[Pg i]

ROGER WILLIAMS

[Pg iii]

Statue of Roger Williams in Roger Williams Park,

Providence, R. I.

[Pg v]

By

ARTHUR B. STRICKLAND

THE JUDSON PRESS

| BOSTON | CHICAGO | ST. LOUIS | NEW YORK |

| LOS ANGELES | KANSAS CITY | SEATTLE | TORONTO |

[Pg vi]

Copyright, 1919, by

GILBERT N. BRINK, Secretary

Published June, 1919

[Pg vii]

TO

My Wife

SYMPATHETIC HELPER

AND

INSPIRING COMPANION

IN ALL MY WORK

THIS BOOK IS LOVINGLY

INSCRIBED

[Pg viii]

[Pg ix]

BAPTIST SPARKS FROM A HEBREW ANVIL

“Even the absence of a definite experiment must not deter him. He would create a society where the principles would be put to the test. He would fashion a State where the Church and the crown would be mutually helpful though independent. He would create a condition of humanity where the sovereignty of the soul before God would be respected, and where every man, believer or disbeliever, Gentile, Jew, or Turk, would have untrammeled opportunity for the display and exercise of the faith within him. Here lies the core of his heroism!”

CONCERNING THE MONUMENT AT

ROGER WILLIAMS PARK

“This one monument speaks the gratitude of one State. But the whole country has an eloquent voice of appreciation. Even as the tombstone of Sir Christopher Wren, the builder of St. Paul’s Cathedral, intones the larger praise when it says, ‘If you would see his monument, look around you,’ so would we point to the great principles of equal and religious freedom, written into the Constitution of forty-eight States, and engraven on the minds of ninety millions of people in our country and making their moral and civic influence felt all over the civilized globe, as worthy tributes to the genius of Roger Williams.”

—Extracts from Thanksgiving Address on “Roger Williams,” delivered by Rabbi Abram Simon, Ph. D., to Reformed Congregation Keneseth Israel, Philadelphia, November 24, 1912.

[Pg xi]

PREFACE

The four years of the great war have witnessed two astounding facts, namely, the recrudescence of an ancient barbarism and the world-wide application of the ideals of Christianity. During these momentous times the frontiers of barbarism and of civilization were clearly marked. The greater part of the world declared its position and took sides with one or other of the contestants. The whole world was either for or against, either friend or foe to, the essential principles of a Christian civilization.

It was no accident that the torch of the Hun and the Cross of the Christ should meet again on the old historic battle-ground between the Somme and the Rhine, and especially at the Marne. We thank God in victory’s hour that the Cross of the Christ is again triumphant, and we trust the torch of the Hun is extinguished forever. Autocracy’s serpent head has been crushed beneath the heel of a militant democracy. That bruised heel is our reminder of the cost of victory. It staggers the imagination to state in terms of manhood, materials, and money the price we have paid to make a world safe for democracy.

The eyes of a world have been opened. Men have thought of Calvary, the price the Son of God paid to redeem the wayward, wicked world. Men through their Calvary have come to understand the message of Christ’s Cross—that all men are of equal value in the sight of humanity’s God, and therefore are entitled to equal privileges in the world he has made for their happiness. Out from the shambles of these war-torn years there has come forth, slowly and certainly, with ever-increasing clearness, the shining form of the ideal supreme, the truth triumphant, the principle of full, free, absolute soul-liberty.

As the thirsty caravan turns to the springs, as the mariner turns to his compass in the darkest night, so the war-weary world—all parts of it, both that of friend and that of foe—looks beseechingly to America and to the ideal of which she is the great exemplar. From her shores there went forth an army which under God turned the tide against barbarism and made[Pg xii] possible the final victory for civilization. That army was composed of men whose fathers represented every nation under heaven. Some who received the highest honor for distinguished service were born under the very flags they sought to overthrow. It was humanity’s army, dominated by ideals distinctly American, which fought, not for military glory, not for hellish hatred, not for selfish gain, but as the crusaders of a new order, of an international fraternity.

The distinctive feature of America’s greatness is not her boundless wealth, not her limitless resources, not her inimitable versatility. It is the ideal which she has inherited from her fathers. That ideal, in the forefront of the world’s thought today, had its yesterday of suffering and of sacrifice.

It is timely in the hour of democracy’s triumph to turn our thoughts toward the genesis of soul-liberty in America. Today millions of men espouse her sacred cause. In the dawn of American history, in the early colonial times, a misunderstood, maligned, and persecuted refugee, Roger Williams, stood almost alone as her defender. Driven from motherland and from adopted home, he found among the savages of the wilderness a place where he could live out his principles of soul-liberty and grant freely to others what he desired for himself. He has been rightly called “The First American,” because he was the first to actualize in a commonwealth the distinctively American principle of freedom for mind and body and soul.

Roger Williams was not the discoverer of the principle of soul-liberty. What Jesus did and said was the torch of truth destined to illumine the whole world. His death on the cross was the voice of God in eloquent terms, telling us that all men were equal sharers in his love and entitled to equal opportunities and privileges in the world which he had made for man’s well-being. Christ taught clearly that men should not force others to belief in him or to Christian conduct, nor destroy those who failed to follow his teachings as they saw them.

For centuries faithful witnesses kept alive in the world these precious truths. In fact, for a millennium the name Anabaptist or Baptist was synonymous with soul-liberty. Baptists on the Continent and in England sowed broadcast these seeds which led to a glorious harvest in the new world. After the death of Roger[Pg xiii] Williams the Baptists in the colonies continued the work so nobly begun by him. In the face of bitterest persecution they labored for a century before the much-desired principle of soul-liberty was interwoven into our National Constitution and protected by the First Amendment.

Our Western Hemisphere represents two types of civilization. The Rio Grande is the dividing line between a civilization which is Baptist in its distinctive and essential character and one which is non-Baptist. To the north we see what the democracy of the soul can do when associated with the democracy of political rights. To the south we see but the twilight of civilization, a place where there is political democracy in name, but where it is rendered powerless because the mind and soul do not enjoy full freedom. It is the difference between religious democracy and religious autocracy. To the north the Bible is loved, it is studied freely, and its principles are followed. It is a land where the Bible is unchained and where the prevailing religions are of a church without a bishop in a land without a king. To the south the Bible is practically suppressed, its study is discouraged, and its truths go unheeded.

Europe, thou art looking across the seas to America. Look to all three Americas. Political democracy is universal in North, Central, and South America. Ask thyself the question, Why is the civilization of the north so attractive? It is because Religious Liberty is married to Political Liberty. Dost thou want our blessedness? Then see to it that thy new-born democracies and thine ancient ones have complete soul-liberty. Give the Bible a chance to bless thy stricken lands. Let the truths from God’s book do their revolutionary work for thee as they have for God’s liberty land on this side of the sea.

Religious liberty has unchained the Bible, scattered the darkness of superstition, flooded our continent with light and blessing. It has toppled selfish autocrats from their thrones, it has unlocked the shackles from the feet of millions who were living in spiritual and physical slavery. Religious liberty opens the doors and lets God’s sunlight of truth enter to warm and bless the world.

To Roger Williams and the historic Baptist denomination we turn for the story of the genesis and growth of this great blessing in America. There is an effort, in evidence in the secular[Pg xiv] and religious press of America, and, in some sections, in many of our public schools, to rob both Williams and the Baptists of their crown of glory. In certain quarters both Protestants and Catholics are attributing the honor of giving birth to religious liberty to communions which centuries ago persecuted our Baptist forefathers unto banishment and death.

The early American Colonies can be divided into three classes. One class included those who sought for uniformity in religion. Exile and death were resorted to to make that religious uniformity possible. Baptists were martyred in Massachusetts and Virginia. Another class included those who granted a toleration to other Christian religions, but who denied political privileges to Jews, infidels, or Unitarians. Maryland and Pennsylvania, although far advanced from the persecuting spirit of some of the colonies, belong to this second class. There was another class, represented at first by the smallest of the colonies, little Baptist Rhode Island, which gave full, absolute, religious liberty. No political privilege was dependent on religious belief. The attitude of the early colonists to the Jews is the acid test of their claim to priority as the advocates of soul-liberty in America.

Hebrew scholars and statesmen do not hesitate to give their tribute of honor to Roger Williams and the Baptists. The Hon. Oscar S. Straus, twice American Ambassador to Turkey, Secretary of Labor and Commerce in the late President Roosevelt’s Cabinet, and President of the League to Enforce Peace, said on January 13, 1919, on the eve of sailing for Europe and the Peace Conference:

If I were asked to select from all the great men who have left their impress upon this continent from the days that the Puritan Pilgrims set foot on Plymouth Rock, until the time when only a few days ago we laid to rest the greatest American in our generation—Theodore Roosevelt; if I were asked whom to hold before the American people and the world to typify the American spirit of fairness, of freedom, of liberty in Church and State, I would without any hesitation select that great prophet who established the first political community on the basis of a free Church in a free State, the great and immortal Roger Williams.... He became a Baptist, or as they were then called, Anabaptist, because to his spirit and ideals the Baptist faith approached nearer than any other—a community and a church which is famous for never having stained its hands with the blood of persecutors.

[Pg xv]

CONTENTS

| Page | ||

| I. | The Apostle of Soul-liberty | 1 |

| II. | The Founding of Providence | 27 |

| III. | The Historic Custodians of Soul-liberty | 57 |

| IV. | Soul-liberty at Home in a Commonwealth | 79 |

| V. | From Soul-liberty to Absolute Civil Liberty | 103 |

| VI. | The Torch-bearers of the Ideal of Roger Williams Until Liberty Enlightened the World |

119 |

| VII. | The World-wide Influence of Roger Williams’ Ideal |

137 |

| Study Outline of the Life and Times of Roger Williams |

145 | |

| A Selected Bibliography | 149 | |

| An Itinerary for a Historic Pilgrimage | 151 |

[Pg xvi]

[Pg xvii]

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The author desires to express his indebtedness to the John Carter Brown Library, Providence, R. I., to the “Providence Magazine,” to the Rhode Island Historical Society, to the Roger Williams Park Museum, and to the New York City Public Library, for valuable assistance rendered in securing illustrations for this book.

[Pg xix]

