INTO MEXICO WITH

GENERAL SCOTT

The American Trail Blazers

“THE STORY GRIPS AND THE HISTORY STICKS”

These books present in the form of vivid and fascinating fiction, the early and adventurous phases of American history. Each volume deals with the life and adventures of one of the great men who made that history, or with some one great event in which, perhaps, several heroic characters were involved. The stories, though based upon accurate historical fact, are rich in color, full of dramatic action, and appeal to the imagination of the red-blooded man or boy.

Each volume illustrated in color and black and white

12mo. Cloth.

WHEN ATTACHED TO THE FOURTH UNITED STATES INFANTRY, DIVISION OF MAJOR-GENERAL WILLIAM J. WORTH, CORPS OF THE FAMOUS MAJOR-GENERAL WINFIELD SCOTT, KNOWN AS OLD FUSS AND FEATHERS, CAMPAIGN OF 1847, LAD JERRY CAMERON MARCHED AND FOUGHT BESIDE SECOND LIEUTENANT U. S. GRANT ALL THE WAY FROM VERA CRUZ TO THE CITY OF MEXICO, WHERE SIX THOUSAND AMERICAN SOLDIERS PLANTED THE STARS AND STRIPES IN THE MIDST OF ONE HUNDRED AND FIFTY THOUSAND AMAZED PEOPLE

BY

AUTHOR Of “LOST WITH LIEUTENANT PIKE,” “OPENING THE

WEST WITH LEWIS AND CLARK,” “BUILDING THE

PACIFIC RAILWAY,” ETC.

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY

PORTRAIT AND 2 MAPS

1920

COPYRIGHT, 1920, BY J. B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY

PRINTED BY J. B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY

AT THE WASHINGTON SQUARE PRESS

PHILADELPHIA, U. S. A.

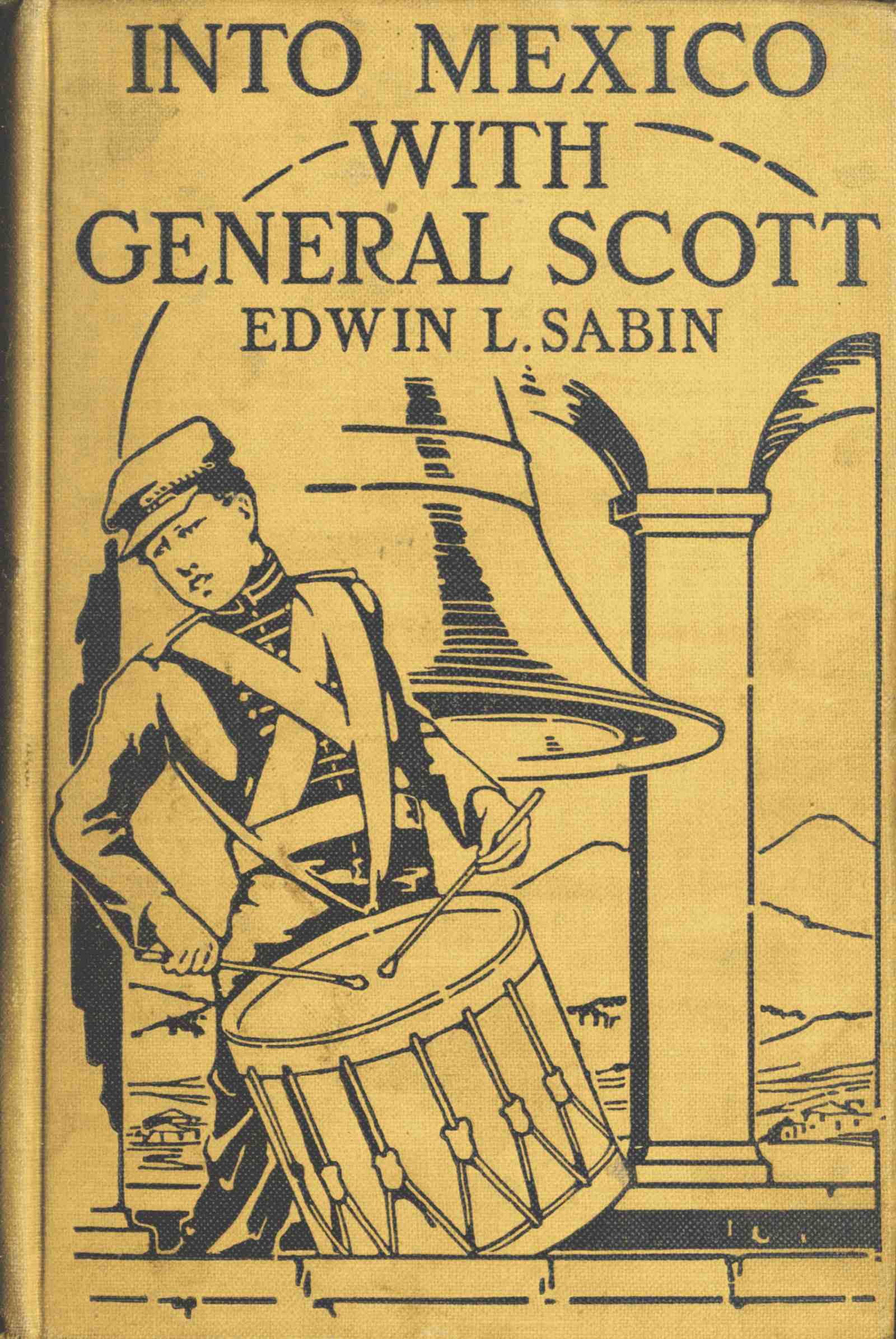

Although General Winfield Scott was nicknamed by the soldiers “Old Fuss and Feathers,” they intended no disrespect. On the contrary, they loved him, and asked only that he lead them. No general ever lived who was more popular with the men in the ranks. They had every kind of confidence in him; they knew that “Old Fuss and Feathers” would look out for them like a father, and would take them through.

His arrival, all in his showy uniform, upon his splendid horse, along the lines, was the signal for cheers and for the bands to strike up “Hail to the Chief.” At bloody Chapultepec the soldiers crowded around him and even clasped his knees, so fond they were of him. And when he addressed them, tears were in his eyes.

General Scott was close to six feet six inches in height, and massively built. He was the tallest officer in the army. His left arm was partially useless, by reason of two wounds received in the War of 1812, but in full uniform he made a gallant sight indeed. He never omitted any detail of the uniform, because he felt that the proper uniform was required for discipline. He brooked no unnecessary slouchiness among officers and men; he insisted upon regulations and hard drilling, and the troops that he commanded were as fine an army as ever followed the Flag.

While he was strict in discipline, he looked keenly also after the comforts and privileges of his soldiers. He realized that unless the soldier in the ranks is well cared for in garrison and camp he will not do his best in the field, and that victories are won by the men who are physically and mentally fit. He did not succeed in doing away with the old practice of punishment by blows and by “bucking and gagging,” but he tried; and toward the ill and the wounded he was all tenderness.

As a tactician he stands high. His mind worked with accuracy. He drew up every movement for every column, after his engineers had surveyed the field; then he depended upon his officers to follow out the plans. His general orders for the battle of Cerro Gordo are cited to-day as model orders. Each movement took place exactly as he had instructed, and each movement brought the result that he had expected; so that after the battle the orders stood as a complete story of the fight.

His character was noble and generous. He had certain peculiar ways—he spoke of himself as “Scott” and like Sam Houston he used exalted language; he was proud and sensitive, but forgiving and quick to praise. He prized his country above everything else, and preferred peace, with honor, to war. Although he was a soldier, such was his justice and firmness and good sense that he was frequently sent by the Government to make peace without force of arms, along the United States borders. He alone it was who several times averted war with another nation.

General Scott should not be remembered mainly[9] for his battles won. He was the first man of prominence in his time to speak out against drunkenness in the army and in civil life. He prepared the first army regulations and the first infantry tactics. He was the first great commander to enforce martial law in conquered territory, by which the conquered people were protected from abuse. He procured the passage of that bill, in 1838, which awarded to all officers, except general officers like himself, an increase in rations allowance for every five years of service. The money procured from Mexico was employed by him in buying blankets and shoes for his soldiers and in helping the discharged hospital patients; and $118,000 was forwarded to Washington, to establish an Army Asylum for disabled enlisted men. From this fund there resulted the present system of Soldiers’ Homes.

The Mexican War itself was not a popular war, among Americans, many of whom felt that it might have been avoided. Lives and money were expended needlessly. Of course Mexico had been badgering the United States; American citizens had been mistreated and could obtain no justice. But the United States troops really invaded when they crossed into southwestern Texas, for Mexico had her rights there.

The war, though, brought glory to the American soldier. In the beginning the standing army of the United States numbered only about eight thousand officers and men, but it was so finely organized and drilled that regiment for regiment it equalled any army in the world. The militia of the States could not be depended upon to enter a foreign country; they had to be called upon as volunteers. Mexico[10] was prepared with thirty thousand men under arms; her Regulars were well trained, and her regular army was much larger than the army of the United States.

