Alleged “interference” with the Heavenly Twins.

See “The Universal Conflict.”

[Pg iv]

Alleged “interference” with the Heavenly Twins.

See “The Universal Conflict.”

[Pg v]

BY

REGINALD BERKELEY

Author of

“French Leave” and “Eight O’Clock”

Part Author of “The Oilskin Packet”

and “Decorations and Absurdities”

With an Introduction

By J. C. SQUIRE

And Drawings by

BOHUN LYNCH

Cecil Palmer

Forty-nine

Chandos Street

W.C.2

[Pg vi]

FIRST

EDITION

1924

COPYRIGHT

Printed in Great Britain

[Pg vii]

[Pg viii]

Certain of the papers that make up this book have appeared, either in this present or in some modified form, in the “Outlook.” Others have been published in the “Nottingham Journal,” the “Yorkshire Observer,” and other provincial dailies. Others again are hitherto unpublished. To the Editors of those journals in which his work has appeared the author wishes to express his gratitude and acknowledgments.

[Pg ix]

I happen to frequent Captain Berkeley’s company on the cricket field. When he is there, and the wicket is bumpy, it might suitably be called a stricken field. He bowls very fast and very straight.

As his publisher usually keeps wicket for him, I dare not suggest that the crooked ones go for four byes. In any event that parallel would not be necessary here; but the general characteristics of Captain Berkeley’s bowling are certainly in evidence. He goes direct at his object, and when he hits it the middle stump whirls rapidly in the air. He is all for hitting the wicket; slip catches and cunningly arranged chances to cover are not for him. This blunt going for the main point it is that gives his parodies their greatest charm. I like it when I see a reference to “Count Puffendorff Seidlitz, the Megalomanian Minister”: if we are being funny, why not laugh aloud instead of merely tittering? “Lord Miasma” pleases me as a coinage full of meaning in these days; there is a refreshing lack of compromise about the name of the Galsworthy parson, “The Rev. Hardy Heavyweight”; and how better could one name two of Sir James Barrie’s minor characters than by the twin appellations of McVittie and Price, who here take, as they elsewhere give, the biscuit? This agreeable couple appear in one of the mock plays which, to one reader at least,[Pg x] seem to be the very best part of this very miscellaneous volume. Captain Berkeley is himself a successful playwright, and dog has here very entertainingly eaten dog. Mr. Galsworthy’s passion for abstract titles; his hostile preoccupation with the normal sporting man; his agonised sympathy with maltreated women; his determination to load the dice against his heroines: all these things are made clear in language very like his own, and yet in a way that suggests (to return to our imagery) that the bowler, however fast and determined, has a respect for the batsman. I don’t know that it is quite fair to ascribe “the Manchester Drama” especially to Mr. St. John Ervine or even to Manchester; but we know the type, and if a few more blows like this will kill it, so much the better. It is well enough to be harrowed in the theatre, but not to be made to feel as though we had chronic dyspepsia. The Russian Drama is beautifully apt; and “The Slayboy of the Western World” also. They reproduce idioms and mannerisms perfectly, and exhibit limitations unanswerably.

Perhaps the most refreshing thing about this book is its diversity. It is an age (excluding the merely vulgarly versatile) of specialists and specialist labels. A man is not expected to see life whole, much less steadily; he is encouraged to describe himself as “poet,”[Pg xi] “parodist,” “politician,” “business man” or what not; and it is regarded as almost improper that a person who takes an interest in Synge should so much as admit a knowledge of Mr. Winston Churchill’s existence. Captain Berkeley refuses to subject himself to any such limitations. He surveys everything around him, and where he sees anything he thinks funny, he has a go at it. This should not be regarded—any more than Canning’s squibs were regarded—as militating against his trustworthiness as a politician. Rather the reverse. A knowledge of humanity and the humanities is serviceable in legislation and administration, and a sense of humour usually goes with the sense which is called common.

J. C. Squire.

[Pg xiii]

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

| Unparliamentary Papers:— | |

| The Universal Conflict | 3 |

| An Eminent Georgian | 12 |

| My First Derby | 20 |

| On Eternal Life | 28 |

| The Next War—and Military Service | 31 |

| First Plays for Beginners | 39 |

| Hats | 45 |

| Shareholders’ Blood | 52 |

| The Personal Column | 60 |

| Society Sideshows | 64 |

| Latter-Day Dramas:— | |

| Morality | 75 |

| Eternity and Post-Eternity | 87 |

| The Enchanted Island | 101 |

| President Wilson | 112 |

| Jemima Bloggs | 125 |

| Under Eastern Skies | 132 |

| The Vodka Bottle | 144 |

| King David I | 153 |

| The Slayboy of the Western World | 158 |

| Impolitics:— | |

| A Member of Parliament | 167 |

| Woes of the Whips | 174[Pg xiv] |

| Young Men and “Maidens” | 180 |

| Front Benches and Back Benches | 188 |

| “Order, Order” | 196 |

| Lords and Commons | 203 |

| Irreverent Interviews and Other Irrelevances:— | |

| With Lord Balfour at the Washington Conference | 211 |

| With Monsieur Briand after the Washington Conference | 219 |

| With Mr. Lloyd George during his Premiership | 227 |

| With Lord Birkenhead on the Woolsack | 235 |

| Old Tory | 243 |

| Edward and Eustace | 244 |

| The Two Wedgwoods | 249 |

| Songs of a Die-Hard | 253 |

| Nursery Rhyme | 254 |

| The Old Member | 255 |

[Pg xv]

