TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE

Footnote anchors are denoted by [number], and the footnotes have been placed at the end of each chapter.

Some minor changes to the text are noted at the end of the book. These are indicated by a dashed blue underline.

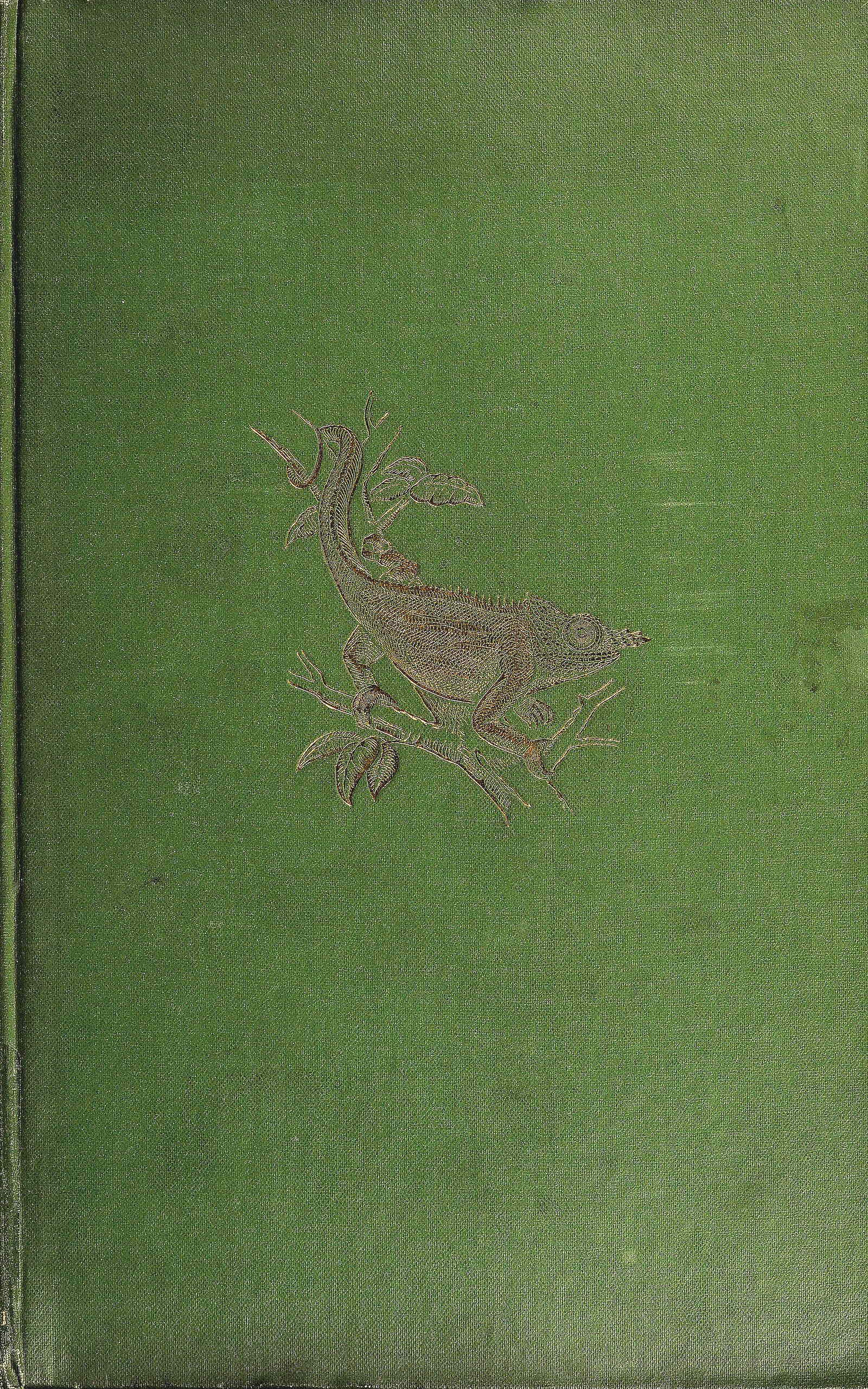

The stone is levered into position closing the opening. A deep fosse or ditch surrounding the village completes its fortification. The man in front is carrying two packages secured to a pole in the usual manner of the country

A Record of Observation Experiences and

Impressions made during a period of over Fifty Years’

Intimate Association with the Natives and Study of the

Animal & Vegetable Life of the Island

BY

JAMES SIBREE, F.R.G.S.

Membre de l’Academie Malgache

AUTHOR OF “THE GREAT AFRICAN ISLAND,” “MADAGASCAR ORNITHOLOGY,”

&c., &c., &c.

WITH 52 ILLUSTRATIONS & 3 MAPS

PHILADELPHIA

J. B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY

LONDON: SEELEY, SERVICE & CO. LTD.

1915

Dedicated

WITH MUCH AFFECTION TO

MY DEAR WIFE

MY CONSTANT COMPANION IN MADAGASCAR

AND FAITHFUL HELPER IN ALL

MY WORK FOR FORTY-

FOUR YEARS

THE title of this book may perhaps be considered by some as too ambitious, and may provoke comparison with others somewhat similar in name, but with whose distinguished authors I have no claim at all to compete.

I have no tales to tell of hair-breadth escapes from savage beasts, no shooting of “big game,” no stalking of elephant or rhinoceros, of “hippo” or giraffe. We have indeed no big game in Madagascar. The most dangerous sport in its woods is hunting the wild boar; the largest carnivore to be met with is the fierce little fòsa, and the crocodile is the most dangerous reptile.

But I ask the courteous reader to wander with me into the wonderful and mysterious forests, and to observe the gentle lemurs in their home, as they leap from tree to tree, or take refuge in the thickets of bamboo; to come out in the dusk and watch the aye-aye as he stealthily glides along the branches, obtaining his insect food under the bark of the trees; to listen to the song of numerous birds, and to note their habits and curious ways; to hear the legends and folk-tales in which the Malagasy have preserved the wisdom of their ancestors with regard to the feathered denizens of the woods and plains, and to admire the luxuriant vegetation of the forests, and the trees and plants, the ferns and flowers, and even the grasses, which are to be found in every part of the island.

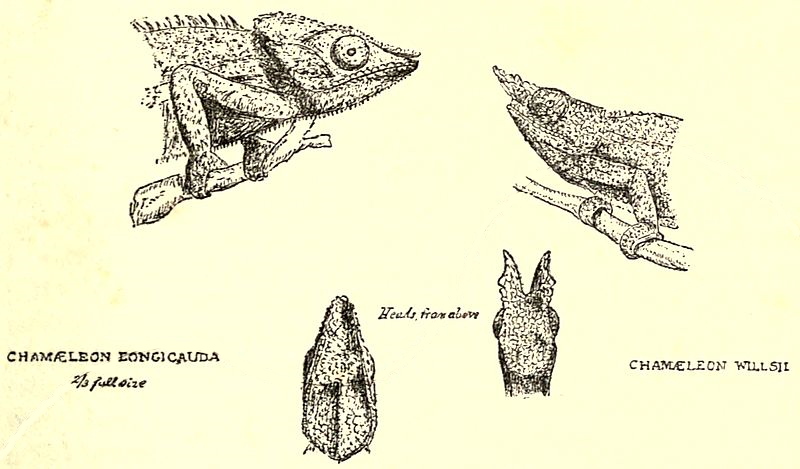

I invite those who may read these pages to look with me at the little rodents and insect-eaters which abound in and near the woods; to mark the changing chameleons which are found here in such variety; to watch the insects which gambol in the sunshine, or hide in the long grass, or sport on the streams. If such unexciting pleasures as these can interest my readers, I[6] can promise that there is in Madagascar enough and to spare to delight the eye and to charm the imagination.

I confess that I am one of those who take much more delight in silently watching the birds and their pretty ways in some quiet nook in the woods, than in shooting them to add a specimen to a museum; and that I feel somewhat of a pang in catching even a butterfly, and would much rather observe its lovely colours in life, as it unfolds them to the sunshine, than study it impaled on a pin in a cabinet. No doubt collections are necessary, but I have never cared to make them myself.

Nothing is here recorded but facts which have come under my own observation or as related by friends and others whose authority is unquestionable. And while my main object is to convey a vivid and true impression of the animal and vegetable life of Madagascar, I have also given many sketches of what is curious and interesting in the habits and customs of the Malagasy people, among whom I have travelled repeatedly, and with whom I have lived for many years. I have no pretensions to be a scientific naturalist or botanist, I have only been a careful observer of the beautiful and wonderful things that I have seen and I have constantly noted down what many others have observed, and have here included information which they have given in the following pages.

I have long wished that someone far more competent than myself would write a popular book upon the natural history and botany of this great island; but as I have not yet heard of any such, I venture with some diffidence to add this book to the large amount of literature already existing about Madagascar, but none of it exactly filling this place. For many years I edited, together with my late friend and colleague, the Rev. R. Baron, the numbers of The Antanànarìvo Annual, a publication which was “a record of information on the topography and natural productions of Madagascar, and the customs, traditions, language and religious beliefs of its people,” and for which I was always on the look-out for facts of all kinds[7] bearing on the above-mentioned subjects. But as this magazine was not known to the general public, and was confined to a very limited circle of readers, I have not hesitated to draw freely on the contents of its twenty-four numbers, as I am confident that a great deal of the information there contained is worthy of a much wider circulation than it had in the pages of the Annual.

Finally, as preachers say, although this book is written by a missionary, it is not “a missionary book”; not, certainly, because I undervalue missionary work, in which, after nearly fifty years’ acquaintance with it, and taking an active part in it, I believe with all my heart and soul, but because that aspect of Madagascar has already been so fully treated. Books written by the Revs. W. Ellis, Dr Mullens, Mr Prout, Dr Matthews, Mr Houlder, myself and others, give all that is necessary to understand the wonderful history of Christianity in this island. Despite what globe-trotting critics may say, as well as colonists who seem to consider that all coloured peoples may be exploited for their own benefit, mission work, apart from its simply obeying the last commands of our Lord, is the great civilising, educational and benevolent influence in the world, deny it who can! But in this book I want to show that Madagascar is full of interest in other directions, and that the wonderful things that live and grow here are hardly less worthy of study than those events which have attracted the attention of Christian and benevolent people for nearly a hundred years past.

The author thanks very sincerely his friends, Mr John Parrett, Monsieur Henri Noyer, and Razaka, for their freely accorded permission to reproduce many photographs taken by them and used to illustrate this book. And his grateful thanks are also due to his old friend, the Rev. J. Peill, for the care he has taken in going through the proof sheets, especially in seeing that all Madagascar words are correctly given.

Two or three chapters of this book cover, to some extent, the same ground as those treated of in another book on[8] Madagascar by the author, published some years ago by Mr Fisher Unwin. The author here acknowledges, with many thanks, Mr Fisher Unwin’s kindness in giving full permission to produce these, which are, however, rewritten and largely added to.

