King Edward

STORY OF THE

MAKING OF THE EMPIRE.

BY THE

REV. C. S. DAWE, B.A.,

Author of "Queen Victoria, and her People," &c.

London:

THE EDUCATIONAL SUPPLY ASSOCIATION, LIMITED,

HOLBORN VIADUCT.

1902

PREFACE

As Englishmen we have been born to a great inheritance, which we hold in common with our kinsmen in all parts of the empire. It is quite time that all who share in its possession should have some knowledge of the way in which it has been founded and built up, and should learn something of the great men under whose guidance and inspiration the work has been done.

The writer has attempted to impart such knowledge in an attractive form, avoiding mere dry details, and that closely-packed synopsis of facts which may be desirable in a work intended for a student preparing for examination. But this little work is not written for the student, but as a pleasant course of reading for young or old, who desire to know something of the men who have made the empire, and of the principal events which stand out as mile-stones on the road along which our nation has travelled.

Whilst selecting the more picturesque parts of the story of the empire for special treatment, an endeavour has been made to keep up the continuity of the narrative, so as to enable the reader to trace the connection between events, their results and causes, and to help in sustaining his intelligent interest from page to page throughout the book. An endeavour has also been made to foster that imperial spirit which takes a true pride in what our forefathers have achieved, which resolves to hold what they have won, and which broadens our view of public questions by setting them in relation to the interests of the empire at large.

CONTENTS.

The Empire and its Living Link.

England Preparing for Empire

(1475-1603).

(1) Invention of Printing

(2) Invention of Fire-Arms

(3) Discovery of a Sea-Route to India

(4) Discovery of a World to the West

(5) Rise of the English Navy

(6) Queen Elizabeth at the Helm

(7) Coming Struggle with Spain

(8) An Elizabethan Mariner

(9) A Celebrated Voyage Round the World

(10) Singeing the King of Spain's Beard

(11) Arming for the Fight

(12) Defeating the "Invincible"

(13) Expansion of England into the "United Kingdom"

Early English Colonisation

(1603-1688).

(1) England's Success in Colonizing

(2) England's First Colony

(3) "Farewell, dear England"

(4) Progress in Colonizing

(5) Struggle for the Mastery at Sea

(6) Our Great "General-at-Sea"

Expansion by Conquest

(1688-1763).

(1) What we owe to William of Orange

(2) A Famous Victory and a Lucky Capture

(3) Grandmotherly Government of the French in Canada

(4) Ripening for War

(5) "The Great Commoner" and his "Mad General"

(6) Capture of a Second Gibraltar

(7) First Founder of our Indian Empire

(8) Beginning of British Rule in India

Time of Trial and Triumph

(1763-1815).

(1) Tightening our Hold on India

(2) A Great Loss to the Empire

(3) Australasia brought to Light

(4) First Settlement in Australia

(5) Pioneer Work in Australia

(6) Remarkable Industrial Progress

(7) Nelson and Napoleon

(8) Nelson's Crowning Victory

(9) India's New Masters

(10) Wellington and Napoleon

Progress of India and the Colonies

(Since 1815).

(1) Colonial Self-Government

(2) Birth of a Nation

(3) Promise of National Greatness

(4) "The Good of the Governed"

(5) Spoils of Victory

(6) Deeds of Heroism

(7) British Rule on a New Footing

(8) Bars to Progress

(9) Effect of the Discovery of Gold

(10) Exploration & its Martyrs

(11) Mutual Advantage of Motherland & Colony

(12) A Difficult British State to Build

(13) Great Extension of British Territory

Unity of the Empire.

(1) Growth of Freedom

(2) Imperial Spirit of our Race

(3) The Sovereign in Relation to the Empire

KING EDWARD'S REALM.

The Empire and its Living Link.

1. A glance at the map of the world in which the parts of the British Empire are coloured red may well fill us with astonishment that the little spot marked England has expanded into an empire that covers one-sixth of the habitable globe, and measures more than one hundred times as much as the little island that forms its heart and home.

2. The only other empire that approaches it in size is that of Russia, and we can well imagine a patriotic Russian thinking that his sovereign had a much better realm than had ours, even if it was not so large. "For see," he might say to a countryman of ours, "what a sprawling, disjointed empire yours is, whereas ours is so compact that we can pass through its length and breadth without crossing a single sea."

What reply should a Briton make to this boast?

3. "True," he might say, "the British Empire looks like a giant with his limbs outstretched, having his head in one sea, and his arms and legs in as many others; true it is that our king's realm is so widely spread that the sun never sets on his dominions, still it is far easier for us to go from end to end of our empire than it would be if built like yours."

4. We could not expect the Russian to agree to this, but nevertheless it is true; for the sundered portions of the British dominions are connected by the sea, and the sea offers a ready-made road to every ship that sails. No hills have to be levelled, no tunnels bored, no rails laid down, and hence it is much cheaper to travel on sea than on land, and often much easier and quicker. We may rightly regard the seas that come between our shores and the rest of the empire, not as separating but as connecting its several parts, and enabling the motherland to keep in constant touch with her daughter states in other lands.

5. Steam and electricity have worked wonders in bringing all the members of the English family of nations into close connection with each other in spite of the many thousands of miles that separate them. By means of our great ocean-liners we can cross a wide ocean in a few days, and by means of electric cables beneath the sea each part of the empire can converse with any other part in the course of a few hours, or even in a few minutes.

6. This ready means of communicating with each other, draws us all more closely together in thought and feeling. The same incidents and events, to a great extent, occupy the minds of all our race at the same time, and send a thrill of joy or sorrow throughout the empire. Whether living in London, Sydney, or Montreal, the Briton finds in his daily paper a great deal of the same news, showing how much of common interest there is between ourselves and our brothers beyond the seas.

7. Away then with the idea that seas act as barriers. They serve rather to unite. Has not steam bridged the ocean, and electricity brought its shores within speaking distance? For trading purposes, especially, the sea is much more a uniter than a divider, since goods may be carried so much more cheaply by water than by land. It costs less to bring wheat by sea from Montreal or New York to London, a distance of 3500 miles, than to bring the same by rail from Liverpool to London.

8. The British Empire, it is true, is scattered over the face of the globe, but in some respects this is an advantage. Being so widely sundered its different portions differ much in climate and productions, and thus can the better supply each others' wants. England, for instance, serves as the great manufacturing shop for her colonies, whilst they in return send her the raw material for her factories and food for her children. England, indeed, would soon suffer from famine if a constant supply of food did not come from other lands. To insure this supply without interruption to our traffic, we must be able to keep the seas open to our merchant-ships, whether in peace or war, and for this purpose our navy must be supreme.

9. Nothing is more interesting in the story we have to tell than the daring exploits of our seamen, by which we have risen to the command of the seas, and are able to sing Rule Britannia with the proud happy feeling that Britannia does indeed still rule the waves, and that as far as in us lies it shall never cease to do so, since it is only by thus "ruling the waves" that we can look to the sea as a friend that unites the whole family of English-speaking peoples, and enables them to aid one another.

10. But we need something warmer than sea-water to unite us all, and make us in heart and mind one people, in whatever quarter of the globe we live, and that is the spirit and sentiment that spring from the fact that we are of kindred race, that we all speak the same language, read the same books, enjoy the same freedom, make our own laws, and passionately love justice and fair-play. We have recently had striking evidence of the warm feeling that pervades the whole empire, and welds its several parts into one. When the Boer war broke out and the British arms met with reverses, the whole empire throbbed with one heart and kindled with one spirit, revealing to ourselves and the whole world that though the British Empire is widely scattered, it is in heart and mind closely united.

11. As a symbol of that unity we have one king, one flag. The king, indeed, is more than a symbol of unity, he is a link, a living link, that actually binds the parts together. Every true Briton, throughout the empire, looks to the sovereign as the head and centre of the national life, from whom all who administer the laws, or exercise command in the army or navy, derive their authority. Whilst the king takes a personal share in the government in the homeland only, he has his representatives who act as governors, in his name, in every province of the empire. The king, therefore, may be regarded as the living link which unites the sundry and sundered parts of his mighty empire.

