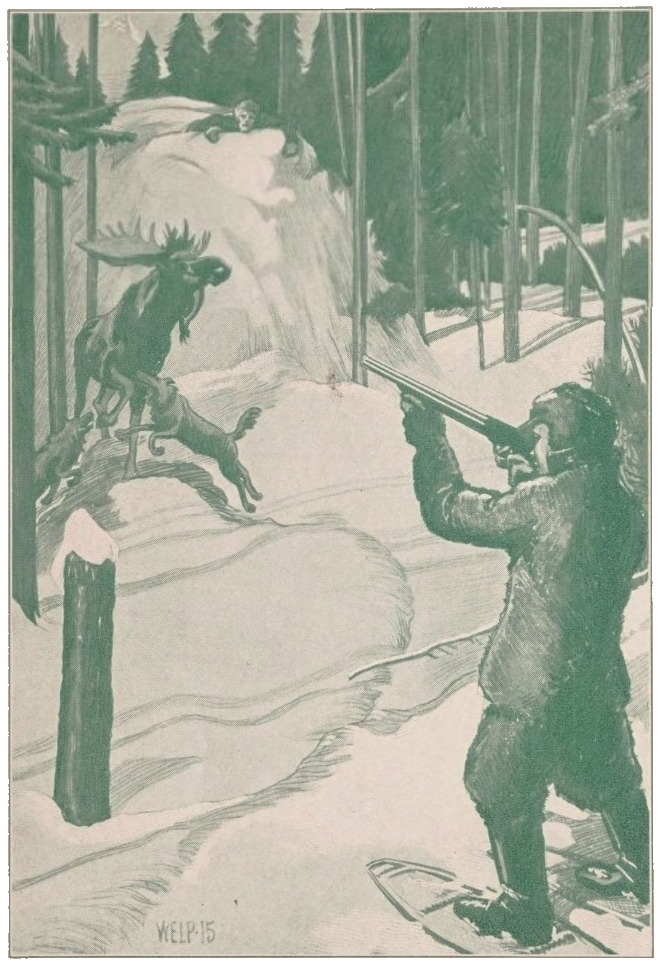

“Shoot! Shoot! For God’s sake shoot, Larry!”

The Project Gutenberg eBook of The Forest Pilot, by Edward Huntington

Title: The Forest Pilot

A Story for Boy Scouts

Author: Edward Huntington

Release Date: July 11, 2022 [eBook #68506]

Language: English

Produced by: Roger Frank and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

“Shoot! Shoot! For God’s sake shoot, Larry!”

The November sun that had been red and threatening all day, slowly disappeared behind a cloud bank. The wind that had held steadily to the south for a week, now shifted suddenly to the northeast, coming as a furious blast. In a moment, it seemed, the mild Indian Summer breeze was changed to a fierce winter gale.

The little schooner yacht that had been riding in the bay not more than a half mile from the jagged, rocky shore line, began dancing about like a cork. For a swell had come driving in from the ocean just as the wind changed, and now the two tall masts waved back and forth, bending in wide sweeps before the gale. Unfortunately for the little craft the change of the direction of the wind exposed it to the storm’s full fury.

The captain, a weatherbeaten old Yankee who had sailed vessels of his own as well as those belonging to other people for forty years, was plainly worried. With a glass in his hand he scanned the shore line of the bay in every direction, occasionally giving a sharp order to the four sailors who hurried about the deck to carry out his commands.

The only other persons on the yacht were a man and a boy who had been sitting together beside the forward mast when the wind changed. The man was a tall, straight figure, with the erect carriage that sinewy, muscular men who are accustomed to hard work retain well into old age. His face, with its leathery skin, which contrasted sharply with his iron gray beard, was softened by a pair of deep blue eyes—the kind of blue eyes that can snap with determination on occasion, in contrast to their usually kindly expression.

Obviously this man was past his prime, or, better perhaps, was past that period of life reckoned in years that civilized man has become accustomed to speaking of as “prime.” Yet he was old only in years and experience. For his step was quick and elastic, and every movement showed the alertness of youth. Were it not for the gray hairs peeping out from under his hat and his grizzled beard, he might have passed for a man of forty. Martin MacLean was his name, and almost any one in the New Brunswick forest region could tell you all about him. For Martin was a famous hunter and guide, even in a land where almost every male inhabitant depends upon those two things for his livelihood.

Needless to say, then, this man was something quite out of the ordinary among woodsmen. When the woods people gossiped among themselves about their hunting and trapping experiences, old Martin was often the theme of many a story. And the story was always one of courage or skill.

But you must remember that in this land, deeds of courage and skill were every-day occurrences. So that the man who could earn the admiration of his fellow woodsmen must possess unusual qualities. Martin had repeatedly demonstrated these qualities. Not by any single act at any one time, but by the accumulated acts of many years had he earned his title of leader in his craft.

The older woodsmen would tell you of the terrible winter when Martin had made a journey of fifty miles through the forests to get medicines from the only doctor within a hundred miles for a boy injured by a falling tree. They would tell you of the time that a hunting party from the States were lost in the woods in a great November blizzard, and how Martin, frost-bitten and famished, had finally found them and brought them back to the settlement. They could tell of his fight with a wounded moose that had gored another hunter, and would have killed him but for the quick work of Martin’s hunting knife. Indeed, once the old hunter became the theme of their talk, there was no end to the tales the woodsmen would tell of his adventures.

The boy who was with him on the yacht was obviously from an entirely different walk of life. Any woodsman could have told you that he had been reared far from the country of lakes and forests. He was, indeed, a city boy, who except for one winter spent in the Adirondacks, had scarcely been beyond the suburbs of his native city. In the north country he would have passed for a boy of twelve years; but in reality he was just rounding his fifteenth birthday.

He was a medium sized boy for his age, with bright red hair, and a rosy complexion. He had the appearance of a boy just outgrowing a “delicate constitution” as one of the neighbor women had put it, although he had every appearance of robustness. Nevertheless it was on account of his health that he was now on the little schooner yacht rolling in the gale of a bleak Labrador inlet. His neighbor in the city, Mr. Ware, the owner of the yacht, thinking that a few weeks in the woods and on the water would be helpful to him, had made him a member of his hunting party into the northern wilderness.

The old guide was obviously apprehensive at the fury of the gale that had struck them, while the boy, Larry, seemed to regard it as a lark designed for their special amusement. Noticing the serious expression of Martin’s face, and mistaking its meaning, he could not help jibing the old fellow, boy fashion, at his solicitude.

“You look as if you thought we were going to the bottom sure enough, Martin,” Larry laughed. “Why, there isn’t any more danger on this boat than there is on an ocean liner. You’re no seaman, I can see that.” And he threw back his bushy head and laughed heartily at his companion’s serious face.

“Besides,” he added, “there’s the land only half a mile away even if we did spring a leak or something. It’s only a step over there, so we surely could get ashore.”

“That’s just the trouble,” said a deep voice beside him. “That’s just the trouble. And if you knew the first thing about a ship or the ocean you would know it.” And the captain strode aft, giving orders to his seamen as he went.

“What does he mean?” Larry asked of Martin, clinging to a brass stanchion to keep from being thrown into the scuppers as the little boat rolled heavily until the rail dipped the water.

“Why, just this,” Martin told him. “The real danger to us now is that we are so near the shore. Out in the open sea we could roll and tumble about and drift as far as we liked until the storm blew over. But here if we drift very far we will go smash against those rocks—and that would be the end of every one of us.”

“Well, if we went ashore why couldn’t we just jump and swim right to land a few feet away?” Larry asked, looking serious himself now, his blue eyes opening wide.

Martin’s little laugh was lost in the roar of the wind.

“That shows how much of a landlubber you are, Larry,” he said. “If you had been brought up near the ocean you would know that if this boat struck on this shore where all the coast is a lot of jagged rocks, it would be smashed into kindling wood. And no man can swim in the waves at the shore. They pick a man up like a cork; but they smash him down on those rocks like the hammer of the old Norse Sea god. That is why the sailor prays for the open sea.”

All this time Martin had been clinging to the rail with one hand, and trying to scan the shore line with his hunting glasses. But the blinding spray and the ceaseless rolling and pitching made it impossible for him to use them.

