“Shut up your yapping,” Peter Zinn greeted his wife. “Shut up and take care of this pup. He’s my kind of dog.”

“Shut up your yapping,” Peter Zinn greeted his wife. “Shut up and take care of this pup. He’s my kind of dog.”

When Zinn came home from prison, no one was at the station to meet him except the constable, Tom Frejus, who laid a hand on his shoulder and said: “Now, Zinn, let this here be a lesson to you. Give me a chance to treat you white. I ain’t going to hound you. Just remember that because you’re stronger than other folks you ain’t got any reason to beat them up.”

Zinn looked down upon him from a height. Every day of the year during which he had swung his sledge hammer to break rocks for the State roads, he had told himself that one good purpose was served: his muscles grew harder, the fat dropped from his waist and shoulders, the iron square of his chin thrust out as in his youth, and when he came back to town he would use that strength to wreak upon the constable his old hate. For manifestly Tom Frejus was his archenemy. When he first came to Sioux Crossing and fought the three men in Joe Riley’s saloon—oh, famous and happy night!—Constable Frejus gave him a warning. When he fought the Gandil brothers and beat them both senseless, Frejus arrested him. When his old horse, Fidgety, balked in the back lot and Zinn tore a rail from the fence in lieu of a club, Tom Frejus arrested him for cruelty to dumb beasts. This was a crowning torment, for, as Zinn told the judge, he’d bought that old skate with good money and he had a right to do what he wanted with it. But the judge, as always, agreed with Tom Frejus. These incidents were only items in a long list which culminated when Zinn drank deep of bootleg whisky and then beat up the constable himself. The constable, at the trial, pleaded for clemency on account, he said, of Zinn’s wife and three children; but Zinn knew, of course, that Frejus wanted him back only that the old persecution might begin. On this day, therefore the ex-convict, in pure excess of rage, smiled down on the constable.

“Keep out of my way, Frejus,” he said, “and you’ll keep a whole skin. But some day I’ll get you alone, and then I’ll bust you in two—like this!”

He made an eloquent gesture; then he strode off up the street. As the sawmill had just closed, a crowd of returning workers swarmed on the sidewalks, and Zinn took off his cap so that they could see his cropped head. In his heart of hearts he hoped that some one would jibe, but the crowd split away before him and passed with cautiously averted eyes. Most of them were big, rough fellows and their fear was pleasant balm for his savage heart. He went on with his hands a little tensed to feel the strength of his arms.

The dusk was closing early on this autumn day with a chill whirl of snowflakes borne on a wind that had been iced in crossing the heads of the white mountains, but Zinn did not feel the cold. He looked up to the black ranks of the pine forest which climbed the sides of Sandoval Mountain, scattering toward the top and pausing where the sheeted masses of snow began. Life was like that—a struggle, an eternal fight, but never a victory on the mountaintop which all the world could see and admire. When the judge sentenced him he said: “If you lived in the days of armor, you might have been a hero, Zinn; but in these times you are a waster and an enemy of society.” He had grasped dimly at the meaning of this. Through his life he had always aimed at something which would set him apart from and above his fellows; now, at the age of forty, he felt in his hands an undiminished authority of might, but still those hands had not given him the victory. If he beat and routed four men in a huge conflict, society, instead of applauding, raised the club of the law and struck him down. It had always done so, but, though the majority voted against him, his tigerish spirit groped after and clung to this truth: to be strong is to be glorious!

He reached the hilltop and looked down to his home in the hollow. A vague wonder and sorrow came upon him to find that all had been held together in spite of his absence. There was even a new coat of paint upon the woodshed and a hedge of young firs was growing neatly around the front yard. In fact, the homestead seemed to be prospering as though his strength were not needed! He digested this reflection with an oath and looked sullenly about him. On the corner a little white dog watched him with lowered ears and a tail curved under its belly.

“Get out, cur!” snarled Zinn. He picked up a rock and threw it with such good aim that it missed the dog by a mere inch or two, but the puppy merely pricked its ears and straightened its tail.

“It’s silly with the cold,” said Zinn himself, chuckling. “This time I’ll smear it.”

