TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE

Footnote anchors are denoted by [number], and the footnotes have been placed at the end of the book after the Index.

The 3-star inverted asterism symbol is denoted by ***.

The cover image was created by the transcriber, by adding the title and author to the original cover; it is hereby placed in the public domain.

Some minor changes to the text are noted at the end of the book.

The Recollections of a Spy

BY

MAJOR HENRI LE CARON

With Portraits and Facsimiles

“No citizen has a right to consider himself as belonging to himself; but all ought to regard themselves as belonging to the State, inasmuch as each is a part of the State; and care for the part naturally looks to care for the whole.”

—Aristotle.

LONDON

WILLIAM HEINEMANN

1892

[All rights reserved]

It has seemed good in the sight of many people that I should place on record, in some permanent and acceptable form, the story of my eventful life. And so I am about to write a book. The task is a daring one—perhaps the most daring of the many strange and unlooked-for incidents which have marked my career of adventure. I approach it with no light heart, but rather with a keen appreciation of all its difficulties.

To cater, and cater successfully, for the reading public of this fin de siècle period is an undertaking which fairly taxes all the powers of resource and experience of the most brilliant writers of our time. And I am in no sense a practised writer, much less a professional litterateur. I have spent my life working at too high a pressure, and in too excited an atmosphere, to allow of my qualifying in any way for the rôle of author.

Nor am I handicapped in this way alone. I am, unfortunately for my purpose, deprived of the[iv] most important of collaborators a writer ever called to his aid—the play of imagination. For me there is no such thing as romance to be indulged in here. The truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth is what I have set myself to tell regarding all those matters with which I shall deal. There are many things, of course, to which I may not refer; but with respect to those upon which I feel at liberty to touch, one unalterable characteristic will apply all through, and that will be the absolute truthfulness of the record.

This may seem strange language coming from one who, for over a quarter of a century, has played a double part, and who to-day is not one whit ashamed of any single act done in that capacity. Men’s lives, however, are not to be judged by the outward show and the visible suggestion, but rather by the inward sentiments and promptings which accept conscience at once as the inspirer of action and arbiter of fate. It is hard, I know, to expect people in this cold prosaic age of ours to fully understand how a man like myself should, of his own free will, have entered upon a life such as I have led, with such pureness of motive and absence of selfish instinct as to entitle me to-day[v] to claim acceptance at the bar of public opinion as an honest and a truthful man.

Yet such is my claim. When years ago, as these subsequent pages will show, I was first brought into contact with Fenian affairs, no fell purpose, no material consideration prompted me to work against the revolutionary plotters. A young man, proud of his native land and full of patriotic loyalty to its traditions, I had no desire, no intention to do aught but frustrate the schemes of my country’s foes. When, later on, I took my place in the ranks of England’s defenders, the same condition of mind prevailed, though the conditions of service varied.

And so the situation has remained all through. Forced by a variety of circumstances to play a part I never sought, but to which, for conscientious motives, I not unwillingly adapted myself, I can admit no shame and plead no regret. By my action lives have been saved, communities have been benefited, and right and justice allowed to triumph, to the confusion of law-breakers and would-be murderers. And in this recollection I have my consolation and my reward. Little else indeed is left me in the shape of either the one or the other. There is a popular fiction, I know,[vi] which associates with my work fabulous payments and frequent rewards. Would that it had been so. Then would the play of memory be all the sweeter for me. But, alas! the facts were all the other way. As I will show later, in the Secret Service of England there is ever present danger, and constantly recurring difficulty, but of recompense, a particularly scant supply.