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

| Page | |

| Statue of Roger Williams | Frontispiece |

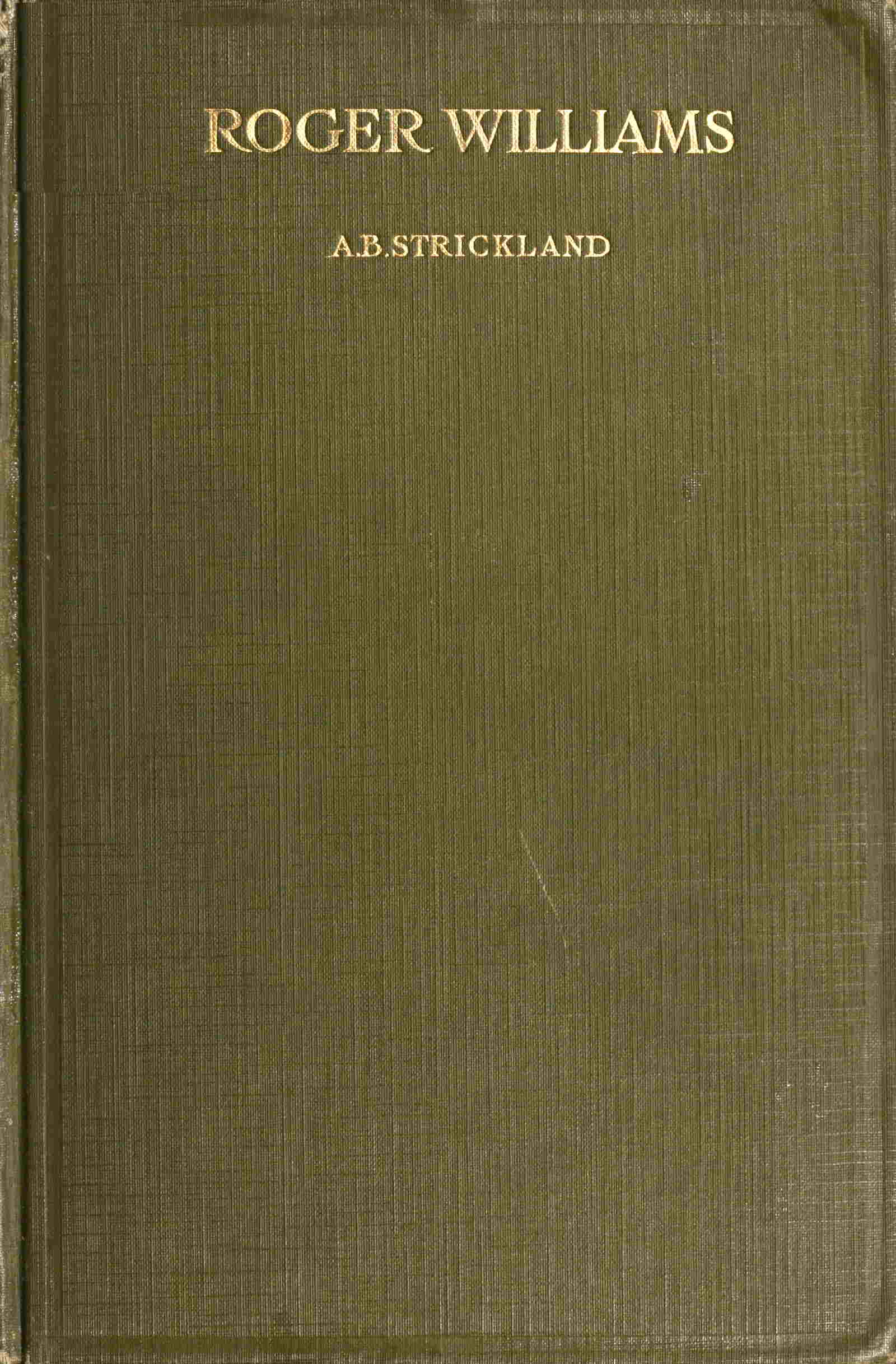

| Copy of Shorthand Found in Indian Bible | 4 |

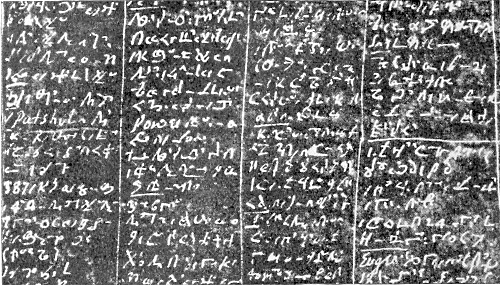

| Sir Edward Coke | 5 |

| Charterhouse School | 9 |

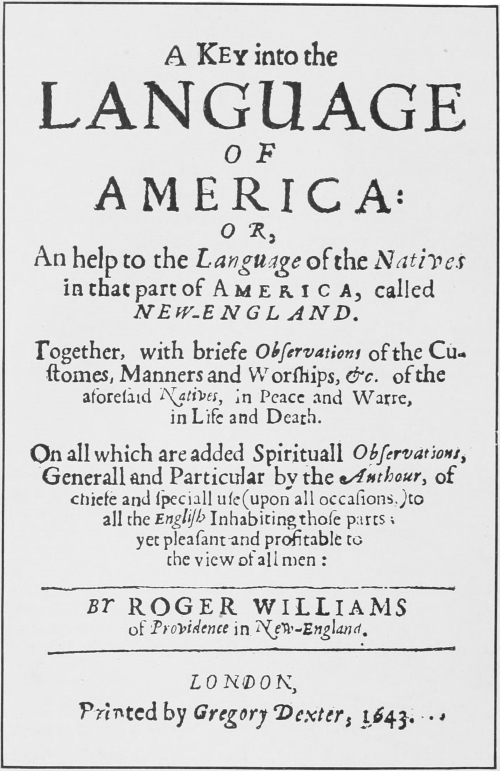

| “A Key into the Language of America” | 12 |

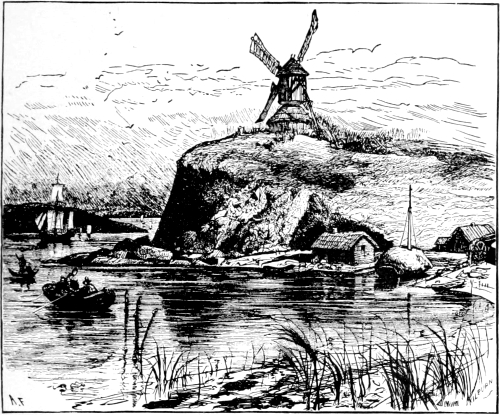

| Boston, 1632 | 13 |

| The Fort and Chapel on the Hill Where Roger Williams Preached |

13 |

| Pembroke College | 17 |

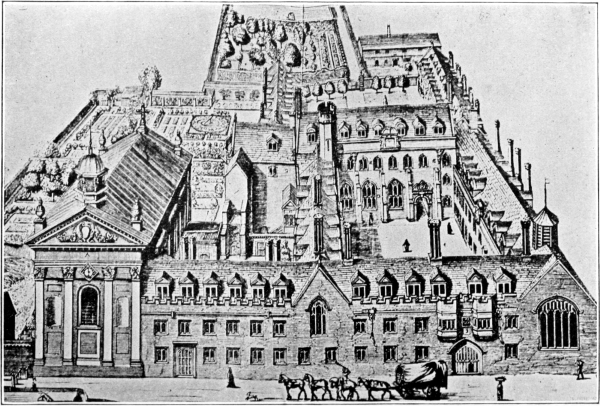

| Fac-simile from Original Records of the Order for the Banishment of Roger Williams |

