The Chattanooga Campaign

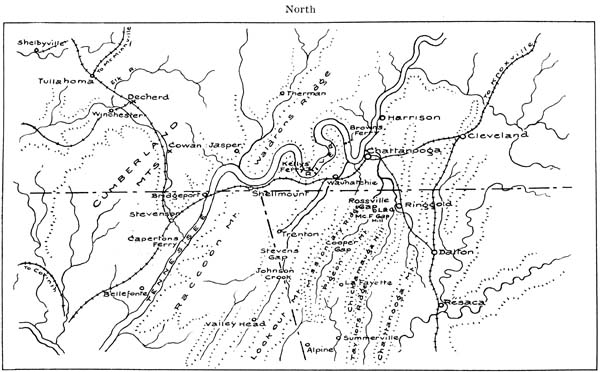

Adapted from Fiske’s The Mississippi Valley in the Civil War, p. 260

Wisconsin History Commission: Original Papers, No. 4

THE CHATTANOOGA CAMPAIGN

With especial reference to Wisconsin’s

participation therein

BY MICHAEL HENDRICK FITCH

Lieutenant-Colonel of the Twenty-first Wisconsin Infantry

Brevet Colonel of Volunteers, Author of “Echoes

of the Civil War as I hear Them”

WISCONSIN HISTORY COMMISSION

MARCH, 1911

TWENTY-FIVE HUNDRED COPIES PRINTED

Copyright, 1911

THE WISCONSIN HISTORY COMMISSION

(in behalf of the State of Wisconsin)

Opinions or errors of fact on the part of the respective authors of the Commission’s publications (whether Reprints or Original Narratives) have not been modified or corrected by the Commission. For all statements, of whatever character, the Author alone is responsible.

DEMOCRAT PRINTING CO., STATE PRINTER

| PAGE | |

| Wisconsin History Commission | ix |

| Introduction | xi |

| The Chattanooga Campaign: | |

| Chapter I. The Preliminary Campaign | 1 |

| Organization | 11 |

| Organization of the Confederate Army | 33 |

| The advance of the Union Army | 39 |

| Chapter II. The Chickamauga Campaign and Battle | 51 |

| The Confederate line on September 20 | 95 |

| The Confederate attack upon the Union right | 104 |

| Wisconsin troops at Chickamauga | 126 |

| Chapter III. The occupation and battles of Chattanooga | 155 |

| The Battle of Lookout Mountain | 194 |

| Wisconsin troops in the Battle of Missionary Ridge | 225 |

| Index | 235 |

| PAGE | |

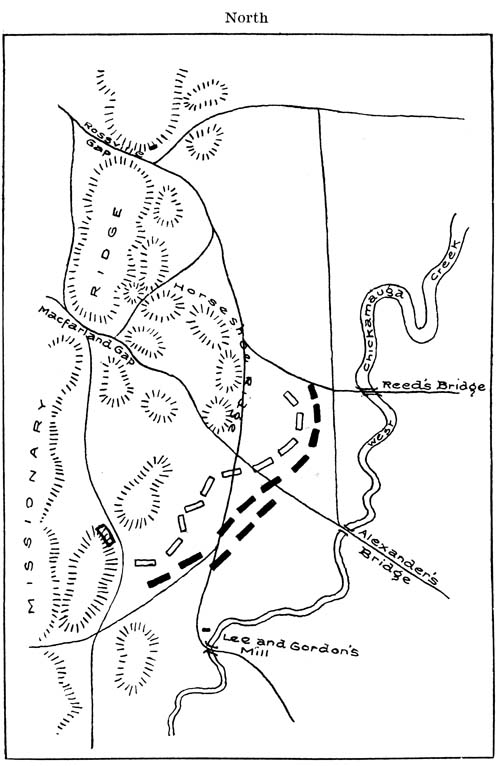

| The Chattanooga Campaign | Frontispiece |

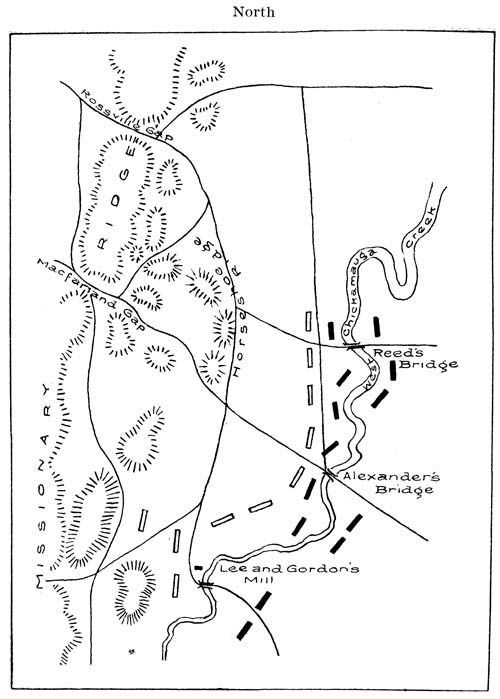

| Chickamauga, September 19, 1863 | 82 |

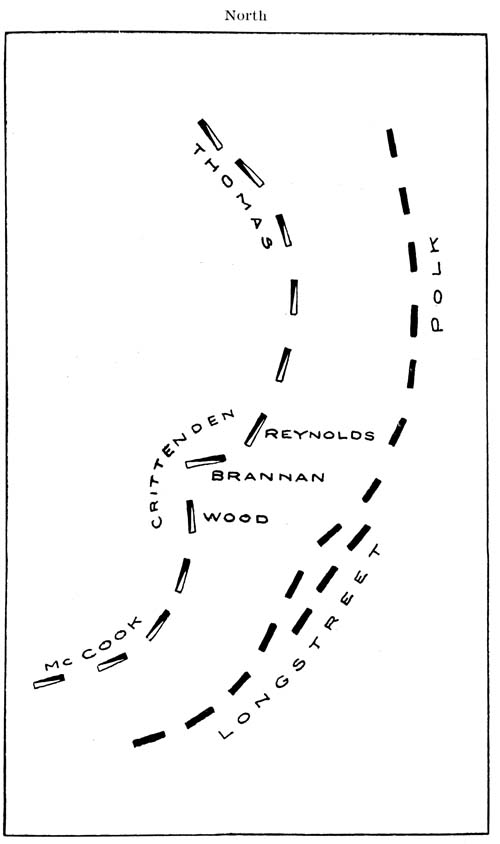

| Chickamauga, morning of September 20, 1863 | 98 |

| The fatal order to Wood, at Chickamauga | 112 |

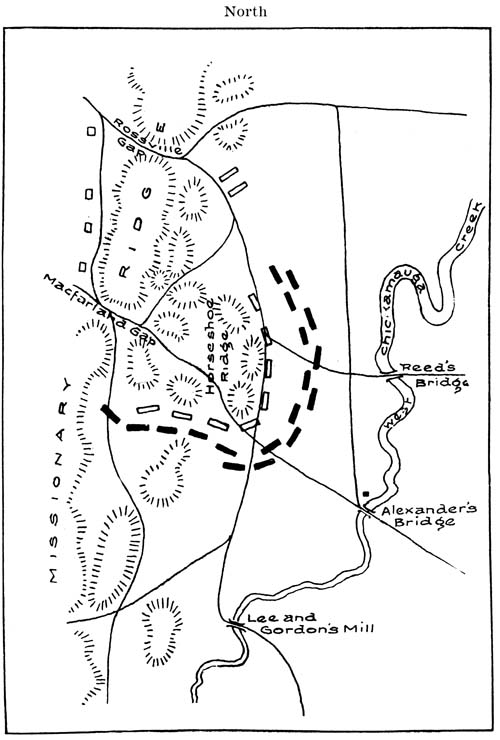

| Chickamauga, evening of September 20, 1863 | 114 |

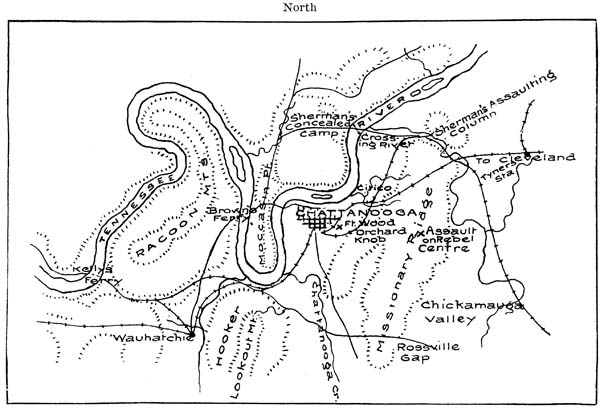

| Chattanooga and Vicinity, November, 1863 | 194 |

(Organized under the provisions of Chapter 298, Laws of 1905, as amended by Chapter 378, Laws of 1907 and Chapter 445, Laws of 1909)

FRANCIS E. McGOVERN

Governor of Wisconsin

CHARLES E. ESTABROOK

Representing Department of Wisconsin, Grand

Army of the Republic

REUBEN G. THWAITES

Superintendent of the State Historical Society of

Wisconsin

CARL RUSSELL FISH

Professor of American History in the University of

Wisconsin

MATTHEW S. DUDGEON

Secretary of the Wisconsin Library Commission

Chairman, Commissioner Estabrook

Secretary and Editor, Commissioner Thwaites

Committee on Publications, Commissioners Thwaites and Fish

[x]

After the battle of Gettysburg in the East, and the siege of Vicksburg in the West, attention was riveted during the later summer and autumn of 1863 on the campaign around Chattanooga. Seated on the heights along the southern border of Tennessee, that city commanded highways running through the very heart of the Confederacy. The result at Gettysburg had demonstrated that no Southern army could invade the North; the Union victory at Vicksburg determined that the Mississippi should run unhindered to the sea. The battles of Chickamauga, Lookout Mountain, and Missionary Ridge not only decided that Kentucky and Tennessee should remain in the Union, but they opened the way for Sherman’s advance on Atlanta and his March to the Sea, which cut the Confederacy in two and made Lee’s surrender a necessity.

