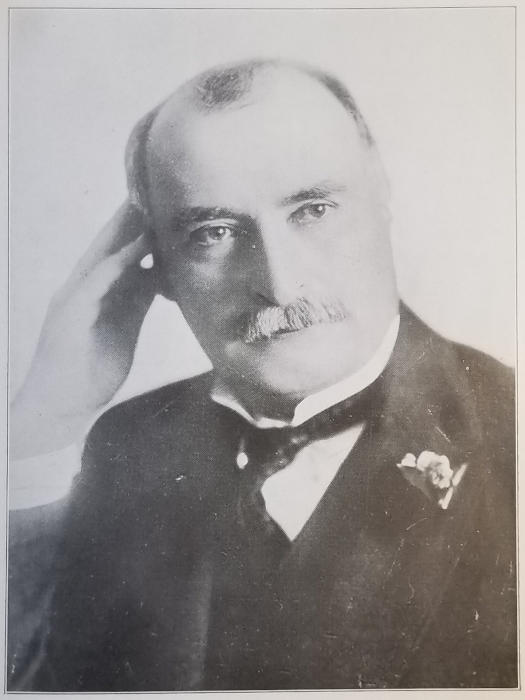

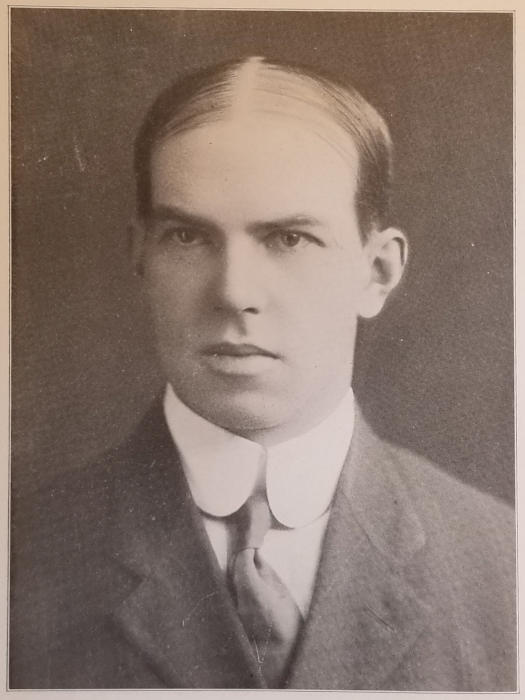

Hon. James D. Phelan, Ex-Mayor of San Francisco and U. S. Senator from California.

One of the men most conspicuous in obtaining water and power for San Francisco from Hetch Hetchy Valley.

by

MARTIN S. VILAS, A. M.,

Member of the

Bars of California, Vermont and Washington.

Copyrighted 1915 by

Martin Samuel Vilas

Washington, D. C., March 14, 1914.

I can assure you that your clean, clear presentation of the matter was admirable and much appreciated.

John E. Raker.

(Member of Congress from California and author of the Raker Bill).

San Francisco, Cal., February 4, 1914.

I think it was a valuable contribution to the data on that subject and indicates a considerable study upon your part.

Andrew J. Gallagher.

(Member of Board of Supervisors, City of San Francisco).

San Francisco, Cal., February 2, 1914.

I read your article in the Chronicle on Hetch Hetchy and want to compliment you on the thoroughness with which you handled the subject.

J. S. Dunnigan.

(Clerk, Board of Supervisors, City of San Francisco).

San Francisco, Cal., January 29, 1914.

I ... feel that you are entitled to considerable praise for the concise and clear manner in which you have covered a very comprehensive subject.

Wm. McCarthy.

(Member of Board of Supervisors, City of San Francisco).

San Francisco, Cal., January 29, 1914.

I read with much interest and satisfaction your very comprehensive and accurate article on the Hetch-Hetchy.

James D. Phelan.

(Ex-Mayor of San Francisco and U. S. Senator elect from California).

San Francisco, Cal., January 26, 1914.

I beg to compliment you on the clearness and conciseness with which you have stated many of the controversial points involved in same. I have had so much of it in the past year and I had to take up so many angles of the conflict that your resumé is decidedly refreshing.

M. M. O’Shaughnessy.

(City Engineer, City of San Francisco).

San Francisco, Cal., January 29, 1914.

... I beg to say to you in person what I long since wrote to the editor of the Chronicle. I stated to him that the article was a very valuable contribution to the literature on the Hetch-Hetchy subject, and was the best general exposition of the case that I had read in any newspaper and that, furthermore, the article was practically free from error. I have long since added it to my scrap book.

Alexander T. Vogelsang.

(Member of Board of Supervisors, City of San Francisco, and member of law firm of Vogelsang & Brown).

San Francisco, Cal., February 6, 1914.

I consider it the best resumé of the Hetch-Hetchy scheme that has been written. I sent to the Chronicle for ten more copies after reading it in order that I might use it in the future.