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

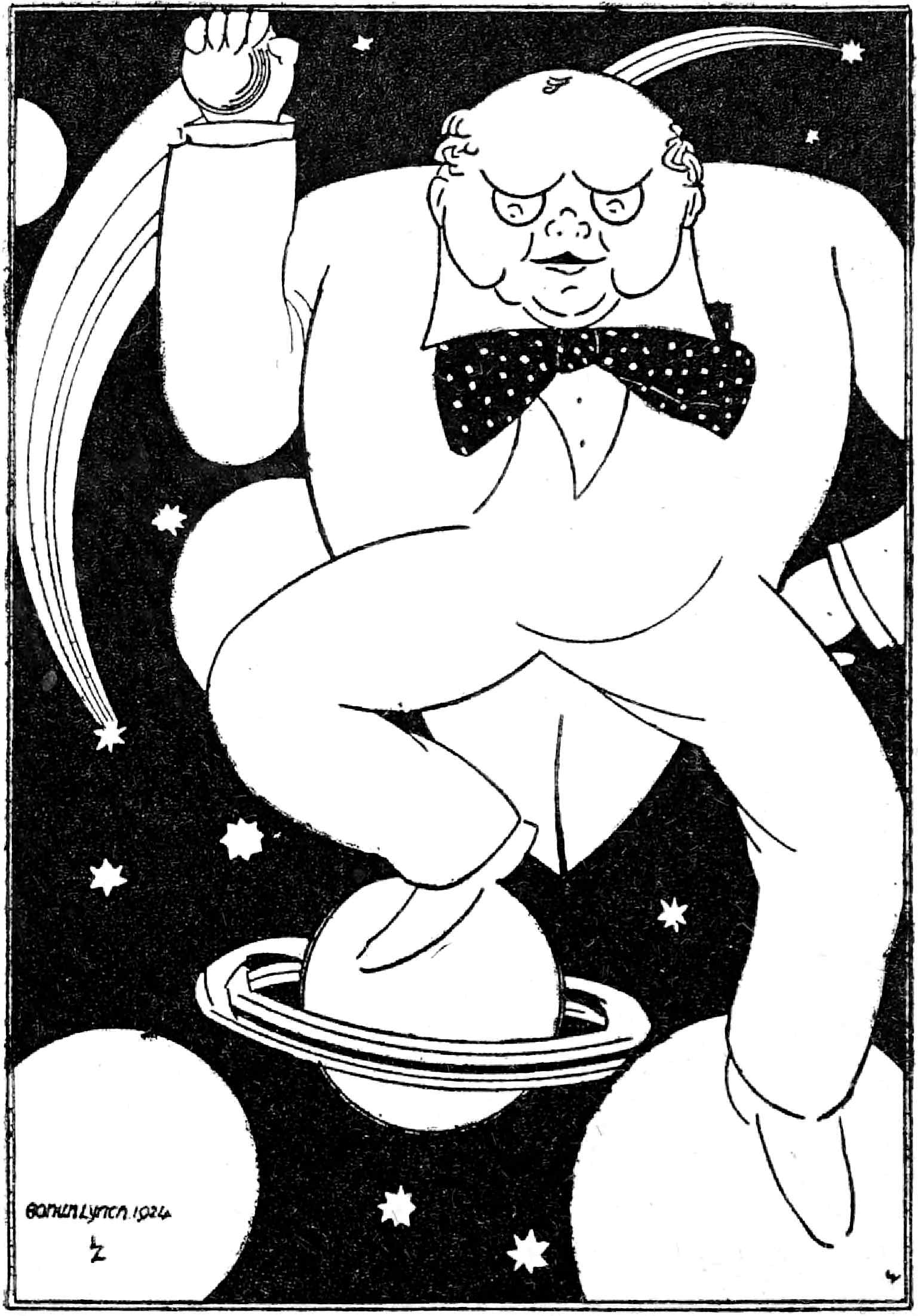

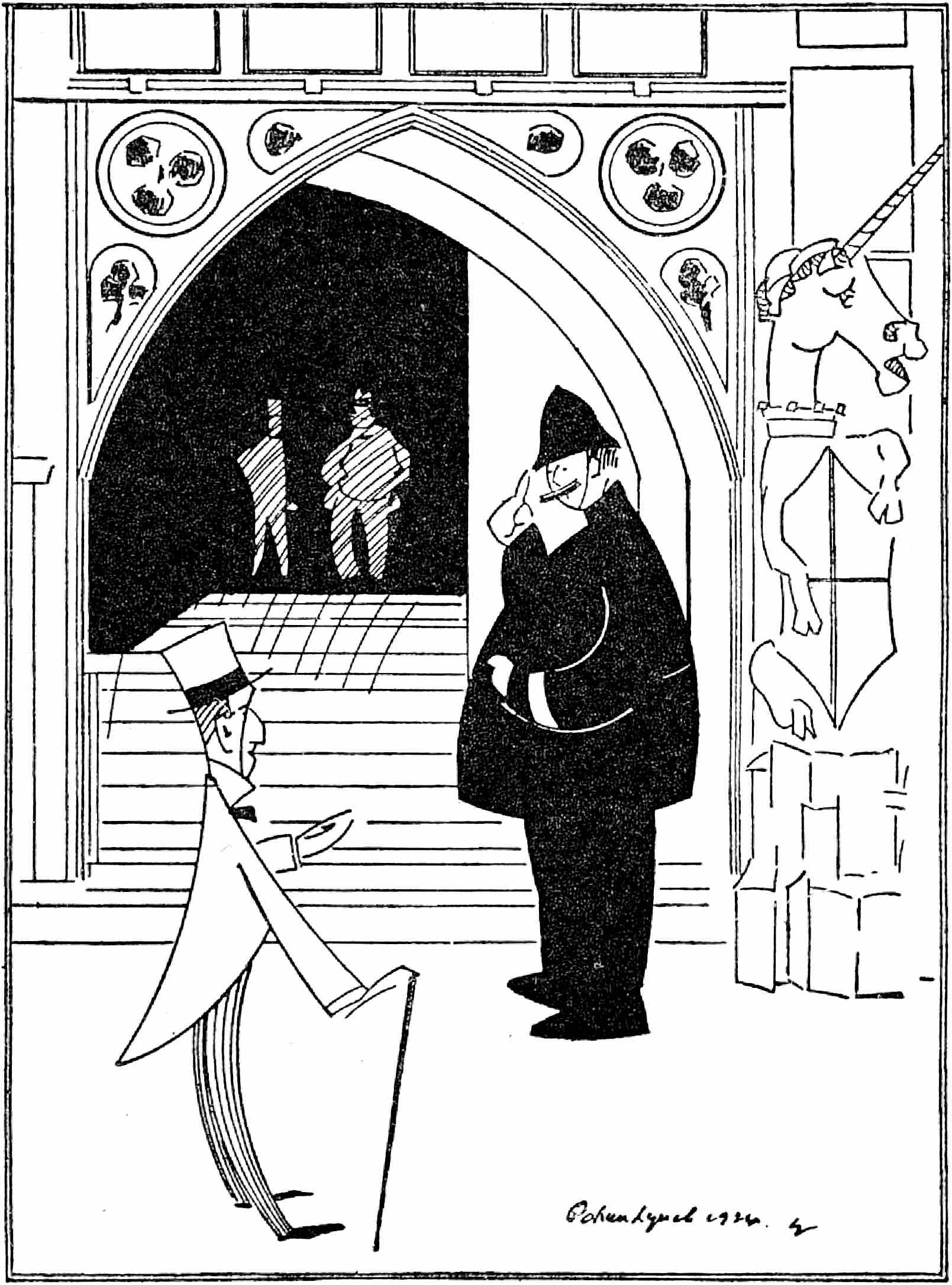

| Alleged “Interference” with the Heavenly Twins | Frontispiece |

| “Done Down on the Downs” | 23 |

| “In Which I Shall Look Less Ridiculous” | 47 |

| “And Obligingly Overturns Down an Embankment” | 71 |

| “The Influence of That Man Shaw” | 89 |

| “Life’s Very Hard” | 127 |

| “Ah! Little Fathers, This Poison——” | 151 |

| “New Member, Sir?” | 169 |

| Edward and Eustace | 245 |

| Jovial Josiah Wedgwood and Bold Wedgwood Benn | 251 |

[Pg 1]

[Pg 3]

NINETEEN ANYTHING—NINETEEN SOMETHING ELSE

By the Rt. Hon. Winsom Stunster Chortill

CHAPTER MXCVII

Golgotha

More criticisms—My “interference” with the Heavenly Twins—Suggested operations against Venus—My memoranda on Venus and Jupiter—Detailed proposals—Our new super-planetary battering-ram—Lord Krusher baffled—Correspondence between us—Lord Krusher’s objections—My reply—His antagonism—Meeting of the Allied Planetary Council—Serious position—The Archangel Gabriel’s shortcomings—My plan for saving the situation—The crisis—My resignation—Reflections.

Scarcely had died away the reverberations of criticism, enhanced by venomous personal attacks upon myself for my so-called “interference” in the operations against the Heavenly Twins, when a new crisis of even more momentous significance was sprung upon the Cabinet. In the previous December, with the fullest concurrence of the First Air Lord and the Board of Aerial Operations, I had planned a lightning raid on the planet of Venus to be carried out by our obsolete comets. The political[Pg 4] situation has so important a bearing upon this project that I must here interpolate a memorandum which, as long before as the previous July, I had addressed to the Secretary of State for Extra Planetary Affairs and circulated to my colleagues.

Memorandum.

Mr. Chortill to the Extra Planetary Secretary.

I can no longer preserve silence on the subject of Venus. Venusian hostility may quite well be fatal to the whole grand operation which we and our planetary allies are at present co-ordinating against the Central Planets. The grip of Mars upon Venus is unquestionably tightening; and, if no intervention is undertaken, but, on the contrary, the spirit of laissez-faire is allowed to prevail, we shall not only lose a strong potential adherent, but, which is equally important, also forfeit considerable sympathy amongst our own people. The plan of the Martians is quite plain. Availing themselves of that well-known astronomical phenomenon—the Transit of Venus—they will undoubtedly utilise that period of uncertainty to detach this wavering planet from our cause and bind her irrevocably to themselves. That would be nothing short of a disaster.

At the same time, knowing his difficulties in[Pg 5] coping with the tasks of his office, I instructed the faithful Smashterton Jones to convey the following message to the Prime Minister himself:

Mr. Chortill to the Prime Minister.

I am seriously exercised in my mind about Jupiter. I fear that, by confining ourselves to the narrow requirements of tactical gain, we are neglecting inter-planetary strategy. Do, I beg you, consider this point. If Jupiter can be induced—I don’t suggest that this proposal is necessarily the best, but, let us say, by the offer of one or both of the rings of Saturn under a Mandate of the League of Planets—if Jupiter could in this or some other manner be induced to take an active part, at least in the aerial blockade to cut off from the Central Planets the communication which at present they enjoy outside the Solar System, there is no doubt but that the conflict would be sensibly shortened, and it might make a difference of centuries. I enclose a Memorandum on Venus which I have sent to the Extra Planetary Secretary, and upon which I should value your remarks.

W. S. C.

Reverting now to the plan for an aerial raid on the planet of Venus. We had the old comets, quite ineffective for operations against the major Planets, but powerful and not at all to be despised;[Pg 6] we had a satisfactory surplus of meteors which could be employed in support; and we had in addition the newly constructed, and in all respects novel, planetary battering-ram, specially designed for jarring, or, as the technical word is, “boosting” heavenly bodies out of their orbits—the apple of the eye of old Lord Krusher and the Board of Aerial Construction. This formidable engine, unique, as we were led to believe, in the whole stellar universe, must in any case carry out her trials somewhere, and might as well be utilised in toppling a potential antagonist out of our path, instead of being sent to the Milky Way for the usual two months’ test. So much for material. Of trained personnel we had, though not an abundance, a reasonable margin. Only one thing seemed to baffle the mighty war mind of old Lord Krusher and our experts—a satisfactory jumping-off place. Accordingly, the day before the Cabinet met, I dictated the following:—

First Lord to the First Air Lord.

Referring to our conversation with regard to the Venus Striking Force, and the necessity for a jumping-off place, has it occurred to you that the Mountains of the Moon are in every way adapted for this purpose? A force of comets and meteors with the necessary reserves, L. of C.[Pg 7] troops, etc., based upon this strategic point, not only dominates the principal airways and traffic routes, but points a spear directly at the heart of the enemy. Request therefore that you will examine this proposition, and, in conjunction with Aerial Operations, furnish me immediately with an estimate of the material, plant, etc., required to convert these natural fastnesses into a suitable base.

W. S. C.

To this he replied in a characteristic letter:—

Trusty and well-beloved Winsom,

Your plan is, like yourself, marvellous! Nobody but you could have thought of it. I could turn the Mountains of the Moon into the base you require in forty-eight hours, but for one overriding difficulty, which your memorandum does not meet. There is no AIR on the Moon, my Winsom, and human beings being what they are, air is necessary IF THEY ARE NOT TO PERISH.

Only THREE things are necessary to win the war: air, SPEED, and GUTS. I have got the last, you are providing the second, but where are we to get the AIR?

Skegness?

We had better try the Valley of the Dry Bones instead, if the archæologists can find it for us. Failing that, Sinbad’s cavern.

Yours till Ginger pops,

Krusher.