“But I’m not worrying about what may happen to this boat,” he shouted presently, putting the glasses in his pocket. “Either we will come out all right or else we won’t. And in any case we will have to grin and take what comes. What I’m worried about is Mr. Ware and the fellows in the boat with him. If they have started out from shore to come aboard before this gale hit us they are lost, sure. And I am certain they had started, for I caught a glimpse of the boat coming out of a cove fifteen minutes before the storm broke.”

For a minute Larry stared at the old man, comprehending the seriousness of the situation at last. “You mean then—” he asked, clutching the brass rail as the boat lurched forward,—“You mean that you think they will be drowned—really drowned, Martin?”

“That’s it, Larry,” Martin replied, seriously. “They haven’t one chance in a thousand, as I see it. Even if they could reach us we couldn’t get them aboard; and if they are blown ashore it will end everything. They haven’t a chance.”

As if to emphasize the seriousness of the situation the yacht just then dug her nose deep into the trough of a great wave, then rose, lifting her bowsprit high in the air like a rearing horse tugging at a restraining leash. It was a strain that tested every link of the anchor chain to its utmost. But for the moment it held.

“A few more like that, Larry,” Martin shouted above the gale, “and that chain will snap. The anchor is caught fast in the rocks at the bottom.”

Meanwhile the sailors and the captain were working desperately to cut loose the other anchor and get it over the side as their only chance of keeping the boat off the rocks. The gale, the rolling of the vessel, and the waves buffeted them about, however, so that before they could release the heavy mass of iron, the yacht again plunged her nose into the waves, then rose on her stern, trembling and jerking at the single anchor chain. For a moment it held. Then there was a sharp report, as a short length of chain flew back, knocking two of the sailors overboard, and gouging a great chunk of wood from the fore mast. At the same time the boat settled back, careening far to port with the rail clear under.

The violence of the shock had thrown Larry off his feet, but for a moment he clung to the railing with one hand. Then as the boat righted herself, quivering and creaking, the flood of water coming over the bow tore loose his hands, and hurled him blinded and stupified along the deck. The next thing he knew he found himself lying in a heap at the foot of the narrow companionway stairs down which he had been thrown by the waves.

He was dazed and bruised by the fall, yet above the roar of the storm, he heard faintly the howling of the huskie dogs, confined in a pen on the forward deck. Then there was the awful roar of the waves again, the crash of breaking timbers, and again a deluge of water poured down the companionway. At the same time Larry was struck with some soft, heavy object, that came hurtling down with the torrent of water. Gasping for breath and half choked with the water, he managed to cling to the steps until the water had rushed out through the scuppers as the boat heeled over the other way. Then crawling on hands and knees he succeeded in reaching the cabin door, the latch of which was not over six feet away.

With a desperate plunge he threw it open and fell sprawling into the room. At the same time two great malamoot dogs, who had been washed down the companionway with the preceding wave, sprang in after him, whining and cowering against him. Even in his fright he could not help contrasting the present actions of these dogs with their usual behavior. Ordinarily they were quiet, reserved fellows, given to minding their own business and imparting the general impression that it would be well for others to do the same. Now all their sturdy independence was gone, and cowering and trembling they pressed close to the boy for protection, apparently realizing that they were battling with an enemy against whom they had no defence.

But the storm gave Larry little time to think of anything but his own safety. Even as he struggled to rise and push the cabin door shut, the boat heeled over and performed that office for him with a crash. The next moment a torrent of water rushed down the companionway, but only a few drops were forced through the cracks of the door casing, fitted for just such an occasion, so that the cabin remained practically dry. Over and over again at short intervals this crash of descending waters shook the cabin and strained at the door casing. And all the time the movements of the boat kept Larry lying close to the floor, clinging to the edge of the lower bunk to keep from being thrown violently across the cabin.

The dogs, unable to find a foothold when the cabin floor rose beneath them, were often thrown violently about the room, their claws scratching futilely along the hard boards as they strove to stop the impetus of the fall. But the moment the boat righted itself, they crawled whimpering back and crouched close to the frightened boy.

Little enough, indeed, was the protection or comfort Larry could give the shivering brutes. He himself was sobbing with terror, and at each plunge and crash of the boat he expected to find himself engulfed by the black waters. Now and again, above the sound of the storm, he heard the crash of splintering timbers, with furious blows upon the decks and against the sides of the hull. He guessed from this that the masts had been broken off and were pounding for a moment against the hull, held temporarily by the steel shrouds until finally torn away by the waves.

Vaguely he wondered what had become of Martin, and the Captain, and the two remaining members of the crew. Perhaps they had been washed down the after companionway as he had gone down the forward one. But far more likely they were now in their long resting place at the bottom of the bay. There seemed little probability that they had been as lucky as he, and he expected to follow them at any moment. Yet he shut his teeth and clung fast to the side of the bunk.

It was terribly exhausting work, this clinging with one’s hands, and at each successive plunge he felt his grip weakening. In a very few minutes, he knew he should find himself hurled about the cabin like a loose piece of furniture, and then it would only be a matter of minutes until he was flung against some object and crushed. He would not be able to endure the kind of pounding that the dogs were getting. The protection of their thick fur, and the ability to relax and fall limply, saved them from serious injury.

Little by little he felt his fingers slipping from the edge of the bunk. He shut his teeth hard, and tried to get a firmer grip. At that moment the boat seemed to be lifted high into the air, and poised there for a breathless second. Then with a shock that bumped Larry’s head against the floor, it descended and and stopped as if wedged on the rocks at the bottom, with a sound like a violent explosion right underneath the cabin.

Larry, stupified by the crash, realized vaguely that the boat had struck something and was held fast. In his confusion he thought she had gone to the bottom, but he was satisfied that he was no longer being pounded about the cabin. And presently as his mind cleared a little, and he could hear the roar of the waves with an occasional trickle of water down the companionway, he reached the conclusion that they were not at the bottom of the sea. Nor did he care very much one way or the other at that time. It was pitch dark in the cabin, and as he was utterly worn out, he closed his eyes and lay still, a big trembling dog nestling against him on either side. And presently he and his two companions were sleeping the dreamless sleep of the exhausted.

It seemed only a moment later that Larry was roused by a thumping on the planks over his head. Half awake, and shivering with cold, he rubbed his eyes and tried to think where he was. Everything about the cabin could be seen now, a ray of light streaming in through the round port. For a little time he could not recall how he happened to be lying on the cold floor and not in his bunk; but the presence of the two dogs, still lying beside him, helped to freshen his memory.

The thumping on the deck seemed to have a familiar sound; there was somebody walking about up there. Some one else must have been as lucky as he in escaping the storm. And presently he heard some one come clumping down the companionway stairs. The dogs, who had been listening intently with cocked ears to the approaching footsteps, sprang across the cabin wagging their tails and whining, and a moment later old Martin stood in the doorway. He greeted the dogs with a shout of surprise and welcome, followed by another even louder shout when his eyes found Larry. For once the reserved old hunter relaxed and showed the depths of his nature. He literally picked the astonished boy up in his arms and danced about the little room with delight.

“Oh, but I am sure glad to see you, boy,” he said, when he finally let Larry down on his feet. “I didn’t suppose for a minute that I should ever see you or any one else here again—not even the dogs. I thought that you and everybody else went over the side when the first big wave struck us.”

“Why, where are all the rest of them, and why is the boat so still?” Larry asked, eagerly.

The old man’s face grew grave at once at the questions.

“Come out on deck and you can see for yourself,” he said quietly, and led the way up the companionway.

With his head still ringing, and with aching limbs and sore spots all over his body from the effects of bumping about the night before, Larry crawled up the companionway. He could hear the waves roaring all about them, and yet the boat was as stationary as a house. What could it mean?

When he reached the deck the explanation was quickly apparent. The boat was wedged hard and fast in a crevice of rock, her deck several feet above the water, and just below the level of the rocky cliff of the shore. She had been picked up bodily by the tremendous comber and flung against the cliff, and luckily for them, had been jammed into a crevice that prevented her slipping back into the ocean and sinking. For her bottom and her port side were stove in, and she was completely wrecked.

For a few minutes the boy stood gazing in mute astonishment. Old Martin also stood silently looking about him. Then he offered an explanation.