20 |

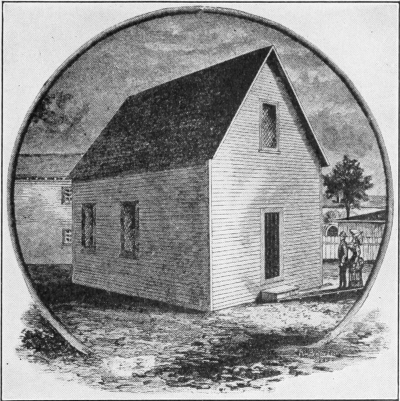

| Original Church at Salem, Mass. | 21 |

| Site of Home of Roger Williams in Providence, R. I. | 21 |

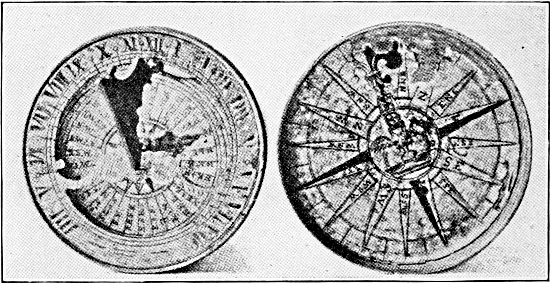

| Sun-dial and Compass Used by Roger Williams in His Flight |

30 |

| Spring at the Seekonk Settlement | 31 |

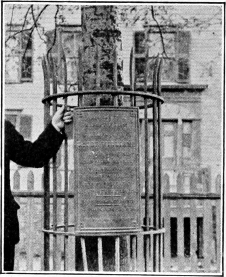

| Tablet Marking Seekonk Site | 31 |

| What Cheer Rock. Landing-place of Roger Williams | 31 |

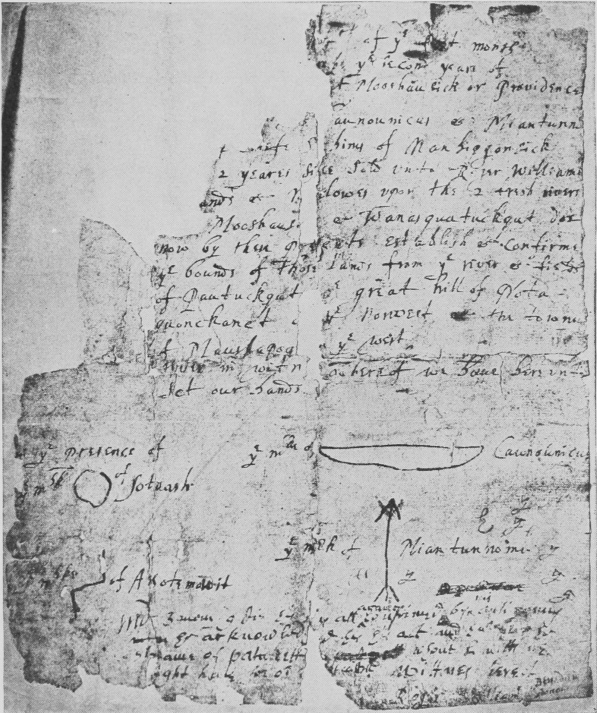

| Original Deed of Providence from the Indians | 35 |

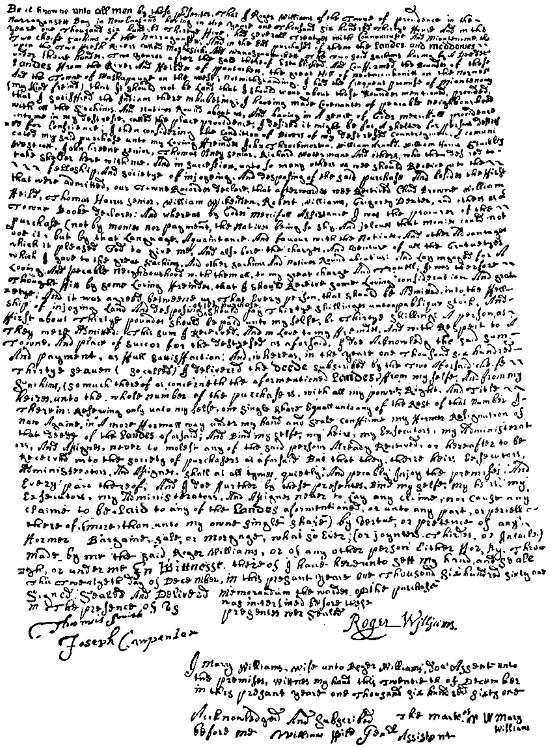

| Williams’ Letter of Transference to His Loving Friends | 39 |

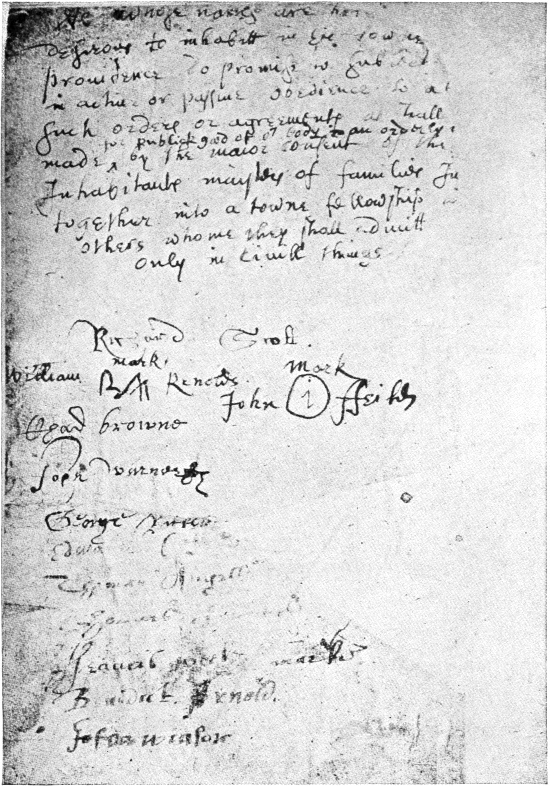

| The Original Providence “Compact” | 41 |

| The First Division of Home Lots in Providence | 45 |

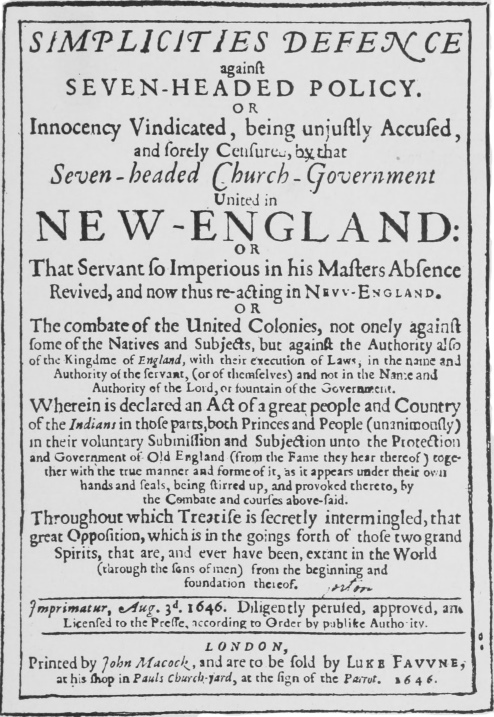

| “Simplicities Defence” | 47 |

| The Arrival of Roger Williams with the Charter | 49 |

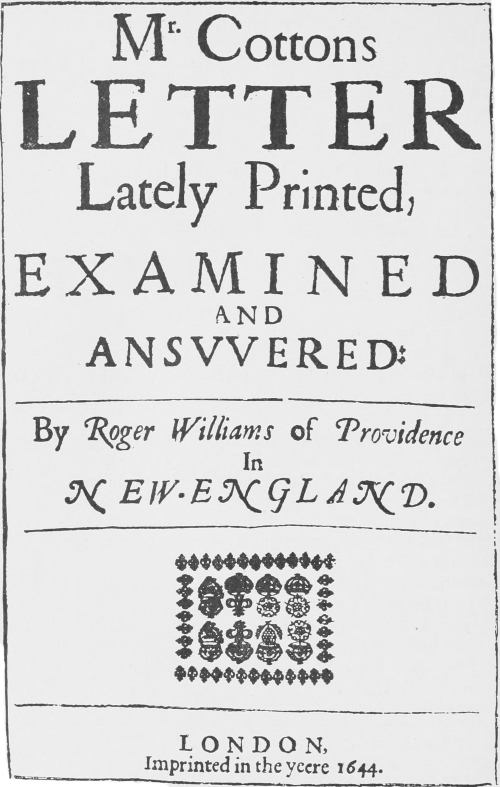

| “Mr. Cotton’s Letter Lately Printed” | 52 |

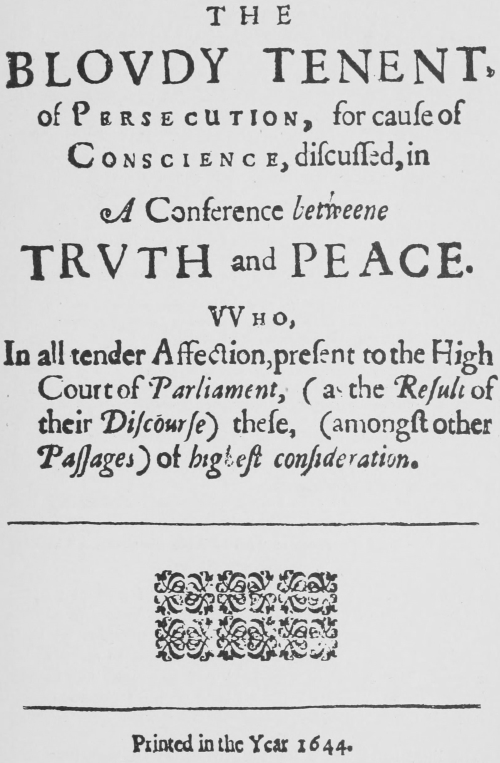

| “The Bloudy Tenent, ... discussed” | 53 |

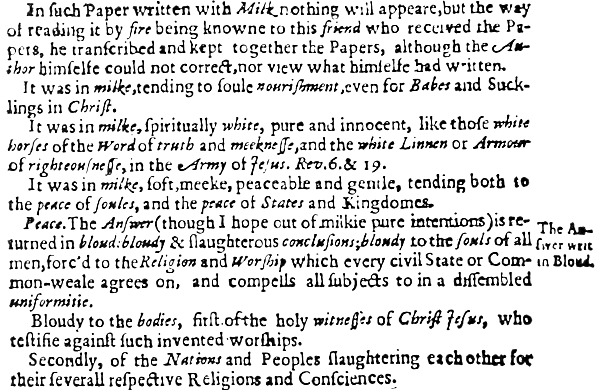

| Roger Williams’ Reference to “An Humble Supplication” in His “Bloudy Tenent” |

54 |

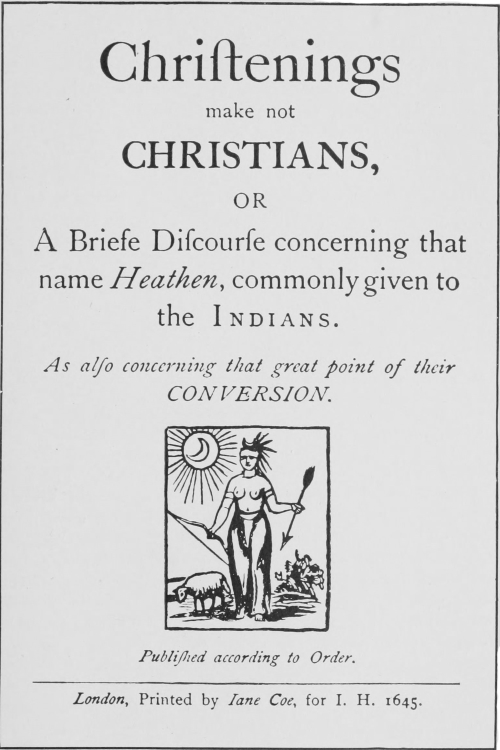

| “Christenings make not Christians” | 63 |

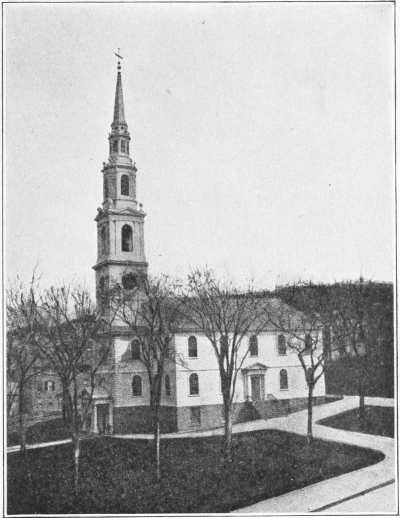

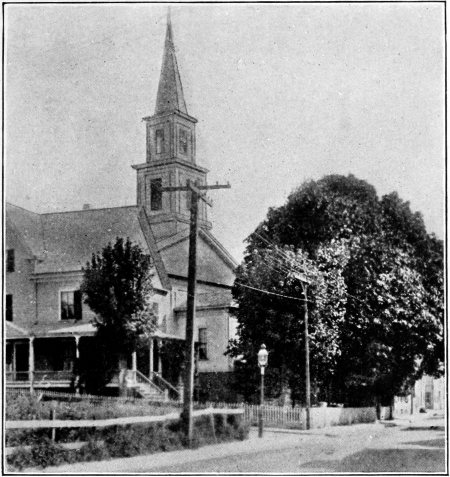

| First Baptist Church of Providence | 65 |

| Roger Mowry’s “Ordinarie.” Built 1653, Demolished 1900 | 65[Pg xx] |

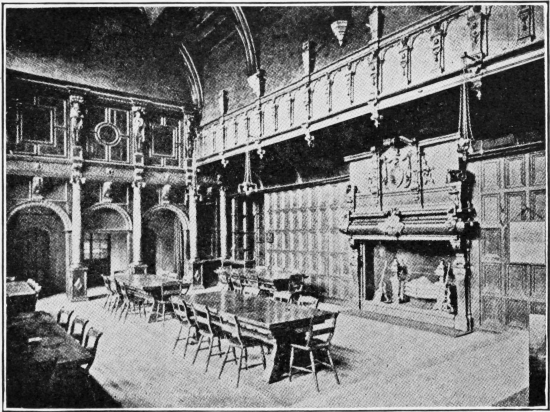

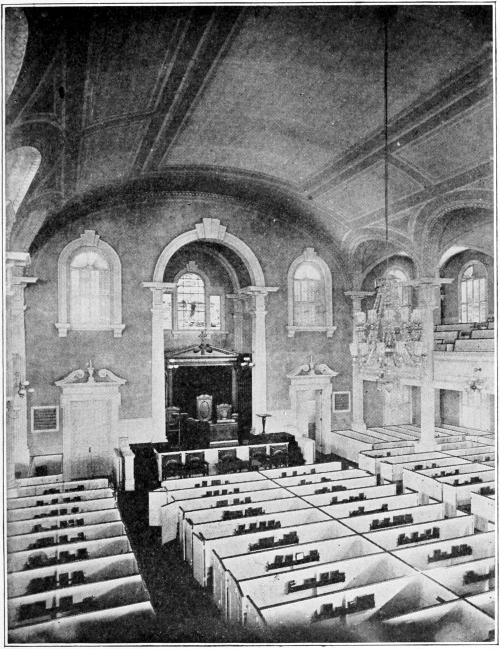

| Interior of First Baptist Church, Providence | 69 |

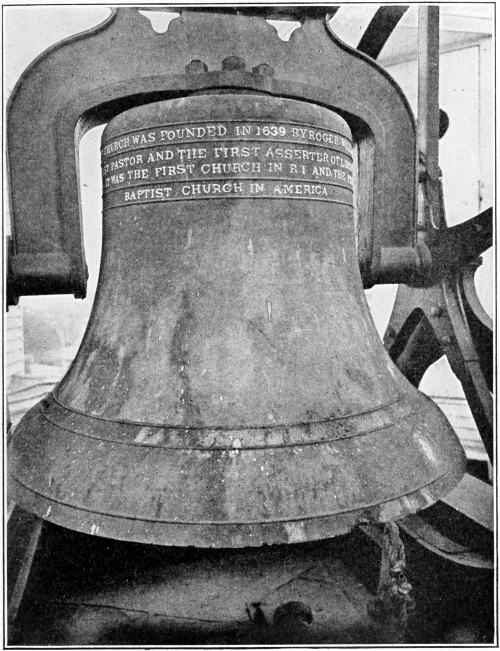

| Bell of First Baptist Church, Providence | 73 |

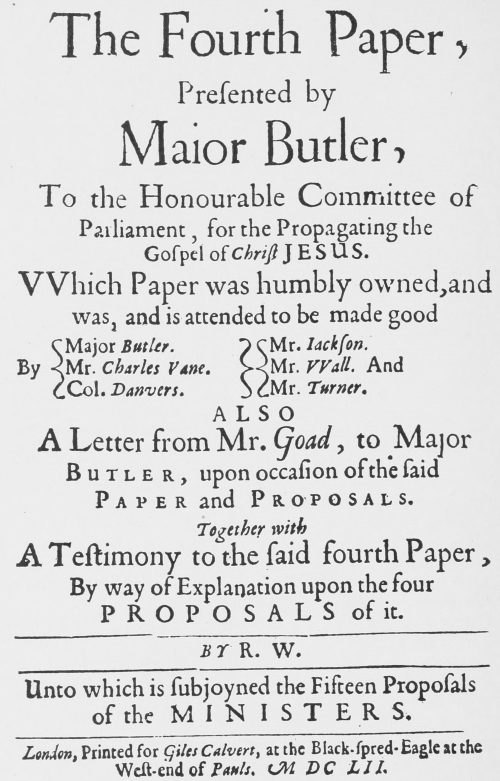

| “The Fourth Paper, ... by Maior Butler” | 82 |

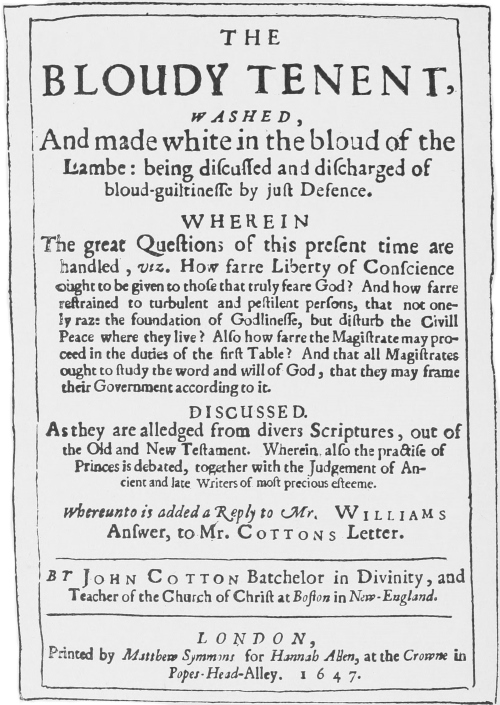

| “The Bloudy Tenent, Washed” | 84 |

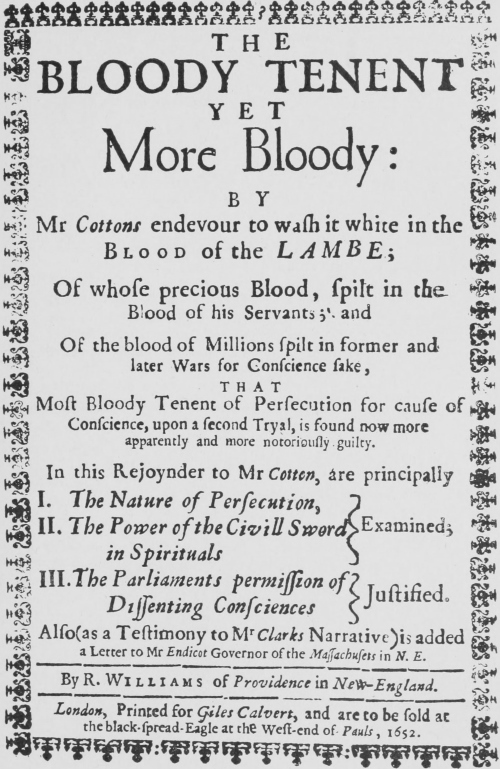

| “The Bloody Tenent yet More Bloody” | 85 |

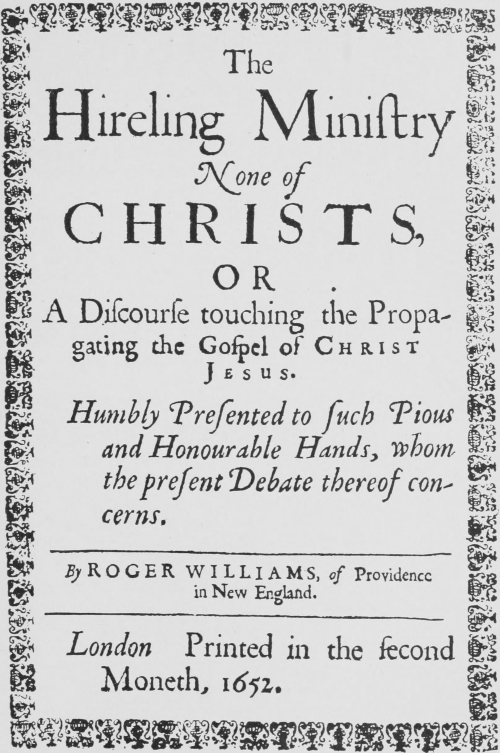

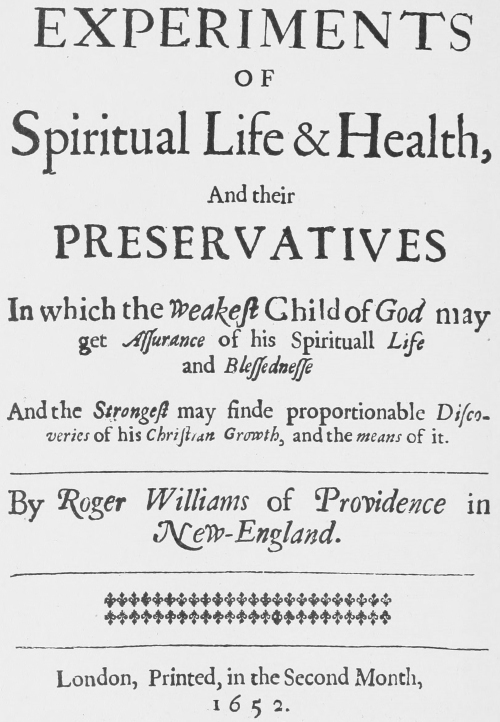

| “The Hireling Ministry” | 87 |

| “Experiments of Spiritual Life and Health” | 88 |

| “George Fox Digg’d out of his Burrowes” | 90 |

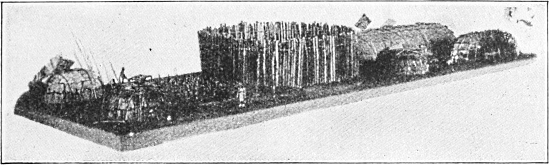

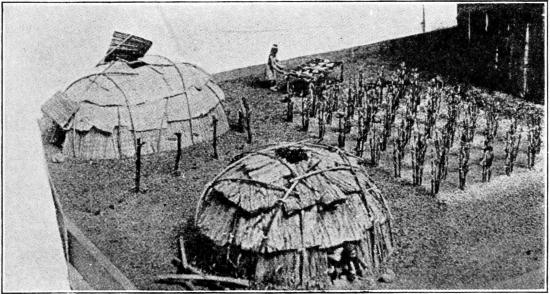

| Models of Indian Village in Roger Williams Park Museum | 91 |

