*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 68604 ***

The few footnotes have been collected at the end of each chapter, and are

linked for ease of reference.

Minor errors, attributable to the printer, have been corrected. Please

see the transcriber’s note at the end of this text

for details regarding the handling of any textual issues encountered

during its preparation.

The title and author, as well as the publication date, have been

added to the image of the front cover.

Any corrections are indicated using an underline

highlight. Placing the cursor over the correction will produce the

original text in a small popup.

Any corrections are indicated as hyperlinks, which will navigate the

reader to the corresponding entry in the corrections table in the

note at the end of the text.

EUROPE AND ELSEWHERE

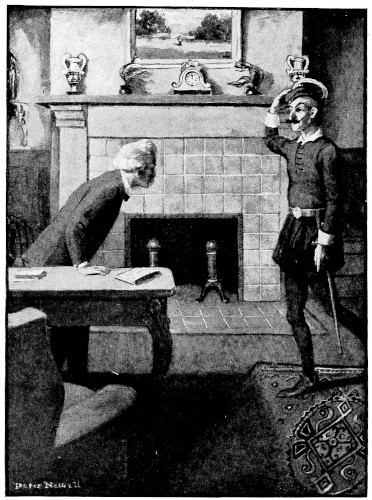

AND I ROSE TO RECEIVE MY GUEST, AND BRACED MYSELF FOR THE

THUNDERCRASH AND THE BRIMSTONE STENCH WHICH

SHOULD ANNOUNCE HIS ARRIVAL

EUROPE

AND ELSEWHERE

By

MARK TWAIN

WITH AN APPRECIATION BY

BRANDER MATTHEWS

AND AN INTRODUCTION BY

ALBERT BIGELOW PAINE

HARPER & BROTHERS, PUBLISHERS

NEW YORK AND LONDON

Copyright, 1923

By The Mark Twain Company

Printed in the U.S.A.

v

CONTENTS

| CHAP. |

|

PAGE |

| |

An Appreciation |

vii |

| |

Introduction |

xxxi |

| I. |

A Memorable Midnight Experience |

1 |

| II. |

Two Mark Twain Editorials |

14 |

| III. |

The Temperance Crusade and Woman’s Rights |

24 |

| IV. |

O’Shah |

31 |

| V. |

A Wonderful Pair of Slippers |

87 |

| VI. |

Aix, the Paradise of the Rheumatics |

94 |

| VII. |

Marienbad--A Health Factory |

113 |

| VIII. |

Down the Rhône |

129 |

| IX. |

The Lost Napoleon |

169 |

| X. |

Some National Stupidities |

175 |

| XI. |

The Cholera Epidemic in Hamburg |

186 |

| XII. |

Queen Victoria’s Jubilee |

193 |

| XIII. |

Letters to Satan |

211 |

| XIV. |

A Word of Encouragement for Our Blushing Exiles |

221 |

| XV. |

Dueling |

225 |

| XVI. |

Skeleton Plan of a Proposed Casting Vote Party |

233 |

| XVII. |

The United States of Lyncherdom |

239 |

| XVIII. |

To the Person Sitting in Darkness |

250 |

| XIX. |

To My Missionary Critics |

273 |

| XX. |

Thomas Brackett Reed |

297 |

| XXI. |

The Finished Book |

299 |

| XXII. |

As Regards Patriotism |

301 |

| XXIII. |

Dr. Loeb’s Incredible Discovery |

304 |

| XXIV. |

The Dervish and the Offensive Stranger |

310 |

| XXV. |

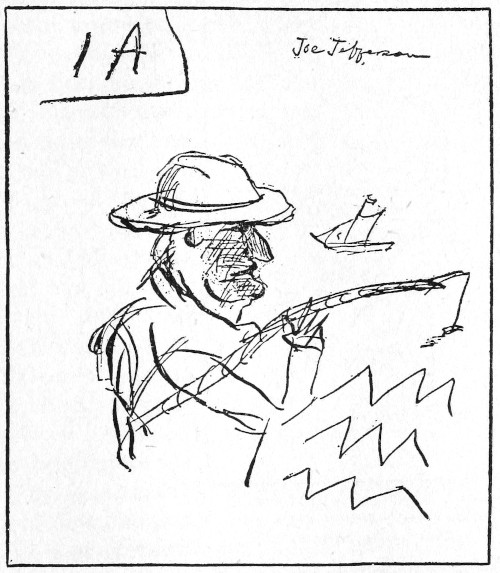

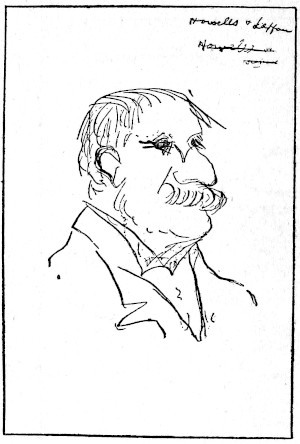

Instructions in Art |

315 |

| XXVI. |

Sold to Satan |

326 |

| XXVII. |

That Day in Eden |

339 |

| XXVIII. |

Eve Speaks |

347 |

| XXIX. |

Samuel Erasmus Moffett |

351 |

| XXX. |

The New Planet |

355 |

| XXXI. |

Marjorie Fleming, the Wonder Child |

358 |

| XXXII. |

Adam’s Soliloquy |

377 |

| XXXIII. |

Bible Teaching and Religious Practice |

387 |

| XXXIV. |

The War Prayer |

394 |

| XXXV. |

Corn-pone Opinions |

399 |

vii

AN APPRECIATION

(This “Biographical Criticism” was prepared by Prof.

Brander Matthews, as an introduction to the Uniform Edition

of Mark Twain’s Works, published in 1899).

It is a common delusion of those who discuss contemporary

literature that there is such an entity

as the “reading public,” possessed of a certain uniformity

of taste. There is not one public; there are

many publics--as many, in fact, as there are different

kinds of taste; and the extent of an author’s popularity

is in proportion to the number of these separate

publics he may chance to please. Scott, for example,

appealed not only to those who relished

romance and enjoyed excitement, but also to those

who appreciated his honest portrayal of sturdy characters.

Thackeray is preferred by ambitious youth

who are insidiously flattered by his tacit compliments

to their knowledge of the world, by the disenchanted

who cannot help seeing the petty meannesses of society,

and by the less sophisticated in whom sentiment

has not gone to seed in sentimentality. Dickens in

his own day bid for the approval of those who liked

broad caricature (and were therefore pleased with

Stiggins and Chadband), of those who fed greedily

on plentiful pathos (and were therefore delighted

with the deathbeds of Smike and Paul Dombey and

viiiLittle Nell) and also of those who asked for unexpected

adventure (and were therefore glad to disentangle

the melodramatic intrigues of Ralph

Nickleby).

In like manner the American author who has

chosen to call himself Mark Twain has attained to an

immense popularity because the qualities he possesses

in a high degree appeal to so many and so

widely varied publics--first of all, no doubt, to the

public that revels in hearty and robust fun, but also

to the public which is glad to be swept along by the

full current of adventure, which is sincerely touched

by manly pathos, which is satisfied by vigorous and

exact portrayal of character, and which respects

shrewdness and wisdom and sanity and a healthy

hatred of pretense and affectation and sham. Perhaps

no one book of Mark Twain’s--with the possible

exception of Huckleberry Finn--is equally a

favorite with all his readers; and perhaps some of

his best characteristics are absent from his earlier

books or but doubtfully latent in them. Mark

Twain is many sided; and he has ripened in knowledge

and in power since he first attracted attention

as a wild Western funny man. As he has grown

older he has reflected more; he has both broadened

and deepened. The writer of “comic copy” for a

mining-camp newspaper has developed into a liberal

humorist, handling life seriously and making his

readers think as he makes them laugh, until to-day

Mark Twain has perhaps the largest audience of any

author now using the English language. To trace

the stages of this evolution and to count the steps

ixwhereby the sagebrush reporter has risen to the rank

of a writer of world-wide celebrity, is as interesting

as it is instructive.

