Miss America

PEN AND CAMERA SKETCHES

OF THE AMERICAN GIRL

BY

ALEXANDER BLACK

Author of “Miss Jerry,” etc.

WITH DESIGNS AND PHOTOGRAPHIC

ILLUSTRATIONS

BY THE AUTHOR

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

NEW YORK: M DCCC XC VIII

Copyright, 1898, by

Charles Scribner’s Sons

All rights reserved

University Press:

John Wilson and Son, Cambridge, U. S. A.

TO

THE AMERICAN GIRL WHOM

I HAVE KNOWN BEST

MY WIFE

THIS BOOK IS GRATEFULLY

AND AFFECTIONATELY

DEDICATED

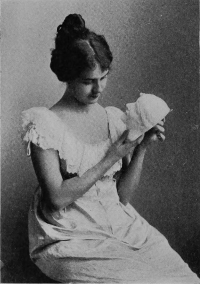

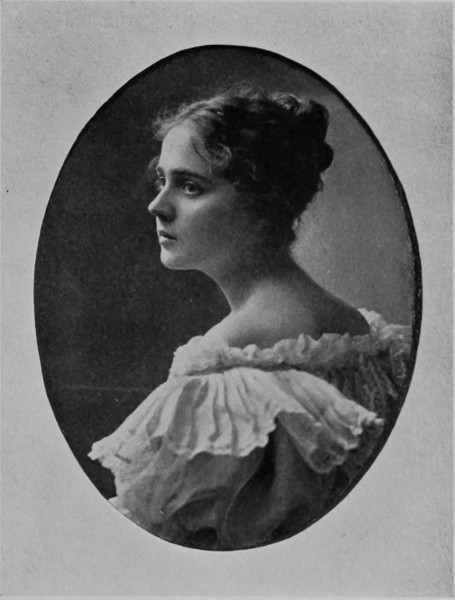

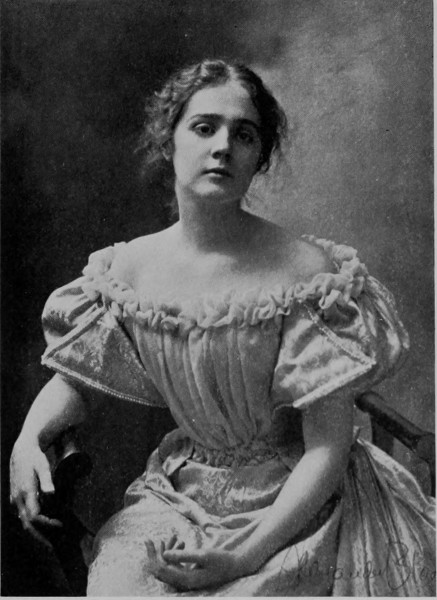

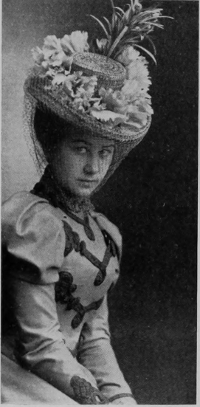

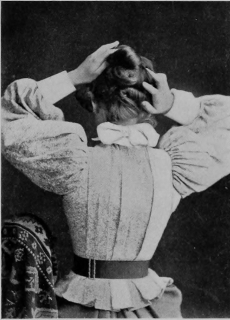

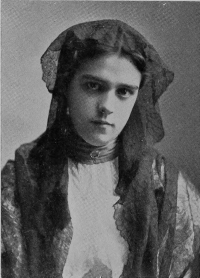

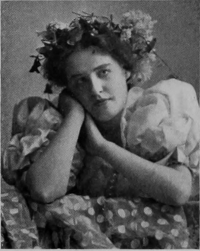

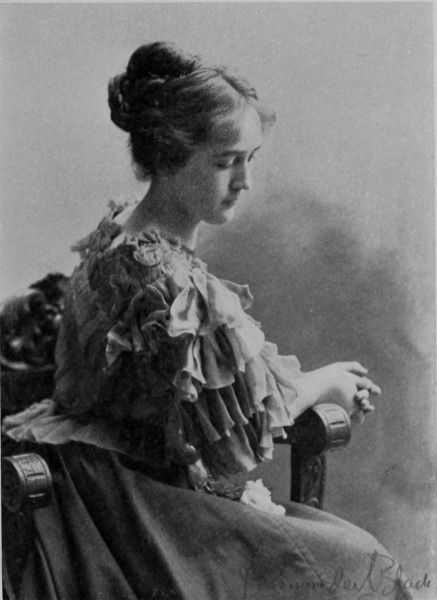

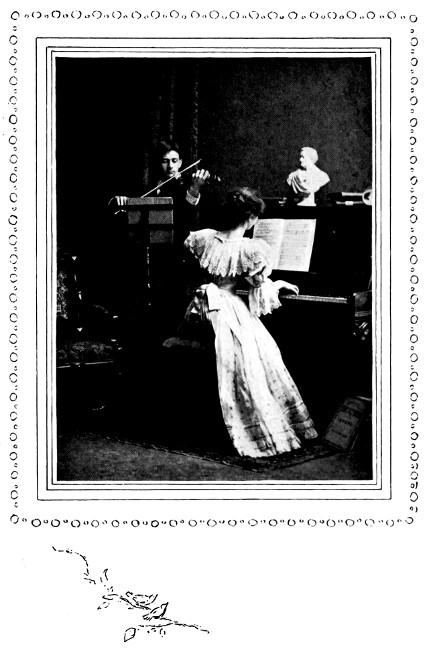

It will be suspected, perhaps, that in saying “sketches,” I have wished to escape some of the responsibility which might have been incurred by a more formal approach to a momentous theme, though the entire truth of the description should carry its own justification. And if the term be permitted in describing the text, it has equal appropriateness in describing the pictures; for the photograph seldom can be more than a sketch, and must be content with the limitations as well as with the privileges of the sketch. The feminine eye will discern unaided by data the chronological range of my pictures. To other eyes, possibly, I should explain that the portraits represent a period of six or seven years, and that those in conventional dress are supplemented by various costume sketches with the camera recalling eras in which there was no photography. What I have said of the American type in the first chapter will explain my own difficulty in expressing the American type by the aid of the lens, a difficulty which has not been diminished by the privilege of wide travel. If I have not revealed the geographical identity of any of the types reflected here, the reservation may, I hope, seem to be as fully justified as certain other reservations which the American girl herself so frequently chooses to hold.

I often have wished that it were easier to substitute for “American” some name which should more specifically indicate the United States. It is the United States girl I am talking about; it is the United States spirit which I have sought to discover, and not the spirit of the wider America of which the foreigner, and even the British foreigner, so frequently, and so reasonably, seems to be thinking when he uses the name “American.” Now that Miss America for the first time has seen her soldier brothers go abroad to fight and to conquer, it may be that in one way or another there will be a further modification of the term, in which direction it would be difficult to say at this hour.

Because this is an apology and not a mere preface, I may be permitted, I hope, to express to the American girls in various States of the Union, from Boston to San Antonio, who have sat before my camera, my regret that I should have translated them so inadequately. It would, indeed, be hard to do justice to the American girl, and one well might hesitate to describe, or even to discuss her, were not her always gracious generosity so safely to be looked for.

A. B.

| I. | THE AMERICAN TYPE | Page 1 |

| II. | THE TWIG | 23 |

| III. | A CENTURY’S RUN | 47 |

| IV. | STITCHES AND LINKS | 75 |

| V. | “WHAT IS GOING ON IN SOCIETY” | 95 |

| VI. | LACE AND DESTINY | 121 |

| VII. | CHANCE AND CHOICE | 143 |

| VIII. | THE NEW OLD MAID | 165 |

| IX. | “AND SO THEY WERE MARRIED” | 187 |

[1]

The tradition that the women of the region in which we live illustrate all of those traits that give an abiding charm to the sex, is one that sometimes may be unreasonable, perhaps even comic; yet it cannot be discreditable. Balzac, who remarks somewhere that nothing unites men so much as a certain conformity of view in the matter of women, may seem unphilosophical when he remarks somewhere else upon the absurdity of English women. His French antipathy has an unreasonably affirmative sting. But we do not care how many Thackerays regard the English girl as the bright particular flower of creation. We like and expect the author[2] of “The Newcomes” to say: “I think it is not national prejudice which makes me believe that a high-bred English lady is the most complete of all Heaven’s subjects in this world.” For the same reason we delight in N. P. Willis’s confidence when he declares that “there is no such beautiful work under the sky as an American girl in her bellehood.” And Mr. Willis adds with the same whimsical consciousness of national partiality: “I think I am not prejudiced.”