J. S.

| CHAPTER I | |

| PAGE | |

| INTRODUCTORY | 17 |

| Natural History of the Island—Still Little Known—Roads and Railway—We travel by Old-Fashioned Modes—Great Size and Extent of Madagascar | |

| CHAPTER II | |

| TAMATAVE AND FIRST IMPRESSIONS OF THE COUNTRY | 20 |

| “The Bullocker”—Landing at Tamatave—Meet with New Friends—Landing our Luggage—Bullocks and Bullock Ships—Native Houses—Strange Articles of Food—A Bed on a Counter—First Ride in a Filanjàna—At the Fort—The Governor and his “Get-Up”—A Rough-and-Ready Canteen | |

| CHAPTER III | |

| FROM COAST TO CAPITAL: ALONG THE SEASHORE | 27 |

| Travelling in Madagascar—Absence of Roads—“General Forest and General Fever”—Pleasures and Penalties of Travel—Start for the Interior—My Private Carriage—Night at Hivòndrona—Native Canoes—Gigantic Arums—Crows and Egrets—Malagasy Cattle—Curious Crabs—Shells of the Shore—Coast Lagoons—Lovely Scenery—Pandanus and Tangèna Trees—Pumice from Krakatoa—Sea and River Fishes—Prawns and Sharks—Hospitable Natives—Trees, Fruits and Flowers—“The Churchyard of Foreigners”—Unpleasant Style of Cemetery—“The Hole of Serpents”—Killing a Boa-constrictor—The White-fronted Lemur—Andòvorànto—How the Aye-Aye was caught—What he is like—And where he lives—A Damp Journey | |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| FROM COAST TO CAPITAL: ANDÒVORÀNTO TO MID-FOREST | 48 |

| A Canoe Voyage—Crocodiles and their Ways—River Scenery—Traveller’s Tree—Which is also “The Builder’s Tree”—Maròmby—Coffee Plantation—Orange Grove—We stick in the Mud—Difficulties of Road—Rànomafàna and its Hot Springs—Lace-leaf Plant—Native Granaries—Endurance of Bearers—Native Traders—Appearance of the People—Native Music and Instruments—Bamboos—Ampàsimbé—Cloth Weaving—Native Looms—Rofìa-palms—“A Night with the Rats”—Hard Travelling—Béfòrona—The Two Forest Belts—The Highest Mountains—Forest of Alamazaotra—Villages on Route—The Blow-Gun | |

| CHAPTER V [10] | |

| FROM COAST TO CAPITAL: ALAMAZAOTRA TO ANTANÀNARÌVO | 63 |

| “Weeping-place of Bullocks”—“Great Princess” Rock—Grandeur of the Vegetation—Scarcity of Flowers—Orchids, Bamboos, and Pendent Lichens—Apparent Paucity of Animal Life—Remarkable Fauna of Madagascar—Geological Theories thereon—Lemurs—The Ankay Plain—An Ancient Lake—Mòramànga—River Mangòro—Grand Prospect from Ifòdy—The Tàkatra and Its Nest—Hova Houses—Insect Life—Angàvo Rock—Upper Forest—Treeless Aspect of Imèrina—Granite Rocks—Ambàtomànga—And its big House—Grass Burning—First View of Capital—Its Size and Situation—Hova Villages—A Cloud of Locusts—Reach Antanànarìvo | |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| THE CHANGING MONTHS IN IMÈRINA: CLIMATE, VEGETATION AND LIVING CREATURES OF THE INTERIOR | 75 |

| The Seasons in Madagascar—Their Significant Names—Prospect from Summit of Antanànarìvo—Great Rice-plain—An Inundation of the Same—Springtime: September and October—Rice-planting and Rice-fields—Trees and Foliage—Common Fruits—“Burning the Downs”—Birds—Hawks and Kestrels—Summer: November to February—Thunderstorms and Tropical Rains—Lightning and its Freaks—Effects of Rain on Roads—Rainfall—Hail—Magnificent Lightning Effects—Malagasy New Year | |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| SPRING AND SUMMER | 90 |

| Native Calendar—Conspicuous Flowers—Aloes and Agaves—Uniformity of Length of Days—Native Words and Phrases for Divisions of Time—And for Natural Phenomena—Hova Houses—Wooden and Clay—Their Arrangement—And Furniture—“The Sacred Corner”—Solitary Wasps—Their Victims—The Cell-builders—The Burrowers—Wild Flowers | |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| THE CHANGING MONTHS IN IMÈRINA: CLIMATE, VEGETATION, AND LIVING CREATURES OF THE INTERIOR | 103 |

| Autumn: March and April—Rice Harvest—The Cardinal-Bird—The Egret and the Crow—Harvest Thanksgiving Services—Rice, the Malagasy Staff of Life—Queer “Relishes to Rice”—Fish—Water-beetles—A Dangerous Adventure with One—Dragonflies—Useful Sedges and Rushes—Mist Effects on Winter Mornings—Spiders’ Webs—The “Fosse-Crosser” Spider—Silk from it—Silk-worm Moths—And Other Moths—The “King” Butterfly—Grasshoppers and Insect Life on the Grass—The Dog-Locust—Gigantic Earthworms—Winter: May to August—Winter the Dry Season | |

| CHAPTER IX [11] | |

| AUTUMN AND WINTER | 116 |

| Old Towns—Ancient and Modern Tombs—Memorial Stones—Great Markets—Imèrina Villages—Their Elaborate Defences—Native Houses—Houses of Nobles—Hova Children—Their Dress and Games—Village Churches—And Schools—A School Examination—Aspects of Nightly Sky Epidemics in Cold Season—Vegetation | |

| CHAPTER X | |

| AT THE FOREST SANATORIUM | 127 |

| A Holiday at Ankèramadìnika—The Upper Forest Belt—The Flora of Madagascar—Troubles and Joys of a Collector—A Silken Bag—Ants and their Nests—In Trees and Burrows—Caterpillars and Winter Sleep—Butterflies’ Eggs—Snakes, Lizards and Chameleons—An Arboreal Lizard—Effects of Terror—Some Extraordinary Chameleons—The River-Hog—Sun-birds | |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| FOREST SCENES | 140 |

| Forest Scenes and Sounds—The Goat-sucker—Owls—Flowers and Berries—Palms and other Trees—The Bamboo-palm—Climbing Plants—Mosses, Lichens and Fungi—Their Beautiful Colours—Honey—The Madagascar Bee—Its Habits and its Enemies—Forest People—The Bétròsy Tribe—A Wild-Man-of-the-Woods—A Cyclone in the Forest—A Night of Peril | |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| RAMBLES IN THE UPPER FOREST | 150 |

| Forest Parts—Lost in the Woods—Native Proverbs and Dread of the Forest—Waterfalls—A Brilliant Frog—Frogs and their Croaking—A Nest-building Frog—Protective Resemblances and Mimicry—Beetles—Brilliant Bugs—Memorial Mounds—Iron Smelting—Feather Bellows—Depths of the Ravines—Forest Leeches—Ferns—Dyes, Gums and Resins—Candle-nut Tree—Medicinal Trees and Plants—Useful Timber Trees—Superstitions about the Forest—Marvellous Creatures—The Ball Insect—Millipedes and Centipedes—Scorpions | |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

| FAUNA | 162 |

| The Red-spot Spider—Various and Curious Spiders—Protective Resemblances among them—Trap-door Spiders—The Centetidæ—Malagasy Hedgehogs—The Lemurs—The Propitheques—The Red Lemur—Pensile Weaver-bird—The Bee-eater—The Coua Cuckoos—The Glory and Mystery of the Forests—A Night in the Forest | |

| CHAPTER XIV [12] | |

| ROUND ANTSIHÀNAKA | 173 |

| Object of the Journey—My Companions—The Antsihànaka Province—Origin of the People—Anjozòrobé—“Travellers’ Bungalow”—A Sunday there—“Our Black Chaplain”—The “Stone Gateway”—Ankay Plain—Ants and Serpents—Hair-dressing and Ornaments—Tòaka Drinking—Rice Culture—Fragrant Grasses—The Glory of the Grass—Their Height—Capital of the Province—We interview the Governor—Flowers of Oratory—The Market—Fruits and Fertility—A Circuit of the Province—Burial Memorials—Herds of Oxen—Horns as Symbols—Malagasy Use of Oxen—A Sihànaka House—Mats and Mat-making—Water-fowl—Their Immense Numbers—Teal and Ducks—The Fen Country—Physical Features of Antsihànaka—The Great Plain—Ampàrafàravòla—Hymn-singing—Sihànaka Bearers—“Wild-Hog’s Spear” Grass—Dinner with the Lieutenant-Governor—“How is the Gun?”—Volcanic Action—Awkward Bridges—Fighting an Ox—Occupations of the People—Cattle-tending—Rice Culture—Fishing—Buds | |

| CHAPTER XV | |

| LAKE SCENERY | 193 |

| The Alaotra Lake—Lake Scenery—A Damp Resting-place—Shortened Oratory—We cross the Lake—An Ancient and Immense Lake—The Crocodile—Mythical Water-creatures—A Pleasant Meeting—“Manypoles” Village—A Sihànaka Funeral—Treatment of Widows—A Village in the Swamp—Unlucky Days and Taboos—Madagascar Grasses—We turn Homewards | |

| CHAPTER XVI | |

| LAKE ITÀSY | 208 |

| Old Volcanoes—Lake Itàsy—Distant Views of it—Legends as to its Formation—Flamingoes—Water-hens—Jacanas—Other Birds—Antsìrabé—Hot Springs—Extinct Hippopotami—Gigantic Birds—Enormous Eggs | |

| CHAPTER XVII | |

| VOLCANIC DISTRICT | 215 |

| Crater Lake of Andraikìba—Crater Lake of Trìtrìva—Colour of Water—Remarkable Appearance of Lake—Legends about it—Its Depth—View from Crater Walls—Ankàratra Mountain—Lava Outflows—An Underground River—Extinct Lemuroid Animals—Graveyard of an Ancient Fauna—The Palæontology—And Geology of Madagascar—Volcanic Phenomena—The Madagascar Volcanic Belt—Earthquakes—A Glimpse of the Past Animal Life of the Island | |

| CHAPTER XVIII [13] | |

| SOUTHWARDS TO BÉTSILÉO AND THE SOUTH-EAST COAST | 228 |

| Why I went South—How to secure your Bearers—The Old Style of Travelling—Route to Fianàrantsòa—Scenery—Elaborate Rice Culture—Bétsiléo Ornament and Art—Burial Memorials—We leave for the Unknown—A Bridal Obligation—Mountains and Rocks—Parakeets and Parrots—A Dangerous Bridge—Ant-hills—The Malagasy Hades—Brotherhood by Blood—Bétsiléo Houses—“The Travelling Foreigners in their Tent”—A Tanàla Forest—Waterfalls—A Tanàla House—Female Adornment | |