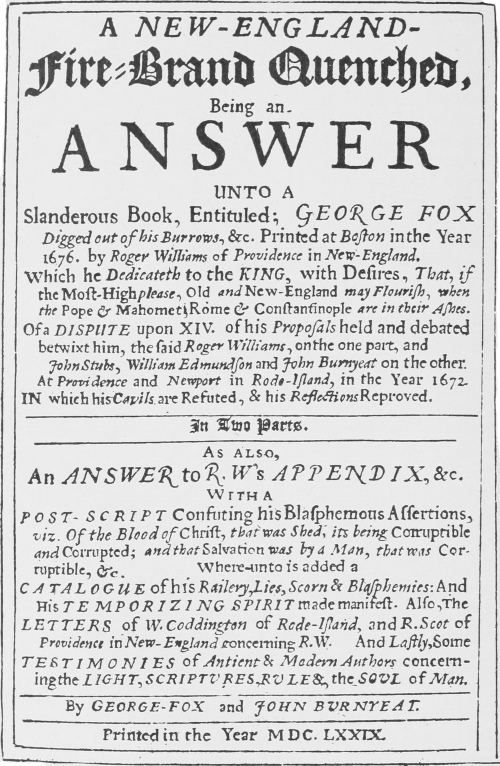

| “A New-England Fire-Brand Quenched” | 94 |

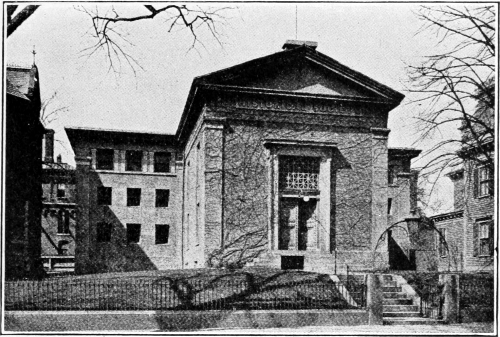

| Rhode Island Historical Society Museum | 95 |

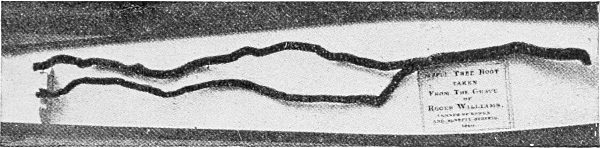

| Apple Tree Root from the Grave of Roger Williams | 95 |

| Grave of Roger Williams | 95 |

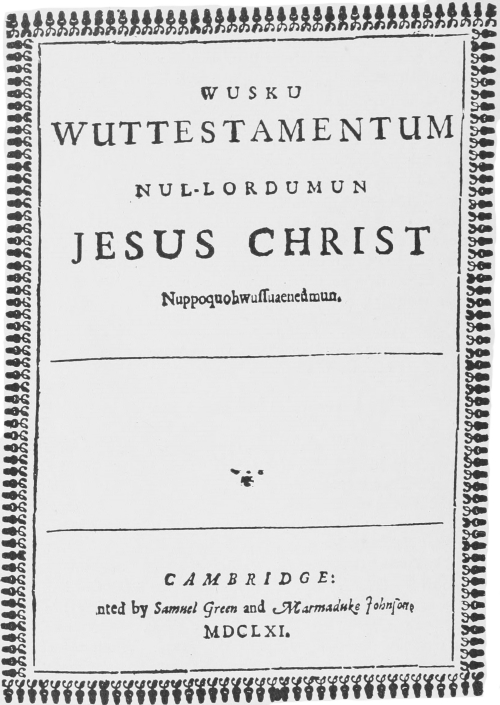

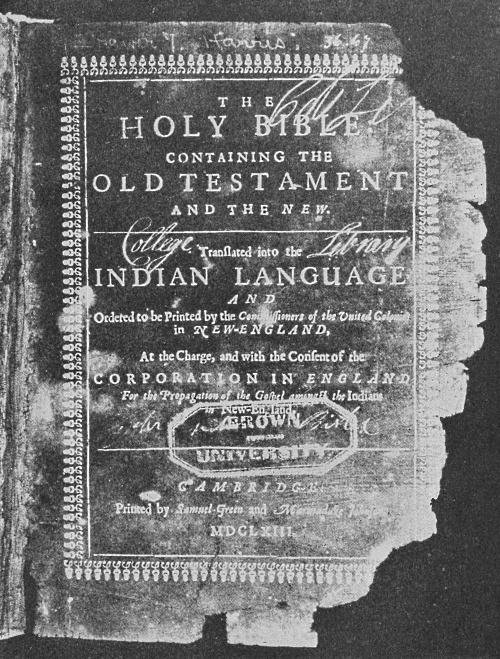

| New Testament Title-page of Roger Williams’ Indian Bible | 98 |

| Indian Bible Used by Roger Williams, the Pioneer Missionary to the American Indians |

99 |

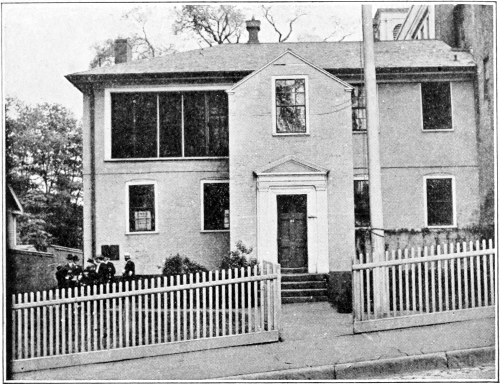

| Original Home of Brown University, in Providence, R. I. | 109 |

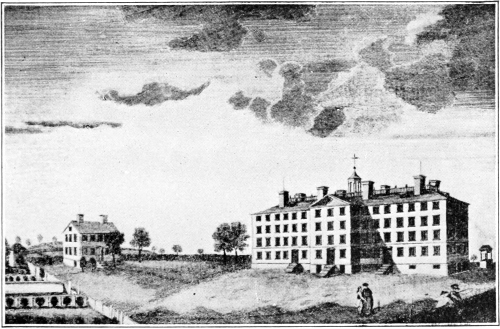

| Brown University in Early Nineteenth Century | 109 |

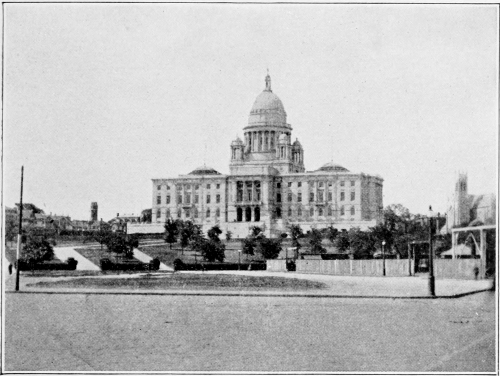

| Capitol Building in Providence, Where the Charter is Kept | 113 |

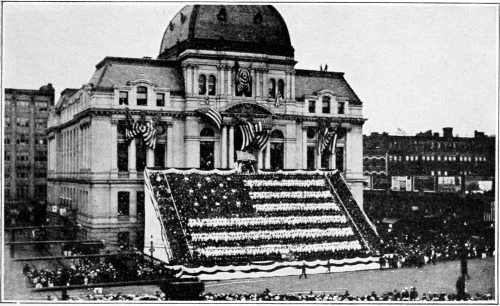

| City Hall, Providence, Where the Compact, Indian Deed, and Letter of Transference Are Kept |

113 |

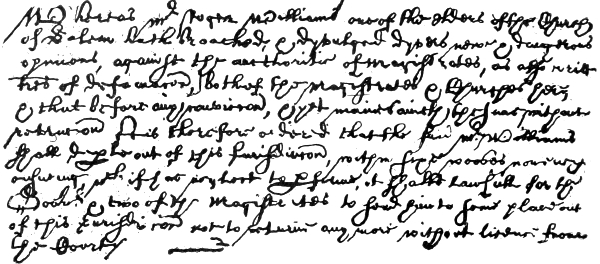

| Order Banishing the Founders of the First Baptist Church in Boston |

123 |

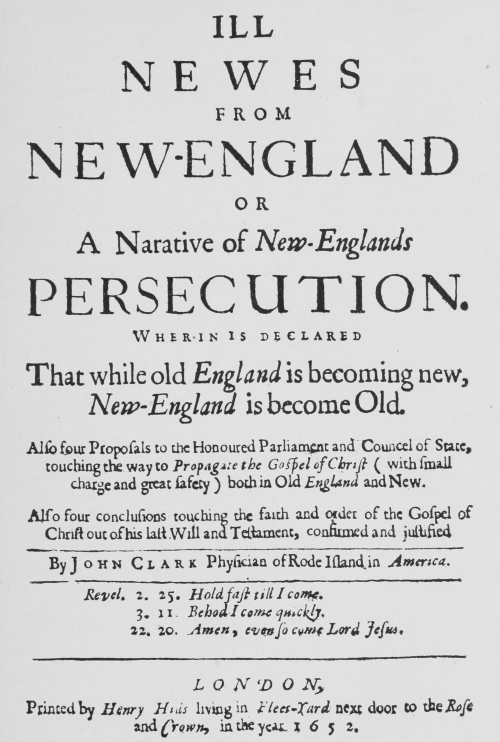

| “Ill Newes from New-England” | 125 |

| John Clarke Memorial, First Baptist Church of Newport, R. I. | 127 |

| Grave of John Clarke | 127 |

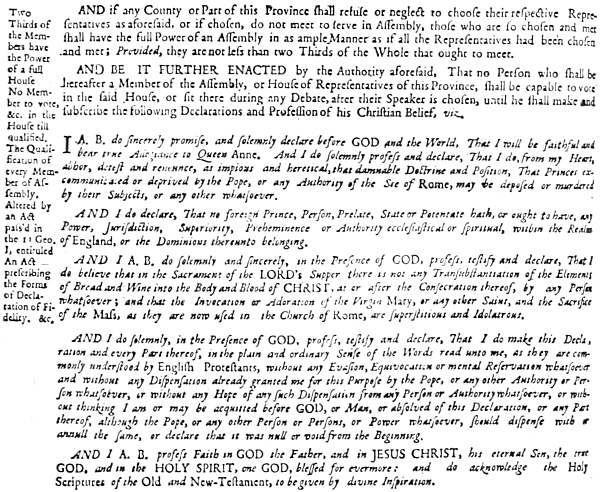

| The Law in William Penn’s Colony | 129 |

| The Law Concerning Religious Toleration in Maryland Colony |

130 |

| Puritan-Religious-Liberty! | 131 |

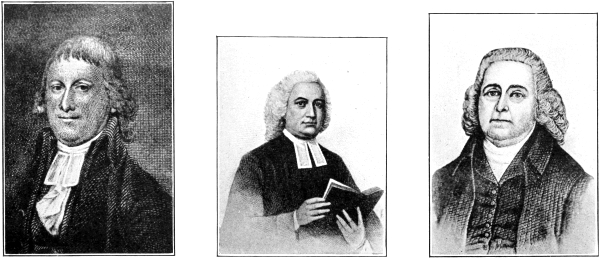

| William Rogers | 133 |

| James Manning | 133 |

| Isaac Backus | 133 |

[Pg 1]

THE APOSTLE OF SOUL-LIBERTY

[Pg 2]

That body-killing, soul-killing, state-killing doctrine of not permitting but persecuting all other consciences and ways of worship but his own in the civil state.... Whole nations and generations of men have been forced (though unregenerate and unrepentant) to pretend and assume the name of Jesus Christ, which only belongs, according to the institution of the Lord Jesus, to truly regenerate and repentant souls. Secondly, that all others dissenting from them, whether Jews or Gentiles, their countrymen especially (for strangers have a liberty), have not been permitted civil habitation in this world with them, but have been distressed and persecuted by them.—Roger Williams’ Estimate of Religious Persecution.

