[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Startling Stories, July 1947.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

CHAPTER I

Amnesiac!

Doctor Pollard, psychologist, seemed puzzled.

"This has happened before," he remarked.

"Too often," said the director of the laboratory.

Doctor Pollard nodded in silent agreement. He faced the well-dressed man seated asprawl in the chair before him and asked, "You have never heard of James Forrest Carroll?"

"No," said the other man.

"But you are James Forrest Carroll."

"No."

The laboratory director shrugged. "This is no place for me," he said. "If I can do anything—?"

"You can do nothing, Majors. As with the others this case is almost complete amnesia. Memory completely shot. Even the trained-in mode of speech is limited to guttural monosyllables and grunts."

John Majors shook his head, partly in pity and partly in sheer withdrawal at such a calamity.

"He was a brilliant man."

"If he follows the usual pattern, he'll never be brilliant again," Doctor Pollard continued. "From I.Q. one hundred and eighty down to about seventy. That's tough to take—for his friends and associates, that is. He'll be alone in the world until we can bring his knowledge up to the low I.Q. he owns now. He'll have to make new friends for his old ones will find him dull and he'll not understand them. His family—"

"No family."

"None? A healthy specimen like Carroll at thirty-three years? No wife, chick nor child? No relations at all."

"Uncles and cousins only," sighed John Majors.

The psychologist shook his head. "Women friends?"

"Several but few close enough."

"Could that be it?" mused the psychologist. Then he answered his own question by stating that the other cases were not devoid of spouse or close relation.

"I am about to abandon the study of the Lawson Radiation," said Majors seriously. "It's taken four of my top technicians in the last five years. This—affliction seems to follow a set course. It doesn't happen to people who have other jobs that I know of. Only those who are near the top in the Lawson Laboratory."

"It might be sheer frustration," offered Dr. Pollard. "I understand that the Lawson Radiation is about as well understood now as it was when discovered some thirty years ago."

"Just about," smiled Majors wearily. "However, you know as well as I that people going to work at the Lawson Laboratory are thoroughly checked to ascertain and certify that frustration will not drive them insane.

"Research is a study in frustration anyway, and most scientists are frustrated by the ever-present inability of getting something without having to give something else up for it."

"Perhaps I should check them every six months instead of every year," suggested the psychologist.

"Good idea if it can be done without arousing their fears."

"I see what you mean."

Majors took his hat from the rack and left the doctor's office. Pollard addressed the man in the chair again.

"You are James Forrest Carroll."

"No."

"I have proof."

"No."

"Remove your shirt."

"No."

This was getting nowhere. There had to be a question that could not be answered with a grunted monosyllable.

"Will you remove your shirt or shall I have it done by force?"

"Neither!"

That was better—technically.

"Why do you deny my right to prove your identity?"

This drew no answer at all.

"You deny my right because you know that you have your name, blood type, birth-date and scientific roster number tattooed on your chest below your armpit."

"No."

"But you have—and I know it because I've seen it."

"No."

"You cannot deny your other identification. The eye-retina pattern, the Bertillion, the fingerprints, the scalp-pattern?"

"No."

"I thought not," said the doctor triumphantly. "Now understand, Carroll. I am trying to help you. You are a brilliant man—"

"No." This was not modesty cropping up, but the same repeating of the basic negative reply.

"You are and have been. You will be once again after you stop fighting me and try to help. Why do you wish to fight me?"

Carroll stirred uneasily in his chair. "Pain," he said with a tremble of fear in his voice.

"Where is this pain?" asked the doctor gently.

"All over."

The doctor considered that. The same pattern again—a psychotic denial of identity and a fear of pain at the dimly-grasped concept of return. Pollard turned to the sheets of notes on his desk. James Forrest Carroll had been a brilliant theorist and excellent from the practical standpoint too.

Thirty-three years old and in perfect health, his enjoyment of life was basically sound and he was about as stable as any physicist in the long list of scientific and technical men known to the Solar System's scientists.

Yesterday he had been brilliant—working on a problem that had stumped the technicians for thirty years. Today he was not quite bright, denying his brilliance with a vicious refusal to help. He remembered nothing of his work, obviously.

"You know what the Lawson Radiation is?"

"No," came the instant reply but a slight twinge of pain-syndrome crossed his face.

"You do not want to remember because you think you will have to go back to the Lawson Lab?"

"I—don't know it—" faltered James Forrest Carroll. It was obviously a lie.

"If I promise that you will never be asked about it?"

"No," said Carroll uneasily. Then with the first burst of real intelligence he had shown since his stumbling body had been picked up by the Terran Police, Carroll added, "You cannot stop me from thinking about it."

"Then you do know it?"

Carroll relapsed instantly. "No," he said sullenly.

Dr. Pollard nodded. "Tomorrow?" he pleaded.

"Why?"

Pollard knew that the wish to aid Carroll would fall on deaf ears. Carroll did not care to be helped. There were other ways.

"Because I must do my job or I shall be released," said Pollard. "You must permit me to try, at least. Will you?"

"I—yes."

"Good. No one will know that I am not trying hard. But we'll make it look good?"

"Yes."

"Do you know where your home is?" asked Pollard with his mental fingers crossed.

"No."

Pollard sighed.

"Then you stay here. Miss Farragut will show you a quiet room where you can sleep. Tomorrow we'll find your home from the files. Then you can go home."

Pollard got out of there. He knew that Carroll would not leave—could not leave. He prescribed a husky sedative to be put in Carroll's last drink of water for the night and went home himself, his mind humming with speculation.

The conference was composed of Pollard, Majors, and most of the other key men in the Lawson Laboratory. Pollard spoke first.

"James Carroll is a victim of a rather deep-seated amnesia," he said. "Amnesia is, of course, a mechanism of the mind set up to avoid some bitter reality. In Carroll's case, not only is the amnesia passive—some warning agency in Carroll's amnesiac mind warns him that regaining his true identity will result in great pain.

"It is something concerned with his work. We'd like to know what about the study of the Lawson Radiation could produce such a painful reality."

"We all get a bit fed up at times," remarked Tom Jackwell. "It's heartbreaking to sit daily and try things that never do anything."

"We are like an aborigine, born on an isolated island three hundred yards in diameter who has just discovered that certain blackish rocks tend to attract one another and point north. Amusing for a time, but what is it good for and what ungodly mechanism causes it?" said Majors with a shrug.

"Just what is the latest theory on the Lawson Radiation?" asked Pollard.

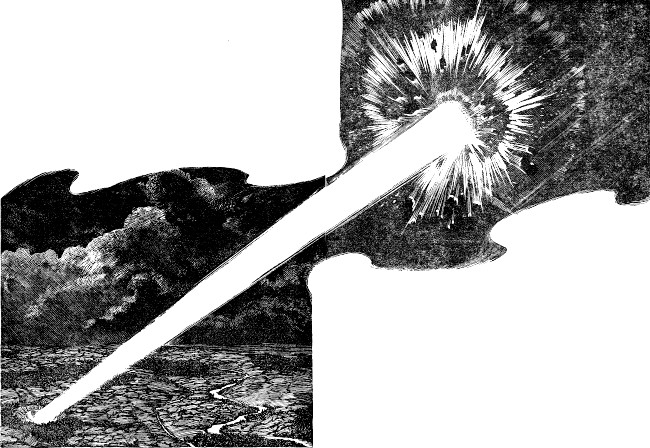

"You guess," said John Majors ruefully. "We've had too many theories already. The Lawson Radiation is a strange creation out of Boötes by Arcturus, and borne like Zephyr on the wind.

"Certain elemental minerals, when in contact with other minerals, produce a pulsing radiofrequency current which can be detected after more amplification than the human mind can contemplate sensibly.

"The frequency output depends upon the type of minerals used, and it is completely random so far as any consistent pattern goes. Some elemental minerals are no good, some are excellent."

"You've made determinant charts?"

"Naturally. But there's no determinant. After I said elemental minerals, I should have said that this was the original premise. Now we have a detector working with helium gas surrounding a block of lead bromide.