I

Samuel Langhorne Clemens was born November

30, 1835, at Florida, Missouri. His father was a

merchant who had come from Tennessee and who

removed soon after his son’s birth to Hannibal, a

little town on the Mississippi. What Hannibal was

like and what were the circumstances of Mr. Clemen’s

boyhood we can see for ourselves in the convincing

pages of Tom Sawyer. Mr. Howells has

called Hannibal “a loafing, out-at-elbows, down-at-the-heels,

slave-holding Mississippi town”; and

Mr. Clemens, who silently abhorred slavery, was of

a slave-owning family.

When the future author was but twelve his father

died, and the son had to get his education as best

he could. Of actual schooling he got little and of

book learning still less, but life itself is not a bad

teacher for a boy who wants to study, and young

Clemens did not waste his chances.chances. He spent six

years in the printing office of the little local paper,--for,

like not a few others on the list of AmericanAmerican

authors that stretches from Benjamin Franklin to

William Dean Howells, he began his connection with

literature by setting type. As a journeyman printer

the lad wandered from town to town and rambled

even as far east as New York.

When he was nineteen he went back to the home

of his boyhood and presently resolved to become a

xpilot on the Mississippi. How he learned the river

he has told us in Life on the Mississippi, wherein his

adventures, his experiences, and his impressions

while he was a cub pilot are recorded with a combination

of precise veracity and abundant humor

which makes the earlier chapters of that marvelous

book a most masterly fragment of autobiography.

The life of a pilot was full of interest and excitement

and opportunity, and what young Clemens saw and

heard and divined during the years when he was

going up and down the mighty river we may read in

the pages of Huckleberry Finn and Pudd’nhead

Wilson. But toward the end of the ’fifties the railroads

began to rob the river of its supremacy as a

carrier; and in the beginning of the ’sixties the Civil

War broke out and the Mississippi no longer went

unvexed to the sea. The skill, slowly and laboriously

acquired, was suddenly rendered useless, and at

twenty-five the young man found himself bereft of

his calling. As a border state, Missouri was sending

her sons into the armies of the Union and into the

armies of the Confederacy, while many a man stood

doubting, not knowing which way to turn. The ex-pilot

has given us the record of his very brief and

inglorious service as a soldier of the South. When

this escapade was swiftly ended, he went to the

Northwest with his brother, who had been appointed

Territorial Secretary of Nevada. Thus the man who

had been born on the borderland of North and South,

who had gone East as a jour-printer, who had been

again and again up and down the Mississippi, now

went West while he was still plastic and impressionable;

xiand he had thus another chance to increase

that intimate knowledge of American life and

American character which is one of the most precious

of his possessions.

While still on the river he had written a satiric

letter or two which found their way into print. In

Nevada he went to the mines and lived the life

he has described in Roughing It, but when he failed

to “strike it rich,” he naturally drifted into journalism

and back into a newspaper office again. The

Virginia City Enterprise was not overmanned, and

the newcomer did all sorts of odd jobs, finding time

now and then to write a sketch which seemed important

enough to permit of his signature. He now

began to sign himself Mark Twain, taking the name

from a call of the man who heaves the lead on a

Mississippi River steamboat, and who cries, “By the

mark, three,” “Mark Twain,” and so on. The

name of Mark Twain soon began to be known to

those who were curious in newspaper humor. After

a while he was drawn across the mountains to San

Francisco, where he found casual employment on

the Morning Call, and where he joined himself to a

little group of aspiring literators which included Mr.

Bret Harte, Mr. Noah Brooks, Mr. Charles Henry

Webb, and Mr. Charles Warren Stoddard.

It was in 1867 that Mr. Webb published Mark

Twain’s first book, The Celebrated Jumping Frog of

Calaveras; and it was in 1867 that the proprietors

of the Alta California supplied him with the

funds necessary to enable him to become one of the

passengers on the steamer Quaker City, which had

xiibeen chartered to take a select party on what is now

known as the Mediterranean trip. The weekly letters,

in which he set forth what befell him on this

journey, were printed in the Alta Sunday after Sunday,

and were copied freely by the other Californian

papers. These letters served as the foundation of a

book published in 1869 and called The Innocents

Abroad, a book which instantly brought to the

author celebrity and cash.

Both of these valuable aids to ambition were increased

by his next step, his appearance on the

lecture platform. Mr. Noah Brooks, who was

present at his first attempt, has recorded that Mark

Twain’s “method as a lecturer was distinctly unique

and novel. His slow, deliberate drawl, the anxious

and perturbed expression of his visage, the apparently

painful effort with which he framed his sentences,

the surprise that spread over his face when

the audience roared with delight or rapturously applauded

the finer passages of his word painting, were

unlike anything of the kind they had ever known.”

In the thirty years since that first appearance the

method has not changed, although it has probably

matured. Mark Twain is one of the most effective

of platform speakers and one of the most artistic,

with an art of his own which is very individual and

very elaborate in spite of its seeming simplicity.

Although he succeeded abundantly as a lecturer,

and although he was the author of the most widely

circulated book of the decade, Mark Twain still

thought of himself only as a journalist; and when

he gave up the West for the East he became an

xiiieditor of the Buffalo Express, in which he had

bought an interest. In 1870 he married; and it is

perhaps not indiscreet to remark that his was

another of those happy unions of which there have

been so many in the annals of American authorship.

In 1871 he removed to Hartford, where his home

has been ever since; and at the same time he gave

up newspaper work.

In 1872 he wrote Roughing It, and in the following

year came his first sustained attempt at

fiction, The Gilded Age, written in collaboration

with Mr. Charles Dudley Warner. The character

of “Colonel Mulberry Sellers” Mark Twain soon

took out of this book to make it the central figure

of a play which the late John T. Raymond acted

hundreds of times throughout the United States,

the playgoing public pardoning the inexpertness of

the dramatist in favor of the delicious humor and the

compelling veracity with which the chief character

was presented. So universal was this type and so

broadly recognizable its traits that there were few

towns wherein the play was presented in which some

one did not accost the actor who impersonated the

ever-hopeful schemer to declare: “I’m the original

of Sellers! Didn’t Mark ever tell you? Well, he

took the Colonel from me!”

Encouraged by the welcome accorded to this first

attempt at fiction, Mark Twain turned to the days

of his boyhood and wrote Tom Sawyer, published

in 1875. He also collected his sketches, scattered

here and there in newspapers and magazines. Toward

the end of the ’seventies he went to Europe

xivagain with his family; and the result of this journey

is recorded in A Tramp Abroad, published in 1880.

Another volume of sketches, The Stolen White

Elephant, was put forth in 1882; and in the same

year Mark Twain first came forward as a historical

novelist--if The Prince and the Pauper can fairly

be called a historical novel. The year after, he

sent forth the volume describing his Life on the

Mississippi; and in 1884 he followed this with the

story in which that life has been crystallized forever,

Huckleberry Finn, the finest of his books, the deepest

in its insight, and the widest in its appeal.

This Odyssey of the Mississippi was published by

a new firm, in which the author was a chief partner,

just as Sir Walter Scott had been an associate

of Ballantyne and Constable. There was at first

a period of prosperity in which the house issued

the Personal Memoirs of Grant, giving his widow

checks for $350,000 in 1886, and in which Mark

Twain himself published A Connecticut Yankee at

King Arthur’s Court, a volume of Merry Tales, and a

story called The American Claimant, wherein

“Colonel Sellers” reappears. Then there came a

succession of hard years; and at last the publishing

house in which Mark Twain was a partner failed,

as the publishing house in which Walter Scott was

a partner had formerly failed. The author of

Huckleberry Finn at sixty found himself suddenly

saddled with a load of debt, just as the author of

Waverley had been burdened full threescore years

earlier; and Mark Twain stood up stoutly under it,

as Scott had done before him. More fortunate than

xvthe Scotchman, the American has lived to pay the

debt in full.

