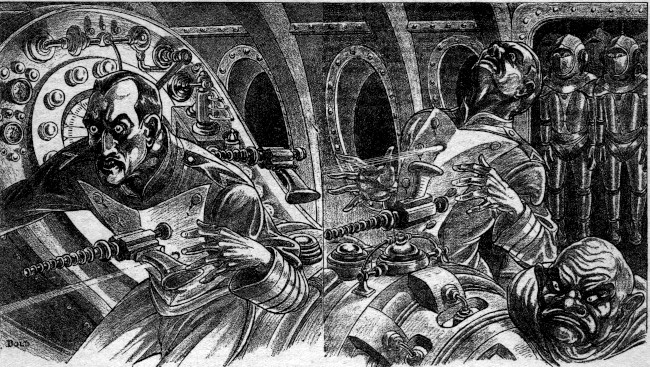

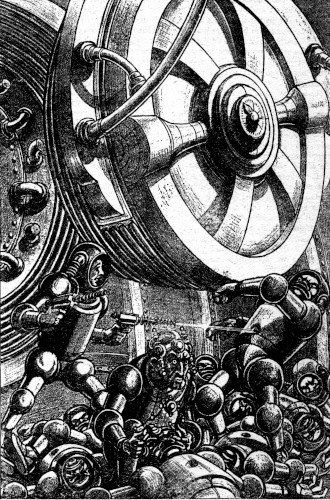

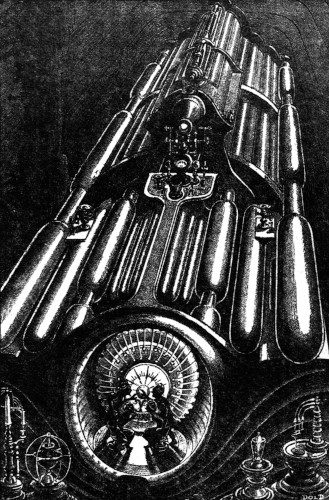

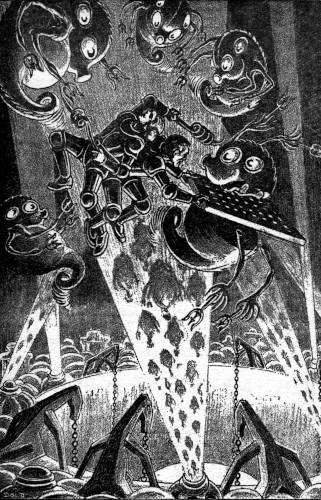

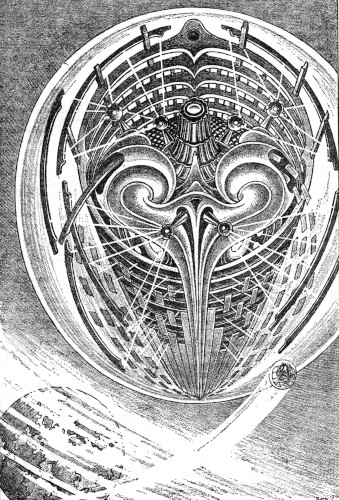

Illustrated by Elliot Dold

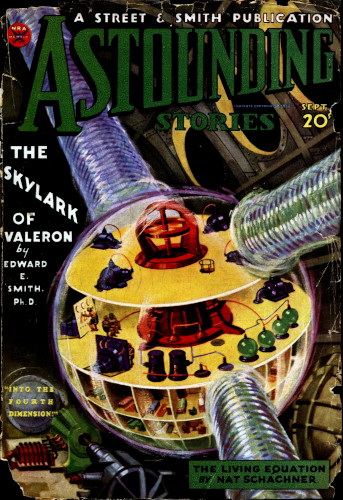

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

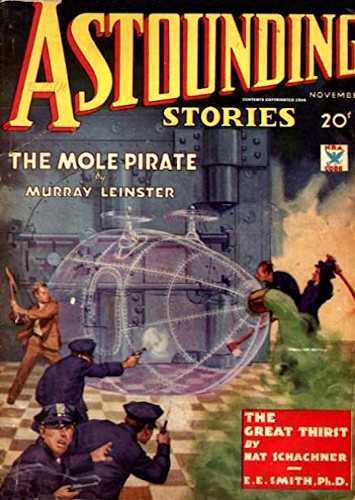

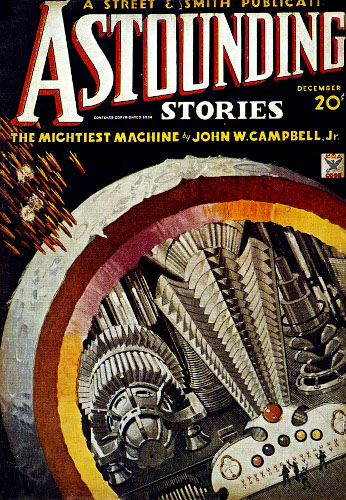

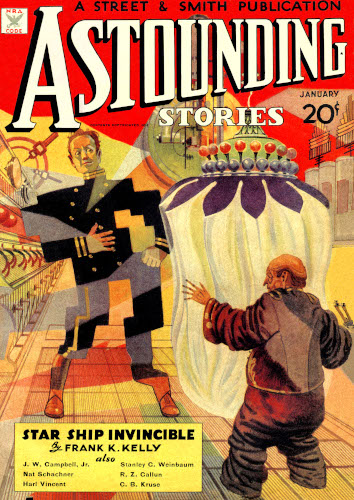

Astounding Stories August, September, October,

November, December 1934, January, February 1935.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

PROLOGUE

"Mother-r-r!" A sturdy, auburn-haired urchin of twelve—Richard Ballinger Seaton the fourteen hundred and seventy-first—turned to the queenly young matron who was his mother as the viewing area before them went blank. "You said that as soon as I was old enough you would let me see the rest of the 'Exploits of Seaton One.' Now grandfather's the chief of the Galactic Council, and I'm twelve, and I'm old enough."

"Perhaps you are, son." Into the beautiful eyes of the young woman came that indefinable, indescribable something; the knowledge that her oldest was no longer a baby. "Tell me the story as it is run for the holiday, and I shall see."

"Richard Ballinger Seaton the First was a Ph. D. in chemistry," the boy began. "He lived in the city of Washington, in what was then the United States of America. He was born—"

"Never mind dates and such things, sonny. It would take too long to give all the details. I just want to make sure that you really understand the story—conditions were so different then from what they are now."

"Well, Seaton One discovered Rovolon, which he called 'X' metal at first. He found out that it would turn copper into energy, and he and Martin Reynolds Crane One built the very first space ship that was ever known. But the World Steel Corporation wanted all the Rovolon that Seaton had found; so Dr. DuQuesne, a chemist of theirs, and a kind of a spy named Perkins, tried to steal it away from him. They got a little of it, but it exploded some copper and killed a lot of people.

"When Seaton heard about the explosion he found out that some of his Rovolon was gone, and they hired some detectives and had an awful time. A lot more people were killed, and a Japanese assistant of Crane's, named Shiro, was almost killed, too. Then they went to work and invented a lot of new instruments, such as a compass that pointed at any one thing forever; and attractors and repellers and rays and screens and explosives and lots of things that are good yet.

"This DuQuesne tried for a long time to get the Rovolon and couldn't, so they built a space ship from Seaton's plans that they stole, and he carried off Dorothy Vaneman and Margaret Spencer, the girls that Seaton One and Crane One were going to marry—and they did marry them, afterward, too. Well, Dorothy kicked Perkins in the stomach, and the space ship ran away and kept on going until it got caught by the attraction of the Dark Mass that the First of Energy has always had so much trouble with, and while they were falling toward it that Perkins went crazy and tried to kill Margaret, but DuQuesne killed him instead, and then Seaton One caught up with them and rescued them and—"

"Just a minute, son; there is no great hurry. How did Seaton One get way out there?"

"Well, they had their big new space ship, the Skylark of Space, all built by then, and Seaton One had an object-compass set on DuQuesne, because he'd been watching him a long time since he'd been making lots of trouble for him. So Seaton One and Crane One followed the object-compass and found them and rescued them all but Perkins, because he was dead already.

"They had an awful time getting away from the Dark Mass, but they did it, but they were about out of copper, so they had to hunt up a planet that had some. They landed on one that dinosaurs and things like that lived on, and got a lot more Rovolon, but didn't find any copper, so they hunted up more planets. One had poison gas instead of air, and another had people that were pure intellectuals, so that they had bodies whenever they wanted to, but not all the time. They pretty nearly dematerialized Seaton One and all the rest of them, and we're awfully glad they didn't.

"Well, anyway, they got away, but they had an awful time, and after a while they saw the green suns of the Central System. There's lots of copper there, you know; so much that Grandfather Seaton wouldn't let me swim in the ocean last year when we were there because it was copper solution and it would have made me sick. They went to Osnome first, one of the inside worlds, and landed in a country named Mardonale.