The principle of religious liberty did not assert itself, save in one instance, at once that American colonization was begun. For the most part, the founders of these colonies came to this country imbued with the ideas concerning the relations between government and religion, which had been universal in Europe.... This makes the attitude of our American exception, Roger Williams, the more striking and significant. More than one hundred years in advance of his time, he denied the entire theory and practice of the past.—Sanford Cobb.

Roger Williams advocated the complete separation of Church and State, at a time when there was no historical example of such separation.—Newman.

[Pg 3]

A GOVERNMENT of the people, formed by the people for the people, with Church and State completely separate, and with political privileges not dependent on religious belief, was organized and maintained successfully for the first time in Christendom in Rhode Island, the smallest of the American Colonies. Its inspiration and founder was Roger Williams, the apostle of soul-liberty. Because he was the first asserter of the principle which has since been recognized as the distinctive character of our national greatness, he has been called “The First American.”

Little is known of the personal appearance of Roger Williams. His contemporaries describe him as a man of “no ordinary parts,” with “a never-failing sweetness of temper and unquestioned piety.” They also said he was a man of “unyielding tenacity of purpose, a man who could grasp a principle in all its bearings and who could incorporate it in a social compact.” “He was no crude, unlearned agitator, but a scholar and thinker.” Governor Bradford speaks of him as “having many precious parts.” Governor Winthrop refers to him as “a godly minister.”

The artist’s conception, based upon these characteristics, is best expressed by a monument in Roger Williams Park, Providence, R. I. It is the work of Franklin Simmons, and was erected by the city of Providence in 1877. In a beautiful park of over four hundred acres with hills and drives and lakes, surrounded by trees and shrubbery, and on land originally purchased from the Indians by Williams, the illustrious pioneer of a new order is seen in heroic form. He seems to be looking out over the very colony he formed. In his hand he holds a volume, entitled “Soul-Liberty, 1636,” a title which has since become synonymous with his name. History is seen writing “1636,” the birth year of soul-liberty in America. She continues to write with increasing appreciation of the far-reaching influence of this illustrious hero of religious and political democracy.

[Pg 4]

Copy of Shorthand Found on Fly-leaf of Roger Williams’ Indian Bible

For many years scholars thought that Roger Williams was born at the close of the sixteenth century at Gwinear, Cornwall, England. Now it is generally believed that he was born in London, England, in the opening years of the seventeenth century. He had two brothers and a sister. His father was a tailor. About this time Timothy Bright and Peter Bales introduced into England a new method of writing which was called “shorthand.” The boy Roger Williams learned it and visited the famous Star Chamber to put it into practice. The judge noticed the lad and inspected his work. To his amazement, the record was complete and accurate. This judge, Sir Edward Coke, the most distinguished lawyer and jurist of his day, immediately took an interest in the lad, and became his patron, securing for Williams admission to the Charterhouse School. This was the school where John Wesley, Thackeray, Addison, and others were educated. He was admitted as a pensioner, in June, 1621. Later, through Coke’s influence, he was admitted to Pembroke College, Cambridge, in June, 1623. He was graduated with the degree of bachelor of arts in 1627, and the year following was admitted to holy orders. About this time he was disappointed in a love affair, the lady of his choice being Jane Whalley. He sought permission of her aunt, Lady Barrington, to marry her. When [Pg 7]refused, he wrote a striking letter in which he predicted for Lady Barrington a very unhappy hereafter unless she repented.

Sir Edward Coke

Courtesy of “Providence Magazine”

In 1629, we find him at High Laves, Essex, not far from Chelmesford, where Thomas Hooker, later the founder of Hartford Colony, was minister. Here he also met John Cotton. Men’s views at that time were changing. The people of the Established Church were divided into three classes. One stood by the Established Order in all things; another class of Puritans sought to stay by the Church, but aimed to purify the movement; the third class was for absolute separation. Williams, with hundreds of others, was disturbed. The anger of Lady Barrington and the suspicions of Archbishop Laud started a persecution which drove him out of England. He said:

I was persecuted in and out of my father’s house. Truly it was as bitter as death to me when Bishop Laud pursued me out of the land, and my conscience was persuaded against the national church, and ceremonies and bishops.... I say, it was as bitter as death to me when I rode Windsor way to take ship at Bristol.

Many years later he wrote:

He (God) knows what gains and preferments I have refused in universities, city, country, and court in old England, and something in New England, to keep my soul undefiled in this point and not to act with a doubting conscience.

Before leaving England, he was married. The only information we have in regard to his wife, up to that time, is that her name was Mary Warned. They sailed on the ship Lyon, from Bristol, England, December 1, 1630. After a tempestuous journey of sixty-six days they arrived off Nantasket, February 5, 1631. Judge Durfee speaks thus of this flight:

He was obliged to fly or dissemble his convictions, and for him, as for all noblest natures, a life of transparent truthfulness was alone an instinct and a necessity. This absolute sincerity is the key to his character, as it was always the mainspring of his conduct. It was this which led him to reject indignantly the compromises with his conscience which from time to time were proposed to him. It was this which impelled him when he discovered a truth to proclaim it, when he detected an error to expose it, when he saw an evil, to try and remedy it, and when he could do a good, even to his enemies, to do it.

[Pg 8]

Upon his arrival in Boston he was invited to become the teacher in the Boston church, succeeding Mr. Wilson who was about to return to England. To his surprise, he discovered that the Boston church was a church unseparated from the Established Church of England, and he felt conscientiously bound to decline their invitation. The Boston people, who believed their church to be the “most glorious on earth,” were astonished at his refusal. Williams would not act as their teacher unless they publicly repented of their relation to the Established Order. It was perfectly natural that a soul with convictions, such as Williams possessed, should desire to be absolutely separated from the Established Order. One incident from many will show the spirit of the Established Church in England toward those within its ranks who had become Puritan, let alone Separatist. Neal, in his “History of the Puritans,” tells, of Doctor Leighton’s persecution in England. He was arrested by Archbishop Laud and the following sentence was passed upon him: That he be

committed to the prison of the Fleet for life, and pay a fine of ten thousand pounds; that the High Commission should degrade him from his ministry, and that he should be brought to the pillory at Westminster, while the court was sitting and be publicly whipped; after whipping be set upon the pillory a convenient time, and have one of his ears cut off, one side of his nose split, and be branded in the face with a double S. S. for a sower of sedition: that then he should be carried back to prison, and after a few days be pilloryed a second time in Cheapside, and have the other side of his nose split, and his other ear cut off and then be shut up in close prison for the rest of his life.

In the district in which Roger Williams lived this sentence was carried out in all its hellish cruelty just prior to Williams’ banishment from England. Do we blame the exile Williams for repudiating the movement which at that hour was so wicked in its persecutions? He meant to have a sea between him and a thing so hateful. John Cotton said that Williams looked upon himself as one who “had received a clearer illumination and apprehension of the state of Christ’s kingdom, and of the purity of church communion, than all Christendom besides.” Cotton Mather said that Williams had “a windmill in his head.” Well for America that such a windmill was there and that he was a prophet with clear visions of truth.[Pg 9]

[Pg 10]

Charterhouse School

Courtesy of “Providence Magazine”[Pg 11]

After refusing the Boston church, Roger Williams was invited by the Salem church to be assistant to Mr. Skelton, their aged teacher. He accepted their invitation and became Teacher, April 12, 1631. The General Court in Boston remonstrated with the Salem church. The persecution of this court led doubtless to his retirement from Salem at the close of that summer.

He left the Massachusetts Bay Colony and became assistant to Ralph Smith, the pastor at Plymouth. The Plymouth people, being strict Separatists, were more congenial company, since they had withdrawn from the Established Order to form a church after the pattern of the Primitive Church model. Williams remained in Plymouth for about two years. Governor Bradford soon detected his advanced positions, relative to separation of Church and State, but considered it “questionable judgment.” He praised his qualities as a minister, writing thus of him:

His teaching, well approved, for þe benefit whereof I still bless God, and am thankful to him, even for his sharpest admonitions and reproofs, so far as they agreed with truth.

Governor Winthrop, with Mr. Wilson, teacher of the Boston church, visited Plymouth at this time.

They were very kindly treated and feasted every day at several houses. On the Lord’s Day, there was a sacrament which they did partake in; and, in the afternoon, Mr. Roger Williams (according to their custom) propounded a question, to which the Pastor, Mr. Smith, spoke briefly; then Mr. Williams prophesied; and after the Governor of Plymouth spoke to the question. Then the elder (Mr. William Brewster) desired the Governor of Massachusetts and Mr. Wilson to speak to it, which they did. When this was ended, the deacon, Mr. Fuller, put the congregation in mind of their duty of contribution; whereupon the Governor and all the rest went down to the deacon’s seat, and put into the box and then returned.

Williams came in contact with the Indians who visited Plymouth from time to time, and gained the confidence of Massasoit, the father of the famous Philip. He studied their language and cultivated their friendship. He writes in one of his letters, “My soul’s desire was to do the natives good!” Near the close of his life he referred to this early experience: “God was pleased to give me a painful patient spirit, to lodge with them [Pg 15]in their filthy smoke, to gain their tongue.” Surely the Providence of God was thus preparing the way for the founding of a new colony, to be made possible through these very Indians who had implicit confidence in this man of God.

A Key into the

LANGUAGE

OF

AMERICA:

OR,

An help to the Language of the Natives

in that part of America, called

NEW-ENGLAND.

Together, with briefe Observations of the Customes,

Manners and Worships, &c. of the

aforesaid Natives, in Peace and Warre,

in Life and Death.

On all which are added Spirituall Observations,

Generall and Particular by the Authour, of

chiefe and speciall use (upon all occasions,) to

all the English Inhabiting those parts;

yet pleasant and profitable to

the view of all men:

BY ROGER WILLIAMS

of Providence in New-England.

LONDON,

Printed by Gregory Dexter, 1643.

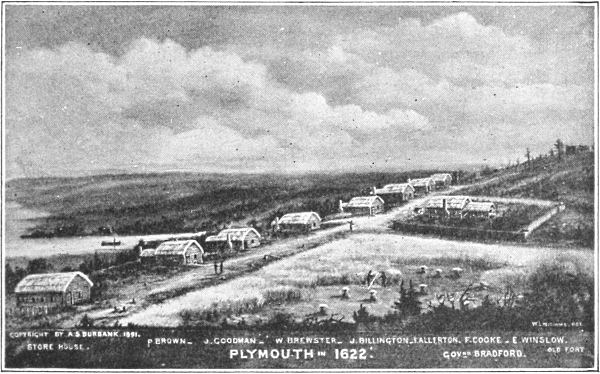

Boston, 1632

From an old print

The Fort and Chapel on the Hill Where Roger Williams Preached

Used by permission of A. S. Burbank, Plymouth, Mass.

Williams was Pauline in his self-supporting ministry. He wrote: “At Plymouth I spake on the Lord’s Day and week days and worked hard at my hoe for my bread (and so afterward at Salem until I found them to be an unseparated people).” His ministry made friends and foes. His foes feared he would run the same course of Anabaptist behavior as did John Smith, the Se-Baptist, at Amsterdam. Early in August his first child was born, and was named Mary after her mother. Later in the same month, he became for a second time the assistant to Mr. Skelton, at Salem. A number of choice spirits, who had been attracted to his ministry, went with him. He requested a letter of dismission from the Plymouth church to unite with the Salem church. This was granted, but with a caution as to his advanced views. To advocate the separation of Church and State placed a man at that time with the “Anabaptists,” as this was considered their great distinctive doctrine.

He commenced his labors at Salem under this cloud and also with the General Court in Boston very suspicious of his work. Already there was the distant rumbling of a storm which would eventually drive him into exile.