[Pg 8]

This was the kind of thoughtless criticism to which I was occasionally subjected by the old air-dog.[1] Magnificent in his courage, more often right than wrong, a splendid example of British brain-power, there were times when he made the error of estimating other people’s mental capacity by his own. Time was pressing, so I wirelessed the following reply:—

First Lord to First Air Lord:

Take Supply of Oxygen in Canisters,

which settled the matter. Alas! I was to discover later that this too speedy resolution of his difficulties was merely to succeed in antagonising the bluff old warrior against the whole project.

Meanwhile the great Council of the Allied Planets met, and it became all too apparent that the operations, as a whole, were being pursued with even more than our customary hesitation and delay. The Archangel Gabriel, an excellent First Minister in times of peace, was beginning to give unmistakable signs of being too old and slow-witted for his work. Since his well-remembered and highly successful controversy with Lucifer, some æons before, his powers had been steadily waning; and it was speedily becoming apparent that he had no longer the mental alertness[Pg 9] and vigour of body for a prolonged campaign conducted under the stress of modern conditions. At times—as, for instance, over the thunderbolt shortage—he would arouse himself to prodigious efforts, equalling, if not outstripping, his ancient prowess. And then he would fall into always increasing periods of apathy, from which there was no extracting him.

In these circumstances I wrote the following memorandum:—

Memorandum by the Rt. Hon. Winsom Stunster Chortill on the general situation:

We have now been at war for forty-three years and eleven days. A prodigious expenditure of blood and treasure has so far secured for us no material advantage. The essential services are suffering from lack of co-ordination. Much valuable energy is being wasted in duplication of effort.

I have indicated in the accompanying appendices (36 in number) detailed plans for a change of policy on all the fronts, and I attach also an additional memorandum with 7 sequellæ, 41 maps and a detailed schedule of supplies, dealing with the political situation likely to arise on the Transit of Venus, and outlining a scheme of operations for immediate consideration and adoption.

[Pg 10]

After all these years it becomes necessary to say that the Allied cause is suffering from a want of decision. As each new problem arises we seem to be more and more unprepared. This cannot be indefinitely prolonged, and only one sensible solution presents itself—namely, that the control of all policy, operations and forces should be centred under one hand. Modesty forbids the suggestion that the serious crisis in our national fortunes demands that I should indicate myself as the most suitable person to have charge of this enterprise; but if consulted I should be willing to express my opinion on the matter.

W. S. C.

On the following day, the most fateful of my life, I was unable to resist a foreboding that things were not yet destined to go right for the Allied cause. The careful records I had kept of my administration satisfied me, as I looked through them, that for all I had done I could assure myself of the approval of posterity. We had created, equipped and maintained a gigantic aerial machine. No hostile forces had so much as come within sight of our planet. My further schemes, to which I had applied every existing intellectual test, made us reasonably certain of a speedy result; and I left my room and strode across to the Council with a conviction in my[Pg 11] heart that I could carry through my proposals—and yet with a haunting fear of the unexpected. On arriving at the Council Chamber my forebodings became heavier. The proceedings were of a most perfunctory nature. All controversial business was adjourned to a later meeting, and we were informed that a crisis made it necessary for the head of the Government to demand the resignations of his entire Ministry. With a heavy heart I parted with the insignia of my office, realising, as I did so, that the struggle must now be indefinitely prolonged. The head of the Government, animated by that spirit of kindliness towards myself which he had ever shown, pressed me to accept a gilded sinecure. With every wish to avoid giving him pain I felt myself obliged to decline. Posterity, he told me, would appreciate my zeal in the public service.

Posterity, I felt to myself, as I left the building, would, thanks to my diaries, at least understand.

FOOTNOTES:

[1] A kind of Skye terrier.—W. S. C.

[Pg 12]

Some Extracts from an Essay in the Manner of a Distinguished Writer

During the latter part of the closing year of the nineteenth century, an English traveller, sojourning with his wife and daughter near the hot springs of Rotorua in New Zealand, was observed one day to dash from the verandah of his hotel, hatless, into the street, and accost a passing urchin. The lad was singularly unprepossessing; he squinted, his right shoulder was strangely deformed, and his ears were much too large for his head. Unlike most children in receipt of flattering attentions from an elderly and distinguished stranger, he snarled, spat on the ground, and hurried away muttering oaths. The astonished relatives of the traveller, hurrying out in pursuit of him—in the belief, as the wife said afterwards, that he was suddenly demented—found their husband and parent almost beside himself with excitement. “That boy,” he said, pointing towards the receding figure a hand that shook with emotion—“that boy will end as Prime Minister of England.” Convinced that his mind was wandering, they led him back with soothing words to the hotel; but his unerring judgment was once again to be confirmed by the verdict of time. The speaker was Dr. Quank[Pg 13] Brane, the eminent psychologist; the boy, soon to be known to the greater part of the universe, equally for the profundity of his wisdom and the variety of his gifts and achievements, was Erasmus Galileo McCann, philosopher, scientist, theologian, naval and military strategist, scholar, economist and some time First Minister of the Crown.

The boyhood of this monument of versatile genius, no less than his manhood, was remarkable. At the age of one, when dropped by his nurse, a fact which accounted for the deformity of his shoulder, he was distinctly heard, as if in anticipation of his interjectional habits of later life, to rip out an accusing oath; and, when the startled slattern turned up her hands and eyes in horror, he added, “Don’t stare like a fool, go and get the doctor!” At three years old his father presented him with all the volumes of Buckle’s History of Civilisation, which he had completely mastered before he was five. His dissertation of The Lesser Cists in Invertebrates, published at the age of seven, is still a standard work of this little known branch of biological science. Many years later an old friend of the family told an admiring conclave of relatives of an encounter with the young McCann, in which he himself was considerably worsted. In the course of a journey across the Warraboora plains,[Pg 14] a wild and almost uninhabited tract of country, his provisions gave out. Some friendly natives whom he encountered contrived to spare him a few dried corn cobs, but these could hardly last him indefinitely. Starvation stared him in the face. One day, however, as he was making a frugal meal of a large aboriginal lizard, that he found entangled in the undergrowth, a strange urchin dropped on his head from out of a tree fern, uttering savage whoops, tore the carcass from his astonished fingers, and devoured it without a word of apology.

“That,” said the older man with resignation, “was my last morsel of food. I must now die.”

“Je n’en vois pas la nécessité,” returned the youth (it was McCann), quoting La Rochefoucauld with the nonchalance of complete familiarity; wherewith he swung himself into the branches of a Kauri pine, and disappeared without another word. Giving himself up for lost, the lonely traveller prepared for death; but before nightfall the youth returned with a wallet of provender, and accompanied by guides who piloted them back to civilisation. The boy appeared blissfully unaware that he had done anything remarkable. “Such astonishing sang-froid,” the traveller used to conclude, “I never encountered before or since. I knew he was destined for greatness.”

[Pg 15]

His schooldays and college life were curiously uneventful. He secured the uncoveted distinction of remaining at the bottom of the bottom form of the school for three years, and of failing ignominiously in the Cambridge Junior Local. Wiseacres shook their heads and quoted scores of instances of infantile precocity. It began to look as though the early promise was after all no more than a false dawn; and then, to everyone’s astonishment, at the age of 19½ he planned, financed and brought out The People’s Piffle, a daily journal exactly corresponding to the literary appetites of the masses of the British reading public. Among other novel features of this newspaper, alternative opinions were presented in parallel columns on the leader page, the appointment of the editor was subject to confirmation or change every three months by a referendum of the readers, and, in place of the obsolete insurances against accident, continued subscription for a period of 25 years or longer conferred a pensionable right upon the subscriber.

So momentous a development in the literary activities of the country created a profound impression. More than one well-known actress sent him her autograph unsolicited. A film star was heard to refer to him as “some guy.” The Prime Minister of the day shook hands with him in public. Lord Thundercliffe shook in his[Pg 16] shoes, and redoubled his fulminating denunciations of everything. But the day of Lord Thundercliffe was over: a new era was at hand, the era of universal genius; and McCann, its prophet and its leader, was even then poising himself on the crest of the wave that was to sweep away the wreckage of the old century, and sweep in the reforms of the new, and sweep him personally into a position of eminence hitherto unknown in our annals.

Just at about this time a resident at Claydamp-on-the-Wash was astonished, in the course of a country walk, to see a tall, thin gentleman leaning over a gate in an attitude of insupportable dejection. The enormous brogues; the ill-fitting brown suit; the high-domed forehead; the bushy brown spade beard; the huge spectacles perched on the lofty sensitive nose; the dreamy eyes looking far away into the mists, all suggested a certain literary personage. Could it be? Was it possible? Overcoming a natural hesitation at intruding upon the privacy of one who was obviously a recluse, he hesitatingly ventured to approach. “I beg your pardon,” he said, “but surely I am addressing Mr. Lytton Strachey?” and without giving the stranger time to answer he added, “Is anything the matter? Can I help in any way?”

[Pg 17]

The solitary turned upon him eyes that were suffused with tears. “Oh, no,” he replied, “no. Nothing. I was born too early, that is all.” And on being pressed for a further explanation he continued, “By the ordinary processes of Nature I must inevitably predecease this monstrosity of talent; and I am excluded from the possibility of writing the only Georgian biography that offers any kind of scope for my abilities.”