"They were bad people and wanted to kill Seaton One and steal his ship, and they had already captured Dunark, the Kofedix or crown prince of the other nation, Kondal. Then Dunark helped Seaton One get away, and they all went home with Dunark. But the Skylark was pretty nearly ruined in the battle they had getting away from Mardonale, so Seaton One and Dunark built it over out of arenak, which was much better than the funny, soft steel they used to use in the old days. Of course, arenak doesn't amount to much beside the inoson we have now, but even Seaton One didn't know anything about inoson then.

"Then they got married. Seaton married Dorothy, and they're our great-great—fourteen hundred and seventy times—grandparents. Crane married Margaret, and they're awfully famous, too. And Shiro is, too, especially in Asiatica. Well, anyway, after they got married they had a fight with a monster Karlon, and were just going to start back here for Tellus when the whole Mardonalian fleet attacked Kondal. The Skylark Two beat them all, and DuQuesne helped, too, and then of course Dunark's father was Karfedix or emperor of the whole planet of Osnome, and he made Seaton One the overlord. Then they came back home. Seaton One and Crane One didn't know just what to do with DuQuesne, but he jumped out of Skylark Two in a parachute and got away.

"They hadn't been back on Tellus very long when Dunark came to visit them, from Osnome, after some salt which they needed to make arenak, and some more Rovolon. He was going to blow up another planet of the Central Sun because they were having a war. But Seaton One didn't have enough Rovolon, so both Skylark Two and the Kondal started out to go to the 'X' planet after some, and on the way there they were attacked by a space ship of the Fenachrone, who were a race of terrible men who were going to conquer the whole universe. The Fenachrone blew up the Kondal, and pretty nearly destroyed the Skylark, too, but Seaton One could use zones of force as well as they could—I don't know much about zones of force because they're in advanced physics, but they're barriers in the ether and space ships use them yet because nothing above the fifth level can get through them—and finally Seaton One cut the Fenachrone ship all up into little pieces. Then he rescued Dunark, and one of his wives named Sitar, but one of the bad men got away without being killed and DuQuesne picked him up—"

"But you haven't said anything about DuQuesne being out there, sonny."

"Well, he was. He kept on trying to get the Rovolon away from Seaton One, but couldn't, so he took his own space ship and went to Osnome. You see, while he was there he had found out something about the Fenachrone and was going to join them. Well, he got to Osnome and stole a better space ship than the one he had and started out to go to the Fenachrone System, but on the way he passed close to where Skylark Two was fighting the big Fenachrone ship, which was the flagship Y427W. The chief engineer of the ship got away, and DuQuesne rescued him, and he showed DuQuesne how to get to the Fenachrone world, and he installed his own super-drive on the Violet, which was the name of DuQuesne's ship. But when they got there something funny happened. A Fenachrone patrol ship apparently captured the Violet, and they burned up what they thought were DuQuesne and Loring—this Loring was DuQuesne's helper—and the engineer reported over the visirecorder everything that had happened to the flagship, and Seaton and Crane were listening in on their projector. Now's the funny part. Some of the visirecorder report was right, but some of it didn't really happen that way at all, because Dr. DuQuesne knew all the time what was going—"

"You are getting ahead of the story, sonny. You have heard that part, of course, but you haven't actually seen the record of it yet."

"Well, anyway, Seaton One found out the Fenachrone's plans by reading their brains with a mechanical educator, and he made Dunark's people make peace with the other planet, the one that they were going to blow up. He knew from some old legends that there was a race of green men somewhere in the Central System that knew everything, so he went hunting for them. They went to Dasor first, where those funny porpoise men live, and a Dasorian named Sacner Carfon was councilor then. A Sacner Carfon is councilor there yet, too, and I beat his boy shooting a ray, but he beat me all hollow swimming, because he's got web feet and hands. The Dasorians told Seaton One where to go, and that's how they found Norlamin, where the oldest and wisest men in the whole Galaxy live. Rovol, the First of Rays, and Drasnik, the First of Psychology, and Caslor, the First of Mechanism, and lots of the other Firsts of Norlamin helped them build things.

"Oh, yes; I almost forgot about the way the Norlaminian scientists learn things. When one of them gets old he makes a record of his brain on a tape, and when his son takes his place he just transfers all his knowledge to the son's brain with a mechanical educator, and then he—the son, I mean—knows everything that every specialist in that line ever did find out, and he goes on from there. Rovol and Drasnik and some of the others gave Seaton One and Crane One copies of their own brains that way, and that's why they knew so much. And then they built a projector that would take images of themselves clear across the Galaxy in a couple of seconds on fifth-order rays, and into the middle of suns and anywhere else they wanted to be or work, and then they built Skylark Three, a space ship about five kilometers long. Not so much these days, of course, but she was the biggest thing in the ether then.

"But by that time the Fenachrone fleet had started out to conquer the Galaxy, and Seaton One and Crane One and all the other Ones and the Firsts of Norlamin hunted them up with the projector and blew them up by exploding their power bars, which were made of copper instead of uranium, like Three used. And then Dunark blew up the whole Fenachrone planet, so that they'd never make any more trouble, but one Fenachrone ship got away and started out for another Galaxy, 'way out of range of the projector. So Seaton One chased it and caught it out in space, halfway to the other Galaxy. They had a terrible battle, but Seaton One blew it up and the picture stopped, and I want to see some more of the 'Exploits,' mother, please!"

"Very well told, son—I believe that you are old enough to follow One and his friends of ancient times. You will have them next year, anyway, in your history classes, and you might as well see them now; particularly since it is our own family history as well as that of civilization." The young woman pressed a contact in the arm of her chair and spoke:

"Central Library of History, please.... Mrs. R. B. Seaton fourteen seventy. Please put on reel three of the 'Exploits.' Wave point one nine four six.... Thank you."

I.

Day after day a spherical space ship of arenak tore through the illimitable reaches of the interstellar void. She had once been a war vessel of Osnome; now, rechristened the Violet, she was bearing two Terrestrials and a Fenachrone—Dr. Marc C. DuQuesne of World Steel, "Baby Doll" Loring, his versatile and accomplished assistant, and the squat and monstrous engineer of the flagship Y427W—from the Green System toward the Solar System of the Fenachrone. The mid-point of the stupendous flight had long since been passed; the Violet had long been "braking down" with a negative acceleration of five times the velocity of light.

Much to the surprise of both DuQuesne and Loring, their prisoner had not made the slightest move against them. He had thrown all the strength of his supernaturally powerful body and all the resources of his gigantic brain into the task of converting the atomic motors of the Violet into the space-annihilating drive of his own race. This drive, affecting alike as it does every atom of substance within the radius of action of the power bar, entirely nullifies the effect of acceleration, so that the passengers feel no motion whatever, even when the craft is accelerating at maximum—and that maximum is almost three times as great as the absolutely unbearable full power of the Skylark of Space.

The engineer had not shirked a single task, however arduous. And, once under way, he had nursed those motors along with every artifice known to his knowing clan; he had performed such prodigies of adjustment and tuning as to raise by a full two per cent their already inconceivable maximum acceleration. And this was not all. After the first moment of rebellion, he did not even once attempt to bring to bear the almost irresistible hypnotic power of his eyes; the immense, cold, ruby-lighted projectors of mental energy which, both men knew, were awful weapons indeed. Nor did he even once protest against the attractors which were set upon his giant limbs.

Immaterial bands, these, whose slight force could not be felt unless the captor so willed. But let the prisoner make one false move, and those tiny beams of force would instantly become copper-driven tornadoes of pure energy, hurling the luckless body against the wall of the control room and holding him motionless there, in spite of the most terrific exertions of his mighty body.

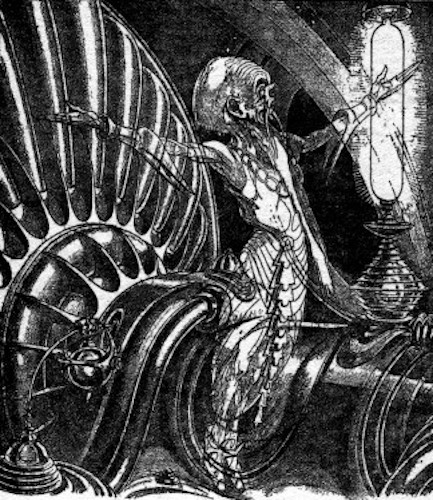

DuQuesne lay at ease in his seat; rather, scarcely touching the seat, he floated at ease in the air above it. His black brows were drawn together, his black eyes were hard as he studied frowningly the Fenachrone engineer. As usual, that worthy was half inside the power plant, coaxing those mighty motors to do even better than their prodigious best.