“’Tisn’t anything short of a miracle, I should say,” he explained to Larry. “I have heard of some such things happening, but I never believed that they did really. You see the waves just washed everything overboard—captain, crew, masts, everything—except you and me, and the two dogs. It washed me just as it did you, but I went down the after hatchway by luck, and I hung on down there in the companionway until the thing struck. But all the time that the waves were washing over us we were being driven along toward this ledge of rock full tilt. And when we were flung against this rock we should by good rights, have been battered to kindling wood at one blow, and then have slipped back into the water and sunk.

“But right here is the curious part of it all. Just as she got to the foot of this cliff, an unusually big comber must have caught her, raised her up in its arms fifteen or twenty feet higher than the usual wave would have done, and just chucked her up on the side of this bluff out o’ harm’s way—at least for the time being. The sharp edge of the ledge happened to be such a shape that it held her in place like the barb of a fish-hook. And all that the smaller waves could do was to pound away at the lower side of her, without hurting her enough to make her fall to pieces.

“But of course they’ll get her after a while—almost any hour for that matter; for this storm is a long way from being blown out yet, I’m afraid. And so it’s up to us to just get as much food and other things unloaded and up away from this shore line as fast as we can. Most of the stores are forward, and that is where she is stove in the least.

“I suppose we’ve got to take off five minutes and cram a little cold food into ourselves, so that we can work faster and longer. For we surely have got to work for our lives to-day. If this boat should suddenly take it into her head to slide off into the ocean again, as she may do at any minute, we’re goners, even if we are left on shore, unless we get a winter’s supply unloaded and stored on the rocks. For we are a long way from civilization, I can tell you.”

With that Martin rushed Larry to the galley, dug out some bread, cold meat, and a can of condensed milk. And, grudging every minute’s delay, they stood among the wreckage of the once beautiful cabin, cramming down their cold breakfast as hastily as possible. In the excitement Larry forgot his bruises and sore spots.

As soon as they had finished Martin hurried the boy to the forward store-room door, bursting it open with a heavy piece of iron.

“Now pick up anything that you can handle,” he instructed, “run with it up on deck, and throw it on to the bank. I’ll take the heavier things. But work as hard and as fast as you can, for our lives depend upon it.”

For the next two hours they worked with furious energy rushing back and forth from the store-rooms, staggering up the tilted steps to the deck, and hurling the boxes across the few feet that separated the boat from the ledge. Every few minutes Martin would leap across the gap, and hastily toss the boxes that had been landed further up on the shore, to get them out of the way for others that were to follow.

The enormous strength and endurance of the old hunter were shown by the amount he accomplished in those two hours. Boxes and kegs, so heavy that Larry could hardly budge them, he seized and tossed ashore in tireless succession, only pausing once long enough to throw off his jacket and outer shirt. For the perspiration was running off his face in streams, despite the fact that the air was freezing cold.

Fortunately most of the parcels were relatively small, as they had been prepared for the prospective inland hunting excursion which was to have been made on sledges. Many of the important articles were in small cans, and Larry rushed these ashore by the armful. He was staggering, and gasping for breath at times, and once he stumbled and fell half way down a stairway from sheer exhaustion. But he had caught Martin’s spirit of eager haste, and although the fall had shaken him up considerably, he picked himself up and went on as fast as his weary limbs would carry him.

At last Martin paused, wiping his face with his coat sleeve. “Sit down and rest,” he said to the boy. “We’ve got a whole winter’s supply on shore there now, if food alone was all we needed. So we can take a little more time about the rest of the things; and while you rest I’ll rig up some tackle for getting what we can of the heavier things ashore. You’ve done pretty well, for a city boy,” he added.

Then he went below, and Larry heard the sounds of blows and cracking timber. Presently Martin appeared, dragging some heavy planks after him. With these he quickly laid a bridge from the deck to the shore. Then he hunted out some long ropes and pulleys, and, carrying them to a tree far up on the bank, he rigged a block and tackle between this anchorage and the yacht.

“Now we’re ready for the heavy things,” he said.

With this new contrivance nothing seemed too big to handle. Martin and Larry would roll and push the heavy cases into a companionway, or near a hatch, and then both would seize the rope, and hand over hand would work the heavy object up to the deck across the bridge, and finally far out on shore. In this way the greater part of everything movable had been transferred from the boat by the middle of the afternoon; but not until the last of the more precious articles had been disposed of did Martin think of food, although they had breakfasted at daylight.

In the excitement Larry, too, had forgotten his hunger; but now a gnawing sensation reminded him that he was famished. Martin was “as hungry as a wolf in winter” he admitted. But he did not stop to eat. Calling the dogs and filling his pockets with biscuit to munch as he walked, he started out along the rocky shore of the inlet, to see if by any chance some survivor had washed ashore. Meanwhile Larry built a big fire at the edge of the woods to act as a signal, and to keep himself warm.

In two hours the old man returned from his fruitless search. He had found some wreckage strewn among the rocks, but no sign of a living thing. “And now we must get these things under cover,” he said, indicating the pile of stores.

For this purpose he selected a knoll some little distance from the shore above where any waves could possibly reach. Over this he laid a floor of planks, and spread a huge canvas over the boards. Then they began the task of piling all the landed goods on top of this, laying them up neatly so as to occupy as little space as possible, and over this great mound of food-boxes, gun-cases, canned goods, and miscellaneous objects, they pulled a huge canvas deck covering.

By the time they had finished the daylight was beginning to wane. Taking the hint from the approaching darkness, Martin dug into the mass of packages and produced a small silk tent, which he set up under one of the scrub trees which was sheltered by a big rock well back from the shore.

“Take that axe,” he told Larry, pointing to a carefully forged hunting axe that had been landed with the other things, “and collect all the wood you can before dark.”

Larry, scarcely able to stand, looked wistfully at the yacht. “The cabin is dry in there,” he suggested, “why don’t we sleep in there to-night?”

Old Martin shook his head. “I don’t dare risk it,” he said. “I am tired, and I’d sleep too soundly. I don’t think I’d wake up, no matter what happened. And something may happen to-night. The storm is still brewing, and the waves are still so high that they pound the old hull all the time. A little more hammering and she may go to pieces. We couldn’t tell from the noise whether the storm was coming up or not, because there is so much pounding all the time anyway. And wouldn’t it be a fine thing for us to find ourselves dropped into the ocean after we have just finished getting ourselves and our things safely ashore? No, you get the wood and I’ll give you a sample of the out-door suppers that we are likely to have together every night for the next few months.”

Larry picked up the axe and dragged his weary feet off to the thicker line of trees a short distance away. There was really little use for the axe, as the woods were filled with fallen trunks and branches that could be gathered for the picking up. So he spared himself the exertion of chopping and began dragging branches and small logs to the tent.

He found that the old hunter, while he was collecting the wood, had unearthed a cooking outfit, and had pots, pans, and kettles strewn about ready for use. Best of all he had hunted out two fur sleeping bags, and had placed a pile of blankets in the little tent, which looked very inviting to the weary boy.

Martin saw his wistful look and chuckled. “Too tired to eat I suppose?” he inquired.

“Well, pretty near it,” Larry confessed. “I was never half so tired in my whole life.”

“All right,” said Martin; “you’ve worked like a real man to-day. So you just crawl into those blankets and have a little snooze while I and the doggies get the supper. I’ll call you when the things are ready.”

“Don’t you ever get tired, ever, Martin?” Larry asked as he flung himself down. But if Martin answered his question he did not hear it. He was asleep the moment he touched the blankets.

The next thing Larry knew he was being roused by old Martin’s vigorous shakes. Something cold was pressing against his cheek,—the black muzzle of one of the malamoots. Martin and the big dog were standing over him, the man laughing and the dog wagging his bushy tail. It seemed to the boy that he had scarcely closed his eyes, but when he had rubbed them open he knew that he must have been asleep some little time, for many things seemed changed.

It was night now, and the stars were out. But inside the tent it was warm and cozy, for before the open flap a cheerful fire was burning. The odor of coffee reached his nostrils and he could hear the bacon frying over the fire, and these things reminded him that he was hungry again.

“Sit right up to the table and begin,” Martin said to him, pointing to a row of cooking utensils and two tin plates on the ground in front of the tent. “Every one for himself, and Old Nick take the hindmost.”