I trust that the article will have a very wide circulation, for it cannot but help convince every fair minded individual not only that San Francisco’s application for rights has not been hastily considered but fair play demanded the grant.

Speaking for myself, I thank you very much for your kindly interest in the matter and for your very careful and comprehensive article.

Percy V. Long.

(City Attorney of the City of San Francisco).

Hon. James D. Phelan, Ex-Mayor of San Francisco and U. S. Senator from California.

One of the men most conspicuous in obtaining water and power for San Francisco from Hetch Hetchy Valley.

Hon. James Rolph, Jr., Mayor of San Francisco, Cal.

One of the men most conspicuous in obtaining water and power for San Francisco from Hetch Hetchy Valley.

Facts Regarding Mountain Supply

History of City’s Fight for Pure and Adequate Water

BENEFITS TO BE DERIVED

Bay Counties and Irrigation Districts Provided for In National Grant

By MARTIN S. VILAS

The Raker Bill, named for John E. Raker of Modoc county, Cal., a member of Congress, was reported unanimously by the House Committee on the Public Lands at the special session of Congress in the summer of 1913, after a hearing occupying several days, and under its recommendation passed the House. This bill was reported favorably by the Senate Committee on the Public Lands, and, after a hard fought contest, occupying a week on the floor of the Senate, passed that body December 6th, 1913, by a vote of 43 to 25. It received the approval of President Wilson and became a law on December 19, 1913.

The enactment of this bill ended a continuous effort on the part of San Francisco, covering a period of many years, to obtain the legal right to take water from Hetch-Hetchy. It marked the end of a contest, spirited and hard fought, which was participated in by the magazines and press the country over, and in which the great majority of publications outside of California opposed the plan of San Francisco.

As this legislation affords legal opportunity for a water project primarily for domestic use, which is in itself a signal and notable work of engineering; as it affects vitally and strongly the irrigation interests of a state having a length of about 775 miles and a land surface greater than the combined areas of the six New England States, of New York, New Jersey, Delaware and Ohio—a State which James Bryce characterized as an empire within itself; as it gives a State a very important easement, likely to be enduring, in a national park sharing alone with the great Yellowstone National Park in distinctiveness and notoriety; as it is designed to provide the legal means of furnishing water and much power for the next 100 years for a rapidly growing metropolitan section, now more numerously peopled than any other west of Chicago, the Raker Bill and its accessories are of national interest.

For the foregoing reasons inquiry is made:

First—What is Hetch-Hetchy, and what, if any, are the present holdings and interests of San Francisco in the Yosemite National Park?

Second—What is the Raker Bill?

Third—What will be the operative effects of the Raker Bill on San Francisco and the rest of California outside the Yosemite National Park?

Fourth—What will be the operative effects of the Raker Bill on the Yosemite National Park?

(1) Until the agitation connected with obtaining water for San Francisco brought in the name of Hetch-Hetchy, the writer supposed Hetch-Hetchy to be probably the name of some Indian chief, some new brand of cigars or some noted trotting horse. Possibly some of those who read this article are still nearly as ignorant as was the writer then.

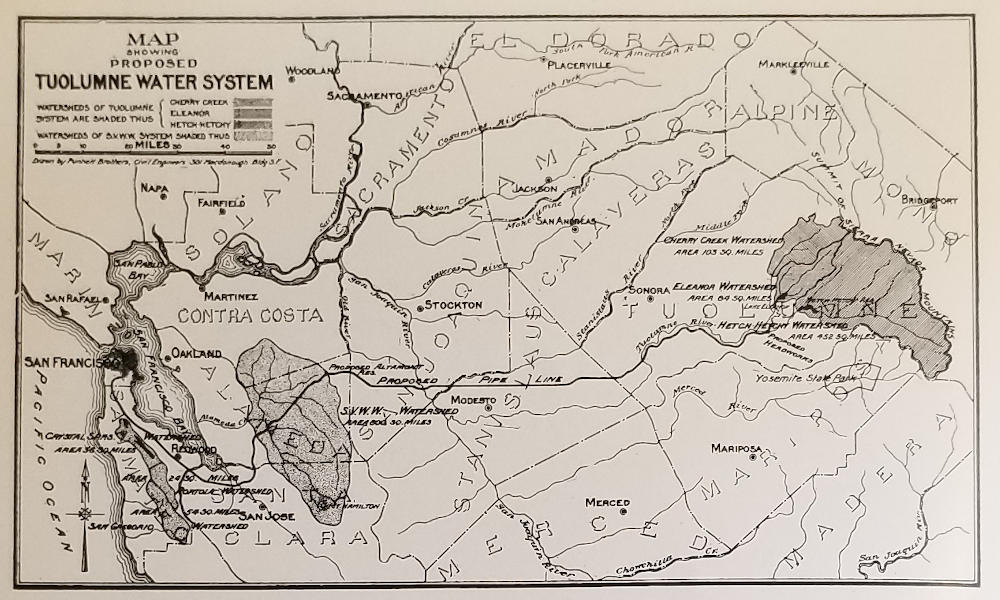

Hetch-Hetchy is the name of a valley through which flows the Tuolumne River, and has tributary to it a watershed comprising 459 square miles. It lies entirely in Tuolumne County, California, entirely in the Yosemite National Park, of which it is the northern portion, and about 165 miles from San Francisco.