The War between the States saw no more stubborn fighting than raged on September 19th and[xii] 20th around the old Cherokee stronghold of Chickamauga. Two months later, occurred the three days’ battle around the hill city of Chattanooga. In all these events, the citizen soldiers of Wisconsin played a conspicuous part, which is herein described by a participant and student of these famous contests. In these battles the reputations of officers were made and unmade, and from them emerged the great generals who were to carry the Union arms to complete victory—Thomas, Sherman, Sheridan, and Grant.

Colonel Fitch, the author of this volume, began his service July 16, 1861, as Sergeant-Major of the Sixth Wisconsin; he was commissioned First-Lieutenant in October following, and in the succeeding April was appointed Adjutant of the Twenty-first; he became, in succession, Major and Lieutenant-Colonel of that regiment, and in March, 1865, was brevetted Colonel of Volunteers “for gallant and meritorious services during the war.” He served chiefly with the Army of Potomac, Army of Virginia, Army of Ohio, and Army of Cumberland. He commanded his regiment from July 1, 1864; and on the March to the Sea; and in the Carolinas headed a wing of the[xiii] brigade, consisting of the Twenty-first Wisconsin, the Forty-second Indiana, and the One Hundred-and-fourth Illinois. Later, he was assigned to the command of the Second Brigade of the Fourteenth Army Corps. He now lives at Pueblo, Colorado.

The maps illustrating the text are adaptations from John Fiske’s The Mississippi Valley in the Civil War (Boston, 1900), which we are permitted to use through the generosity of the publishers, Houghton Mifflin Company.

The Commission is also under obligations to the editorial staff of the Wisconsin Historical Society for having seen the volume through the press. The index was compiled by Dr. Louise Phelps Kellogg, a member of that staff; the proof-reading has been the work chiefly of Misses Annie A. Nunns and Daisy G. Beecroft.

R. G. T.

WISCONSIN HISTORICAL LIBRARY

MARCH, 1911

[1]

The Chattanooga Campaign

The Union Army of the Cumberland, commanded by Major-General William S. Rosecrans, was, in June, 1863, encamped at Murfreesboro, Tennessee, thirty-two miles south of Nashville. It had been lying here since January 5, 1863, having marched from the adjacent field of Stone’s River. The Confederate Army of the Tennessee, was, at the same time, in camp near Tullahoma, forty miles south of Murfreesboro. The Confederates had been defeated at Stone’s River, and had fallen back to Tullahoma at the same time the Union forces had taken up their camp at Murfreesboro.

I will designate the campaign of the latter army, beginning on June 23, 1863, by marching from[2] Murfreesboro, as the “Chattanooga Campaign of 1863.” The various engagements in that campaign, beginning with Hoover’s[1] and Liberty gaps[2] on June 24, down to that of Missionary Ridge, at Chattanooga, on November 25, are incidents of that campaign, and necessary parts of it. A description of the campaign immediately preceding, which started when General Rosecrans assumed command of the army of the Cumberland at Bowling Green, Kentucky, in October, 1862, and ended with the victory of the Union forces in the battle of Stone’s River, and the occupation of Murfreesboro—would give a preliminary historical setting.

In fact, a full history of the Chattanooga campaign may well include the entire movements of the army under General Buell, from October 1, 1862, when it marched out of Louisville, Kentucky, in pursuit of Bragg’s army. The latter was then supposed to be in the vicinity of Frankfort, the capital of that State, engaged[3] in the inglorious occupation of coercing the legislature to pass an ordinance of secession. It was also trying to recruit its ranks from the young citizens of Kentucky, and was restocking its commissary from the rich farms of the blue-grass region. Buell found it, on October 8, at Perryville, seventy-five miles southeast of Louisville. He drove it out of Kentucky, and then marched to Bowling Green, on the railroad between Louisville and Nashville, where in the same month he was superseded, as commander, by Rosecrans.

The Atlanta campaign, immediately following that of Chattanooga—beginning on May 4, 1864, and ending in the capture of Atlanta on September 8 of that year—gives a subsequent historical setting: a connection in time as well as in space, to the operations of the Army of the Cumberland in 1863. By referring to these several important military campaigns of the war, the reader may obtain a synchronous perspective of the most important events in the Middle West, in the department occupied by that army.

A larger setting can be given to this campaign for the capture of Chattanooga, by framing it into[4] the two military fields of the Potomac on the east, and the Tennessee on the west. The Army of the Potomac was opposed to General Lee’s forces. It operated generally between Washington, D. C., and Richmond, Virginia, the latter being the objective. At the time the Army of the Cumberland marched out of Murfreesboro, Lee had taken advantage of the defeat of the army under Hooker from May 1 to 3, 1863, at Chancellorsville, Virginia, and invaded Maryland and Pennsylvania. He was decisively defeated in the battle of Gettysburg, on July 3 following, by Major-General George C. Meade, which closed his campaigning into the North. The old field north of Richmond was reoccupied by the Army of the Potomac, then in command of Meade, as successor to Hooker. It was the latter who, in October, brought the Eleventh and Twelfth corps from the Army of the Potomac to the Army of the Cumberland, at Chattanooga.

On the west of the Army of the Cumberland, was the field of the Army of the Tennessee. Its task was the opening of the Mississippi River. At this time, General U. S. Grant was in command,[5] and had his army at Vicksburg. That stronghold surrendered to him on July 4. Thus the great river was opened. This left the greater part of the Army of the Tennessee free to cooperate in the autumn with the Army of the Cumberland in the battles around Chattanooga; and from that date to assist in the Atlanta campaign, and the March to the Sea, the following year.

It will thus be seen that victory crowned all three of the great armies during the time of the Chattanooga campaign. The confidence and discipline of the Union forces, increased at this time; the discovery, by the governing powers at Washington, of those of the general officers who displayed the most ability; the placing of such officers in the command of the Union armies; and the gradual weakening of the secession armies, were the principal factors contributing to the final end of the war. The resulting campaigns of 1864 and the early part of 1865, sufficed to crush the most powerful rebellion in history.

During its long occupancy of Murfreesboro, the Army of the Cumberland had been somewhat recruited; its equipment was restored to its former[6] condition; and it had also been very much improved, as well as reorganized. During this time the formidable Fortress Rosecrans was built at Murfreesboro, so that a small force might continue to hold the place after the army moved on. This fort proved of great value during the Hood campaign against Franklin and Nashville, in November and December, 1864. Nashville had to be permanently occupied. In fact, the line of railway running from Louisville through Kentucky and Tennessee to Chattanooga, through Bowling Green, Nashville, Murfreesboro, Tullahoma, and Bridgeport, formed the line for carrying supplies, as well as the line of operations. This line, about three hundred and forty miles long, had to be defended and kept open, as the Union Army advanced. As part of it—if not the whole—lying in southern Kentucky and Tennessee, was in the enemy’s country, it was necessary to build and man as the army advanced, a line of forts and block houses, for the protection of this railroad from Nashville to Chattanooga.

By glancing at a good map, the reader can see the immense difficulty involved in the maintenance[7] and defense of this line of supplies consisting of but a single-track railroad. The task required the services of about a fourth of the entire army. The field of operations contained no navigable rivers parallel with the line of advance, upon which gunboats might assist the army in its conflicts with the enemy, and by which the railroad could be assisted in carrying supplies. Two somewhat important streams traversed the field, or rather ran at right angles to it—the Cumberland, on which Nashville is located; and the Tennessee, flowing past Chattanooga. These run westward from the Cumberland Mountains, and for very small craft plying for limited distances only, were navigable within the field of the Army of the Cumberland. But they were of practically no use to the Union Army, except at Chattanooga after its occupation—when for a time, supplies were thus transported from Bridgeport and Stevenson pending the repairing of the railway from those places. There were also two smaller streams in southern Tennessee, running at right angles to the line of operation, called the Duck and the Elk. It was necessary that the[8] Union commander consider these in his advance from Murfreesboro, for they were fordable only in places, and not even there when floods were rampant. They were bridged on the main wagon roads, but these bridges were easily destroyed by the enemy. In its campaigns from Louisville, Kentucky, to Chattanooga, the Army of the Cumberland did not have any assistance from the navy.