No second invitation was necessary. In a moment he was bending over a plate heaped with bacon and potatoes, while the big malamoots sat watching him wistfully keeping an expectant eye on Martin as he poured the coffee. Such potatoes, such bacon, and such coffee the boy had never tasted. Even the soggy bread which Martin had improved by frying in some bacon fat, seemed delicious. This being shipwrecked was not so bad after all.

Old Martin, seated beside him and busy with his heaping plate seemed to read his thoughts.

“Not such a bad place, is it?” he volunteered presently.

“Bad?” the boy echoed. “It’s about the best place I ever saw. Only perhaps it will get lonesome if we have to wait long,” he added thoughtfully.

“Wait?” repeated Martin, poising his fork in the air. “Wait for who and for what, do you suppose, boy?”

“Well, aren’t we going to wait for some one to come for us?” the boy inquired.

Old Martin emptied his plate, drank his third cup of coffee, and threw a couple of sticks on the fire before answering.

“If we waited for some one to come for us,” he said presently and in a very serious tone, “we’d be waiting here until all these provisions that we landed to-day are gone. And there’s a good full year’s supply for us two up there under the canvas. Did you suppose we are going to wait here?”

The boy looked thoughtful.

“But we can’t get the yacht off the rocks, and she’d sink if we did. And anyhow you couldn’t sail her home. You told me only yesterday that you didn’t know a yacht from a battleship, Martin.”

“I told you the truth, at that,” Martin chuckled. “But I’m something of a navigator all the same. I can navigate a craft as well as poor old Captain Roberts himself, only I use a different craft, and I navigate her on land. And, what’s more to the point, I’ve got the land to do it on, the craft, and the crew.” And Martin pointed successively at the pile of supplies in the distance, the two dogs, and Larry.

“I don’t understand at all what you mean,” the boy declared; “tell me what you intend to do, Martin, won’t you?”

“Why, boy, if I started in to tell you now you’d be asleep before I could get well into the story,” said the old hunter.

“No, I wouldn’t,” the boy protested. “I never was more wide awake in my life. I feel as if I could do another day’s work right now.”

“That’s the meat and potatoes and coffee,” old Martin commented. “It’s marvellous what fuel will do for a tired engine. Well, if you can keep awake long enough I’ll tell you just what we are going to do in the next few weeks—or months, maybe.

“Here we are stranded away up on the Labrador coast, at least two or three hundred miles from the nearest settlement, perhaps even farther than that. And the worst of it is that I haven’t the least idea where that nearest settlement is. It may be on the coast, somewhat nearer than I think; and then again it may be ’cross country inland still farther away than I judge. What we’ve got to do is to make up our minds where we think that settlement is, and find it. And we’ve got to go to it by land and on foot.”

“On foot!” Larry cried in amazement. “Three or four hundred miles on foot in the winter time in a strange country where nobody lives!”

“That’s the correct answer,” the hunter replied: “and we’re two of the luckiest dogs in the world to have the chance to do it in the style we can. If we hadn’t been given the chance to save all that plunder from the ship to-day we would be far better off to be in the bottom of the ocean with Mr. Ware and the other poor fellows. But we had the luck, and now we have a good even fighting chance to get back home. But it means work—work and hardships, such as you never dreamed of, boy. And yet we’ll do it, or I’ll hand in my commission as a land pilot.

“Did you notice those cans of stuff that you were throwing ashore to-day—did you notice anything peculiar about those cans?” Martin asked, a moment later.

“E—er, no I didn’t,” Larry hesitated. “Unless it was that some of the bigger ones seemed lighter than tin cans of stuff usually do.”

“That’s the correct answer again,” the old man nodded; “that’s the whole thing. They were lighter, for the very good reason that they are not made of tin. They are aluminum cans. They cost like the very sin, those cans do, many times more than tin, you know. But Mr. Ware didn’t have to think about such a small thing as cost, and when he planned this hunting trip, where every ounce that we would have to haul by hand or with the dogs had to be considered, he made everything just the lightest and best that money could get it made. If there was a way of getting anything better, or more condensed, whether it was food or outfit, he did it. And you and I will probably owe our lives to this hobby of his, poor man.

“Among that stuff that we unloaded to-day there are special condensed foods, guns, tents, and outfits, just made to take such a forced tramping trip through the wilderness as we are to take. You see Mr. Ware planned to go on a long hunt back into the interior of this land, a thing that has never been done at this time of year to my knowledge. And as no one knows just what the conditions are there, he had his outfit made so that he could travel for weeks, and carry everything that he needed along with him.

“So it’s up to us to take the things that Mr. Ware had made, and which we are lucky enough to have saved, and get back to the land where people live. In my day I have undertaken just as dangerous, and probably difficult things in the heart of winter; only on those trips I didn’t have any such complete equipment as we have here.

“Why, look at that sleeping bag, for example,” the old man exclaimed, pointing to one of the bags lying in the tent. “My sleeping outfit, when I hiked from upper Quebec clear to the shore of old Hudson’s Bay in the winter, consisted of a blanket. Whenever my fire got low at night I nearly froze. But mind you, I could lie out of doors in one of these fur bags without a fire on the coldest night, and be warm as a gopher. They are made of reindeer skin, fur inside, and are lined with the skin of reindeer fawn. So there are two layers of the warmest skin and fur known, between the man inside and the cold outside. Those bags will be a blessing to us every minute. For when we strike out across this country we don’t know what kind of a land we may get into. We may find timber region all the way, and if we do there will be no danger of our freezing. But it’s more than likely that we shall strike barren country part of the time where there will be no fire-wood; and then we will appreciate these fur bags. For I don’t care how cold it gets or how hard it blows, we can burrow down into the snow and crawl into the bags, and always be sure of a warm place to sleep.

“Then again, the very luckiest thing for us was the saving of those two dogs,” Martin continued. “If they had gone overboard with the other twelve I should be feeling a good deal sadder to-night than I am. For there is nothing to equal a malamoot dog for hauling loads through this country in winter. Look at this fellow,” he said indicating one of the big shaggy dogs curled up a few feet from the tent, caring nothing for the biting cold. “There doesn’t seem to be anything very remarkable about him, does there? And yet that fellow can haul a heavier load on a sled, and haul it farther every day, than I can. And his weight is less than half what mine is.

“The dogs that Mr. Ware had selected were all veteran sledge dogs, and picked because they had proved their metal. So we’ll give this fellow a load of two hundred and fifty pounds to haul. And he could do better than that I know if he had to.”

The wind, which had died down a little at dusk, had gradually risen and was now blowing hard again, and fine flakes of snow and sleet hissed into the camp-fire. The rock which sheltered the tent protected it from the main force of the blast, but Larry could hear it lashing its way through the spruce trees with an ominous roar. Martin rose and examined the fastenings of the tent, tightened a rope here and there, and then returned to his seat on the blankets.

“We can’t start to-morrow if it storms like this,” Larry suggested presently.

“Well, we can’t start to-morrow anyhow,” the old trapper answered. “And we surely can’t start until there is more snow. How are we going to haul a pair of toboggans over the snow if there is no snow to be hauled over, I’d like to know? But there is no danger about the lack of snow. There’ll be plenty of it by the time we are ready to start.”

“And when will that be?” the boy asked.

“In about ten days, I think,” Martin answered, “——that is, if you have learned to shoot a rifle, harness the dogs, pitch a camp, set snares, walk on snow-shoes, and carry a pretty good-sized pack on your back,” he added, looking at Larry out of the corner of his eyes. “Did you ever shoot a rifle?”

“Sure I have,” the boy answered proudly; “and I hit the mark, too—sometimes.”

“I suppose you shot a Flobert twenty-two, at a mark ten feet away,” Martin commented with a little smile. “Well, all that helps. But on this trip you are not going to hit the mark sometimes: it must be every time. And the ‘mark’ will be something for the camp kettle to keep the breath of life in us. I’ve been turning over in my mind to-day the question of what kind of a gun you are going to tote on this trip. We’ve got all kinds to select from up there under the canvas, from elephant killers to squirrel poppers, for Mr. Ware did love every kind of shooting iron. I’ve picked out yours, and to-morrow you will begin learning to use it—learning to shoot quick and straight—straight, every time. For we won’t have one bullet to waste after we leave here.”