"Lead and helium are no good, helium and bromine equally poor. Lead and bromide are no good—as long as it lasts. Now don't ask me if the combination of the elements interferes. One good detector operates so wonderfully all the time, that a bit of yellow phosphorus is forming phosphorus pentoxid because it is suspended in an atmosphere of pure oxygen."

"No apparent determining factors, hey?"

"None. You might as well pick out the elements with six-letter names. The periodic chart looks like the scatter-pattern of an open-choke shotgun. Water works fine when it is contained in a glass vessel, but in anything else we know of—no dice."

"You seem to have covered a multitude of things," said Dr. Pollard approvingly.

"We've had a corps of brilliant, imaginative technicians working on the theory and practise for thirty years. Every one of them has come up with a number of elemental detecting combinations. We're now working on four and five element permutations.

"With and without plain and complex electrostatic and magnetic fields—and mixtures of both. We've gone logically as far as we can under a system that demands that we try everything. In each set of permutations, we cover all. You know our motto."

Majors finished with a slight laugh. He pointed to the end of the conference room, where, lettered on the wall above the blackboard was—

LEAVE NO TURN UNSTONED!

"Where does it come from?" asked Pollard innocently.

"Take a fifteen-degree angle from the middle of Boötes. Maybe Arcturus for all we know. Somewhere within fifteen degrees of an arbitrary point up there. A total conic solid angle of thirty degrees will encompass all but wisps of the stuff that filter through once in a year or so."

"And the velocity of propagation?"

"That's the simplest thing to check. The pulses from the Lawson Radiation follow random patterns. A segment printed along a time-scale can be matched to another segment of the same radiation taken from the other side of the solar system.

"It's never perfect enough to do more than approximate the answer, but we've got to get a lot more dispersion than the breadth of the orbit of the planet Pluto before we can detect any time-delay—and if we go too far the synchronization of our test equipment gets more and more difficult. You guess."

Pollard thought for a moment. "I can't hope to know all the angles," he said. "This is sufficient until I have to know more about it. Now tell me what might drive a man into instability?"

"You tell us," laughed Majors shortly. His laugh was not genuine for he felt the loss of Carroll deeply.

"Is there any insoluble dilemma in this at all?"

"Not that we know of."

Pollard nodded. "People are always confronted with insoluble dilemmas of one sort or another, but most of them could be avoided entirely by a slight change in personal attitude. The man who cannot get a job because of inexperience, and can get no experience for lack of job is in an insoluble dilemma.

"But it is usually resolved before the subject gets too deeply involved with his whirly. Someone always turns up needing some sort of help at any cost, and that gives the required experience which can be magnified by the applicant.

"Is it safe to assume that all of these four people who have turned up with the same affliction might have turned up with some terrific answer that drove them into a tizzy?" asked Pollard.

"Who knows?" grumbled Majors irritably. "Might be."

"What sort of answer would drive a man insane?" asked Jackwell. "If a man is seeking an answer to a specific question, and he has no penalty for not answering, what then?"

Majors wrinkled his forehead. "If the answer meant danger—of any sort?"

"No," said Pollard positively. "If it were social danger he would call for aid and tell the authorities. If it were personal danger, he'd run, and use his mind to avoid it."

"And if it could not be averted?"

Pollard still shook his head. "Men of Carroll's stability do not go insane when faced with personal danger or even certain death. How about his notes?"

"Nothing in them that seems out of line," said Majors. "Just the same 'no effect' or 'no improvement' conclusions."

"See here," said Pollard. "Do you have to use these improved detectors on the natural radiation?"

"Of course," said Majors. "We don't know what the Lawson Radiation is, and therefore we have no way of simulating it in our lab. What has us stumped is that the detectors go on detecting Lawson Effects while they're sitting on a fission-pile with no increase in noise-level or signal." Majors smiled unhappily.

"That is, they do until the nuclear bombardment transmutes one of the detector-elements into another one that is ineffective. So far nothing we can pour into any of them will result in an indication."

Dr. Pollard shook his head. "This has been of some help," he said. "But the big job of gaining his confidence and bringing him back is still ahead of me. I think this will be all for now. May I count on your co-operation again?"

"Any time," said Majors. "We need Carroll—which is quite aside from the fact that we all like him and it hurts to see him as he is now."

The conference broke up, and Dr. Pollard left the Lawson Laboratory and headed slowly toward the hospital where James Carroll was still sleeping.

He was praying for a miracle. A mere human, he felt ignorant, helpless, blind against the sheer disinterest that emanated from Carroll's blacked-out intelligence. Not so much for the problem of the Lawson Radiation would Pollard like to bring James Carroll back to himself as for the benefit of the man—and mankind—for Carroll had been a definite asset.

And then Pollard stopped thinking on the subject, for he found himself rolling around in a tight circle in the problem. Did he want Carroll or did he want to find out what Carroll had learned that drove him crazy?

To bring him back to full usefulness—that was admitting that his interest was as much for the benefit of science as for the man. Science in Carroll's case meant years and years of intense study of that one particular field.

He was rationalizing, he knew, and he went further by admitting that bringing Carroll back to full intelligence again meant that, unless the man regained his ability to remember and work on the Lawson Radiation, his return was incomplete. Would he bring Carroll back—only to have the man return to this rare state of amnesia at the first touch of something—and who knew what?

Pollard closed his mind and returned to the hospital.

But the days passed with no hope. Carroll was forced to admit his identity and that was all. His mind meticulously avoided any contact with the Lawson Radiation. In fact, any minor gains Pollard made were lost instantly when any phase of Carroll's former studies was mentioned.

Eventually James Carroll went home. Pollard could keep him there no longer. The former physicist returned daily, and Pollard helped the man to make plans for the future. That hurt deeply, for Pollard had to sit there, helpless to do anything about the man's lack of intellect.

Things that a normal man would take for granted in his daily life Pollard had to outline in detail as planning. Luckily Carroll had financial independence—or unluckily, perhaps, for maybe a job of some sort might have been good therapy.

The trouble was that Pollard could not make his own mental adjustment to see the former, very brilliant James Forrest Carroll working for a pittance by digging ditches or slogging away his life in a menial job.

As the days grew into weeks the pattern of Carroll's new life became fixed in the man's mind and he found it unnecessary to return daily to the hospital for advice.

And Dr. Pollard gave up, himself a fine case of frustration.

CHAPTER II

Double Trouble

James Forrest Carroll was lazily happy with himself. His needs were quite simple and the apartment he lived in was far beyond them. He had a gnawing doubt that he could keep it forever, because there was something about money that did not jibe.

He could not make enough money to maintain it—and he did not need it anyway. But it was very nice and he viewed it as any normal man might view living in his own ideal home, complete with everything that he ever hoped to have.

He awoke in the morning by physical habit, dressed by instinct and his breakfast was served by the housekeeper. Then he left the place and roamed. He saw the parks and enjoyed with primitive pleasure the greenery and the natural settings of tree, grass and sky. The park squirrels knew no fear of him and he found them interesting. Perhaps he subconsciously envied their obvious adjustment to their environment.

He visited an art institute once but never returned because it made him uneasy. The same was true of the museum of natural history, though it was more to his liking than the artificial art.

On the same street was a museum of science which, because of a strange arrangement of windows, portico, and row of columns, took on a distorted picture of a grinning giant that threatened to swallow whoever entered. Carroll, without knowing the subconscious connection, feared and avoided it even though he had to cross the street to pass it.

They took him from a planetarium once—screaming in fear and crying to be set free. Claustrophobia, one "expert" said, but he didn't know that Carroll had been mentally sitting in deep space with no solidity beneath him when he started to scream.

He—got along.

There was no apparent advance. His actions in life were normal to his preamnesiac self on minor items. He preferred the better restaurants, took an instinctive liking to the same good clothing that he had lived with before. In all outward respects James Forrest Carroll was a well-to-do man without the mental right to carry that position.

Occasionally it bothered him that something was wrong but he avoided the reason for it.

Why am I? he asked himself again and again. What has happened? His evenings were spent in roaming, just walking the quiet streets and trying to think of why he was puzzled. On these walks he noticed little of his fellow men and their actions. If they wanted to be as they were, James Carroll was not to bother them.