The ministers of the Bay Colony, from the churches of Boston, Newtowne (Cambridge), Watertown, Roxbury, Dorchester, Salem, and elsewhere, were accustomed to meet for discussion and common interest. Roger Williams feared that this might lead to a presbytery or superintendency, to the prejudice of local church liberty. He loathed everything which might make for intolerance.

In December, 1633, he forwarded to the governor and his assistants a document which he had prepared at Plymouth, in which he disputed their right to have the land by the king’s grant. Williams claimed, “they have no title except they compounded with the natives.” He also accused King James of telling a lie in claiming to be “the first Christian prince to discover this new land.” This treatise had never been published or made public. Its appearance now terrified the governor and the assistants,[Pg 16] for at that very time they were holding the possession to their colony on a charter originally given for a different purpose. It had been granted in England to a trading company, and its transfer was questionable. They feared the king might withdraw it. This treatise of Williams would be considered treason by the king. They met on December twenty-seventh and counseled with Williams. Seeing the grave danger to the colony, he agreed to give evidence of loyalty. Today we do not question the ethical correctness of the advanced position held by Williams.

It was not long before this pioneer of soul-liberty raised a new question concerning “the propriety of administering an oath, which is an act of worship, to either the unwilling or the unregenerate.” Williams’ position was peculiarly obnoxious to the magistrates who were then on the point of testing the loyalty of the colonists by administering an oath of allegiance which was to be, in reality, allegiance to the colony instead of to the king. The Court was called to discuss the new objection to its policy. Mr. Cotton informs us that the position was so well defended by Williams that “it threatened the court with serious embarrassment.” The people supported Williams’ position, and the court was compelled to desist. On the death of Skelton, in August, 1634, the Salem church installed Roger Williams as their teacher. This act gave great offense to the General Court in Boston. Williams commenced anew his agitation against the right to own land by the king’s patent. The Salem church and Williams were both cited to appear before the General Court, July 18, 1635, to answer complaints made against them.

The elders gave their opinion:

He who would obstinately maintain such opinions (whereby a church might run into heresy, apostasy, or tyranny, and yet the civil Magistrates may not intermeddle) ought to be removed, and that the other churches ought to request the Magistrates so to do.

The church and the pastor were notified “to consider the matter until the next General Court, and then to recant, or expect the court to take some final action.” At this same court, the Salem people petitioned for a title to some land at Marblehead Neck, which was theirs, as they believed, by a just claim. The court refused even to consider this claim, “until there shall be time [Pg 19]to test more fully the quality of your allegiance to the power which you desire should be interposed on your behalf.” Professor Knowles says:

Here is a candid avowal that justice was refused to Salem, on the question of civil right, as a punishment for the conduct of church and pastor. A volume could not more forcibly illustrate the danger of a connection between the civil and ecclesiastical power.

Pembroke College

Reduced from Loggan’s print, taken about 1688

Teacher and people at Salem were indignant, and a letter was addressed to the churches of the colony in protest against such injustice. The churches were asked to admonish the magistrates and deputies within their membership. These churches refused or neglected to do this. In some cases the letters never came before the church. Williams then called on his own church to withdraw communion with such churches. It declined to do this, and he withdrew from the Salem church, preaching his last sermon, August 19, 1635. Here was a repetition of the first conflict. Straus writes:

Here stood the one church already condemned, with sentence suspended over it. Against it were arrayed the aggregate power of the colony—its nine churches, the priests, and the magistrates. What could the Salem church and community do, threatened with disfranchisement, its deputies excluded from the General Court, and its petition for land to which it was entitled, denied? Dragooned into submission it had to abandon its persecuted minister to struggle alone against the united power of Church and State. To deny Williams the merit of devotion to a principle in this contest, wherein there was no alternative but retraction or banishment, is to belie history in order to justify bigotry, and to convert martyrdom into wrong-headed obstinacy. This is exactly what Cotton sought to do in his version of the controversy given ten years later in order to vindicate himself and his church brethren from the stigma of their acts in the eyes of a more enlightened public opinion in England. Williams pursued no half-hearted or half-way measures. He stood unshaken upon the firm ground of his convictions, and declared to the Salem church that he could no longer commune with them, thereby entirely separating himself from them and them from him.

He went so far as to refuse to commune with his own wife in the new communion which he formed in his own home, until she would completely withdraw from the Salem church.

The time for the next General Court drew near. The Salem church letter and Williams’ withdrawal from his church made[Pg 20] his foes determined to crush him. They had thoughts of putting him to death.

Whereas Mr. Roger Williams, one of the elders of the church of Salem, hath broached and divulged dyvers newe and dangerous opinions against the aucthorite of magistrates, as also with others of defamcon, both of the magistrates and churches here, and that before any conviccon, and yet maintaineth the same without retraccon, it is therefore ordered, that the said Mr. Williams shall depte out of this jurisdiccon within sixe weekes nowe nexte ensueing, wch if hee neglect to pforme, it shall be lawfull for the Gouv’r and two of the magistrates to send him to some place out of this jurisdiccon, not to returne any more without licence from the Court.

Fac-simile from Original Records of the Order for the Banishment

of Roger Williams.

The General Court convened in the rude meeting-house of the church in Newtowne (Cambridge), on the corner of Dunster and Mill Streets. Williams maintained his positions. He was asked if he desired a month to reflect and then come and argue the matter before them. He declined, choosing “to dispute presently.” Thomas Hooker, minister at Newtowne, was appointed to argue with him on the spot, to make him see his errors. Williams’ positions had a “rockie strength” and he was ready, “not only to be bound and banished, but to die also in New England; as for the most holy truths of God in Christ Jesus.” He would not recant. So the Court met the following day, Friday, October 9, 1635, and passed the following sentence:

Whereas Mr. Roger Williams, one of the elders of the church of Salem, hath broached and divulged dyvers newe and dangerous opinions against the aucthorite of magistrates, as also with letters of defamcon, both of the magistrates and churches here, and that before any conviccon, and yet maintaineth the same without retraccon, [Pg 23]it is therefore ordered, that the said Mr. Williams shall depte out of this jurisdiccon within sixe weekes nowe nexte ensueing, wch if hee neglect to pforme, it shall be lawfull for the Gouv’r and two of the magistrates to send him to some place out of this jurisdiccon, not to returne any more without licence from the Court.

Original Church at Salem, Mass.

Site of Home of Roger Williams in Providence, R. I.

Although Williams had withdrawn from the church at Salem, yet his character was such that the town was indignant at this decree of the court. About this time, his second child was born. Like the prophets of old, he gave the child a significant name, calling her “Freeborn.” Mr. Williams’ health at this time was far from being robust. A stay of sentence was therefore granted, and he was to be allowed to remain until the following spring. He did not refrain from advocating his opinions, and soon the authorities heard of meetings in his house at Salem and of twenty who were prepared to go with him to found a new colony at the head of the Narragansett Bay. At its January meeting, the Court decided to send him to England at once in a ship then about to return. He was cited to appear in Boston, but reported inability due to his impaired health. They then sent a pinnace for him by sea. Being forewarned, he fled to the wilderness in the depths of which, for fourteen weeks, he suffered the hardships of a New England winter.

******

The original Roger Williams Church is still preserved at Salem. The first church in the first town of the Massachusetts Bay Colony was at the corner of Washington and Essex Streets. There is a brick structure there now and a marble tablet marks it as the site of the first church in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. On another tablet, is the inscription:

The frame of the first Meeting House in which the civil affairs of the Colony were transacted, is preserved and now stands in the rear of Plummer Hall.

Plummer Hall is on Essex Street not very far from the First Church. In the rear is the Roger Williams Church, a small building, measuring twenty feet long by seventeen wide by twelve high at its posts. Originally it had a gallery over the door at the entrance and a minister’s seat in the opposite corner. On the[Pg 24] wall opposite to the entrance is a list of its succession of pastors and the years of their service:

| Francis Higginson | 1629-1630 | |

| Samuel Skelton | 1629-1634 | |

| Roger Williams | 1631-1635 | |

| Hugh Peters | 1636-1641 | etc., etc. |

It could accommodate about one hundred people. There were only forty families in Salem in 1632. There were only six houses, besides that of Governor Endicott, when Higginson arrived in 1629. Here in this ancient meeting-house Roger Williams preached those truths which led to his banishment. From its pulpit came, clearly stated, the ideals that millions have since accepted. The glory of the Sistine Chapel in Rome, or the Royal Sancte Chapella, of Paris, can never equal the glory of this crude edifice, the cradle of religious liberty in the New World.

The Roger Williams Home at Salem is still preserved. It is better known as “the Witch House” because it was occupied by Judge Carwin, one of the judges connected with the tragedy of 1692. It stands at the western corner of Essex and North Streets. It was built by the founder of Rhode Island and was at that time second only to the Governor’s home. Though it has been altered and repaired, the original rooms in this building are as follows: The eastern room on the first floor, 18 × 21½, and the room directly over it, 20 × 21½; the western room on the first floor, 16½ × 18, and the room over it, 16½ × 20. The chimney is 8 × 12. The part of the house which retains its original appearance is the projecting corner of the western part, fronting on Essex Street. Roger Williams mortgaged this house, “for supplies,” to establish the colony at Providence.

Mr. Upham, in his report to the Essex Institution, says of this wonderful house:

Here, within these very walls, lived, two hundred and fifty years ago, that remarkable and truly heroic man, who, in his devotion to the principle of free conscience, and liberty of belief, untrammeled by civil power, penetrated in midwinter in the depths of an unknown wilderness to seek a new home, a home which he could find only among savages, whose[Pg 25] respect for the benevolence and truthfulness of his character made them, then and ever afterward, his constant friends. From this spacious and pleasant mansion, he fled through the deep snows of a New England forest, leaving his wife and young children to the care of Providence, whose silent “voice” through the conscience, was his only support and guide. The State which he founded may ever look back with a just pride upon the history of Roger Williams.

[Pg 27]

THE FOUNDING OF PROVIDENCE

[Pg 28]

A community on the unheard-of principles of absolute religious liberty combined with perfect civil democracy.—Professor Mason.

Thus for the first time in history a form of government was adopted which drew a clear and unmistakable line between the temporal and the spiritual power, and a community came into being which was an anomaly among the nations.—Prof. J. L. Diman.

No one principle of political or social or religious policy lies nearer the base of American institutions and has done more to shape our career than this principle inherited from Rhode Island, and it may be asserted that the future of America was in a large measure determined by that General Court which summoned Roger Williams to answer for “divers new and dangerous opinions,” and his banishment became a pivotal act in universal history.—Prof. Alonzo Williams.

In summing up the history of the struggle for religious liberty it may be said that papal bulls and Protestant creeds have favored tyranny. Theologians of the sixteenth century and philosophers of the seventeenth, Descartes, Spinoza, and Hobbes, favored the State churches. It was bitter experience of persecution that led jurists, and statesmen of Holland and France, in face of the opposition of theologians and philosophers, to enforce the toleration of dissent. While there was toleration in Holland and France, there was, for the first time, in the history of the world in any commonwealth, liberty and equality and separation of Church and State in Rhode Island.—W. W. Evarts, in “The Long Road to Freedom of Worship.”

In the code of laws established by them, we read for the first time since Christianity ascended the throne of the Cæsars, the declaration that conscience should be free and men should not be punished for worshiping God in the way they were persuaded he requires.—Judge Story.

[Pg 29]

ROGER WILLIAMS left Salem on or about January 15, 1636, making the journey alone through the forests. With a pocket compass, and a sun-dial to tell the hours, he set out, probably taking the road to Boston for some distance. Nearing Boston, presumably at Saugus, he went west for a while and then straight south until he reached the home of Massasoit, the Wampanoag sachem, at Mount Hope, near Bristol. The ground was covered with snow, and he must have suffered sorely on this journey of eighty or ninety miles. Thirty-five years later in a letter to Major Mason, he refers to this experience:

First, when I was unkindly and unchristianly, as I believe, driven from my house and land, and wife and children (in the midst of a New England winter, now about thirty-five years past), at Salem, that ever-honored Governor, Mr. Winthrop, privately wrote me to steer my course to Narragansett Bay and the Indians, for many high and public ends, encouraging me, from the freeness of the place from any English claims or patents. I took his prudent notion as a hint and voice from God, and waving all other thoughts and notions, I steered my course from Salem (though in winter snow, which I feel yet) unto those parts wherein I may say “Peniel”; that is, I have seen the face of God.

He also wrote: “I was sorely tossed for one fourteen weeks, in a bitter winter season, not knowing what bread or bed did mean!” In his old age he exclaimed, “I bear to this day in my body the effects of that winter’s exposure.” In one of his books he refers to “hardships of sea and land in a banished condition.”

The precious relics of this flight are the sun-dial and compass, now in the possession of the Rhode Island Historical Society.

