ILLUSTRATED BY BEECHAM

The Olympus could never return to her home planet;

her crew was destined to live out their lives among

the savages of this new planet. But savages could be

weaned from their superstitions and set on the road

to knowledge, Theusaman thought. Or could they?

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Rocket Stories, July 1953.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Baiel had always shown me the degree of respect prescribed in the Space Code. Aboard the Olympus we clashed only once, and that was when I ordered the emergency landing.

"You've no right to risk it, Captain Theusaman," he protested.

"We can't do anything else," I answered. "We're ninety-three million light years away from the Earth, and twenty-five outside the patrol area."

"Sir, this star sector is totally new to us!" Baiel was standing by the control panel, a tall, thin man in his early thirties. His face was hollowly angular, sun-bronzed and capped with a brush of thick, black hair. He looked away from the sight dome and I saw bitterness and anger blazing in his blue eyes. "This is an exploratory expedition, Captain Theusaman. We were sent out to record the conditions beyond the periphery of the Earth charts, and it's vitally important for us to return with the data."

"I'm aware of that, Baiel."

"Then face the facts. We've blown our dorsal tubes and lost our emergency fuel. Unless we restock with fissionable material, we've no chance of getting back to Earth. You believe we can restock on that unknown planet out there, but—"

"I know we can. I've seen the spectroanalysis; it doesn't lie."

"Not in the statement of data. But—with the best of intentions—a man can lie in the generalization he draws from the data. The spectroanalysis tells us that planet out there has an atmosphere like ours. It tells us there's an abundance of fissionable material in the mineral chemistry. But suppose it can't be recovered with any of the machines we have aboard? If we land, we'll have no chance of rising again."

"It's a necessary risk."

"No, Captain Theusaman! We have almost enough energy in our functioning tubes to reach the outer fringe of the patrol area. From there we'd be close enough to beam an emergency call back to Earth. One of the patrols might pick it up in time to—"

"Might," I snapped. "I'm glad you recognize that as a possibility, Baiel."

"Even if none of us survives, our data will still be there; sooner or later an Earth ship would find the Olympus."

"You risk more than I do, Baiel."

"But our information would be saved for the scientific processors."

"I prefer to save the men. We know they can live on that planet, even if we find no fissionable material. The issue is settled."

"There's one other consideration, Captain Theusaman. With our dorsal tubes gone, we can't maneuver. Even you can understand, sir, that a crash-landing—"

"I've given the orders, Baiel. Will you execute them, or must I have you cabinized for insubordination?"

"Very well, sir."

He departed without saluting.

Baiel was right, on both counts. I knew there was a chance he might be. Yet I had made emergency landings before. Nothing had ever gone wrong.

This time it did. As soon as we nosed into the stratosphere we were in trouble. The Olympus angled down too sharply. The gyrometers failed, since they were engineered to make use of the compensating drive from the dorsal tubes. I tried to bring the ship up into the freedom of space again, but the best I could manage was a slow, corkscrew dive toward the unknown planet.

As we spun through the cloud wreath, I studied the globe carefully. Within limits, I could still select the place where I wanted to land. The planet was capped at both poles by gleaming ice fields which spread down over the sphere like giant hands. Only a narrow equatorial band was free of ice. The landing site I chose was a wooded area at the edge of the glacier. The nearby ridge of jagged mountains suggested volcanic action, and the possible presence of the fissionable metals we wanted.

We crash-landed at the base of the glacier, skipping over the ragged ice until the bow caught and shattered in a deep ice gorge. The safety stabilizers functioned in all the cabins that were not pierced by ice. Our heaviest casualties were among the tube-room crew and the astrographers. Only one of the scientists survived. I ordered station formation on the frozen meadow outside the ship. Baiel bawled out the roster, while I ticked off the names of the survivors: forty crewmen, none seriously wounded; one scientist, fatally hurt; and fifteen of the female staff of astrographical clerks. Counting Baiel and myself, we numbered fifty-eight.

As the last of the names was read off, we stood for a moment shivering in the icy wind. Slowly Baiel looked up from the ship's roll and let his blue eyes move along the buckled hulk of the Olympus. Then he glanced at me, and the set of his jaw was as coldly emotionless as the ice bank behind him.

"Have you any further orders to give, Captain Theusaman?" His tone was frankly insolent. I clenched my fists, but checked the response I might have made. Baiel and I were the only Space Officers with the expedition; any difference between us would be disastrous.

"Turn all hands into the stern cabins," I said, "and break out the landing gear. It'll keep us warm. Detail five men to check on the damage, and have them report to me."

An hour later Baiel and I stood at the control panel reading through the list of damages. Remarkably little had happened—nothing, at least, that we could not repair with material we had at hand. We organized all survivors into repair crews of five each; even the women were given assignments.

Baiel and I made preliminary soil tests for fissionable metals. The computer prognosis from such highly selective data is never infallible, but the probable degree of error is no more than .0006. Over a period of two hours we made five tests, with the same results. There was fissionable matter on the planet—no doubt of that—but it was locked in a chemical combination we could not release without building a giant separation plant such as we used on Earth.

"Our data is too limited if we sample so close to the ship," I told Baiel.

"Possibly." There was a long pause before he added the prescribed, "sir."

I nodded toward the hill sloping away from the glacier toward a forest of tangled pines. "We'll make another test down there." With a shrug, Baiel followed after me obediently.

Three miles from the Olympus, in a thick grove of trees, we found the man. Naked, he lay bound over a heap of boulders, his dead eyes staring up at the sky. A gash had been torn in his chest and his blood had spilled out over chunks of glacial ice arranged in a crude pyramid beside him.

To both of us, the sight of a man and the thing it implied was vaguely terrifying. For almost five centuries expeditions of Earthmen had explored the skies, slowly reaching beyond our own solar system toward the stars. Where the atmosphere was hospitable, we had built thriving colonies. But nowhere had we found a race of people like ourselves. The planets had been so consistently untenanted that we had grown to expect nothing else.

Now here, on this unknown world, twenty-five million light years beyond the periphery of the Earth patrols—here we found men, men like ourselves!