The Yosemite National Park contains about 1500 square miles. Hetch-Hetchy Valley is separated from the Yosemite Valley by a mountain range having a mean elevation of over 8500 feet, and distant from that valley about thirty-five miles by mountain trail. The floor of the valley is between 3000 and 4000 feet in altitude, is level and grass covered, and two or three miles long and nearly half a mile wide. It is surrounded by steep cliffs, out of which extend deep gorges. Just back of Hetch-Hetchy is a gorge a mile deep and one and a half miles wide. The sides of the valley are granite and very steep and precipitous, rising to a height of between 2000 and 5000 feet in different places. The valley is divided into two parts by a large ridge of rocks extending nearly across the middle. The upper end of it is a high, dry area, covered with tall pine trees, varying between 200 and 300 feet high, and with live oak and other kinds of trees, thus forming a natural park. The grasses, shrubs, flowers and trees are beautiful. Several distinguished naturalists have pronounced the natural growth as very unusual. There are a greater variety of trees and larger oaks in the Hetch-Hetchy Valley than in the Yosemite.

The area tributary to Hetch-Hetchy is very rough. Edmund A. Whitman, a lawyer of Boston and president of the Society for the Protection of National Parks; who has several times visited Hetch-Hetchy, in his testimony before the House Committee on the Public Lands last summer, stated:

“I cannot attempt to describe to you the character of the country. It is some of the roughest God ever made. You do not find little places here and there with grass and water, but the largest part of the country is the roughest sort, where camping is as impossible as it would be on the top of this table. Camping and the use of the park reduces itself to one thing—the feed of horses. There are only three places in the entire park where you can take care of horses.”

Hetch-Hetchy Valley is difficult of access. Because of the high, rough country surrounding it but few people visit it. Thus while 6000 or 7000 people visit the Yosemite Valley each year, less than 300 visit Hetch-Hetchy Valley. The valley, difficult to reach in summer, is rendered almost inaccessible as soon as the early snows begin to fall, and in winter is enshrouded in four or five feet of snow.

The summer season in that high altitude is short, and rendered shorter than the ordinary in Hetch-Hetchy by the cooling effect of the mountain streams, almost icy cold, and by the surrounding mountain peaks, snow-capped except for a small part of the year.

MAP SHOWING PROPOSED TUOLUMNE WATER SYSTEM

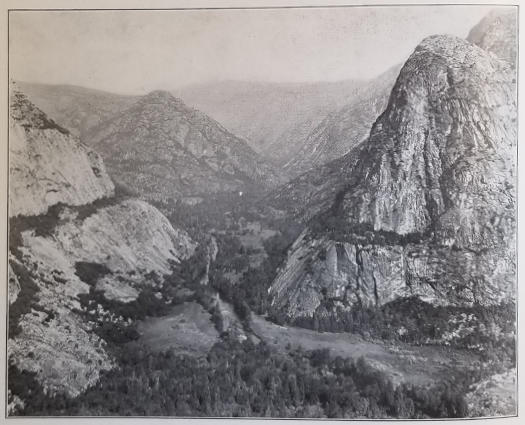

The Upper Hetch-Hetchy Valley

The American City.

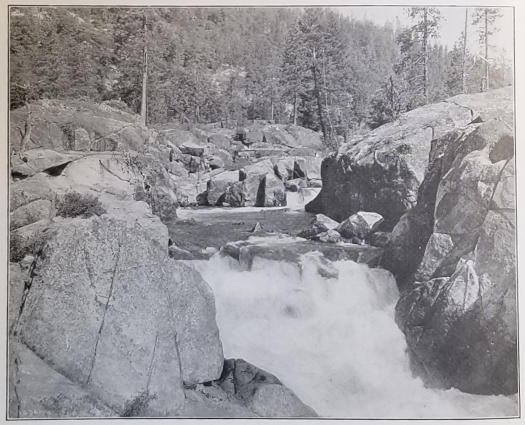

The Tuolumne River rises on the eastern side of California among the highest crests of the Sierras and for five or six miles flows through a meadow, but during the next twenty miles drops 3000 feet, in which distance some of the falls in the river are beautiful and picturesque. Next it flows for about two miles through Hetch-Hetchy Valley, then becomes a rushing mountain torrent for twenty miles more, and finally empties into the San Joaquin River in Stanislaus County, almost directly east of the southern end of San Francisco Bay.