He was of politics; and he was not of politics. He built up abstract theories of Government in his articles in the morning Press: and demolished them in the evening in his speeches in the House of Commons. He attracted the sympathies of simple folk by a life of Spartan discipline; and disgusted them by a profuse and shameless bestowal of peerages and honours. He angled for the votes of the mercenary and idle by a wholesale creation of state benevolences; and threw away what he had gained by an almost niggardly supervision and husbandry of the national income. As Controller and chief proprietor of the great Press Trust, he denounced the infamies and exactions of the great profiteering combines in which he himself was the principal partner: and as Prime Minister of a secular Government he disestablished the Church of which he, as[Pg 18] Cardinal Archbishop, was the protesting head. Writing at about this time Count Puffendorff Seidlitz, the Megalomanian Ambassador, reported to his Government that it was perfectly vain to cherish the slightest hope of undermining the national popularity of one who so supremely embodied in himself the qualities, and the inconsistencies, and the portentous humbug that chiefly characterised the nation of which he was the head. Nothing could be done at present. Above all there must be no haste. “But I do not despair,” he added, “for, though ignorant of music, the man has a certain coarse feeling for the arts—and that, in a country of Philistines, must in the long run betray him into our hands.”

Fatal self-complacency! At the very moment when those words were being penned, McCann was—where? He was in the anteroom of the Princess Vodkha, that luckless Ambassador’s sovereign, waiting to seal with a courtly handclasp the Trade Agreement between Megalomania and this country. Poor Count Puffendorff Seidlitz! Where Lord Thundercliffe and his brother Lord Miasma has failed, it was hardly to be supposed that he would succeed.

So ended, in a thin filmy haze, a life of service and sacrament. To the very end they thought[Pg 19] he might be saved. The general public, brought suddenly to the realisation of the approaching calamity, stood dumbly in the streets, or hurried away—hoping. But the sands were running down; the tide, long since turned, was ebbing with inexorable swiftness; the night was indeed at hand. A greater and more terrible accuser than Lord Thundercliffe hovered over the sick man’s bed; and a greater and wiser Judge than public opinion was waiting to pronounce the verdict from which there is no appeal.

[Pg 20]

“No,” I said, “as a matter of fact I’ve never been to the Derby—and to tell you the truth——” I went on.

He winced. He did not want me to tell him the truth. If the truth was (as it was) that I didn’t care two cassowary’s eggs whether I went to the Derby or not, that was the very last thing he desired to hear. He wanted to keep his opinion of me as unimpaired by such idiosyncrasies, as I would permit. These thoughts rippled over the mild surface of his features like gusts of wind across the waters of a pond. I allowed the words to die away in my throat. After all, to give pain flagrantly—

“Promise me,” he urged, “p-p-promise me you’ll take a day off and go to-morrow. It’s one of the sights of the world. The Downs black with people——”

“Black?” I murmured, “surely not in this heat?”

“Oh, well, covered with people then, stiff with people, crowded for miles and miles with millions and millions of all classes in the land——”

“Dear, dear,” I said, “first, second, and third!”

He ignored this miserable attempt at buffoonery.

[Pg 21]

“Yes,” he averred, “all classes in the land, thimble-rigging, cocoanut shying, confidence tricking, eating, drinking, laughing, cheering. Vehicles of all sorts, shapes, sizes, motive power, blocking all the roads in the neighbourhood. And the horses, my dear boy, the horses! Until you’ve seen those horses, trained to a hair, with coats like satin, ready to run for their lives, why, you simply haven’t seen anything. And the crowd in the paddock. You must see the crowd in the paddock. And the bookies. No man’s lived, till he’s been done down on the Downs. Now promise me faithfully——”

“Very well,” I said hurriedly to forestall the otherwise inevitable repetition, “I promise....”

It was rather fun, I admit. From the moment when the wheel-barrow on which, apparently, I had made the journey in the company of a Zulu chief, Lady Diana Manners, Mr. Justice Salter, and a dear little Eskimo girl aged seven, drew up at Boulter’s Lock—no, no—not Boulter’s Lock—Tattenham Corner, I knew I was in for one of the great days of my life. There, glittering in the sunlight in all its pristine colouring, stood the brand-new Tattenham Corner House, erected for the occasion by Sir Joseph Lyons himself, who, with Lord Howard de Walden on one side of him and the Prime Minister on the other,[Pg 22] stood in the doorway receiving his guests. A prodigious negro, with an unexpectedly small voice, announced me (for some reason) as “Mr. Mallaby Deeley,” and I found myself walking on a vast deep verandah, laid out with innumerable little luncheon tables, through which a long procession of horses was intricately manœuvring.

“The paddock,” murmured my Zulu companion. “It’s an idea of Sir Joseph’s. The combination of a sit-down luncheon and form at a glance. Extraordinarily convenient.”

We sat down at a table. Immediately a jockey and his horse sat down opposite to us.

“Order us a drink each, dearie,” said the jockey, “it’s a fearful business this perambulatin’ about; and you get nothing for it. Eh? Oh, gin for ’er, and I’ll take a glass o’ port.”

“And what is your young friend’s name?” enquired the judge, suddenly putting his head from under the table.

“Ah,” said the jockey, knowingly, “that ’ud be telling, that would.” He tapped his nose mysteriously and drank.

“But, my good sir,” complained the judge, “how can I back your horse if I don’t know its name?”

“By the process of elimination,” said the jockey sagely.

[Pg 23]

[Pg 25]

“Done down on the Downs.”

[Pg 24]

“Elimination,” said the judge, “what of?”

“Yourself,” said the jockey; and his mount choked coyly in her glass.

At this moment the King appeared, followed by Aristotle, Sir Thomas Beecham, and others.

“The next race is about to begin,” he said severely, “and you’ve none of you brushed your hair.”

It was a long time before I found the bookmaker. Any number of spurious ones rose up in my path and taunted me; but He always escaped. At last I thought of looking under one of the thimbles; and there he was in deep calculation.

“What price Poltergeist?” I demanded. I wanted to say Psychology, but the word somehow refused to shape itself.

“It all depends,” he replied shrewdly, “on whether you want to buy or to sell,” wherewith he crossed his legs, smiled on only one side of his face, and returned to his calculations.

“Aren’t you a bookmaker?” I faltered.

“Certainly,” he cried shrilly, “and I’m making a book now, can’t you see?” He held up a kind of primitive loose-leaf ledger, made of calico pages bound in sheepskin.

“Very durable,” he explained, and broke into a harsh chant:

[Pg 26]

He broke off abruptly and rose to his feet. The miscellany in his lap was scattered upon the ground.

“Pick up my work-basket,” he exclaimed, “and give me the kaleidoscope,” I handed him the strange black instrument at which he was pointing, and began groping on my knees among the pins and needles. He turned towards the sun, and gazed at it through the object in his hand.

“Look out,” he exclaimed suddenly, “they’re off.”

Simultaneously a voice near me said, “The King’s calling you,” and I began to run. Immediately the hounds were slipped from the leash, and the hunt settled down in my wake. The ship began to sway from side to side, and the roaring grew louder and louder. Still I ran, flashing past the booths, past upturned umbrellas with cards scattered over them, past the stewards’ enclosure, past the Royal Box. The thundering[Pg 27] grew louder and more insistent. I was flying along the track with the whole field plunging after me. Hoarse cries. I redouble my efforts. My head is going to burst. The Royal Box whizzes past again. The winning post. I’m falling....

A long time afterwards, a voice said:

“He’s quite all right. A touch of heat-stroke is nothing, really, you know. Quiet. Couple of days in bed.”

I opened my eyes.

“Sir Joseph Lyons——” I began.

“All right,” said the doctor, “you shut up.”

“I’ve promised to go to the Derby,” I protested.

“Next year,” replied the doctor. “Just drink this, will you?”

[Pg 28]

Somebody—a certain Dr. Friedenberg to be truthful—has thrown out suggestions of the dreadful possibility of indefinitely prolonging the human existence; in fact of bringing about a kind of mundane immortality. Hair is to be made to grow upon bald heads (no, mine is not bald); short men will increase in stature by several inches; and fat men will become slender and graceful. The last is perhaps an attractive prospect. Wait. Tell me this.

Who wants to live for ever? And having disposed of that pertinent question, in the affirmative if you will, who wants his neighbour to live for ever?

Who wants to stereotype the control of human affairs in the hands that find it so difficult to control them? What becomes of young ideas, new movements and general progress, in a universe of bald pates thatched, short men grown taller and corpulence made small? For in all this one hears nothing about recharging the brain; and bodily vigour does little to stave off mental paralysis of the kind that usually comes on with age. Would flowing hair and graceful figure countervail the growth of avarice, deceit and malice; or check the relentless march of stupidity? Would it not rather be the case, that from year[Pg 29] to year all the more unpleasant of human characteristics would intensify and harden?

And, by the way, think of the population of this miserable little globe in a thousand years or so. Nobody dies. We all live and multiply for eternity. It increases by geometric progression. To-day we are, let us say, a paltry thousand million of people. In a year’s time, at a conservative estimate, we should double our population. In a few hundred years—good heavens! Life would become like the platform of Piccadilly Circus at six o’clock in the evening.

Piccadilly! This subject is inextricably bound up in my mind with Piccadilly. I will explain why.

Not long ago, when musing upon Dr. Friedenberg’s discoveries, I had occasion to use the railway of that name. I boarded a crowded train, thinking deeply. I took my place (most incautiously, I admit, but there happened to be no other place to take) standing beside a forbidding military gentleman, whose arms were full of brown paper parcels. In the immediate vicinity stood a large stern woman, solidly planted near the door, who disdained the help of the strap and supported herself, with arms akimbo and legs wide apart.