Baiel cut the thongs and lifted the rigid body off the pile of rock. "If you don't mind, Captain," he said, "I'd like to examine—this—up in the ship lab. Since there's a chance—just a chance, sir"—His sarcasm was unmistakable, "—that we'll be staying here, I want to know what we're up against."

Late that night, while the rest of the expedition slept, Baiel and I carried the body into the laboratory. Baiel performed a thoroughgoing, workman-like autopsy. It was impossible not to admire his efficiency and skill. We were momentarily united in the rising excitement of mutual curiosity.

"There's a fascinating structural similarity to our own," Baiel pointed out. "Identical organs; identical blood composition. All the differences are minor—a smaller brain case, with a retreating forehead, and pronounced orbital ridges. And look at those teeth and the chinless jaw!"

"In a way, it suggests Bonn's Hypothesis," I said.

"Aubrey Bonn? Why, he's the laughing stock of the Anthropological Academy. We've never found a whisper of evidence to suggest a basis for his Hypothesis."

"How could we? There have never been any people on any of the planets we've explored."

Baiel dropped his scalpel and stepped back from the table, kneading his chin thoughtfully. "Bonn said that an identical chemistry and atmosphere, plus identical time phase, would produce an identical chronology of the species. This planet may do that. It should have been obvious when we had the negative tests for fissionable material. The Earth itself is the only planetary body we know where we've had to build separation plants to recover the metal."

"But, according to Bonn's Hypothesis, the resemblance should be exact." With disgust, I glanced at the torn corpse on the table. "None of us has an idiot's skull like that."

"We may have had once, Captain. You're forgetting the time phase. This planet is the Earth as it was millennia in the past, in the age of the great glaciers. The ice cap here has obviously reached its maximum penetration. It will begin to recede now, decade by decade, and civilization will slowly take root where now there is nothing but primitive savagery."

"Civilization, out of that brain, Baiel?"

He smiled at the ape-face of the corpse. "Not that, but the one that comes after. Perhaps the new man will evolve, Captain." Baiel licked his lips thoughtfully. "Or perhaps he will be created."

"I don't think I quite follow—"

"Created by the gods!" Laughing, Baiel ripped off his laboratory jacket and flung it over the corpse. "I think, Captain, that we shouldn't tell the others about him quite yet. You and I have some investigating to do first."

The next morning Baiel called me into the control room. When the door was shut, he turned up the viewscreen. By adjusting the angle of the beam, he had focused the projection upon the Olympus and the frozen terrain surrounding the ship in a ten mile radius.

The ship lay on a tilted, empty meadow above a forest of pines. Five miles away a limestone cliff rose out of the forest. A crude, semicircular clearing was beneath the cliff and on it we saw a tribe of men and women gathered around a fire built at the mouth of a cave. Baiel turned up a section enlargement and we studied the men carefully. There was no doubt that they were the counterparts of the corpse lying in the laboratory of the Olympus.

That same morning Baiel and I made our first visit to the village. Fortunately we went armed, for they received us with violent hostility, attempting to drive us away with a volley of spears.

A peculiar greeting from a people we now understand to be cordial and open in their friendship! But their motivation was entirely logical. Faced by a diminishing source of food, the tribe saw every stranger as a potential threat to tribal survival.

Baiel and I used our Haydens to curb their belligerence. The sight of red flame blasting their spears into dust awed them into a sullen kind of submission. But it was not until our second visit, when we took them a gift of bear meat, that we began to make any progress in communication.

We watched curiously while the tribe wolfed the meat, crudely searing it over an open fire. As hungry as they obviously were, each of them nonetheless set aside a liberal portion which was later taken to a grizzled old man who never moved from the mouth of the cave. In response to our gestures, they made it clear to us that the old man was their equivalent of high priest. He apparently commanded the wind and the sun, and he had some sort of a terrifying blood relationship with the glacier.

Comfortably fed, the tribe became cordial. Baiel and I had found a touchstone. Whenever we visited the village after that, we always took them food. In less than a week we knew their dialect. It was a very small vocabulary, built chiefly of denotative symbols. Baiel concentrated his attention upon the high priest; I stayed with the tribal Chief.

It was a tactical error on my part, since Baiel already knew what he intended to do. I did not. I wasn't aware, then, that the conflict between us had already begun.

As our degree of communication improved, the various members of the tribe shyly began to express curiosity about us. Our Haydens aroused no interest, except for a vague and superstitious awe. The mechanism of the weapon was entirely beyond their comprehension; they wrote it off as a kind of magic closely allied to the mysteries practiced by their priest. Our garments were of greater significance. The tribe was irresistibly drawn to caress the sleek material, to hold it against their cheeks and chatter excitedly over its unexpected warmth.

Once, as we sat in a circle around the fire, the Chief asked me the name of our tribe.

"We are Earthmen."

"The Earth tribe? I do not know it."

"It is not a tribe, but a place." I picked up a handful of soil. "This is earth to you—everything that you see around you. We came from another place like this, a place in the sky."

They stared at me blankly. Then one of the young hunters scooped up soil, as I had, and said brightly, "Earth. Yes, your name for the hunting ground. Earth! It is a good name."

"No. We are Earthmen!"

"Yes, Earthmen—all of us. Not beasts that howl by night and haunt the forest trails. Men. We are men. But also we have a tribe."

I tried to make my explanation more explicit. "We came here in a sky carrier which is named the Olympus. It rests now up by the great ice wall. There are others like us, too, who may—" I stopped, because one by one they were rising and moving away from me.

"You are wrong!" the Chief cried. "Your tribe cannot live by the glacier, on the tabooed ground!"

As he mentioned the name, it threw the whole tribe into a panic. Nothing I could say would undo their rising fear. They shrank from me, running into the dark recesses of the cave. Eventually the high priest—with Baiel standing beside him—restored order by crying shrill prayers up at his brother, the glacier. Fortunately, the harm I had done did not seem to call for the drastic remedy of human sacrifice.

After the tumult had passed, the Chief said to me, "It was a cruel thing to say, Seus-man." (The tribe always had trouble pronouncing my name; sometimes they would drop whole syllables from it.)