Of course this instinctive preference is fundamental. We are prepared to hear from science that the African savage prefers the thick lips and flat nose of the African girl to any other sort; that this is why the African girl has a flat nose and thick lips; that gallantry is a phase of natural selection, and so on. We can understand that there is a merely relative difference of attitude between the savage lover who woos his lady with a club, and the modern suitor who swears to give up all of his clubs for her sake. What perplexes us is our anxiety to explain our modern instinct, and (what is more perplexing) our anxiety to explain her; to ascertain and even to catalogue her essential traits—to discover, if not why we prefer the American girl, at least what manner of girl it is that we thus are instinctively preferring.

What is the American type? Is the typical American girl as the British novelist so often has described her—rich, noisy, wasp-waisted and slangy? Is she a “Daisy Miller” or a “Fair Barbarian”? Is she[3] what Richard Grant White feared she too often was, “a creature composed in equal parts of mind and leather”? Is she Emerson’s “Fourth of July of Zoology,” or is she illustrating the discovery which Irving claimed to have made among certain philosophers “that all animals degenerate in America and man among the number”?

From those foreigners who make a Cook’s tour examination of us, the evidence in favor of the proposition that we grow more pretty and witty women to the acre than any other country in the world, is overwhelming. But there are obvious reasons why we must distrust this foreign comment. Too often it plainly is a propitiatory item, when it is not illustrating a flippant wish among men writers to occupy Disraeli’s position “on the side of the angels.” That traveller has a profound distaste for a country who does not find that it has pretty women.

If anything is more inevitable than this, it is that the traveller will find fault with the type preferred[4] by the men of the country he is visiting. “What is most amazing,” says the observer in Zululand or elsewhere, “is that the prettiest women, the women without this or that hideous deformity, are not admired by the men.” The Kaffir prince on a visit to England, or the Apache chief among the palefaces in the city of the Great Father, invariably are astounded at the obtuseness of the white men. I remember once listening to a group of New York artists who were discussing preferred types of women, and it was agreed, with a hopeless and resentful unanimity, that most New Yorkers preferred fat women, since most of the good clothes and diamonds were worn by fat women. All of which goes to show, perhaps, that natural selection is an exclusive affair.

Probably even patriotism does not demand of us an admiration for the beauty of the very first American girls—the dusky darlings of our primitive tribes. These earliest American girls were not dowered with the fatal gift of beauty as we understand beauty. Indeed, it is quite generally admitted that the American Indian girl is not and never was so pretty as the girls of some of the Pacific islands, for example. Far be it from me to attack any precious traditions concerning the red man, or the red woman, either. Far be it from me to touch with impious hand the romantic panoply of Pocahontas. I am not writing a scientific treatise. I have no point to prove. It is quite possible that there is something distinctive in the [7]personality of the Indian girl, whether she be as poetry has painted her or as she stands in the analysis of science. If I pass her by it is in no spirit of partisanship toward either view. She is an old story, and some day when she is a new story we may have occasion for surprise.

The fact is that I must content myself here with a glance at the American girl of more recent times, though she also will seem to be an old story if we permit ourselves to remember the number of things which have been said. We are not likely to forget the unction with which foreign visitors sketched the daughters of Colonial America. Indeed, we are in a measure dependent upon those sketches for a knowledge of these ancestral daughters. As in all judgments of remote appearances, we here must lean upon mere opinion. There was no camera in the days of Priscilla, nor in the days of Dolly Madison, and painted portraiture, unchallenged by the photograph, had reached heights of admirable gallantry. For purposes of pictorial reconstruction we have an enthusiastic description, the dubious confessions of a diary, a charming little miniature or a mellowing canvas in an old frame, a quaint gown, wrinkled by time; but we have no photograph. I hear the Romanticist mutter, “Thank Heaven for that!” Alas! the photograph is an expert witness, and how he can disagree! Was ever any human specialist on the witness stand so dogmatic, so insinuating, so sophistical as the photograph? Who, without an obstinately anthropological mind, shall regret[8] that the beginnings of our national life are veiled in the Ante-Photographic era—that we may invest them with qualities we wish they might have had, as well as with those qualities of which we think we know? Who shall say that humanity, A. P., dwelling in a softening haze beyond the harshly illuminated era of Realism, is worse off than humanity thereafter? Looking at the matter practically, who shall regret that Lady Washington never had her pretty head in a vise, her face masked a ghastly white with powder to make her countenance more actinic, and her eyes instructed to glare at a fixed point for upward of sixty mortal seconds! Surely there are some compensations in being handed down like the Iliad or the masonic ritual by word of mouth rather than by agencies associated with the arrogant stare of the lens.

But, after all, we do not conduct the trial wholly with expert witnesses, and the camera has been a useful commentator—perhaps we are more willing to say that it will be than that it has been, though we never shall surpass in delicately literal perfection the image of the daguerreotype. A new confusion may arise from the fact that photography wants to be more than a science—is tired of being literal, and seeks to be an art. If it shall become an art—that is to say, an agency of personal opinion—posterity must, like ourselves, go on being influenced in its judgments of pictorial fact by the expressions of art, which the world has been doing from the beginning of time.

[9]

Certainly it would be very hard for us to think of the English girl, for example, however well we might know her personally, without feeling the influence of the English artists, of Romney, and Reynolds, and Sir John Millais, and Sir Frederick Leighton, and the multitudinous expressions of her from the pencil of the author of “Trilby.” Du[10] Maurier’s English girl is an image, agreeable or not according to one’s taste, which we cannot get out of our minds. A number of years before he achieved a second fame by writing romances, Du Maurier made a sketch in which he undertook to indicate his idea of a pretty woman. He wrote of his ideal at that time: “She is rather tall, I admit, and a trifle stiff; but English women are tall and stiff just now; and she is rather too serious; but that is only because I find it so difficult, with a mere stroke of black ink, to indicate the enchanting little curved lines that go from the nose to the mouth corners, causing the cheeks to make a smile—and without them the smile is incomplete.” I always have been glad to hear Mr. Ruskin say of the Venus of Melos, with her “tranquil, regular and lofty features,” that she “could not hold her own for a moment against the beauty of a simple English girl, of pure race and kind heart.”

And in the same way our notion of the American girl, of the typical American girl, is inevitably affected by the pictures we see of her. Our illustrators naturally have the best opportunity to mould our judgments in this matter. I recall hearing one woman say of another at a tea: “That girl is[11] always sitting around in Gibson poses.” They used to say the same thing in England of the girls who imitated Du Maurier. Thus we see that the illustrator of life not only is reflecting but creating forms and manners; and if you would know not merely what the American girl is, but what she is going to be, study the picture-makers and story-makers who influence her.

Mr. Gibson would have us believe that Miss America is essentially a statuesque girl, that, in general, there are good chances that she will be tall, commanding, well-dressed, rather English in the shoulders. Mr. Wenzell and Mr. Smedley present her to us as more willowy, with more of what, if we had to go abroad for a prototype, we should be obliged to call French grace and lightness. We have been[12] under the spell of the girl Castaigne can draw, have enjoyed the dainty femininity pictured by Toaspern and Sterner and Mrs. Stephens. None has grudged a flattering stroke, a prophetic outline. It is the old story. If we are to measure a nation’s civilization by the degree of its deference to women, we surely shall find much to confuse us in art, which in all lands, like some joyous, enthusiastic child,[13] always has heaped unstinted homage at the feet of its goddesses, its Madonnas, its Magdalens and its nymphs; which always has been ready to give to its fruit-venders and flower-girls in the market-place the same refined beauty it bestows upon its princesses; which has made its Pandoras beautiful with no sign of resentment for any mischief its Pandoras ever may have done, grateful only for the privilege of saying to the world as to her precious private self, that she is very charming indeed. Germany, while sending women to the plough, paints her radiantly as a deity, and when England was selling wives at the end of a halter in the market-place, there was no abatement in the ardor of her artistic tributes to feminine loveliness.

While the American artist has painted Miss America appreciatively, with an enthusiasm creditable alike to his art and to his patriotism, and seldom, surely, in the spirit of one who could say, “she is rather stiff just now,” unquestionably, like the rest of us, he has been bothered at times by the fact that she is so various, that she has so many pictorial as well as temperamental and (may I say) vocal variations.