He pried from the roadway a stone of three or four pounds, took good aim, and hurled it as lightly as a pebble flies from the sling. Too late the white dog leaped to the side, for the flying missile caught it a glancing blow that tumbled it over and over. Zinn, muttering with pleasure, scooped up another stone, but when he raised it this time the stone fell from his hand, so great was his surprise. The white dog, with a line of red along its side where a ragged edge of the stone had torn the skin, had gained its feet and now was driving silently straight at the big man. Indeed, Zinn had barely time to aim a kick at the little brute, which it dodged as a rabbit turns from the jaws of the hound. Then two rows of small, sharp teeth pierced his trousers and sank into the flesh of his leg. He uttered a yell of surprise rather than pain. He kicked the swaying, tugging creature, but still it clung, working the puppy teeth deeper with intent devotion. He picked up the fallen stone and brought it down heavily with a blow that laid open the skull and brought a gush of blood, but though the body of the little savage grew limp, the jaws were locked. He had to pry them apart with all his strength. Then he swung the loose, senseless body into the air by the hind legs.

What stopped him he could not tell. Most of all it was the stabbing pain in his leg and the marvel that so small a dog could have dared so much. But at last he tucked it under his arm, regardless of the blood that trickled over his coat. He went down the hill, kicked open the front door, and threw down his burden. Mrs. Zinn was coming from the kitchen with a shrill cry that sounded more like fear than like a welcome to Zinn.

“Peter! Peter!” she cried at him, clasping her hands together and staring.

“Shut up your yapping,” said Peter Zinn. “Shut up and take care of this pup. He’s my kind of a dog.”

His three sons wedged into the doorway and gaped at him with round eyes and white faces.

“Look here,” he said, pointing to his bleeding leg. “That damned pup done that. That’s the way I want you kids to grow up. Fight anything. Fight a buzz saw. You don’t need to go to no school for lessons. You can foller after Blondy, there.”

So Blondy was christened; so he was given a home. Mrs. Zinn, who had been a trained nurse in her youth, nevertheless stood by with moans of sympathy while her husband took the necessary stitches in the head of Blondy.

“Keep still, fool,” said Mr. Zinn. “Look at Blondy. He ain’t even whining. Pain don’t hurt nothing. Pain is the making of a dog—or a man! Look at there—if he ain’t licking my hand! He knows his master!”