| CHAPTER XIX | |

| IVÒHITRÒSA | 246 |

| Ivòhitròsa—Native Dress—a Grand Waterfall—Wild Raspberries—The Ring-tailed Lemur—The Mouse-Lemur—A Heathen Congregation—Unlucky Days—Month Names—The Zàhitra Raft—A Village Belle and her “Get-up”—The Cardamom Plant—Beads, Charms and Arms—Bamboos and Pandanus—A Forest Altar—Rafts and Canoes—Crocodiles—Their Bird Friends—Ordeal by Crocodile—Elegant Coiffure—A Curious Congregation—Ambòhipèno Fort—We reach the Sea—Gigantic Arums—Sea-shells—Pulpit Decoration—Butterflies—Protective Structure in a Certain Species—An Arab Colony—Arabic Manuscripts—Frigate-birds and Tropic-birds—Other Sea-birds | |

| CHAPTER XX | |

| AMONG THE SOUTH-EASTERN PEOPLES | 257 |

| Hova Conquest of and Cruelties to the Coast Tribes—The Traveller’s Tree and its Fruits—A Hova Fort—Ball Head-dressing—Rice-fields—Volcanic Phenomena—Vòavòntaka Fruit—A Well-dunged Village—Water from the Traveller’s Tree—We are stopped on our Way—A Native Distillery—Taisàka Mat Clothing—Bark Cloth—Native Houses and their Arrangement—Secondary Rocks—Ankàrana Fort—A Hospitable Reception—A Noisy Feast—“A Fine Old Malagasy Gentleman”—A Hearty “Set-Off”—Primitive Spoons and Dishes—Burial Memorials | |

| CHAPTER XXI | |

| THE SOUTH-EASTERN PEOPLES | 270 |

| A Built Boat—In the Bush—A Canoe Voyage—Canoe Songs—The Angræcum Orchids—Pandanus and Atàfa Trees—Coast Lagoons—A Native Dance—A Wheeled Vehicle—Lost in the Woods—A Fatiguing Sunday—Dolphins and Whales—Forest Scenery—A Tanàla Funeral—Silence of the Woods—The Sound of the Cicada—Mammalian Life—Hedgehogs and Rats—Why [14]are Birds comparatively so few?—Insect Life in the Forest—A Stick-Insect—Protective Resemblances—The Curious Broad-bill Bird—Minute Animal Life in a River Plant—Ambòhimànga in the Forest—A Tanàla Chieftainess—River-fording and Craft—We reach the Interior Highland—Bétsiléo Tombs—Return to Antanànarìvo | |

| CHAPTER XXII | |

| TO SÀKALÀVA LAND AND THE NORTH-WEST | 285 |

| North-West Route to the Coast—River Embankments—Mission Stations—A Lady Bricklayer—In a Fosse with the Cattle—An Airy Church on a Stormy Night—A Strange Chameleon—The “Short” Mosquitoes—Ant-hills and Serpents—A Sacred Tree—Andrìba Hill and Fort—An Evening Bath and a Hasty Breakfast—Parakeets, Hoopoes, and Bee-eaters—The Ikòpa Valley—Granite Boulders—Mèvatanàna: a Birdcage Town—We form an Exhibition for the Natives—Our Canoes—Crocodiles—Shrikes and Fly-catchers—Tamarind-trees—Camping Out—The “Agy” Stinging Creeper—River Scenery—Fan-palms—Scaly Reptiles and Beautiful Birds—Fruit-eating and Other Bats—Secondary Rocks—Sparse Population—The Sàkalàva Tribes—A Vile-smelling Tree | |

| CHAPTER XXIII | |

| TO THE NORTH-WEST COAST | 301 |

| Tortoises—Gigantic Tortoises of Aldabra Island—Park-like Scenery—The Fierce Little Fòsa—Small Carnivora—Beautiful Woods—“Many Crocodiles” Town—A Curious Pulpit—A Hot Night—A Voyage in a Dhow—Close Quarters on its Deck—An Arab Dhow and its Rig—Bèmbatòka Bay—Mojangà—An Arab and Indian Town—An Ancient Arab Colony—Baobab-trees—Valuable Timber Trees—The Fishing Eagle—Turtles and Turtle-catching—Herons—The North-West Coast—A Fishing Fish—Oysters and Octopus—Nòsibé and Old Volcanoes—Our Last Glimpses of Madagascar | |

| Old Village Gateway with Circular Stone | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