| PORTRAITS. | ||

| Major Henri Le Caron | Frontispiece | |

| Alexander Sullivan | To face p. | 62 |

| Patrick Egan | ” | 160 |

| “Number One”—P. J. Tynan | ” | 168 |

| Charles Stewart Parnell | ” | 178 |

| FACSIMILES. | ||

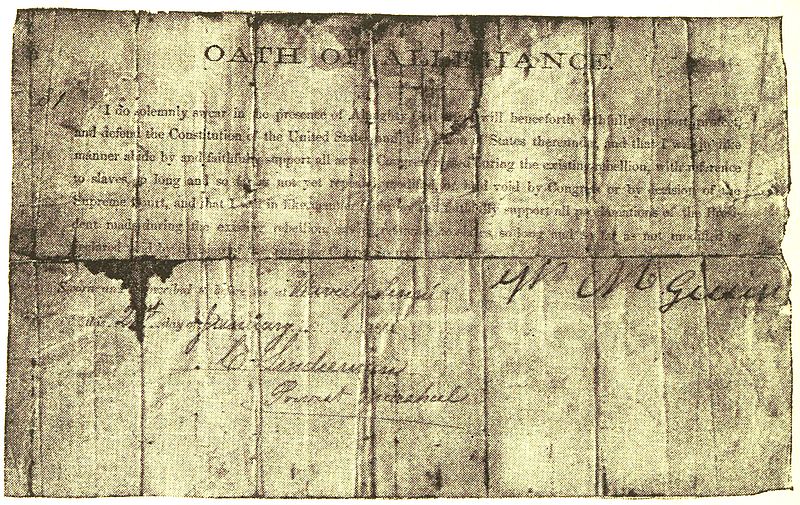

| The Oath of Allegiance | 16 | |

| A Fenian Twenty-dollar Bond | 27 | |

| My Commission as Major in the Army of the Irish Republic | 54 | |

| Patrick Egan’s Letter of Introduction | 234 | |

| Alexander Sullivan’s Cheque for Thirty Thousand Dollars | 264 | |

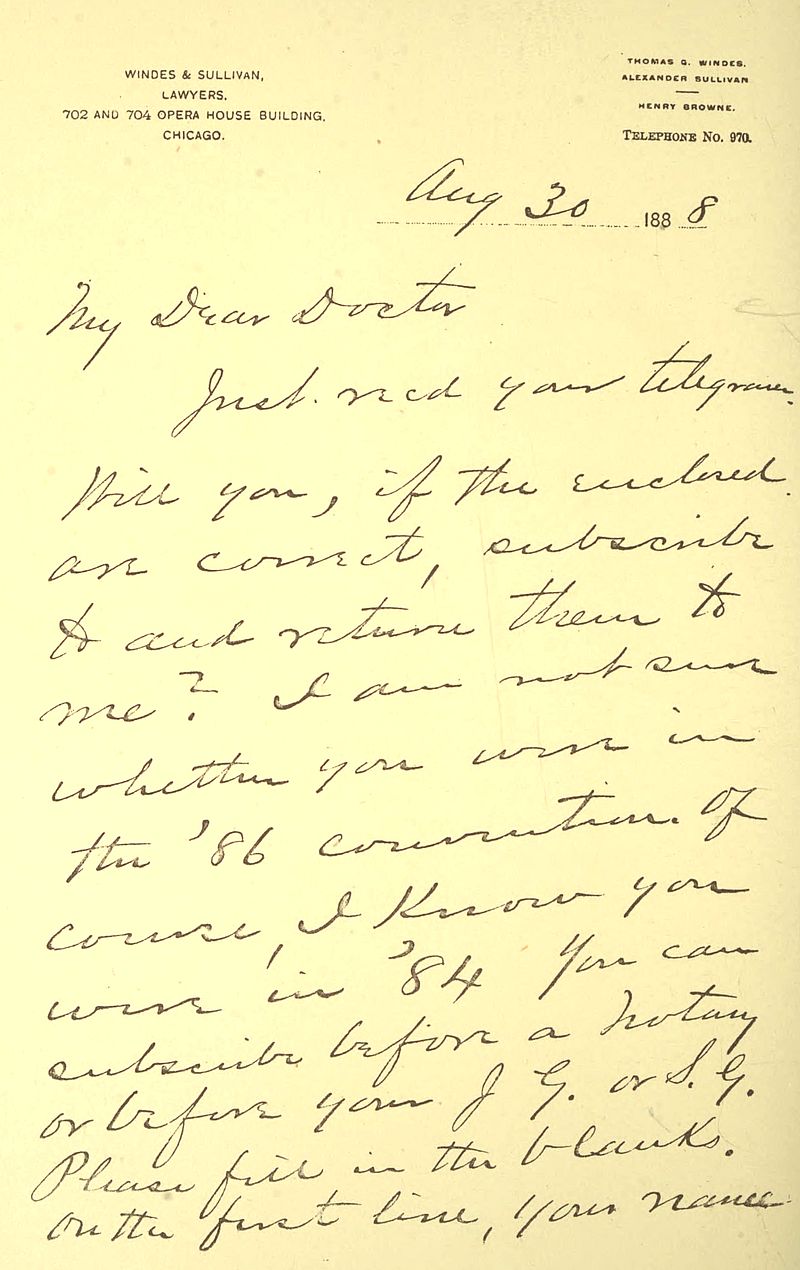

| Alexander Sullivan’s Letter | Appendix III. | |

Of my early youth little that is very interesting or exciting can be told. A faded entry in the aged records of the ancient borough of Colchester evidences the fact that a certain Thomas Beach, to wit myself, came into this world some fifty and one years ago, on the 26th day of September 1841. My parents were English, as the American would phrase it, “from far away back,” my grandfather tracing his lineage through many generations in the county of Berkshire. The second son of a family of thirteen, I fear I proved a sore trial to a careful father and affectionate mother, by my erratic methods and the varied outbursts of my wild exuberant nature. My earliest recollection is of the teetotal principle on which we were all brought up, and the absence of strong drink from all our household feasts. The point is a trivial one, but not unworthy of note, as it supplies the key to some of my successes in later life, in keeping clear of danger[2] through intoxication, when almost all of those with whom I dealt were victims to it. When others lost their heads, and their caution as well, I was enabled, through my distaste for drink, to benefit in every way.

Living in a military town as I did, and coming into daily contact with all the pomp and circumstance of soldiering, it was but natural that the glory of the redcoat life should affect me, and that, like so many other foolish boys, I should feel drawn to the ranks. Of course I wanted to enlist, and what wonder that for me life held no nobler ambition and success, no grander figure than that clothed with the uniform of the bold drummer-boy. All my efforts, however, were naturally of no avail, and I found the path to glory blocked at every point. The fever, nevertheless, was upon me, and my want of success only made me the more determined to achieve my object in the long run. Home held no promise of success, and at home I decided I would no longer remain. So it came about that one fine morning, when little more than twelve years of age, I packed my marbles, toys, and trophies, and in the early light slipped quietly out on to the high-road en route for that Mecca of all country boys—the great glorious city of London!

I had run away from home in grim earnest.[3] Not for very long, however. Fortunately for me—unfortunately as I thought in those young days—I committed a grave blunder in tactics. Meeting one of my school-fellows on the journey, I was foolish enough to inform him of my proceeding and intention, and in this way my anxious parents were soon put upon my track, and my interesting and exciting escapade was brought to an ignominious conclusion. I had, however, tasted of the sweets of adventure, and it was not very long before I made another attempt to rid myself of the trammels of home life. Here again I was fated to meet with defeat, but not before I had made a distinct advance upon my first effort, for two weeks were allowed to elapse before I was discovered on this occasion. The natural consequences attended these attempts of mine, and soon I was written down as the black sheep of the family, from whom no permanent good could ever be expected.

The idea of keeping me longer at school was quite given up, and in order the better to tie me down, I was apprenticed for a period of seven years to Mr. Thomas Knight, a Quaker, and well-known draper in my native town. The arrangement suited me not at all. Nothing could be more uncongenial than a life worked out in the solemn atmosphere of a staid and strict Quaker’s home,[4] where the efforts to curb my impulsive nature resulted in increasing bitterness of spirit on my part every day. In eleven months it was conceded on both sides that the continuation of the arrangement was distinctly undesirable, and so I was free once more. A short residence with my parents followed; but the old promptings to wander afar were too strong for me, and once more, for the third and last time, I broke away, and reached London at last, in the month of May 1857.

Through the kindness of relatives, employment was secured for me in a leading business house; but my stay there was of short duration. With my usual facility for doing everything wrong at this period of my existence, I happened to accidentally set fire to the premises, and was politely told that after this my services could not be properly appreciated. I was not long out of employment, and strangely enough, through the agency of one of the gentlemen whose house had suffered through my carelessness, I was later on enabled to obtain a much better situation than I had held in their house.

From London I subsequently made my way to Bath, and from Bath to Bristol, always in search of change, though everywhere doing well. When in Bristol, however, I was struck down with fever, and reduced to a penniless condition.[5] Then came the idea of returning to London, which I duly carried out, walking all the way. My foolhardiness proved almost fatal, for ere I got to the metropolis, my illness came back upon me, and I was scarce able to crawl to St. Bartholomew’s Hospital in search of relief.

My stay at St. Bartholomew’s was not a very long one. Horrified at the terrible death of a patient lying next to me, and fearful that, if I remained, something equally horrible might be my fate, I managed to obtain possession of my clothes and to leave the institution. Thoughts of home and mother decided my return to Colchester, and thither I immediately proceeded to make my way on foot. Again the fever attacked me, and once more I had to seek the friendly shelter of an hospital, this time taking refuge in the Colchester and East Essex Institution. Here I remained till I was permanently recovered, after which I entered the service of Mr. William Baber of the town. However, my efforts to lead a sober conventional life were all in vain. The wild longing for change came back in renewed strength, and in a little while I had left London altogether behind and journeyed to Paris viâ Havre.

I am amused as I look back now upon the utter recklessness and daring of this proceeding of mine. I knew not a soul in France; of the language, not a word was familiar; and yet somehow the longing to get away from England and to try my luck on a new soil was irresistible. One place was as good as another to me, and Paris seemed rather more familiar than the other few centres of activity with the names of which I was then acquainted. And so to Paris I went. It was my good fortune to hit upon an hotel kept by an Englishwoman in the Faubourg St. Honoré, and here I tarried for a time while my little stock of money lasted. This was not by any means a long period, and soon I found myself reduced once more to a condition of penury, having in the interval gained little but an acquaintance with the principal thoroughfares and their shops, and a slight knowledge of the language, to which latter I was helped in no inconsiderable degree by a wonderfully retentive memory.

Things were at a very low ebb for me indeed, when help came from an entirely unexpected quarter. Happening one Sunday to pass by the[7] English Church in the Rue d’Aguesseau, of which, by the way, the Rev. Dr. Forbes was at that time chaplain, I was attracted by the music of the service then proceeding, and entered the little unpretentious place of worship. Here I joined heartily in the service, with the order and details of which I was perfectly familiar, having already sung in the choir of my native town. My singing and generally strange appearance attracted the attention of a member of the church, with whom I formed an acquaintance. We left the church together—not however before I had promised my assistance in the choir—and at his request I breakfasted with my English friend at one of the crêmeries in the Faubourg. Now, as then, a respected citizen of Paris, I am happy to number this countryman among the truest and most steadfast of my friends.

We passed the day together, attending the remaining two services at the church, and in the hours we spent in each other’s company I told him my history and my needs. Warm-hearted and impulsive, he immediately suggested that I should vacate my room and share his lodging, even going the length of advancing me money to enable me to do so. Before a week had passed, he had capped his goodness by securing a situation for me; and I found myself at length comfortably[8] installed in the house of Withers, à la Suissesse, 52 Faubourg St. Honoré. Through his influence also I became a paid member of the church choir, and in a very short time I was the recipient of the friendship and confidence of Dr. Forbes and his wife, from both of whom I received very many kindnesses. Thanks to them, I was very soon enabled to better my position, and to change to the house of Arthur & Co., where matters improved for me in every way. There then succeeded some of the happiest days of my life. Freed from care and anxiety, with all the necessaries of life at my control, and a fund of boyish spirits and perfect health, I was without a trouble or a dark hour, happy and contented in my daily task.

So the weeks and months came and went without discovering any change in my position, till an unlooked-for incident once more brought the wild mad thirst for change and excitement back to me, and sounded the death-knell of my quiet life. On the 9th April 1861, the shot was fired at Fort Sumpter which inaugurated the war of the Rebellion of the United States. That shot echoed all over the world, but in no place was the effect more keenly marked than in the American colony in Paris, which even in these early days was a very numerous one.

Arthur’s, the place of business of which I speak, was one of the most favoured of the American resorts, and here the excitement raged at fever heat, as little by little the news came over the sea. Those were not the days of the cable, flashing the news of success or defeat simultaneously with its occurrence, and picturing in vivid phrase and description every incident and climax of warfare, till almost the figures move before us, and our eyes and ears are deadened by the smoke and sound of shot. The tidings came in snatches, and the absence of completeness and detail only served to give the greater impetus to discussion and imagination.