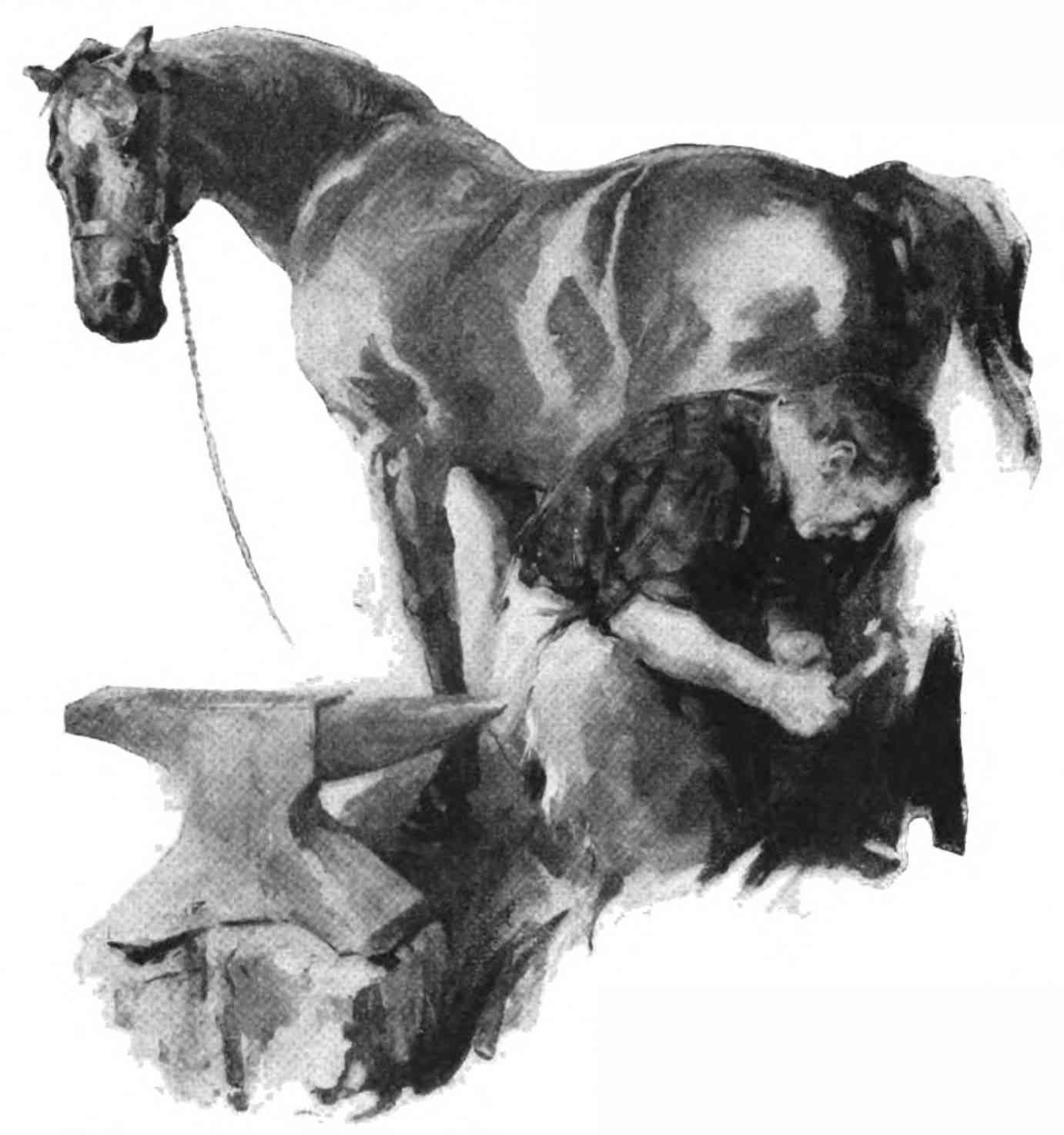

A horse kicked old Joe Harkness the next day, and Peter Zinn took charge of the blacksmith shop. He was greatly changed by his stay in the penitentiary, so that superficial observers in the town of Sioux Crossing declared that he had been reformed by punishment, inasmuch as he no longer blustered or hunted fights in the streets of the village. He attended to his work, and as everyone admitted that no farrier in the country could fit horseshoes better, or do a better job at welding, when Joe Harkness returned to his shop he kept Zinn as a partner. Neither did Peter Zinn waste time or money on bootleg whisky, but in spite of these new and manifold virtues some of the very observant declared that there was more to be feared from the silent and settled ferocity of his manner than from the boisterous ways which had been his in other days. Constable Tom Frejus was among the latter. And it was noted that he practiced half an hour every day with his revolver in the back of his lot.

So Peter Zinn took charge of the blacksmith shop, and the town declared him reformed.

Blondy, in the meantime, stepped into maturity in a few swift months. On his fore and hind quarters the big ropy muscles thrust out. His neck grew thicker and more arched, and in his dark brown eyes there appeared a wistful look of eagerness which never left him saving when Peter Zinn was near. The rest of the family he tolerated, but did not love. It was in vain that Mrs. Zinn, eager to please a husband whose transformation had filled her with wonder and with awe, lavished attentions upon Blondy and fed him with dainties twice a day. It was in vain that the three boys petted and fondled and talked kindly to Blondy. He endured these demonstrations, but did not return them. But when five o’clock came in the evening of the day, Blondy went out to the gate of the front yard and stood there like a white statue until a certain heavy step sounded on the wooden sidewalk up the hill. That noise changed Blondy into an ecstasy of impatience, and when the big man came through the gate, Blondy raced and leaped about him with such a muffled whine of joy, coming from such deeps of his heart, that his whole body trembled. At meals Blondy lay across the feet of the master. At night he curled into a warm circle at the foot of the bed.

There was only one trouble with Blondy. When people asked: “What sort of a dog is that?” Peter Zinn could never answer anything except: “A hell of a good fighting dog; you can lay to that.” It was a stranger who finally gave them information, a lumber merchant who had come to Sioux Crossing to buy timber land. He stopped Peter Zinn on the street and crouched on his heels to admire Blondy.

“A real white one,” said he. “As fine a bull terrier as I ever saw. What does he weigh?”

“Fifty-five pounds,” said Zinn.

“I’ll give you five dollars for every pound of him,” said the stranger.

Peter Zinn was silent.

“Love him too much to part with him, eh?” asked the other, smiling up at the big blacksmith.

“Love him?” snorted Zinn. “Love a dog! I ain’t no fool.”

“Ah?” said the stranger. “Then what’s your price?”

Peter Zinn scratched his head; then he scowled, for when he tried to translate Blondy into terms of money, his wits failed him.

“That’s two hundred and seventy-five dollars,” he said finally.

“I’ll make it three hundred, even. And, mind you. my friend, this dog is useless for show purposes. You’ve let him fight too much, and he’s covered with scars. No trimming can make that right ear presentable. However, he’s a grand dog, and he’d be worth something in the stud.”