In this sketch, it is not necessary to give a tedious account of the most difficult natural obstacles, such as streams, mountains, and distances. These are apparent upon the study of any good map. But mention must be made, that the Union Army faced a chain of mountains lying between it and Chattanooga, at the northwestern edge of which then lay the Confederate Army. This is the plateau of the Cumberland Mountains, extending in a southwest direction from West Virginia to northern Alabama, and covering what is known as East Tennessee. This plateau is about 2,200 feet above tidewater.

Chattanooga is the commercial gateway through which run both the Tennessee River and[9] the railways from north, east, and south. It lies near the junction of the boundary line between Alabama and Georgia, with the south line of Tennessee, at the eastern edge of the Cumberland Mountains, where the Tennessee River, flowing westward, cuts through the range. It is in a direct southeast line from Nashville. The occupation of Chattanooga by the Union Army cut the Confederacy asunder. Hence, the struggle for this position became a fierce one. It cost both sides strenuous campaigns, an immense number of lives, and the destruction of an incalculable amount of property. Its possession by a Union Army was an inhibition of any serious Confederate invasion into Middle Tennessee or Kentucky. The object of the Chattanooga campaign was, therefore, the capture of that city; and ultimately, the destruction of the Confederate Army. Should the capture of the city be accomplished, but the army of the Confederate escape, Chattanooga could be made the sub-base of a new campaign, which would effectually dismember the Confederacy, and greatly hasten its downfall. Such was the Union theory, and this actually occurred.

[10]Followed by the “March to the Sea,” the Atlanta campaign dismembered the enemy’s domain and made possible the end of the war. Lee’s surrender would not have occurred at the time it did (April, 1865), if the homes of his soldiers in the Carolinas, Georgia, Tennessee, and Alabama had not been invaded by the Western armies of the Union; and his rear threatened by Sherman’s troops. These results were made possible only by the capture and continued possession of Chattanooga.

After Sherman had marched through Georgia and South Carolina, and penetrated North Carolina, with a large part of the old Army of the Cumberland and troops from other armies, thousands of Lee’s army deserted, and lined the roads leading back to their homes. When captured and paroled, as they were in immense numbers, by Sherman’s “bummers,” they invariably said that they left Lee when Richmond was abandoned; and would not longer fight for a Confederacy that could not defend their homes. Love of home is greater than love of country; unless the state or nation can protect the homes from invasion and[11] desecration, there is little incentive for its volunteers to fight for the abstract principles of patriotism.

A description of the contour of the field, from Murfreesboro to the Chickamauga, would be only an interminable and profitless account; it being a tangle of flat and rolling land, from Murfreesboro to the gaps in the first hills, where the enemy was met; and thenceforth steep mountains and deep valleys. But the grand strategy subsequently adopted by Rosecrans, depended so entirely upon this contour, that when each separate movement or battle shall hereafter be described, a somewhat minute account of the country contiguous to that particular military event will be given.

After the battle of Stone’s River and while lying at Murfreesboro, the Army of the Cumberland was reorganized. As previously stated, Rosecrans joined it as the successor of Buell, at Bowling Green, in October, 1862. Stone’s River was the army’s first battle under Rosecrans.[12] In that, the army was called the Fourteenth Corps, Department of the Cumberland; and it was divided into three divisions—the centre, right, and left wings. General George H. Thomas commanded the centre, General Alexander McD. McCook the right, and General Thomas L. Crittenden the left. In the new organization, the command was called the Army of the Cumberland, and divided into three corps, the Fourteenth, the Twentieth, and the Twenty-first. Thomas was assigned to the command of the Fourteenth, General McCook to the Twentieth, and Crittenden to the Twenty-first.

Rosecrans came to the Army of the Cumberland with considerable prestige. He was then forty-three years old, having graduated from West Point in 1842. As brigadier-general he had gained the battle of Rich Mountain, Virginia, in July, 1861; won the battle of Carnifex Ferry, Virginia, in September of the same year; as commander of the Army of the Mississippi was victorious in the battles of Iuka in September, 1862, and of Corinth in October following. He came to the Army of the Cumberland with a record of unbroken[13] successes behind him. He was genial, and had untiring industry. His heart and head were devoted to the Union cause. His troops saw him frequently. He was a lover of approbation, and had the confidence of his generals, and the love of his rank and file. The men affectionately nicknamed him “Old Rosy,” and that was his usual cognomen with the whole army. He was a strategist of high order. A study of his Chattanooga campaign will show his eminent ability, in so maneuvering as to compel the enemy to fight in the open. When an engagement was thus brought on, and the actual combat occurred, he lacked (in those which he fought with the Army of the Cumberland) the proper supervision of his line of battle. He too implicitly relied upon his subordinates. During the whole of the Chattanooga campaign his strategy was of the first order; but at both Stone’s River and Chickamauga, the right of his line was too attenuated; in both engagements, disaster occurred to this part of his troops.

The chief of staff to Rosecrans was General James A. Garfield, who was then thirty-one years[14] old, brainy and very energetic. Although not a graduate of West Point, he was possessed of decided military instincts. Before the war he was an instructor in, and later president of, Hiram College, Ohio; and later was a member of the Ohio Senate. Entering the army as lieutenant-colonel of an Ohio regiment, he defeated Humphrey Marshall in the battle of Middle Creek, Eastern Kentucky, January 10, 1862, and was that year promoted to be a brigadier-general. Able and conscientious as an officer, he was perhaps rather too democratic and academic to become a typical soldier. He became very nervous at the delay in moving from Murfreesboro, and instituted an inquiry into the reasons, both for and against an earlier advance on Tullahoma. A majority of the subordinate generals in the Army of the Cumberland supported General Rosecrans in his delay. Later on, notice will be taken of Garfield’s service in the battle of Chickamauga, and his retirement to a seat in Congress.

Next to Rosecrans, the most important figure among the subordinate commanders was Thomas. He was then forty-seven years old, and a graduate[15] of West Point in 1840. Between that time and the Civil War, he served in the war with Mexico, and against the Indians in the West. At the beginning of the War between the States he was major of the Second Cavalry, of which Albert Sidney Johnston was colonel, Robert E. Lee lieutenant-colonel, and William J. Hardee senior major. Thomas was the only field officer of that regiment who remained loyal to the Union. He was commissioned colonel of the regiment, reorganized it, and during the first battle of Bull Run served in General Patterson’s detachment, in the Shenandoah Valley. He was commissioned brigadier-general in August, 1861, and was sent to Kentucky to serve in the then Army of the Ohio (afterwards the Army of the Cumberland), under General Robert Anderson of Fort Sumter fame. Thomas organized the first real little army of that department at camp Dick Robinson, Kentucky, between Danville and Lexington; and in January, 1862, with this force defeated the Confederate troops under Zollicoffer, at Mill Springs, Kentucky, on the Cumberland River. This force and this place were then the extreme[16] right of the Confederate line of defense, of which Forts Donelson and Henry, in Tennessee, and Paducah, Kentucky, constituted the left. This line was fortified, and extended through Bowling Green. A month after General Thomas had turned its right at Mill Springs, General Grant also turned its left, by capturing both Forts Donelson and Henry. This necessitated the establishment of a new Confederate line farther south, the evacuation of Kentucky, and the eventual loss to the Confederates of Middle Tennessee. Just before the battle of Perryville, Kentucky, the President offered General Thomas, on September 29, 1862, the command of the Army of the Cumberland at Louisville, but he declined it. Buell was in command of the army during the battle of Perryville; after which he was superseded by Rosecrans. Thomas was a soldier, pure and simple, having never resigned from the army after his graduation from the Military Academy. He had shown great ability in the recent battle of Stone’s River, as well as in every position in which he was placed, prior to that battle. It will be seen, further on, what important movements[17] he directed in the battle of Chickamauga, which saved the Army of the Cumberland from imminent disaster.

General McCook, who commanded the Twentieth Corps, belonged to the younger class of West Point graduates, of which General Sheridan was a type. He graduated in 1853, and was thirty-two years old in April, 1863. He was a handsome man, of striking presence, and commanded with some dramatic effect.

General Crittenden, commanding the Twenty-first Corps, was then a year older than Rosecrans—forty-four years. He was not a graduate of West Point, but had served as a volunteer in the Mexican War. He was a son of U. S. Senator John J. Crittenden, of Kentucky.

The Fourteenth Corps was made up of four divisions. These were commanded respectively by Major-General Lovell H. Rousseau, Major-General James S. Negley, Brigadier-General John M. Brannan, and Major-General Joseph J. Reynolds. Each of these divisions contained three brigades, and three light field batteries.[18] The brigades were generally composed of four regiments, but sometimes of five.

The Twentieth Corps contained three divisions, commanded respectively by Brigadier-General Jefferson C. Davis, Brigadier-General Richard W. Johnson, and Major-General Philip H. Sheridan. These were made up of brigades of four and five regiments of infantry and three batteries of artillery.

The Twenty-first Corps likewise was organized into three divisions, commanded by Brigadier-General Thomas J. Wood, Major-General John M. Palmer, and Brigadier-General Horatio P. Van Cleve, each with three brigades and several batteries. The artillery of each division of the army was commanded by a chief of artillery.