12. The relation of King Edward to the different portions of his realm is thus expressed in the title which he has assumed: Edward the Seventh, by the Grace of God, of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and of the British Dominions beyond the Seas, King; Defender of the Faith; Emperor of India.

England Preparing for Empire

(1475-1603).

1. We will begin our "Story of the Making of the Empire" with that of the Making of England, the centre around which the whole empire has grown, and try to show how she was shaped and prepared to be the mother of nations. To become fit for her high calling, it was essential for her to become wise and powerful. And as nothing has contributed more to this end than the spread of knowledge, we will start with the brighter day that dawned upon our land when printing was invented.

2. The first printing-press was brought to our country by William Caxton, about 1475, that is ten years before Henry VII., the first Tudor, began his reign. He set it up near Westminster Abbey, and astonished all the great men of the land who came to see his wonderful machine.

3. Formerly all books were written by hand, and consequently were so scarce and expensive that only few could get them to read. Much knowledge was hidden away in Greek and Latin manuscripts, but it had been hard to get at it. The invention of printing altered all this. It brought books within easier reach, and men who were athirst for knowledge could satisfy their craving.

4. Caxton was a great worker. More than fifty years old when he began his new labours, he printed ninety-nine books before his death. Though busy as a printer, he was even busier as a translator. The first book he printed was The Tales of Troy, which he translated from the French. In the preface to this book Caxton tells us how tired he had become of writing books with pen and ink, how his eyes had become dim "with overmuch looking on the white paper," and how gladly he had learned the new art of printing. Having finished the printing of his first book, he said proudly to his visitors: "It is not written with pen and ink as other books be, but all the books of this story here imprinted as ye see were begun and finished in one day."

5. The printing-press worked wonders in the world. Many books which had been left to moulder in the dust for more than a thousand years now saw the light of day. Printed copies of these works were soon in circulation. The great thoughts of famous writers who had lived in ages past once more stirred the human heart. Men seemed to awake from the sleep of centuries, to open their eyes to the light of knowledge, and to begin to think for themselves.

6. Within fifty years from the introduction of the printing-press nearly all the great works of Greek and Latin authors were in print. Greek scholars were everywhere in great request as teachers. By many earnest students in our land the knowledge of Greek was chiefly sought because it was as a key to unlock the meaning of the New Testament, the books of which were originally written in that language. This study of Greek and the new learning that shed its light around, led in England to considerable changes in men's religious opinions.

7. The new art of printing had also a considerable effect on the Englishman's mother tongue. Caxton tells us that he found great difficulty in choosing his words when translating because "the common language of one shire differs from that of another so much that travellers from one part of England have much ado to make themselves understood in another part." When a language only lives on men's lips it soon becomes altered in various ways; but when it is not only spoken but printed it is wont to become fixed, and all who read become accustomed to the same form of speech.

8. In the course of the century that followed Caxton's labours, some years before any emigrants left our shores, the English language assumed its final form. When at length Englishmen began to emigrate, they carried with them the same tongue that continued to be spoken at home. This is a matter of no small importance; for a common language is a strong bond of union. Happily, all who have left the old country to form colonies in other parts, however distant or widely separated, still speak the same language as ourselves. We all read the same books, and clothe our thoughts and feelings in almost the same words. This tends to keep us in heart and mind one people, however wide the seas between us.

9. When now-a-days an Englishman lands in the United States, or in any British Colony, he hears men speaking his own tongue. The people of other nations rarely enjoy this privilege. The German emigrant, for example, seldom desires to settle in a German Colony. He usually makes his new home in the United States or in some British Colony, and there he finds himself in the midst of an English-speaking people, and forced to learn their language in order to get on. An Englishman it is said, is always ready to grumble, but no nation has less cause than our own to be discontented with its lot.

10. Lastly, printing had a great effect in giving a lift to men of the humbler classes. Thousands of people who never before had a chance of learning were now able to buy and read books, and gain valuable knowledge. Of course, in our own day, books are so cheap, and free libraries so common, that all who have the will can read and learn. But even in Tudor times—in the century that followed the introduction of printing into England—the wider spread of knowledge, due to the new invention, made people more equal than before, and gave a clever boy in humble life a better chance of turning his talents to good account, both for himself and his fatherland.

1. Gunpowder had been invented long before printing, but it was much longer in making its influence felt. Cannon had been used as early as the battle of Crecy, 1346, but they were of little use, being rudely constructed of wood, hooped with iron, and almost as dangerous to the gunners who fired them as to the enemy they were intended to kill. In time, however much better cannon were turned out, and before the end of the War of the Roses great guns were used with much success both on board ship and in the siege of castles and walled-towns.

2. Hand-guns came into use somewhat later than cannon, but in the times of the Tudors they gradually superseded the bow and arrow. Henry VIII. was much opposed to the change, for the English archer excelled all others in his art. Excellence is never a mere accident. It was due, in this case, to a long and careful training begun in boyhood and enforced by law. Fathers and masters of apprentices were obliged to teach the lads under their care the use of the bow, to provide them with weapons suited to their strength, and to compel them to practise at stated times. Our forefathers have set us an excellent example. If Old England is to ward off all danger from her shores, and to hold her proud place among the nations, she must see that her lads are in like manner provided with rifles suited to their strength, and encouraged to practise regularly at the target. Lads' Brigades and Cadet Corps must become the order of the day.

3. The use of gunpowder made sweeping changes in the art of warfare, just as smokeless powder and quick-firing rifles and guns are doing to-day. Both the archer and the mailed knight disappeared. The old castles became quite useless as fortresses, and the barons in consequence lost much of their old power. In the reign of Henry VII. we find them, for the first time, quite unable to stand up against the king, who took care to keep in his own possession the only great guns in the kingdom, much in the same way as in India, at the present day, we are careful to keep the artillery wholly in the hands of British soldiers.

4. Gunpowder is a great leveller. It puts the weak and strong, the short and tall more nearly on a level. It is the men, small or large, who can shoot straight that are likely to win the battle. As soon as fire-arms displaced the bow and arrow, success in battle no longer turned mainly upon the valour of the gentlemen in armour, but upon the right handling and steady discipline of the rank and file. A volley of shots from a line of common soldiers could scatter death and disorder among the ranks of the bravest knights in armour. The gentlemen-at-arms soon found that their armour was only an encumbrance, and that its proper place was on the walls of their grand old halls, or, for people to look at, in some public gallery, like that in the Tower of London. The sword and the lance still hold their ground, but there are many signs that the rifle will soon supplant them in actual warfare.

5. In the last chapter we have spoken of the beneficial effects of the invention of printing. Can we speak in the same way of gunpowder? It may seem strange to talk about gunpowder as if anything good could result from its use, but it would be a mistake to think that the work it has done in the world has been wholly bad, for there are times when force is the only argument that can convince, when force is the only way of putting down evil. In reality it has played a large part in the making of our empire, and, therefore, in establishing the reign of justice and order.

6. It was by means of fire-arms that our forefathers were able to gain a secure footing in the countries of uncivilized races, to make new homes among them, and to establish law and order in their midst. It was by the superior weapons of the white man—a superiority due mainly to the use of gunpowder—that he was able to prevail over the Red Indians of America, the Negroes and Kaffirs of Africa, and the Cannibals of New Zealand. To the simple savage there is something magical in the effect of fire-arms. He sees a distant object struck down, and perhaps killed, but his eye cannot follow the flight of the bullet that has dealt the blow. He sees the flash, he trembles at the thunder, and in a moment the messenger of death unseen has sped.

7. Of course the natives in time learn that there is no magic in all this, but a knowledge of the reality brings them no comfort. They are obliged to admit that their own weapons, such as rude spears or feeble bows and arrows, are no match for the arms of thunder and lightning in the hands of the white man. And so they sullenly submit to their fate, and leave the white strangers to settle in their country.

8. The effect of superior weapons is equally striking in our own day, whenever Europeans come in contact with half-civilized people, like the blacks of West Africa. It is true these men are often armed with muskets, but they are of such an out-of-date pattern, that they do little damage compared with ours. Consequently, a few hundred well-armed and well-drilled natives, under British officers, can go to battle with as many thousands of the enemy and carry off the victory.

