THE ALDINE READERS

A SECOND READER

By

Frank E. Spaulding

Superintendent of Schools, Newton, Mass.

and

Catherine T. Bryce

Supervisor of Primary Schools, Newton, Mass.

With Illustrations by

Margaret Ely Webb

NEW YORK

NEWSON & COMPANY, PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1907, by

Newson and Company

All rights reserved

The authors and publishers desire to acknowledge their obligation to Mr. Nathaniel L. Berry, Supervisor of Drawing in the Public Schools of Newton, Massachusetts, for valuable assistance in planning and arranging the illustrations in this book.

This Second Reader, like the two preceding books of the Aldine Series, combines material and method in such a way that the former does not suffer, while the latter gains by the combination. That is, the subject-matter of the book, both the text and the illustrations, is just as suitable and just as interesting as it could be made were there no such thing as method; indeed, the sole sign of method, as one reads the book, is the parenthesis about certain words preceding the stories. At the same time, this subject-matter, both the text and the illustrations, embodies in systematic arrangement the most effective principles of mastering the mechanics of reading.

Children who have read thoroughly the preceding books of this Series have acquired independence, the habit of self-reliance, and the power of self-help to such a degree that they will be able to master this book with little or no direct aid from the teacher. And when they have thus mastered this book, they will be good readers. That is, so far as the mechanics of reading is concerned, they will be able to read unaided anything which they can[vi] understand; so far as the subject-matter is concerned, they will be able to understand from the printed page anything which they can understand through the spoken word. More than this, if the teacher has contributed her part, most such children will have realized the utility and tasted the real delights of reading to such an extent that they will continue to read of their own accord; most of them will also be good oral readers, reading with appropriate expression and genuine enthusiasm.

These statements are not mere predictions of the hoped-for results of untried theories; they are simple, unexaggerated expressions of facts which have been observed in the work of thousands of children of a score of nationalities.

To secure such results a complete mastery and intelligent observation is necessary of the principles and plans described in the authors’ Manual for Teachers, entitled “Learning to Read.”

The authors gratefully acknowledge their indebtedness to Miss Marie Van Vorst for the use of “Three of us Know” and “The Sandman”; to Mrs. Emily Huntington Miller for “The Bluebird”; to Messrs. Houghton, Mifflin & Co. for the use of the poem “Discontented,” by Sarah Orne Jewett, and “Calling the Violet,” by Lucy Larcom; to Messrs. Charles Scribner’s Sons for “The Wind,” by Robert Louis Stevenson.

| PAGE | ||

| Out of Door Neighbors | 1 | |

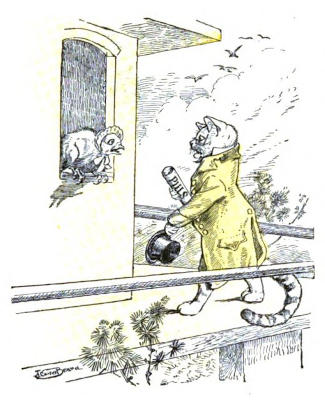

| The Cat and the Birds | 3 | |

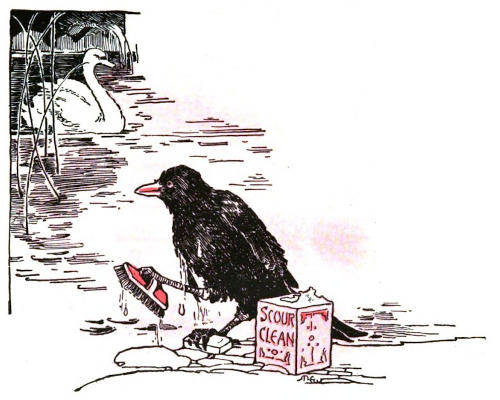

| Why Ravens Croak | 6 | |

| The Proud Crow | 8 | |

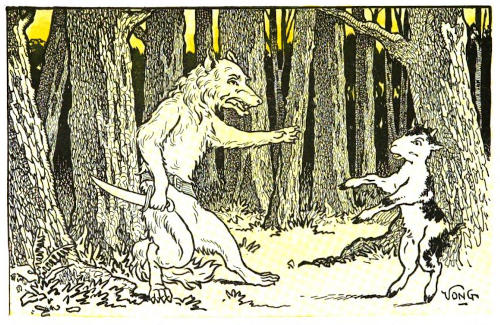

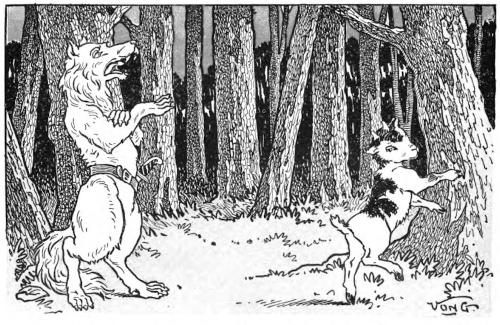

| The Wolf and the Kid | 12 | |

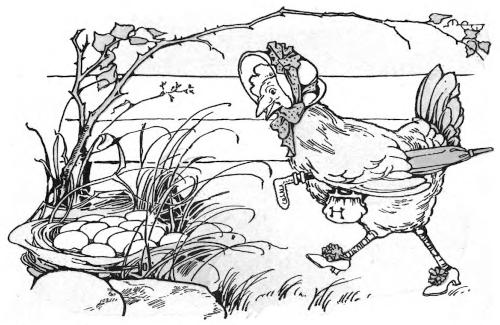

| Queer Chickens | 17 | |

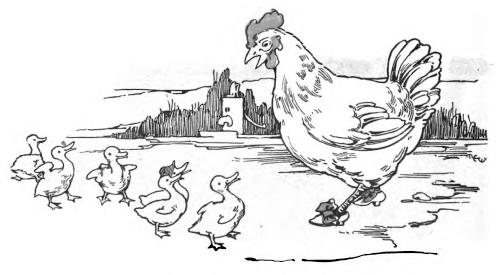

| Little Ducks | Robert Mack | 21 |

| Once Upon a Time | 23 | |

| The Caterpillar | 25 | |

| Who is Strongest? | 27 | |

| Lambikin | 37 | |

| The Ant and the Mouse | 46 | |

| Songs of Life | 51 | |

| The Brook | 53 | |

| The Little Brook | 55 | |

| Calling the Violet | Lucy Larcom | 59 |

| The Wind | Mary Lamb | 61 |

| The Wind | Christina Rossetti | 62 |

| The Wind | R. L. Stevenson | 63 |

| The Leaf’s Journey | 64[viii] | |

| Sweet and Low | Tennyson | 69 |

| Sleep, Baby, Sleep! | From the German | 70 |

| Stars and Daisies | 71 | |

| Lady Moon | Lord Houghton | 73 |

| With Nature’s Children | 75 | |

| The Little Shepherdess | 77 | |

| Discontent | Sarah Orne Jewett | 81 |

| Belling the Cat | 84 | |

| Three of us Know | Marie Van Vorst | 91 |

| The Dandelion | 93 | |

| The Magpie’s Lesson | 95 | |

| The Bluebird | Mrs. Emily Huntington Miller | 100 |

| The Wolf and the Stork | 102 | |

| The Indian Mother’s Lullaby | Charles Myall | 103 |

| In Story Land | 105 | |

| How Mrs. White Hen helped Rose | 107 | |

| The Sandman | Marie Van Vorst | 115 |

| Billy Binks | 117 | |

| Some Things to think About | 131 | |

| When the Little Boy ran Away | 133 | |

| How the Bean got its Black Seam | 138 | |

| Friends | L. G. Warner | 145 |

| Help One Another | 147 | |

| With our Feathered Friends | 149 | |

| The Drowning of Mr. Leghorn | 151 | |

| The Starving of Mrs. Leghorn | 160 | |

| Mr. and Mrs. Leghorn to the Rescue | 172 | |

| Vocabulary | 179 |

An old cat lived near a bird house.

Every day he saw the birds flying in and out.

Every day he said to himself, “How I wish I had one of those nice fat birds for my dinner!”

One day he heard that the birds were ill.

“Now is my time,” he said. “I will get a bird to eat to-day.”

So he put on a tall hat and a coat.

He took a cane in one hand and a box of pills in the other.

Then he went to the bird house and rapped at the door.

“Who is there?” asked an old bird.

“It is I, the doctor,” said the cat. “I heard that you were ill. So I have come to see you. I have some pills that will make you well. Open the door.”

The old bird looked out.

“Your words are kind,” he said, “like the words of the good doctor. Your hat, coat, cane, and box of pills are like his. But your paws are those of the old cat. Go away! We will not let you in. We do not want your pills. We are more likely to get well without your help than with it.”

Then all the birds flew at him.

They pecked at his eyes; they pecked at his ears.

They tore his coat.

Away flew his high hat; away flew his cane; away flew his box of pills.

Then away flew the old cat himself, and he never went back.

A raven was very unhappy because his feathers were black.

One day he saw a beautiful white swan swimming in a lake.

“How beautiful and white her feathers are,”[7] he thought. “It must be because she washes them so much. Why, she almost lives in the water. If I should wash my feathers all day long, they might get white, too. I will try it.”

So he flew from his nest in the woods, and lived for days near the lake.

Every day he washed his feathers from morning to night.

But his feathers did not get white.

They were just as black as ever.

But as the raven was not used to living in water, he caught a very bad cold.

So, at last, he flew back to his nest in the wood.

“It is no use,” he croaked. “I can never be white. I do not want to be white. Black feathers are pretty enough for me. Croak! Croak!”

All ravens have said “Croak! Croak!” ever since.

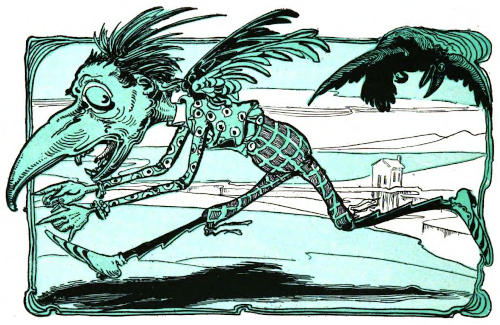

One day a crow found a lot of peacock feathers.

“My,” cried the silly crow, “how lucky I am. No other crow in the world will look as fine as I. How all my old friends will envy me!”

And the proud crow stuck the peacock feathers all over his back.

Then he flew away to show himself to his friends.

He strutted up and down before them.

But they only laughed at him.