Since the disheartening crash came, he has given

to the public a third Mississippi River tale, Pudd’nhead

Wilson, issued in 1894; and a third historical

novel Joan of Arc, a reverent and sympathetic

study of the bravest figure in all French

history, printed anonymously in Harper’s Magazine

and then in a volume acknowledged by the author in

1896. As one of the results of a lecturing tour

around the world he prepared another volume of

travels, Following the Equator, published toward

the end of 1897. Mention must also be made of a

fantastic tale called Tom Sawyer Abroad, sent

forth in 1894, of a volume of sketches, The Million

Pound Bank-Note, assembled in 1893, and also

of a collection of literary essays, How to Tell a Story,

published in 1897.

This is but the barest outline of Mark Twain’s life--such

a brief summary as we must have before us

if we wish to consider the conditions under which the

author has developed and the stages of his growth.

It will serve, however, to show how various have

been his forms of activity--printer, pilot, miner,

journalist, traveler, lecturer, novelist, publisher--and

to suggest the width of his experience of life.

II

A humorist is often without honor in his own

country. Perhaps this is partly because humor is

likely to be familiar, and familiarity breeds contempt.

xviPerhaps it is partly because (for some strange

reason) we tend to despise those who make us

laugh, while we respect those who make us weep--forgetting

that there are formulas for forcing tears

quite as facile as the formulas for forcing smiles.

Whatever the reason, the fact is indisputable that the

humorist must pay the penalty of his humor; he

must run the risk of being tolerated as a mere fun

maker, not to be taken seriously, and unworthy

of critical consideration. This penalty has been

paid by Mark Twain. In many of the discussions

of American literature he is dismissed as though

he were only a competitor of his predecessors,

Artemus Ward and John Phœnix, instead of being,

what he is really, a writer who is to be classed--at

whatever interval only time may decide--rather

with Cervantes and Molière.

Like the heroines of the problem plays of the

modern theater, Mark Twain has had to live down

his past. His earlier writing gave but little promise

of the enduring qualities obvious enough in his later

works. Mr. Noah Brooks has told us how he was

advised, if he wished to “see genuine specimens of

American humor, frolicsome, extravagant, and audacious,”

to look up the sketches which the then almost

unknown Mark Twain was printing in a Nevada

newspaper. The humor of Mark Twain is still

American, still frolicsome, extravagant, and audacious;

but it is riper now and richer, and it has taken

unto itself other qualities existing only in germ in

these firstlings of his muse. The sketches in The

Jumping Frog and the letters which made up The

xviiInnocents Abroad are “comic copy,” as the phrase is

in newspaper offices--comic copy not altogether

unlike what John Phœnix had written and Artemus

Ward, better indeed than the work of these newspaper

humorists (for Mark Twain had it in him to develop

as they did not), but not essentially dissimilar.

And in the eyes of many who do not think for

themselves, Mark Twain is only the author of these

genuine specimens of American humor. For when

the public has once made up its mind about any

man’s work, it does not relish any attempt to force

it to unmake this opinion and to remake it. Like

other juries, it does not like to be ordered to reconsider

its verdict as contrary to the facts of the case.

It is always sluggish in beginning the necessary readjustment,

and not only sluggish, but somewhat

grudging. Naturally it cannot help seeing the later

works of a popular writer from the point of view it

had to take to enjoy his earlier writings. And thus

the author of Huckleberry Finn and Joan of Arc

is forced to pay a high price for the early and abundant

popularity of The Innocents Abroad.

No doubt, a few of his earlier sketches were inexpensive

in their elements; made of materials worn

threadbare by generations of earlier funny men, they

were sometimes cut in the pattern of his predecessors.

No doubt, some of the earliest of all were

crude and highly colored, and may even be called

forced, not to say violent. No doubt, also, they

did not suggest the seriousness and the melancholy

which always must underlie the deepest humor, as

we find it in Cervantes and Molière, in Swift and in

xviiiLowell. But even a careless reader, skipping

through the book in idle amusement, ought to have

been able to see in The Innocents Abroad that the

writer of that liveliest of books of travel was no

mere merry-andrew, grinning through a horse collar

to make sport for the groundlings; but a sincere observer

of life, seeing through his own eyes and setting

down what he saw with abundant humor, of

course, but also with profound respect for the eternal

verities.

George Eliot in one of her essays calls those who

parody lofty themes “debasers of the moral currency.”

Mark Twain is always an advocate of the

sterling ethical standard. He is ready to overwhelm

an affectation with irresistible laughter, but he never

lacks reverence for the things that really deserve

reverence. It is not at the Old Masters that he

scoffs in Italy, but rather at those who pay lip service

to things which they neither enjoy nor understand.

For a ruin or a painting or a legend that does not

seem to him to deserve the appreciation in which

it is held he refuses to affect an admiration he does

not feel; he cannot help being honest--he was born

so. For meanness of all kinds he has a burning

contempt; and on Abelard he pours out the vials

of his wrath. He has a quick eye for all humbugs

and a scorching scorn for them; but there is no

attempt at being funny in the manner of the cockney

comedians when he stands in the awful presence

of the Sphinx. He is not taken in by the glamour

of Palestine; he does not lose his head there; he

keeps his feet: but he knows that he is standing on

xixholy ground; and there is never a hint of irreverence

in his attitude.

A Tramp Abroad is a better book than The Innocents

Abroad; it is quite as laughter-provoking,

and its manner is far more restrained. Mark Twain

was then master of his method, sure of himself,

secure of his popularity; and he could do his best

and spare no pains to be certain that it was his

best. Perhaps there is a slight falling off in Following

the Equator; a trace of fatigue, of weariness,

of disenchantment. But the last book of

travels has passages as broadly humorous as any of

the first; and it proves the author’s possession of a

pithy shrewdness not to be suspected from a perusal

of its earliest predecessor. The first book was the

work of a young fellow rejoicing in his own fun and

resolved to make his readers laugh with him or at

him; the latest book is the work of an older man,

who has found that life is not all laughter, but whose eye

is as clear as ever and whose tongue is as plain-spoken.

These three books of travel are like all other books

of travel in that they relate in the first person what

the author went forth to see. Autobiographic also

are Roughing It and Life on the Mississippi, and

they have always seemed to me better books than

the more widely circulated travels. They are

better because they are the result of a more intimate

knowledge of the material dealt with. Every traveler

is of necessity but a bird of passage; he is a mere

carpetbagger; his acquaintance with the countries

he visits is external only; and this acquaintanceship

is made only when he is a full-grown man. But

xxMark Twain’s knowledge of the Mississippi was acquired

in his youth; it was not purchased with a

price; it was his birthright; and it was internal and

complete. And his knowledge of the mining camp

was achieved in early manhood when the mind is

open and sensitive to every new impression. There

is in both these books a fidelity to the inner truth,

a certainty of touch, a sweep of vision, not to be

found in the three books of travels. For my own

part I have long thought that Mark Twain could

securely rest his right to survive as an author on

those opening chapters in Life on the Mississippi

in which he makes clear the difficulties, the seeming

impossibilities, that fronted those who wished to

learn the river. These chapters are bold and brilliant,

and they picture for us forever a period and a

set of conditions, singularly interesting and splendidly

varied, that otherwise would have had to forego

all adequate record.

III

It is highly probable that when an author reveals

the power of evoking views of places and of calling

up portraits of people such as Mark Twain showed

in Life on the Mississippi, and when he has the

masculine grasp of reality Mark Twain made evident

in Roughing It, he must needs sooner or later turn

from mere fact to avowed fiction and become a

story-teller. The long stories which Mark Twain

has written fall into two divisions--first, those of

which the scene is laid in the present, in reality, and

mostly in the Mississippi Valley, and second, those

xxiof which the scene is laid in the past, in fantasy

mostly, and in Europe.