Zinn hardly heard the last of this. He was considering that for three hundred dollars he could extend the blacksmith shop by one-half and get a full partnership with Harkness, or else he could buy that four-cylinder car which young Thompson wanted to sell. Yet even the showy grandeur of an automobile would hardly serve. He did not love Blondy. Love was an emotion which he scorned as beneath the dignity of a strong man. He had not married his wife because of love, but because he was tired of eating in restaurants and because other men had homes. The possession of an automobile would put the stamp upon his new prosperity, but could an automobile welcome him home at night or sleep at his feet?

“I dunno,” he said at last. “I guess I ain’t selling.”

And he walked on. He did not feel more kindly toward Blondy after this. In fact, he never mentioned the circumstance, even in his home, but often when he felt the warmth of Blondy at his feet he was both baffled and relieved.

In the meantime Blondy had been making history in Sioux Crossing hardly less spectacular than that of Zinn. His idea of play was a battle; his conception of a perfect day embraced the killing of two or three dogs. Had he belonged to anyone other than Zinn, he would have been shot before his career was well started, but his owner was such a known man that guns were handled but not used when the white terror came near. It could be said in his behalf that he was not aggressive and, unless urged on, would not attack another. However, he was a most hearty and capable finisher of a fight if one were started.

He first took the eye of the town through a fracas with Bill Curry’s brindled bulldog, Mixer. Blondy was seven or eight pounds short of his magnificent maturity when he encountered Mixer and touched noses with him; then the bulldog reached for Blondy’s left foreleg, snapped his teeth in the empty air, and the fun began. As Harkness afterward put it: “Mixer was like thunder, but Blondy was lightning on wheels.” Blondy drifted around the heavier dog for five minutes as illusive as a phantom. Then he slid in, closed the long, pointed, fighting jaw on Mixer’s gullet, and was only pried loose from a dead dog.

After that the great Dane which had been brought to town by Mr. Henry Justice, the mill owner, took the liberty of snarling at the white dog and had his throat torn out in consequence. When Mr. Justice applied to the law for redress, the judge told him frankly that he had seen the fight and that he would sooner hang a man than hang Blondy. The rest of the town was of the same opinion. They feared but respected the white slayer, and it was pointed out that though he battled like a champion against odds, yet when little Harry Garcia took Blondy by the tail and tried to tie a knot in it, the great terrier merely pushed the little boy away with his forepaws and then went on his way.

However, there was trouble in the air, and Charlie Kitchen brought it to a head. In his excursions to the north he had chanced upon a pack of hounds used indiscriminately to hunt and kill anything that walked on four legs, from wolves to mountain lions and grizzly bears. The leader of that pack was a hundred-and-fifty-pound monster—a cross between a gigantic timber wolf and a wolfhound. Charlie could not borrow that dog, but the owner himself made the trip to Sioux Crossing and brought Gray King, as the dog was called, along with him. Up to that time Sioux Crossing felt that the dog would never be born that could live fifteen minutes against Blondy, but when the northerner arrived with a large roll of money and his dog, the town looked at Gray King and pushed its money deeper into its pocket. For the King looked like a fighting demon, and in fact was one. Only Peter Zinn had the courage to bring out a hundred dollars and stake it on the result.

They met in the vacant lot next to the post office where the fence was loaded with spectators, and in this ample arena it was admitted that the wolf dog would have plenty of room to display all of his agility. As a matter of fact, it was expected that he would slash the heart out of Blondy in ten seconds. Slash Blondy he did, for there is nothing canine in the world that can escape the flash of a wolf’s side rip. A wolf fights by charges and retreats, coming in to slash with its great teeth and try to knock the foe down with the blow of its shoulder. The Gray King cut Blondy twenty times, but they were only glancing knife-edge strokes. They took the blood, but not the heart from Blondy, who, in the meantime, was placed too low and solidly on the ground to be knocked down. At the end of twenty minutes, as the Gray King leaped in, Blondy side-stepped like a dancing boxer, then dipped in and up after a fashion that Sioux Crossing knew of old, and set that long, punishing jaw in the throat of the King. The latter rolled, writhed, and gnashed the air, but fate had him by the windpipe, and in thirty seconds he was helpless. Then Peter Zinn, as a special favor, took Blondy off.

Afterward the big man from the north came to pay his bet, but Zinn, looking up from his task of dressing the terrier’s wounds, flung the money back in the face of the stranger.

Dogs ain’t the only things that fight in Sioux Crossing, he announced, and the stranger, pocketing his pride and his money at the same time, led his staggering dog away.