When General Zachary Taylor, “Old Rough and Ready,” advanced with his three thousand five hundred Regulars (almost half the United States army) for the banks of the Rio Grande River, he braved a Mexican army of eight thousand, better equipped than he was, except in men.

A military maxim says that morale is worth three men. All through the war it was skill and spirit and not numbers that counted; quality proved greater than quantity. “Old Zach,” with seventeen hundred Regulars, beat six thousand Mexican troops at Resaca de la Palma. At Buena Vista his four thousand Volunteers and only four hundred and fifty or five hundred Regulars repulsed twenty thousand of the best troops of Mexico. General Scott reached the City of Mexico with six thousand men who, fighting five battles in one day, had defeated thirty thousand. Rarely has the American soldier, both Regular and Volunteer, so shone as in that war with Mexico, when the enemy outnumbered three and four to one, and chose his own positions.

The battles were fought with flint-lock muskets, loaded by means of a paper cartridge, from which the powder and ball were poured into the muzzle of the piece. The American dragoons were better mounted than the Mexican lancers, and charged harder. The artillery was the best to be had and was splendidly served on both sides, but the American guns were the faster in action.

Thoroughly trained officers and men who had confidence[11] in each other and did not know when they were beaten, won the war. Many of the most famous soldiers in American history had their try-out in Mexico, where Robert E. Lee and George B. McClellan were young engineers, U. S. Grant was a second lieutenant, and Jefferson Davis led the Mississippi Volunteers. The majority of the regular officers were West Pointers. General Scott declared that but for the military education afforded by the Academy the war probably would have lasted four or five years, with more defeats than victories, at first.

Thus the Mexican War, like the recent World War, proved the value of officers and men trained to the highest notch of efficiency.

In killed and wounded the war with Mexico cost the United States forty-eight hundred men; but the deaths from disease were twelve thousand, for the recruits and the Volunteers were not made to take care of themselves. In addition, nearly ten thousand soldiers were discharged on account of ruined health. All in all the cost of the war, in citizens, footed twenty-five thousand. The expense in money was about $130,000,000.

By the war the United States acquired practically all the country west from northern Texas to the Pacific Ocean, which means California, Utah, Nevada, the western half of Colorado and most of New Mexico and Arizona. This, it must be said, was an amazing result, for in the outset we had claimed only Texas, as far as the Rio Grande River.

E. L. S.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| The War with Mexico | 18 | |

| Lieutenant-General Winfield Scott | 27 | |

| I. | The Star-Spangled Banner | 37 |

| II. | A Surprise for Vera Cruz | 53 |

| III. | The Americans Gain a Recruit | 61 |

| IV. | Jerry Makes a Tour | 67 |

| V. | In the Naval Battery | 84 |

| VI. | Second Lieutenant Grant | 92 |

| VII. | Hurrah for the Red, White and Blue! | 110 |

| VIII. | Inspecting the Wild “Mohawks” | 120 |

| IX. | The Heights of Cerro Gordo | 130 |

| X. | Jerry Joins the Ranks | 146 |

| XI. | In the Wake of the Fleeing Enemy | 154 |

| XII. | An Interrupted Toilet | 164 |

| XIII. | Getting Ready at Puebla | 175 |

| XIV. | A Sight of the Goal at Last | 188 |

| XV. | Outguessing General Santa Anna | 194 |

| XVI. | Facing the Mexican Host | 203 |

| XVII. | Clearing the Road to the Capital | 218 |

| XVIII. | In the Charge at Churubusco | 229 |

| XIX. | Before the Bristling City | 240 |

| XX. | The Battle of the King’s Mill | 250 |

| XXI. | Ready for Action Again | 269 |

| XXII. | Storming Chapultepec | 279 |

| XXIII. | Forcing the City Gates | 291 |

| XXIV. | In the Halls of Montezuma | 311 |

His motto in life: “If idle, be not solitary; if solitary, be not idle.”

At Queenstown Heights, 1812: “Let us, then, die, arms in hand. Our country demands the sacrifice. The example will not be lost. The blood of the slain will make heroes of the living.”

At Chippewa, July 5, 1814: “Let us make a new anniversary for ourselves.”

To the Eleventh Infantry at Chippewa: “The enemy say that Americans are good at long shot, but cannot stand the cold iron. I call upon the Eleventh instantly to give the lie to that slander. Charge!”

From an inscription in a Peace Album, 1844: “If war be the natural state of savage tribes, peace is the first want of every civilized community.”

At Vera Cruz, March, 1847, when warned not to expose himself: “Oh, generals, nowadays, can be made out of anybody; but men cannot be had.”

At Chapultepec, 1847: “Fellow soldiers! You have this day been baptized in blood and fire, and you have come out steel!”

To the Virginia commissioners, 1861: “I have served my country under the flag of the Union for more than fifty years, and, so long as God permits me to live, I will defend that flag with my sword, even if my own native State assails it.”

March 2, 1836, by people’s convention the Mexican province of Texas declares its independence and its intention to become a republic.

April 21, 1836, by the decisive battle of San Jacinto, Texas wins its war for independence, in which it has been assisted by many volunteers from the United States.

May 14, 1836, Santa Anna, the Mexican President and general who had been captured after the battle, signs a treaty acknowledging the Texas Republic, extending to the Rio Grande River.

September, 1836, in its first election Texas favors annexation to the United States.

December, 1836, the Texas Congress declares that the southwestern and western boundaries of the republic are the Rio Grande River, from its mouth to its source.

The government of Mexico refuses to recognize the independence of Texas, and claims that as a province its boundary extends only to the Nueces River, which empties into the Gulf of Mexico, about 120 miles from the mouth of the Rio Grande.

This spring and summer petitions have been circulated through the United States in favor of recognizing the Republic of Texas. Congress has debated upon that and upon annexation. The South especially desires the annexation, in order to add Texas to the number of slave-holding States.

February, 1837, President Andrew Jackson, by message to Congress, relates that Mexico has not observed a treaty of friendship signed in 1831, and has committed many outrages upon the Flag and the citizens of the United States; has refused to make payments for damages and deserves “immediate war” but should be given another chance.

March, 1837, the United States recognizes the independence of the Texas Republic.

Mexico has resented the support granted to Texas by the United States and by American citizens; she insists that[19] Texas is still a part of her territory; and from this time onward there is constant friction between her on the one side and Texas and the United States on the other.

In August, 1837, the Texas minister at Washington presents a proposition from the new republic for annexation to the United States. This being declined by President Martin Van Buren in order to avoid war with Mexico, Texas decides to wait.

Mexico continues to evade treaties by which she should pay claims against her by the United States for damages. In December, 1842, President John Tyler informs Congress that the rightful claims of United States citizens have been summed at $2,026,079, with many not yet included.

Several Southern States consider resolutions favoring the annexation of Texas. The sympathies of both North and South are with Texas against Mexico.

In August, and again in November, 1843, Mexico notifies the United States that the annexation of Texas, which is still looked upon as only a rebellious province, will be regarded as an act of war.

October, 1843, the United States Secretary of State invites Texas to present proposals for annexation.

In December, 1843, President Tyler recommends to Congress that the United States should assist Texas by force of arms.

April 12, 1844, John C. Calhoun, the Secretary of State, concludes a treaty with Texas, providing for annexation. There is fear that Great Britain is about to gain control of Texas by arbitrating between it and Mexico. The treaty is voted down by the Senate on the ground that it would mean war with Mexico, would bring on a boundary dispute, and that to make a new State out of foreign territory was unconstitutional.

Throughout 1844 the annexation of Texas is a burning question, debated in Congress and by the public. In the presidential election this fall the annexation is supported by the Democratic party and opposed by the Whig party. The Democrats had nominated James K. Polk for President, George M. Dallas for Vice-President; the Democrats’ campaign banners read: “Polk, Dallas and Texas!” Polk and Dallas are elected.

March 1, 1845, a joint resolution of Congress inviting Texas into the Union as a State is signed by President Tyler[20] just before he gives way to President-elect Polk. The boundaries of Texas are not named.

March 6 General Almonte, Mexican minister to the United States, denounces the resolution as an act of injustice to a friendly nation and prepares to leave Washington.

March 21 orders are issued by President Polk to General Zachary Taylor to make ready for marching the troops at Fort Jesup, western Louisiana, into Texas.

This same month the Texas Secretary of State has submitted to Mexico a treaty of peace by which Mexico shall recognize the republic of Texas, if Texas shall not unite with any other power.

In May, this 1845, Mexico signs the treaty with Texas.

May 28 the President of the United States directs General Taylor to prepare his command for a prompt defence of Texas.

June 4 President Anson Jones, of the Texas Republic, proclaims that by the treaty with Mexico hostilities between the two countries have ended. But—

June 15 President Polk, through the Secretary of War, directs General Taylor to move his troops at once, as a “corps of observation,” into Texas and establish headquarters at a point convenient for a further advance to the Rio Grande River. A strong squadron of the navy also is ordered to the Mexican coast. And—

June 21 the Texas Congress unanimously rejects the treaty with Mexico, and on June 23 unanimously accepts annexation to the United States.

July 4, this 1845, in public convention the people of Texas draw up an annexation ordinance and a State constitution.