“Just look at that silly bird!” they cried.[9] “See him strut! Did you ever see anything so proud? Caw, caw, caw!”

The proud crow was now very angry.

“Do not speak to me,” he said. “I have fine feathers. I am a peacock. I will have nothing to do with you crows.”

So off he strutted to the peacocks.

“How do you do, my dear friends?” he said in his sweetest voice.

“Who are you?” cried the peacocks scornfully.

“Do you not see that I am a peacock?” answered the crow. “Look at my fine feathers.”

“Fine feathers, indeed! We threw those old feathers away long ago. You are no peacock. Yon are just an old black crow.”

Then the peacocks fell upon the old crow, and pulled off all his fine feathers.

They tore out many of his own feathers, too.

The foolish crow was a sight!

He crept back to his old friends.

He tried to steal in among them without being seen.

But they all cried out, “Who are you? What do you want here?”

“Don’t you see that I am your old friend?” croaked the crow. “I am going to live with you always.”

“No, you are not,” answered a wise old crow. “You are no friend of ours. A few old peacock feathers made you think you were a peacock. So you left your old friends. The peacocks saw you were a cheat and drove you away. Hereafter you must live alone. Be off with you!”

And all the crows said, “Caw, caw, caw! Caw, caw, caw!”

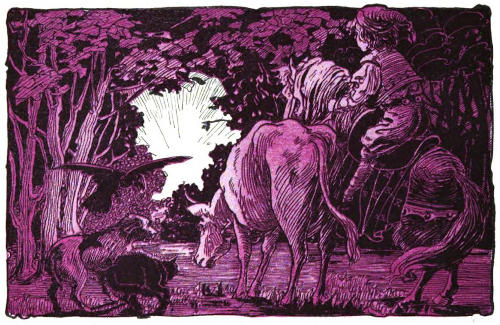

One day a little kid was lost in a dark wood.

He ran on and on, but could not find his way out.

At last he became frightened and began to bleat.

A hungry wolf heard him.

How glad the wolf was to find such a good dinner!

“Oh, Mr. Wolf!” cried the little kid, “please show me the way home.”

“Show you the way home!” growled the wolf. “I am hungry and I’m going to eat you.”

“Oh, please, please, Mr. Wolf,” begged the frightened kid, “please let me go!”

“No, no, I’ll eat you,” growled the wolf.

And he sprang at the kid, now almost dead with fright.

Just then a lucky thought came to the little kid.

“Oh, Mr. Wolf,” said he, “I have heard that[14] you make very fine music. I love to dance. Will you not sing for me, so that I may have one more dance before I die? It is not much to ask.”

This pleased the wolf, for he was proud of his voice.

“Well,” he growled, “music is good before eating. I often sing before my dinner. To-day I was too hungry to think of it. But I will sing just one song. Then I will eat you. Dance lively, now!”

So the wolf sang a song, and the kid danced his best.

When the wolf stopped, the kid cried, “That was good. But you did not sing loud enough or fast enough for me. Is that the best you can do?”

“No,” said the wolf. “I can sing louder and faster than any one in the woods. Listen!”

So the wolf sang louder and faster.

And the kid danced livelier and better than before.

But the wolf made so much noise that the dogs heard it.

They came running into the woods to see what the matter was.

The wolf had to run for his life.

But the wise little kid trotted safely home to his mother.

“I have to go without my dinner,” growled the wolf. “I alone am to blame. I should kill and eat kids, not sing for them.”

An old hen found a nest behind the gate.

It was full of eggs. Such beautiful eggs!

They would make any old hen’s heart glad.

“I will sit on these eggs. I will keep them warm,” thought the hen. “Then a little chicken will come out of each one.”

So the old hen spread her wings over the eggs.

How very wide she had to spread them!

For many days she sat there waiting.

One morning she awoke to find her nest full of little ones.

One, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine, ten, eleven, twelve, there were.

“Cluck, cluck, what dear little chickens,” said the hen.

“Come and get breakfast. Cluck, cluck, cluck, cluck! What hungry chickens!

Now I will let you play in the meadow. Come down to the brook first and get a drink.

The water is clear and cool. Do not go too near, or you will fall in.”

Now, what do you think those little ones did?

You never could guess, so I will tell you.

As soon as they saw the brook they ran to it. They ran as fast as ever they could go.

They rushed right into the water.

“Cluck, cluck! Cluck, cluck! Come back! Come back!” called the old hen. “Come back, come back to your mother!”

But they did not come back.

They did not even listen.

They sailed clear across the stream.

They sailed up stream and they sailed down stream.

But they did not come back to their mother.

She could only run up and down the bank, looking and calling.

“What shall I do? What shall I do?” she cried. “Come back! Come back, you naughty[19] chickens. You will drown, every one of you. I know you will drown. O, why will you not mind your mother?”

How frightened she was!

She just knew all her dear chicks would drown.

Still she did not dare to follow them into the water. She never swam a stroke in all her life. She never even waded in the water.

But such fun as her little ones were having!

They were not the least bit afraid.[20] They swam and splashed around all day.

All day the old mother hen ran up and down the bank calling and begging, “Come back! Come back! Come right back to your mother!”

At last the little ones were tired.

Then they came back to their frightened mother.

One after another came up the bank and ran to her.

How glad she was to gather them again under her warm wings.

But what queer chickens they were.

Once upon a time Tumtollo climbed a tree.

The wind blew hard and uprooted the tree.

Tumtollo was thrown to the ground.

“Oh, oh, oh!” he cried with pain, “oh, oh, oh!”

“My, isn’t the tree strong!” cried he; “it can throw Tumtollo to the ground.”

“You are wrong,” creaked the tree. “I am not strong. If I were, could I be uprooted by the wind?”

“Ah, I see,” said Tumtollo, “it is the wind that is strong.

The wind uprooted the tree.

The tree threw Tumtollo to the ground.”

“No, friend, you are wrong,” sighed the wind. “If I were strong, could I be stopped by the hill?”

“Oh, I see now,” said Tumtollo, “it is the hill that is strong.

The hill stopped the wind.

The wind uprooted the tree.

The tree threw Tumtollo to the ground.”

“Wrong again,” said the hill. “I am not strong. If I were, I should not be burrowed by mice.”

“Oh,” said Tumtollo, “then it is the mouse that is strong.

The mouse burrowed the hill.

The hill stopped the wind.

The wind uprooted the tree.

The tree threw Tumtollo to the ground.”

“Still wrong,” squeaked the mouse. “It is not I who am strong. If I were, could the cat catch me?”

“Well, then, it is the cat that is strong,” said Tumtollo.

“The cat caught the mouse.

The mouse burrowed the hill.

The hill stopped the wind.

The wind uprooted the tree.

The tree threw Tumtollo to the ground.”

“No, Tumtollo, I am not strong,” mewed the cat. “If I were, could the dog frighten me?”

“Then it is the dog who is strong,” said Tumtollo.

“The dog frightened the cat.

The cat caught the mouse.

The mouse burrowed the hill.

The hill stopped the wind.

The wind uprooted the tree.

The tree threw Tumtollo to the ground.”

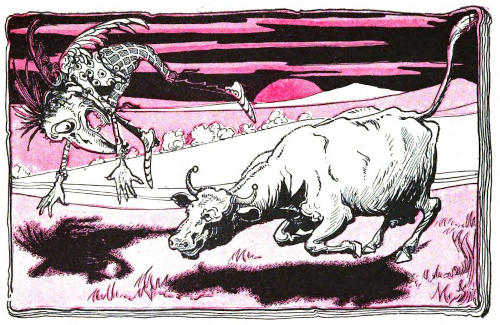

“It is not I who am strong,” barked the dog. “If I were, would the ox hook me with his horns?”

“Then it must be the ox who is strong,” said Tumtollo.

“The ox hooked the dog.

The dog frightened the cat.

The cat caught the mouse.

The mouse burrowed the hill.

The hill stopped the wind.

The wind uprooted the tree.

The tree threw Tumtollo to the ground.”

“No,” bellowed the ox, “I am not strong. If I were, would the bee sting me?”

“Ah, ha! it is the little bee that is strong,” said Tumtollo.

“The bee stung the ox.

The ox hooked the dog.

The dog frightened the cat.

The cat caught the mouse.

The mouse burrowed the hill.

The hill stopped the wind.

The wind uprooted the tree.

The tree threw Tumtollo to the ground.”

“No, no!” buzzed the bee, “it is not I who am strong. If I were, would the bear steal my honey?”

“Indeed, then it is the bear who is strong,” said Tumtollo.

“The bear robbed the bee.

The bee stung the ox.

The ox hooked the dog.

The dog frightened the cat.

The cat caught the mouse.

The mouse burrowed the hill.

The hill stopped the wind.

The wind uprooted the tree.

The tree threw Tumtollo to the ground.”

“You are wrong, Tumtollo,” growled the bear.

“If I were strong, could the lion drive me away from my dinner?”

“Very well, then it is the lion who is strong,” said Tumtollo.

“The lion drove away the bear.

The bear robbed the bee.

The bee stung the ox.

The ox hooked the dog.

The dog frightened the cat.

The cat caught the mouse.

The mouse burrowed the hill.

The hill stopped the wind.

The wind uprooted the tree.

The tree threw Tumtollo to the ground.”

“It is not I who am strong,” roared the lion.

“If I were, could the rope bind me?”

“Just as you say,” said Tumtollo, “then it is the rope that is strong.”

“The rope bound the lion.

The lion drove away the bear.

The bear robbed the bee.

The bee stung the ox.

The ox hooked the dog.

The dog frightened the cat.

The cat caught the mouse.

The mouse burrowed the hill.

The hill stopped the wind.

The wind uprooted the tree.

The tree threw Tumtollo to the ground.”

“It is not I, indeed, that am strong,” said the rope. “If I were, could the fire burn me?”

“Well, well, then the fire must be strong,” said Tumtollo.

“The fire burned the rope.

The rope bound the lion.

The lion drove away the bear.

The bear robbed the bee.

The bee stung the ox.

The ox hooked the dog.

The dog frightened the cat.

The cat caught the mouse.

The mouse burrowed the hill.

The hill stopped the wind.

The wind uprooted the tree.

The tree threw Tumtollo to the ground.”

“No, no, Tumtollo,” snapped the fire, “I am not strong. If I were, could the water put me out?”

“The water it is, then, that is strong,” said Tumtollo.

“The water put out the fire.

The fire burned the rope.

The rope bound the lion.

The lion drove away the bear.

The bear robbed the bee.

The bee stung the ox.

The ox hooked the dog.

