Larsoe laughed as he gave the slighter man a shove.

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Startling Stories, July 1947.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

The rings of Saturn stretched like a level sheet in all directions, though actually composed of millions of tiny bodies. Homer Timkin carefully braked with the nose rockets till he floated motionlessly with respect to the ring's own rotary motion around its primary. Then he eagerly donned his vac-suit.

Had he struck it rich this time? Through his binoculars, a moment ago, he had seen the glint of one small jagged lump among the ring debris—and it had glinted like gold or silver. There was vast treasure among the rings, if one could find it....

In his vac-suit he used his reaction pistol to propel him down toward the glinting mass. In his eagerness, he almost failed to see the other ring body which now hurtled up, pursuing its own independent orbit within the grander sweep of the rings.

Timkin braked with his reaction pistol only in time to let the marauder lumber past, scraping his foot. He let out his breath with a hiss. That had been close. Many a ring prospector never returned to the Titan docks, because of some such accident as this, creeping up on you unawares.

More than prospecting in earth's out-of-the-way spots had ever been it was a hazardous occupation among Saturn's rings. But it had its enticing rewards and lures. Some prospectors returned with a load of precious metals or uncut virgin diamonds that made them rich for life.

Timkin reached the glinting body he had previously spied. It was irregular in shape, some five feet in its greatest diameter. And it had a yellow tinge in the soft light shed by huge Saturn over his shoulder. Timkin permitted himself wild hope as he chipped off a piece with his belt pick. He held the chip up to his glassine visor, squinting at the grain.

His face fell slack.

"Fool's gold!" he muttered, flinging the piece away in a small fury.

It was just pyrites, worth a few cents a pound in the market and not worth the hauling. Timkin sat down on the miniature worldlet and cursed all the gods of luck and ill luck. He had been out a month now, and no bonanza. Of course, it had been so for the past ten years. Each year the old prospector hoped for his big find, and each year he only eked out a precarious living, picking up odd bits from the rings.

He looked with bleary eye over the plane of the rings, stretching vastly in all directions. Timkin was not young any more. His lean spare body could not stand the rigors of space much longer. His leathery, seamed face showed the strain of countless near-escapes from death. If he didn't strike it rich this trip he'd have to retire—poor. He'd be one of those derelicts, haunting the Titan docks and mooching meals.

He shuddered.

Hopelessly, he watched the endless parade of the rings. By far the most of their expanse was just worthless rock. Then he saw a jet black lump not far off. It was coal. Timkin grinned mirthlessly.

Coal had been used as an industrial fuel and chemical storehouse some 200 years ago. Today it was no more than a curiosity in museums. That was his luck—spotting things in the rings that would barely pay the expenses of his trip.

As he sat he also saw a whitish mass further along—fossil bones. And nearby, a dully shining angular object, probably a bit of machinery.

Sighing, Timkin got up. "Got to make expenses," he muttered. "Might as well collect those odds and ends."

His reaction pistol took him to the lump of coal. It was four feet in diameter but in weightless space it was no strain for Timkin to push it toward his ship and stow it through the back lock into the hold.

Then he went back for the space-bleached bones. Theory had it that there had once been a moon of Saturn within two-and-a-half diameters of the giant planet. Gravitational stresses had then exploded the moon into countless fragments, which took up the same orbit after spreading out and thus came to be the unique rings.

Seemingly, there had once been life, and civilization, on the destroyed moon. Fossil bones, once buried within the moon's crust, now floated within the ring debris—and bits of machinery of some vanished and unknown race. There was no oxygen or moisture in space to rust them and thus the metal remained perfectly preserved through eons of time.

Timkin looked musingly at the bones, as he shoved them to his ship. They made up part of the skeleton of an ancient creature that possibly resembled an earthly tiger. The Saturn Archeological Museum would pay five SS-dollars for this—Solar System Dollars, the standard currency. Not too bad.

Finally, Timkin got the bit of machinery. It consisted of a broken portion of a huge cogged wheel with dangling wires and bits of other enigmatic mechanical devices. Timkin wondered just how advanced the people had been who once inhabited the first moon. That was something even the experts didn't know with the few poor clues they had collected.

For a moment, Timkin's imagination wandered. He pictured life on the first moon, before the debacle. Towering cities—humming wheels—busy, industrious people. Then, abruptly, their world cracking apart, into a billion bits. And now only this remained ... the rings of Saturn.

As Timkin brought the broken wheel to his ship he took one last look around and saw another museum item. It had circled in slow gyrations and come into view from the back of his ship. Timkin got that too, perhaps the most intriguing find of the lot, for it was a stone with mysterious "writing" on it. The museum had quite a collection of such stones, evidently parts of temples or buildings.