On July 7 Texas asks the United States to protect her ports and to send an army for her defence.

August 3 General Zachary Taylor lands an army of 1500 men at the mouth of the Nueces River, and presently makes his encampment at Corpus Christi, on the farther shore.

In October the Mexican Government, under President Herrera, agrees to receive a commissioner sent by the United States to discuss the dispute over Texas, and President Polk withdraws the ships that have been stationed at Vera Cruz.

December 6, 1845, John Slidell, the envoy from the United States, arrives in the City of Mexico to adjust the matter of Texas and also the claims held by American citizens against Mexico.

The Mexican Republic is in the throes of another revolution.[21] It declines to include the claims in the proposed discussion; December 30 President Herrera is ousted and Don Maria Paredes, who favors war rather than the loss of Texas, becomes head of the republic. Minister Slidell finally has to return home, in March, 1846. But long before this President Polk had decided to seize the disputed Texas boundary strip.

January 13, 1846, General Taylor is directed by the President to advance and occupy the left or Texas bank of the Rio Grande River; he has been reinforced by recruits, and is authorized to apply to the Southern States for volunteer troops.

March 8 the first detachment is started forward to cross the disputed strip between the Nueces River and the Rio Grande. Other detachments follow. Part way General Taylor is officially warned by a Mexican officer that a farther advance will be deemed a hostile act. He proceeds, with his 4000 Regulars (half the army of the United States), and establishes a base of supplies at Point Isabel, on the Gulf shore, about thirty miles this side of the Rio Grande River.

March 28 the American army of now 3500 men, called the Army of Occupation, encamps a short distance above the mouth of the Rio Grande River, opposite the Mexican town of Matamoros and 119 miles from the mouth of the Nueces.

The Mexican forces at Matamoros immediately commence the erection of new batteries and the American force begins a fort.

April 10 Colonel Truman Cross, assistant quartermaster general in the American army, is murdered by Mexican bandits.

April 12 General Ampudia, of the Mexican forces at Matamoros, serves notice upon General Taylor either to withdraw within twenty-four hours and return to the Nueces out of the disputed territory, or else accept war. General Taylor replies that his orders are for him to remain here until the boundary dispute is settled. He announced a blockade of the Rio Grande River.

April 19 Second Lieutenant Theodoric Henry Porter, Fourth Infantry, is killed in action with Mexican guerillas.

April 25, this 1846, occurs the first battle of the war, when at La Rosia a squadron of sixty-three Second Dragoons under Captain Seth B. Thornton, reconnoitering up the Rio Grande River, is surrounded by 500 Mexican regular cavalry. Second[22] Lieutenant George T. Mason and eight enlisted men are killed, two men wounded, Captain Thornton, two other officers and forty-six men are captured.

By this victory the Mexicans are much elated; the flame of war is lighted in the United States.

May 11 President Polk announces a state of war, and a bloody invasion of American soil by the Mexican forces that had crossed the Rio Grande.

May 13 Congress passes a bill authorizing men and money with which to carry on the war, and declaring that the war has been begun by Mexico. There were objections to the bill on the ground that the President had ordered troops into the disputed territory without having consulted Congress, and that war might have been avoided. But all parties agree that now they must support the Flag.

General Taylor calls on the governors of Louisiana and Texas for 5000 volunteers.

April 28 Captain Samuel Walker and some seventy Texas Rangers and Volunteers are attacked and beaten by 1500 Mexican soldiers near Point Isabel, the American base of supplies. Captain Walker and six men make their way to General Taylor with report that his line of communication has been cut.

May 1, having almost completed the fort opposite Matamoros above the mouth of the Rio Grande, General Taylor leaves a garrison of 1000 men and marches in haste to rescue his supplies at Point Isabel. The Mexican troops are appearing in great numbers, and matters look serious for the little American army.

May 3 the Mexican forces at Matamoros open fire upon the fort, thinking that General Taylor has retreated.

May 8 General Taylor, hurrying back to the relief of the fort, with his 2300 men defeats 6500 Mexicans under General Arista in the artillery battle of Palo Alto or Tall Timber, fought amidst the thickets and prairie grasses about sixteen miles from Point Isabel. American loss, four killed, forty wounded; Mexican loss, more than 100 in killed alone.

The next day, May 9, “Old Rough and Ready” again defeats General Arista in the battle of Resaca de la Palma, or Palm Draw (Ravine), a short distance from Palo Alto. Having withstood a fierce bombardment of seven days the fort, soon named Fort Brown, of present Brownsville, Texas, is safe. The Mexican forces all flee wildly across the Rio Grande River.

May 18 General Taylor throws his army across the river[23] by help of one barge, and occupies Matamoros. Here he awaits supplies and troops.

August 20 he begins his advance into Mexico for the capture of the city of Monterey, 150 miles from the Rio Grande River and 800 miles from the City of Mexico.

Meanwhile General Paredes, president of Mexico, has been deposed by another revolution, and General Santa Anna has been called back.

September 21–22–23 General Taylor with his 6600 men assaults the fortified city Monterey, in the Sierra Madre Mountains of northeastern Mexico, and defended by 10,000 Mexican soldiers under General Ampudia.

September 24 the city is surrendered. American loss, 120 officers and men killed, 368 wounded; Mexican loss, more than 1000.

General Taylor proceeds to occupy northeastern Mexico. In November he receives orders to detach 4000 men, half of whom shall be Regulars, for the reinforcement of General Scott’s expedition against Vera Cruz.

February 22, 1847, with 4300 Volunteers and 450 Regulars he encounters the full army of General Santa Anna, 20,000 men, at the narrow mountain pass of Buena Vista, near Saltillo seventy-five miles southwest of Monterey.

The American army, holding the pass, awaits the attack. In the terrible battle begun in the afternoon of February 22 and waged all day February 23, the Mexican troops are repulsed; and by the morning of February 24 they have retreated from the field. American loss, 267 killed, 456 wounded, 23 missing; Mexican loss, 2000.

The battle of Buena Vista leaves the American forces in possession of northeastern Mexico. General Santa Anna now hastens to confront General Scott and save the City of Mexico. General Taylor returns to Louisiana, and there is no further need for his services in the field.

March 9, 1847, General Winfield Scott, with the assistance of the naval squadron under Commodore Conner, lands his Army of Invasion, 12,000 men transferred in sixty-seven surf-boats, upon the beach three miles below the fortified city of Vera Cruz, without loss or accident.

In spite of shot and shell and terrific wind storms the[24] army advances its trenches and guns to within 800 yards of the city walls. On March 22 the bombardment of Vera Cruz is begun.

March 27 the surrender of the city and of the great island fort San Juan de Ulloa is accepted. The siege has been so scientifically conducted that 5000 military prisoners and 400 cannon are taken with the loss to the American forces of only sixty-four officers and men killed and wounded.

Having been detained at Vera Cruz by lack of wagons and teams, on April 8 General Scott starts his first detachment for Mexico City, 280 miles by road westward.

The March to the City of Mexico, 279 Miles

April 12, arrangements being completed, he hastens to the front himself and is received with cheers for “Old Fuss and Feathers” all along the way.

April 18 storms and captures the heights of Cerro Gordo, sixty miles inland, where his 8000 men are opposed by 12,000 under Santa Anna. Three thousand prisoners, among them five generals, are taken; 5000 stands of arms and forty-three pieces of artillery. American loss, 431, thirty-three being officers; Mexican casualties, over 1000.

April 19 he occupies the town of Jalapa, fifteen miles onward. April 22 the castle of Perote, some fifty miles farther, is captured without a struggle. On May 15 the advance division of 4300 men enters the city of Puebla, 185 miles from Vera Cruz. In two months General Scott has taken 10,000 prisoners of war, 700 cannon, 10,000 stands of small-arms, 30,000 shells and solid shot.

The term of enlistment of 4000 twelve-months Volunteers being almost expired, he waits in Puebla for reinforcements.

August 7 he resumes the march for the Mexican capital, ninety-five miles. His force numbers 10,800, and he needs must cut loose from communications with Vera Cruz, his base.

August 9, from Rio Frio Pass, elevation 10,000 feet, on the summit of the main mountain range of Mexico, the army gazes down into the Valley of Mexico, with the city of Mexico visible, thirty-five miles distant.

By a new and difficult route he avoids the defences of the main road to the city, and on August 18 has approached to within nine miles and striking distance of the outer circle of batteries.