Lake Eleanor and Cherry Valley are northwest of Hetch-Hetchy. Lake Eleanor, distant about eight miles, is approximately 1000 feet higher than Hetch-Hetchy. Cherry Valley is distant about twelve miles and is approximately 1000 feet higher than Eleanor. Cherry Valley has tributary to it 114 square miles of territory, all in the Stanislaus National Park. Lake Eleanor and the seventy-nine square miles tributary to it are entirely in the Yosemite National Park. The outlets of Cherry Valley and of Lake Eleanor empty into the Tuolumne River several miles nearer the San Joaquin than Hetch-Hetchy.

(2) A report of the State Geologist of California in 1879 suggested Hetch-Hetchy Valley and Lake Eleanor as possible sources of water supply for the city of San Francisco.

In 1883 a corporation was formed to supply water to San Francisco from the sources of the Tuolumne River. Filings were made and considerable work put in. In 1901 the City Engineer was directed to examine the available sources of water supply for San Francisco. He investigated fourteen different sources and under suggestion of the reclamation service spent about $50,000 in detailed investigation of the sources of the Tuolumne, with a view to utilization at Hetch-Hetchy and Lake Eleanor. That was before the section was taken into the Yosemite National Park in 1905.

The city engineer made his report in 1901 when James D. Phelan was Mayor. This report was immediately approved by the Board of Public Works and since then has been the settled municipal policy of San Francisco so far as water is concerned. This report recommended the Tuolumne River in the following words:

“This source presents the following unrivalled advantages: Absolute purity by reason of the unhabitable character of the entire watershed tributary to the reservoirs and largely within a forest reservation. Abundance far beyond possible future demands for all purposes. Largest and most numerous sites for storage; freedom from complication of water rights; power possibilities outside the reservation.

“It has the drawback of distance to overcome, requiring the constructing of conduits aggregating 142 miles in length. But considering the partial and rapid rate of pollution to which all other sources may in the future be subjected, particularly nearby sources, the Tuolumne River is far superior to any other.”

Thereupon, Mayor Phelan posted notices on the banks of the Tuolumne on July 29, 1901, of his claim to 10,000 miner’s inches of the waters of that river, “for irrigation, manufacturing purposes, water power and domestic use.” Phelan, when his rights matured, assigned them to the city, as the law did not allow a municipality to make a filing.

Under a grant issued May 11, 1908, by James R. Garfield, Secretary of the Interior, San Francisco obtained permission to store the waters of Lake Eleanor and Cherry Valley, develop them to their highest capacity, and when they should prove insufficient for the needs of the city, to store water in the Hetch-Hetchy Valley by crossing it with a dam. Secretary Garfield conditioned in this grant that San Francisco should submit the proposition to the people of the city for ratification, should buy up all the land held by private owners around Hetch-Hetchy and Lake Eleanor and hold such land for the city.

This proposition was voted upon by the legal voters of San Francisco in November, 1909, in a resolution as to whether or not they wished to acquire a means of water supply in the sources of the Tuolumne River, according to the terms of the Garfield permit, and to vote a municipal bond issue of $600,000 to obtain the land and water rights necessary therefor. The proposition was carried by a vote of more than five to one.

Thereupon San Francisco paid $174,311.20 for 720 acres of privately owned land in the Hetch-Hetchy Valley and for certain other lands so held which were not on the floor of the valley, but which, under the permit, the city must buy for camp sites, so that when campers were excluded from the floor of the valley they still might have a place to camp. These 720 acres comprise about two-thirds of the floor of Hetch-Hetchy Valley. They are now held by San Francisco in fee simple title. Next the city bought standing timber from the Government around Lake Eleanor for $13,428.77. Then out of the $600,000 voted, the city bought the land and water rights claimed by private owners around Lake Eleanor for $400,000.

In January, 1910, under the suggestion of Secretary of the Interior Ballinger, the proposition to obtain water for the city from the sources of Tuolumne and to authorize the issuance of bonds in the amount of $45,000,000 was submitted to the legal voters of San Francisco. Some 30,000 votes were cast and only about 1200 votes were in opposition.

The city supposed it had bought all available water rights of Lake Eleanor and Cherry Valley. That the city had not soon developed, and it expended $600,000 more to control these rights. The expense of investigations around the sources of the Tuolumne has been $300,000 or $400,000. Hence, upon the project San Francisco has already paid out in excess of $1,500,000, probably nearly $1,700,000.

Of the $174,000 spent on lands in Hetch-Hetchy, $81,306.18 were spent for 720 acres. For the exchange lands $92,457.02 were expended. 640 acres outside the valley proper were bought for camp sites under the order of the Secretary of the Interior. At Lake Eleanor private persons owned nearly all the dam sites. Now San Francisco owns about one-half and the United States Government about one-half. Here the development will be very expensive.