As my own liking is a little less for the latter

group, there is no need for me now to linger over

them. In writing these tales of the past Mark Twain

was making up stories in his head; personally I prefer

the tales of his in which he has his foot firm on

reality. The Prince and the Pauper has the essence

of boyhood in it; it has variety and vigor; it has

abundant humor and plentiful pathos; and yet I

for one would give the whole of it for the single

chapter in which Tom Sawyer lets the contract for

whitewashing his aunt’s fence.

Mr. Howells has declared that there are two kinds

of fiction he likes almost equally well--“a real

novel and a pure romance”; and he joyfully accepts

A Connecticut Yankee at King Arthur’s Court as

“one of the greatest romances ever imagined.”

It is a humorous romance overflowing with stalwart

fun; and it is not irreverent, but iconoclastic, in that

it breaks not a few disestablished idols. It is intensely

American and intensely nineteenth century

and intensely democratic--in the best sense of that

abused adjective. The British critics were greatly

displeased with the book;--and we are reminded of

the fact that the Spanish still somewhat resent Don

Quixote because it brings out too truthfully the

fatal gap in the Spanish character between the ideal

and the real. So much of the feudal still survives in

British society that Mark Twain’s merry and elucidating

assault on the past seemed to some almost an

insult to the present.

xxiiBut no critic, British or American, has ventured to

discover any irreverence in Joan of Arc, wherein,

indeed, the tone is almost devout and the humor

almost too much subdued. Perhaps it is my own

distrust of the so-called historical novel, my own disbelief

that it can ever be anything but an inferior

form of art, which makes me care less for this worthy

effort to honor a noble figure. And elevated and

dignified as is the Joan of Arc, I do not think that

it shows us Mark Twain at his best; although it

has many a passage that only he could have written,

it is perhaps the least characteristic of his works.

Yet it may well be that the certain measure of success

he has achieved in handling a subject so lofty and so

serious, will help to open the eyes of the public to

see the solid merits of his other stories, in which his

humor has fuller play and in which his natural gifts

are more abundantly displayed.

Of these other stories three are “real novels,” to

use Mr. Howells’s phrase; they are novels as real

as any in any literature. Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry

Finn and Pudd’nhead Wilson are invaluable

contributions to American literature--for American

literature is nothing if it is not a true picture of

American life and if it does not help us to understand

ourselves. Huckleberry Finn is a very amusing

volume, and a generation has read its pages and

laughed over it immoderately; but it is very much

more than a funny book; it is a marvelously accurate

portrayal of a whole civilization. Mr. Ormsby, in

an essay which accompanies his translation of Don

Quixote, has pointed out that for a full century

xxiiiafter its publication that greatest of novels was

enjoyed chiefly as a tale of humorous misadventure,

and that three generations had laughed over it

before anybody suspected that it was more than a

mere funny book. It is perhaps rather with the

picaresque romances of Spain that Huckleberry Finn

is to be compared than with the masterpiece of

Cervantes; but I do not think it will be a century

or take three generations before we Americans generally

discover how great a book Huckleberry Finn

really is, how keen its vision of character, how close

its observation of life, how sound its philosophy, and

how it records for us once and for all certain phases of

Southwestern society which it is most important for

us to perceive and to understand. The influence of

slavery, the prevalence of feuds, the conditions and

the circumstances that make lynching possible--all

these things are set before us clearly and without

comment. It is for us to draw our own moral, each

for himself, as we do when we see Shakespeare

acted.

Huckleberry Finn, in its art, for one thing, and

also in its broader range, is superior to Tom Sawyer

and to Pudd’nhead Wilson, fine as both these are in

their several ways. In no book in our language,

to my mind, has the boy, simply as a boy, been

better realized than in Tom Sawyer. In some

respects Pudd’nhead Wilson is the most dramatic

of Mark Twain’s longer stories, and also the most

ingenious; like Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn,

it has the full flavor of the Mississippi River, on

which its author spent his own boyhood, and

xxivfrom contact with the soil of which he always rises

reinvigorated.

It is by these three stories, and especially by

Huckleberry Finn, that Mark Twain is likely to

live longest. Nowhere else is the life of the Mississippi

Valley so truthfully recorded. Nowhere else

can we find a gallery of Southwestern characters as

varied and as veracious as those Huck Finn met in

his wanderings. The histories of literature all praise

the Gil Blas of Le Sage for its amusing adventures,

its natural characters, its pleasant humor, and

its insight into human frailty; and the praise is deserved.

But in everyone of these qualities Huckleberry

Finn is superior to Gil Blas. Le Sage set

the model of the picaresque novel, and Mark Twain

followed his example; but the American book is

richer than the French--deeper, finer, stronger. It

would be hard to find in any language better specimens

of pure narrative, better examples of the

power of telling a story and of calling up action so

that the reader cannot help but see it, than Mark

Twain’s account of the Shepherdson-Grangerford

feud, and his description of the shooting of Boggs

by Sherburn and of the foiled attempt to lynch

Sherburn afterward.

These scenes, fine as they are, vivid, powerful,

and most artistic in their restraint, can be matched

in the two other books. In Tom Sawyer they can

be paralleled by the chapter in which the boy and

the girl are lost in the cave, and Tom, seeing a gleam

of light in the distance, discovers that it is a candle

carried by Indian Joe, the one enemy he has in the

xxvworld. In Pudd’nhead Wilson the great passages

of Huckleberry Finn are rivaled by that most pathetic

account of the weak son willing to sell his own

mother as a slave “down the river.” Although

no one of the books is sustained throughout on this

high level, and although, in truth, there are in each of

them passages here and there that we could wish

away (because they are not worthy of the association

in which we find them), I have no hesitation in

expressing here my own conviction that the man who

has given us four scenes like these is to be compared

with the masters of literature; and that he can abide

the comparison with equanimity.

IV

Perhaps I myself prefer these three Mississippi

Valley books above all Mark Twain’s other writings

(although with no lack of affection for those also)

partly because these have the most of the flavor of

the soil about them. After veracity and the sense

of the universal, what I best relish in literature is this

native aroma, pungent, homely, and abiding. Yet

I feel sure that I should not rate him so high if

he were the author of these three books only. They

are the best of him, but the others are good also,

and good in a different way. Other writers have

given us this local color more or less artistically,

more or less convincingly: one New England and

another New York, a third Virginia, and a fourth

Georgia, and a fifth Wisconsin; but who so well as

Mark Twain has given us the full spectrum of the

xxviUnion? With all his exactness in reproducing the

Mississippi Valley, Mark Twain is not sectional in

his outlook; he is national always. He is not narrow;

he is not Western or Eastern; he is American with

a certain largeness and boldness and freedom and certainty

that we like to think of as befitting a country

so vast as ours and a people so independent.

In Mark Twain we have “the national spirit as

seen with our own eyes,” declared Mr. Howells;

and, from more points of view than one, Mark Twain

seems to me to be the very embodiment of Americanism.

Self-educated in the hard school of life, he

has gone on broadening his outlook as he has grown

older. Spending many years abroad, he has come

to understand other nationalities, without enfeebling

his own native faith. Combining a mastery of the

commonplace with an imaginative faculty, he is a

practical idealist. No respecter of persons, he has a

tender regard for his fellow man. Irreverent toward

all outworn superstitions, he has ever revealed

the deepest respect for all things truly worthy of

reverence. Unwilling to take pay in words, he is

impatient always to get at the root of the matter, to

pierce to the center, to see the thing as it is. He

has a habit of standing upright, of thinking for himself,

and of hitting hard at whatsoever seems to him

hateful and mean; but at the core of him there is

genuine gentleness and honest sympathy, brave

humanity and sweet kindliness. Perhaps it is boastful

for us to think that these characteristics which we see

in Mark Twain are characteristics also of the American

people as a whole; but it is pleasant to think so.

xxviiMark Twain has the very marrow of Americanism.

He is as intensely and as typically American as

Franklin or Emerson or Hawthorne. He has not a

little of the shrewd common sense and the homely

and unliterary directness of Franklin. He is not

without a share of the aspiration and the elevation

of Emerson; and he has a philosophy of his own as

optimistic as Emerson’s. He possesses also somewhat

of Hawthorne’s interest in ethical problems,

with something of the same power of getting at the

heart of them; he, too, has written his parables and

apologues wherein the moral is obvious and unobtruded.