"On my word, it was not meant so," I replied. After a silence, I asked cautiously, "Suppose it had been true?"

"It may not be. The brother glacier is a great threat to us all. He is not a friend. In my time and in the time of my father before me, the ice has always moved closer to us, everywhere destroying more and more of our hunting ground."

"Can your people not move away from it, into better land?"

"We have, as far as we dare. Beyond the forest the ground is taboo. There the sun god strikes fire from the mountain tops, to warn us away from his domain."

"Is there no land on the other side of the fire mountains?"

"The hunting ground of the dead. It is not for us, the living."

When Baiel and I returned at dusk to the Olympus, I walked thoughtfully through the swirling snow, saying very little. For the first time I faced, without regret, the fact that we were doomed to live out our lives on this frozen, nameless world. I had found a purpose, and it seemed good.

This friendly, impoverished tribe was man himself, as he had been on the Earth in the remote darkness of our own uncharted past—man, clinging precariously to a hard-won savagery, plagued by ice and wind, threatened by a vanishing supply of food.

To the nearly insurmountable problems set by nature, this tribe had added one final prison of their own creation, the taboos and superstitions that penned them fast on the brink of the glacier. As things stood, the tribe would not survive. To become men as we were, they had to be freed of the weight of the gods, freed of superstition so they could deal with the facts of reality. With our help the tribe might eventually learn how to create a civilization. Without it, they were doomed.

Hesitantly I explained myself to Baiel.

"Of course," he said. "It's obvious. We can't allow nature to forget the proper chronology of the species, can we?"

"It will be slow work, but—"

"But not impossible. Their life span averages less than thirty years; ours exceeds a century. That's time enough."

He agreed with me at once and, I think, he was entirely sincere. We were simply using the same words to express two totally opposed ideas. Neither of us, I'm sure, was aware of the ambiguity.

The need for decision came immediately. That night the power failed in the Olympus and the winter cold settled slowly into the cabins. The residue of fuel energy left in the tanks was not enough to power the heating grids, and our portable solar heaters were ineffectual in the cavernous space of our cabins. Our food tanks froze over; the producing cultures died. Baiel and I built an open furnace in the control room, and the expedition crowded there around the fire.

Baiel and I had already told them about the primitive village; the expedition had learned the tribal tongue as we brought the knowledge back to the Olympus. Now, for the first time, I told them frankly that we were never going to leave the planet. Hand-picked, psycho-processed personnel, the expedition adjusted readily to the new reality. Without the benefits of the machines of our earthly civilization, we were faced with extreme hardships on such an unfriendly world. Our only sound course was to join the village tribe and survive through mutual efforts.

The following morning I went to the Chief to propose the merger. He refused until I offered to guarantee a food supply for both groups. It was a safe enough promise. We had the Haydens and enough energized rounds to kill anything that walked the forest, for at least a year or more. I counted heavily on the fact that, within that period, we would be able to unhinge the paralyzing weight of tribal gods and taboos. The tribe could then be encouraged to migrate into a more fertile area.

The business of negotiation was concluded in less than an hour. But the elaborate ceremony of union lasted for two days. It was not a frequent occurrence, and yet tribes had occasionally united in the past. There was, therefore, a rigid body of custom proscribing the form; it was interpreted entirely by the priest.

Since I symbolized the chief of the incoming tribe, I was expected to spend the first night in the village alone, while the rest of the expedition shivered around the improvised fire in the Olympus. The Chief sealed me in tribal brotherhood by the gift of his daughter. Dayhan was shy, filthy, repulsive with the stench of the animal skins she wore. Lice ran in her matted hair and grime streaked her cheeks. She smiled at me with an idiot's grin.

Yet I went willingly with Dayhan to the dark recess of the cave, which was traditionally reserved to the new wedded. It was painfully obvious that the success of my negotiations depended upon our mating. I stomached my revulsion in silence. In the morning, when Dayhan first addressed me publically as "My Lord," the tribe was satisfied.

Throughout the day the ceremony became general, climaxed by the symbolic mingling of blood. To satisfy custom, each member of the expedition—except for the women—was paired with a tribesman of equal status. Curiously, they seemed to accept Baiel as our high priest. With decided misgiving, I watched while he complacently established himself in the priest's portion of the cave.

At sundown the ceremony ended. The old priest mounted a granite pedestal erected near the fire. Raising his long arms to the sky, he screamed guttural syllables at the gathering darkness. As the sun tinged the distant glacial wall with scarlet, the priest looked down upon the throng and proclaimed the need for sacrifice to brother glacier.

The members of our expedition reacted with shocked silence, but the primitive tribe matter-of-factly went through the deadly lottery. The chosen hunter moved out toward the sacrificial grove, followed by the priest who held his blade naked in his hand.

I cried reason at them, to hold them back. But the tribe neither heard nor comprehended. With glazing eyes they were lost in the terrifying ecstacy of tradition. Satisfy brother glacier, and the village would be safe.

At the grove Baiel suddenly joined the priest. They whispered together for a moment. Then Baiel raised his arms and spoke.

"Wait! We bring the tribe the new gods of the sun. Our gods are stronger than brother glacier. Let them speak to the ice, and no life need be given."

"Let the new gods satisfy the old!" the tribal priest echoed.

His statement gave Baiel's innovation the stamp of approval. The tribe began to chant a sing-song thanksgiving. Baiel, like the priest, raised his arms and shouted gibberish which they took as prayer. When he lowered his hand, he pointed at the pile of rock in the grove. Red flame flashed. The stones dissolved. The surrounding ice wasted into a pool of water, slowly seeping into the blackened earth.

It was a simple enough trick. Baiel had concealed a Hayden in his sleeve. But it impressed the tribe. They sang their exaltation, clapping hands on the broad shoulders of the young hunter who had been spared.

Baiel joined me as we walked back to the village.

"I knew something had to be done, Captain Theusaman," he explained. "Fortunately, my idea worked."

"It's wrong, Baiel; all wrong."

"I saved the man, didn't I?"

"By substituting new gods for theirs. We want to free them, Baiel."

"Is there any other way to do it?"

"By teaching them the truth. By destroying their burden of gods and superstitions—not by creating more."