There was no more excited student of the situation than myself; and very soon, of course, I was fired with the idea of playing a part in the scenes which I was following with such enthusiasm and zest. Friends and associates, many of them American, were leaving on every hand for the seat of war; and at last, throwing care and discretion to the winds, I took the plunge and embarked on the Great Eastern on her first voyage to New York.

I reached that city in good time, and without delay enlisted in the Northern Army, in company with several of my American associates from Paris. In connection with my enlistment[10] there occurred a circumstance, trivial in itself at the moment, yet fraught with the most important consequences in regard to my after-life. This was the taking to myself of a new name and a new nationality. I had no thought of remaining in America for any length of time—at the outset, indeed, I only enlisted for three months, the period for which recruits were sought—and, regarding the whole proceeding more in the light of a good joke than anything else, I came to the conclusion that I should not cause anxiety to my parents by disclosing my position, and decided to sustain the joke by playing the part of a Frenchman and calling myself Henri le Caron. So came into existence that name and character which, in after years, proved to be such a marvellous source of protection and success to me personally, and of such continued service to my native country, whose citizenship I had, by my proceeding, to resign.

As subsequent events proved, however, I was not to carry out my original idea of returning. The three months came and went, and many more followed in their wake, till five years had passed and left me still in the United States’ service. The life suited me. I made many friends; soldiering was a pleasant experience; and I was particularly fortunate in escaping[11] its many mishaps. I had no care for the morrow, and, happily for me, I found my morrows to bring little if any care to me. Only on one occasion was I seriously wounded. This was when, during an engagement near Woodbury, Tennessee, I had my horse killed under me by a shell, my companion killed at my side, and myself wounded by a splinter from the explosive, which laid me up for about a month.

Interesting and animated as was my career as a soldier, I must not delay to deal with it too fully in detail, but must hurry on to that subsequent life of mine in America, which possesses the greatest interest for the public at large. I shall, however, before leaving it, run over very shortly the different stages of my soldiering experience. The facts may be interesting to the many people in this country and America who are familiar with the history of the American war of the Rebellion. I enlisted as a private soldier on August 7, 1861, in the 8th Pennsylvanian Reserves, changing therefrom to the Anderson Cavalry, commanded by Colonel William J. Palmer. Here I remained for a year and ten months, serving through the Peninsula campaign of the army of the Potomac, including the battles of Four Oaks, South Mountain, Antietam, and Williamsport, all of which were[12] fought under the command of General George B. MacClellan.

In October 1862, I joined, with my regiment, the Western Army, under General William S. Rosencranz, and participated in the advance from Louisville, Nashville, and Murfreesboro’, including the engagements at Tullahoma and Winchester, and ending with the capture of Chattanooga and Chicamanga in September of the same year. The failure of Rosencranz at Chicamanga closed his career. He was succeeded by General George H. Thomas, who remained in command up to the end of my service in the army. By this time I had obtained a warrant as a noncommissioned officer, and was principally engaged in scouting duty. On the command in which I served being ordered to the relief of General Burnside at Knoxville, I left Chattanooga, then in a state of siege and semi-famine, and reaching Knoxville, I took part during the whole of the winter of 1863 in the East Tennessee campaign against the rebel General Longstreet, my engagements including Strawberry Plain, Mossy Creek, and Dandridge. I was fortunate enough to be recommended for a commission in 1864, and, after my examination before a military board, was gazetted Second Lieutenant in the United States Army in the month of July of[13] that year. For the next twelve months I was exclusively employed in scouting duty, in charge of a mounted company, serving in this capacity under General Lovel L. Rousseau in West Tennessee. In December 1864, being attached to General Stedman’s division of the Army of the Cumberland, I was present at the battle of Nashville, and took part in all the engagements through Tennessee and Alabama, being promoted in the course of them to the rank of First Lieutenant.

During 1865 I was appointed upon detached service of various descriptions, filling amongst other positions those of Acting Assistant-Adjutant-General and Regimental Adjutant. At the close of the war I joined the veteran organisations of the Army of the Cumberland, and the Grand Army of the Republic, and held the appointment therein of Vice-Commander and Post-Surgeon, ranking as Major.

Long ere this I had, of course, given up all idea of returning to France, and had communicated my whereabouts and position to my parents, much to their anxiety and dismay.

Tragedy and comedy blended together in strange fellowship in our experiences of those days; and, as I write, a couple of amusing examples of this occur to me. It was in 1865, when engaged on scouting duty in connection with the[14] guerilla warfare carried on by irregular bands of Southerners, that I received the following order:—

“Head-Quarters, Third Sub-District, Middle Tennessee,

“Acting Assistant-Adjutant-General’s Office,

“Kingston Springs, Tenn., May 17, 1865.

“Sir,—The following despatch has been received:—

“Nashville, May 16, 1865.

“Brig.-Gen. Thompson.

“In accordance with orders heretofore published of the Major-Gen. Commanding Dept. of Cumberland, Champ Fergusson and his gang of cut-throats having refused to surrender, are denounced as outlaws, and the military forces of this district will deal with and treat him accordingly.

“By Command of Major-Gen. Rousseau,

“(Signed) H. C. Whitlemore,

“Capt. and A.A.A.G.”

This, of course, meant sudden death to any of the band who might come within range of our rifles. The men, indeed, were nothing less than murderers and robbers, carrying on their devilish work under the plea of fighting for Southern independence. It was not long before an opportunity was afforded me of coming in contact with a specimen of the class, and it is on this meeting that one of my anecdotes will turn.

A few days after, when riding ahead of my troop, in company with a couple of my men, in order to “prospect” the country, with a view to finding suitable accommodation for our wants, I came to a well-built farmhouse a few miles from[15] the Duck River. As we approached the front, my attention was attracted by an armed man, in the well-known butter-nut grey uniform of the enemy, escaping from the back in a very hasty and suspicious manner. Reading his true character in a moment, I shouted to him to halt, at the same time directing my troopers to “head him off” right and left. Disregarding our cries, he started off in hot haste, while we pursued him in equally hurried fashion. The chase was a hard and a stern one, his flight being only broken for a moment to allow of his discharging his carbine at me. Not desiring to kill him, I saved my powder, and in the end ran him to earth, and stunned him with a blow from the butt-end of my revolver.

When my companions arrived, we proceeded to examine our prisoner, and found, on stripping him of his grey covering, that underneath he wore the unmistakable blue coat of our own regiment, with the plain indication of a corporal’s stripes having been torn therefrom. As we had a few days previously discovered the stripped, bullet-riddled body of a brave corporal of ours, who had been murdered by some of these scoundrels, we at once concluded that this was one of his assassins, and my troop, coming up at this point, dealt him scant mercy, and filled his body with[16] their bullets ere consciousness returned. A search of his pockets revealed his identity, his pocket-book containing some two hundred dollars in bills, and an oath of allegiance to the U.S. Government, which he had doubtless used many times to save his wretched life. The following is a facsimile of the original document, which I have kept through all these years—the stains being those of the man’s blood:—

Making our way back to the house, we discovered two weeping women, and half-a-dozen small children. A single question elicited the fact that the elder of the two was the mother, while subsequent inquiries proved that the dead man was the notorious William M. Guin, a nephew of ex-U.S. Senator Guin, of California, and one[17] of the leaders of as notorious a gang of cut-throats as ever operated in the South-West. Our custom was to burn the houses of any persons found harbouring these guerillas, but the heartrending entreaties of the wretched women and children caused me to leave them unmolested. Some time afterwards, when peace was finally declared, I was quartered at Waverley, in the same vicinity, and often met the unfortunate mother, who knew me as “the man who killed her boy,” though, as she told me, she never blamed me, having often warned her son that he would come to a bad end.

And now for the other side of the picture. During these operations, my men were principally mounted on horses captured from the citizens, who were invariably rebels; and as our habit was to take every available animal when found, the methods adopted to hide them in caves, ravines, and swamps were sometimes very remarkable. Upon one of my expeditions at the time, in the direction of Vernon, on the Duck River, I came across a fine black horse, which I speedily confiscated to the use of “Uncle Sam.” My prize, however, did not long remain in my possession, for in a few days my quarters were invaded by a deputation of the fair sex, who presented me with the following amusing appeal:—

“Mary Barr.