| On the Coast Lagoons | 28 |

| A Forest Road | 32 |

| Low-class Girl fetching Water | 50 |

| A Sihànaka Woman playing the Vahiha | 50 |

| Bétsimisàraka Women | 58 |

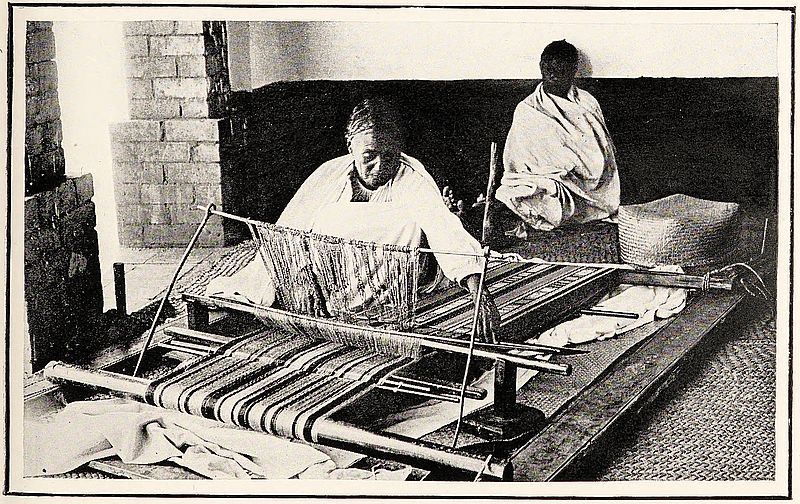

| Hova Women weaving | 58 |

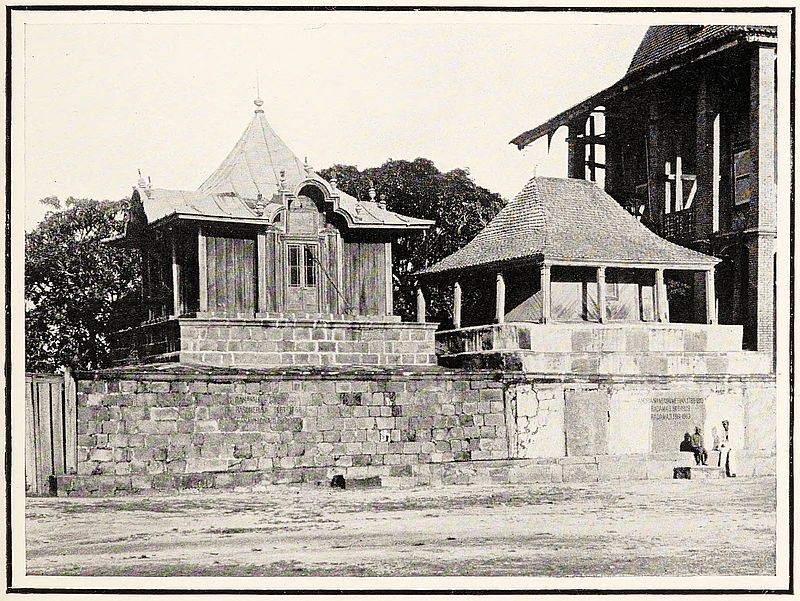

| Family Tomb of the late Prime Minister, Antanànarìvo | 66 |

| Royal Tombs, Antanànarìvo | 66 |

| Earthenware Pottery | 76 |

| Digging up Rice-fields | 76 |

| Pounding and winnowing Rice | 78 |

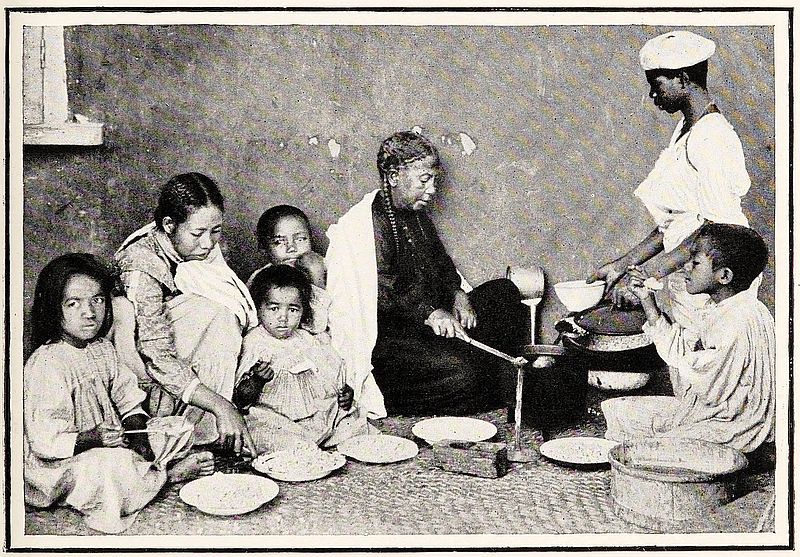

| Hova Middle-class Family at a Meal | 78 |

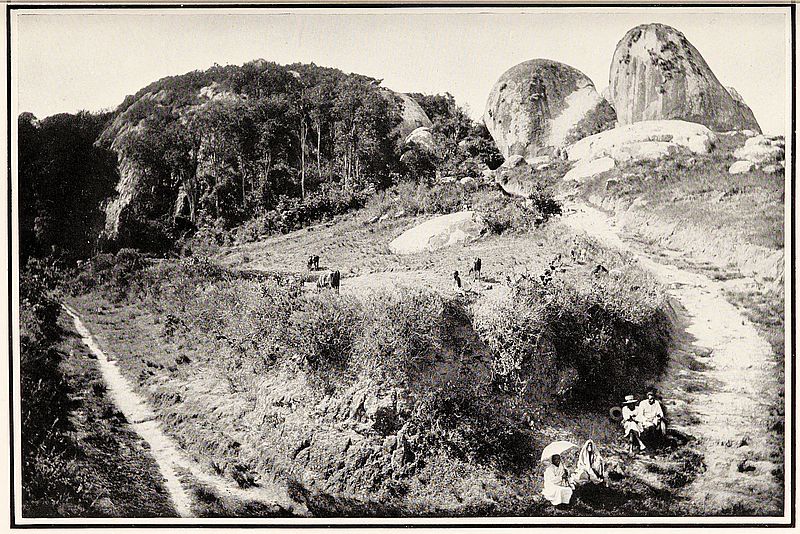

| Rocks near Ambàtovòry | 92 |

| Typical Hova House in the Ancient Style | 96 |

| On the Coast Lagoons | 106 |

| Transplanting Rice | 112 |

| Hova Tombs | 118 |

| Friday Market at Antanànarìvo | 120 |

| Ancient Village Gateway | 124 |

| A Forest Village | 134 |

| Chameleons | 136 |

| Anàlamazàotra | 146 |

| Memorial Carved Posts and Ox Horns | 156 |

| Blacksmith at Work | 156 |

| On the Coast Lagoons [16] | 166 |

| Some Curious Madagascar Spiders | 168 |

| Sihànaka Men | 176 |

| Forest Village | 176 |

| A Wayside Market | 180 |

| Water-carriers | 218 |

| Hide-bearers resting by the Roadside | 230 |

| Bétsiléo Tombs | 230 |

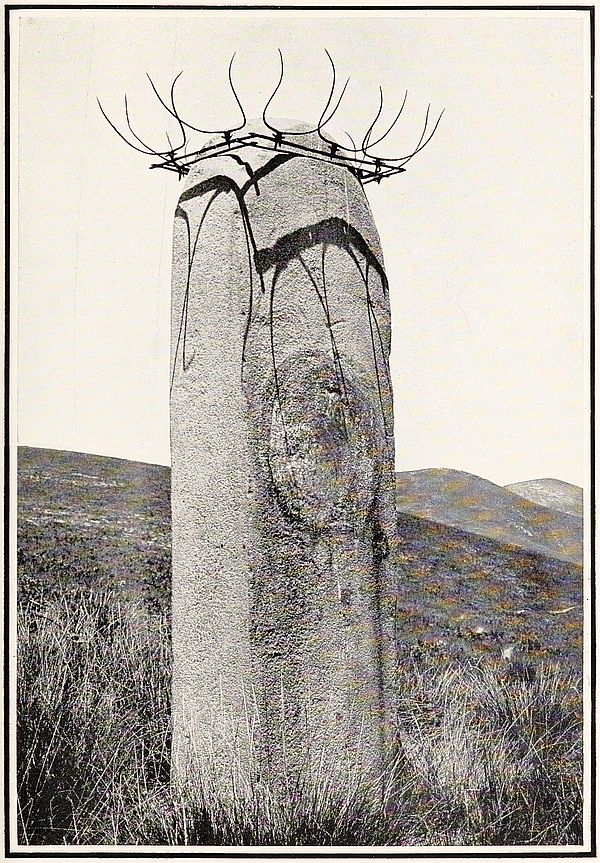

| Memorial Stone | 234 |

| Types of Carved Ornamentation in Houses | 236 |

| ” ” ” | 238 |

| Group of Tanàla Girls in Full Dress | 242 |

| Tanàla Girls singing and clapping Hands | 242 |

| Tanàla Spearmen | 248 |

| Coiffures | 250 |

| A Forest River | 252 |

| Tree Ferns | 260 |

| Traveller’s Trees | 260 |

| A Malagasy Orchid | 272 |

| Malagasy Men dancing | 274 |

| Woman of the Antànkàrana Tribe | 278 |

| Woman of the Antanòsy Tribe | 278 |

| The Fòsa | 302 |

| Malagasy Oxen | 302 |

| MAPS | |

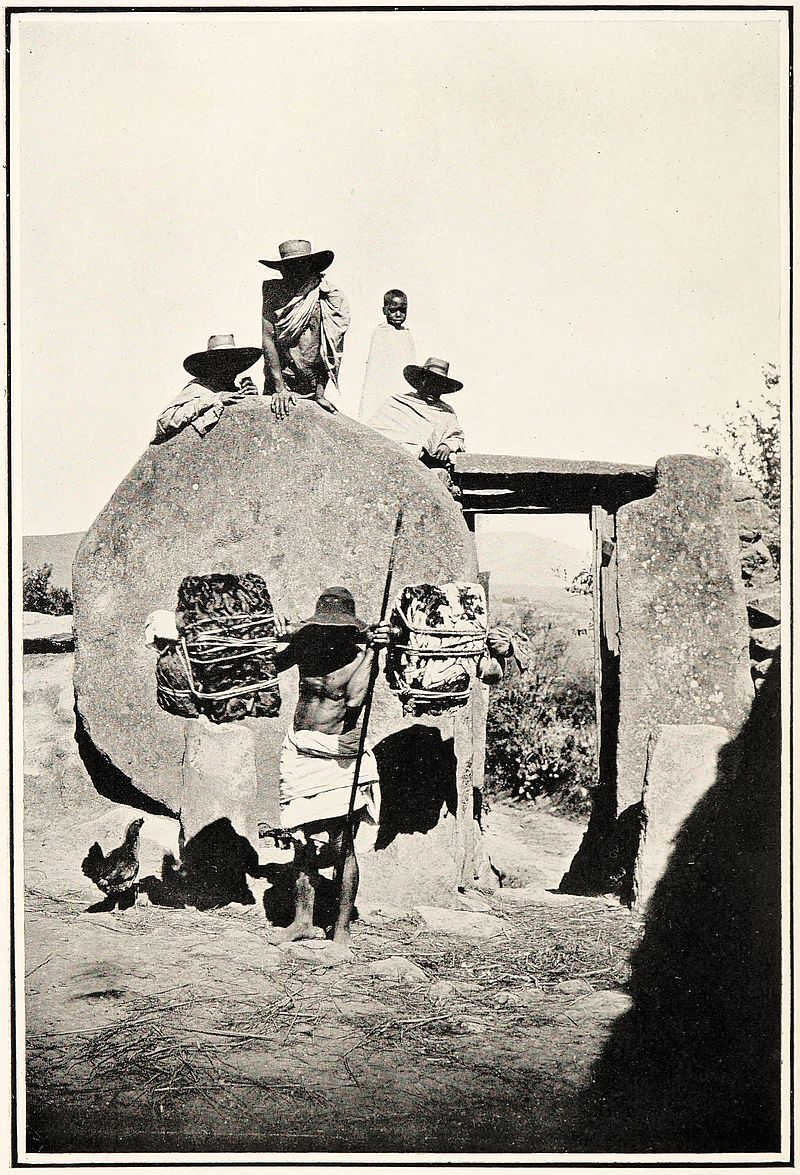

| Physical Sketch Map of Madagascar | 16 |

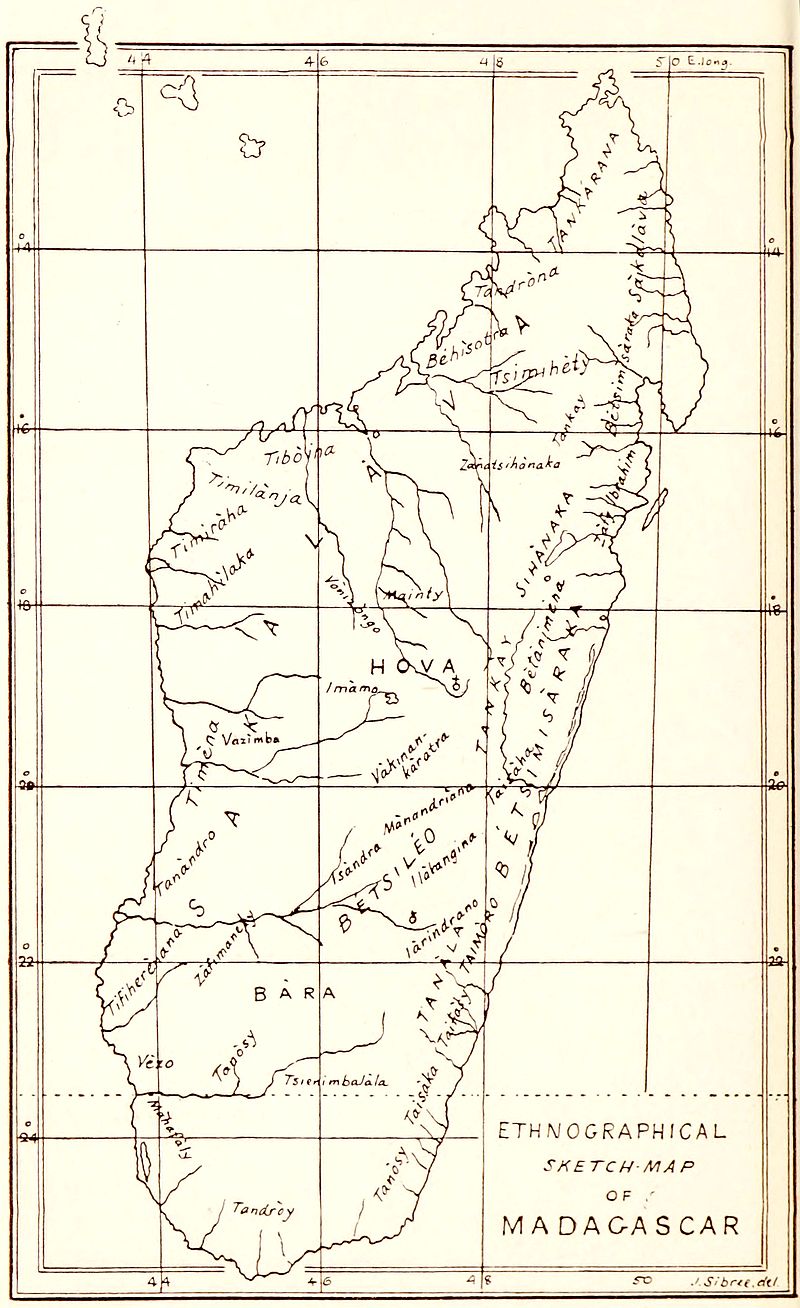

| Ethnographical Sketch Maps of Madagascar | 17 |

| General Map of Madagascar | 314 |

THE great African island of Madagascar has become well known to Europeans during the last half-century, and especially since the year 1895, when it was made a colony of France. During that fifty years many books—the majority of these in the French language—have been written about the island and its people; what was formerly an almost unknown country has been traversed by Europeans in all directions; its physical geography is now clearly understood; since the French occupation it has been scientifically surveyed, and a considerable part of the interior has been laid down with almost as much detail as an English ordnance map. But although very much information has been collected with regard to the country, the people, the geology, and the animal and vegetable productions of Madagascar, there has hitherto been no attempt, at least in the English language, to collect these many scattered notices of the Malagasy fauna and flora, and to present them to the public in a readable form.

In several volumes of a monumental work that has been in progress for many years past, written and edited by M. Alfred Grandidier,[1] the natural history and the botany of the island are being exhaustively described in scientific fashion; but these great quartos are in the French language, while their costly character renders them unknown books to the general reader. It is the object of the following pages to describe, in as familiar and popular a fashion as may be, many of the most interesting facts connected with the exceptional animal life of Madagascar, and with its forestal and other vegetable productions. During[18] nearly fifty years’ connection with this country the writer has travelled over it in many directions, and while his chief time and energies have of course been given to missionary effort, he has always taken a deep interest in the living creatures which inhabit the island, as well as in its luxuriant flora, and has always been collecting information about them. The facts thus obtained are embodied in the following pages.