This amused him and he laughed. I thought his reaction was odd, but I still misinterpreted it.

For the next two months I became more and more involved in helping the tribe find its way toward civilization. We could not impose anything remotely like our Earth culture. The answer to the problem, without the technique for reaching the solution, would be meaningless. But in small things, like the brief spring thaws that slowly ate away their planet-capping glacier, we could erode and destroy their shell of savagery.

Because of its application to my own situation with Dayhan, the first teaching I undertook was cleanliness. On the Earth it is an old joke that, when we build, we plan the bathing facilities first; our space ships are notably awkward to maneuver because we include so many elaborate baths. To us, filth equates with savagery. Cleanliness was a concept which the tribe quickly adopted and understood, because the reward was both visible and immediate.

We erected stone culverts above the fire, melting chunks of ice and channeling the warm water into a stone pool built inside the cave. Following the example set by the expedition, the tribe shortly took to daily bathing as a matter of course. We taught them to scrape the filth from their skins, to comb the lice out of their hair.

I was amazed—and enormously pleased—with the physical change a bath brought in Dayhan. Her stringy hair took on a golden luster. Her dirty skin softened and color came slowly into her yellow cheeks. The running sores dried, caked, and disappeared. Instinctively she came to be aware of her potential loveliness. She began to experiment with braiding her hair in various ways over her slanting skull. Once I found her trying sprigs of greenery in the knot and studying the effect in her reflection in the bathing pool.

The cave was always warm, particularly when the wind and snow howled through the village; but it was uncomfortably crowded. Because the fire was built at the mouth of the cave, the oxygen inside was inadequate. We never slept through a night without feeling a nagging nausea from the foul air we breathed.

Therefore, as soon as the tribe understood how the stone culvert had been built, we proposed building stone cabins. So rapidly had they learned that most of the labor was performed by the tribe. The Earth people merely advised and suggested. And we did very little of that, allowing them a great deal of trial and error experimentation.

It was the happiest time of our merger with the tribe. Everyone worked, and worked in unison. I had never made any explanation of my point of view to the other members of the expedition. I hadn't considered it necessary. No Earthman was certified for space travel unless he had first been successfully psycho-processed. In effect, that meant that we took a scientific rather than an emotional view of any given set of data. Since each of us was faced with an identical pattern of facts, I assumed that each of us would approximate the same generalization.

To a degree, that happened. We all realized the need to teach the tribe; no one proposed bringing machines from the Olympus to give the savages the products of our culture without their specifics. One by one members of the expedition followed my lead and mated with the women of the tribe.

Only our own women—the fifteen astrographical clerks—and half a dozen men held off. I failed to perceive the significance until it was too late. The six men were Baiel's closest friends; each of them had spent at least a year at the Academy, while the rest of us were Rankers, traditionally considered their inferiors. And the women, being clerks rather than crewmen, had not been psycho-processed.

The breach into factions came when our village of stone huts was completed. We were faced with the problem of heating. I wanted the solution to be worked out by the tribe without our help. Slowly they made progress in their efforts to discover how to build fires within the huts without filling the rooms with smoke. They had just discovered how to pierce the roofs with chimneys when I awoke, one morning, to find that Baiel had presented them with a pat answer to the problem.

During the night he had stealthily returned to the Olympus with four of his men. They had brought back to the village a dozen solar heaters. Before I was awake, he had presented the heaters to the tribe as gifts of the sun god.

In wonder the tribe gathered around the tiny machines, holding out their hands to feel the mysterious warmth. Then they thronged at Baiel's feet as he stood on the rock pedestal above the village fire. They swayed and chanted their prayers which had once been reserved solely for the majesty of brother glacier.

As I approached, Baiel began to address them.

"The sun god sends you these because of your obedience to his ways. Through me—through Baiel, the high priest—he makes you promise of even greater gifts than this, if your faith continues."

The tribal chanting arose in ecstacy. The old priest knelt at Baiel's feet, offering up a chunk of glacial ice in token of brother glacier's submission.

"There is one all-powerful god!" Baiel cried. "Only one. And I, Baiel, I am his priest."

"All-powerful; the only one," the villagers responded.

It was at that point that I intervened. The tribe stared at me in bewilderment. I took one of the heaters and dismantled it.

"This was made by men," I explained. "By men like yourselves. See, this is no more than a substance like the hard veins of metal you find in your rocks. In time you can learn to make these as we do."

For a quarter of an hour I talked, patiently repeating and demonstrating the facts. But still their eyes were glazed with bewilderment and the ghosts of hidden fears. Since they had no understanding of the processing of ore, how could I explain away the appearance of the supernatural? Even when I disassembled the machine, I proved nothing except that I was tinged with godhood myself.

Baiel stood smirking, saying nothing. When I turned on him in anger, he said quietly:

"Earthmen understand reason, Theusaman." It was the first time he had dropped my title, and he did so intentionally. "These animals—this amusing burlesque of real men—I'm afraid you ask too much of them."

"I ask nothing but their right to survive and evolve, as we did."

"But they can't. Haven't you learned that yet?"

Still smiling, he slid off the pile of rock and went into the cave. I followed him. One by one, the members of the expedition gathered around us. Slowly fifteen women and six men grouped themselves behind Baiel. The rest of the Earthmen were with me. Baiel was outnumbered and most of his people were unarmed, but they faced us with a peculiarly firm kind of confidence.

"I think it's time we had an understanding," I said. "I'm still in command here, Baiel, and—"

"In command? Of a ship that will never fly again, and an expedition that can never return to Earth? In another ten years, Theusaman, the glacier will have moved over the Olympus. It will be ground into dust."

"That's hardly the point."

"It writes finale to the past. It means this planet is ours—it must be—whether we want it or not."

"Ours, and theirs, Baiel."

He threw back his head and laughed. "In the Academy, Theusaman, we're taught to face reality, not to romanticize it. This tribe is semi-human, if you like; I'm charitable enough to grant that. But they aren't men, any more than the primitive species on the Earth were men. Observe the skull of your—your bride, if you will; observe the idiocy in her vacant eyes; observe—"

"This is man as he was, Baiel! You pointed that out to me yourself."