9. Even when the natives are brave and well-armed, like the Zulus, with their terrible assegais, they cannot stand against one-tenth as many Englishmen armed with repeating rifles, and supported by maxim guns, grinding out bullets by the score. It was never more evident than it is to-day that "Knowledge is Power," and that the greatness of a nation is based on knowledge and character. Of this we shall have repeated evidence in the course of this story.

(3) DISCOVERY OF A SEA-ROUTE TO INDIA.

1. Let me again carry your minds back to the time when Caxton set up his printing-press in England, about 1475; for that date we may take as a convenient starting-point in telling our tale. At that time the larger portion of the earth was unknown to even the best geographers. A glance at the map will enable you to see how limited was their knowledge of the size and surface of the earth. You will look there in vain for the larger portion of the British Empire as we know it to-day. You will find there no Canada, no Australasia, no South Africa.

2. It was known indeed that the earth was round like a globe, but no one had ever gone round it. Mariners in their voyages had always kept near the coasts, and never ventured very far from home. But when men awoke, with the rattle of the printing-press, from the sleep of centuries, a new spirit of enquiry took hold of them. The same spirit that led some men to search out old truths hidden away in musty manuscripts, urged others of a more daring turn of mind to go in search of new lands.

3. It was not, I regret to say, our own countrymen that took the lead in the discovery of new lands. That honour belongs to the Portuguese. By the middle of the fifteenth century they had sailed along the coast of Africa as far as Cape Verde, and seen men with skins as black as ebony. At the sight, some of the sailors, it is said, began to fear that if they proceeded still further south, their skins would turn black under the scorching rays of the tropical sun, and their hair become frizzled as the negro's. Before turning back, however, they explored the coast of Guinea, and found the natives ready to traffic in ivory and gold.

4. The wonders that the sailors had to tell on their return, and the sight of the gold and ivory, the monkeys and curiosities they brought with them, kindled an eager spirit of adventure among their countrymen. Lisbon became the headquarters of bold mariners bent on exploring new lands, with the King of Portugal as patron. It was his ardent wish to find a sea-route to India and the East, whence came the rich carpets and shawls, the silks and gems, the drugs and spices so highly valued in Europe.

5. The King of Portugal, accordingly, fitted out a small fleet, and directed Diaz, its commander, to follow the coasts of Africa and try to make his way to India. But the distance was much greater than the king supposed. Diaz sailed a thousand miles further along the African coast than any yet had dared to go, and reached the southern end of that continent. But he could go no further. Stormy weather and the crazy condition of his ships compelled him to turn their prows homeward.

6. The king named the "lands-end" Diaz had reached the Cape of Good Hope, for he believed that by rounding that Cape the sea-route to India would be gained. And he was right. This, however, was not actually proved until 1498, when Vasco da Gama, another Portuguese mariner, rounded the Cape, crossed the Indian Ocean, and anchored in the harbour of Calicut, on the west coast of India.

7. The discovery of a sea-route to India had important results, and in time proved a great advantage to English commerce. Hitherto the merchandise of India and the East had been carried overland on the backs of camels to the ports of Syria and Asia Minor, and thence shipped chiefly to Venice. When once the treasures of the East reached that port they were safe from plunder; for Venice with its sea-girt walls was perfectly secure. But in the course of their long passage from India and the East, the goods were always exposed to plunder. The caravans, with their long string of loaded camels, were often attacked by bands of Arab robbers; and the merchant-ships, though armed, were often boarded by Turkish pirates.

8. The sea-route, via the Cape, offered great advantages. It was both cheaper and safer; cheaper, because the goods could be brought the whole way in ships; and safer, because the voyage was made across the open ocean, where the risk from pirates was not nearly so great. The Portuguese were the first to take advantage of the new route, and for many years kept the whole trade to themselves; for in those days it was generally thought that the discoverer of new lands had the sole right to trade with them.

9. The Venetians soon found themselves unable to compete with the Portuguese. Lisbon, accordingly, became the centre of trade for the spices, silks, calicoes, gums and drugs of the East, and the glory of Venice departed. The Dutch were not slow to avail themselves of this new opening for trade. They freighted their ships at Lisbon, and made Antwerp the chief entrepôt of trade for the countries round. London dates its rise as the great centre of the world's commerce from the capture and sack of Antwerp by the Duke of Parma about a hundred years later (1585). It was not till the year 1600, near the end of Elizabeth's reign, that our English merchants ventured on trade with India direct, and then the East India Company was chartered by the queen for that purpose. It was destined to take a large share, not only in trade with the East, but in the great work of making the empire.

(4) DISCOVERY OF A WORLD TO THE WEST.

1. Across the Atlantic lay a double continent unknown to the rest of the world until discovered by Christopher Columbus (1492). This extraordinary man was born at Genoa, and in the early years of his manhood "sailed," as he tells us, "wherever ship had sailed." He came to the conclusion that, as the world was round, India might be reached by sailing westward across the Atlantic. But he knew not, of course, how far it was in that direction, or what lay between his goal and his starting-point.

2. Columbus having prevailed on Isabella of Spain to put three small ships under his command, began his voyage of discovery on setting out from the Canary Islands. He soon reached the part where the trade-wind blows, and was carried by it steadily along to the westward, day after day, without the necessity of shifting a sail. But the greater the progress of the ships, the greater became the alarm of the sailors.

3. There arose murmurs among the terrified crews, and some of them talked of throwing the admiral overboard and returning to Spain. At length, when more than thirty days had passed, and still nothing could be seen but sea and sky, Columbus promised that, if in three days longer no land was discovered, he would tack about and make for home. Before the three days had passed, there arose from the foremost ship the joyful cry of "Land! Land!"

4. The men soon manned the boats and pulled to shore, whilst the natives flocked to the beach and gazed in wondering admiration. Columbus, clad in scarlet, leapt ashore, with the royal banner of Spain in his hands. In a few moments a crucifix was erected, and then "all gave thanks to God, kneeling upon the shore, and kissing the ground with tears of joy." The simple natives regarded the strangers as a superior order of beings descended from the sun. They were shy at first through fear, but soon became familiar with the Spaniards; and received with transports of joy, in exchange for their gold ornaments, hawk's bells, glass beads, and other baubles.

5. Columbus was not aware that he had hit upon a new continent, but supposed he had come upon some islands lying off India. He had really landed upon one of the Bahama Islands. In consequence of his mistake the islands he had discovered were called the Indies, and the natives were spoken of as Indians. Cruising among the islands, now called the West Indies, Columbus discovered Cuba and Hayti, and then returned to Spain in triumph, taking with him gold, cotton, parrots, and other products of the islands, and a few natives besides.

6. The famous voyage of Columbus soon became the common talk among seafaring men. At that time, in the port of Bristol, were two skilful mariners, father and son, named Cabot. John Cabot was a seaman of Venice, but his son Sebastian was born at Bristol. They were bent on finding a short way to India by sailing westward, like Columbus, only keeping in a much higher latitude. They obtained permission from King Henry VII. "to seek out, subdue and occupy any regions which before had been unknown to all Christians," and they were authorised to set up the royal banner in any such land and to take possession in the king's name.

7. On an old map drawn by the younger Cabot it is stated: "In the year of our Lord 1497, John Cabot, with his son Sebastian, discovered that country which no one before his time had ventured to approach, on the 24th of June, about five o'clock in the morning. He called the country The-land-first-seen, and the island opposite, St. John, because discovered on the festival of St. John the Baptist." "The-land-first-seen" was probably Nova Scotia or the island of Cape Breton.

8. Next year, Sebastian Cabot came upon Newfoundland and sailed along the coast of Labrador, picking his way among the icebergs, in his effort to discover an open channel to India. He then retraced his course and examined the coast of the United States as far as Virginia without finding the desired opening. He had, however, mapped out roughly 1800 miles of the North American coast, and secured for England the prior claim to the northern half of that continent. But nothing came of this adventure until the reign of Elizabeth, when steps were taken to occupy some part of the new-found territory.