He often pondered the question of how he would react if one of them called upon him or spoke to him. Then, he thought, he would act. But he was not to criticize nor object to the way in which his fellow man conducted himself so long as it did not bother James Forrest Carroll.

This wonder of what he would do took ups and downs. There were times when he wished someone would act toward him so that he could find out about himself. At other times he did not care. At still other times he knew that how he would act depended entirely upon the circumstances. In the final analysis, however, Carroll's first act toward anyone came from sheer instinct rather than from any plan.

A girl emerged from a building carrying a file-box of papers. It was dusk and she was hurrying along the street before him by fifty feet. It was obvious that her last job for the day was the delivery of this box of papers to some other building and, once it was delivered, she was finished. That Carroll understood.

She stopped for traffic at the end of the block and as she stood there, a large car drove up to the curb and stopped beside her. Idly she turned and walked to the car slowly, opened the door and started to enter.

That struck a hidden chord in Carroll's mind.

"Hey!" he exploded, running forward to the car. His voice startled her and she partly turned. A hand emerged from within the car and grabbed the box of papers. Carroll arrived at that instant and grabbed for the other end. There was a quick struggle and the box opened and a hundred sheets of notes were strewn on the sidewalk.

The girl stooped and scooped the papers up roughly, shoving them back in the box helter-skelter and clapping the top back on. Carroll did not see this, for the occupant of the back seat was coming out angrily at this instant.

Carroll reached forward and clipped the stranger on the nose, driving him back into the car. The driver's companion snapped his door open, grabbed the box, hurled the girl asprawl on the floor of the back seat. The car leaped away, leaving Carroll standing there in wonder.

That girl—he should know her. Those papers were important to someone. He stooped and picked one last one up and stared at it. It made no sense.

He took it home. It pained him to read it but someone was in bad trouble because of it, and Carroll did not like the idea of a woman being in trouble over a sheet of paper—or a hundred sheets of paper. It made no sense, and he gave up, tired.

But he returned to the same corner at dusk the following evening. And the same girl emerged from the same building with the same box and hurried along the same walk. The same car came up and she entered it this time, and it drove slowly off in the direction she wanted to go.

Carroll's instinctive shout died in his throat. The car turned off about one square further and disappeared. Carroll stood idly on the corner, wondering what to do next. For fifteen minutes he stood there, thinking. Then the car returned, turned the corner, and stopped. The girl emerged and walked up the street for a thousand yards and turned into a building with her box of papers.

Carroll waited in front of the building for her. As she came out she saw him and her face lighted up with mingled pleasure and puzzlement.

"Hello, Mr. Carroll," she said brightly.

"Are you all right?" he asked her.

"Fine," she said. "And you?"

"I was concerned about you last night," he told her. "What happened?"

"Why—nothing happened to me." Her eyes widened in wonder and in them he saw some unknown uneasiness. He smiled at her paternally.

"Do this every night?" he asked.

"Uh-huh. You know that I have for years."

Her name was Sally. And Carroll wondered how he should come to know her name. But—she knew his. Or at least she knew what everybody claimed was his name, and what was tattooed on his body.

He wondered again, and in wondering, let the opportunity for further conversation pass. The girl was impatient and said, "You must come back to us someday."

"That I will," he said—but it was to her retreating back. Sally was hurrying up the street again.

Strange, he thought. Does she ride in that car every night? And if he—or they—were friends, why was there a bit of fight last evening? Why was Sally surprised at his question about last evening? She seemed to ignore the fact that she had been roughly hurled into the black car and that he had tried to help her. She shouldn't be riding in strange cars all over the city when important papers were in her possession.

He watched her every evening for a week after that, just to see. And every night the same performance was played. It bothered Carroll, and he determined to see what was going on.

The next evening he was in front of her building as she came out. Her face again lighted up.

"Hello, Mr. Carroll," she said brightly. "Can't stay away?"

"No," he smiled, wondering away from what? "Mind if I walk along?"

"Not at all," she said. There was no uneasiness in her now. Carroll was safe enough, an amnesia victim according to Dr. Pollard, who had told her to cultivate his friendship if she could. Sally and Dr. Pollard had been in a three hour conference on the day after Carroll had met her outside of the typing bureau. So Sally was prepared.

"Mind?" he said, reaching for the box.

"I shouldn't let you," she said seriously. "I'm charged with their delivery, you know. But—I guess you may, Mr. Carroll. I know it makes a man feel foolish to walk along with a woman carrying a big bundle. Go ahead."

He took it. Now they'd have to deal with him!

They came to the corner, stopped for traffic and Carroll looked about him nervously. He was expecting trouble of some sort, but no trouble came. The lights changed with absolutely no sign of that black sedan and, as they were in mid-street, Sally said, "Mind if we stop off at the drug store for a sandwich?"

"Is that all right?" he countered.

"Yes," she said. "I live a long ride from here and the typing bureau is on the way to the station. I asked Mr. Majors if this was okay, and he said it was. I've been doing this every night, now, for months."

"But the—" he stubbed his toe on the far curb and stumbled.

She laughed. "I'm sorry," she said, "but the picture of the great James Carroll stumbling over a curb—"

"What's so peculiar about me falling over a curb?" he demanded.

Sally blushed. Her remark had been instinctive. To her youth, barely out of adolescence, a brilliant physicist of thirty-five years should not be heir to the mundane misfortunes of the ordinary mortal. But she knew that she should not call attention to his past at all.

"Nothing," she chuckled. "Excepting the sight of a man trying to keep his balance and hang on to a box at the same time. Just struck my funnybone. I was not laughing at you; I was laughing more at the situation. Please—"

He nodded absently. They entered the drug store and sat down. She ordered and he repeated it.

"Doesn't this spoil your dinner?" he asked.

"Nope. It's a long ride home and by the time I get there I'm hungry all over again."

"I suppose this snack is a sort of habit," he remarked idly.

"Uh-huh," she answered. "But it isn't too bad a habit."

He nodded in silent agreement. The sandwich came and was finished in a short time, after which Carroll and his young companion left the drug store.

Carroll took a quick look around him as they left but there was no car near them. He walked with her to the typing bureau, waited outside for her and then walked with her to the station. Then he went home to ask himself a multitude of questions.

This was her regular procedure. She said so. But which procedure was regular? Her drugstore and sandwich habit or the taking of a joyride with the characters in the car?

He picked up the paper she had dropped on the first encounter and looked it over. It was a formal report on the testing of some equipment that was too complex to understand. Something about a trimetal contact in an atmosphere of neon, completely sealed in a double-wall shield of copper with a low noise-level radio amplifier stage enclosed with the samples of metal in gas.

It became vaguely familiar after about an hour of study but it was painfully difficult for him to concentrate on such an abstract idea.

He considered again. Perhaps his presence had scared off the men in the black car. He'd do it differently next time. Again he watched her for a solid week—watched her reach the corner, turn, enter the black car—watched her return and continue on down the street with her box after fifteen minutes of being completely gone.

Then for the second week he watched from the drugstore.

And he emerged more puzzled than ever. For Sally joined him daily and talked with him as she had learned to do.

Then, to top his confusion, he watched the girl enter the car and drive off one day, after which he entered the store across the corner, to see Sally sitting there waiting for her sandwich and obviously expecting him.

"You're late," she said with a smile.

"I'm confused," he said dully.

"Did you ever see a big black sedan?" he asked her.

"Lots of them," she said. "Why?"

"Any one that you especially noted?"

"No. Most of them are filled with people going somewhere in a hurry," she returned with a laugh. "I often wish I had a car—or a friend with a car. I haven't got any—at least none that work in this region of the city."

"Uh," he grunted. "I've got to hurry," he said with what he knew to be unpardonable shortness. "See you tomorrow?"

She nodded, and Carroll went out on the street in time to see her emerge from the black car and finish her delivery of the package to the typing bureau. He looked back into the store, but she was gone. Nor had she passed him.

That was enough for Carroll. He sought Dr. Pollard and told him the story. Pollard looked up with pleasure. James Carroll's acceptance of such a problem and the attempt to figure it out was an excellent sign. He could give no answer, of course until ...

"Then come along," said Carroll. "We've time."