“Cynthia Barr.

“Polly Hassell.

“Mary L. G., a sympathiser.

“Vernon, Tennessee,

“July 1865.

“To Captain Le Caron.”

I naturally pursued the only course which a soldier could, and surrendered the horse. Strange to say, one of my lieutenants afterwards surrendered his affections and future happiness to one of these fair damsels, and still lives with her as his wife, surrounded by a charming family, away out in central Kansas.

In the midst of all my soldiering, I wooed and won my wife. She is the principal legacy left me of those old campaigning days of mine, as[20] bonny a wife and as sympathetic and valuable a helpmate as ever husband was blessed with in this world. Many years have gone by since we first met away in Tennessee, where she, a bright-eyed daring horsewoman, and I, a happy-go-lucky cavalry officer, scampered the plains together in pleasant company. Little thought either of us then what the future years held in store. Yet when these years came, and with them the anxious moments, the uncertain intervals, and the perilous hours, none was more brave, more sympathetic than she. Carrying the secret of my life close locked up in that courageous heart of hers, helping me when need be, silent when nought could be done, she proved as faithful an ally and as perfect a foil as ever man placed like me could have been given by Heaven. A look, a gasp, a frightened movement, an uncertain turn might have betrayed me, and all would have been lost; a jealous action, a curious impulse, and she might have wrecked my life; a letter misplaced, a drawer left open, a communication miscarried, and my end was certain. But those things were not to be. Brave, affectionate, and fearless, frequently beseeching me to end this terrible career in which each moment of the coming hours was charged with danger if not death, she tended her family lovingly, and faced the world with a countenance[21] which gave no sign, but a caution which never slumbered.

I had not to wait for these later years, however, to prove her readiness and resource. These had been shown me long ere marriage was dreamt of by either of us, and when, in one of the most exciting episodes of my military career, she gave me my freedom and my life. For our wooing was not without its romance. Our first meeting was quite a casual one. An officer in charge of a party of thirty, engaged in scouting duty, I stopped my little troop one night, in the winter of 1862, at a house some fifteen miles from Nashville, Tennessee, in order to rest our horses and prepare our supper. We selected the house, and stopped there without any prearrangement. This, however, was in no way extraordinary. It was quite the common practice to stop en route and buy hospitality from the residents. The house was the property of my wife’s uncle, and here she lived. While our supper was being prepared, we chatted agreeably together, and the time swept pleasantly along, We were in fancied security, and gave no thought to immediate danger. In a moment, however, all was confusion. The house was suddenly surrounded by a band of irregular troops, calling themselves Confederates, but in reality nothing more or less than marauders,[22] and soon the fortunes of war were turned against us.

Half my little command, fortunately, escaped, owing to their being with the horses at the time of the enemy’s approach, and so enabled to take to flight. The other half, however, with myself, were not so fortunate. We were in the house, surprised, and immediately taken prisoners. A large log smoke-house was improvised for a prison, and in this my comrades and myself were placed, tortured with indignation and hunger, as the riotous sounds which followed proclaimed to us that our captors were partaking of the supper which had been originally intended for ourselves. Our position altogether was anything but a happy one. Death was very near. Irregular troops like those with whom we had to deal seldom gave quarter. If we escaped immediate death, it would be only to be brought within the Southern line to be condemned to a living death in prison.

We sat and pondered; and as the probabilities of the future loomed heavily and darkly before us, the sounds of revelry in the adjoining house gradually died away. Our captors, filled with the good things provided for us, gradually dropped to sleep, and soon nothing was heard but the measured movement and breathing of the guard stationed at our door. In a little time, however,[23] there was perfect silence, and our watchful ears detected the absence of our sentry’s person. Curious but silent we anxiously waited, and soon heard the withdrawal of the bolt by some unknown hand. Opening the door, we found the pathway clear. My brave Tennessee girl, finding the gang of irregulars all steeped in heavy slumber, had decoyed our guard away on pretence of his obtaining supper, and returning, had unbolted our prison-house, prepared to face the consequences when the sleeping ruffians awoke. Through her action our safety was assured, and after walking fifteen miles, we reached camp in the morning to join our comrades, who had given us up for lost.

This happened on Christmas Eve 1862; and it was not until April 1864—sixteen months afterwards—that I again met the girl who had done so much for me, and who was subsequently to become my wife.

The house in which these exciting events had taken place had meantime been totally destroyed by the ravages of war, and she was now living with her aunt in Nashville itself. I was stationed in camp, there awaiting my examination before a board of officers for further promotion, and here occurred the most eventful engagement in which I ever took part, where, conquering yet conquered, I ignored all the articles of war and subscribed[24] to those of marriage, entering into a treaty of peace freighted with the happiest of results.

The war was now over and done, a thing of the past. I was situated in Nashville with my wife and family, and with my savings, happy in the enjoyment of the moment, and the pleasant reminiscences of the past. Henri le Caron, the agent of the British Government in the camps of American Fenianism, did not exist, and I had not the shadow of a conception as to what the future held in store for me. The future indeed troubled me not one whit. Looking back, as I do now, upon all that has happened since then, I am filled with astonishment as great and sincere as that which affected the world when I first told my story in its disjointed way before the Special Commission. It may be that I am somewhat of a fatalist—I know not what I may be called—but my ideas, strengthened by the experience of my life, are very clear on one point. We may be free agents to a certain extent; but, nevertheless, for some wise purpose matters are arranged for us. We are impelled by some unknown force to carry out, not of our own volition or possible design, the work of this life, indicated by a combination of circumstances, to which unconsciously we adapt ourselves. In such a[25] manner did I become connected with Fenianism and the Irish Party in America. For I never sought Fenianism; Fenianism rather came to me.

I use the phrase Fenianism as one that is familiar, and requires no explanation from me. All the world must surely know by this that almost from time out of mind there has existed in America a body of discontented and rebellious Irish known as Fenians, who, working in harmony with so-called Nationalists in this country, seek the repeal of the Union between Great Britain and Ireland. It will, however, be necessary for me to say something about the position of Fenianism at this time—I speak, of course, of the year 1865—in order that what follows may be quite clearly understood.

Fenianism at this period was in a rather bad way. Its adherents in America and Ireland were divided into two hostile camps, and its most recent effort had been of a very poor and depressing character. In fact, the division of forces had been brought about by the failure of this selfsame effort, an attempt at the emancipation of Ireland, which is known as “the ’65 movement.” It was organised by the Fenians in Ireland and America, under the direction of James Stephens; and for the purpose of its development very many officers and men crossed to Ireland from American[26] soil. The attempted rising, however, proved, like almost all Fenian efforts, a fiasco. It was found that Stephens had wofully misrepresented the state of affairs at home, both as regards preparation and enthusiasm; and those who had come from America returned to their homes, disgusted and indignant at the way in which they had been sold.

In the result disaffection quickly spread, and the organisation in America broke up into hostile camps, the majority, under the leadership of Colonel W. R. Roberts, revolting from the leadership of Stephens and Mahoney, and declaring their belief that “no direct invasion or armed insurrection in Ireland would ever be successful in establishing an Irish Republic upon Irish soil, and setting her once more in her proper place as a nation amongst the nations of the earth.” Not content, however, with the situation, the seceders met in convention in September 1865 in Cincinnati, and formed themselves into what was known for the next eventful five years of its existence as the Senate Wing of the Fenian Brotherhood. They scoffed at the idea of invading Ireland successfully, but by no means advocated a policy of inaction. They simply sought to change the base of operations. “The invasion of Canada” became their cry; and with this as their programme[27] they succeeded in gaining the allegiance of some thousands of the disaffected Irish, whose support was attracted by the familiar device of a de facto civil and military Irish Government upon paper, framed upon the model of the United States. A good deal of money was subscribed, and with funds so obtained ammunition was purchased and shipped along the Canadian border.

The methods of obtaining money were many and varied, but none was more successful than the issue of Fenian bonds. The following is a reproduction of a twenty-dollar bond in my possession. These bonds were given in exchange for ready money to the many simple souls who believed in the possibility of an Irish republic, and who were quite ready to part with their[28] little all, in the belief that later on, when their country was “a nation once again,” they would be repaid with interest. Very many of the persons displaying this credulity were Irish girls in service in the States, and thus came into vogue the sneering reference to the agitation being financed by the servant-girls of New York.