All of the cavalry were organized into a separate corps, commanded by Major-General David S. Stanley. This was divided into two divisions; the First was composed of two brigades, and commanded by Brigadier-General Robert B. Mitchell; the Second, also of two brigades, was commanded at first by Brigadier-General John B. Turchin.[19] Prior to the battle of Chickamauga, Turchin was assigned to an infantry brigade. These cavalry brigades were much larger than the infantry brigades, for they contained five or six regiments. Generally there was a battery attached to each brigade of cavalry.

On June 8, 1863, a reserve corps was organized, with Major-General Gordon Granger in command. It contained three divisions, commanded by Brigadier-General James D. Morgan, Brigadier-General Robert S. Granger, and Brigadier-General Absalom Baird, respectively. The last-named was afterwards transferred to the First Division, Fourteenth Corps, being succeeded by General James B. Steedman. It was the duty of this reserve corps to guard the communications in the rear of the army; but it was also subject, in emergency, to be ordered to the front, as will be seen further on—for example, when General Granger with three brigades, marched from Bridgeport, Alabama, to Rossville Gap, Georgia, and assisted very greatly in the battle of September 20, at Chickamauga. In this reserve corps should also be included certain miscellaneous[20] troops, scattered in forts along the line of the Louisville & Chattanooga railroad, such as Nashville, Clarksville, and Gallatin, Tennessee. At this time Colonel Benjamin J. Sweet of the Twenty-first Wisconsin Infantry was in command of the forces at Gallatin. He had been wounded severely in the battle of Perryville, Kentucky, on October 8, 1862, and was not able to endure active service at the front.

The First Brigade of the Third Division, reserve corps, was stationed at Fort Donelson, Tennessee, and commanded by Colonel William P. Lyon, of the Thirteenth Wisconsin Infantry, that regiment being a part of the garrison. The First Wisconsin Cavalry, commanded by Colonel Oscar H. LaGrange, was attached to the Second Brigade of the First Division of the cavalry corps. Captain Lucius H. Drury, of the Third Wisconsin Battery, was chief of artillery to the Third Division of the Twenty-first Corps.

This organization of the Army of the Cumberland remained substantially the same, until after the battle of Chickamauga. Sometime in the latter part of July, or first part of August, General[21] Rousseau received leave of absence, and General Absalom Baird was assigned on August 24 to command the First Division of the Fourteenth Corps in his stead. Baird remained in command of this division until after the battle of Chickamauga, when Major-General Lovell H. Rousseau again took the command. Rousseau was a loyal Kentuckian, who at the very beginning of hostilities had raised a regiment for the service of the Union. He was then forty-five years old and had served in the Mexican War. He was a spectacular officer of great bravery, who is entitled to much credit for his unflinching devotion to the Union, under circumstances which made other men desert our cause.

Major-General John M. Palmer of Illinois, a lawyer of eminence in his State, was an officer of more than usual ability. He was not a West Point graduate, and was forty-six years old.

General Granger was then forty-two years old, a graduate of West Point in the class of 1845, and had fought in the Mexican War. It will be noticed that many of the general officers of the Army of the Cumberland served in the Mexican[22] War. The experience they then acquired in the field, in actual campaigning, and by some of them in actual battle, undoubtedly served to give to the Army of the Cumberland much of its esprit de corps, and its general success in winning battles and in holding the territory over which it marched. General Granger was an unusually able and gallant officer. Later on, it will be told what important service he rendered General Thomas in the battle of Chickamauga.

Major-General Philip H. Sheridan was then thirty-two years old. He graduated at West Point, rather low in his class, in 1853. At the outbreak of the war he was promoted to a captaincy. In May, 1862, he was commissioned colonel of cavalry in the volunteer service, and brigadier-general of volunteers July 1, 1862, being made a major-general on December 31, 1862. He had commanded a division in the battle of Perryville, Kentucky, in October, 1862, and was at Stone’s River December 31, 1862, to January 3, 1863. He is entitled to this special notice more for what he became, than for what he had done prior to the Chattanooga campaign. He[23] had as yet shown no extraordinary ability as a commander. His age was the same as that of his corps commander, General McCook, and they graduated in the same class at West Point.

Generals Absalom Baird, John M. Brannan, Jefferson C. Davis, Thomas J. Wood, R. W. Johnson, and David S. Stanley were all officers of the old regular army, soldiers by profession, whose minds were not distracted from their duties in the field by politics or academic proclivities. They were brave and always at the front, working for success with military spirit. All of them served faithfully until the close of the war. Davis, Wood, and Stanley afterwards commanded corps—commanded them ably and with notably unassuming manners. There was no taint about these officers of “playing to the galleries.” They were not expecting applause, and did their work without brass bands or reporters to sound their achievements to the country. Such were the officers of this great central army.

What of the musket bearers? Who were they? Where did they come from? Were they soldiers by profession or merely citizens in[24] arms for a special purpose? I have already said that very many of the general officers of the Army of the Cumberland were of the regular army. The United States regular army was represented only, however, by one brigade of the regular troops, namely, the Third Brigade of the First Division of the Fourteenth Corps, commanded by Brigadier-General John H. King. Thus almost the entire rank and file of the army were volunteers. The regiments were filled and officered by the executives of the different states. The men were mustered into the service of the General Government as volunteers for three years or during the war. These volunteers were citizens of the states, and each company elected its officers among those who had originally enlisted as privates. The musket bearers were men from all callings in life—farmers, mechanics, merchants, teachers, students, and laborers. They were the voters who made up the political divisions of the townships, counties, and states, whose ultimate power lay in their voting franchise which they shared with the men, who—for various reasons—remained at their homes during the war. The volunteer-regiments[25] which composed the Army of the Cumberland were mostly from the states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Kentucky, Wisconsin, and Minnesota; Pennsylvania had three infantry and two cavalry regiments; Missouri had two regiments, and Kansas one; Tennessee was represented by several regiments. The great bulk of the troops came, however, from the states north of the Ohio River—the Northwest Territory. No drafted men in the army partook in the Chattanooga Campaign of 1863. These volunteers sought the service and understood what it involved. Very few of them knew what regimentation meant, and the great majority had never before handled a musket. But they were young and teachable. They readily learned the drill, and became good marksmen. These soldiers realized very soon that a clean musket, plenty of ammunition, and obedience to orders, composed the military moral code of efficiency. By the laws of their states, they were entitled to vote for officers and affairs at home, and to have their votes counted, just as if they had been cast at home. The soldiers received during the prolonged war as many[26] furloughs as were compatible with the exigencies at the front, and thus they were occasionally enabled to visit the folks at home during their strenuous service. The intelligence of the private soldier was often superior to that of his officer. Nevertheless he obeyed faithfully that officer’s commands, because he fully understood that discipline could be maintained only by implicit obedience and the object of his service, viz: the suppression of a rebellion be accomplished. Many of these volunteers enlisted directly from the public schools, which they were attending. They had been taught the history of their country; how its independence from the tyranny of a foreign power had been gained by the valor and patriotism of Washington and his volunteers, that by the discipline and perseverance of the revolutionary soldiers the sovereignty of a foreign king had been transferred to the citizens of their native land; that a new foe was now trying to dismember the nation, and that the corner stone of the Union was the principle, that all power is derived from the people. These volunteers were convinced that no power had the right to protect the maintenance and perpetuation[27] of slavery. They were soldiers therefore until the Union was re-established; and they tacitly resolved to fight until slavery was abolished. Such was the personnel of the Army of the Cumberland.

Wisconsin was well and ably represented in this army by the following organizations, viz: The First, Tenth, Fifteenth, Twenty-first, and Twenty-fourth volunteer infantry; the First Cavalry; and the Third, Fifth, and Eighth light batteries.

The First Wisconsin Infantry was a noted regiment in more than one way. It served as the only three-months regiment from Wisconsin, and was organized under President Lincoln’s first call for 75,000 men. It was mustered out after the ninety days’ service August 21, 1861, and reorganized under the second call for three years’ service. This second mustering was completed October 19, 1861. The regiment proceeded from Milwaukee to Louisville, Kentucky, and the volunteers served during the next three years in the Army of the Cumberland. It was active in various parts of Tennessee during the first year of its service,[28] marching as far as Bridgeport, Alabama, to which place it returned during the campaign of Tullahoma. John C. Starkweather was its first colonel. He was made commander of the brigade when it was reorganized at Murfreesboro, and Lieutenant-Colonel George B. Bingham commanded the regiment. This regiment had fought in both the battles of Perryville and Stone’s River. It was assigned to the Second Brigade of the First Division of the Fourteenth Corps.

The Tenth Wisconsin Infantry was mustered into the service October 14, 1861, at Milwaukee. Alfred R. Chapin was its first colonel. Proceeding to Louisville, Kentucky, it became part of the future Army of the Cumberland, and advanced with General O. M. Mitchell’s forces to Stevenson and Huntsville, Alabama, in the spring and summer of 1862. The regiment returned to Louisville in September with Buell’s army and engaged in the battles of Perryville and Stone’s River. When the reorganization at Murfreesboro took place this regiment became a part of Scribner’s Brigade of Rousseau’s Division of the Fourteenth Corps. Almost side by side with the[29] First and Twenty-first infantries, it took part in all engagements.