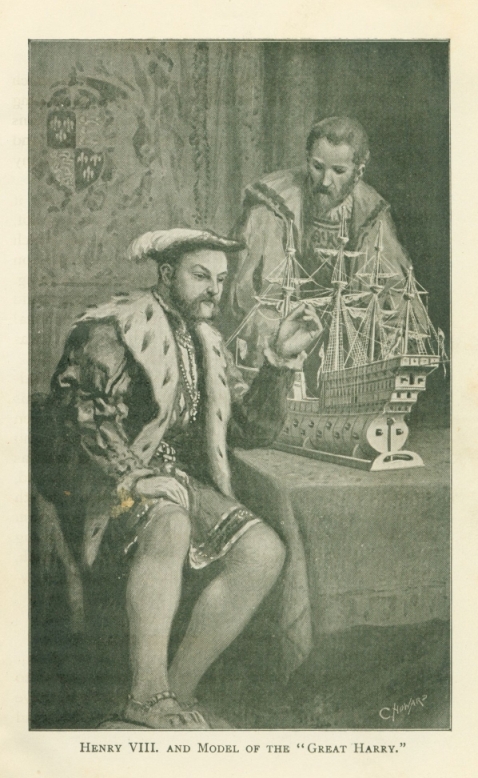

1. We owe the founding of the royal navy to Henry VIII. Before his time there seems to have been no standing navy, private ships being hired and armed when a war-fleet was needed. With the accession, however, of Henry VIII. (1509), England began to take her right place as a naval power. The new king was rich and clever, bluff and hearty, a thorough "John Bull," with a proud resolute spirit that would brook no denial.

HENRY VIII. AND MODEL OF THE "GREAT HARRY."

2. Henry at once made up his mind to have a powerful navy that England and her sovereign might become "second to none." He knew well that if England was to secure her share of trade with other nations she must have a navy strong enough to enforce her claims and protect her merchantmen. Henry, therefore, lost no time in establishing dockyards at Deptford and Woolwich, and in procuring from Italy and elsewhere skilled shipbuilders and cannon founders.

3. A great change took place in Henry's reign in the kind of warship chiefly built. Before his time the warship was usually a kind of long boat, called a galley, propelled by oars. But when cannon came into use, it was found advisable to build larger vessels, and substitute sails for oars, just as in the reign of Queen Victoria sails had to give place to steam. The change, however, was gradually wrought, and oared galleys held their ground, as a secondary force, to the end of Henry's reign.

4. The early Tudor ships were, of course, far from perfect. They had towering castles both at bow and stern which made them top-heavy. Their rigging also was too unwieldy for stormy weather, and made it unsafe to keep the sea in winter. The fate of that "flower of ships," the Mary Rose, shows how easily vessels of the time were upset. Coming out of Portsmouth Harbour, on her way to join in battle with the French, her crew were tacking her, when she heeled over and rapidly sank, carrying with her some 400 soldiers and 200 sailors.

5. Some of Henry's ships were evidently of large dimensions. The Great Harry, for instance, was of 1000 tons, and carried twenty-three great guns, some of which were loaded with shot weighing at least thirty pounds. Besides his great ships, Henry built smaller ones, called pinnaces; and fast, handy sailing ships they proved. Guns also of all sizes and patterns, bronze and iron, were cast in his reign, many of them little inferior to those in Nelson's time.

6. In the early years of Henry's reign, his ships were armed principally with small guns for use as mankillers, rather than for damaging the hull or rigging of the enemy's ships. The aim in a sea-fight, at that time, was for each ship to get on the windward side of the enemy, and then sail down with the wind to ram its adversary and board her, if she did not sink with the collision. Only on getting quite close were the guns discharged, and at the moment of boarding the stones, lances, and other implements of war in the castles, "fore and aft," were brought into play. A sharp fight then ensued on the enemy's deck, the boarders being either driven back into their own ship, or left in possession of their prize.

7. The whole object in this mode of fighting was to close with the enemy as quickly as possible. But before the end of Henry's reign a great change of tactics had taken place. Henry was one of the first to perceive that a great advantage would be gained by the introduction of heavy guns. Larger ships were, accordingly, built and the lower decks furnished with port-holes, thus enabling them to carry two tiers of guns.

8. This change in the structure of the ships and the weight of the guns brought about a change in the mode of attack. The aim now was for each big ship by clever seamanship to place itself so as to deliver a "broadside," while avoiding one of the enemy, and thus to disable or sink its adversary while pounding away at a distance. Thus a complete revolution in naval warfare was made in the course of Henry's reign. That revolution was not confined to England, but the English king took the foremost place in carrying it out. While other nations on the continent were intent on establishing standing armies, Henry devoted himself to the creation of a standing navy that should be able to compete with the best on the sea.

9. At the close of his reign the navy belonging to the Crown consisted of 53 vessels, carrying 250 guns of bronze and 1850 of iron, the crews numbering about 7000 men. Henry VIII., therefore, has a good right to be considered the founder of the English navy. He had the satisfaction of knowing that some of the finest ships that sailed the seas flew the flag of St. George. We say the flag of St. George because at that time there was no union of England and Scotland, and consequently no Union Jack. It was Henry VIII. who first ordered that every king's ship should fly at the masthead and at the bowsprit, the flag of St. George, with its red cross on a white ground. This flag is still carried by every ship in the British navy when an Admiral is on board and in command.

(6) QUEEN ELIZABETH AT THE HELM.

1. Elizabeth, who came to the throne in 1558, did much for the making of England. To her reign we can trace the beginning of much that constitutes the glory and greatness of the England of to-day. Her reign, indeed, may be considered the seed-time of England's greatness. When the crown passed from the head of Queen Mary to that of her sister Elizabeth the fortunes of England were at a very low ebb. The kingdom had just been worsted in a war with France, and felt a rankling sore at the loss of Calais.

2. The one hope of England centred in Elizabeth, whose coming to the throne was as the rising of the sun. In addressing her first Parliament she struck the keynote of her reign, and thrilled the hearts of her hearers with joy. "Nothing, no worldly thing under the sun, is so dear to me as the love and goodwill of my subjects.... My greatest desire is to be the mother of my people." And so well did she study the interests of her people that they learned to call her "Good Queen Bess."

3. It was no easy task which lay before the young queen. She had to govern a people sharply divided into two parties, calling themselves Catholics and Protestants, ever ready in those days to bite and devour one another. Elizabeth endeavoured from the first to reign, not as queen of this party or that, but as queen of all her people. In her religious opinions, however, she leaned to the Protestant side. She was decidedly in favour of a National Church, in which the Pope had no power, and at her request her first Parliament restored the English Bible and Prayer-book to their former place in public worship.

4. Elizabeth was not without her faults. She was vain and fond of flattery, and sometimes mean and deceitful. But in the management of affairs of state she always sought the greatness of England. Although she had able ministers, she steered the ship of state herself. She loved to pilot her vessel in troubled waters, and to take a zigzag course, but so skilfully did she handle the helm that she avoided the shoals and rocks that lay in her course.

5. Elizabeth's great endeavour was to keep her country out of war. And so well did she succeed that she secured for England almost unbroken peace for thirty years, not peace at any price, but "peace with honour." She never yielded to threats, she never drew back a single inch when the honour of England bade her stand firm. She stood again and again on the brink of war, either with France or Spain. But so jealous were these powers of each other, and so full were their hands of their own home troubles, that the wily queen was able to play off one against the other, and get her own way without going to war. Owing to the long peace she secured, and the strict economy she practised, England constantly grew in prosperity and power.

6. Another lasting good Elizabeth wrought for her country. Before her day Scotland had always joined France when the latter went to war with England, and so close was the alliance at the time of Elizabeth's accession that Queen Mary of Scotland was married to the King of France, and French troops were quartered in Edinburgh. Elizabeth put herself at the head of the Scotch Protestants, who, with the help of her fleet and army, soon drove out the French. This action of Elizabeth put an end for ever to the alliance between France and Scotland. It created a friendly feeling between the Protestants of England and Scotland, and prepared the way for the peaceful union between the two crowns on Elizabeth's death.

7. Happily, that death was far distant, and when it occurred all England was ready to acknowledge James of Scotland as king. But had Elizabeth died young, the country would have been thrown into utter disorder, if not civil war. That danger at one time seemed imminent.