The dog frightened the cat.

The cat caught the mouse.

The mouse burrowed the hill.

The hill stopped the wind.

The wind uprooted the tree.

The tree threw Tumtollo to the ground.”

“You are still wrong, Tumtollo,” sang the water in a spring near by. “I am not strong. But I will tell you who is truly strong. It is Man.

Man drinks the water.

Man lights the fire.

Man makes the rope.

Man cages the lion.

Man tames the bear.

Man eats the bee’s honey.

Man drives the ox.

Man keeps the dog.

Man feeds the cat.

Man kills the mouse.

Man digs the hill.

Man breathes the wind.

Man fells the tree.

Man rises when he is thrown to the ground.”

Tumtollo rose, drank deeply from the sweet spring, and went on his way.

Once upon a time there was a wee, wee Lambikin.

He frolicked about on his tottery legs from morning to night.

He was always happy.

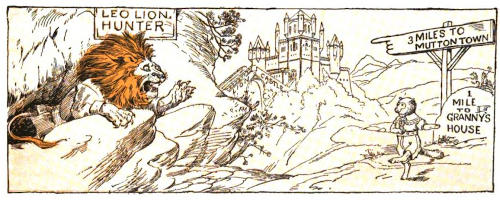

One day Lambikin set off to visit his Granny.

He was jumping with joy to think of the good things he would get.

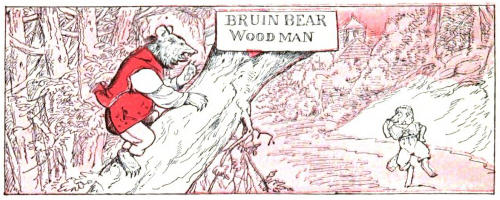

As he frisked along, he met but a wolf!

The wolf howled, “Lambikin! Lambikin! I’ll eat YOU!”

But with a hop and a skip, a hump and a jump, Lambikin said,

The wolf thought this wise and so let Lambikin go.

Away frisked Lambikin.

He had not gone far, when whom should he meet but a bear!

The bear growled, “Lambikin! Lambikin! I’ll eat YOU!”

But with a hop and a skip, a hump and a jump, Lambikin said,

The bear thought this wise and so let Lambikin go.

Away frisked Lambikin.

He had not gone far when whom should he meet but a lion!

The lion roared, “Lambikin! Lambikin! I’ll eat you!”

But with a hop and a skip, a hump and a jump, Lambikin said,

The lion thought this wise and so let Lambikin go.

Away frisked Lambikin.

At last he reached his Granny’s house.

“Granny dear,” he cried, all out of breath, “I have said I would get fat. I ought to keep my word. Please put me in the corn-bin at once.”

“You are a good Lambikin,” said his Granny.

And she put him into the corn-bin.

There the greedy little Lambikin stayed for seven days and seven nights.

He ate, and ate, and ate, and he ate until he could hardly waddle.

“Come, Lambikin,” said his Granny, “you are fat enough. You should go home now.”

“No, no,” said cunning little Lambikin, “that will never do. Some animal would surely eat me on the way, I am so plump and tender.”

“Oh, dear! Oh, dear!” cried old Granny in a fright.

“Never fear, Granny dear,” said cunning Lambikin. “I’ll tell you what to do. Just make me a little drumikin out of the skin of my little brother who died. I can get into it and roll along nicely.”

So old Granny made Lambikin a drumikin out of the skin of his dead brother.

And cunning Lambikin curled himself up into a round ball in the drumikin.

And he rolled gayly away.

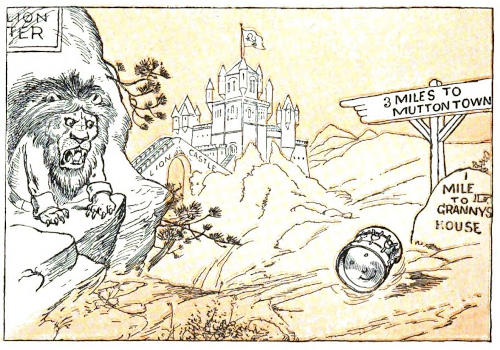

Soon he met the lion, who called out,

Lambikin answered sweetly as he rolled along,

“Too bad, too bad,” sighed the lion, as he thought of the sweet, fat morsel of a Lambikin.

So away rolled Lambikin, laughing gayly to himself and sweetly singing,

Soon he met the bear, who called out,

Lambikin answered sweetly as he rolled along,

“Too bad, too bad,” sighed the bear, as he thought of the sweet, fat morsel of a Lambikin.

So away rolled Lambikin, laughing gayly to himself and sweetly singing,

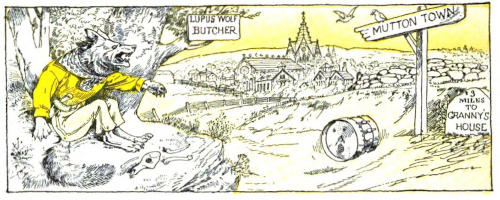

Soon he met the wolf, who called out,

Lambikin answered sweetly as he rolled along,

“Oh, ho, little Lambikin, curled up snug in your little drumikin,” said the wolf, “you can’t fool me. I know your voice. So you have become too fat to hop and to skip, to hump and to jump. You can only roll along like a ball.”

And the wolf’s mouth watered as he thought of the sweet, fat morsel of a Lambikin.

Little Lambikin’s heart went pit-a-pat, but he cried out gayly,

The wolf was frightened and stopped to listen for the dogs.

And away rolled cunning Lambikin faster and faster, laughing to himself and sweetly singing,

There was once an ant.

While sweeping her house one day, this ant found three pieces of money.

“What shall I buy?” said she.

“Shall I buy fish?”

“No, fish is full of bones. I can’t eat bones. I’ll not buy fish.”

“Shall I buy bread?”

“No, bread has crust. I can’t eat crust. I’ll not buy bread.”

“Shall I buy peaches?”

“No, peaches have stones. I can’t eat stones. I’ll not buy peaches.”

“Shall I buy corn?”

“No, corn grows on a cob. I can’t eat cobs. I’ll not buy corn.”

“Shall I buy apples?”

“No, apples have seeds. I can’t eat seeds I’ll not buy apples.”

“Shall I buy a ribbon?”

“Yes, that’s just what I want. I will buy a ribbon.”

And away ran Miss Ant to the store and bought her a bright red ribbon.

She tied the ribbon about her neck and sat in her window.

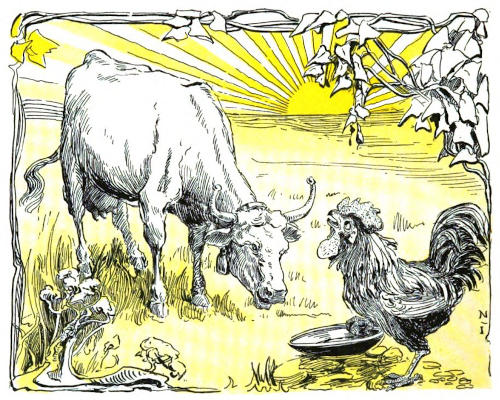

An ox came along and said, “How pretty you are, Miss Ant! Will you marry me?”

“Sing,” said the ant, “so I may hear your voice.”

The ox was very proud of his voice and he bellowed with all his might.

“No, no,” cried the ant, “I’ll not marry you, Mr. Ox. Your bellow frightens me. Go away.”

Soon a lion came that way and said, “How pretty you are, Miss Ant! Will you marry me?”

“Sing,” said the ant, “so I may hear your voice.”

The lion was proud of his voice and he roared with all his might.

“No, no,” cried the ant, “I’ll not marry you, Mr. Lion. Your loud roar frightens me. It shakes the very hills. Go away.”

The lion had not been gone long when a proud rooster came strutting along that way.

“How pretty you are, Miss Ant! Will you marry me?” said the rooster.

“Sing,” said the ant, “so I may hear your voice.”

The rooster was very proud of his shrill voice and he crowed with all his might.

“No, no,” cried the ant, “I’ll not marry you, Mr. Rooster. Your shrill crow frightens me. Go away.”

The rooster was hardly out of sight when a big dog came trotting that way.

“How pretty you are, Miss Ant! Will you marry me?” said the dog.

“Sing,” said the ant, “so I may hear your voice.”

The dog was very proud of his voice and he barked with all his might.

“No, no,” cried the ant, “I’ll not marry you, Mr. Dog. Your sharp bark frightens me. Go away.”

After a time a wee little mouse came frisking that way.

“How pretty you are, Miss Ant! Will you marry me?” said the mouse.

“Sing,” said the ant, “so I may hear your voice.”

Now the wee little mouse was not at all proud of his voice. But he squeaked as sweetly as he could, “Wee, wee, wee!”

“Yes, yes,” cried the ant, “I’ll marry you, dear Mouse. Your sweet little voice pleases me. Come right in.”

In scampered the mouse.

The ant gave him two pieces of money, for she had spent only one for her ribbon.

He hurried away to the store, and came quickly back bringing apples and bread.

Mrs. Ant Mouse now sat down to a feast.

Mr. Mouse ate the crusts and the seeds, so nothing was lost.

See the little brook rushing down the steep hillside!

How it hurries!

How it leaps over the falls!

Hear it dash and splash among the rocks!

See its waters flash and sparkle in the sun!

“Stop, stop, little brook! Wait, I want to talk with you.”

“No, no, I must hurry on. I have a long way to go.”

“I will go with you, then. I will run along your banks. Please do not hurry so. I can hardly keep up with you.”

Now we come to the wide meadow.

Here the little brook flows more slowly and quietly.

But it never stops.

It must flow ever on and on.

Bright flowers are hiding along its banks.

They peep out from the grass.

They look into the clear flowing water.

“Stay, little brook, play with us,” they whisper.

“Why do you always hurry so? Are you not weary?”

“No, no, I am never weary, never tired,” murmurs the brook.

“I never stop to play.

It is play for me to rush swiftly down the steep hill.

It is fun to flow gently across the meadow.

I like to see you peeping over my banks as I pass.

But I cannot stop.

I must hurry on to meet the river.

Good-by, sweet flowers, good-by.”

Now the brook glides into the woodland.

Here the sad willows droop over the gliding waters.

High above them tower the oak, the ash, and the pine trees.

“Do not hurry, little brook,” whisper their leaves.

“Are you not tired?

You have come a long way.

Here the bright sun never comes.

Stay with us, and we will shade you.

Rest a while under our spreading branches.

In the meadow the burning sun is so hot.