From that time forward Blondy was one of the sights of the town—like Sandoval Mountain. He was pointed out constantly and people said: “Good dog!” from a safe distance, but only Tom Frejus appreciated the truth. He said: “What keeps Zinn from getting fight-hungry? Because he has a dog that does the fighting for him. Every time Blondy sinks his teeth in the hide of another dog, he helps to keep Zinn out of jail. But some day Zinn will bust through!”

This was hardly a fair thing for the constable to say, but the nerves of honest Tom Frejus were wearing thin. He knew that sooner or later the blacksmith would attempt to execute his threat of breaking him in two, and the suspense lay heavily upon Tom. He was still practicing steadily with his guns; he was still as confident as ever of his own courage and skill; but when he passed on the street the gloomy face of the blacksmith, a chill of weakness entered his blood.

That dread, perhaps, had sharpened the perceptions of Frejus, for certainly he had looked into the truth, and while Peter Zinn bided his time the career of Blondy was a fierce comfort to him. The choicest morsel of enjoyment was delivered into his hands on a morning in September, the very day after Frejus had gained lasting fame by capturing the two Minster brothers, with enough robberies and murders to their credit to have hanged a dozen men.

The Zinns took breakfast in the kitchen this Thursday, so that the warmth of the cookstove might fight the frost out of the air, and Oliver, the oldest boy, announced from the window that old Gripper, the constable’s dog, had come into the back yard. The blacksmith rose to make sure. He saw Gripper, a big black-and-tan sheep dog, nosing the top of the garbage can, and a grin of infinite satisfaction came to the face of Peter Zinn. First he cautioned the family to remain discreetly indoors. Then he stole out by the front way, came around to the rear of the tall fence which sealed his back yard and closed and latched the gate. The trap was closed on Gripper, after which Zinn returned to the house and lifted Blondy to the kitchen window. The hair lifted along the back of Blondy’s neck; a growl rumbled in the deeps of his powerful body. Yonder was his domain, his own yard, of which he knew each inch, the smell of every weed and rock; yonder was the spot where he had killed the stray chicken last July; near it was the tall, rank nettle, so terrible to an over-inquisitive nose; and behold a strange dog pawing at the very place where, only yesterday, he had buried a stout bone with rich store of marrow hidden within!

“Oh, Peter, you ain’t—” began Mrs. Zinn.

Her husband silenced her with an ugly glance; then he opened the back door and tossed Blondy into the yard. The bull terrier landed lightly, and running. He turned into a white streak which crashed against Gripper, turned the latter head over heels, and tumbled the shepherd into a corner. Blondy wheeled to finish the good work, but Gripper lay at his feet, abject upon his belly, with ears lowered, head pressed between his paws, wagging a conciliatory tail and whining a confession of shame, fear, and humility. Blondy leaped at him with a stiff-legged jump and snapped his teeth at the very side of one of those drooped ears, but Gripper only melted a little closer to the ground. For, a scant ten days before, he had seen that formidable warrior, the Chippings’ greyhound, throttled by the white destroyer. What chance would he have with his worn old teeth? He whined a sad petition through them and closing his eye he offered up a prayer to the god who watches over all good dogs: Never, never again would he rummage around a strange back yard if only this one sin were forgiven!

The door of the house slammed open; a terrible voice was shouting: Take him, Blondy! Kill him, Blondy.

Blondy, with a moan of battle joy, rushed in again; his teeth clipped over the neck of Gripper; but the dreadful jaws did not close. For, even in this extremity. Gripper only whined and wagged his tail the harder. Blondy danced back.

“You damn quitter!” yelled Peter Zinn. “Tear him to bits! Take him, Blondy!”

The tail of Blondy flipped from side to side to show that he had heard. He was shuddering with awful eagerness, but Gripper would not stir.

“Coward! Coward! Coward!” snarled Blondy. “Get up and fight. Here I am—half turned away—offering you the first hold—if you only dare to take it!”

Never was anything said more plainly in dog talk, saving the pitiful response of Gripper: “Here I lie; kill me if you will. I am an old, old man with worn-down teeth and a broken heart!”

Blondy stopped snarling and trembling. He came a bit nearer, and with his own touched the cold nose of Gripper. The old dog opened one eye.

“Get up,” said Blondy very plainly. “But if you dare to come near my buried bone again, I’ll murder you, you old rip!”

And he lay down above that hidden treasure, wrinkling his eyes and lolling out his tongue, which, as all dogs know, is a sign that a little gambol and play will not be amiss.