The Fifteenth Wisconsin Infantry was a Scandinavian regiment, and its first colonel was Hans C. Heg. It was mustered into the service on February 14, 1862, at Madison. It had taken part in the siege of Island Number Ten. It did not join the Army of the Cumberland until just before the battle of Perryville, in which it took active part, as in the battle of Stone’s River. In the reorganization at Murfreesboro, it became a part of the Third Brigade—and was commanded by its colonel, Hans C. Heg, of the First Division, Twentieth Corps.

The Twenty-first Wisconsin Infantry was organized at Oshkosh, in August, 1862, and on September 11, 1862, it joined the Army of the Cumberland at Louisville, Kentucky. Benjamin J. Sweet was its first colonel; he was so severely wounded in the battle of Perryville as to be disabled for further field service. This regiment was brigaded with the First Wisconsin Infantry at Louisville, and served also in the battles of Perryville and Stone’s River. At the time of[30] the reorganization at Murfreesboro it was commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Harrison C. Hobart, and it was assigned to the Second Brigade of the First Division of the Fourteenth Corps.

The Twenty-fourth Wisconsin Infantry was mustered into the service at Milwaukee, August 21, 1862. It proceeded to Louisville, where it became a part of the Army of the Cumberland. This regiment engaged in the battles of Perryville and Stone’s River, and was assigned to the First Brigade, Third Division, Twentieth Corps in the reorganization at Murfreesboro; its commander was Lieutenant-Colonel Theodore S. West.

The First Wisconsin Cavalry was mustered into the service at Kenosha, on March 8, 1862, with Edward Daniels as its first colonel. It was sent to Benton Barracks, near St. Louis. There and in various parts of Missouri its first year of service was performed. On June 14, 1863, at Nashville, it was made a part of the Army of the Cumberland, with which it was from that time identified until the close of its service. This regiment’s activity in the Tullahoma campaign, the Chickamauga campaign, and in pursuit of Confederate[31] cavalry in the Sequatchie Valley on October 2, 1863, and along the line of communication during the battles around Chattanooga is mentioned in more appropriate places, relating to the general movements of the army. It was commanded by Colonel Oscar H. LaGrange, and assigned to the Second Brigade, First Division, Cavalry Corps, during the reorganization.

The Third Wisconsin Light Battery was mustered into the service at Racine, Wisconsin, October 10, 1861. Lucius H. Drury was its first captain. The regiment went first to Louisville, then to Nashville, whence it marched with Buell’s army in order to reinforce General Grant at Shiloh. It was engaged in the battles of Perryville and Stone’s River. The regiment was assigned to the Third Brigade, Third Division of the Twenty-first Corps, and was commanded by Lieutenant Courtland Livingston.

The Fifth Wisconsin Battery was mustered into the service at Racine, October 1, 1861. Oscar F. Pinney was its first captain. March 16, 1862, it arrived at St. Louis. Afterwards it proceeded to New Madrid, Missouri (on the Mississippi[32] River), and became a part of General John Pope’s army, in the reduction of Island Number Ten. It was also active at the siege of Corinth, and marched about two hundred miles from Iuka, Mississippi, to Nashville, Tennessee, where the regiment joined the forces of General Buell. On the northward march in September, 1862, these forces engaged in the battles of Perryville and Stone’s River; the service of the Fifth Wisconsin Battery was of the most active and valuable kind. It was commanded by Captain George Q. Gardner, and was assigned to the First Brigade, First Division, of the Twentieth Corps.

The Eighth Wisconsin Battery was mustered into the service on January 8, 1862, and moved to St. Louis on March 8, 1862. Its first captain was Stephen J. Carpenter. It formed a part of the force that moved to Forts Leavenworth and Riley, Kansas, in April and May, 1862, whence it moved to Columbus, Kentucky, and finally took part in the campaign at Corinth and Iuka, Mississippi. From there it marched to Nashville, and Louisville, engaging in the battles of Perryville and Stone’s River. It was commanded[33] by John D. McLean, lieutenant, and was assigned to the Third Brigade, First Division of the Twentieth Corps.

The Confederate Army which confronted the Army of the Cumberland on June 24, 1863, was officially called the Army of the Tennessee. It was divided into four corps—two of infantry and two of cavalry. General Leonidas Polk commanded one infantry corps, and General William J. Hardee the other. The cavalry corps were commanded by General Joseph Wheeler, and General N. B. Forrest. In addition to the artillery, attached to the regular corps, there was also a reserve artillery. In General Bragg’s return of the “aggregate present” of his army in the field on June 20, 1863, his figures are 55,070. His reserve troops were not included in this statement; they were scattered throughout the districts of Tennessee and northern Alabama.

At this same date the return of the Army of the Cumberland was 71,409 of all arms—exclusive[34] of the reserve corps—as “aggregate present.” It will be noticed later on, that the Confederates greatly increased their numbers prior to the battle of Chickamauga, but that the Union Army received no reinforcements; on the contrary, it lost heavily by sickness as the army advanced.

General Bragg was at that time forty-six years old. He had distinguished himself in the Mexican War. He commanded the Confederate Army in both the battles of Perryville and Stone’s River. He did not win either of these, having in both of them abandoned the field to the Union forces.

Perhaps the most distinguished officer in Bragg’s army was Major-General John C. Breckenridge. He was more distinguished, however, as a politician, than as a military leader. He was forty-two years old. Before the war he had been a member of Congress, vice-president of the United States, and in 1860 the presidential candidate of the Southern democrats. At the breaking out of the war, he was a United States Senator from Kentucky. He was a Confederate officer at Shiloh in April, 1862, and commanded the[35] right wing of the Southern forces at Stone’s River.

General Leonidas Polk was fifty-seven years old in 1863. He was a bishop of the Episcopal church. He graduated from West Point in 1827, but resigned his commission in the army in the same year. He entered the Confederate Army as a major-general, but was soon promoted to lieutenant-general.

General William J. Hardee was forty-seven years old at this time. He graduated from West Point in the class of 1838. He served with distinction in the Mexican War. He entered the Confederate service as colonel, commanded a corps at Shiloh in 1862; was appointed lieutenant-general in October, 1862; and commanded the left wing of the Southern Army at Perryville.

General Simon Bolivar Buckner, another officer in the Confederate Army, was forty years old, and a West Pointer. He surrendered Fort Donelson to General Grant in February, 1862.

Of the two Confederate cavalry commanders, General Nathan B. Forrest was by far the greater. He was a rough, uneducated man, but of great force as a partisan leader. When Lord[36] Wolseley was at the head of the British Army, he said of Forrest that he was the ablest cavalry leader that was produced by our War between the States. He was personally brave, possessed a fine physique, and had sufficient magnetism to inspire the soldiers of his command to great activity and endurance. During the war twenty-nine horses were shot under him, and he took active part in thirty-one encounters, it has been stated. He was wounded several times.

The rank and file of the Confederates were made up of the citizens of the Southern states, in much the same manner that the Union Army was composed of Northern citizens. They fought with a certain fanaticism, for what they deemed their rights. It is singular, that at the beginning of the war, so universal a desire to dissolve the Union seized the great majority of the white people of the South, although they might not be slave owners. They made most efficient soldiers and suffered many hardships, unknown to the soldiers of the Union Army. The martial temperament, inherited as well as acquired through personal habits, was more predominant in the South than in[37] the North. The Southerners lived largely a country-life before the war; they rode horseback, hunted with hounds, and had become more familiar with firearms than the Northerners. The practice of duelling continued longer with them than with the men of the North, who were not as fiery tempered as those of the South. These traits made them soldiers by nature; they liked to serve in the field, and were therefore difficult to conquer. They seemed more lithe and active, than the staid volunteers from the colder North. They have claimed, that they were largely outnumbered; that is true in the aggregate, but not so true on the firing line. The battles of Stone’s River and Chickamauga illustrate these facts. The numbers in both armies were quite evenly matched. During the last year of this war there was little difference in the fighting qualities of the veteran regiments on both sides. The rebellion was put down according to the rules of warfare, and whatever that result may have cost in numbers, it was worth the price. Not every revolt against authoritative power has been suppressed by superior numbers, not even that of the[38] thirteen colonies against England’s. At first, the power of England seemed so overwhelming, that scarcely any one expected that colonial independence could be gained. Foreign nations did not believe that this rebellion could be suppressed, notwithstanding the superiority in numbers of the Union Army.

The wonderful thing about it is, that Lincoln persevered to the end, against discouragements and disasters which seemed, at the time, to be insurmountable. Fortunately there was no compromise, the rebellion was simply crushed, no terms were made; and no promises given to embarrass the reconstruction. Of course, it required large armies and grim determination to reach the goal. The great fact is, not that the Union armies outnumbered the Confederate forces, but that the Union itself was restored. The war was merciless; all wars are. Mercy, pity, and the extension of the hand of helpfulness came after the war was over, not while it was going on. Each side did all it could to fight and win its battles. The North had the larger number of citizens from which to draw, and of course, availed itself of that advantage. The[39] South would have put larger armies into the field if it could have done so; it did use every available man, however, and fought its best. The South might have conquered the Union by overwhelming forces, could such have been secured, but available men were lacking. At all events, the rebellion was crushed by means of legitimate warfare, and the Union was restored.