But here it is cool.

Why can you not stay with us?

Why must you always hurry on?”

“Because I have to meet the river.

I love your wide spreading branches.

I love the gentle murmur of your green leaves.

I love your cool shade.

You are very kind to me.

But I cannot stay with you.

The great river needs me.

I shall have to hurry on.

Good-by, noble trees.

Good-by, drooping willows.”

So the never resting brook rushes, and glides and flows on forever.

On the steep hillside grew a tall ash tree.

Right on the bank of the rushing brook it grew.

Its branches spread far out across the little stream.

Its leaves looked down into the flashing water.

There, when the sun shone brightly, they saw leaves looking up at them.

They called these “water leaves.”

The little tree leaves wished to go to the water leaves.

Many of them had already fluttered down.

But one leaf, very young, could not let go her hold of the twig.

At last a raging wind tore away the little leaf.

Over and over she turned.

Down, down, down, she fell.

She was so afraid the wind would carry her away.

But the friendly stream leaped up the rocks to meet her.

It bore her away, swiftly but gently.

The little leaf was afraid. She was lonesome.

The dear little “water leaves” were nowhere to be seen.

“Don’t be afraid, little leaf,” murmured the kind brook.

“I will give you a fine ride.

And I’ll talk to you all the time.

I’ll tell you all about the things we pass.

Here we are, already in the meadow.

Now I don’t have to hurry.

See the pretty flowers peeping over my banks.

They all love me.

I give them cool water to drink.

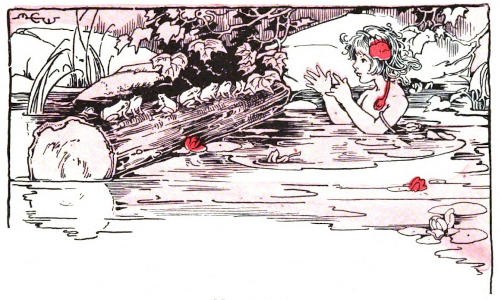

Here we go past the old mossy log.

Just see the frogs on it!

They are all in a row.

One, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, of them!

They love me, too.

When anything makes them afraid, they leap into me.

They hide in some of my deep pools.

Here is the shady woodland.

Now I glide more slowly.

Soon I shall meet the great river.

I will not carry you into it.

For there you would be afraid.

I will land you here with lots of other leaves.”

And the stream pushed her gently upon the low bank of sand.

“Good-by,” he murmured; “good-by, little leaf.”

And the little leaf lay quietly thinking.

How many different things she had seen!

She never dreamed there were so many things in the whole world.

Do you know what daisies are?

Do you know what stars are?

I will tell you what I think.

At night we see the stars shining in the sky.

There are so very many of them, more than we can count.

I think the sky is a beautiful meadow.

And the stars are little white daisies growing in the sky meadow.

Sometimes the moon comes into the meadow.

She is a beautiful lady.

All night she walks among the flowers.

She gathers the little sky daisies.

In the morning we cannot see the stars.

Where are they?

In the meadow near our home are many bright-eyed daisies.

There are so very many of them, more than we can count.

How did they get there?

Where did they come from?

Daisies look like stars, you know.

So I think the lady moon threw them down from the sky.

One morning a pretty little shepherdess drove her flock of sheep to the meadow. There she[78] watched them while they ate the fresh, green grass. How sweet it tasted to the hungry sheep!

A large dog went with the shepherdess to help care for the sheep. He was the shepherd.

The shepherd let no lamb go astray. If one got too far from the flock, Mr. Shepherd ran after him.

“Bow-wow! Go back!” cried the shepherd.

The shepherdess took good care of her flock, too. She led them where the grass was greenest and sweetest.

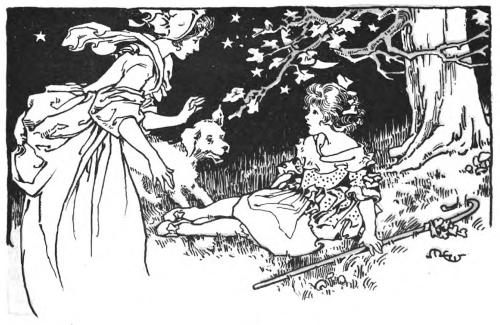

When noon came all the sheep had eaten enough. So they lay down quietly in the cool shade of some old oak trees. Little Bo-peep lay down too, with her good shepherd dog beside her.

How cool and still it was there! Little Bo-peep could hear only the gentle rustling of the leaves overhead. She could feel only the soft wind on her cheek.

The wind blew more and more softly; the leaves rustled more and more gently. Soon little Bo-peep was fast asleep.

“Bo-peep, Bo-peep, where are you?”

“Bow-wow, bow-wow, bow-wow-wow!”

“Bo-peep, Bo-peep!”

Little Bo-peep awoke with a start. She sat upright, her eyes wide open. Not a sheep could she see. Her dog was not beside her. It was dark;[80] the stars were twinkling overhead. How frightened the little shepherdess was!

“Bow-wow!”

“Bo-peep, Bo-peep! Where are you, child?” Surely that was her mother’s voice.

“Here, mother, here I am, under the big oak tree!” called Bo-peep.

Up rushed the dog, and mother followed close behind.

“Where are my sheep, mother? I fear they are lost.”

“Where is my little Bo-peep? I feared she was lost.”

“Here is your Bo-peep, dear mother. How long I must have slept!”

“Your sheep are all safe at home. Old Rover drove them in long ago.”

This is the way Bo-peep lost her sheep; this is the way she found them. And this is the way Bo-peep was lost; and this is the way she was found.

A family of rats had their home in a barn.

They made many snug nests in the warm hay.

They dug holes through the hay from nest to nest.

They ran in and out and all about the barn. They had nothing to fear.

When they were hungry they could always find nice grain in the stalls. They became very fat.

And they were as happy a family of rats as one could wish to see.

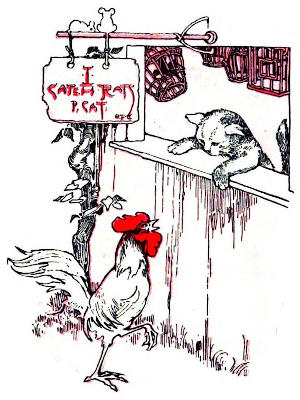

But one day a big black cat found the rats’ barn.

That was a sad day for the rat family!

This cat was not fat and he was not happy.

He was very thin, very cross, and very hungry.

One thing he liked to eat best of all things in the world—rats.

How he did love nice, fat, happy rats! At last he had found them, a whole big family of them!

This hungry, greedy cat now had rat for breakfast, rat for dinner, and rat for supper. And sometimes he had rat between meals.

Very soon this cat began to grow fat and happy.

But happy cats make unhappy rats. While this cat grew fat, these rats grew thin.

Yet in the stalls there was just as much grain as ever. But it was only a very hungry rat that[86] dared go for it. For no rat could tell when the cat might pounce upon him.

That sly cat stole about without a sound.

The most watchful rat could hear nothing, could see no living thing.

Then, pounce! The wicked cat’s claws held him fast.

So, many a poor rat went to the stall, and never came back. And the rat family was growing smaller day by day.

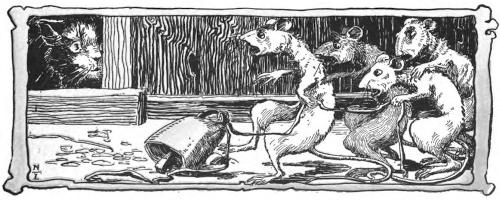

At last the wise old rats saw that something must be done. So they called a meeting of the whole family of rats, as many as were still alive.

When all had come together in a safe place and were still, the oldest and wisest rat rose up on his hind legs.

He stood up very straight, very tall, and very thin.

“My dear brothers and sisters, my dear children and grandchildren!” began the wise old rat.

“You all know the one fear of our lives.” Every rat trembled.

“That wicked cat has grown fat and sleek feeding on your brothers, your mothers, your wives, and your children.

No one of you knows when his turn may come to make a meal for that ever hungry monster.

He steals upon you without warning.

He is never seen, he is never heard, until it is too late.

But you were not called together to hear what you already know only too well.

You were called here to do something to make your lives safer and happier.

What can be done? Who has a plan?”

The old rat waited.

All the other rats looked from one to another, but no one spoke.

“Well, then,” said the wise old rat at last, “listen to me.

If we only knew where the cat was, we could not be caught. If we could only hear him coming, we might get out of his reach.

Now, my plan is this. We will hang a bell to that cat’s neck.”

“The very thing! Hurrah! Hurrah!” cried all the rats together.

“Why haven’t we thought of that before?

No more of us will go to make dinners for that old cat.

Now, for all the corn we can eat!”

And away sprang the hungry rats for the stalls.

“Stop! Stop!” cried the wise old rat. “Back to your places!

The bell isn’t on the cat’s neck yet.”

Slowly and sadly the starving rats settled back.

“Now,” the old rat went on, “who will tie the bell around the cat’s neck?”

“Not I! Not I! Not I!” squeaked the poor frightened rats.

And they trembled all over at the very thought.

Then they sat very still and looked at each other.

Oh! how hungry they were! How sweet that yellow corn in the stall would taste.

One by one they began to steal away softly.

Where do you think they were going?

Rat families still live in barns.

Cats still feed upon them.

But no rat has ever tried to make life safer by belling a cat.

Years and years ago—ever so many years ago—only one bird in the whole world knew how to build a nest. That wise bird was the magpie.

One day all the other birds came to the magpie. They wanted to learn how to build nests. They begged the magpie to teach them.

“Indeed, I am glad to teach you,” said Mrs. Magpie. “Just listen and watch me. First, you must choose a tall tree, like this great maple. Then take sticks—”

“A tree,” broke in the bold eagle, “a tree here in this valley! No trees nor valleys for me! My nest shall be on the highest cliff of yonder mountain.”

And away flew the eagle without waiting to hear more of the magpie’s lesson.[96] To this day he puts together a few rough sticks on a rocky mountain cliff, and calls them a nest.

The magpie began again. “Take sticks like these,” she said, “to a high branch.”

“Are you a fool?” cried the lark. “Don’t you know that the first strong wind will blow your nest to the ground?” “And the first boy who comes this way will throw stones at it,” put in Mrs. Bob-o-link.

“No high branches for us,” sang the lark and the bob-o-link together. And down they flew into the tall grass of the meadow. There they have made their nests ever since.