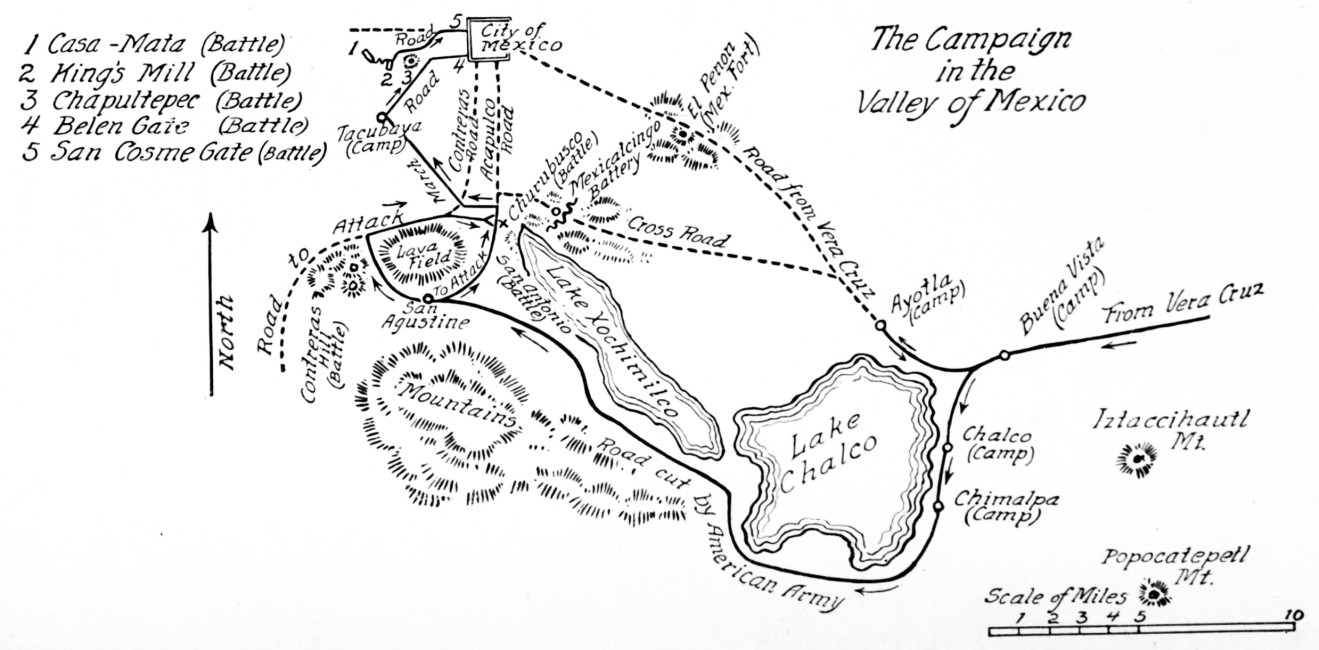

August 19–20, by day and night attack, 3500 Americans carry the strong entrenchments of Contreras defended by[25] 7000 Mexicans. American loss, in killed and wounded, 60; Mexican casualties, 700 killed, 1000 wounded.

The same day, August 20, 1847, the outpost of San Antonio is taken, the high citadel of Churubusco stormed. There are five separate actions, all victorious, and the dragoons charge four miles to the very gates of the city. Thirty-two thousand men have been defeated by 8000. The total Mexican loss is 4000 killed and wounded, 3000 prisoners, including eight generals; the American loss is 1052, of whom seventy-six are officers.

August 21 President and General Santa Anna proposes an armistice.

September 7 the armistice is broken and General Scott resumes his advance upon the city.

September 8 the General Worth division, reinforced to 3000 men, in a bloody battle captures the outpost Molino del Rey or King’s Mill, and the Casa-Mata supporting it—the two being defended by 14,000 Mexicans. American loss, killed, wounded and missing is 789, including fifty-eight officers. The Mexican loss is in the thousands.

September 12, by a feint the Scott army of 7000 able-bodied men is concentrated before the Castle of Chapultepec, situated upon a high hill fortified from base to summit and crowned by the Military College of Mexico, with its garrison of cadets and experienced officers.

September 13 Chapultepec is stormed and seized; the road to the city is opened, the suburbs are occupied and the General Quitman division has forced the Belen gateway into the city itself. Twenty thousand Mexicans have been routed.

At daybreak of September 14 the city council of Mexico informs General Scott that the Mexican Government and army have fled. At seven o’clock the Stars and Stripes are raised over the National Palace and the American army of 6000 proceeds to enter the grand plaza.

This fall of 1847 there is still some fighting in the country along the National Road between Vera Cruz and the City of Mexico, and the fleeing Santa Anna attacks Puebla in vain.

February 2, 1848, a treaty of peace is signed at Guadaloupe Hidalgo by the United States commissioner and the Mexican commissioners.

May 30, 1848, the treaty of Guadaloupe Hidalgo is ratified by both parties.

June 19, 1848, peace is formally declared by President Polk, who on July 4 signs the treaty.

At the end of June, 1846, the Army of the West, composed of 2500 Volunteers and 200 First Dragoons, under General Stephen W. Kearny, leaves Fort Leavenworth on the Missouri River to march 1000 miles and seize New Mexico.

August 18 General Kearny enters the capital, Santa Fé, and takes possession of New Mexico.

This same month the Army of the Center, 2500 Volunteers and 500 Regulars under General John E. Wool, assembles at San Antonio of Texas for a march westward to seize Chihuahua, northwestern Mexico, distant 400 miles.

General Wool is ordered to join General Scott; but in December, 1846, Colonel A. W. Doniphan, of the Missouri Volunteers of the Kearny army, leaves Santa Fé with 800 men to march to Chihuahua, 550 miles, and reinforce him.

December 25 he defeats General Ponce de Leon, commanding 500 Mexican regular lancers and 800 Chihuahua volunteers, in the battle of Brazitos, southern New Mexico.

February 28, 1848, in the battle of Sacramento, he defeats General Heredia and 4000 men, entrenched on the road to Chihuahua. American loss, one killed, eleven wounded; Mexican loss, 320 killed, over 400 wounded.

On March 1 the American advance enters the city of Chihuahua.

Meanwhile, during all these events, on July 7, 1846, Commodore John D. Sloat, of the navy’s Pacific Squadron, has hoisted the Flag over Monterey, the capital of Upper California. The explorer, John C. Fremont, already has supported an uprising of Americans in the north, and the flag is raised at San Francisco and Sacramento.

On September 25 (1846) General Kearny starts from Santa Fé with 400 First Dragoons to occupy California, 1100 miles westward. On the way he learns that California has been taken. He proceeds with only 100 Dragoons. A battalion of 500 Mormons enlisted at Fort Leavenworth is following.

December 12 he arrives at San Diego, California, and forthwith military rule is established in California.

General-in-Chief of the Armies of the United States at the Period of his Commanding in Mexico. From the Picture by Chappel

Born on the family farm, fourteen miles from Petersburg, Virginia, June 13, 1786.

His father, William Scott, of Scotch blood, a captain in the Revolution and a successful farmer, dies when Winfield is only six years old. Until he is seventeen the boy is brought up by his mother, Ann Mason, for whose brother, Winfield Mason, he is named. All the Scott family connections were prominent and well-to-do.

Winfield is given a good education. When he is twelve he enters the boarding-school of James Hargrave, a worthy Quaker, who said to him after the War of 1812: “Friend Winfield, I always told thee not to fight; but as thou wouldst fight, I am glad that thou weren’t beaten.” When he is seventeen he enters the school, of high-school grade, conducted in Richmond, Virginia, by James Ogilvie, a talented Scotchman. Here he studied Latin and Greek, rhetoric, Scotch metaphysics, logic, mathematics and political economy.

In 1805, when he is approaching nineteen, he enters William and Mary College, of Virginia. Here he studies chemistry, natural and experimental philosophy, and law, expecting to become a lawyer.

This same year he leaves college and becomes a law student in the office of David Robinson, in Petersburg. He has two companion students: Thomas Ruffin and John F. May. The three lads all rose high. Thomas Ruffin became chief justice of North Carolina; John May became leader of the bar in southern Virginia; Winfield Scott became head of the United States Army.

In 1806 he is admitted to the bar and rides his first circuit in Virginia. At Richmond, in 1807, he hears the arguments by the greatest legal orators of the day in the trial of ex-Vice-President Aaron Burr for high treason.

While the trial is in progress the British frigate Leopard enforces the right of search upon the United States frigate Chesapeake, off the capes of Virginia. On July 2 (1807) President Thomas Jefferson forbids the use of the United[28] States harbors and rivers by the vessels of Great Britain, and volunteer guards are called for to patrol the shores.

Young Lawyer Scott, now twenty-one years of age, becomes, as he says, “a soldier in a night.” Between sunset and sunrise he travels by horse twenty-five miles, from Richmond to Petersburg, and having borrowed the uniform of a tall absent trooper and bought the horse he joins the first parade of the Petersburg volunteer cavalry.

While lance corporal in charge of a picket guard on the shore of Lynnhaven Bay he captures a boat crew of six sailors under two midshipmen, coming in from Admiral Sir Thomas Hardy’s British squadron for water. The Government orders him to release the prisoners, and not to do such a trick again, which might bring on war.

England having made amends for the attack upon the Chesapeake the volunteers are disbanded. Corporal Scott resumes his practice of law. On Christmas Eve, 1807, he arrives in Charleston, South Carolina, to practice there. But he hears that war with Great Britain is again likely. Thereupon he hastens to Washington and applies for a commission in the increased regular army. He is promised a captaincy.

The Peace Party in the United States gains the upper hand over the War Party. In March, 1808, Lawyer Scott returns to Petersburg without his commission.

May 3, 1808, he receives his commission at last, and is appointed to a captaincy in the regiment of light or flying artillery then being raised. He recruits his company from Petersburg and Richmond youths and is ordered to New Orleans. For the next fifty-three years he is a soldier, and he outlives every other officer of 1808.