"On the contrary, I was simply discussing the Bonn Hypothesis. I never said I believed it. On the Earth, Theusaman, before true man appeared, nature created a number of semi-men—homo-failures, you might say. They weren't men; they grew to the limits of their physical potential, but they never achieved human rationality. At the end of the Earth's ice age, the continents were widely populated by the last of nature's failures. Then, abruptly—we've never known where he originated, or how—man himself came on the scene. Overnight he wiped out the half-men and took over the planet. Man has come here, now, Theusaman; these failures will survive only so long as we need them. At the moment, they constitute a convenient labor force. A handful of us can control them by controlling their gods."

I drew my Hayden. "As I said, Baiel, I'm still in command of this expedition."

He shrugged. "You've out-Haydened me, naturally; any Ranker could. If I reach for mine, you'll burn me where I stand."

"I'm glad you understand that. Give me your weapons—you, Baiel, and all your followers. Make any excuse you like to the tribe. You'll never have an activated Hayden again, for hunting or any other purpose."

Without resistance, they allowed themselves to be disarmed. I pulled the charges on all their weapons and negativized them.

"You settle everything so smoothly," Baiel laughed. "Next, of course, you'll propose a—"

I cut him short. "All the expedition is here in the cave with us. They all understand the differences between Baiel's objectives and mine. The issue is clear enough for a vote." Slowly the hands went up. I counted twenty-two in Baiel's faction, more than thirty in my own.

"So typical!" Baiel snorted. "So much like an Earthman! The will of the majority—our universal cure-all for all things."

"You agree to abide by it, Baiel?"

His eyebrows arched in a mocking imitation of surprise. "Can an Earthman do anything else, Captain?"

"So that we won't have a repetition of this morning's episode," I said, "I'm giving this order: None of us will return to the Olympus again for any reason without my consent. If it is violated, I'll take disciplinary action under the terms of the Space Code."

There was a mutter of agreement, primarily from my faction, and the angry meeting broke up. Nothing had been settled, except the division of the expedition into two camps. We never worked together again in harmony. Since Baiel's group was unarmed, their greatest potential danger seemed to be gone; yet the village tension persisted.

Baiel could no longer use his Hayden to make a spectacular display of the power of the sun god; slowly the old priest began to reassert the cult of brother glacier. It seemed to me that Baiel encouraged the change; certainly he and the old priest became more intimate than before. I wanted to order an end to their close association, but my own faction was against it.

"Baiel's harmless," they told me again and again. "Don't ride him, Captain. Let this thing simmer down and we'll have them all on our side again."

Gradually I realized that the very existence of the Olympus was a constant threat to the precarious stability of our community. There were still countless machines aboard which could be converted into further enervating gifts of the sun god. The Olympus had to be destroyed, and yet I had no means to accomplish it.

Built to withstand the extreme radiations of spatial sunlight unfiltered by any atmosphere, the metal of the hull was immune to the relatively low degree of heat generated by the Hayden. Only the converted energy used to fuel the tubes could be used for emergency welding if repairs had to be made away from our Earth bases. While there was still a residue sealed in the tanks, I knew it was not enough to liquidate even a part of the ship.

The alternative was to move the community to a place where it would be physically impractical to return to the Olympus. To the south the land would be more fertile in any case, the game more plentiful. To migrate had always been one of my goals for the tribe.

But, when I proposed migration, I came face to face with the strongest of their taboos. The volcanic mountains to the south were more terrifying than brother glacier, which moved inexorably closer with the passing years. No argument, no logic, no patient persuasion could weaken the force of the taboo. Even Dayhan, who had learned so much, refused to listen to me. Beyond the fire mountains lay the hunting ground of the dead; it was forever forbidden to the living.

Suddenly, one night, the sky to the south blazed orange-red as the slumbering volcano erupted. The ground trembled and we heard long crevices cracking through the glacial ice; a gray ash settled down from the sky, smearing the snow heaped around our stone huts.

The tribe flocked in terror to the old priest. Brother glacier, he told them, was angry because he had been neglected; brother glacier demanded sacrifices.

Baiel stood on the stone pedestal beside the priest, smirking helplessly. When he caught my eye, he pointed to his sleeve to show me that it was empty. Since I had negativized his Hayden, he could do nothing to prevent the orgy of human slaughter.

I climbed the pedestal and tried reason. For a moment it seemed that the tribe might listen. But the earth shook again and, panic stricken, they started their lottery. Even then I would not have resorted to Baiel's trick, if they had not chosen one of the Earthmen for the sacrifice.

I made a display of the sun god's power; it worked, of course. The old priest responded as if he had been waiting for my cue, and swayed the mob with him. Then Baiel began to exhort them, crying that the quaking ground was a sign sent by his god, not brother glacier. I slid blindly back to my stone hut, sick with self-revulsion; I felt soiled with the same deception of which Baiel stood accused.

The next morning, while the ground still shook periodically, Baiel returned to the Olympus. It was whispered on all sides, from both his faction and my own.

I had to follow him. I had to know what he was up to. But the undercurrent of feeling ran so high, it seemed necessary to conceal my intention. I said I was going root-digging in the forest. According to custom, Dayhan went with me.

I had taught her a great deal, but not enough to overcome her fear of the tabooed ground. She was willing to wait for me at the edge of the forest, just outside the sacrificial grove, but I hated to leave her alone and relatively unprotected. With some misgiving, I gave her my Hayden.

"My Lord!" Dayhan's almond eyes widened as she fingered the weapon. It was the first time I had allowed any of the tribe to touch an energized Hayden.

"Do you trust a woman's hand with the brother-of-the-sun?" she asked. "Can I hope to understand the bark of your great god?"

"It is only a weapon, like your spear or arrow."

"So my Lord has taught me."

"It will burn any animal that threatens you while you wait."

"As I have seen when you go hunting. I point this small end at the beast, and then call upon the sun god for—"

"No, Dayhan. Aim well and push the small handle. It is not a god that makes the power, but the skill of man. Do not change the nozzle dial, or you will blast the whole forest into flame."

"Enough sun-fire to burn the forest! Yet you say he is no god. I am truly your mate, my Lord, when you share such power with me."