Mrs. Magpie didn’t even look at the birds flying away. “Weave the sticks together so, in and[97] out,” said she cheerfully. “That will make the bottom of the nest.”

“I don’t mean to set my nest on a branch like that,” spoke up the oriole. “The wind surely would blow it off, as the lark just said.”

And the oriole flew away and hung her nest from little twigs. There you may see it to-day swinging in the wind far out at the end of a long branch.

“Plaster the inside of your nest with mud,” Mrs. Magpie went on again. “Then line it with soft grass, so.”

“Dear, dear, so much work to make a nest!” yawned the whip-poor-will. “I’m not going to take the trouble.” And that lazy bird hasn’t made a nest from that day to this. She just lays her eggs in a hollow on the ground, or perhaps on a log.

“Who, who, who would go to all that trouble!” hooted the owl. “I think I have a better plan.”

She looked very wise, but said no more. You can guess what her plan was when you find her eggs in a crow’s or a hawk’s old nest.

“Now take more mud and sticks,” began the patient magpie once more. “You need to build a dome over your nest. That is to hide the little ones and to keep out the rain.”

“Oh, never mind the dome,” said the robin. “I will cover my little ones with my wings. I can hide them and keep off the rain.”

“You are right, Mrs. Robin,” said the crow. “We have no use for domes.” And to this day neither robins nor crows have built domes over their nests.

Mrs. Magpie paid no more[99] heed to these birds than to the others who had already left her. She went quietly on building her nest, just as she knew it ought to be built. Soon it was done, dome and all.

“Indeed, Mrs. Magpie,” said the swallows, “we like your nest. The dome is a fine thing, but why should we build it? There are plenty of domes already built; we need only to make our nests under them.”

Ever since then some swallows have made their nests under banks. Others have made theirs under roofs of open barns; and still others under eaves.

So all the birds flew away and left Mrs. Magpie with never a “thank you.” Each one built her nest as she pleased. And each one thought her way so much better than the magpie’s.

But the magpie still builds her nest in the top of a high tree. She makes it of mud and sticks and covers it with a dome.

A greedy wolf got a bone stuck in his throat. Try as he would, he could not get the bone out. At last he lay down to die, as he thought. But just then a stork came that way.

“Good day, Mr. Wolf,” said the stork, kindly.

But the wolf could not answer a word.

The stork soon saw what the matter was, and with his long beak pulled the bone out of the wolf’s throat. Without a word, the greedy wolf sprang up and went on with his dinner.

The stork, who was very hungry, began to pick up a few morsels of meat.

“Be off with you!” snapped the wolf. “How dare you touch my meat!”

“Is that the thanks I get for saving your life?” said the stork.

“Thanks!” answered the wolf, “did I not let you draw your bill out of my jaws in safety? It is you who should be thankful.”

A beautiful rose tree grew in the garden. Every morning she smiled up at the golden sun. But one morning when the sun rose, he was surprised to see that his friend, the rose, drooped sadly. He sent one of his warm rays down to earth to find out what the matter was.

“Dear Rose,” said the bright sunbeam, “why do you droop and look so sad?”

“Ah, me!” sighed the rose, “I am so unhappy! An ugly worm is eating my leaves, and he will not crawl away.”

The sun felt very sorry for the rose. “I will not shine,” he said, “until Rose is happy.” So he hid behind a dark cloud.

The wind came hurrying along. “Father Sun,” he cried, “why are you not shining to-day?”

“Ah, me!” answered the sun, “dear Rose is so unhappy! An ugly worm is eating her leaves, and he will not crawl away. I will shine no more until Rose is happy.”

“I, too, am so sorry,” whispered the wind. “I will blow no more until Rose is happy.” So saying he dropped to the earth and was still.

A bird was surprised when the wind stopped.

“Mr. Wind,” he called, “why have you stopped blowing?”

“Ah, me!” sighed the wind. “Dear Rose is so unhappy! An ugly worm is eating her leaves, and he will not crawl away. So Sun will shine no more and I will blow no more until Rose is happy.”

“I, also, love Rose,” sang the bird; “and I will sing no more until Rose is happy.” He flew away silently to his nest in the oak tree.

“It is not night,” said the old tree; “why are you not flying and singing, little bird?”

“Ah, me!” chirped the bird. “Dear Rose is so unhappy! An ugly worm is eating her leaves, and he will not crawl away. So Sun will shine no more, Wind will blow no more, and I will sing no more until Rose is happy.”

“That is all very sad,” whispered the tree. “I shall drop no more acorns until Rose is happy.”

Soon the squirrel came to gather some nuts. But he could find very few.

“Dear Tree,” he chattered, “please drop down some acorns.”

“No,” answered the tree. “I cannot, now.”

“Why not?” asked the squirrel.

“Ah, me!” rustled the tree. “Dear Rose is so unhappy! An ugly worm is eating her leaves, and he will not crawl away. So Sun will shine no more, Wind will blow no more, Bird will sing no more, and I will drop no more acorns until Rose is happy again.”

“And I will work no more,” chirped the squirrel. “I will run away to my nest in the old hollow tree.”

On the way to his home the squirrel met Mrs. Brown Duck.

“Good morning, Mr. Squirrel,” quacked the duck. “Why are you not working this morning?”

“Ah, me!” replied the squirrel. “Dear Rose is so unhappy! An ugly worm is eating her leaves, and he will not crawl away. So Sun will shine no more, Wind will blow no more, Bird will sing no more, Oak Tree will drop no more acorns, and I will work no more till Rose is happy.”

“Then I will swim no more,” said Mrs. Brown Duck. And she waddled off to the barnyard. There she met Mrs. White Hen.

“Why do you look so sad, Mrs. Duck?” said the hen.

“Ah, me!” quacked the duck. “Dear Rose is so unhappy! An ugly worm is eating her leaves, and he will not crawl away. So Sun will shine no more, Wind will blow no more, Bird will sing no more, Oak Tree will drop no more acorns, Squirrel will work no more, and I will swim no more until Rose is happy again.”

“Indeed! Indeed!” cackled Mrs. White Hen. “Pray tell me how stopping your work will help Rose. If you wish Rose to be happy, you must do something for her. Come with me.”

Away hurried the hen and the duck until they came to the rose. The old hen asked no questions. She did not even take time to say “Good morning.” But she cocked her head first[113] on one side, then on the other, searching through the leaves of the rosebush with her bright little eyes. Suddenly she darted forward. “Snap!” went her bill, and the worm was swallowed.

“There, Mrs. Duck,” clucked the hen, “see how I have helped Rose and at the same time got a nice breakfast for myself.”

At once the rose looked up toward the sun and smiled. Thereupon the sun began to shine.

“If I had only thought,” said the sun, “I might have burned that worm with my hot rays.”

“And I might have blown him away,” whistled the wind, springing up suddenly.

“If I had only thought,” sang the bird, “I might have had a nice fat worm for breakfast.”

“And so might I,” quacked the duck as she waddled away toward the pond.

The oak tree shook down a great shower of acorns, and the squirrel hastened to gather them. They, too, wished they had thought of some way to help Rose.

But the clever old white hen said nothing at all.

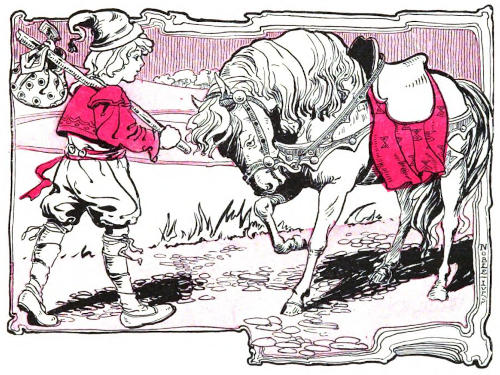

Once upon a time a little boy named Billy Binks set out to seek his fortune. He traveled alone for many a weary mile, but at last he met a little gray pony.

“Where are you going, Billy Binks?” neighed the pony.

“I am going to seek my fortune,” said Billy Binks.

“May I go, too?”

“If I take you, will you help me win my fortune?”

“Yes.”

“How?”

“I will carry you on my back and kick all your enemies with my hard hoofs.”

“Very well, you may come along.”

Then they went on a little farther and met a cow.

“Where are you going, Billy Binks?” mooed the cow.

“I am going to seek my fortune,” answered Billy Binks.

“May I go, too?”

“If I take you, will you help me win my fortune?”

“Yes.”

“How?”

“I will moo, and toss your enemies on my sharp horns.”

“Very well, you may come.”

When they had walked on a little farther they met a dog.

“Where are you going, Billy Binks?” barked the dog.

“I am going to seek my fortune,” answered Billy Binks.

“May I go, too?”

“If I take you, will you help me win my fortune?”

“Yes.”

“How?”

“I will bark, and bite your enemies with my sharp teeth.”

“Very well, you may come.”

After walking a little farther they met a cat.

“Where are you going, Billy Binks?” mewed the cat.

“I am going to seek my fortune,” answered Billy Binks.

“May I go, too?”

“If I take you, will you help me win my fortune?”

“Yes.”

“How?”

“I will purr, and scratch your enemies with my sharp claws.”

“Very well, you may come.”

They continued their journey and presently met a raven.

“Where are you going, Billy Binks?” croaked the raven.

“I am going to seek my fortune.”

“May I go, too?”

“If I take you, will you help me win my fortune?”

“Yes.”

“How?”

“I will croak, and peck your enemies’ eyes out with my sharp beak.”

“Very well, you may come.”

On and on they walked till at last they entered a deep, dark wood. All day they journeyed through this forest, which grew denser and darker as night came on.

“We are near a clearing in this wood,” croaked the raven, who had been soaring above the treetops. “Let us keep right on.”

Suddenly all were startled by a bright light, the brightest any of them had ever seen. It flashed out through the trees directly in front of them. It fairly dazzled and blinded them. Then it as suddenly disappeared, and left them standing terrified in the pitch-black darkness of the night.

Again the light flashed out, and again disappeared.

“What can it be?” asked Billy Binks, hoarsely, as soon as he could find his voice.

“Perhaps it is a lamp,” mewed the cat.

“No, it is too bright for a lamp,” answered Billy Binks.

“It might be a house on fire,” barked the dog.

“No, if it were, we could see the light all[123] the time; and besides, there is no house here. I have flown this way before,” answered the raven.

“It may be a lighthouse,” said Billy Binks.

“No,” replied the raven, “the sea is miles from here. You all keep still while I fly over the treetops and find out what it is.”

Billy Binks and his animal friends kept ever so quiet, while the raven flew up and quickly disappeared[124] in the darkness. It seemed hours before he returned.