Williams finally reached Seekonk Cove, about the twenty-third of April. The spot was at Manton’s Neck, near the cove, where there was a good spring of water. Here he was joined by four companions, his wife, and two children. “I gave leave to William Harris, then poor and destitute,” said Williams, “to come along in my company. I consented to John Smith, miller[Pg 30] at Dorchester (banished also), to go with me, and, at John Smith’s desire, to a poor young fellow, Francis Wickes, as also a lad of Richard Waterman’s.” The latter was doubtless Thomas Angell. Joshua Verein came later. Some historians think that others joined them at the Seekonk before they were compelled to leave. Here they remained for two months. After providing rude shelters and sowing seeds, they received a warning to move on. “I received a letter,” said Williams,

from my ancient friend, Mr. Winslow, the Governor of Plymouth, professing his own and others’ love for me, yet lovingly advising me, since I was fallen into the edge of their bounds, and they were loathe to displease the Bay, to remove to the other side of the water, and there, he said, I had the country free before me, and might be free as themselves, and we should be loving neighbors together.

Sun-dial and Compass Used by Roger Williams in His Flight

Courtesy of “Providence Magazine”

His removal cost him the “loss of a harvest that year.” Historians are agreed that about the end of June he left Seekonk. The two hundred and fiftieth anniversary was celebrated, June 23 and 24, 1886. Embarking in a crude Indian canoe, Williams and his companions, six in all, crossed over the river to a little cove on the west side, where they were halted by a party of Indians, with the friendly interrogation, “What cheer?” Here the party landed on a rock which has been known ever since as “What Cheer Rock.” The cove is now filled and the rock covered [Pg 33]from sight. A suitable monument has been erected over the rock. It is in an open park space at the corner of Roger and Williams Streets, Providence. A piece of this rock is preserved at the First Baptist Church of Providence, and another has recently been placed in cross form in the lobby floor of the new Central Baptist Church of the same city. It is hoped that a piece of this rock will be worked into the National Baptist Memorial in our country’s capital.

Spring at the Seekonk Settlement

Tablet Marking Seekonk Site

What Cheer Rock. Landing-place of Roger Williams

After friendly salutations with the Indians, they reembarked and made their way down the river around the headland of Tockwotten and past Indian and Fox points, where they reached the mouth of the Moshassuck River. Rowing up this beautiful stream, then bordered on either side with a dense forest, they landed on the east side of the river, where there was an inviting spring. Here, on the ascending slopes of the hill, they commenced a new settlement, which Williams called “Providence,” in gratitude to God’s merciful Providence to them in their distress. Later, when they spread out in larger numbers and in all directions from this place, it was called “Providence Plantations.” They prepared shelters for their families, probably wigwams made of poles covered with hemlock boughs and forest leaves. We can in imagination see them climb the hill to a point where Prospect Street now runs, to enjoy a wider view of their new territory.

From that height of almost two hundred feet they saw to the westward, through openings in the forest, the cove at the head of the great salt river with broad sandy beaches on the eastern and northern shores and salt marshes bordering the western and southern. From the north the sparkling waters of the Moshassuck River came leaping over the falls as it emptied itself into the estuary at its mouth. Bordering this stream was a valley of beauty and fertility. The clear waters of the Woonasquatucket threaded their way from the west through another fertile valley. Between these rivers and also southward (of the Woonasquatucket) was a sandy plateau, covered with pine forests stretching to the Indian town of Mashapaug on the southwest and Pawtuxet Valley to the south. Between the edge of the tidal flow and the open waters of the great salt river there was a salt marsh dotted with islands, beyond which rose the bold peak[Pg 34] of Weybosset Hill. Down the river to the south they saw the steep hills of Sassafras and Field’s Point, beyond which could be seen the lower bay and its forest-covered shores and islands. The eastern slope of the hill stretched a mile toward the shore of the Seekonk. To the northeast the view was cut off by a higher eminence covered with oak and pine. In all directions, save that of the bay itself, the farther distances were lost in an indistinguishable maze of forest-crowned heights. At the feet of the spectators was the place of their immediate settlement, where the western slope of the hill gradually diminished in height toward the south. At its lowest extremity, Fox Point projected into the bay. This slope was covered with a growth of oak and hickory.

A Purchased Possession

Roger Williams differed from the ordinary colonists of his age, who held that the Indian, being heathen, had no real ownership of the land. It belonged to the Christians who might first claim it by right of discovery. Williams, who “always aimed to do the Indians only good,” recognized Indian ownership and secured his colony from them by purchase. Here among them he first sought to apply his doctrine of soul-liberty. To him they were humans with equal rights and privileges. He bitterly fought the Puritan position that the pagan heathen had no property rights which the Christian, with his superior culture, was bound to respect. Roger Williams insisted that the land should be purchased from the Indians, the original owners. He gained the lasting respect of the Indian and the undying animosity of the Puritan for holding to ideals which have since come to be recognized as American. He thus laid the foundation for the belief in America that the weaker and smaller powers have rights which the greater powers must respect, a belief which led us into the recent great war. While this principle is receiving world-wide application, let us not forget that Roger Williams was the pioneer of international justice in America, if not in the world. The land viewed from the top of the hill was owned by five distinct Indian tribes. The Narragansetts dominated over all the lands now occupied by Rhode Island, and ruled over all other lesser tribes in this territory. In the northern part of this State, [Pg 37]the Nipmucs lived in the place now occupied by Smithfield, Glocester, and Burrilville. On the southern seacoast border dwelt the Niantics. Part of the Wampanoag tribe dwelt in Cumberland and extended to the western side of the river which we now call the Blackstone. The Pequots lived in Connecticut Colony. Indian government was monarchial, and became extinct with the slaughter of the last of the line of rulers or sachems in the massacre of July 2, 1676. Canonicus was the ruling sachem when the English first came. As he grew old he needed an assistant and his nephew, Miantonomo, was appointed. Miantonomo worked well with the elder chief. He never succeeded to the position of ruling chief, being murdered in 1643. Roger Williams secured his land from these sachems. Williams wrote in 1661 as follows:

I was the procurer of the purchase, not by monies, nor payments, the natives being so shy and jealous, that monies could not do it, but by that language, acquaintance, and favor with the natives and other advantages which it pleased God to give me, and also bore the charges and venture of all the gratuities which I gave to the great Sachems and natives round about us, and lay engaged for a loving and peaceable neighborhood with, to my great charge and travel.

Original Deed of Providence from the Indians

He found Indian gifts very costly. Presents were made frequently. He allowed the Indians to use his pinnace and shallop at command, transporting and lodging fifty at his home at a time. He never denied them any lawful thing. Canonicus had freely what he desired from Roger Williams’ trading-post at Narragansett. William Harris stated in 1677 that Roger Williams had paid thus one hundred and sixty pounds ($800) for Providence and Pawtucket.

Mr. Williams generously admitted the first twelve proprietors of the Providence Purchase to an equal share with himself, without exacting any remuneration. The thirty pounds which he received were paid by succeeding settlers, at the rate of thirty shillings each. This was not a payment for the land but what he called “a loving gratuity.” Straus says:

He might have been like William Penn, the proprietor of his colony, after having secured it by patent from the rulers in England, and thus have exercised a control over its government and enriched himself and[Pg 38] family. But this was not his purpose, nor was it directly or remotely the cause for which he suffered banishment and misery. Principle—not profit; liberty—not power; conviction—not ambition, were his impelling motives which he consistently maintained, theoretically and practically then, and at all times.

Williams’ own words were:

I desired it might be for a shelter for persons distressed for conscience. I then considering the conditions of divers of my distressed countrymen, I communicated my said purchase unto my loving friends (whom he names) who desired to take shelter with me.

He afterward purchased, jointly with Governor Winthrop, the Island of Prudence from Canonicus. He also purchased, a little later, the small islands of Patience and Hope, afterward selling his interest in them to help pay his expenses to England on business for the colony.

Following is a true copy of the Original Deed of Land for Providence from Canonicus and Miantonomo:

At Nanhiggansick, the 24th of the first month, commonly called March, in the second year of the Plantations of Plantings at Mooshausick or Providence. Memorandum that we Caunaunicus and Meauntunomo, the two chief sachems of Nanhiggansick, having two years since sold unto Roger Williams, the lands and meadows upon the two fresh rivers, called Mooshausick and Wanasquatucket, do now by these presents, establish and confirm the bounds of those lands, from the river and fields at Pawtucket, the great hill of Neotackonkonutt, on the northwest, and the town of Mashapauge on the west. As also in consideration of the many kindnesses and services he hath continually done for us, both with our friends of Massachusetts, as also at Quinickicutt and Apaum, or Plymouth, we do now freely give unto him all the land from those rivers reaching to Pawtuxet River, as also the grass and meadows upon the said Pawtuxet River. In witness whereof we have hereunto set our hands.

In the presence of

The Mark * of Setash,

The Mark * of Assotenewit,

The Mark * of Caunaunicus,

The Mark * of Meauntunomo.

This original deed is preserved, as a precious relic, in the City Hall at Providence.

[Pg 39]

Williams’ Letter of Transference to His Loving Friends

[Pg 40]

Early Experiences in Providence

The Providence planters soon built their crude homes. The Indian name of the plantation was Notaquonchanet. In their early records of Providence this name is spelt in at least forty-two different forms. Other settlers came and swelled their numbers. The original six were bound together by a compact. It was verbal, or if written, the copy has been lost. When new settlers came and Wickes and Angell had reached majority, a copy of the original agreement was drawn up and signed by those not included in the first compact. Williams was familiar with the great compact signed in the Mayflower by the Pilgrims and probably it suggested to his mind the need of one in Providence. This Providence Compact is as follows:

We, whose names are hereunder written, being desirous to inhabit in the town of Providence, do promise to submit ourselves in active or passive obedience, to all such orders or agreements as shall be made for the public good of the body, in an orderly way, by the major consent of the present inhabitants, masters of families, incorporated together into a township, and such others whom they shall admit unto the same, ONLY IN CIVIL THINGS.

Edmund J. Carpenter says of this Compact:

A compact of government, which in its terms, must be regarded as the most remarkable political document theretofore executed, not even excepting the Magna Charta. It was a document which placed a government, formed by the people, solely in the control of the civil arm. It gave the first example of a pure democracy, from which all ecclesiastical power was eliminated. It was the first enunciation of a great principle, which years later, formed the corner-stone of the great republic. It was the act of a statesman fully a century in advance of his time.

At the west entrance to the street railroad tunnel in Providence a bronze tablet commemorates the fact that there in the open air the first town meetings were held.

Roger Williams’ house was opposite the spring, forty-eight feet to the east of the present Main Street and four feet north of Howland Street. Next, to the north of his residence, was the house and lot of Joshua Verein. North of this was Richard Scott’s. The first house south of Williams’ was that of John [Pg 43]Throckmorton and, beyond, that of William Harris. At first the struggle for existence was hard, more so because of the loss of the crops planted at Seekonk. Governor Winslow, of Plymouth, conscious of the wrong Plymouth Colony had done to Williams, visited the little settlement that first summer and left a gift of gold with Mrs. Williams. In the spring and summer of the following year, new houses were built along the street. The new settlers brought money with them, and Williams enlisted outside capital to help develop the colony.

The Original Providence “Compact”

Drawn up by the men of Providence, August 20, 1638, and now contained in the City Hall. One of the most valuable documents in existence, under which Williams and his companions promised to subject themselves in active and passive obedience, but “Only in Civil Things.”

“You must look to the Magna Charta, for another such epoch-making decree, for these, with the Declaration and the Emancipation Proclamation, are the four great dynamic forces of American Freedom.”—R. B. Burchard.

Courtesy of “Providence Magazine,” October, 1915

The number of town lots increased. The land lay between the present Main Street and Hope Street. Each lot was of equal width and ran eastward. Eventually there were one hundred and two of these lots extending from Mile End Brook, which enters the river a little north of Fox Point, to Harrington’s Lane, now the dividing line between Providence and North Providence. Meeting and Power Streets were the dividing streets in those early days. In addition to the home lot, each proprietor had an “out six-acre lot” assigned to him. Williams’ “out lot” was at “What Cheer Rock.”

The Threatened Indian Trouble

Williams, although suffering from Puritan persecution, had an opportunity that first year of doing good to his persecutors. He became the savior of all the New England Colonies. The Pequot Indians planned the annihilation of the English. Williams, hearing of this, did his utmost to break up an Indian league, and kept the Narragansetts from joining the Pequots and Mohicans. He describes this experience in the following statement:

The Lord helped me immediately to put my life into my hands, and scarce acquainting my wife, to ship alone, in a poor canoe, and to cut through a stormy wind, with great seas, every minute in hazard of life, to the sachem’s house. Three days and nights my business forced me to lodge and mix with the bloody Pequod ambassadors, whose hands and arms, methought, reeked with the blood of my countrymen, murdered and massacred by them on the Connecticut River, and from whom I could not but nightly look for their bloody knives at my own throat also. God wondrously preserved me, and helped me to break the Pequod’s negotiation and design; and to make and finish, by many travels and charges, the English league with the Narragansetts and Mohegans against the Pequods.

[Pg 44]

As a result of this, the tribe of Pequots was obliterated completely and a danger hanging over all the colonies was removed.