It is probably well known to most readers of this book that a railway now connects Tamatave, the chief port of the east coast, with Antanànarìvo, the capital, which is about a third of the way across the island. So that the journey from the coast to the interior, which, up to the year 1899, used to take from eight to ten days, can now be accomplished in one day. Besides this, good roads now traverse the country in several directions, so that wheeled vehicles can be used; and on some of these a service of motor cars keeps up regular communication with many of the chief towns and the capital.

But we shall not, in these pages, have much to do with these modern innovations, for a railway in Madagascar is very much like a railway in Europe. Our journeys will mostly be taken by the old-fashioned native conveyance, the filanjàna or light palanquin, carried by four stout and trusty native bearers. We shall thus not be whirled through the most interesting portion of our route, catching only a momentary glimpse of many a beautiful scene. We can get down and walk, whenever we like, to observe bird or beast or insect, to gather flower or fern or lichen or moss, or to take a rock specimen, things utterly impracticable either by railway or motor car, and not very easy to do in any wheeled conveyance. Our object will be, not to get through the journey as fast as possible, but to observe all that is worth notice during the journey. We shall therefore, in this style of travel, not stay in modern hotels, but in native houses, notwithstanding their drawbacks and discomforts; and thus we shall see the Malagasy as they are, and as their ancestors have been for generations gone by, almost untouched by European influence, and so be able to observe their manners and customs, and learn something of their ideas, their superstitions, their folk-lore, and the many other ways in which they differ from ourselves.

Let us, however, first try to get a clear notion about this great[19] island, and to realise how large a country it is. Take a fair-sized map of Madagascar, and we see that it rises like some huge sea-monster from the waters of the Indian Ocean; or, to use another comparison, how its outline is very like the sole—the left-hand one—of a human foot. As we usually look at the island in connection with a map of Africa, it appears as a mere appendage to the great “Dark Continent”; and it is difficult to believe that it is really a thousand miles long, and more than three hundred miles broad, with an area of two hundred and thirty thousand square miles, thus exceeding that of France, Belgium and Holland all put together.[2] Before the year 1871 all maps of Madagascar, as regards its interior, were pure guesswork. A great backbone of mountains was shown, with branches on either side, like a huge centipede. But it is now clear that, instead of these fancy pictures, there is an extensive elevated region occupying about two-thirds of the island to the east and north, leaving a wide stretch of low country to the west and south; and as the watershed is much nearer the east than the west of the island, almost all the chief rivers flow, not into the Indian Ocean, but into the Mozambique Channel. When we add that a belt of dense forest runs all along the east side of Madagascar, and is continued, with many breaks, along the western side, and that scores of extinct volcanoes are found in several districts of the interior, we shall have said all that is necessary at present as to the physical geography. Many more details of this, as well as of the geology, will come under our notice as we travel through the country in various directions.

[1] Histoire Physique, Naturelle et Politique de Madagascar, publiée par Alfred Grandidier, Paris, à l’Imprimerie Nationale; in fifty-two volumes, quarto.

[2] I have often been astonished and amused by the notions some English people have about Madagascar. One gentleman asked me if it was not somewhere in Russia!—and a very intelligent lady once said to me: “I suppose it is about as large as the Isle of Wight!”

IT was on a bright morning in September, 1863, that I first came in sight of Madagascar. In those days there was no service of steamers, either of the “Castle” or the “Messageries Maritimes” lines, touching at any Madagascar port, and the passage from Mauritius had to be made in what were termed “bullockers.” These vessels were small brigs or schooners which had been condemned for ordinary traffic, but were still considered good enough to convey from two to three hundred oxen from Tamatave to Port Louis or Réunion. It need hardly be said that the accommodation on board these ships was of the roughest, and the food was of the least appetising kind. A diet of cabbage, beans and pumpkin led one of my friends to describe the menu of the bullocker as “the green, the brown, and the yellow.” Happily, the voyage to Madagascar was usually not very long, and in my case we had a quick and pleasant passage of three days only; but I hardly hoped that daylight on Wednesday morning would reveal the country on which my thoughts had been centred for several weeks past; so it was with a strange feeling of excitement that soon after daybreak I heard the captain calling to me down the hatchway: “We are in sight of land!” Not many minutes elapsed before I was on deck and looking with eager eyes upon the island in which eventually most of my life was to be spent. We were about five miles from the shore, running under easy sail to the northward, until the breeze from the sea should set in and enable us to enter the harbour of Tamatave.

There was no very striking feature in the scene—no towering volcanic peaks, as at Mauritius and Aden, yet it was not without beauty. A long line of blue mountains in the distance, covered with clouds; a comparatively level plain extending from the hills to the sea, green and fertile with cotton and sugar and rice plantations; while the shore was fringed with the tall[21] trunks and feathery crowns of the cocoanut-palms which rose among the low houses of the village of Tamatave. These, together with the coral reefs forming the harbour, over which the great waves thundered and foamed—all formed a picture thoroughly tropical, reminding me of views of islands in the South Pacific.

The harbour of Tamatave is protected by a coral reef, which has openings to the sea both north and south, the latter being the principal entrance; it is somewhat difficult of access, and the ribs and framework of wrecked vessels are (or perhaps rather were) very frequently seen on the reef. The captain had told me that sometimes many hours and even days were spent in attempting to enter, and that it would probably be noon before we should anchor. I therefore went below to prepare for landing, but in less than an hour was startled to hear by the thunder of the waves on the reef and the shouts of the seamen reducing sail that we were already entering the harbour. The wind had proved unexpectedly favourable, and in a few more minutes the cable was rattling through the hawsehole, the anchor was dropped, and we swung round at our moorings.

There were several vessels in the harbour. Close to us was H.M.’s steamer Gorgon, and, farther away, two or three French men-of-war, among them the Hermione frigate, bearing the flag of Commodore Dupré, their naval commandant in the Indian Ocean, as well as plenipotentiary for the French Government in the disputes then pending concerning the Lambert Treaty. I was relieved to find that everything seemed peaceful and quiet at Tamatave, and that the long white flag bearing the name of Queen Ràsohèrina, in scarlet letters, still floated from the fort at the southern end of the town. I had been told at Port Louis that things were very unsettled in Madagascar, and that I should probably find Tamatave being bombarded by the French; but it is unnecessary to refer further to what is now ancient history, or to touch upon political matters, which lie quite outside the main purpose of this book.

Tamatave, as a village, has not a very inviting appearance from the sea, and man’s handiwork had certainly not added much to the beauty of the landscape. Had it not been for the luxuriant vegetation of the pandanus, palms, and other tropical productions, nothing could have been less interesting than the[22] native town, which possessed at that time few European residences and no buildings erected for religious worship.[3] Canoes, formed out of the trunk of a single tree, soon came off to our ship, but I was glad to dispense with the services of these unsafe-looking craft, and to accept a seat in the captain’s boat. Half-an-hour after anchoring we were rowing towards the beach, and in a few minutes I leaped upon the sand, with a thankful heart that I had been permitted to tread the shores of Madagascar.

Proceeding up the main street—a sandy road bordered by enclosures containing the stores of a few European traders—we came to the house of the British Vice-Consul. Here I found Mr Samuel Procter, who was subsequently the head for many years of one of the chief trading houses in the island, and also Mr F. Plant, a gentleman employed by the authorities of the British Museum to collect specimens of natural history in the then almost unknown country. From them I learned that a missionary party which had preceded me from Mauritius had left only two days previously for the capital, and that Mr Plant had kindly undertaken to accompany me on the journey for the greater part of the distance to Antanànarìvo. At first we thought of setting off on that same evening, so as to overtake our friends, but finding that this would involve much fatigue, we finally decided to wait for two or three days and take more time to prepare for the novel experiences of a Madagascar journey. In a little while I was domiciled at Mr Procter’s store, where I was hospitably entertained during my stay in Tamatave.

The afternoon of my first day on shore was occupied in seeing after the landing of my baggage. This was no easy or pleasant task; the long rolling swell from the ocean made the transfer of large wooden cases from the vessel to the canoes a matter requiring considerable dexterity. More than once I expected to be swamped, and that through the rolling of the ship the packages would be deposited at the bottom of the harbour. It was therefore with great satisfaction that I saw all my property landed safely on the beach.

Although Tamatave has always been the chief port on the east coast of Madagascar, there were, for many years after my arrival there, no facilities for landing or shipping goods. The bullocks, which formed the staple export, were swum off to the ships, tied by their horns to the sides of large canoes, and then[23] slung on board by tackles from the yard-arm. From the shouting and cries of the native drovers, the struggles of the oxen, and their starting back from the water, it was often a very exciting scene. A number of these bullockers were always passing between the eastern ports of Madagascar and the islands of Mauritius and Réunion, and kept the markets of these places supplied with beef at moderate rates. The vessels generally ceased running for about four months in the early part of the year, when hurricanes are prevalent in the Indian Ocean; and it may easily be supposed that the passenger accommodation on board these ships was not of the first order. However, compared with the discomforts and, often, the danger and long delays endured by some, I had not much to complain of in my first voyage to Madagascar. It had, at least, the negative merit of not lasting long, and I had not then the presence of nearly three hundred oxen as fellow-passengers for about a fortnight, as on my voyage homewards, when I had also a severe attack of malarial fever.

The native houses of Tamatave, like those of the other coast villages, were of very slight construction, being formed of a framework of wood and bamboo, filled in with leaves of the pandanus and the traveller’s tree. In a few of these some attempts at neatness were observable, the walls being lined with coarse cloth made of the fibre of rofìa-palm leaves, and the floor covered with well-made mats of papyrus. But the general aspect of the native quarter of the town was filthy and repulsive; heaps of putrefying refuse exhaled odours which warned one to get away as soon as possible. In almost every other house a large rum-barrel, ready tapped, showed what an unrestricted trade was doing to demoralise the people.

I could not help noticing the strange articles of food exposed for sale in the little market of the Bétsimisàraka quarter. Great heaps of brown locusts seemed anything but inviting, nor were the numbers of minute fresh-water shrimps much more tempting in appearance. With these, however, were plentiful supplies of manioc root, rice of several kinds, potatoes and many other vegetables, the brilliant scarlet pods of different spices, and many varieties of fruit—pine-apples, bananas, melons, peaches, citrons and oranges. Beef was cheap as well as good, and there was a lean kind of mutton, but it was much like goat-flesh.[24] Great quantities of poultry are reared in the interior and are brought down to the coast for sale to the ships trading at the ports.