He is uncompromisingly honest; and his

conscience is as rugged as his style sometimes is.

No American author has to-day at his command a

style more nervous, more varied, more flexible, or

more various than Mark Twain’s. His colloquial

ease should not hide from us his mastery of all the

devices of rhetoric. He may seem to disobey the

letter of the law sometimes, but he is always obedient

to the spirit. He never speaks unless he has something

to say; and then he says it tersely, sharply,

with a freshness of epithet and an individuality of

phrase, always accurate, however unacademic. His

vocabulary is enormous, and it is deficient only in

the dead words; his language is alive always, and

actually tingling with vitality. He rejoices in the

daring noun and in the audacious adjective. His instinct

for the exact word is not always unerring, and

now and again he has failed to exercise it; but there

is in his prose none of the flatting and sharping he

censured in Fenimore Cooper’s. His style has

xxviiinone of the cold perfection of an antique statue; it is

too modern and too American for that, and too completely

the expression of the man himself, sincere

and straightforward. It is not free from slang,

although this is far less frequent than one might expect;

but it does its work swiftly and cleanly. And

it is capable of immense variety. Consider the tale

of the Blue Jay in A Tramp Abroad, wherein the

humor is sustained by unstated pathos; what could

be better told than this, with every word the right

word and in the right place? And take Huck Finn’s

description of the storm when he was alone on the

island, which is in dialect, which will not parse, which

bristles with double negatives, but which none the

less is one of the finest passages of descriptive prose

in all American literature.

V

After all, it is as a humorist pure and simple that

Mark Twain is best known and best beloved. In

the preceding pages I have tried to point out the

several ways in which he transcends humor, as the

word is commonly restricted, and to show that he is

no mere fun maker. But he is a fun maker beyond

all question, and he has made millions laugh as no

other man of our century has done. The laughter

he has aroused is wholesome and self-respecting; it

clears the atmosphere. For this we cannot but be

grateful. As Lowell said, “let us not be ashamed

to confess that, if we find the tragedy a bore, we

take the profoundest satisfaction in the farce. It is

xxixa mark of sanity.” There is no laughter in Don

Quixote, the noble enthusiast whose wits are unsettled;

and there is little on the lips of Alceste the

misanthrope of Molière; but for both of them life

would have been easier had they known how to

laugh. Cervantes himself, and Molière also, found

relief in laughter for their melancholy; and it was

the sense of humor which kept them tolerantly interested

in the spectacle of humanity, although life had

pressed hardly on them both. On Mark Twain also

life has left its scars; but he has bound up his

wounds and battled forward with a stout heart, as

Cervantes did, and Molière. It was Molière who

declared that it was a strange business to undertake

to make people laugh; but even now, after two

centuries, when the best of Molière’s plays are acted,

mirth breaks out again and laughter overflows.

It would be doing Mark Twain a disservice to liken

him to Molière, the greatest comic dramatist of all

time; and yet there is more than one point of similarity.

Just as Mark Twain began by writing comic

copy which contained no prophecy of a masterpiece

like Huckleberry Finn, so Molière was at

first the author only of semiacrobatic farces on the

Italian model in no wise presaging Tartuffe and

The Misanthrope. Just as Molière succeeded first

of all in pleasing the broad public that likes robust

fun, and then slowly and step by step developed into

a dramatist who set on the stage enduring figures

plucked out of the abounding life about him, so

also has Mark Twain grown, ascending from The

Jumping Frog to Huckleberry Finn, as comic as its

xxxelder brother and as laughter-provoking, but charged

also with meaning and with philosophy. And like

Molière again, Mark Twain has kept solid hold of

the material world; his doctrine is not of the earth

earthy, but it is never sublimated into sentimentality.

He sympathizes with the spiritual side of

humanity, while never ignoring the sensual. Like

Molière, Mark Twain takes his stand on common

sense and thinks scorn of affectation of every sort.

He understands sinners and strugglers and weaklings;

and he is not harsh with them, reserving his

scorching hatred for hypocrites and pretenders and

frauds.

At how long an interval Mark Twain shall be rated

after Molière and Cervantes it is for the future to

declare. All that we can see clearly now is that it is

with them that he is to be classed--with Molière

and Cervantes, with Chaucer and Fielding, humorists

all of them, and all of them manly men.

xxxi

INTRODUCTION

A number of articles in this volume, even the

more important, have not heretofore appeared

in print. Mark Twain was nearly always writing--busily

trying to keep up with his imagination and

enthusiasm: A good many of his literary undertakings

remained unfinished or were held for further

consideration, in time to be quite forgotten. Few

of these papers were unimportant, and a fresh interest

attaches to them to-day in the fact that they present

some new detail of the author’s devious wanderings,

some new point of observation, some hitherto

unexpressed angle of his indefatigable thought.

The present collection opens with a chapter

from a book that was never written, a book about

England, for which the author made some preparation,

during his first visit to that country, in 1872.

He filled several notebooks with brief comments,

among which appears this single complete episode, the

description of a visit to Westminster Abbey by

night. As an example of what the book might have

been we may be sorry that it went no farther.

It was not, however, quite in line with his proposed

undertaking, which had been to write a more or

less satirical book on English manners and customs.

Arriving there, he found that he liked the people

and their country too well for that, besides he was

xxxiiso busy entertaining, and being entertained, that he

had little time for critical observation. In a letter

home he wrote:

I came here to take notes for a book, but I haven’t done much

but attend dinners and make speeches. I have had a jolly good

time, and I do hate to go away from these English folks; they

make a stranger feel entirely at home, and they laugh so easily

that it is a comfort to make after-dinner speeches here.

England at this time gave Mark Twain an even

fuller appreciation than he had thus far received in

his own country. To hunt out and hold up to

ridicule the foibles of hosts so hospitable would have

been quite foreign to his nature. The notes he made

had little satire in them, being mainly memoranda of

the moment....

“Down the Rhône,” written some twenty years

later, is a chapter from another book that failed of

completion. Mark Twain, in Europe partly for his

health, partly for financial reasons, had agreed to

write six letters for the New York Sun, two of which--those

from Aix and Marienbad--appear in this

volume. Six letters would not make a book of

sufficient size and he thought he might supplement

them by making a drifting trip down the Rhône,

the “river of angels,” as Stevenson called it, and

turning it into literature.

The trip itself proved to be one of the most delightful

excursions of his life, and his account of it,

so far as completed, has interest and charm. But he

was alone, with only his boatman (the “Admiral”)

and his courier, Joseph Very, for company, a monotony

of human material that was not inspiring. He

xxxiiimade some attempt to introduce fictitious characters,

but presently gave up the idea. As a whole

the excursion was too drowsy and comfortable to

stir him to continuous effort; neither the notes nor

the article, attempted somewhat later, ever came to

conclusion.

Three articles in this volume, beginning with “To

the Person Sitting in Darkness,” were published in

the North American Review during 1901-02, at a

period when Mark Twain had pretty well made up

his mind on most subjects, and especially concerning

the interference of one nation with another on

matters of religion and government. He had

recently returned from a ten years’ sojourn in Europe

and his opinion was eagerly sought on all public

questions, especially upon those of international

aspect. He was no longer regarded merely as a

humorist, but as a sort of Solon presiding over a

court of final conclusions. A writer in the Evening

Mail said of this later period:

Things have reached the point where, if Mark Twain is not at

a public meeting or banquet, he is expected to console it with one

of his inimitable letters of advice and encouragement.

His old friend, W. D. Howells, expressed an

amused fear that Mark Twain’s countrymen, who in

former years had expected him to be merely a

humorist, should now, in the light of his wider

acceptance abroad, demand that he be mainly

serious.