Feeling his companion's eyes upon him, the doctor turned his inscrutable stare upon Loring, who had been studying his chief even as DuQuesne had been studying the outlander. Loring's cherubic countenance was as pinkly innocent as ever, his guileless blue eyes as calm and untroubled; but DuQuesne, knowing the man as he did, perceived an almost imperceptible tension and knew that the killer also was worried.

"What's the matter, Doll?" The saturnine scientist smiled mirthlessly. "Afraid I'm going to let that ape slip one over on us?"

"Not exactly." Loring's slight tenseness, however, disappeared. "It's your party, and anything that's all right with you tickles me half to death. I have known all along you knew that that bird there isn't working under compulsion. You know as well as I do that nobody works that way because they're made to. He's working for himself, not for us, and I had just begun to wonder if you weren't getting a little late in clamping down on him."

"Not at all—there are good and sufficient reasons for this apparent delay. I am going to clamp down on him in exactly"—DuQuesne glanced at his wrist watch—"fourteen minutes. But you're keen—you've got a brain that really works—maybe I'd better give you the whole picture."

DuQuesne, approving thoroughly of his iron-nerved, cold-blooded assistant, voiced again the thought he had expressed once before, a few hours out from Earth; and Loring answered as he had then, in almost the same words—words which revealed truly the nature of the man:

"Just as you like. Usually I don't want to know anything about anything, because what a man doesn't know he can't be accused of spilling. Out here, though, maybe I should know enough about things to act intelligently in case of a jam. But you're the doctor—if you'd rather keep it under your hat, that's all right with me, too. As I've said before, it's your party."

"Yes; he certainly is working for himself." DuQuesne scowled blackly. "Or, rather, he thinks he is. You know I read his mind back there, while he was unconscious. I didn't get all I wanted to, by any means—he woke up too soon—but I got a lot more than he thinks I did.

"They have detector zones, 'way out in space, all around their world, that nothing can get past without being spotted; and patrolling those zones there are scout ships, carrying armament to stagger the imagination. I intend to take over one of those patrol ships and by means of it to capture one of their first-class battleships. As a first step I'm going to hypnotize that ape and find out absolutely everything that he knows. When I get done with him, he'll do exactly what I tell him to, and nothing else."

"Hypnotize him?" Curiosity was awakened in even Loring's incurious mind at this unexpected development. "I didn't know that was one of your specialties."

"It wasn't until recently, but the Fenachrone are all past masters, and I learned about it from his brain. Hypnosis is a wonderful science. The only drawback is that his mind is a lot stronger than mine. However, I have in my kit, among other things, a tube of something that will cut him down to my size."

"Oh, I see—pentabarb." With this hint, Loring's agile mind grasped instantly the essentials of DuQuesne's plan. "That's why you had to wait so long, then, to take steps. Pentabarb kills in twenty-four hours, and he can't help us steal the ship after he's dead."

"Right! One milligram, you know, will make a gibbering idiot out of any human being; but I imagine that it will take three or four times that much to soften him down to the point where I can work on him the way I want to. As I don't know the effects of such heavy dosages, since he's not really human, and since he must be alive when we go through their screens, I decided to give him the works exactly six hours before we are due to hit their outermost detector. That's about all I can tell you right now; I'll have to work out the details of seizing the ship after I have studied his brain more thoroughly."

Precisely at the expiration of the fourteen allotted minutes, DuQuesne tightened the attractor beams, which had never been entirely released from their prisoner; thus pinning him helplessly, immovably, against the wall of the control room. He then filled a hypodermic syringe and moved the mechanical educator nearer the motionless, although violently struggling, creature. Then, avoiding carefully the baleful outpourings of those flame-shot volcanoes of hatred that were the eyes of the Fenachrone, he set the dials of the educator, placed the headsets, and drove home the needle's hollow point. One milligram of the diabolical compound was absorbed, without appreciable lessening of the blazing defiance being hurled along the educator's wires. One and one half—two milligrams—three—four—five—

That inhumanly powerful mind at last began to weaken, but it became entirely quiescent only after the administration of the seventh milligram of that direly potent drug.

"Just as well that I allowed only six hours." DuQuesne sighed in relief as he began to explore the labyrinthine intricacies of the frightful brain now open to his gaze. "I don't see how any possible form of life can hold together long under seven milligrams of that stuff."

He fell silent and for more than an hour he studied the brain of the engineer, concentrating upon the several small portions which contained knowledge of most immediate concern. Then he removed the headsets.

"His plans were all made," he informed Loring coldly, "and so are mine, now. Bring out two full outfits of clothing—one of yours and one of mine. Two guns, belts, and so on. Break out a bale of waste, the emergency candles, and all that sort of stuff you can find."

DuQuesne turned to the Fenachrone, who stood utterly lax, inanimate, and stared deep into those now dull and expressionless eyes.

"You," he directed crisply, "will build at once, as quickly as you can, two dummies which will look exactly like Loring and myself. They must be lifelike in every particular, with faces capable of expressing the emotions of surprise and of anger, and with right arms able to draw weapons upon signal—my signal. Also upon signal their heads and bodies will turn, they will leap toward the center of the room, and they will make certain noises and utter certain words, the records of which I shall prepare. Go to it!"

"Don't you need to control him through the headsets?" asked Loring curiously.

"I may have to control him in detail when we come to the really fine work, later on," DuQuesne replied absently. "This is more or less in the nature of an experiment, to find out whether I have him thoroughly under control. During the last act he'll have to do exactly what I shall have told him to do, without supervision, and I want to be absolutely certain that he will do it without a slip."

"What's the plan—or maybe it's something that is none of my business?"

"No; you ought to know it, and I've got time to tell you about it now. Nothing material can possibly approach the planet of the Fenachrone without being seen, as it is completely surrounded by never less than two full-sphere detector screens; and to make assurance doubly sure our engineer there has installed a mechanism which, at the first touch of the outer screen, will shoot a warning along at tight communicator beam, directly into the receiver of the nearest Fenachrone scout ship. As you already know, the smallest of those scouts can burn this ship out of the ether in less than a second."

"That's a cheerful picture. You still think we can get away?"

"I'm coming to that. We can't possibly get through the detectors without being challenged, even if I tear out all his apparatus, so we're going to use his whole plan, but for our benefit instead of his. Therefore his present hypnotic state and the dummies. When we touch that screen you and I are going to be hidden—well hidden. The dummies will be in sole charge, and our prisoner will be playing the part I have laid out for him.

"The scout ship that he calls will come up to investigate. They will bring apparatus and attractors to bear to liberate the prisoner, and the dummies will try to fight. They will be blown up or burned to cinders almost instantly, and our little playmate will put on his space suit and be taken across to the capturing vessel. Once there, he will report to the commander.

"That officer will think the affair sufficiently serious to report it directly to headquarters. If he doesn't, this ape here will insist upon reporting it to general headquarters himself. As soon as that report is in, we, working through our prisoner here, will proceed to wipe out the crew of the ship and take it over."

"And do you think he'll really do it?" Loring's guileless face showed doubt, his tone was faintly skeptical.

"I know he'll do it!" The chemist's voice was hard. "He won't take any active part—I'm not psychologist enough to know whether I could drive him that far, even drugged, against an unhypnotizable subconscious or not—but he'll be carrying something along that will enable me to do it, easily and safely. But that's about enough of this chin music—we'd better start doing something."

While Loring brought space clothing and weapons, and rummaged through the vessel in search of material suitable for the dummies' fabrication, the Fenachrone engineer worked rapidly at his task. And not only did he work rapidly, he worked skillfully and artistically as well. This artistry should not be surprising, for to such a mentality as must necessarily be possessed by the chief engineer of a first-line vessel of the Fenachrone, the faithful reproduction of anything capable of movement was not a question of art—it was merely an elementary matter of line, form, and mechanism.

Cotton waste was molded into shape, reënforced, and wrapped in leather under pressure. To the bodies thus formed were attached the heads, cunningly constructed of masticated fiber, plastic, and wax. Tiny motors and many small pieces of apparatus were installed, and the completed effigies were dressed and armed.

DuQuesne's keen eyes studied every detail of the startlingly lifelike, almost microscopically perfect, replicas of himself and his traveling companion.

"A good job," he commented briefly.

"Good?" exclaimed Loring. "It's perfect! Why, that dummy would fool my own wife, if I had one—it almost fools me!"

"At least, they're good enough to pass a more critical test than any they are apt to get during this coming incident."

Satisfied, DuQuesne turned from his scrutiny of the dummies and went to the closet in which had been stored the space suit of the captive. To the inside of its front protector flap he attached a small and inconspicuous flat-sided case. He then measured carefully, with a filar micrometer, the apparent diameter of the planet now looming so large beneath them.

"All right, Doll; our time's getting short. Break out our suits and test them, will you, while I give the big boy his final instructions?"