Larry fairly hugged himself. Think of having a rifle of his very own, a real rifle that would kill things, with the probability of having plenty of chances for using it! One of his fondest dreams was coming true. The old hunter read his happiness in his face, and without a word rose and left the tent. When he returned he carried in his hand a little weapon which, in its leather case, seemed like a toy about two feet long. Handing this to Larry he said, simply: “Here’s your gun.”

The boy’s countenance fell. To be raised to the height of bliss and expectation, and then be handed a pop-gun, was a cruel joke. Without removing the gun from its case he tossed it contemptuously into the blankets behind him.

“Mr. Ware killed a moose with it last winter,” the old hunter commented, suspecting the cause of the boy’s disappointment. “And it shoots as big a ball, and shoots just as hard as the gun I am going to carry,” he added. “You’d better get acquainted with it.”

There was no doubting the old man’s sincerity now, and Larry picked up the gun and examined it.

It was a curious little weapon, having two barrels placed one above the other, and with a stock like a pistol. Attached to the pistol-like handle was a skeleton stock made of aluminum rods, and so arranged that it folded against the under side of the barrels when not in use. The whole thing could be slipped into a leather case not unlike the ordinary revolver holster, and carried with a strap over the shoulder. When folded in this way it was only two feet long, and had the appearance of the toy gun for which Larry had mistaken it.

Yet it was anything but a toy. The two barrels were of different calibre, the upper one being the ordinary .22, while the lower one, as Martin had stated, was of large calibre and chambered for a powerful cartridge.

The old hunter watched the boy eagerly examining the little gun, opening it and squinting through the barrels, aiming it at imaginary objects, and strutting about with it slung from his shoulder in the pure joy that a red-blooded boy finds in the possession of a fire arm. Then, when Larry’s excitement cooled a little, he took the gun, and explained its fine points to his eager pupil.

“From this time on,” he began, “I want you to remember everything I am going to tell you just as nearly as you can, not only about this gun, but everything else. For you’ve got to cram a heap of knowledge into your head in the next few days, and I haven’t time to say things twice.

“This gun was made specially for Mr. Ware after his own design and to fit his own idea. He wanted a gun that was as light as possible and could be carried easily, and at the same time be adapted to all kinds of game, big and little. This upper barrel, the smaller one you see, shoots a cartridge that will kill anything up to the size of a jack rabbit, and is as accurate a shooter as any gun can be made. Yet the cartridges are so small that a pocket full will last a man a whole season.

“Now the best rule in all hunting is to use the smallest bullet that will surely kill the game you are aiming at, and in every country there are always ten chances to kill small things to one chance at the bigger game. Up in this region, for example, there will be flocks of ptarmigan, the little northern grouse, and countless rabbits that we shall need for food, but which we couldn’t afford to waste heavy ammunition on. And this smaller barrel is the one to use in getting them.

“If you used the big cartridge when you found a flock of these ptarmigans sitting on a tree, the noise of the first shot would probably frighten them all away, to say nothing of the fact that the big ball would tear the little bird all to pieces, and make it worthless for food. With the .22 you can pop them over one at a time without scaring them, and without spoiling the meat.

“But suppose, when you were out hunting for ptarmigan or rabbits you came upon a deer, or even a moose. All right, you’ve got something for him, too, and right in the same gun. All you have to do is to shift the little catch on the hammer here which connects with the firing-pin in the lower barrel, draw a bead, and you knock him down dead with the big bullet—as Mr. Ware did last fall up in New Brunswick. There will be a louder report, and a harder kick, but you won’t notice either when you see the big fellow roll over and kick his legs in the air.”

The very suggestion of such a possibility was too much for the boy’s imagination. “Do you really think that I may kill a deer, or a moose, Martin?” he asked eagerly. “Do you, Martin?”

“Perhaps,” the old man assented, “if you will remember all I tell you. But first of all let’s learn all we can about the thing you are going to kill it with.

“Mr. Ware and I had many long talks, and tried many experiments before he could decide upon the very best size of cartridge for this larger barrel. You see there scores of different kinds and sizes to choose from. There are cartridges almost as long and about the same shape as a lead pencil, with steel jacketed bullets that will travel two or three miles, and go through six feet thickness of wood at short range. It is the fad among hunters these days to use that kind. But if a man is a real hunter he doesn’t need them.

“Mr. Ware was a real hunter. When he pulled the trigger he knew just where the bullet was going to land. And when a man is that kind of a shot he doesn’t have to use a bullet that will shoot through six feet of pine wood. So he picked out one of the older style of cartridges, one that we call the .38-40, which is only half as long as the lead-pencil kind. By using a steel jacketed bullet and smokeless powder this cartridge is powerful enough to kill any kind of game in this region, if you strike the right spot.

“So don’t get the idea, just because this gun won’t shoot a bullet through an old fashioned battleship, that it’s a plaything. It will penetrate eighteen inches of pine wood, and the force of its blow is very nearly that of a good big load of hay falling off a sled. This little three-pound gun—just a boy’s sparrow gun to look at—shoots farther and hits harder than the best rifle old Daniel Boone ever owned. And yet Boone and his friends cleaned out all the Indians and most of the big game in several States. So you see you’ve got the better of Boone and all the great hunters and Indian killers of his day—that is, as far as the gun is concerned. To-morrow I will begin teaching you how to use it as a hunter should; but now we had better turn in, for there are hard days ahead of us.”

And so Larry crawled into his snug fur-lined bag, too excited to wish to sleep, but so exhausted by the hard day’s work that his eyes would not stay open.

At daylight the next morning old Martin roused the boy, reminding him that he “was to begin learning his trade” that day. “And there are many things to learn about this land-piloting, too,” he told him. Meanwhile the old hunter took the axe and went into the woods for fuel while Larry was putting on his shoes and his coat—the only garments he had removed on going to bed the night before.

The air was very cold and everything frozen hard, and Larry’s teeth were chattering before Martin returned and started the fire. “Now notice how I lay these sticks and make this fire,” Martin instructed. “I am making it to cook our breakfast over, so I’ll build it in a very different way from what I should if I only wanted it for heating our tent. Learning how to build at least three different kinds of fires is a very important part of your education.”

The old man selected two small logs about four feet long and seven inches in diameter. He laid these side by side on the ground, separating them at one end a distance of about six inches and at the other end something over a foot. In the space between the logs he laid small branches and twigs, and lighted them, and in a jiffy had a hot fire going.

Larry noticed that Martin had placed the logs so that they lay at right angles to the direction from which the wind was blowing; and now as the heat thawed out the ground, the hunter took a sharp pointed stick and dug away the earth from under the log almost its whole length on the windward side. The wind, sucking in under this, created a draught from beneath, which made the fire burn fiercely.

Then Martin placed two frying pans filled with slices of ham and soggy, grease-covered bread over the fire, the tops of the two logs holding the pans rigidly in place. Next he took the wide-bottomed coffee pot, filled it with water, threw in a handful of coffee, and placed the pot at the end where the logs were near enough together to hold it firmly.

“Pretty good stove, isn’t it,” he commented, when he had finished.

“You see that kind of a fire does several things that you want it to, and doesn’t do several others that you don’t want. It makes all the heat go right up against the bottom of the pans where you need it most, and it only takes a little wood to get a lot of heat. What is more, the sides of the logs keep the heat from burning your face and your hands when you have to stir things, as a big camp-fire would. You can always tell a woodsman by the kind of fire he builds.”

Presently the coffee boiled over and Martin set it off, and by that time the ham and the bread were ready. And while they were eating their breakfast he set a pail of water on the fire to heat. “That’s to wash the dishes in,” he said. “A real woodsman washes his dishes as soon as he finishes each meal—does it a good deal more religiously than he washes his face or his hands, I fear.”

When breakfast was finished, and the last dish cleaned, Martin said: “Now you’ll have an hour’s practice at target-shooting. Take your gun and come along.”

He led the way to the pile of boxes, and hunted out three or four solid looking cases. These were filled with paper boxes containing cartridges—enough to supply an army, Larry thought. Tearing some of these open, Martin instructed the boy to fill the right hand pocket of his jacket with the little twenty-twos. “And always remember that they are in that pocket and nowhere else,” he instructed.