8. The queen, while staying at Hampton Court, felt herself one day faint and unwell. Never suspecting that small-pox was the cause, she went out for a ride, caught cold, and in a few hours was in a high fever. The eruption was checked. She grew rapidly and alarmingly worse. The thin cord that held England together was threatening to snap. Should the queen die no ray of hope or light could be seen for England. In the evening she sank into a stupor without speech; and with blank faces, in the ante-chamber of the room where she was believed to be dying, the Council sat into the night to consider the thorny question of the succession to the throne. At midnight the fever cooled, the skin grew moist, the spots began to appear. By the morning the eruption had come out—and the danger was over.

9. Among the queenly qualities of Elizabeth was her unfailing insight into men's character. She knew worthy men when she saw them, and showed unerring judgment in the selection of her ministers and agents. She made the interests of the kingdom her chief concern, and those who shared her counsels were of the same spirit. Her chief minister was William Cecil, and for forty years he served the queen with rare ability and loyalty. He had much to endure from the shifty and uncertain ways of his royal mistress, but he bore all with wonderful patience, and was ever at her elbow with his sage advice when the right moment had come. Elizabeth knew that she could trust him, and was never offended when he plainly showed that he disliked her crooked policy. Blunt of speech herself, she required her ministers to be plain-spoken; always ready to listen to their counsel, though not always ready to follow their advice.

10. Her great minister Elizabeth created Lord Burleigh, and gave him great wealth and power, which he always used in the interests of his country. No other minister has directed the affairs of state for so long a period, or ever directed them more wisely. Lord Burleigh, therefore, deserves a place of high honour among the makers of England. The family of Cecil has often since taken an active part in the government of the kingdom, a conspicuous example of which we have seen in the case of Robert Cecil, Marquess of Salisbury, who has held the office of Prime Minister both in the last reign and the present.

11. Every Englishman recalls the reign of Queen Elizabeth with patriotic pride. In it he can find the roots of our national life and character. Many faults the queen certainly had, but they were such as affected the few who lived at her court. To the many who looked from afar her virtues only were known. Her ministers might know the weaknesses of her character and the windings of her policy, all her other subjects saw only the good results of the guiding hand at the helm. Whatever mistakes she made, there was one she never committed. She never forgot that she was Queen of England, and that it was her duty to make England great, prosperous, and powerful.

(7) COMING STRUGGLE WITH SPAIN.

1. During the long peace of Elizabeth's reign, England was repeatedly on the brink of war with Spain. That war was bound to come. It came with the sailing of the Spanish Armada, in the thirtieth year of Elizabeth's reign. It would have come much sooner but for the long war between Philip King of Spain, and his Dutch subjects in the Netherlands, which at that time formed part of the Spanish dominions. Our business now is to unfold the causes that made war with Spain inevitable.

2. King Philip had married Mary of England, and on her death, offered his hand to Elizabeth, who declined the honour. At the time of his accession Spain was the foremost state in the world. The discovery made by Columbus had given the Spaniards possession of the West Indies and Central America, and by conquest they had gained Mexico and Peru with their rich mines of silver and gold.

3. The natives, so-called Indians, were forced to work in the mines for their new masters, and every year the harvest of the mines was collected and poured into the royal treasury of Spain. The sugar plantations were also a source of wealth. As the poor natives could not stand the hard toil in the mines and plantations, and their numbers in consequence began rapidly to dwindle, the cruel slave trade was set afoot. Negroes were purchased on the coast of West Africa and taken across the sea to work for the Spaniards.

4. We wish it could be said that England stood forth as the champion of freedom, and that the shameful traffic in slaves was the chief cause of the war with Spain. But this was not so. In enslaving their fellow-men the Spaniards were no worse than other peoples. All alike in that age seemed to think the traffic in slaves to be right and lawful.

5. No, the chief cause of the coming war was King Philip's determination to shut the door of Spanish America against our trade, and the equally strong determination of our merchants and mariners to force that door open. Nor can it be said that Philip was going beyond his rights according to the common opinion of his time; for it was then generally held that the nation which first made the discovery of new lands had the sole right to trade with the same. In the discovery of new lands the Portuguese and the Spaniards had got the start of the other nations of Europe, and both alike warned off all ships except their own from their respective domains.

6. But it soon became pretty clear that the English seamen did not intend to be frightened off. Wherever ship sailed, they would sail too. They did not wait for Queen Elizabeth to make a formal demand for the right to trade with the newly-discovered lands, but with her secret connivance set sail in armed merchantmen, some to trade with the Portugese possessions on the coast of Guinea, others to trade with the Spanish settlements in America. They were resolved to trade in an honest peaceable way, if permitted; and if not, to take the law into their own hands and do what was right in their own eyes. We shall see presently what deeds of violence and bloodshed this led to in America, many years before the war was actually declared that brought the Armada to our shores.

7. Of that war the necessities of trade were not the sole cause. Religious differences were scarcely less responsible. In those days men thought it their duty to force others, if they could, to hold the same faith as themselves. Fines, imprisonment, and even death were often thought too good for those who dared to differ from the common faith of their countrymen. Nor were all nations content to limit their interference to men of their own nationality. The chief offenders were the Spaniards. All "heretics"—that is, such as held what they considered false doctrine—who came within their reach had to pay the penalty for their supposed misbelief. Woe to the English seamen who fell into their clutches!

8. We would gladly throw a veil over the horrible scenes in the Spanish dungeons and torture-chambers, but they cannot be wholly passed over as they palliate in some measure the wild, reckless plunderings and piracies of English seamen when Elizabeth was queen. To plunder a ship or town belonging to the hated Spaniard was, in their view, to take a just revenge for his cruelties, to fight for God against misbelievers, and at the same time to fill their pockets with gold. There was certainly a strange mixture of greed, revenge and religion in the hearts of England's bold mariners in their lawless proceedings, such as we are about to relate.

1. The prince of Elizabeth's bold mariners was Francis Drake, a native of Tavistock, in the county of Devon. He spent his early days on the sea as an apprentice, and when twenty-one joined his kinsman, the celebrated mariner, John Hawkins, a man who ventured to carry on trade with the Spanish Colonies in spite of the King of Spain's prohibition.

2. In this way Drake acquired much skill in seamanship, and much knowledge of Spanish America. He ascertained, among other things, that every year the harvest of the mines of Peru was carried in ships to Panama, a town on the Pacific coast, and then taken on the backs of mules across the Isthmus, to Nombre de Dios, a town on the Gulf of Mexico. Here the precious metals brought from Peru were hoarded up until fetched by a fleet from Spain.

3. Now Drake was a man of splendid audacity, fearless, energetic, and full of resource. It occurred to his daring mind that he might capture the town, where the treasure was stored, or pounce upon the treasure itself while on its way from Panama. The means employed were, as usual in that age of wonders, ridiculously small for the end proposed. The fleet placed under the command of our hero for this great enterprise, consisted of two ships no larger than many pleasure yachts of the present day, the Pasha of seventy tons, and the Swan of twenty-five. On board these ships were taken "three dainty pinnaces made in Plymouth, taken asunder all in pieces, and stowed away to be set up as occasion served." The vessels were manned by seventy-three men all told, all under thirty except one.

4. Having crossed the Atlantic, Drake found a secluded harbour, and there set up his "dainty pinnaces." One moonlight night he fell upon the town, where the treasure was stored, and captured it, but had to retire empty-handed; for while trying to break open the strong door of the treasure-house, he was wounded in the leg and carried off by his men, who declared their captain's life was worth more than all the gold of the Indies.

5. Our hero withdrew to some retired spot on the coast where he could hide his ships and refit. And here in a clearing in the tropical forest he set up his forges, and built a leafy village in the manner of the natives. To the hard-worked seamen it must have been a paradise. The woods swarmed with game, the sea teemed with fish; archery butts and a bowling green were got ready, and while one half of the men worked, the other half played. Here they remained until the time came round for the annual transit of the treasure, across the Isthmus, from Panama; for it was their captain's purpose to seize the treasure on its way to Nombre de Dios.