Rapidly those commands flowed over the wires of the mechanical educator, from DuQuesne's hard, keen brain into the now-docile mind of the captive. The Earthly scientist explained to the Fenachrone, coldly, precisely, and in minute detail, exactly what he was to do and exactly what he was to say from the moment of encountering the detector screens of his native planet until after he had reported to his superior officers.

Then the two Terrestrials donned their own armor of space and made their way into an adjoining room, a small armory in which were hung several similar suits and which was a veritable arsenal of weapons.

"We'll hang ourselves up on a couple of these hooks, like the rest of the suits," DuQuesne explained. "This is the only part of the performance that may be even slightly risky, but there is no real danger that they will spot us. That fellow's message to the scout ship will tell them that there are only two of us, and we'll be out there with him, right in plain sight.

"If by any chance they should send a party aboard us they would probably not bother to search the Violet at all carefully, since they will already know that we haven't got a thing worthy of attention; and they would of course suppose us to be empty space suits. Therefore keep your lens shields down, except perhaps for the merest crack to see through, and, above all, don't move a millimeter, no matter what happens."

"But how can you manipulate your controls without moving your hands?"

"I can't; but my hands will not be in the sleeves, but inside the body of the suit—shut up! Hold everything—there's the flash!"

The flying vessel had gone through the zone of feeble radiations which comprised the outer detector screen of the Fenachrone. But though tenuous, that screen was highly efficient, and at its touch there burst into frenzied activity the communicator built by the captive to be actuated by that very impulse. It had been built during the long flight through space, and its builder had thought that its presence would be unnoticed and would remain unsuspected by the Terrestrials.

Now automatically put into action, it laid a beam to the nearest scout ship of the Fenachrone and into that vessel's receptors it passed the entire story of the Violet and her occupants. But DuQuesne had not been caught napping. Reading the engineer's brain and absorbing knowledge from it, he had installed a relay which would flash to his eyes an inconspicuous but unmistakable warning of the first touch of the screen of the enemy. The flash had come—they had penetrated the outer lines of the monstrous civilization of the dread and dreaded Fenachrone.

In the armory DuQuesne's hands moved slightly inside his shielding armor, and out in the control room the dummy that was also, to all outward seeming, DuQuesne moved and spoke. It tightened the controls of the attractors, which had never been entirely released from their prisoner, thus again pinning the Fenachrone helplessly against the wall.

"Just to be sure you don't try to start anything," it explained coldly, in DuQuesne's own voice and tone. "You have done well so far, but I'll run things myself from now on, so that you can't steer us into a trap. Now tell me exactly how to go about getting one of your vessels. After we get it I'll see about letting you go."

"Fools, you are too late!" the prisoner roared exultantly. "You would have been too late, even had you killed me out there in space and had fled at your utmost acceleration. Did you but know it you are as dead, even now—our patrol is upon you!"

The dummy that was DuQuesne whirled, snarling, and its automatic pistol and that of its fellow dummy were leaping out when an awful acceleration threw them flat upon the floor, a magnetic force snatched away their weapons, and a heat ray of prodigious power reduced the effigies to two small piles of gray ash. Immediately thereafter a beam of force from the patrolling cruiser neutralized the attractors bearing upon the captive and, after donning his space suit, he was transferred to the Fenachrone vessel.

The dummy that was DuQuesne whirled, snarling, and its automatic pistol and that of its fellow dummy were leaping out when a magnetic force snatched away their weapons and a heat ray of prodigious power reduced the effigies to two small piles of gray ashes. And DuQuesne, motionless inside his space suit, waited—

Motionless inside his space suit, DuQuesne waited until the airlocks of the Fenachrone vessel had closed behind his erstwhile prisoner; waited until the engineer had told his story to Fenal, his emperor, and to Fenimal, his general in command; waited until the communicator circuit had been broken and the hypnotized, drugged, and already dying creature had turned as though to engage his fellows in conversation. Then only did the saturnine scientist act. His finger closed a circuit, and in the Fenachrone vessel, inside the front protector flap of the discarded space suit, the flat case fell apart noiselessly and from it there gushed forth volume upon volume of colorless and odorless, but intensely lethal, vapor.

"Just like killing goldfish in a bowl." Callous, hard, and cold, DuQuesne exhibited no emotion whatever; neither pity for the vanquished foe nor elation at the perfect working out of his plans. "Just in case some of them might have been wearing suits, for emergencies, I had some explosive copper ready to detonate, but this makes it much better—the explosion might have damaged something we want."

And aboard the vessel of the Fenachrone, DuQuesne's deadly gas diffused with extreme rapidity, and as it diffused, the hellish crew to the last man dropped in their tracks. They died not knowing what had happened to them; died with no thought of even attempting to send out an alarm; died not even knowing that they died.

II.

"Can you open the airlocks of that scout ship from the outside, doctor?" asked Loring, as the two adventurers came out of the armory into the control room where DuQuesne, by means of the attractors, began to bring the two vessels together.

"Yes. I know everything that that engineer of a first-class battleship knew. To him, one of these little scouts was almost beneath notice, but he did know that much about them—the outside controls of all Fenachrone ships work the same way."

Under the urge of the attractions, the two ships of space were soon door to door. DuQuesne set the mighty beams to lock the craft immovably together and both men stepped into the Violet's airlock. Pumping back the air, DuQuesne opened the outer door, then opened both outer and inner doors of the scout.

As he opened the inner door the poisoned atmosphere of the vessel screamed out into space, and as soon as the frigid gale had subsided the raiders entered the control room of the enemy craft. Hardened and conscienceless killer though Loring was, the four bloated, ghastly objects that had once been men gave him momentary pause.

"Maybe we shouldn't have let the air out so fast," he suggested, tearing his gaze away from the grisly sight.

"The brains aren't hurt, and that's all I care about." Unmoved, DuQuesne opened the air valves wide, and not until the roaring blast had scoured every trace of the noxious vapor from the whole ship did he close the airlock doors and allow the atmosphere to come again to normal pressure and temperature.

"Which ship are you going to use—theirs or our own?" asked Loring, as he began to remove his cumbersome armor.

"I don't know yet. That depends largely upon what I find out from the brain of the lieutenant in charge of this patrol boat. There are two methods by which we can capture a battleship; one requiring the use of the Violet, the other the use of this scout. The information which I am about to acquire will enable me to determine which of the two plans entails the lesser amount of risk.

"There is a third method of procedure, of course; that is, to go back to Earth and duplicate one of their battleships ourselves, from the knowledge I shall have gained from their various brains concerning the apparatus, mechanisms, materials, and weapons of the Fenachrone. But that would take a long time and would be far from certain of success, because there would almost certainly be some essential facts that I would not have secured. Besides, I came out here to get one of their first-line space ships, and I intend to do it."

With no sign of distaste DuQuesne coupled his brain to that of the dead lieutenant of the Fenachrone through the mechanical educator, and quite as casually as though he were merely giving Loring another lesson in Fenachrone matters did he begin systematically to explore the intricate convolutions of that fearsome brain. But after only ten minutes' study he was interrupted by the brazen clang of the emergency alarm. He flipped off the power of the educator, discarded his headset, acknowledged the call, and watched the recorder as it rapped out its short, insistent message.

"Something is going on here that was not on my program," he announced to the alert but quiescent Loring. "One should always be prepared for the unexpected, but this may run into something cataclysmic. The Fenachrone are being attacked from space, and all armed forces have been called into a defensive formation—Invasion Plan XB218, whatever that is. I'll have to look it up in the code."

The desk of the commanding officer was a low, heavily built cabinet of solid metal. DuQuesne strode over to it, operated rapidly the levers and dials of its combination lock, and took from one of the compartments the "Code"—a polygonal framework of engraved metal bars and sliders, resembling somewhat an Earthly multiplex squirrel-cage slide rule.

"X—B—Two—One—Eight." Although DuQuesne had never before seen such an instrument, the knowledge taken from the brains of the dead officers rendered him perfectly familiar with it, and his long and powerful fingers set up the indicated defense plan as rapidly and as surely as those of any Fenachrone could have done. He revolved the mechanism in his hands, studying every plane surface, scowling blackly in concentration.

"Munition plants—shall—so-and-so—We don't care about that. Reserves—zones—ordnance—commissary—defensive screens—Oh, here we are! Scout ships. Instead of patrolling a certain volume of space, each scout ship takes up a fixed post just inside the outer detector zone. Twenty times as many on duty, too—enough so that they will be only about ten thousand miles apart—and each ship is to lock high-power detector screens and visiplate and recorder beams with all its neighbors.

"Also, there is to be a first-class battleship acting as mother ship, protector, and reserve for each twenty-five scouts. The nearest one is to be—Let's see, from here that would be only about twenty thousand miles over that way and about a hundred thousand miles down."