“Oh, my friends,” croaked the raven, alighting in their midst at last, “you never saw such a sight! There’s the most horrible, monstrous hob-goblin over there in the clearing. He has a nose as long as a broomstick—”

“Oh! Oh! Oh!” cried Billy Binks and his friends.

“—Eyes as big as saucers and as green as the sea—”

“Oh! Oh! Oh!” cried Billy Binks and his friends.

“—And a mouth big enough to swallow us all!”

“Oh! Oh! Oh!” cried Billy Binks and his friends.

“He has a great fire blazing among some rocks. That is the light you saw. When he walks in front of it you cannot see the light. That is why you thought it disappeared.”

“I see! I see! I see!” said Billy Binks and his friends.

“He is busy melting gold, and he has piles of gold and jewels hidden in his cave—”

“Ah, ha!” laughed Billy Binks, as he climbed bravely upon his gray pony.

“His cave is full of nice plump field mice—”

“Mew! Mew!” cried the cat, as she scrambled up behind Billy Binks.

“In the bushes back of the cave live many rabbits—”

“Bow-wow!” barked the dog, as he bounded toward Billy Binks.

“Near the cave is a large green meadow, with the sweetest grass and the coolest brook in the world—”

“Moo! Moo!” lowed the cow, as she, too, hurried up beside Billy Binks.

“And there is a tall tree that will make a fine home for me,” finished the raven, as she flew over Billy Binks’s head.

“Come on, friends,” whispered Billy Binks, boldly. “It is time to win my fortune. Remember you have all promised to help me.”

“Yes, yes, I’ll help. And I think I see my fortune, too,” answered each of the animals, now as bold as Billy Binks.

Softly, quietly, and slowly they crept through the forest. Presently they came to the clearing.[127] There stood the ugly, black hob-goblin, bending over his fire. His back was turned toward them.

“Now!” shouted Billy Binks, and they all rushed at the terrible monster.

The raven dashed into his face and pecked at his large green eyes.

The cat scratched great gashes in his long nose.

The dog bit him, and the horse kicked him.

The enraged cow rushed upon him with lowered[128] head, caught him on her horns, and tossed him as high as the treetops.

Then the cow began to bellow.

The dog began to howl.

The cat began to waul.

The raven began to caw.

The pony began to prance.

And Billy Binks began to shout with all his might.

Such a frightful din that old hob-goblin had never heard! He picked himself up from the sharp rocks where he had fallen, and dashed away with might and main through the forest. If he hasn’t stopped, he is running still.

“Ho, ho!” cried Billy Binks, springing from the gray pony and running to the mouth of the cave. “This heap of gold and this pile of jewels will do for my fortune. If you carry them safely home for me, Pony, I will build you a beautiful stable, and you shall have a full crib of oats before you all the rest of your life. That will be your fortune.”

“This cave, full of good, plump mice, is my fortune,” called the cat, as she pounced on the first unlucky mouse.

“All these rabbits shall be my fortune,” barked the dog, as he set off in hot haste after a fleeing bunny.

“And this green meadow is my fortune,”[130] mooed the cow, as she began to crop the sweet grass.

“Who could have a better fortune than this?” croaked the raven, flying to the top of a tall tree.

So Billy Binks said “Good-by” to his friends, and left them each with his fortune. He quickly bagged the gold and jewels, threw them across the pony’s back, and mounting, hurried off homeward.

The pony smelled oats all the way, while Billy Binks saw castles and lands on all sides.

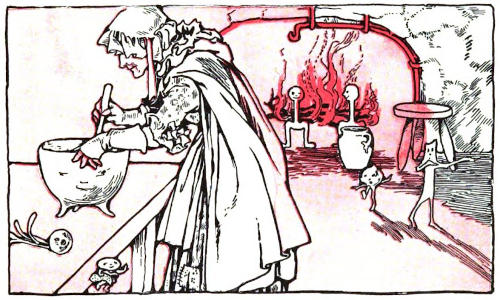

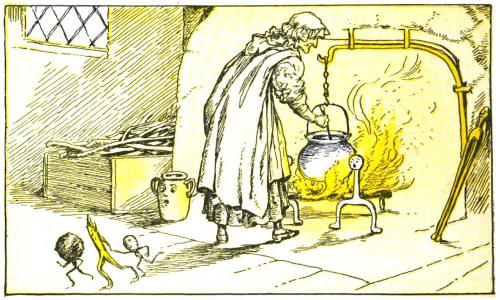

Once upon a time there was a poor old woman living in a village of a far country. She had gathered some beans and was making ready to cook them. She built a fire of sticks, but, as these were damp, they did not burn well. So she thrust in a handful of dry straw. Now the flames leaped up, and the sticks snapped and crackled in the blaze.

A live red coal flew out of the fire, fell on the ground beside a straw, and lay there smoking.[139] Just then a bean dropped from the pot which the old woman was filling, rolled away, and came to rest close to the coal and the straw.

“Hullo, Mr. Coal,” said the straw. “How you smoke! Are you frightened? Where did you come from?”

“I just sprang out of that fire,” answered the coal. “Had I not jumped just as I did, I should now be nothing but ashes. My, look at that blaze!”

“I, too, jumped in the nick of time,” spoke up the bean. “That cruel old woman was just pouring me into the pot when I leaped over the edge, and here I am.”

“Yes, here you are, silly thing,” broke out the coal and the straw together. “But what are you going to do? As soon as the old woman turns around she will spy you, then back you’ll go into the pot. It’s hotter now than when you left it.”

“Don’t bother about me; think of yourselves,” answered the bean, angrily. “When the old woman picks me up, she’ll tread on you, Mr. Coal, and crush your life out. And you, Mrs. Straw, she’ll stick into the blaze. It’s hotter there than in the pot.”

“Come, come,” said the straw, softly, “let’s not quarrel. Let’s be friends and stick together. Perhaps we can save ourselves yet.”

“You are quite right, Mrs. Straw,” said the coal.

The bean said nothing, but she listened eagerly to the plans of the two others. These soon agreed to travel together to a far country, where they hoped to find their fortune. They set out without delay, and the bean rolled along behind.

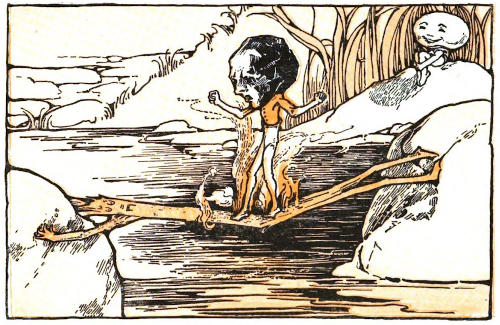

Soon the three travelers came to a little gurgling brook. It seemed to them a mighty rushing and roaring torrent.

“Oh, dear, what shall we do now?” asked the bean, speaking for the first time since the journey[142] began. “We can never get across these awful waters. Hear them thunder down the rocky cliffs!”

“Don’t worry, little Bean,” said the straw, proudly. “I’ll help you and Mr. Coal across in a twinkling.”

Thereupon the straw laid herself across the stream. She was just long enough to reach from bank to bank.

“Now walk over the bridge, Mr. Coal and Miss Bean,” called the straw.

The coal hastened on to the straw bridge while the bean watched in wonder. All went well until the middle of the stream was reached, when the bridge bent so low under the weight of the coal and the waters thundered so loudly that the coal stopped in fright.

The coal stood still for only a moment. But, alas, that was a moment too long.

The dry straw smoked, burst into a tiny flame,[143] and broke in two. Down fell the coal into the water below and was instantly drowned. The burning straw bridge also fell into the water, which put out the flames, and the two pieces of straw went floating away down stream.

All this the little bean saw, watching safely from the bank. And she thought it the funniest thing that ever happened. So she laughed and she laughed—until she burst!

This would have been the end of little Miss Bean, had not a tailor passed that way just then. He was sorry for the poor bean, so he picked up the two parts tenderly, and quickly sewed them together. But the thread that he used was black. And ever since that time some beans have a black seam around them.

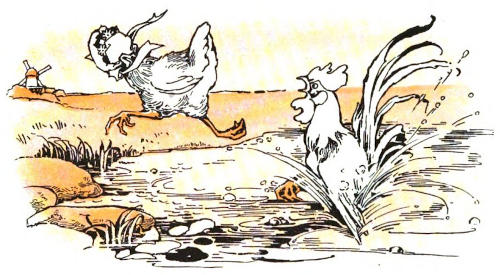

One day Mr. Leghorn, the rooster, and Mrs. Leghorn, the hen, were out walking. They came to a wide, deep brook. Mrs. Leghorn, who was light and quick, flew safely across; but Mr. Leghorn,[152] who was heavy and slow, fell, splash! into the water.

Mrs. Leghorn was sure Mr. Leghorn was drowned. So, without turning to see, she flew screaming and cackling toward the farmyard.

“What does ail you, Mrs. Leghorn? Why are you screaming and cackling so loudly?” asked the Wind-Mill as Mrs. Leghorn flew past.

“Mr. Leghorn has fallen into the brook and is drowned. That’s why I am screaming and cackling so loudly,” replied Mrs. Leghorn.

“What a pity! I’ll swing my arms and creak. That’s the best I can do for poor Mr. Leghorn.”[153] And the Wind-Mill fell to swinging his arms and creaking with all his might.

When the Big Barn Door heard the Wind-Mill creaking and saw him swinging his long arms, he called out, “What ails you, Wind-Mill? Why do you swing your arms and creak so?”

“Why, Mr. Leghorn has fallen into the brook and is drowned, and Mrs. Leghorn is screaming and cackling. That’s why I swing my arms and creak,” answered the Wind-Mill.

“Poor Mr. Leghorn, poor Mrs. Leghorn!” said the Big Barn Door. “I’ll slam and bang. That’s the best I can do.” And the Big Barn Door fell to slamming and banging with all his might.

The Old Red Ox heard the Big Barn Door slamming and banging, and cried out, “O, Big Barn Door, why are you slamming and banging so?”

“Reason enough,” answered the Big Barn Door. “Mr. Leghorn has fallen into the brook and is drowned; Mrs. Leghorn is screaming and cackling; and Wind-Mill is swinging his arms and creaking. That’s why I am slamming and banging so.”

“How sorry I am,” said the Old Red Ox. “I’ll paw the ground and bellow. What else can I do?” And he fell to pawing and bellowing with all his might.