There are several reasons why she should be various. The “Mayflower” was a small ship and could not hold all of our ancestors. Like the English who followed after the Conqueror, some of our ancestors had to be content to “come over” at a later time, some of them at a shockingly recent date. Thus we have greater divergences in type[14] than exist in countries wherein the “coming over” process was neither so protracted nor from so many points of the compass. The American girl blossoms like the pansy in so many and in such unexpected shades and combinations that science falters, and bewildered art, determined to paint types that will “stay put,” bolts for Brittany and sulkily draws sabots and the Norman nose. We are a vast anthropological department store in which the polite sociological clerk will show you human goods, not only in the primary colors, but in every conceivable tint and texture; and when you ask him, Is this foreign or domestic? he lies to meet the requirements. Yes, Miss America sometimes, like our cotton, “comes over” a second time with a foreign label, which is puzzling!

It is our habit to think that the American girl of English ancestry presents precisely the right modification of the—what shall I call it?—austerity of the purely English type, and which scorns the melancholy of Burne-Jones and Rossetti. The American girl of German parents is conspicuously with us, and very often is found supplying a fascinatingly fair phase without which our galaxy scarcely would be complete, adding a delightful sparkle to the demureness which we might not find so modified in Berlin or Bremen. The American girl of French parentage is found uniting the traits of the people which has produced De Staël, and Récamier and George Sand, to the perhaps not greatly different vivacity of l’Américaine. We trace the auburn[15] tresses of the Scottish lass, the teasing Irish eyes, the winsome oval of the Dutch face. We see the too emphatic contrasts of the Spanish, the Italian and the Russian types mellowed and refined; while Oriental blood, the civilized African, the octoroon and the occasional Asiatic each add an element of picturesque variety.

And this is not saying a word about the differentiating fact that this is a big country, and that Miss America in one section is by no means the same as Miss America in another. I do not mean to say that when we meet her in or from Boston we always know her by sight, but when we come to average her in that neighborhood we are able to see clearly enough that her quality is distinctive, that it is different from the quality of Miss America elsewhere—in New York, for example, where, by a trivial tradition, she is supposed to lay less stress upon intellectuality, but where, under whatever guise of habit or manner, you will find that she knows enough and has what she knows sufficiently at her command to make you nervous. Again, the Philadelphia girl upsets your preconceived notions, if you are foolish enough to have these, by being nothing that suggests even remote relationship to the bronze Quaker on the municipal tower. It is the familiar joke that the Boston girl asks what you know, that the New York girl asks what you own, and that the Philadelphia girl asks who your grandfather was. If this amiable satire should have any foundation in fact, I wonder what the Chicago girl[16] is expected to ask. I myself have a theory, not wholly dissociated from experience, that she does not ask anything, being content to know that she, personifying the great traditionless middle west, has been called the hardest riddle of them all.

And, as I have said, we must admit that geography has much to do with the case. Does any one deny that climate and history have made the Kentucky girl a being apart—that the Kentucky horses which she has ridden with so much spirit have had their effect in her whole style and personality? Could we fail to look for a distinctive flowering in the verdant slopes beyond the Sierras or amid that intensely American human environment on the plains of Texas? Have you heard the Creole sing? Have you heard the music of the Georgia girl’s talk? Have you ever let a Virginia girl drive you, or danced with Miss Maryland?

A southern dance! Perhaps it is inevitable that we should find ourselves thinking of the Continental and early Federal society; of old Georgetown and the powdered heads, and the minuet, and the blinking candles behind the darkey orchestra; of the clinking swords of the young Revolutionary soldiers, and the satin breeches of the foreign lordlings, studying the precocious young republic and the young republic’s daughters: of the quaint gowns Miss America used to wear, and the taunting little caps and head-dresses, reflecting now the whimsies of the Empire, now the furbelows of the Restoration, and always her engagingly different [19]self. Yes, time is working its wizard tricks up and down the land, slowly here and quickly there, now (as it might seem) in a romantic spirit, and again in brusque paradoxical contrast to the thing we expect.

We live quickly hereabouts, and to say that the vast changes which have taken place in our national life have been mostly external is not to say that the spectacle is on that account any easier to understand. In an especial degree social situation with us, like the age limit defining old maids, is wholly relative, subject to continual change. To the foreign spectator who ignores this relativity, the American girl naturally is bewildering, and we are likely to find her typified in foreign comment in the words which Schlegel irreverently applied to Portia, as a “rich, beautiful, clever heiress.” No, the typical American girls are not all heiresses, nor all cow-camp heroines. They were not always demure in the colonies, nor are they always disconcertingly self-possessed in our own time. The girls with whom Lafayette went sled-riding on the Newburg hills do not actually appear to have been amazingly different from those who teased the Prince of Wales in the fifties (I mean our fifties), nor from those who sent in their cards to Li Hung Chang in the nineties. It is very shocking to us moderns, who let women preach and plead and vote, to learn of the number of elopements in the days when women were theoretically tethered to the spinning-wheel and forbidden everything but hypocrisy.[20] Which is to say, perhaps, that how much we shall regard as distinctive in the modern woman may depend upon how little we happen to know of the woman who has gone before.

But time and place must leave their mark, and Miss America, though she be like changeable silk, of varying hue in varying lights, is undoubtedly, being the precocious product of a new era in new territory, a new variety in the species, as new as if she were grotesquely instead of subtly different. And in her presence the American himself frequently seems to be awed and quelled, like the Greek hero when Athena’s “dreadful eyes shone upon him.” His devotion to her has excited derision; his deference has been misconstrued, his boastful admiration has been catalogued as characteristic. Italy once spoke of England as “the paradise of women”; and England in a later day began to say the same thing about the United States, which may or may not have something to do with the “star of empire,” and probably, in any case, has some definite relation to the Anglo-Saxon spirit, concerning which so much has been said of late. As for Miss America herself, the sovereignty at which the foreign observer marvels is a real appearance, however profound the misapprehension of its philosophy. Miss America is no illusion, if some spectators have doubted their senses.

By the grace of nature she is that she is. If the American man continues to pay her the supreme compliment of not understanding her, that is his[21] affair. It always is easier to perceive the other’s folly than our own—especially when the exciting cause is a woman. We know better than the spectator why we permit certain seeming tyrannies! We analyze the American girl in a purely Pickwickian[22] spirit, not because we expect actually to discover facts, but for the immediate pleasure of the speculation. We neither seek nor assume to comprehend this marvellous organism. We know better. When we pretend to delineate the American girl it is in the spirit of Fielding’s aside in “Tom Jones”: “We mention this observation not with any view of pretending to account for so odd a behavior, but lest some critic should hereafter plume himself on discovering it.”

[23]

As I said one day to the Professor—

But first I must tell you about the Professor. She is a young woman—young even in an era that classes authors among the “younger writers” until they are sixty, and is pushing the “proper age at which to marry” into the period of severe and undebatable maturity. She is young, but she exemplifies that educated precocity tolerated and fostered by our era. She knows the past like a book and the present like a man. She does not vulgarly bristle with knowledge like the first products of the higher education. Her acquirements sit upon her less like starched linen than like a silken gown that flows[24] with the figure. She is the educated woman in her “second manner,” as the art critics would say. I do not know what the educated woman’s third manner will be. No one acquainted with the charms of the Professor could help hoping that there never would be any.

The Professor graduated and post-graduated. She pottered in laboratories, and at certain intervals wholly disappeared into the very abysses of science. She read law tentatively, and made a feint at going into medicine, but was deterred in each case, I fancy, by the fact, repugnant to her exuberant energy, that a practice had to grow and could not be mastered ready made. At one time there were both hopes and fears that she would enter the ministry. Those who hoped banked on her earnestness and wisdom. Those who feared quailed before her ruthless independence and sense of humor. She delighted in the paradox of not scorning social life, welcoming Emerson’s admonition with regard to solitude and society by keeping her head in one and her hands in the other. Indeed, she dances remarkably well when we consider that here the dexterity is so far removed from the brain, and I have seen her swim like—a mermaid, I suppose. She took a long course in cookery for the pleasure of more pungently abusing certain of her lecture audiences. One day when the plumbers didn’t come I saw her actually “wipe a joint” in lead pipe with her own hands. Heaven knows where she picked that up!

[25]

When she accepted the position at the Academy, doubtless it was with a view to certain liberties of action in the sociological direction. She was not quite through with the college settlement idea, and I suspect that she had a feeling that city politics at close range might be productive to her in certain ways. Because she is neither erratic nor formidable, she has experienced various offers of marriage, and has shed them all without visible disturbance. Just at present, panoplied in learning, tingling with modernity, yet always charmingly unconscious of her power, she stands, poised and easy, like a sparrow on a live wire.

In other words the Professor is one of those rare women with whom you may enjoy the delights of a purely impersonal quarrel. She can wrangle affectionately and cleave you in twain with a tender sisterly smile. Indeed, she can make you feel of intellectual fisticuffs, and, notwithstanding an occasional effect of too greatly accentuated excitement, that it is, on the whole, a superior pleasure. And you arise again conscious that she has no greater immediate grudge against you than against St. Paul or any other of her historical opponents.