A curious feature of the intended invasion was the publicity given to the design, and, more remarkable still, the action, or rather want of action, of the United States Government in regard to it. This latter, indeed, was the subject of very angry comment at the time on the part of Englishmen resident in the States. It certainly seemed strange, and passing all comprehension, that the United States Government, although in full possession of the facts, and quite peaceful in its relations with England, could have permitted the organisation of a raid upon a portion of English possessions without movement or demur on their part of any kind whatever. Yet such is the deplorable fact. From the commencement of the preparations till five days after the Fenians had crossed at Black Rock, the government of President Andrew Johnson did nothing whatever to prevent this band of marauders from carrying out their much-talked-of invasion.

Let it not be thought that I exaggerate or draw[29] on my imagination. I do not. If evidence in support of my statement be needed, it is to be found in the speeches made from public platforms, in open meetings, fully reported throughout the country at the time.

It was during this period that I was brought into close acquaintance with Fenianism and its workings. Strangely enough, it was my army associations which formed the medium. Through an old companion-in-arms, the man O’Neill mentioned above, by whose side I had served and fought, I learnt, at first casually, and in broken conversation, what was transpiring in the circles of the conspiracy. Indignant as I was at learning what was being done against the interest of my native country, I knew not how to circumvent the operations of the conspirators, and did nothing publicly in the matter. Without my own knowledge, however, I was to become one of the instruments for upsetting all these schemes. Writing as I regularly did to my father, I mentioned simply by way of startling news the facts I learned from O’Neill. My letters, written in the careless spirit of a wanderer’s notes, were destined to become political despatches of an important character. Without reference to me, my father made immediate and effective use of them. Startled and dismayed at the tidings I conveyed, he, true[30] Briton that he was, could not keep the information to himself, but handed over my letters immediately to John Gurdon Rebow, the sitting member for Colchester.

Mr. Rebow, fully concurring with my father as to the importance of my news, proposed that he should, without delay, communicate with the Government of the day, to which my father agreed. In this way my first connection with the Government was brought about. So keenly alive to the position of affairs did the Home Secretary show himself, that he, as I learnt subsequently, in the most earnest way requested my father to correspond with me on the subject, and to arrange for my transmitting through him to the Government every detail with which I could become acquainted. This I did, and continued so doing until the raid into Canada had been attempted, and attended with failure.

Before proceeding further, I had perhaps better give some idea of what the raid was like. The details should prove of interest, if for no other purpose than that of contrast with those of the second attempted invasion, of which I shall have to speak more fully later on. This, which was the first invasion of Canada by the Fenian organisation,[31] took place upon the morning of the 1st of June 1866. As I have already stated, the design had been flourished in the face of government and people for six months previously. All this time active preparations were proceeding, and thousands of stands of arms, together with millions of rounds of ammunition, had been purchased from the United States Government and located at different points along the Canadian border; while during the spring of the year, military companies, armed and uniformed as Irish Fenian soldiers, were drilled week by week in many of the large cities of the United States.

No opposition was offered to the proceedings; indeed, John F. Finerty, the editor of the Chicago Citizen, in a public speech made by him at Chicago so late as February 5, 1886, declared with great glee that Andrew Johnson, the then President of the United States, openly encouraged the movement for the purpose of turning it to political account in the settlement of the Alabama claims. Be the blame whose it may, however, the result was not unsatisfactory. The attempt proved a complete failure. The Fenians were driven out of Canada, sixty of them killed and two hundred taken prisoners, with the loss of but six lives in the Canadian ranks. All the same, however, the unsatisfactory condition[32] of things I speak of existed, while, to make matters worse, not a single one of the defeated invaders was called to account by the United States for the violation of the Neutrality Laws.

The whole affair, viewed from any but an imaginative Fenian standpoint, was of a ludicrous character. The time for the operation was chosen by the Fenian Secretary for War, General T. W. Sweeny, then commanding the 16th United States Infantry stationed at Nashville, Tennessee. A particular route had been selected, but when the amount of funds came to be questioned, the original idea of carrying the men by steamer to Goodrich, Canada, had to be abandoned for the less romantic but more economical process of crossing the Niagara River in flat boats with a steam tug called into requisition. Under the command of General John O’Neill, and a number of other gentlemen of high-sounding ranks, and distinctly Irish patronymics, the raid actually came off on the morning of the 1st of June, when about 3 A.M. some 600 or 800 Irish patriots, full of whisky and thirsting for glory, were quietly towed across the Niagara River to a point on the Canadian side called Waterloo!

At 4 A.M. the Irish flag was planted on British soil by Colonel Owen Starr, commanding the contingent from Kentucky, one of the first to[33] land. Unfortunately no Canadian troops were in the vicinity, and O’Neill’s command, which had by the next day decreased to some 500, marched upon and captured Fort Erie, containing a small detachment of the Welland battery. Matters, however, were not long allowed to go in favour of the invaders. In a very little time the 22nd Battalion of Volunteers of Toronto—a splendid band of citizen-soldiers—appeared upon the scene, and at Ridgeway, a few miles inland, there occurred a fair stand-up fight, in which the Fenians in the end got the worst of the day’s work. Ridgeway has frequently since been claimed by the Fenian orators as a glorious victory, but without justification. It is true that at first, flushed with their almost bloodless victory at Fort Erie, the Fenians advanced fiercely upon their opponents, and for the moment repulsed them; but in the end the Canadians triumphed, and succeeded in putting the invaders to flight, driving them back to Fort Erie a frenzied, ungovernable mob, only too thankful to be taken as prisoners by the United States war steamer Michigan, and protected from total annihilation at the hands of the, by this time, thoroughly aroused and wrathful Canadian citizens.

The following extracts from the official report made by General O’Neill to Colonel William R.[34] Roberts, President of the Fenian Brotherhood, though very highly coloured, admits the defeat:—

“Here truth compels me to make an admission I would fain have kept from the public. Some of the men who crossed over with us the night before (i.e., the morning of the 1st of June) managed to leave the command during the day, and re-crossed to Buffalo, while others remained in houses around the fort marauding. (Real Irish patriots these!) This I record to their lasting disgrace.

“On account of this shameful desertion, and the fact that arms had been sent out for 800 men, I had to destroy 300 stand to prevent them from falling into the hands of the enemy....

“At this time I could not depend upon more than 500 men, one-tenth of the reputed number of the enemy, which I knew was surrounding me—rather a critical position.

“Thus situated, and not knowing what was going on elsewhere, I decided that the best course was to return to Fort Erie and ascertain if crossings had been made at other points; and, if so, I was content to sacrifice myself and my noble little command for the sake of leaving the way open.

“I returned to the old fort (Erie), and about six o’clock sent word to Captain W. J. Hynes, and his friends at Buffalo, that the enemy would surround me with 5000 men before morning, fully provided with artillery; that my little command, which had by this time considerably decreased, could not hold out long; but that, if a movement was going on elsewhere, I was perfectly willing to make the old fort a slaughter-pen, which I knew would be the case the next day if I remained.

“Previous to this time, some of the officers and men, realising the danger of their position, availed themselves of the small boats and re-crossed the river; but the greater portion of them—317, including officers—remained until 2 A.M., June 3rd, when all, except a few wounded men, went safely on board a large[35] scow attached to a tug-boat, and were hauled into American waters.

“Here they were hailed by the United States steamer, which fired across their bows and demanded their surrender. With this request we complied, not because we feared the twelve-pounders or the still more powerful guns of the Michigan, but because we respected the authority of the United States.”!!!

Thus fought the Irish patriots of 1866. Thus ended the first Fenian raid upon Canada. Not a glorious achievement, by any means. Quite the reverse, in fact. Even the leader of the expedition himself has to subscribe to failure and defeat. And yet there have been, and are to-day, men who boast of all this as a glorious victory, and proudly vaunt the statement that they were present at and participated in it.

Lucky it was that the movement was thus defeated at its very start. If it had not, the consequences might have been very different indeed. The news of the temporary victory at Fort Erie had a wonderful effect, and by the 7th of June not less than 30,000 men had assembled in and around Buffalo. The defeat of their comrades, however, and the tardy issue of Andrew Johnson’s proclamation enforcing the Neutrality Laws, left them no opening, and so the whole affair fizzled out in the most undignified manner. Undignified indeed it was for all parties concerned. The prisoners were, without a single exception,[36] released on their own recognisances, and sent home by the United States authorities; while the arms seized by the United States Government, through General Meade, commanding in Buffalo, were returned to the Fenian organisation, only to be used for the same purpose some four years later.