“Dad!” cried Oliver Zinn. “He won’t touch old Gripper. Is he sick?”

“Come here!” thundered Zinn, and when Blondy came he kicked the dog across the kitchen and sent him crashing into the wall. “You yaller-hearted cur!” snarled Peter Zinn and strode out of the house to go to work.

His fury did not abate until he had delivered a shower of blows with a fourteen-pound sledge upon a bar of cold iron on his anvil, wielding the ponderous hammer with one capacious hand. After that he was able to try to think it out. It was very mysterious. For his own part, when he was enraged it mattered not what crossed his path—old and young, weak and strong, they were grist for the mill of his hands and he ground them small indeed. But Blondy, apparently, followed a different philosophy and would not harm those who were helpless.

Then Peter Zinn looked down to the foot which had kicked Blondy across the room. He was tremendously unhappy. Just why, he could not tell, but he fumbled at the mystery all that day and the next. Every time he faced Blondy the terrier seemed to have forgotten that brutal attack, but Peter Zinn was stabbed to the heart by a brand-new emotion—shame! And when he met Blondy at the gate on the second evening, something made him stoop and stroke the scarred head. It was the first caress. He looked up with a hasty pang of guilt and turned a dark red when he saw his wife watching from the window of the front bedroom. Yet when he went to sleep that night he felt that Blondy and he had been drawn closer together.

The very next day the crisis came. He was finishing his lunch when guns began to bark and rattle—reports with a metallic and clanging overtone which meant that rifles were in play; then a distant shouting rolled confusedly upon them. Peter Zinn called Blondy to his heels and went out to investigate.