One day I asked the Professor, not with any controversial inflection, what she thought of Herbert Spencer, a bachelor, talking about the rearing of children.

“Well,” said the Professor, “it certainly is no more absurd than the spectacle of Herbert Spencer analyzing love, or Ernest Renan doing the same thing.”

[26]

“Mind you,” I went on, “I don’t say that the unmarried may not discuss with entire competency—”

“I hope not,” interrupted the Professor. “I hope you wouldn’t say any such absurd thing. Must a man have robbed a bank to write intelligently of penology?”

“My point is,” I went on—the Professor and I never take the slightest offence at each other’s interruptions—“my point is that it almost seems at times as if the unmarried should, in such an emergency, assume, if they did not feel, a certain diffidence. To tell you the truth, Professor, if it were not for you, I should doubt whether the unmarried had a developed sense of humor.”

“That is simply pitiful,” flung the Professor. “Can you not see that it is a sense of humor that keeps many people from marrying? But that is not the point. Who is better fitted than Mr.[27] Spencer, who has enjoyed freedom from an entangling alliance, who is unbiased by social situation or personal obligation, to discuss with scientific judiciality the problems of child-rearing?”

“Theoretically, Professor, that is all right. But when Mr. Spencer advises more sugar, it is awfully hard to forget that Mr. Spencer never, presumably never, sat up nights with a youngster who had the toothache. It is all very well for Mr. Spencer to suggest that when a child craves more sugar it probably needs more sugar, but the parent who manages his offspring on that basis is going to lose sleep. A good rule, if you will permit me a platitude, is a rule that works. The way that children should be brought up is the way they can be brought up.”

“My friend,” said the Professor—

Now, I am several years older than the Professor. By sheer age I am entitled to her deference; but the Professor can ignore years as well as sex or previous condition of servitude. Her impersonality is adjusted to time, to space, and to matter. I am simply a Person.

“My friend,” said the Professor, “it is another platitude that there is a right way to do everything,[28] even to bring up children. The way children are brought up probably is not right, and no theory or method of bringing them up is, of course, or could be more than relatively right. But in getting as near the right as we humanly may there is no wisdom in despising the advice of the spectator. The man digging a hole in the ground may be less competent than a man not in the hole to perceive that presently the earth is going to cave in. As a matter of fact, old maids, for example, have been known to bring up children very well indeed, for the reason, possibly, that nothing is more detrimental to successful authority over children than relationship to them. All experience shows that the scientific, the abstract management of children is more successful, in the average, than the traditional parental method. This scientific method, I need not say, is not less kindly than the other; it actually is more kindly. Witness the absolute triumph of kindergartens—”

“Now, Professor,” I interposed, foreseeing the spectacle of Froebel and Plato moving down arm-in-arm between the Professor’s periods, “understand me—”

“A very difficult thing at times,” she murmured.

“Understand me—I am speaking now with my eye on the American child.”

“And that,” twinkled the Professor, “requires some dexterity.”

“The American child,” I pursued, “is accused by many of threatening our destruction, and if the [31]American view of rearing children is wrong or requires modification, this radical suggestion of Mr. Spencer, looking to greater rather than less liberty in making terms with the instincts of children, becomes a matter for serious concern. If the American idea has stood for anything it is more sugar—that is to say, yielding something to the instinct, the personality of the child. I think we have gone a long way with it. Our children are becoming very self-possessed. Sometimes I have qualms. Take the American girl child—”

“A vast subject,” commented the Professor.

“The American girl child is getting a good deal of sugar—figuratively. The question comes, Is it good for her? Is her freedom, her undomestic training, her intellectual development, to the advantage of the race? I believe with Mr. Ruskin that you can’t make a girl lovely unless you make her happy. But how can we expect her to know what will make her happy? Aren’t you afraid, Professor, that she is becoming a trifle frivolous? Of course you yourself are a living contradiction—”

“Don’t try to deceive me,” warned the Professor. “I perceive in what you say, not the doubts of an incipient cynic, but the remorse of a doting and indulgent man. Most really typical American men are in the same situation. They are wondering if they haven’t overdone it, and, being too busy to find out for themselves, are eager for outside judgment, upon which they may act, de jure. The vice[32] of the American man is his indulgence of the American girl. The foreigner commiseratingly thinks that the American girl demands this indulgence. The American man in his secret soul knows that he has pampered her for his own pleasure, and because, to a busy man, pampering is easier than regulating.”

“Yes,” I complained, “in the new paradise Adam is always to blame.”

“No,” protested the Professor, “not always; just humanly often. And don’t think that you have invented this modern anxiety for the welfare of girl children. Before and since ‘L’Éducation des Filles,’ they all have been ‘harping on my daughter.’ Women have been even more despairing than men. Hannah More thought that ‘the education of the present race of females’ was ‘not very favorable to domestic happiness.’ Mrs. Stowe thought ‘the race of strong, hearty, graceful girls’ was daily decreasing, and that in its stead was coming ‘the fragile, easily fatigued, languid girls of the modern age, drilled in book learning and ignorant in common things.’ Now that sort of thing has been going on since our race stopped speaking with the arboreal branch of the family. There is perpetual opportunity for a treatise on ‘The Antiquity of New Traits.’ We are apt to think that we of this era have invented the idea of educating girls, but civilized children always have been educated early in something. Nowadays it is in science. In our colonial days it was in piety. Miss Repplier, who [35]has a most relishable antipathy for prigs, in fiction and in life, reminds us of Cotton Mather’s son, who ‘made a most edifying end in praise and prayer at the age of two years and seven months,’ and of Phoebe Bartlett, who was ‘ostentatiously converted at four.’ You are not sorry to be rid of all that, are you?”

“No,” I assented, “most assuredly I am not. It is pretty hard to find the Juvenile Prig on this soil nowadays outside of the most inhuman ‘books for the young.’ And we all are glad of it. You may remember the passage in the Chesterfield letters in which the father writes to the son: ‘To-morrow, if I am not mistaken, you will attain your ninth year; so that for the future I shall treat you as a youth. You must now commence a different course of life, a different course of studies. No more levity; childish toys and playthings must be thrown aside, and your mind directed to serious objects. What was not unbecoming of a child would be disgraceful of a youth.’ We certainly have outgrown that view of things, and the American youngster comes nearer being without hypocrisy than any product of civilization that I ever have studied. But what have we in place of the piety and affectation? What is the working result of so much independence? Are not the American girl children, as well as the boys, a trifle irreverent?”

“Yes, I know,” admitted the Professor, “the American child often seems a shade too unawed. Balzac says somewhere that modesty is a relative[36] virtue—there is ‘that of twenty years, that of thirty years, and that of forty years.’ Our ancestors believed in a severe, hypocritical modesty for the young, trusting that they would get over it. They did worse than that when they asked youth to anticipate the hypocrisies of age. The same elegant person whom you have just quoted once wrote to that same son: ‘Having mentioned laughing, I want most particularly to warn you against it; and I could heartily wish that you may often be seen to smile, but never heard to laugh while you live.’ Although Chesterfield insisted that he was ‘neither of a melancholy or cynical disposition,’ he was proud to be able to say to his boy ‘Since I have had the full use of my reason, nobody has ever heard me laugh.’ The next time you feel inclined to say mean things about the Puritans remember that declaration by the Earl. Now, the American seems to me not only to look at children differently, but to look at life differently, and any[37] new traits in the American child probably represent one fact as much as the other. The American idea—I say idea, but I mean the American habit; we explain our habits and call the explanation a theory—merely obliterates age discriminations. The American child is simply the diminutive American. The American girl is her mother writ small. I don’t think that she is a whit more independent or irreverent than her mother.”

“You don’t mean to say, Professor, that a child should not, for instance, be taught to keep a proper silence in company.”

“Not an absolute silence. A child either has a right to be in a company or it has not. If it is in the company it has a right to be articulate like the other members of the company. If it is a sensible child it will listen to its elders, not because they are its elders but because they are its betters, because they know more, are more competent to speak. If it is not sensible it will be made to suffer for its foolishness, just as older members of the company are[38] made to suffer. From my observation, children naturally brought up take their reasonable place very naturally in company.”