After a voyage of two months in a sailing vessel he arrives at New Orleans April 1, 1809.

The trouble with Great Britain having quieted down this summer, he despairs of seeing active service and attempts to resign. While in New Orleans he has said that he believed General James Wilkinson, commanding that department, to have been a partner of Aaron Burr in the conspiracy against the United States government. Now when he arrives in Virginia he hears that he is accused of having left the army through fear of punishment for his words. So he immediately turns about and goes back to face the charges. He rejoins the army at Washington, near Natchez, Mississippi, in November.

In 1810 he is court-martialed under the Articles of War and found guilty of “conduct unbecoming a gentleman,” in having spoken disrespectfully of his commanding officer. He is sentenced to twelve months’ suspension from duties, with the recommendation that nine of the months be remitted.

Under this sentence he returns to Petersburg. He spends every evening, when at home, reading English literature with his friend Benjamin Watkins Leigh, in whose family he is staying. His motto is: “If idle, be not solitary; if solitary, be not idle.” During this period he again despairs of seeing active service; but he writes: “Should war come at last, who knows but that I may yet write my history with my sword?”

In the fall of 1811 he rejoins the army at department headquarters at Baton Rouge, Louisiana, having made the journey by land over a new road through the country of the Creeks and Choctaws.

This winter of 1811–1812 he is appointed superior judge-advocate for the trial of a prominent colonel. He also serves upon the staff of Brigadier General Wade Hampton, commander of the Southern Department, and is much in New Orleans.

The inactive life of a soldier in peace palls upon him. In February, 1812, the news arrives that Congress has authorized an increase of the regular army by 25,000 men. This looks like war. May 20, as a member of General Hampton’s staff, he embarks with the general for Washington. Upon entering Chesapeake Bay their ship passes a British frigate standing on and off; in less than an hour they pass a pilot boat bringing to the frigate the message that the United States has declared for war with Great Britain. Thus by a narrow margin they have escaped capture by the frigate.

July 6, 1812, is appointed lieutenant-colonel, Second Artillery, at the age of twenty-six.

Is ordered with his regiment to the Canadian border; reports at Buffalo October 4, 1812.

On October 13 leads 450 regulars and militia in a final attack upon Queenstown Heights, opposite Lewiston, New York. The Heights are held by a greatly superior force of British regulars and militia and 500 Indians. The United States militia left on the American side of the Niagara River refused to cross and support, and the attack failed for lack of reinforcements. There were no boats for retreat; two flags of truce had been unheeded; with his own hand young[30] Lieutenant-Colonel Scott, tall and powerful and wearing a showy uniform (“I will die in my robes,” he said), bears the third flag forward into the faces of the raging Indians to save his men. He is rescued with difficulty by British officers. After the surrender he is held prisoner with the other Regulars until paroled on November 20 and sent to Boston.

In January, 1813, is released from parole. Is ordered to Philadelphia to command a double battalion of twenty-two companies.

March 12, 1813, promoted to colonel, Second Artillery.

March 18, appointed adjutant general, rank of colonel.

May, 1813, appointed chief of staff to Major-General Henry Dearborn on the Niagara frontier, New York, and reorganizes the staff departments of the Army.

May 27 commands the advance again in the attack on Fort George, Canada. Every fifth man is killed or wounded. By the explosion of a powder magazine his collar-bone is broken and he is badly bruised; but he is the first to enter the fort and he himself hauls down the colors.

July 18 he resigns his adjutant generalcy in order to be with his regiment as colonel. Leads in several successful skirmishes.

March 9, 1814, aged twenty-eight, is appointed brigadier-general. He has become noted as a student of war—a skilful tactician and a fine disciplinarian. At the Buffalo headquarters he is set at work instructing the officers. The United States has no military text-book, but he has read the French system of military training and employs that.

July 3, 1814, leads with his brigade to the attack upon Fort Erie, opposite Buffalo. Leaps from the first boat into water over his head, and laden with sword, epaulets, cloak and high boots swims for his life under a hot fire, until he can be hauled in again. The fort is captured.

July 4, again leading his brigade he drives the enemy back sixteen miles.

July 5 fights and wins the decisive battle of Chippewa against a much superior force. The war on the land had been going badly for the United States. Now the victory of Chippewa sets bonfires to blazing and bells to ringing throughout all the Republic; the American army had proved itself with the bayonet and General Scott is hailed as the National hero.

July 25 he distinguishes himself again in the night battle of Niagara or Lundy’s Lane. He is twice dismounted, and is bruised by a spent cannon ball. Receives an ounce musket ball through the left shoulder and is insensible for a time. Is borne from the field in an ambulance.

July 25 brevetted major-general for gallantry at Chippewa and Lundy’s Lane.

The wound in his shoulder refuses to heal properly. He is invalided and is unable to take part in further active service for the rest of the war. Travels upon a mattress in a carriage. Stops at Princeton College on Commencement Day, is given an ovation and the degree of Master of Arts. Congress votes him a special gold medal; the States of Virginia and New York vote him each a sword. His wound slowly heals under treatment by noted surgeons, but leaves him with a left arm partially paralyzed.

He is placed in charge of operations in defence of Baltimore and is made president of the National Board of Tactics, sitting in Washington.

After the close of the war he presides, May, 1815, upon the board convened to reduce the army.

Declines to accept the office of Secretary of War.

July, 1815, sails for Europe, where he witnesses the reviews of 600,000 soldiers, following the defeat of Napoleon by the allied troops. He meets distinguished commanders and statesmen of the Old World, and is awarded many honors.

Returning from Europe in 1816 he marries Miss Maria Mayo, of Richmond, Virginia. Seven children—five girls and two boys—were born. Of these, four died early in life.

As brigadier-general, in 1818, he begins the preparation of a system of General Regulations or Military Institutes for the United States Army. This was approved of by the War Department and Congress.

September 22, 1824, he writes and has printed “A Scheme for Restricting the Use of Ardent Spirits in the United States.” This essay was the basis of the temperance movement in the country.

In 1824 is president of the Board of Infantry Tactics, meeting at West Point.

In 1826 is president of a board of militia officers and regular officers, convened at Washington to devise an organization and system of tactics for the militia of the United States.

In 1828, while inspecting the Indian frontier of Arkansas[32] and Louisiana, is approved of by the cabinet for appointment to commander-in-chief of the army, but loses to General Alexander Macomb.

In the summer of 1832 is ordered from his Eastern Department to proceed in person against the Sacs and Foxes under Chief Blackhawk, in northern Illinois and southern Wisconsin. The cholera is raging in the Great Lakes region. Before leaving New York he takes instructions from a doctor, and when his force is attacked by the disease on the boats he himself applies the remedies and prevents a panic.

Arrives at Fort Crawford, Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin, after Blackhawk’s surrender. Descends the Mississippi to Fort Armstrong, on Rock Island, and holds grand council with the Sacs, Foxes, Sioux, Menominees and Winnebagos. Is congratulated by the Secretary of War for his services and his high moral courage in combating the cholera.

On his way home to West Point he narrowly escapes a severe attack of the cholera himself.

November, 1832, is sent to South Carolina, which has threatened to secede unless the tariff laws of the Government are modified. General Scott takes command in Charleston, and by his firmness and good sense among his fellow Southerners averts civil war.

In 1834–1835 translates and revises the new French infantry tactics for use by the United States. These, known as “Scott’s Infantry Tactics,” were the first complete tactics adopted by the army and were used up to 1863.

January 20, 1836, is directed by the President to proceed against the Seminole Indians of Florida. Asked at four in the afternoon when he could start, he says: “This night.” Through failure of supplies and by reason of the short-time enlistment of the majority of the troops, the campaign is unsuccessful. For this, and for a similar delay in a march against the Creeks, he is court-martialed by order of President Jackson. The court approves of his campaign plans and acquits him. Returning to his headquarters in New York he is tendered a public dinner April, 1837. This he declines.

January, 1838, is ordered to the Niagara frontier again, where misguided Americans and Canadians are attempting a movement to annex Canada to the United States. In dead of winter he travels back and forth along the American border, quieting the people by his words and the force of his presence.

In the spring of this 1838 he is sent into Alabama to[33] remove the Cherokee Indians to new lands given them by treaty, west of the Mississippi River. The Indians had refused to go, but by using reason and gentleness he avoids bloodshed and persuades them to move of their own accord.

In February, 1839, is sent by the President as special agent to northern Maine, where the State of Maine and the Canadian province of New Brunswick are in arms against each other over a dispute upon the boundary between. Again by his rare good judgment and by his influence with the authorities upon either side, he averts what might easily have resulted in another war.

In 1840 he is proposed as the Whig candidate for President, but he declines in favor of General William Henry Harrison, who is elected.

June 25, 1841, appointed full major-general.

July 5, 1841, appointed chief of the Army, a position that he occupies for twenty years.

From 1841 to 1846 is busied with the duties of his office. He aims to enforce justice and discipline among the rank and file. August, 1842, he issues general orders forbidding the practice of officers striking enlisted men and cursing them, and directs that in cases of offense the regulations of the service be employed.