The Indian villages of southern New England were composed at times of as many as fifty houses or wigwams. Most of these wigwams were shaped like the half of an orange, with the flat or cut surface down. They were ten to twelve feet in diameter and could accommodate two families. Other houses were like the half of a stovepipe cut lengthwise, twenty to thirty feet long, and accommodated from two families in the summertime to fifty in the winter, when the people crowded together for the sake of warmth. The council-chamber was often as long as one hundred feet with a width of thirty feet. It was used only for councils. A fortified stockade in the center of the village was made of logs set into the ground. Such was the shelter afforded Williams when he fled from Salem, and such was the place when he met the Indian sachems in council seeking to avert the massacre of the whites. In these villages he preached the everlasting gospel of the Son of God. He had the constant confidence of Indian sachems because he applied to them the principle of soul-liberty which he sought to practise among the whites.

In the autumn of 1638, Roger Williams’ third child and first son was born and named “Providence.” He was the first white male child born in this colony. In the year 1639-1640 the town grew and felt the need of a system of town government. On July 23, 1640, an organization was decided upon in which they vested the care of the general interests of the town in five “disposers” or arbitrators. The people retained the right to appeal from the “disposers” to the general town meeting. They were careful to provide that as “formerly hath been the liberties of the town, so still to hold for the liberty of conscience.”

In 1638 a settlement had been made at Portsmouth on Rhode Island. John Clarke and Mrs. Ann Hutchinson were the leaders of this new band who were looking for a place where they might have religious freedom, which was denied them at Boston. They went first to New Hampshire, but, finding it too cold there, turned to the south. By the friendly assistance of Mr. Williams, they secured from Canonicus and Miantonomo, for a consideration of forty fathoms of white beads, Aquidneck and other islands in Narragansett Bay. The natives residing on the island itself [Pg 46]were induced to remove for a consideration of ten coats and twenty hoes. The new settlers chose Mr. Coddington to be their judge and united in a covenant with each other and with their God. They made Mr. Coddington their governor in 1640.

About this same time a number of Providence people settled in Pawtuxet, four miles south of Providence in territory ceded to Williams. Warwick and Shawomet were settled by Samuel Gorton and his friends. Gorton was a strange character who did not find things congenial for him at Boston, Plymouth, and Newport in turn. Roger Williams, however, gave him shelter in Providence. Finally he went to Pawtuxet and later to Shawomet, for which he paid four fathoms of wampum to the Indians. At once Boston Colony claimed that Shawomet was under their jurisdiction. Gorton and his associates refused to come to Boston at the bidding of the authorities. Forty soldiers came to Shawomet and seized Gorton and ten of his friends and imprisoned them in Boston. They were tried for their lives, escaping only by two votes. They were then imprisoned in the various towns. Each one was compelled to wear a chain fast bolted around his legs. If they spoke to any person, other than an officer of the Church or of the State, they were to be put to death. They were kept at labor that winter and then banished in the spring. Gorton escaped to England and secured an order from the Earl of Warwick and the Commissioners of the Colonies requiring Massachusetts not to molest the settlers at Shawomet. Thereafter Gorton and his friends occupied their lands in peace.

Gorton wrote his side of the question in “Simplicities Defence,” in which he referred to his persecutors as “That Servant so Imperious in his Master’s Absence Revived.” This is another indictment against the persecuting Puritans by one who found shelter in the Baptist colony of Rhode Island.

SIMPLICITIES DEFENCE

against

SEVEN-HEADED POLICY.

OR

Innocency Vindicated, being unjustly Accused,

and sorely Censured, by that

Seven-headed Church-Government

United in

NEW-ENGLAND:

OR

That Servant so Imperious in his Masters Absence

Revived, and now thus re-acting in New-England.

OR

The combate of the United Colonies, not onely against

some of the Natives and Subjects, but against the Authority also

of the Kingdme of England, with their execution of Laws, in the name and

Authority of the servant, (or of themselves) and not in the Name and

Authority of the Lord, or fountain of the Government.

Wherein is declared an Act of a great people and Country

of the Indians in those parts, both Princes and People (unanimously)

in their voluntary Submission and Subjection unto the Protection

and Government of Old England (from the Fame they hear thereof) together

with the true manner and forme of it, as it appears under their own

hands and seals, being stirred up, and provoked thereto, by

the Combate and courses above-said.

Throughout which Treatise is secretly intermingled, that

great Opposition, which is in the goings forth of those two grand

Spirits, that are and ever have been, extant in the World

(through the sons of men) from the beginning and

foundation thereof.

Imprimatur, Aug. 3ᵈ. 1646. Diligently perused, approved, and

Licensed to the Presse, according to Order by publike Authority.

LONDON,

Printed by John Macock, and are to be sold by Luke Favvne,

at his shop in Pauls Church-yard, at the sign of the Parrot. 1646.

The Story of the First Charter

As the colony grew, it was found necessary that there should be some vested authority which would command respect from the neighbors. Notwithstanding what Williams had done for the Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay colonies in connection with the Pequot War, and the personal friendships he had with the governors, they would not consider that he or his had any separate[Pg 48] colony rights whatever. He had been their Joseph driven from home and country by hostile brethren. In exile, he became the savior of his brethren from a dreadful massacre by the Indians. Nevertheless, Plymouth claimed jurisdiction over all the plantations in Narragansett Bay, and Massachusetts claimed it over Providence, Pawtuxet, and Shawomet. The Dutch had formed a trading-post at Dutch Island and elsewhere and could strike a blow at the colony at any time. Out of these conditions grew the demand for a charter. Roger Williams, at a great personal sacrifice, went to England from Manhattan, now New York City, because the two colonies to the north forbade his departure from their ports.

Arriving in England, he found the country in the midst of the great Civil War. King Charles was powerless because Parliament controlled the realm. Parliament had placed colonial interest in charge of a committee of which the Earl of Warwick was chairman or “Governor in Chief, and Lord High Admiral of the Colonies.” From this council a charter was granted, March 17, 1644. The colony was incorporated as “Providence Plantations” and embraced the territory now covered by the State of Rhode Island. There was granted to the inhabitants of Providence, Portsmouth, and Newport, a

free and absolute charter of incorporation ... together with full power and authority to govern themselves and such others as shall hereafter inhabit within any part of said tract of land by such form of civil government as by the voluntary consent of all or the greatest part of them shall be found most serviceable to their estate and condition, etc.

Upon the return of Williams, the inhabitants of Providence, learning of his approach, came out in fourteen canoes to meet him at the Seekonk. They traveled over the historic course which he had traveled six years before when he was an exile. Now in triumph they escorted their beloved leader to home and native town. A picture of his return with the charter, by Grant, is on the walls of the Court House at Providence.

The Arrival of Roger Williams with the Charter

The earliest published work of Mr. Williams is entitled,

A Key into the Language of America: or, an help to the Language of the Natives in that part of America, called New-England. Together,[Pg 51] with briefe Observations of the Customes, Manners and Worships, etc. of the aforesaid Natives, in Peace and Warre, in Life and Death. On all which are added Spirituall Observations, Generall and Particular by the Authour, of chiefe and speciall use (upon all occasions) to all the English Inhabiting those parts; yet pleasant and profitable to the view of all men: By Roger Williams of Providence in New-England. London, Printed by Gregory Dexter, 1643.

It was written at sea, en route to England, in the summer of 1643. Copies of the original edition are in the Bodleian Library, at Oxford, the British Museum, also in the Library of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Harvard College, Brown University, and the American Antiquarian Society at Worcester. It comprises two hundred and sixteen small duodecimo pages, including preface and table.

The second published work of Roger Williams is entitled, “Mr. Cottons Letter Lately Printed, Examined and Answered. By Roger Williams of Providence, in New-England. London, Imprinted in the Yeere 1644.” Mr. Cotton had sought to “take off the edge of Censure from himself”—that he was no procurer of the sorrow which came to Williams in his flight and exile. It is a small quarto of forty-seven pages, preceded by an address of two pages. The letter referred to was written by John Cotton, and was published in London, 1643. The author vindicated the act of the magistrates in banishing Roger Williams from Massachusetts. He denies that he himself had any agency in it. It consists of thirteen small quarto pages. Good copies of both the Letter and the reply are in the Library of Brown University. Two copies of the reply are in England, one in the British Museum, the other in Bodleian Library. A mutilated copy of the reply is also in the Library of Yale College.

Roger Williams wrote also, when in England, securing the Charter for Rhode Island, a work entitled, “The Bloudy Tenent, of Persecution for cause of Conscience, discussed.” It is considered the best written of all his works. These discussions were prepared in London,

for publike view, in charge of roomes and corners, yea, sometimes in variety of strange houses, sometimes in the fields, in the midst of travel, where he hath been forced to gather and scatter his loose thoughts and papers.

[Pg 54]

It is written in an animated style and has the adornment of beautiful imagery. Original copies are rare, eight only are known to exist, one in the British Museum, one in Bodleian Library, one in Brown University Library, one in Harvard College Library.

Mʳ Cottons

LETTER

Lately Printed,

EXAMINED

AND

ANSVVERED:

By Roger Williams of Providence

In

New·England.

LONDON,

Imprinted in the yeere 1644.

THE

BLOVDY TENENT,

of Persecution, for cause of

Conscience, discussed, in

A Conference betweene

TRVTH and PEACE.

Who,

In all tender Affection, present to the High

Court of Parliament, (as the Result of

their Discourse) these, (amongst other

Passages) of highest consideration.

Printed in the Year 1644.

This work is based on a Baptist publication, entitled “An Humble Supplication to the King’s Majesty, as it was presented 1620.” This latter was a clear and concise argument against persecution and for liberty of conscience. It was written by Murton, or some other London Baptist, who was imprisoned in Newgate for conscience sake. His confinement was so rigid that he was denied pen, paper, and ink. A friend in London sent him sheets of paper, as stoppers for the bottles containing his daily allowance of milk. He wrote his thoughts on these sheets with milk, returning them to his friends as stoppers for the empty bottles. They were held to the fire and thus became legible. Roger Williams based his book on the argument of this “Humble Supplication.”

In such Paper written with Milk nothing will appeare, but the way of reading it by fire being knowne to this friend who received the Papers, he transcribed and kept together the Papers, although the Author himselfe could not correct, nor view what himselfe had written.

It was in milke, tending to soule nourishment, even for Babes and Sucklings in Christ.

It was in milke, spiritually white, pure and innocent, like those white horses of the Word of truth and meeknesse, and the white Linnen or Armour of rightousnesse, in the Army of Jesus. Rev. 6. & 19.

It was in milke, soft, meeke, peaceable and gentle, tending both to the peace of soules, and the peace of States and Kingdomes.

Peace. The Answer (though I hope out of milkie pure intentions) is returned in bloud: bloudy & slaughterous conclusions; bloudy to the souls of all men, forc’d to the Religion and Worship which every civil State or Common-weale agrees on, and compells all subjects to in a dissembled uniformitie.

Bloudy to the bodies, first of the holy witnesses of Christ Jesus, who testifie against such invented worships.

Secondly, of the Nations and Peoples slaughtering each other for their severall respective Religions and Consciences.

Roger Williams’ Reference to “An Humble Supplication” in His “Bloudy Tenent”

******

The little band which settled Providence on that June day, 1636, had grown into a large town. With other towns they[Pg 55] suffered the same injustice from neighboring colonies. The assembly in Newport, September 19, 1642, which intrusted the work of securing a charter to Williams, was in reality fusing together these separate groups, which had a common enemy and common principles, into a State. The Town of Providence, a great monument to Roger Williams, must now give way to the State of Rhode Island, which was destined to become a still larger monument to the ideals of this great exponent of civil and religious liberty, “a liberty which does not permit license in civil [Pg 56]matters in contempt of law and order.”

[Pg 57]

THE HISTORIC CUSTODIANS OF

SOUL-LIBERTY

[Pg 58]

Roger Williams must forever rank as one of the great epoch-makers of the world, and to him impartial historians accord the honor of being the first democrat. It was not until his expulsion from Salem Colony that he became a Baptist, but the evidence is indisputable that he had long been a Baptist at heart. He had spent much time among the Baptists in England and was familiar with their doctrines and writings. No sooner had Williams set foot in America than he found himself in conflict with the authorities, both civil and religious.—S. Z. Batten, in “The Christian State.”

There is not a confession of faith, nor a creed, framed by any of the Reformers, which does not give the magistrate a coercive power in religion, and almost every one at the same time curses the resisting Baptists.—E. B. Underhill, in “Struggles and Triumphs.”

Godly princes may lawfully issue edicts for compelling obstinate and rebellious persons to worship the true God and to maintain the unity of the faith.—Calvin.

Democracy, I do not conceyve that ever God did ordeyne as a fit government eyther for Church or Commonwealth.... As for monarchy and aristocracy, they are both of them clearly approved, and directed in Scripture.—John Cotton.

It is said that Men ought to have Liberty of their Conscience, and that it is Persecution to debar them of it; I can stand amazed than reply to this: It is an astonishment to think that the brains of men should be parboiled in such impious ignorance.—Rev. Nathaniel Ward, Lawyer Divine, of Ipswich, who drew up the first legal code for Massachusetts Bay Colony.

[Pg 59]