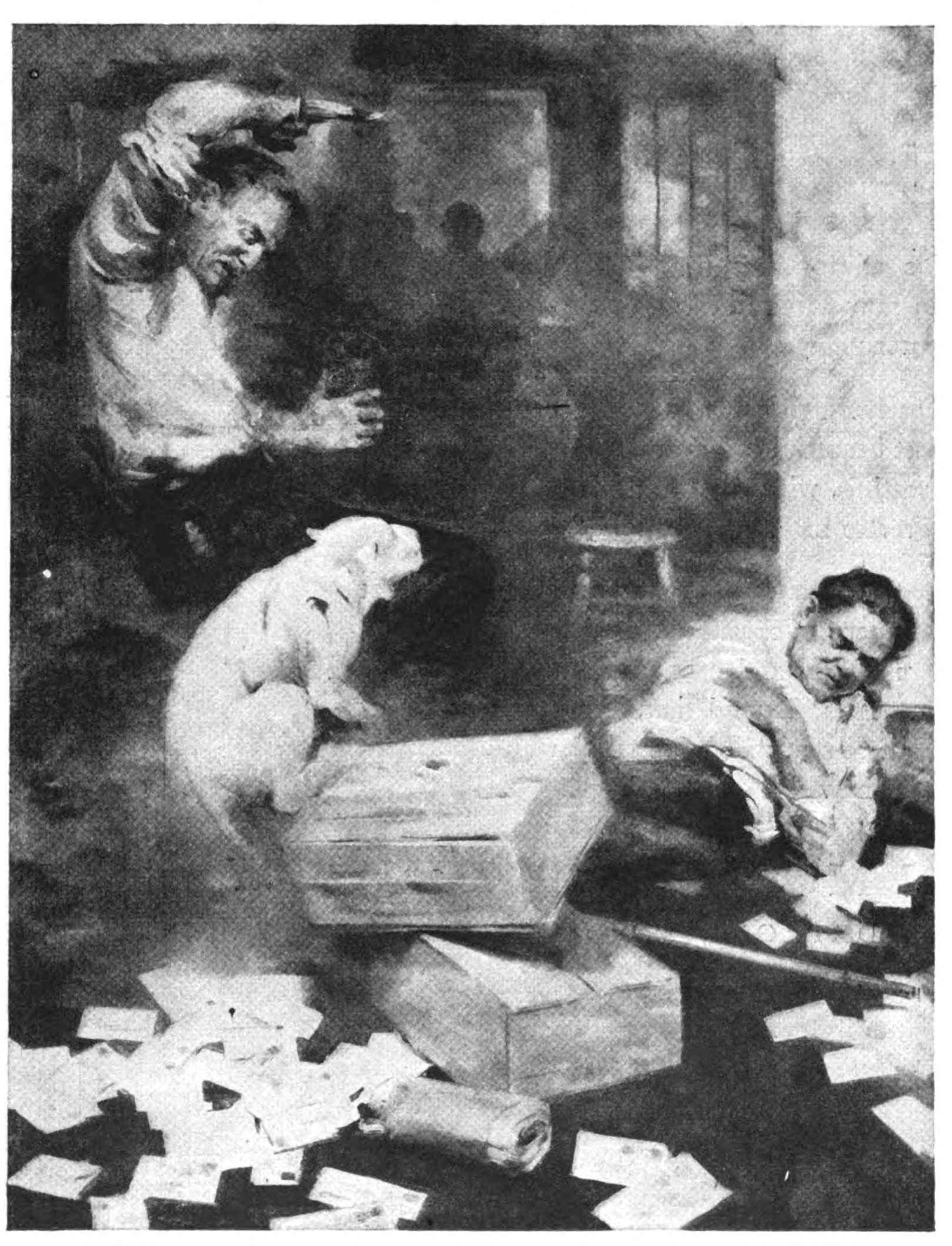

The first surmise that jumped into his mind had been correct. Jeff and Lew Minster had broken from jail, been headed off in their flight, and had taken refuge in the post office. There they held the crowd at bay, Jeff taking the front of the building and Lew the rear. Vacant lots surrounded the old frame shack since the general merchandise store burned down three years before, and the rifles of two expert shots commanded this no-man’s-land. It would be night before they could close on the building, but when night came the Minster boys would have an excellent chance of breaking away with darkness to cover them.

“What’ll happen?” asked Tony Jeffreys of the blacksmith as they sat at the corner of the hotel where they could survey the whole scene.

“I dunno,” said Peter Zinn, as he puffed at his pipe. “I guess it’s up to the constable to show them that he’s a hero. There he is now!”

The constable had suddenly dashed out of the door of Sam Donoghue’s house, directly facing the post office, followed by four others, in the hope that he might take the defenders by surprise. But when men defend their lives they are more watchful thar wolves in the hungry winter of the mountains. A Winchester spoke from a window of the post office the moment the forlorn hope appeared. The first bullet knocked the hat from the head of Harry Daniels and stopped him in his tracks. The second shot went wide. The third knocked the feet from under the constable and flattened him in the road. This was more than enough The remnant of the party took to it heels and regained shelter safely before the dust raised by his fall had cease curling above the prostrate body of the constable.

Tony Jeffreys had risen to his feel repeating over and over an oath of his childhood: “Jimminy whiskers! Jimminy whiskers! Jimminy whiskers! They’ve killed poor Tom Frejus!” But Peter Zinn, holding the trembling! eager body of Blondy between his hands, jutted forth his head an grinned in a savage warmth of contentment.

“He’s overdue!” was all he said.

But Tom Frejus was not dead. His leg had been broken between the knee and hip, but he now reared himself upon both hands and looked about him. He had covered the greater part of the road in his charge. It would be easier to escape from fire by crawling close under the shelter of the wall of the post office than by trying to get back to Donoghue’s house. Accordingly, he began to drag himself forward. had not covered a yard when the Winchester cracked again and Tom crumpled on his face, with both arms flung around his head.

Peter Zinn stood up with a gasp. Here was something quite different. The constable was beaten, broken, and he reminded Zinn of one thing only—old Gripper cowering against the fence with Blondy towering above, ready to kill. Blondy had been merciful, but the marked man behind the window was still intent on murder. His next bullet raised a white furrow of dust near Frejus. Then a wild voice, made thin and high by the extremity of fear and pain, came through the air and smote the heart Peter Zinn: “Help! For God’s sake, mercy!”

Tom Frejus was crushed indeed, and begging as Gripper had begged. A hundred voices were shouting with horror but no man dared venture out in the face of that cool-witted marksman. Then Peter Zinn knew the thing which he had been born to do, for which he had been granted strength of hand and courage of heart. He threw his long arms out before him as though he were running to embrace a bodiless thing; great wordless voice swelled in his breast and tore his throat; and he ran out toward the fallen constable.

Some woman’s voice was screaming: “Back! Go back, Peter! Oh, God! Stop him! Stop him!”

Minster had already marked his coming. The rifle cracked, and a blow to the side of his head knocked Peter Zinn into utter blackness. A searing pain and the hot flow of blood down his face brought back his senses. He leaped to his feet again; he heard a yelp of joy as Blondy danced away before him; then he drove past the writhing body of Tom Frejus. The gun spoke again from the window; the red-hot torment stabbed him again, he knew not where. Then he reached the door of the building and gave his shoulder to it.