At Cherry Valley almost everything is owned by San Francisco. Owners of property around Cherry Valley and Lake Eleanor received $1,000,000 for property which cost them approximately $100,000. The area in the irrigation districts below the dam sites is mostly included in the Turlock-Modesto district. In the vicinity of Hetch-Hetchy Valley the city owns 1040 acres and around Lake Eleanor, all in the National Park, 920.33 acres more, making a total inside the park of 1960.33 acres. In Cherry Creek the city owns 860 acres below Hetch-Hetchy, in Hog Ranch 322.45 acres, and in Ike Dye Ranch 163.68 acres, making a total of 3406.46 acres.

Secretary Ballinger, in 1909, requested the matter be taken up de novo. At the direction of President Taft a board of three army officers was assigned by the Chief of Engineers to investigate and report on the subject of water supply for San Francisco as bearing particularly upon the need of the sources of the Tuolumne for San Francisco. This board of engineers was appointed in 1911 and consisted of Colonel John Biddle, Colonel Spencer Cosby and Colonel Harry Taylor. It occupied two years in a thorough investigation of all available sources of water supply for San Francisco and made a complete, detailed report, February 19, 1913. This board testified at length before the Committee on the Public Lands of the House of Representatives in its hearings on the Raker Bill. The statements of its chairman, Colonel John Biddle, formed the most exhaustive, detailed and apparently accurate testimony there given upon the available water supplies for San Francisco.

Secretary of the Interior Fisher, successor of Secretary Ballinger, wished the subject investigated as an absolutely new proposition. John R. Freeman of Providence, R. I., perhaps the ablest engineer in the country upon water supplies, was engaged and spent much time in California upon the subject at a cost of about $300,000. Two years were occupied by these investigations, entirely independent of the work of the board of army engineers. The result of the research of Engineer John R. Freeman was a comprehensive report recommending that this source is preferable to all others, and that the Hetch-Hetchy Valley be developed first and Lake Eleanor Valley and Cherry Creek be made secondary and accessory to Hetch-Hetchy. In November, 1913, Secretary Fisher came to San Francisco and held a hearing lasting ten days, when the entire matter was presented. Within a week of the retirement of Secretary Fisher from the Cabinet with the going out of President Taft, the Secretary recommended that some action be taken on the part of Congress, as the acts of 1901 to 1905, together with the Garfield permit, were somewhat indefinite and the precise authority of the Secretary of the Interior therein questionable. Hence the Raker Bill.

This bill is entitled “A bill granting to the city and county of San Francisco certain rights of way in, over and through certain public lands, the Yosemite National Park and Stanislaus National Forest, and the public lands in the State of California, and for other purposes.” It is in eleven sections.

The bill grants to the city and county of San Francisco necessary rights of way through the public lands of the United States to Hetch-Hetchy Valley, Lake Eleanor and Cherry Valley for the purpose of constructing, operating and maintaining aqueducts “for conveying water for domestic purposes and uses to the city and county of San Francisco, and such other municipalities and water districts as, with the consent of the city and county of San Francisco, or in accordance with the laws of the State of California in force at the time application is made, may hereafter participate in the beneficial use of the rights and privileges of this act,” and “for the purpose of constructing, operating and maintaining power and electric plants, poles and lines for generation, sale and distribution of electric energy; also for the purpose of constructing, operating and maintaining telephone and telegraph lines.”

The whole construction and maintenance is under such conditions and regulations as may be fixed by the Secretary of the Interior and the Secretary of Agriculture within their respective jurisdictions.

Section 7 is as follows:

“That for and in consideration of the grant by the United States as provided for in this act, the said grantee shall be required to assign free of cost to the United States all roads and trails built under the provisions hereof; and, further, after the expiration of five years from the passage of this act the grantee shall be required to pay to the United States the sum of $15,000 annually for a period of ten years, beginning with the expiration of the five-year period before mentioned, and for the remainder of the term of the grant, shall, unless otherwise provided by Congress, pay the sum of $30,000 annually, said sums to be paid on the 1st day of July of each year. Said sums shall be kept in a separate fund by the United States, to be applied to the building and maintenance of roads and trails and other improvements in the Yosemite National Park and other national parks in the State of California. The Secretary of the Interior shall designate the uses to be made of sums paid under the provisions of this section, under the conditions specified herein.”

The sanitary regulations are strict under this bill. No offal or refuse can be placed “in the waters of any reservoir or stream or within 300 feet thereof within the watershed above and around said reservoir sites.”

A filtration plant may be installed at the discretion of the grantee.

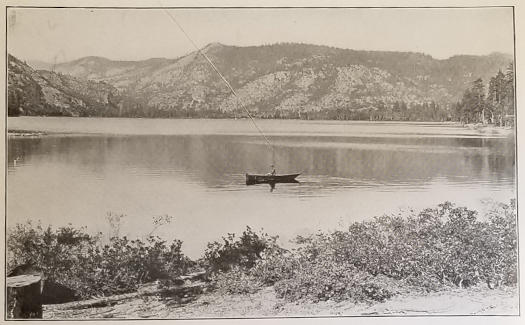

Lake Eleanor as it now is.