6. It was in the course of this expedition that Drake first set eyes on the great Pacific, then almost an unknown ocean, called the South Sea. We are told that in a glade the natives had cleared away for one of their hamlets, there rose "a goodly and great tree, in which they had cut divers steps to ascend near the top, where they had also made a convenient bower, wherein ten or twelve men might easily sit. After our captain had ascended to this bower and had seen that sea of which he had heard such golden reports, he besought Almighty God of His goodness to give him life and leave to sail once in an English ship in that sea."

7. The march through the forest was then continued until they came in full view of Panama harbour, crowded with the treasure ships from Peru. On hearing from a native spy that the mule trains were ready to start at sunset—for they always crossed the Isthmus in the cool of the night—Drake posted his men for a night attack, every man being ordered to put his shirt on outside his clothes, that friend might be known from foe.

8. When the right moment came Drake's shrill whistle broke the stillness. In a second his men were on their feet; there was a rush through the grass in front and rear; and almost without a blow the two foremost strings of mules were in their hands. To the chagrin of the captors, among all the hundred mules not more than two carried silver. All the others were laden with victuals. The alarm was given, and the rest of the train hastened back to Panama.

9. Drake disappeared. The muleteers after some days set out again. This time they fell into an ambush near the end of their journey. Before help could arrive, the marauders were struggling back to their vessels staggering under heavy packs of the precious metals. With his two little ships ballasted with gold and silver, and his crew reduced, through sickness and wounds, to thirty men, Drake laid his course for home.

10. The story here told will serve as an example of the daring and audacity of the Elizabethan mariners, who were possessed of an adventurous spirit that seemed to laugh at difficulties and dangers. No odds made them quail. It was enough that they were Englishmen, and therefore bound to prevail. The adventure we have related is of slight importance, but it well illustrates the spirit of reckless daring and the wonderful resource and dogged perseverance of the men who had the fortunes of England in their keeping in the days of Queen Elizabeth.

(9) A CELEBRATED VOYAGE ROUND THE WORLD.

1. Drake's next exploit was still more extraordinary though hardly more daring. Towards the end of 1577 he started on his famous voyage round the world. He was then in the prime of life, and is described by one who saw him as "low of stature, of strong limbs, broad-breasted, round-headed, with brown hair and a full beard, his eyes round, large and clear, well-favoured, fair, and of a cheerful countenance." When at sea he wore a scarlet cap with a gold band, and about his neck a plaited cord with a ring attached to it. He exacted every mark of respect from all on board. A sentinel stood always at his cabin door, and on special occasions "he was served with sound of trumpets and other instruments at his meals."

2. Drake sailed in the Pelican—afterwards called the Golden Hind—a ship scarcely as big as a Channel schooner, and the remainder of his little squadron consisted of four vessels still smaller. They were, however, swift sailers, and carried in abundance wildfire, chainshot, guns, pistols, bows, and other weapons. The whole force on board the squadron did not exceed 164 men, a surprisingly small number for the perilous task in hand.

3. Before reaching Port Julian, in Patagonia, the two smallest of the vessels had to be abandoned. Having refitted at this port, Drake made for the Straits of Magellan, through which no Englishman had yet passed. This was the only known way from the Atlantic into the Pacific, for Tierra del Fuego was supposed, at that time, to be a great continent stretching far southwards. Being without charts, they had to grope their way by means of the lead, which was kept in constant use. To relieve the toil-worn crews, halts were made at various islands on the route, where the sailors amused themselves in procuring fresh provisions by killing seals and penguins, everything they saw being strange, wild, and wonderful. After a perilous passage of three weeks the three ships reached the open Pacific, where they were greeted with a violent storm, which swept them far to the south. The smallest vessel went to the bottom. Another losing sight of the Pelican returned to England.

4. Drake, with his one ship, and eighty men, having weathered the storm turned his prow northwards, determined to plunder the Spanish settlements along the unguarded coasts of Chile and Peru, where no hostile ship had ever been seen. Drake's task was, in consequence, much easier than he could have anticipated. The inhabitants, when they saw a sail approaching, never dreamt that it could be other than a friend. It was as when men visit some island where no human foot had ever trod, the animals come fearlessly around, and the birds perch upon their hands.

5. At Valparaiso, in Chile, there lay in the harbour a great galleon which had come from Peru. Drake sailed in, and the Spanish seamen, who had never seen a foreigner in those waters, ran up their flags, beat their drums, and prepared a banquet for their supposed countrymen. They were only undeceived when the English sailors leapt on board and rifled the ship of its wedges of gold. Off the coast of Peru, near Potosi, world-famed for its silver mines, they swept off the silver bars laid out on the pier, whilst the weary labourers who had brought them from the mines were peacefully sleeping. The last bars had scarcely been stowed away in the boats, when a train of llamas was seen descending the hills with a second freight as rich as the first. This too found its way on board the Pelican.

6. All sail was now set for Lima, the chief port of Peru. Here they learned that a ship had sailed for Panama a few days before, taking with her all the bullion that the mines had yielded for the season. Not a moment was to be lost. Every inch of canvas was spread and the chase begun. Drake promised his gold chain to the man who should first descry the golden prize. For eight hundred miles the Pelican flew on, and then the man at the mast-head claimed the promised chain.

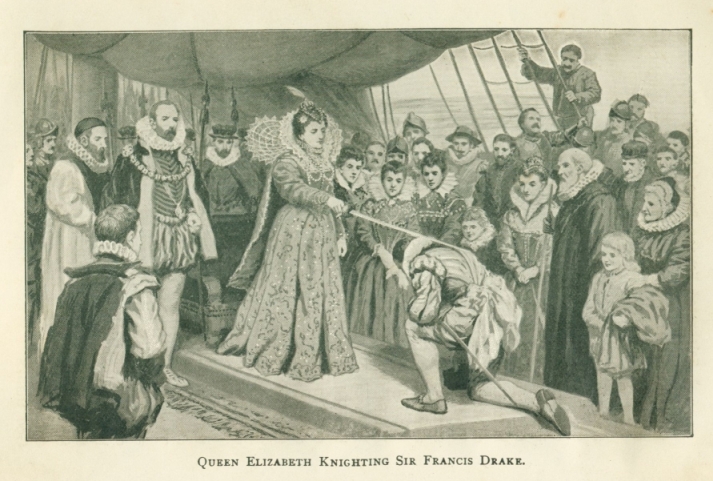

Queen Elizabeth Knighting Sir Francis Drake

7. Not wishing to come up with his prize till dusk, Drake filled his empty wine casks with water and trailed them astern, thus slackening his pace whilst avoiding the suspicion that might have been awakened by taking in sail. On coming within ear-shot our commander hailed the Spanish captain to "strike" his flag. The next moment a cannon-ball shot his mast overboard and a volley of arrows cleared the decks. The master, who was wounded, at once yielded his ship. Besides gold, pearls, emeralds, and diamonds, the booty included twenty-six tons of silver bullion. With spoils of above half-a-million in value the daring adventurer sought the safest way home.

8. That way, he considered, lay across the Pacific, and around the Cape of Good Hope. But before starting on his journey across the fifteen thousand miles of unknown water that lay between him and the Cape, it was necessary to repair his ship and scour her keel; for before the days of copper sheathing, the ships' bottoms grew foul with sea-weed, barnacles formed in clusters, and the sea-worms bored holes in the planking. Finding a suitable harbour Drake beached his ship, and setting up forge and workshop, refitted her, with a month's labour, from stem to stern.

9. After passing across the chartless waters of the Pacific, they arrived at the end of three months at the Moluccas, or Spice Islands. The ship was again beached, scraped, and patched. The crew found refreshment in the fruits and turtles that abounded, and great delight in the countless fire-flies that lit up the tropical forests at night. At the end of their stay, the fifty-six men who survived were all as sound and hearty as the day they left England.

10. On putting to sea again, and while threading their unknown way between the numerous islands they chanced to strike on a sand-bank. All seemed lost. The crew were mustered, and to every man the chaplain administered the Sacrament. The captain then cheerily called to his men to hearten up, and having done the best they could for their souls to have a thought for their bodies. All their efforts to get the ship off failed, but the wind happily changing, "we hoisted our sails and were lifted off into the sea again, for which we gave God thanks." Without further adventures, the Pelican sailed in triumph into Plymouth harbour in October, 1580, after an absence of three years, and after completing the circuit of the globe.