The Confederate Army, commanded by General Braxton Bragg, lay in front of Tullahoma,[3] where Bragg had his headquarters. There was a large entrenched camp at the junction of the Nashville & Chattanooga railroad. This camp and the McMinnville branch was each a secondary depot for commissary stores, while the base of supplies was at Chattanooga. Its front was covered by the defiles of the Duck River, a deep narrow stream edged by a rough range of hills, which divides the “Barrens” from the lower level of Middle Tennessee. The Manchester Pike[40] passes through these hills at Hoover’s Gap, nineteen miles south of Murfreesboro, ascending through a long and difficult canon to the “Barrens”. The Wartrace road runs through Liberty Gap, thirteen miles south of Murfreesboro and five miles west of Hoover’s. There were other passes through these hills, but the enemy held all of them. Bragg’s main position was in front of Shelbyville, about twenty-eight miles southwest of Murfreesboro, and was strengthened by a redan line extending from Horse Mountain, located a little to the north of Shelbyville, to Duck River on the west, covered by a line of abatis. The road from Murfreesboro to Shelbyville was through Guy’s Gap, sixteen miles south of Murfreesboro. Polk’s corps was at Shelbyville, Hardee’s held Hoover’s, Liberty, and Bellbuckle gaps, all in the same range of hills. It was not wise to move directly against the entrenched line at Shelbyville, therefore Rosecrans’s plan was to turn the Confederate right and move on to the railroad bridge, across Elk River, nine miles southeast of Tullahoma. To accomplish this, it was necessary to make Bragg believe that the advance would be[41] by the Shelbyville route. The following dispositions were therefore made: General Granger’s command was at Triune on June 23, fifteen miles west of Murfreesboro; some infantry and cavalry advanced that same day toward Woodbury seventeen miles to the east of Murfreesboro; simultaneously Granger sent General Mitchell’s cavalry division on the Eaglesville and Shelbyville Pike, seventeen miles southwest of Murfreesboro, in order to make an attack on the enemy’s cavalry, and to drive the enemy’s infantry guards on their main line. General Granger, with his own infantry troops and Brannan’s division, moved—with ten days rations—to Salem.[4]

On June 24, Granger moved to Christiana, a small village a few miles southwest of Murfreesboro, south of Salem, towards Shelbyville. On the same day Palmer’s division, and a brigade of cavalry, were ordered to move to the vicinity of Bradyville, fourteen miles southeast of Murfreesboro; his advance columns were to seize the head of the defile leading up to the “Barrens” by an obscure[42] road to Manchester thirty-five miles southeast, and by way of Lumley’s Stand seven miles east of Hoover’s Gap. General Mitchell accomplished his work after a sharp and gallant fight. McCook’s corps advanced on the Shelbyville road, and turning to the left, six miles out, moved two divisions via Millersburg, a small village eleven miles south of Murfreesboro. By advancing on the road to Wartrace[5] he seized and held Liberty Gap.

Five companies of the Thirty-ninth Indiana mounted infantry opened the fight for Liberty Gap on June 24; they were followed by Willich’s brigade. General R. W. Johnson, in his report[6] says: “Here I placed at the disposal of General Willich a portion of the Second Brigade, Colonel Miller commanding, who sent the Seventy-seventh Pennsylvania and the Twenty-ninth Indiana to the right of the Fifteenth Ohio, then to change direction to the left, sweeping the hillside on which the Confederates were posted. This movement was handsomely executed. As[43] soon as the change to the left had been made, General Willich ordered his entire line forward. Under his own eye and management, the Confederates were driven at every point, their camps and camp equipages falling into our hands, and Liberty Gap was in our possession.” The next morning Carlin’s and Post’s brigades of Davis’s division came to Johnson’s support. The Confederates attacked quite fiercely, but were repulsed, and finally retired. The enemy here was Cleburne’s division; he reported a loss of 121.

General Thomas advanced on the Manchester Pike with the Fourteenth Corps in order to make an attempt to take possession of Hoover’s Gap. Major-General Crittenden was to leave Van Cleve’s division of the Twenty-first Corps at Murfreesboro, concentrate at Bradyville, fourteen miles southeast of Murfreesboro, and there await orders. All these movements were executed with success in the midst of a continuous rain, which so softened the surface of the roads, as to render them next to impassable. The advance of the Fourteenth Corps on Hoover’s Gap, June 24, was Wilder’s brigade of mounted infantry, of[44] Reynolds’s division; it was followed by the other two brigades of the same division. Wilder struck the enemy’s pickets within two miles of his camp at Murfreesboro and drove them through Hoover’s Gap to McBride’s Creek. The two rear brigades moved up and occupied the Gap. Soon afterwards Wilder’s brigade was attacked by a portion of Stewart’s division; this brought the rest of Reynolds’s division, and eventually the regular brigade of Rousseau’s division to his assistance.

On June 25 and 26, Rousseau’s, Reynolds’s, and Brannan’s divisions cooperated in an advance on the enemy; after a short resistance the enemy fled to Fairfield, five miles southwest of Hoover’s Gap, towards which place the Union pickets had advanced.

The First and the Twenty-first Wisconsin infantry were actively engaged at Hoover’s Gap, but suffered no casualties. The Seventy-ninth Pennsylvania, in the same brigade, lost twelve men, one wounded. General John T. Wilder’s brigade lost sixty-one men killed and wounded.

On June 27, Gordon Granger captured Guy’s Gap and the same evening took Shelbyville,[45] the main Confederate Army having retreated. The Union headquarters reached Manchester on June 27. Here the Fourteenth Corps concentrated during the night. Part of McCook’s arrived on the 25th; the rest of it did not reach Manchester before the night of the 29th. The troops and animals were very jaded. Crittenden’s Twenty-first Corps was considerably delayed. The troops encountered continuous rains and bad roads, and the last division did not arrive at Manchester before June 29, although an order to march there speedily was received on the 26th. On arrival it was badly worn out.

The forces were at last concentrated on the enemy’s right flank, about ten miles northeast of Tullahoma. During the incessant rain of June 30, an effort was made to form them into position in anticipation of an attack by the enemy. The wagons and horses could scarcely traverse the ground, which was quite swampy. Fortunately the enemy’s forces suffered likewise. What was trial and hardship to one of the armies—on account of the weather—was equally detrimental to the other side. That[46] army which could overcome quickly and victoriously the climatic conditions, had the best chances to win in the martial contest. In forming a line at Manchester to resist an attack, the Fourteenth Corps occupied the centre, with one division in reserve, the Twentieth Corps on the right and the Twenty-first on the left. The last two corps had each one division in reserve. The Union Army was on the right flank of the Confederate line of defense, and of course expected to be attacked. But it was not.

In the meantime Stanley’s cavalry, supported by General Gordon Granger’s infantry and all troops under Granger’s direction, had attacked the enemy at Guy’s Gap—sixteen miles south of Murfreesboro and five miles west of Liberty Gap—and had driven the Confederate troops back to their entrenchments. Then, finding that the enemy’s main army had fallen back, Stanley captured the gap by a direct and flank movement with only three pieces of artillery. The cavalry unexpectedly captured Shelbyville with a number of prisoners, a quantity of arms, and the commissary stores. The reports of this cavalry[47] battle show the retreat of the enemy to Tullahoma forty miles southeast of Murfreesboro, where it was supposed that he intended to make a stand. But on July 1, General Thomas ascertained that the enemy had retreated during the night from Tullahoma. Some Union divisions occupied Tullahoma about noon that same day, while Rousseau’s and Negley’s divisions pushed on by way of Spring Creek overtaking late in the afternoon the rear guard, with which these divisions had a sharp skirmish.

On July 2, the pursuit was made by the Fourteenth and Twentieth corps. The bridge over the Elk River had been burned by the enemy while retreating. The stream had risen and the cavalry could barely ford the river. On July 3, Sheridan’s and Davis’s divisions of the Twentieth Corps, having succeeded in crossing the Elk River, pursued the enemy to Cowan, on the Cumberland plateau, eighteen miles southeast of Tullahoma. Here it was learned that the enemy had crossed the mountains; and that only cavalry troops covered its retreat. Meanwhile the Union Army halted to await needed supplies,[48] which had to be hauled by wagon from Murfreesboro over miserable roads. These supplies had to be stored at the railway station, nearest to the probable battlefield; and before the army could advance over the Cumberland plateau—where a battle would probably soon ensue—the railway had to be repaired. General Rosecrans in his official report says: “Thus ended a nine days’ campaign, which drove the enemy from two fortified positions and gave us possession of Middle Tennessee, conducted in one of the most extraordinary rains ever known in Tennessee at that period of the year, over a soil that became almost a quicksand.”[7] He claims—perhaps justly—that it was this extraordinary rain and bad roads, which prevented his getting possession of the enemy’s communications, and debarred him from forcing the Confederate Army to fight a disastrous battle. He speaks very highly of James A. Garfield, his chief of staff, saying: “He possesses the instincts and energy of a great commander.”

The Union losses during the “Tullahoma[49] Campaign”—thus named in the official record—were as follows: 14 officers killed, and 26 wounded; 71 non-commissioned officers and privates killed, and 436 wounded; 13 missing. Total, 85 killed, 462 wounded, and 13 missing. 1,634 prisoners were taken, some artillery and small arms of very little value; 3,500 sacks of corn and cornmeal were secured.