They went silently. Carroll pointed out the black car as it approached the curb and then took Pollard into the store to meet Sally. She greeted them pleasantly and did not demur when they left precipitately because she knew that Dr. Pollard was trying to help Mr. Carroll out of his difficulty. Carroll showed Sally's return from the black car, and the subsequent delivery of the box of papers to the typing bureau.

"Carroll," said the psychologist sadly, "forget it!"

"Forget it?" demanded Carroll.

"I saw no black car. You claim that Sally walked to the corner, turned away and entered a black sedan. Actually—though I said nothing—Sally crossed the street and entered the store. As we finished there and left she followed us, passed us on the sidewalk and delivered her package. This is merely a delusion, James."

"Delusion?" said Carroll doubtfully. "Am I—Am I...?

"I plead with you, James. Let me give you psychiatric help? Please?"

Carroll considered. Delusion—he must be going mad. "I'll be in to see you tomorrow," he said.

Pollard took a deep breath.

"Thank God!" he said.

James Carroll returned home in a dither. Regardless of the pain of—whatever it was—he was going to go through with this. Delusions and hallucinations of that vividness should not be. He must be in a severe mental state. He hadn't believed them when they told him that he had been a brilliant physicist. But this well-proven hallucination was final. And before he got worse....

James Carroll was in a state over his state by the time he opened his front door. He entered the room, looking idly about him, half in fear of what he might see next.

What he saw was the sheet of paper with the report on it.

Could you feel an hallucination? Could you read an hallucination? How could a man with five nominal senses, all run by one brain, reach any decision?

He pressed the button on his wall and the housekeeper entered.

"Mrs. Bagby, I am in a slight mental turmoil. Please trust me to the extent of asking no questions but I beg of you to tell me exactly what I will be doing for the next few minutes?"

"I'll try," she said, knowing from Dr. Pollard all about Mr. Carroll's state of mind. She was willing to help.

"You are sitting at your desk, reading a sheet of paper upon which are some handwritten notes and a sketch. Now you are rising. You have just torn off an inch from the bottom of the page—where there is no writing. You are lighting a match, touching it to the end of the paper. It burns.

"You are walking toward the fireplace—moving swiftly now because the paper is burning rapidly. You drop it on the hearth—and the already-laid fire is catching. The chimney is smoking a bit and you are poking the fresh blaze."

He turned and faced her.

"Thanks," he said. "That's what I thought I was doing. Now, to avoid a mental discussion of personal metaphysics, I must establish the validity of this sheet of paper!"

The housekeeper asked if there were anything more to do, and Carroll shook his head idly. She left, and James Carroll faced himself in the mirror.

"Whose hallucination?" he asked himself. "Mine—or Pollard's?"

He recalled a tale of a man so convinced of his hallucination of utter smallness that he prepared trick pictures of himself, completely overwhelmed in size by the common water-hydra and its associated animalcules. Could he have prepared this report to support his own belief?

He smiled. Tomorrow he would know for certain! If his sheet were valid, it would be missing from the files. If anybody had interfered with the official channels of the reports it had been someone other than James Forrest Carroll. Perhaps Dr. Pollard could identify the report.

Then he'd know who was hallucinating!

CHAPTER III

Kidnaped!

Dr. Pollard finished telling his story to John Majors and said, "The whole thing jells, John. Everything fits perfectly."

"I don't see it," objected Majors. "How can a man driven into a psychosis by overwork turn up concocting such a wild-eyed yarn as this hallucination?"

"Easily. Supposing that Carroll had come upon something basically unsound. Suppose all the rest had done the same, the other three or four. The tinkering with the notes is a normal justification for him—if someone hadn't been tinkering with the notes, the problem might have been solved long ago.

"Mrs. Bagby called me just before you came in, remember. I've taken time to inspect all the compiled notes prepared by the typing bureau from a couple of days before Carroll's illness to the present date. They're all present. I've also inspected the originals. There are none missing. Carroll's note must be a psychotic attempt to prove his sanity."

"How could he prepare such?" wondered Majors.

"Easily. It was done under a psychic block and the patient remembers only the true—his true—facts of how he found it on the street."

"Then you believe that Carroll was not on that corner on the day he first saw Sally get hauled into that black sedan?"

"He may not have been there at all. We all knew Sally's habits and that corner very well. That Carroll returned on the following days is a part of his justification pattern. The whole thing is very logical. And it is too bad. I was hoping that Carroll's interest in Sally was a glimmer of returning interest in life and work."

"The child is half his age," snorted Majors in derision.

"All right. So she's about seventeen. I don't expect any real attraction to develop—I'd feel much the same way about them if Sally happened to have been Tommy, the co-op student. All I want is for Carroll to have an interest in something or somebody. I'd gladly offer my wife up as an item for his interest because I know that no fixations would come of it."

Majors scowled. "I couldn't say the same," he observed.

"That's because you do not know Carroll's underlying personality. I do."

"But you admit he's not the same man."

"He isn't—but his sense of loyalty is not changed. So long as he's that way there's hope for him."

"But what do you intend to do about him?"

Dr. Pollard laughed. "Me? I'm going to admit that maybe he has something there, but that this thing is problematical. Oh-oh. He's here," said Pollard, pointing to a winking pilot light above the door. An instant later his nurse entered and was told to send Mr. Carroll in.

"Can you prove the identity of anything?" demanded Carroll once the opening greetings and informalities were finished.

"It depends," said Pollard cautiously.

"Well, I have a sheet of paper here that came from that first day when I saw Sally confronted by the black sedan. Is this valid or is it false?"

"Since I can show you the original of that report, it must be false," replied Pollard. "You see, Jim, regardless of whether you admit it or not, you've been so close to the Lawson Radiation that you could easily fake up what might be a quite valid report if you hoped to show some proof."

"But, good heavens, would I fake a report that I know will be matched by the original?"

"In your right mind, no. I don't know how much this last couple of weeks of problem did to sharpen you up, Carroll. But remember that you were hitting an I.Q. of about seventy after your—accident. A seventy I.Q. might be that dense and can be that dense.

"And, of course, the subconscious mind, hoping to salve your conscious mind, might do it. Now that you know it is false, perhaps your subconscious mind will bring forth something of a more convincing nature."

"If what I think is true," said Carroll slowly, "the same men who intercept Sally every day are quite capable of producing as good a counterfeit as I am!"

"I claim that there are no men in a black sedan."

"Oh?"

"Tell me, Carroll, how do you rationalize the fact of two Sallys?"

"I think there is something to all this that is far deeper than our five senses will admit," said Carroll flatly. "Some agency is doing all it can to prevent us from finding out about the Lawson Radiation!"

Pollard scribbled "persecution complex, too," on his scratchpad in a brand of his own unreadable shorthand. Then he said, "You're convinced to the contrary?"

"I am."

"Tell you what I'll do," said Pollard. "Since you think this affair is what you claim, I'm going to give you a chance to prove it. I'm going to advance Sally into the mailing department and let you take over the job of delivering those reports yourself. You feel that they might not be able to pull the wool over your eyes?"

"You know what I think?" said Carroll sharply. "I think that the days that I joined Sally for her sandwich I took a ride with her in that car, instead!"

"How do you come to that conclusion?" asked the psychologist, scribbling on his scratchpad.

"Because every day that I watched I saw her enter the car. Every day I was with her we saw no car. Could it be mass-hypnosis?"

"It might—but why weren't you hypnotized?"

"I don't know. Why have I got this amnesia?"

"It isn't amnesia anymore," said the psychologist ruefully. "It is now a definite psychic block against your former line of work, coupled with self-justified hallucination."

"I hate to puncture that bubble," said Pollard. "But I must. Take that job and find out for yourself!"

"I will," said James Carroll flatly. "You watch!"

"Good!"

"And I will not be stopping for sandwiches, either!" snapped Carroll. "Or, I might add, anything else!"

James Carroll tucked the box underneath his arm and set out along the street. He walked warily, keeping a sharp lookout for the black sedan. A few hundred feet ahead of him he saw Sally turn into the drug store for her habitual snack but he suppressed very quickly the impulse to follow her and talk to her about the job.

He stood on the corner of the square, waiting for traffic. It was a reasonably long-time light for the crosstown road, and Carroll reached for a cigarette. His pack was empty, so he crumpled it and tossed it in the nearby waste-chute and looked about him questingly.