“My fear is, Professor, that your naturalistic method overlooks much of what we have become accustomed to think when we speak of ‘breeding.’ Now, children, even American children, do not acquire this instinctively. Breeding includes restraint, externally applied restraint—I don’t mean applied with a slipper or a rattan, though restraint to have a really fine catholicity should, in my opinion, include these symbols—but restraint inculcated by a wise, or at least a wiser, authority. I believe sincerely that we have, in the past, tried to bend the twig too far. But the beneficial results of guiding twigs has been, I think, indisputably proved. Taking away too many guides and supports must have its dangers. I think of these things when I see the unhampered American girl of to-day. She is a lovely spectacle. Yet I sometimes wonder, in a trite and old-fashioned way, if her sort of training or absence of training is going to make her a woman who will know how to manage a household and children. I can see clearly enough that she is going to know how to manage a husband; but the house—and the children—”

The Professor was musing. “Your anxiety makes me think of the early criticisms of the kindergarten. ‘What!’ they used to exclaim, ‘a mob of unmanageable brats and no ferule?’ Yet it is so. Your[39] misgivings overlook, I think, the latitudes of training, the obligations of breeding. The American seems to me to be guiding his children as he guides his civic affairs, not by brute force but by giving and taking. If his child is born with the right to the pursuit of happiness, he believes in starting the pursuit early. I suppose that children in the United States have greater liberty than children in any other country. The conferring of liberty has its dangers, and those who confer it cannot expect to escape the obligations that go with the gift. It has cost the American some annoyance to confer liberty and privileges on grown-up folks from various quarters. If he decides—and he does so quite reasonably I think—to include his children, he is bound to stand with the emancipated.”

“Professor,” I said, “your words are soothing. They are alluringly optimistic. I don’t want to reform the American child. I like him—and especially her—as at present conditioned. I believe that the irreverence is largely a seeming irreverence—an irreverence toward traditions rather than toward people and principles; which simply is saying what we should say of grown-up Americans. And I believe that in any case the boy will knock his way out somehow. But the girl—I am not doubting her; I am not believing that she is so petted a darling as Paul Bourget, for instance, seems to think she is. I am not questioning the intrinsic charm of her style, the piquing prophecies of her[40] mind, the perfection of her beauty, the delight of her companionship; I am wondering whether this immediately agreeable sort of product is going to meet the requirements of life as it is opening up to us in this land, if—”

“Well,” swung in the Professor, “if you were going to have a worry, it is a pity you couldn’t have had a new one—the new ones keep us busy enough. You are very trite this time. You sound like a reformer—”

“Heaven forbid!” I cried.

“—and a reformer nowadays has a passion for beginning on the children. Please don’t. Some of these reforming women remind me of the advertisement in the London paper: ‘Bulldog for sale. Will eat anything. Very fond of children.’ These reforming women will reform anything—and they are very fond of children.”

“It is particularly the American girl,” I went on, “who is illustrating the modern yearning to skip intervals, to ignore the ordinary processes of time. She is like Horace Walpole, who found that the deliberation with which trees grow was ‘extremely inconvenient to his natural impatience.’ It doesn’t seem to make any difference how rigidly her ‘coming out’ time is fixed, she is getting to be a woman before her time. Mark me, Professor, she knows too much, she—”

“A strictly masculine anxiety, sir.”

“—she knows too much, to the exclusion of some other things she doesn’t know.”

[43]

“Now don’t mention the kitchen,” cried the Professor, “I am dreadfully tired of that.”

“No, Professor, her general cleverness always seems to me to make the kitchen anxiety needless to a great extent. I mean that in knowing so much and assuming so much the American girl child may be missing some of that sweetness that for her lies in a more old-fashioned girlhood. As a kind of unbent twig she is losing some of the more dependent happiness belonging to her and not grudged to her. Mind you, Professor, if a crime has been committed, I am accessory—”

“I began with that assumption,” remarked the Professor.

“—and I am hoping that there has been no crime, that the unbent twig is growing all right on its own account, that our spoiled daughters, weary of privilege, may be longing to serve, that if her modesty is not expressed in meek eyes ‘full of wonder,’ her lofty glance is not, Hermes-like, given to lying. Whatever the future may have in store, she at least is what she seems to be. Her sentiments may sometimes be irreverent, but they are her own. Perhaps the reason she seems more of an individual than the archetypal girl is, as you have suggested, that we have stripped her of the hypocrisy by which she pretended not to be a unit but only the mute shadow of a unit.”

“O, you will come around!” chuckled the Professor.

[44]

“‘Come around,’ Professor? You mean sink back into the Slough of Idolatry. I feel it in my bones that in spite of a gleam of intelligent interrogation as to the wisdom of pampering the American girl, I am going to keep right on—”

“You mean, if you will be honest,” blurted the Professor, “that you will keep on letting her alone as you do the boy child. That is all. Own up. The most that you have done is cease the special repression of the girl. For better or for worse the American has done simply that: forget sex in rearing his young.”

“Ah, Professor! when we forget sex are we not in danger of a costly transgression? Are we not combating nature?”

“On the contrary, my friend, you are ceasing to combat nature. There is nothing nature is more definitely certain to do than to look out for sex on her own account. Is not all of creation trying to[45] teach us this lesson? Is not all of creation trying to teach us the folly and the futility of meddling? Let nature alone. She knows her business. Sex duality is universal. No amount of sitting up nights will help you to think out a way of successfully interfering.”

I looked at the Professor. She is very much a woman. She suggested a type that had been “let alone.” She is not a freak. Both her body and her mind are well dressed, and she is good to look upon. To look upon her sometimes fills me with a certain misgiving. But it is not a misgiving for her.

“And yet,” it came to me to say, though not precisely in rebuke, “there is such a thing as human humility.”

“Humility?” The Professor looked over at me with affected scorn. “Then illustrate it, please. I cannot see the humility of interference. The American does not repress his daughter. You admit that you like the result. Why wrinkle your brow in contemplation of the future? Why not believe that what seems to be true is true, that the American girl flourishes agreeably in her freedom? Give her the natural privileges bestowed elsewhere throughout creation. Let her[46] grow. She is not like Jupiter, without seasons. And you must take one of her seasons at a time.”

“Professor,” I said solemnly, “you remember Artemis?”

“Yes,” she returned with equal solemnity, “and I remember the daughters of Pandareas.”

[47]

We are a very young nation, yet we have a past. In popular acceptance we have little to live down, which should be a comfort. Just at present there is a tendency to be disrespectful toward the past, to smile at ancestral pretension, to humanize the Fathers of the Republic, to sneer at the straw and bones on the floor of King Arthur’s dining hall, to uncover the littleness of the ancient giants, to question the beauty of the ancient heroines. Probably this needed to be done, particularly in defence of the abused Present, which always hitherto has had a hard time of it. “Every age since the golden,” says George Eliot, “may be made more or less prosaic by minds that attend only to the vulgar and sordid elements, of which there[48] are always an abundance, even in Greece and Italy, the favorite realms of the respective optimists.” The author of “Romola” was willing not to have lived sooner, and to possess even Athenian life “solely as an inodorous fragment of antiquity.”

But even the past, sinfully boastful and complacent as it appears, has rights which we must make some show of respecting, and we need not too effusively applaud the present. Possibly the one good excuse for finding out and confessing the whole truth about the past, is the need to show, at whatever cost, that neither all of our vices nor all of our virtues are entirely new. The passion for discovery is so strong that some one always is ready to prove that the most trite and fundamental of traits are absolutely novel, and the same passion appears in the unction with which the pretension is ridiculed and overthrown. I talked one day with a distinguished American historian, who confessed that the supreme difficulty for the commentator on human character and events was that arising from a tendency to “think disproportionately well of facts which he himself has discovered.” Admit this to be a human trait and we have a sufficient explanation of the ardor of the discoverer.

Now, no man can regard as insignificant any fact concerning woman, disproportionate as the importance of the fact may be made to appear in comparison with other facts concerning her, so that we have no greater difficulty in appreciating the noisy announcement of the New Woman than in[49] appreciating the only less audible contention that there is no such appearance. Happily the foolish discussion is over. Only a few catch-words now remind us of the hopeless debate. Of course, Eve was the only new woman. She alone was incontrovertibly new; and to seek by trick of title to invest with newness any woman who came after her, was a frivolous and degenerate conspiracy. Not, indeed, that newness is intrinsically a defect, though heraldry and afternoon teas may be arranged upon that assumption; but in effect it is belittling, destructive of certain benefits of the doubt, insulting to the woman of the past and skeptical as to the woman of the present.

However, our national past and our national present are so full of superficial and even of fundamental contrasts, that if ever a merciful sentence is to be passed upon one who, peering through the “turbid media” of sociological analysis, mistakes the Zeitgeist for a new woman, it is in our own longitudes. Like a child growing up under the eye of an arrogant and pompous parent, we have, nationally, been made to feel from the beginning that we are new, even tentative, that we are unclassified, all but vagrant in the ethnological sense. It is possible that recent events will modify in certain important ways, external contemplation of us as a nation, that, in spite of certain new effects which we may be accused of producing, a consciousness and a recognition of our definite maturity may have some responsive effect in ourselves.