I left the forest and walked across the ice-covered meadow toward the glacier. Three miles away, nestled like a black beetle at the foot of the ice wall, lay the smashed cylinder of the Olympus, already nearly covered with ice and snow. A thin ribbon of smoke curled up from the open furnace.

Baiel met me at the door of the control room. Over his fraying officer's uniform he wore a clumsy cloak of animal skins, as I did myself. Particles of ice were frozen into his black beard, transforming it into a jutting blade of ebony. I was suddenly aware how much he had changed since our crash-landing. Always thin, he now appeared emaciated. His youth was gone. Only the blaze in his blue eyes remained the same—glittering, self-confident, determined. Denied the dress, the grooming, the daily ritual of shaving, both Baiel and I had become bearded, stoop-shouldered patriarchs, imposing hulks in our animal cloaks.

"I expected you would follow me," Baiel said.

"Why did you come?" For a moment, I felt a peculiar warmth and pity for him. "It's insubordination. I'll have to take disciplinary action when we go back."

"I'm only trying to help, Captain." The words seemed right, but the voice was mocking.

Baiel turned to the viewscreen and dialed the focus on the area of the planet south of the volcanic mountains. I saw rolling hills and rich forests, green plains watered by a network of streams; the land was a broad peninsula surrounded by the calm, blue water of an immense sea. There was no indication of human inhabitants.

"I know you've been trying to encourage the tribe to move," Baiel explained. "I came up here to see if I could locate a place for us to migrate. This peninsula is ideal, Captain. It's far enough from the glacier for agriculture to be practical, and—"

"The problem isn't to find the place, Baiel, but to conquer their taboo against migration."

"But you can do that, Captain; just teach the little savages to reason the way men do. Nothing to it." He smiled, then, and held out his hand. "Face it, Captain Theusaman; admit you're wrong! Last night you had to call on the gods; you couldn't control them any other way. If the sun god orders a migration, we can have them on their way in two hours."

"So you're still trying to convince me that you're right."

"Of course; that's why I wanted you to follow me here. Would I have any other reason?"

His answer seemed too quick. I looked at him, frowning, but the smile on his face was unreadable.

"Tell me, Baiel: What did you really want on the Olympus?"

He shrugged. "I came to use the viewscreen."

"You risked discipline for something so foolish?"

"What else? I can't bring any of the machines back to the village; you would throw them out. I can't power the tubes and go back to Earth."

It was all so glibly logical; yet I knew he was lying. I moved toward him, snatching the fringe of his cloak in my clenching fists. "I'm asking once again, Baiel: What did you expect to find here?"

"My Lord! My Lord!"

Baiel and I both whirled toward the open cabin door. Dayhan was outside, slowly crossing the last fifty feet of icy meadow toward the ship. When Baiel saw her, the smile sagged on his lips and he sprang from the ship.

"You're on tabooed ground!" he cried. "Go back!"

"I have no fear." Her words were brave, but her voice was a choked whisper as she looked up at the towering undulations of the glacier glaring in the sun. "Where my Lord can go, I will follow. Brother glacier is no god. See! I defy him." She raised my Hayden and aimed it unsteadily at the wall of ice above the Olympus.

"No!" Baiel screamed. "The sun god will destroy you!"

Baiel was ten paces ahead of me. He reached her as she fired. He knocked the Hayden from her hand with such force that Dayhan was thrown sprawling on the slick ground.

Above us tons of ice, dislodged by the Hayden blast, broke and slid down the face of the glacier upon the Olympus, rocking the ship over on its side. Baiel flung up his hands in terror, but lowered them a moment later. Behind his facial mask of stark fear, I saw a strange expression of uneasy surprise and calculation.

I moved toward him, my fists doubled.

"Even when they begin to conquer the taboos," I cried, through clenched teeth, "you still try to prevent it!"

"No, Captain; you've got it wrong. I just wanted—you—you had no right to give her the Hayden." Baiel spoke in a hoarse, nervous whisper, backing away from me slowly.

"Dayhan's my wife."

"She's still a primitive animal."

I lunged at him. He turned and ran. I would have followed, but Dayhan began to call after me frantically. I returned to help her. The ground beneath her was stained red; a jagged blade of ice had ripped a deep gash in her leg.

With my knife I cut a strip from my fur jacket and wound it as a tourniquet above the pulsing wound. My fingers were numb with cold. I worked slowly and awkwardly, but at last the bleeding ceased. Dayhan tried to stand, but she could not.

"Leave me here, my Lord," she whispered. "Brother glacier is angry; he wants my blood."

"It was simply an accident, Dayhan. The glacier had nothing to do with it."

"I trod on tabooed ground. I defied him."

"Man makes the taboos and the punishments and the sacrifices!"

"So you have said, my Lord, and yet—"

"I have taught you truth. You walked alone and without harm on tabooed ground. You must tell that to your people. The harm came to you after you found us, Dayhan—from Baiel. Only man is cruel to man, not the gods."

I pulled her arm around my shoulder and we began the slow, painful walk back to the village. We had to stop frequently to rest. Twice I loosed the tourniquet to permit the blood to circulate in her lower leg.

It was four hours before we reached the edge of the forest. There two of my men met us. They had begun to search the forest for me when Baiel returned to the village alone. We improvised a stretcher for Dayhan and carried her between us. The bleeding of her wound had stopped. With a pinpoint Hayden beam, I turned a drift of snow into steam and used the boiled water residue to cleanse the caked blood away from the cut. I seared a strip of skin and used it as a bandage. On the gently swaying stretcher Dayhan closed her eyes and slept.

When we were still a quarter of a mile from the village, the chief and a small band of his hunters met us on the forest trail.

"The sun god speaks to us in a giant voice," the chief said. "It thunders in every corner of our village!"

"What does the god say?"

"He orders to take up our goods and go. He gives us the hunting ground of the dead, beyond the fire mountains."

"And your people fear to obey?"

"No. Your sun god is all-powerful. It is your own people who prevent us. They hold the priest, Baiel, with his followers, imprisoned in the cave by means of your weapons, the brothers-of-the-sun. They tell us it is not the sun god who speaks, but Baiel himself."