The corner upon which he stood held a cigar store and James Carroll entered the shop to buy cigarettes. The store was rather full and he was forced to wait.

And it came to him, then. During that wait it came to his feebly-groping mind that this was the same sort of pattern that he had seen before. Was this truth—or reality? He smiled, and as the storekeeper came towards him, he looked the man in the eye and said:

"When did you split me off?"

There was a look of amazement on the proprietor's face—wonder, puzzlement and a scowl of slight anger.

"You heard me," said Carroll flatly. "What are you doing to my reports?"

"You're nuts," said the storekeeper.

"Am I?" replied Carroll lightly. "Then I'll tell you why. The Lawson Radiation comes from a system of interstellar travel, used by some race out in the Boötes region of the sky. The insoluble dilemma is how to go out to learn the secret of interstellar travel when I need interstellar travel to go out and ask the questions—"

The man's face faded, distorted like a cheap oil-clay image under too warm a light.

The store flowed down, too, and swirled around in a grand melee of semiplastic matter. The light inside the store darkened and the only illumination within the rolling, churning store came from a light that swung back and forth madly in front of the door.

Carroll fell backwards into a cushion of soft-plastic floor which bounced slightly under him from time to time. A low roaring mutter came to his ears. The light continued to swing but it was swinging past a window now and only in one direction.

He opened his eyes wide and faced the man in the seat beside him.

"Well?" he asked.

"It isn't, very," growled the man.

The driver turned, swore in a strange tongue and then turned the car back. The driver's companion picked up a small phone and spoke rapidly into it. The car rounded the block, re-passed the corner long enough to pick up a man dressed as Carroll was.

Halfway down the next block the man got out and took the box of reports. Then the car drove away and, as it pulled away, Carroll felt the jab of a needle in his thigh.

CHAPTER IV

Face to Face

Slowly, the initial thought that filtered through the velvety, comfortable blackness was that he was James Forrest Carroll. That established, the rest came with a swift flow of fact and acceptance in chronological order that brought him to the present date.

It seemed almost instantaneous, this return to reality. Yet in his drugged state, or rather the state of fighting off the last dregs of the potion, Carroll did not recognize the long interim periods of slumber. Actually it took him six hours to return to a full state of wakefulness. He was unaware of the slumber periods and they subtracted from his time-consciousness.

When finally he did come fully awake, it was to look into the faces of the two men who had abducted him.

"Wh—?" he grunted, believing that he uttered a complete sentence asking what the score was.

"You know too much," said the man on the left.

The implication did not filter in at first. It came very slowly that one who knew too much was often prevented from telling it to the right people.

Then he said, "What are you going to do to me?"

"Eliminate you," came the cold answer.

The other man shook his head slowly. "No," he said. "Not at once."

The first one turned abruptly. "Look, Kingallis," he snapped, "This one is a definite threat."

"And there may be others," smiled Kingallis. "We could easily eliminate him. And we will but only after we locate exactly what there is about him that permits him to be a threat to us. There may be others. We must stop them."

Sargenuti nodded in a sardonic manner. "Even in the face of a threat the great Doctor Kingallis must experiment!"

"I'll have none of your sarcasm!" snapped Kingallis. "You are not my equal by four groups. You are my underling and will therefore do my bidding with no quarrel."

"Yes, master," sneered Sargenuti.

Kingallis stepped forward and slapped the other across the face with the back of his hand. Sargenuti stood four inches taller than the doctor and outweighed him by at least thirty pounds. He could have broken Kingallis in half with his bare hands but he accepted the insult across his face without flinching nor attempt to retaliate.

"Because we are isolated here, far from our normal surroundings, you have become slovenly in your attitude," snapped Kingallis. "You are no planner, Sargenuti. Your method is acceptable in some cases but you have not the intellectual equipment to cope with a situation as involved as this is.

"Whether you continue as you are, advance in your work or are dropped a group depends upon the future. Suppose there were several people involved that have his power?"

"There cannot be," returned Sargenuti.

"Fool! If there is one there may be others. Now do as I say without argument!"

Carroll listened to this discussion with interest. From it he learned that there was obviously some plot against the Solar System and that he, Carroll, was possessed of some factor that made his continuance dangerous to their plotting.

He half-smiled and said, "There are many like me."

Kingallis turned back to his captive and shook his head.

"No," he said. "There are not! Sargenuti had no trouble until he ran into James Forrest Carroll. That is why he is bloated with delusions of grandeur. He thinks because he has had no competition that he is supreme.

"He forgets the platitude, 'It is a sharp blade that cuts but cheese!' It is notable, however, that the first time he met James Forrest Carroll he was forced to call for help."

"I was puzzled," admitted Sargenuti.

"A slightly more intelligent moron would have known that this man was capable of avoiding your block," snapped Kingallis. "When he came forward to interfere the first time. That is when you should have caught him. Instead you ignored him for too long. Idiot!"

"All right," grumbled Sargenuti. "But this is just telling Carroll things he wants to know."

Kingallis smiled sourly. "Perhaps it is better that way," he said. "When he sees what he is up against he may be less violent."

"And if he again escapes?"

"He will not escape."

Sargenuti laughed roughly. "It would be drastically amusing to find that James Forrest Carroll is smarter than the great Doctor Kingallis."

"Shut up!" snapped Kingallis angrily.

He turned to Carroll. "You know too much," he said. "Yet I have no qualms about telling you more. It is our job to prevent the spread of knowledge about the Lawson Radiation, to discourage research and to cause the importance of the Radiation to diminish.

"We employ mass hypnotism to intercept the reports, to read them, to make the minor changes that prevent correlation of certain data that would lead to some discovery of importance. This happens only once in a few months.

"We can tell by the title of the experiment whether it may or may not include a clue. When someone comes upon a real find we erase his mind."

"And I came upon something?"

"You did."

"What was it?"

Kingallis smiled tolerantly. "You wouldn't expect me to tell you?"

Carroll shrugged. "I suppose not," he said. "But just why do you think I am a basic threat to your plans?"

"Obvious. Of all, you are the first that ever came back to full control of his faculties after we erased your mind. The others have pain syndromes every time they consider research at all. You do not.

"Not only that, you were capable of avoiding the block. We used mass hypnosis on the people within a visible radius of that corner. Of them all, you alone can see the black sedan and the resulting interception."

"But when I went with Sally you intercepted me, too."

"Of course. But you were then right in the main focus of the control beam."

Kingallis turned to Sargenuti. "I thank you for not killing him under the beam," he said. "Your unimaginative mind might have done that. It would have erased a danger, true, but would have prevented our study of the danger at first hand."

Then he turned back to Carroll. "We might not have been able to kill you, at that," he said. "I don't know. You seem to have become stronger each time you underwent the control instead of becoming weaker like the average subject of hypnotism."

"But—?"

Kingallis shrugged. "Most interesting," he said reflectively. "Most interesting."

"What is so interesting?" grunted Sargenuti.

"Consider," said Kingallis. "He finally entered direct control alone. He was the focus. You did succeed in controlling him to a certain point but James Forrest Carroll—mentally living in a perfect dream—recognized the fact that this was not true.

"He broke the dream, the power of our beam. His unaided will-power, Sargenuti, came up from below a sensory delusion and forced recognition of the truth against the evidence presented by his physical senses."

"So?"

"So," concluded Kingallis, "We shall find out what it is about this man's mind that is powerful enough to overcome the power of our beam. For, Sargenuti, we may encounter others."

In the days that followed, one upon the next in a never varying monotony, James Forrest Carroll increased both his store of knowledge and his judgment. It has been said that wide experience is a condition wherein the possessor can fall back upon some personal precedent for any situation that arises.

Carroll, however, could have no such precedent, nor is it likely that any man or all men combined could piece together a reasonable decision based on piecemeal precedent. Therefore Carroll faced the situation with a complete lack of experience.

He realized that making any decision now would be so much tossing of a coin. Lacking the full particulars, the reasons, the understanding of the other race's motives, he could make no plans.

Yet he did know from experience that the best way to lay a cornerstone upon which to build a plan was to wait, to study and then, when the final returns were in, to decide.