Next he opened a bundle and took out a belt on which there were a row of little leather pockets with snap fasteners. He filled these pockets with the larger calibre cartridges, six to each pocket, and instructed Larry to buckle it on over his coat. Then he led the way to a level piece of ground just above the camp, and having paced off fifty yards he fastened the round top of a large tin can against a tree and stepped back to the firing line.

“I’ll try one shot first to see if the sights are true,” he said, as he slipped a cartridge into each barrel. Then raising the gun to his shoulder he glanced through the sights and fired. “Go and see where that hit,” he told the boy.

Larry, running to the target, found the little hole of the .22 bullet almost in the center of the tin, and shouted his discovery exultantly. Martin had fired so quickly after bringing the gun to his shoulder that the boy could scarcely believe his eyes, although the result of the shot did not seem to surprise the old hunter.

“Don’t try the .38 yet,” he instructed, handing Larry the gun. “Fire twenty shots with the .22, and go and see where each shot strikes as soon as you fire and have loaded. And don’t forget to bring the gun to half-cock, and to load before you leave your tracks. That is one of the main things to remember. After a little practice you will do it instinctively, so that you will always have a loaded gun in your hands. It may save your life sometime when you run up to a buck that you have knocked over and only stunned.”

The boy took the gun and began his lesson, the hunter leaving him without waiting to see how he went about it. A few minutes later, when Larry had finished the twenty rounds, he found the old man going through the dismantled yacht.

“Just making a final inspection to see if there is anything left that we may need,” the old hunter said. “There’s a king’s ransom in here yet, but we can’t use it on our trip, and in another twenty-four hours it may be on the bottom of the ocean.”

Larry, trying to conceal the pride he felt, handed Martin the tin target he had brought with him. The old hunter examined it gravely, counting the number of bullet holes carefully. There were ten of them, including the one Martin had made.

“Eleven misses in twenty shots,” he commented, simply.

The boy, who was swelling with pride, looked crestfallen.

“But the last five all hit it,” he explained. “At first I hit all around it, and then I hit it almost every other time, and at last I hit it five times straight.”

“Put up a new target and try ten more,” was Martin’s only comment. But when Larry had gone he chuckled to himself with satisfaction. “Some shooting for a city boy!” he said to himself; “but I won’t spoil him by telling him so.”

When Larry returned with the second target there were seven bullet holes in it; but still the old hunter made no comment on the score. “Now go back and try ten of the big ones, and remember that you are shooting at big game this time,” he admonished.

Larry returned slowly to his shooting range. Martin was a very hard and unreasonable task-master, he decided. But, remembering that he had hit the mark so frequently before, he resolved to better his score this time. This was just the resolution Martin had hoped he would make.

So the boy fastened the target in place, adjusted the hammer for firing the larger cartridge. Then he shut his teeth together hard, took a careful but quick aim, for Martin had explained that slow shooting was not the best for hunting, and pulled the trigger. The sound of the loud report startled him, and his shoulder was jerked back by the recoil. It didn’t hurt, exactly, for the aluminum butt plate was covered with a springy rubber pad; but it showed him very forcibly what a world of power there must be in those stubby little cylinders of brass and lead.

He forgot his astonishment, however, when on going to the target, he found that the big bullet had pierced the tin almost in the center; and as he stood gazing at the hole he heard a low chuckle that cleared away all his dark clouds. Old Martin had slipped up behind him quietly; and there was no mistaking the old hunter’s wrinkled smile of satisfaction.

“Now you see what you can do with her,” the old man said, his eyes twinkling. “If that tin had been a moose’s forehead he’d be a dead moose, sure enough. Did the noise and the kick surprise you?”

“Yes, it did,” Larry admitted honestly; “but it won’t next time—it never will again. And I am going to kill just nine more moose with these cartridges.”

“That’s the way to talk,” said Martin, with frank admiration; “after a few more shots you’ll get used to the recoil, and pretty soon you won’t even feel it. But you musn’t expect to make nine more bull’s-eyes just yet.”

The old hunter went back to his work at the pile of plunder under the big canvas, and Larry fired his nine remaining rounds. Then he sought the old man again, but as Martin asked no question about the result of the shots, Larry did not volunteer any information. Presently Martin looked up from his work.

“I suppose you’ve cleaned the rifle now that you have finished practice for the morning?” he inquired.

Larry shook his head.

“Well that’s the very first thing to do, now, and always,” said the hunter.

It took quite a time for the boy to clean and oil the gun so that he felt it would pass inspection, and when he returned to Martin the old man was busy with an assortment of interesting looking parcels, placing them in separate piles. He was making notes on a piece of paper, while both the dogs were sniffing about the packages, greatly interested.

The old hunter sent Larry to bring two of the toboggans that he had saved from the yacht. They looked like ordinary toboggans to the boy, but Martin called his attention to some of their good points which he explained while he was packing them with what he called an “experimental load,” made up from the pile of parcels he had been sorting.

Each of the toboggans had fastened to its top a stout canvas bag, the bottom of which was just the size of the top of the sled. The sides of the bag were about four feet high, each bag forming, in effect, a canvas box fastened securely to the toboggan. Martin pointed out the advantages of such an arrangement in one terse sentence. “When that bag is tied up you can’t lose anything off your sled without losing the sled itself,” he said. “And if you had ever done much sledging,” he added, “you’d know what that means.”

“The usual way of doing it,” Martin explained, “is to pack your sled as firmly as you can, and then draw a canvas over it and lash it down. And that is a very good way, too. But this bag arrangement beats it in every way, particularly in taking care of the little things that are likely to spill out and be lost. With this bag there is no losing anything, big or little. You simply pack the big things on the bottom, and then instead of having to fool around half an hour fastening the little things on and freezing your fingers while you do it, you throw them all in on top, close up the end of the bag, and strap it down tight. You see it will ride then wherever the sled goes, for it is a part of the sled itself.”

Larry noticed that most of the larger parcels on the sled were done up in long, slender bags, and labeled. Martin explained that the bags were all made of waterproof material, and carefully sealed, and that narrow bags could be packed more firmly and rode in place better than short, stubby ones. A large proportion of these bags were labeled “Pemmican” and the name excited the boy’s curiosity.

“It’s something good to eat, I know,” he said; “but what is it made of, Martin?”

“It’s an Indian dish that made it possible for Peary to reach the Pole,” Martin assured him. “It is soup, and fish, and meat and vegetables, and dessert, all in one—only it hasn’t hardly any of those things in it. If you eat a chunk of it as big as your fist every day and give the same sized chunk to your dog, you won’t need any other kind of food, and your dog won’t. It has more heat and nourishment in it, ounce for ounce, than any other kind of food ever invented. That’s why I am going to haul so much of it on our sleds.”

While he was talking he had slit open one of the bags and showed Larry the contents, which resembled rather dirty, tightly pressed brown sugar.

“Gee, it looks good!” the boy exclaimed. “Let’s have some of it for supper.”

“You needn’t wait for supper,” Martin told him. “Eat all you want of it, we’ve got at least a ton more than we can carry away with us.” And he cut off a big lump with his hunting knife and handed it to the boy.

Larry’s mouth watered as he took it. He had visions of maple-sugar feasts on this extra ton of Indian delicacy close at hand, as he took a regular boy’s mouthful, for a starter. But the next minute his expression changed to one of utmost disgust, and he ran to the water pail to rinse his mouth. He paused long enough, however, to hurl the remaining piece at the laughing hunter. But Martin ducked the throw, while Kim and Jack, the dogs, raced after the lump, Kim reaching it first and swallowing it at a gulp.

“What made you change your mind so suddenly?” the old hunter asked when he could get his breath. “You seemed right hungry a minute ago, and I expected to see you eat at least a pound or two.”

“Eat that stuff!” Larry answered, between gulps from the water bucket. “I’d starve to death before I’d touch another grain of it.”

“That’s what you think now,” the old man answered, becoming serious again;—“that’s what I thought, too, the first time I tasted it. It tasted to me then like a mixture of burnt moccasin leather and boot grease. But wait until you have hit the trail for ten hours in the cold, when you’re too tired to lift your feet from the ground, and you’ll think differently. You’ll agree with me then that a chunk of this pemmican as big as your two fists is only just one third big enough, and tastes like the best maple sugar you ever ate.”