(10) "SINGEING THE KING OF SPAIN'S BEARD."

1. Drake had safely returned from his voyage round the world, but how would his royal mistress receive him? He knew that the queen secretly approved of all that he had done, but would she sacrifice him in order to keep at peace with Spain? At length a message came from Elizabeth, summoning him to London, and assuring him of her protection. With a lightened heart Drake set out for London, taking with him all his most precious jewels as a present for the queen. She received him graciously, accepted his magnificent present, and made no secret of her royal favour.

2. Elizabeth ordered the Golden Hind, as Drake's ship was now called, to be anchored off Greenwich for all the world to see. And in honour of her great mariner, she went in state to dine on board his ship, wearing in her crown the rich jewels he had given her. Here in the presence of a vast concourse of people she gave open defiance to King Philip of Spain. He had demanded Drake's head. Making the culprit kneel before her, she took a sword as if to strike it off, and giving him a gentle stroke bade him rise Sir Francis Drake. And instead of restoring the plunder to the king, she ordered it into safe keeping in the Tower. Such was the response Elizabeth made, having at last thrown off all disguise, to the King of Spain's demand.

3. The Spanish ambassador thus writes to his sovereign respecting an interview he had now with the queen: "I complained that I had been able to obtain no redress, either from her Council or herself, for any wrong that had been done. 'Your Majesty, I said, 'will not hear words, so we must come to the cannon, and see if you will hear them.' Quietly, in her most natural voice, she replied, that if I used threats of that kind she would fling me into a dungeon."

4. It was now quite plain that the queen thought war with Spain inevitable. But strange to say open war did not break out till four years later, although the two peoples wanted but a word from their sovereigns to fly like bull-dogs at each other's throats. That word Philip was in no haste to speak. He was content to nurse his wrath and meditate revenge. He had but recently annexed Portugal, and was fully occupied in securing his new dominions. The possession of Lisbon gave Philip one of the finest and most powerfully-defended seaports in the world. Lisbon was also most conveniently placed for the head-quarters of the Spanish fleet in the event of war with England.

5. Philip began the war by the seizure of every English ship in his ports (1585). Sir Francis Drake was ordered to repair to the various ports and demand the release of the arrested ships. On hearing that the famous "corsair" was on the coast, all Spain became alarmed. Drake did not linger long on the coast of Spain. He suddenly disappeared, no one knew whither. When next heard of, he was on the other side of the Atlantic, playing great havoc among the Spanish towns of the Indies. This was easily done, for his name had become a terror and bore victory before it. "The daring of the attempt," wrote the king, "was even greater than the damage done."

6. The chief result of Drake's achievements was to set the world talking of the great Sea Power that England bade fair to become. It is very difficult for us now-a-days—when little England has grown into a mighty empire, and great Spain has dwindled to her natural size—to realise the wonder which opened men's eyes, at the daring exploits of the English navy. The blows dealt by Drake aroused the indignation of Spain. The English, said Philip, were running up a long score which he would call upon them to pay to the uttermost farthing. But he was in no hurry to present his bill. He was determined to make such preparations for the invasion of England as to insure success.

7. Whilst Philip was busy in his preparations Drake unexpectedly appeared, with a small squadron at Cadiz (1587), the harbour of which was then crowded with transports and store-ships. There were many scores of these vessels loaded with wine, oil, corn, dried fruits, biscuits—all going to Lisbon for the use of the great Armada. The entrance was narrow with batteries on the sides, whilst in the harbour itself was a number of galleys on guard.

8. Drake, like most great admirals, probably thought that the fewer and simpler the orders the better. He had, at any rate, but one to give his men. They were to follow him in and destroy the shipping when they got there. His little fleet glided into the harbour unhurt, and fell instantly upon the only man-of-war there. The galleys were rowed to the rescue; but in a short time the great warship sank and the galleys drew off. Meanwhile, the crews of the store-ships rowed to land, leaving their cargoes at the disposal of the English.

9. When Drake withdrew from Cadiz his own ships were crammed with good things, and the harbour was filled with ransacked vessels all on fire. Well might the bold captain boast as he retired, that he "had singed the King of Spain's beard." Drake next moved off to the Azores in the hope of capturing some rich merchant vessel from the East Indies.

10. Almost immediately hove in sight an East Indiaman, "the greatest ship in all Portugal, richly laden, to our happy joy and great gladness." No such prize had ever been seen. In her hold were hundreds of tons of spices and precious gums; chests upon chests of costly china, bales of silks and velvets, and coffers of bullion and jewels. This great merchantman, the San Philipe, was soon on its unwilling way to England. The whole fleet arrived safely with their prize at Plymouth, "to their own profit and due commendation," says one of the happy company, "and to the great admiration of the whole kingdom."

1. The fateful day was fast approaching when England and Spain would meet in deadly encounter. Both sides were straining every nerve to prepare for the great event. It seemed like a war between a dwarf and a giant. Spain at that time was mistress of the East and West Indies; she had conquered Mexico and Peru, and her dominions in Europe included Portugal, a large part of Italy, and the Netherlands. Spain could thus command the services of a vast population, her navy was the largest in the world, and she had at her disposal many thousands of brave soldiers inured to war, whilst her coffers were full to overflowing. She had, in short, ships, men, and money in abundance.

2. England, on the other hand, was then but a little kingdom. Scotland was not yet incorporated with it, and Ireland was a source of weakness rather than of strength. Her whole population did not exceed five millions. But the spirit which animated little England was indomitable. We have seen its high mettle in Drake's daring adventures. And England's queen was as high-spirited as the boldest in the kingdom. She called upon her people to stand by her, and do or die in defence of "Queen and country."

3. But how would the Catholics of England respond to her appeal? Would they throw in their lot with the Spaniards, who were of their own religion, or stand true to their flag as Englishmen, side by side with their Protestant countrymen? The fortunes of England seemed placed in their hands; and to their honour, be it remembered, they proved themselves true Englishmen. Not a word of treason or treachery was whispered. Loyal England forgot its difference of creed. It knew only that the invader was at the gate.

4. On every side volunteers came forward in thousands. There was no standing army, but some thousands had seen service in the Netherlands, in France, and in Ireland. Forts were built at the mouth of the Thames, and an army was stationed at Tilbury. The queen visited their camps and heartened the soldiers by her presence and her words. "My loving people," she said, "we have been persuaded by some that are careful of our safety to take heed how we commit ourselves to armed multitudes for fear of treachery; but I assure you I do not desire to live to distrust my faithful and loving people. Let tyrants fear! I have always so behaved myself that, under God, I have placed my chiefest strength and safeguard in the loyal hearts and goodwill of my subjects. I know that I have the body but of a weak and feeble woman, but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and of a king of England, too, and think foul scorn that Parma or Spain, or any prince of Europe, should dare to invade the borders of my realm."

5. The chief command of the fleet was given to Lord Howard of Effingham, with Drake as vice-admiral. "True it is," says an old writer, "Howard was no deep seaman; but he had skill enough to know those who had more skill than himself." All the great seamen of Queen Elizabeth, such as Hawkins and Frobisher, served under him, with 9000 hardy sailors. Merchants offered their ships for the war, and offered them with powder, shot, and crews all ready on board. And so splendid was the spirit that stirred the country, that when the queen asked the Lord Mayor of London to supply fifteen ships, he requested her to accept double that number.

6. Most of these merchantmen were of small size, and would be quite unable to cope with the great Spanish galleons, although useful as auxiliaries, serving to cut off stragglers, and to capture disabled ships. In the great fight with the Armada the brunt of the fighting must fall on the Royal Navy. But there were only thirty-eight ships, of all sorts and sizes, carrying the queen's flag. They were, however, in prime condition. The celebrated Sir John Hawkins, a kinsman of Drake's, had long been in charge of the royal ships, and he had taken such good care in their construction and equipment, that they had no match in the world for speed, handiness, and soundness.