Kingallis had confirmed Carroll's suspicion that an Extrasolar agency was doing its utmost to prevent the spread of knowledge about the Lawson Radiation.

Kingallis had not mentioned why.

The facts that Carroll had were sketchy. He knew only what he had already suspected. He had been kidnaped. He knew why. The latter reason was both logical and also a perfect answer to a paranoid question.

He shied away from it, and recognized his own unwillingness to face the fact. That in itself bothered Carroll because he disliked to think himself insane, even though he often questioned his sanity.

Carroll found that none of this was reassuring. There was no equitable yardstick that the mind could apply to itself. It is often said that the insane cannot question their own sanity—that to question your own sanity is a sign of stability.

Yet it may be quite true that a clever paranoid might question his own sanity regularly as a means of proving to himself that he is sane. Carroll played with this mad spiral often and found it a vicious circle.

So in between his sessions of study, James Forrest Carroll tried to delve into his own mind. He had come to only one conclusion: That so long as Kingallis was studying him, he was able also to study Kingallis.

The problem of why bothered Carroll.

Mankind has never ceased to study anything that might prove dangerous. Almost any discovery made is dangerous in some manner. It is just that mankind has learned to handle its discoveries with care as they became useful. Or else—

He tried broaching the why to Kingallis and was brushed off openly with, "It is of no consequence."

Carroll considered two possible answers. One, of course, was that Kingallis and his people were suppressing all study to prevent the Terrans from learning about interstellar travel for purely personal reasons. You do not give away your military secrets to a people you hope to destroy.

The other reason was the complete opposite—the other race, knowing the dangers of research, were trying to keep Terra from becoming involved until Terra grew up. Handing the secrets of nuclear fission to a race not yet ready for it was one example, though a bad one, for it takes considerable technical excellence to handle it.

A simpler case is plain black gunpowder—sulfur, charcoal and potassium nitrate. Boys in chemistry class have lost their hands and their eyes because they played with that which they did not understand well enough. The nitration of glycerine is not too hard to perform, yet in the hands of an amateur it may take the house skyward before the project is finished.

For, strangely enough, the amateur at any science feels that he must make a large batch in order to do it at all. In electricity he wants excessive powers and lethal voltages to do that which a trained technician can accomplish with less deadly items.

However—was the motive avarice or altruism?

James Forrest Carroll studied them as they studied him.

CHAPTER V

Kingallis

Kingallis himself put an end to one of Carroll's worries. After several days of study, the alien doctor called him aside.

"Carroll, you know that you are helpless," he said. "We know that you are helpless. The point is just this: We can study your mind better if you are not worrying. Therefore I am going to put an end to one major worry of yours. Remember, always, we know that you are studying us!

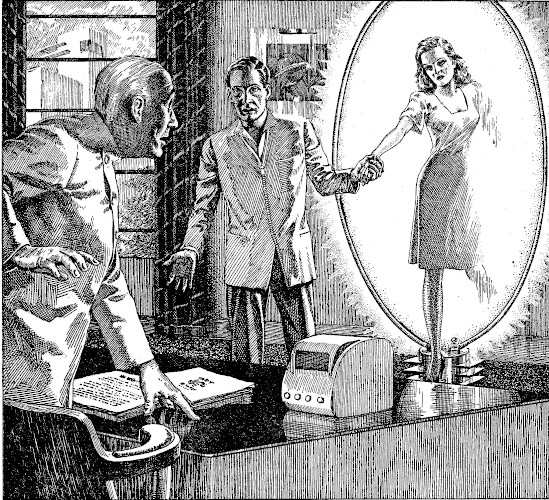

"We are using the forerunner of our mental control beam to study you, Carroll. You know that. The mental educator came first, the mental control without wearing electrodes came long afterwards."

"Understandable," nodded Carroll easily. "Men learned to communicate along a wire long before they used radio."

"The gadget we've been using is none other than a person-to-person telepathy aid. It was first developed as a means of placing men en rapport while studying a complex problem. Thus, for instance, a machinist can do a job for an electrical project while understanding perfectly just why this must or must not be done despite its mechanical desirability.

"It was but a step from that to its use in educating the youth of our race. A rather complex problem, Carroll, and one that cannot be appreciated until the whole problem is studied complete with both successes and failures.

"We taught then, Carroll, from a teacher-to-student plan. Later it was discovered how to record certain phases of lessons. The latter removes one main difficulty of the automatic educator."

"Mind telling me what?" asked Carroll, fencing for more information.

"Not at all. You see, the living hookup produces a double flow of information—which is what I meant to tell you. You are studying me as I am studying you—and, as in the case of an infant with erroneous information, you are placing errata in the teacher's mind."

"All children know—from their limited visible evidence—that the earth is flat. Only deep study proves otherwise. I can see where a continued youthful insistence upon a flat earth might cause a bit of mental collision in any teacher's mind." Carroll's voice was sharp.

"You have the point exactly," smiled Kingallis.

"Then tell me," Carroll said suddenly, "why I cannot find out why you are suppressing the information I want?"

"Because we are not studying that," smiled the alien doctor. "I surprise you? You expected me to wish my answer recalled? No, Carroll, I care not that you know some things about us."

Carroll shrugged. Kingallis was clever. Had Carroll known that worry hampered the study he would have felt relieved even though he tried to worry more. That would have been a minor defeat.

But the fact that Kingallis knew and cared not, removed all concern from Carroll's mind but one, and that one was how to hamper the research alone. It was not a satisfactory question as there was no satisfactory answer.

It was many hours later that both a possible answer and a complete impossibility of its use came to a sleepless man. Carroll arose from his bed and tried the door. It was open. Carroll's enforced residence was a large estate, a good many miles from town, in the center of a hilly country.

Carroll left his room and went down the hallway to the laboratory. He prayed that no one was following him with a mind-reading beam of some sort. He guessed that if these aliens could control an entire community with a mental beam, it would be no trouble to read his mind.

He found the cabinets that contained the records of knowledge used by the aliens. These were large reels of wire in metal magazines. On the face and back of each case was its title in the—to Carroll—completely unreadable alien characters.

That was a problem in itself. A lot of good it would do to acquire useless knowledge. Carroll wanted scientific facts or perhaps a recording of their plans. A complete course in alien geography, for instance, would be completely useless—the aliens seemed disinclined to take him from earth.

Yet Carroll had no way of knowing what these characters represented. A book might have given a clue—books often contain pictures. There was no telling on a reel of wire.

Carroll wondered whether the reels were stored in some sort of alphabetical order, in some numerical order or according to some semantic plan that gave the initial startings first and permitted the selector to progress. He knew, however, that if he were running such an expedition, he would not include Guffey's First Reader among the collection of texts. His chances of learning the rudiments of the alien tongue were remote.

In selecting a book one scans through the pages. In selecting a reel one must try it.

So, making a guess, James Forrest Carroll selected a container at random and, still amused at the guesswork quality, he carried it to the machine used by Kingallis to study his mind.

He flipped the switches as he had seen Kingallis do it. He inserted the reel magazine in the obvious slot and fiddled with some tiny toggles until the reel started to feed through the machine.

Then quickly, Carroll slipped the head electrodes on and reclined on the soft couch to let the flow of knowledge enter.

In complete oblivion as the machine ran, Carroll had no control over his actions. It ran on and on and the unreeling wire passed its knowledge into Carroll's brain. It concluded finally and Carroll sat up.

It was faintly light outside and by that faint light Carroll looked at his watch and was amazed to find that it was almost six o'clock in the morning. He quickly replaced the reel and turned to go back to his room.

"Pleased with yourself?" asked a quiet voice.

Carroll jumped a foot. Then in the dim light he saw the form of a woman, fully dressed, sitting in an easy chair not far from the door. To add to his complete surprise he hadn't known that women were with this outfit.

"Who are you?" he demanded.

"Plead, do not demand," she said. "For you have not the right to courtesy."

"Madam, I am a prisoner here. Courtesy per se has no meaning at all. I have as much right to prowl the place, picking up what I can, as you have to imprison me in the first place."