Meantime the conditions of peace, in purely American matters, had set in, and the army was reduced to a nominal footing. I took advantage of the state of affairs to settle down to a civilian style of life. The first question that called for thought and care was my future vocation in life. The father of a family, it became necessary for me to look out for some means of obtaining a settled income. Acting under the advice of an old comrade, now a Senator of Illinois, I finally determined to study medicine, and set to work in this direction without delay.

While so engaged, I paid my first visit to Europe in the autumn or “fall” of 1867, and once more met my father and mother in the flesh. My letters regarding Fenian matters were naturally a topic of interesting conversation between us, and my father with much pride showed me the written acknowledgments he had received[37] for his action in the matter. Poor old father! Never was Briton prouder than he of the service he had been enabled to do his country—services unpaid and as purely patriotic as ever Englishman rendered. No payment was ever made—none was asked or expected—for whatever little good I had been enabled to accomplish up to this time. Matters, however, were now to develop in a new and unexpected way. Mr. Rebow expressed a desire to see me, and, accompanied by my father, I visited him at his seat, Wyvenhoe Park. He subsequently visited me on several occasions at my father’s house, and had many chats on the all-absorbing topic of Fenianism. Learning from me that the organisation was still prosperous and meant mischief—my friend O’Neill having succeeded Colonel Roberts as president—he gained my consent to enter into personal communication with the English Government. In a few days I received through him an official communication requesting me to attend at 50 Harley Street. To Harley Street I went, and there met two officials, by whom a proposition was made that I should become a paid agent of the Government, and that on my return to the United States I should ally myself to the Fenian organisation, in order to play the rôle of spy in the rebel ranks. I knew that this proposal was coming. I had[38] thought over the whole matter carefully, and I had come to the conclusion that I would consent, which I did. My adventurous nature prompted me to sympathy with the idea; my British instincts made me a willing worker from a sense of right, and my past success promised good things for the future.

I returned, therefore, to the States in the Government service; and, taking advantage of an early meeting with O’Neill in New York, I proffered him my services as a military man in case of active warfare. O’Neill, delighted at the idea, promised me a position in the near future, and I returned to my home in the West, pledged to help the cause there meantime.[1]

And now a few words as to O’Neill. Taking the prominent part he did in Fenian affairs at this time, he certainly proved a very interesting personality. General O’Neill, Irish by birth, was born on the 8th of March 1834, in the town of Drumgallon, parish of Clontifret, Co. Monaghan. He emigrated when young with his family to the United States, and settled at Elizabeth, New Jersey. Enlisting in the 2nd U.S. Cavalry as a[39] private soldier in 1857, he was engaged in fighting Indians in the Far West for some three years. Upon the breaking out of the War of the Rebellion, he was commissioned as lieutenant in the 5th Indiana Cavalry. From this he received promotion in the 15th U.S. Coloured Infantry, with which regiment he continued to the end of the war. Resigning his command at the conclusion of hostilities, he commenced business as a United States Claim Agent in Nashville, Tennessee, where, it will be remembered, I was stationed with my regiment for a long time after the cessation of active operations.

When freed from the discipline of his military service, O’Neill—ardent Fenian that he was—threw himself heart and soul into the Irish rebel movement in the States. He raised and commanded the Tennessee contingent in the movement upon Canada in 1866, taking command of the entire expedition by reason of his seniority of rank and his proved knowledge of military tactics. I have already quoted his report of the termination of this “invasion.”

At the Cleveland Convention of September 1867, he was elected a senator of the Fenian Brotherhood; and on the 31st of December 1867, owing to the resignation of Colonel W. R. Roberts, he was elected President of the Brotherhood.

In personal appearance O’Neill was a very fine-looking man. Nature had dealt kindly with him. Within a couple of inches of six feet in height, possessing a fine physique and a distinctive Celtic face, he combined an undoubted military bearing with a rich sonorous voice, which lent to his presence a certain persuasive charm. He had one fault, however—a fault which developed to the extremest point when he attained the presidency of the Fenian Brotherhood. This was his egotism. He was the most egotistical soul I ever met in the whole course of my life. In his belief, the Irish cause lived, moved, and had its being in John O’Neill; and this absurd self-love contributed to many disasters, which a more even-headed leader would never have brought about.

On my return to my Western home, I lost no time in commencing my double life. I organised a Fenian “circle” or camp in Lockport, Illinois, and took the position of “centre” or commander of it, thus becoming the medium for receiving all official reports and documents issued by O’Neill, the contents of which documents were, of course, communicated by me to the Home Government. I went to work with a will, and was soon in the[41] very thick of the conspiracy, organised a military company for the Irish Republican Army, and eventually attended the Springfield Convention in the position of a delegate.

While so engaged, I entered the Chicago Medical College, and commenced my medical studies in earnest. I was much assisted in this direction by the kindly help of an old friend, Dr. Bacon, who had been attached to my regiment in war times as surgeon. He was then surgeon to the Illinois State Penitentiary, and through him I obtained the position created at this time of Hospital Steward, or, in other words, Resident Medical Officer in that institution. There was a comfortable salary attached to the office, which I found to be in every sense a useful post. Although, as matters turned out, I was only to spend some few months there, I gained even in this short time a vast amount of experience in almost every branch of medical study.

Life, indeed, in the Illinois Penitentiary gave me experience in many ways. It brought me for the first time into direct contact with many of the evils which then affected official administration. Things, of course, are different now, though it must be confessed still anything but perfect; but when compared with the usages of olden times, the shortcomings of the present[42] system are of no account whatever. At the time of which I speak, money could accomplish everything, from the obtaining of luxuries in prison to the purchase of pardon and freedom itself. Everything connected with the prison administration was rotten to the core. Corruption was in every place. The penitentiary contained some fifteen hundred prisoners, and the whole management of affairs affecting these men was vested in three Commissioners, as they were styled, whose proceedings were of the most flagrant and jobbing character. So great did the scandals of their doings become at one period, that one of the three had to abscond; but so demoralised was the condition of affairs that no attempt was made to arrest and bring him back. These three men had no object save that of gaining money. They were the proprietors of a general shop inside the prison, from which the prisoners purchased luxuries at usurious rates; and the work of the prisoners themselves was let out to contractors, who paid heavily for the privilege of remaining undisturbed in their monopoly. Everything was turned to money. In one case I knew of a prisoner, failing to win his cause on appeal, and having thereby to undergo a period of seven years’ imprisonment, being offered his release for a sum of 10,000 dollars, which offer he[43] refused, stating in the most business-like way that he would only give 7000. This was not considered satisfactory, and so the negotiations fell through.

No popular idea of prison life now indulged in at all fits in with the actual condition of affairs five-and-twenty years ago. Money was useful for the purpose of commerce in the Commissioners’ interest, and therefore was allowed free circulation amongst those confined. Those who could afford it, and whose cases were not finally decided—appeals were constantly being heard—were allowed to board at the Governor’s table, to wear their own clothes, and in every way conduct themselves as if in a private house. In those days the prisoners were not shaved—they wore their hair and whiskers as they pleased. Those who could not afford to live the lives of gentlemen had the store to go to for petty luxuries; and so, no matter how matters turned, the Commissioners were the gainers. The Governor, or Warden, as he was called, was their nominee, dependent upon them for office; and everything was governed by their wishes and desires.

In such a vast assembly of criminals there were many whose characters and careers formed subjects for very interesting study to me. I was fortunate in being connected with the prison at a time when some more than usually clever and[44] facile scoundrels were temporarily resident there. Towering head and shoulders over the whole crowd was that king of forgers, Colonel Cross, perhaps the most daring, successful, and expert penman of our time. About forty years of age at this period, a man of fine commanding presence, splendid diction, and gentlemanly demeanour, Cross attracted me from the first day I was brought into contact with him. The son of one of the most prominent Episcopalian clergymen in the United States, he was possessed of a wide classical education, and discoursed with intelligence and wondrous fluency on theology, medicine, and every kind of science.