Seemingly the people of the first moon had inscribed most of their stone walls with their writings. But these writings had never been translated. They were a riddle that baffled the best archeological minds of the System.

He also put this carved stone in the hold.

"Huh," he grunted. "I'm just a scavenger for the museum, that's what I am."

Timkin looked over the things crammed in his hold, gleaned from the rings for a month. Their total value would possibly pay for the trip with a few SS-dollars to spare. Yet one find of gold or precious stone and he would dump the whole mess out and be far the richer.

Growling to himself, Timkin took off his vac-suit and went to the controls. He debated. He still had food and fuel enough for three days before he had to return to the Titan docks. What should he do?

"I'm going to the Crêpe Ring," he finally told himself. "I had no luck in Rings A and B, so why not try C just to play it out to the finish?"

Timkin had started, a month ago, at the outer ring—Ring A. This portion of the rings had an outer diameter of 171,000 miles and extended inward toward Saturn for 11,100 miles.

Then there was a separation of 2,200 miles between rings A and B named Cassini's Division when first seen through earthly telescopes centuries ago.

Ring B was 145,000 miles, outer diameter, and some 18,000 miles wide. Another space of 1000 miles and then came Ring C or the Crêpe Ring, 11,000 miles wide. So had the rings of Saturn distributed themselves, under the laws of gravitation, when the first moon exploded ages before. The first moon had not been large, for the total mass of all the rings was estimated at no more than one-quarter of earth's moon.

Timkin urged his old rattletrap Jetabout up from the plane of the rings till he had a clear path before him and then jetted straight toward mighty Saturn, which hung in the sky like a bloated, vari-colored marble.

He crossed the narrow empty space between Rings B and C and finally cruised over the outer edges of the Crêpe Ring. Saturn was only 17,000 miles distant and Timkin could feel the faint tug of its powerful gravitation.

"Now," Timkin said between set teeth, "let's see if I have any luck. I've got three days to nose around through the Crêpe Ring, searching. I know there's gold or diamonds ahead ... if I can just stumble on them."

As he slowly cruised above the Crêpe Ring, with his binoculars to his eyes, Timkin munched a sandwich and now and then took a swig of coffee. In all their explorations of other worlds earthmen had never found any beverage better than time-honored coffee, though the Martians tried hard to sell a green-tinted product called tukka.

Timkin's hand gave a little jerk, and his binoculars wavered. Watching him one would have thought he had spied something exciting—like gold. But it was something else, almost equally as startling....

"Another Jetabout!" Timkin murmured. "Gave me a start, seeing it so suddenly."

It was a rare event when two wandering Jetabouts happened to cross paths in the vast area of the rings, almost like two explorers in the heart of Africa meeting each other. Timkin grinned humorlessly.

"Another chump!" he thought. "He wouldn't have a bonanza, or he'd be streaking back for Titan. He's cruising and looking for something like me."

Timkin flashed his heliograph, reflecting the light of Saturn, at the other ship. An answering greeting flashed back. Timkin watched it as it kept going on its course and slowly faded into distance. He felt less lonely for a moment.

Timkin went back to his scanning of the ring bodies with his glasses. He saw another lump of coal but was too wearied at the thought of donning his vac-suit for it, and let it go by under him. It was not till a minute later that he snapped to attention. For now he remembered, belatedly, that he had also seen a yellow glow near the black coal.

"Day-dreaming, that's what I was!" he yelled, hastily braking and spinning the Jetabout around. "If that was gold, and I don't find it again, I'll...."

It was not easy to backtrack in the rings, and find a certain spot you had passed over. The rings were constantly in motion, in their orbit around Saturn. And each body in the rings had its own private motion in respect to the others. Some gyrated fantastically around others.

A huge body might in turn exert enough gravitation of its own to hold smaller bodies in its grip, and force them to become its "moons." And these satellites then perturbed nearby bodies, causing them to weave and shuttle within the ring.

In short, any body in the ring might shift position enough in the space of a minute or two to be lost forever.

Timkin shot back to the coal lump. Yes, the coal lump was there, not having a complicated private motion. But where was the yellow lump that his blind eyes had seen—and ignored? There were a hundred other little bodies around the coal lump and to look them all over one by one....

Timkin's heart sank to its lowest ebb before suddenly he saw the yellow glint again. Then, thankfully, he shot the Jetabout over it and hovered, locking the controls. Minutes later in his vac-suit he was propelling himself down to the yellow lump via reaction pistol.