The Lake Eleanor Dam Site.

The American City.

Section 9 provides:

“That the said grantee shall recognize the prior rights of the Modesto irrigation district and the Turlock irrigation district as now constituted under the laws of the State of California, or as said districts may be hereafter enlarged to contain in the aggregate not to exceed 300,000 acres of land to receive 2350 second feet of the natural daily flow of the Tuolumne River, measured at the La Grange dam, whenever the same can be beneficially used by said irrigation districts; and that the grantee shall never interfere with said rights.”

The last of section 9 provides:

“That at such time as the aggregate daily natural flow of the watershed of the Tuolumne and its tributaries, measured at the La Grange dam shall be less than said districts can beneficially use and less than 2350 second feet, then and in that event the said grantee shall release, free of charge, the entire natural daily flow of the streams which it has under this grant intercepted.”

Proviso is also made that if the lower irrigation districts desire more than the usual amount they may have it up to a certain quantity by paying a rate fixed by the Secretary of the Interior.

Under section 9 other provisions are:

“That the said grantee shall not divert beyond the limits of the San Joaquin Valley any more of the waters from the Tuolumne watershed than, together with the waters which it now has or may hereafter acquire, shall be necessary for its beneficial use for domestic and other municipal purposes.

“That when the said grantee begins the development of the Hetch-Hetchy reservoir site it shall undertake and vigorously prosecute to completion a dam at least 200 feet high, with a foundation capable of supporting said dam when built to its greatest economic and safe height.

“That the said grantee shall upon request sell or supply to said irrigation districts and also to the municipalities within either or both said irrigation districts, for the use of any land owner or owners therein for pumping subsurface water for drainage or irrigation, or for the actual municipal public purposes of said municipalities (which purposes shall not include sale to private persons or corporations), any excess of electrical energy which may be generated and which may be so beneficially used by said irrigation districts or municipalities.

“That the right of said grantee in the Tuolumne water supply to develop electric power for either municipal or commercial use is to be made conditional upon its installing, operating and maintaining apparatus capable of developing and transmitting, under a general increase in amount, not less than 60,000 horse-power at the end of twenty years. The said grantee shall develop and use hydro-electric power for the use of its people and shall at prices to be fixed under the laws of California, or, in the absence of such laws, at prices approved by the Secretary of the Interior, sell or supply such power for irrigation, pumping or other beneficial use.”

The bill further provides that after twenty years the Secretary of the Interior may require the grantee to develop, transmit and use or offer for sale such additional power less than 60,000 horse-power as the grantee may have failed to develop, transmit, use or sell within the twenty years. In case of the failure of the grantee to carry out these requirements, the Secretary of the Interior is authorized to provide for the development, transmission, use and sale of such power and power not developed or used. For that purpose the Secretary “may take possession of and lease to such person or persons as he may designate” such portion of the property of the grantee as may be necessary for the purpose in view.

The bill also provides that the grantee shall build certain roads and trails in and near Hetch-Hetchy Valley.

(1) The situation of San Francisco at the end of a long peninsula is not one favorable naturally for an abundance of water for a city of nearly half a million. During the golden days of ’49 the water supply came from a stream within the limits of the city. This stream is now in the Presidio and consequently is the property of the United States. Next Lobos Creek water was carried along the shores of the Golden Gate in a wooden flume and through a tunnel, then pumped to high reservoirs, from which it flowed through the city.

As the city grew, the Spring Valley Water Company came into existence and furnished water for the city from a storage reservoir on Pilarcitos Creek, about twenty-five miles from the city. This company has gradually developed its system and about twenty years ago in Alameda county, on the east side of the Bay, began to obtain water from a large area of gravel beds. This water was taken into a reservoir, thence through aqueducts and submarine pipes into San Francisco. San Francisco is now consuming about 50,000,000 gallons of water per day. Of this amount over 8,000,000 gallons come from private wells in different parts of the peninsula. The Spring Valley Water Company furnishes about 41,500,000 gallons, of which about 17,000,000 gallons come from San Mateo County.

City Engineer M. M. O’Shaughnessy of San Francisco testified before the House Committee on the Public Lands in Washington, June, 1913 that this city now needs 75,000,000 gallons of water per day and that about one-third of the city is without water and obliged to haul it in barrels and wagons. Development of the city has been considerably retarded through lack of water. Engineer O’Shaughnessy stated before the committee “for the past three or four months I have been making explorations all over the city in our narrow peninsula, trying to develop what strata there are that will be capable in an emergency of relieving our situation.”