"They tell you truly."

"But no man can have so great a voice as that we hear!"

So that was why Baiel had gone back to the Olympus! He had returned to the village with a portable amplifier concealed under his fur cloak. "Baiel is no priest," I told the Chief. "He speaks for no god. The great voice you hear is made by a machine, such a thing as this weapon that we use to slay meat for the tribe."

"You speak knowingly, Seus-man, because you, too, are a priest of the sun. You showed us that much last night. Some of my tribe say you and all your people are not simple priests, but brother gods."

"We are men."

"I have married my daughter to the brother-god of the sun!"

"We are men; men!"

"But have you not advised us to move, as the sun god does now? In our blindness we have heard and not obeyed. And now the sun god gives orders that we must be gone before he rides directly overhead; yet your people will not allow it."

"So Baiel's putting a time limit on the migration," I mused aloud. "Why? Tell me, Chief, how it was, from the beginning."

"As soon as you left, Seus-man, our old priest walked in the village, declaring we would have a great sign from the sun today. Later the priest, Baiel, returned and went into the cave, with some of your people. We began to hear the voice of the sun. The others of your people—the ones who carry the weapons—gathered outside, shooting streaks of fire at the cave, but above it so that no man was harmed. They cried to Baiel to come forth and give himself to them. He refused, and so things stand. I came seeking you. Only you can intercede with your priests so they allow us to obey the god. Come quickly, for our time is short."

We gave Dayhan's stretcher to four of the hunters. I turned to follow the chief back to the village. Only then did he seem to notice his daughter. With deference he glanced at her pale face. Trembling, he asked:

"She is dead?"

"No; but she has been hurt."

"Her Lord has punished her?"

"She was harmed by a piece of ice."

"Brother glacier still means to be revenged on us! If we do not hasten to obey the voice of the sun, who will protect us?"

"Protect yourselves, as men. No god has any power to equal yours."

"You speak as a priest of the sun. You hold the weapon of the sun in your hand. You are not like us."

"I am no different. I am a man, the husband of your daughter. Here, take my weapon." I thrust the Hayden into his hand. "Does it make you different? Are you transformed into a god?"

He caressed the cold metal, slowly raising the nozzle and pointing it at a drift of snow. The red flame sputtered and steam swirled up, coating the pines overhead with a film of ice.

"The power of the sun," he whispered. "Come, Lord, we must go quickly to our people."

In the village I found the men of my faction arranged in a semi-circle in front of the cave mouth. Huddled behind them was perhaps three-fourths of the tribe, the women my men had taken as mates and their families. The rest of the tribe was packed densely at the mouth of the cave, swaying and shouting their worship as the voice of Baiel thundered at intervals out of the darkness of the cavern.

One of my men saluted raggedly, explaining how the situation had developed. He added: "We have been aiming above their heads, trying to frighten them away from the cave. No luck, so far."

"Of course Baiel's people aren't armed?"

"No, but too many of the tribe would be killed if we tried to rush the cave."

"I think we can starve them out."

To hesitate was the natural result of our psycho-processing. Violence, we had always been taught, was the resort of the disoriented, not a solution to any problem. Even now we could not bring ourselves to give up the pattern of our Earthly civilization.

Since it was the prescribed rational procedure, I tried to talk to the tribe. From the beginning my argument was weak, for I was opposing the migration which I had myself advocated. It meant nothing to them when I tried to point out the difference in motivation; but it symbolized everything to me. The migration to a better land had to come as a result of their conquest of tribal taboos, not as an exchange of allegiances from brother glacier to the sun god.

As soon as Baiel heard my voice, he began to jeer at me over the amplifier. When I made no reply, his tone gradually changed. Over and over he repeated the orders of the sun god, that the migration must begin by high noon. But his mockery was slowly tainted with fear, as the sun mounted the heavens and my armed men still held the tribe in the village.

The stretcher bearers arrived with Dayhan. She was awake. She sat up against my shoulder, holding tight to my hand. Softly she spoke to the tribe as I had:

"It is not the gods that rule us. There are no taboos; the glacier is but a thing of ice, without life. I have seen for myself. I have walked unharmed on the tabooed ground. In truth, we must migrate to the south, but my Lord has taught us that we must go of our own will and not because of fear of the sun god."

She was one of the tribe. They knew her as they knew their own children. She spoke in their words, in terms of their concepts. It should have convinced them, but it did not. Instead they retreated from her, cringingly respectful, muttering among themselves that Dayhan's mating had changed her into a brother-god.

Suddenly there was a stirring at the cave mouth. The massed tribesmen shifted aside reluctantly. Eight of the women who had been in Baiel's faction slid down toward us, weeping with fear. At once Baiel's voice boomed out:

"The time is up. You have not obeyed. I was sent by the sun god to lead you to safety, and you have not heeded me. The god will strike, now, at the glacier and tear this ground from beneath your feet. I give you one chance more. Offer up Captain Theusaman in sacrifice and I, Baiel, will lead you to a new world. But you must make the sacrifice at once. The god grows impatient."

My men closed around Dayhan and me protectively, but at first there was no need. The concept bewildered the tribe. They had accepted me, too, as priest of the sun; the god could not demand my blood. According to the theory of their superstitions, it made no sense.

One of the women who had fled from the cave was brought to me. White-faced, she twisted her hands together in anguish while she talked.

"We didn't know he'd done it, Captain Theusaman—I swear it!"

"Who?"

"Baiel—this morning at the Olympus. He just told us."

"But what? Speak up! Tell me!"

"He put on the automatic power in the control room, timed to energize the dorsal tubes at noon."

"No harm in that. The tubes are blown. The blast will simply send open flame soaring into the sky."

"There's forty hours' residue in the tank. Baiel thought the sight of the flame would terrify the tribe into obeying him. But he says the ship was overturned this morning, after he had set the dials; so the broken tubes are pointing down toward the base of the glacier."

I understood the woman's terror, then, and my own body tensed with cold fear. Instead of making a harmless display, the sun-hot energy, blasting through the naked dorsal tubes for the next forty hours, would be fed into the glacier and the ground beneath it. In half that time the liquefying flame could pierce the planetary crust and reach its molten core.