It was a thing of paper that ripped open before him. He plunged through into the room beyond, where he saw the long, snarling face of the young Minster in the shadow of a corner with the gleam of the leveled rifle barrel. He dodged as the gun spat fire, heard brief and wicked humming beside his ear, then scooped up in one hand heavy chair and flung it at the gunman.

Minster went down with his legs and arms sprawled in an odd position, and Peter Zinn gave him not so much as another glance, for he knew that this part of his work was done.

“Lew! Lew!” cried a voice from the back of the building. “What’s happened? What’s up? D’you want help?”

“Ay!” shouted Peter Zinn. “He wants help. You damn’ murderer, it’s me—Peter Zinn! Peter Zinn!”

He kicked open the door beyond and ran full into the face of a lightning flash. It withered the strength from his body. He slumped down on the floor with his loose shoulders resting against the wall. In a twilight dimness he saw big Jeff Minster standing in a thin swirl of smoke with the rifle muzzle twitching down and steadying for the finishing shot, but a white streak leaped through the doorway, over his shoulder, and flew at Minster.

Before the sick eyes of Peter Zinn, the man and the dog whirled into a blur of darkness streaked with white. There passed two long, long seconds, thick with stampings, the wild curses of Jeff Minster, the deep and humming growl of Blondy. Moreover, out of the distance a great wave of voices was rising, sweeping toward the building.

Jeff Minster, yelling with pain and rage, caught out his hunting knife and raised it. He stabbed, but still Blondy clung.

The eyes of Peter cleared. He saw Blondy fastened to the right leg of Jeff Minster above the knee. The rifle had fallen to the floor and Jeff Minster, yelling with pain and rage, had caught out his hunting knife, had raised it. He stabbed. But still Blondy clung. “No, no!” screamed Peter Zinn.

“Your damned dog first—then you!” gasped Minster.

The weakness struck Peter Zinn again. His great head lolled back on his shoulders. “God,” he moaned, “gimme strength! Don’t let Blondy die!”

And strength poured hot upon his body, a strength so great that he could reach his hand to the rifle on the floor, gather it to him, put his finder on the trigger, and raise the muzzle slowly, slowly as though it weighed a ton.

The knife had fallen again. It was a half crimson dog that still clung to the slayer. Feet beat, voices boomed like a waterfall in the next room. Then, as the knife rose again, Zinn pulled the trigger, blind to his target, and as the thick darkness brushed across his brain, saw something falling before him.

He seemed, after a time, to be walking down an avenue of utter blackness. Then a thin star ray of light glistened before him. It widened. A door of radiance opened through which he stepped and found himself—lying between cool sheets with the binding grip of bandages holding him in many places and wherever the bandages held, the deep, sickening ache of wounds. Dr. Burney leaned above him, squinting as though Peter Zinn were far away. Then Peter’s big hand caught him.

“Doc,” he said. “What’s happened? Gimme the worst of it.”

“If you lie quiet, my friend,” said the doctor, “and husband your strength, and fight for yourself as bravely as you fought for Constable Frejus, you’ll pull through well enough. You have to pull through, Zinn, because this town has a good deal to say that you ought to hear. Besides—”

“Hell, man,” said Peter Zinn, the savage, “I mean the dog. I mean Blondy—how—what I mean to say is—”

But then a great foreknowledge came upon Peter Zinn, His own life having been spared, fate had taken another in exchange, and Blondy would never lie warm upon his feet again. He closed his eyes and whispered huskily: “Say yes or no, Doc. Quick!”

But the doctor was in so little haste that he turned away and walked to the door, where he spoke in a low voice.

“He’s got to have help,” said Peter Zinn to his own dark heart. “He’s got to have help to tell me how a growed-up man killed a poor pup.”

Footsteps entered. “The real work I’ve been doing,” said the doctor, “hasn’t been with you. Look up, Zinn!”

Peter Zinn looked up, and over the edge of the doctor’s arm he saw a long, narrow white head, with a pair of brown-black eyes and a wistfully wrinkled forehead. Blondy, swathed in soft white linen, was laid upon the bed and crept up closer until the cold point of his nose, after his fashion, was hidden in the palm of the master’s hand. Now big Peter beheld the doctor through a mist spangled with magnificent diamonds, and he saw that Burney had found it necessary to turn his head away. He essayed speech which twice failed, but at the third effort he managed to say in a voice strange to himself: “Take it by and large, doc, it’s a damn good old world.”