The Spring Valley Water Company is endeavoring to relieve the stress of the situation by starting the construction of the so-called Calaveras dam in Calaveras Valley. But the supply of water behind this is uncertain. The company has built galleries seven or eight feet deep in the gravel beds, into which the water percolates.

After the disaster of 1906 San Francisco bonded itself for $6,000,000 and thereby constructed a high pressure auxiliary water system, operating about seventy-two miles of pipe. A reservoir was built at an elevation of 600 feet, filled through a pumping station drawing salt water from the bay. Another pumping station is now under construction at Fort Mason.

The city expects to buy the Spring Valley Water Company by condemnation in case purchase cannot be effected otherwise. Since the passage of the Raker Bill condemnation proceedings have been begun.

The territory on both sides of the Bay, extending southThe proposition of San Francisco is to build a dam across Hetch-Hetchy Valley 100 feet at the bottom, 760 feet at the top and 300 feet high. This will cover 1930 acres of land with water and extend the water back between seven and eight miles and one and one-half miles wide at the widest point. It is also proposed to build a dam 150 feet high and 1500 feet long at Lake Eleanor. This will flood 1443 acres. The Hetch-Hetchy dam and reservoir will supply in dry seasons 250 gallons a day per capita for 1,000,000 people. Colonel John Biddle of the Board of Army Engineers estimated the cost of the Hetch-Hetchy supply at $77,000,000.

The final development will give to the command of San Francisco between 400 and 500 million gallons a day. The dams will be of massive masonry. The water will be carried through cement-lined steel pressure pipes and concrete lined tunnels ten feet in diameter, cut through the mountains of the coast range. There will be about eighty-three miles of water tunnels. Under the formation of water districts this water can be divided between the two sides of the Bay and approximately 1,000,000 people can now use it. At the upper end of the aqueduct will be two main power-houses capable of developing 145,000 mechanical horse-power twenty-four hours each day of the year.

The present plans of the city provide for its water needs as far ahead as the year 2,000, when at the present rate of growth there will be over 3,000,000 people around the Bay, causing a necessity for 540,000,000 gallons of water daily.

(2) Before the House Committee in Washington, June, 1913, Colonel Biddle testified that he had made a personal examination of every available source of water for the city and in detail described the features of each source, its advantages and disadvantages. Each one was considered not merely as to benefits to San Francisco, but as to whether or not the taking of water would be harmful to other sections now using it for other than domestic purposes, especially for irrigation.

The testimony of Colonel Biddle was that all the water of California was needed for domestic use and irrigation; that as the State is settled more and more, and as better and better facilities are devised for irrigation, more and more the streams are becoming used for these purposes; and that the only available sources of water for San Francisco would reach either the Sacramento or San Joaquin rivers, both flowing into San Francisco Bay, one from the north and one from the south, and together forming a valley about 500 miles long.

The chairman of this committee, Scott Ferris, conducted the examination as follows:

“With the information before you, coupled with the results of these two investigations, if you were a member of this committee, having due regard for the rights of the irrigation people, those of the nature lovers, who believe that you should not interfere with the Yosemite National Park, and the needs of San Francisco, which system would you vote for?”

“Biddle—I would vote for the Hetch-Hetchy system.”

“Chairman—Would you feel, in casting a vote of that kind, that you had inflicted a greater wrong upon the irrigation people and the nature lovers than if you had voted for one of the other systems?”

“Biddle—No, sir.”

The other two members of the Board of Engineers gave this testimony:

“Colonel Cosby—I concur fully with the statement of Colonel Biddle. There is not the slightest question in my mind but that this should be used as the source of water supply, and not only that, but that it will be used as a water supply in a very short time independently of whether this project is adopted or not. I think the pressure will be so great to conserve the water up there that it will be used as a storage reservoir. It is by far the best storage reservoir in that section of the country, and water is so valuable there that they cannot afford to let it run to waste. If you deny the use of it to San Francisco, sooner or later the water will be put to other uses. Somebody will be asking for permission to utilize the Hetch-Hetchy Valley as a storage reservoir for irrigation purposes.”

“Chairman—What do you think of the equitable distribution made of it under the terms of this bill?”

“Colonel Taylor—I do not think the irrigation people have anything to complain of in this bill.”

In 1913 the official report of this Board of Army Engineers is stated:

“The Board believes that on account of the fertility of the lands under irrigation and their aridness without water the necessity of preserving all available water in the valleys of California will sooner or later make the demand for the use of Hetch-Hetchy as a reservoir practically irresistible.”

The testimony of the members of the Board obtained great weight because of their unquestioned technical skill and experience and their positions, entirely disconnected from local prejudice and interest.

That the Raker Bill will prove of considerable advantage to nearly all, if not to all, other interests of the State of California outside the Bay section affected by the Bill seems to have been clearly established.