"Does that change your plans, chief?"

"Since my plans were not made, I cannot say that it does—it changes the background, however, and introduces an element of danger that did not previously exist. It makes it impossible to go out through the detector zone—but it was practically impossible before, and we have no intention of going out, anyway, until we possess a vessel powerful enough to go through any barrage they can lay down. On the other hand, there is bound to be a certain amount of confusion in placing so many vessels, and that fact will operate to make the capture of our battleship much easier than it would have been otherwise."

"What danger exists that wasn't there before?" demanded Loring.

"The danger that the whole planet may be blown up," DuQuesne returned bluntly. "Any nation or race attacking from space would of course have atomic power, and any one with that power could volatilize any planet by simply dropping a bomb on it from open space. They might want to colonize it, of course, in which case they wouldn't destroy it, but it is always safest to plan for the worst possible contingencies."

"How do you figure on doing us any good if the whole world explodes?" Loring lighted a cigarette, his hand steady and his face pinkly unruffled. "If she goes up, it looks as if we go out, like that—puff!" And he blew out the match.

"Not at all, Doll," DuQuesne reassured him. "An atomic explosion starting on the surface and propagating downward would hardly develop enough power to drive anything material much, if any, faster than light, and no explosion wave, however violent, can exceed that velocity. The Violet, as you know, although not to be compared with even this scout as a fighter, has an acceleration of five times that, so that we could outrun the explosion in her. However, if we stay in our own ship, we shall certainly be found and blown out of space as soon as this defensive formation is completed.

"On the other hand, this ship carries full Fenachrone power of offense and defense, and we should be safe enough from detection in it, at least for as long a time as we shall need it. Since these small ships are designed for purely local scout work, though, they are comparatively slow and would certainly be destroyed in any such cosmic explosion as is manifestly a possibility. That possibility is very remote, it is true, but it should be taken into consideration."

"So what? You're talking yourself around a circle, right back to where you started from."

"Only considering the thing from all angles." DuQuesne was unruffled. "We have lots of time, since it will take them quite a while to perfect this formation. To finish the summing up—we want to use this vessel, but is it safe? It is. Why? Because the Fenachrone, having had atomic energy themselves for a long time, are thoroughly familiar with its possibilities and have undoubtedly perfected screens through which no such bomb could penetrate.

"Furthermore, we can install the high-speed drive in this ship in a few days—I gave you all the dope on it over the educator, you know—so that we'll be safe, whatever happens. That's the safest plan, and it will work. So you move the stores and our most necessary personal belongings in here while I'm figuring out an orbit for the Violet. We don't want her anywhere near us, and yet we want her to be within reaching distance while we are piloting this scout ship of ours to the place where she is supposed to be in Plan XB218."

"What are you going to do that for—to give them a chance to knock us off?"

"No. I need a few days to study these brains, and it will take a few days for that battleship mother ship of ours to get into her assigned position, where we can steal her most easily." DuQuesne, however, did not at once remove his headset, but remained standing in place, silent and thoughtful.

"Uh-huh," agreed Loring. "I'm thinking the same thing you are. Suppose that it is Seaton that's got them all hot and bothered this way?"

"The thought has occurred to me several times, and I have considered it at some length," DuQuesne admitted at last. "However, I have concluded that it is not Seaton. For if it is, he must have a lot more stuff than I think he has. I do not believe that he can possibly have learned that much in the short time he has had to work in. I may be wrong, of course; but the immediately necessary steps toward the seizure of that battleship remain unchanged whether I am right or wrong; or whether Seaton was the cause of this disturbance."

When the conversation was thus definitely at an end, Loring again incased himself in his space suit and set to work. For hours he labored, silently and efficiently, at transferring enough of their Earthly possessions and stores to render possible an extended period of living aboard the vessel of the Fenachrone.

He had completed that task and was assembling the apparatus and equipment necessary for the rebuilding of the power plant before DuQuesne finished the long and complex computations involved in determining the direction and magnitude of the force required to give the Violet the exact trajectory he desired. The problem was finally solved and checked, however, and DuQuesne rose to his feet, closing his book of nine-place logarithms with a snap.

"All done with Violet, Doll?" he asked, donning his armor.

"Yes."

"Fine! I'll go aboard and push her off, after we do a little stage-setting here. Take that body there—I don't need it any more, since he didn't know much of anything, anyway—and toss it into the nose compartment. Then shut that bulkhead door, tight. I'm going to drill a couple of holes through there from the Violet before I give her the gun."

"I see—going to make us look disabled, whether we are or not, huh?"

"Exactly! We've got to have a good excuse for our visirays being out of order. I can make reports all right on the communicator, and send and receive code messages and orders, but we certainly couldn't stand a close-up inspection on a visiplate. Also, we've got to have some kind of an excuse for signaling to and approaching our mother battleship. We will have been hit and punctured by a meteorite. Pretty thin excuse, but it probably will serve for as long a time as we will need."

After DuQuesne had made sure that the small compartment in the prow of the vessel contained nothing of use to them, the body of one of the Fenachrone was thrown carelessly into it, the air-tight bulkhead was closed and securely locked, and the chief marauder stepped into the airlock.

"As soon as I get her exactly on course and velocity, I'll step out into space and you can pick me up," he directed briefly, and was gone.

In the Violet's engine room DuQuesne released the anchoring attractor beams and backed off to a few hundred yards' distance. He spun a couple of wheels briefly, pressed a switch, and from the Violet's heaviest needle-ray projector there flashed out against the prow of the scout patrol a pencil of incredibly condensed destruction.

Dunark, the crown prince of Kondal, had developed that stabbing ray as the culminating ultimate weapon of ten thousand years of Osnomian warfare; and, driven by even the comparatively feeble energies known to the denizens of the Green System before Seaton's advent, no known substance had been able to resist for more than a moment its corrosively, annihilatingly poignant thrust.

And now this furious stiletto of pure energy, driven by the full power of four hundred pounds of disintegrating atomic copper, at this point-blank range, was hurled against the mere inch of transparent material which comprised the skin of the tiny cruiser. DuQuesne expected no opposition, for with a beam less potent by far he had consumed utterly a vessel built of arenak—arenak, that Osnomian synthetic which is five hundred times as strong, tough, and hard as Earth's strongest, toughest, or hardest alloy steel.

Yet that annihilating needle of force struck that transparent surface and rebounded from it in scintillating torrents of fire. Struck and rebounded, struck and clung; boring in almost imperceptibly as its irresistible energy tore apart, electron by electron, the surprisingly obdurate substance of the cruiser's wall. For that substance was the ultimate synthetic—the one limiting material possessing the utmost measure of strength, hardness, tenacity, and rigidity theoretically possible to any substance built up from the building blocks of ether-borne electrons. This substance, developed by the master scientists of the Fenachrone, was in fact identical with the Norlaminian synthetic metal, inoson, from which Rovol and his aids had constructed for Seaton his gigantic ship of space—Skylark Three.

For five long minutes DuQuesne held that terrific beam against the point of attack, then shut it off; for it had consumed less than half the thickness of the scout patrol's outer skin. True, the focal area of the energy was an almost invisibly violet glare of incandescence, so intensely hot that the concentric shading off through blinding white, yellow, and bright-red heat brought the zone of dull red far down the side of the vessel; but that awful force had had practically no effect upon the spaceworthiness of the stanch little craft.

"No use, Loring!" DuQuesne spoke calmly into the transmitter inside his face plate. True scientist that he was, he neither expressed nor felt anger or bafflement when an idea failed to work, but abandoned it promptly and completely, without rancor or repining. "No possible meteorite could puncture that shell. Stand by!"

He inspected the power meters briefly, made several readings through the filar micrometer of number six visiplate and checked the vernier readings of the great circles of the gyroscopes against the figures in his notebook. Then, assured that the Violet was following precisely the predetermined course, he entered the airlock, waved a bloated arm at the watchful Loring, and coolly stepped off into space. The heavy outer door clanged shut behind him, and the globular ship of space rocketed onward; while DuQuesne fell with a sickening acceleration toward the mighty planet of the Fenachrone, so many thousands of miles below.

That fall did not long endure. Loring, now a space pilot second to none, had held his vessel dead even with the Violet; matching exactly her course, pace, and acceleration at a distance of barely a hundred feet. He had cut off all his power as DuQuesne's right foot left the Osnomian vessel, and now falling man and plunging scout ship plummeted downward together at the same mad pace; the man drifting slowly toward the ship because of the slight energy of his step into space from the Violet's side and beginning slowly to turn over as he fell. So consummate had been Loring's spacemanship that the scout did not even roll; DuQuesne was still opposite her starboard airlock when Loring stood in its portal and tossed a space line to his superior. This line—a small, tightly stranded cable of fiber capable of retaining its strength and pliability in the heatless depths of space—snapped out and curled around DuQuesne's bulging space suit.