As I sprang to my feet the first shock stabbed into the frozen ground. The shattering explosion of the crumbling glacier rocked the air. In the distance a cloud of steam arose, blood red from the flames raging beneath it. In seconds the sun was blotted over with thick clouds. Hot rain began to fall.

The earth quivered so violently it was almost impossible to stand. Yet still Baiel's voice boomed through the village.

"Give me the blood of Theusaman and I spare the tribe!"

From priest, he had become the sun god himself.

The rain fell in a deluge. The snow dissolved into slush, and the village ran with mud.

Dayhan screamed. I turned and saw one of the tribal hunters atop the stone pedestal, drawing careful aim on me with his bow and arrow. I caught the shaft in the air with a wide angle beam from my Hayden.

"Give me the blood of Theusaman!" Baiel cried.

The quaking increased steadily. Small landslides of stone began to slither from the face of the cliff. The roof of the cave shook and sagged. The tribe backed away, swirling around me in fury and brandishing their spears in the bleary air.

The distant rending of the glacier reached a new climax of thunder, and the deluge swelled into a torrent. The draining water became a stream, racing muddily through the village and eating at the crumbling cliffs. The skies darkened as if it were dusk. It was difficult to recognize faces in the frenzy of squirming bodies.

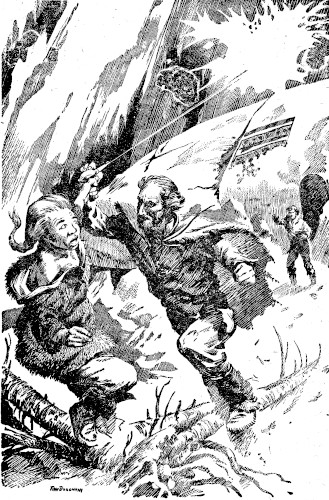

Driven by the madness of Baiel's chanting voice, many of the young hunters threw themselves upon us. We used Haydens only as a last resort, and the sluggish, hand-to-hand fighting in the rising mud went on indecisively. No one was badly hurt. It was too easy to escape clutching arms; it was too hard to know the face of friend from foe in the gloom. Shouting voices were drowned by the rising wind, the ceaseless din of crumbling glacial ice.

Abruptly the battle was over. A terrified whisper swept the throng: the god was gone! Someone had looked into the cave and found it empty. Baiel and ten of his faction had fled; thirty of the tribe had departed with them.

The shock was paralyzing to those who stayed behind. The tribe began to wail its lamentation. The god had deserted them! I moved from group to group, repeating my familiar theme:

"The gods can neither harm nor save you. That you must do for yourselves."

It had no effect. They stared at me with vacant eyes. They repeated dumbly in reply: "The sun god is gone. He leaves us to the mercy of brother glacier."

The stream coursing through the village had risen slowly until it became a raging river. Still the tribe made no effort to escape. They had violated their code of the supernatural, and they believed they must resign themselves to their punishment. I watched as a woman was carried away by the flood, drowned screaming beneath a part of the cliff which washed down upon her.

During a momentary lull in the din, the old chief mounted the swaying stone pedestal, brandishing the Hayden I had given him.

"The sun god has not gone," he cried. "See, I share his power, and I know he is still among us." He pointed the Hayden at the mouth of the cave, and the stone crumbled in the caress of red flame. "Seus-man is the sun god; Baiel was false, sent of evil things."

"Seus-man," the crowd whispered. After a moment, they began to shout with new hope. "Seus-man! Seus-man! Seus! Seus!"

On their shoulders they lifted me up and carried me to the pedestal. As I began to speak, I saw a wall of water moving down upon us, crested by a foaming wave. It was the first flood tide from the melting glacier. If it reached the village unbroken, the tribe would be wiped out.

I snatched the Hayden from the Chief, aiming the point of flame at the base of the cliff. Dirt and granite toppled into the path of the flood. The tribe dropped on its knees in the thick mud, shouting praise of my name.

My crude dam might hold for an hour, certainly no longer. I had no time to convince them by persuasion. It would be opposing the full violence of reality with the thin web of philosophy. The important thing at the moment was to lead the tribe to safety.

I looked down upon them and I began to speak wearily.

"I am Theusaman, god of the sun," I said. "Take up your possessions and follow me...."

Baiel had won, after all.

All that happened more than fifty years ago.

I did lead the tribe to safety; that much I accomplished. They have since built many villages and they have learned the art of agriculture and of domesticating cattle. They have thrived and grown and joined with other tribes. They will survive and someday rule their planet.

As Baiel once predicted, the glacier is rapidly retreating. The process began with the heat generated by the exposed dorsal tube of the dead Olympus. Each spring the run-off of melting water is greater than the ice which accumulates during the winter. When the glacier is gone, it will give my people a fertile world like our own Earth.

For that I am glad, because I have given them nothing else.

Nothing else!

I have, instead, saddled them with a hierarchy of gods. The tribes which migrated across the sea have taken a part of my name as their sun god; they call me Amon. Here at home they call me Zeus. Dayhan has become Diana, the goddess of the forests. Even Baiel leaves his name with a people settled in the desert, though to us Baal persists as a god of evil things.

Ironically, the one thing of Earth that I have given these people is the name itself. This planet they call the Earth, unaware of any other. They think of themselves as Earthmen. And I? I am called Zeus of Olympus, father of all the gods!

Perhaps I judge my failure too bitterly. I am an old man, now, the last living survivor of the expedition. I have looked into the face of my sons and my grandsons, as I have the sons and grandsons of the other Earthmen who were with our expedition. Our children have our features, not the slant skulls and ape arms of their mothers. Have we, by chance, left on this lonely planet something of our potential ability as Earthmen?

Though I cannot live long enough to know the answer, I would like to believe that we have. Because I want to believe, I leave this written account of the truth. I address it to my sons of tomorrow—to men who have finally made themselves free of taboo and superstition. To them I say: Lift up your eyes to the sky, to that other Earth across the emptiness of space. Seek them out, those other Earthmen, and know them for your brothers.