But the boy still made wry faces, and shook his head. “What do they put into it to make it taste so?” he asked. “Or why don’t they flavor it with something?”

“Oh, they flavor it,” Martin explained, laughing. “They flavor it with grease poured all over it after they have dried the meat that it is made of, and pounded it up into fine grains. But take my word for it that when you try it next time, somewhere out there in the wilderness two or three weeks from now, you’ll say that they flavor it just right.”

“But we needn’t worry about that now,” he added. “What we need more than anything else for to-night is a big lot of fire-wood, green and dry both. Take the axe and get in all you can between now and night. I want plenty of wood to use in teaching you how to make two other kinds of fires. Do you suppose you could cut down a tree about a foot in diameter?”

Larry thought he could. Some lumbermen in the Adirondacks had shown him how a tree could be felled in any direction by chopping a deep notch low down, and another higher up on the opposite side. He knew also about stepping to one side and away from the butt to avoid the possible kick-back of the trunk when the tree fell.

So he selected a tree of the right size as near the tent as he could find one, felled it after much futile chopping and many rests for breath, and cut it into logs about six feet long. When he had finished he called the two dogs, put a harness on each, hitched them up tandem, and fastened the hauling rope to the end of one of the logs. Martin had suggested that he do this, so as to get accustomed to driving the dogs, and get the big fellows accustomed to being driven by him.

The dogs, full of energy were eager for the work, and at the word sprang forward, yelping and straining at the straps, exerting every ounce of strength in their powerful bodies. The log was a heavy one, and at first they could barely move it; but after creeping along for a few inches it gradually gained speed on the thin snow, and was brought into camp on the run. Even in the excitement of shouting to the struggling dogs and helping with an occasional push, Larry noticed the intelligence shown by the animals in swinging from one side to the other, feeling for the best position to get leverage, and taking advantage of the likely places.

They seemed to enter into the spirit of the work, too, rushing madly back to the woods after each log or limb had been deposited at the tent, and waiting impatiently for Larry to make up the bundles of wood and fasten the draw rope. Working at this high pressure the boy and dogs soon had a huge pile of fire-wood at Martin’s disposal, and by the time the old hunter had finished his task, had laid in a three days’ supply.

“Now you build a ‘cooking fire,’ such as I made this morning, and get supper going,” said Martin, coming over to the tent; “and while you are doing that I’ll be fixing up another kind of a fire—one called a ‘trapper’s fire,’ which is built for throwing heat into a tent.”

The old hunter then drove two stakes into the ground directly in front of the opening of the tent and six feet from it, the stakes being about five feet apart and set at right angles to the open flaps. Against these stakes he piled three of the green logs Larry had cut, one on top of the other like the beginning of a log house, and held them in place by two stakes driven in front, opposite the two first stakes. Next he selected two green sticks about four inches in diameter and three feet long, and placed them like the andirons in a fireplace, the wall of logs serving as a reflecting surface like the back wall of a chimney. Across these logs he now laid a fire, just as one would in a fireplace.

Larry all this time had been busy getting the supper, Martin offering a suggestion now and then. When he saw that the meal was almost ready the old man spread a piece of canvas on the ground just inside the opening of the tent and before the log fire he had laid, and set out the plates and cups, and when Larry announced that the feast was ready Martin lighted the fire in front of the logs.

He had a double motive in this—to show the boy how to make a heating fire and to furnish heat for the evening. For the weather was growing very cold, and he had some work that he wished to do which would require light to guide his fingers and heat for keeping them warm.

With the protection of the tent back of them and the roaring fire in front they toasted their shins and ate leisurely. To Larry it all seemed like one grand lark, and he said so.

“I’m afraid you will change your mind about it being such a lark before we are through with it,” the old man said presently. “It won’t be a lark for either of us. But I’m beginning to feel more hopeful about it, now that I see that you can learn things, and are willing to try.”

He lighted his pipe and smoked thoughtfully for a few minutes. Larry too, was thoughtful, turning over in his mind the old hunter’s last remark.

“And so you have been thinking all this time that I might be in the way—that perhaps you would be better off if you were alone, and didn’t have a boy like me on your hands?” the boy asked presently.

For a little time the old man did not answer, puffing his pipe and gazing silently at the fire. At last he said:

“I couldn’t help feeling a little that way at first, Larry. The job on our hands is one for a strong man, not for a city boy. But I’m feeling different now that I see how you take hold and are willing to work, and try to learn all the things I tell you. And wouldn’t it be funny,” he added, with a twinkle in his kindly eye, “if, sometime, I should get into trouble and you have to help me out of it instead of my helping you all the time? A fellow can never tell what strange things may happen on the trail; and that is one reason why no man should start on a journey through the woods in the winter time alone.”

Presently the old man knocked the ashes from his pipe and set about cleaning the dishes, Larry helping him; but neither of them were in talking mood, each busy with his own thoughts. When they had finished the hunter said:

“Now I’ll show you how to make an Indian fire, the kind the Indian still likes best of all, and the best kind to use when wood is scarce or when you want to boil a pot of tea or get a quick meal.”

The old hunter then gathered an armful of small limbs, and laid them on the ground in a circle like the spokes of a wheel, the butts over-lapping at the center where the hub of the wheel would be. With a few small twigs he lighted a fire where the butts joined, the flames catching quickly and burning in a fierce vertical flame.

“This fire will make the most heat for the least amount of wood and throw the heat in all directions,” Martin explained. “And that is why it is the best kind of a fire for heating a round tent, such as an Indian tepee.”

“But why did the Indian have to care about the amount of wood he burned?” Larry asked. “He had all the wood he wanted, just for the chopping of it, didn’t he?”

The old man smiled indulgently. “Yes, he surely had all the wood he wanted just for the chopping—millions of cords of it. But how was he going to chop it without anything to chop it with, do you think? You forget that the old Indians didn’t have so much as a knife, let alone an axe. And that explains the whole thing: that’s why the Indian made small fires and built skin tepees instead of log houses.

“If you left your axe and your knife here at the tent and went into the woods to gather wood, Larry, how long do you suppose it would take you to collect a day’s supply for our big fire? You wouldn’t have much trouble in getting a few armfuls of fallen and broken branches but very soon you’d find the supply running short. The logs would be too large to handle, and most of the limbs too big to break. And so you would soon be cold and hungry, with a month’s supply of dry timber right at your front dooryard.

“But it’s all so different when you can give a tap here and there with your axe, or a few strokes with your hunting knife. And this was just what the poor Indian couldn’t do; for he had no cutting tool of any kind worth the name until the white man came. So he learned to use little sticks for his fire, and built his house of skins stretched over small poles.

“It is hard for us to realize that cutting down a tree was about the hardest task an Indian could ever attempt. Why the strongest Indian in the tribe, working as hard as he could with the best tool he could find, couldn’t cut down a tree as quickly as you could with your hunting knife. He could break rocks to pieces by striking them with other rocks, and he could dig caves in the earth; but when it came to cutting down a tree he was stumped. The big trees simply stood up and laughed at him. No wonder he worshipped the forests and the tree gods!

“Of course when the white man came and supplied axes, hatchets, and knives, he solved the problem of fire-wood for the Indian. But he never changed the Indian’s idea about small fires. Too many thousand generations of Indian ancestors had been making that kind of a fire all their lives; and the Indian is a great fellow to stick to fixed habits. He adopted the steel hatchet and the knife, but he stuck to his round fire and his round tepee.

“And yet, although he had never seen a steel hatchet until the white man gave him one, he improved the design of the white man’s axe right away. The white man’s hatchet was a broad-bladed, clumsy thing, heavy to carry and hard to handle. The Indian designed a thin, narrow-bladed, light hatchet—the tomahawk—that would bite deeper into the wood and so cut faster than the white man’s thick hatchet. And every woodsman now knows that for fast chopping, with little work, a hatchet made on the lines of the tomahawk beats out the other kind.”

The old man took his own hunting axe from the sheath at his belt and held it up for inspection.