"I thought you'd use an attractor, but this is probably better, at that," DuQuesne commented, as he seized the line in a mailed fist.

"Yeah. I haven't had much practice with them on delicate and accurate work. If I had missed you with this line I could have thrown it again; but if I missed this opening with you on a beam and shaved your suit off on this sharp edge, I figured it'd be just too bad."

The two men again in the control room and the vessel once more leveled out in headlong flight, Loring broke the silence:

"That idea of being punctured by a meteorite didn't pan out so heavy. How would it be to have one of the crew go space-crazy and wreck the boat from the inside? They do that sometimes, don't they?"

"Yes, they do. That's an idea—thanks. I'll study up on the symptoms. I have a lot more studying to do, anyway—there's a lot of stuff I haven't got yet. This metal, for instance—we couldn't possibly build a Fenachrone battleship on Earth. I had no idea that any possible substance could be so resistant as the shell of this ship is. Of course, there are many unexplored areas in these brains here, and quite a few high-class brains aboard our mother ship that I haven't even seen yet. The secret of the composition of this metal must be in some of them."

"Well, while you're getting their stuff, I suppose I'd better fly at that job of rebuilding our drive. I'll have time enough all right, you think?"

"Certain of it. I have learned that their system is ample—automatic and foolproof. They have warning long before anything can possibly happen. They can, and do, spot trouble over a light-week away, so their plans allow one week to perfect their defenses. You can change the power plant over in four days, so we're well in the clear on that. I may not be done with my studies by that time, but I shall have learned enough to take effective action. You work on the drive and keep house. I will study Fenachrone science and so on, answer calls, make reports, and arrange the details of what is to happen when we come within the volume of space assigned to our mother ship."

Thus for days each man devoted himself to his task. Loring rebuilt the power plant of the short-ranging scout patrol into the terrific open-space drive of the first-line battleships and performed the simple routines of their Spartan housekeeping. DuQuesne cut himself short on sleep and spent every possible hour in transferring to his own brain every worth-while bit of knowledge which had been possessed by the commander and crew of the patrol ship which he had captured.

Periodically, however, he would close the sending circuit and report the position and progress of his vessel, precisely on time and observing strictly all the military minutiae called for by the manual—the while watching appreciatively and with undisguised admiration the flawless execution of that stupendous plan of defense.

The change-over finished, Loring went in search of DuQuesne, whom he found performing a strenuous setting-up exercise. The scientist's face was pale, haggard, and drawn.

"What's the matter, chief?" Loring asked. "You look kind of peaked."

"Peaked is good—I'm just about bushed. This thing of getting a hundred and ninety years of solid education in a few days would hardly come under the heading of light amusement. Are you done?"

"Done and checked—O.K."

"Good! I am, too. It won't take us long to get to our destination now; our mother ship should be just about at her post by this time."

Now that the vessel was approaching the location assigned to it in the plan, and since DuQuesne had already taken from the brains of the dead Fenachrone all that he wanted of their knowledge, he threw their bodies into space and rayed them out of existence. The other corpse he left lying, a bloated and ghastly mass, in the forward compartment as he prepared to send in what was to be his last flight report to the office of the general in command of the plan of defense.

"His high-mightiness doesn't know it, but that is the last call he is going to get from this unit," DuQuesne remarked, leaving the sender and stepping over to the control board. "Now we can leave our prescribed course and go where we can do ourselves some good. First, we'll find the Violet. I haven't heard of her being spotted and destroyed as a menace to navigation, so we'll look her up and start her off for home."

"Why?" asked the henchman. "Thought we were all done with her."

"We probably are, but if it should turn out that Seaton is back of all this excitement, our having her may save us a trip back to the Earth. Ah, there she is, right on schedule! I'll bring her alongside and set her controls on a distance-squared decrement, so that when she gets out into space she'll have a constant velocity."

"Think she'll get out into free space through those screens?"

"They will detect her, of course, but when they see that she is an abandoned derelict and headed out of their system they'll probably let her go. It will be no great loss, of course, if they do burn her."

Thus it came about that the spherical cruiser of the void shot away from the then feeble gravitation of the vast but distant planet of the Fenachrone at a frightful but constant speed. Through the outer detector screens she tore. Searching beams explored her instantly and thoroughly; but since she was so evidently a deserted hulk and since the Fenachrone cared nothing now for impediments to navigation beyond their screens, she was not pursued.

On and on she sped, her automatic controls reducing her power in exact ratio to the square of the distance attained; on and on, her automatic deflecting detectors swinging her around suns and solar systems and back upon her original right line; on and on toward the Green System, the central system of this the First Galaxy—our own native island universe.

III.

"Now we'll get ready to take that battleship." DuQuesne turned to his aid as the Violet disappeared from their sight. "Your suggestion that one of the crew of this ship could have gone space-crazy was sound, and I have planned our approach to the mother ship on that basis.

"We must wear Fenachrone space suits for three reasons: First, because it is the only possible way to make us look even remotely like them, and we shall have to stand a casual inspection. Second, because it is general orders that all Fenachrone soldiers must wear suits while at their posts in space. Third, because we shall have lost most of our air. You can wear one of their suits without any difficulty—the surplus circumference will not trouble you very much. I, on the contrary, cannot even get into one, since they're almost a foot too short.

"I must have a suit on, though, before we board the battleship; so I shall wear my own, with one of theirs over it—with the feet cut off so that I can get it on. Since I shall not be able to stand up or to move around without giving everything away because of my length, I'll have to be unconscious and folded up so that my height will not be too apparent, and you will have to be the star performer during the first act.

"But this detailed instruction by word of mouth takes altogether too much time. Put on this headset and I'll shoot you the whole scheme, together with whatever additional Fenachrone knowledge you will need to put the act across."

A brief exchange of thoughts and of ideas followed. Then, every detail made clear, the two Terrestrials donned the space suits of the very short, but enormously wide and thick, monstrosities in semihuman form who were so bigotedly working toward their day of universal conquest.

DuQuesne picked up in his doubly mailed hands a massive bar of metal. "Ready, Doll? When I swing this we cross the Rubicon."

"It's all right by me. All or nothing—shoot the works!"

DuQuesne swung his mighty bludgeon aloft, and as it descended the telemental recorder sprang into a shower of shattered tubes, flying coils, and broken insulation. The visiray apparatus went next, followed in swift succession by the superficial air controls, the map cases, and practically everything else that was breakable; until it was clear to even the most casual observer that a madman had in truth wrought his frenzied will throughout the room. One final swing wrecked the controls of the airlocks, and the atmosphere within the vessel began to whistle out into the vacuum of space through the broken bleeder tubes.

"All right, Doll, do your stuff!" DuQuesne directed crisply, and threw himself headlong into a corner, falling into an inert, grotesque huddle.

Loring, now impersonating the dead commanding officer of the scout ship, sat down at the manual sender, which had not been seriously damaged, and in true Fenachrone fashion laid a beam to the mother ship.

"Scout ship K3296, Sublieutenant Grenimar commanding, sending emergency distress message," he tapped out fluently. "Am not using telemental recorder, as required by regulations, because nearly all instruments wrecked. Private 244C14, on watch, suddenly seized with space insanity, smashed air valves, instruments, and controls. Opened lock and leaped out into space. I was awake and got into suit before my room lost pressure. My other man, 397B42, was unconscious when I reached him, but believe I got him into his suit soon enough so that his life can be saved by prompt aid. 244C14 of course dead, but I recovered his body as per general orders and am saving it so that brain lesions may be studied by College of Science. Repaired this manual sender and have ship under partial control. Am coming toward you, decelerating to stop in fifteen minutes. Suggest you handle this ship with beam when approach as I have no fine controls. Signing off—K3296."

"Superdreadnought Z12Q, acknowledging emergency distress message of scout ship K3296," came almost instant answer. "Will meet you and handle you as suggested. Signing off—Z12Q."

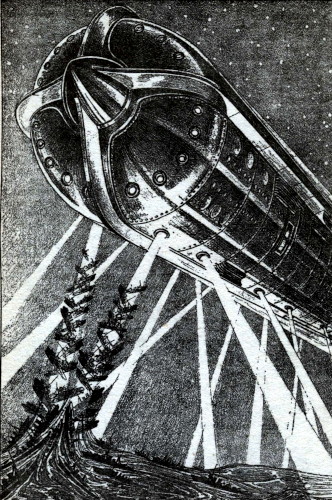

Rapidly the two ships of space drew together; the patrol boat now stationary with respect to the planet, the huge battleship decelerating at maximum. Three enormous beams reached out and, held at prow, mid-section, and stern, the tiny flier was drawn rapidly but carefully against the towering side of her mother ship. The double suction seals engaged and locked; the massive doors began to open.