In the summer and fall of 1846, believing that the campaign by General Zachary Taylor to conquer Mexico by invasion from the Rio Grande River border cannot succeed, he advises an advance upon the City of Mexico from Vera Cruz on the Gulf. He asks permission to lead the army in person.

November 23, 1846, he is directed by the Secretary of War to conduct the new campaign.

Leaves Washington for New Orleans November 25.

In his absence a bill is introduced in Congress to create the rank of lieutenant-general, and thus place over him a superior officer. This movement for politics was defeated, but General Scott felt that he had “an enemy in his rear.”

Under these conditions he goes to meet General Taylor at the Rio Grande in January, 1847, and detaches a portion of the forces for the Vera Cruz campaign. This makes an enemy of General Taylor.

February 19, 1847, he issues general orders declaring martial law in Mexico, for the purpose of restraining the Volunteers from abusing the people of the conquered territory. This wins over the natives and restores discipline.

March 9 to September 14, 1847, he conducts the campaign by which the City of Mexico, is captured.

September 14, 1847, to February 18, 1848, he remains in charge of the military government in Mexico. By his enforcement of martial law that respects the persons and property of the Mexican people he gains the leaders’ confidence. He is proposed for dictator of the Mexican Republic, with a view to annexation to the United States, but declines.

February 18, 1848, he receives orders from President Polk to turn over his command to Major-General William O. Butler, and report for trial by a court of inquiry, on charges that he had unjustly disciplined Generals Quitman and Pillow, and Lieutenant-Colonel Duncan. He is acquitted.

March 9, by joint resolution of Congress, he is voted the National thanks for himself and his officers and men, and the testimony of a specially struck gold medal in appreciation of his “valor, skill and judicious conduct.”

May 20, 1848, he arrives home to his family at Elizabeth, near Philadelphia.

Is assigned to command of the Eastern Department of the Army, with headquarters in New York.

In 1850, after the death of President Taylor, he resumes his post in Washington as commander-in-chief of the Army.

In 1850 he is awarded the honorary degree of LL.D. by Columbia College (University).

June, 1852, he is nominated by the Whig party for President. He is opposed by President Fillmore and Secretary of State Daniel Webster, who had been candidates. Is badly defeated in the election by Franklin Pierce of the Democratic party.

February, 1855, he is brevetted lieutenant-general from date of March 29, 1847—the surrender of Vera Cruz. This rank had not been in use since the death of Lieutenant-General George Washington, and was now revived by special act of Congress.

In November, 1859, he sails in the steamer Star of the West for Puget Sound, by way of Panama, to adjust difficulties arising between Great Britain and the United States over the possession of San Juan Island of the international boundary.

In 1860 he counsels the Government to garrison the forts and arsenals on the Southern seaboard with loyal troops, and thus probably prevent the threatened secession of the Southern States. His advice is disregarded.

In March, 1861, submits other plans by which he still hopes that the rebellion may be averted.

Is offered high command by his native State, Virginia, and declines to forsake the Flag.

October 31, 1861, being seventy-five years of age and long a cripple, almost unable to walk from wounds and illness, he retires from the army. President Lincoln and the cabinet call upon him together and bid him farewell. There are tears in the old hero’s eyes.

November, 1861, he sails for a visit in Europe.

December, 1861, is recommended by President Lincoln in first annual message to Congress for further honors, if possible.

June 10, 1862, his wife dies, leaving him with three daughters, now grown.

He removes from New York to West Point, and on June 5, 1864, after a year’s work he completes his autobiography in two volumes.

He dies at West Point, May 29, 1866, aged eighty, lacking two weeks.

“The North Americans! They are getting ready to attack the city!”

“Who says so? Where are they?”

“At Point Anton Lizardo, only sixteen miles down the coast. A great fleet of ships has arrived there, from North America. The sails looked like a cloud coming over the ocean. The harbor is crowded with masts and flags. Yes, they are getting ready.”

That was the word which spread through old Vera Cruz on the eastern coast of Mexico, at the close of the first week of March, 1847.

“Well, the castle will sink them all with cannon balls. It will be another victory. We shall see a fine sight, like on a fiesta (holiday). Viva!”

“Bien! Viva, viva!” Or: “Good! Hurrah, hurrah!”

There was excitement, but the news travelled much faster than the Americans, for they seemed to be still staying at desolate Anton Lizardo.

Now, March 9, up here at the city of Vera Cruz, was as fine a day as anybody might wish for. The sun had risen bright and clear above the Gulf of[38] Mexico, and one could see land and ocean for miles and miles.

From the sand dunes along the beach about three miles southeast of Vera Cruz, where Jerry Cameron was helping old Manuel and young Manuel cut brush for fagots, the view was pleasant indeed. To the northward, up the sandy coast, the fine city of Vera Cruz—the City of the True Cross—surrounded by its fortified wall two miles in length, fairly shone in the sunlight. Its white-plastered buildings and the gilded domes of its many churches were a-glitter. In the far distance, inland behind the city, the mountain ranges up-stood, more than ten thousand feet high, with Orizaba Peak glimmering snowy, and the square top of Perote Peak (one hundred miles west) deeply blue, in shape of a chest or strong-box. Outside the sea-wall in front of the city there was the sparkling bay, dotted with the sails of fishing boats, and broken by shoals.

Upon a rocky island about a third of a mile out from the city there loomed the darkly frowning Castle of San Juan de Ulloa—the fort which guarded the channel into the harbor. And almost directly opposite the place where Jerry worked as a woodcutter there basked the island of Sacrificios or Sacrifices, about two miles out, with the flags of the foreign men-of-war anchored near it streaming in the breeze. While farther out, beyond Sacrificios, appeared Green Island, where the ships of the United States had been cruising back and forth, blockading Vera Cruz itself.

The United States and Mexico were at war. They had been at war for well-nigh a year, but the[39] fighting was being done in the north, where the Americans had tried to invade by crossing the Rio Grande River and had been thrashed. At least, those were the reports. General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna himself, Mexico’s famous leader, had returned from exile in Cuba to command the army. He had been landed at Vera Cruz without the Americans objecting. The Americans had foolishly thought that he would advise peace—or else they were afraid to stop him. At any rate, he had gone on to Mexico City, had gathered an army, and not a week ago word had arrived that he had completely routed the army of the American general named Taylor, in the battle of Buena Vista, north Mexico!

It was said that the crack Eleventh Infantry of the Mexican regular army had alone defeated the North Americans. The Eleventh had marched to war last summer, carrying their coats and shirts and pantaloons slung on the ends of their muskets, because the weather was hot. The soldiers had not looked much like fighters, to Jerry; many of the muskets were without locks, and most of the soldiers were barefoot.

But the news of the great victory filled all Vera Cruz with rejoicing. The guns of the forts were fired, the church bells were rung, and the people cheered in the streets, and from the sea-wall shook their fists at the American fleet in the offing.

It had been unpleasant news to Jerry, he being an American boy whose father had died in Vera Cruz, from the yellow fever, and had left him alone. He hated to believe that Mexico actually was whipping the United States. But he and the few[40] other Americans stranded here did not dare to say anything.

Now that the North Americans (as they were called) had been driven out, in the north, very likely they would try to invade Mexico at another point. Yes, no doubt they might be foolish enough to try Vera Cruz, hoping to march even to the City of Mexico from this direction! Of course, the notion was absurd, for the City of Mexico was two hundred and eighty miles by road, and on the other side of the mountains. So the Vera Cruzans laughed and bragged.

“No hay cuidado, no hay cuidado! Somos muy valientes. Es una ciudad siempre heroica, esta Vera Cruz de nosotros,” they said. Or, in other words; “No fear, no fear! We are very brave. It is a city always heroic, this Vera Cruz of ours.”

“That is right,” had agreed old Manuel and young Manuel, with whom Jerry lived and worked. “If those North Americans wish to come, let them try. We have two hundred great guns on the walls, and three hundred in the castle—some of them the largest in the world. Yes, and five thousand soldiers, and the brave General Morales to lead us.”

“The Vera Cruz walls are ten feet thick, and those of the castle are fifteen feet thick,” old Manuel added. “Cannon balls stick fast; that is all.”

“The guns will kill at two miles,” young Manuel added. “Never once have those North American ships dared to come within reach. The commander at the castle laughs. He says to the American commander: ‘Bring on your fleet. You may fire all your shot at us and we will not take the trouble to reply. We only despise you.’”

“Así es—that is so,” grunted old Manual. “The castle has stood there for two hundred and fifty years. Please God, it will stand there two hundred and fifty more years, for all that those Yahnkee savages can do.”

It was true that the American fighting ships had stayed far out from shore. They cruised back and forth, preventing supplies from being brought in. That was a blockade, but Vera Cruz did not care. It had plenty to eat. It went about its business: the fishing boats of the native Indians caught vast quantities of fish in the harbor, the ranches raised cattle and vegetables and fruits, and peons or laborers like the two Manuels cut fagots and carried loads of it on their burros into town, to sell as cooking fuel.

Thus it happened that Jerry, who worked hard with the two Manuels for his living, was out here amidst the sand hills, as usual, on this bright morning of March 9, 1847.