“What is the matter, Old Red Ox?” asked the Watch Dog. “Why are you pawing and bellowing so?”

“Matter enough,” answered the Old Red Ox. “Mr. Leghorn has fallen into the brook and is drowned; Mrs. Leghorn is screaming and cackling; Wind-Mill is swinging his arms and creaking; and Big Barn Door is slamming and banging. That’s why I am pawing and bellowing so.”

“O dear me,” said the Watch Dog. “I’ll bark and whine. That’s all I can do.” And he fell to barking and whining with all his might.

The Old Gray Horse heard the Watch Dog barking and whining, and said, “What is the matter with you, Watch Dog? Why do you bark and whine so?”

“Wouldn’t you bark and whine if you could?” answered the Watch Dog. “Mr. Leghorn has fallen into the brook and is drowned; Mrs. Leghorn is screaming and cackling; Wind-Mill is swinging his arms and creaking; the Big Barn Door is slamming and banging; and the Old Red Ox is pawing and bellowing. That’s why I am barking and whining.”

“The poor things!” said Old Gray Horse. “I’ll prance and neigh. What more can I do?” And he fell to prancing and neighing with all his might.

The Weather-Vane looked down from his high perch and saw the Old Gray Horse prancing and neighing. “What’s the trouble, Old Gray Horse?” he called out. “Why are you prancing and neighing so?”

“Trouble indeed,” answered the Old Gray Horse. “Mr. Leghorn has fallen into the brook and is drowned; Mrs. Leghorn is screaming and cackling; Wind-Mill is swinging his arms and creaking; the Big Barn Door is slamming and banging; the Old Red Ox is pawing and bellowing; and the Watch Dog is barking and whining. That’s why I am prancing and neighing so?”

“O dear, O dear,” said the Weather-Vane, “what shall I do? I’ll whirl and point. That’s all I can do.” And he fell to whirling and pointing with all his might.

Pussy Cat looked up and saw Weather-Vane whirling and pointing. “O, Weather-Vane,” she cried out. “Why do you whirl and point so?”

“Because I can do nothing else,” answered the Weather-Vane. “Mr. Leghorn has fallen into the brook and is drowned; Mrs. Leghorn is screaming and cackling; Wind-Mill is swinging his arms and creaking; the Big Barn Door is slamming and banging; the Old Red Ox is pawing and bellowing; the Watch Dog is barking and whining; and the Old Gray Horse is prancing and neighing. That’s why I am whirling and pointing so.”

“O, how sad!” said Pussy Cat. “I’ll waul and squall. That’s the best I can do.” And she fell to wauling and squalling with all her might.

At this moment, when Pussy Cat was wauling and squalling, when the Weather-Vane was whirling and pointing, when the Old Gray Horse was prancing and neighing, when the Watch Dog was barking and whining, when the Old Red Ox was[159] pawing and bellowing, when the Big Barn Door was slamming and banging, when the Wind-Mill was swinging his arms and creaking, when Mrs. Leghorn was screaming and cackling, Mr. Leghorn flew to the highest rail on the fence and crew,

Mr. and Mrs. Leghorn often went nutting. Mr. Leghorn was very polite and kind to Mrs. Leghorn. He ran about searching everywhere for nuts. When he found one he would call to Mrs. Leghorn, who would hasten to him. Then he would pick up the nut, roll it over and over, lay it down, and pick it up again a dozen times, all the time telling Mrs. Leghorn what a very nice nut that was, what a good hen she was, and how smart he was to find nuts for her. At last he would drop the nut before Mrs. Leghorn, who would peck it once or twice to make sure that all[161] Mr. Leghorn had said of it was true, and then swallow it whole, without once offering to share it with Mr. Leghorn.

One day Mr. Leghorn found a very large nut, the largest nut he had ever seen. How proudly he called to Mrs. Leghorn! It took him a long time to tell all about that big nut and how he had found it, to praise Mrs. Leghorn’s goodness, and to brag about his own smartness. But finally he finished and turned the nut over to Mrs. Leghorn. She seized it greedily and was about to swallow it, but—it wouldn’t go down! She tried again and again, she stretched her beak wider and wider, but it was no use. The nut was too large.

Mr. Leghorn, who had been watching Mrs.[162] Leghorn from a little distance, became alarmed.

“O, my poor Mrs. Leghorn,” he cried, “what shall I do? You can’t eat that nut; you’ll surely starve. What shall I do?”

“Run and ask Mr. Wise Owl,” said Mrs. Leghorn. “He can tell us what to do.”

So away ran Mr. Leghorn to the Wise Owl, screaming with all his might.

“O, Mr. Wise Owl,” he cried, “my poor Mrs. Leghorn is starving. She can’t swallow the big nut. What shall I do?”

“Who, who, who?” hooted the Wise Owl, blinking his great round eyes.

“Mrs. Leghorn, my Mrs. Leghorn, my own dear Mrs. Leghorn,” fairly shrieked Mr. Cock. “She can’t swallow the big nut. She will starve. Can you tell me what to do?”

Mr. Wise Owl stared straight ahead a moment—it seemed an age to Mr. Leghorn—then answered slowly, “Yes, Mr. Leghorn, I can tell you what to do. But you must first bring me a mouse.”

Away rushed Mr. Leghorn to Pussy Cat. “My good Miss Pussy Cat,” he cried, “dear Mrs.[164] Leghorn is starving. Will you please catch me a mouse? I want it to take to Mr. Wise Owl, who is going to tell me what to do.”

“Yes, Mr. Leghorn,” answered Pussy Cat, “I will catch you a mouse, but you must first bring me a saucer of milk.”

Off flew Mr. Leghorn to Mrs. Mooly Cow.

“Dear, kind Mrs. Mooly Cow,” he said, “poor Mrs. Leghorn is starving. Will you please give me a saucer of milk? I want it to take to Miss Pussy Cat, who is going to catch me a mouse for Mr. Wise Owl, who is going to tell me what to do.”

“Yes, Mr. Leghorn,” answered Mrs. Mooly Cow, “I will give you a saucer of milk, but you must first bring me a bundle of corn.”

Away sped Mr. Leghorn to the Farmer.

“O, Mr. Farmer,” said Mr. Leghorn, “Mrs. Leghorn[166] is starving. Please will you be so kind as to cut me a bundle of corn? I want it to take to Mrs. Mooly Cow, who is going to give me a saucer of milk for Miss Pussy Cat, who is going to catch me a mouse for Mr. Wise Owl, who is going to tell me what to do.”

“Yes, indeed, Mr. Leghorn,” said the Farmer, “I will cut you a bundle of corn, but you must first bring me a new coat.”

Off hastened Mr. Leghorn to the Tailor.

“O, Mr. Tailor,” cried Mr. Leghorn, “Mrs. Leghorn is starving. Won’t you please give me a new coat? I want it to take to Mr. Farmer, who is going to cut me a bundle of corn for Mrs. Mooly[167] Cow, who is going to give me a saucer of milk for Miss Pussy Cat, who is going to catch me a mouse for Mr. Wise Owl, who is going to tell me what to do.”

“Yes, Mr. Leghorn,” answered Mr. Tailor, “I shall be very glad to give you a new coat, but you must first bring me a pound of wool.”

Away hurried Mr. Leghorn to Mrs. Sheep.

“O, good Mrs. Sheep,” he said, “Mrs. Leghorn[168] is starving. Do, please, give me a pound of wool. I want it to take to Mr. Tailor, who is going to give me a new coat for Mr. Farmer, who is going to cut me a bundle of corn for Mrs. Mooly Cow, who is going to give me a saucer of milk for Miss Pussy Cat, who is going to catch me a mouse for Mr. Wise Owl, who is going to tell me what to do.”

“To be sure, Mr. Leghorn,” said Mrs. Sheep, “I will give you a pound of wool, but you must first bring me a bunch of clover.”

Away ran Mr. Leghorn to the Farmer’s Wife.

“O, good, kind Farmer’s Wife,” cried Mr. Leghorn, “Mrs. Leghorn is starving. Won’t you, please, pull me a bunch of clover? I want it to take to Mrs. Sheep, who is going to give me a pound of wool for Mr. Tailor, who is going to give me a new coat for Mr. Farmer, who is going to cut me a bundle of corn for Mrs. Mooly Cow, who is going to give me a saucer of milk for Miss Pussy Cat, who is going to catch me a mouse for Mr. Wise Owl, who is going to tell me what to do.”

“Yes, yes,” answered the kind Farmer’s Wife, “I will gladly pull you a bunch of clover, but you must first bring me a dozen eggs.”

Mr. Leghorn fairly flew back to Mrs. Leghorn, who was still trying vainly to swallow the large nut. He seemed to forget all his politeness.

“Where’s your nest, Mrs. Leghorn, where’s your nest? Tell me this instant!” he shrieked.

Mrs. Leghorn had never told any one where her[170] nest was. That was her secret; and she would not have told her secret now—not even to keep herself from starving—had she not been so frightened at Mr. Leghorn, who stood glaring at her fiercely. She thought he had gone mad and would do her harm. So she answered faintly,

“Under the corner of the barn.”

Away to the corner of the barn rushed Mr. Leghorn, where he found Mrs. Leghorn’s nest full of eggs. He took a dozen in a basket and hurried off to the Farmer’s Wife, who pulled him a bunch of clover, which he carried to Mrs. Sheep, who gave him a pound of wool, which he took to Mr. Tailor, who gave him a new coat, which he brought to Mr. Farmer, who cut him a bundle of corn, which he carried to Mrs. Mooly Cow, who gave him a saucer of milk, which he took to Miss[171] Pussy Cat, who caught him a mouse, which he carried to Mr. Wise Owl.

“There, Mr. Wise Owl,” cried Mr. Leghorn, quite out of breath, “there’s a nice fat mouse. Now tell me what I shall do for poor Mrs. Leghorn, who is starving because she can’t swallow the big nut.”

“Who, who, who?” cried Mr. Wise Owl, staring sleepily at the fat mouse.

“Mrs. Leghorn, she is starving!” screamed Mr. Leghorn, now quite angry. “She can’t swallow the big nut. You said you would tell me what to do.”

“O, yes,” said Mr. Wise Owl, “to be sure, that’s easy. Just go and find Mrs. Leghorn some smaller nuts.”

Mr. and Mrs. Leghorn went for a stroll one afternoon. They had never been far from home and they soon came into unknown places. But they wandered on and on, chasing grasshoppers and crickets, and now and then stopping to scratch for a worm, until they finally came to the bank of a frog pond.