Now came the most crucial point of DuQuesne's whole scheme. For that warship carried a complement of nearly a hundred men, and ten or a dozen of them—the lock commander, surgeons and orderlies certainly, and possibly a corps of mechanics as well—would be massed in the airlock room behind those slowly opening barriers. But in that scheme's very audacity lay its great strength—its almost complete assurance of success. For what Fenachrone, with the inborn superiority complex that was his heritage, would even dream that two members of any alien race would have the sheer, brazen effrontery to dare to attack, empty-handed, a full-manned Class Z superdreadnought, one of the most formidable structures that had ever lifted its stupendous mass into the ether?

But DuQuesne so dared. Direct action had always been his forte. Apparently impossible odds had never daunted him. He had always planned his coups carefully, then followed those plans coldly and ruthlessly to their logical and successful conclusions. Two men could do this job very nicely, and would so do it. DuQuesne had chosen Loring with care. Therefore he lay at ease in his armor in front of the slowly opening portal, calmly certain that the iron nerves of his assassin aid would not weaken for even the instant necessary to disrupt his carefully laid plan.

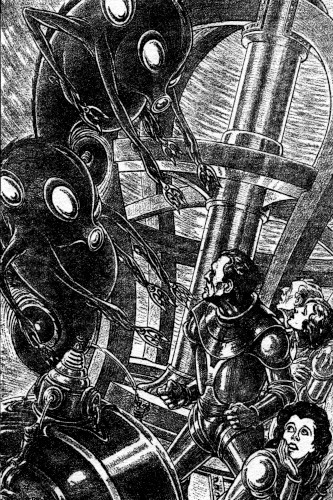

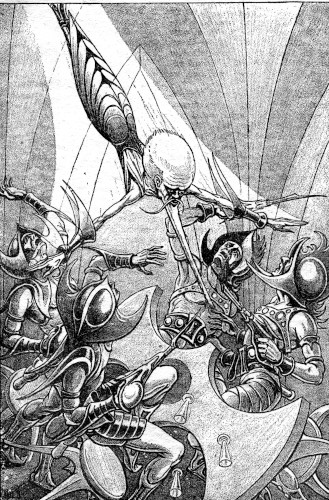

As soon as the doors had opened sufficiently to permit ingress, Loring went through them slowly, carrying the supposedly unconscious man with care. But once inside the opaque walls of the lock room, that slowness became activity incarnate. DuQuesne sprang instantly to his full height, and before the clustered officers could even perceive that anything was amiss, four sure hands had trained upon them the deadliest hand weapons known to the superlative science of their own race.

Since DuQuesne was overlooking no opportunity of acquiring knowledge, the heads were spared; but as the four furious blasts of vibratory energy tore through those massive bodies, making of their every internal organ a mass of disorganized protoplasmic pulp, every Fenachrone in the room fell lifeless to the floor before he could move a hand in self-defense.

Dropping his weapons, DuQuesne wrenched off his helmet, while Loring with deft hands bared the head of the senior officer of the group upon the floor. Headsets flashed out—were clamped into place—dials were set—the scientist shot power into the tubes, transferring to his own brain an entire section of the dead brain before him.

DuQuesne clamped the headset into place, shot power into it and transferred to his own brain an entire section of the brain of the dead Fenachrone.

His senses reeled under the shock, but he recovered quickly, and even as he threw off the phones Loring slammed down over his head the helmet of the Fenachrone. DuQuesne was now commander of the airlocks, and the break in communication had been of such short duration that not the slightest suspicion had been aroused. He snapped out mental orders to the distant power room, the side of the vessel opened, and the scout ship was drawn within.

"All tight, sir," he reported to the captain, and the Z12Q began to retrace her path in space.

DuQuesne's first objective had been attained without untoward incident. The second objective, the control room, might present more difficulty, since its occupants would be scattered. However, to neutralize this difficulty, the Earthly attackers could work with bare hands and thus with the weapons with which both were thoroughly familiar. Removing their gauntlets, the two men ran lightly toward that holy of Fenachrone holies, the control room. Its door was guarded, but DuQuesne had known that it would be—wherefore the guards went down before they could voice a challenge. The door crashed open and four heavy, long-barreled automatics began to vomit forth a leaden storm of death. Those pistols were gripped in accustomed and steady hands; those hands in turn were actuated by the ruthless brains of heartless, conscienceless, and merciless killers.

His second and major objective gained, DuQuesne proceeded at once to consolidate his position. Pausing only to learn from the brain of the dead captain the exact technique of procedure, he summoned into the sanctum, one at a time, every member of the gigantic vessel's crew. Man after man they came, in answer to the summons of their all-powerful captain—and man after man they died.

"Take the educator and get some of their surgeon's skill," DuQuesne directed curtly, after the last member of the crew had been accounted for. "Take off the heads and put them where they'll keep. Throw the rest of the rubbish out. Never mind about this captain—I want to study him."

Then, while Loring busied himself at his grisly task, DuQuesne sat at the captain's bench, read the captain's brains, and sent in to general headquarters the regular routine reports of the vessel.

"All cleaned up. Now what?" Loring was as spick-and-span, as calmly unruffled, as though he were reporting in one of the private rooms of the Perkins Café. "Start back to the Earth?"

"Not yet." Even though DuQuesne had captured his battleship, thereby performing the almost impossible, he was not yet content. "There are a lot of things to learn here yet, and I think that we had better stay here as long as possible and learn them; provided we can do so without incurring any extra risks. As far as actual flight goes, two men can handle this ship as well as a hundred, since her machinery is all automatic. Therefore we can run away any time.

"We could not fight, however, as it takes about thirty men to handle her weapons. But fighting would do no good, anyway, because they could outnumber us a hundred to one in a few hours. All of which means that if we go out beyond the detector screens we will not be able to come back—we had better stay here, so as to be able to take advantage of any favorable developments."

He fell silent, frowningly concentrated upon some problem obscure to his companion. At last he went to the main control panel and busied himself with a device of photo cells, coils, and kino bulbs; whereupon Loring set about preparing a long-delayed meal.

"It's all hot, chief—come and get it," the aid invited, when he saw that his superior's immediate task was done. "What's the idea? Didn't they have enough controls there already?"

"The idea is, Doll, not to take any unnecessary chances. Ah, this goulash hits the spot!" DuQuesne ate appreciatively for a few minutes in silence, then went on: "Three things may happen to interfere with the continuation of our search for knowledge. First, since we are now in command of a Fenachrone mother ship, I have to report to headquarters on the telemental recorder, and they may catch me in a slip any minute, which will mean a massed attack. Second, the enemy may break through the Fenachrone defenses and precipitate a general engagement. Third, there is still the bare possibility of that cosmic explosion I told you about.

"In that connection, it is quite obvious that an atomic explosion wave of that type would be propagated with the velocity of light. Therefore, even though our ship could run away from it, since we have an acceleration of five times that velocity, yet we could not see that such an explosion had occurred until the wave-front reached us. Then, of course, it would be too late to do anything about it, because what an atomic explosion wave would do to the dense material of this battleship would be simply nobody's business.

"We might get away if one of us had his hands actually on the controls and had his eyes and his brain right on the job, but that is altogether too much to expect of flesh and blood. No brain can be maintained at its highest pitch for any length of time."

"So what?" Loring said laconically. If the chief was not worried about these things, the henchman would not be worried, either.

"So I rigged up a detector that is both automatic and instantaneous. At the first touch of any unusual vibration it will throw in the full space drive and will shoot us directly away from the point of the disturbance. Now we shall be absolutely safe, no matter what happens.

"We are safe from any possible attack; neither the Fenachrone nor our common enemy, whoever they are, can harm us. We are safe even from the atomic explosion of the entire planet. We shall stay here until we get everything that we want. Then we shall go back to the Green System. We shall find Seaton."

His entire being grew grim and implacable, his voice became harder and colder even than its hard and cold wont. "We shall blow him clear out of the ether. The world—yes, whatever I want of the Galaxy—shall be mine!"

IV.

Only a few days were required for the completion of DuQuesne's Fenachrone education, since not many of the former officers of the battleship had added greatly to the already vast knowledge possessed by the Terrestrial scientists. Therefore the time soon came when he had nothing to occupy either his vigorous body or his voracious mind, and the self-imposed idleness irked his active spirit sorely.

"If nothing is going to happen out here we might as well get started back; this present situation is intolerable," he declared to Loring one morning, and proceeded to lay spy rays to various strategic points of the enormous shell of defense, and even to the sacred precincts of headquarters itself.

"They will probably catch me at this, and when they do it will blow the lid off; but since we are all ready for the break we don't care now how soon it comes. There's something gone sour somewhere, and it may do us some good to know something about it."

"Sour? Along what line?"