[50]

Meanwhile it is pleasantly easy to detect many interesting changes in the situation of the American girl within the span of the century. Whether she merely illustrates the social and political changes which have taken place, or, as we so often have been urged to believe, actually indicates why they have taken place, she presents a spectacle of peculiar interest, a spectacle which has so successfully piqued the analytical spirit of the period that it would be expounding the commonplace to do more than quickly sketch a few of the outlines.

We have seen her bidding good-bye to the schoolma’am at a time when any education was good enough for a girl,—good enough not only because neither the kitchen nor the drawing-room exacted Greek, but because heavier pabulum would utterly ruin her mental digestion; and we have seen her at a later time when no education is too good for her, bidding good-bye to an army of instructors at commencement time, radiant in her cap and gown, the class song ringing pleasantly in her ears, the breath of June in her life, with a crisp diploma to symbolize her triumphs. In fact, we have seen the morality of educating her dismissed as a settled question, and the matter of the quantity and quality left to the perhaps not easy but at least final arbitrament of her individual capacity.

We have seen her yield up to strenuous and inventive man, one by one, various and many offices once regarded as essentially domestic, and even as bounding that debatable domain, her “sphere”; [53]we have seen the spinning wheel go into the garret and come down again years later, pertly polished, with pink ribbons on the distaff and spindle; we have seen the superseded milkmaid gathering bottled cream at the basement door, the superseded seamstress wearing a man-made jacket; and all without audible murmur at the displacement.

We have seen the trained nurse succeed Sairy Gamp, many nostrums disappearing gratefully in the transformation, and have found in the new sisterhood of bedside saints a cheering sign of a finer civilization, a prophecy of the future of medicine. We have seen the amanuensis penning “Paradise Lost” and law briefs and grave history and exhausting letters—the amanuensis celebrated in sentimental fiction and unsentimental commerce, fulfil the promise of her own invaluable service in the modern typewriter, whose little white fingers help move the lever of the great mercantile machine, without whom modern trade could scarcely stir, and[54] whose taking away would rob all business life of an inestimably sweetening influence.

We have seen her needle placed in the jaws of a machine, and have seen her yoked with men in service to this iron master. We have seen her leave the fireside armchair to climb the tall stool of the counting-room and the railway station. We have seen the bodkin displaced by the scalpel, the lace cap by the mortar-board, the apron by the vestment. We have seen her emerge from the shadows of the sanctuary to speak in the councils of the elders, we have seen her hurry the breakfast dishes to go and vote.

We have seen her, once content to be the theme of art, become a master of every medium, even of architecture, and throwing aside at last, and without petulance, the insulting tributes that come under a sex label. We have seen her, once forbidden to read newspapers, successful in making them; committing errors, but under bad counsel and direction rather than by any failure of her own taste, and winning highest honors in journalistic art and conflict.

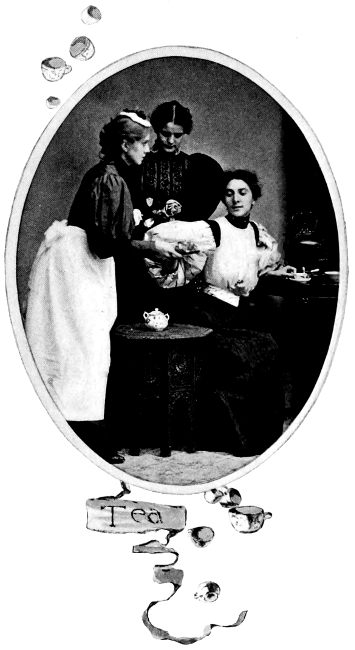

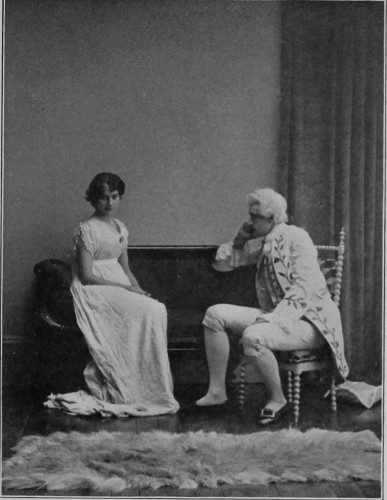

The Amanuensis of the Past

The Amanuensis of the Present

The philosophy of all these changes naturally is complex and difficult. It is a truism to remark that the danger always is of assuming that they mean more than they do. We perhaps instinctively measure a change by the mere picturesqueness of the contrast. We require to be reminded much that humanity changes very little from century to century, that whatever the appearances, great revolutions in human sentiment and motive probably [59]have not happened. No student of human nature comes oftener upon any discovery than upon that of the simple persistence in the twilight of the century of the old human instincts that prevailed at the dawn. So that we need not think to find in all these new clothes any greatly different people. When the century’s clock strikes the hundredth year, and Father Time, acting as master of ceremonies, shouts “Masks off!” there, among all the masqueraders, are the same faces that have grown familiar in the every-day of life.

If the reader detects in this attitude any wish to escape the burdens of an explanation, an anxiety to dodge the awful Why? in all these outward modifications of Miss America, he, and especially she, is quite at liberty to do so, for, as I perhaps have indicated, and must repeat defensively from time to time, definitely to explain Miss America is farthest from my thoughts; though I cannot deny an intention, which doubtless appeared at an early stage, to express respectfully certain untested, and, it may be, actually impulsive, personal opinions regarding her. To refrain from exercising such a privilege under circumstances which forbid interruption would be superhuman.

More interesting to me at the moment are some appearances already fairly familiar, yet new in garb and situation. The young woman in new lights and new places has a natural fascination. I realized this vividly one day in the hotel of a Western city, when I became conscious that an[60] unusual guest had arrived. She was a sturdy young woman, yet delicate of feature, with a mild, undismayed blue eye. She came swinging into the hotel, a darkey lad at her russet shoe heels with a telescope bag. She herself carried a sleek yellow satchel which she placed in front of the desk. She wrote her name in a firm, small hand, took a heap of letters handed to her by the clerk, and dropped into a near-by chair to open several of them with a quick flip of her gloved finger. In no way was she radically dressed. Her tailor-made suit was of a fine cloth, richly trimmed. Her clothes, like her manner, had not an unnecessary touch. Later, I saw her interviewing the porter, who presently was rolling three large sample trunks into one of those first floor rooms provided by certain hotels for the use of drummers, whose goods for display cannot well be taken upstairs. I saw her come in at different times with three different shopkeepers, and others came, evidently by appointment, to inspect many rolls of carpet which soon littered the display room.

Thanksgiving Day: Old Style

Thanksgiving Day: New Style

“She’s a trump!” muttered the clerk, with an admiring glance across the corridor; “the best drummer Warp & Woof ever had. She succeeded one of their New York men, and she beat his orders by forty thousand dollars the first year. And there’s no fooling about her either. She doesn’t try to mesmerize the customers, though she’s pretty enough to do that if she cared to. She simply makes them want the goods, and she sells so square [65]that she doesn’t have any trouble coming back to the same people.”

“Is she a single woman?” I asked. Something in this inquiry amused the clerk. Then he said: “Well, they say she’s engaged to a drummer for Felt, Feathers & Co., and that if they ever manage to get into Chicago at the same time they will get married.”

One day in mid-Missouri a lean, brown, bare-footed boy was driving me across country to a railway station. Suddenly the boy said: “We ain’t goin’ t’ have no dog show.”

“No?” The boy shook his head. Presently he added: “And that girl’s dead sore on this town.”

“What girl?” I demanded.

The boy turned to me with a look of incredulity. “Didn’t you see ’er?”

“You don’t mean that girl in the blue dress that was at the hotel breakfast this morning?”

“That’s her, yes.”

I remembered that she had very dark eyes, and no color; that she wore an Alpine hat and a neat gown, that she looked straight before her with an almost sullen expression when she spoke to the waiter.

“I drove her over to Bimley’s,” the boy said, “and she sat there where you are for two miles without saying a word. Then she turned at me quick and says, ‘Have you got a cigarette?’ and I said yes I had, just one. Then she said, ‘Have yer got a match?’ and I give her that, and she[66] smoked for a long time without sayin’ anything. After a while she let out and said this was the meanest, low-down town she ever struck, that they was meaner’n dirt here, especially the college, and that she never wanted t’ see it n’r hear of it agin. Yer see, she goes from one town to another and gits up dog shows for the people that have fine dogs, and they have the town band, an’ lemonade an’ cake an’ prizes. Anyway, she had a hard time stirrin’ them up here; but she could have got through all right only for the president of the college. He said he wouldn’t let the girls go, and that settled it. They gave it up after this girl’d blown in a two days’ bill at the hotel, and she got mad and lit out. Well, she quieted down agin before we got to Bimley’s, and when we was in the hollow by Moresville I looked at her and she was cryin’.”