The houses of the Malagasy officials and the principal foreign traders were substantially built of wooden framework, with walls and floors of planking and thatched with the large leaves of the traveller’s tree. No stone can be procured near Tamatave, nor can bricks be made there, as the soil is almost entirely sand; the town itself is indeed built on a peninsula, a sand-bank thrown up by the sea, under the shelter of the coral reefs which form the harbour. The house where I was staying consisted of a single long room, with the roof open to the ridge; a small sleeping apartment was formed at one corner by a partition of rofìa cloth. There was no window, but light and air were admitted by large doors, which were always open during the day. A few folds of Manchester cottons, to serve as mattress, and a roll of the same for a pillow, laid on Mr Procter’s counter, formed a luxurious bed after the discomforts of a bullock vessel. All around us, in the native houses, singing and rude music, with drumming and clapping of hands, were kept up far into the night; and these sounds, as well as the regular beating of the waves all round the harbour, and the excitement of the new and strange scenes of the past day, kept me from sleep until the small hours of the morning.

The following day I went to make a visit to the Governor of Tamatave, as a new arrival in the country. My host accompanied me, as I was of course quite unable to talk Malagasy. As this was a visit of ceremony, it was not considered proper to walk, so we went by the usual conveyance of the country, the filanjàna. This word means anything by which articles or persons are carried on the shoulder, and is usually translated “palanquin,” but the filanjàna is a very different thing from the little portable room which is used in India. In our case it was a large easy-chair, attached to two poles, and carried by four stout men, or màromìta, as they are called. They carried us at a quick trot; but this novel experience struck me—I can hardly now understand why—as irresistibly ludicrous, and I could not restrain my laughter at the comical figure—as it then seemed to me—that we presented, especially when I thought of the sensation we should make in the streets of an English town.

The motion was not unpleasant, as the men keep step together. Every few minutes they change the poles from one shoulder to the other, lifting them over their heads without any slackening of speed.

A few minutes brought us to the fort, at the southern end of the town; this was a circular structure of stone, with walls about twenty feet high, which were pierced with openings for about a dozen cannon. We had to wait for a few minutes until the Governor was informed of our arrival, and thus had time to think of the scene this fort presented not twenty years before that time, when the heads of many English and French sailors were fixed on poles around the fort. These ghastly objects were relics of those who were killed in an attack made upon Tamatave in 1845, by a combined English and French force, to redress some grievances of the foreign traders. But we need not be too hard on the Malagasy when we remember that, not a hundred years before that time, we in England followed the same delectable custom, and adorned Temple Bar and other places with the heads of traitors.

Presently we were informed that the Governor was ready to receive us. Passing through the low covered way cut through the wall, we came into the open interior space of the fort. The Governor’s house, a long low wooden structure, was opposite to us; while, on the right, he was seated under the shade of a large tree, with a number of his officers and attendants squatting around him. They were mostly dressed in a mixture of European and native costume—viz. a shirt and trousers, over which were thrown the folds of the native làmba, an oblong piece of calico or print, wrapped round the body, with one end thrown over the left shoulder. Neat straw hats of native manufacture completed their costume. The Governor, whose name was Andrìamandròso, was dressed in English fashion, with black silk “top hat” and worked-wool slippers. He had a very European-looking face, dark olive complexion, and was an andrìana—that is, one of a clan or tribe of the native nobility. He did not speak English, but through Mr Procter we exchanged a few compliments and inquiries. I assured him of the interest the people of England took in Madagascar, and their wish to see the country advancing. Presently wine was brought, and after drinking to the Governor’s health we took our[26] leave. The Hova government maintained, until the French conquest, a garrison of from two to three hundred men at Tamatave. These troops had their quarters close to the fort, in a number of houses placed in rows and enclosed in a large square or ròva, formed of strong wooden palisades, with gateways.

The following day was occupied in making preparations for the journey, purchasing a few of the most necessary articles of crockery, etc., and unpacking my canteen. This latter was a handsome teak box, and fitted up most neatly with plates, dishes, knives and forks, etc. But Mr Plant said that both the box and most of its contents were far too good to be exposed to the rough usage they would undergo on the journey; so I took out some of the things and repacked the box in its wooden case. Subsequent experience showed the wisdom of this advice, and that it was a mistake to use too expensive articles for such travelling as that in Madagascar, or to have to spend much time in getting out and putting in again everything in its proper corner. Upon reaching the halting-place after a fatiguing journey of several hours, it is a great convenience to get at one’s belongings with the least possible amount of exertion; and when starting before sunrise in the mornings, it is not less pleasant to be able to dispense with an elaborate fitting of things into a canteen. By my friend’s advice, I therefore bought a three-legged iron pot for cooking fowls, some common plates, and a tin coffee-pot, which also served as a teapot when divested of its percolator. These things were stowed away in a mat bag, which proved the most convenient form of canteen possible for such a journey The contents were quickly put in, and as readily got out when wanted; and, thus provided, we felt prepared to explore Madagascar from north to south, quite independent of inns and innkeepers, chambermaids and waiters, had such members of society existed in this primitive country.

[3] It is perhaps hardly necessary to say that for some years past Tamatave has been a very different place from what is described above. Many handsome buildings—offices, banks, shops, hotels and government offices—have been erected; the town is lighted at night by electricity; piers have been constructed; and in the suburbs shady walks and roads are bordered by comfortable villa residences and their luxuriant gardens.

TRAVELLING in Madagascar fifty years ago, and indeed for many years after that date, differed considerably from what we have any experience of in Europe. It was not until the year 1901 that a railway was commenced from the east coast to the interior, and it is only a few months ago that direct communication by rail has been completed between Tamatave and Antanànarìvo. But until the French occupation, in 1895, a road, in our sense of the word, did not exist in the island; and all kinds of merchandise brought from the coast to the interior, or taken between other places, were carried for great distances on men’s shoulders. There were but three modes of conveyance—viz. one’s own legs, the làkana or canoe, and the filanjàna or palanquin. We intended to make use of all these means of getting over the ground (and water); but by far the greater part of the journey of two hundred and twenty miles would be performed in the filanjàna, carried on the sinewy shoulders of our bearers or màromìta. This was the conveyance of the country (and it is still used a good deal); for during the first thirty years and more of my residence in Madagascar there was not a single wheeled vehicle of any kind to be seen in the interior, nor did even a wheelbarrow come under my observation during that time.

This want of our European means of conveyance arose from the fact that no wheeled vehicles could have been used owing to the condition of the tracks then leading from one part of the country to another. The lightest carriage or the strongest waggon would have been equally impracticable in parts of the forest where the path was almost lost in the dense undergrowth, and where the trees barely left room for a palanquin to pass. Nor could any team take a vehicle up and down some of the tremendous gorges, by tracks which sometimes wind like a corkscrew[28] amidst rocks and twisted roots of trees, sometimes climb broad surfaces of slippery basalt, where a false step would send bearers and palanquin together into steep ravines far below, and again are lost in sloughs of adhesive clay, in which the bearers at times sink to the waist, and when the traveller has to leap from the back of one man to another to reach firm standing-ground. Shaky bridges of primitive construction, often consisting of but a single tree trunk, were frequently the only means of crossing the streams; while more often they had to be forded, one of the men going cautiously in advance to test the depth of the water. It occasionally happened that this pioneer suddenly disappeared, affording us and his companions a good deal of merriment at his expense. At times I have had to cross rivers when the water came up to the necks of the bearers, the shorter men having to jump up to get breath, while they had to hold the palanquin high up at arm’s-length to keep me out of the water.

It was often asked: Why do not the native government improve the roads? The neglect to do so was intentional on their part, for it was evident to everyone who travelled along the route from Tamatave to the capital that the track might have been very much improved at a comparatively small expense. The Malagasy shrewdly considered that the difficulty of the route to the interior would be a formidable obstacle to an invasion by a European power, and so they deliberately allowed the path to remain as rugged as it is by nature. The first Radàma is reported to have said, when told of the military genius of foreign soldiers, that he had two officers in his service, “General Hàzo,” and “General Tàzo” (that is, “Forest and Fever”), whom he would match against any European commander. Subsequent events so far justified his opinion that the French invasion of the interior in 1895 did not follow the east forest road, but the far easier route from the north-west coast. The old road through the double belt of forests would have presented formidable obstacles to the passage of disciplined troops, and at many points it might have been successfully contested by a small body of good marksmen, well acquainted with the localities.

It may be gathered from what has been already said that travelling in Madagascar in the old times had not a little of[29] adventure and novelty connected with it. Provided the weather was moderately fine, there was enough of freshness and often of amusing incident to render the journey not unenjoyable, especially if travelling in a party; and even to a solitary traveller there is such a variety of scenery, and so many and beautiful forms of vegetation, to arrest the attention, that it was by no means monotonous. Of course there must be a capacity for “roughing it,” and for turning the very discomforts into sources of amusement. We must not be too much disturbed at a superabundance of fleas or mosquitoes in the houses, nor be frightened out of sleep by the scampering of rats around and occasionally even upon us. It sometimes happens, too, that a centipede or a scorpion has to be dislodged from under the mats upon which we are about to lay our mattresses, but, after all, a moderate amount of caution will prevent us taking much harm.

It must be confessed, however, that if the weather prove unfavourable the discomforts are great, and it requires a resolute effort to look at the bright side of things. To travel for several hours in the rain, with the bearers slipping about in the stiff adhesive clay—now sinking to the knees in a slough in the hollows, and then painfully toiling up the rugged ascents—with a chance of being benighted in the middle of the forest, were not enjoyable incidents in the journey. Added to this, occasionally the bearers of baggage and bedding and food would be far behind, and sometimes would not turn up at all, leaving us to go supperless, not to bed, but to do as well as we could on a dirty mat. But, after all said and done, I can look back on many journeys with great pleasure; and my wife and I have even said to each other at the end, “It has been like a prolonged picnic.” And by travelling at the proper time of the year—for we never used, if possible, to take long journeys in the rainy season—and with ordinary care in arranging the different stages, there was often no more discomfort than that inseparable from the unavoidable fatigue.

Soon after breakfast on the morning of the 3rd October the yard of Mr Procter’s house was filled with the bearers waiting to take their packages, and, as more came than were actually required, there was a good deal of noise and confusion until all the loads had been apportioned. Most of my màromìta were[30] strong and active young men, spare and lithe of limb, and proved to possess great powers of endurance. The loads they carried were not very heavy, but it was astonishing to see with what steady patience they bore them hour after hour under a burning sun, and up and down paths in the forest, where their progress was often but a scrambling from one foothold to another. Two men would take a load of between eighty and ninety pounds, slung on a bamboo, between them; and this was the most economical way of taking goods, for, on account of the difficulty of the paths, four men found it more fatiguing to carry in one package a weight which, divided into two, could easily be borne by two sets of bearers.