"A nice point of ethics and quite devoid of rational answer," smiled the woman. In the gaining light James Forrest Carroll saw that she was passably good looking though certainly no raving beauty. When she spoke, her white teeth gleamed in the dim light.

"However," she said, "I am Rhinegallis, King's sister." Then she laughed. "And that," she said, "is the only thing you learned this evening!"

"Oh, I'd not say that," said Carroll.

"Then tell me," she said amusedly, "how you justify yourself."

Carroll paused. Somehow it seemed normal to him that he should not care to appear weak or helpless in front of a woman, even an alien woman. Yet the truth of the matter was that Carroll was a complete captive and at the mercy of this bunch.

Whatever he did he did at their sufferance. There was little to be gained by quiet ridicule in explaining that he had taken a recording by sheer blind guesswork because there was no other way.

There was little to be gained but open ridicule to be forced to admit to this woman that he, James Forrest Carroll, reputed to be one of the Solar System's foremost physicists, was in a position seldom if ever occupied by any human being.

He knew and he knew that he knew, but he knew not what he knew!

He laughed helplessly. "Son lava tin quil norwham enectramic colvay si tin mer vo si—"

"Very lucid," she replied in English. "So in the course of the evening, James Forrest Carroll has a complete course in our science—in our language-pattern in our manner of thinking. And," she laughed merrily, "of none of which he has the slightest comprehension.

"That was a nice try, Carroll, but availing nothing. I'll tell you this, however—what you have learned this night is of no more use to you than a complete knowledge of archeology so far as an answer to your present problem goes.

"And for your trouble—it is a rather complimentary thing that you'd make such a try, and we'll all commend you—I'll be your guest for breakfast."

"Thank you," said Carroll cryptically. "I hope I'm amusing."

Rhinegallis stood up and faced Carroll. "You are quite a man," she said earnestly. "And though we must—use you—we still admire you."

"One might admire the tenacity and ability of a pet dog who is working its way through a maze toward a hunk of steak," he said quietly. "Yet one does not consider the dog our equal."

Rhinegallis shook her head. "Would it please you to know that you are a threat to us?"

"I've known that," he returned quickly. "And so is a dog a threat to man. Dogs can kill. They do not because they know that they are dependent for life upon becoming man's friend."

"And you?"

He smiled sourly. "Again the question of ethics," he said. "For no matter what I say you know that I shall do anything I find necessary to defeat you."

"We will never accept your word as bond," she told him. "Were it a simple matter of personal integrity and honor we could take it and be satisfied. But there is too much at stake. A man would be a complete fool to give his word and keep it when his future hangs in the balance."

"I'd not give it," he said simply. And then he turned to her with a cryptic smile. "So my future and the future of Sol are really at stake?"

"Yes," she replied.

"Then you are a threat."

Rhinegallis smiled at him. "Is one a threat that does not permit the child to play with fire?" she said coolly.

"May I point out that I am not a child," he said crossly.

"Ros nile ver tan si vol klys," she said in her own tongue. "And if you know what I said you'd know what you studied last night."

"When a child is deprived of matches, he is told why—in many cases he is shown mildly what happens. So go ahead, Rhinegallis, treat me as a child—and tell me, Rhinegallis, why I must not play with the Lawson Radiation."

"It is dangerous," she replied.

"In my lifetime," he said, "I have been responsible for the direction of many children. I have yet to turn away a curious—honestly curious—child. Mankind is always curious—providing we know why."

"It is dangerous," she repeated.

"Dangerous," he echoed. "Dangerous, Rhinegallis, to whom? You?"

"Mr. Carroll," she said quietly, "you think you have trapped me into an admission. You have not. Tell me, do you honestly think you can take the position of demanding an answer?"

"I think so."

"You cannot. You have not."

"No?" he said with a bitter laugh, "then if your race has no evil intent it could stop a lot of trouble, suspicion and labor by guiding us instead of blocking our efforts. Add to that your own refusal to tell me one thing that would frighten me away. I come up with a rather unhappy answer, Rhinegallis."

The girl turned away and left. Her offer to join him for breakfast was forgotten. Carroll watched her back as she went down the hallway and considered himself lucky. Even considering that their way of life was alien to Terran thinking, no advancing race could ever deny honest curiosity unless it had some ulterior motive. Ergo, they were suppressing the truth about the Lawson Radiation because they were afraid that Terra would find the answer!

From behind him he heard Kingallis chuckling.

"Val tas Winel yep frah?"

Carroll turned angrily. "Sell it to Tin Pan Alley," he snapped. "I've heard worse jangle songs!"

He stamped off angrily to his room.

CHAPTER VI

Proof

Once in his room, Carroll gave way to a period of complete slump, both mental and physical. He just sat there and felt—not thought about—the sheer impossibility of a single man successfully fighting an entire inimical culture.

The more he considered it the more he felt the futility of it all. The fact that he of all the teeming billions of Sol's heritage, was cognizant made it that more hopeless.

Then out of that last, single, hopeless fact James Forrest Carroll took a new hope.

For upon himself and himself alone rested the salvation of mankind! Regardless of what the world might think of him, regardless of life itself, he must carry on!

And when he returned to confront Doctor Pollard he must have visible proof!

The day dragged slowly. As usual, Kingallis did his studying, but found it hopeless because of Carroll's deep funk. Kingallis gave up and left Carroll, which was worse for Carroll because he had all those long hours in which to sit and stew.

Evening came, and with it came more hope.

Whatever it was that Carroll learned it was there and stuck tight. Whether valid or useless it was there. It seemed useful but he could not tell.

For instance there was a concept of a circlet of silvery wire. This was mounted on a small cylindrical slug of metal that enclosed a bimorph crystal. The picture concept showed contour surfaces of force or energy that grew progressively fainter as they retreated from the circlet of wire.

Not magnetism—for Carroll could see no energizing current. Not electrostatic field—for there could be no gradient. The word-concept for the thing was "Selvan thi tan vi son klys vornakal ingra rol vou."

Well—whenever Carroll knew words he would know what the circlet of wire did—and why.

But as he drew the diagram on a sheet of paper and labeled each part with a Terran symbol-system representing the alien sounds Carroll understood one other thing. No book is complete without an index!

Wire recordings of text books are impractical otherwise. An engineer seeking information on the winding, packing fraction of a certain type of wire would not care to wade through four hours of facts. Of course he should know it already, for the facts would be indelibly impressed upon his mind.

But there was the forgetting-factor that comes from disuse of any fact and doubtless this automatic means of education did not forever endow the owner with an eidetic memory of everything—never to be lost no matter how long the facts lie in disuse. But every text book has an index.

And so Carroll sought the laboratory again that night and selected another roll at random. He placed it in the machine and, as he started it, hurled a thought into the machine.

Not words, but mere concept—the abstract idea of listing hurled into the machine and the wire reel sang swiftly through the machine to slow down at a listing.

Useless, of course—there were things like, "Walklin—norva Kin. Fol sa ganna mel zin." Chapter and verse, probably. What Carroll sought was a dictionary.

He tried another reel and found it as mystifying. A third reel came upon a listing that seemed vaguely familiar. Along with the mere words, of course, there were mental pictures.

"Zale," he learned, was a measure of distance equivalent to seventeen thousand times ten to the eighth power times the wavelength of the spectroscopic line of evaalorg.

Carroll had hit upon a section of physical identities found in most physics texts.

He also learned a large number of physical identities of no consequence. The unit of gravity expressed in the alien terms meant nothing to a man used to dynes and poundals. There was too much left unsaid.

What the element evaalorg might be Carroll had no idea, although if he persisted he might hit upon a chemistry text—and it was safe to assume that the Periodic Chart of the atoms would be the same in any of the galaxy.

He smiled. It was like trying to calculate the true size of Noah's Ark by assuming the length of a cubit. When you have finished calculating you have a plus or minus thirty percent.

He was about to select another case when the door opened softly and Rhinegallis entered.

"Why do you try?" she asked. Her voice and her manner were as though she had not walked away from his question of almost eighteen hours ago.

"Why?" he repeated dully.

"Yes why? Why do you insist in the face of the impossible?"

"Because," he said, facing her deliberately, "when I admit defeat James Forrest Carroll dies!"

"You're not suicidal."