The train ran smoothly enough through Dover Street and Down Street, and my line of thought, on this problem of perpetual life, developed into[Pg 30] a kind of saga to the rhythm of the movement over the rails. The whole subject went before my eyes like a glorious vision. I knew just what I was going to say in this essay....

And then the train back-jumped, and the large stern woman, in the effort to retain her balance, planted one of her feet with relentless precision, exactly on one of mine, and simultaneously drove her right elbow into my ribs. In really considerable agony I recoiled, involuntarily loosening my grip of the supporting strap. Immediately the train swerved, and threw me into the bosom of the military gentleman, whose armful of parcels burst from his control and smothered the occupants of the neighbouring seats. Muttering imprecations, he crouched on the swaying floor and began to pick them up. I stooped to help him; and our heads met with a grinding crash....

Meanwhile the woman—the—the unspeakable monster who had caused the calamity, stood entirely unmoved, gazing through the glass doors at the conductor.

Think of such a person going down through all eternity committing outrages of this kind—probably one a day. Eternal life? Penal servitude for life is more to her deserving.

[Pg 31]

Russia and Germany have joined hands; France and Belgium have banded together; Italy has made a secret treaty with the Kemalists—a fact which can hardly afford much satisfaction to the kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, leave alone the Greeks! Poland and her neighbours are on much the same terms of cordiality as rival opera singers. There is Bessarabia; there is (so to call it for convenience) Germania Irridenta; there is the Burgenland; all simmering merrily away. There are heartburnings in Transylvania. I cannot think that even the Sanjak is really placid—it has always wallowed in grievances from time immemorial. Indeed (so I am told), it needs but a spark to set the whole contraption in a blaze. Only a spark!... We are sitting on a wood pile soaked in petrol; and the boys at Paris and elsewhere are out with their tinder-boxes.

Viewed from one point of view, this situation has arisen very appositely to certain investigations conducted not long ago by The Times, and provides a capital solution to the problems of how to find careers for our sons, and what to do with our[Pg 32] daughters. But there are some of us[2] to whom even the satisfaction of starting our children in (or rather out of) the world, would be but a poor recompense for the physical discomfort (it’s not the danger; we none of us mind danger; we rather like it) of resuming active hostilities ourselves. As Leggitt says[3]: “Danger I scorn; but discomfort is the parent of anxiety; and anxiety is the handmaid of despair.” That’s good enough for me.

Besides, wars are not what they were. The last war was, to a great extent, won, and the next war will be entirely won, behind the lines. “Lord Northcliffe,” says a military historian[4] in his article on war in the Encyclopædia, “Lord Northcliffe dealt heavier blows than Haig. Haig hit harder than Rawlinson, Rawlinson than Godley, and Godley (through a long string of intermediary Blenkinsops and Chislehursts) than Private Muggins. In fact, the whole lesson of the war was that Muggins didn’t matter twopennyworth of gin. The further back you were, the more you could do. If Captain Slogger, the Company Commander, stopped one—why,[Pg 33] anybody else could carry on. But if the R.T.O.’s clerk at the base went down with writer’s cramp, the repercussions might be felt all over Europe. And in the next war....” And so on.

Push this to its logical conclusion and what do you find? An entirely new conception of the theory of national service. The duty of every man, with love of country in his heart, is to fit himself to play a far-reaching, noble, and adequate part in the next war—from a distance at which brains will really tell. As Sir Cuthbert puts it, “The duty of the soldiers of the future is to consolidate the front behind the front.” No mawkish sentimental considerations should interfere with the attainment of this. “If others have to fall in the front line, drop a tear, good citizen, or if you feel so disposed, drop two tears. But for the sake of your country, and its final victory in the struggle, see to it that you are not the one who falls.”

I will. I will see to it with punctilious care. It is my duty; and I shall discharge it with the same devotion as I displayed in the last war, when I rose from assistant warehouse clerk (graded as bombardier) in the E.F.C. receiving shed, via R.T.O.’s clerk at Boulavre (graded as Staff Sergeant of Musketry), assistant press censor (graded as Squadron Leader of Cavalry with rank[Pg 34] of Captain) and Base Commandant (graded as G.S.O. 2, but with rank of colonel on the staff and pay and allowances of a Lieutenant-General) to the proud position which I occupied at the end. I have nothing to complain of.... I cannot deny that I had all kinds of obstacles to overcome. Ignorant prejudiced fools, blind to the interests of their country, were constantly endeavouring to comb me out. And so it will be in the next war. The earnest patriot will find himself thwarted and misunderstood at every turn. Nothing but a knowledge of the niceties of the medical board, will avail to defeat these busybodies. Indeed, it may at times be necessary to indulge in a little pardonable deception. Thus, a cigarette soaked in laudanum, and smoked half an hour before the doctor’s examination, will produce all the symptoms of general paralysis, heart failure, and abdominal catarrh; yet, in an hour or two at most, the smoker will have recovered most of his faculties, and the remainder will return in, at the outside, a few days. A glass of vinegar, swallowed without deglutition, produces the pallor of a ghost and the pulse and temperature of a lizard; yet the effects have rarely lasted longer than a week. And there are, of course, such well-known (but to my thinking too crude) expedients as self-inflicted wounds and even amputations.

[Pg 35]

Perhaps it is best, indeed, to make preparations in advance. It must never be forgotten that a large civilian population is necessary to carry on what are called “the essential public services.” No one should disdain to do his duty in one of these capacities. And if, as in the last war, the only sons of widowed mothers are to be given special consideration, we must not hesitate to take full advantage of such a provision. A judicious use of the knife or poison cup, or possibly a combination of the two, will place many a strapping fellow in the necessary condition of exemption.

Promptski-Buzzoff, in his elaborate, but too little known, treatise “Die Vermeidung des Kriegesdienstes”[5] lays down that “the spinal marrow of a nation is to be found in the conscience of its citizens.” This is profoundly and undeniably true. The pages of history are bespattered with the fragments of empires that have disintegrated through the decay of their moral fibre. Every good citizen, says Buzzoff, should cultivate a conscience as inflexible as Bessemer steel. A properly cultivated conscience will no more permit its owner to kill, or be killed, than a vacuum brake will let a train run away. It’s automatic. You mention the word war, and[Pg 36] there’s an instant inhibition. This kind of thing however, needs considerable preparation. It is always open to misinterpretation if your conscience doesn’t develop until the outbreak of war; although that, in itself, is not a consideration which ought to deter a man with the interests of his country at heart.

Many of us, again, are indispensable. Until late in 1917, I was indispensable myself. And next time I fully intend to be indispensable all through the war. I shall get elected to some legislative body—say the London County Council; and my devotion to duty will do the rest. But, of course, in case of mischance I shall be prepared with an alternative plan, several alternative plans in fact. And, in the last resort, I shall place my services at the disposal of the Director-General of Lines of Communication. After all, speaking as one who has already fought a campaign in that capacity, one has a sense of responsibility and power, even in the humblest posts behind the line, of which even Divisional and Corps commanders might be envious. As an R.T.O.’s assistant, one is conscious of a control over the destinies of others, that almost partakes of divinity. A motion of the hand, a word on a scrap of paper, and divisions and their baggage may be separated for ever; provisions consigned to one country may find themselves devoured in another; and Generals[Pg 37] waiting to begin a battle may awake on zero day to the fact that they have no forces, except their staffs, wherewith to fight.

It will be understood that I offer these suggestions on the understanding that we find ourselves allied to a country in which there will be some approximation, in the amenities offered to L. of C., to those enjoyed in the larger cities in France during the war. Otherwise, frankly, nothing doing! I have been studying the appendices to Splitz’s book on the Russian Army[6]; and the feeding is hardly up to what I might call a civilised war standard. Thus, on L. of C., the weekly ration allowance appears to be four gold roubles’ worth of straw soup, three poods of lycopodium seed cake, and two samovars of liquorice water, together with thirty-seven foot-calories of bonemeal and a packet of spearmint—which, although it compares favourably with the diet of Divisional and Corps Commanders in that country[7], has but little attraction for the gourmet. And in any case what about the residuum? After all, we can’t all of us expect carte blanche to[Pg 38] send trains backwards and forwards—passed to you, please, and to you, please, and so on. Even on the grander scale, there’ll never be room for more than a million or so R.T.O.’s all told (and that will include the other side). Something’s got to be done for the rest of us. Even the L. of C. troops will be up to full strength at last. They’ll absorb a number of millions; but they’ll fill up eventually. Even the essential public services at home can’t be swelled indefinitely. There will come a time when everything useful has been filled up, and there are still people left over.

Well, we can’t all be satisfied in this world. It was never intended that we should. And, so far as I can see, the overplus will have to make themselves comfortable in the trenches. It will be a galling thought to them that they’re poked away there out of everything, with no real work to do. But it doesn’t really matter, for we’ll win the war all right.

We’ll win it in spite of them.

FOOTNOTES:

[2] I except, of course, Drigg, Bootlecut, Volmer, and their insignificant following.

[3] The Psychology of Post-Metempsychosis. J. Swift Leggitt. The Mangy Press. 5s.

[4] Sir Cuthbert Limpitt, K.B.E., a former Director of the Ministry of Misinformation.

[5] Berlin, 1921. Published in an English translation under the title Military Service and its Avoidance. Blottow and Windupp, 1922. 7s. 6d.

[6] The Russian Army, its Organisations and Morale. By Hermann Splitz. Boonkum and Co., New York. Two vols. $4.

[7] And that is only in the larger cities such as Yekanakaterinakanaka. In the smaller towns and villages the amount would be much less!