One other glimpse: Miss Linnett was the typewriter at Stoke Brothers’. At first she had been just the typewriter, coming highly recommended from the typewriter school. She appeared at the minute of nine and went away at the minute of five, unless one of the Stokes stayed beyond that hour, or late letters and the copying book delayed her. She unvaryingly dressed in black, wore her brown hair simply in a knot, and in the depth of winter always had a flower of some sort on her table. The elder Stoke was feeble, and his eyesight grew to be so poor that she read his letters to him. The junior Stoke would never let her take formal dictation,[67] preferring to give her the gist of what he wanted to say and letting her put it in her own way. In this habit they both came greatly to depend upon her. After a time, too, her growing knowledge of the business induced the cashier and bookkeeper to go to her in certain contingencies, and she acquired, without either seeking or rejecting it, various discretionary powers in regard to the machinery of the business. If anything went wrong they resorted to Miss Linnett. If old Stoke forgot anything Miss Linnett was a second memory to him. If the younger Stoke was in a hurry he would hand over the letters to Miss Linnett to answer as she saw fit. She knew all the correspondents of the house and their prejudices. She knew the combination of old Stoke’s private safe after Stoke himself had forgotten it. She had a way of her own in putting away documents, and nobody ever thought of studying the scheme. She met all of these obligations with a dispassionate serenity, and everything she did was done with an easy and amiable quickness. She became the brain centre of the office. She was Stoke Brothers.

Then one night she broke down, fainted, there before old Stoke, who fell on his knees beside her and wept in real anguish while the little white bookkeeper ran for a doctor, and the cashier tremblingly fetched water to sprinkle her face. When she did not come the next day at nine the situation in the office was pitiful. Old Stoke was useless, and the younger Stoke shifted his letters from one hand to[68] the other in utter misery. The bookkeeper and cashier fumbled through their work dazed and unstrung. In the days of doubt that followed the situation grew more gloomy. There was great excitement when one morning she came down town in a cab, white and fluttering, and, leaning on the bookkeeper’s arm, made her way from the elevator to the office. She smiled at the little group, accepted the homage quietly, insisted on showing them where certain papers were, promised them that she should be back very soon, and went away again, old Stoke patting her hand and telling her to be careful. At the end of the month she died.

“What did they ever do without her?” I asked when I had heard the story.

“They didn’t do without her. Stoke Brothers went out of business. I suppose they had been thinking of doing that; they were pretty well on in years—and they couldn’t get on without Miss Linnett.”

Yes, of all the changes that have marked this changeful century, of all the transformations, social, political and economic, that have affected the situation of women since the establishment of the Republic, that change is most significant and potent which has placed her so widely and so potently in business. Miss America is in business: patiently ambitiously, grotesquely, indispensably in business. The social changes have not been great,—indeed, one is often startled to find how slight they have been.[69] Political changes, important and prophetic as they are, have not as yet sensibly affected the life of women in general; while the extraordinary extent of women’s entrance into business in co-operation with and competition with men, has had an unexampled effect upon the American girl’s domestic, social and political situation.

The American girl is not, as yet, very definitely conscious of this effect, although she has been told about it often and vehemently in one way or another. Unless she is writing a paper for her club she hasn’t time to think much about it. She enjoys business as distinguished from plain work. The idea of a business training rather piques the fancy of an era that has laughed away the tradition of a “sphere,” and the sort of young lady who in a past era would have no obligations beyond needlework, is found dabbling in shorthand and bookkeeping, as the princes learn a trade.

[70]

And so the scientific observer is greatly distressed at times by the thought that there must be a mighty readjustment before things can come out smooth again. You might think that the whole thing had come upon science unawares, that it was, in the phrase of a young woman who was not new, all “too rash, too unadvised, too sudden.” But no sound authority exhibits real worriment on this point. If it is man who complains, it is man who refuses to get along without [73]her. From this time forth business is going to be a co-educational affair. We shall be told many times again that somehow all this will detract from woman’s charm, and whether we believe or mistrust so much, we shall, I suspect, go on taking the interesting risk.

The Editor’s Busy Day

By the natural processes of time, women, young and old, will, I suppose, like the rest of creation, continue to become better off. Doubtless this is optimism. Pessimism says that two and two make three. Sentimentalism says that two and two make five. It is optimism that is content, and with good reason, to say that two and two make four.

The traveller in a scurrying railroad train becomes familiar with few more thought-suggesting sights than the farm woman in the cottage door. She comes forward with her hands in her apron, if not with a baby on her arm. Sometimes she waves her hand to the unanswering train. Sometimes she leans against the door-post and looks, one might fancy wistfully, at the clattering cars, at the people who are going somewhere. Sometimes the doorway is in a cabin with one room. Sometimes the woman is slatternly, drooping; sometimes she has the glow of content. The spectator in the car cannot but wonder what are the emotions of the spectator in the doorway. Doubtless there is both envy and commiseration on each side. If the spectator in the cars sometimes pities the woman in the cabin door as one who is left out and left behind, the spectator in the cabin door[74] sometimes pities the haste-hunted spectator who is being noisily flung about in the great loom of life.

To glance backward over a century is to feel that life constantly reiterates this situation. We all of us are roughly divided—very roughly, sometimes—into the two groups: the people in the cars and the people in the doorways. The look of things must go on being affected by the point of view. There is a view-point aloof from either situation, but it is not one which the merely human sojourner ever can be privileged to occupy.

[75]

“Did it ever occur to you,” demanded the Professor, “how few people actually do fashionable things?—that we probably are just as hyperbolical in assuming that young women once amused themselves with embroidery as that they now amuse themselves with golf?”

“Stitches and links,” I pondered, knowing that the Professor did not expect an answer.

“What proportion of folks should you say actually do concentrate their functions in the ‘barbaric swat’?”

I lifted my head; and she went on:

“Yes, I know that there always must be a fashionable, a dominating pastime, and I have no disparagement of golf as golf. It is a good enough game in its way. I am bound to admit this after having made a very good score myself. Moreover,[76] it is Scottish, which is a guarantee of a latent profundity. It is a large game, and, as Sir Walter said of eating tarts, is ‘no inelegant pleasure.’ I have been told by those who have had an opportunity to know, that it calls out a great variety of qualities. That may be said of many other things; but no matter. My suggestion is that the assumption of prevalence in a so-called fashionable thing leaves something unexplained, something that may be very important, a philosophical hiatus—”

“Professor,” I said, “have you never stopped to think that fashionable fads and fads that are not fashionable are potent in two ways, that is to say, first and primarily, in participation, and second, in contemplation? There is less golf than talk about golf. One game of golf may be repeated any day, for example, one hundred million times in print. As the newspapers play golf with type, so the physically present spectators on the links are repeated many-fold in those who not less are participants and spectators, who wear ostentatious golf stockings without ever having seen a teeing ground. This secondary participation and appreciation is the breath of life to social fads. Probably this may be said of all not absolutely primary pleasures. And so society says, ‘We are all playing golf,’ which is not true at all, but which instantly produces a situation that amounts to the same thing. We shall say that one woman in ten thousand who may be in a situation, so far as opportunity is concerned, to play anything, is playing golf, but this shall not[77] make it possible for the other nine thousand nine hundred and ninety-nine who are not playing golf, to play anything else and make it fashionable at the same time. This could not be, any more than that we could have more than one Napoleon, more than one most-talked-of book, more than one absorbing scandal, at a time. All epidemics present this feature of concentration. Napoleon was just as much an epidemic as crinoline or ‘Robert Elsmere.’ The hypnotists have a word for this which has escaped me at the moment—”

“Multo-suggestion,” contributed the Professor, patiently.

“Something to that effect, in which we have a scientific explanation of the exclusiveness of fashion, an explanation of fashion itself. And the thing could not be different. That susceptibility to the contagion of enthusiasm which inspires the American with so passionate an interest in all of his hobbies, is a susceptibility which explains his[78] keener interest in life, his democracy of sentiment, his ardent yet generally cautious and sane pursuit of entertainment.”

“Much of this,” interposed the Professor, in her ruthless way, “might, it seems to me, be said with equal propriety of any civilized people.”

“I think, Professor, that there are some significant points of difference—points of difference associated very largely, I think, with the American sense of humor, which we are in the habit of complacently arrogating. I think, Professor, that your philosophical hiatus is occupied very largely by a sense of humor.”