“You see it’s just a modified tomahawk,” he said, “with long blade and thin head, and only a little toy axe, to look at. But it has cut down many good-sized trees when I needed them, all the same. And the axe you were using this afternoon, as you probably noticed, is simply a bigger brother of this little fellow, exactly the same shape. It’s the kind the trappers use in the far North, because it will do all the work of a four-pound axe, and is only half as heavy. We’ve got some of those big axes over there under the tarpaulin, but we’ll leave them behind when we hit the trail, and take that small one with us.”

While they were talking Martin had been getting out a parcel containing clothing and odds and ends, and now he sat down before the fire to “do some work” as he expressed it.

“If you’re not too sleepy to listen,” he said, “I’ll tell you a story that I know about a little Algonquin Indian boy.”

Larry was never too tired to listen to Martin’s stories; and so he curled up on a blanket before the fire, while the old man worked and talked.

It had been a hard day’s work for both of them, and strange as everything was to Larry, and awful as the black woods seemed as he peeped out beyond the light of the fire, he had a strange feeling of security and contentment. It might be that there were terribly hard days of toil and danger and privations ahead, but he was too cozily situated now to let that worry him.

Besides he was feeling the satisfaction that every boy feels in the knowledge that he has done something well. And even the exacting old Martin, always slow to praise or even commend, had told him over his cup of tea and his soup at supper, that he “would make a hunter of him some day.” And what higher praise could a boy hope for?

“Nobody knows just how old Weewah was when he became a mighty hunter,” Martin began presently, without looking up from his sewing, “because Indians don’t keep track of those things as we white folks do. But he couldn’t have been any older than you are, perhaps not quite so old.

“He was old enough to know how to handle his bow and arrows, though, to draw a strong enough bow to shoot an arrow clean through a woodchuck or a muskrat, or even a beaver, although he had never found the chance to try at the beaver. He carried his own tomahawk, too—a new one that the factor at Hudson Bay Post had given him,—and was eager to show his prowess with it on larger game.

“But the hunting was done by the grown up men of the village, who thought Weewah too small to hunt anything larger than rabbits. Yet there were other boys of his own age who found more favor in the hunters’ eyes because they were larger than he. ‘Some day you will be a hunter,’ they told him, ‘but now you are too small.’

“Weewah’s heart was big, even if his body was small. And so one day he took all his long arrows, his strongest bow, and his tomahawk and resolved to go into the big woods at some distance from the village, and do something worthy of a hunter.

“It was winter time, and the snow on the ground was knee-deep with just a little crust on it. On his snow-shoes Weewah glided through the forest, noticing everything he passed and fixing it in his memory instinctively so that he could be sure of finding the back trail. For this day he meant to go deep, deep into the spruce swamp in his hunting. There he would find game worthy of the bow of the mighty hunter he intended to prove himself.

“The tracks of many animals crossed his path, little wood dwellers such as rabbits and an occasional mink. But these did not interest him to-day. He had brought his snares, of course, for he always carried them; but to-day his heart was too full of a mighty ambition to allow such little things as rabbit snares to interrupt his plans.

“Once he did stop when he saw, just ahead of him on the snow, a little brown bunch of fur with two big brown eyes looking at him wonderingly. In an instant he had drawn the poised arrow to his cheek and released it with a twang. And a moment later the little brown bunch of fur was in Weewah’s pouch, ready for making into rabbit stew in the evening.

“Weewah took it as a good omen that he had killed the rabbit on the very edge of the spruce swamp that he had selected for his hunting ground. Soon he would find game more worthy of his arrows or his axe. And so he was not surprised, even if his heart did give an extra bound, when presently he came upon the track of a lynx. It was a fresh track, too, and the footprints were those of a very big lynx.

“Weewah knew all this the moment he looked at the tracks, just as he knew a thousand other things that he had learned in the school of observation. He knew also that in all probability the animal was not half a mile away, possibly waiting in some tree, or crouching in some bushes looking for ptarmigan or rabbit. He was sure, also, that he could run faster on his snow-shoes than the lynx could in that deep soft snow.

“So for several minutes he stood and thought as fast as he could. What a grand day for him it would be if he could come back to the village dragging a great lynx after him! No one would ever tell him again that he was too small to be a hunter.

“But while he was sorely tempted to rush after the animal with the possibility of getting a shot, or a chance for a blow of his axe, he knew that this was not the surest way to get his prey. He had discovered the hunting ground of the big cat, and he knew that there was no danger of its leaving the neighborhood so long as the supply of rabbits held out. By taking a little more time, then, Weewah knew he could surely bring the fellow into camp. And so he curbed his eagerness.

“Instead of rushing off along the trail, bow bent and arrow on the string, he opened his pouch and took out a stout buckskin string—a string strong enough to resist the pull of the largest lynx. In one end of this he made a noose with a running knot. Next he cut a stout stick three inches thick and as tall as himself. Then he walked along the trail of the lynx for a little distance, looking sharply on either side, until he found a low-hanging, thick bunch of spruce boughs near which the animal had passed. Here the boy stopped and cut two more strong sticks, driving them into the ground about two feet apart, so that they stood three feet above the snow and right in front of a low-hanging bunch of spruce boughs.

“At the top of each he had left a crotch, across which he now laid his stick with the looped string dangling from the center. The contrivance when completed looked like a great figure H, from the cross-bar of which hung the loop just touching the top of the snow.

“Now Weewah carefully opened the loop of the noose until it was large enough for the head of any lynx to pass through, and fastened it deftly with twigs and blades of dead grass, so as to hold it in place firmly. From its front the thing looked like a miniature gallows—which, indeed, it was.

“Next Weewah took the rabbit from his pouch, and creeping under the thicket carefully so as not to disturb his looped string, he placed the still warm body an arm’s length behind the loop, propping the head of the little animal up with twigs, to look as lifelike as possible. In an hour, at most, the rabbit would freeze and stiffen, and would then look exactly like a live rabbit crouching in the bushes.

“Then the little Indian broke off branches, thrusting them into the snow about the rabbit, until he had formed a little bower facing the snare. Any animal attempting to seize it would thrust its own head right through the fatal hangman’s loop.

“When Weewah had finished this task he gathered up his tomahawk and bow and arrows, and started back along his own trail. He made no attempt to cover up the traces of his work, as he would if trapping a fox; for the lynx is a stupid creature, like all of his cousins of the cat family, and will blunder into a trap of almost any kind.

“The little Indian hurried along until he reached the point from which he had first crossed the lynx tracks. Here he turned sharply, starting a great circle, which would be about a mile in diameter. He did this to make sure that the lynx had not gone on farther than he thought. If he found no sign of fresh tracks he could feel certain that the animal was still close at hand.

“This took him several hours, and it was almost dark when he pulled back the flap and entered his home lodge in the village. He was tired, too, but his eyes shone with suppressed emotion.

“As soon as he entered his mother set before him a smoking bowl of broth without a word of comment or a question as to what his luck might have been in his rabbit hunting. His father was there, gorging himself on fat beaver meat that he had just brought in; but neither he, nor Weewah’s brothers and sisters, offered any comment at the little boy’s entrance.

“It is not correct etiquette, in Algonquin families, to ask the hunter what luck he has had until he has eaten. Even then a verbal question is not asked. But when the repast is finished the Indian woman takes a pouch of the hunter and turns its contents out upon the floor.

“The emptiness of Weewah’s pouch spoke for itself, for he had flung it upon the floor on entering, where it lay flat. His father scowled a little when he noticed it; for he wanted his son to be a credit to him as a hunter. But his scowl turned into a merry twinkle when he saw how radiant his son’s face was despite his ill luck, and what a small, delicately formed little fellow he was. Besides the old warrior was in an unusually good humor. Had he not killed a fat beaver that day? And was not beaver tail the choicest of all foods?

“In a few hours Weewah’s brothers and sisters, rolled in their warm Hudson Bay blankets, were breathing heavily, and his father and mother were far away in dreamland. Weewah was in dreamland, too; but not the land that comes with sleep. He was in the happy state of eager expectation that comes when to-morrow is to be a great day in one’s life. And so he lay, snugly wrapped in his blanket, his black eyes shining as he watched the embers of the fire in the center of the tepee slowly grow dim and smoulder away. Meanwhile the very thing he was dreaming about was happening out in the dark spruce swamp.