He was serious enough, and fiercely humorous as

well, in his article “To the Person Sitting in Darkness”

xxxivand in those which followed it. It seemed to

him that the human race, always a doubtful quantity,

was behaving even worse than usual. On New

Year’s Eve, 1900-01, he wrote:

A GREETING FROM THE NINETEENTH TO THE

TWENTIETH CENTURY

I bring you the stately nation named Christendom, returning,

bedraggled, besmirched, and dishonored, from pirate raids in

Kiao-Chau, Manchuria, South Africa, and the Philippines, with

her soul full of meanness, her pocket full of boodle, and her

mouth full of pious hypocracies. Give her soap and a towel,

but hide the looking-glass.

Certain missionary activities in China, in particular,

invited his attention, and in the first of the

Review articles he unburdened himself. A masterpiece

of pitiless exposition and sarcasm, its publication

stirred up a cyclone. Periodicals more or

less orthodox heaped upon him denunciation and

vituperation. “To My Missionary Critics,” published

in the Review for April, was his answer. He

did not fight alone, but was upheld by a vast following

of liberal-minded readers, both in and out of

the Church. Edward S. Martin wrote him:

How gratifying it is to feel that we have a man among us who

understands the rarity of plain truth, and who delights to utter

it, and has the gift of doing so without cant, and with not too

much seriousness.

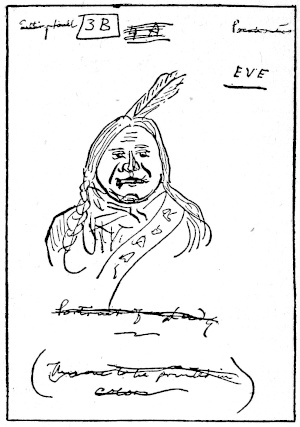

The principals of the primal human drama, our

biblical parents of Eden, play a considerable part in

Mark Twain’s imaginative writings. He wrote

“Diaries” of both Adam and Eve, that of the latter

xxxvbeing among his choicest works. He was generally

planning something that would include one or both

of the traditional ancestors, and results of this

tendency express themselves in the present volume.

Satan, likewise, the picturesque angel of rebellion

and defeat, the Satan of Paradise Lost, made a

strong appeal and in no less than three of the articles

which follow the prince of error variously appears.

For the most part these inventions offer an aspect of

humor; but again the figure of the outcast angel is

presented to us in an attitude of sorrowful kinship

with the great human tragedy.

Albert Bigelow Paine

1

A MEMORABLE MIDNIGHT EXPERIENCE

(1872)

“Come along--and hurry. Few people have got

originality enough to think of the expedition

I have been planning, and still fewer could carry it

out, maybe, even if they did think of it. Hurry,

now. Cab at the door.”

It was past eleven o’clock and I was just going to

bed. But this friend of mine was as reliable as he

was eccentric, and so there was not a doubt in my

mind that his “expedition” had merit in it. I put

on my coat and boots again, and we drove away.

“Where is it? Where are we going?”

“Don’t worry. You’ll see.”

He was not inclined to talk. So I thought this

must be a weighty matter. My curiosity grew with

the minutes, but I kept it manfully under the surface.

I watched the lamps, the signs, the numbers,

as we thundered down the long streets, but it was of

no use--I am always lost in London, day or night. It

was very chilly--almost bleak. People leaned

against the gusty blasts as if it were the dead of

winter. The crowds grew thinner and thinner and

the noises waxed faint and seemed far away. The

sky was overcast and threatening. We drove on,

and still on, till I wondered if we were ever going

to stop. At last we passed by a spacious bridge and

2a vast building with a lighted clock tower, and

presently entered a gateway, passed through a sort

of tunnel, and stopped in a court surrounded by the

black outlines of a great edifice. Then we alighted,

walked a dozen steps or so, and waited. In a little

while footsteps were heard and a man emerged from

the darkness and we dropped into his wake without

saying anything. He led us under an archway of

masonry, and from that into a roomy tunnel, through

a tall iron gate, which he locked behind us. We

followed him down this tunnel, guided more by his

footsteps on the stone flagging than by anything

we could very distinctly see. At the end of it we

came to another iron gate, and our conductor

stopped there and lit a little bull’s-eye lantern. Then

he unlocked the gate--and I wished he had oiled it

first, it grated so dismally. The gate swung open

and we stood on the threshold of what seemed a

limitless domed and pillared cavern carved out of the

solid darkness. The conductor and my friend took off

their hats reverently, and I did likewise. For the

moment that we stood thus there was not a sound,

and the silence seemed to add to the solemnity of the

gloom. I looked my inquiry!

“It is the tomb of the great dead of England--Westminster

Abbey.”

(One cannot express a start--in words.) Down

among the columns--ever so far away, it seemed--a

light revealed itself like a star, and a voice came

echoing through the spacious emptiness:

“Who goes there!”

“Wright!”

3The star disappeared and the footsteps that accompanied

it clanked out of hearing in the distance.

Mr. Wright held up his lantern and the vague

vastness took something of form to itself--the

stately columns developed stronger outlines, and a

dim pallor here and there marked the places of lofty

windows. We were among the tombs; and on every

hand dull shapes of men, sitting, standing, or stooping,

inspected us curiously out of the darkness--reached

out their hands toward us--some appealing,

some beckoning, some warning us away. Effigies,

they were--statues over the graves; but they

looked human and natural in the murky shadows.

Now a little half-grown black-and-white cat squeezed

herself through the bars of the iron gate and came

purring lovingly about us, unawed by the time or

the place--unimpressed by the marble pomp that

sepulchers a line of mighty dead that ends with a

great author of yesterday and began with a sceptered

monarch away back in the dawn of history more

than twelve hundred years ago. And she followed

us about and never left us while we pursued our

work. We wandered hither and thither, uncovered,

speaking in low voices, and stepping softly by

instinct, for any little noise rang and echoed there

in a way to make one shudder. Mr. Wright flashed

his lantern first upon this object and then upon that,

and kept up a running commentary that showed

that there was nothing about the venerable Abbey

that was trivial in his eyes or void of interest. He is

a man in authority--being superintendent of the

works--and his daily business keeps him familiar

4with every nook and corner of the great pile. Casting

a luminous ray now here, now yonder, he would

say:

“Observe the height of the Abbey--one hundred

and three feet to the base of the roof--I measured

it myself the other day. Notice the base of this

column--old, very old--hundreds and hundreds of

years; and how well they knew how to build in

those old days. Notice it--every stone is laid

horizontally--that is to say, just as nature laid it

originally in the quarry--not set up edgewise; in

our day some people set them on edge, and then

wonder why they split and flake. Architects cannot

teach nature anything. Let me remove this

matting--it is put there to preserve the pavement;

now, there is a bit of pavement that is seven hundred

years old; you can see by these scattering clusters

of colored mosaics how beautiful it was before time

and sacrilegious idlers marred it. Now there, in the

border, was an inscription once; see, follow the

circle--you can trace it by the ornaments that have

been pulled out--here is an A, and there is an O,

and yonder another A--all beautiful old English

capitals--there is no telling what the inscription

was--no record left, now. Now move along in this

direction, if you please. Yonder is where old King

Sebert the Saxon, lies--his monument is the oldest

one in the Abbey; Sebert died in 616, and that’s as

much as twelve hundred and fifty years ago--think

of it!--twelve hundred and fifty years. Now yonder

is the last one--Charles Dickens--there on the floor

with the brass letters on the slab--and to this day

5the people come and put flowers on it. Why, along

at first they almost had to cart the flowers out, there

were so many. Could not leave them there, you

know, because it’s where everybody walks--and

a body wouldn’t want them trampled on, anyway.

All this place about here, now, is the Poet’s

Corner. There is Garrick’s monument, and Addison’s,

and Thackeray’s bust--and Macaulay lies

there. And here, close to Dickens and Garrick, lie

Sheridan and Doctor Johnson--and here is old Parr--Thomas

Parr--you can read the inscription:

“Tho: Par of Y Covnty of Sallop Borne A :1483. He

Lived in Y Reignes of Ten Princes, viz: K. Edw. 4

K. Ed. 5. K. Rich 3. K. Hen. 7. K. Hen. 8. Edw. 6. QVV. Ma.

Q. Eliz. K. IA. and K. Charles, Aged 152 Yeares, And

Was Buryed Here Novemb. 15. 1635.