"Madness," he said, "is suicide of the mind!"

Rhinegallis nodded and then looked down. He went to her and lifted her face by placing a hand under her chin.

"Rhinegallis," he said softly, "place yourself in my position. You are a prisoner of a culture that is inimical to your own. You are kept alive as a museum piece, a sample of life that refuses to be swayed by your mind-directing machinery. Of all the people of your race, you are the only one that knows and believes.

"Death—or worse—awaits you and yours at the end of some unknown time. You are in the position of being the only one that can do anything at all. Tell me, Rhinegallis, would you sit quietly and accept it?"

"Since I would be unable to do anything alone," replied Rhinegallis, "I would accept fate."

"Then die!" snapped Carroll. "Do nothing? Try nothing? That is stagnation—and stagnation is death!"

"I think Kingallis knows that," said the alien girl with a flash of recognition.

"Oh," said Carroll, crestfallen. "Then Kingallis gives me some old outdated volumes of books to play with, as a willful child is directed to cut old rags instead of the lace curtains. Since I must play games, by all means give me games that will harm no one!

"Mumbletypeg labeled 'dangerous' and celluloid toys made up to resemble fierce knives on the theory that children prefer such toys of the block and rattle nature. Bottles full of colored sand with skull-and-crossbones on them and directions against certain mixtures.

"The amusement-park roller coaster that seems dangerous—in fact someone knows someone who knows of a bad accident on it—but is, in fact, less dangerous than a ride in an automobile through traffic."

Rhinegallis was silent.

"Then what am I to do?" he stormed. "I have no one here of my own kind. Not a single understanding soul to lean upon in a moment of stress. A man alone in an inimical environment—and I am expected to play your tricks for you!"

"You—"

"Am I expected to aid you?"

"No," she said honestly. "Yet in deference to your—"

"Deference!" he laughed scornfully. "Deference? No, Rhinegallis, not deference nor even respect. I am the experimental dog that must be pampered because my life and my mind and my body must be studied. Not deference, Rhinegallis, but the deadly fear of a spreading poison. Isolation."

"I am afraid that I should not have come," she said—but it was more a spoken thought than an attempt to convey anything.

"Then you tell Kingallis that no man will strive forever with no result. The donkey must once in a while get a taste of the carrot."

"What do you want?" she asked softly.

"And if I tell you will I get the truth—or just more runaround?" he asked.

"You are too suspicious," she said softly. "Deference you may not have, really. But you do have respect."

"What manner of respect can you possibly have for me?" he said with an open sneer.

"You are a strong man," replied Rhinegallis. "Your strength is sufficient to penetrate the mental beam. To defy King's attempts to study you, bar my tries at following your reason. Kingallis can point the remote hypnosis beam at me and from it can read my innermost thought.

"Against all resistance the hypnoscope is best—except against James Forrest Carroll. You, Carroll, resent this studying and prying. Know—and feel gratified—that as little as you have learned from my brother he knows less of you!"

"And after defying all to completion the defiance is obliterated," replied Carroll bitterly. "For me—oblivion. For mine—what?"

"It need not be—loneliness," she said in a soft voice.

"Joy in the shadow of the sword?" he said sourly. "Pleasures of the flesh with an alien race that would not even understand my passionate gesture?"

He laughed shortly and roughly.

"Affection is but a prelude to understanding between mates. Tell me," he said with extreme cynicism, "have you laid your egg this year?"

"You—no!" she said quickly. "I was but trying to ease your lot."

He dropped his cynicism instantly. Rhinegallis seemed honestly hurt at his calloused attitude.

"You cannot, Rhinegallis," he said softly. "I am no longer a youth, to whom personal passion and pleasure is the ultimate. I give you a demonstration of affection." He placed both hands upon her shoulders and squeezed gently. He leaned down and kissed her lightly "Not deep, but still a genuine gesture. Do you respond? No, you do not, for your race is utterly alien despite your appearance. Do you then expect me to continue, knowing that you do not even understand why I might derive sensual pleasure from such contact?"

"Even though we be alien," she said, "the fact that you do enjoy contact might give me—"

"Stop rationalizing," he said roughly.

"I'm not," she said. "There is a meeting of minds that far exceeds any crude mating of bodies."

"Then," he said with a queer crooked smile, "let's keep this on a mental basis, huh?"

Rhinegallis nodded quietly. She went to a side cupboard and took out a single reel of wire.

"Here is what you want," she told him. "Swiftly now, for Kingallis must never know."

"A nibble of the carrot," he observed.

"You want a whole meal?" she returned angrily. "Are you devoid of understanding?"

"I am permitted to play with innocuous trifles," he said. "When I discover their ineffectiveness I am invited to seduction. Failing that, I am offered some trifle of value. Tell me, Rhinegallis, how far will you go to lull my mind into inactivity?"

For answer, Rhinegallis turned and left him. Perhaps if Rhinegallis had been one of Sol's children she might have been crying or at least racked with the bitterness that comes of having an honest gesture scorned. Whatever her reaction Carroll shrugged as she left the room and he forgot her as he looked at the single recording.

"I hope," he said, "that this carrot is sweet...."

Carroll came out of the semi-coma produced by the machine with a premonition of danger—not danger to himself, but a vague unrest, as though someone near to him were being threatened. He was alone and he knew at once that Rhinegallis was the only one of the aliens who knew the truth of this night.

Had any of the others come, they would have seen at once that he was working on a volume of importance and would have stopped him. However, as the minutes passed, the feeling of worry ceased and Carroll felt relief.

He attributed the feeling to a situation known as "wandering concern" which is based upon insecurity. He had been in the mental coma for hours, during which time much might have happened. He had succeeded, with Rhine's aid, in delving into the truth about the alien culture.

This placed him in jeopardy for while they laughed behind his back for toying with the useless records, their derision would change to far deeper distrust and hate were he known to have outguessed them. There is nothing more dangerous than turning a man's bitter joke against him.

So for hours Carroll had been both helpless under the machine and also doing that which was forbidden. He was like the small boy who has been swimming and is not certain of his future until he meets his parents and discovers whether they know of his truancy.

Carroll replaced the record. There was no sense in permitting Rhinegallis to be trapped. Besides, this might go on for some time—and if he could he would fight this out to the very bitter end. Who knew what he might learn next.

This night's work had been language. Not that the volume taught him Alien. It was a volume for aliens, to teach them the Terran languages. But by reverse reasoning it also taught Carroll the alien tongue as well as a couple of good Terran tongues he did not know. He was—because he formerly possessed an excellent knowledge of American—now possessed of Russian, Chinese and Spanish, as well as the single alien tongue.

For the record dealt with concepts and then impressed the word-symbol of the idea in all tongues. And if Hombre means Man, conversely, Man means Hombre!

Best of all it was a specialized course that dealt with the kind of language scientists and engineers would use, though not exclusively so. Carroll felt cheered. Now he might mingle with them if he wanted to. Stealthily he left the laboratory to return to his room.

CHAPTER VII

Free-for-all

Carroll passed a partly opened door down the corridor, and as he passed, he heard Kingallis utter a single word of dislike at someone unknown. Though it was in the alien tongue Carroll's well-trained mind gave him the translation in terms of real meaning rather than the transliteration of the word in terms of his mother tongue, as is often the case with a language learned after the initial schooling as a child.

Carroll paused instantly, and as he did so, the door opened more, showing both Kingallis and his sister. Kingallis shook his head angrily.

"So you gave him the record," he said flatly.

Rhinegallis was silent. It was obvious to Carroll that there had been accusal and denial previously but that his instant recognition of the alien word had been perfect evidence. Carroll sailed in instantly.

"She's given me nothing," he said sharply. "I just happen to be curious."

Kingallis turned from his sister to face Carroll.

"That is a bald-faced lie," he said.

Carroll's reply was in the alien tongue, a rather harsh alien platitude pertaining to the fact that a guilty man always requires a sucker to account for his own mistakes, whereas an honest man can admit an error.

Kingallis sneered and his eyes became glittery-hard.

"She gave it to you," he said. "This I know." He pointed to the minute temple-electrode—flesh-colored—and the spider-web thin wire that ran to the flat bulge in his coat pocket.