He was no ordinary criminal. Even in prison he commanded admiration from his fellows, and I was often amazed to see how respectful were the salutations accorded him as he moved about. He boasted, I learned afterwards with truth, that he had never robbed a poor man; and, strange being that he was, he had borne almost all the cost of the education of his brother’s children. Indeed, at the time I met him, he was educating in the most expensive manner a poor little girl whom, in a moment of generous caprice, he had adopted as his daughter.

When I was first brought into contact with him, Cross had his case before the courts on[45] appeal, and, pending the decision, he was living in the most expensive way in prison, boarding at the Governor’s table, dressing in the most fashionable way, and smoking the best of cigars. Having no work to do, he interested himself in the affairs of his fellow-prisoners; and so clever and capable was he, and so great a knowledge of law did he possess, that he succeeded in preparing the cases of many of them for appeal in such a way as to allow of their regaining their liberty.

I had not been in the prison very long before he appealed to me to take him as my assistant in the hospital; and attracted by the man as I was, I acceded to his request, to discover subsequently that I had a most valuable attendant, whose knowledge of medicine was both extensive and practical.

The career of Cross would supply material for a most exciting novel. He always went in for “big things,” as he phrased it. Nothing troubled him more than the fact that he was then undergoing punishment for a small affair which he contemptuously referred to as being too paltry altogether for association with him. Perhaps the “biggest thing” he ever did was the forgery of a cheque for £80,000 in Liverpool, and his escape[46] with the booty. Like many other talented criminals, if he had but turned his ability to proper account, he would undoubtedly have won a place and name in the foremost ranks of honest men to-day. He planned his enterprises with the most consummate care, and worked them out for months before reaching the final stage. An illustration of his method was very well afforded by his forgery on the Park National Bank of New York.

Determining to commit a forgery on this bank, he set to work to obtain the needful introduction and guarantee for his accomplice, who should eventually present the forged cheque. He, by the way, never presented a forged cheque himself—this was always the work of an accomplice. In order, therefore, to obtain the introduction to the bank, he opened some business with a certain firm of brokers in Wall Street who happened to “deposit” at the particular bank in question. In this way he ran up an account for a respectable sum, to obtain the repayment for which he one day went to the office in Wall Street accompanied by one Simmons, the accomplice in the future forgery. The cheque—a draft for twelve hundred dollars—was duly drawn, when Cross asked his friend Simmons to go to the bank to cash it, requesting in a free-and-easy way that the broker might send one of his clerks with him to identify[47] Simmons, he being a stranger. No suspicion was indulged in—there was no ground for such, and the request was willingly complied with. Simmons, coached by Cross beforehand, had a hundred-dollar bill in his pocket, the use for which will be apparent in a moment. When the clerk and he reached the bank, the necessary introduction took place; and in reply to the usual question how he wished the money, Simmons replied, “In hundred-dollar bills.” As the clerk counted the notes, Simmons drew his bill out of his pocket, and mixing all up as he stood aside to check his payment, he recalled the clerk’s attention by the announcement that he had given him thirteen instead of twelve bills. The clerk indignantly protested he had made no mistake. Simmons, playing the rôle of honest man, became distressed, the manager was appealed to, one of the notes eventually received back, and Simmons retired, the recipient of most fulsome thanks, his character and reputation fully established in the minds of the banking officials. Of course the clerk was one hundred dollars to the good at the end of the day, but Simmons’ claim to honesty in no way suffered by the fact, as no one for a moment thought of a plot.

Content to lose the hundred-dollar bill, in the promise of things to come, Cross continued his[48] legitimate traffic with the brokers, Simmons, on the most friendly terms at the bank, cashing the cheques, which increased in amount as the time passed. Months had passed, and nothing of an illegal nature had been attempted, when at the end of the fifth month a genuine cheque for thirty dollars was by Cross changed to 30,000, and cashed by Simmons without the slightest hesitation or suspicion at the bank, both Cross and he escaping with the booty.

Many and varied as were Cross’s tricks with his pen, none was more daring or successful than that which led to his escape from Sing-Sing Prison, that famous home of criminals in New York. Obtaining through outside agency a printed and properly headed sheet of note-paper and envelope from the Governor of the States’ Office at Albany, he actually forged the order for his own release, had it posted formally from Albany, and, on its receipt, obtained his freedom without provoking the slightest suspicion or inquiry.

I am glad to say that Colonel Cross still lives, and is now working out an honest existence under another name in the north-west of America.

My life at the Illinois Penitentiary was crowded with incidents, and little leisure was left me. Where real sickness did not exist, shamming and malingering in their most ingenious phases were[49] resorted to. I was amazed at the talent brought to bear upon their attempts to escape work by those with whom I had to deal. Some of the methods adopted were simply marvellous in their conception and execution. A more quick-witted lot of men it has never been my fate to meet. Every twist and turn of daily life was subordinated to the needs of the trickster, and not one single daily incident seemed to be without its possibility of application, either to assist in the attempt to shirk work or to escape from imprisonment altogether. Nothing in this way impressed me more than the case of a man known as Joe Devine, an eminent hotel sneak thief, some two-and-thirty years of age, and of very distinguished appearance.

It happened that one afternoon about five o’clock a negro prisoner died of consumption. It was the practice to bury the dead immediately the coffin was made ready; but, owing to the fact that the coffin in this case was not ready till after the prison gates had been locked for the night, the burial had to be postponed till the following morning.

Under the circumstances, I arranged that the coffin with the body enclosed should remain for the night in the prison bath-room. This Joe Devine of whom I speak happened to be in charge of the bath-room at this period, and it[50] therefore became his duty to see that proper arrangements were made for the disposal of the coffin for the night. Early the next morning, as was customary, Devine and some of his fellow-prisoners were allowed out of their cells some little time before the others, in order to prepare the bath-room and other places for their use. With assistance Devine unscrewed the coffin, took the dead negro out, and concealed himself in his place, not, however, before he had worn down the thread of the screws in the lid, so that they could be thrust out with a heavy push from the inside. The time for the funeral arrived in due course, and the coffin was removed in a little cart accompanied by two prisoners whose time was nearly expired, and who were therefore trusted outside the gates of the prison (being known by the name of “trusties”), together with the clergyman of the jail.

Nothing happened till the grave was reached, when Devine, presumably concluding that it would be dangerous to remain longer where he was, burst the lid of the coffin and jumped out, immediately starting off at a run. The clergyman and “trusties” being too horrified to offer any resistance, he escaped without molestation. The first I heard of the matter was on the return of the clergyman and the “trusties” with the news that[51] the man had come to life; but, as they explained in their horrified way, he was white, not a nigger! The roll was called, and Devine was missing; so we concluded he was the white man in question. We then set to work to find the corpse of the poor negro. For two hours the prisoners searched up and down without any result. Eventually, however, the body was discovered underneath a pile of towels in one of the box-seats of the bath-room, the corpse being doubled up in two, the head and feet meeting, in order to permit of its being concealed in its narrow hiding-place.

Another escape equally effective, for the moment at least, was that of a man known as Bill Forester, a notorious bank robber, and one of the suspected murderers of Nathan the Jew, whose death in New York created a profound interest at the time. Forester, fortunately for himself, selected as his medium of exit one of the many boxes employed by Mack & Co., contractors for shoe-making, who employed some four hundred of the convicts. Surrounded and hedged in between boots and shoes, in one of the large boxes used for their transport, Forester passed through the prison gates in one of Mack’s vans, and not till he had got a distance of a mile and a half from the jail did he venture to emerge from his hiding-place. His liberty, however, proved to[52] be only of a temporary character, for, caught in another State a little later, the enterprising burglar was again arrested, and carried back to the Penitentiary to complete his term of imprisonment.

His method had many imitations. None was more novel or disastrous than that employed by a fellow-convict whose name I cannot at the moment recall. This poor fellow hit upon the ingenious idea of getting out of durance vile inside a load of horse-manure, and when the load was half-way packed, he lay at full length with a breathing space arranged, while the remainder of the loading was completed. His intention, of course, was to be freed from his uncomfortable position within an hour, when the manure would be discharged at the quay adjoining the prison. To his horror, however, he discovered, when the cart reached the quay, that a gang of fellow-convicts were engaged unloading a boat under the charge of armed wardens or sentries. To attempt escape meant instant death, and there he lay for hours with the heavy weight of the upper portion of the cart’s load pressing upon him. Six o’clock came and with it the return of the men and sentries to prison. Through the long weary hours of the night the poor fellow lay, unable now to move from the consequences of his continued prostration in the manure; and[53] when the morning arrived he was found but too willing a captive. He was immediately placed under my charge, but his recovery proved by no means a rapid affair.