[Pg 39]

This is the Truth about the production of first plays.

First the author, in the secrecy of his chamber, painfully gives birth to an idea, and clothes it in words—if possible of not more than one syllable. Then he shows it to his best friend, who obligingly points out that the whole conception is faulty, and that the dialogue is beneath contempt. He then reads it to his second-best friend, who wakes from his slumber greatly refreshed. By the end of a short period he has no friends left: but he has learnt a few of the more obvious imperfections of his work. In despair of ever reconciling the conflicting criticisms to which it has been subjected, he posts it defiantly to Grossmith and Malone, Sir Alfred Butt, Mr. Charles Cochran, Mr. Laurillard, Mr. de Courville, and the whole gang of impresarios. It returns from each of them accompanied by a printed slip. He then slinks to the office of a dramatic agent.

The dramatic agent is a florid man with a super-silk hat. He receives the author with the gracious condescension of royalty greeting an inferior. The author, overcome at the honour which is being conferred, gratefully deposits his[Pg 40] precious MS. in the luxurious plush-padded basket which is held out by an underling. The basket is reverently placed upon the table; mutual expressions of goodwill are exchanged; the author is bowed out.

Then the dramatic agent shakes the MS. out of the basket, as though it were verminous; pitchforks it into the recesses of a safe; locks the safe with a loud clang, and loses the key for two years.

At the end of two years Cyrus K. Bimetaller, the celebrated “Stunt” King, visits the dramatic agent to throw in his teeth the forty-seven separate scripts of forty-seven separate plays—but why go into this? He says that all dealings between them are at an end, and demands his account. The dramatic agent mechanically opens the safe to get out his books—and there lies the neglected MS. As a last bid for fortune he places it eloquently in the hands of Cyrus K. The latter grunts, and sprawls on the sofa to “size it up.” This process occupies five minutes. At the end of that time he remarks laconically, “This is the goods.”

The author is now summoned from Kilimanjaro, where he is growing grape-fruit, in order to give his assistance at rehearsals. He arrives, however, only just in time for the first night, when scores of hands drag him on to a prodigiously vast stage to abase himself before a jeering[Pg 41] audience. His spasmodic efforts to speak merely confirm the impression that he is a congenital epileptic.

Next day the newspapers, after a flattering reference to his personal appearance, unite in denouncing the play as the work of a man with the intelligence of a crossing-sweeper and the originality of a jackass. These comments are judiciously edited and made up as posters. The effect is stupendous, and the public flocks to the theatre. The author is a made man.

At least, he hopes he is.

Letters pour in upon him from all quarters demanding more plays from his pen. Actresses lie in wait for him at garden parties, and say, archly, “Oh, Mr. Blotto, when are you going to write a play for me?” Actor-managers call him “old boy”; and allow themselves to be seen shaking hands with him. The gifted gods and goddesses who are performing his play make no secret of his acquaintance. The great Cyrus K. Bimetaller strokes a mighty stomach in silence. The dramatic agent grunts, “I told you so,” and gives another polish to the super-silk hat. Melisande, writing her customary column in the Evening Quacker, observes: “Last night, at Mr. Blotto’s delightful play which is charming London, I saw the Duchess of Dripp, Count Sforzando, Mr. and Miss Mossop, and the Hon. ‘Toothy’[Pg 42] Badger. The house was crowded, of course. Mr. Blotto himself looked in during the evening, but hurried away on being recognised. He is so retiring.”

In the middle of this chorus of enthusiasm the author bashfully brings forward another play. Everyone scrambles to read it. Each points out a separate defect. All unite in pronouncing it “essentially undramatic.” It finds its way into that limbo of lost manuscripts, the safe of the silk-hatted agent. Setting his teeth, the author completes another play. It passes from hand to hand, becoming dog-eared in the journey, and finally returns to him, in silence and tatters. It seems hardly worthwhile adding it to the mountains of paper on the Agent’s shelves, so somebody tosses it behind a book-case, where it is treated with the scorn it merits by mice and insects. By now the first play has been supplanted by a Bessarabian allegory, and the author’s name has long been forgotten. Still buoyed up with hope, he plans a chef d’œuvre—a drama. “Something Shakespearian,” he modestly proclaims. Very few people, however, even bother to read this, all eyes being fixed on a genius from Kurdistan, who is taking away the breath of theatrical London in a play written entirely in Esperanto. The author spends his last few shillings on a ticket to the Argentine, and begins a fresh life as a herdsman.

[Pg 43]

Years pass. The author is far from unsuccessful in his new venture. In fact, he becomes extremely wealthy. He buys up his employer’s hacienda. He buys up several other people’s haciendas. He buys up the greater part of the Argentine Republic. He has serious thoughts of buying up South America and selling it to the United States. But his better nature prevails, and he returns to England and buys a peerage instead. On the day appointed for him to be introduced to the House of Lords, his eye happens to see the poster of a new play—The Dusky Child. The name touches a chord. He recognises it as his own work. He forgets his engagement with the Peers of the Realm, and hurries off once again in pursuit of literary reputation.

His old friend the dramatic agent is comparatively unchanged. He is a little more silk-hatted, a little more rotund, and a little more contemptuous of every one else. He recognises the author at once, ejaculates laconically: “I told you so,” and takes him to meet Erasmus W. Bogg, the new impresario who is producing the play. They hurriedly prepare for the first night. The Lord Chancellor is very annoyed. The author snaps his fingers. At last literary fame is in his grasp. It seems an extraordinarily cold winter, but that doesn’t really matter. He hurries on the rehearsals, snapping his fingers.

[Pg 44]

How amazingly chilly it has become.

The House of Lords are sending the Lieutenant of the Tower to arrest him. Ha, ha, let them. He snaps his fingers.

Really, this weather, after the climate of the Argentine, is beyond a joke. For goodness sake hurry up with that scenery. What’s that about the Lord Chancellor? Mr. Ramsay MacDonald—what? The who?

Eh?

He wakes up to find his cherished first play still unperformed—still, indeed, uncompleted. Kilimanjaro, a dream. The Argentine, a dream. The peerage—a dream, too. He shudders at that escape.

Brr! Why, dammit, the fire’s out!

[Pg 45]

The hat, says my copy of the Concise Oxford Dictionary, is “man’s, woman’s outdoor headcovering, usually with brim.” Not unto me the glory of writing about woman’s outdoor headcovering. These mysteries are too sacred to be profaned. But man’s hats are another thing. I have a number of my own. There is none of which I am not, in secret, ashamed.

Some men have the faculty of knowing what hats they can wear with credit—or, if not with credit, at least without sacrifice of self-respect. They go to the hatter, pick out a perfectly ordinary “headcovering” (usually “with brim”), and leave the shop gorgeously transformed. Their very discards can be reblocked and made to look, if anything, better than new. And I? I go from one hatter to another in an endless pilgrimage in search of something in which I shall look less ridiculous (observe I say “less ridiculous”—I am easy to please), and find it never. I follow my friends into the places where they hat themselves; I allow myself to be persuaded into buying some hateful contrivance—“a perfect fit, sir”; and in three days the damn thing shrinks so that I can’t get it on my head. Or again, I try to allow for this by ordering a larger size, whereafter, either I spend the whole of my spare[Pg 46] time stuffing the lining with paper or else it gradually but relentlessly sinks, and settles on the bridge of my nose.

The very brims play tricks with me. I have a bowler. I bought it, I distinctly remember, on account of the width of its brim. I have always liked a wide brim. Not that it ever keeps off the sun or rain, but somehow it gives confidence. There is something spacious about a wide brim. Something suggestive of an opulence to which I have in no other way ever pretended.

Well. Anyhow. I gave up wearing my bowler, because it insisted on shrinking. It perched itself higher and higher on my head, until I began to think it really wasn’t safe. It might fall off and get run over. Nobody wants to expose even a rebellious hat to the dangers of London traffic. I went to my hatter (why I say my hatter I can’t think. Nobody is my hatter. Many have tried, none has succeeded). I went to a hatter; bought a large brown felt hat, wore it away (like a bride setting out for the honeymoon); and arranged for the bowler to be safely conveyed to my home, hoping that all would be well.

Well? Not a bit of it. The brown hat swelled and swelled. All the newspapers in London contributed in their turn to keeping us from parting. In vain. That hat had a craving for adventure; it wanted to make its way in the[Pg 49] world alone; and a gust of east wind carried it (together with so much of the “Evening News” as had enabled it to maintain a precarious balance on my brow) under a passing bus. I hurried home with feelings almost of friendship for my erring bowler. I said magnanimously that forgiveness——

“In which I shall not look so ridiculous.”

Somehow it didn’t look the same. I was prepared to swear that when I handed it over to the hatter (my hatter, very well) it did in some sort cover my head. But now—it had diminished to the size of a child’s toy. And the brim—the brim had shrunk to the merest shadow.

I have at last given up the struggle. I wear anything that comes along. Not that it matters. People have survived their hats before now. These, after all, are the merest idiosyncrasies of head-covering. Observe, for instance, the hats of the great. There you find something of real distinction.

It is one of the curious things about really great men that they are unable to resist the bizarre in hats. They don’t turn out in strange trousers, or curiously contrived coats. You don’t see them walking about in sandals, or veldtschoons. They don’t tie up their beards with ribbon; or shave their eyebrows; or put caste-marks on their faces. Right up to their head-coverings they are[Pg 50] indistinguishable from you and me. I don’t wish to flatter us, but very often they are less pleasant to look at ... and then their greatness declares itself, or their originality breaks loose, or some other eerie characteristic finds its appropriate expression, in the form of an article of apparel about as distinctive and ugly as Britannia’s helmet.