“Very old man indeed, and saw a deal of life.

(Come off the grave, Kitty, poor thing; she keeps

the rats away from the office, and there’s no harm

in her--her and her mother.) And here--this is

Shakespeare’s statue--leaning on his elbow and

pointing with his finger at the lines on the scroll:

“The cloud-capt towers, the gorgeous palaces,

The solemn temples, the great globe itself,

Yea, all which it inherit shall dissolve,

And, like the baseless fabric of a vision,

Leave not a wrack behind.

“That stone there covers Campbell the poet.

Here are names you know pretty well--Milton, and

Gray who wrote the ‘Elegy,’ and Butler who wrote

‘Hudibras,’ and Edmund Spencer, and Ben Jonson--there

are three tablets to him scattered about the

6Abbey, and all got ‘O Rare Ben Jonson’ cut on

them--you were standing on one of them just now--he

is buried standing up. There used to be a tradition

here that explains it. The story goes that he

did not dare ask to be buried in the Abbey, so he

asked King James if he would make him a present of

eighteen inches of English ground, and the king

said yes, and asked him where he would have it, and

he said in Westminster Abbey. Well, the king

wouldn’t go back on his word, and so there he is

sure enough--stood up on end. Years ago, in Dean

Buckland’s time--before my day--they were digging

a grave close to Jonson and they uncovered him and

his head fell off. Toward night the clerk of the

works hid the head to keep it from being stolen, as

the ground was to remain open till next day. Presently

the dean’s son came along and he found a

head, and hid it away for Jonson’s. And by and by

along comes a stranger, and he found a head, too,

and walked off with it under his cloak, and a month

or so afterward he was heard to boast that he had

Ben Jonson’s head. Then there was a deal of correspondence

about it, in the Times, and everybody

distressed. But Mr. Frank Buckland came out and

comforted everybody by telling how he saved the

true head, and so the stranger must have got one

that wasn’t of any consequence. And then up speaks

the clerk of the works and tells how he saved the

right head, and so Dean Buckland must have got a

wrong one. Well, it was all settled satisfactorily at

last, because the clerk of the works proved his head.

And then I believe they got that head from the

7stranger--so now we have three. But it shows you

what regiments of people you are walking over--been

collecting here for twelve hundred years--in

some places, no doubt, the bones are fairly matted

together.

“And here are some unfortunates. Under this

place lies Anne, queen of Richard III, and daughter

of the Kingmaker, the great Earl of Warwick--murdered

she was--poisoned by her husband. And

here is a slab which you see has once had the figure of

a man in armor on it, in brass or copper, let into the

stone. You can see the shape of it--but it is all

worn away now by people’s feet; the man has been

dead five hundred years that lies under it. He was

a knight in Richard II’s time. His enemies pressed

him close and he fled and took sanctuary here in the

Abbey. Generally a man was safe when he took

sanctuary in those days, but this man was not. The

captain of the Tower and a band of men pursued

him and his friends and they had a bloody fight here

on this floor; but this poor fellow did not stand

much of a chance, and they butchered him right

before the altar.”

We wandered over to another part of the Abbey,

and came to a place where the pavement was being

repaired. Every paving stone has an inscription on

it and covers a grave. Mr. Wright continued:

“Now, you are standing on William Pitt’s grave--you

can read the name, though it is a good deal

worn--and you, sir, are standing on the grave of

Charles James Fox. I found a very good place here

the other day--nobody suspected it--been curiously

8overlooked, somehow--but--it is a very nice place

indeed, and very comfortable” (holding his bull’s

eye to the pavement and searching around). “Ah,

here it is--this is the stone--nothing under here--nothing

at all--a very nice place indeed--and very

comfortable.”

Mr. Wright spoke in a professional way, of course,

and after the manner of a man who takes an interest

in his business and is gratified at any piece of good

luck that fortune favors him with; and yet withwith all

that silence and gloom and solemnity about me,

there was something about his idea of a nice, comfortable

place that made the cold chills creep up my

back. Presently we began to come upon little

chamberlike chapels, with solemn figures ranged

around the sides, lying apparently asleep, in sumptuous

marble beds, with their hands placed together

above their breasts--the figures and all their surroundings

black with age. Some were dukes and

earls, some where kings and queens, some were

ancient abbots whose effigies had lain there so many

centuries and suffered such disfigurement that their

faces were almost as smooth and featureless as the

stony pillows their heads reposed upon. At one time

while I stood looking at a distant part of the pavement,

admiring the delicate tracery which the now

flooding moonlight was casting upon it through a

lofty window, the party moved on and I lost them.

The first step I made in the dark, holding my hands

before me, as one does under such circumstances,

I touched a cold object, and stopped to feel its

shape. I made out a thumb, and then delicate

9fingers. It was the clasped, appealing hands of one

of those reposing images--a lady, a queen. I

touched the face--by accident, not design--and

shuddered inwardly, if not outwardly; and then

something rubbed against my leg, and I shuddered

outwardly and inwardly both. It was the cat. The

friendly creature meant well, but, as the English say,

she gave me “such a turn.” I took her in my arms

for company and wandered among the grim sleepers

till I caught the glimmer of the lantern again. Presently,

in a little chapel, we were looking at the sarcophagus,

let into the wall, which contains the bones

of the infant princes who were smothered in the

Tower. Behind us was the stately monument of

Queen Elizabeth, with her effigy dressed in the royal

robes, lying as if at rest. When we turned around,

the cat, with stupendous simplicity, was coiled up

and sound asleep upon the feet of the Great Queen!

Truly this was reaching far toward the millennium

when the lion and the lamb shall lie down together.

The murderer of Mary and Essex, the conqueror of

the Armada, the imperious ruler of a turbulent

empire, become a couch, at last, for a tired kitten!

It was the most eloquent sermon upon the vanity of

human pride and human grandeur that inspired

Westminster preached to us that night.

We would have turned puss out of the Abbey, but

for the fact that her small body made light of railed

gates and she would have come straight back again.

We walked up a flight of half a dozen steps and,

stopping upon a pavement laid down in 1260, stood

in the core of English history, as it were--upon the

10holiest ground in the British Empire, if profusion of

kingly bones and kingly names of old renown make

holy ground. For here in this little space were the

ashes, the monuments and gilded effigies, of ten of

the most illustrious personages who have worn

crowns and borne scepters in this realm. This

royal dust was the slow accumulation of hundreds of

years. The latest comer entered into his rest four

hundred years ago, and since the earliest was sepulchered,

more than eight centuries have drifted by.

Edward the Confessor, Henry the Fifth, Edward the

First, Edward the Third, Richard the Second, Henry

the Third, Eleanor, Philippa, Margaret Woodville--it

was like bringing the colossalcolossal myths of history

out of the forgotten ages and speaking to them face

to face. The gilded effigies were scarcely marred--the

faces were comely and majestic, old Edward the

First looked the king--one had no impulse to be

familiar with him. While we were contemplating

the figure of Queen Eleanor lying in state, and

calling to mind how like an ordinary human being

the great king mourned for her six hundred years

ago, we saw the vast illuminated clock face of the

Parliament House tower glowering at us through a

window of the Abbey and pointing with both hands to

midnight. It was a derisive reminder that we were a

part of this present sordid, plodding, commonplace

time, and not august relics of a bygone age and the

comrades of kings--and then the booming of the

great bell tolled twelve, and with the last stroke

the mocking clock face vanished in sudden darkness

and left us with the past and its grandeurs again.