These sand hills fringed all the beach on both sides of the city, and extended inland half a mile. The winter gales or northers piled them up and moved them about. Some of them were thirty feet high—higher than the walls of the city. From their crests one could look right into Vera Cruz. They were grown between, and even to their tops, with dense brush or chaparral, of cactus and thorny shrubs, forming regular jungles; and there were many stagnant lagoons that bred mosquitoes and fevers.

From the city the National Road ran out, heading westward for the City of Mexico, those two hundred and eighty miles by horse and foot.

To-day, of all the flags flying off shore scarcely one was the American flag. The American warships had disappeared entirely, unless that sloop tacking back and forth several miles out might be American. At first it had been thought that the Yankees had grown discouraged by the news of the defeats of their armies on land, and now did not know what to do. The very sight of the grim castle of San Juan de Ulloa had made them sick at their stomachs, the Vera Cruzans declared. But the reports from Anton Lizardo had changed matters.

The morning passed quietly, with the flags of the city and castle—flags banded green, white and red and bearing an eagle on a cactus in the center—floating gaily, defying the unseen Americans. At noon the two Manuels and Jerry ate their small lunch, and drank water from a hole dug near a shallow lagoon. Then, about two o’clock, old Manuel, who had straightened up for a breath and to ease his back, uttered a loud cry.

“Mira! See! The Americans are coming again!”

He was gazing to the east, down the coast. Young Manuel and Jerry gazed, squinting through the chaparral. Out at sea, to the right of the little island Sacrificios, there had appeared against the blue sky a long column of ships, their sails shining whitely. They came rapidly on, bending to the gentle breeze, and swinging in directly for the island anchorage. Scrambling like a monkey, old Manuel hustled for a high, clear place and better view; young Manuel and Jerry followed.

The foremost were ships of war; they looked[43] too trim and large, and kept in too good order, for merchantmen, and they held their positions, in the lead and on the flanks, as if guarding. But what a tremendous fleet this was—sail after sail, until the ships, including several steamers, numbered close to one hundred! Soon the flags were plain: the red-and-white striped flags of the United States, streaming gallantly from the mast ends.

“The Americans!” young Manuel scoffed. “They want another beating? They think to frighten us Vera Cruzanos? Bah! We will show them. We are ready. See?”

That was so. How quickly things had happened! As if by a miracle the sea wall of Vera Cruz was alive with people clustered atop; yes, and people were gathering upon all the roofs, and even in the domes of the churches. From this distance they were ants. The news had spread very fast. The notes of the army bugles sounded faintly, rallying the gunners to the batteries.

Now out at the anchorage near Sacrificios the mastheads and the yards of the foreign men of war and the other vessels, from England, France, Spain, Prussia, Germany, Italy, were heavy with sailors clustered like bees, watching the approach of the American fleet.

Straight for Sacrificios the fleet sped, silent and beautiful, before a steady six-knot breeze which barely ruffled the gulf. A tall frigate (the American flagship Raritan) forged to the fore, and in its wake there glided a vessel squat and bulky, leaving a trail of black smoke.

“Un barco de vapor—a steamboat!”

“Yes, yes! But it has no paddles—it moves like a snake!”

“No matter,” said old Manuel. “Everybody knows that the North Americans are in league with the Evil One. Only the Evil One could make a boat to move without paddles. But the saints will protect us.”

“They are bringing soldiers!” young Manuel cried. “Look! The decks of the warships are crowded!”

The American warships all forged to the fore; in line behind the tall Raritan and the smoking new steamer (which was only a propeller) they filed past the foreign ships at the Sacrificios anchorage, and about a mile from the beach they cast anchor also. Now it might be seen that each ship had towed a line of rowboats, and that every deck was indeed crowded with soldiers, for muskets and bayonets flashed, uniforms glittered, bands played, and a clatter and hum drifted with the music to the shore.

The merchant ships stayed outside the anchorage, as if waiting. There seemed to be seventy-five or eighty of them; too many for the space inside.

The warships lost no time. Small launches instantly began to tow the rowboats to their gangways; soldiers began to descend——

“What! They are going to land here, on our beach of Collado?” old Manuel gasped.

“No! Viva, viva!” young Manuel cheered. “Our brave soldiers are there, waiting! Viva, viva!”

“Now we shall see!” And old Manuel cheered, waving his ragged hat. “There will be a battle. Maybe we shall have to run.”

From the brush and sand hills a troop of Mexican lancers, in bright uniforms of red caps and red jackets and yellow capes, had cantered down to the open beach, their pennons flapping, their lance tips gleaming. They rode and waved defiantly, daring the Americans to come ashore.

A row of little flags broke out from the mizzen mast of the Raritan. At once two gunboat steamers and five sloops of war left the squadron, they ploughed in, a puff of whitish smoke jetted from the bows of a gunboat, and as quick as a wink another puff burst close over the heads of the lancer troop. Boom-boom!

The gay lancers, bending low in their saddles, scudded like mad back into the sand hills and the brush, with another shell peppering their heels.

“Hurrah! Hurrah!” Jerry cheered, for it looked as though that beach was going to be kept clear.

He got such a box on the ear that it knocked him sprawling and set his head to ringing.

“You shut up!” old Manuel scolded. “You little American dog, you! Your Americans are cowards. They dare not land and fight. They think to stand off out at sea and fight. The miserable gringos from the north! That’s the Mexican name for them: gringos. You understand?”

No, Jerry did not understand. “Gringo” was a new word—a contempt word recently invented by the Mexicans, when they spoke of the North Americans—his Americans. But he wasn’t caring, now; he was wild with the box on the ear, and the sight of the United States soldiers. Boxes on the ear never[46] had angered him so, before. It was pretty hard to be cuffed, here in front of the Flag; cuffed by the enemies of the Flag.

“That isn’t so,” he snarled hotly. “They aren’t cowards. You’ll see. They’ll land where they please. And all your army and guns can’t keep them off. Then they’ll walk right over your walls.”

“Shut up!” young Manuel bawled, and cuffed him on the other side of the head. “Of course they are cowards. They’ve been beaten many times by our brave men. Your General Taylor has been captured. He dressed like a woman and tried to hide. Now your gringos are so afraid that they think to land out of reach of our cannon. If they do land, what will they do? Nothing. The minute they come closer the guns of the castle will blow them to pieces.”

“Yes; and soon the yellow fever will kill them. They will find themselves in a death-trap,” old Manuel added. “Bah! Our brave General Morales may let them land. He sees how foolish they are. All he needs do is to wait. Where can they go? Nowhere! They will fight mosquitoes. That is it: they are come to fight the mosquitoes!”

Jerry saw that there was no use in arguing; not with two men whose hands were heavy, and who preferred to believe lies. They did not know American soldiers and sailors.

The cannon of the city and castle had not yet spoken, but the walls of San Juan de Ulloa, like those of Vera Cruz, a little nearer, were thronged with people, watching. And that was a busy scene, yonder toward Sacrificios. The two gunboats and the[47] five sloops cruised lazily only eight hundred yards out from the beach, their guns trained upon it; the sailors stood prepared at the pieces, and spy-glasses, pointed at the beach, occasionally flashed with light. Well it was, thought Jerry, that he and the two Manuels were securely hidden. He did not wish an American shot coming his way. But there, beyond the seven patrol boats, the rowboats were being loaded at the gangways of the men-of-war; for the soldiers of his country evidently were determined to land.

Boat after boat, crammed to the gunwales with men, left the gangways, was pulled a short distance clear, and lay to.

“How many boats?” young Manuel uttered. “Many, many. It is wonderful.”

“And a crazy idea,” old Manuel insisted, “to land here where the ships cannot follow, right in sight of Vera Cruz. But the more the better; the yellow fever will have a feast, and so will the vultures.”

The loading of the boats took two hours. The sun was almost set when the last one appeared to have been filled. No shot had been fired by the Mexican batteries. Suddenly a great cheer rang from the ships and the boats; yes, even from the English, and French and Spanish ships. The boats had started; they were coming in at last, and a brave spectacle they made: a half-circle more than three-quarters of a mile front, closing upon the beach, with oars flashing and bayonets gleaming and the trappings of the officers glinting, all in the crystal air of sunset, upon the smooth sea. The breeze had died[48] down, as if it, too, were astonished; but above the boats a myriad seagulls swerved and screamed.

Five, ten, twenty, forty, sixty, sixty-seven! Sixty-seven surf-boats each holding seventy-five or one hundred soldiers! Sixty-seven surf-boats, and one man-of-war gig!

“Sainted Mary! Where did the Americans get them all?” old Manuel gasped.

Jerry thrilled with pride. Hurrah! He was an American boy, and those were American ships and American boats, manned by American soldiers and American sailors, under the American flag. He shivered a little with fear, also; for when the guns of the castle and the city began to throw their shells, what would happen to those blue-coated men, helpless upon the bare beach of Collado?

The music from the bands in the boats and upon the ships sounded plainly. The bands were playing “Yankee Doodle,” “Hail, Columbia!” and “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Even the dip of the oars from the sixty and more boats, pulled by sailors, sounded like a tune of defiance, as the blades rose and fell and the oar-shafts thumped in their sockets.