Not long ago I met a noble Viscount, a man who might easily become Prime Minister—I saw him, I mean; I encountered him in the street. He was wearing a hat that suggested a bowler, but was not a bowler—that might have been a “Daily Mail” hat, only it was black with a dull surface, and, if I may so put it, had soft rounded lines in place of sharp ones—that—that in fact was indescribable. The rest of his garments were those of a normal citizen. There were no unfamiliar excrescences on his coat. His collar and tie were much like my own.

Later in the day I saw in front of me a tall, hurrying figure striding towards the House of Commons. The stooping gait and sombre clothing might easily have been those of a mere scholar or clergyman. But the figure bore upon its head a shapeless contrivance of purple velvet; and by that I knew it was—(well, you know who it was as well as I do).

Look at Mr. Winston Churchill. Look at[Pg 51] Admiral Beatty. Whoever saw a service hat quite like Admiral Beatty’s? Though I admit, in his case, the oddity is accentuated by his way of wearing it. Look at the hats of foreign potentates. Look at——

Look at Mr. Lloyd George. I have never actually seen him in one of his “family” hats—but I know his hatted appearance intimately through a picture. It is a photograph representing “the man who won the war,” as a vigorous smiling personage in a grey tweed suit. It seems to be very much the kind of suit that you or I might select for golf. But—here distinction creeps in—the upper part of his body is swathed in something that resembles a horse blanket ... and he is crowned with the headdress of a Tyrolean brigand.

I am going to be a great man. I know it by my hats.

[Pg 52]

GRAND (TRUNK) FEATURE SERIAL.

CANADIAN FILMS LIMITED.

We are in the Wild West of Canada—a land full of mustangs and moccasins. People with hard faces are riding about in strange clothes. Gently nurtured maidens are scrubbing out the cowshed, or digging up the manure heap. The hired-woman is sitting in the sunlight with a book. It is a typical scene in a British Dominion; we know it is Canada, however, because there’s a flick, and the screen says:

THIS IS THE CITY OF BISON SNOUT,

FED BY THE GRAND TRUNK RAILWAY,

CANADA’S PREMIER RAILROAD.

Then there’s another flick, and, lo! a magnificent train, racing across the prairie, gives us a hint that we are watching Canada’s premier railroad in operation. The screen obligingly confirms this impression by—Flick:

LUXURY, SPEED, AND SECURITY.

THE GRAND TRUNK MILLIONAIRES’

LIMITED THUNDERING ACROSS THE

CONTINENT

ON ITS JOURNEY TO BISON SNOUT.

[Pg 53]

The scene changes, now, to a precipitous hill overlooking the smiling valley through which the train is thundering. Far away you can see her plume of smoke, racing across the sky. And here, in the foreground, are two sinister figures, mounted on the inevitable mustangs, masked and visored, grim and silent. Oo! They look like Irish gunmen; and as soon as they espy the train they turn simultaneously to each other and exclaim with sinister emphasis—Snick:

THERE’S BOODLE IN THIS.

Click—and we’re back again with our two desperadoes, galloping like mad from their point of vantage towards their luckless prey. (Noise off—cloppety, cloppety, cloppety, clop.)

Next we have a close-up of the train as it speeds over the landscape. The passengers are sitting back in their places, wreathed in smiles. They like their train. They think it particularly safe; and behind it all there is the feeling of immense security derived from the thought that they are travelling in a British Dominion of the British Empire under the waving protection of the Union Jack on which the sun never sets. The orchestra interprets their thoughts, and ours, by playing a selection of patriotic melodies.

[Pg 54]

Now we are shown something really out of the way. Thus: Snick:

ON THE FOOTPLATE.

Flick:

SWAYING ALONG AT HUNDREDS OF

MILES AN HOUR, THE JOVIAL

ENGINEER AND HIS MERRY COLLABORATORS

PASS THE TIME WITH

DANCE AND SONG.

Click: And there they are, swaying like dipsomaniacs, dancing like dervishes, and opening their mouths like bullfrogs in a drought. Of course, you can’t hear what they’re singing, but a gramophone (off) obligingly strikes up at this moment:

and so on. A little inappropriate to the setting perhaps; but, oh, how apposite to what follows!

Suddenly the face of the jovial engineer clouds over. He shades his eyes with his hands. Rushing to the eyeholes, he peers out into the day. His collaborators copy him. We know something is coming. We stir uneasily in our seats. Somehow we can’t help associating this action with the two sinister——What’s that? He’s beckoning[Pg 55] to the chief mate (or whatever the fellow’s called). The chief mate’s beckoning to him. Neither dares leave the eyeholes. How can they communicate with each other? Still the train speeds on. Oh! the engineer’s drawing his revolver. Ah! it’s empty! So is the chief mate’s. So is everybody’s. He flings it down with a curse. He’s going to speak to the chief mate. He’s speaking: Snick:

SAY, YOU GUYS, IT’S HELL OR HOME.

AND ME FOR HOME!

Flick:

STOKE UP YOUR BOILERS, YOU BLEAR-EYED

SKUNKS!

An underling flings open the door of the furnace. He staggers back. Empty! He rushes with a shovel to the coal bunkers. The others rush after him. Oh, there’s no coal! The train’s slowing down every minute. The desperadoes are riding nearer and nearer. We can hear the thunder of their hoofs—I mean their horses’ hoofs. (Noise off—cloppety, cloppety, cloppety, clop.)

Ah! what are they doing now? They’re going to throw one of the underlings into the furnace to keep the train going. They’re going to burn the engineer and the chief mate. They’re going[Pg 56] to pull the engine to pieces and burn that. Anything to escape. Anything to escape....

Suddenly the chief mate, who’s looking through the eyehole, gives a great shout. He’s very excited and relieved. He’s speaking—listen, look, I mean.

Flick:

WHY IT’S ONLY THE SHERIFF’S BOYS

HAVING A GAME WITH US!

The others do not agree with him. They point rudely at him, and curse him for a fool. But he only smiles and says through his smile:

Click:

SURE—IT’S THE SHERIFF RIGHT

ENOUGH. I SEEN HIS LIL’ BUTTON.

HIS DEPUTY’S WITH HIM.

I DONE SEE HIS BUTTON, TOO.

They rush to the eyeholes again. There’s no doubt this time. They throw up their hats and cheer. They are beside themselves. They even go so far as to pull up the train. The passengers crowd to the windows. At first they are alarmed. They shrink back. They mutter among themselves. Click:

IT’S A HOLD-UP.

BUSH-RANGERS.

and so on. But the engineer puts all that right.[Pg 57] He descends royally from the footplate and walks along the train reassuring them. Flick:

IT’S ALL RIGHT, LADIES AND GENTS.

IT’S ONLY THE SHERIFF OF THE

DOMINION COME TO PAY US A SURPRISE

VISIT.

What a joke! How they laugh! And cheer! They crowd to the window. They swarm out on to the line. They offer expensive drinks to the engineer and his collaborators, which are accepted. They pass round the hat.

And then the sheriff approaches. He asks them to line up. They are delighted. Another priceless joke. Ha! Ha! Ha! What a wit the man has, to be sure! He suggests they should produce their valuables. Only too delighted. Their stocks and shares, jewellery—everything, in fact, they have with them.

THEY’RE “OF NO VALUE” TO YOU

NOW.

Ha! Ha! Ha! They’re doubled up with laughter. They’re holding their sides. What a funny man. What a very fun——Eh? He’s speaking again.

GET A MOVE ON IF YOU DON’T WANT

A DOSE OF LEAD!

[Pg 58]

Oh, of course, very subtle. It’s all part of the joke. He’s acting so well, isn’t he?

What’s he doing? He’s putting all their valuables into a bag. He’s taking them away. He’s a——He’s a robber! Oh, no! Oh, not that! But he is. Old men are weeping over the loss of their life’s savings. Old women——Oh, this isn’t funny at all!

A handsome young woman is speaking to him. She’s pleading, she’s on her knees.

Click:

IF YOU TAKE THAT IT MEANS I

CAN’T GET MARRIED. WE WERE

GOING TO START HOUSEKEEPING

ON MY FIRST PREFERENCE STOCK.

She’s broken down. He’s laughing, the brute! He’s roaring with laughter. So’s his fellow desperado.

Who’s this? What a funny fat man! Oh, it’s going to end happily after all. He’s a policeman, I suppose, but his hat looks a bit queer. Oh, an American hat—I see. He’s very angry with the brigands—the sheriffs, I mean. He’s speaking.

Click:

THIS OUTFIT’S WORTH AT PAR

£37,073,492.

[Pg 59]

Flick:

“THIS WOULD MAKE MY APPRAISEMENT

OF ALL THE STOCK, THE VALUE

OF WHICH IS HERE IN ISSUE, NOT

LESS THAN $48,000,000.”

Oh, it’s too bad! They’re laughing at him, too.

Plick:

GET AWAY HOME, YOU FAT OLD GUY,

BACK TO THE STATES WHERE YOU

BELONG.

He’s very angry indeed. He’s turning away in high dudgeon. He makes a last appeal.

Flick:

BUT AIN’T YOU THE SHERIFF?

Blick:

WHY, YES; BUT WHAT’S THAT GOT TO DO WITH IT?