In the midst of all these exciting incidents of prison life, I received a telegram from O’Neill in New York, as follows: “Come at once, you are needed for work.” To comply was to surrender my pleasant and interesting position, and to lose for the moment all chance of pursuing my medical study. On the other hand, however, the opportunity of doing good service to my native land presented itself. I did not hesitate. Communicating immediately with the “Warden” or Governor, I resigned my position, much to his disgust. He sought an explanation. I could give none. He offered an increased salary. I was unable to explain why even this could not tempt me, and so I left in a way which was misunderstood, and under circumstances which, by the very reason for their existence, could not be appreciated.

Hurrying to New York, I soon presented myself in person to O’Neill at the headquarters of the Fenian Brotherhood, then situated in the mansion at 10 West Fourth Street. Here[54] I found the President of the Brotherhood, surrounded by his staff of officials, transacting the duties of their various positions with all the pomp and ceremony usually associated with the representatives of the greatest nations on earth. I was not long left in suspense as to what was required of me. Commissioned at the very outset as Major and Military Organiser of the Irish Republican Army (at a salary of sixty dollars per month, with seven dollars per day expenses), I was instructed to proceed to the Eastern States in company with a civil organiser, in order to visit and reorganise the different military bodies attached to the rebel society. To my unhappy amazement, I learned that I was, while engaged[55] on this work, to address public meetings in support of the cause, and my miserable feelings were accentuated by O’Neill’s desire that I should accompany him, the very evening of my arrival, to a large demonstration being held at Williamsburg, a suburb of Brooklyn. I was in a regular mess, for if called on to speak—as I feared—I should be found absolutely ignorant of Irish affairs. There was nothing for it, however, but to keep a brave face, for I had undertaken my work, and in its lexicon there was no such word as fail.

The evening came, and with it our trip to Williamsburg. On arrival there, in the company of O’Neill and some brother officers, I found several thousands of persons assembled. We were greeted with the greatest enthusiasm, and given the seats of honour to the right and left of the chairman. My position was a very unhappy one. I was in a state of excessive excitement, for I greatly feared what was coming. Seated as I was next to O’Neill, I could hear him tell the chairman on whom to call, and how to describe the speakers; and, as each pause took place between the speeches, I hung with nervous dread on O’Neill’s words, fearing my name would be the next. The meeting proceeded apace; some four or five of my companions had already spoken, and I was beginning to think that, after all, the[56] evil hour was postponed, and that for this night at least I was safe. Not so, however. All but O’Neill and myself had spoken, when, to my painful surprise, I heard the General call upon the chairman to announce Major Le Caron. The moment was fraught with danger; my pulses throbbed with maddening sensation; my heart seemed to stop its beating; my brain was on fire, and failure stared me in the face. With an almost superhuman effort I collected myself, and as the chairman announced me as Major M‘Caron, tickled by the error into which he had fallen, and the vast cheat I was playing upon the whole of them, I rose equal to the occasion, to be received with the most enthusiastic of plaudits.

The hour was very late, and I took advantage of the circumstance. Proud and happy as I was at being with them that evening, and taking part in such a magnificent demonstration, they could not, I said, expect me to detain them long at so advanced an hour. All had been said that could be said upon the subject nearest and dearest to their hearts. (Applause.) If what I had experienced that night was indicative of the spirit of patriotism of the Irish in America—(tremendous cheering)—then indeed there could be no fears for the result. (Renewed plaudits.) And now I would sit down. They were all impatiently waiting,[57] I knew, to hear the stirring words of the gallant hero of Ridgeway, General O’Neill—(thunders of applause)—and I would, in conclusion, simply beg of them as lovers of liberty and motherland—(excited cheering)—to place at the disposal of General O’Neill the means (cash) necessary to carry out the great work on which he was engaged. This work, I was confident, would result in the success of our holy cause, and the liberation of dear old Ireland from the thraldom of the tyrant’s rule, which had blighted and ruined her for seven hundred years.

These last words worked my hearers up to the highest pitch of enthusiasm, and amidst their excited shouts and cheers I resumed my seat, with the comforting reflection that if it took so little as this to arouse the Irish people, I could play my rôle with but little difficulty. And as time passed on, and my experience widened, the justice of the reflection was fully assured. With a little practice and scarce any labour, save that necessitated by the use of a pair of scissors and some paste, I succeeded in hoodwinking the poor and deluded, together with the unprincipled, blatant, professional Irish patriots.

Before, however, starting on my travels as organiser, I had an experience which went far to justify all I had previously thought and heard as[58] regards the part played by Andrew Johnson in connection with the first Canadian raid. I recall the incident as important, as showing to what extremes American political exigencies have carried men in catering for the Irish vote in America. About American politics generally I shall have something to say later on; but as this matter fits in chronologically here, I think it better to deal with it now. Johnson, it must be remembered, was not by any means a man above suspicion. In 1868, so great was the disaffection with his administration of the Presidency, that he was impeached, though unsuccessfully, by the Senate.

It was in this year—1868—that, at O’Neill’s request, I accompanied him to the White House to have an interview with Johnson. O’Neill and he had been personal friends from ’62, when Johnson had acted as Military Governor in Tennessee. The precise object of our visit was the securing of Johnson’s influence in the return of the arms to the Fenian Brotherhood, previously seized by the American Government. It will be remembered that I mentioned, some pages back, that every gun taken by the United States Government, after the first raid in 1866, was returned to the Fenian organisation by this government under a promise, only made to be broken, that they should not be used in any[59] unlawful enterprise; and in consideration of certain worthless bonds.

Our reception at the White House was a cordial one, O’Neill’s distinctly so. During the conversation the President used some remarkable words. So strange did they sound in my ears, that they impressed themselves upon my memory, and are even now fresh in my recollection.

“General,” said Johnson, addressing O’Neill, “your people unfairly blame me a good deal for the part I took in stopping your first movement. Now I want you to understand that my sympathies are entirely with you, and anything which lies in my power I am willing to do to assist you. But you must remember that I gave you five full days before issuing any proclamation stopping you. What, in God’s name, more did you want? If you could not get there in five days, by God, you could never get there; and then, as President, I was compelled to enforce the Neutrality Laws, or be denounced on every side.”

Such was the language used, such the position assumed, and such the apology tendered to the Fenian leader of 1868 by the President of the United States Government. Can any comment of mine point the moral and adorn the tale of all this better than the incident itself can do when left in its naked and startling significance? I think not.

I entered with a will upon my duties as travelling organiser, and was alike successful in winning the confidence of almost every Fenian with whom I was brought into contact, and in obtaining the most important information and details for the Home Government. Matters had meantime proceeded apace, so that when the Philadelphia Convention of 1868 was held, O’Neill’s determination to invade Canada a second time was ratified without a dissentient voice. I was now promoted to the rank of Inspector-General, and was from time to time sent along the Canadian border to locate the arms and ammunition. The situation was becoming critical where British interests were concerned; and, in order to grapple with the pressure of the moment, I was placed in direct communication with Lord Monck, then Governor-General of Canada. I paid a visit to Ottawa, and when there, planned a system of daily communication with the Chief Commissioner of Police in Canada, Judge J. G. M‘Micken, with whom, from this date to the total disruption of the Fenian organisation in 1870, I acted in concert and in the most perfect harmony.

I cannot speak too highly of the treatment I[61] received at Judge M‘Micken’s hands. Comparatively young in years as I was then, distinctly youthful in Secret Service experience, I found him ever ready and willing to help me, meeting me at a moment’s notice, placing everything at my disposal, and watching over my safety and my interests with a fatherly care which I shall ever recall with thoughts of the keenest appreciation. Equally pleasant and agreeable was my connection with the Home Government. Many changes had taken place since my visit to England, and those with whom I had first had communication had disappeared from this work to give place to Mr. Anderson, with whom alone I had to deal from this time forward. I shall have a good deal to say about Mr. Anderson further on, and therefore I shall only delay here to repeat what I have said above, that with England as with Canada my connection was of the most satisfactory and pleasant character.