The total area flooded in the National Park will be 3373 acres. Of these the city owns about 1300 acres. The Government under the Raker Bill will get, by exchange, the difference between 1300 acres and 3142.78 acres, which is 1842.78. The city will take from the Government the difference between 1300 acres and 3373 acres, which is 2072. Hence, the city will trade to the Government as much land as it takes for flooding, lacking 129.22 acres. The forests to be covered by the flooding are in no part of the large redwoods, but are of a size frequently found in a California forest.

Mr. M. M. O’Shaughnessey, City Engineer of San Francisco, Cal.

One of the men most conspicuous in obtaining water and power for San Francisco from Hetch Hetchy Valley.

Mr. Percy V. Long, City Attorney of San Francisco, Cal.

One of the men most conspicuous in obtaining water and power for San Francisco from Hetch Hetchy Valley.

The Chairman of the House Committee before mentioned, finally conducted this examination:

“Chairman—Don’t you think, as a matter of fact, that the roads, trails, telephones, etc., that would come with this water supply development would enhance the usefulness of the park from the standpoint of poor people who cannot now go there?”

“Colonel Biddle—Yes, sir.”

“Chairman—As matters now stand, it would be pretty extravagant for poor people to undertake to go there.”

“Colonel Biddle—It is impossible for them, unless they go in with knapsacks on their backs.”

“Chairman—Poor people do not visit it at all, do they?”

“Colonel Biddle—I would not say that, because it is one of the great delights of Californians, even if they are not well off, to take knapsacks on their backs and go to the Sierras; but they do not really stay long in the Hetch-Hetchy Valley. In the early summer the mosquitoes are bad, in the late summer it is too hot.”

Colonel Cosby of the Board of Engineers gave this testimony:

“Taylor of Colorado—Do you think these roads, provided for in this bill, will make it accessible to a greater number of people?”

“Colonel Cosby—I do. At present I think there are practically only two classes of people who use it, people who are unusually wealthy or people who are unusually strong and healthy and are able to make the trip.”

Seattle, Portland, Oregon, and Pueblo, Col., go into national parks for their water supplies. Los Angeles goes into a government forest reserve and brings its water from Inyo County, 220 miles, by aqueduct and more than twenty miles by tunnels.

Gifford Pinchot, testifying before this Committee, stated: “As we all know, there is no use of water higher than the domestic use. Now the fundamental principle of the whole conservative policy is that of use, to take every part of the land and its resources and put it to that use in which it will best serve the most people.”

George Otis Smith, director of the Geological Survey, stated: “I think we will agree that municipal use is the highest value, next irrigation and lastly power—the generation of hydro-electric energy. I believe the highest possible utilization of the Tuolumne, or of any river, is that which provides, as far as possible for a combination of these three values and the harmonizing of the different uses.”

The Bay section is the largest urban section in California and is doing more business than any other. Its growth is rapid. San Francisco is coming into control of all her municipal utilities. The four great cities on the Bay are one in interest. They will before long probably be one in municipal government. This water power will be of tremendous commercial advantage to these cities. To desire to obtain this water power, is not sordid commercialism or base greed on the part of this section. It is an endeavor to make use of the beneficial forces of nature. It is evidence of a high state of advanced civilization. It is a manifestation of enlightened government. It is fitting and highly proper. It is a cause for praise to this city and the lesser municipalities, not for recrimination and abuse.

That the lake in Hetch-Hetchy will not add to the attractiveness of the beautiful valley is undetermined. Opinions are divided. The lake and its accessories will be the means of bringing thousands to a spot hitherto secluded, isolated and, to many, inaccessible. The highest beneficial use of nature to civilization is conservation. Were nature allowed to rest, grand and gloomy, the tall forests and virgin prairie still would lie between Plymouth Rock and the Golden Gate. The march of civilization may still go on and adopt unto itself the high forces of nature in an age of mighty progress and development, and still usually leave “for him who, in the love of nature, holds communion with her visible forms,” the tall cliff, the high waterfall, the grassy flower-strewn valley, and here and there the virgin forest.

It is easy for the sensitive, the fanciful, and the one of moods and tenses to make themselves believe that an infringement upon what they regard as proper is an outrage upon decency, and an indication that the sordid and mercenary are prevailing, and that unless all of the good and true shall rally to the defense the last bulwarks of decency will be stormed and the citadel of high purpose, noble resolve and immaculate life will be forever lost to a ruthless commercialized greed. The forces of darkness and of distortion are not in overwhelming numbers marching down the pike.

This bill is not an indication that the grisly hand of avarice and the cold hand of ambition are seizing hold of the sacred and inviolate. San Francisco may obtain this water, as good as any in the world, and sufficient for her thousands to come for the next 100 years. She may thereby obtain such water power as during the same time will cause all the wheels of industry on her great Bay to whirl and to whirr. Yet the Yosemite National Park in the entire and Hetch-Hetchy in particular will remain, visited by more than ever before, a thing of beauty and a joy unto the ages yet to be.—San Francisco Chronicle, Jan. 18, 1914.