Snick:

WELL, I MEAN TO SAY——

Click:

A MAN’S GOTTER LIVE, AIN’T HE,

EVEN IF HE IS A SHERIFF? AND

THEY’RE ONLY DURNED ENGLISH

GUYS, ANYWAY.

[Pg 60]

The big events of the world, the things so remote from most of us, float serenely down the midstream of the day’s news, little heeded, I confess, by me; but the flotsam of life is brought to one’s very feet by the undercurrents and eddies of the Personal Column.

The news headings of one’s morning paper deal with subjects whole worlds away from one’s own humble existence. The movements of Marshal Foch; the Japanese Earthquake; the Recognition of Russia. Even (long since) when the “Date of the Peace Celebrations” was announced, it was a comparatively lifeless statement. To vitalise it, to humanise it, one had to go to the neighbourhood of the Personal Column. Thus:—

“Champagne. Approaching Peace Celebrations. Advertiser representing principals holding stocks of the best known brands of Champagne, etc., etc.... Apply to ‘Benefactor.’”

Here at last we were in the heart of things. “Stocks of the best known brands of champagne.” This unlocked the tongue, set speculation working. What brands? What is your favourite brand? One reviewed a pageant of sparkling[Pg 61] names such as Ayala, Irroy, Heidsieck, Mumm, Moet, Pommery, Roederer and the Widow, the dainty Clicquot.... And then arose the question what to do on Peace Night—Jazz? Theatre? Opera? Or should it be a quiet dinner (preferably at home) with Jones, who shared one’s last Xmas in the Salient, and Smith the Silent, who never let one down, and Robinson?... I seem to remember that I wrote to “Benefactor.”

Actually “Benefactor” was not, so to speak, a Member of the Personal Column, though he dwelt very near to it. His announcement abutted on a poignant appeal for a “Suitable Place to Stop” from a young minesweeping lieutenant who, having exhausted his patience in ransacking London for a bed, had lit upon the discovery that a large part of the hotel accommodation in this city was still in the clutches of Sir Alfred Mond and his Merry Men; but it was published (wrongly, of course) under the heading: “Business Opportunities.” What creature would sink so low as to make a business opportunity out of the sale of that golden drink, of those “best brands of Champagne”—and in the Peace season, too? Perish the thought! To the Personal Column let “Benefactor” be admitted.

The Personal Column is the quintessence of[Pg 62] journalism, an inexhaustible lucky-bag of strange communications and curious announcements. Do you want a furnished caravan? Napoleon relics? Are you a philatelist? Would you like a summer outing in Kew Gardens? Have you a haunted house? These, after all, are things that touch one’s daily life. Marshal Foch might go to the Sandwich Islands, and the philatelist and I would wish him God-speed, and think of it no more; but a haunted house (even if it be only haunted by mice) brings one “up against it!” Are you bored with your life? The Personal Column is a constant provocation to plunge into the whirlpool of the unknown. Thus at random: An officer, aged 20, of cheerful artistic and musical tastes, wishes to correspond with somebody with a view to “real friendship.” There’s your chance. And what dark story, think you, is concealed behind the following:

“The Black Cat is watching: green eyes. S?”

What tale of a temptation spurned lurks in:

“Scalo: I may be poor but I love truth far better than gold—Misk?”

Under the influence of what jealous pangs came this to be penned:

“Ralph—Who is BABS—Remember Olga?” (The following, in a happier vein, tells presumably of a lovers’ quarrel made up:

[Pg 63]

“Whitewings. Darling you know really you are the only thing on earth I love. Snowdrop.”)

The big news columns tell us what our intellectuals consider it good for us to know, in the manner in which they consider it good for us to be told. The Ruhr Occupation, denounced by Mr. Garvin, upheld by Lord Rothermere—The Betrayal of the Country to Labour (in the Gospel according to Mr. Churchill)—The League of Nations—Bootlegging and Prohibition. But the Personal Column—ah!—the Personal Column gives us a peep into the throbbing lives of our neighbours; we become partakers in the bliss of Whitewings and Snowdrop, we share “S’s” apprehension of the Black Cat, and our hearts go out to Misk and Olga—poor forgotten Olga. Here are no world politics dished up by statesmen manqué, or camouflaged by great journalists, no subjects to be discussed in catchwords and manufactured phrases, but the myriad voices, from the streets around, crying out at the impulse of the eternal verities.

[Pg 64]

Extracted from the Private Diary of the Hon. “Toothy” Badger

Dined at the House last night. Ridiculous party given by “Bulgy” Gobblespoon to celebrate his wife’s election: the first husband and wife to sit together. To everyone’s dismay, it proved that she had only scraped in by the Prohibitionist vote, to win which she had to pledge herself never to allow any form of alcohol on any table at which she sat. Very restrictive of her dining out, I should imagine, and utterly destructive of her own dinners, which used to be rather fun. Impossible to imagine the gloom of that gathering! Even old Bitters, who was wheedled off the Front Bench to come down and say something amusing, was quite unable to sparkle on Schweppes’ ginger ale. Hurried away with little “Squeaky” Paddington (old Ponto’s new wife) to sample a drink and a spot of foot shuffling at Sheep’s. Very stuffy and a lot of ghastly people.

Somebody, turning out their lumber-room, has presented a whole shoot of pictures to the National Gallery; so I went to see who was looking at them. What that place exists for I[Pg 65] can never understand. Hardly anyone there except a herd of frowsy old women, with paint-boxes, who took jolly good care that nobody should come within a mile of anything worth looking at. One rather jolly girl—but very severe. The rest awful. A couple of anxious-looking people walking up and down, looking intense and making speeches about Ghirlandajo or Cimabue to an audience of yokels that doesn’t know either from cream cheese; and the remainder of London seems to use the portico as a convenient meeting-place, and never goes inside at all.

Broke my rule against large parties last night in order to go and stare at the women Members of Parliament, who allowed themselves to be shown off by old Lady Paramount Nectar at Ambrosia House. Never again. The rooms are big enough Heaven knows; but they seemed to have invited everyone in London, who had a dress-suit. Lady Biltong, whose figure needs to be put under restraint, was carried out fainting. Poor Bottisford had two ribs stove in going up the staircase and didn’t know it till he got home—kept murmuring that he must have got a touch of pleurisy in the fog. And old Sir William Bylge trod on a lady’s train and brought it clean away from the gathers (whatever those may be). Needless to[Pg 66] say, it proved to be a Royalty, but only a minor one. Never saw so many foreign potentates and creatures gathered together in my life before: the Duca di Corona Largo, Count Papryka da Chili, the Prince and Princess of Asta Mañana, a woman from New York, the Gizzawd of Abbyssinia, old Ramon Allones, looking younger than ever, and heaps of others. Nothing to eat, of course, and sickly sherbetty stuff masquerading as champagne. Hurried away to Stag’s with George Mossop to wash the taste out of our mouths. If old Paramount Nectar had lived, how different that supper would have been! As it is, if they took a bottle out of his cellar now, and poured it on his tomb, I believe he’d rise from the dead in very shame. Seems a bit too low to accept old Lady P.’s hospitality, and then slang the food; but, after all, he was my father’s cousin, and one feels it reflects on one’s own palate that a relation by marriage should give inferior wine.

Country house parties nowadays are becoming absurd. In the old days there was a lot to be said for country house visits. Even quite recently they could be profitably undertaken. But now! Nous avons changê tout cela. The advent of a Labour Government has put the final kybosh on even the limited hospitality one enjoyed last year. Three invitations this morning. One from Ditchwater Abbey—a place I loathe; one from[Pg 67] Hugo Hamstringer, the fellow that made a fortune out of glue in the war, bought everything, lost the whole boiling in multiple eggshops during the slump, and is now trying to make two ends meet in that awful barrack of a place, Dundahead Hall, that he took over from “Wacker” with a block of dud oil shares in payment for his “calls” in Hamstringer, Limited, before the Company went bust—(nothing would induce me to go near him); and one from dear little Phyllis Biddiker, whose husband has lost everything in Southern Ireland, and who is scraping along somehow by letting off apartments at the Weir House (their place in Berkshire) to wealthy Colonials over here for the British Empire Exhibition. None asked me for more than a week-end. All say “Bring your own whisky if you want any.” Phyllis has had a present of Australian Burgundy from one of her lodgers, and offers to share it. I shall stay at home.

Because my brother Henry chose to marry, why should his almost-a-flapper daughter be motted on me to cart about London? A jade, a sly boots and a minx, she makes my life a burden. She makes me give her expensive meals, which I rather like; but I draw the line at being a decoy duck. Last night, having bled me of my entire[Pg 68] income at Mah Jongg—a game I shall never hope to learn—she demanded to be taken to an unintelligibly highbrow play, knowing, I suppose, that, after the agony of listening to it, I should be as wax in her hands. Then she led me by easy stages to Sheep’s Club, by pretending she wanted to dance with me. There (by the merest accident, of course) we found young Geoffrey Bannister, the one young man in London I was cautioned against allowing her to meet—as if an uncle has any control whatever—and the whole plot stood revealed. Before I could contort my features into a frown, they were dancing in the middle of the room, where they seemed to spend the remainder of the evening. I was allowed to give them supper; they allowed me to take them away at two a.m. They were almost too good to be true till we got home—driving back in Geoffrey’s car; and then they suddenly insisted on starting off to “be in at the death” at the Hunt Ball at Hillsbury, looking in at Bridget Hanover’s dance in Brook Street on the way. Told them to go to the Hunt Ball at another place beginning with the same initial, sent Geoffrey home, and packed her off to bed. No more nieces for me.