Eight of the strongest and most active young men, accustomed to work together, were selected to carry my palanquin, and took it in two sets of four each, carrying alternately. Most of the articles of my baggage were carried by two men; but my two large flat wooden cases, containing drawing boards, paper and instruments, required four men each. All baggage was carried by the same men throughout the journey, without any relay or change, except shifting the pole from one shoulder to the other; but my palanquin, as already said, had a double set. The personal bearers, therefore, naturally travel quicker than those carrying the baggage, and we generally arrived at the halting-places an hour or more before the others came up. The hollow of the bamboos to which boxes and cases were slung served for carrying salt, spoons, and various little properties of the bearers, and sometimes small articles of European make for selling at the capital. The men were, and still are, very expert in packing and securing goods committed to their charge. Prints, calicoes and similar materials were often covered with pandanus leaves and so made impervious to the wet; and even sugar and salt were carried in the same way without damage.

As the conveyance of myself and my baggage required more than thirty men, and Mr Plant took a dozen in addition, it was some time before everything was arranged, and there was a good deal of contention as to getting the lightest and most convenient packages to carry. We had hoped to start early in the forenoon, but it was after one o’clock when we sent off the last cases and I stepped into my filanjàna to commence the novel experience of a journey in Madagascar. We formed quite a large party as[31] we set off from Tamatave and turned southwards into the open country. The rear was brought up by a bearer of some intelligence and experience, who only carried a spear, and was to act as captain over the rest and look out accommodation for us in the villages, etc. He had also to see after the whole of the luggage, and take care that everyone had his proper load and came up to time.

My filanjàna was a different kind of thing from the chair in which I had gone to visit the Governor. It was of the same description as that commonly used by Malagasy ladies—made of an oblong framework of light wood, filled in with a plaited material formed of strips of sheepskin, and carried on poles, which were the midrib of the enormous leaves of the rofìa-palm. In this I sat, legs stretched out at full length, a piece of board fixed as a rest for the back, and the whole made fairly comfortable by means of cushions and rugs. There was plenty of space for extra wraps, waterproof coat, telescope, books, etc. When ladies travel any distance in this kind of filanjàna a hood of rofìa cloth is fixed so as to draw over the head and to protect them from the sun and rain. In my case, a stout umbrella served instead, and a piece of waterproof cloth protected me fairly well from the little rain that fell on the journey. (I may add here that this was the first, and the last, journey I ever took in this kind of filanjàna.) The late Dr Mullens, who also travelled up in a similar way in 1873, said it reminded him of a picture in Punch, of a heavy swell driving himself in a very small basket carriage, and being remarked on by a street arab to his companion thus: “Hallo, Bill, here’s a cove a-driving hisself home from the wash.” My companion’s filanjàna was a much simpler contrivance than mine, and consisted merely of two light poles held together by iron bars, and with a piece of untanned hide nailed to them for a seat. It was much more conveniently carried in the forest than my larger and more cumbrous conveyance. It may be added that certainly one was sometimes danced about “like a pea in a frying-pan” in this rude machine; and it was not long before a much more comfortable style of filanjàna was adopted, with leather-covered back and arms, padded as well as the seat, and with foot-rest, and leather or cloth bags strapped to the side for carrying books and other small articles.

It was a fine warm day when we set off, the temperature not[32] being higher than that of ordinary summer weather in England. Our course lay due south, at no great distance from the sea, the roar of whose waves we could hear distinctly all through the first stage of the journey. In proceeding from Tamatave to Antanànarìvo the road did not (and still does not, by railway) lead immediately into the interior, but follows the coast for about fifty miles southward. Upon reaching Andòvorànto, we had to leave the sea and strike westward into the heart of the island, ascending the river Ihàroka for nearly twenty miles before climbing the line of mountains which form the edge of the interior highland, and crossing the great forest.

We soon left Tamatave behind us and got out into the open country, a portion of the plain which extends for about thirty miles between the foothills and the sea. Our men took us this first day’s journey of nine or ten miles at a quick walk or trot for the whole way, without any apparent fatigue. The road—which was a mere footpath, or rather several footpaths, over a grassy undulating plain—was bounded on one side by trees, and on the other by low bushes and shrubs. Besides the cocoanut-palms and the broad-leaved bananas, which were not here very numerous, the most striking trees to a foreigner were the agave, with long spear-shaped prickly leaves, on a high trunk, and another very similar in form, but without any stem, both of which might be counted by thousands. Nearer the sea was an almost unbroken line of pandanus, which is one of the most characteristic features of the coast vegetation. I also noticed numbers of orchids on the trees, of two or three species of Angræcum, but just past the flowering; a smaller orchid, also with pure white flowers, was very abundant.

I had enough to engage my attention with these new forms of vegetation, as well as in noticing the birds, and the many butterflies and other insects which crossed our path every moment, until we arrived at Hivòndrona, a large straggling village on a broad river of the same name, which here unites with other streams and flows into the sea. Among the many birds to be seen were flocks of small green and white paroquets, green pigeons, scarlet cardinal-birds, and occasionally beautiful little sun-birds (Nectarinidæ) with metallic colours of green, brown and yellow. We had intended to go farther, but finding that, owing to our late starting, we should not reach another village before[33] dark, we decided to stay of Hivòndrona for the night. A house at most of the villages on the road to the capital was provided for travellers, who took possession at once, without paying anything for its use. The house here, which was somewhat better than at most of the other places, consisted, like all the dwellings in this part of the country, of a framework of poles, thatched with the leaves of the traveller’s tree, and the walls filled in with a kind of lathing made of the stalks of the same leaves. The walls and floor were both covered with matting, made from the fibre of leaves of the rofìa palm. In one corner was the fireplace, merely a yard and a half square of sand and earth, with half-a-dozen large stones for supporting the cooking utensils. As in most native houses, the smoke made its way out through the thatch.

Our men soon came up with the baggage and proceeded to get out kitchen apparatus, make a fire, and put on pots and pans; and in a short time beef, fowls and soup were being prepared. Meanwhile Mr Plant and I walked down to the seashore and then into the village, to call upon a creole trader, who was the only European resident in the place. We brought him back with us, and found dinner all ready on our return to the house. My largest case of drawing boards formed, when turned upside down and laid on other boxes, an excellent table; we sat round on other packages, and found that one of our bearers, who officiated as cook, was capable of preparing a very fair meal; and although the surroundings were decidedly primitive, we enjoyed it all the more from its novelty. After our visitor had left us we prepared to sleep; three or four boxes, with a rug and my clothes-bag, formed a comfortable bed for myself, while Mr Plant lay on the floor, but found certain minute occupants of the house so very active that his sleep was considerably disturbed.

Next morning we were up long before daybreak, and after a cup of coffee started a little before six o’clock. We walked down to the river, which had to be crossed and descended for some distance, and embarked with our baggage in seven canoes. These canoes, like those at Tamatave, are somewhat rude contrivances, and are hollowed out of a single tree. They are of various lengths, from ten to thirty or forty feet, the largest being about four feet in breadth and depth. There is no keel, so that they are rather apt to capsize unless carefully handled[34] and loaded. At each end is a kind of projecting beak, pierced with a hole for attaching a mooring-rope. From the smoothness of the sides, and the great length compared with the beam, they can be propelled at considerable speed with far less exertion than is required to move a boat of European build. Instead of oars, paddles shaped like a wooden shovel are employed, and these are dug into the water, the rower squatting in the canoe and facing the bows; the paddle is held vertically, a reverse motion being given to the handle. We went a couple of miles down the stream, which here unites with others, so that several islands are formed, all the banks being covered with luxuriant vegetation. Conspicuous amongst this, and growing in the shallow water close to the banks, were great numbers of a gigantic arum endemic in Madagascar (Typhonodorum lindleyanum), and growing to the height sometimes of twelve or fifteen feet, and possessing a large white spathe of more than a foot in length, enclosing a golden-yellow pistil, or what looks like one. The leaves are most handsome and are about a yard long. After about twenty minutes’ paddling we landed, and, when all our little fleet had arrived, mounted our palanquins, and set off through a narrow path in the woods. The morning air, even on this tropical coast, was quite keen, making an overcoat necessary before the sun got up.

Our road for some miles lay along cleared forest, with stumps of trees and charred trunks, white and black, in every direction. It is believed that the white ants are responsible for this destruction of the trees. We saw numbers of a large crow (Corvus scapulatus), not entirely black, like our English species, but with a broad white ring round the neck and a pure white breast, giving them quite a clerical air. This bird, called goàika by the Malagasy—evidently an imitation of his harsh croak—is larger than a magpie, and his dark plumage is glossy bluish-black. He is very common everywhere in the island, being often seen in large numbers, especially near the markets, where he picks up a living from the refuse and the scattered rice. He is a bold and rather impudent bird, and will often attack the smaller hawks. There were also numbers of the white egret (Ardea bubulcus) or vòrom-pòtsy (i.e. “white bird”), also called vòron-tìan-òmby (i.e. “bird liked by cattle”), from their following the herds to feed upon the ticks which torment them. One may[35] often see these egrets perched on the back of the oxen and thus clearing them from their enemies. Wherever the animals were feeding, these birds might be seen in numbers proportionate to those of the cattle. This egret has the purest white plumage, with a pale yellow plume or crest, and is a most elegant and graceful bird.

The oxen of Madagascar have very long horns, and a large hump between the shoulders. In other respects their appearance does not differ from the European kinds, and the quality and flavour of the flesh is not much inferior to English beef. The hump, which consists of a marrow-like fat, is considered a great delicacy by the Malagasy, and when salted and eaten cold is a very acceptable dish. When the animal is in poor condition the hump is much diminished in size, being, like that of the camel in similar circumstances, apparently absorbed into the system. It then droops partly over the shoulders. These Malagasy oxen have doubtless been brought at a rather remote period from Africa; their native name, òmby, is practically the same as the Swahili ngombe.

We reached Trànomàro (“many houses”) at half-past nine, and there breakfasted. My bearers proved to be a set of most merry, good-tempered, willing fellows. As soon as they got near the halting-places they would set off at a quick run, and with shouts and cries carry me into the village in grand style, making quite a commotion in the place. Leaving again at noon, in a few minutes we came down to the sea, the path being close to the waves which were rolling in from the broad expanse of the Indian Ocean. I was amused by the hundreds of little red crabs, about three inches long, taking their morning bath or watching at the mouth of their holes, down which they dived instantaneously at our approach. One or more species of the Madagascar crabs has one of its pincers enormously enlarged, so that it is about the same size as the carapace, while the other claw is quite rudimentary. This great arm the little creature carries held up in a ludicrous, threatening manner, as if defying all enemies. I was disappointed in not seeing shells of any size or beauty on the sands. The only ones I then observed which differed from those found on our own shores were a small bivalve of a bluish-purple hue, and an almost transparent whorled shell, resembling the volute of an Ionic[36] capital, but so fragile that it was difficult to find a perfect specimen.