11We descended, and entered the nave of the

splendid Chapel of Henry VII. Mr. Wright said:

“Here is where the order of knighthood was conferred

for centuries; the candidates sat in these

seats; these brasses bear their coats of arms; these

are their banners overhead, torn and dusty, poor old

things, for they have hung there many and many a

long year. In the floor you see inscriptions--kings

and queens that lie in the vault below. When this

vault was opened in our time they found them lying

there in beautiful order--all quiet and comfortable--the

red velvet on the coffins hardly faded any.

And the bodies were sound--I saw them myself.

They were embalmed, and looked natural, although

they had been there such an awful time.

Now in this place here, which is called the chantry,

is a curious old group of statuary--the figures are

mourning over George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham,

who was assassinated by Felton in Charles I’s

time. Yonder, Cromwell and his family used to lie.

Now we come to the south aisle and this is the grand

monument to Mary Queen of Scots, and her effigy--you

easily see they get all the portraits from this

effigy. Here in the wall of the aisle is a bit of a

curiosity pretty roughly carved:

Wm. WEST TOOME

SHOWER

1698

“William West, tomb shower, 1698. That fellow

carved his name around in several places about the

Abbey.”

12This was a sort of revelation to me. I had been

wandering through the Abbey, never imagining but

that its shows were created only for us--the people

of the nineteenth century. But here is a man (become

a show himself now, and a curiosity) to whom

all these things were sights and wonders a hundred

and seventy-five years ago. When curious idlers

from the country and from foreign lands came here

to look, he showed them old Sebert’s tomb and those

of the other old worthies I have been speaking of, and

called them ancient and venerable; and he showed

them Charles II’s tomb as the newest and latest

novelty he had; and he was doubtless present at the

funeral. Three hundred years before his time some

ancestor of his, perchance, used to point out the

ancient marvels, in the immemorial way and then

say: “This, gentlemen, is the tomb of his late

Majesty Edward the Third--and I wish I could see

him alive and hearty again, as I saw him twenty

years ago; yonder is the tomb of Sebert the Saxon

king--he has been lying there well on to eight

hundred years, they say. And three hundred years

before this party, Westminster was still a show, and

Edward the Confessor’s grave was a novelty of some

thirty years’ standing--but old “Sebert” was

hoary and ancient still, and people who spoke of

Alfred the Great as a comparatively recent man

pondered over Sebert’s grave and tried to take in all

the tremendous meaning of it when the “toome

shower” said, “This man has lain here well nigh five

hundred years.” It does seem as if all the generations

that have lived and died since the world was

13created have visited Westminster to stare and wonder--and

still found ancient things there. And some

day a curiously clad company may arrive here in a

balloon ship from some remote corner of the globe,

and as they follow the verger among the monuments

they may hear him say: “This is the tomb of Victoria

the Good Queen; battered and uncouth as it

looks, it once was a wonder of magnificence--but

twelve hundred years work a deal of damage to these

things.”

As we turned toward the door the moonlight was

beaming in at the windows, and it gave to the

sacred place such an air of restfulness and peace

that Westminster was no longer a grisly museum of

moldering vanities, but her better and worthier self--the

deathless mentor of a great nation, the guide

and encourager of right ambitions, the preserver of

just fame, and the home and refuge for the nation’s

best and bravest when their work is done.

14

TWO MARK TWAIN EDITORIALS

(Written 1869 and 1870, for the Buffalo Express, of which

Mark Twain became editor and part owner)

I

“SALUTATORY”

Being a stranger, it would be immodest and

unbecoming in me to suddenly and violently

assume the associate editorship of the Buffalo Express

without a single explanatory word of comfort

or encouragement to the unoffending patrons of the

paper, who are about to be exposed to constant attacks

of my wisdom and learning. But this explanatory

word shall be as brief as possible. I only

wish to assure parties having a friendly interest in

the prosperity of the journal, that I am not going to

hurt the paper deliberately and intentionally at any

time. I am not going to introduce any startling

reforms, or in any way attempt to make trouble. I

am simply going to do my plain, unpretending duty,

when I cannot get out of it; I shall work diligently

and honestly and faithfully at all times and upon all

occasions, when privation and want shall compel

me to do it; in writing, I shall always confine myself

strictly to the truth, except when it is attended

with inconvenience; I shall witheringly rebuke all

forms of crime and misconduct, except when committed

15by the party inhabiting my own vest; I shall

not make use of slang or vulgarity upon any occasion

or under any circumstances, and shall never use

profanity except in discussing house rent and taxes.

Indeed, upon second thought, I will not even use it

then, for it is unchristian, inelegant, and degrading--though

to speak truly I do not see how house rent

and taxes are going to be discussed worth a cent

without it. I shall not often meddle with politics,

because we have a political editor who is already

excellent, and only needs to serve a term in the

penitentiary in order to be perfect. I shall not write

any poetry, unless I conceive a spite against the

subscribers.

Such is my platform. I do not see any earthly use

in it, but custom is law, and custom must be obeyed,

no matter how much violence it may do to one’s

feelings. And this custom which I am slavishly following

now is surely one of the least necessary that

ever came into vogue. In private life a man does

not go and trumpet his crime before he commits it,

but your new editor is such an important personage

that he feels called upon to write a “salutatory” at

once, and he puts into it all that he knows, and all

that he don’t know, and some things he thinks he

knows but isn’t certain of. And he parades his list

of wonders which he is going to perform; of reforms

which he is going to introduce, and public evils which

he is going to exterminate; and public blessings

which he is going to create; and public nuisances

which he is going to abate. He spreads this all out

with oppressive solemnity over a column and a half

16of large print, and feels that the country is saved.

His satisfaction over it, something enormous. He

then settles down to his miracles and inflicts profound

platitudes and impenetrable wisdom upon a

helpless public as long as they can stand it, and then

they send him off consul to some savage island in the

Pacific in the vague hope that the cannibals will like

him well enough to eat him. And with an inhumanity

which is but a fitting climax to his career

of persecution, instead of packing his trunk at once

he lingers to inflict upon his benefactors a “valedictory.”

If there is anything more uncalled for

than a “salutatory,” it is one of those tearful,

blubbering, long-winded “valedictories”--wherein

a man who has been annoying the public for ten

years cannot take leave of them without sitting

down to cry a column and a half. Still, it is the

custom to write valedictories, and custom should be

respected. In my secret heart I admire my predecessor

for declining to print a valedictory, though

in public I say and shall continue to say sternly, it is

custom and he ought to have printed one. People

never read them any more than they do the “salutatories,”

but nevertheless he ought to have honored

the old fossil--he ought to have printed a valedictory.

I said as much to him, and he replied:

“I have resigned my place--I have departed this

life--I am journalistically dead, at present, ain’t I?”

“Yes.”

“Well, wouldn’t you consider it disgraceful in a

corpse to sit up and comment on the funeral?”

I record it here, and preserve it from oblivion, as

17the briefest and best “valedictory” that has yet

come under my notice.

Mark Twain.

P. S.--I am grateful for the kindly way in which

the press of the land have taken notice of my irruption

into regular journalistic life, telegraphically

or editorially, and am happy in this place to express

the feeling.

II

A TRIBUTE TO ANSON BURLINGAME

On Wednesday, in St. Petersburg, Mr. Burlingame

died after a short illness. It is not easy

to comprehend, at an instant’s warning, the exceeding

magnitude of the loss which mankind sustains

in this death--the loss which all nations and

all peoples sustain in it. For he had outgrown the

narrow citizenship of a state and become a citizen

of the world; and his charity was large enough and

his great heart warm enough to feel for all its races

and to labor for them. He was a true man, a brave

man, an earnest man, a liberal man, a just man, a

generous man, in all his ways and by all his instincts

a noble man; he was a man of education and culture,

a finished conversationalist, a ready, able, and graceful

speaker, a man of great brain, a broad and deep

and weighty thinker. He was a great man--a very,

very great man. He was imperially endowed by

nature; he was faithfully befriended by circumstances,

and he wrought gallantly always, in whatever

station he found himself.

18He was a large, handsome man, with such a face

as children instinctively trust in, and homeless and