"It's only fool's gold, of course," he told himself to calm his wildly racing pulse. "Just think of it as fool's gold, so you won't be disappointed again. Or it could be cheap copper. So don't get excited—yet."

Timkin reached the yellow body, fumbled with his pick and finally chipped off a piece. He noticed it sheared off under the hard pick, rather than chipped. He dared to hope it was soft gold. And when he held the bit to his visor....

"Gold!"

He said the one word quietly. Then he sat down on the lump, shaken.

"Gold," he repeated. "I hit it—gold! My bonanza! My dream for ten years!"

It was minutes before he could control his shaking nerves and allow the warm glow of exultation to spread through him like wine, giving him new strength. He arose and, like a bird, made a circle around the lump, using his reaction pistol. He estimated its weight as a thousand pounds, earth measure. Then he stopped to stand on it again, a king on an island.

"Of course, it ain't pure gold," Timkin told himself. "But it looks like about fifty percent pure. They say the first moon before it exploded didn't have many seas to dissolve and thin out ore deposits. So I can figure about five hundred pounds of gold. At the pegged rate of thirty-seven SS-dollars an ounce...."

Timkin's head was too light and buzzy to reach the total.

"But I'm rich," he exulted. "Filthy rich. Gold is even more valuable today than it used to be on earth in the old days."

Timkin was right. Contrary to all fanciful and unfounded predictions, gold had never lost its value. True, the nations of earth had all gone off the gold-standard in the 20th century and for a while gold was a forgotten metal, buried in vaults.

But then it came into its own as one of the most non-corrodable metals. When space travel came into being, an alloy of gold became the standard coating for all equipment used on other worlds, some of which had noxious atmospheres that could rust iron or copper in days to worthless dust.

But gold in its alloy-hardened form defied the worst other worlds had to offer. Thereupon gold became a metal of commerce and its value rose even higher than its one-time value as a money standard.

And so, with his find of gold, Homer Timkin was as suddenly wealthy as any Spanish explorer of the New World, back in earth's past.

"It's sure going to be a pleasure," crowed Timkin, "to drag this lump of gold back to Titan!"

"Yeh, it is—for me!"

Timkin jumped at the sound of the voice behind him, coming out of nowhere. He turned, gaping, to see another man in a vac-suit slowly approaching, with a reaction pistol. Timkin could see the newcomer's Jetabout now, parked alongside his own. Timkin had been too engrossed in his find to see the approach of the ship.

"Huck Larsoe!" said Timkin in recognition for he knew all the other prospectors back at the Titan docks.

"Yeh, Timkin," returned Huck Larsoe, grinning. "I was the Jetabout that passed you a while ago. Just before you went out of my sight, I saw your ship suddenly scoot on a backtrack. That spelled a find to me! So I turned and came back, and followed you up."

Timkin didn't like it. Huck Larsoe was a younger man and filled out his vac-suit with a powerful, hulking body. His stubble of unshaven black beard formed an unkempt fringe to the hard-bitten face that peered out of the visor. There was something in his cold grey eyes that froze Timkin. There was such a thing as claim-jumping here in the lawless territory of the rings.

"You sure struck it rich," Huck Larsoe went on. "But maybe you didn't hear me before. I said it was lucky—for me!"

"Y-you can't take this from me," Timkin began, his voice tinny as it came out of the chin-transmitter to impinge on the radio vibrators at Larsoe's ears. "It's mine! I found it!"

"Sure, you found it," agreed Larsoe. "But I'm taking it away from you, see?"

"No!" shrilled Timkin. "That's plain robbery—piracy! I'll tell the police back at Titan."

Larsoe leered. "And what witnesses have you got? You and me are the only two humans around here for 50,000 miles. It'll be your word against mine back at Titan. If I say I found it myself and you're trying to cut in on it they'll have to believe me. Because I'll have the gold."