“That,” laughed the Professor, “reminds me of that story of the boy who was seeking to explain to his companion the characteristics of spaghetti. ‘You know maccaroni?’ ‘Yes.’ ‘And you know the hole through it?’ ‘Yes.’ ‘Well, spaghetti’s the hole.’ I do wish I could believe more completely in your sense of humor theory. In the first place it is hard to explain some of the things the young people do by their possession of a sense of humor.”

“On the contrary, Professor, I think American young folks develop a sense of humor earlier than any other in the world, which is a Yankee enough thing to say. This may be an odd contention from me, but to me one of the most distinctive traits of the American girl is her gift for being unserious. It is not always a sense of humor, either; if it is, it is a sense entirely her own, for it [81]certainly is not associated with traits which we ascribe to a sense of humor in men. In any case it is a saving sense, a sense that keeps her from taking things so tragically as the unknowing or unsympathetic spectator might expect. The American has a genius for radicalism, a creative defiance of logic and tradition. Once in a while some philosopher discovers that the frivolities of life have an immense importance. Scientifically the physical distortions of a laugh are ridiculous. Yet we almost have ceased to defend it, even in young ladies.”

“A ready laugh,” the Professor said, “is no indication of a sense of humor. The comic and the humorous are sometimes even antagonistic. You have heard me defend irreverence in girls, but a want of seriousness often indicates a want of humor, for a sense of humor, my friend, is essentially a sense of proportion. Now, to my mind, the American girl does not indicate so keen a sense of proportion in her golf, for instance, as in her clubs.”

“Well,” I ventured, “she is serious enough in them, surely.”

“Only to those who do not understand her,” returned the Professor severely. “That women take their clubs too seriously, too improvingly, has been a matter of complaint for a long time. There has been almost a missionary spirit among those who have sought to save our girls from clubs. Some of the missionaries have preached total abstinence among the girls. ‘If you take one club,’[82] they have said, ‘you will take another. The appetite will grow on you. You pride yourself on your power of resistance now; but after you have taken a club, a dreadful, unappeasable craving will spring up within you, and you will want more. You will not be able to pass a club without wanting it. Even after you have yielded to a morning, afternoon, and evening indulgence, you will find a temptation to take a luncheon club too,—and when you take them with your meals they have a particularly insidious effect. From this it is but a step to a Browning bracer at nine A. M. and a Schopenhauer cocktail just before dinner. Take no clubs at all—especially the subtle, supposed-to-be-innocuous reading club—’”

“Look not upon the club when it is read,” I murmured.

“‘—for these,’” the Professor continued, with her inimitable chuckle, “‘for these lead surely to more deadly stimulants. Indeed, these are, to those who truly know them, more deadly than many another sort.’ Then there is the more moderate school of missionaries which is for limiting the number of clubs to so many a week, or to cutting them down gradually on the theory that a girl who has been taking clubs right along cannot stop short without peril to her health. By dropping, say, one club a week for a whole season, a girl may, from a repulsive intellectual sot be brought back, by patient nursing, and in due time, to decency and three clubs a week.”

[83]

“But, Professor,” I said, “they must believe in clubs as a medicine, as a stimulant in the case of a threatening mental chill—”

“Don’t be frivolous,” commanded the Professor; “my irony was incidental to the statement that all of this talk about the seriousness of women’s clubs is based on a misapprehension. In outward form the clubs are serious, and the theme, their ostensible raison d’être, almost justifies the misapprehension. When you see a batch of women setting in upon civil government, or mediæval pottery, or Sanskrit, or Homer’s hymn to the Dioscuri, or the Heftkhan of Isfendiyar, it is, perhaps, instinctive that the uninformed should jump to the conclusion that these women are serious, though a moment’s thought might suggest a wiser view. If women really took these things seriously they would not survive. The truth is that the French Revolution, and the Rig-Veda, and the Ramayana are all very amusing if you know how to go at them. If the physical culture classes took the exercises as seriously as the teachers I am sure the members would all break down. And it is[84] the same way with the study of cathedrals or street-cleaning.”

I reminded the Professor of the lady I had heard of, who wanted to know at the club whether the Parliamentary drill then organizing was anything like the Delsarte movements, and of the other, who, at her first meeting, being appointed a teller, wanted to know what she was to tell. “I trust, Professor, that you will not take from me my simple, unquestioning faith in the earnestness of these light-seeking ladies.”

“Those instances,” smiled the Professor, “illustrate the first phase. You must not be misled by them, for they actually are confirmatory. You may discern in them the attitude of mind favorable to the feminine way of taking things lightly. A woman who asks why, never gets nervous prostration. It is when she gets above asking why that you may watch for shipwreck.”

“Well, Professor, all I can say is that you have left me in a state of miserable darkness as to women’s clubs. Surely there are vast misapprehensions somewhere.”

“There surely are,” admitted the Professor.

“But how do you explain them?”

“The women?”

“The clubs.”

“By woman’s revolt against her segregation. Not, in my opinion, that she is protesting against the gregarious advantages of man, but because she is beginning to discover that her sisters are worth[85] knowing. She has begun to be impersonally interested in, as well as interesting to, the other woman. The woman’s desire is not improvement; it is, whether she knows it or not, the other woman, precisely as a man’s interest in his club is the other man. It has been said that a man often goes to his club to be alone, and that there is this advantage in a club that is a place, over a club that is a state of mind. But a woman goes to a club not to be alone. I suppose there are times when it would do a woman good to get away from her family, not into company, but into lonesome quiet. Mrs. Moody, who has said so many wise things, declares in her ‘Unquiet Sex’ that college girls are too little alone for the health of their nerves. This may be so, yet women’s clubs are contemporaneous with girls’ colleges. It begins to look as if it was at college that the American girl learned that it is not good for woman to be alone—even with her family. At any rate, that independence which is so characteristic of the American girl, which is, as I have been informed and believe, somewhat disconcerting to men, is, undoubtedly, largely the result of the American girl’s improved relations with her sister women. When she is as successfully gregarious with regard to women as men are with regard to men, her sex maturity will be complete. I know that you are wondering what sort of a woman she is going to be in that matured state. Have no anxiety. She will not be less agreeable, but more so. She will overdo the clubs, but she will recover[86] from that; she will shed them the moment they cease to serve her purpose. I am going to a club now. I am going to talk to it about Savonarola. The club will be very well dressed, and so shall I, if I know myself, and we neither of us shall let smoke from the fateful fires of the fifteenth century blind us to the fact that we are living in the nineteenth.”

“All of which,” I said, in a severe tone, “is illustrative of the fact that woman is a sophist—though perhaps I should say an artist, for she uses life as so much material with which to construct an effect.”

“Life is an art,” remarked the Professor at the mirror.

“And you, Professor—”

But she was gone. I understood well enough that the Professor had just given an exhibition of her dexterity in taking the other side, taking it in a feminine rather than in a pugnacious spirit. The Professor’s negatives always remind me of how[87] affirmative the American girl is. There is an English painting called “Summer,” in which the artist (Mr. Stephens) gracefully symbolizes the drowsy indolence of June. This classic allegory may not have the English girl specifically in mind, but I am quite certain that we should not be satisfied with an American symbol for the same idea which did not in some way indicate that Miss America, even in summer, is likely to be representing some enthusiasm, Pickwickian or not as you may choose to make it out. The spirit of fantasy, sitting in the midst of our variegated life, who should call up the American Summer Girl, must summon a different company. The spirit of fantasy would know that the American summer girl, though she can be a sophist, and agree that this or that is the fashion this summer, is nevertheless not to be painted as a reiteration. It frequently was remarked of the Americans at Santiago that they had great individual[88] force as fighters. There always will be critics to remark upon the hazard of this trait in war. At all events it was and is an American trait. And in conducting her summer campaign against an elusive if not altogether a smokeless enemy, Miss America is displaying the same trait. She can accept a social sophistry, but you must leave her individuality. She will not have tennis wholly put aside if she does not choose. She will not give up her horse because a little steed of steel has entered the lists, nor give up her bicycle because it has become profanely popular. She may choose to arm herself solely with a parasol, to detach herself from even the suggestion of a hobby, which, to one who has the individual skill, is a notoriously potent way in which to establish one of those absolute despotisms so familiar and so fatal in society. There is the girl with a butterfly net, the girl who goes a-fishing, the girl who swims, the girl who wears bathing suits, the girl who gives a sparkle to the Chautauqua meetings in the summer, the girl who gets up camping parties, the girl who gets up the dances, the girl who plots theatricals, the girl with the camera, the girl who can shoot like a cowboy,—where should we end that remarkable list? How impossible to express the summer girl in any single type?