"The mobilization has slowed down. The first phase went off beautifully, you know, right on schedule; but lately things have slowed down. That doesn't seem just right, since their plans are all dynamic, not static. Of course general headquarters isn't advertising it to us outlying captains, but I think I can sense an undertone of uneasiness. That's why I am doing this little job of spying, to get the low-down—Ah, I thought so! Look here, Doll! See those gaps on the defense map? Over half of their big ships are not in position—look at those tracer reports—not a battleship that was out in space has come back, and a lot of them are more than a week overdue. I'll say that's something we ought to know about—"

"Observation Officer of the Z12Q, attention!" snapped from the tight-beam headquarters communicator. "Cut off those spy rays and report yourself under arrest for treason!"

"Not to-day," DuQuesne drawled. "Besides, I can't—I am in command here now."

"Open your visiplate to full aperture!" The staff officer's voice was choked with fury; never in his long life had he been so grossly insulted by a mere captain of the line.

DuQuesne opened the plate, remarking to Loring as he did so; "This is the blow-off, all right. No possible way of stalling him off now, even if I wanted to; and I really want to tell them a few things before we shove off."

"Where are the men who should be at stations?" the furious voice demanded.

"Dead," DuQuesne replied laconically.

"Dead! And you have reported nothing amiss?" He turned from his own microphone, but DuQuesne and Loring could hear his savage commands:

"X1427—Order the twelfth squadron to bring in the Z12Q!"

He spoke again to the rebellious and treasonable observer: "And you have made your helmet opaque to the rays of this plate, another violation of the code. Take it off!" The speaker fairly rattled under the bellowing voice of the outraged general. "If you live long enough to get here, you will pay the full penalty for treason, insubordination, and conduct unbecom—"

"Oh, shut up, you yapping nincompoop!" snapped DuQuesne.

Wrenching off his helmet, he thrust his blackly forbidding face directly before the visiplate; so that the raging officer stared, from a distance of only eighteen inches, not into the cowed and frightened face of a guiltily groveling subordinate, but into the proud and sneering visage of Marc C. DuQuesne, of Earth.

And DuQuesne's whole being radiated open and supreme contempt, the most gallingly nauseous dose possible to inflict upon any member of that race of self-styled supermen, the Fenachrone. As he stared at the Earthman the general's tirade broke off in the middle of a word and he fell back speechless—robbed, it seemed, almost of consciousness by the shock.

"You asked for it—you got it—now just what are you going to do with it or about it?" DuQuesne spoke aloud, to render even more trenchantly cutting the crackling mental comments as they leaped across space, each thought lashing the officer like the biting, tearing tip of a bull whip.

"Better men than you have been beaten by overconfidence," he went on, "and better plans than yours have come to nought through underestimating the resources in brain and power of the opposition. You are not the first race in the history of the universe to go down because of false pride, and you will not be the last. You thought that my comrade and I had been taken and killed. You thought so because I wanted you so to think. In reality we took that scout ship, and when we wanted it we took this battleship as easily.

"We have been here, in the very heart of your defense system, for ten days. We have obtained everything that we set out to get; we have learned everything that we set out to learn. If we wished to take it, your entire planet could offer us no more resistance than did these vessels, but we do not want it.

"Also, after due deliberation, we have decided that the universe would be much better off without any Fenachrone in it. Therefore your race will of course soon disappear; and since we do not want your planet, we will see to it that no one else will want it, at least for some few eons of time to come. Think that over, as long as you are able to think. Good-by!"

Duquesne cut off the visiray with a vicious twist and turned to Loring. "Pure boloney, of course!" he sneered. "But as long as they don't know that fact it'll probably hold them for a while."

"Better start drifting for home, hadn't we? They're coming out after us."

"We certainly had." DuQuesne strolled leisurely across the room toward the controls. "We hit them hard, in a mighty tender spot, and they will make it highly unpleasant for us if we linger around here much longer. But we are in no danger. There is no tracer ray on this ship—they use them only on long-distance cruises—so they'll have no idea where to look for us. Also, I don't believe that they'll even try to chase us, because I gave them a lot to think about for some time to come, even if it wasn't true."

But DuQuesne had spoken far more truly than he knew—his "boloney" was in fact a coldly precise statement of an awful truth even then about to be made manifest. For at that very moment Dunark of Osnome was reaching for the switch whose closing would send a detonating current through the thousands of tons of sensitized atomic copper already placed by Seaton in their deep-buried emplantments upon the noisome planet of the Fenachrone.

DuQuesne knew that the outlying vessels of the monsters had not returned to base, but he did not know that Seaton had destroyed them, one and all, in free space; he did not know that his arch-foe was the being who was responsible for the failure of the Fenachrone space ships to come back from their horrible voyages.

Upon the other hand, while Seaton knew that there were battleships afloat in the ether within the protecting screens of the planet, he had no inkling that one of those very battleships was manned by his two bitterest and most vindictive enemies, the official and completely circumstantial report of whose death by cremation he had witnessed such a few days before.

DuQuesne strolled across the floor of the control room, and in mid-step became weightless, floating freely in the air. The planet had exploded, and the outermost fringe of the wave-front of the atomic disintegration, propagated outwardly into spherical space with the velocity of light, had impinged upon the all-seeing and ever-watchful mechanical eye which DuQuesne had so carefully installed. But only that outermost fringe, composed solely of light and ultra-light, had touched that eye. The relay—an electronic beam—had been deflected instantaneously, demanding of the governors their terrific maximum of power, away from the doomed world. The governors had responded in a space of time to be measured only in fractional millionths of a second, and the vessel leaped effortlessly and almost instantaneously into an acceleration of five light-velocities, urged onward by the full power of the space-annihilating drive of the Fenachrone.

The eyes of DuQuesne and Loring had had time really to see nothing whatever. There was the barest perceptible flash of the intolerable brilliance of an exploding universe, succeeded in the very instant of its perception—yes, even before its real perception—by the utter blackness of the complete absence of all light whatever as the space drive automatically went into action and hurled the great vessel away from the all-destroying wave-front of the atomic explosion.

As has been said, there were many battleships within the screens of the distant planet, supporting a horde of scout ships according to Invasion Plan XB218; but of all these vessels and of all things Fenachrone, only two escaped the incredible violence of the holocaust. One was the immense space traveler of Ravindau the scientist which had for days been hurtling through space upon its way to a far-distant Galaxy; the other was the first-line battleship carrying DuQuesne and his killer aid, which had been snatched from the very teeth of that indescribable cosmic cataclysm only by the instantaneous operation of DuQuesne's automatic relays.

Everything on or near the planet had of course been destroyed instantly, and even the fastest battleship, farthest removed from the disintegrating world, was overwhelmed without the slightest possibility of escape. For to human eyes, staring however attentively into ordinary visiplates, these had practically no warning at all, since the wave-front of atomic disruption was propagated with the velocity of light and therefore followed very closely indeed behind the narrow fringe of visible light which heralded its coming.

Even if one of the dazed commanders had known the meaning of the coruscant blaze of brilliance which was the immediate forerunner of destruction, he would have been helpless to avert it, for no hands of flesh and blood, human or Fenachrone, could possibly have thrown switches rapidly enough to have escaped from the advancing wave-front of disruption; and at the touch of that frightful wave every atom of substance, alike of vessel, contents, and hellish crew, became resolved into its component electrons and added its contribution of energy to the stupendous cosmic catastrophe.

Even before his foot had left the floor in free motion, however, DuQuesne realized exactly what had happened. His keen eyes saw the flash of blinding incandescence announcing a world's ending and sent to his keen brain a picture; and in the instant of perception that brain had analyzed that picture and understood its every implication and connotation. Therefore he only grinned sardonically at the phenomena which left the slower-minded Loring dazed and breathless.

He continued to grin as the battleship hurtled onward through the void at a pace beside which that of any ether-borne wave, even that of such a Titanic disturbance as the atomic explosion of an entire planet, was the veriest crawl.

At last, however, Loring comprehended what had happened. "Oh, it exploded, huh?" he ejaculated.

"It most certainly did." The scientist's grin grew diabolical. "My statements to them came true, even though I did not have anything to do with their fruition. However, these events prove that caution is all right in its place—it pays big dividends at times. I'm very glad, of course, that the Fenachrone have been definitely taken out of the picture."

Utterly callous, DuQuesne neither felt nor expressed the slightest sign of pity for the race of beings so suddenly snuffed out of existence. "Their removal at this time will undoubtedly save me a lot of trouble later on," he added, "but the whole thing certainly gives me furiously to think, as the French say. It was done with a sensitized atomic copper bomb, of course; but I should like very much to know who did it, and why; and, above all, how they were able to make the approach."

"Personally, I still think it was Seaton," the baby-faced murderer put in calmly. "No reason for thinking so, except that whenever anything impossible has been pulled off anywhere that I ever heard of, he was the guy that did it. Call it a hunch, if you want to."