Splash, splash, chug, chug, all together in a measured chant; and still the guns of the city and castle were silent, biding their time.

Now it was a race between the boats, to see which should land its men first. The sailors were straining at the oars; the figures of the soldiers—their bristling muskets, their cross-belts and cartridge boxes, their haversacks—were clear; their officers might be picked out, and also the naval officers, one in the stern of each boat, urging the rowers.

The gig beat. One hundred yards from the beach it grounded. It scarcely had stopped when a fine, tall officer leaped overboard into the water waist deep; with his sword drawn and waved and pointed he surged for the shore. He wore a uniform frock coat, with a double row of buttons down the front and with large gold epaulets on the shoulders. Upon his head was a cocked hat; and as he gained the shallows the gold braid of his trousers seams showed between boots and skirts. He was of high rank, then; perhaps a general—perhaps the general of the whole army! And his face had dark side-whiskers.

Close behind him there hurried a soldier with the flag. All the men, mainly officers, his staff, had leaped overboard; and from the other boats, fast and faster, the men were leaping, and surging in, and in, holding their muskets and cartridge boxes high, and cheering.

“Boom!” A cannon shot! Smoke floated from the bastion fort of Santiago, in the nearest corner of the city walls, three miles up the shore; but the ball must have fallen short.

“Boom!” A great gun in San Juan castle, three miles and a half, had tried. By the spurt of sand this ball also was short.

“We’d better get out of here,” old Manuel rapped. “To the city! Quick! The Americans are surely landing. We don’t want to have our ears cut off; and we don’t want to be blown up, either. The guns are beginning; they are playing for the dance.”

“Yes; and you come, too, you little gringo,” young Manuel exclaimed, grabbing Jerry by the arm.[50] “We’ll not have you running to those other gringos and telling them tales.”

Away scuttled old Manuel and young Manuel, dragging Jerry and shoving him before them while they followed narrow trails amidst the dunes and the thick, thorny brush. Presently they all heard another hearty shout from a thousand and more throats; but it was not for them.

Pausing and looking back they saw the whole broad beach blue with the American uniforms; flags of blue and gold were fluttering—a detachment of the soldiers had marched to the very top of one high dune and had planted the Stars and Stripes. Already some of the boats were racing out to the ships, for more soldiers. The bands upon the shore were playing “The Star-Spangled Banner” again.

“Hurrah!”

“Shut up, gringito (little gringo)!”

“You will sing another tune if you don’t take care. There!” And Jerry received a third and fourth cuff. “Your soldiers are cowards. They land out of reach of the guns. And now maybe we have lost our burro.”

“Why don’t you go back for it, then?” Jerry demanded. “Why don’t your own soldiers march out and stop the soldiers of my country?”

“Because we Mexicans are too wise. The Americans never can get near the city. Why should we waste any lives on them? Now you come along, gringito.”

And Jerry had to go, wild with rage and hot with hopes.

The balls from the city and castle were falling[51] short; the patrol vessels and the soldiers and sailors paid no attention to them; but from all the ranches and fields and huts outside the city walls the people were hastening in, for protection. This was another sight: those men, women and children, carrying bundles, and driving laden donkeys, and chattering, threatening, bragging and laughing.

Hustling on, Jerry and the two Manuels joined with the rest, crossing the open strip a half a mile wide, bordering the walls, and pushing in through the gate on this side, named the Gate of Mexico and commanded by batteries.

Inside the city there were hubbub and excitement. The broad paved streets of the down-town among the two-story stone buildings were crowded as on a feast day. Bugles were pealing, drums were beating, soldiers in the bright blue and white of the infantry and the red and green of the artillery were marching hither thither, lancers in their red and yellow clattered through, while the roof-tops and the church belfries above swarmed with gazers.

Nobody showed much fear.

“Wait, until the cannon get the range.”

“Or until the northers bury the gringos in the sand!”

“And then the vomito, the yellow fever! That is our best weapon.”

“Indeed, yes. All we Vera Cruzanos need do is to wait.”

The northers, as everybody should know, were the terrific winds that blew in the winter and early spring; they blew so fiercely, from the gulf and a clear sky, that anyone lying for a few moments in[52] the sand would be covered up. Neither man nor beast could face a norther, there in the open where the sand drifted like snow.

And the vomito, or yellow fever! Ay de mi! That was worse. It came in the spring as soon as the northers ceased and stayed all summer. Some days and nights it appeared like a yellow mist, rising from the lagoons of the coast and spreading toward the city; men and women and children died by the hundreds, even in the city streets, so that the buzzards feasted on the bodies. The City of the Dead: this was the name for Vera Cruz during the vomito season. Everyone who was able fled to the higher country inland, and stayed there above the vomito fog.

Until ten o’clock this night the American boats landed the American soldiers; by token of the twinkling lights and the distant shouts the beach was occupied for a mile of length, and the bivouacs extended back into the dunes.

“Boom!”

It was such a tremendous explosion that it shook the solid buildings of the city. It also brought Jerry upon his feet, all standing, where he had been asleep for the night in a vacant niche against a stone warehouse. A great many of the people slept this night in the open air, just where they chanced to be, so that they might miss no excitement.

The explosion awakened them all. There was a rush for good viewpoints; perhaps the battle had begun. Right speedily Jerry had scrambled atop the wall at a place between batteries, from which he could see the harbor and the Americans’ beach eastward. Nobody objected to him, here.

“Boom—Boom!” A double explosion well-nigh knocked him backward. A cloud of black smoke had spurted from the walls of San Juan de Ulloa castle, a quarter of a mile before; but yonder amidst the sand hills the louder “Boom!” had raised a much greater, blacker smoke, where the shell had burst.

The people upon the wall cheered.

“Viva, viva!”

“Now we shall see. San Juan is speaking with his giants.”

“Yes, the Paixhans,” said a Volunteer. “It is the Paixhans that he is turning loose, to blow the Yankees up. Viva!”

The Paixhan guns were large pieces that threw shells in a line, instead of solid shot or high-sailing bombs like the mortars.

“Boom!” from the castle; and in a moment, “Boom!” from the thickets of the dunes. The smoke jetted angrily; the people imagined that they could see brush and trees and bodies flying through the air; but just how much damage was being done no one might say, because most of the American army was out of sight, concealed in the wilderness of the jungle.

General Morales, commanding the city and castle, had issued a proclamation calling upon the soldiers and citizens to rally for the defense. All this day the American boats, large and small, plied back and forth between the fleet and the shore, out of range, bringing in horses and mules and cannon and supplies; when the cannon had been landed, soldiers and sailors fell to like ants and helped the long teams drag them across the beach, into the sand hills. The larger part of the army had been swallowed by the chaparral; but now and again a column of blue-uniformed men could be sighted, winding through a cleared spot, as if gradually encircling the city on the land side.

All day the city forts and outworks and the castle pitched round-shot and shell into the dunes. There were several little battles when the Mexican lancers and infantry outposts met the American advance. A number of wounded Mexican soldiers were carried in; but the American flags kept coming on, bobbing here and there, bound inland.

“To-morrow it will blow,” the weather prophets[55] asserted, noting the yellow sunset. “A norther! Then those gringos will wish they were somewhere else.”

“Yes, that is so.”

Sure enough, about noon the next day (which had dawned calm), far out at sea a sharp, vivid line of white appeared, approaching rapidly.

“The norther! Hurrah! It is the norther!”

A norther never had been so welcomed before. The shipping was frantically lowering sails and putting out storm anchors. The war vessels at Sacrificios were riding under bare poles. The line of white reached them—they bowed to it, their masts sweeping almost to the water. On it came, at prodigious speed, in a front miles long. The white was foam, whipped feathery by wind. Suddenly all the shipping in the harbor was in a confusion of scud; the few American small boats plying between war vessels and beach were striving desperately, and see! The dunes had been veiled in a cloud of yellow dust driven by the gale.

The change was miraculous. So strong was the wind that it cleaned the walls of people. Like the rest, Jerry crouched in shelter, while the gale howled overhead.

The dunes were completely shut from view by the cloud of scud and sand. Firing from the city and castle ceased. There was nothing to do but wait and let the norther work. Somewhere under that sand cloud the Americans crouched also, fighting for breath and to keep from being buried. Here in Vera Cruz everybody was safe and happy, except Jerry Cameron. He was safe, but he was sorry for[56] those other Americans, although he did not dare to say so.

It was a bad norther. It blew without a pause for two nights and days. Then, about noon of the third day, which was March 13, it quit about as suddenly as it had arrived. It left the ocean tossing with white caps and thundering against the sea-wall and upon the beach, but the air over the dunes cleared and all eyes peered curiously to see what had become of the American army.

Why, the flags were nearer! Some of them fluttered at the very inside edge of the hills, not much more than half a mile away, across the open space which skirted the city walls. There were signs that the ground was being dug out, as if for batteries. As soon as the ocean quieted a little, the boats again hustled back and forth, landing more guns and supplies. The forts and castle fired furiously at the American camps. But the Americans had not been stopped by the norther and they were not to be stopped by shot and shell.