“Look, Mrs. Leghorn,” said Mr. Leghorn, “there’s the ocean, the wide, blue ocean that we have heard so much about.”

“Indeed it is,” answered Mrs. Leghorn. “Could you believe we had come so far!”

Splash!... Splash!

“What was that?” cried Mrs. Leghorn.

“What was that?” cried Mr. Leghorn.

“Help me out! Help me out!” came a deep voice from the pond.

“Me, too! Me, too!” came a little, peeping voice from the same place.

“Why, that’s our good master and his little boy,” cried Mr. and Mrs. Leghorn together.

“They’ve fallen into the ocean!”

“Help me out! Help me out! Me, too! Me, too!” came again from the pond.

“Yes, good Master, yes,” screamed Mr. Leghorn, “we’ll help you. But what shall we do?”

“Bring a rope! A rope!” came the answer.

“A rope, a rope!” cried Mr. Leghorn. “O, where shall we find one?”

“Just beyond! Just beyond!”

Mr. Leghorn ran wildly along the bank with Mrs. Leghorn following close on his heels. They looked to the right, and they looked to the left; they looked up, and they looked down; but no rope could they see.

“Hurry up! Hurry up!” came from the water.

“O dear, O dear!” cried Mrs. Leghorn.

“O, where is that rope?” cried Mr. Leghorn.

“Follow your nose! Follow your nose!” came the voice.

At that, Mr. Leghorn flew along faster than ever. Mrs. Leghorn could hardly keep in sight of him. But no rope could they find.

“Hurry up! Hurry up!” came from the pond and urged them on, whenever they began to slacken their pace.

“Going down! Going down!” came the deep voice.

“Me, too! Me, too!” came the peeping voice.

“O, they are drowning, they are drowning!” screamed Mr. and Mrs. Leghorn.

“Let ’em drown! Let ’em drown!” came the voice.

“What!” cried Mr. Leghorn.

“What!” cried Mrs. Leghorn.

“Better go home! Better go home!” called the deep voice.

Mr. and Mrs. Leghorn stood staring at each other. They could scarcely believe their ears.

“Go to roost! Go to roost!” came the voice.

Mr. and Mrs. Leghorn began to look silly. The sun had set and it was growing dark. They turned about and started off homeward.

“You’re fooled! You’re fooled!” sounded after them as they left the banks of the pond.

“He told the truth that time, even if he is only a frog,” said Mrs. Leghorn.

GOOD-BYE

Most of the words used in the preceding books of the Aldine Series are used frequently in this Second Reader. They are not listed in this vocabulary, however; here are given only the words used for the first time in this book. The number at the left of a word refers to the page on which the story begins in which that word is first used. New words are listed in the text immediately before the lesson in which they are used.

| A | |

| 36. | about |

| 53. | above |

| 163. | across |

| 16. | afraid |

| 172. | afternoon |

| 21. | age |

| 160. | ahead |

| 151. | ail |

| 151. | alarmed |

| 138. | alas |

| 65. | already |

| 8. | among |

| 8. | angry |

| 36. | animal |

| 46. | ant |

| 151. | arm |

| 5. | ash |

| 77. | astray |

| 133. | awful |

| 16. | awoke |

| B | |

| 91. | ballad |

| 115. | bang |

| 16. | bank |

| 26. | bark |

| 84. | barn |

| 160. | basket |

| 138. | bean |

| 26. | bear |

| 160. | became |

| 46. | began |

| 12. | begged |

| 21. | believe |

| 26. | bellow |

| 172. | beyond |

| 6. | black |

| 117. | blazed |

| 160. | blinking |

| 138. | bother |

| 62. | bow |

| 160. | brag |

| 53. | branch |

| 81. | bravely |

| 26. | breathes |

| 102. | breeze |

| 138. | bridge |

| 16. | brook |

| 117. | broom |

| 145. | brown |

| 94. | build |

| 160. | bunch |

| 160. | bundle[180] |

| 26. | burrowed |

| 107. | bush |

| 138. | burst |

| 46. | buy |

| C | |

| 151. | cackling |

| 117. | castle |

| 26. | catch |

| 172. | chasing |

| 77. | cheek |

| 16. | chicken |

| 107. | chirped |

| 94. | choose |

| 107. | clever |

| 94. | cliff |

| 26. | climbed |

| 107. | cloak |

| 138. | coal |

| 46. | cob |

| 151. | cock |

| 81. | color |

| 145. | comforted |

| 160. | corner |

| 138. | country |

| 81. | crazy |

| 26. | creak |

| 117. | crib |

| 6. | croak |

| 100. | crocus |

| 138. | cruel |

| 138. | crush |

| 46. | crust |

| 36. | curled |

| 160. | cut |

| D | |

| 100. | daffodils |

| 12. | dance |

| 16. | dare |

| 12. | dark |

| 145. | darlings |

| 55. | dash |

| 12. | dead |

| 138. | delay |

| 117. | dense |

| 71. | diamond |

| 12. | die |

| 63. | different |

| 117. | directly |

| 117. | disappeared |

| 160. | distance |

| 3. | doctor |

| 94. | dome |

| 59. | don’t |

| 3. | door |

| 160. | dozen |

| 26. | drank |

| 65. | dream |

| 26. | drink |

| 26. | drive |

| 8. | drove |

| 36. | drumikin |

| 81. | duller |

| E | |

| 16. | each |

| 138. | eager |

| 94. | eagle |

| 3. | ears |

| 107. | earth |

| 160. | easy |

| 94. | eaves |

| 133. | echo |

| 16. | eight |

| 16. | eleven |

| 151. | else |

| 117. | enemy |

| 12. | enough |

| 117. | enter |

| 8. | envy |

| 16. | even |

| F | |

| 160. | faintly |

| 160. | fairly |

| 84. | family |

| 151. | farm[181] |

| 117. | farther |

| 68. | father |

| 36. | feared |

| 6. | feathers |

| 151. | fence |

| 145. | ferns |

| 160. | fiercely |

| 160. | finally |

| 12. | find |

| 172. | fine |

| 117. | finished |

| 46. | fish |

| 55. | flash |

| 133. | foaming |

| 8. | foolish |

| 117. | forest |

| 160. | forget |

| 117. | fortune |

| 107. | forward |

| 8. | found |

| 147. | fountain |

| 160. | frightened |

| 36. | frisked |

| 36. | frolicked |

| 117. | front |

| G | |

| 36. | gayly |

| 145. | gentians |

| 93. | gild |

| 117. | gladly |

| 117. | glaring |

| 60. | goat |

| 117. | grasshoppers |

| 117. | gray |

| 117. | greedily |

| 36. | greedy |

| 12. | growled |

| 16. | guess |

| 138. | gurgling |

| 93. | gypsy |

| H | |

| 160. | harm |

| 107. | hasten |

| 117. | heap |

| 151. | heavy |

| 172. | heel |

| 60. | height |

| 94. | held |

| 117. | hoarsely |

| 84. | hole |

| 94. | hollow |

| 36. | home |

| 172. | homeward |

| 81. | honest |

| 94. | hoot |

| 138. | hope |

| 117. | horrible |

| 151. | horse |

| 36. | hullo |

| 36. | hump |

| 12. | hungry |

| 107. | hunt |

| 46. | hurried |

| I | |

| 93. | idle |

| 138. | immediately |

| 102. | Indian |

| 138. | instant |

| J | |

| 117. | jewel |

| 65. | journey |

| 81. | June |

| L | |

| 63. | ladies |

| 77. | lamb |

| 37. | lambikin |

| 77. | large |

| 8. | laughed |

| 81. | lazy |

| 65. | leaped |

| 94. | learn |

| 16. | least[182] |

| 36. | left |

| 94. | lesson |

| 84. | life |

| 26. | lion |

| 12. | lively |

| 46. | lost |

| 8. | lucky |

| M | |

| 21. | ma’am |

| 94. | magpie |

| 102. | Manitou |

| 94. | maple |

| 46. | marry |

| 172. | master |

| 151. | matter |

| 84. | meal |

| 94. | mean |

| 117. | melt |

| 100. | merry |

| 26. | mice |

| 117. | mile |

| 160. | milk |

| 46. | miss |

| 138. | moment |

| 46. | money |

| 84. | monster |

| 36. | morsel |

| 59. | mossy |

| 94. | mountain |

| 26. | mouse |

| 36. | mouth |

| 55. | murmur |

| N | |

| 21. | naughty |

| 46. | neck |

| 117. | neigh |

| 62. | neither |

| 55. | noble |

| 12. | noise |

| 77. | noon |

| 62. | nor |

| 145. | North |

| 100. | note |

| O | |

| 172. | ocean |

| 160. | offering |

| 12. | often |

| 21. | once |

| 8. | only |

| 94. | oriole |

| 172. | owl |

| 160. | own |

| P | |

| 172. | pace |

| 94. | paid |

| 73. | pale |

| 102. | pappoose |

| 133. | parents |

| 55. | pass |

| 81. | passion |

| 138. | past |

| 94. | patient |

| 46. | peach |

| 8. | peacock |

| 3. | peck |

| 151. | perch |

| 81. | perhaps |

| 46. | pieces |

| 117. | pitch |

| 138. | pity |

| 60. | plainly |

| 94. | plaster |

| 81. | pleasant |

| 12. | please |

| 36. | plump |

| 151. | point |

| 160. | polite |

| 107. | pond |

| 138. | poor |

| 84. | pounce |

| 160. | pound |

| 138. | pouring |

| 102. | prairie[183] |

| 160. | praise |

| 117. | prance |

| 117. | presently |

| 6. | pretty |

| 8. | proud |

| 8. | pulled |

| 117. | purr |

| 25. | push |

| Q | |

| 138. | quarrel |

| 16. | queer |

| 107. | question |

| 138. | quite |

| R | |

| 117. | rabbits |

| 151. | rail |

| 3. | rapped |

| 81. | rather |

| 6. | raven |

| 36. | reach |

| 151. | reason |

| 117. | replied |

| 160. | rescue |

| 46. | ribbon |

| 25. | rise |

| 53. | river |

| 21. | roam |

| 26. | roared |

| 26. | robbed |

| 102. | roebuck |

| 68. | roll |

| 94. | roof |

| 46. | rooster |

| 26. | rope |

| 94. | rough |

| 73. | roving |

| 77. | rustling |

| S | |

| 16. | sail |

| 117. | saucer |

| 81. | save |

| 46. | scampered |

| 172. | scarcely |

| 8. | scornfully |

| 117. | scramble |

| 107. | scratching |

| 147. | screaming |