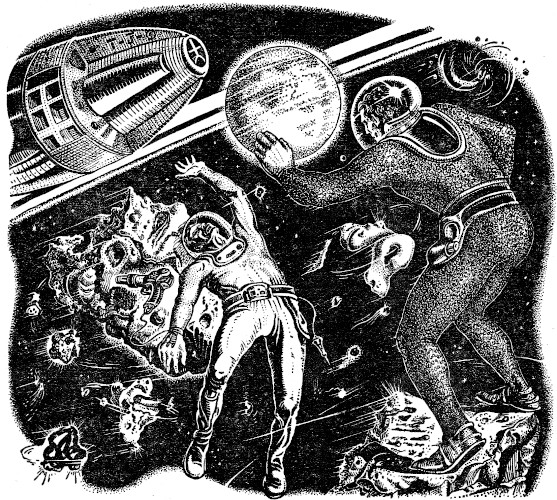

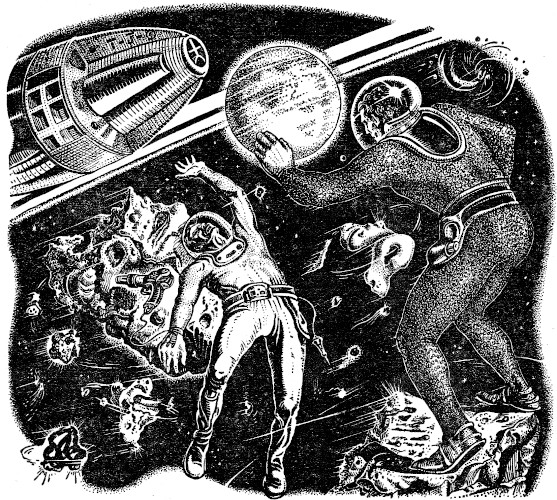

Timkin had no weapon. The reaction "pistol" was not a weapon at all, merely a device for moving in space by means of short, harmless rocket blasts. He struggled against the bigger man. Larsoe laughed as he gave the slighter man a shove that sent him spinning off the lump and almost into another ring body with jagged edges.

Larsoe laughed as he gave the slighter man a shove.

Then, still laughing, Huck Larsoe shoved the mass of gold to his own ship, his reaction pistol streaming red flame behind him. He turned his mocking face.

"I ain't even going to kill you, Timkin, like I could. No need going to the trouble. It's still your word against mine, back at Titan. You ain't got a ghost of a chance to prove this is your find."

Slowly Timkin rocketed back to his own ship. He watched Larsoe stow the gold in his hold and cast out a mess of fossil bones, lumps of coal, bits of machinery and pieces of carved stone.

"Here, Timkin," Larsoe chortled. "You can have this other junk of mine now. It'll help you pay for your trip, anyways. See? I ain't such a bad guy at heart."

And with a mocking laugh, Larsoe slipped into his cabin lock. A moment later his ship rocketed away and was lost in black space, leaving a broken old man behind.

Timkin floated beside his ship for long bitter minutes without the energy to do anything. Ten years of searching and hope wasted—ten years of hardship and toil. Fate had at last rewarded him with a magnificent bonanza—and then had kicked him in the teeth.

Timkin was on the verge of madness. For a moment he thought of opening his reaction pistol wide, gunning straight for the ring bodies and seeking peace and eternal rest there.

But then, shudderingly, he brought himself back to sanity. The will to live triumphed as it did in all living creatures in the universe. He looked at the stuff which Larsoe had cast from his ship, which was slowly drifting away, scattering.

Rousing himself, Timkin began collecting it and stowing it in his hold. No need to let the stuff go, even if it was a mocking gift from the hated thief. He still had to make a profit on the trip.

Timkin held one carved stone in his hand for a moment, staring at its ancient writings. It was a triangular piece and seemed to have two sets of writing on it. To keep his mind from plunging into black despair Timkin tried to picture again the ancient civilization of the first moon.

But a slight huddled figure sobbed aloud at the controls as the Jetabout left the rings and aimed for Titan.

At the Titan docks two days later Homer Timkin was calm and resigned. There was nothing he could do. No use to put in a complaint against Huck Larsoe, to the police. As Larsoe had said, it was one man's word against another's. With no witnesses the legal battle could only end with Larsoe the winner.

Sighing, Timkin hired a rocket truck and piled the museum stuff aboard and drove to the center of Titan City. Here the Saturn Archeological Museum reared, stately and imposing on its marble pillars.

Timkin drove to the service entrance and rang the bell. An elderly man answered and flashed a smile of greeting.

"Well, Timkin again," he said. "Back with another load of relics from the rings? I take it you didn't hit any bonanza then, eh?"

"Well, I—" Timkin stopped. No need to go into his story, and broadcast his shame and misery to the universe. "No, Professor Blick. No bonanza. But I've got a load of stuff for you to look over for your museum."

Professor Blick, adjusting his thick glasses, came out and looked over each item as Timkin took it off the truck.

"Our prices are still standard, Timkin," he said. "Two SS-dollars for a specimen of coal. Three for fossil bones. Five for bits of machinery. And ten for the carved stones."

"Why," asked Timkin curiously, "do you pay more for the stones than anything?"

"Because if they could speak they would tell us far more about the ancient civilization of the first moon, than any of the other items. We have a sizeable collection now. We can't translate the writing yet. But some day we're going to find the Rosetta Stone that will give us the clue and open up the whole vast story."

"Rosetta Stone?" Timkin was puzzled.