7. So well pleased was Howard with the fleet placed under his command, that he declared, "Our ships do show themselves like gallants, and I assure you it will do a man's heart good to behold them. I think there were never seen worthier ships, and as few as we are, if the King of Spain's force amount not to hundreds, we will make good sport with them." Howard tells us that he had crept into every place, in every queen's ship, wherever man could get, and there was never one of them knew what a leak meant. And when the Bonaventure ran hard on a sand bank, it was got off without a spoonful of water in her.

8. Comparing the ships of Drake with those of Nelson, we find them considerably smaller but more heavily armed for their size. Between the times of these two great admirals but little advance seems to have been made in the arming of our ships. Drake could even boast a few sixty-five pounder guns with a range of over a mile. In what were called "fireworks" the English fleet was particularly strong. They included grenades to be shot out of great mortars and to explode by means of a fuse; illuminating shells for detecting an enemy's movements by night; and shells containing "wild-fire" that would burn in water and could only be extinguished with sand or ashes.

9. Whilst England is sharpening her weapons and marshalling her forces, King Philip is assembling his squadrons. His preparations were made on such a grand scale, that he may well have thought his Armada "invincible." By the end of July, 1588, all was ready for the great task of conquering England.

10. The "Invincible Armada" was composed of 130 ships, the majority being of great size "with lofty turrets like castles." There were on board 8000 seamen, whose sole duty was to work the ships, with 20,000 soldiers to do the fighting, and it was provided with no less than 2500 cannon. The whole fleet was under the command of the Duke of Medina Sidonia. The duke's orders were very strict. He was to sail up the Channel till he got to Dunkirk. Nothing was to stop him. If the English attacked, he was not to delay, but merely keep up a running fight. On reaching Dunkirk, he was to escort the Duke of Parma and his army to the shores of England.

11. The Armada was expected long before it appeared. Meanwhile, the whole people from Berwick to the Land's End were waiting in anxious expectation for the first news of the enemy. Beacons were prepared along the coast, and on every high point throughout the country. As soon as the enemy were sighted, the beacons were kindled.

(12) DEFEATING THE INVINCIBLE.

1. The main English fleet awaited the arrival of the Armada at Plymouth, whilst a smaller fleet kept watch at Dover, to prevent the crossing of the Spanish army assembled at Dunkirk, a few leagues from Calais. At last, the long-expected Armada was seen off Plymouth Sound, on Saturday, July 30th, 1588. The little English fleet kept out of sight till the Armada had passed the Sound. On Sunday morning the Spaniards saw their enemy hovering about their rear just out of cannon-shot.

2. The English admirals well knew their business, and wisely planned their mode of action. They knew that the Spaniards had not only the advantage in the number and size of their ships, but that they carried on each ship some hundreds of soldiers. They judged, therefore, that it would be best for the English to avoid coming to close quarters, to hang on the rear, to cut off stragglers, and "to pluck the feathers of the Spaniard one by one."

3. Thus day after day passed without any pitched battle, but the damage wrought by the English guns was considerable. The contrast between the build and action of the ships in the two fleets was manifest to all. The English vessels sailed at much greater speed, and "with such nimble steerage," says a Spanish writer, "that they could turn and wield themselves with the wind as they listed, coming oftentimes quite close to the Spaniards, giving them one broadside and then tacking round to give them the other." Their guns also were handled with much greater rapidity, firing, gun for gun, four shots to the Spaniards' one.

4. "The enemy constantly pursue me," wrote Sidonia, off the Isle of Wight, to the Duke of Parma. "They fire upon me most days from morning till nightfall; but they will not close and grapple. I have given them every opportunity; I have purposely left ships exposed to tempt them to board; but they decline to do it, and there is no remedy, for they are swift and we are slow. If these calms last, and they continue the same tactics, as they assuredly will, I must request your Excellency to send me two shiploads of shot and powder immediately, for I am in urgent need."

5. Calms so prevailed that it took a week for the Armada to reach Calais Roads, when the Spanish admiral dropped anchor, intending to remain there until the Duke of Parma was ready to embark his troops. The English promptly let go their anchors at the same instant two miles astern. The two fleets lay watching each other all the next day. At a council of war called towards evening in Admiral Howard's cabin, it was resolved to convert eight vessels into fire-ships. The ships having been smeared with pitch, resin, and wild-fire, and filled with combustibles, they were set on fire, and sent in the dead of night, with wind and tide, straight for the Spanish fleet.

6. The galleons at once cut their anchor cables, and made all haste to escape from the threatened danger, "Happiest they who could first be gone, though few or none could tell which way to take." Some of the ships had no spare anchors, and when they got outside the harbour could not anchor again, and were carried far away from their flag-ship. When morning broke Sidonia saw his fleet widely scattered. Signals were sent up for them to collect and make back for Calais.

7. The hour for the English to close was now come. A hot attack was begun before the enemy had time to rally and reform. The battle raged with fury from dawn to sunset. By the end of the day the Armada was in a hopeless state. Three great galleons had sunk, three had drifted helplessly on to the Flemish coast, whilst those afloat were in a battered condition, with sails torn and masts shot away.

8. The Spanish admiral was in despair. He saw there was nothing left but to get away by the easiest road. Not daring to return by the Channel, he resolved on making his way home by sailing round the Orkneys. A terrible tempest pursued him, and so many vessels were dashed against the rock-bound coasts of Scotland and Ireland that only fifty-three storm-shattered ships ever reached Spain. Out of thirty thousand men who had set sail in the Armada at least twenty thousand never returned.

9. In England one voice of joy and thanksgiving rang through the land. The great victory had been won with the loss of only one vessel and very few men. Not a single hostile foot had been planted on English soil. A solemn thanksgiving service was held in St. Paul's Cathedral; and in memory of the great deliverance a medal was struck, around the edge of which was inscribed in Latin, "God blew with His breath and they were scattered."

10. The war with Spain did not come to a close with the destruction of the Great Armada, but the long-dreaded danger of invasion had passed away. The navy of the greatest power in the world had been smitten and shattered. And the only result of Spain's attempt to enslave England was to raise her to a higher place among the nations. Hence the poet sings in his song of Rule Britannia:—

Still more majestic shall thou rise,

More dreadful from each foreign stroke;

As the loud blast that tears the skies

Serves but to root thy native oak.

11. The war with Spain lasted until the death of Philip (1598). It was carried on almost wholly at sea, but the only story of much interest relates to Sir Richard Grenville, who for fifteen hours resisted all the efforts of a Spanish fleet to take or sink his ship, the Revenge. The unequal contest went on right through the night. When day dawned the Revenge was riddled with shot, Grenville mortally wounded, and hardly a man still alive and unwounded.

12. The dying admiral ordered the ship to be scuttled and sent to the bottom with all on board, "Trust to God," he said, "and to none else. Lessen not your honour now by seeking to prolong your lives." But his men thought they had done enough for honour, and hauled down the flag of St. George. The Spaniards showed their admiration of the heroism they had witnessed by doing all they could for the remnant alive. They carried the hero on board the San Pablo, where lie died three days later. His last words were, "Here die I, Richard Grenville, with a joyful and quiet mind having ended my life like a true soldier that has fought for his country, queen, religion, and honour."

(13) EXPANSION OF ENGLAND INTO THE "UNITED KINGDOM."

1. Elizabeth's realm was very small compared with that which King Edward reigns over. It only embraced England, Wales and Ireland, and the last-named was in a chronic state of discontent and rebellion. On the death of Elizabeth, the crowns of England and Scotland were united in the person of James I. (1603), the first king of Great Britain and Ireland. Thus the Scots had the satisfaction of feeling that they had given a king to England instead of England forcing a king on them.

2. This union of the crowns of England and Scotland was the first step towards bringing about that real union between the two countries which exists at the present day; for they now form parts of a truly "United Kingdom," having one sovereign, one parliament, one army and navy, having the same friends and the same foes among the nations. But this happy result was long in coming. The jealousy and enmity which had so long existed between the two countries did not come to an end with the union of the two crowns. Each country still cared only for its own interests, and each people regarded the other as foreigners. They were not even permitted to trade freely with each other; but duties were levied on each other's goods in crossing the Border or entering each other's ports.