But although that portion of the shore did not yield much of conchological interest, there are many parts of the coasts of Madagascar which produce some of the most beautifully marked species of the genus Conus (Conus tessellatus and C. nobilis, if I am not mistaken, are Madagascar species), while large handsome species of the Triton (T. variegatum) are also found. These latter are often employed instead of church bells to call the congregations together, as well as to summon the people to hear Government orders. A hole is pierced on the side of the shell, and it requires some dexterity to blow it; but the sound is deep and sonorous and can be heard at a considerable distance. The circular tops of the cone shells are ground down to a thin plate and extensively used by the Sàkalàva and other tribes as a face ornament, being fixed by a cord on the forehead or the temples. They are called félana. I have also picked up specimens, farther south, of Cypræa (C. madagascariensis), a well-known handsome shell, as well as of Oliva, Mitra, Cassis, and others (C. madagascariensis). The finest examples are, however, I believe, only to be got by dredging near the shore.

After some time we left the shore and proceeded through the woods, skirting one of those lagoons which run parallel with the coast nearly all the way from Tamatave to Andòvorànto. A good recent map of Madagascar will show that on this coast, for about three hundred miles south of Hivòndrona, there is a nearly continuous line of lakes and lagoons. They vary in distance from the sea from a hundred yards to a couple of miles; and in many places they look like a very straight river or a broad canal, while frequently they extend inland, spreading out into extensive sheets of water, two or three miles across. This peculiar formation is probably owing, in part at least, to slight changes of level in the land, so that the inner banks of the lagoons were possibly an old shore-line. But this chain of lagoons and lakes is no doubt chiefly due to east coast rivers being continually blocked up at their outlets by bars of sand, driven up by the prevailing south-east trade-wind and the southerly currents. So that the river waters are forced back into the lagoons until the pressure is so great that a breach is made, and the fresh water rushes through into the sea. On[37] account of these sand-bars, hardly any east coast river can be entered by ships. The rivers, in fact, flow for the most of the time, not into the sea, but into the lagoons. These are not perfectly continuous, although out of that three hundred miles there are only about thirty miles where there are breaks in their continuity and where canoes have to be hauled for a few hundred yards, or for a mile or two, on the dry land separating them.

It will at once occur to anyone travelling along this coast, as we did, that an uninterrupted waterway might be formed by cutting a few short canals to connect the separate lagoons, and so bring the coast towns into communication with Tamatave. That enlightened monarch, Radàma I. (1810-1828), did see this, and several thousand men were at one time employed in connecting the lagoons nearest Tamatave; but this work was interrupted by his death and never resumed by his successors. But soon after the French conquest the work was again taken in hand; canals were excavated, connecting all the lakes and lagoons between Tamatave and Andòvorànto; and for about twelve years a service of small steamers took passengers and goods between Hivòndrona and Brickaville, where, until quite recently, the railway commenced. Since the line of rails has now been completed direct to Tamatave, this waterway will not be of the same use, at least for passenger traffic.

The scenery of this coast is of a very varied and beautiful nature, and the combinations of wood and water present a series of pictures which constantly recalled some of the loveliest landscapes that English river and lake scenery can present. Our route ran for most of the way between the lagoons and the sea, among the woods. On the one hand we had frequent glimpses through the trees of sheets of smooth water fringed by tropical vegetation, and on the other hand were the tumbling and foaming waves of the ever-restless sea. In many places islands studded the surface of the lakes, and I noticed thousands of a species of pandanus, with large aerial roots, spreading out as if to anchor it firmly against floods and violent currents. In the woods were the gum-copal tree and many kinds of palms with slender graceful stems and crowns of feathery leaves. The climbing plants were abundant, forming ropes of various thicknesses, crossing from tree to tree and binding all together in inextricable confusion, creeping on the ground, mounting to[38] the tree-tops and sometimes hanging in coils like huge serpents. Great masses of hart’s-tongue fern occurred in the forks of the branches, and wherever a tree trunk crossed over our path it was covered with orchids.

Among other trees I recognised the celebrated tangèna, from which was obtained the poison used in Madagascar from a remote period as an ordeal. The tangèna is about the size of an ordinary apple-tree, and, could it be naturalised in England, would make a beautiful addition to our ornamental plantations. The leaves are peculiarly grouped together in clusters and are somewhat like those of the horse-chestnut. The poison was procured from the kernel of the fruit, and until the reign of Radàma II. (1861) was used with fatal effect for the trial of accused persons, and caused the death of thousands of people, mostly innocent, every year during the reign of the cruel Rànavàlona I.

We arrived at Andrànokòditra, a small village with a dozen houses, early in the afternoon. From our house there was a lovely view of the broad lake with its woods and islands, while the sea was only two or three hundred yards’ distance in the rear. Wild ducks and geese of several kinds were here very plentiful, but my friend was not very successful with his gun, as a canoe was necessary to reach the islands where they chiefly make their haunts. After our evening meal Mr Plant slung his hammock to the framework of our hut, and happily did not come to grief, as occasionally happened. I was somewhat disturbed by the cockroaches, which persisted in dropping from the roof upon and around me. There was no remedy, however, except to forget the annoyance in sleep.

I may here notice that when travelling along this coast a few years later (in August 1883) the sands were everywhere almost covered with pieces of pumice, varying from lumps as big as one’s head to pieces as small as a walnut. They were rounded by the action of the waves, and on some of the larger pieces oysters, serpulæ and corals had begun to form. This pumice had no doubt been brought by the ocean currents, as well as by the winds, both setting to the west, from the Straits of Sunda, where they were ejected by the tremendous eruption of Krakatoa, off the west coast of Java, during the previous May. This fact supplies not only an interesting illustration of the[39] distances to which volcanic products may be carried by ocean currents, but also throws light upon the way in which the ancestors of the Malagasy came across the three thousand miles of sea which separate Madagascar from Malaysia. It is easy to understand how, in prehistoric times, single prahus, or even a small fleet of them, were occasionally driven westward by a hurricane, and that the westerly current aided in this, until at length these vessels were stranded or gained shelter on the coast of Madagascar, stretching north and south, as it does, for a thousand miles. From what I have been told, the pumice was found, if not everywhere on the east coast, at any rate over a considerable extent of it.

We were up soon after four o’clock on the following morning, and started while it was still twilight. After going a short distance through the woods we came again to the seashore, and proceeded for some miles close to the waves, which broke repeatedly over our bearers’ feet as they tramped on the firm wet sand. For a considerable distance there was only a low bank of sand between the salt water of the ocean and the fresh water of the lake. In many places the opposite shore showed good sections of the strata, apparently a red sandstone, with a good deal of quartz rock. We left the sea again and went on through the woods, a sharp shower coming on as we entered them. We did not notice any fish in the lagoons, but I was afterwards informed by a correspondent, Mr J. G. Connorton, who lived for several years at Mànanjàra, and paid much attention to natural history, that there is a great variety of fish, crustaceans and mulluscs in the lagoons and rivers, as well as in the sea. He kindly sent me a list of about one hundred and twenty of these, together with many interesting particulars as to their habits and appearance, etc. From this account I will give a few extracts:

“Ambàtovàzana, a sea-fish which comes also into the entrance of the rivers; it has silvery scales and yellow fins. In both upper and lower jaws are four rows of teeth very like pebbles; these are for crushing crabs, its usual food. Its name is derived from its peculiarly shaped teeth (vàto, stone; vàzana, molar teeth). Botàla, a small sea and river fish; it is covered all over with rough prickles. These fish inflate their bodies by filling their stomachs with air as soon as they are taken out of the[40] water; if replaced in the water suddenly, out goes the air, and they are off like a flash. It is probably Tetrodon fàhaka. Hìntana, a river-fish, with purple colouring and darker purple stripes from back to belly. It is generally found among weeds, and has four long spines, one on the dorsal fin, two just behind the gills, and one close under the tail. These spines are very poisonous, and anyone pricked by them suffers great pain for several hours, the parts near the wound swelling enormously. I have not, however, heard of the wound ever proving fatal. Horìta, a small species of octopus found clinging to the rocks. The Malagasy esteem them highly, but I found them gluey and sticky in the mouth, as well as rank in flavour. Tòfoka, a sea and river fish, probably Mugil borbonicus. It has a habit of jumping out of the water, and if chased by a shark it swims at the surface with great rapidity, making enormous leaps into the air every now and then and often doubling upon the enemy. Perhaps the best of the many edible fish is the Zòmpona, a kind of mullet, only feeding on soft substances such as weeds. It is silvery in colour, with large scales, and is probably the best-known fish on the east coast. When fresh from the sea, its tail and fins have a yellowish tinge, and it is then splendid eating; but if this tinging is lost it shows that the fish has been for some time in fresh water, and the flesh has a muddy flavour. It varies in size from nine to thirty inches long. The coast people are very fond of zòmpona; and when a person is dying and is so far gone that the case is a hopeless one, some outsider is almost sure to say, ‘He (or she) won’t get zòmpona again.’”

I can confirm my correspondent’s statements as to the excellence of the last-named fish, having frequently eaten it when on the coast. He also mentions several kinds of prawns and shrimps; some of these are large and make an excellent curry. One species of prawn, called Oronkosìa, is long and slender, with immense antennæ, often a foot in length. One species of shrimp has one large claw, like the crab already mentioned, the other being hardly at all developed. Several species of shark are seen off this coast, among them that extraordinary-looking fish, the hammer-headed shark (Zygæna malleus), which I have never seen in Madagascar waters, but have noticed with great interest in South African harbours. “The saw-fish (Pristis sp.), called by the natives Vavàno,[41] sometimes comes into the rivers in search of food. One was caught in the river Mànanjàra which measured fourteen feet from tip of saw to end of tail; the saw alone was three feet six inches in length, seven inches broad at base, and four inches at tip. The flesh is coarse eating, but the liver is very palatable.”

I may remark here that we seldom stopped, either at midday or in the evening, at any village without a visit from the headman of the place and his family, who always carried some present. Fowls, rice, potatoes, eggs and honey were constantly brought to us, preceded by a speech in which the names and honours of the Queen were recited, and compliments to us on our visiting their village. The Malagasy are a most hospitable people, always courteous and polite to strangers; and my first experience of them on this journey was confirmed in numberless instances in travelling in other parts of the country.

Leaving Vavòny, where we had our morning repast, between eleven and twelve o’clock, we went on again through the woods along the shores of the lake, which here spreads out into broad sheets of water, two or three miles wide. The scenery was delightful, both shores being thickly wooded, reminding me in some places of the Wye, in others of the lake at Longleat, and in narrow parts of Studley Park. Our road for miles resembled a footpath through a nobleman’s park in England: clumps of trees, shrubberies, and short smooth turf, all united to complete the resemblance. These all seemed more like the work of some expert landscape gardener than merely the natural growth. In some parts, where the more distinctly tropical vegetation—pandanus, cacti and palms—were not seen, the illusion was complete. In many places we saw many sago palms (Cycas thouarsii), a tree much less in height than the majority of the palms and not exceeding twelve or fourteen feet, but with the same long pinnate leaves characteristic of so many of the Palmaceæ.