The professor went on conversationally.

"Yes. You see, back on earth many centuries ago, the archeologists of that time also found carved writings—the ancient records of the Egyptians. And they too were a riddle.

"But one day a stone was found with not only Egyptian heiroglyphics on it but another language! The text on this stone had been written in Egyptian and then copied in the other language. And that second language—ancient Greek—was known! So this enabled all the Egyptian writing to be translated and...."

The professor's voice stopped, with a queer gurgle. Timkin stared. He had just handed him the triangular stone which had been among Larsoe's "gifts."

"Timkin!" screeched the professor. "This is it! This stone has two sets of writing on it. One is the unknown script of the first moon. And the other is—oh, thank the stars!—it's early Rhean, which is a language we know!"

It was all rather confusing for Timkin after that. The professor bawled at the top of his voice and more men came rushing out. They all fell to talking as if the greatest event in the history of the universe had taken place. Timkin hovered on the outskirts of the group, forgotten for the time being.

But then all the men turned to him. They looked at him as if he were some king or some awesome potentate from another star.

"And there, gentlemen!" said Professor Blick, waving at him, "is the man who brought the stone back!"

Timkin was in an agony of embarrassment as one by one the archeologists came up and shook his hand silently with reverent respect in their eyes.

"Professor," pleaded Timkin when this ordeal was over. "I—I want to get away. Just pay me for the stone, and let me go. If it's so important to you, maybe you could up the price a little, eh? Maybe—uh—a hundred dollars?"

Timkin was amazed at his own audacity.

The professor looked at him queerly, almost pityingly, and said slowly, "One hundred dollars? Timkin, you don't realize the value of this stone. The museum will make you out a check for one hundred thousand SS-dollars!"

Timkin stood stunned, unbelieving.

The professor smiled.

"Yes, that's what I said—one hundred thousand. If we could afford it, we'd pay you ten times that. Actually, you see, the stone is priceless. The check will be sent to you. You can go now, Timkin."

Timkin drove the rocket truck back, in a dream, and passed a red light. The traffic cop wrote a ticket.

"That'll cost you twenty-five dollars, bud," he growled.

Timkin burst out laughing and kept laughing all the way back to the garage. He was fined 25 dollars. It would have been an economic tragedy before. Now it was a joke. He could pay a hundred fines like that and still laugh.

The next day, when the check arrived at his room, Timkin knew it was not a dream. The amount was 150,000 dollars. They had even upped the price voluntarily.

Timkin went out, with the check in his pocket, and headed for the Spaceman's Nook. He had one more piece of unfinished business to do. He knew he would find Huck Larsoe there and saw him at a corner table. Strangely he seemed depressed, not at all like a man who had just brought in a fortune in gold.

"Hello, Huck!"

Larsoe looked up sourly as Timkin sat down cheerfully.

"Listen, punk, you got nothing on me," he growled.

"I know," said Timkin. "But why so glum? What did you get for my—pardon me, your—gold bonanza when you cashed it in?"

Larsoe smashed his fist down on the table, spilling his drink.

"Don't talk to me about that blasted bonanza!" he roared. "You know what it was? It was just plain rock with a film of rich gold ore over it. A fake! A flop! I just got enough out of it to pay expenses and that's all."

"Too bad," Timkin grinned, feeling his cup running over.

"Oh, don't go gloating," said Larsoe. "I still put one over on you. I took the thing away from you, didn't I?"

"Sure," agreed Timkin. "But you gave me something back which was worth—"

At this moment, Larsoe sat up, as something came over the tavern radio, working through the hum. An announcer was saying....

"—biggest news of the day! The Saturn Museum has just announced the find of a carved stone, from the rings, which will allow them to translate all the hitherto unknown writings of the first moon! And in honor of the man who brought it back from the rings, they have named it—the Timkin Stone!"

Timkin was shocked himself. His name would reverberate down through the ages now, attached to a stone as famed as the Rosetta Stone of earth!

But the effect on Huck Larsoe was like that of a knife in his heart. He turned slow, stunned eyes to his companion.

"Th-the Timkin Stone?" he mumbled. "What—"

Timkin drew the check out of his pocket and showed it to Larsoe.

"Yes, I brought it in. Look, they paid me one hundred and fifty thousand dollars for it. And Huck—I hope you have a strong heart—Huck, that stone was among the stuff you gave me after stealing my bonanza!"

"Then I made the find!" yelled Larsoe. "It's me they should name the stone after. And you've got to turn over that money to me, Timkin! It's mine! I found the stone and...."

Timkin looked him straight in the eye and said quietly, "Any witnesses, Huck?"