On July 3, General Braxton Bragg sent the following dispatch from Bridgeport, Alabama—twenty-eight miles directly west from Chattanooga—to Richmond, Virginia: “Unable to obtain a general engagement without sacrificing my communications, I have, after a series of skirmishes, withdrawn the army to this river. It is now coming down the mountains. I hear of no formidable pursuit.”[8] The Confederate Army crossed the mountains to the Tennessee River and on July 7, 1863, encamped near Chattanooga. The Union Army went into camp along the northwestern base of the Cumberland plateau. The object of the Army of the Cumberland for the ensuing campaign was Chattanooga;[50] the Tullahoma campaign was only a small part of the greater one which had yet to take place.

In the Tullahoma campaign the Tenth Wisconsin Infantry lost 3 enlisted men, wounded, and the First Wisconsin Cavalry 2 enlisted men. All the Wisconsin troops bore their full share of the fatigues of the campaign, but only the losses mentioned were reported.

There was one feature of the Tullahoma campaign that was very peculiar. A part of the Union Army had the previous year passed over this same region, while marching to the relief of Grant at Shiloh. Now returning by the way of Chattanooga, where Buell had marched on his way back to Louisville, they again came to this section of the country where the inhabitants mostly sympathized with the South. They were surprised and shocked in 1862 when the hated Yankees invaded their towns and farms. The Confederate authorities told them, that another invasion would never occur, that they could plant their crops and pursue their business without fear. Therefore, when their country was again overrun by the Union Army in 1863, their confidence in the Confederate generals was quite shaken.

A distinguished Confederate general—speaking of the importance of the city of Chattanooga to the Confederacy—said: “As long as we held it, it was the closed doorway to the interior of our country. When it came into your [the Union’s] hands the door stood open, and however rough your progress in the interior might be, it still left you free to march inside. I tell you that when your Dutch general Rosecrans commenced his forward movement for the capture of Chattanooga we laughed him to scorn; we believed that the black brow of Lookout Mountain would frown him out of existence; that he would dash himself to pieces against the many and vast natural barriers that rise all around Chattanooga; and that then the northern people and the government at Washington would perceive how hopeless were their efforts when they came to attack the real[52] South.” With regard to the claim that Chickamauga was a failure for the Union arms, he said: “We would gladly have exchanged a dozen of our previous victories for that one failure.” It is correctly said, that even Richmond was but an outpost, until the success of the Union armies—in the centre of the Confederacy—left Lee’s legions nowhere to go, when they were expelled from Richmond.[9] This was accomplished or made possible only by the operations of the Army of the Cumberland in the Chattanooga Campaign of 1863.

After the retreat of the Confederate Army of the Tennessee from the region about Tullahoma, across the Cumberland Plateau to Chattanooga, Rosecrans established his headquarters at Winchester, Tennessee.[10] He began the repair of the railroad back to Murfreesboro and forward to Stevenson, Alabama, ten miles southeast of Bridgeport and eight miles north of the Tennessee River. The three corps were put into[53] camp in their normal order. The Twentieth Corps occupied the country adjacent to Winchester; the Fourteenth Corps the region near to Decherd;[11] the Twenty-first Corps occupied the country near McMinnville.[12] Detachments were thrown forward as far as Stevenson. The campaign had so far been mere child’s play, compared with what lay before the army in the next movement against Chattanooga and the Confederate Army. The straight line of the plateau is thirty miles across from Winchester to the Tennessee River; the distance is perhaps forty miles by the available roads. The railroad after reaching the summit of the plateau followed down Big Crow Creek to Stevenson, then turned sharply up the valley of the Tennessee, crossing the river at Bridgeport to the South side; then winding among numerous hills, which constitute the south end of the Sand Mountain, continued around the northern nose of Lookout Mountain, close to the river bank, into Chattanooga.[54] Bridgeport is on the Tennessee River twenty-eight miles in a straight line west of Chattanooga. Just opposite, towards the northern nose of Sand Mountain, on the north side of the river, is the southern end of Walden’s Ridge which extends northward from the river, and parallel with the plateau, from which it is separated by the Sequatchie River and Valley. In short the Cumberland Mountains are here a series of ridges and valleys which run from northeast to southwest in a uniform trend, parallel with each other. The Tennessee River rises in southwestern Virginia, and runs between the Cumberland Plateau and Sand Mountain; but between Chattanooga and Bridgeport it cuts a zigzag channel towards the west, between Sand Mountain and Walden’s Ridge, which is the name given to that portion of the ridge lying on the north of the river. What the Army of the Cumberland intended to do was to cross the ridge, called the Cumberland Plateau, then the river, and the Sand Mountain into Lookout Valley and then the Lookout Ridge, in order to reach the Chattanooga Valley south of Chattanooga. Such a movement would force Bragg to[55] march out of the city to defend his communications. These ridges are all linked together at different places. Sand and Lookout at Valley Head, Alabama; the Cumberland Plateau and Walden’s at the head of Sequatchie Valley and River. Pigeon Mountain is a spur of Lookout Ridge. Chattanooga is located on the south side of the river, between the northern nose of Lookout and Missionary Ridge. The latter is a separate and low ridge about three miles southeast of Chattanooga. Without a map it will be difficult for the reader to perceive the rugged and almost impassable field of operations, which General Rosecrans faced, while his army lay at the northwestern base of the Cumberland Plateau, waiting for suitable preparation for the intended campaign.

There was an alternative line of advance open to Rosecrans, namely to cross the plateau into the Sequatchie Valley, or to march around the head of the valley at Pikeville, then over Walden’s Ridge, and thus attack Chattanooga directly from the north; or, to cross the river above and to the east of Chattanooga, at the north end[56] of Missionary Ridge, that is, at the mouth of the Hiawassie River. This last route would have exposed his line of retreat or communications, and he therefore chose to operate at his right and enter into the valley south of Chattanooga.

Early in August the railroad was repaired to Stevenson and Bridgeport; also the branch to Tracy City on the plateau.

Sheridan’s division of the Twentieth Corps was pushed forward to Stevenson and Bridgeport. The commissary and quartermaster-stores were accumulated at Stevenson as rapidly as possible. By the 8th of August these supplies were sufficient in quantity to justify a distribution of them to the different commands, preparatory to an advance across the river and over the difficult ridges, that lay at almost right angles to the line of movement. The advance of the main army began August 16.

The Fourteenth Corps crossed along the railroad line, or near to it. Its advance was soon at Stevenson and some of it at Bridgeport. The Twenty-first Corps—which formed the left of the army at McMinnville—crossed by the way of[57] Pelham, a small village on the plateau, to Thurman’s in the Sequatchie Valley. Minty’s cavalry covered the left flank by way of Pikeville, a village at the head of Sequatchie Valley. The Twentieth Corps also came to Stevenson and its vicinity, but by another route—to the right—than that taken by the Fourteenth, namely, via Bellefont, ten miles southwest of Stevenson, and Caperton’s Ferry, which is the river point nearest to Stevenson.

All these crossings of the plateau were made without resistance by the enemy, although there were small Confederate cavalry outlooks here and there, which fell back when the Union troops appeared. It seemed as if Bragg desired to have the Union Army advance as far as possible from its base of supplies into the mountain gorges and over a long and difficult line of communications. That course would afford him a better chance, as his army being reinforced would be in better condition to successfully attack and destroy the Union Army.

In order to save the hauling of full forage for the animals, General Rosecrans had delayed his movement until the corn should be sufficiently ripe.[58] No detail seemed wanting in the preparations for the difficult campaign. Enough ammunition was provided for at least two battles, and twenty-five days rations for the troops were hauled in wagons.

The Tennessee River had to be crossed by the different corps; in order to conceal this movement and deceive the enemy at Chattanooga, Hagen’s brigade of Palmer’s division, and Wagner’s of Wood’s of the Twenty-first Corps, accompanied by Wilder’s mounted infantry of Reynolds’s division, crossed Walden’s Ridge from the Sequatchie Valley into the valley of the Tennessee. These troops made ostentatious demonstrations upon Chattanooga from the north side of the river. Wilder—with four guns of Lilly’s battery—appeared suddenly before Chattanooga, threw some shells into the city, sunk the steamer “Paint Rock,” lying at the city landing, then ascending the river, feigned to examine the crossings, making frequent inquiry as to their difficulty and the character of the country. On the other side of the river east of Chattanooga, General Cleburne was sent by Bragg to make preparations for defending the crossings against the supposed advance of Rosecrans’s[59] army. He fortified the ferry crossings. General Buckner—who commanded in East Tennessee against the forces of Burnside—expressed as his opinion on August 21, that General Rosecrans would cross above the mouth of Hiawassie River—a stream flowing northwards—and transfer his forces into Tennessee on its south bank, some thirty-five miles northeast of Chattanooga. Buckner’s army was at the point mentioned.

Rosecrans’s intention was, however, to cross at Caperton’s Ferry—near Bridgeport and not far from Stevenson—and at Shellmound; these places are from twenty to forty miles below and to the west of Chattanooga. On August 20 at daybreak, Heg’s brigade, of Davis’s division of the Twentieth Corps, in which served the Fifteenth Wisconsin Infantry, crossed in pontoon boats at Caperton’s Ferry, drove away the enemy’s cavalry and occupied the southern bank. Here a twelve hundred feet pontoon bridge was soon completed, and Davis’s division of the Twentieth Corps, crossed and advanced to the foot of Sand Mountain, preceded by cavalry. Johnson’s division of the same corps crossed the following day[60] on the same bridge. Sheridan’s division of the Twentieth Corps crossed at Bridgeport on a bridge constructed by them of pontoons and tressels; it was 2,700 feet long. Baird’s—formerly Rousseau’s—and Negley’s divisions of the Fourteenth Corps followed Sheridan’s division. The Twenty-first Corps marched down the Sequatchie Valley and crossed at Battle Creek, nine miles up the river from Bridgeport. Hazen’s, Wagner’s, and Wilder’s brigades were, as before mentioned, in the Tennessee Valley to the north of Chattanooga, and did not cross with their corps. The whole movement across the river began on August 29 and ended on September 4. The Third brigade of Van Cleve’s division of the Twenty-first Corps was left at McMinnville as a garrison. The railway was protected by the reserve corps; the Fourteenth Corps was ordered to concentrate in Lookout Valley and to send immediate detachments to seize Cooper’s and Stevens’s gaps of Lookout Mountain, the only passable routes to McLemore’s Cove, down which runs the west Chickamauga Creek in a northeasterly direction, towards Chattanooga. The Twentieth[61] Corps was to move to Valley Head at the head of Lookout Valley, and seize Winston’s Gap forty miles south of Chattanooga. The Twenty-first Corps with the exception of Hazen’s and Wagner’s infantry and Minty’s cavalry—which were still north and east of Chattanooga—were to march to Wauhatchie, at the lower end of Lookout Valley, near Lookout Mountain, and to communicate with the Fourteenth Corps at Trenton in the same valley, and threaten Chattanooga by way of the Tennessee River via the nose of Lookout Mountain. The cavalry crossed at Caperton’s and at a ford near Island Creek, in Lookout Valley, from which point they reconnoitered towards Rome, Georgia, fifty-five miles south of Chattanooga, via Alpine. This last mentioned hamlet is forty-two miles south of Chattanooga. In the absence of Major-General Stanley—the chief of cavalry—its movements were not prompt. If the reader will refer to a good topographical map of the region around Chattanooga, he will see how sagacious these movements were, and what grand strategy they displayed. The Army of the Cumberland was[62] stretched in line through the whole length of Lookout Valley, between Sand Mountain and Lookout Mountain, on the south side of the Tennessee River; it faced east towards the Chattanooga Valley, with only one range between them and the Confederate line of retreat and supplies; while on the northeast side of Chattanooga was a Union force of several brigades to prevent any counter movement by the Confederates upon the Union line of supplies.

After crossing the Tennessee River, Rosecrans continued his feints to make Bragg think that the real movement was the feigned one. He had sent Wagner’s infantry, and Wilder’s and Minty’s cavalry brigades to report to Hazen with a force amounting to about 7,000. Hazen caused the enemy to believe that the whole army was there, intending to cross the river above Chattanooga. This was done by extensive firings, marchings, countermarchings, and by bugle calls, at widely separated points; while Wilder moved his artillery continuously across openings in sight from the opposite bank.

The Confederates occupied in force the point[63] of Lookout Mountain at Chattanooga. To carry this by an attack of the Twenty-first Corps seemed too risky; therefore the original movement was continued, namely, against the line south of Chattanooga, over Lookout Ridge, south of the point where it was held in force. The cavalry was ordered to advance on the extreme right to Summerville, in Broomtown Valley, a village eighteen miles south of Lafayette, Georgia. McCook was to support this movement by a division thrown forward to the vicinity of Alpine forty-two miles southwest of Chattanooga. These movements were made on September 8 and 9.

General Thomas crossed his corps over Frick’s, Cooper’s, and Stevens’s gaps of Lookout Mountain, to McLemore’s Cove.

These movements forced Bragg to evacuate Chattanooga on September 8. Then Crittenden with the Twenty-first Corps and its trains marched the same day around the point of Lookout and camped that night at Rossville, at the gap through Missionary Ridge, five miles south of Chattanooga. Through this gap runs the wagon road from Lafayette to Chattanooga.

[64]General Rosecrans claimed to have evidence that Bragg was moving towards Rome, and had therefore ordered Crittenden to hold Chattanooga with one brigade, call all the troops of Hazen’s command across from the north side of the river, an follow the enemy’s retreat vigorously.

On September 11, Crittenden was ordered to advance as far as Ringgold, but not farther, and to make a reconnoisance as far as Lee and Gordon’s Mill.[13] Crittenden’s report as well as other evidence convinced General Rosecrans that Bragg had only gone as far as Lafayette—twenty-five miles south of Chattanooga—and then halted. General Crittenden’s whole corps was therefore sent to Lee and Gordon’s Mill, where he found Bragg’s rear guard. He was ordered to communicate with General Thomas, who by that time had reached the eastern foot of Lookout Mountain in McLemore’s Cove, at the eastern base of Stevens’s gap. Wilder’s mounted brigade followed and covered the Twenty-first Corps in its[65] movements to Lee and Gordon’s Mill, and had a severe fight with the enemy at Leet’s tan yard, five miles to the southeast. Although Bragg made his headquarters at Lafayette in his retreat from Chattanooga, his rear guard did not get beyond Lee and Gordon’s Mill.

On September 10 Negley’s division of the Fourteenth Corps marched—after having crossed the ridge—from the foot of Stevens’s Gap, across McLemore’s Cove, towards Dug Gap in the Pigeon Mountains and then directly towards Lafayette. Dug Gap is six miles west of Lafayette. Negley found this gap heavily obstructed, but Baird’s division came to his support on the morning of September 11. They became convinced by some sharp skirmishing, which occurred on the 11th, that the enemy’s forces were advancing; and therefore fell back from Davis’s cross roads to a good position near the foot of Stevens’s Gap. These two officers are entitled to great credit for their coolness and skill in withdrawing their divisions from a very perilous trap. The forces of the enemy would have been overwhelming in their immediate front, if the Confederates had been[66] more expeditious and made the attack on the afternoon of September 10 or on the morning of the 11th. Hindman, Buckner, and Cleburne, with several divisions were there, but failed to cooperate in an attack at the right time. The obstructions placed in the gap by the Confederates favored Negley and Baird.

On September 12 Reynolds’s and Brannan’s divisions following over the mountain closed up to Negley and Baird. Bragg’s army was at Lafayette, near Dug Gap, in force. Having official information that Longstreet was coming from Virginia with large reinforcements, and having already received troops from Mississippi and the eastern part of Tennessee, Bragg halted in his retreat. He was preparing to give battle to the Union forces at the first good opportunity.

Two divisions of Joseph E. Johnston’s troops from Mississippi and Buckner’s Corps from Tennessee—where Burnside’s forces were—had joined Bragg before he moved north from Lafayette to Chickamauga, where he was joined by three divisions of Longstreet’s Corps from Virginia on the 18th, if not earlier. At the same time Halleck,[67] chief of the army at Washington, D. C., telegraphed Rosecrans September 11, 1863, as follows: “It is reported here by deserters that a part of Bragg’s army is reinforcing Lee. It is important that the truth of this should be ascertained as early as possible.”[14]

The fact stands out in bold relief, that the Confederate Government at Richmond hastened reinforcements to General Bragg; while the Washington Government sent none to Rosecrans, although Burnside was in the eastern part of Tennessee with 16,000 troops, and was at that time at leisure. Because the force, lately in his front, had reinforced Bragg at Lafayette, Burnside did not obey Halleck’s order to join Rosecrans; on the contrary, he drove Buckner’s force, which united with Bragg; thus Burnside enabled Buckner’s men to take part against the Union Army in the battle of Chickamauga.

Bragg in his official report, says: “During the[68] 9th it was ascertained that a column, estimated at from 4,000 to 8,000 had crossed Lookout Mountain into the cove by way of Cooper’s and Stevens’s gaps. Thrown off his guard by our rapid movement, apparently in retreat, when in reality we had concentrated opposite his center, and deceived by the information, by deserters and others sent into his lines, the enemy pressed on his columns to intercept us, and thus exposed himself in detail.”[15] He says further that he ordered Hindman, Cleburne, and Buckner to join and attack the forces—Negley and Baird—at Davis’s cross roads, near Dug Gap; but because Dug Gap was obstructed by felled timber, which required twenty-four hours to remove, and because Buckner, when he joined Hindman, wanted to change the plans, Negley and Baird had been allowed to move back in a position not wise to follow. Bragg drew Buckner, Hindman, and Cleburne back to Lafayette and prepared to move in order to attack Crittenden at Lee and Gordon’s Mill. Polk’s and Walker’s corps were moved immediately in that direction.

[69]The only Wisconsin troops in the affair at Dug Gap on September 10 and 11 were the First, Tenth, and Twenty-first Infantry. Lieutenant Robert J. Nickles of the First Wisconsin Infantry, aide to General J. C. Starkweather, commanding the brigade, was killed when reconnoitering alone the enemy’s skirmishers. This was the only casualty to the Wisconsin troops.